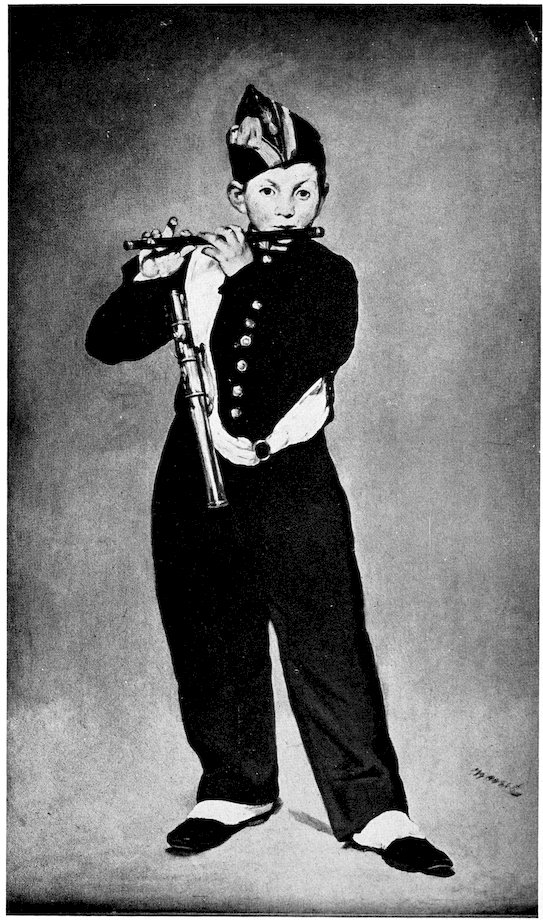

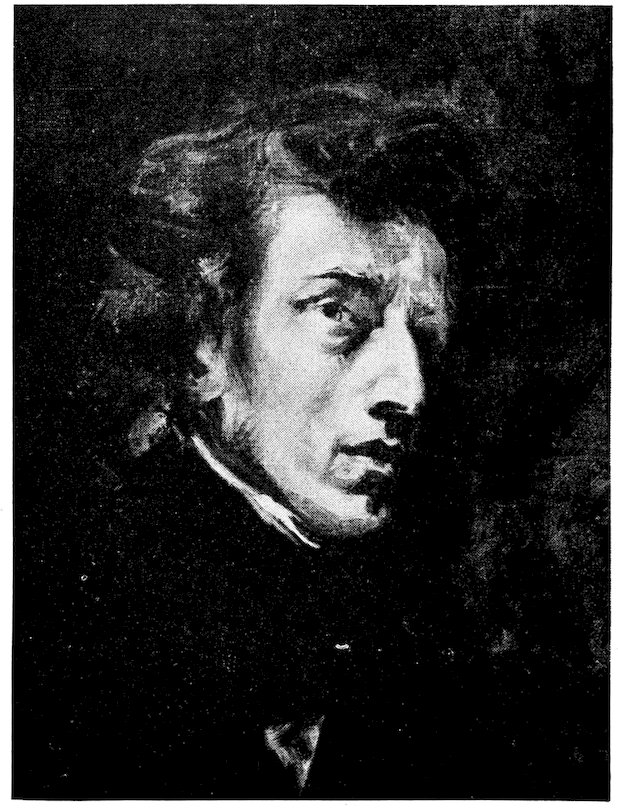

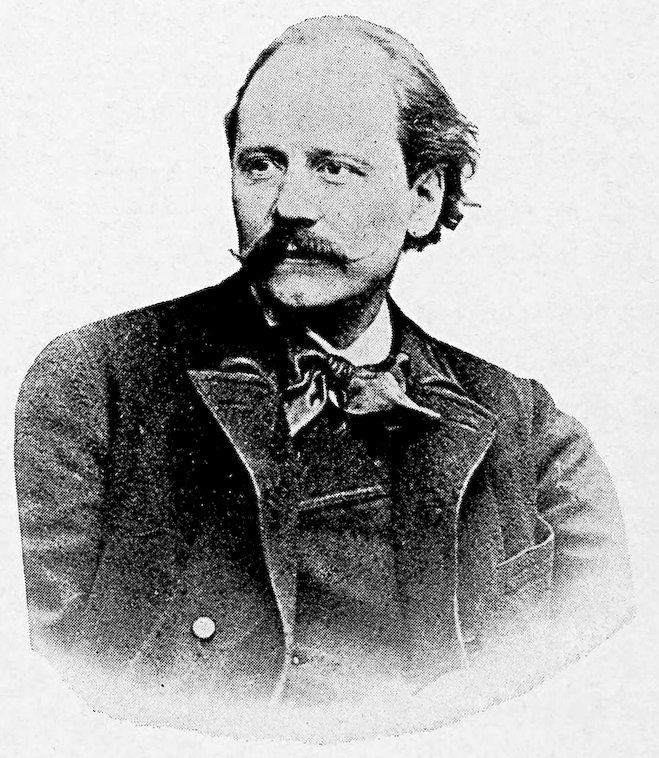

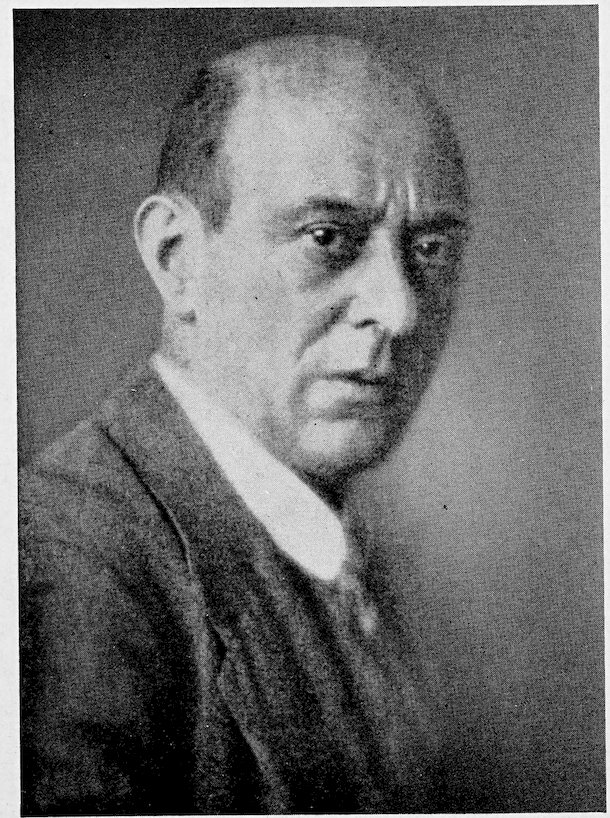

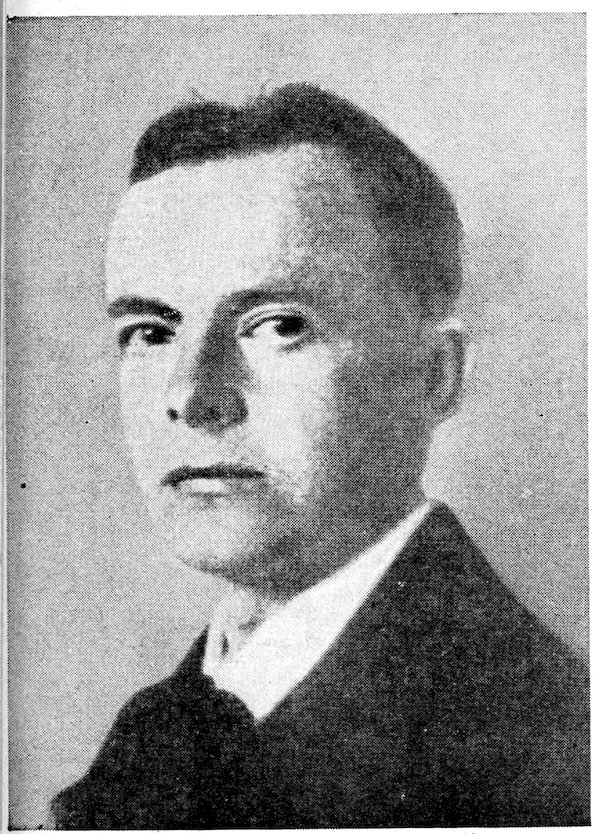

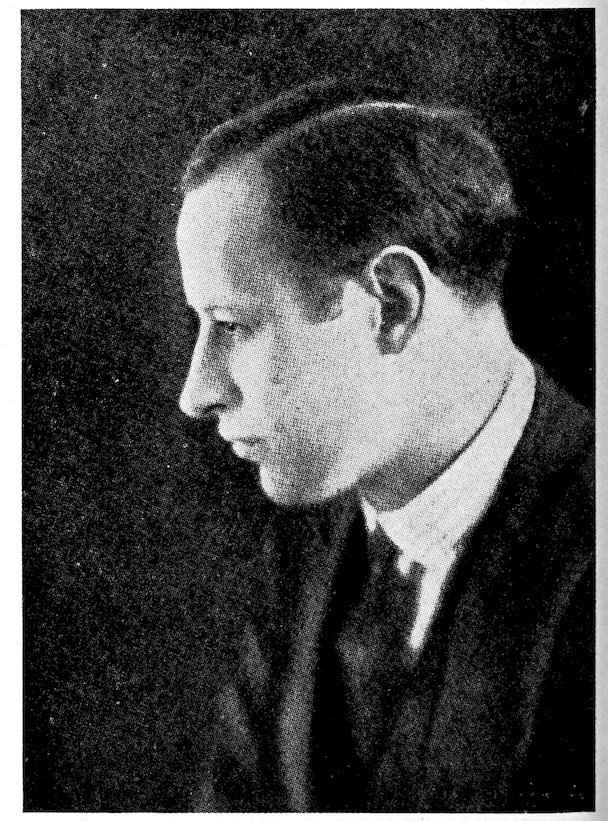

From the painting by Manet—in the Louvre, Paris.

The Fifer.

Title: How music grew, from prehistoric times to the present day

Author: Marion Bauer

Ethel R. Peyser

Release date: November 19, 2023 [eBook #72171]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1925

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Tim Lindell, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

From the painting by Manet—in the Louvre, Paris.

The Fifer.

“It takes three to make music: one to create, one to perform, one to appreciate. And who can tell which is the most important?”

In writing this book we have not tried to write a history but rather have attempted to follow a lane parallel to the road along which music has marched down to us through the ages.

For this reason you will find what may seem upon first glance peculiar omissions, but which to us were prayerfully and carefully relinquished, lest the book become an encyclopedia and lest our kind publisher look upon us ungraciously and our readers despair.

Among the omissions which may be regarded as serious is a chapter on the singers, those who have delighted and thrilled the public through the years, but the nature of this book, in the minds of its authors, precludes details of the executive side of music, adhering as closely as possible to the actual creators.

In our experience every history of music, and we have read scores of them, leaves out many things, so our “lane” touches things in passing, only, owing to mechanical as well as willful reasons.

On the other hand we have enlarged greatly on many topics. This we have done when we have considered a subject particularly picturesque in order to attract and stimulate the novice reading about music, perhaps, for the first time!

Lastly we have tried to explain as simply as possible, without becoming infantile, the varying steps in Music’s viiigrowth. Therefore, the book has assumed larger proportions than if we had been able to use scientific terms and cut the Gordian knot of explanation with one swiftly aimed blow, rather than three or four.

So, with the sincere hope that our book will help you to love music better, because you will have seen its struggle with politics, religion and its critics, we leave you to read it—from cover to cover—we hope!

Our book has had friends other than its authors. It has, in fact, had makers as well as authors, so it cannot go out into the world without proclaiming its “thank-yous.” First it would thank Flora Bernstein, its indefatigable and patient typist, editor and general adviser, who worked night and day for many moons; second, it must thank Dorothy Lawton of the Music Library of the City of New York for her graceful but poignant criticism, and third it must thank Grace Bliss Stewart, who did some research and anything needed.

No one questions the need of histories of music. Few, however, define the need. It seems to be generally agreed that people ought to know something about the history of the principal arts. Who designed St. Peter’s, who painted the Descent from the Cross, who wrote The Faerie Queen and who composed the Ninth Symphony. These are things one ought to know. The reasons why one ought to know them are seldom made clear. But just at this time, when the word “appreciation” is so active in the world’s conversation, there should be little difficulty in separating from the mass of unformed comment at least one reason for acquaintance with the history of music.

No one can “appreciate” an art work without knowing its period, the state of the art in that period, the ideals and purposes of composers, the capacity of their public and the particular gifts and aims of the writer of the work under consideration. It is extremely difficult for any person to begin the study of “appreciation” after he is old enough to have acquired a stock of prejudices and burdened his mind with a heavy load of misconceptions. It is better to absorb good art, music or other, in the early years and to grow up with it than to try at 18 or 20 to put away childish things and understand Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion.”

Miss Bauer and Miss Peyser have written a history of music for young people. It is not for the kindergarten class and yet it is not out of the reach of mere children. It xiiis not for the seniors in a university and yet they might profit by examining it. The authors have surveyed the entire field. They have touched ancient music and the music of nations not usually considered in some more pretentious histories. They have apparently tried to give a bird’s-eye view of the art as practiced by all the civilized and some of the uncivilized races of the earth. With this in mind they have shown how the supreme art forms and the greatest art works developed among the western European peoples, who, it is interesting to note, produced also the metaphysical and philosophical bases of the world’s scientific thought, the mightiest inventions, and with all regard for Buddhistic poetry and speculation, the highest achievements in literature.

It seems to me that they have made a history of music singularly well adapted to young minds. They do not treat their readers as if they were infants—which might offend them—nor as college professors, which would certainly bore them. The book will undoubtedly have a large audience, for teachers of young music students, of whom there are legions, will surely exclaim: “This is just what we have needed.”

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| The Authors’ Greetings | vii | |

| Acknowledgments | ix | |

| Introduction, by W. J. Henderson | xi | |

| BABYHOOD OF MUSIC | ||

| CHAPTER | ||

| I.— | Music is Born—How, When and Where | 3 |

| II.— | The Savage Makes His Music | 8 |

| III.— | The Ancient Nations Made Their Music—Egyptian, Assyrian, and Hebrew | 20 |

| IV.— | The Greeks Lived Their Music—The Romans Used Greek Patterns | 31 |

| V.— | The Orientals Make Their Music—Chinese, Japanese, Siamese, Burmese, and Javanese | 46 |

| VI.— | The Arab Spreads Culture—The Gods Give Music to the Hindus | 55 |

| CHILDHOOD OF MUSIC | ||

| VII.— | What Church Music Imported from Greece | 67 |

| xiv | ||

| VIII.— | Troubadours and Minnesingers Brought Music to Kings and People | 87 |

| IX.— | The People Dance and Sing—Folk Music | 107 |

| X.— | National Portraits in Folk Music | 128 |

| MUSIC BECOMES A YOUTH | ||

| XI.— | Makers of Motets and Madrigals—Rise of Schools, 15th and 16th Centuries | 146 |

| XII.— | Music Gets a Reprimand—Reformation and Rebirth of Learning—How the Reforms Came to Be | 162 |

| XIII.— | Birth of Oratorio and Opera—Monteverde and Heart Music | 171 |

| XIV.— | Musicke in Merrie England | 187 |

| MUSIC COMES OF AGE | ||

| XV.— | Dance Tunes Grow Up—Suites—Violin Makers of Cremona | 208 |

| XVI.— | Opera in France—Lully and Rameau—Clavecin and Harpsichord Composers | 222 |

| XVII.— | Germany Enters—Organs, Organists and Organ Works | 235 |

| xv | ||

| MUSIC HAS GROWN UP | ||

| XVIII.— | Bach—The Giant | 244 |

| XIX.— | Handel and Gluck—Pathmakers | 255 |

| XX.— | “Papa” Haydn and Mozart—the Genius | 275 |

| XXI.— | Beethoven the Colossus | 293 |

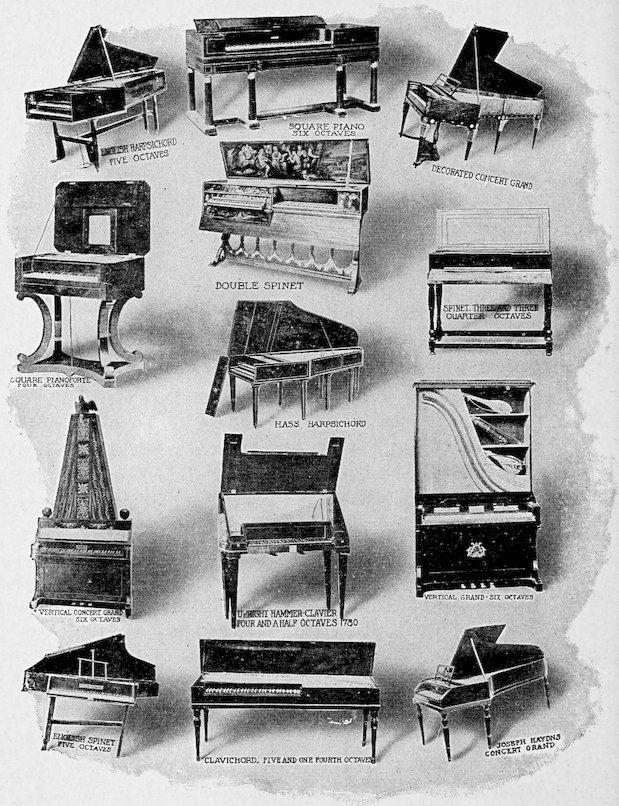

| XXII.— | The Pianoforte Grows Up—The Ancestry of the Pianoforte | 307 |

| XXIII.— | Opera Makers of France, Germany and Italy—1741 to Wagner | 326 |

| XXIV.— | The Poet Music Writers—Romantic School | 343 |

| XXV.— | Wagner—the Wizard | 359 |

| XXVI.— | More Opera Makers—Verdi and Meyerbeer to Our Day | 377 |

| XXVII.— | Some Tone Poets | 397 |

| XXVIII.— | Late 19th Century Composers Write New Music on Old Models | 418 |

| XXIX.— | Music Appears in National Costumes | 441 |

| XXX.— | America Enters | 456 |

| XXXI.— | America Comes of Age | 475 |

| XXXII.— | Twentieth Century Music | 515 |

| xvi | ||

| Some of the Books we Consulted | 547 | |

| Some Music Writers According to Forms of Composition | 551 | |

| Index | 587 | |

| FACING PAGE | |

|---|---|

| The Fifer | Frontispiece |

| Some Instruments of the American Indian | 20 |

| Hieroglyphics on an Egyptian Tablet | 21 |

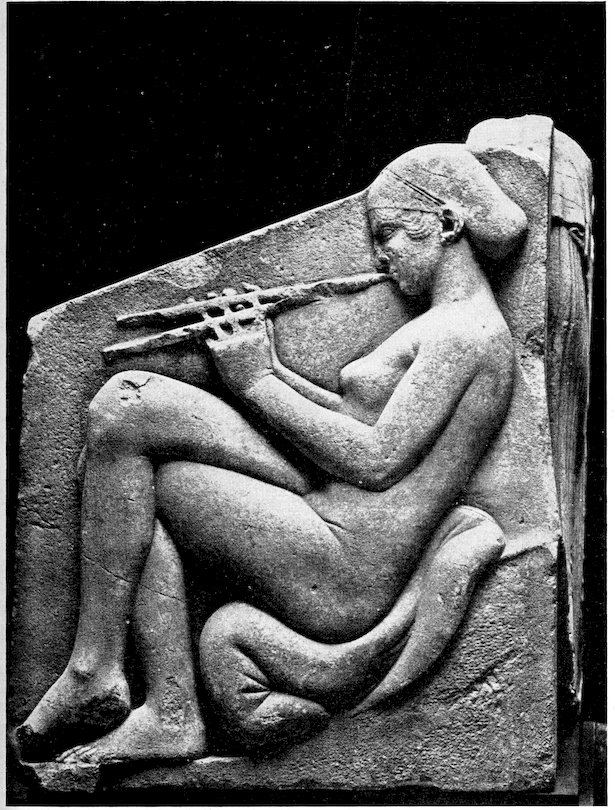

| Greek Girl Playing a Double Flute (Auloi) | 30 |

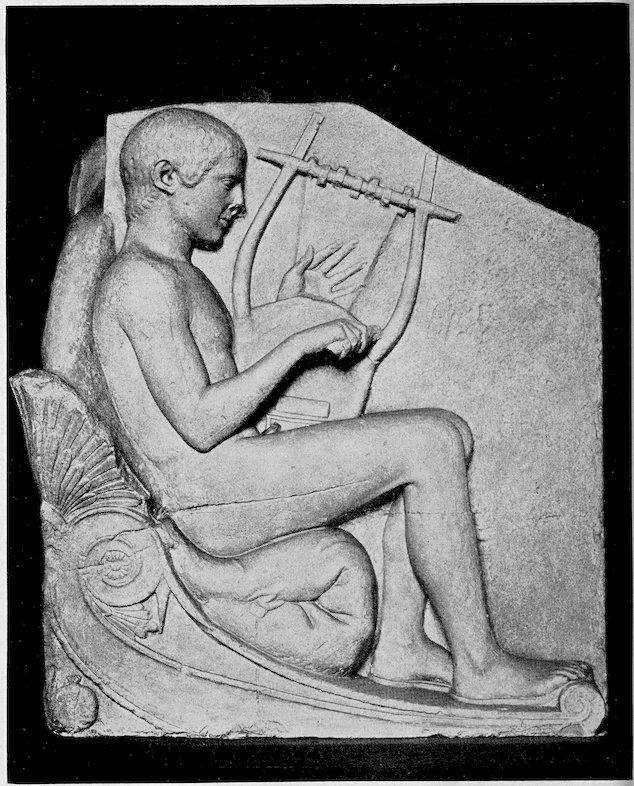

| Greek Boy Playing the Lyre | 31 |

| Chinese Instruments | 44 |

| Fiddles from Arabia, Japan, Corea and Siam | 45 |

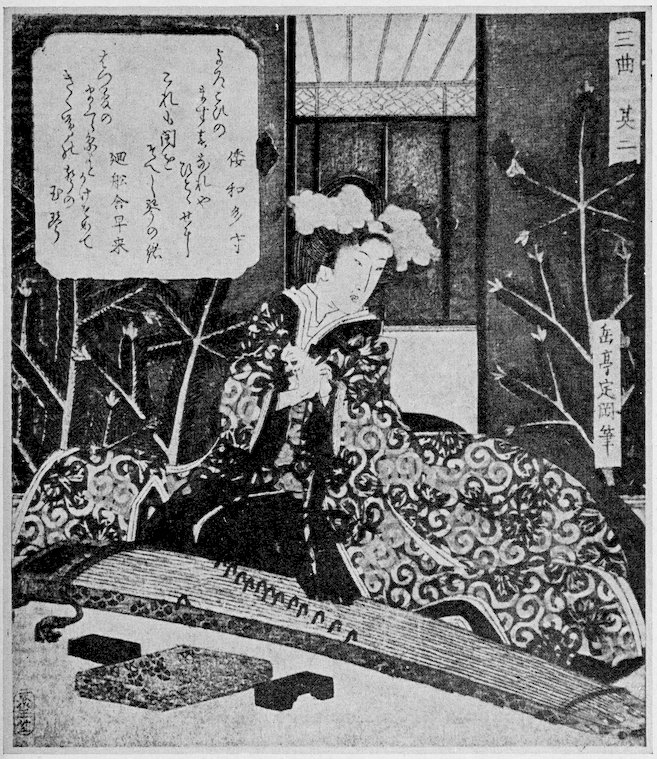

| The Koto-Player | 46 |

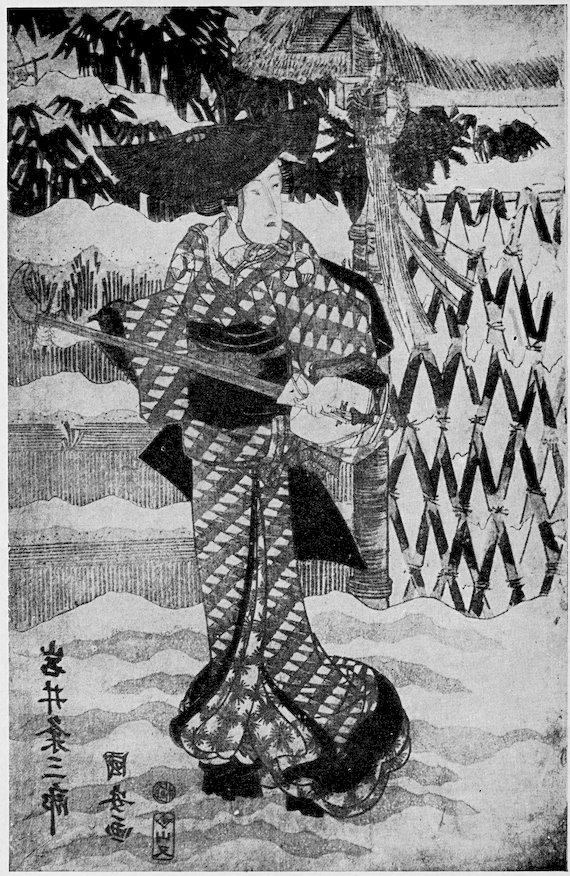

| The Wandering Samisen-Player | 47 |

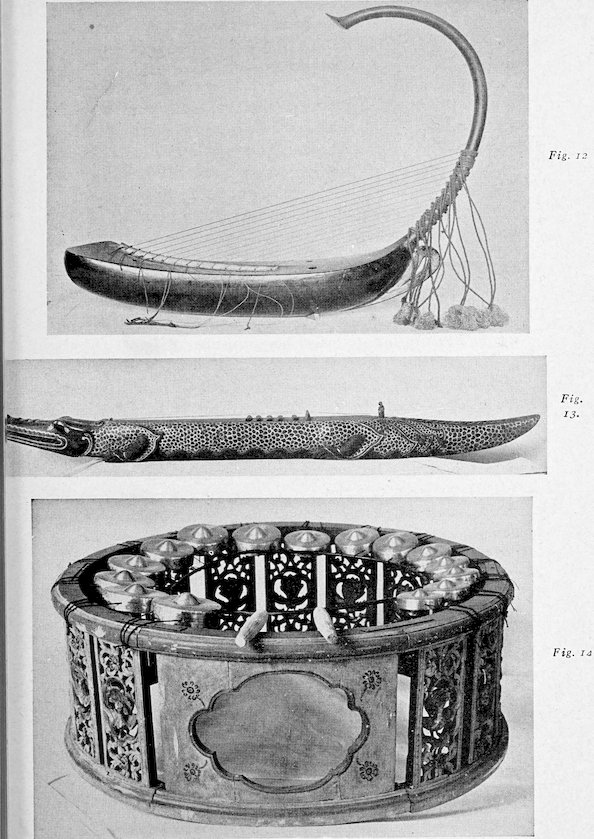

| Instruments of Burmah and Siam | 52 |

| A Burmese Musicale | 53 |

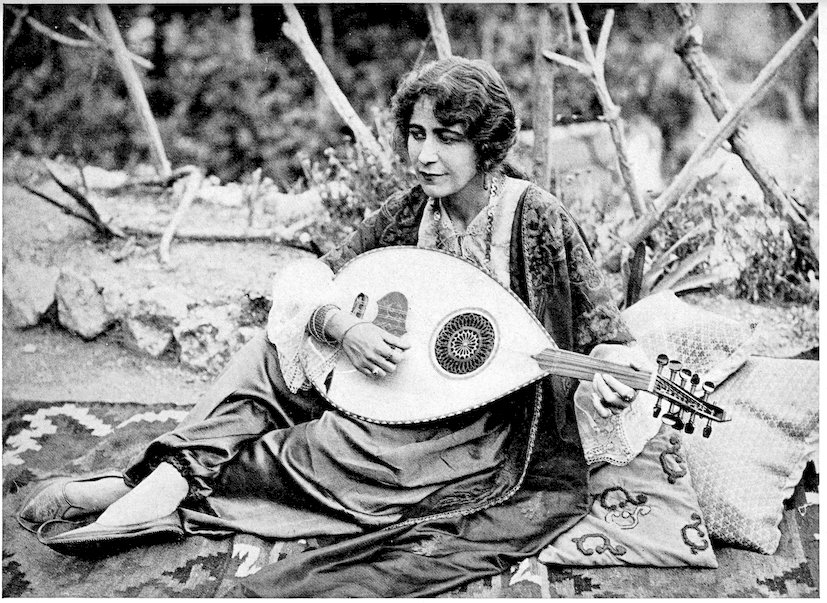

| Laura Williams, American Singer of Arab Songs | 58 |

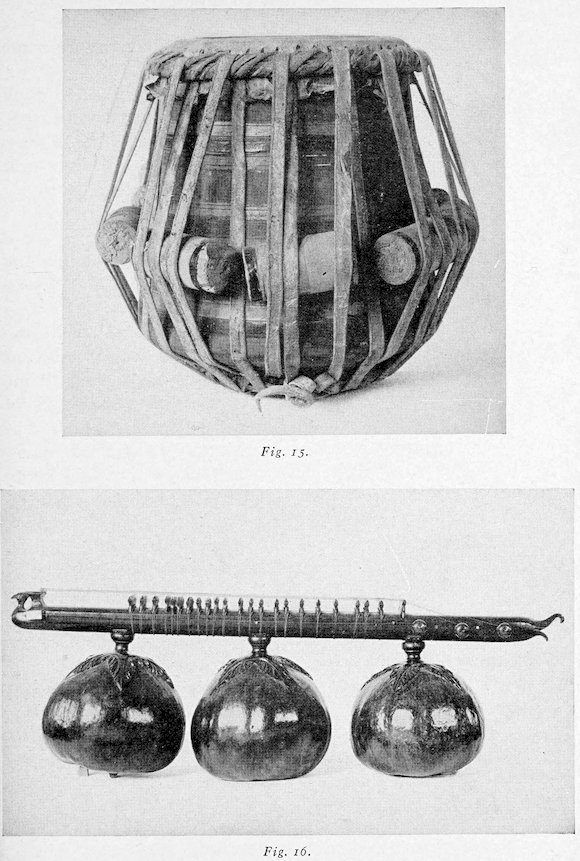

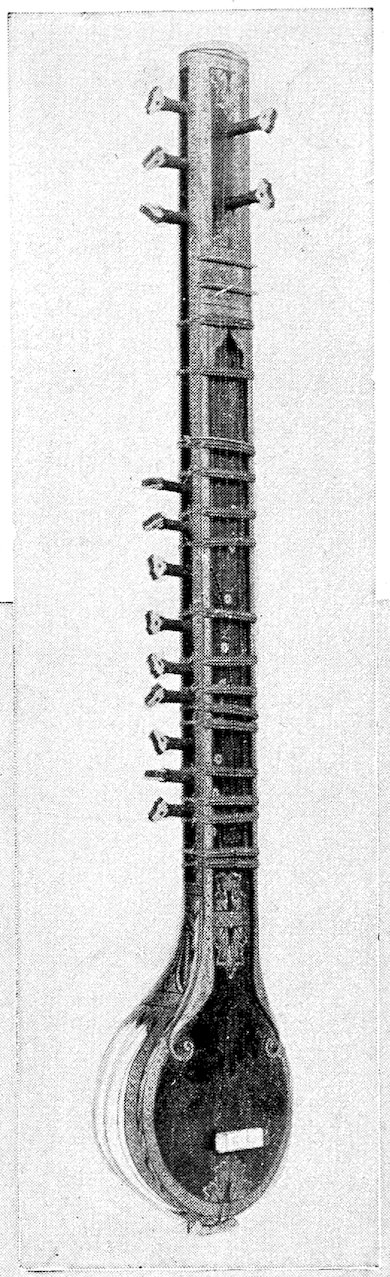

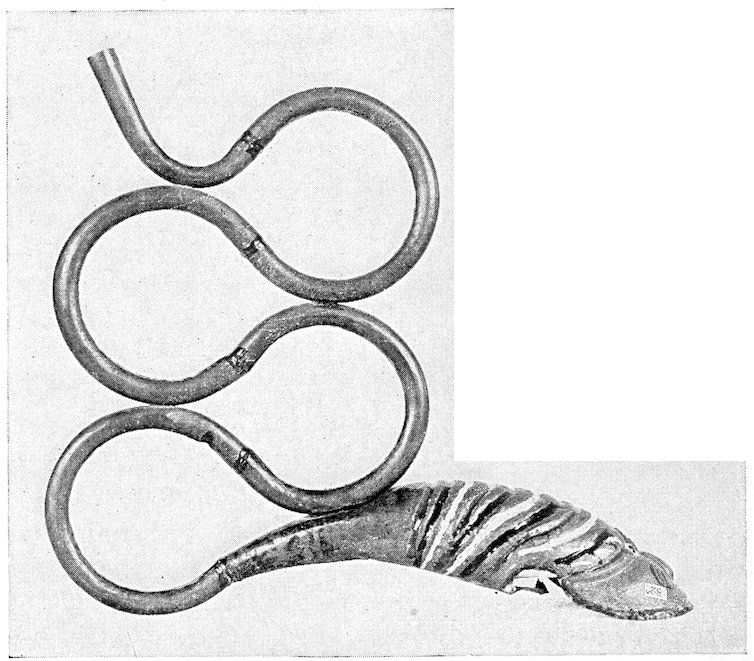

| Hindu Instruments 66, | 67 |

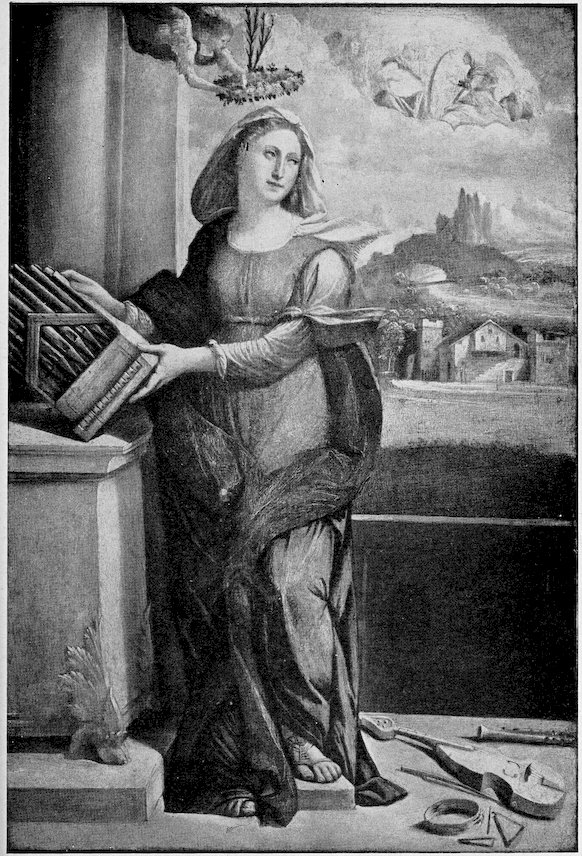

| St. Cecelia, Patron Saint of Music | 72 |

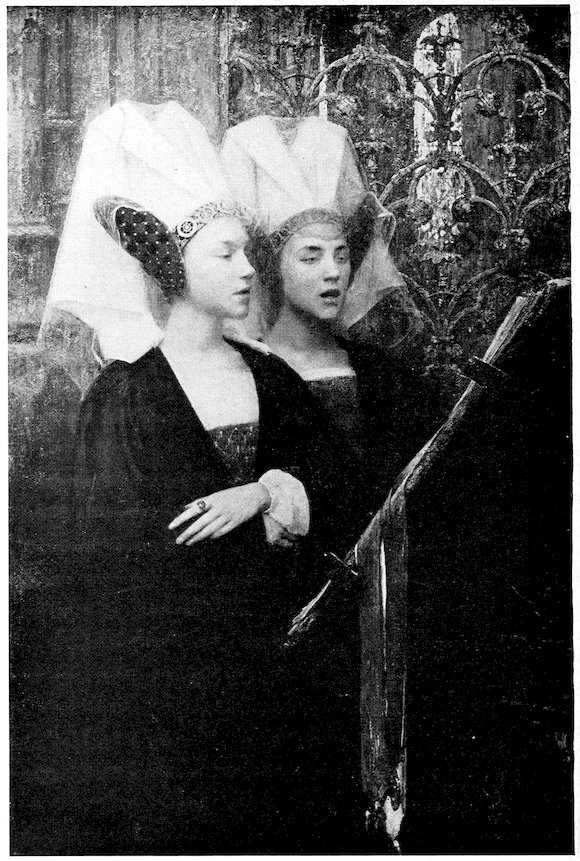

| The Book of Peace | 73 |

| Boys with a Lute | 128 |

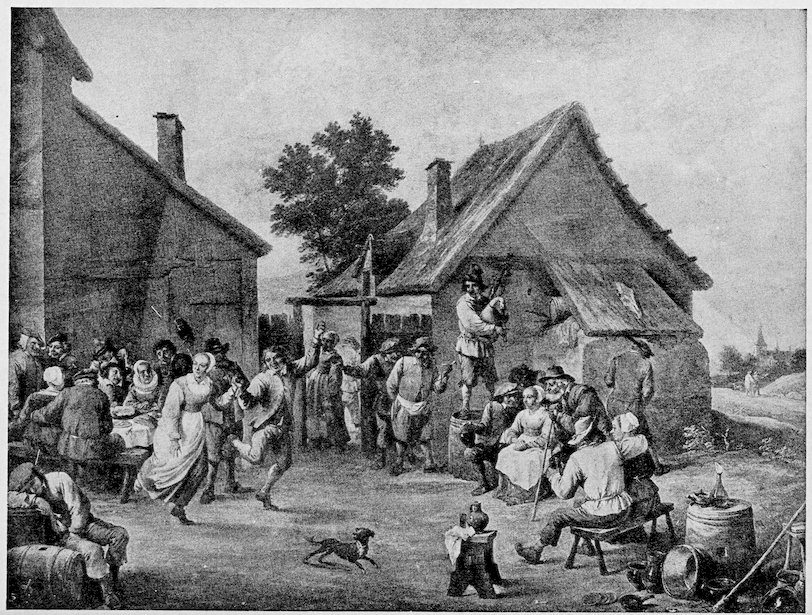

| A Peasant Wedding | 129 |

| A Lady at the Clavier (Clavichord) | 186 |

| xviiiA Lady Playing the Theorbo (Luth) | 187 |

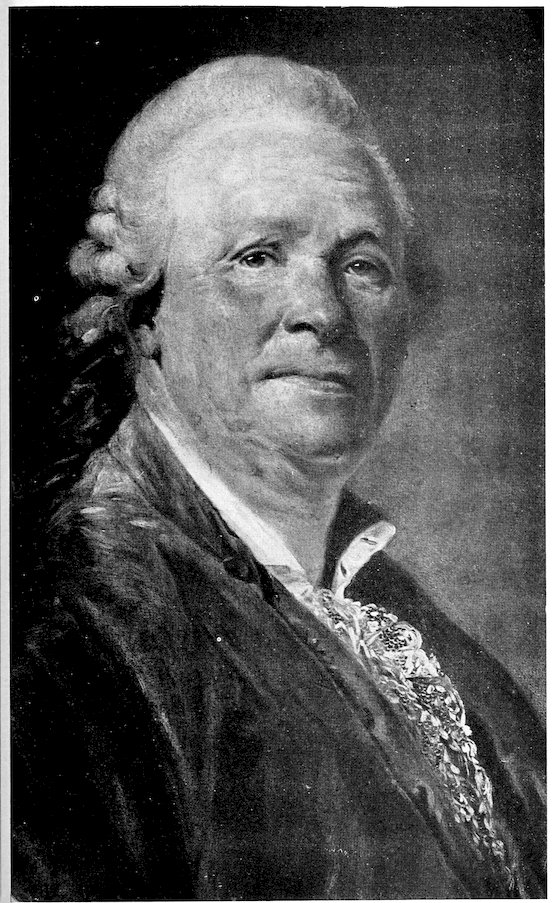

| Chevalier Christoph Willibald von Gluck | 274 |

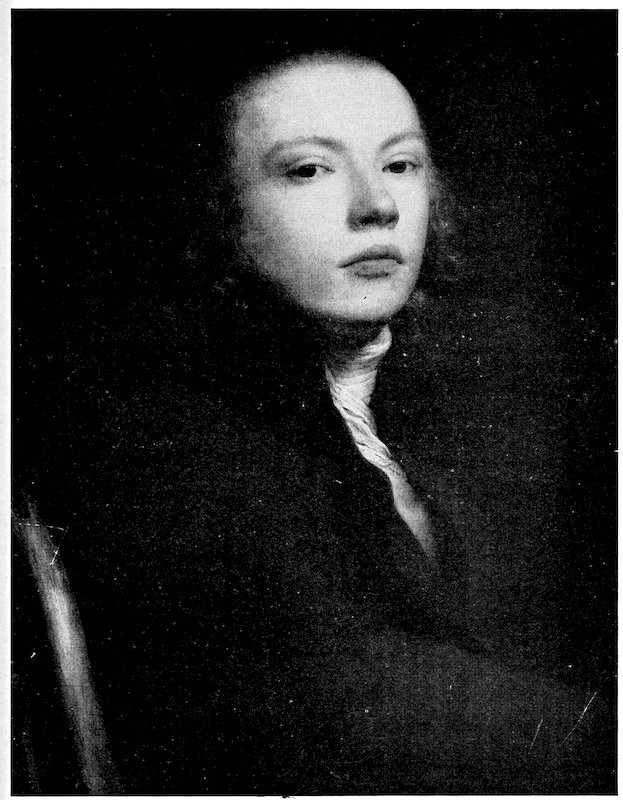

| The Boy Mozart | 275 |

| Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart | 292 |

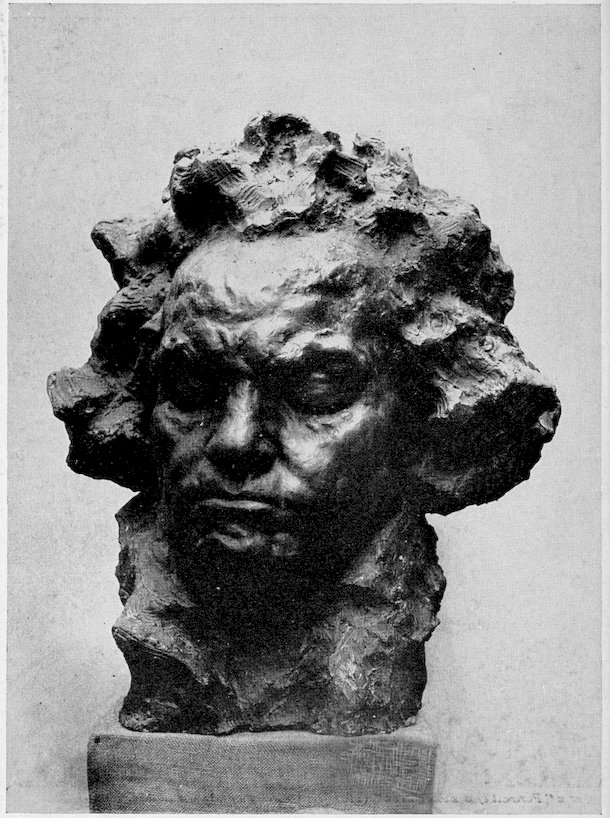

| Ludwig van Beethoven | 293 |

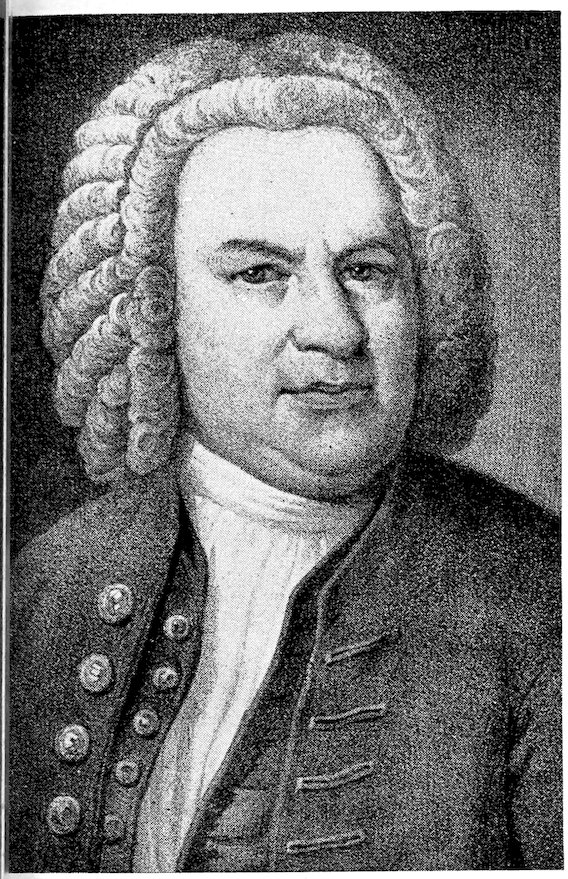

| Johann Sebastian Bach | 306 |

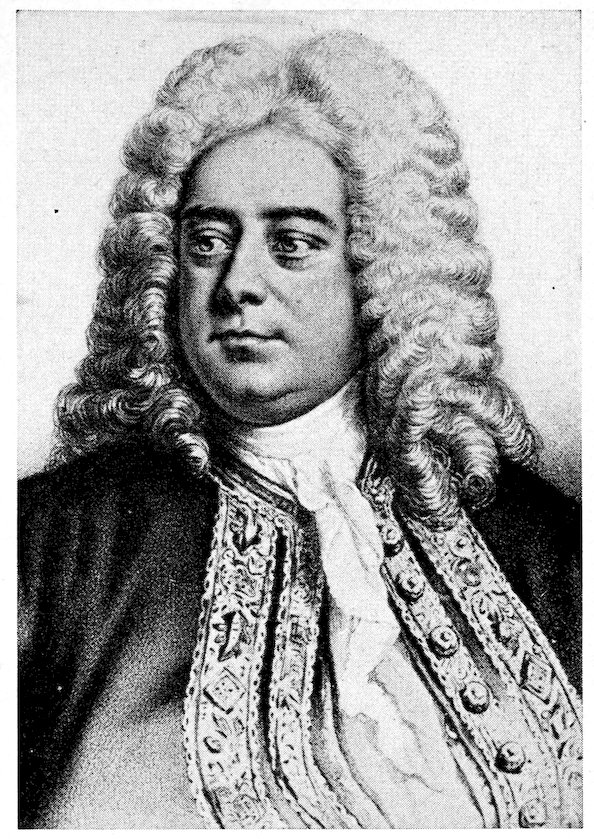

| George Frederick Handel | 306 |

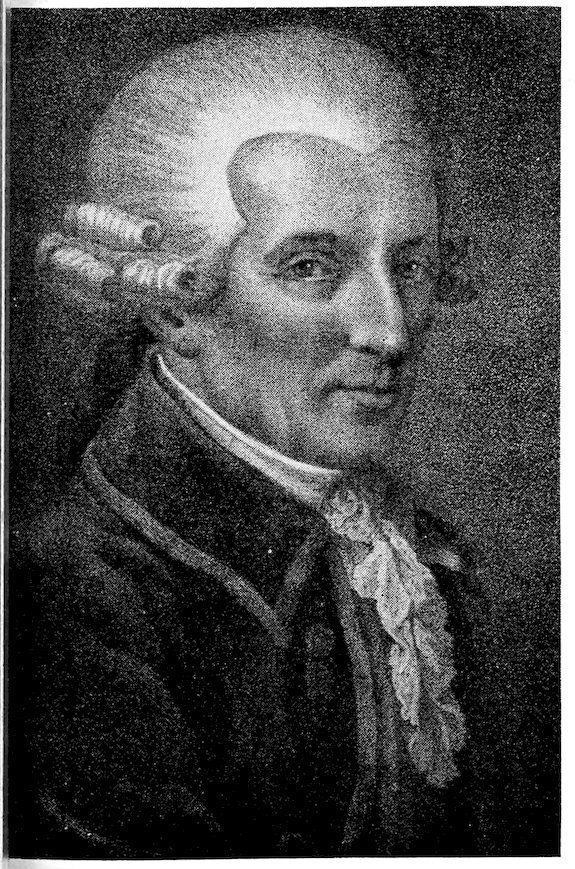

| Franz Josef Haydn | 306 |

| Carl Maria van Weber | 306 |

| The Piano and its Grand-parents | 307 |

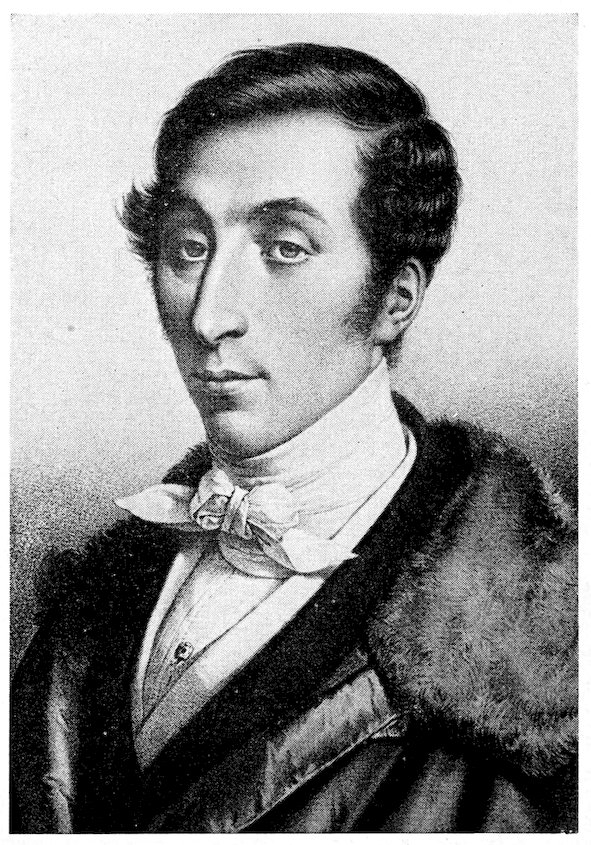

| Franz Schubert | 358 |

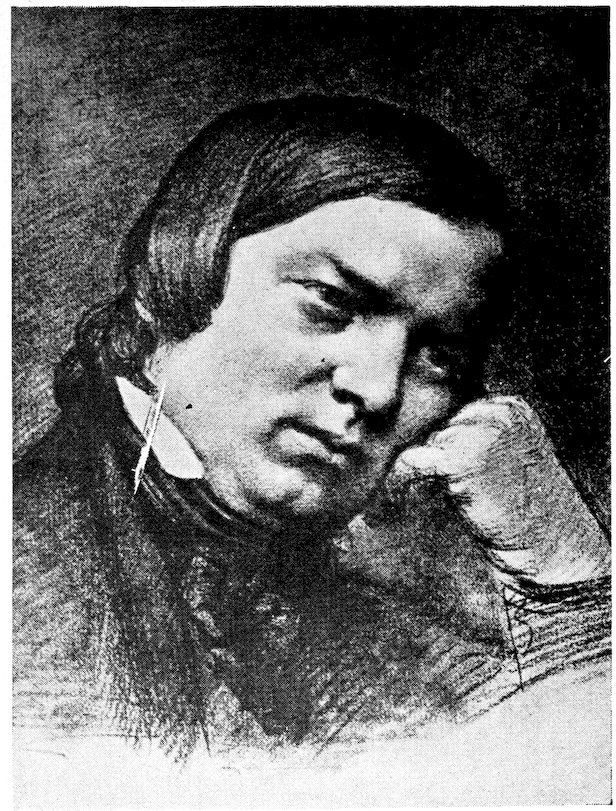

| Robert Schumann | 358 |

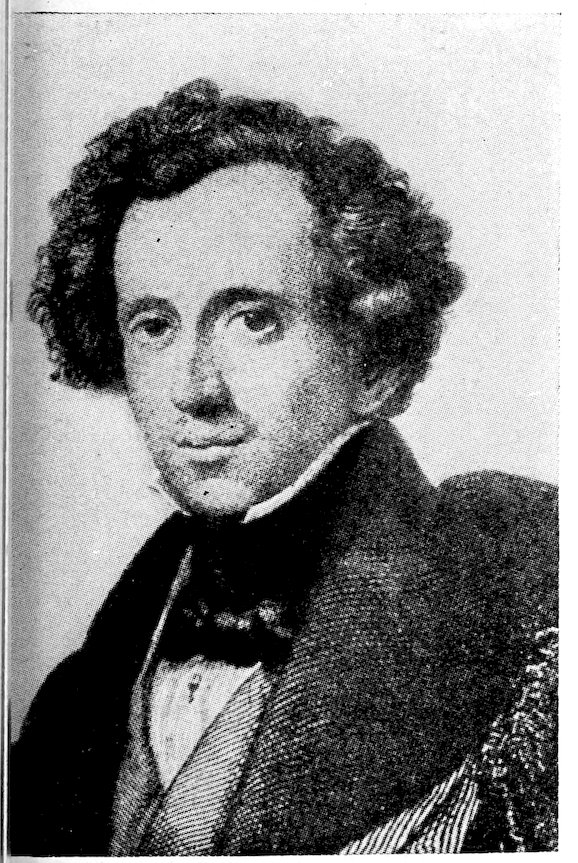

| Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy | 358 |

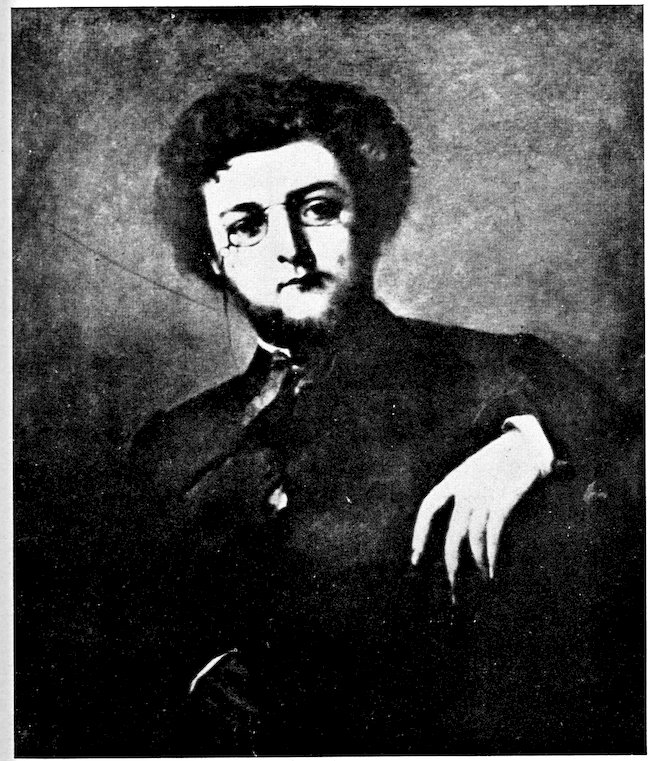

| Frédéric Chopin | 358 |

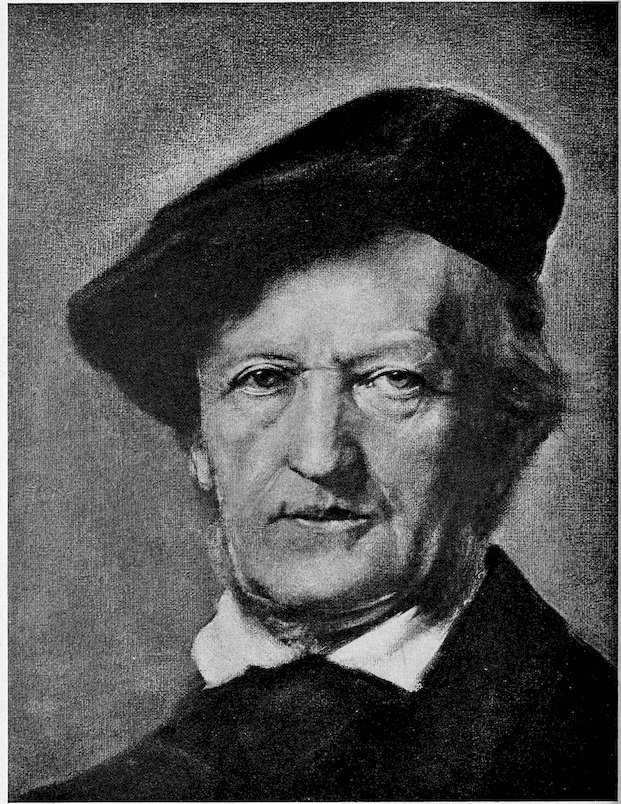

| Richard Wagner, the Wizard | 359 |

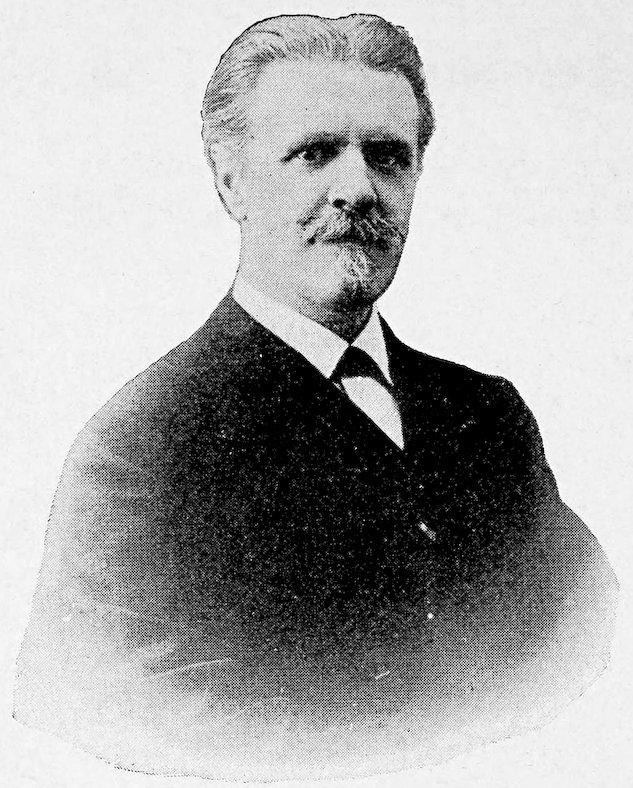

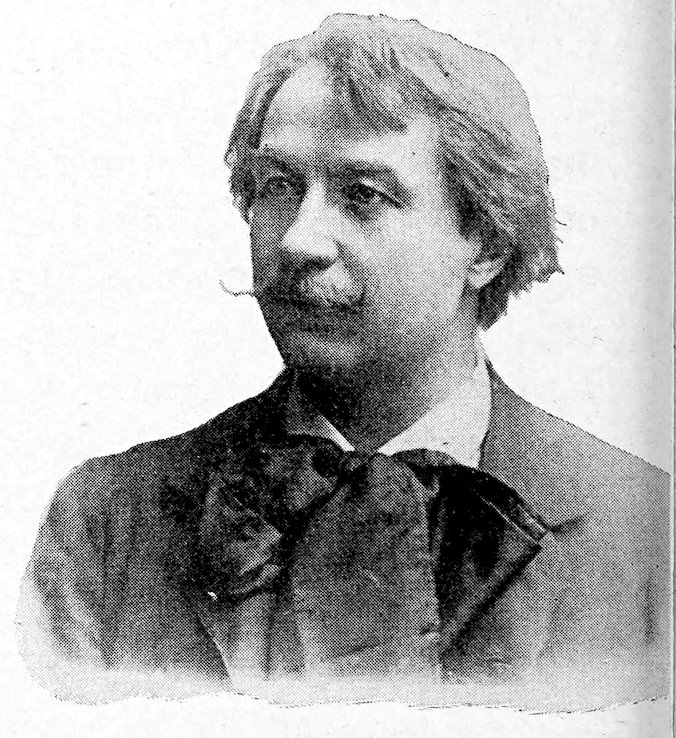

| Georges Bizet | 388 |

| Vincent d’Indy | 389 |

| Camille Saint-Saëns | 389 |

| Jules Massenet | 389 |

| Gustave Charpentier | 389 |

| Hector Berlioz | 402 |

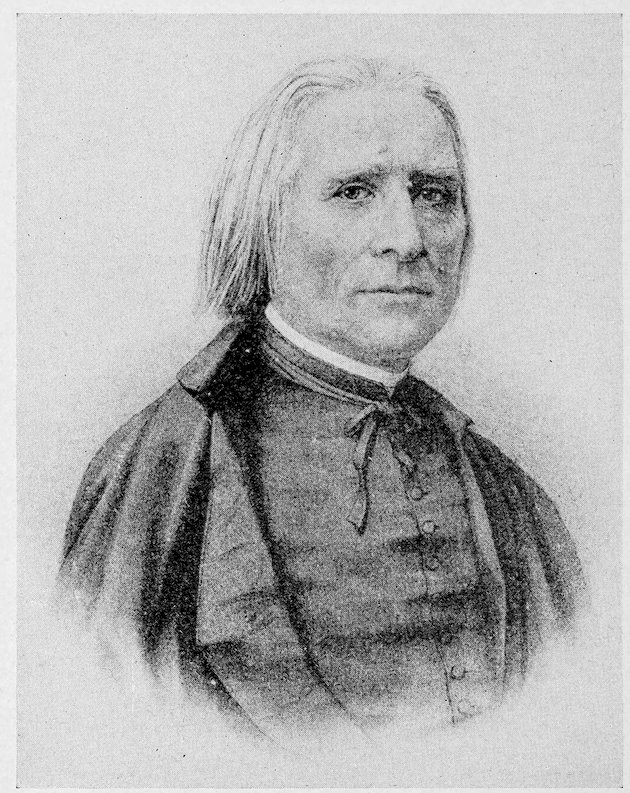

| Franz Liszt | 403 |

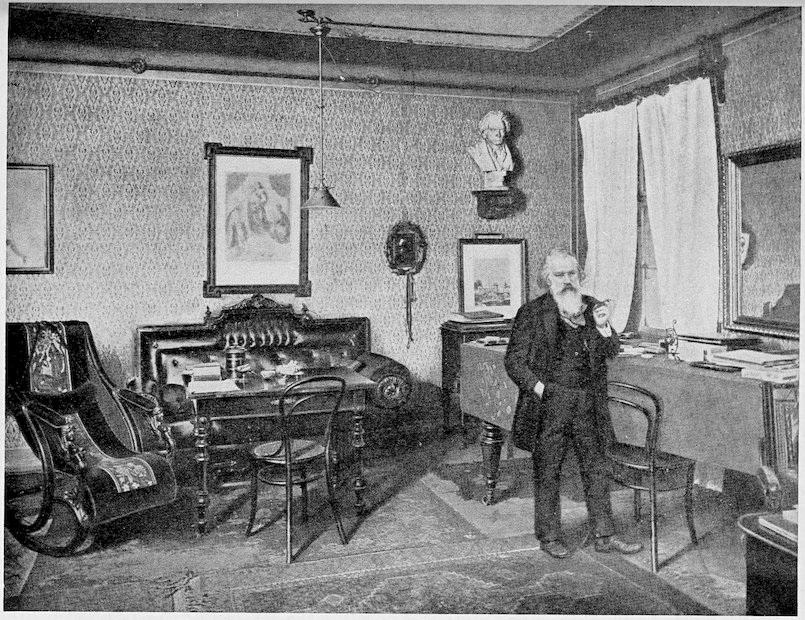

| Johannes Brahms at Home | 418 |

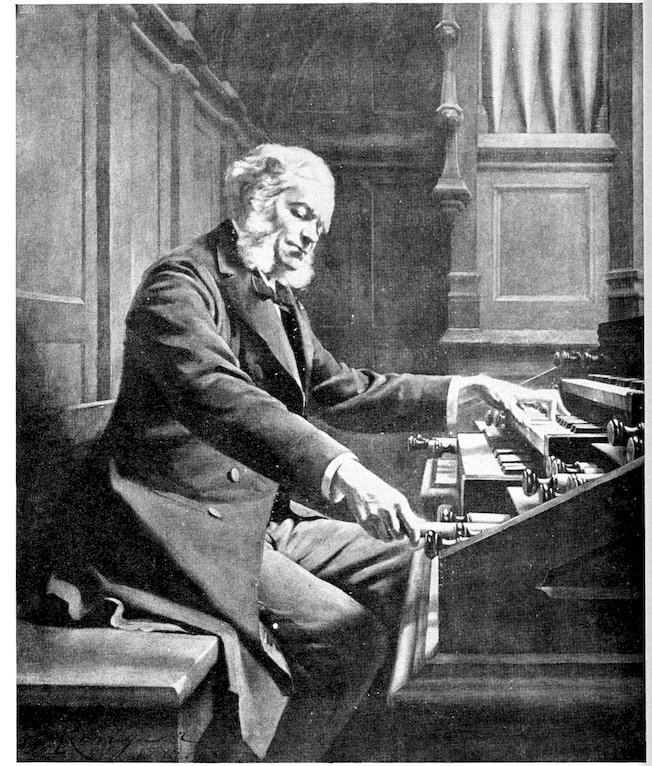

| xixCésar Franck | 419 |

| Edward MacDowell | 492 |

| Charles Griffes | 493 |

| Claude Achille Debussy | 516 |

| Maurice Ravel | 516 |

| Arnold Schoenberg | 517 |

| Igor Stravinsky | 517 |

| Arthur Honegger | 538 |

| Darius Milhaud | 538 |

| Béla Bartók | 538 |

| Louis Gruenberg | 538 |

| G. Francesco Malipiero | 539 |

| Alfredo Casella | 539 |

| Arnold Bax | 539 |

| Eugene Goossens | 539 |

There was once a time when children did not have to go to school, for there were no schools; they did not have to take music lessons because there was no music; there was not even a language by which people could talk to each other, and there were no books and no pencils. There were no churches then, no homes nor cities, no railroads, no roads in fact, and the oldest and wisest man knew less than a little child of today.

Step by step men fought their way to find means of speaking to each other, to make roads to travel on, houses to live in, fire to cook with, clothes to wear, and ways to amuse themselves.

During this time, over one hundred thousand years ago, called “prehistoric” because it was before events were recorded, men had to struggle with things that no longer bother us.

Picture to yourselves this era when people lived out-of-doors, in mounds and caves surrounded by wild beasts which 4though dangerous, were not much more so than their human neighbors. Remember, too, that these people did not know that light followed darkness as the day the night; summer followed winter as the seasons come and go; that trees lost their leaves only to bear new ones in the spring, and that lightning and thunder were natural happenings; and so on through the long list of things that we think today perfectly simple, and not in the least frightening.

Because they did not understand these natural things, they thought that trees, sun, rain, animals, birds, fire, birth, death, marriage, the hunt, caves and everything else had good and bad gods in them. In order to please these gods they made prayers to them quite different from our prayers, as they danced, sang and acted the things they wanted to have happen. When a savage wanted sun or wind or rain, he called his tribe together and danced a sun dance, or a wind dance, or a rain dance. When he wanted food, he did not pray for it, but he acted out the hunt in a bear dance. As the centuries went by they continued to use these dances as prayers, and later they became what we call religious rites and festivals. So here you see actually the beginning of what we know as Easter festivals, Christmas with its Christmas tree and mistletoe, spring festivals and Maypole dances with the Queen of the May, Hallowe’en and many other holiday celebrations.

This is how music, dancing, poetry, painting and drama were born. They were the means by which primitive men talked to their gods. This they did, to be sure, very simply, by hand-clapping and foot-stamping, by swaying their bodies to and fro, by shouting, shrieking, grunting, crying and sobbing, and as soon as they knew enough, used language, and repeated the same word over and over again. These movements and sounds were the two roots from which music grew.

If you can call these queer grunts and yells singing, the 5men of those far-off days must have sung even before they had a language, in fact, it must have been difficult to know whether they were singing or talking. In these cries of joy, sorrow, pain, rage, fear, or revenge, we find another very important reason for the growth of music. These exclamations, however barbaric and rough, were man’s first attempt at expressing his feelings.

We still look upon music as one of the most satisfying ways to show our emotions, and the whole story of music from prehistoric times to the present day is a record of human feelings expressed in rhythm and melody.

Gradually these early men learned to make not only musical instruments, but also the knife for hunting and utensils for cooking. The first step towards a musical instrument was doubtless the striking together of two pieces of wood or stone in repeated beats. The next step was the stretching of the skin of an animal over a hollowed-out stone or tree trunk forming the first drum. Another simple and very useful instrument was made of a gourd (the dried hollow rind of a melon-like fruit) filled with pebbles and shaken like a baby’s rattle.

As early in the story of mankind as this, the love of decoration and need of beauty were so natural that they decorated their bodies, the walls of their caves, and their everyday tools with designs in carving, and in colors made from earth and plants. You can see some of these utensils and knives, even bits of wall pictures, in many of the museums in collections made by men who dig up old cities and sections of the countries where prehistoric peoples lived. These men are called archaeologists, and devote their lives to this work so that we may know what happened before history began.

A few years ago tools of flint, utensils made of bone, and skeletons of huge animals, that no longer exist, were found in a sulphur spring in Oklahoma; pottery and tools of stone, wood, and shell were dug up in Arizona; carvings, spear 6heads, arrow points, polished stone hatchets and articles of stone and ivory in Georgia, Pennsylvania and the Potomac Valley. This shows that this continent also had been inhabited by prehistoric people.

Even as we see prehistoric man using the things of nature for his tools, such as elephant tusks, flint, and wood; and as we see him making paint from earth and plants, we also see him getting music from nature. It would have been impossible for these early men and children to have lived out-of-doors and not to have listened to the songs of the birds, the sound of wind through the trees, the waves against the rocks, the trickling water of brooks, the beat of the rain, the crashing of thunder and the cries and roars of animals. All of these sounds of nature they imitated in their songs and also the motions and play of animals in their dances.

In Kamchatka, the peninsula across the Behring Strait from Alaska, there still live natives who sing songs named for and mimicking the cries of their wild ducks.

The natives of Australia, which is the home of the amusing-looking kangaroo, have a dance in which they imitate the peculiar leaps and motions of this animal. When you recall its funny long hind legs and short forelegs, you can imagine how entertaining it would be to imitate its motions. The natives also try to make the same sounds with their voices, as the kangaroo. The women accompany these dances by singing a simple tune of four tones over and over, knocking two pieces of wood together to keep time. If ever you go to the Australian bush (woods or forests) you will see this kangaroo dance. This is different, isn’t it, from sitting in a concert hall and listening to some great musician who has spent his life in hard work and study so that he may play or sing for you?

We can learn much about the beginnings of music from tribes of men who, although living today, are very near the birthday of the world, so far as their knowledge and habits are concerned.

7Primitive men love play; they love to jump, to yell, to fling their arms and legs about, and to make up stories which they act out, as children do who “make believe.”

This love of mankind for make believe, and his desire to be amused, along with his natural instinct to express what he feels, are the roots from which music has grown. But, of course, in prehistoric times, men did not know that they were making an art, for they were only uttering in sound and movement their wants, their needs, in fact, only expressing their daily life and their belief in God.

Fortunately for our story there live groups of people today still in the early stages of civilization who show us the manners and customs of primitive man, because they are primitive men themselves.

We are going to learn how music grew from the American Indian and the African. We are using these two as examples for two reasons: because they are close enough to us to have influenced our own American music, and because all savage music has similar traits. The American Indian and the African show us the steps from the primitive state of music to the beginning of music as an art. In other words, these people are a bridge between prehistoric music and that of the civilized world.

In Chapter I about prehistoric man, we spoke of the two roots of music—movement and sound. Hereafter when we speak of rhythm it will mean movement either in tones or in gestures. Rhythm expressed in tones makes music; rhythm expressed in gestures makes the dance. The reason we like dance music and marches is that we feel the rhythm, the thing that makes us want to mark the beat of the music with our feet, or hands, or with head bobbings. This love of the beat is strong in the savage, and upon this he builds his music.

Our American Jazz is the result of our desire for strong rhythms and shows that we, for all our culture, have something in us of the savage’s feeling for movement.

We have a name for everything, but the American Indian has a name and a song for everything. He has a song for his moccasins, for his head-gear, for his teepee, the fire in it, the forest around him, the lakes and rivers in which he fishes and paddles, for his canoe, for the fish he catches, for his gods, his friends, his family, his enemies, the animal he hunts, the maiden he woos, the stars, the sun, and the moon, in fact for everything imaginable. The following little story will explain the Indians’ idea of the use of their songs:

An American visitor who was making a collection of Indian songs, asked an old Ojibway song-leader to sing a hunting song. The old Indian looked at him in surprise and left him. A little later the son-in-law of the Indian appeared and with apologies told the American that “the old gentleman” could not sing a hunting song because it was not the hunting season.

The next time the old Indian came, the American asked him for a love song, but he politely refused, saying that it was not dignified for a man of his age to sing love songs. However, the old warrior suddenly decided that as he was making a call, it was quite proper for him to sing Visiting Songs, which he did, to his host’s delight.

This old man had been taught to sing when he was a very little boy, as the Indian boy learns the history of his tribe through the songs. He is carefully trained by the old men and women so that no song of the tribe or family should be forgotten. These songs are handed down from one family to another, and no one knows how many hundreds of years old they may be. So, you see, these songs become history and the young Indians learn their history this way, not as we do, from text books.

“What new songs did you learn?” is the question that 10one Indian will ask of another who has been away on a visit, and like the announcer at the radio broadcasting station, the Indian answers:

“My friends, I will now sing you a song of—” and he fully describes the song. Then he sings it. After he finishes, he says, “My friends, I have sung you the song of—” and repeats the name of the song!

So great a part of an Indian’s life is music, that he has no word meaning poetry in his language. Poetry to the Indian is always song. In fact an Indian puts new words to an old tune and thinks he has invented a new song.

When the Indian sings, he starts on the highest tone he can reach and gradually drops to the lowest, so that many of his songs cover almost two octaves. He does not know that he sings in a scale of five tones. For some reason which we cannot explain, most primitive races have used this same scale. It is like our five black keys on the piano, starting with F sharp. This is called the pentatonic scale, (penta, Greek word for five, tonic meaning tones). This scale is a most amazing traveler, for we meet it in our musical journeys in China, Japan, Arabia, Scotland, Africa, Ireland, ancient Peru and Mexico, Greece and many other places. The reason we find these five tones popular must be because they are natural for the human throat. At any rate we know that it is difficult for the Indian to sing our scale. He does not seem to want the two notes that we use between the two groups of black keys which make our familiar major scale.

It is very difficult to put down an Indian song in our musical writing, because, the Indians sing in a natural scale that has not been changed by centuries of musical learning. They sing in a rhythm that seems complicated 11to our ears in spite of all our musical knowledge, and this, too, is difficult to write down. Another thing which makes it hard to set down and to imitate Indian music, is that they beat the drum in different time from the song which they sing. They seldom strike the drum and sing a tone at the same time. In fact, the drum and the voice seem to race with each other. At the beginning of a song, for example, the drum beat is slower than the voice. Gradually the drum catches up with the voice and for a few measures they run along together. The drum gains and wins the race, because it is played faster than the voice sings. The curious part of it is, that this is not an accident, but every time they sing the same song, the race is run the same way. We are trained to count the beats and sing beat for beat, measure for measure with the drum. Try to beat on a drum and sing, and see how hard it is not to keep time with it.

The Indian slides from tone to tone; he scoops with his voice, somewhat like the jazz trombone player.

The Indian’s orchestra is made up of the rattle and the drum. The white man cannot understand the Indian’s love of his drum. However, when he lives among them he also learns to love it. When Indians travel, they carry with them a drum which is hidden from the eyes of the strange white man. When night comes, they have song contests accompanied by the drum which is taken out of its hiding place.

These contests are very real to the Indians and they are similar to the tournaments held in Germany in the Middle Ages.

The drummer, who is also the singer, is called the leading voice and is so important that he ranks next to the chief. 12His rank is high, because through knowing the songs he is the historian of his tribe.

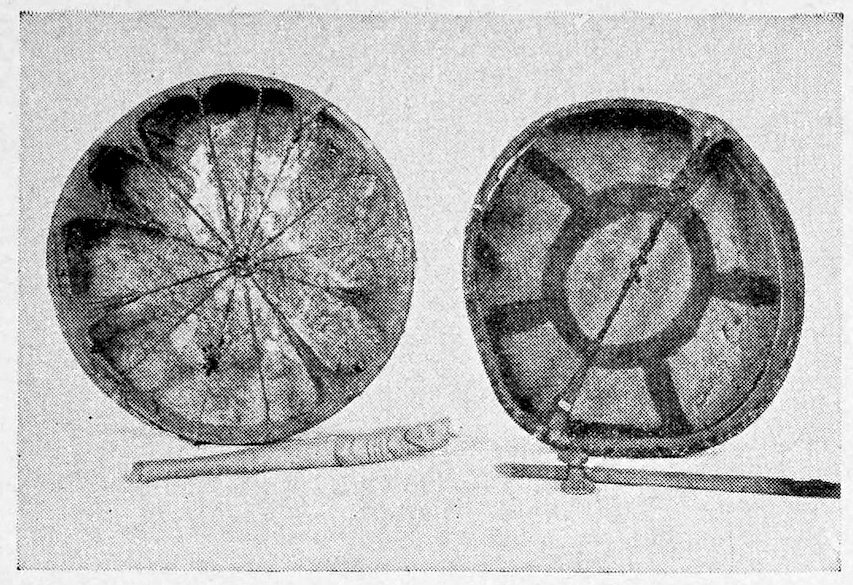

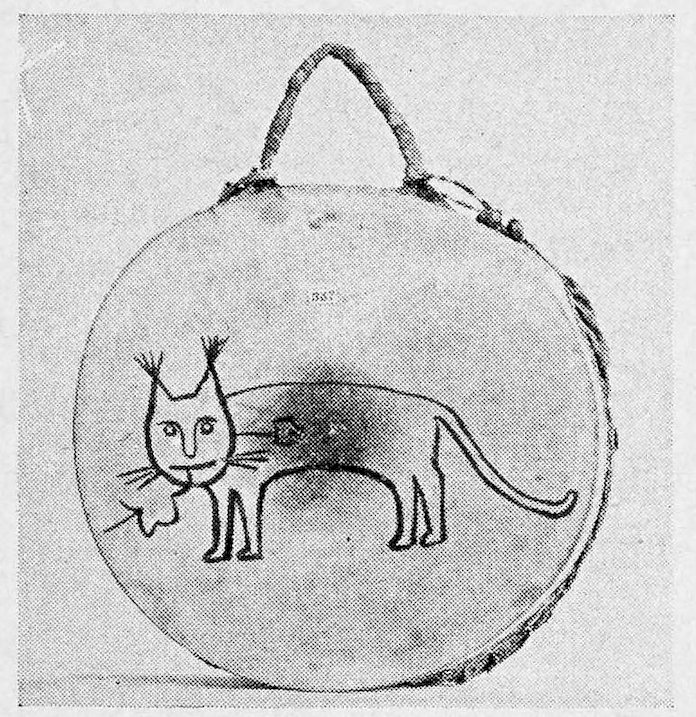

The drum is made of a wooden frame across which is stretched the skin of an animal, usually a deer. Sometimes it is only a few inches across, and sometimes it is two feet in diameter. When it has two surfaces of skins, they are separated four to six inches from each other. It is held in the left hand by a leather strap attached to the drum frame, and beaten with a short stick. (Figure 1.)

The Sioux Indian sets his drum on the ground; it is about the size of a wash tub and has only one surface. Two or more players pound this drum at the same time and the noise is often deafening. The Ojibway drum always has two surfaces and is usually decorated with gay designs in color. (Sioux drum, Figure 2.)

The drum makes a good weather bureau! The Indian often forecasts the weather by the way his drum answers to his pounding. If the sound is dull, he knows there is rain in the air, if it is clear and sharp and the skin is tight, he can have out-door dances without fear of a wetting. You could almost become a weather prophet yourself by watching the strings of your tennis racket, which act very much like the drum skin.

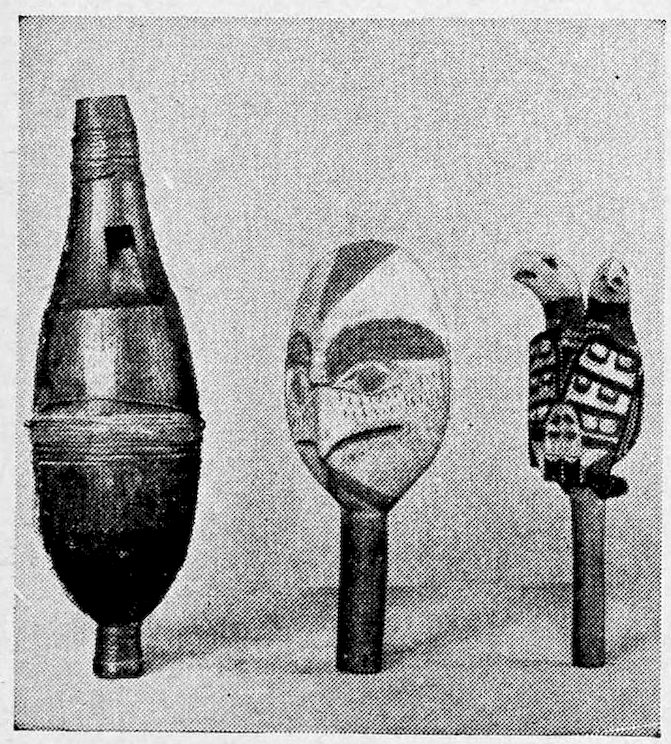

Another instrument beloved of all Indians is the rattle. There are many different sizes and shapes of rattles made of gourds, horns of animals and tiny drums filled with pebbles and shot. Some of them are carved out of wood in the shape of birds and animal heads. (Figure 3.)

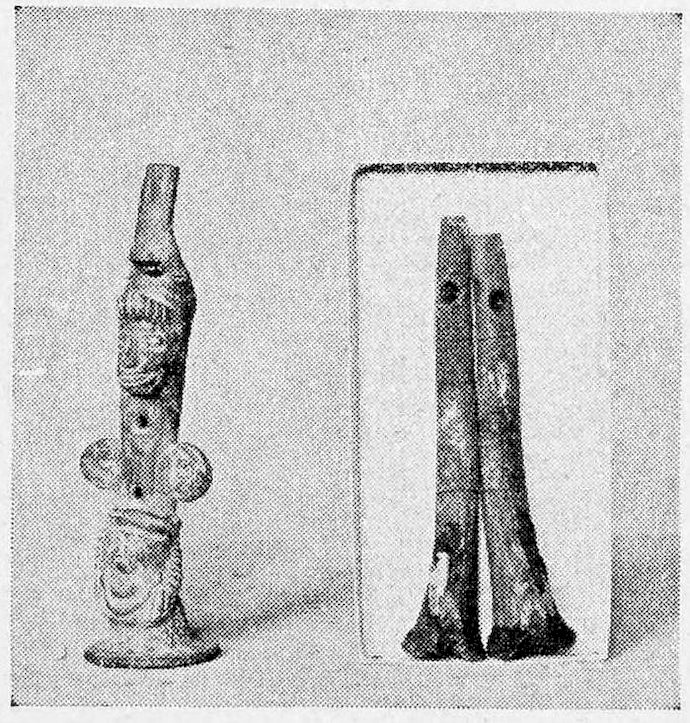

The Indians also have the flute, and although there is no special music for it, it is of great importance in their lives. No two flutes are made to play exactly the same tones, that is, they are not drawn to scale. They are like home-whittled whistles made of wood in which holes are burned. (Figure 4.)

The flute is never used in the festivals or in the dance 13but it is the lover’s instrument. A young man who is too bashful to ask his sweetheart to marry him, hides among the bushes near her teepee, close to the spring where she goes every morning for water. When he sees her, he plays a little tune that he makes up just for her. Being a well brought up little Indian maid, she pretends not to notice it, but very soon tries to find out who played to her. If she likes him, she gives him a sign and he comes out of his hiding place, but if she does not wish to marry him, she lets him go on playing every morning until he gets tired and discouraged and returns no more to the loved spring near her teepee in the early morning.

And this is the reason the Indian love songs so often refer to sunrise, spring and fountains, and why we use the melancholy flute when we write Indian love songs.

Because of the ceaseless beating of the drum, the constant repetition of their scale of five tones, and the rambling effect of the music like unpunctuated sentences, we find the Indian music very monotonous. But they return the compliment and find our music monotonous, probably, because it is too well punctuated. Mr. Frederick Burton in his book on Primitive American Music, tells of having given to two Indian friends tickets for a recital in Carnegie Hall, in New York City, where they heard songs by Schubert and Schumann. When he asked them how they enjoyed the music they politely said, “It is undoubtedly very fine, it was a beautiful hall and the man had a great voice, but it seemed to us as though he sang the song over, over and over again, only sometimes he made it long and sometimes short.”

The Indian is a great club man; every Indian belongs to some society. The society which he joins is decided by 14what he dreams. If he dreams of a bear, he joins the Bear Society; if he dreams of a Buffalo, he joins the Buffalo Society. Other names of clubs are: Thunder-bird, Elks and Wolves.

Dreams play a great part in the Indian’s life. If he dreams of a small round stone, a sacred thing to him, he is supposed to have the power to cure sickness, to foretell future events, to tell where objects are which cannot be seen.

Every one of the societies or clubs has its own special songs. The Indians also have songs of games, dances, songs of war and of the hunt, songs celebrating the deeds of chiefs, conquering warriors, war-path and council songs.

In the first chapter we spoke of primitive man imitating animals and here we find that the Indians, in their societies named for animals, imitate the acts of the clubs’ namesakes.

They have a dance called the grass dance, in which they decorate their belts with long tufts of grass, a reminder of the days when they wore scalps on their belts after they had been on the “war-path.” In this dance they imitate the motions of the eagle and other birds. Even the feathers used in their head-dress is a part of their custom of imitating animals and birds. Some of these head-dresses are like the comb, and the Indian who wears this will imitate the cries of the bird to which the comb belongs. His actions always correspond with his costume.

The Indians have lullabies and children’s game-songs,—the moccasin game, in which they search for sticks hidden in a moccasin. Then too, there is the Rain Dance of the Junis and the Snake Dance of the Hopis, in which they carry rattlesnakes, sometimes holding them between the teeth.

Dance often means a ceremony lasting several days. The Indians are worshippers of the Sun, and have a festival, which lasts several days, called the Sun Dance. This 15festival took place particularly among the Indians of the plains: the Cheyennes, the Chippewas and others. The last Sun Dance took place in 1882. In this the Indian offered to the “Great Spirit” what was strongest in his nature and training,—the ability to stand pain. Self inflicted pain was a part of the ceremony and seemed noble to the Indian, but to the white man it was barbarous and heathenish and he put a stop to it.

Have you ever heard of the medicine man? He is doctor, lawyer, priest, philosopher, botanist, and musician all in one. The society of “Grand Medicine” is the religion of the Chippewas. It teaches that one must be good to live long. The chief aims of the society are to bring good health and long life to its followers, and music is as important in the healing as medicine.

Every member of the society carries a bag of herbs, the use of which he has learned, and if called upon to heal the sick, he works the cure by singing the right song before giving the medicine. The medicine is not usually swallowed in proper fashion as a child takes a dose, but it is carried by the sick person, or is placed among his belongings, or a little wooden figure is carved roughly by the Medicine Man and must be carried around with the herbs to heal the patient. But the song, and it must be the right song for the occasion, counts as much as the medicine. Wouldn’t you like to be an Indian?

Often the Medicine Man is called upon for a love-charm, for which there is a song. There are also songs of cursing which are supposed to work an evil charm when used with a certain kind of cursing herbs.

Both men and women may become members of the Great Medicine Society, and they must go through eight 16degrees or stages in which they are taught the use of the medicines and the songs. Each member of the society has his own set of songs, some of which he has composed himself and others he has had to buy for large sums of money or goods. No man is allowed to sing another man’s song unless he has bought the right to it. With the sale of a song goes the herb to be used with that particular song. The ceremony is very elaborate. It lasts for several days, and sounds very much like a story book.

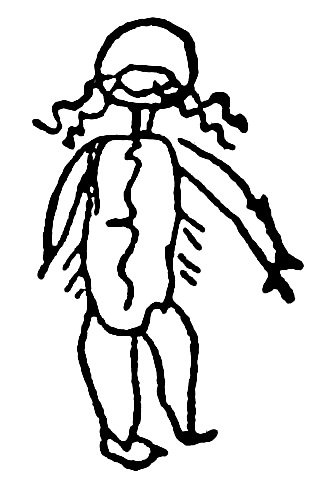

The Chippewa Indians have had a written picture language by means of which they read the different songs. These pictures were usually drawn on white birch-bark. Here are a few samples:

Indian Song Picture

In form like a bird it appears.

Indian Song Picture

On my arm behold my pan of food.

Indian Song Picture

Wavy lines indicate “the song.”

Straight lines indicate “strength.”

Indian Song Picture

I have shot straight.

Indian Song Picture

The sound of flowing water comes toward my home.

17When we tell you about American music we will speak again of the Indian and how we have used in our own music what he has given us.

The place of the negro in the world of music has been the cause of many questions:

Is his music that of a primitive man?

Is it American?

Is it American Folk Music?

As we tell you the story of music we shall have to speak of the negro music from all these different sides. But, for you to understand why there is a question about it, we must tell you where the negro came from and what he brought from his primitive home.

When the English first came to Virginia and founded Jamestown in 1607 they started to grow tobacco on great plantations, and for this they needed cheap labor. They tried to use Indians, but as the work killed so many of them, they had negroes sent over from Africa to do it. A year before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock in 1620, negroes were already being sold as slaves in Virginia. Until 1808 these negroes were brought over from Africa; they were not all of one tribe, nor were they of one race. There were Malays from Madagascar, Movis from northern Africa, red skins and yellow skins as well as black.

These people were primitive and they all used song and dance in their religion, their work and their games. They brought from Africa a great love for music and ears that heard and remembered more than many a trained musician. A well-known writer has said that wherever the African negro has gone, he has left traces in the music of that country. The Spanish Habanera, which we have danced by the name of Tango came from Africa; even the 18name is African, “tangara,” and was a vulgar dance unfit for civilized people. The rhythm of the African dance and of our tango is the same.

Like other savages, the African negro loved rhythm better than melody. His songs were monotonous and were made up of a few tones and short repeated phrases. They used the scale, of five tones (called pentatonic), the same as the Indian’s.

The African negro was a master at drumming. The Indian drumming was regular like the clock or pulse, but the negro played most difficult and complicated rhythms, almost impossible for a trained musician, to imitate. He had drums of all sizes and kinds.

These savages sang groups of tones which we call chords, which were not used by any of the ancient civilized people. By means of different rhythms they had hundreds of ways of combining the three tones of a chord as C-E-G. It is curious that these primitive people should have used methods more like our own than many of the races that had reached a much higher degree of civilization.

The Africans had an original telegraph system in which they did not use the Morse code, but sent their messages by means of drums that were heard many miles away. They had a special drum language which the natives understood; and the American Indians flashed their messages over long distances by means of the reflection of the sun on metal.

It is only a little more than a hundred years ago since we stopped bringing these primitive people into America and making slaves of them. Their children have become thoroughly Americanized now, from having lived alongside of the white people all this time and some have forgotten their African forefathers. But in the same way that the children of Italian, German, French or Russian parents remember the songs of their forefathers and often show 19traces of these songs in the music they make, so the negro without knowing it has kept some of the primitive traits of African music.

Later, we will tell you how this grew into two kinds of music, the beautiful religious song called the Negro Spiritual, and the dance which has grown into our popular ragtime and jazz.

If we were to study in detail the music of many savage tribes of different periods from prehistoric day to the uncivilized people living today, we should find certain points in common. They all have festival songs, songs for religious ceremonials, for games, work songs, war songs, hunting songs and love songs. In fact it is a beautiful habit for primitive people to put into song everything they do and everything they wish to remember. With them music has not been a frill or a luxury, but a daily need and a natural means for expressing themselves.

Another thing alike among these early peoples, is that all of them had drums and rattles of some kind and a roughly made instrument that resembles our pipes. But they had no stringed instruments and for their beginnings you will have to journey on with us in this,—your book.

Since giving this book to the public, we have come in direct contact with some remarkable songs of the Nootka (Canadian) Indians and of the Eskimos. Juliette Gaultier de la Verendry, a young French Canadian, has sung them in New York in the original dialect. They have been given to her by D. Jenness, an anthropologist who lived among the Eskimos for several years, studying their traits and at the same time he took the opportunity of writing down their songs. They are truly savage music and have the characteristics of which we have spoken in the use of intervals, drums, and in the type of songs, such as weather and healing incantations (medicine songs), work songs, and dances.

Three thousand years before Jesus was born, a corner of southwestern Asia and northeastern Africa was the home of people who had reached a very high degree of civilization. They were the first to pass the stage of primitive man, and to make for themselves beautiful buildings, beautiful cities, monuments, decorations and music. Among these ancient, civilized people were the Egyptians, the Assyrians and the Hebrews. We will talk first about the Egyptians because they had the greatest influence not only on the Assyrian and Hebrew music, but also on the Greeks who went to Egypt. So, in European music we can trace the Egyptian influence through the Greeks.

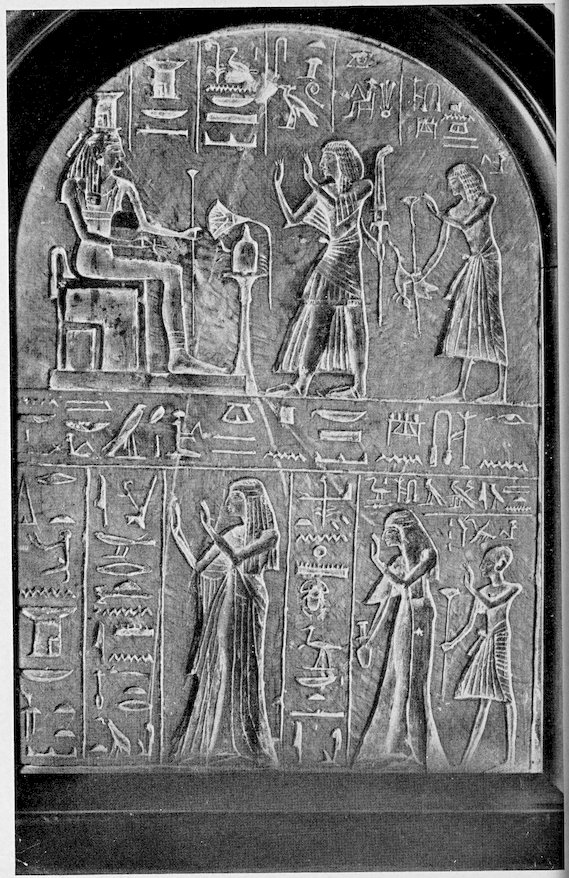

The Egyptians were very fond of building and they decorated what they built with pictures in vivid colorings called hieroglyphics (heiro—sacred, glyphics—writings). As they had neither newspapers nor radio sets, they carved or painted the records of their daily lives, their festivals, battles, entertainments, and even marketing journeys on the walls and on the columns of the temples, on the obelisks, and in the tombs, some of which were the pyramids.

The climate saved these records from destruction, and the archaeologists re-discovered them for us in the tombs full of Egyptian treasure and the temples and lost cities, buried for thousands of years.

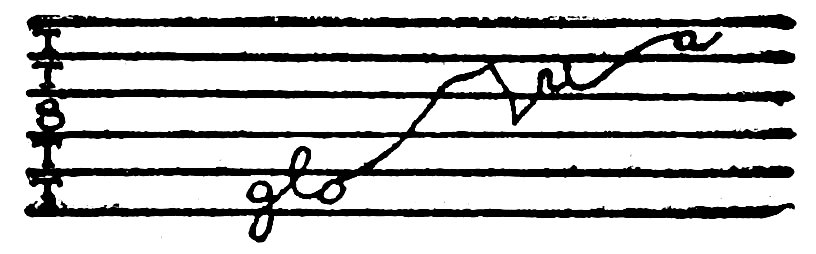

Fig. 1.

Drums and Sticks.

Fig. 2.

Sioux Drum.

Fig. 3.

A Pipe and Rattles from Alaska.

Fig. 4.

Bone Flutes.

From the Egyptian Collection in the Louvre, Paris.

Hieroglyphics on an Egyptian Tablet.

(Telling a story of a Prince.)

21The Egyptians built to inspire feelings of awe, mystery and grandeur. You probably remember pictures of obelisks, temples, pyramids, tombs and sphinxes, alongside of which a man looks but a few inches high.

They were very young as the world goes, and built huge structures because they were still filled with wonder at the immensity and power of the things they saw in Nature,—the Nile; the great desert which seemed vaster to them because they had only slow-moving camels, elephants and horses to take them about; they saw very long rainy seasons and the Nile overflowing its banks yearly, long dry seasons and the terrible wind and sand storms; the great heat of the sun, and the glory of their huge flowers, such as the lotus.

Just as primitive people did, they personified Nature in the gods. They had Osiris—god of Light, Health and Agriculture; Isis—goddess of the Arts and Agriculture; Horus (hawk-headed), the Sun god; Phtah, first divine King of Memphis, and many others. Again like primitive people, they had music for their gods, for their temple services, for their state ceremonies, festivals, martial celebrations and amusements.

Primitive music, we saw, had no laws to bind it, but was guided by the savage’s natural feeling and he could make up anything he wished. In Egypt, because of state law which prevented it from changing, music was held down to the same system for three thousand years. New music was forbidden, and much of the old was considered sacred and so closely connected with religious ceremonies that it was allowed to be used only in the temples.

The priests lived in these magnificent temples and were the philosophers, artists and musicians, very like the medicine men of the Indians, but much more advanced in learning.

Like the American Indians, too, the profession of music 22was handed down from father to son, and only the children of singers, whether they had good voices or not, could sing in the temples.

On the monuments we see these singers followed by players of instruments. The singers were of the highest caste, or Priest caste; the players were usually of the lower classes, or the Slave caste, although as pictured on the tombs of Rameses, one of Egypt’s greatest rulers and builders, we see the priests dressed in splendid robes and playing large harps.

The temples of Egypt were so huge that the music had to be on a large scale. They thought nothing of an orchestra of six hundred players of harps, lyres, lutes, flutes and sistrums (bell rattles), whereas we today advertise in large type the fact of one hundred men in one orchestra! We see no trumpets in the picture writings of the Egyptian orchestra, for these were only used in war, and we find them only in their pictures of war and triumphal marches; nor do we see large drums, because the Egyptians clapped their hands to mark rhythm. However, the military instruments in the hands of players pictured on the monuments, show that they used trumpets and tambourines in the army.

From the names we find in the tombs—“Singers of the King” and “Singers of the Master of the World,” we know that the Kings had musicians of high rank in their courts. The paintings on the walls and columns of the ruins of the temple Karnak, show funeral services with kneeling singers, playing harps of seven strings and other instruments.

Ptolemy Soter II, another famous Egyptian ruler, gave a fête in which were heard a chorus of twelve hundred voices, accompanied by three hundred Greek kitharas and many flutes.

It seems like a fairy tale that we can bring back the 23manners and customs of three thousand years ago through studying the writings in stone called hieroglyphics, and by examining the things used every day, that were found in the excavations. For a long time the hieroglyphics were unsolved riddles until the discovery in 1799 A.D. of the Rosetta stone, on which was an inscription in hieroglyphics with its Greek translation. Although ancient Greek is called a dead language, it still has enough life in it to bring back the history and records of antiquity. Through this knowledge of Greek, the Egyptian inscriptions speak to us and tell us marvelous stories of ancient Egypt.

In one of the tombs at Thebes, was a harp with strings of catgut, which when plucked, still gave out sounds although the harp had probably not been played upon in three thousand years!

Going once more to our ancient stone library—or collections of monuments in our museums or in Egypt—we see many pictures of dancers. The Egyptians danced in religious ceremonies as well as in private entertainments. They loved lively dances, and the men did all sorts of acrobatic steps and even toe-dancing like our Pavlowa, while the women did the slow, languorous dances.

Egyptian music was greatest as far back as 3000 B.C.! After that it grew poorer until 525 B.C. when Egypt was conquered by Persia.

The Egyptians must have used a musical scale of whole steps and half steps, covering several octaves, not unlike ours. Think of the piano keyboard with its black and its white keys and you will get an idea of the Egyptian scale. We learned this through the discovery of a flute that played a scale of half steps from a below middle c to d above the staff with only a few tones missing.

In the British Museum in London and in the Louvre in Paris, you can see ancient records which archaeologists unearthed from three mounds near the River Tigris in Asiatic Turkey. These mounds were the remains of the Assyrian cities of Nimroud (Babylon), Khorsabad, and probably the famous Nineveh, and date from 3000 to 1300 B.C.

Did Assyria influence Egypt or was it the other way around? The Egyptians excelled in making mechanical things such as instruments, utensils, tools, and in building temples and pyramids; while the Assyrians were sculptors, workers in metals and enamel, and knew the secret of dyeing and weaving stuffs, and of making beautiful pottery. But whose music was the better, the Egyptians or the Assyrians, is impossible to say. We do know, however, that the Assyrians, as well as the Egyptians and Hebrews, had perfected music far beyond the standard reached by many nations of our own time.

The Assyrians had the same families of instruments that we have,—the percussion (or drums), wind, and strings; and they used different combinations of instruments in concerts, either in instrumental performances or for accompanying vocal music. Everything that we know about them shows that the Assyrians were greater noisemakers than the Egyptians, for they not only had drums and trumpets, but they also marked rhythm by stamping their feet instead of clapping their hands.

The instruments pictured on the monuments, probably existed many centuries before the building of these monuments, which would make them very old indeed. In fact, almost all of them are still in use in the Orient today and are played in the same way. The monuments also prove that some of the special ceremonies in which music was used are still in existence.

25Both the Assyrians and the Egyptians had flutes, and double flutes which were actually two flutes connected by one mouthpiece and looked like the letter v. The Assyrians also had harps that varied in size from some that could be carried in the hand, to some that stood seven feet high and had as many as twenty-two strings. The dulcimer, an instrument something like a zither, was very popular and was made so that it could be played standing upright or lying flat. They also had drums, castanets, cymbals, tambours or tambourines, and lyres, all of which could be easily carried.

The Assyrians being a warlike nation made their instruments so that they could be strapped to their bodies. So it seems that people in 3000 B.C. were practical.

The Assyrians were so fond of music that when their war-prisoners were musicians they were not put to death.

We get our knowledge of the Hebrew music not from stone monuments and wall pictures, but from Biblical writings and other ancient Hebrew records. In the Second Commandment, God forbids the Hebrews to make images:

“Thou shalt not make unto thyself any graven image, nor the likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or in the earth beneath, or in the waters under the earth.” (Exodus XXI: 4.) With so strict a commandment, you can understand why there are no pictures of singers and of instruments, and that we have to go to the greatest literary gift to the world,—the Old Testament, to find out about their music.

The first musician mentioned in the Bible is Jubal. It says in Genesis IV: 21, “he was the father of all such as handle the harp and pipe (or organ).” From an old Spanish book found in the early 18th century in a Mexican 26monastery, comes the story that Jubal was listening to Tubal-Cain’s forge, and noticed the difference in pitch of the sounds made by the strokes on the anvil. Some tones were high, some low, and some were medium. He compared this to the human voice, and tried to imitate the sounds, high, low and medium, of the forge. Thus he became the first singer of the Hebrews. Jubal invented a flute and a little three-cornered harp called the kinnor. These small instruments were most convenient to carry about, for at this time the Hebrews were shepherd tribes wandering from place to place. Their music was simple as is the music of all primitive peoples.

We know from the Biblical story that the Children of Israel were sold into captivity and remained many centuries in Egypt; that Moses was found in the bulrushes by Pharoah’s daughter, and was educated as an Egyptian boy and “was learned in all the wisdom of the Egyptians.” Therefore, he must have learned music from the priests. It is natural then, that the Hebrews must have borrowed the music and instruments of their adopted country in the making of their own.

After Moses had been commanded by the Lord to lead the children of Israel out of the land of captivity, and after the Red Sea had divided to allow them to pass through, we read the great song of triumph sung by Moses:

“Then sang Moses and the Children of Israel: ‘I will sing unto Jehovah, for he hath triumphed gloriously, the horse and his rider hath he thrown into the sea, Jehovah is my strength and my song and he is become my salvation.’” etc.—(Exodus XV: 1–2).

And “Miriam, the prophetess, the sister of Aaron, took a timbrel in her hand, and all the women went out after her with timbrels and with dances.” (The timbrel is a small tambourine-like instrument.)

This story, like others in the Old Testament, is full of 27the accounts of musical instruments, singing and dancing, and shows us that the ancient Hebrews used music and the dance for nearly every event. If you read carefully you will get the musical history of this poetic people.

While the Children of Israel were in the wilderness, Moses received from Jehovah the command: (Numbers X.)

“Make thee two trumpets of silver; of a whole piece shalt thou make them; that thou mayest use them for the calling of the assembly, and for the journeyings of the camp.”

Then follow directions as to the meaning of the blowing of the trumpets. One trumpet alone called the princes; two trumpets called the entire tribe together; an “alarm” gave the signal for the camps to go forward, and so on. So, you see the ancient Hebrews used trumpets much as we today use the army bugle. The trumpets mentioned as one of the earliest of all instruments called the people to religious ceremonies too; it announced festivals, the declaration of a war, the crowning of a king, proclaimed the jubilee year, and gave warning of the anger of God.

One instrument has come down to our times and is still used in the Hebrew temple services. This is called the shofar and is usually a ram’s horn on which two tones may be blown. Probably, as the ram was one of the animals of sacrifice, they used its horn as a sacred instrument. This shofar is 5,000 years old, at least. It is sounded in all the synagogues of the world on the Jewish New Year and on the Day of Atonement in memory of the wanderings of the Children of Israel.

When the twelve tribes, after their wanderings in the wilderness, had settled down in Palestine, they gave music a most important place in their daily life. Samuel, the last and most respected of the judges, built a school of prophecy and music. Here it was that young David hid himself to escape the persecutions of Saul. You remember that David 28is called the Great Musician and he gave us many of the Psalms, the most beautiful religious verse in the world. How much it would mean to us if we knew the music David sang to these songs! In spite of the fact that the music in which they were originally sung has been lost, the Psalms have been an inspiration to all composers of religious music throughout the ages. David learned so much at Samuel’s school that he created a most beautiful musical service for the temple, which is the basis of the one used today in Jewish synagogues (temples).

The number that were instructed in the songs of the Lord was two hundred, four score and eight (288). There were in all four thousand, including assistants, students, players of instruments and the two hundred and eighty-eight professional singers.

All of these people did not perform at one time; for the ordinary services they used twelve male singers, twelve players on instruments,—nine harps, and two players of the psaltery and one of cymbals. Women were not allowed to sing in the temples but they were a part of the court and sang at funerals and at public festivities and banquets.

The great Jewish historian, Josephus, tells us that Solomon had two hundred thousand singers, forty thousand harpists, forty thousand sistrum players and two hundred thousand trumpeters. This is hard to believe, but as everything belonged to the kings in bygone days, probably this was only Solomon’s musical directory.

The psaltery was an instrument something like our zither, with thirteen strings on a flat wooden sounding board, rectangular in shape. The sistrum was a metal rattle which made a very sweet sound.

It isn’t easy to describe the instruments used thousands of years ago, for the names have become changed through the ages, and we find the same type of instruments called by different names in different countries and periods. For 29example, the psaltery is much the same instrument as the dulcimer, the Arab’s kanoun and the Persian santir. We find the same psaltery in Chaucer’s “Miller’s Tale” as sautrie. By the addition of a keyboard this Biblical instrument became the spinet, which you will meet again in the 15th and 16th centuries. In the 13th century, in Italy, we find a kind of psaltery hung around the neck and called “Istroménto di porco” because it looked like the head of a pig.

Not all the songs of the Bible are religious. The Song of Solomon, a most beautiful poem of marriage, gives us a vivid picture of luxury and magnificence, as well as showing us that music was used for other than religious ceremonies.

After the death of Solomon, the music in the temple lost its splendor and again the Children of Israel were made captive. When one hundred years later Nebuchadnezzar (586 B.C.) the King of Babylon, destroyed their temple, the song of the Hebrews became sad and mournful, as you can read in the Book of Lamentations and in this beautiful song of grief, the 137th Psalm:

During the next few centuries the Hebrews became scattered over the world, carrying with them their reverence for God, their love of poetry and song, and their religious customs. These qualities have persisted throughout the centuries, and some of the greatest musicians in the world have been of Hebrew origin.

Although most of the old music has passed away, there is still enough of its spirit left in their temple services to give some idea of the ancient Hebrew music.

From a panel in a Museum (delle Terme) in Rome.

Greek Girl Playing a Double Flute (auloi).

From a frieze in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Greek Boy Playing the Lyre.

The Greeks “dwelt with beauty” and believed it to be a part of being good, and they strove to make everything beautiful. Beauty to the Greeks was a religion. Had this not been so, we would not have the Venus de Milo, the Parthenon in Athens, the Hermes, the Winged Victory (Niké of Samothrace) and all the other Greek masterpieces which no modern sculptor or builder has surpassed.

It is interesting to see a nation 400 years before the time of Christ and even earlier, making glorious art works in stone, and writing the greatest plays the world has ever had, being more grown up than modern nations, and yet as far as we know an infant in the art of music. We have only the slightest idea of how their music sounded as they had no accurate way of writing it, and had only very primitive instruments. Although when compared to their other arts their music was not great, still it was very important to them and they used it constantly with poetry, dancing, and in the drama.

The word music was first used by the Greeks and has been carried into nearly every language; we find musique in French, Musik in German, musica in Italian, and so on.

Music, according to the Greeks, was an art which combined not only the playing of instruments, singing and dancing, but also all the arts and sciences, including mathematics 32and everything in the universe. It took its name from the Muses, and they believed that it led to the beautiful accord and harmony of the world.

The nine Muses were daughters of Jupiter, and each presided over some particular department of literature, art and science.

Clio: Muse of History and Epic Poetry. She is shown in statues and pictures holding a half open scroll.

Thalia: Muse of Joy and Comedy (drama) with a comic mask in one hand and a crooked staff in the other.

Erato: Muse of Lyric Poetry, inspired those who wrote of love. She plays on a nine-stringed lyre.

Euterpe: Muse of Lyric Song, patroness of music especially of flute players. She holds two flutes (auloi).

Polyhymnia: Muse of Sacred Song. She holds her forefinger to her lips or carries a scroll.

Calliope: Muse of Eloquence and Epic Poetry, holds a roll of parchment, or a trumpet.

Terpsichore: Muse of the Dance, presiding over choral, dance and song. She appears dancing with a seven-stringed lyre.

Urania: Muse of Astronomy, holds the globe and traces mathematical figures with a wand.

Melpomene: Muse of Tragedy (drama), leans on a club and holds a tragic mask.

The myths and legends of the ancient Greeks read like fairy tales, but to the Greeks they were what our Bible stories are to us. In their rich mythology we find many stories about the beginnings of music.

To Pan, the god of woods and fields, of flocks and shepherds, is given the credit of inventing the shepherd’s pipe, or Pan’s Pipes. He lived in grottoes, wandered on the 33mountains and in the valleys, and amused himself hunting, leading the dances of the nymphs, and playing on his pipes.

A beautiful nymph named Syrinx was loved by Pan, but every time that he tried to tell her of his love, she became frightened and ran away, for Pan was a funny looking lover with goat’s legs, a man’s body, and long pointed ears. One day he chased her through the woods to the bank of a river; she called out in fright, and was suddenly changed by her friends the Water Nymphs, into a clump of tall reeds. When he reached out to embrace her, instead of Syrinx, he had the clump of reeds in his arms! As he sighed in disappointment, his breath passing through the reeds, produced a sad wail. Pan, hearing in it a plaintive song, broke off the reeds in unequal lengths, bound them together, and made the first musical instrument, which he called a syrinx in memory of his lost sweetheart. These pipes comforted Pan, and he played many tender melodies, and often without being seen, was known to be near by his lovely music.

Pan, although adored, was feared. At one time, Brennus, a warrior, with a company of Gauls (a tribe from ancient France), attacked the Temple of Delphi (in Greece), and was about to destroy it, when suddenly they turned and fled in fear although no one pursued them. Their terror was supposed to have been of Pan’s making, and to this day we use the word “panic” (Pan-ic) for all sudden overpowering fright.

Pan is supposed to have taught music to Apollo, the god of Music and of the Sun. You have seen statues of him with a lyre in his hands. As Pan’s pupil he learned to play the syrinx so beautifully that he won a prize in a contest with Marsyas, a mortal who played the flute invented (according 34to the Greek legend), by Pallas Athene. This goddess was sometimes known as Musica or Musician. When Cupid saw her play the flute he laughed at her because she made such queer faces. This angered her, and she flung her flute away. It fell down from Mt. Olympus to the earth, and Marsyas picked it up and became such a skilful player that he challenged the god Apollo to a contest for flute championship of the world! The day came and Apollo won the prize, but put Marsyas to death for daring to challenge him—a god. Apollo afterwards was very sorry and broke all the strings of his lyre and placed it with his flutes in a haunt of Dionysus (god of Wine), to whom he consecrated these instruments.

These stories are not only a part of the ancient Greek religion but they have become, on account of their beauty, a rich source of plot and story for the works of musicians, artists and writers from the days of antiquity to our own time.

One of the favorite Greek stories has been that of Orpheus, who went down to Hades to bring his dead wife whom he adored, back to earth, and about whom Peri, Gluck, and others wrote operas. He was son of Apollo and of Calliope, the Muse of Epic Poetry, and became such a fine performer on all instruments, that he charmed all things animate and inanimate. He tamed wild birds and beasts, and even the trees and rocks followed him as he played, the winds and the waves obeyed him, and he soothed and made the Dragon, who guarded the Golden Fleece, gentle and harmless.

On the cruise of the Argo in search of the Golden Fleece, Orpheus not only succeeded in launching the boat when the strength of the heroes had failed in the task, but when they 35were passing the islands of the Sirens, he sang so loudly and so sweetly that the Sirens’ songs could not be heard and the crew were saved.

When a people have legends about music you may know that they love it. Such was the case with the Greeks. They did not call their schools high schools and colleges but Music schools, and everything that we call learning they included under the name of music. Every morning the little Greek boy was sent to the Music school where he was taught the things that were considered necessary for a citizen to know. Here he learned gymnastics, poetry, and music. At home too, music was quite as important as in school, and we know that they had folk songs which had to do with the deeds of ordinary life, such as farming and winemaking and grape-picking, and the effect and beauty of the seasons of the year. (See Chap. IX.) They can well be divided into songs of joy and songs of sorrow, and seem to have existed even before Homer the Blind Bard. If you ever have tried to dance or do your daily dozen without music, you will understand at once how much help music always has been to people as they worked.

All harvest songs in Greece had the name of Lytiersis. Lytiersis was the son of King Midas, known as the richest king in the world. Lytiersis was a king himself but also a mighty reaper, and according to Countess Martinengo-Cesaresco who has written a book called Essays in the Study of Folk-Songs it was his “habit to indulge in trials of strength with his companions and with strangers who were passing by. He tied the vanquished up in sheaves and beat them. 36One day he defied an unknown stranger, who proved too strong for him and by whom he was slain.” The first harvest song was composed to console King Midas for the death of his son. We can make a fable from this story which means that Nature and Man are always struggling against each other.

The harvest festivals founded in Greece led to others in Brittany, France, North Germany and England. So does the deed of one race affect other races.

Among the taxes, or five special liturgies, that the Greeks had to pay, was the obligation for certain rich citizens to supply the Greek tragedies with the chorus. Every Greek play had its chorus and every chorus had to have its structures; a choregic monument to celebrate it; one or more flute players, costumes, crowns, decorations, teachers for the chorus and everything else to make it succeed. This cost, which would equal many thousands of dollars, was undertaken as a duty quite as easily as our men of wealth pay their income taxes. You can see a greatly enlarged copy of a choregic monument, the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ monument at 89th Street and Riverside Drive, in New York City, and also one at the Metropolitan Museum.

In old Greece the musicians were also poets. Homer, Hesiod, Pindar, Æschylus, Sophocles, Sappho, Euripides, Plato, not only wrote their dramas but knew what music should be played with them. In fact no play was complete without its chorus and its music and its flute-player. You have heard of the Greek chorus. Don’t for a moment think it was like our chorus. It consisted of a group of masked actors (all actors in those days wore masks), who appeared between the acts and intoned (chanted) the meaning of the play and subsequent events. In fact the chorus took the 37place of a libretto,—“words and music of the opera,” for it explained to the audience what it should expect. It spoke and sang some of the most important lines of the play and danced in appropriate rhythms. So it brought together word, action and music, and was a remote ancestor of opera, oratorio and ballet.

Besides the occupational songs and those for the drama festivals, the Greeks had the great game festivals where in some, not only competitions in sports took place but also flute playing and singing. The oldest of these festivals was the Olympic games, first held in 776 B.C. and every four years thereafter. These games played so important a part in the lives of the Greeks that their calendar was divided into Olympiads instead of years. While music was evident in the Olympic games, music and poetry were never among the competitions.

The Pythian games were chiefly musical and poetic contests and were started in Delphi, 586 B.C., where they were held every nine years in honor of the Delphian Apollo whose shrine was at Delphi. The Isthmian and Nemean games were also based on poetic and musical contests. Warriors, statesmen, philosophers, artists and writers went to these games and took part in them. Maybe some time we will realize the power of music as did the Greeks nearly one thousand years before the birth of Jesus.

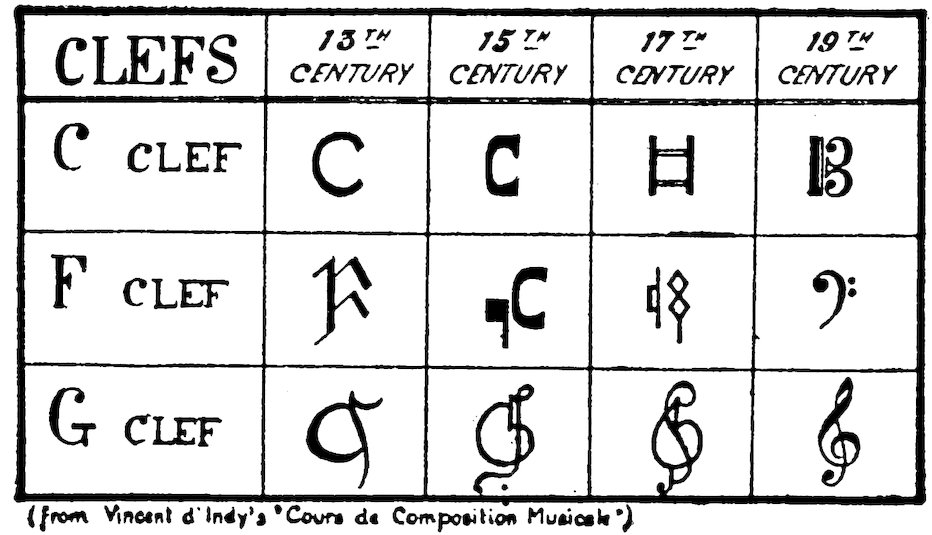

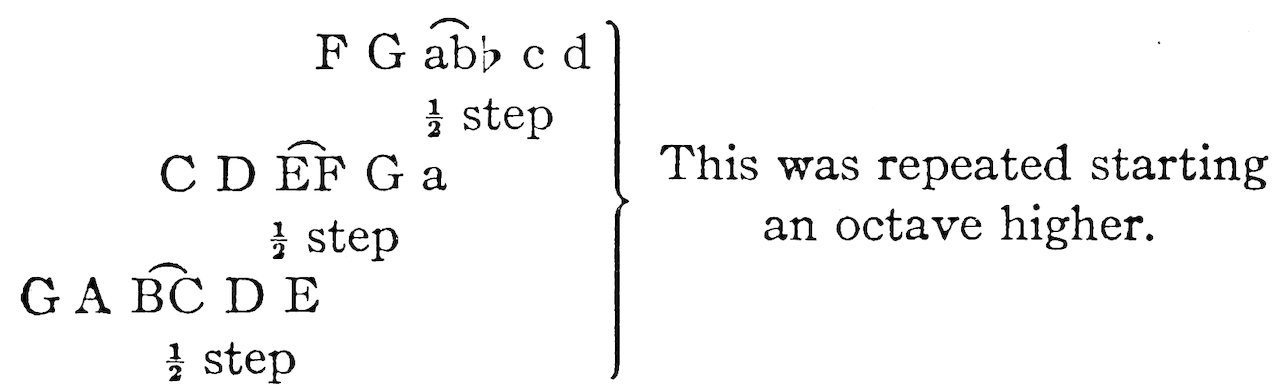

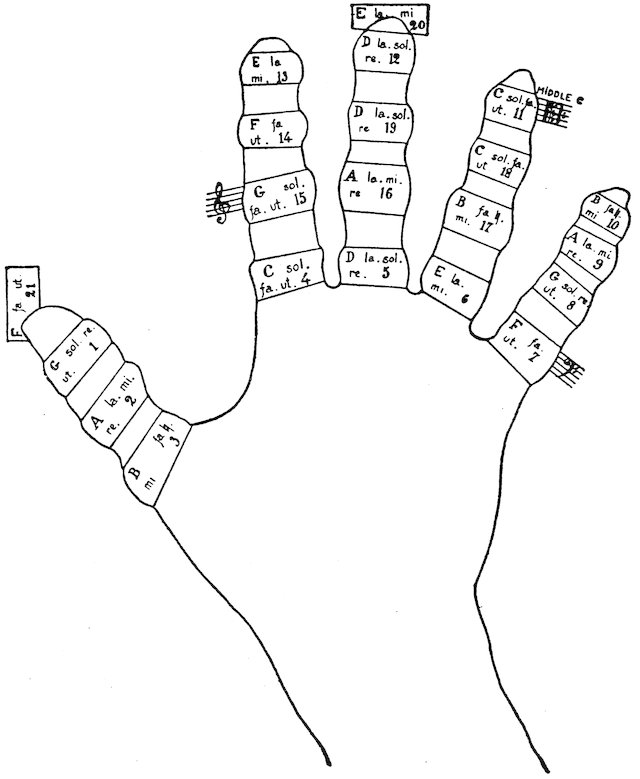

While, as we said before, we know very little about the melodies of the Greeks, we do know something about their scales, upon which the church music of the Middle Ages was based, as are our own major and minor scales. In 38fact the most important contribution Greece made to our music was the scale. They had a very complicated system and no one is quite sure how it worked.

We have the two modes or kinds of scales, major and minor, which we use in different keys, but the Greeks had at least seven different modes used in many different ways. They used one mode for martial or military music, another for funeral ceremonies, another for their temple music, and curiously enough, our own C major scale they used for their popular music, for drinking songs, and light festivities.

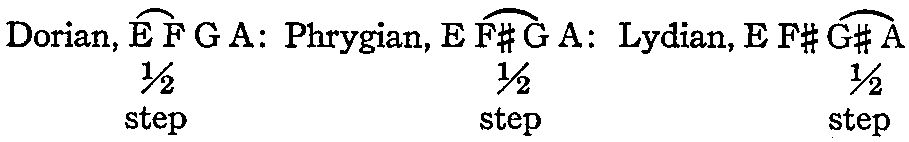

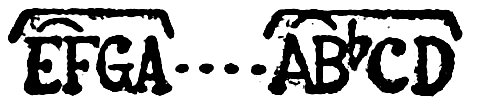

The Greek scales were based on tetrachords, from the Greek words tetra-four, chord-string that is, a group of four strings. If you play on the piano B C D E and C D E F and D E F G you will find the three tetrachords that formed the primary modes of the Greeks:—Dorian, Phrygian and Lydian.

Perhaps you have heard in Greek architecture of the Doric column which came from Doria, a province in Greece, and the Ionic column, from Ionia, and so on. In the same way the scales were named for sections of the country from which they first came, Dorian mode, Ionian, Æolian, Phrygian, Lydian, etc.

The Greek tetrachord was formed on the interval of a fourth, for example from E to A—these were called standing tones, because the intervals between the two standing tones or permanent tones could be changed but the first and the fourth always remained the same—

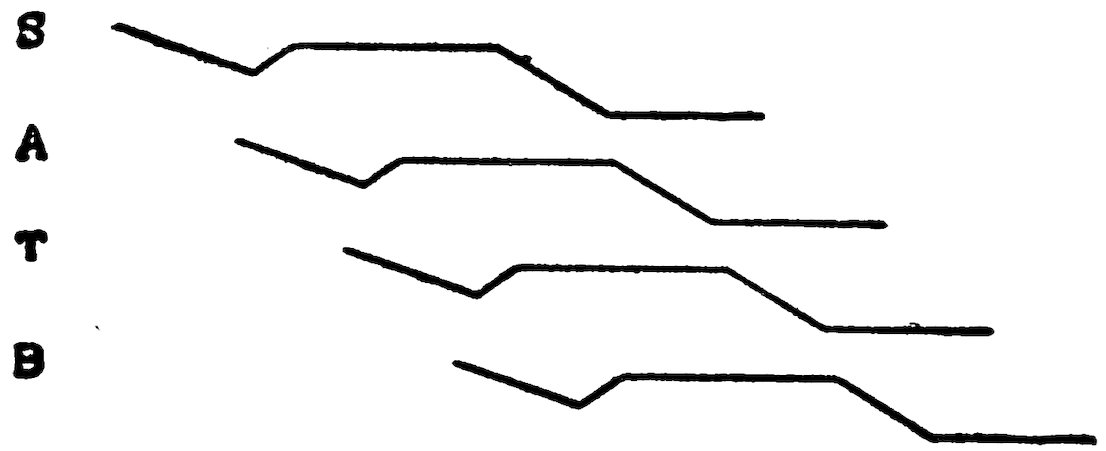

By putting two tetrachords together all the other Greek scales were formed. These fell into two classes, and according to Cecil Forsyth in his History of Music these 39classes were called the join and the break. When the second tetrachord began on the fourth tone of the first tetrachord, Mr. Forsyth calls it the joining method, thus.

When the second tetrachord began on the tone above the fourth tone of the first tetrachord, he calls it the breaking method, thus:

By using the join and the break with each of the three modes, Dorian, Phrygian and Lydian, you can see to what a great variety of scales and names this would lead. The Greeks spoke of their scales from the top note down, instead of from the lowest note up, as we do.

The first kithara was supposed to have been an instrument of four strings that could be tuned in any of these different ways, with the half-step either between the first and second strings, or between the second and third, or between the third and fourth. Two instruments tuned differently formed the complete scale, but it did not take long to add strings to their lyres and kitharas so that they could play an entire scale on one instrument.

The little Greek boy was taught in school to tune the scale according to the fourth string of his lyre, which was the home tone or what we should call tonic. Our tonic falls on the first degree of the scale, but in the primary modes of the Greeks, the tonic fell on the fourth degree, and was called the final. When the final was on pitch all the other strings had to be tuned to it.

These tetrachords are supposed to have been perfected by Terpander, in the six hundreds before Christ. His melodies were called nomes and were supposed to have had a fine 40moral effect on the Spartan youth in giving him spirit and courage. The Greeks thought that all music and that every one of their modes had a special effect on conduct and character.

After the Messenian war, Sparta was in such a state of upheaval that the Delphian oracle was consulted. The answer was:

So the Spartans called upon Terpander to help them, and through the power of his song all was peace again.

Terpander collected Asiatic, Egyptian, Æolian and Bœotian melodies all of which are unfortunately lost; he invented a new notation and enlarged the kithara from four strings to seven. Arion, Alcæus and the great poetess Sappho were his pupils, and Sappho is often shown in statues with a six stringed kithara.

Most of these poet singers were called “lyric poets” because they sang to the accompaniment of the lyre.

The Greeks were the first to write down their music, or to make a musical notation whereby the singers and players knew what tones to use. Their system was their alphabet with certain alterations. They had names describing each tone not unlike our use of the word tonic for the first degree of the scale, and dominant for the fifth and so on.

Of course they did not have the staff and treble and bass clefs as we have, but they were groping for some way of recording music in those far away days.

Pythagoras as far back as 584–504 B.C., not only influenced the music in the classical Greek period (400 B.C.), 41but down to and throughout the Middle Ages to the Renaissance (1500s). To this day music is based on his mathematical discovery. He worked out a theory of numbers based on the idea that all nature was governed by the law of numbers and modern scientists have proven that he was correct in many of his ideas. In fact our orchestras and pianos are tuned in accordance with his theories.

He invented an instrument called the monochord which consisted of a hollow wooden box with one string and movable fret. He discovered that when he divided the string exactly in half by means of the fret, the tone produced was an octave higher than the tone given out by striking the entire string; one-third of the string produced the interval of a fifth above the octave; one-fourth the length of the string produced a fourth above the fifth; one-fifth produced a third (large or major) above the fourth; one-sixth produced a third (small or minor); one-seventh produced a slightly smaller third and one-eighth produced a large second, three octaves above the sound of the entire string:

The truth of Pythagoras’ theory of tone relationship has been proven by an experiment in physics showing that all of the above tones belong to the same tone family. An amusing experiment can be made by pressing silently any one of the tones marked 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, or 8, and striking the fundamental tone sharply, the key you are pressing silently will sound so that you can distinctly hear its pitch.

The Greeks seem to have had no harmony (that is, combining of two or more tones in chords) outside of the natural result of men’s voices and women’s singing together. But they had groups of singers answering each other in what is called antiphony (anti-against, phony-sound). Even our 42American Indians have their song leader and chorus answering each other.

Greek rhythm followed the rhythm of the spoken word and was considered a part of their poetic system.

We have already spoken of the syrinx, Pan’s Pipes, the instrument of Pan, the satyrs and of the shepherds; the monochord, Pythagoras’ invention; the lyre and kithara; and the flute or aulos.

The lyre, of the family of stringed instruments, was the Greek national instrument. It was the first to be used in their musical competitions, and helped in the forming of the Greek modes. These were of two types, the lyre and the kithara. The first lyres which came down from the age of myths and fables were originally made of the shell of a tortoise and had four strings (the tetrachord) and later seven and even more strings. This form of the lyre was called chelys, or the tortoise, and was used for accompanying drinking songs and popular love songs.

The kithara was also called lyre, but was not made of the body of the tortoise, and it became the Greek concert instrument, and was only used by professionals, while the chelys was used in the home. It came originally from Asia Minor and Egypt. It had four strings at first but these were gradually added to, until there were fifteen and eighteen strings. It was sometimes small and sometimes large, and was held to the body by means of a sling and was played with a plectrum or pick.

The Greek flute or aulos was a wood-wind instrument more like our oboe than our flute. It was usually played in pairs, that is, one person played two flutes or auloi of different sizes at one time, and they were V shaped. There was a group of auloi differing in range like the human voice 43differs, and covering three octaves from the bass aulos to the soprano.

The aulos was first a single wooden pipe with three or four finger holes which later were increased to fifteen or sixteen so that the three modes Dorian, Phrygian and Lydian, could be played on one pair of auloi. About six centuries before the Christian era, the double flute became the instrument of the Delphian and Pythian musical competitions.

In the chorus too, we read that for each drama there was a special aulos soloist who always played the double flute.

There were other type instruments such as the war trumpets, trumpets used in the temple services, and harps (magadis) that were brought from Egypt, but the real instruments of the Greeks pictured in their sculpture and on their vases and urns, and spoken of in their literature, are the lyres and auloi.

The Romans, law givers, world conquerors and road builders, gave little new to music, for they did not show a great talent for art. They were influenced by Greek ideals and Greek methods. They were warlike by nature, and from defenders of their state they became conquerors. As they grew nationally stronger and more secure, they learned music, oratory, architecture and sculpture from Greek teachers. Many Romans well known in history were singers and gifted players on the Greek kithara, lyre, and flute (aulos).

The Romans seemed to have cared more about the performing of music than for the composing of it, and “offered prizes to those who had the greatest dexterity, could blow the loudest or play the fastest.” (Familiar Talks on History of Music.—Gantvoort.)

44As they come to America today the musicians of other lands flocked to Rome, especially those who played or sang, because they were received with honor and were richly paid.

The Romans, among them Boethius (6th century B.C.), wrote treatises on the Greek modes, were very much interested in the theory of music, and built their scales like the Greeks. To each of the seven tones within an octave they gave the name of a planet, and to every fourth tone which was the beginning of a new tetrachord, the name of a day of the week which is named for the planet.

| B | C | D | E | F | G | A |

| Saturn | Jupiter | Mars | Sun | Venus | Mercury | Moon |

| Saturday | Sunday | Monday | ||||

| B | C | D | E | F | G | A |

| Saturn | Jupiter | Mars | Sun | Venus | Mercury | Moon |

| Tuesday | Wednesday | |||||

| B | C | D | E | F | G | A |

| Saturn | Jupiter | Mars | Sun | Venus | Mercury | Moon |

| Thursday | Friday |

The days of the week in French show much more clearly than in English the names of the planets, in the case of Tuesday—mardi, (Mars); Wednesday—mercredi (Mercury); Thursday—jeudi, (Jupiter); Friday—vendredi, (Venus).

The Greeks brought their instrument, the kithara, to Rome, and with it a style of song called a kitharoedic chant, which was usually a hymn sung to some god or goddess. The words, until three hundred years after the birth of Jesus, were in the Greek language; the Latin kitharoedic songs like those of the poets Horace and Catullus were sung at banquets and private parties, Cicero too, was musical.

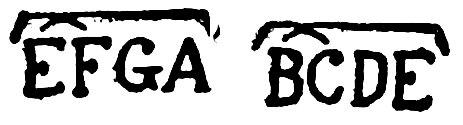

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Chinese Instruments.

Fig. 5.—Trumpets.

Fig. 6.—Te’ch’ing—sonorous stone.

Fig. 7.—Yang-Ch’in or Dulcimer.

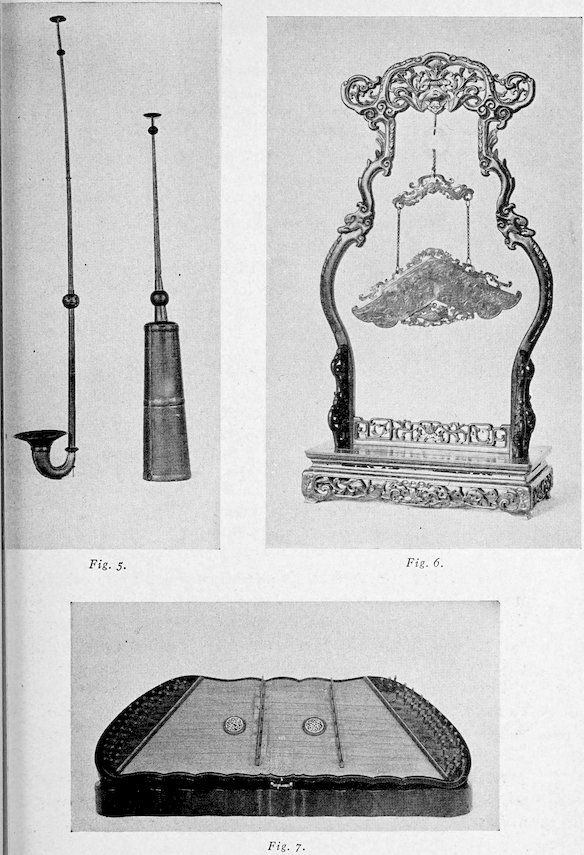

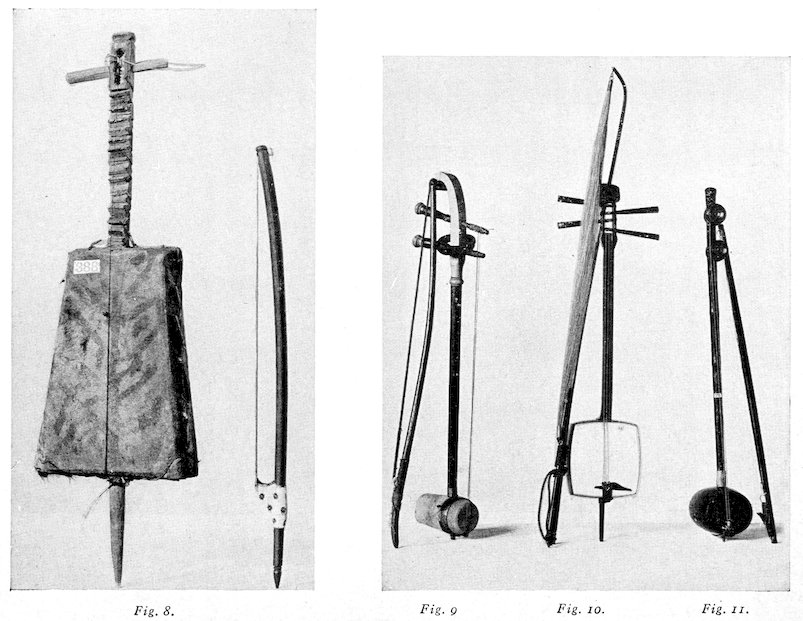

Fiddles from Arabia (Fig. 8, Rebab); Japan (Fig. 9, Kokin); Corea (Fig. 10, Haggrine) and Siam (Fig. 11, See Saw Duang).