Title: Fearful Rock

Author: Manly Wade Wellman

Illustrator: H. S. De Lay

Release date: July 11, 2024 [eBook #74018]

Language: English

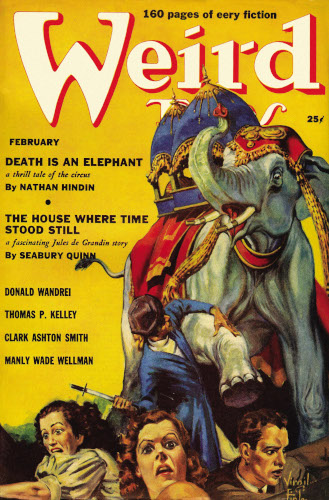

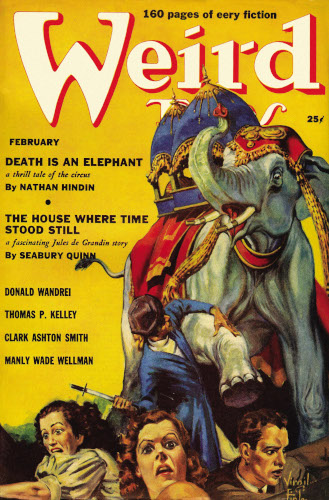

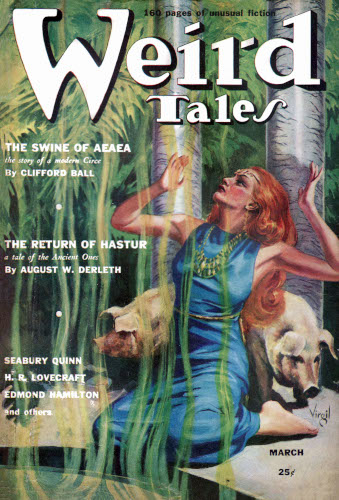

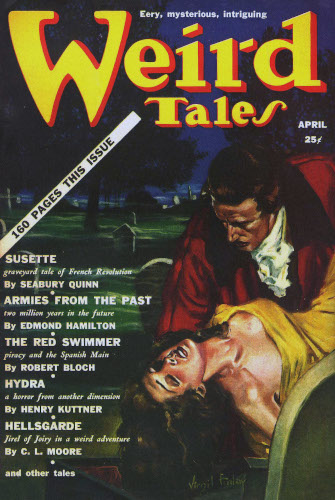

Original publication: New York, NY: Weird Tales, 1939

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/74018

Credits: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By MANLY WADE WELLMAN

An eery tale of the American Civil War, and the uncanny evil being who called himself Persil Mandifer, and his lovely daughter—a tale of dark powers and weird happenings.

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Weird Tales February, March, April 1939.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

1. The Sacrifice

Enid Mandifer tried to stand up under what she had just heard. She managed it, but her ears rang, her eyes misted. She felt as if she were drowning.

The voice of Persil Mandifer came through the fog, level and slow, with the hint of that foreign accent which nobody could identify:

"Now that you know that you are not really my daughter, perhaps you are curious as to why I adopted you."

Curious ... was that the word to use? But this man who was not her father after all, he delighted in understatements. Enid's eyes had grown clearer now. She was able to move, to obey Persil Mandifer's invitation to seat herself. She saw him, half sprawling in his rocking-chair against the plastered wall of the parlor, under the painting of his ancient friend Aaron Burr. Was the rumor true, she mused, that Burr had not really died, that he still lived and planned ambitiously to make himself a throne in America? But Aaron Burr would have to be an old, old man—a hundred years old, or more than a hundred.

Persil Mandifer's own age might have been anything, but probably he was nearer seventy than fifty. Physically he was the narrowest of men, in shoulders, hips, temples and legs alike, so that he appeared distorted and compressed. White hair, like combed thistledown, fitted itself in ordered streaks to his high skull. His eyes, dull and dark as musket-balls, peered expressionlessly above the nose like a stiletto, the chin like the pointed toe of a fancy boot. The fleshlessness of his legs was accentuated by tight trousers, strapped under the insteps. At his throat sprouted a frill of lace, after a fashion twenty-five years old.

At his left, on a stool, crouched his enormous son Larue. Larue's body was a collection of soft-looking globes and bladders—a tremendous belly, round-kneed short legs, puffy hands, a gross bald head between fat shoulders. His white linen suit was only a shade paler than his skin, and his loose, faded-pink lips moved incessantly. Once Enid had heard him talking to himself, had been close enough to distinguish the words. Over and over he had said: "I'll kill you. I'll kill you. I'll kill you."

These two men had reared her from babyhood, here in this low, spacious manor of brick and timber in the Ozark country. Sixteen or eighteen years ago there had been Indians hereabouts, but they were gone, and the few settlers were on remote farms. The Mandifers dwelt alone with their slaves, who were unusually solemn and taciturn for Negroes.

Persil Mandifer was continuing: "I have brought you up as a gentleman would bring up his real daughter—for the sole and simple end of making her a good wife. That explains, my dear, the governess, the finishing-school at St. Louis, the books, the journeys we have undertaken to New Orleans and elsewhere. I regret that this distressing war between the states," and he paused to draw from his pocket his enameled snuff-box, "should have made recent junkets impracticable. However, the time has come, and you are not to be despised. Your marriage is now to befall you."

"Marriage," mumbled Larue, in a voice that Enid was barely able to hear. His fingers interlaced, like fat white worms in a jumble. His eyes were for Enid, his ears for his father.

Enid saw that she must respond. She did so: "You have—chosen a husband for me?"

Persil Mandifer's lips crawled into a smile, very wide on his narrow blade of a face, and he took a pinch of snuff. "Your husband, my dear, was chosen before ever you came into this world," he replied. The smile grew broader, but Enid did not think it cheerful. "Does your mirror do you justice?" he teased her. "Enid, my foster-daughter, does it tell you truly that you are a beauty, with a face all lustrous and oval, eyes full of tender fire, a cascade of golden-brown curls to frame the whole?" His gaze wandered upon her body, and his eyelids drooped. "Does it convince you, Enid, that your figure combines rarely those traits of fragility and rondure that are never so desirable as when they occur together? Ah, Enid, had I myself met you, or one like you, thirty years ago——"

"Father!" growled Larue, as though at sacrilege. Persil Mandifer chuckled. His left hand, white and slender with a dark cameo upon the forefinger, extended and patted Larue's repellent bald pate, in superior affection.

"Never fear, son," crooned Persil Mandifer. "Enid shall go a pure bride to him who waits her." His other hand crept into the breast of his coat and drew forth something on a chain. It looked like a crucifix.

"Tell me," pleaded the girl, "tell me, fa——" She broke off, for she could not call him father. "What is the name of the one I am to marry?"

"His name?" said Larue, as though aghast at her ignorance.

"His name?" repeated the lean man in the rocking-chair. The crucifix-like object in his hands began to swing idly and rhythmically, while he paid out chain to make its pendulum motion wider and slower. "He has no name."

Enid felt her lips grow cold and dry. "He has no——"

"He is the Nameless One," said Persil Mandifer, and she could discern the capital letters in the last two words he spoke.

"Look," said Larue, out of the corner of his weak mouth that was nearest his father. "She thinks that she is getting ready to run."

"She will not run," assured Persil Mandifer. "She will sit and listen, and watch what I have here in my hand." The object on the chain seemed to be growing in size and clarity of outline. Enid felt that it might not be a crucifix, after all.

"The Nameless One is also ageless," continued Persil Mandifer. "My dear, I dislike telling you all about him, and it is not really necessary. All you need know is that we—my fathers and I—have served him here, and in Europe, since the days when France was Gaul. Yes, and before that."

The swinging object really was increasing in her sight. And the basic cross was no cross, but a three-armed thing like a capital T. Nor was the body-like figure spiked to it; it seemed to twine and clamber upon that T-shape, like a monkey on a bracket. Like a monkey, it was grotesque, disproportionate, a mockery. That climbing creature was made of gold, or of something gilded over. The T-shaped support was as black and bright as jet.

"The swinging object was increasing in her sight."

Enid thought that the golden creature was dull, as if tarnished, and that it appeared to move; an effect created, perhaps, by the rhythmic swinging on the chain.

"Our profits from the association have been great," Persil Mandifer droned. "Yet we have given greatly. Four times in each hundred years must a bride be offered."

Mist was gathering once more, in Enid's eyes and brain, a thicker mist than the one that had come from the shock of hearing that she was an adopted orphan. Yet through it all she saw the swinging device, the monkey-like climber upon the T. And through it all she heard Mandifer's voice:

"When my real daughter, the last female of my race, went to the Nameless One, I wondered where our next bride would come from. And so, twenty years ago, I took you from a foundling asylum at Nashville."

It was becoming plausible to her now. There was a power to be worshipped, to be feared, to be fed with young women. She must go—no, this sort of belief was wrong. It had no element of decency in it, it was only beaten into her by the spell of the pendulum-swinging charm. Yet she had heard certain directions, orders as to what to do.

"You will act in the manner I have described, and say the things I have repeated, tonight at sundown," Mandifer informed her, as though from a great distance. "You will surrender yourself to the Nameless One, as it was ordained when first you came into my possession."

"No," she tried to say, but her lips would not even stir. Something had crept into her, a will not her own, which was forcing her to accept defeat. She knew she must go—where?

"To Fearful Rock," said the voice of Mandifer, as though he had heard and answered the question she had not spoken. "Go there, to that house where once my father lived and worshipped, that house which, upon the occasion of his rather mysterious death, I left. It is now our place of devotion and sacrifice. Go there, Enid, tonight at sundown, in the manner I have prescribed...."

2. The Cavalry Patrol

Lieutenant Kane Lanark was one of those strange and vicious heritage-anomalies of one of the most paradoxical of wars—a war where a great Virginian was high in Northern command, and a great Pennsylvanian stubbornly defended one of the South's principal strongholds; where the two presidents were both born in Kentucky, indeed within scant miles of each other; where father strove against son, and brother against brother, even more frequently and tragically than in all the jangly verses and fustian dramas of the day.

Lanark's birthplace was a Maryland farm, moderately prosperous. His education had been completed at the Virginia Military Institute, where he was one of a very few who were inspired by a quiet, bearded professor of mathematics who later became the Stonewall of the Confederacy, perhaps the continent's greatest tactician. The older Lanark was strongly for state's rights and mildly for slavery, though he possessed no Negro chattels. Kane, the younger of two sons, had carried those same attitudes with him as much as seven miles past the Kansas border, whither he had gone in 1861 to look for employment and adventure.

At that lonely point he met with Southern guerrillas, certain loose-shirted, weapon-laden gentry whose leader, a gaunt young man with large, worried eyes, bore the craggy name of Quantrill and was to be called by a later historian the bloodiest man in American history. Young Kane Lanark, surrounded by sudden leveled guns, protested his sympathy with the South by birth, education and personal preference. Quantrill replied, rather sententiously, that while this might be true, Lanark's horse and money-belt had a Yankee look to them, and would be taken as prisoners of war.

After the guerrillas had galloped away, with a derisive laugh hanging in the air behind them, Lanark trudged back to the border and a little settlement, where he begged a ride by freight wagon to St. Joseph, Missouri. There he enlisted with a Union cavalry regiment just then in the forming, and his starkness of manner, with evidences about him of military education and good sense, caused his fellow recruits to elect him a sergeant.

Late that year, Lanark rode with a patrol through southern Missouri, where fortune brought him and his comrades face to face with Quantrill's guerrillas, the same that had plundered Lanark. The lieutenant in charge of the Federal cavalry set a most hysterical example for flight, and died of six Southern bullets placed accurately between his shoulder blades; but Lanark, as ranking non-commissioned officer, rallied the others, succeeded in withdrawing them in order before the superior force. As he rode last of the retreat, he had the fierce pleasure of engaging and sabering an over-zealous guerrilla, who had caught up with him. The patrol rejoined its regiment with only two lost, the colonel was pleased to voice congratulations and Sergeant Lanark became Lieutenant Lanark, vice the slain officer.

In April of 1862, General Curtis, recently the victor in the desperately fought battle of Pea Ridge, showed trust and understanding when he gave Lieutenant Lanark a scouting party of twenty picked riders, with orders to seek yet another encounter with the marauding Quantrill. Few Union officers wanted anything to do with Quantrill, but Lanark, remembering his harsh treatment at those avaricious hands, yearned to kill the guerrilla chieftain with his own proper sword. On the afternoon of April fifth, beneath a sun bright but none too warm, the scouting patrol rode down a trail at the bottom of a great, trough-like valley just south of the Missouri-Arkansas border. Two pairs of men, those with the surest-footed mounts, acted as flanking parties high on the opposite slopes, and a watchful corporal by the name of Googan walked his horse well in advance of the main body. The others rode two and two, with Lanark at the head and Sergeant Jager, heavy-set and morosely keen of eye, at the rear.

A photograph survives of Lieutenant Kane Lanark as he appeared that very spring—his breadth of shoulder and slimness of waist accentuated by the snug blue cavalry jacket that terminated at his sword-belt, his ruddy, beak-nosed face shaded by a wide black hat with a gold cord. He wore a mustache, trim but not gay, and his long chin alone of all his command went smooth-shaven. To these details be it added that he rode his bay gelding easily, with a light, sure hand on the reins, and that he had the air of one who knew his present business.

The valley opened at length upon a wide level platter of land among high, pine-tufted hills. The flat expanse was no more than half timbered, though clever enemies might advance unseen across it if they exercised caution and foresight enough to slip from one belt or clump of trees to the next. Almost at the center of the level, a good five miles from where Lanark now halted his command stood a single great chimney or finger of rock, its lean tip more than twice the height of the tallest tree within view.

To this geologic curiosity the eyes of Lieutenant Lanark snapped at once.

"Sergeant!" he called, and Jager sidled his horse close.

"We'll head for that rock, and stop there," Lanark announced. "It's a natural watch-tower, and from the top of it we can see everything, even better than we could if we rode clear across flat ground to those hills. And if Quantrill is west of us, which I'm sure he is, I'd like to see him coming a long way off, so as to know whether to fight or run."

"I agree with you, sir," said Jager. He peered through narrow, puffy lids at the pinnacle, and gnawed his shaggy lower lip. "I shall lift up mine eyes unto the rocks, from whence cometh my help," he misquoted reverently. The sergeant was full of garbled Scripture, and the men called him "Bible" Jager behind that wide back of his. This did not mean that he was soft, dreamy or easily fooled; Curtis had chosen him as sagely as he had chosen Lanark.

Staying in the open as much as possible, the party advanced upon the rock. They found it standing above a soft, grassy hollow, which in turn ran eastward from the base of the rock to a considerable ravine, dark and full of timber. As they spread out to the approach, they found something else; a house stood in the hollow, shadowed by the great pinnacle.

"It looks deserted, sir," volunteered Jager, at Lanark's bridle-elbow. "No sign of life."

"Perhaps," said Lanark. "Deploy the men, and we'll close in from all sides. Then you, with one man, enter the back door. I'll take another and enter the front."

"Good, sir." The sergeant kneed his horse into a faster walk, passing from one to another of the three corporals with muttered orders. Within sixty seconds the patrol closed upon the house like a twenty-fingered hand. Lanark saw that the building had once been pretentious—two stories, stoutly made of good lumber that must have been carted from a distance, with shuttered windows and a high peaked roof. Now it was a paint-starved gray, with deep veins and traceries of dirty black upon its clapboards. He dismounted before the piazza with its four pillar-like posts, and threw his reins to a trooper.

"Suggs!" he called, and obediently his own personal orderly, a plump blond youth, dropped out of the saddle. Together they walked up on the resounding planks of the piazza. Lanark, his ungloved right hand swinging free beside his holster, knocked at the heavy front door with his left fist. There was no answer. He tried the knob, and after a moment of shoving, the hinges creaked and the door went open.

They walked into a dark front hall, then into a parlor with dust upon the rug and the fine furniture, and rectangles of pallor upon the walls where pictures had once hung for years. They could hear echoes of their every movement, as anyone will hear in a house to which he is not accustomed. Beyond the parlor, they came to an ornate chandelier with crystal pendants, and at the rear stood a sideboard of dark, hard wood. Its drawers all hung half open, as if the silver and linen had been hastily removed. Above it hung plate-racks, also empty.

Feet sounded in a room to the rear, and then Jager's voice, asking if his lieutenant were inside. Lanark met him in the kitchen, conferred; then together they mounted the stairs in the front hall.

Several musty bedrooms, darkened by closed shutters, occupied the second floor. The beds had dirty mattresses, but no sheets or blankets.

"All clear in the house," pronounced Lanark. "Jager, go and detail a squad to reconnoiter in that little ravine east of here—we want no rebel sharpshooters sneaking up on us from that point. Then leave a picket there, put a man on top of the rock, and guards at the front and rear of this house. And have some of the others police up the house itself. We may stay here for two days, even longer."

The sergeant saluted, then went to bellow his orders, and troopers dashed hither and thither to obey. In a moment the sound of sweeping arose from the parlor. Lanark, to whom it suggested spring cleaning, sneezed at thought of the dust, then gave Suggs directions about the care of his bay. Unbuckling his saber, he hung it upon the saddle, but his revolver he retained. "You're in charge, Jager," he called, and sauntered away toward the wooded cleft.

His legs needed the exercise; he could feel them straightening by degrees after their long clamping to his saddle-flaps. He was uncomfortably dusty, too, and there must be water at the bottom of the ravine. Walking into the shade of the trees, he heard, or fancied he heard, a trickling sound. The slope was steep here, and he walked fast to maintain an easy balance upon it, for a minute and then two. There was water ahead, all right, for it gleamed through the leafage. And something else gleamed, something pink.

That pinkness was certainly flesh. His right hand dropped quickly to his revolver-butt, and he moved forward carefully. Stooping, he took advantage of the bushy cover, at the same time avoiding a touch that might snap or rustle the foliage. He could hear a voice now, soft and rhythmic. Lanark frowned. A woman's voice? His right hand still at his weapon, his left caught and carefully drew down a spray of willow. He gazed into an open space beyond.

It was a woman, all right, within twenty yards of him. She stood ankle-deep in a swift, narrow rush of brook-water, and her fine body was nude, every graceful curve of it, with a cascade of golden-brown hair falling and floating about her shoulders. She seemed to be praying, but her eyes were not lifted. They stared at a hand-mirror, that she held up to catch the last flash of the setting sun.

3. The Image in the Cellar

Lanark, a young, serious-minded bachelor in an era when women swaddled themselves inches deep in fabric, had never seen such a sight before; and to his credit be it said that his first and strongest emotion was proper embarrassment for the girl in the stream. He had a momentary impulse to slip back and away. Then he remembered that he had ordered a patrol to explore this place; it would be here within moments.

Therefore he stepped into the open, wondering at the time, as well as later, if he did well.

"Miss," he said gently. "Miss, you'd better put on your things. My men——"

She stared, squeaked in fear, dropped the mirror and stood motionless. Then she seemed to gather herself for flight. Lanark realized that the trees beyond her were thick and might hide enemies, that she was probably a resident of this rebel-inclined region and might be a decoy for such as himself. He whipped out his revolver, holding it at the ready but not pointing it.

"Don't run," he warned her sharply. "Are those your clothes beside you? Put them on at once."

She caught up a dress of flowered calico and fairly flung it on over her head. His embarrassment subsided a little, and he came another pace or two into the open. She was pushing her feet—very small feet they were—into heelless shoes. Her hands quickly gathered up some underthings and wadded them into a bundle. She gazed at him apprehensively, questioningly. Her hastily-donned dress remained unfastened at the throat, and he could see the panicky stir of her heart in her half-bared bosom.

"I'm sorry," he went on, "but I think you'd better come up to the house with me."

"House?" she repeated fearfully, and her dark, wide eyes turned to look beyond him. Plainly she knew which house he meant. "You—live there?"

"I'm staying there at this time."

"You—came for me?" Apparently she had expected someone to come.

But instead of answering, he put a question of his own. "To whom were you talking just now? I could hear you."

"I—I said the words. The words my faith——" She broke off, wretchedly, and Lanark was forced to think how pretty she was in her confusion. "The words that Persil Mandifer told me to say." Her eyes on his, she continued softly: "I came to meet the Nameless One. Are you the—Nameless One?"

"Are you the Nameless One?"

"I am certainly not nameless," he replied. "I am Lieutenant Lanark, of the Federal Army of the Frontier, at your service." He bowed slightly, which made it more formal. "Now, come along with me."

He took her by the wrist, which shook in his big left hand. Together they went back eastward through the ravine, in the direction of the house.

Before they reached it, she told him her name, and that the big natural pillar was called Fearful Rock. She also assured him that she knew nothing of Quantrill and his guerrillas; and a fourth item of news shook Lanark to his spurred heels, the first non-military matter that had impressed him in more than a year.

An hour later, Lanark and Jager finished an interview with her in the parlor. They called Suggs, who conducted the young woman up to one of the bedrooms. Then lieutenant and sergeant faced each other. The light was dim, but each saw bafflement and uneasiness in the face of the other.

"Well?" challenged Lanark.

Jager produced a clasp-knife, opened it, and pared thoughtfully at a thumbnail. "I'll take my oath," he ventured, "that this Miss Enid Mandifer is telling the gospel truth."

"Truth!" exploded Lanark scornfully. "Mountain-folk ignorance, I call it. Nobody believes in those devil-things these days."

"Oh, yes, somebody does," said Jager, mildly but definitely. "I do." He put away his knife and fumbled within his blue army shirt. "Look here, Lieutenant."

It was a small book he held out, little more than a pamphlet in size and thickness. On its cover of gray paper appeared the smudged woodcut of an owl against a full moon, and the title:

John George Hohman's

POW-WOWS

or

LONG LOST FRIEND

"I got it when I was a young lad in Pennsylvania," explained Jager, almost reverently. "Lots of Pennsylvania people carry this book, as I do." He opened the little volume, and read from the back of the title page:

"'Whosoever carries this book with him is safe from all his enemies, visible or invisible; and whoever has this book with him cannot die without the holy corpse of Jesus Christ, nor drown in any water nor burn up in any fire, nor can any unjust sentence be passed upon him.'"

Lanark put out his hand for the book, and Jager surrendered it, somewhat hesitantly. "I've heard of supposed witches in Pennsylvania," said the officer. "Hexes, I believe they're called. Is this a witch book?"

"No, sir. Nothing about black magic. See the cross on that page? It's a protection against witches."

"I thought that only Catholics used the cross," said Lanark.

"No. Not only Catholics."

"Hmm." Lanark passed the thing back. "Superstition, I call it. Nevertheless, you speak this much truth: that girl is in earnest, she believes what she told us. Her father, or stepfather, or whoever he is, sent her up here on some ridiculous errand—perhaps a dangerous one." He paused. "Or I may be misjudging her. It may be a clever scheme, Jager—a scheme to get a spy in among us."

The sergeant's big bearded head wagged negation. "No, sir. If she was telling a lie, it'd be a more believable one, wouldn't it?" He opened his talisman book again. "If the lieutenant please, there's a charm in here, against being shot or stabbed. It might be a good thing, seeing there's a war going on—perhaps the lieutenant would like me to copy it out?"

"No, thanks." Lanark drew forth his own charm against evil and nervousness, a leather case that contained cheroots. Jager, who had convictions against the use of tobacco, turned away disapprovingly as his superior bit off the end of a fragrant brown cylinder and kindled a match.

"Let me look at that what-do-you-call-it book again," he requested, and for a second time Jager passed the little volume over, then saluted and retired.

Darkness was gathering early, what with the position of the house in the grassy hollow, and the pinnacle of Fearful Rock standing between it and the sinking sun to westward. Lanark called for Suggs to bring a candle, and, when the orderly obeyed, directed him to take some kind of supper upstairs to Enid Mandifer. Left alone, the young officer seated himself in a newly dusted armchair of massive dark wood, emitted a cloud of blue tobacco smoke, and opened the Long Lost Friend.

It had no publication date, but John George Hohman, the author, dated his preface from Berks County, Pennsylvania, on July 31, 1819. In the secondary preface filled with testimonials as to the success of Hohman's miraculous cures, was included the pious ejaculation: "The Lord bless the beginning and the end of this little work, and be with us, that we may not misuse it, and thus commit a heavy sin!"

"Amen to that!" said Lanark to himself, quite soberly. Despite his assured remarks to Jager, he was somewhat repelled and nervous because of the things Enid Mandifer had told him.

Was there, then, potentiality for such supernatural evil in this enlightened Nineteenth Century, even in the pages of the book he held? He read further, and came upon a charm to be recited against violence and danger, perhaps the very one Jager had offered to copy for him. It began rather sonorously: "The peace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with me. Oh shot, stand still! In the name of the mighty prophets Agtion and Elias, and do not kill me...."

Lanark remembered the name of Elias from his boyhood Sunday schooling, but Agtion's identity, as a prophet or otherwise, escaped him. He resolved to ask Jager; and, as though the thought had acted as a summons, Jager came almost running into the room.

"Lieutenant, sir! Lieutenant!" he said hoarsely.

"Yes, Sergeant Jager?" Lanark rose, stared questioningly, and held out the book. Jager took it automatically, and as automatically stowed it inside his shirt.

"I can prove, sir, that there's a real devil here," he mouthed unsteadily.

"What?" demanded Lanark. "Do you realize what you're saying, man? Explain yourself."

"Come, sir," Jager almost pleaded, and led the way into the kitchen. "It's down in the cellar."

From a little heap on a table he picked up a candle, and then opened a door full of darkness.

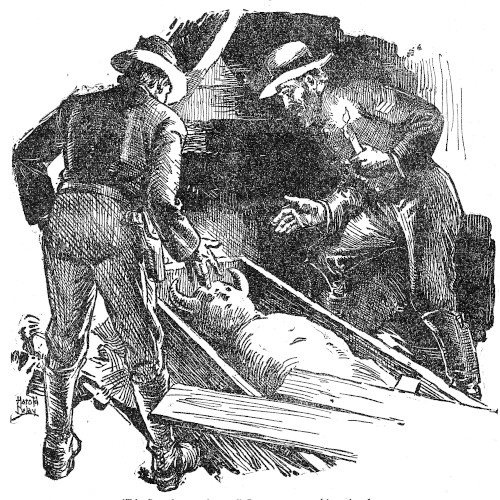

The stairs to the cellar were shaky to Lanark's feet, and beneath him was solid black shadow, smelling strongly of damp earth. Jager, stamping heavily ahead, looked back and upward. That broad, bearded face, that had not lost its full-blooded flush in the hottest fighting at Pea Ridge, had grown so pallid as almost to give off sickly light. Lanark began to wonder if all this theatrical approach would not make the promised devil seem ridiculous, anti-climactic—the flutter of an owl, the scamper of a rat, or something of that sort.

"You have the candle, sergeant," he reminded, and the echo of his voice momentarily startled him. "Strike a match, will you?"

"Yes, sir." Jager had raised a knee to tighten his stripe-sided trousers. A snapping scrape, a burst of flame, and the candle glow illuminated them both. It revealed, too, the cellar, walled with stones but floored with clay. As they finished the descent, Lanark could feel the soft grittiness of that clay under his bootsoles. All around them lay rubbish—boxes, casks, stacks of broken pots and dishes, bundles of kindling.

"Here," Jager was saying, "here is what I found."

He walked around the foot of the stairs. Beneath the slope of the flight lay a long, narrow case, made of plain, heavy boards. It was unpainted and appeared ancient. As Jager lowered the light in his hand, Lanark saw that the joinings were secured with huge nails, apparently forged by hand. Such nails had been used in building the older sheds on his father's Maryland estate. Now there was a creak of wooden protest as Jager pried up the loosened lid of the coffin-like box.

Inside lay something long and ruddy. Lanark saw a head and shoulders, and started violently. Jager spoke again:

"An image, sir. A heathen image." The light made grotesque the sergeant's face, one heavy half fully illumined, the other secret and lost in the black shadow. "Look at it."

Lanark, too, stooped for a closer examination. The form was of human length, or rather more; but it was not finished, was neither divided into legs below nor extended into arms at the roughly shaped shoulders. The head, too, had been molded without features, though from either side, where the ears should have been it sprouted up-curved horns like a bison's. Lanark felt a chill creep upon him, whence he knew not.

"It's Satan's own image," Jager was mouthing deeply. "'Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image——'"

"It's Satan's own image," Jager was mouthing deeply.

With one foot he turned the coffin-box upon its side. Lanark took a quick stride backward, just in time to prevent the ruddy form from dropping out upon his toes. A moment later, Jager had spurned the thing. It broke, with a crashing sound like crockery, and two more trampling kicks of the sergeant's heavy boots smashed it to bits.

"Stop!" cried Lanark, too late. "Why did you break it? I wanted to have a good look at the thing."

"But it is not good for men to look upon the devil's works," responded Jager, almost pontifically.

"Don't advise me, sergeant," said Lanark bleakly. "Remember that I am your officer, and that I don't need instruction as to what I may look at." He looked down at the fragments. "Hmm, the thing was hollow, and quite brittle. It seems to have been stuffed with straw—no, excelsior. Wood shavings, anyway." He investigated the fluffy inner mass with a toe. "Hullo, there's something inside of the stuff."

"I wouldn't touch it, sir," warned Jager, but this time it was he who spoke too late. Lanark's boot-toe had nudged the object into plain sight, and Lanark had put down his gauntleted left hand and picked it up.

"What is this?" he asked himself aloud. "Looks rather like some sort of strong-box—foreign, I'd say, and quite cold. Come on, Jager, we'll go upstairs."

In the kitchen, with a strong light from several candles, they examined the find quite closely. It was a dark oblong, like a small dispatch-case or, as Lanark had commented, a strong-box. Though as hard as iron, it was not iron, nor any metal either of them had ever known.

"How does it open?" was Lanark's next question, turning the case over in his hands. "It doesn't seem to have hinges on it. Is this the lid—or this?"

"I couldn't say." Jager peered, his eyes growing narrow with perplexity. "No hinges, as the lieutenant just said."

"None visible, nor yet a lock." Lanark thumped the box experimentally, and proved it hollow. Then he lifted it close to his ear and shook it. There was a faint rustle, as of papers loosely rolled or folded. "Perhaps," the officer went on, "this separate slice isn't a lid at all. There may be a spring to press, or something that slides back and lets another plate come loose."

But Suggs was entering from the front of the house. "Lieutenant, sir! Something's happened to Newton—he was watching on the rock. Will the lieutenant come? And Sergeant Jager, too."

The suggestion of duty brought back the color and self-control that Jager had lost. "What's happened to Newton?" he demanded at once, and hurried away with Suggs.

Lanark waited in the kitchen for only a moment. He wanted to leave the box, but did not want his troopers meddling with it. He spied, beside the heavy iron stove, a fireplace, and in its side the metal door to an old brick oven. He pulled that door open, thrust the box in, closed the door again, and followed Suggs and Jager.

They had gone out upon the front porch. There, with Corporal Gray and a blank-faced trooper on guard, lay the silent form of Newton, its face covered with a newspaper.

Almost every man of the gathered patrol knew a corpse when he saw one, and it took no second glance to know that Newton was quite dead.

4. The Mandifers

Jager, bending, lifted the newspaper and then dropped it back. He said something that, for all his religiosity, might have been an oath.

"What's the matter, sergeant?" demanded Lanark.

Jager's brows were clamped in a tense frown, and his beard was actually trembling. "His face, sir. It's terrible."

"A wound?" asked Lanark, and lifted the paper in turn. He, too, let it fall back, and his exclamation of horror and amazement was unquestionably profane.

"There ain't no wound on him, Lieutenant Lanark," offered Suggs, pushing his wan, plump face to the forefront of the troopers. "We heard Newton yell—heard him from the top of the rock yonder."

All eyes turned gingerly toward the promontory.

"That's right, sir," added Corporal Gray. "I'd just sent Newton up, to relieve Josserand."

"You heard him yell," prompted Lanark. "Go on, what happened?"

"I hailed him back," said the corporal, "but he said nothing. So I climbed up—that north side's the easiest to climb. Newton was standing at the top, standing straight up with his carbine at the ready. He must have been dead right then."

"You mean, he was struck somehow as you watched?"

Gray shook his head. "No, sir. I think he was dead as he stood up. He didn't move or speak, and when I touched him he sort of coiled down—like an empty coat falling off a clothes-line." Gray's hand made a downward-floating gesture in illustration. "When I turned him over I saw his face, all twisted and scared-looking, like—like what the lieutenant has seen. And I sung out for Suggs and McSween to come up and help me bring him down."

Lanark gazed at Newton's body. "He was looking which way?"

"Over yonder, eastward." Gray pointed unsteadily. "Like it might have been beyond the draw and them trees in it."

Lanark and Jager peered into the waning light, that was now dusk. Jager mumbled what Lanark had already been thinking—that Newton had died without wounds, at or near the moment when the horned image had been shattered upon the cellar floor.

Lanark nodded, and dismissed several vague but disturbing inspirations. "You say he died standing up, Gray. Was he leaning on his gun?"

"No, sir. He stood on his two feet, and held his carbine at the ready. Sounds impossible, a dead man standing up like that, but that's how it was."

"Bring his blanket and cover him up," said Lanark. "Put a guard over him, and we'll bury him tomorrow. Don't let any of the men look at his face. We've got to give him some kind of funeral." He turned to Jager. "Have you a prayer-book, sergeant?"

Jager had fished out the Long Lost Friend volume. He was reading something aloud, as though it were a prayer: "... and be and remain with us on the water and upon the land," he pattered out. "May the Eternal Godhead also——"

"Stop that heathen nonsense," Lanark almost roared. "You're supposed to be an example to the men, sergeant. Put that book away."

Jager obeyed, his big face reproachful. "It was a spell against evil spirits," he explained, and for a moment Lanark wished that he had waited for the end. He shrugged and issued further orders.

"I want all the lamps lighted in the house, and perhaps a fire out here in the yard," he told the men. "We'll keep guard both here and in that gulley to the east. If there is a mystery, we'll solve it."

"Pardon me, sir," volunteered a well-bred voice, in which one felt rather than heard the tiny touch of foreign accent. "I can solve the mystery for you, though you may not thank me."

Two men had come into view, were drawing up beside the little knot of troopers. How had they approached? Through the patroled brush of the ravine? Around the corner of the house? Nobody had seen them coming, and Lanark, at least, started violently. He glowered at this new enigma.

The man who had spoken paused at the foot of the porch steps, so that lamplight shone upon him through the open front door. He was skeleton-gaunt, in face and body, and even his bones were small. His eyes burned forth from deep pits in his narrow, high skull, and his clothing was that of a dandy of the forties. In his twig-like fingers he clasped bunches of herbs.

His companion stood to one side in the shadow, and could be seen only as a huge coarse lump of a man.

"I am Persil Mandifer," the thin creature introduced himself. "I came here to gather from the gardens," and he held out his handfuls of leaves and stalks. "You, sir, you are in command of these soldiers, are you not? Then know that you are trespassing."

"The expediencies of war," replied Lanark easily, for he had seen Suggs and Corporal Gray bring their carbines forward in their hands. "You'll have to forgive our intrusion."

A scornful mouth opened in the emaciated face, and a soft, superior chuckle made itself heard. "Oh, but this is not my estate. I am allowed here, yes—but it is not mine. The real Master——" The gaunt figure shrugged, and the voice paused for a moment. The bright eyes sought Newton's body. "From what I see and what I heard as I came up to you, there has been trouble. You have transgressed somehow, and have begun to suffer."

"To you Southerners, all Union soldiers are trespassers and transgressors," suggested Lanark, but the other laughed and shook his fleshless white head.

"You misunderstand, I fear. I care nothing about this war, except that I am amused to see so many people killed. I bear no part in it. Of course, when I came to pluck herbs, and saw your sentry at the top of Fearful Rock——" Persil Mandifer eyed again the corpse of Newton. "There he lies, eh? It was my privilege and power to project a vision up to him in his loneliness that, I think, put an end to his part of this puerile strife."

Lanark's own face grew hard. "Mr. Mandifer," he said bleakly, "you seem to be enjoying a quiet laugh at our expense. But I should point out that we greatly outnumber you, and are armed. I'm greatly tempted to place you under arrest."

"Then resist that temptation," advised Mandifer urbanely. "It might be disastrous to you if we became enemies."

"Then be kind enough to explain what you're talking about," commanded Lanark. Something swam into the forefront of his consciousness. "You say that your name is Mandifer. We found a girl named Enid Mandifer in the gulley yonder. She told us a very strange story. Are you her stepfather? The one who mesmerized her and——"

"She talked to you?" Mandifer's soft voice suddenly shifted to a windy roar that broke Lanark's questioning abruptly in two. "She came, and did not make the sacrifice of herself? She shall expiate, sir, and you with her!"

Lanark had had enough of this high-handed civilian's airs. He made a motion with his left hand to Corporal Gray, whose carbine-barrel glinted in the light from the house as it leveled itself at Mandifer's skull-head.

"You're under arrest," Lanark informed the two men.

The bigger one growled, the first sound he had made. He threw his enormous body forward in a sudden leaping stride, his gross hands extended as though to clutch Lanark. Jager, at the lieutenant's side, quickly drew his revolver and fired from the hip. The enormous body fell, rolled over and subsided.

"You have killed my son!" shrieked Mandifer.

"Take hold of him, you two," ordered Lanark, and Suggs and Josserand obeyed.

The gaunt form of Mandifer achieved one explosive struggle, then fell tautly motionless with the big hands of the troopers upon his elbows.

"Thanks, Jager," continued Lanark. "That was done quickly and well. Some of you drag this body up on the porch and cover it. Gray, tumble upstairs and bring down that girl we found."

While waiting for the corporal to return, Lanark ordered further that a bonfire be built to banish a patch of the deepening darkness. It was beginning to shoot up its bright tongues as the corporal ushered Enid Mandifer out upon the porch.

She had arranged her disordered clothing, had even contrived to put up her hair somehow, loosely but attractively. The firelight brought out a certain strength of line and angle in her face, and made her eyes shine darkly. She was manifestly frightened at the sight of her stepfather and the blanket-covered corpses to one side; but she faced determinedly a flood of half-understandable invectives from the emaciated man. She answered him, too; Lanark did not know what she meant by most of the things she said, but gathered correctly that she was refusing, finally and completely, to do something.

"Then I shall say no more," gritted out the spidery Mandifer, and his bared teeth were of the flat, chalky white of long-dead bone. "I place this matter in the hands of the Nameless One. He will not forgive, will not forget."

Enid moved a step toward Lanark, who put out a hand and touched her arm reassuringly. The mounting flame of the bonfire lighted up all who watched and listened—the withered, glaring mummy that was Persil Mandifer, the frightened but defiant shapeliness of Enid in her flower-patterned gown, Lanark in his sudden attitude of protection, the ring of troopers in their dusty blue blouses. With the half-lighted front of the weathered old house like a stage set behind them, and alternate red lights and sooty shadows playing over all, they might have been a tableau in some highly melodramatic opera.

"Silence," Lanark was grating. "For the last time, Mr. Mandifer, let me remind you that I have placed you under arrest. If you don't calm down immediately and speak only when you're spoken to, I'll have my men tie you flat to four stakes and put a gag in your mouth."

Mandifer subsided at once, just as he was on the point of hurling another harsh threat at Enid.

"That's much better," said Lanark. "Sergeant Jager, it strikes me that we'd better get our pickets out to guard this position."

Mandifer cleared his throat with actual diffidence. "Lieutenant Lanark—that is your name, I gather," he said in the soft voice which he had employed when he had first appeared. "Permit me, sir, to say but two words." He peered as though to be sure of consent. "I have it in my mind that it is too late, useless, to place any kind of guard against surprise."

"What do you mean?" asked Lanark.

"It is all of a piece with your offending of him who owns this house and the land which encompasses it," continued Mandifer. "I believe that a body of your enemies, mounted men of the Southern forces, are upon you. That man who died upon the brow of Fearful Rock might have seen them coming, but he was brought down sightless and voiceless, and nobody was assigned in his place."

He spoke truth. Gray, in his agitation, had not posted a fresh sentry. Lanark drew his lips tight beneath his mustache.

"Once more you feel that it is a time to joke with us, Mr. Mandifer," he growled. "I have already suggested gagging you and staking you out."

"But listen," Mandifer urged him.

Suddenly hoofs thundered, men yelled a double-noted defiance, high and savage—"Yee-hee!"

It was the rebel yell.

Quantrill's guerrillas rode out of the dark and upon them.

5. Blood in the Night

Neither Lanark nor the others remembered that they began to fight for their lives; they only knew all at once that they were doing it. There was a prolonged harsh rattle of gun-shots like a blast of hail upon hard wood; Lanark, by chance or unconscious choice, snatched at and drew his sword instead of his revolver.

A horse's flying shoulder struck him, throwing him backward but not down. As he reeled to save his footing, he saved also his own life; for the rider, a form all cascading black beard and slouch hat, thrust a pistol almost into the lieutenant's face and fired. The flash was blinding, the ball ripped Lanark's cheek like a whiplash, and then the saber in his hand swung, like a scythe reaping wheat. By luck rather than design, the edge bit the guerrilla's gun-wrist. Lanark saw the hand fly away as though on wings, its fingers still clutching the pistol, all agleam in the firelight. Blood gushed from the stump of the rider's right arm, like water from a fountain, and Lanark felt upon himself a spatter as of hot rain. He threw himself in, clutched the man's legs with his free arm and, as the body sagged heavily from above upon his head and shoulder, he heaved it clear out of the saddle.

The horse was plunging and whinnying, but Lanark clutched its reins and got his foot into the stirrup. The bonfire seemed to be growing strangely brighter, and the mounted guerrillas were plainly discernible, raging and trampling among his disorganized men. Corporal Gray went down, dying almost under Lanark's feet. Amid the deafening drum-roll of shots, Sergeant Jager's bull-like voice could be heard: "Stop, thieves and horsemen, in the name of God!" It sounded like an exorcism, as though the Confederate raiders were devils.

Lanark had managed to climb into the saddle of his captured mount. He dropped the bridle upon his pommel, reached across his belly with his left hand, and dragged free his revolver. At a little distance, beyond the tossing heads of several horses, he thought he saw the visage of Quantrill, clean-shaven and fierce. He fired at it, but he had no faith in his own left-handed snap-shooting. He felt the horse frantic and unguided, shoving and striving against another horse. Quarters were too close for a saber-stroke, and he fired again with his revolver. The guerrilla spun out of the saddle. Lanark had a glimpse he would never forget, of great bulging eyes and a sharp-pointed mustache.

Again the rebel yell, flying from mouth to bearded mouth, and then an answering shout, deeper and more sustained; some troopers had run out of the house and, standing on the porch, were firing with their carbines. It was growing lighter, with a blue light. Lanark did not understand that.

Quantrill did not understand it, either. He and Lanark had come almost within striking distance of each other, but the guerrilla chief was gazing past his enemy, in the direction of the house. His mouth was open, with strain-lines around it. His eyes glowed. He feared what he saw.

"Remember me, you thieving swine!" yelled Lanark, and tried to thrust with his saber. But Quantrill had reined back and away, not from the sword but from the light that was growing stronger and bluer. He thundered an order, something that Lanark could not catch but which the guerrillas understood and obeyed. Then Quantrill was fleeing. Some guerrillas dashed between him and Lanark. They, too, were in flight. All the guerrillas were in flight. Somebody roared in triumph and fired with a carbine—it sounded like Sergeant Jager. The battle was over, within moments of its beginning.

Lanark managed to catch his reins, in the tips of the fingers that held his revolver, and brought the horse to a standstill before it followed Quantrill's men into the dark. One of his own party caught and held the bits, and Lanark dismounted. At last he had time to look at the house.

It was afire, every wall and sill and timber of it, burning all at once, and completely. And it burnt deep blue, as though seen through the glass of an old-fashioned bitters-bottle. It was falling to pieces with the consuming heat, and they had to draw back from it. Lanark stared around to reckon his losses.

Nearest the piazza lay three bodies, trampled and broken-looking. Some men ran in and dragged them out of danger; they were Persil Mandifer, badly battered by horses' feet, and the two who had held him, Josserand and Lanark's orderly, Suggs. Both the troopers had been shot through the head, probably at the first volley from the guerrillas.

Corporal Gray was stone-dead, with five or six bullets in him, and three more troopers had been killed, while four were wounded, but not critically. Jager, examining them, pronounced that they could all ride if the lieutenant wished it.

"I wish it, all right," said Lanark ruefully. "We leave first thing in the morning. Hmm, six dead and four hurt, not counting poor Newton, who's there in the fire. Half my command—and, the way I forgot the first principles of military vigilance, I don't deserve as much luck as that. I think the burning house is what frightened the guerrillas. What began it?"

Nobody knew. They had all been fighting too desperately to have any idea. The three men who had been picketing the gulley, and who had dashed back to assault the guerrillas on the flank, had seen the blue flames burst out, as it were from a hundred places; that was the best view anybody had.

"All the killing wasn't done by Quantrill," Jager comforted his lieutenant. "Five dead guerrillas, sir—no, six. One was picked up a little way off, where he'd been dragged by his foot in the stirrup. Others got wounded, I'll be bound. Pretty even thing, all in all."

"And we still have one prisoner," supplemented Corporal Googan.

He jerked his head toward Enid Mandifer, who stood unhurt, unruffled almost, gazing raptly at the great geyser of blue flame that had been the house and temple of her stepfather's nameless deity.

It was a gray morning, and from the first streaks of it Sergeant Jager had kept the unwounded troopers busy, making a trench-like grave halfway between the spot where the house had stood and the gulley to the east. When the bodies were counted again, there were only twelve; Persil Mandifer's was missing, and the only explanation was that it had been caught somehow in the flames. The ruins of the house, that still smoked with a choking vapor as of sulfur gas, gave up a few crisped bones that apparently had been Newton, the sentry who had died from unknown causes; but no giant skeleton was found to remind one of the passing of Persil Mandifer's son.

"No matter," said Lanark to Jager. "We know that they were both dead, and past our worrying about. Put the other bodies in—our men at this end, the guerrillas at the other."

The order was carried out. Once again Lanark asked about a prayer-book. A lad by the name of Duckin said that he had owned one, but that it had been burned with the rest of his kit in the blue flame that destroyed the house.

"Then I'll have to do it from memory," decided Lanark.

He drew up the surviving ten men at the side of the trench. Jager took a position beside him, and, just behind the sergeant, Enid Mandifer stood.

Lanark self-consciously turned over his clutter of thoughts, searching for odds and ends of his youthful religious teachings. "'Man that is born of woman hath but short time to live, and is full of misery'," he managed to repeat. "'He cometh up, and is cut down, like a flower'." As he said the words "cut down," he remembered his saber-stroke of the night before, and how he had shorn away a man's hand. That man, with his heavy black beard, lay in this trench before them, with the severed hand under him. Lanark was barely able to beat down a shudder. "'In the midst of life'," he went on, "'we are in death'."

There he was obliged to pause. Sergeant Jager, on inspiration, took one pace forward and threw into the trench a handful of gritty earth.

"'Ashes to ashes, dust to dust'," remembered Lanark. "'Unto Almighty God we commit these bodies'"—he was sure that that was a misquotation worthy of Jager himself, and made shift to finish with one more tag from his memory: "'... in sure and certain hope of the Resurrection unto eternal life'."

He faced toward the file of men. Four of them had been told to fall in under arms, and at his order they raised their carbines and fired a volley into the air. After that, the trench was filled in.

Jager then cleared his throat and began to give orders concerning horses, saddles and what possessions had been spared by the fire. Lanark walked aside, and found Enid Mandifer keeping pace with him.

"You are going back to your army?" she asked.

"Yes, at once. I was sent here to see if I could find and damage Quantrill's band. I found him, and gave at least as good as I got."

"Thank you," she said, "for everything you've done for me."

He smiled deprecatingly, and it hurt his bullet-burnt cheek.

"I did nothing," he protested, and both of them realized that it was the truth. "All that has happened—it just happened."

He drew his eyes into narrow gashes, as if brooding over the past twelve hours.

"I'm halfway inclined to believe what your stepfather said about a supernatural influence here. But what about you, Miss Mandifer?"

She tried to smile in turn, not very successfully.

"I can go back to my home. I'll be alone there."

"Alone?"

"I have a few servants."

"You'll be safe?"

"As safe as anywhere."

He clasped his hands behind him. "I don't know how to say it, but I have begun to feel responsible for you. I want to know that all will be well."

"Thank you," she said a second time. "You owe me nothing."

"Perhaps not. We do not know each other. We have spoken together only three or four times. Yet you will be in my mind. I want to make a promise."

"Yes?"

They had paused in their little stroll, almost beside the newly filled grave trench. Lanark was frowning, Enid Mandifer nervous and expectant.

"This war," he said weightily, "is going to last much longer than people thought at first. We—the Union—have done pretty well in the West here, but Lee is making fools of our generals back East. We may have to fight for years, and even then we may not win."

"I hope, Mr.—I mean, Lieutenant Lanark," stammered the girl, "I hope that you will live safely through it."

"I hope so, too. And if I am spared, if I am alive and well when peace comes, I swear that I shall return to this place. I shall make sure that you, too, are alive and well."

He finished, very certain that he could not have used stiffer, more stupid words; but Enid Mandifer smiled now, radiantly and gratefully.

"I shall pray for you, Lieutenant Lanark. Now, your men are ready to leave. Go, and I shall watch."

"No," he demurred. "Go yourself, get away from this dreadful place."

She bowed her head in assent, and walked quickly away. At some distance she paused, turned, and waved her hand above her head.

Lanark took off his broad, black hat and waved in answer. Then he faced about, strode smartly back into the yard beside the charred ruins. Mounting his bay gelding, he gave the order to depart.

6. Return

It was spring again, the warm, bright spring of the year 1866, when Kane Lanark rode again into the Fearful Rock country.

His horse was a roan gray this time; the bay gelding had been shot under him, along with two other horses, during the hard-fought three days at Westport, the "Gettysburg of the West," when a few regulars and the Kansas militia turned back General Sterling Price's raid through Missouri. Lanark had been a captain then, and a major thereafter, leading a cavalry expedition into Kentucky. He narrowly missed being in at the finish of Quantrill, whose death by the hand of another he bitterly resented. Early in 1865 he was badly wounded in a skirmish with Confederate horsemen under General Basil Duke. Thereafter he could ride as well as ever, but when he walked he limped.

Lanark's uniform had been replaced by a soft hat and black frock coat, his face was browner and his mustache thicker, and his cheek bore the jaggedly healed scar of the guerrilla pistol-bullet. He was richer, too; the death of his older brother, Captain Douglas Lanark of the Confederate artillery, at Chancellorsville, had left him his father's only heir. Yet he was recognizable as the young lieutenant who had ridden into this district four years gone.

Approaching from the east instead of the north, he came upon the plain with its grass-levels, its clumps of bushes and trees, from another and lower point. Far away on the northward horizon rose a sharp little finger; that would be Fearful Rock, on top of which Trooper Newton had once died, horrified and unwounded. Now, then, which way would lie the house he sought for? He idled his roan along the trail, and encountered at last an aged, ragged Negro on a mule.

"Hello, uncle," Lanark greeted him, and they both reined up. "Which way is the Mandifer place?"

"Mandifuh?" repeated the slow, high voice of the old man. "Mandifuh, suh, cap'n? Ah doan know no Mandifuh."

"Nonsense, uncle," said Lanark, but without sharpness, for he liked Negroes. "The Mandifer family has lived around here for years. Didn't you ever know Mr. Persil Mandifer and his step-daughter, Miss Enid?"

"Puhsil Mandifuh?" It was plain that the old fellow had heard and spoken the name before, else he would have stumbled over its unfamiliarities. "No, suh, cap'n. Ah doan nevah heah tella such gemman."

Lanark gazed past the mule and its tattered rider. "Isn't that a little house among those willows?"

The kinky head turned and peered. "Yes, suh, cap'n. Dat place b'long to Pahson Jaguh."

"Who?" demanded Lanark, almost standing up in his stirrups in his sudden interest. "Did you say Jager? What kind of man is he?"

"He jes a pahson—Yankee pahson," replied the Negro, a trifle nervous at this display of excitement. "Big man, suh, got red face. He Yankee. You ain' no Yankee, cap'n, suh. Whaffo you want Pahson Jaguh?"

"Never mind," said Lanark, and thrust a silver quarter into the withered brown palm. He also handed over one of his long, fragrant cheroots. "Thanks, uncle," he added briskly, then spurred his horse and rode on past.

Reaching the patch of willows, he found that the trees formed an open curve that faced the road, and that within this curve stood a rough but snug-looking cabin, built of sawn, unpainted planks and home-split shingles. Among the brush to the rear stood a smaller shed, apparently a stable, and a pen for chickens or a pig. Lanark reined up in front, swung out of his saddle, and tethered his horse to a thorny shrub at the trail-side. As he drew tight the knot of the halter-rope, the door of heavy boards opened with a creak. His old sergeant stepped into view.

Jager was a few pounds heavier, if anything, than when Lanark had last seen him. His hair was longer, and his beard had grown to the center of his broad chest. He wore blue jeans tucked into worn old cavalry boots, a collarless checked shirt fastened with big brass studs, and leather suspenders. He stared somewhat blankly as Lanark called him by name and walked up to the doorstep, favoring his injured leg.

"It's Captain Lanark, isn't it?" Jager hazarded. "My eyes——" He paused, fished in a hip pocket and produced steel-rimmed spectacles. When he donned them, they appeared to aid his vision. "Indeed it is Captain Lanark! Or Major Lanark—yes, you were promoted——"

"I'm Mr. Lanark now," smiled back the visitor. "The war's over, Jager. Only this minute did I hear of you in the country. How does it happen that you settled in this place?"

"Come in, sir." Jager pushed the door wide open, and ushered Lanark into an unfinished front room, well lighted by windows on three sides. "It's not a strange story," he went on as he brought forward a well-mended wooden chair for the guest, and himself sat on a small keg. "You will remember, sir, that the land hereabouts is under a most unhallowed influence. When the war came to an end, I felt strong upon me the call to another conflict—a crusade against evil." He turned up his eyes, as though to subpoena the powers of heaven as witnesses to his devotion. "I preach here, the gospels and the true godly life."

"What is your denomination?" asked Lanark.

Jager coughed, as though abashed. "To my sorrow, I am ordained of no church; yet might this not be part of heaven's plan? I may be here to lead a strong new movement against hell's legions."

Lanark nodded as though to agree with this surmise, and studied Jager anew. There was nothing left in manner or speech to suggest that here had been a fierce fighter and model soldier, but the old rude power was not gone. Lanark then asked about the community, and learned that there were but seven white families within a twenty-mile radius. To these Jager habitually preached of a Sunday morning, at one farm home or another, and in the afternoon he was wont to exhort the more numerous Negroes.

Lanark had by now the opening for his important question. "What about the Mandifer place? Remember the girl we met, and her stepfather?"

"Enid Mandifer!" breathed Jager huskily, and his right hand fluttered up. Lanark remembered that Jager had once assured him that not only Catholics warded off evil with the sign of the cross.

"Yes, Enid Mandifer." Lanark leaned forward. "Long ago, Jager, I made a promise that I would come and make sure that she prospered. Just now I met an old Negro who swore that he had never heard the name."

Jager began to talk, steadily but with a sort of breathless awe, about what went on in the Fearful Rock country. It was not merely that men died—the death of men was not sufficient to horrify folk around whom a war had raged. But corpses, when found, held grimaces that nobody cared to look upon, and no blood remained in their bodies. Cattle, too, had been slain, mangled dreadfully—perhaps by the strange, unidentifiable creatures that prowled by moonlight and chattered in voices that sounded human. One farmer of the vicinity, who had ridden with Quantrill, had twice met strollers after dusk, and had recognized them for comrades whom he knew to be dead.

"And the center of this devil's business," concluded Jager, "is the farm that belonged to Persil Mandifer." He drew a deep, tired-sounding breath. "As the desert is the habitation of dragons, so is it with that farm. No trees live, and no grass. From a distance, one can see a woman. It is Enid Mandifer."

"Where is the place?" asked Lanark directly.

Jager looked at him for long moments without answering. When he did speak, it was an effort to change the subject. "You will eat here with me at noon," he said. "I have a Negro servant, and he is a good cook."

"I ate a very late breakfast at a farmhouse east of here," Lanark put him off. Then he repeated, "Where is the Mandifer place?"

"Let me speak this once," Jager temporized. "As you have said, we are no longer at war—no longer officer and man. We are equals, and I am able to refuse to guide you."

Lanark got up from his chair. "That is true, but you will not be acting the part of a friend."

"I will tell you the way, on one condition." Jager's eyes and voice pleaded. "Say that you will return to this house for supper and a bed, and that you will be within my door by sundown."

"All right," said Lanark. "I agree. Now, which way does that farm lie?"

Jager led him to the door. He pointed. "This trail joins a road beyond, an old road that is seldom used. Turn north upon it, and you will come to a part which is grown up in weeds. Nobody passes that way. Follow on until you find an old house, built low, with the earth dry and bare around it. That is the dwelling-place of Enid Mandifer."

Lanark found himself biting his lip. He started to step across the threshold, but Jager put a detaining hand on his arm. "Carry this as you go."

He was holding out a little book with a gray paper cover. It had seen usage and trouble since last Lanark had noticed it in Jager's hands; its back was mended with a pasted strip of dark cloth, and its edges were frayed and gnawed-looking, as though rats had been at it. But the front cover still said plainly:

John George Hohman's

POW-WOWS

Or

LONG LOST FRIEND

"Carry this," said Jager again, and then quoted glibly: "'Whoever carries this book with him is safe from all his enemies, visible or invisible; and whoever has this book with him cannot die without the holy corpse of Jesus Christ, nor drown in any water, nor burn up in any fire, nor can any unjust sentence be passed upon him.'"

Lanark grinned in spite of himself and his new concern. "Is this the kind of a protection that a minister of God should offer me?" he inquired, half jokingly.

"I have told you long ago that the Long Lost Friend is a good book, and a blessed one." Jager thrust it into Lanark's right-hand coat pocket. His guest let it remain, and held out his own hand in friendly termination of the visit.

"Good-bye," said Lanark. "I'll come back before sundown, if that will please you."

He limped out to his horse, untied it and mounted. Then, following Jager's instructions, he rode forward until he reached the old road, turned north and proceeded past the point where weeds had covered the unused surface. Before the sun had fallen far in the sky, he was come to his destination.

It was a squat, spacious house, the bricks of its trimming weathered and the dark brown paint of its timbers beginning to crack. Behind it stood unrepaired stables, seemingly empty. In the yard stood what had been wide-branched trees, now leafless and lean as skeleton paws held up to a relentless heaven. And there was no grass. The earth was utterly sterile and hard, as though rain had not fallen since the beginning of time.

Enid Mandifer had been watching him from the open door. When she saw that his eyes had found her, she called him by name.

7. The Rock Again

Then there was silence. Lanark sat his tired roan and gazed at Enid, rather hungrily, but only a segment of his attention was for her. The silence crowded in upon him. His unconscious awareness grew conscious—conscious of that blunt, pure absence of sound. There was no twitter of birds, no hum of insects. Not a breath of wind stirred in the leafless branches of the trees. Not even echoes came from afar. The air was dead, as water is dead in a still, stale pond.

He dismounted then, and the creak of his saddle and the scrape of his boot-sole upon the bald earth came sharp and shocking to his quiet-filled ears. A hitching-rail stood there, old-seeming to be in so new a country as this. Lanark tethered his horse, pausing to touch its nose reassuringly—it, too, felt uneasy in the thick silence. Then he limped up a gravel-faced path and stepped upon a porch that rang to his feet like a great drum.

Enid Mandifer came through the door and closed it behind her. Plainly she did not want him to come inside. She was dressed in brown alpaca, high-necked, long-sleeved, tight above the waist and voluminous below. Otherwise she looked exactly as she had looked when she bade him good-bye beside the ravine, even to the strained, sleepless look that made sorrowful her fine oval face.

"Here I am," said Lanark. "I promised that I'd come, you remember."

She was gazing into his eyes, as though she hoped to discover something there. "You came," she replied, "because you could not rest in another part of the country."

"That's right," he nodded, and smiled, but she did not smile back.

"We are doomed, all of us," she went on, in a low voice. "Mr. Jager—the big man who was one of your soldiers——"

"I know. He lives not far from here."

"Yes. He, too, had to return. And I live—here." She lifted her hands a trifle, in hopeless inclusion of the dreary scene. "I wonder why I do not run away, or why, remaining, I do not go mad. But I do neither."

"Tell me," he urged, and touched her elbow. She let him take her arm and lead her from the porch into the yard that was like a surface of tile. The spring sun comforted them, and he knew that it had been cold, so near to the closed front door of Persil Mandifer's old house.

She moved with him to a little rustic bench under one of the dead trees. Still holding her by the arm, he could feel at the tips of his fingers the shock of her footfalls, as though she trod stiffly. She, in turn, quite evidently was aware of his limp, and felt distress; but, tactfully, she did not inquire about it. When they sat down together, she spoke.

"When I came home that day," she began, "I made a hunt through all of my stepfather's desks and cupboards. I found many papers, but nothing that told me of the things that so shocked us both. I did find money, a small chest filled with French and American gold coins. In the evening I called the slaves together and told them that their master and his son were dead.

"Next morning, when I wakened, I found that every slave had run off, except one old woman. She, nearly a hundred years old and very feeble, told me that fear had come to them in the night, and that they had run like rabbits. With them had gone the horses, and all but one cow."

"They deserted you!" cried Lanark hotly.

"If they truly felt the fear that came here to make its dwelling-place!" Enid Mandifer smiled sadly, as if in forgiveness of the fugitives. "But to resume; the old aunty and I made out here somehow. The war went on, but it seemed far away; and indeed it was far away. We watched the grass die before June, the leaves fall, the beauty of this place vanish."

"I am wondering about that death of grass and leaves," put in Lanark. "You connect it, somehow, with the unholiness at Fearful Rock; yet things grow there."

"Nobody is being punished there," she reminded succinctly. "Well, we had the chickens and the cow, but no crops would grow. If they had, we needed hands to farm them. Last winter aunty died, too. I buried her myself, in the back yard."

"With nobody to help you?"

"I found out that nobody cared or dared to help." Enid said that very slowly, and did not elaborate upon it. "One Negro, who lives down the road a mile, has had some mercy. When I need anything, I carry one of my gold pieces to him. He buys for me, and in a day or so I seek him out and get whatever it is. He keeps the change for his trouble."

Lanark, who had thought it cold upon the porch of the house, now mopped his brow as though it were a day in August. "You must leave here," he said.

"I have no place to go," she replied, "and if I had I would not dare."

"You would not dare?" he echoed uncomprehendingly.

"I must tell you something else. It is that my stepfather and Larue—his son—are still here."

"What do you mean? They were killed," Lanark protested. "I saw them fall. I myself examined their bodies."

"They were killed, yes. But they are here, perhaps within earshot."

It was his turn to gaze searchingly into her eyes. He looked for madness, but he found none. She was apparently sane and truthful.

"I do not see them," she was saying, "or, at most, I see only their sliding shadows in the evening. But I know of them, just around a corner or behind a chair. Have you never known and recognized someone just behind you, before you looked? Sometimes they sneer or smile. Have you," she asked, "ever felt someone smiling at you, even though you could not see him?"

Lanark knew what she meant. "But stop and think," he urged, trying to hearten her, "that nothing has happened to you—nothing too dreadful—although so much was promised when you failed to go through with that ceremony."

She smiled, very thinly. "You think that nothing has happened to me? You do not know the curse of living here, alone and haunted. You do not understand the sense I have of something tightening and thickening about me; tightening and thickening inside of me, too." Her hand touched her breast, and trembled. "I have said that I have not gone mad. That does not mean that I shall never go mad."

"Do not be resigned to any such idea," said Lanark, almost roughly, so earnest was he in trying to win her from the thought.

"Madness may come—in the good time of those who may wish it. My mind will die. And things will feed upon it, as buzzards would feed upon my dead body."

Her thin smile faded away. Lanark felt his throat growing as dry as lime, and cleared it noisily. Silence was still dense around them. He asked her, quite formally, what she found to do.

"My stepfather had many books, most of them old," was her answer. "At night I light one lamp—I must husband my oil—and sit well within its circle of light. Nothing ever comes into that circle. And I read books. Every night I read also a chapter from a Bible that belonged to my old aunty. When I sleep, I hold that Bible against my heart."

He rose nervously, and she rose with him. "Must you go so soon?" she asked, like a courteous hostess.

Lanark bit his mustache. "Enid Mandifer, come out of here with me."

"I can't."

"You can. You shall. My horse will carry both of us."

She shook her head, and the smile was back, sad and tender this time. "Perhaps you cannot understand, and I know that I cannot tell you. But if I stay here, the evil stays here with me. If I go, it will follow and infect the world. Go away alone."

She meant it, and he did not know what to say or do.

"I shall go," he agreed finally, with an air of bafflement, "but I shall be back."

Suddenly he kissed her. Then he turned and limped rapidly away, raging at the feeling of defeat that had him by the back of the neck. Then, as he reached his horse he found himself glad to be leaving the spot, even though Enid Mandifer remained behind, alone. He cursed with a vehemence that made the roan flinch, untied the halter and mounted. Away he rode, to the magnified clatter of hoofs. He looked back, not once but several times. Each time he saw Enid Mandifer, smaller and smaller, standing beside the bench under the naked tree. She was gazing, not along the road after him, but at the spot where he had mounted his horse. It was as though he had vanished from her sight at that point.

Lanark damned himself as one who retreated before an enemy, but he felt that it was not as simple as that. Helplessness, not fear, had routed him. He was leaving Enid Mandifer, but again he promised in his heart to return.

"He was leaving Enid Mandifer, but he promised in his heart to return."

Somewhere along the weed-teemed road, the silence fell from him like a heavy garment slipping away, and the world hummed and sighed again.

After some time he drew rein and fumbled in his saddlebag. He had lied to Jager about his late breakfast, and now he was grown hungry. His fingers touched and drew out two hardtacks—they were plentiful and cheap, so recently was the war finished and the army demobilized—and a bit of raw bacon. He sandwiched the streaky smoked flesh between the big square crackers and ate without dismounting. Often, he considered, he had been content with worse fare. Then his thoughts went to the place he had quitted, the girl he had left there. Finally he skimmed the horizon with his eye.

To north and east he saw the spire of Fearful Rock, like a dark threatening finger lifted against him. The challenge of it was too much to ignore.

He turned his horse off the road and headed in that direction. It was a longer journey than he had thought, perhaps because he had to ride slowly through some dark swamp-ground with a smell of rotten grass about it. When he came near enough, he slanted his course to the east, and so came to the point from which he first approached the rock and the house that had then stood in its shadow.

A crow flapped overhead, cawing lonesomely. Lanark's horse seemed to falter in its stride, as though it had seen a snake on the path, and he had to spur it along toward its destination. He could make out the inequalities of the rock, as clearly as though they had been sketched in with a pen, and the new spring greenery of the brush and trees in the gulley beyond to the westward; but the tumbledown ruins of the house were somehow blurred, as though a gray mist or cloud hung there.

Lanark wished that his old command rode with him, at least that he had coaxed Jager along; but he was close to the spot now, and would go in, however uneasily, for a closer look.

The roan stopped suddenly, and Lanark's spur made it sidle without advancing. He scolded it in an undertone, slid out of the saddle and threaded his left arm through the reins. Pulling the beast along, he limped toward the spot where the house had once stood.

The sun seemed to be going down.

8. The Grapple by the Grave

Lanark stumped for a furlong or more, to the yard of the old house, and the horse followed unwillingly—so unwillingly that had there been a tree or a stump at hand, Lanark would have tethered and left it. When he paused at last, under the lee of the great natural obelisk that was Fearful Rock, the twilight was upon him. Yet he could see pretty plainly the collapsed, blackened ruins of the dwelling that four years gone had burned before his eyes in devil-blue flame.