Title: The golden heart, and other fairy stories

Author: Violet Jacob

Illustrator: May Sandheim

Release date: July 4, 2024 [eBook #73964]

Language: English

Original publication: London: William Heinemann, 1904

Credits: This eBook was produced by: Delphine Lettau, Pat McCoy & the online Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

Great blue lotos-flowers were covering the brink of the water’s edge.

THE GOLDEN HEART

&

Other Fairy Stories

BY

VIOLET JACOB

AUTHOR OF “THE SHEEPSTEALERS,” “THE INTERLOPER”

With Illustrations by May Sandheim

LONDON

WILLIAM HEINEMANN

1904

DEDICATED

TO

THREE LITTLE BOYS,

HARRY, EVAN, and RAYMOND,

AND THREE LITTLE GIRLS,

MARJORY, SUSAN, and GWYNETH.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| The Golden Heart | 1 |

| The Sorcerer’s Sons and the Two Princesses of Japan | 45 |

| Grimaçon | 67 |

| The Dovecote | 102 |

| The Peacock’s Tail | 122 |

| The Pelican | 127 |

| The Cherry Trees | 146 |

| Jack Frost—A Story for Very Little Children | 164 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| Great blue Lotos-Flowers were covering the brink to the water’s edge | Frontispiece |

| “Oh!” cried the Little Boy, “I see a dark thing far away in front” | 10 |

| A Thing which looked like a Human Figure was lying by a Fire | 20 |

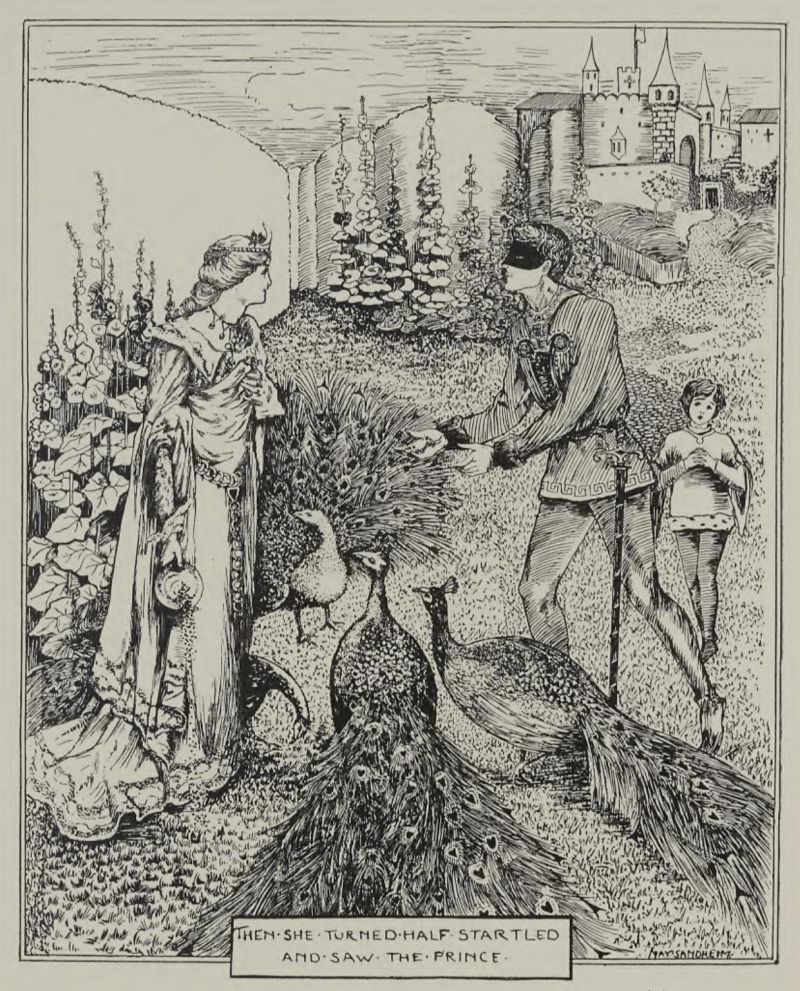

| Then she turned half-startled and saw the Prince | 42 |

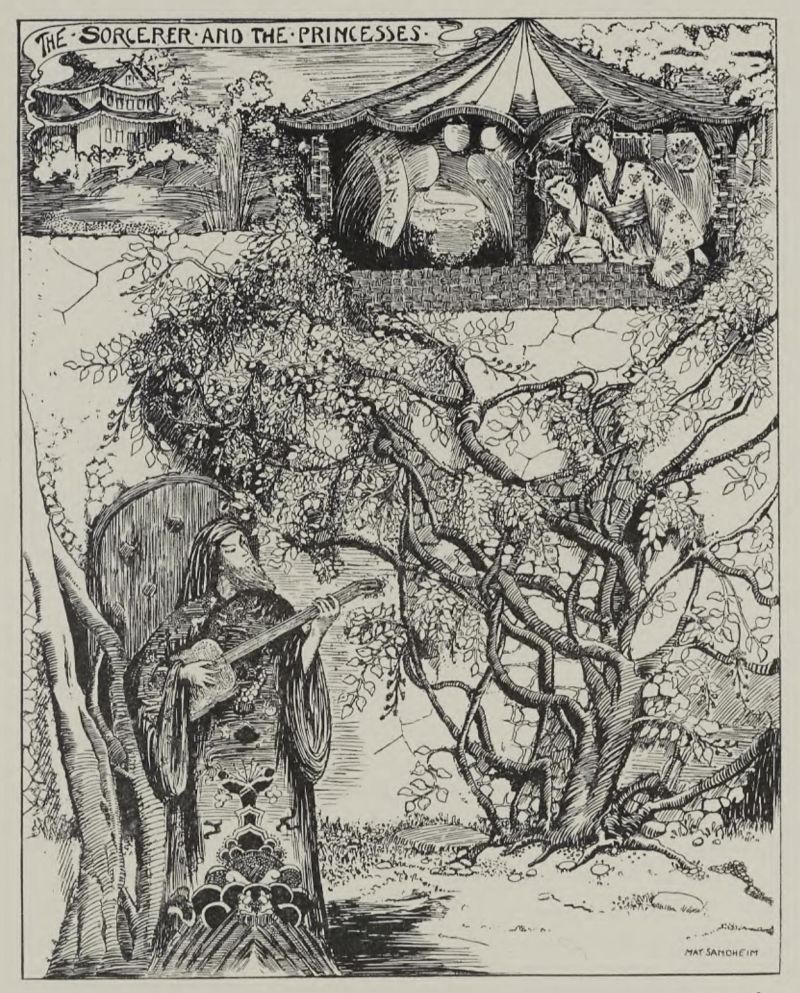

| The Sorcerer and the Princesses | 48 |

| The Procession was several miles long | 56 |

| She found her sitting at the window watering her flowers | 70 |

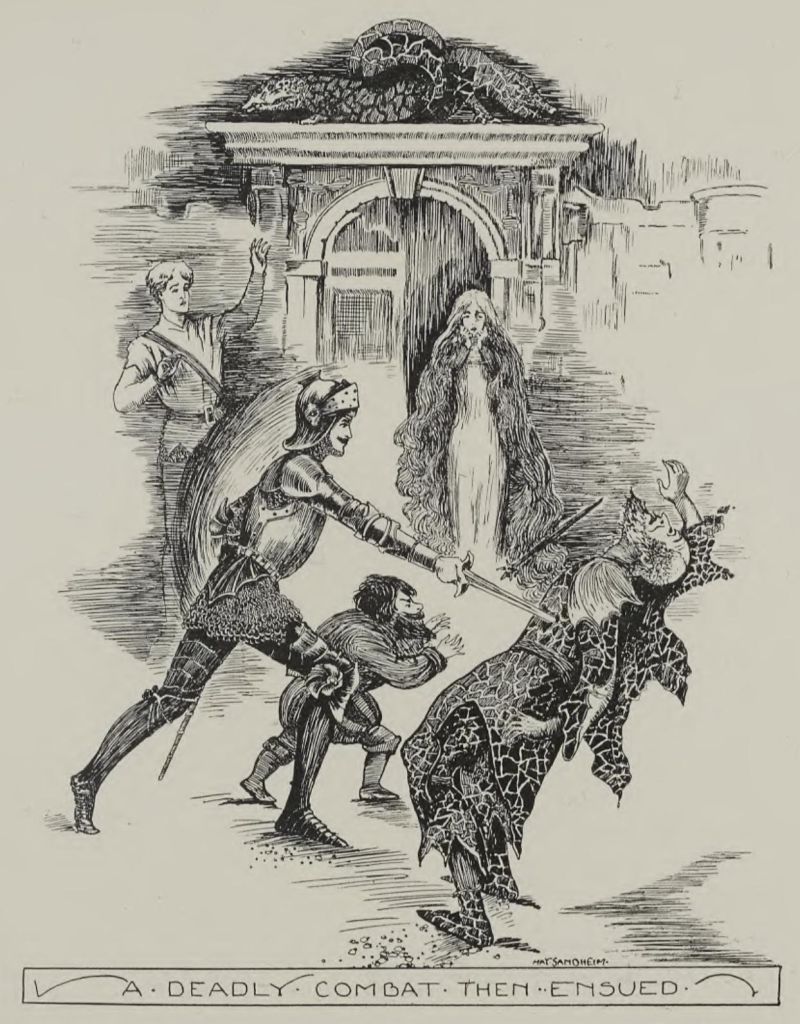

| A Deadly Combat then ensued | 96 |

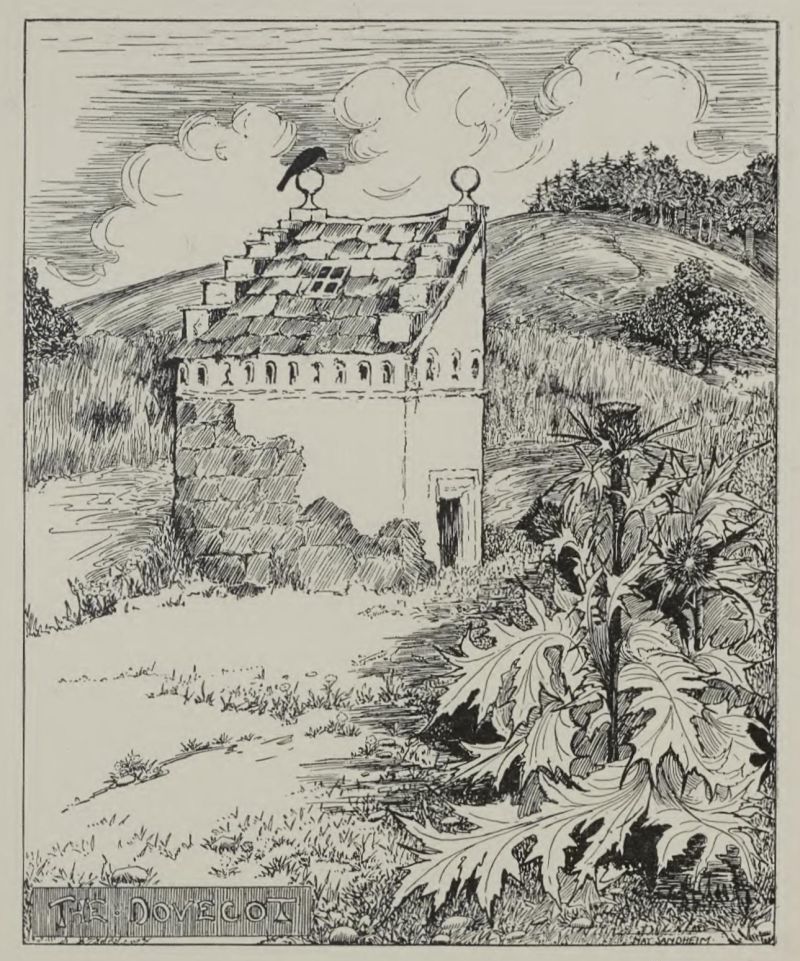

| The Dovecote | 102 |

| Maddy Norey shows the Queen the room behind the fiery Roses | 108 |

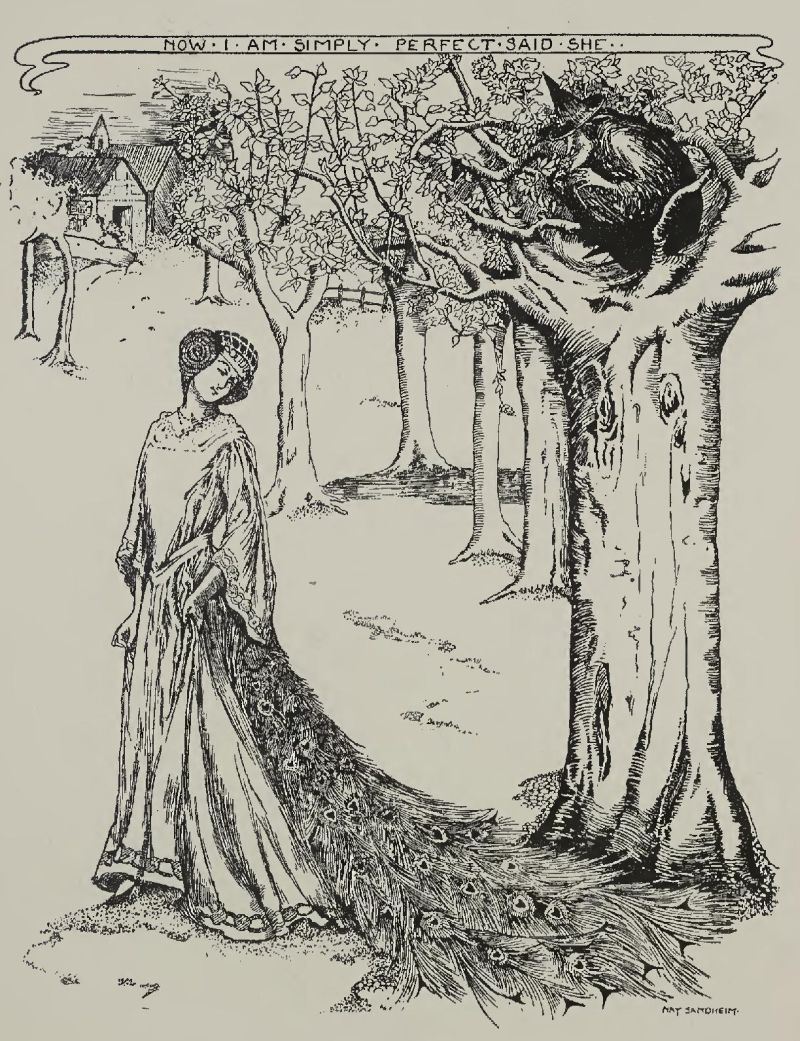

| “Now I am simply perfect,” said she | 122 |

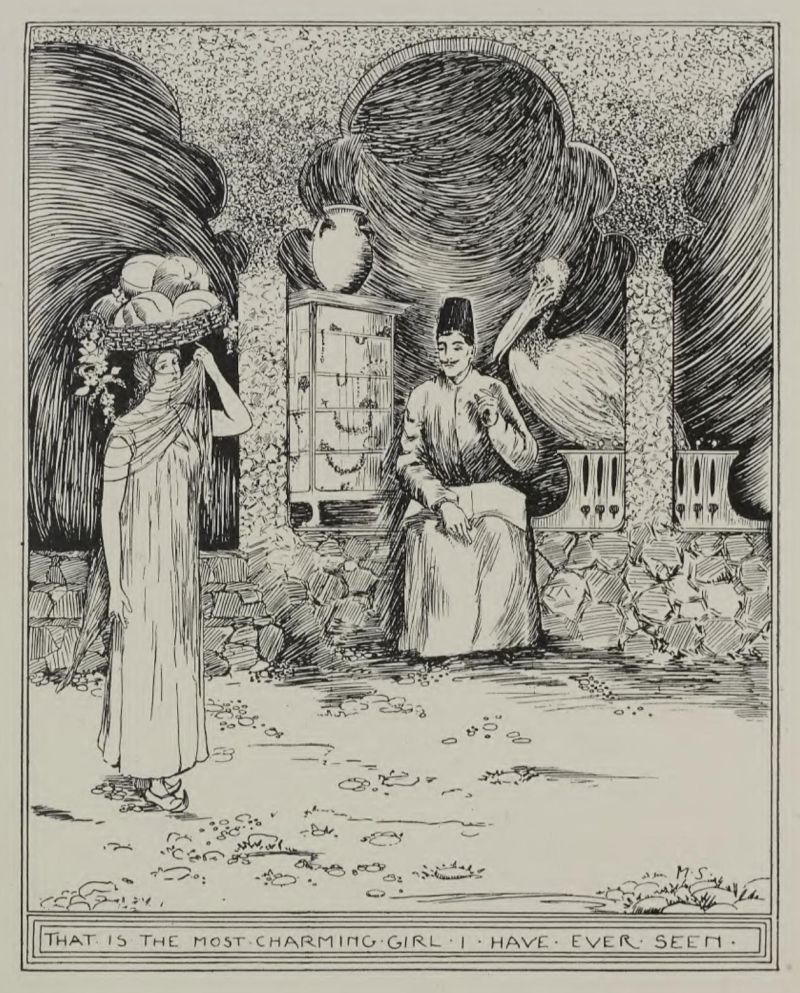

| That is the most charming girl I have ever seen | 128 |

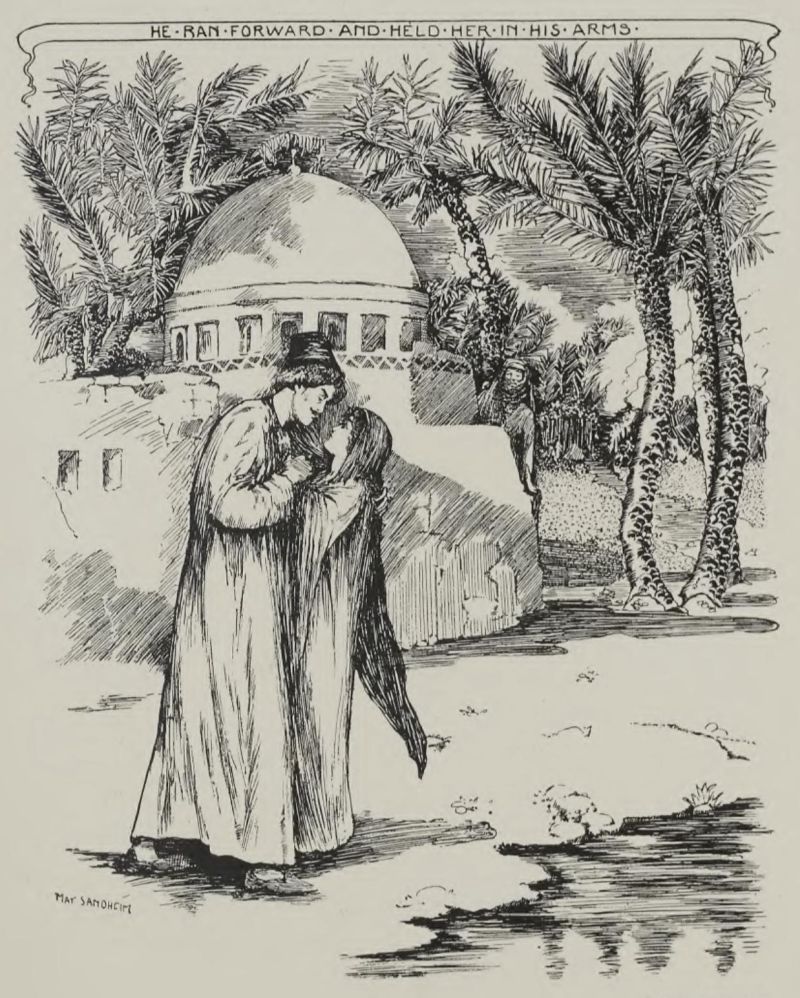

| He ran forward and held her in his arms | 142 |

| The Daffodil Princess | 146 |

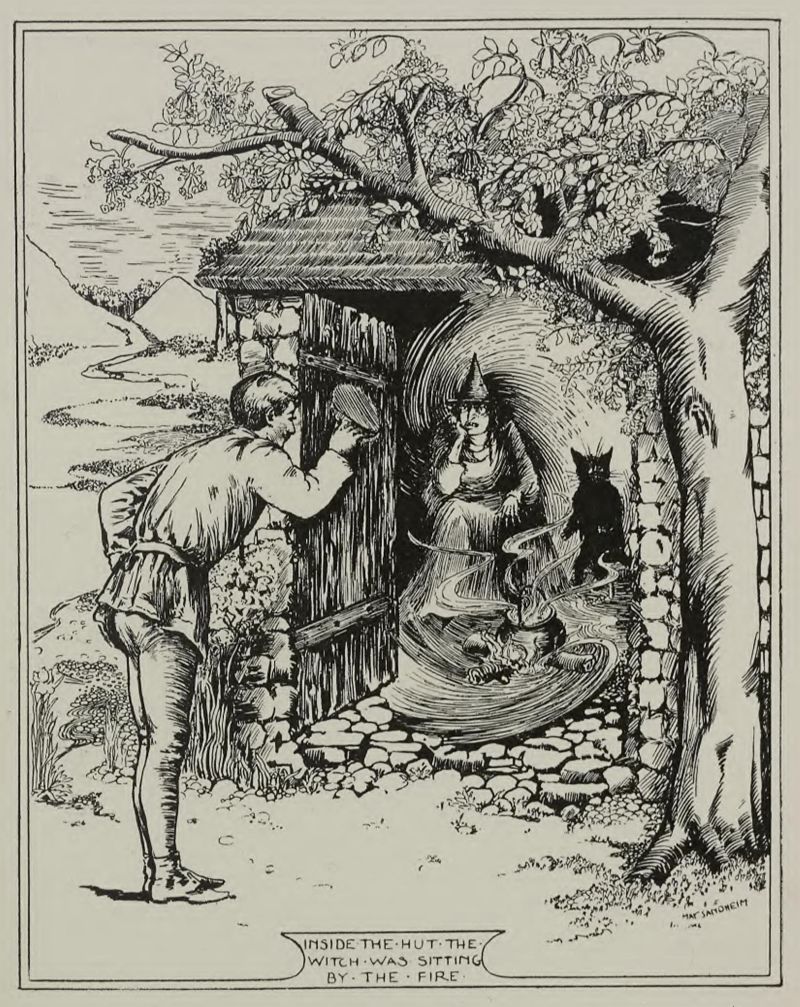

| Inside the hut the witch was sitting by the fire | 152 |

| In the very middle of the feast the Prince stood up in his place, calling on all to listen | 158 |

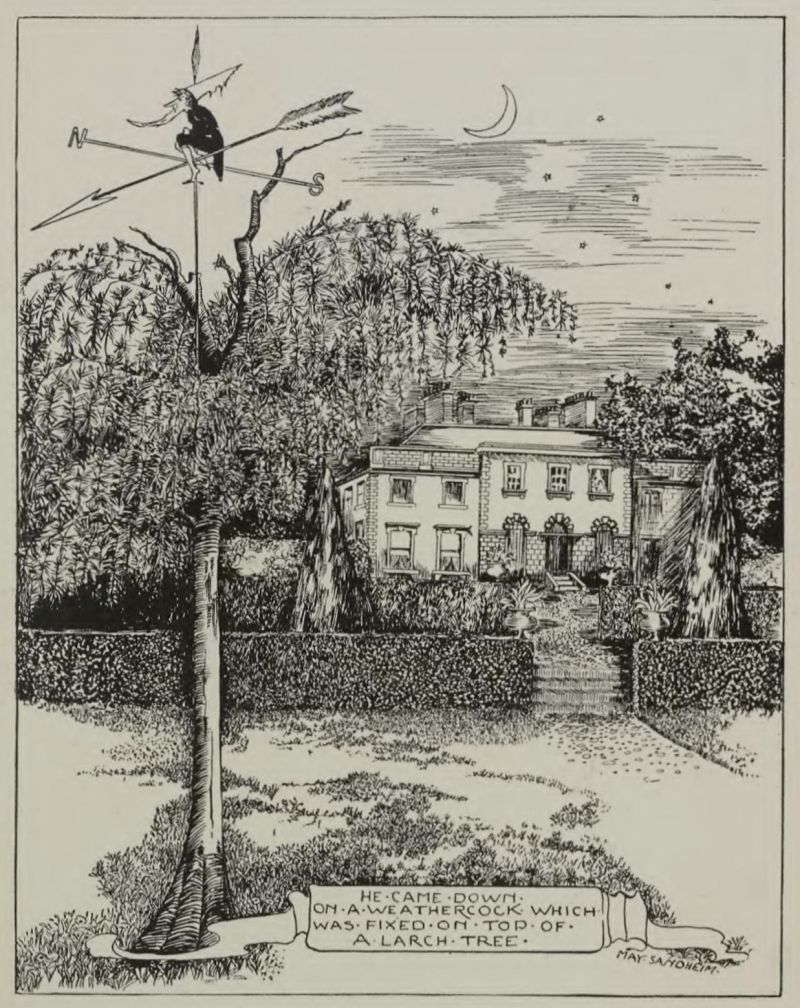

| He came down on a weathercock, which was fixed on top of a larch-tree | 164 |

THE GOLDEN HEART

&

Other Fairy Stories

The night lay clear upon the North Sea, but now and then a soft wind came floating by; it whistled through the rigging of a fishing smack in which a little boy lay under a tarpaulin, peeping over the side of the boat down into the water below.

His father had told him to be still and to go to sleep, so he lay looking up at the spangled sky above, and the masts rocking to and fro against the stars as the boat swayed about. Sometimes he thought the tall, dark forms looked like black arms trying to reach the bright lamps and put them out. He did not feel sleepy as he lay by himself and he began to wonder, as he gazed into the water, how deep it was down there, and whether the little fishes among the shells and seaweeds were ever told by their fish-fathers to go to sleep, and, if so, whether they found it as hard to do as he did.

Presently he saw the eyes of a great shining fish staring up at him. It opened its mouth as if it wished to be friendly, but hardly knew how to begin, so the little boy plucked up courage, though he had never met a fish before and was not quite sure how to address one.

“Is it very cold in the sea?” he inquired shyly.

“That depends on what you are accustomed to,” replied the fish. “For my part, I should say it was a particularly warm night for the time of year. What in the world do you find to do in that monstrous boat? Is there anything worth eating up there?”

“It’s very dull,” said the little boy. “My father said I was to go to sleep, but I can’t. I’m not sleepy.”

“Why don’t you come down here?” suggested the fish. “It stands to reason that it must be much more amusing in the water.”

“I should be drowned; I can’t swim like you.”

“How dreadfully ignorant,” remarked the fish.

The little boy was rather hurt at this, and made no reply.

“Well,” continued the hoarse voice from below, “if you like to come with me, I can show you some of the most wonderful things in the world; you can hold by my tail and I’ll pull you along. You can’t drown so long as you don’t let go.”

The little boy was much tempted.

“But are you sure you won’t leave me?” he asked anxiously.

“Goodness, no,” replied the fish, “I’ll see that no harm comes to you. You are evidently a shockingly ignorant child, and it would be real charity to show you something of the world. Come along and don’t be silly.”

The little boy looked round to see that there was no one near, then he slipped over the side and, in another minute, was in the sea and holding firmly to the tail of his new acquaintance.

Away they shot through the clear water; it was not nearly so cold as it had looked, and the rapid motion was very exciting.

On they flew, smoothly and easily; they passed tall ships and curiously-shaped masses of rock sticking up out of the sea. Great twisted pieces of sea-weed floated by them, and the flashing lights of Orion’s Belt seemed suspended from the dark blue arch overhead, while, up in the north, the Northern Lights shot their trembling streamers far into the centre of the sky.

By the time day was dawning they had reached a tract of ocean where there was neither sail nor coast, and where the rolling line of water stretched for miles around.

“Now,” said the fish, “I will show you one of the strangest things in the world. Can you see anything between us and the horizon?”

“I see a dark spot a long way off.”

The light was growing brighter every moment, and pale streaks in the sky began to kindle the sea when the fish and his companion drew near the object of which they had been speaking. In the midst of the heaving water there rose a steep rock; on its grim sides grew neither sea-weed nor anything to give sign of life. There was an oppressive silence hanging over everything, and the water lay dark and still; no little wave played against the relentless stone. On the top of this rock a beautiful woman sat with her hands clasped together. She wore a black robe against which her arms shone like ivory, and her hair flowed in a shower over her shoulders. Now and then she raised her eyes and looked out to sea; they wandered over the horizon and rested with a look of sad expectation upon it, then she sighed and glanced down at something which she held in her hand.

Beside her stood the only living creature excepting herself visible on that desolate place—a gigantic grey cormorant of terrible aspect and size. A gleam of light from the rising sun shot over the waters, and, as it touched the woman’s hair with its first rays, the cormorant flew up into the air. From some hidden place in the rock another bird appeared, and, joining its mate, rose with him far above their bleak abode; then the two sailed away and were soon lost in the distance.

“What does it all mean? Oh, do tell me!” begged the little boy.

“I thought I could show you something surprising,” chuckled the fish; “this is the history of it. I am one of the very few who know anything about it. Inside that rock, in a cavern which is reached by a passage to which no one knows the entrance, sits an old witch; she is very wicked, and is sometimes able to cast dreadful spells upon her enemies. That Princess who sits there is the daughter of a King, whose country is an immense way off, and who once had the ill-luck to offend the old woman. So, when the Princess was a child, she went to the King’s palace and stole her away; here she has kept her sitting, year after year, upon this lonely rock with no one to speak to but the old cormorant. Every day he keeps guard in case someone should come to take her away, and every morning he flies off to fish with his mate, who has a nest just now and young ones in a cave of the rock. Once in two days the hag comes out to bring the Princess food and to ask her whether she sees anyone coming, and when she gets no reply, she laughs and leaves her again.”

“Will she ever get away?” asked the little boy.

“How can I tell?” said the fish. “She has sat there for so long that it doesn’t seem like it. There is only one chance that I can see. She holds in her hand a little heart made of gold; if she could only find someone to whom she could give it, she might be saved. For, whoever possesses it can ask any question, and the heart will answer and tell its owner how to act under all difficulties. But he who takes it has to accept trouble and pain with the gift.”

“But then, why doesn’t she ask it herself how to get away?”

“The heart is of no use to any one but a man,” said the fish.

“And I suppose no man has ever been here?”

“Two or three have come sailing by; one who came was anxious to help the Princess, but, as she was about to throw him the Golden Heart, she told him that if he took it he would have to face as much trouble as a man could bear. So he would not have it and sailed away. But that was years ago—and now, we really can’t stay here any longer, nor do any good if we do—let us be off.”

And he swam away.

The little boy would have liked to stay and speak to the Princess and his eyes were full of tears.

“What are you sniffling at behind there?” exclaimed the fish, who was getting rather tired of his load.

“I am so sorry for her!” he sobbed.

“Dear! Dear! If you cry for all the troubles you see, you will have enough to do; try to think of something else, and, for goodness’ sake, strike out a little with your legs and help me along—I have to do all the work.”

The little boy was so frightened when he heard this that he kicked out with might and main for fear that his protector should shake him off.

When evening was coming on and when they had travelled some distance, they saw a large ship; as she approached, the fish suggested that they should swim alongside, and the little boy was charmed with the idea. They saw that the sails were embroidered with gold and silver, and that, on the prow, there was an immense carved crown glittering with precious stones. Closer and closer she came till they were almost touching her. A man was looking over the bulwark into the water; he was young and very richly dressed, and a sword hung at his side. Over his face was a black mask which hid it completely, leaving only the mouth visible.

“There!” remarked the fish, “look at that man. That is another wonderful sight. He is young and rich and a king’s son, but he chooses to sail about by himself. He is so ugly that he wears a mask day and night and never takes it off, and he roams about on the high seas so that he need see none but his own crew who love him so much that they would go with him anywhere.”

“What a pity,” said the little boy, wondering. “He looks very nice standing up there with those beautiful clothes on. And I can see his mouth; it does not look so very ugly.”

“It’s simply enormous,” replied the fish.

“Oh, I don’t think so—really,” answered the little boy, “it isn’t any bigger than yours, you know.”

“That’s neither here nor there,” said the fish; “and don’t pull my tail so. You hold it so clumsily that I can hardly move.”

“I wish I could see him nearer,” continued the little boy, lost in admiration of the figure above him, “I’ve never seen any one like him.”

“You haven’t seen much,” answered the fish, who had not been best pleased by the allusion to his mouth, “now come along.”

“Oh, wait a minute, do, please! He’s looking at us.”

The Prince was gazing over the bulwark at them.

“Well!” exclaimed the fish, “if you’re so devoted to him you had better stay with him altogether. I’m getting sick of dragging you along like this.”

The poor little boy was horrified and looked imploringly up at the Prince, who called one of his men to see the strange pair. “Lower a boat and fetch me that child,” he said, “and the fish too, if you can.”

When the fish heard this, he began to flounder so violently that he twitched his tail free and swam quickly off, leaving his friend gasping in the waves. The Prince threw off his beautiful coat, plunged into the sea and caught the struggling figure, holding it till the boat picked them both up. Soon they stood safe on deck, dripping with salt water, the little boy sobbing with terror and excitement. “Oh,” he cried, “look! look! your lovely clothes are all spoilt.”

“Never mind, little man, never mind,” laughed the Ugly Prince, “and don’t cry. You are quite safe with me and I have plenty of other clothes in my cabin.”

Then he sent for a great tall sailor, who took the little boy below, where he was undressed and dried, then rolled up in one of the Prince’s cloaks and carried on deck. “Come here,” said the Prince, “and tell me all about yourself.”

The child came up shyly and climbed upon his knee. “And how was it,” continued he, “that you came to be swimming about with that great fish? Little boys don’t travel in that sort of way as a rule.”

His voice was so soft and he stroked the child’s hair so kindly, that the little fellow began to think he was a much nicer friend to have than the fish, with all its knowledge; so he told him of everything that had happened and especially of the marvellous sights he had seen since he slipped over the side of his father’s smack a day ago. When he had finished there was a long silence and he glanced up at the Prince, for he felt, somehow, that he was looking grave. But the black mask hid everything.

In a short time the Ugly Prince set him down and spoke a few words to his helmsman. Then the ship turned slowly round and sailed off in the direction from which the fish had come.

As night drew on they still kept steadily forward, and when the stars had come out and the last light departed, the little boy was put to bed in a beautiful cabin all painted sea-green, with a pale green curtain hanging over the door on which was embroidered a silver crescent moon. He was laid in a soft bed with a quilt of the same colour, and soon he was far away in the land of dreams, dreaming that he was again in the sea, sinking into a world of branching sea-weed and silver sand through which swam the little fishes about which he had so often wondered.

When he opened his eyes next morning the light was peeping in through the port-hole, and his clothes, which had been dried, were lying beside a bath which was waiting for him. He washed and dressed and then went on deck, where the Ugly Prince stood looking out over the ship’s bows. When he saw the child he lifted him up in his arms.

“Oh!” cried the little boy. “I see a dark thing far away in front! Why, it is the rock where the Princess is! Are we going there?”

The Prince did not answer.

As the sun rose out of the ocean a short time later, the vessel was drawing very near to the rock which rose, like some dark monster, out of the sea, and the Prince and the little boy were on deck, the latter looking eagerly out for the captive Princess.

There she sat, just as she had sat the day before and all those weary days in the years gone by with her hands clasped over her one hope, the Golden Heart. Two dark spots could be seen in the distant sky growing smaller and smaller; they were the two cormorants flying off for food.

As the Princess saw the ship the colour rushed back into her pale cheeks; she fixed her eyes on the advancing sails, and at last distinguished the tall form of the Ugly Prince standing out against the sea and sky beyond. As the vessel came under the shadow of the rock he looked up at the sweet face above him and told her to have courage, and that he had come to take her from her long imprisonment, back to the world she had left.

“Throw me,” he said, “the Golden Heart that you hold.”

The Princess stood up. “Thank Heaven that the cormorant is gone!” she cried. “He stands there so that, if I throw it to anyone, he may catch it in his beak and rob me of my last chance.”

“But throw it carefully,” begged the little boy, “or the Prince won’t catch it.”

The Prince smiled. “Now,” he called.

“But, before I do so,” said the Princess, “I must tell you this; if you take it, it will bring you pain and sorrow—perhaps more than you can bear. Can you really accept it? Are you willing to take the trouble that must come?”

The Ugly Prince simply held out his hands. “Throw,” he said.

The little boy thought he had never seen anybody look so noble as he did, standing there with his outstretched hands and his masked face turned up to the lovely, sad figure above him.

A flash pierced the air, and the Heart lay safe in the hands of the Ugly Prince.

“And now,” he said as he held it, “remember that there is nothing I will not do for your sake; whatever this thing tells me to do, that will I do; wherever it tells me to go, there will I go; and, as long as there is life in me, I will not rest until I have accomplished my end.”

The evil birds were now seen returning over the waters, and at the sight of the ship lying anchored under the rock, they were dreadfully disturbed, and made such a flapping of wings that the witch came up from her lair to see what could be the matter. When she saw the vessel her fury knew no bounds, and when she observed that the Golden Heart was gone, she nearly wrung the old cormorant’s neck.

“The next time you go away,” she cried, “I will sit here and watch myself! And, as for you,” she went on, turning to the Princess, “you need never think you can escape, for you shall be guarded day and night!”

But the Princess said nothing.

Meantime, the Ugly Prince was taking counsel of his treasure; he looked long and curiously at it; then, as he felt a little tremor fluttering between his palms, he inquired of it what he was to do to save the Princess from her bondage. A radiance like a flame rose all round the Heart, and a small, soft voice spoke. It was so low that he had to bend down his head to catch the words. “To-night,” it said, “you must watch on deck until morning, and when the two cormorants fly away at sunrise, be careful to notice from which part of the rock the female bird comes; then, when they have started on their flight, slip down into the water and swim to the place. It is a large cave, black and gloomy, but, nevertheless, swim in. The water is deep at the entrance, but when you have gone forward a few strokes, you will find a great stone rising a couple of feet above its level; let your eyes get accustomed to the darkness and you will see upon the top of this stone the cormorant’s nest. Climb to it very softly, for in it will be the three little cormorants asleep. Be sure you do not wake them. Beside them you will find three grey feathers which you must take; the first feather will give you the power of becoming invisible when you please, the second will enable you to see in the dark, and the third will enable you to understand the language of birds. When you have secured them, make yourself invisible and stay in the cavern until the mother-bird comes home. Then, keep your ears open to hear all that passes.”

The voice ceased, and the Prince, knowing he would be told no more, buttoned the Golden Heart into his doublet and prepared to wait patiently till night should come and he could take up his post on deck to watch for the coming sunrise.

The hours wore on and day slowly faded. When the dark set in he lay down, with his eyes fixed on the heavens, hardly able to bear the time which lay between him and the morning, and, when dawn came creeping on, he distinguished the dim figure of the old cormorant at his post.

He stood as though carved out of the stone beneath him until the sun’s disc appeared over the horizon-line, when, with a loud flapping, he rose in the air. The Ugly Prince lay looking at the rock as though his life depended upon it, and, from out of a deep shadow in the right side of the huge mass, the mother-bird came flying to join her mate. He kept his eyes on the spot till the last rush of wings had died upon the air, then he looked up at the Princess and plunged into the sea.

The green water had a cold chill which struck him to the marrow, but he swam steadily on, stroke after stroke, till he reached the mouth of a rugged cavern where the rock towered above his head as though poised for a moment ere it fell to crush him to atoms; and, through the darkness, he saw the outline of the flat-topped stone described by the Golden Heart.

With long strokes he swam to it, and, clinging to its jagged sides, drew himself out of the water. To climb to the top was the work of a moment. Once there, he stood staring through the gloom at the nest, which was built, as he had been told, on the summit. There lay the three little cormorants asleep, like three fluffy balls; he could just distinguish their soft bodies and their breasts heaving up and down in the deep breathing of their slumbers. Not a sound was to be heard but the lapping of the water, stirred by his swimming as it rose and fell against the stone’s foot. As his eyes became more accustomed to the darkness he saw, beside the sleeping birds, the three feathers for which he was searching. He put in his hand and took them, his heart beating high as he felt all three in his grasp and knew that the first step of his labours was accomplished. He slid down again into the salt water, having placed his new treasures carefully in his pocket. Then he seated himself in a little niche above water-mark to await the mother-bird, wishing with all his might for the promised power of seeing in the dark. Immediately every cranny in the cave became visible and he began to wonder where the mysterious passage might be which led to the witch’s dwelling.

In a short time the narrow slit of light was darkened by the form of the cormorant-mother coming back to the nest; she flew in and alighted by the side of her young ones. The Prince lost no time in wishing for the power of understanding bird-language, and, as the little birds awoke, he strained every nerve to catch any speech which might pass between the four creatures.

“Lie still, you tiresome little things,” said the mother as they all began chattering at once, “I have got some very good fish here; but not one of you shall taste a bit if you make such a noise.”

“What a long time you’ve been getting it,” squeaked one of the little birds.

“That is not the way to speak,” observed the mother, “and you must learn not to make remarks when you are not spoken to. If your father heard you talking like that he would punish you severely. I am always very quick about getting your food, and greediness is a very shocking fault—remember that.”

“But I’m not greedy, I’m hungry.”

“Be silent, sir, at once!”

The three little birds were very much frightened at this and kept quiet while the fish were being broken up and divided into four parts. When this was done a great gobbling began, and no one spoke for some time.

“Now,” said the old bird, when every piece had disappeared. “I am going to speak to you very seriously.”

At this there was a dead silence, for all the little birds felt that their mother was in no humour to be trifled with this morning.

“Remember that I forbid you all distinctly to make any noise to-day or to scream or chatter loudly. I have a very good reason for doing so, and as I wish you to see for yourselves how very important it is, I will tell you about it. Are you all listening?”

“Yes! Yes!” cried the little birds.

“Your father is in great trouble,” she began, “for a most disagreeable thing has happened and our mistress is very angry. A ship is close by and there is a strange man on board who wears a black mask. We are afraid that he has come to take the Princess away. Yesterday, on our return from fishing, we found the ship here, and, what was far worse, discovered that the Heart which the Princess held in her hand had gone. Your father thinks there is every reason to believe that the man with the black mask has got it and he is much distressed, for our mistress has used words to him which have hurt his feelings deeply. Now, if any of you scream and make a noise, it may draw the attention of that wicked man in the ship to this place and he may discover the way to our mistress’s cave, which lies, as I suppose you all know, behind that piece of rock shaped like a fish’s head sticking out in yonder corner. If he got to her he might do her some mischief, or perhaps force her to give him the Princess. Besides which, he would certainly wring all your necks—and then, how would you like that?”

Here one of the little birds began to cry.

“How dare you make that noise!” said his mother, prodding him with her beak. “Stop crying instantly, sir, or we may all be lost!”

The squeaking soon ceased and, quiet being restored, one of the little birds, being of an argumentative turn of mind, began to ask questions. “But if that dreadful man got to our mistress,” he inquired, “how could he find his way to the Princess afterwards?”

“If he were in the cave he might see how our mistress goes to her; you know, she takes off her left shoe and knocks at the wall with it. Then she says:

“ ‘Left-foot shoe, left-foot shoe,

Open, rock, and I’ll pass through.’

And the rock opens in a straight passage and she goes up to the top of it, right outside to where your father and the Princess sit. Now, I’ve told you enough—be quiet.”

All this time the Ugly Prince was looking for the stone like a fish’s head, and soon saw it sticking out in the remotest part of the cavern, so he began climbing towards it. It was weary work, for the cold had made his limbs stiff, and he feared to go quickly in case any sound should attract the old bird’s attention. With much trouble he reached the place, and, looking behind the fish’s head, saw an opening which seemed much too small for a human being to enter. He determined, however, to try what he could do and began to creep in, finding that he could just push himself along, and although he could see no light at the other end, he pressed forward. A horrible sickening sensation came over him when he had gone some way, and he felt as though he should be suffocated in this stifling place, from which none could deliver him, and which his crew, if they began to search for him, could never find. The air grew so close and the tunnel so narrow that he had almost given up all hope of life when his head struck against the rock and he lay half stunned. “Now,” he thought, “all is really lost, for I can get no further, and must die in this loathsome place.”

As he lay in his cramped position he saw what seemed to be a white pebble embedded in the rock somewhere on his left. He stretched out his hand with great difficulty, and found that it came in contact with nothing solid, though it hid the white spot from his view, and he realised that the object was not a pebble at all, but a speck of light in the far distance, and that he was groping with his arm down a narrow passage, starting away at right angles from the place in which he was imprisoned. A new hope sprang up in his heart, and he dragged himself round the corner. The tunnel grew a little wider, and, with every few inches that he moved forward, his courage rose, and the outer air grew nearer. The stones tore his hands, and he was bruised in every limb as he crept along, but he pressed on till the light became larger and yellower and the air less oppressive, and, at last, after many struggles, he stood upright outside the tunnel’s mouth.

An enormous hall met his eyes; bare rock formed its walls and ceiling and the ground under his feet was covered with fine sand.

From the sides of this place hung twisted shapes. He could hardly see what they were. First he thought that they must be great ropes of sea-weed, then human forms; grinning faces seemed to start from them at every side, and yet he could never really make out that they were the forms of either men or beasts, for, as each thing appeared to take some definite shape, it would speedily turn into something else, like the wild and fleeting images in a dream.

As he stood, the noise of the sea roaring underground in remote hollows of the rocks smote desolately on his ear, and, for a moment, the dreary sound made his heart sink in his body. But he thought of the Princess, and courage leaped up in his soul.

A column of stone, reaching to the roof, stood in the middle of the cave, and, at its foot, was a thing which looked like a human figure lying by a fire. He approached, thanking Heaven for the power of becoming invisible, and saw that he was in the presence of the witch. By a happy chance she had overslept herself, and had not yet gone up to the Princess.

As he looked there was a stir in her recumbent form. She rose, and, drawing off her left shoe, approached the wall.

“Left-foot shoe, left-foot shoe,

Open, rock, and I’ll pass through,”

she muttered, striking it. Then the wall cracked open and she gathered her skirt more closely round her and disappeared through the opening, which closed behind her.

He paced up and down, straining his ears to catch any sound that might steal through some chink in the rock, and give him an idea of what was going on above. But no sound came.

At last the wall opened and his enemy appeared. An evil smile was on her face, and he guessed that she had been taunting her victim. His blood boiled. When the chasm closed, the hag, instead of replacing her shoe, drew off its fellow and, putting them both in a corner, flung herself down by the fire. The Prince had not expected such luck and he bounded towards them. At this she looked up quickly; he had forgotten, in his excitement, that, though invisible, his movements could be heard, and for a minute he stood waiting to see if she would notice the footprints he had made in the sand. But after sitting erect to listen, she seemed re-assured and lay down, while he, pausing a little space ere he moved again, heard her breathing grow heavier and saw that she was falling asleep again over her fire. Then he picked up her left shoe.

He advanced to the wall and struck it, saying the words he had heard her use.

It flew open before him and the fresh air rushed against his face. With one backward glance at the sleeper he climbed the incline, and, in a moment, had wished himself visible again and was standing on the rock by the Princess.

Her eyes were fixed on his ship, but she turned on hearing a step. Her face was almost fierce, for she expected nothing better than to meet the witch. Then she saw the Ugly Prince and rose, with a cry, stretching out her hand to him. Her great sorrow seemed to be looking out of her eyes, and the beauty of her face was so far beyond anything he had imagined that he stood before her dumbfounded, more like a culprit than the man who had fought his way to her through peril and fatigue. He took her hand and pressed his lips upon it. As he did so there was a rushing in the air, and the old cormorant, who had just returned from his fishing, began raining the blows of his heavy wings upon his shoulders. He fought it off as well as he could with his left arm while he drew his sword, and, as the savage bird swung back to make a fresh swoop, the steel blade flashed and it fell dead on the rock at his feet.

The Princess covered her eyes; she almost sank upon the ground, but the Ugly Prince caught her in his arms.

“How can we escape? How are we to reach the ship?” she cried.

He drew out the Golden Heart. The same tremor ran through it as it said: “Cut off the cormorant’s wings and strike them with the witch’s shoe. They will fasten themselves upon your shoulders and you will be able to fly as well as the bird.”

The Prince obeyed, then he stood ready to leave for ever the scene of his conflict. “Come,” he said to the Princess.

We must now return to the little boy, who had never left the deck all the hours his friend had been away. As he saw him rise into the air with his living burden he clasped his hands, standing breathless until the cormorant’s wings had borne him over the strip of water. His joy knew no bounds as he saw him land safely beside him, and he looked with admiration and awe upon the lovely Princess who had suffered so much.

“Who is this?” she asked, pointing to the child.

“That is more than I can tell you,” said the Prince, smiling, “for I picked him out of the water. But he is very dear to me all the same.”

“Shall I love you too?” she said, looking down at him with her sweet, mysterious eyes. “I have had no one to love for so very long.”

The Golden Heart was their guide, for it knew everything—even the way over the trackless seas—and soon the terrible rock was no more than a fast disappearing speck, far astern.

After a happy voyage they reached the country where the Princess’s father still reigned, an old man bowed down by grief.

When they got to the shore and the people saw that it was their own Princess who had returned and heard the tale of her captivity and rescue, their joy knew no bounds and they conducted the Ugly Prince and his crew with great rejoicings to the royal palace, which lay at some distance off. Messengers were sent forward to the poor old King, who, in spite of age and infirmity, mounted his horse for the first time for many years and came out to meet them.

He could hardly believe the news, and, when the meeting was over and he had held his daughter in his arms and knew that it was no dream, but the real, happy truth, he turned to the Prince. “I cannot speak to you now,” he said, “but to-morrow you must tell me the story with your own lips, and, were you to ask me for my kingdom, it should be yours.”

The next morning the Ugly Prince was summoned to the old man’s presence. He told the story of the Princess’s rescue, making very light of his own brave deeds, but the King was not easily deceived; and, as he sent also for the little boy, he soon got at the whole truth.

“And now,” he said, at the end of the tale, “is there anything in the wide world that I can do for you? My kingdom and all I have is yours if you will only take it. Have you no wish—no matter what it may be—that I can gratify?”

“I have loved your daughter since the first moment that I saw her,” said the Ugly Prince.

One evening the Ugly Prince and the Princess were walking on the terrace of the palace garden. The sunset glowed along the western sky, the birds were twittering in the deepening silence, and the heavy scent of masses of roses which climbed over balconies and pillars steeped the air. A minstrel was singing softly inside one of the open windows, and his song reached them as they stood looking out over the balustrade on to the country lying spread before them.

“Do you remember,” said the Prince, “that, when you threw me the Golden Heart, you told me I should have to suffer almost more trouble than I could bear?”

“Yes,” she answered.

“Well,” continued he, “I nearly gave myself up for lost in the tunnel of rock; but, after all, I came safely through it. And it was a small price to pay for this,” he added, taking her hand.

“How brave you are!” said she.

He laughed. “But now,” he said, “I cannot imagine anything happier than the present. I have no wish unfulfilled but one, and that is to make you my wife, which I shall do in a few days.”

The Princess looked down. “I have one wish ungratified,” she replied.

“But you have only to say it,” exclaimed he; “surely you know I would do anything for you—anything. I promise it.”

“I can hardly ask you. It would seem as though I did not trust you. It troubles me very much,” she said, with tears in her eyes.

“Do not keep anything from me,” he implored. “I cannot be content now until I know what it is. You shall not go from here until you tell me.”

“If you would, only once, before our wedding-day, let me see your face.”

The Prince groaned.

“But you promised,” urged the Princess.

For a moment he hesitated, then he turned away and took off the black mask. When he faced her again a shriek rang over the garden and she fell senseless.

He had just time to replace it before the King, alarmed by the sound, came out followed by several servants. The Princess was carried into the palace and laid upon a couch, and, when many restoratives had been administered, she opened her eyes; but, on seeing her lover, an expression of terror came into her face and she fainted again.

The Prince withdrew, asking the King to go with him. When the old man heard what had happened, he wrung his hands and begged him to refrain from seeing his daughter until the next morning; then he returned to her bedside, saying that he would come back on the following day and give him news of her.

The Ugly Prince spent most of the night in walking up and down his room; the little boy, who had come to him as soon as he knew what had happened, did all he could to comfort him, and, at last, the unhappy lover fell into a heavy sleep with his hand clasped in that of the child, who refused to leave him, and who sat watching with his friend until he, too, became drowsy and lost consciousness.

It was almost noon when they were aroused by the sound of footsteps, and, looking up, saw the King.

“My son,” he said to the Prince, “I have come with weary tidings; my daughter has recovered; but early this morning she sent to me.”

He paused for a moment, and went on in a shaking voice.

“She implores you to release her from her promise to marry you. She will give no reason for what she asks, and when I suggested that she should speak to you herself, she grew so pale that I feared she would faint again. I reasoned with her, I prayed her to consider her words again, but all to no effect. I knew not how to act. She owes her very life to you. I would compel her to fulfil her promise if I could force myself to do so, but alas! alas! I cannot when I see her in such a state!”

The Prince was standing before the weeping old man. “And do you think I would accept such a sacrifice?” he said, slowly.

The King made no reply, but covered his face. There was a long silence.

Then the Ugly Prince spoke, and his voice seemed to the little boy as though it were miles away.

“Sire,” he said, “tell the Princess that my only wish is to serve her. I release her from this moment.”

Then the King went slowly away, and, as the curtain fell behind him, the Ugly Prince was left alone with the little boy.

He remembered what the Princess had told him when he took the Heart from her, and he knew that the time had come.

When the King’s subjects heard that the marriage was not to be, they were sorely troubled, and gloom fell over the Palace. The King refused to be comforted, and, when the Prince announced his coming departure, he begged for a last interview before he left.

“What you have told me about the Golden Heart is very wonderful,” he said. “Could it be of no use now?”

“Nothing can be of any use,” sighed the Prince. “It cannot alter my face.”

“But it seems to work miracles,” persisted the old man, “and one cannot tell how far its powers may extend.”

So they consulted the Golden Heart.

“There is,” said the voice, “in a far country beyond a vast desert, almost impossible to cross, a marsh traversed by a stream. On the further bank of that stream, at a place where rises a tall crag like the entrance to a tomb, there grows a plant bearing a cluster of pale red berries. It only shows itself once in a thousand years, and on this day three months the time for it to appear will be due. You must reach the place on the evening before its appearance, and allow nothing to tempt you from the spot, for it grows up in one night, and lasts but a few hours. When it has grown as high as your knee, break off the spike of berries, crush them in your hands, and anoint your face with the juice. It has the power of restoring perfect beauty, as well as perfect health, and it can only benefit one person in a thousand years. Hardly any one in the world has heard of its existence. You must start at once, as the way is long, and you must go by the Great Gates, which are at the other side of the world, and which lead to the desert.”

That evening the Ugly Prince set out. He took with him the witch’s shoe, and the old cormorant’s wings hung at his saddle; he also placed the three feathers in his cap. Before he went he called the little boy.

“I am going on a long journey,” he said, “and it will be many months before I can return; you must be very good until I come back. Stay here with the Princess. If I never come back the King has promised that this palace shall be your home. And now, my dear little child, my faithful friend, good-bye, for I must go. Good-bye. You will not forget me?”

The little boy clung round his neck till the servants came to tell the Prince that his horse was saddled; then he rushed up to the highest tower of the Palace, and, leaning far out of the window, watched the gallant figure riding away, as it seemed to him, into the sunset.

It was in the eleventh week after his departure that the Ugly Prince drew near the Great Gates that lie at the other side of the world. He had only one week left in which to cross the desert beyond them, and he saw, on approaching, that they were locked; he had not counted on such a possibility, and it was with a heavy heart that he marked how strong they were, and how they towered in the air above him. As he dismounted to lead his horse nearer—for the animal looked with terrified eyes upon the huge bars through which the wind was humming and vibrating—something fell from the saddle. It was the witch’s shoe. He picked it up and ran to the Gates, striking the lock and saying:

“Left-foot shoe, left-foot shoe,

Open, Gates, and I’ll go through.”

They burst open, and he turned to re-mount his horse. But the creature stood with planted fore-feet and quivering nostrils, and he saw that there was no time in which to urge him forward, as the Gates were closing again. He tore the cormorant’s wings from where they hung on the saddle, together with his few provisions and a water-flask, and was just in time to rush through them before they swung together with a crash that rang through the air like thunder, and sent the frightened horse tearing over the plain. Then he stood unhorsed and alone on the confines of the desert.

His only chance now lay in making use of the cormorant’s wings, which he had hitherto omitted to do, preferring to travel on horseback. But he fastened them to his shoulders by the power of the magic shoe and toiled on, directed by the Golden Heart, going straight forward until his provisions were nearly done. One morning he reached a green oasis on which rose a fountain, bubbling in a grove of feathery acacia trees, and, as he lay resting in the shade, he saw two birds sitting among the boughs and talking together. Remembering the feathers in his cap, he wished to be invisible and to understand their language.

“Look at that cool water,” said one. “When we have arranged our wings and tails a little after our flight, we will go down and drink. We shall not get a chance again till we reach the stream flowing through the marsh land for which we are bound.”

“Very well,” replied the other, “and, after that, we will start at once, for I am anxious to get home. I have not seen my family for an age, and I think it is really time I put in an appearance. We can be there by nightfall.”

When the Prince heard this he resolved to follow them; and when the two birds had satisfied their thirst and set off on their journey, he spread his wings and sailed with rapid strokes after them.

“What an odd rushing there is in the air beside us,” observed one; “the wind must be going to change.”

By the time it was dark they entered the marsh land and saw a glimmer of the stream for which the Prince was looking. In due time they flew across it, and he alighted on the further bank and dropped his wings while he sat down to rest. His hopes were high as he thought of his lost Princess—lost perhaps no longer—and he anticipated the moment of finding the plant with joy almost amounting to dread. He rose to his feet and wished for the power of seeing in the dark.

He saw that he stood in the midst of so wonderful a piece of scenery that he could hardly believe himself awake. Just in front of him appeared the rock which the Golden Heart had described as being like the entrance to a tomb. It rose upwards out of a deep, dark pool, and a great star which stood in silver radiance over the summit threw a long steel-blue reflection trailing across the silent water. Down the face of the rock, and all round on a tangle of low bushes which closed him in on every side, hung thick wreaths of white convolvulus; strange lights flashed in and out among the heavy foliage, and from the blossoms rolled drops of scented dew like the tears of a weeping enchantress.

The air was faint with enchantment; the Ugly Prince felt a languor creeping over his body. His senses seemed to be fading from him, and, fearing that he might be overcome by the strange atmosphere of the place, he dashed through the bushes towards an open space not far off. There his eyes fell on a tall, solitary plant growing in the very centre of the clearing, and perceiving it to be none other than the object of his search, he threw himself upon the ground beside it, took the Golden Heart from his bosom and pressed it to his lips, covering it with passionate kisses.

His journey was done, his troubles ended; he had now only to wait till the plant had grown as high as his knee to bathe his face in the juice of the berries and all would be well. He would go back across the desert, through the Great Gates and over the world to his Princess’s kingdom, a changed man, with his happiness lying before him. He pictured the joy of the King, the delight of the faithful little boy who awaited him, and the clinging arms of his adored Princess, as he lay hour after hour beside the green stem and watched it grow taller and saw the berries begin to take shape and colour. At last, it had grown almost to the height of his knee, and, as he sat waiting in the breaking daylight for the moment when he should pluck his treasure, the Prince heard footsteps behind him, and, springing to his feet, beheld a tattered figure which started on seeing him, and then, with a long cry, fell prostrate upon the earth.

In a moment he was beside it and raising in his arms a man still young, but so bowed and emaciated by illness and trouble, that he seemed scarcely able to stand.

“Leave me! leave me!” he cried, as the Ugly Prince held him in the grasp of his strong arms. “What brings you here? Have you, too, come for the plant—the magic plant?”

“I have,” said the Prince firmly.

The unhappy man dropped his hands. “Then I am too late,” he cried, “and I must die—for what can I do against you?” And he glanced from his own trembling form to the straight, strong limbs of the Ugly Prince.

And he bowed his head and wept till the Prince’s heart bled to hear him.

“I beseech you, stop your tears,” he said kindly, “and tell me what has brought you here?”

As he spoke these words his breath almost stopped, for he foresaw, dawning on the very horizon of his mind, the vague outlines of a possible sacrifice, so great, so overwhelming, that he hardly dared to put it into thoughts, and yet—it was there.

“I have come,” said the stranger, “from a long, long distance and crossed the desert on foot. See my feet, how they are bruised. My journey has taken two years (for I am a poor man and must travel as best I may) and, at times, I have hardly hoped to live to the end; for I am suffering from a slow, fatal disease. I have tried every cure in vain, and have been told by a learned magician to seek out this plant as a last hope of life. I have a wife whose whole heart is bound up in mine, and little children. Their hopes have been centred in me through these sad years since I left them to begin my journey. I shall never see them again, and they will go on, day by day, hoping for my return. But that will never be now. That is my history. And you, why are you here? What is yours?”

For answer, the Prince drew off his mask. “That is mine,” he said.

His companion recoiled from him, shuddering.

The two men remained gazing dumbly upon each other; then the Ugly Prince broke the silence.

“We are in the most horrible position,” he said, “that two miserable men have ever been placed in. Look,” and he pointed to the now fully-developed plant, “in a few minutes one of us will have his hopes fulfilled, and one of us will be in despair. Let us suppose for a moment that I am that unhappy man and that you, in your good fortune, will grant me a favour. Let me have a little space in which to think it all over. Give me your word to hold your hand from plucking the berries while I try to face this trial and make up my mind to what is coming. Should I take the golden chance that lies here for one of us, a few moments of respite will do you no injury; and, should you profit by it, your happiness will be none the less sweet for having granted the prayer of a man into whose life no joy can ever shine again. Will you do this?”

The man looked at him narrowly. “I am in your power,” he said, “for you are the stronger.”

“Let that go for nothing,” answered the Prince, waving his hand impatiently. “I shall leave you alone. I want your word that you will do nothing till I come back.”

“I promise it,” replied the stranger.

And the Ugly Prince went, leaving the black mask lying at his feet.

He entered a grove of trees which stood near, and flung his arms round the stem of a tall ash, pressing his unmasked face against the bark; dreadful thoughts assailed him on every side. He had only to go back and drive his sword into that powerless body and the happiness which had seemed so real a short time ago would still be his. None could see the deed or tell of it. His mind was as though filled with evil mists, and, above them, rose the alluring form of his Princess, golden-haired, white-armed, beckoning. But he thrust her from him. No, such a thing could not be. Better to die a thousand times than to sink into such dishonour as that.

And if he relinquished his chance? If he were to give up to that suffering mortal the thing that he had striven and toiled for during the two years through which he had dragged his poor aching limbs to this spot, what then? Whose happiness would he destroy by so doing? Not the Princess’s, certainly. She had given him up of her free will, had shrunk from the sight of him and the thought of becoming his wife. The King, her father, would sorrow indeed, but he would still have his daughter. The little boy would welcome him back should he return as he had left him. No, it would be his loss alone.

He thought of that evening in the Palace garden, his last evening of happiness. He saw it all again, the golden sky, the roses, the far-stretching landscape, and he felt again the soft hand of his love clinging to his arm as they talked together. He groaned, and, as he thought of these things, some words came back to his memory, words he had remembered on that last happy evening, words which had once been spoken by the Princess when she threw him the Golden Heart. “If you take it, it will bring you pain and sorrow, perhaps more than you can bear. Can you really accept it? Are you willing to take the trouble that must come?” He had not realised them then. Once more they had returned to his mind when she asked him to release her, and he had then imagined that he understood them. He understood them now.

And his rival? Perhaps he adored that wife as he himself had adored, and did adore, his lost love. And the wife, to whom his own success would mean a life-long grief? He tried to put himself in the unhappy man’s place. He tried to suppose that the Princess was waiting for him, that she was sitting watching as this woman watched. What should he feel if another and a stronger hand were to grasp the prize upon which all their hopes of meeting depended? And the little children?

A great lump rose in his throat and a hand seemed to clutch at his heartstrings; he looked up at the early mist rolling away from stream and plain, and a load of black temptation lifted heavily from his bursting heart. The stranger stood waiting a little way off; he approached him and laid a hand on his shoulder.

“Go!” he said, pointing to the plant. “It is yours. Take it. I give up my claim freely.”

A few minutes more and he was lying on the earth near the still pool he had seen the night before, his cheek resting on the cool moss, trying to realise and accept the loveless life which was all he had now left. Every hope was gone and the future lay before him like the vast, sterile desert he had lately crossed, bare and bleak. There was nothing to live for now, nothing. The fact rushed over him in its full meaning, and for the first time since his boyhood he burst into tears and sobbed like a little child.

After a while he remembered the mask which lay on the grass where he had left it. There was nothing for him to do but resume it and go back to the world with his old trouble unchanged; but, before rising, he went to bathe his heated eyes in the water and he leaned over the brink. Just as he put in his hand he saw that another face was looking up at him It startled him. Was it some poor, drowned man who lay staring up at the sky? Impossible, surely. None knew of this place but himself and that one stranger, and, moreover, there was no sign of death in those living eyes that met his own so fearlessly. He plunged down his hand and it only touched the bed of the pool; the water lay deep and still but for the ripples which his action had stirred into widening rings. He was simply bewildered. Still gazing downwards he drew his hand over his eyes, thinking they must be bewitched, and, as he did so, a hand passed over the face in the water. It could not be his own. He laughed bitterly at the idea. It had no resemblance to himself, and was the face of a handsome man, not a monster whose very look was unendurable. Thinking that he must be going mad, he felt the Golden Heart beating and fluttering against his breast. He wondered that he had forgotten it for so long as he took it out.

“Am I crazed?” he asked excitedly. “What is this illusion?”

“It is no illusion,” replied the voice, “but the truth. That face looking from the water is your own. Look once more, for the ripples have ceased.”

The Prince obeyed.

He saw the most noble countenance that it had ever entered his mind to imagine; no defect was there, no feature which was not perfection, and over all was an expression of such sublime grandeur, strength, and fortitude, that the Ugly Prince, ugly no longer, drew back, almost awed by what he saw.

“It is only the reflection of your own great soul,” said the voice—and it seemed to fill the air around him—“what you see is the beauty of honour and truth, of courage and sacrifice, and there is nothing which can be compared to it in the whole world. Now rise, for you must go from here and begin your homeward journey. Go back to reap the reward which is awaiting you, for there is no reward too great for such as you.”

So the Prince went. The cormorant’s wings bore him safely over the desert, and the witch’s shoe opened for him the Great Gates. Once through them, he procured himself a horse, and at last reached the borders of the kingdom where his heart lay; here he proceeded more slowly, only journeying by night, as he wished no one to see him who might tell the Princess of his return.

One morning early the little boy rose and went, as he always did, to a high turret in the palace to look down the road leading to the nearest city, and to see whether his Prince was coming home.

As he sat with the morning breeze lifting his hair, straining his eyes towards the white road which lay between the ripening corn-fields, he saw a solitary horseman approaching, and, in great excitement, he watched him as he advanced. When he was still some way off, the rider put his horse to a gallop, waving his hand, and the child, doubting no longer, rushed at the top of his speed down the turret stair, through the courtyard gate, across the drawbridge, and down the road till he reached the horse’s side and clung, transported with joy, to the stirrup. The Prince stooped and lifted him into the saddle before him.

When the first rapture of greeting was over, the little boy raised his head from his friend’s shoulder.

“Where is your mask?” he inquired.

“It is here, but I do not wear it any more. You see, I am not so ugly now,” said the Prince, smiling.

The little boy hugged him again with delight. “I never saw your face before,” he said, “but I don’t believe you were ever ugly. There is no one in the world like you.”

Then the Prince asked him a thousand questions about the Princess.

“She is not very happy,” replied the child, shaking his head, “for, after you left, she began to miss you and to cry because you had gone, and she has watched for you so long, that she grows paler and sadder every day.”

“Do you think she would love me if I came back with my mask on, as I left her?” asked the Prince.

“Try,” said the little boy.

They rode together through the gate and crossed the courtyard hand in hand, the Prince in his travel-worn clothes with the black mask on his face. Through the wide hall they went, down the corridor, and out into the Princess’s garden. She was standing in the morning sunlight feeding her peacocks, the gorgeous birds crowding round her; the eyes in their sweeping tails flashed blue and green, and their slim necks bent hither and thither as they picked up the grain. They trod as softly as they could, like two conspirators, so that she did not hear their footsteps until they were close behind her. Then she turned, half-startled, and saw the Prince.

For one moment she stood gazing at him with her hands clasped over her heart; then, with a low cry of joy, she sprang forward like some beautiful wild animal and threw herself into his arms.

“And can you really receive me back like this?” he asked a short time later, “when you see that it is the same man who has returned unaltered?”

“Ah, do not remind me of my folly,” she begged, “I can hardly believe that you have come back to me at last; I fear to wake and find it is all a dream.” And she rested her head against his shoulder with a sigh of content.

“But,” persisted he, “could you bear to see me without my mask?”

“I can bear anything,” she replied, “but losing you again.”

Then he took off his mask and threw it on the ground. She glanced up at him and stood transfixed, for never in her whole life had she seen any one who looked as he looked.

She sank on her knees beside him, and covered her face with her hands. “I am not worthy to be your wife,” she faltered, “let me go, for it cannot be.”

But he did not listen to her.

Once upon a time there were two Princesses of Japan who lived with their father in a tall palace. It stood on the banks of a river, and they used to watch from the walls to see the boats plying up and down, and the great cranes standing in the shallows fishing.

They had never in their lives been outside the gardens, except when they were carried in a litter covered with paintings and carvings, and shut in by curtains. They peeped through the chinks as they went along, and Princess Azalea, the elder, used to tell Princess Anemone long stories which she invented about the passers-by. Once, indeed, when the servants had put down the litter for a moment’s rest, Princess Anemone, who was bolder than her sister, though not quite so good at making up stories, had slipped quietly out and gone off for a little exploring expedition of her own; while Princess Azalea sat terrified on the cushions, hiding her face behind her little fan. It seemed an age to her till the truant came back, breathless and rather pink in the face.

“Oh! Sister! Sister! What did you see?” she asked, “and how you have torn your dress! What will Utuka say?”

Utuka was their nurse; she had brought them up since Azalea was born, sixteen years before.

Anemone looked down at her white silk dress, all covered with silver flowers, and at the three-cornered slit which ran right across the front. “Never mind,” she said, “I’ll sew it up before she sees it. I know where she keeps her needles. Azalea, there was a man with a long staff who scowled at me so. I ran back as hard as I could, but O sister! look what I found! The world is a charming place, I know.”

And she held up a great cream and pink peony.

So the two stood, day after day, looking out over the palace wall, two white and gold figures with their hair done up in little knobs on the tops of their heads, and their fans fluttering like butterflies’ wings. The sun poured down on them, and the blue sky stretched above, and the great, unlimited world, which they knew nothing about, lay all round them.

Now, the Princesses’ father was such a popular man that there was only one person on that side of the world so much talked about, and that was the Sorcerer Badoko. The Emperor thought very seldom of the Sorcerer, because he had little time for thinking of anything but how to be kind to his neighbours; but Badoko could hardly sleep in his bed at night for thinking of the Emperor. He tossed about in his lonely cave, saying under his breath that, come what might, he would make himself the more celebrated of the two. He said it under his breath, so that his two sons, who were lying close by, should not hear him. He did not like his two sons very much.

He could not at all make out why the Princesses’ father was more admired than himself, for even Sorcerers are stupid sometimes—generally because they think themselves so clever. The real reason was because the old man was so kind, but the Sorcerer did not know that. He was clever enough to see that the Emperor was more thought of than himself, but he wasn’t clever enough to know why. At last he made up his mind that it must be because he was richer, and, having come to that conclusion, he determined to steal away the two Princesses. Then he would go to the palace and demand a great ransom—in fact, half the Emperor’s money—and he felt sure that it would be paid.

The Emperor’s garden was full of beautiful trees. In one corner a fountain played, and, near this, a flight of steps ran up to a summer-house on the wall in which the Princesses sat nearly every day and looked down on the world below.

As they were sitting there one afternoon they saw an old man passing by. It was the same person who had scowled at Anemone when she ran away from the litter, and she pointed him out to her sister. He glanced up at the two girls. Under his arm he carried a kind of guitar; Azalea looked at it with interest, for, besides making up stories, she could sing and play very prettily to a little instrument she had, which was rather like this one.

The Sorcerer—for it was he—made an extremely low bow.

“Shall I sing you a song, my ladies?” he asked.

Anemone felt bolder than ever, for was not the wall between them? “Yes, please,” she said.

Then the Sorcerer began to sing; and his voice was like liquid gold. It made one think of all the most beautiful things in the world: of the dawn in the sky, of great birds with white wings, of rushing waters, of prancing horses and waving plumes, of the deep velvet sky with its armies of stars.

“Oh, how lovely! How wonderful!” cried the Princesses. “Oh, sir! where did you learn those songs?”

The Sorcerer smiled. “It is this little guitar,” he said, holding it up. “It is bewitched. One has only to strike the strings and the song comes out of it. Your ladyships think, no doubt, that it is I who sing, but I have only to open my mouth and the guitar does all the rest.”

Now this was a lie, for the Sorcerer’s two sons made all the songs; they were very clever young men.

“Sing one more; please sing one more!” cried the Princesses.

“Very well,” replied he, “one more, but that must be the last. Here is one which I hope you will like. It is called ‘The Peach Trees in the Valley.’ ”

“What a charming name,” said Anemone, who was fond of flowers.

And the Sorcerer sang:—

“My Love sits high in a golden chair,

And my Love looks softly down;

With a golden pin she pins her hair,

But it shines like a golden crown.

And oh, my Love! look down to me

With a smile in your almond eyes,

For the blue doves nest in the willow tree

And the Spring rides up the skies;

Come down, O Love, in the morning glow,

For the day mounts high though the hours run slow,

And I’ll show you where the lilies grow,

And the peach trees blow in the valley!

“But my Love looks down from her chair of gold

With a smile in her cruel eyes;

Her face is fair but her heart is cold

As the stars in the winter skies.

Give me the pin that pins your hair

And stabs like a poisoned blade,

Look once, O Love without compare,

At the wound the point has made;

And come when the morning hours run slow

To see the place where I lie low,

Where the blue doves nest, and the lilies grow,

And the peach trees blow in the valley!”

The girls were charmed, and, as for Azalea, she was so much excited she was almost in tears.

“If your ladyships like my guitar so much why do you not buy it?” said Badoko. “I am very poor, and I am taking it into the city to sell.”

Azalea wrung her hands; she had never been in such a predicament before. “But we have no money,” she exclaimed.

It had never entered the Princesses’ minds to think of money. Everything they wanted was always there ready for them, and it had never in their lives occurred to them to ask how it came.

The Sorcerer laughed rather slyly. “But surely his Imperial Majesty will not grudge you the money,” said he.

“Run, Anemone, run, and ask our father!” cried Azalea.

“It would be better for you to look at the guitar before buying it,” remarked the Sorcerer.

Anemone was practical, and this idea struck her as being very wise. “Wait,” she said to her sister, “we will go down to the gate and see it.”

And the two ran down the stairs with a great rustling of silks and clacking of little heels.

When they got out of the door the Sorcerer made another low bow, and held out the musical instrument. Azalea took it eagerly in her hand, and at the same time Badoko made a whistling sound. Two men sprang from behind a bush and threw heavy cloaks over the sisters, winding them so tightly over their mouths that they could not scream, though they tried to with all their might. The wicked Sorcerer laughed aloud, and ordered his men to carry the Princesses down to the river.

The garden opened on a lonely piece of waste ground, so they met no one on the way, reaching the shore and embarking under the shade of a thick tree in a long flat boat. Soon they had pushed off and were floating down the stream, Azalea and Anemone lying covered up under some grass matting, and Badoko steering while his men rowed. Behind them, the city was losing itself in the distance.

When the Princesses were allowed to come out of their hiding-place they found themselves in a wide country; the river wound on through stretches of sand; barren mountains, like great blue stone-heaps, covered the desert. They wept very piteously as they sat huddled together. Before them, Badoko’s grim image sat stiffly against the sky, and behind them, the bare country into which they were going spread for miles and miles; all round was sand and the dry reeds rustled as they passed. They held each other’s hands, and sobbed softly for fear he should hear. They would have liked to ask him if he was going to kill them, but they were much too frightened. Besides this, they were very uncomfortable, and they had left their little fans behind. It was all very dreadful. Just before sunset they stopped by the bare stump of a tree which was sticking up among the rushes; on it sat a black raven looking very wise and cawing loudly. He looked at the matting which covered the girls, and pointed at the Sorcerer with his claw.

“What have you got there?” he asked.

“Mind your own business,” said Badoko, throwing a great stone at him.

He flew away, flapping his wings angrily, but he turned his head round as he went and saw Azalea and Anemone getting out upon the bank. The Sorcerer was offering them some horrible black bread and some dried peas, for he did not want them to die of hunger. If they did, he would lose all the money he hoped to get from their father.

But they were not hungry, and only shuddered as they sat close together on the sand.

“If you don’t want any food,” said Badoko, “don’t sit there whining and wasting my time.” And he dragged them into the boat again.

The raven spread his wings and flew far away up the river, and when he had gone nearly a hundred miles, he saw the Emperor’s palace underneath him. He lit upon the roof and began to caw and squall at the top of his voice, and to dance in such a way that everybody below crowded to look at him. The Emperor, who was inside, put out his head to see what all the laughter meant. The tears had been running down his face as he thought of his two little girls who had disappeared so strangely, and his nose was quite red, poor old gentleman, but he rubbed his face on his silk handkerchief and went down to the courtyard, followed by his Prime Minister. All the servants were collected and were staring up at the raven.

“What is all this about?” inquired the Prime Minister, as he strutted after his master.

“Sir, it is a raven which is dancing on the roof in a very diverting manner,” said a bystander.

The Prime Minister was accustomed to be the principal person in any crowd, and he was not best pleased at finding himself scarcely regarded; nobody was regarding the Emperor either, but he did not think of that. He put on his spectacles and looked up.

“How very unsuitable!” he exclaimed, turning his back. “Really, what we are all coming to I don’t know!”

The bird danced still more extravagantly, and even the Emperor began to smile.

“Come down from there immediately!” shouted the Prime Minister; “I wonder you are not ashamed of making such an exhibition of yourself.”

“All right,” said the bird; and he flew down, alighting at his Majesty’s feet, making so polished an obeisance that all were astonished.

The Emperor was much gratified. “What can I do for you?” he inquired.

“I have important news,” replied the bird, “and I would ask to communicate it.”

“Impudent scoundrel!” exclaimed the Prime Minister, “your right place would be in the cooking-pot if you were not so nasty.”

“It would certainly be fitter for me than for you,” observed the raven, “seeing that you are old and tough and that I am young and tender.”

“Your Majesty must not think of giving the audience unattended,” said the Prime Minister; “this disreputable creature may have some design upon your royal life. Someone should be present.”

“Anyone, so long as it is not yourself,” replied the raven.

And with that, he hopped into the palace in front of the Emperor, who was too much agitated to notice the breach of etiquette. The Prime Minister hurried after, hoping to get in also, but he was too late, for the guard who stood at the door shut it behind his Majesty according to custom. The Emperor seated himself and the bird stood respectfully before him.

“Is it anything about my poor little daughters that you have come to tell me?” he asked, looking very pitifully into the raven’s face.

“Your Majesty is right,” was the reply. “I myself saw them, not twenty-four hours ago, but in great distress. The Sorcerer Badoko has stolen them away.”

“Where has he taken them to? Where? Where?” cried the Emperor.

“They were rowing down the river in the direction of Badoko’s country. I have put myself to great inconvenience to bring this news to your Majesty; and it is lucky that that pig of a Prime Minister did not dissuade you from listening to me. Why such a mud-headed gander should be allowed near your sacred person, I don’t know.”

“He means well, he means well,” said the Emperor.

“He means to put me in a pot if he can get me,” replied the raven. “I only hope and trust he may not catch me until I have restored the young ladies to their illustrious parent.”

At this moment there was a loud knocking at the door.

“Who is there?” cried the Emperor.

“May it please your Imperial Majesty,” said the guard outside, “the Prime Minister says it is cold in the palace and that you have forgotten your Imperial Majesty’s muffler, and he will bring it in himself.”

“What does he say?” asked the monarch, who was rather deaf.

The raven repeated the message.

“Thanks, thanks; tell him I am very comfortable,” said the Emperor.

The raven hopped to the door.

“Tell him,” he bawled, “that his Majesty says he is to mind his own business and keep his bald head away from the key-hole.”

When the Emperor heard what the bird had got to say he determined to set out with a great force for Badoko’s country.

When the expedition was ready, they started, travelling in great force. The procession was several miles long, and, in the centre of it, immediately behind his Majesty, the raven was carried on a silver perch which was made in the form of a bower. Over his head swung a scarlet canopy, like an umbrella, which protected him from the rays of the sun, and under which he languished with all the airs of royalty. This he did because the Prime Minister’s litter was close behind, and because he knew that its occupant could see him. The slaves who carried him hated him, for his voice was never silent and he poured abuse upon them from dawn till dusk.

And now we must ask what had been happening all this time to the two Princesses. When the raven had flown away from the spot where he had seen them, they were hurried into the boat again, and continued their way till they reached the place where Badoko lived. It was a sandy desert with great rocks in which there were caves. To these caves, which were high up, staircases were cut in the stone, and the Sorcerer’s servant sat in the entrance of one, boiling a cauldron from which the steam went up in a column. They disembarked, and Badoko marched them up one of the flights of steps. “Here,” said he, “is the cave you are to live in. If you want anything to eat you can ask for something out of the cauldron.”

Azalea and Anemone were very hungry, so they begged a little food and went into their cave, glad to be away from his terrible eye. After some time they heard Badoko giving orders down below.

“Now,” he cried to his servant, “I am going on a journey. You are to take care that the Princesses do not escape, for if I come back and find them gone, I will put everybody to death for miles round!”

The servant fell at his feet and promised he would do all he was told, and Badoko, calling together the men who had rowed his boat, mounted a white donkey with pink eyes and rode away at their head across the sand.

When night came, Azalea and Anemone lay down, but they could not rest; and, as it was bright moonlight, they sat at the top of their staircase, looking out over the shining ground.

It was not long before they saw two figures ride up and dismount below. They did not know what new enemies these might be, so they crept softly back into the cave and tried to sleep.

The Sorcerer’s two sons—for the riders were none other—were named Tiger and Gold-Eagle, for Badoko had thought these names lucky. They had come a long distance and were very tired, and as, when at home, they inhabited a cave next to the one in which the Princesses lay, they went in and threw themselves down on the piles of skins which served them for beds. In the middle of the night Tiger woke his companion.

“Brother,” he said, “what is that strange noise?”

Gold-Eagle sat up; he was very cross at being awakened from his first sleep. “If you annoy me again,” he said, throwing a handful of sand at Tiger, “I will get out of bed and beat you.”

As he spoke the noise grew more distinct.

“There’s someone crying close by,” said Tiger; “I shall go in and see what it means.”

Gold-Eagle was quite as inquisitive as his brother, so he rose, in spite of his bad humour, and followed. What was their astonishment at seeing two girls lying weeping on the floor. Azalea and Anemone fell at their feet. The Sorcerer’s sons knew very well that these must be some prisoners of their father’s, and as they disapproved of his wickedness, they were horrified at seeing the distress in which the poor little things were plunged. They soon heard their history, for, when the Princesses saw how kindly they looked at them, they were only too glad to have someone to talk to, and they implored Tiger and Gold-Eagle to protect them.

The two brothers were so much charmed that they immediately fell head-over-ears in love, and it was fortunate that Tiger preferred Azalea and Gold-Eagle Anemone, or there might have been a fight. They promised to help them to escape from Badoko and to take them back to their father, for, though they would be dreadfully sorry to part with them, they could not bear to think of them in the power of the wicked Sorcerer. Next day they went to the servant who was left in charge of the captives and asked where Badoko had gone.

“Young sirs,” said he, “his Honour has gone to consult the illustrious Dragon about the ransom which he will ask for the Princesses.”

Now the Sorcerer had a friend, a very rich Dragon who lived on an island some way off, and it was to visit him that he had set out on the pink-eyed donkey. The brothers knew that he could not get back for several days, and they told Azalea and Anemone that they would start as soon as their horses should be rested.

It was night when they left; the sky was clear and the steam from the servants’ cauldron rose in the moonlight. When he saw what the brothers were doing he remonstrated loudly, but nobody listened, so he could only promise to tell Badoko which way they had gone the moment he returned.