MAP OF PART

OF

ABYSSINIA

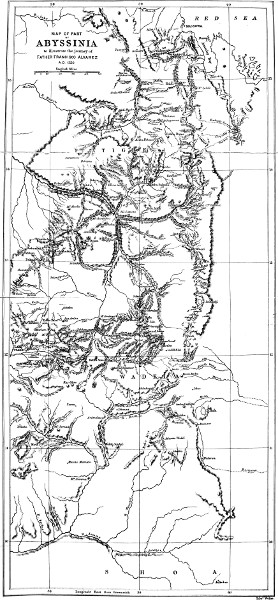

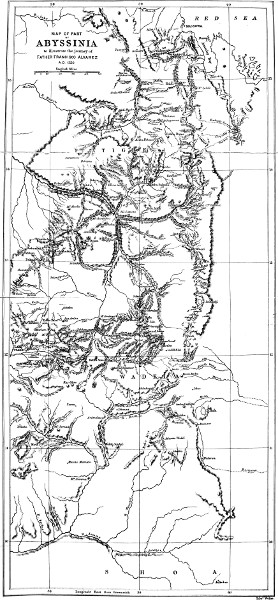

to illustrate the journey of FATHER FRANCISCO ALVAREZ A.D. 1520

Title: Narrative of the Portuguese embassy to Abyssinia during the years 1520-1527

Author: Francisco Alvares

Translator: Baron Henry Edward John Stanley Stanley

Release date: January 4, 2024 [eBook #72622]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Printed for the Hakluyt society, 1881

Credits: Peter Becker, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BY

FATHER FRANCISCO ALVAREZ.

TRANSLATED FROM THE PORTUGUESE,

AND EDITED,

With Notes and an Introduction,

BY

LORD STANLEY OF ALDERLEY.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR THE HAKLUYT SOCIETY.

MDCCCLXXXI.

T. RICHARDS, PRINTER, 37, GREAT QUEEN STREET.

WORKS ISSUED BY

The Hakluyt Society.

NARRATIVE OF THE PORTUGUESE

EMBASSY TO ABYSSINIA.

No. LXIV.

COUNCIL

OF

THE HAKLUYT SOCIETY.

[v]

The present work on Abyssinia is the earliest extant; for though Pedro de Covilham, the explorer of King John II, who was despatched from Portugal in May 1487, reached Abyssinia more than thirty years before our author, he does not appear to have left any written memorial of his long residence in that country.

This work of Francisco Alvarez has been translated from the original edition printed in black letter by Luis Rodriguez, bookseller of the King, on the 22nd October 1540, the British Museum Catalogue supposes at Coimbra.

The narrative of Alvarez has been translated into several languages, but most of these translations are considerably abridged. The following are a list of the translations:—

“Viaggio fatta nella Ethiopia, Obedienza data a Papa Clemente Settimo in nome del Prete Gianni.” Primo Volume delle navigazione. 1550. Fol.

“Viaggio nella Ethiopia, Ramusio.” 1 vol. 1554.

“Description de l’Ethiopie.” 1556. Fol.

“Historia de las cosas de Etiopia.” Traduzida de Portugues en Castillano, por Thomas de Padilla. Anvers: Juan Steelsio, 1557. 8vo.

“Description de l’Ethiopie.” Translated by J. Bellere, from the Italian version of Ramusio. Anvers: C. Plautin, 1558. 8vo.

[vi]

“Historia de las cosas de Ethiopia.” By Miguel de Suelves. Printed in black letter. Saragoza, 1561. Fol.

“Warhafftiger Bericht von den Landen ... des Königs in Ethiopien.” Eisslebë, 1566. FOL——Another edition. Eisslebë, 1576. Fol.

“Die Reiss zu dess Christlichen Königs in hohen Ethiopien.” 1576. Fol.

“Historia de las cosas de Ethiopia,” traduzida por M. de Selves. Toledo, 1588. 8vo.

“The Voyage of Sir Francis Alvarez.” Purchas, his Pilgrims, Part II. 1625.

Francisco Alvarez relates in this volume how much he desired, on his return to Portugal, to be sent on a mission to Rome, to present the Prester John’s letters to the Pope, and it appears from the Portuguese Biographical Dictionary of Innocencio da Silva, that he succeeded in going to Rome, and afterwards returned to Lisbon.

Figaniere, and José Carlos Pinto de Souza say, in their Portuguese Bibliographies, that Alvarez was a native of Coimbra.

The utility and good effect of this Portuguese mission to Abyssinia suffered very much by the dissensions and quarrels which arose between Don Rodrigo de Lima, the Ambassador, and Don Jorge d’Abreu, the Secretary of Embassy, quarrels which, as usual in such cases, caused disunion amongst the whole staff of the Embassy. Father Alvarez acted a most useful part as peace-maker on all occasions; but he is very reticent, and has avoided saying upon which side the blame for these quarrels should be laid. It appears from the narrative that the Ambassador was very selfish, and thought too much of[vii] his personal interests; his conduct appears all the more blameable, from the account of the very different conduct of Hector da Silveira, who brought away the mission from Africa; but Jorge d’Abreu was very quarrelsome, and carried his quarrels further than can be excused, even by the fact that he could not refer his complaints home to his Government. The conduct of the Ambassador must, however, have been even worse than appears from the narrative, or the Abyssinians would hardly have supported Jorge d’Abreu as much as they did.

The reader is invited to compare the description of the entrance to the mountain in which the Abyssinian Princes were confined at the time of our author’s visit, at pp. 140–144, and the motives for this confinement, with this opening passage of Rasselas, describing the Happy Valley.

“The place which the wisdom or policy of antiquity had destined for the residence of the Abyssinian Princes was a spacious valley in the kingdom of Amhara, surrounded on every side by mountains, of which the summits overhang the middle part. The only passage by which it could be entered, was a cavern that passed under a rock, of which it has long been disputed whether it was the work of nature, or of human industry. The outlet of the cavern was concealed by a thick wood, and the mouth which opened into the valley was closed with gates of iron....

“This lake discharged its superfluities by a stream, which entered a dark cleft of the mountain on the[viii] northern side, and fell with dreadful noise from precipice to precipice, till it was heard no more.”

These descriptions agree sufficiently to leave no doubt that Johnson borrowed the idea of Rasselas from actual descriptions of Abyssinia, and from the translation of Alvarez in Purchas’s Pilgrimes, when he wrote that work in 1759; but the matter is proved beyond doubt, by the fact that Johnson’s first literary work was a translation from the French of Lobo’s Voyage to Abyssinia. It was published in 1735, by Bettesworth and Hicks, of Paternoster Row, and for this task Johnson received only five guineas, which he was in want of for the funeral expenses of his mother.

Therefore, whatever frivolous persons in society may have done on insufficient information, Mr. Justin McCarthy, in his History of our Own Times, should have avoided the inaccuracy of writing: “He (Lord Beaconsfield) wound up by proclaiming that ‘the standard of St. George was hoisted upon the mountains of Rasselas’. All England smiled at the mountains of Rasselas. The idea that Johnson actually had in his mind the very Abyssinia of geography and of history, when he described his Happy Valley, was in itself trying to gravity.”

Mr. McCarthy goes on to say that: “When the expedition to Abyssinia is mentioned in any company, a smile steals over some faces, and more than one voice is heard to murmur an allusion to the mountains of Rasselas”.

It is unfortunate that Mr. Justin McCarthy should[ix] not have fallen in with those Englishmen who sighed over the excuse for the expedition to Abyssinia, that “it would keep the Bombay army in wind”, or who reprobated the conduct of Lord Napier of Magdala to King Theodore, after having accepted from him a present of cows. But accurate ideas of political morality are not to be expected from an advocate of the most extreme proposals of the Irish Land League.[1]

The reader will find many descriptions of Abyssinian Ritual, and interesting discussions between the Abyssinians and Father Alvarez, who always showed much tact in these arguments.

It appears from this book, that the population of Abyssinia was far larger at that time than at the present; and that the contact of Europeans with the Abyssinians has not been to the advantage of the latter.

An interesting part of the narrative of Alvarez is the description of the churches cut out of the rock; he is very enthusiastic over the beauty of these structures. The style of Alvarez is never very clear; and there was much difficulty in translating this portion of his book, owing to the number of architectural terms, some of which are almost obsolete. No modern traveller has described these churches. Mr. Markham was within a short distance of them, but was unable to visit them.

[x]

M. Antoine d’Abbadie visited them, but he has not yet written any account of his long residence in Ethiopia, having been occupied with the publication of his very copious astronomical observations, and being now engaged in printing a dictionary of the Ethiopic language.

M. d’Abbadie is anxious that the work on Ethiopia of the Jesuit Almeida, a MS. of which is in the British Museum, should be translated and published, as he considers it to be the most exact account of that country. I am indebted to M. d’Abbadie for several explanations of Ethiopic words and names which have been given in the notes: many of these were too much disfigured to be recognisable.

On one occasion, the Portuguese performed before Prester John a representation of the Adoration of the Magi, or an Epiphany miracle play. This would probably be similar to one that was found in a thirteenth century Service Book of Strasbourg, and which was published by Mr. Walter Birch in the tenth volume of the Transactions of the Royal Society of Literature.

The Abyssinian envoy, Mattheus, who went to Portugal and returned to his country with the Portuguese Embassy, suffered much on his way to Portugal, and also on his return, by reason of the doubts cast upon the authenticity of his mission. What happened to him in India on his way to Portugal, is mentioned at length in Mr. Birch’s translation of the Commentaries of Albuquerque, vol. iii, p. 250. The truth appears to be that he was sent by Queen Helena, the queen-mother.

[xi]

In several cases, the dates given by Alvarez of the days of the week and the days of the month do not agree, but as these dates refer to the departure from some village, and not to any historical event, I have not thought it worth while to verify and correct these discrepancies.

Mr. Clements Markham has compiled a map of Abyssinia for this volume, extending from Massowah to Shoa.

Some years ago a rather savage criticism of the publications of the Hakluyt Society complained of the excessive length of their Introductions. This one is much shorter than it should have been, not in deference to the critic, but because the researches necessary for doing justice to the work of Alvarez have been interfered with and prevented by other less agreeable occupations; but the delivery of this volume could not be delayed any longer, and the members of the Society are entreated to excuse its brevity.

June 29th, 1881.

| Prologue to the King our Sovereign | 1 |

| CAP. I. | |

|---|---|

| How Diogo Lopez de Sequeira succeeded to the government of India after Lopo Soarez, who was governor before him, and how he brought Mattheus to the port of Maçua | 3 |

| CAP. II. | |

| How the Captain of Arquiquo came to visit the Captain General, and also some Friars of Bisam | 4 |

| CAP. III. | |

| How the Captain General ordered mass to be said in the chief mosque of Maçua, and ordered it to be named St. Mary of the Conception, and how he sent to see the things of the Monastery of Bisam | 6 |

| CAP. IV. | |

| How the Captain General and the Barnagais saw each other, and how it was arranged that Rodrigo de Lima should go with Mattheus to Prester John | 7 |

| CAP. V. | |

| Of the goods which the Captain sent to Prester John | 10 |

| CAP. VI. | |

| Of the day that we departed and the fleet went out of the port, and where we went to keep the feast, and of a gentleman who came to us | 11 |

| CAP. VII. | |

| How Mattheus made us leave the road, and travel through the mountain in a dry river bed | 12 |

| CAP. VIII. | |

| How Mattheus again took us out of the road, and made us go to the monastery of Bisam | 14 |

| CAP. IX. | |

| How we said mass here, and Frey Mazqual separated from us, and we went to a monastery, where our people fell sick | 16 |

| CAP. X. | |

| How Don Rodrigo sent to ask the Barnagais for equipment for his departure | 20 |

| CAP. XI. | |

| Of the fashion and situation of the monasteries and their customs, first this of St. Michael | 21 |

| CAP. XII. | |

| Where and how the bread of the Sacrament is made, and of a Procession they made, and of the pomp with which the mass is said, and of entering into the church | 28 |

| CAP. XIII. | |

| How in all the churches and monasteries in the country of Prester John only one mass is said each day; and of the situation of the monastery of Bisan where we buried Mattheus; and of the fast of Lent | 30 |

| CAP. XIV. | |

| How the monastery of Bisan is the head of six monasteries, of the number of the brothers, and ornaments, of the “castar” which they do to Philip, whom they call a Saint | 33 |

| CAP. XV. | |

| Of the agriculture of this country, and how they preserve themselves from the wild beasts, and of the revenues of the monastery | 35 |

| CAP. XVI. | |

| How the friars impeded our departure, and of what happened to us on the road | 37 |

| CAP. XVII. | |

| How we passed a great mountain in which there were many apes, on a Saturday, and on the following Sunday we said mass in a village called Zalote | 39 |

| CAP. XVIII. | |

| How we arrived at the town of Barua, and how the Ambassador went in search of the Barnagais, and of the manner of his state | 41 |

| CAP. XIX. | |

| How they gave us to eat in the house of the Barnagais, and how in this country the journeys are not reckoned by leagues | 43 |

| CAP. XX. | |

| Of the town of Barua, and of the women and their traffic, and of the marriages which are made outside of the churches | 44 |

| CAP. XXI. | |

| Of their marriages and benedictions, and of their contracts, and how they separate from their wives, and the wives from them, and it is not thought strange | 46 |

| CAP. XXII. | |

| Of the manner of baptism and circumcision, and how they carry the dead to their burial | 48 |

| CAP. XXIII. | |

| Of the situation of the town of Barua, chief place of the kingdom of the Barnagais, and of his hunting | 50 |

| CAP. XXIV. | |

| Of the lordship of the Barnagais, and of the lords and captains who are at his orders and commands, and of the dues which they pay | 52 |

| CAP. XXV. | |

| Of their method of guarding their herds from wild beasts, and how there are two winters in this country: and of two churches that are in the town of Barua | 54 |

| CAP. XXVI. | |

| How the priests are, and how they are ordained, and of the reverence which they pay to the churches and their churchyards | 56 |

| CAP. XXVII. | |

| How we departed from Barua, and of the bad equipment we had until we arrived at Barra | 58 |

| CAP. XXVIII. | |

| How the goods arrived at the town of Barra, and of the bad equipment of the Barnagais | 59 |

| CAP. XXIX. | |

| Of the church of the town of Barra, and its ornaments, and of the fair there, and of the merchandise, and costumes of the friars, nuns, and priests | 61 |

| CAP. XXX. | |

| Of the state of the Barnagais and manner of his house, and how he ordered a proclamation to be made to go against the Nobiis, and the method of his justice | 63 |

| CAP. XXXI. | |

| How we departed from Barra to Temei, and of the quality of the town | 66 |

| CAP. XXXII. | |

| Of the multitude of locusts which are in the country, and of the damage they do, and how we made a procession, and the locusts died | 67 |

| CAP. XXXIII. | |

| Of the damage which we saw in another country caused by the locusts in two places | 71 |

| CAP. XXXIV. | |

| How we arrived at Temei, and the ambassador went in search of Tigrimahom, and sent to call us | 72 |

| CAP. XXXV. | |

| How the Tigrimahom sent a captain in search of our goods, and of the buildings which are in the first town | 74 |

| CAP. XXXV.[2] | |

| How we departed from Bafazem, and went to the town called Houses of St. Michael | 76 |

| CAP. XXXVI. | |

| Which speaks of the town of Aquaxumo, and of the gold which the Queen Saba took to Solomon for the temple, and of a son that she had of Solomon | 78 |

| CAP. XXXVII. | |

| How St. Philip declared a prophecy of Isaiah to the eunuch of Queen Candace, through which she and all her kingdom were converted, and of the edifices of the town of Aquaxumo | 80 |

| CAP. XXXVIII. | |

| Of the buildings which are around Aquaxumo, and how gold is found in it, and of the church of this town | 84 |

| CAP. XXXIX. | |

| How close to Aquaxumo there are two churches on two peaks, where lie the bodies of two saints | 86 |

| CAP. XL. | |

| Of the countries and lordships that are to the west and to the north of Aquaxumo, where there is a monastery, named Hallelujah, and of two other monasteries to the east | 87 |

| CAP. XLI. | |

| How we departed from the church and houses of St. Michael, and went to Bacinete, and from there to Maluc; and of the monasteries which are near it | 89 |

| CAP. XLII. | |

| Of the animals which are in the country, and how we turned back to where the ambassador was | 92 |

| CAP. XLIII. | |

| How the Tigrimahom being about to travel, the ambassador asked him to despatch him, and it was not granted to him, and the ambassador sent him certain things, and he gave him equipment, and we went to a monastery, where the friars gave thanks to God | 94 |

| CAP. XLIV. | |

| How we went to the town of Dangugui, and Abefete, and how Balgada Robel came to visit us, and the service which he brought, and of the salt which is in the country | 97 |

| CAP. XLV. | |

| How we departed, and our baggage before us, and how a captain of the Tigrimahom who conducted us was frightened by a friar who came in search of us | 99 |

| CAP. XLVI. | |

| How we departed from the town of Corcora, and of the luxuriant country through which we travelled, and of another which was rough, in which we lost one another at night, and how the tigers fought us | 101 |

| CAP. XLVII. | |

| How the friar reached us in this town, and then we set out on our way to a town named Farso: of the crops which are gathered in it, and of the bread they eat, and wine they drink | 105 |

| CAP. XLVIII. | |

| How we departed from the town of Farso, well prepared, because we had to pass the skirt of the country of the Moors | 108 |

| CAP. XLIX. | |

| How the people of Janamora have the conquest of these Doba Moors, and of the great storm of rain that came upon us during our halt in a river channel | 112 |

| CAP. L. | |

| How we departed from this poor place, and of the fright they gave us, and how we went to sleep Saturday and Sunday at a river named Sabalete | 114 |

| CAP. LI. | |

| Of the church of Ancona, and how in the kingdom of Angote iron and salt are current for money, and of a monastery which is in a cave | 117 |

| CAP. LII. | |

| Of a church of canons who are in another cave in this same lordship, in which lie a Prester John and a Patriarch of Alexandria | 119 |

| CAP. LIII. | |

| Of the great church edifices that there are in the country of Abuxima, which King Lalibela built, and of his tomb in the church of Golgotha | 122 |

| CAP. LIV. | |

| Of the fashion of the church of San Salvador, and of other churches which are in the said town, and of the birth of King Lalibela, and the dues of this country | 125 |

| CAP. LV. | |

| How we departed from Ancona, and went to Ingabelu, and how we returned to seek the baggage | 131 |

| CAP. LVI. | |

| How the ambassador separated from the friar, and how those of us who remained with the friar were stoned, and some captured, and how the ambassador returned, and we were invited by the Angote Ras, and went with him to church, and of the questions he asked, and dinner he gave us | 133 |

| CAP. LVII. | |

| How the ambassador took leave of the Ras of Angote, and the friar, with most of us, returned to the place where we were stoned, and from there we went to a fertile country, and a church of many canons | 138 |

| CAP. LVIII. | |

| Of the mountain in which they put the sons of the Prester John, and how they stoned us near it | 140 |

| CAP. LIX. | |

| Of the greatness of the mountain in which they put the sons of Prester John, and of its guards, and how his kingdoms are inherited | 143 |

| CAP. LX. | |

| Of the punishment that was given to a friar, and also to some guards, for a message which he brought from some princes to the Prester; and how a brother of the Prester and his uncle fled, and of the manner in which they dealt with them | 145 |

| CAP. LXI. | |

| In what estimation the relations of the Prester are held, and of the different method which this David wishes to pursue with his sons, and of the great provisions applied to the mountain | 148 |

| CAP. LXII. | |

| Of the end of the kingdom of Angote, and beginning of the kingdom of Amara, and of a lake and the things there are in it, and how the friar wished to take the ambassador to a mountain, and how we went to Acel, and of its abundance | 150 |

| CAP. LXIII. | |

| How we came to another lake, and from there to the church of Macham Celacem, and how they did not let us enter it | 153 |

| CAP. LXIV. | |

| How the Presters endowed this kingdom with churches, and how we went to the village of Abra, and from there to some great dykes | 156 |

| CAP. LXV. | |

| How we came to some gates and deep passes difficult to travel, and we went up to the gates, at which the kingdom begins which is named Xoa | 158 |

| CAP. LXVI. | |

| How the Prester John went to the burial of Janes Ichee of the monastery of Brilibanos, and of the election of another Ichee, who was a Moor | 161 |

| CAP. LXVII. | |

| How we travelled for three days through plains, and of the curing of infirmities and of the sight of the people | 163 |

| CAP. LXVIII. | |

| How a great lord of title was given to us as a guard, and of the tent which he sent us | 165 |

| CAP. LXIX. | |

| How the ambassador, and we with him, were summoned by order of the Prester, and of the order in which we went, and of his state | 166 |

| CAP. LXX. | |

| Of the theft which was done to us when the baggage was moved, and of the provisions which the Prester sent us, and of the conversation the friar had with us | 170 |

| CAP. LXXI. | |

| How the Prester moved away with his court, and how the friar told the ambassador to trade if he wished, and how the ambassador went to the court | 172 |

| CAP. LXXII. | |

| Of the Franks who are in the country of the Prester, and how they arrived here, and how they advised us to give the pepper and goods which we brought | 174 |

| CAP. LXXIII. | |

| How they told the ambassador that the grandees of the court were counselling the Prester not to let him return, and how he ordered him to change his tent, and asked for a cross, and how he sent to summon the ambassador | 177 |

| CAP. LXXIV. | |

| How the ambassador having been summoned by the Prester, he did not hear him in person | 180 |

| CAP. LXXV. | |

| How the ambassador was summoned another time, and he took the letters he had brought, and how we asked leave to say mass | 184 |

| CAP. LXXVI. | |

| Of the questions which were put to the ambassador by order of Prester John, and of the dress which he gave to a page, and also whether we brought with us the means of making wafers | 187 |

| CAP. LXXVII. | |

| How the Prester John sent to call me, the priest Francisco Alvarez, and to take to him wafers and vestments, and of the questions which he asked me | 188 |

| CAP. LXXVIII. | |

| Of the robbery which took place at the ambassador’s, and of the complaint made respecting it to Prester John, and how we were robbed, and how Prester John sent a tent for a church | 194 |

| CAP. LXXIX. | |

| How the Prester sent to call the ambassador, and of the questions he put to him, and how he sent to beg for the swords which he had, and some pantaloons, and how they were sent | 195 |

| CAP. LXXX. | |

| How Prester John sent certain horses to the ambassador for them to skirmish, and how they did it, and of a chalice which the Prester sent him, and of questions which were put, and of the robbery in the tent | 197 |

| CAP. LXXXI. | |

| How the Prester sent to show a horse to the ambassador, and how he ordered the great men of his Court to come and hear our mass, and how the Prester sent to call me, and what he asked me | 199 |

| CAP. LXXXII. | |

| How the Ambassador was summoned, and how he presented the letters which he had brought to Prester John, and of his age and state | 202 |

| CAP. LXXXIII. | |

| How I was summoned, and of the questions which they put to me respecting the lives of St. Jerome, St. Dominick, and St. Francis | 205 |

| CAP. LXXXIV. | |

| How the lives of the said Saints were taken to him, and how he had them translated into his language, and of the satisfaction they felt at our mass, and how Prester John sent for us and clothed us | 209 |

| CAP. LXXXV. | |

| Of the sudden start which Prester John made for another place, and of the way in which they dealt with the ambassador respecting his baggage, and of the discord there was, and of the visit the Prester sent | 212 |

| CAP. LXXXVI. | |

| How the Prester was informed of the quarrels of the Portuguese, and entreated them to be friends, and what more passed, and of the wrestling match and the baptism we did here | 214 |

| CAP. LXXXVII. | |

| Of the number of men, horse and foot, who go with the Prester when he travels | 217 |

| CAP. LXXXVIII. | |

| Of the churches at Court, and how they travel, and how the altar stones are reverenced, and how Prester John shows himself to the people each year | 219 |

| CAP. LXXXIX. | |

| How Prester John sent to call me to say mass for him on Christmas-day, and of confession and communion | 220 |

| CAP. XC. | |

| How the Prester gave leave to go to the ambassador and the others, and ordered me to remain alone with the interpreter, and of the questions about Church matters, and how we all sang compline, and how Prester John departed that night | 224 |

| CAP. XCI. | |

| How the Prester went to lodge at the church of St. George, and ordered it to be shown to the people of the embassy, and after certain questions ordered me to be shown some rich umbrellas | 228 |

| CAP. XCII. | |

| Of the travelling of Prester John, and the manner of his state when he is on the road | 231 |

| CAP. XCIII. | |

| How the Prester went to the church of Macham Selasem, and of the procession and reception that they gave him, and what passed between His Highness and me respecting the reception | 233 |

| CAP. XCIV. | |

| Of the fashion and things of this church of the Trinity, and how the Prester sent to tell the ambassador to go and see the church of his mother, and of the things which happened in it | 236 |

| CAP. XCV. | |

| How Prester John sent to tell those of the embassy and the Franks to go and see his baptism, and of the representation which the Franks made for him, and how he ordered that I should be present at the baptism, and of the fashion of the tank, and how he desired the Portuguese to swim, and gave them a banquet | 240 |

| CAP. XCVI. | |

| How I went with an interpreter to visit the Abima Mark, and how I was questioned about circumcision, and how the Abima celebrates the holy orders | 245 |

| CAP. XCVII. | |

| How the Prester questioned me about the ceremony of holy orders, and also how I went to the lesser orders which they call zagonais, and what sort of people are ordained | 248 |

| CAP. XCVIII. | |

| How long a time the Prester’s country was without an Abima, and for what cause and where they go to seek them, and of the state of the Abima, and how he goes when he rides | 253 |

| CAP. XCIX. | |

| Of the assembly of clergy, which took place in the church of Macham Selasem when they consecrated it, and of the translation of the King Nahum, father of this Prester, and of a small church there is there | 256 |

| CAP. C. | |

| Of the conversation which the ambassador had with the Prester about carpets, and how the Prester ordered for us an evening’s entertainment and banquet | 258 |

| CAP. CI. | |

| How the Prester sent to call the ambassador and those that were with him, and of what passed in the great church | 261 |

| CAP. CII. | |

| How the ambassador and all the Franks went to visit the Abima, and of what passed there | 263 |

| CAP. CIII. | |

| How Pero de Covilham, Portuguese, is in the country of the Prester, and how he came there, and why he was sent | 265 |

| CAP. CIV. | |

| How Prester John determined to write to the King and to the Captain-major, and how he behaved with the ambassador and with the Franks who were in his country, and of the decision as to departure | 270 |

| CAP. CV. | |

| How the Prester sent to the ambassador thirty ounces of gold, and fifty for those that came with him, and a crown and letters for the King of Portugal, and letters for the Captain-major, and how we left the Court and of the road we took | 273 |

| CAP. CVI. | |

| Of what happened in the town of Manadeley with the Moors | 277 |

| CAP. CVII. | |

| How two great gentlemen from the Court came to us to make friendship between us, and committed us to the captain-major | 279 |

| CAP. CVIII. | |

| How they took us on the road to the Court, and how they brought us back to this country | 283 |

| CAP. CIX. | |

| In what time and day Lent begins in the country of Prester John, and of the great fast and abstinence of the friars, and how at night they put themselves in the tank | 284 |

| CAP. CX. | |

| Of the fast of Lent in the country of Prester John, and of the office of Palms and of the Holy Week | 289 |

| CAP. CXI. | |

| How we kept a Lent at the Court of the Prester, and we kept it in the country of Gorage, and they ordered us to say mass, and how we did not say it | 293 |

| CAP. CXII. | |

| How Don Luis de Meneses wrote to the ambassador to depart, and how they did not find him at Court, and how the King Don Manuel had died | 298 |

| CAP. CXIII. | |

| Of the battle which the Prester had with the King of Adel, and how he defeated Captain Mahomed | 304 |

| CAP. CXIV. | |

| How the Prester sent us a map of the world which we had brought him, for us to translate the writing into Abyssinian, and what more passed, and of the letters for the Pope | 311 |

| CAP. CXV. | |

| How in the letters of Don Luis it was said that we should require justice for certain men of his who had been killed, and the Prester sent there the Chief Justice of the Court, and Zagazabo, in company of Don Rodrigo to Portugal | 314 |

| CAP. CXVI. | |

| How Zagazabo the ambassador returned to the Court, and I with him, for business which concerned him, and how they flogged the Chief Justice and two friars, and why | 317 |

| CAP. CXVII. | |

| How, after the death of Queen Helena, the great Betudete went to collect the dues of her kingdom, and what they were, and how the Queen of Adea came to ask assistance, and what people came with her on mules | 321 |

| CAP. CXVIII. | |

| How assistance was given to the Queen of Adea, and how the Prester ordered the great Betudete to be arrested, and why, and how he became free, and also he ordered other lords to be arrested | 325 |

| CAP. CXIX. | |

| How the Tigrimahom was killed, and the other Betudete deposed, also Abdenago from his lordship, and the ambassador was provided for, and Prester John went in person to the kingdom of Adea | 329 |

| CAP. CXX. | |

| Of the manner in which the Prester encamps with his Court | 331 |

| CAP. CXXI. | |

| Of the tent of justice and method of it, and how they hear the parties | 333 |

| CAP. CXXII. | |

| Which speaks of the manner of the prison | 335 |

| CAP. CXXIII. | |

| Where the dwellings of the Chief Justices are situated, and the site of the market place, and who are the merchants and hucksters | 336 |

| CAP. CXXIV. | |

| How the lords and gentlemen and all other people pitch their tents, according to their regulations | 337 |

| CAP. CXXV. | |

| Of the manner in which the lords and gentlemen come to the Court, and go about it, and depart from it | 338 |

| CAP. CXXVI. | |

| How those who go to and come from the wars approach the Prester more closely, and of the maintenance they get | 340 |

| CAP. CXXVII. | |

| Of the manner in which they carry the Prester’s property when he travels, and of the brocades and silks which he sent to Jerusalem, and of the great treasury | 340 |

| CAP. CXXVIII. | |

| How three hundred and odd friars departed from Barua in pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and how they killed them | 342 |

| CAP. CXXIX. | |

| Of the countries and kingdoms which are on the frontiers of Prester John | 345 |

| CAP. CXXX. | |

| Of the kingdom of Adel, and how the king is esteemed as a saint amongst the Moors | 346 |

| CAP. CXXXI. | |

| Of the kingdom of Adea, where it begins and where it ends | 346 |

| CAP. CXXII. | |

| Of the lordships of Ganze and Gamu, and of the kingdom of Gorage | 347 |

| CAP. CXXXIII. | |

| Of the kingdom of Damute, and of the much gold there is in it, and how it is collected, and to the south of this are the Amazons, if they are there | 347 |

| CAP. CXXXIV. | |

| Of the lordships of the Cafates, who they say had been Jews, and how they are warriors | 349 |

| CAP. CXXXV. | |

| Of the kingdom of Gojame which belonged to Queen Helena, where the river Nile rises, and of the much gold there is there | 350 |

| CAP. CXXXVI. | |

| Of the kingdom of Bagamidri, which is said to be very large, and how silver is found in its mountains | 351 |

| CAP. CXXXVII. | |

| Of some lordships which are called of the Nubians, who had been Christians, and of the number of churches which are in the country which they border upon | 351 |

| CAP. CXXXVIII. | |

| Of the officials that Solomon ordained for his son that he had of the Queen Sabba when he sent him to Ethiopia; and how they still draw honour from these offices | 353 |

| CAP. CXXXIX. | |

| How the ambassador of Prester John took possession of his lordship, and the Prester gave him a title of all of it, and we departed to the sea | 354 |

| CAP. CXL. | |

| How the Portuguese came for us, and who was the captain | 356 |

| CAP. CXLI. | |

| How the Barnagais made ready, and we travelled with him on the road to the sea | 360 |

| _______________________ | |

| In this Part is related the Journey which was made from the country of the Prester John to Portugal. | |

| CAP. I. | |

| Of how we departed from the port and island of Masua until arriving at Ormuz | 364 |

| CAP. II. | |

| Of the translation of the letter which Prester John sent to Diego Lopez, and which was given to Lopo Vaz de Sampayo | 368 |

| CAP. III. | |

| Of the voyage we made from Ormuz to India, as far as Cochim | 374 |

| CAP. IV. | |

| Of the voyage we made from Cananor to Lisbon, and of what happened to us by the way | 378 |

| CAP. V. | |

| Of the journey we made from Lisbon to Coimbra, and how we remained at Çarnache | 382 |

| CAP. VI. | |

| How we departed from Çarnache on the way to Coimbra, and the reception that was made, and how the embassage was given, and of the welcome which the King our Sovereign gave us | 385 |

| CAP. VII. | |

| Of the translation of the letter which the Prester sent to Don Manuel | 389 |

| CAP. VIII. | |

| Translation of the letter of Prester John to the King Don Joam our Sovereign | 396 |

| CAP. IX. | |

| Of certain questions which the Archbishop of Braga put to Francisco Alvarez, and the answers which he gave | 401 |

Page 36, line 22, for “Rodrigro”, read “Rodrigo”.

„ 84 note, “mancal”. “Baton ferré des deux bouts”.—Roquette’s Dict.

„ 151, line 18, for “sleeep”, read “sleep”.

„ 178, line 28, “a crucifix painted on it”, or perhaps, “a painted crucifix on it”.

„ 186, note. See Grove’s Dictionary of Music for a note on the Monochord.

„ 199, note. “Alaqueca, laqueca, pierre des Indes qui arrête le flux de sang.”—Roquette’s Dict.

„ 228, line 25, for “Bruncaliam”, read “Brancaliam”.

„ 241. Col. Meadows Taylor describes a similar miracle play represented at Aurungabad by the Portuguese monks.—Story of my Life, p. 39.

„ 295, line 2, for “pesons”, read “persons”.

„ 324, last line, for “littlo”, read “little”.

„ 325, “cap. cxvii”, read “cxviii”.

„ 344, line 33, “Cosme, Damiano”, or the church of Saints Cosmo and Damian, martyrs united in the Calendar under 27th September.

„ 408, note, “Tahu.” This is the Tau-cross or T-shaped crutch emblem of St. Anthony, so called from the name of the letter in the Greek alphabet.

[1]

Very high and very powerful Prince,

Perchance your Highness may judge me to be as ignorant as over bold, since with such weak knowledge, and little capacity, I have desired to offer to you my poor works: but the love which I bear to your service excuses my error, because I have done it with such strenuous daring, as in truth I would do other greater things, if the favour of your Highness should also oblige me as in this work of Prester John of the Indies. Because, besides that the Bishop of Lamego incited me to this, your Highness bade me print it, saying that you would receive much satisfaction from it, which was a great favour to me; I give for it great thanks to God, because with this commencement others came to me with hope of a good end, blessed ends I hope. And if, my Lord, you keep this in your remembrance, I well believe that with a royal mind you will so accept the little, as you will bestow much. For a poor man passing by one day where his King travelled, brought him a little water with both his hands, saying: drink my Lord, for the heat is great. He accepted it gaily from him, not looking to the small quality of that service, but only to the good will with which he offered it. Therefore, though in this same manner I offer to your Highness this small service of the book of Prester John, receive with content its usefulness; for in it are related many notable things; the truth of which is as much shown in the deeds as in the words. Because it is a very important thing for a Prince to recall to memory the examples of profitable lives that have passed away, for a[2] lesson to the living. And as, my Lord, always since I have been yours my desire has been directed to your service in order to derive some fruit by it, even though power may have been wanting to me, good will has not failed: with this I went to Paris to seek for printing types of official letters and other things fitting for printing, which are no less of the best quality than those of Italy, France, and Germany, where this art most flourishes, as your Highness may see by the work which I have established in this city, with no small satisfaction, because it seemed to me that your Highness took pleasure in it, as has been shewn by the favours which you have done to me, and which I hope you will do. Thus, with this confidence, I took this little opportunity of Prester John, which (as the poets say) is not the less to be praised on this account. May your Highness receive with a royal and benignant mind this small service, the first fruits of my small capacity, which may bring profit and recreation from the labours which your great and arduous affairs bring with them. And if your Highness should find in this book any words that do not please you, remember that the men there abroad are lords of the words, and that Princes are lords of deeds and of fortune.

[3]

The treatise commences with the entry into the country of Prester John.

Cap. i.—How Diogo Lopez de Sequeira succeeded to the government of India after Lopo Soarez, who was governor before him, and how he brought Mattheus to the port of Maçua.

I say that I came with Duarte Galvan, may God keep him, and this is the truth, and he died in Camaran, an island of the Red sea, and his embassy ceased in the time when Lopo Soarez was Captain General and Governor of the Indies, as I have already written at length, and here I omit to write it as it is not necessary: I shall write that which is necessary. I say that Diogo Lopez de Sequeira succeeding to the government of India after Lopo Soarez, he set to work to do that which Lopo Soarez had not completed, that is to bring Mattheus the ambassador, who went to Portugal as ambassador of Prester John, to the port of Maçua, which is near to Arquiquo, port and country of Prester John. And he fitted out his large and handsome fleet, and we set sail for the said Red sea, and arrived at the said island of Maçua on Monday of the Octave of Easter, the seventh day of April of the year fifteen hundred and twenty, which we found empty, because for about five or six days they had had news of us. The main land is about two crossbow shots, more or less, from the island, and to it the Moors of the island had carried off their goods for safety: this mainland belongs to Prester John. The fleet having come to anchor between the island[4] and the mainland, on the following Tuesday there came to us from the town of Arquiquo a Christian and a Moor: the Christian said that the town of Arquiquo belonged to Christians, and to a lord who was called Barnagais, a subject of Prester John, and that the Moors of this island of Maçua and town of Arquiquo, whenever Turks or Roumys who do them injury came to this port, all fled to the mountains and carried off such of their property as they could carry, and now they had not chosen to fly because they had heard that we were Christians. Hearing this the great captain gave thanks to God for the news, and name of Christians which he had met with, and which greatly favoured Mattheus, who came rather unfavourably: and he ordered a rich garment to be given to the Christian, and to the Moor he showed great favour, and told them that they had done what they ought in not stirring from the town of Arquiquo, since it belonged to Christians, and the Prester, as they said, and that his coming was only for the service and friendship of the Prester John and all his people, and that they might go in peace and be in security.

Cap. ii.—How the Captain of Arquiquo came to visit the Captain General, and also some Friars of Bisam.

The following day, Wednesday of the Octave, the captain of the said town of Arquiquo came to speak to the Captain General, and he brought him a present of four cows: and the Captain General received him with much show and honour, and gave him rich stuffs, and learned from him more details about the Christianity of the country, and how he was already summoned by the Barnagais, the lord of that country, to go there. This captain came in this manner: he brought a very good horse, and he wore a cloak over a rich Moorish shirt, and with him there were thirty horsemen, and quite[5] two hundred men on foot. After the long and agreeable conversation which they held by interpreters, the Captain General speaking Arabic well, the captain of Arquiquo went away with his people much pleased, as it appeared from what they said. At a distance of seven or eight leagues from this town of Arquiquo, in a very high mountain, there is a very noble monastery of friars, which Mattheus talked of a great deal, and which is called Bisan.[3] The friars had news of us, and on Thursday after the Octave there came to us seven friars of the said monastery. The Captain General went out to receive them on the beach with all his people with much pleasure and rejoicing, and likewise the friars showed that they felt much pleasure. They said that for a long time they had been looking forward for Christians, because they had prophecies written in their books, which said that Christians were to come to this port, and that they would open a well in it, and that when this well was opened there would be no more Moors there. They talked of many other things in similar fitting conversations, the ambassador Mattheus being present at all; and the said friars did great honour to Mattheus, kissing his hand and shoulder, because such is their custom, and he also was much delighted with them. These friars said that they kept eight days after the feast of Easter, and that during that time they did not go on a journey or do any other service, but that as soon as they heard say that Christians were in the port, a thing they so much desired, they had begged leave of their superior to come and make this journey in the service of God; and also that news of our arrival had been taken to the Barnagais; but that he would not leave his house except after the eight days after Easter had passed. The conversation with these friars and their reception having been concluded, the Captain General returned to his galleon with his captains, and the friars with him. These friars[6] were received on board with the cross and priests with surplices, giving them the cross to kiss, which they did with great reverence. They were treated with many conserves which the Captain General ordered to be given them, and much conversation passed with them of joy and pleasure over a matter so much desired on both parts. The said friars departed and went to sleep at Arquiquo.

Cap. iii.—How the Captain General ordered mass to be said in the chief mosque of Maçua, and ordered it to be named St. Mary of the Conception, and how he sent to see the things of the Monastery of Bisam.

On Friday after the Octave of Easter, the thirteenth day of the said month of April, very early in the morning, the said friars returned to the beach, and they sent for them with honour; and the governor with his captains passed over with the friars to the island of Maçua, and he ordered mass to be said in the principal mosque, in honour of the five wounds, as it was Friday. At the end of the mass the Captain General said that the mosque should be named St. Mary of the Conception: from that time forward we said mass every day in the said mosque. At the end of that mass, on betaking ourselves to the ships, some of the friars went with Mattheus, others with the Captain General: to all cloths were given for their clothes, that is to say, stuffs of coarse cotton, for that is the stuff which they wear; they also gave them pieces of silk for the monastery, and some pictures and bells for the same monastery. These friars all carried crosses in their hands, for such is their custom, and the laymen wore small crosses of black wood at their necks. Our people in general bought those crosses which the laymen wore, and brought them with them, because they were novelties to which we were not accustomed. Whilst these friars were[7] going about amongst us, the Captain General ordered a man named Fernan Diaz, who knew Arabic, to go and see the monastery; and for greater authority, and for the matter to be better known for it to be written to the King our sovereign, he sent besides the said Fernan Diaz, the licentiate Pero Gomez Teixeira, auditor of the Indies. These each for their own part said that it was a great and good thing, because we ought to give great thanks and praise to the Lord for that we had come from such distant lands and seas, through so many enemies of our faith, and that we here fell in with Christians with a monastery and houses of prayer where God was served. The said auditor brought from the monastery a parchment book written in their writing,[4] to send to the King our sovereign.

Cap. iv.—How the Captain General and the Barnagais saw each other, and how it was arranged that Rodrigo de Lima should go with Mattheus to Prester John.

On Tuesday, the seventeenth day of the said month of April, the Barnagais came to the town of Arquiquo, and sent a message to the Governor of his having come. As it seemed likely to the governor that he would come to speak to him on the beach, he ordered a tent to be pitched and stuffs to be arranged in the best manner possible, and ordered seats to be made for sitting on. When all was done, a message arrived that the Barnagais would not come there: then the same day Antonio de Saldanha went to this town of Arquiquo to speak to the Barnagais, and he brought a message and agreement that they should meet and see one another midway, and so we all got ready to go with the[8] governor: some by sea and some by land, as far as half way where they were to see one another. There the Governor ordered his tents to be pitched and seats to be made. The Barnagais coming first would not come to the place where the tents were spread and the seats made. The Captain General having landed, and learned that the Barnagais would not come to the tents, ordered them to go with the seats and leave the tents; but still he would not stir with his people to where the seats were placed. The Captain General again sent Antonio de Saldanha and the ambassador Mattheus to him: then they agreed that both should approach each other, that is, the Captain General and the Barnagais. So they did, and they saw each other and spoke in a very wide plain, seated on the ground upon carpets. Among many other things that they talked of, the principal one was that both gave thanks to God for their meeting, the Barnagais saying that they had it written in their books, that Christians from distant lands were to come to that port to join with the people of Prester John, and that they would make a well of water, and that there would be no more Moors there: and since God fulfilled this, that they should affirm and swear friendship. They then took a cross which was there for that purpose, and the Barnagais took it in his hand, and said that he swore on that sign of the cross, and on that on which our Lord Jesus Christ suffered, in the name of Prester John and in his own, that he would always favour and help to favour and assist the men and affairs of the king of Portugal and his captains who came to this port, or to other lands where they might be able to give them assistance and favour, and also that he would take the ambassador Mattheus into his safe keeping, and likewise other ambassadors and people, if the Captain General should wish to send them through the kingdoms and lordships of Prester John. The Captain General swore in like manner to do the same for the affairs of Prester John and the Barnagais, wherever he might meet[9] with them, and that the other captains and lords of the kingdom of Portugal would act likewise. The Captain General gave to the Barnagais arms, clothes, and rich stuffs: and the Barnagais gave the Captain General a horse and a mule, both of great price. So they took leave of each other very joyful and contented, the Captain General to the ships, and the Barnagais to Arquiquo.[5] The Barnagais brought with him quite two hundred horsemen, and more than two thousand men on foot. When our gentlemen and captains saw this novelty which God had so provided, and how a path was opened for aggrandising the holy Catholic faith, where they had small hopes of finding such; because they all held Mattheus to be false and a liar, so that there were grounds for putting him on shore and leaving him alone; many then clamoured and asked favour of the Governor, each man for himself to be allowed to go with Mattheus on an embassy to Prester John, and here they all affirmed by what they saw that Mattheus was a true ambassador. Since many asked for it, it was given to Don Rodrigo de Lima; then the Captain General settled who were to go with him. We were the following: First, Don Rodrigo de Lima, Jorge d’Abreu, Lopo da Gama, Joam Escolar, clerk of the embassy, Joam Gonzalvez, its interpreter and factor, Manoel de Mares, player of organs, Pero Lopez, mestre Joam, Gaspar Pereira, Estevan Palharte, both servants of Don Rodrigo; Joam Fernandez, Lazaro d’Andrade, painter, Alonzo Mendez, and I, unworthy priest, Francisco Alvarez.[6] These went in company[10] with Don Rodrigo; the Captain General here said, in the presence of all: Don Rodrigo, I do not send the father Francisco Alvarez with you, but I send you with him, and do not do anything without his advice. There went with Mattheus three Portuguese, one was named Magalhaēs, another Alvarenga, another Diogo Fernandez.

Cap. v.—Of the goods which the Captain sent to Prester John.

They then prepared the present which was to be sent to the Prester: not such as the King our Sovereign had sent by Duarte Galvan, because that had been dispersed in Cochim by Lopo Soarez: and what we now brought was poor enough, and we took for excuse that the goods which we brought had been lost in the ship St. Antonio, which was lost near Dara in the mouth of the straits. These were the goods which we took to Prester John: first, a gold sword with a rich hilt, four pieces of tapestry, some rich cuirasses, a helmet and two swivel guns, four chambers, some balls, two barrels of powder, a map of the world, some organs. With these we set out from the ships to Arquiquo, where we went to present ourselves to the Barnagais. Thence we went to rest about two crossbow shots distance above the town, in a plain at the foot of a mountain. There they soon sent us a cow, and bread and wine of the country. We waited there because they had to[11] send to us, or give us from the country, riding horses and camels for the baggage. This day was Friday, and because in this country they keep Saturday and Sunday, Saturday for the old law and Sunday for the new, therefore we remained thus both the two days. In these days the ambassador Mattheus settled with Don Rodrigo and with all of us, that we should not go with the Barnagais because he was a great lord, and that we should do much better to go to the monastery of Bisam: and that from that place we should get a better equipment than from the Barnagais. Don Rodrigo, doing this at his wish, sent to tell the Barnagais that we were not going with him, and that we were going to Bisam. And the Barnagais, not grieving on this account, went away and left us. And because our equipment had to be made by his order, they gave us eight horses and no more, and thirty camels for the baggage. So we remained discontented, knowing the mistake we were making in leaving Barnagais to please Mattheus.

Cap. vi.—Of the day that we departed and the fleet went out of the port, and where we went to keep the feast, and of a gentleman who came to us.

We departed from this plain close to the town of Arquiquo, on Monday the thirtieth of April. On this day, as soon as we lost sight of the sea, and those of the sea lost sight of us, the fleet went out of the port, although the Captain General had said he would wait there until he saw our message, and knew in what country we had arrived. And we did not go more than half a league from where we departed from, and then rested at a dry channel, which had no water except in a few little pools. We held the midday rest here on account of the great drought of the land: for further on we should not have water, and the heat was very[12] great. We all carried our gourds, and leather ewers, and waterskins of the country, with water. In this dry river bed there were many trees of different species, amongst which were jujube trees, and other trees without fruit. Whilst we were thus resting at the river bed there came to us a gentleman named Frey Mazqual, which in our tongue means servant of the cross. He in his blackness was a gentleman, and said he was a brother-in-law of the Barnagais, a brother of his wife. Before he reached us he dismounted, because such is their custom, and they esteem it a courtesy. The ambassador Mattheus, hearing of his arrival, said he was a robber, and that he came to rob us and told us to take up arms: and he Mattheus took his sword, and put a helmet on his head. Frey Mazqual, seeing this tumult, sent to ask leave to come up to us. Mattheus was still doubtful, and withal he came up to us like a well born man, well educated, and courteous. This gentleman had a very good led horse and a mule on which he came, and four men on foot.

Cap. vii.—How Mattheus made us leave the road, and travel through the mountain in a dry river bed.

We departed from this resting place all together, with many other people who had been resting there; and this gentleman went with us on his mule, leading his horse: and he approached the ambassador, Don Rodrigo, and caused the interpreter we had with us to approach, and they went for a good distance talking and conversing. He was in his speech, conversation, questions, and answers, a well informed and courteous man, and the ambassador Mattheus could not bear him, saying that he was a robber. And while we were going by a very good wide and flat road, by which were travelling all the people who had[13] rested with us at the rest, and many others who were travelling behind, Mattheus, who was in front, left this road and entered some bushes and hills without any road, and made the camels go that way, and all of us with them, saying that he knew the country better than anyone else, and that we should follow him. When Frey Mazqual saw this he said that we were out of any road, and that he did not know why that man did this. We all began to cry out at him, because he was taking us through the rough ground to lose and break what we carried with us, leaving the highroads, and that we were travelling where the wolves went. Mattheus, perceiving our outcry, and that we were all against him, took a turn, and we went round some mountains to the road, more than two leagues before reaching it. And before we reached it Mattheus had a fainting fit, during which we thought he was dead for more than an hour. When he came to himself we put him on a mule, and two men on each side to assist him. So we went, all accompanying and looking after him, and Frey Mazqual with us, until we arrived at the road, which was a long way off. When we reached it we found a very large cafila of camels and many people who were coming to Arquiquo, because they only travel in cafilas for fear of robbers. These were all amazed at the road we had travelled. We all slept at a hill where there was water and a certain place for cafilas to halt at, and Frey Mazqual also. We all slept, we and the two cafilas keeping good watch all night. From here we set out next morning, always travelling by dry river beds, and on either side very high mountain ridges, with large woods of various kinds of trees, most of them without fruit: for among them are some very large trees which give a fruit which they call tamarinds, like clusters of grapes, which are much prized by the Moors, for they make vinegar with them, and sell them in the markets like dried raisins. The dry channels and road by which we went[14] showed very deep clefts, which are made by the thunder storms: they do not much impede travelling, as they told us, and as we afterwards saw similar ones. All that is necessary is to turn aside and wait for two hours the overflow of the storm, they then set out travelling again. However great these rivers may be with the waters of these storms, as soon as they issue forth from the mountains and reach the plains, they immediately spread out and are absorbed, and do not reach the sea: and we could not learn that any river of Ethiopia enters into the Red sea, all waste away when they come to the flat plains. In these mountains and ridges there are many animals of various kinds, such as lions, elephants, tigers, ounces, wolves, boars, stags, deer,[7] and all other kinds which can be named in the world, except two which I never saw nor heard tell that there are any of them here, bears and rabbits. There are birds of all kinds that can be named, both of those known to us and of those not known, great and small: two kinds of birds I did not see nor hear say that there are, these are magpies and cuckoos; the other herbs of these mountains and rivers are basil and odorous herbs.

Cap. viii.—How Mattheus again took us out of the road, and made us go to the monastery of Bisam.

When it was the hour for resting ourselves, Mattheus was still determined on taking us out of the high road, and taking us to the monastery of Bisam, through mountain ridges and bushes,[8] and we took counsel with frey Mazqual, who told us that the road to the monastery was such that baggage could not go there on men’s backs, and that the road we were leaving was the high road by which travelled[15] the caravans of Christians and Moors, where no one did them any harm, and that still less would they do harm to us who were travelling in the service of God and of Prester John. Nevertheless, we followed the will and fancy of Mattheus. At the halt,[9] where we slept, there were great altercations as to the said travelling, and as to whether we should turn back to the high road which we had left. Seeing this, Mattheus begged of me to entreat the ambassador Don Rodrigo and all the others to be pleased to go to the monastery of Bisam, because it was of great importance to him, and that he would not remain there more than six or seven days (he remained there for ever, for he died there); and that when those seven or eight days were passed, in which he would trade in what belonged to him, we should be welcome to go on our road. At my request all determined to do his wish, since it was important to him, saying that we would remain at a village at the foot of the monastery. We departed from this halt by much more precipitous ground and channels than those of the day before, and larger woods. We on foot and the mules unridden in front of us, we could not travel; the camels shrieked as though sin was laying hold of them. It seemed to all that Mattheus was bringing us here to kill us; and all turned upon me because I had done it. There was nothing for it but to call on God, for sins were going about in those woods: at midday the wild animals were innumerable and had little fear of people. Withal we went forward, and began to meet with country people who kept fields of Indian corn, and who come from a distance to sow these lands and rocky ridges which are among these mountains: there are also in these parts very beautiful flocks, such as cows and goats. The people that we found here are almost naked, so that all they had showed, and they were very black. These people were Christians, and the women[16] wore a little more covering, but it was very little. Going a little further in another forest which we could not pass on foot, and the camels unladen, there came to us six or seven friars of the monastery of Bisam, among whom were four or five very old men, and one more so than all the rest, to whom all showed great reverence, kissing his hand. We did the same, because Mattheus told us that he was a bishop; afterwards we learned that he was not a bishop, but his title was David, which means guardian, and besides, in the monastery there is another above him, whom they call Abba, which means father: and this father is like a provincial. From their age and from their being thin and dry like wood, they appear to be men of holy life. They go into the forests collecting their millet, both that grown by their own labour, and the produce of the dues paid to them by those who sow in these mountains and forests. The clothes which they wear are old yellow cotton stuffs, and they go barefooted. From this place we went forward until the camels had taken rest, and in the space of a quarter of a league we arrived at the foot of a tree with all our baggage, and Mattheus with his, and frey Mazqual with us, also the friars, particularly the old ones, were there with us: and the oldest, whom Mattheus called a Bishop, gave us a cow, which we at once killed for supper. We were here in doubt by what way we could get out, and as there was no help for it we all slept here together, ambassadors, friars and frey Mazqual, ready to start.

Cap. ix.—How we said mass here, and Frey Mazqual separated from us, and we went to a monastery where our people fell sick.

The following day was Holy Cross of May; we said mass at the foot of a tree in honour of the true cross, that it might please to direct us well, entreating our Portuguese to[17] make this petition with much devotion to our Lord, that like as He had opened a way to Saint Helena to find it, so He would open a road for our salvation which we saw to be so closed up. Mass being ended we dined, and the ambassador Mattheus ordered his baggage to be loaded on the backs of negroes, and taken to a small monastery which was half a league from where we were, and they name the patron of it St. Michael, and they call the site of the monastery Dise. Joam Escolar, the clerk of the Embassy, and I, went with this baggage on foot, as it was not ground or a road fit for mules. We went to see what country it was there, and whether we should go to that monastery, or whether we should turn back. Here frey Mazqual departed from us. With the journey we made, the clerk and I, we were almost dead when we arrived at the monastery, both from the precipitous path and steep ascent, and the great heat. After having taken rest, and seen the said monastery, and seen that it had buildings in which to lodge our goods, and ourselves also, the clerk returned to the company, and I remained at the monastery. On the following day, fourth of May, all our people came with the goods we were bringing with us, and which had remained at the foot of this mountain, all being carried on the backs of negroes. And on the night on which our people remained and slept there, Satan did not cease from weaving his wiles, and caused strife to arise among our people, and this on account of the ambassador’s carrying out that which he had to do, and ought to do for the service of God and the King, and for the safety of our lives and honour: and one said that there were men in the company who were not going to do all that seemed fit to him, upon this they came to using their spears. God be praised that no one was wounded. As soon as we were all at the monastery I made them good friends, blaming them for using such words, since he was our captain, and that which was for the service of God and[18] the King was an advantage to us all, and that we ought not to do anything without mature deliberation. We lodged in this monastery of St. Michael under the impression that we should depart at the end of seven or eight days, as Mattheus had said, and they gave us very good lodgings. Upon this Mattheus came and told us that he had written to the court of Prester John, and to Queen Helena, and to the patriarch, and that the answer could not come in less than forty days, and that we could not depart without this answer, because from there mules had to be sent for us and for the baggage. And he did not stop at this, but went on to say that the winter was beginning, which would last three months, and that we could not travel during that time, and that we should buy provisions for the winter. Besides, he said that we should wait for the Bishop of Bisam, who was coming from the court, and that he would give us equipment. This one that he called Bishop is not one, but is the Abba or provincial of Bisam. In this matter of the winter, and the coming of this provincial, the friars of this monastery concerted with Mattheus, and they did not lie, for nobody in this country travels for three months, that is, from the middle of June, July, August, to middle of September, and the winter is general: also as to the coming of him they called Bishop, he did not delay much. A few days after our arrival the people fell sick, both the Portuguese and also our slaves, few or none remained who were not affected, and many in danger of death from much bloodletting and purging. Among the first mestre Joam fell sick, and we had no other remedy. The Lord was pleased that purging and bloodletting came to him of itself, and he regained his health. After that the sickness attacked others with all its force, among them the ambassador Mattheus fell sick, and many remedies were used for him. And thinking that he was already well, and as though delighted and pleased, he ordered his baggage to be got ready and sent to a village of[19] Bisam named Jangargara, which is half way between this monastery and Bisam. In that village are friars of the said monastery, who keep their cows there, and there are many good houses in it. He had his baggage taken there, and went with it, and two days after his arrival he sent to call the mestre, for he had fallen ill again. He left all the sick people and went, and we did not wait long after him, the ambassador, Don Rodrigo, and I, but went to visit him, and we found him very suffering. Don Rodrigo returned, and I remained with him three days, and I confessed him and gave him the sacraments, and at the end of the three days he died, on the 23rd of May 1520; and he made his will in the Portuguese language by means of mestre Francisco Gonzalves, his spiritual father, and also in the Abyssinian language by a friar of the said monastery. As soon as he was dead there came thither at once the ambassador, and Jorge d’Abreu, and Joam Escolar the clerk, and a great number of the friars of Bisam. We took him with great honour to bury him at the said monastery, and did the office for the dead after our custom, and the friars after their custom. In the same night that Mattheus died, Pereira, servant of Don Rodrigo, died. When the burial of Mattheus was done, the ambassador, Don Rodrigo, and Jorge d’Abreu, and Joam Escolar, clerk, and certain friars of the monastery, returned to the village where Mattheus died, and where his goods remained. And it was intended to make an inventory of his goods, in order that they should be correctly sent to the person whom he named, by Francisco Mattheus, his servant, whom the King of Portugal, our Sovereign, had given him and had set free, because before he was a Moorish slave, and the goods were in his keeping. The said Francisco Mattheus took it into his head not to choose that the inventory should be made: and the friars for their part hoping to get a share of the goods. Seeing this, Don Rodrigo left them to their devices and came away in peace;[20] and Francisco Mattheus and the friars took these goods to the monastery of Bisam, and thence sent them to the court of the Prester for them to be given to the Queen Helena, to whom he, Mattheus, ordered them to be given.

Cap. x.—How Don Rodrigo sent to ask the Barnagais for equipment for his departure.

As we were thus without any remedy, and had been waiting for a month and no message came, and we did not know what to do, and Mattheus having died, we determined on sending to ask the Barnagais to send us some equipment for our departure, so that we might not remain here for our destruction. Knowing this the friars grieved much at it, and pressed Don Rodrigo not to send, and to wait for the arrival of the said provincial, as he would be at the monastery within ten days, and that if he did not come that they would provide the means for our departure. And because these people are unconfiding they would not trust in the ambassador, although he had promised it them; and they took an oath from all of us on a crucifix that we would wait for the said ten days, and they also swore to fulfil that which they had promised. And in order that we might not be disappointed on one side or the other, or in case both should take effect, we might choose the best, Don Rodrigo arranged to send Joam Gonzalves, interpreter and factor, and Manoel de Mares and two other Portuguese to the Barnagais to ask him to remember the oath which he swore and promised to the Captain General of the King of Portugal, which was to favour and take into his keeping the affairs of the King, and to be pleased to give us an equipment for our travelling. When the ten days were ended the factor sent one of the Portuguese that went with him with a good message, and with him came a man from[21] the Barnagais saying that he came to give us oxen for the baggage and mules for ourselves. On the part of the friars nothing came.

Cap. xi.—Of the fashion and situation of the monasteries and their customs, first this of St. Michael.