Title: The art of music, Vol. 05 (of 14)

The voice and vocal music

Editor: Daniel Gregory Mason

Author of introduction, etc.: David Bispham

Editor: Leland Hall

Edward Burlingame Hill

Hiram Kelly Moderwell

César Saerchinger

David C. Taylor

Release date: September 4, 2024 [eBook #74367]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: National Society of Music, 1915

Credits: Andrés V. Galia, Jude Eylander and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTES

In the plain text version Italic text is denoted by _underscores_. Small Caps are represented in UPPER CASE. The text in bold is represented like =this=.

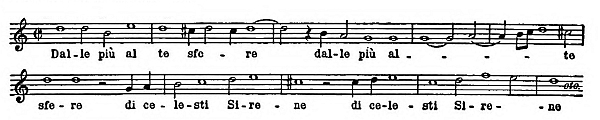

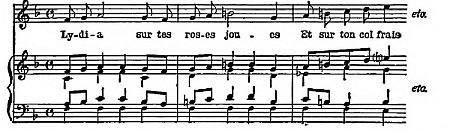

The musical files for the musical examples discussed in the book have been provided by Jude Eylander. Those examples can be heard by clicking on the [Listen] tab. This is only possible in the HTML version of the book. The scores that appear in the original book have been included as “jpg” images.

In some cases the scores that were used to generate the music files differ slightly from the original scores. Those differences are due to modifications that were made by the Music Transcriber during the process of creating the musical archives. They were made to make the music play accurately on modern musical transcribing programs. These scores are included as PNG images, and can be seen by clicking on the [PNG] tag in the HTML version of the book.

Obvious punctuation and other printing errors have been corrected.

The cover art included with this eBook has been modified from the original by the Transcriber and is granted to the public domain.

THE ART OF MUSIC

A Comprehensive Library of Information

for Music Lovers and Musicians

Editor-in-Chief

DANIEL GREGORY MASON

Columbia University

Associate Editors

EDWARD B. HILL LELAND HALL

Harvard University Past Professor, Univ. of Wisconsin

Managing Editor

CÉSAR SAERCHINGER

Modern Music Society of New York

In Fourteen Volumes

Profusely Illustrated

NEW YORK

THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC

Saint Cecilia

After the painting by Rubens (Kaiser-Friedrich Museum, Berlin)

THE ART OF MUSIC: VOLUME FIVE

The Voice and Vocal Music

Department Editors:

DAVID C. TAYLOR

Author of ‘The Psychology of Singing,’ etc.

AND

HIRAM KELLY MODERWELL

Musical Correspondent, Boston Evening Transcript, etc.

Author of ‘The Theatre of Today,’ etc.

Introduction by

DAVID BISPHAM, LL.D.

NEW YORK

THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC

Copyright, 1915, by

THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC, Inc.

[All Rights Reserved]

[Pg vii]

All the Arts, being emanations from the superman, are of the highest significance to the human race therapeutically—the word being used in its broadest possible significance. They are curative, they do us good. There is happily no longer a ban put upon any one of them in the modern world, except by an occasional religious sect, and even those survivors of a prohibitory past are rapidly disappearing.

Enough can scarcely be said of the value of the literature of song as it exists to-day. Whatever has been written or is yet to appear, is a natural growth, and should be recognized as welling up from the unsounded depths of the human mind, as something to be used for the benefit, here and now, of young and old, male and female, rich and poor, well and ill—as a fruit ‘for the healing of the nations.’ When performed under proper circumstances, music—and particularly song, because it is so individual—has a power for good that is amazing. But this is not generally recognized; only by poets and dreamers has it been stated. The words of such are accepted by the world at large as beautiful generalizations, having no immediate or personal significance, applicable to some realm of fancy, some Celtic fairyland, as impossible as an Oriental heaven, but not to the sombre facts of existence upon this earth—facts so discordant that none but a prophet could by any stretch of the imagination reconcile them with a life of harmony [Pg viii] here. Personally I believe in the foresight of the prophets and poets, and hope that Science will ere long come forward to set the seal of authority upon their utterances. When this is done, song will be accorded the position that so justly belongs to it, and its place will not be an inferior one in the scheme of man’s development through savagery into civilization, and beyond. The seers spoke better than we know; they saw, and do see, through the veil of the present into the beyond, through the paradoxical Paradise of parable into the theoretical perfection in which the effort to attain practical results will be one of the chiefest of joys. Is it not wonderful to realize that music and song are so prominent in the utterances of these hitherto misunderstood soothsayers? Truth-sayers are they in sooth!

There is a noble work to be done in the endeavor to bring about sensibly, systematically and scientifically, the realization of their visions as they pertain to music, and a recognition of the value of song and singing and the application of this beautiful and all but universal gift to the betterment of conditions both personal and social.

To the musical enthusiast society seems to be divided into two classes: those who are musical and those who are not. The fact remains, however, that every normal person is musical to a certain degree, though some may believe it of themselves more readily than others believe it of them. To paraphrase Shakespeare, some are born musical, some achieve music, but all should have music thrust upon them. In one way or another, everyone should be educated in music, to the degree at least of knowing from childhood about it and its makers, being able to participate in musical performance, or at least to appreciate the performance of others, for the musical gift is a fundamental part of human nature; but unfortunately the vast majority of people seem to be unaware of the importance and value of this precious [Pg ix] possession, which has indeed by too many come to be considered as a mere source of amusement, and not as a thing to be taken seriously.

We have now reached a period when all music, and particularly singing, should receive most careful consideration. The voice is so intimate a thing that no one can avoid it in himself or escape it in others, and so great is its power when properly used, whether in speech or song, that it is amazing that its qualities are not more fully realized by all educators and treated accordingly. But up to the present time it seems that those who have influence in educational matters have not had their eyes opened to the fact that every human being should be taught to speak properly and to sing as well as may be, and that these things are perfectly easy of accomplishment, if only correct models are put before children as they grow up. Languages, the most difficult to acquire by adults, are learned by children with perfect ease from those with whom they come into contact; they will speak them well or ill, according as they have heard others speak. In short, example is, where voice is concerned, better than precept; and the ear, so intimately associated with everything vocal, should be given more to do than has hitherto been considered necessary either in schools or by private teachers. While most young people do not begin to take singing lessons until their voices are reasonably settled and can bear the strain of study, it does not seem incompatible with the dictates of common sense to say that the training of voices, as of bodies and minds, may be undertaken much earlier than has generally been thought advisable. ‘The precious morning hours’ of youth are too often shamefully wasted; in them this natural and beautiful gift should be brought out. Vocal music should be learned by ear as well as by eye, pieces suited to varying vocal capacities and wisely selected by those competent to choose should be taught, while certain [Pg x] of the musical masterpieces should be made familiar to all.

This seems so obvious as to be hardly worth saying, but as a matter of fact, song is by too many looked upon merely as a luxury to be enjoyed by the few, whereas it is in reality a necessity that should be used by all, for all have not only a latent impulse toward vocal expression, but much more of a natural gift than is usually granted. Persons selected for the purity of their enunciation and beauty of their voices should every day, in all schools, speak and sing to the pupils, who in turn would unconsciously imitate what they heard; and so there would grow a regard for purity and beauty of tone, both in speech and in song, which later would find expression in the study of the various branches of vocal music—from folk-song to the art-song, from sacred music and oratorio to opera. Only those especially gifted should be permitted by their masters to take up the profession of singer or teacher of singing, and thus there would be selected from the great field of those who know much the few specialists in this or that phase of the art who know more, and who are by nature better fitted to exercise their talents in public.

So many people are able to sing after a fashion that sufficient care is not always taken to separate those who are entitled to enter with joy into the ranks of the interpreters of song from those who are fit only for the comparative outer darkness of the auditor. But if that be darkness, how great is the light of those who, by common consent, are adjudged competent to bear so glorious a lamp before the footsteps of the world!

The desire to sing is so universal that many enthusiasts overlook the fact that they have neglected to train their vocal apparatus until it is too late to make serious study worth while. Little can then be done beyond what will give pleasure to the individual himself. But [Pg xi] this universal desire to sing should be universally recognized. When in future it shall be not only so recognized but sensibly and scientifically satisfied, then it will no doubt be found that very great benefit will result to musical art and, through it, to the daily lives of well-nigh everyone on earth.

When the science of education shall have advanced further, music, and especially singing, will hold a very important place in the scheme, and the difference will become clearly apparent between the average normal being with the average vocal equipment and the artist to the manner born. As with those whose trend toward mathematics or languages is unmistakable, so the truly musical are to be distinguished with ease from their fellows; but all such, and especially singers, should be educated with great care and in a broad and comprehensive manner.

Great geniuses have written music to the words of great poets because they were compelled by the inmost needs of their natures to supplement the message of poetry by that of music. What does the world at large care for these things? Only the educated in musical art know that they exist, but the time is now at hand when the storehouses of music will be opened, and their treasures disseminated among the general public through the schools. Instrumental music is so costly in comparison to vocal music that the obvious course to pursue is to train that wonderful instrument, the voice, which all carry about with them, but the value of which is realized by only a few.

The many-sided occupation of the singer should be as carefully studied as that of the pianist, the violinist, or the organist. The vocalist requires a technique comparable to that of any of these virtuosi, a memory trained to answer the demands not only of music but of words, a knowledge not merely of one’s own but of several other languages, a training in the manner of [Pg xii] speaking and singing intelligibly in these tongues, a mastery of the actor’s art with all that it means in gesture, deportment and expression, and, finally, a comprehension of the whole of vocal literature. Would-be singers should be well educated men and women, subjected to rigorous examination in all branches of their art at every stage of progress; for only thus may vocal artists be prepared for their exacting and important career and be made worthy to tread in future our concert platforms and operatic stages. For this way singing will become a dignified profession instead of a spurious and uncertain career, at which the vast majority of those who follow it can expect to earn but a pittance.

The fact should be very clearly forced home upon students that voice alone does not make a public singer any more than the possession of a Stradivarius makes a violinist, but if either has a good instrument the possessor of so valuable a thing should train himself to play upon it with more than ordinary care, and intelligently study not only the classics of his branch of the profession, but, in the case of a singer especially, enlarge his knowledge of poetry, literature, the drama, and the fine arts in general. Thus equipped he may with safety and with reasonable expectations of success take the hazardous path that leads to the supreme honor of lasting public esteem. Every student should recognize this necessity and work with this end in view. The way is long and the task is hard, but it is not impossible.

Ignorance and daring have long gone hand in hand with an assurance which is at times amazing, but the rising generation should be obliged to learn not only how to sing, but what to sing—both equally important. And then, with intelligence awakened, and the dawn of a new day breaking in through the windows of the mind, we may look for the beginnings of an interest in the advancement of a vocal art that has too long been [Pg xiii] harnessed to the car of Fashion, and under the yoke of Commercialism.

As before the Renaissance of plastic art all had been said in painting and sculpture that could be said in the old formulæ, so in music the few notes of the scale had in the hands of the older masters been worked to their ultimate possibilities of expression, when lo! a new light was shed upon the situation, and presently the flood-gates of sound were opened, and undreamed-of works appeared in rapid succession to amaze and affright the senses. Song reflects this, and the limits of vocal capacity have seemingly been reached. It is not to be believed, however, that, to whatever lengths this new musical Renaissance may go, the appeal of simple melody will ever want for an audience. The past has enough and to spare of song that we have not even tasted, much less digested. Let us set ourselves to teach the multitudes of the uninitiated rising generation all the beauties of the classics of song. They are as full as ever of worth and loveliness, and must form a part of the heritage of the generations yet unborn. The peasant from afar has in him the blood of the peoples from which sprang the great artists and musicians of the past, and it is not for a moment to be supposed that under the freer circumstances of life in America works of originality and charm will soon be forthcoming. This is no place nor time for the sadness of a conquered race that by the waters of another land hung up its harps, and refused to sing the songs of home. Here, on the contrary, may all the accumulated wealth of the beauty of song be joyously revealed to the people by the people, and for the people’s good.

No words can describe music. Talk of it as we may, only music can tell us of itself. How profound its appeal to the very essence of human nature! In the works that have been left to us we have a marvellous heritage. Let it not be neglected, but preserved, honored, and [Pg xiv] taught to all, from the least even unto the greatest; for when sound has been wedded to words by one of the anointed hierarchy of the priests of music, what a mystic union is there. How potent the spell of a voice lifted in song informed by the spirit of poetry!

[Pg xv]

We have here at hand that which makes our Paradise—the gift of song. Let us no longer disregard this fundamental possession, but use it well, and with it enter into the peace that song can give to all who have ears to hear its wondrous message. It is the Evangel that has for so long been knocking at our doors. Let us open wide and welcome this friend and comrade whose voice goes throbbing through the aisles of the vast Temple of Music—that structure not made with hands; heard, not seen, present only to the spirit of mortals, place of worship and refreshment for all generations.

David Bispham.

August, 1914.

[Pg xvi]

[Pg xvii]

CONTENTS OF VOLUME FIVE

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction by David Bispham | vii | |

| Part I. The Vocal Mechanism | ||

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | The Vocal Organs, Their Operation and Hygiene | 1 |

| The vocal instrument; anatomy of the vocal organs; the healthy mechanism—The larynx; the laryngoscope; operations of the laryngeal muscles—Tone production; the resonating cavities; vowel formation; articulation—Vocal hygiene; incorrect tone production; throat stiffness and its cure. |

||

| II. | Vocal Cultivation and the Old Italian Method | 24 |

| Historical aspect of vocal cultivation—The modern conception of voice culture; the mechanical and psychological methods—Ancient systems—Mediæval Europe—The revival of solo singing; the rise of coloratura—The old Italian method—The bel canto teachers: Caccini; Tosi and Mancini; the Conservatoire method; the Italian course of instruction; theoretical basis of the Italian method. |

||

| III. | Modern Scientific Methods of Voice Culture | 55 |

| The transition from the old to the modern system; historical review of scientific investigation; Manuel García; progress of the scientific idea; Helmholtz, Mandl, and Merkel—Diversity of practices in modern methods; the scientific system; breathing; laryngeal action; registers; resonance; emission of tone; the singer’s sensations; correction of faults; articulation—General view of modern voice culture. |

||

| Part II. The Development of the Art Song | ||

| IV. | The Nature and Origin of Song | 70 |

| The origin of song—The practical value of primitive song—The cultural value of primitive song—Biography of primitive song—The lyric impulse—Folk-song and art-song—Characteristics of the art-song; style, the singer and the song. |

||

| V. | Folk-songs | 100 |

| The nature and value of folk-songs—Folk-songs of the British Isles—Folk-song in the Latin lands—German and Scandinavian folk-song—Hungarian folk-song—Folk-songs of the Slavic countries; folk-song in America. |

||

| VI. | The Early Development of Song | 130 |

| Song in early Christian times—The age of chivalry—The troubadours and trouvères—The minnesingers—The mastersingers; the Lutheran revival—Polyphonic eclipse of song. |

||

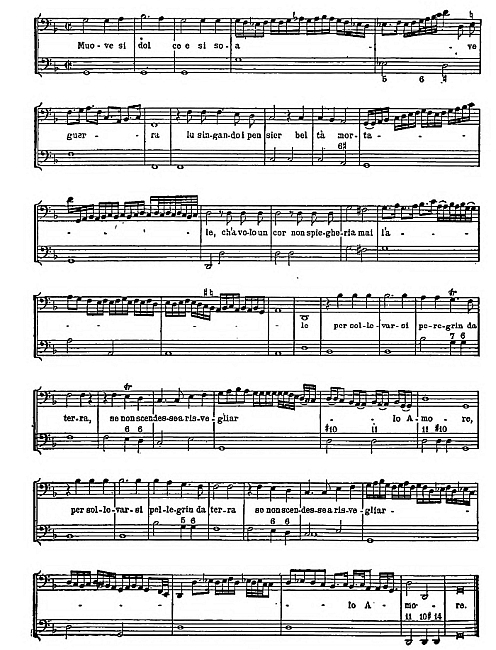

| VII. | The Classic Song and the Aria | 151 |

| Italy and the monodic style—Song in the seventeenth century; Germany; France—Song in England—The aria—German song in the eighteenth century; French song in the eighteenth century; forerunners of Schubert. |

||

| Part III. The Romantic Song | ||

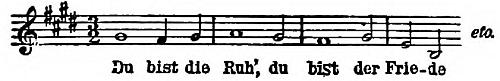

| VIII. | Franz Schubert | 186 |

| Art-song and the romantic spirit—Precursors of Schubert—Schubert’s contribution to song; Schubert’s poets—Classification of Schubert’s songs—Faults and virtues—The songs in detail; the cycles—Schubert’s contemporaries. |

||

| IX. | Robert Schumann | 231 |

| Romantic music and romantic poetry—Schumann as a song-writer—The earlier songs—The ‘Woman’s Life’ cycle; the ‘Poet’s Love’ cycle; the later songs—Schumann’s contemporaries. |

||

| X. | The Contemporaries of Schubert and Schumann | 258 |

| The spirit of the ‘thirties’ in France; the lyric poets of the French romantic period—Monpou and Berlioz—Song-writers of Italy; English song-writers—Robert Franz—Löwe and the art-ballad. |

||

| XI. | Brahms, Wagner and Liszt | 276 |

| Brahms as a song-writer—Classification of Brahms’ songs; the ‘folk-songs’; analysis of Brahms’ songs—Wagner’s songs; Liszt as a song-writer. |

||

| XII. | Late Romantics in Germany and Elsewhere | 296 |

| The dilution of the romantic spirit—Grieg and his songs—Minor romantic lyricists: Peter Cornelius, Adolph Jensen, Eduard Lassen, George Henschel, and Halfdan Kjerulf; Dvořák’s songs—French song-writers: Gounod and others; Saint-Saëns and Massenet; minor French lyricists—Edward MacDowell as song-writer; Nevin and others—Rubinstein and Tschaikowsky—English song. |

||

| Part IV. Modern Song Literature | ||

| XIII. | Hugo Wolf and After | 330 |

| Wolf and the poets of his time; Hugo Wolfs songs; Gustav Mahler; Richard Strauss as song-writer; Max Reger’s songs—Schönberg and the modern radicals. |

||

| XIV. | Modern French Lyricism | 346 |

| Fauré and the beginning of the new—Chabrier, César Franck, and others—Bruneau, Vidal, and Charpentier—Debussy and Ravel. |

||

| XV. | Modern Lyricists Outside of Germany and France | 364 |

| The new Russian school: Balakireff, etc.; Moussorgsky and others—The Scandinavians and Finns—Recent English song-writers. |

||

| Appendix. The French-Canadian Folk-song | 375 | |

| Index | 380 |

[Pg xviii]

ILLUSTRATIONS IN VOLUME FIVE

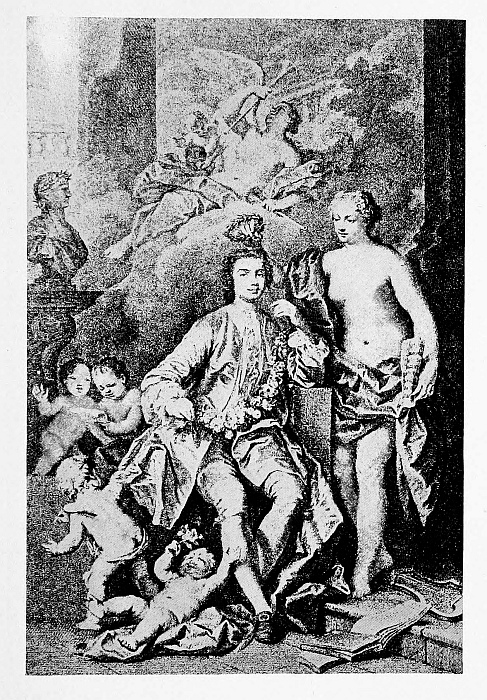

| ‘Saint Cecilia’; painting by Rubens | Frontispiece |

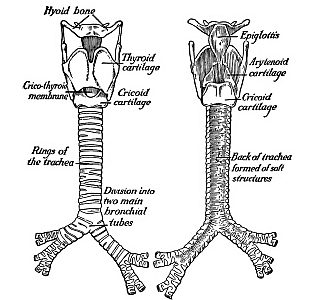

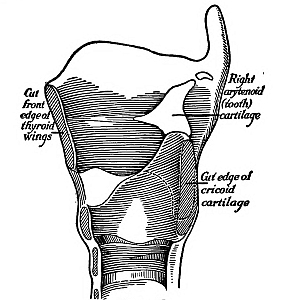

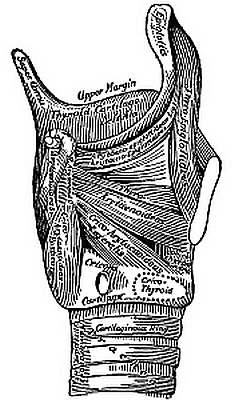

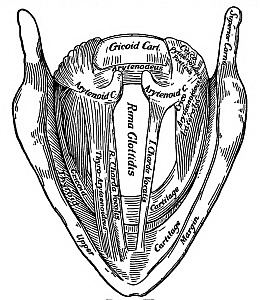

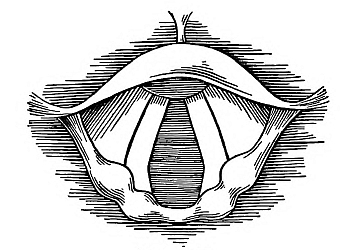

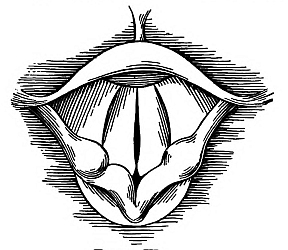

| The Larynx (Line-cuts in text) | 6-13 |

| Facing Page | |

| Apotheosis to Farinelli | 44 |

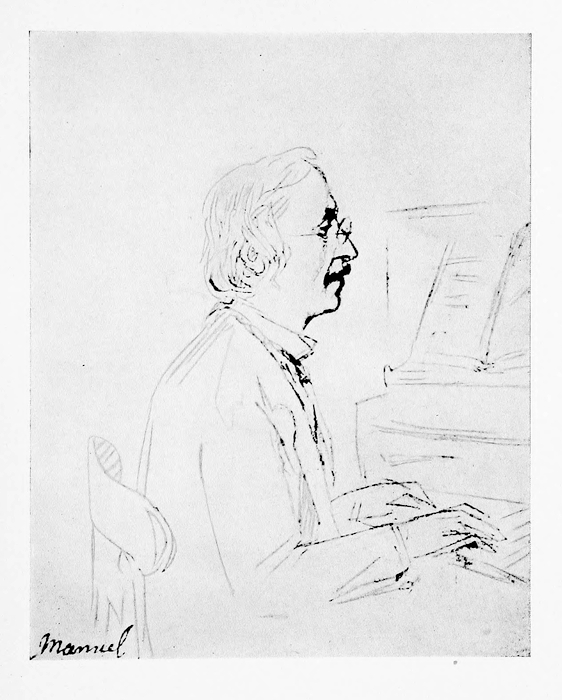

| Manuel García | 58 |

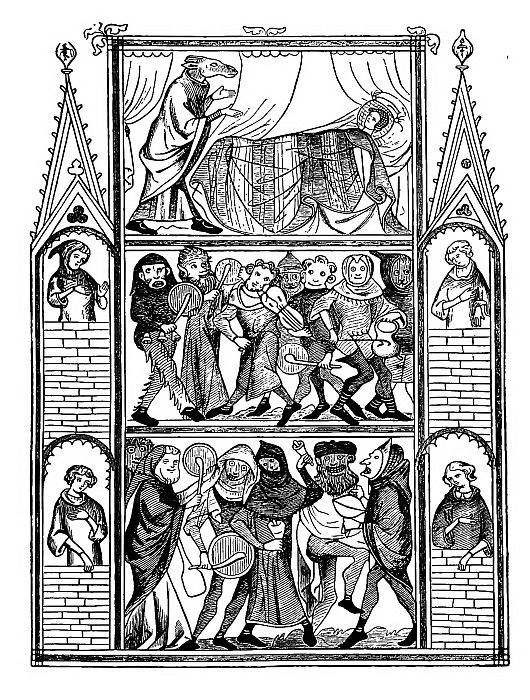

| Illustration for the ‘Roman de Fauvel’; fifteenth century print | 74 |

| Famous Singers of the Past (Malibran, Rubini, Lablache) | 98 |

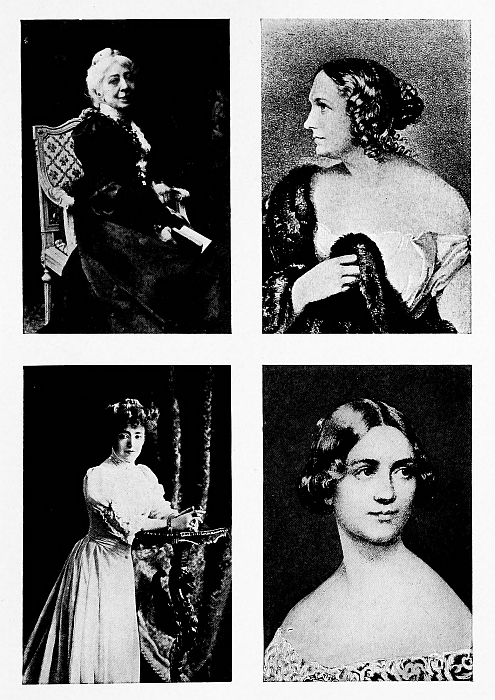

| Famous Singers of the Past (Jenny Lind, Patti, Schroeder-Devrient, Viardot-García) | 152 |

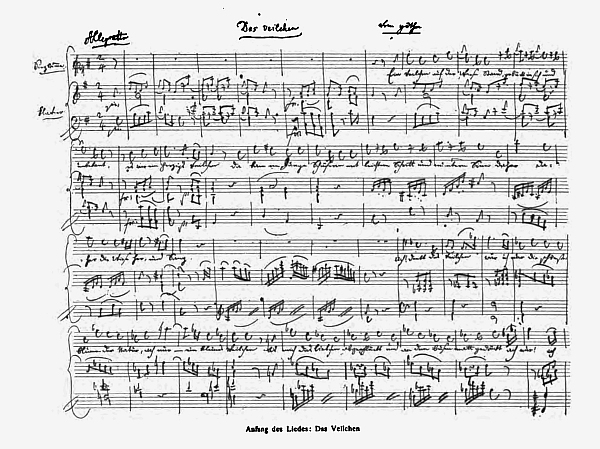

| ‘Das Veilchen’; Fac-simile of Mozart’s manuscript | 178 |

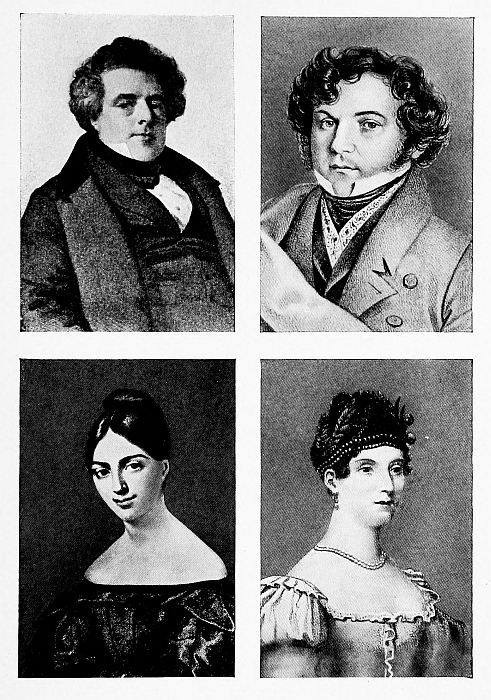

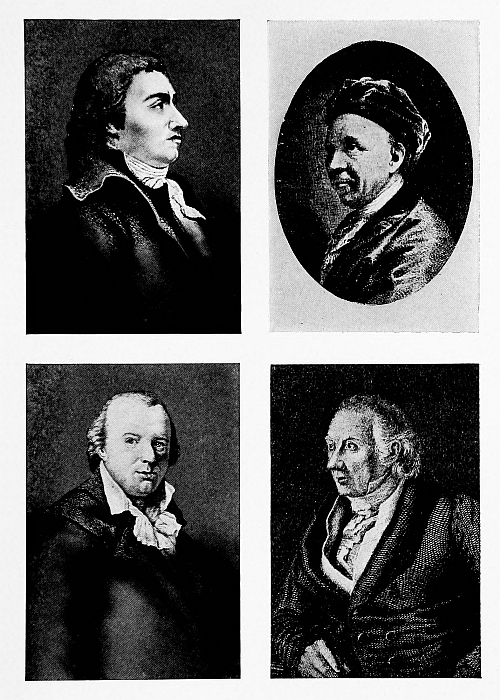

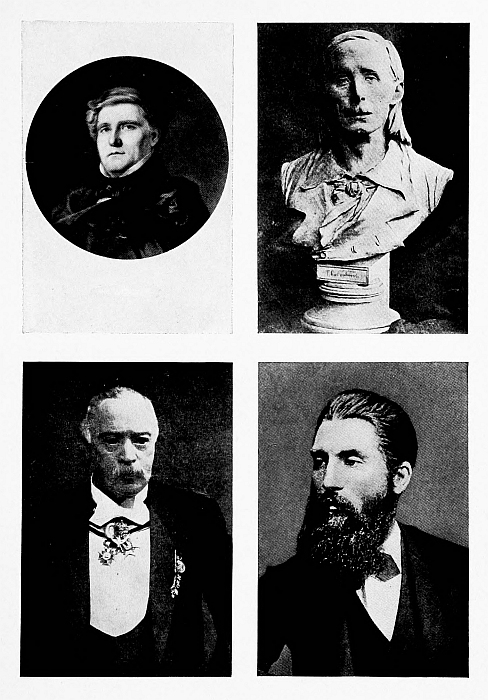

| Precursors of Schubert (Hiller, Reichardt, Zelter, Zumsteeg) | 192 |

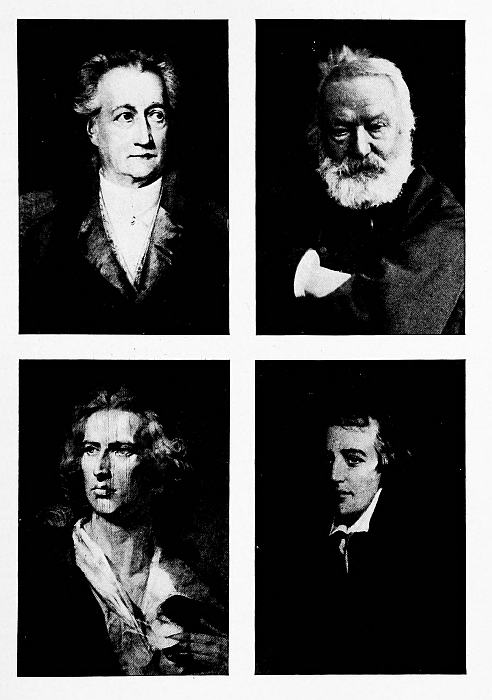

| Poets of the Romantic Period (Hugo, Goethe, Schiller, Heine) | 200 |

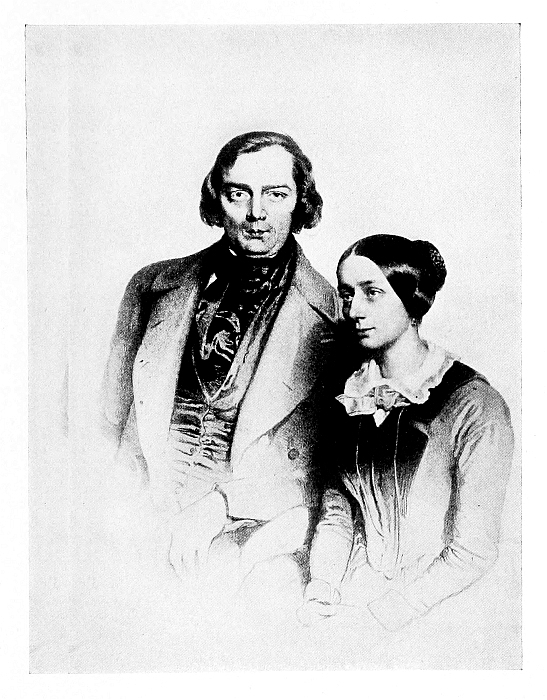

| Robert and Clara Schumann | 238 |

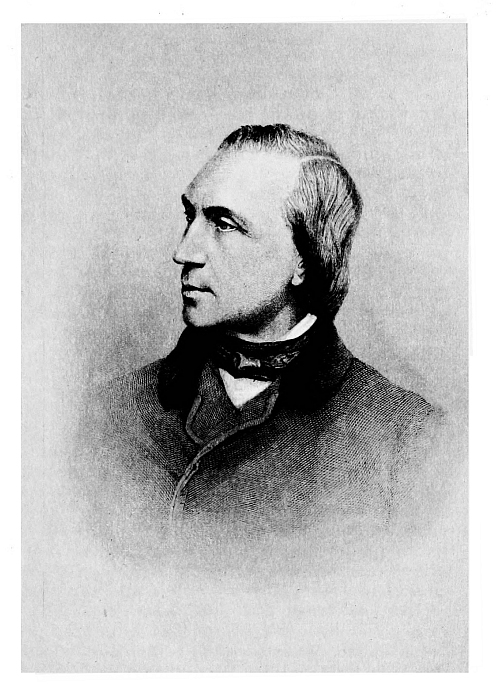

| Robert Franz | 268 |

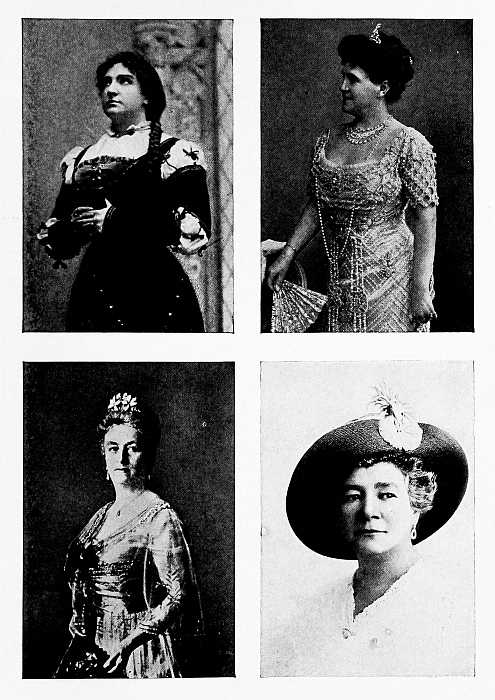

| Famous Singers (Lilli Lehmann, Marcella Sembrich, Melba, Schumann-Heink) | 286 |

| Minor Romanticists (Löwe, Jensen, Lassen) | 306 |

| Hugo Wolf | 332 |

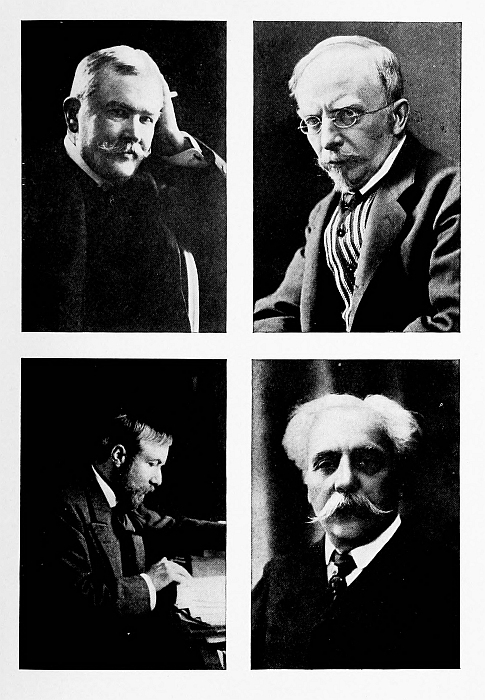

| French and Scandinavian Song-Writers (Fauré, Pierné, Sjögren, Sinding) | 346 |

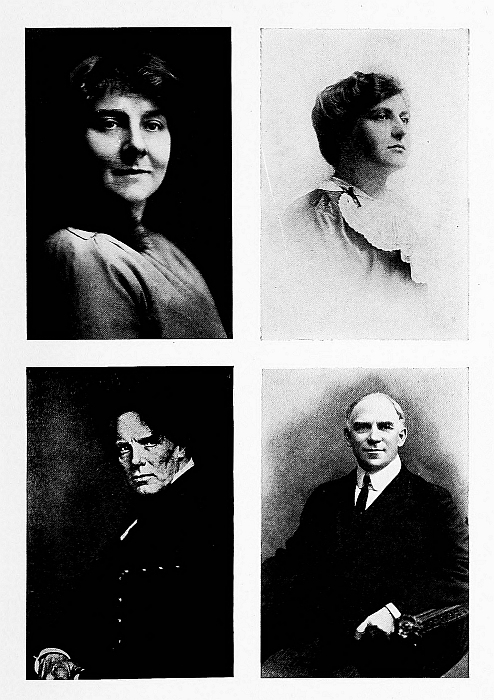

| Lieder Singers of Today (Julia Culp, Ludwig Wüllner, David Bispham, Elena Gerhardt) | 364 |

[Pg xix]

[Pg xx]

THE VOICE AND VOCAL MUSIC

[Pg xxi]

[Pg xxii]

[Pg 1]

The vocal instrument; anatomy of the vocal organs; the healthy mechanism—The larynx; the laryngoscope; operations of the laryngeal muscles—Tone production; the resonating cavities; vowel formation; articulation—Vocal hygiene; incorrect tone production; throat stiffness and its cure.

An acquaintance with the anatomical structure of the vocal organs, together with an understanding of the acoustic laws bearing on their operations, is usually held necessary to a competent knowledge of the principles of voice culture. A rather tedious course of study is indeed demanded for this purpose. But it will be our aim to present this portion of our subject briefly, touching only on those points which are essential to a practical grasp of vocal methods. For a more extended treatment of the anatomy of the organs of voice and breathing any standard text-book of anatomy may be consulted. It is, however, hoped that our outline of the subject will suffice for the purposes of the general reader.

As the subject of acoustics is dealt with in Vol. XII, the present chapter does not cover this topic. A sufficient understanding of the laws of vibration and resonance is also assumed on the part of the reader.

No man-made musical instrument can compare with the human voice in complexity and delicacy of structure. Yet, so far as the general principles of its construction are concerned, it does not differ materially from the voices of air-breathing mammals and birds in general. In each case the vocal organs form a complex wind instrument, consisting of an air chamber[Pg 2] (the lungs), a vibrating mechanism (the vocal cords), and a set of reinforcing resonance cavities. The human voice differs from the voices of other air-breathing animals only in its vastly higher development and complexity.

The vocal organs of all the various species of animal life we are now considering were developed as a part of the respiratory system. In the early stages of the evolution of air-breathing animal forms the lungs had only one function, that of supplying air for the oxidizing of the red corpuscles of the blood. No other use was made of the respiratory organs; the breath served no purpose beyond that of furnishing oxygen for the needs of the circulatory system. This was the condition of those forms which were the forerunners of present mammal and bird life. In the course of evolution a gradual change took place in a part of the respiratory tract. This modification was an example of what is called in evolutionary science ‘adaptive change.’ The organs of respiration were modified and developed in such a way that the pressure of the expired air could be utilized in the production of sound.

As evolution progressed the organs of voice which thus had their origin took on an ever-increasing complexity of structure. This process of evolution has reached its highest development in man. As a musical instrument the human vocal organs may fairly be said to have reached the point of perfection.

From the anatomist’s standpoint the vocal organs consist of four parts:

1. The lungs, together with the bones by which they are inclosed and the muscles which fill and empty them.

[Pg 3]

2. The larynx and its appendages.

3. The resonating cavities—trachea, pharynx, mouth, and the cavities of the nose and head.

4. The organs of articulation—the tongue, lips, teeth, etc.

Each of these organs performs a different function in the production of useful and beautiful sounds. It is the generally accepted view among vocal scientists that each portion of the vocal mechanism has one and only one correct mode of operation. Many forms of incorrect action are also possible; indeed, the untrained voice is believed to be liable in almost every case to faulty operation in some respect. Scientific investigation of the voice has for its purpose the determining of the correct muscular actions of the various parts of the vocal mechanism, and the formulation of exercises whereby the student is enabled to acquire command of these actions.

Modern methods of voice culture embody the results of scientific study of the vocal mechanism. It must be observed that not all investigators are agreed upon what constitutes the correct vocal action. Several conflicting theories have been urged concerning the proper movements of the breathing and laryngeal muscles and the operations of the resonating cavities. An exhaustive treatment of these various theories is, however, not called for here. Some of them have been discarded, others have but few followers. The majority of authorities are in fair agreement concerning the theoretical basis of voice culture. In the present chapter only the theoretical aspect of the subject will be considered; the third chapter will be devoted to the practical methods which embody the doctrines of vocal science.

Two opposed sets of muscles are concerned in the operations of breathing, those which, respectively, fill and empty the lungs. The action of inspiration consists[Pg 4] of an expansion of the chest cavity, which by increasing its cubical capacity draws in air from the outside to fill what would otherwise be a vacuum. The chest cavity is conical in shape, its base being formed by the diaphragm, and its sides and apex by the ribs, the breast-bone, and the intercostal muscles.

Broadly speaking, there are two distinct forms of muscular action by which the chest cavity can be expanded in inspiration: one is the sinking of the base of the chest cavity, the other the broadening of the chest by raising the ribs. Either of these can with some little practice be performed independently of the other.

The sinking of the base of the cavity is accomplished by the contraction of the diaphragm. This muscle is roughly circular in outline. In its relaxed state it rises to a dome in the middle and might be compared in shape to an inverted bowl. As it contracts the diaphragm flattens out and increases the length of the vertical axis of the chest cavity. In its descent it pushes the viscera downward and forces the abdomen to protrude slightly. This manner of breathing is commonly called abdominal, although the muscles of the abdomen are not directly concerned in the filling of the lungs.

The expansion of the chest cavity may be accomplished by the raising of the ribs. Owing to their curved shape and sloping position, a slight elevation of the ribs causes them to rotate outward from the central axis of the chest cavity. This increases the horizontal diameter of the cavity in every direction—forward, backward, and sidewise.

In the judgment of the most competent investigators the best form of breathing combines the two muscular actions just described. At the start of the inspiration the diaphragm descends, but the protruding of the abdomen is checked almost instantly by a contraction[Pg 5] of the abdominal muscles. The inspiration is then completed by the lateral expansion of the chest. In this manner the lungs are filled to their greatest capacity in the least possible time. Another great advantage of this type of breathing is that it imparts a peculiarly erect and graceful carriage, a matter of much importance to the singer and public speaker.

In the action of expiration following the taking of a full breath in the manner just described two sets of muscles are involved. These are: first, the abdominal muscles, which push the diaphragm back to its original position; second, the muscles which lower the ribs (the internal intercostals and some of the external abdominal muscles). The actions of both these sets of muscles can easily be observed. When correctly performed the two actions are simultaneous, the whole chest cavity being gradually and uniformly contracted.

A highly important feature of correct breathing, in the opinion of most authorities, is the control of the expiration. In the first place, all the expired air must be converted into tone and none of it allowed to escape unused. Further, the vocal cords must not be exposed to the full force of a powerful expiratory blast, as they are too small and weak to withstand this pressure without strain and injury. The air must be fed to the vocal cords in just sufficient quantity to serve the purposes of tone production.

It is generally held that this economy of breath can be secured, without strain on the vocal cords, only by opposing the action of the inspiratory muscles to the action of the muscles of expiration. Instead of allowing the inspiratory muscles to relax completely at the beginning of the expiration these muscles are to be held on tension throughout the expiration. By this means both the force and the speed of the expiration can be regulated at will; no undue pressure is exerted[Pg 6] on the vocal cords, and the tone is prolonged steadily and evenly so long as the expiration lasts.

The main passage from the lungs to the outer air is the trachea or windpipe, a tube formed of from sixteen to twenty rings of cartilage, united by tendons and muscular fibres, and lined with mucous membrane. At the top of the trachea is situated the larynx, the organ of phonation, strictly speaking. The larynx is built up of two cartilages, the thyroid and cricoid, which represent developments of what once were the[Pg 7] uppermost two rings of the trachea. The cricoid cartilage, forming the base of the larynx, is shaped like a seal ring, with the bezel to the back. The thyroid cartilage, just above the cricoid, has the form of an open book, V-shaped in horizontal section. In the interior of the larynx are two tiny cartilages, the right and left arytenoids. These rest on top of the rear portion of the cricoid, on which they rotate freely.

Figure I shows two views, front and rear, of the cartilages of the trachea and larynx. Immediately above and connected with the thyroid cartilage is the hyoid bone, which serves as the attachment of the base of the tongue. It is shaped like a horseshoe, the ends pointing to the rear.

Figure II presents a section of the interior of the larynx, all the muscular tissues having been removed. In this cut the position of the arytenoid cartilages is plainly shown.

[Pg 8]

By feeling the outside of the throat with the thumb on one side and the forefinger on the other, the hyoid bone and the thyroid and cricoid cartilages can easily be located. The space between the two cartilages in front is covered by the crico-thyroid membrane.

The muscles of the larynx are considered in two groups, the extrinsic, those which connect the larynx with the other parts of the body, and the intrinsic, those which belong to the larynx strictly speaking. By the extrinsic muscles the larynx is held in its place in the throat. These muscles are usually held to have no direct office in phonation.

The intrinsic muscles of the larynx are nine in number, as follows:

[Pg 9]

2 Thyro-arytenoids, right and left.

2 Crico-thyroids, right and left.

2 Lateral crico-arytenoids, right and left.

2 Posterior crico-arytenoids, right and left.

1 Arytenoideus.

In Figure III these muscles are plainly shown. This cut presents a view of the interior of the left half of the larynx; the right half of the thyroid cartilage has been removed, together with the muscles which lie to the right of the middle line of the larynx. We see the muscles of the left side of the interior of the larynx and also the right posterior crico-arytenoideus and the right crico-thyroid.

The thyro-arytenoideus muscles are attached in front to the interior angle of the thyroid cartilage, and at the back to the arytenoid cartilages. To their outer edges the vocal cords are attached and the space between them is called the glottis. The crico-thyroids[Pg 10] are attached to the outer surfaces of the cartilages. The lateral and posterior crico-arytenoids have very complex attachments, which can be seen in Figure III. The arytenoideus connects the rear surfaces of the two arytenoid cartilages. In Figure IV a drawing of the larynx is presented, looked at from above, the surrounding parts having been dissected away to allow a clear view of the muscles just considered.

It is impossible to state with absolute certainty just what office the various intrinsic laryngeal muscles have in the production of tones of different pitches and qualities. Most of our information regarding this subject has been obtained by means of the laryngoscope. People interested in singing are now very generally acquainted with this little instrument, although it was invented by Manuel García so recently as 1855. While it is generally used only by physicians, anyone who wishes to can easily procure one and by its means observe the actions of his own vocal cords. The laryngoscope consists of a little mirror fitted to a handle at an angle of about 100 degrees. When used by a physician, it is held in the back of the subject’s throat, the tongue being pulled forward and to one side. A ray of strong light is reflected into it from another mirror, which the observer straps to his forehead. This ray of light is again reflected by the laryngeal mirror so as to illuminate the vocal cords. At the same time the observer sees in the laryngeal mirror the image of the vocal cords and so studies their movements.

While laryngoscopic observation has thrown much valuable light on the operations of the laryngeal muscles, it has not by any means cleared up all the mysteries pertaining to this peculiarly intricate subject. All the muscles concerned are very small. Each one contains a vast and intricate number of tiny fibres, extending in widely varying directions. As each one[Pg 11] of these sets of fibres can be contracted with a greater or less degree of strength than those most intimately connected with it, the possibility of variety in the combined actions of the laryngeal musculature is seen to be almost unlimited. Many conflicting theories have been offered to explain the details of the laryngeal action, but a comprehensive review of the subject is not called for here. Our purpose will be served by stating the most generally accepted theory, without committing ourselves as to its accuracy or sufficiency. This theory is as follows:

In quiet breathing all the laryngeal muscles are in a state of relaxation, with the possible exception of the posterior crico-arytenoids. These muscles draw the arytenoid cartilages apart, and so open the glottis. For the production of a tone the glottis is closed by the contraction of the arytenoideus, which pulls the arytenoid cartilages together. The tension of the vocal cords is regulated by two sets of muscles: first, the thyro-arytenoids, to which the cords are directly attached; second, the lateral crico-arytenoids, which rotate the arytenoid cartilages, bringing their forward spurs together.

The pitch of the tone is determined in two ways: first, by the tension of the vocal cords; second, by their effective length. In different parts of the vocal range the manner of adjustment for pitch varies. For the lowest notes of the voice, the chest register, the cords vibrate in their full length. As the pitch rises in singing an ascending scale passage in this part of the voice, the tension of the vocal cords is gradually increased by a corresponding increase in the strength of the contraction of the thyro-arytenoids. When the limit of the chest register has been reached, a further ascent in pitch is brought about by the gradual shortening of the vocal cords. This is effected by the contraction of the lateral crico-arytenoids, which rotate[Pg 12] the arytenoid cartilages inward, as has just been described. The forward spurs of these cartilages are slightly curved in shape, so that, as they continue to rotate, their point of contact is gradually brought further and further forward. As the vocal cords are held tightly together behind this point, the portion of the cords left free to vibrate is shortened with each material increase in the tension of the lateral crico-arytenoids.

With each shortening of the vibrating parts of the cords the pitch is correspondingly raised. The portion of the vocal range thus produced is called the medium register. The highest note of the medium register is reached when the forward spurs of the arytenoid cartilages are in contact at their tips. Beyond this point there can be no further shortening of the vocal cords in this way. The remaining notes of the compass, known as the head register, are secured through a shortening of the effective length of the vocal cords at their forward ends, as well as by a further increase in their tension. Both these actions are accomplished by the contraction of the thyro-arytenoids.

Figure V shows a laryngoscopic view of the larynx, as it appears in quiet breathing. It will be observed that the vocal cords are widely separated, and the[Pg 13] glottis is opened to its full extent. A similar view of the larynx during the production of tone is given in Figure VI. The vocal cords are closely approximated and the glottis is narrowed to a tiny slit-like opening.

What was said about the uncertainty of our present knowledge concerning the laryngeal action applies with almost equal force to the other operations of tone production. Beyond the basic facts that the tones of the voice are produced by the vibration of the vocal cords and are reinforced and modified by the influence of the resonance cavities, little can be stated with absolute certainty. There is, of course, no question as to the definiteness of our knowledge of the anatomical structure of the parts involved. But, with regard to the muscular operations of the resonance cavities and the application of acoustic and mechanical principles in these operations, the same uncertainty is encountered as in the laryngeal actions. We shall continue therefore to outline the most widely accepted theories, without entering into a discussion as to their soundness.

Considered acoustically, the voice is a wind instrument[Pg 14] of the reed class. It differs, however, from all other reed instruments in several particulars. It is capable of producing a wide range of pitches, covering more than three octaves in many cases, by the operation of a single pair of reeds. Further, it has command of an immense range of tone qualities, through the combined action of its reed mechanism and its resonating cavities.

For the production of tone the vocal cords are

brought together and held on tension with sufficient

strength momentarily to close the glottis and check

the outflow of the expired breath. As a slight degree

of condensation takes place in the air behind the cords,

they are forced apart and a tiny puff of air is allowed

to escape. Immediately the cords spring back, once

more close the glottis, and again check the outflow of

the breath. This is repeated a varying number of

times per second, the rate of rapidity of the succession

of puffs being regulated by the degree of tension of

the vocal cords, and by their effective vibrating length.

The pitch of the tone thus produced is determined

by the rate of the air puffs; these range from 75 per

second for the lowest usual bass note,

to 1,417

per second for the highest usual soprano note,

to 1,417

per second for the highest usual soprano note,  .

.

The tone produced by the vibration of the vocal cords is complex in its acoustic character, containing the fundamental note and a large number of its overtones. Yet as it leaves the cords the tone is weak in power and of rather characterless quality. In order to be of musical quality, volume, and carrying power, the primary or vocal cord tone requires to be modified and reinforced by the resonance cavities.

The resonating cavities of the voice, mastery of which is considered essential to the scientific management of the voice, are the chest, the mouth-pharynx,[Pg 15] the nasal passages, and the sphenoid, ethnoid, and frontal sinuses. Each of these is adapted by its size and shape to reinforce either the fundamental note or certain of its overtones with especial prominence. In order to produce a satisfactory tone each resonance cavity must exercise its particular influence in the proper way, their combined effect being necessary to a correct use of the voice.

Much importance is attached by most vocal authorities to the subject of chest resonance. It is believed that the size of the chest cavity,[1] much greater than that of the other resonating spaces, adapts it especially to the reinforcement of the fundamental note and its lower overtones.[2] The mouth-pharynx cavity is capable of extreme variability in both size and shape. This mobility enables it to reinforce a wide variety of overtones, and so to exercise a most important influence in determining the quality of the tone. Another function of this cavity is to increase the power of the primary or vocal cord tone. To secure the effect of crescendo in a single tone, the force of the expiratory blast is gradually increased. In order that the tone may be of uniform musical quality as it swells from soft to loud, a corresponding increase must take place in the size of the mouth-pharynx cavity. This is effected by the gradual opening of the mouth by a lateral expansion of the pharynx and by a lowering of the base of the tongue. A slight elevation of the soft [Pg 16]palate may also contribute to the expansion of the cavity.

A highly important feature of mouth-pharynx resonance is the forming of the various vowel sounds. Each vowel is simply a distinct quality of sound, caused by the special prominence of some one or two overtones. Helmholtz investigated this aspect of voice production exhaustively. At first thought, it seems strange that a tone on some one pitch gives the effect of a particular vowel. Yet we can readily hear this in the steam siren whistle commonly used for alarms of fire. This produces a screaming sound, caused by a gradual rise and fall of pitch through a range of several octaves. Its almost vocal effect of ‘Ooh-oh-ah-eh-ee’ gives us a clear idea of the manner in which these vowels are each the sound of a note somewhat higher than the one preceding.

Helmholtz gives as the determining notes for certain of the German vowels the following table:

For each vowel the mouth-pharynx must assume a shape and size adapted to reinforce with special prominence its particular note or notes. Anyone can readily observe for himself what the positions of the tongue and lips are for the various vowels. For ee the tongue is arched high in the mouth and the lips are only slightly parted. For ah the mouth is opened slightly wider, while the tongue lies flat, etc.

No variation can be made in the size or shape of the nasal and head cavities. As these hollow spaces are small and very various in form, they reinforce only the higher overtones. Special prominence given to the higher upper partials[3] has the effect of making [Pg 17]the tone brilliant and somewhat metallic in quality, and it is here that the special function of nasal resonance is seen. A certain degree of nasal resonance is therefore essential to the correctly used voice, but this must be kept within well-defined bounds. Excessive prominence of this resonance is the cause of the unpleasantly nasal sound which is absolutely out of place in correct tone production.

There remains to be treated under this head the production of consonant sounds. Consonant sounds are of various acoustic characters and are formed in a variety of ways. They may best be considered as of two classes: those into which a tone produced by the vocal cords enters and those devoid of this element. The other determining factor in consonant formation is the point at which an interruption takes place in the outflow of the breath.

There are a number of allied pairs of consonants, one with and the other without an accompanying vocal sound. These are:

v and f

b and p

z and s

d and t

j and ch

th (as in that) and th (as in think)

z (as in azure) and sh

g and k

In each of these pairs the interruption takes place at the same point—v and f between the lower lip and the upper teeth, b and p at the lips, etc.

Another class of consonants are the so-called sonants or liquids, l, m, n, and ng. In these the vocal tone may have appreciable duration; we can hum a tune on any one of them; m, n, and ng are emitted solely through the nostrils, the orifice of the mouth being completely closed.

[Pg 18]

R may be pronounced in two ways, the trilled or rolled r being best for the purposes of singing. Another form of this consonant, made by the vibration of the uvula in contact with the back of the tongue, is essential to a correct (conversational) pronunciation of both French and German, although it has no place in English. The rolled r, however, is generally used in singing by both the French and the Germans.

A highly beneficial form of physical exercise is found in the regular daily practice of singing. All the muscles of the abdomen and thorax are strengthened by this exercise; the lungs are developed to their greatest normal capacity, and the habit is formed of breathing at all times in the most healthful manner. Both the circulation and the digestion share in the benefits derived from regular vocal practice, and the general health inevitably reflects the advantages incident to a proper performance of these most important bodily functions. An erect and graceful bearing, with well poised head and shoulders and firm, elastic step, can be secured through the correct practice of singing more readily than in almost any other way.

Yet the professional use of the voice imposes considerable restrictions on the singer’s habits of daily life. As Sir Morell Mackenzie has said, the singer is an athlete who must always be in training. A perfect condition of the voice demands a perfect state of general health. The singer must plan his whole life in conformity with the demands imposed on him by his art. The slightest indisposition of any kind is almost invariably reflected in the voice. Under the conditions in which people in the usual walks of life are placed, slight colds and trifling upset states of the digestive[Pg 19] organs are a matter of almost no concern. But with the professional singer conditions are entirely different. So delicate and finely adjusted are the laryngeal muscles of the cultivated voice that their ‘tone’ may be upset by apparently insignificant causes. The mucous membranes of the larynx and throat are also highly sensitive to severe and unfavorable conditions.

It is necessary, therefore, for the singer to study himself, to learn by experience what is good and what is bad for him. This is a matter in which individual peculiarities play so great a part that only very general rules can safely be laid down. Singing within less than two hours after the eating of a hearty meal is almost certain to have an injurious effect on the voice. Exposure and over-fatigue must be carefully avoided. Stimulants, especially alcohol and tobacco, have a markedly bad influence on the mucous membranes of the throat. But beyond general statements of this kind, so obvious indeed that their truth is fairly well known, little can with safety be said as to the regimen imposed on the singer. That one man’s meat is another man’s poison is most strikingly true in its application to the voice. Many famous singers have been excessive smokers without seeming to suffer any ill results from the habit. Yet with most vocalists tobacco has a very irritating effect on the mucous membranes. So, also, with regard to eating and drinking, the widest differences of individual constitution are seen. Hot drinks are beneficial to some voices, injurious to others; cold drinks and ices are equally contradictory in their influence on the voice. All these questions of daily habit must be decided by each singer for himself and experience is the only safe guide.

There is a class of dangers to which the voice is exposed, entirely distinct from the influence of unfavorable[Pg 20] conditions of the general health. Most of the throat troubles to which singers and public speakers are liable are directly traceable to a wrong use of the vocal organs. One of the most striking facts regarding the voice is this: If the voice is correctly produced it is benefited by exercise and improves steadily, year after year, in power, beauty, and facility of execution. On the other hand, when the voice is wrongly or imperfectly used exercise has exactly the opposite effect. Badly produced voices constantly deteriorate; their use results in course of time in throat troubles, of which the number and variety seem almost inconceivably great.

One general trouble lies at the bottom of all the throat ailments which follow on a wrong use of the vocal organs. This is a state of muscular strain suffered by the delicate muscles of the larynx. Every incorrect manner of producing vocal tone imposes an excessive degree of effort on these muscles. On the practical side the difference between the correct production of tone and any wrong use of the voice may be stated thus: When the voice is correctly used each tiny muscle of the larynx exerts exactly the right degree of effort in its contraction. To just this amount of exertion the muscles are fitted by Nature and in it they find their normal and healthful exercise. Incorrect tone production, on the other hand, always involves an excessive expenditure of effort on the part of the laryngeal muscles. The throat is in a state of muscular stiffness, in which all the muscles are contracted with more than their normal and appropriate degree of effort.

Muscular stiffness is indeed possible in any part of the body. It can be well illustrated as follows: Take a pencil and a sheet of paper and copy a few lines of what you are reading; grasp the pencil with all the strength of your fingers and exert all the power of your[Pg 21] hand and arm in forming the letters. You will find that your arm and hand tire after a few minutes of writing in this manner. This follows from the expenditure of vastly more effort than is required for the purpose of writing.

All the muscles of the body are arranged in opposed pairs and groups. As your hand rests on the table, the contraction of one set of muscles brings the thumb and the first two fingers together so as to grasp the pencil. An opposed set will, by their contraction, spread these fingers apart, and the pencil will be released. If, now, both these sets of muscles are contracted at the same time the pencil is held stiffly, and the hand moves to form the letters only by the exertion of considerable effort. The muscles themselves are stiffened by this simultaneous contraction of opposed pairs and groups.

Throat stiffness, the characteristic feature of all incorrect vocal actions, is exactly similar in its nature to the stiffness of the hand and arm just considered. The laryngeal muscles are also arranged in sets which oppose their action one to another. One set (the posterior crico-arytenoids) opens the glottis, another set (the arytenoideus and the lateral crico-arytenoids) closes the glottis and brings the vocal cords on tension. Now, if the glottis opening muscles are contracted during tone production, the opposed muscles must put forth enough strength to overcome the effects of this contraction in addition to that which they are normally called upon to exert. This applies also to all the other sets of laryngeal muscles. Through this excessive tension the delicate laryngeal muscles are strained and weakened, and in the course of time the voice is permanently injured. This condition of throat stiffness is by no means uncommon, a matter for which modern methods of voice culture are to a certain degree responsible. The attempt to manage[Pg 22] the vocal organs directly is very apt to lead to excessive tension of the muscles.

Throat stiffness is very insidious in its workings. It tends always to become more pronounced and to impose a constantly greater strain on the voice. Yet in its beginnings the singer may be completely unaware of any trouble. The muscles of the larynx are very poorly supplied with sensory nerves, so poorly, indeed, that under ordinary circumstances we are utterly unconscious of their movements. Owing to this fact, a condition of strain may exist without making itself manifest by any painful sensation. It thus comes about that a singer may suffer from the constantly progressing effects of throat stiffness before its results are so pronounced as to be painful.

Yet there is one infallible way of determining whether a voice is correctly used, or whether, on the contrary, its production is characterized by excessive muscular tension. This is found in the sound of the tones. Any degree of throat stiffness is invariably reflected in the sound of the voice. A throaty quality of tone always results from an incorrect manner of production, and this quality can result in no other way. While a keen and highly experienced ear is needed to detect a slight degree of throatiness, any ordinary observer can hear this condition when it is very pronounced. True, it is very much easier to detect a throaty quality in the voice of some one else than in one’s own voice. The singer labors under this disadvantage, that he can never hear his own voice as clearly and with the same discrimination as can the people who listen to him. Yet by practice and careful attention this difficulty can in great measure be overcome.

For the cure of throat stiffness and its attendant ills the physician can do but little. Even the diagnosis of the condition can hardly be said to lie within his province. In very bad cases a swelling of the muscles[Pg 23] inside the larynx can be detected, as well as a sympathetic congestion of the mucous membranes. The existence of nodes on the vocal cords, rather a rare condition resulting from long-continued vocal strain, can also be determined by laryngoscopic examination. But in the case of the great majority of singers suffering from the effects of throat stiffness the only competent diagnosis is made by the vocal teacher, whose ear is sufficiently trained and experienced to hear the exact nature of the trouble. Further, it is the vocal teacher alone who can relieve and permanently cure the condition. The physician can allay the inflammation of the mucous membranes and can temporarily stimulate the vocal muscles. But no lasting relief can be given in this way. Only one real cure is possible. That is the abandonment of the incorrect habits of tone production and the adoption of the correct manner of using the voice.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] A certain allowance must be made for popular forms of speech in dealing with the subject of chest resonance. It is plain that the air in the chest cavity could not possibly be thrown into regular vibrations. In the acoustic sense the chest is not a hollow space, but a solid body. Filled as it is with the spongy tissue of the lungs, as well as the heart and the great blood vessels, there is no room for the formation of air waves or the oscillation of air particles. Another form of resonance is involved here, what is known in acoustics as sounding-board resonance. The reinforcing vibrations of the chest are those of its bony structure, which vibrates according to the same principle as the sounding-board of a piano.

[2] Overtones, or harmonics, are the tones produced by the vibrations of the individual parts of a resonating body, into which it automatically divides itself. See Vol. XII.

[3] Overtones. Cf. note above.

[Pg 24]

Historical aspect of vocal cultivation—The modern conception of voice culture; the mechanical and psychological methods—Ancient systems—Mediæval Europe—The revival of solo singing; the rise of coloratura—The old Italian method—The bel canto teachers: Caccini; Tosi and Mancini; the Conservatoire method; the Italian course of instruction; theoretical basis of the Italian method.

Musical historians generally agree that the training of voices for the purposes of artistic singing had its beginnings about the year 1600. Voice culture as a distinct department of musical education is held to date no further back than the time when solo singing first began to attract the attention of educated musicians. This view, however, is altogether misleading. From its very beginnings the art of music in Europe was built upon the foundation of singing; no other type of music was, indeed, recognized as a legitimate branch of the art until music had progressed through several centuries of development. Music was brought up to the beginning of its present stage of evolution through the working out of theories which were exemplified in practice only by the use of voices. Counterpoint, the basis of musical composition until well along in the seventeenth century, had its origin in vocal music; throughout its entire history, up to its highest expression in the music of Palestrina and his school, contrapuntal writing was applied only to works composed for voices. Even if no records were to be found of any means used for training the voice, the conclusion would be inevitable that, throughout all these centuries (roughly speaking, from the sixth to the seventeenth),[Pg 25] some attention must have been paid to vocal development and technique. It is true that anyone endowed with a good voice can sing, with some degree of facility, any simple music which he has the ability to memorize. No technical training of the voice is needed to enable one to sing simple songs. Folk-music was the possession of the great mass of the people to whom any ideas of vocal management were utterly unknown. This was also true of the various classes of minstrels, troubadours, etc. Although theirs was purely a vocal art, the only training their voices ever received was that incidental to the actual singing of their music. But for the performance of the music incorporated in the Roman ritual throughout all its history this untutored style of singing would not have sufficed. A much better command of the voice was needed than can be acquired merely through the unguided singing of simple folk-songs and lays. Precision, power, and facility of voice were demanded in the music of the church and these could not have been hit upon by accident. The chances are all against a voice falling into the correct manner of production if called upon to sing music of any difficulty without some definite instruction. This will be made clearer by a consideration of the peculiar problem involved in any extended use of the voice.

Modern thought on the subject of vocal cultivation has crystallized along well-defined lines. For one thing, it has emphasized in a striking way the problem of the management of the vocal organs. The fact is now clearly recognized that the voice has one correct mode of operating, as well as an almost limitless possibility of wrong or incorrect forms of activity. When the voice is correctly produced it can be used daily in large halls and churches without strain or undue fatigue.[Pg 26] By judicious exercise, when rightly produced, the voice is greatly increased in volume and power; it acquires facility in the singing of difficult and elaborate music; its compass is increased, giving it command of a wider range of notes than is possessed by the untrained voice.

Yet vocal cultivation demands the adoption of the correct management of the vocal organs. When the voice is correctly produced nothing more than judicious exercise is needed to bring it to the condition of technical mastery. But if the proper manner of producing tone is not acquired, then the exercise of the voice is fraught with peril to the vocal organs. Instead of the voice being benefited by practice the contrary result is almost inevitable. The use of a wrongly produced voice on an extended scale, involving, as it must, the daily attempt to produce tones powerful enough to fill a large space, strains and injures the vocal organs. This results in a weakening of the voice, in loss of control, in discomfort and pain to the singer, in a strained, harsh quality of tone, and finally, if persisted in long enough, in complete loss of voice.

The difference between the correct use of the voice and any incorrect manner of producing tone is inherent in the organ itself. No one who wishes to sing can elude the problem which Nature thus propounds. On the contrary, the problem of vocal management must be solved some time in the course of a singer’s vocal studies or the technical command of the voice can never be attained. Vocal cultivation is that form of exercise of the voice which leads, through the correct management of the organ, to a command of all the voice’s resources of beauty, range, power, and flexibility.

Even on the earliest singers of the church a solution of the vocal problem was imposed. These singers had to perform daily in large cathedrals and churches;[Pg 27] they had to sing their music in time and in tune. Some measure of vocal cultivation was of necessity involved in their training. We are, fortunately, not left in ignorance of the methods applied in vocal training in the centuries which preceded the rise of solo singing. Many references to this subject found in the writings of early musical historians have been gathered together by H. F. Mannstein in his Geschichte, Geist, und Ausübung des Gesanges von Gregor dem Grossen bis auf unsere Zeit (Leipzig, 1845). Fétis also contains many passages which throw valuable light on the subject It is true that the subject has been considered rather obscure, owing to the fact that students have looked for something not to be found, that is, for rules bearing on the mechanical management of the vocal organs. In order to understand this subject fully the modern conception of voice culture must first be briefly considered.

Modern methods of voice culture are based upon the doctrine that the vocal organs must be consciously guided by the singer in the correct performance of their functions. The idea is that the voice must be led to adopt the correct manner of action by direct attention to its mechanical processes. According to the present conception, the singer must see to it that his vocal cords act in a certain way; that his breath is controlled at the proper point; that the tones have the correct origin and receive the influence of resonance in the correct manner. Even back of this conception lies a belief in the helplessness of the vocal organs to hit upon the proper mode of acting without the conscious direction of the singer. The singer must impose a certain manner of operating on the voice and carefully supervise all the processes of tone production. This is the scientific view of voice culture; until quite recently it was almost universally held.

It is almost incredible that this view is thoroughly[Pg 28] modern and that its origin cannot be traced further back than the invention of the laryngoscope in 1855. Not until 1883 did the scientific view of vocal cultivation find definite expression in the writings of any authority on the voice; in that year Browne and Behnke, in their book entitled ‘Voice, Song, and Speech,’ stated the scientific doctrine in plain terms, and asserted that the voice cannot be controlled in any other way than by attention to the mechanical processes of the vocal organs. For many years thereafter this doctrine went unchallenged, and methods of voice culture treated as the most important materials of instruction the means they embodied for enabling students of singing to acquire direct conscious control over their vocal organs.

An entirely different conception of voice culture has recently been advanced and has indeed made great headway. From the fact that the new doctrine found its first complete statement in the writer’s ‘Psychology of Singing’ (New York, 1908), it has come to be known as the psychological theory, in contradistinction to the mechanical theory embodied in the scientific system.

Briefly stated, the psychological theory of voice production is as follows: To the vocal problem propounded by nature the solution has also been furnished by nature herself. Nature has endowed the voice with a sufficient guide and monitor—the sense of hearing. There is a direct connection between the cerebral centres of hearing and the centres governing the muscles of the vocal organs. The volitional impulse to produce a certain sound involves the hearing of the sound in imagination; through the nerve fibres connecting the centres of hearing and of voice, the nerve impulse is sent to the vocal organs which causes them to assume the positions and perform the muscular contractions necessary for the production of the desired tone. Thus the voice is controlled by the ear, and it needs no other[Pg 29] form of control than that furnished by the ear. A correct management of the voice in singing results in the production of tones of a distinct characteristic sound, while any incorrect use of the voice produces tones which differ from the correct type, more or less, according to the degree of faultiness in the vocal management. The ear is the only reliable judge of the voice. Only by listening to the tones it produces can it be determined whether a voice is correctly used or not. The object of vocal cultivation is first of all to enable the voice to produce the correct type of tone. This is accomplished by practice, which consists of repeated efforts to sing tones of the type recognized by the ear as correct. If the ear has the right conception of pure tone, the vocal organs gradually fall into the way of producing correct tones, that is, of operating in the correct manner. In this the voice is guided by its own instincts, which offer a safer and more efficient guidance than that provided by the conscious management of the vocal organs. No attention whatever need be paid to the mechanical operations of tone production. The vocal organs are informed by the mental ear what is expected of them, and perform their functions instinctively without any help from the intellect.

One advantage of the psychological doctrine is that it at once dispels all the mystery which has seemed to surround the early history of the subject, and which has extended even to the method of the Italian teachers of bel canto. Little notice has indeed been taken of the systems of vocal cultivation which flourished before the rise of the Italian school of vocal teachers. But since the universal adoption of the scientific doctrine, repeated efforts have been made to penetrate the secret of the old method. These efforts have always resulted in failure, for the reason already mentioned. Investigators have sought to re-discover the form of instruction used for the purpose of imparting[Pg 30] a direct conscious control of the vocal organs; their conviction that no other means of vocal command is possible has blinded students of the subject to the instinctive processes actually followed. As our main purpose in the present chapter is to describe the system now known as the old Italian method, a fuller treatment of its records, both literary and traditional, will be reserved for a later section. A review of the early history of voice culture will lead most readily to the consideration of the old Italian method.

Ancient systems of vocal culture call for only passing mention. In the early civilizations of Egypt, Chaldea and Assyria the art of singing was cultivated assiduously. In the services of the temples this ancient art found its most serious and dignified employment. Each of the countries named possessed, at the time of its highest civilization, a highly elaborate ritual of worship, in which singing played a most important part. Every temple had its corps of trained singers, who were especially educated for this office. The most important feature of the education of the temple singers was the memorizing of the musical settings to which the various poems and chronicles of the ritual were sung and chanted. The course of instruction consisted of the actual singing of the music, under the tuition of a master whose memory was stored with the entire devotional repertoire of the cult. A proper performance of the music was the object sought, and to this the most earnest attention was paid. But incident to this was the production of the quality and type of tones which experience had shown to be best adapted to the use of the voice in the massive temples and in the open-air services. The temple music schools were under the constant supervision of the priests and other[Pg 31] officials in charge and the classes met regularly for instruction and practice.

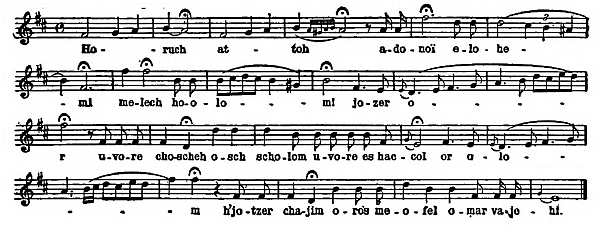

Very much the same system was followed in the Temple at Jerusalem. Of the musical system developed there we have a highly complete and satisfactory record. Here the art of singing was carried to a very high pitch of development. At the time of Solomon there were 4,000 Levites attached to the Temple, whose office it was to sing and intone the various services. The elaborate ritual contained musical settings for the Psalms and certain of the historical and prophetic books, which demanded a high degree of vocal ability for their rendition. Both the priests and the Levites received a lengthy training in the singing of the music allotted to them. The music of the Temple is especially interesting to the student of the history of singing, for the reason that it included a remarkably developed system of vocal ornamentation. It would have been impossible to sing this music without a thorough command of the voice, and the education of the priests and Levites therefore included a comprehensive system of vocal cultivation.

The experience of the early masters of the old Italian school taught them that the best means for training the voice in facility and flexibility is the actual singing of ornamental florid music. This was also the plan followed in the school attached to the Temple. A system of notation was in use, somewhat similar to that of the neumes used in Europe from the ninth to the thirteenth century. Every standard ornament and melodic phrase was represented by a letter, according to a strictly arbitrary system. A most important part of the Temple method of musical instruction was the memorizing of the various phrases, groups, runs, etc., represented by the significant letters. This was purely a matter of convention, that is, the meaning of the letters was recorded only in the memories of the instructors[Pg 32] and the graduate students. The instructor taught the phrase for which a letter stood by singing it for his students and having them sing it after him until they had committed it to memory and learned to associate it with the letter. As the musical phrases were all melodious and in most cases ornamental, the voice thus received an effective training. One of the puzzling aspects of the first solo singing in European music is the difficulty found in tracing the origin of the vocal embellishments of which it so largely consisted. A possible explanation of this mystery may be found in the music of the Temple. How the traditions so carefully treasured there could have found their way into Italy after the lapse of nearly 2,000 years will be considered in a later section of this chapter.

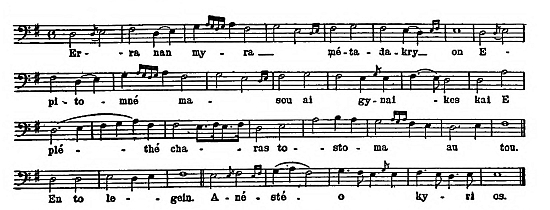

In classic Athens the voice was trained for the purposes of both oratory and singing. A specially recognized profession was that of the vocal trainer or phonascus, whose duties embraced the vocal cultivation of both singers and public speakers. A well-developed system of voice culture was followed by these teachers, who superintended classes in the daily practice of systematic exercises. For the training of the speaking voice a pupil began his daily practice by repeating detached sentences at short intervals. From this he passed to the declamation of long phrases, beginning on the lowest notes of the voice, raising the pitch gradually until the highest notes were reached, and then again descending to the lowest range. The exercises in singing were very similar, although greater attention was paid to the sustaining of high notes. Owing to the immense size of the Greek open-air theatres, and to the masks that were always worn by the actors, volume and power of voice were of the utmost importance. The actors might justly be described as singers, as all their speeches were delivered in a style of vocal declamation not unlike our modern recitative.

[Pg 33]

Very much the same methods of vocal cultivation were followed in ancient Rome, although much more attention was paid to oratory than to singing. There is no reason to believe that voice culture in Europe was influenced in any way by the classic systems of either Greece or Rome.

Vocal cultivation in Europe had an independent beginning. It may be that some of the musical traditions of the Hebrew Temple had been carried over into the earlier churches which were founded in Italy, as there is no doubt that the same traditions were adopted as the basis of the Eastern church ritual at Constantinople. Certain it is that prior to the reform of St. Ambrose much of the music of the early Roman church was highly ornamental in character. At any rate, with the founding of the choir school attached to the Pontifical chapel at Rome in the year 590 voice culture made a new start; it underwent a steady development, and continued to progress without interruption until it reached its fullest fruition in the Italian school of singing in the seventeenth century. The choir school at Rome was intended to serve as a model for the entire Western church; it supplied singers for the papal choir, which was established to illustrate the proper rendition of Gregorian music. At the beginning the course of instruction followed in the Roman choir school was extremely rudimentary, and so it continued for several centuries. The maestro di cappella had as part of his duties the training of the singers’ voices. This was accomplished according to the purely instinctive system followed in the similar schools of the ancient temples. The students committed to memory the music as it was sung by the choir master; in the course of their constant repetition of the various musical numbers their voices received the necessary training[Pg 34] and development. Schools similar to that at Rome were established at all the great cathedrals and the Roman system of musical instruction was thus spread over the entire church.

Throughout the Middle Ages musical learning and culture—what little there was of them—were the exclusive property of the church, and the only centres of musical instruction were the choir schools. Every advance which music made during these centuries involved an extension of the art of singing, and this necessitated of course a corresponding progress of the art of vocal training. Progress was painfully slow; indeed little can be pointed out as marking any distinct advance until the invention of the sol-fa system of instruction by Guido d’Arezzo about the year 1100.[4] On the basis of this system an entirely new form of musical education was erected, which continued to flourish until well along in the 17th century. The new system of musical instruction consisted of what we should now call a training in sight singing.