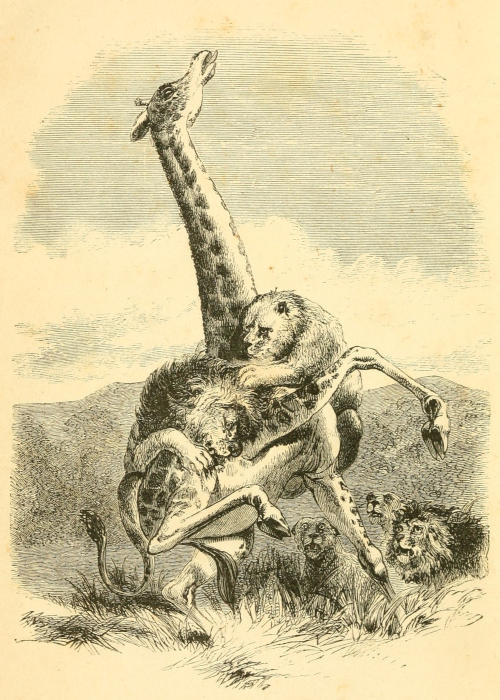

LIONS PULLING DOWN GIRAFFE.

Title: Lake Ngami

or, Explorations and discoveries during four years' wanderings in the wilds of southwestern Africa

Author: Charles John Andersson

Release date: June 2, 2024 [eBook #73758]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Harper & Brothers, 1856

Credits: Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

LIONS PULLING DOWN GIRAFFE.

LAKE NGAMI;

OR,

EXPLORATIONS AND DISCOVERIES

DURING

FOUR YEARS’ WANDERINGS IN THE WILDS

OF

SOUTHWESTERN AFRICA.

BY

CHARLES JOHN ANDERSSON.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS,

REPRESENTING SPORTING ADVENTURES, SUBJECTS OF NATURAL HISTORY,

DEVICES FOR DESTROYING WILD ANIMALS, &c.

NEW YORK:

HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS,

FRANKLIN SQUARE.

1856.

The following Narrative of Explorations and Discoveries during four years in the wilds of the southwestern parts of Africa contains the account of two expeditions in that continent between the years 1850 and 1854. In the first of these journeys, the countries of the Damaras (previously all but unknown in Europe) and of the Ovambo (till now a terra incognita) were explored; in the second, the newly-discovered Lake Ngami was reached by a route that had always been deemed impracticable. It is more than probable that this route (the shortest and best) will be adopted as the one by which commerce and civilization may eventually find their way to the Lake regions.

The first journey was performed in company with Mr. Francis Galton, to whom we are indebted for a work on “Tropical South Africa;” on the second the Author was alone, and altogether dependent on his own very scanty resources.

It was suggested to the Author, as regards the first journey, that, from the ground having been preoccupied, it would be best for him to commence where his friend left off. There was some reason for this; but, on mature consideration, he deemed it desirable to start from the beginning, otherwise he could not have given[iv] a connected and detailed account of the regions he visited. Moreover, from the Author having remained two years longer in Africa than Mr. Galton, he has not only been enabled to ascertain the truth respecting much that at first appeared obscure and doubtful, but has had many opportunities of enlarging the stock of information acquired by himself and friend when together. Besides, they were often separated for long periods, during which many incidents and adventures occurred to the Author that are scarcely alluded to in “Tropical South Africa.” And, lastly, the impressions received by different individuals, even under similar circumstances, are generally found to vary greatly, which, in itself, would be a sufficient reason for the course the Author has decided on pursuing.

As will be seen, the present writer has not only described the general appearance of the regions he visited, but has given the best information he was able to collect of the geological features of the country, and of its probable mineral wealth; and, slight though it may be, he had the gratification of finding that the hints he threw out at the Cape and elsewhere were acted upon, that mining companies were formed, and that mining operations are now carried on to some extent in regions heretofore considered as utterly worthless.

The Author has also spoken at some length of the religion, and manners, and customs of such of the native tribes (previously all but unknown to Europeans) visited by him during his several journeys. He also noted many of their superstitions, for too much attention, as has been truly observed, can not be paid to the mythological traditions of savages. Considerable discretion[v] is, of course, needful in this matter, as, if every portion were to be literally received, we might be led into grievous errors; still, by attending to what many might call absurd superstitions, we not only attain to a knowledge of the mental tendencies of the natives, but are made acquainted with interesting facts touching the geographical distribution of men and inferior animals.

Since the different members constituting the brute creation are so intimately connected with the economy of man, and since many of the beasts and birds indigenous to those parts of Africa visited by the Author are still but imperfectly known, he has thought it advisable to enter largely into their habits, &c., the rather as natural history has from childhood been his favorite pursuit, and is a subject on which he therefore feels conversant; and though part of what he has stated regarding the rhinoceros, the hippopotamus, the koodoo, the ostrich, and others of the almost incalculable varieties of animals found in the African wilderness may be known to some inquirers, it is still hoped that the general reader will find matter he has not previously met with.

The larger portion of the beautiful plates to be found in this work (faithfully depicting the scenes described) are by Mr. Wolf—“the Landseer of animals and vegetation,” to quote the words of the Earl of Ellesmere in a note which his lordship did me the honor to write to me.

The Author has endeavored in the following pages faithfully, and in plain and unassuming language, to record his experiences, impressions, feelings, and impulses, under circumstances often peculiarly trying.[vi] He lays claim to no more credit than may attach to an earnest desire to make himself useful and to further the cause of science.

It is more than probable that his career as an explorer and pioneer to civilization and commerce is terminated; still he would fain hope that his humble exertions may not be without their fruits.

When he first arrived in Africa, he generally traveled on foot throughout the whole of the day, regardless of heat, and almost scorning the idea of riding on horseback, or using any other mode of conveyance; indeed, he was wont to vie with the natives in endurance; but now, owing to the severe hardships he has undergone, his constitution is undermined, and the foundation of a malady has been laid that it is feared he will carry with him to the day of his death; yet such is the perverseness of human nature that, did circumstances permit, he would return to this life of trial and privation.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Departure from Sweden.—Day-dreams.—Fraternal Love.—A tempting Offer.—Preparations for Journey to Africa.—Departure from England.—Arrival at the Cape.—Town and Inhabitants.—Table Mountain.—Curious Legend.—Preparation for Journey into the Interior.—Departure for Walfisch Bay | Page 19 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Arrival at Walfisch Bay.—Scenery.—Harbor described.—Want of Water.—Capabilities for Trade.—Fish.—Wild-fowl.—Mirage.—Sand Fountain.—The Bush-tick.—The Naras.—Quadrupeds scarce.—Meeting the Hottentots.—Their filthy Habits.—The Alarum.—The Turn-out.—Death of a Lion.—Arrival at Scheppmansdorf.—The Place described.—Mr. Bam.—Missionary Life.—Ingratitude of Natives.—Missionary Wagons | 29 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Preparations for Journey.—Breaking-in Oxen.—Departure from Scheppmansdorf.—An infuriated Ox.—The Naarip Plain.—The scarlet Flower.—The Usab Gorge.—The Swakop River.—Tracks of Rhinoceros seen.—Anecdote of that Animal.—A Sunrise in the Tropics.—Sufferings from Heat and Thirst.—Arrival at Daviep: great resort of Lions.—A Horse and Mule killed by them.—The Author goes in pursuit.—A troop of Lions.—Unsuccessful Chase.—Mules’ flesh palatable | 44 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| The Gnoo and the Gemsbok.—Pursuit of a Rhinoceros.—Venomous Fly.—Fruit of the Acacia nutritious.—Sun-stroke.—Crested Parrot.—A Giraffe shot.—Tjobis Fountain.—Singular Omelet.—Nutritious Gum.—Arrival at Richterfeldt.—Mr. Rath and the Missions.—The Damaras: their Persons, Habits, &c.—Lions Troublesome.—Panic.—Horse Sickness | 56[viii] |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Hans Larsen.—His Exploits.—He joins the Expedition.—How people travel on Ox-back.—Rhinoceros Hunt.—Death of the Beast.—“Look before you Leap.”—Anecdote proving the Truth of the Proverb.—Hans and the Lion.—The Doctor in Difficulties.—Sufferings on the Naarip Plain.—Arrival at Scheppmansdorf | 68 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Return to Scheppmansdorf.—Training Oxen for the Yoke.—Sporting.—The Flamingo.—The Butcher-bird: curious Superstition regarding it.—Preparing for Journey.—Servants described | 76 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Departure from Scheppmansdorf.—Cattle refractory at starting.—Tincas.—Always travel by Night.—Rhinoceros Hunt.—The Author in danger of a second Sun-stroke.—Reach Onanis.—A Tribe of Hill-Damaras settled there.—Singular Manner in which these People smoke.—Effects of the Weed.—The Euphorbia Candelabrum.—Remarkable Properties of this vegetable Poison.—Guinea-fowl: the best Manner of shooting them.—Meet a troop of Giraffes.—Tjobis Fountain again.—Attacked by Lions.—Providential Escape.—Arrival at Richterfeldt | 83 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| A hearty Welcome.—We remove the Encampment.—An Apparition.—Audacity of wild Beasts.—Depriving Lions of their Prey.—Excessive Heat.—Singular effects of great Heat.—Depart for Barmen.—Meet a troop of Zebras.—Their flesh not equal to Venison.—The Missionary’s Wall.—A sad Catastrophe.—The “Kameel-Doorn.”—Buxton Fountain.—The Scorpion.—Arrival at Barmen | 95 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Barmen.—Thunder-storm in the Tropics.—A Man killed by Lightning.—Warm Spring.—Mr. Hahn: his Missionary Labor; Seed sown in exceeding stony Ground.—The Lake Omanbondè.—Mr. Galton’s Mission of Peace.—The Author meets a Lion by the way; the Beast bolts.—Singular Chase of a Gnoo.—“Killing two Birds with one Stone.”—A Lion Hunt.—The Author escapes Death by a Miracle.—Consequences of shooting on a Sunday | 106[ix] |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| A Christmas in the Desert.—Mr. Galton’s Return from the Erongo Mountain.—He passes numerous Villages.—Great Drought; the Natives have a Choice of two Evils.—The Hill-Damaras.—The Damaras a Pastoral People.—The whole country Public Property.—Enormous herds of Cattle.—They are as destructive as Locusts to the Vegetation.—Departure from Richterfeldt.—The Author kills an Oryx.—The Oxen refractory.—Danger of traversing dry Water-courses on the approach of the Rainy Season.—Message from the Robber-chief Jonker.—Emeute among the Servants.—Depart for Schmelen’s Hope | 119 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

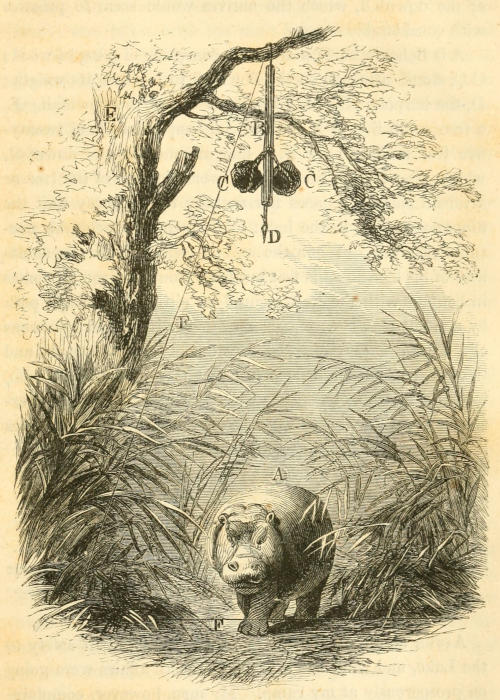

| Schmelen’s Hope.—Scenery.—Missionary Station.—Raid of the Namaquas.—Ingratitude of the Natives.—Jonker’s Feud with Kahichenè; his Barbarities; his Treachery.—Mr. Galton departs for Eikams.—Author’s successful sporting Excursions.—He captures a young Steinbok and a Koodoo.—They are easily domesticated.—Hyænas very troublesome; several destroyed by Spring-guns.—The latter described.—Visit from a Leopard; it wounds a Dog; Chase and Death of the Leopard.—The Caracal | 126 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Wild-fowl abundant.—The Great Bustard.—The Termites.—Wild Bees.—Mushrooms.—The Chief Zwartbooi.—Return of Mr. Galton.—He makes a Treaty with Jonker.—He visits Rehoboth.—Misdoings of John Waggoner and Gabriel.—Change of Servants.—Swarm of Caterpillars.—A reconnoitring Expedition.—Thunder-storm.—The Omatako Mountains.—Zebra-flesh a God-send.—Tropical Phenomenon.—The Damaras not remarkable for Veracity.—Encamp in an Ant-hill.—Return to Schmelen’s Hope.—Preparations for visiting Omanbondè | 135 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Depart from Schmelen’s Hope.—Meeting with Kahichenè.—Oxen Stolen.—Summary Justice.—Superstition.—Meeting an old Friend.—Singular Custom.—Gluttony of the Damaras.—How they eat Flesh by the Yard and not by the Pound.—Superstitious Custom.—A nondescript Animal.—The Author loses his Way.—Ravages of the Termites.—“Wait a bit, if you please.”—Magnificent Fountain.—Remains of Damara Villages.—Horrors of War.—Meet[x] Bushmen.—Meet Damaras.—Difficulties encountered by African Travelers.—Reach the Lake Omanbondè.—Cruel Disappointment | 146 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Omanbondè visited by Hippopotami.—Vegetation, &c., described.—Game somewhat scarce.—Combat between Elephant and Rhinoceros.—Advance or Retreat.—Favorable reports of the Ovambo-land.—Resolve to proceed there.—Reconnoitre the Country.—Depart from Omanbondè.—Author shoots a Giraffe.—Splendid Mirage.—The Fan-palm.—The Guide absconds.—Commotion among the Natives.—Arrive at Okamabuti.—Unsuccessful Elephant-hunt.—Vegetation.—Accident to Wagon.—Obliged to proceed on Ox-back.—The Party go astray.—Baboon Fountain.—Meeting with the Ovambo; their personal Appearance, &c.—Return to Encampment.—An Elephant killed.—Discover a curious Plant.—Immorality.—Reflections | 162 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Depart from Okamabuti.—Visit from a Lion.—Amulets.—Revisit Baboon Fountain.—Otjikoto; a wonderful Freak of Nature; Remarkable Cavern.—Natives unacquainted with the Art of Swimming.—Fish abundant in Otjikoto; frequented by immense Flocks of Doves.—Panic of the Ovambo on seeing Birds shot on the Wing.—Arrive at Omutjamatunda.—A greasy Welcome.—Ducks and Grouse numerous.—Author finds himself somewhat “overdone.”—“Salt-pans.”—All “look Blue.”—A second Paradise.—Hospitable Reception.—Vegetation.—People live in Patriarchal Style.—Population.—Enormous Hogs.—Arrive at the Residence of the redoubtable Nangoro | 178 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Visit from Nangoro.—His extreme Obesity.—One must be fat to wear a Crown.—His non-appreciation of Eloquence.—Singular Effects of Fireworks on the Natives.—Cure for making a wry Face.—Ball at the Palace.—The Ladies very attractive and very loving.—Their Dress, Ornaments, &c.—Honesty of the Ovambo.—Kindness to the Poor.—Love of Country.—Hospitality.—Delicate manner of Eating.—Loose Morals.—Law of Succession.—Religion.—Houses.—Domestic Animals.—Implements of Husbandry.—Manner of Tilling the Ground.—Articles of Barter.—Metallurgy | 190[xi] |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| The River Cunenè.—The Travelers are Prisoners at large.—Kingly Revenge.—Kingly Liberality.—Depart from Ondonga.—Sufferings and Consequences resulting from Cold.—Return to Okamabuti.—Damara Women murdered by Bushmen.—Preparations for Journey.—Obtain Guides.—Depart from Tjopopa’s Werft.—Game abundant.—Author and three Lions stalk Antelopes in Company.—Extraordinary Visitation.—The Rhinoceros’s Guardian Angel.—The Textor Erythrorhynchus.—The Amadina Squamifrons; singular Construction of its Nest.—Return to Barmen | 201 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| The Damaras.—Whence they came.—Their Conquests.—The Tide turns.—Damara-land only partially inhabited.—Climate.—Seasons.—Mythology.—Religion.—Superstitions.—Marriage.—Polygamy.—Children.—Circumcision.—Bury their Dead.—Way they mourn.—Children interred alive.—Burial of the Chief, and Superstitions consequent thereon.—Maladies.—Damaras do not live long; the Cause thereof.—Food.—Music and Dancing.—How they swear.—Power of the Chieftain limited.—Slothful People.—Numerals.—Astronomy.—Domestic Animals; their Diseases | 214 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Dispatch a Messenger to Cape-Town.—Depart from Barmen.—Eikhams.—Eyebrecht.—Depart from Eikhams.—Elephant Fountain.—Tunobis.—Enormous quantities of Game.—Shooting by Night at the “Skarm.”—The Author has several narrow Escapes.—Checked in attempt to reach the Ngami.—The Party set out on their Return.—Reach Elephant Fountain.—How to make Soap.—Pitfalls.—A night Adventure.—Game scarce.—Join Hans.—The Party nearly poisoned.—Arrival at Walfisch Bay.—A tub Adventure.—Extraordinary Mortality among the Fish.—Author narrowly escapes Drowning.—Arrival of the Missionary Vessel.—Letters from Home.—Mr. Galton returns to Europe.—Reflections | 229 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

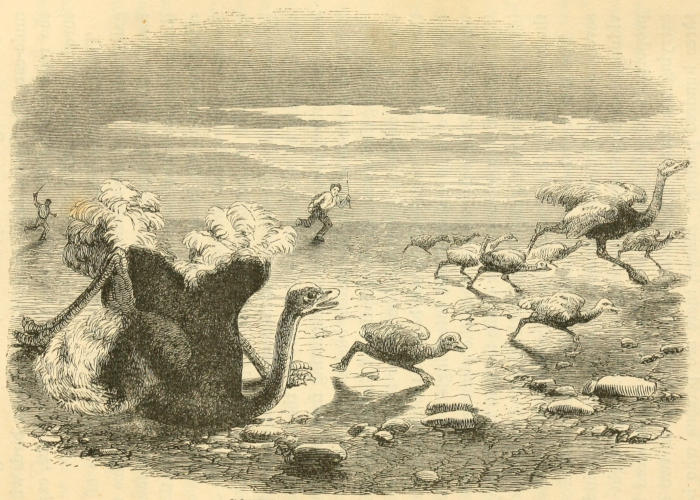

| Capture of young Ostriches.—Natural History of the Ostrich; where found; Description of; Size; Weight; Age; Voice; Strength; Speed; Food; Water; Breeding; Incubation; Cunning; Stones found in Eggs; Chicks; Flesh.—Brain in request among the Romans.—Eggs highly prized.—Uses of Egg-shells.—Feathers an article[xii] of Commerce.—Ostrich Parasols.—The Bird’s destructive Propensities.—Habits.—Resembles Quadrupeds.—Domestication.—The Chase.—Snares.—Ingenious Device.—Enemies of the Ostrich | 247 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Sudden Floods.—John Allen’s Sufferings.—Hans and the Author enter into Partnership.—Young Grass injurious to Cattle.—Depart from Walfisch Bay.—Attractive Scenery.—Troops of Lions.—Extraordinary Proceedings of Kites.—Flight of Butterflies.—Attachment of Animals to one another.—Arrival at Richterfeldt; at Barmen.—Hans’s narrow Escape.—Self-possession.—Heavy Rains.—Runaway Ox; he tosses the Author.—Depart from Barmen.—Difficulty of crossing Rivers.—Encounter great numbers of Oryxes | 264 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

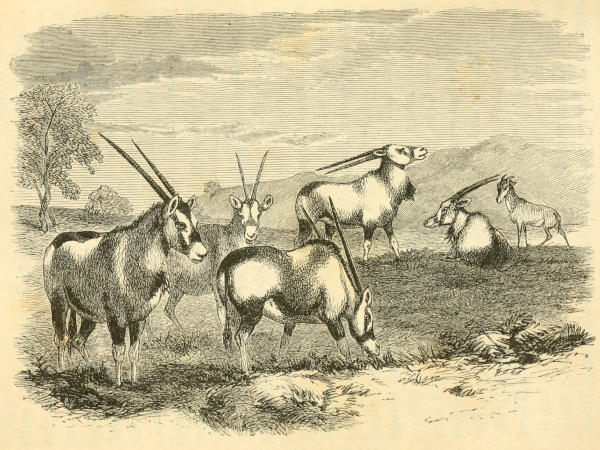

| The Oryx; more than one Species.—Where found.—Probably known in Europe previous to the discovery of the Passage round the Cape of Good Hope.—Description of the Oryx.—Gregarious.—Speed.—Food.—Water not necessary to its existence.—Will face the Lion.—Formidable Horns.—Their Use.—Flesh.—The Chase of this Animal | 272 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Arrival at Eikhams.—Native Dogs; cruelly treated.—Jonker Afrikaner.—The Author visits the Red Nation; the bad Repute of these People.—The Author attacked by Ophthalmia.—The embryo Locust.—The “flying” Locust; its Devastations.—The Locust-bird.—Arrival at Rehoboth; the Place described | 277 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Return to Eikhams.—Ugly Fall.—Splendid Landscape.—Jonker’s Delinquencies.—How to manage the Natives.—The Ondara.—It kills a Man.—How his Comrade revenges him.—Medical Properties of the Ondara.—The Cockatrice.—The Cobra di Capella.—The Puff-adder.—The Spitting Snake.—The Black Snake.—Few Deaths caused by Snakes.—Antidotes for Snake-bites.—Return to Rehoboth | 287 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| The Author’s Tent takes Fire.—He loses every thing but his Papers.—He is laid on a bed of Sickness.—Want of Medicine, &c.—Reflections.—Whole Villages infected with Fever.—Abundance of[xiii] Game.—Extraordinary Shot at an Ostrich.—A Lion breakfasts on his Wife.—Wonderful shooting Star.—Remarkable Mirage.—Game and Lions plentiful.—The Ebony-tree.—Arrival at Bethany, a Missionary Station.—The Trouble of a large Herd of Cattle.—A thirsty Man’s Cogitation.—Curious Superstition.—The Damara Cattle described.—People who live entirely without Water.—Cross the Orange River.—Sterile Country | 299 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Great Namaqua-land.—Its Boundaries and Extent.—Its Rivers.—Nature of the Country.—Vegetation and Climate.—Geological Structure.—Minerals.—“Topnaars” and “Oerlams.”—Houses.—Mythology and Religion.—Tumuli.—Wonderful Rock.—Curious Legend of the Hare.—Coming of Age.—The Witch-doctor.—Amulets.—Superstitions.—A Namaqua’s notion of the Sun.—Marriage.—Polygamy.—Children.—Barbarous Practice.—Longevity.—Singular Customs.—Ornaments.—Tattooing.—Arms.—Idle Habits.—Fond of Amusements.—Music and Dancing.—Spirits.—Mead.—Domestic Animals | 311 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Leave the Orange River.—Arrival at Komaggas.—Gardening and Agriculture.—The Author starts alone for the Cape.—Colony Horses.—Enmity of the Boers to “Britishers.”—Dutch Salutation.—The Author must have been at Timbuctoo, whether or no.—He arrives at Cape-Town.—Cuts a sorry figure.—Is run away with.—A Feast of Oranges.—Ghost Stories.—Cattle Auction.—Hans and John Allen proceed to Australia.—Preparations for Journey to the Ngami.—Departure from the Cape | 325 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Arrival at Walfisch Bay.—Atrocities of the Namaquas.—Mr. Hahn.—His Philanthropy.—Author departs for Richterfeldt.—Shoots a Lion.—Lions unusually numerous.—Piet’s Performances with Lions.—The Lion a Church-goer.—Barmen.—Eikhams.—Kamapyu’s mad Doings and Consequences thereof.—Kamapyu is wounded by other Shafts than Cupid’s.—Author visits Cornelius; here he meets Amral and a party of Griqua Elephant-hunters.—Reach Rehoboth.—Tan’s Mountain.—Copper Ore.—Jonathan Afrika.—A Lion sups on a Goat.—A Lion besieges the Cattle | 339[xiv] |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Dispatch Cattle to the Cape.—Terrible Thunder-storm.—Trees struck by Lightning.—The Nosop River.—A Comet.—The Author nearly poisoned.—Some of the Men abscond; they return to their Duty.—Babel-like confusion of Tongues.—Game abundant.—Author shoots a Giraffe.—Meet Bushmen.—Unsuccessful Elephant-hunt.—Sufferings from Hunger.—Tunobis.—Game scarce.—Author and Steed entrapped.—Pitfalls.—The Men turn sulky.—Preparations for departure from Tunobis.—Vicious Pack-oxen.—Consequences of excessive Fatigue.—The Jackal’s handiwork.—Tracks of Elephants.—More Pitfalls.—Loss of the Anglo-Saxon Lion and the Swedish Cross.—Reach Ghanzé | 351 |

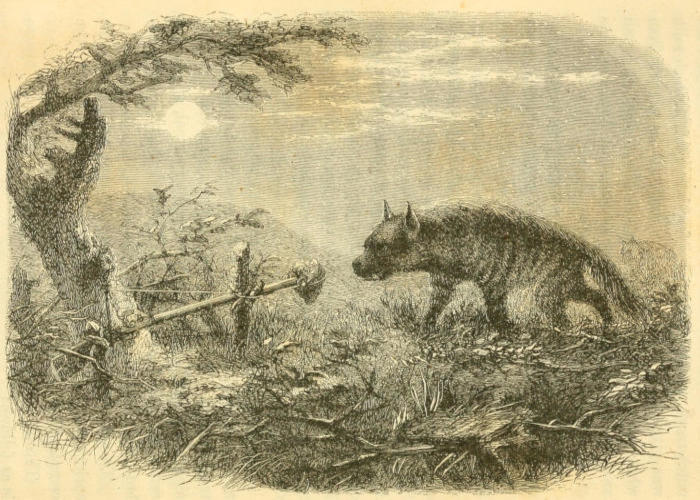

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

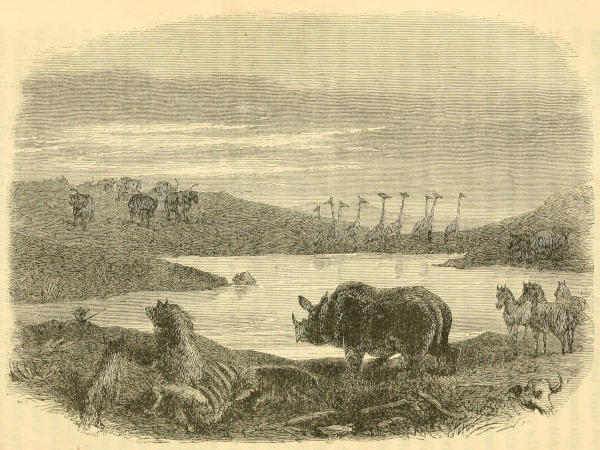

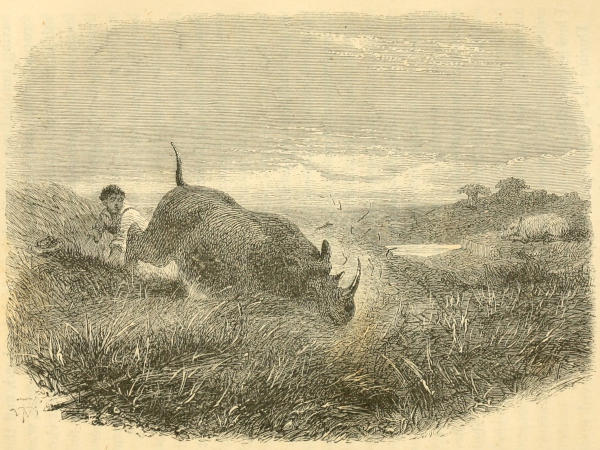

| Ghanzé.—Spotted Hyæna.—The Rhinoceros.—Where found.—Several Species.—Description of Rhinoceros.—Size.—Appearance.—Age.—Strength.—Speed.—Food.—Water.—The Young.—Affection.—Senses.—Disposition.—Gregarious.—Indolence.—Domestication.—Flesh.—Horns.—The Chase.—Mr. Oswell’s Adventures with Rhinoceroses.—A Crotchet.—Where to aim at the Rhinoceros.—Does not bleed externally when wounded.—Great numbers slain annually | 368 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

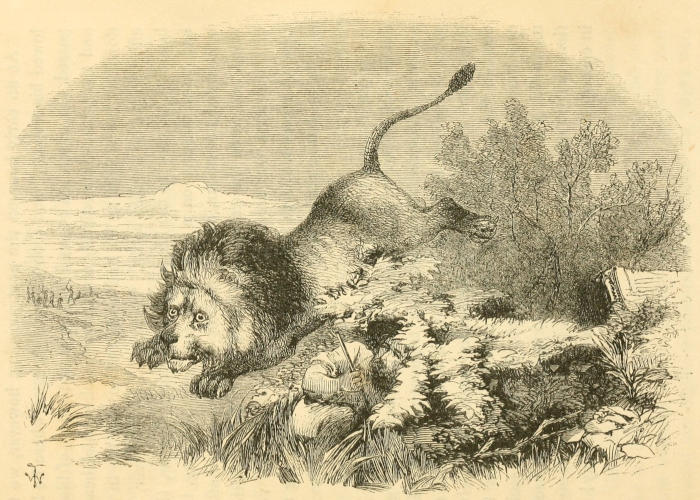

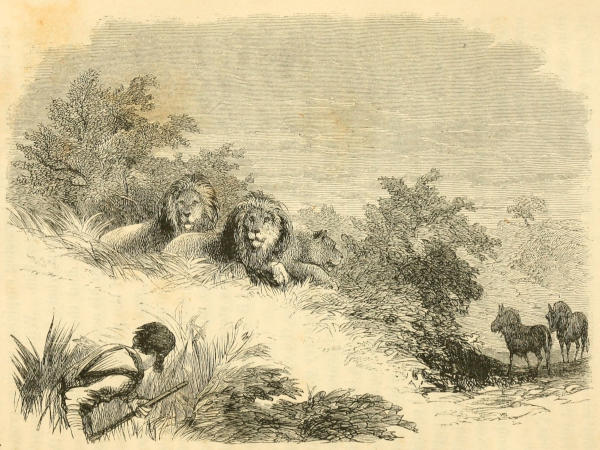

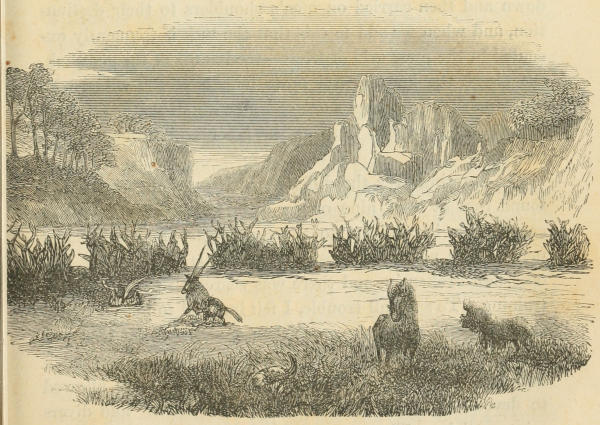

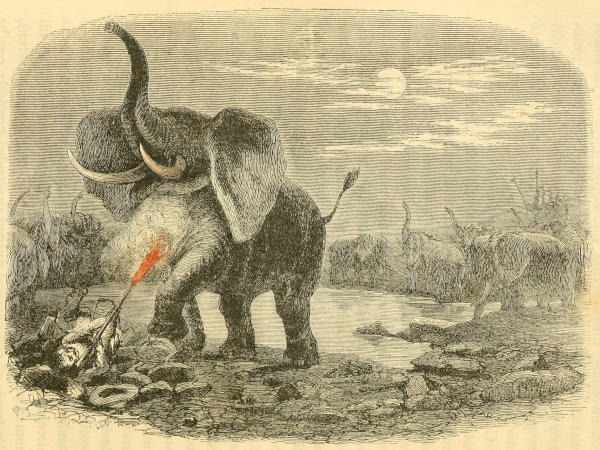

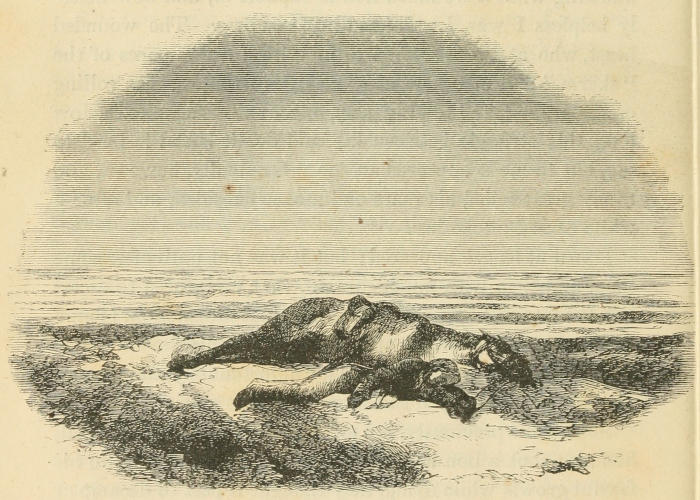

| Departure from Ghanzé.—Nectar in the Desert.—Difficulty in finding Water.—Arrive at Abeghan.—Unsuccessful Chase.—A “Charm.”—How to make the undrinkable drinkable.—An Elephant wounded and killed.—Bold and courageous Dog.—Kobis.—Author seized with a singular Malady.—Messengers dispatched to the Chief of the Lake Ngami.—A large troop of Elephants.—Author kills a huge Male.—Lions and Giraffe.—Author’s hair-breadth Escapes: from a black Rhinoceros; from a white Rhinoceros; from two troops of Elephants; he shoots a couple of his Adversaries.—Where to aim at an Elephant | 386 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| Timbo’s Return from the Lake; his Logic; he takes the Law in his own Hands.—Calf of Author’s Leg goes astray.—A troop of Elephants.—Author is charged by one of them, and narrowly escapes Death.—He shoots a white Rhinoceros.—He disables a black Rhinoceros.—He is charged and desperately bruised and wounded by[xv] the latter.—He saves the Life of his Attendant, Kamapyu.—Author again charged by the Rhinoceros, and escapes Destruction only by the opportune Death of his Antagonist.—Reflections.—He starts for the Ngami | 402 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Start from Kobis.—Meet Bechuanas.—False Report.—Wonderful Race of Men.—The Baobob-tree.—The Ngami.—First Impressions of the Lake.—Reflections.—Experience some Disappointment.—Reach the Zouga River and encamp near it.—Interview with Chief Lecholètébè.—Information refused.—Immoderate Laughter.—Presents to the Chief.—His Covetousness.—His Cruelty.—Formidable Difficulties.—Author permitted to proceed northward | 413 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| The Ngami.—When discovered.—Its various Names.—Its Size and Form.—Great Changes in its Waters.—Singular Phenomenon.—The Teoge River.—The Zouga River.—The Mukuru-Mukovanja River.—Animals.—Birds.—Crocodiles.—Serpents.—Fish | 423 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

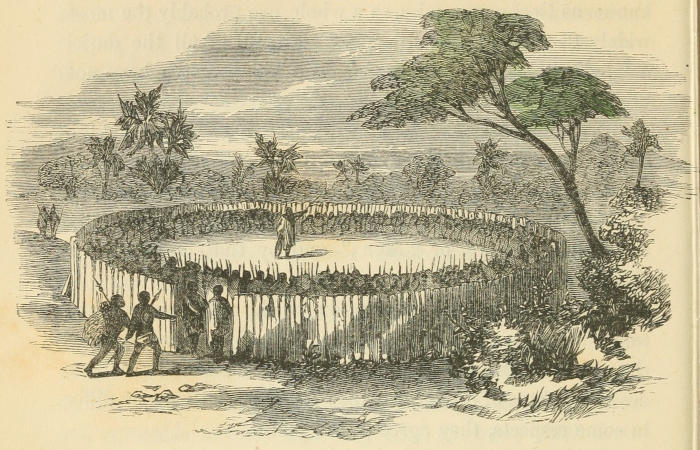

| The Batoana.—Government.—Eloquence.—Language.—Mythology.—Religion.—Superstition.—The Rain-maker.—Polygamy.—Circumcision.—Burial.—Disposition of the Bechuanas.—Thievish Propensities.—Dress.—Great Snuff-takers.—Smoking.—Occupations.—Agriculture.—Commerce.—Hunting and Fishing | 436 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

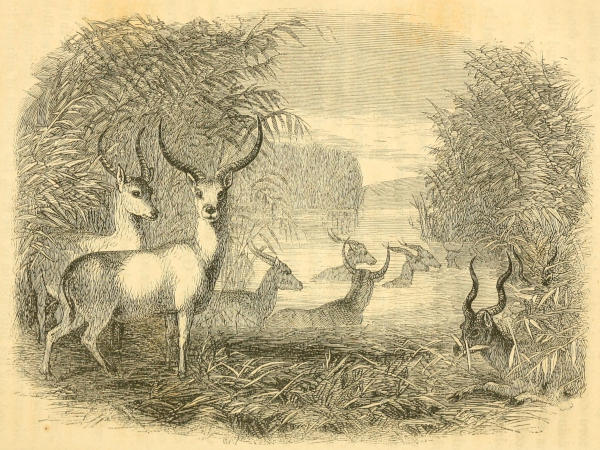

| Departure for Libèbé.—The Canoe.—The Lake.—Reach the Teoge.—Adventure with a Leché.—Luxurious Vegetation.—Exuberance of animal Life.—Buffaloes.—The Koodoo.—His Haunts.—Pace.—Food.—Flesh.—Hide.—Disposition.—Gregarious Habits.—The Chase | 456 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

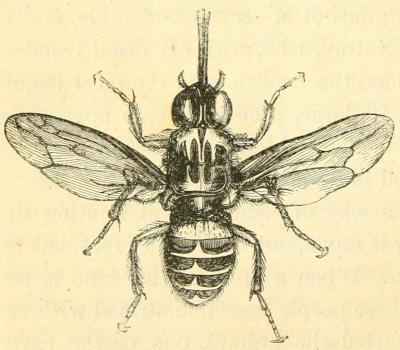

| Tsetse Fly.—Confined to particular Spots.—Its Size.—Its Destructiveness.—Fatal to Domestic Animals.—Symptoms in the Ox when bitten by the Tsetse | 468 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| The Crocodile.—An Englishman killed by one of these Monsters.—The Omoroanga Vavarra River.—Hardships.—Beautiful Scenery.—Lecholètébè’s Treachery.—The Reed-ferry | 471[xvi] |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| The Bayeye.—Their Country; Persons; Language; Disposition; Lying and Pilfering Habits.—Polygamy practiced among the Bayeye.—Their Houses; Dress; Ornaments; Weapons; Liquors; Agriculture; Grain; Fruits; Granaries.—Hunting.—Fishing.—Nets.—Diseases.—The Matsanyana.—The Bavicko.—Libèbé | 476 |

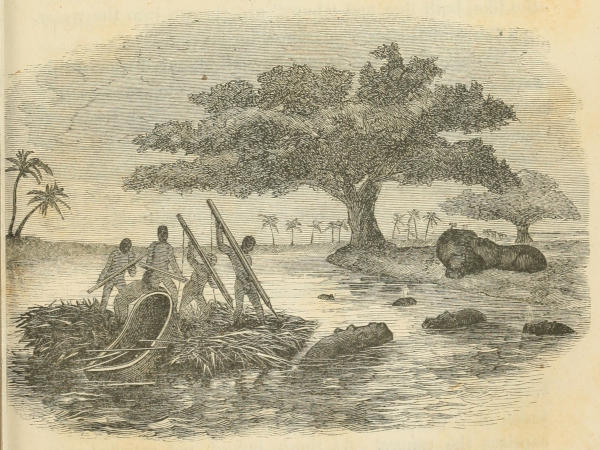

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| Departure from the Bayeye Werft.—The Reed-raft.—The Hippopotamus.—Behemoth or Hippopotamus.—Where found.—Two Species.—Description of Hippopotamus.—Appearance.—Size.—Swims like a Duck.—Food.—Destructive Propensities of the Animal.—Disposition.—Sagacity.—Memory.—Gregarious Habits.—Nocturnal Habits.—Domestication.—Food.—Flesh.—Hide.—Ivory.—Medicinal Virtues | 485 |

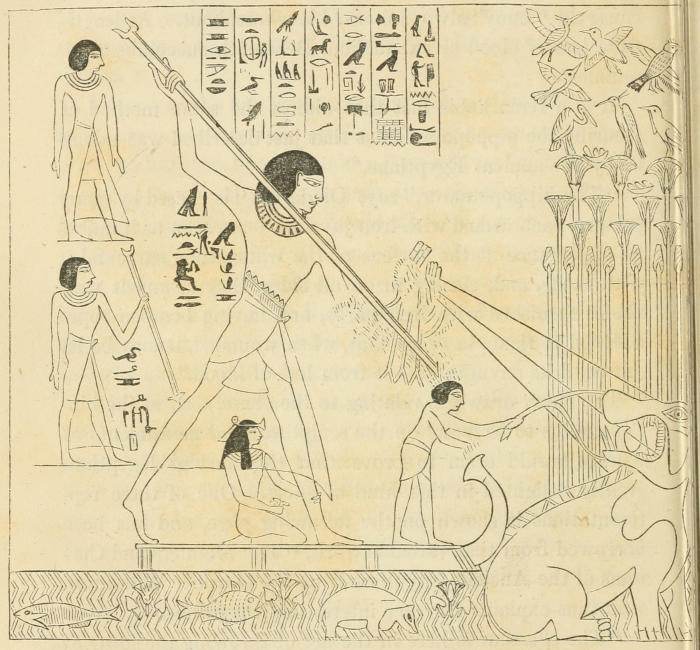

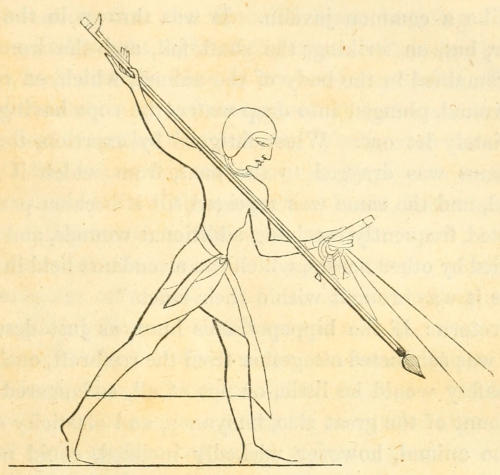

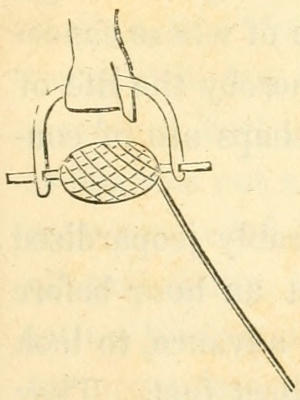

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

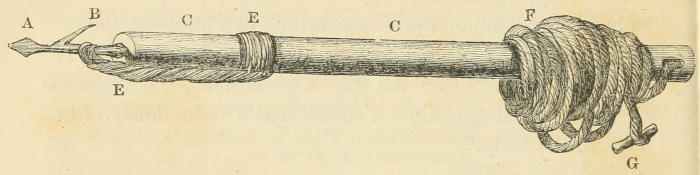

| The Bayeye harpoon the Hippopotamus.—The Harpoon described.—How the Chase of the Hippopotamus is conducted by the Bayeye.—How it was conducted by the ancient Egyptians.—The Spear used by them.—Ferocity of the Hippopotamus.—Killed by Guns.—Frightful Accident.—The Downfall | 495 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| Return to the Lake.—The Author starts for Namaqua-land to procure Wagons.—Night Adventure with a Lion.—Death of the Beast.—Sufferings of the Author | 506 |

| Page | |

| LIONS PULLING DOWN GIRAFFE | To face Title. |

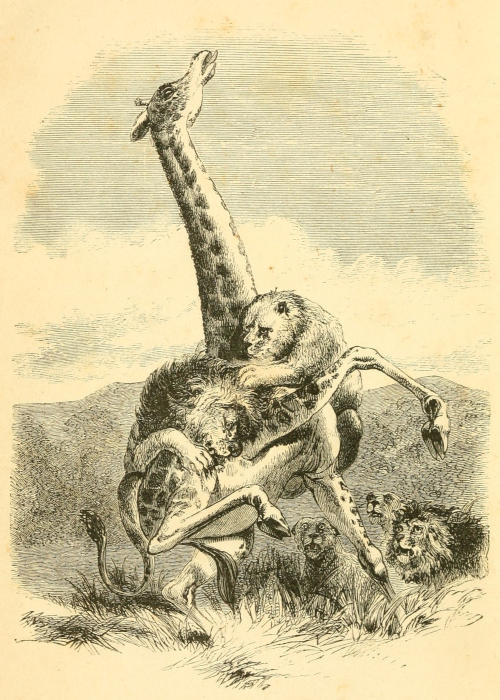

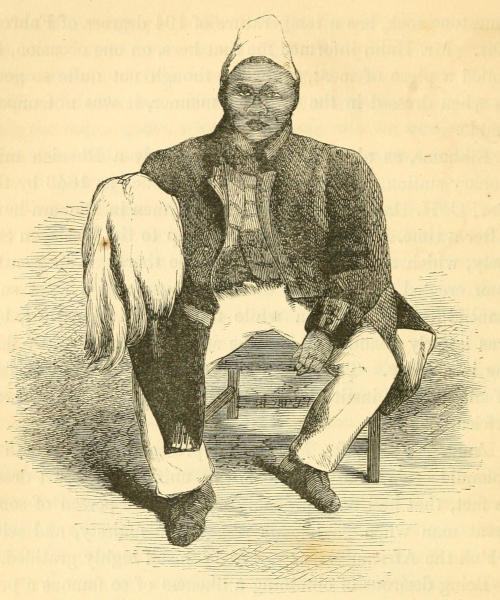

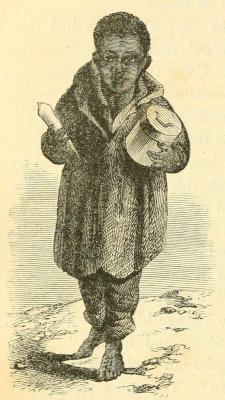

| MALAY | 24 |

| VIEW OF WALFISCH BAY | 30 |

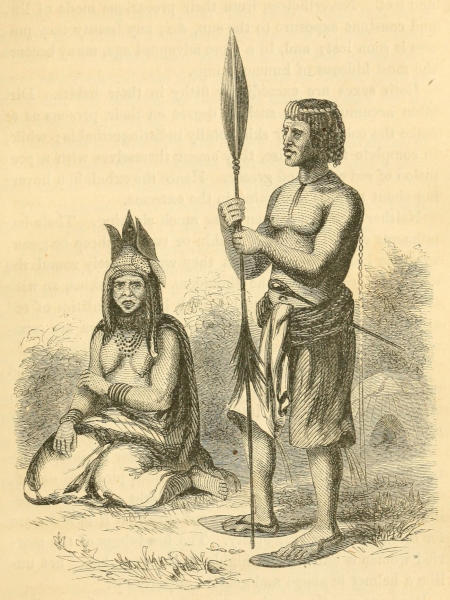

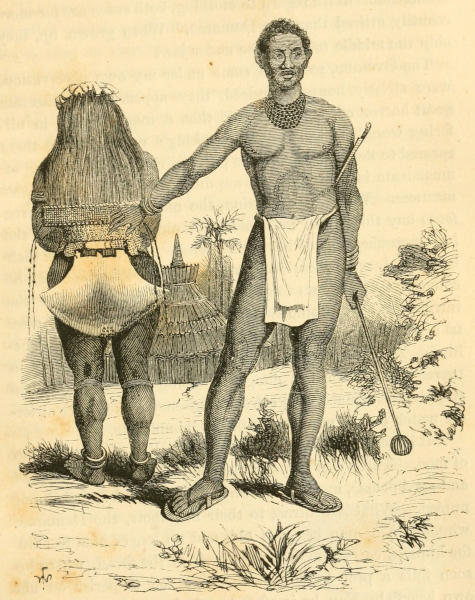

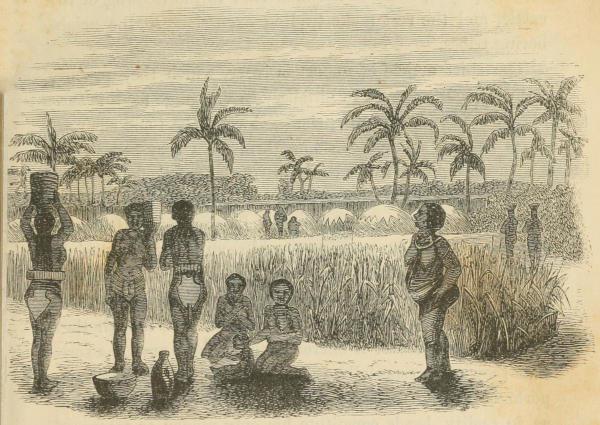

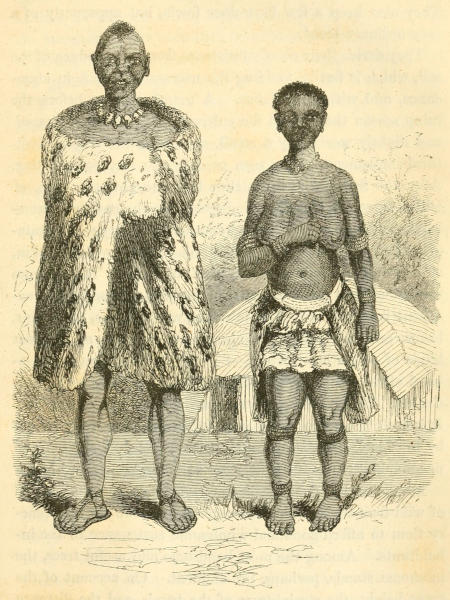

| DAMARAS | 63 |

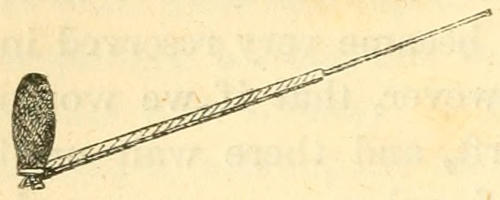

| HILL-DAMARA PIPE | 89 |

| THE LUCKY ESCAPE | 117 |

| SHOOTING-TRAP | 132 |

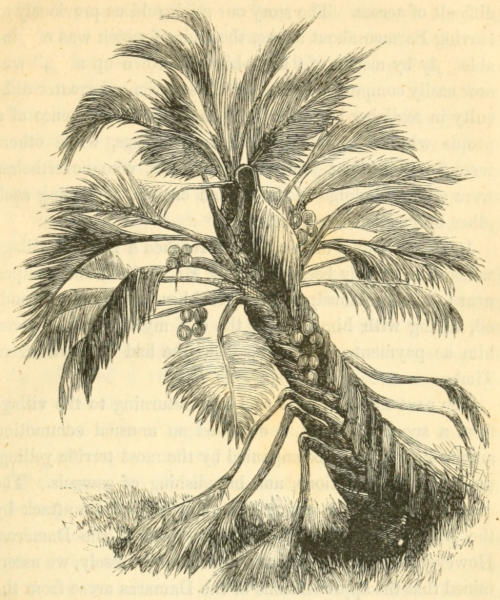

| FAN-PALM | 167 |

| OVAMBO PIPE | 174 |

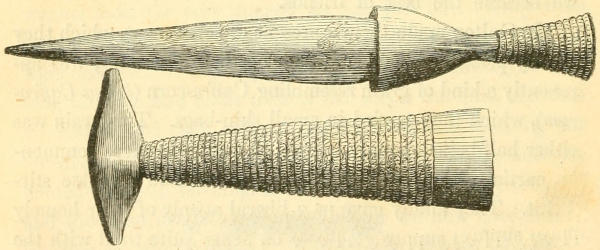

| OVAMBO DAGGER AND SHEATH | 174 |

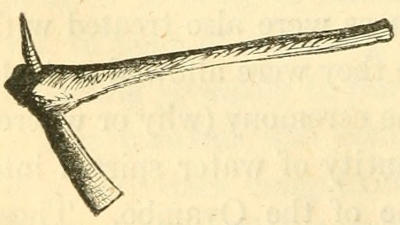

| OVAMBO HATCHET | 174 |

| OVAMBO BASKET FOR MERCHANDISE | 174 |

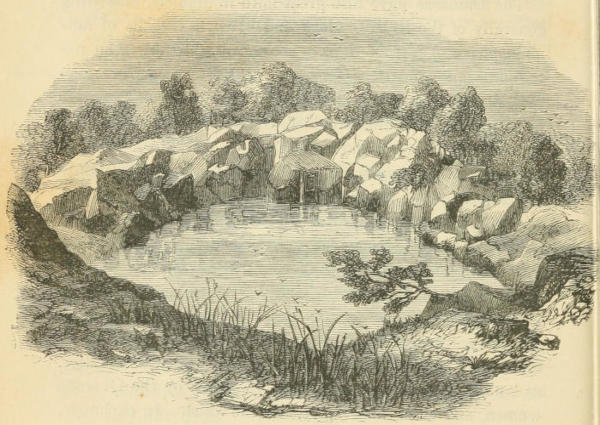

| OTJIKOTO FOUNTAIN | 180 |

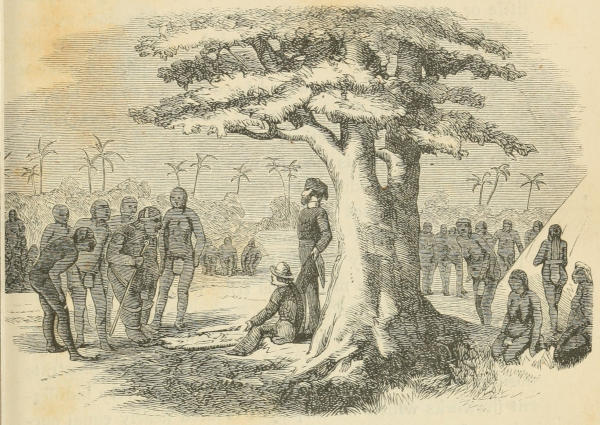

| INTERVIEW WITH KING NANGORO | 191 |

| OVAMBO BEER-CUP AND BEER-SPOON | 193 |

| OVAMBO GUITAR | 193 |

| OVAMBO | 195 |

| OVAMBO MEAT-DISH | 197 |

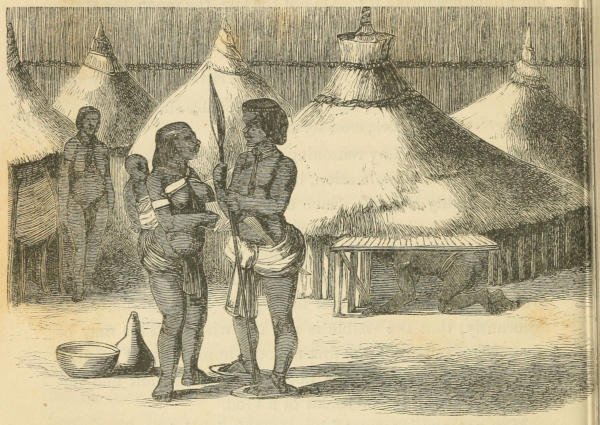

| OVAMBO DWELLING-HOUSE AND CORN-STORES | 200 |

| VIEW IN ONDONGA | 201 |

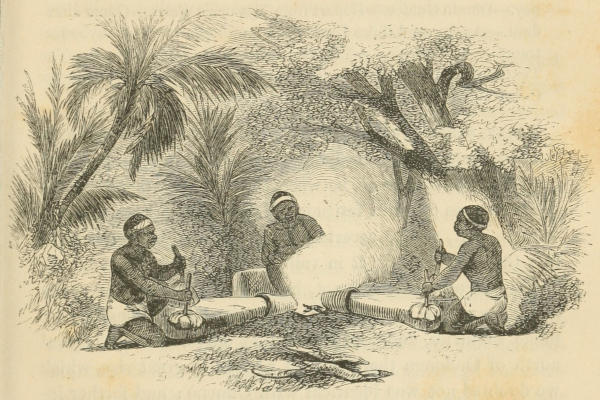

| OVAMBO BLACKSMITHS AT WORK | 203 |

| UNWELCOME HUNTING COMPANIONS | 211 |

| DAMARA GRAVE | 224 |

| JONKER AFRIKANER | 232 |

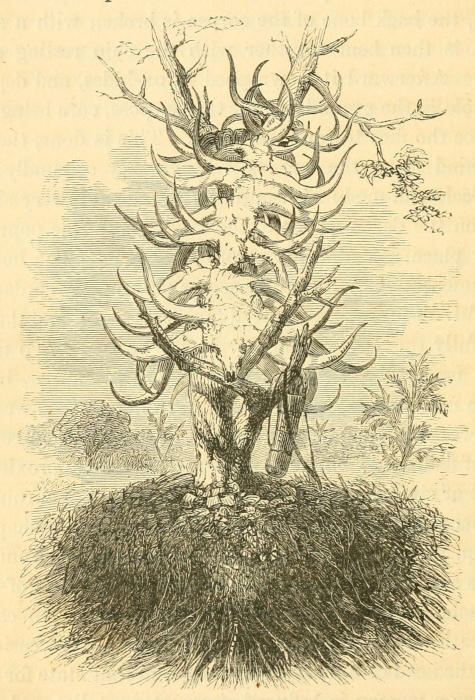

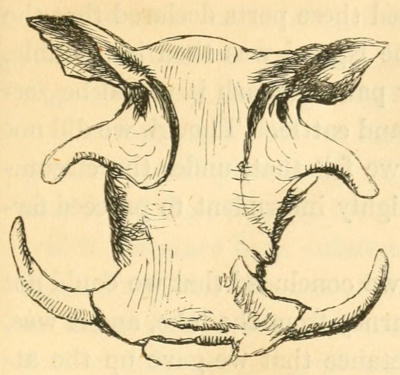

| WILD BOAR’S HEAD | 233 |

| COURSING YOUNG OSTRICHES | 249 |

| ORYX OR GEMSBOK | 273 |

| SKULL OF A BECHUANA OX | 308 |

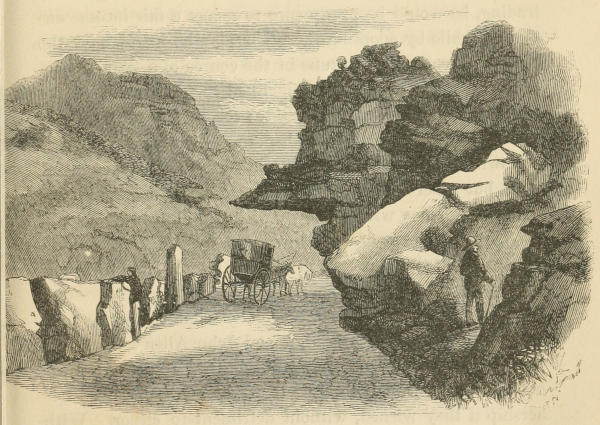

| DACRE’S PULPIT | 333 |

| NEGRO BOY | 338 |

| PITFALLS | 361 |

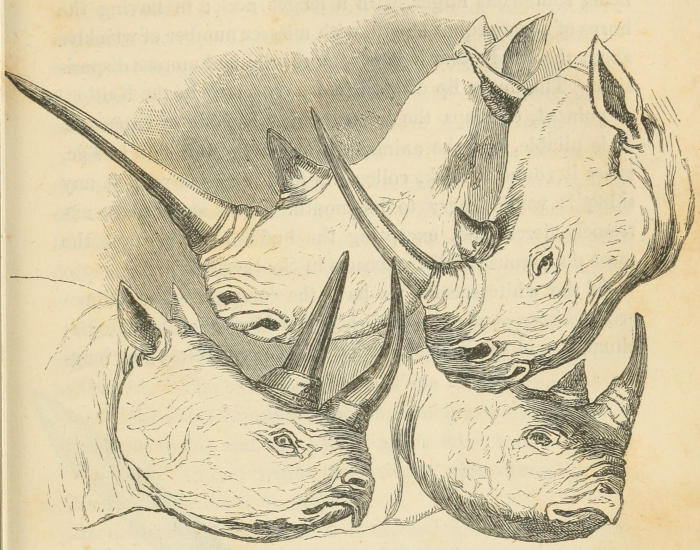

| HEADS OF RHINOCEROSES | 371 |

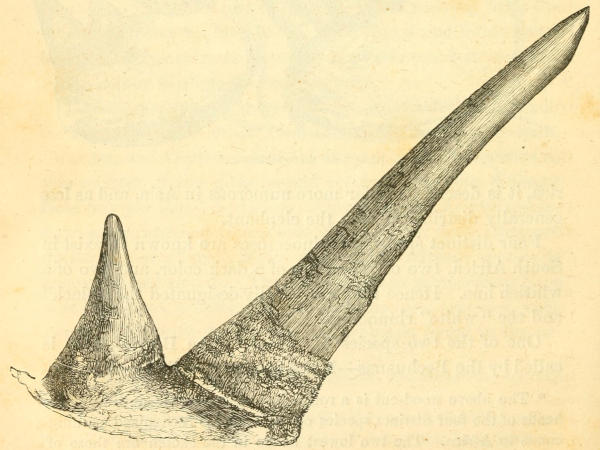

| HORNS OF RHINOCEROS OSWELLII | 372[xviii] |

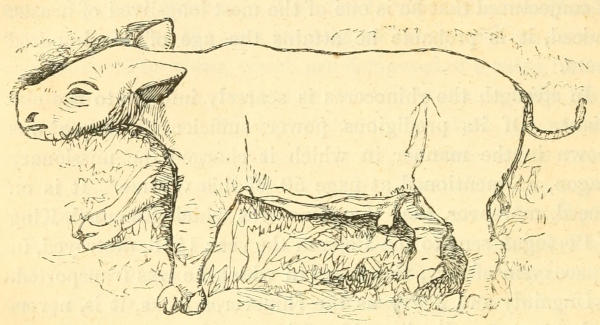

| FŒTUS OF RHINOCEROS KEITLOA | 376 |

| THE APPROACH OF ELEPHANTS | 398 |

| MORE CLOSE THAN AGREEABLE | 406 |

| DESPERATE SITUATION | 409 |

| NAKONG AND LECHÉ | 432 |

| THE BECHUANA PICHO | 438 |

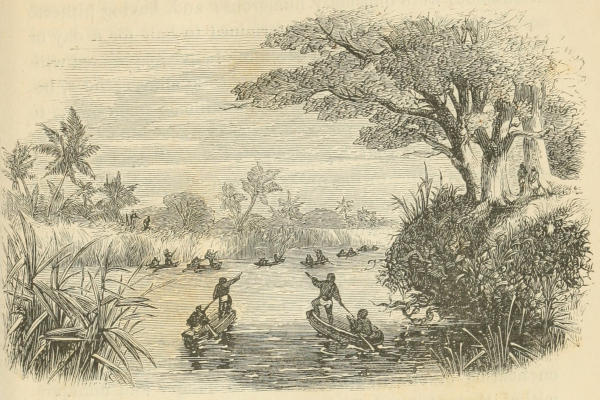

| ASCENDING THE TEOGE | 461 |

| TSETSE FLY | 468 |

| THE REED-FERRY | 476 |

| BAYEYE | 481 |

| MEDAL | 493 |

| HIPPOPOTAMUS HARPOON | 496 |

| THE REED-RAFT AND HARPOONERS | 497 |

| THE SPEAR | 498 |

| EGYPTIANS AND HIPPOPOTAMUS | 500 |

| THE SPEAR | 501 |

| THE REEL | 501 |

| THE DOWNFALL | 505 |

| AUTHOR AND STEED BROKEN DOWN | 510 |

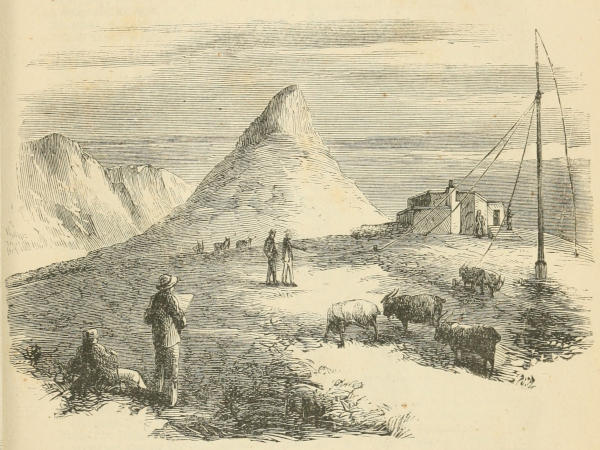

| SIGNAL STATION AT CAPE-TOWN | 511 |

Departure from Sweden.—Day-dreams.—Fraternal Love.—A tempting Offer.—Preparations for Journey to Africa.—Departure from England.—Arrival at the Cape.—Town and Inhabitants.—Table Mountain.—Curious Legend.—Preparation for Journey into the Interior.—Departure for Walfisch Bay.

It was at the close of the year 1849 that I left Gothenbourg, in a sailing vessel, for Hull, at which place I arrived in safety, after a boisterous and somewhat dangerous passage of about fourteen days’ duration. Though a Swede by birth, I am half an Englishman by parentage; and it was with pleasure that I visited, for the second time, a country endeared to me by the ties of kindred and the remembrance of former hospitality.

My stay in England, however, was intended to be only of short duration. I carried with me thither a considerable collection of living birds and quadrupeds, together with numerous preserved specimens of natural history, the produce of many a long hunting excursion amid the mountains, lakes, and forests of my native country. These I was anxious to dispose of in England, and then proceed in my travels, though to what quarter of the globe I had scarcely yet determined.

From my earliest youth, my day-dreams had carried me into the wilds of Africa. Passionately fond of traveling, accustomed from my childhood to field sports and to the study of natural history, and (as I hope I may say with truth) desirous of rendering myself useful in my generation, I earnestly[20] longed to explore some portion of that continent where all my predilections could be fully indulged, and where much still remained in obscurity which might advantageously be brought to light. The expense, however, of such a journey was to me an insurmountable obstacle. I had, therefore, long since given up all idea of making it, and had turned my thoughts northward to Iceland, a country within my reach, and where I purposed studying the habits and characteristics of the rarer species of the northern fauna. While at Hull, accordingly, I consulted some whaling captains on the subject of my enterprise, and had almost completed my arrangements, when a visit to London, on some private affairs, entirely changed my destination.

Before leaving Hull I witnessed a striking example of that attachment toward each other so frequently found to exist in the most savage animals. By the kindness of the secretary, I had been permitted to place my collection in the gardens of the Hull Zoological Society. Among others were two brown bears—twins—somewhat more than a year old, and playful as kittens when together. Indeed, no greater punishment could be inflicted upon these beasts than to disunite them for however short a time. Still, there was a marked contrast in their dispositions. One of them was good-tempered and gentle as a lamb, while the other frequently exhibited signs of a sulky and treacherous character. Tempted by an offer for the purchase of the former of these animals, I consented, after much hesitation, to his being separated from his brother.

It was long before I forgave myself this act. On the following day, on my proceeding, as usual, to inspect the collection, one of the keepers ran up to me in the greatest haste, exclaiming, “Sir, I am glad you are come, for your bear has gone mad!” He then told me that, during the night, the beast had destroyed his den, and was found in the morning roaming wild about the garden. Luckily, the keeper[21] managed to seize him just as he was escaping into the country, and, with the help of several others, succeeded in shutting him up again. The bear, however, refused his food, and raved in so fearful a manner that, unless he could be quieted, it was clear he would do some mischief.

On my arrival at his den, I found the poor brute in a most furious state, tearing the wooden floor with his claws, and gnawing the barricaded front with his teeth. I had no sooner opened the door than he sprang furiously at me, and struck me repeated blows with his powerful paws. As, however, I had reared him from a cub, we had too often measured our strength together for me to fear him now; and I soon made him retreat into the corner of his prison, where he remained howling in the most heartrending manner. It was a most sickening sight to behold the poor creature with his eyes bloodshot, and protruding from the sockets; his mouth and chest white with foam, and his body crusted with dirt. I am not ashamed to confess that at one time I felt my own eyes moistened. Neither blows nor kind words were of any effect: they only served to irritate and infuriate him; and I saw clearly that the only remedy would be, either to shoot him, or to restore him to his brother’s companionship. I chose the latter alternative; and the purchaser of the other bear, my kind friend Sir Henry Hunloke, on being informed of the circumstance, consented to take this one also.

Shortly after my arrival in London, Sir Hyde Parker, another valued friend of mine, and “The King of Fishermen,” introduced me to Mr. Francis Galton, who was then just on the point of undertaking an expedition to Southern Africa; his intention being to explore the unknown regions beyond the boundary of the Cape of Good Hope Colony, and to penetrate, if possible, to the recently discovered Lake Ngami. Upon finding that I also had an intention of traveling, and that our tastes and pursuits were in many respects similar, he proposed to me to give up my talked-of trip to the far[22] north, and accompany him to the southward; promising, at the same time, to pay the whole of my expenses. This offer awoke within me all my former ambition; and, although I could not be blind to the difficulties and dangers that must necessarily attend such an expedition, I embraced, after some hesitation, Mr. Galton’s tempting and liberal proposal.

Preparations for our long and hazardous journey were now rapidly made. An immense quantity of goods of every kind was speedily amassed, intended partly for barter and partly for presents to barbarous chiefs. Muskets, long sword-knives, boar-spears, axes, hatchets, clasp and strike-light knives, Dutch tinder-boxes, daggers, burning-glasses, compasses, gilt rings (copper or brass), alarums, beads of every size and color, wolf-traps, rat-traps, old military dresses, cast-off embassador’s uniforms—these, and a host of other articles too various to enumerate, formed our stock in trade.

To the above we added, mostly for our own use, guns and rifles, a vast quantity of ammunition of all kinds, instruments for taking observations, arsenical and other preparations for preserving objects of natural history, writing materials, sketch-books, paints, pencils, canteens, knives, forks, dishes, &c.

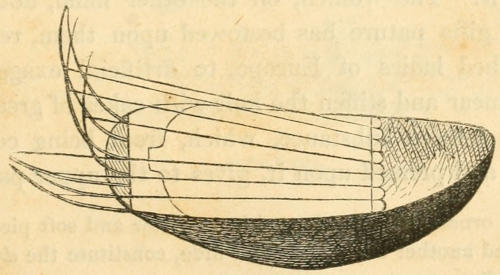

It was also deemed advisable that we should take with us boats for the navigation of Lake Ngami, those used by the natives being unsafe. We therefore supplied ourselves with three, each adapted for a specific purpose.

Having thus provided, as far as possible, for all emergences, we transferred ourselves and baggage on board the splendid but unfortunate ship, the Dalhousie.[1] Here we[23] found, to our dismay, in addition to a number of other passengers, several hundred emigrants, destined to the Cape of Good Hope. Instead, however, of these people proving, as we had at first anticipated, a great annoyance, we found that they contributed considerably toward enlivening and diverting us during a long and tedious passage.

I am not, however, about to inflict upon my readers the particulars of our voyage to the Cape. Suffice it to say that, after a few days’ delay at Plymouth, we put to sea in half a gale of wind, on the 7th of April, 1850, and experienced subsequently the usual vicissitudes of rough and smooth weather. At one time we were carried by a gentle breeze past the lovely island of Madeira, and so near as to distinguish its pleasant vineyards, and neat, pretty cottages, scattered over the mountain side to the very summit; at another we were driven so far westward by gales and adverse winds as to sight the coast of South America, until, at length, on the night of the 23d of June, the much-wished-for land was descried, and on the following noon we anchored safely in Table Bay, after a passage of eighty-six days—a time at least a third longer than the average. How truly welcome to my eyes, as we sailed into the bay, was the fine panoramic view of Cape-Town, with the picturesque Table Mountain rising immediately in the background!

Upon landing, we took up our quarters at Welch’s hotel. Our design was to stay a short time at Cape-Town, in order to obtain information respecting our intended route, and to procure whatever was still wanting for our journey. We then proposed to proceed by land northward, taking the course of the Trans-Vaal river. It will presently be seen, however, that our desires in this respect were entirely frustrated.

To give to an English reader a full description of Cape-Town would, indeed, be a superfluous task. I fear, also, that in some respects I should be found to differ from other travelers.

Cape-Town is generally described as a clean and neat place. With all due deference, I must dissent widely from this opinion. All the streets, for instance, are unpaved, and are, moreover, half filled with rubbish, swept from the shops and warehouses, until some friendly shower carries it away. Undoubtedly the town is regularly built, with broad streets, laid out at right angles to each other; but as almost every person of property resides in the country, few handsome dwelling-houses are to be met with—and by far the greater number are in the Dutch style. Here, however, as every where else where the English have obtained firm footing, improvements are very apparent; and, doubtless, now that the colony has obtained its own Legislature, such improvements will become still more visible.

No one can be at Cape-Town for a single day without being struck by the infinite variety of the human race encountered in the streets: Indians, Chinese, Malays, Caffres, Bechuanas, Hottentots, Creoles, “Afrikanders,” half-castes of many kinds, negroes of every variety from the east and west coasts of Africa, and Europeans of all countries, form the motley population of the place.

MALAY.

Of all these, with the exception of the Europeans, the Malays are by far the most conspicuous and important. They comprise, indeed, no inconsiderable portion of the inhabitants, and are, moreover, distinguished for their industry and sobriety. Many of them are exceedingly well off, and, not unfrequently, keep their carriages and horses. They profess the Mohammedan religion, and have their own clergy and places of worship. Two thirds of the week they work hard,[25] and devote the remainder to pleasure, spending much of their time and money on their dress, more especially the women. These latter seldom have any covering for the head; but the men tie round it a red handkerchief, over which they wear an enormous umbrella-shaped straw hat, admirably adapted to ward off the sun’s rays, but useless and inconvenient in windy weather.

The Malays are usually very honest; but, strange to relate, on a certain day of the year they exert their ingenuity in purloining their neighbors’ poultry, and, Spartan-like, do not consider this dishonorable, provided they are not detected in the fact:

To be at Cape-Town, without ascending the far-famed Table Mountain, was, of course, not to be thought of. The undertaking, however, is not altogether without danger. On the side of the town, access to the summit is only practicable on foot, and that by a narrow and slippery path; but on the opposite side the Table may be gained on horseback, though with some difficulty. The whole mountain side, moreover, is intersected by deep and numerous ravines, which are rendered more dangerous by the dense fogs that, at certain seasons of the year, arise suddenly from the sea.

One fine afternoon I had unconsciously approached the foot of the mountain, and the top looked so near and inviting, that, though the sun was fast sinking, I determined to make the ascent. At the very outset I lost the road; but, having been all my life a mountain-climber, I pushed boldly forward. The task, however, proved more difficult than I expected, and the sun’s broad disk had already touched the horizon when I reached the summit. Nevertheless, the magnificent panorama that now lay spread before me amply rewarded me for my trouble. It was, however, only for a very short time that I could enjoy the beautiful scene; darkness[26] was rapidly encroaching over the valley below; and as in these regions there is but one step from light to darkness, I was compelled to commence the descent without a moment’s delay. I confess that this was not done without some apprehension; for, what with the quick-coming night, and the terrible ravines that lay yawning beneath my feet, the task was any thing but agreeable. I found it necessary for safety to take off my boots, which I fastened to my waist; and at length, after much exertion, with hands torn, and trowsers almost in rags, I arrived late in the evening at our hotel, where they had begun to entertain some doubt of my safety. As a proof that my fears were not altogether groundless, a short time before this, a young man, who was wandering about the mountain in broad daylight, missed his footing, was precipitated down its sides, and brought in the next day a mutilated corpse.

When Europeans first arrived in the Cape Colony, it would appear that almost all the larger quadrupeds indigenous to Southern Africa existed in the neighborhood of Table Mountain. A curious anecdote is preserved in the archives of Cape-Town relating to the death of a rhinoceros, which, for its quaintness and originality, is perhaps worthy of record.

Once upon a time—so runs the legend—some laborers employed in a field discovered a huge rhinoceros immovably fixed in the quicksands of the salt river which is within a mile of the town. The alarm being given, a number of country people, armed with such weapons as were at hand, rushed to the spot with an intention of dispatching the monster. Its appearance, however, was so formidable, that they deemed it advisable to open their battery at a most respectful distance. But, seeing that all the animal’s efforts to extricate itself were fruitless, the men gradually grew more courageous, and approached much nearer. Still, whether from the inefficiency of their weapons, or want of skill, they were unable to make any impression on the tough and almost impenetrable hide[27] of the beast. At length they began to despair, and it was a question if they should not beat a retreat; when an individual, more sagacious than the rest, stepped forward, and suggested that a hole should be cut in the animal’s hide, by which means easy access might be had to its vitals, and they could then destroy it at their leisure! The happy device was loudly applauded; and though, I believe, the tale ends here, it may be fairly concluded that, after such an excellent recommendation, success could not but crown their endeavors.

We had now been at Cape-Town somewhat less than a week, and had already added considerably to the stock of articles of exchange, provisions, and other necessaries for our journey. To convey the immense quantity of luggage, we provided ourselves with two gigantic wagons, each represented to hold three or four thousand pounds’ weight, together with a sort of cart[2] for ourselves.

Mr. Galton bought also nine excellent mules, which could be used either for draft or packing; two riding horses; and, in addition to these, he secured about half a dozen dogs, which, if the truth be told, were of a somewhat mongrel description.

Mr. Galton also engaged the needful people to accompany us on our travels, such as wagon-drivers, herdsmen, cooks, &c., in all amounting to seven individuals.

Our preparations being now complete, we were about to set out on our journey, when, to our dismay, we received information which entirely overthrew our plans. It was reported to us that the Boers on the Trans-Vaal River (the very line of country we purposed taking) had lately turned back several traders and travelers who were on their way northward,[28] and had, moreover, threatened to kill any person who should attempt to pass through their territories with the intention of penetrating to Lake Ngami. This intelligence being equally unexpected and unwelcome, we were at a loss on what to decide. On asking the opinion of the Governor of the Cape, Sir Harry Smith, to whose kindness and hospitality we were, on several occasions, indebted, he strongly dissuaded us from attempting the route in question. “The Boers,” he said, “are determined men; and, although I have no fear for the safety of your lives, they will assuredly rob you of all your goods and cattle, and thus prevent your proceeding farther.” The counsel given us by his excellency settled the point. We were, however, determined not to be idle; but it was by no means easy to decide on what course to pursue. As the whole of the interior, by which a passage could be obtained to the lake, was either occupied by the Boers, or served as their hunting-ground, we were compelled to choose between the eastern and western coasts. The former of these, however, was well known to be infected by fevers fatal to Europeans; while the latter presented, for a considerable distance northward, nothing but a sandy shore, destitute of fresh water and vegetation. The country intervening between the western coast and the lake, moreover, was represented as very unhealthy.

While in this state of uncertainty, we made the acquaintance of a Mr. M⸺, who lately had an establishment at Walfisch Bay, on the west coast of Africa, about seven hundred geographical miles north of the Cape. He strongly recommended us to select this place as the starting-point for our journey into the interior, which opinion was confirmed by some missionaries whom we met in Cape-Town, and who had a settlement in the neighborhood of the bay in question.

This route was ultimately adopted by us; but, as vessels only frequented Walfisch Bay once or twice in the course of every two years, Mr. Galton at once chartered a small schooner,[29] named the Foam, the sixth part of the expense of which was defrayed by the missionaries referred to, who were anxious not only to forward some supplies, but to obtain a passage for a young member of their society, the Rev. Mr. Schöneberg, who was about proceeding on a mission of peace and good-will into Damara-land.

As our plans were now so entirely changed, and as we were about to travel through an almost unknown region, we thought it expedient to disencumber ourselves of whatever could in any way be spared. We left, accordingly, at the Cape, among other things, two of our boats; taking with us, however, the other, a mackintosh punt, as being light and portable, hoping some day or other to see her floating on the waters of the Ngami.

Our arrangements being finished, and the goods, &c., shipped, we unfurled our sails on the 7th of August, and bade farewell to Cape-Town, where, during our short stay, we had experienced much kindness and hospitality.

Arrival at Walfisch Bay.—Scenery.—Harbor described.—Want of Water.—Capabilities for Trade.—Fish.—Wild-fowl.—Mirage.—Sand Fountain.—The Bush-tick.—The Naras.—Quadrupeds scarce.—Meeting the Hottentots.—Their filthy Habits.—The Alarum.—The Turn-out.—Death of a Lion.—Arrival at Scheppmansdorf.—The Place described.—Mr. Bam.—Missionary Life.—Ingratitude of Natives.—Missionary Wagons.

In the afternoon of the 20th of August we found ourselves safely anchored at the entrance of Walfisch Bay. From the prevalence of southerly winds, this voyage seldom occupies more than a week, but on the present occasion we were double that time performing it.

The first appearance of the coast, as seen from Walfisch Bay, is little calculated to inspire confidence in the traveler[30] about to penetrate into the interior. A desert of sand, bounded only by the horizon, meets the eye in every quarter, assuming, in one direction, the shape of dreary flats; in another, of shifting hillocks; while in some parts it rises almost to the height of mountains.

VIEW OF WALFISCH BAY.

Walfisch Bay has been long known to Europeans, and was once hastily surveyed by Commodore Owen, of the Royal Navy. It is a very spacious, commodious, and comparatively safe harbor, being on three sides protected by a sandy shore. The only winds to which it is exposed are N. and N.W.; but these, fortunately, are not of frequent occurrence. Its situation is about N. and S. The anchorage is good. Large ships take shelter under the lee of a sandy peninsula, the extremity of which is known to navigators by the name of “Pelican Point.” Smaller craft, however, ride safely within less than half a mile of the shore.

The great disadvantage of Walfisch Bay is that no fresh water can be found near the beach; but at a distance of three miles inland abundance may be obtained, as also good pasturage for cattle. I mention this circumstance as being essential to the establishment of any cattle-trade in future.

During the time the guano trade flourished on the west coast of Africa, Walfisch Bay was largely resorted to by vessels of every size, chiefly with a view of obtaining fresh provisions. At that period, certain parties from the Cape had an establishment here for the salting and curing of beef. They, moreover, furnished the guano-traders, as also Cape-Town,[31] with cattle; and had, in addition, a contract with the British government for supplying St. Helena with live-stock. The latter speculation proved exceedingly lucrative for a time, and a profit of many hundred per cent. was said to be realized. From some mismanagement, however, the contract for St. Helena was thrown up by the government, and the parties in question were fined a large sum of money for its non-fulfillment. Shortly afterward the establishment was broken up, and for several years the house and store remained unoccupied; but they are now again tenanted by people belonging to merchants from Cape-Town.

Walfisch Bay affords an easy and speedy communication with the interior. By the late explorations of Mr. Galton and myself in that quarter, we have become acquainted with many countries previously unknown, or only partially explored, to which British commerce might easily be extended.

Walfisch Bay and the neighborhood abounds with fish of various kinds: at certain seasons, indeed, it is much frequented by a number of the smaller species of whale, known by the name of “humpbacks,” which come here to breed. Several cargoes of oil, the produce of this fish, have been already exported.

At the inner part of the harbor, a piece of shallow water extends nearly a mile into the interior, and is separated from the sea, on the west side, by Pelican Point. This lagoon teems with various kinds of fish, and at low water, many that have lingered behind are left sprawling helplessly in the mud. At such times, the natives are frequently seen approaching; and, with a gemsbok’s horn affixed to a slender stick, they transfix their finny prey at leisure. Even hyænas and jackals seize such opportunities to satisfy their hunger.

Walfisch Bay is frequented by immense numbers of water-fowl, such as geese, ducks, different species of cormorants, pelicans, flamingoes, and countless flocks of sandpipers. But, as the surrounding country is every where open, they are difficult[32] of approach. Nevertheless, with a little tact and experience, tolerably good sport may be obtained, and capital rifle-practice at all times. Hardly any of the water-fowl breed here.

Every morning, at daybreak, myriads of flamingoes, pelicans, cormorants, &c., are seen moving from their roosting-places in and about the bay, and flying in a northerly direction. About noon they begin to return to the southern portion of the bay, and continue arriving there, in an almost continuous stream, until nightfall.

The way in which the “duikers” (cormorants and shags) obtain their food is not uninteresting. Instead of hovering over their prey, as the gull, or waiting quietly for it in some secluded spot, like the kingfisher, they make their attacks in a noisy and exciting manner. Mr. Lloyd, in his “Scandinavian Adventures,” has given a very interesting account of the manner in which the Arctic duck (harelda glacialis, Steph.) procures its food; and, as it applies to the birds above named, I can not do better than quote him on the subject.

“The hareld is a most restless bird,” says he, “and perpetually in motion. It rarely happens that one sees it in a state of repose during the daytime. The flock—for there are almost always several in company—swim pretty fast against the wind; and the individuals comprising it keep up a sort of race with each other. Some of the number are always diving; and, as these remain long under water, and their comrades are going rapidly ahead in the mean while, they are, of course, a good way behind the rest on their reappearance at the surface. Immediately on coming up, therefore, they take wing, and, flying over the backs of their comrades, resume their position in the ranks, or rather fly somewhat beyond their fellows, with the object, as it would seem, of being the foremost of the party. This frequently continues across the bay or inlet, until the flock is “brought[33] up” by the opposing shore, when they generally all take wing and move off elsewhere.... ‘Fair play is a jewel,’ says the old saw, and so, perhaps, thinks the hareld; for it would really appear as if it adopted the somewhat curious manœuvre just mentioned to prevent its companions from going over the ground previously.”

The day after our arrival we moved our small craft within half a mile of the shore, and, as soon as she was safely anchored, we proceeded to reconnoitre the neighborhood. The first thing which attracted our attention was a mirage of the most striking character and intensity of effect. Objects, distant only a few hundred feet, became perfectly metamorphosed. Thus, for instance, a small bird would look as big as a rock, or the trunk of a tree; pelicans assumed the appearance of ships under canvas; the numerous skeletons and bones of stranded whales were exaggerated into clusters of lofty houses, and dreary and sterile plains presented the aspect of charming lakes. In short, every object had a bewildering and supernatural appearance, and the whole atmosphere was misty, tremulous, and wavy. This phenomenon is at all times very remarkable, but during the hot season of the year it is more surprising and deceptive. At an after period Mr. Galton tried to map the bay, but this mirage frustrated all his endeavors. An object that he had, perhaps, chosen for a mark, became totally indistinguishable when he moved to the next station.

On the beach we found a small house, constructed of planks, in tolerable preservation, which at high water was completely surrounded by the sea. This had originally been erected by a Captain Greybourn for trading purposes, but was now in the possession of the Rhenish Missionary Society. It was kindly thrown open to our use, and proved of the greatest comfort to us; for at this season the nights were bitterly cold, and the dew so heavy as completely to saturate every article of clothing that was exposed.

We had not been many minutes on shore when some half-naked, half-starved, cut-throat-looking savages made their appearance, armed with muskets and assegais. Nothing could exceed the squalid, wretched, and ludicrous aspect of these people, which was increased by a foolish endeavor to assume a martial bearing, no doubt with a view of making an impression on us. Without noticing either their weapons or swaggering air, and in order to disarm suspicion, we walked straight up to them, and shook hands with apparent cordiality. Our missionary friend, Mr. Schöneberg, then explained to them, by signs and gestures, that he wished to have a letter conveyed to Mr. Bam, his colleague, residing at Scheppmansdorf, some twenty miles off, in an easterly direction. It soon became apparent that they were accustomed to similar errands; for, on receiving a small gratuity of tobacco on the spot, with a promise of further payment on their return, they set out immediately, and executed their task with so much dispatch, that, before the dawn of next morning, Mr. Bam had arrived.

In the mean time, we made an excursion to a place called Sand Fountain, about three miles inland. On our way there we crossed a broad flat, which in spring tides is entirely flooded. In spite of this submersion, the tracks of wagons, animals, &c., of several years’ standing, were as clear and distinct as if imprinted but yesterday! At Sand Fountain we found another wooden house, but uninhabited, belonging to Mr. D⸺, a partner of Mr. M⸺. The natives had taken advantage of the absence of the owner to injure and destroy the few pieces of furniture left behind, and leaves of books and panes of window glass were wantonly strewn about the ground. We next visited the so-called “fountain,” which was hard by; but, instead of a copious spring—as the name of the place gave us reason to expect—we found, to our dismay, nothing but a small hole, some five or six inches in diameter, and half as many deep; the water, moreover,[35] was of so execrable a quality as to make it totally undrinkable. However, on cleaning away the sand, it flowed pretty freely, and we flattered ourselves that, by a little care and trouble, we might render it fit for use, if not exactly palatable.

After having thus far explored the country, we returned to the vessel. On the following morning, at daybreak, we set about landing our effects, mules, horses, &c., which was not done without some difficulty. As soon as the goods belonging to the missionary should have been removed to Scheppmansdorf, Mr. Bam most considerately promised to assist us with his oxen. In the interval—as there was no fresh water on the beach—we deemed it advisable to remove our luggage, by means of the mules, to Sand Fountain, where we should, at least, be able to obtain water—though bad of its kind—and be better off in other respects.

On the fourth day, the schooner which had conveyed us to Walfisch Bay set sail for the Cape, leaving us entirely to our own resources on a desert coast, and—excepting the several missionary stations scattered over the country—at several months’ tedious journey by land to the nearest point of civilization.

On returning to Sand Fountain, our first care was to sink an old perforated tar-barrel in a place dug for the purpose; but instead of improving the quality of the water, it only made matters worse! Fortunately, we had taken the precaution to bring with us from the Cape a “copper distiller;” but the water, even thus purified, could only be used for cooking, or making very strong coffee and tea. Strange enough, when the owner of the house resided here, water was abundant and excellent; but the spot where it was obtained was now hidden from view by an immense sand-hill, which defied digging.

At Sand Fountain we had the full benefit of the sea-breeze, which made the temperature very agreeable, the thermometer[36] never exceeding seventy-five degrees in the shade at noon. The sand, however, was a cruel annoyance, entering into every particle of food, and penetrating our clothes to the very skin. But we were subjected to a still more formidable inconvenience; for, besides myriads of fleas, our encampment swarmed with a species of bush-tick, whose bite was so severe and irritating as almost to drive us mad. To escape, if possible, the horrible persecutions of these bloodthirsty creatures, I took refuge one night in the cart, and was congratulating myself on having at last secured a place free from their attacks. But I was mistaken. I had not been long asleep before I was awakened by a disagreeable irritation over my whole body, which shortly became intolerable; and, notwithstanding the night air was very sharp, and the dew heavy, I cast off all my clothes, and rolled on the icy-cold sand till the blood flowed freely from every pore. Strange as it may appear, I found this expedient serviceable.

On another occasion, a bush-tick, but of a still more poisonous species, attached itself to one of my feet; and, though a stinging sensation was produced, I never thought of examining the part, till one day, when enjoying the unusual luxury of a cold bath, I accidentally discovered the intruder deeply buried in the flesh, and it was only with very great pain that I succeeded in extracting it, or rather its body, for the head remained in the wound. The poisonous effect of its bite was so acrimonious as to cause partial lameness for three following months!

The bush-tick does not confine its attacks to men only, for it attaches itself with even greater pertinacity to the inferior animals. Many a poor dog have I seen killed by its relentless persecutions; and even the sturdy ox has been known to succumb under the poisonous influence of these insects.[3]

Sand Fountain, notwithstanding its disagreeable guests, had its advantages. Almost every little sand-hillock thereabout was covered with a “creeper,” which produced a kind of prickly gourd (called by the natives naras), of the most delicious flavor. It is about the size of an ordinary turnip (a Swede), and, when ripe, has a greenish exterior, with a tinge of lemon. The interior, again, which is of a deep orange color, presents a most cooling, refreshing, and inviting appearance. A stranger, however, must be particularly cautious not to eat of it too freely, as otherwise it produces a peculiar sickness, and great soreness of the gum and lips. For three or four months in the year it constitutes the chief food of the natives.

The naras contains a great number of seeds, not unlike a peeled almond in appearance and taste, and being easily separated from the fleshy parts, they are carefully collected, exposed to the sun, dried, and then stored away in little skin bags. When the fruit fails, the natives have recourse to the seeds, which are equally nutritious, and perhaps even more wholesome. The naras may also be preserved by being boiled. When of a certain consistency, it is spread out into thin cakes, in which state it presents the appearance of brown moist sugar, and may be kept for almost any length of time. These cakes are, however, rather rich and luscious.

But it is not man alone that derives benefit from this remarkable plant, for every animal, from the field-mouse to the ox, and even the feline and canine race, devour it with great avidity. Birds[4] are also very partial to it, more especially ostriches, who, during the naras season, are found in great abundance in these parts.

It is in such instances, more especially, that the mind becomes powerfully impressed with the wise provisions of nature, and the great goodness of the Almighty, who even from the desert raises good and wholesome sustenance for man and all his creatures.

In this barren and poverty-stricken country, food is so scarce that, without the naras, the land would be all but uninhabitable. The naras serves, moreover, a double purpose; for, besides its usefulness as food, it fixes with wonderful tenacity, by means of extensive ramifications, the constantly shifting sands; it is, indeed, to those parts what the sand-reed (ammophila arundinacia) is to the sandy shores and downs of England.

The naras only grows in the bed of the Kuisip River, in the neighborhood of the sea. A few plants are to be met with at the mouth of the Orange River, as also, according to Captain Messum, in a few localities between the Swakop and the Nourse River.

The general aspect of the country about Sand Fountain is very dreary and desolate. The soil is entirely composed of sand. The vegetation, moreover, is stunted in the extreme, consisting chiefly of the above-mentioned creeper, a species of tamarisk tree (or rather bush), and a few dew-plants. Consequently, the animal world, as might be expected, did not present any great variety. Nevertheless, being an enthusiastic sportsman, and devoted to the study of natural history, I made frequent short excursions into the neighborhood, on which occasions my spoils consisted for the most part of some exquisitely beautiful lizards, a few long-legged beetles, and some pretty species of field-mice. Once in a time, moreover, I viewed a solitary gazelle in the distance.

A few miles from our encampment resided a small kraal of Hottentots, under the chief Frederick, who occasionally brought us some milk and a few goats as a supply for the larder, in exchange for which they received old soldiers’ coats (worth sixpence a piece), handkerchiefs, hats, tobacco, and a variety of other trifling articles. But they infinitely preferred to beg, and were not the least ashamed to ask for even the shirt on one’s back.

These men were excessively dirty in their habits. One fine morning I observed an individual attentively examining his caross, spread out before him in a sunny and sheltered spot. On approaching him, in order to ascertain the cause of his deep meditation, I found, to my astonishment and disgust, that he was feasting on certain loathsome insects, that can not with propriety be named to ears polite. This was only one instance out of a hundred that might be named of their filthy customs.

As Frederick the chieftain, and a few of his half-starved and Chinese-featured followers, were one day intently watching the process of our packing and unpacking divers trunks, I placed alongside of him, as if by accident, a small box-alarum, and then resumed my employment. On the first shrill sound of the instrument, our friend leaped from his seat like one suddenly demented; and during the whole time the jarring notes continued, he remained standing at a respectful distance, trembling violently from head to foot.

As no draft cattle could be obtained in the neighborhood, nor, indeed, within a less distance than from one hundred and fifty to two hundred miles, Mr. Galton started on an excursion into the interior with a view of obtaining a supply.

His “turn-out” was most original, and would have formed an excellent subject for a caricature. From both ends of the cart with which he made the journey protruded a number of common muskets and other articles intended for barter. The mules harnessed to the vehicle kept up a most discordant concert,[40] viciously kicking out to the right and left. The coachman, bathed in perspiration, kept applying his immense Cape-whip to their flanks with considerable unction, while a man sitting alongside of him on the front seat abused the stubborn animals with a burst of all the eloquent epithets contained in the Dutch-Hottentot vocabulary. Two sulky goats, tied to the back of the cart, were on the point of strangling themselves in their endeavors to escape. To complete the picture, Galton himself, accompanied by half a dozen dogs of nondescript race, toiled on cheerfully through the deep sand by the side of the vehicle, smoking a common clay pipe.

On my friend’s arrival at Scheppmansdorf, however, he found it necessary to adjourn his trip into the interior for a few days.

In the mean time, as Mr. Bam’s oxen had arrived at Sand Fountain, I busied myself with conveying the baggage to Scheppmansdorf; but, on account of its great weight and bulk, and the badness of the road, this occupation lasted several days. In the last trip we had so overloaded the wagons, that, after about three miles, the oxen came to a dead stand-still. The two teams were now yoked to one of the vehicles, and it proceeded on its way without further interruption, while I remained alone in charge of the other. It was agreed that some of the men should return with the cattle on the following night; but, on arriving at Scheppmansdorf, they and the oxen were so exhausted that it was found necessary to give both the one and the other two days’ rest. For this delay I was not at all prepared. My small supply of water had been exhausted on the second day, and I began, for the first time in my life, to experience the misery of thirst. I was, however, fortunately relieved from my embarrassing situation by the arrival of a Hottentot, who, for a trifling consideration, brought me an ample supply of water.

At length all the baggage was safely deposited at Scheppmansdorf, where I rejoined Mr. Galton.

He had not, I found, been many days at that place, when a magnificent lion suddenly appeared one night in the midst of the village. A small dog, that had incautiously approached the beast, paid the penalty of its life for its daring. The next day a grand chase was got up, but the lion, being on his guard, managed to elude his pursuers. The second day, however, he was killed by Messrs. Galton and Bam; and, on cutting him up, the poor dog was found, still undigested, in his stomach, bitten into five pieces.

The natives highly rejoiced at the successful termination of the hunt; for this lion had proved himself to be one of the most daring and destructive ever known, having, in a short time, killed upward of fifty oxen, cows, and horses. Though he had previously been chased, he had always escaped unscathed, and every successive attack made upon him only served to increase his ferocity.

I regretted much being prevented from taking part in so interesting and exciting an event, but, on the other hand, I felt pleased that my friend had thus early had an opportunity of exercising his skill on one of the most noble and dreaded of the animal creation. My turn was yet to come.

Scheppmansdorf—Roëbank—Abbanhous—as it is indifferently called—was first occupied as a missionary station in the year 1846, by the Rev. Mr. Scheppman, from whom it takes its name. It is situated on the left bank of the River Kuisip, and immediately behind rise enormous masses and ridges of sand. The Kuisip is a periodical stream, and is dependent on the rains in the interior; but, from the great uncertainty of this supply, and the absorbing nature of the soil, it is seldom that it reaches Walfisch Bay, where it has its estuary. On our arrival, the Kuisip had not flowed for years; but when it does send down its mighty torrent, it fertilizes and changes the aspect of the country to a wonderful[42] degree. Rain falls seldom or never at this place, but thirsty nature is relieved by heavy dews. Fresh water and fuel, however, two of the great necessaries of life, are found in abundance.

Sandy and barren as the soil appears to the eye, portions of it, nevertheless, are capable of great fertility. From time to time, Mr. Bam has cultivated small spots of garden ground in the bed of the river; but, although many things thrive exceedingly well, the trouble, risk, and labor were too great to make it worth his while to persevere. A sudden and unexpected flood, the effect of heavy rains in the interior, often lays waste in a few minutes what has taken months to raise.

The principal trees thereabouts are the ana and the giraffe-thorn (acacia giraffæ); and the chief herbage, a species of sand-reed, which is much relished by the cattle when once accustomed to it, but more especially by horses, mules, and donkeys, which thrive and fatten wonderfully on this diet.

During our stay at Scheppmansdorf we were the constant guests of Mr. and Mrs. Bam, but we felt almost sorry to trespass on a hospitality that we knew they could ill afford, for it was only once in every two years that they received their supplies from the Cape, and then only in sufficient quantities for their own families. The genuine sincerity, however, with which it was offered overruled all scruples.

Mr. Bam had long been a dweller in various parts of Great Namaqua-land.[5] His present residence, however, in this its western portion, was of comparatively recent date. Although he had used every effort to civilize and Christianize his small community, all his endeavors had hitherto proved nearly abortive; but as we become acquainted with the character of the Namaquas, who are partially-civilized Hottentots, the wonder ceases, and we discover that they possess every vice[43] of savages, and none of their noble qualities. So long as they are fed and clothed, they are willing enough to congregate round the missionary, and to listen to his exhortation. The moment, however, the food and clothing are discontinued, their feigned attachment to his person and to his doctrines is at an end, and they do not scruple to treat their benefactor with ingratitude, and load him with abuse.

The missionary is more or less dependent on his own resources. Such assistance as he obtains from the natives is so trivial, and procured with so much trouble, that it is often gladly dispensed with. The good man is his own architect, smith, wheelwright, tinker, gardener, &c., while his faithful spouse officiates as nurse, cook, washerwoman, and so forth. Occasionally, to get the drudgery off their hands, they adopt some poor boy and girl, who, after they have been taught with infinite labor to make themselves useful, and have experienced nothing but kindness, will often leave their protectors abruptly, or, what is nearly as bad, become lazy and indolent.

A Namaqua, it would appear, is not able to appreciate kindness, and no word in his language, as far as I can remember, is expressive of gratitude! The same is the case, as I shall hereafter have occasion to mention, with their northern neighbors, the Damaras, and though a sad, it is nevertheless a true picture.

When wagons were first introduced into Great Namaqua-land, they caused many conjectures and much astonishment among the natives, who conceived them to be some gigantic animal possessed of vitality. A conveyance of this kind, belonging to the Rev. Mr. Schmelen, once broke down, and was left sticking in the sand. One day a Bushman came to the owner, and said that he had seen his “pack-ox” standing in the desert for a long time with a broken leg, and, as he did not observe it had any grass, he was afraid that it would soon die of hunger unless taken away!

Preparations for Journey.—Breaking-in Oxen.—Departure from Scheppmansdorf.—An infuriated Ox.—The Naarip Plain.—The scarlet Flower.—The Usab Gorge.—The Swakop River.—Tracks of Rhinoceros seen.—Anecdote of that Animal.—A Sunrise in the Tropics.—Sufferings from Heat and Thirst.—Arrival at Daviep: great resort of Lions.—A Horse and Mule killed by them.—The Author goes in pursuit.—A troop of Lions.—Unsuccessful Chase.—Mules’ flesh palatable.

Mr. Galton had now so far altered his plans that, instead of proceeding up the country with only one half of his party for the purchase of cattle, it was arranged that we should make the journey together. The wagons and the bulk of our effects were to be left at Scheppmansdorf, and we were only to take with us some few articles of exchange, a small quantity of provisions, and a moderate supply of ammunition.

Finding, however, that the cart could not conveniently hold all our baggage, though now reduced to the smallest quantity possible, it was resolved to pack a portion on oxen. These animals, on account of their great hardihood, are invaluable in South Africa; the more so, as they can be equally well used for draft, the “pack,” or the “saddle.” But as we had no cattle trained for either of these purposes, and only one or two were procurable at the missionary station, we were necessitated, prior to our departure thence, to break in a few. No easy matter, by-the-by; for oxen are of a wild and stubborn disposition, and it requires months to make them tractable. We were, however, totally at a loss how to set to work.

But fortunately, at this time, Mr. Galton had engaged a[45] Mr. Stewardson, tailor by profession, but now “jack of all trades,” to accompany us up the country in the capacity of cicerone, etc.; and as this man, from long residence among the Hottentots, was thoroughly conversant with the mysteries of ox-breaking, to him, therefore, we deputed the difficult task.

At the end of a “riem,” or long leather thong, a pretty large noose is made, which is loosely attached to, or rather suspended from, the end of a slight stick some five or six feet in length. With this stick in his hand, a man, under shelter of the herd, stealthily approaches the ox selected to be operated on. When sufficiently near, he places the noose (though at some little distance from the ground) just in advance of the hind feet of the animal; and when the latter steps into it, he draws it tight. The instant the ox finds himself in the toils, he makes a tremendous rush forward; but, as several people hold the outer end of the “riem,” he—in sailor language—is quickly “brought up.” The force of the check is indeed such as often to capsize one or more of the men. He now renews his efforts; he kicks, foams, bellows; and his companions, at first startled, return and join in chorus; the men shout, the dogs bark furiously, and the affair becomes at once dangerous and highly exciting. The captured animal not unfrequently grows frantic with rage and fear, and turns upon his assailant, when the only chance of escape is to let go the hold of the “riem.” Usually he soon exhausts himself by his own exertions, when one or two men instantly seize him by the tail, another thong having also been passed round his horns; and by bringing the two to bear in exactly opposite directions, or, in other words, by using the two as levers at a right angle with his body, he is easily brought to the ground. This being once effected, the tail is passed between his legs and held forcibly down over his ribs, and the head is twisted on one side, with the horns fixed in the ground. A short, strong stick, of peculiar shape, is then[46] forced through the cartilage of the nose, and to either end of this stick is attached (in bridle fashion) a thin, tough leathern thong. From the extreme tenderness of the nose he is now more easily managed; but if he is still found very vicious, he is either packed in his prostrate position, or fastened with his head to a tree, while two or three persons keep the “riem” tight about his legs, so as to prevent him from turning round or injuring any person with his feet. For the “packing,” however, a more common and convenient plan is to secure him between two tame oxen, with a person placed outside each of these animals.

For the first day or two, only a single skin, or empty bag, is put on his back, which is firmly secured with a thong eighty or ninety feet in length (those employed by the Namaquas for the same purpose are about twice as long); but bulk as well as weight is daily added; and though he kicks and plunges violently, and sometimes with such effect as to throw off his pack, the ox soon becomes more tractable. Strange enough, those who show the most spirit in the beginning are often the first subdued. But an ox that lies down when in the act of “packing” him generally proves the most troublesome. Indeed, not one in ten that does so is fit for any thing.

I have seen oxen that no punishment, however severe, would induce to rise; not even the application of fire. This would seem a cruel expedient; but when it is remembered that his thus remaining immovable is entirely attributable to obstinacy, and that a person’s life may depend on getting forward, the application of this torture admits of some excuse.