Title: The life of Florence Nightingale

Author: Sarah A. Tooley

Release date: January 15, 2024 [eBook #72732]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Cassell and Company, ltd, 1916

Credits: Brian Wilson, Turgut Dincer, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of the illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

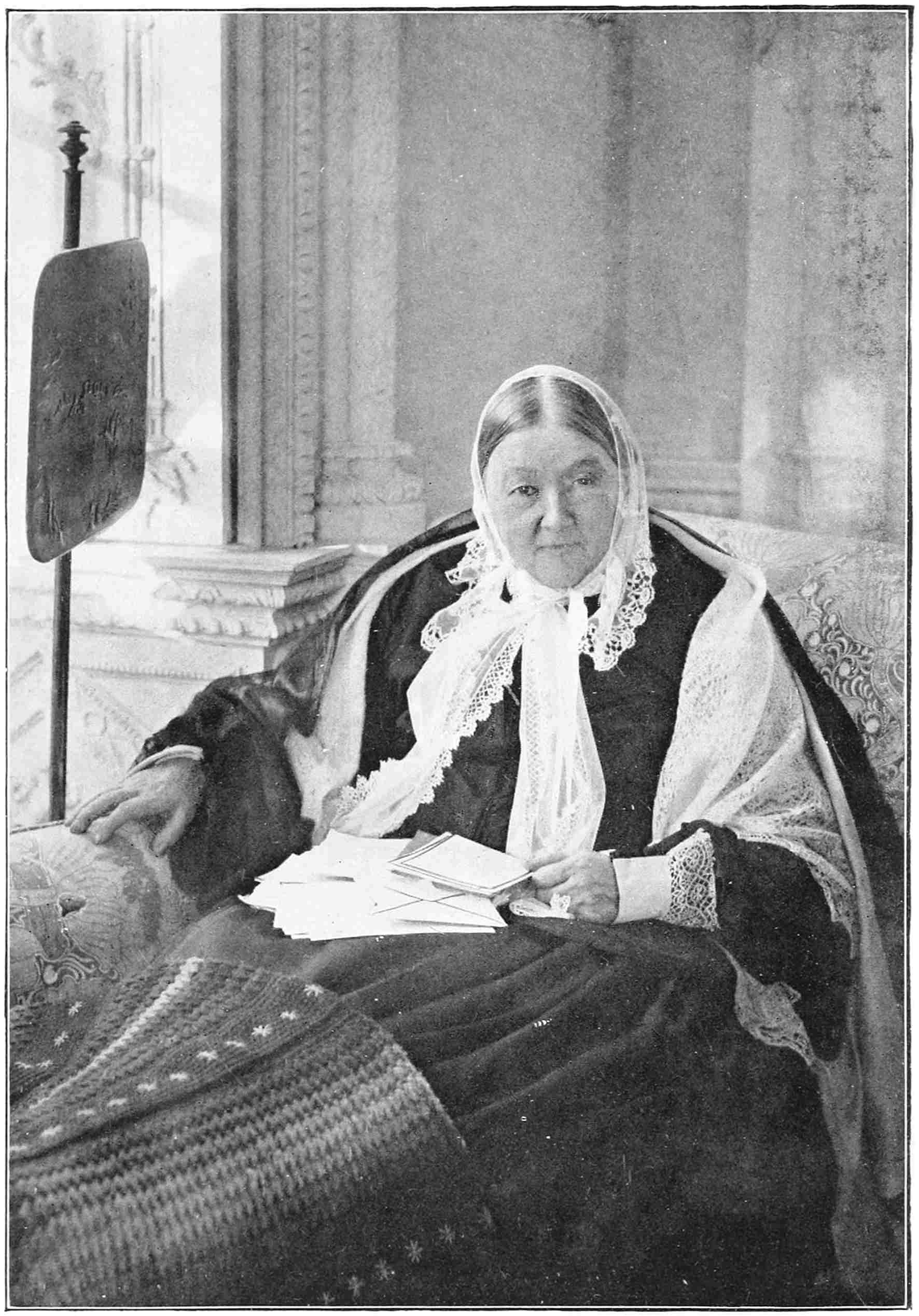

MISS NIGHTINGALE.

(From a photograph by S. G. Payne & Son.)

THE LIFE

OF

FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE

BY

SARAH A. TOOLEY

AUTHOR OF “PERSONAL LIFE OF QUEEN VICTORIA,” “LIFE OF QUEEN

ALEXANDRA,” “ROYAL PALACES AND THEIR MEMORIES,” “THE

HISTORY OF NURSING IN THE BRITISH EMPIRE,” ETC.

MEMORIAL EDITION

CASSELL AND COMPANY, Ltd.

LONDON, NEW YORK, TORONTO AND MELBOURNE

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

TO

THE LADY HERBERT OF LEA

THE LIFE-LONG FRIEND OF

FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE

THIS BOOK

IS BY PERMISSION

Dedicated

vii

The writing of the Life of Florence Nightingale was undertaken with the object of marking the jubilee of the illustrious heroine who left London on October 21st, 1854, with a band of thirty-eight nurses for service in the Crimean War. Her heroic labours on behalf of the sick and wounded soldiers have made her name a household word in every part of the British Empire, and it was a matter for national congratulation that Miss Nightingale lived to celebrate such a memorable anniversary.

A striking proof of the honour in which her name is held by the rising generation was given a short time ago, when the editor of The Girl’s Realm took the votes of his readers as to the most popular heroine in modern history. Fourteen names were submitted, and of the 300,000 votes given, 120,776 were for Florence Nightingale.

No trouble has been spared to make the bookviii as accurate and complete as possible, and when writing it I spent several months in the vicinity of Miss Nightingale’s early homes, and received much kind assistance from people of all classes acquainted with her. In particular I would thank Lady Herbert of Lea for accepting the dedication of the book and for portraits of herself and Lord Herbert; Sir Edmund Verney for permission to publish the picture of the late Lady Verney and views of Claydon; Pastor Düsselhoff of Kaiserswerth for the portrait of Pastor Fliedner and some recollections of Miss Nightingale’s training in that institution; the late Sister Mary Aloysius, of the Convent of Sisters of Mercy, Kinvara, co. Galway, for memories of her work at Scutari Hospital; and Mr. Crowther, Librarian of the Public Library, Derby, for facilities for studying the collection of material relating to Miss Nightingale presented to the Library by the late Duke of Devonshire.

In the preparation of the revised edition I am indebted to Lady Verney, the late Hon. Frederick Strutt, and Mrs. Dacre Craven for valuable suggestions.

SARAH A. TOOLEY

Kensington.ix

| CHAPTER I | |

| BIRTH AND ANCESTRY | |

| PAGE | |

| Birth at Florence—Shore Ancestry—Peter Nightingale of Lea—Florence Nightingale’s Parents | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| EARLIEST ASSOCIATIONS | |

| Lea Hall first English Home—Neighbourhood of Babington Plot—Dethick Church | 8 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| LEA HURST | |

| Removal to Lea Hurst—Description of the House—Florence Nightingale’s Crimean Carriage preserved there | 15 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| THE DAYS OF CHILDHOOD | |

| Romantic Journeys from Lea Hurst to Embley Park—George Eliot Associations—First Patient—Love of Animals and Flowers—Early Education | 22x |

| CHAPTER V | |

| THE SQUIRE’S DAUGHTER | |

| An Accomplished Girl—An Angel in the Homes of the Poor—Children’s “Feast Day” at Lea Hurst—Her Bible-Class for Girls—Interests at Embley—Society Life—Longing for a Vocation—Meets Elizabeth Fry—Studies Hospital Nursing—Decides to go to Kaiserswerth | 38 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE’S ALMA MATER AND ITS FOUNDER | |

| Enrolled a Deaconess at Kaiserswerth—Paster Fliedner—His Early Life—Becomes Pastor at Kaiserswerth—Interest in Prison Reform—Starts a Small Penitentiary for Discharged Female Prisoners—Founds a School and the Deaconess Hospital—Rules for Deaconesses—Marvellous Extension of his Work—His Death—Miss Nightingale’s Tribute | 54 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| ENTERS KAISERSWERTH: A PLEA FOR DEACONESSES | |

| An Interesting Letter—Description of Miss Nightingale when she entered Kaiserswerth—Testimonies to her Popularity—Impressive Farewell to Pastor Fliedner | 68 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| A PERIOD OF WAITING | |

| Visits the Sisters of St. Vincent de Paul in Paris—Illness—Resumes Old Life at Lea Hurst and Embley—Interest in John Smedley’s System of Hydropathy—Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Herbert’s Philanthropies—Work at Harley Street Home for Sick Governesses—Illness and Return Home | 80xi |

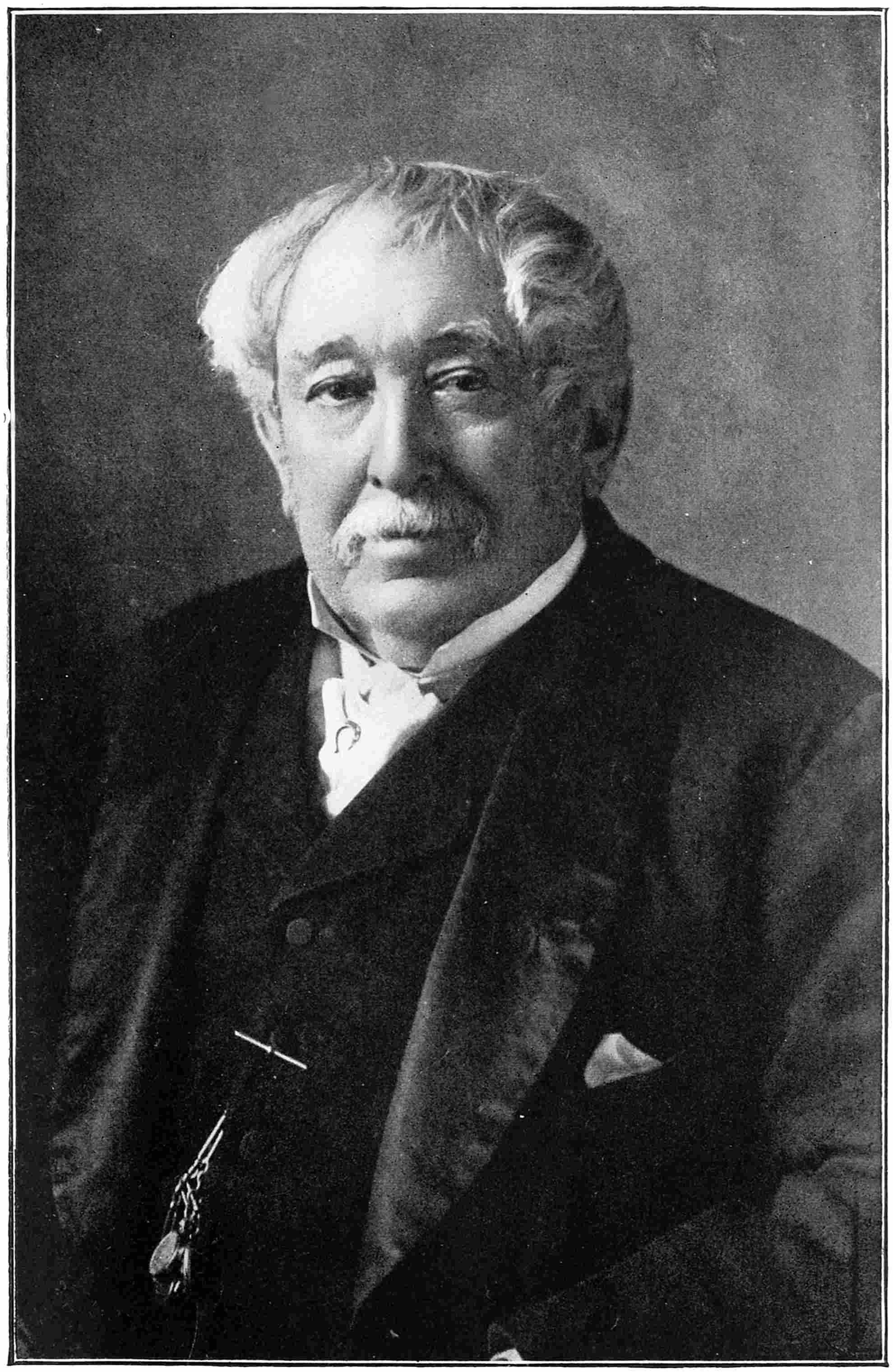

| CHAPTER IX | |

| SIDNEY, LORD HERBERT OF LEA | |

| Gladstone on Lord Herbert—Early Life of Lord Herbert—His Mother—College Career—Enters Public Life—As Secretary for War—Benevolent Work at Salisbury—Lady Herbert—Friendship with Florence Nightingale—Again Secretary for War | 87 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| THE CRIMEAN WAR AND CALL TO SERVICE | |

| Tribute to Florence Nightingale by the Countess of Lovelace—Outbreak of the Crimean War—Distressing Condition of the Sick and Wounded—Mr. W. H. Russell’s Letters to The Times—Call for Women Nurses—Mr. Sidney Herbert’s Letter to Miss Nightingale—She offers her Services | 94 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| PREPARATION AND DEPARTURE FOR SCUTARI | |

| Public Curiosity Aroused—Description of Miss Nightingale in the Press—Criticism—She selects Thirty-Eight Nurses—Departure of the “Angel Band”—Enthusiasm of Boulogne Fisherwomen—Arrival at Scutari | 110 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| THE LADY-IN-CHIEF | |

| The Barrack Hospital—Overwhelming Numbers of Sick and Wounded—General Disorder—Florence Nightingale’s “Commanding Genius”—The Lady with the Brain—The Nurses’ Tower—Influence over Men in Authority | 123xii |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| AT WORK IN THE BARRACK HOSPITAL | |

| An Appalling Task—Stories of Florence Nightingale’s Interest in the Soldiers—Lack of Necessaries for the Wounded—Establishes an Invalids’ Kitchen and a Laundry—Cares for the Soldiers’ Wives—Religious Fanatics—Letter from Queen Victoria—Christmas at Scutari | 140 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| GRAPPLING WITH CHOLERA AND FEVER | |

| Florence Nightingale describes the Hardships of the Soldiers—Arrival of Fifty More Nurses—Memories of Sister Mary Aloysius—The Cholera Scourge | 160 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| TIMELY HELP | |

| Lavish Gifts for the Soldiers—The Times Fund—The Times Commissioner visits Scutari—His Description of Miss Nightingale—Arrival of M. Soyer, the Famous Chef—He Describes Miss Nightingale | 171 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| THE ANGEL OF DEATH | |

| Death of Seven Surgeons at Scutari—The First of the “Angel Band” Stricken—Deaths of Miss Smythe, Sister Winifred, and Sister Mary Elizabeth—Touching Verses by an Orderly | 183xiii |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| SAILS FOR THE CRIMEA AND GOES UNDER FIRE | |

| On Board the Robert Lowe—Story of a Sick Soldier—Visit to the Camp Hospitals—Sees Sebastopol from the Trenches—Recognised and Cheered by the Soldiers—Adventurous Ride Back | 192 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| STRICKEN BY FEVER | |

| Continued Visitation of Hospitals—Sudden Illness—Conveyed to Sanatorium—Visit of Lord Raglan—Convalescence—Accepts Offer of Lord Ward’s Yacht—Returns to Scutari—Memorial to Fallen Heroes | 204 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| CLOSE OF THE WAR | |

| Fall of Sebastopol—The Nightingale Hospital Fund—A Carriage Accident—Last Months in the Crimea—“The Nightingale Cross”—Presents from Queen Victoria and the Sultan—Sails for Home | 217 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| THE RETURN OF THE HEROINE | |

| Arrives Secretly at Lea Hurst—The Object of Many Congratulations—Presentations—Received by Queen Victoria at Balmoral—Prepares Statement of “Voluntary Gifts”—Tribute to Lord Raglan | 239xiv |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| THE SOLDIER’S FRIEND AT HOME | |

| Ill Health—Unremitting Toil—Founds Nightingale Training School at St. Thomas’s Hospital—Army Reform—Death of Lord Herbert of Lea—Palmerston and Gladstone pay Tributes to Miss Nightingale—Interesting Letters—Advises in American War and Franco-German War | 252 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| WISDOM FROM THE QUEEN OF NURSES | |

| Literary Activity—Notes on Hospitals—Notes on Nursing—Hints for the Amateur Nurse—Interest in the Army in India—Writings on Indian Reforms | 275 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| THE NURSING OF THE SICK POOR | |

| Origin of the Liverpool Home and Training School—Interest in the Sick Paupers—“Una and the Lion” a Tribute to Sister Agnes Jones—Letter to Miss Florence Lees—Plea for a Home for Nurses—On the Question of Paid Nurses—Queen Victoria’s Jubilee Nursing Institute—Rules for Probationers | 298 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| LATER YEARS | |

| The Nightingale Home—Rules for Probationers—Deaths of Mr. and Mrs. Nightingale—Death of Lady Verney—Continues to Visit Claydon—Health Crusade—Ruralxv Hygiene—A Letter to Mothers—Introduces Village Missioners—Village Sanitation in India—The Diamond Jubilee—Balaclava Dinner | 314 |

| CHAPTER XXV | |

| AT EVENTIDE | |

| Miss Nightingale To-day—Her Interest in Passing Events—Recent Letter to Derbyshire Nurses—Celebrates Eighty-fourth Birthday—King confers Dignity of a Lady of Grace—Appointed by King Edward VII. to the Order of Merit—Letter from the German Emperor—Elected to the Honorary Freedom of the City of London—Summary of her Noble Life In Memoriam | 338 |

xvi

| MISS NIGHTINGALE (From a photograph) Frontispiece | |

| PAGE | |

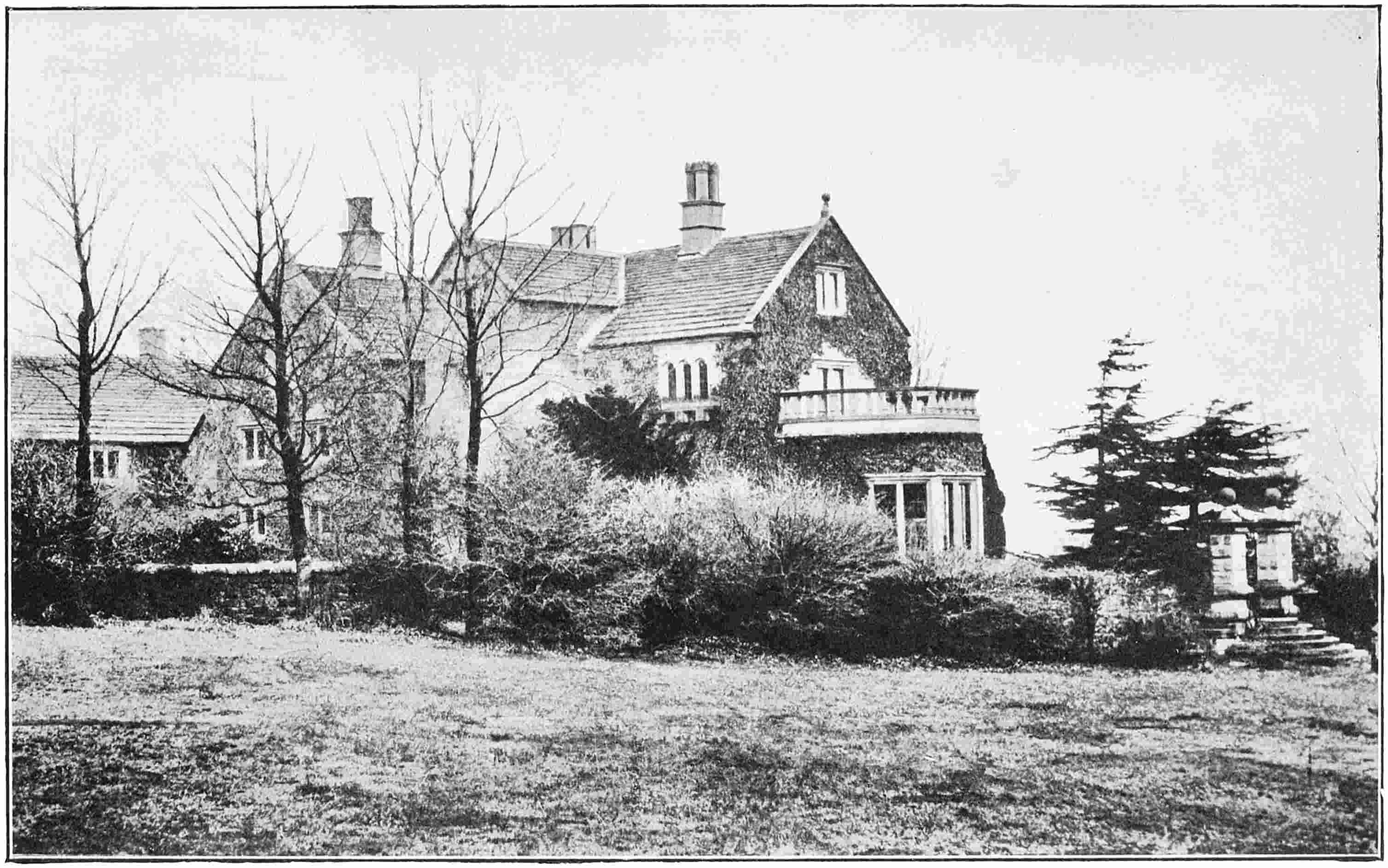

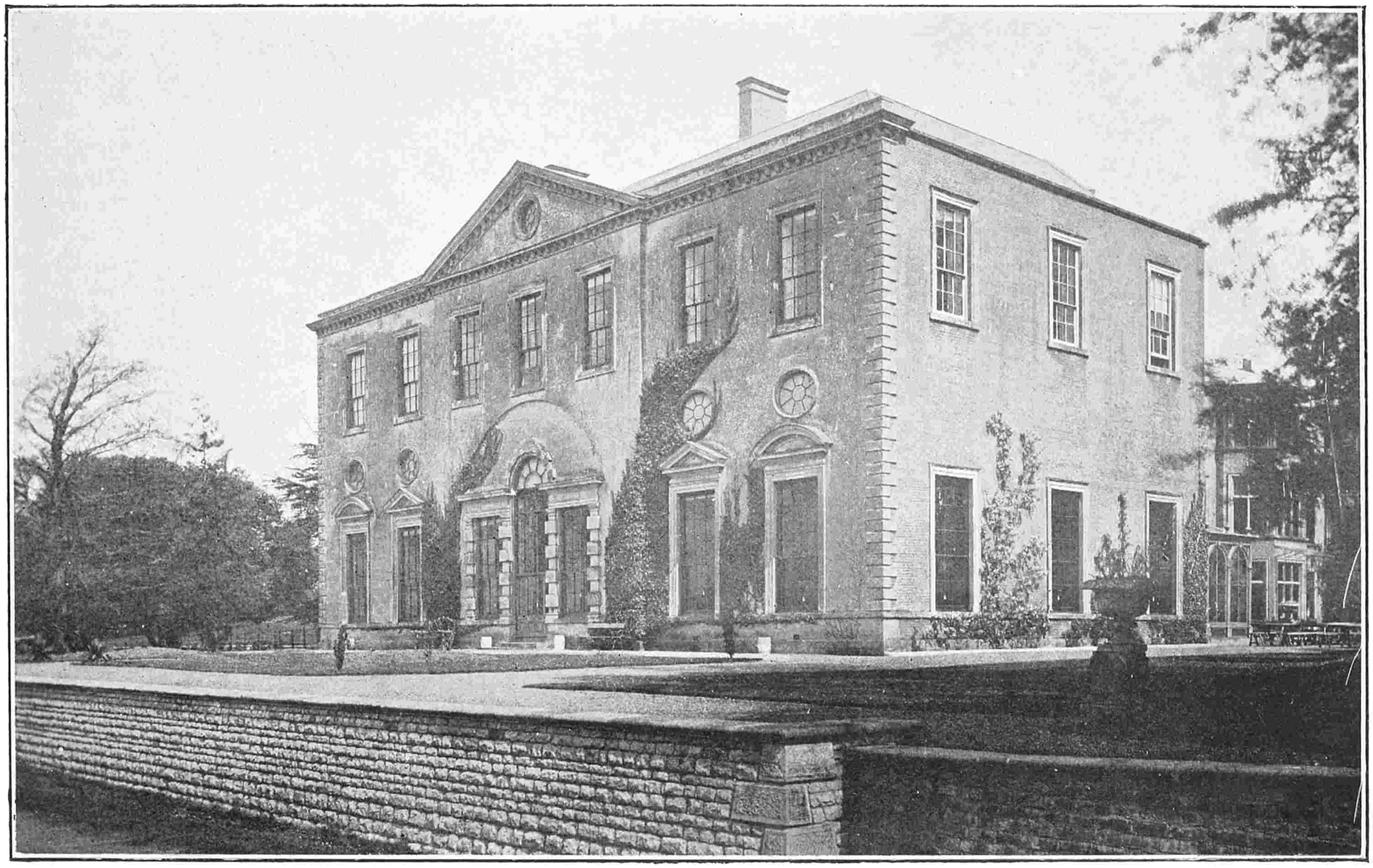

| LEA HURST, DERBYSHIRE | 16 |

| EMBLEY PARK, HAMPSHIRE | 32 |

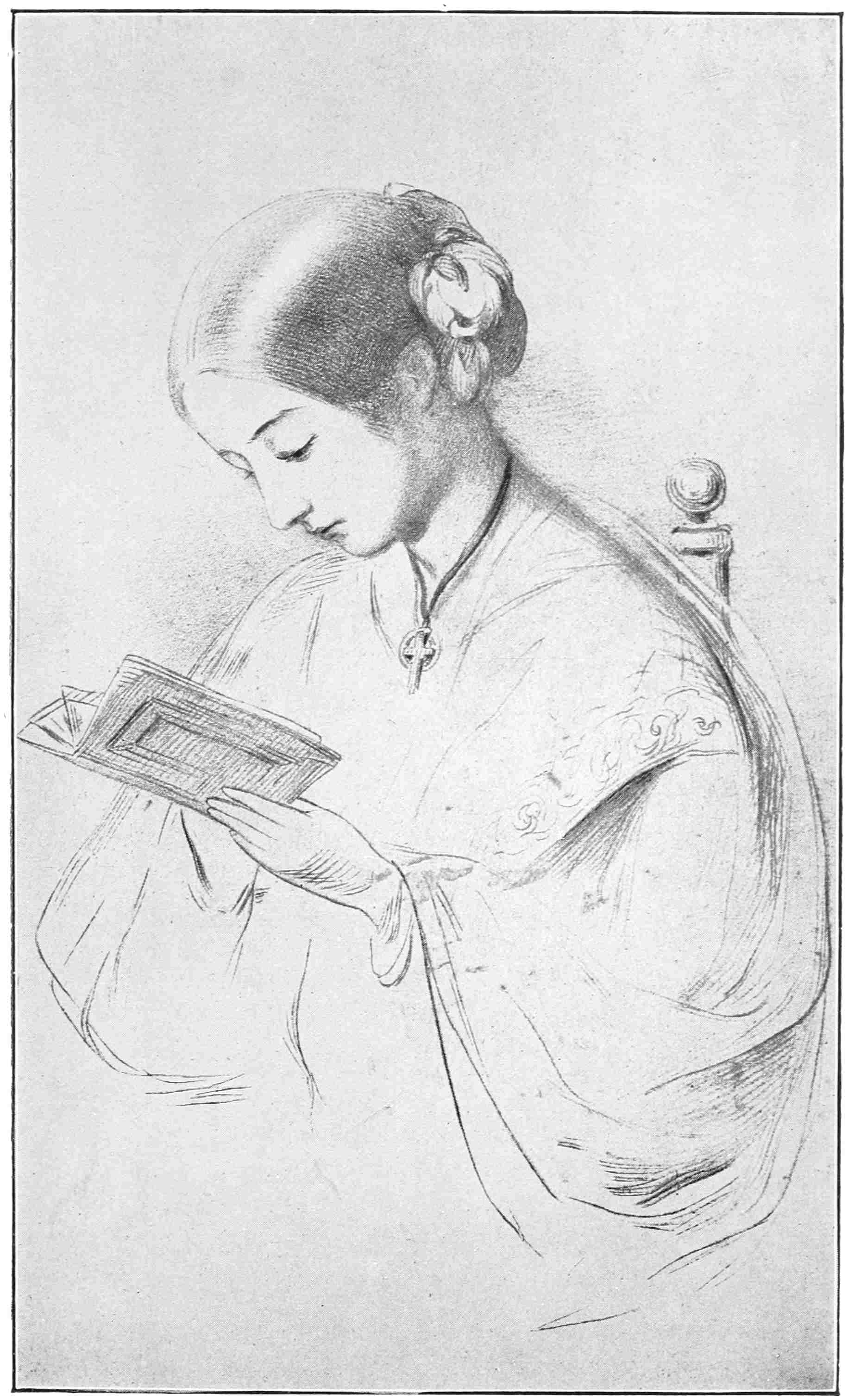

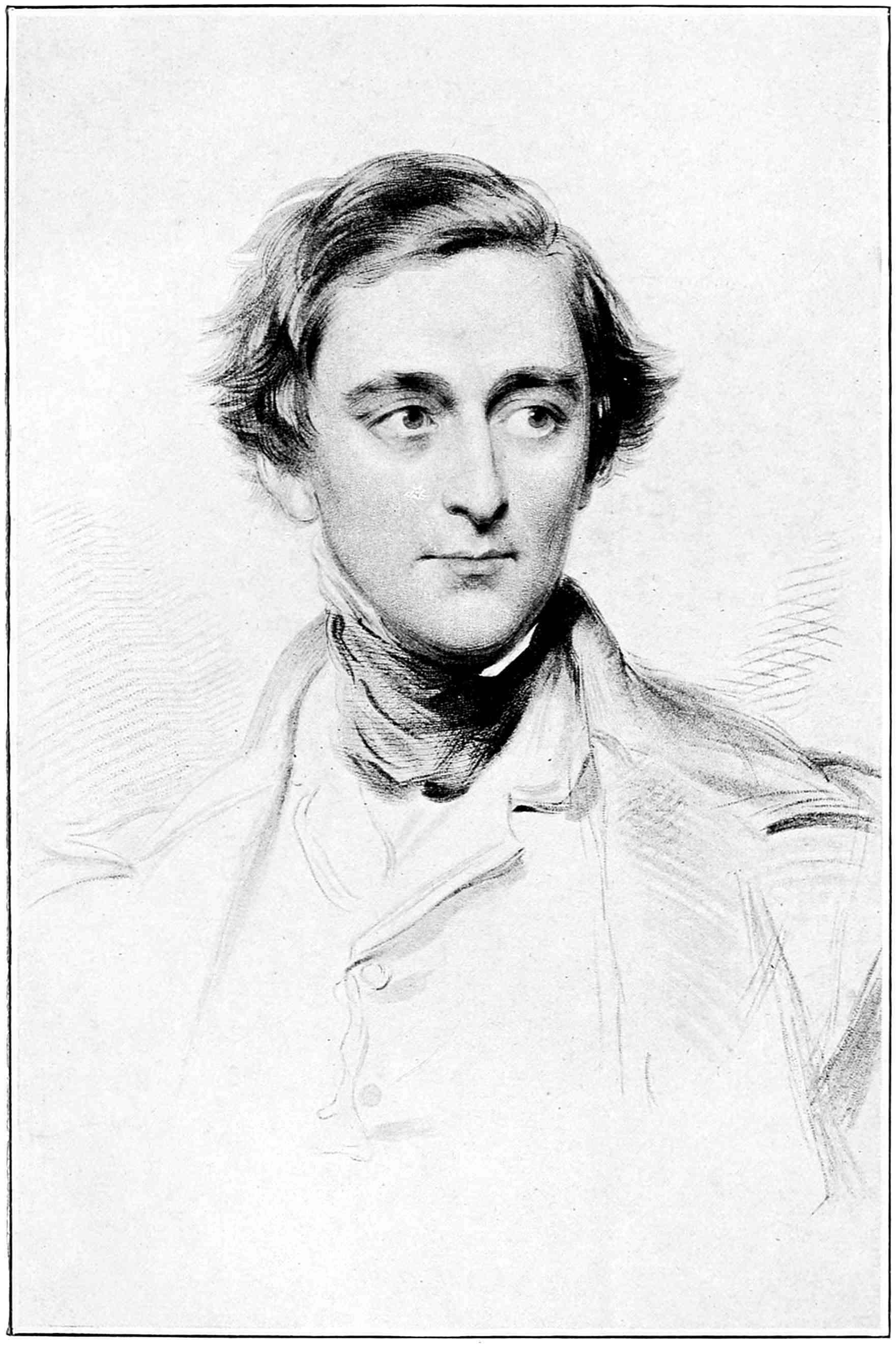

| MISS NIGHTINGALE (From a drawing) | 48 |

| PASTOR FLIEDNER | 55 |

| MISS NIGHTINGALE (From a bust at Claydon) | 61 |

| SIR WILLIAM HOWARD RUSSELL | 80 |

| SIDNEY, LORD HERBERT OF LEA | 96 |

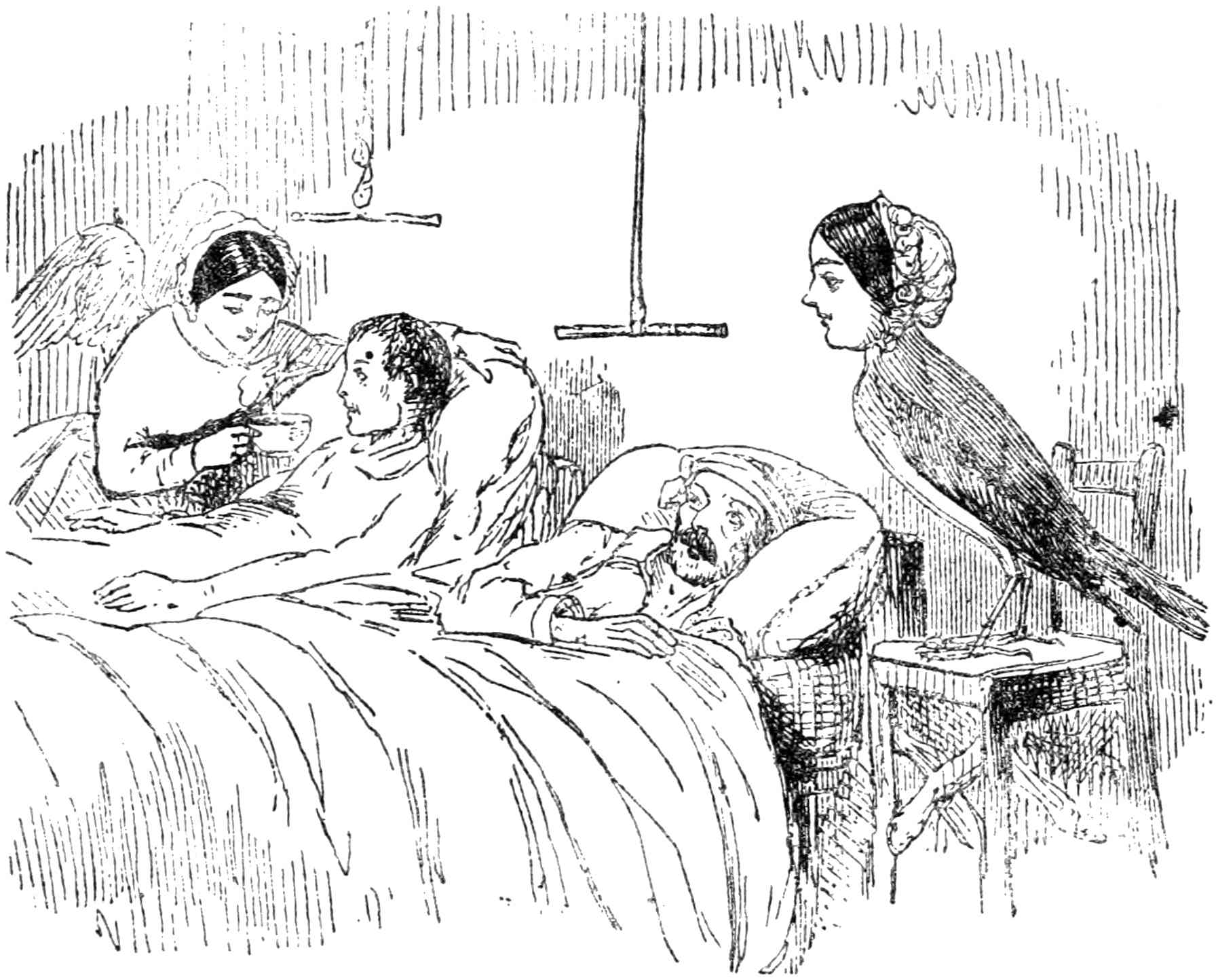

| MR. PUNCH’S CARTOON OF “THE LADY-BIRDS” | 113 |

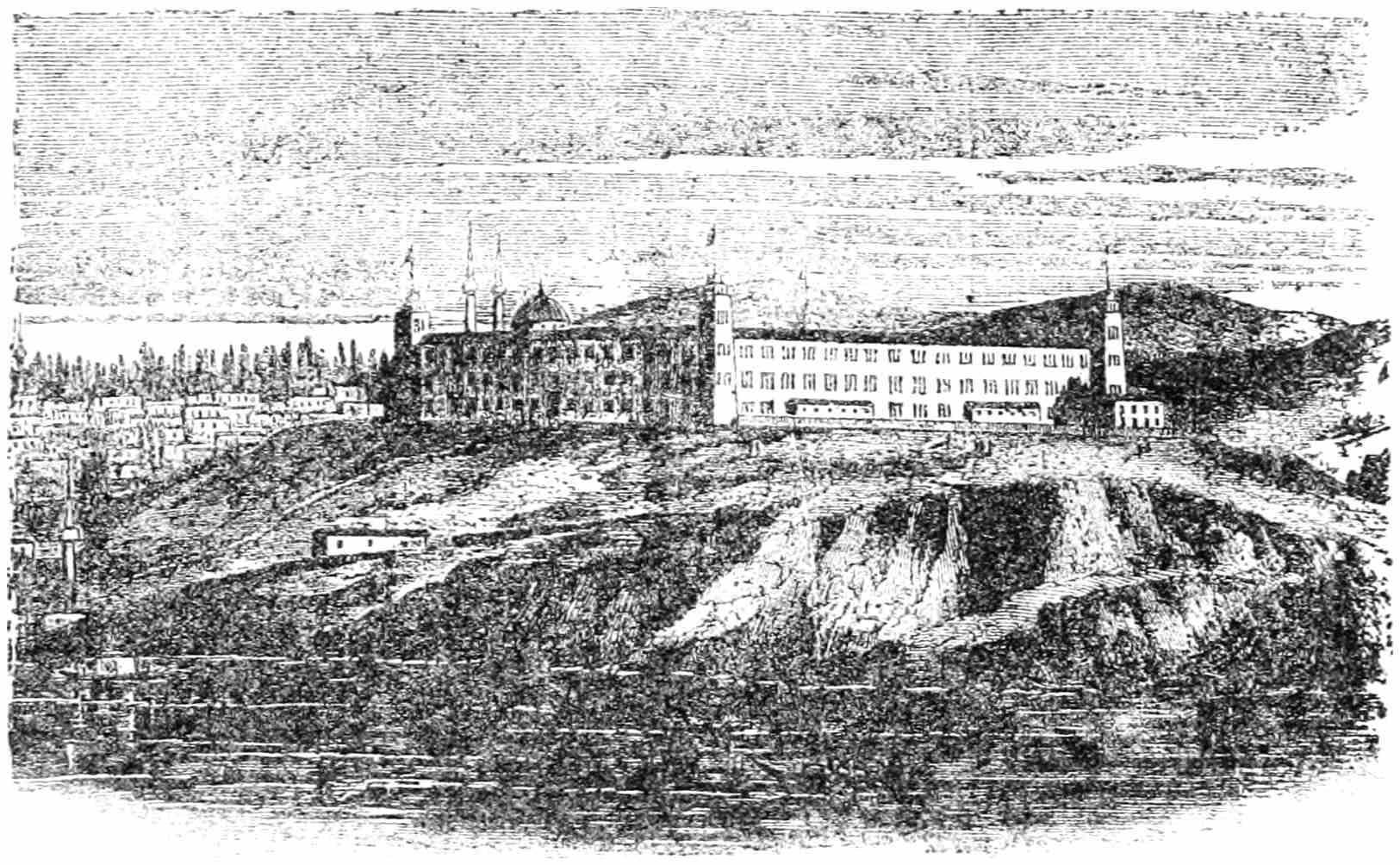

| THE BARRACK HOSPITAL AT SCUTARI | 125 |

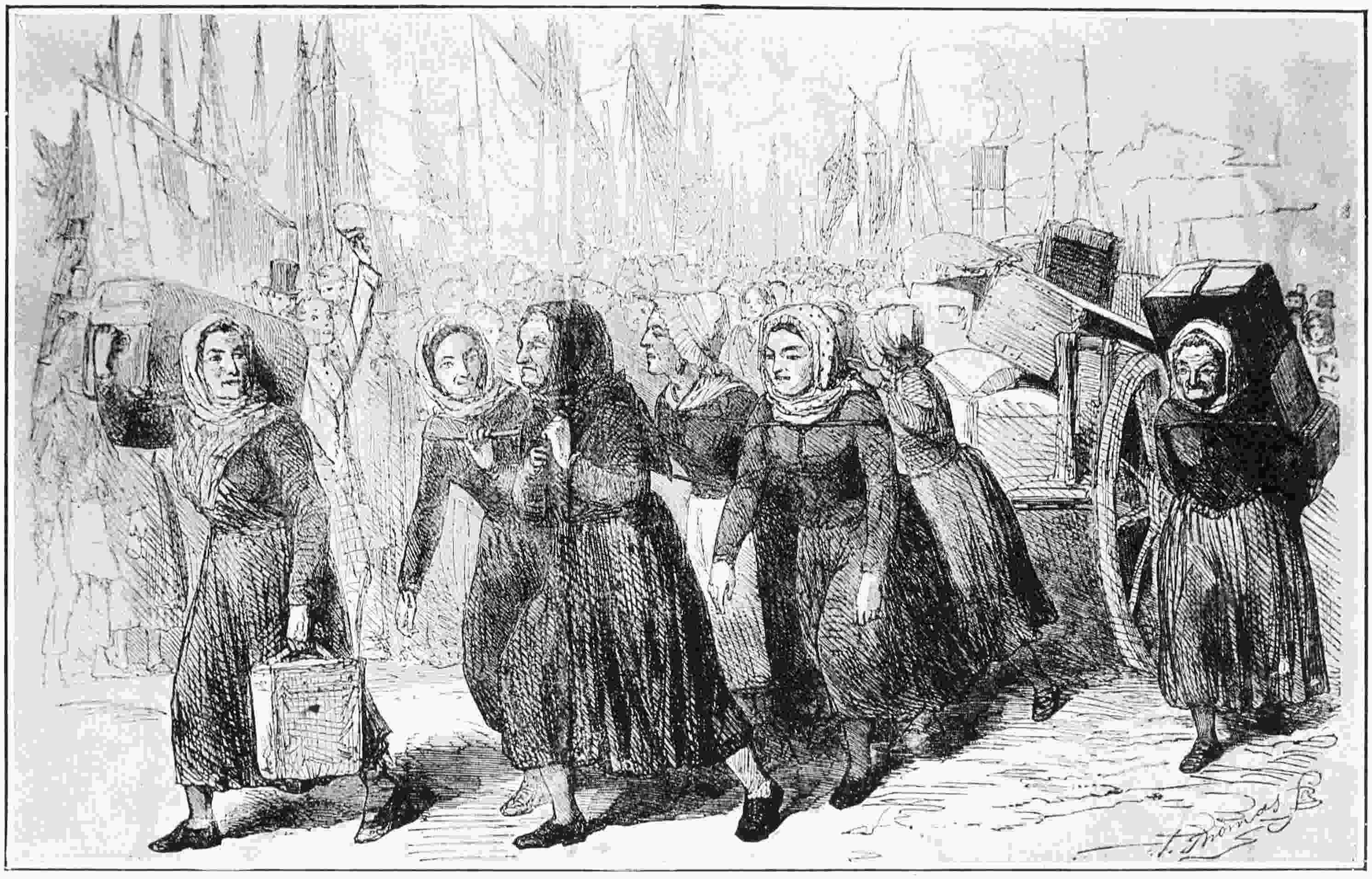

| BOULOGNE FISHERWOMEN CARRYING THE LUGGAGE OF MISS NIGHTINGALE AND HER NURSES | 128 |

| THE LADY-IN-CHIEF IN HER QUARTERS AT THE BARRACK HOSPITAL | 133 |

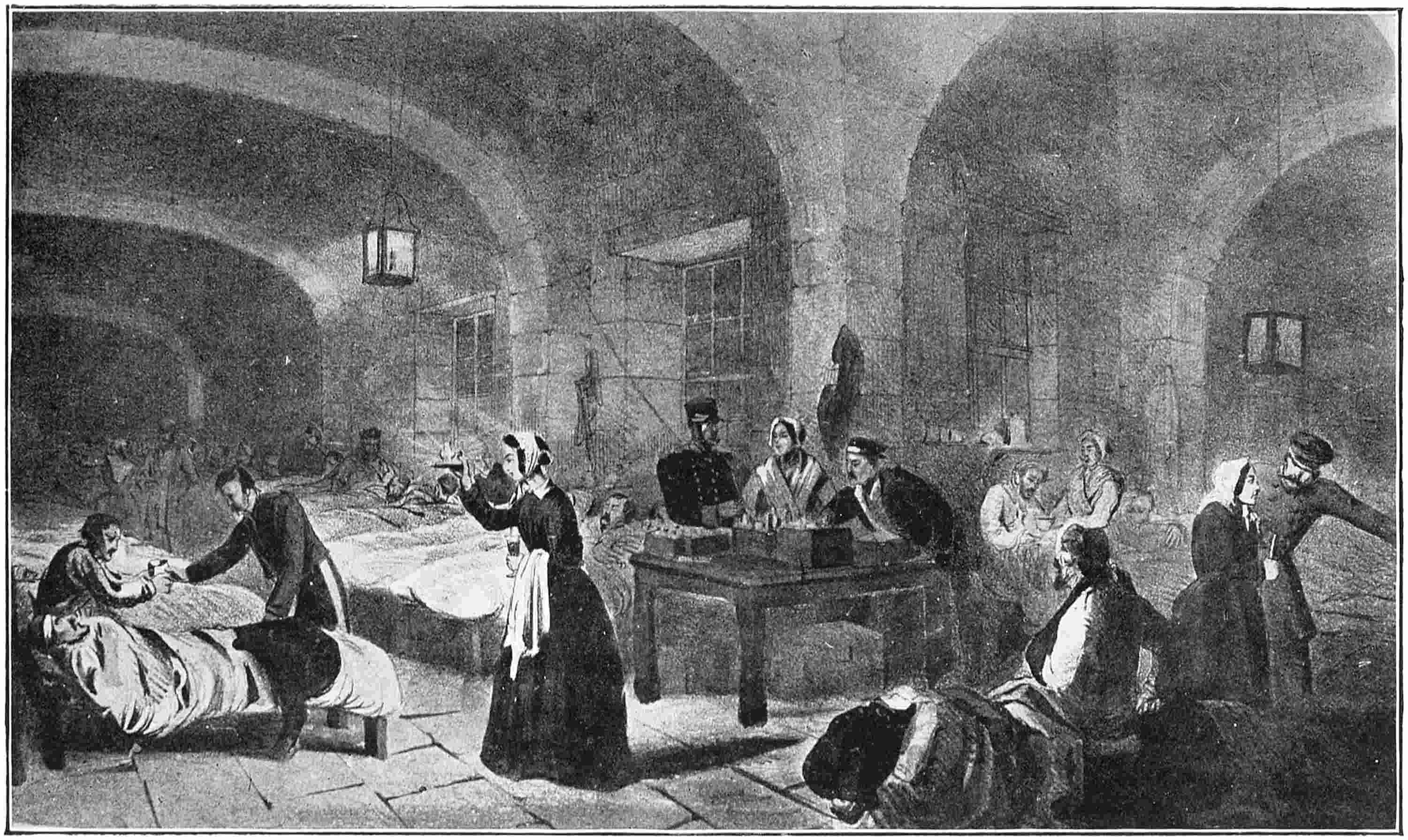

| MISS NIGHTINGALE IN THE HOSPITAL AT SCUTARI | 144 |

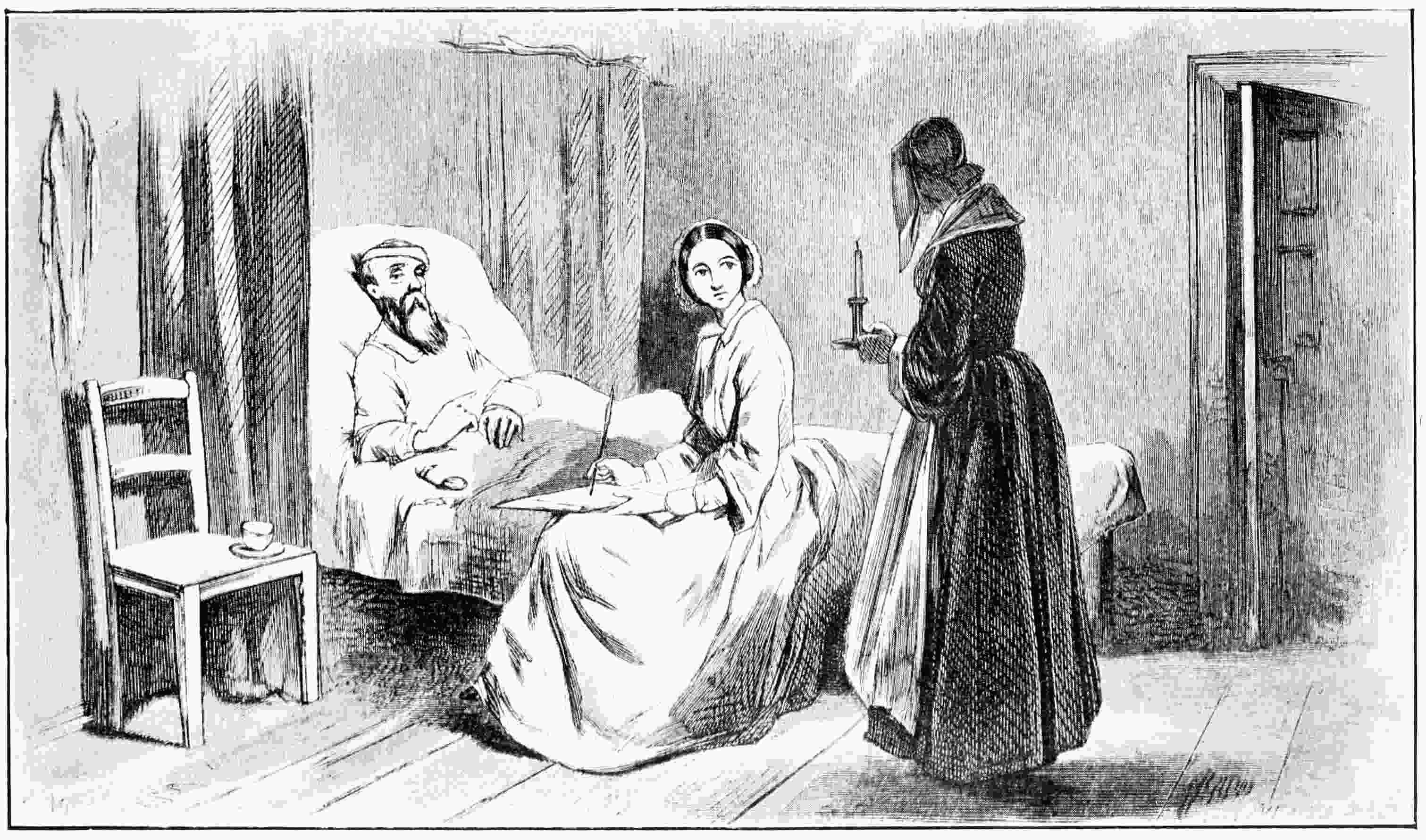

| MISS NIGHTINGALE AND THE DYING SOLDIER—A SCENE AT SCUTARI HOSPITAL WITNESSED BY M. SOYER | 176 |

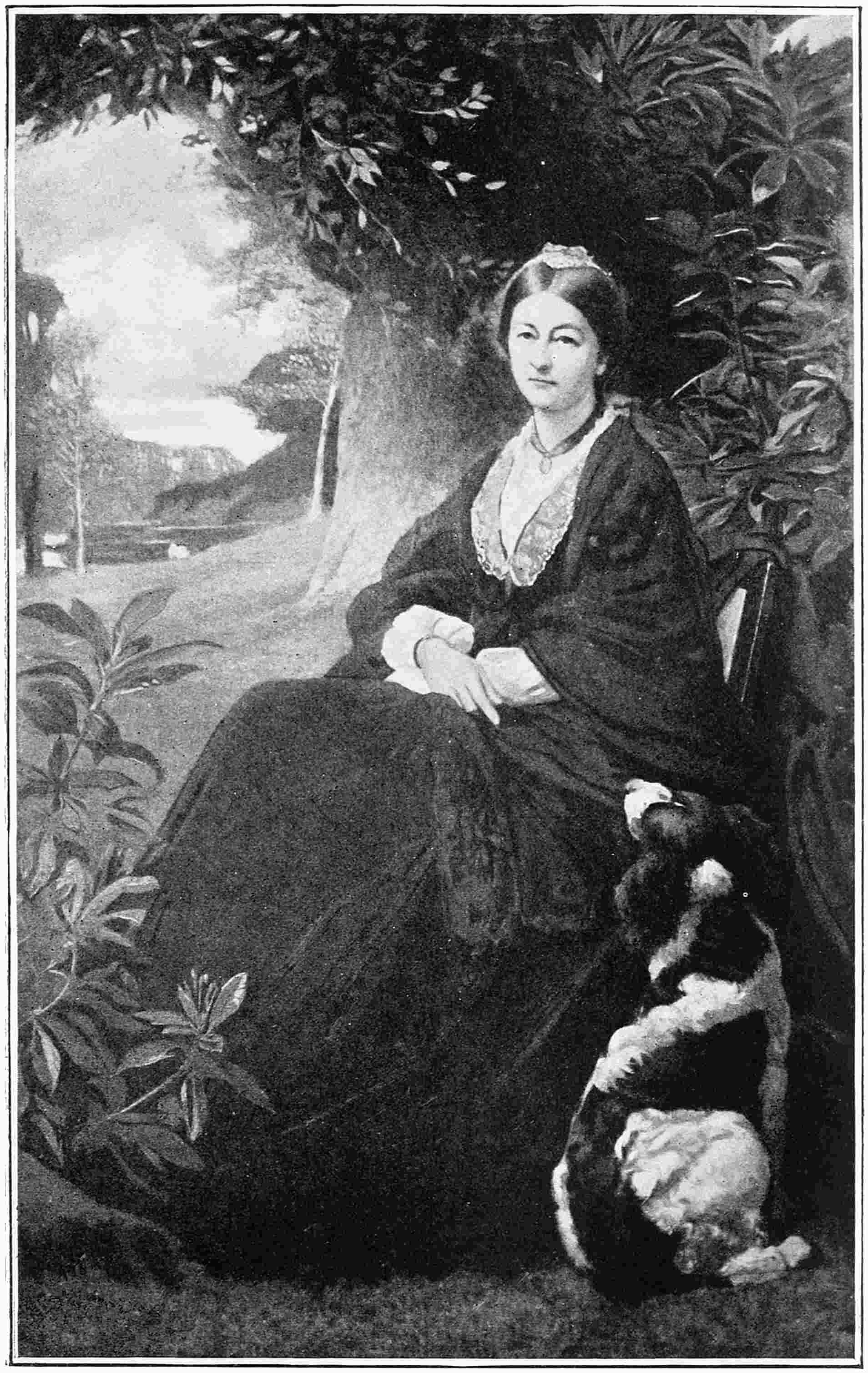

| LADY HERBERT OF LEA | 192 |

| FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE AS A GIRL | 208 |

| THE NIGHTINGALE JEWEL | 237 |

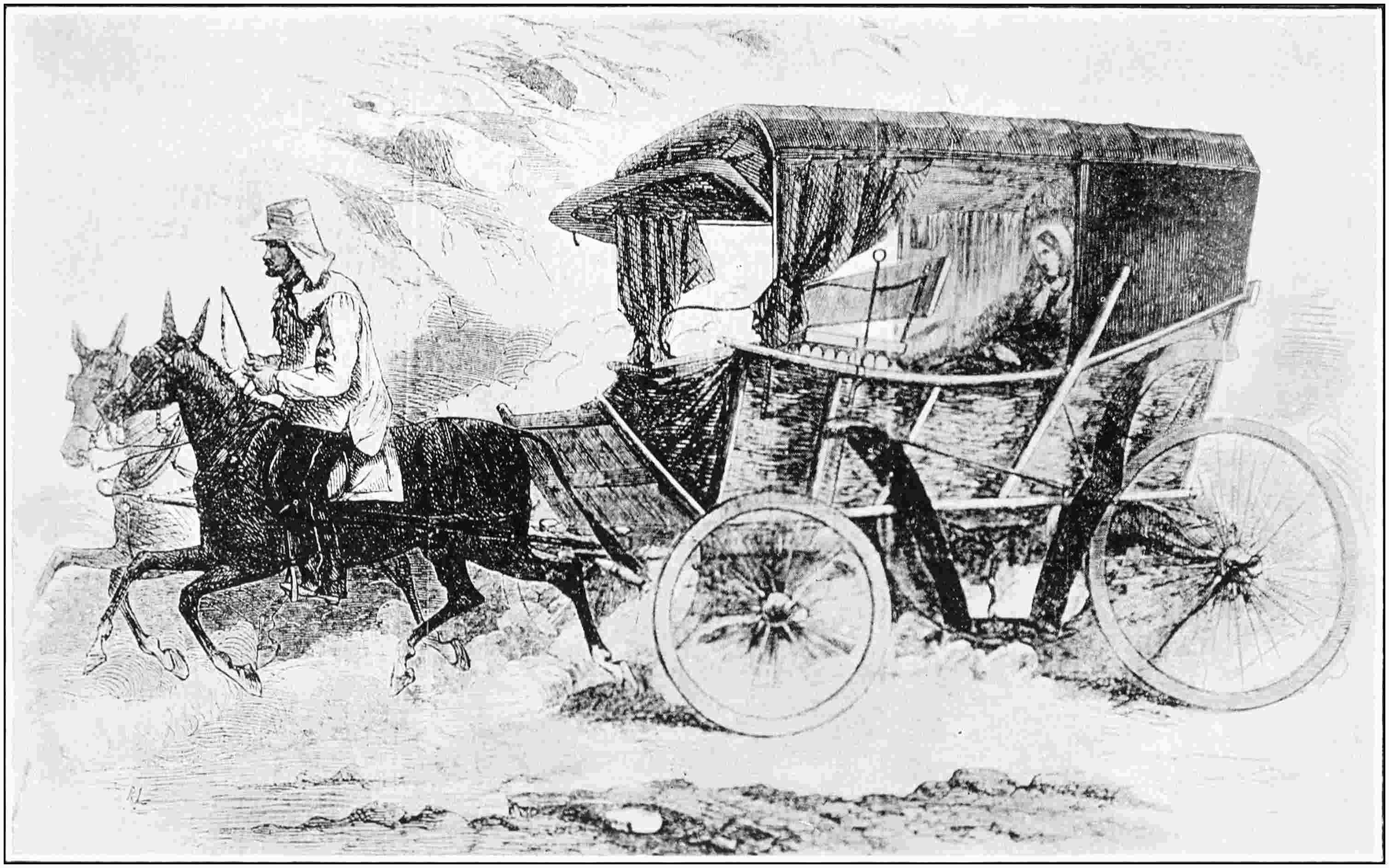

| THE CARRIAGE USED BY MISS NIGHTINGALE IN THE CRIMEA | 240 |

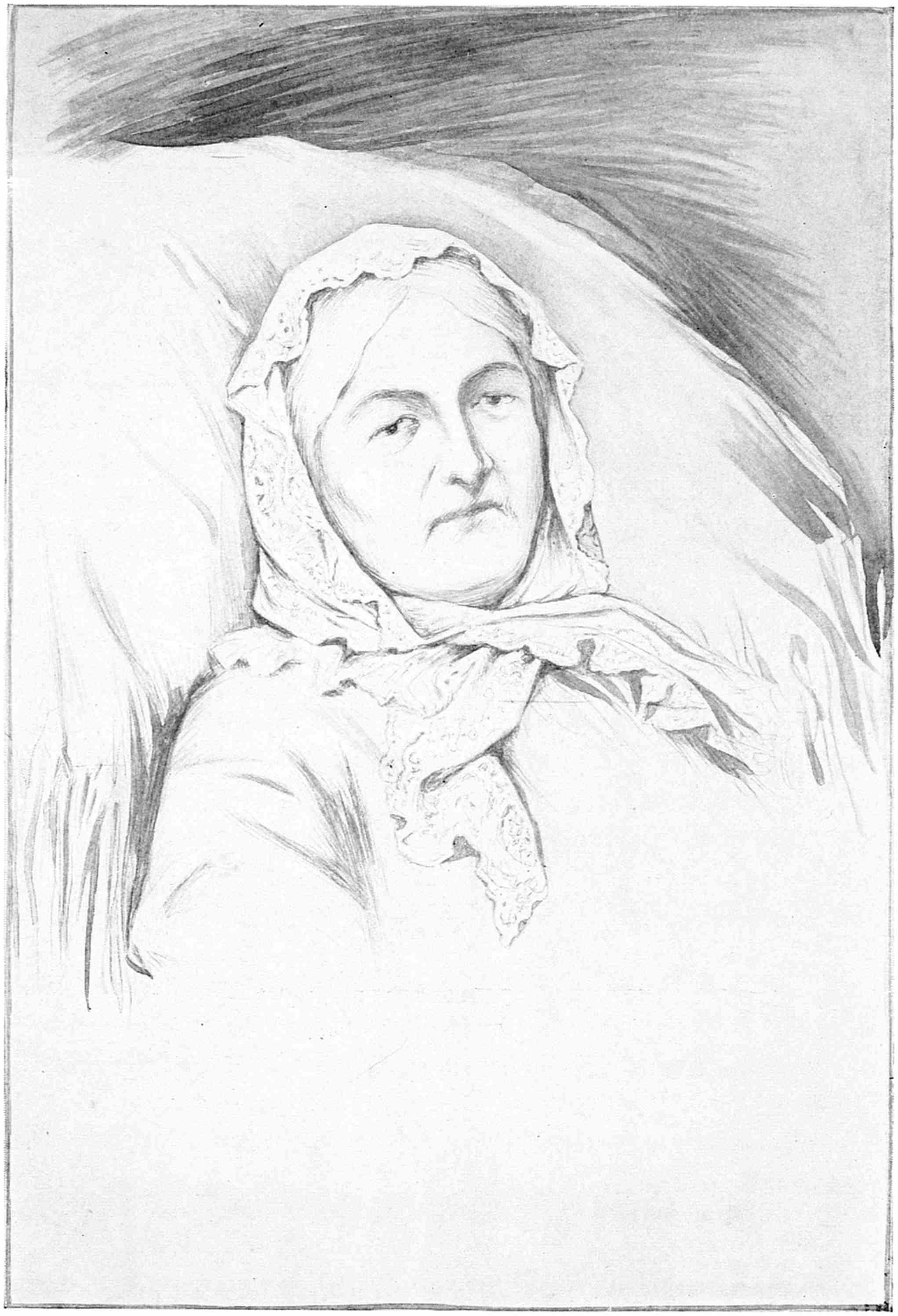

| MISS NIGHTINGALE AFTER HER RETURN FROM THE CRIMEA | 272 |

| PARTHENOPE, LADY VERNEY | 288 |

| MRS. DACRE CRAVEN (née FLORENCE LEES) | 304 |

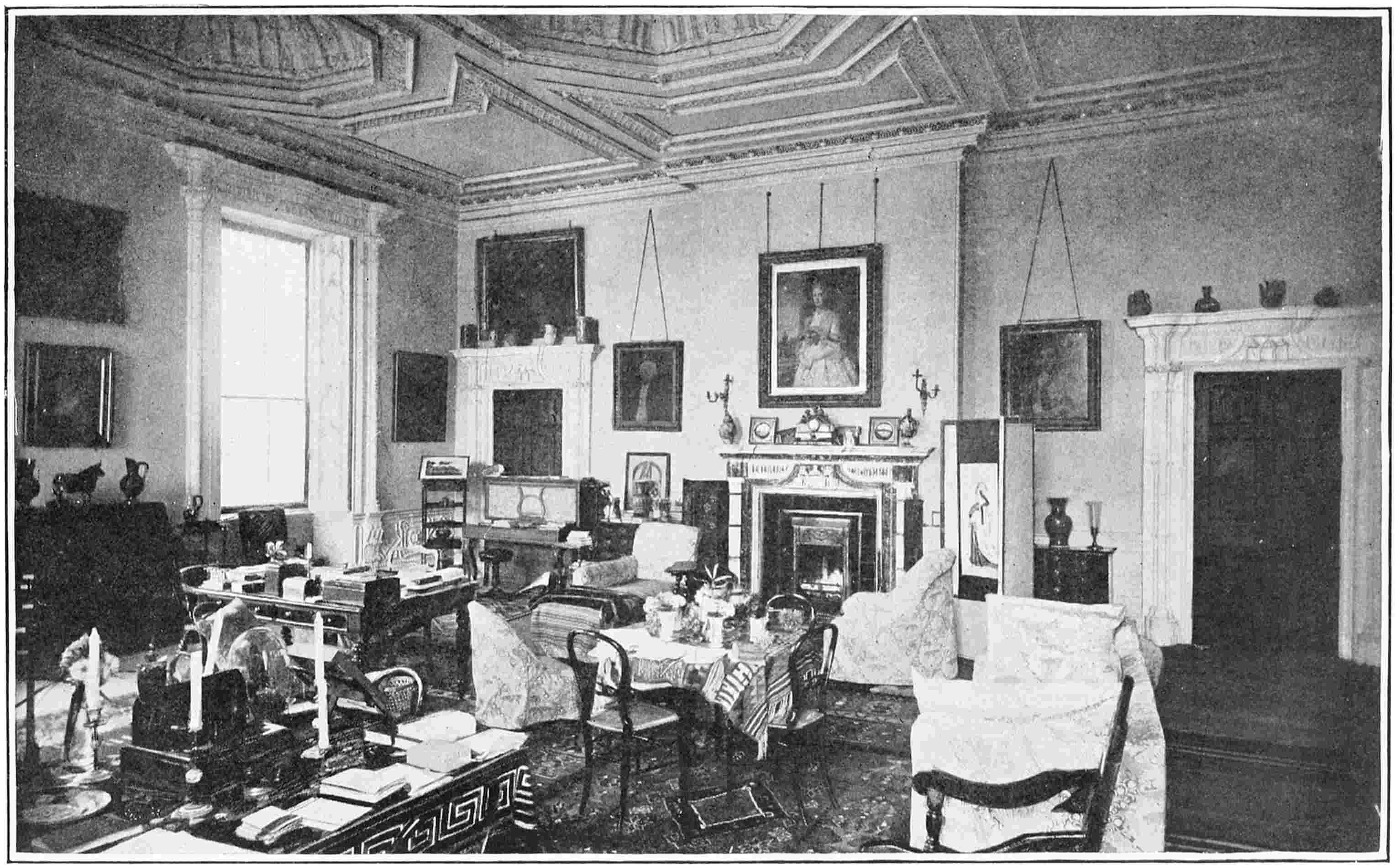

| CLAYDON HOUSE, THE SEAT OF SIR EDMUND VERNEY, WHERE THE “FLORENCE NIGHTINGALE” ROOMS ARE PRESERVED | 320 |

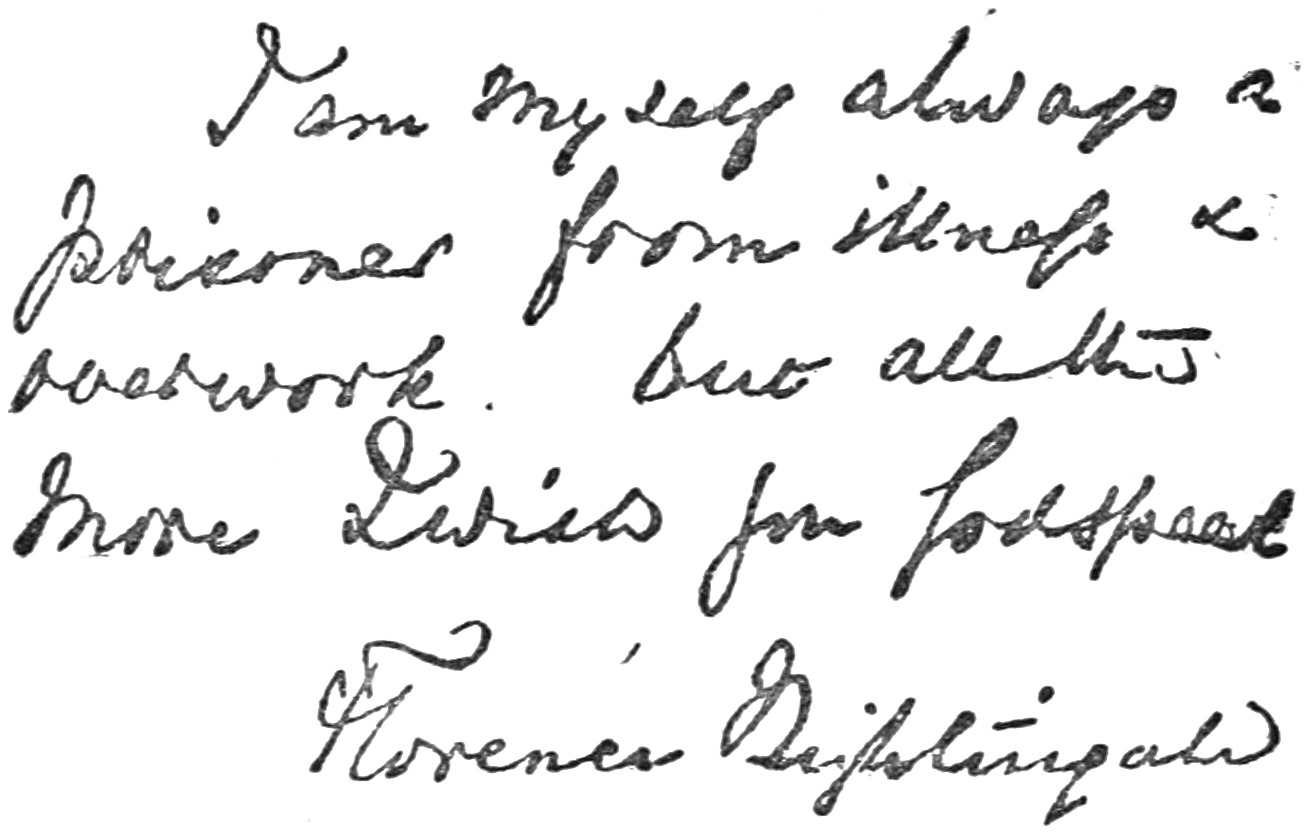

| SPECIMEN OF MISS NIGHTINGALE’S HANDWRITING | 335 |

| MISS NIGHTINGALE’S OLD ROOM AT CLAYDON | 336 |

| MISS NIGHTINGALE | 340 |

1

Birth at Florence—Shore Ancestry—Peter Nightingale of Lea—Florence Nightingale’s Parents.

Thought and deed, not pedigree, are the passports to enduring fame.—General Skobeleff.

At a dinner given to the military and naval officers who had served in the Crimean War, it was suggested that each guest should write on a slip of paper the name of the person whose services during the late campaign would2 be longest remembered by posterity. When the papers were examined, each bore the same name—“Florence Nightingale.”

The prophecy is fulfilled to-day, for though little more than fifty years have passed since the joy-bells throughout the land proclaimed the fall of Sebastopol, the majority of people would hesitate if asked to name the generals of the Allied Armies, while no one would be at a loss to tell who was the heroine of the Crimea. Her deeds of love and sacrifice sank deep into the nation’s heart, for they were above the strife of party and the clash of arms. While Death has struck name after name from the nation’s roll of the great and famous, our heroine lives in venerated age to shed the lustre of her name upon a new century.

Florence Nightingale was born on May 12th, 1820, at the Villa Colombaia near Florence, where her parents, Mr. and Mrs. William Shore Nightingale, of Lea, Derbyshire, were staying.

“What name should be given to the baby girl born so far away from her English home?” queried her parents, and with mutual consent they decided to call her “Florence,” after that fair city of flowers on the banks of the Arno where she first saw the light. Little did Mr. and Mrs. Nightingale then think that the name thus chosen was destined to become one of the most popular throughout the3 British Empire. Every “Florence” practically owes her name to the circumstances of Miss Nightingale’s birth.

It seemed as though the fates were determined to give an attractive designation to our heroine. While “Florence” suggested the goddess of flowers, “Nightingale” spoke of sweet melody. What could be more beautiful and euphonious than a name suggesting a song-bird from the land of flowers? The combination proved a special joy to Mr. Punch and his fellow-humorists when the bearer of the name rose to fame.

However, Miss Nightingale’s real family name was Shore. Her father was William Edward Shore, the only son of William Shore of Tapton, Derbyshire, and he assumed the name of Nightingale, by the sign manual of the Prince Regent, when he succeeded in 1815 to the estates of his mother’s uncle, Peter Nightingale of Lea. This change took place three years before his marriage, and five before the birth of his illustrious daughter.

Through her Shore ancestry Miss Nightingale is connected with the family of Baron Teignmouth. Sir John Shore, Governor-General of India, was created a baron in 1797 and took the title of Teignmouth. Another John Shore was an eminent physician at Derby in the reign of Charles II., and a Samuel Shore married the heiress of the Offleys, a Sheffield family.

4

It is through her paternal grandmother, Mary, daughter of John Evans of Cromford, the niece and sole heir of Peter Nightingale, that Florence Nightingale is connected with the family whose name she bears. Her great-great-uncle, Peter Nightingale, was a typical Derbyshire squire who more than a century ago lived in good style at the fine old mansion of Lea Hall. Those were rough and roystering days in such isolated villages as Lea, and “old Peter” had his share of the vices then deemed gentlemanly. He could swear with the best, and his drinking feats might have served Burns for a similar theme to The Whistle. His excesses gained for him the nickname of “Madman Nightingale,” and accounts of his doings still form the subject of local gossip. When in his cups, he would raid the kitchen, take the puddings from the pots and fling them on the dust-heap, and cause the maids to fly in terror. Nevertheless, “old Peter” was not unpopular; he was good-natured and easy going with his people, and if he drank hard, well, so did his neighbours. He was no better and little worse than the average country squire, and parson too, of the “good old times.” His landed possessions extended from Lea straight away to the old market town of Cromford, and beyond towards Matlock. It is of special interest to note that he sold a portion of his Cromford5 property to Sir Richard Arkwright, who erected there his famous cotton mills. The beautiful mansion of Willersley Castle, which the ingenious cotton-spinner built, and where he ended his days as the great Sir Richard, stands on a part of the original Nightingale property. When “old Peter” of jovial memory passed to his account, his estates and name descended to his grand-nephew, William Edward Shore.

The new squire, Florence Nightingale’s father, was a marked contrast to his predecessor. He is described by those who remember him as a tall, slim, gentlemanly man of irreproachable character. He had been educated at Edinburgh and Trinity College, Cambridge, and had broadened his mind by foreign travel at a time when the average English squire, still mindful of the once terrifying name of “Boney,” looked upon all foreigners as his natural enemies, and entrenched himself on his ancestral acres with a supreme contempt for lands beyond the Channel. Mr. Nightingale was far in advance of the county gentry of his time in matters of education and culture. Sport had no special attraction for him, but he was a student, a lover of books and a connoisseur in art. He was not without a good deal of pride of birth, for the Shores were a very ancient family.

As a landlord he had a sincere desire to benefit6 the people on his estates, although not perhaps in the way they most appreciated. “Well, you see, I was not born generous,” is still remembered as Mr. Nightingale’s answer when solicited for various local charities. However, he never begrudged money for the support of rural education, and, to quote the saying of one of his old tenants, “Many poor people in Lea would not be able to read and write to-day, if it had not been for ‘Miss Florence’s’ father.” He was the chief supporter of what was then called the “cheap school,” where the boys and girls, if they did not go through the higher standards of the present-day schools, at least learned the three R’s for the sum of twopence a week. There was, of course, no compulsory education then, but the displeasure of the squire with people who neglected to send their children to school was a useful incentive to parents. Mr. Nightingale was a zealous Churchman, and did much to further Christian work in his district.

Florence Nightingale’s mother was Miss Frances Smith, daughter of William Smith, Esq., of Parndon in Essex, who for fifty years was M.P. for Norwich. He was a pronounced Abolitionist, took wide and liberal views on the questions of the time, and was noted for his interest in various branches of philanthropy. Mrs. Nightingale was imbued with her father’s spirit, and is remembered7 for her great kindness and benevolence to the poor. She was a stately and beautiful woman in her prime and one of the fast-dying-out race of gentlewomen who were at once notable house-keepers and charming and cultured ladies. Her name is still mentioned with gratitude and affection by the old people of her husband’s estates.

It was from her mother, whom she greatly resembles, that Florence Nightingale inherited the spirit of wide philanthropy and the desire to break away, in some measure, from the bonds of caste which warped the county gentry in her early days and devote herself to humanitarian work. She was also fortunate in having a father who believed that a girl’s head could carry something more than elegant accomplishments and a knowledge of cross-stitch. While our heroine’s mother trained her in deeds of benevolence, her father inspired her with a love for knowledge and guided her studies on lines much in advance of the usual education given to young ladies at that period.

Mr. and Mrs. Nightingale had only two children—Frances Parthenope, afterwards Lady Verney, and Florence, about a year younger. Both sisters were named after the Italian towns where they were born, the elder receiving the name of Parthenope, the classic form of Naples, and was always known as “Parthe,” while our heroine was Florence.

8

Lea Hall first English Home—Neighbourhood of Babington Plot—Dethick Church.

When Mr. and Mrs. Nightingale returned from abroad with their two little daughters, they lived for a time at the old family seat of Lea Hall, which therefore has the distinction of being the first English home of Florence Nightingale, an honour generally attributed to her parents’ subsequent residence of Lea Hurst.

Lea Hall is beautifully situated high up amongst the hills above the valley of the Derwent. I visited it in early summer when the meadows around were golden with buttercups and scented with clover, and the long grass stood ready for the scythe. Wild roses decked the hedgerows, and the elder-bushes,9 which grow to a great size in this part of Derbyshire, made a fine show with their white blossoms. Seen then, the old grey Hall seemed a pleasant country residence; but when the north wind blows and snow covers the hillsides, it must be a bleak and lonely abode. It is plainly and solidly built of grey limestone from the Derbyshire quarries, and is of good proportions. From its elevated position it has an imposing look, and forms a landmark in the open country. Leading from it, the funny old village street of Lea, with its low stone houses, some of them very ancient, curls round the hillside downwards to the valley. The butcher proudly displays a ledger with entries for the Nightingale family since 1835.

The Hall stands on the ancient Manor of Lea, which includes the villages of Lea, Dethick, and Holloway, and which passed through several families before it became the property of the Nightingales. The De Alveleys owned the manor in the reign of John and erected a chapel there. One portion of the manor passed through the families of Ferrar, Dethwick, and Babington, and another portion through the families of De la Lea, Frecheville, Rollestone, Pershall, and Spateman to that of the Nightingales.

The house stands a little back from the Lea road in its own grounds, and is approached by a10 gate from the front garden. Stone steps lead up to the front door, which opens into an old-fashioned flag-paved hall. Facing the door is an oak staircase of exceptional beauty. It gives distinction to the house and proclaims its ancient dignity. The balustrade has finely turned spiral rails, the steps are of solid oak, and the sides of the staircase panelled in oak. One may imagine the little Florence making her first efforts at climbing up this handsome old staircase.

In a room to the left the date 1799 has been scratched upon one of the window-panes, but the erection of the Hall must have been long before that time. For the rest, it is a rambling old house with thick walls and deep window embrasures. The ceilings are moderately high. There is an old-fashioned garden at the back, with fruit and shady trees and a particularly handsome copper beech.

The Hall has long been used as a farmhouse, and scarcely one out of the hundreds of visitors to the Matlock district who go on pilgrimages to Lea Hurst knows of its interesting association. The old lady who occupied it at the time of my visit was not a little proud of the fact that for forty-four years she had lived in the first English home of Florence Nightingale.

The casual visitor might think the district amid which our heroine’s early years were spent was a pleasant Derbyshire wild and nothing more,11 but it has also much historic interest. Across the meadows from Lea Hall are the remains of the stately mansion of Dethick, where dwelt young Anthony Babington when he conspired to release Mary Queen of Scots from her imprisonment at Wingfield Manor, a few miles away. Over these same meadows and winding lanes Queen Elizabeth’s officers searched for the conspirators and apprehended one at Dethick. The mansion where the plot was hatched has been largely destroyed, and what remains is used for farm purposes. Part of the old wall which enclosed the original handsome building still stands, and beside it is an underground cellar which according to tradition leads into a secret passage to Wingfield Manor. The farm bailiff who stores his potatoes in the cellar has not been able to find the entrance to the secret passage, though at one side of the wall there is a suspicious hollow sound when it is hammered.

The original kitchen of the mansion remains intact in the bailiff’s farmhouse. There is the heavy oak-beamed ceiling, black with age, the ponderous oak doors, the great open fireplace, desecrated by a modern cooking range in the centre, but which still retains in the overhanging beam the ancient roasting jack which possibly cooked venison for Master Anthony and the other gallant young gentlemen who had sworn to liberate the12 captive Queen. In the roof of the ceiling is an innocent-looking little trap-door which, when opened, reveals a secret chamber of some size. This delightful old kitchen, with its mysterious memories, was a place of great fascination to Florence Nightingale and her sister in their childhood, and many stories did they weave about the scenes which transpired long ago in the old mansion, so near their own home. It was a source of peculiar interest to have the scenes of a real Queen Mary romance close at hand, and gave zest to the subject when the sisters read about the Babington plot in their history books.

Dethick Church, where our heroine attended her first public service, and continued to frequently worship so long as she lived in Derbyshire, formed a part of the Babingtons’ domain. It was originally the private chapel of the mansion, but gradually was converted to the uses of a parish church. Its tall tower forms a picturesque object from the windows of Lea Hall. The church must be one of the smallest in the kingdom. Fifty persons would prove an overflowing congregation even now that modern seating has utilised space, but in Florence Nightingale’s girlhood, when the quality sat in their high-backed pews and the rustics on benches at the farther end of the church, the sitting room was still more limited. The interior of the13 church is still plain and rustic, with bare stone walls, and the bell ropes hanging in view of the congregation. The service was quaint in Miss Nightingale’s youth, when the old clerk made the responses to the parson, and the preaching sometimes took an original turn. The story is still repeated in the district that the old parson, preaching one Sunday on the subject of lying, made the consoling remark that “a lie is sometimes a very useful thing in trade.” The saying was often repeated by the farmers of Lea and Dethick in the market square of Derby.

Owing to the fact that Dethick Church was originally a private chapel, there is no graveyard. It stands in a pretty green enclosure on the top of a hill. An old yew-tree shades the door, and near by are two enormous elder-bushes, which have twined their great branches together until they fall down to the ground like a drooping ash, forming an absolutely secluded bower, very popular with lovers and truants from church.

The palmy days of old Dethick Church are past. No longer do the people from the surrounding villages and hamlets climb its steep hillside, Sunday by Sunday, for, farther down in the vale, a new church has recently been built at Holloway, which, if less picturesque, is certainly more convenient for the population. On the first Sunday in each month,14 however, a service is still held in the old church where, in days long ago, Florence Nightingale sat in the squire’s pew, looking in her Leghorn hat and sandal shoes a very bonny little maiden indeed.

15

Removal to Lea Hurst—Description of the House—Florence Nightingale’s Crimean Carriage preserved there.

When Florence Nightingale was between five and six years old, the family removed from Lea Hall to Lea Hurst, a house which Mr. Nightingale had been rebuilding on a site about a mile distant, and immediately above the hamlet of Lea Mills. This delightful new home is the one most widely associated with the life of our heroine. To quote the words of the old lady at the lodge, “It was from Lea Hurst as Miss Florence set out for the Crimea, and it was to Lea Hurst as Miss Florence returned from the Crimea.”16 For many years after the war it was a place of pilgrimage, and is mentioned in almost every guidebook as one of the attractions of the Matlock district. It has never been in any sense a show house, and the park is private, but in days gone by thousands of people came to the vicinity, happy if they could see its picturesque gables from the hillside, and always with the hope that a glimpse might be caught of the famous lady who lived within its walls. Miss Nightingale remains tenderly attached to Lea Hurst, although it is eighteen years since she last stayed there. After the death of her parents it passed to the next male heir, Mr. Shore Smith, who later assumed the name of Nightingale.

LEA HURST, DERBYSHIRE.

(Photo by Keene, Derby.)

[To face p. 16.

Lea Hurst is only fourteen miles from Derby, but the following incident would lead one to suppose that the house is not as familiar in the county town as might be expected. Not long ago a lady asked at a fancy stationer’s shop for a photograph of Lea Hurst.

“Lea Hurst?” pondered the young saleswoman, and turning to her companion behind the counter, she inquired, “Have we a photograph of Lea Hurst?”

“Yes, I think so,” was the reply.

“Who is Lea Hurst?” asked the first girl.

“Why, an actor of course,” replied the second.

17

There was an amusing tableau when the truth was made known.

Miss Nightingale’s father displayed a fine discrimination when he selected the position for his new house. One might search even the romantic Peak country in vain for a more ideal site than Lea Hurst. It stands on a broad plateau looking across to the sharp, bold promontory of limestone rock known as Crich Stand. Soft green hills and wooded heights stud the landscape, while deep down in the green valley the silvery Derwent—or “Darent,” as the natives call it—makes music as it dashes over its rocky bed. The outlook is one of perfect repose and beauty away to Dove’s romantic dale, and the aspect is balmy and sunny, forming in this respect a contrast to the exposed and bleak situation of Lea Hall.

The house is in the style of an old Elizabethan mansion, and now that time has mellowed the stone and clothed the walls with greenery, one might imagine that it really dated from the Tudor period. Mr. Nightingale was a man of artistic tastes, and every detail of the house was carefully planned for picturesque effect. The mansion is built in the form of a cross with jutting wings, and presents a picture of clustering chimneys, pointed gables, stone mullioned windows and latticed panes. The fine oriel window of the drawing-room forms a projecting18 wing at one end of the house. The rounded balcony above the window has become historic. It is pointed out to visitors as the place where “Miss Florence used to come out and speak to the people.” Miss Nightingale’s room opened on to this balcony, and after her return from the Crimea, when she was confined to the house with delicate health, she would occasionally step from her room on to the balcony to speak to the people, who had come as deputations, while they stood in the park below. Facing the oriel balcony is a gateway, shadowed by yew-trees, which forms one of the entrances from the park to the garden.

In front of the house is a circular lawn with gravel path and flower-beds, and above the hall door is inscribed N. and the date 1825, the year in which Lea Hurst was completed. The principal rooms open on to the garden or south front, and have a delightfully sunny aspect and a commanding view over the vale. From the library a flight of stone steps leads down to the lawn. The old schoolroom and nursery where our heroine passed her early years are in the upper part of the house and have lovely views over the hills.

In the centre of the garden front of the mansion is a curious little projecting building which goes by the name of “the chapel.” It is evidently an ancient building effectively incorporated into Lea19 Hurst. There are several such little oratories of Norman date about the district, and the old lady at Lea Hurst lodge shows a stone window in the side of her cottage which is said to be seven hundred years old. A stone cross surmounts the roof of the chapel, and outside on the end wall is an inscription in curious characters. This ancient little building has, however, a special interest for our narrative, as Miss Nightingale used it for many years as the meeting place for the Sunday afternoon Bible-class which she held for the girls of the district. In those days there was a large bed of one of Miss Nightingale’s favourite flowers, the fuchsia, outside the chapel, but that has been replaced by a fountain and basin, and the historic building itself, with its thick stone walls, now makes an excellent larder.

The gardens at Lea Hurst slope down from the back of the house in a series of grassy terraces connected by stone steps, and are still preserved in all their old-fashioned charm and beauty. There in spring and early summer one sees wallflowers, peonies, pansies, forget-me-nots, and many-coloured primulas in delightful profusion, while the apple trellises which skirt the terraces make a pretty show with their pink blossoms, and the long border of lavender-bushes is bursting into bloom. In a secluded corner of the garden is an old summer-house with20 pointed roof of thatch which must have been a delightful playhouse for little Florence and her sister.

The park slopes down on either side the plateau on which the house stands. The entrance to the drive is in the pleasant country road which leads to the village of Whatstandwell and on to Derby. This very modest park entrance, consisting of an ordinary wooden gate supported by stone pillars with globes on the top, has been described by an enthusiastic chronicler as a “stately gateway” with “an air of mediæval grandeur.” There is certainly no grandeur about Lea Hurst, either mediæval or modern. It is just one of those pleasant and picturesque country mansions which are characteristic of rural England, and no grandeur is needed to give distinction to a house which the name of Florence Nightingale has hallowed.

Beyond the park the Lea woods cover the hillside for some distance, and in spring are thickly carpeted with bluebells. A long winding avenue, from which magnificent views are obtained over the hills and woodland glades for many miles, skirts the top of the woods, and is still remembered as “Miss Florence’s favourite walk.”

The chief relic preserved at Lea Hurst is the curious old carriage used by Miss Nightingale21 in the Crimea. What memories does it not suggest of her journeys from one hospital to another over the heights of Balaclava, when its utmost carrying capacity was filled with comforts for the sick and wounded! The body of the carriage is of basket-work, and it has special springs made to suit the rough Crimean roads. There is a hood which can be half or fully drawn over the entire vehicle. The carriage was driven by a mounted man acting as postilion.

It seems as though such a unique object ought to have a permanent place in one of our public museums, for its interest is national. A native of the district, who a short time ago chanced to see the carriage, caught the national idea and returned home lamenting that he could not put the old carriage on wheels and take it from town to town. “There’s a fortune in the old thing,” said he, “for most folks would pay a shilling or a sixpence to see the very identical carriage in which Miss Florence took the wounded about in those Crimean times. It’s astonishing what little things please people in the way of a show. Why, that carriage would earn money enough to build a hospital!”

22

Romantic Journeys from Lea Hurst to Embley Park—George Eliot Associations—First Patient—Love of Animals and Flowers—Early Education.

The childhood of Florence Nightingale, begun, as we have seen, in the sunny land of Italy, was subsequently passed in the beautiful surroundings of her Derbyshire home, and at Embley Park, Hampshire, a fine old Elizabethan mansion, which Mr. Nightingale purchased when Florence was about six years old.

The custom was for the family to pass the summer at Lea Hurst, going in the autumn to Embley for the winter and early spring. And what an exciting23 and delightful time Florence and her sister Parthe had on the occasions of these alternative “flittings” between Derbyshire and Hampshire in the days before railroads had destroyed the romance of travelling! Then the now quiet little town of Cromford, two miles from Lea Hurst, was a busy coaching centre, and the stage coaches also stopped for passengers at the village inn of Whatstandwell, just below Lea Hurst Park. In those times the Derby road was alive with the pleasurable excitements of the prancing of horses, the crack of the coach-driver’s whip, the shouts of the post-boys, and the sound of the horn—certainly more inspiring and romantic sights and sounds than the present toot-toot of the motor-car, and the billows of dust-clouds which follow in its rear.

Sometimes the journey from Lea Hurst was made by coach, but more frequently Mr. and Mrs. Nightingale with their two little girls drove in their own carriage, proceeding by easy stages and putting up at inns en route, while the servants went before with the luggage to prepare Embley for the reception of the family.

How glorious it was in those bright October days to drive through the country, just assuming its dress of red and gold, or again in the return journey in the spring, when the hills and dales of Derbyshire were bursting into fresh green beauty.24 The passionate love for nature and the sights and sounds of rural life which has always characterised Miss Nightingale was implanted in these happy days of childhood. And so, too, were the homely wit and piquant sayings which distinguish her writings and mark her more intimate conversation. She acquired them unconsciously, as she encountered the country people.

In her Derbyshire home she lived in touch with the life which at the same period was weaving its spell about Marian Evans, when she visited her kinspeople, and was destined to be immortalised in Adam Bede and The Mill on the Floss. Amongst her father’s tenants Florence Nightingale knew farmers’ wives who had a touch of Mrs. Poyser’s caustic wit, and was familiar with the “Yea” and “Nay” and other quaint forms of Derbyshire speech, such as Mr. Tulliver used when he talked to “the little wench” in the house-place of the ill-fated Mill on the Floss. She met, too, many of “the people called Methodists,” who in her girlhood were establishing their preaching-places in the country around Lea Hurst, and she heard of the fame of the woman preacher, then exercising her marvellous gifts in the Derby district, who was to become immortal as Dinah Morris. In Florence Nightingale’s early womanhood, Adam Bede lived in his thatched cottage by Wirksworth25 Tape Mills, a few miles from Lea Hurst, and the Poysers’ farm stood across the meadows.

The childhood of our heroine was passed amid surroundings which proved a singularly interesting environment. Steam power had not then revolutionised rural England: the counties retained their distinctive speech and customs, the young people remained on the soil where they were born, and the rich and the poor were thrown more intimately together. The effect of the greater personal intercourse then existing between the squire’s family and his people had an important influence on the character of Florence Nightingale in her Derbyshire and Hampshire homes. She learned sympathy with the poor and afflicted, and gained an understanding of the workings and prejudices of the uneducated mind, which enabled her in after years to be a real friend to those poor fellows fresh from the battlefields of the Crimea, many of whom had enlisted from the class of rural homes which she knew so well.

When quite a child, Florence Nightingale showed characteristics which pointed to her vocation in life. Her dolls were always in a delicate state of health and required the utmost care. Florence would undress and put them to bed with many cautions to her sister not to disturb them. She soothed their pillows, tempted them with imaginary26 delicacies from toy cups and plates, and nursed them to convalescence, only to consign them to a sick bed the next day. Happily, Parthe did not exhibit the same tender consideration for her waxen favourites, who frequently suffered the loss of a limb or got burnt at the nursery fire. Then of course Florence’s superior skill was needed, and she neatly bandaged poor dolly and “set” her arms and legs with a facility which might be the envy of the modern miraculous bone-setter.

The first “real live patient” of the future Queen of Nurses was Cap, the dog of an old Scotch shepherd, and although the story has been many times repeated since Florence Nightingale’s name became a household word, no account of her childhood would be complete without it. One day Florence was having a delightful ride over the Hampshire downs near Embley along with the vicar, for whom she had a warm affection. He took great interest in the little girl’s fondness for anything which had to do with the relief of the sick or injured, and as his own tastes lay in that direction, he was able to give her much useful instruction. However, on this particular day, as they rode along the downs, they noticed the sheep scattered in all directions and old Roger, the shepherd, vainly trying to collect them together.

27

“Where is your dog?” asked the vicar as he drew up his horse and watched the old man’s futile efforts.

“The boys have been throwing stones at him, sir,” was the reply, “and they have broken his leg, poor beast. He will never be any good for anything again and I am thinking of putting an end to his misery.”

“Poor Cap’s leg broken?” said a girlish voice at the clergyman’s side. “Oh, cannot we do something for him, Roger? It is cruel to leave him alone in his pain. Where is he?”

“You can’t do any good, missy,” said the old shepherd sorrowfully. “I’ll just take a cord to him to-night—that will be the best way to ease his pain. I left him lying in the shed over yonder.”

“Oh, can’t we do something for poor Cap?” pleaded Florence to her friend; and the vicar, seeing the look of pity in her young face, turned his horse’s head towards the distant shed where the dog lay. But Florence put her pony to the gallop and reached the shed first. Kneeling down on the mud floor, she caressed the suffering dog with her little hand, and spoke soothing words to it until the faithful brown eyes seemed to have less of pain in them and were lifted to her face in pathetic gratitude.

That look of the shepherd’s dog, which touched28 her girlish heart on the lonely hillside, Florence Nightingale was destined to see repeated in the eyes of suffering men as she bent over them in the hospital at Scutari.

The vicar soon joined his young companion, and finding that the dog’s leg was only injured, not broken, he decided that a little careful nursing would put him all right again.

“What shall I do first?” asked Florence, all eagerness to begin nursing in real earnest.

“Well,” said her friend, “I should advise a hot compress on Cap’s leg.”

Florence looked puzzled, for though she had poulticed and bandaged her dolls, she had never heard about a compress. However, finding that in plain language it meant cloths wrung out of boiling water, and laid upon the affected part, she set nimbly to work under the vicar’s directions. Boiling water was the first requisite, and calling in the services of the shepherd’s boy, she lighted a fire of sticks in the cottage near by, and soon had the kettle boiling.

Next thing, she looked round for cloths to make the compress. The shepherd’s clean smock hung behind the door, and Florence seized it with delight, for it was the very thing.

“If I tear it up, mamma will give Roger another,” she reasoned, and, at an approving nod from the29 vicar, tore the smock into suitable lengths for fomentation. Then going back to the place where the dog lay, accompanied by the boy carrying the kettle and a basin, Florence Nightingale set to work to give “first aid to the wounded.” Cap offered no resistance—he had a wise confidence in his nurse—and as she applied the fomentations the swelling began to go down, and the pain grew less.

Florence was resolved to do her work thoroughly, and a messenger having been despatched to allay her parents’ anxiety at her prolonged absence, she remained for several hours in attendance on her patient.

In the evening old Roger came slowly and sorrowfully towards the shed, carrying the fatal rope, but no sooner did he put his head in at the door than Cap greeted him with a whine of pleasure and tried to come towards him.

“Deary me, missy,” said the old shepherd in astonishment, “why, you have been doing wonders. I never thought to see the poor dog greet me again.”

“Yes, doesn’t he look better?” said the youthful nurse with pardonable pride. “You can throw away that rope now, and help me to make compresses.”

“That I will, missy,” said Roger, and stooping down beside Florence and Cap, he was initiated into the mysteries.

30

“Yes,” said the vicar, “Miss Florence is quite right, Roger—your dog will soon be able to walk again if you give it a little rest and care.”

“I am sure I can’t thank your reverence and the young lady enough,” replied the shepherd, quite overcome at the sight of his faithful dog’s look of content and the thought that he would not lose him after all; “and you may be sure, sir, I will carry out the instructions.”

“But I shall come again to-morrow, Roger,” interposed Florence, who had no idea of giving up her patient yet. “I know mamma will let me when I tell her about poor Cap.” After a parting caress to the dog, and many last injunctions to Roger, Florence mounted her pony and rode away with the vicar, her young heart very full of joy. She had really helped to lessen pain, if only for a dumb creature, and the grateful eyes of the suffering dog stirred a new feeling in her opening mind. She longed to be always doing something for somebody, and the poor people on her father’s estates soon learned what a kind friend they had in Miss Florence. They grew also to have unbounded faith in her skill, and whenever a pet animal was sick or injured, the owner would contrive to let “Miss Florence” know.

She and her sister were encouraged by Mr. and Mrs. Nightingale in a love of animals, and31 were allowed to have many pets. It was characteristic of Florence that her heart went out to the less favoured ones, those which owing to old age or infirmity were taken little notice of by the servants and farm-men. She was particularly attached to Peggy, an old grey pony long since past work, who spent her days in the paddock at Lea Hurst. Florence never missed a morning, if she could help it, without going to talk to Peggy, who knew her footstep, and would come trotting up to the gate ready to meet her young mistress. Then would follow some good-natured sport.

“Would you like an apple, poor old Peggy?” Florence would say as she fondled the pony’s neck; “then look for it.”

At this invitation Peggy would put her nose to the dress pocket of her little visitor and discover the delicacy. Or it might be a carrot, held well out of sight, which Peggy was invited to play hide-and-seek for. If the stable cat had kittens, it was Florence who gave them a welcome and fondled and played with the little creatures before any one else noticed them. She had, too, a quick eye for a hedge-sparrow’s nest, and would jealously guard the brooding mother’s secret until the fledgelings were hatched and ready to fly. Some of the bitterest tears of her childhood were shed over the broken-up homes of some of her32 feathered friends. The young animals in the fields were quickly won by her kind nature, and would come bounding towards her. Out in those beautiful Lea Hurst woods she made companions of the squirrels, who came fearlessly after her as she walked, to pick up the nuts mysteriously dropped in their path. Then, when master squirrel least expected it, Florence turned sharp round and away raced the little brown creature up the tall beech, only to come down again with a quizzical look in his keen little eye at nuts held too temptingly for any squirrel of ordinary appetite to resist. With what delight she watched their funny antics, for she had the gift to make these timid creatures trust her.

EMBLEY PARK, HAMPSHIRE.

(From a drawing by the late Lady Verney.)

[To face p. 32.

Then in spring-time there was sure to be a pet lamb to be fed, and Florence and her sister were indeed happy at this acquisition to the home pets. The pony which she rode and the dog which was ever at her side were of course her particular dumb friends. I am not sure, however, that she thought them dumb, for she and they understood one another perfectly. The love of animals, which was so marked a characteristic in Florence Nightingale as a child, remained with her throughout life and made her very sympathetic to invalids who craved for the company of some favourite animal. Many nurses and doctors disapprove33 of their patients having pets about them, but, to quote the Queen of Nurses’ own words, “A small pet animal is often an excellent companion for the sick, for long chronic cases especially. An invalid, in giving an account of his nursing by a nurse and a dog, infinitely preferred that of the dog. ‘Above all,’ he said, ‘it did not talk.’”

It was a great source of pleasure to Florence in her early years to be allowed to act as almoner for her mother. Mrs. Nightingale was very kind and benevolent to the people around Lea Hurst and Embley, and supplied the sick with delicacies from her own table. Indeed, she made her homes centres of beneficence for several miles around, and, according to the best traditions of those times, was ready with remedies for simple ailments when the doctor was not at hand. Owing to the fact that Florence had never had measles and whooping cough, her parents had to exercise great caution in permitting her to visit the cottage people; however, she could call at the doors on her pony and leave jelly and puddings from the basket at her saddle-bow without incurring special risk. And she could gather flowers from the garden to brighten a sick-room, or in the lovely spring days load her basket with primroses and bluebells and so carry the scent of the woods to some delicate girl who, like Tennyson’s May Queen, was pining for the34 sight of field and hedgerow and the flowers which grew but a little distance from her cottage door.

Such attentions to the fancies of the sick were little thought of in those times, before flower missions had come into vogue, or the necessity for cheering the patients by pleasing the eye, as well as tending the body, was recognised, but in that, as in much else, our heroine was in advance of her time. Her love of flowers, like fondness for animals, was a part of her nature: it came too as a fitting heritage from the city of flowers under whose sunny sky she had been born.

Both at Embley and Lea Hurst, Florence and her sister had their own little gardens, in which they digged and sowed and planted to their hearts’ delight, and in summer they ran about with their miniature watering cans, bestowing, doubtless, an almost equal supply on their own tiny feet as on the parched ground. In after years this early love of flowers had its pathetic sequel. When, after months of exhausting work amongst the suffering soldiers, Florence Nightingale lay in a hut on the heights of Balaclava, prostrate with Crimean fever, she relates that she first began to rally after receiving a bunch of flowers from a friend, and that the sight of them beside her sick couch helped her to throw off the languor which35 had nearly proved fatal. She dated her recovery from that hour.

In every respect the circumstances of Florence Nightingale’s childhood were calculated to fit her for the destiny which lay in the future. Not only was she reared among scenes of exceptional beauty in both her Derbyshire and her Hampshire homes and taught the privilege of ministering to the poor and sick, but she was mentally trained in advance of the custom of the day. Without that equipment she could not have held the commanding position which she attained in the work of army nursing and organisation.

She and her sister Parthe, being so near in age, did their lessons together. Their education was conducted entirely at home under a private governess, and was assiduously supervised by their father. Mr. Nightingale was a man of broad sympathies, artistic and intellectual tastes, and much general cultivation, and, having no sons, he made a hobby of giving a classical education to his girls, and found a fertile soil in the quick brain of his daughter Florence. He was a strict disciplinarian, and none of the desultory ways which characterised the home education of young ladies in the early Victorian days was allowed in the schoolrooms at Embley and Lea Hurst. Rules were rigidly fixed for lessons and play, and careless work was never36 passed unpunished. It was in the days of childhood that the future heroine of the Crimea laid the foundation of an orderly mind and a habit of method which served her so admirably when suddenly called to organise the ill-regulated hospital at Scutari.

As a child Florence excelled in the more intellectual branches of education and showed a great aptitude for foreign languages. She attained creditable proficiency in music and was clever at drawing, but in these artistic branches her elder sister Parthe excelled most. From her father Florence learned elementary science, Greek, Latin, and mathematics, and under his guidance, seated in the dear old library at Lea Hurst, made the acquaintance of standard authors and poets. But doubtless the sisters got an occasional romance not included in the paternal list and read it with glowing cheeks and sparkling eyes in a secluded nook in the garden.

If study was made a serious business, the sisters enjoyed to the full the healthy advantages of country life. They scampered about the park with their dogs, rode their ponies over hill and dale, spent long days in the woods amongst the bluebells and primroses, and in summer tumbled about in the sweet-scented hay. During the summer at Lea Hurst, lessons were a little relaxed in favour37 of outdoor life, but on the return to Embley for the winter, schoolroom routine was again enforced on very strict lines.

Mrs. Nightingale supervised the domestic side of her little girls’ education, and before Florence was twelve years old she could hemstitch and seam, embroider bookmarkers, and had worked several creditable samplers. Her mother trained her too in matters of deportment, and nothing was omitted in her early years which would tend to mould her into a graceful and accomplished girl.

38

An Accomplished Girl—An Angel in the Homes of the Poor—Children’s “Feast Day” at Lea Hurst—Her Bible-Class for Girls—Interests at Embley—Society Life—Longing for a Vocation—Meets Elizabeth Fry—Studies Hospital Nursing—Decides to go to Kaiserswerth.

When Florence Nightingale reached her seventeenth year she began to take her place as the squire’s daughter, mingling in the county society of Derbyshire and Hampshire and interesting herself in the people and schools of her father’s estates. She soon acquired the reputation of being a very lovable young lady as well as a very talented one. She had travelled abroad, could speak French, German, and Italian, sang very sweetly, and was clever at sketching, and when39 the taking of photographs became a fashionable pastime, “Miss Florence” became an enthusiast for the art. There were no hand-cameras in those days and no clean and easy methods for developing, and young lady amateur photographers were obliged to dress for their work. Nothing daunted “Miss Florence,” and she photographed groups on the lawn and her pet animals to the admiration of her family and friends, if sometimes to the discoloration of her dainty fingers.

She was also a skilful needlewoman, and worked cushions and slippers, mastered the finest and most complicated crochet patterns, sewed delicate embroideries, and achieved almost invisible hems on muslin frills. At Christmas-time her work-basket was full of warm comforts for the poor. She was invaluable at bazaars, then a newly introduced method of raising money for religious purposes, and was particularly happy at organising treats for the old people and children.

The local clergy, both at Embley and Lea, found the squire’s younger daughter a great help in the parish. The traits of character which had shown themselves in the little girl who tended the shepherd’s injured dog, and was so ready with her sympathy for all who suffered or were in trouble, became strengthened in the budding woman and made Florence Nightingale regarded as an angel40 in the homes of the poor. Her visits to the cottages were eagerly looked for, and she showed even in her teens a genius for district visiting. The people regarded her not as the “visiting lady,” whom they were to impress with feigned woes or a pretence of abject poverty, but as a real friend who came to bring pleasure to their homes and to enter into their family joys and sorrows. She had a bright and witty way of talking which made the poor folks look forward to her visits quite apart from the favours she might bring.

If there was sickness or sorrow in any cottage home, the presence of “Miss Florence” was eagerly sought, for even at this period she had made some study of sick nursing and “seemed,” as the people said, “to have a way with her” which eased pain and brought comfort and repose to those who were suffering. She had, too, such a clear, sweet voice and sympathetic intonation that the sick derived great pleasure when she read to them.

As quite a young girl the bent of her mind was in the direction of leading a useful and beneficent life. She was in no danger of suffering from the ennui which beset so many girls of the leisured classes in those times, when there was so little in the way of outdoor sport and amusements or independent interests to fill up time. In whatsoever circumstances of life Florence Nightingale had been41 placed, her nature would have prompted her to discover useful occupation.

The “old squire,” as Mr. Nightingale is still called at Lea, took a great interest in the village school, and Florence became his right hand in looking after the amusements of the children. There were many little treats devised for them from time to time, but the great event of the year was the children’s “feast day,” when the scholars assembled at the school-house and walked in procession to Lea Hurst, carrying “posies” in their hands and sticks wreathed with garlands of flowers. A band provided by the squire headed the procession. Arrived at Lea Hurst, the company were served with tea in the field below the garden, Mrs. Nightingale and her daughters assisting the servants to wait upon their guests. After tea, the band struck up lively airs and the lads and lasses danced in a style which recalled the olden times in Merrie England, while the squire and his family beamed approval.

Then there were games for the little ones devised by “Miss Florence,” who took upon herself their special entertainment; and so the summer evening passed away in delightful mirth and recreation until the crimson clouds began to glow over the beautiful Derwent valley, and the children re-formed in line and marched up the garden to the top terrace of the lawn. Meantime “Miss Florence” and42 “Miss Parthe” had mysteriously disappeared, and now they were seen standing on the terrace behind a long table laden with presents. As the procession filed past, each child received a gift from one or other of the young ladies, and there were kindly words from the squire and gracious smiles from Mrs. Nightingale and much bobbing of curtseys by the delighted children, and so the “feast day” ended in mutual joy and pleasure.

The scene was described to me by an old lady who had many times as a child attended this pretty entertainment at Lea Hurst, and still treasures the little gifts—fancy boxes, books, thimble cases and the like—which she had received from the hands of the then beloved and now deeply reverenced “Miss Florence.” She recalls what a sweet young lady she was, with her glossy brown hair smoothed down each side of her face, and often a rose placed at the side, amongst the neat plaits or coils. Her appearance at this period can be judged from the pencil sketch by her sister, afterwards Lady Verney, in which, despite the quaint attire, one recognises a tall, graceful girl of charm and intelligence.

In Derbyshire, Florence Nightingale’s interest in Church work was divided between the historic little church of Dethick, described in a former chapter, and the beautiful church which Sir Richard Arkwright had built at Cromford on the opposite43 side of the river from his castle of Willersley. To-day, Cromford Church is thickly covered with ivy and embowered in trees, and, standing on the river bank with greystone rocks towering on one side and the wooded heights of Willersley on the other, presents a mellowed and picturesque appearance. In our heroine’s girlhood it was comparatively new and regarded as the wonder of the district for the architectural taste and decoration which Sir Richard had lavished upon it. The great cotton-spinner himself had been laid beneath its chancel in 1792, but an Arkwright reigned at Willersley Castle in Miss Nightingale’s youth—as indeed there does to-day—and carried on the beneficent schemes of the founder for the people of the district. Then the Arkwright Mills—long since disused—gave employment to hundreds of people, and the now sleepy little town of Cromford was alive with an industrial population. It was something of a model village, as the neat rows of low stone houses which flank Cromford hill testify, and there were schools, reading-rooms, and other means devised for the betterment of the people. Many schemes originated with the vicar and patron of Cromford Church, and the young ladies from Lea Hurst sometimes assisted at entertainments.

We may imagine “Miss Florence” when she44 drove with her parents down to Cromford Church making a very pretty picture indeed, dressed in her summer muslin, with a silk spencer crossed over her maiden breast and her sweet, placid face beaming from out the recesses of a Leghorn bonnet, wreathed with roses.

It was, however, in connection with the church of Dethick and the adjoining parishes of Lea and Holloway that Florence Nightingale did most of her philanthropic work. This district was peculiarly her father’s domain, and also embraced the church and village of Crich. Like Cromford, it was the seat of a village industry. Immediately below Lea Hurst were Smedley’s hosiery mills, which employed hundreds of women and girls, many of whom lived on the Nightingale estate, and Miss Florence took great interest in their welfare. As she grew into womanhood, she started a Bible-class for the young women of the district, holding it in the old building at Lea Hurst known as the “chapel.” The class was unsectarian, for “Smedley’s people,” following the example of their master, “Dr.” John Smedley, were chiefly Methodists. However, religious differences were not bitter in the neighbourhood, and Miss Nightingale welcomed to her class all young girls who were disposed to come, whether their parents belonged to “chapel” or “church.”

45

The memory of those Sunday afternoons, as they sat in the tiny stone “chapel” overlooking the sunny lawns and gardens of Lea Hurst, listening to the beautiful expositions of Scripture which fell from their beloved “Miss Florence,” or following her sweet voice in sacred song, is green in the hearts of a few elderly people in the neighbourhood. A softness comes into their voice, and a smile of pleasure lights up their wrinkled faces, as they tell you how “beautifully Miss Florence used to talk.” In years long after, when she returned for holiday visits to Lea Hurst, nothing gave Miss Nightingale greater pleasure than for the young girls of the district, some of them daughters of her former scholars, to come on summer Sunday afternoons and sing on the lawn at Lea Hurst as she sat in her room above. Infirmity prevented her from mingling with them, but the girls were pleased if they could only catch a sight of her face smiling down from the window.

During the winter months spent in her Hampshire home, Florence Nightingale was also active amongst the sick poor and the young people. Embley Park is near the town of Romsey, in the parish of East Willow, and Mr. Nightingale and his family attended that church. “Miss Florence” had many friends amongst the cottagers, and a few of the old people still recall seeing the “young46 ladies” riding about on their ponies, and stopping with kind inquiries at some of the house doors. Although the sisters were such close companions, it is always “Miss Florence” who is remembered as the chief benefactress. She had the happy gift for gaining the love of the people, and the instinct for giving the right sort of help, though “Miss Parthe” was no less kind-hearted.

At Christmas, Embley Park was a centre from which radiated much good cheer. “Florence” was gay indeed, as, in ermine tippet and muff and beaver hat, she helped to distribute the parcels of tea and the warm petticoats to the old women. She devised Christmas entertainments for the children and assisted in treats for the workhouse poor. Local carol-singers received a warm welcome at Embley, especially from Miss Florence, who would come into the hall to see the mince-pies and coin distributed as she chatted with the humble performers. Training the boys and girls to sing was to her a matter of special interest, and she did much in those far-away days to promote a love of music amongst the villagers both at Lea Hurst and Embley. It would afford her pleasure to-day could she listen to the well-trained band formed by the mill-workers at Lea, which one hears discoursing sweet music outside the mills on a summer’s evening.

Embley overlooked the hills of the Wiltshire47 border, and the cathedral city of Salisbury, only some thirteen miles distant, afforded Miss Nightingale a wider field of philanthropic interest. She was always willing to take part in beneficent work in the neighbourhood, and the children’s hospital and other schemes founded and conducted by her friends Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Herbert, afterwards Lord and Lady Herbert of Lea, formed a special interest for her in the years immediately preceding the outbreak of the Crimean War.

It must not, however, be supposed that in the early years of her womanhood Miss Nightingale gave herself up entirely to religious and philanthropic work, though it formed a serious background to her social life. Mr. Nightingale, as a man of wealth and influence, liked to see his wife and daughters taking part in county society. During the winter he entertained a good deal at Embley, which was a much larger and handsomer residence than Lea Hurst. Mr. and Mrs. Nightingale had a large circle of friends, and their house was noted as a place of genial hospitality, while their charming and accomplished daughters attracted many admirers.

The family did not confine themselves only to county society. They sometimes came to London for the season, and Florence and her sister made their curtsey to Queen Victoria when in the48 heyday of her early married life, and entered into the gaieties of the time.

However, as the years passed by Florence Nightingale cared less and less for the excitement and pleasures of society. Her nature had begun to crave for some definite work and a more extended field of activity than she found in private life. Two severe illnesses among members of her family had developed her nursing faculty, and when they no longer required her attention, she turned to a systematic study of nursing.

MISS NIGHTINGALE.

(From a Drawing.)

[To face p. 48.

To-day it seems almost impossible to realise how novel was the idea of a woman of birth and education becoming a nurse. Miss Nightingale was a pioneer of the pioneers. She herself had not then any clear course before her for the future, but she realised the important point that she could not hope to accomplish anything without training. The faculty was necessary and the desire to be helpful to the sick and suffering, but a trained knowledge was the important thing. In a letter which Miss Nightingale wrote in after years to young women on the subject of “Work and Duty” she remarked: “I would say to all young ladies who are called to any particular vocation, qualify yourselves for it as a man does for his work. Don’t think you can undertake it otherwise. Submit yourselves to the rules of business as men do, by49 which alone you can make God’s business succeed; for He has never said that he will give His success and his blessing to sketchy and unfinished work.” And on another occasion she wrote: “Three-fourths of the whole mischief in women’s lives arises from their excepting themselves from the rules of training considered needful for men.”

This was the spirit in which Miss Nightingale entered upon her chosen work, for she was the last person to “preach and not practise.” The advice which she gave to other women, when she had herself risen to the head of her profession, had been the guiding influence of her own probation.

The beneficent work which distinguished her as the squire’s daughter had given her useful experience, and had opened her eyes to the need of trained nurses for the sick poor. What is now called “district nursing” at this period exercised the mind of Florence Nightingale, and her attention to military nursing was called forth later by a national emergency.

It was at this critical period of her life, when her mind was shaping itself to such high purpose, that Florence Nightingale met Elizabeth Fry. The first grasping of hands of these two pioneer women would serve as subject for a painter. We picture the stately and beautiful old Quakeress in the characteristic garb of the Friends extending a sisterly50 welcome to the young and earnest woman who came to learn at her feet. The one was fast drawing to the close of her great work for the women prisoners, and the other stood on the threshold of a philanthropic career to be equally distinguished. We have no detailed record of what words were spoken at this meeting, but we know that the memory of the heavenly personality of Elizabeth Fry was an ever-present inspiration with Florence Nightingale in the years which followed.

It was a meeting of kindred spirits, but of distinct individualities. We do not find Miss Nightingale making any attempt to take up the mantle fast falling from the experienced philanthropist: she had her own line of pioneer work forming in her capable brain, but was eager to glean something from the wide experience through which her revered friend had passed. Mrs. Fry had during the past few years been visiting prisons and institutions on the Continent, and had established a small training home for nurses in London. She was a friend of Pastor Fliedner, the founder of Kaiserswerth, and had visited that institution. The account of his work, and of the order of Protestant deaconesses which he had founded for tending the sick poor, given by Mrs. Fry, made a profound impression on Florence Nightingale, and resulted51 a few years later in her enrolment as a voluntary nurse at that novel institution.

In the meantime she studied the hospital system at home, spending some months in the leading London hospitals and visiting those in Edinburgh and Dublin. Then she undertook a lengthened tour abroad and saw the different working of institutions for the sick in France, Germany, and Italy. The comparison was not favourable to this country. The nursing in our hospitals was largely in the hands of the coarsest type of women, not only untrained, but callous in feeling and often grossly immoral. There was little to counteract their baneful influence, and the atmosphere of institutions which, as the abodes of the sick and dying, had special need of spiritual and elevating influences, was of a degrading character. The occasional visits of a chaplain could not do very much to counteract the behaviour of the unprincipled nurse ever at the bedside. The habitual drunkenness of these women was then proverbial, while the dirt and disorder rampant in the wards was calculated to breed disease. The “profession,” if the nursing of that day can claim a title so dignified, had such a stigma attaching to it that no decent woman cared to enter it, and if she did, it was more than likely that she would lose her character.

52

In contrast to this repulsive class of women, whom Miss Nightingale had encountered to her horror in the hospitals of London, Edinburgh, and Dublin, and to the “Sairey Gamps” who were the only “professional” nurses available for the middle classes in their own homes, she found on the Continent the sweet-faced Sister of Charity—pious, educated, trained.

For centuries the Roman Catholic community had trained and set apart holy women for ministering to the sick poor in their own homes, and had established hospitals supplied with the same type of nurse. A large number of these women were ladies of birth and breeding who worked for the good of their souls and the welfare of their Church, while all received proper education and training, and had abjured the world for a religious life. An excellent example of the work done by the nun-nurses is seen in the quaint old-world hospital of St. John, with which visitors to Bruges are familiar. It was one of the institutions visited by Miss Nightingale, and, religious differences apart, she viewed with profound admiration the beneficent work of the sisters.

After pursuing her investigations from city to city, Miss Nightingale decided to take a course of instruction at the recently founded institution for deaconesses at Kaiserswerth on the Rhine. There53 a Protestant sisterhood were working on similar lines to Sisters of Charity, and had already done much to mitigate the poverty, sickness, and misery in their own district, and were beginning to extend their influence to other German towns. At Kaiserswerth the ideal system of trained sick nursing which Miss Nightingale had been forming in her own mind was an accomplished fact.

54

Enrolled a Deaconess at Kaiserswerth—Paster Fliedner—His Early Life—Becomes Pastor at Kaiserswerth—Interest in Prison Reform—Starts a Small Penitentiary for Discharged Female Prisoners—Founds a School and the Deaconess Hospital—Rules for Deaconesses—Marvellous Extension of his Work—His Death—Miss Nightingale’s Tribute.

The year 1849 proved a memorable one in the career of Florence Nightingale, for it was then that she enrolled herself as a voluntary nurse in the Deaconess Institution at Kaiserswerth on the Rhine, which may be described as her Alma Mater. It was the first training school for sick nurses established in modern times, and it seems a happy conjunction of circumstances that she who was destined to hold the blue riband of the nursing sisterhood of the world should have studied within its walls.

55

Although she had already gained valuable insight into hospital work and management during her visits to various hospitals at home and abroad, it was not until she came to Kaiserswerth that she found her ideals realised. Here was a Protestant institution which had all the good points of the56 Roman Catholic sisterhoods without their restrictions. It further commended itself as being under the guidance of Pastor Fliedner, a man of simple and devoted piety and a born philanthropist.

He had had the perspicacity to see that the world needed the services of trained women to grapple with the evils of vice and disease, and to this end he revived the office of deaconess which had been instituted by the early Christian Church. The idea of training women to minister to the sick and the poor seems natural enough to-day, but in Miss Nightingale’s young womanhood it was entirely novel. The district nurse had not then been invented. The Kaiserswerth institution combined hospital routine and instruction with beneficent work among the poor and the outcast.

Pastor Fliedner, the founder, was indeed a kindred spirit, and it seems fitting to give a little account of the man who exercised such a remarkable influence over our heroine in the days of her probation. Theodore Fliedner was just twenty years her senior, having been born in 1800 at Eppstein, a small village near the Rhine. He was “a son of the manse,” both his father and grandfather having been Lutheran clergymen. At an early age he showed a desire to become a power for good in the world, and his sensitive feelings were much hurt when a child, by his father playfully57 calling him “the little beer-brewer” on account of his plump round figure. The jest caused little Theodore much heart-searching and made him feel that his nature must be very carnal and in need of great discipline. In these days he would probably have resorted to Sandow’s exercises or a bicycle.

Of course Theodore was poor and had to work his way from school to college. He studied at the Universities of Giessen and Göttingen, giving instruction in return for food and lodging, and was not above doing manual labour also. He sawed wood, blacked boots, and did other odd jobs. He also mended his own clothes, but in a somewhat primitive fashion, for in a letter to his mother he says that he sewed up the holes in his trousers with white thread which he afterwards inked over. His vacations were spent in tramping long distances and subsisting on the barest necessaries of life, in order to gain an acquaintance with the world. He studied foreign languages, read widely, and as a college student showed the after bent of his mind by collecting songs and games for children which later were used in his own kindergarten, and have spread throughout the world. He also learned the use of herbs and acquired much homely knowledge on the treatment of disease.