Title: Marigold's decision

Author: Agnes Giberne

Illustrator: W. Lance

Release date: June 30, 2024 [eBook #73955]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: James Nisbet & Co, 1896

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

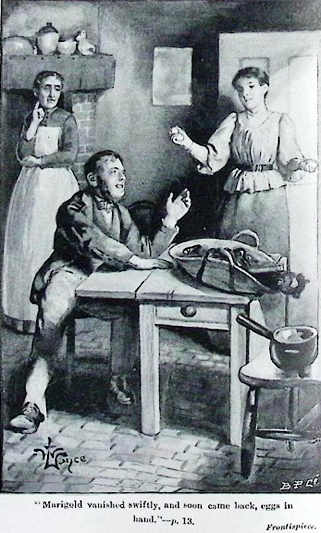

Marigold vanished swiftly, and soon came back,

eggs in hand. Frontispiece.

BY

AGNES GIBERNE

AUTHOR OF "MISS CON," "ST. AUSTIN'S LODGE," "DECIMA'S PROMISE,"

"THE ANDERSONS," ETC. ETC.

ILLUSTRATIONS BY W. LANCE

London

JAMES NISBET & CO.

21 BERNERS STREET

1896

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER

I. WHAT SORT OF PEOPLE THEY WERE

MARIGOLD'S DECISION.

WHAT SORT OF PEOPLE THEY WERE.

"MARIGOLD!" cried a loud voice, rough in tone, as working-men's voices are sometimes apt to be.

"I'm coming, father."

There was a pause, but no Marigold appeared; and Josiah Plunkett set down his bag of tools with a decisive bump, which showed disapproval. He was undersized as to height, but broad in build, with long powerful arms, and a large good-humoured face. Even when he frowned, as at this moment, the look of good humour did not vanish. Like most of his sex, he had a particular dislike to being kept waiting. Of course, he often kept other people waiting, and thought nothing of it; but to be made to wait himself was a different matter.

"I say! Mari-gold!" he shouted, with a vigour which made the walls of the little house to ring.

It was a very small house, a mere rattle-trap in build, with lath and plaster walls, from which paper peeled and damp exuded, and into which no nails could be driven with the least prospect of remaining there. Josiah Plunkett, being a carpenter, had done the best he could for the inside of his home under the circumstances; but he could not make a good house out of a bad one. Such untidiness as existed was not his fault.

"What's that noise for?" demanded a sour voice, and a woman appeared in the passage.

She was taller than Plunkett, and sallow skinned; not thin in figure, but thin in face, while from the acidity of her expression, it would seem that all the sweetness which once existed in her had been turned to vinegar. There is always some original sugar in everybody's composition, but the sugar does not always keep its sweetness.

"What's it all about?" she demanded sharply.

"What about! It's about me!" declared the husband. "Now, you just look here. I've got to be off, and I want some'at to eat. I haven't a minute to lose."

"Well, there's nothing ready for you, nothing at all!" Mrs. Plunkett spoke as if rather gratified to be able to say this. "You said you'd go and pick up something at the coffee-stall, to save the long tramp back; and you know you did. We've had our dinner—just scraps—and I didn't get anything fresh, and we've finished everything. There's no cheese, nor bread, nor nothing left—only a bit of butter."

"You might as well make short work with what you've got to say, and not go on for ever like the clapper of a bell," said Plunkett. "That's a nice tale for a hungry man, ain't it? Where's Marigold?"

"Mary's up—"

"Now, I say!—You, Jane!"

"Well, I never do bother to call her nought but Mary, unless you're by. Don't mean to, neither. It's ridiculous."

"She's not Mary, I tell you—she's Marigold. And Narcissus ain't Ciss, she's Narcissus. That's what they was christened, in full—Marigold and Narcissus—and I won't have 'em called by any other names. If they'd got common names, you'd go out of your way to make 'em uncommon. Women's that perverse!"

"If I was you, I'd be ashamed to have my girls called by such outlandish names. It ain't respectable. The very lads in the street calling out after 'em."

"They'd best let me catch them at that!"

"Well, it's no kindness to the girls, anyway; and Ciss cries."

"Narcissus is a little goose. Marigold don't cry. Marigold's got more stuff in her. Now, I say, you be sharp, and get me something. I'm famished, and I've got to work late; for I've promised Mr. Heavitree faithful as I won't leave that schoolroom till the work's done, and there's a lot to get done."

Plunkett followed his wife's retreating figure into the kitchen, and took a look round. It was not very tidy; not such a kitchen as he had been used to all his earlier married life, when the mother of Marigold and Narcissus was living. She had died four years earlier; and about two years and a half after her death, or eighteen months before this time, Plunkett had married again.

When first he brought home the new wife, people thought that he had made a good and wise choice, and that she would be a true friend to his two girls. She was a fine-looking woman, rather stout, almost handsome, with pleasant smile and manner, careful as to her appearance, and, indeed, rather fond of dressing well. The girls showed very nice feeling, welcoming her for their father's sake, and for a time all went well.

Then a gradual and extraordinary change came over her. She grew miserably gaunt and plain, untidy and careless, fretful and unhappy. What had caused the transformation, nobody knew; her husband least of all. She was plainly not in good health, seeming at times to suffer much, and talking of "rheumatism"; but she would not or could not say where the pain was, and she utterly refused to see a doctor.

Beside all this, she developed a grumbling and discontented temper, which might or might not have belonged to her in earlier days. It did not come to light until more than three months after her marriage. During those three months all had been smooth, and the girls were growing fond of their stepmother. Plunkett congratulated himself on the step he had taken; friends and neighbours said what a good arrangement it was. Then came the alteration in her, which altered the home, and cast a shadow on the lives of those who lived with her. One ill-temper in a house is quite enough to mar the happiness of the whole family.

Plunkett, reaching the kitchen, where pots and pans, plates and cloths, lay about in a haphazard fashion, dropped or rather plumped down on a chair, and stuck out his two legs in front of him.

"Now, then! Look sharp! I've got no time to lose."

Mrs. Plunkett slowly poked up the decaying fire, and placed a kettle thereon. Her husband watched with attentive eyes, which could never be otherwise than good-humoured, whatever tone of voice he chose to speak in.

"Now, then! What's that kettle for?"

"I thought you'd like a cup of tea, as I haven't got—"

"Cup o' tea, when I'm famished for want o' some'at substantial. I like that, I do! I'm to work like a slave, and have a cup o' tea to keep me going. Here's Marigold and Narcissus. Nice state o' things, ain't it, girls? Here am I come home to dinner, and not a scrap o' victuals for me to eat."

"Why, it's father," said Marigold.

She looked about seventeen years old, perhaps eighteen, and was not remarkably pretty; but what of that? Most people are more or less pretty in the eyes of those who love them; and as for those who do not, it matters little. Some girls think a great deal of having strangers say, "What a pretty face!" But when the stranger has said the words, and has passed on, forgetting, what has the pretty face gained?

If Marigold were not strictly pretty, except as seen by loving eyes, she was not without her charms. She had a neat figure, and rounded rosy cheeks, and her brown hair was smooth as satin, and when her light grey eyes smiled, they were full of sweetness. The mother's tidiness had descended in full measure upon her eldest daughter. Everything about Marigold seemed to have just come out of a band-box.

Narcissus, though eighteen months the younger, was the taller; a pale-faced girl, too colourless and thin, and too much disposed to stoop, for good looks. She had light-tinted hair, and rather listless eyes, suiting her listless manner.

But Josiah Plunkett admired his girls with all his heart—both of them in different ways; and Marigold the most, because of her likeness to his first wife. He might be rough in speech, and not too mannerly in manners; yet he really was a loving father, and he did not believe there were any two girls in the world equal to his Marigold and Narcissus. He was ready to back them any day against all the young women in the neighbourhood, for sense and niceness. So he often told his wife; but at the present moment he was too hungry for compliments.

"Not a scrap of victuals for me to eat! See, Marigold, what's to be done? I've got no time to lose. There's a lot of carpentering yet in the schoolroom, and I've promised Mr. Heavitree I'll get it all done to-night."

"Why, father, you said you wouldn't come back to dinner."

"That's what I've been telling of him! And then to be expecting a reg'lar spread, waiting for him on the chance!" complained Mrs. Plunkett.

"Well, if I didn't mean, I've changed my mind; and now I've got to eat. A cup o' tea ain't enough for my inside, without there's some'at more substantial to be washed down."

"Father, you wouldn't mind two nice fresh eggs! They've got a lot next door; and they'll lend me half a-loaf. Eggs don't take long to boil. We're out of cheese, but there's butter."

"Well, well, I shouldn't wonder if I could make shift with the eggs. Get three when you're about it, my girl; and be quick."

Marigold vanished swiftly, and soon came back, eggs in hand, nice big brown ones, appetising in look. The neighbours kept fowls in their little back garden, and had often an abundance of eggs to use or sell.

Why do not English working-men and their wives oftener keep fowls? The outlay and trouble are not great, and it would be well worth their while. Enormous quantities of eggs come to England from abroad; and the money which pours out of England to pay for all those foreign eggs might just as well be poured into English pockets for English eggs, if only fowls were more plentifully kept. Of course, people need to learn how to manage their fowls, how to feed them economically, and how to balance the good and bad times of the year, so as on the whole to be gainers.

"What's that there dirty saucepan lying on the chair for?" demanded Plunkett, as Marigold gave the eggs to Mrs. Plunkett. She would have cooked them herself, but the elder woman stood guarding the fire.

"It's been all the morning," murmured Marigold.

"Well, why don't somebody clean it, and put it away? Eh? That's what I want to know."

"I'd do it, if I might, father."

"She's not a-going to meddle with me nor my work. So there!" spoke Mrs. Plunkett aggressively, dropping the two biggest eggs into a saucepan, and keeping back one.

"All three!" ordered Plunkett. "I'm famished, I can tell you! What's an egg to a hungry man—eh?"

"Mother, that water don't boil," said Marigold.

"You just mind your business, and I'll mind mine," said Mrs. Plunkett.

Marigold gave her father a look, and he returned it with meaning. Hers said, "You see, I can't help myself!" His said, "What next, I wonder?"

Then Marigold brought out a clean cloth, and spread it neatly on one end of the kitchen table. Bread and butter, plate and cup, followed. Plunkett watched her with satisfaction.

"That's something like!" he said. "Them eggs ain't ready yet!"

"They're boiled," said his wife; and she brought them.

"There! I told you so!" Plunkett gave a sharp tap with his spoon, and thin liquid spurted from the crack. "'Tain't begun to be cooked. Here, Marigold—you know how! Put 'em in again, and boil 'em properly. Not you, Jane! Marigold!"

Plunkett raised his voice, and his wife retreated. Marigold did not wish to show any triumph, but perhaps she looked rather too well pleased, as was natural, though not wise. She covered the crack with salt, brought the water to boiling pitch, and dropped the eggs lightly in. This time the venture was successful.

"I've been having a talk with Mrs. Heavitree," said Plunkett, taking a gulp of tea.

"What about, father?"

"About Narcissus. Mrs. Heavitree wants to have her for a year—now. Not to put off no longer. She said she thought Narcissus was turned sixteen, and I said, yes, she was. So then she said, now was the time. The nursery girl is leaving next week, and Mrs. Heavitree thinks that 'ud suit Narcissus better than house-work. And I've promised she shall go."

"Rubbish!" said Mrs. Plunkett.

"May be, or mayn't be. That's neither here nor there. Anyway, I've given my word. I promised the girls' mother I'd let 'em go, each in turn, and I'm not a-going to draw back from that for nothing nor nobody. And I've promised Mrs. Heavitree, too."

"She's not going, though."

"She is going," said Plunkett.

"It's rubbish, I tell you," repeated his wife. "And what's more, it can't be. I can't spare Ciss. She's a deal more use to me than Marigold. Mary likes her own way a lot too much."

"Most folks do. Anyhow, you've got to manage. I've promised, and I'll stick to my word. Narcissus 'll go next week."

"I don't mean her to."

"She'll go, all the same. I don't want to part with her, but I'm not the man to go back from my word. I've promised, and I'll do it." Plunkett took another large mouthful of bread, and another huge gulp of tea. "Look here, you just talk it over with the girls, and see what's wanted. Caps and aprons, and all the rest. Marigold knows."

"I wish I was going!" said Marigold.

"Can't spare the two of you at once! You'll be a good girl, and help your mother. And Narcissus 'll be as happy as the day is long. So now that's all settled, and what do you think? I'm going to take you both to-morrow to see the wild beast show."

SERVICE.

"THE menagerie! O father, will you?" cried Narcissus. "I do want to see the lions and tigers, and they'll be here such a short time. But mother said you wouldn't think of it."

"Throwing away money on foolery," murmured Mrs. Plunkett.

"The beasts ain't always such fools as men and women, after all," quoth Plunkett. "Anyway, they're worth looking at. I do believe Narcissus has never seen a tiger in her life. There hasn't been a beast show here since I don't know when."

"Since I was so high," Marigold said, putting out her hand. "Narcissus was too little, but I went, and I haven't forgotten. Only there was no elephant that time, and they've got one now—such an enormous creature!"

"Narcissus won't be called by her name at the Parsonage," broke in Mrs. Plunkett. "I know that. It's no name for a servant."

"The name's given, and it can't be ungiven; Narcissus she is, and Narcissus she'll have to be all her life through. If you'd ha' been my wife sixteen years agone, why then she'd have been Betsy or Jane, as like as not. But you wasn't!"

"They 'll call her Betsy or Jane at the Parsonage, you'll see."

"Shouldn't wonder if they didn't do nothing of the sort. Anyway she's going. I've promised, and she's got to go." Then in an undertone to the girls, "All right about the beast show!" And losing no more time, he went off.

"Well, I say it's rubbish, and I don't care who I says it to," observed Mrs. Plunkett. "Sending a girl away for a year, just when she's beginning to be useful. And how I'm to manage—"

"I shall be more useful when I come back, mother."

"No, you won't. You'll be full of notions, like Marigold; and set on your own way. I know that. I like you a deal best as you are,—a girl that'll do as she's told, and ask no questions. Marigold is for ever meddling in what don't concern her; and I don't mean to stand it. I wish Mrs. Heavitree would just let folks alone."

Marigold presently stole away to an upstairs room; and Narcissus slipped after her.

"I'm glad to be going. I didn't feel sure at the first moment, but I'm glad now," said Narcissus. "Mother does worry so; and you say Mrs. Heavitree isn't hard to please."

"Never hard. She does expect the work to be done properly. She works a lot herself, and she means others to work. Oh, I don't mean that she sweeps and dusts, though she wouldn't be above that if there was need; but she's always seeing after everybody and everything, and thinking and planning, and doing kindnesses, and looking to the poor. Mrs. Heavitree's never idle; and she never gives in so long as she's got the power to go on. You like her now, and you'll like her ever so much better when you're in the same house."

"I don't mind if she doesn't scold. It's being scolded I mind."

"You won't have that to bear, for she doesn't scold. She'll tell you if you do wrong, but she don't scold. I only wish I was going too, and I would if it wasn't for father. He'd be miserable if he hadn't one of us. I can't think what in the world has come over mother in the last year. Why, when she first came, she was as different! She couldn't be just the same as our own mother, of course; but she did seem nice; and now—"

"There's no getting along straight," said Narcissus. "Everybody is wrong, and everything goes crooked. There! She's calling. One of us has got to answer."

"I'll go. Don't you mind. I'll run," said Marigold, suiting her action to the word. She had a peculiarly light way of going about, a quick noiseless step and capable manner, such as one sees in a well-trained servant. Mrs. Plunkett walked heavily, and Narcissus did everything in a limp style; but it was a treat to look at Marigold.

The first Mrs. Plunkett had been, before her marriage, a very efficient servant; and she had done her best to train her girls well. Nobody can do so much as a mother in that line. If the early home-training in cleanliness, order, diligence, good management, be absent, later training will seldom entirely take the place of it. When mothers carelessly allow children to waste their time, to grow into untidy and dirty ways, they little think how hard they are making it for those children to become afterward either good servants or good wives and mothers.

But these girls had had the advantage of good early training. They had never been allowed to go about with soiled hands and faces, nor with torn clothes. They had been taught to darn and mend well, to scour and clean thoroughly, to put everything away in the right place directly it was done with, to keep the house always neat, and to do unhesitatingly whatever needed to be done.

Marigold had profited the most by these instructions, because she was the older, also because she was the more spirited and firm in character. Narcissus was not very energetic naturally, and as the youngest, she had been just a degree spoilt; still she was a gentle-mannered nice girl, generally liked.

In addition to early training, Marigold had had the advantage of a year in the family of the Rev. Henry Heavitree, Incumbent of St. Philip's, a church outside the town beyond the farther extremity, a good two miles off. Mr. Heavitree was son of the lady in whose house the first Mrs. Plunkett had been for many years a servant, and his wife gave herself a great deal of trouble in training young girls for service, preparing them well and wisely, showing them how to put their heart into their work, and to make a duty of it all, by doing everything as in the sight of God.

Mrs. Heavitree had always promised the first Mrs. Plunkett that, when Marigold and Narcissus should be old enough, she would have them at the Parsonage, each for a year's training. Plunkett himself did not greatly care for the plan, since he was loth to part with his girls, and he was not one to look far ahead into their future; but the wiser mother wanted them to be fitted to make their own way in life, whenever need should arise. She knew well that for domestic service, as for every other kind of service, preparation is necessary. A good housemaid or parlourmaid can no more be turned out ready-made, at an hour's notice, than a good soldier or a good business man. Success in any manner of life has to be worked for, through steady learning and steady practice.

Some people dislike the word "service," as if there were something lowering in the term. Yet who is there in this world, worth anything at all, who does not serve somebody? The husband serves his wife, and the wife serves her husband. The mother serves her children, and the children serve, or ought to serve, their mother. The clergyman serves his flock, the statesman serves his country, the Queen serves her people; and the very motto of the Queen's eldest son, the Prince of Wales, is "Ich dien," which means "I serve." And, to go far higher, we know that ONE, Who lived among men, One Who is Himself the LORD of lords, said to His disciples: "I am among you as he that serveth."

So when we speak of service, whether domestic or any other kind, we speak of that which may be beautiful and grand, because Christ Himself came among us as a SERVANT.

Though Plunkett did not so clearly as his wife see the need for his girls to be trained, yet he gave in to her judgment; and before she died, he promised that her wish should be carried out.

It was not until nearly three months after his second marriage, when things still seemed fair and pleasant in the little home, that Mrs. Heavitree reminded him of this promise, and asked for Marigold. Plunkett grumbled, but did not resist, for he was not a man to fail in keeping his word. He held to it scrupulously, indeed; allowing Marigold to spend a whole year at St. Philip's Parsonage.

Mr. Heavitree was a man comfortably off in point of money, far more so than is usual with clergymen. Not that the living was a good one. Had he had only the little stipend of St. Philip's to depend on, he would have been a poor man; but having private property of his own made all the difference.

Nothing delighted him more than to spend much of this property for the good of his parish; not by giving to lazy beggars who ought to have worked for themselves, but in helping the really needy who could not work, the aged and the sick especially; and in making countless improvements in schools, almshouses, etc.

Mr. Heavitree's was often called "a model parish," everything in it was so beautifully managed, and so well worked.

His wife lent an active helping hand in all these things; and in addition, she made the training of young girls her especial work. The Parsonage was large, and she had several children. While keeping two or three good old servants, she used to have a succession of young ones, as housemaids and nursemaids, constantly taken in, taught their duties, and passed onward to other places. Those who know the worry of young and untrained maids in a large household, where everything goes like clockwork, will appreciate the self-denial of Mrs. Heavitree in undertaking such a task.

Marigold went to the Parsonage three months after her father's second marriage, remained a year, and came home just about three months before my story begins—came home to a changed household, because of the change in Mrs. Plunkett. In the three months before she left home, all had gone smoothly; but now she found herself in an atmosphere of fretting, of worry and ill-temper, of disorder and carelessness, of all that in a small way could make life hard to bear.

She had heard something of this before, but not much. Mrs. Heavitree had not encouraged perpetual running home; while Plunkett and Narcissus had resolved to say as little as might be.

Now, however, when Marigold was living at home, the transformation became clear, and the new variety tried Marigold greatly.

The contrast between home and Parsonage proved severe. Everything there had been cheery and bright, the whole household in perfect order. Each person had his or her own duties, and was expected to do them well. To pass from such a state of calm regularity, order, and kindliness, to a house where all was mess and muddle, where things were used and set down anywhere to be left unwashed for hours, where a white tablecloth for meals was thought too much trouble, and where not a smile lightened the day's duties, Marigold felt acutely. She had been used to so different a condition, not only in the past year, but during all her life. It was not the smallness or the comparative poverty of home which distressed her, but the lack of order and of prettiness.

Marigold at first threw herself into the breach, so to say, and tried to improve matters. She washed whatever wanted washing, put away whatever was left lying about, scoured and scrubbed, dusted and swept, endeavoured in all ways to bring back the home to its olden state.

There, however, she met with a check. Words of pleasure and of praise spoken by Plunkett to Marigold roused his wife's annoyance. "Why, this is old days over again," he said. "Home hasn't been home since—" and anybody might understand the half-finished sentence.

Mrs. Plunkett began irritably to oppose Marigold from that hour. She did not choose to be interfered with, she said. Marigold no longer found herself free to put straight Mrs. Plunkett's untidinesses; but only to do as she was told. If a soiled utensil were flung down, and left unwashed, there it had to remain. Thus difficulties began and increased. Marigold, who had a quick temper, would speak sharply, and Narcissus would cry, and the household generally would be overshadowed.

WILD BEASTS.

PLUNKETT was, as he had foretold, late in reaching home that night. He had a goodly amount of work to get through, and he had undertaken to finish, if possible, before retiring.

In the course of the evening, Mrs. Heavitree appeared by his side, as he worked. Plunkett had quite expected her to do this, after his morning talk about Narcissus. It was not her fashion to leave matters long unsettled.

"You went home to dinner, after all, Plunkett," she said.

"Yes, ma'am. It's all right about my girl."

"She will come to me next week? Is your wife willing?"

"I didn't ask her, ma'am. I said Narcissus was to go."

Mrs. Heavitree smiled. She had an alert practical manner, and a particularly kind smile. "Then I am to consider the matter settled. Another girl wishes to come, but she must wait for the next vacancy. Narcissus has the first choice, for her mother's sake. By-the-by, what is her second name?"

"Narcissus Plunkett. Nought else." Plunkett thought his wife had shown some shrewdness.

"Is that all? You should have given her a good work-a-day name for common use. It does not matter in our house, where she is well known; but if she takes to service later, she will have to be called 'Plunkett.' So you mean to keep Marigold at home for the present?"

"I do, ma'am. Couldn't get along without one on 'em, and that's a fact. She's a good girl, is Marigold."

"A thoroughly good and nice girl. We all grew fond of her."

"She is that, and no mistake, ma'am. But it's Narcissus as is my wife's favourite. She and Marigold don't rub on together comfortable."

"Do they not? I am sorry for that. Marigold must try to bear patiently with little difficulties. She has had her year away, and now it is Narcissus' turn. I shall have a quiet talk with Marigold some day, and see how things are going on."

"Six o'clock, sharp, I'll be home. So mind!" said Plunkett next day, at the close of his early dinner. "Don't you go and say I haven't told you, and dawdle about and get nothing ready."

Plunkett had a big voice, and an authoritative manner of speaking, but his eyes twinkled.

"As like as not you won't be here till seven," Mrs. Plunkett answered.

"Yes, I shall. So don't you count upon that, nor act according. I'm going to take these girls off to the beast show, and it's half-price after six. We'll get the worth of our money."

"And we'll stay all the evening?" begged Narcissus.

"What for not? I ain't in the way of doing business nor pleasure shilly-shally like. See you're both ready. And you, too, if you'll come—" dubiously, to his wife.

"Likely I should, when it's all you want to get away with the girls," she retorted.

Plunkett might have replied that this was by no means all he wanted. He honestly wished for his wife too, only under the condition that she would don a good-tempered face for the occasion. If she must needs wear a mask of acidity, he would undoubtedly prefer her absence to her presence. But an explanation of this sort is difficult to make. Plunkett considered so long what to say that he ended by saying nothing.

"I'm glad mother ain't going; she'd spoil it all," Narcissus said later in the day, when she and Marigold had run upstairs to change their dresses. "She looks so cross about everything."

"I'm glad, too . . . But I wonder if she wouldn't like it, really," debated Marigold. "I mean, I wonder if we oughtn't to ask her again."

"Why, Marigold! What do you mean? Wouldn't you rather have father to ourselves? We shall have lots of fun with him; and if she's there, she'll just spoil everything. She'll want to go where we don't like, and she'll hurry us home before we've half done."

"Father 'll take care about that. He won't let us be hurried home. I'm only thinking—doesn't it seem rather dull for her being left behind, if she does really want to go?"

"Why doesn't she say so, then?"

"I suppose she thinks we don't want her."

"Well,—and we don't—if she can't be nice."

Marigold went on buttoning her neat brown dress, and said nothing.

"I can't make you out, Marigold. I'm sure I shouldn't have thought you cared particularly about her—now she's so horridly cross."

"I don't. That's the very thing. I don't care, and I don't want her, and it doesn't seem right."

Marigold's conscience was quicker and more wide-awake than that of Narcissus; at the same time, that her independence was greater, and her sense of resentment more prompt.

"That isn't our fault. If she was different—if she was like when she first came. But when a person does nothing except grumble, grunt, all day, one can't love her. I can't and I don't. And I don't see what you want her to come for this evening."

"I don't want it. I only want to do right."

"O well, I think you can leave that to her and father. There's nothing she hates like being meddled with. I wouldn't interfere if I was you. It'll just mean burning your own fingers, and making her crosser than before."

Marigold was not easily convinced.

Something in Mrs. Plunkett's look, when she had said sharply to her husband, "All you want is to get away with the girls," had touched the feelings of one of those girls. Marigold, though very bright and active, and not demonstrative, had a tender heart. The thought had come keenly—"I shouldn't like to feel that they all wanted to get away from me." It had haunted her all day, not finding expression until now.

"I shall say something, Narcissus," she remarked in the last moment before going downstairs.

"If you do, you'll be sorry. Much best to let well alone," said Narcissus.

But if Marigold once formed a purpose, she was not easily bent from it.

"Mother, wouldn't you like to see the wild beasts too?" she asked a few minutes later.

Mrs. Plunkett looked all over Marigold, as if trying to divine the motive for so unexpected a question.

"You'll be dull here, all alone. Why shouldn't you come? It'll be such fun all of us together."

To Marigold's surprise a gleam of positive softness stole into the vinegary visage.

"Well—I don't mind if I do! I've been nowhere for ever so long."

A protesting sigh from Narcissus was audible.

"There, that's the way!" said Mrs. Plunkett, suddenly overclouded. "As sure as ever I say I'll do anything, I'm made to feel as nobody wants me."

"Narcissus didn't mean that really—not really and truly," said Marigold. "She couldn't, because it would be selfish; and Narcissus isn't selfish. You'll come, mother? Then you've got to dress sharp. Father will be back in ten minutes. I'll see to everything."

Mrs. Plunkett betook herself off with some semblance of haste, and Narcissus said despairingly,—"There! Now you've spoilt it all."

"No, I haven't. Did you see how she looked—just for one moment? Just like what she was when she first came to us."

"I don't care. I know how she will look there,—as glum and sour as anything."

"She won't, if she doesn't get put out."

"But every single thing puts her out, and she's for ever thinking people mean what they don't mean. It's so awfully silly. And I did mean that I didn't want her."

"Then you've got to begin to want her. It won't do for us to get into this sort of way. We shall just be miserable," said Marigold with some energy, as she laid the table for tea. "I know she's tiresome, and it's difficult to love her, and she makes me feel so angry sometimes, I don't know how to bear myself. But all the same she has her rights, and I can't stand seeing her left out of everything. She's father's wife. Don't you see?"

"I wish she wasn't," responded Narcissus; and with the words Plunkett came in.

"Ready, girls?" said he. "See here, I've brought a knot of flowers for each of you. I like my girls to look nice. Got your Sunday frocks on—that's right. Where's she?"

"Mother's coming with us, father," said Marigold.

It must be confessed that a little of the jollity died out of Plunkett's face with this announcement.

"She is, is she? I thought she said—Oh well, it's all right. Tea ready?"

"Marigold did it! Mother wasn't coming; and Marigold went like a goose and asked her," pouted Narcissus.

"And she was pleased," added Marigold.

"Marigold's a very good girl," said Plunkett. "A very good girl indeed! So there! We'll all go, and we'll have a good time together."

It really seemed hopeful that they might. Mrs. Plunkett came down in her best dress and bonnet, actually looking quite agreeable, almost smiling.

"Marigold seemed to think I might as well see the show too," she said. "And I don't know why I shouldn't. It isn't often as we have the chance."

The lions and tigers, having dined not long before, were enjoying a calm after-dinner nap, as mild and sleepy in aspect as overgrown grimalkins.

"I can't fancy one of them tigers carrying off an ox," Plunkett remarked, contemplating the cage. "He looks sort of easy-going—blinking his eyes. Shouldn't think he was big enough neither. Though they do say a tiger can pick up an ox like a cat picking up a mouse, and heave it over his shoulder, and make nothing of it."

"They 'do say' a great many mistaken things," remarked a voice close behind, and Plunkett turned to find himself addressed by an elderly gentleman, military as to his moustache, and placid as to his expression. "The proportionate sizes of a tiger and an ox are rather different from those of a cat and a mouse."

"But a tiger can kill an ox, sir," protested Plunkett.

"Kill it! Ay, with a single blow of his paw! And drag it away to his lair. That's one thing. To toss the ox over his shoulder would be another thing. I doubt if the biggest Bengal tiger would quite accomplish that with a full-grown ox. At all events, the dragging is the more usual plan."

"Mighty unpleasant customer to meet in the open," said Plunkett.

He told a story of Indian life.

"He's quiet enough now, and just like an enormous striped cat," said Marigold.

"Cat-like in his ways too," responded the gentleman.

He told a story of Indian life—of an unfortunate man who had fallen a victim. The man's comrades, safe in surrounding treetops, but powerless to help him, because unarmed, had watched the tragedy—had seen the tigress playing with her victim as a cat plays with a mouser—teaching her cubs, as a cat teaches her kittens in similar circumstances. She did not kill the man outright, but only disabled him a little. Then she would let him run, and the cubs—kitten-like—would scramble after him; and if he showed any chance of escaping from the cubs, the tigress would bound up and pat him down again, before she let him have another try, and then another chase.

"It's an awful story, I think," said Mrs. Plunkett, shuddering. Quite a little crowd had gathered round to listen.

"And those men safe in the tops of the trees weren't English. I'm glad of that, anyway," said Plunkett.

"No; they were natives. Poor fellows! They were completely scared. They could do nothing."

"It's horrible," said Narcissus.

"One comfort is, that the man probably did not suffer. A kind of stupefaction seems to come over the victim at such a time. Some who have been in the clutch of a lion or tiger, and all but killed, have described such a sense—rather like having taken an opiate. One hopes it is always so—with mice and birds as well as men."

"Anyway it's awful," repeated Mrs. Plunkett. "I don't wonder those men stayed up in the trees. I wouldn't have come down."

"And yet there have been men who could face lions and tigers without fear," said the gentleman musingly.

"Have there?" asked Plunkett; and "Yes, I know," said Marigold—the two speaking simultaneously.

"That's General Heavitree," whispered a voice near. "Mr. Heavitree's uncle."

Plunkett nodded back an assent, and General Heavitree looked at Marigold.

"You know—what?" he asked.

"The early Christians," said Marigold modestly. "Wasn't it them you meant, sir? They weren't afraid to meet tigers and lions, and to be eaten up by them, sooner than give up their faith."

"Quite true, quite right! I'm glad you know so much. But I was thinking of one who dared to meet lions face to face 'in the open'—a bishop of our own days. Did you ever hear of Bishop Hannington? If not, I'd get his Life some day to read, if I were you. It is worth reading. He was an African bishop, and one day in Africa, he faced a lion and lioness so steadily that they were afraid to attack him. Yes, actually afraid, though he had no gun, no weapons of defence, except his tremendous courage. He ran towards them, looked them in the face, threw up his arms,—and they fled! It's not the only instance of the kind known. Man may master beast by the power of the eye alone; but then he must be perfectly fearless, perfectly confident. The moment he begins to fear, all is up with him. Well, I advise you to get that little book for yourselves—the 'Life of Bishop Hannington'—and to read it," said General Heavitree, looking round on the group.

"I don't mind reading about the bishop, but I know I couldn't ever face a lion or a tiger," said Mrs. Plunkett. "The very thought of it turns me cold all over."

Then the General moved away, and the Plunketts passed on to a great centre of attraction, in the shape of a huge good-humoured elephant. Neither of the girls had ever seen an elephant before.

"Oh, isn't he big! Oh, isn't he ugly! And what a great queer trunk he has! And such little eyes! And, oh dear! What a red mouth. Look, father, when he puts up his trunk."

"Well, so have you got a red mouth too, Narcissus."

"But I haven't got a trunk, father. If I had, that would make all the difference. Oh, look; do look! What enormous legs—like great thick pillars."

A VISITOR.

HALF the evening went as nicely as possible, all the four being pleased and happy. Then, with no previous warning, a cloud came. The look which the girls well knew, came over Mrs. Plunkett's face—her "temper-look" they called it between themselves—and all brightness was gone. She lagged slowly by her husband's side, snapped at Marigold, silenced Narcissus, disagreed with whatever was said, refused to be interested, and finally declared that it was time to go home.

"But we can't! Father, need we? There's ever so many more creatures to see. Why, we haven't come across the snakes yet," protested Narcissus.

"You'll just do whatever you are told," said Mrs. Plunkett.

"Need we go?" implored Narcissus, appealing to her father.

Plunkett was at a loss. His wife turned her face towards the main entrance, with the air of one who had made up her mind; and he knew that she did not intend to go alone. He was capable of a blustering resistance under excitement, but in cooler moments, his extreme good nature made him yielding.

"Well, but now, Jane—" he expostulated.

"We've been long enough. A set of nasty beasts! I've had enough of 'em; and the girls aren't going to stay behind alone."

"Maybe you'll sit down here, and rest a bit, while I take them round," suggested Plunkett.

"Maybe I'll do nothing of the sort," returned she.

"But you'd like to see the snakes too, mother," urged Marigold, dismayed with the results of her own kind action. "The boa constrictor, you know, and the—"

"I don't care. I'm tired. Much you all care for that! I'm not going a step farther, not for nobody."

"Come now, Jane. You don't want to spoil the girls' treat. You don't really, you know," urged Plunkett. "And they haven't seen half yet."

"Then they needn't!" snapped Mrs. Plunkett. "It's time to get home."

But the blank face of Narcissus was too much for her father. "Well, then, if you're bent on going, you'll just have to go alone," he said, speaking roughly by way of showing courage. "I ain't going yet, nor the girls neither. We've lots more to look at. And you'll sit here quiet, till we're ready."

Mrs. Plunkett's face worked. "I'm not a-going to sit here, like a naughty child, and you three enjoying of yourselves," said she.

The others exchanged looks.

"Yes, of course, that's it! That's all you want. Just to get rid of me! Well, you may get along, and leave me; I'll manage." Wherewith she began to cry, and people around began to stare.

"I'll stay with mother, if you like, while you take Narcissus to see the snakes," proposed Marigold, with a mighty effort at self-denial.

"I say, now, you know that's all rubbish, Jane," protested the husband, direfully conscious of being under observation. "Nobody don't want to get rid of you. That's all nonsense. The girls want to see the snakes, and that's natural enough; and if you can't walk no farther, why then—"

Mrs. Plunkett jerked herself away, with a kind of indignant grunt, and went swiftly off towards the entrance, crying still. Marigold made a half movement to follow, and paused, because the other two waited.

"It don't matter," said Plunkett easily. "She's best at home; and we'll find her all right there by-and-by. Shouldn't wonder if she isn't well, and that makes folks cross, you know. Anyway, I don't mean to have you two disappointed. I promised you should see it all, and you shall."

"But if I ought to go after Mother?" said Marigold.

"She'll be a deal better, left alone for a while. Come—here's the way to the snakes."

"You can't go now. Mother would be home before you could get there; and father don't like us wandering about the streets alone so late," said Narcissus.

"No, that I don't," promptly added Plunkett. "It's a bad way girls get into, and I don't mean my girls to get into it. And Mrs. Heavitree don't allow it neither."

Marigold felt the matter to be settled for her, and settled as she wished; yet the thought of Mrs. Plunkett weighed upon her enjoyment like a wet blanket. Narcissus wont into raptures of admiration and disgust over the snakes; and Marigold looked on soberly, only half disposed to smile.

"That sort's a boa constrictor, Narcissus. He'd squash you to a jelly, if he got a chance, and swallow you whole," said Plunkett, who liked to air such knowledge as he had, and who, in so doing, was rather apt to outrun his knowledge.

"Would it really? But, father, I shouldn't think he was big enough! Not nearly!"

"Can't judge, looking at him so. Them boa constrictors can swallow pretty near anything. Make nothing of a man or two for a mouthful. And here's another sort—a small follow—and that's the kind that kills by stinging. You just see his forked tongue. If it wasn't for the glass, he'd stick his tongue into you, in a moment, and you'd be dead of the poison in an hour."

Plunkett suddenly found the General to be looking at the same object—not only looking, but listening, with an amused curl of his military moustache,—and the confident tone was lowered.

"That's it, sir, ain't it?" Plunkett ventured to ask.

"Well, no—not precisely 'it'," responded the General. "There is a widespread delusion afloat on the subject, and snakes are popularly said to 'sting.' The tongue, however, is perfectly harmless, though I grant that it has a vicious look."

"And wouldn't a man die of that creature's sting?" asked Plunkett, privately holding to his own view.

"Of its bite certainly, for the cobra is a deadly snake. But the mischief is in the teeth, not in the tongue. He has poison fangs,—sharp hollow teeth, each with a little bag of virulent poison at its root. If he could strike at you, and bite you, one tiny drop of that poison getting into the wound would be enough to put a quick end to your life. Sometimes the poison fangs are taken away from a living snake; and then, though he has the forked tongue still, he is powerless to injure anybody."

"Could that other big snake swallow a man, sir?" asked Marigold shyly; for she, like Narcissus, felt sceptical on the subject.

"The boa yonder? No! He might manage to get down something rather bigger than a rabbit, possibly. Boa constrictors do exist big enough to swallow a man, or even an ox; but these are comparatively small specimens. Not that you would enjoy a squeeze, even from them," added the General, smiling, as he again passed on.

"Well, I suppose he knows," said Plunkett dubiously.

"Why, father, he has been in India for years and years," said Marigold.

Plunkett rather objected to being found out in a mistake. He turned to other subjects, and soon led the girls away from the snakes.

Time passed more quickly than any of them knew; and though they meant to be home early, it was considerably past ten before they really did arrive. Mrs. Plunkett was still up. This they expected, and they expected also to find her crouching over the kitchen fire, peevish and unhappy. Instead of which she sat at the table, needlework in hand, and opposite to her sat a big fresh-faced young man, apparently doing his best to make himself agreeable.

"Todd himself? Well, I never," said Plunkett. "Why, I thought you was off in Africa for the rest of your life."

"So I thought, too," Todd answered, with an admiring glance at Marigold. "How d'you do,—eh? Not forgot your old playfellow?" he asked, as he shook hands with both the girls. "So I thought, too; but I got tired of Africa. Didn't seem to pay somehow. And I thought I'd come home."

Plunkett moved his head dubiously. There was nothing of the rolling stone in Plunkett's nature. He liked to see an old acquaintance, but to approve was not possible. James Todd was one of those people who are always turning up on hand, when their friends count them to be comfortably disposed of. He was so big, bodily, that there was no chance of overlooking him, wherever he might happen to be; and he had such a genial manner, that everybody liked him; but, none the less, what to do with Todd had been a problem of long standing, and it recurred with embarrassing frequency. Two years earlier he had gone out as an emigrant to South Africa, having failed to find at home any work suited to his capacities and inclinations.

His affectionate relatives did at last hope that he was safely off their hands; but the hope proved futile. Here he was again, big and good-humoured, self-satisfied and lazy, as ever.

"Thought you'd come home—for what?" asked Plunkett.

"That's what I've been asking," put in Mrs. Plunkett. "And he don't know."

"I am ready for anything as may turn up. That's what it is," declared Todd cheerfully.

"Things don't turn up without they're looked for," said Plunkett.

"I'll look for 'em. Never you fear. I'm not come back to live an idle life." Todd spoke with an air of virtuous resolution. "There's always something wants doing, and there ain't many things I can't do." He kept his seat with the air of one very much at home, and in no hurry to depart.

Narcissus gaped sleepily.

"Getting late, and we're early folks," said Plunkett, glancing round the untidy kitchen. "Should have thought—she might ha' put things a bit straight,—" in an undertone, as he noted the supper things still unwashed on the table. His mutter was audible, and Mrs. Plunkett's face gloomed over.

"I'll clear away," said Marigold.

"No, you won't; it's time to go to bed, and I ain't going to have no more sitting up," said Mrs. Plunkett. "Them things can wait till morning."

"But—" began Marigold, and stopped.

"So good-night," said Mrs. Plunkett to Todd.

Todd smiled good-temperedly, rose slowly, lounged against the table for a few last words with Plunkett,—and failed to calculate his own weight. The loose leaf upon which he rested collapsed without warning, and the crockery thereupon descended to the floor with a startling crash. Todd nearly went down backwards, and a mass of broken china lay upon the ground.

"Oh!" Marigold exclaimed.

"There now!" said Plunkett. "If that had been put away—as it ought to ha' been—"

"Well now, I'm sure I'm very sorry. Didn't mean to do no harm," apologised Todd, regarding the ruin with mild amazement. "Why, the leaf o' the table couldn't ha' been properly fastened up."

"Shouldn't wonder! Nothing never is properly done in this house,—without Marigold has the doing of it," declared Plunkett.

"You needn't stand staring there!" said Mrs. Plunkett shortly to Marigold. "What's done can't be undone. You'd best sweep it up sharp."

Marigold flushed at the tone, but she at once knelt to obey; and James Todd, after looking slowly from one to the other, as if trying to understand the position of affairs, followed suit, with much deliberation.

"Take care, don't you cut your hands," he said to Marigold. "Them edges are worse than a knife. I say,—" in a lower tone, as Mrs. Plunkett moved off—"she wasn't here when I went away. Nor she don't seem improved by marrying. Why, she was as different—"

Marigold made no answer, and Todd was impressed with her silence. She carefully lifted away the larger pieces of broken china, gathered together the smaller bits, and swept into a dustpan all the finer remains. After which, Todd stood up to say good-bye, with a promise to reappear speedily, and Mrs. Plunkett shut the door behind him with an air of satisfaction.

"He won't come here often if I've my way," she said.

"Why, there's no harm in Todd. He's a nice young fellow. Not but what he might be more fond of work, but I always did like him," responded Plunkett. "One would ha' thought you was enjoying your talk with him. When we come in, you looked as if you was enjoying of it."

"Which, I wasn't! I just wished he'd make haste and go."

"He's seen a lot o' queer things abroad, no doubt. We'll get him to tell us all about it. As good as going to a beast show," laughed Plunkett.

LATE AT NIGHT.

"WELL, I hope you are satisfied," Narcissus remarked sleepily, when she and Marigold had retired to their bedroom. "You'd better have left things alone, and not have got mother to go with us. It just spoilt half our pleasure. I told you, she'd be sure to turn cross."

"I can't think what it was that put her out."

"Anything puts her out. If nothing at all is said, she fancies something is meant. I know how it is. I've lived with her longer than you."

"Yes, I know you have."

"And I told you how it would turn out."

"Yes, I know you did." Marigold spoke dreamily.

"Then why couldn't you believe me?"

"I think I did. It wasn't believing or not believing. It was because I thought I ought."

Narcissus sat down on the bed, and leant against the iron frame at the foot. "Oh dear, I'm so tired—I don't know how to undress," she said. "Thought you ought to do what?"

"Get mother to come with us, if she was willing. Or at least—I thought she ought to feel free."

"She was free, of course. She could do as she liked."

"Yes; only if she fancied we none of us wanted her—"

"Well, that's only what was true."

"I don't think it ought to be true. Mother has her rights. She is father's wife, and it isn't right that we should leave her out of everything. It isn't fair."

"Then you don't mean ever to do anything, or go anywhere, without dragging her in!"

"I don't mean her to feel that we'd rather leave her behind."

"After this evening!"

"Yes—after this evening," echoed Marigold. She turned towards Narcissus with a wistful look.

"It isn't what I want to do," she said; "it is what I know I ought to do. And I think you ought to help me—not hinder. You haven't half such a quick temper as I have; and so it isn't so hard for you as for me. You ought to do all you can to help me to conquer, instead of—"

Narcissus was on the verge of tears. "I don't want to do wrong," she said. "Only if you knew how mother worries and worries. At least, I suppose you do know now, but you haven't had it so long. I don't feel inclined to fly out, but I do long to get away from her. If it wasn't for that, I shouldn't like leaving home at all."

"Only it must be even worse for her than for us—always to feel so cross," said Marigold. She came close to her sister, speaking more softly. "Narcissus, I've been praying lately, and making up my mind to try to have things happier—and then all at once I seemed to see what I ought to do. And you mustn't hinder. You must help me."

"You're a great deal better than I am," murmured Narcissus, in subdued accents. "Yes, of course I'll try—and I—I'll pray too. I will really, Marigold!"

James Todd strolled comfortably home in the darkness, not in the least troubled by the fact that his old mother would be worried by his long absence. He had not told her when he would return, or where he was going; and anxiety on her part seemed to him unreasonable. Todd liked to be perfectly free, and to have his own way on all occasions. It did not occur to him that the old parents, who, though by no means too well off, had given him a loving welcome, and had taken him in without a word of reproach or blame, possessed a claim to their way also.

In fact, he was not thinking about them at all, but about Marigold. She was a very nice girl, nice-looking, nice-mannered, nice in every way. He had known Marigold from childhood, and had always found her attractive; but she was very much more charming now than he had expected her to become. He liked particularly her resolute silence about Mrs. Plunkett's manner of faultfinding. A girl who was so cautious in blaming a stepmother would be also cautious in blaming a husband.

This idea developed slowly; for Todd's mental movements were not quicker than his bodily movements. It did develop, however, as he lounged homeward, turning Marigold admiringly over in his mind.

She might be just the very girl who would suit him for a wife! Why not? He had not seen her for two years, and those two years had made a woman of her. True, she was young still, barely eighteen, but her air was womanly.

What the two years had made of him—whether or no he was a man who would suit Marigold for a husband—how far he was in a position to support a wife at all—these were questions which did not enter into Todd's calculations. In fact, he was not in such a position. He had failed to make his way in England, and had been sent out to Africa with just enough money to start him. He had failed to get on as an emigrant, and had reached England in a penniless condition. The kind old parents, who had taken him in, were by no means able to undertake the support of a big useless son without a wife, much less of such a son with a wife. James meant, as he said, to do something; but he had no definite plans, no particular idea of what that something might be. It was as likely as not that he would try half-a-dozen things, and would fail in each as he had done in the past.

He knew all this, and it made not one iota of difference. James never troubled himself, and he never had troubled himself, to look forward. If he had a shilling in his pocket, and no prospect of any more to come, he would spend that shilling unhesitatingly on the first thing that he desired, without a qualm. He had flung up work in England because the fancy took him, and had emigrated by his friends' advice because he liked the notion. He had come home again, with equal light-heartedness, because he found that life in Africa could be no more a success than life in England without the trouble of steady toil.

If he wanted a wife, he would take her just so easily, unburdened by care for the future, untroubled by any thought of responsibility. James Todd was an absolute child still, as regarded any sense of responsibility. He did whatever he felt inclined to do, so far as lay in his power. If he wished to marry, he would marry; if he married, his wife might take her chance. He supposed that something would turn up in the way of work; and, should it fail, he would never blame himself for the consequent misery of his wife or children.

Such men as Todd never do blame themselves. If things go wrong, it is always somebody else's fault, never their own.

His notion of marriage was, in fact, simply of an event which should add to his comfort, and should give him pleasure. In a good-natured and easy fashion, Todd was eaten through and through with selfishness. The possible comfort or pleasure of his wife lay outside the range of his imagination; and the mere suggestion that he was strictly accountable, not only before man, but unto God Himself, for the well-being, the happiness, the training, of his future children, should he have any, would have made him open his eyes widely, with slow amazement.

Such a notion had never occurred to his imagination. He thought only of what he wanted, and of what would be agreeable to himself. Following this line of thought, he resolved to cultivate a closer acquaintance thenceforward with the Plunkett family.

"How long is that there young fellow going to hang dawdling about, doing nothing?" demanded Mrs. Plunkett of her husband, two or three weeks later. "He's got a lot too much time on his hands, and that's a fact."

"Todd? Well, he says he's on the look-out for work, and it isn't easy to find just the thing. He's had a job or two."

"And threw up the chance of something more than a job, because it wasn't to his mind!"

"Well, he said that sort o' thing wasn't in his line."

"Nor nothing else—seems to me—except dangling round and talking nonsense."

"Don't see that neither. If he can't do nothing else, he can talk."

"I'd like you just to hear him when you ain't at hand. That's all."

"Anyway, it ain't our business. I'm not given to meddling with other folk's concerns—never was."

"Shouldn't wonder if it is your business—more than you think." Plunkett shook his head; and she added with sharpness—"If you don't see to it, you'll lose Marigold—next thing."

"Lose Marigold!" Plunkett stared as if his wife were demented.

"Oh, you don't see—of course you don't. You men never see nothing! 'Tisn't you he comes mooning after, and you needn't think it! Marigold's tiresome enough some ways, but she ain't a bad-looking girl by any manner of means, and a young fellow like him knows it too."

"Marigold! Why—bless me! The girl ain't hardly eighteen."

"That's it! And James Todd is twenty-three. I won't go for to say that a man mayn't never marry at twenty-three, if he's got enough to marry on, and to keep a family in comfort. But if he hasn't—and James Todd hasn't—I say it's a sin and a shame. Who does he mean to keep his wife for him, I wonder?"

"I'll tell you what it is, Jane!" Plunkett waxed red in the face, and brought down his hand with a thump upon the table. "I'll tell you what it is—I'm not a-going to have nothing of that sort! A lass barely eighteen, and a lad without a penny to his name! It's folly. I've not got a word to say agin my girls marrying, all in good time, if it's a man I can approve of; and when that time comes, I'll not say no. But Todd,—why, he's got nothing to put in his own mouth, except what his old father gives him. I like him well enough; but I do say it's a disgrace for a lusty young fellow to be depending on his old father, and I wouldn't mind if I said it to Todd's face. And what's more, though I like the lad, I'm afraid he's not got much work in him. Never had, and maybe never will have. That's what it is; and a man who's got no work in him, ain't good for anything. If Todd marries, as like as not his wife 'll have to keep him; and that's a nice look-out for any girl. But Marigold ain't a fool. Marigold's got sense in her head, and she knows better than to take to Todd."

"Don't you be too sure. If she does take a fancy to him, her sense won't have much to say in the matter. I know the ways of girls."

"Well, it isn't to be! You mind that. She shan't have him, and he shan't have her. So you just see to it. I'll have no sort of nonsense between them two. So mind you take care."

"Anyway you needn't shout the house down. I ain't deaf," said Mrs. Plunkett.

"What makes you think anything o' the sort?" demanded Plunkett, in a lower key.

"Well, he said yesterday he'd had a chance of work, some miles off; and he said he wasn't going. He didn't mean to leave the place, not for nobody. And he looked at Marigold, and Marigold she got as red as anything. That's more work he's thrown up, when he might have got it."

"Marigold shan't marry Todd. That's settled," said Plunkett decisively.

But to say that a thing is settled is by no means identical with actually settling it.

Todd continued to come often to the house, despite a rigidly cold shoulder turned to him by Mrs. Plunkett. He did not care a brass farthing for Mrs. Plunkett, so long as Marigold smiled upon him. Plunkett, who might have done more, was not at all a good hand at turning cold shoulders. He could get into a brief rage, and speak out his mind loudly; but a course of quiet checking was beyond his power. He enjoyed seeing a friend; and, apart from Todd's idle inclinations, he liked the young fellow, and he preferred to leave disagreeable lines of action to his wife. So he welcomed Todd genially still, when the latter appeared, while privately exhorting Mrs. Plunkett to "see that things didn't go wrong."

Perhaps it was not surprising that Marigold liked Todd's attentions. She was, it is true, a very sensible girl in most respects; but she was extremely young, and she had of course her little feminine vanities. It flattered her vanity to be admired and run after by so big and comely a young man. To be sure, his slowness was sometimes a little exasperating; and she did wish he would find something to do, and would stick to it. But he always assured her that he was only waiting for "the right thing," and she did not realise that "the right thing" in Todd's eyes meant simply no hard work at all.

Mrs. Plunkett's frequent harsh words of blame about his laziness acted in a reverse fashion upon Marigold, driving her to find excuses for him. She was sure Todd was not lazy, only unfortunate so far; and indeed, to hear him talk, one might almost have imagined that he was the steadiest toiler in existence, when only he had the chance.

Moreover, he had such a pleasant manner. Everybody was agreed on that point. The manner alone was enough to take captive Marigold's girlish fancy.

Beside all this, she was not happy in her home.

Narcissus had gone to the Vicarage for a year of training, Plunkett was away all day, and Mrs. Plunkett grew more irritable, more worrying, more untidy than ever. Things really were most trying to a well-brought-up girl, tidy in her ways and affectionate in disposition, like Marigold. Jars between herself and her stepmother were incessant. Marigold could not see how to avoid them. She wanted to be on pleasant terms, but Mrs. Plunkett's gloom and ill-temper rendered pleasantness out of the question; and the disorder of the little house, which she would seldom permit Marigold to put right, was a perpetual misery.

If only Marigold might have worked hard, and have "kept everything nice" as she expressed it, she would have been happy; but she was checked and foiled at every turn. It could scarcely be wondered at, that the contrast of Todd's bearing caused her to think of him much more than she would otherwise have done. Whenever Mrs. Plunkett was especially cross, Marigold's mind fled straight to James Todd.

MARIGOLD'S LIKING.

"WHAT have you been such a time about?" demanded Mrs. Plunkett one day, when Marigold came in from some shopping. She had been sent by her stepmother. Mrs. Plunkett for days past had not stirred out of the house.

"I met James, and he went round with me,—just for a little walk." Marigold confessed the fact unhesitatingly, for she was a thoroughly truthful girl.

"Oh, he did, did he? A great stupid idle fellow. I wonder how much longer he means to hang about, letting his poor old father support him." Mrs. Plunkett had a vein of common sense, which warned her that it was wisest not to suggest what Marigold might not yet have thought of. "I don't mean to put into her head that Todd wants to marry her," she had said to Plunkett; and the resolution was a wise one, only it made the keeping of Marigold out of Todd's way more difficult.

"It isn't James' fault. He has only waited till he could find something to do here. He doesn't want to go away," said Marigold, with a blush.

"Folks can't always do as they want. I wish to goodness he would go."

"I can't think why you dislike poor James so much, mother."

"I can't abide idleness," said Mrs. Plunkett.

Marigold's eyes travelled round the kitchen, and inwardly she echoed, "I can't abide untidiness and temper!"

Mrs. Plunkett saw the glance, and understood. It jarred her into hasty speech. "Well, I can tell you your father don't mean to have nothing between you and Todd, so you just needn't think it. If you wasn't too young yourself, Todd's got no means to support a wife, and he's too easy-going ever to do it properly; and he's got no business now to think of such a thing!"

The words were hardly uttered, before Mrs. Plunkett regretted them. Marigold made no immediate answer. She stood considering,—as if that which before had been only a shadow, had suddenly taken shape. Then she put down the duster that she held, and said quietly, "James has found work now, and he means to keep to it," and went out of the kitchen.

The subject was not resumed when they again met. Mrs. Plunkett, vexed with her own indiscretion, resolved to say no more: and unfortunately she was ashamed to confess the blunder to her husband, or she might have aroused him to action. But the mischief was done. If Marigold had not before understood Todd's wishes, she understood them now; and the thought of James as her future husband had a definite place in her mind. With the clue supplied by her stepmother, Todd's bearing became unmistakable. Marigold could no longer go on unconsciously; and when Mrs. Plunkett was especially trying, her thoughts flew more swiftly than ever to James Todd's pleasant face. A home with him had so bright a look, by contrast. She would be able to do as she liked, to keep the place so beautifully neat and clean.

Nobody there would ever look cross, and nothing would ever go wrong. James might have been a little unsettled and lazy in the past, but once married he would be so no more. She would keep him up to the mark, and he would work hard, and they would be so happy!

But no woman, however good a wife, has power to change her husband's nature. Divine power alone can do that. It was all very well for James to say now: "I'd do anything for you, Marigold!" Had she been not quite so young, not quite so ignorant of life and of human nature, she must have known that a higher motive is needed to transform a man's life.

One day a message came, asking Marigold to go to tea at St. Philip's Vicarage, with Narcissus. This would be her first sight of Narcissus, since the latter's year of training began, and Marigold was delighted. She wondered if perhaps she might get a little talk alone with her sister. It would be nice to speak to her about James, since at home Marigold scarcely ventured to mention his name.

"I s'pose your father 'll walk back with you," James said beforehand. One way and another, he contrived to see a good deal of Marigold.

"Oh, there's no need. I shan't be late. Mrs. Heavitree won't let me, because she does so dislike girls walking about alone late. Father will be busy."

"You won't get away early, and it's a long stretch. I'll be there, you may be sure. I'll be somewhere about outside."

Marigold hesitated. "I don't think father 'd like it," she said.

"Rubbish! Of course he'd like it. Mrs. Plunkett mayn't, and what then?"

"I don't think I ought to go against her. Mrs. Heavitree says I oughtn't."

"Well, you needn't. You've got nothing to do with the matter. If I just choose to be there, you can't help it."

Marigold's truthful nature rose against this crooked reasoning. She knew that she would be wrong to consent, yet she could not resolve to forbid him. Mrs. Plunkett had been fearfully irritable all day, and Marigold's patience was worn to a shred.

She let the question pass, and asked, "How do you like your work?"

"Oh, I've given that up. It meant a lot more than I expected. I shouldn't have had a moment, morning, noon, nor night. I've a mind now to get something to do with the care of horses. I like horses—always did—and I can manage 'em first rate."

"But you're not likely to get that here," said Marigold, experiencing a sense of disappointment.

"Don't see why not. There's Selby,—if one of his drivers was to fall ill, and give up, why, I might step into his shoes."

"But Selby's men have been with him for years. It isn't in the least likely they should give up."

"Well, they might. Or something else might happen. It's just waiting a while. I'm not come back to the old country, to slave. The old folks are as pleased as can be to have me at home. Of course I could get something to do any day, but it's no manner of use to be impatient. Once I get into the right line, I'll stick to it."

"I'm afraid—people will say—"

"Say what? Out with it."

"They'll say—you don't keep long to anything."

"They won't say that, when they see how long I'll keep to you."

Marigold blushed, and was pleased in spite of herself.

"But I do wish—" she began.

"Wish I'd make haste. Why, so do I. I wish the right thing 'ud turn up this minute. And don't you be afraid but what I'll stick to it then. Maybe I've changed about a pretty good deal; but I promise you that's not going on. I'd do anything for you, Marigold."

Marigold's remonstrances died out. She was so sure that all would be right in the end—or rather, she was so anxious to be sure, that she would not look doubts in the face.

When James said casually, a little later, "Well, what time shall you be leaving the Vicarage to come home?"

She answered without thought, though not without a conscience prick, "Oh, somewhere about seven o'clock. Tea's at five, and I always stay a good two hours there."

The Vicarage nursery was a big low room, with three windows, plenty of cupboards, picture-covered walls, and generally toy-strewn floor.

There were four children, ranging from eight years old to almost babyhood. When Marigold arrived, tea was already laid, with cakes and jam as a treat. The children were eagerly looking out for her, since Marigold was their especial favourite. They liked Narcissus,—"but not so much as Marigold," Minnie the eldest would say, sagely shaking her little head.

Narcissus had no chance of even getting near Marigold, till the welcomes of the little ones were ended; and then Marigold could not but notice how well and happy Narcissus looked—how nice, too, in her neat black dress, and pretty white cap and apron. Quite a colour was in her cheeks, and already she had gained in plumpness. One glance satisfied Marigold that Narcissus had thoroughly fitted into her new life, and that the plan would prove a success.

"I do declare, Narcissus looks the best of you two; and she's always been such a puny thing till now," declared old Nurse, who had known both girls from infancy. "It's the regular living, and regular food, and plenty of fresh air, and plenty to do. That's what it is. Lots of girls that come here get like that."

"Aren't you well, Marigold?" asked Narcissus.

"O yes; only—of course there are worries."

"I know," murmured Narcissus. "I'm glad enough to be out of it all."

"Out of what? Narcissus, you shall tell us," cried Minnie, overhearing.

"Miss Minnie, I'm ashamed of you," said Nurse. "Whatever business is it of yours, I wonder?"

The child subsided, deeply abashed, and Nurse added:

"I advise you both to wait. You shall have a talk together after tea."

"Nurse always says we're little pitchers, you know, 'cause we've got such long ears," declared mischievous Polly, the next small girl; and nobody could help laughing.

Tea was a merry meal—the merriest Marigold had known since she left the Vicarage. When it ended, Mrs. Heavitree came in for a few kind words.

"Now what are you going to do?" she asked. "You and Narcissus will like to be together. Suppose you take your work out into the arbour at the end of the kitchen garden for an hour. Marigold has work with her, of course." Mrs. Heavitree had no notion of idleness; and Marigold, smiling, produced a thimble. "If not, nurse can find something, I dare say, to keep your fingers busy. You can have a nice chat there, undisturbed. Nurse said she would spare Narcissus."

"To be sure I will, ma'am," added Nurse; and the plan was forthwith carried out.

MRS. PLUNKETT'S TROUBLE.

"ISN'T that like Mrs. Heavitree?" said Marigold, as the sisters reached the arbour. "Always thinking of other people, and planning for them. Don't you like her, now you're here?"

"I should just think I did. It's all true, every bit of what you told me, and I'm as happy as the day is long. I wish I could live here always."

"That's what I felt."

"Yes, I know you did; and I thought it was funny of you. But I don't think so now. I understand quite well, now I'm here. Everything is so nice and clean and pretty; and everybody is so kind. But I want to know about you at home. Is mother as cross as ever?"

"Worse, I think. She gets worse some days. Nothing I can do or say is right; and the mess the house is in!—It makes me miserable. Father isn't at home near so often in the evenings now; and I know that is the reason. He does like a tidy place to come to; and she won't have things tidy. He can't stand the mess, nor her temper."

Narcissus was silent for two or three seconds.

"That don't seem—" she said slowly.

"Don't seem what?"

"As if—our praying had done much good."

Marigold blushed a little. Had she prayed steadily—following out her own advice to Narcissus? This question arose at once.

"I don't seem to have heart for it sometimes," she said, "living in the midst of all that worry."

"But you wanted me to ask that things might be different; and I have. I've thought of it every night, when I said my prayers. I have, really."

"I suppose answers don't always come directly," said Marigold, in a subdued voice. "Mr. Heavitree says we often have to wait. But if you'll go on—I will, too. I have been wrong."

She hardly acknowledged, even to herself, how the main hindrance to prayer had been pre-occupation about James Todd.

"Yes, of course, I'll go on. Why shouldn't home be happier? It might be. Mother was so different at first."

"Sometimes she is now, just for a little while; and then it goes off, and she's as bad as ever again. I do try to bear with her, because I know I ought; but it is hard;" and Marigold's eyes were full of tears. "I can't make out what's the matter, and why she's so cross. Sometimes I think it's all jealousy. She don't seem to like father to be so fond of us."

"Mrs. Heavitree says mother is ill."

"Does she?"

"Well, she did one day lately. At least, she said she'd never seen anybody so altered, nor grown so different, and she couldn't help feeling sure that mother had a lot of pain to bear. She asked me if I didn't know what was wrong, and I said mother had rheumatism now and then; and Mrs. Heavitree said it must be something worse than rheumatism. And I don't see why mother shouldn't tell us, if there was."

"I don't know. People are so funny about health. Some are always fussing about nothing, and others won't say a word if they're downright bad. I'll keep a look-out and see if she does seem ill. That would make a lot of difference."

"It wouldn't make her any sweeter to live with."

"No; only there 'd be an excuse. I could bear with her temper, if I knew it only meant that she was in pain, poor thing! I never thought of that."

The mind of Narcissus was on a fresh tack, and she asked abruptly, "What is this about you and James Todd?"

Marigold coloured, not expecting the question.

"They do say you and he are making up together—and some say it's a downright engagement. But I couldn't believe I shouldn't have been told."

"O no, indeed—"

"But you are seen about with him."

"Well, he's been to our house pretty often since that night. Father likes him, though mother doesn't. Sometimes he meets me when I'm out, and comes a little way with me . . . I don't see why he shouldn't! . . . I'm sure he's such a nice steady fellow; and he wants to work, only he has been so unfortunate. But he'll get something regular soon . . . I don't see why I need snub him, like mother does, only because he's been unfortunate."

"But he did get work. What made him give it up?"

"He said it wasn't the right sort. It wasn't what he is fitted for. He'd like something to do with horses."

"And if he gets the horses, I suppose he'll want something next to do with cows and sheep." The keenness of this rejoinder made Marigold stare at Narcissus, and Narcissus relented. "Please don't think me unkind, only people do say things—"