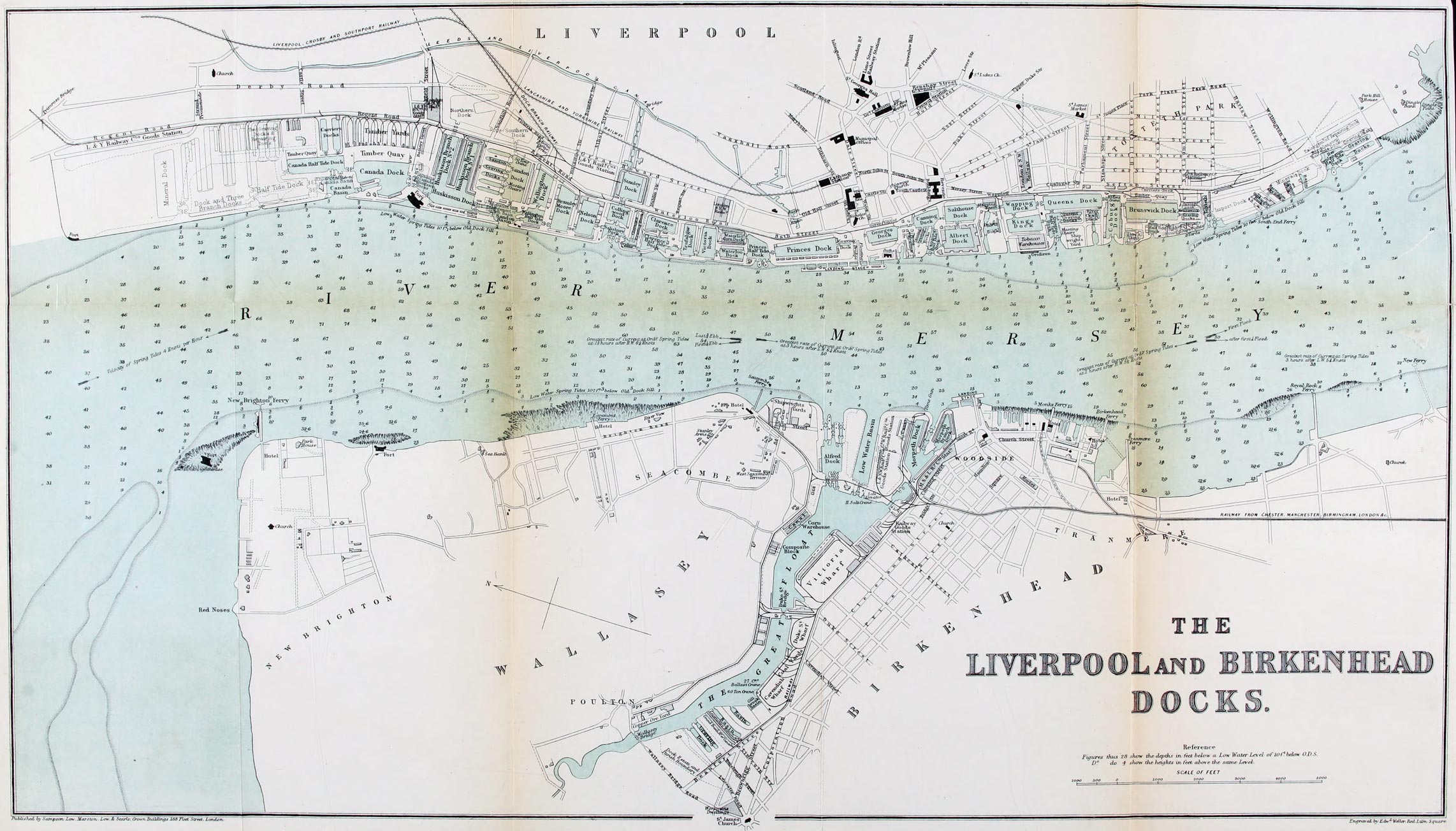

LIVERPOOL AND BIRKENHEAD

DOCKS.

Published by Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle, Crown Buildings 188 Fleet Street, London.

Engraved by Edwd. Weller. Red Lion Square

Title: History of merchant shipping and ancient commerce, Volume 2 (of 4)

Author: W. S. Lindsay

Release date: June 29, 2024 [eBook #73949]

Most recently updated: October 31, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low, and Searle, 1874

Credits: Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BY

W. S. LINDSAY.

IN FOUR VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

With numerous Illustrations.

LONDON:

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, LOW, AND SEARLE.

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188 FLEET STREET.

1874.

[All Rights reserved.]

LONDON.

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS,

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Dom John of Portugal prosecutes his researches for India—Expedition under Vasco de Gama, 1497—Description of the ships—The expedition sails 9th July, 1497—Doubles the Cape of Good Hope, 25th Nov.—Sights land at Natal, 25th Dec., 1498—Meets the first native vessel and obtains information about India—Arrives at Mozambique, 10th March—Departs for Quiloa, 8th April—Arrives at Melinde, 29th April—Sails for Calicut, 6th August—Reaches the shores of India, 26th August—Arrives at Calicut—Vasco de Gama disembarks and concludes a treaty with the king—His treachery—Leaves Calicut for Cananore—Enters into friendly relations and leaves Cananore, 20th Nov.—Reaches Melinde, 8th Jan., 1499—Obtains pilots and sails for Europe, 20th Jan.—Doubles the Cape of Good Hope—Death of Paul de Gama—The expedition reaches the Tagus, 18th Sept., 1499—Great rejoicings at Lisbon—Arrangements made for further expeditions—Departure of the second expedition, 25th March, 1502—Reaches Mozambique and Quiloa, where De Gama makes known his power and threatens to capture the city—His unjust demands—Arrives at Melinde—Departs, 18th Aug., 1502—Encounter with the Moors—Levies tribute, and sails for Cananore—Disgraceful destruction of a Calicut ship and massacre of her crew—De Gama’s arrangement with the king of Cananore—Departure for Calicut—Bombards the city—Horrible cruelties—Arrives at Cochym 7th Nov., where he loads, and at Coulam—Opens a factory at Coulam—Calicut declares war against Dom Gama—Success of the Portuguese—Desecration of the Indian vessels, and further atrocities—Completes his factory and fortifications at Cananore, and sails for Lisbon, where he arrives, 1st Sept., 1503—De Gama arrives in India for the third time 11th Sept., 1524—His death, 24th Dec., 1524—His character as compared with that of Columbus—Discovery of the Pacific by Vasco Nuñez de Bilboa—Voyage of Magellan[Pg iv] | Pages 1-48 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Progress of maritime discovery—Henry VII., 1485-1509—His encouragement of maritime commerce and treaties with foreign nations—Voyages to the Levant—Leading English shipowners—Patent to the Cabots, 1496—Discovery of the north-west coast of America, June 21, 1497—Second patent, Feb. 3, 1498—Rival claimants to the discovery of the North American continent—Sebastian Cabot and his opinions—Objects of the second expedition—Third expedition, March 1501—How Sebastian Cabot was employed from 1498 to 1512—He enters the service of Spain, 1512—Letter of Robert Thorne to Henry VIII. on further maritime discoveries—Sebastian Cabot becomes pilot-master in Spain, 1518, and afterwards (1525) head of a great trading and colonising association—Leaves for South America, April 1526, in command of an expedition to the Brazils—A mutiny and its suppression—Explores the river La Plata while waiting instructions from Spain—Sanguinary encounter with the natives—Returns to Spain, 1531, and remains there till 1549, when he settles finally in Bristol—Edward VI., A.D. 1547-1553—Cabot forms an association for trading with the north, known as the “Merchant Adventurers”—Despatch of the first expedition under Sir H. Willoughby—Instructions for his guidance, probably drawn up by Cabot—Departure, May 20, 1553—Great storm and separation of the ships—Death of Sir H. Willoughby—Success of Chancellor—His shipwreck and death at Pitsligo—Arrival in London of the first ambassador from Russia, Feb. 1557—His reception—Commercial treaty—Early system of conducting business with Russia—The benefits conferred by the Merchant Adventurers upon England—The Steelyard merchants partially restored to their former influence—Cabot loses favour with the court, and dies at an advanced age | 49-87 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

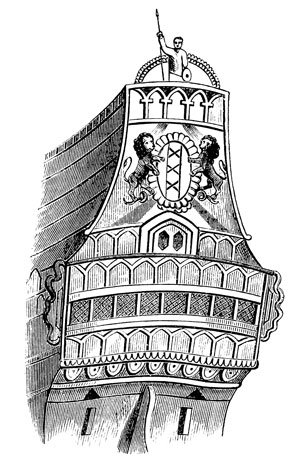

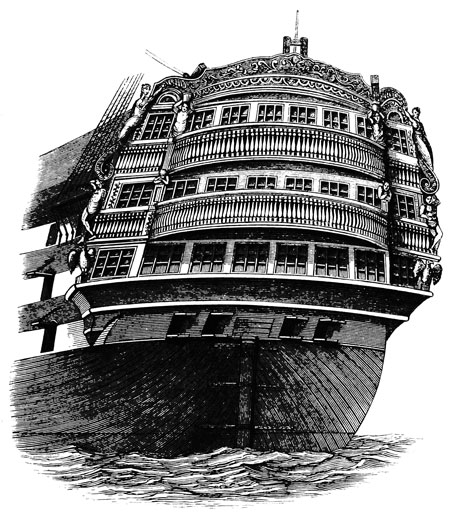

| Henry VIII. resolves to establish a permanent Royal Navy—Derives his first supply of men from English fishermen—Royal fleet equipped and despatched from Portsmouth—Its first engagement—Increase of the French fleets—Extraordinary exertions of the English to meet the emergency—The rapidity with which they supplied men and vessels—Outfit of the ships—The Great Harry—Number and strength of the fleet at the death of Henry VIII., 28 Jan., 1547—The Great Michael—Trade monopolies—Mode of conducting business—Mistaken laws—The Bridport petition—Chartered companies—Prices regulated by law, and employment provided—The petition of the weavers—State of the currency, A.D. 1549—Its depreciation—Corruption of the government—Recommendation of W. Lane to Sir W. Cecil, who acts upon it, A.D. 1551, August—The corruption of the council extends[Pg v] to the merchants—Accession of Elizabeth, A.D. 1558—War with Spain—Temporary peace with France, soon followed by another war—Demand for letters of marque—Number of the Royal fleet, A.D. 1559—The desperate character of the privateers—Conduct of the Spaniards—Daring exploits and cruelty of Lord Thomas Cobham, and of other privateers or marauders—Piratical cruises of the mayor of Dover—Prompt retaliation of the king of Spain—Reply of Elizabeth—Elizabeth attempts to suppress piracy, 29th Sept., 1564—Her efforts fail, but are renewed with increased vigour, though in vain—Opening of the African slave-trade—Character of its promoters—John Hawkins’ daring expedition—Fresh expeditions sanctioned by Elizabeth and her councillors—Cartel and Hawkins—They differ and separate, 1565—Hawkins reaches the West Indies with four hundred slaves, whom he sells to much advantage, and sails for England—Fresh expeditions, 1556—They extend their operations, 1568—The third expedition of Sir John Hawkins departs, October 1567, and secures extraordinary gains—Attacked by a Spanish fleet and severely injured—Reaches England in distress—Prevails on the Queen to make reprisals—Questionable conduct of Elizabeth—Vigorous action of the Spanish ambassador—Prompt retaliation—Injury to English trade less than might have been supposed—Hatred of the Catholics—Increase of the privateers, 1570—Their desperate acts, 1572 | 88-140 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Certainty of war with Spain—Secret preparations for the invasion of England, and restoration of the Catholic faith—Philip intrigues with Hawkins, and is grossly deceived—The Spanish Armada, and England’s preparations for defence—Destruction of the Armada, July 19, 1588—Voyages of discovery by Johnson—Finner and Martin Frobisher—Drake’s voyage round the world, 1577—His piratical acts and return home, 1580—First emigration of the English to America—Discovery of Davis’s Straits—Davis directs his attention to India—Fresh freebooting expeditions—Voyage of Cavendish to India, 1591, which leads to the formation of the first English India Company, in 1600—First ships despatched by the Company—The Dutch also form an East India Company—Extent of their maritime commerce—They take the lead in the trade with India—Expedition of Sir Henry Middleton—Its failure and his death—Renewed efforts of the English East India Company—They gain favour with the Moghul Emperor of India, and materially extend their commercial operations—Treaty between English and Dutch East India Companies—Soon broken—Losses of East India Company—Sir Walter Raleigh’s views on maritime commerce, 1603—His views confirmed by other writers opposed to his opinions—The views of Tobias, 1614—His estimate of the[Pg vi] profits of busses—The effect of these publications—Colonising expeditions to North America—Charles I. assumes power over the colonies—English shipowners resist the demand for Ship-Money—Its payment enforced by law—Dutch rivalry—Increase of English shipping—Struggles of the East India Company—Decline of Portuguese power in India—The trade of the English in India—Increase of other branches of English trade—Ships of the Turkey and Muscovy Company—The Dutch pre-eminent—The reasons for this pre-eminence | 141-181 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| English Navigation Laws—First Prohibitory Act, 1646—Further Acts, 1650-1651—Their object and effect—War declared between Great Britain and Holland, July 1652—The English capture Prizes—Peace of 1654—Alleged complaints against the Navigation Acts of Cromwell—Navigation Act of Charles II.—The Maritime Charter of England—Its main provisions recited—Trade with the Dutch prohibited—The Dutch navigation seriously injured—Fresh war with the Dutch, 1664—Its naval results—Action off Harwich, 1665—Dutch Smyrna fleet—Coalition between French and Dutch, 1666—Battle of June 1 and of July 24, 1666—Renewed negotiations for peace, 1667—Dutch fleet burn ships at Chatham, threaten London, and proceed to Portsmouth—Peace concluded—Its effects—The colonial system—Partial anomalies—Capital created—Economical theories the prelude to final free-trade—Eventual separation from the mother-country considered—Views of Sir Josiah Child on the Navigation Laws—Relative value of British and Foreign ships, 1666—British clearances, 1688, and value of exports—War with France—Peace of Ryswick, 1697—Trade of the Colonies—African trade—Newfoundland—Usages at the Fishery—Greenland Fishery—Russian trade—Peter the Great—Effect of the legislative union with Scotland, 1707—The maritime commerce of Scotland—Buccaneers in the West Indies—State of British shipping, temp. George I.—South Sea Company, 1710 | 182-214 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| English voyages of discovery, 1690-1779—Dampier—Anson—Byron—Wallis and Carteret—Captain Cook—His first voyage, in the Endeavour—Second voyage, in the Resolution—Third voyage—Friendly, Fiji, Sandwich, and other islands—His murder—Progress of the North American colonies—Commercial jealousy in the West Indies—Seven Years’ War, 1756-1763—Its effect on the colonies—Unwise legislative measures—Effect of the new restrictions—Passing of the Stamp Act—Trade interrupted—Non-intercourse resolutions—Recourse[Pg vii] to hostilities—Position of the colonists—Fisheries—Shipping of North American Colonies, A.D. 1769—Early registry of ships not always to be depended on—Independence of United States acknowledged, May 24, 1784—Ireland secures various commercial concessions—Scotch shipping—Rate of seamen’s wages—British Registry Act, Aug. 1, 1786—American Registry Act—Treaty between France and England, 1786—Slave-trade and its profits—Trade between England and America and the West Indies re-opened—Changes produced by the Navigation Laws consequent on the separation—New disputes—English Orders in Council—Negotiations opened between Mr. Jay and Lord Grenville—Tonnage duties levied by them | 215-256 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Great Britain, A.D. 1792—War with France, Feb. 1, 1793—Commercial panic—Government lends assistance—High price of corn—Bounties granted on its importation—Declaration of Russia, 1780—Confederacy renewed when Bonaparte had risen to power—Capture of merchant vessels—Do “free ships make free goods?”—Neutral nations repudiate the English views—Their views respecting blockades—Right of search—Chief doctrines of the neutrals—Mr. Pitt stands firm, and is supported by Mr. Fox—Defence of the English principles—Nelson sent to the Sound, 1801—Bombardment of Copenhagen—Peace of Amiens, and its terms—Bonaparte’s opinion of free-trade—Sequestration of English property in France not raised—All claims remain unanswered—Restraint on commerce—French spies sent to England to examine her ports, etc.—Aggrandisement of Bonaparte—Irritation in England—Bonaparte’s interview with Lord Whitworth—The English ministers try to gain time—Excitement in England—The King’s message—The invasion of England determined on—War declared, May 18, 1803—Joy of the shipowners—Preparations in England for defence—Captures of French merchantmen—Effect of the war on shipping—Complaints of English shipowners—Hardships of the pressing system—Apprentices—Suggestions to secure the Mediterranean trade, and to encourage emigration to Canada—Value of the Canadian trade | 257-289 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Mr. Fox tries to make peace with France, 1806—Napoleon’s Proclamation—English Order in Council, April 8, 1806—Berlin Decree, Nov. 10, 1806—Its terms, and the stringency of its articles—Napoleon’s skill and duplicity—Russian campaign conceived—Berlin Decree enforced—Increased rates of insurance—English Orders in Council, 1807—Preamble of third Order in Council—Terms of this Order—Neutrals—The[Pg viii] Orders discussed—Embargo on British ships in Russia—Milan Decree, Dec. 17, 1807—Preamble and articles—Bayonne Decree, April 17, 1808—Effect of the Decrees and Orders in Council in England—Interests of the shipowners maintained—Napoleon infringes his own decrees—Moniteur, Nov. 18, 1810—Rise in the price of produce and freights, partly accounted for by the Orders in Council—Ingenuity of merchants in shipping goods—Smuggling—Licence system in England—Cost of English licences—Their marketable value—Working of the licensing system in England—Simulated papers—Agencies for the purpose of fabricating them | 290-319 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Effect of the Orders in Council on American trade, A.D. 1810—Complaints of the Americans against England—Policy of Napoleon towards neutrals—Non-intercourse Act—Secret terms with America—Partiality of the United States towards France—Contentions at home respecting the Orders in Council—Declaration of war with America—Motives of the Americans—England revokes her Orders in Council—Condemnation of the conduct of the United States—Impressment of American seamen—Fraudulent certificates—Incidents of the system—War with America—Necessity of relaxing the Navigation Laws during war—High duties on cotton—Great European Alliance—Napoleon returns to Paris—Germans advance to the Rhine—Treaty of Chaumont—The Allies enter Paris—End of the war by the Treaty of Paris, 1814—Napoleon’s escape from Elba—His landing in France and advance on Paris—British troops despatched to Belgium—Subsidies to European Powers—Fouché—Last campaign of Napoleon, and defeat at Waterloo—Reflections | 320-344 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| United States of America—Her independence recognised, 1783—Commercial rights—Retaliatory measures—Threatening attitude of Massachusetts—Constitution of the United States—Good effects of an united Government—Maritime laws and laws respecting Neutrals—Feeling on both sides the water—Treaty between Great Britain and United States—The right to impose a countervailing tonnage duty reserved—Difficulty of the negotiation—Remarkable omission respecting cotton—Indignation in France at the Treaty—The French protest against its principles—Interest of England to have private property free from capture at sea—Condemnation of ships in the West Indies and great depredations—Outrages on the Americans—Torture practised by French cruisers—The advantages of the war to the Americans—Impulse given to shipping—Progress of American[Pg ix] civilisation—Advances of maritime enterprise—Views of American statesmen—The shipwrights of Baltimore seek protection—Great Britain imposes countervailing duties—Effect of legislative measures on both sides—Freight and duty compared—Conclusions drawn by the American shipowners—Alarm in the United States at the idea of reciprocity—Objections to the British Navigation Act—Threatened destruction to American shipping—Popular clamour—Opinions in Congress—Great influence of the shipowners—Early statesmen of the United States—Their efforts to develop maritime commerce—First trade with the East—European war of 1803—Its effect on their maritime pursuits | 345-380 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| A special mission sent to England—Concessions made in the Colonial trade—Blockades in the Colonies, and of the French ports in the Channel—The dispute concerning the trade with the French Colonies—What is a direct trade?—Reversal of the law in England—Effect in America—Instructions to Commissioners—Proceedings of the shipowners of New York—Duties of neutrals—Views of the New York shipowners—Conditions with respect to private armed vessels—Authorities on the subject—Negotiations for another treaty—Circuitous trade—Commercial stipulations—Violation of treaties—Complaints of the Americans against the French—Language of the Emperor—Bayonne Decree, April 17, 1808—American Non-intervention Act, March 1, 1809—Intrigues in Paris against England—Hostile feelings in United States against England—Diplomatic proceedings in Paris—Convention with Great Britain—Retaliatory Acts to be enforced conditionally—Hostile legislation against Great Britain—Bonds required—Treaty negotiations renewed—Dutch reciprocity—Bremen reciprocity | 381-407 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Earliest formation of wet docks and bonded warehouses—System of levying duties—Opposition to any change—Excise Bill proposed, 1733—but not passed till 1803—Necessity of docks for London—Depredations from ships in London—The extent of the plunder—Instances of robberies—Scuffle hunters—“Game” ships—Rat-catchers—River-pirates—Their audacity—Light-horsemen—Their organisation—“Drum-hogsheads”—Long-shore men—Harbour accommodation—Not adequate for the merchant shipping—East and West India ships—Docks at length planned—West India Docks—Regulations—East India Docks—Mode of conducting business at the Docks—London Docks—St. Katharine’s Docks—Victoria and Millwall Docks—Charges[Pg x] levied by the Dock Companies—Docks in provincial ports, and bonded warehouses—Liverpool and Birkenhead Docks—Port of Liverpool, its commerce, and its revenue from the docks—Extent of accommodation—Extension of docks to the north—Hydraulic lifts and repairing basins—Cost of new works—Bye-laws of the Mersey Board—The pilots of the Mersey—Duties of the superintendents—Conditions of admission to the service—Pilot-boats and rates of pilotage | 408-442 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| East India Company—Early struggles—Rival company—Private traders—Coalition effected—Their trade, 1741-1748, and continued difficulties up to 1773—Their form of charter—Rates of freight—Gross earnings—Evidence of Sir Richard Hotham before the Committee of Inquiry—The effect of his evidence—Reduction of duties, August 1784—Extent of tea trade—Opposition of independent shipowners—India-built ships admitted to the trade—Board of Control established, 1784—Value of the trade, 1796—Charter renewed, with important provisions, from 1796 to 1814—Restrictions on private traders—East India Company’s shipping, 1808-1815—The trade partially opened—Jealousy of free-traders—Efforts of the free-traders at the out-ports—Comparative cost of East India Company’s ships and of other vessels—Opposition to the employment of the latter—Earl of Balcarras—Her crew—Actions fought by the ships of the Company—Conditions of entering the service—Uniforms—Discipline—Promotion—Pay and perquisites—Abuse of privileges—Direct remuneration of commanders—Provisions and extra allowances—Illicit trade denounced by the Court, and means adopted to discover the delinquents—Connivance of the officers of the Customs—Pensions, and their conditions—Internal economy of the ships—Watches and duties—Amusements—Gun-exercise—Courts-martial—Change in the policy of the East India Company—Results of free-trade with India, and of the Company’s trading operations—China trade thrown open, 1832-1834—Company abolished, 1858—Retiring allowances to commanders and officers—Compensations and increased pensions granted—Remuneration of the directors—Their patronage | 443-488 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Progress of shipping—Thetis, West Indiaman—A “Free-trader”—Internal economy—Provisioning and manning—Shipping the crew—Crimps and agents—Duties on departure of ship—Watches—Duties of the Master—Who has control over navigation—Making and shortening sail—Tacking, etc.—Ordinary day’s work, how arranged—Right[Pg xi] of the Master over the cabin—Authority and usages in the English, Dutch, and Prussian marine—Danish and Norwegian system—Duties of Chief Mate—His duties in port—Tacking “’bout ship”—Reefing topsails—Log-book—Mate successor in law to the Master—Mode of address to Chief and Second Mates—Duties of Second Mate—Ordinary day’s work—Care of spare rigging—Stores—Third Mate—His general duties—Carpenter—Sail-maker—Steward—Cook—Able seamen, their duties—Division of their labour—Duties of ordinary seamen—Boys or apprentices—Bells—Helm—“Tricks” at the helm—Relieving duty—Orders at the wheel—Repeating of orders at wheel—Conversation not allowed while on duty—Colliers. | 489-538 |

| APPENDICES. | |

| PAGE | |

| Appendix No. 1 | 541 |

| Appendix No. 2 | 555 |

| Appendix No. 3 | 557 |

| Appendix No. 4 | 559 |

| Appendix No. 5 | 561 |

| Appendix No. 6 | 563 |

| Appendix No. 7 | 564 |

| Appendix No. 8 | 570 |

| Appendix No. 9 | 572 |

| Appendix No. 10 | 576 |

| Appendix No. 11 | 578 |

| Appendix No. 12 | 583 |

| Appendix No. 13 | 585 |

| Appendix No. 14 | 586 |

| Appendix No. 15 | 588 |

| Index | 593 |

Published by Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle, Crown Buildings 188 Fleet Street, London.

Engraved by Edwd. Weller. Red Lion Square

[Pg 1]

MERCHANT SHIPPING.

Dom John of Portugal prosecutes his researches for India—Expedition under Vasco de Gama, 1497—Description of the ships—The expedition sails 9th July, 1497—Doubles the Cape of Good Hope, 25th Nov.—Sights land at Natal, 25th Dec., 1498—Meets the first native vessel and obtains information about India—Arrives at Mozambique, 10th March—Departs for Quiloa, 8th April—Arrives at Melinde, 29th April—Sails for Calicut, 6th August—Reaches the shores of India, 26th August—Arrives at Calicut—Vasco de Gama disembarks and concludes a treaty with the king—His treachery—Leaves Calicut for Cananore—Enters into friendly relations and leaves Cananore, 20th Nov.—Reaches Melinde, 8th Jan., 1499—Obtains pilots and sails for Europe, 20th Jan.—Doubles the Cape of Good Hope—Death of Paul de Gama—The expedition reaches the Tagus, 18th Sept., 1499—Great rejoicings at Lisbon—Arrangements made for further expeditions—Departure of the second expedition, 25th March, 1502—Reaches Mozambique and Quiloa, where De Gama makes known his power, and threatens to capture the city—His unjust demands—Arrives at Melinde—Departs, 18th Aug., 1502—Encounter with the Moors—Levies tribute, and sails for Cananore—Disgraceful destruction of a Calicut ship, and massacre of her crew—De Gama’s arrangements with the king of Cananore—Departure for Calicut—Bombards the city—Horrible cruelties—Arrives at Cochym 7th Nov., where he loads, and at Coulam—Opens a factory at Coulam—Calicut declares war against Dom Gama—Success of the Portuguese—Desecration of the Indian vessels, and further atrocities—Completes his factory and fortifications at Cananore, and sails for Lisbon, where he arrives, 1st Sept., 1503—De Gama arrives in India for the third time, 11th Sept., 1524—His death, 24th Dec., 1524—His character as compared with that of Columbus—Discovery of the Pacific by Vasco Nuñez de Bilboa—Voyage of Magellan.

While the Spaniards under Columbus were prosecuting their researches for India among the islands[Pg 2] and along the coasts of a new-found world, Dom John, of Portugal, was vigorously following up the voyages of discovery which Prince Henry had commenced in the early part of the fifteenth century. “He had heard,” remarks Gaspar Correa,[1] “from a Caffre or Negro king of Benin, who in 1484 took up his quarters in Lisbon, many marvellous things about India, and its affairs.” But though this sable monarch spoke of “Prester John,” he does not appear to have had any idea of the position of the golden land, over which he was the traditional ruler. Dom John, however, resolved to ascertain this fact, and despatched “secretly two young men of his equerries, to learn of many lands, and wander in many parts, because they knew many languages.”

“The king,” continues Correa, “promised them a large recompense for their labour, and for such great services as they would be rendering him; and for as long as they should continue in this service, he would take good care for the support of their wives and children.” He directed them to separate and to go by different roads, giving to each of them letters of acknowledgment of the recompense which he promised them if they returned alive, or to their sons and widows if they should die in this service. He likewise[Pg 3] ordered a plate of brass like a medal to be given to each of them, bearing an inscription engraved in all languages, with the name of ‘The King Dom Joam of Portugal, brother of the Christian King,’ which they might show to Prester John, and to whomsoever they thought fit.[2]

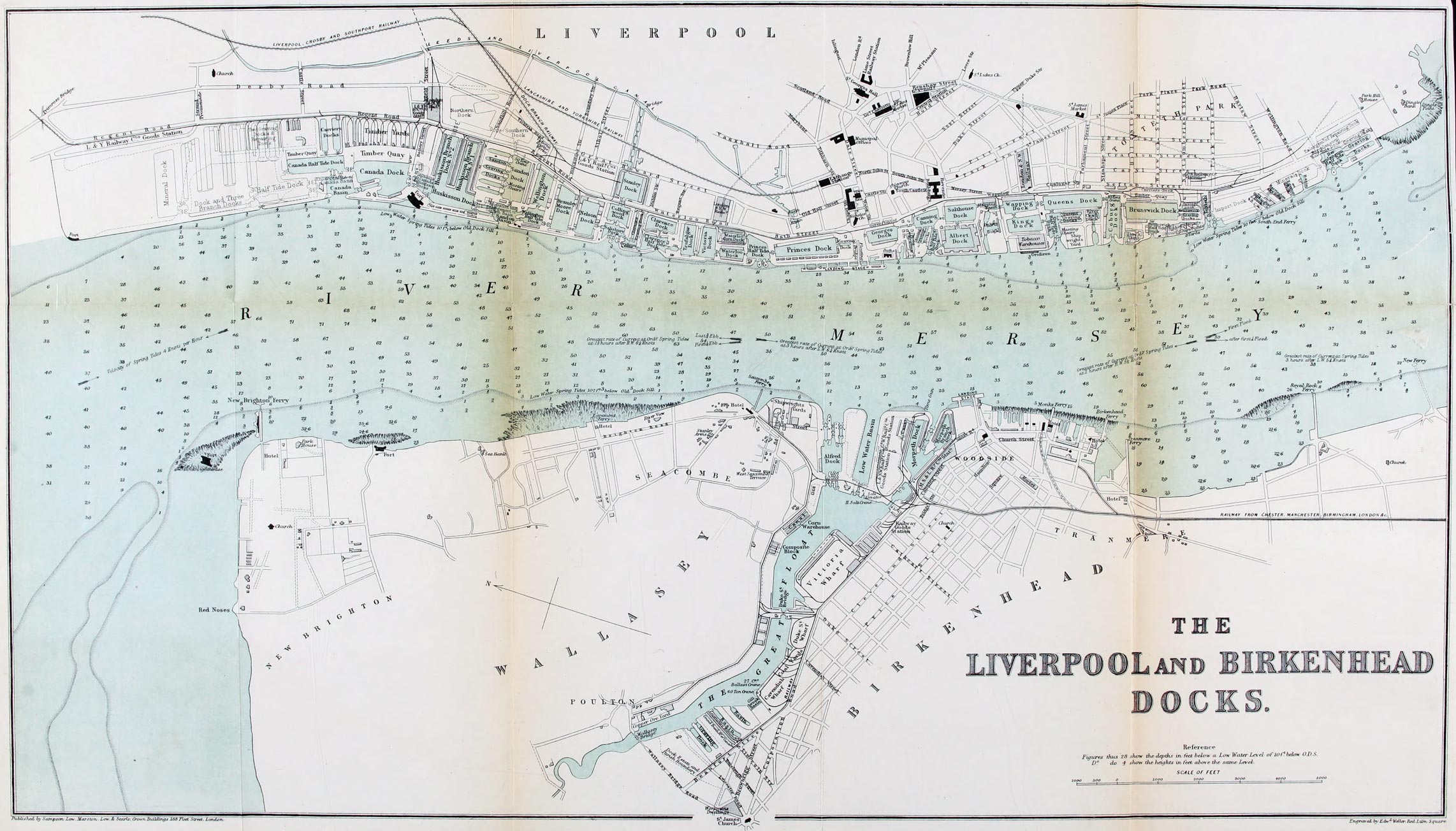

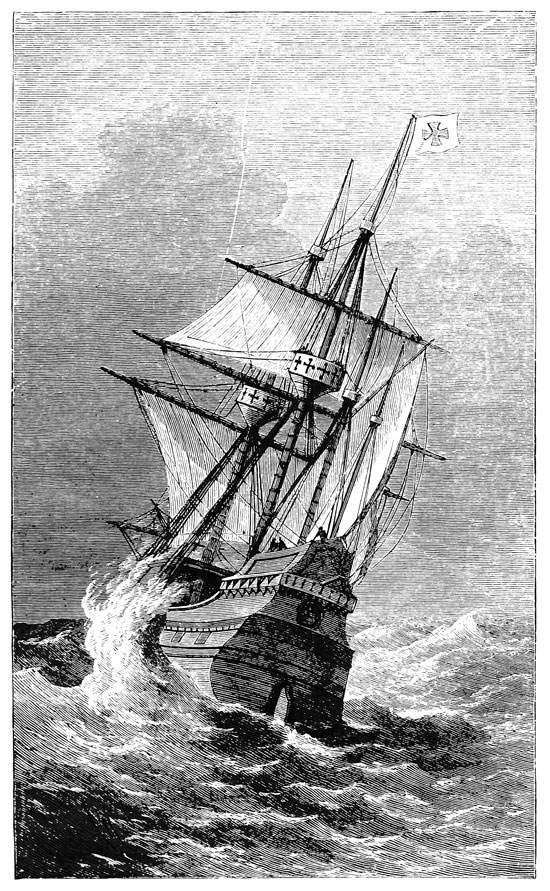

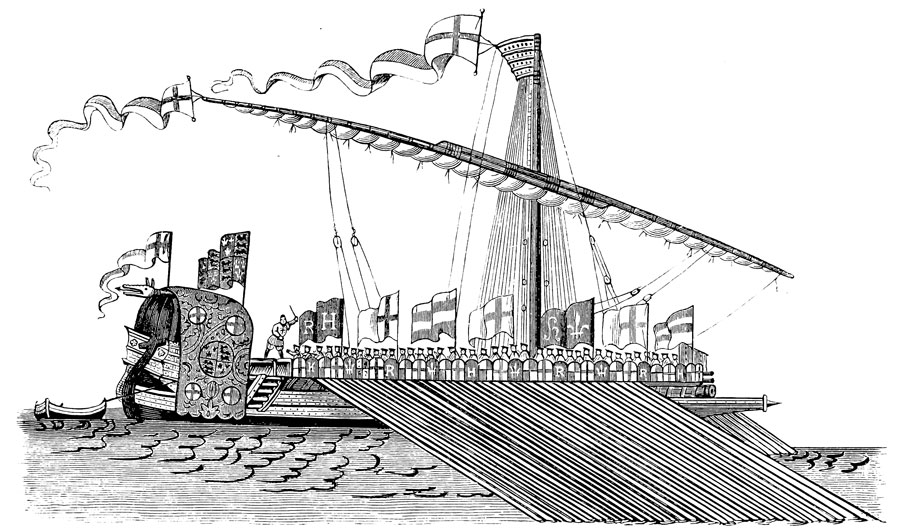

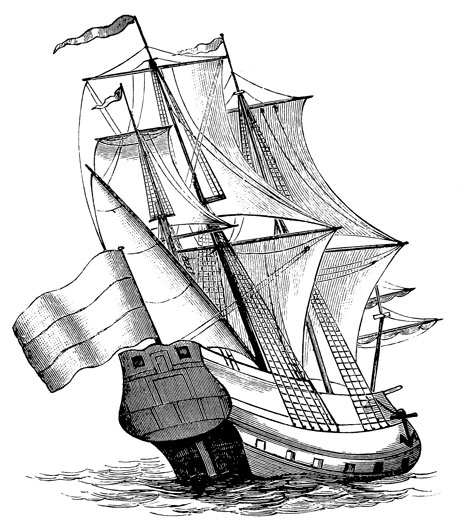

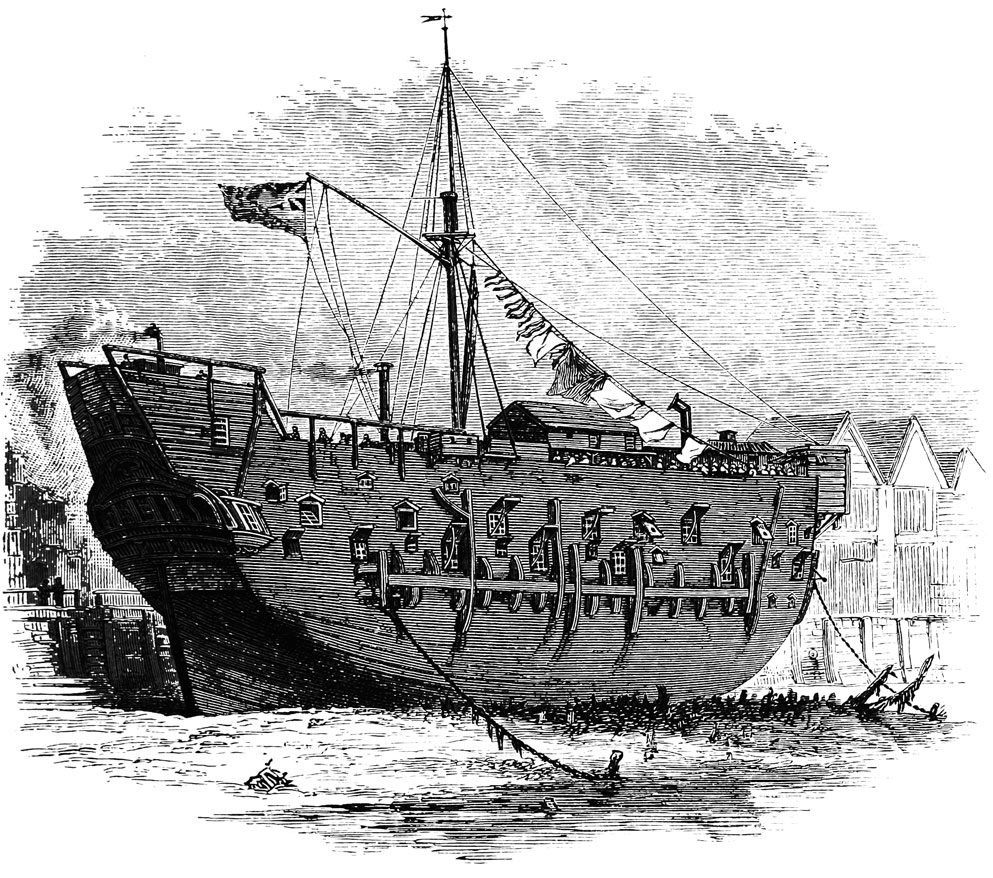

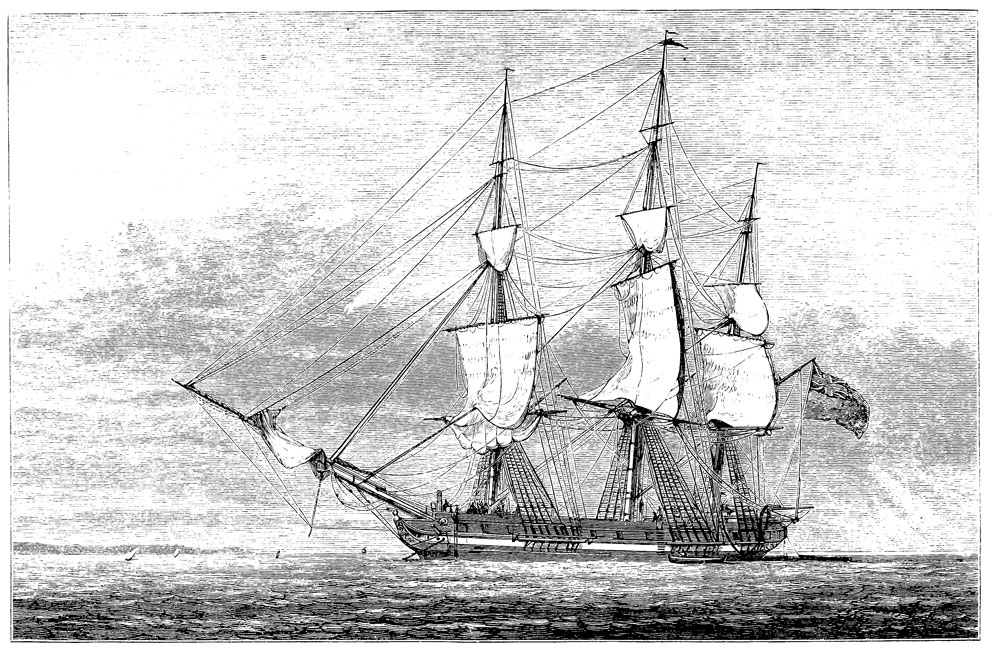

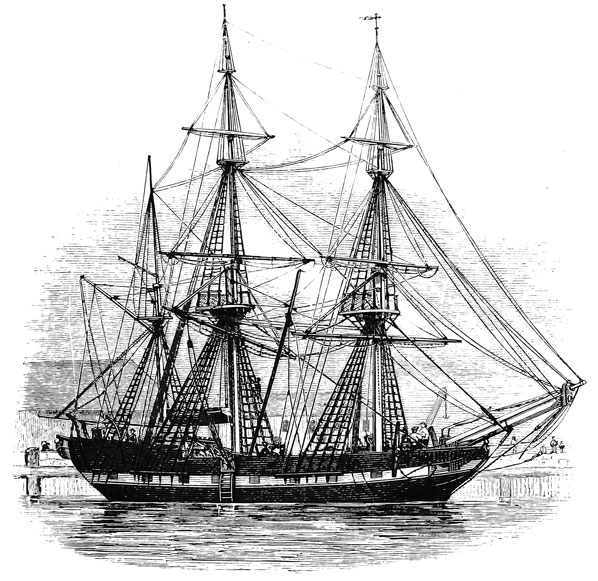

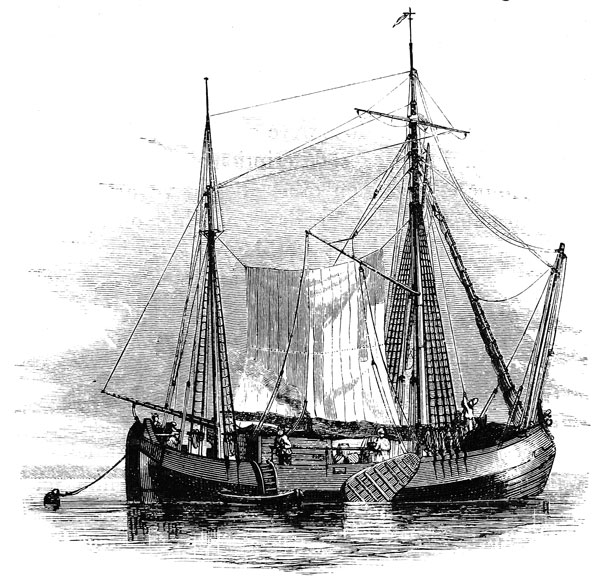

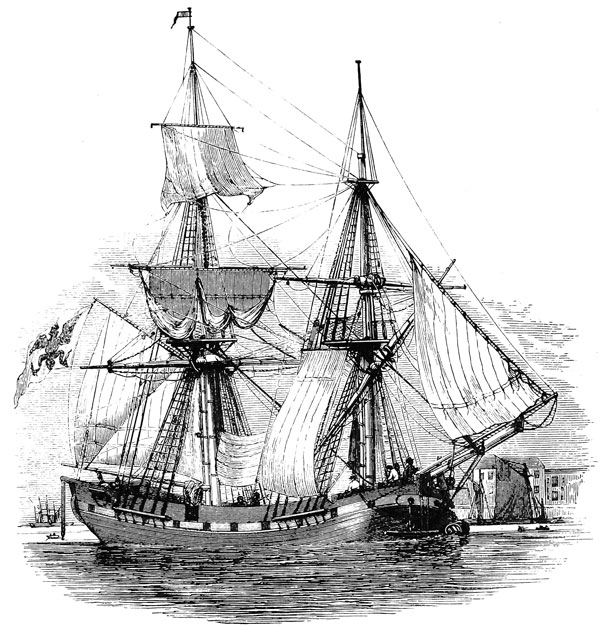

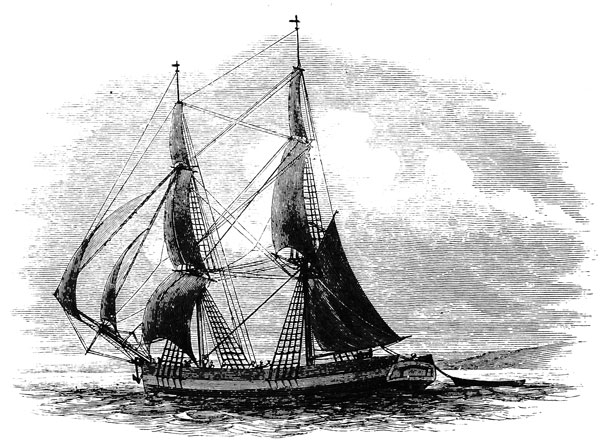

The celebrated expedition of Vasco de Gama which followed this inquiry is generally described as consisting of three vessels, one of 120 tons, another of 100 tons, and the third somewhat less.[3] Correa says[Pg 4] they were all very similar in size and equipment, in order that each ship might avail itself of any part of the tackle and fittings; and he describes their outfit and cargoes as follows: “The king ordered the ships to be supplied with double tackle and sets of sails, and artillery and munitions in great abundance; above all, provisions, with which the ships were to be filled, with many preserves and perfumed waters, and in each ship all the articles of an apothecary’s shop for the sick; a master, and a priest for confession. The king also ordered all sorts of merchandise of what was in the kingdom and from outside of it, and much gold and silver, coined in the money of all Christendom and of the Moors. And cloths of gold, silk, and wool, of all kinds and colours, and many jewels of gold, necklaces, chains, and bracelets, and ewers of silver and silver-gilt, yataghans, swords, daggers, smooth and engraved, and adorned with gold and silver workmanship. Spears and shields, all adorned so as to be fit for presentation to the kings and rulers of the countries where they might put into port; and a little of each kind of spice.[Pg 7] The king likewise commanded slaves to be bought who knew all the languages which might be fallen in with, and all the supplies which seemed to be requisite were provided in great abundance and in double quantities.”

Such was the equipment of De Gama’s ships for this perilous and unknown voyage; and, though a man of indefatigable energy, he had to accomplish a task of an extraordinary character; no less than the discovery of a land of which nothing was known, but the vague idea that it lay beyond distant seas “where there would not be navigation by latitude nor charts, only the needle to know the points of the compass, and the sounding plummets for running down the coast.”[4]

On the Sunday fixed for the purpose of offering prayers before the departure of this memorable expedition, the king, with his nobles and most of the leading families of Lisbon, assembled in that beautiful cathedral which still adorns the northern bank of the Tagus, to hear mass from the Bishop Calçadilha, who with deep solemnity offered up prayers, beseeching God “that the voyage might be for His holy service, for the exaltation of His holy faith, and the good and honour of the kingdom of Portugal.” At the conclusion of mass, the king stood before the curtain where Vasco de Gama and his brother Paulo de Gama placed themselves, with the captains of the expeditions, on their knees, and devoutly prayed that they might have strength of mind and body to carry out the wishes of the king, to increase the power and greatness of his dominion,[Pg 8] and to spread the Christian religion into other and far distant lands.

With these professed objects and amid splendid demonstrations, in which the whole population of Lisbon took part, Vasco de Gama set sail on the 9th of July 1497. Favoured by a northerly wind and fine weather, the expedition reached St. Iago, Cape Verde Islands, in thirteen days from the time of its departure. Having replenished his stock of provisions, De Gama shaped his course to the south, and on the 4th of November anchored in the bay of St. Helena, on the west coast of Africa. Though aided by the skill and knowledge of Pedro d’Alemquer, Dias’s pilot, it was not until the 22nd November that he succeeded in doubling the now famous Cape of Good Hope, entering on the 25th the bay to the eastward of it, which Dias had named San Bras. Here he encountered one of those storms so frequent on the Agulhas banks, which Correa graphically describes.[5] The ships were in imminent danger, the crews mutinied and resolved to put back; and the fine weather, as had been anticipated, did not restore either contentment or resignation. At length on Sunday, the 17th of December, they passed the Rio do Iffante, the limit of the discoveries of Dias, and on the 25th of that month sighted land. In commemoration of the birthday of Christ, De Gama gave to this spot the name of Costa de Natal. Continuing his course along the coast to the north-east, he arrived on the 22nd of January, 1498, at a river which he named the Rio de Bons Sinaes[6] (now called the Quillimane), where he was detained for a month,[Pg 9] owing to an outbreak of scurvy among the crew. His ships, too, had suffered so severely, that they had to be careened and thoroughly caulked, and many of the ropes and shrouds replaced by others, to provide which the transport, as unworthy of repair, was broken up, and the best of her spars and stores appropriated to the equipment of the other vessels.

When the ships were repaired “they sailed with much satisfaction along the coast, keeping a good look-out by day and night,” and at length fell in with a small native vessel, in which there was an intelligent Moor. From this man, whom the captain-major luxuriously entertained, a great deal of information was obtained as to the character and habits of the people on the coast; and, when spices were presented to him, he intimated that he knew where they could be obtained abundantly. Ultimately the Moor, who appears to have been a trader or broker in the produce of the East, agreed to conduct De Gama to Cambay of which he was a native, asserting that it was a rich country, and “the greatest kingdom in the world.”

Having arrived at the island of Mozambique, which was then in the territory of the king of Quiloa, Vasco de Gama sent the Moor on shore with a scarlet cap, a string of small coral beads, and other presents, to conciliate the natives, and induce them to visit his ships. The sheikh of the district was naturally suspicious at first of the strangers, whom he took for Turks, the only white men known to him who had ships unlike the trading vessels of India. When, however, he was satisfied of their friendly intentions, he paid the[Pg 10] Portuguese ships a visit in great state; but, on being shown samples of the merchandise brought to exchange for the produce of the East, though making many professions of assistance and friendship, he seems to have treacherously designed obtaining unlawful possession of them. In this scheme, however, he was frustrated by the Moor, who, faithful to his new friends, revealed the plot to De Gama, who was thus enabled to proceed in safety on his voyage.

From Mozambique the expedition proceeded to Quiloa, described as an important city, trading in “much merchandise,” which came from abroad in a great many ships from all parts, especially from Mecca. Here were “many kinds of people,” including Armenians, who “called themselves Christians” like the Portuguese; here also pilots could be obtained for Cambay. But the sheikh of Mozambique, frustrated in his treacherous designs, had anticipated the arrival of the expedition, by sending a swift boat to inform his chief, the king of Quiloa, that the strangers “were Christians and robbers who came to plunder and spy the countries, under the device that they were merchants, and that they made presents and behaved themselves very humbly in order to deceive, and afterwards come with a fleet and men to take possession of countries; and, therefore, he knowing that, had wished to capture them, and they had fled from the port.” This king appears to have been as treacherous as his sheikh; but though after sending many presents, he endeavoured, by means of false pilots, to run De Gama’s ships on the shoals at the entrance of his port, his plan signally failed.

[Pg 11]

Soon after leaving Quiloa, the expedition fell in with a native vessel, which conducted them in safety to Melinde, described as a city on the open coast, containing many noble buildings, surrounded by walls, and of a very imposing appearance from the sea. Here they anchored in front of the city, “close to many ships which were in the port, all dressed out with flags,” in honour of the Portuguese, whose reputation for wealth and power had spread along the coast to such an extent as to induce the king’s soothsayer to recommend that they should “be treated with confidence and respect, and not as Christian robbers.” Large supplies of fresh provisions were sent on board of the vessels; and the king having spoken with his “magistrates and counsellors,” resolved that they should be received in a peaceable and amicable manner, because “there were no such evil people in the world as to do evil to any who did good to them.”

The king having arranged to visit the Portuguese ships, Vasco de Gama received him with royal honours, presenting him with many articles of European manufacture, which were highly prized. After frequent interchanges of civilities, the king informed De Gama that Cambay, of which he was in search, did not contain the produce he desired, for it was not of the growth of that country, but was conveyed thither “from abroad, and cost much there.” “I will give you pilots,” he added, “to take you to the city of Calicut, which is in the country where the pepper and ginger grows, and thither come from other parts all the other drugs, and whatever merchandise there is in these parts, of which you can buy that which you[Pg 12] please, enough to fill the ships, or a hundred ships if you had so many.”[7]

Towards the close of May, 1498, the expedition was again ready to sail, but finding they had little chance of successful progress, De Gama resolved to wait till the change of the monsoons. The interval was spent in a more thorough repair of their ships. The pilots whom the king had furnished appear to have been well skilled in their profession, and were not surprised when Vasco de Gama showed them the large wooden astrolabe he had brought with him, and the quadrants of metal with which he measured at noon the altitude of the sun. They informed him that some pilots of the Red Sea used brass instruments of a triangular shape and quadrants for a similar purpose, but more especially for ascertaining the altitude of a particular star, better known than any other, in the course of their navigation. Their own mariners, however, they explained, and those of India were generally guided by various stars both north and south, and also by other notable stars which traversed the middle of the heavens from east to west, adding that they did not take their distance with instruments such as were in use amongst the Red Sea pilots, but by means of three tables, or the cross-staff, sometimes described as Jacob’s staff. In those days the seamen of the eastern nations were, indeed, as far advanced in the art of navigation as either the Spaniards or the Portuguese, having gained their knowledge from the Arabian mariners, who, during the Middle Ages, carried on, as we have seen, an extensive trade[Pg 13] between the Italian republics and the whole of the Malabar coast.

After a passage of twenty (or twenty-three) days, Vasco de Gama first sighted the high land of India, at a distance of about eight leagues from the coast of Cananore. The news of the strange arrival spread with great rapidity, and the soothsayers and diviners were consulted, the natives having a legend, “that the whole of India would be taken and ruled over by a distant king, who had white people, who would do great harm to those who were not their friends;”[8]—a prophecy which has been remarkably fulfilled, not merely by the Portuguese, but more especially as regards the government of India by the English people. The soothsayers, however, added that the time had not yet arrived for the realisation of the prophecy.

On the arrival of the expedition at Calicut,[9] multitudes of people flocked to the beach, and the Portuguese were at first well received; for the king, having ascertained the real wealth of the strangers, and that Vasco de Gama had gold, and silver, and rich merchandise on board, to exchange for the pepper, spices, and other produce of the East, immediately sent him presents of “many figs, fowls, and cocoa-nuts, fresh and dry,” and professed a desire to enter into relations with the “great Christian king,” whom he represented. Calicut, the capital of the Malabar district, was then one of the chief mercantile cities of India, having for centuries carried on an extensive[Pg 14] trade with Arabia and the cities of the West, in native and Arabian vessels. Hence among its merchants were many Moors,[10] who, holding in their hands the most profitable branches of the trade, naturally “perceived the great inconvenience and certain destruction which would fall upon them and upon their trade if the Portuguese should establish trade in Calicut.”[11] These men therefore took counsel together, and at length succeeded in persuading the king’s chief factor, and his minister of justice, that the strangers had been really sent to spy out the nature of the country, so that they might afterwards come and plunder it at their leisure. But, as Correa remarks, “it is notorious that officials take more pleasure in bribes than in the appointments of their offices,” so the factor and the minister did not hesitate to receive bribes, both from the Moors and from the strangers, and recommended the king, whose interests were opposed to his fears, to open up a commercial intercourse with Vasco de Gama. Accompanied by twelve men, of “good appearance,” composing his retinue, and taking with him numerous presents, De Gama at last presented himself on shore. The magnificent display of scarlet cloth, the crimson velvet, the yellow satin, the hand-basins and ewers chased and gilt, besides a splendid gilt mirror, fifty sheaths of knives of Flanders, with ivory handles and glittering blades, and many other objects of curiosity and novelty, banished, at least for the time,[Pg 15] any doubts in the mind of the Malabar monarch with regard to the honest intentions of the strangers.

Having concluded a treaty, whereby it was stipulated that the Portuguese should have security to go on shore and sell and buy as they pleased, and that they should be placed in all respects on the same footing as other foreign merchants, the king added his desire that the stranger should be treated “with such good friendship as if he was own brother to the king of Portugal.”[12]

De Gama was fully satisfied with the arrangement, and had he been dealing with the king only, it seems probable that everything would have gone on well; the more so as the Malabar monarch was already realising large profits from the new trade. But the merchant Moors were less easily satisfied. They knew from the covetous character of the king that so long as the Portuguese were willing to buy, he would continue to supply whatever they required, and that thus the market would be stripped of the articles best adapted for their annual shipments to the Red Sea. They felt that “whenever the Christians should come thither, he would prefer selling his goods to them to supplying cargoes for the Moors;” and that, in the end, they would be “entirely ruined;” a plea, indeed, repeatedly used in many other countries whenever competition first made its appearance. The Moors further argued that the Portuguese could not be merchants, but “evil men of war,” for they paid whatever price was demanded for the produce they required, and made no difference between articles of inferior and superior qualities. But the[Pg 16] king refused to listen to their complaints until he had obtained all he desired from the strangers; then, giving heed to the reports of the Moors, and to the entreaties of his factor and minister, who had been doubly bribed, he turned round upon Gama, and by stratagem endeavoured to capture him and his ships. Finding it unsafe to remain any longer in port, the expedition, although only half laden, prepared to take its departure from Calicut, after a sojourn of about seventy days, the captain-major remarking that he was “not going to return to the port, but that he would go back to his country to relate to his king all that had happened to him; that he should also tell him the truth about the treachery of his own people with the Moors; and that, if at any time he should return to Calicut, he would revenge himself upon the Moors.”[13]

Terrified by this threat of revenge, the king repented, and believing that the expedition would proceed to Cananore, wrote a letter to the king of that place giving him an account of all that had taken place and of his ill-treatment of the Portuguese, and, at the same time, entreating him to induce De Gama to return to his country, that he might “see the punishment he would inflict on those who were in fault, and complete the cargo of his ships.” The Portuguese, however, had seen enough of the fickle ruler of Calicut, and declined to accede to his urgent entreaties to return. In the king of Cananore they found a monarch equally disposed to trade, and one who, at the same time, having consulted his soothsayers, had decided that it would be alike profitable[Pg 17] and politic to enter into commercial relations with strangers who could, if they pleased, destroy their enemies at sea or ruin their trade on land. How they were received and how they conducted their trade with this monarch is told at much length by Correa, in his quaint and graphic relation of the incidents of this remarkable voyage.[14]

Suffice it to state that, after many fine speeches on both sides, the king swore eternal friendship with the Christian king of Portugal, and as a trustworthy proof of their oaths, presented to De Gama a sword, with a hilt enamelled with gold, and a velvet scabbard, the point of which was sheathed with that precious metal.

Abundant presents followed these solemn pledges—pledges made only to be broken; while gifts of golden collars, mounted with jewels and pearls, and chains of gold, and rings set with valuable gems, were offered to and accepted by the Portuguese as tokens of a friendship which was to last “for ever,” but which in a few years afterwards they rudely destroyed. “A factory,” said the king, “you may establish in this country; goods your ships shall always have of the best quality, and at the prices they are worth.” But as the sequel shows, in the case alike of the Portuguese, the Dutch, and the English, around the factory there arose fortifications, and from these there went forth, not merely traders to collect the produce of the country, but conquerors to overthrow ancient dynasties, and claim as their own the land to which a few years before they had been utter strangers.[15]

Having fully completed their cargoes, the Portuguese[Pg 18] ships took their departure from Cananore on the 20th of November, 1498, but finding that the monsoons were not then sufficiently set in to be favourable for the homeward voyage, they anchored at “Angediva,”[16] an island on the coast of Malabar, where there were good water springs, and where they “enjoyed themselves much.” After remaining there ten days, they departed on their voyage to Melinde. They were, however, delayed for a time by corsairs, fitted out at Goa, in the hope that the Portuguese ships might be captured by stratagem, a hope which was rudely demolished; the fleet of “fustas” were entirely destroyed, and Vasco de Gama arrived, homeward bound, without further molestation or misfortune, safely at the African port (Melinde), on the 8th January, 1499.

Having been received with great rejoicings, De Gama, in reply to the affectionate welcome of the king, made a glowing speech, in which by the way he remarked that “the king, our sovereign, will send many ships and men to seek India, which will be all of it his, he will confer great benefits on his friends, and you will be the one most esteemed above them all, like a brother of his own; and when you see his power, then your heart will feel entire satisfaction.”

A letter, written “on a leaf of gold,” was then prepared for the king of Portugal, in which all that had taken place at Melinde was mentioned, with many requests that the Christian sovereign[Pg 19] would send his fleets and men to his ports. Rich presents were at the same time placed in the charge of De Gama to be delivered on the part of his majesty of Melinde to the king and queen of Portugal; while presents of a similar kind, and scarcely less valuable, were given to De Gama and his officers. In return for these handsome gifts, De Gama, “desiring that the king of Portugal should excel all others in greatness,” ordered to be put into the boats ten chests of different sorts of uncut coral, a considerable quantity of amber, vermilion, and quicksilver; numerous pieces of brocade, velvet, satin, and coloured damasks, with many other things which he considered it was “not worth while to take back to Portugal, as of little value there.” The king, besides furnishing him with pilots, presented to them various things that might be useful or pleasant on the voyage; such as jars of ginger, preserved with sugar, for the captain-major, and for Paul de Gama, “which they were to eat at sea when they were cold,” and two hundred cruzados in gold, “to be distributed among their wives.” Thus enriched and replenished, the expedition set sail for Europe on the day of St. Sebastian, the 20th of January, 1499.[17]

Having shaped a course along the coast, the captains gave orders to note with care the various headlands, and every conspicuous landmark, especially the outlines and marks presented by the land when seen astern of the vessels, and also to note down the names of the towns and the rivers, and their position from the more conspicuous headlands, for the guidance of future voyagers. With a fair wind, and under the[Pg 20] direction of the native pilots, who were familiar with the navigation, the expedition passed swiftly through the Mozambique channel, and without calling at any place, rounded, in fine weather, the dreaded Cape of Good Hope, and saw “the turn which the coast takes towards Portugal with shouts of joy, and prayers and praises for the benefits that had been granted to them.”

“When it was night,” continues Correa in his narrative, “the Moorish pilots took observations with the stars, so that they made a straight course. When they were on the line they met with showers and calms, so that our men knew that they were in the region of Guinea. Here they encountered contrary winds, which came from the Straits of Gibraltar, so that they took a tack out to sea on a bowline, going as close to the wind as possible. They sailed thus, with much labour at the pumps, for the ships made much water with the strain of going on a bowline, and in this part of the sea they found some troublesome weed, of which there was much that covered the sea, which had a leaf like sargarço,[18] which name they gave to it, and so named it for ever. Our pilots got sight of the north star at the altitude which they used to see it in Portugal, by which they knew they were near Portugal. They then ran due north until they sighted the islands, at which their joy was unbounded, and they reached them and ran along them to Terceira, at which they anchored in the port of Angra, at the end of August. There the ships could hardly keep afloat by means of[Pg 21] the pumps, and they were so old that it was a wonder how they kept above water, and many of the crews were dead, and others sick, who died on reaching land. There also Paul de Gama died, for he came ailing ever since he passed the Cape; and off Guinea he took to his bed, and never again rose from it.”[19]

The death of Paul de Gama was a source of the greatest grief to his brother Vasco. His body was buried in the monastery of St. Francis with much honour, and amidst the lamentations of the crews, and the chief inhabitants of the island, who followed it to the grave. The crews having, chiefly by death, been reduced to fifty-five, and many of the men being in a weak state, the government officers of Terceira sent an extra supply of seamen on board, to navigate the ships to Lisbon, for which port the expedition sailed as soon as the vessels had received the necessary refit, reaching the Tagus on the 18th of September, 1499, after an absence of two years and eight months, on one of the most remarkable and interesting voyages on record.

But the news of the arrival of the fleet at Terceira had preceded its actual arrival at Lisbon, more than one adventurer having started thence while De Gama was detained, so as to secure the reward for bringing the first good tidings to the king, then at Cintra.

It spread, indeed, far and wide. Another road had been discovered to a country which, famed for its riches, had been the envy of the Western nations from the earliest historic period, as well as the dream of the youth of every age and land since the days of Solomon and Semiramis. Well might Lisbon be in a state of the greatest ecstasy when the tidings of[Pg 22] the great discovery reached its people. They were indeed tidings of the highest importance, not merely to them, but to the people of every maritime and commercial city of Europe.

The information reaching the king at midnight, he resolved to start with his retinue early in the morning for Lisbon, to receive further intelligence, and to welcome the ships on their entry into the Tagus. There the glad tidings were confirmed. The king waited at the India House until the ships arrived at the bar, where there were boats with pilots, who brought them into port, decorated with numerous flags, and firing a salute as they anchored. When Vasco de Gama landed on the beach before the city, he was received by “all the nobles of the court, and by the Count of Borba and the Bishop of Calçadilha; and he went between these two before the king, who rose up from his chair, and did him great honour,” conferring upon him the title of “Dom,” with various grants and privileges, and creating him high admiral, an office which the Marquis of Niza, his lineal descendant, holds to this day. “Then the king mounted his horse, and went to the palace above the Alcasoba, where his apartments then were, and took Vasco de Gama with him, who, on entering where the queen was, kissed her hand, and she did him great honour.”[20]

While rewards were freely bestowed upon all persons who had taken part in the expedition, costly offerings were made to the monastery of Belem, with gifts to numerous churches, as also to various holy houses and convents of nuns, that “all might give thanks and praises to the Lord for the great favour[Pg 23] which He had shown to Portugal.” The king, with the queen, went in splendid state and in solemn procession from the cathedral to St. Domingo, where Calçadilha preached on the grandeur of India, and its “miraculous discovery.”

Soon afterwards the king arranged to send another fleet, consisting of large and strong ships of his own, with great capacity for cargo, which, if navigated in safety, “would bring him untold riches.” All these matters his majesty talked over very fully with Vasco de Gama, who was to proceed as captain-major, if he pleased, in any fleet fitted out from Portugal to India, with power to supersede all other persons, and to appoint or discharge at his will the captains or officers of any of the vessels belonging to every expedition for India that might be equipped from the Tagus.

Indeed, the first expedition had yielded such immense profits, that arrangements for various others were readily entered into without delay. Correa states that a quintal of pepper realised eighty cruzados, cinnamon one hundred and eighty, cloves two hundred, nutmegs one hundred, ginger one hundred and twenty, while mace sold for three hundred cruzados the quintal.[21] So great were the profits, that when the accounts of the cost of the expedition were made up, by order of the king, and added to the prices paid for the merchandise when shipped, it was found that “the return was fully sixty-fold.”

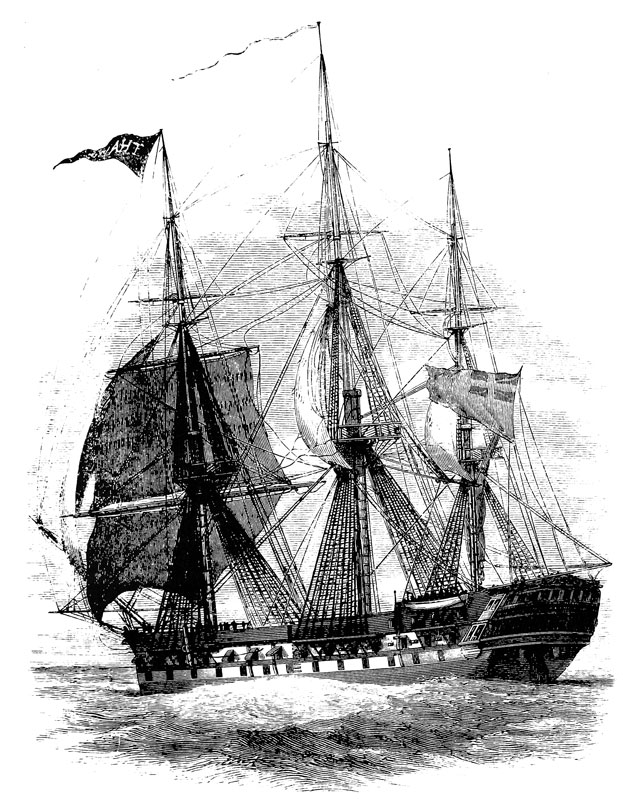

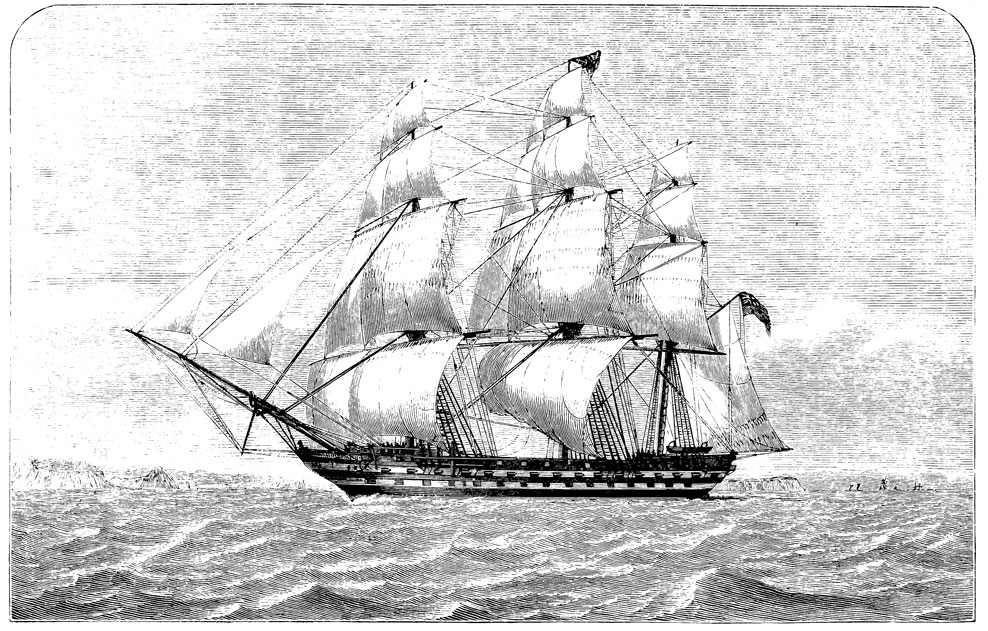

The second expedition, however, under Vasco de Gama’s direct control, was destined for other and[Pg 24] less laudable objects than commerce.[22] Dom Manuel had resolved to punish “the treachery of the king of Calicut.” Ten large ships were therefore prepared, fitted with heavy guns and munitions of war of every kind then known, besides abundance of stores, and with these, and five lateen-rigged caravels, Dom Vasco set sail for India on Lady-day, the 25th March, 1502, to wreak his sovereign’s “vengeance” on those contumacious kings of the East who had not treated his subjects with the respect which he felt was due to the representatives of “a great Christian monarch.” In this instance, as has been the case before and since in numerous other instances, solemn prayers were offered that the depredations about to be committed in the name of God and under the banner of a Christian king might be attended with success. “I feel in my heart,” exclaimed De Gama, addressing his sovereign, “a great desire and inclination to go and make havoc of him (the king of Calicut), and I trust in the Lord that He will assist me, so that I may take vengeance of him, and that your highness may be much pleased.” But though “vengeance is Mine, saith the Lord,” has been the text of every Christian church from the earliest ages, a solemn mass and numerous prayers were offered in the cathedral, at which the king was present and all his court, to invoke Heaven to strengthen the arm of Dom Gama in his openly-avowed mission of vengeance.

[Pg 25]

In the fifteen sail of vessels composing the second expedition, there were “eight hundred men at arms, honourable men, and many gentlemen of birth, with the captain-major and others, his relations and friends, with the captains.”[23] Each soldier had three cruzados a month, and one for his maintenance on shore, besides the privilege of shipping on his own account two quintals of pepper, at a nominal rate of freight, and subject only to a small tax, “paid towards the completion of the monastery at Belem.” Considerably greater space was allowed in the ship to the masters, pilots, bombardiers, and other officers, a practice which prevailed to our own time in the ships of the English East India Company.

“When the fleet was quite ready to set sail from the river off Lisbon, after cruising about with a great show of banners, and standards, and crosses of Christ on all the sails, and saluting with much artillery, they went to Belem, where the crews were mustered, each captain with his crew, all dressed in livery and galas, and the king was present, and showed great favour and honour to all.”[24] Here the fleet lay for three days, and when the wind became fair, the king went in his barge to each ship, dismissing them with good wishes, the whole of the squadron saluting him with trumpets as they took their departure.

With the exception of some sickness, when crossing the equator in the vicinity of Guinea, of which one of the captains and a few of the men died, the expedition had a favourable passage round the Cape of Good Hope, but immediately afterwards encountered a heavy gale, which lasted for six days.[Pg 26] During this storm most of the vessels were dispersed and one of them lost, though her crew and cargo were saved. When the weather moderated, each ship, in accordance with previous instructions, steered for Mozambique as the appointed rendezvous, where they again assembled under the captain-major, some of them, however, having joined company before reaching that place. Here the sheikh, who does not appear to have been the same person who held that office on Gama’s first expedition, sent to the ships presents of cows, sheep, goats, and fowls, for which, however, the captain-major paid, and ordered a piece of scarlet cloth to be given to him. From Mozambique the expedition proceeded to Quiloa, but remembering the treachery of the king of that place, De Gama, after he had moved his fleet within range of the town, sent the following message to his sable majesty: “Go,” he said to an ambassador whom the king had sent on board, “go and say to the king that this fleet is of the king of Portugal, lord of the sea and of the land, and I am come here to establish with him good peace and friendship and trade, and for this purpose let him come to me to arrange all this, because it cannot be arranged by messenger. And in the name of the king of Portugal, I give him a safe conduct to come and return, without receiving any harm, even though we should not come to an agreement; and if he should not come, I will at once send people on shore, who will go to his house to take and bring him.”[25]

The king, on receipt of this apparently friendly, but very peremptory message, was with his chiefs[Pg 27] amazed and greatly alarmed. Having held a council, he despatched a reply to the captain-major, that he would send him a signed paper to the effect that he and his crew might land freely, if no injury were done to him or the city. De Gama, however, resolved to put pressure upon the king; who, over persuaded by a crafty and rich Moor, ventured on board the ship of the Portuguese admiral, with large, and, so far as we can judge, true professions of friendship and amity.

But the captain-major required something more than this. “If,” said he, “the king of Quiloa became a friend of the king, his sovereign, he must also do as did the other kings and sovereigns who newly became his friends, which was that each year he should pay a certain sum of money or a rich jewel, which they did as a sign that by this yearly payment it was known that they were in good friendship.”[26] In a word, that he should subject himself and his dominion to the government of Portugal. The African king seems to have clearly understood and felt the force of this plausible mode of abdicating his sovereign rights, for he replied, “That to have to pay each year money or a jewel was not a mode of good friendship, because it was tributary subjection, and was like being a captive; and, therefore, if the captain-major was satisfied with good peace and friendship without exactions, he was well pleased, but that to pay tribute would be his dishonour.” The captain-major, however, cared little for anything except submission. “I am the slave of the king, my sovereign,” he haughtily replied, “and all the men[Pg 28] whom you see here, and who are in that fleet, will do that which I command; and know for certain, that if I chose, in one single hour your city would be reduced to embers; and if I chose to kill your people, they would all be burned in the fire.” Thus the Western nations, under the plea of peace and friendship, and on the pretence at first of only desiring to establish factories for the purposes of peaceful and mutually beneficial commerce, became lords of the East, and for centuries exercised a dominion founded on despotism and injustice over its native sovereigns. The king of Quiloa might remonstrate as he pleased, submission was his only course. “If I had known,” he replied, with great warmth and energy, “that you intended to make me a captive, I would not have come, but have fled to the woods, for it is better to be a jackal at large than a greyhound bound with a golden leash.”[27] “Go on shore and fly to the woods,” said the now exasperated representative of the Christian king—“go on shore to the woods, for I have greyhounds who will catch you there, and fetch you by the ears, and drag you to the beach, and take you away with an iron ring round your neck, and show you throughout India, so that all might see what would be gained by not choosing to be the captive of the king of Portugal.” And this Christian speech was accompanied with an order to his captains “to go to their ships, and bring all the crews armed, and go and burn the city.”

As De Gama refused to grant the king even one hour for consultation, he submitted, and this submission, having been ratified on a leaf of gold, and[Pg 29] signed by the king and all who were with him, presents were exchanged, while the rich Arab, whose treachery soon afterwards became known, was left on board, by way of security for the delivery of other articles which had been promised; but the king sent word that Mahomed Arcone “might pay himself, since he had deceived him.” On receipt of this information the captain-major became very angry with the rich Moor, and ordered him and the Moors who had accompanied him to be “stripped naked, and bound hand and foot, and put into his boat, and to remain thus roasting in the sun until they died, since they had deceived him; and when they were dead he would go on shore and seek the king, and do as much for him, lading his ships with the wealth of the city, and making captive slaves of its women and children.” It was not, however, necessary to carry into effect these terrible threats. The Moor sent to fetch from his house a ransom, valued at 10,000 cruzados (£1,000 sterling), which he gave with other perquisites to the “Christian” ambassador, who immediately afterwards pursued his voyage to Melinde.

On arriving in sight of the port, the king, who had already received the news, was prepared with “much joy to welcome his great friend Dom Vasco de Gama;” while the fleet anchored amidst a salvo of artillery. The king with haste embarked in a barge which he had ready, to visit and pay his respects to the captain-major, “bringing after him boats spread with green boughs, accompanied by festive musical instruments; and De Gama, as soon as he was aware that it was the king, went to receive[Pg 30] him on the sea, the two at once embracing and exchanging many courtesies.”[28]

An exchange of presents continued for the three days the fleet remained at Melinde, and much rejoicing and festivity prevailed. Fresh provisions of every kind were sent in abundance for each of the vessels, as also tanks for water, which the king of Melinde had prepared in anticipation of the arrival of the expedition, with pitch for the necessary repairs to the ships, and coir sufficient for a fresh outfit of hawsers and cordage for the whole expedition. On the day of departure the king went on board, and gave De Gama a valuable jewelled necklace for his sovereign, worth three thousand cruzados, and others of not much less value for himself, with various other gifts, among which were a bedstead of Cambay, wrought with gold and mother of pearl, a very beautiful thing, and he gave him letters for the king, and a chest full of rich stuffs for the queen, with a white embroidered canopy for her bed, the most delicate piece of needlework, “like none other that had ever been seen.”[29]

Soon after their departure the expedition fell in with five ships, which had been fitting out in the Tagus for India when Vasco de Gama sailed, and which had been placed under the command of his relation Estevan de Gama. The combined fleets proceeding on their voyage, called at the “port of Baticala,[30] where there were many Moorish ships loading rice, iron, and sugar, for all parts of India.” The[Pg 31] Moors, on the approach of the Portuguese, prepared to offer resistance to them entering the harbour, by planting some small cannon on a rock which was within range of the bar. The boats, however, belonging to the Portuguese ships made their way into the harbour without damage, although amid showers of stones from the dense mass of people who had collected to resist their approach, until they reached some wharves, which had been erected for the convenience of loading the vessels frequenting the port. The Moors then fled in great disorder, leaving behind them a large quantity of rice and sugar, which lay on the wharf ready for shipment, and the Portuguese returned to their boats in order to proceed to the town, which was situated higher up the river. On their way, however, a message was sent from the king of Baticala to say that, though he “complained of their carrying on war in his port, without first informing themselves of him, whether he would obey him or not, he would do whatever the captain-major commanded.” Upon which De Gama replied, “that he did not come with the design of doing injury to him, but when he found war, he ordered it to be made; for this is the fleet of the king of Portugal, my sovereign, who is lord of the sea of all the world, and also of all this coast.”[31]

In this spirit the trade between Europe and India, by way of the Cape of Good Hope, was opened by the Portuguese. It was thus continued by them and the Dutch for somewhere about a century, and perpetuated in the same domineering manner by the servants of the English East India Company, even[Pg 32] until our own time.[32] To the demand for gold or silver, the king of Baticala could only reply that he had none. His country was too poor to possess such treasure, but such articles as his country possessed he would give as tribute to Portugal; and having signed the requisite treaty of submission, he despatched in his boats a large quantity of rice and other refreshments for the fleet, on the receipt of which the captain-major set sail for Cananore.

On the passage the expedition encountered a heavy storm, and sustained so much damage, that it was necessary to anchor in the bay of Marabia for repairs. Here they fell in with a large Calicut ship from Mecca, laden with very valuable produce, which the captain-major pillaged, and afterwards burned, because the vessel belonged to a wealthy merchant of Calicut, who he alleged had counselled the king of that place to plunder the Portuguese on their previous voyage. Nor were these Christian adventurers satisfied by this act of impudent piracy; they slaughtered the whole of the Moors belonging to the ship, because they had stoutly resisted unjust demands, the boats from the fleet “plying about, killing the Moors with lances,” as they were swimming away, having leapt from their burning and scuttled ship into the sea.[33]

[Pg 33]

On the arrival of the expedition at Cananore, De Gama related to the king how gratified his sovereign had been by the reception which his fleet had formerly received, and presented him with a letter and numerous presents. He then narrated the course of retaliation which he intended to pursue with the king of Calicut, expressing a hope that the merchants of Cananore would have no dealings with those of Calicut, for he intended to destroy all its ships, and ruin its commerce. This vindictive policy seems to have gratified the jealous Cananore king, for “he swore upon his head, and his eyes, and by his mother’s womb which had borne him, and by the prince, his heir,” that he would assist the captain-major in his work of revenge by every means in his power. Upon which De Gama “made many compliments of friendship to the king on the part of the king his sovereign, saying that kings and princes of royal blood used to do so amongst one another; and maintained good faith, which was their greatest ornament, and was of more value than their kingdoms.”[34]

Having arranged how the king of Calicut and his subjects were to be disposed of, his majesty of Cananore returned to his palace, and matured with his council the measures to be taken so as to carry out wishes of his friend and ally the king of Portugal. In matters of trade it was agreed that a fixed price should be set upon all articles offered for sale, and that there should be no bargaining between the buyer or seller for the purpose of either lowering or raising prices. The chief merchants of the city and natives of the country were to arrange with the[Pg 34] factors from the ships what the prices were to be, and these “should last for ever.” A factory was to be established where goods were to be bought and sold; and all these things were written down by the scribes, so as to constitute an agreement, which both parties signed. When completed, De Gama took counsel with his captains, and settled that two divisions of the fleet should cruise along the coast, “making war on all navigators, except those of Cananore, Cochym, and Coulam,”[35] while the factors should remain on shore, with a sufficient number of men to buy and gather into their warehouse at Cananore, “for the voyage to the kingdom, much rice, sugar, honey, butter, oil, dried fish, and cocoa-nuts, to make cables of coir and cordage.”

Having arranged all these matters to the satisfaction of everybody at the place, except the Moorish merchants, who were “very sad” when they saw their ancient trade by the Red Sea passing into the hands of strangers, Dom Gama sailed with his combined fleet for Calicut, where, on arrival, he found the port deserted of its shipping, the news of his doings at Onor and Baticala having reached the ears of the people of Calicut; the king, however, sent one of the chief Brahmins of the place, with a white flag of truce, in the vain hope that some terms of peace might be agreed upon. But the captain-major rejected every condition, and ordering the Indian boat to return to the shore, and the Brahmin to be safely secured on board of his ship, he bombarded the city, “by which he made a great destruction.” Nor was his vengeance satisfied by this wanton destruction of[Pg 35] private property, and the sacrifice of the lives of many of the inhabitants of the city; while thus engaged “there came in from the offing two large ships, and twenty-two sambacks and Malabar vessels from Coromandel, laden with rice for the Moors of Calicut:” these he seized and plundered, with the exception of six of the smaller vessels belonging to Cananore. Had the acts of this representative of a civilised monarch been confined to plunder, and the destruction of private property at sea and on shore, they might have been passed over without comment as acts of too frequent occurrence; but besides this, they were deeply dyed with the blood of his innocent victims. The prayers he had offered to God with so much solemnity on the banks of the Tagus proved, indeed, a solemn farce; his own historian adding the shameful statement, that after the capture of these peaceable vessels, “the captain-major commanded them” (his soldiers) “to cut off the hands, and ears, and noses of all the crews of the captured vessels, and put them into one of the small vessels, in which he also placed the friar, without ears, or nose, or hands, which he ordered to be strung round his neck with a palm-leaf for the king, on which he told him to have a curry made to eat of what his friar brought him.”[36]

Perhaps no more refined acts of barbarity are to be found recorded in the page of history than those which Correa relates with so much simplicity of his countryman; they would seem, indeed, to have been almost matters of course in the early days of the maritime supremacy of the Portuguese, and may in[Pg 36] some measure account for the unsatisfactory condition into which that once great nation has now fallen. Supposing, however, the exquisite barbarism of sending to the king the hands, ears, and nose of his ambassador, to whom Dom Gama had granted a safe conduct, not enough to convey to the ruler of Calicut a sufficiently strong impression of the greatness, and grandeur, and power, and wisdom, and civilisation of the Christian monarch, whose subjects he had offended, the captain-major ordered the feet of these poor innocent wretches, whom he had already so fearfully mutilated, “to be tied together, as they had no hands with which to untie them; and in order that they should not untie them with their teeth, he ordered them” (his crew) “to strike upon their teeth with staves, and they knocked them down their throats, and they were thus put on board, heaped up upon the top of each other, mixed up with the blood which streamed from them; and he ordered mats and dry leaves to be spread over them, and the sails to be set for the shore, and the vessel set on fire.”[37]

In this floating funeral pile eight hundred Moors, who had been captured in peaceful commerce, were driven on shore as a warning to the people of Calicut, who flocked in great numbers to the beach to extinguish the fire, and draw out from the burning mass those whom they found alive, over whom “they made great lamentations.” When the friar reached the king with his revolting message, and deprived of his hands, ears, and nose, an object of the deepest humiliation, he found himself in the midst of[Pg 37] the wives and relations of those who had been so shamefully massacred, bewailing in the most heart-rending manner their loss, and imploring the king to render them aid and protection from further injury. Although the king’s power was feeble compared to that of the Portuguese, with their trained men of war, and vastly superior instruments of destruction, the sight of his faithful Brahmin, whom he had despatched in good faith to offer any conditions of peace which Dom Gama might demand, led him to resolve with “great oaths” that he would expend the whole of his kingdom in avenging the terrible wrongs which had been inflicted upon his people. Summoning to his council his ministers and the principal Moors of the city, he arranged measures for their protection from the even still greater dishonour and ruin which was threatened with awful earnestness by their invaders. The Moors, with one voice, “offered to spend their lives and property for vengeance.” In every river arrangements were made for the construction of armed proas, large rowing barges and sambacks, and as many vessels of war as the means which their country afforded could produce. But long before this fleet was ready, Dom Gama had sailed with his expedition for Cochym, where he arrived on the 7th of November, having on his passage done as much harm as he could to the merchants of Calicut, many of whose vessels he fell across in his cruise along the coast.

Cochym, like Cananore, had resolved from the first to court the friendship of Portugal. Its rulers conceived it more to their interests to submit to the conditions of Dom Gama, however humiliating, than[Pg 38] to resist his assumed authority. Consequently when his fleet made its appearance, the king of Cochym was ready to receive him with every honour; and when his boat, with its canopy of crimson velvet, very richly dressed, approached the shore, the king, accompanied by his people, came to the water-side to meet him, prepared to secure his friendship by any submission, however abject. Numerous rich and valuable presents having been interchanged, arrangements were made to provide the cargo the captain-major required, on similar conditions to those which had been entered into at Cananore.

When the queen of Coulam, a neighbouring and friendly state, where the pepper was chiefly produced, heard of the wealth which the king of Cochym and his merchants were making by their commercial intercourse with the Portuguese, she sent an ambassador to Dom Gama to entreat him to enter into similar arrangements with herself and her people, saying that “she desired for her kingdom the same great profit, because she had pepper enough in her kingdom to load twenty ships each year:” but Dom Gama was a diplomatist, or at least a dissembler, as well as an explorer. To fall out with the king of Cochym did not then suit his purpose, which he would very likely have done had he allowed the queen of Coulam to share in the lucrative trade without his sanction; but he nevertheless appears to have made up his mind to reap the advantage of the queen’s trade under any circumstances. Consequently, he sent word to the queen “that he was the vassal of so truthful a king, that for a single lie or fault which he might commit against good faith, he would order his[Pg 39] head to be cut off; therefore he could not answer anything with certainty, nor accept her friendship, nor the trade which she offered, and for which he thanked her much, without the king (of Cochym) first commanded him.”[38]

After this palaver he recommended that she should ask the king of Cochym’s permission to open up commercial intercourse with the Portuguese, an arrangement he was not likely to assent to, as besides curtailing his profits, he would lose the revenue he derived from the queen’s pepper, which now passed through his kingdom for shipment. The king was naturally perplexed and “much grieved, because he did not wish to see the profit and honour of his kingdom go to another.” So after talking the matter over with De Gama’s factor, he resolved to leave it entirely in the hands of the captain-major, and informed the queen’s messenger that the matter was left altogether to his good pleasure, no doubt himself believing that the trade would be therefore declined. But the king of Cochym had made a sad mistake, for the Portuguese navigator was a diplomatist far beyond the king’s powers of comprehension; to his discomfiture and amazement Gama informed the ambassador of Coulam “that he was the king’s vassal, and in that port was bound to obey him as much as the king his sovereign, and, therefore, he would obey him in whatever was his will and pleasure; and since the queen was thus his relation and friend, he was happy to do all that she wished!”[39] Consequently he despatched two of his ships to load pepper, at “a river called Calle[Pg 40] Coulam,” sending the queen a handsome mirror and corals, and a large bottle of orange-water, with scarlet barret-caps for her ministers and household, and thirty dozen of knives with sheaths for her people. Soon afterwards he established a factory in her kingdom.