Title: The Taylor-Trotwood Magazine, Vol. IV, No. 5, February 1907

Author: Various

Editor: John Trotwood Moore

Robt. L. Taylor

Release date: December 1, 2023 [eBook #72276]

Language: English

Original publication: Nashville: The Taylor-Trotwood Publishing Co, 1907

Credits: hekula03 and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

SUCCESSOR TO

BOB TAYLOR’S MAGAZINE and TROTWOOD’S MONTHLY

Published by THE TAYLOR-TROTWOOD PUBLISHING COMPANY, 11, 13, 16, 19 Vanderbilt

Law Building, Nashville, Tenn.

GOVERNOR BOB TAYLOR and JOHN TROTWOOD MOORE, Editors

| $1.00 A YEAR | MONTHLY | 10c. A COPY |

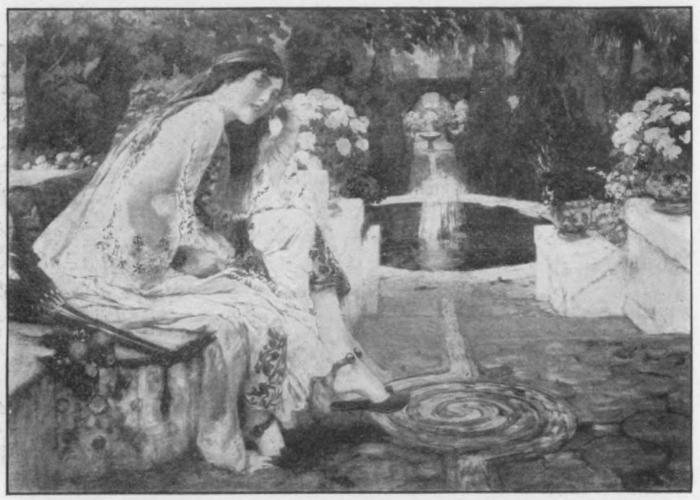

| Frontispiece—From a painting by Gilbert Gaul | ||

| The Jamestown Exposition | James Hines | 455 |

| Illustrated. | ||

| Once More the Dream. (Poem) | W. M. Shields | 462 |

| General Joseph E. Johnston | Robert L. Taylor | 463 |

| Illustrated. | ||

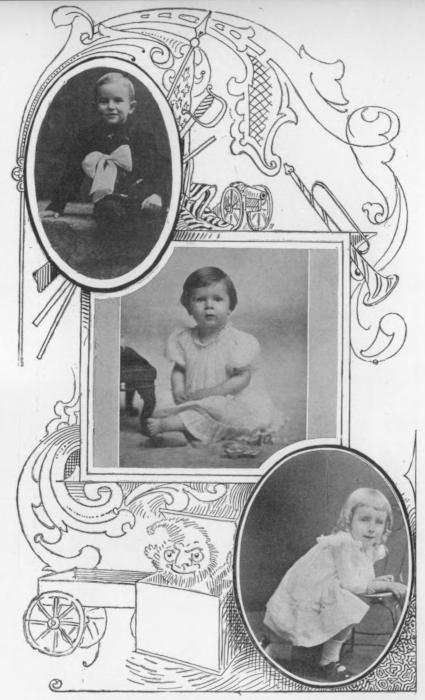

| Little Citizens of the South | 467 | |

| Illustrated. | ||

| Historic Highways of the South—Chapter XVII. | John Trotwood Moore | 472 |

| Americans at the Peace Congress | Hayne Davis | 483 |

| Illustrated. | ||

| Frederick A. Bridgman | Lillian Kendrick Byrn | 489 |

| Illustrated. | ||

| Men of Affairs | 493 | |

| Illustrated. | ||

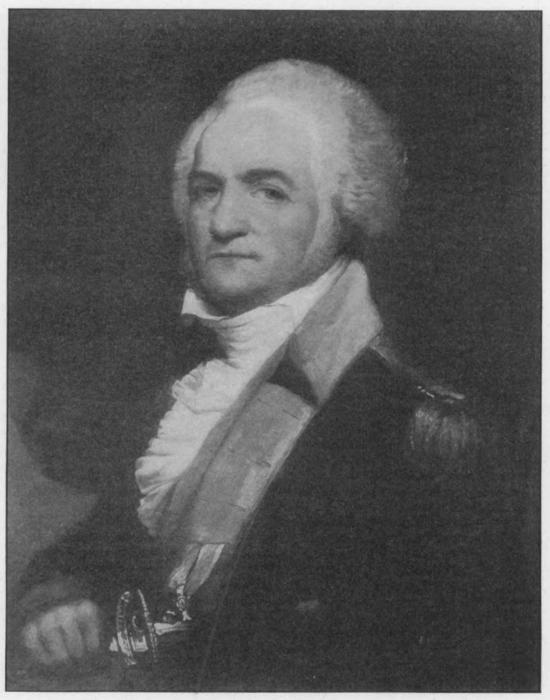

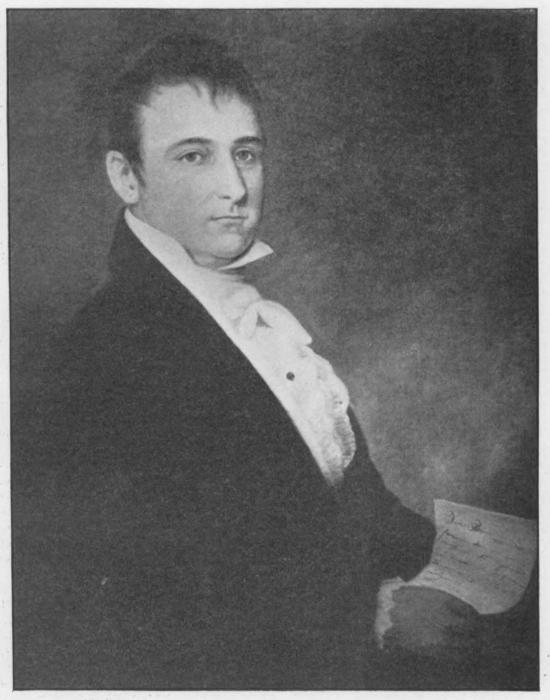

| The First Two Governors of Mississippi | A. C. Chase | 498 |

| Illustrated. | ||

| How Old Wash Played Santa Claus. (Story) | Old Wash | 505 |

| Because. (Story) | Catherine Carr | 508 |

| The Shadow of the Attacoa. (Serial Story) | Thornwell Jacobs | 511 |

| History of the Hals—Chapter XVII. | John Trotwood Moore | 523 |

| A Valentine Toast. (Poem) | Ethel Morrison Lackey | 529 |

| Napoleon—Part VI. | Anna Erwin Woods | 530 |

| The Measure of a Man. (Serial Story) | John Trotwood Moore | 535 |

| Mellie’s Man. (Story) | William McLeod Raine | 540 |

| With Bob Taylor | 545 | |

| Sentiment and Story. | ||

| The Paradise of Fools. | ||

| With Trotwood | 550 | |

| When I Wake Up in the Morning. (Poem.) | ||

| Two Novels of the Year. | ||

| What Constitutes a Surprise. | ||

| Two Women and a Horse. | ||

| Little Miss Fiddle. (Poem.) | ||

| Samuel Spencer as a Factor in National Affairs | Ismay Dooly | 554 |

| Illustrated. | ||

| Books and Authors | Lillian Kendrick Byrn | 557 |

Copyright, 1907, by The Taylor-Trotwood Publishing Co. All rights reserved.

Entered as second-class matter, January 12, 1907, at the post-office at Nashville, Tennessee.

THE TAYLOR-TROTWOOD MAGAZINE ADVERTISEMENTS

In writing to advertisers please mention the Taylor-Trotwood Magazine

“As they went out they saw some firemen trying to put out the flames....”—The Shadow of the Attacoa, page 511

| VOL. IV | FEBRUARY, 1907 | NO. 5 |

By James Hines

It would be impossible to estimate the loss to the world had the first white English-speaking settlement, founded at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607, resulted in failure. Had it been abandoned, as was once the intention of the surviving colonists, it would have had a deterrent effect on similar and subsequent expeditions, and would have changed the complexion of American history.

Those who comprised the first settlement encountered almost insurmountable obstacles before reaching these shores. For months they braved the perils of the sea, and were buffeted by storms, but their heroism and tenacity of purpose never faltered. The real test, however, of endurance was manifested after landing and in establishing the settlement that definitely dates the United States.

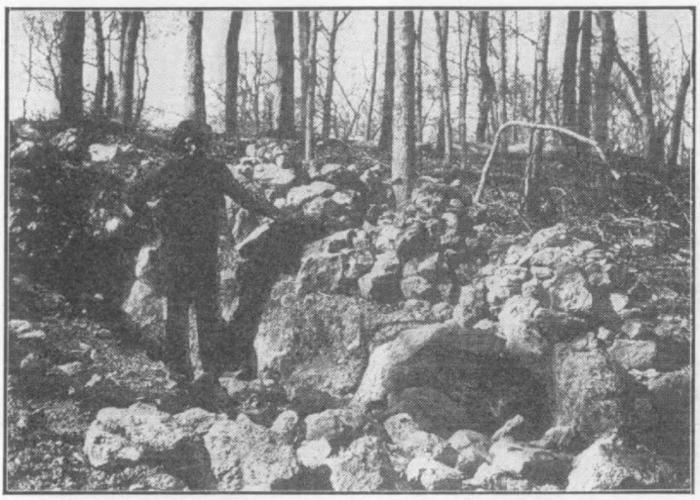

During December, 1606, this history-making party sailed from England, and on May 16, 1607, they landed on a peninsula which juts into the James River. They named the place Fort James. Subsequently it was called James City, and finally James Town. For nearly two centuries it has been an island, and for more than two hundred years it has been abandoned. Two fires destroyed the town, one during Bacon’s rebellion, in 1676, the other an accident, twenty years later, after which the seat of government was moved to Williamsburg. The ruins of the old church tower remain on the site,—a crumbling monument of the first colonial settlement. The excavations showing where the Governor’s mansion and the House of Burgesses stood; the Ambler mansion, twice destroyed by fire, and the old graveyard, with its historic tombs and inscriptions, are still to be seen.

The work of these hardy pioneers in establishing the colony was often interrupted by savage attacks of Indians, and their energies were greatly impaired by fever and lack of necessary sustenance. Indeed, so greatly had their ranks been depleted that, when Newport arrived from England, a few months later, with men and provisions, but thirty-eight of the original party were alive. It was greatly due to John Smith, the heroic leader, that the settlers held out as long as they did.

An untimely accident deprived the colony of the valuable services of Smith, and caused it to come nearly to an end. Smith’s successor had not the ability, courage or prestige to govern as he had done, and a turbulent element began to assume an aggressive attitude toward the Indians, who resented it. The result of this aggression was that trading parties, bent on peaceful measures, were massacred, and, consequently, in the spring of 1610 famine together with all its accompanying sufferings, stared the colonists in the face.

They were a haggard, disheartened, miserable group of men and women. To continue at James Town appeared[456] impossible, and, by popular vote it was decided, though the bravest could not restrain their emotion at failure, that it must be abandoned. Accordingly, June 7, the dejected aggregation boarded their ships and cleared for home. When they reached Hampton Roads, a sail was observed, which proved to be the Governor’s boat. His ships were in the Roads, and the settlers returned to their village, and there enacted one of the most pitiful, yet dramatic, scenes in the world’s history.

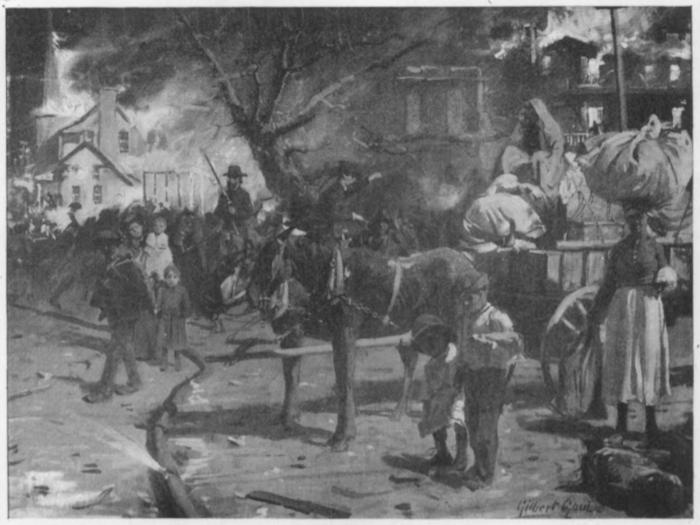

BIRD’S-EYE VIEW OF JAMESTOWN EXPOSITION

Copyright, 1906. Jamestown Official Photograph Corporation, Norfolk

The timely and unexpected arrival of the Governor was greeted with frantic shouts of welcome and joy by the discouraged colonists. His coming immediately infused new life, and their affectionate embraces of one another gave way to fervent prayer. Their story was related to Lord Delaware, and, as he landed, he fell upon the ground and offered thanks to God that his arrival had saved Virginia.

Following that memorable day in 1610, there was never a question concerning the continuance of the Virginia colony. Before the arrival of Lord Delaware, the settlement had been ruled by more or less despotic measures. Under Smith, the despotism had been beneficent, if not benevolent. Following the rule of Delaware and Sir Thomas Dale, a more liberal policy was inaugurated, with the administration of Yeardley, and Virginia began to make gigantic strides. Cattle and sheep were raised; crops were planted; poultry and domestic animals received attention; horses were brought over and utilized for farming and travel. In addition to these necessaries of life, tobacco, which was destined to become the standard of value and exchange, was extensively cultivated. From out of a condition of chaos, everything became plentiful, and Virginia began to offer attractive inducements to immigrants. The pioneers had conquered dangers and enjoyed comparative affluence.

Finally, the colonists insisted on the right of self-government, and received[457] limited recognition. In the old church, at James Town, June, 1619, Governor Yeardley summoned the first legislative body ever assembled in America, and formally opened the General Assembly of Virginia. It was modeled after the English Parliament, an upper and lower house, called the House of Burgesses and the Council.

WESTERN VIEW OF COPPER, SILVER AND WOOD-WORKING SHOPS.

Copyright, 1906. Jamestown Official Photograph Corporation, Norfolk

This legislative body had the effect of making the people proud of their home and confident of themselves. From James Town grew all the settlements that overspread Virginia, and its prosperity induced the settlements which dotted the coast from Florida to Canada.

It is the great achievements intervening between the founding of this settlement and the present period that the Jamestown Ter-Centennial will commemorate by a historic, educational and industrial exhibition, in conjunction with the greatest naval and military display ever witnessed in the world, to be held this year on the waters and historic shores of Hampton Roads, near Norfolk, Virginia.

The heroic deeds and collateral events in all the colonies will be fully and faithfully portrayed, and place before the people a contrasting picture of seventeenth century civilization with that of the nineteenth. It will be a veritable epilogue of the nation’s development from the little Virginia village to a republic of nearly one hundred million people, stretched from ocean to ocean, and from the Great Lakes to the Gulf, with insular possessions in both tropics, and an empire in the frozen Arctic.

In observing the three hundredth anniversary of this important historical event, the State of Virginia, very properly, took the initiative, and, by a joint resolution of the General Assembly, provided that a fitting ceremonial should attend the event. President Roosevelt issued a proclamation inviting all the nations of the world to participate, and declared that “The first settlement of English-speaking people on American soil, at Jamestown, in 1607, marks the beginning of the United States. The three hundredth anniversary of the event must[458] be commemorated by the people of our Union as a whole.”

Nearly every world-power has accepted this invitation, and will send warships, soldiers and marines to take part in the greatest naval rendezvous ever assembled, while the troops will unite in international drills, maneuvers and demonstrations. Aside from this participation, many foreign countries will be represented by industrial exhibits.

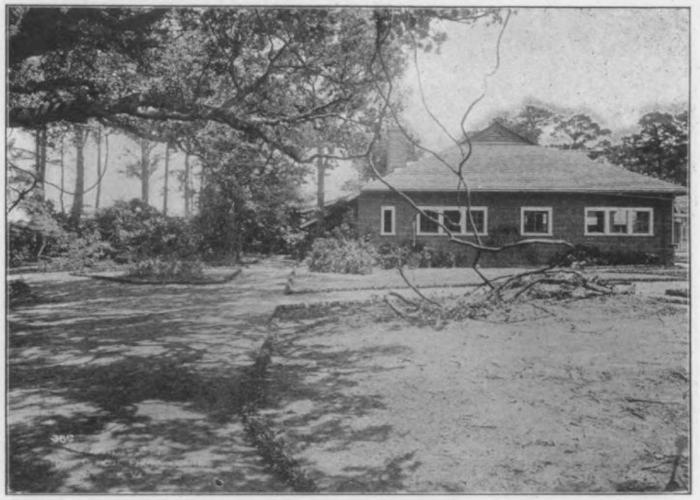

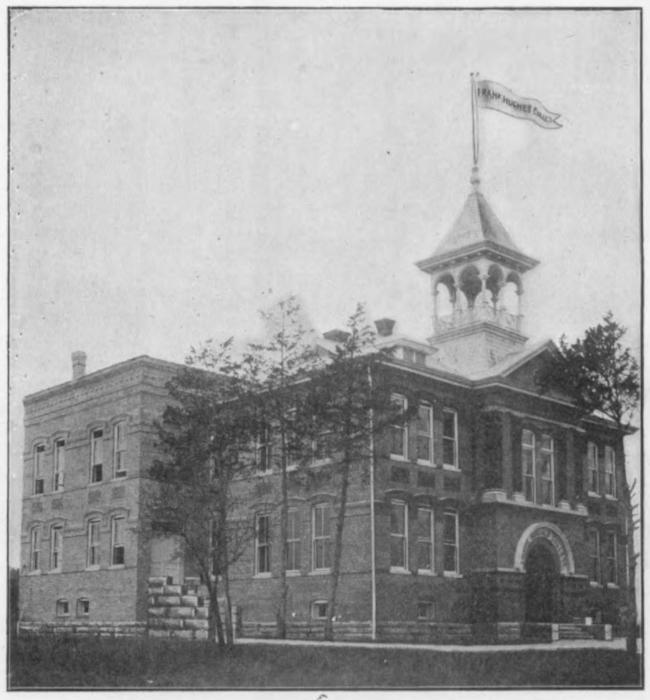

CORNER OF MODEL SCHOOL. SCHOOL GARDEN IN THE REAR CARED FOR BY THE SCHOOL CHILDREN OF NORFOLK

Copyright, 1906. Jamestown Official Photograph Corporation, Norfolk

It will be the most historical exposition ever attempted, the dominating motive being to impress upon the visitor the history of this nation. Situated in the most historic section of the country, amid the scenes of great civil and naval conflicts, whose outcome have more than once been decisive in national affairs, the very atmosphere is redolent of the nation’s story. Congress has approved the exposition, and has endorsed its purpose with splendid appropriations, exceeding those made for any exposition, with the exception of the Chicago and St. Louis World’s Fairs. Every executive department of the Government will make an exhibit; the Smithsonian Institution and National Museum; Bureau of American Republics; the Library of Congress, and the Fish Commission. The Life Saving Service will give exhibitions, and a building is provided for a separate negro exhibit. Alaska, Porto Rico and the Philippines will also be represented in the Government display.

Nearly all of the states have joined in the celebration, and have made liberal appropriations. In addition, others are expected to participate, thus insuring a display of the resources of the states in such magnitude as cannot fail to attract and interest all classes of visitors.

Within twenty minutes’ ride of Norfolk, Portsmouth, Hampton, Newport News and Old Point Comfort is Sewell’s Point, the site of the exposition. In this vicinity nature and man have combined to create a territory supremely attractive and beautiful. The grounds face Hampton Roads, and embrace more than four hundred acres in area, forming a beautiful setting for the[459] architecture of the exhibit buildings, which will be entirely of the colonial period. The beautiful and commodious buildings under construction are the Auditorium, History and Art, Education and Social Economy, Manufactures and Liberal Arts, Virginia Manufactures, Medicine and Sanitation, Machinery, Electricity and Ordnance, Transportation, Marine Appliance, Foods, Agriculture and Horticulture, Forestry, Fish and Game, Mines and Metallurgy buildings, aside from numerous special buildings and pavilions. There are no less than six buildings devoted to Arts and Crafts alone.

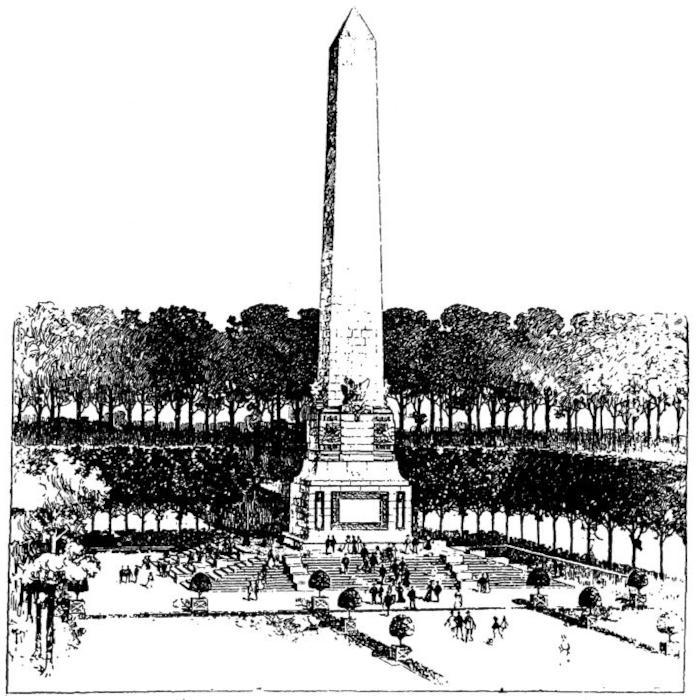

COMMEMORATIVE MONUMENT TO JOHN SMITH, ERECTED BY THE UNITED STATES, AT JAMESTOWN, VIRGINIA.

Copyright, 1906. Jamestown Official Photograph Corporation, Norfolk

The whole group will suggest the baronial structures of the seventeenth century in England. With massive Corinthian columns, surrounded by verdant trees, they will constitute an everlasting picture of grandeur and beauty. Several enlarged replicas of old American homes will preserve the identical outlines, and will conform in proportion. The Arts and Crafts Village will be a scene of active interest, where skilled hand-workers will display the possibilities of the finished products in metals and wood, in which machinery has no part.

Within sight of the exposition are forts, a navy yard, and one of the largest shipbuilding plants in the world; while on the banks of the James river stand the finest examples of colonial architecture in America. Hampton, just across the Roads, is the oldest continuous settlement of Englishmen in America. The most famous naval encounter of the Civil War, between the Monitor and Merrimac, took place within sight of the exposition grounds. This naval duel revolutionized battleship construction and naval warfare. Upon these same historic waters will ride at anchor the greatest fleet of warships, representing every type of fighting machine in the navies of the world. The evolution of shipbuilding will be interestingly illustrated by the reproduction of the three ships, Susan Constant, the Godspeed and Discovery, which brought the Jamestown colonists to this country. This display of marine architecture of different periods makes possible a comprehensive study of its development. The shores hereabout are crowded with earthworks erected by Southern and Federal troops during the Civil War. There is hardly a strategic position near these waters[460] which does not bear evidence of fortifications, and the final negotiations which ended the conflict were concluded at a conference on Hampton Roads between President Lincoln, Mr. Seward and Alexander Stephens. Hence, it is possible to traverse the ground consecrated by those patriots whose names are household words in American history; to view the monuments commemorative of events from the first landing of the colonists in 1607, through the stirring events of 1776, through the later historical epoch of 1812 and 1860, Yorktown and Great Bridge, and to 1865, when this section was enriched by the blood of heroes who fought with Lee, Jackson and Grant in the most sanguinary strife ever recorded.

Another distinguishing feature of the exposition will be the military display of the United States, the troops of which, together with those of foreign countries, will form a permanent encampment during the exhibition.

The horticultural and cut flower exhibit will surpass in design and beauty all previous attempts along this line. Displays of flowers and potted plants will be made in the Court of the States, where will be shown in profusion of number and variety—asters, chrysanthemums, dahlias, gladioli, peonies, rhododendrons, sweet peas, roses, etc. The work of transplanting trees, plants and shrubs in the general decorative scheme has been practically completed. A unique feature is the floral fence, which forms a semi-circle around the exposition grounds. The frame is of wire, upon which crimson rambler, honeysuckle and trumpet vine intertwine in artistic effect. Monster oaks, tall pines, cedars, maples, willows and elms are on the grounds to afford ample shade, while native flower-bearing and evergreen shrubs and fruit trees will enter into the general scheme of landscape beautification.

By comparison, from a monetary standpoint, with the St. Louis Exposition, the management of the latter expended $50,000,000, while the Jamestown will hardly exceed $5,000,000. But it must be remembered that the amount spent at St. Louis produced everything at the fair by purchase. There were no monuments of national or historic interest, hence, the wide discrepancy in the amount invested. The sum expended by the Jamestown Exposition will simply pay for the exhibit buildings, beautifying the site and adorning the water front. An estimate by a competent statistician places the money value to be represented at this exposition at no time less than $150,000,000, while the foreign display on the water will probably represent twice the sum, or $300,000,000, six times the cost of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. The difference is at once strikingly obvious.

The Jamestown Exposition will differ from the St. Louis Fair in that it will be historic, while the latter was mainly industrial. Every conceivable object of historic interest which can be secured will be on view at the Ter-Centennial, and as the surrounding country is a prolific source from which to gather this class of exhibits, it will far excel in historic interest.

A few of the distinctive features of the exposition will include: the first international submarine races; prize drills by regiments of all countries; the largest motor boat regatta ever held; yacht races in which all nations will compete; more naval and military bands than were ever before gathered together; the highest tower ever erected in America, if not in the world; the largest parade ground; sea bathing at the border of the grounds; dirigible airships for commercial uses; an enclosed sea basin with an area of 1,280,000 square feet; an exact reproduction of old Jamestown; stupendous pyrotechnic reproduction of war scenes and unique night harbor illumination.

Norfolk, the exposition city and “Golden Gate of the Atlantic,” penetrated by the salt air of the ocean, is free from climatic complaints. Its geographical location and the fortunes of war add to its interest and prominence, and it is replete with reminiscent features. It is a great commercial center, within twelve hours’ ride of[461] more than 21,000,000 population, and within twenty-four hours’ ride of 39,000,000 people. Possibly its most historic structure standing, in a well preserved condition, is old St. Paul’s Church, erected in 1739, twice fired on by the British, and still retaining, imbedded in its walls, a shell fired by Lord Dunmore’s fleet, January 1, 1776.

The descendants of hardy settlers contemporaneous with Captain John Smith and his associates, followed by the cavaliers that settled Virginia, are to be found now, as then, foremost in business, social, religious and political affairs. From them have issued those who have made names that are referred to with pride in the conduct of state and national affairs. Although the “Mother of States,” and foremost in the making of American history, all of her children did not yield to the temptation of forsaking their birthright of fair lands, and it is the present generation that has made possible the splendid celebration commemorative of the first settlement of this country by their ancestors.

It is small wonder, then, that all roads this year will lead to Tidewater Virginia and the Jamestown Ter-Centennial, which will throw open its gates to the world April 26.

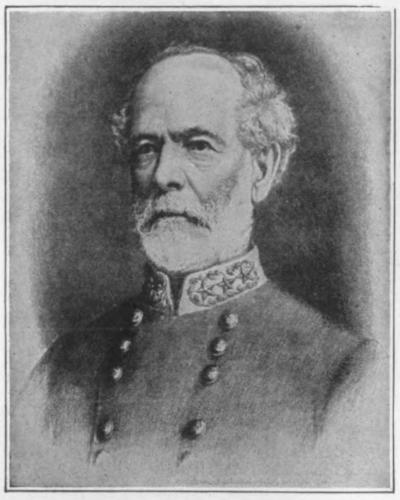

Born at Longwood, Prince Edward County, Virginia, February 3, 1807

Died at Washington, District of Columbia, March 21, 1891

By Robert L. Taylor

When the restless spirit of Johnston took its flight from earth the South bade farewell to as brave a knight as ever shivered a lance “when knighthood was in flower.” His death following so quickly that of William T. Sherman, was a dramatic coincidence. They had fought a long and bloody duel—hilt to hilt and toe to toe, and the arena extended from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean. Sherman advanced with sword and torch in the hands of his splendid army; Johnston met him with strategy and the stubborn resistance of his thin lines of gray; the duel ended only when the resources of military art were exhausted and the shattered remnant of Johnston’s weary columns was overthrown by Sherman’s overwhelming numbers. When the conflict was ended and the battle flags were furled, these two great captains met in the capital of the republic and shook hands across the bloody chasm. Sherman died in February, 1891, and Johnston, broken in health and feeble with age, was one of his pall-bearers, an office which he had also performed at the funeral of his friend, General Grant. A month later he joined the silent hosts to which these antagonists on many a field of glory had preceded him.

Joseph Johnston was the eighth son of Judge Peter Johnston and Mary Woods, of Virginia, whose Scotch ancestors had lived and prospered and passed away on the old plantation at Osborne’s Landing. The boy was a born soldier and foreshadowed his brilliant career, even when a child at his mother’s knee. The story is told that his father took him coon-hunting one night, and he became so interested in describing and illustrating military tactics to the negro boy who attended him that they became separated from the hunters, and fell so far behind that they could not reach them with their voices. Jo made the boy dismount and kneel on the ground with his gun presented, in imitation of a hollow square of infantry. Then he withdrew and re-appeared as a regiment of cavalry, charging down upon the hollow square; but his horse was not a war-steed and was totally untrained in battle, and suddenly shying from the squatted infantry, threw the cavalry regiment to the ground. His biographer, Robert M. Hughes, says, “of course he was wounded—he always was on every available occasion.”[1]

The growth and development of the lad increased his determination to be a soldier. So marked was his predilection that his father, who had served under “Light Horse Harry Lee” in the Revolution, gave him his sword, although he was next to the youngest son. Young Johnston treasured it, and kept it bright till 1861, when the tocsin of Civil War was sounded, and, like Lee, he drew it in defense of his[464] native State, although, like Lee, he was opposed to secession.

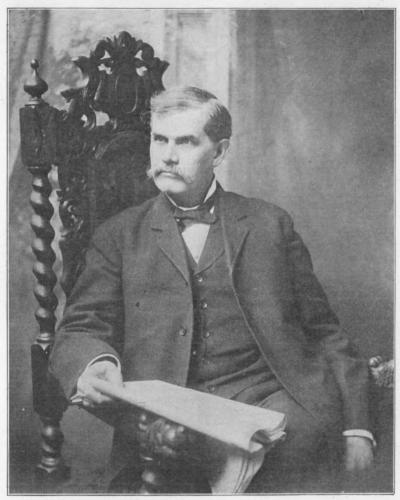

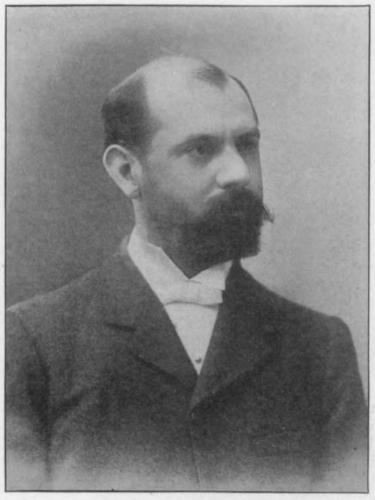

GENERAL JOSEPH E. JOHNSTON

The comparison of the characters of Johnston and Lee is most interesting. Born in the same year, entering West Point at the same time and graduating in the same class (that of 1829), they both saw their first active military service under General Scott. Johnston accompanied Scott on his arduous campaign in the Florida Indian war, and later to Mexico. While Lee was engaged in boundary work in Texas, Johnston was performing a similar work for his government on the Canadian line. From early manhood they were fast friends and were bound together by the same associations, the same surroundings and the same interests throughout all their lives. Both came from the Mexican War with the title of colonel. Both were opposed to secession, but both resigned their commissions in the United States army and entered the service of the Stars and Bars with the rank of colonel. Both supported, with consummate ability and unfaltering courage, the cause they held dear, and when this cause went down in defeat both met the verdict with quiet dignity. Both refused safety and honors abroad, preferring to give their abilities to rebuilding a united nation, and both lived to have abundant proof of the respect and esteem in which all people held them.

It would be useless to seek to measure the relative capacity of these two classmates. The circumstances surrounding their operations were not the same, the generals opposing them were unlike and their methods of campaign were necessarily different. It is safe to say that both applied, as far as possible, the tactics and principles of war taught them at their alma mater. “Johnston’s Narrative,” which he wrote and published in 1875, explains his tactics and his reasons for adopting them and have been held in high repute by students of military art on both sides of the ocean ever since their publication.

Like Lee, Johnston never failed to gain the respect and confidence of his men. “Although,” says Mr. Hughes in his admirable biography, “Johnston was never allowed to retain command of one army long enough to achieve the great results which only flow from long association ... he never failed to win the love of his men. They trusted him because they knew that their blood would not be wasted.... They admired him because they knew he would not ask them to go where he would not go himself. His order was ‘Follow,’ not ‘Go.’... They called him their Game Cock, because of his gallantry and martial bearing, and strove to emulate him in courage and coolness.”

“Farewell, old fellow,” was the parting salute of one of his men, “we privates loved you because you made us love ourselves.”

Johnston’s personal character was no less admirable than his public career. Unselfishness, modesty, purity, courtesy, charity, devotion to home and family ties ever characterized him in public and in private.

After his surrender to Sherman at Durham’s Station, North Carolina, he retired to Savannah, Georgia, putting the war and its issues behind him, using his great influence to renew the national allegiance and to cultivate a new patriotism that should embrace the whole country. In 1877 he returned to Richmond, and in the following year was elected to the House of Representatives. On the expiration of his term he was appointed Commissioner of Railroads by President Cleveland and continued to reside in Washington until his death. He met here both Grant and Sherman, and, as already said, became fast friends with his former foes and acted as pallbearer at the funeral of each.

I sat with Jo Johnston in the Forty-sixth Congress of the United States. I was young and he was ripe in years and experience. I sought him and cultivated him and never tired of listening to the story from his lips of his maneuvers in the last days of the Confederacy. He was small of stature, square built, and straight as an arrow, with a big round bald head and keen gray eyes that glittered like stars. Congress was not congenial to him—he was not an orator but a soldier; he was not a statesman, but a general. He knew how to wield an army but was helpless on the battlefield of argument. During the fiercest fights of the two great contending parties on the floor of the house, he daily walked to and fro like a caged lion, his head up, his eyes sparkling and his whole attitude one of excitement, yet taking no part in the struggle. But he was a faithful representative of his people, and was loved by all who knew him.

In 1887 he received a crushing blow in the death of his wife. Their childlessness and her invalidism and the long years of army life had drawn them together in an unusual degree, and he was never able to recover his old time joy in life after his loss.

Naturally the distinguished veteran was in great demand on the occasion of re-union and memorial exercises. Always averse to anything savoring of publicity, he attempted to fill these engagements in an unobtrusive way, but at times the enthusiasm of his old followers put all his efforts to naught. This was shown at the memorial exercises at Atlanta in the spring of 1890, of which an Atlanta paper gives the following account:

“As the last carriage drove away, the Governor’s Horse Guard came up the street, forty strong, under command of Captain Miller. The company was an escort to the hero of the day. With the Governor’s Horse Guard came a carriage drawn by two black horses. In that carriage was General Joseph E. Johnston. The old hero sat upon the rear seat, and beside him was General Kirby Smith.... The carriage was covered with flowers. ‘That’s Johnston! that’s Jo Johnston!’ yelled some one. Instantly the Governor’s Horse Guard, horses and men, were displaced by eager, battle-scarred veterans. The men who fought under the hero surrounded the carriage. They raised it off the paved street, and they yelled themselves[466] hoarse. Words of love, praise, and admiration were wafted to the hero’s ears. Hands pushed through the sides of the carriage and grasped the hands of the man who defended Atlanta. The crowd grew and thickened. Captain Ellis tried to disperse it, but could not. Then the police tried; but the love of the old soldiers was greater than the strength of both Captain Ellis and Atlanta’s police force. For ten minutes the carriage stood still; then, as it began to move, some one called out, ‘Take the horses away!’ Almost instantly both horses were unhitched, and the old men fought for their places in the traces. Then the carriage began to move. Men who loved the old soldier were pulling it. Up Marietta street it went to the Custom-house, then it was turned, and back toward the opera house it rolled. The rattle of the drum and the roll of the music were drowned by the yell of the old soldiers; they were wild, mad with joy; their long pent-up love for the old General had broken loose. Just before the carriage reached the opera house door a tall, bearded veteran on a horse rode to the side. Shoving his hand through the open curtain, he grasped the hand of General Johnston just as a veteran turned it loose. The General looked up. ‘General Johnston!’ cried the veteran. General Johnston continued to look up. His face showed a struggle. He knew the horseman, but he could not call his name. ‘Don’t you know me, General—don’t you know me?’ exclaimed the horseman. In his voice there was almost agony. ‘General Anderson, General,’ said Mrs. Milledge. General Johnston heard the words, and, rising almost from his seat, exclaimed, ‘Old Tige! Old Tige! Old Tige!’ The two men shook hands warmly. Tears were flowing down the cheeks of each. ‘Yes, Old Tige it is, General,’ said General Anderson, ‘and he loves you as much now as ever.’”

A simple headstone in the Greenmount Cemetery, at Baltimore, marks the sleeping place of Johnston, beside his wife, who was Miss Lydia McLane, of Baltimore.

[1] General Johnston. By R. M. Hughes, New York: D. Appleton & Co. Great Commanders Series.

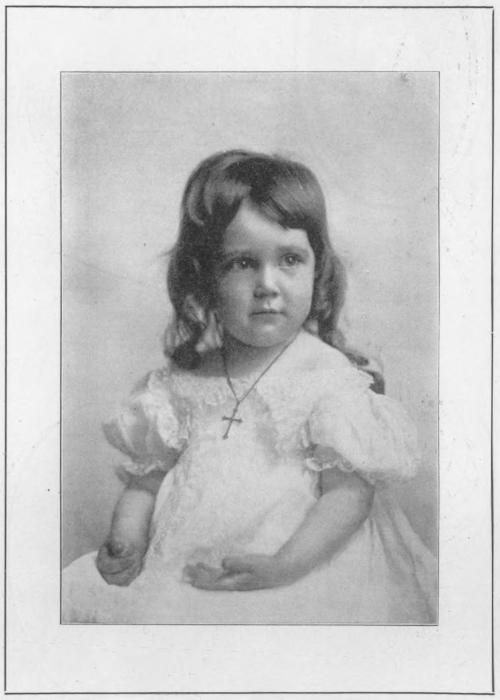

MARGARET MCNUTT

Crossville, Tennessee

Taylor, Nashville

CLAUDE DESHA ANDERSON, JR.

Memphis

HAMILTON PARKS, JR.

Nashville

JAMES HARBERT BENNETT

Trenton, Tennessee

FLORENCE KENT WULFF

Louisville

Standiford, Louisville

ALBERT STOCKTON LINDSEY, JR.

Jackson, Tennessee

Strauss, St. Louis

WILLIAM STATES JACOBS, JR.

Houston, Texas

Taylor, Nashville

EDITH HOLT

McMinnville, Tennessee

Southern School of Photography, McMinnville

By John A. Cockerill

Mr. John Trotwood Moore, Editor of Taylor-Trotwood Magazine:

Dear Sir: There are many persons who credit to the pen of Mr. John A. Cockerill the best war story ever written. As you will remember, Mr. John A. Cockerill was the distinguished editor of the St. Louis Post Dispatch, also editor-in-chief of the Cincinnati Enquirer. Later he was the editor-in-chief of the New York World, and altogether was one of the most brilliant descriptive writers this country has ever produced. He died a few years ago in Cairo, Egypt, being at the time of his death connected with the New York Herald.

At the outbreak of the war in 1861, John A. Cockerill was about fifteen years old, and the recruiting officers had refused to enlist him in the ranks of the fighting line by reason of his youth, but accepted him as a drummer boy in the Twenty-fourth Ohio Infantry, in which regiment his brother was then a first lieutenant and later captain and colonel.

It is in no way surprising to the personal friends of John A. Cockerill that anything written by him should be the best of its kind. The best war story ever written is on the Battle of Shiloh, as seen by John A. Cockerill, which story I send you herewith, with the earnest request that you permit it to occupy a place in your interesting and valuable Historic Highways of the South.

Yours very truly,

Theodore F. Allen,

Cincinnati, Ohio.

[The editor agrees with Mr. Allen that this story is above praise and should find an abiding place in history.]

Shiloh Church, April 6th, 1862.

Here is a date and a locality indelibly burned into my memory. I was then an enlisted fourth-class musician in the Twenty-fourth Ohio Regiment, in which my elder brother was a first lieutenant, and afterwards captain and colonel, successively. I had campaigned in Western Virginia, and had seen some of the terrors and horrors of war at Philippi and Rich Mountain, and some of its actualities in a winter campaign in the Cheat Mountain district. During the winter of 1861, my command was sent to Louisville, Kentucky, where General Buell was organizing his splendid army of the Ohio for active operations against Bowling Green and Nashville. My regiment was assigned to General Nelson’s command, and the early spring found us on the left flank of the army, on the north side of Green River. With unexpected suddenness Nelson’s division was sent back one day in March to the Ohio River, where it was placed on transports and headed for the Cumberland River to participate in Grant’s movement against Fort Donelson. Before reaching that point, intelligence was received of the capture of that stronghold, and our flotilla proceeded to Paducah, Kentucky. At that point General W. T. Sherman was organizing his recruits from Ohio, Indiana and Illinois for the forward movement up the Tennessee River. I had been taken ill on the steamer en route, and my father, who at that time commanded the Seventieth Ohio, stationed at Paducah, took me in his personal charge. Two days later my regiment sailed up the Cumberland River and was with the[473] first brigade to enter Nashville. When I had reached the convalescent stage, I asked permission to rejoin my command, but General Sherman said the armies of Grant and Buell would form a coalition somewhere up the Tennessee River, and I would be better off in my father’s care than elsewhere.

Thus it happened that I was with the army of General Sherman when it felt its way up the turbid Tennessee as far as Pittsburg Landing, and it so happened that I was at Shiloh Church on the morning of that terrible onslaught by General Johnston’s army on Sherman’s division, which held the advance of Grant’s army.

I have often wondered what sort of a soldier I must have appeared at that time. I can remember myself as a tall, pale, hatchet-faced boy, who could never find in the Quartermaster’s department a blouse or a pair of trousers small enough for him, nor an overcoat cast on his lines. The regulation blue trousers I used to cut off at the bottom, and the regulation overcoat sleeves were always rolled up, which gave them the appearance of having extra military cuffs, which was a consolation to me.

The headquarters mess had finished its early breakfast, and I had just taken my place at the table on Sunday morning, April 6th, when I heard ominous shots along our adjacent picket lines. In less than ten minutes there was a volley firing directly in our front, and from my knowledge of campaigning I knew that a battle was on, though fifteen minutes before I had no idea that any considerable force of the enemy was in the immediate front of our cantonment. The Seventieth Ohio Regiment, and the brigade to which it was attached, commanded by Colonel Buckland, of Ohio, formed on its color lines under fire, and although composed of entirely new troops, made a splendid stand. At the first alarm, I dropped my knife and fork and ran to my father’s tent, to find him buckling on his sword. My first heroic act was to gather up a beautiful Enfield rifle which he had saved at the distribution of arms to his regiment because of its beautiful curly maple stock. I had been carrying it myself on one or two of the regimental expeditions to the front, and had some twenty rounds of cartridges in a box which I had borrowed from one of the boys of Company I. By the time I had adjusted my cartridge box and seized my rifle, my father was mounted outside, and, with a hurried good-bye, he took his place with his regiment. By this time the bullets were whistling through the camp and shells were bursting overhead.

Not exactly clear in my mind what I intended to do, I ran across to the old log Shiloh Church, which stood on the flank of my father’s regiment. On my right the battle was raging with great ferocity, and stretching away to my left and front one of the most beautiful pageants I have ever beheld in war was being presented. In the very midst of the thick wood and rank undergrowth of the locality was what is known as a “deadening,” a vast, open, unfenced district, grown up with rank, dry grass, dotted here and there with blasted trees, as though some farmer had attempted to clear a farm for himself and had abandoned the undertaking in disgust. From out of the edge of this great opening came regiment after regiment, and brigade after brigade of the Confederate troops. The sun was just rising in their front, and the glittering of their arms and equipments made a gorgeous spectacle for me. On the farther edge of this opening, two brigades of Sherman’s command were drawn up to receive the onslaught. As the Confederates sprang into this field, they poured out their deadly fire, and, half obscured by their smoke, advanced as they fired. My position behind the old log church was a good one for observation. I had just seen General Sherman and his staff pushing across to the Buckland brigade. The splendid soldier, erect in his saddle, looked a veritable war eagle, and I knew history was being made in that immediate neighborhood. Just then a field battery from Illinois, which had been[474] cantoned a short distance in the rear, came galloping up with six guns and unlimbered three of them between Shiloh Church and the left flank of the Seventieth Ohio. This evolution was gallantly performed. The first shot from this battery, directed against the enemy on the right opposite, drew the fire of a Confederate battery and the old log church came in for a share of its compliments. This duel had not lasted more than ten minutes when a Confederate shell struck a caisson in our battery and an explosion took place, which made things in that spot exceedingly uncomfortable. The captain was killed, and his lieutenant, thinking he had done his duty, and, doubtless, satisfied in his own mind that the war was over so far as he was concerned, limbered up his remaining pieces, and, with such horses as he had, galloped to the rear and was not seen at any other time, I believe, during the two days’ engagement.

By this time the enemy was pressing closely on my left flank, and Shiloh Church, with its ancient logs, was no longer a desirable place for military observation. I hurried over to my father’s camp, taking advantage of such friendly trees as presented themselves on the line of my movement, and there found a state of disorder. The tents were pretty well ripped with shells and bullets, and wounded men were being carried past me to the rear. As I stood there, debating in my mind whether to join my father’s command or continue my independent action, three men approached, carrying a sorely wounded officer in a blanket. They called me to assist them, and as my place really was with the hospital corps, being a non-combatant musician, I complied with their request. We carried the poor fellow some distance to the rear, through a thick wood, and found there a scene of disorder amounting to panic. Men were flying in every direction, commissary wagons were struggling through the underbrush, and the roads were packed with fugitives and baggage trains, trying to carry off the impedimenta of the army. Finding a comparatively empty wagon, we placed our wounded officer inside, and then, left at liberty, I started on down toward the river. I had not proceeded more than a mile when I encountered a brigade of Illinois troops, drawn up in battle array, apparently waiting for orders. It was General McArthur’s Highland Brigade, the members of which wore Scotch caps, and I must say that a handsomer body of troops I never saw. These fellows had been at Fort Donelson, and they counted themselves as veterans. They had their regimental band with them, their flags were all unfurled, and they were really dancing impatiently to the music of the battle in front of them. As I sauntered by a chipper young lieutenant, sword in hand, stopped me and said: “Where do you belong?”

“I belong to Ohio,” was my reply.

“Well, Ohio is making a bad show of herself here to-day,” he said. “I have seen stragglers from a dozen Ohio regiments going past here for half an hour. Ohio expects better work from her sons than this.” As I was one of Ohio’s youngest sons, my state pride was touched. “Do you want to come and fight with us?” he asked. I responded that I was willing to take a temporary berth in his regiment. He asked me my name and especially inquired whether I had any friends on the field. I gave him my father’s name and regiment, and saw him make a careful entry in a little pass book, which he afterward placed in the bosom of his coat, as he rather sympathetically informed me that he would see, in case anything should happen to me, that my friends should know of it. Thus I became temporarily attached to Company B, of the Ninth Illinois Regiment, McArthur’s brigade. Several other men from other regiments who had been touched by this young officer’s patriotic appeals also took places in our ranks.

Rather a strange situation that for a boy—enlisting on a battle field, in a command where there was not a face that he had ever seen before; only one face indeed, that had the least touch of[475] sympathy in it, and that belonging to the young officer who had mustered him.

We waited here for three-quarters of an hour before receiving the command to move. During that time, one of the regimental bands played “Hail, Columbia.” It was the first and only time that I heard music on a battle field. Finally the order came to move to the front. By this time the stream of fugitives on the road rendered it almost impassable, but we forced our way through them, and in due time reached the point where our men were being severely driven. At first we were sent to strengthen the line from point to point, and twice that morning our brigade was moved up to support field batteries, which service, I must say from my brief experience, is the most annoying in modern warfare. These batteries drew not only the artillery file of the enemy, but they furnished a point for the concentrated fire of all the infantry in front. To be in supporting position was to receive all the bullets that were aimed at the battery, and which, of course, usually vexed the rear. The shells intended for the battery in your front have a habit always of flying too high or bursting just high enough in air to make it pleasant for the troops who are held in comparative inactivity. Under these conditions, we hugged the ground very closely, and fallen timber of every kind was most gratefully and thankfully recognized. It is amazing how slowly time passes under these circumstances. I am sure there were occasions that morning when twenty minutes’ exposure to fire behind these field batteries seemed to me an entire week. Everything looked weird and unnatural. The very leaves on the trees, though scarcely out of bud, seemed greener than I had ever seen leaves, and larger. The faces of the men about me looked like no faces that I had ever seen on earth. The roar and din of the battle in all its terror outstripped my most fanciful dreams of pandemonium. The wounded and butchered men who came out of the blue smoke in front of us and were dragged or sent hobbling to the rear, seemed like bleeding messengers come to tell us of the fate that awaited us.

It was with the greatest sense of relief that we received orders to move to the left, to face again that awful wave of fire which seemed to be all the morning moving toward our flank. The Confederate divisions came into action at Shiloh Church by the right, with a view to penetrating to the river, and taking us in flank and rear. It was along in the afternoon some time that we were pushed over to the extreme left of the forward line. I had no watch, and could have no idea of the hour of the day, except as I saw the shadows formed by the sun. Up to this time our command had suffered but little, but a dreadful baptism of fire was awaiting us. For a moment I realized that we were on the extreme left of our army; that my regiment was the left of the brigade; that I was temporarily attached to Company B of the regiment, which practically placed me on the left flank of that heroic army. I know all this because there was no firing in our front, and no sound of battle to our left, but steady, steady, steady from the right of us rolled the volleys which told us that the enemy was working around to our vicinity. I saw General McArthur, our commander, at this point, and as I remember, his hand was wrapped with a handkerchief, as though he had been wounded. By his orders, we pushed across a deep ravine which ran parallel with our front, and in five minutes we had taken up a position on its opposite bank, facing the enemy. Everybody felt that the critical moment had come. The terrible nervous strain of that day was nothing compared with the feeling that now the time had come for us to show our mettle. The faces of that regiment were worth studying at that moment. Not one that was not pale; not a lip that was not close shut; not an eye that was not wild; not a hand that did not tremble in this awful, anxious moment. Presently the messengers came—pattering shots from[476] out the dense growth in our front, telling of the advance of the skirmish line. On our part, no response. No enemy could be seen, but the purple wreaths of smoke here and there told of the men who were feeling their way toward our lines. A nervous man, unable to stand the strain, let off his musket in our line. This revealed our presence. With a suddenness that was almost appalling, there came from all along our front a crash of musketry, and the bullets shrieked over our heads and through our ranks. Then we delivered our fire. In an instant the engagement was general at this point. There were no breech-loaders in that command, and the process of loading and firing was tedious. As I delivered my second shot, a musket ball struck a small bush in my front, threw the splinters in my face, and whistled over my shoulder. I may say that I was startled, but I kept loading and firing without any idea whatever as to what I was firing at. Soon the dry leaves, which covered the ground about us, were on fire, and the smoke from them added to the general obscurity. Two or three men had fallen in my vicinity. At this moment the young lieutenant who had my descriptive list in his coat bosom, and who was gallantly waving his sword in the front, was struck by a bullet and fell instantly dead, almost at my feet. Then it was that I realized my utter isolation and shuddered at the thought of a fate impending—“Dead and unknown.”

By this time the fire from the enemy in our front—it was the division of General Hardee turning the flank of the Federal position—became so terrible that we were driven back into the ravine. Here we were comparatively safe. We could load our pieces, crawl up the bank of the ravine, fire and fall back, as it were. But many poor fellows who crawled up this friendly embankment fell back dead or wounded; and in one instance, as I crouched down loading my piece, a man who had been struck above me, fell on top of me and died by my side. It was here, in this terrible moment, that I, boylike, thought of the peaceful Ohio home, where a loving, anxious mother was doubtless thinking of me, and with the thought that perhaps my father had been killed, came a natural desire to be well out of the scrape. Notwithstanding, I kept firing as long as my cartridges lasted. These gone, a fierce sergeant, with a revolver in his hand, placed its muzzle close to my ear and fiercely demanded why I was not fighting. I told him that I had no cartridges. “Take cartridges from the box of the man there,” he said, pointing to the dead man who had just fallen upon me. Mine was an Enfield rifle, and my deceased neighbor’s cartridges were for a Springfield rifle. I had clung to this beautiful Enfield, with its maple stock, which my father had selected, and I was determined that it should not leave my hands. While this scene was passing, the enemy came upon us full charge, and, looking up through the smoke of the burning leaves and beyond a washout which connected with our ravine, I saw their gray, dirty uniforms. I heard their fierce yells, I saw their flag flapping sullenly in the grimy atmosphere. That was a sight which I have never forgotten; I can see the tiger ferocity in those faces yet; I can see them in my dreams. For what might they not have appeared to me, terrified boy that I was!

It was at this point that our blue line first wavered. Out of the ravine, over the bank, we survivors poured, pursued by the howling enemy. I remember my horror at the thought of being shot in the back, as I retreated from the top of the bank and galloped as gracefully as I could with the refluent human tide. Just by my side ran a youthful soldier, perhaps three years my senior, who might, for all I knew, have been recruited as I was. I heard him give a scream of agony, and, turning, saw him dragging one of his legs, which I saw in an instant had been shattered by a bullet. He had dropped his rifle, and as I ran to his support he fell upon my shoulder, and begged me, for God’s sake, to help[477] him. I half carried him for some distance, still holding to my Enfield rifle, with its beautiful curly stock, and then, seeing that I must either give up the role of good Samaritan or drop the rifle, I threw it down and continued to aid my unfortunate companion. All this time the bullets were whistling more fiercely than at any time during the engagement, and the woods were filled with flying men, who, to all appearances, had no intention of rallying on that side of the Tennessee River. My companion was growing weaker all the while, and finally I set him down beside a tree, with his back toward the enemy, and watched him for a few moments, until I saw that he was slowly bleeding to death. I knew nothing of surgery at that time, and did not even know how to staunch the flow of blood. I called to a soldier who was passing, but he gave no heed. A second came, stood for a moment, simply remarked “he’s a dead man,” and passed on. I saw the poor fellow die without being able to render the slightest assistance. Passing on, I was soon out of range of the enemy, and in a moment I realized how utterly famished and worn out I was. My thirst was something absolutely appalling. I saw a soldier sitting upon the rough stump of a tree gazing toward the battle, and, observing that he had a canteen, I ran to him and begged him for a drink. He invited me to help myself. I kneeled beside the stump, and, taking his canteen, drained it to the last drop. He did not even deign to look at me during the performance, but he anxiously inquired how the battle was going in the front. I gave him information which did not please him in the least, and moved on toward the point known as the landing, toward which all our fugitives seemed to be tending. But my friend on the stump—I shall never forget him. How gratefully I remember that drink of warm water from his rusty canteen! Bless his military soul, he probably never knew what a kindness he rendered me!

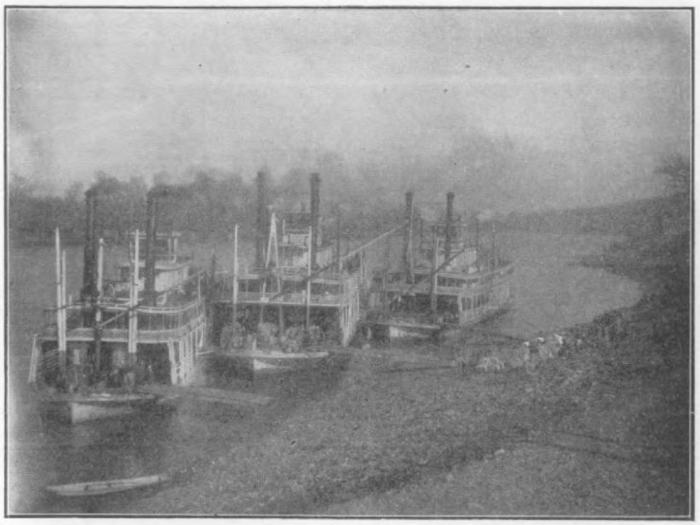

A short distance beyond the place where I had obtained my water supply I found a squadron of jaded cavalry drawn up, and engaged in the interesting work of stopping stragglers. In the crowd of fear-stricken and dejected soldiers I found there, I saw a man who belonged to my father’s regiment; I recognized him by the letters and number on his hat. Inquiring the fate of the regiment, he told me that it had been entirely cut to pieces, and that he had personally witnessed the death of my father—he had seen him shot from his horse. This intelligence filled me with dismay, and I then determined, non-combatant that I was, that I would retire from that battlefield. Watching my opportunity, I joined an ambulance which was passing, loaded with wounded, and by some means escaped the vigilance of the cavalrymen, who seemed to be almost too badly scared to be on any sort of duty. When through this line, I pushed my way on down past the point where stragglers were being impressed and forced to carry sand bags up from the river, to aid in the construction of batteries for some heavy guns which had been brought up from the transports. I passed these temporary works, by the old warehouse, turned into a temporary field hospital, where hundreds of wounded men, brought down in wagons and ambulances, were being unloaded, and where their arms and legs were being cut off and thrown out to form gory, ghastly heaps. I made my way down the plateau overlooking the river. Below lay thirty transports at least, all being loaded with the wounded. All around me were baggage wagons, mule teams, disabled artillery teams, and thousands of panic-stricken men. I saw, here and there, officers gathering these men together into volunteer companies, and marching them away to the scene of battle. It took a vast amount of pleading to organize a company of even fifteen or twenty, and I was particularly struck by the number of officers who were engaged in this interesting occupation. It seemed to me that they were out of all proportion to the number of fugitives in the[478] vicinity. While sitting on the bank, overlooking the road below, between the beach and the river, I saw General Grant. I had seen him the day before review his troops on the Purdy road, while a company of Confederate cavalrymen, a detachment of Johnston’s army, watched the performance from a skirt of woods some two miles away. When I saw him at this moment he was doing his utmost to rally his troops for another effort. It must have been about half past four in the afternoon. The General rode to the landing, accompanied by his staff and a bodyguard of twenty-five or thirty cavalrymen. I heard him begging the stragglers to go back and make one more effort to redeem themselves, accompanying his pleadings with the announcement that reinforcements would soon be on the field, and that he did not want to see his men disgraced. Again I heard him proclaim that if the stragglers before him did not return to their commands he would send his cavalry down to drive them out. In less than fifteen minutes his words were made good. A squadron of cavalry, divided at either end of the landing, and riding towards each other with drawn sabres, drove away every man found between the steep bank and the river. The majority of the skulkers climbed up the bank, hanging by the roots of the trees, and in less than ten minutes after the cavalry had passed, they were back in their old places. I never saw General Grant again until I saw him as President of the United States.

While sitting on the high bank of the river I looked across to the opposite side, and saw a body of horsemen emerging from the low cane brakes back of the river. In a moment I saw a man waving a white flag with a red square in the center. I knew that he was signalling, for I had seen the splendid corps of Buell’s army, and I recognized that the men with that flag were our friends. Sitting by me were two distracted fugitives, who also saw the movement on the other side of the river. Said one of them to his companion: “Bill, we are gone now. There’s the Texas cavalry on the other side of the river!” The red square had misled him. Fifteen minutes later I saw the head of a column of blue emerge from the woods beyond and move hurriedly down toward the river’s edge. Immediately the empty transports moved over to that side of the river, and the first boat brought over a figure which I recognized. The vessel was a peculiar one, belonging in Southern waters, and had evidently been used as a ferry boat. On its lower forward deck, which was long and protruding, sat a man of tremendous proportions, on a magnificent Kentucky horse, with bobbed tail. The officer was rigged out in all his regimentals, including an enormous hat with a black feather in it. I knew that this was General Nelson, commonly known as “Fighting Bull Nelson.” I ran down to the point where I saw his boat was going to land, and as she ran her prow up on the sandy beach, Nelson put spurs to his horse and jumped him over the gunwale. As he did this, he drew his sword and rode right into the crowd of refugees, shouting: “Damn your souls, if you won’t fight, get out of the way and let men come here who will!” I realized from the presence of Nelson that my regiment (the Twenty-fourth Ohio) was probably in that vicinity. I asked one of the boat hands to take me on board, and, after some persuasion, he did so. The boat recrossed, and as soon as I got on shore, I ran down to where the troops were embarking to cross the river to the battlefield. I soon found Ammen’s Brigade, and my regiment. Hurrying on board one of the transports, I climbed to the hurricane deck and there found my brother with his company. He was looking across the river, where the most appalling sight met his vision. The shore was absolutely packed with the disorganized, panic-stricken troops who had fled before the terrible Confederate onslaught, which had not ceased for one moment since early that morning. The noise of the battle was deafening. It may be imagined that my brother was somewhat surprised[479] to see me. I made a hurried explanation of the circumstances which had brought me there, and gave him news of my father’s death. Then I asked him for something to eat. Astonished, he referred me to his negro servant, who luckily had a broiled chicken in his haversack, together with some hard bread. I took the chicken, and as we marched off the boat, I held a drumstick in each hand, and kept by my brother’s side as we forced our way through the stragglers, up the road from the landing and on to the plateau, where the battle was even then almost concentrating. Right there I saw a man’s head shot off by a cannon-ball and saw, immediately afterward, an aide on General Nelson’s staff dismounted by a shot, which took off the rear part of his saddle and broke his horse’s back. At the same time I did not stop eating. My nerves were settled, and my stomach was asserting its rights. My brother finally turned to me, and, after giving me some papers to keep, and some messages to deliver in case of death, shook me by the hand and told me to keep out of danger, and, above all things, to try and get back home. This part of his advice I readily accepted. I stood and saw the brigade march by, which, in less than ten minutes, met the advance of the victorious Confederates, and checked the battle for that day. It was then that the gunboats in the river, and the heavy siege guns on the bank above, added their remonstrating voices as the sun went down, and the roar of battle ceased entirely.

That night on the shore of the Tennessee River was one to be remembered. Wandering along the beach among the rows of wounded men waiting to be taken on board the transports, I found another member of the Seventieth Ohio named Silcott. He had a harrowing tale of woe to relate, in which nearly all his friends and acquaintances figured as corpses, and together we sat down on a bale of hay near the river’s edge. By this time the rain had set in. It was one of those peculiar, streaming, drenching, semi-tropical downpours, and it never ceased for a moment from that time until far into the next day. With darkness came untold misery and discomfort. After my companion had related the experiences of the day, I curled myself up on one side of the hay bale, while he occupied one edge of it, and soon fell asleep. Every few moments I was awakened by a terrible broadside, delivered from the two gunboats which lay in the center of the river a hundred yards or so above me. They were the Lexington and the A. O. Tyler, I believe; wooden vessels, reconstructed from western steamboats and supplied with ponderous columbiads. These black monsters, for some reason, kept up their fire all through the night, and the roar of this cannonading and the shrieking of the shells, mingled with the thunders of the rainstorm, gave very little opportunity for slumber. Still, I managed to doze very comfortably between broadsides. And my recollection of the night is that from these peaceful naps I was aroused every now and then by what appeared to be a tremendous flash of lightning, followed by the most awful thunder ever heard on the face of the earth. These discharges seemed to me to lift me four or five inches from my water-soaked couch. To add to the general misery the transports which were bringing over Buell’s troops had a landing within twenty feet of my lodgment. All night long they wheezed and groaned and came and went, with their freight of humanity, and right by my side marched all night long the poor fellows who were being pushed out to the front to take the places on the battle line for the morrow. By this time the roadway was churned into mud knee deep, and as regiment after regiment went by with that peculiar slosh, slosh of marching men in mud, and the rattling of canteens against bayonets and scabbards, so familiar to the ear of the soldier, I could hear in the intervals the low complaining of the men and the urging of the officers: “Close up, boys, close up,” until it seemed to me that if[480] there was ever such a thing as Hades on earth, I was in the fullest enjoyment of it. As fast as a transport unloaded its troops, the gangway was hauled in, the vessel dropped out, and another took the vacant place and the same thing was gone over again. Now and then a battery of artillery would come off the boat, the wheels would stick in the mud, and then a grand turmoil of half an hour would follow, during which time every man found in the neighborhood would be impressed to aid in relieving the embargoed gun. The whipping of the horses and the cursing of the drivers was less soothing, if anything, than those soul shattering gunboat broadsides. There never was a night so long, so hideous, or so utterly uncomfortable.

As the gray streaks of dawn began to appear, the band of the Thirteenth Regulars on the deck of one of the transports, came into the landing, playing a magnificent selection from “Il Trovatore.” How inspiring that music was! Even the poor, wounded men lying in front on the shore seemed to be lifted up, and every soldier seemed to receive an impetus. Soon there was light enough to distinguish objects around, and then came the ominous patter of musketry over beyond the river’s bluff, which told that the battle was on again. It began just as a shower of rain began and soon deepened into a terrible hail storm, with the booming artillery for thunder accompaniment. I was up and around and started immediately toward the front, for everybody felt now that the battle was to be ours. Those fresh and sturdy troops from the Army of the Ohio had furnished a blue bulwark, behind which the incomparable one-day fighters of Grant and Sherman were to push to victory. The whole aspect of the field in the rear changed. The skulkers of the day before seemed to be imbued with genuine manhood, and thousands of them returned to the front to render good service. In addition to this, six thousand fresh men under General Lew Wallace, who had marched from Crump’s Landing, ten miles away, had arrived during the night, and the tide of battle was now setting towards Corinth. I met a comrade drying himself out by a log fire, about a quarter of a mile from the landing, who had by some process secured a canteen of what was known as Commissary Whisky. He gave me one drink of it and that constituted my breakfast. Cold, wet and depressed, as I was, that whisky, execrable though it was, brought such consolation as I had never found before. I have drunk champagne in Epernay, I have sipped Johannisberger at the foot of its sunny mount, I have tasted the regal Montpulsanio, but, by Jove, I never enjoyed a drink as I did that swig of common whisky, on the morning of the 7th of April, 1862! While drying myself by this fire I saw a motley crowd of Confederate prisoners marched past, under guard. As they waded along the muddy road, some of the cowardly skulkers indulged in the badinage usual on such occasions, and one of our fellows called out to know what company that was. A proud young chap in gray threw his head back, and replied, “Company Q, of the Southern Invincibles, and be damned to you.” That was the spirit of the day and the hour.

At 10 o’clock, the sound of the battle indicated that our lines were being pushed forward, and I made up my mind to go to the front. I started with my companion, and in a very short time we began to see about us traces of the terrible battle of the day before. We were then on the ground which had been fought over late Sunday evening. The underbrush had literally been mowed off by the bullets and great trees had been shattered by the terrible artillery fire. In places, the bodies of the slain lay upon the ground so thick that I could step from one to the other. This without exaggeration. The pallid faces of the dead men in blue were scattered among the blackened corpses of the enemy. This to me was a horrible revelation, and I have never yet heard a scientific explanation of why the majority of the dead Confederates on that field turned black. All the bodies had been[481] stripped of their valuables, and scarcely a pair of boots or shoes could be found upon the feet of the dead. In most instances, pockets had been cut open, and one of the pathetic sights that I remember was a poor Confederate, lying on his back, while by his side was a heap of ginger cakes and sausage, which had tumbled out of his trousers pockets, cut by some infamous thief. The unfortunate man had evidently filled his pocket the day before with the edibles, found in some sutler’s tent, and had been killed before he had an opportunity to enjoy his bountiful store. There was something so sad about this that it brought tears to my eyes. Farther on I passed by the road the corpse of a beautiful boy in gray, who lay with his blonde curls scattered about his face, and his hands folded peacefully across his breast. He was clad in a bright and neat uniform, well garnished with gold, which seemed to tell the story of a loving mother and sisters who had sent their household pet to the field of war. His neat little hat lying beside him bore the number of a Georgia regiment, embroidered, I am sure, by some tender fingers, and his waxen face, washed by the rain of the night before, was that of one who had fallen asleep, dreaming of loved ones who waited his coming in some anxious home. He was about my age. He may have been a drummer! At the sight of that poor boy’s corpse I burst into tears, and started on. Here beside a great oak tree I counted the corpses of fifteen men. One of them sat stark against the tree, and the others lay about as though during the night, suffering from wounds, they had crawled together for mutual assistance and there had died. The blue and the gray were mingled together. This peculiarity I observed all over the field. It was no uncommon thing to see the bodies of Federal and Confederate lying side by side as though they had bled to death, while trying to aid each other. In one spot I saw an entire battery of Federal artillery, which had been dismantled in Sunday’s fight, every horse of which had been killed in his harness, every tumbrel of which had been broken, every gun of which had been dismounted, and in this awful heap of death lay the bodies of dozens of cannoneers. One dismounted gun was absolutely spattered with the blood and brains of the men who had served it. Here and there in the field, standing in the mud, were the most piteous sights of all the battlefield—poor, wounded horses, their heads drooping, their eyes glassy and gummy, waiting for the slow coming of death, or for some friendly hand to end their misery. How those helpless brutes spoke in pleading testimony of the horror, the barbarism and the uselessness of war! No painter ever did justice to a battlefield such as this, I am sure.

As I pushed onward to the front, I passed the ambulances and the wagons bringing back the wounded, and talked with the poor, bleeding fellows who were hobbling toward the river, along the awful roads or through the dismal chaparral. They all brought news of victory. Toward evening I found myself in the neighborhood of the old Shiloh Church, but could get no tidings of my father’s regiment. Night came on and I lay down and fell asleep at the foot of a tree, having gathered up a blanket soaked with water, which I could only use for a pillow. It rained all night. The battle had practically ended at 4 o’clock that evening, and the enemy had slowly and silently withdrawn toward Corinth. Next morning I learned that my father’s regiment had been sent in pursuit of the enemy, and nobody could tell when it would return. I found the camp, and oh, what desolation reigned there! Every tent had been pillaged, and in my father’s headquarters, the gentlemen of the enemy who had camped there two nights before had left a duplicate of nearly everything they had taken. They had exchanged their dirty blankets for clean ones, and had left their old, worn brogans in the place of boots and shoes which they had appropriated, and all about were the evidences of the feasting that had gone on during that one night of[482] glorious possession. I remained there during the day, and late that evening the Seventieth Ohio came back to its deserted quarters after three days and two nights of most terrible fighting and campaigning.

At its head rode my father, whom I had supposed to be dead, pale, haggard and worn, but unscathed. He had not seen me nor heard of me for sixty hours. He dismounted, and, taking me in his arms, gave me the most affectionate embrace my life had ever known, and I realized then how deeply he loved me. That night we stayed in the old bullet ridden and shot torn tent and told of our adventures, and the next day I had the pleasure of hearing General Sherman compliment my father for his bravery, and say, “Colonel, you have been worth your weight in gold to me.”

Many years after, speaking one day to General Sherman, I asked him,

“What do you regard as the bloodiest and most sanguinary battle of the Civil War?”

“Shiloh,” was the prompt response.

And in this opinion I heartily concur.

Note—The killed and wounded in the two days’ Battle of Shiloh numbered nearly twenty thousand Federals and Confederates, or about thirty per cent of the entire number engaged. These figures become the more significant when it is remembered that a very large proportion of the troops engaged on both sides were absolutely raw and were at Shiloh in their first baptism of fire. These losses again become most significant when compared with the losses in the world’s most noted battles. Waterloo is considered one of the most desperate and bloody fields chronicled in European history, and yet Wellington’s casualties were less than twelve per cent. In the great battles of Marengo and Austerlitz, sanguinary as they were, Napoleon lost less than fifteen per cent, while at Shiloh, Americans fighting against Americans, the killed and wounded numbered more than twice the casualties of the Duke of Wellington’s Army at Waterloo.

The fourteenth Session of the Interparliamentary Union was notable in many respects. First, it was held in the capital of the greatest country in the world, not only in its area, but in the fact that it is the oldest representative of the idea of Parliamentary Government. It was in the year 1253 that the first Representative Parliament of England assembled at London. This was the first appearance of this idea in the presence of the royal families which were then reigning in Europe. Indeed, it may be properly called the first appearance of this idea in the modern political world, though of course parliaments have existed in other parts of the world in previous centuries. But between those early efforts at democratic government and the modern regime, a long period of darkness came over the world, and it is perhaps safe to say that the modern era in the political world began with the assembling of the first Representative Parliament in England.

The fundamental idea of democracy is government in the affairs of to-day by persons who are elected by the people of to-day, whereas the fundamental proposition in all other forms of government is that the people of the past have a right to impose their ideas upon the people of the present, through the form of hereditary office-holding and established religious organizations. This being true, it is nothing but right that the United States should be strongly represented at this great conference composed of the people’s representatives from practically every nation in the world. The United States Congress has been represented by a delegation at only three previous conferences of the Interparliamentary Union, namely, the one at St. Louis, in 1904; the one at Brussels, in 1905; and the present one. At each of these, except this present one, the Democratic side of the American delegation has been much weaker than the Republican side, there being as a rule only a few Democrats in the delegation, and in no case a Democrat of national reputation. The Democratic side of the delegation at this fourteenth conference of the Interparliamentary Union was as large in numbers as the Republican side, and contained the leader of the Democratic party in Congress, Mr. John Sharpe Williams, and the leader of the Democratic party in this country, Hon. W. J. Bryan. This fact is of great importance to the cause of international arbitration, not only in the United States, but also in Europe, because it has resulted in perfect unity between Mr. Bartholdt, who is a Republican, and the leaders of the Democratic party in the United States. Mr. Bartholdt has taken the lead in this progressive movement, not only among the law-makers of the United States, but of the whole world, by calling for a second conference at The Hague, and by putting forward a proposition which has now received the express approval of the ablest leaders of the Democratic party in the United States. Both Mr. Williams and Mr. Bryan have expressly and powerfully espoused the ideas which Mr. Bartholdt has put forward, and which have now received the sanction of the Interparliamentary Conference. Furthermore, both Mr. Williams and Mr. Bryan have come forward with propositions of their own. With Mr. Roosevelt already committed to the plans of the Interparliamentary Union, and with the probable[484] Democratic candidate at the next election committed even more strongly, the lovers of peace and justice in the Old and in the New World have a right to count absolutely upon the support of the next President of the United States, not only for these progressive steps toward permanent peace which have heretofore been advocated in Europe, but for more advanced steps than were deemed practical at any time in the past, either in Europe or America.

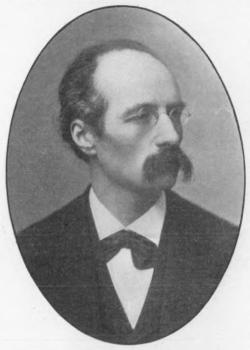

WILLIAM RANDAL CREWER

Originator of the Interparliamentary Union