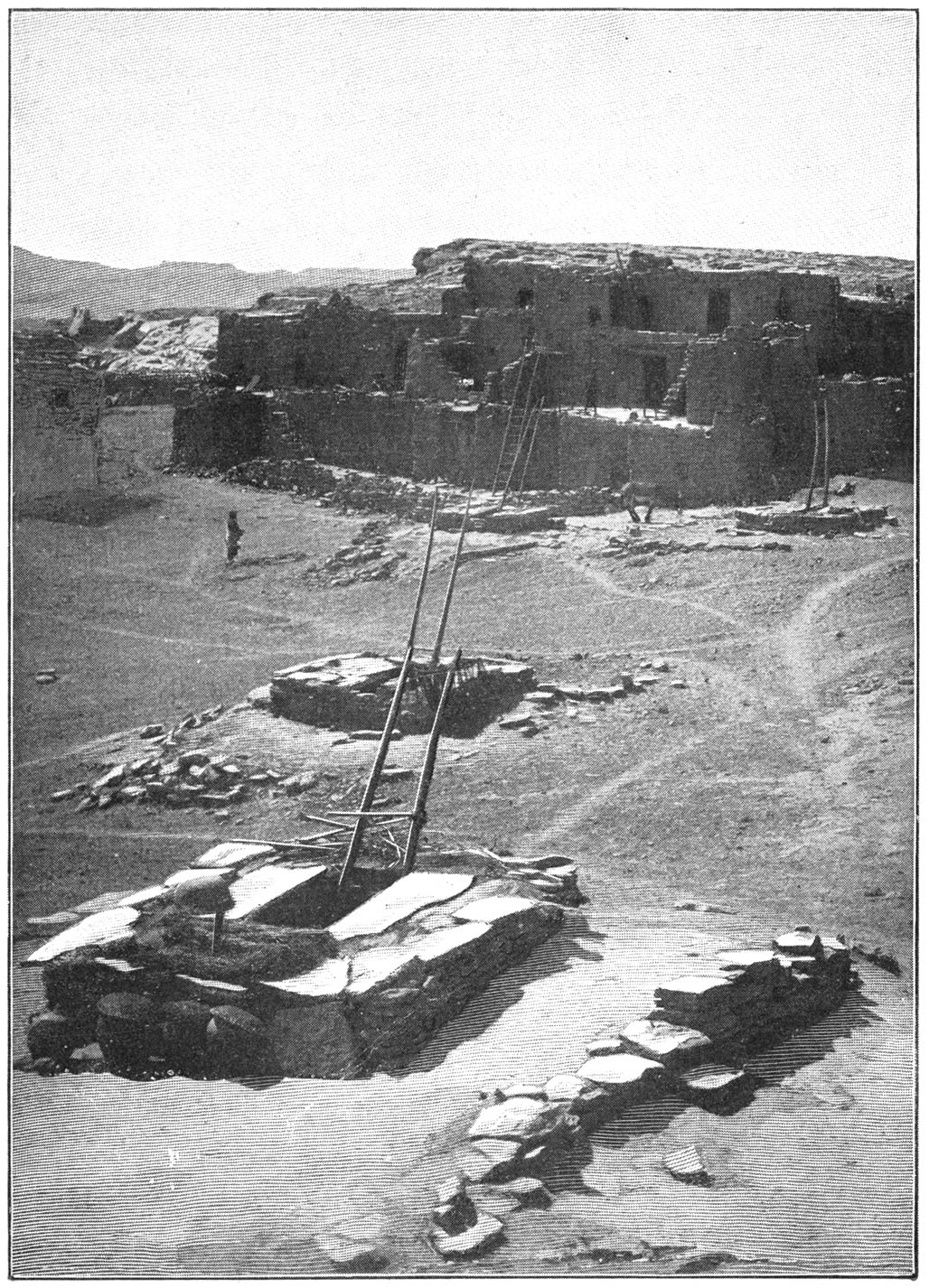

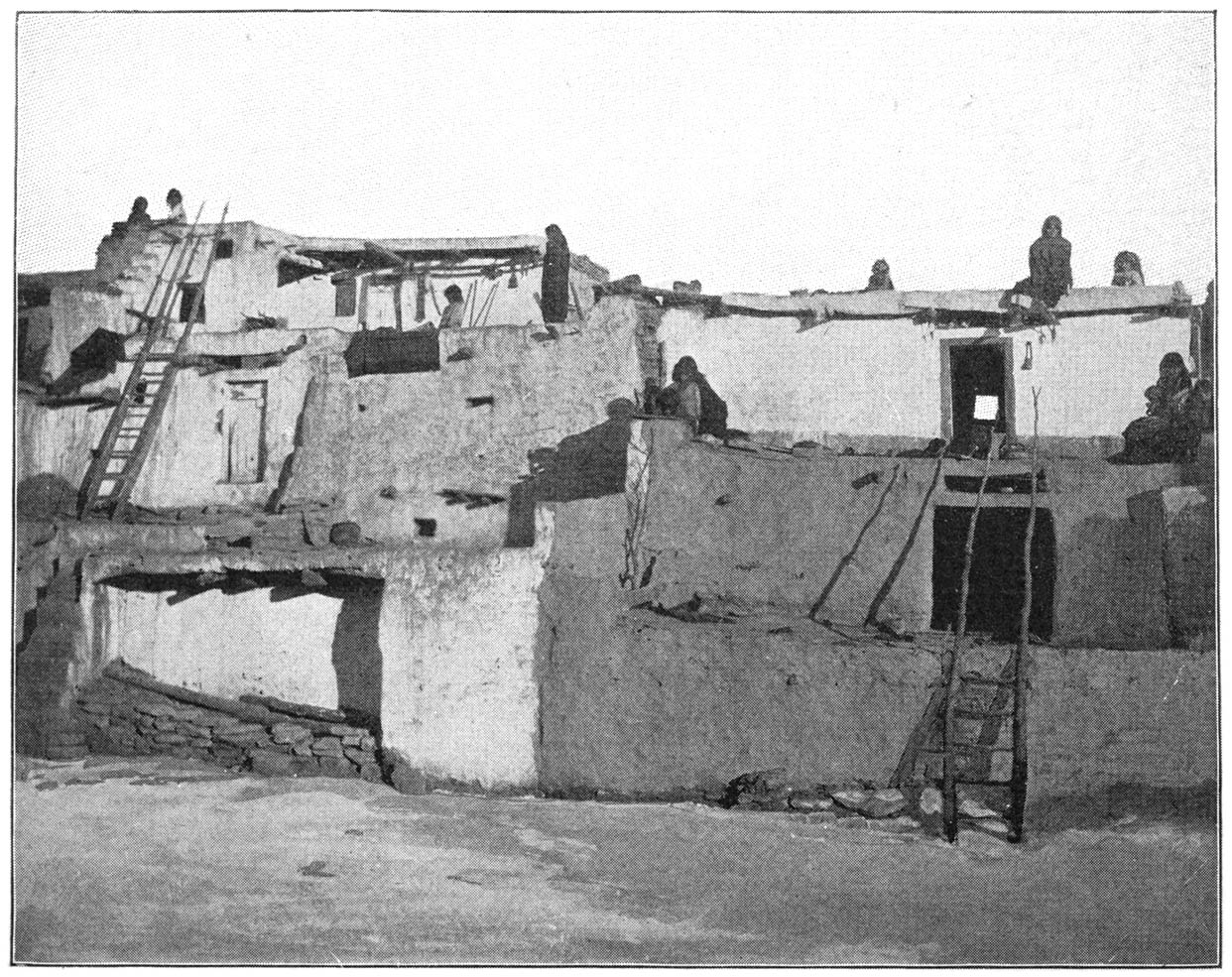

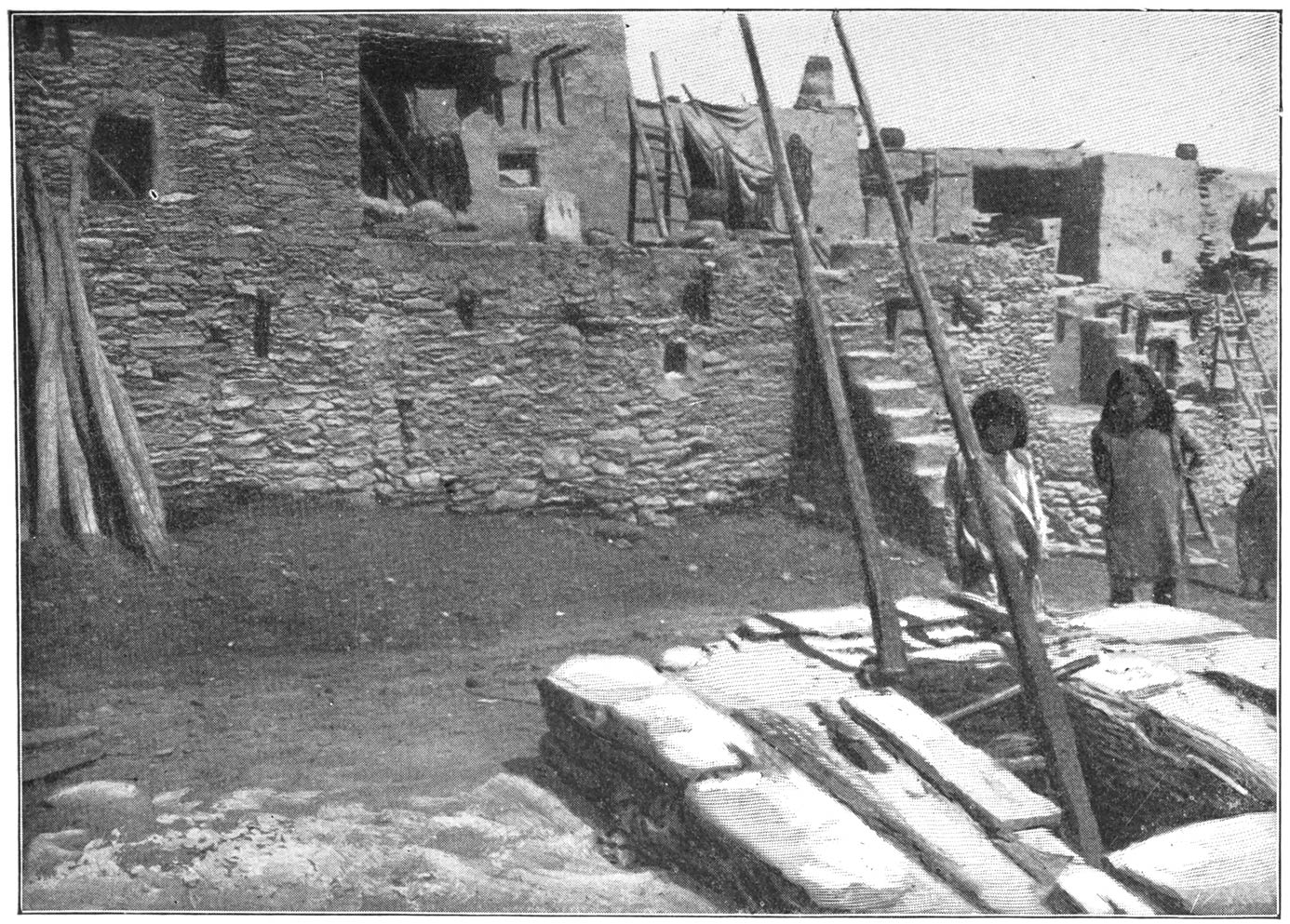

Ā dō′ be̱. Sun-dried brick used by the Indians and others in the southwestern part of the United

States in the making of walls and huts.

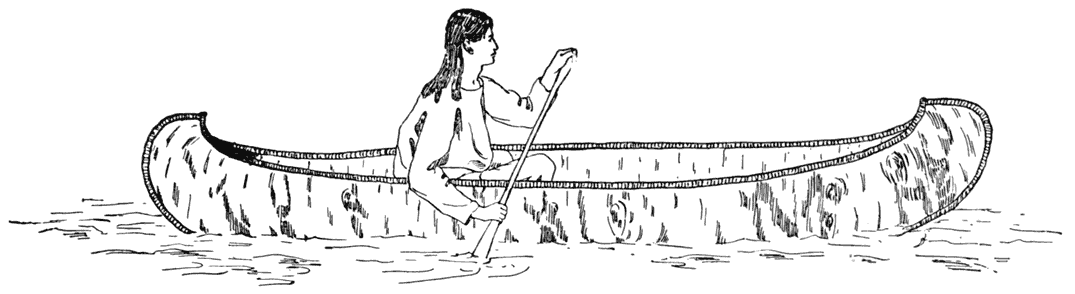

Ăl gŏn′ quin (kĭn). A very large division of the North American Indians, including Ojibways, Delawares,

Pottawottomi, Blackfeet, New England tribes, and some other branches. They were the

friends of the French in the early colonial wars, and often the enemy of the Iroquois.

Ăm pā′ ta. The name of a squaw.

A păch′ ē. A warlike western tribe, related to the Tennay. Many of the Apaches were sent to

a reservation in Arizona in 1874.

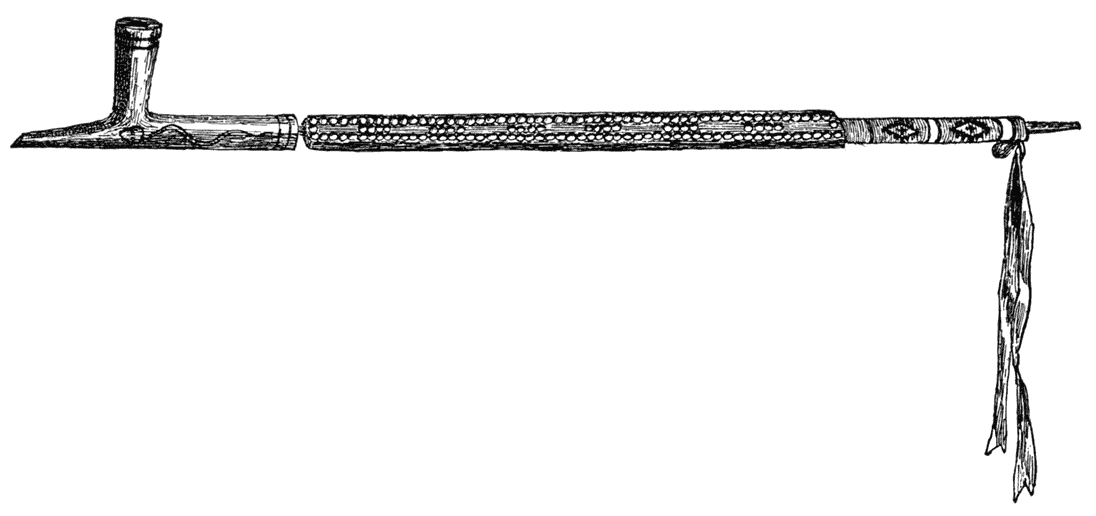

Căl′ u met. French name for pipe of peace.

Car′ i bo̤u. American woodland reindeer, the flesh of which is excellent meat.

Cayuga (Kā yü′gä). “The people of the marsh”; a tribe which once lived at the foot of Cayuga Lake, N.

Y.; they are now living upon reservations in Indian Territory, Wisconsin, and Ontario,

Can.

Cayuse (kī ūse′). Indian pony, formerly used by the Cayuse Indians of the northern Rocky Mountains.

Chaska (Shăs′ ka). First son of a Dakota Indian.

Chĭp′ pe wa. The Ojibway nation.

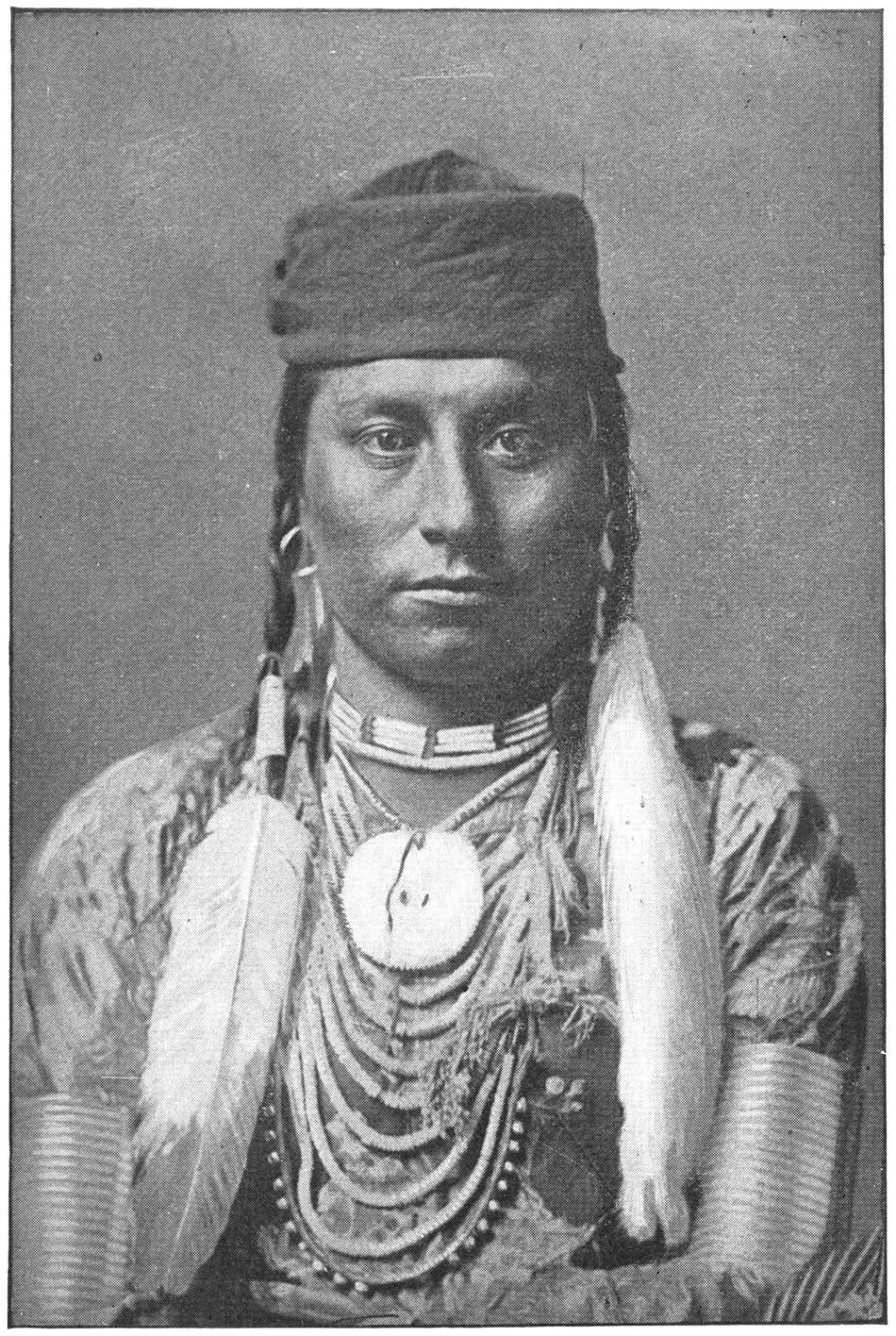

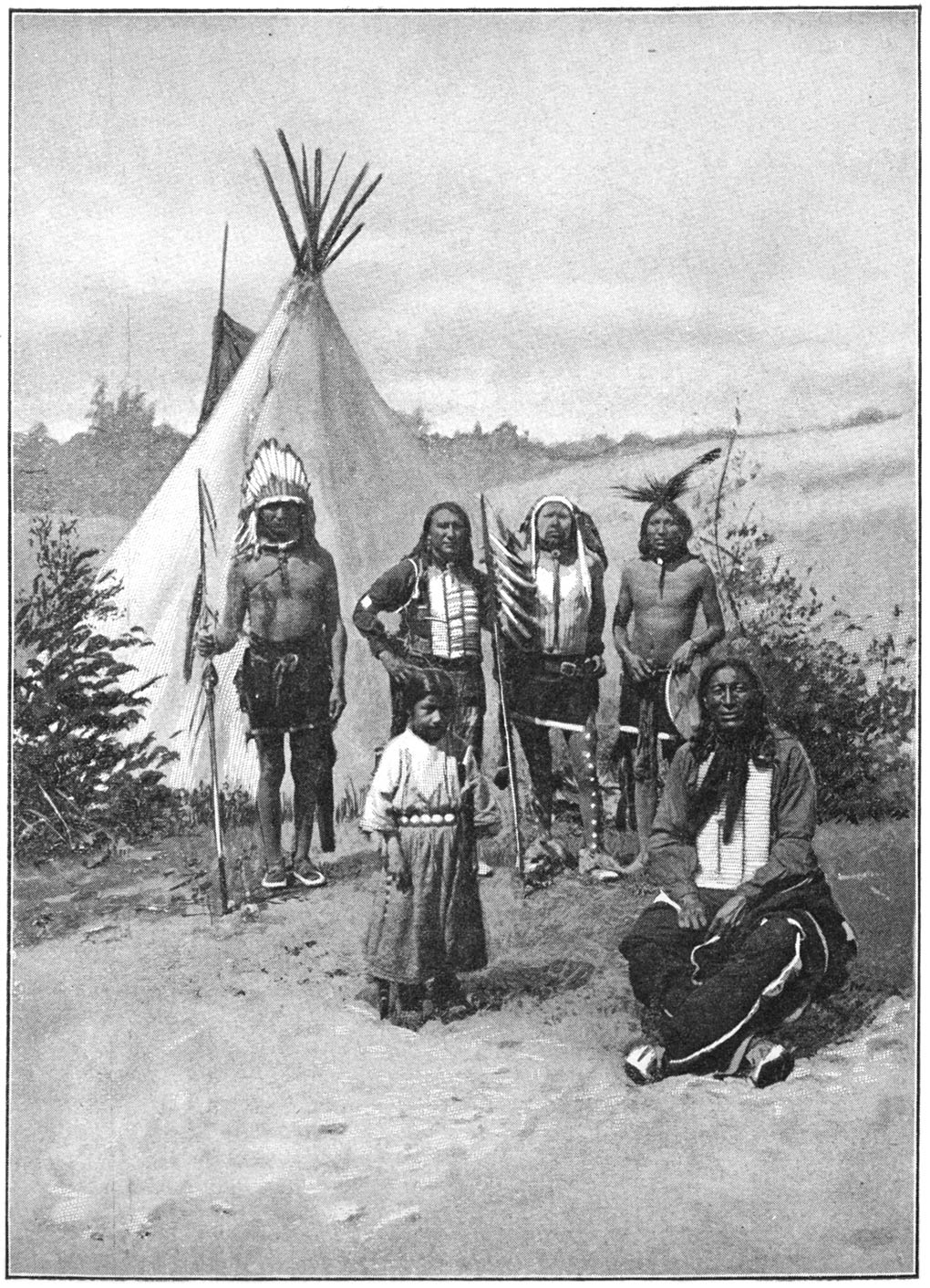

Dā kō′ tȧ. This name means “united.” The Dakotas were strong tribes and were called The Seven

Council Fires. Their home was in Montana, North and South Dakota, Minnesota, and the

Northwest Territory. They belong to the Sioux nation.

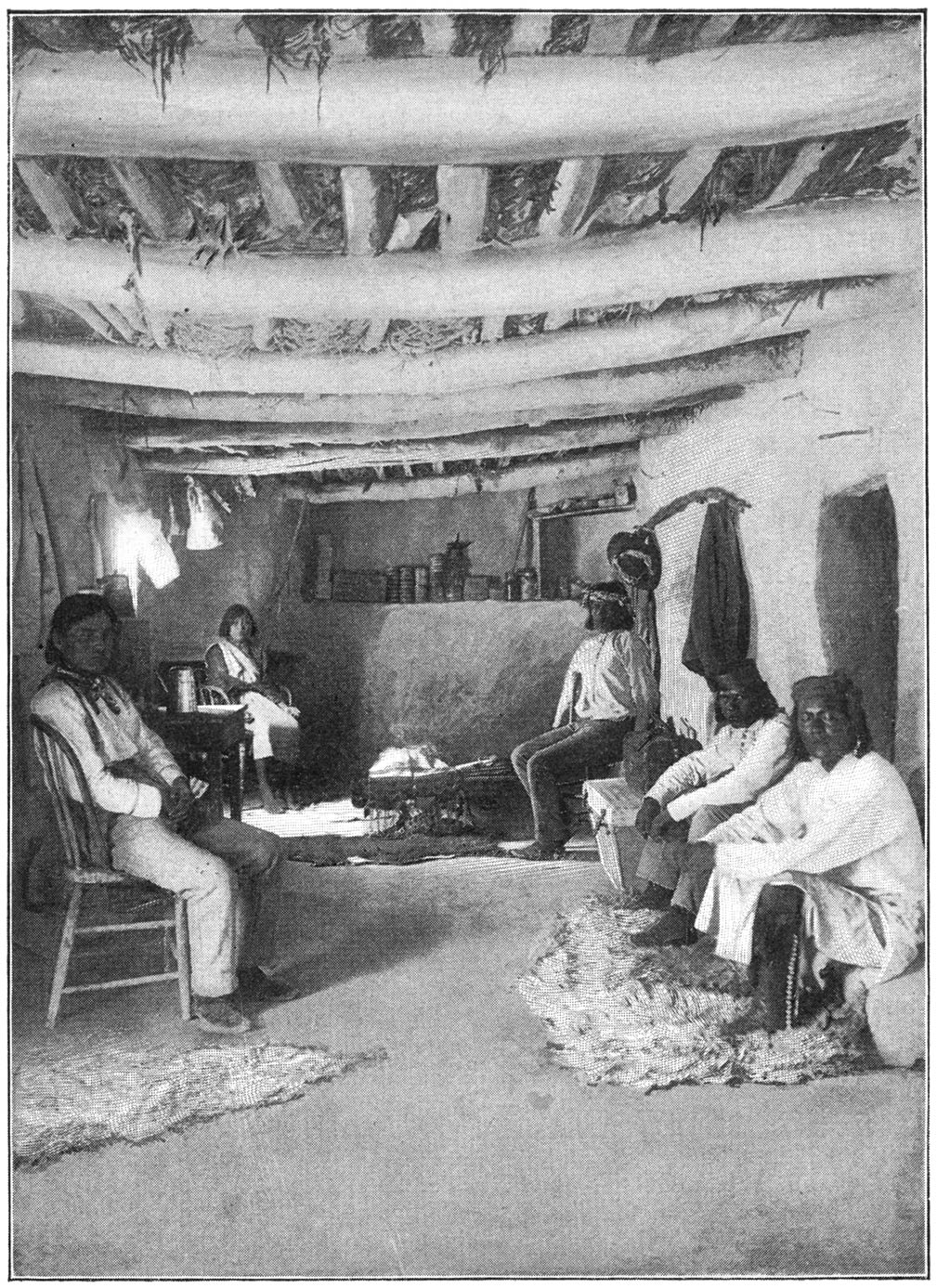

Ĕs tu′ fä. Spanish name for the kiva, or secret room; also the family room in Zuñi houses.

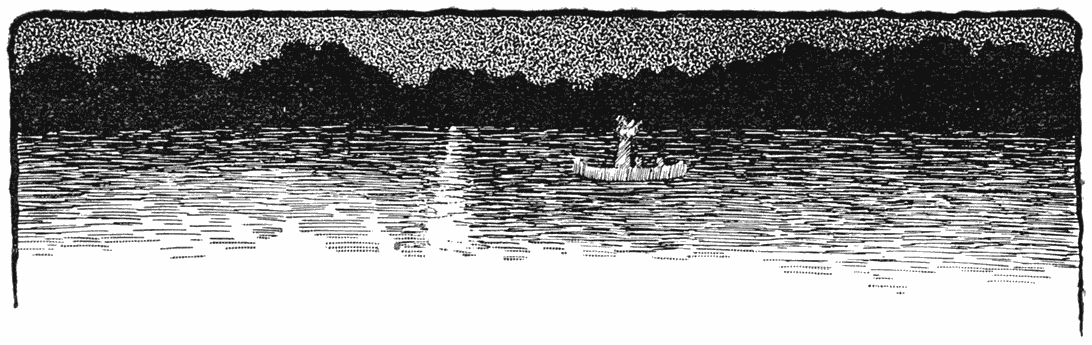

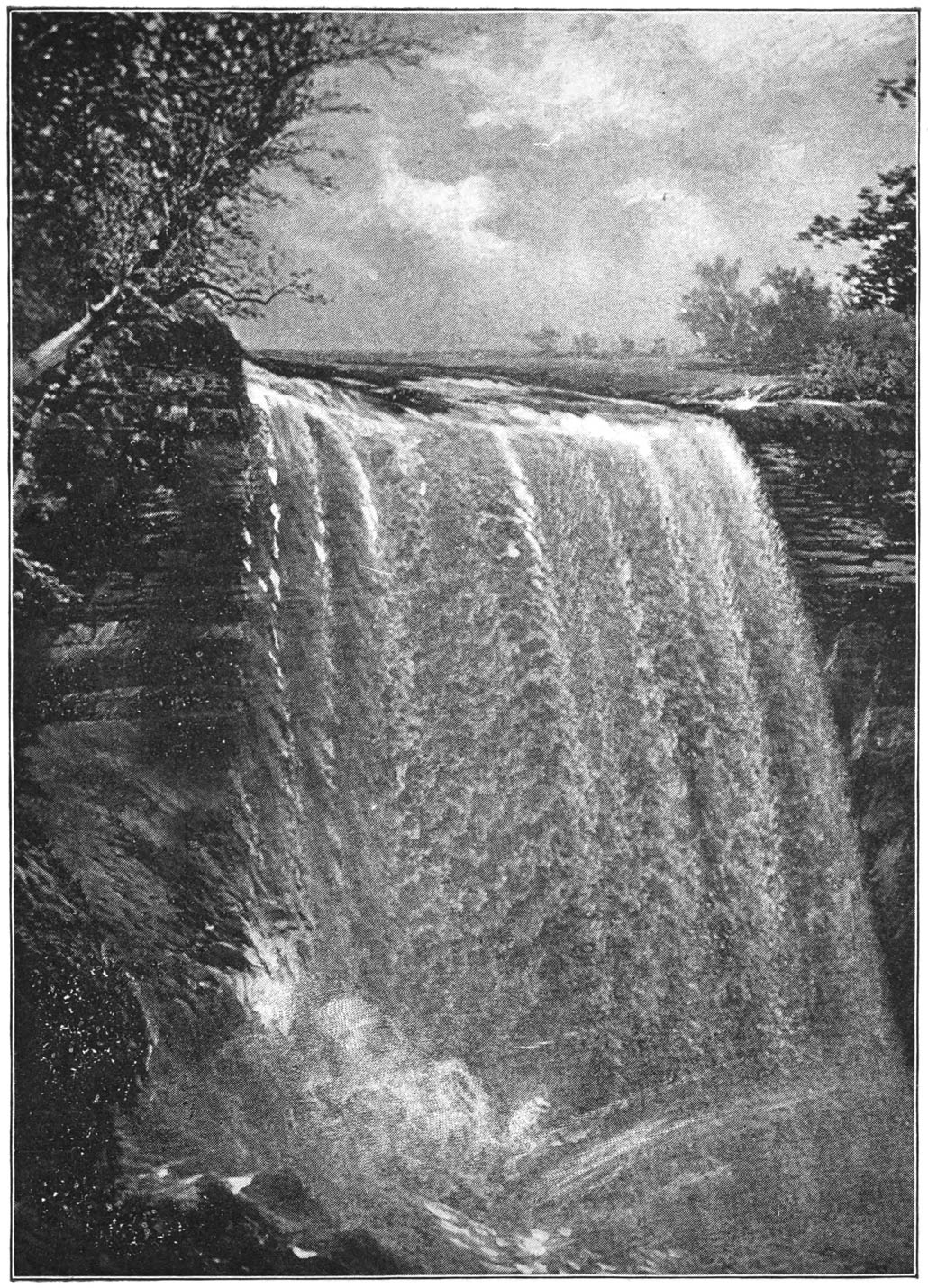

Gitch′ ee Gu′ mee. Indian name for Lake Superior, the Big Sea Water.

Hăn năn′ nä. The dawn, or morning light.

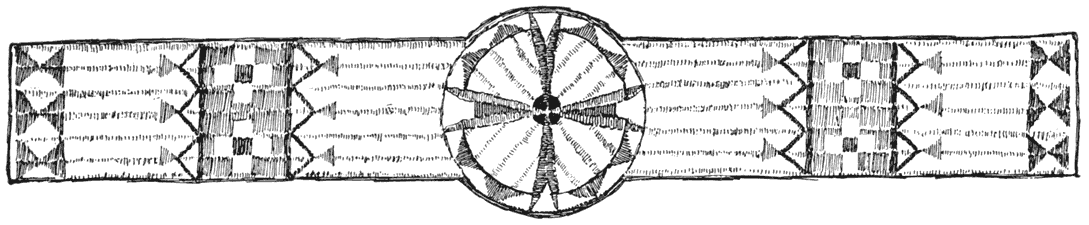

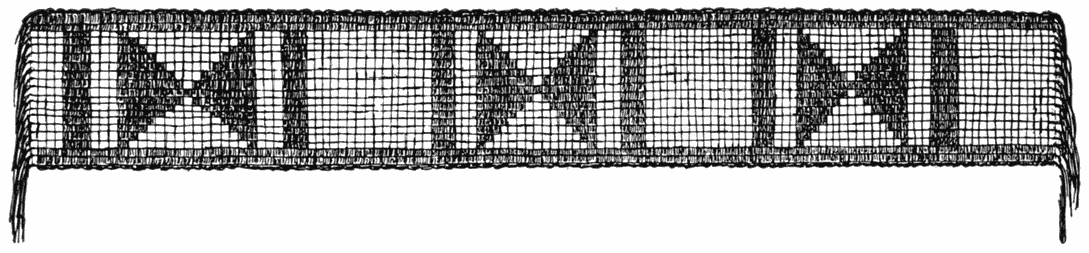

Hī′ ȧ quȧ. Siwash shell money, made of tusk shells; not wampum.

Hī a wäth′ a. A wonderful personage, still much honored by the Iroquois. He was very dignified,

very wise, and believed to be more than mortal. There are no stories of his childhood.

[274]

Hi′ nun. The spirit believed by the Senecas to rule the clouds and air.

I̤ ä go͞o. The boaster, the story-teller.

Iroquois (Ir′ o quoy). The French name for the united tribes of central New York. The Iroquois were the

friends of the English in 1775. They are a division by themselves, akin to the Sioux.

Käcluge (Ka cloozh′). The Navajo butterfly spirit.

Kāi′ dah. A Canadian tribe.

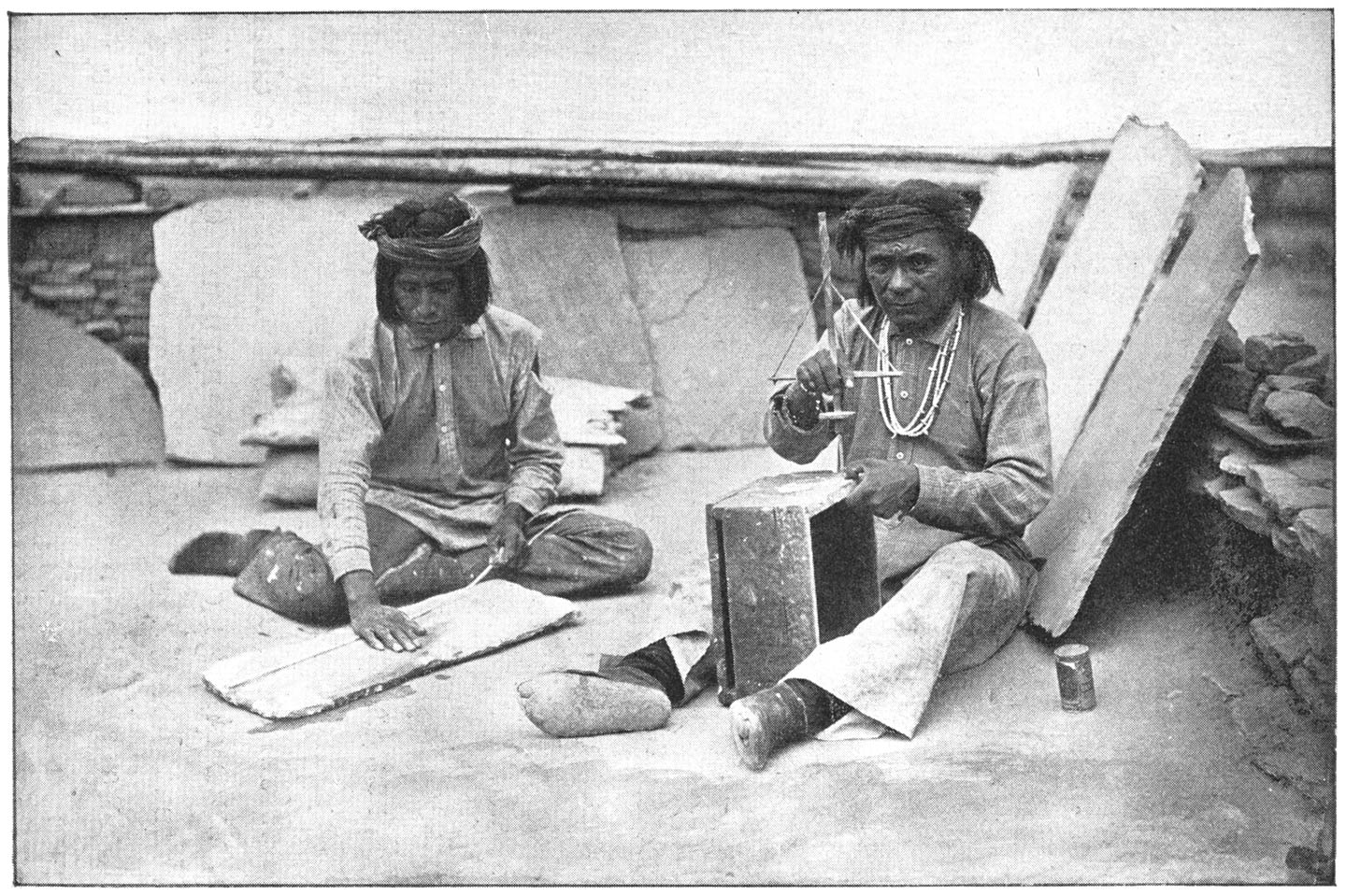

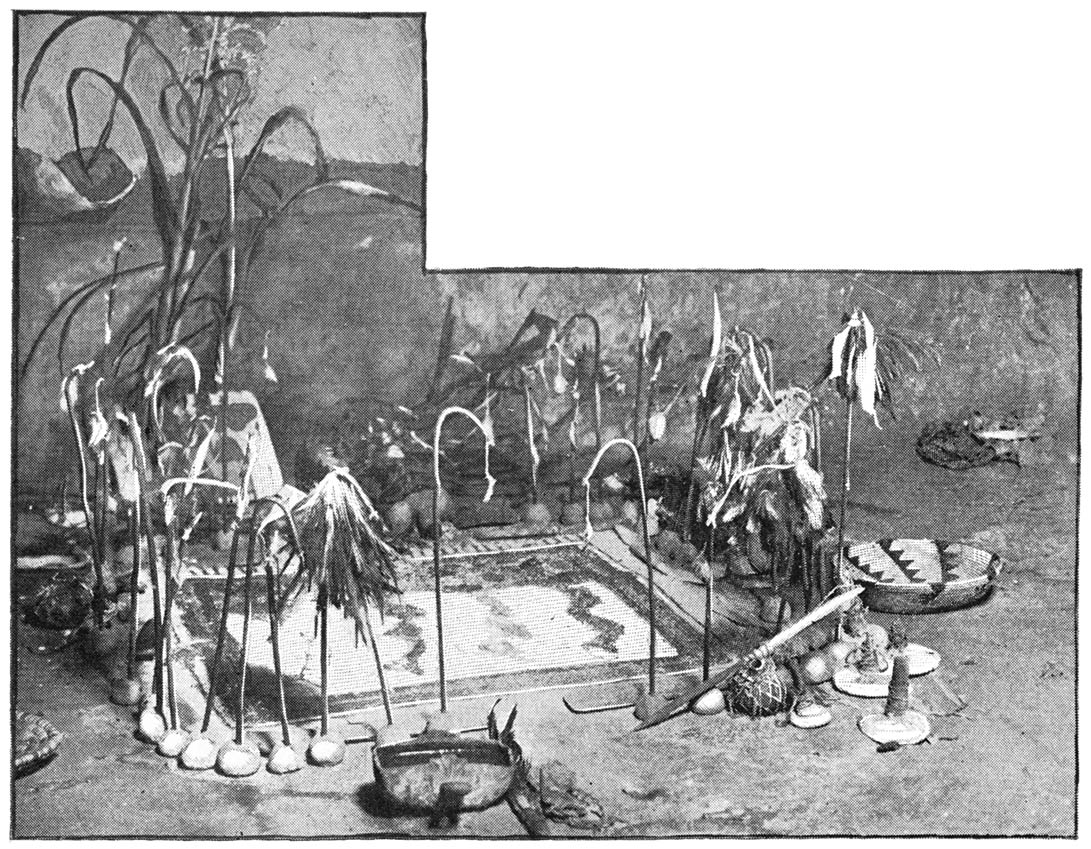

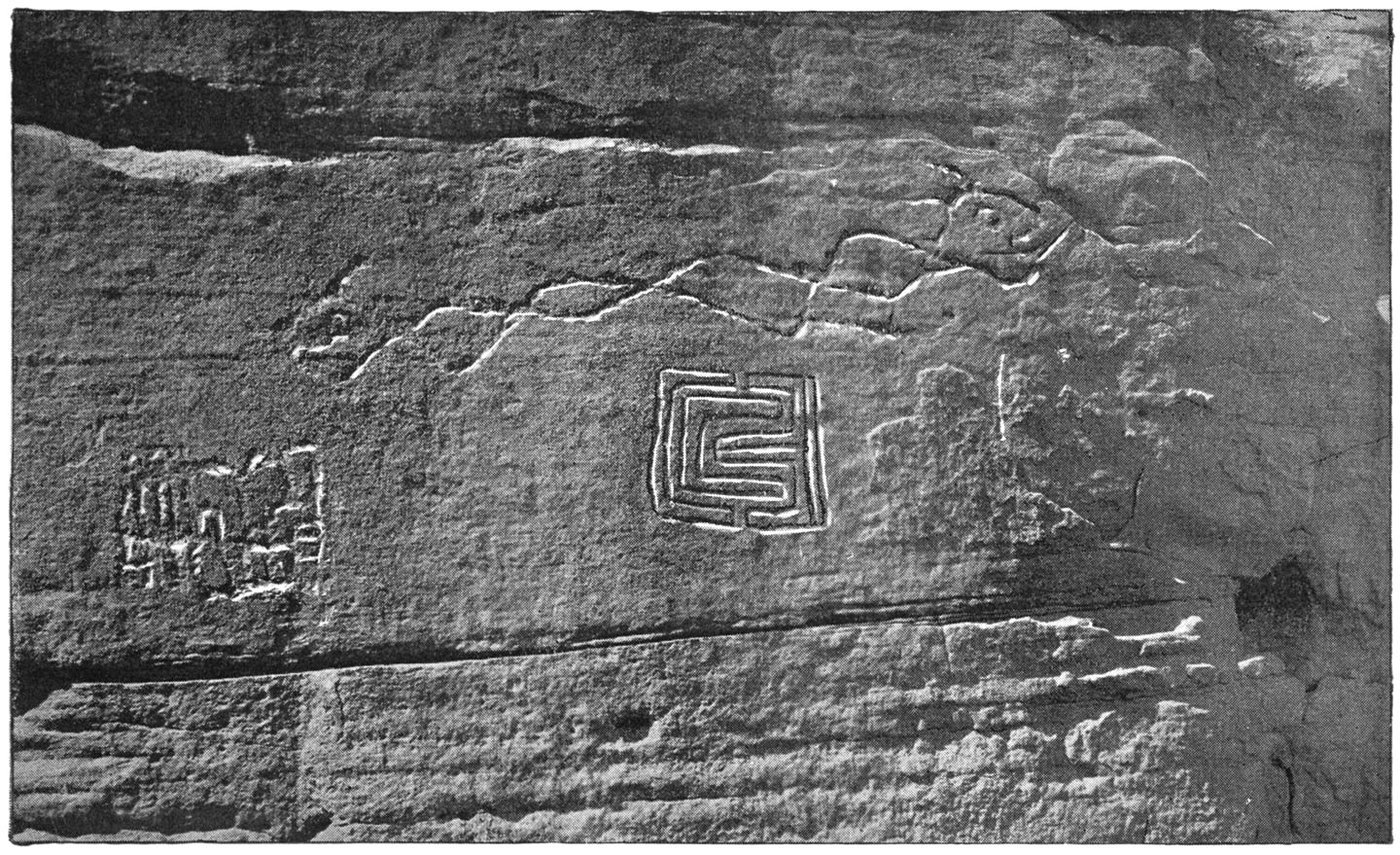

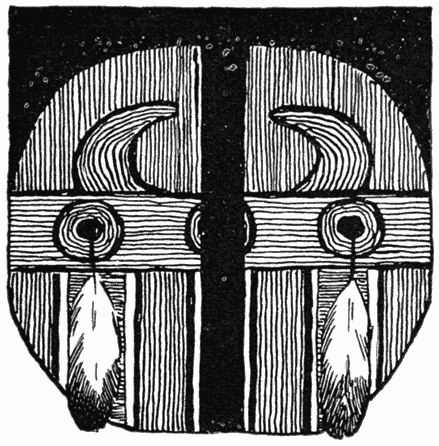

Kiva (kee′ vah). The secret room or sweat-house of the Pueblos. The priests of the tribe use these

kivas in giving instructions in the secret rites of their religious orders to the

young men of the tribe.

Leel′ i naw. An Indian girl who became a tree, according to a Lake Superior myth.

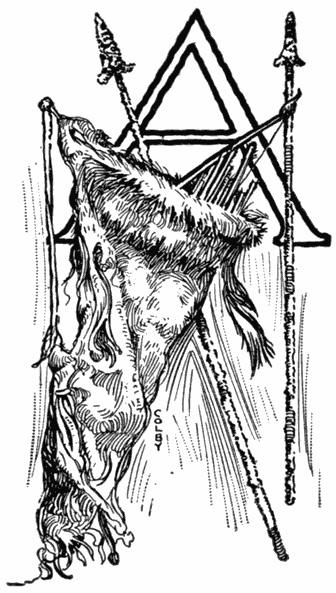

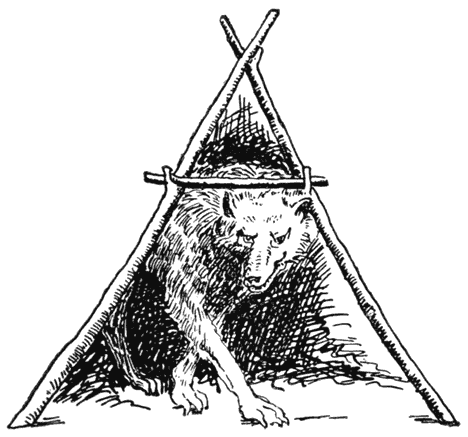

Len i Len napes′. One of the Algonquin tribes. They were called Loups, or Wolves, by the French, as

their chief totem was the wolf. The English called them Delawares, for they found

them near the Delaware River. Their chiefs were celebrated for their wisdom. Their

name is sometimes spelled Leni-Lenapes.

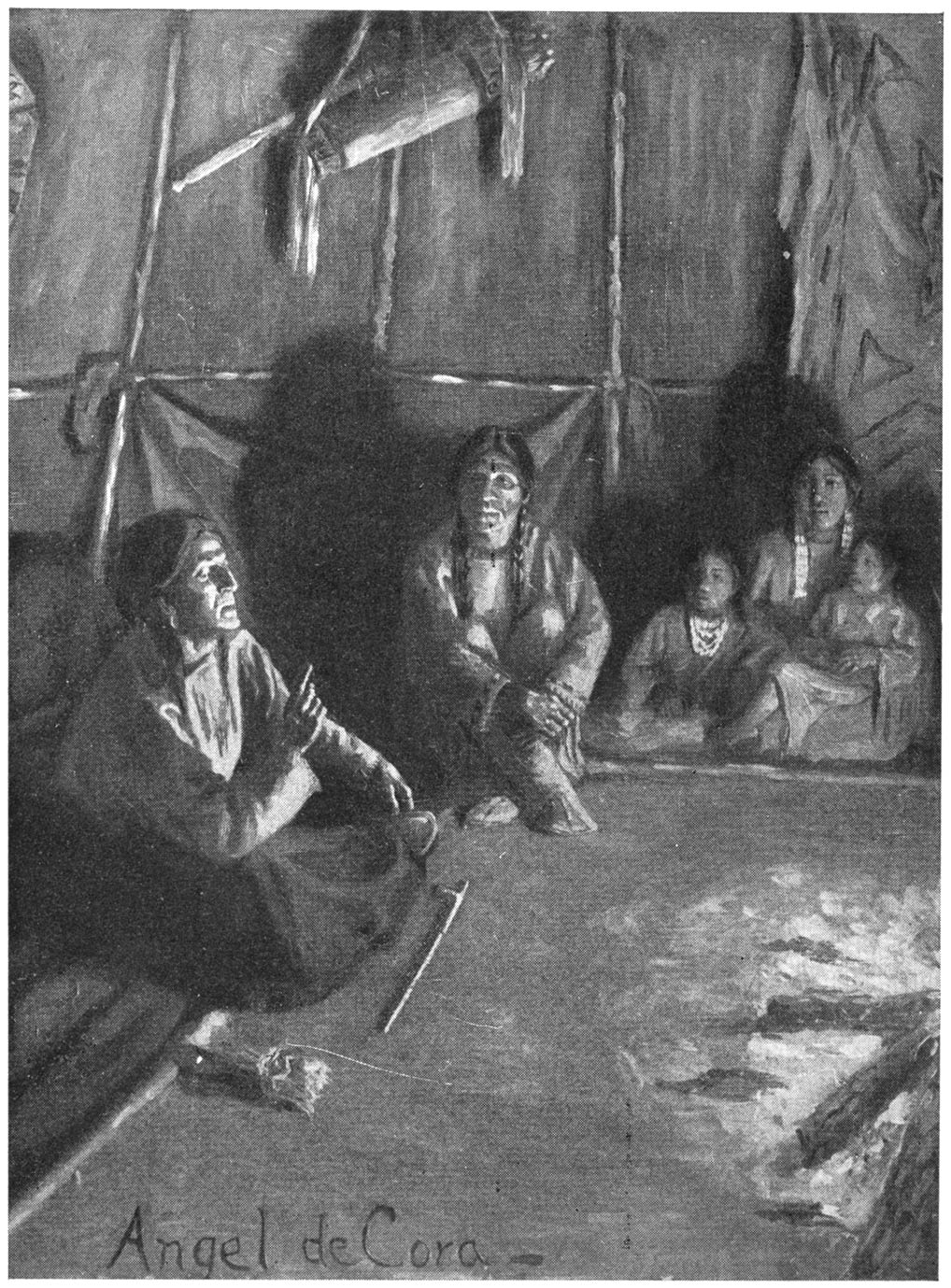

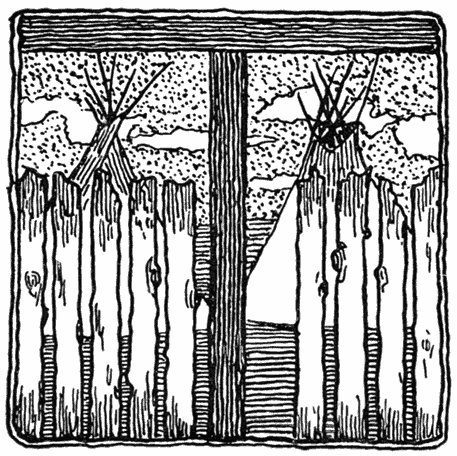

Lodge. An English name for a wigwam, teepee, or other dwelling built by Indians.

Mah′ to. The white bear.

Man′ i tou. A spirit, whether good or evil. All created things were once believed by some tribes

to have their manitous which lived in them. The Great Manitou ruled over all of them.

An Algonquin word not used by other nations.

Mechabo (Me sha′ bo). Another French form of the name of the Ojibway Foolish One. Also spelled Missaba,

Mesaba; and there are some other similar forms. The Ojibways also give him a name

which means the Great Hare.

Mē maing′ gwah. The butterfly.

Men a bō′ zhō. The French form of the name of the Foolish One of the Ojibways. He was believed to

be the creator of the land after the deluge, and ruler of all creatures upon it. He

is constantly doing many tricks to annoy the water manitous, who annoy him in return.

The land creatures often attempt to outwit him; many humorous stories told of him

by the Ojibways have become famous as a part of the story of Hiawatha.

Me̱′ sä. Spanish name for a broad, flat river-terrace or tableland.

[275]

Me tik′ o mēēsh. The oak tree.

Min ne hä′ hä Falls. A cascade sixty feet high in Minnehaha Creek, near Minneapolis, Minn.

Mo′ hawks. A tribe which lived in northern New York. Their name is derived from Mukwa, meaning

“bear.” They were the first tribe to use firearms.

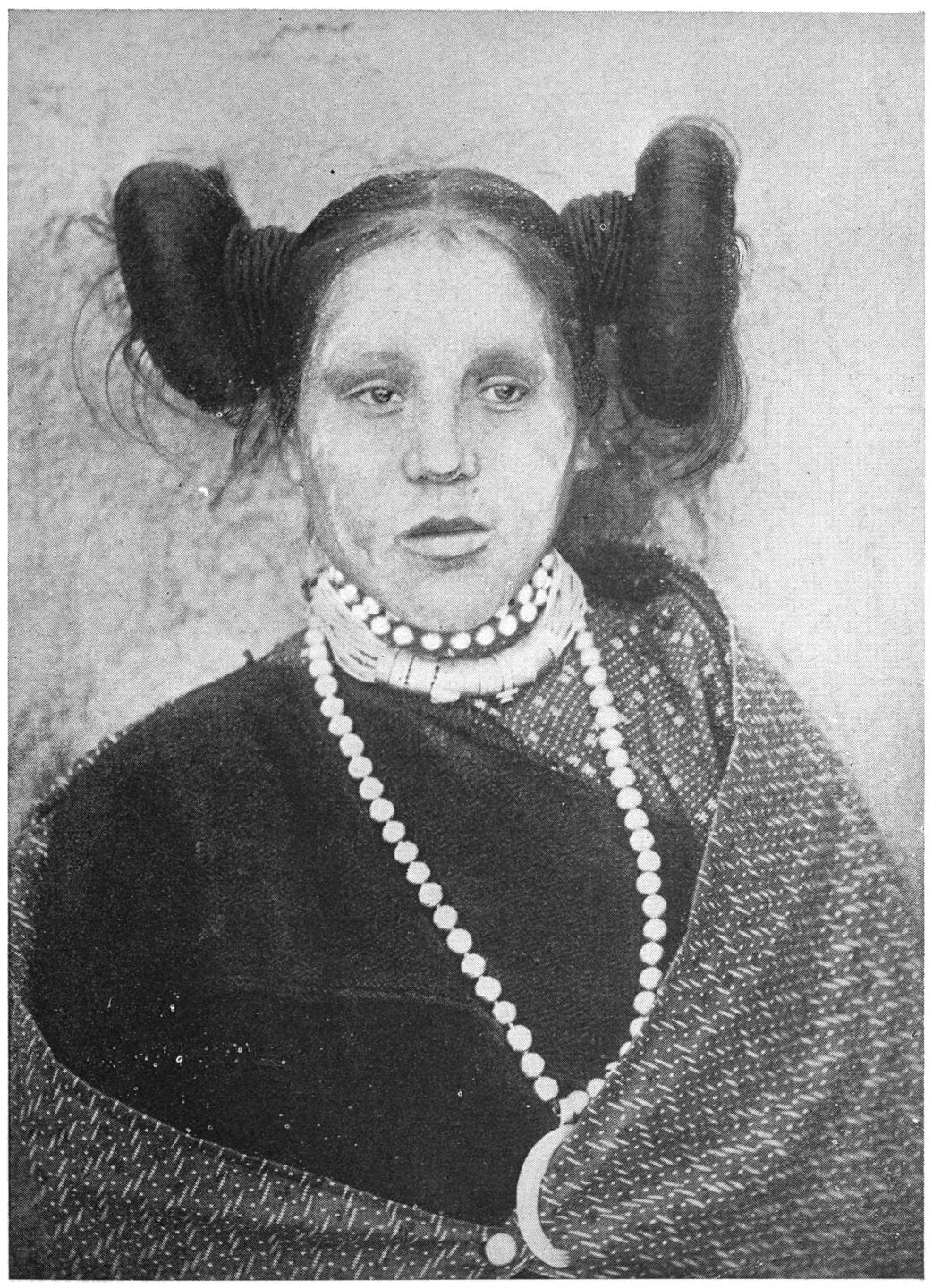

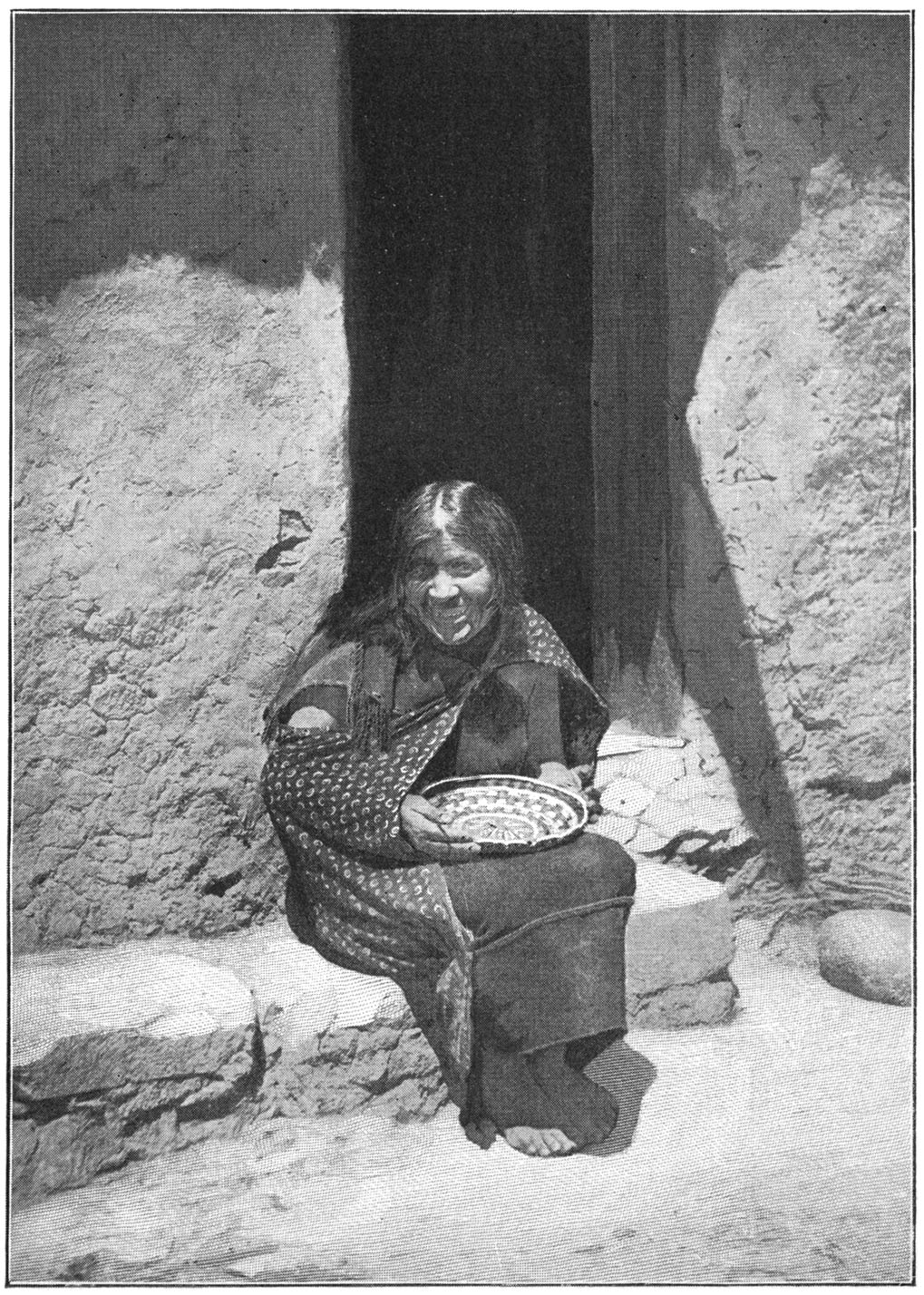

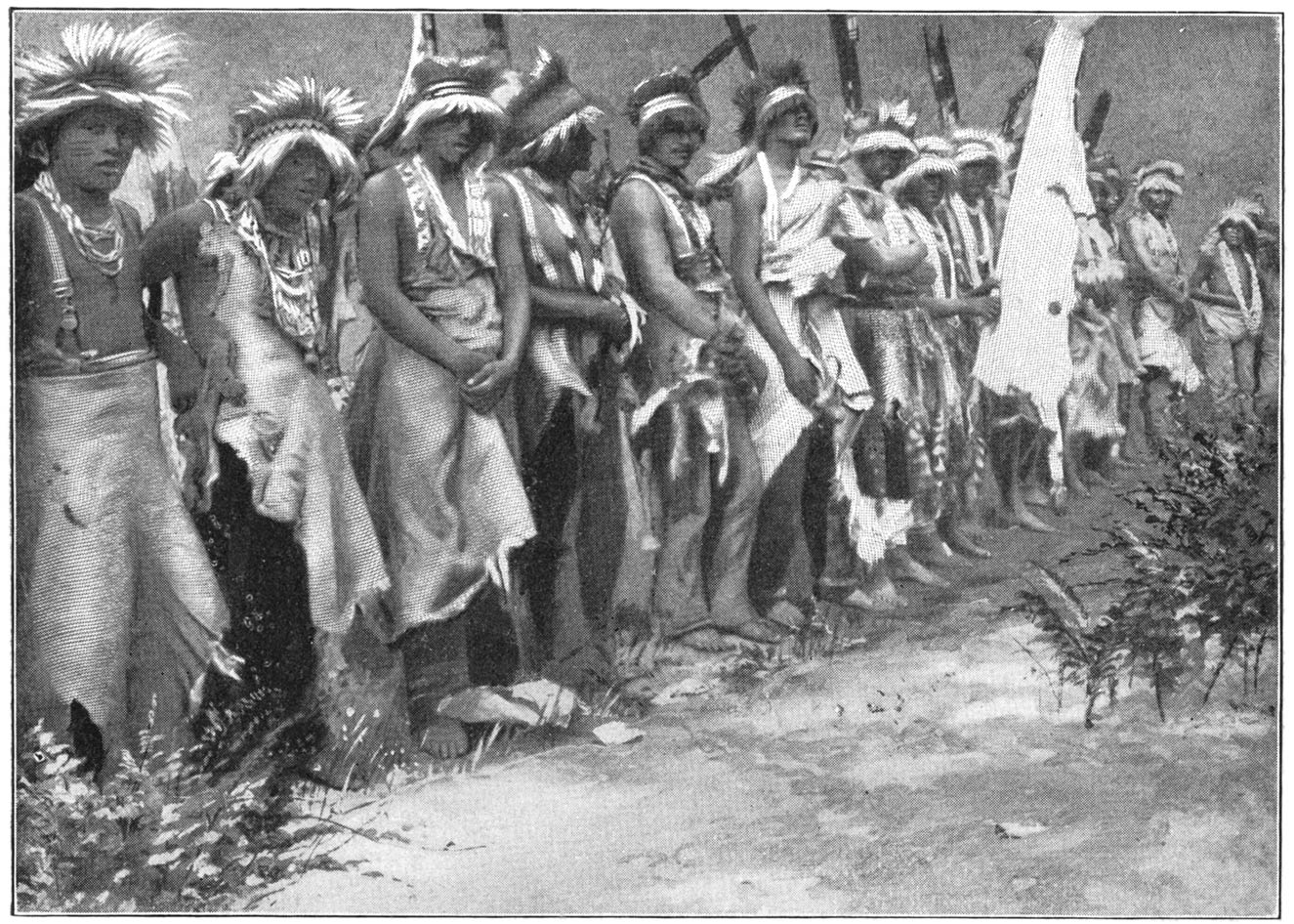

Moki or Moqui (Mō′ kee). A tribe of the Pueblos. The United States government has recently decided to use

the form Moki instead of Moqui. Their true name is Hōpitah, or People of Peace. Many

call them the Hōpi. Moki is a Navajo word of reproach.

Mŭk′ wa. The bear.

Navajo (Nä′ vä hō). Spanish name for the Tennay, a very intelligent tribe of North American Indians now

living on reservations in Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona.

Nĭb a năb′ as. Little water spirits, so called by the Chippewas.

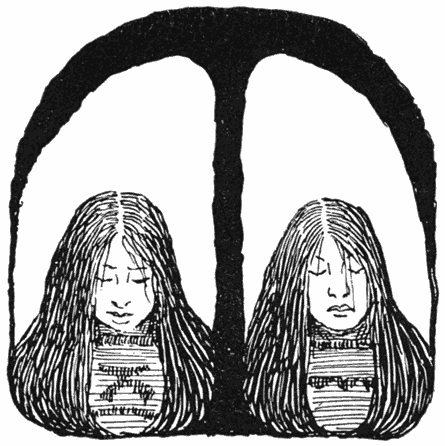

No kō′ mis. Chippewa word, meaning “grandmother.”

O jib′ ways. The Chippewa Indians. They are a strong tribe of the Algonquins, who, with others,

have been driven by the wars with the Iroquois to the regions about Lake Superior.

Many live on reservations in Minnesota and Wisconsin. From the Ojibways and other

Algonquin tribes the whites learned to make maple sugar, hominy, and corn cake. They

have for generations raised corn, beans, and pumpkins.

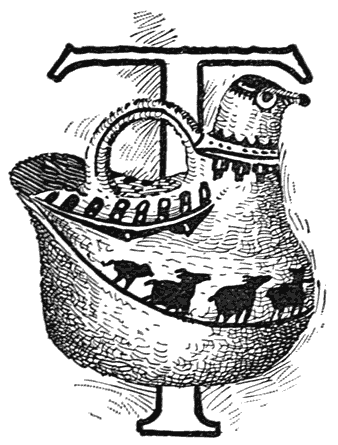

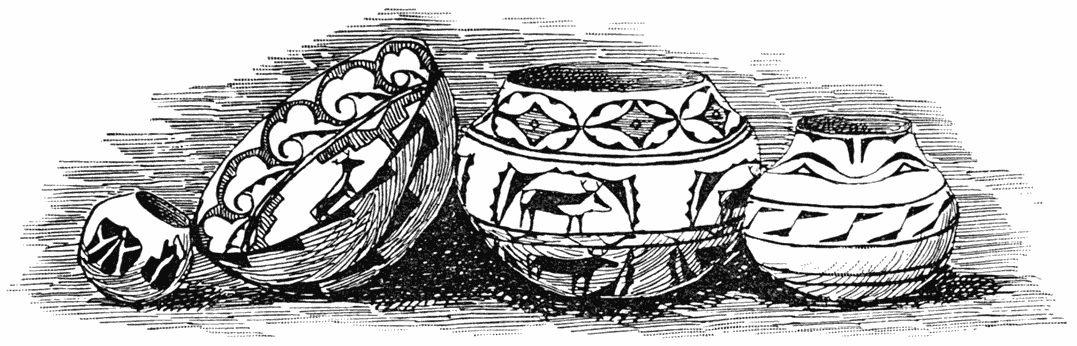

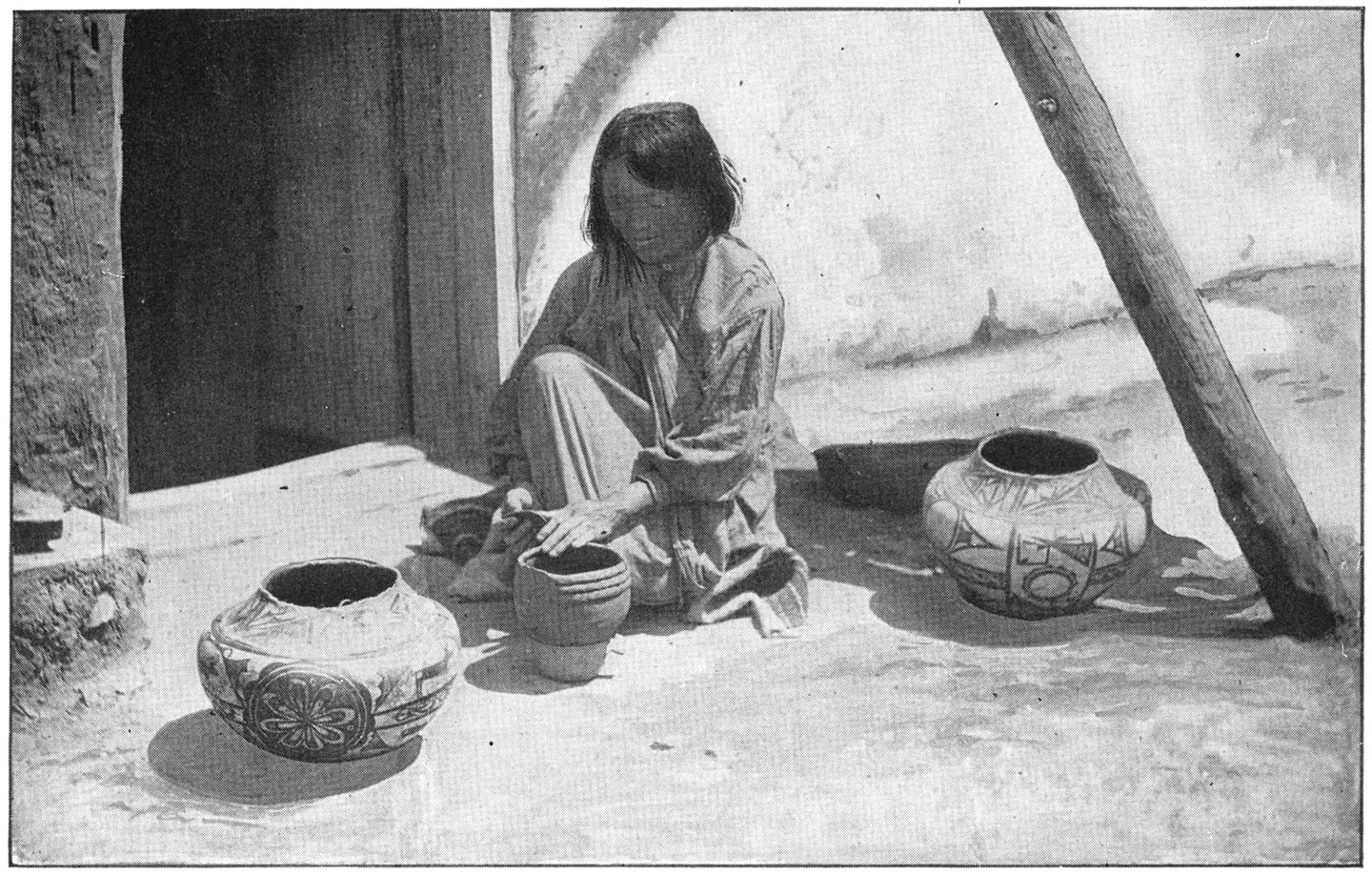

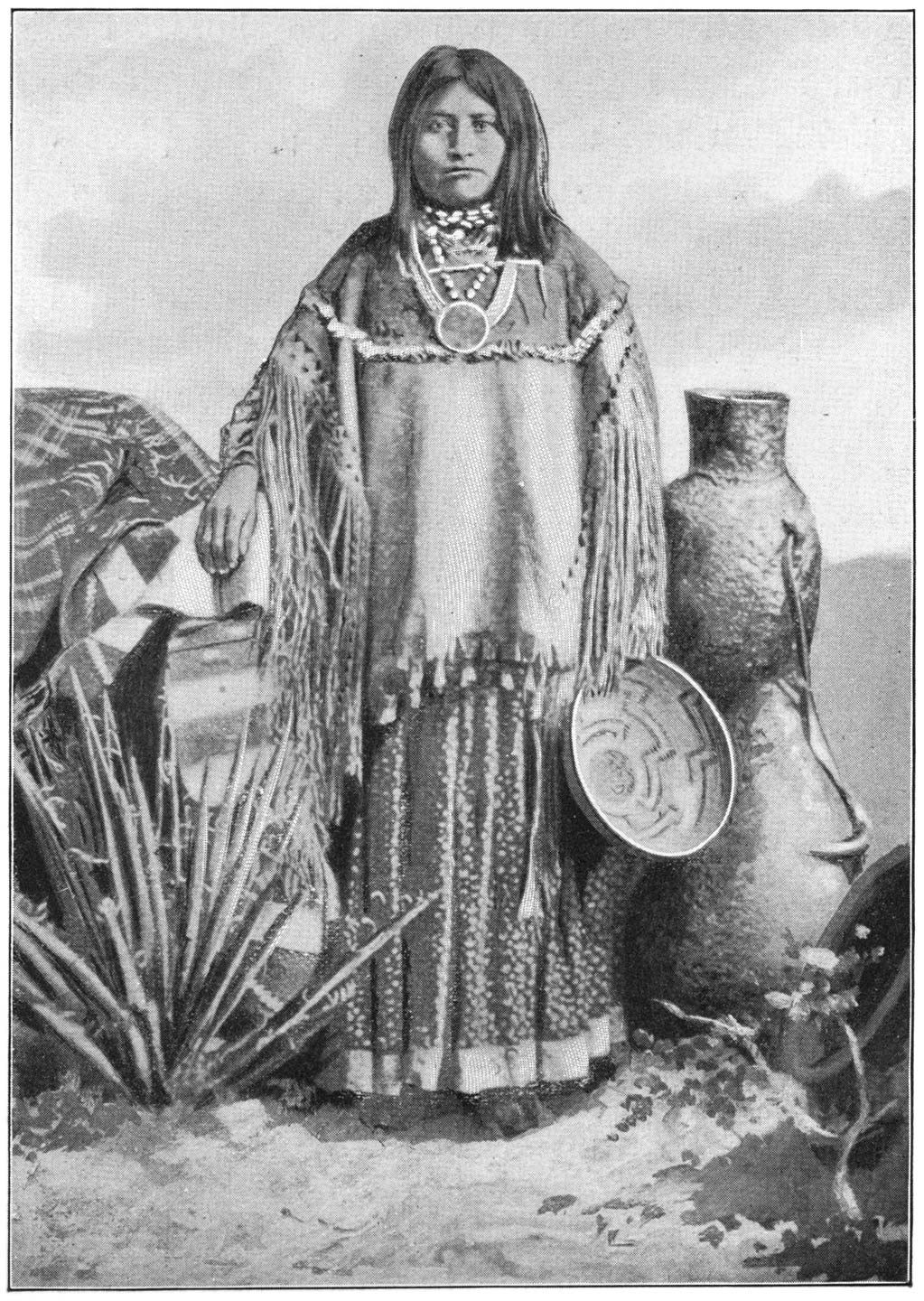

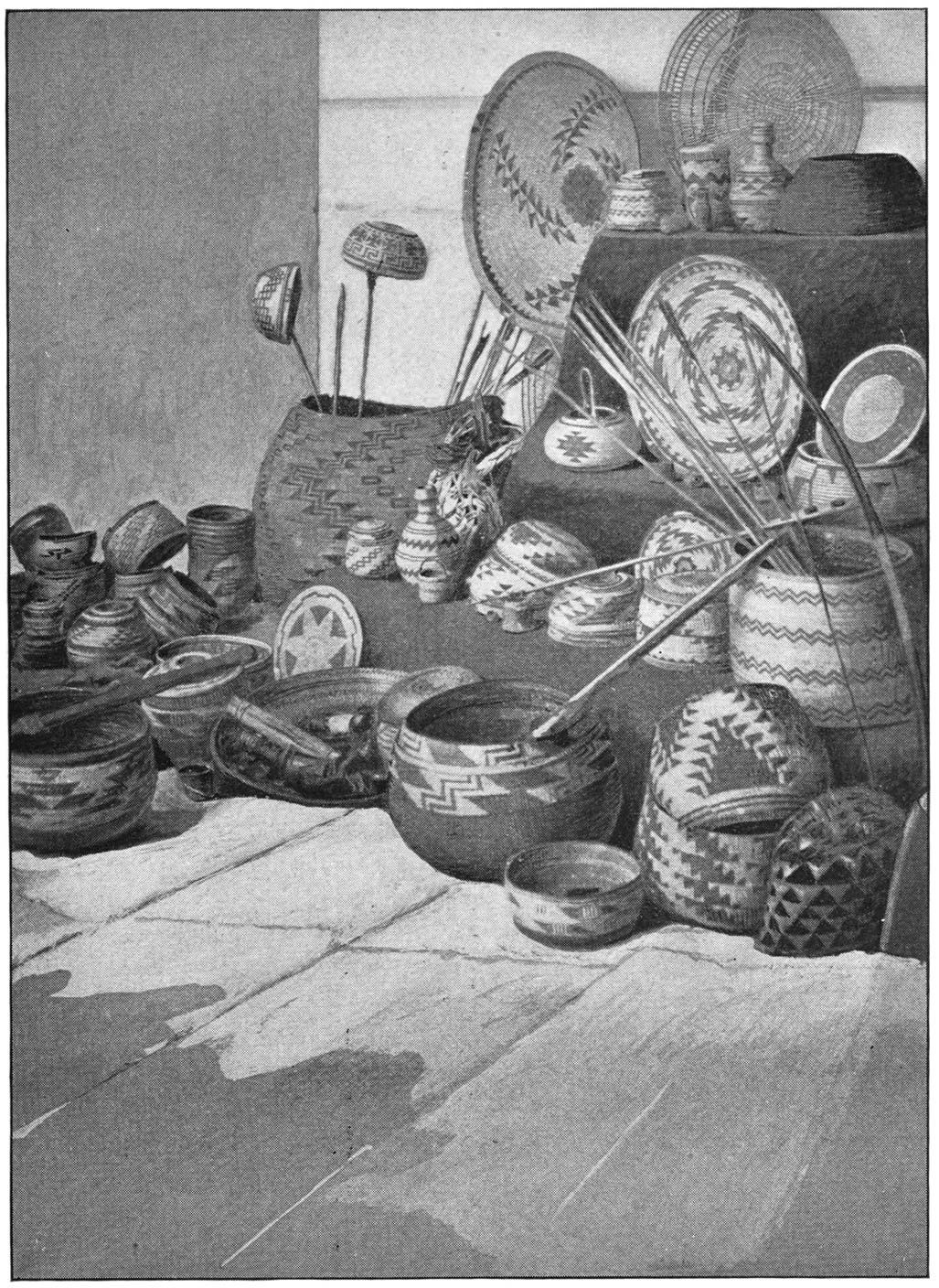

Olla (ol′ la or ol′ ya). Spanish name for the earthenware water jar commonly used in the southwestern part

of the United States by Indians and others for the cooling of water.

Oneidas (O nī′ das). One tribe of the Iroquois.

Paw nee′. Indian tribe always at war with the Sioux; now living in Indian Territory.

Pē bō′ an. The manitou of winter.

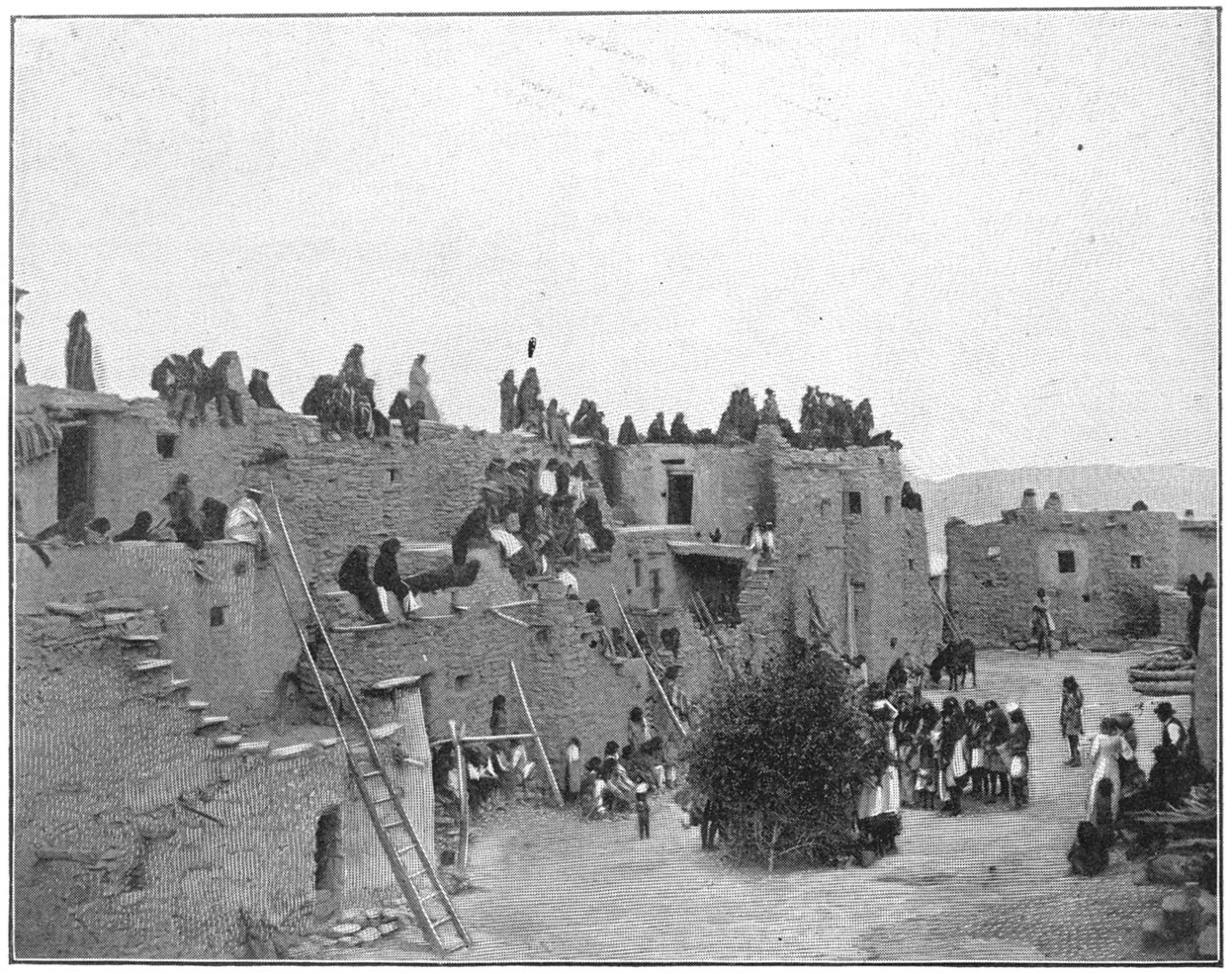

Pu eb′ lo. Spanish name for village.

Puk wud jin′ nies. Fairies in the woods.

Sault Ste. Marie (Soo′ sent mä ree′). French name for the river which connects Lake Superior and Lake Huron.

Sē′ gun. The manitou of summer and spring.

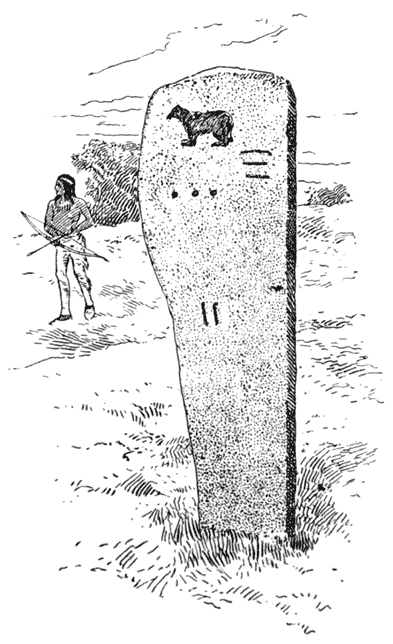

Se-quoy′ ah. Guesser, a famous Cherokee Indian.

Shaw on dä′ see. The south wind.

[276]

Sioux (Soo). The French name for the people called by the Algonquins nadiwe-ssiwag, or the treacherous

ones, from their manner of warfare. The Sioux nation comprised the Dakota and Assiniboin

tribes; those Indians living in the middle west of the United States from the Rocky

Mountains to the Mississippi River; and also many tribes in Virginia, Kentucky, North

and South Carolina, and Mississippi. They are noted for bravery and intelligence.

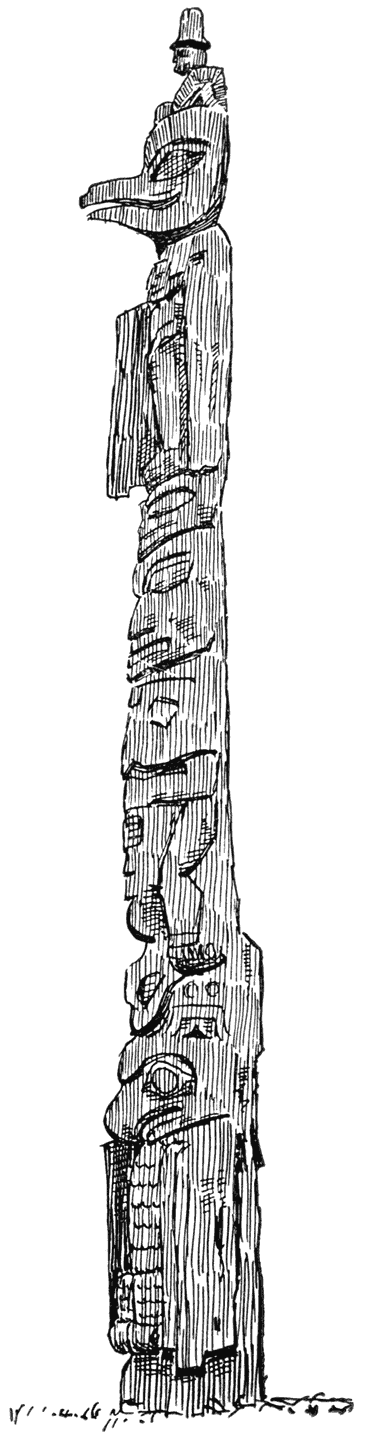

Sī′ wash. Sauvage. Indians living near Puget Sound and northward.

Suc′ co tash. Indian corn and beans cooked in one dish.

Tä män′ ous. Siwash word for guardian spirit.

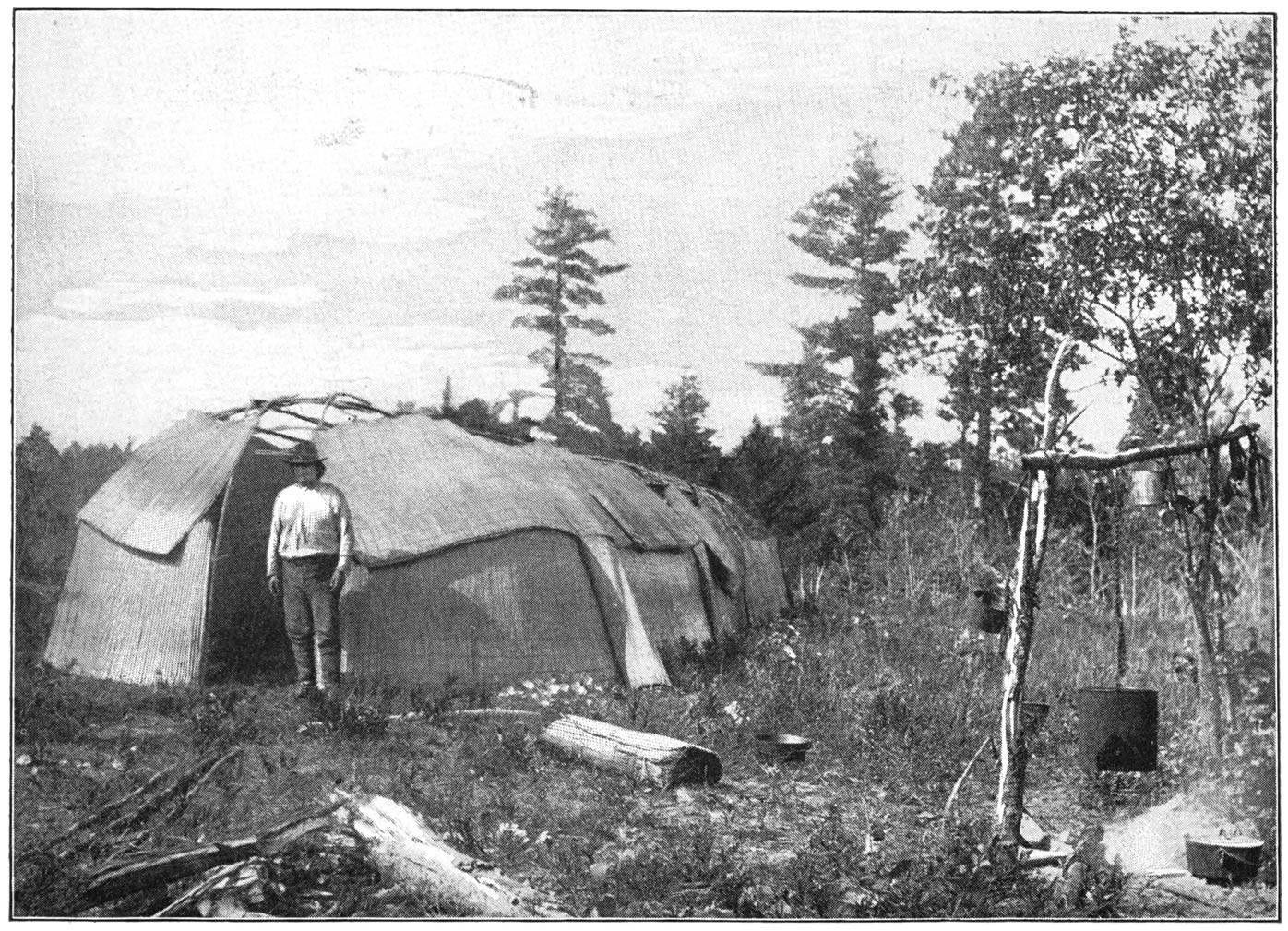

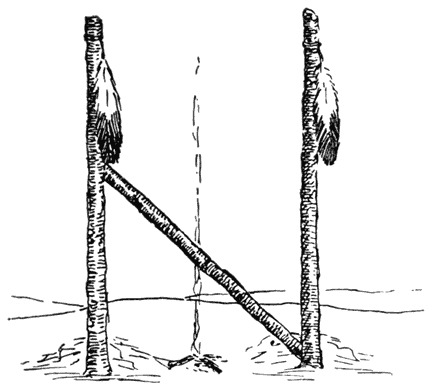

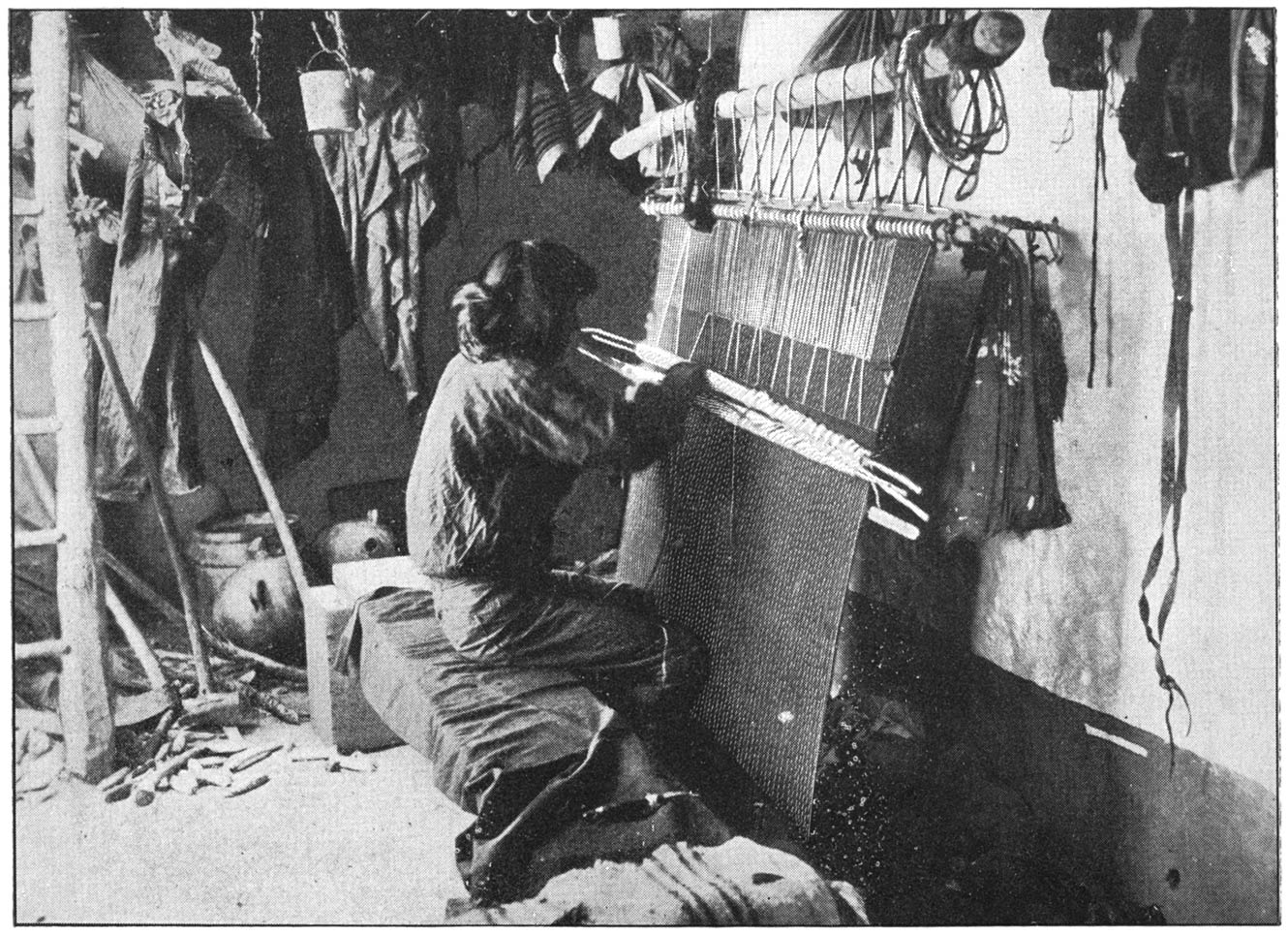

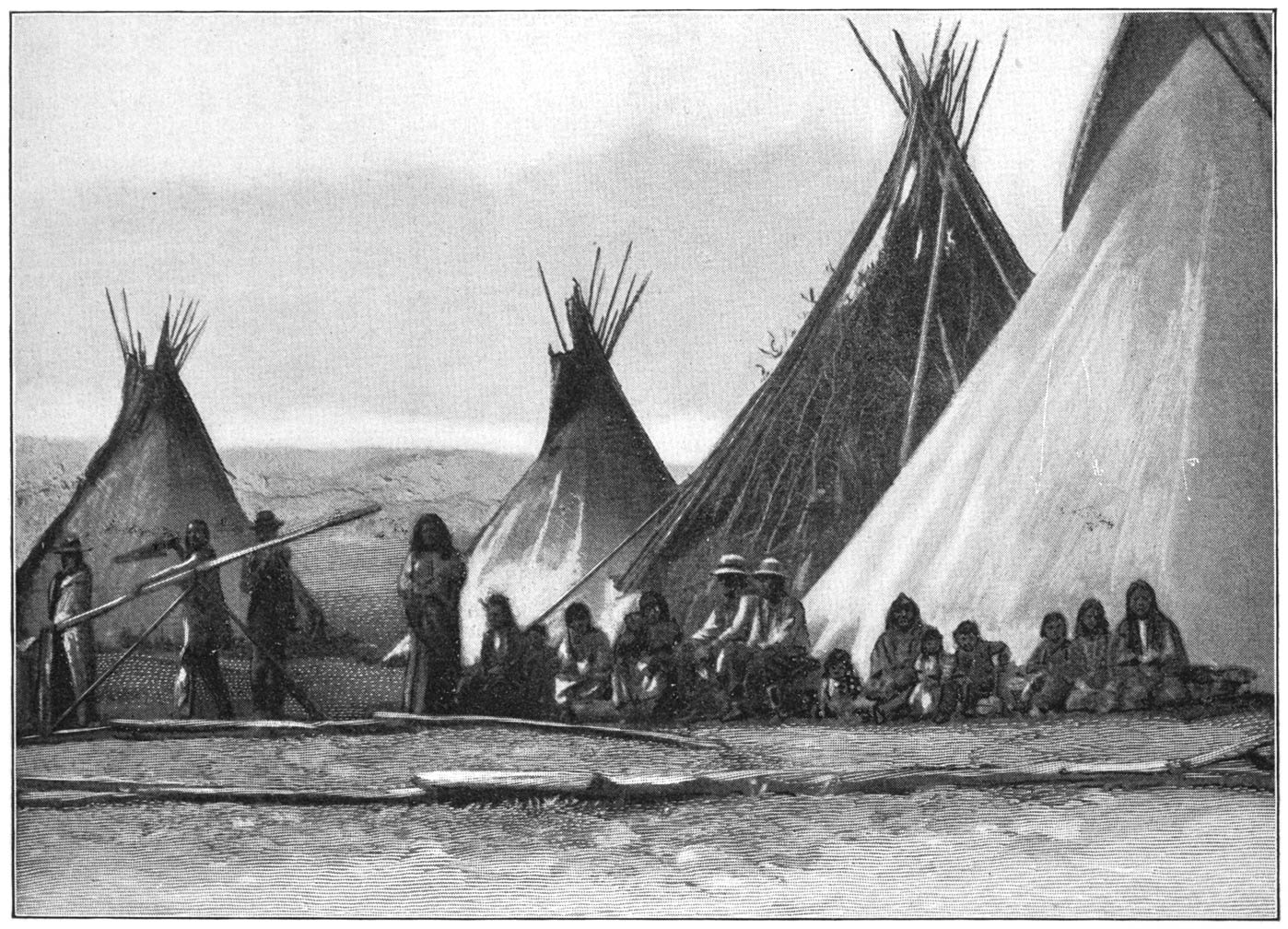

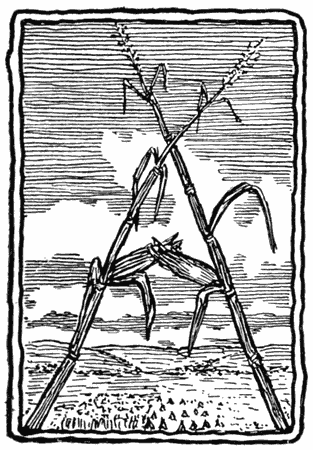

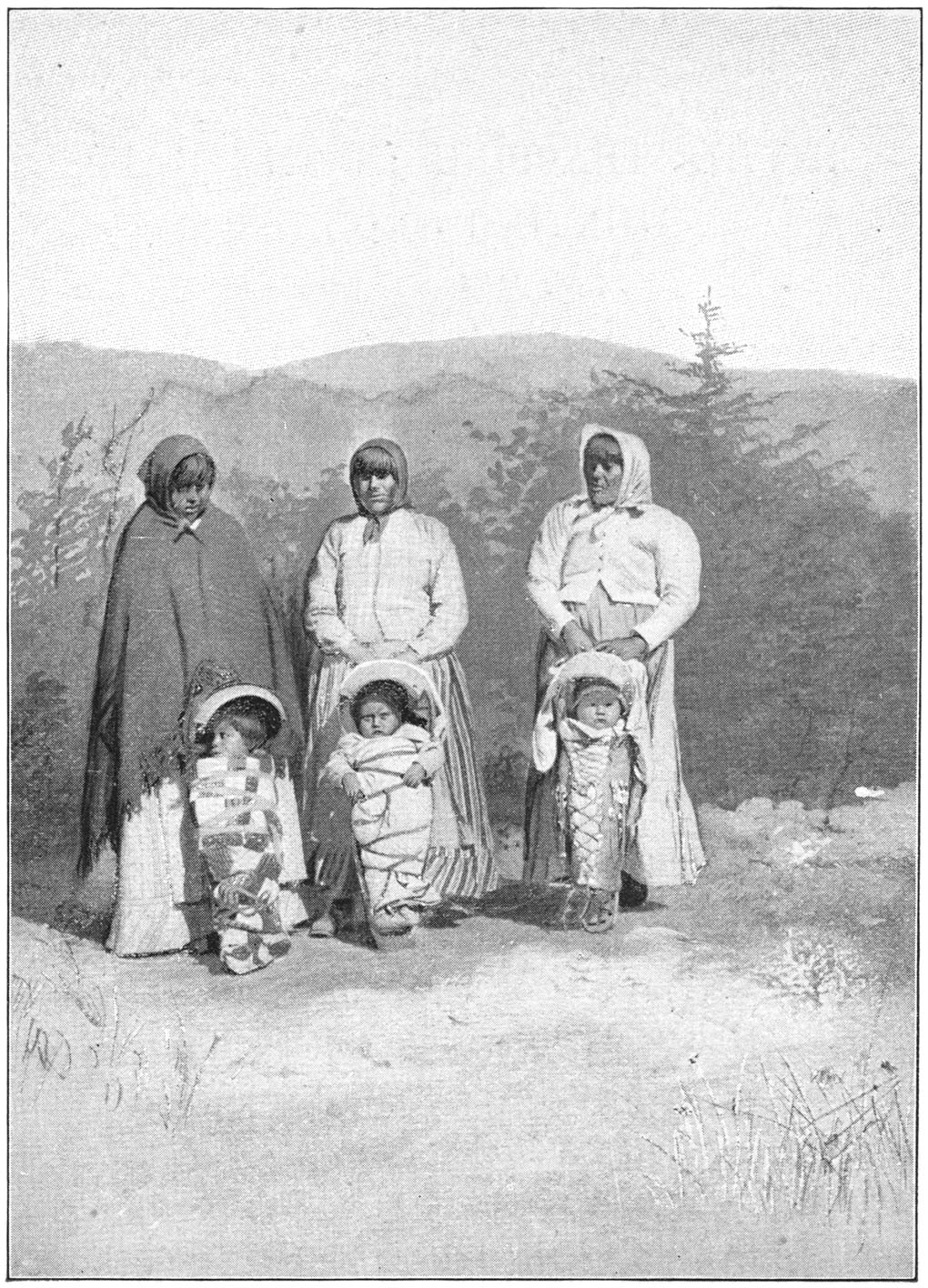

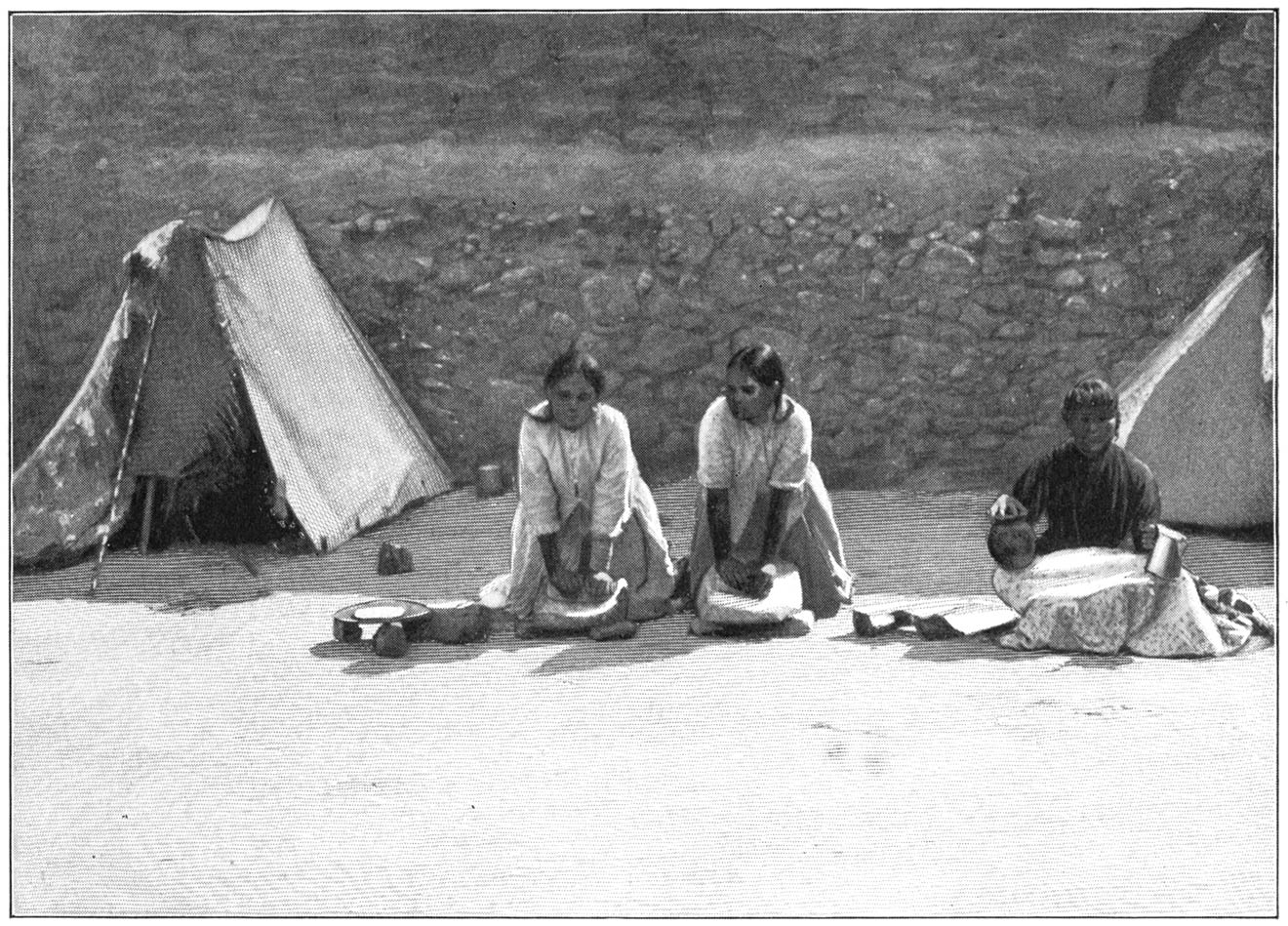

Tee′ pee. Indian circular house or tent made of poles covered with skins or cloth.

Ten′ nay. See Apache and Navajo.

Ti ō′ ta. A lake in central New York.

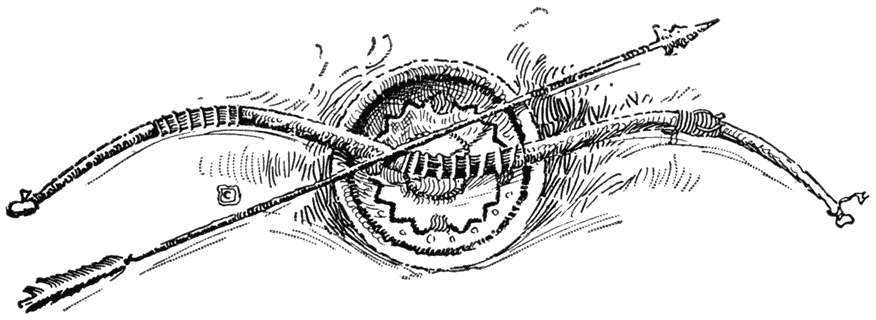

Tom′ a hawk. An Indian battle ax.

Tŭs ca ro′ ras. A tribe from North Carolina which joined the Iroquois in 1712. They now live upon

a reservation in western New York, near Niagara Falls, and are noted for their fine

farms, schools, and churches.

Wä bas′ so. The Chippewa word for rabbit.

Wau bē′ sē. The wild swan.

Wee′ di goes. Mythical giants. A Chippewa word.

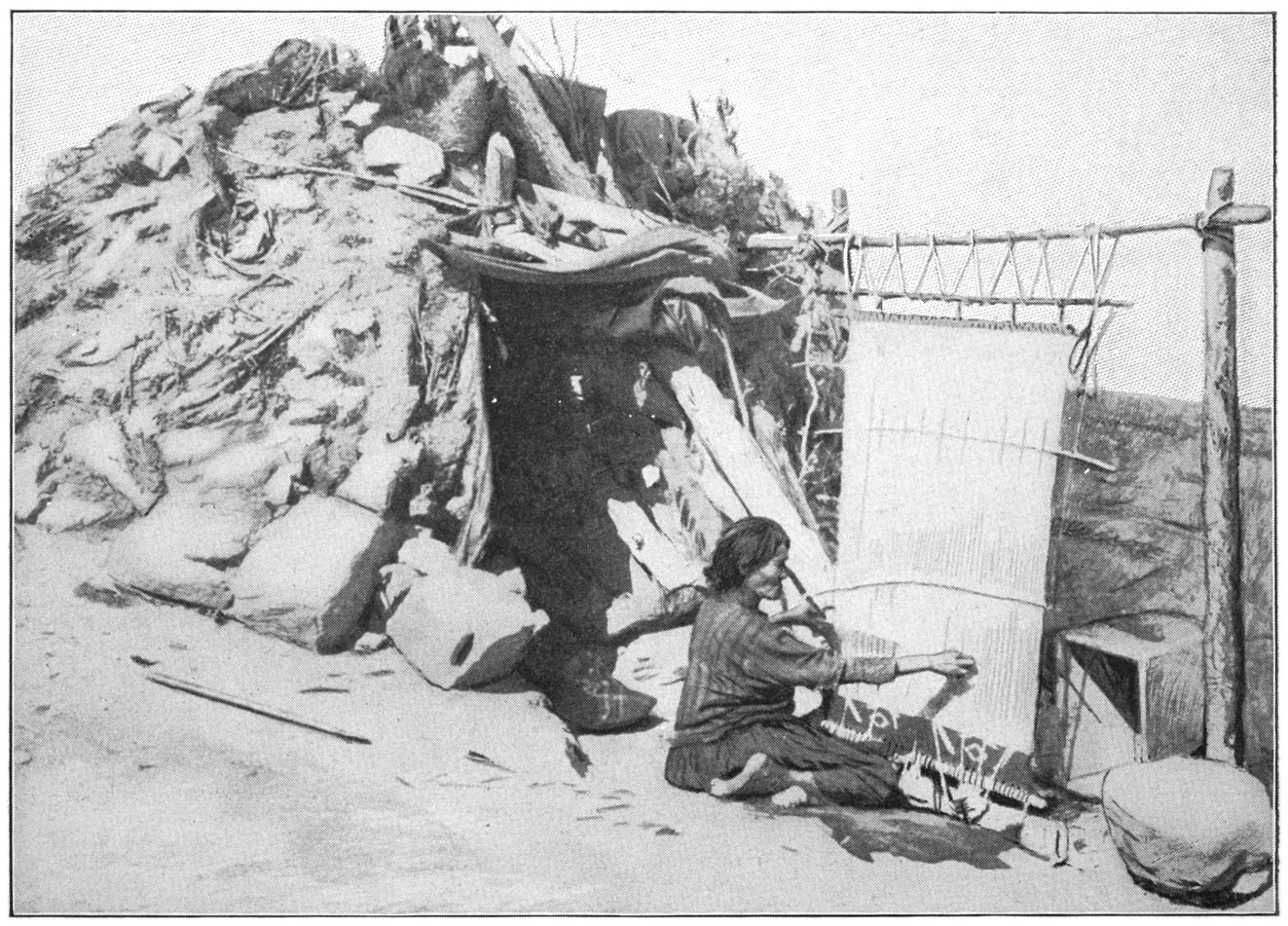

Wick′ i up. A brushwood tent-like house used by the Apaches and other roving tribes. It is made

of short poles or brush bent over, fastened together, and covered hastily with skins,

blankets, or other covering. It is never carried from place to place as the teepee

and wigwam are by other tribes.

Wig′ wam. A circular tent-like house made of birch bark or other bark by the New England tribes

and others. It is easily rolled and carried from place to place.

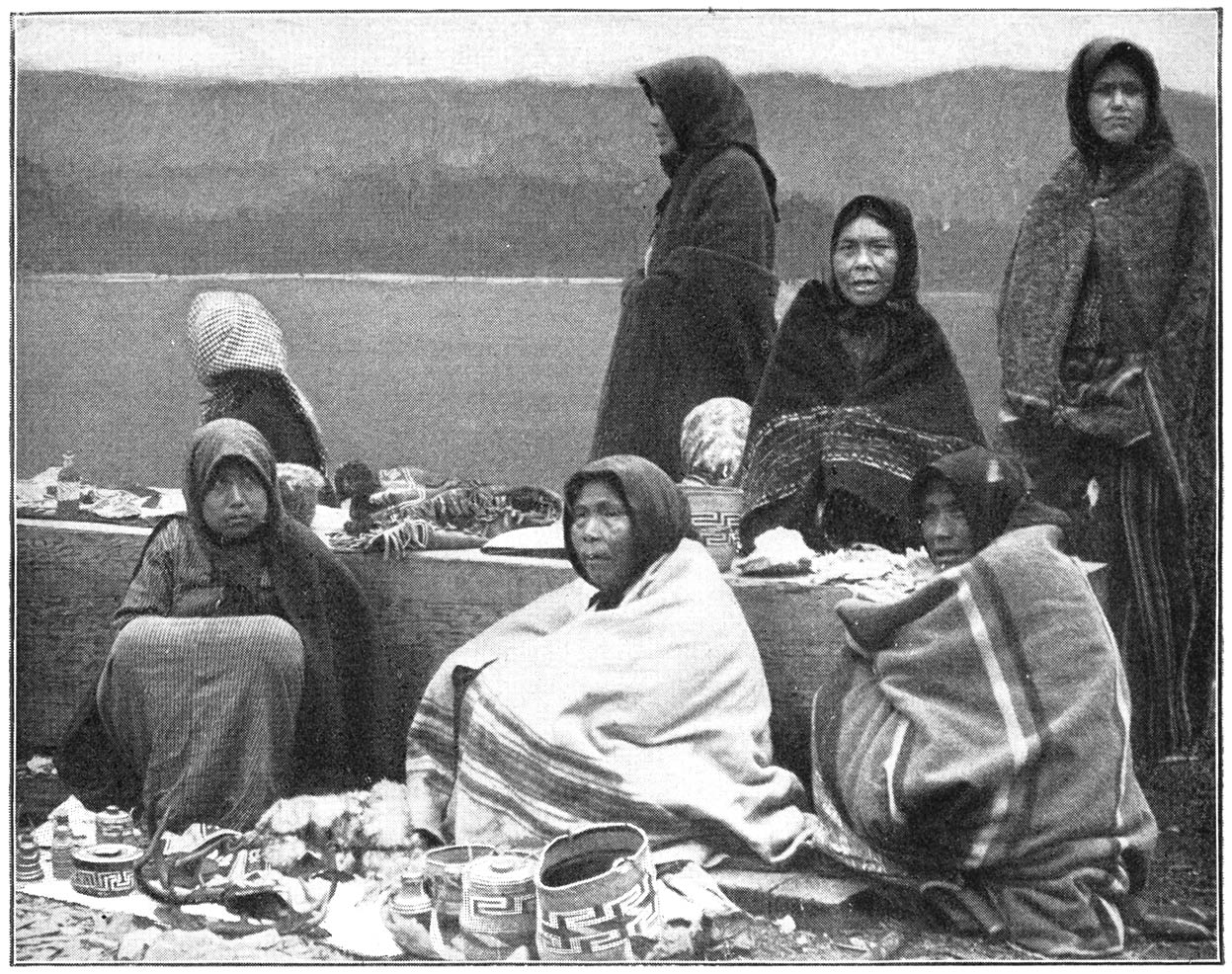

Zuñi (Zoon′ ye). A semi-civilized Pueblo tribe, perhaps the best known of any of the Village Indians

of the United States. They have a governor and lieutenant-governor of their own; good

laws, good farms, and are a remarkable people. Very few of them can understand English.

[277]