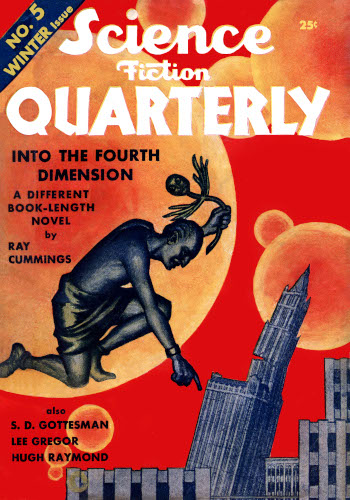

Title: Into the fourth dimension

Author: Ray Cummings

Release date: April 12, 2024 [eBook #73382]

Language: English

Original publication: New York, NY: Columbia Publications, Inc, 1927

Credits: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By RAY CUMMINGS

Are there other worlds existing side by side with ours,

yet unseen and unsuspected? Here is the incredible

tale of three who went through the wall that bars the

way to this shadowy realm and found a strange land,

a stranger people, and a fantastic enemy.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Science Fiction Quarterly Winter 1941-1942.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

IN RESPONSE TO THE MANY REQUESTS WE HAVE RECEIVED, WE ARE

REPRINTING THIS FAMOUS NOVEL—ONE OF THE MOST UNUSUAL EVER

CONCEIVED BY A SCIENCE FICTION AUTHOR.

THE GHOSTS OF '46

The first of the "ghosts" made its appearance in February of 1946. It was seen just after nightfall near the bank of a little stream known as Otter Creek, a few miles from Rutland, Vermont. There are willows along the creek-bank at this point. Heavy snow was on the ground. A farmer's wife saw the ghost standing beside the trunk of a tree. The evening was rather dark. Clouds obscured the stars and the moon. A shaft of yellow light from the farmhouse windows came out over the snow; but the ghost was in a patch of deep shadow. It seemed to be the figure of a man standing with folded arms, a shoulder against the tree-trunk. It was white and shimmering; it glowed; its outlines were wavy and blurred. The farmer's wife screamed and rushed back into the house.

Up to this point the incident was not unusual. It would have merited no more than the briefest and most local newspaper attention; reported perhaps to some organization interested in psychical research to be filed with countless others of its kind. But when the farmer's wife got back to the house and told her husband what she had seen, the farmer went out and saw it also; and with him, his two grown sons and his daughter. There was no doubt about it; they all saw the apparition still standing motionless exactly where the woman had said.

There was a telephone in the farmhouse. They telephoned their nearest neighbors. The telephone girl got the news. Soon it had spread to the village of Procter; and then to Rutland itself. The ghost did not move. By ten o'clock that evening the road before the farmer's house was crowded with cars; a hundred or more people were trampling the snow of his corn-field cautiously, from a safe distance regarding that white motionless figure.

It chanced that I was also an eyewitness to this, the first of the ghosts of '46. My name is Robert Manse. I was twenty-six years old that winter—correspondent in the New York office of a Latin-American export house. With Wilton Grant and his sister Beatrice—whom I counted the closest of my few real friends—I was in Rutland that Saturday evening. Will was a chemist; some business which he had not detailed to me had called him to Vermont from his home near New York. In spite of the snowy roads he had wanted to drive up, and had invited me to go along. We were dining in the Rutland Hotel when people began talking of this ghost out toward Procter.

It was about ten-thirty when we arrived at the farm. Cars were lined along the road in both directions. People trampling the road, the fields, clustering about the farmhouse; talking, shouting to one another.

The field itself was jammed, but down by the willows along the creek there was a segment of snow as yet untrampled, for the crowd had dared approach so far but no farther. Even at this distance we could see the vague white blot of the apparition. Will said, "Come on, let's get down nearer. You want to go, Bee?"

"Yes," she said.

We began elbowing and shoving our way through the crowd. It was snowing again now. Dark; but some of the people had flashlights which darted about; and occasionally a smoker's match would flare. The crowd was good-natured; with courage bolstered by its numbers, the awe of the supernatural was gone. But they all kept at a safe distance.

Somebody said, "Why don't they shoot at it? It won't move—can't they make it move?"

"It does move—I saw it move, it turned its head. They're going up to it pretty soon—see what it is."

I asked a man, "Has it made any sound?"

"No," he said. "They claim it moaned, but it didn't. The police are there now, I think—and they're going to shoot at it. I don't see what they're afraid of. If they wanted me to I'd walk right up to it." He began elbowing his way back toward the road.

We found ourselves presently at the front rank, where the people were struggling to keep themselves from being shoved forward by those behind them. Thirty feet across the empty snow was the ghost. It seemed, as they had said, the figure of a man, blurred and quivering as though moulded of a heavy white mist at every instant about to dissipate. I stared, intent upon remembering what I was seeing. Yet it was difficult. With a quick look the imagination seemed to picture the tall lean figure of a man with folded arms, meditatively leaning against the tree-trunk. But like a faint star which vanishes when one stares at it, I could not see a single detail. The clothes, the face, the very outlines of the body itself seemed to quiver and elude my sight when I concentrated my attention upon them.

Yet the figure, motionless, was there. Half a thousand people were now watching it. Bee said, "See its shoulder, Rob! It isn't touching the tree—it's inside the tree! It's leaning against something else, inside the tree!"

The dark outline of the tree-trunk was steady reality; it did seem as though that shadowy shoulder were within the tree.

A farmer's boy beside us had a handful of horseshoes. He began throwing them. One of them visibly went through the ghost. Then a man with a star on the lapel of his overcoat fired a shot. It spat yellow flame. Where the bullet went no one could have told, save that it hit the water of the creek. The specter was unchanged.

The crowd was murmuring. A man near us said, "I'll walk up to it. Who wants to go along?"

"I'll go," said Will unexpectedly; but Bee held him back.

The volunteer demanded, "Officer, may I go?"

"I ain't stoppin' you," said the man with the star. He retreated a few steps, waving his weapon.

"Well then put that gun away. It might go off while I'm down there."

Somebody handed the man a broken chunk of plank. He started slowly off. Others cautiously followed behind him. One was waving a broom. A woman shouted shrilly, "That's right—sweep it away—we don't want it here." A laugh went up, but it was a high-pitched, nervous laugh.

The man with the plank continued to advance. He called belligerently, "Get out of there, you! We see you—get away from there!" Then abruptly he leaped forward. His waving plank swept through the ghost; as he lunged, his own body went within its glow. A panic seemed to descend upon him. He whirled, flailing his arms, kicking, striking at the empty air as one tries to fight off the attack of a vicious wasp. Panting, he stumbled backward over his plank, gathered himself and retreated.

The white apparition was unchanged. "It was just like a glow of white light," the attacker told us later. "I could see it—but couldn't feel it. Not a thing—there wasn't anything there!"

The ghost had not moved, though some said that it turned its head a trifle. Then from the crowd came a man with a powerful light. He flooded it on the specter. Its outlines dimmed, but we could still see it. A shout went up. "Turn that light off! It's moving! It's moving away!"

It was moving. Floating or walking? I could not have told. Bee said that distinctly she saw its legs moving as it walked. It seemed to turn; and slowly, hastelessly it retreated. Moving back from us. As though the willows, the creek-bank, the creek itself were not there, it moved backward. The crowd, emboldened, closed in. At the water's edge we stood. The figure apparently was now within or behind the water. It seemed to stalk down some invisible slope. Occasionally it turned aside as though to avoid some obstruction. It grew smaller, dimmer by its greater distance from us until it might have been the mere reflection of a star down there in the water of the creek; then it blinked, and vanished.

There were thousands who watched for that ghost the following night, but it did not appear. The affair naturally was the subject of widespread newspaper comment; but when after a few days no one else had seen the ghost, the newspapers began turning from the serious to the jocular angle.

Then, early in March, the second ghost was reported. In the Eastern Hemisphere this time. It was discovered in midair, near the Boro Badur, in Java. Thousands of people watched it for over an hour that evening. It was the figure of a man, seated on something invisible in the air nearly a hundred feet above the ground. It sat motionless as though contemplating the crowd of watchers beneath it. And then it was joined by other figures! Another man, and a woman. The reports naturally were confused, contradictory. But they agreed in general that the other figures came from the dimness of distance; came walking up some invisible slope until they met the seated figure. Like a soundless motion picture projected into the air, the crowd on the ground saw the three figures in movement; saw them—the reports said—conversing; saw them at last move slowly backward and downward within the solid outlines of the great temple, until finally in the distance they disappeared.

Another apparition was seen in Nome; another in Cape Town. From everywhere they were now reported. Some by daylight, but most at night. By May the newspapers featured nothing else. Psychical research societies sprang into unprecedented prominence and volubility. Learned men of spiritualistic tendencies wrote reams of ponderous essays which the newspapers eagerly printed.

Amid the reports now, the true from the false became increasingly difficult to distinguish. Notoriety seekers, cranks, and quacks of every sort burst into print with weird tales of ghostly manifestations. Hysterical young girls, morbidly seeking publicity, told strange tales which in more sober days no newspaper would have dared to print. And in every country charlatans were doing a thriving business with the trappings of spiritualism.

In late July the thing took another turn. A new era began—a sinister era which showed the necessity for something more than all this aimless talk. Four men were walking one night along a quiet country road near a small English village. They were men of maturity, reputable, sober, middle-aged citizens. Upon the road level they observed the specters of four or five male figures, which instead of remaining motionless rushed forward to the attack. These ghosts were ponderable! The men distinctly felt them; a vague feeling, indescribable, perhaps as though something soft had brushed them. The fight, if such it could be called, amounted to nothing. The men flailed their arms in sudden fear; and the apparitions sped away. Greenish, more solid-looking than those heretofore seen.

This was more than mere visibility—an actual encounter. These four men were of the type who could be believed. The report was reliable. And the next night, in a Kansas farmhouse, the farmer and his wife were awakened by the scream of their adolescent daughter. They rushed into her bedroom. She was in bed, and bending over her was the apparition of a man. Its fingers were holding a lock of the girl's long black hair. At the farmer's shout, the ghost turned; its hand was raised—and the farmer and his wife both saw that the shadowy fingers had lifted the girl's tresses which they were clutching. Then it dropped them and moved away, not through the walls of the room, but out through the open window.

The girl was dead. She had suffered from heart trouble; was dead of fright, undoubtedly. It was the beginning of the era of menace. And that next afternoon Wilton Grant telephoned me. His voice had a strange tenseness to it, though it was grave and melodious as always.

"Come out and see us this evening, will you, Rob?"

"Why, yes," I said. I had not seen them for over a month—an estrangement which I had not understood and which hurt me had fallen between us. "Of course I will," I added. "How's Bee?"

"She's been quite ill.... No, not dangerous, she's better now. Don't fail us, Rob. About eight o'clock.... That's fine. We—I need you. You've been a mighty good friend, letting us treat you the way we have—"

He hung up. With an ominous sense of danger hanging over me, I went out to see them at the hour he had named.

GROPING AT THE UNKNOWN

Wilton Grant was at that time just under forty. He was a tall, spare man of muscular build, lean but not powerful. His smooth-shaven face was large-featured, rough-hewn, with a shock of brown hair above it—hair turning grey at the temples. Beneath heavy brows his grey eyes were deep-set, somber. His ruddy-brown complexion, the obvious strength of his frame at a quick glance gave him an out-of-doors look; a woodsman cast in the mould of a gentleman. Yet there was something poetic about him as well; that wavy, unruly hair, the brooding quality of his eyes. When he spoke, those eyes frequently twinkled with the good nature characteristic of him. But in repose, the somberness was there, unmistakable; an unvoiced, brooding melancholy.

Yet there was nothing morbid about Wilton Grant. A wholesomeness, mental and physical, radiated from him. He was a jolly companion, a man of intellectuality and culture. His deep voice had a pleasing resonance suggestive of the public speaker. Normally rather silent, chary of speech, he could upon occasion draw fluently from a vocabulary of which many an orator would be proud.

He was a bachelor. I often wondered why, for he seemed of a type that would be immensely attractive to women. He did not avoid them; the pose of a woman-hater would have been abhorrent to him. Yet no woman to my knowledge had ever interested him, even mildly. Except his sister. They were orphans and she was his constant companion. They were both in fact, rather chary of friends; absorbed in their work, in which she took an active part. Their home and laboratory was an unpretentious frame cottage in a Westchester village of suburban New York. They lived quietly, modestly, with only one automobile, and no 'plane.

Will opened the door for me himself, smiling as he extended his big, hearty hand. "Well! You came, Rob? You're very forgiving—that's the mark of a true friend." He led me into the old-fashioned sitting room. "I'm not going to apologize—"

"Don't," I said. "I knew of course you had some reason—"

We were seated. He said with a nod, "Yes. A reason—you'll hear it now—tonight—"

His voice trailed away. It made my heart beat faster. He had changed. I saw him suddenly older.

"Where's Bee?" I asked out of the silence.

He jerked himself back from his reverie. "Upstairs. She'll be down in a moment. She's been ill, Rob."

"But you said not seriously."

"No. She's better now. It's been largely mental—she's been frightened, Rob. A terrible strain—that's why I thought it better for us to isolate ourselves for a while—"

"Oh, then that's why—"

"That's why I wrote you so peremptorily not to come to see us any more. I was upset myself, I needn't have been so crude—"

"Please don't apologize, Will. I—I didn't understand, but—"

"I'm not. I'm just telling you. But now Bee thought we should have you with us. Our best friend, you understand? And it will make things easier for her—naturally she's frightened—"

My hand went to his arm. What I had meant to say I do not know, for Bee at that moment entered the room. A girl of twenty-four. Tall, slim and graceful.

She was dressed now in a clinging negligee which seemed to accentuate the slim grace of her. But the marks of illness were plain upon her face; a pallor; her eyes, though they smiled at me with the smile of greeting upon her lips, had the light of fear in them; her hand as I took it was chill, and its fingers felt thin and wan.

"Bee!"

"It's good to see you, Rob. Will has been apologizing for us, I suppose—"

These friends of mine calling me to them in their hour of need. I had been annoyed, hurt; I had not realized how deep was my affection for them ... for Bee.... Vaguely I wondered now if their trouble—this fear that lay so obviously upon them both—concerned the coming of the ghosts....

Bee sat close beside me, as though by my nearness she felt a measure of protection.

Will faced us. For a moment he was silent. Then he began, "I have a good deal to say, Rob—I want to be brief—"

I interrupted impulsively, "Just tell me this. Does it, this thing, whatever it is—does it concern the ghosts?"

I was aware of a shudder that ran over Bee. Will did not move. "Yes," he said. "It does. And these ghosts have changed. We knew they would—we've been expecting it."

"That poor girl," Bee said softly. "Dead—dead in her bed of fright. You read about it, Rob?"

"A menace," Will went on. "The world is just realizing it now. Ghosts, changing from shadow to substance—" He stopped, then added abruptly, "We've never told you much about our work—our business—have we?"

They had in truth always been reticent. I had never been in their laboratory. They were engaged, I understood, chiefly with soil analysis; sometimes people would come out to consult them. Beyond such a meager idea I knew nothing about it.

Will said abruptly, "Our real work we have never told anyone. It concerns—well, a research into realms of chemistry and physics unknown. I have been delving into it for nearly ten years, and then Bee grew old enough to help me. We've made progress—" His smile was very queer. "Tonight—I'm ready to show you something that I can do."

They seemed to torture Bee, these words of her brother's. I heard the sharp intake of her breath, saw her white fingers locked tensely in her lap.

"Not—not tonight, Will."

"Tonight—as good a night as any other.... Rob, would it surprise you to know we anticipated the coming of the ghosts years ago? Not that they would come, but the possibility of it. Ghosts! What do you think they are, Rob?"

"Why ghosts—ghosts are—"

"Spirits of the dead made visible?" His manner was suddenly vehement; his tone contemptuous. "Earth-bound spirits! Astral bodies housing souls whose human bodies are in their graves! Rubbish! These are not that sort of ghosts."

I stammered, "But then—what are they?"

"Call them ghosts, the word is as good as any other." His voice grew calmer; he went on earnestly, "I want you to understand me—it's necessary—and yet I must not be too technical with you. Let me ask you this—you'll see in a moment that none of this is irrelevant. How many dimensions has a point?"

At my puzzled look he smiled. "I'd better not question you, Rob, but you won't find me hard to understand. A point—an infinitesimal point in space—has no dimension. It has only location. That's clear, isn't it? A line has one dimension—length. A plane surface has length and breadth; a cube, length, breadth and thickness. The world of the cube, Rob, is the world we think we live in—the world of three dimensions. You've heard of that intangible something they call the fourth dimension? We think it does not concern us—but it does. We ourselves have four dimensions. We are the world of the fourth dimension. But the fourth is not so readily understood as the other three."

He paused for an instant, then added, "The fourth dimension is time, Rob. Not a new conception to scientists—think a moment—how would you define time?"

"Time," I said, "Well, I read somewhere that time is what keeps everything from happening at once."

He did not smile. "Quite so. It is something in the universe of our consciousness along which we progress in measured rate from birth to death—from the beginning to the end.

"We are living in a four-dimensional world—a world of length, breadth, thickness and time. The first three, to our human perception, have always been linked together. Time—I do not know why—seems to our minds something essentially different. Yet it is not. Our universe is a blending of all four.

"Let me give you an example. That book there on the table—it exists because it has length, breadth and thickness. But Rob, it also has duration. It is matter, persisting both in space and in time. You see how the element time is involved? I'll go further. We know that two material bodies cannot occupy the same space at the same time. With three of the dimensions only—that is, if theoretically we remove the identical time-factor—they do not conflict. You're confused, Rob?"

"I'm not quite sure what you're aiming at," I said.

"You'll understand in a moment. Matter, as we know it, is merely a question of vibration. It is, isn't it?"

"I know light is vibration," I responded. "And sound. And heat, and—"

He interrupted me. "The very essence of matter is vibration. Do you know of what matter is composed? What is the fundamental substance? Let us see. First, we find matter is composed only of molecules. They are substances, vibrating in space. But of what are molecules composed? Atoms, vibrating in space. Atoms are substance. Of what are they composed?"

"Electrons?" I said dubiously.

"Protons and rings of electrons. Let us cling to substance, Rob. These electrons are merely negative, disembodied electricity—not matter, but mere vibration. They—these electrons—revolve around a central, positive nucleus. This then, is all the substance that matter has. But when you penetrate this inner nucleus, what do you find? Substance? Not at all. This proton, as they sometimes term it, this last inner strong-hold of substance, is itself a mere vortex—a whirlpool in space!"

I groped at the thought. Matter, substance, everything tangible in my whole conscious universe, robbed of its entity, reduced to mere vibration in empty space. Vibration of what?

"It's appalling, Rob, the unreality of everything. Metaphysicians say that nothing exists save in the perception of it by our human senses.... I was talking of the dimension, time. It is the indispensable factor of vibration. That's obvious. Motion is nothing but the simultaneous change of matter in space and time. You see how blended all the factors are? You cannot deal with one without the others. And mark you this, Rob—you can subdivide matter until it becomes a mere vortex in empty space. Can you wonder then—"

I had noticed Bee gazing intently across the room. "Will!" she said suddenly; her voice was hardly more than a whisper. "It's there now, Will!"

The room was brightly illuminated by a cluster of globes near the ceiling. Will left his seat, calmly, unhurried, and switched them off. There was only the small table light left. It cast a yellow circle of light downward; most of the room was in shadow. And over in a corner I saw the glowing apparition of a recumbent man no more than ten feet from us.

Will said, "Come here, Rob—let me show you this." His voice was grave and unflurried. As I crossed the room hesitatingly, Bee was with me, forcing herself to calmness. She said, "It's here most of the time. Watching us! It seems to be on guard—always watching—"

Will drew me beside him. Together we stood within a foot of the spectre. It took my courage, but after a moment the grewsome element seemed to leave me for Will stood as though the thing were a museum specimen, explaining it.

I saw, so far as I can put the sight into words, the vibrating white shape of a man reclining on one elbow. It was slightly below the level of the floor, most of it within or behind the floor, the outlines of which were plainer than the apparition mingled with them. The head and shoulders were raised about to the level of our ankles.

A man? I could not call it that. Yet there was a face which after a moment I could have sworn was human-featured; I could almost think I saw its eyes, staring at me intently.

Will stooped down and passed his hand slowly through the face. "You can feel nothing. It has visibility—that property only in common with us. Try it."

I forced my hand down to the thing, held it there. It was like putting one's fingers into a dim area of light.

"Is it—it is alive?" I asked.

"Alive?" Will's tone was grim. "That depends on what you mean by alive. It can reason, if that answers you."

"I mean—can it move?"

"It moves," said Bee. "It watches us—follows us—" She shuddered.

The details of the figure? I stepped back to see it better. It seemed now a man clothed in normal garments ... a malevolent face, with eyes watching me.... Was that face my imagination, or did I really see it?

I must have stammered my thoughts aloud, for Will said, "What we see, and what really exists, has puzzled metaphysicians for centuries. Who knows what this thing really looks like? You do not, nor do I. Our minds are capable of visualizing things only within the limits of an accustomed mould. You see that thing as a man of fairly human aspect, and so do I. The details are elusive; but stare at them for a day and your imagination will supply them all. That's what you do in infancy with the whole material world about you—mould it to fit our human perceptions. But what everything really looks like—who can tell?"

"Can it—can it hear us?" I demanded.

"No—I do not think so. It can see us, no more. And it has no fear." With a belligerent gesture he added humorously, "Get up, you, or I'll wring your neck!"

"Will, don't joke like that!" Bee protested.

He turned away and switched on the main lights. I could still see the thing there, but now it was paler—wan like starlight before the coming dawn. Will turned his back on it and sat down. His face had gone solemn again.

"These things are materializing, Rob. They have become a menace. That's why what I'm planning to do should be done at once.... Bee! Will you please not interrupt me!" It was the first time I had ever heard his tone turn sharp with her, and I realized then the strain he was under. "Rob, listen to me. Science has given me the power to do what I'm planning, but we won't discuss that now. Call this anything you like. What I want you to know is—there is another realm about us into which—under given conditions—our consciousness can penetrate. Call it the Unknown. The realm of Unthought Things. A material world? I've shown you, Rob, that nothing is substance if you go to the inside of it."

Dimly I was groping at a hundred will-o'-the-wisps, my mind trembling upon the verge of his meaning, my imagination winging into distant caverns of unthought things that hid in the elusive dark. Could this be science?

He was saying, "My mind cannot fathom such another realm, nor can yours. You think of land, water, trees, houses, people. Those are only words for what we think we see and feel. But there are beings—sentient beings—in this other state of consciousness, we can now be sure. For Rob, they are coming out! Don't you understand? They have already come into the borderland between the consciousness of their realm and ours."

He would not let me interrupt him. "Wait, Rob! Let us say they have a lust for adventure—or a lust for something else—they are coming out nevertheless. A menace to us—that girl in Kansas is dead." He swept his hand in gesture at the apparition behind him. "That thing is watching me. As Bee says, it is on guard here. Because, Rob, I found a way of transmuting my identity out of this conscious realm of ours into that same borderland where these things we call ghosts are roaming. And they know it—and so they're on guard—watching me."

He paused for the space of a breath. Bee, white-faced, tremulous, turned to me. "Don't let him do it, Rob!"

"I must," he declared vehemently. "Rob, that's why we needed you here—to wait here with Bee. I'm going in there tonight—into the shadows, the borderland, whatever it is. These—nameless things are striving to come out—but I'm going to turn them back if I can!"

INTO THE SHADOWS

There were few preparations to make, for Wilton Grant had planned this thing very carefully. Our chief difficulty was with Bee. The girl was quite distraught; illness, the fear which for weeks had been dragging her down, completely submerged the scientist in her. And then abruptly she mastered herself, smiled through her tears.

"That's more like it, Bee." Will glanced aside at me with relief. "I couldn't understand you. Why Bee, we've been working at this thing for years."

"I'm all right now." She smiled at us—a brave smile though her lips were still trembling. "You're—about ready, aren't you?"

They had set aside a small room on the lower floor of the house—a sort of den which now was stripped of its accustomed hangings and furniture. It had two windows, looking out to the garden and lawn about the house. They were some six feet above the ground. It was a warm mid-summer evening; we had the lower sashes opened, but the shades fully drawn lest some neighbor or passerby observe us from without. On the floor of this room lay a mattress. There was a small table, a clock, two easy chairs. For the rest it was bare. Its white plaster walls, devoid of hangings, gave it somewhat the sanitary look of a room in a hospital.

We had been so occupied with Bee that Will had as yet given me no word of explanation. He left the little room now, returning in a moment with some articles which he deposited on the table. I eyed them silently; a shiver of fear, apprehension, awe—I could not define it—passed over me. Will had placed on the table a carafe of water; a glass; a small vial containing a number of tiny pellets; a cylindrical object with wires and terminal posts which had the appearance of a crude home-made battery—four wires each some ten feet in length, terminating each in a circular metallic band.

I glanced at Bee. Outwardly now she was quite composed. She smiled at me. "He'll explain in a moment, Rob. It's quite simple."

We were ready. By the clock on the table it was twenty minutes of ten. Will faced us.

"I'd like to start by ten o'clock," he began quietly. "The time-factor will be altered—I want to compute the difference—when I return—as closely as I can."

I had the ill grace to attempt an interruption, but he silenced me.

"Wait, Rob—twenty minutes is not a long time for what I have to say and do." He had motioned us to the easy chairs, and seated himself cross-legged on the mattress before us. His gaze was intent upon my face.

"This is not the moment for any detailed explanation, Rob. I need only say this: As I told you a while ago, the fundamental substance of which our bodies are composed is—not substance, but a mere vortex. A whirlpool, a vibration let me term it. And the quality of this vibration—this vortex—the time-factor controlling it, governs the material character of our conscious universe. From birth to death—from the beginning to the end—we and all the substance of our universe move along this unalterable, measured flow of time.

"Do I make my meaning clear? From—nothing but a vibrating whirlpool the magic of chemistry has built with this unalterable time-factor what we are pleased to call substance—material bodies. These material bodies have three varying dimensions—length, breadth and thickness. But each of them inherently is endowed also with the same basic time-factor. The rate of time-flow governing them, let me say, is identical."

He spoke now more slowly, with measured words as though very carefully to reach my understanding.

"You must conceive clearly, Rob, that every material body in our universe is passing through its existence at the same rate. Now if we take any specific point in time—which is to say any particular instant of time—and place in it two material bodies, those two material bodies must of necessity occupy two separate portions of space. That's obvious, isn't it? Two bodies cannot occupy the same space at the same time.

"Now Rob, I have spoken of this unalterable measured flow of time along which all our substance is passing. But it is not unalterable. I have found a way of altering it."

He raised his hand against my murmur, and went on, carefully as before. "What does this do? It gives a different basic vibration to matter. It gives a different rate of time-flow, upon which, building up from a fundamental vortex of changed character, we reach substance—a state of matter—quite different from that upon which our present universe reposes. A different state of matter, Rob—it still has length, breadth and thickness—but a different flow of time.

"You follow me? Now, if we take a material body of this—call it secondary state—and place it in the same space with a body of our primary state, they can and do occupy that space without conflict at the same instant of time.

"Why? Ah Rob, it would take a keener mind than mine or yours to answer that, or to answer the why of almost anything. The knowledge we poor mortals have is infinitesimal compared to the knowledge we have not. I can conceive vaguely, however, that two primary bodies, placed in identical points of space and time would be moving through time at identical rates and thus stay together and conflict. Whereas, with a primary and secondary body, their differing time-flows would separate them after what we might call a mere infinitesimal instant of coincidence."

His gesture waved away that part of the subject. He rose to his feet. "I have particularized even more than I intended, Rob. Let me say now, only that the pellets in this little vial contain a chemical which acts upon the human organism in the way I have pictured. It alters the fundamental vibration upon which this substance—these bones, this flesh we call a body—this substance of my being, is built.

"Just a moment more, Rob, then you shall question me all you like. So much for the transmutation of organic substance. Inorganic substance—that table, my shirt, that glass of water—theoretically all of them could be transmuted as well. I have not, however, practically been able to accomplish that. But I have—invented, if you like, an inorganic substance which I can transmute. It is nameless; it is this."

He was coatless, and now he stripped off his white linen shirt. Like a bathing suit, he had on a low-cut, tight-fitting garment. It seemed a fabric thin as silk, yet I guessed that it was metallic, or akin to metal. A dull putty-color, but where the light struck it there was a gleam, a glow as of iridescence.

"This substance," he added, "I can—take with me." He indicated the wires, the battery if such it were. "By momentarily charging it, Rob, with the current I have stored here. It is not electrical—though related to it of course—everything is—our very bodies themselves—a mere form of what we call electricity."

He was disrobing; the gleaming garment fitted him from shoulder to thigh. About his waist was a belt with pouches; in the pouches small objects all of this same putty-colored substance.

I burst out, "This is all very well. But how—how will you get back?"

"The effect will wear off," he answered. "The tendency of all matter, Rob, is to return to its original state. I conceive also that in the case of the human organism, the mind—the will—to some extent may control it. Indeed I am not altogether sure but that the mind, properly developed, might control the entire transmutation. Perhaps in this secondary state, it can. I am leaving that to chance, to experimentation."

I said, "How long will you be gone?"

He considered that gravely. "Literally, Rob, there is no answer to that—but I know what you mean, of course. I may undergo a mental experience that will seem a day, a week, a month—measured by our present standards. But to you, sitting here waiting for me—" He shrugged. "By that clock there, an hour perhaps. Or five hours—I hope no more."

My mind was groping with all that he had said. I was confused. There was so much that I no more than vaguely half understood; so much that seemed just beyond the grasp of my comprehension. I seemed to have a thousand questions I would ask, yet scarce could I frame one of them intelligently. I said finally:

"You say you may be gone what will seem a day, yet by our clock here it will be only a few hours. This—This other state of existence then moves through time faster?"

"I conceive it so, yes."

"But then—are you going into the future, Will? Is that what it will be?"

He smiled, but at once was as grave as before. "Your mind is trying to reconcile two conditions irreconcilable. You may take an apple and try to add it to an orange and think you get two apple-oranges. But there is no such thing. Our future—let us call it that which has not yet happened to us but is going to happen. I cannot project myself into that. If I could—if I did—at once would the future be for me no longer the future, but the present.

"The conception is impossible. Or again—in this other state—I must of necessity exist always in the present. Nor can you compare them—reconcile one state of existence with the other." He stopped abruptly, then went on with his slow smile. "Don't you see, Rob, there are no words even, with which I can express what I am trying to make you realize. That being reclined there in the other room a while ago and watched us. Perhaps for what it conceived to be what we would conceive a day were we to experience it."

His smile turned whimsical. "The words become futile. Don't you see that? The future of that being is merely what has not yet happened to it. To compare that with our own consciousness is like trying to add an apple to an orange."

During all this Bee had sat watching us, listening to our talk, but had not spoken. And as, an hour before in the other room I had noticed her glancing fearsomely around, again now her gaze drifted away; and I heard her murmur.

"Oh, I hoped it would be gone—not come to us in here!"

We followed her gaze. Standing perhaps a foot lower than the floor of our room and slightly behind the side wall was that self-same spectral figure. The intent to watch us, to enter perhaps into a frustration of our plans, with which my imagination now endowed its purpose, made me read into its attitude a tenseness of line; an alertness, even a guarded wariness which had not seemed inherent to it before. Was this thing indeed aware of our purpose? Was it waiting for Wilton Grant to come into the shadows to meet it upon its own ground? With an equality of contact, was it then planning to set upon him?

Bee was murmuring, "It's waiting for you. Will, it's waiting for you to come—" Shuddering words of apprehension, of which abruptly she seemed ashamed for she checked them, going to the table where she began adjusting the apparatus.

"I'm coming," said Will grimly. "It will do well to wait, for I shall be with it presently." He stood for a moment before the thing, contemplating it silently. Then he turned away, turned his back to it; and a new briskness came to his manner.

"Rob, I'm ready. Bee knows exactly what we are to do. I want you to know also, for upon the actions of you two, in a measure depends my life. I shall sit here on the mattress. Perhaps, if I am more distressed than I anticipate, I shall lie down. Bee will have charge of the current. There will come a point in my departure when you must turn off the current, disconnect the wires from me. If I am able, I will tell you, or sign to you when that point is reached. If not—well then, you must use your own judgment."

"But I—I have no idea—" I stammered. Suddenly I was trembling. The responsibility thrust thus upon me seemed at that moment unbearable.

"Bee has," he interrupted quietly. "In general I should say you must disconnect when I have reached the point where I am—" He halted as though in doubt how to phrase it—"the point where I am half substance, half shadow."

To my mind came a mental picture which then seemed very horrible; but resolutely I put it from me.

"You're ready, Bee?" he asked.

"Quite ready, Will." She was counting out a number of the tiny pellets with hands untrembling. The woman in Bee was put aside; she stood there a scientist's assistant, cool, precise, efficient.

"I think I should like less light," he said; and he turned off all the globes but one. It left the room in a flat, dull illumination. He took a last glance around. The window sashes were up, but the shades were lowered. A gentle breeze from outside fluttered one of them a trifle. Across the room the spectre, brighter now, stood immobile. The clock marked one minute of ten.

"Good," said Will. He seated himself cross-legged in the center of the mattress. In an agony of confusion and helplessness I stood watching while Bee attached the four wires to the garment he wore. One on each of his upper arms, and about his thighs where the short trunks ended.

Again I stammered, "Will, is this—is this all you're going to tell us?"

He nodded. "All there is of importance.... A little tighter, Bee. That's it—we must have a good contact."

"I mean," I persisted, "when you are—are shadow, will we be able to see you?"

He gestured. "As you can see that thing over there, yes."

His very words seemed unavoidably horrid. Soon he would be—a thing, no more.

"Shall you stay here, Will, where we can see you?"

He answered very soberly, "I do not know. That, and many other things, I do not know. I will do my best to meet what comes."

"But you'll come back here—here to this room, I mean?"

"Yes—that is my intention. You are to wait here, in those chairs. One of you always awake, you understand—for I will need you, in the coming back."

There seemed nothing else I could ask, and at last the moment had come. Bee handed him the pellets, and held the glass of water. For one brief instant I had the sense that he hesitated, as though here upon the brink the human fear that lies inherent to every mortal must have rushed forth to stay his hand. But an instant only, for calmly he placed the pellets in his mouth and washed them down with the water.

"Now—the current, Bee."

His voice had not changed; but a moment after I saw him steady himself against the mattress with his hands; momentarily his eyes closed as though with a rush of giddiness, but then they opened and he smiled at me while anxiously I bent over him.

"All right—Rob." He seemed breathless. "I think—I shall lie down." He stretched himself at full length on his back; and with a surge of apprehension I knelt beside him. I saw Bee throw on the little switch. She stood beside the table, and her hand remained upon the switch. Her face was pale, but impassive of expression. Her gaze was on her brother and I think I have never seen such an alert steadiness as marked it.

A moment passed. The current was on, but I remarked unmistakably that no sound came from it. The room indeed had fallen into an oppressive hush. The flapping shades momentarily had stilled. Only the clock gave sound, like the hurried thumping of some giant heart, itself of all in the room most alive.

Wilton Grant lay quiet. His eyes were fixed on the ceiling; he had gone a trifle pale and moisture was on his forehead, but his breathing, though faster, was unlabored.

I could not keep silent. "You—all right, Will?"

At once his gaze swung to me. A smile to reassure me plucked at his parted lips. "All—right, yes." His voice a half-whisper, not stressed, almost normal; and yet it seemed to me then that a thinness had come to it.

Another moment. The putty-colored garment he wore had lost the vague sheen of its reflected light and was glowing with an illumination now inherent to it. A silver glow, bright like polished metal; then with a greenish cast as though phosphorescent. And then, did I fancy that its light, not upon it or within it, but behind it, showed the garment turning translucent?

I became aware now of a vague humming. An infinitely tiny sound—a throbbing hum fast as the wings of a hummingbird, near at hand, very clear, yet infinitely tiny. The battery—the current; and yet in a moment with a leaping of my heart, I knew it was not the current but a humming vibration from the body of Wilton Grant. A sense of fear—I have no memory adequately to name it—swept me. I rose hastily to my feet; as though to put a greater distance between us I moved backward, came upon a leather easy chair, sank into it, staring affrighted, fascinated at the body recumbent before me.

The change was upon it. A glow had come to the ruddy pink flesh of the arms and legs, bared chest, throat and face. The pink was fading, replaced, not by the white pallor of bloodlessness but by a glow of silver. A mere sheen at first; but it grew into a dissolving glow seeming progressively to substitute light for the solidity of human flesh.

And then I gasped. My breath stopped. For behind that glowing, impassive face I saw the solid outlines of the mattress taking form, saw the mattress through the face, the chest, the body lying upon it.

Wilton's eyes were closed. They opened now, and his arm and hand with a wraith-like quality come upon them, were raised to a gesture. The signal. I would have stammered so to Bee, but already she had marked it and shut the current off. And very quietly, unhurried, she bent over and disconnected the wires, casting them aside.

The humming continued; so faint, so rapid I might have fancied it was a weakness within my own ears. And presently it ceased.

Bee sat in the chair beside me. The body on the mattress was more than translucent now; transparent so that all the little tufts of the mattress-covering upon which it lay were more solidly visible than anything of the shadowy figure lying there. A shadow now; abruptly to my thought it was Wilton Grant no longer.

And then it moved. No single part of it; as a whole it sank gently downward, through the mattress, the floor, until a foot or so beneath, it came to rest. With realization my gaze turned across the room. The silent spectre was still there, standing beneath the floor, standing I realized, upon the same lower level where the shadow of Wilton Grant now was resting.

I turned back, saw Bee sitting beside me with white face staring at the mattress; and I heard myself murmur. "Is he all right do you think? He hasn't moved. Shouldn't he move? It's over now, isn't it?"

She did not answer. And then this wraith of Will did move. It seemed slowly to sit up; and then it was upright, wavering. I stared. Could I see the face of my friend? Could I mark this for the shadow of his familiar figure, garbed in that woven suit? It seemed so. And yet I think now that I was merely picturing my memory of him; for surely this thing wavering then before me was as formless, as indefinable, as elusive of detail as that other, hostile spectre across the room.

Hostile! It stood there, and then it too was moving. It seemed to sweep sidewise, then backward. Ah, backward! A thought came to me that perhaps now fear lay upon it. Backward, floating, walking or running I could not have told. But backward, beyond the walls, the house, smaller into the dimness of distance.

Was the shadow of Wilton Grant following it? I could not have said so. But it too was now beyond the room. Moving away, growing smaller, dimmer until at last I realized that I no longer saw it.

We were alone, Bee and I; alone to wait. The mattress at my feet was empty. I heard a sound. I turned. In the leather chair beside me Bee was sobbing softly to herself.

THE RETURN

The hours seemed very long. A singular desire for silence had fallen upon us. For myself, and it is my thought that the same emotion lay upon Bee, there were a myriad questions upon which idly I would have spoken. Yet of themselves so horrible, so fearsome seemed their import that to voice them would have been frightening beyond endurance.

Thus, we did not speak; save that at first I comforted Bee, clumsily as best I could, until at last she was calmer, smiling at me bravely, suggesting perhaps that I would sleep while she remained on watch.

The clock ticked off its measured passing of the minutes. An hour. Then midnight. The window shade was flapping again with the night wind outside. I rose to close the sash, but Bee checked me.

"He might want to come in that way. You understand, Rob—"

Memory came to me of the half-materialized spectre of that Kansas farmhouse, that apparition so ponderable of substance that it must perforce escape by the opened window. I turned back to my chair.

"Of course, Bee. I had forgotten."

We spoke in hushed tones, as though unseen presences not to be disturbed were around us. Another hour. Throughout it all with half-closed eyes I lay back at physical ease in my chair, regarding the white walls of our little room so empty. We still kept the single dull light; dull, but it was enough to illuminate the solid floor, that starkly empty mattress, the white ceiling, the four walls, closed door at my side, the two windows, one of gently flapping shade. And as musingly I stared the sense of how constricted was my vision grew upon me. I could see a few feet to one blank wall or another, or to the ceiling above, the floor below, but no farther. Yet a while ago, following the retreat of those white apparitions, my sight had penetrated beyond the narrow confines of this room into distances illimitable. And to me then came a vague conception of the vast mystery that lay unseen about us, unseen until peopled by things visible to which our sight might cling.

The realm of unthought things! Yet now I was struggling to think them. The realm of things unseen. Yet I had seen of them some little part. The wonder came to me then, were not perchance, unthought things non-existent until some mind had thought them, thus to bring them into being?

Two o'clock. Then three. Five hours. He had said he might return in five hours. I stirred in my chair, and at once Bee moved to regard me.

"He will be coming, soon," I said softly. "It is five hours, Bee."

"Yes, he will be coming soon," she answered.

Coming soon! Again I strove with tired eyes to strain my vision through those solid walls. He would be coming soon; I would see him, far in the distance which his very presence would open up to me.

And then I saw him! Straight before us. Beyond the wall, with unfathomable distances of emptiness around him. It might have been our light gleaming upon an unnoticed protuberance of the rough plaster of the wall, so small was it; but it was not, for it moved, grew larger, probably coming toward us.

Bee saw it. "He's there! See him, Rob!" Relief in her tone, so full to make it almost tearful; but apprehension as well, for to her as to me came the knowledge that it might not be he.

Breathless we watched; waited; and the white luminosity came forward. Larger, taking form until we both could swear it was the figure of a man. Lower now, beneath the level of our floor. It came, stopped before us almost within the confines of the room.

We were on our feet. Was it Wilton Grant? Was this his tall, spare figure—this luminous, elusive white shape at which I gaped? Did I see his shaggy hair? Was that his brief woven garment? I prayed that my imagination might not be tricking me.

Bee's agonized call rang out. "Will! Is this you, Will?"

We stood together; she clung to me. The figure advanced, stood now quite within our walls. No longer wholly spectral, a cast of green had come to it; a first faint semblance of solidity. It stood motionless; drooping, as though tired and spent. Was it Wilton Grant? It moved again. It advanced, sank into the floor as though sitting down—sitting almost in the center of the mattress, though a foot beneath it. Significant posture! It had come to the mattress from whence it had departed. It was Wilton Grant!

We bent down. Bee was on her knees. Now we could see details, clearly now beyond all possibility of error. Will's drawn face, haggard, with the luminosity every moment fading from it, the lines of opaque human flesh progressively taking form.

He was sitting upright, his hands bracing him against that unseen level below us. Then one of his hands came up, queerly as though he were dragging it, and rested on the higher level of the mattress. His eyes, still strangely luminous, were imploring us. And then his voice; a gasp; and a tone thin as air.

"Raise—me! Lift—me up!"

Bee's cry was a horror of self-reproach, and I knew then that she must have neglected the instructions he had given her. We touched him; gripped him gently. Beneath my fingers his half-ponderable flesh seemed to melt so that I scarce dared press against it. We raised him. There was little weight to resist us; but as we held him, the weight grew. Progressively more rapidly; and within my fingers I could feel solidity coming.

Again he gasped, and now in a voice of human-labored accents. "Put me—down. Now—try it, Bee."

We lowered him. The mattress held him. At once he sank back to full length, exhausted, distressed—but uninjured. Bee gave him a restorative to drink. He took it gratefully; and now, quite of human aspect once more, he lay quiet, resting.

Bee's arms went down to him. "Will, you must go to sleep now—then you can tell us—"

"Sleep!" He sat up so abruptly it was startling; more strength had already come to him than I had realized. "Sleep!" He mocked the word; his gaze with feverish intensity alternated between us.

"Bee—Rob, this is no time for talk.... No, I'm all right—quite recovered. Listen to me, both of you. What I have been through—seen, felt—you could never understand unless you experienced it. No time for talk—I must go back!"

A wildness had come to him, but I could see that he was wholly rational for all that; a wildness, born of the ordeal through which he had passed.

"I must go back, at once. The danger impending to our world here—is real—far worse than we had feared. Impending momentarily—I had feared it—but now I know. And I must go back. With you—I want you two with me. You'll go, Bee. Rob, will you go? Will you, Rob?"

A sudden calmness had fallen upon Bee. "I'll go of course," she said quietly.

"Yes, of course. And you, Rob? Will you go with us? We need you."

Would I go? Into the unnameable, the shadows of unthought, unseen realms, to encounter—what? A rush of human fear surged over me; a trembling; a revulsion; a desire to escape, to ward off this horror crowded thus upon me. Would I go? I heard my own voice say strangely:

"Why—why yes, Will, I'll go."

Go! Leave this world!

And my voice was telling them calmly that I would go!

LAST PREPARATIONS

Committed thus by my own quiet words, involuntarily spoken as though by a volition apart from me, I strove for calmness. A confusion of mind possessed me. But Bee was quite calm; and presently, though within me the surge of apprehension continued, outwardly I believed I did not show it.

Three of us going into the shadows. And Will said, not to linger this time in the Borderland, but to go on—to penetrate into the depths of the Unknown realm beyond. The very thought of it brought a score of anxious questions to my mind; but when I tried to voice them Will crisply checked me.

I realized now, with an emotion tinged by a faint whimsicality, that Will and Bee had summoned me here this evening with an anticipation of just this outcome. They had foreseen that we all three would make the trip together. They were prepared for it; and Will's first trial had been experimental wholly.

Thus, I found them ready. Two others of the knitted suits were at hand. Two other batteries. But we—Bee and I—had been seemingly indispensable in aiding Will. His departure—Bee had been by his side to remove the battery wires. And far more important, when he returned, his solidifying shadow had lain beneath the mattress. We had been there to raise him up, to hold him until the substance of his body was great enough for the mattress to sustain it. Suppose we had not raised him? Suppose while yet within the mattress space—or within the space the floor of the room itself was occupying—the growing solidity of him had demanded empty space of its own? The thought brought a shudder—a thought too horrible to be dwelt upon.

During our brief preparations—which Will hurried with a grim haste—he did not once volunteer to explain his experience. And only once did Bee question him.

"You'll tell us exactly what we are to do?"

"Yes. Presently—before we start."

"You said there was need of haste? A real danger to our world here—from those—other beings?"

He was arranging the batteries. "Yes, Bee. A real danger."

"You think we can repulse them? Just three of us going in there? Strangers—"

Strangers indeed. No adventurers into other lands in all the dim pages of history could have felt, or been, such strangers.

He interrupted her. "We will do our best. It is necessary—our efforts.... We will have plenty of time for consultation, Bee. You will understand, when we are there.... Pour three glasses of water, Rob."

My fingers were trembling; it seemed strange that Bee could maintain such calmness. But it was simulated for she said:

"Will, is it—is it very horrible—the changing, I mean?"

He stopped before her, put his hands on her shoulders. His face, so set with its purpose he had forgotten the human feelings of her, softened momentarily with affection.

"No—it is strange—frightening at first. But not horrible. And you forget it soon. Then it's merely strange, awesome—you'll see—"

He broke off, turned away, and as momentarily his gaze touched me, he smiled. "Awesome, Rob. But for me, this second time, it will be no great ordeal. Even exhilarating—strangely so. You'll see.... We're about ready, Bee."

She took her woven suit and retired. I was soon undressed and into mine. Its fabric was queerly light of weight, and for all its metallic quality it stretched readily, almost like rubber as I put it on. Somehow donning that garment made me shudder. It seemed unnaturally chill as it touched my skin.

Bee presently returned, garbed as we were. In spite of my perturbation, my fear of the dread experience which lay before me, I felt a thrill of admiration as I beheld her. So slim of figure, straight of limb, graceful; and with her grave, intelligent face full of one set purpose—to aid us in every way she could.

"We're ready," said Will briefly. "Here are your belts."

We fastened the broad belts about our waists. The pouches each contained some small object.

"Don't bother them now," Will objected, as I would have examined them. "Later, when we get—in there, will be time enough.... We're ready. What we are to do now is simple—I think there will be no mishap. We will seat ourselves on the mattress. You two may lie down; I shall sit up this time."

"Why?" I demanded.

He smiled. "It is only the first time one feels the sensations that they are disturbing. I'm confident of that. We will have the batteries beside us—" Bee was already placing them on the mattress. "At my signal, we will each disconnect our own. Should either of you be unable—be overcome—I will do it for you."

"But the coming back," I suggested. "We raised you up—"

His smile held a faint ironic amusement. "Don't you think, Rob, we can leave that to its proper time?" He saw my look and added, with the ready apology which made him so lovable:

"Naturally you are apprehensive. But I've planned for that, of course. There are many places where the level of this Borderland—as I call it—coincides exactly with the surface of our own realm. The back corner of the garden outside, for instance. I have remarked it—I can find it—when the time comes for us to return."

Bee said, "Will, I've been wondering—you were gone five or six hours. Were you in there very long?"

His smile was enigmatic. "You can have no conception of this experience—I cannot answer that, Bee—that's why I haven't told you anything—you are so soon to feel and see it for yourself." He was impatient for the start. "I think we're ready. There is so little to do—no chance to forget anything."

With sudden irrelevant thought my heart leaped. That hostile watching spectre.... My anxious glance traveled the room. Bee said, "It's not here—I've been expecting—I'm so thankful it's not here."

It was not to be seen. I was relieved for that, at least. With a last deliberation we all three seated ourselves on the mattress. Will was between Bee and me. We connected the batteries; I held mine at my side, my nerve-shaken fingers trembling, though inwardly I cursed them, fumbled at the switch to make sure I could control it. The pellets were in the palm of my other hand; the glass of water was within reach.

Will said earnestly, "One last thing—and this is important—more important than you realize. Whatever comes, we must keep together. Remember that. You two—strive always to keep with me—close beside me. Whatever impulse you feel—fight it—do not yield to it. Remember you must stay by me."

The words themselves were simple to grasp. Yet beneath them lay a vague import, a suggestion of what was to come, which seemed unutterably sinister. I heard Bee murmuring.

"Yes, I understand."

I said, and marveled at the steadiness of my voice, "Very well, Will—I'll remember."

He said, "Now." I saw his hand go to his mouth. Now I must take the pellets. Within me a torrent of revulsion surged. I must take the pellets—at once. Bee was raising her glass of water. My hand went up; I felt the pellets in my mouth. Acrid. A faint acrid taste spread on my tongue. And then with a gulp of the water I had swallowed them. Breathless I waited, with heart thumping like a hammer, my head reeling, not from the pellets but from this excitement, fright, which swept me uncontrolled.

Will's voice said, "Rob. Your battery—switch it on."

My fingers found the little switch; pushed it. I felt a faint tingling of my limbs; a sudden nausea possessed me; my senses whirled; the room, which all at once had grown very sharp of outline, turned nearly black.

THE MIND SET FREE

I did not faint, and in a moment I felt better. My vision cleared; the room regained almost its normal aspect. But the nausea persisted. I felt a desire to lie down. Will was sitting erect, but beyond him I saw Bee lying on her side, facing us. I reclined on one elbow, holding up my head that I might look around me.

The faintness was gone. The sweat of weakness was upon me, my forehead cold and clammy; but I could feel my heart beating strongly. When was the change to start? It seemed ages since I had taken those pellets.

Then I heard the hum. It sounded as though apart from me; but I knew it was not for I could feel it. A vibration. Not of my knitted suit; a vibration within me; within the very marrow of my bones.

My gaze was fixed upon the table across the room. Its outlines were very sharp and clear, unnaturally so, with that sharpness of detail which sometimes comes to the vision of one who is ill. Now they began to blur—an unsteadiness as though I were looking through waves of heat. Had the change started? I raised my hand, examined it. No change, save that the receding blood had made it a little pale.

The nausea was now leaving me. A sense of relief, of triumph that I was not ill, possessed me. With every alert faculty I determined to remark my sensations.

The vibration within me grew stronger, though to my ears it was unaltered. And then, abruptly the change began. My whole being was quivering. Not my muscles, my flesh, my nerves, but the very matter which composed them suddenly made sensible to my consciousness. The essence of me, trembling, quivering, vibrating—a tiny force, rapid beyond conception. It swept me with a tingling; grew stronger, possessed me until for a moment nothing of my consciousness remained but the knowledge of it.

Frightening, horrible. But the horror passed. Again my brain and vision cleared. My whole being was humming; and then I realized that I could no longer hear the hum, merely felt it. The knowledge of sound, not the sound itself. And an exhilaration was coming to me. A sense of lightness. My body growing lighter, less ponderable. But it was far more than that. An exhilaration of spirit, as though from me shackles of which I was newly conscious, were melting away. A lightness of being. A freedom.... A new sense of freedom, frightening with the vague wild triumph it brought.... Frightening too, for in the background of my mind was the realization that all my physical perceptions were dulling. My elbow was resting sharp against the rough mattress. I dragged my arm a trifle; and dull, far away as though detached from me, I could faintly feel it. I moved my leg. It was not numb. The reverse, it was thrilling in its every fibre. It moved, but I could only feel it move as in a dream. I even wondered if I felt it move at all. Was it not, perhaps, only my knowledge that it moved?

Abruptly I became aware that the table across the room had changed. My mental faculties, with all this morbid change of the physical taking place about them, were still alert. I had vaguely expected the table, the room, the visible, material objects of the realm I was leaving, to remain unaltered of aspect. But they did not. The table had lost its color; a monochrome of greyness possessed it. The table, the chairs, the whole room, had turned flat and grey. Flat of tone; and flat of dimensions as well. The flat printed picture of a room.

But in a moment even that had changed. The grey outlines of the table were dim and blurred; the grey substance of it, no longer dull and opaque, seemed growing luminous. Faintly phosphorescent. Translucent, then transparent. Through the table leg, through the wavering grey image of the room-wall, I saw opening up to me the vast darkness of an abyss of distance. A phantom room in which I lay. The shadow of a room hovering in empty space.

There was no horror within me now. That thrilling sense of lightness, that vague unreasoning triumph of loosened shackles had no thought of horror; and to me came a faint contempt for this phantom room, these imponderable shadows which once had been solid chairs and walls.

Then I heard Will's voice. "The battery! Turn off your current, Rob!"

Heard his voice? I believe I barely heard it—physically a thin wraith of human voice striking my ear-drums. Yet, mingled with that realization, was the sense that he was speaking quite normally. With my mind's ear, the memory of his normal voice made me hear his hurried, anxious admonition. "Turn off your battery. Rob! Rob!"

My battery. Of course, the moment had arrived when I must turn it off. I glanced down at it. A shadowy, unreal, phantom battery lying beside me; my grey hand resting upon it seemed to my vision far more ponderable. And then I received my first real perception as to the nature of this change. My fingers groped for the switch, found it. But this shadow battery, of which even then I was dimly contemptuous, was solid beyond all solidity of which I had ever formed conception. My fingers fumbling with it—dulled as were my physical sensations, I could feel those fingers groping as though the adamant steel of that switch were penetrating them. A feeling indescribable—uncanny, morbidly horrible, though the incident was so brief the horror scarce had time to reach my confused consciousness. My fingers, not the battery, were shadow—half-ponderable fingers, feeling their way within the solid steel of that tiny switch. For a terrifying instant I thought I could not move it. Then—it moved; the current was off. I sank back, exhausted of spirit with the effort. But at once Will's voice aroused me.

"Disconnect the wires. Can you do it, Rob? Quickly—or it will be too late."

I fumbled for the wires; cast them off—gigantic cables they might have been to the futile wraiths of my fingers. Will helped me, I think; and at last I was free, lying back upon the mattress. Dimly I could feel it beneath me, my thrilling, vibrating body resting upon it as though I were a feather newly drifted down.

Moments passed; I do not know how long, I could not have told for my thoughts were winging away unfettered, untrammelled as in a dream.... A dream ... the past, the present—all of it savoured of a vaguely pleasant unreality.

And presently I realized that I was moving; my body—could I indeed call this vanished consciousness of the physical, a body?—my being was floating, drifting gently downward, I could no longer feel the mattress; I saw it—a blurred, grey, transparent shadow, coming upward. Beside me, within me; then over me as I sank through it a foot or two and came to rest.

Beneath me now, there was a dull sensation. I could feel myself lying upon something apparently solid. Feel it? The feeling was barely physical; rather was it a mere knowledge that I was lying there.

I tried to keep my scattering thoughts together. It was an effort to hold them—an effort to think coherently; an effort to cling to anything—even mental—of reality. I told myself that the change must be nearly complete. I was the spectre; this phantom mattress, this wraith of a room—those ghost-like chairs and table floating in space above me—that was my own real world, lost and gone.

A silence had fallen. The hum within me no longer sounded. It was a shock to see that little phantom clock; the movement of its pendulum was visible, but its ticking heart gave no sound. A preternatural silence hung like a grey shroud over a universe of shadows. Then I heard Will's soundless voice—heard it clearly now with the knowledge that it was wholly mental, a transference of thought which only my imagination and memory endowed with a familiar physical timbre.

"Rob. Come back to us! Hold your thoughts. Stay here with us."

And Bee's imploring voice, "We are here, Rob. All here together. Sit up—look at us—speak to us."

Was I indeed, nothing now but a mind? Were my thoughts all that remained of me? I fought for reality; for stability; fought for anything real that I could clutch, to which desperately I might cling. Where were Will and Bee? Somewhere here in the shadows. An abyss of shadows everywhere. I thought I could see a thousand miles into that pregnant darkness. I could wander in it at will; my thoughts could wander everywhere.

But I must have conquered, for I found myself sitting up, with Bee and Will beside me.

"There, that's better." I felt the relief in Will's tone. "Hold yourself firm—you'll be used to it in a moment. It's strange, isn't it?"

Strange; scarce have I words—and even those I choose are almost futile—to picture what I saw and felt. The world I had left lay all about me—dim, transparent shadows of familiar things. The room of Will's house—we were sitting just below the level of its floor. Around the room—above it, to one side of it—the phantom house itself was visible. Beyond the house, the gardens, the sombre ghosts of trees standing about—a shadowy semblance of the winding village street—other houses—a hill in the distance—

Mingled with all these shadows—the reality I had left—was the reality in which now I existed. The Borderland, we had been calling it. A vast realm of luminous darkness. A rolling slope upon which we were sitting—a slope, something newly tangible at least, which I could vaguely see and vaguely feel beneath me. A realm of pregnant darkness, filled with the shadows of the world I had left; and filled also with things as yet unseen—things as yet unthought.... The realm of unthought things....

Will's voice seemed saying, "So strange—but you'll be used to it presently."

I turned to regard him and Bee—these spectres like myself, sitting beside me. What did I see? What was their aspect to this new mind's eye which was mine? I cannot say. I think now that my intelligence saw the intelligence which was theirs, and clothed it out of habit with a semblance of substance for a body—familiar of outline and form since there was no other aspect I could conceive. I saw—or thought I saw, which perhaps is quite the same—luminous grey ghosts of my companions as last I had seen them. Of themselves they appeared not transparent. Through them the spectral walls of the room were not visible; of everything around me, the bodies of my friends seemed the most real.

Will was smiling at me reassuringly. Bee's gaze was affectionate. Their voices, save that I knew I heard no sound, seemed not abnormal. I spoke. It was like thinking words with moving lips. But they heard me; not to read my lips, but to hear my thoughts. Heard with a result quite normal, for they nodded and smiled and answered me.

Then Will touched me; experimentally with a smile, he laid his hand upon my arm. It was not unreal, save that only dimly, as though my senses were dulled, could I feel him. Yet there was a weight to his grip. His tenuous ghostly fingers (as I would have counted them in my former state) were not ghostly of grip to me now. His fingers, my arm, were identical of substance. His fingers could not occupy the space with me; they were ponderable, real, with a dulled reality which gave me at last something to cling to; brought my scattering thoughts together. I was here—Robert Manse; alive—living, breathing—sitting beside my friends. From that moment a measure of the strangeness left me and took to itself the externals only. I was real; Bee and Will were real; it was only the things around us which were strange. The body which momentarily I seemed to have lost, was restored to me. A sense of the physical; dulled of perception, but still a body to house my mind. To house it—yet not to hold it firmly. A body which now was not a prison; shackles fallen away. Yet there was a danger to that. Already I had tasted of it—for the mind, too free, is difficult to control.

I was saying, "I'm—all right.... I was dreaming—I got confused."

Bee said whimsically, "We're here. Will, there is so much I want to ask you—"

"Not now, Bee." His voice was full of its old decisiveness. "We must start. Keep together—you understand now, Rob, what I meant. Keep together—keep thinking, firmly, what you are doing. And do—what I do. We must start."

He drew himself erect. As though I were dreaming—or thinking of the act—I felt myself standing erect. Then walking—vaguely I could feel the substance of the slope beneath my feet—walking with a lightness, a lack of effort weird but pleasant. And I clung physically to Will, and saw Bee on his other side clinging to him also—as though a breath of wind might blow us all away.

The thought was whimsical. There could be no wind. Wind was moving air. I had the sense that I was still breathing, of course. But how could there be air? Air itself was infinitely more solid than these, our bodies. Yet I was breathing something. Call it air. The word of itself means nothing—and there are no words with which to clothe the realities of any unthought realm....

We were walking through the phantom room which had been the reality of Will's home—through its wall—out through its garden. Our slope was rolling, uneven. The shadowy ground of the garden was above us, then below us; then, for a moment, we seemed standing exactly on its level. I remembered. This was the place Will had mentioned to which we could safely return.

We spoke seldom; Will did not seem to care to talk. I realized he knew where he was going—had some definite purpose in his mind. Alert now with every mental faculty, I wondered what it was, yet would not question him.

We stalked onward. The shadowy village lay about us, above us now. Soundless, colorless phantoms, these streets, trees and houses. I saw the railway station—the ghost of a train stood off there and then moved forward soundlessly. I was touched with a faint amusement to see it—a luminous ghost sliding along its narrow enslaving rails. It could not go up or down, or sidewise. And it seemed so imponderable I would fearlessly have walked into it.

This Borderland, full of these shadows of our other world, yet seemed empty. Nothing of its own reality was visible. In every direction I could look into seemingly infinite distance; and overhead was a vast darkness—the emptiness of infinite space. Was nothing here with us in this Borderland? Those other spectres—those beings coming out from their world as we were coming in from ours?...

A thrill of quite normal excitement swept me at the thought. We had come in to encounter those spectres. And now they would be spectres no longer. Ponderable beings upon an equality with ourselves; and we were here to thwart them of their purpose....

I heard Bee give a faint, alarmed cry. Ahead of us a shape had appeared! It became visible and I felt that perhaps it had been hiding behind some unseen obstacle. It stood, solid and grey, with the shadow of a barn, a haystack above and behind it. Stood directly in our path, as though waiting for us.

I pulled at Will, but he ignored me. Hastened his pace.

We stalked forward with that waiting thing standing immobile in our path!

THE STRUGGLE AT THE BORDERLAND

The thing stood waiting as Will drew us toward it. Fear swept over me. Yet the very sense of fear brought with it a reassurance, for it was the physical I feared; the vanished sense of my body was not entirely gone, for now I was fearing its welfare.

My voice protested, "Will. Wait. That thing there—"

"It is friendly, Rob."

The fear died. I remembered what now seemed obvious; Will had been leading us somewhere with a set purpose. To meet this friendly thing, of course; this thing which doubtless he had met before. I stared at it as we approached. A dim, opaque grey shape like ourselves but it seemed formless, sexless; neither human nor unhuman—a shape merely—a something poised there of which my mind seemed able to form no conception. Then I heard Will say to Bee:

"A girl, Bee—you understand—Rob, listen. We must cling to the realities of our world. There are no other words—no other conceptions—with which we can think these unthought things. This is a girl——"