Title: Puzzles and oddities

Found floating on the surface of our current literature, or tossed to dry land by the waves of memory

Compiler: Mary A. A. Dawson

Release date: November 14, 2023 [eBook #72129]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Russell Brothers, 1876

Credits: Debrah Thompson and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[Pg 3]

Found Floating on the Surface of our Current Literature,

OR

TOSSED TO DRY LAND BY THE WAVES OF MEMORY.

GATHERED AND ARRANGED

BY

New York:

RUSSELL BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS,

17, 19, 21, 23 ROSE STREET.

1876.

[Pg 4]

RUSSELL BROTHERS,

1876.

[Pg 5]

of St. Aloysius Gonzaga that while, at the usual time of recreation, he was engaged in playing chess, question arising among his brother novices as to what each would do were the assurance to come to them that they would die within an hour, St. Aloysius said he should go on with his game of chess.

If our recreations as well as our graver employments are undertaken with a pure intention, we need not reproach ourselves though Sorrow, we need not fear though Death surprise us while engaged in them.

Addison, N. Y., January, 1876.

[Pg 7]

PART I.

CHARADES.

Nos. 1, 10, 25, 43, 44, 53, 88, 91, 110, 152, 153, 154, 155, 167, 176, 177, 182, 183, 192, 193, 201, 217, 279, 281, 285, 290, 291, 297, 316, 331, 332, 333, 345, 350, 354, 357, 368, 371, 372, 374.

CONUNDRUMS.

Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 17, 18, 21, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 46, 47, 51, 52, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 92, 93, 94, 95, 97, 98, 106, 108, 109, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 184, 185, 186, 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 196, 197, 198, 199, 200, 204, 205, 206, 207, 208, 209, 214, 252, 253, 254, 257, 258, 259, 260, 261, 262, 263, 264, 265, 266, 267, 268, 269, 270, 274, 275, 278, 280, 286, 294, 299, 300, 301, 303, 318, 319, 320, 321, 322, 323, 325, 326, 327, 329, 330, 359, 360, 361.

FRENCH AND LATIN RIDDLES.

Nos. 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 78.

MATHEMATICAL.

Nos. 48, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 346, 362, 373.

NOTABLE NAMES.

Nos. 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142.

POSITIVES AND COMPARATIVES.

Nos. 218, 219, 220, 221, 222, 223, 224, 225, 226, 227, 228, 229, 230, 231, 232, 233, 234, 235, 236, 237, 238, 336, 337, 338, 339, 340, 341, 342, 343, 344.

POSITIVES, COMPARATIVES AND SUPERLATIVES.

Nos. 239, 240, 241, 242, 243, 244, 245, 246, 247, 248, 249, 250.

[Pg 8]ELLIPSES.

Nos. 307, 308, 309, 312, 313, 352, 355, 365, 366.

NUMERICAL ENIGMA.

No. 306.

SQUARE WORD.

No. 304.

XMAS DINNER.

No. 315.

DINNER PARTY.

No. 360.

UNANSWERED RIDDLES.

UNANSWERABLE QUESTIONS.

PARADOXES.

OTHER VARIETIES OF PUZZLES.

Nos. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 45, 49, 50, 54, 55, 64, 65, 75, 76, 79, 80, 81, 89, 90, 96, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 107, 151, 156, 157, 178, 179, 180, 182, 194, 195, 202, 203, 210, 211, 212, 213, 215, 216, 251, 255, 256, 271, 272, 273, 276, 277, 282, 283, 284, 287, 288, 289, 292, 293, 295, 296, 298, 302, 305, 310, 311, 314, 317, 324, 328, 334, 335, 347, 348, 349, 351, 353, 354, 358, 363, 364, 367, 369, 370.

PART II.

| ACROSTICS: | PAGE. |

| Adelina Patti | 145 |

| Emblematic | 131 |

| Spring | 146 |

| ALLITERATION: | |

| Siege of Belgrade | 144 |

| Example in French | 145 |

| ALPHABET, THE, in One Sentence | 133 |

| AMERICANS, Characteristic Sayings of | 113 |

| ANAGRAMS | 131, 133 |

| ANN HATHAWAY | 140 |

| AN ORIGINAL LOVE STORY | 126 |

| BEHEADED WORDS | 133 |

| BOOKS, Fancy Titles of | 83 |

| CLUBS | 85 |

| CONCEALED MEANINGS | 129 |

| CONCEITS OF COMPOSITION: | |

| When the September eves | 152 |

| Oh! come to-night | 153 |

| Thweetly murmurth the breethe | 154 |

| CONTRIBUTION TO AN ALBUM | 125 |

| DIALECTS: | |

| Yankee | 116 |

| London Exquisite’s | 116 |

| Legal | 118 |

| Wiltshire | 118 |

| ENEID, The Newly Translated | 122 |

| EPIGRAM | 129 |

| ETIQUETTE OF EQUITATION | 88 |

| EXTEMPORE SPEAKING | 147 |

| FACETLÆ | 84, 105 |

| FRENCH SONG | 139 |

| GEOGRAPHICAL PROPRIETY | 102 |

| GEORGE AND HIS POPPAR | 121 |

| HISTORY | 133 |

| INSTRUCTIVE FABLES | 141 |

| LATIN POEM | 139 |

| MACARONIC POETRY: | |

| Felis et Mures | 137 |

| Ego nunquam audivi | 138 |

| Tres fratres stolidi | 138 |

| The Rhine | 138 |

| Ich Bin Dein | 139 |

| In questa casa | 140[Pg 10] |

| MACARONIC PROSE | 136 |

| MEDLEYS: | |

| I only know | 159 |

| The curfew tolls | 160 |

| The moon was shining | 161 |

| Life | 162 |

| NAMES: | |

| Fantastic | 98 |

| Ladies’, their Sound | 100 |

| “ their Signification | 101 |

| ODE TO SPRING | 127 |

| OTHER WORLDS | 86 |

| OUR MODERN HUMORISTS | 148 |

| PALINDROME | 132 |

| PARODIES: | |

| Song of the Recent Rebellion | 89 |

| Come out in the garden, Jane | 91 |

| Brown has pockets running over | 93 |

| When I think of him I love so | 94 |

| Never jumps a sheep that’s frightened | 95 |

| How the water comes down at Lodore | 96 |

| Tell me, my secret soul | 97 |

| PRINTER’S SHORT-HAND | 119 |

| PRONUNCIATION | 142 |

| RHYME | 122 |

| RHYTHM | 127 |

| SECRET CORRESPONDENCE | 130 |

| SEEING IS BELIEVING | 97 |

| SOUND AND UNSOUND: | |

| See the fragrant twilight | 151 |

| Brightly blue the stars | 152 |

| SORROWS OF WERTHER | 84 |

| STANZAS from J. F. CRAWFORD’S Poems | 128 |

| STILTS | 87 |

| ST. ANTHONY’S FISH-SERMON | 135 |

| THE CAPTURE | 103 |

| THE NIMBLE BANK-NOTE | 154 |

| THE QUESTION | 144 |

| THE RATIONALISTIC CHICKEN | 158 |

| WORD PYRAMID | 132 |

[Pg 11]

[Pg 13]

What is that which we often return, but never borrow?

Can you tell me of what parentage Napoleon the First was?

What was Joan of Arc made of?

Why ought stars to be the best Astronomers?

[Pg 14]

What colors were the winds and the waves in the last violent storm?

In what color should a secret be kept?

How do trees get at their summer dress without opening their trunks?

Why am I queerer than you?

A BUSINESS ORDER.

“J. Gray:

Pack with my box five dozen quills.”

What is its peculiarity?

[Pg 15]

Those who have me not, do not wish for me; those who have me, do not wish to lose me; and those who gain me, have me no longer.

Although Methusaleh was the oldest man that ever lived, yet he died before his father.

If Moses was by adoption the son of Pharaoh’s daughter, was he not, “by the same token,” the daughter of Pharaoh’s son?

What is the best time to study the book of Nature?

What is the religion of Nature in the spring?

There is an article of common domestic consumption, whose name contains six letters, from which may be formed twenty-two nouns, without using the plurals. What is it?

What word is that, of two syllables, to which if you prefix one letter, two letters, or two other letters, you form, in each instance, a word of one syllable?

What was the favorite salad at the South, in the spring of 1861?

[Pg 16]

The three most forcible letters in our alphabet?

The two which contain nothing?

The four which express great corpulence?

The four which indicate exalted station?

The three which excite our tears?

What foreign letter is an English title?

[Pg 17]

What foreign letter is a yard and a half long?

What letter will unfasten an Irish lock?

When was B the first letter of the alphabet, while E and O were the only vowels?

What letter is always more or less heavily taxed?

What letter is entirely out of fashion?

Why is praising people like a certain powerful opiate?

Prove that a man has five feet.

WHAT AM I?

I was once the harbinger of good to prisoners.

I add to the magnitude of a mighty river.

I am a small portion of a large ecclesiastical body.

I represent a certain form of vegetable growth.

A term used by our Lord in speaking to His disciples.

A subordinate part of a famous eulogy.

I am made useful in connection with the Great Western Railway.

5005E1000E,

5005E1000E.

The name of a modern novel.

[Pg 18]

My FIRST is company; my SECOND shuns company; my THIRD calls together a company; and my WHOLE entertains company.

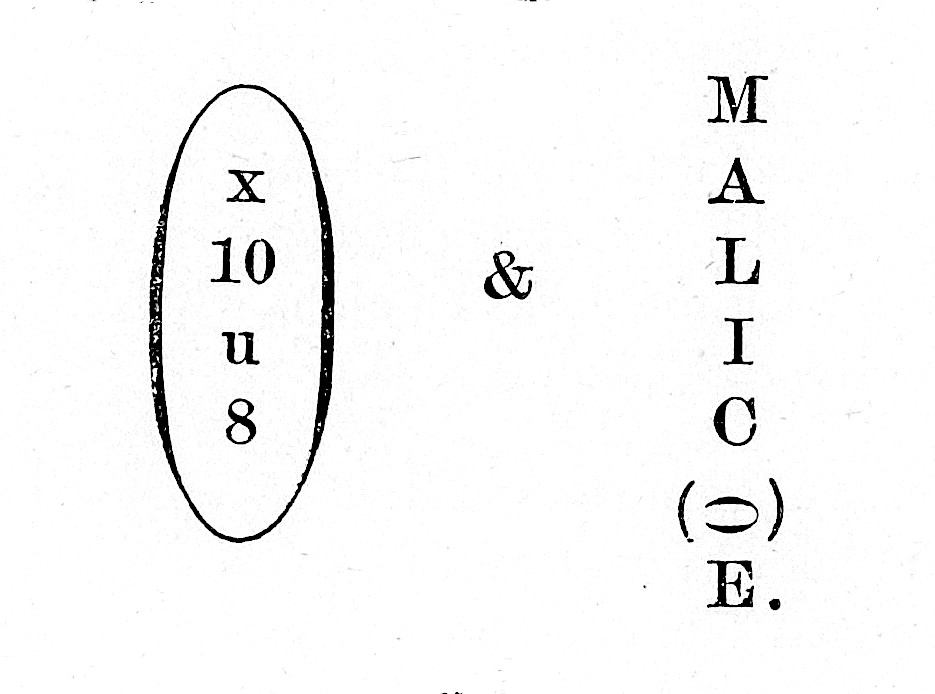

Dr. Whewell being asked by a young lady for his name “in cipher,” handed her the following lines:

[Pg 19]

Why was the execution of Charles the First voluntary on his part?

How is Poe’s “Raven” shown to have been a very dissipated bird?

Set down four 9’s so as to make one hundred.

The cc 4 put 00000000.

si

| John Doe to Richard Roe, | Dr. |

| To 2 bronze boxes | $3 00 |

| 1 wooden do | 1 50 |

| 1 wood do | 1 50 |

| —— |

This bill was canceled by the payment of $1.50. How?

When was Cowper in debt?

What animal comes from the clouds?

An incredulous friend actually ventured to doubt the above plain statement of facts, but was soon convinced of its literal truth.

Charles the First walked and talked half an hour after his head was cut off.

At the time of a frightful accident, what is better than presence of mind?

Why was the year preceding 1871 the same as the year following it?

[Pg 21]

Why do “birds in their little nests agree?”

What did Io die of?

Why did a certain farmer out West name his favorite rooster ROBINSON?

How do sailors know there’s a man in the moon?

How do sailors know Long Island?

What does a dog wear in warm weather, besides his collar?

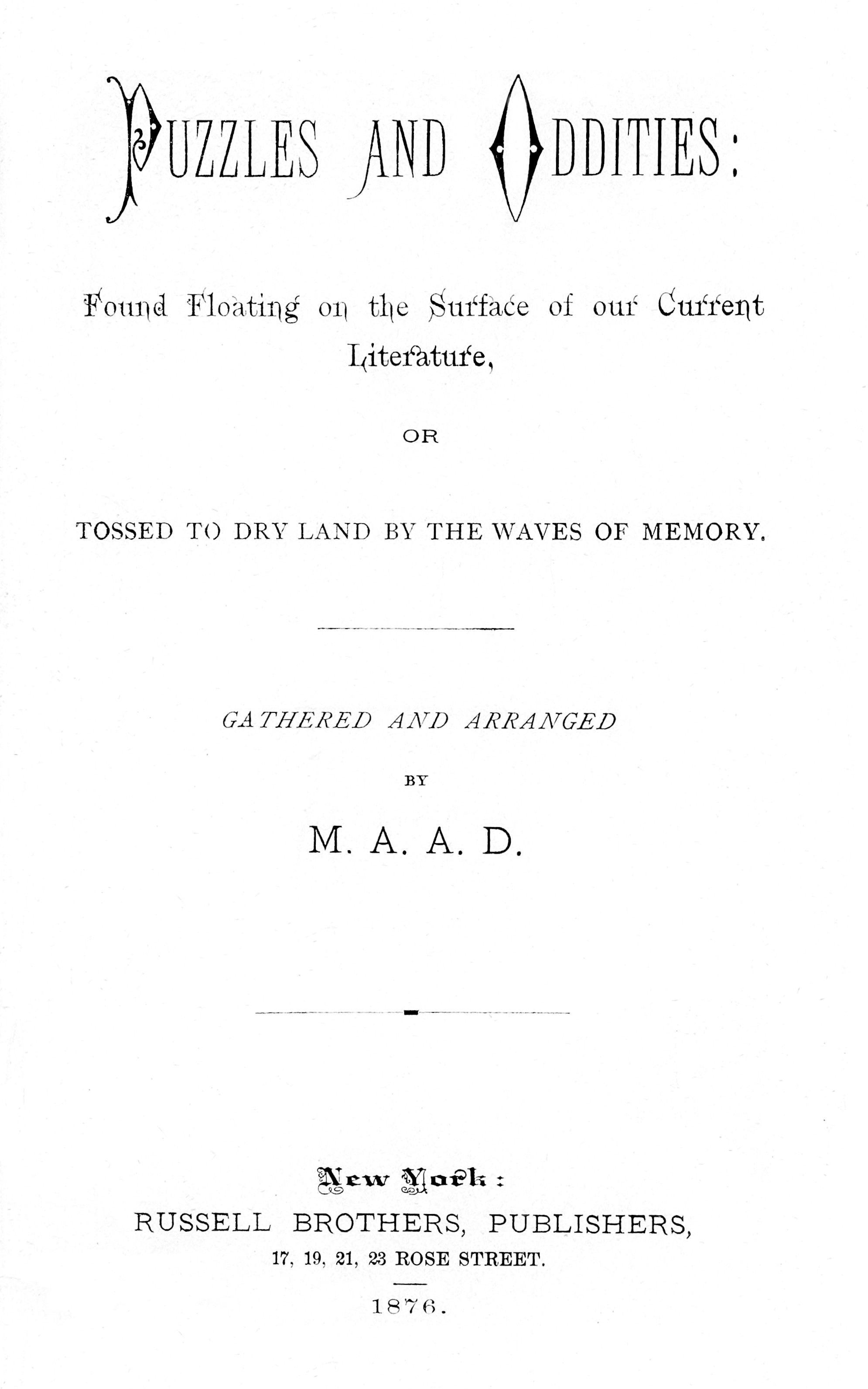

Translate:

Je suis capitaine de vingt-cinq soldats; et, sans moi, Paris serait pris.

Je suis ce que je suis, et je ne suis pas ce que je suis. Si j’étais ce que je suis, je ne serais pas ce que je suis.

Mens tuum ego!

The title of a book: Castra tintinnabula Poëmata.

Motto on a Chinese box: Tu doces!

Translate:

Quis crudus enim lectus, albus, et spiravit!

Ecrivez: “J’ai grand appétit,” en deux lettres.

[Pg 23]

In my FIRST my SECOND sat; my THIRD and FOURTH I ate; and yet I was my WHOLE.

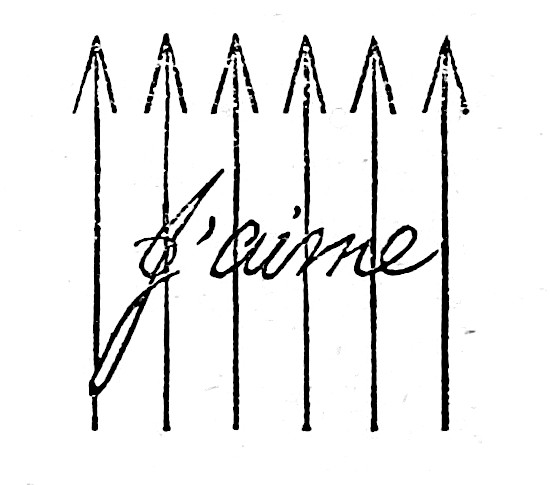

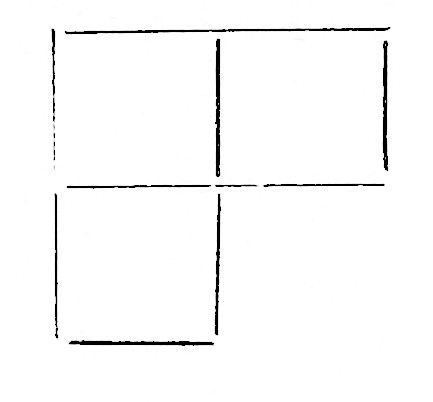

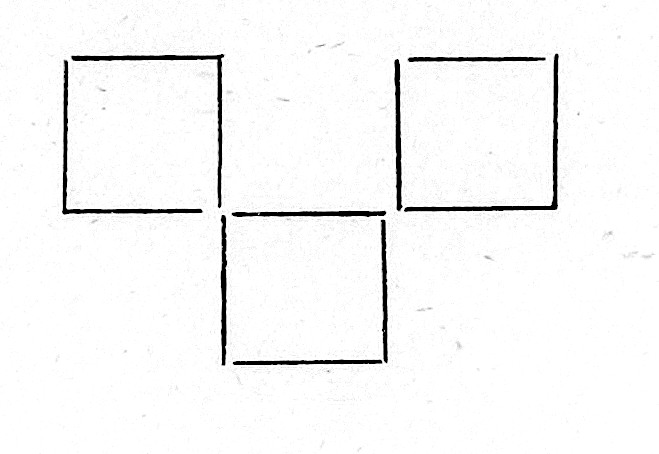

From these five squares

take three of the fifteen sides, and leave three squares.

From these five squares

take three of the fifteen sides, and leave three squares.

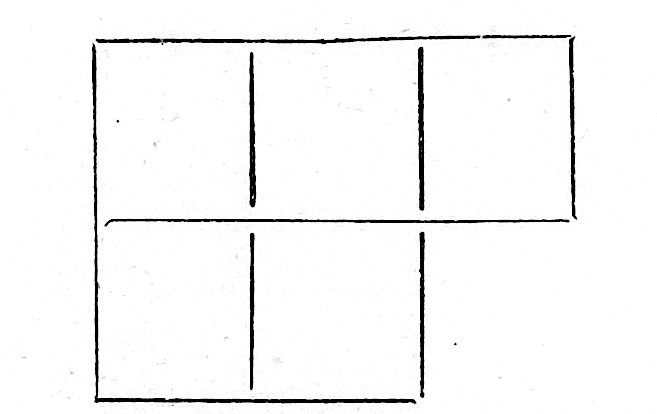

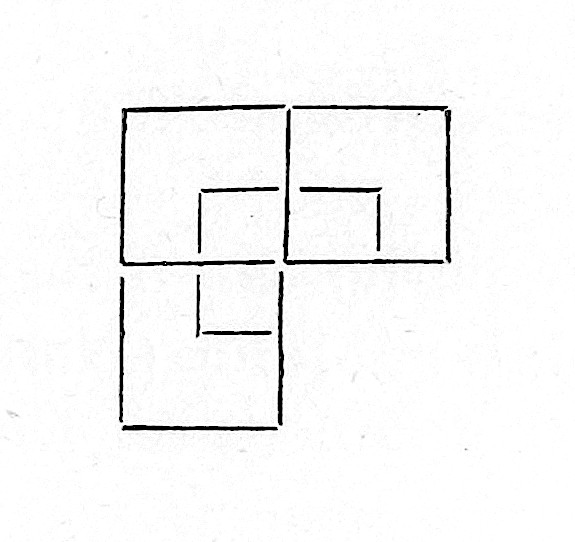

Divide this figure into

four equal and uniform parts.

Divide this figure into

four equal and uniform parts.

To divide eight gallons of vinegar equally between two persons; using only an eight-gallon, a five-gallon, and a three-gallon measure?

A certain miller takes “for toll” one tenth of the meal or flour he grinds. What quantity must he grind in order that a customer may have just a bushel of meal after the toll has been taken?

[Pg 25]

To prove that two are equal to one:

Where is the fallacy?

As two Arabs, who had for sole provision, the one five, and the other three loaves of bread, were about to take their noonday meal in company, they were joined by a stranger who proposed to purchase a third part of their food. In payment he gave them, when their repast was finished, eight pieces of silver, and they, unable to agree as to the division of the sum referred the matter to the nearest Cadi, who gave seven pieces to the owner of the five loaves, and but one piece to the owner of the three loaves. And the Cadi was right.

A man went to a store and bought a pair of boots for six dollars. He put down a ten dollar bill, and the merchant having no change, sent for it to a neighboring bank, and gave it to him. Later in the day one of the bank clerks came in to say that the ten dollar bill was a bad one, and insisted that the merchant should make it right, which he did. Now, how much did he lose by the whole transaction?

A man bought twelve herrings for a shilling; some were two pence apiece, some a halfpenny, and some a farthing. How many did he buy of each kind?

[Pg 26]

When may a man reasonably complain of his coffee?

Why does a duck put her head under water?

Why does she take it out again?

In what terms does Shakespeare allude to the muddiness of the river on which Liverpool lies?

[Pg 27]

If the B mt put: If the B. putting:

So said one, but another replied: How can I put: when there is such a-der?

Why is a man who never bets, as bad as one who bets habitually?

When is a bonnet not a bonnet?

Helen, after sitting an hour, dressed for a walk, at length set out alone, leaving the following laconic note for the friend who, she had expected, would accompany her:

2 2 8.

[Pg 29]

A blind beggar had a brother. This blind beggar’s brother went to sea and was drowned. But the man that was drowned had no brother. What relation to him, then, was the blind beggar?

Two brothers were walking together down the street, and one of them, stopping at a certain house, knocked at the door, observing: “I have a niece here, who is ill.” “Thank Heaven,” said the other, “I have no niece!” and he walked away. Now, how could that be?

“How is that man related to you?” asked one gentleman of another.

Describe a cat’s clothing botanically.

What is that which boys and girls have once in a lifetime, men and women never have, and Mt. Parnassus has twice in one place?

Why is the highest mountain in Wales always white?

To what two cities of Massachusetts should little boys go with their boats?

[Pg 31]

NOTABLE NAMES.

A head-dress.

Inclining to one of the four parts of the compass.

A mineral and a chain of hills.

A metal, and a worker in metals.

A sound made by an insect; and a fastening.

A sound made by an animal; and a fastening.

[Pg 32]

A sound made by an animal, and a measure of length.

A Latin noun and a measure of quantity.

A bodily pain.

The value of a word.

A manufactured metal.

To agitate a weapon.

A domestic animal, and what she cannot do.

Which is the greater poet, William Shakespeare or John Dryden?

A barrier before an edible; a barrier built of an edible.

One-fourth of the earth’s surface, and a preposition.

One-fourth of the earth’s surface, and a conjunction.

A song; to follow the chase.

A solid fence, a native of Poland.

An incessant pilgrim; fourteen pounds weight.

[Pg 33]

A quick succession of small sounds.

Obsolete past participle of a verb meaning to illuminate.

A carriage, a liquid, a narrow passage.

To prosecute, and one who is guarded.

A letter withdraws from a name to make it more brilliant.

A letter withdraws from a name and tells you to talk more.

Why is a man who lets houses, likely to have a good many cousins?

What relation is the door-mat to the door-step?

What is it that gives a cold, cures a cold, and pays the doctor’s bill?

What is brought upon the table, and cut but never eaten?

What cord is that which is full of knots which no one can untie, and in which no one can tie another?

What requires more philosophy than taking things as they come?

What goes most against a farmer’s grain?

[Pg 34]

Which of Shakespeare’s characters killed most poultry?

THE BISHOP OF OXFORD’S RIDDLE.

I have a large box,1 two lids,2 two caps,3 two musical instruments,4 and a large number of articles which a carpenter cannot dispense with.5 I have always about me a couple of good fish,6 and a great number of small size;7 two lofty trees,8 and four branches of trees;9 some fine flowers,10 and the fruit of an indigenous plant.11 I have two playful animals,12 and a vast number of smaller ones;13 also, a fine stag,14 and a number of whips without handles.15

I have two halls or places of worship,16 some weapons of warfare,17 and innumerable weather-cocks;18 the steps of a hotel;19 the House of Commons on the eve of a division;20 two students or scholars,21 and ten Spanish gentlemen to wait upon their neighbors.22

To these may be added, a rude bed;a the highest part of a building;b a roadway over water;c leaves of grass;d a pair of rainbows;e a boat;f a stately pillar;g a part of a buckle;h several social assemblies;i part of the equipments of a saddle-horse;j a pair of implements matched by another pair of implements much used by blacksmiths;j several means of fastening.k

[Pg 35]

I have a little friend who possesses something very precious. It is a piece of workmanship of exquisite skill, and was said by our Blessed Saviour to be an object of His Father’s peculiar care; yet it does not display the attribute of either benevolence or compassion. If its possessor were to lose it, no human ingenuity could replace it; and yet, speaking generally, it is very abundant. It was first given to Adam in Paradise, along with his beautiful Eve, though he previously had it in his possession.

It will last as long as the world lasts, and yet it is destroyed every day. It lives in beauty after the grave has closed over mortality. It is to be found in all parts of the earth, while three distinct portions of it exist in the air. It is seen on the field of carnage, yet it is a bond of affection, a token of amity, a pledge of pure love. It was the cause of death to one famed for beauty and ambition. I have only to add that it has been used as a napkin and a crown, and that it appears like silver after long exposure to the air.

[Pg 36]

When the king found that his money was nearly all gone, and that he really must live more economically, he decided on sending away most of his wise men. There were some hundreds of them—very fine old men, and magnificently dressed in green velvet gowns with gold buttons. If they had a fault, it was that they always contradicted each other when he asked their advice—and they certainly ate and drank enormously. So, on the whole, he was rather glad to get rid of them. But there was an old lay which he did not dare to disobey, which said there must always be:

Query: How many did he keep?

Why are not Lowell, Holmes, and Saxe the wittiest poets in America?

Why did they call William Cullen Bryant, Cullen?

Why do we retain only three hundred and twenty-five days in our year?

What seven letters express actual presence in this place; and, without transposition, actual absence from every place?

Is Florence, (Italy,) on the Tiber? If not, on what river does it lie? Answer both questions in one word.

[Pg 37]

Is there a word in our language which answers this question, and contains all the vowels?

What is it that goes up the hill; and down the hill, and never moves?

What ’bus has found room for the greatest number of people?

In describing a chance encounter with your doctor, what kind of a philosopher do you name?

What physician stands at the top of his profession?

Would you rather an elephant killed you, or a gorilla?

Why is an amiable and charming girl like one letter deep in thought, another on its way toward you, another bearing a torch, and another slowly singing psalms?

Why is Emma, in a sorrowful mood, one of a certain sect of Jews?

Why is she, always, one of another sect?

What English writer would have been a successful angler?

[Pg 39]

What is that which you and every living man have seen, but can never see again?

Which is the strongest day in the week?

[Pg 41]

What is the smallest room in the world?

What is often found where it does not exist?

What is that which is lengthened by being cut at both ends?

When do your teeth usurp the functions of your tongue?

What word is that to which if you add one syllable, it will be shorter?

What is that which is lower with a head than without one?

What vice is that which people shun if they are ever so bad?

Which travels at greater speed, heat or cold?

[Pg 42]

[Pg 43]

When a blind man drank tea, how did he manage to see?

Why is a mouse like grass?

What is the key-note of good breeding?

What is the typical “Yankee’s” key-note?

If you were on the second floor of a burning house and the stairs were away, how would you escape?

A carpenter made a door and made it too large; he cut it again and cut it too little; he cut it again and made it fit.

[Pg 44]

A wagoner, being asked of what his load consisted, made the following (rather indirect) reply:

What is it?

Why need people never suffer from hunger on such a desert as Sahara?

How do the arks used for freight on the Mississippi River, differ from Noah’s Ark?

In what order did Noah leave the Ark?

What is Majesty deprived of its externals?

[Pg 45]

John went out; his dog went with him; he went not before, behind, or on one side of him; then where did he go?

If spectacles could speak to their wearers, what ancient writer would they name?

My FIRST implies equality; my SECOND is the title of a foreign nobleman; and my WHOLE is asked and given a hundred times a day with equal indifference; yet is of so much importance that it has saved the lives of thousands.

POSITIVES AND COMPARATIVES.

[Pg 46]

[Pg 47]

POSITIVES, COMPARATIVES, SUPERLATIVES.

Pos., A pronoun; Com., A period of time; Sup., Fermenting froth.

Pos., A knot of ribbon; Com., An animal; Sup., Self-praise.

Pos., A reward; Com., Dread; Sup., A festival.

Pos., To reward; Com., A fruit; Sup., An adhesive mixture.

Pos., A meadow; Com., An unfortunate king; Sup., The smallest.

[Pg 48]

Pos., An American genius; Com., To turn out or to flow; Sup., An office, an express, a place, a piece of timber.

Pos., To depart; Com., To wound; Sup., A visible spirit.

A gentleman who had sent to a certain city for a car-load of fuel, wrote thus to his nephew residing there:

“Dear Nephew

;

Uncle John.”

[Pg 49]

Presently he received the following reply:

“Dear Uncle

:

James.”

Why is a man up stairs, stealing, like a perfectly honorable man?

Why is a ship twice as profitable as a hen?

Why can you preserve fruit better by canning it, than in any other way?

[Pg 50]

What best describes, and most impedes, a pilgrim’s progress?

Why is a girl not a noun?

What part of their infant tuition have old maids and old bachelors most profited by?

What is that which never asks any questions, and yet requires many answers?

What quadrupeds are admitted to balls, operas, and dinner-parties?

If a bear were to go into a linen-draper’s shop, what would he want?

[Pg 51]

When does truth cease to be truth?

How many dog-stars are there?

What is worse than raining cats and dogs?

Why is O the only vowel that can be heard?

Why is a man that has no children invisible?

What is it which has a mouth, and never speaks; a bed, and never sleeps?

Which burns longer, a wax or sperm candle?

Why is a watch like an extremely modest person?

[Pg 53]

A lady was asked “What is Josh Billings’ real name? What do you think of his writings?” How did she answer both questions by one word?

Why is Mr. Jones’ stock-farm, carried on by his boys, like the focus of a burning-glass?

A by <. The name of a book, and of its author.

What word in the English language contains the six vowels in alphabetical order?

If the parlor fire needs replenishing, what hero of history could you name in ordering a servant to attend to it?

My FIRST is an insect, my SECOND a quadruped, and my WHOLE has no real existence.

If the roof of the Tower of London should blow off, what two names in English history would the uppermost rooms cry out?

[Pg 54]

I am composed of five letters. As I stand, I am a river in Virginia, and a fraud. Beheaded, I am one of the sources of light and growth. Beheaded again, I sustain life; again, and I am a preposition. Omit my third, and I am a domestic animal in French, and the delight of social intercourse in English. Transpose my first four, and I become what may attack your head, if it is a weak one, in your efforts to find me out.

[Pg 55]

There is a certain natural production that is neither animal, vegetable, nor mineral; it exists from two to six feet from the surface of the earth; it has neither length, breadth, nor substance; is neither male nor female, though it is found between both; it is often mentioned in the Old Testament, and strongly recommended in the New; and it answers equally the purposes of fidelity and treachery.

The eldest of four brothers did a sound business; the second, a smashing business; the third, a light business; and the youngest, the most wicked business. What were they?

What tree bears the most fruit for the Boston market?

Why is the end of a dog’s tail, like the heart of a tree?

[Pg 58]

Why is a fish-monger not likely to be generous?

Take away my first five, and I am a tree. Take away my last five, and I am a vegetable. Without my last three, I am an ornament. Cut off my first and my last three, and I am a titled gentleman. From his name cut off the last letter, and an organ of sense will remain. Remove from this the last, and two parts of your head will be left.

Divide me into halves, and you find a fruit and an instrument of correction. Entire, I can be obtained of any druggist.

Why was Elizabeth of England a more marvelous sovereign than Napoleon?

A SQUARE-OF-EVERY-WORD PUZZLE.

I.

II.

III.

[Pg 59]

IV.

A prophet exists, whose generation was before Adam; who was with Noah in the Ark, and was present at the trial of our Lord. The only sermon he preached, was so convincing as to bring tears to the eyes and repentance to the heart of a sinner. He neither lies in a bed nor sits in a chair; his clothing is neither dyed, spun nor woven, but is of finest texture and most brilliant hue. His warning cry ought to call all sluggards from their slumbers: he utters it in every land and every age; and yet he is not the Wandering Jew.

(Fill the blanks with the names of British Authors.)

[Pg 60]

Blanks to be filled with the names of noted authors.

Than myself in my normal condition, nothing could be lighter or more airy. I am composed of six letters[Pg 61] and four syllables. Deprived of my first two and transposed, I am the haunt of wild beasts; transposed, I am a human being more dangerous than a wild beast; transposed again, I am part of a fence; robbed of my last letter, and again transposed, I am a melody; or I am that noun without which there would be no such adjective as my WHOLE.

CHRISTMAS DINNER.

The first course consisted of a linden tree, and some poles. The second, of a red-hot bar of iron, a country in Asia, and an ornament worn by Roman ladies, accompanied by a vegetable carefully prepared as follows: one-sixth of a carrot, one-fourth of a bean, one-half of a leaf of lettuce, and one-third of a cherry. For dessert, a pudding made of the interment of a tailor’s implement; some points of time, and small cannon-shot from Hamburg.

[Pg 62]

NUTS TO CRACK.

What nuts were essential to the safety of ancient cities?

What nut is a garden vegetable?

What nut is a dairy product?

What nut is dear to bathers?

What nut is used to store away things in?

What nut is a breakfast beverage?

FOR AMATEUR GARDENERS.

Plant the early dawn, and what flower will appear?

What spring flowers are found in the track of an avalanche?

What early vegetable most resembles a pain in the back?

What flower is most cultivated by bad-tempered persons?

If a dandy be planted, what tree will come up?

Why is a gardener a most fortunate antiquary?

[Pg 63]

What herbs will spoil your brood of chickens?

FIRST.

SECOND.

THE WHOLE.

I am useful on a farm, and on shipboard. Transpose me and I am not out of place on your tables, though I am most at home on the other side of the world. Change me to my original form, and remove my middle, and I become a part of your face.

POSITIVES AND COMPARATIVES.

[Pg 65]

The following puzzle was first published in 1628, and was reprinted in Hone’s Every-Day Book for 1826:

A vessel sailed from a port in the Mediterranean, with thirty passengers, consisting of fifteen Jews and fifteen Christians. During the voyage a heavy storm arose, and it was found necessary to throw overboard one-half the passengers, in order to lighten the ship. After consultation, they agreed to a proposal from the[Pg 66] captain, that he should place them all in a circle, and throw overboard every ninth man until only fifteen should be left. The treacherous wretch then arranged them in such a way, that all the Jews were thrown overboard, and all the Christians saved. In what order were they placed?

| pOl | pol | pol |

| Pol | POL | PoL |

| ST |

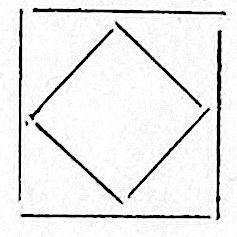

A man building a barn, wished to place in it a window 3 ft. high by 3 ft. wide. But, finding there was not room enough, he had it made half the size intended, without altering height or width.

PERSIAN RIDDLE.

I contain only two syllables. My FIRST implies plurality; my SECOND, sound health. My WHOLE is the name of a profligate earl who was the third husband of a queen noted alike for her beauty and her misfortunes. He died insane and in exile; and the beautiful queen, after being queen consort in one country, and reigning sovereign in another, spent nineteen years in captivity, and was finally beheaded on the 8th of January, 1587.

A celebrated line from Shakespeare.

[Pg 67]

TRANSMUTATIONS.

1. A letter made crazy by being placed in order.

2. A letter becomes an island when surrounded by a belt.

3. A letter is pleased when set on fire.

4. A letter falls in love when it is beaten.

5. A letter is hated when it is examined.

6. A letter becomes a sailor when it leaves the house.

7. A letter is filled with crystals when it becomes a creditor.

8. A letter becomes musical when it is made thick.

9. A letter changes its shape when empty.

10. A letter is seen when it is spotted.

11. Another is seen when taken in hand.

12. When a letter is perforated it draws near the ocean.

13. It costs money for a letter to be thoughtful.

14. A letter is always slandered when it becomes noted.

What letters are they?

What kind of paper is most like a sneeze?

Why did Edward Everett like to write his own name?

Why would not the same name be a good exercise in writing?

A farmer had ten apple trees to plant. He desired to place them in five rows, having four in each row. This he succeeded in doing. How?

Quotation from Shakespeare:

One little boy said to another: “I have an own and only sister, but she has no brother.” How was that?

[Pg 71]

Convert the following into a couplet, perfect in rhyme and rhythm, without adding or omitting a single letter:

One and the same word of two syllables, answers each of the following triplets:

| I. | MY FIRST springs in the mountains; |

| MY SECOND springs out of the mountains; | |

| MY WHOLE comes with a spring over the mountains. |

| II. | MY FIRST runs up the trees; |

| MY SECOND runs past the trees; | |

| MY WHOLE spreads over the trees. |

| III. | MY FIRST runs on two feet; |

| MY SECOND runs without feet; | |

| MY WHOLE just glides away. |

| IV. | To catch MY FIRST, men march after it; |

| To capture MY SECOND, they march over it; | |

| To possess MY WHOLE, they go through a march before it. |

Query: Why was the Moon so angry?

[Pg 73]

My FIRST is a little river in England that gave name to a celebrated university; my SECOND is always near; my THIRD sounds like several large bodies of water; and my WHOLE is the name of a Persian monarch, the neighing of whose horse gave him a kingdom and a crown.

[Pg 74]

A DINNER PARTY.

THE GUESTS,

(Who are chiefly Anachronisms and other Incongruities.)

The First: Escaped his foes by having his horse shod backward.

Second: Surnamed, The Wizard of the North.

3d: Dissolved pearls in wine; “herself being dissolved in love.”

4th: Was first tutor to Alexander the Great.

5th: Said “There are no longer Pyrenees.”

6th: The Puritan Poet.

7th: The Locksmith King.

8th: The woman “who drank up her husband.”

9th: The Architect of St. Peter’s, Rome.

10th: The Miner King.

11th: Surnamed The King Maker.

12th: The woman who married the murderer of her husband, and of her husband’s father.

13th: The Architect of St. Paul’s, London.

14th: The man who spoke fifty-eight languages; whom Byron called “a Walking Polyglot.”

15th: A death-note, and a father’s pride.

16th: The Bard of Ayrshire.

17th: The Knight “without fear, and without reproach.”

18th: Refused, because he dared not accept, the crown of England.

19th: Whose vile maxim was “every man has his own price.”

20th: The king who had an emperor for his foot-stool.

21st: The conqueror of the conqueror of Napoleon.

[Pg 75]

22d: The inventor of gunpowder.

23d: The king who entered the enemy’s camp, disguised as a harper.

24th: The greatest English navigator of the eighteenth century.

25th: The inventor of the art of printing.

26th: Whom Napoleon called “the bravest of the brave.”

27th: Who first discovered that the earth is round.

28th: The diplomatic conqueror of Napoleon.

29th: The inventor of the reflecting telescope.

30th: The conqueror of Pharsalia.

31st: The inventor of the safety lamp.

32d: First introduced tobacco into England.

33d: Discovered the Antarctic Continent.

34th: The present poet laureate of England.

35th: His immediate predecessor.

36th: The first of the line.

37th: Surnamed “the Madman of the North.”

38th: The young prince who carried a king captive to England.

39th: First sailed around the world.

40th: Said “language was given us to enable us to conceal our thoughts.”

41st: The Father of History.

DISHES, RELISHES, DESSERT.

1: Natural caskets of valuable gems.

2: Material and immaterial.

3: The possessive case of a pronoun and an ornament.

4: A sign of the zodiac, (pluralized).

5: One-third of Cesar’s celebrated letter, and the centre of the solar system.

[Pg 76]

6: Where Charles XII. went after the battle of Pultowa.

7: Whose English namesake Pope called “the brightest, wisest, meanest of mankind.”

8: A celebrated English essayist.

9: Formerly a workman’s implement.

10: The ornamental part of the head.

11: An island in Lake Ontario.

12: Timber, and the herald of the morning.

13: A share in a rocky pathway.

14: The unruly member.

15: The earth, and a useful article.

16: An iron vessel, and eight ciphers.

17: A letter placed before what sufferers long for.

18: Like values, and odd ends.

19: A preposition, a piece of furniture, and a vowel, (pluralized).

20: An insect, followed by a letter, (pluralized).

21: The employment of some women, and the dread of all.

22: A kind of carriage, and a period of time.

23: A net for the head, an organ of sense, an emblem of beauty.

24: By adding two letters, you’ll have an Eastern conqueror.

25: Five-sevenths of a name not wholly unconnected with Bleak House and Borrioboola Gha.

26: An underground room, and a vowel.

27: Skill, part of a needle, and to suffocate, (pluralized).

28: Antics.

29: An intimation burdens.

30: What if it should lose its savor?

31: Where you live a contented life; a hotel, and a vowel.

[Pg 77]

32: The staff of life.

33: What England will never become.

34: Scourges.

35: Running streams.

36: A domestic fowl, and the fruit of shrubs.

37: Married people.

38: A Holland prince serene, (pluralized).

39: To waste away, and Eve’s temptation, (pluralized).

40: Four-fifths of a month, and a dwelling, (pluralized).

41: Busybodies.

42: What Jeremiah saw in a vision.

43: Very old monkeys.

44: Approach convulsions.

45: Small blocks for holding bolts.

As, on Louis Gaylord Clarke’s authority, “no museum is complete without the club that killed Captain Cook”—he had seen it in six—so no collection of riddles can be considered even presentable without the famous enigma so often republished, and always with the promise of “£50 reward for a solution.” It was first printed in the Gentlemen’s Magazine, London, in March, 1757.

The compiler of this little book has no hope of winning the prize, and leaves the lists open to her readers, with a hope that some one of them may succeed in “guessing” not only this, but the next riddle, of whose true answer she has not the faintest idea.

The other unguessed, if not unguessable, riddle claims to come from Cambridge, and is as follows:

(See Key.)

QUESTIONS NOT TO BE ANSWERED UNTIL THE WORLD IS WISER.

Considering how useful the ocean is to mankind, are poets justified in calling it “a waste of waters”?

How can we catch soft water when it is raining hard?

Where is the chair that “Verbum sat” in?

How does it happen that Fast days are always provokingly slow days?

How is it that a storm looks heavy when it keeps[Pg 79] lightening? And the darker it grows, the more it lightens?

When it is said of a man that “he never forgets himself,” are we to understand that his conduct is absolute perfection, or that it is the perfection of selfishness?

PARADOXES.

1st. Polus instructed Ctesiphon in the art of pleading. Teacher and pupil agreed that the tuition-fee should be paid when the latter should win his first case. Some time having gone by, and the young man being still without case or client, Polus, in despair of his fee, brought the matter before the Court, each party pleading his own cause. Polus spoke first, as follows:

“It is indifferent to me how the Court may decide this case. For, if the decision be in my favor, I recover my fee by virtue of the judgment; but, if my opponent wins the case, this being his first, I obtain my fee according to the contract.”

Ctesiphon, being called on for his defense, said:

“The decision of the Court is indifferent to me. For, if in my favor, I am thereby released from my debt to Polus. But, if I lose the case, the fee cannot be demanded, according to our contract.”

2d. A certain king once built a bridge, and decreed that all persons about to cross it, should be interrogated as to their destination. If they told the truth they should be permitted to pass unharmed; but, if they answered falsely, they should be hanged on a gallows erected at the centre of the bridge. One day a man, about to cross, was asked the usual question, and replied:

[Pg 80]

“I am going to be hanged on that gallows!”

Now, if they hanged him, he had told the truth, and ought to have escaped; but, if they did not hang him, he had “answered falsely,” and ought to have suffered the penalty of the law.

[Pg 81]

[Pg 83]

FANCY TITLES FOR BOOKS.

Furnished by Thomas Hood for a blind door in the Library at Chatsworth, for his friend the Duke of Devonshire.

Percy Vere. In Forty Volumes.

Dante’s Inferno; or Descriptions of Van Demon’s Land.

Ye Devyle on Two Styx: (black letter).

Lamb’s Recollections of Suet.

Lamb on the Death of Wolfe.

Plurality of Livings: with Regard to the Common Cat.

Boyle on Steam.

Blaine on Equestrian Burglary; or the Breaking-in of Horses.

John Knox on Death’s Door.

Peel on Bell’s System.

Life of Jack Ketch, with Cuts of his own Execution.

Cursory Remarks upon Swearing.

Cook’s Specimens of the Sandwich Tongue.

Recollections of Banister. By Lord Stair.

On the Affinity of the Death-Watch and Sheep-Tick.

Malthus’ Attacks of Infantry.

McAdam’s Views of Rhodes.

The Life of Zimmermann. By Himself.

Pygmalion. By Lord Bacon.

Rules of Punctuation. By a Thoroughbred Pointer.

Chronological Account of the Date Tree.

Kosciusko on the Right of the Poles to Stick up for Themselves.

Prize Poems. In Blank Verse.

Shelley’s Conchology.

Chantry on the Sculpture of the Chipaway Indians.

The Scottish Boccaccio. By D. Cameron.

Hoyle on the Game Laws.

Johnson’s Contradictionary.

[Pg 84]

When Hood and his family were living at Ostend for economy’s sake, and with the same motive Mrs. Hood was doing her own work, as we phrase it, he wrote to a friend in England: “Jane is becoming an excellent cook and housemaid, and I intend to raise her wages. She had nothing a week before, and now I mean to double it.”

It has been estimated that of all possible or impossible ways of earning an honest livelihood, the most arduous, and at the same time the way which would secure the greatest good to the greatest number, would be to go around, cold nights, and get into bed for people! To this might be added, going around cold mornings and getting up for people; and, most useful and most onerous of all, going around among undecided people and making up their minds.

In these days of universal condensation—of condensed milk, condensed meats, condensed news—perhaps no achievement of that kind ought to surprise us; but it must be acknowledged that Thackeray’s condensing feat was the most extraordinary on record. To compress “The Sorrows of Werther”—that three volumed novel: a book of size—and tears, full of pathos and prettiness, of devotion and desperation—into four stanzas that tell the whole story, was a triumph of art which—which it is very possible GOETHE would admire less than we do.

Theodore Hook was celebrated not more for his marvelous readiness in rhyming than for the quality of the rhymes themselves. In his hands the English language seemed to have no choice: plain prose appeared impossible. Motley was the only wear; fantastic verse the only method of expression. No less does he press into his service phrases from the languages, as in the curious verses which follow, in praise of

CLUBS.

OTHER WORLDS.

Mr. Mortimer Collins indulges in sundry very odd speculations concerning them.

STILTS.

The Home Journal having published a set of rather finical rules for the conduct of equestrians in Central Park, a writer in Vanity Fair supplemented and satirized them as follows:

ETIQUETTE OF EQUITATION.

When a gentleman is to accompany a lady on horseback,

1st. There must be two horses. (Pillions are out of fashion, except in some parts of Wales, Australia and New Jersey.)

[Pg 89]

2d. One horse must have a side saddle. The gentleman will not mount this horse. By bearing this rule in mind he will soon find no difficulty in recognizing his own steed.

3d. The gentleman will assist the lady to mount and adjust her foot in the stirrup. There being but one stirrup, he will learn upon which side to assist the lady after very little practice.

4th. He will then mount himself. As there are two stirrups to his saddle, he may mount on either side, but by no means on both; at least, not at the same time. The former is generally considered the most graceful method of mounting. If he has known Mr. Rarey he may mount without the aid of stirrups. If not, he may try, but will probably fail.

5th. The gentleman should always ride on the right side of the lady. According to some authorities, the right side is the left. According to others, the other is the right. If the gentleman is left handed, this will of course make a difference. Should he be ambidexter, it will be indifferent.

6th. If the gentleman and lady meet persons on the road, these will probably be strangers, that is if they are not acquaintances. In either case the gentleman and lady must govern themselves accordingly. Perhaps the latter is the evidence of highest breeding.

7th. If they be going in different directions, they will not be expected to ride in company, nor must these request those to turn and join the others; and vice versa. This is indecorous, and indicates a lack of savoir faire.

8th. If the gentleman’s horse throw him he must not expect him to pick him up, nor the lady; but otherwise the lady may. This is important to be borne in mind by both.

9th. On their return, the gentleman will dismount first and assist the lady from her horse, but he must not expect the same courtesy in return.

N. B.—These rules apply equally to every species of equitation, as pony riding, donkey riding, rocking horse riding, or “riding on a rail.” There will, of course, be modifications required, according to the form and style of the animal.

SONG OF THE RECENT REBELLION.

AIR: “Lord Lovell.”

OTHER PARODIES.

“Come into the garden, Maud!”

CLEON HATH A MILLION ACRES.

“WHEN I THINK OF MY BELOVED.”

(Algonquin Song, in “Hiawatha.”)

“NEVER STOOPS THE SOARING VULTURE.”

(Also from “Milkanwatha.”)

THE FALLS OF LODORE.

A disappointed, “disillusioned,” tourist expresses below his view of the subject, which slightly differs from Southey’s.

And the moral of that is, said the Duchess, that tourists shouldn’t see NIAGARA before they visit Lodore.

“TELL ME, YE WINGED WINDS.”

SEEING IS BELIEVING: SEEING IS DECEIVING.

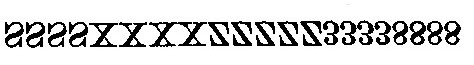

Here is a row of capital letters, and of figures, of ordinary size and shapes:

SSSSXXXXZZZZZ33338888

They are such as are made up of two parts, of similar form. Look carefully at these, and you will perceive that the upper halves of the characters are a[Pg 98] very little smaller than the lower halves—so little that, at a mere glance, we should declare them to be of equal size. Now, turn the page upside down, and, without any careful looking, you will see that this difference in size is very much exaggerated—that the real top half of the letter is very much smaller than the other half. It will be seen by this that there is a tendency in the eye to enlarge the upper part of any object upon which it looks. Thus two circles of unequal size might be drawn and so placed that they would appear exactly alike.

FANTASTIC NAMES.

An Ohio lady told me that she knew three young ladies belonging to one family, named severally:

Regina, Florida Geneva, and Missouri Iowa. And that an ill-starred child, born about the time of the first Atlantic cable furor, was threatened with the name of Atalanta Telegrapha Cabelletta!

The cable collapsed, and the child escaped; but a young lady of Columbus, born January 1, 1863, was less fortunate. She was named by her parents in honor of the event of that day, Emancipation Proclamation, and is known by the pet name “Proklio.”

I knew a boy named Chief Justice Marshall; a young man, (greatness was thrust upon him,) named Commodore Perry V——r, and have been told of a little girl named by her novel-loving mother, Lady Helen Mar.

Mrs. C., of Western New York, was, in her girlhood, acquainted with a boy who by no means “rejoiced in the name” of John Jerome Jeremiah Ansegus P. S. Brown McB——e.

A colored woman in Dunkirk named her infant son in honor of two lawyers there: Thomas P. Grosvenor William O. Stevens D——s; and, at an Industrial[Pg 99] school in Detroit, there was some years ago a colored boy named Nicholas Evans Esquire Providence United States of America Jefferson Davis B——s.

In Cazenovia there once lived a young lady named Encyclopedia Britannica D——y.

There, too, Messrs. Hyde and Coop lived side by side for several years. Then Mr. Hyde moved out of town, and spoiled that little game.

It was noted as a coincidence when a Mr. Conkrite, of Tecumseh, Mich., sold his dwelling-house and lot to Mrs. Cronkite.

A farmer in Allegany county, N. Y., named his children Wilhelmina Rosalinda, Sobriski Lowanda, Eugertha Emily, Hiram Orlaska, Monterey Maria and Delwin Dacosti. The following are also vouched for as genuine American names: Direxa Polyxany Dodge, Hostalina Hypermnestra Meacham, Keren Habuch Moore and Missouri Arkansas Ward.

There lived in Greenfield, N. Y., a certain Captain Parasol; and, at Niagara Falls, for a time, a Methodist minister named Alabaster.

I have lately heard of a Mrs. Achilles, a Mr. and Mrs. December, a John January, and a Mr. Greengrass; and of an Indiana girl, at school in Cincinnati, named Laura Eusebia Debutts Miranda M’Kinn Parron Isabella Isadora Virginia Lucretia A——p.

In 1874 one of the young ladies at a certain convent school in West Virginia, was Miss Claudia Deburnabue Bellinger Mary Joseph N——p.

The following are names of stations on the “E. and N. A. Railway,” New Brunswick: Quispamsis, Nanwigewank, Ossekeag, Passekeag, Apohaqui, Plumweseep, Penobsquis, Anagance, Petitcodiac, Shediac, Point du Chene; and we should particularly like to hear a conductor sing them.

[Pg 100]

LADIES’ NAMES.

Their Sound.

LADIES’ NAMES.

THEIR SIGNIFICANCE.

GEOGRAPHICAL PROPRIETY.

THE CAPTURE.

When, in the tenth century, the Tartars, led by their ruthless chief, invaded Hungary, and drove its king from the disastrous battle-field, despair seized upon all the inhabitants of the land. Many had fallen[Pg 104] in conflict, many more were butchered by the pitiless foe, some sought escape, others apathetically awaited their fate. Among the last was a nobleman who lived retired on his property, distant from every public road. He possessed fine herds, rich corn fields, and a well stocked house, built but recently for the reception of his wife, who now for two years had been its mistress.

Disheartening accounts of the general misfortune had reached his secluded shelter, and its peaceful lord was horror-stricken. He trembled at every sound, at every step; he found his meals less savory; his sleep was troubled; he often sighed, and seemed quite lost and wretched. Thus anxiously anticipating the troubles which menaced him, he sat, one day, at his well closed window, when suddenly a Tartar, mounted on a fiery steed, galloped into the court. The Hungarian sprang from his seat, ran to meet his guest, and said:

“Tartar, thou art my lord; I am thy servant; all thou seest is thine. Take what thou fanciest; I do not oppose thy power. Command; thy servant obeys.”

The Tartar immediately leaped from his horse, entered the house, and cast a careless glance on all the precious adornments it contained. His eyes rested upon the brilliant beauty of the lady of the house, who appeared, tastefully attired, to greet him there, no less graciously than her consort.

The Tartar seized her, with scarcely a moment’s hesitation, and, unheedful of her shrieks, swung himself upon the saddle, and spurred away, carrying off his lovely booty.

All this was but an instant’s work. The nobleman was thunderstruck, yet he recovered, and hastened to the gate. He could hardly distinguish, in the distance, the figures of the lady and her relentless captor. At[Pg 105] length a deep sigh burst from his overcharged heart, and he exclaimed in the bitterness of his bereavement:

“Alas! poor Tartar!”

Matrimony has been defined An insane desire on the part of a young man to pay a young woman’s board. But it might be said, with equal justice, to be An insane desire on the part of a young woman, to secure—a master.

THE FIRST MARRIAGE.—And Adam said: “This is now bone of my bone, and flesh of my flesh: she shall be called woman because she was taken out of man. Therefore shall a man leave his father and mother and cleave unto his wife. They shall be one flesh.”

No cards.

In a country church-yard is found this epitaph: “Here lie the bodies of James Robinson and Ruth his wife;” and, underneath, this text: “Their warfare is accomplished.”

A lady having died unmarried at the age of sixty-five, the following epitaph was engraved upon her tombstone:

“She was fearfully and wonderfully maid.”

“This animal,” said a menagerie-man, “is exceedingly timid and retired in its habits. It is seldom seen by the human eye—sometimes never!”

If it was Talleyrand who described language as a gift bestowed upon man in order to enable him to conceal his thoughts, he scarcely made that use of it, when, in reply to some friend who asked his opinion of[Pg 106] a certain lady, he said: “She has but one fault—she is insufferable!”

“What do you want?” demanded an irate house-holder, called to the window at eleven o’clock, by the ringing of the door-bell:

“Want to stay here all night.”

“Stay there, then!” Window closed emphatically.

“I want to go to the Revere,” said a stranger in Boston to a citizen on the street.

“Well, you may go, if you’ll come back pretty soon,” was the satisfactory reply.

“I wish to take you apart for a few moments,” one gentleman said to another in a mixed company.

“Very well,” said the person addressed, rising and preparing to follow the first speaker; “but I shall insist on being put together again!”

Two gentlemen meeting at the door of a street-car in Toledo, and entering together, both faultlessly dressed for the evening, one of them, glancing at his companion’s attire, asked briskly: “Well! who is to be bored to-night?” “I don’t know,” said the other, as briskly, “Where are you going?”

This is the way it sounded to the congregation:

[Pg 107]

this is what the choir undertook to sing:

Mary Wortley Montague was epigrammatic when she divided mankind into “three classes—men, women, and the Hervey family”; an English writer of the present century, when he summed up Harriet Martineau’s creed, in a travesty on the Mohammedan confession of faith, “There is no God, and Harriet is his prophet;” an English critic, who described Forster’s Life of Charles Dickens as a “Biography of John Forster, with Reminiscences of Dickens”; an American, who said of one of his own noted countrymen (and it is equally true of many others), “He is a self-made man, and he worships his Creator;” finally, President Grant, when he exclaimed: “Sumner does not believe the Bible! I am not surprised; he didn’t write it!”

Charles Francis Adams, in his eloquent eulogy on W. H. Seward, lapses into a mixed metaphor which is, perhaps, all things considered, one of the most remarkable on record. “One single hour,” he says, “of the will displayed by General Jackson, at the time when Mr. Calhoun—the most powerful leader secession ever had—was abetting active measures, would have stifled the fire in its cradle.”

This is scarcely excelled even by Sir Roche Boyle’s celebrated trope: “I smell a rat. I see him floating in the air. But, mark me, I shall nip him in the bud!”

M. B. was planning plank walks from the front doors of his Ellicottville cottage to the gate, wishing to[Pg 108] combine greatest convenience with least possible encroachment upon the verdure of the modest lawn. “Friends in council,” assisting at his deliberations, took diverse views of the case. One would have the walks meet obliquely in the form of a Y. Another insisted that whatever angles there were, should be right angles, etc. Finally, M. B. remarked: “Well! we don’t seem to agree. No two of us agree. I think I’ll plank the yard all over, and, where I want the grass to grow BORE HOLES!”

Readers who admire the elliptical and suggestive style, and who, therefore, adore Mrs. R. H. D. and Mrs. A. D. T. W., ought to be pleased with the instructions given by a Philadelphian million-heiress to her agent, in this wise, (audivi):

“Where the men are at work, they will throw stones and earth and timbers against that tree, and there is no use in it. By a little care they could avoid it, but they won’t be careful. So I’d like you, as soon as possible, to put a protection around it—because it isn’t necessary.”

... “No, you needn’t drive her out of the grounds. Cows are not allowed to run in the street, and the owner is liable for trespass if they do. Shut her up in the yard, and if the owner don’t come for her to-morrow—Pound her—because there is a law against it.”

“Aha!” said a Hibernian gentleman, surprised at his neighbor’s unusual promptness; “Aha! So you’re first, at last! you were always behind before!”

Another Emerald Islander, speaking at his breakfast table of the difference between travel by steam and the old mode, thus illustrated the point: “Afore the rail-road was built, if ye left Elmira at noon, and[Pg 109] drove purty fast, ye might likely get to Corning to tea. But to-day, if ye were to start from Elmira at noon on an Express train for Corning, why, ye’re there Now!”

Caledonian shrewdness and the Caledonian dialect, alike speak for themselves, in a “bonny Scot’s” definition of metaphysics: “When the mon wha is listenin’, dinna ken what the ither is talkin’ aboot, and the mon wha is talkin’ dinna ken it himsel’, that is metapheesicks.”

“Be what you would seem to be,” said the Duchess, in Lewis Carroll’s delightfully droll story of “Alice’s Adventures,”—“or, if you like it put more simply: Never imagine yourself not to be otherwise than what it might appear to others, that what you were or might have been, was not otherwise than what you had been would have appeared to them to be otherwise.”

That is slightly metapheesickal, perhaps; and the same objection might be urged against Dr. Hunter’s favorite motto: “It is pretty impossible, and, therefore, extremely difficult for us to convey unto others those ideas whereof we are not possessed of ourselves.”

It was Dr. Hunter, who, some years before the war, returned from Florida, where he had spent the winter in a vain quest of health, and exhibited to one of his friends a thermometer he had procured there, marked from 120° only down to zero.

“It was manufactured at the South, I suppose?” she said.

“Oh, no!” was his reply: “It was made in Boston. It’s a Northern thermometer, with Southern principles.”

Colonel Bingham, of brave and witty memory, had resigned his commission in the Union army, and come [Pg 110] home to die. During his lingering illness, the family received a visit from a distant relative, a Carolina lady, with strong secession proclivities, but with sufficient tact not to express them freely before her Northern friends. However, she could not altogether conceal them, but would often express her sympathy for “the soldiers, on both sides”—wish she could distribute the fruit of the peach-orchard among them, “on both sides,” &c.

One day when the Colonel was suffering, with his usual fortitude, one of his severest paroxysms of pain, the lady looked in at the door of his room, and, after watching him a few moments with an expression of the keenest commiseration, she turned away. Just as soon as he could breathe again, he gasped out:

“Cousin—Sallie—looked—as if—she was—sorry for me—on both sides!”

A young lady who had married and come north to live, visited, after the lapse of a year or two, her southern home. It was in the palmy days of the peculiar institution, and she was as warmly welcomed by the colored as by the white members of the household. Just before her arrival, a bottle of medicine with a strong odor of Bourbon had been uncorked, and, afterward, set away. After the first greetings were over, she exclaimed:

“I smell spirits. What have you been doing?”

Old Aunt Chloe, who had lingered in the room so as to be near the beloved new-comer, turned with an air of triumph to her mistress, who had often rebuked her belief in ghosts, and burst out with:

“Dar, Missus! Didn’t I allus tole yo dere was sperits in dis yere house? Sometimes I see ’em, sometimes I hear ’em, an’ yo wood’n b’lieve me; but now, Miss Lizzie’s done gone SMELL ’em!”

[Pg 111]

The first chapter of a Western novel is said to contain the following striking passage:

All of a sudden the fair girl continued to sit on the sands, gazing upon the briny deep, upon whose bosom the tall ships went merrily by, freighted, ah! who can tell with how much joy and sorrow, and pine lumber, and emigrants, and hopes and salt fish!

“The story,” said our host, with his inexhaustible humor and irresistible brogue, “is of a man who died, and forthwith presented himself at Heaven’s gate, requesting admittance.

‘Have ye bin to Purgatory, my mon?’ says St. Peter.

‘No, yer Riverence.’

‘Thin it’s no good. Ye’ll have to wait awhile.’

While the unlucky ‘Peri’ was slowly withdrawing, another candidate approached, and the same question was asked him.

‘No, yer Riverence, but I’ve been married.’

‘Well, that’s all the same,’ says St. Peter; ‘Come in!’

At this, the first arrival taking heart of grace, advanced again, and says he:

‘Plaze yer Riverence, I’ve been married twice!’

‘Away wid ye! Away wid ye!’ says St. Peter: ‘Heaven is no place for fools!’”

When, some years since, a coalition was talked of between the New York World, the Times, and the Herald, the Tribune remarked that, after all, it would be nothing new; it was only the old story of “the world, the flesh, and the devil.”

In 1871, when the French President was undecided and inactive, in the face of all the frightful dangers[Pg 112] that threatened the nation, some wit quoted at him the well known verse from Tennyson:

“Thiers! Idle Thiers! We know not what you mean!”

In ’73 a print was widely circulated in Germany, representing Bismarck pulling away at a rope which was fastened to the massive pillars of a Cathedral. At his side stood His Satanic Majesty, who thus questioned him:

“Well, my friend, what are you doing?”

“Trying to pull down the Church.”

“Trying to pull down the Church? And how long do you think it will take you?”

“Oh, perhaps three or four years.”

“Very good, my friend, very good! I have been trying that for the last eighteen hundred years; and, if you succeed in three or four, I’ll resign in your favor!”

When a certain United States Senator disappointed his Ohio constituents by voting on what they thought the wrong side of a question, some one (who must have enjoyed his opportunity) hit him with the following quotation: “He’s Ben Wade, and found wanting.”

“John P. Hale is an old goose!” exclaimed General Cass. Some friend was kind enough to repeat this saying to the Senator; who replied with a smile, (and, surely this was the “retort courteous,”) “Tell General Cass that he’s a Michi-gander!”

At a public dinner in Boston, nearly twenty years ago, Judge Story proposed as a toast: “The Orator of the Day: Fame follows merit wherEVER IT goes!”[Pg 113] To which Mr. Everett responded: “The President of the Day: To whatever height the fabric of jurisprudence may aspire in this country, it can never rise above one Story!”

A newspaper wit announces the discovery of a buried city in the following pathetic terms: Another lost city has been found on the coast of Siberia. Now let the man who lost it make his appearance, pay for this advertisement, and take his old ruins away.

It has been said that the faculty of generalization belongs equally to childhood and to genius. Was she a genius, clad in sable robes, and bewailing the recent loss of her husband—she was certainly not a child—who observed in conversation, with most impressive pathos: “For we are all liable to become a widow!”

CHARACTERISTIC SAYINGS OF AMERICANS.

Franklin said many things that have passed into maxims, but nothing that is better known and remembered than “He paid dear, very dear, for his whistle.”

Washington made but very few epigrammatic speeches. Here is one: “To be prepared for war is the most effectual means of preserving peace.”

Did you ever hear of old John Dickinson? Well, he wrote of Americans in 1768: “By uniting we stand, by dividing we fall.”

Patrick Henry, as every school-boy knows, gave us, “Give me liberty, or give me death,” and “If this be treason, make the most of it.”

Thomas Paine had many quotable epigrammatic sentences: “Rose like a rocket; fell like a stick;”[Pg 114] “Times that try men’s souls;” “One step from the sublime to the ridiculous,” etc., etc.

Jefferson’s writings are so besprinkled that it is difficult to select. In despair we jump at “Few die and none resign,” certainly as applicable to office-holders now as in Jefferson’s time.

Henry Lee gave Washington his immortal title, “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Charles Cotesworth Pinckney declared in favor of “Millions for defence, but not one cent for tribute.”

“Peaceably if we can; forcibly if we must,” is from Josiah Quincy, 1841.

John Adams did not say, “Live or die, survive or perish, I am for the constitution,” but Daniel Webster said it for him.

The revolutionary age alone would give us our article, had we time to gather pearls. Coming down, we pass greater, but not more famous men.

Davy Crockett was the illustrious author of “Be sure you are right, and then go ahead.”

Andrew Jackson gave us “The Union—it must be preserved.”

Benton almost lost his original identity in “Old Bullion,” from his “hard money” doctrines.

Governor Throop, of New York, was called “Small Light Troop” for years, from a phrase in a thanksgiving proclamation.

Scott’s “hasty plate of soup” lasted his lifetime.

Taylor’s battle order, “A little more grape, Captain Bragg,” will be quoted after he is forgotten by “all the world and the rest of mankind.”

Seward is known for the “irrepressible conflict,” wherever the English language is spoken.

To Washington Irving we owe “The Almighty Dollar.”

[Pg 115]

Rufas Choate gave us “glittering generalities.”

Tom Corwin’s “welcome with bloody hands to hospitable graves,” gave him more unenviable criticism than any other saying in his life.

Calhoun gave us “state rights” as a most pernicious and absurd equivalent for national supremacy under the constitution.

Douglas applied “squatter sovereignty,” though it is probable that Cass invented it and Calhoun named it.

Stringfellow was the original “Border Ruffian.”

War times gave us no end of epigrammatic utterances. Those of Lincoln alone would fill a volume—chief of these, is that noble sentiment: “With charity to all, and malice toward none.”

McClellan’s “All quiet along the Potomac” was repeated so often that its echo will “ring down through the ages.”

To Gen. Butler the country was indebted for the phrase “Contraband of War,” as applied to fugitive negroes found within our lines.

Grant gave us “Fight it out on this line,” “Unconditional surrender,” “I propose to move immediately upon your works,” “Bottled up,” and a hundred others. It seems to have escaped notice that Grant is responsible for more of these characterizing, elementary crystallizations of thought, than any other military leader of modern times.

One odd example occurs, in his response to Gen. Sheridan’s telegram: “If things are pushed, Lee will surrender.” “Push things!” was the reply, and that has passed into a proverb.

DIALECTICAL.

The peculiarities of the Yankee dialect are most amusingly exemplified by James Russell Lowell, in the[Pg 116] Biglow Papers, especially in the First Series, from which the following extract is taken:

I ’spose you wonder where I be; I can’t tell fur the soul o’ me

Exactly where I be myself, meanin’ by thet, the hull o’ me.

When I left hum, I hed two legs, an’ they wa’n’t bad ones neither;

The scaliest trick they ever played, wuz bringin’ on me hither—

Now one on ’em’s I dunno where, they thought I was a-dyin’,

An’ cut it off, because they said ’twas kind of mortifyin’;

I’m willin to believe it wuz, and yet I can’t see, nuther,

Why one should take to feelin’ cheap a minute sooner ’n t’other,

Sence both wuz equilly to blame—but things is ez they be;

It took on so they took it off, an’ thet’s enough for me.

Where’s my left hand? Oh, darn it! now I recollect wut’s come on’t.

I haint no left hand but my right, and thet’s got jest a thumb on’t,

It aint so handy as it wuz to calkylate a sum on’t.

I’ve lost one eye, but then, I guess, by diligently usin’ it,

The other’ll see all I shall git by way of pay fer losin’ it.

I’ve hed some ribs broke, six I b’lieve, I haint kep’ no account of ’em;

When time to talk of pensions comes, we’ll settle the amount of ’em.

An’ talkin’ about broken ribs, it kinder brings to mind

One that I couldn’t never break—the one I left behind!

Ef you should see her, jest clean out the spout o’ your invention,

And pour the longest sweetnin’ in about a annooal pension;

And kinder hint, in case, you know, the critter should refuse to be

Consoled, I aint so expensive now to keep, as wut I used to be:—

There’s one eye less, ditto one arm, an’ then the leg that’s wooden,

Can be took off, an’ sot away, whenever there’s a pudden!

(Letter from Birdofreedom Sawin, a Mexican volunteer, to a friend at home.)

The Dundreary “dialect” is admirably illustrated in

A LONDON EXQUISITE’S OPINION OF “UNCLE TOM’S CABIN.”

It must be this same kind of Englishman, of whom the following story is told: He was traveling on some American railroad, when a tremendous explosion took place; the cars, at the same time, coming to a sudden halt. The passengers sprang up in terror, and rushed out to acquaint themselves with the cause and extent of the mischief, all but His Serene Highness, who continued reading his newspaper. In a moment some one rushed back, and informed him that the boiler had burst. “Awe!” grunted the Englishman.

“Yes, and sixteen people have been killed!”

“Awe!” he muttered again.

“And—and,” said his interlocutor, with an effort,[Pg 118] “your own man—your servant—has been blown into a hundred pieces!”

“Awe! Bring me the piece that has the key of my portmanteau!”

THE LEGAL “DIALECT.”

ODE TO SPRING.

WRITTEN IN A LAWYER’S OFFICE.

“Broad Wiltshire” is sampled below, in a psalm given out by the Clerk of Bradford Parish Church during an Episcopal visitation:

Let us zing to the praayze an’ glawry ’o God, dree verses of the hundred an’ vourteenth zaam,—a version specially ’dapted to the ’casion, by myself:

Persons fond of economizing words, sometimes use figures (are they figures of speech?) and letters, in their stead. Thus, the fate of all earthly things is presented by the consonants DK—a view of the case entirely consonant with our own observation.

The following is a printer’s short-hand method of expressing his emotions:

2 KT J.

AN AFFECTING STORY.

GEORGE AND HIS POPPAR.

FEB. 22, A.D. 1738.

The preceding poem, while it places in a new light the immortal history of the hatchet, also illustrates the wonderful adaptability of the English language to the purposes of the poet. Thus, in the last stanza, a rhyme is required for “down,” while the sense demands the word “man” at the end of the corresponding line. Instantly the ingenious author perceives the remedy, and changes “man” to “moun,” which doesn’t mean anything to interfere with the sense, and rhymes with “down” in the most satisfactory manner.

Other fine illustrations of this kind are found in that learned translation of a part of the Eneid, published a few years since at Winsted, Connecticut. Thus:

[Pg 123]

The temptation is strong to quote just here several parallel passages from Davidson’s very literal translation and from this Winsted version. We will give one, for the sake of the contrast.

“Returning Aurora now illuminates the earth with the lamp of Phœbus, and has chased away the dewy shades from the sky, when Dido, half-frenzied, thus addressed her sympathizing sister:

Sister Anna, what dreams terrify and distract my mind! What think you of this wondrous guest who has come to our abode? In mien how graceful he appears! In manly fortitude and warlike deeds how great! I am fully persuaded, (nor is my belief groundless,) that he is the offspring of the gods. Had I not been fixed and steadfast in my resolution never to join myself to any in the bonds of wedlock, since my first love by death mocked and disappointed me, I might, perhaps, give way. Anna, since the death of my unhappy spouse Sichæus, since the household gods were stained with his blood, shed by a brother, this stranger alone has warped my inclinations, and interested my wavering mind. I recognize the symptoms of my former flame. But he who first linked me to himself, hath borne away my affection. May he possess it still, and retain it in the grave. (Liber Quartus. Ibid.)

Prizes having been offered for rhymes corresponding to “Ipecacuanha,” and “Timbuctoo,” it is to be hoped that the ingenious authors of the following verses gained them:

“And the moral of that is,” as the Duchess observed:

Also: (“month” having been declared unrhymable;)

[Pg 125]

In W. G. Clarke’s youth he was requested by a young lady in the millinery line to contribute a poem to her album. Her “Album” was an account book diverted from its original purpose, and he responded as follows:

To Miss Lucretia Sophonisba Matilda Jerusha Catling:

| Thou canst not hope, O nymph divine | 3 | 9 |

| That I should ever court the | ||

| Or that, when passion’s glow is done, | 1 | |

| My heart can ever love but | ||

| When, from Hope’s flowers exhales the dew, | 2 | |

| Then Love’s false smiles desert us | ||

| Then Fancy’s radiance ’gins to flee, | 3 | |

| And life is robbed of all the | ||

| And Sorrow sad her tears must pour | 4 | |

| O’er cheeks where roses bloomed be | ||

| Yes! life’s a scene all dim as Styx; | 6 | |

| Its joys are dear at | ||

| Its raptures fly so quickly hence | 18d | |

| They’re scarcely cheap at | ||

| Oh! for the dreams that then survive! | 25 | |

| They’re high at pennies | ||

| The breast no more is filled with heaven | 27 | |

| When years it numbers | ||

| And yields it up to Manhood’s fate | 28 | |

| About the age of | ||

| Finds the world cold and dim and dirty | 30 | |

| Ere the heart’s annual count is | ||

| Alas! for all the joys that follow | 25 | |

| I would not give a quarter dollar. | ||

| 1 | 97½ | |

[Pg 126]

“FRAGMENTS OF AN ORIGINAL LOVE STORY.”

BY

J. G. STAUNTON, AND A SOUTH

CAROLINA LADY.

But perhaps the most “pronounced” example of adaptability, as referred to above, is found in a poem recently contributed to a Rochester paper.

If “the exigencies of rhyme” need not be considered in constructing English verse, neither need the[Pg 128] exigencies of rhythm, as shown by the following highly artistic couplets:

In ’73, a modest volume of poems was published by an Hon. and Rev. gentleman of Central New York,[3] in which occur the following rather surprising verses: (not consecutively, but here and there.)

[Pg 129]

To find the “concealed sense” (concealed nonsense!) of the verses that follow, the first and third, second and fourth lines, are read consecutively:

This is nonsense, too; though, certainly, women are the faultiest of human beings—except men.

Be that as it may, few women have ever been more severely, or, perhaps, more justly, cauterized, than poor Job’s poor wife, in Coleridge’s celebrated Epigram:

SECRET CORRESPONDENCE.

A young lady, newly married, being obliged to show her husband all the letters she wrote, sent the following to an intimate friend:

(The key to the above letter is to omit every alternate line: reading the first, third, fifth, &c., consecutively.)

It is said that among ancient Christian devices the figure of a fish occurs very frequently, with the inscription anthropou (in Greek letters), signifying of man. The following explanation has been given: The Greek word for fish is ichthus, and each of the five letters composing the Greek word, (ch and th being each represented by only one letter,) is the initial of a significant word, as follows:

The whole, followed by anthropou, (the word inscribed upon the figure of the fish,) forms a profession of Christian faith:

JESUS CHRIST, SON OF GOD, SAVIOUR OF MEN.

Pilate’s question addressed to our Lord, “What is truth?” “Quid est Veritas?” contains in itself, by a perfect anagram, its own answer: “Est vir qui adest:” “It is the Man who stands before you.”

[Pg 132]

The following very curious sentence, “Sator arepo teret opera rotas,” is not first-class Latin, but may be freely translated: “I cease from my work; the mower will wear his wheels.” It is, in fact, something like a nonsensical verse, but has these peculiarities: 1st. It spells backward and forward the same. 2d. Then, the first letter of each word spells the first word. 3d. Then, all the second letters of each word spell the second word. 4th. Then, all the third, and so on through, the fourth and fifth. 5th. Then, commencing with the last word, the last letter of each word spells the first word. 6th. Then, the next to the last, and so on, through.

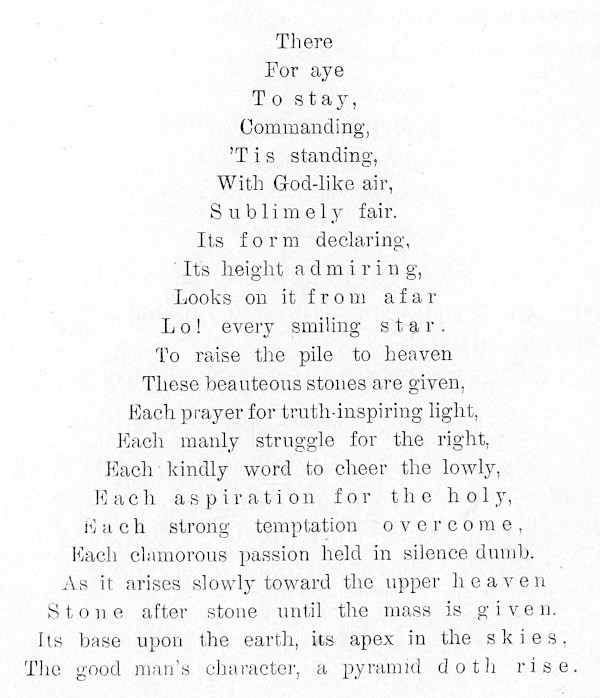

The lines which constitute the Pyramid below, may be read from the base upward, or from the apex downward, indifferently.

[Pg 133]

“Revolution” is transposed “to love ruin,” and “French Revolution,” “Violence run forth.”