Title: Afghanistan

Author: A. Hamilton

Release date: March 24, 2024 [eBook #73258]

Language: English

Original publication: London: William Heinemann, 1906

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/73258

Credits: Carol Brown, Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BOOKS OF TRAVEL

THROUGH FIVE REPUBLICS (OF SOUTH AMERICA). A Critical Description of Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, and Venezuela in 1905. By Percy F. Martin, F.R.G.S. With 128 Illustrations and 3 Maps. In one vol., demy 8vo, price 21s. net.

GRANADA. Memories, Adventures, Studies, and Impressions. By Leonard Williams. Post 8vo, illustrated, price 7s. 6d. net.

IN THE COUNTRY OF JESUS. By Matilde Serao. In one vol., crown 8vo, illustrated, price 6s. net.

CARTHAGE OF THE PHŒNICIANS. By Mabel Moore. With numerous illustrations and coloured frontispiece. One vol., crown 8vo, price 6s.

KOREA. By Angus Hamilton. With a map and many illustrations. In one vol., demy 8vo, price 15s. net.

London: WILLIAM HEINEMANN

AFGHANISTAN

BY

FELLOW OF THE ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY

AUTHOR OF “KOREA,” “THE SIEGE OF

MAFEKING,” ETC.

WITH A MAP AND NUMEROUS

ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

WILLIAM HEINEMANN

1906

Copyright 1906 by William Heinemann

All rights reserved

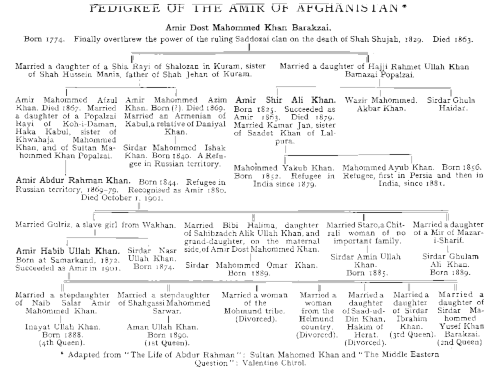

Since 1871, when Sir Charles MacGregor drew up a very exhaustive précis of information on Afghanistan for the use of the Government of India, no book dealing with our buffer state in a general manner has been issued. The thirty-five years which have intervened have not been without important contributions to our knowledge of Afghanistan, but those works which have appeared cannot altogether be described as presenting a single comprehensive study of contemporary conditions in the country. In 1886 Lieutenant A. C. Yate, and in 1888 Major C. E. Yate, C.S.I., C.M.G., described in two very interesting volumes the proceedings of the Afghan Boundary Commission. Ten years elapsed before anything of importance appeared, when, by a rare coincidence, two books dealing with Afghanistan saw the light in 1895: Mr. Stephen Wheeler’s admirable account of The Amir Abdur Rahman, and that most entertaining and graphic volume, My Residence at the Court of the Amir, by the late Amir’s private physician, Dr. A. J. Gray. In 1900 Sultan Mahomed Khan, Mir Munshi to Abdur Rahman, presented to the public his remarkable production, The Life of Abdur Rahman, as well as a treatise on The Constitution and Laws of Afghanistan. In the following year, 1901, Colonel Sir Thomas Holdich embodied in The Indian Borderland many graceful descriptions of scenery and various centres in Afghanistan while, in 1905, in a series of articles in the Wide World Magazine, Mrs. Kate Daly, physician to Habib Ullah’s harem and the Government of Afghanistan, illustrated with many delightful touches a sojourn of Eight Years Among the Afghans. These few works practically exhaust contemporary [Pg viii] literature on Afghanistan, and it is in an endeavour to provide a more complete record of the subject than has hitherto existed that the author of Korea has compiled this little book. Mistakes are those of his own making; reflections and criticisms arise from his own opinions; but, in hoping that his critics may find something of value in the results of two years’ toil, the author wishes to say that if good qualities exist in it, they are attributable to the encouragement and gracious assistance which he has received and here wishes to acknowledge.

With a view to the careful preparation of this volume the author, after returning to London from the war in Manchuria, visited Central Asia, his travels terminating abruptly in an attack of small-pox contracted from the natives, while he was wandering in the region of the Pamirs. Descending viâ Gilgit to India from the Taghdumbash, twelve months have been spent in the labour of writing, in the examination of a number of works, and in reference to those authorities who are so justly distinguished for their knowledge of the heart of Mid-Asia. In this direction it is perhaps of interest to point out that in order to establish a standard of accuracy, certain chapters have been submitted in page proof to the criticism of this little group of Central Asian experts, and their corrections embodied in its final form. The author very warmly appreciates the help which has in this way been given him, and to Colonel de la Poer Beresford and Captain Charles Bancroft in connection with chaps. i., ii., iii.; to Colonel Sir Thomas Holdich, K.C.I.E., K.C.M.G., C.B., in chap. iv.; to Colonel C. E. Yate, C.S.I., C.M.G., in chaps. v. and vi.; to Colonel Sir Henry McMahon, K.C.I.E., C.S.I., in chap. ix.; to Dr. A. J. Gray, Mrs. Kate Daly, and Major Cleveland, I.M.S., in chaps. xiv. and xv. he is very much indebted, as the indulgent manner in which his inquiries have been received has materially assisted the conclusion of his task.

In other quarters similar help has been given, and the author desires to express his deep obligation to the [Pg ix] Secretary of State for India, Mr. Morley, to Mr. John E. Ellis, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for India, to Sir William Lee-Warner, and to Mr. Thomas, of the Political Department, India Office, for the considerate way in which services have been rendered him. The very pleasant hospitality bestowed upon the author by Mr. George Macartney, C.S.I., the representative of the Government of India in Kashgar, Chinese Turkestan; by Mr. L. G. Fraser, the editor of The Times of India; by Mr. C. F. Meyer, Standard Oil Company’s Agent in Bombay; by Major Cleveland, in Poona; and by Mr. Ivor Heron-Maxwell, late of Baku in that centre, has provided him with many haunting memories which, in a later volume, will be more suitably described. To Dr. Chalmers Mitchell, Secretary of the Zoological Society of London, and to Mr. J. Bryant Sowerby, Secretary of the Royal Botanic Society, the author is indebted for assistance in compiling the tables of species which illustrate chap. xii.; while to the Librarian of the India Office, and to the Librarian of the Royal Geographical Society, he would express his grateful thanks.

As correspondent to The Pall Mall Gazette, and to The Times of India from Central Asia, it is the pleasant duty of the author to acknowledge the permission of Sir Douglas Straight and Mr. L. G. Fraser to make use of certain articles which, although entirely altered and greatly amplified since their original appearance, were first presented in the respective columns of these organs. These extracts, a few brief paragraphs on various pages, are confined solely to the first six chapters of the book. Acknowledgments are also due to the proprietors of that esteemed Indian journal The Pioneer, whose London staff permitted the files of their well-known paper to be inspected; to the proprietors of The Daily Graphic for permission to reproduce the block of the Amir’s proclamation, and accompanying translation, appearing on pages 370, 371; to Messrs. Macmillan for the right to reproduce their copper engraving of Dr. A. J. Gray’s painting of the Amir Abdur Rahman; to [Pg x] Baron Herbert de Reuter, Managing Director of Reuter’s Telegram Company, for courteous assistance; to Mr. J. D. Holmes, an Indian photographer of renown, whose unique photographs of the Khyber Pass illustrate chaps. xvi. and xvii.; to Lieutenant Stewart, whose photographs appear in chap. ix.; to Lieutenant Olufsen for the right to reproduce certain interesting photographs from that informative work Through the Unknown Pamirs; to Colonel Sir Thomas Holdich for authority to base upon his original sketches enlarged drawings of Herat and Kandahar, by Mr. Percy Home; to Major Cleveland, I.M.S., to whose great credit very many of the illustrations in this volume must be placed; to Major Molesworth Sykes, H.B.M. Consul at Meshed, for photographs appearing in chap. vii.; to Professor Victor Marsden, of Moscow University, for general courtesies; to Captain Charles Bancroft for assistance in translating extracts from papers placed at the author’s disposal by his Excellency Prince Khilkoff, Russian Minister of Railways; to that well-known military novelist, Mr. Horace Wyndham, who has been good enough to assist the author in the revision of his proofs; and to Mr. Thomas Bumpus, of Messrs. J. and E. Bumpus, Limited.

The final, but by no means the least gratifying, duty now remains to be fulfilled. It is concerned with the dedication of this volume which, by special permission, is inscribed:

TO HIM

WHO,

BY THE SPLENDOUR OF HIS GIFTS

AND

THE WISDOM OF HIS RULE,

HAS LEFT

AN INDELIBLE AND MEMORABLE

IMPRESSION

UPON INDIA:

LORD CURZON OF KEDLESTON,

G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E., P.C.

ETC. ETC. ETC.

The works consulted in the preparation of this volume, including references to the Encyclopædia Britannica, embrace most of the well-known writers on Asiatic Russia, Persia, Afghanistan, and the Indian Frontier. Among those of less recent date are the books of Bellew, Connelly, Elphinstone, Ferrier, Lansdell, MacGregor, Marvin, Pottinger, Rawlinson, Vambéry, Wood and Yule.

Contemporary authorities, to which the author is more especially indebted, are as follows:

| Bruce, R. I. | The Forward Policy and its Results. |

| Chirol, Valentine | The Middle Eastern Question. |

| Curzon, Lord | Russia in Central Asia. |

| ” ” | Persia and the Persian Question. |

| ” ” | The Pamirs and the Source of the Oxus. |

| Daly, Mrs. Kate | Eight Years among the Afghans. |

| Gray, Dr. A. J. | My Residence at the Court of the Amir. |

| Holdich, Colonel Sir T. H. | The Indian Borderland. |

| Keane, A. H. | Asia. |

| Lansdell, H. | Russia in Central Asia. |

| Olufsen, O. | Through the Unknown Pamirs. |

| Roberts, Field Marshal Lord | Forty-one Years in India. |

| Ronaldshay, Earl of | Sport and Politics under an Eastern Sky. |

| ” ” ” | On the Outskirts of Empire in Asia. |

| Shoemaker, M. M. | The Heart of the Orient. |

| Skrine, F. H., and Ross, E. D. | The Heart of Asia. |

| Sultan Mahomed Khan | Laws and Constitution of Afghanistan. |

| ” ” ” | The Life of Abdur Rahman, Amir of Afghanistan. |

| Thorburn, S. S. | The Punjab in Peace and War. |

| Yate, A. C. | England and Russia Face to Face. |

| Yate, C. E. | Kurasan and Seistan. |

| ” ” | Northern Afghanistan. |

[Pg xiv] Together with scientific papers, lectures and articles by:

And including all Parliamentary, Consular, and other official publications, the files of The Times, Morning Post, Standard, Daily Chronicle in England; and The Pioneer, Times of India, and Indian Daily News in India; besides the more prominent Continental organs.

Royal Societies Club, St. James’s

June 1, 1906.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | The Orenburg-Tashkent Railway | 1 |

| II. | The Khanate of Bokhara, the Province of Samarkand, the Districts of Tashkent and Merv | 25 |

| III. | From Tashkent to Merv | 58 |

| IV. | The Northern Border and the Oxus River: its Character, Tributaries and Fords | 81 |

| V. | The Murghab Valley Railway | 110 |

| VI. | The Murghab Valley | 131 |

| VII. | Herat and the Western Border | 147 |

| VIII. | Kandahar | 178 |

| IX. | Seistan and the McMahon Mission | 211 |

| X. | Provinces and District Centres, Ethnographical and Orological Distribution | 242 |

| XI. | Administration, Laws and Revenue | 269 |

| XII. | Trade: Industries and Products | 288 |

| XIII. | Army, Forts and Communications | 308 |

| XIV. | Kabul: its Palaces and Court Life | 342 |

| XV. | Kabul and its Bazaars | 376 |

| XVI. | Anglo-Afghan Relations | 400 |

| XVII. | Anglo-Afghan Relations (continued) | 427 |

APPENDICES | ||

| I. | Names of Stations on the Orenburg-Tashkent Railway | 461 |

| II. | (A) List of Stations from Tashkent to Merv, with Distances from Krasnovodsk and Tashkent | 463 |

| II. | (B) Murghab Valley Railway: List of Stations from Merv to Kushkinski Post, with Distances from Krasnovodsk and Merv | 464[Pg xvi] |

| III. | Table of Measurements | 465 |

| IV. | The Treaty of Gandamak, etc. etc. | 466 |

| V. | Time Tables of the Oxus Flotilla | 519 |

| VI. | Return of Articles Exported from Russia to Khorassan during the Period March 21, 1903, to March 20, 1904, compared with 1900-03 | 522 |

| VII. | Return of Articles Exported from Khorassan to Russia during the Period March 21, 1903, to March 20, 1904, compared with 1900-03 | 526 |

| VIII. | Return of Articles Exported from Afghanistan to Khorassan and Seistan during the Period March 21, 1903, to March 20, 1904, compared with 1900-03 | 529 |

| IX. | Return of Articles Exported from Khorassan and Seistan to Afghanistan during the Period March 21, 1903, to March 20, 1904, compared with 1900-03 | 531 |

| X. | Return of Articles Exported from India to Khorassan viâ the Seistan Route during the Period March 21, 1903, to March 20, 1904 | 534 |

| XI. | Return of Articles Exported from Khorassan to India viâ the Seistan Route during the Period March 21, 1903, to March 20, 1904 | 535 |

| XII. | Trade Value of the Seistan Route compared with Competing Routes | 536 |

| XIII. | Agreement between the United Kingdom and Japan | 537 |

| XIV. | Chronological Sketch of Afghan History | 540 |

| Index | 547 | |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

| Lord Curzon of Kedleston | Frontispiece |

| Market-cart, Orenburg | 1 |

| Tomb in the Market-place, Samarkand | 3 |

| Palace of the Governor, Baku | 5 |

| The Picturesque Camel | 6 |

| The Shir Dar Medresse, Samarkand | 7 |

| On the Road in Asia | 9 |

| Kirghiz Elders | 17 |

| Kirghiz Women | 19 |

| Native Quarter, Tashkent | 21 |

| Shir Dar, Samarkand | 25 |

| The Amir of Bokhara on Palace Steps | 27 |

| The Gates of Bokhara | 31 |

| The Prison, Bokhara | 35 |

| The Minar Kalan, Bokhara | 36 |

| The Ark, Bokhara | 37 |

| The Tomb of Tamerlane, Samarkand | 41 |

| Samarkand—the Hour of Prayer | 44 |

| Samarkand—a Bird’s-eye View | 45 |

| Sobornaya Boulevard in Tashkent | 47 |

| Bazaar Scene | 51 |

| Breaking Camp on Manœuvres, Tashkent | 53 |

| Native Quarter, Tashkent | 58 |

| Koran Stand, Samarkand | 58 |

| Peasants from the Golodnaya Steppe | 60 |

| The Column of Tamerlane, Samarkand | 63 |

| The Registan, Samarkand | 65[Pg xviii] |

| Throne-Room—Palace of the Amir of Bokhara | 68 |

| Amir’s Palace, Bokhara | 70 |

| The Dervishes of Bokhara | 72 |

| The Kara Kum—Black Sands | 76 |

| Mosque at Bairam Ali | 77 |

| The Gur Amir | 78 |

| The Military Quarter, Merv | 80 |

| The Amu Daria Bridge | 81 |

| Near the Source of the Oxus | 83 |

| The Valley of the Oxus | 83 |

| Beside the Oxus | 87 |

| The Wakhan Valley | 87 |

| Type from Wakhan | 89 |

| Bridge over the Upper Oxus | 90 |

| Difficult Going | 92 |

| Village on the Lower Oxus | 95 |

| Petro Alexandrovsk | 99 |

| Native Church at Khiva | 101 |

| Temple on the Banks of the Oxus | 103 |

| The Shrine of Hazrat Ali | 105 |

| Village on the Middle Oxus | 107 |

| Street Scene, Andijan | 110 |

| A Notable Gathering | 113 |

| On the Central Asian Railway | 115 |

| School Children | 118 |

| Hindu Traders at Pendjeh | 120 |

| Native Water-Sellers | 123 |

| Khorassan Dervish | 125 |

| The Murghab Valley Railway | 127 |

| Native School | 130 |

| The Russian Cossack on the Afghan Border | 131 |

| Tamarisk Scrub in the River Valley | 133 |

| Bokharan Traders at Pendjeh | 139 |

| The Russo-Afghan Boundary | 141 |

| Meshed Traders at Pendjeh | 143 |

| Gandamak Bridge, where the Famous Treaty was signed | 151[Pg xix] |

| Plan of Herat | 153 |

| A Street Shrine | 155 |

| The Irak Gate | 159 |

| Herat Citadel | 163 |

| Kitchen in Native House | 165 |

| Household Utensils | 167 |

| A Caravansary Compound | 170 |

| Religious Festival on the Perso-Afghan Border | 171 |

| Afghan Post at Kala Panja | 175 |

| A Water Seller | 177 |

| Typical Street Scene | 180 |

| Crossing the Helmund River | 183 |

| Constructing the Quetta-Nushki Line | 188 |

| Plan of Kandahar | 191 |

| The Walls of Kandahar | 195 |

| Always a popular and central Meeting-place | 199 |

| Typical Street Scenes | 207 |

| Carrying Cotton to Market | 210 |

| Camel Bazaar, Nasratabad | 212 |

| Lakeside Dwellers | 214 |

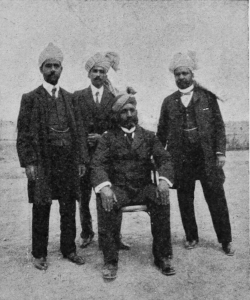

| The Native Staff attached to the Mission | 215 |

| Officers of the McMahon Mission | 217 |

| Baluchistan Camel Corps | 220 |

| Baluchi Chiefs who accompanied Colonel McMahon | 221 |

| Gates at Nasratabad | 224 |

| The Walls at Nasratabad | 225 |

| Bazaar Scene, Nasratabad | 227 |

| Dâk Bungalow on the Nushki Route | 236 |

| Infantry with the Persian Commissioner | 238 |

| The Persian Commissioner | 240 |

| A Caravan of Pack-Ponies | 242 |

| Women pounding Grain | 245 |

| A Baluchi Shepherd | 248 |

| Elders from Wakhan | 251 |

| Kasi Khoda da of Ishkashim | 261 |

| Children from the Upper Oxus | 265[Pg xx] |

| A Mountain Village | 268 |

| Entrance to Amir’s Pavilion at Jelalabad | 269 |

| Tomb of the Emperor Baber near Kabul | 272 |

| Spinning Cotton | 275 |

| A Customs Station in the Plains | 285 |

| Abdur Rahman’s Memorial to the Soldiers who fell in the War of 1878-1880 | 287 |

| Caravan of Wool and Cotton | 288 |

| Cotton Fields under Irrigation from the Amu Daria | 299 |

| Across the Passes | 307 |

| Typical Afghan Fortress | 310 |

| Picket of the Household Troops | 313 |

| Troop of Cavalry | 315 |

| Men of the Amir’s Bodyguard | 317 |

| Infantry in Parade State | 319 |

| Patrols of Household Troops | 322 |

| Infantry on the March | 325 |

| Miss Brown, Physician to the Amir’s Harem | 342 |

| Winter Palace of the Amir | 348 |

| Amir’s Summer Residence—Indikki Palace | 351 |

| Major Cleveland, I.M.S. Physician to the Amir of Afghanistan | 354 |

| Mrs. Cleveland | 355 |

| His Highness Prince Nasr Ulla Khan | 361 |

| The Amir’s Bodyguard | 363 |

| His Highness Habib Ullah, Amir of Afghanistan | 367 |

| A Proclamation | 370 |

| Major Cleveland’s Residence at Kabul | 375 |

| The famous Cage on the Summit of the Lataband Pass | 376 |

| Weighing Wood in the Bazaar | 377 |

| Playground of Amir’s School, Kabul | 381 |

| Afghan Women | 383 |

| A Saint’s Tomb | 385 |

| The Bala Hissar Kabul | 389 |

| Remains of the Roberts Bastion at Shirpur | 393 |

| Bazaar Children | 398 |

| In the Khyber Pass | 400[Pg xxi] |

| Abdur Rahman’s Palace at Jelalabad | 404 |

| The Road to Lundi Khana, Khyber Pass | 412 |

| Ali Masjid Fort | 420 |

| Jamrud Fort | 426 |

| Jamrud Fort | 428 |

| Caravansary at Dakka | 430 |

| Grounds of Palace occupied by the Dane Mission | 437 |

| Takht-i-Rawan | 447 |

| Festival in Honour of the Dane Mission | 453 |

| Scene of the Audiences between Habib Ullah and Sir Louis Dane | 455 |

| Escort outside the Gate of the Quarters occupied by the Dane Mission | 457 |

| The Walls of Bokhara | 458 |

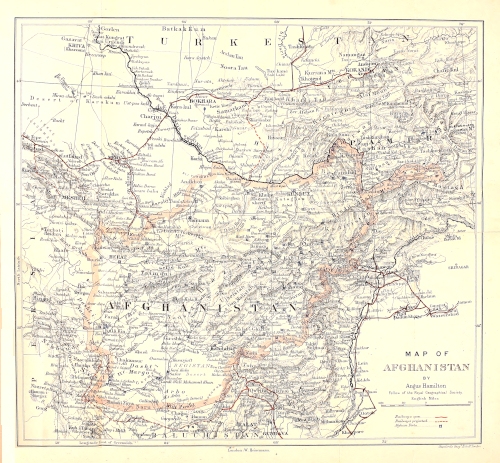

| Map of Afghanistan | At end |

By a coincidence of singular interest in Central Asian affairs the completion of the Orenburg-Tashkent railway occurred simultaneously with the evacuation of Lhassa by the troops of the Tibetan Mission, the two events measuring in a manner the character of the policies pursued by the respective Governments of Great Britain and Russia in Mid-Asia. Moreover, if consideration be given to them and the relation of each to contemporary affairs appreciated, it becomes no longer possible to question the causes which have determined the superior position now held in Asia by our great opponent. If this situation were the result of some sudden cataclysm of nature by which Russia had been violently projected from her territories in Europe across the lone wastes of the Kirghiz steppe into and beyond the region of the Pamirs or over the desert sands of the Kara Kum to the southern valleys of the Murghab river, our periodic lament at the mastery of Central Asia by Russia would be more comprehensible. But, unfortunately, the forward advance of Russia to the borders of Persia, along the frontiers of Afghanistan to the north-eastern slopes of the Hindu Kush, has been gradual; so gradual indeed that as each successive step became accomplished we have [Pg 2] had time to register recognition of the fact in bursts of indignant chatter, accompanied as is not unusual with us by a frothy clamour of empty threats. Unluckily noisy outcry has been mistaken for action; but from the moment when Russia first moved into Trans-Caspian territory there appears to have been nothing but vague realisation of the acute possibilities with which the situation in Central Asia from that hour became impressed. As time passed and the several phases vanished our indifference and supineness have increased, until no chapter in the history of our Imperial affairs offers more melancholy reading than that which deals with the period covering the “peaceful” penetration of Asia by Russia.

In order to secure sufficient momentum for her descent railways were needed; and, while the line so lately completed between Orenburg and Tashkent is a more material factor in the situation than hitherto has been recognised, the laying of the permanent way between Samarkand and Termes, Askhabad and Meshed, approximately gauges the duration of the interval separating Russia from the day when she will have rounded off her position in Mid-Asia. Just now, therefore, and for ten years to come, strategic requirements should alone be permitted to influence the arrangement of our policy in High Asia. Commercial developments within the vexed sphere of the Russian and British territories in this region should be regulated by circumstances which, actually inherent in our Asiatic position, have been too long ignored. No question of sentiment, no considerations of trade influenced the creation of railway communication between Orenburg and Tashkent, the construction of the Murghab Valley line or the extension of the Trans-Caspian system from Samarkand to Osh. Strategy, steely and calculating, required Mid-Russia to be linked with Mid-Asia, the irresistible expansion of empire following not so much the line of least resistance as the direction from which it would be placed in position for the next move. Continents have been crossed, kingdoms annihilated and provinces absorbed by Russia in her steady, inimical progression towards the heart of Central Asia; until there is nothing so important nor so intimately associated with our position in Afghanistan to-day as the intricate perplexities which have emanated from this untoward approach. From time to time attempts have been made to effect an adjustment of the points at issue. The result [Pg 3] has been unsatisfactory since the patchwork application of pen and paper has come, as a rule, in response to some accomplished coup upon the part of our astute opponent. Indeed, there is nothing in the result of any of these compromises which can be said to do credit to our knowledge of the existing situation. Indifference, coupled with a really lamentable ignorance, distinguishes the conditions, if not the atmosphere, under which these rectifications of frontier and modifications of clauses in previously accepted treaties have been carried out. But now that we have witnessed the joining of the rails between Orenburg and Tashkent let us put an end to our absurd philandering; and, appraising properly the true position of affairs, let us be content to regard all further extension of the Russian railway system in Mid-Asia as the climax of the situation. To do this we must understand the points at issue; and to-day in Central Asia there are many causes which of themselves are sufficient to direct attention to them.

[Pg 4] Years have passed since the delimitation of the Russo-Afghan frontier and the definition of the Anglo-Russian spheres of influence in the Pamirs were made. In the interval, beginning with the acceptance of the findings of the Pamir Boundary Commission of 1896, Russia ostensibly has been engaged in evolving an especial position for herself in North China and providing railway communication between Port Arthur, Vladivostock and St. Petersburg. In this direction, too, war has intervened, coming as the culminating stroke to the policy of bold aggression and niggardly compromise which distinguished the diplomatic activities of Russia in Manchuria. Yet throughout these ten years the energies of Russia in Mid-Asia have not been dormant. Inaction ill becomes the Colossus of the North and schemes, which were en l’air in 1896, have been pushed to completion, others of equal enterprise taking their place. Roads now thread the high valleys of the Pamirs; forts crown the ranges and the military occupation of the region is established. Similarly, means of access between the interior of the Bokharan dominions and the Oxus have been formed; caravan routes have been converted into trunk roads and the services of the camel, as a mode of transport, have been supplemented by the waggons of the railway and military authorities.

The great importance attaching to the Orenburg-Tashkent railway and its especial significance at this moment will be appreciated more thoroughly when it is understood that hitherto the work of maintaining touch between European Russia and the military establishment of Russian Turkestan devolved upon a flotilla of fourteen steamers in the Caspian sea—an uncertain, treacherous water at best—and the long, circuitous railway route viâ Moscow and the Caucasus. This necessitated a break of twenty hours for the sea-passage between Baku and Krasnovodsk before connection with the Trans-Caspian railway could be secured. The military forces in Askhabad, Merv, Osh and Tashkent—including, one might add, the whole region lying between the south-eastern slopes of the Pamirs, Chinese Turkestan, the Russo-Afghan and the Russo-Persian frontiers—embracing the several Turkestan Army Corps, were dependent upon a single and interrupted line. Now, however, under the provision of this supplementary and more direct Orenburg-Tashkent route the entire military situation in [Pg 5] Central Asia has been dislocated in favour of whatever future disposition Russia may see fit to adopt. All the great depôts of Southern and Central Russia—Odessa, Simpheropol, Kieff, Kharkoff and Moscow, in addition to the Caucasian bases as a possible reserve of reinforcements—are placed henceforth in immediate contact with Merv and Tashkent, this latter place at once becoming the principal military centre in these regions. Similarly, equal improvement will be manifested in the position along the Persian and Afghan borders, to which easy approach is now obtained over the metals of this new work and for which those military stations—Askhabad, Merv, Samarkand—standing upon the Trans-Caspian railway, and Osh, now serve as a line of advanced bases. It is, therefore, essential to consider in detail this fresh state of affairs; and as knowledge of the Orenburg-Tashkent railway is necessary to the proper understanding of the position of Afghanistan, the following study of that kingdom is prefaced with a complete description of the Orenburg-Tashkent work, together with the remaining sections of railway communication between Orenburg and Kushkinski Post.

The journey between St. Petersburg and Orenburg covers 1230 miles and between Orenburg and Tashkent 1174 miles, the latter line having taken almost four years to lay. [Pg 6] Work began on the northern section in the autumn of 1900 and many miles of permanent way had been constructed before, in the autumn of 1901, a start was made from the south. The two sections were united in September of 1904; but the northern was not opened to general traffic until July, nor the southern before November, 1905. Prior to the railway communications were maintained by means of tarantass along the post-road, which led from Aktiubinsk across the Kirghiz steppes viâ Orsk to Irghiz and thence through Kazalinsk to Perovski, where the road passed through Turkestan to run viâ Chimkent to Tashkent—a journey of nineteen days. In addition to the galloping patyorka and troika—teams of five and three horses respectively—which were wont to draw the vehicles along the post-road and the more lumbering Bactrian camels, harnessed three abreast and used in the stages across the Kara Kum, long, picturesque processions of camels, bound for Orenburg and carrying cotton and wool from Osh and Andijan, silks from Samarkand and Khiva, tapestries from Khokand, lambs’-wool, skins and carpets from Bokhara and dried fruits from Tashkent, annually passed between Tashkent and Orenburg from June to November.

Of late years, the Trans-Caspian railway, begun by Skobeleff in 1880 and gradually carried forward by Annenkoff to Samarkand, has supplanted the once flourishing traffic of the post-road, along which the passing of the [Pg 7] mails is now the sole movement. The new railway, too, is destined to eliminate even these few links with the past, although in the end it may revive the prosperity of the towns which through lack of the former trade have shrunk in size and diminished in importance. The line does not exactly follow the postal route; but from Orenburg, which is the terminus of the railway from Samara on the Trans-Siberian system, it crosses the Ural river to Iletsk on the Ilek, a tributary of the Ural. From Iletsk the metals run viâ Aktiubinsk and Kazalinsk along the Syr Daria valley viâ Perovski to Turkestan and thence to the terminus at Tashkent.

Originally one of three suggested routes the Orenburg-Tashkent road was the more desirable because the more direct. Alternative schemes in favour of connecting the Trans-Siberian with the Central Asian railway on one hand and the Saratoff-Uralsk railway with the Central [Pg 8] Asian railway on the other were submitted to the commission appointed to select the route. Prudence and sentiment, as well as the absence of any physical difficulties in the way of prompt construction, tempered the resolution of the tribunal in favour of the old post-track. It was begun at once and pushed to completion within four years—a feat impossible to accomplish in the case of either of the two rival schemes. The former of these, costly, elaborate and ambitious, sought to connect Tashkent with Semipalatinsk, the head of the steamboat service on the Irtish river, 2000 miles away, viâ Aulie-ata, Verni and Kopal. Passing between the two lakes Issyk and Balkash alternative routes were suggested for its direction from Semipalatinsk: the one securing a connection with the Trans-Siberian system at Omsk, the other seeking to pass along the post-road to Barnaul, terminating at Obi where the Trans-Siberian railway bridges the Obi river. The supporters of the scheme, which aimed at uniting the Saratoff-Uralsk railway with the Central Asian railway, proposed to carry the line beyond Uralsk to Kungrad, a fishing village in close proximity to the efflux of the Amu Daria and the Aral sea. From Kungrad, passing east of Khiva, the line would have traversed the Black Sands following a straight line and breaking into the Central Asian system at Charjui, opposite which, at Farab, a line to Termes viâ Kelif has been projected; and where, too, an iron girder bridge, resting on nineteen granite piers, spans the Amu Daria. It is useless at this date to weigh the balance between the several schemes; one of which, the Orenburg-Tashkent route, has become an accomplished fact to provide, doubtless in the near future, matter for immediate concern.

From Orenburg, of which the population is 80,000, the line 4 versts[1] from the station crosses the Ural river by an iron bridge, 160 sagenes[2] in length, running from there south to Iletsk, formerly the fortress Iletskaya Zashchita and at present a sub-district town of the Orenburg government with a population of 12,000.

From Iletsk a short branch line, rather more than three versts in length, proceeds to the Iletsk salt mines. Running eastwards and crossing the Ilek river from the right to the left bank by an iron bridge 105 sagenes in length it reaches Aktiubinsk, a district town in Turhai province. At this stage the railway traverses the main watershed of the Ural, Temir, [Pg 9] Kubele and Embi rivers, arriving at the Kum Asu pass across the Mugodjarski range. The passage of the line through the mountains, extending 26 versts and a veritable triumph of engineering, imposed a severe test upon the constructive ability of the railway staff. Beyond the range the line turns southward following the valleys of the Bolshoi, Mali Karagandi and Kuljur rivers until, 600 versts from Orenburg, it arrives at Lake Tchelkar. The line now runs across the Bolshiye and Maliye Barsuki sands, where there is abundance of underground fresh water, to the northern extremity of the Sari Tchegonak inlet on the Aral sea, where it descends to sea-level moving along the north-eastern [Pg 10] shore. The military depôt at Kazalinsk—sometimes called Fort No. 1—now approaches. This point founded in 1854 has lost its exclusive military character, ranking merely among the district centres of the Syr Daria province. Thirty-six versts from Kazalinsk, at the next station Mai Libash situated in a locality quite suitable for colonisation, a branch line, 4 versts in length, links up the important waterway of the Syr Daria with the Orenburg-Tashkent system, extending the facilities of the railway to shipping which may be delayed through stress of bad weather in the gulf or through inadequacy of the draught over the bar at the mouth of the river.

The main line keeps to the Syr Daria, running through the steppe along the post-road to Karmakchi or Fort No. 2. On leaving Karmakchi it diverges from the post-road to wind round a succession of lakes and marshes which lie at a distance of 50 versts from the river. The railway continuing its original direction now runs along the basins of the Syr Daria and the Karauzyak, a tributary which it crosses twice by small bridges, each constructed with two spans 60 sagenes in length. The character of the country from Karmakchi to Perovski, a distance of 138 versts, differs considerably from the region preceding it. The low-lying ground, broken by swamps, is everywhere covered with a thick overgrowth of reeds; while the more elevated parts, watered by ariks, are devoted to the cultivation of crops. The town of Perovski is situated in flat country 1½ versts from the station. From there to Djulek the line returns to the post-road and some distance from the Syr Daria passes between the river and the Ber Kazan lakes to Ber Kazan. At Djulek, the name being adopted from a small adjacent hamlet, it diverges from the post-road to run direct to the village of Skobelevski, one of those curious peasant settlements which located in the uttermost parts of Central Asia preserve in their smallest detail every characteristic of remote Russia. At such a place life savours so strongly of the middle ages that one scarcely heeds the purely modern significance which attaches to the Iron Horse.

Barely 30 versts from Skobelevski and situated close to the Syr Daria there is the station of Tumen Arik, which gives place to Turkestan, beyond which for 120 versts the line runs parallel with the post-road. The station is 2½ versts to the north of the town of Turkestan, one of the most important towns in the Syr Daria province and only 40 versts [Pg 11] from the Syr Daria. The next station Ikan is associated with the conquest of Turkestan, a famous battle having been fought about the scene where the station buildings now stand. Twenty versts to the north of the station, close to the post-road, there is a memorial to Ural Cossacks who fell during the fight. Otrar the following station is identified with the tradition, derived from the existence of an enormous mound standing amid the ruins of the old-time city of Otrar, that Timur when his army crossed the Syr Daria ordered each of his soldiers to throw a handful of earth upon the ground at the point where the river was crossed in safety. Beyond Otrar the line runs along the right bank of the Aris river, crossing it at 1570 versts from Orenburg by a bridge of 90 sagenes in three spans of 30 sagenes each. Aris station is placed further along the river bank at a point where at some future date branch lines between it and the town of Verni, as well as to a junction with the Trans-Siberian system, will be laid. After leaving it the railway, still ascending, ultimately crosses the pass of Sari Agatch in the Kizi Kurt range, 267 sagenes above the sea.

The descent from the pass leads to Djilgi valley where the line crosses three bridges; passing over the Keless river by a single span bridge of 25 sagenes, over the Bos-su arik by a bridge of 18 sagenes, and over the Salar river by a bridge of 12 sagenes. Seventy-two versts further the line runs into its terminus at Tashkent which is now classed as a station of the first degree, although commercially it stands only sixth among the stations of the Central Asian railway ranking with Andijan and yielding priority of place to Krasnovodsk, Samarkand, Khokand, Askhabad and Bokhara. It is proposed at Tashkent, which lies 1762 versts from Orenburg, 1747 versts from Krasnovodsk and 905 versts from Merv and where it is evident that the needs of the railway have been carefully studied, to double the track between Orenburg and Tashkent. Large stocks of spare rails and railway plant are held in reserve in sheds, one important feature of this very efficient preparation being the possession of 20 versts of light military railway. The erection of engine-sheds, waggon-sheds, workshops, supply stores and quarters for the staff has followed a most elaborate scale, these buildings being arranged in three groups around the station. The railway medical staff and the subordinate traffic and traction officials occupy the first; the chiefs of the traffic, telegraph and traction departments [Pg 12] are in possession of the second; the remaining employés securing accommodation in the third set of buildings placed at the end of the Station Square. Along the opposite face are the spacious workshops where between five and six hundred men find daily employment; in juxtaposition with the general depôt are the railway hospital, where there is accommodation for 10 beds, the main supply stores and a naphtha reservoir with a capacity of 50,000 poods.[3]

The country in the neighbourhood of Tashkent as seen from the railway presents the picture of a bountiful oasis. For 20 versts there is no interruption to a scene of wonderful fertility. Market gardens, smiling vineyards and fruitful orchards, not to mention cotton-fields and corn-lands, cover the landscape. This abundance in a measure is due to careful irrigation and to the excellent system of conserving water which has been introduced. In support of this 113 specific works have been completed, each of which—and the giant total includes water-pipes by the mile and innumerable aqueducts—was a component part of that scheme of irrigation by which life in Central Asia alone can be made possible.

Although work upon the Orenburg-Tashkent line began in 1900 immediately after the completion of the original survey, wherever more careful examination has shown an advantage to be possible alterations have been made. The cost of construction, estimated at 70,000 roubles[4] per verst, has been materially lessened by these means—a reduction of 24 versts equally divided between the Orenburg and Kazalinsk, Kazalinsk and Tashkent sections having been effected. By comparison with the old post-road the railway is much the shorter of the two lines of communication, the advantage in its favour amounting to 134 versts on one section of the road alone; the actual length between Tashkent and Kazalinsk being by post-road 953¼ versts and by railway 819¼.

In its local administration the railway is divided into four sections:

No. 1. From Orenburg to the Mugodjarski mountains about 400 versts.

No. 2. From Mugodjarski mountains to the sands of Bolshiye Barsuki, 400 to 560 versts.

No. 3. From the sands of Bolshiye Barsuki to Kazalinsk, 560 to 845 versts.

[Pg 13] No. 4. From Kazalinsk to Tashkent, 845 to 1762 versts.

In the northern section the line is supplied everywhere with fresh water—in the first instance from the Ural river and then by the smaller rivers Donguz, Elshanka, Ilek, Kulden, Kubele, Temir and Embi; Koss lake and finally from wells.

Here are the Iletsk mines, famous for their rock salt. They despatch annually to Orenburg more than 1,500,000 poods of salt. The deposits cover a field 4 versts in extent with an unvarying thickness of more than 85 sagenes. The section now in working contains 100 milliard poods of salt. The annual yield may be reckoned at 7,000,000 poods. At the present time considerably less than this output is obtained, the high freight charges upon land-carried goods and the insufficiency of the labour available being responsible for the disproportion.

In another direction the Iletsk district is of importance; the veterinary station Temir Utkul, through which pass large herds of cattle on their way to Orenburg from the Ural province, having been established there. In the course of the year many thousands of cattle are examined by the surgeons of the Veterinary Board—the existence of the numerous cattle-sheds and the constant arrival of the droves adding to the noise and bustle of Iletsk, if not exactly increasing its gaiety. Further on, in the Aktiubinsk district of the Turgai province and along the whole valley of the Ilek river, where much of the land is under cultivation, wide belts are given over to the pasturage of these travelling mobs of cattle. Upon both banks of the river, too, there are Kirghiz villages. The area of the Aktiubinsk district is:

| Area. | Population. |

| 40,000 sq. versts | 120,000 |

From an agricultural point of view this locality, on account of its paucity of population and fertile soil, is regarded with high favour by the immigration authorities. In the town of Aktiubinsk itself there is a yearly market of cattle, corn, manufactures and agricultural implements. This as a rule returns a quarter of a million roubles. Now that the railway has been completed and opened to passenger and commercial traffic, it is expected that it will give an immediate impetus to this region and that it will be possible to carry out a more careful examination of its mining resources, of which at the present time there are [Pg 14] only indications. Copper has been traced along the Burt, Burl, Khabd and Kutchuk Sai rivers; deposits of coal have been found near the Maloi Khabd, Teress Butak and Yakshi Kargach rivers; iron has been located by the Burt river and naphtha on the Djus river; while there is reason to believe that gold exists in the vicinity.

On the second section, the line derives its water from springs in the Djaksi mountains, the basin of the Kuljur river, the Khoja and Tchelkar lakes. It abounds with Kirghiz villages but minerals do not play an important part in it. A few seams of coal are believed to exist in the ravine of the Alabass stream; and there are lodestone mines in the Djaman mountains and in the Kin Asu defile. Cattle-farming is more remunerative to the local settlers than cereal production; as a consequence there is very little cultivation. The district, which is 160 versts in length, occupies:

| Area. | Population. |

| 127,300 sq. versts | 85,000 |

On the third section, which extends from the sands of Bolshiye Barsuki to Kazalinsk covering an area of 285 versts, the water-supply is obtained at first from shallow surface wells; but 45 versts from Kazalinsk the railway enters the Syr Daria valley, where water is abundant. The southern areas of this belt alone possess any commercial importance, owing to Kirghiz from the northern part of the Irgiz district who, to the number of some 10,000 kibitkas, winter there. The northern part is largely the continuation of a sparse steppe. The Kazalinsk district, beyond which the Orenburg-Tashkent railway enters Turkestan, is one of the least important divisions of the Syr Daria province. It embraces:

| Area. | Population. |

| 59,550 sq. versts | 140,598 |

Around Kazalinsk itself, however, there has been but little agricultural activity. In the main, development is confined to the fertile Agerskski valley and along the Kuban Daria, a tributary of the Syr Daria. The return is meagre and the population has not sufficient corn for its own needs. Large quantities of grain are annually imported into the neighbourhood from the Amu Daria district by boat across [Pg 15] the Aral sea or by camel caravan. Railway traffic in this section nevertheless will not rely upon the carriage of cereal produce—live stock, which until the advent of the railway was sent to Orenburg by boat along the Syr Daria and then by caravan-road to the city, representing the prospective return which the district will bring to the line. The population is composed of:

| Males. | Females. | Total. |

| 4478 | 4002 | 8480 |

| Orthodox Russians | 2205 |

| Dissenters | 1165 |

| Jews | 115 |

| Mahommedans | 4995 |

In the town there are:

| Private houses | 578 |

| Orthodox church | 1 |

| Synagogue | 1 |

| Mosques | 2 |

| Schools | 4 |

| Native universities | 2 |

The revenue of Kazalinsk is 21,880 roubles. The town contains the residences of a district governor and an inspector of fisheries, together with district military headquarters, the administrative offices of the treasury and the district court, besides a district hospital and a public library. There are no hotels. In early days in the conquest of Turkestan, when the Kazalinsk road served as the only line of communication with European Russia, the town became a busy mart for Orenburg, Tashkent, Khiva and Bokhara; even now the Kirghiz in the district possess 770,000 head of cattle. Trade was obliterated by the advent of the Central Asian railway; but it is hoped that now the Orenburg-Tashkent line has been opened to traffic it may revive.

The village of Karmakchi which is situated on the banks of the Syr Daria is another point in this district. It boasts only a small population, in all some 300 odd, an Orthodox church, post and telegraph office, two schools, hospital and military base office. Importance attaches to the post as it is upon the high road along which is conducted the winter trek of the Kirghiz.

The value of the annual export trade of the region is:

Exports.

| Poods. | Roubles. | |||

| Wool | ||||

| Sheep | } 200,000 | ⎫ | 2,000,000 | |

| Camel | ⎪ | |||

| Hides | 150,000 | ⎬ | ||

| Lard | 150,000 | ⎭ | ||

| Cattle | 400,000 | |||

[Pg 16] The value of the annual import trade amounts to:

Imports.

| Merchandise. | Value. |

| 110,000 poods | 1,800,000 roubles. |

With the opening of the line to traffic the transportation of fish by the railway has shown a tendency to increase. It is believed that the development of the fishing industry throughout the Aral basin is only a matter of time. At present the yearly catch of fish there reaches a total of 300,000 poods of which not less than one half is sent to Orenburg, the trade realising about 1,000,000 roubles. Hitherto little has been attempted. With the assistance of the railway a speedy expansion of the trade is assured—the interests of the fishing population and the general welfare of the river traffic having been advanced through the construction of a harbour upon the gulf of Sari Cheganak, in connection with the railway and only 5 versts distant. Aral sea, the station at this point, is 790 versts from Orenburg.

The fourth and last division, from Kazalinsk to Tashkent, runs along the valley of the Syr Daria. It is fully supplied with good water and possesses a larger population than either the second or the third sections. In it the line traverses the following districts of the Syr Daria province:

| District. | Area. | Population. | |

| Perovski | 95,965 | sq. versts | 133,784 |

| Chimkent | 100,808 | ” ” | 285,180 |

| Tashkent | 40,380 | ” ” | 500,015 |

The Perovski district notwithstanding the good qualities of its soil produces very little corn; its chief population consists of nomadic Kirghiz who together own 990,000 head of cattle, the export cattle trade for the district amounting to 2,000,000 roubles annually. Small tracts of wheat and millet are cultivated here and there with the aid of tchigirs, native watering-pumps. The water is brought up from the river by means of a wheel, along the rim of which are fixed earthenware jugs or cylindrical vessels of sheet iron. These vessels raise the water to the height of the bank, whence it is very readily distributed. The best corn-lands are [Pg 17] situated in the Djulek sub-district; but the primitive methods of agriculture existing amongst the nomads, in conjunction with the deficiencies in the irrigation system, explain at once the lack of cereal development in these areas.

Perovski was taken by Count Perovski on July 28, 1853, and in honour of the occasion by Imperial order the fortress was renamed Fort Perovski. Close to the town there is a memorial to the Russian soldiers who fell during that engagement.

The present population comprises:

| Males. | Females. | Total. |

| 3197 | 1969 | 5166 |

| Orthodox Russians | 1050 |

| Jews | 130 |

| Dissenters | 210 |

| Tartars | 450 |

| Sarts and Kirghiz | 3326 |

[Pg 18] The town contains:

| Private houses | 600 |

| Orthodox church | 1 |

| Synagogue | 1 |

| Mosques | 5 |

| Schools | 3 |

| Military hospital | 1 |

together with district administrative offices similar to those established at Kazalinsk. The water-supply is drawn from the Syr Daria by means of wells. There are no hotels. The town revenue is only 12,350 roubles; although the importation of various goods from Russia into the Perovski district represents an annual sum of 2,900,000 roubles. With the advent of the Central Asian railway the commercial importance of Perovski, once a point through which caravans destined for Orenburg or Tashkent passed, waned. Now its trade is dependent upon the numerous Tartars and Ural Cossacks who have settled there. The place is unhealthy, and the settlement is affected by the malaria arising from the marshes which surround it. In spring and summer the lagoons swarm with myriads of mosquitoes and horse-flies; so great is the plague that the Kirghiz together with their flocks and herds after wintering along the Syr Daria beat a hurried retreat into the steppe, driven off by the tiresome insects. Many months elapse before the nomads return; it is not until the cold weather has set in that they appear in any numbers. Quite close to Perovski there are two immigrant villages—Alexandrovski and Novo Astrakhanski—erected in 1895, where the inhabitants are occupied with cattle-farming and the sale of hay in winter time to the Kirghiz. The district possesses nothing save a pastoral population and a small settlement of 200 souls at Djulek. This place, formerly a fortress founded in 1861 and now half destroyed by the floods of the Syr Daria, contains the administrative offices of the commissioner of the section, with a postal and telegraphic bureau and a native school. To the south of Djulek there is Skobelevski, another small village founded by immigrants in 1895 and containing some fifty-six houses. It is watered by the Tchilli arik. Skobelevski is rapidly developing into a trade-mart, the source of its good fortune being contained in the advantageous position which it fills in the steppe. Throughout this region, plots of land with a good quality soil and well watered have been granted to colonists.

The Chimkent district similarly possesses a rich and fertile [Pg 19] soil, derived in the main from its network of irrigating canals. Its population is more numerous than other adjacent settlements and it supports altogether seventeen immigrant villages with a population of 5135. Chimkent contains in itself all the features necessary to the development of a wide belt of agriculture; but at the present time the most extensive tracts of wheat land are along the systems of the Aris, Aksu, Badam, Buraldai, Burdjar, Tchayan and Bugun rivers. In the valley of the Arisi, along the middle reaches, there are rice-fields; and in the country round Chimkent the cotton industry has begun to develop. Experiments are being tried in the cultivation of beetroot as the soil and climatic conditions of the district are especially favourable to its growth. The present quality of the Chimkent beetroot is not inferior to that grown in the Kharkoff Government; so that Chimkent may well become, in the near future, the centre of a sugar-producing industry not only for Turkestan but for the whole of Central Asia, which so far has imported its sugar exclusively from European Russia.

[Pg 20] The district town of Chimkent, formerly a Khokand fortress taken by the Russian forces under the command of General Chernaieff September 22, 1864, lies upon the eastern side of the railway. Its population comprises:

| Males. | Females. | Total. |

| 6887 | 5554 | 12,441 |

| Orthodox Russians | 768 |

| Jews | 150 |

| Natives | 11,523 |

There are in the

| Russian Quarter. | Native Quarter. | ||

| Houses | 105 | Houses | 1886 |

| Orthodox churches | 2 | Schools | 3 |

| Mosques | 34 | Native schools | 16 |

Government offices similar to those in other towns are also found.

The town revenue is 11,760 roubles.

The trade returns of the Chimkent district amount to 5,000,000 roubles.

| Exports. | Imports. | ||||

| Wool | ⎫ | 2,000,000 roubles | Manufactured goods | ⎫ | 3,000,000 roubles |

| Hides | ⎪ | Iron | ⎪ | ||

| Lard | ⎬ | Agricultural Implements | ⎬ | ||

| Butter | ⎪ | Tea | ⎪ | ||

| Wheat | ⎪ | Sugar | ⎭ | ||

| Santonin | ⎭ | ||||

Through Chimkent passes a road from Tashkent to Verni. In the northern part of the district the line runs close to the ruins of the ancient town of Sauran and the fortress of Vani Kurgan, from where it proceeds to Turkestan. This was occupied in 1864 by the Russian forces under the command of General Verevkin.

Turkestan is situated 40 versts to the east of the right bank of the Syr Daria, at a height of 102 sagenes above sea level. It is watered by canals diverted from springs and small rivers which flow from the southern slopes of the Kara mountains. The combined population of the place comprises:

| Males. | Females. | Total. |

| 7624 | 6461 | 14,085 |

| Orthodox Russians | 441 |

| Dissenters | 31 |

| Jews | 460 |

| Natives | 13,153 |

The outward appearance of the town is extremely handsome. There is much vegetation, many wide streets and large open spaces.

[Pg 23] There are:

| Russian Quarter. | Native Quarter. | ||

| Houses | 73 | Houses | 2140 |

| Orthodox churches | 2 | Schools | 5 |

| Synagogues | 2 | Native schools | 22 |

| Mosques | 58 | Medresse | 1 |

| Military hospital | 1 | ||

together with the administrative bureau of the sectional commissioner, besides district military headquarters, a district court and a post and telegraph office.

In respect of trade Turkestan occupies a prominent place. The great bulk of the raw products of the nomad cattle-farming industry is brought to it for the purpose of exchanging with articles of Russian manufacture. The yearly returns of the bazaars amount to 4,000,000 roubles; an increase upon this sum is expected now that in the Karatavski mountains, which are close at hand, lead mines have been discovered. The town revenue is 19,350 roubles.

The Tashkent district is more densely populated and possesses a more productive soil than Chimkent. The mineral resources, too, present greater promise while the trade returns reach a total of 50,000,000 roubles a year. Merchandise comes from Siberia into Orenburg and Tashkent; while, in addition, there are the local products and those from the interior of European Russia. The line serves, also, as the shortest route between Tashkent and the rich corn region at Chelyabinsk and Kurgan. Undoubtedly it will assist to supply the whole of Turkestan with Siberian corn, thereby setting free some of the land now under corn for the cultivation of cotton. Further, it connects Tashkent with the centre of the mining industry in the Ural mountains; and dense streams of Russian colonisation and trade pass by it into the heart of Central Asia.

The prosperity introduced both into Orenburg and Tashkent by the creation of railway communication between these two centres will exercise a very beneficial effect upon the capacity of their markets. Already improvement has been marked, the flow of fresh trade through these new channels following closely upon the advance of the construction parties. The period available for statistics does not represent the effect of the new railway upon local trade. [Pg 24] The work of construction had not begun at the time the returns, which are given below, were drawn up. At that moment the commercial activity of Tashkent was shown by the following table:

| Table of Imports—1901 | ||

| Manufactured goods | 204,530 | poods. |

| Iron and steel | 68,501 | ” |

| Dried fruits | 101,156 | ” |

| Raisins | 49,233 | ” |

| Black tea | 20,718 | ” |

| Green tea | 6,061 | ” |

| Wine grapes | 14,105 | ” |

| Kerosene | 104,317 | ” |

| Naphtha refuse | 23,402 | ” |

| Refined sugar | 85,246 | ” |

| Sanded sugar | 23,905 | ” |

| Salt | 24,442 | ” |

| Military stores | 112,506 | ” |

Table of Exports—1901 | ||

| Wheat | 378,058 | poods. |

| Rice | 194,574 | ” |

| Skins and undressed hides | 44,409 | ” |

| Hemp seed, flax seed, and grasses | 19,784 | ” |

| Spirits | 26,620 | ” |

| Undressed sheep-skins | 57,899 | ” |

| Cotton | 241,484 | ” |

| Military stores | 108,794 | ” |

The passenger traffic into Tashkent over the Central Asian line was:

| 1901 | |

| Arrivals. | Departures. |

| 48,515 | 47,213 |

During the few years which have elapsed since the figures were compiled the Orenburg-Tashkent railway has been opened, this happy accomplishment at once becoming a factor of the greatest economic importance in the commerce of Central Asia.

[1] 1 Verst = ⅔ mile English.

[2] 1 Sagene = 7 feet English.

[3] 1 pood = 36 lbs.

[4] 1 rouble = two shillings.

The Khanate of Bokhara, across which lies the direct line of any advance upon Afghanistan, is the most important of the Russian protected states in Central Asia. It is situated in the basin of the Amu Daria between the provinces of Trans-Caspia on the west, of Samarkand and Ferghana on the north and east; while, in the south, the course of the Oxus separates, along 500 versts of the frontier, the dominions of Bokhara from those of Afghanistan.

The area occupied by Bokhara, including the sub-territories Darwaz, Roshan and Shignan situated upon the western slopes of the Pamirs, amounts to 80,000 square miles, over which in the western part certain salt marshes and desolate stretches of sandy desert extend. The eastern area is confined by the rugged chains of the Alai and Trans-Alai systems, the Hissar mountains, the immediate prolongation of the Alai range and crowned with perpetual snow, attaining considerable altitude. This group divides the basins of the Zerafshan and Kashka Daria from the basin of the Amu Daria. The rivers of Bokhara belong to the Amu Daria system, the Oxus flowing for 490 versts through the Khanate itself. Constant demands for purposes of irrigation are made upon its waters as well as upon the waters of its many tributaries, [Pg 26] a fact which rapidly exhausts the lesser streams. In the western portion of the Khanate the Zerafshan river is the great artery; and although it possesses a direct stream only 214 versts in length it supplies a system of canals, the aggregate length of which amounts to more than 1000 versts. These again are divided to supply a further thousand channels, from which the water actually used for irrigating the various settlements and fields is finally drawn. The second most important river in the western part of the Khanate is the Kashka Daria, which waters the vast oases of Shakhri, Syabz and Karshine. In the eastern areas numerous streams are fed by the snows and glaciers of the Alai mountain system.

The western region of Bokhara possesses an extremely dry climate which, while hot in summer, tends to emphasise the severe cold of the winter months. Occasionally at that time the Amu Daria freezes, when the ice remains about the river for two or three weeks. The break-up of winter is manifested by heavy rains which, falling in February, continue until the middle of March when, after a short month of spring, a hot sun burns up the vegetation. At this period the nomadic tribes abandon the plains for the mountains, large areas of the Khanate now presenting the appearance of a sparsely populated desert in which the sole vegetation is found along the banks of the rivers or in oases watered by the canals. With the advent of autumn, the steppe once more reflects the movements of these people.

In its eastern part the altitude varies between 2500 and 8500 feet above sea-level. The climate, warm and mild in summer, is of undue severity in winter, the period of extreme cold lasting some four months. Snow, commencing to fall in October, remains upon the ground until April, the frosts always being severe. At such a season the winds, blowing from the north-east, possess an unusual keenness in contradistinction to the strong south-south-westerly winds which, prevailing in summer, are the precursor to burning sand-storms.

The total population of the Khanate amounts approximately to 2,500,000; the well-watered, flourishing oases bear in some places as many as 4000 people to the square mile. The steppe and mountainous regions are sparsely populated. The most important inhabited centres of the Khanate are as follows:

[Pg 29]

Distribution of Population.

| Town. | Population. |

| Bokhara | 100,000 |

| Karshi | 60,000 |

| Shaar | 10,000 |

| Guzar | 25,000 |

| Kara Kul | 5,000 |

| Ziadin | 8,000 |

| Hissar | 15,000 |

| Shir Abad | 20,000 |

| Karki | 10,000 |

| Charjui | 15,000 |

| Kermine | 12,000 |

| Kelif | 7,000 |

According to ethnographic distribution the population falls into two divisions. To the first belong those of Turki extraction and to the second the Iranian group. Amongst those of Turki descent the Uzbegs take the most prominent place, constituting not only a racial preponderance but the ruling power in the Khanate. Among the remaining constituents of the Turki division are the Turcomans (chiefly Ersaris) and the Kirghiz. To the Iranian category belong the Tajiks—the original inhabitants of the country, even now constituting the principal section of the population throughout its eastern and southern portions; the Sarts, a conglomeration of Turki and Iranian nationalities, comprise a considerable proportion of the urban and rural population. In smaller numbers are the various colonies of Jews, Afghans, Persians, Arabs, Armenians, Hindus and others. With the exception of the Jews and the Hindus the entire population is Mahommedan.

It will be seen that the population is represented by sedentary, semi-nomadic and nomadic classes. The first, constituting about 65 per cent. of the whole population, is distributed principally in the plains, a considerable proportion comprising Tajiks, Sarts, Jews, Persians, Afghans and Hindus. The semi-nomadic population forms about 15 per cent., consisting partly of Uzbegs, Turcomans and Tajiks dwelling in the hills. The nomads, who make up 20 per cent. of the population, live in the steppes of the western portion of the Khanate, in Darwaz and along the slopes of the Hissar mountains. They comprise Uzbegs, Turcomans and Kirghiz.

The soil, in general adapted to agriculture, yields with irrigation excellent harvests. The amount of cultivated land in the Khanate is little in excess of 8000 square miles; but, in order to make full use of the waters of the Amu Daria, Surkan, Kafirnigan and Waksh rivers, a large expenditure would be required, the present system of irrigation being very inadequate. Apart from cotton which [Pg 30] is exported in the raw state to the value of several million poods annually and the silk industry which, owing to disease among the worms, has deteriorated, the chief agricultural interest lies in the production of fruit, the produce of the orchards forming a staple food during the summer months. As a consequence, many different varieties of grapes, peaches, apricots, melons, water-melons, plums, apples, and pears are cultivated in the several gardens and orchards. Cattle-farming is conducted extensively in the valleys of the Hissar and Alai ranges and in Darwaz; in Kara Kul, situated in the vast Urta Chul steppe between the towns of Bokhara and Karsi, is the home of the famous caracal sheep. Other industries are the manufacture of leathern goods: shoes, saddles, saddle-cloths, metal and pottery ware; while a staple product, employed in the manufacture of felts, carpets and the clothes of the people, is cotton wool.

The yearly budget of the Khanate amounts to 8,000,000 roubles, 1,005,000 roubles of which are spent upon the army. The standing army, comprising Guards, battalions of the line, cavalry regiments, a brigade of mounted rifles and a small corps of artillerists, possesses a strength of 15,000 men with twenty guns. In addition there is a militia liable for duty in case of necessity but, equally with its more imposing sister service, of little practical utility.

The city of Bokhara is surrounded by massive walls which were built in the ninth century, 28 feet in height, 14 feet in thickness at the base, with 131 towers and pierced at irregular intervals by eleven gates. These ramparts contain, within a circuit of 7½ miles, an area of 1760 acres. The population numbers some hundred thousand and the variety of types included in this estimate is immense. The Tajiks, who predominate, are well favoured in their appearance; they have clear, olive complexions with black eyes and hair. Polite, hard-working and intelligent, they possess considerable aptitude for business. Against these excellent traits, however, must be noted the fact that they are inclined to cowardice and dishonesty. On this account they are regarded with contempt by the Uzbegs, a race whose physical characteristics cause them to resemble the rude warriors of the Osmanlis who supplanted the Cross by the Crescent in the fifteenth century. Independent in their bearing, the Uzbegs possess high courage together with something of the inborn dignity [Pg 33] of the Turk; but they are distinguished from that nation by a greater grossness of manner and less individuality. Equally with the Kirghiz and the Turcomans, the Uzbegs are divided in their classes between sedentary people and nomads. Then, also, in this dædalus there is the Jewish community, which is traditionally believed to have migrated hither from Baghdad. The Jews in Bokhara are forbidden to ride in the streets; while they must wear a distinctive costume, the main features of which include a small black cap, a dressing-gown of camel’s hair and a rope girdle. They are relegated to a filthy ghetto; and, although they may not be killed with impunity by a good believer, they are subjected to such grinding persecution that their numbers have been reduced in the course of half a century to something less than 75 per cent. of the 10,000 who originally composed the colony. The Jew in Bokhara shares with the Hindu settler there the profits of money-lending and the two classes are keen hands at a bargain. In addition to the Hindus there are a few Mahommedan merchants from Peshawar who are concerned in the tea trade. Other races among the moving mass comprise Afghans, Persians and Arabs, the variety of features shown by a Bokharan crowd suggesting so many different quarters as their place of origin that one would need to recite the map of High Asia to describe them.

The town of Bokhara is supplied with water from the Shari Rud canal, which, in turn, is fed by the Zerafshan river. A considerable amount is stored locally in special reservoirs, of which there are eighty-five. As their contents are seldom changed the supply soon assumes a thick, greenish consistency, the use of which is extremely detrimental to the health of the inhabitants. The deficiency of fresh water for drinking purposes, the oppressiveness of the summer heat and the propinquity of numerous cemeteries, together with the dust and dirt of the crowded streets, make life in Bokhara almost intolerable. The city, too, is a hot-bed of disease, malaria being specially prominent at certain seasons. The filaria medinesis, a worm of burrowing propensity, is endemic.

In Bokhara, as in most Eastern cities, the feminine element is entirely excluded from the street. The emancipation of women has not begun in the Middle East; should any have to venture forth they are muffled up so carefully that not even a suggestion of their personal [Pg 34] appearance can be gathered. Yet there is a certain charm and mystery in the flitting of the veiled Beauty and one would fain linger to speculate further, if such dallying with fortune were not eminently injudicious. If there is no revelation of the female form divine in the bazaar there is, at least, a wonderful wealth of gorgeous colouring. In time of festival the scene, welling up to break away in endless ripples, suggests the myriad beauties of a rainbow splintered into a million fragments.

There is relief, too, from the burning sunshine in the cool, lofty passages: shady, thronged and tortuous they extend in endless succession for mile after mile. The roof of the bazaar is a rude contrivance of undressed beams upon which there is a covering of beaten clay. Behind each stall is an alcove in the wall serving as home and office to the keen-visaged merchant who presides. In this little recess, piled upon innumerable shelves, rammed into little niches or strewn upon the floor, are the different articles which his trade requires. Carpets and rugs of harmonious hues, a wealth of parti-coloured shawls, innumerable lengths of dress pieces, cutlery, trinkets, snuff-boxes, gorgeous velvets and brilliant silks, the shimmer of satin and the coarse tracing of gold-wire embroidery, are here all displayed in prodigal confusion. As to the sources of supply, a good deal of the merchandise is the produce of Russian markets. For the rest, a certain proportion comes from Germany and a small amount is imported from France. England, it may be noted, is not represented at all.

The money-changers have a quarter to themselves, as have also the metal-workers and the vendors of silks and velvets. At every corner and odd twist of the passages there are the sweet-sellers, the tea merchants and the booths for food. China is the principal source of the tea supply, but of late a certain amount has found its way into Bokhara from the gardens of India and Ceylon. It is before the steaming samovars that the crowd of prospective purchasers is apt to be thickest. Beyond the bazaar boundaries are the wonderful relics of a bygone grandeur—imposing buildings and mosques, touched with the glory of the sunlight and capacious enough to contain within their courtyards 10,000 people at one time.

Although the chief interest of Bokhara centres in the portion just described, its public buildings well repay leisurely examination. The Registan, the market-place of [Pg 35] the north-west quarter, acts as a central zone. On one side standing upon a vast artificial mound is the citadel or Ark, its mighty walls forming a square of 450 yards, its parapet crenellated and its corners set with towers. The building dates from the era of the Samanides. In addition to the Amir’s palace the walls of the Ark enclose the houses of the chief ministers, the treasury, the State prison and various offices. The entrance to the citadel, which is defended by two imposing towers, is closed by massive gates above which there is a clock. None save the highest officials are permitted to enter the Ark; visitors, irrespective of rank, are compelled to dismount at its doors and to proceed on foot to the Amir’s quarters. Opposite the Ark stands the largest mosque in Bokhara, the Medjidi Kalan or Kok Gumbaz—the Mosque of the Green Cupola—which the Amir attends every Friday when he is in residence.

A smaller market-place, where transactions in cotton are carried out, is surrounded by several imposing edifices that rise with infinite grace to the sky, besides countless minarets of prayer acting as landmarks to the faithful. Here is the Great Mosque, the Masjid-i-Jama, while facing it is the Medresse Mir-i-Arab. This latter building ranks first among the many stately colleges of Bokhara. Near at hand is the Minar Kalan, 36 feet at the base and tapering to a height of over 200 feet. From a small platform just below the lofty pinnacle, miscreants were hurled to destruction in bygone days. With the exception of these buildings the city contains little of antiquity.

For its size the native quarter is a centre of the greatest importance; and its streets, although mean and sinuous, are filled by a crowd most typical of Asia. Ten thousand students receive instruction in its schools. It contains:

| Streets | 360 |

| Caravansaries | 50 |

| Covered bazaars | 50 |

| Mosques | 364 |

| Native schools | 138 |

| Russian school | 1 |

| Russian hospital and dispensary | 1 |

The houses, which are set in small compounds approached [Pg 39] by narrow alleys, are composed of clay with low roofs and without windows. A hole in the roof suffices for a chimney, and the open door affords light.

Samarkand, the administrative centre of the province of the same name and founded in 1871, is a close reproduction of a large Indian cantonment. The streets are wide, well paved, fringed with tall poplars and set with shops which are kept by Europeans. For the Russians, as the centre of the province and the location of army headquarters, it has special importance. Although without any architectural pretensions—the buildings are all one-storey structures on account of frequent visitations from earthquakes—its comparatively lofty position makes it an agreeable station and one of the most attractive gathering-places for Europeans in Asiatic Russia. The city is situated upon the south-western slopes of the Chupan Ata range, 7 versts from the Zerafshan river. The close proximity of the hills naturally influences its rainfall, which is greatest in March and April. The period from June to September is dry; and by February or March the trees are in bloom. By a happy choice in construction it has been planned upon exceptionally generous lines which, although imparting to the outskirts a desolate aspect, have been the cause of securing to the community a number of spacious squares, around which are placed the barracks and certain parks. The principal square, named after General Ivanoff, a former Governor of the province, is Ivanovski Square. Another interesting memento of the Russian conquest of Turkestan is situated between the military quarter and the green avenues of the Russian town, in a spot where the heroes who fell in the defence of the citadel in 1868 were buried. At the same place, too, a memorial has been erected to Colonel Sokovnin and Staff-Captain Konevski, who were killed in 1869.

The population of Samarkand at the census of 1897 was 54,900:

| Males. | Females. |

| 31,706 | 23,194 |

According to the statistics of 1901, which are the most recently available, these figures had increased by a few thousands; they were then 58,194:

| Males. | Females. |

| 36,621 | 21,573 |

| Russians | 10,621 |

| Poles | 315 |

| Germans | 378 |

| Armenians | 335 |

| Jews | 4,949 |

| Sarts | 40,184 |

| Kirghiz | 36 |

| Afghans | 186 |

| Persians | 237 |

| Hindus | 10 |

In the town itself there are:

| Orthodox churches | 4 |

| Private houses | 1,100 |

| Clubs | 2 |

| Library | 1 |

| Schools | 9 |

| Hospital | 1 |

| Theatre | 1 |

| Museum | 1 |

and various medical, charitable and other institutions.

The native quarter, which is separated from the Russian town by the Abramovski Boulevard—so named in honour of General Abramoff, another military Governor of the province—covers an area of 4629 dessiatines. It was built by Timur the Lame. The streets with few exceptions are narrow, winding and unpaved; the houses are of baked mud, mean and cramped, with flat earthen roofs and no windows. In this division there are:

| Shops | 1,169 |

| Caravansaries | 28 |

| Market-places | 4 |

| Squares | 2 |

| Medresses | 14 |

| Mosques | 105 |

| Jewish synagogue | 1 |

| Jewish prayer-houses | 6 |

| Mektebs | 91 |

The value of Government property in the Russian and native areas of the city is estimated at 4,077,681 roubles. The city revenue approximates 147,616 roubles. The native quarter is the great commercial centre of the province and the trade returns for the city and its surrounding district amount to 17,858,900 roubles out of 24,951,320 roubles for the entire province. Of the squares the most celebrated is the Registan, with a length of 35 sagenes and width of 30 sagenes. It is bounded by three large mosques: the Tillah Kori—the Gold Covered; Ulug Beg; and Shir Dar—the Lion Bearing.