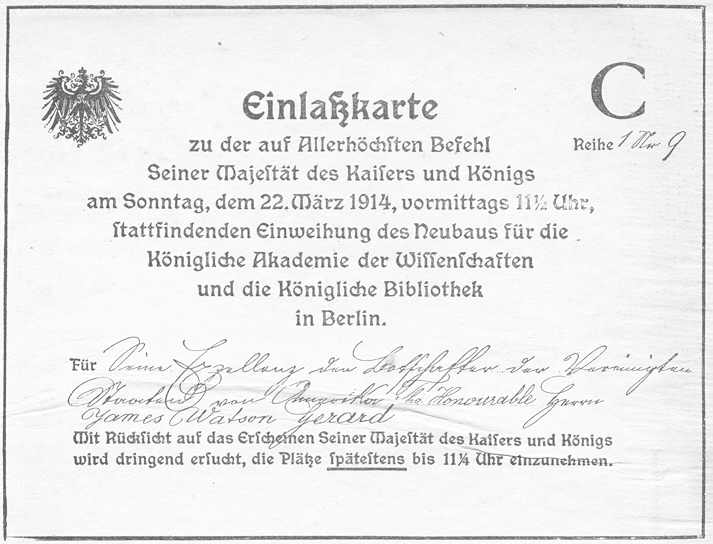

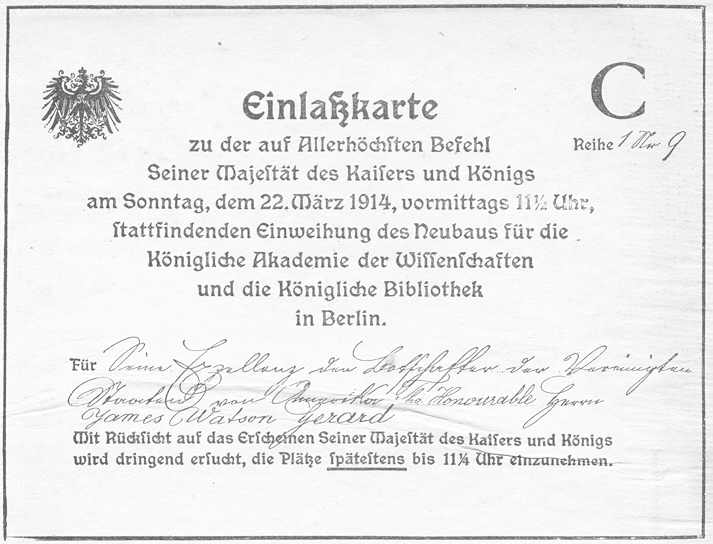

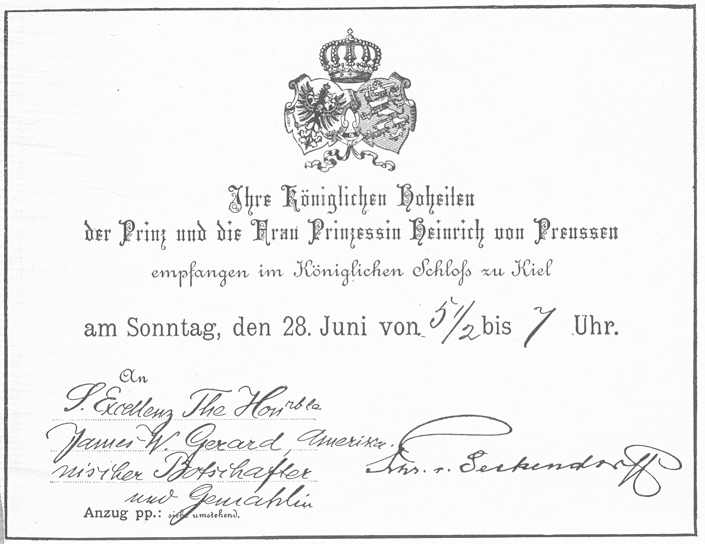

AN INVITATION TO ATTEND THE OPENING OF THE ROYAL ACADEMY.

Title: My Four Years in Germany

Author: James W. Gerard

Release date: January 1, 2005 [eBook #7238]

Most recently updated: May 10, 2022

Language: English

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/7238

Credits: Robert J. Hall

TO MY SMALL BUT TACTFUL FAMILY OF ONE

MY WIFE

I am writing what should have been the last chapter of this book as a foreword because I want to bring home to our people the gravity of the situation; because I want to tell them that the military and naval power of the German Empire is unbroken; that of the twelve million men whom the Kaiser has called to the colours but one million, five hundred thousand have been killed, five hundred thousand permanently disabled, not more than five hundred thousand are prisoners of war, and about five hundred thousand constitute the number of wounded or those on the sick list of each day, leaving at all times about nine million effectives under arms.

I state these figures because Americans do not grasp either the magnitude or the importance of this war. Perhaps the statement that over five million prisoners of war are held in the various countries will bring home to Americans the enormous mass of men engaged.

There have been no great losses in the German navy, and any losses of ships have been compensated for by the building of new ones. The nine million men, and more, for at least four hundred thousand come of military age in Germany every year, because of their experience in two and a half years of war are better and more efficient soldiers than at the time when they were called to the colours. Their officers know far more of the science of this war and the men themselves now have the skill and bearing of veterans.

Nor should anyone believe that Germany will break under starvation or make peace because of revolution.

The German nation is not one which makes revolutions. There will be scattered riots in Germany, but no simultaneous rising of the whole people. The officers of the army are all of one class, and of a class devoted to the ideals of autocracy. A revolution of the army is impossible; and at home there are only the boys and old men easily kept in subjection by the police.

There is far greater danger of the starvation of our Allies than of the starvation of the Germans. Every available inch of ground in Germany is cultivated, and cultivated by the aid of the old men, the boys and the women, and the two million prisoners of war.

The arable lands of Northern France and of Roumania are being cultivated by the German army with an efficiency never before known in these countries, and most of that food will be added to the food supplies of Germany. Certainly the people suffer; but still more certainly this war will not be ended because of the starvation of Germany.

Although thinking Germans know that if they do not win the war the financial day of reckoning will come, nevertheless, owing to the clever financial handling of the country by the government and the great banks, there is at present no financial distress in Germany; and the knowledge that, unless indemnities are obtained from other countries, the weight of the great war debt will fall upon the people, perhaps makes them readier to risk all in a final attempt to win the war and impose indemnities upon not only the nations of Europe but also upon the United States of America.

We are engaged in a war against the greatest military power the world has ever seen; against a people whose country was for so many centuries a theatre of devastating wars that fear is bred in the very marrow of their souls, making them ready to submit their lives and fortunes to an autocracy which for centuries has ground their faces, but which has promised them, as a result of the war, not only security but riches untold and the dominion of the world; a people which, as from a high mountain, has looked upon the cities of the world and the glories of them, and has been promised these cities and these glories by the devils of autocracy and of war.

We are warring against a nation whose poets and professors, whose pedagogues and whose parsons have united in stirring its people to a white pitch of hatred, first against Russia, then against England and now against America.

The U-Boat peril is a very real one for England. Russia may either break up into civil wars or become so ineffective that the millions of German troops engaged on the Russian front may be withdrawn and hurled against the Western lines. We stand in great peril, and only the exercise of ruthless realism can win this war for us. If Germany wins this war it means the triumph of the autocratic system. It means the triumph of those who believe not only in war as a national industry, not only in war for itself but also in war as a high and noble occupation. Unless Germany is beaten the whole world will be compelled to turn itself into an armed camp, until the German autocracy either brings every nation under its dominion or is forever wiped out as a form of government.

We are in this war because we were forced into it: because Germany not only murdered our citizens on the high seas, but also filled our country with spies and sought to incite our people to civil war. We were given no opportunity to discuss or negotiate. The forty-eight hour ultimatum given by Austria to Serbia was not, as Bernard Shaw said, "A decent time in which to ask a man to pay his hotel bill." What of the six-hour ultimatum given to me in Berlin on the evening of January thirty-first, 1917, when I was notified at six that ruthless warfare would commence at twelve? Why the German government, which up to that moment had professed amity and a desire to stand by the Sussex pledges, knew that it took almost two days to send a cable to America! I believe that we are not only justly in this war, but prudently in this war. If we had stayed out and the war had been drawn or won by Germany we should have been attacked, and that while Europe stood grinning by: not directly at first, but through an attack on some Central or South American State to which it would be at least as difficult for us to send troops as for Germany. And what if this powerful nation, vowed to war, were once firmly established in South or Central America? What of our boasted isolation then?

It is only because I believe that our people should be informed that I have consented to write this book. There are too many thinkers, writers and speakers in the United States; from now on we need the doers, the organisers, and the realists who alone can win this contest for us, for democracy and for permanent peace!

Writing of events so new, I am, of course, compelled to exercise a great discretion, to keep silent on many things of which I would speak, to suspend many judgments and to hold for future disclosure many things, the relation of which now would perhaps only serve to increase bitterness or to cause internal dissension in our own land.

The American who travels through Germany in summer time or who spends a month having his liver tickled at Homburg or Carlsbad, who has his digestion restored by Dr. Dapper at Kissingen or who relearns the lost art of eating meat at Dr. Dengler's in Baden, learns little of the real Germany and its rulers; and in this book I tell something of the real Germany, not only that my readers may understand the events of the last three years but also that they may judge of what is likely to happen in our future relations with that country.

| FOREWORD. | |

| I | MY FIRST YEAR IN GERMANY. |

| II | POLITICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL. |

| III | DIPLOMATIC WORK OF FIRST WINTER IN BERLIN. |

| IV | MILITARISM IN GERMANY AND THE ZABERN AFFAIR. |

| V | PSYCHOLOGY AND CAUSES WHICH PREPARED THE NATION FOR WAR. |

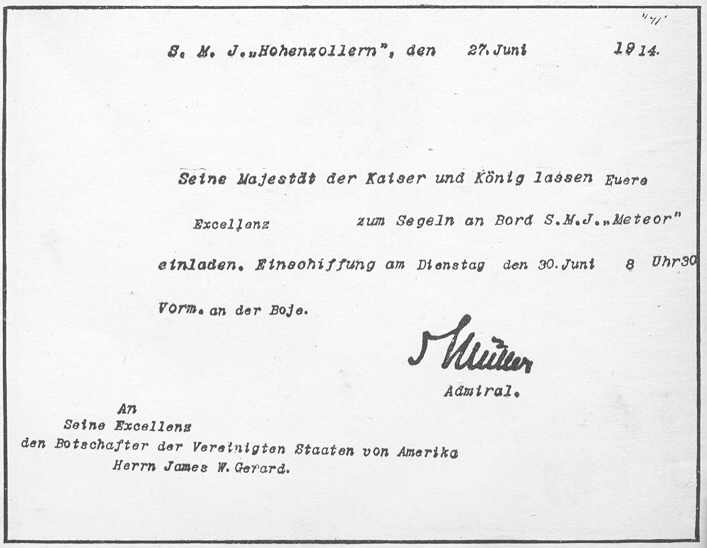

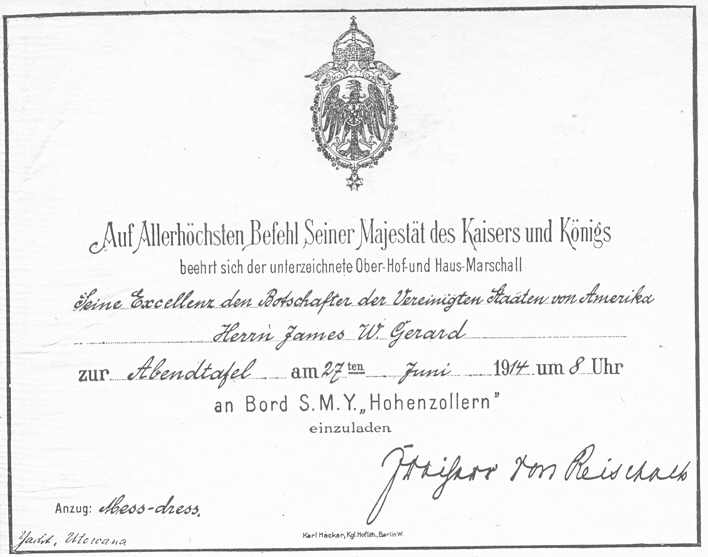

| VI | AT KIEL JUST BEFORE THE WAR. |

| VII | THE SYSTEM. |

| VIII | THE DAYS BEFORE THE WAR. |

| IX | THE AMERICANS AT THE OUTBREAK OF HOSTILITIES. |

| X | PRISONERS OF WAR. |

| XI | FIRST DAYS OF THE WAR: POLITICAL AND DIPLOMATIC. |

| XII | DIPLOMATIC NEGOTIATIONS. |

| XIII | MAINLY COMMERCIAL. |

| XIV | WORK FOR THE GERMANS. |

| XV | WAR CHARITIES. |

| XVI | HATE. |

| XVII | DIPLOMATIC NEGOTIATIONS. (Continued). |

| XVIII | LIBERALS AND REASONABLE MEN. |

| XIX | THE GERMAN PEOPLE IN WAR. |

| XX | LAST. |

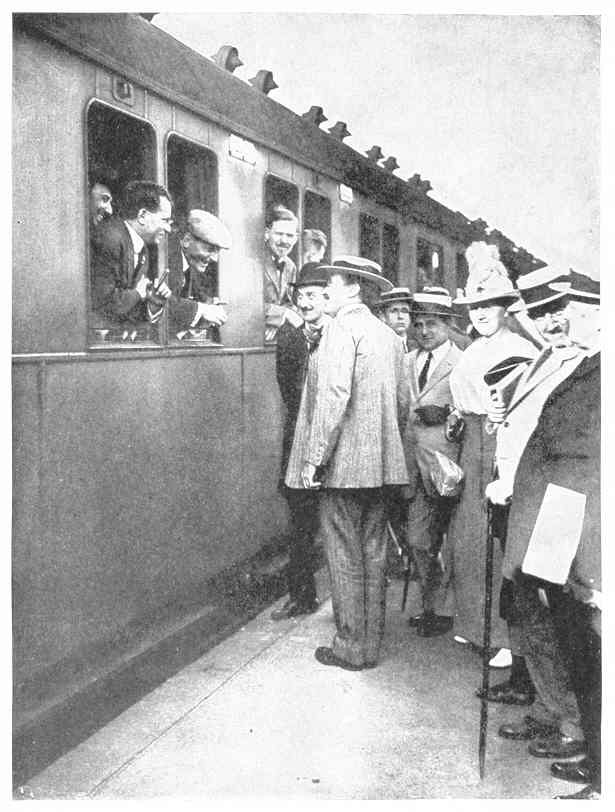

| AMBASSADOR GERARD SAYING GOOD-BYE TO THE AMERICANS LEAVING ON A SPECIAL TRAIN, AUGUST, 1914. |

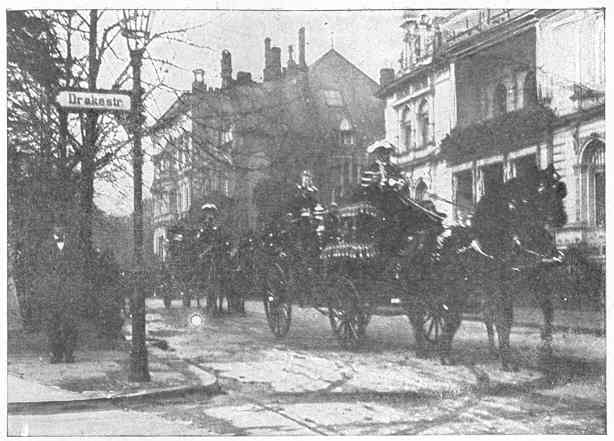

| AMBASSADOR GERARD ON HIS WAY TO PRESENT HIS LETTERS OF CREDENCE TO THE EMPEROR. |

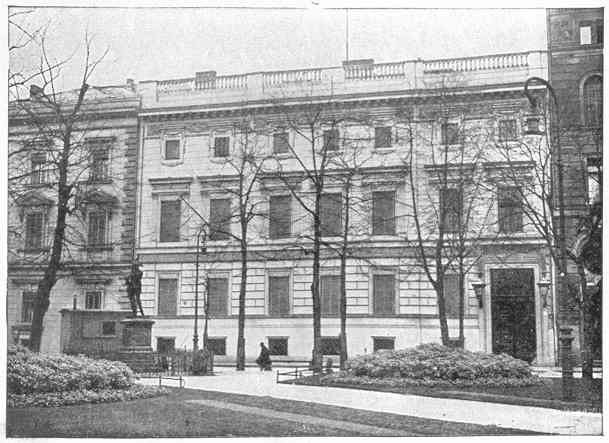

| THE HOUSE RENTED FOR USE AS EMBASSY. |

| A SALON IN THE EMBASSY. |

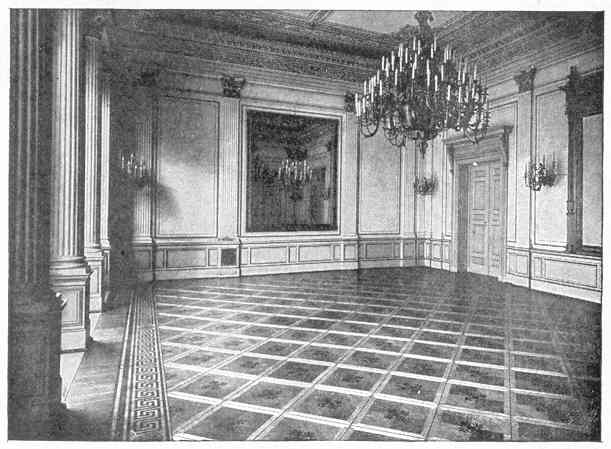

| THE BALL-ROOM OF THE EMBASSY. |

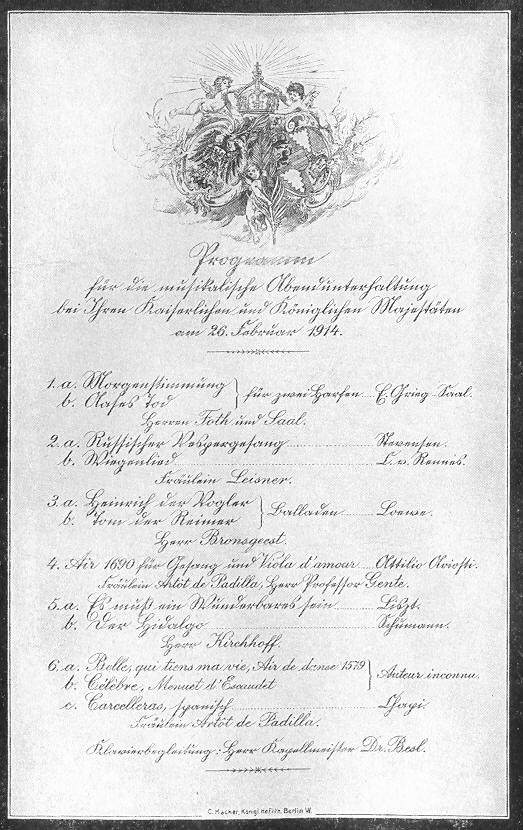

| PROGRAMME OF THE MUSIC AFTER DINNER AT THE ROYAL PALACE. |

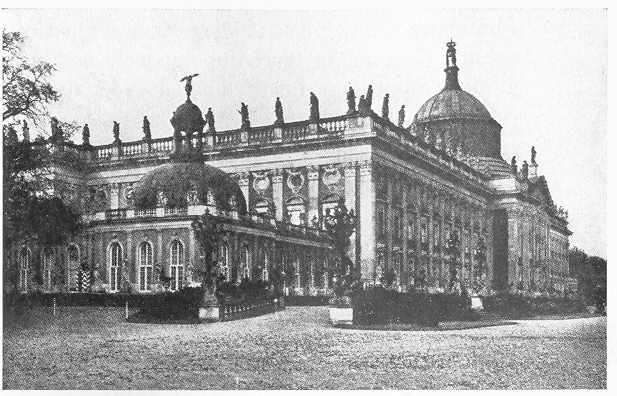

| THE ROYAL PALACE AT POTSDAM. |

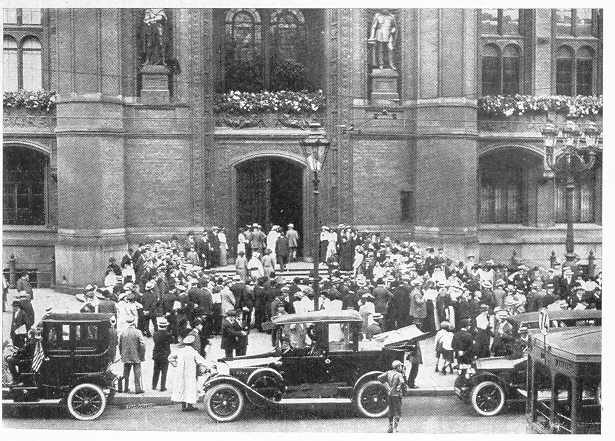

| DEMONSTRATION OF SYMPATHY FOR THE AMERICANS AT THE TOWN HALL, AUGUST, 1914. |

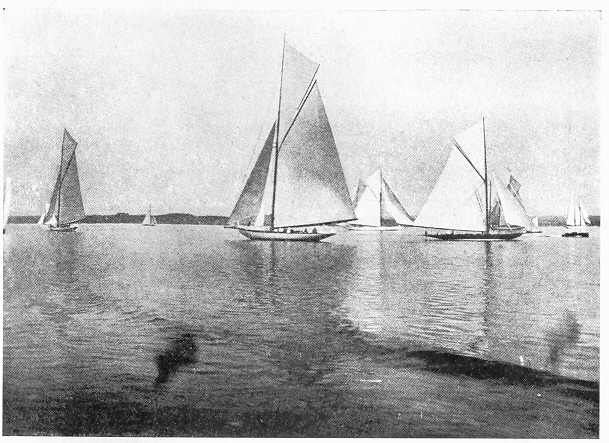

| RACING YACHTS AT KIEL. |

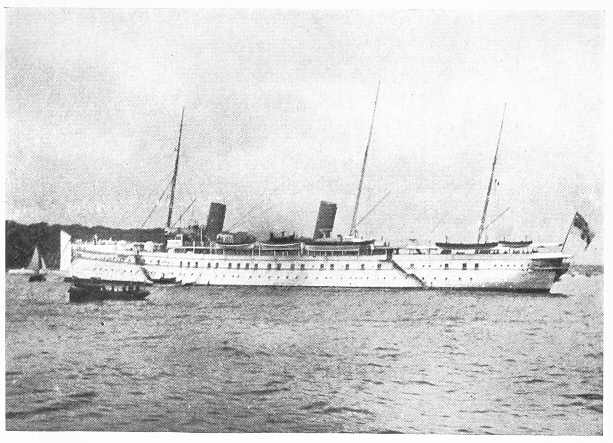

| THE KAISER'S YACHT, "HOHENZOLLERN". |

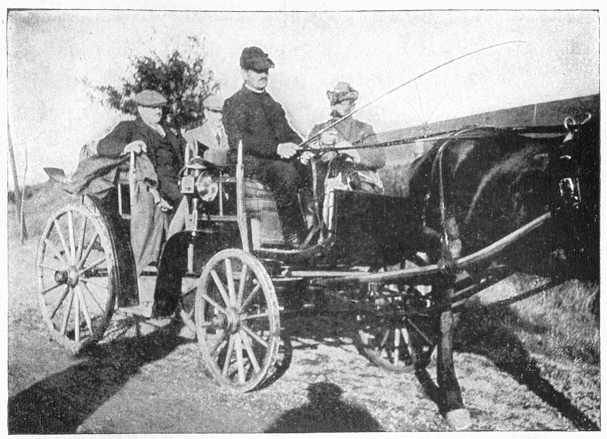

| AMBASSADOR GERARD ON HIS WAY TO HIS SHOOTING PRESERVE. |

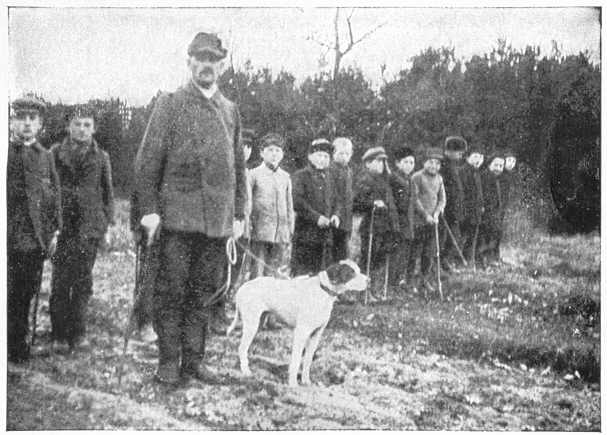

| A KEEPER AND BEATERS ON THE SHOOTING PRESERVE. |

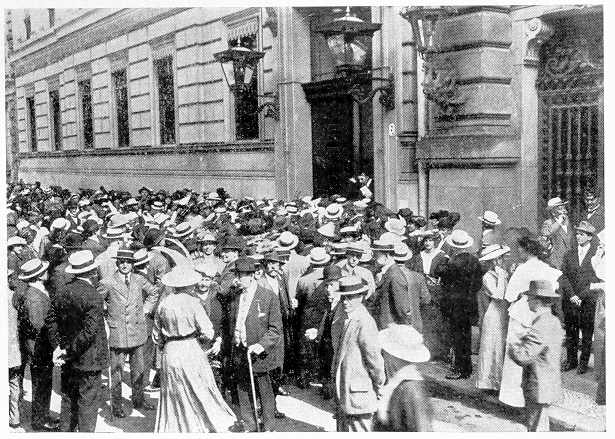

| CROWDS IN FRONT OF THE EMBASSY, AUGUST, 1914. |

| OUTSIDE THE EMBASSY IN THE EARLY DAYS OF THE WAR. |

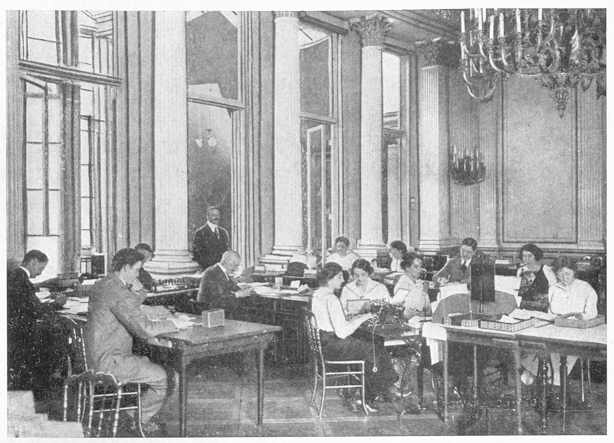

| AT WORK IN THE EMBASSY BALL-ROOM, AUGUST, 1914. |

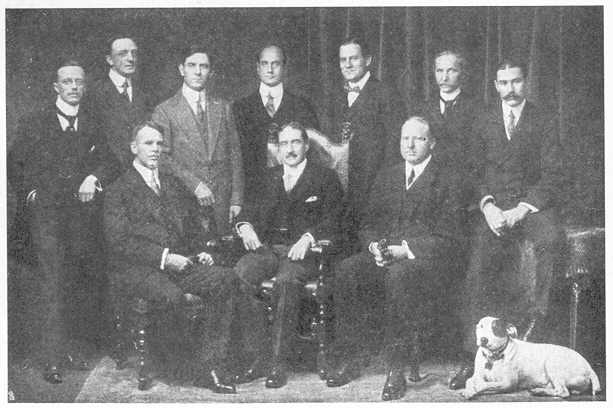

| AMBASSADOR GERARD AND HIS STAFF. |

| COVER OF THE RUHLEBEN MONTHLY. |

| SPECIMEN PAGE OF DRAWINGS FROM THE RUHLEBEN MONTHLY. |

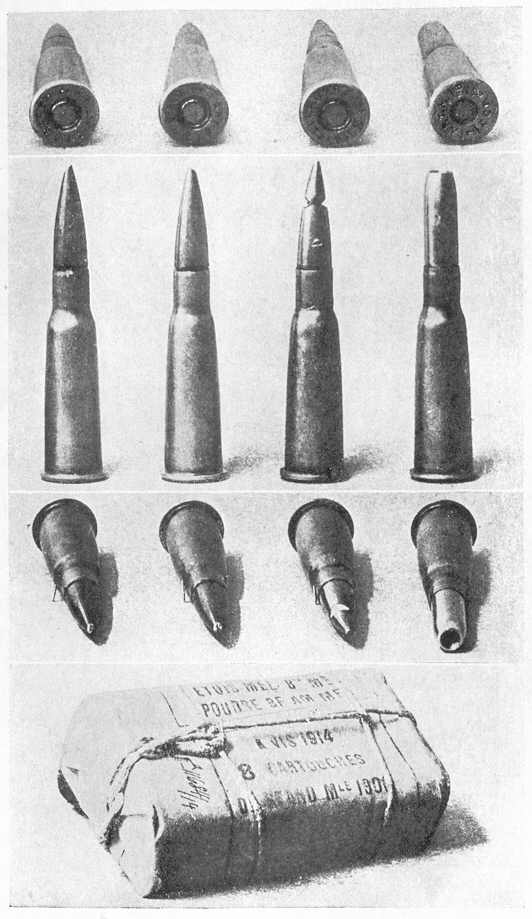

| ALLEGED DUM-DUM BULLETS. |

| THE "LUSITANIA" MEDAL. |

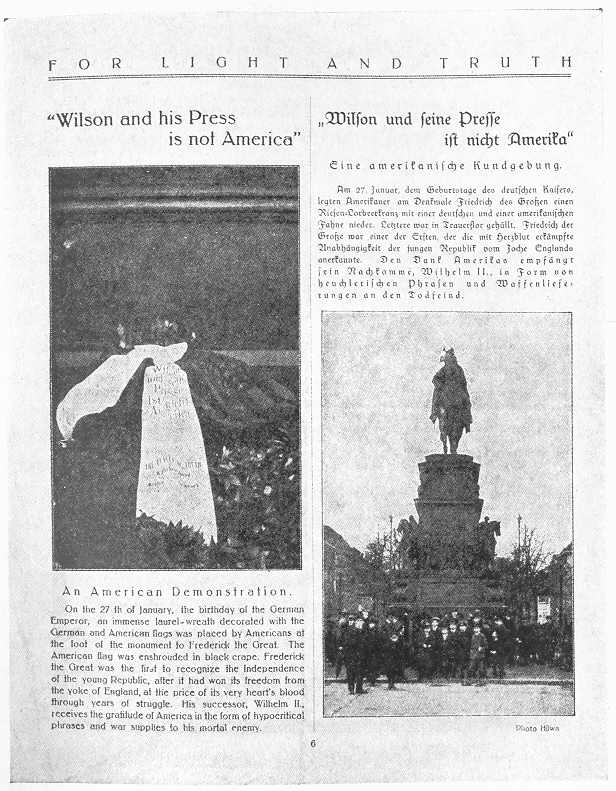

| PAGE FROM "FOR LIGHT AND TRUTH". |

| AMBASSADOR GERARD AND PARTY IN SEDAN. |

| IN FRONT OF THE COTTAGE AT BAZEILLES. |

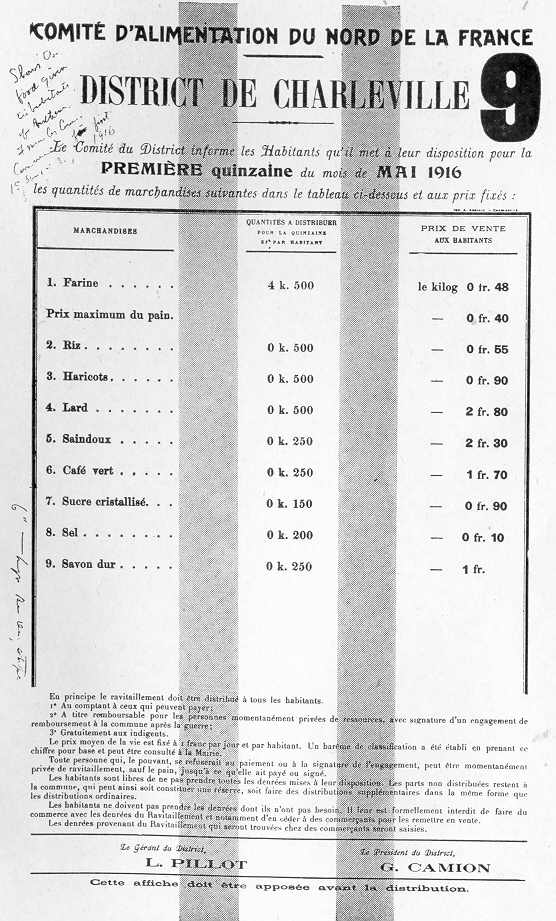

| FOOD ALLOTMENT POSTER FROM THE CHARLEVILLE DISTRICT. |

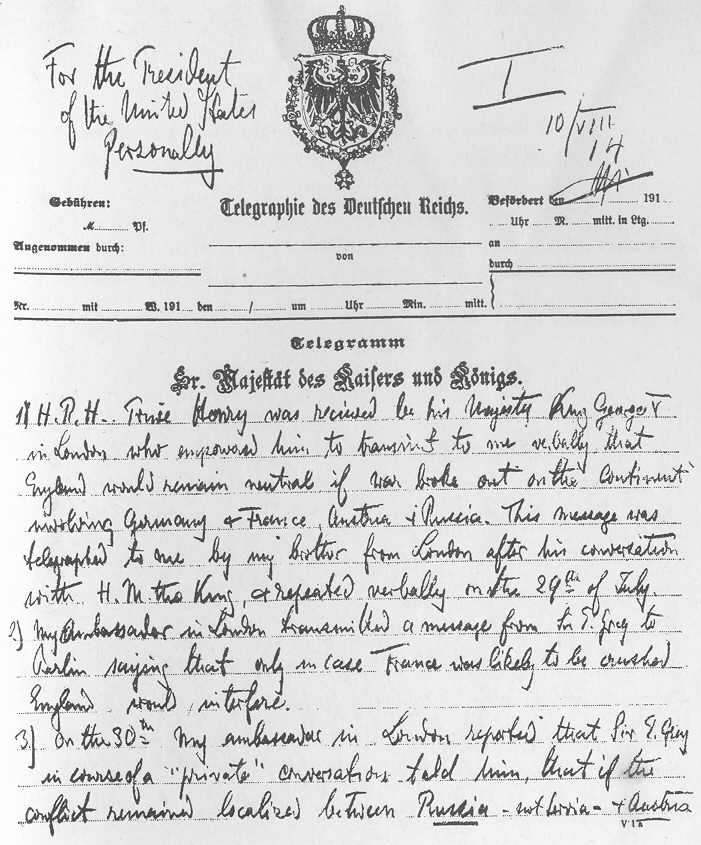

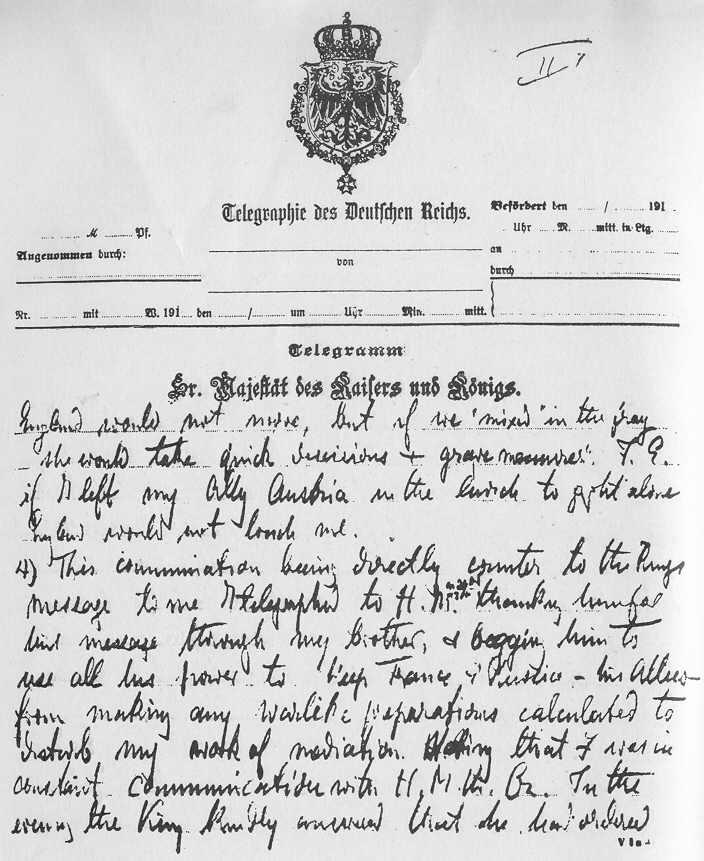

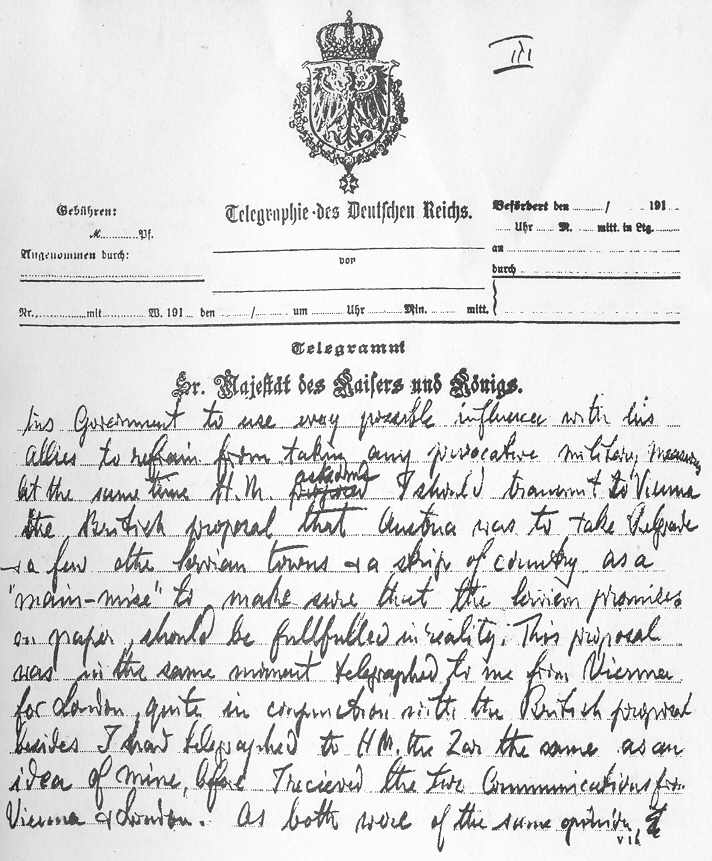

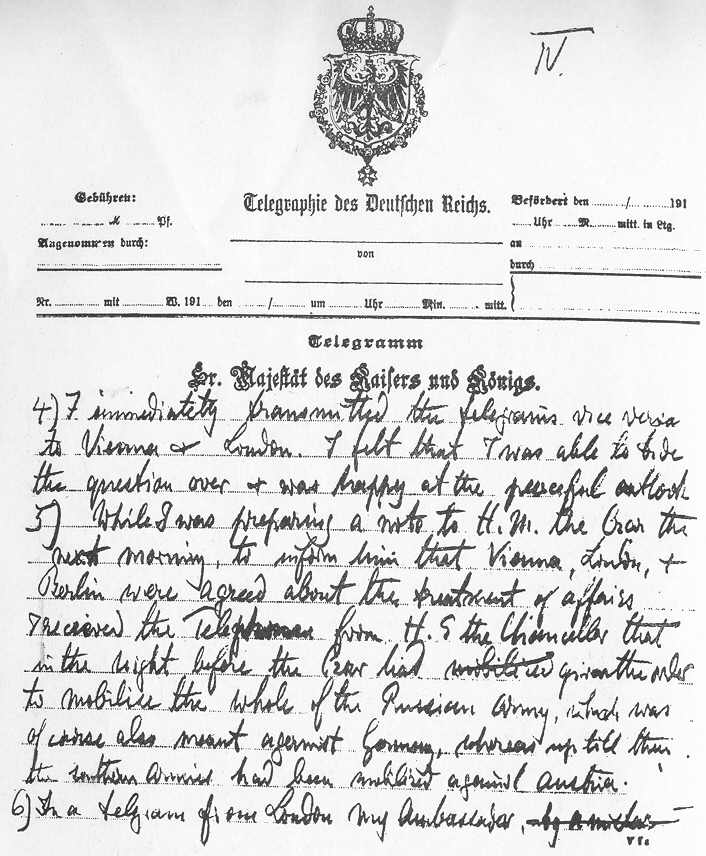

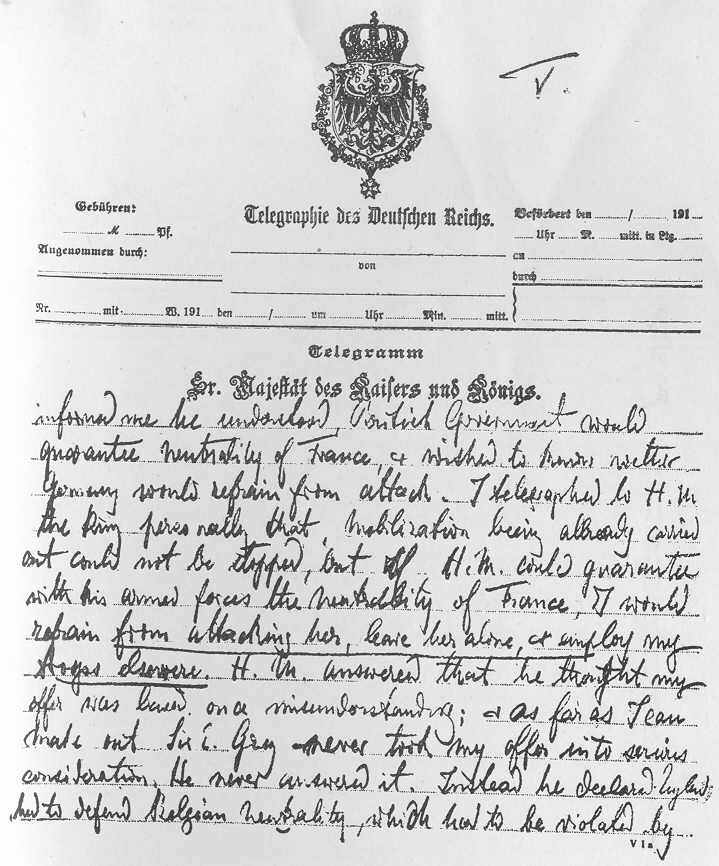

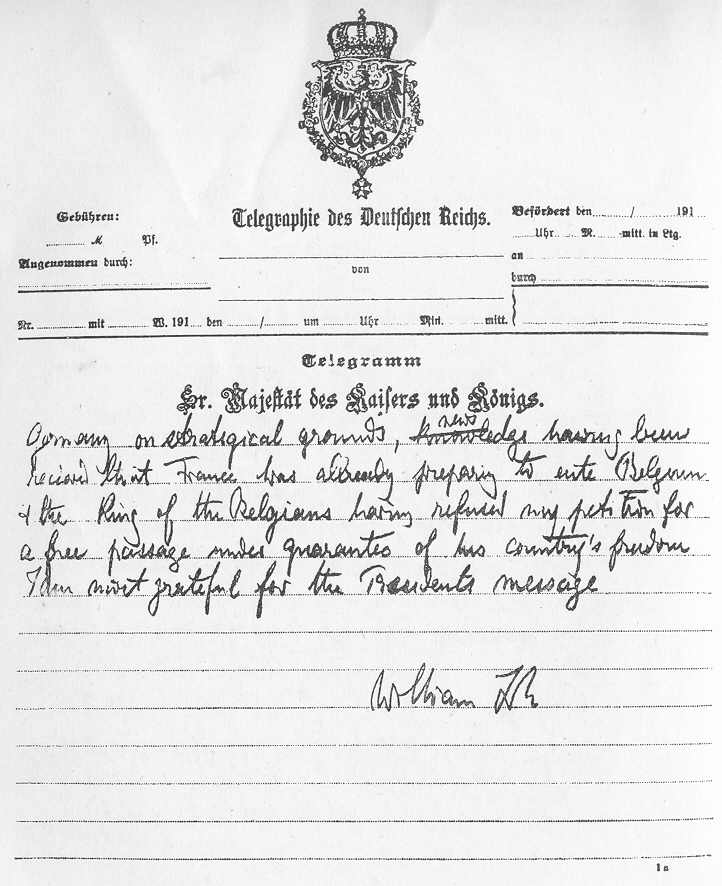

| FAC-SIMILE REPRODUCTION OF THE KAISER'S PERSONAL TELEGRAM TO PRESIDENT WILSON. |

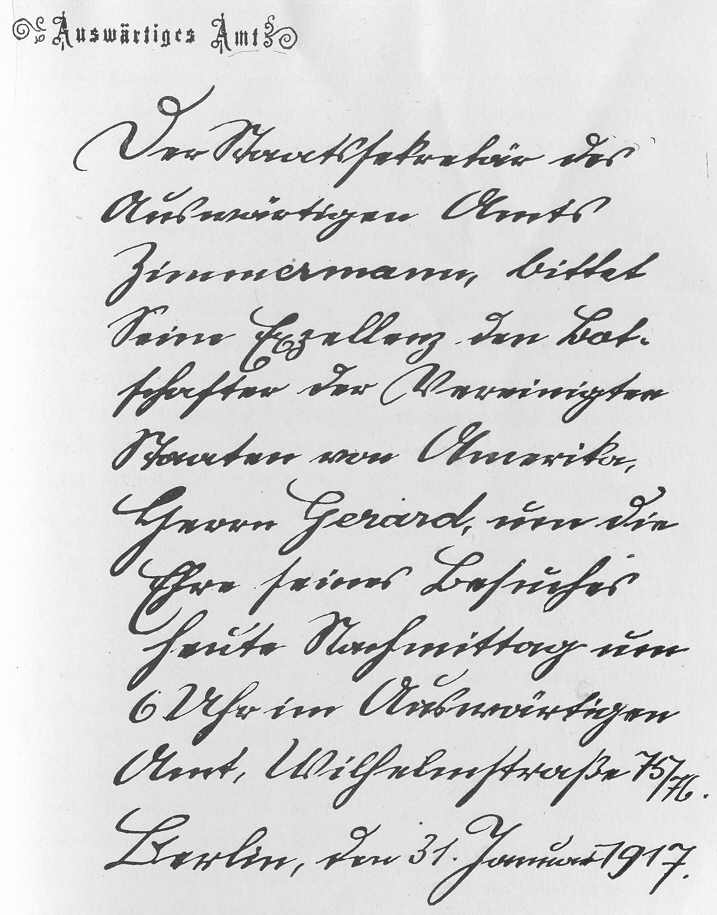

| FAC-SIMILE OF SECRETARY OF STATE'S REQUEST TO AMBASSADOR GERARD TO CALL IN ORDER TO RECEIVE SUBMARINE ANNOUNCEMENT. |

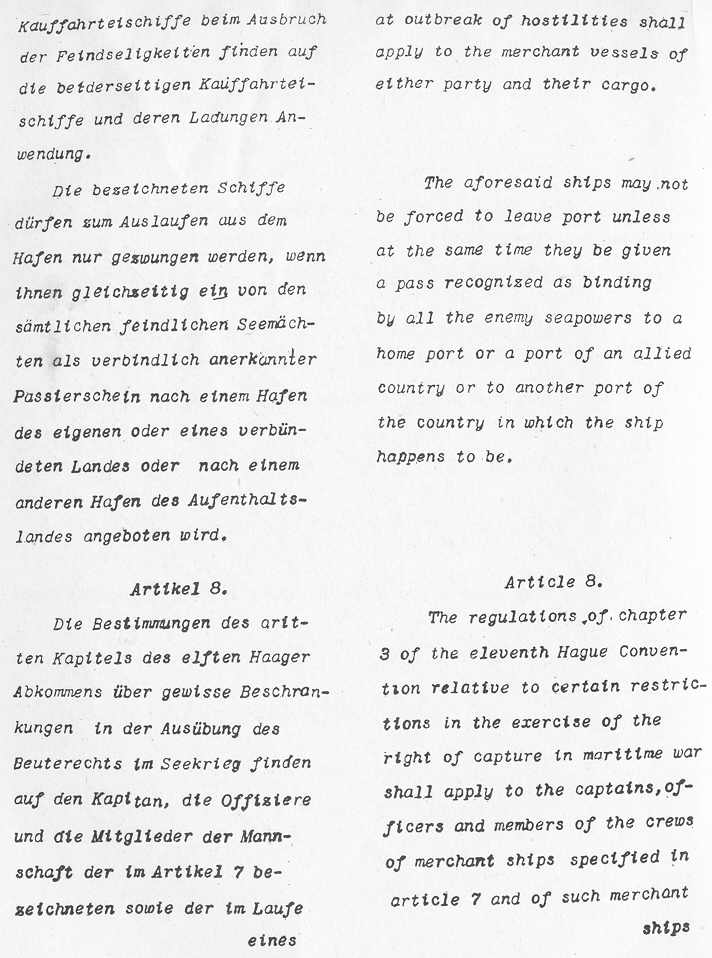

| THE REMODELLED DRAFT OF THE TREATY OF 1799. |

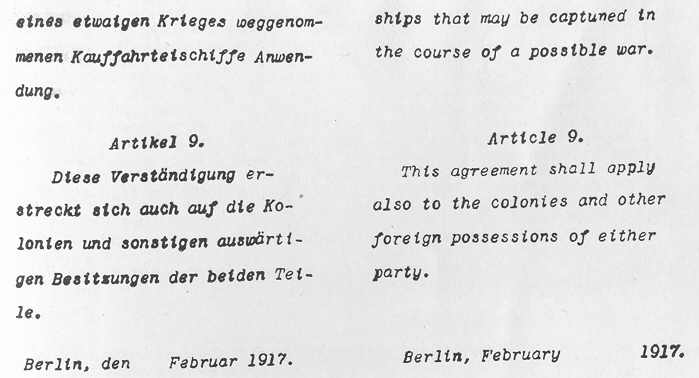

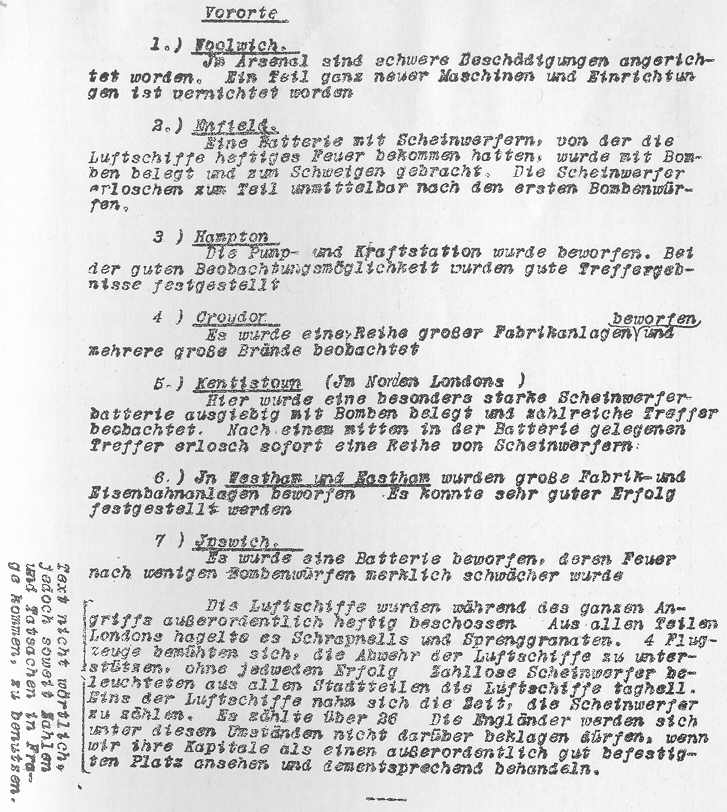

| INSTRUCTIONS SENT TO THE GERMAN PRESS ON WRITING UP A ZEPPELIN RAID. |

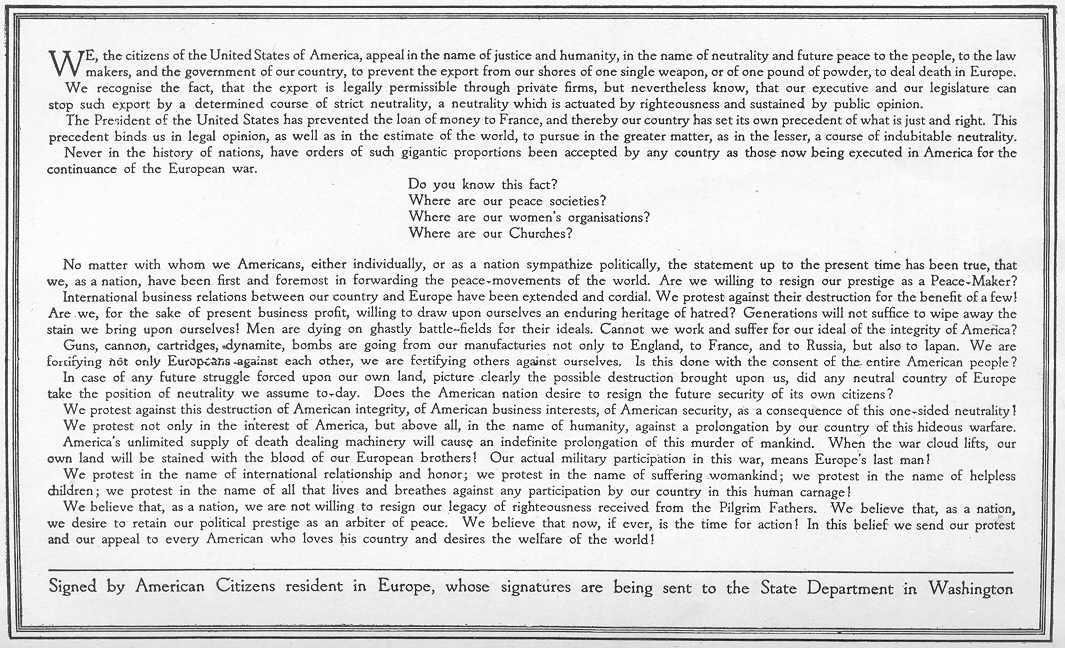

| PETITION CIRCULATED FOR SIGNATURE AMONG AMERICANS IN EUROPE. |

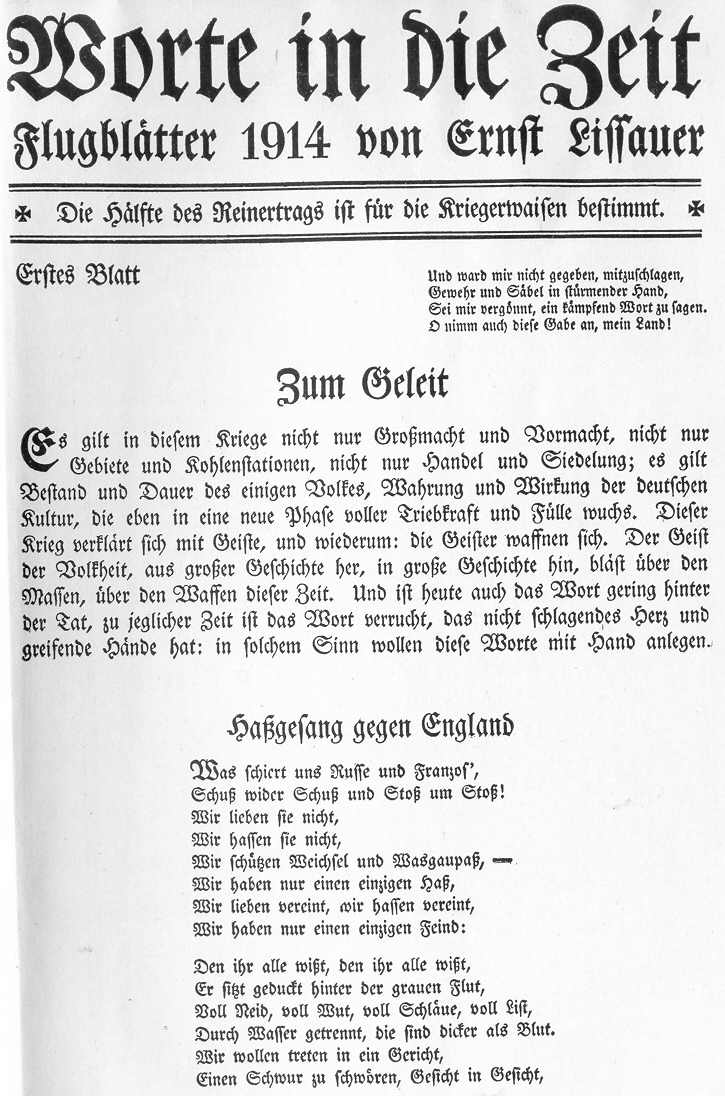

| PAGE FROM LISSAUER'S PAMPHLET SHOWING "HYMN OF HATE". |

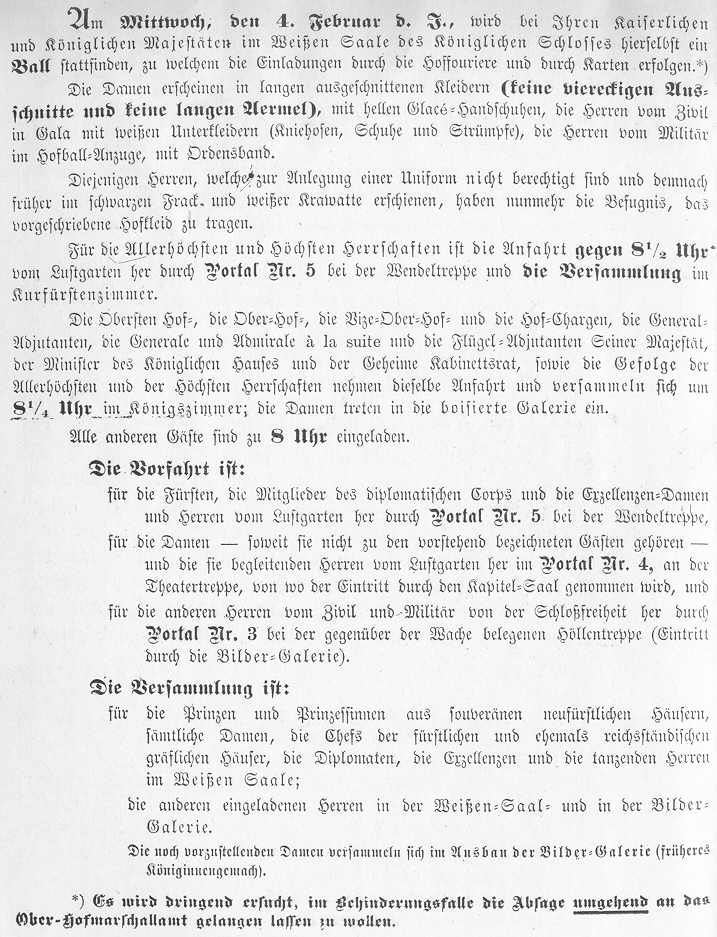

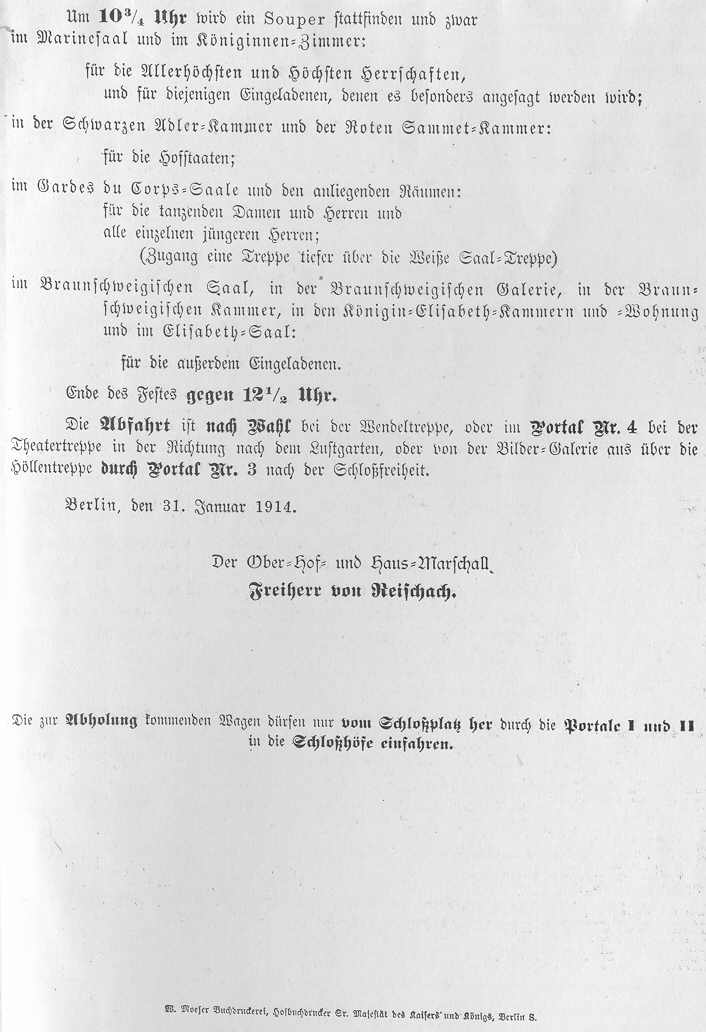

| INSTRUCTIONS REGULATING APPEARANCE AT COURT. |

| A BERLIN EXTRA. |

The second day out on the Imperator, headed for a summer's vacation, a loud knocking woke me at seven A. M. The radio, handed in from a friend in New York, told me of my appointment as Ambassador to Germany.

Many friends were on the ship. Henry Morgenthau, later Ambassador to Turkey, Colonel George Harvey, Adolph Ochs and Louis Wiley of the New York Times, Clarence Mackay, and others.

The Imperator is a marvellous ship of fifty-four thousand tons or more, and at times it is hard to believe that one is on the sea. In addition to the regular dining saloon, there is a grill room and Ritz restaurant with its palm garden, and, of course, an Hungarian Band. There are also a gymnasium and swimming pool, and, nightly, in the enormous ballroom dances are given, the women dressing in their best just as they do on shore.

Colonel Harvey and Clarence Mackay gave me a dinner of twenty-four covers, something of a record at sea. For long afterwards in Germany, I saw everywhere pictures of the Imperator including one of the tables set for this dinner. These were sent out over Germany as a sort of propaganda to induce the Germans to patronise their own ships and indulge in ocean travel. I wish that the propaganda had been earlier and more successful, because it is by travel that peoples learn to know each other, and consequently to abstain from war.

On the night of the usual ship concert, Henry Morgenthau translated a little speech for me into German, which I managed to get through after painfully learning it by heart. Now that I have a better knowledge of German, a cold sweat breaks out when I think of the awful German accent with which I delivered that address.

A flying trip to Berlin early in August to look into the house question followed, and then I returned to the United States.

In September I went to Washington to be "instructed," talked with the President and Secretary, and sat at the feet of the Assistant Secretary of State, Alvey A. Adee, the revered Sage of the Department of State.

On September ninth, 1913, having resigned as Justice of the Supreme Court of the State of New York, I sailed for Germany, stopping on the way in London in order to make the acquaintance of Ambassador Page, certain wise people in Washington having expressed the belief that a personal acquaintance of our Ambassadors made it easier for them to work together.

Two cares assail a newly appointed Ambassador. He must first take thought of what he shall wear and where he shall live. All other nations have beautiful Embassies or Legations in Berlin, but I found that my two immediate predecessors had occupied a villa originally built as a two-family house, pleasantly enough situated, but two miles from the centre of Berlin and entirely unsuitable for an Embassy.

There are few private houses in Berlin, most of the people living in apartments. After some trouble I found a handsome house on the Wilhelm Platz immediately opposite the Chancellor's palace and the Foreign Office, in the very centre of Berlin. This house had been built as a palace for the Princes Hatzfeld and had later passed into the possession of a banking family named von Schwabach.

The United States Government, unlike other nations, does not own or pay the rent of a suitable Embassy, but gives allowance for offices, if the house is large enough to afford office room for the office force of the Embassy. The von Schwabach palace was nothing but a shell. Even the gas and electric light fixtures had been removed; and when the hot water and heating system, bath-rooms, electric lights and fixtures, etc., had been put in, and the house furnished from top to bottom, my first year's salary had far passed the minus point.

The palace was not ready for occupancy until the end of January, 1914, and, in the meantime, we lived at the Hotel Esplanade, and I transacted business at the old, two-family villa.

There are more diplomats in Berlin than in any other capital in the world, because each of the twenty-five States constituting the German Empire sends a legation to Berlin; even the free cities of Hamburg, Lübeck and Bremen have a resident minister at the Empire's capital.

Invariable custom requires a new Ambassador in Berlin to give two receptions, one to the Diplomatic Corps and the other to all those people who have the right to go to court. These are the officials, nobles and officers of the army and navy, and such other persons as have been presented at court. Such people are called hoffähig, meaning that they are fit for court.

AMBASSADOR GERARD ON HIS WAY TO PRESENT HIS LETTERS OF CREDENCE TO THE EMPEROR. |

THE HOUSE ON THE WILHELM PLATZ, RENTED FOR USE AS THE EMBASSY. |

It is interesting here to note that Jews are not admitted to court. Such Jews as have been ennobled and allowed to put the coveted "von" before their names have first of all been required to submit to baptism in some Christian church. Examples are the von Schwabach family, whose ancestral house I occupied in Berlin, and Friedlaender-Fuld, officially rated as the richest man in Berlin, who made a large fortune in coke and its by-products.

These two receptions are really introductions of an Ambassador to official and court society.

Before these receptions, however, and in the month of November, I presented my letters of credence as Ambassador to the Emperor. This presentation is quite a ceremony. Three coaches were sent for me and my staff, coaches like that in which Cinderella goes to her ball, mostly glass, with white wigged coachmen, outriders in white wigs and standing footmen holding on to the back part of the coach. Baron von Roeder, introducer of Ambassadors, came for me and accompanied me in the first coach; the men of the Embassy staff sat in the other two coaches. Our little procession progressed solemnly through the streets of Berlin, passing on the way through the centre division of the arch known as the Brandenburger Thor, the gateway that stands at the head of the Unter den Linden, a privilege given only on this occasion.

We mounted long stairs in the palace, and in a large room were received by the aides and the officers of the Emperor's household, of course all in uniform. Then I was ushered alone into the adjoining room where the Emperor, very erect and dressed in the black uniform of the Death's Head Hussars, stood by a table. I made him a little speech, and presented my letters of credence and the letters of recall of my predecessor. The Emperor then unbent from his very erect and impressive attitude and talked with me in a very friendly manner, especially impressing me with his interest in business and commercial affairs. I then, in accordance with custom, asked leave to present my staff. The doors were opened. The staff came in and were presented to the Emperor, who talked in a very jolly and agreeable way to all of us, saying that he hoped above all to see the whole of the Embassy staff riding in the Tier Garten in the mornings.

The Emperor is a most impressive figure, and, in his black uniform surrounded by his officers, certainly looked every inch a king. Although my predecessors, on occasions of this kind, had worn a sort of fancy diplomatic uniform designed by themselves, I decided to abandon this and return to the democratic, if unattractive and uncomfortable, dress-suit, simply because the newspapers of America and certain congressmen, while they have had no objection to the wearing of uniforms by the army and navy, police and postmen, and do not expect officers to lead their troops into battle in dress-suits, have, nevertheless, had a most extraordinary prejudice against American diplomats following the usual custom of adopting a diplomatic uniform.

Some days after my presentation to the Emperor, I was taken to Potsdam, which is situated about half an hour's train journey from Berlin, and, from the station there, driven to the new palace and presented to the Empress. The Empress was most charming and affable, and presented a very distinguished appearance. Accompanied by Mrs. Gerard, and always, either by night or by day, in the infernal dress-suit, I was received by the Crown Prince and Princess, and others of the royal princes and their wives. On these occasions we sat down and did not stand, as when received by the Emperor and Empress, and simply made "polite conversation" for about twenty minutes, being received first by the ladies-in-waiting and aides. These princes were always in uniform of some kind.

At the reception for the hoffähig people Mrs. Gerard stood in one room and I in another, and with each of us was a representative of the Emperor's household to introduce the people of the court, and an army officer to introduce the people of the army. The officer assigned to me had the extraordinary name of der Pfortner von der Hoelle, which means the "porter of Hell." I have often wondered since by what prophetic instinct he was sent to introduce me to the two years and a half of world war which I experienced in Berlin. This unfortunate officer, a most charming gentleman, was killed early in the war.

The Berlin season lasts from about the twentieth of January for about six weeks. It is short in duration because, if the hoffähig people stay longer than six weeks in Berlin, they become liable to pay their local income tax in Berlin, where the rate is higher than in those parts of Germany where they have their country estates.

The first great court ceremonial is the Schleppencour, so-called from the long trains or Schleppen worn by the women. On this night we "presented" Mr. and Mrs. Robert K. Cassatt of Philadelphia, Mrs. Ernest Wiltsee, Mrs. and Miss Luce and Mrs. Norman Whitehouse. On the arrival at the palace with these and all the members of the Embassy Staff and their wives, we were shown up a long stair-case, at the top of which a guard of honour, dressed in costume of the time of Frederick the Great, presented arms to all Ambassadors, and ruffled kettle-drums. Through long lines of cadets from the military schools, dressed as pages, in white, with short breeches and powdered wigs, we passed through several rooms where all the people to pass in review were gathered. Behind these, in a room about sixty feet by fifty, on a throne facing the door were the Emperor and Empress, and on the broad steps of this throne were the princes and their wives, the court ladies-in-waiting and all the other members of the court. The wives of the Ambassadors entered the room first, followed at intervals of about twenty feet by the ladies of the Embassy and the ladies to be presented. As they entered the room and made a change of direction toward the throne, pages in white straightened out the ladies' trains with long sticks. Arrived opposite the throne and about twenty feet from it, each Ambassador's wife made a low curtsey and then stood on the foot of the throne, to the left of the Emperor and Empress, and as each lady of the Embassy, not before presented, and each lady to be presented stopped beside the throne and made a low curtsey, the Ambassadress had to call out the name of each one in a loud voice; and when the last one had passed she followed her out of the room, walking sideways so as not to turn her back on the royalties,--something of a feat when towing a train about fifteen feet long. When all the Ambassadresses had so passed, it was the turn of the Ambassadors, who carried out substantially the same programme, substituting low bows for curtsies. The Ambassadors were followed by the Ministers' wives, these by the Ministers and these by the dignitaries of the German Court. All passed into the adjoining hall, and there a buffet supper was served. The whole affair began at about eight o'clock and was over in an hour.

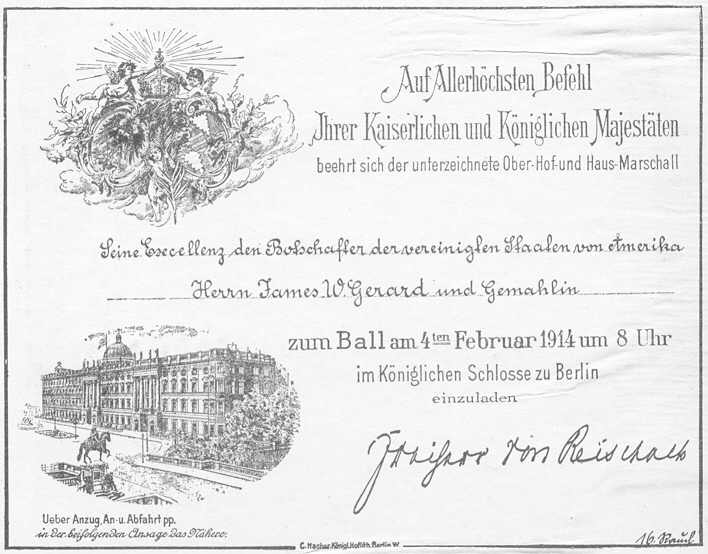

At the court balls, which also began early in the evening, a different procedure was followed. There the guests were required to assemble before eight-twenty in the ball-room. As in the Schleppencour, on one side of the room was the throne with seats for the Emperor and Empress, and to the right of this throne were the chairs for the Ambassadors' wives who were seated in the order of their husbands' rank, with the ladies of their Embassy, and any ladies they had brought to the ball standing behind them. After them came the Ministers' wives, sitting in similar fashion; then the Ambassadors, standing with their staffs behind them on raised steps, with any men that they had asked invitations for, and the Ministers in similar order. To the left of the throne stood the wives of the Dukes and dignitaries of Germany and then their husbands. When all were assembled, promptly at the time announced, the orchestra, which was dressed in mediæval costume and sat in a gallery, sounded trumpets and then the Emperor and Empress entered the room, the Emperor, of course, in uniform, followed by the ladies and gentlemen of the household all in brilliant uniforms, and one or two officers of the court regiment, picked out for their great height and dressed in the kind of uniform Rupert of Hentzau wears on the stage,--a silver helmet surmounted by an eagle, a steel breast-plate, white breeches and coat, and enormous high boots coming half way up the thigh. The Grand Huntsman wore a white wig, three-cornered hat and a long green coat.

On entering the room, the Empress usually commenced on one side and the Emperor on the other, going around the room and speaking to the Ambassadors' wives and Ambassadors, etc., in turn, and the Empress in similar fashion, chatting for a moment with the German dignitaries and their wives lined up on the opposite side of the room. After going perhaps half way around each side, the Emperor and Empress would then change sides. This going around the room and chatting with people in turn is called "making the circle", and young royalties are practised in "making the circle" by being made to go up to the trees in a garden and address a few pleasant words to each tree, in this manner learning one of the principal duties of royalty.

The dancing is only by young women and young officers of noble families who have practised the dances before. They are under the superintendence of several young officers who are known as Vortänzer and when anyone in Berlin in court society gives a ball these Vortänzer are the ones who see that all dancing is conducted strictly according to rule and manage the affairs of the ball-room with true Prussian efficiency. Supper is about ten-thirty at a court ball and is at small tables. Each royalty has a table holding about eight people and to these people are invited without particular rule as to precedence. The younger guests and lower dignitaries are not placed at supper but find places at tables to suit themselves. After supper all go back to the ball-room and there the young ladies and officers, led by the Vortänzer execute a sort of lancers, in the final figure of which long lines are formed of dancers radiating from the throne; and all the dancers make bows and curtsies to the Emperor and Empress who are either standing or sitting at this time on the throne. At about eleven-thirty the ball is over, and as the guests pass out through the long hall, they are given glasses of hot punch and a peculiar sort of local Berlin bun, in order to ward off the lurking dangers of the villainous winter climate.

At the court balls the diplomats are, of course, in their best diplomatic uniform. All Germans are in uniform of some kind, but the women do not wear the long trains worn at the Schleppencour. They wear ordinary ball dresses. In connection with court dancing it is rather interesting to note that when the tango and turkey trot made their way over the frontiers of Germany in the autumn of 1913, the Emperor issued a special order that no officers of the army or navy should dance any of these dances or should go to the house of any person who, at any time, whether officers were present or not, had allowed any of these new dances to be danced. This effectually extinguished the turkey trot, the bunny hug and the tango, and maintained the waltz and the polka in their old estate. It may seem ridiculous that such a decree should be so solemnly issued, but I believe that the higher authorities in Germany earnestly desired that the people, and, especially, the officers of the army and navy, should learn not to enjoy themselves too much. A great endeavour was always made to keep them in a life, so far as possible, of Spartan simplicity. For instance, the army officers were forbidden to play polo, not because of anything against the game, which, of course, is splendid practice for riding, but because it would make a distinction in the army between rich and poor.

A SALON IN THE AMERICAN EMBASSY. |

THE BALLROOM OF THE EMBASSY. THIS WAS AFTERWARD TURNED INTO A WORKROOM FOR THE RELIEF OF AMERICANS IN WAR DAYS. |

The Emperor's birthday, January twenty-seventh, is a day of great celebration. At nine-thirty in the morning the Ambassadors, Ministers and all the dignitaries of the court attend Divine Service in the chapel of the palace. On this day in 1914, the Queen of Greece and many of the reigning princes of the German States were present. In the evening there was a gala performance in the opera house, the entire house being occupied by members of the court. Between the acts in the large foyer, royalties "made the circle," and I had quite a long conversation with both the Emperor and Empress and was "caught" by the King of Saxony. Many of the Ambassadors have letters of credence not only to the court at Berlin but also to the rulers of the minor German States. For instance, the Belgian Minister was accredited to thirteen countries in Germany and the Spanish Ambassador to eleven. For some reason or other, the American and Turkish Ambassadors are accredited only to the court at Berlin. Some of the German rulers feel this quite keenly, and the King of Saxony, especially. I had been warned that he was very anxious to show his resentment of this distinction by refusing to shake hands with the American Ambassador. He was in the foyer on the occasion of this gala performance and said that he would like to have me presented to him. I, of course, could not refuse, but forgot the warning of my predecessors and put out my hand, which the King ostentatiously neglected to take. A few moments later the wife of the Turkish Ambassador was presented to the King of Saxony and received a similar rebuff; but, as she was a daughter of the Khedive of Egypt, and therefore a Royal Highness in her own right, she went around the King of Saxony, seized his hand, which he had put behind him, brought it around to the front and shook it warmly, a fine example of great presence of mind.

Writing of all these things and looking out from a sky-scraper in New York, these details of court life seem very frivolous and far away. But an Ambassador is compelled to become part of this system. The most important conversations with the Emperor sometimes take place at court functions, and the Ambassador and his secretaries often gather their most useful bits of information over tea cups or with the cigars after dinner.

Aside from the short season, Berlin is rather dull; Bismarck characterised it as a "desert of bricks and newspapers."

In addition to making visits to the royalties, custom required me to call first upon the Imperial Chancellor and the Minister of Foreign Affairs. The other ministers are supposed to call first, although I believe the redoubtable von Tirpitz claimed a different rule. So, during the first winter I gradually made the acquaintance of those people who sway the destinies of the German Empire and its seventy millions.

I dined with the Emperor and had long conversations with him on New Year's Day and at the two court balls.

All during this winter Germans from the highest down tried to impress me with the great danger which they said threatened America from Japan. The military and naval attachés and I were told that the German information system sent news that Mexico was full of Japanese colonels and America of Japanese spies. Possibly much of the prejudice in America against the Japanese was cooked up by the German propagandists whom we later learned to know so well.

It is noteworthy that during the whole of my first winter in Berlin I was not officially or semi-officially afforded an opportunity to meet any of the members of the Reichstag or any of the leaders in the business world. The great merchants, whose acquaintance I made, as well as the literary and artistic people, I had to seek out; because most of them were not hoffähig and I did not come in contact with them at any court functions, official dinners or even in the houses of the court nobles or those connected with the government.

A very interesting character whom I met during the first winter and often conversed with, was Prince Henkel-Donnersmarck. Prince Donnersmarck, who died December, 1916, at the age of eighty-six years, was the richest male subject in Germany, the richest subject being Frau von Krupp-Böhlen, the heiress of the Krupp cannon foundry. He was the first governor of Lorraine during the war of 1870 and had had a finger in all of the political and commercial activities of Germany for more than half a century. He told me, on one occasion, that he had advocated exacting a war indemnity of thirty milliards from France after the war of 1870, and said that France could easily pay it--and that that sum or much more should be exacted as an indemnity at the conclusion of the World War of 1914. He said that he had always advocated a protective tariff for agricultural products in Germany as well as encouragement of the German manufacturing interests: that agriculture was necessary to the country in order to provide strong soldiers for war, and manufacturing industries to provide money to pay for the army and navy and their equipment. He made me promise to take his second son to America in order that he might see American life, and the great iron and coal districts of Pennsylvania. Of course, most of these conversations took place before the World War. After two years of that war and, as prospects of paying the expenses of the war from the indemnities to be exacted from the enemies of Germany gradually melted away, the Prince quite naturally developed a great anxiety as to how the expenses of the war should be paid by Germany; and I am sure that this anxiety had much to do with his death at the end of the year, 1916.

Custom demanded that I should ask for an appointment and call on each of the Ambassadors on arrival. The British Ambassador was Sir Edward Goschen, a man of perhaps sixty-eight years, a widower. He spoke French, of course, and German; and, accompanied by his dog, was a frequent visitor at our house. I am very grateful for the help and advice he so generously gave me--doubly valuable as coming from a man of his fame and experience. Jules Cambon was the Ambassador of France. His brother, Paul, is Ambassador to the Court of St. James. Jules Cambon is well-known to Americans, having passed five years in this country. He was Ambassador to Spain for five years, and, at the time of my arrival, had been about the same period at Berlin. In spite of his long residence in each of these countries, he spoke only French; but he possessed a really marvellous insight into the political life of each of these nations. Bollati, the Italian Ambassador, was a great admirer of Germany; he spoke German well and did everything possible to keep Italy out of war with her former Allies in the Triple Alliance.

Spain was represented by Polo de Bernabe, who now represents the interests of the United States in Germany, as well as those of France, Russia, Belgium, Serbia and Roumania. It is a curious commentary on the absurdity of war that, on leaving Berlin, I handed over the interests of the United States to this Ambassador, who, as Spanish minister to the United States, was handed his passports at the outbreak of the Spanish-American war! I am sure that not only he, but all his Embassy, will devotedly represent our interests in Germany. Sverbeeu represented the interests of Russia; Soughimoura, Japan; and Mouktar Pascha, Turkey. The wife of the latter was a daughter of the Khedive of Egypt, and Mouktar Pascha himself a general of distinction in the Turkish army.

An Ambassador must keep on intimate terms with his colleagues. It is often through them that he learns of important matters affecting his own country or others. All of these Ambassadors and most of the Ministers occupied handsome houses furnished by their government. They had large salaries and a fund for entertaining.

During this first winter before the war, I saw a great deal of the German Crown Prince as well as of several of his brothers.

I cannot subscribe to the general opinion of the Crown Prince. I found him a most agreeable man, a sharp observer and the possessor of intellectual attainments of no mean order. He is undoubtedly popular in Germany, excelling in all sports, a fearless rider and a good shot. He is ably seconded by the Crown Princess. The mother of the Crown Princess is a Russian Grand Duchess, and her father was a Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. She is a very beautiful woman made popular by her affable manners. The one defect of the Crown Prince has been his eagerness for war; but, as he has characterised this war as the most stupid ever waged in history, perhaps he will be satisfied, if he comes to the throne, with what all Germany has suffered in this conflict.

The Crown Prince was very anxious, before the war, to visit the United States; and we had practically arranged to make a trip to Alaska in search of some of the big game there, with stops at the principal cities of America.

The second son of the Kaiser, Prince Eitel Fritz, is considered by the Germans to have distinguished himself most in this war. He is given credit for great personal bravery.

Prince Adalbert, the sailor prince, is quite American in his manners. In February, 1914, the Crown Prince and Princes Eitel Fritz and Adalbert came to our Embassy for a very small dance to which were asked all the pretty American girls then in Berlin.

It is never the custom to invite royalties to an entertainment. They invite themselves to a dance or a dinner, and the list of proposed guests is always submitted to them. When a royalty arrives at the house, the host (and the hostess, if the royalty be a woman) always waits at the front door and escorts the royalties up-stairs. Allison Armour also gave a dance at which the Crown Prince was present, following a dinner at the Automobile Club. Armour has been a constant visitor to Germany for many years, usually going in his yacht to Kiel in summer and to Corfu, where the Emperor goes, in winter. As he has never tried to obtain anything from the Emperor, he has become quite intimate with him and with all the members of the royal family.

The Chancellor, von Bethmann-Hollweg, is an enormous man of perhaps six feet five or six. He comes of a banking family in Frankfort. It is too soon to give a just estimate of his acts in this war. When I arrived in Berlin and until November, 1916, von Jagow was Minister of Foreign Affairs. In past years he had occupied the post of Ambassador to Italy, and with great reluctance took his place at the head of the Foreign Office. Zimmermann was an Under Secretary, succeeding von Jagow when the latter was practically forced out of office. Zimmermann, on account of his plain and hearty manners and democratic air, was more of a favourite with the Ambassadors and members of the Reichstag than von Jagow, who, in appearance and manner, was the ideal old-style diplomat of the stage.

Von Jagow was not a good speaker and the agitation against him was started by those who claimed that, in answering questions in the Reichstag, he did not make a forceful enough appearance on behalf of the government. Von Jagow did not cultivate the members of the Reichstag and his delicate health prevented him from undertaking more than the duties of his office.

As a matter of fact, I believe that von Jagow had a juster estimate of foreign nations than Zimmermann, and more correctly divined the thoughts of the American people in this war than did his successor. I thought that I enjoyed the personal friendship of both von Jagow and Zimmermann and, therefore, was rather unpleasantly surprised when I saw in the papers that Zimmermann had stated in the Reichstag that he had been compelled, from motives of policy, to keep on friendly terms with me. I sincerely hope that what he said on this occasion was incorrectly reported. Von Jagow, after his fall, took charge of a hospital at Libau in the occupied portion of Russia. This shows the devotion to duty of the Prussian noble class, and their readiness to take up any task, however humble, that may help their country.

My commission read, "Ambassador to Germany."

It is characteristic of our deep ignorance of all foreign affairs that I was appointed Ambassador to a place which does not exist. Politically, there is no such place as "Germany." There are the twenty-five States, Prussia, Bavaria, Württemberg, Saxony, etc., which make up the "German Empire," but there is no such political entity as "Germany."

These twenty-five States have votes in the Bundesrat, a body which may be said to correspond remotely to our United States Senate. But each State has a different number of votes. Prussia has seventeen, Bavaria six, Württemberg and Saxony four each, Baden and Hesse three each, Mecklenburg-Schwerin and Brunswick two each, and the rest one each. Prussia controls Brunswick.

The Reichstag, or Imperial Parliament, corresponds to our House of Representatives. The members are elected by manhood suffrage of those over twenty-five. But in practice the Reichstag is nothing but a debating society because of the preponderating power of the Bundesrat, or upper chamber. At the head of the ministry is the Chancellor, appointed by the Emperor; and the other Ministers, such as Colonies, Interior, Education, Justice and Foreign Affairs, are but underlings of the Chancellor and appointed by him. The Chancellor is not responsible to the Reichstag, as Bethmann-Hollweg clearly stated at the time of the Zabern affair, but only to the Emperor.

It is true that an innovation properly belonging only to a parliamentary government was introduced some seven years ago, viz., that the ministers must answer questions (as in Great Britain) put them by the members of the Reichstag. But there the likeness to a parliamentary government begins and ends.

The members of the Bundesrat are named by the Princes of the twenty-five States making up the German Empire. Prussia, which has seventeen votes, may name seventeen members of the Bundesrat or one member, who, however, when he votes casts seventeen votes. The votes of a State must always be cast as a unit. In the usual procedure bills are prepared and adopted in the Bundesrat and then sent to the Reichstag whence, if passed, they return to the Bundesrat where the final approval must take place. Therefore, in practice, the Bundesrat makes the laws with the assent of the Reichstag. The members of the Bundesrat have the right to appear and make speeches in the Reichstag. The fundamental constitution of the German Empire is not changed, as with us, by a separate body but is changed in the same way that an ordinary law is passed; except that if there are fourteen votes against the proposed change in the Bundesrat the proposition is defeated, and, further, the constitution cannot be changed with respect to rights expressly granted by it to anyone of the twenty-five States without the assent of that State.

In order to pass a law a majority vote in the Bundesrat and Reichstag is sufficient if there is a quorum present, and a quorum is a majority of the members elected in the Reichstag: in the Bundesrat the quorum consists of such members as are present at a regularly called meeting, providing the Chancellor or the Vice-Chancellor attends.

The boundaries of the districts sending members to the Reichstag have not been changed since 1872, while, in the meantime, a great shifting of population, as well as great increase of population has taken place. And because of this, the Reichstag to-day does not represent the people of Germany in the sense intended by the framers of the Imperial Constitution.

Much of the legislation that affects the everyday life of a German emanates from the parliaments of Prussia, Bavaria and Saxony, etc., as with us in our State Legislatures. The purely legislative power of the ministers and Bundesrat is, however, large. These German States have constitutions of some sort. The Grand Duchies of Mecklenburg have no constitution whatever. It is understood that the people themselves do not want one, on financial grounds, fearing that many expenses now borne by the Grand Duke out of his large private income, would be saddled on the people. The other States have Constitutions varying in form. In Prussia there are a House of Lords and a House of Deputies. The members of the latter are elected by a system of circle votes, by which the vote of one rich man voting in circle number one counts as much as thousands voting in circle number three. It is the recognition by Bethmann-Hollweg that this vicious system must be changed that brought down on him the wrath of the Prussian country squires, who for so long have ruled the German Empire, filling places, civil and military, with their children and relatives.

In considering Germany, the immense influence of the military party must not be left out of account; and, with the developments of the navy, that branch of the service also claimed a share in guiding the policy of the Government.

The administrative, executive and judicial officers of Prussia are not elected. The country is governed and judged by men who enter this branch of the government service exactly as others enter the army or navy. These are gradually promoted through the various grades. This applies to judges, clerks of courts, district attorneys and the officials who govern the political divisions of Prussia, for Prussia is divided into circles, presidencies and provinces. For instance, a young man may enter the government service as assistant to the clerk of some court. He may then become district attorney in a small town, then clerk of a larger court, possibly attached to the police presidency of a large city; he may then become a minor judge, etc., until finally he becomes a judge of one of the higher courts or an over-president of a province. Practically the only elective officers who have any power are members of the Reichstag and the Prussian Legislature, and there, as I have shown, the power is very small. Mayors and City Councillors are elected in Prussia, but have little power; and are elected by the vicious system of circle voting.

Time and again during the course of the Great War when I made some complaint or request affecting the interests of one of the various nations I represented, I was met in the Foreign Office by the statement, "We can do nothing with the military. Please read Bismarck's memoirs and you will see what difficulty he had with the military." Undoubtedly, owing to the fact that the Chancellor seldom took strong ground, the influence which both the army and navy claimed in dictating the policy of the Empire was greatly increased.

Roughly speaking there are three great political divisions or parties in the German Reichstag. To the right of the presiding officer sit the Conservatives. Most of these are members from the Prussian Junker or squire class. They are strong for the rights of the crown and against any extension of the suffrage in Prussia or anywhere else. They form probably the most important body of conservatives now existing in any country in the world. Their leader, Heydebrand, is known as the uncrowned king of Prussia. On the left side the Social Democrats sit. As they evidently oppose the kingship and favour a republic, no Social Democratic member has ever been called into the government. They represent the great industrial populations of Germany. Roughly, they constitute about one-third of the Reichstag, and would sit there in greater numbers if Germany were again redistricted so that proper representation were given to the cities, to which there has been a great rush of population since the time when the Reichstag districts were originally constituted.

In the centre, and holding the balance of power, sit the members of the Centrum or Catholic body. Among them are many priests. It is noteworthy that in this war Roman Catholic opinion in neutral countries, like Spain, inclines to the side of Germany; while in Germany, to protect their religious liberties, the Catholic population vote as Catholics to send Catholic members to the Reichstag, and these sit and vote as Catholics alone.

Germans high in rank in the government often told me that no part of conquered Poland would ever be incorporated in Prussia or the Empire, because it was not desirable to add to the Roman Catholic population; that they had troubles enough with the Catholics now in Germany and had no desire to add to their numbers. This, and the desire to lure the Poles into the creation of a national army which could be utilised by the German machine, were the reasons for the creation by Germany (with the assent of Austria) of the new country of Poland.

This Catholic party is the result in Germany of the Kulturkampf or War for Civilisation, as it was called by Bismarck, a contest dating from 1870 between the State in Germany and the Roman Catholic Church.

Prussia has always been the centre of Protestantism in Germany, although there are many Roman Catholics in the Rhine Provinces of Prussia, and in that part of Prussia inhabited principally by Poles, originally part of the Kingdom of Poland.

Baden and Bavaria, the two principal South German States, and others are Catholic. In 1870, on the withdrawal of the French garrison from Rome, the Temporal Power of the Pope ended, and Bismarck, though appealed to by Catholics, took no interest in the defence of the Papacy. The conflict between the Roman Catholics and the Government in Germany was precipitated by the promulgation by the Vatican Council, in 1870, of the Dogma of the Infallibility of the Pope.

A certain number of German pastors and bishops refused to subscribe to the new dogma. In the conflict that ensued these pastors and bishops were backed by the government. The religious orders were suppressed, civil marriage made compulsory and the State assumed new powers not only in the appointment but even in the education of the Catholic priests. The Jesuits were expelled from Germany in 1872. These measures, generally known as the May Laws, because passed in May, 1873, 1874 and 1875, led to the creation and strengthening of the Centrum or Catholic party. For a long period many churches were vacant in Prussia. Finally, owing to the growth of the Centrum, Bismarck gave in. The May Laws were rescinded in 1886 and the religious orders, the Jesuits excepted, were permitted to return in 1887. Civil marriage, however, remained obligatory in Prussia.

Ever since the Kulturkampf the Centrum has held the balance of power in Germany, acting sometimes with the Conservatives and sometimes with the Social Democrats.

In addition to these three great parties, there are minor parties and groups which sometimes act with one party and sometimes with another, the National Liberals, for example, and the Progressives. Since the war certain members of the National Liberal party were most bitter in assailing President Wilson and the United States. In the demand for ruthless submarine war they acted with the Conservatives. There are also Polish, Hanoverian, Danish and Alsatian members of the Reichstag.

There are three great race questions in Germany. First of all, that of Alsace-Lorraine. It is unnecessary to go at length into this well-known question. In the chapter on the affair at Zabern, something will be seen of the attitude of the troops toward the civil population. At the outbreak of the war several of the deputies, sitting in the Reichstag as members from Alsace-Lorraine, crossed the frontier and joined the French army.

If there is one talent which the Germans superlatively lack, it is that of ruling over other peoples and inducing other people to become part of their nation.

It is now a long time since portions of the Kingdom of Poland, by various partitions of that kingdom, were incorporated with Prussia, but the Polish question is more alive to-day than at the time of the last partition.

The Poles are of a livelier race than the Germans, are Roman Catholics and always retain their dream of a reconstituted and independent Kingdom of Poland.

It is hard to conceive that Poland was at one time perhaps the most powerful kingdom of Europe, with a population numbering twenty millions and extending from the Baltic to the Carpathians and the Black Sea, including in its territory the basins of the Warta, Vistula, Dwina, Dnieper and Upper Dniester, and that it had under its dominion besides Poles proper and the Baltic Slavs, the Lithuanians, the White Russians and the Little Russians or Ruthenians.

The Polish aristocracy was absolutely incapable of governing its own country, which fell an easy prey to the intrigues of Frederick the Great and the two Empresses, Maria Theresa of Austria and Catherine of Russia. The last partition of Poland was in the year 1795.

Posen, at one time one of the capitals of the old kingdom of Poland, is the intellectual centre of that part of Poland which has been incorporated into Prussia. For years Prussia has alternately cajoled and oppressed the Poles, and has made every endeavour to replace the Polish inhabitants with German colonists. A commission has been established which buys estates from Poles and sells them to Germans. This commission has the power of condemning the lands of Poles, taking these lands from them by force, compensating them at a rate determined by the commission and settling Germans on the lands so seized. This commission has its headquarters in Posen. The result has not been successful. All the country side surrounding Posen and the city itself are divided into two factions. By going to one hotel or the other you announce that you are pro-German or pro-Polish. Poles will not deal in shops kept by Germans or in shops unless the signs are in Polish.

The sons of Germans who have settled in Poland under the protection of the commission often marry Polish women. The invariable result of these mixed marriages is that the children are Catholics and Poles. Polish deputies voting as Poles sit in the Prussian legislature and in the Reichstag, and if a portion of the old Kingdom of Poland is made a separate country at the end of this war, it will have the effect of making the Poles in Prussia more restless and more aggressive than ever.

In order to win the sympathies of the Poles, the Emperor caused a royal castle to be built within recent years in the city of Posen, and appointed a popular Polish gentleman who had served in the Prussian army and was attached to the Emperor, the Count Hutten-Czapski, as its lord-warden. In this castle was a very beautiful Byzantine chapel built from designs especially selected by the Emperor. In January, 1914, we went with Allison Armour and the Cassatts, Mrs. Wiltsee and Mrs. Whitehouse on a trip to Posen to see this chapel.

Some of our German friends tried to play a joke on us by telling us that the best hotel was the hotel patronised by the Poles. To have gone there would have been to declare ourselves anti-German and pro-Polish, but we were warned in time. The castle has a large throne room and ball-room; in the hall is a stuffed aurochs killed by the Emperor. The aurochs is a species of buffalo greatly resembling those which used to roam our western prairies. The breed has been preserved on certain great estates in eastern Germany and in the hunting forests of the Czar in the neighbourhood of Warsaw.

Some of the Poles told me that at the first attempt to give a court ball in this new castle the Polish population in the streets threw ink through the carriage windows on the dresses of the ladies going to the ball and thus made it a failure. The chapel of the castle is very beautiful and is a great credit to the Emperor's taste as an architect.

While being shown through the Emperor's private apartments in this castle, I noticed a saddle on a sort of elevated stool in front of a desk. I asked the guide what this was for: he told me that the Emperor, when working, always sits in a saddle.

In Posen, in a book-store, the proprietor brought out for me a number of books caricaturing the German rule of Alsace-Lorraine. It is curious that a community of interests should make a market for these books in Polish Posen.

Although not so well advertised, the Polish question is as acute as that of Alsace-Lorraine.

After its successful war in 1866 against Austria, Bavaria, Saxony, Baden, Hanover, etc., Prussia became possessed of the two duchies of Schleswig-Holstein, which are to the south of Denmark on the Jutland Peninsula. Here, strangely enough, there is a Danish question. A number of Danes inhabit these duchies and have been irritated by the Prussian officials and officers into preserving their national feeling intact ever since 1866. Galling restrictions have been made, the very existence of which intensifies the hatred and prevents the assimilation of these Danes. For instance, Amundsen, the Arctic explorer, was forbidden to lecture in Danish in these duchies during the winter of 1913-14, and there were regulations enforced preventing more than a certain number of these Danish people from assembling in a hotel, as well as regulations against the employment of Danish servants.

In 1866, after its successful war, Prussia wiped out the old kingdom of Hanover and drove its king into exile in Austria. To-day there is still a party of protest against this aggression. The Kaiser believes, however, that the ghost of the claim of the Kings of Hanover was laid when he married his only daughter to the heir of the House of Hanover and gave the young pair the vacant Duchy of Brunswick. That this young man will inherit the great Guelph treasure was no drawback to the match in the eyes of those in Berlin.

There is a hatred of Prussia in other parts of Germany, but coupled with so much fear that it will never take practical shape. In Bavaria, for example, even the comic newspapers have for years ridiculed the Prussians and the House of Hohenzollern. The smashing defeat by Prussia of Austria and the allied German States, Bavaria, Saxony, Hesse, Hanover, etc., in 1866, and the growth of Prussianism since then in all of these countries, keep the people from any overt act. It is a question, perhaps, as to how these countries, especially Bavaria, would act in case of the utter defeat of Germany. But at present they must be counted on only as faithful servants, in a military way, of the German Emperor.

Montesquieu, the author of the "Esprit des Lois," says, "All law comes from the soil," and it has been claimed that residence in the hot climate of the tropics in some measure changes Anglo-Saxon character. It is, therefore, always well in judging national character to know something of the physical characteristics and climate of the country which a nation inhabits.

The heart of modern Germany is the great north central plain which comprises practically all of the original kingdom of Prussia, stretching northward from the Saxon and Hartz mountains to the North and Baltic seas. It is from this dreary and infertile plain that for many centuries conquering military races have poured over Europe. The climate is not so cold in winter as that of the northern part of the United States. There is much rain and the winter skies are so dark that the absence of the sun must have some effect upon the character of the people. The Saxons inhabit a more mountainous country; Württemberg and Baden are hilly; Bavaria is a land of beauty, diversified with lovely lakes and mountains. The soft outlines of the vine-covered hills of the Rhine Valley have long been the admiration of travellers.

The inhabitants of Prussia were originally not Germanic, but rather Slavish in type; and, indeed, to-day in the forest of the River Spree, on which Berlin is situated, and only about fifty miles from that city, there still dwell descendants of the original Wendish inhabitants of the country who speak the Wendish language. The wet-nurses, whose picturesque dress is so noticeable on the streets of Berlin, all come from this Wendish colony, which has been preserved through the many wars that have swept over this part of Germany because of the refuge afforded in the swamps and forests of this district.

The inhabitants of the Rhine Valley drink wine instead of beer. They are more lively in their disposition than the Prussians, Saxons and Bavarians, who are of a heavy and phlegmatic nature. The Bavarians are noted for their prowess as beer drinkers, and it is not at all unusual for prosperous burghers of Munich to dispose of thirty large glasses of beer in a day; hence the cures which exist all over Germany and where the average German business man spends part, at least, of his annual vacation.

In peace times the Germans are heavy eaters. As some one says, "It is not true that the Germans eat all the time, but they eat all the time except during seven periods of the day when they take their meals." And it is a fact that prosperous merchants of Berlin, before the war, had seven meals a day; first breakfast at a comfortably early hour; second breakfast at about eleven, of perhaps a glass of milk or perhaps a glass of beer and sandwiches; a very heavy lunch of four or five courses with wine and beer; coffee and cakes at three; tea and sandwiches or sandwiches and beer at about five; a strong dinner with several kinds of wines at about seven or seven-thirty; and a substantial supper before going to bed.

The Germans are wonderful judges of wines, and, at any formal dinner, use as many as eight varieties. The best wine is passed in glasses on trays, and the guests are not expected, of course, to take this wine unless they actually desire to drink it. I know one American woman who was stopping at a Prince's castle in Hungary and who, on the first night, allowed the butler to fill her glasses with wine which she did not drink. The second evening the butler passed her sternly by, and she was offered no more wine during her stay in the castle.

Many of the doctors who were with me thought that the heavy eating and large consumption of wine and beer had unfavourably affected the German national character, and had made the people more aggressive and irritable and consequently readier for war. The influence of diet on national character should not be under-estimated. Meat-eating nations have always ruled vegetarians.

During this first winter in Berlin, I spent each morning in the Embassy office, and, if I had any business at the Foreign Office, called there about five o'clock in the afternoon. It was the custom that all Ambassadors should call on Tuesday afternoons at the Foreign Office, going in to see the Foreign Minister in the order of their arrival in the waiting-room, and to have a short talk with him about current diplomatic affairs.

In the previous chapter I have given a detailed account of the ceremonies of court life, because a knowledge of this life is essential to a grasp of the spirit which animates those ruling the destinies of the German Empire.

My first winter, however, was not all cakes and ale. There were several interesting bits of diplomatic work. First, we were then engaged in our conflict with Huerta, the Dictator of Mexico, and it was part of my work to secure from Germany promises that she would not recognise this Mexican President.

I also spent a great deal of time in endeavouring to get the German Government to take part officially in the San Francisco Fair, but, so far as I could make out, Great Britain, probably at the instance of Germany, seemed to have entered into some sort of agreement, or at any rate a tacit understanding, that neither country would participate officially in this Exposition.

After the lamentable failure of the Jamestown Exposition, the countries of Europe were certainly not to be blamed for not spending their money in aid of a similar enterprise. But I believe that the attitude of Germany had a deeper significance, and that certain, at least, of the German statesmen had contemplated a rapprochement with Great Britain and a mutual spanking of America and its Monroe Doctrine by these two great powers. Later I was informed, by a man high in the German Foreign Office, that Germany had proposed to Great Britain a joint intervention in Mexico, an invasion which would have put an end forever to the Monroe Doctrine, of course to be followed by the forceful colonisation of Central and South America by European Powers. I was told that Great Britain refused. But whether this proposition and refusal in fact were made, can be learned from the archives of the British Foreign Office.

During this period of trouble with Mexico, the German Press, almost without exception, and especially that part of it controlled by the Government and by the Conservatives or Junkers, was most bitter in its attitude towards America.

The reason for this was the underlying hatred of an autocracy for a successful democracy, envy of the wealth, liberty and commercial success of America, and a deep and strong resentment against the Monroe Doctrine which prevented Germany from using her powerful fleet and great military force to seize a foothold in the Western hemisphere.

Germany came late into the field of colonisation in her endeavour to find "a place in the sun." The colonies secured were not habitable by white men. Togo, Kameroons, German East Africa, are too tropical in climate, too subject to tropical diseases, ever to become successful German colonies. German Southwest Africa has a more healthy climate but is a barren land. About the only successful industry there has been that of gathering the small diamonds that were discovered in the sands of the beaches and of the deserts running back from the sea.

On the earnest request of Secretary Bryan, I endeavoured to persuade the German authorities to have Germany become a signatory to the so-called Bryan Peace Treaties. After many efforts and long interviews, von Jagow, the Foreign Minister, finally told me that Germany would not sign these treaties because the greatest asset of Germany in war was her readiness for a sudden assault, that they had no objection to signing the treaty with America, but that they feared they would then be immediately asked to sign similar treaties with Great Britain, France and Russia, that if they refused to sign with these countries the refusal would almost be equivalent to a declaration of war, and, if they did sign, intending in good faith to stand by the treaty, that Germany would be deprived of her greatest asset in war, namely, her readiness for a sudden and overpowering attack.

I also, during this first winter, studied and made reports on the commercial situation of Germany and especially the German discriminations against American goods. To these matters I shall refer in more detail in another chapter.

Opposition and attention to the oil monopoly project also occupied a great part of my working hours. Petroleum is used very extensively in Germany for illuminating purposes by the poorer part of the population, especially in the farming villages and industrial towns. This oil used in Germany comes from two sources of supply, from America and from the oil wells of Galicia and Roumania. The German American Oil Company there, through which the American oil was distributed, although a German company, was controlled by American capital, and German capital was largely interested in the Galician and Roumanian oil fields. The oil from Galicia and Roumania is not so good a quality as that imported from America.

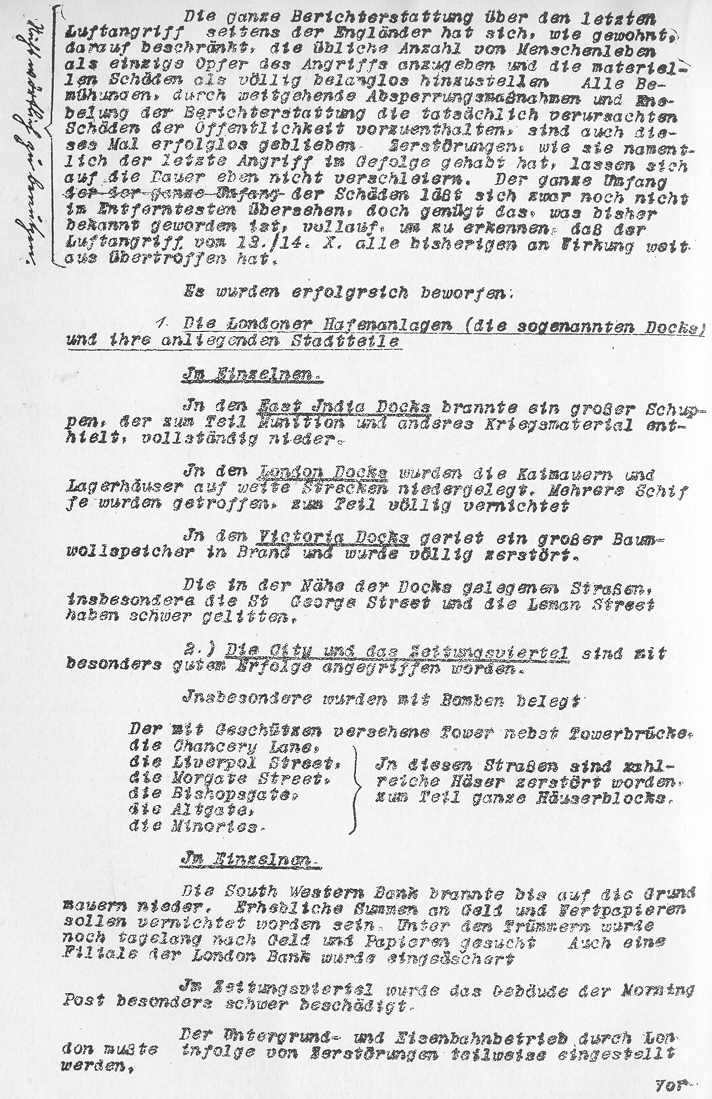

PROGRAMME OF THE MUSIC AFTER DINNER WITH THE KAISER AT THE ROYAL PALACE, BERLIN. |

Before my arrival in Germany the government had proposed a law creating the oil monopoly; that is to say, a company was to be created, controlled by the government for the purpose of carrying on the entire oil business of Germany, and no other person or company, by its provisions, was to be allowed to sell any illuminating oil or similar products in the Empire. The bill provided that the business of those engaged in the wholesale selling of oil, and their plants, etc., should be taken over by this government company, condemned and paid for. The German American Company, however, had also a retail business and plant throughout Germany for which it was proposed that no compensation should be given. The government bill also contained certain curious "jokers"; for instance, it provided for the taking over of all plants "within the customs limit of the German Empire," thus leaving out of the compensation a refinery which was situated in the free part of Hamburg, although, of course, by operation of this monopoly bill the refinery was rendered useless to the American controlled company which owned it.

In the course of this investigation it came to light that the Prussian state railways were used as a means of discriminating against the American oil. American oil came to Germany through the port of Hamburg, and the Galician and Roumanian oil through the frontier town of Oderberg. Taking a delivery point equally distant between Oderberg and Hamburg, the rate charged on oil from Hamburg to this point was twice as great as that charged for a similar quantity of oil from Oderberg.

I took up this fight on the line that the company must be compensated for all of its property, that used in retail as well as in wholesale business, and, second, that it must be compensated for the good-will of its business, which it had built up through a number of years by the expenditure of very large sums of money. Of course where a company has been in operation for years and is continually advertising its business, its good-will often is its greatest asset and has often been built up by the greatest expenditure of money. For instance, in buying a successful newspaper, the value does not lie in the real-estate, presses, etc., but in the good-will of the newspaper, the result of years of work and expensive advertising.

I made no objection that the German government did not have a perfect right to create this monopoly and to put the American controlled company entirely out of the field, but insisted upon a fair compensation for all their property and good-will. Even a fair compensation for the property and good-will would have started the government monopoly company with a large debt upon which it would have been required to pay interest, and this interest, of course, would have been added to the cost of oil to the German consumers. In my final conversation on the subject with von Bethmann-Hollweg, he said, "You don't mean to say that President Wilson and Secretary Bryan will do anything for the Standard Oil Company?" I answered that everyone in America knew that the Standard Oil Company had neither influence with nor control over President Wilson and Secretary Bryan, but that they both could and would give the Standard Oil Company the same measure of protection which any American citizen doing business abroad had a right to expect from his government. I also said that I thought they had done enough for the Germans interested in the Galician and Roumanian oil fields when they had used the Prussian state railways to give these oil producers an unfair advantage over those importing American oil.

Shortly after this the question of the creation of this oil monopoly was dropped and naturally has not been revived during the war, and I very much doubt whether, after the war, the people of liberalised Germany will consent to pay more for inferior oil in order to make good the investments of certain German banks and financiers in Galicia and Roumania. I doubt whether a more liberal Germany will wish to put the control of a great business in the hands of the government, thereby greatly increasing the number of government officials and the weight of government influence in the country. Heaven knows there are officials enough to-day in Germany, without turning over a great department of private industry to the government for the sole purpose of making good bad investments of certain financiers and adding to the political influence of the central government.

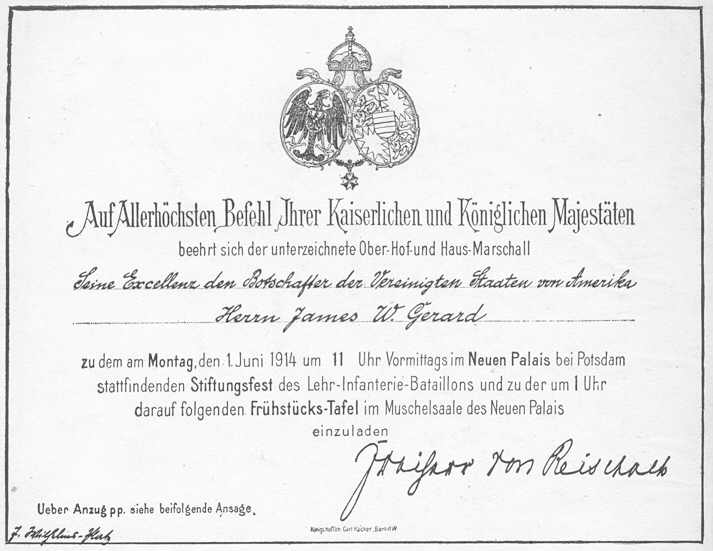

In May, 1914, Colonel House and his beautiful wife arrived to pay us a visit in Berlin. He was, of course, anxious to have a talk with the Emperor, and this was arranged by the Emperor inviting the Colonel and me to what is called the Schrippenfest, at the new palace at Potsdam.

For many years, in fact since the days of Frederick the Great, the learning (Lehr) battalion, composed of picked soldiers from all the regiments of Prussia, has been quartered at Potsdam, and on a certain day in April this battalion has been given a dinner at which they eat white rolls (Schrippen) instead of the usual black bread. This feast has been carried on from these older days and has become quite a ceremony.

The Colonel and I motored to Potsdam, arrayed in dress-suits, and waited in one of the salons of the ground floor of the new palace. Finally the Emperor and the Empress and several of the Princes and their wives and the usual dignitaries of the Emperor's household arrived. The Colonel was presented to the royalties and then a Divine Service was held in the open air at one end of the palace. The Empress and Princesses occupied large chairs and the Emperor stood with his sons behind him and then the various dignitaries of the court. The Lehr Battalion was drawn up behind. There were a large band and the choir boys from the Berlin cathedral. The service was very impressive and not less so because of a great Zeppelin which hovered over our heads during the whole of the service.

After Divine Service, the Lehr Battalion marched in review and then was given food and beer in long arbours constructed in front of the palace. While the men were eating, the Emperor and Empress and Princes passed among the tables, speaking to the soldiers. We then went to the new palace where in the extraordinary hall studded with curious specimens of minerals from all countries, a long table forming three sides of a square was set for about sixty people. Colonel House and I sat directly across the table from the Emperor, with General Falkenhayn between us. The Emperor was in a very good mood and at one time, talking across the table, said to me that the Colonel and I, in our black dress-suits, looked like a couple of crows, that we were like two undertakers at a feast and spoiled the picture. After luncheon the Emperor had a long talk with Colonel House, and then called me into the conversation.

On May twenty-sixth, I arranged that the Colonel should meet von Tirpitz at dinner in our house. We did not guess then what a central figure in this war the great admiral was going to be. At that time and until his fall, he was Minister of Marine, which corresponds to our Secretary of the Navy Department, and what is called in German Reichsmarineamt. The Colonel also met the Chancellor, von Jagow, Zimmermann and many others.

There are two other heads of departments, connected with the navy, of equal rank with the Secretary of the Naval Department and not reporting to him. These are the heads of the naval staff and the head of what is known as the Marine Cabinet. The head of the naval staff is supposed to direct the actual operations of warfare in the navy, and the head of the Marine Cabinet is charged with the personnel of the navy, with determining what officers are to be promoted and what officers are to take over ships or commands.

While von Tirpitz was Secretary of the Navy, by the force of his personality, he dominated the two other departments, but since his fall the heads of these two other departments have held positions as important, if not more important, than that of Secretary of the Navy.

On May thirty-first, we took Colonel and Mrs. House to the aviation field of Joachimsthal. Here the Dutch aviator Fokker was flying and after being introduced to us he did some stunts for our benefit. Fokker was employed by the German army and later became a naturalised German. The machines designed by him, and named after him, for a long time held the mastery of the air on the West front.

The advice of Colonel House, a most wise and prudent counsellor, was at all times of the greatest value to me during my stay in Berlin. We exchanged letters weekly, I sending him a weekly bulletin of the situation in Berlin and much news and gossip too personal or too indefinite to be placed in official reports.

War with Germany seemed a thing not even to be considered when in this month of May, 1914, I called on the Foreign Office, by direction, to thank the Imperial Government for the aid given the Americans at Tampico by German ships of war.

Early in February, Mr. S. Bergmann, a German who had made a fortune in America and who had returned to Germany to take up again his German citizenship, invited me to go over the great electrical works which he had established. Prince Henry of Prussia, the brother of the Emperor, was the only other guest and together we inspected the vast works, afterwards having lunch in Mr. Bergmann's office. Prince Henry has always been interested in America since his visit here. On that visit he spent most of his time with German societies, etc. Of course, now we know he came as a propagandist with the object of welding together the Germans in America and keeping up their interest in the Fatherland. He made a similar trip to the Argentine just before the Great War, with a similar purpose, but I understand his excursion was not considered a great success, from any standpoint. A man of affable manners, no one is better qualified to go abroad as a German propagandist than he. If all Germans had been like him there would have been no World War in 1914.

On March eighteenth, we were invited to a fancy-dress ball at the palace of the Crown Prince. The guests were mostly young people and officers. The Crown Princess wore a beautiful Russian dress with its characteristic high front piece on the head. The Crown Prince and all the officers present were in the picturesque uniforms of their respective regiments of a period of one hundred years ago. Prince Oscar, the fifth son of the Kaiser, looked particularly well.

The hours for balls in Berlin, where officers attended, were a good example for hostesses in this country. The invitations read for eight o'clock and that meant eight o'clock. A cold dinner of perhaps four courses is immediately served on the arrival of the guests, who, with the exception of a very few distinguished ones, are not given any particular places. At a quarter to nine the dancing begins, supper is at about eleven and the guests go home at twelve, at an hour which enables the officers to get to bed early. During the season there were balls at the British and French Embassy and performances by the Russian Ballet, then in Berlin, at the Russian Embassy.

The wonderful new Royal Library, designed by Ihne, was opened on March twenty-second. The Emperor attended, coming in with the beautiful Queen of Roumania walking by his side. She is an exceedingly handsome woman, half English and half Russian. Some days later I was presented to her at a reception held at the Roumanian Minister's and found her as pleasant to talk to as good to look upon.

At the end of March there was a Horse Show. The horses did not get prizes for mere looks and manners in trotting and cantering, as here. They must all do something, for the horse is considered primarily as a war horse; such, for instance, as stopping suddenly and turning at a word of command. The jumping was excellent, officers riding in all the events. It was not a function of "society," but all "society" was there and most keenly interested; for in a warlike country, just as in the Middle Ages, the master's life may depend upon the qualities of his horse.

I have always been fond of horses and horse-racing, and the race-tracks about Berlin were always an attraction for me.