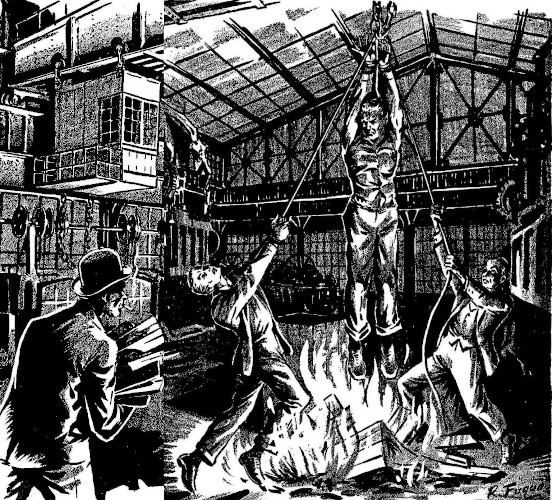

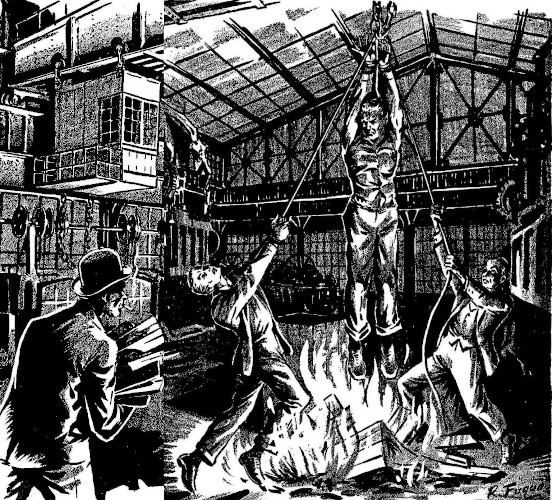

Horsesense Hank was suspended over the blazing debris.

Title: Horsesense Hank does his bit

Author: Nelson S. Bond

Illustrator: Robert Fuqua

Release date: August 10, 2024 [eBook #74226]

Language: English

Original publication: New York, NY: Ziff-Davis Publishing Company, 1942

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/74226

Credits: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By NELSON S. BOND

Pearl Harbor got Horsesense Hank mad.

Something ought to be done about it—and

he was the man who was going to do it!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Amazing Stories May 1942.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Like the rain-drenched angler said as he reeled in a fish, "Life is just one damp thing after another!" I thought I'd fixed everything all hunky-dory around the campus of dear old Midland U. when I finally got my friend "Horsesense Hank" Cleaver engaged to Helen MacDowell. Which just goes to prove that you shouldn't count your chickens until they're hitched. Because That Man stepped in and messed up everything.

You know the guy I mean. The chief germ in Germany. The little ex-housepainter with a scrap of old paintbrush on his upper lip. First he "protected" himself against the poor Austrians. Then the Czechs and the Poles. Then came Norway, Denmark, Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg—it sounds like a geography lesson, doesn't it?—then France, the Balkans, Greece and Crete. And finally, as his armies, having come a cropper against the outraged Russian bear, stalled on the icy steppes of Moscow's doorway, he invoked the aid of his yellow-skinned and -spined allies, the Japs.

While their envoys calmed Washington with soft words of peace, their air-arm bombed Pearl Harbor with grim weapons of war. It was then that Horsesense Hank came to me and said soberly, "Well, so long, Jim. I'll see you later."

I asked, "Where are you going? Down to Mike's for a hamburger? Wait a minute; I'll go with."

"I'm goin' further'n that, Jim," said Hank, "an' the chances are I'll be gone a mite longer. I—" He wriggled a bulldog-tipped shoe into the carpet embarrassedly—"I reckon I'm agonna sign up for the duration."

I gasped. "You mean the army?"

"Well, not eggsackly. I don't figger they'd want me in the fightin' forces, me bein' skinny like I am. But folks say I'm right quick with math'matics an' things like that, so if I c'n be of any help to my country—"

Hank was not exaggerating a bit. Almost everyone on the Midland campus, including sweet little me, had known more formal education than H. Cleaver. Eighty-five per cent of the faculty members dangled alphabets after their names till they looked like government projects, but Hank could give them all a running start and beat them silly on any question requiring the use of good, old-fashioned common sense.

A marveling commentator had awarded Hank the name of "Scientific Pioneer" for his uncanny ability to reach answers to problems intuitively, without knowing or understanding the so-called "natural laws" involved. Hank's aptitude at things mechanical, his infinitely accurate mathematical computations and homely approach to abstract ponderables, had promoted him from a rural turnip patch to the Chair of General Sciences at our (alleged) institute of higher learning.[1]

"It ain't," scowled Hank, "as if I was a hard man to git along with. Gosh knows I'm easy-goin' enough—"

There was no gainsaying that. Hank was as quiet and gentle as a Carnation cow. The fact that he had, despite his humble background, won the favor and affections of bilious old H. Logan MacDowell, president of Midland, proved his power to Win Friends. And the fact that he, handicapped by a rawboned homeliness that would have discouraged any scarecrow, had won the heart and hand of Prexy's daughter Helen, a lass ardently pursued by every male in four counties, proved beyond a doubt his ability to influence people.

"—but they jest ain't no gittin' along," continued Hank, "with that there Hitler guy. The more he gits the more he wants. An' now that him an' his Japanee pals is forced us into it, I'm agonna offer my services to whoever c'n use me."

"And where would that be, Hank?"

"Why, I was thinkin' o' one o' them plants that make war stuff," he said. "They got plenty o' problems, nowadays, tryin' to reorganize f'r defense work, changin' work methods, expandin' their facilities, an' so on. There's that Northern Bridge, Steel and Girder Comp'any, f'r instance—"

"But, Hank," I reminded him, "how about Helen?"

"I reckon Helen an' me'll jest have to wait a spell, Jim. Atter all, they's a job to be done. We got to pitch in an' do it, or they ain't gonna be no Helen or no Hank Cleaver, or mebbe even no U.S.A. f'r us to git married in."

So that was that. When Hank Cleaver gets those grim lines about the corners of his mouth, there's nothing you can do to stop him. I helped him pack his battered old suitcase, then we went to say goodbye to Helen. She reacted quite as I had expected. She listened in astonishment to Hank's awkward explanation. Then she expostulated loudly. Then she sniffled a little. Finally she wept for a minute, kissed Hank moistly and told him she was proud of him.

"Anyway," she said, "you'll come home every week-end to see me, won't you?" So Hank promised he would, and off we went. Yeah—that's right. We. I had decided to volunteer, too. That's me all over. Snoopy Jim Blakeson; can't keep my nose out of anything.

The Northern Bridge, Steel and Girder Co. was not so far from our town—only fifty miles—but it was like moving into a strange, new world to pass through the portals of that concern. Clatter and bang and hubbub ... men roaring orders ... staccato tattoo of rivets hammering home ... the keen, metallic smell of molten metal ... the bite of rasps and the chuff-chuff of panting locomotives ... these were the symphonic diapason of our new headquarters.

About us, whistles blew, throngs of sweating workmen bustled about their fathomless tasks, racing to and fro in an endless stream. Beyond sturdy buildings black with age there ranged yellow rows of newer, flimsier structures.

The place had a strangely jejeune look. The look of an adolescent who has outgrown his knee-britches, but has not yet the bulk and substance to fill his new long pants. Still this was a husky youngster. He would grow. He would grow to fill his new trousers. We both felt that.

We found the office of the company owner. Its doors were guarded by a bevy of underlings who protested hopelessly that, "Mr. MacDonald was too busy to see anyone." We brushed them aside and found ourselves, at last, before the irascible president of the NBS&G.

He stared at us in amazement. He was a huge, brawny Scotsman with eyebrows like feather-dusters and a jutting jaw that might have been poured from one of his ingots. After he got his breath:

"And who," he demanded thunderously, "micht you be?"

"'Lo, Mr. MacDonald," said Hank amiably. "My name's Hank Cleaver."

"And who," roared the old man, "micht 'Hank Cleaver' be to coom abargin' into my office wi'oot inveetation? Speak oop, mon! Time is money!"

"'Pears to me," pointed out Hank reasonably, "as how if time's money, like you say, you'd stop wastin' time askin' foolish questions. It don't matter much who I am. The p'int is: whut did I come for. Ain't it?"

Old MacDonald's fiery face turned two shades redder.

"Why, ye impairtenant yoong scoundrel—" he roared; then he paused. He said thoughtfully, "Ye're richt. So what did ye coom for?"

"A job," said Hank.

"A jawb! Ye mean t' tell me ye fairced y'r way into my office to osk f'r a jawb? The employment office lies doon the hall, yoong mon, twa doors t' y'r richt—"

Hank fidgeted uncomfortably.

"Well, that ain't eggsackly the kind o' job I had in mind, Mr. MacDonald. Whut I mean is—"

I decided to stick in my two cents. Bashful as Hank is, it would have taken him all day to explain. "Hank means, Mr. MacDonald, that he would like to offer his services in an executive capacity."

"Exec—!" This time MacDonald couldn't even finish the word. He pawed his graying thatch wildly. "Ye dinna say so? Ond would the title o' preseedent sotisfy him, ye think? Or mayhop he'd ruther be Chairmon o' the Board o' Deerectors? Who are you?"

"I'm Jim Blakeson. I was the publicity man for Midland University," I explained, "but now I'm at your disposal. Where Hank goes, I go. I don't believe you quite realize who Mr. Cleaver is, sir. He is 'Horsesense Hank'."

"And I'm 'Horsesense Hector'!" snorted old MacDonald witheringly. "So what?" It was obvious that he was no newspaper reader, or he would have known Hank's reputation.

"Mr. Cleaver," I told him severely, "is a teacher of General Sciences at our school. He is well versed in a score of subjects germane to your business. Mathematics, civil and chemical engineering ballistics—"

"Motheematics," bellowed MacDonald, "be domned! The NBS&G needs no figgerer! I've gawt one o' the cleverest ones in the coontry wairkin' f'r me. My future son-in-law, Jawnny Day! Jawnny!" He strode to a doorway, flung it open, bawled his command. In the doorway appeared a nice looking kid with fine lips and eyes. "Jawnny, this mon claims to be a—"

But young Day had stepped forward eagerly, extending a hand to Hank.

"Mr. Cleaver! This is an unexpected pleasure!"

MacDonald's jaw played tag with his weskit buttons.

"Ye—ye know him, Jawnny?"

"Know him! Why, every mathematician in this country knows and envies the logic of Horsesense Hank. Are you going to work here with us, Mr. Cleaver?"

"Well," squirmed Hank embarrassedly, "that's f'r Mr. MacDonald to say. Seems sorta like he don't want me."

But MacDonald, the ozone spilled from his Genoa jib, now backed water like a duck in a whirlpool.

"Bide a wee!" he puffed hastily. "Dinna be in sooch a roosh, yoong mon. If Jawnny recommends ye, there's a place in this organeezation f'r ye. Ond f'r y'r friend, too. Now, let's talk ways and means—"

Thus it was that Hank Cleaver and I became employees of the Northern Bridge, Steel and Girder Company. The job to which Hank was finally assigned was that of Estimator. I was given a desk in the Advertising Department offices, though to tell the truth I was no great shakes as a ballyhoo artist for structural steel girders and forged braces, having previously boosted the merits of nothing more substantial than a 200-lb. line and a 175-lb. backfield.

But we got along all right. Until one day, after we had been working there for a couple of weeks, the boss called Hank into his private office. I tagged along. Old Mac had a visitor. A slim, prim man with a ramrod up his spinal column and pince-nez on a beak that would dull a razor.

"Cleaver," said Hector MacDonald, "I want you should meet Mr. Grimper. Mr. Grimper, shake honds wi' Hank Cleaver, my Chief Estimator." The Old Man, I saw was happy as a lark about something; happy and excited, too. "Mr. Grimper," said he, "is a Government mon, Hank. From the R.O.T.C.—"

"O.P.M.," corrected Grimper sourly. "At the moment, I also unofficially represent the O.E.M., the O.P.A., and the S.P.A.B.—"

"No motter," chuckled MacDonald joyfully. "'Tis all the same alphabet. Hank, laddy, we've been drofted! F'r the duration o' the war the auld mon in the top hat is takin' our plont over f'r defense wairk. From now on we're not buildin' bridges and girrders; we're rollin' armament plate and makin' shells to bomb to the de'il-and-gane yon bloody scoundrel wi' the foony moostache! What d'ye think o' that?"

Hank said soberly, "Why—why, that's wonderful!"

"The United States Government," said Grimper tautly, "will assume all expenses necessary for the expansion of your facilities. When the war is over the plant, with all its improvements, will be turned back to you. Meanwhile, a reasonable profit will be allowed you on all defense materials produced."

"Gosh," gulped Hank enthusiastically, "that's swell! We won't let you down, Mr. Grimper. If you'll give me a sort of idea what kind of additional facilities you need, I'll git right to work on it. We mustn't waste no time—"

Grimper coughed peremptorily.

"Er—that's just the point I was about to bring up, Mr. Cleaver. We must waste neither time nor money. This war effort is far too important to be disturbed by—ahem—other factors. That is why I asked Mr. MacDonald to call you. You see, our organization has its own Estimate staff, composed of men trained to do precisely the type of work that will be required here. Consequently, under the new set-up, you will be an unnecessary cog in an already perfect machine. I—er—I trust you understand, Mr. Cleaver?"

Hank stared at him, stricken.

"You—you mean you won't want me here any more?"

"To be more accurate," replied the government agent, "we won't need you. That is, in your present capacity. However, I have no doubt that a man like yourself, familiar with all angles of the steel industry, will find a niche—"

"But—but I ain't!" moaned Hank. "I wasn't in this business till a couple of weeks ago!"

"What?" Grimper stared at him, then at the owner of the company. "I don't understand, Mr. MacDonald. Isn't this man your Chief Estimator? He must have had some experience."

"Hank," confessed the Old Man, "was a puffessor."

"A—a what?"

"Teacher," said Hank miserably. "I taught stuff and things at Midland U. Algebra, a little, an' general science, an' a smatterin' o' this an' that."

"You mean that with such a background—"

"I know whut y'r thinkin'," interposed old MacDonald hastily, "and 'tisna so. Mr. Cleaver airned his job the hard way. The fairst day he set foot in here I ordered him oot—but he's made me swallow my wairds. Now I consider his sairvices invaleeable."

"Still," frowned Grimper, "Mr. Cleaver's talents are not sufficiently remarkable to justify his presence on such a project as that which we are about to embark on. We have our own engineers and mathematicians in Washington. Why, I am an efficiency expert, myself, trained to handle emergencies—"

At that moment the office door inched open. The Old Man glanced up worriedly. "Aye, Miss Cole? What is it?"

"Three of the shop foremen, sir. They say they must see you immediately."

"Ye'll excuse me, Mr. Grimper? Verra well. Let 'em in, Miss Cole." Then, as three grim and grimy men shouldered angrily into the room: "Well, what's the motter? Don't stond there glarin' at each ither! Time is money; speak oop!"

Gorman, foreman of the Maintenance Department, spoke for the trio.

"Well, it's the new tools we ordered, Mr. MacDonald. The shipment just arrived—"

"Then what're ye blatherin' aboot? Ye've been howlin' blue murrder f'r weeks because they were delayed. Divide 'em oop and get to wairk!"

"That's just it," fumed Hendricks of Testing. "They couldn't send us our complete order, Mr. Mac. They sent only seventeen sets. And we can't divide 'em up. They don't come out even."

"Even?" repeated Grimper superciliously.

Mulvaney, the Construction foreman, complained, "I'm supposed to get one half of all materials ordered, sir, but I can't take a half of seventeen. Gorman's supposed to get one third, and Henny's supposed to get one ninth. Our problem is how are we going to divide them?"

Grimper said, "Er—aren't you gentlemen making much ado about nothing? The answer seems to be very simple. Just open the crates and distribute the tools in their proper proportions."

And he beamed at Old Mac triumphantly. But his grin was short-lived. Gorman's sniff was one of pure disdain.

"Didn't you hear Henny say them tools come in sets?" he snorted. "I'd look pretty, wouldn't I, Mister, screwin' a loose nut with one third of a screwdriver? And Henny'd go to town measurin' rivet-precision with one ninth of a caliper!"

Old MacDonald guffawed loudly.

"I'm afeared he's gawt ye there, Grimper. Hank, ha' ye any idee whut to do?"

Cleaver had been scratching his cranium; now he said thoughtfully, "We-e-ell, mebbe I have, Mr. Mac. Joe, c'n you borry another set o' them tools from Supplies?"

Gorman said swiftly, "I can, but I won't. I want my full share of the order, Hank. I don't want no debit against my department in Supplies—"

"There won't be. But let's suppose, f'r the moment, you have borryed a set. Now how many sets would you have?"

"Why—why, eighteen, of course."

"Sure. Now, Mike, you git half o' them sets. Nine, right? An' Joe, you git one third, or six; satisfied? Bill, your department gits one ninth o' the order—or two complete sets. Okay? Well, boys, there you are. Evabuddy happy?"

"Everybody but me!" stormed Joe Gorman. "I've got a set of tools charged against me in Supplies! That idea's all right for these lugs, maybe, but I got my rights! I—"

"Now, take it easy," soothed Hank. "Two an' six an' nine is oney seventeen, Joe. They's still one set left over. So now you can return that one to Supplies!"

"Well, I'll be damned!" said Mulvaney.

And on that note of sincere (if profane) admiration, the department heads disappeared to divvy up the disputatious shipment. With an air of "I told you so!" Old Mac turned to a rather acid-looking Grimper.

"Y' see, Mr. Grimper? Indeespenseeable, that's whut he is! Ye maun do weel f'r to reconsider this motter—"

But there was a streak of mule six feet tall and two feet wide in the Federal man. He sniffed down his long, thin nostrils and studied Hank through his pince-nez with detached interest.

"Hrrumph!" he hrrumphed. "Very interesting, but not at all new, you know. Hardly mathematics at all, in fact. A numerical paradox based on an old Arabian legend, if I am not mistaken—"

I did what Flatbushers would call a "slow berl." In other words, I was boined up. But while I was still striving for words, young Johnny Day, who had entered from his office, came charging to Hank's defense.

"Maybe it's not mathematics," he raged, "in the pure sense. But it's something more valuable—common sense! Any man who can pop up with a quick answer to a problem like that is a handy guy to have around. You are an efficiency expert, Mr. Grimper, but you had no solution to offer—"

Grimper's lean jaw tightened. His eyes grew as cold as a ditchdigger's ears in Siberia. Whatever slow beginnings of humanity might have been wakening in his bosom died now.

"I am sorry, gentleman," he said in a tone of finality which meant he wasn't at all, "but I am not convinced. I presume, Mr. MacDonald, you do want this Government order?"

"Notcherally," grudged Old Mac.

"Then—" Primly—"you must accept my decisions on questions of policy. Mr. Cleaver, you are hereby granted two weeks in which to clear up your affairs around this plant, at the end of which time your services will no longer be needed. I trust you will find suitable employment elsewhere...."

And he smiled, a mean, oily little smile. The heel!

So that, lads and lassies, was that. Hank was o-u-t on called strikes, but if you think he just quit trying to do his share because a fortnight's deadline was hanging over his head, you don't know old turnip-torturer Cleaver.

The Northern Bridge, Steel and Etcetera still needed estimating, so Hank labored straight on through till the last day, lending his individual—if unwanted—talents. Thus it was that on the Saturday afternoon he drew his final paycheck he had still not cleared out his desk drawers and lockers for the next incumbent.

He told me so at dinner. I asked, "Well, what's the program, Hankus? After we feed we grab a choo-choo?"

But he just stared at me. "We, Jim? But you wasn't laid off."

"Birds of a feather," I told him, "flop together. I go where you go."

He shook his head.

"Oh, no, Jim. Thanks a lot, but—you got to stick. This ain't no time f'r individjuls to fuss an' argue. We got a war to win, an' wherever a man's needed he's got to stay."

"But how about you, Hank?"

"I'll find somethin' else to do. When we're through eatin' I got to go back to the plant an' pick up whut belongs to me, then I'll mosey along."

I sighed.

"Well, all right, chum. If that's the way it is—"

That, he assured me, was the way it was. So we went back to the plant about 8:30 p.m. And that's where the final insult was added to injury. For after we had passed the gate a slim, forbidding figure stepped from the shadows to halt us with a challenge.

"Just a moment! Who goes there?"

I started, then I grinned impudently. It was friend Grimper, in person, and not an effigy. I said, "Just a brace of Nazi spies, pal. Don't shoot till you see the yellow down our backs."

The government man edged forward austerely.

"And what are you two doing back this time of night? Blakeson, you have no right to be here after six o'clock, and your friend has no right here at any hour!"

I said, "Why, you two-for-a-nickel imitation of a G-man—"

But Hank, unruffled as ever, said calmly, "Easy does it, Jim. Why, Mr. Grimper, I jest come back to gather up the stuff in my locker an' desk. It won't take me long."

Grimper said sourly, "We-e-ell, all right. But I'll have to go along with you. We can't afford to give strangers the run of the mill nowadays. Constant vigilance is our only defense against saboteurs and espionage agents, and there are valuable military stores within these gates."

"Strangers!" I spat disgustedly. "You've got a hell of a nerve, Grimper. Hank Cleaver volunteered his talents to this concern before you ever knew it existed—"

"Services," said Grimper coldly, "which ended today. And I should not be surprised, Mr. Blakeson, if yours were to be terminated soon. Well, come along."

So we entered the plant. And of course it was black as a whale's belly in there, but do you think Dopey Joe would let us turn on any lights? Oh, no! He had ideas about that, too. He was fuller of ideas than a Thanksgiving turkey is of chestnuts. He commanded, "You will use a flashlight, please. One never knows what prying eyes may be upon us."

"There are a couple of eyes," I glared, "I'd like to pry—with doubled pinkies. Hurry up, Hank. Get your things and let's scram out of here. There's a bad odor around here, and it's not oil fumes."

Hank emptied his desk drawers, and we picked our way down darkened corridors, through the machine-shop and turning room, toward the lockers. We had but one more room to cross: the drafting-room, wherein were stored all the blueprints and testing-models. We were halfway across this, our tiny flashlight beam a dim beacon before our stumbling feet, when—

Out of the gloom, suddenly, terrifyingly, a voice!

"Halten Sie sich! Not a move! Otto—get them!"

Don't ever ask me about the next few minutes. I was there in body only. My mind was as blank as a Fourth of July cartridge. I remember seeing figures—two, three, or twenty—darting toward us; I remember yelling, ducking, and punching with one and the same motion; I remember hearing guttural voices snarling commands that ended mostly in "geworden sein" so it must have been German. I remember feeling, with satisfaction, a spurt of sticky warmth deluge my knuckles as I hit the jackpot on something spongy that howled.

I remember, too, hearing Hank gasp, "Judas priest—German spies!" just before his lanky length toppled under the impact of an accurately wielded blackjack. And I remember my last conscious thought: that when I got a chance I must offer an apology to sour-puss Grimper. Because that thin, hawk-nosed stencil of superiority-plus was—what-ever else his faults—a bang-up fighting man in a pinch! With a fury incredible in one his size and build, he was laying about him like a demon. One Heinie was peacefully slumbering at his ankles already, a second was bawling for assistance.

Then three, or four, or a thousand of them rushed me at the same time. I remember something playing "Heavy, heavy—what hangs over your head?" above my cranium—then that's all I do remember. A bomb exploded in my cerebrum and I went to beddy-bye.

I had a nice little dream, then. I dreamed I was in Spain during the Inquisition, and a black-robed priest had me fastened to a windlass. As he murmured pious paternosters in my ears, he was gently screwing the instrument tighter, and I was gasping with pain as my arms slowly, grindingly, withdrew from their sockets.

I wriggled, emitting a muffled howl, and awakened to find the dream based on cold, brutal fact! My mouth was full of cotton waste—slightly the worse for wear—explaining my muffled tones. My arms were tied together with a short scrap of hemp; this length had been passed through the draw-chain of a skylight, and thus, securely locked, I hung dangling like a pendulum with my toes barely scraping the floor.

Nor was I the only trussed duck in this tableau. My pal Hank was swinging from another skylight chain a few yards away, while Grimper made it three-on-a-ratch. The government agent was the luckiest of us all. He was out cold, and so he didn't have to listen—as did Cleaver and I—to the gleeful chucklings of the saboteurs.

And chuckling they were, like the hooded villains in a Victorian meller-drammer. Apparently one or two thousand of them had gone home, because there were now only a half dozen, but these six were the nastiest looking Nazis I ever hope not to see again. Beetle-browed thugs, fine examples of the pure Aryanism Herr Shickelgruber is always bragging on.

They had been rifling the plant as we happened in, I guess, because the floors were strewn with a litter of papers and blueprints, diagrams, schematics, formulae. As my bleary eyes opened, one of the foragers was complaining to the chief rascal:

"—nothing here, Schlegel. This has a search of no value been."

"And you," I piped up rather feebly, "a nest of rats are! What's the big idea? Untie us, or—"

The ringleader turned, grinning unpleasantly. "Or," he sneered, "what schweinhund? So, Karl, nothing we can use there is here? Very well; it matters not. When we leave, we shall the plant make useless to the verdammt Amerikanisch."

He called to others of his cohorts, scattered around the room. "You are ready? When I give the word—ignite!"

Polecat No. 2 jerked a dirty thumb in our direction.

"And how about them, Schlegel?"

Schlegel's grin would have congealed hot toddy.

"We leave them here."

"Of course, but—" The other man fingered a blunt-nosed automatic hopefully—"would it not be safer to—?"

"Nein!" chuckled Schlegel boastfully. "We shall not make bulletholes in their carcasses. That the cleverest part of my plan is. That is why we tied them thus. The same fire that destroys them will devour the ropes around their wrists, dropping their bodies to the floor, leaving no evidence. The investigators will believe they started the fire, and so will not search further for us."

He laughed coarsely and poked me in the ribs. "That amusing is, nichts wahr, mein Freund?"

"Yeah," I answered grimly. "It's a howl. Just like kidnapping Polish girls and executing innocent hostages. You filthy—" I wrestled savagely with my bonds, but my efforts just sent lancets of pain burning through my already groaning armpits. I glanced at Hank, but he was still hanging quietly from his chain, his eyes closed, his head loud forward upon his chest. He, like Grimper, was blissfully unconscious.

Now came an end to the German's taunts. He swung to his aides, rapped swift commands. Matches scratched, flared, were thrust instantly into heaps of piled rubble. Tongues of flame rose, wavering; strengthened; licked hungrily higher as the inflammable material ignited.

For the first time, a sense of real fear filled me. Up till this moment the whole affair had seemed so fantastic, so maddeningly unreal, that it had been a sort of wild dream. Now I realized belatedly, suddenly, completely, that this was really happening to me, here in the heart of the U.S.A. This was War! We had met the enemy in battle—and had lost!

Horsesense Hank was suspended over the blazing debris.

I realized, too, that something more vital than just our three lives was in danger. This building—up the wooden walls of which angry rivulets of fire were now creeping—was an important cog in Uncle Sam's total war effort. Destroyed, it meant loss of precious materiel to the Allies, hundreds of eager hands restrained from putting into employment the tools which forged the weapons of Democracy, thousands of tanks and guns and aircraft withheld from fighters who needed them.

But we were helpless! The more so, now, because our captors were scurrying from the room like rats from a sinking ship. As the gloom lighted to ochre, they hurried to a door, slipped through it—and the clank! of metal upon metal meant they had dropped the lockbar into place behind them.

Trapped! Trapped to die like moths in a flame. But a moth had wings; we had none. Our hands were pinioned to an inaccessible pillory. I writhed again, a moan wrenching from my lips as my shoulder-muscles strained and tore. And then:

And then a calm, familiar voice speaking to me! The voice of Horsesense Hank.

"I wouldn't do that if I was you, Jim. 'Twon't help none, an' it may jest make matters wuss."

I gasped, "Hank! Thank the Lord you're alive. I was afraid maybe you—"

"I'm awright," said Cleaver gently. "Jest stunned a little. I come to a few minutes ago, but I figgered as how I mought as well keep my eyes an' mouth shut. No sense lettin' the enemy know you got y'r wits about you, I calc'late." His eyes studied the ever-fanning flame with incredibly detached interest. "Hmm! Thing's spreadin' fast, hey? Do you reckon the fire department'll be able to ketch it afore it ruins the whole plant?"

"I'd give a million bucks," I told him honestly, "to be here to find out."

"'Pears to me," mused Hank, "like they will. That's green wood, you know. Don't burn as quick as seasoned timber would. Yep, I 'low as how them spies won't do as much damage as they planned on."

"That," I moaned, "will be a great consolation to us when they bury our ashes!"

"Our which?" Hank stared at me curiously. "Oh, you mean—Why, hell, Jim, we ain't dead yet!"

At this point another voice intruded itself into the conversation. The dry, resigned voice of Mr. Grimper.

"No, not yet, gentlemen. But I am afraid it is time to prepare for that fate. For we are hopelessly secured, the doors are locked and bolted upon us, and in a few minutes the room will be a furnace of flame!"

I shuddered. Of course his prophecy was not news to me. But it made our peril more real to hear it thus spoken.

His words, however, completely failed to disturb the placidity of Horsesense Hank. Hank just said, "Why, 'lo, Mr. Grimper! I was hopin' you'd snap out of it purty soon. Die? Why, we ain't agonna die. Not sence them Nazies was too dumb to tie us up."

My heart gave a sudden leap; I had to swallow before I could choke, "Tie us—What do you mean, Hank? We are tied—and to something far above our heads. We can't even reach the bar we're chained to—"

"We don't have to, Jim. They give us a loophole almost within reach. You notice that there skylight chain is a right thin one. I can't get these rope loops off'n my wrists but I think I c'n squeeze the skylight chain through a loop."

He straightened his legs, and I realized suddenly he had purposely kept them slightly bent at the knees during the time our enemies had been in the room. Now his toes gave him a reasonable foothold on the floor. Using this, he leaped up and gripped the steel chain above his ropes ... drew himself up hand-over-hand until he was swinging comfortably in the loop.

What he did then was weird and inexplicable to me—until, of course, a long time afterward. He pushed the steel chain through one of the rope loops about his wrist, pulled a wide, metal bight through this opening, stepped into the loop—and dropped lightly to the floor, free!

The only encumbrance on him was a length of hemp between his arms. Now that he was at liberty to approach us it was a matter of minutes for him to unloose our bonds and have us untie his!

Grimper's jaw had dropped to his bottom vest button. Slow comprehension dawned on his features. He gasped, "A—a problem in applied topography![2] Astounding! I can hardly believe my eyes—but it's completely logical. Mr. Cleaver—I owe you an apology. Please allow me to—"

"Topogra-which?" asked Hank interestedly. "I didn't know it had no name, Mr. Grimper. Just 'peared to me like as if a circle's got an inside an' an outside, an' we was in the inside, so we wasn't tied up at all, rightly speakin'. Well, let's git out o' here!"

Well he might make the suggestion. For all this had taken time. As we labored to free each other we had heard an excited hubbub gathering outside, the wail of fire sirens had sounded, the yammer of voices raised in command, and a stream of water was already beginning to play upon one wall. But in the meantime, the fire had gained headway. The walls of this room were ruddy sheets of flame. The narrow circle of safety in which we stood was rapidly dwindling. And my skin was beginning to crack and blister with oven-fierce heat.

I croaked despairingly, "But how, Hank? We're free, yes! But the doors are still locked, and the windows—"

"Why, the skylight, Jim!" drawled Hank. "That's our exit—Hey! Grab him!"

I whirled just in time to catch the falling frame of government agent Grimper. The thin man had come to an end of his endurance. His heart was stout and courageous out of all proportion to his physical makeup. With a stifled cry he had fainted dead away!

Well, there you are! One moment we were on our road to a Happy Ending, and bing!—all of a sudden the Three Gray Ladies slap us in the puss with a damp mackerel! I stared at Hank fearfully, and moistened parched lips.

"Wh-what will we do with him, Hank? W-we can't just leave him here to die!"

Hank stroked a lean and thoughtful jaw.

"Sort o' complicates matters, don't it?" he queried. "Let's see—we couldn't h'ist him up, could we?"

I said bitterly, "I can't, Hank. I hate to admit it—but I'd be a damned liar if I pretended otherwise. I'm so weak, and my armpits so badly strained, that it will be all I can do to lift myself. Can—can you?"

Hank shook his head miserably.

"Nup. I didn't jump off'n that chain just now, Jim, I fell off. Hangin' up there like jerked meat wrenched somethin' in my back. I calc'late I c'n climb that chain myself, but I couldn't h'ist nobody else's weight.

"Wait a minute! Weight!" He repeated the word more loudly. A gleam brightened in his eye. "Sure! Dead weight! That's the answer! Here—gimme a hand, Jim. We got to lash him to one strand o' this pulley-chain. Use them ropes. Got it? Okay—tie him tight, now."

"He—he's tied!" I puffed. The smoke was beginning to get me now. Tears were coursing down my cheeks. Time was getting perilously short. "W-what do we do next?"

"Git on the other end o' that chain," ordered Hank, "an' climb!"

"W-what? And leave him dangling here below? But it only saves our lives, Hank! See, the flames are right on us. We won't have time to reach the skylight and haul him up—"

"Do whut I tell you!" roared Hank, "An' hurry!"

There was more vehemence in his voice than I'd heard at any previous time. It shocked, startled me into activity. I leaped for the side of the draw-chain opposite to that upon which Grimper was hanging limp; began climbing like a monkey, hand-over-hand. The dangling chain drew taut above me, and I saw that Hank, too, was climbing. I looked for Grimper—

And Grimper was above me! As Hank and I climbed one side of the chain, the agent's inert body was being hauled up the other. He reached the cool sanctuary of the skylight before we did, lifted to safety by our combined weights, before I remembered the old monkey-weight-and-pulley puzzle that one time caused a near-riot in a staid academy of savants!

So all's well that ends well. It was an easy matter to unlash Grimper when we had reached the roof, an easier job yet to hurry him down a fire escape to the ground. And as my ever-logical friend had guessed, the fire-laddies put out the blaze before it spread to adjacent buildings; thus what might have proved a serious loss to America's offense was held to a minimum. One building which could be easily replaced.

We didn't leave town that night. We were exhausted, for one thing; for another, Hank was in no condition to board a train. His suitcase had been destroyed in the fire, and as he ruefully confessed to me when I asked his reason for backing away from the wildly cheering mob that escorted us to our hotel, the fire had got in one last, farewell lick just as we escaped. Said caress had singed a neat, round hole in Hank's southern exposure.

And the next day there came a hurry-call from Johnny Day. They had caught the saboteurs, or thought they had, and would we please come and identify them?

So we did, and they were, and the Jerries were taken into custody by a detail of granite-eyed soldiers who gripped their Garands as if they hoped Hitler's hirelings would break for freedom. Which of course they didn't. No longer holding the whip-hand, they were the meekest, humblest looking skunks you ever saw.

It was then that Grimper, so trim and fresh that you would never know he'd almost been baked Grimper au jus, moved forward to shake Hank's hand.

"Last night, Mr. Cleaver," he said, "I apologized to you. This morning I want to repeat that apology and wish you all possible success when you leave here."

Hank just blushed and wriggled a bulldog-tipped shoe into the carpet. "Aw, that's all right, Mr. Grimper—"

But if he could take it like that, I couldn't. In a fury I stepped forward and shoved my nose into Grimper's pan.

"You may be an agent for Uncle Sam," I snarled, "and a joy to your loving mama—but you're a pain in the pants to me, Grimper! You've got one hell of a nerve. This man saved your life and MacDonald's plant after you fired him. And now you've got the almighty guts to wish him bon voyage! Well, I for one—"

But, surprisingly, it was Old Mac who stopped me.

"Now, take it easy, Blakeson," he said. "'Tisna the time to gripe and growse. Mr. Grimper kens his dooties as an agent o' Oncle Som. There's a cairtain amount o' accuracy in whut he says. There is no fitting place here for Hank's peecoolyar talents—"

"If not here," I howled, "then where on earth—?"

"Now, Jim!" begged Hank mildly.

But the answer came from Mr. Grimper. A smile split the lips of the scrawny little fighting-cock.

"Why, in Washington, of course," he said. "Like all humans, I make mistakes, Mr. Blakeson. But when I discovered I erred, I try to rectify my hastiness. Therefore I have today wired Washington that Mr. Cleaver is on his way. He will act as personal and confidential adviser to—the President. Mr. Cleaver, do you think you'll like that?"

But he got no answer from Horsesense Hank. For that gentleman had fainted dead away on the floor. And me? Well, I slumbered blissfully beside him. Where Hank goes ... I go....

THE END

[1] "The Scientific Pioneer," AMAZING STORIES, March, 1940.—Ed.

[2] Hank's problem here was similar to those interesting ones presented by Messrs. Krasna and Newman in their fascinating volume, Mathematics and the Imagination: The captives were not truly bound so long as freedom of leg movement permitted them to convert their bonds into a simply-connected manifold.

By way of illustration (and for your own amusement) tie a 36" piece of string to each of your wrists. Tie a second piece of string to each of the wrists of a friend in such a fashion that the second piece loops the first. By experiment, you will discover it is quite possible to disengage yourself from your companion without breaking or cutting the string.

Another interesting example of topological freedom is that achieved in removing the vest without first removing the coat. Try it. The coat may be unbuttoned, but your arms must not slip out of the coat sleeves.—Ed.