Title: The Cornhill Magazine (vol. XLII, no. 251 new series, May 1917)

Author: Various

Release date: November 25, 2023 [eBook #72225]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Smith, Elder and Co, 1860

Credits: hekula03 and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

[All rights, including the right of publishing Translations of Articles in this Magazine are reserved.]

Registered for Transmission to Canada and Newfoundland by Magazine Post.

A PAYING HOBBY

QUICK AND EASY TO EXECUTE

A PLEASANT OCCUPATION

STENCILLING

IN OIL COLOURS

Will not run or spoil delicate fabrics.

NECESSARY OUTFIT 5/- ALL MATERIALS.

Large Stock of Designs for Curtains, Table Covers, Lamp Shades, Cushions, Fire Screens, Table Centres, Blouses, &c.

Illustrated List of all Leading Artists’ Colourmen, Stationers & Stores.

WINSOR & NEWTON, Ltd.,

RATHBONE PLACE, W.1.

By Special Appointment to Their Majesties the King and Queen and H.M. Queen Alexandra.

THE

CHURCH ARMY

HAS MANY HUNDREDS OF

RECREATION HUTS,

TENTS, AND CLUBS,

which are giving REST, COMFORT and RECREATION to men of both the Services (all are welcomed), at home and on the Western Front (many of them actually under the enemy’s shell-fire), at ports and bases in France, in Malta, Egypt, Macedonia, East Africa, Mesopotamia, and India. Light refreshments, games, music, provision for drying clothing, baths, letter-writing, &c., &c.; also facilities for Sunday and weekday services.

MORE ARE URGENTLY NEEDED,

especially in the devastated area captured from the enemy on the West Front.

Huts cost £400; Tents £200;

Equipment £100; Maintenance

£5 abroad, £2 at home, weekly.

Cheques crossed ‘Barclay’s, a/c Church Army,’ payable to Prebendary Carlile, D.D., Hon. Chief Secretary, Headquarters, Bryanston Street, Marble Arch, London, W.1.

You do not miss

Potatoes and Tomatoes

so much when you use

PAN YAN

THE WORLD’S BEST

PICKLE

It adds 50% to the value of your Meat Purchases.

On sale everywhere at Popular Prices.

Maconochie Bros., Ltd. London

MAY 1917.

When Jack Duncan and Hugh Morrison suddenly had it brought home to them that they ought to join the New Armies, they lost little time in doing so. Since they were chums of long standing in a City office, it went without saying that they decided to join and ‘go through it’ together, but it was much more open to argument what branch of the Service or regiment they should join.

They discussed the question in all its bearings, but being as ignorant of the Army and its ways as the average young Englishman was in the early days of the war, they had little evidence except varied and contradictory hearsay to act upon. Both being about twenty-five they were old enough and business-like enough to consider the matter in a business-like way, and yet both were young enough to be influenced by the flavour of romance they found in a picture they came across at the time. It was entitled ‘Bring up the Guns,’ and it showed a horsed battery in the wild whirl of advancing into action, the horses straining and stretching in front of the bounding guns, the drivers crouched forward or sitting up plying whip and spur, the officers galloping and waving the men on, dust swirling from leaping hoofs and wheels, whip-thongs streaming, heads tossing, reins flying loose, altogether a blood-stirring picture of energy and action, speed and power.

‘I’ve always had a notion,’ said Duncan reflectively, ‘that I’d like to have a good whack at riding. One doesn’t get much chance of it in city life, and this looks like a good chance.’

‘And I’ve heard it said,’ agreed Morrison, ‘that a fellow with any education stands about the best chance in artillery work. We’d might as well plump for something where we can use the bit of brains we’ve got.’

‘That applies to the Engineers too, doesn’t it?’ said Duncan. ‘And the pottering about we did for a time with electricity might help there.’

‘Um-m,’ Morrison agreed doubtfully, still with an appreciative eye on the picture of the flying guns. ‘Rather slow work though—digging and telegraph and pontoon and that sort of thing.’

‘Right-oh,’ said Duncan with sudden decision. ‘Let’s try for the Artillery.’

‘Yes. We’ll call that settled,’ said Morrison; and both stood a few minutes looking with a new interest at the picture, already with a dawning sense that they ‘belonged,’ that these gallant gunners and leaping teams were ‘Ours,’ looking forward with a little quickening of the pulse to the day when they, too, would go whirling into action in like desperate and heart-stirring fashion.

‘Come on,’ said Morrison. ‘Let’s get it over. To the recruiting-office—quick march.’

And so came two more gunners into the Royal Regiment.

When the long, the heart-breakingly long period of training and waiting for their guns, and more training and slow collecting of their horses, and more training was at last over, and the battery sailed for France, Morrison and Duncan were both sergeants and ‘Numbers One’ in charge of their respective guns; and before the battery had been in France three months Morrison had been promoted to Battery Sergeant-Major.

The battery went through the routine of trench warfare and dug its guns into deep pits, and sent its horses miles away back, and sat in the same position for months at a time, had slack spells and busy spells, shelled and was shelled, and at last moved up to play its part in The Push.

Of that part I don’t propose to tell more than the one incident—an incident of machine-pattern sameness to the lot of many batteries.

The infantry had gone forward again and the ebb-tide of battle was leaving the battery with many others almost beyond the water-mark of effective range. Preparations were made for an advance. The Battery Commander went forward and reconnoitred the new position the battery was to move into, everything was packed up and made ready, while the guns still continued to pump out long range fire. The Battery Commander came in again and explained everything to his officers and gave the necessary detailed[499] orders to the Sergeant-Major, and presently received orders of date and hour to move.

This was in the stages of The Push when rain was the most prominent and uncomfortable feature of the weather. The guns were in pits built over with strong walls and roofing of sand-bags and beams which were weather-tight enough, but because the floors of the pits were lower than the surface of the ground, it was only by a constant struggle that the water was held back from draining in and forming a miniature lake in each pit. Round and between the guns was a mere churned-up sea of sticky mud. As soon as the new battery position was selected a party went forward to it to dig and prepare places for the guns. The Battery Commander went off to select a suitable point for observation of his fire, and in the battery the remaining gunners busied themselves in preparation for the move. The digging party were away all the afternoon, all night, and on through the next day. Their troubles and tribulations don’t come into this story, but from all they had to say afterwards they were real and plentiful enough.

Towards dusk a scribbled note came back from the Battery Commander at the new position to the officer left in charge with the guns, and the officer sent the orderly straight on down with it to the Sergeant-Major with a message to send word back for the teams to move up.

‘All ready here,’ said the Battery Commander’s note. ‘Bring up the guns and firing battery waggons as soon as you can. I’ll meet you on the way.’

The Sergeant-Major glanced through the note and shouted for the Numbers One, the sergeants in charge of each gun. He had already arranged with the officer exactly what was to be done when the order came, and now he merely repeated his orders rapidly to the sergeants and told them to ‘get on with it.’ When the Lieutenant came along five minutes after, muffled to the ears in a wet mackintosh, he found the gunners hard at work.

‘I started in to pull the sand-bags clear, sir,’ reported the Sergeant-Major. ‘Right you are,’ said the Lieutenant. ‘Then you’d better put the double detachments on to pull one gun out and then the other. We must man-handle ’em back clear of the trench ready for the teams to hook in when they come along.’

For the next hour every man, from the Lieutenant and Sergeant-Major down, sweated and hauled and slid and floundered in slippery mud and water, dragging gun after gun out of its pit and back a[500] half dozen yards clear. It was quite dark when they were ready, and the teams splashed up and swung round their guns. A fairly heavy bombardment was carrying steadily on along the line, the sky winked and blinked and flamed in distant and near flashes of gun fire, and the air trembled to the vibrating roar and sudden thunder-claps of their discharge, the whine and moan and shriek of the flying shells. No shells had fallen near the battery position for some little time, but, unfortunately, just after the teams had arrived, a German battery chose to put over a series of five-point-nines unpleasantly close. The drivers sat, motionless blotches of shadow against the flickering sky, while the gunners strained and heaved on wheels and drag-ropes to bring the trails close enough to drop on the hooks. A shell dropped with a crash about fifty yards short of the battery and the pieces flew whining and whistling over the heads of the men and horses. Two more swooped down out of the sky with a rising wail-rush-roar of sound that appeared to be bringing the shells straight down on top of the workers’ heads. Some ducked and crouched close to earth, and both shells passed just over and fell in leaping gusts of flame and ground-shaking crashes beyond the teams. Again the fragments hissed and whistled past and lumps of earth and mud fell spattering and splashing and thumping over men and guns and teams. A driver yelped suddenly, the horses in another team snorted and plunged, and then out of the thick darkness that seemed to shut down after the searing light of the shell-burst flames came sounds of more plunging hoofs, a driver’s voice cursing angrily, threshings and splashings and stamping. ‘Horse down here ... bring a light ... whoa, steady, boy ... where’s that light?’

Three minutes later: ‘Horse killed, driver wounded in the arm, sir,’ reported the Sergeant-Major. ‘Riding leader Number Two gun, and centre driver of its waggon.’

‘Those spare horses near?’ said the Lieutenant quickly. ‘Right. Call up a pair; put ’em in lead; put the odd driver waggon centre.’

Before the change was completed and the dead horse dragged clear, the first gun was reported hooked on and ready to move, and was given the order to ‘Walk march’ and pull out on the wrecked remnant of a road that ran behind the position. Another group of five-nines came over before the others were ready, and still the drivers and teams waited motionless for the clash that told of the trail-eye dropping on the hook.

‘Get to it, gunners,’ urged the Sergeant-Major, as he saw some[501] of the men instinctively stop and crouch to the yell of the approaching shell. ‘Time we were out of this.’

‘Hear, bloomin’ hear,’ drawled one of the shadowy drivers. ‘An’ if you wants to go to bed, Lanky’—to one of the crouching gunners—‘just lemme get this gun away fust, an’ then you can curl up in that blanky shell-’ole.’

There were no more casualties getting out, but one gun stuck in a shell-hole and took the united efforts of the team and as many gunners as could crowd on to the wheels and drag-ropes to get it moving and out on to the road. Then slowly, one by one, with a gunner walking and swinging a lighted lamp at the head of each team, the guns moved off along the pitted road. It was no road really, merely a wheel-rutted track that wound in and out the biggest shell-holes. The smaller ones were ignored, simply because there were too many of them to steer clear of, and into them the limber and gun wheels dropped bumping, and were hauled out by sheer team and man power. It took four solid hours to cover less than half a mile of sodden, spongy, pulpy, wet ground, riddled with shell-holes, swimming in greasy mud and water. The ground they covered was peopled thick with all sorts of men who passed or crossed their way singly, in little groups, in large parties—wounded, hobbling wearily or being carried back, parties stumbling and fumbling a way up to some vague point ahead with rations and ammunition on pack animals and pack-men, the remnants of a battalion coming out crusted from head to foot in slimy wet mud, bowed under the weight of their packs and kits and arms; empty ammunition waggons and limbers lurching and bumping back from the gun line, the horses staggering and slipping, the drivers struggling to hold them on their feet, to guide the wheels clear of the worst holes; a string of pack-mules filing past, their drivers dismounted and leading, and men and mules ploughing anything up to knee depth in the mud, flat pannier-pouches swinging and jerking on the animals’ sides, the brass tops of the 18-pounder shell-cases winking and gleaming faintly in the flickering lights of the gun flashes. But of all these fellow wayfarers over the battlefield the battery drivers and gunners were hardly conscious. Their whole minds were so concentrated on the effort of holding and guiding and urging on their horses round or over the obstacle of the moment, a deeper and more sticky patch than usual, an extra large hole, a shattered tree stump, a dead horse, the wreck of a broken-down waggon, that they had no thought for anything[502] outside these. The gunners were constantly employed manning the wheels and heaving on them with cracking muscles, hooking on drag-ropes to one gun and dragging it clear of a hole, unhooking and going floundering back to hook on to another and drag it in turn out of its difficulty.

The Battery Commander met them at a bad dip where the track degenerated frankly into a mud bath—and how he found or kept the track or ever discovered them in that aching wilderness is one of the mysteries of war and the ways of Battery Commanders. It took another two hours, two mud-soaked nightmare hours, to come through that next hundred yards. It was not only that the mud was deep and holding, but the slough was so soft at bottom that the horses had no foothold, could get no grip to haul on, could little more than drag their own weight through, much less pull the guns. The teams were doubled, the double team taking one gun or waggon through, and then going back for the other. The waggons were emptied of their shell and filled again on the other side of the slough; and this you will remember meant the gunners carrying the rounds across a couple at a time, wading and floundering through mud over their knee-boot tops, replacing the shells in the vehicle, and wading back for another couple. In addition to this they had to haul guns and waggons through practically speaking by man-power, because the teams, almost exhausted by the work and with little more than strength to get themselves through, gave bare assistance to the pull. The wheels, axle deep in the soft mud, were hauled round spoke by spoke, heaved and yo-hoed forward inches at a time.

When at last all were over, the teams had to be allowed a brief rest—brief because the guns must be in position and under cover before daylight came—and stood dejectedly with hanging ears, heaving flanks, and trembling legs. The gunners dropped prone or squatted almost at the point of exhaustion in the mud. But they struggled up, and the teams strained forward into the breast collars again when the word was given, and the weary procession trailed on at a jerky snail’s pace once more.

As they at last approached the new position the gun flashes on the horizon were turning from orange to primrose, and although there was no visible lightening of the Eastern sky, the drivers were sensible of a faintly recovering use of their eyes, could see the dim shapes of the riders just ahead of them, the black shadows of the holes, and the wet shine of the mud under their horses’ feet.

The hint of dawn set the guns on both sides to work with trebled[503] energy. The new position was one of many others so closely set that the blazing flames from the gun muzzles seemed to run out to right and left in a spouting wall of fire that leaped and vanished, leaped and vanished without ceasing, while the loud ear-splitting claps from the nearer guns merged and ran out to the flanks in a deep drum roll of echoing thunder. The noise was so great and continuous that it drowned even the roar of the German shells passing overhead, the smash and crump of their fall and burst.

But the line of flashes sparkling up and down across the front beyond the line of our own guns told a plain enough tale of the German guns’ work. The Sergeant-Major, plodding along beside the Battery Commander, grunted an exclamation.

‘Boche is getting busy,’ said the Battery Commander.

‘Putting a pretty solid barrage down, isn’t he, sir?’ said the Sergeant-Major. ‘Can we get the teams through that?’

‘Not much hope,’ said the Battery Commander, ‘but, thank Heaven, we don’t have to try, if he keeps barraging there. It is beyond our position. There are the gun-pits just off to the left.’

But, although the barrage was out in front of the position, there were a good many long-ranged shells coming beyond it to fall spouting fire and smoke and earth-clods on and behind the line of guns. The teams were flogged and lifted and spurred into a last desperate effort, wrenched the guns forward the last hundred yards and halted. Instantly they were unhooked, turned round, and started stumbling wearily back towards the rear; the gunners, reinforced by others scarcely less dead-beat than themselves by their night of digging in heavy wet soil, seized the guns and waggons, flung their last ounce of strength and energy into man-handling them up and into the pits. Two unlucky shells at that moment added heavily to the night’s casualty list, one falling beside the retiring teams and knocking out half a dozen horses and two men, another dropping within a score of yards of the gun-pits, killing three and wounding four gunners. Later, at intervals, two more gunners were wounded by flying splinters from chance shells that continued to drop near the pits as the guns were laboriously dragged through the quagmire into their positions. But none of the casualties, none of the falls and screamings of the high-explosive shells, interrupted or delayed the work, and without rest or pause the men struggled and toiled on until the last gun was safely housed in its pit.

Then the battery cooks served out warm tea, and the men drank[504] greedily, and then, too worn out to be hungry or to eat the biscuit and cheese ration issued, flung themselves down in the pits under and round their guns and slept there in the trampled mud.

The Sergeant-Major was the last to lie down. Only after everyone else had ceased work, and he had visited each gun in turn and satisfied himself that all was correct, and made his report to the Battery Commander, did he seek his own rest. Then he crawled into one of the pits, and before he slept had a few words with the ‘Number One’ there, his old friend Duncan. The Sergeant-Major, feeling in his pockets for a match to light a cigarette, found the note which the Battery Commander had sent back and which had been passed on to him. He turned his torch light on it and read it through to Duncan—‘Bring up the guns and firing battery waggons ...’ and then chuckled a little. ‘Bring up the guns.... Remember that picture we saw before we joined, Duncan! And we fancied then we’d be bringing ’em up same fashion. And, good Lord, think of to-night.’

‘Yes,’ grunted Duncan, ‘sad slump from our anticipations. There was some fun in that picture style of doing the job—some sort of dash and honour and glory. No honour and glory about “Bring up the guns” these days. Na poo to-night anyway.’

The Sergeant-Major, sleepily sucking his damp cigarette, wrapped in his sopping British Warm, curling up in a corner on the wet cold earth, utterly spent with the night’s work, cordially agreed.

Perhaps, and anyhow one hopes, some people will think they were wrong.

Our common memories? Well, are they so many of this nature which brings closer those who recollect them together? They are indeed! Let this article be a friendly protest, a grounded protest against the idea which is no doubt, still, the prevalent popular idea on both sides of the Channel, I mean this one: ‘The Entente Cordiale is something splendid, but when one comes to think about it, how wonderful, how new!’ Yes, when we think about it superficially, how wonderful, how new, but when we think somewhat more deeply and with a little more knowledge of the past, how natural! Not a miracle: the logical result, only too long deferred, of the long centuries of our common history. It is not mere pastime to show it. How important on the contrary, how practically important for the present and for the future of our alliance, to make conscious again the old moral ties and to reawaken the sleeping sense of historical fellowship!

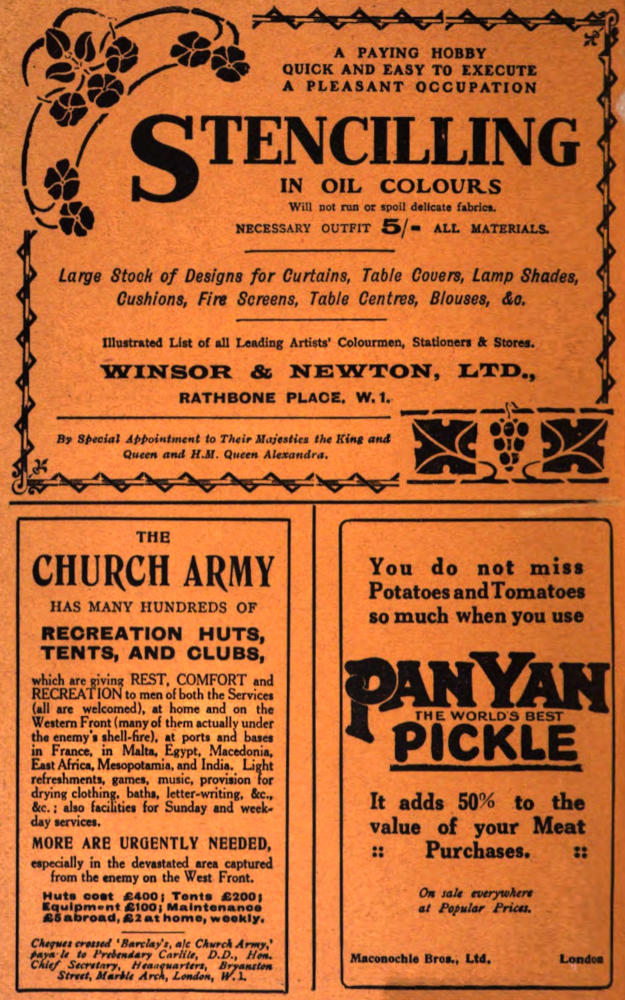

To make that fellowship apparent, at a glance, at least from certain points of view, I have devised the appended diagram. There you see represented, as it were, the streams of the history of our two nations from their farthest origins down to our own times. Please note the scale of centuries. See both streams rising about eight or six centuries before Christ in the same mountain—if I may say so figuratively—in the same mountain of the Celtic race. They spring, as you see, from the same source, and, though geographically divided, their waters remain a long time of the same colour—green in my draught.

SYMBOLIC DRAUGHT ILLUSTRATING THE HISTORY OF FRANCO-BRITISH RELATIONS.

We have, on that point of their origins, very interesting and very numerous testimonies, chiefly in the contemporary Greek and Roman writers. Very striking in particular was the fellowship[507] of ancient Britons and Gauls with regard to religion. If you open one—I may say any one—of our French history text-books, you will see that it begins exactly as one of yours, with the same story, and pictures, of Druids, priests, teachers, and judges—some of them bards; the same story of the solemn gathering of the mistletoe verdant in winter on the bare branches of oaks, symbol of the cardinal creed of the race: the immortality of the soul. Caesar, who had a Druid among his best friends, observes that the young Gauls who wanted to go deeper into the study of their religion generally used to go over to Britain in order to graduate, if I may say so, in this mysterious and lofty science.[1] It appears, therefore, that, though the Celts had passed originally from Gaul into Britain, yet Britain had become and remained the sanctuary of their common religion. Note that nothing of the sort was to be found elsewhere. Here we have characteristics of ancient Britain and ancient Gaul and of them alone. Now observe that though this Celtic colour is to be later on—in fact much later—modified by waters from other sources, yet it will never completely disappear. The Celtic element remains visible to our day in our two nations: you have your green Celtic fringe in Cornwall, Wales, part of Scotland, and the greater part of Ireland;—we have something of the kind in Brittany.

During the first century B.C. a very big event took place which was to stamp the whole of our ulterior history on this side of the Channel with its principal character: I am referring to the Romanisation of Gaul.

For many reasons which I omit, the advent of the Romans, though of course it met with some strenuous and even splendid resistance for a short time, could hardly be called a conquest in the odious meaning of the word. Now, you know that Caesar in the very midst of his campaigns in Gaul found time to carry out two bold expeditions into Britain. It is very interesting to note his motives. He was not, as one could easily imagine, impelled by an appetite of conquest. This appetite, by the way, was much less among the Romans than is generally imagined, and Caesar himself had enough to do at that time with the turbulent Gallic tribes without entering, if it could be avoided, upon a doubtful enterprise beyond the[508] Channel. But he could not do otherwise, and he gives us himself his motives, which are extremely interesting from the point of view of the history of our early relations. He felt that he could not see an end to his Gallic war if he did not at least intimidate the British brothers of the Gauls always ready to send them help! Let me quote his own words (remember that he speaks of himself in the third person):

‘Though not much was left of the fine season—and winter comes early in those parts—he resolved to pass into Britain, at least, to begin with, for a reconnoitring raid, because he saw well that in almost all their wars (the Romans’ wars) with the Gauls, help came from that country to their enemies.’[2]

His two bold raids into Britain had some of the desired effect. His successors achieved more, leisurely, without too much trouble, but very incompletely too, both as regards extent of territory and depth of impression. You see how I have expressed all this in my draught.

In Gaul, on the contrary, the transformation was complete and lasting, lasting to our days. The civilisation of Rome, which had already fascinated Gaul from afar, was so eagerly and so unanimously adopted all over the country that, in the space of a few decades, this country was nearly as Roman as Rome. The fame of the Gallo-Roman schools, the great number of Latin writers and orators of Gallic origin, the numberless remains of theatres, temples, bridges, aqueducts—some in marvellous state of preservation—which are even now to be found in hundreds of places, not only in the south but even in the north of this country, from the Mediterranean to the Rhine, and still more than anything else our language, so purely Romanic, abundantly testify to the willingness, nay to the enthusiasm, with which Gaul made her own the civilisation of Rome.

But why do I insist on this fact? Because much of all this we were to transmit to you later on, chiefly on the Norman vehicle. The direct impression of Rome on your country was to remain superficial—though it would be a mistake to overlook it altogether—but the indirect influence through us was nearly to balance any other influence and to become one of the chief factors of your moral and intellectual history.

But before we reach that time we have to take note of two nearly simultaneous events. In the fifth century the Franks established themselves in Roman Gaul and the Angles and Saxons in Roman Britain. You see in my draught each of these rivers—English and Frankish—flowing respectively into the streams of British and Gallic history. I have given about the same bluish colour to these new rivers to point out that Anglo-Saxons and Franks were originally cousins and neighbours. Their establishment was more or less attended with some rough handling, but even in their case, and chiefly in our case, the strict propriety of the word conquest to describe their coming can be questioned. There had been previous and partial agreements with the old people to come over, besides they were few in numbers. Yet the results were strikingly different. On our side the Franks were gradually absorbed, though giving their name to the country—France—and constituting, specially in the north, a small aristocracy of soldiers. On your side, on the contrary, the Anglo-Saxons converted the old country into a new one. Instead of giving up their own language they imposed it, at least to a large extent. Between them and their Frankish cousins established in old Roman Gaul relations remained quite cordial. A king of Kent, who had married a Christian daughter of a king of Paris, showed remarkable good will for the second introduction of Christianity into Britain. He and his Anglo-Saxon comrades would not accept Christianity from the ancient Britons who had already become Christian, more or less, under the Romans, but they accepted it eagerly at the recommendation of the Romanised and Christianised Franks. May I say that the Franks went so far as to provide the Mission under Augustine with the necessary interpreters! Very soon the Anglo-Saxons became so eager themselves for Christianity that they became foremost in the spreading of it to the last country which remained to be converted to the new faith, I mean Germany. This is a very interesting story, though an old one, and, I am afraid, much forgotten: your Winfrid—he and his pupils—with the recommendation and support of Charles Martel—the founder of our Carolingian dynasty—Christianising Germany, founding there a dozen bishoprics, with British bishops, becoming himself the first archbishop of Mayence, and then dying a martyr on German soil.... Is not it interesting, this now forgotten story, in which[510] we see early England and early France friendly co-operating to Christianise and to civilise Germany?

The next stage in the history of both countries was again analogous. About the same time—the ninth century—we, and you, had troubles from the same people: the Northmen. They were few in numbers, but gave much annoyance for some time. The result was the same on both sides: you practically turned your Northmen into Anglo-Saxons, and we turned ours into Romanised Frenchmen of the best sort. The process was much more rapidly completed on our side than on yours, and you were still engaged in it when our Romanised Normans arrived in Britain and nearly succeeded in achieving what the Romans themselves had failed to achieve. And more than that—more from the point of view of our relations—they very nearly succeeded in building out of our two countries a practically unified but short-lived empire.

In 1180 the whole of the present United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and nearly two-thirds of France were practically acknowledging, under one title or another, only one sovereign: Henry II. Plantagenet. Let me say—though I own it is not the view which is generally prevalent in our schools, and far from it!—that it is a pity they did not succeed altogether! Henry II. had against him untoward circumstances and, above all, Philip Augustus! He had finally to give up that fine dream. Now, union failing to be achieved that way, it is a pity, I think, that it failed also the other way, a little time after in 1216. Then the far greater part of your people, barons and clergy, revolting against one of the unworthiest rulers ever known, King John, agreed to invite over the eldest son, and heir, of the French king to be their own king. He came over, of course, was received at Westminster, accepted and confirmed Magna Charta, the charter of your liberties, and was going to be acknowledged in all parts of the kingdom when John—allow me these strong terms—did the stupidest and wickedest thing of his stupid and wicked life by dying at the wrong time! at that time! He died when by living a little longer he might have been the occasion of joining our two countries into one empire! Fancy for a moment what this would have meant, the course our common history would have taken for our common glory and the future of the whole human race! But, dying, he left an heir, a[511] boy of nine years of age, and the idea of innocent legitimacy, with the strenuous support of the Papal legate, prevailed over the half-accomplished fact! And thus this splendid chance was lost!

Another occasion presented itself hardly more than a century afterwards, when the Capetian line of our own kings became extinct and the nearest heir was the English king Edward III. In fact, he was as much French as English, and the king of a country whose official language was still French and whose popular language was now permeated with French. I think it was no more difficult for France, in 1328, to accept this king, and be united with England under the same sovereign while remaining herself, than for England in 1603 to accept a king from Scotland. Well, there was some hesitation among the French barons and clergy, and a solemn discussion was held on the point of law. In fact, there was no law at all on the subject and they had a free choice. To my mind the interest of the country pointed to the recognition of Edward, that is to union. No doubt, on the other hand, that it was the way pointed to by civil and by canon laws. They preferred the other course. No doubt they meant well, but to be well-meaning and far-seeing are two things, and I for one, in the teeth of all adverse and orthodox teaching, lament the decision which they took and the turn which they gave to national feelings yet in their infancy. The other decision would have spared the two countries not only one, but several hundred years’ wars, and would have secured to the two sister countries all the mutual advantages of peaceful development and cordial co-operation.

I can only briefly refer to the famous Treaty of Troyes, 1420, by which in the course of the Hundred Years’ War our King—insane literally speaking—and his German wife, disinherited their son to the profit of their son-in-law, the English king, and handed over to him, at once, as Regent, the crown of France. This treaty of course, under such circumstances, and when national feelings had been roused—however unfortunately—in the contrary direction, had little moral and political value. Yet, had your Henry V. lived—he died two years after the treaty—he might possibly have got it accepted by France. Professor A. Coville in his contribution to what is presently the latest, the leading, history of France, commenting on Henry’s love of justice and the stern discipline he maintained in his army—the Army of Agincourt—concludes in the following remarkable terms, which I beg to translate:

‘After so many years of strife the people of this Kingdom [the French Kingdom] looked up to his stern government to turn this anarchy into order. Paris accepted as a deliverance this yoke, heavy no doubt but protective.’[3]

It is interesting to observe that this view of this French historian is in complete agreement with Shakespeare’s ‘Henry V.’ Such an agreement between an English poet and a French scientist is certainly worthy of attention!

Well, Henry V. died, and national feelings being decidedly roused, flaming into the stupendous miracle of Joan of Arc, decided otherwise.

What about this otherwise, I mean this definitive political separation and these centuries of hostility which fill our history text-books? We can speak of it without the slightest uneasiness, not only because all this seems now to be so far in the past, a past which can never revive, but, above all, because of the remarkable characters of this hostility and of its brilliant interludes.

I say that this hostility had, on the whole, this remarkable character, to be lofty rivalry, not low hatred. It may have been—it was indeed at times—fierce and passionate, but it was all along accompanied by mutual respect. Our two countries aimed at surpassing much more than at destroying each other. It was more like a world race for glory than a grip for death. Its spirit was quarrelsome animosity taking immense delight in stupid pinpricks and daring strokes, not cold hate dreaming of mortal stabs to the heart.

Your great poet Rudyard Kipling has expressed this very finely in the poem he wrote three years ago on the occasion, if I remember well, of your King’s first visit to Paris. Let me quote from this poem:

I could illustrate this spirit by many stories. One of the most typical is about the encounter on the battlefield of Fontenoy, in 1745, of the massive English column and of the French centre. There is in that story a mixture of fine legend and historical truth, but anyway it is illustrative of the spirit. The very fact that the legend could grow out of the truth is a proof of the spirit by itself.

There is another story much less known, but which is as much illuminating. It was at the beginning of the American war, thirty-four years after Fontenoy, in 1779. Your famous seaman Rodney was in Paris, which he could not leave on account of certain debts, yet he was perfectly free to walk about as any ordinary private man, though France and England were at war. Concentration camps had not been invented as yet! One day, then, as he was dining with some French military friends—always remember, please, that we were at war—they came to talk of some recent successes we had just had at sea, among them the conquest of Grenada in the West Indies. Rodney expressed himself on these successes with polite disdain, saying that if he was free—he Rodney—the French would not have it so easy! Upon which old Marshal de Biron paid for his debts and said: ‘You are free, sir, the French will not avail themselves of the obstacles which prevent you from fighting them.’ Well, it cost us very dear to have let him go, but was not it fine!

I am glad to hear from my friend, your Oxford countryman, Mr. C.R.L. Fletcher, the author of a brilliantly written ‘Introductory History of England’ in four volumes, that the story is told in substantially the same terms on your side, by all the authorities on the subject: Mundy’s ‘Life and Correspondence of Lord Rodney’ (vol. i. p. 180); Laughton in the ‘Dictionary of National Biography’; Captain Mahan in his ‘Influence of Sea Power in History,’ p. 377.

We could tell many, many stories of that kind, but let these two be sufficient for our purpose to-day. And yet, even with all these extenuating circumstances, how pitiful it would have been if this enmity had been continuous! But it was not, and even far from it! Even the worst of all our wars, the Hundred Years’ War, was interrupted by very numerous and very long truces lasting years and even decades of years! In fact, that war consisted generally of mere raids with handfuls of men, though it must be said that they often did harm out of all proportion to their numbers. As to the other wars in more modern times they were pleasantly intermingled[514] with interludes of co-operation and alliance. The simple enumeration of them is instructive and may even appear surprising.

In the sixteenth century there was a temporary alliance between your Henry VIII. and our Francis the First, against the Emperor of Germany, Charles V. In fact Henry VIII., at first, had allied himself with the German Emperor against the French king, but when the latter, attacked from all cardinal points (Spain and most of Italy were then in the hands of the Emperor), had been beaten at Pavia and taken prisoner to Madrid, your King perceived his mistake, i.e. England’s ultimate danger. He consequently offered his alliance to Francis for the restoration of this balance of power, which, for want of something better, was the guarantee of the independence of all states. In Mignet’s study[4] of these times I find this extract from your King’s instructions to his ambassadors in France, in March 1526, as to the conditions forced upon the French king, in his Spanish prison, by the Emperor of Germany:

‘They [the English ambassadors] shall infer what damage the crown of France may and is likely to stand in by the said conditions—this be the way to bring him [Charles] to the monarchy of Christendom.’

You know that, after all, the world-wide ambition of the then Emperor of Germany was defeated, to the point that he resigned in despair and ended his life in a monastery.

Again, towards the end of the same century Queen Elizabeth was on quite friendly terms with our Henry the Fourth. They had the same enemy: Philip the Second of Spain, son of Charles the Fifth and heir to the greater part of his dominions. This friendship ripened into alliance, and there was a very strong English contingent in the French army which retook Amiens, from the Spaniards, in 1597. Both sovereigns united also in helping the Low Countries in their struggle for independence against Spain.

In the seventeenth century your Cromwell and our Mazarin renewed the same alliance against Spain, and in 1657 a Franco-British army under the ablest of the French soldiers of that time, Marshal Turenne, beat the Spaniards near Dunkirk and took Dunkirk itself, which was handed over to you as the price previously agreed upon of the alliance.

After the Restoration your Stuarts were on so friendly terms with the French Government that they were accused, sometimes[515] with some show of justice, of forgetting the national interests. There is no doubt that they tried, and to a certain extent successfully, to evade the just demands and control of your Parliament by becoming pensioners of the King of France. Their selling Dunkirk to France in 1662, five years after its capture from Spain, made them particularly unpopular. Of course, when they were finally expelled by your revolutions of 1688, they found, with hundreds of followers, a hospitable reception at the French court, causing thereby on the other hand a revival of hostility between our government and your new one. May I observe, by the way, that the head of this new government of yours was the Prince of Orange—French Orange, near Avignon—and that this little, practically self-governing principality was suffered to remain his until his death, in 1702, when Louis XIV. annexed it to France?

In the eighteenth century itself, marked by so keen a rivalry, there were temporary periods of understanding, specially during the two or three decades following the peace of Utrecht, with a view of preserving the peace of Europe. The names of Sir Robert Walpole and Cardinal Fleury are attached to this period.

In the nineteenth century, from the fall of Napoleon, the improvement of our relations—down to the present day—has been nearly continuous and marked by a series of remarkable facts. It was first the union of our navies, with that of Russia, for the destruction of the Turkish fleet at Navarino, in 1827, thereby securing the independence of Greece—an independence which was completed in the ensuing years by French and Russian armies—(we wish the present Greek Government, the Royal government, remembered this better!). It was then the union of our policies for the liberation of Belgium from Dutch vassalage, a liberation which Prussia wanted to oppose but durst not, seeing that France and England had made up their minds about it. Then came the union of our armies for the mistaken object of protecting Turkey against Russia (how strange it sounds now!), or of opening China to the European trade. Chief of all, how could we forget that—some way or other—France and Britain have been godmothers to Italian unity!

Well, all this is rather a long record and it may appear surprising to many as an aggregate, though nearly each component part of it is well known! The reason for this impression of surprise is this: in spite of this political co-operation, and side by side with it, much of the acrimonious spirit long survived, unwilling to die.[516] The twentieth century, thank God! and the present alliance have given it the ‘coup de grâce’!

I have adverted until now to the political side only of our relations, but if we look at our past relations from another standpoint—the standpoint of the mind, of moral progress, of civilisation—we have a somewhat simpler story to tell, yet a chequered story too. Whatever our political relations may have been—with perhaps the only exception of the time when you opposed all reforms, because we were making revolutionary, disconcerting reforms!—we have been generally emulating for all that ennobles the life of man: higher thought, justice, and liberty. There is here such a formidable accumulation of interesting facts that I can scarcely refer to them except in very general terms, lest I should lose sight of the limits within which I must compress this article.

French and English writers rarely took much account of the political hostility which prevailed between the two countries. Your writers have generally paid, from Chaucer’s time down to our own, the closest attention to our literature, whether they have followed its lead or reacted against its influence. On the other hand, all our political philosophers have always found in the study of your institutions a source of inexhaustible interest, whether they have been admirers of them like Montesquieu or sharp critics like Rousseau. And let no one imagine that this side of the question is devoid of practical interest. It is owing to this continuous interchange of ideas that both countries have been equipped for these intellectual, moral and political achievements by which, in spite of all their shortcomings, they have won the glory of being generally acknowledged, on so many points, as the joint leaders of modern civilisation. It is the fact that they have been more or less conscious all along, or nearly so, of this joint leadership, which has so happily counteracted and at the end got the better of political acrimony and popular prejudices. The Entente Cordiale between our two countries is largely a triumph of the mind, the finest in history and certainly the most far-reaching. Let us not underestimate therefore the influence of intellectual workers. It has been the glory of most of them in this country and in yours to plead for the noblest ideals: for liberty and justice at home, and also, abroad, for a cordial understanding of all nations, for[517] harmony between national interests and the rights of humanity. In modern Germany, on the contrary, most of those who are supposed to be the representatives of the mind have not been ashamed of ministering, long before this war, to the brutal appetites of a feudal and military caste by spreading among their own people a monstrous belief in the divine right of the German race to oppress all the world. The best of them, with extremely rare exceptions, have done nothing to oppose this dangerous fanaticism and to maintain the nobler traditions of German thought. Both instances therefore, ours and theirs—I mean French and British intellectual history on one side, German later intellectual history on the other side—sufficiently illustrate the power of spiritual factors for good or for evil. The only thing to be deplored in our case is that our Entente was so long deferred. Things would have turned otherwise if our Entente had ripened somewhat earlier into a closer association, gradually extending by a moral attraction to all peace-loving nations. Had it been so who would have dared to attack them? At least let the bitter lesson be turned to account for the future!

And chief of all let us think of the new chapter of our common history. There is being written on the banks and hills of the Somme such a chapter of our common history as will live eternally in the souls of Britons and Frenchmen. Let the memory of it, added to all those I have recounted, bind together in eternal alliance the hearts and the wills of the two nations. Let it be known to all the world that this present alliance is not like so many of the past a temporary combination of governments, but the unanimous and for ever fixed will of both nations as the crowning and logical conclusion of their glorious history. Let this close and intimate association include all our noble allies, and all such nations as may be worthy to join it; let it become the Grand Alliance, the only one really and completely deserving of this name, to which it will have been reserved to establish, at last, the reign of Right and Peace on earth.

Gaston E. Broche.

[1] Caesar, B.G. vi. 13.

[2] Caesar, B.G. iv. 20.

[3] See Histoire de France publiée sous la direction de Mr. Lavisse: Tome IV. par A. Coville, Recteur de l’Académie de Clermont-Ferrand, Professeur honoraire de l’Université de Lyon.

[4] Mignet, Rivalité de François 1er et de Charles-Quint, II ch. ix.

To the July number of Cornhill I last year contributed an article gleaned from the Recollections of an anonymous observer of the House of Commons from the year 1830 to the close of the session of 1835. It contained a series of thumb-nail personal sketches of eminent members long since gone to ‘another place,’ leaving names that will live in English history. A portion of the musty volume was devoted to descriptions of Parliamentary surroundings and procedure interesting by comparison with those established at the present day.

‘Q,’ as for brevity I name the unknown recorder, describes the old House of Commons destroyed by fire in 1834 as dark, gloomy and badly ventilated, so small that not more than 400 out of the 658 members could be accommodated with any measure of comfort. In those days an important debate was not unfrequently preceded by ‘a call of the House,’ which brought together a full muster. On such occasions members were, ‘Q’ says, ‘literally crammed together,’ the heat of the House recalling accounts of the then recent tragedy of the Black Hole of Calcutta. Immediately over the entrance provided for members was the Strangers’ Gallery; underneath it were several rows of seats for friends of members. This arrangement exists in the new House. Admission to the Strangers’ Gallery was obtained on presentation of a note or order from a member. Failing that, the payment of half a crown to the doorkeeper at once procured admittance.

When the General Election of 1880 brought the Liberals into power, parties in the House of Commons, in obedience to immemorial custom, crossed over, changing sides. The Irish members, habitually associated with British Liberals, having when in Opposition shared with them the benches to the left of the Speaker, on this occasion declined to change their quarters, a decision ever since observed. They were, they said, free from allegiance to either political party and would remain uninfluenced by their movements. This was noted at the time as a new departure. Actually they were following a precedent established half a century earlier.

In the closing sessions of the unreformed Parliament, a group of extreme Radicals, including Hume, Cobbett and Roebuck, remained seated on the Opposition Benches whichever party was in power. Prominent amongst them was Hume, above all others most constant in attendance. He did not quit his post even during the dinner hour. He filled his pockets with fruit—pears by preference—and at approach of eight o’clock publicly ate them.

In the old House of Commons a bench at the back of the Strangers’ Gallery was by special favour appropriated to the reporters. The papers represented paid the doorkeepers a fee of three guineas a session. As they numbered something over threescore this was a source of snug revenue in supplement to the strangers’ tributary half-crown. Ladies were not admitted to the Strangers’ Gallery. The only place whence they could partly see, and imperfectly hear, what was going on was by looking down through a large hole in the ceiling immediately above the principal candle-stocked chandelier. This aperture was the principal means of ventilating the House, and the ladies circled round it regardless of the egress of vitiated air. Mr. Gladstone, who sat in the old House as member for Newark, once told me that during progress with an important debate he saw a fan fluttering down from the ceiling. It had dropped from the hand of one of the ladies, who suddenly found herself in a semi-asphyxiated condition. Something more than half a century later Mr. Gladstone was unconsciously the object of attention from another group of ladies indomitable in desire to hear an historic speech. On the night of the introduction of the first Home Rule Bill there was overflowing demand for seats in the Ladies’ Gallery. When accommodation was exhausted, the wife of the First Commissioner of Works happily remembered that the floor of the House is constructed of open iron network, over which a twine matting is laid. These cover the elaborate machinery by which fresh air is constantly let into the Chamber, escaping by apertures near the ceiling. Standing or walking along the Iron Gallery that spans the vault, it is quite easy to hear what is going on in the House. Here, on the invitation of the First Commissioner’s wife, were seated a company of ladies who, unseen, their presence unsuspected, heard every word of the Premier’s epoch-making speech.

‘Q’ incidentally records details of procedure in marked contrast with that of to-day. In these times, on the assembling of a newly elected Parliament, the Oath is administered by the Clerk to members[520] standing in batches at small tables on the floor of the House. In the old Parliament, members were sworn in by the Lord Steward of His Majesty’s Household. At the same period a new Speaker being duly elected or re-elected was led by the Mover and Seconder from his seat to the Bar, whence he was escorted to the Chair. To-day he is conducted direct to the Chair. When divisions were taken in Committee of the whole House, members did not, as at present, go forth into separate lobbies. The ‘ayes’ ranged themselves to the right of the Speaker’s Chair, the ‘noes’ to the left, and were counted accordingly. The practice varied when the House was fully constituted, the Speaker in the Chair and the Mace on the Table. In such circumstances one only of the contending parties, the ‘ayes’ or the ‘noes’ according to the nature of the business in question, quitted the Chamber. The tellers first counted those remaining in the House, and then, standing in the passage between the Bar and the door, counted the others as they re-entered. The result of the division was announced in the formula: ‘The ayes that went out are’ so many. ‘The noes who remained are’ so many, or otherwise according to the disposition of the opposing forces. A quorum then as now was forty, but when the House was in Committee the presence of eight members sufficed. ‘Q’ makes no reference to the use of a bell announcing divisions. But he mentions occasions on which the Mace was sent to Westminster Hall, the Court of Request, or to the several Committee Rooms to summon members to attend.

At the period of Parliamentary history of which ‘Q’ is the lively chronicler, the ceremony of choosing a Speaker and obtaining Royal Assent to the choice was identical with that first used on the occasion of Sir Job Charlton’s election to the Chair in the time of Charles II. The title of Speaker was bestowed because he alone had the right to speak to or address the King in the name and on behalf of the House of Commons. Of this privilege he customarily availed himself at considerable length. On being summoned to the presence of the Sovereign in the House of Lords he, in servile terms, begged to be excused from undertaking the duties of Speaker, ‘which,’ he protested, ‘require greater abilities than I can pretend to own.’ The Lord Chancellor, by direction of the Sovereign, assured the modest man that ‘having very attentively heard your discreet and handsome discourse,’ the King would not consent to refusal of the Chair. Thereupon the Speaker-designate launched forth into a fresh, even more ornate, address, claiming[521] ‘renewal of the ancient privileges of Your most loyal and dutiful House of Commons.’ Whereto His Majesty, speaking again by the mouth of the Lord Chancellor, remarked, not without a sense of humour, that ‘he hath heard and well weighed your short and eloquent oration and in the first place much approves that you have introduced a shorter way of speaking on these occasions.’

Up to 1883 the Speaker’s salary was, as it is to-day, £5000 a year. In addition to his salary he received fees amounting to £2000 or £3000 per session. On his election he was presented with 2000 ounces of plate, £1000 of equipment money, two hogsheads of claret, £100 per annum for stationery, and a stately residence in convenient contiguity to the House. These little extras made the post worth at least £8000 per annum.

In the present and recent Parliament an ancient tradition is kept up by a member for the City of London seating himself on the Treasury Bench. Two members are privileged to take their places there, but after his election for the City Mr. Arthur Balfour left Sir Frederick Banbury in sole possession of the place. To-day, by the strange derangement of party ties consequent on the war, the ex-Prime Minister has permanently shifted his quarters to the Treasury Bench under the leadership of a Radical Premier. In the first third of the nineteenth century the City of London returned four members, who not only sat on the Treasury Bench on the opening day of the new Parliament, but arrayed themselves in scarlet gowns. Sir Frederick Banbury stopped short of acquiring that distinction.

During the first two sessions of the reformed Parliament the Commons met at noon for the purpose of presenting petitions and transacting other business of minor importance. These morning sittings, precursors of others instituted by Disraeli and since abandoned, usually lasted till three o’clock, the House then adjourning till five, when real business was entered upon. Subsequently this arrangement was abandoned, the Speaker taking the Chair at half-past three. Even then the first and freshest hour and a half of the sitting were spent in the presentation of petitions or in debate thereupon. The interval can be explained only upon the assumption that the petitions were read verbatim.

In the Parliamentary procedure of to-day petitions play a part of ever decreasing importance. Their presentation takes precedence of all other business. But the member in charge of one is not permitted to stray beyond briefest description of its prayer and a[522] statement of the number of signatories. Thereupon, by direction of the Speaker, he thrusts the petition into a sack hanging to the left of the Speaker’s chair, and there an end on’t. There is, it is true, a Committee of Petitions which is supposed to examine every document. As far as practical purposes are concerned, petitions might as well be dropped over the Terrace into the Thames as into the mouth of the appointed sack.

At times of popular excitement round a vexed question—by preference connected with the Church, the sale of liquor, or, before her ghost was laid, marriage with the deceased wife’s sister—the flame systematically fanned is kept burning by the presentation of monster petitions. Amid ironical cheers these are carried in by two elderly messengers, who lay them at the foot of the Table. Having been formally presented, they are, amid renewed merriment, carried forth again and nothing more is heard of them, unless the Committee on Petitions reports that there is suspicious similarity in the handwriting of blocks of signatures, collected by an energetic person remunerated by commission upon the aggregate number.

The most remarkable demonstration made in modern times happened during the short life of the Parliament elected in 1892. Members coming down in time for prayers discovered to their amazement the floor of the House blocked with monster rolls, such as are seen in the street when the repair of underground telegraph wires is in progress. The member to whose personal care this trifle had been submitted rising to present the petition, Mr. Labouchere, on a point of order, objected that sight of him was blocked by the gigantic cylinders. ‘The hon. gentleman,’ he suggested, ‘should mount one and address the Chair from the eminence.’ The suggestion was disregarded, and in time the elderly messengers put their shoulders to wheels and rolled the monsters out of the House.

‘Q,’ whose eagle eye nothing escapes, comments on the preponderance of bald heads among Ministers. Occupying an idle moment, he counted the number of bald heads and found them to amount to one-third of the full muster. ‘Taking the whole 658,’ he writes in one of his simple but delightful asides, ‘I should think that perhaps a fourth part are more or less baldheaded. The number of red heads,’ he adds, ‘is also remarkable. I should think they are hardly less numerous than bald ones. When I come to advert to individual members of distinction it cannot fail to strike the reader how many are red-headed.’

This interesting inference is, if it be accepted as well-founded, damaging to the status of the present House of Commons. I do not, on reflection, recall a single member so decorated.

As to baldheadedness—which in the time of the prophet Elisha was regarded as an undesirable eccentricity, public notice of which, it will be remembered, condemned the commentators to severe disciplinary punishment—it was, curiously enough, a marked peculiarity among members of the House of Commons in an early decade of the nineteenth century. I have a prized engraving presenting a view of the interior of the House of Commons during the sessions of 1821-3. Glancing over the crowded benches, I observe that the proportion of baldheaded men is at least equal to that noted by ‘Q’ in the Parliament sitting a dozen years later.

What are known as scenes in the House were not infrequent in ‘Q’s’ time. He recalls one in which an otherwise undistinguished member for Oxford, one Hughes Hughes, was made the butt. It was a flash of the peculiar, not always explicable, humour of the House of Commons, still upon occasion predominant, to refuse a gentleman a hearing. ‘Hughes’s rising was the signal for continuous uproar,’ ‘Q’ writes. ‘At repeated intervals a sort of drone-like drumming, having the sound of a distant hand organ or bagpipes, arose from the back benches. Coughing, sneezing and ingeniously extended yawning blended with other sounds. A voice from the Ministerial benches imitated very accurately the yelp of a kennelled hound.’

For ten minutes the double-barrelled Hughes faced the music, and when he sat down not a word save the initial ‘Sir’ had been heard from his lips.

The nearest approach to this scene I remember happened in the last session of the Parliament of 1868-74, when, amidst similar uproar, Cavendish Bentinck, as one describing at the time the uproar wrote, ‘went out behind the Speaker’s Chair and crowed thrice.’ This was the occasion upon which Sir Charles Dilke made his Parliamentary début. In Committee of Ways and Means he, in uncompromising fashion that grated on the ears of loyalists, called attention to the Civil List of Queen Victoria and moved a reduction. Auberon Herbert, now a staid Tory, at that time suspected of a tendency towards Republicanism, undertook to second the amendment. Sir Charles managed amid angry interruptions to work off his speech. Herbert, following him, was met by a storm of resentment that made his sentences inaudible.

After uproar had prevailed for a full quarter of an hour a shamefaced member, anxious for the dignity of the Mother of Parliaments, called attention to the presence of strangers. Forthwith, in accordance with the regulation then in force, the galleries were cleared. As the occupants of the Press Gallery reluctantly departed, they heard above the shouting the sound of cock-crowing. Looking over the baluster they saw behind the Chair Little Ben, as Cavendish Bentinck was called to distinguish him from his bigger kinsman, vigorously engaged upon a vain effort to preserve order by a passable imitation of Chanticleer saluting the happy morn.

From ‘Q’s’ report of another outbreak of disorder it would appear that in the House meeting in the ‘thirties of the nineteenth century, exchange of personalities went far beyond modern experience. The once heated Maynooth question was to the fore. In the course of an animated set-to between a Mr. Shaw and Daniel O’Connell, the former shouted ‘The Hon. Member has charged me with being actuated by spiritual ferocity. My ferocity is not of the description which takes for its symbol a death’s head and cross bones.’ O’Connell, as a certain fishwife locally famous for picturesque language discovered, was hard to beat in the game of vituperation. Turning upon Shaw, he retorted ‘Yours is a calf’s head and jaw bones.’

‘Q’ records that the retort was greeted with deafening cheers from the Ministerial side where O’Connell and his party were seated. Mr. Shaw’s polite, but perhaps inconsequential, remark had been received with equal enthusiasm by the Opposition.

‘Caesar,’ said a Sub-lieutenant to his friend, a temporary Lieutenant R.N.V.R., who at the outbreak of war had been a classical scholar at Oxford, ‘you were in the thick of our scrap yonder off the Jutland coast. You were in it every blessed minute with the battle cruisers, and must have had a lovely time. Did you ever, Caesar, try to write the story of it?’

It was early in June of last year, and a group of officers had gathered near the ninth hole of an abominable golf course which they had themselves laid out upon an island in the great landlocked bay wherein reposed from their labours long lines of silent ships. It was a peaceful scene. Few even of the battleships showed the scars of battle, though among them were some which the Germans claimed to be at the bottom of the sea. There they lay, coaled, their magazines refilled, ready at short notice to issue forth with every eager man and boy standing at his action station. And while all waited for the next call, officers went ashore, keen, after the restrictions upon free exercise, to stretch their muscles upon the infamous golf course. It was, I suppose, one of the very worst courses in the world. There were no prepared tees, no fairway, no greens. But there was much bare rock, great tufts of coarse grass greedy of balls, wide stretches of hard, naked soil destructive of wooden clubs, and holes cut here and there of approximately the regulation size. Few officers of the Grand Fleet, except those in Beatty’s Salt of the Earth squadrons, far to the south, had since the war began been privileged to play upon more gracious courses. But the Sea Service, which takes the rough with the smooth, with cheerful and profane philosophy, accepted the home-made links as a spirited triumph of the handy-man over forbidding nature.

‘Yes,’ said the naval volunteer, ‘I tried many times, but gave up all attempts as hopeless. I came up here to get first-hand material, and have sacrificed my short battle leave to no purpose. The more I learn the more helplessly incapable I feel. I can describe the life of a ship, and make you people move and speak like live things. But a battle is too big for me. One might as well try to realise and set on paper the Day of Judgment. All I did was to[526] write a letter to an old friend, one Copplestone, beseeching him to make clear to the people at home what we really had done. I wrote it three days after the battle, but never sent it. Here it is.’

Lieutenant Caesar drew a paper from his pocket and read as follows:

‘My dear Copplestone,—Picture to yourself our feelings. On Wednesday we were in the fiery hell of the greatest naval action ever fought. A real Battle of the Giants. Beatty’s and Hood’s battle cruisers—chaffingly known as the Salt of the Earth—and Evan Thomas’s squadron of four fast Queen Elizabeths had fought for two hours the whole German High Seas Fleet. Beatty, in spite of his heavy losses, had outmanœuvred Fritz’s battle cruisers and enveloped the German line. The Fifth Battle Squadron had stalled off the German Main Fleet, and led them into the net of Jellicoe, who, coming up, deployed between Evan Thomas and Beatty, though he could not see either, crossed the T of the Germans in the beautifullest of beautiful manœuvres, and had them for a moment as good as sunk. But the Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away; it is sometimes difficult to say Blessed be the Name of the Lord. For just when we most needed full visibility the mist came down thick, the light failed, and we were robbed of the fruits of victory when they were almost in our hands. It was hard, hard, bitterly hard. But we had done the utmost which the Fates permitted. The enemy, after being harried all night by destroyers, had got away home in torn rags, and we were left in supreme command of the North Sea, a command more complete and unchallengeable than at any moment since the war began. For Fritz had put out his full strength, all his unknown cards were on the table, we knew his strength and his weakness, and that he could not stand for a moment against our concentrated power. All this we had done, and rejoiced mightily. In the morning we picked up from Poldhu the German wireless claiming the battle as a glorious victory—at which we laughed loudly. But there was no laughter when in the afternoon Poldhu sent out an official message from our own Admiralty which, from its clumsy wording and apologetic tone, seemed actually to suggest that we had had the devil of a hiding. Then when we arrived at our bases came the newspapers with their talk of immense losses, and of bungling, and of the Grand Fleet’s failure! Oh, it was a monstrous shame! The country which depends utterly upon us for life and honour, and had trusted us utterly, had been struck to the heart. We had come back glowing, exalted by the battle, full of admiration for the skill of our leaders and for the serene intrepidity of our men. We had seen our ships go[527] down and pay the price of sea command—pay it willingly and ungrudgingly as the Navy always pays. Nothing that the enemy had done or could do was able to hurt us, but we had been mortally wounded in the house of our friends. It will take days, weeks, perhaps months, for England and the world to be made to understand and to do us justice. Do what you can, old man. Don’t delay a minute. Get busy. You know the Navy, and love it with your whole soul. Collect notes and diagrams from the scores of friends whom you have in the Service; they will talk to you and tell you everything. I can do little myself. A Naval Volunteer who fought through the action in a turret, looking after a pair of big guns, could not himself see anything outside his thick steel walls. Go ahead at once, do knots, and the fighting Navy will remember you in its prayers.’

The attention of others in the group had been drawn to the reader and his letter, and when Lieutenant Caesar stopped, flushed and out of breath, there came a chorus of approving laughter.

‘This temporary gentleman is quite a literary character,’ said a two-ring Lieutenant who had been in an exposed spotting top throughout the whole action, ‘but we’ve made a Navy man of him since he joined. That’s a dashed good letter, and I hope you sent it.’

‘No,’ said Caesar. ‘While I was hesitating, wondering whether I would risk the lightning of the Higher Powers, a possible court martial, and the loss of my insecure wavy rings, the business was taken out of my hands by this same man to whom I was wanting to write. He got moving on his own account, and now, though the battle is only ten days old, the country knows the rights of what we did. When it comes to describing the battle itself, I make way for my betters. For what could I see? On the afternoon of May 31, we were doing gun drill in my turret. Suddenly came an order to put lyddite into the guns and follow the Control. During the next two hours as the battle developed we saw nothing. We were just parts of a big human machine intent upon working our own little bit with faultless accuracy. There was no leisure to think of anything but the job in hand. From beginning to end I had no suggestion of a thrill, for a naval action in a turret is just gun drill glorified, as I suppose it is meant to be. The enemy is not seen; even the explosions of the guns are scarcely heard. I never took my ear-protectors from their case in my pocket. All is quiet, organised labour, sometimes very hard labour when for any reason[528] one has to hoist the great shells by the hand purchase. It is extraordinary to think that I got fifty times more actual excitement out of a squadron regatta months ago than out of the greatest battle in naval history.’

‘That’s quite true,’ said the Spotting Officer, ‘and quite to be expected. Battleship fighting is not thrilling except for the very few. For nine-tenths of the officers and men it is a quiet, almost dull routine of exact duties. For some of us up in exposed positions in the spotting tops or on the signal bridge, with big shells banging on the armour or bursting alongside in the sea, it becomes mighty wetting and very prayerful. For the still fewer, the real fighters of the ship in the conning tower, it must be absorbingly interesting. But for the true blazing rapture of battle one has to go to the destroyers. In a battleship one lives like a gentleman until one is dead, and takes the deuce of a lot of killing. In a destroyer one lives rather like a pig, and one dies with extraordinary suddenness. Yet the destroyer officers and men have their reward in a battle, for then they drink deep of the wine of life. I would sooner any day take the risks of destroyer work, tremendous though they are, just for the fun which one gets out of it. It was great to see our boys round up Fritz’s little lot. While you were in your turret, and the Sub. yonder in control of a side battery, Fritz massed his destroyers like Prussian infantry and tried to rush up close so as to strafe us with the torpedo. Before they could get fairly going, our destroyers dashed at them, broke up their masses, buffeted and hustled them about exactly like a pack of wolves worrying sheep, and with exactly the same result. Fritz’s destroyers either clustered together like sheep or scattered flying to the four winds. It was just the same with the light cruisers as with the destroyers. Fritz could not stand against us for a moment, and could not get away, for we had the heels of him and the guns of him. There was a deadly slaughter of destroyers and light cruisers going on while we were firing our heavy stuff over their heads. Even if we had sunk no battle cruisers or battleships, the German High Seas Fleet would have been crippled for months by the destruction of its indispensable “cavalry screen.”’

As the Spotting Officer spoke, a Lieutenant-Commander holed out on the last jungle with a mashie—no one uses a putter on the Grand Fleet’s private golf course—and approached our group, who, while they talked, were busy over a picnic lunch.

‘If you pigs haven’t finished all the bully beef and hard tack,’[529] said he, ‘perhaps you can spare a bite for one of the blooming ’eroes of the X Destroyer Flotilla.’ The speaker was about twenty-seven, in rude health, and bore no sign of the nerve-racking strain through which he had passed for eighteen long-drawn hours. The young Navy is as unconscious of nerves as it is of indigestion. The Lieutenant-Commander, his hunger satisfied, lighted a pipe and joined in the talk.

‘It was hot work,’ said he, ‘but great sport. We went in sixteen and came out a round dozen. If Fritz had known his business, I ought to be dead. He can shoot very well till he hears the shells screaming past his ears, and then his nerves go. Funny thing how wrong we’ve been about him. He is smart to look at, fights well in a crowd, but cracks when he has to act on his own without orders. When we charged his destroyers and ran right in he just crumpled to bits. We had a batch of him nicely herded up, and were laying him out in detail with guns and mouldies, when there came along a beastly intrusive Control Officer on a battle cruiser and took him out of our mouths. It was a sweet shot, though. Someone—I don’t know his name, or he would hear of his deuced interference from me—plumped a salvo of twelve-inch common shell right into the brown of Fritz’s huddled batch. Two or three of his destroyers went aloft in scrap-iron, and half a dozen others were disabled. After the first hour his destroyers and light cruisers ceased to be on the stage; they had flown quadrivious—there’s an ormolu word for our classical volunteer—and we could have a whack at the big ships. Later, at night, it was fine. We ran right in upon Fritz’s after-guard of sound battleships and rattled them most tremendous. He let fly at us with every bally gun he had, from four-inch to fourteen, and we were a very pretty mark under his searchlights. We ought to have been all laid out, but our loss was astonishingly small, and we strafed two of his heavy ships. Most of his shots went over us.’

‘Yes,’ called out the Spotting Officer, ‘yes, they did, and ricochetted all round us in the Queen Elizabeths. There was the devil of a row. The firing in the main action was nothing to it. All the while you were charging, and our guns were masked for fear of hitting you, Fritz’s bonbons were screaming over our upper works and making us say our prayers out loud in the Spotting Tops. You’d have thought we were at church. I was in the devil of a funk, and could hear my teeth rattling. It is when one is fired on and can’t hit back that one thinks of one’s latter end.’

‘Did any of you see the Queen Mary go?’ asked a tall thin man with the three rings of a Commander. ‘Our little lot saw nothing of the first part of the battle; we were with the K.G. Fives and Orions.’

‘I saw her,’ spoke a Gunnery Lieutenant, a small, quiet man with dreamy, introspective eyes—the eyes of a poet turned gunner. ‘I saw her. She was hit forward, and went in five seconds. You all know how. It was a thing which won’t bear talking about. The Invincible took a long time to sink, and was still floating bottom up when Jellicoe’s little lot came in to feed after we and the Salt of the Earth had eaten up most of the dinner. I don’t believe that half the Grand Fleet fired a shot.’

There came a savage growl from officers of the main Battle Squadrons, who, invited to a choice banquet, had seen it all cleared away before their arrival. ‘That’s all very well,’ grumbled one of them; ‘the four Q.E.s are getting a bit above themselves because they had the luck of the fair. They didn’t fight the High Seas Fleet by their haughty selves because they wanted to, you bet.’

The Gunnery Lieutenant with the dreamy eyes smiled. ‘We certainly shouldn’t have chosen that day to fight them on. But if the Queen Elizabeth herself had been with us, and we had had full visibility—with the horizon a hard dark line—we would have willingly taken on all Fritz’s twelve-inch Dreadnoughts and thrown in his battle cruisers.’

‘That’s the worst of it,’ grumbled the Commander, very sore still at having tasted only of the skim milk of the battle; ‘naval war is now only a matter of machines. The men don’t count as they did in Nelson’s day.’

‘Excuse me, sir,’ remarked the Sub-Lieutenant; ‘may I say a word or two about that? I have been thinking it out.’