Title: The old English dramatists

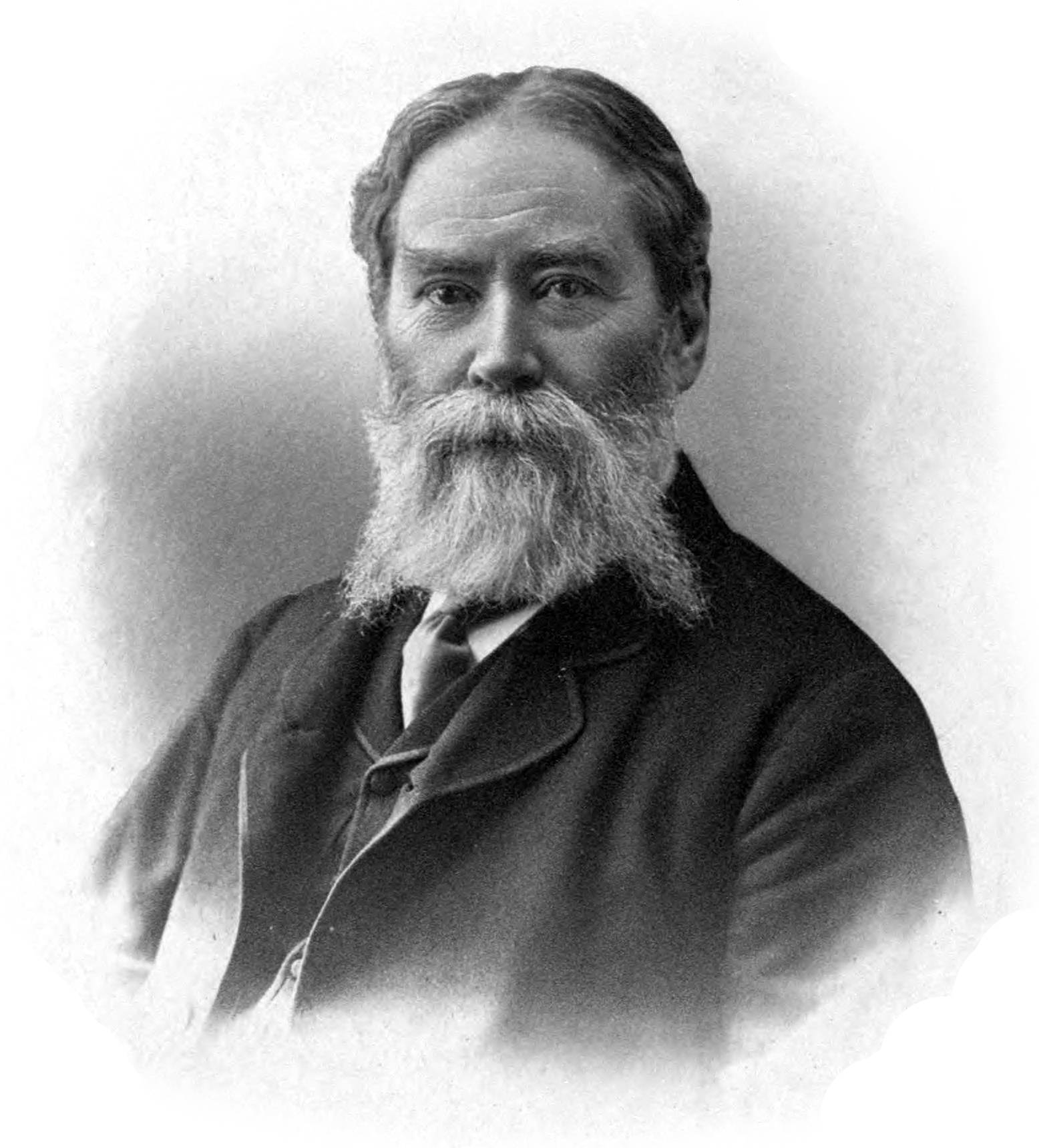

Author: James Russell Lowell

Author of introduction, etc.: Charles Eliot Norton

Release date: December 5, 2023 [eBook #72335]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1892

Credits: Charlene Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of the illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

Lowell’s Works.

COMPLETE WORKS OF JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL. New Riverside Edition. In same style as the Riverside Editions of Longfellow’s and Whittier’s Works. With Portraits, Indexes, etc. 11 vols, crown 8vo, gilt top, each (except vol. 11), $1.50; the set, 11 vols. $16.25; half calf, $30.00; half calf, gilt top, $33.00; half levant, $44.00.

1–4. Literary Essays (including My Study Windows, Among My Books, Fireside Travels). 5. Political Essays. 6. Literary and Political Addresses. 7–10. Poems. 11. Latest Literary Essays and Addresses ($1.25).

PROSE WORKS. New Riverside Edition. With Portrait. 7 vols. crown 8vo, gilt top, $10.25; half calf, $19.25; half calf, gilt top, $21.00; half levant, $28.00.

LITERARY ESSAYS. New Riverside Edition. With Portrait. 4 vols. crown 8vo, gilt top, $7.25; half calf, $13.50; half calf, gilt top, $15.00; half levant, $20.00.

POEMS. New Riverside Edition. With Portraits; 4 vols. crown 8vo, gilt top, $6.00; half calf, $11.00; half calf, gilt top, $12.00; half levant, $16.00.

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & COMPANY,

Boston and New York.

BY

JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

1893

Copyright, 1892,

By CHARLES ELIOT NORTON.

All rights reserved.

The Riverside Press, Cambridge, Mass., U. S. A.

Electrotyped and Printed by H. O. Houghton & Co.

In the spring of 1887, Mr. Lowell read, at the Lowell Institute in Boston, six lectures on the Old English Dramatists. They had been rapidly written, and in their delivery much was said extemporaneously, suggested by the passages from the plays selected for illustration of the discourse. To many of these passages there was no reference in the manuscript; they were read from the printed book. The lectures were never revised by Mr. Lowell for publication, but they contain such admirable and interesting criticism, and are in themselves such genuine pieces of good literature, that it has seemed to me that they should be given to the public.1

CHARLES ELIOT NORTON.

1 Before their publication in this volume, these Lectures appeared in Harper’s Magazine, in the numbers from June to November, 1892.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | Introductory | 1 |

| II. | Marlowe | 28 |

| III. | Webster | 55 |

| IV. | Chapman | 78 |

| V. | Beaumont and Fletcher | 100 |

| VI. | Massinger and Ford | 113 |

1

When the rule limiting speeches to an hour was adopted by Congress, which was before most of you were born, an eminent but somewhat discursive person spent more than that measure of time in convincing me that whoever really had anything to say could say it in less. I then and there acquired a conviction of this truth, which has only strengthened with years. Yet whoever undertakes to lecture must adapt his discourse to the law which requires such exercises to be precisely sixty minutes long, just as a certain standard of inches must be reached by one who would enter the army. If one has been studying all his life how to be terse, how to suggest rather than to expound, how to contract rather than to dilate, something like a strain is put upon the conscience by this necessity of giving the full measure of words, without reference to other considerations which a judicious ear may esteem of more importance. Instead of saying things compactly and pithily, so that they may be easily carried away, one is tempted into a certain generosity and circumambience of phrase, which, if not adapted2 to conquer Time, may at least compel him to turn his glass and admit a drawn game. It is so much harder to fill an hour than to empty one!

These thoughts rose before me with painful vividness as I fancied myself standing here again, after an interval of thirty-two years, to address an audience at the Lowell Institute. Then I lectured, not without some favorable acceptance, on Poetry in general and what constituted it, on Imagination and Fancy, on Wit and Humor, on Metrical Romances, on Ballads, and I know not what else—on whatever I thought I had anything to say about, I suppose. Then I was at the period in life when thoughts rose in coveys, and one filled one’s bag without considering too nicely whether the game had been hatched within his neighbor’s fence or within his own,—a period of life when it doesn’t seem as if everything had been said; when a man overestimates the value of what specially interests himself, and insists with Don Quixote that all the world shall stop till the superior charms of his Dulcinea of the moment have been acknowledged; when he conceives himself a missionary, and is persuaded that he is saving his fellows from the perdition of their souls if he convert them from belief in some æsthetic heresy. That is the mood of mind in which one may read lectures with some assurance of success. I remember how I read mine over to the clock, that I might be sure I had enough, and how patiently the clock listened, and gave no opinion except as to duration, on which point it assured me that I always ran over. This is the3 pleasant peril of enthusiasm, which has always something of the careless superfluity of youth. Since then, and for a period making a sixth part of my mature life, my mind has been shunted off upon the track of other duties and other interests. If I have learned something, I have also forgotten a good deal. One is apt to forget so much in the service of one’s country,—even that he is an American, I have been told, though I can hardly believe it.

When I selected my topic for this new venture, I was returning to a first love. The second volume I ever printed, in 1843, I think it was,—it is now a rare book, I am not sorry to know; I have not seen it for many years,—was mainly about the Old English Dramatists, if I am not mistaken. I dare say it was crude enough, but it was spontaneous and honest. I have continued to read them ever since, with no less pleasure, if with more discrimination. But when I was confronted with the question what I could say of them that would interest any rational person, after all that had been said by Lamb, the most sympathetic of critics, by Hazlitt, one of the most penetrative, by Coleridge, the most intuitive, and by so many others, I was inclined to believe that instead of an easy subject I had chosen a subject very far from easy. But I sustained myself with the words of the great poet who so often has saved me from myself:—

4

If I bring no other qualification, I bring at least that of hearty affection, which is the first condition of insight. I shall not scruple to repeat what may seem already too familiar, confident that these old poets will stand as much talking about as most people. At the risk of being tedious, I shall put you back to your scales as a teacher of music does his pupils. For it is the business of a lecturer to treat his audience as M. Jourdain wished to be treated in respect of the Latin language,—to take it for granted that they know, but to talk to them as if they did n’t. I should have preferred to entitle my course Readings from the Old English Dramatists with illustrative comments, rather than a critical discussion of them, for there is more conviction in what is beautiful in itself than in any amount of explanation why, or exposition of how, it is beautiful. A rose has a very succinct way of explaining itself. When I find nothing profitable to say, I shall take sanctuary in my authors.

It is generally assumed that the Modern Drama in France, Spain, Italy, and England was an evolution out of the Mysteries and Moralities and Interludes which had edified and amused preceding generations of simpler taste and ruder intelligence. ’T is the old story of Thespis and his cart. Taken with due limitations, and substituting the word stage for drama, this theory of origin is satisfactory enough. The stage was there, and the desire to be amused, when the drama at last appeared to occupy the one and to satisfy the other. It seems to have5 been, so far as the English Drama is concerned, a case of post hoc, without altogether adequate grounds for inferring a propter hoc. The Interludes may have served as training-schools for actors. It is certain that Richard Burbage, afterwards of Shakespeare’s company, was so trained. He is the actor, you will remember, who first played the part of Hamlet, and the untimely expansion of whose person is supposed to account for the Queen’s speech in the fencing scene, “He’s fat and scant of breath.” I may say, in passing, that the phrase merely means “He’s out of training,” as we should say now. A fat Hamlet is as inconceivable as a lean Falstaff. Shakespeare, with his usual discretion, never makes the Queen hateful, and made use of this expedient to show her solicitude for her son. Her last word, as she is dying, is his name.

To return. The Interlude may have kept alive the traditions of a stage, and may have made ready a certain number of persons to assume higher and graver parts when the opportunity should come; but the revival of learning, and the rise of cities capable of supplying a more cultivated and exacting audience, must have had a stronger and more direct influence on the growth of the Drama, as we understand the word, than any or all other influences combined. Certainly this seems to me true of the English Drama at least. The English Miracle Plays are dull beyond what is permitted even by the most hardened charity, and there is nothing dramatic in them except that they are in the form of6 dialogue. The Interludes are perhaps further saddened in the reading by reminding us how much easier it was to be amused three hundred years ago than now, but their wit is the wit of the Eocene period, unhappily as long as it is broad, and their humor is horse-play. We inherited a vast accumulation of barbarism from our Teutonic ancestors. It was only on those terms, perhaps, that we could have their vigor too. The Interludes have some small value as illustrating manners and forms of speech, but the man must be born expressly for the purpose—as for some of the adventures of mediæval knight-errantry—who can read them. “Gammer Gurton’s Needle” is perhaps as good as any. It was acted at Christ’s College, Cambridge, in 1566, and is remarkable, as Mr. Collier pointed out, as the first existing play acted before either University. Its author was John Still, afterwards Bishop of Bath and Wells, and it is curious that when Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge he should have protested against the acting before the University of an English play so unbefitting its learning, dignity, and character. “Gammer Gurton’s Needle” contains a very jolly and spirited song in praise of ale. Latin plays were acted before the Universities on great occasions, but there was nothing dramatic about them but their form. One of them by Burton, author of the “Anatomy of Melancholy,” has been printed, and is not without merit. In the “Pardoner and the Frere” there is a hint at the drollery of those cross-readings with which Bonnell Thornton made our grandfathers laugh:—

7

“Pard. Pope July the Sixth hath granted fair and well—

Fr. That when to them God hath abundance sent—

Pard. And doth twelve thousand years of pardon to them send—

Fr. They would distribute none to the indigent—

Pard. That aught to this holy chapel lend.”

Everything in these old farces is rudimentary. They are not merely coarse; they are vulgar.

In France it was better, but France had something which may fairly be called literature before any other country in Europe, not literature in the highest sense, of course, but something, at any rate, that may be still read with pleasure for its delicate beauty, like “Aucassin and Nicolete,” or for its downright vigor, like the “Song of Roland,” or for its genuine humor, like “Renard the Fox.” There is even one French Miracle Play of the thirteenth century, by the trouvère Rutebeuf, based on the legend of Theophilus of Antioch, which might be said to contain the germ of Calderon’s “El Magico Prodigioso,” and thus, remotely, of Goethe’s “Faust.” Of the next century is the farce of “Patelin,” which has given a new word with its several derivatives to the French language, and a proverbial phrase, revenons à nos moutons, that long ago domiciled itself beyond the boundaries of France. “Patelin” rises at times above the level of farce, though hardly to the region of pure comedy. I saw it acted at the Théâtre Français many years ago, with only so much modernization of language as was necessary to make it easily comprehensible, and found it far more than archæologically entertaining. Surely none of our old English Interludes8 could be put upon the stage now without the gloomiest results. They were not, in my judgment, the direct, and hardly even the collateral, ancestors of our legitimate comedy. On the other hand, while the Miracle Plays left no traces of themselves in our serious drama, the play of Punch and Judy looks very like an impoverished descendant of theirs.

In Spain it was otherwise. There the old Moralities and Mysteries of the Church Festivals are renewed and perpetuated in the Autos Sacramentales of Calderon, but ensouled with the creative breath of his genius, and having a strange phantasmal reality in the ideal world of his wonder-working imagination. One of his plays, “La Devocion de la Cruz,” an Auto in spirit if not in form, dramatizes, as only he could do it, the doctrine of justification by faith. In Spain, too, the comedy of the booth and the plaza is plainly the rude sketch of the higher creations of Tirso and Lope and Calderon and Rojas and Alarcon, and scores of others only less than they. The tragicomedy of “Celestina,” written at the close of the fifteenth century, is the first modern piece of realism or naturalism, as it is called, with which I am acquainted. It is coarse, and most of the characters are low, but there are touches of nature in it, and the character of Celestina is brought out with singular vivacity. The word tragicomedy is many years older than this play, if play that may be called which is but a succession of dialogues, but I can think of no earlier example of its application to a production in9 dramatic form than by the Bachelor Fernando de Rojas in this instance. It was made over into English, rather than translated, in 1520,—our first literary debt to Spain, I should guess. The Spanish theatre, though the influence of Seneca is apparent in the form it put on, is more sincerely a growth of the soil than any other of modern times, and it has one interesting analogy with our own in the introduction of the clown into tragedy, whether by way of foil or parody. The Spanish dramatists have been called marvels of fecundity, but the facility of their trochaic measure, in which the verses seem to go of themselves, makes their feats less wonderful. The marvel would seem to be rather that, writing so easily, they also wrote so well. Their invention is as remarkable as their abundance. Their drama and our own have affected the spirit and sometimes the substance of later literature more than any other. They have to a certain extent impregnated it. I have called the Spanish theatre a product of the soil, yet it must not be overlooked that Sophocles, Euripides, Plautus, and Terence had been translated into Spanish early in the sixteenth century, and that Lope de Rueda, its real founder, would willingly have followed classical models more closely had the public taste justified him in doing so. But fortunately the national genius triumphed over traditional criterions of art, and the Spanish theatre, asserting its own happier instincts, became and continued Spanish, with an unspeakable charm and flavor of its own.

10

One peculiarity of the Spanish plays makes it safe to recommend them even virginibus puerisque,—they are never unclean. Even Milton would have approved a censorship of the press that accomplished this. It is a remarkable example of how sharp the contradiction is between the private morals of a people and their public code of morality. Certain things may be done, but they must not seem to be done.

I have said nothing of the earlier Italian Drama because it has failed to interest me. But Italy had indirectly a potent influence, through Spenser, in supplying English verse till it could answer the higher uses of the stage. The lines—for they can hardly be called verses—of the first attempts at regular plays are as uniform, flat, and void of variety as laths cut by machinery, and show only the arithmetical ability of their fashioners to count as high as ten. A speech is a series of such laths laid parallel to each other with scrupulous exactness. But I shall have occasion to return to this topic in speaking of Marlowe.

Who, then, were the Old English Dramatists? They were a score or so of literary bohemians, for the most part, living from hand to mouth in London during the last twenty years of the sixteenth century and the first thirty years of the seventeenth, of the personal history of most of whom we fortunately know little, and who, by their good luck in being born into an unsophisticated age, have written a few things so well that they seem to have written themselves. Poor, nearly all of them,11 they have left us a fine estate in the realm of Faery. Among them were three or four men of genius. A comrade of theirs by his calling, but set apart from them alike by the splendor of his endowments and the more equable balance of his temperament, was that divine apparition known to mortals as Shakespeare. The civil war put an end to their activity. The last of them, in the direct line, was James Shirley, remembered chiefly for two lines from the last stanza of a song of his in “The Contention of Ajax and Ulysses,” which have become a proverb:—

It is a nobly simple piece of verse, with the slow and solemn cadence of a funeral march. The hint of it seems to have been taken from a passage in that droningly dreary book the “Mirror for Magistrates.” This little poem is one of the best instances of the good fortune of the men of that age in the unconscious simplicity and gladness (I know not what else to call it) of their vocabulary. The language, so to speak, had just learned to go alone, and found a joy in its own mere motion, which it lost as it grew older, and to walk was no longer a marvel.

Nothing in the history of literature seems more startling than the sudden spring with which English poetry blossomed in the later years of Elizabeth’s reign. We may account for the seemingly unheralded apparition of a single genius like Dante or Chaucer by the genius itself; for, given that,12 everything else is possible. But even in such cases as these much must have gone before to make the genius available when it came. For the production of great literature there must be already a language ductile to all the varying moods of expression. There must be a certain amount of culture, or the stimulus of sympathy would be wanting. If, as Horace tells us, the heroes who lived before Agamemnon have perished for want of a poet to celebrate them, so doubtless many poets have gone dumb to their graves, or, at any rate, have uttered themselves imperfectly, for lack of a fitting vehicle or of an amiable atmosphere. Genius, to be sure, makes its own opportunity, but the circumstances must be there out of which it can be made. For instance, I cannot help feeling that Turold, or whoever was the author of the “Chanson de Roland,” was endowed with a rare epical faculty, and that he would have given more emphatic proof of it had it been possible for him to clothe his thought in a form equivalent to the vigor of his conception. Perhaps with more art, he might have had less of that happy audacity of the first leap which Montaigne valued so highly, but would he not have gained could he have spoken to us in a verse as sonorous as the Greek hexameter, nay, even as sweet in its cadences, as variously voluble by its slurs and elisions, and withal as sharply edged and clean cut as the Italian pentameter? It is at least a question open to debate. Mr. Matthew Arnold taxes the “Song of Roland” with an entire want of the grand style; and this is true enough; but it13 has immense stores of courage and victory in it, as Taillefer proved at the battle of Hastings,—yes, and touches of heroic pathos, too.

Many things had slowly and silently concurred to make that singular pre-eminence of the Elizabethan literature possible. First of all was the growth of a national consciousness, made aware of itself and more cumulatively operative by the existence and safer accessibility of a national capital, to serve it both as head and heart. The want of such a focus of intellectual, political, and material activity has had more to do with the backwardness and provincialism of our own literature than is generally taken into account. My friend Mr. Hosea Biglow ventured to affirm twenty odd years ago that we had at last arrived at this national consciousness through the convulsion of our civil war,—a convulsion so violent as might well convince the members that they formed part of a common body. But I make bold to doubt whether that consciousness will ever be more than fitful and imperfect, whether it will ever, except in some moment of supreme crisis, pour itself into and reënforce the individual consciousness in a way to make our literature feel itself of age and its own master, till we shall have got a common head as well as a common body. It is not the size of a city that gives it this stimulating and expanding quality, but the fact that it sums up in itself and gathers all the moral and intellectual forces of the country in a single focus. London is still the metropolis of the British as Paris of the French race. We admit this14 readily enough as regards Australia or Canada, but we willingly overlook it as regards ourselves. Washington is growing more national and more habitable every year, but it will never be a capital till every kind of culture is attainable there on as good terms as elsewhere. Why not on better than elsewhere? We are rich enough. Bismarck’s first care has been the Museums of Berlin. For a fiftieth part of the money Congress seems willing to waste in demoralizing the country, we might have had the Hamilton books and the far more precious Ashburnham manuscripts. Perhaps what formerly gave Boston its admitted literary supremacy was the fact that fifty years ago it was more truly a capital than any other American city. Edinburgh once held a similar position, with similar results. And yet how narrow Boston was! How scant a pasture it offered to the imagination! I have often mused on the dreary fate of the great painter who perished slowly of inanition over yonder in Cambridgeport, he who had known Coleridge and Lamb and Wordsworth, and who, if ever any,

The pity of it! That unfinished Belshazzar of his was a bitter sarcasm on our self-conceit. Among us, it was unfinishable. Whatever place can draw together the greatest amount and greatest variety of intellect and character, the most abundant elements of civilization, performs the best function15 of a university. London was such a centre in the days of Queen Elizabeth. And think what a school the Mermaid Tavern must have been! The verses which Beaumont addressed to Ben Jonson from the country point to this:—

This air, which Beaumont says they left behind them, they carried with them, too. It was the atmosphere of culture, the open air of it, which loses much of its bracing and stimulating virtue in solitude and the silent society of books. And what discussions can we not fancy there, of language, of diction, of style, of ancients and moderns, of grammar even, for our speech was still at school, and with license of vagrant truancy for the gathering of wild flowers and the finding of whole nests full of singing birds! Here was indeed a new World of Words, as Florio called his dictionary. And the face-to-face criticism, frank, friendly, and with chance of reply, how fruitful it must have been!16 It was here, doubtless, that Jonson found fault with that verse of Shakespeare’s,—

which is no longer to be found in the play of “Julius Cæsar.” Perhaps Heminge and Condell left it out, for Shakespeare could have justified himself with the hook-nosed fellow of Rome’s favorite Greek quotation, that nothing justified crime but the winning or keeping of supreme power. Never could London, before or since, gather such an academy of genius. It must have been a marvellous whetstone of the wits, and spur to generous emulation.

Another great advantage which the authors of that day had was the freshness of the language, which had not then become literary, and therefore more or less commonplace. All the words they used were bright from the die, not yet worn smooth in the daily drudgery of prosaic service. I am not sure whether they were so fully conscious of this as we are, who find a surprising charm in it, and perhaps endow the poet with the witchery that really belongs to the vocables he employs. The parts of speech of these old poets are just archaic enough to please us with that familiar strangeness which makes our own tongue agreeable if spoken with a hardly perceptible foreign accent. The power of giving novelty to things outworn is, indeed, one of the prime qualities of genius, and this novelty the habitual phrase of the Elizabethans has for us without any merit of theirs. But I17 think, making all due abatements, that they had the hermetic gift of buckling wings to the feet of their verse in a measure which has fallen to the share of few or no modern poets. I think some of them certainly were fully aware of the fine qualities of their mother-tongue. Chapman, in the poem “To the Reader,” prefixed to his translation of the Iliad, protests against those who preferred to it the softer Romance languages:—

I think Chapman has very prettily maintained and illustrated his thesis. But, though fortunate in being able to gather their language with the dew still on it, as herbs must be gathered for use in certain incantations, we are not to suppose that our elders used it indiscriminately, or tumbled out their words as they would dice, trusting that luck or chance would send them a happy throw; that they did not select, arrange, combine, and make use of the most cunning artifices of modulation and rhythm. They debated all these questions, we may be sure, not only with a laudable desire of excellence, and with a hope to make their native tongue as fitting a vehicle for poetry and eloquence as those of their neighbors, or as those of Greece and Rome, but also with something of the eager joy of adventure and discovery. They must have18 felt with Lucretius the delight of wandering over the pathless places of the Muse, and hence, perhaps, it is that their step is so elastic, and that we are never dispirited by a consciousness of any lassitude when they put forth their best pace. If they are natural, it is in great part the benefit of the age they lived in; but the winning graces, the picturesque felicities, the electric flashes, I had almost said the explosions, of their style are their own. And their diction mingles its elements so kindly and with such gracious reliefs of changing key, now dallying with the very childishness of speech like the spinsters and the knitters in the sun, and anon snatched up without effort to the rapt phrase of passion or of tragedy that flashes and reverberates!

The dullest of them, for I admit that many of them were dull as a comedy of Goethe, and dulness loses none of its disheartening properties by age, no, nor even by being embalmed in the precious gems and spices of Lamb’s affectionate eulogy,—for I am persuaded that I should know a stupid mummy from a clever one before I had been in his company five minutes,—the dullest of them, I say, has his lucid intervals. There are, I grant, dreary wastes and vast solitudes in such collections as Dodsley’s “Old Plays,” where we slump along through the loose sand without even so much as a mirage to comfort us under the intolerable drought of our companion’s discourse. Nay, even some of the dramatists who have been thought worthy of editions all to themselves, may enjoy that seclusion without fear of its being disturbed by me.

19

Let me mention a name or two of such as I shall not speak of in this course. Robert Greene is one of them. He has all the inadequacy of imperfectly drawn tea. I thank him, indeed, for the word “brightsome,” and for two lines of Sephestia’s song to her child,—

which have all the innocence of the Old Age in them. Otherwise he is naught. I say this for the benefit of the young, for in my own callow days I took him seriously because the Rev. Alexander Dyce had edited him, and I endured much in trying to reconcile my instincts with my superstition. He it was that called Shakespeare “an upstart crow beautified with our feathers,” as if any one could have any use for feathers from such birds as he, except to make pens of them. He was the cause of the dulness that was in other men, too, and human nature feels itself partially avenged by this stanza of an elegy upon him by one “R. B.,” quoted by Mr. Dyce:—

Even the libeller of Shakespeare deserved nothing worse than this! If this is “R. B.” when he was playing upon words, what must he have been when serious?

Another dramatist whom we can get on very20 well without is George Peele, the friend and fellow-roisterer of Greene. He, too, defied the inspiring influence of the air he breathed almost as successfully as his friend. But he had not that genius for being dull all the time that Greene had, and illustrates what I was just saying of the manner in which the most tiresome of these men waylay us when we least expect it with some phrase or verse that shines and trembles in the memory like a star. Such are:—

and this, of God’s avenging lightning,—

He also wrote some musically simple stanzas, of which I quote the first two, the rather that Thackeray was fond of them:—

There is a pensiveness in this, half pleasurable, half melancholy, that has a charm of its own.

21

Thomas Dekker is a far more important person. Most of his works seem to have been what artists call pot-boilers, written at ruinous speed, and with the bailiff rather than the Muse at his elbow. There was a liberal background of prose in him, as in Ben Jonson, but he was a poet and no mean one, as he shows by the careless good luck of his epithets and similes. He could rise also to a grave dignity of style that is grateful to the ear, nor was he incapable of that heightened emotion which might almost pass for passion. His fancy kindles wellnigh to imagination at times, and ventures on those extravagances which entice the fancy of the reader as with the music of an invitation to the waltz. I had him in my mind when I was speaking of the obiter dicta, of the fine verses dropt casually by these men when you are beginning to think they have no poetry in them. Fortune tells Fortunatus, in the play of that name, that he shall have gold as countless as

thus giving him a hint also of its ephemeral nature. Here is a verse, too, that shows a kind of bleakish sympathy of sound and sense. Long life, he tells us,—

It may be merely my fancy, but I seem to hear a melancholy echo in it, as of footfalls on frozen earth. Or take this for a pretty fancy:—

22

when do you suppose? I give you three guesses, as the children say. Since 1600! Poor Fancy shudders at this opening of Haydn’s “Dictionary of Dates” and thinks her silver arrows a little out of place, like a belated masquerader going home under the broad grin of day. But the verses themselves seem plucked from “Midsummer-Night’s Dream.”

This is as good an instance as may be of the want of taste, of sense of congruity, and of the delicate discrimination that makes style, which strikes and sometimes even shocks us in the Old Dramatists. This was a disadvantage of the age into which they were born, and is perhaps implied in the very advantages it gave them, and of which I have spoken. Even Shakespeare offends sometimes in this way. Good taste, if mainly a gift of nature, is also an acquisition. It was not impossible even then. Samuel Daniel had it, but the cautious propriety with which it embarrassed him has made his drama of “Cleopatra” unapproachable, in more senses than one, in its frigid regularity. His contemplative poetry, thanks to its grave sweetness of style, is among the best in our language. And Daniel wrote the following sentences, which explain better than anything I could say why his contemporaries, in spite of their manifest imperfections, pleased then and continue to please: “Suffer the world to enjoy that which it knows and what it likes, seeing whatsoever form of words doth move delight, and sway the affections of men, in what Scythian sort soever it be disposed and23 uttered, that is true number, measure, eloquence, and the perfection of speech.” Those men did “move delight, and sway the affections of men,” in a very singular manner, gaining, on the whole, perhaps, more by their liberty than they lost by their license. But it is only genius that can safely profit by this immunity. Form, of which we hear so much, is of great value, but it is not of the highest value, except in combination with other qualities better than itself; and it is worth noting that the modern English poet who seems least to have regarded it, is also the one who has most powerfully moved, swayed, and delighted those who are wise enough to read him.

One more passage and I have done. It is from the same play of “Old Fortunatus,” a favorite of mine. The Soldan of Babylon shows Fortunatus his treasury, or cabinet of bric-à-brac:—

This is, here and there, tremblingly near bombast, but its exuberance is cheery, and the quaintness of Proserpine’s fan shows how real she was to the poet. Hers was a generous gift, considering the climate in which Dekker evidently supposed her to dwell, and speaks well for the song that could make her forget it. There is crudeness, as if the wine had been drawn before the ferment was over, but the arm of Venus is from the life, and that one verse gleams and glows among the rest like the thing it describes. The whole passage is a good example of fancy, whimsical, irresponsible. But there is more imagination and power to move the imagination in Shakespeare’s “sunken wreck and sunless treasures” than all his contemporaries together, not even excepting Marlowe, could have mustered.

We lump all these poets together as dramatists because they wrote for the theatre, and yet how little they were truly dramatic seems proved by the fact that none, or next to none, of their plays have held the stage. Not one of their characters, that I can remember, has become one of the familiar figures that make up the habitual society of any cultivated memory even of the same race and tongue. Marlowe, great as he was, makes no exception. To some of them we cannot deny genius, but creative genius we must deny to all of them, and dramatic genius as well.

25

This last, indeed, is one of the rarest gifts bestowed on man. What is that which we call dramatic? In the abstract, it is thought or emotion in action, or on its way to become action. In the concrete, it is that which is more vivid if represented than described, and which would lose if merely narrated. Goethe, for example, had little dramatic power; though, if taking thought could have earned it, he would have had enough, for he studied the actual stage all his life. The characters in his plays seem rather to express his thoughts than their own. Yet there is one admirably dramatic scene in “Faust” which illustrates what I have been saying. I mean Margaret in the cathedral, suggested to Goethe by the temptation of Justina in Calderon’s “Magico Prodigioso,” but full of horror as that of seductiveness. We see and hear as we read. Her own bad conscience projected in the fiend who mutters despair into her ear, and the awful peals of the “Dies Iræ,” that most terribly resonant of Latin hymns, as if blown from the very trump of doom itself, coming in at intervals to remind her that the

herself among the rest,—all of this would be weaker in narration. This is real, and needs realization by the senses to be fully felt. Compare it with Dimmesdale mounting the pillory at night, in “The Scarlet Letter,” to my thinking the deepest thrust of what may be called the metaphysical imagination26 since Shakespeare. There we need only a statement of the facts—pictorial statement, of course, as Hawthorne’s could not fail to be—and the effect is complete. Thoroughly to understand a good play and enjoy it, even in the reading, the imagination must body forth its personages, and see them doing or suffering in the visionary theatre of the brain. There, indeed, they are best seen, and Hamlet or Lear loses that ideal quality which makes him typical and universal if he be once compressed within the limits, or associated with the lineaments, of any, even the best, actor.

It is for their poetical qualities, for their gleams of imagination, for their quaint and subtle fancies, for their tender sentiment, and for their charm of diction that these old playwrights are worth reading. They are the best comment also to convince us of the immeasurable superiority of Shakespeare. Several of them, moreover, have been very inadequately edited, or not at all, which is perhaps better; and it is no useless discipline of the wits, no unworthy exercise of the mind, to do our own editing as we go along, winning back to its cradle the right word for the changeling the printers have left in his stead, making the lame verses find their feet again, and rescuing those that have been tumbled higgledy-piggledy into a mire of prose. A strenuous study of this kind will enable us better to understand many a faulty passage in our Shakespeare, and to judge of the proposed emendations of them, or to make one to our own liking. There is no better school for learning English, and for learning27 it when, in many important respects, it was at its best.

I am not sure that I shall not seem to talk to you of many things that seem trivialities if weighed in the huge business scales of life, but I am always glad to say a word in behalf of what most men consider useless, and to say it the rather because it has so few friends. I have observed, and am sorry to have observed, that English poetry, at least in its older examples, is less read now than when I was young. I do not believe this to be a healthy symptom, for poetry frequents and keeps habitable those upper chambers of the mind that open toward the sun’s rising.

28

I shall preface what I have to say of Marlowe with a few words as to the refinement which had been going on in the language, and the greater ductility which it had been rapidly gaining, and which fitted it for the use of the remarkable group of men who made an epoch of the reign of Elizabeth. Spenser was undoubtedly the poet to whom we owe most in this respect, and the very great contrast between his “Shepherd’s Calendar,” published in 1579, and his later poems awakens curiosity. In his earliest work there are glimpses, indeed, of those special qualities which have won for him the name of the poet’s poet, but they are rare and fugitive, and certainly never would have warranted the prediction of such poetry as was to follow. There is nothing here to indicate that a great artist in language had been born. Two causes, I suspect, were mainly effective in this transformation, I am almost tempted to say transubstantiation, of the man. The first was his practice in translation (true also of Marlowe), than which nothing gives a greater choice and mastery of one’s mother-tongue, for one must pause and weigh and judge every word with the greatest nicety, and cunningly transfuse idiom into idiom. The other, and by far the more important, was his29 study of the Italian poets. The “Faerie Queene” is full of loving reminiscence of them, but their happiest influence is felt in his lyrical poems. For these, I think, make it plain that Italy first taught him how much of the meaning of verse is in its music, and trained his ear to a sense of the harmony as well as the melody of which English verse was capable or might be made capable. Compare the sweetest passage in any lyric of the “Shepherd’s Calendar” with the eloquent ardor of the poorest, if any be poor, in the “Epithalamion,” and we find ourselves in a new world where music had just been invented. This we owe, beyond any doubt, to Spenser’s study of the Italian canzone. Nay, the whole metrical movement of the “Epithalamion” recalls that of Petrarca’s noble “Spirto gentil.” I repeat that melody and harmony were first naturalized in our language by Spenser. I love to recall these debts, for it is pleasant to be grateful even to the dead.

Other men had done their share towards what may be called the modernization of our English, and among these Sir Philip Sidney was conspicuous. He probably gave it greater ease of movement, and seems to have done for it very much what Dryden did a century later in establishing terms of easier intercourse between the language of literature and the language of cultivated society.

There had been good versifiers long before. Chaucer, for example, and even Gower, wearisome as he mainly is, made verses sometimes not only easy in movement, but in which the language seems30 strangely modern. That most dolefully dreary of books, “The Mirror for Magistrates,” and Sackville, more than any of its authors, did something towards restoring the dignity of verse, and helping it to recover its self-respect, while Spenser was still a youth. Tame as it is, the sunshine of that age here and there touches some verse that ripples in the sluggish current with a flicker of momentary illumination. But before Spenser, no English verse had ever soared and sung, or been filled with what Sidney calls “divine delightfulness.” Sidney, it may be conjectured, did more by private criticism and argument than by example. Drayton says of him:—

But even the affectations of Lilly were not without their use as helps to refinement. If, like Chaucer’s frere,—

it was through the desire

It was the general clownishness against which he revolted, and we owe him our thanks for it. To show of what brutalities even recent writers could be capable, it will suffice to mention that Golding, in his translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, makes a witch mutter the devil’s pater-noster, and Ulysses express his fears of going “to pot.” I should like31 to read you a familiar sonnet of Sidney’s for its sweetness:—

Here is ease and simplicity; but in such a phrase as “baiting-place of wit” there is also a want of that perfect discretion which we demand of the language of poetry, however we may be glad to miss it in the thought or emotion which that language conveys. Baiting-place is no more a homespun word than the word inn, which adds a charm to one of the sweetest verses that Spenser ever wrote; but baiting-place is common, it smacks of the hostler and postilion, and commonness is a very poor relation indeed of simplicity. But doubtless one main cause of the vivacity of phrase which so charms us in our earlier writers is to be found in the fact that there were not yet two languages—that of life and that of literature. The divorce between the two took place a century and a half later, and that process of breeding in and in began which at last reduced the language of verse to a kind of idiocy.

32

Do not consider such discussions as these otiose or nugatory. The language we are fortunate enough to share, and which, I think, Jacob Grimm was right in pronouncing, in its admirable mixture of Saxon and Latin, its strength and sonorousness, a better literary medium than any other modern tongue—this language has not been fashioned to what it is without much experiment, much failure, and infinite expenditure of pains and thought. Genius and pedantry have each done its part towards the result which seems so easy to us, and yet was so hard to win—the one by way of example, the other by way of warning. The purity, the elegance, the decorum, the chastity of our mother-tongue are a sacred trust in our hands. I am tired of hearing the foolish talk of an American variety of it, about our privilege to make it what we will because we are in a majority. A language belongs to those who know best how to use it, how to bring out all its resources, how to make it search its coffers round for the pithy or canorous phrase that suits the need, and they who can do this have been always in a pitiful minority. Let us be thankful that we too have a right to it, and have proved our right, but let us set up no claim to vulgarize it. The English of Abraham Lincoln was so good not because he learned it in Illinois, but because he learned it of Shakespeare and Milton and the Bible, the constant companions of his leisure. And how perfect it was in its homely dignity, its quiet strength, the unerring aim with which it struck once nor needed to strike more! The language is33 alive here, and will grow. Let us do all we can with it but debase it. Good taste may not be necessary to salvation or to success in life, but it is one of the most powerful factors of civilization. As a people we have a larger share of it and more widely distributed than I, at least, have found elsewhere, but as a nation we seem to lack it altogether. Our coinage is ruder than that of any country of equal pretensions, our paper money is filthily infectious, and the engraving on it, mechanically perfect as it is, makes of every bank-note a missionary of barbarism. This should make us cautious of trying our hand in the same fashion on the circulating medium of thought. But it is high time that I should remember Maître Guillaume of Patelin, and come back to my sheep.

In coming to speak of Marlowe, I cannot help fearing that I may fail a little in that equanimity which is the first condition of all helpful criticism. Generosity there should be, and enthusiasm there should be, but they should stop short of extravagance. Praise should not weaken into eulogy, nor blame fritter itself away into fault-finding. Goethe tells us that the first thing needful to the critic, as indeed it is to the wise man generally, is to see the thing as it really is; this is the most precious result of all culture, the surest warrant of happiness, or at least of composure. But he also bids us, in judging any work, seek first to discover its beauties, and then its blemishes or defects. Now there are two poets whom I feel that I can never judge without a favorable bias. One is Spenser,34 who was the first poet I ever read as a boy, not drawn to him by any enchantment of his matter or style, but simply because the first verse of his great poem was,—

and I followed gladly, wishful of adventure. Of course I understood nothing of the allegory, never suspected it, fortunately for me, and am surprised to think how much of the language I understood. At any rate, I grew fond of him, and whenever I see the little brown folio in which I read, my heart warms to it as to a friend of my childhood. With Marlowe it was otherwise. With him I grew acquainted during the most impressible and receptive period of my youth. He was the first man of genius I had ever really known, and he naturally bewitched me. What cared I that they said he was a deboshed fellow? nay, an atheist? To me he was the voice of one singing in the desert, of one who had found the water of life for which I was panting, and was at rest under the palms. How can he ever become to me as other poets are? But I shall try to be lenient in my admiration.

Christopher Marlowe, the son of a shoemaker, was born at Canterbury, in February, 1563, was matriculated at Benet College, Cambridge, in 1580, received his degree of bachelor there in 1583 and of master in 1587. He came early to London, and was already known as a dramatist before the end of his twenty-fourth year. There is some reason for thinking that he was at one time an actor. He was35 killed in a tavern brawl, by a man named Archer, in 1593, at the age of thirty. He was taxed with atheism, but on inadequate grounds, as it appears to me. That he was said to have written a tract against the Trinity, for which a license to print was refused on the ground of blasphemy, might easily have led to the greater charge. That he had some opinions of a kind unusual then may be inferred, perhaps, from a passage in his “Faust.” Faust asks Mephistopheles how, being damned, he is out of hell. And Mephistopheles answers, “Why, this is hell, nor am I out of it.” And a little farther on he explains himself thus:—

Milton remembered the first passage I have quoted, and puts nearly the same words into the mouth of his Lucifer. If Marlowe was a liberal thinker, it is not strange that in that intolerant age he should have incurred the stigma of general unbelief. Men are apt to blacken opinions which are distasteful to them, and along with them the character of him who holds them.

This at least may be said of him without risk of violating the rule of ne quid nímis, that he is one of the most masculine and fecundating natures in the long line of British poets. Perhaps his energy was even in excess. There is in him an Oriental36 lavishness. He will impoverish a province for a simile, and pour the revenues of a kingdom into the lap of a description. In that delightful story in the book of Esdras, King Darius, who has just dismissed all his captains and governors of cities and satraps, after a royal feast, sends couriers galloping after them to order them all back again, because he has found a riddle under his pillow, and wishes their aid in solving it. Marlowe in like manner calls in help from every the remotest corner of earth and heaven for what seems to us as trivial an occasion. I will not say that he is bombastic, but he constantly pushes grandiosity to the verge of bombast. His contemporaries thought he passed it in his “Tamburlaine.” His imagination flames and flares, consuming what it should caress, as Jupiter did Semele. That exquisite phrase of Hamlet, “the modesty of nature,” would never have occurred to him. Yet in the midst of the hurly-burly there will fall a sudden hush, and we come upon passages calm and pellucid as mountain tarns filled to the brim with the purest distillations of heaven. And, again, there are single verses that open silently as roses, and surprise us with that seemingly accidental perfection, which there is no use in talking about because itself says all that is to be said and more.

There is a passage in “Tamburlaine” which I remember reading in the first course of lectures I ever delivered, thirty-four years ago, as a poet’s feeling of the inadequacy of the word to the idea:—

Marlowe made snatches at this forbidden fruit with vigorous leaps, and not without bringing away a prize now and then such as only the fewest have been able to reach. Of fine single verses I give a few as instances of this:—

Here is a couplet notable for dignity of poise describing Tamburlaine:—

This from “Tamburlaine” is particularly characteristic:—

One of these verses reminds us of that exquisite one of Shakespeare where he says that Love is

But Shakespeare puts a complexity of meaning into his chance sayings, and lures the fancy to excursions of which Marlowe never dreamt.

But, alas, a voice will not illustrate like a stereopticon, and this tearing away of fragments that seem to bleed with the avulsion is like breaking off a finger from a statue as a specimen.

The impression he made upon the men of his time was uniform; it was that of something new and strange; it was that of genius, in short. Drayton says of him, kindling to an unwonted warmth, as if he loosened himself for a moment from the choking coils of his Polyolbion for a larger breath:—

And Chapman, taking up and continuing Marlowe’s half-told story of Hero and Leander, breaks forth suddenly into this enthusiasm of invocation:—

Surely Chapman would have sent his soul on no such errand had he believed that the soul of Marlowe was in torment, as his accusers did not scruple to say that it was, sent thither by the manifestly Divine judgment of his violent death.

Yes, Drayton was right in classing him with “the first poets,” for he was indeed such, and so continues,—that is, he was that most indefinable thing, an original man, and therefore as fresh and contemporaneous to-day as he was three hundred years ago. Most of us are more or less hampered by our own individuality, nor can shake ourselves free of that chrysalis of consciousness and give our “souls a loose,” as Dryden calls it in his vigorous way. And yet it seems to me that there is something even finer than that fine madness, and I think I see it in the imperturbable sanity of Shakespeare, which made him so much an artist that his new work still bettered his old. I think I see it even in the almost irritating calm of Goethe, which, if it did not quite make him an artist, enabled him to see what an artist should be, and to come as near to being one as his nature allowed. Marlowe was certainly not an artist in the larger sense, but he was cunning in words and periods and the musical modulation of them. And even this is a very rare gift. But his mind could never submit itself to a40 controlling purpose, and renounce all other things for the sake of that. His plays, with the single exception of “Edward II.,” have no organic unity, and such unity as is here is more apparent than real. Passages in them stir us deeply and thrill us to the marrow, but each play as a whole is ineffectual. Even his “Edward II.” is regular only to the eye by a more orderly arrangement of scenes and acts, and Marlowe evidently felt the drag of this restraint, for we miss the uncontrollable energy, the eruptive fire, and the feeling that he was happy in his work. Yet Lamb was hardly extravagant in saying that “the death scene of Marlowe’s king moves pity and terror beyond any scene, ancient or modern, with which I am acquainted.” His tragedy of “Dido, Queen of Carthage,” is also regularly plotted out, and is also somewhat tedious. Yet there are many touches that betray his burning hand. There is one passage illustrating that luxury of description into which Marlowe is always glad to escape from the business in hand. Dido tells Æneas:—

But far finer than this, in the same costly way, is the speech of Barabas in “The Jew of Malta,” ending with a line that has incorporated itself in the language with the familiarity of a proverb:—

This is the very poetry of avarice.

Let us now look a little more closely at Marlowe as a dramatist. Here also he has an importance less for what he accomplished than for what he suggested to others. Not only do I think that Shakespeare’s verse caught some hints from his,42 but there are certain descriptive passages and similes of the greater poet which, whenever I read them, instantly bring Marlowe to my mind. This is an impression I might find it hard to convey to another, or even to make definite to myself; but it is an old one, and constantly repeats itself, so that I put some confidence in it. Marlowe’s “Edward II.” certainly served Shakespeare as a model for his earlier historical plays. Of course he surpassed his model, but Marlowe might have said of him as Oderisi, with pathetic modesty, said to Dante of his rival and surpasser, Franco of Bologna, “The praise is now all his, yet mine in part.” But it is always thus. The path-finder is forgotten when the track is once blazed out. It was in Shakespeare’s “Richard II.” that Lamb detected the influence of Marlowe, saying that “the reluctant pangs of abdicating royalty in Edward furnished hints which Shakespeare has scarce improved upon in Richard.” In the parallel scenes of both plays the sentiment is rather elegiac than dramatic, but there is a deeper pathos, I think, in Richard, and his grief rises at times to a passion which is wholly wanting in Edward. Let me read Marlowe’s abdication scene. The irresolute nature of the king is finely indicated. The Bishop of Winchester has come to demand the crown; Edward takes it off, and says:—

Then, after a short further parley:—

Surely one might fancy that to be from the prentice hand of Shakespeare. It is no small distinction that this can be said of Marlowe, for it can be said of no other. What follows is still finer. The ruffian who is to murder Edward, in order to44 evade his distrust, pretends to weep. The king exclaims:—

This is even more in Shakespeare’s early manner than the other, and it is not ungrateful to our feeling of his immeasurable supremacy to think that even he had been helped in his schooling. There is a truly royal pathos in “They give me bread and water”; and “Tell Isabel the queen,” instead of “Isabel my queen,” is the most vividly dramatic touch that I remember anywhere in Marlowe. And that vision of the brilliant tournament, not more natural than it is artistic, how does it not deepen by contrast the gloom of all that went before! But you will observe that the verse is rather epic than dramatic. I mean by this that its every pause and every movement are regularly cadenced. There is a kingly composure in it, perhaps, but were the45 passage not so finely pathetic as it is, or the diction less naturally simple, it would seem stiff. Nothing is more peculiarly characteristic of the mature Shakespeare than the way in which his verses curve and wind themselves with the fluctuating emotion or passion of the speaker and echo his mood. Let me illustrate this by a speech of Imogen when Pisanio gives her a letter from her husband bidding her meet him at Milford-Haven. The words seem to waver to and fro, or huddle together before the hurrying thought, like sheep when the collie chases them.

The whole speech is breathless with haste, and is in keeping not only with the feeling of the moment, but with what we already know of the impulsive character of Imogen. Marlowe did not, for he could not, teach Shakespeare this secret, nor has anybody else ever learned it.

There are, properly speaking, no characters in46 the plays of Marlowe—but personages and interlocutors. We do not get to know them, but only to know what they do and say. The nearest approach to a character is Barabas, in “The Jew of Malta,” and he is but the incarnation of the popular hatred of the Jew. There is really nothing human in him. He seems a bugaboo rather than a man. Here is his own account of himself:—

Here is nothing left for sympathy. This is the mere lunacy of distempered imagination. It is47 shocking, and not terrible. Shakespeare makes no such mistake with Shylock. His passions are those of a man, though of a man depraved by oppression and contumely; and he shows sentiment, as when he says of the ring that Jessica had given for a monkey: “It was my turquoise. I had it of Leah when I was a bachelor.” And yet, observe the profound humor with which Shakespeare makes him think first of its dearness as a precious stone and then as a keepsake. In letting him exact his pound of flesh, he but follows the story as he found it in Giraldi Cinthio, and is careful to let us know that this Jew had good reason, or thought he had, to hate Christians. At the end, I think he meant us to pity Shylock, and we do pity him. And with what a smiling background of love and poetry does he give relief to the sombre figure of the Jew! In Marlowe’s play there is no respite. And yet it comes nearer to having a connected plot, in which one event draws on another, than any other of his plays. I do not think Milman right in saying that the interest falls off after the first two acts. I find enough to carry me on to the end, where the defiant death of Barabas in a caldron of boiling oil he had arranged for another victim does something to make a man of him. But there is no controlling reason in the piece. Nothing happens because it must, but because the author wills it so. The conception of life is purely arbitrary, and as far from nature as that of an imaginative child. It is curious, however, that here, too, Marlowe should have pointed the way to Shakespeare. But there is no48 resemblance between the Jew of Malta and the Jew of Venice, except that both have daughters whom they love. Nor is the analogy close even here. The love which Barabas professes for his child fails to humanize him to us, because it does not prevent him from making her the abhorrent instrument of his wanton malice in the death of her lover, and because we cannot believe him capable of loving anything but gold and vengeance. There is always something extravagant in the imagination of Marlowe, but here it is the extravagance of absurdity. Generally he gives us an impression of power, of vastness, though it be the vastness of chaos, where elemental forces hurtle blindly one against the other. But they are elemental forces, and not mere stage properties. Even Tamburlaine, if we see in him—as Marlowe, I think, meant that we should see—the embodiment of brute force, without reason and without conscience, ceases to be a blusterer, and becomes, indeed, as he asserts himself, the scourge of God. There is an exultation of strength in this play that seems to add a cubit to our stature. Marlowe had found the way that leads to style, and helped others to find it, but he never arrived there. He had not self-denial enough. He can refuse nothing to his fancy. He fails of his effect by over-emphasis, heaping upon a slender thought a burthen of expression too heavy for it to carry. But it is not with fagots, but with priceless Oriental stuffs, that he breaks their backs.

Marlowe’s “Dr. Faustus” interests us in another49 way. Here he again shows himself as a precursor. There is no attempt at profound philosophy in this play, and in the conduct of it Marlowe has followed the prose history of Dr. Faustus closely, even in its scenes of mere buffoonery. Disengaged from these, the figure of the protagonist is not without grandeur. It is not avarice or lust that tempts him at first, but power. Weary of his studies in law, medicine, and divinity, which have failed to bring him what he seeks, he turns to necromancy:—

His good angel intervenes, but the evil spirit at the other ear tempts him with power again:—

Ere long Faustus begins to think of power for baser uses:—

And yet it is always to the pleasures of the intellect that he returns. It is when the good and evil spirits come to him for the second time that wealth is offered as a bait, and after Faustus has signed away his soul to Lucifer, he is tempted even by more sensual allurements. I may be reading into the book what is not there, but I cannot help thinking that Marlowe intended in this to typify the inevitably continuous degradation of a soul that has renounced its ideal, and the drawing on of one vice by another, for they go hand in hand like the Hours. But even in his degradation the pleasures of Faustus are mainly of the mind, or at worst of a sensuous and not sensual kind. No doubt in this Marlowe is unwittingly betraying his own tastes. Faustus is made to say:—

This employment of the devil in a duet seems odd. I remember no other instance of his appearing as a musician except in Burns’s “Tam o’ Shanter.” The last wish of Faustus was Helen of Troy. Mephistophilis fetches her, and Faustus exclaims:

51

No such verses had ever been heard on the English stage before, and this was one of the great debts our language owes to Marlowe. He first taught it what passion and fire were in its veins. The last scene of the play, in which the bond with Lucifer becomes payable, is nobly conceived. Here the verse rises to the true dramatic sympathy of which I spoke. It is swept into the vortex of Faust’s eddying thought, and seems to writhe and gasp in that agony of hopeless despair:—

It remains to say a few words of Marlowe’s poem of “Hero and Leander,” for in translating it from Musæus he made it his own. It has great ease and fluency of versification, and many lines as perfect in their concinnity as those of Pope, but infused with a warmer coloring and a more poetic fancy. Here is found the verse that Shakespeare quotes53 somewhere. The second verse of the following couplet has precisely Pope’s cadence:—

It was from this poem that Keats caught the inspiration for his “Endymion.” A single passage will serve to prove this:—

Milton, too, learned from Marlowe the charm of those long sequences of musical proper names of which he made such effective use. Here are two passages which Milton surely had read and pondered:—

This is still more Miltonic:—

54

Spenser, too, loved this luxury of sound, as he shows in such passages as this:—

And I fancy he would have put him there to make music, even had it been astronomically impossible, but he never strung such names in long necklaces, as Marlowe and Milton were fond of doing.

Was Marlowe, then, a great poet? For such a title he had hardly range enough of power, hardly reach enough of thought. But surely he had some of the finest qualities that go to the making of a great poet; and his poetic instinct, when he had time to give himself wholly over to its guidance, was unerring. I say when he had time enough, for he, too, like his fellows, was forced to make the daily task bring in the daily bread. We have seen how fruitful his influence has been, and perhaps his genius could have no surer warrant than that the charm of it lingered in the memory of poets, for theirs is the memory of mankind. If we allow him genius, what need to ask for more? And perhaps it would be only to him among the group of dramatists who surrounded Shakespeare that we should allow it. He was the herald that dropped dead in announcing the victory in whose fruits he was not to share.

55

In my first lecture I spoke briefly of the deficiency in respect of Form which characterizes nearly all the dramatic literature of which we are taking a summary survey, till the example of Shakespeare and the precepts of Ben Jonson wrought their natural effect. Teleology, or the argument from means to end, the argument of adaptation, is not so much in fashion in some spheres of thought and speculation as it once was, but here it applies admirably. We have a piece of work, and we know the maker of it. The next question that we ask ourselves is the very natural one—how far it shows marks of intelligent design. In a play we not only expect a succession of scenes, but that each scene should lead, by a logic more or less stringent, if not to the next, at any rate to something that is to follow, and that all should contribute their fraction of impulse towards the inevitable catastrophe. That is to say, the structure should be organic, with a necessary and harmonious connection and relation of parts, and not merely mechanical, with an arbitrary or haphazard joining of one part to another. It is in the former sense alone that any production can be called a work of art.

And when we apply the word Form in this sense to some creation of the mind, we imply that there56 is a life, or, what is still better, a soul in it. That there is an intimate relation, or, at any rate, a close analogy, between Form in this its highest attribute and Imagination, is evident if we remember that the Imagination is the shaping faculty. This is, indeed, its preëminent function, to which all others are subsidiary. Shakespeare, with his usual depth of insight and the precision that comes of it, tells us that “imagination bodies forth the forms of things unknown.” In his maturer creations there is generally some central thought about which the action revolves like a moon, carried along with it in its appointed orbit, and permitted the gambol of a Ptolemaic epicycle now and then. But the word Form has also more limited applications, as, for example, when we use it to imply that nice sense of proportion and adaptation which results in Style. We may apply it even to the structure of a verse, or of a short poem in which every advantage has been taken of the material employed, as in Keats’s “Ode to a Grecian Urn,” which seems as perfect in its outline as the thing it so lovingly celebrates. In all these cases there often seems also to be something intuitive or instinctive in the working of certain faculties of the poet, and to this we unconsciously testify when we call it genius. But in the technic of this art, perfection can be reached only by long training, as was evident in the case of Coleridge. Of course, without the genius all the training in the world will produce only a mechanical and lifeless result; but even if the genius is there, there is nothing too seemingly trifling to deserve57 its study. The “Elegy in a Country Church-yard” owes much of the charm that makes it precious, even with those who perhaps undervalue its sentiment, to Gray’s exquisite sense of the value of vowel sounds.

Let us, however, come down to what is within the reach and under the control of talent and of a natural or acquired dexterity. And such a thing is the plot or arrangement of a play. In this part of their business our older playwrights are especially unskilled or negligent. They seem perfectly content if they have a story which they can divide at proper intervals by acts and scenes, and bring at last to a satisfactory end by marriage or murder, as the case may be. A certain variety of characters is necessary, but the motives that compel and control them are almost never sufficiently apparent. And this is especially true of the dramatic motives, as distinguished from the moral. The personages are brought in to do certain things and perform certain purposes of the author, but too often there seems to be no special reason why one of them should do this or that more than another. They are servants of all work, ready to be villains or fools at a moment’s notice if required. The obliging simplicity with which they walk into traps which everybody can see but themselves, is sometimes almost delightful in its absurdity. Ben Jonson was perfectly familiar with the traditional principles of construction. He tells us that the fable of a drama (by which he means the plot or action) should have a beginning, a middle, and an end;58 and that “as a body without proportion cannot be goodly, no more can the action, either in comedy or tragedy, without his fit bounds.” But he goes on to say “that as every bound, for the nature of the subject, is esteemed the best that is largest, till it can increase no more; so it behoves the action in tragedy or comedy to be let grow till the necessity ask a conclusion; wherein two things are to be considered—first, that it exceed not the compass of one day; next, that there be place left for digression and art.” The weakness of our earlier playwrights is that they esteemed those bounds best that were largest, and let their action grow till they had to stop it.

Many of Shakespeare’s contemporary poets must have had every advantage that he had in practical experience of the stage, and all of them had probably as familiar an intercourse with the theatre as he. But what a difference between their manner of constructing a play and his! In all his dramatic works his skill in this is more or less apparent. In the best of them it is unrivalled. From the first scene of them he seems to have beheld as from a tower the end of all. In “Romeo and Juliet,” for example, he had his story before him, and he follows it closely enough; but how naturally one scene is linked to the next, and one event leads to another! If this play were meant to illustrate anything, it would seem to be that our lives were ruled by chance. Yet there is nothing left to chance in the action of the play, which advances with the unvacillating foot of destiny. And the characters are59 made to subordinate themselves to the interests of the play as to something in which they have all a common concern. With the greater part of the secondary dramatists, the characters seem like unpractised people trying to walk the deck of a ship in rough weather, who start for everywhere to bring up anywhere, and are hustled against each other in the most inconvenient way. It is only when the plot is very simple and straightforward that there is any chance of smooth water and of things going on without falling foul of each other. Was it only that Shakespeare, in choosing his themes, had a keener perception of the dramatic possibilities of a story? This is very likely, and it is certain that he preferred to take a story ready to his hand rather than invent one. All the good stories, indeed, seem to have invented themselves in the most obliging manner somewhere in the morning of the world, and to have been camp-followers when the famous march of mind set out from the farthest East. But where he invented his plot, as in the “Midsummer Night’s Dream” and the “Tempest,” he is careful to have it as little complicated with needless incident as possible.

These thoughts were suggested to me by the gratuitous miscellaneousness of plot (if I may so call it) in some of the plays of John Webster, concerning whose works I am to say something this evening, a complication made still more puzzling by the motiveless conduct of many of the characters. When he invented a plot of his own, as in his comedy of “The Devil’s Law Case,” the improbabilities60 become insuperable, by which I mean that they are such as not merely the understanding but the imagination cannot get over. For mere common-sense has little to do with the affair. Shakespeare cared little for anachronisms, or whether there were seaports in Bohemia or not, any more than Calderon cared that gunpowder had not been invented centuries before the Christian era when he wanted an arquebus to be fired, because the noise of a shot would do for him what a silent arrow would not do. But, if possible, the understanding should have as few difficulties put in its way as possible. Shakespeare is careful to place his Ariel in the not yet wholly disenchanted Bermudas, near which Sir John Hawkins had seen a mermaid not many years before, and lays the scene for his Oberon and Titania in the dim remoteness of legendary Athens, though his clowns are unmistakably English, and though he knew as well as we do that Puck was a British goblin. In estimating material improbability as distinguished from moral, however, we should give our old dramatists the benefit of the fact that all the world was a great deal farther away in those days than in ours, when the electric telegraph puts our button into the grip of whatever commonplace our planet is capable of producing.

Moreover, in respect of Webster as of his fellows, we must, in order to understand them, first naturalize our minds in their world. Chapman makes Byron say to Queen Elizabeth:—

61

And this is apt to be the only view we take of that Golden Age, as we call it fairly enough in one, and that, perhaps, the most superficial, sense. But it was in many ways rude and savage, an age of great crimes and of the ever-brooding suspicion of great crimes. Queen Elizabeth herself was the daughter of a king as savagely cruel and irresponsible as the Grand Turk. It was an age that in Italy could breed a Cenci, and in France could tolerate the massacre of St. Bartholomew as a legitimate stroke of statecraft. But when we consider whether crime be a fit subject for tragedy, we must distinguish. Merely as crime, it is vulgar, as are the waxen images of murderers with the very rope round their necks with which they were hanged. Crime becomes then really tragic when it merely furnishes the theme for a profound psychological study of motive and character. The weakness of Webster’s two greatest plays lies in this—that crime is presented as a spectacle, and not as a means of looking into our own hearts and fathoming our own consciousness.

The scene of “The Devil’s Law Case” is Naples, then a viceroyalty of Spain, and our ancestors thought anything possible in Italy. Leonora, a62 widow, has a son and daughter, Romelio and Jolenta. Romelio is a rich and prosperous merchant. Jolenta is secretly betrothed to Contarino, an apparently rather spendthrift young nobleman, who has already borrowed large sums of money of Romelio on the security of his estates. Romelio is bitterly opposed to his marrying Jolenta, for reasons known only to himself; at least, no reason appears for it, except that the play could not have gone on without it. The reason he assigns is that he has a grudge against the nobility, though it appears afterwards that he himself is of noble birth, and asserts his equality with them. When Contarino, at the opening of the play, comes to urge his suit, and asks him how he looks upon it, Romelio answers:—

And of this Contarino was sure, the irony of Romelio’s speech having been so delicately conveyed that he was unable to perceive it.

A little earlier in this scene a speech is put into63 the mouth of Romelio so characteristic of Webster’s more sententious style that I will repeat it:—

This recalls to mind the speech of Ulysses to Achilles in “Troilus and Cressida,” a piece of eloquence which, for the impetuous charge of serried argument and poetic beauty of illustration, grows more marvellous with every reading. But it is hardly fair to any other poet to let him remind us of Shakespeare.

Contarino, on leaving Romelio, goes to Leonora, the mother, who immediately conceives a violent passion for him. He, by way of a pretty compliment, tells her that he has a suit to her, and that it is for her picture. By this he meant her daughter, but with the flattering implication that you would not know the parent from the child. Leonora, of course, takes him literally, is gracious accordingly, and Contarino is satisfied that he has won her consent also. This scene gives occasion for a good example of Webster’s more playful style, which is perhaps worth quoting. Still apropos of her portrait, Leonora says:—

64