Title: Partakers of plenty

A study of the first Thanksgiving

Author: James Deetz

Jay Anderson

Release date: January 5, 2024 [eBook #72628]

Language: English

Original publication: Plymouth, Mass: Plimoth Plantation, 1972

Credits: Bob Taylor, Steve Mattern and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

James Deetz and Jay Anderson

This article is printed with the permission of the

Saturday Review of Science and was previously published

under the title of “The Ethnogastronomy of Thanksgiving”

in the November 25, 1972 issue of the

Saturday Review of Science

[Pg 1]

PARTAKERS OF PLENTY

A Study of the First Thanksgiving

“Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors. The four in one day killed as much fowl as, with a little help beside, served the company almost a week. At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain and others. And although it be not always so plentiful as it was at this time with us, yet by the goodness of God, we are so far from want that we often wish you partakers of our plenty.”

So wrote Pilgrim Edward Winslow to a friend in England shortly after the colonists of New Plymouth celebrated their first successful harvest. This brief passage is the only eyewitness description of the events that were to become the basis of a uniquely American holiday: Thanksgiving. As with so many of the facts of the Pilgrims’ first years in America, this occasion has become so imbued with tradition that it is difficult to place it in the perspective it occupied in Winslow’s eyes. Indeed, any reference to giving thanks is notably missing from Winslow’s description. What took place on that fall day some three-and-a-half centuries ago is best understood as the first harvest festival held on American soil, the acting out of an institution of great antiquity in the England the Pilgrims had left behind. It was a time of joy, celebration, and carousing, far removed from any suggestion of solemn religious concern. To appreciate just what it meant to those Englishmen, we must know who they were and what they had endured in the year prior to that first harvest of 1621.

The one hundred and one emigrants who crowded aboard the Mayflower in the fall of 1620 were a mixed lot. Thirty-five[Pg 2] of them were religious dissenters who had known years of persecution, flight, and exile. Another sixty-six were added to the group by its financial backers to bring their total number to a level deemed sufficient to establish a colony in the New World. Whether a non-dissenting cooper like John Alden or a religious leader like William Brewster, each member of the tiny band carried the mark of English culture as it was on the eve of the Renaissance. Save for the higher social classes, which were not represented in the group, the English people of the time were products of a medieval world whose legacy was still felt in the first years of the seventeenth century. It is easy to forget that 1620 is further removed in time from the American Revolution than it is from Columbus’ discovery of the New World in 1492. So it was that the church members—“saints,” as they styled themselves—carried the strong tradition of East Anglican yeoman culture to the New World, its peasant customs deeply rooted in the soil and its bounty. The others in the group—called “strangers” by William Bradford—were a more heterogeneous lot, many coming from the urban world of London, others from the countryside. As a group they were to create a culture in New England that bore unmistakable traces of the Middle Ages, whether it be in dress style, the arrangement of their community, their theology, or their social institutions.

From the start events seemed to conspire against the Pilgrims as they prepared to depart from England. They were originally scheduled to sail in late summer on two ships, but difficulties with one of them resulted in their being crowded aboard the Mayflower, which finally put to sea in mid-September. The crossing itself was, for that time, successful; only one of the company perished. (Just two years before, another group of 180 dissenters had attempted to reach Virginia from Amsterdam; only forty-nine survived.) After sixty-six days at sea land was sighted off Cape Cod, and the weary band, much buffeted by ocean[Pg 3] storms, must have indeed been glad to have arrived. But by then the year was old, and there was no hope of acquiring adequate sustenance from the land in the coming months.

After some preliminary explorations of the Cape, a site for a settlement was finally selected in what had been an extensive Indian cornfield some years in the past. Evidence of the Indians’ former presence was everywhere. Exploring Cape Cod on foot, the Pilgrims discovered and excavated an Indian grave and entered an abandoned Indian encampment, where they found buried corn caches, some of which they appropriated. Later they would repay the Indians for the corn they had taken on that cold November day. But they had only one encounter with living Indians at that time, which was hostile and involved an exchange of shots for arrows; no one was injured in the incident. Had the Pilgrims known the situation, there would have been less concern about the Indians than they must have felt. Three years earlier the Indian population of the New England coast had been ravaged by some European disease, and as much as three-fourths of the population had perished. The Pilgrims were to have no further confrontations with the Indians until the following spring, and their next one was to be dramatically different.

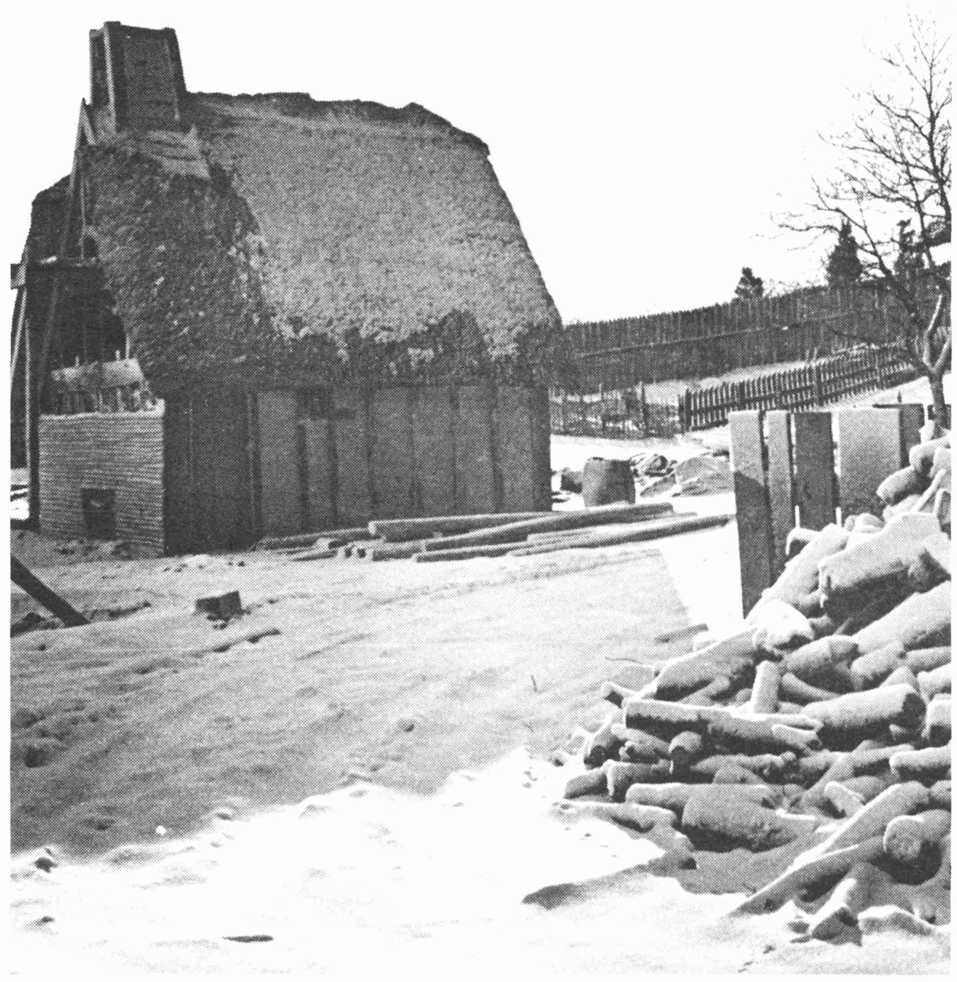

Their first year in the New World started badly. Upon arrival there had been rumblings of dissension from the “strangers” in the company, and anarchy seemed a real threat. This problem was met by framing the famous Mayflower Compact, which established a participatory form of government for the settlers. But even if all had been harmonious among the people, the physical hardships of establishing a colony were genuine and disturbing: using the Mayflower as a base of operations, work parties went ashore daily, constructing a common house and a platform for their guns, laying out house lots, and scavenging food supplies. Slowly, as the winter wore on, a small town began[Pg 4] to grow on shore. The work was done under physical hardship, coupled with the latent threat from Indians, who appeared from time to time in the distance but never came close enough to engage in conversation. At other times smoke from the fires of unseen people appeared in the distance.

As the tiny town grew, its population declined. William Bradford’s account of the winter’s sickness lends a sense of immediacy to what must have been a terrible time:

“So as there died some times two or three of a day in the foresaid time, that of 100 and odd persons, scarce fifty remained. And of these, in the time of most distress, there was but six or seven sound persons who to their great commendations, be it spoken, spared no pains night nor day, but with abundance of toil and hazard of their own health, fetched them wood, made them fires, dressed them meat, made their beds, washed their loathsome clothes, clothed and unclothed them. In a word, did all the homely and necessary offices for them which dainty and queasy stomachs cannot endure to hear named....”

Just how hungry the Pilgrims were during these trying times is less clear. Provisions had been moved ashore from the ship and stored in the common house. That these were not ample for the group is suggested by numerous references in their journal to the other foods they acquired—on one occasion they killed an eagle, ate it, and said that it was remarkably like mutton. The appearance of a single herring on the shore in January raised hopes of more, but they “got but one cod; [they] wanted small hooks,” and this was eaten by the master of the ship “to his supper.” In at least one case they found themselves in competition with both Indians and wild animals: “He[Pg 5] found also a good deer killed; the savages had cut off the horns, and a wolf was eating of him; how he came there we could not conceive.” But it would seem that, while food was never plentiful, actual starvation was held at bay. Yet if death was a constant companion, hunger was almost certainly a regular visitor to them.

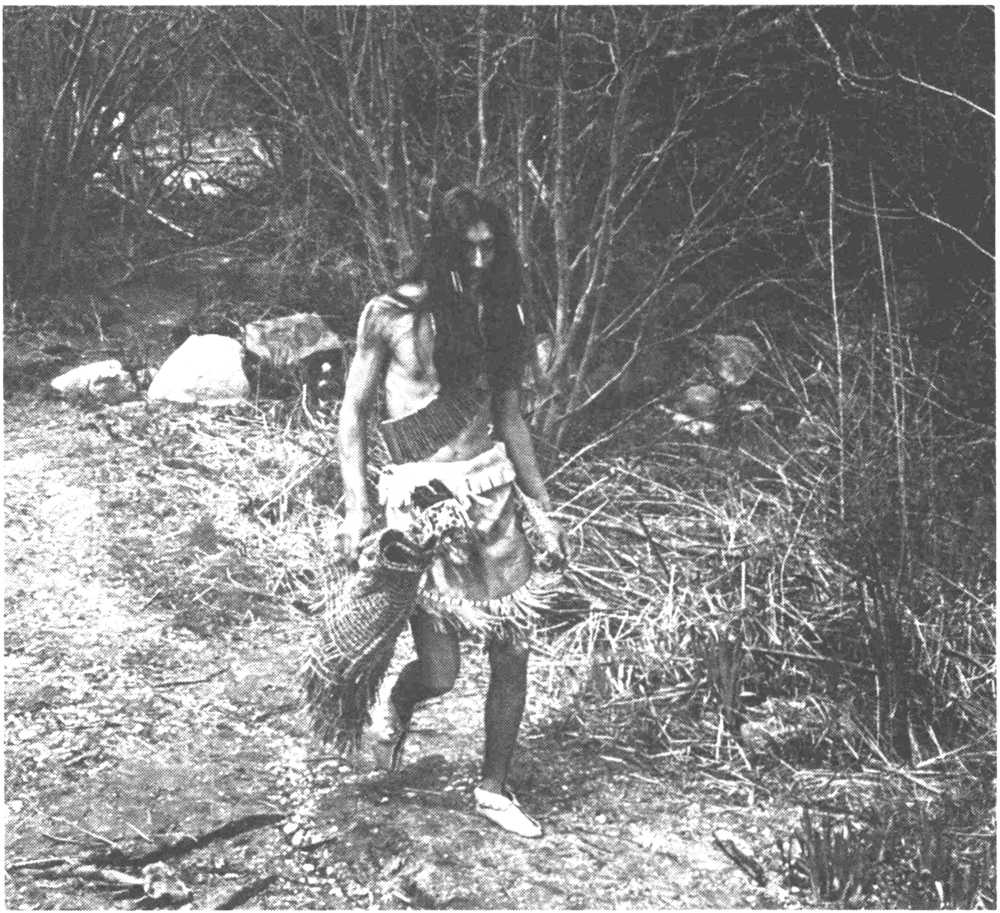

The winter gave way to the warming sun, and on March 3, 1621, “the wind was south, the morning misty, but towards noon warm and fair weather; the birds sang in the woods most pleasantly.” With the coming of spring, there was a welling up of hope. On March 16 a remarkable thing occurred:

“... there presented himself a savage, which caused an alarm. He very boldly came all alone and along the houses straight to the rendezvous, where we intercepted him, not suffering him to go in, as undoubtedly he would, out of boldness. He saluted us in English and bade us welcome....”

The appearance of an English-speaking Indian was truly a source of wonder to the Pilgrims; indeed, it was thought to be providential.

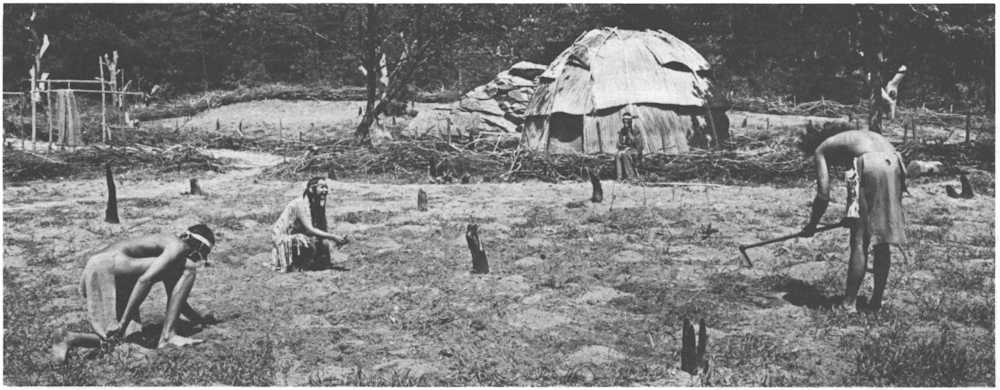

This first Indian to come among the Englishmen was Samoset, whose home was in Maine. He told the Pilgrims of yet another English-speaking Indian, Squanto by name, who had more fluency in the language than he. Small wonder that he did, for Squanto had been kidnapped by one Thomas Hunt in 1614, sold into slavery in Spain only to escape to England, where he found a home with the treasurer of the Newfoundland Company. He made at least one round trip to America and back before returning again in 1618; jumping ship, he made his way back to his home at Plymouth only to find that his people had been wiped out by the disease of the year before. The role of these two Indians in the first years of the Pilgrims’ life in America was immense. Before March had run its course, they had arranged a meeting between the English and Massasoit, the chief of the local Wampanoags, which resulted in the concluding of a treaty of peace and mutual assistance. It was Squanto who instructed the Pilgrims in the ways of planting corn with herring taken from the local brooks where they ran thick in the spring. This first corn crop was to assume a critical role in their life before the year was out.

The Pilgrims were genuinely surprised that the Indians wished to live at peace with them. Their reasons for doing so were doubtless complex. In the first place they were not the fearsome people the Pilgrims had been led to believe inhabited the land. The history of European-Indian relations before the coming of the Pilgrims is marked by trust and friendliness on the Indians’ part, all too often betrayed. Yet, although stories of the Europeans’ actions had circulated among the Indians over all of northeastern North America, it seems that not all Indians were ready to believe the worst. But there was more to it than that. The epidemic of 1617 had upset the balance of power that had prevailed among the native American population for years. The Indians who had suffered most were those along the coast, where the disease had had its most drastic effect. Not far inland were Narragansets and further west Pequots, neither of whom had felt its effects. It would be[Pg 6] insulting to the intelligence of Massasoit and his Wampanoags to believe that they did not perceive the advantage English allies would give them in opposition to their western neighbors. In the words of one of the Pilgrim chroniclers of the time:

“We cannot yet conceive but that he [Massasoit] is willing to have peace with us, for they have seen our people sometimes alone two or three in the woods at work and fowling, when as they offered them no harm as they might easily have done, and especially because he hath a potent adversary the Narragansets, that are at war with him, against whom he thinks we may be some strength to him, for our pieces are terrible unto them.”

And so it was that by the late spring of 1621 the surviving fifty Pilgrims had cause to hope. Their fears of conflict with the Indians had been at least temporarily calmed. Eleven houses had been built along a narrow street. Hardly well appointed, they were sturdy structures built in the timber-framed tradition of their homeland and afforded shelter and comfort to the small band. The sickness had passed, and judging from what William Bradford was to write years later, the food supply did not present a critical problem. By the summer of 1621, nature was favoring the Pilgrims with wild foodstuffs:

“... others were exercised in fishing, about cod and bass and other fish, of which they took good store, of which every family had their portion. All the summer there was no want.... And besides waterfowl there was a great store of wild turkey, of which they took many, besides venison, etc. Besides they had about a peck of meal a week to a person....”

The meal could only have been the remains of the stores brought on the Mayflower, for Bradford added, “or now since harvest, Indian corn to that proportion.” But with the memory of the past winter painfully fresh, the Pilgrims could ill afford to rest and rely on providence to supply them. It was critical that they produce a crop to insure an adequate surplus for the coming winter. To this end they planted their fields with a mixture of English and[Pg 7] Indian crops. Twenty acres were put into Indian corn, after the planting advice tendered by Squanto, and also some six acres of peas and barley. As the summer progressed, the troubles that had earlier dogged the company seemed to threaten a return. The barley failed to measure up to expectations. Worse, the peas were a total disaster. “They came up very well, and blossomed, but the sun parched them in the blossom.”

After the total failure of July’s pea crop and the disappointment with August’s “indifferent good barley,” the Pilgrims faced a real threat of starvation. This may at first seem strange, considering their assessment of wild foods:

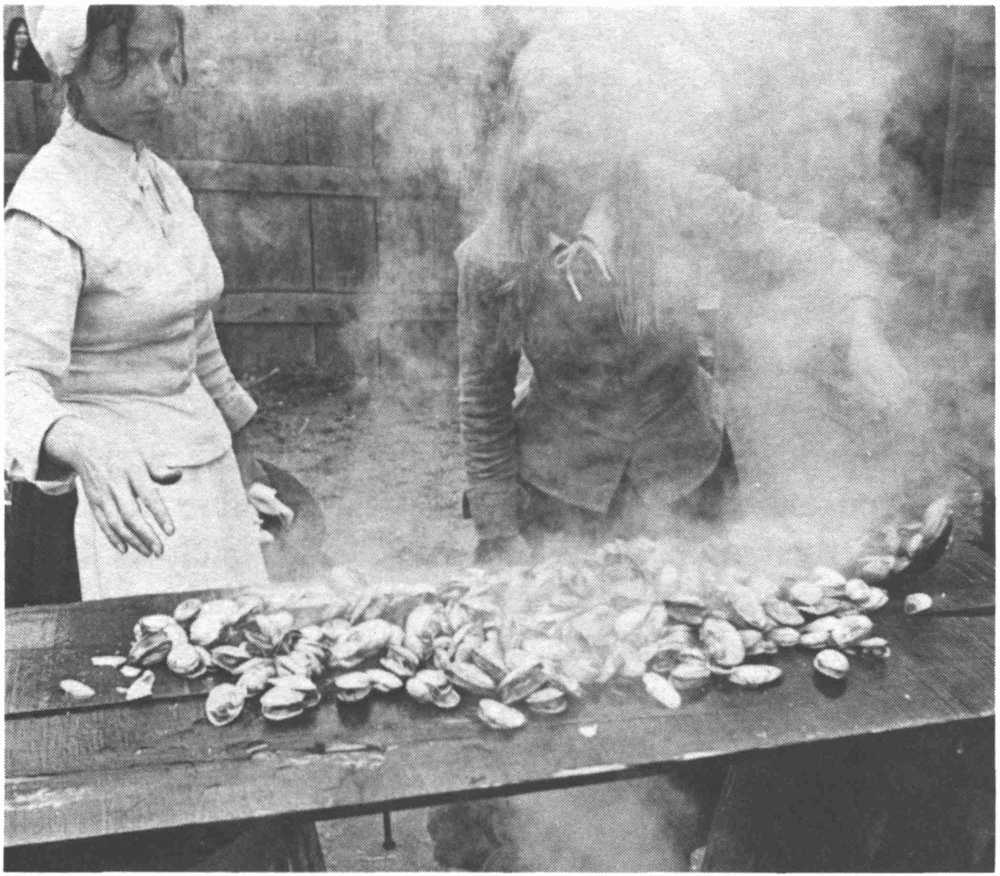

“For fish and fowl, we have great abundance; fresh cod in the summer is but coarse meat with us; our bay is full of lobsters all the summer and affordeth variety of other fish; in September we can take a hogshead of eels in a night, with small labor, and can dig them out of their beds all the winter. We have mussels ... all the earth sendeth forth naturally very good sallet herbs. Here are grapes, white and red, and very sweet and strong also. Strawberries, gooseberries, raspas, etc. Plums of three sorts, with black and red, being almost as good as damson....”

However, none of these foods are high in energy, and the typical English farmer was accustomed to a diet that gave him almost six thousand calories a day. To get these calories, he ate a normal daily diet of one pound of meal or peas cooked up in a porridge, pudding, or bread, over a pound of butter and cheese, and a full gallon of strong, dark ale. Some dried or corned meat and fish were also eaten but usually only in small amounts—quarter pound a day. The Englishmen in the 1620s certainly did not live on flesh alone. William Bradford, for example, described a season of semistarvation, when “the best they could present their friends with was a lobster or a piece of fish without bread or anything else but a cup of fair spring water.” Simply to meet his daily caloric needs, a Pilgrim would have to eat a twenty-pound lobster at breakfast, lunch and supper. As they lacked dairy cows in 1621 and their peas and barley were insufficient, their survival hinged on the Indian corn. If this crop failed, so would the pilgrimage.

[Pg 8]

It did not fail. In October twenty acres of corn, laboriously planted and manured with shads in the Indian manner, ripened beautifully. Describing this bounty, Winslow religiously acknowledged in Puritan fashion that “our corn [grain] did prove well, and, God be praised, we had a good increase of Indian corn....” Thus, the corn yield was unexpectedly high. Each Pilgrim could look forward to two pounds of corn meal every day.

It might have seemed appropriate for the Pilgrims to formalize their thanks to God with a solemn day of thanksgiving. Instead, they opted for an older mode of thanksgiving known as Harvest Home. Most of them as boys had experienced the secular revelry of Harvest Home, when, after the main grain crop was ingathered, it was cakes and ale and hang the cost. Earlier in the sixteenth century it had been so rowdy during harvest time that Henry VIII had attacked the numerous feasts that prevented farmers from “taking the opportunity of good and serene weather offered upon the same in time of harvest.” So by the late 1500s the holiday was begun only after the harvest was safely home. Then came day after day of revelry, sports and feasts. As Thomas Tusser, the Elizabethan farmer-poet, described it:

Why the Pilgrims selected Harvest Home over a solemn day of thanksgiving is not clear. Perhaps, after their long urban exile in Leyden, Holland, they needed to reassure themselves that they were still capable farmers. Harvest Home, the most important of the rural festivals, was a natural symbol of their success.

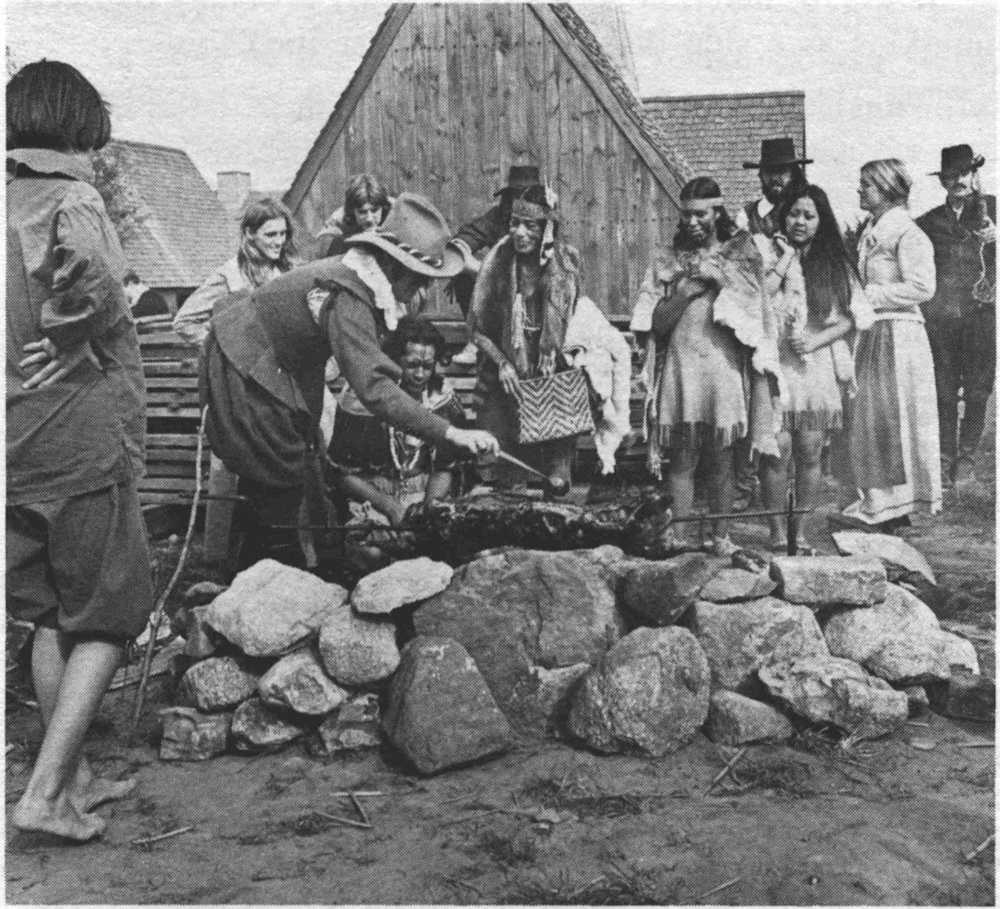

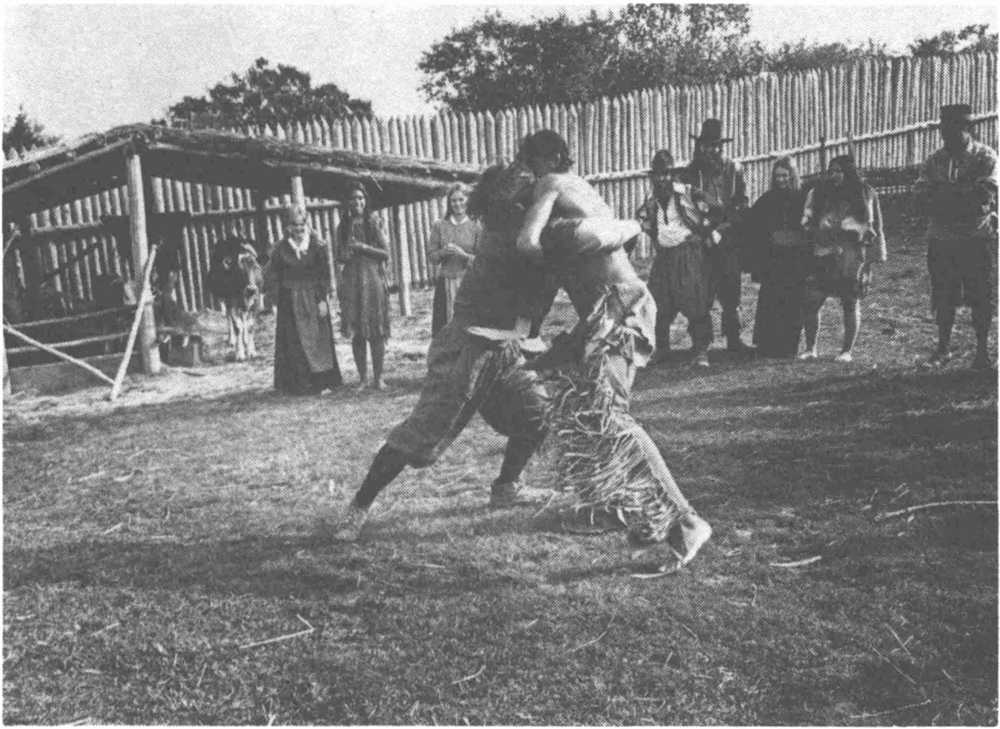

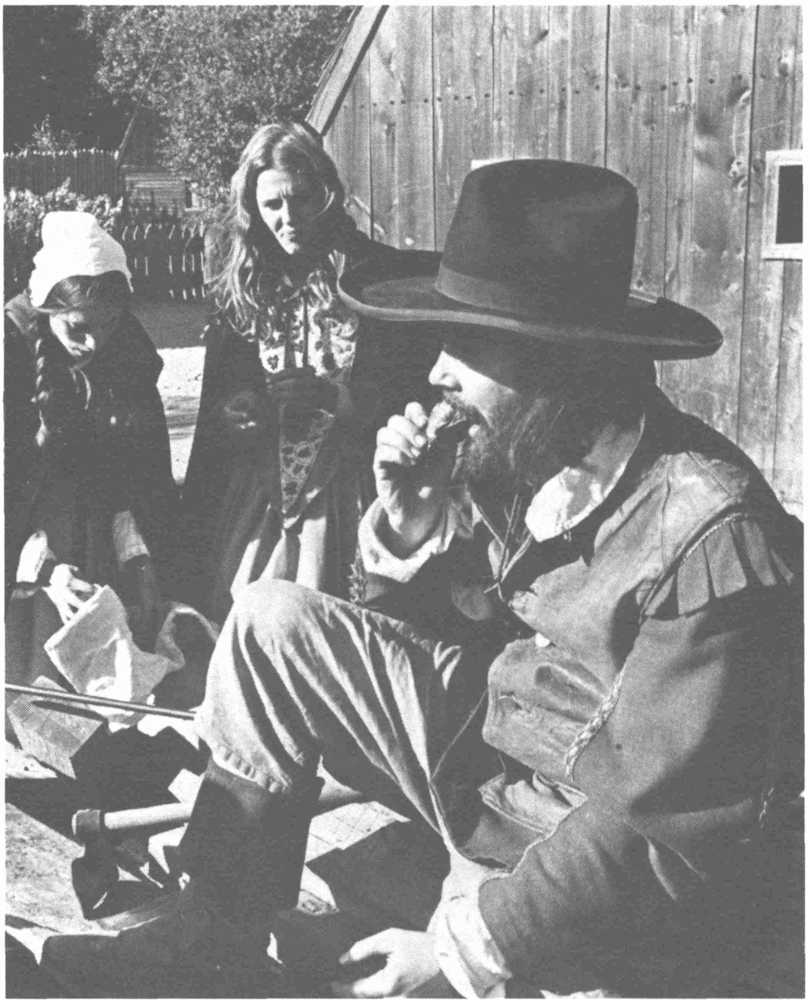

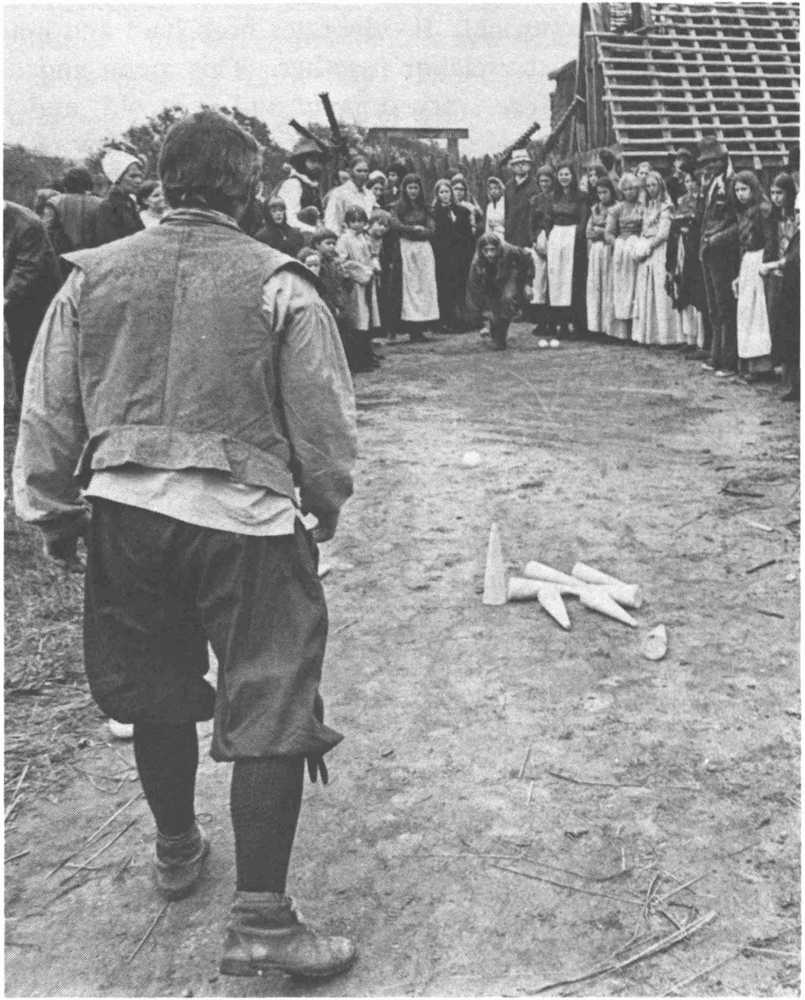

Plymouth’s Harvest Home conformed in most essentials to its English prototype. It was, for example, deliberately long. William Bradford, the governor, began the holiday when he sent out four of the best hunters for fresh meat.[Pg 9] They returned that evening with enough fowl—geese, ducks, and possibly turkeys—to last a week. During this period there were various traditional “recreations,” one of which was parading of sorts. In England villagers customarily marched through the fields of stubble, singing the old harvest songs, waving handfuls of grain often plaited into kern or corn dolls. The men would then demonstrate their prowess with firearms or longbows. When Winslow writes, “... amongst other recreations; we exercised our arms,” he is referring to customs like these. It is doubtful that any kern dolls were fashioned at Plymouth; Puritans did not take kindly to graven images of the Mother Earth or Mary sort. But they had muskets and fowling pieces, and under the command of Miles Standish, a professional soldier, they acquired some of the noisier martial skills. Harvest Home gave them a chance to demonstrate these to each other and to Massasoit’s Indians. The turkey shoot held in many rural communities before Thanksgiving is a modern survival of this harvest custom. Another traditional recreation was athletics. Englishmen were serious sportsmen. King James had even issued a Book of Sports in 1618, which enumerated those “lawfulsports” like “archery for men, leaping, vaulting, or any other such harmless recreation ...” suitable for playing after church. Puritans were not against sports as such, but they were against them on religious holidays; the Sabbath was not made for sporting. For example, on Christmas Day, 1621, William Bradford chided some of the newer settlers in Plymouth for playing “stool ball” (an ancestor of cricket) and “pitching the bar” (weight throwing):

“... he went to them and took away their implements and told them that was against his conscience, that they should play and others work. If they made the keeping of it [Christmas] a matter of devotion, let them keep their houses; but there should be no gaming or reveling in the streets.”

Since Harvest Home was not a religious day, it provided an ideal context for sports.

But by far the most important recreation was feasting. In fact, to Elizabethans the word recreation itself primarily meant enjoying a leisurely, well-prepared meal and so re-creating or renewing mind and body. Farmers were[Pg 10] instructed that at “the feastes that belong to the plough, the meaning is onely to joy and be glad for comfort with labour would sometimes be had.” And there is every reason to believe they were joyful and relaxed. One of the best observers of Elizabethan England wrote:

“Both artificer [craftsman] and husbandman [farmer] are sufficiently liberal and very friendly at their tables; and when they meet they are so merry without malice and plain without inward Italian or French craft and sublety, that it would do a man good to be in company among them ... the inferior sort are somewhat to be blamed that being thus assembled talk is now and then such as savoreth of scurrility and ribaldry, a thing naturally incident to carters and clowns.”

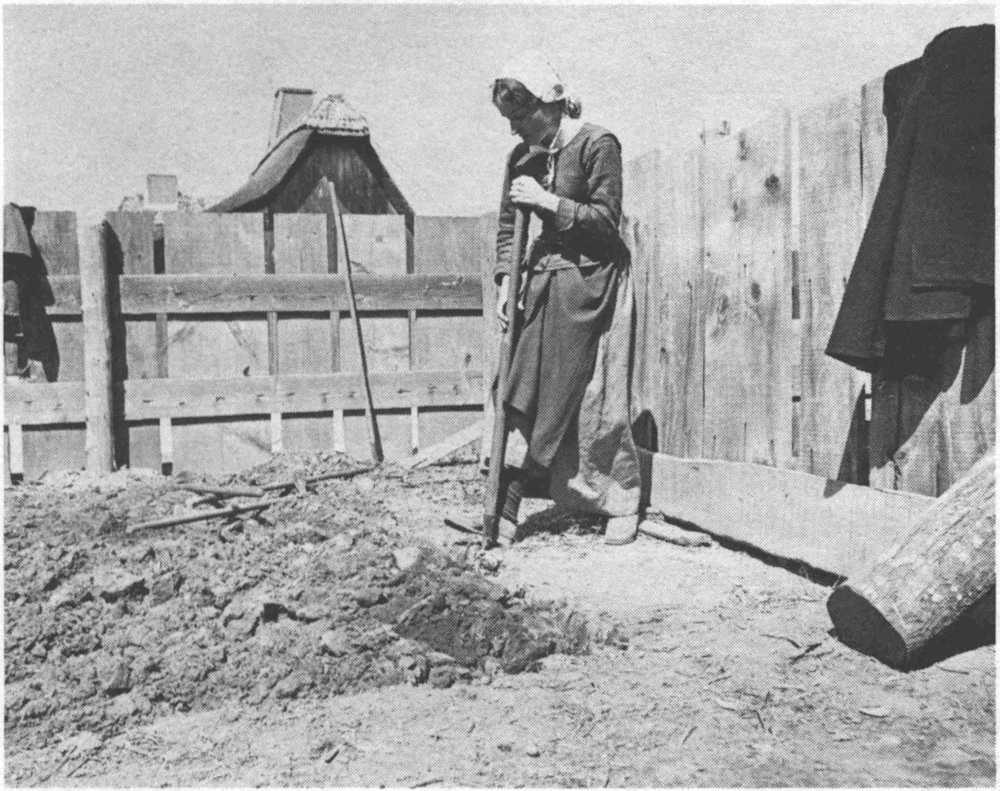

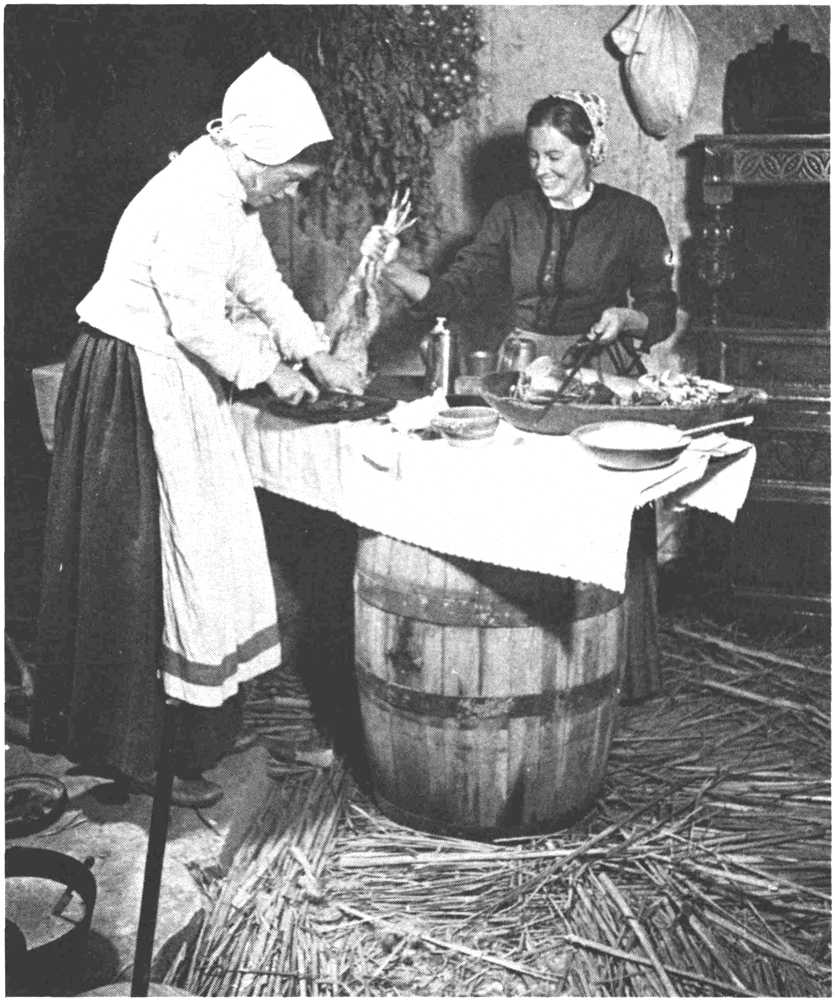

Preparing the feast, however, was seldom so leisurely for the housewife and her daughters. After a month of cooking and carting meals for half a dozen men famished from working nearly twenty hours a day (and frequently being called on to join them in the fields when rains threatened), the housewife was required to set forth

“a humble feast, of an ordinary proportion which any good man may keep in his family, for the entertainment of his true and worthy friends ... that is, dishes of meat that are of substance, and not empty, or for show; and of these sixteen is a good proportion both [for your] first and second and third course....”

This “humble” smorgasbord, totaling forty-eight dishes, from the first popular English cookbook, Gervase Markham’s The English Huswife (1623), was for the housewife more ideal than real. The typical harvest feast was more modest. A Yorkshire farmer, Henry Best, wrote that

“it is usual, in most places, after they get all the pease pulled or the last grain down, to invite all the workfolks and their wives (that helped them that harvest) to supper, and then they have puddings, bacon, or boiled beef, flesh or apple pies, and then cream brought in platters, and every one a spoon; then after all they have hot cakes and ale; for they bake cakes and send for ale against that time.”

[Pg 11]

In communities where labor was pooled at harvest and families helped each other, there would be a round of these meals—in form and function similar to small parish tureen suppers today except that one hostess at a time would assume overall responsibility, excepting neighborly help from other wives.

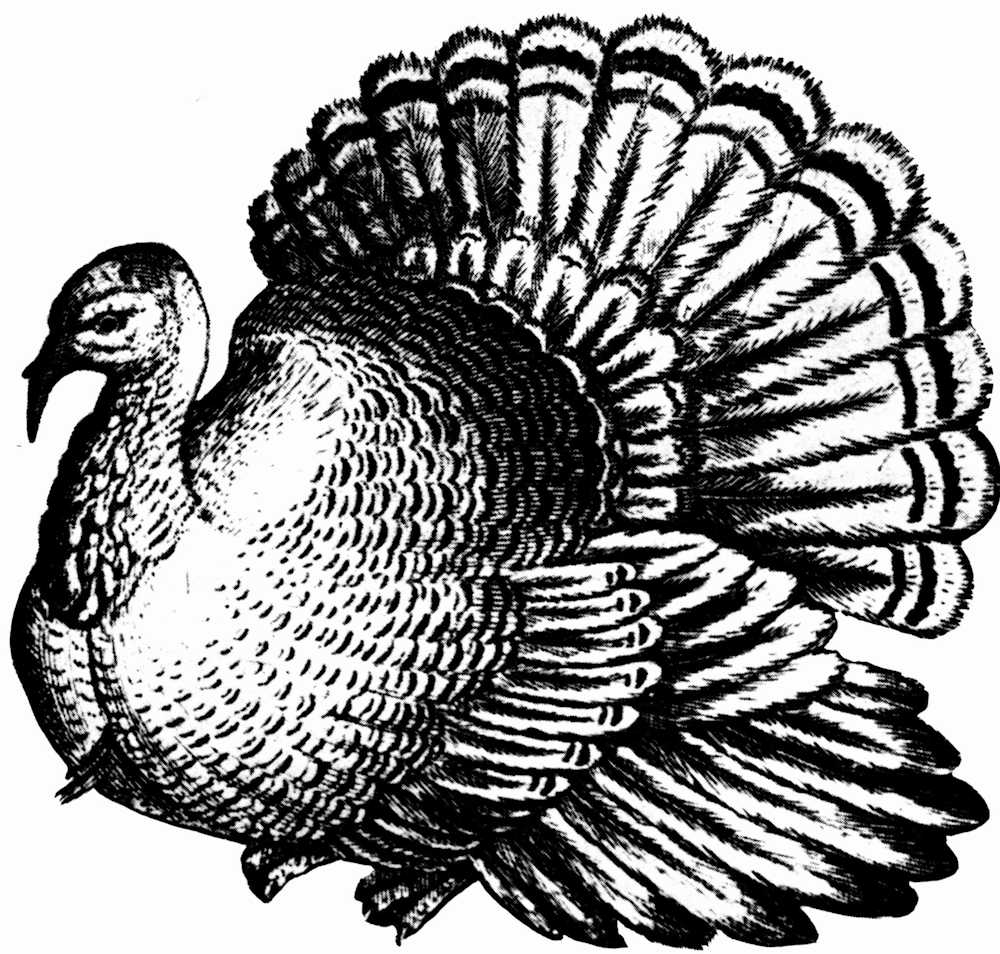

The atmosphere at Plymouth’s Harvest Home feast was similarly warm and close. A year of privation, culminating in the death of half of the community, had pulled the rest together. Communal farming was adopted—cooperation legalized. By breaking bread together in the open, they sanctified in a robust, secular way their communion. The familiar scene to which we have been accustomed, of Pilgrims and Indians feasting together while seated at tables in the open, is mostly a creation of later artists. It is doubtful that there were enough tables to accommodate even a tenth of the number who were celebrating. It is more likely that food was taken, not at an appointed time and place, but at frequent intervals throughout the time of the festival. Seating was almost certainly on the ground for the most part. Lacking forks, which did not appear in Plymouth until a century later, food was taken with fingers, from the tips of knives, and with spoons. Wooden trenchers (small shallow dishes) were probably much in evidence, while other foodstuffs could have been consumed directly from large kettles, or, in the case of meat, eaten with the hands, hot from the roasting fire. Far from the formality of a single meal taken together, the consumption of food at Plymouth’s first Harvest Home was but one event that mixed with the gaming and “exercising of arms” in one happy blend.

What did they eat? Essentially the yeoman fare noted by Henry Best but with some intriguing American additions. Fresh meat was rare in the farmer’s everyday diet, but feasts featured it. The traditional meat was a young, lean goose. Tusser warned that despite

[Pg 12]

In England it would have been a domesticated bird, fattened on the grain stubble. In Plymouth it was a wild one, part of the large haul of fowl that Winslow mentions. William Bradford remembered many years later not only these waterfowl but also a “great store of wild turkeys.” These would certainly have been eaten, and with relish, but roast goose constituted the feast’s foundation. Englishmen preferred its flavor and housewives the ease with which it could be roasted.

The “flesh” pies Best referred to would have in England been filled with old chicken, hare, or pigeon meat, tenderized by hours of simmering and then baking. Plymouth, however, had a spectacular substitute: venison. This was the Elizabethan’s chief culinary status symbol, seldom eaten by ordinary farmers but continually craved. Kept in deer parks by the gentry, “... venison in England [was] neither bought nor sold, as in other countries, but maintained only for the pleasure of the owner and his friends.” The five deer donated by Massasoit were a great luxury. Served up in corn-meal venison “pasties,” they gave the feast an aristocratic aura the Plymouth farmers could never have foreseen, not having the guns or skills necessary to bring down a deer regularly. Ironically, venison soon became a symbol to Englishmen of New England’s natural bounty. A more realistic choice would have been the ducks and geese, which they could and did bring down in droves with their fowling pieces.

Pudding was the Harvest Home’s most typical dish, composed as it was of the cereals and fruits that had just been ingathered. A special harvest version called frumenty (or furmenty) became synonymous with the harvest feast itself and elicited the lines, “The furmenty pot welcomes home the harvestcart.” John Josselyn, a later visitor to New England, described a New England furmenty made [Pg 14]with a variety of oats brought over from East Anglia by the Puritans (although whole-grain wheat, barley, or corn were just as suitable):

“They dry it in an oven, or in a pan upon the fire, then beat it small in a mortar ... they put into a bottle [two quarts] of milk about ten or twelve spoonsfuls of this meal, so boil it leisurely stirring of it every foot, lest it burn too; when it is almost boiled enough, they hand the kettle up higher and let it stew only, in short time it will thicken like a custard; they season it with a little sugar and spice, and so serve it to the table in deep basons.”

It was an expensive dish. To make up for their lack of sugar, the Pilgrims would have added many of the wild fruits mentioned by Winslow: grapes, berries, and plums. Though water can be used in place of milk for frumenty, milk was the preferred ingredient. An available milk supply might have existed, if goats were among the livestock brought on the Mayflower. While there is no specific mention of any animals being brought on that first ship, Winslow’s statement that “if we have once but kine, horses and sheep ... men might live as contented here as in any part of the world” suggests that goats and pigs may well have crossed the Atlantic with the Pilgrims.

The Pilgrims also had an American pudding—which later, encased in a pastry crust, became the Thanksgiving dish pumpkin pie. In October 1621, lacking the wheat or rye flour to make a pie crust, they probably cooked pumpkins as a side dish. Josselyn described this

“ancient New-England standing dish ... the housewives manner is to slice them when ripe, and cut them into dice, and so fill a pot with them of two or three gallons, and stew them upon a gentle fire a whole day, and as they sink, they fill again with fresh pompions, not putting any liquor to them; and when it is stew’d enough, it will look like bak’d apples; this they dish, putting butter to it, and a little vinegar (with some spice, and ginger, etc.) which makes it tart liken an apple, and so serve it up to be eaten with fish or flesh.”

Cakes and ale ended the feast. The cakes were made of corn—roasted, pounded in homemade mortar and pestle, mixed into a paste with water, and fried on a griddle into thin, crisp “pan” cakes. Crumbly and dry, they complemented the strong, sweet ale that was drunk with them. Ale and hop-flavored beer were fermented from malted (germinated and roasted) barley at home. The alcohol content ranged from 4 to 8 per cent—the stronger was brought out for holidays like Harvest Home. The Pilgrims’ first ale and beer were brought over on the Mayflower and soon ran short. So precious were they that, when Bradford was sick and asked the sailors for a small can (quart) of beer, they replied that even if he “were their own father he should have none.” So water was drunk throughout the summer of 1621 but was considered an “enemy of health, cause of disease, consumer of natural vigour, and the bodies of men.” The “indifferent good barley” of August probably became October’s strong harvest beer. It would not last long, but they were fortunate to have it.

[Pg 15]

The food at this first American Harvest Home was notable then, “not for variety of messes [dishes], but for solid sufficiency.” Like the Pilgrims themselves, it was rooted in the good earth and culture of yeoman England. And after the initial shock of transplantation both the people and their food grew strong in their new home. They recognized the significance of what had been done, and, venison pie in one hand and leather mug of ale in the other, each celebrated with gusto the achievement. It was the best of times.

So it is that, when twentieth-century Americans celebrate their Thanksgiving, they are continuing a tradition that is older than the nation itself. Many of the features of the modern version—feasting, the menu in part, and athletic contests—are in the spirit of America’s first Harvest Home. The religious component of Thanksgiving, and even the act of giving thanks, are later additions. In Plymouth the fall observance of harvest and the expressing of thanks to God for his blessing varied from year to year between secular feastings and sacred days of fast. In 1623, only two years after the first Harvest Home festival, the colony formally gave thanks to God for ending a severe drought that threatened their crops. No rain fell from mid-May through late July, and the corn “languished sore.” Bradford tells us that

“they set apart a solemn day of humiliation, to seek the Lord by humble and fervent prayer, in this great distress.... And afterwards the Lord sent them such seasonable showers, with interchange of fair warm weather as, through His blessings, caused a fruitful and liberal harvest, to their no small comfort and rejoicing. For which mercy, in time convenient, they also set apart a day of thanksgiving.”

The day so designated was one of solemn thanks to God, and bore no resemblance to the happy event of two years before. Indeed, such days were set aside with frequent regularity in both the Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies; the records abound with them. They were not exclusively related to bountiful harvests but were set aside for any act of God deemed worthy and in need of acknowledgement.

[Pg 16]

In sharp contrast to our traditional concept of Thanksgiving, the celebration of 1621 was a part of the harvest itself, and had the corn also been “indifferent good,” chances are that some festival, perhaps not as spectacular, would still have occurred. Such is the strength of folk culture and tradition the world over, and so it was at Plymouth in the fall of 1621.

[Pg 17]

Hartley and Elliot

| Roast Goose | |

| Mock Venison | |

| Stewed Pumpkin | Sweet Stuffing |

| Frumenty | |

| Ale | |

Thanksgiving is just too traditional to tamper with—in my home and, I’m sure, in yours. No matter that our roast turkey, cranberry sauce, sweet potatoes, and creamed onions are more Victorian than Pilgrim. We’ve grown accustomed to them, and they rest as comfortably among our memories as that Norman Rockwell painting of Grandma’s table. But Harvest Home has no traditions whatsoever, and although a week-long bacchanalia is beyond our means, a harvest supper isn’t. In an age when we crave a deeper relationship with both our past and our earth, its virtues are obvious. Harvest Home is as ecological as it is historical. It celebrates both land and man and the fruits of their labor together. This menu and its recipes are, therefore, very organic and very old, and if we violate the letter of the Pilgrims’ first feast—few of us seed our corn with fish—its spirit will still be there.

To roast a goose (or any cut of meat) properly, you have to sear the outside, quickly, changing the meat’s surface sugars into crunchy brown caramel thereby creating a natural bag that seals in the fowl’s juices. Inside, the goose literally cooks itself. Outside, all you need to do is baste the skin with fat to prevent it from burning, and if you are using an open fire, regularly turn the bird so that it is heated evenly. An oven solves the latter problem, and although Englishmen had bake ovens in 1621, the Pilgrims didn’t. But a decade or so later they built them into their Plymouth fireplaces and used them regularly for roasts as well as breads. So if you don’t have an outdoor grill with a spit or a fireplace that could be converted into an open hearth, an oven will do fine. In either case cooking time will be between one and two hours, or twenty minutes to the pound. Just rub the goose all over with animal fat (bacon drippings, chicken or goose fat, or butter) and sear close to an open fire or at 450 degrees in an oven. When the skin is brown (after about twenty minutes), lower the[Pg 18] heat by roasting your goose farther from the open fire or turning down the oven to 325 degrees. Baste regularly with the goose fat that escapes. When the legs move easily in their sockets, it is done. The result: juicy rare meat and crispy skin. Carve it roughly and let everyone eat with his hands, making sure each has a good-sized cloth napkin or dish towel. No forks—they were instruments of “Italian or French craft and subtlety” and quite unEnglish.

BOOKE OF DIVERS DEVICES (1597)

Venison and mutton are so similar in texture and taste that even an experienced gourmet has trouble in telling them apart after marinating—a necessary step for large cuts of wild meats like venison and boar, which will spoil if not put in an acid (vinegar) solution. So if you don’t have a friend who hunts, buy a large leg of mutton or lamb; marinate it in an enamel, glass, pottery, or stainless-steel container in a solution of four bottles of dark beer or porter, one cup of malt vinegar, garlic, and spices; cinnamon,[Pg 19] mace, nutmeg, sea salt, peppercorns, juniper berry, bay leaf, fennel, rosemary; thyme, sage, and just about any dried herb you’ve got. Marinate for about three days. The morning of your feast remove it, dry it, and stick it full of cloves. Roast it just like the goose—again about twenty minutes to the pound—basting it with its own juices and with a reduction of the marinade.

The cut can be roasted bone in or out; both methods were popular in 1620. If you do take the bone out, make sure to stuff the roast with bacon, as the loss of its bone tends to dry it out. And the smoky bacon taste is a positive addition, especially if you are oven-roasting your lamb. It can also be imparted to a bone-in roast if you make a dozen half-inch cuts in the tough surface skin and stuff raw bacon in each.

ADRIAEN VAN OSTADE

Elizabethans were fond of a rich, sweet stuffing that was more like a bread pudding than the dry, herbed variety we commonly prepare today. It was used in all sorts of roasts, from boned venison to goose, and when eaten with a gravy made with vinegar and the roast’s juices, a savory, sweet-sour dish resulted. It is made by beating a cup of heavy cream (the Pilgrims used goat’s milk) and two egg yolks together. Add cinnamon, mace, nutmeg, and salt to taste (about a half-teaspoon to mine). Thicken with grated rye or cornbread crumbs (about two cups) and currants (one cup). A little sugar or honey can be mixed, but as the Pilgrims had neither, it would be better to add a tablespoon or two of dark beer or porter, which they did have and used for sweetening. A little spinach juice or saffron will give it a green or yellow color, but this is optional; it looks creamy and good just the way it is. Stuff the goose or butterflied venison with it, making sure you tie or sew up your roast carefully.

[Pg 20]

Simply clean out, peel, and dice a medium pumpkin—a recycled jack-o-lantern is fine. Simmer the diced flesh in a heavy casserole with a cup of dark beer or porter, two or three tablespoons of malt vinegar, salt, pepper, and spices to taste. It will take a couple of hours over a low heat. As a tart “spoon meat” stewed pumpkin balances the fatty goose and bacon-larded mock venison. Similar sweet-sour side dishes can be made with squash, turnips, and parsnips, all common crops in Plymouth that October 1621.

It’s still against federal law to brew beer or ale in your home. The Pilgrim housewife, however, was under no such restriction and made enough for each member of her family to have one-half to one gallon daily. It was dark, sweet, and mildly alcoholic. The best substitute is a bottle of good dark beer or porter mixed with a spoonful of malt extract, which is sold as a powder or syrup. Or you can make your own extract by boiling a cup of crystal or caramel malt (obtainable in stores that sell wine- and beer-making supplies) in a quart of water. Ale was drunk both cold and hot, the latter with chunks of apples and spices often put in for additional sweetening. Homemade ale may take some getting used to, but it has a rewarding honesty that’s lacking in the thin, artificial stuff concocted by the big breweries.

The closest modern counterpart to frumenty is old-fashioned rice pudding—rich, creamy, and aromatic with spices. Many regional variations of it still exist in England—a tribute to its popularity. Begin by boiling two cups of cracked or whole wheat in two quarts of water for ten minutes. Then cover and leave it in a warm place (an unlit oven is perfect) for a day. The wheat will congeal or “cree”—or turn to a jelly in which the inner, golden-red husks are visible. This was eaten on its own or with milk and honey as a cold porridge—nutritionally, it is an almost perfect food.

To make frumenty from creed wheat, simply simmer it with an equal amount of milk or cream and whatever spices, fruits, and sweeteners you prefer. In Plymouth, mace, nutmeg, cinnamon and cloves were common, along with berries, currants and apples, and a little porter or dark beer in place of honey or sugar. Egg yolks were also added if the frumenty was too thin. And brandy. It was served hot or cold and was the symbolic harvest dish. The fourteenth verse of Leviticus 23 in the English 1551 Bible, for example, admonishes: “And ye shall eat neither bread, nor parched corn, nor frumenty of new corne, untill the selfe same daye that ye have brought an offeringe unto your God.” Frumenty has soul.

This Plymouth version is not as rich but still is soulful. Mix two cups of roasted or parched corn meal with an equal amount of milk. Slowly pour this into a quart of boiling water and simmer for at least half an hour, stirring and adding fruits and spices all the while. Eat it hot, or let it cool and congeal.

—Jay Anderson.