Title: House beautiful

or, The Bible museum

Author: A. L. O. E.

Release date: September 4, 2024 [eBook #74370]

Language: English

Original publication: London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1868

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

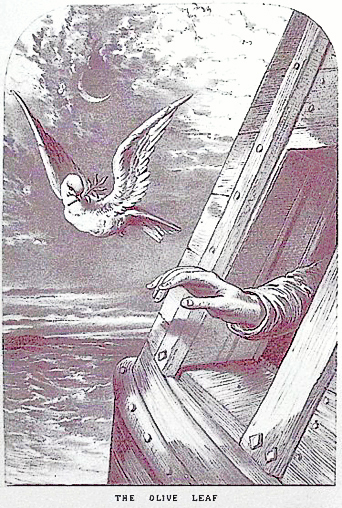

THE OLIVE LEAF

HOUSE BEAUTIFUL

BY

A • L • O • E

THE ARK OF BULRUSHES

THOMAS NELSON & SONS

LONDON, EDINBURGH AND NEW YORK

OR,

The Bible Museum.

By

A. L. O. E.

Authoress of "The Shepherd of Bethlehem," "Exiles in Babylon,"

"Rescued from Egypt," & c.

LONDON:

T. NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW;

EDINBURGH; AND NEW YORK.

————————

1868.

PREFACE

THE narrative portions of the Holy Scriptures are full of striking

biographies of those whose virtues are set before us as examples, or

whose errors as warnings. We are led, as it were, into a Gallery of

Portraits, drawn with faultless accuracy by a sunbeam. But besides

these portraits, there are many objects of deep interest for the

student of Scripture, the accounts of which have been "written for our

learning," objects which we are intended to contemplate with earnest

attention, and from which we may draw rich spiritual lessons. Such

are Noah's Ark, the Brazen Serpent, the Manna from Heaven, which have

been commented upon by apostles, and by our Saviour Himself. If the

biographies in the Bible form the Portrait Gallery of Scripture, such

objects as those to which I have referred—gathered together for our

contemplation—suggest the idea of a Museum, and we are reminded of the

instruction which Bunyan represents to have been gained from such in

House Beautiful. I have never yet met with a work in which a number of

such objects have been specially collected for the contemplation of

Christians, and it has occurred to me that such a volume of reflections

might assist us more vividly to realize much of what is contained in

the Word of God.

Come then with me, my Christian reader, and let us examine together

some of those ancient objects rescued by the inspired writers from

oblivion, and undimmed by the dust of many ages. Let us not handle them

with superstitious reverence as relics, but make use of them to raise

our minds from the absorbing cares and pleasures of the present, to

holy musings on the past. May the Spirit of Wisdom and Truth assist us

in our meditations, and increase our deep reverence for those sacred

Scriptures in which these objects of interest are preserved.

A. L. O. E.

CONTENTS

XII. THE HIGH PRIEST'S MITRE,—Continued

XXIV. SEED CORN FROM BARZILLAI'S GIFT

XXXVI. WRITING TABLE OF ZACHARIAS

XXXIX. THE BED OF THE PARALYTIC

XLI. THE STONE AT THE SEPULCHRE

THE QUEEN AND THE TWELVE NAMES

HOUSE BEAUTIFUL

Forbidden Fruit.

CAN this object, so small, so beautiful, be yet through its effects more deadly than any weapon of war ever forged for man's destruction, more deadly than the poison-flask, the dagger, or the thunderbolt! It lies before us fresh and fair as when, nearly six thousand years ago, it hung amongst the green foliage of Paradise, more beautiful than any fragrant peach on which the last ripening sunbeam glows in a now fallen world.

On the fruit of Eden, which could so lightly yield to Eve's touch, and be marked by the soft pressure of her fingers, we see not the trail of the serpent; it is goodly to look upon, and what mortal dare say that had he been in the place of our first parents, the fair but fatal fruit would have hung untasted on the bough? In looking on it, how awful a lesson we learn of the poisonous nature of what we dare to call "little sins!"

Who amongst us, beholding Eve in her beauty plucking the fruit which tempted her eye, would not have been ready to have echoed the first lie ever breathed on our planet, "thou shalt not surely die." Bright, guileless, and, until now, sinless being; God will not severely judge thee, He has threatened, but He will not perform.

Is not the same deluding idea at the bottom of all our carelessness, our neglect of duty, our grasping at forbidden pleasure? "Thou shalt not surely die" has been the whisper of the Tempter from Eve's time till now. Let us answer him by pointing to that fruit. Was not the death of myriads enclosed, as it were, in its rind? Could the stain left by its fatal juice be washed out by floods of tears or rivers of blood? Had no sin but that one sin of plucking it been ever committed upon earth, could that sin have been atoned for by anything less than the sacrifice of an Incarnate God?

Sin stands not alone by itself: as the seed is contained in the fruit, so one transgression is the parent of many. Coveting what God had withheld, longing for a luxury forbidden, ambitiously aiming at gaining knowledge which should make her independent as a God, Eve at once received into her heart "the lust of the eye, the lust of the flesh, and the pride of life." They came as guests—to remain as tyrants. When we feel their influence within ourselves, when covetousness, love of pleasure, or pride of intellect would draw us from our lowly allegiance to God, from our simple obedience to His word, let us look on the forbidden fruit and tremble—let us look on it, and watch and pray.

The fruit of knowledge still,

Plucked by pride, may death distil.

When we make of intellect an idol; when we exalt reason above revelation, and would draw down God's hidden mysteries to the level of our finite comprehension, we are putting forth our hand, like Eve, to pluck and taste the forbidden fruit; forgetful of the warning of the Saviour: "He that receiveth not the kingdom of heaven as a little child shall in no wise enter therein."

Cain's Offering.

MORE of the fruits of the earth are here, though no longer the fruit of Eden. These, too, are rich and beautiful, and a special interest attaches to them, for they are the offering made to God by the first man who was ever born into a sinful world.

Have we ever realized the feelings with which Adam and his wife must have watched the dawn of intellect in their firstborn son, or the mingled grief, shame, and hope, with which they would tell him the history of the Fall, and the mysterious promise linked with the sentence passed upon them by the righteous Judge? Did young Cain share the hope, which appears at one time to have been his mother's, that he should be the one to whom it would be given to set his foot upon the Serpent's head, and crush the Enemy of his race? We know not whether such thought as this ever passed through the mind of the boy, but he never seems to have entered, like his younger brother, into the solemn meaning of sacrifice for sin.

Cain was not one to neglect all forms of religion; he had his thank-offering for the God of Nature. It is possible that when he looked around him on swelling fruits and ripening grain, and found the earth beneath the labour of his hands yield thirty, sixty, or a hundredfold, a feeling both of adoration and of gratitude may have stirred within his soul. "Cain brought of the fruit of the ground an offering unto the Lord."

But the offering was not accepted. And wherefore was it not? Let us search a little more deeply into this matter, and see, if God help us to understand, wherefore that sacrifice of Cain was rejected, and if there be any danger that ours may be even as his.

It is clear that the case of Cain differs from that of the man utterly indifferent to religion; the man who cares not to make any offering at all. There are those, bearing the name of Christians, whose purses (readily enough opened at any call of pleasure or pride) are kept systematically shut when God's service or His people's need require their contributions. It may well be a startling thought for such that they do "less than Cain."

But what was it that marred the offering of Adam's firstborn son? Why were those mellow fragrant fruits less acceptable to God than the bleeding lamb presented by Cain's younger brother? We have the answer in the words of inspiration. "By faith" Abel offered unto God a more excellent sacrifice than Cain. And what was this acceptable faith? We cannot think that it consisted in a mere belief in the existence of God as the Creator and Preserver of mankind, that vague belief which now satisfies so many who deem it a proof of higher intellect and more liberal thought to reject the peculiar doctrines of Christianity. Doubtless Cain held such belief, yet his offering was "not" the offering of faith.

Abel came before God in God's appointed way, as a transgressor, seeking grace through the medium of a sacrifice. We know not how far he understood the meaning of the rite; whether it was revealed unto him, more or less distinctly, that the promised seed of the woman was also to be the Lamb of God that taketh away the sins of the world; but whether the light granted to Abel was dim or bright, he walked by it in faith. The fruits gathered by the hand of Cain showed no recognition of guilt—no consciousness of needing mercy—no hope of grace to be received through a heaven-sent deliverer. And the offering was not accepted.

If the touchstone contained in the words "by faith" were applied to a multitude of the gifts now placed upon the altar of God, would not many—would not most of them be found to be offerings like those of Cain? Pause, dear reader, and think over your own. Have you helped to raise churches, or to ornament them, to provide for orphans, to assist needy widows, is your name on many a subscription list—your gold often seen on the collection-plate? Do you give the fruits of your intellect to religious work, the best of your time to charitable labours? Are you counted an active and useful member of the church to which you belong? All this may be, and yet it is not impossible that you are presenting the offerings of Cain.

Are you standing in your own righteousness, labouring in your own strength, not deeming yourself a sinner needing forgiveness, but a saint entitled to reward? Search well your motives, look closely at your own heart. We shall not be judged according to the verdict of the world, that sees the action but scans not the motive, but by Him who reads the secret thought and intent.

Herod raised a magnificent temple to the Lord God of Israel, and his liberality may have been lauded to the skies, yet, surely, his was the offering of Cain. Let us be fully persuaded that no sacrifice of ours can be acceptable but as made "for" Christ, and offered through Christ, that we need "the blood of sprinkling" both on ourselves and on our works, if we would not find that sacrifice—these works, however great, however highly extolled—rejected at last!

And there is another way in which we may cause our gifts to be accounted worthless by the Lord, even when we believe them to be offered in faith—when the proud spirit of malice, jealousy, hatred, which was especially the spirit of Cain, is suffered to pollute even that which we bring unto God. Theological hatred has become proverbial for bitterness: so fierce are the disputes upon subjects of religion, that the nature of that "faith that worketh by love" seems to be often entirely forgotten.

If we would not tread in the steps of the first murderer, let us follow the command of our Lord. "If thou bring thy gift to the altar, and there rememberest that thy brother hath ought against thee; leave there thy gift before the altar, and go thy way; first be reconciled to thy brother, and then come and offer thy gift."

Of the deepest importance is it to all who come not empty-handed before their Creator and Judge, to examine whether faith hallows or self-righteousness mars what they bring, whether theirs be the accepted sacrifice of Abel or the rejected offering of Cain.

Noah's Olive Leaf.

PRECIOUS little leaf, symbol of hope and of peace; well worthy art thou of being thus preserved for thousands of years, to be viewed by generation after generation of the sons of men as a pledge of God's lovingkindness! Far more valuable art thou, leaflet once borne in the bill of a bird, than the glittering diadem worn by Solomon in all his glory. With what delight wert thou once hailed by all that survived of mankind, by the whole Church enclosed in the ark; and we can well believe that even in Paradise the spirit of Noah dwells with pleasure on the recollection of that moment when he first looked upon thee!

To conceive what must have been the joy felt by the patriarchs at the sight of the first leaf from a renovated world, let us try to realize their position when the dove flew back with that leaf in its bill.

When Noah and his family first took refuge in the ark, and the windows of heaven were opened, and the fountains of the great deep broken up, their emotions were doubtless those of thankfulness for deliverance and safety, when the great judgment, so long threatened, so long expected, had come at length on the earth. While the storm raged around them, they were secure; the waves that swept over a guilty world could but lift their floating home nearer to heaven! With their emotions of thankfulness would be mixed those of sorrow, pity, regret, for neighbours, perhaps friends and relatives, who had been warned in vain, then perishing beneath the terrible flood. Had not God Himself shut him in, how often would Noah have thrown wide open the door of the ark to receive the poor struggling, drowning wretches, whose dying eyes would be turned to that refuge which they had rejected and despised until it was too late to seek it.

But when the flood had fulfilled its terrible mission; when no cries of the drowning were borne on the blast; when the cataract of rain had ceased, and the dashing of waters was heard no more; then the excitement, the strong emotions of the family in the ark must also have sunk into comparative rest. As the wild raging of the tempest was exchanged for the stillness of death, and the great vessel floated tranquilly over placid waters, and week after week, month after month passed, without bringing a change, great and probably wearisome monotony would pervade the life of the inmates of the ark. That which they had at first rejoiced in as a refuge, would gradually, but increasingly, become to them like a prison. How long were they to be confined within its narrow bounds; when would they be permitted again freely to tread the earth, and partake once more of its fresh produce?

If the Israelites bitterly recalled to memory the riches of the gardens of Egypt—the cucumbers, the melons, the leeks and the onions—would no such regrets be felt by the family of Noah? Would not woman sigh for the flowers that she had been wont to cherish, and an inexpressible yearning oppress all, a yearning to look once more on the green, smiling face of nature? For how many more months, or years, were weary eyes to rest on the same objects, counting the beams above or the planks below of the now familiar prison? A fear might even arise that the supply of provisions, however large at first, might fail, and privation and want ensue. The venerable Noah may have waited with unshaken faith and calm submission for the hour of freedom, but it is more than probable that the younger members of his family grew impatient under the restraint of lengthened confinement.

At last Noah opened the window of the ark and sent forth a raven. In the monotonous routine of the life which he led, this was an event thought worthy of record; the creature appears to have been sent as a messenger, and its return must have been anxiously awaited. But never again did the dark bird re-enter the ark which he once had quitted.

Again Noah sent forth a bird, a dove; but in the beautiful language of Scripture, "the dove found no rest for the sole of her foot, and she returned unto him into the ark, for the waters were on the face of the whole earth: then he put forth his hand, and took her, and pulled her in unto him into the ark."

Not yet had come the signal for release; patience had not yet had its perfect work; the fathers of mankind, the inheritors of the world, must wait longer ere entering into possession. Seven times the sun rose and set ere the dove was sent forth again by Noah. But this time the gleam of the silver wing was to bring joy to the waiting patriarch: "The dove came in to him in the evening; and, lo, in her mouth was an olive leaf pluckt off: so Noah knew that the waters were abated from off the earth." When was earthly treasure ever received with the rapturous welcome given to that leaf; the first brought from a world new-born, as it were, from the dead!

If we regard the Church of Christ as the ark floating now on the troublous waters of the world, the story of Noah's olive leaf becomes a beautiful parable. "How long, Lord, how long," has been for ages the weary cry of the people of God, waiting and watching for the final deliverance and restitution of all things. They are "safe," for they rest in Christ, but the heirs of the new heaven and the new earth may seem to wait in vain. Unbelief suggests the discouraging thought, "since the fathers fell asleep all things continue as they were from the beginning of the creation." Virtue still suffers; evil still spreads; sin and sorrow, like the waters of the flood, are covering the face of the earth.

But there is an olive leaf still for the family of God in the ark. It is the Saviour's promise, "I will come again and receive you unto Myself." To find it and bear it home is not granted to mere human reason, however keen of eye and strong of wing: the raven brought not the emblem of hope. It is the Dove, the Heavenly Comforter alone who brings to the waiting Church, to each weary individual heart, the pledge and promise of a glorious inheritance, when Christ shall return to throw wide open the bolted door, and bid His redeemed come forth to rejoice and to reign for ever!

Has the Dove, dear Reader, brought that olive leaf to your soul; have you rejoiced in the promise? Are you eagerly looking for Him, whom, not having seen, you have loved; and is His word, "I will come again," more precious to you than thousands of silver and gold? Well may the Christian, looking to the promise, adopt the language of the poet,— *

Oh! who could bear life's stormy doom,

Did not Thy Heavenly Dove

Come brightly bearing through the gloom

A peace-branch from above!

Then sorrow, touched by Thee, grows bright

With more than rapture's ray,

As darkness shows us worlds of light

We never saw by day.

* Slightly altered from Moore.

Abraham's Tent.

WE experience natural pleasure in visiting spots celebrated in history. Though corn may wave, and fruit ripen over the scene of some celebrated battle, we cannot look with indifference on the scene where was once held a world-famous struggle for freedom. No modern palace would have the interest which would be attached to the ruin of one which had been trodden by famous monarchs of old. Were there buildings remaining of which it could be said, "here Alexander planned his conquests;" or "there Cyrus administered justice;" we should regard such buildings, however crumbling and defaced, as places gilded by memories which time could never destroy.

But no palace of monarch, no fortress of hero, could ever wake in us such feelings of reverence as a tent of black goat's hair, such as those which the nomade descendants of Abraham now pitch on the sands of Arabia, if it could be certified to us,—"here dwelt the father of the faithful; he who in Scripture is called the friend of God. In that doorway sat the venerable patriarch in the heat of the day, when, raising his eyes, he beheld three mysterious visitors from Heaven stand before him. Behind yon curtain Sarah listened with eager interest to the conversation between her lord and the angel, laughing to herself at tidings which she would not at first believe. There also, when time had rolled on, she laughed with joy over the babe, the promised gift of God; the child from whom should descend a race as the stars in the sky or the sands by the sea for number. It was there that Abraham first embraced his Isaac, and blessed God for the fulfilment of that promise which faith had grasped, when the aged man had 'against hope believed in hope.'"

Though the patriarch's tent was most unlike our own habitations, and though the dwelling of a wealthy sheik would contain fewer comforts than many an English cottage, we turn to it for lessons of what a home should be in all climates, and through all ages. Not that it can be altogether a model even as regards the conduct of its inmates; Sarah's chidings, Hagar's scorn, and Ishmael's mockings must not be forgotten; but in four respects, at least, the tent of Abraham offers a scene which we may contemplate with reverence and profit.

Firstly, it was the dwelling of faith. Wherever its stakes were driven in, its cords stretched, its curtains spread, there rose a habitation in which God was truly worshipped. The ground upon which it stood became in a manner holy. Could that tent speak, of what fervent prayers, what wrestling faith, what earnest adoration, could it tell, and that at a time when idolatry had spread over almost all the earth! In the midst of darkness a bright light shone from that tent; a light which has never been, and never will be, extinguished.

Are our homes thus centres of light? Is God, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, thus constantly honoured in them? Could the word spoken of the patriarch be also spoken, reader, of thee? "I know him, that he will command his children and his household after him, and they shall keep the way of the Lord, to do justice and judgment." Had thy walls a voice, what witness would they bear to earnest pleadings in secret, or humble devotion in family prayer?

Again,—Abraham's tent was the abode of conjugal, parental, and filial affection. Sarah, with all her faults, is held up to us as a model wife. Though, even in advanced life, celebrated for exquisite beauty, Sarah's adorning appears to have been no "outward adorning of plaiting the hair, and of wearing of gold, or of putting on of apparel; she obeyed Abraham, calling him lord," yielding loving reverence to her husband. Isaac was brought up in the nurture and admonition of the Lord; and his obedience to God, and submission to his aged parent, were alike shown when he suffered himself to be bound, an unresisting victim, on the altar of sacrifice.

In these days, when a spirit of lawless independence sometimes pervades even the nursery, and wives too often forget that they have vowed to honour and obey as well as to love, it is well that we should let our thoughts dwell awhile in the tent of Abraham, to see that a home should be as a monarchy, governed by laws of love, the husband and father a wise beneficent ruler, emphatically a power "ordained of God."

Again: Abraham's tent reminds us of the duty of hospitality—that hospitality without grudging, which alone is worthy of the title; not that interchange of worldly courtesies—that asking in order to be asked again—that ostentation which consumes at one luxurious meal what would suffice to feed starving multitudes. Never let the name of hospitality be profaned by being applied to such entertainments as these. But the hearty welcome given even to strangers, the readiness to spread the meal for the guest who may never be able to return the kindness, these we learn from the patriarch. Abraham "entertained angels unawares;" and the same may be said of many of those who exercise hospitality in a spirit like his. In one sense the Lord of angels visits the dwellings of those who welcome His servants for His sake. It is a privilege and an honour to entertain the humblest of His saints; for He hath said, "Inasmuch as ye did it unto the least of these My brethren, ye did it unto Me."

Lastly, let us regard our dwellings, as Abraham did his, as a tabernacle rather than as a settled home. Here we have no continuing city, but we seek one to come. Let not our hearts cling too closely to an earthly habitation, as if it were to be ours for ever, but let us rather remember that, like the family of Abraham, we are strangers and pilgrims on the earth:

"Here in the body pent,

Absent from Heaven we roam,

But nightly pitch our wandering tent,

A day's march nearer home."

Yes; for not only our dwellings, but even these our mortal bodies are but tabernacles, to be taken down and laid aside, to be exchanged for a building of God, a house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens. In the meantime let us pray that they may be the abodes of peace and joy and love, and that the Holy Spirit may be our guest, not as one who tarries but awhile and departs, but as one who comes to abide with us always.

Hagar's Bottle.

AN empty skin-bottle is before us, such as is used by Orientals to the present day to carry what they emphatically term "the gift of God;" a title to which our Saviour appears to have alluded when He said to the woman of whom He had asked water, "If thou knewest the gift of God;" seeking to raise her thoughts from the earthly well to the heavenly Fountain.

Of the value of water in the wilderness, we, in our moist climate, can scarcely form an adequate conception. Let me briefly quote from a description of travelling in an Arabian desert, given by a graphic author: * "On either hand extended one weary plain in a black monotony of lifelessness . . . A dreary land of death, in which even the face of an enemy were almost a relief amid such utter solitude . . . Day after day found us urging our camels to their utmost pace, for fifteen or sixteen hours together out of the twenty-four, under a well-nigh vertical sun . . . Then an insufficient halt for rest or sleep, at most of two or three hours, soon interrupted by the often repeated admonition, 'If we linger here we all die of thirst.'"

* Palgrave.

But the scene which rises before us, the wilderness of Beersheba, is not peopled with pilgrims and travellers urging on their weary camels; there are but two figures in it—an exhausted, grief-stricken woman, and the fainting lad at her side. That skin-bottle is in her hands—empty. She has watched it shrinking as the precious fluid within was gradually used, or wasted by evaporation; dry and parched as is her own tongue, she has feared to relieve her burning thirst lest she should too soon exhaust the priceless treasure. With a sickening feeling of fear Hagar has given the last draught to her Ishmael; and then, with faint hope, squeezed the skin hard with her feverish hands, trying to press out one more drop—but in vain. She looks anxiously around her, but can see no means of refilling that empty bottle.

Then, in anguish, Hagar turns from the parched shrub under which she has cast her son; she wanders away—but let the account be given in the touching words of Scripture: "She went and sat her down over against him a good way off, as it were a bowshot: for she said, Let me not see the death of the child. And she sat over against him, and lift up her voice, and wept."

While Hagar was weeping, her son appears to have been praying; for it is written, "God heard the voice of the lad." Ishmael's cry was answered: "The angel of God called to Hagar out of heaven, and said unto her, What aileth thee, Hagar? fear not; for God hath heard the voice of the lad where he is. And God opened her eyes, and she saw a well of water; and she went, and filled the bottle with water, and gave the lad drink." When the cool bubbling liquid filled out the swelling skin-bottle in the hand of the rejoicing, thankful mother, as she bent eagerly over the well, far more emphatically than the first supply was it to her—the gift of God.

There are times when life appears to us as the wilderness of Beersheba did to Hagar and Ishmael. Our troubles may have been of our own making; like the proud youth who had mocked at his brother, we may, perhaps, be able to trace our sorrows to their source in our sin; but whether it be so or not, we stand in a dry, thirsty land, where no water is; we seem to have drained our last drop of earthly enjoyment—our lips are parched—our bottle is empty—we feel that we can but lie down and die!

Few pass the meridian of life, perhaps few reach it, without knowing something of this desolation of heart, this emptiness of all joy. Blessed to Ishmael was the trouble which made him cry unto the Lord; blessed to us these disappointments which dry up our cherished supplies, if in our baffled thirst for happiness we turn to our Saviour in prayer. The same God who gave to Hagar a well in the desert has also a message of mercy for us: "Ho, every one that thirsteth, come ye to the waters, and he that hath no money; come ye, buy, and eat; yea, come, buy wine and milk without money and without price." Would we seek more specific direction to the Fountain that bursts forth in the desert, to change that desert to an Eden, and supply our deep thirst for peace and joy? The Saviour Himself repeats the invitation; "If any man thirst, let him come unto Me and drink."

What do we need, dear brethren in affliction, to make us come unto Him in whom the weary find refreshment, and the broken-hearted peace? We need that by the Spirit "our eyes should be opened." The Fountain is near us, but we see it not until then. We view the bare waste around us, the withered hopes that strew it; we vainly try to press out one more drop of pleasure from the earthly vessel which once held it, and find the bottle utterly empty and dry. In such moments of dreariness, O Thou who art the Comforter indeed, Thou who canst fill up the empty void, and satisfy the aching soul with abundance, come to us, speak to us, open our eyes to behold the depths of Thy lovingkindness; lead us beside the still waters, and let the promise of our Redeemer be graciously fulfilled unto us: "He that cometh unto Me shall never hunger, and he that believeth on Me shall never thirst."

Jacob's Pillow.

LET us linger before this ancient stone, used first by the benighted patriarch as a resting-place for his head; then raised and anointed by his hands in the morning, as a solemn memorial of a night to be much remembered by him through all his mortal life, and beyond it. If we may judge of the previous spiritual state of Jacob by his conduct towards his father and brother, we shall be inclined to date his conversion to God, the new birth of his soul, to that midnight hour when the wanderer dreamed his glorious dream.

Some of the ideas suggested by Jacob's pillow have been embodied in a beautiful hymn.

"If, in my wanderings,

My sun go down,

Darkness encompass me,

My rest a stone,—

Still in my dreams I'll be

Nearer, my God, to Thee—

Nearer to Thee!

"Then let my ways appear

Steps unto heaven;

All that Thou sendest me,

In mercy given;

Angels to beckon me,

Nearer, my God, to Thee—

Nearer to Thee!

"Then, with my waking thoughts

Bright with Thy praise,

Out of my stony griefs

Bethels I'll raise;

Still by my woes to be

Nearer, my God, to Thee—

Nearer to Thee!"

But a yet deeper meaning seems to be given to the sacred dream by the words of our Saviour, if it be indeed to Jacob's ladder that they allude as type. "Verily, verily, I say unto you, Hereafter ye shall see heaven open, and the angels of God ascending and descending upon the Son of man." What the patriarch beheld in a dream, faith views as a glorious reality. Christ, by His incarnation, linked heaven with earth; by His ascension, joined earth to heaven. He formed a pathway of light, by which the angels ascend and descend. Wherever we receive first into our hearts this glorious truth—first look unto the Saviour as the Way, the Truth, and the Life—that place becomes to us as memory's holy ground, and we can say, as the patriarch said, "This is none other but the house of God—this is the gate of heaven."

Jacob's pillow and his mysterious dream naturally suggest to us meditation on the ministry of angels, of which glimpses are given to us ever and anon in Holy Writ. The bright tenants of a world unseen may be hovering near us, when we have little thought of their presence.

How wondrous was the scene that opened on the servant of Elisha, when, at a time of imminent peril, the prophet's prayer, "Lord, open his eyes, that he may see," was granted! With chariots and horses the fierce enemy was encompassing the city; but lo! Above, a defence, before invisible, was seen to girdle round the prophet: horses and chariots of fire, the legions of Heaven, guarded the servant of God, and no puny arm of flesh had power to hurt one hair of his head. Were our eyes thus enabled to behold the spirits of light, we might see bright winged visitors entering, as familiar guests, the lowly cottage, the attic, the cellar—abodes which proud, luxurious sons of dust would not stoop to enter; we might see angels still encouraging a Peter in prison, refreshing a weary Elisha, rejoicing over a repentant sinner, or bending with celestial smiles over a dying Lazarus, waiting for the signal to welcome a seraph new-born to the skies. But on whatever missions of love these bright beings may come to our earth, we owe their ministry to the Lord of angels: they are "descending upon the Son of man."

And we have our "ascending" angels too—those whose upward flight we fain would follow—blest ones, whom we dare not even wish to detain, as they mount:

"Onward to the glory,

Upward to the prize,

Homeward to the mansions

Far beyond the skies!"

Our eyes are dim with tears, as in vain we try to track their course, lost in a haze of glory; but this we own, with thankful hearts—they owe their exaltation to the King of saints alone: angels are "ascending," as well as "descending, upon the Son of man."

In the dark, bitter gloom of bereavement, we rest our aching heads on the tombstone which covers the relics of one most dear, peacefully sleeping in Jesus. Like Jacob, we feel benighted and alone. But if, in the midnight of sorrow, God reveal Himself to us as He revealed Himself to the patriarch, even that stone will become to us as a Bethel. Does it bear the dear name of our dead—no, rather a name that is written, we trust, in God's Book of Life! Above the stone rises the ladder of light; its foot may rest in the grave, but its summit is hidden in the radiance of Heaven.

The Coat of Many Colours.

A MOURNFUL relic this, all torn and stained, defiled with dust, and blood, and tears! We seem to hear the wail of the miserable father, as with anguish he gazed upon the once goodly garment. "It is my son's coat; an evil beast hath devoured him! Joseph is without doubt rent in pieces!"

In the excess of his grief, "Jacob rent his clothes, and put sackcloth upon his loins, and mourned for his son many days."

In vain they who had inflicted the deep wound in a parent's heart, hypocritically attempted to heal it. His traitor sons "rose up to comfort him;" but Israel refused to be comforted. "And he said, For I will go down into the grave unto my son mourning. Thus his father wept for him."

How bitterly the marred garment of many colours recalled to the mind of Jacob the joy and pride with which he had placed it on his favourite son—the son of his old age, whom he loved more than all his children! Joseph, beauteous in person, gifted in mind, virtuous in character, was well fitted to be the pride and delight of his parent. We marvel not that the son of the beloved Rachel—he who inherited his mother's outward attractions, with the piety of his father—should have been to the heart of Jacob peculiarly dear.

And yet, perhaps, the first thought which this part of Joseph's history suggests to the mind is, how great an evil is partiality shown by a parent! How it draws upon its object many dangers!—Envy, enmity from without, with the yet greater peril arising from fostered vanity and pride within. Had Joseph remained with his doting father, wearing the distinctive garment with which partial affection had robed him, his noble character might have been utterly marred. Presumption, self-righteousness, and vanity, might, and probably would, have sorely tempted his soul. Joseph's Heavenly Father loved him as tenderly as did his earthly father, but with a far wiser love. God gave the bitter antidote to the sweet poison bestowed by a parent's hand. Oh, that those whose blind and cruel partiality is sowing the seed of discord in their families, and that of pride in the hearts of their best beloved, would earnestly consider the history of Jacob and Joseph! How terrible were the trials which the old patriarch's partiality drew upon his boy! His weak affection tended to injure its object: God knew that, and divided—for how many long and bitter years divided—the father from the son!

Again, in yonder torn and bloody garment we see a terrible comment on the inspired declaration, "he that hateth his brother is a murderer." How many thoughts of envy, how many glances of malice, how many bitter words, must there have been in the family of Jacob, before hatred in Joseph's brethren ripened into the horrible crime which deprived a brother of his freedom, almost of his life, and nearly brought the gray hairs of a father with sorrow to the grave! Was there not a time when, if it could have been foretold to the elder sons of Jacob that they would sell their own brother into slavery, and then, by an acted lie of the most cruel kind, try to conceal their guilt by almost breaking their parent's heart—could this have been foretold to them, would not each have exclaimed, in the language of Hazael, "Is thy servant a dog that he should do this thing?"

Let us be watchful against the appearance of envy, even in its least startling form. If we see the crocodile's egg, let us crush it; nor let the destroyer come forth and gain strength, so that it get the mastery over us. The slightest stirring of ill-will towards one more favoured than ourselves, should place us at once on the watch. The humility that is content with a lowly place—the love that rejoices in the exaltation of a brother—these are the guardians of the soul against envy; and, where these are wanting, can the Spirit of God be said to dwell?

Once more, by Joseph's coat of many colours, rent and blood-stained, we are reminded of the marvellous way in which God's providence brings good out of evil, and makes the darkest events in His servants' lives links in a chain of mercies. The beautiful garment given by paternal love, and worn perhaps with some pride, was torn indeed from the persecuted Joseph—first to be replaced by the scanty apparel of a slave, then afterwards by the garb of a criminal in prison; but it was from wearing the dress of humiliation that Joseph was raised to power and honour. It was not the garment made by his father that he put off, in order to assume robes of high office in the court of King Pharaoh. Had Joseph remained in his home at Hebron, unharmed by malice, untouched by persecution, he would never have been the ruler in Egypt, the benefactor of a nation, the friend of a king, the earthly preserver of all Israel's race. It has been said that "evil is good in the making;" so, even from the malice of Joseph's brethren, the grief of his father, and his own anguish when "the iron entered into his soul," God brought forth blessings unnumbered to the man who feared and obeyed Him.

We cannot leave the stained vestment of the ancient patriarch without turning our thoughts to Him of whom it is written, that "He was clothed in a vesture dipped in blood: and His name is called The Word of God." In Joseph we see a remarkable type of our blessed Redeemer, sent by His Father to visit man, as Joseph was sent to his brethren in Shechem. "He came unto His own, and His own received Him not." For envy, the chief priests delivered Christ into the hands of the Gentiles; and the betrayer received money for Him whom the children of Israel did value, even as their fathers sold Joseph for twenty pieces of silver.

But it is in his subsequent exaltation to be a prince and deliverer—it is in his exercise of boundless liberality and free pardoning grace—that Joseph is especially a type of our Lord. "God sent me before you to preserve you a posterity in the earth, and to save your lives by a great deliverance," said the patriarch to his penitent brethren, who owed preservation from famine to him. And it was to those whom He deigned to call brethren that Christ addressed the gracious assurance, "I go to prepare a place for you."

To Him the sun, and the moon, and the stars pay homage; to Him all the world shall bow down; in His hands is the bread of life; and His word is still, "Look unto Me, and be ye saved, all ye ends of the earth." Once sinners parted Christ's garments amongst them, and upon His vesture did they cast lots; but the hour is approaching when they shall look upon Him whom they pierced, and behold His glory,—

"Whose native vesture bright,

Is the unapproached light,

The sandal of whose foot the rapid hurricane!"

The Ark of Bulrushes.

A FRAIL bark, indeed, this cradle of woven bulrushes, to bear so precious a freight! We read of the boat which carried Cæsar and his fortunes; if we measure human greatness by the extent and durability of a man's influence over his kind, the mighty Roman is dwarfed beside Moses, and his "fortunes" appear comparatively a thing of a day. Many ages have passed since Cæsar exercised sway in the world; all that remains of him is a mighty name: Moses, who lived some fourteen hundred years before him, is still a living power on earth. The nation which Moses was the instrument of delivering reverence his laws to this day, while myriads of Christians, yea, all who to the latest time will study the Word of God, will honour Moses as a prophet, obey him as a teacher, and drink in wisdom from his inspired writings.

Cæsar raised a Babel structure of grandeur, cemented not with slime but with blood, and it has not left even a ruin behind it. The work of Moses, heaven-guided as he was, resembled more one of the everlasting hills which the Almighty Himself hath planted and made firm, from which flow, and to the end of time will flow, pure streams to fertilize earth, and which from age to age remain unchanged in their calm majestic beauty. Cæsar was a great conqueror. Moses stands before us in dignity of a loftier kind; so glorious as deliverer, lawgiver, prophet, that we almost forget that he was a mighty conqueror also. Cæsar climbed up to a point where a halo of fame shone around him. Moses soared high above it; the glory which beamed from his countenance was glory derived directly from God.

Did the hopes of Jochebed venture to picture anything like this, as she laboured at forming this little ark, twining in and out every green bulrush with a prayer for her helpless babe? A scene of touching domestic interest rises before the imagination as we think of the home of Amram the Levite, near the bank of the Nile, in these old, old days which the Scripture narratives bring so freshly before us. There is Jochebed, in a retired part of her dwelling, anxiously pursuing her labour of love, working and weeping, and praying as she works, trembling lest a cry from her hidden infant should betray the secret of his existence to any Egyptian ear. Perhaps little Aaron disturbs her ever and anon with innocent prattle, lisping in his childish simplicity dangerous questions which the mother knows not how to answer; while Miriam, the future prophetess, of an age to share her parent's anxieties and guard their secret, watches to give notice of the approach of any stranger, her child-face already stamped with the impress of care too natural to one brought up in the house of bondage.

The story of Jochebed and her little ark of bulrushes seems to be one especially recorded for the comfort of mothers. Though in our peaceful land such perils as those which surrounded the cradle of Moses are unknown, yet every parent who watches by a baby boy may learn a lesson from the Israelite mother who, strong in faith, twined that green nest for her little darling. For every infant born into this world of danger and trouble an ark should be woven of many prayers. In two points of view we may regard every such infant as in a position not unlike that of Jochebed's babe, when found by Pharaoh's daughter in his little floating cradle.

The child has been born to danger, and under the doom of death; he is redeemed, adopted, and may be destined to great usefulness and exalted honour. Should a mother's eye rest on these pages, let her follow out with me a subject which can scarcely fail to be one of deep interest to her heart.

Your child, my Christian sister, has, like Moses, "been born to danger, and under the doom of death." You have transmitted to him a fallen nature; he has first opened his eyes to the light in a world of which Satan is the prince—that Pharaoh whose wages is death, that tyrant who seeks to destroy the babe whom you so tenderly love. You cannot keep your little one from all the perils and temptations which, if he live to manhood, will certainly surround him. You cannot prevent his being exposed to trials as perilous to his soul as the waters of the Nile were to the body of the infant Moses. What can you do to guard your child from dangers in which so many have perished? Like Jochebed, strong in faith, make him a little ark of your prayers.

And to turn to the brighter side of the subject—if you have to share Jochebed's fears, may you not inherit her hopes also? It is no earthly princess, but the gracious Saviour Himself who has raised your child from his low estate, reversed his doom, adopted him as His own, and placed him as a little Christian in your arms, with the words, "Take this child away, and nurse it for Me, and I will give thee thy wages."

The destiny which may await your babe, is one which is more great, more glorious, than your imagination can conceive. Can the human mind grasp all that is contained in the titles, "Member of Christ, child of God, inheritor of the kingdom of Heaven?" You are tending an immortal being; a future seraph may be cradled in your arms! Those soft lips, pressed so closely to your own, may hereafter utter words that shall influence the destiny of souls through the countless ages of eternity; to that mind, which can scarcely yet hold even the sweet assurance of a parent's love, may be unfolded mysteries into which the angels desire to look. If care and anxiety press on your soul when you think of what your child is—feeble, helpless, born to trouble as the sparks fly upward—there is deep rapture in the thought of what that child may be. Oh! Dedicate him now to his God; ask for him not fame, power, or wealth, not the riches of Egypt, but ask for him grace to follow the Lord fully, to choose "the reproach of Christ;" ask for him the spirit of humility, faith, and love, which was given to Jochebed's favoured son. In view of the glorious destiny to which he is called, as well as of the perils which beset him, make him a little ark of your prayers.

An honoured woman was Jochebed, mother of Moses, Aaron, and Miriam, all peculiarly favoured by God; and thrice blessed is every Christian parent, whether her offspring live for usefulness below, or be early taken to bliss above, who at the last day shall appear with an unbroken family before the Heavenly King! "Thou whose blood hath redeemed me and mine, and whose grace has preserved us—lo! Here am I, and the children whom Thou hast given me!"

Pharaoh's Chariot.

IT is much more than three thousand years since the mighty wall of waters fell crashing and thundering on Pharaoh and his host; since over his chariots and his horsemen swept the huge billows of the sea. We will not, however, look on his chariot as drawn from the watery waste, where it lay perhaps imbedded in coral, with the dank sea-weeds wrapped around it, pierced by the ship-worm, with the finny inhabitants of the deep gliding under the decaying axle, or over the broken wheel. We will survey Pharaoh's chariot in all its pomp of colour and gilding; as it was when the tyrant mounted it to pursue after Israel, a chariot meet for one of the mightiest of monarchs, one of the proudest of men. We will look on it as it was when powerful and fiery horses bore it rapidly onward, under the guidance of the skilful charioteer, and armed multitudes followed on its track.

What stern and terrible emotions must have darkened the countenance of Pharaoh as he set his foot on that chariot, which was to bear him on, as he deemed, to his revenge! He was the tyrant from whom the captives were escaping; the lion from whom his prey had been torn; the bereaved father whose bitterness of anguish was turned into thirst for vengeance. To Pharaoh, every forward bound of his horses, every revolution of those massive wheels, seemed to brine him nearer to what he most eagerly desired: "The enemy said, I will pursue, I will overtake, I will divide the spoil; my lust shall be satisfied upon them; I will draw my sword, my hand shall destroy them!"

The speed of the royal chariot would appear too slow for the impatience of the monarch within it. And yet to what goal was Pharaoh so eagerly rushing, to what was he pressing on with such fiery haste? Death and a watery grave! In a few hours he was to be a gasping, struggling, dying man in that chariot, or to be swept out of it like a whirling straw on a cataract by the power of the mighty waves!

As was his chariot to Pharaoh, so is ambition to those whose all-absorbing object is to advance in the course of worldly distinction. There are many, not only in the higher but in the lower ranks of life, whose one great wish and aim might be expressed in the words "to get on in the world." Rapid advancement is their grand object; and they are not careful as to what they crush under their chariot wheels. If conscientious scruples come in their way, they pass over them; regard for the interests of others cannot stay them in their career; success is the goal towards which they eagerly drive, though that success with each individual may take a different shape. With one it may be an empire, with another a thriving business; the soldier's highest mark may be a marshal's baton, while the village girl's dream of distinction is to become one day a lady. With one the chariot of ambition is more richly gilded, more gorgeously emblazoned, than with another, but in some form it is mounted by all who seek worldly advancement in this life as their chief end and goal.

Doubtless there is something exhilarating in the rapid motion; the feeling that every turn of the wheel brings the eager aspirant to rank, or power, or wealth, or fame, nearer to what he desires. This feeling is not confined to hardened sinners like Pharaoh. The world does not judge ambition severely, it rather admires the gilded chariot if it bear a man onward to success. But if any one of my readers should be tempted to mount it, let him first look forward calmly and thoughtfully to that point where, to all earthly ambition, it will be said, "hitherto shalt thou come, but no further."

The waters of death lie before us, high and low; monarch and slave alike are swallowed up there, as the waves of the Red Sea made no distinction between mighty Pharaoh and the meanest of his host. What will the proudest earthly success matter to us when once those waters close over us?

"Can storied urn, or monumental bust,

Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath?

Can honour's voice awake the silent dust,

Or flattery soothe the dull cold ear of death?"

There is another chariot mentioned in Scripture, which affords the most striking contrast to that of Pharaoh. Its circling wheels woke no echoes amongst the rocks, left no impression upon the sands. It was prepared for a poor and weary man, whose feet had long trodden a thorny path of trial. I allude to Elijah's chariot of fire—the noblest car into which a son of Adam was ever permitted to mount. It came from Heaven, and Heaven was its bourne. In that chariot, borne above the waters of death, which might not so much as wet the sole of his foot, in Elijah the corruptible assumed incorruption, and the mortal put on immortality!

The subject is a very sublime one, but the lesson which we may draw from it is practical. If Pharaoh's chariot be an emblem of ambition, we may regard Elijah's as the emblem of a spirit of devotion. It descends from Heaven; it is sent by our God to bear His servants upwards towards Him. Not all the waters of death shall quench or dim its glory, for it is immortal like Him who bestowed it.

Reader, a choice is before us: one of these chariots may receive us, but into whichever we enter, it must be by turning away from the other. The man whose first aim and desire is to push himself forward in the world, to press over whatever impediments conscience may place in his way, though he may possess shining qualities, cannot be a true disciple of the meek and lowly Redeemer. While he who has given himself heartily unto Christ, in a spirit of earnest devotion, cannot rest his chief hopes upon any object, however grand, of mere earthly ambition. "The pride of life" is not of the Father, but of the world. "If any man love the world, the love of the Father is not in him."

What, then, is the direction of our most earnest desires? Is it onwards or upwards? Is the goal towards which we are pressing below the skies or above them? If the career before a man be but that of self-seeking pride, however rapid may be his promotion, however swiftly he may sweep on in the path of distinction, with the gaze of an admiring or an envying crowd fixed upon him, every turn of the wheel but brings him nearer to the dark goal of destruction, where his vain ambition, like the chariot of Pharaoh, must perish with the life of its possessor!

The Tables of Stone.

BROKEN; alas! Shivered and broken! The gift of the Most High—the tables inscribed with the Law which was uttered in the thunders of Sinai, with the commandments which Israel had thrice vowed to keep—all broken through the baseness of man!

But man is not willing to own this. He has gathered the broken fragments together, as the shivered pieces of a precious ancient vase were once gathered, and has placed them together, fitting bit to bit, and has fastened them firmly, as he deems, with the cement of his own self-righteousness. He believes that there are few particles missing. Perhaps, indeed, he has not kept the Fourth Commandment in all its integrity; perhaps some fragments are wanting in the Tenth; but still, on the whole, he believes that he can present fair, almost faultless, tables, on which God will look with approval, and fellow-creatures with applause. When the Pharisee's eye rested on the tables of the Commandments—that proud eye detected no flaw—he cried, "God, I thank Thee that I am not as other men!" When the young ruler was questioned by the Lord, he, too, marked no breach in the heaven-given Law: "all these things have I kept from my youth up," was the complacent answer of a conscience at rest.

The Lord Jesus, the Source and Fountain of Light, threw such radiance on the Law of God, which man had broken, that the flaws and fractures in it became terribly manifest to every unblinded eye. Christ showed that the Commandment extends to the words of the lip and the thoughts of the heart. How self-righteousness melts under the burning power of that declaration from the Saviour, which sums up all the Commandments in two! "Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength: this is the First Commandment. And the Second is like, namely this, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself." No one, but Him who gave the Law, could keep that Law unbroken!

Yet still, even to the present day, man takes self-righteousness to cement the fragments, and in his secret soul believes his work to be successful. He regards the Tables of Stone as holy; he knows that they were given by God; and his object, sometimes secret, but sometimes even avowed, is to make of them stepping-stones in the way to Heaven, so that he may pass the river of death without fear. He says, in his heart, that he has so carefully kept the Commandments, that he may safely rest upon them, and so receive the reward of obedience.

But woe to man, guilty man, if he trust his safety to that which has been broken again and again, and which never can be effectually joined together again by human effort. Not to his faithfulness in keeping God's Commandments, can the highest saint look for salvation. He knows that he might as well place his foot on a foam bubble floating on a torrent, and trust to that bubble to keep him from sinking, as rest on the broken Law to save him from being swept away to everlasting destruction.

They who have tried most carefully to keep the Law, are most ready to own this truth. Well does the Church of England make her children's response to each Commandment a petition for "mercy." Then at the close of all comes a prayer that God would write His Laws in our hearts, in allusion to His own gracious promise: "I will put My laws into their mind, and write them in their hearts; and I will be to them a God, and they shall be to Me a people."

When our Lord sojourned upon earth, a sinner was brought before Him who had notoriously broken the Law. Christ appealed to the consciences of her accusers, and conscience convicted them all of having, likewise transgressed God's Commandment. Twice on that memorable occasion, "Jesus stooped down, and with His finger wrote upon the ground." No action of the Lord recorded in Scripture can be without significance. If we humbly try to penetrate the meaning of this one, may we not find that the Lord would remind man, that though scribe, Pharisee, and those whom they condemned, had all broken the Law contained in the Tables given through Moses, yet that Christ could write that Law so indelibly in dust and ashes, "with the Spirit of the living God, not in tables of stone, but in fleshy tables of the heart," that it should ever remain there? Thus every true believer becomes, in the forcible language of St. Paul, the epistle of Christ; the Law being inscribed therein by "the finger of God," not as a ground of acceptance, but as a token of adoption.

And let us never forget that what is written in the heart will assuredly be read in the life; none will so earnestly endeavour to keep the Commandments in thought, and word, and deed, as he who has received them in the spirit as well as the letter, "whose obedience is the cheerful heart-service of the man whose transgression is pardoned, whose sin is covered."

The High Priest's Mitre.

A VERY remarkable scene is brought before us in the history of Alexander the Great. During his career of conquest, he had been offended by the Jews, then subject to his enemies the Persians. Unlike the Samaritans, who had sent troops to the aid of Macedon's mighty king, the Jews remained faithful to their allegiance to Darius. Alexander, little accustomed to have his imperious will opposed, resolved that as soon as he should have conquered Tyre, to which he was then laying siege, he would march against the Jews, and let them also feel the weight of his wrath.

Tyre fell, merciless slaughter ensued, the city was given to the flames, and many of its inhabitants to the sword; while, with yet more horrible cruelty, Alexander caused two thousand of the miserable Tyrians to be crucified along the sea-shore! Such was the conqueror who was now to march against defenceless Jerusalem!

Let me give the account of what followed in the words of Rollin, the historian: "In this imminent danger, Jaddus, the high priest, who governed under the Persians, seeing himself exposed, with all the inhabitants, to the wrath of the conqueror, had recourse to the protection of the Almighty, gave orders for the offering up of public prayers to implore His assistance, and made sacrifices. The night after, God appeared to him in a dream, and bid him to cause flowers to be scattered up and down the city; to set open all the gates; and go, clothed in his pontifical robes, and all the priests dressed also in their vestments, and all the rest clothed in white, to meet Alexander, and not to fear any evil from that king, inasmuch as He would protect them. This command was punctually obeyed; and, accordingly, this grand procession, the very day after, marched out of the city to an eminence, where there was a view of all the plain, as well as of the temple and city of Jerusalem."

Here the high priest and his company awaited the approach of the terrible conqueror surrounded by his victorious bands. The boldest amongst the Jews might well tremble before the destroyer of Tyre. But great was the astonishment, both of the Macedonians and the Jews, at the scene which ensued, when the victorious monarch met the unarmed and defenceless Jaddus.

"Alexander was struck by the sight of the high priest, on whose mitre and forehead a gold plate was fixed, on which the name of God was written. The moment the king perceived the high priest, he advanced towards him with an air of the most profound respect, bowed his body, adored the august Name upon his front, and saluted him who wore it with a religious veneration . . . All the spectators were seized with inexpressible surprise; they could scarcely believe their eyes. . . Parmenio, who could not yet recover from his astonishment, asked the king how it came to pass that he, who was adored by every one, adored the high priest of the Jews.

"'I do not,' replied Alexander, 'but the God whose minister he is; for whilst I was at Dia in Macedonia, my mind wholly fixed on the great design of the Persian war, as I was revolving the methods how to conquer Asia, this very man, dressed in the same robes, appeared to me in a dream, exhorted me to dismiss every fear, bid me cross the Hellespont boldly, and assured me that God would march at the head of my army, and give me the victory over that of the Persians.' Alexander having thus answered Parmenio, embraced the high priest and all his brethren; then, walking in the midst of them, he arrived at Jerusalem, where he offered sacrifices to God in the temple, after the manner prescribed to him by the high priest."

Let us now see placed before us in the Scriptures the mitre, as appointed by God Himself to be worn by the high priest of Israel: "Thou shalt make a plate of pure gold, and grave upon it, like the engravings of a signet, HOLINESS TO THE LORD. And thou shalt put it on a blue lace, that it may be upon the mitre; upon the forefront of the mitre it shall be. And it shall be upon Aaron's forehead . . . And they made the plate of the holy crown of pure gold, and wrote upon it a writing, like to the engravings of a signet, HOLINESS TO THE LORD." It was before such a mitre as this, or rather before Him whose Name appeared on the mitre, that the proud head of earth's mightiest conqueror was bowed low in adoration.

We know that there was a solemn meaning in the various portions of the high priest's garments, and the words inscribed on his "holy crown" leave us in no doubt as to what it symbolized. He who appeared before the Majesty of Heaven to plead for Israel, and to offer the appointed sacrifices, must be holy unto the Lord. Yet how often must the weak, fallible high priest, have been humbled by the very dignity of his office, when he contrasted his own infirmity and sin with the spotless purity symbolized by his mitre!

With heavy heart must an Aaron or an Eli have bound that holy crown on their brows, when conscious of having fallen under the displeasure of the Most High! When we think of the sacred emblem being proudly worn by a Caiaphas, its being polluted by contact with that man of blood, our Lord's image of the "whited sepulchre" rises vividly before us; how fair, pure, holy, that which was without, while the dark mind within was festering corruption!

There was but one High priest who could appear before God in innate purity, "holy, harmless, undefiled, separate from sinners." It was He who wore on His bleeding temples the crown of thorns instead of the mitre; He who had HOLINESS TO THE LORD not borne aloft on His brow, but woven into every action of His life. What Aaron symbolized, that was the Lord Jesus Christ.

Before Him, arrayed in the majesty of His spotless purity, every knee shall bow, earth's proudest kings shall fall down and adore Him. "Wherefore He is able also to save them to the uttermost that come unto God by Him, seeing He ever liveth to make intercession for them."

The High Priest's Mitre—Continued.

THE high priest's mitre affords to us another, and a very wide field for meditation.

Under the Jewish dispensation, the priesthood was confined to one tribe, and the sacred crown was worn by one man; but since the rending of the veil that shrouded the Holy of Holies, all Christ's servants, even the lowly woman, even the feeble child, become "a royal priesthood," as well as "a peculiar people." The "crown of life" is for those—for all those who love the Lord Jesus supremely. The song of the redeemed is a chorus of thanksgiving unto Him who "hath made us kings and priests unto God and His Father." Surely it is in allusion to the inscription upon Aaron's mitre that it is written of the blessed in the kingdom of Christ, "His name shall be in their foreheads," according to His own gracious promise, "I will write upon him the name of My God."

There is, even in this world, a sealing, a marking of the servants of Christ, which conveys an idea both of dignity and of consecration. Very remarkable is that passage in Ezekiel which records the vision granted to the seer of the mysterious One whose "likeness was as the appearance of fire;" and the six, each with a slaughter-weapon in his hand, who signify the ministers of God's vengeance: "The glory of the God of Israel was gone up from the cherub, whereupon He was, to the threshold of the house. And He called to the man clothed with linen . . . And the Lord said unto him, Go through the midst of the city, through the midst of Jerusalem, and set a mark upon the foreheads of the men that sigh and that cry for all the abominations that be done in the midst thereof. And to the others He said . . . Go ye after him through the city, and smite . . . but come not near any man upon whom is the mark." The ministers of wrath were to spare God's people, marked as those who in the midst of a sinful generation mourned for the general corruption, and by doing so, showed that they at least valued and desired "holiness unto the Lord."

This inscription, the sentence graven upon Aaron's mitre, is, then, what all God's servants should wear—it is for them a distinguishing mark. But does this appear to be the case; is "holiness unto the Lord" the visible sign and seal of the Christian's high calling? There are many who are recognized as active, honourable, useful, zealous servants of God, but how few could we single out as being eminent for holiness!

And how, it may be asked, can holiness be defined? As that purity of thought and heart which the Spirit alone can bestow; that abhorrence of sin which is something far higher than mere abstinence from sin. The man who bears the stamp of holiness, will detect and grieve over the lightest stain upon conscience; the coarse allusion, however witty, the drunkard's song, or the scoffer's jest, will never raise a smile on his lips: nor are they so likely to be heard in his presence; for the world, like Alexander, is often constrained to pay homage where holiness is legibly inscribed, and the silence of one whose habitual walk is with God, impresses more than the open rebuke of a more inconsistent believer. Deep reverence for God and God's Word is an accompaniment of "holiness unto the Lord;" the heavenly-minded Christian will not jest with sacred things, nor lightly use quotations from Scripture.

It is the holy Christian, or to use the much abused, yet most expressive Scripture term, the "saint," who earnestly endeavours to "bring into captivity every thought to the obedience of Christ." How marvellous is that constant current of thought flowing through every mind, silently, secretly, like a narrow stream between banks so steep that we cannot catch a glimpse of its course, and can but trace it by the vegetation on either side, as our usual current of thought is judged of by our words and our actions! How often, when seated amongst silent companions—as, for instance, when travelling with strangers—have we reflected how interesting it would be, could we gain a glimpse of that stream of thought passing unceasingly through each brain; could we know whether it sparkles with hope, or "flows deeply and darkly" in shadow; whether it bears along golden grains of holy meditation, or mere bubbles of folly to break at a touch, or if the current be fetid and polluted with ideas that the lips would not dare for shame to form into words! Could the thoughts of the travellers in one railway-carriage, during a single hour of silence, be so photographed as to become visible to all, how marvellous would appear the difference between those of the worldling and those of the saint; though, alas! the musings of the holiest child of Adam would be found no pure and untainted stream, reflecting Heaven perfectly within its crystal depths.

The contrast would be yet more striking were the thoughts thus laid open to view those which had flowed during an hour of public worship. The posture of the body, the words of the mouth, might be the same, but the current of thought would appear as different in individuals, as the pestilential drainage from a marsh from the clear brooklet bearing health and fertility wherever it flows. It is impossible for us to obtain this glimpse of the stream, this knowledge of the thoughts in the minds of others, but have we ever endeavoured to gain it as regards our own? Have we tried to retrace the windings of the current for one single hour, and so enabled ourselves to estimate more correctly whether God's grace has in any degree purified "the issues of life," and imparted to our souls some measure of "holiness unto the Lord"?

Is such purity of thought actually requisite for—actually indispensable to a true Christian? To judge by the standard of the world, even that which is called the religious world, we should at once conclude that it is not. The pre-eminently spiritual Christian stands almost as singular amongst his brethren as did the high priest of Israel amongst the sons of Levi. But is not this because Christians live below their privileges, so that comparatively few let their light so shine before men that God is glorified in His saints? Let us, ere we close our meditations on Aaron's mitre and its inscription, earnestly, prayerfully, revolve the solemn exhortation addressed to the servants of Christ: "Follow peace with all men, and HOLINESS, without which no man shall see the Lord."

Balaam's Staff.

IT is with a sigh that we look on aught that reminds us of Balaam, the highly honoured, the highly gifted—he "which heard the words of God, and knew the knowledge of the Most High, which saw the vision of the Almighty, falling into a trance, but having his eyes open." In Balaam we behold a mournful example of light without heat, knowledge without practical wisdom, the gift of prophecy without that more excellent gift of charity.

Here is the staff which Balaam grasped when eagerly setting forth upon his unholy errand, desiring to curse those whom he knew that his God had blessed. What was in the heart of the seer, when, with repeated blows from that staff, he strove to urge forward the reluctant, frightened ass which he rode? Not jealousy for the honour of God—not impatience to carry the blessing of religious knowledge to Moab; but one absorbing desire for his own advancement—his own profit, though at the cost of the misery and the ruin of God's chosen people! Most forcible is the expression used by one of our most talented writers to describe a character utterly selfish, such as that of Balaam appears to have been: "A selfish man's heart is 'just the size of his coffin;' it has room to contain but himself." A description which presents to us an image not only of narrowness, but of death.

Balaam was one whose conduct belied his words. He was as a branch drawn back by main strength, but as soon as the outward pressure is removed, returning—springing back into its natural position. Fear was to him as a strong force drawing him back from sin, but only as long as the pressure remained. "Let me die the death of the righteous, and let my last end be like his!" Such was the aspiration on the lips of the prophet; but thoughts of covetousness, followed by an act of sin and the shameful death to which it led, make the history of Balaam a terrible warning to inconsistent professors of religion throughout all ages.

It is, then, possible that a man may preach to others, and yet be himself a cast away; that he may be admired, followed, looked up to as a leader in religion, and yet have no real life in his faith. He may guide others to wealth, yet be himself miserably poor! There is an analogy between the fate of such a man and that of Rose and Dietz, two explorers in North America, who discovered a creek so rich in gold, that its treasures have, for four years in succession, maintained more than sixteen thousand people, some of whom have left the country with large fortunes. *

* "The North-West Passage by Land," by Milton and Cheadle.

Surely those whose feet first trod this land of gold—those who led the way where thousands have triumphantly followed, must have turned their knowledge into boundless wealth, and have been amongst the richest of mankind! So we might well conjecture, till we read the record of their fate. Dietz returned unsuccessful to Victoria, where he was struck down by fever, and obliged to receive help from charity. The fate of Rose was sadder still. He "disappeared for months; and his body was found at length by a party of miners in a journey of discovery, far out on the wilds. On the branch of a tree hard by hung his tin cup, and scratched upon it with the point of a knife, was his name and the words, 'Dying of starvation!'" Did visions flit before the eyes of the famishing man of the vast wealth which he had discovered, but never enjoyed—of thousands feasting on the golden harvest to which he had guided them, while not a single crumb was his portion to save him from a terrible death!

Darker must have been the thoughts of Balaam, if time for thought was left, as his life-blood ebbed away where he lay involved in the fate—as he had been in the guilt—of the enemies of the Lord! To him had been revealed mysterious treasures of knowledge—his eyes had been opened, his mind enlightened. To him the Almighty had spoken—to him an angel had appeared—to him had been vouchsafed a prophetic glimpse of the Star that should come out of Jacob, the Sceptre that should rise out Of Israel. If knowledge had power to secure, or spiritual privileges to save, Balaam surely would never have perished.

"Take heed and beware of covetousness." The warning is addressed to all, but it should come with peculiar force to those who are called on—in however narrow a sphere—to deliver the message of God. Their lips must not teach one thing, and their lives another; they must not guide others to the glorious land, and themselves wander away to perish. If they stand in a clearer light than most men, greater is their guilt and their condemnation if they sin against that light.

Covetousness is a snare into which the enlightened, the honoured, the privileged have fallen; it has ruined a Balaam amongst the prophets, a Judas amongst the apostles. And yet how few dread its power over themselves! To be in haste to grow rich, is perhaps the leading characteristic of men in this age: they are impatient of obstacles in their way, as Balaam at the stumbling of the beast that he rode; they see not the opposing angel that stands before them with the warning: "They that will be rich fall into temptation and a snare, and into many foolish and hurtful lusts, which drown men in destruction and perdition. For the love of money is the root of all evil."

Rahab's Scarlet Cord.

NO fragile cord this, the "scarlet thread" which Rahab fastened in her window. Its firm twist has borne the weight of the two Israelite spies whom this woman of a doomed race, strong in faith, saved from the pursuit of their enemies. It was a moment of deep anxiety when Rahab led the spies to the casement in the darkness of night, and ere they descended by that scarlet cord, earnestly pleaded with them for the family whom she loved.

"Now therefore, I pray you, swear unto me by the Lord, since I have shewed you kindness, that ye will also show kindness unto my father's house, and give me a true token: and that ye will save alive my father, and my mother, and my brethren, and my sisters, and all that they have, and deliver our lives from death!"

"Our life for yours," answered the men to their brave and generous preserver. "Behold," they afterwards said, "when we come into the land, thou shalt bind this line of scarlet thread in the window which thou didst let us down by: and thou shalt bring thy father, and thy mother, and thy brethren, and all thy father's household, home unto thee. And it shall be, that whosoever shall go out of the doors of thy house into the street, his blood shall be upon his head, and we will be guiltless; and whosoever shall be with thee in the house, his blood shall be on our head, if any hand be upon him."