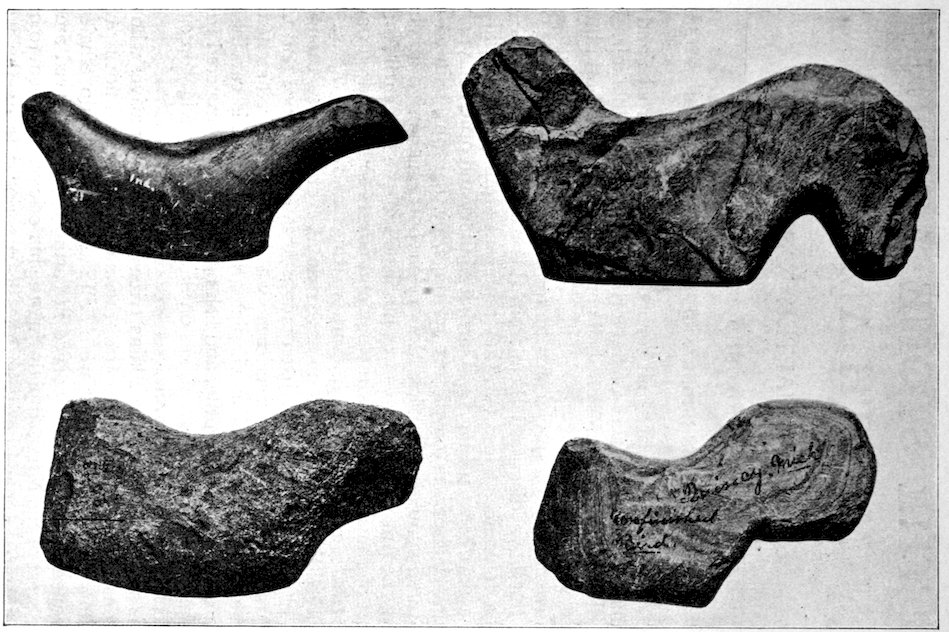

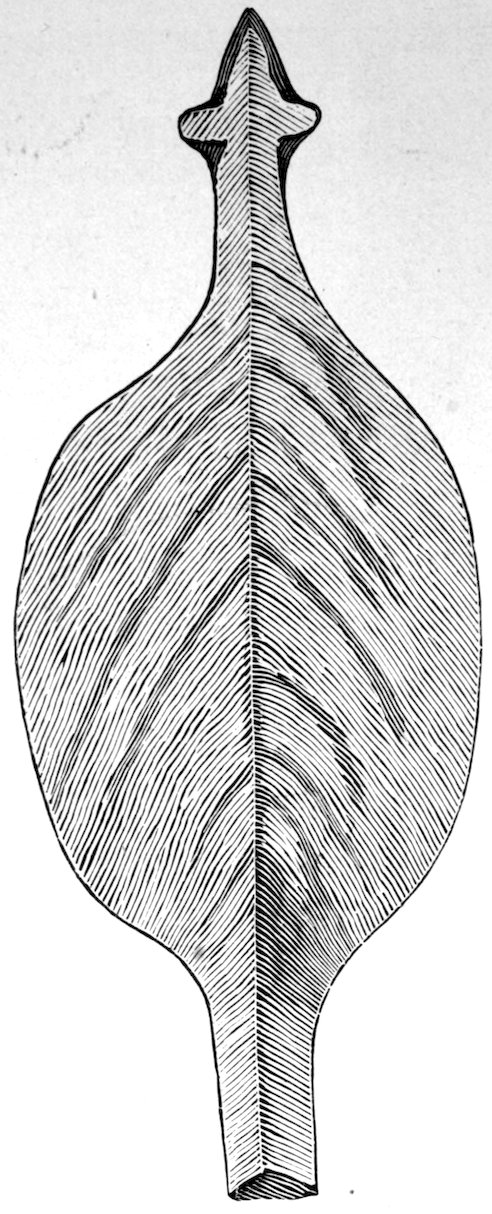

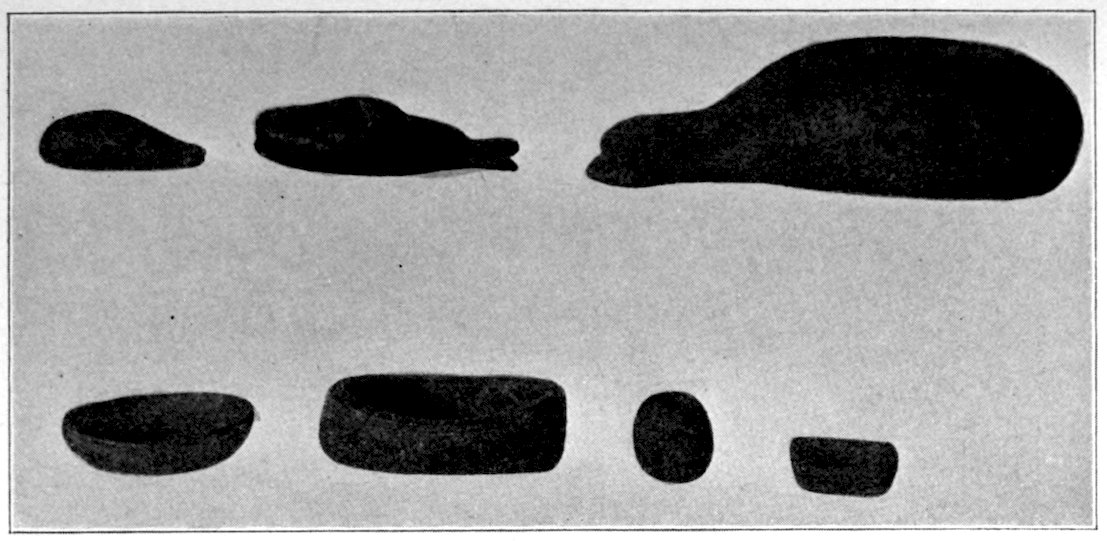

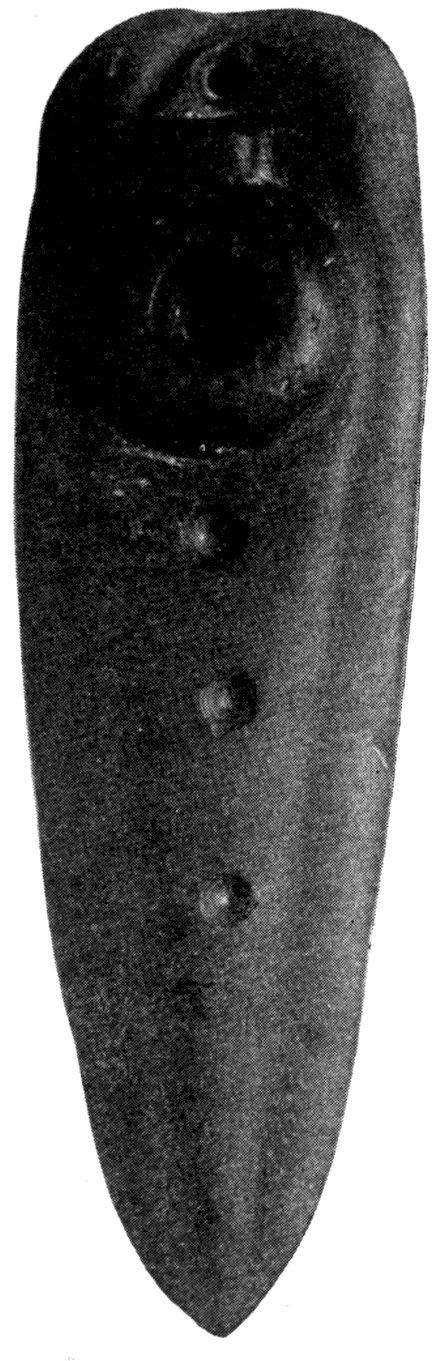

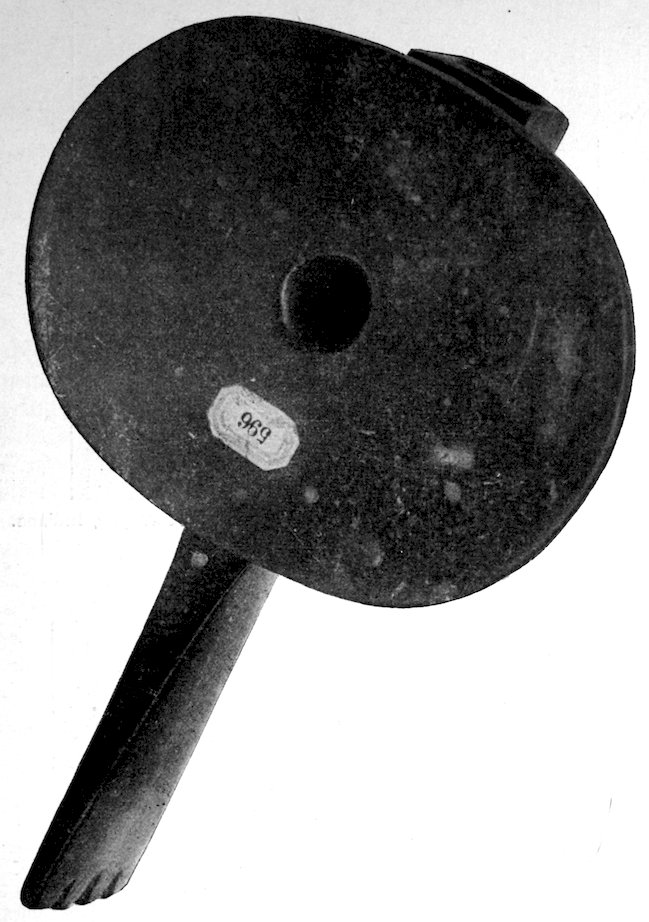

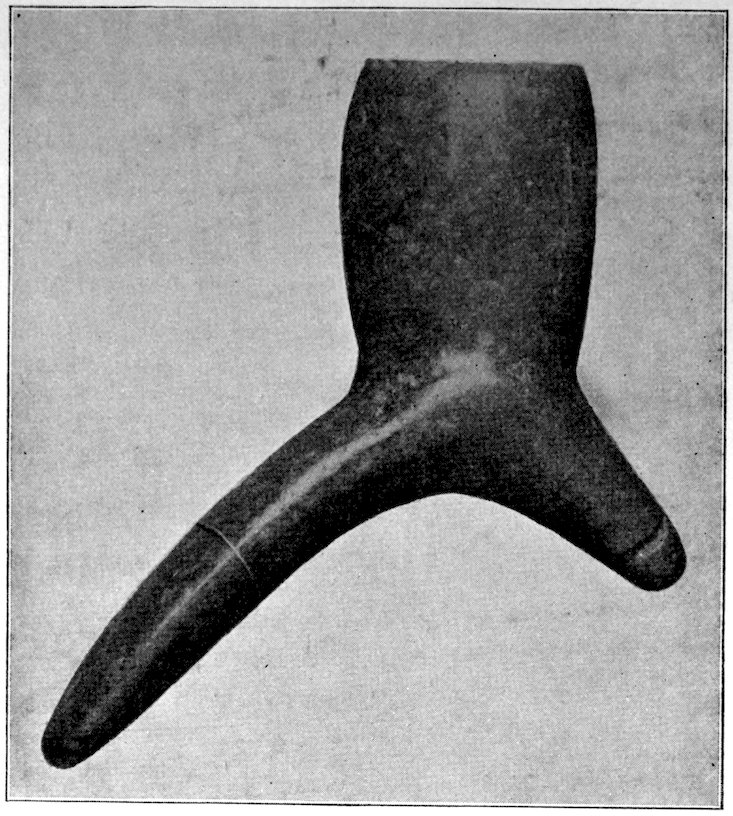

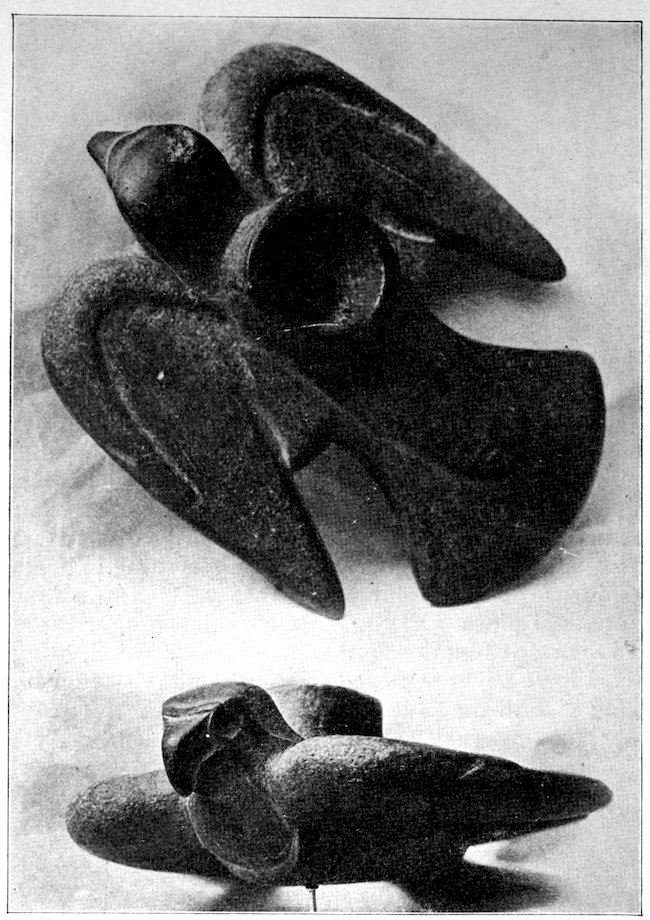

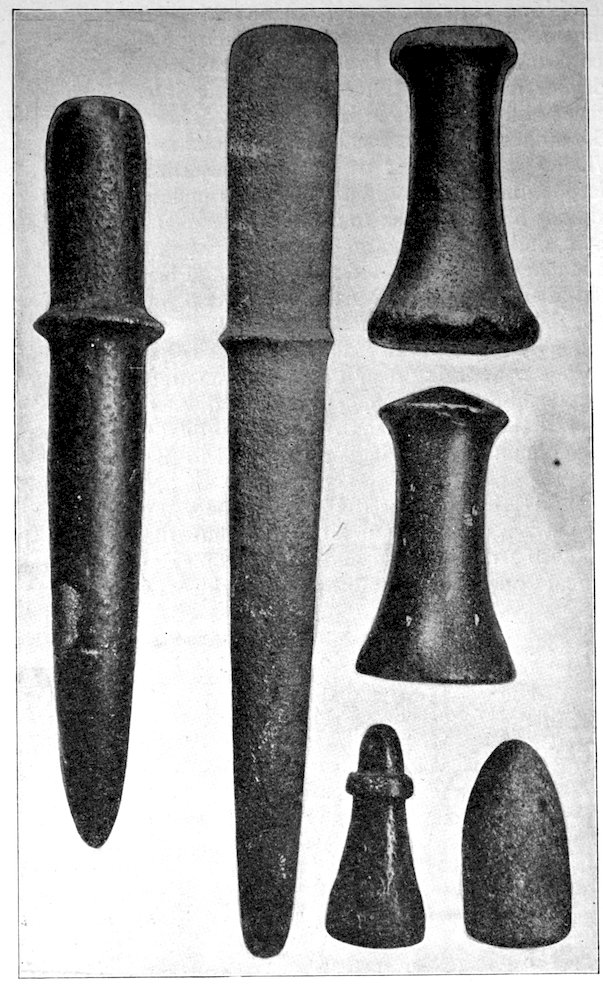

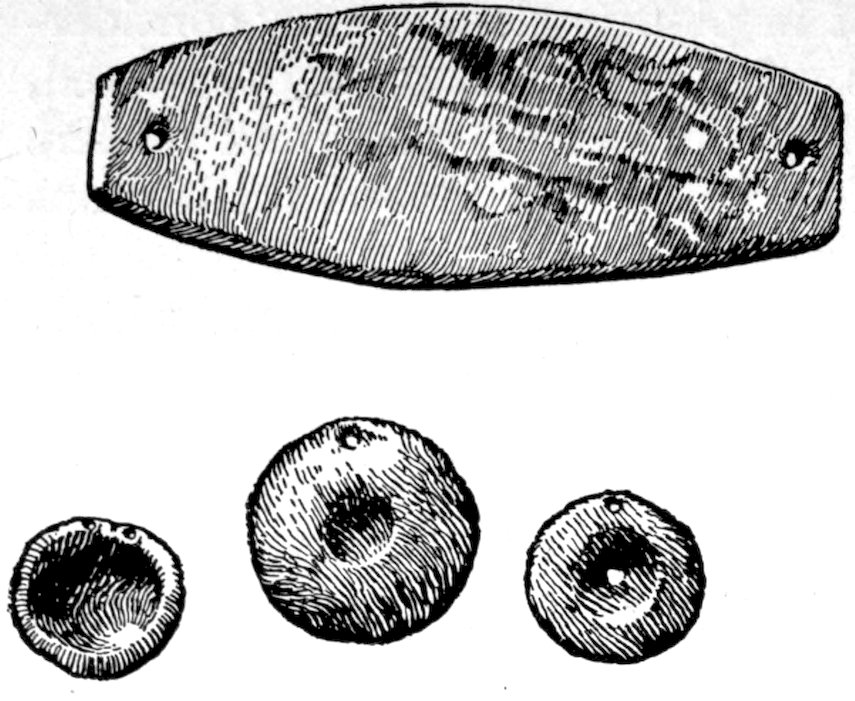

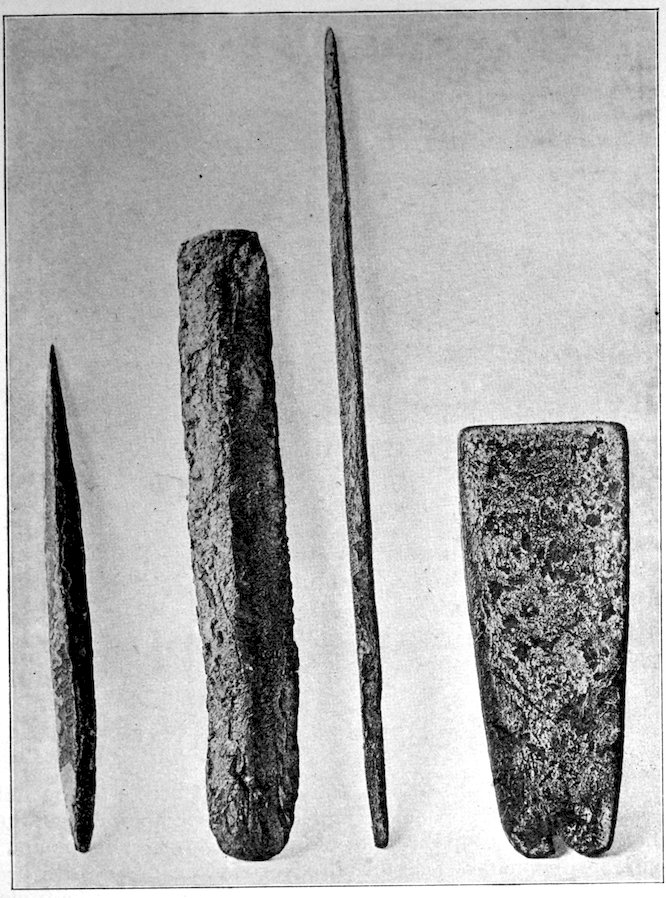

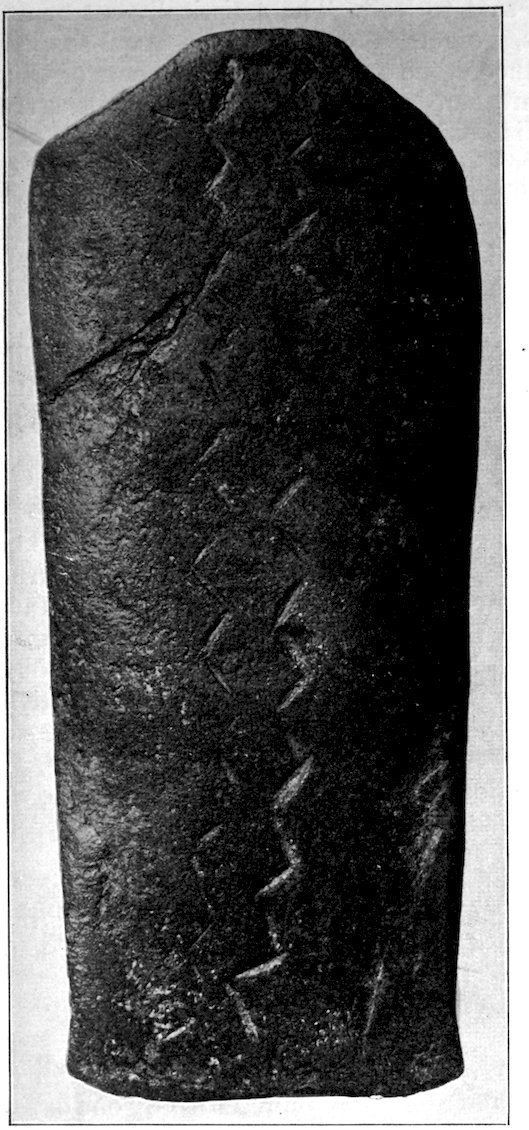

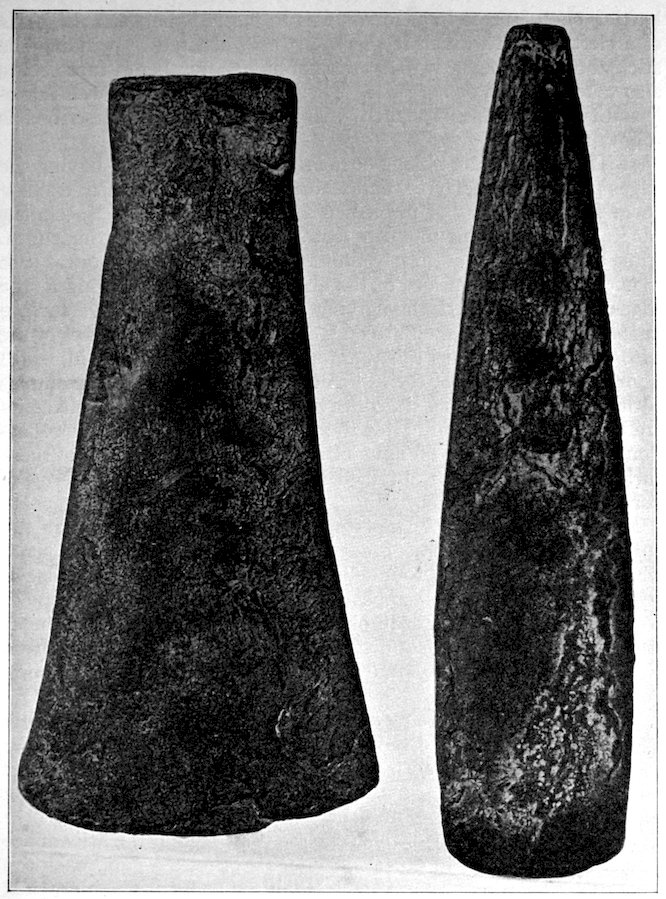

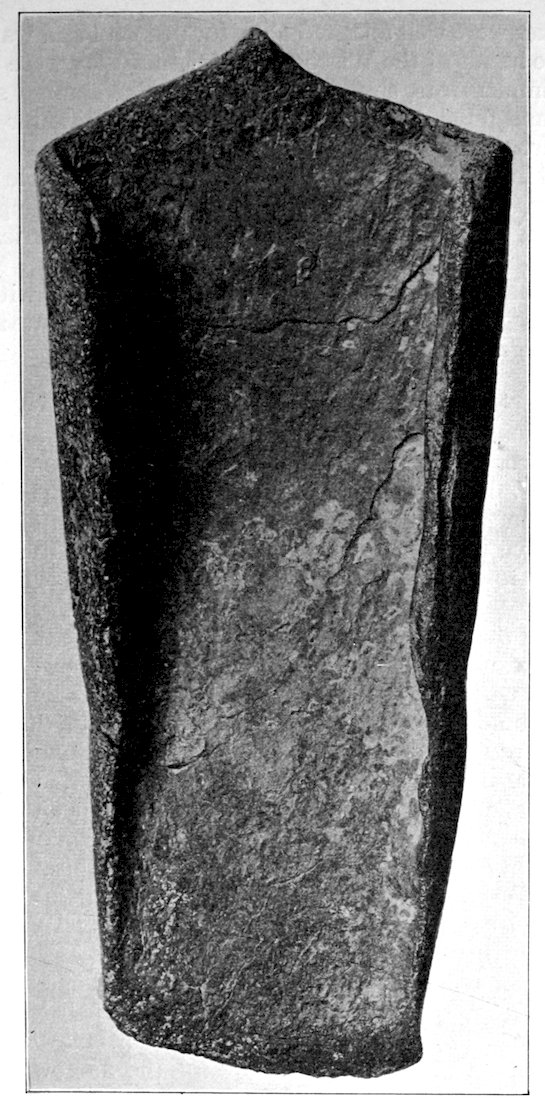

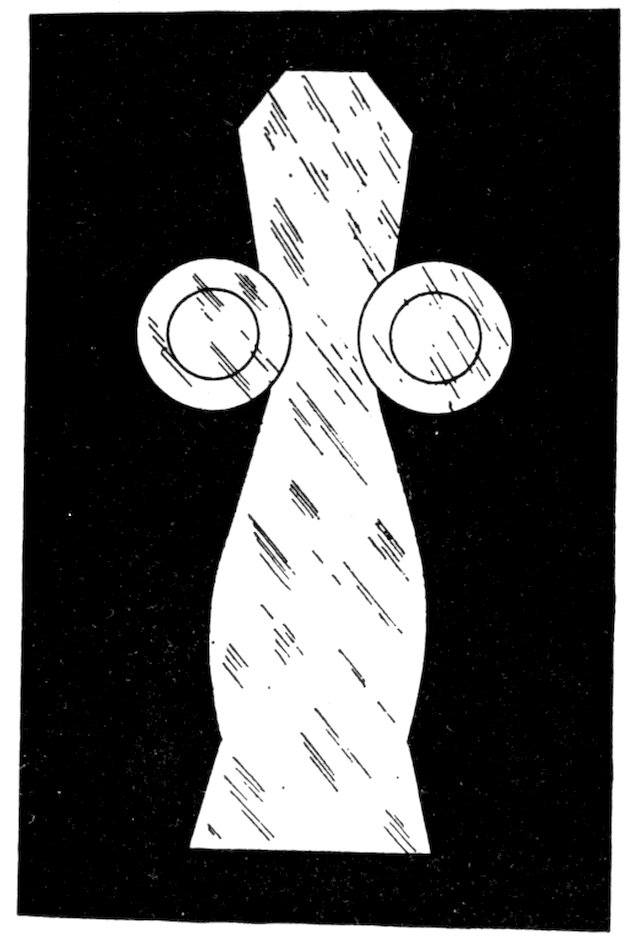

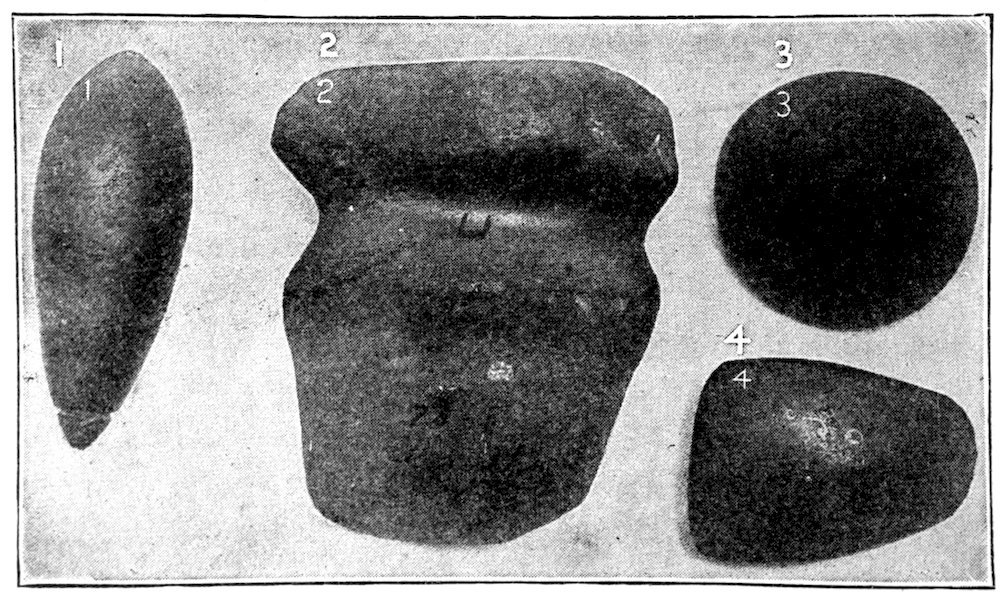

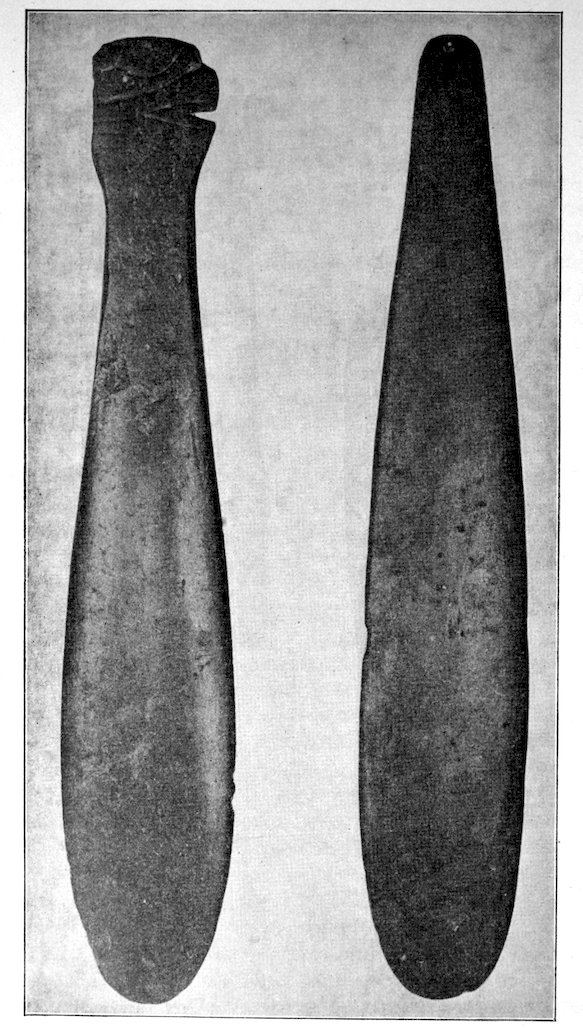

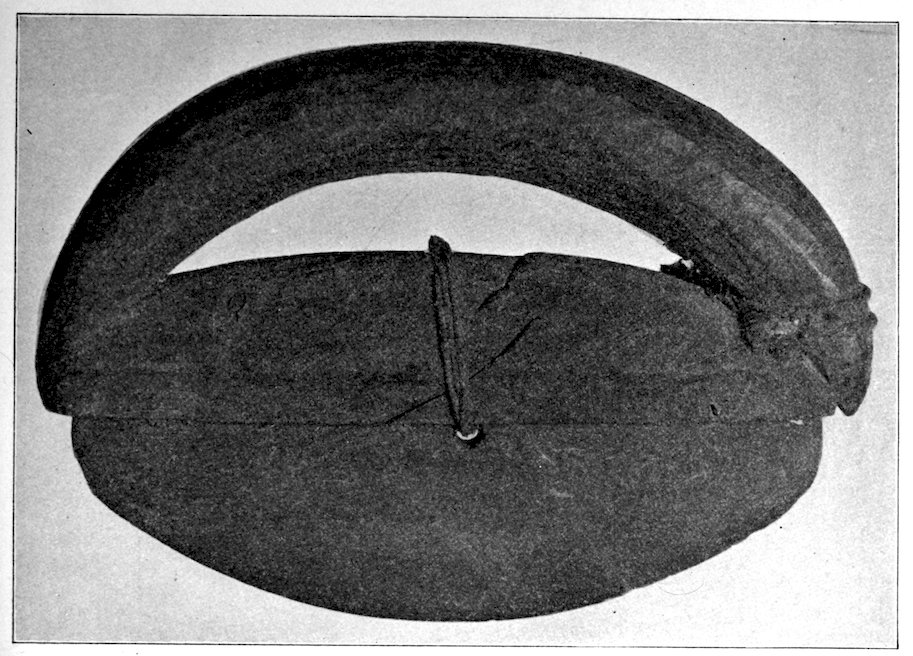

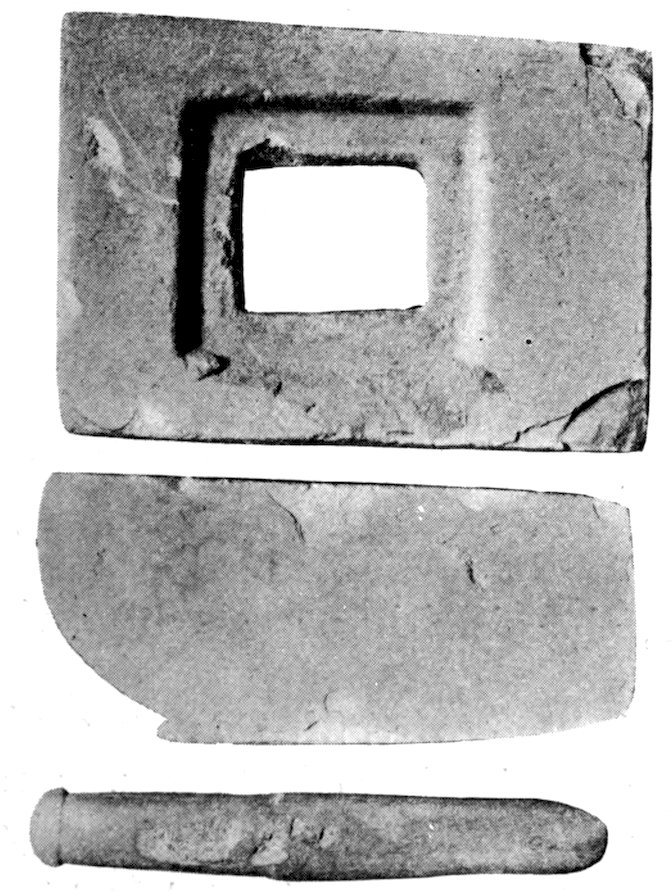

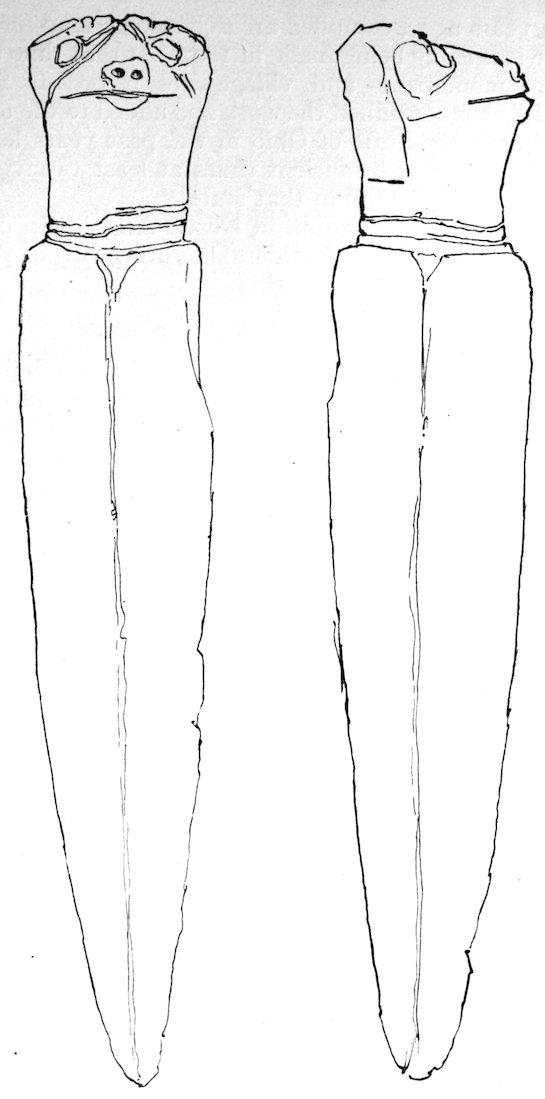

Fig. 223. (S. 1–1.)

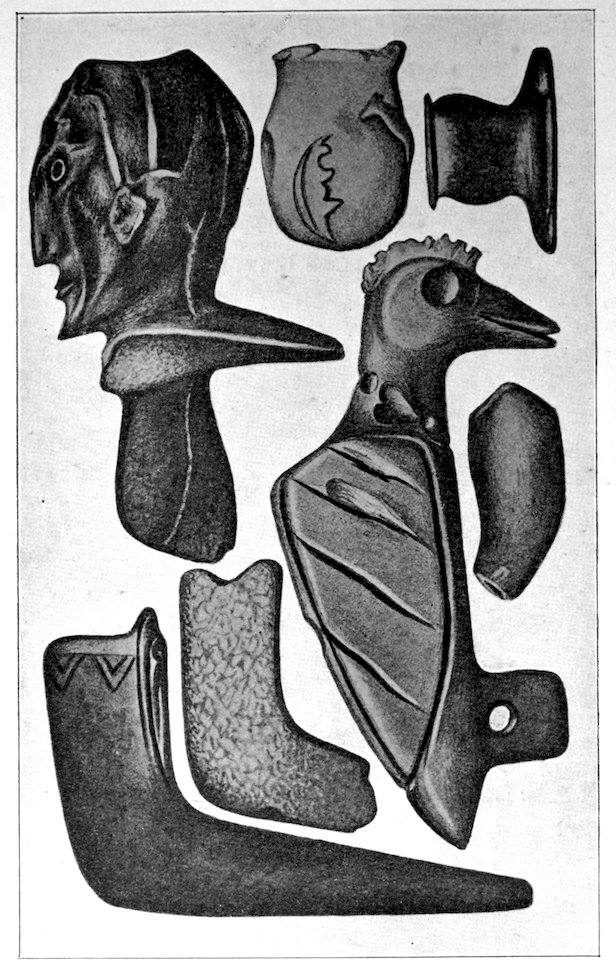

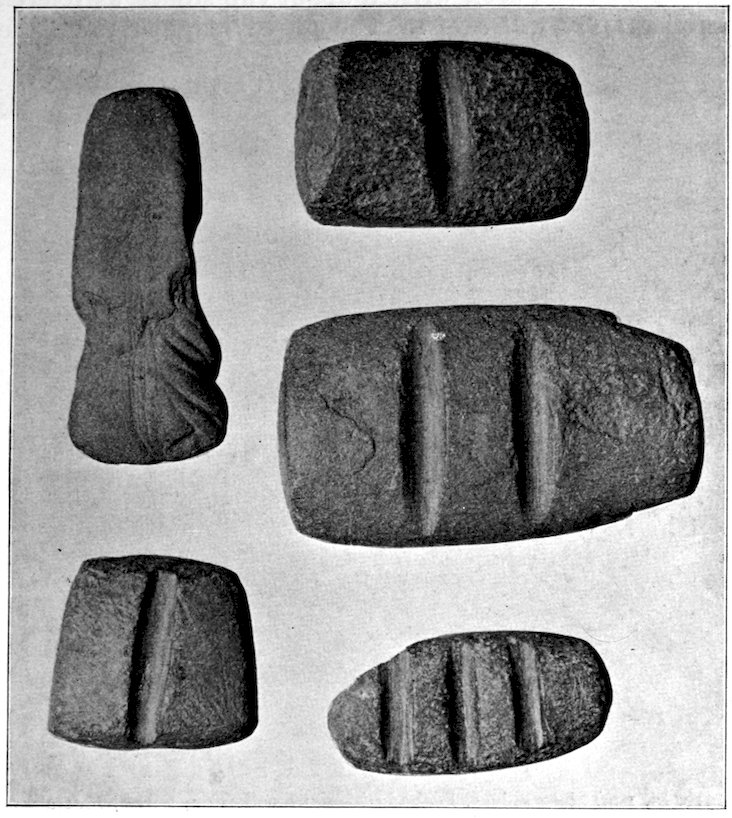

Two grooved effigies and two celts, from the Bahama Islands, West Indies. Reproduced in natural colors. B. W. Arnold’s collection, Albany, New York.

Title: The stone age in North America, vol. 2 of 2

Author: Warren K. Moorehead

Release date: September 7, 2024 [eBook #74390]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: Houghton Mifflin company, 1910

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Peter Becker, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

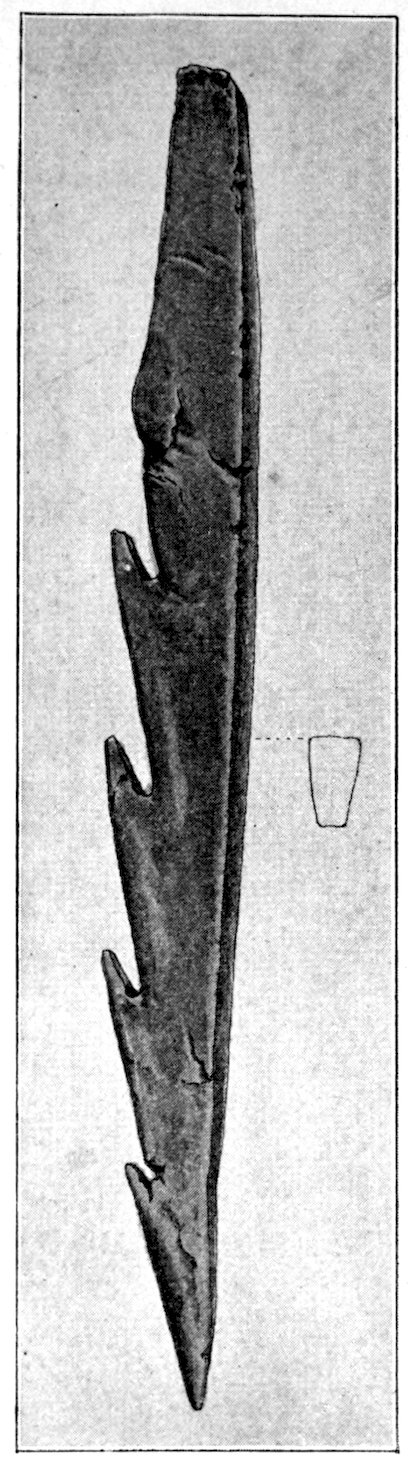

Fig. 223. (S. 1–1.)

Two grooved effigies and two celts, from the Bahama Islands, West Indies. Reproduced in natural colors. B. W. Arnold’s collection, Albany, New York.

![[Logo]](images/title.jpg)

| XXV. | Ground Stone | 1 |

| Effigies in stone and wood—bird-stones | 1 | |

| Animal and human effigies | 20 | |

| XXVI. | Ground Stone | 29 |

| Stone pipes | 29 | |

| The classification of pipes | 32 | |

| XXVII. | Ground Stone | 95 |

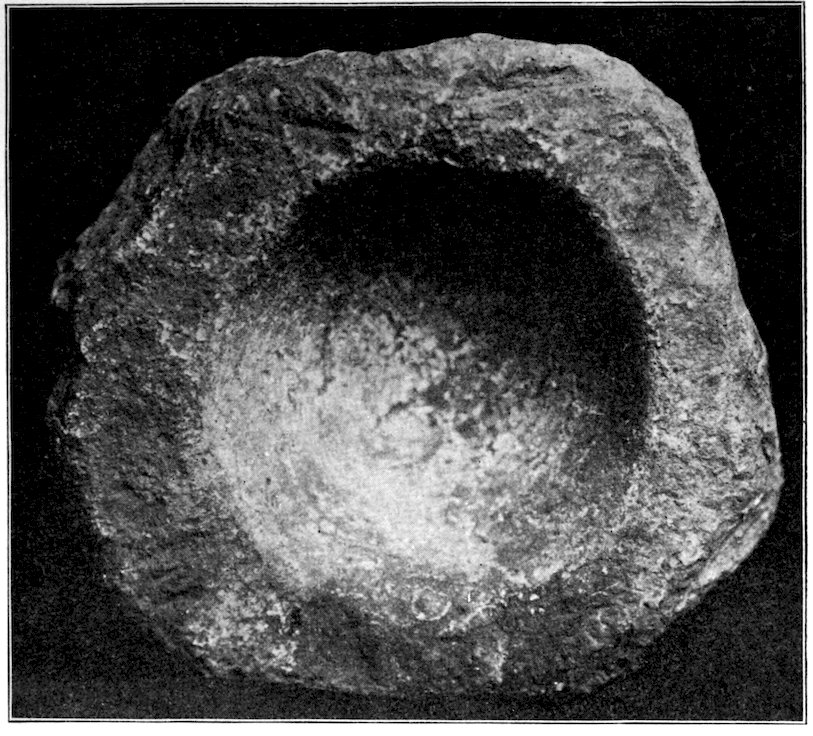

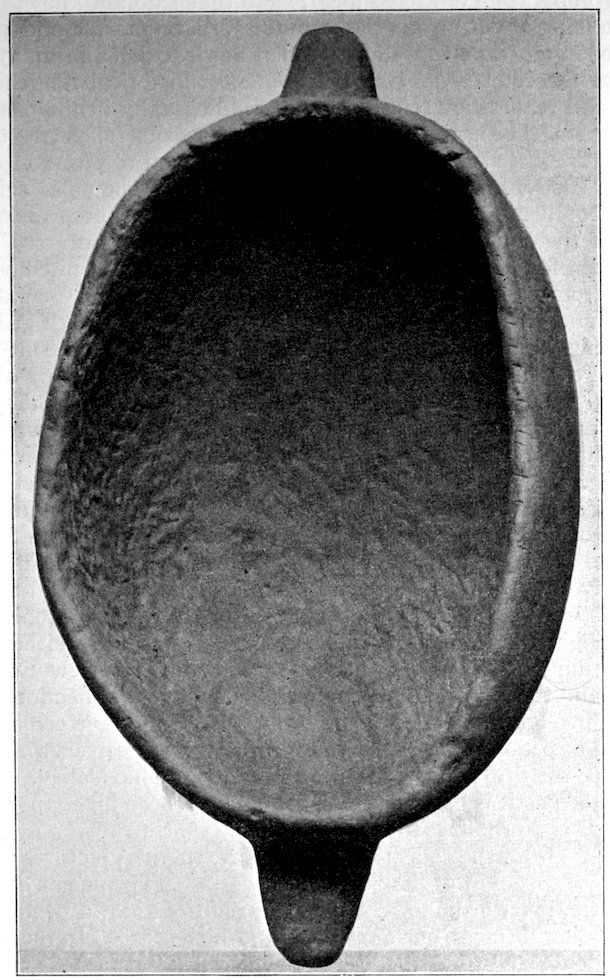

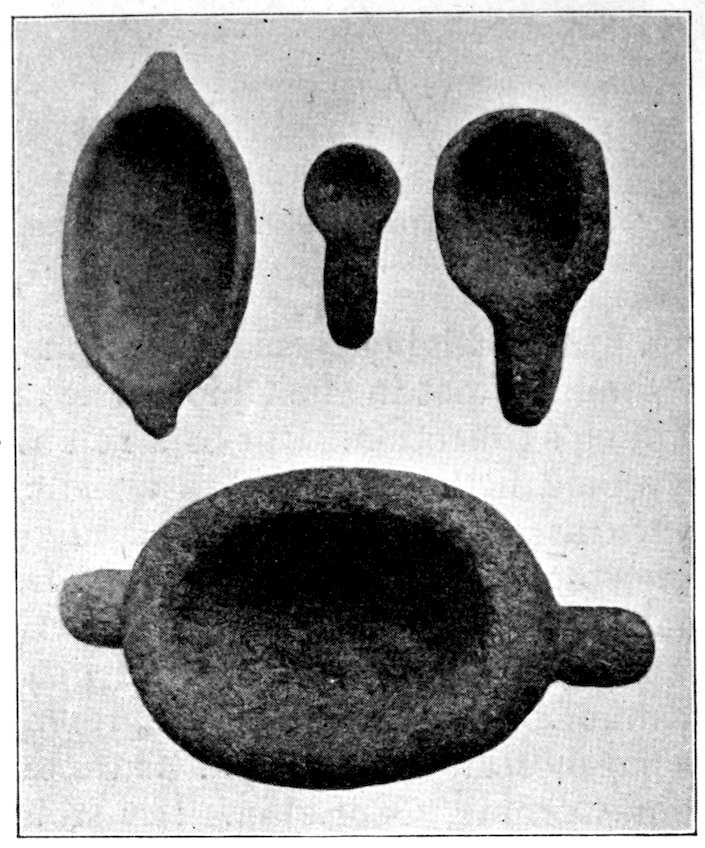

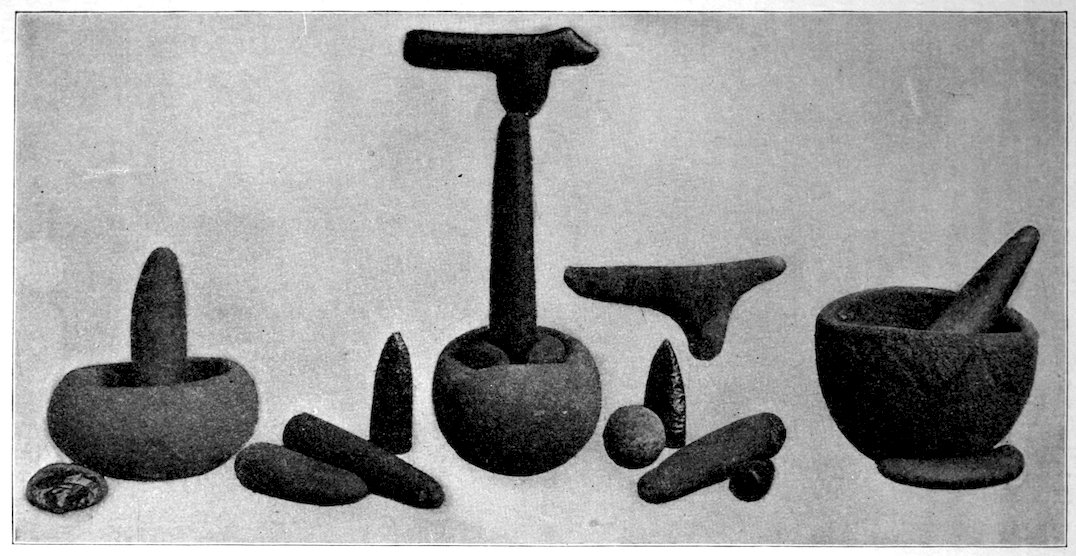

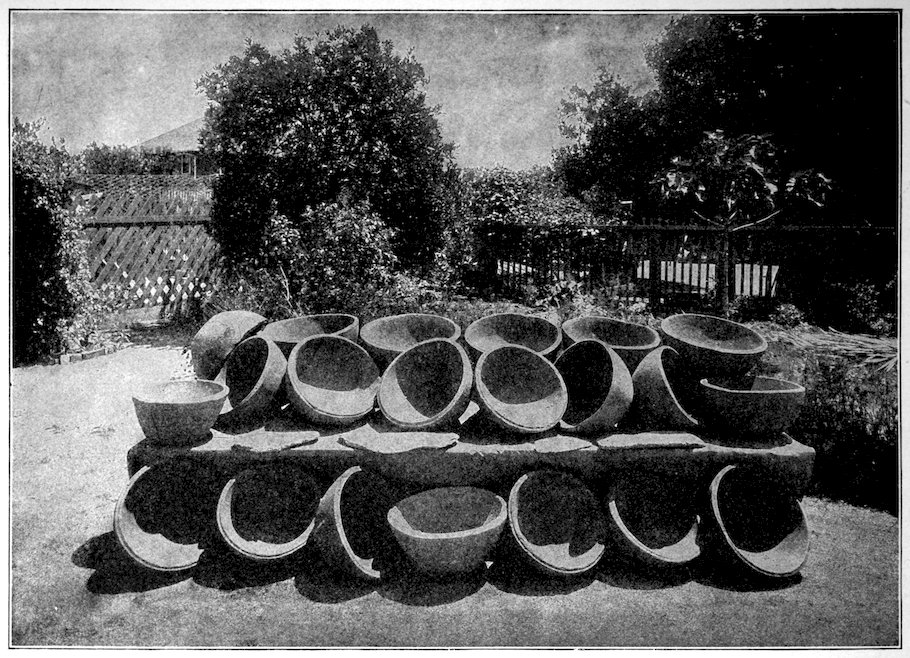

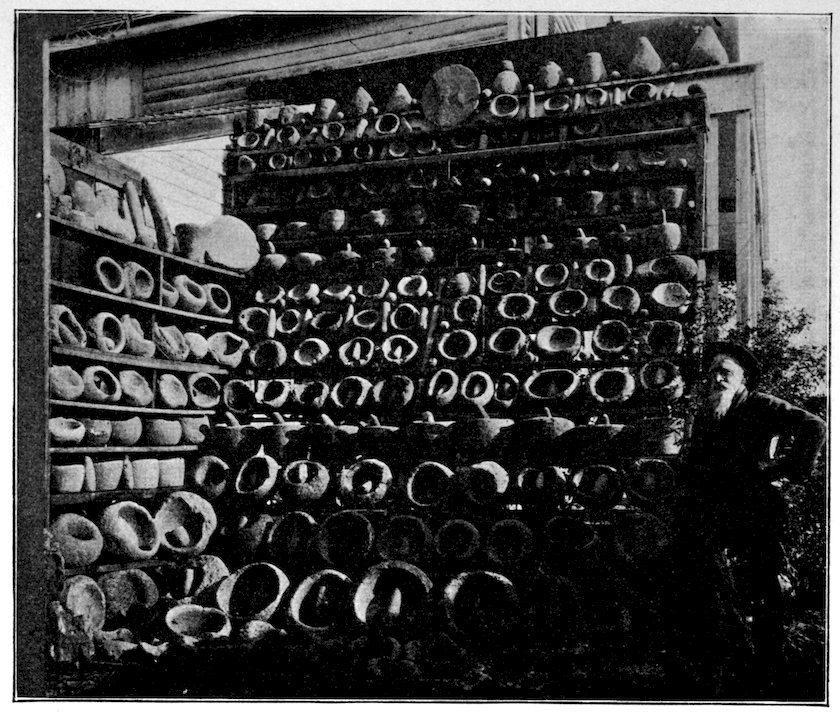

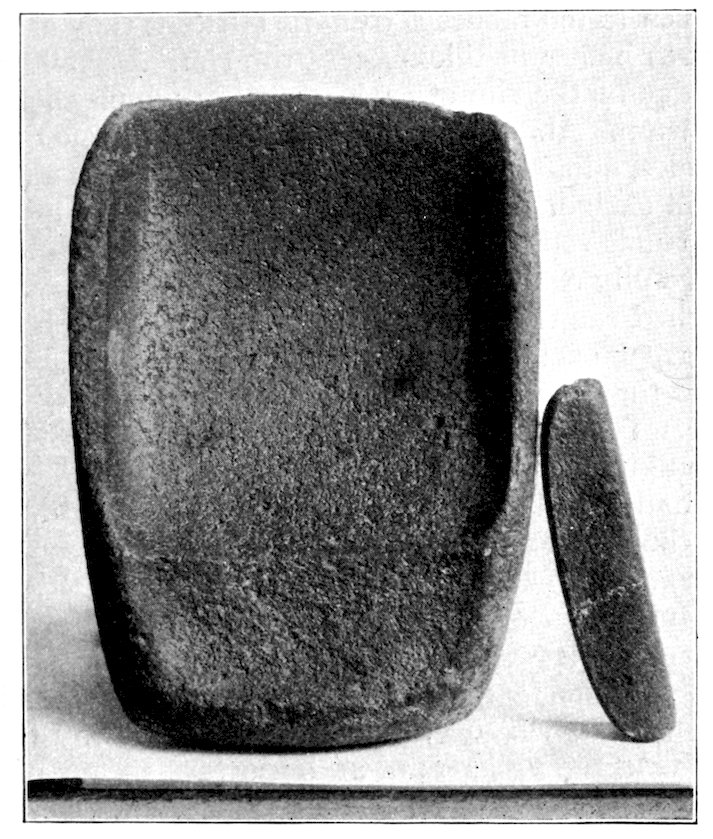

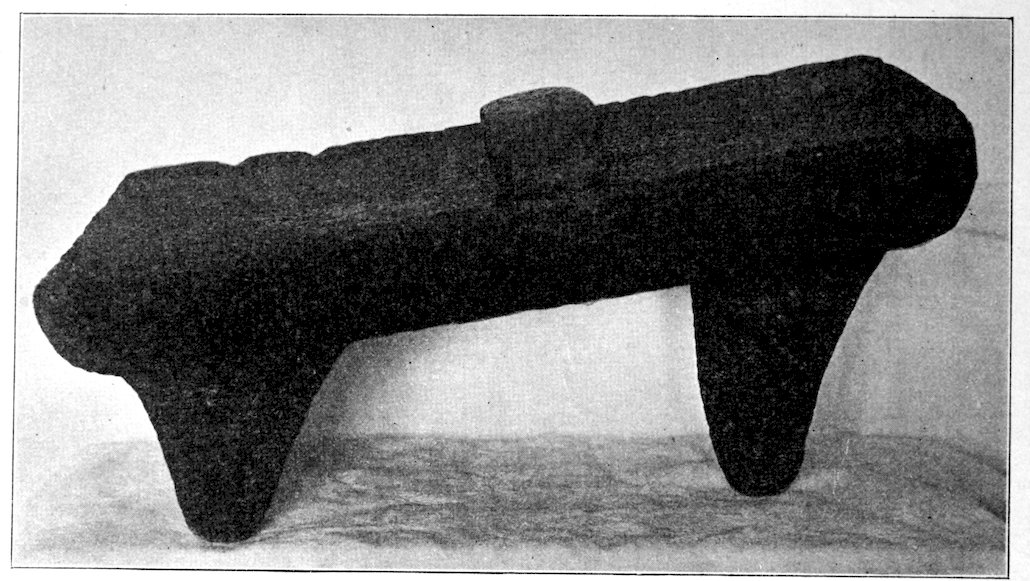

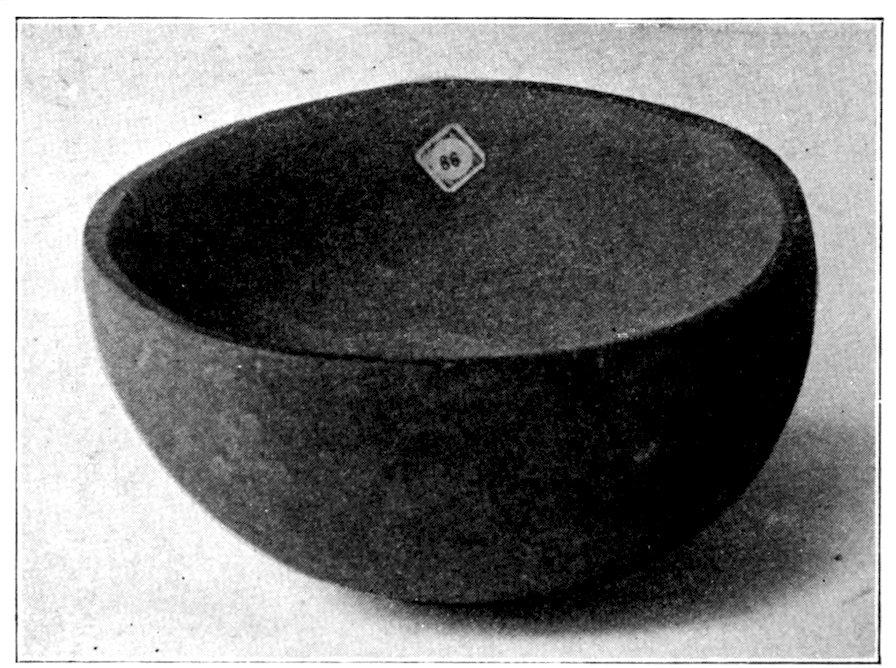

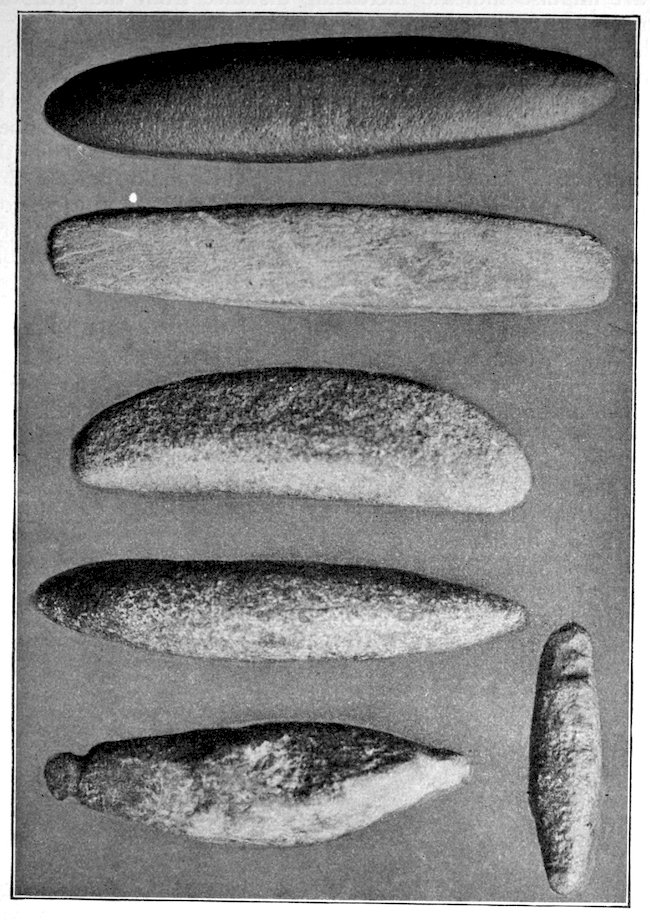

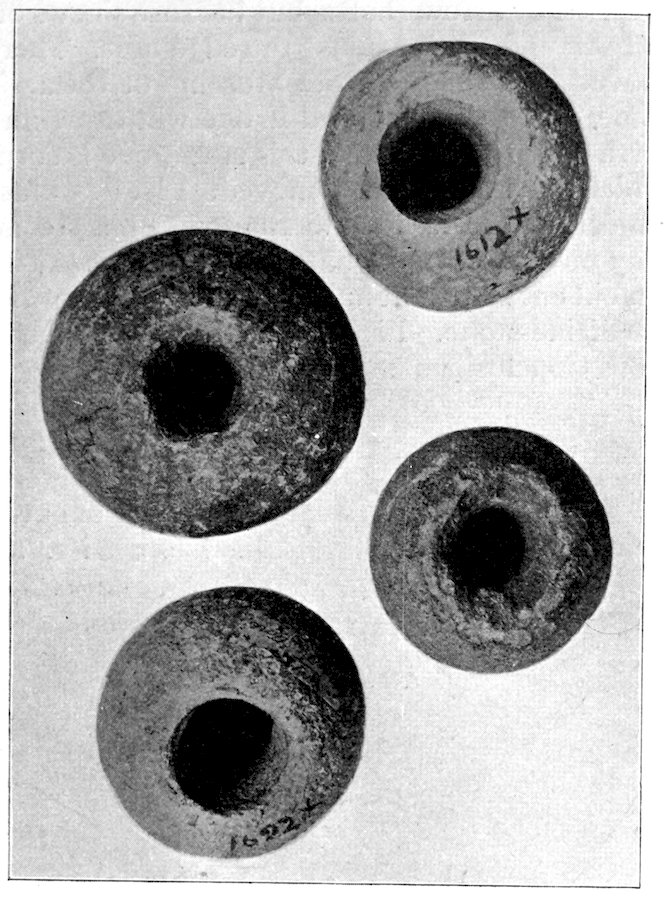

| Mortars and pestles | 95 | |

| XXVIII. | Objects of Shell | 117 |

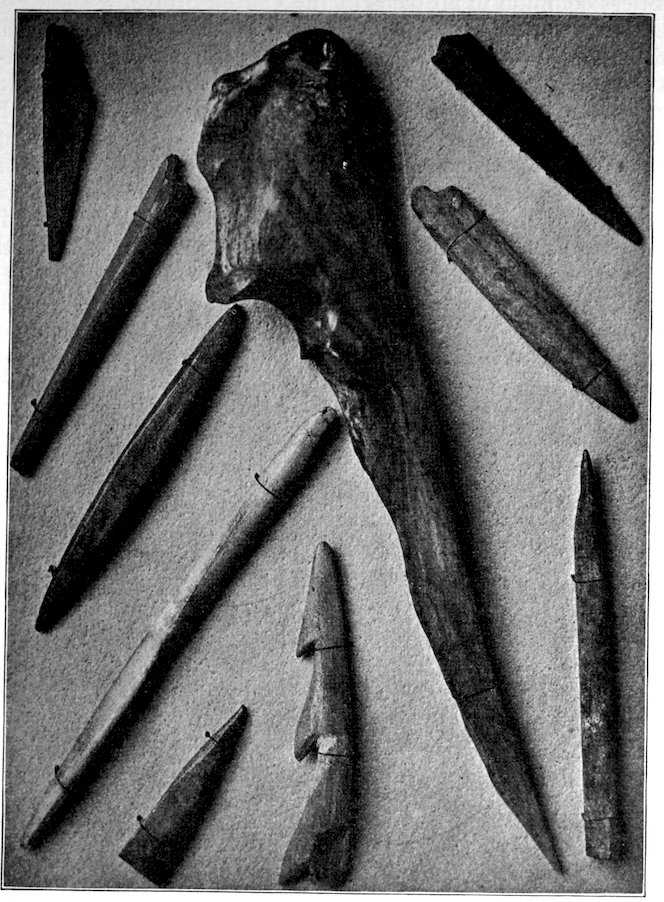

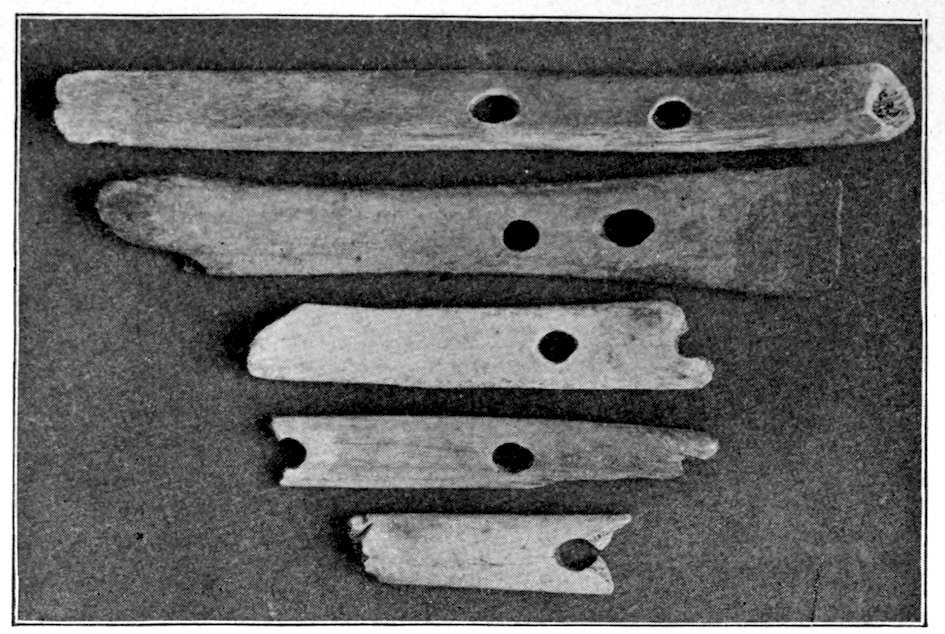

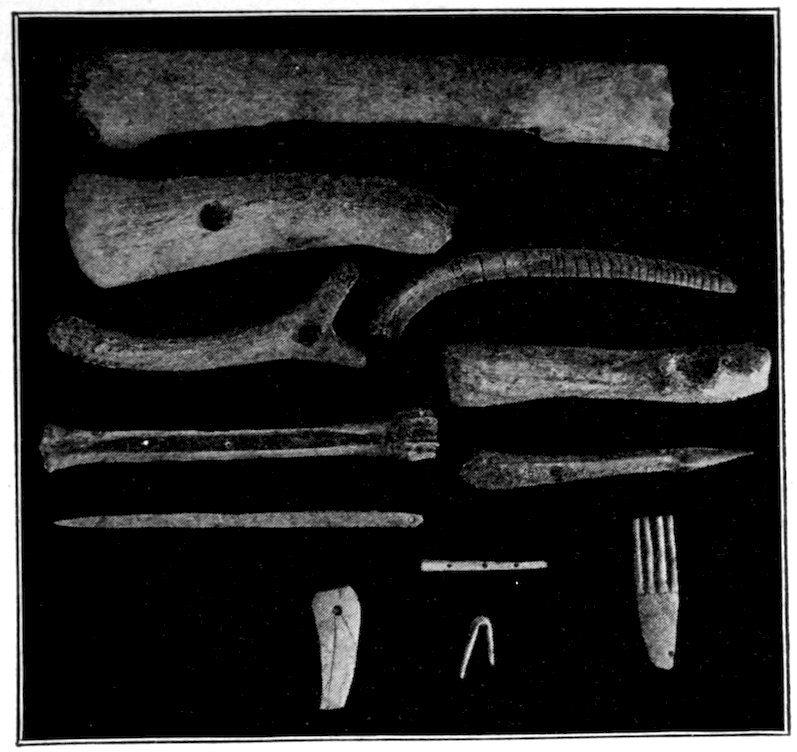

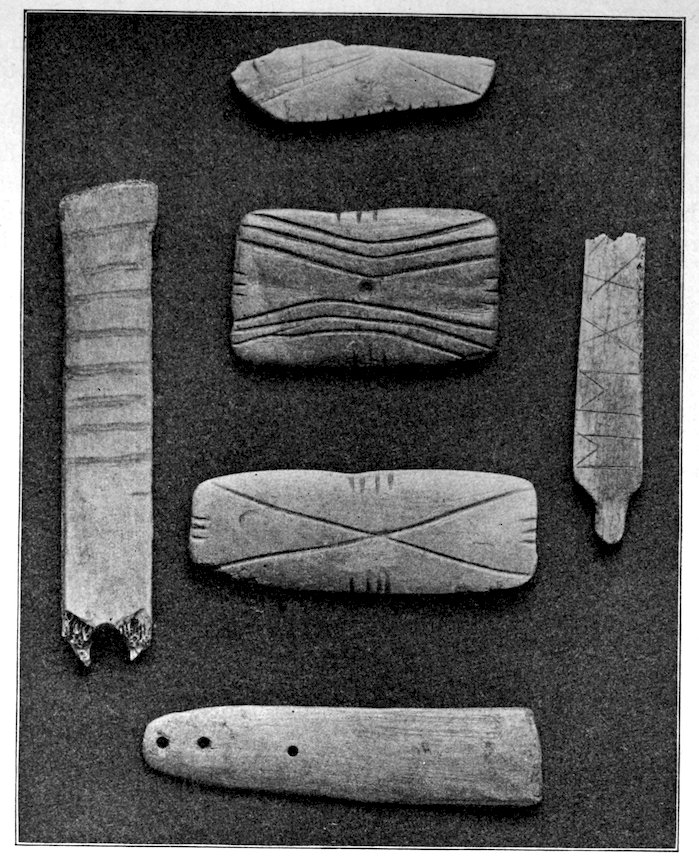

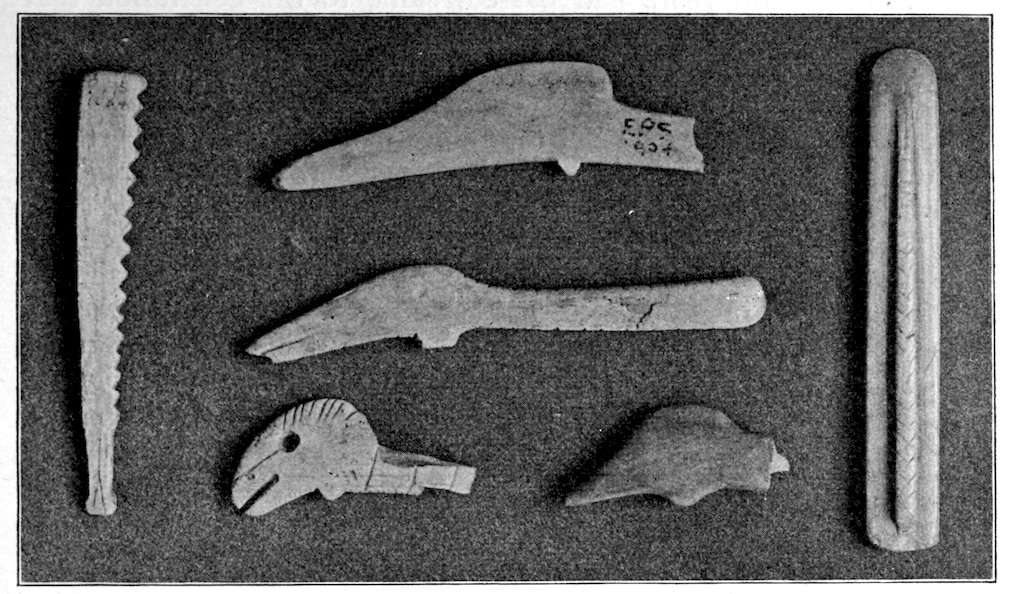

| XXIX. | Objects of Bone | 134 |

| Mandan bone implements | 149 | |

| XXX. | Objects of Copper | 161 |

| The native copper implements of Wisconsin | 161 | |

| Fabrication | 172 | |

| Distribution | 174 | |

| Classes and functions | 178 | |

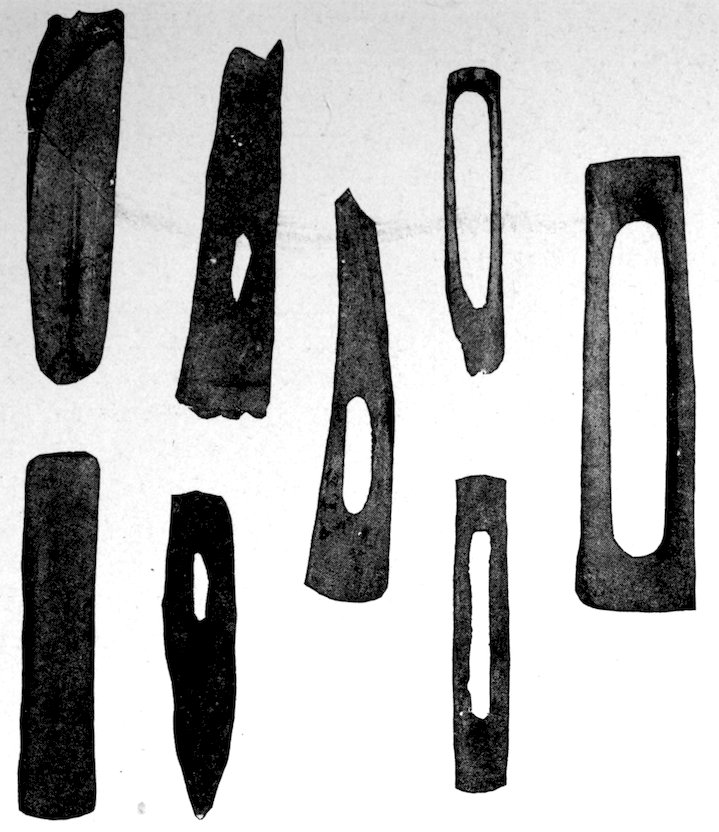

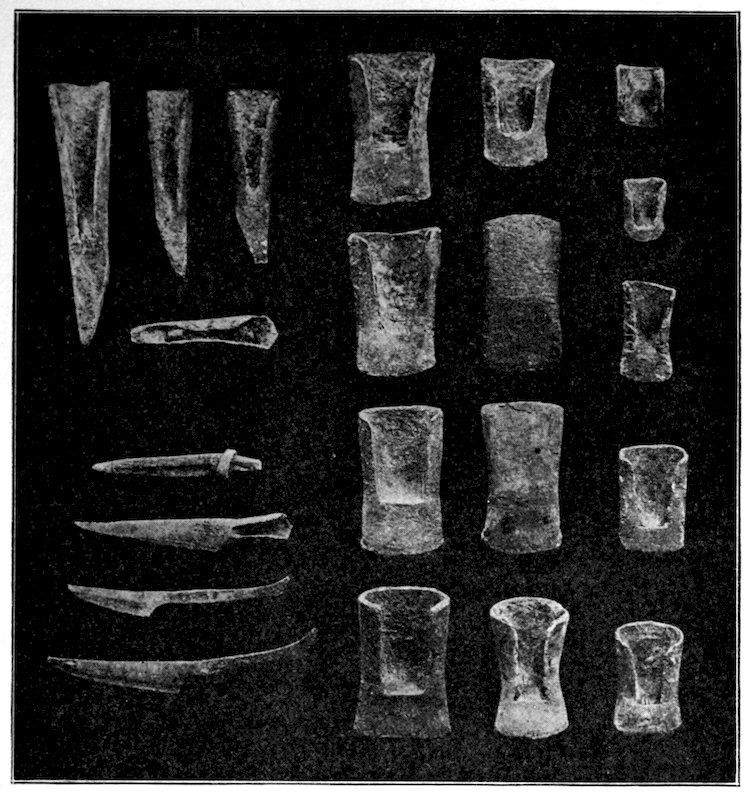

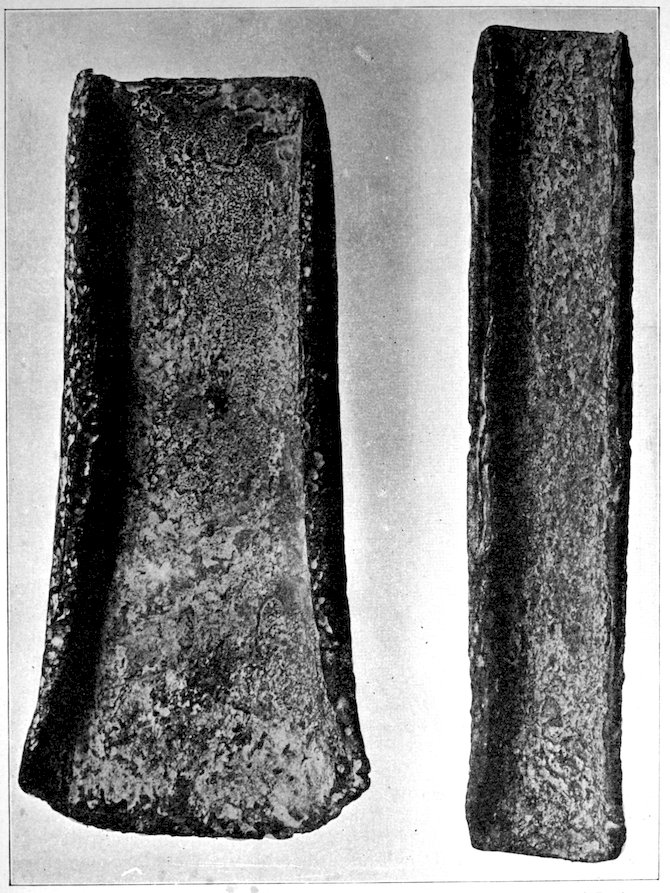

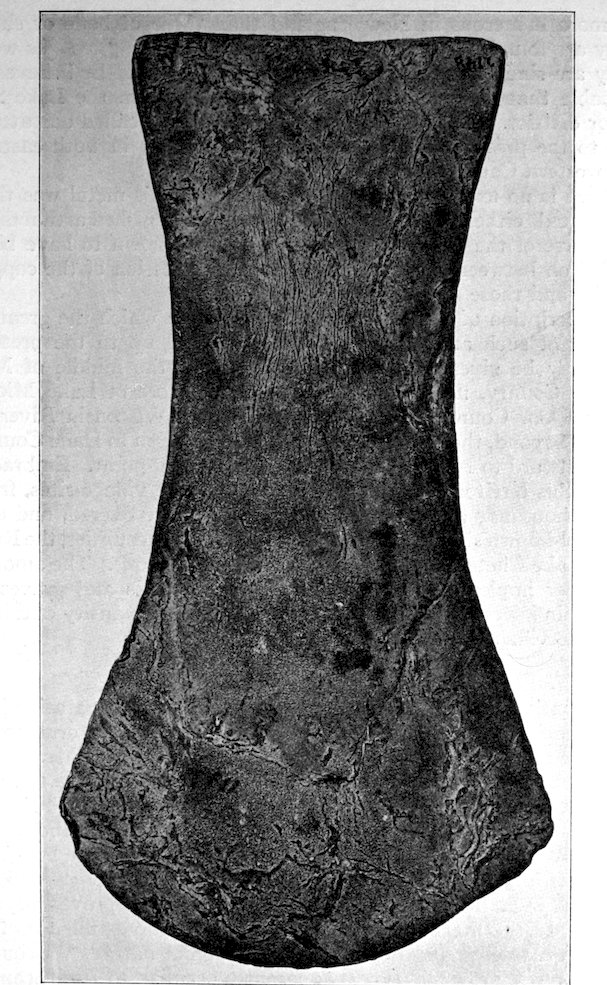

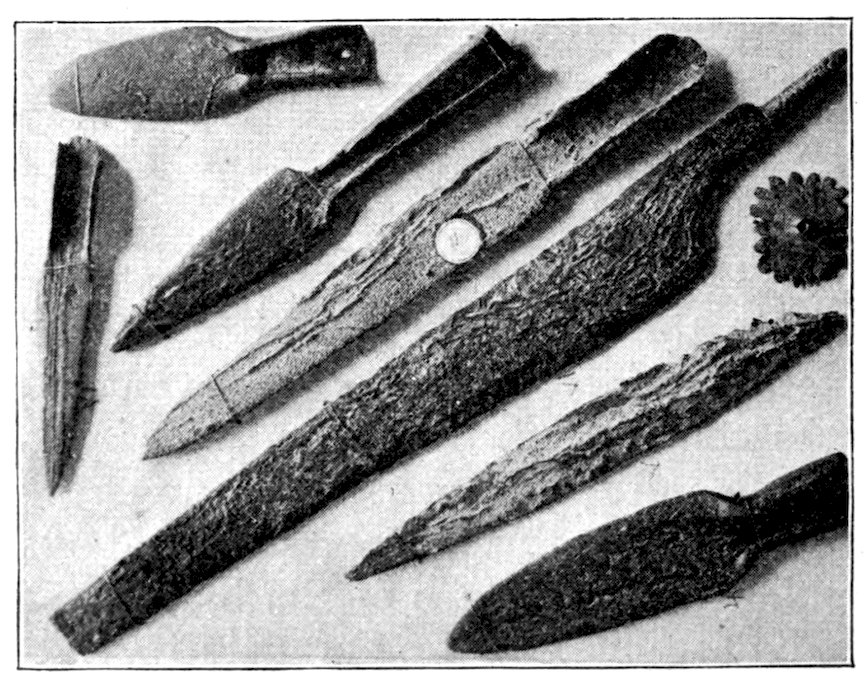

| Axes | 180 | |

| Chisels | 184 | |

| Spuds | 186 | |

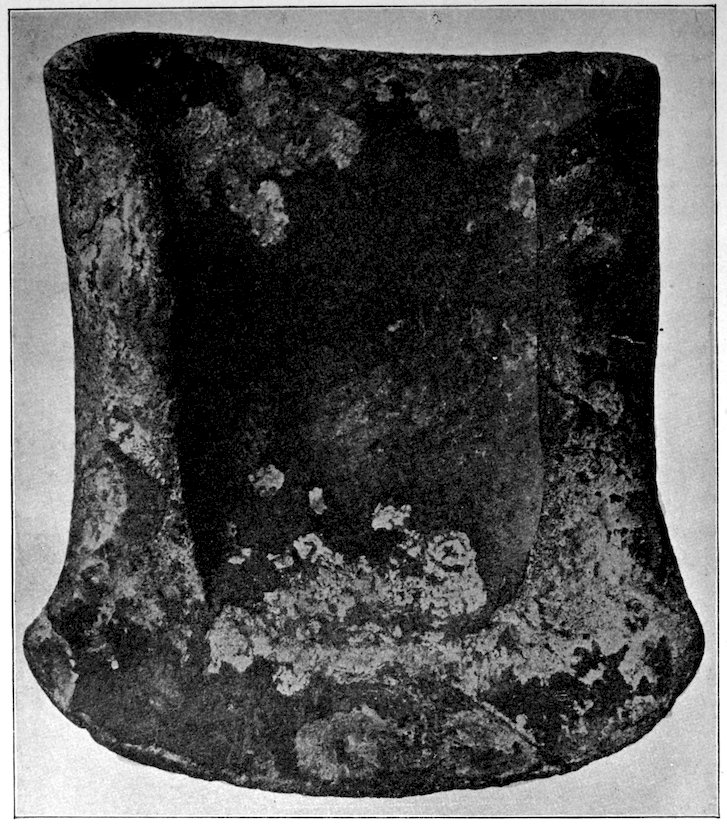

| Gouges | 188 | |

| Adzes | 189 | |

| Spatulas | 192 | |

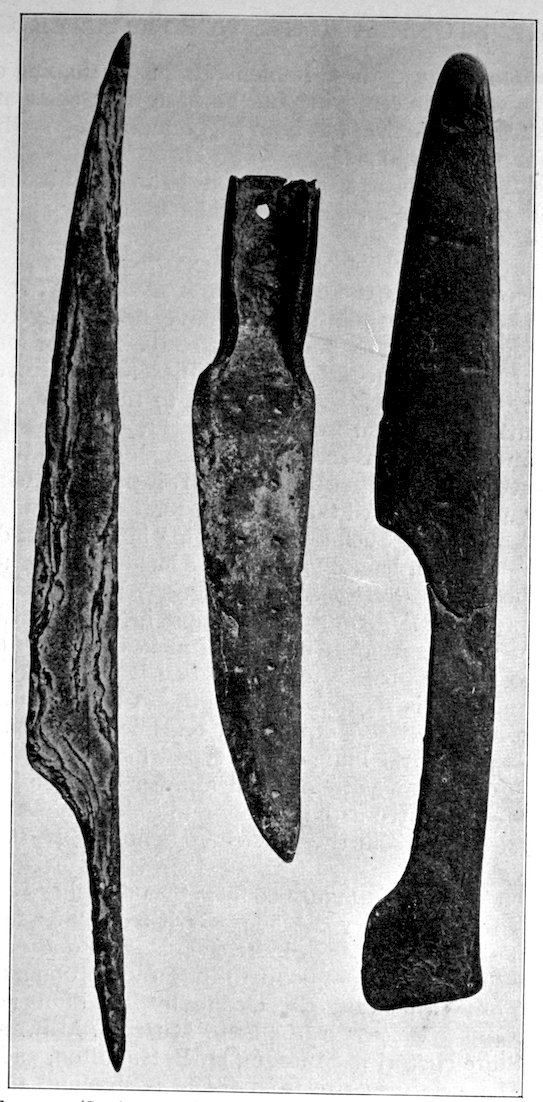

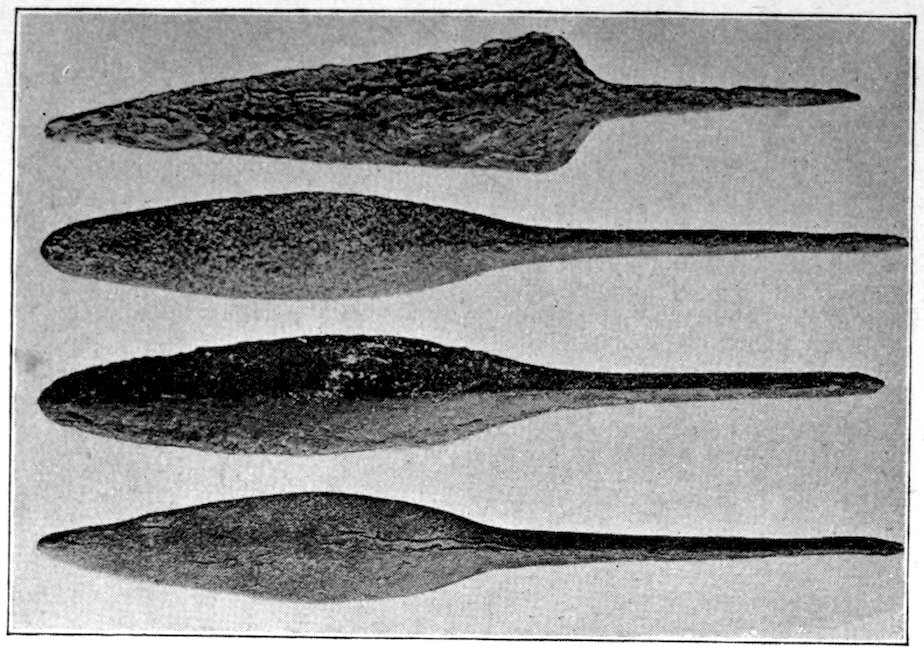

| Knives | 196 | |

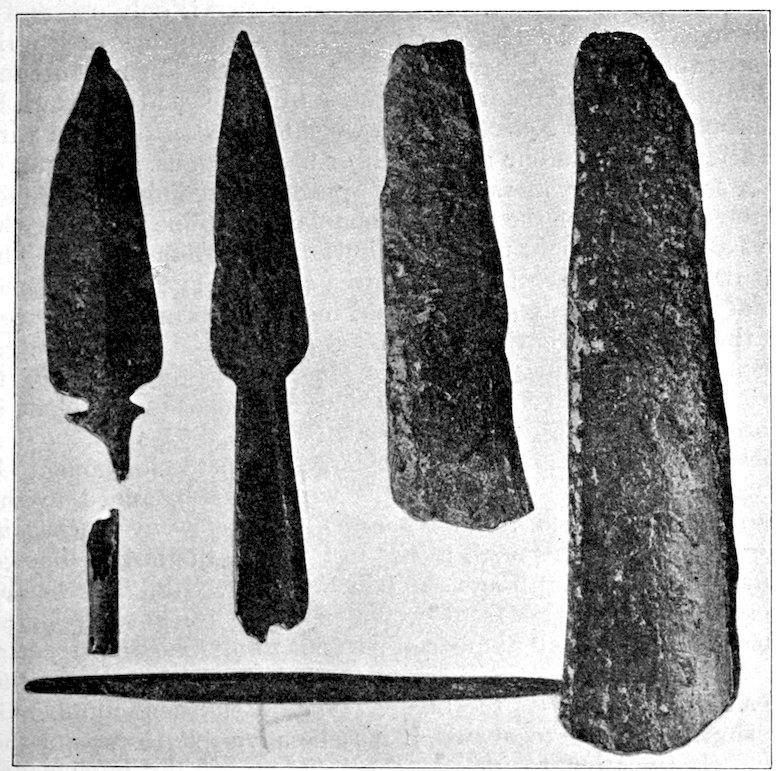

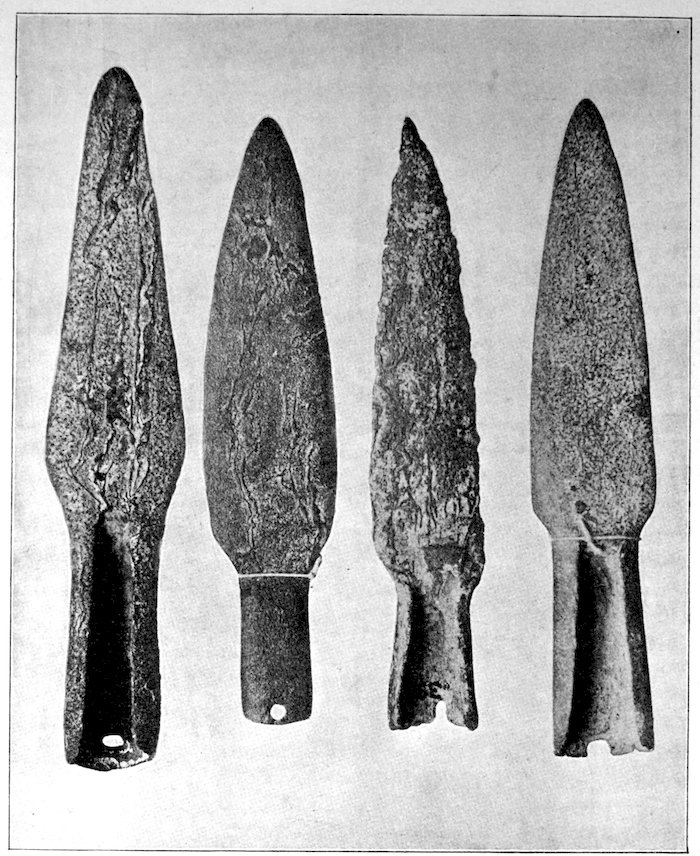

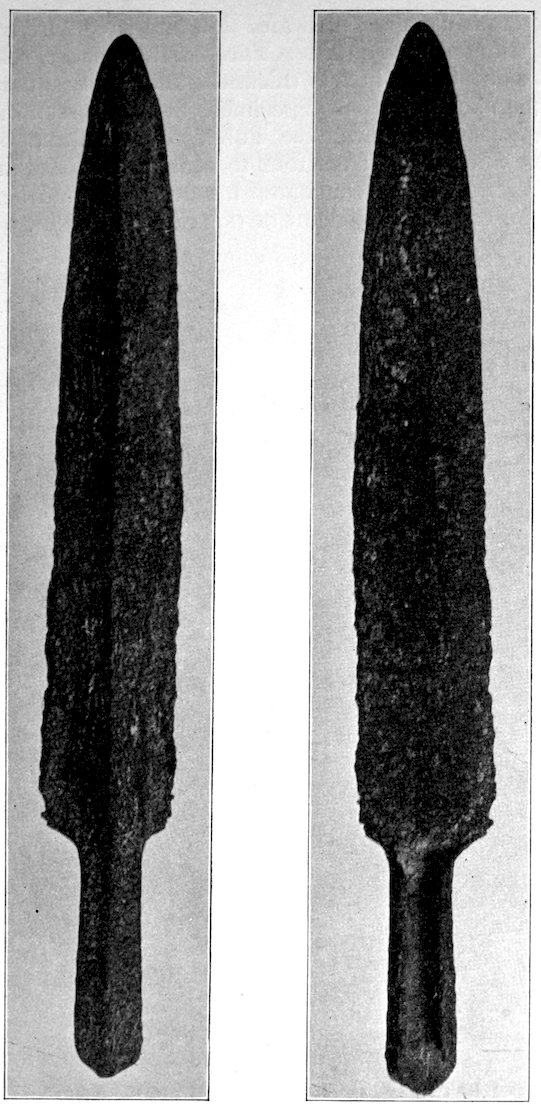

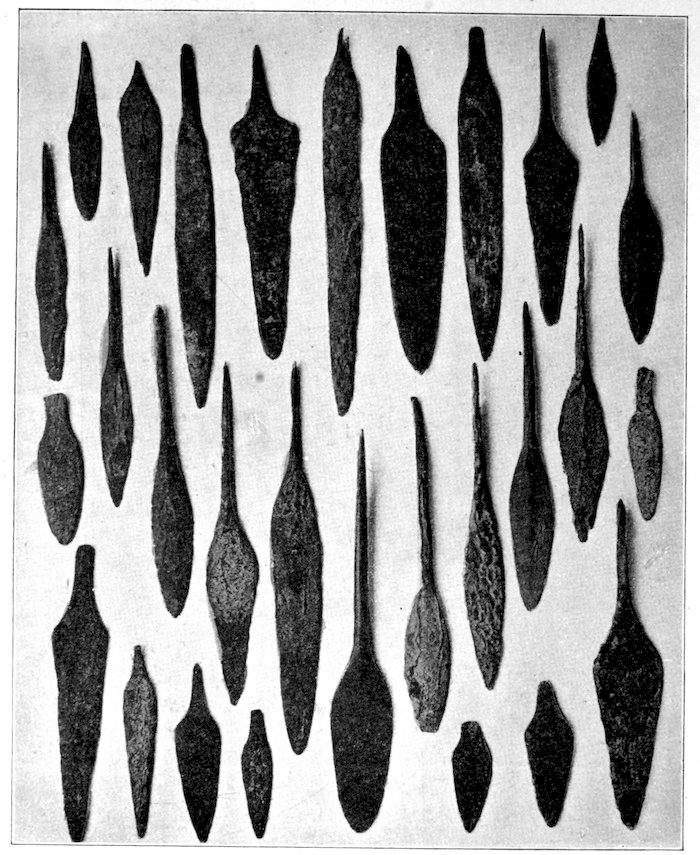

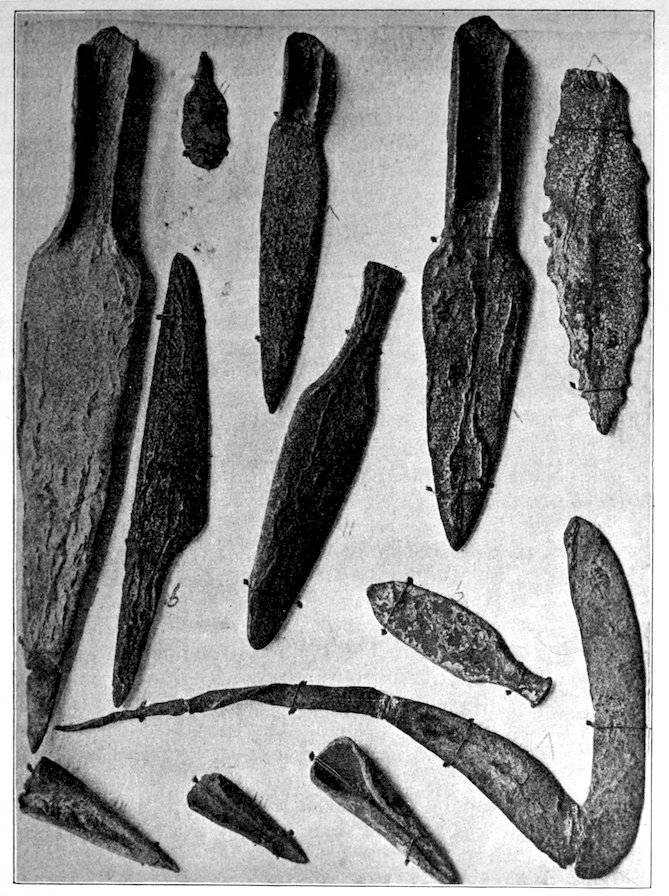

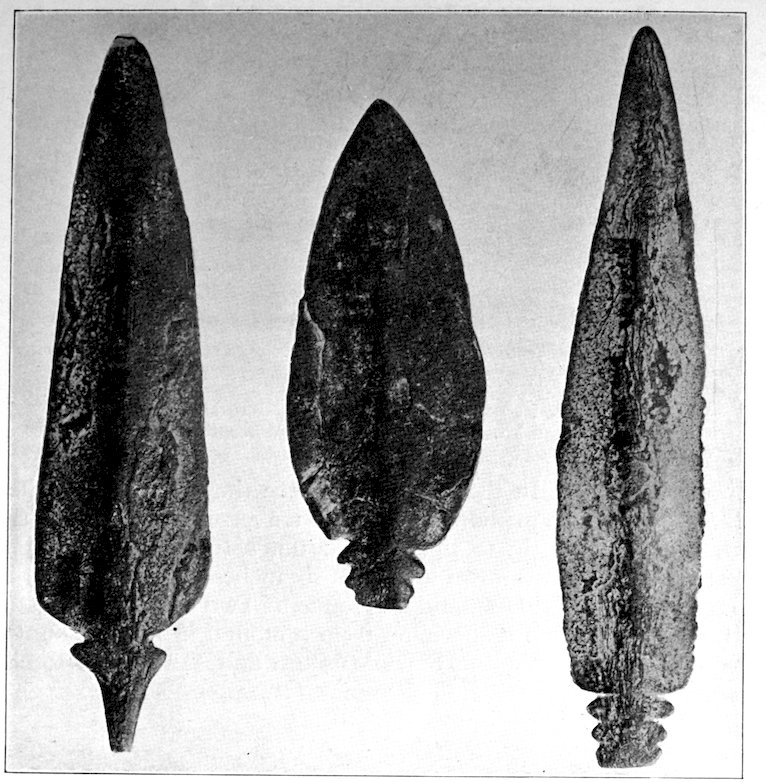

| Arrow- and spear-points | 198 | |

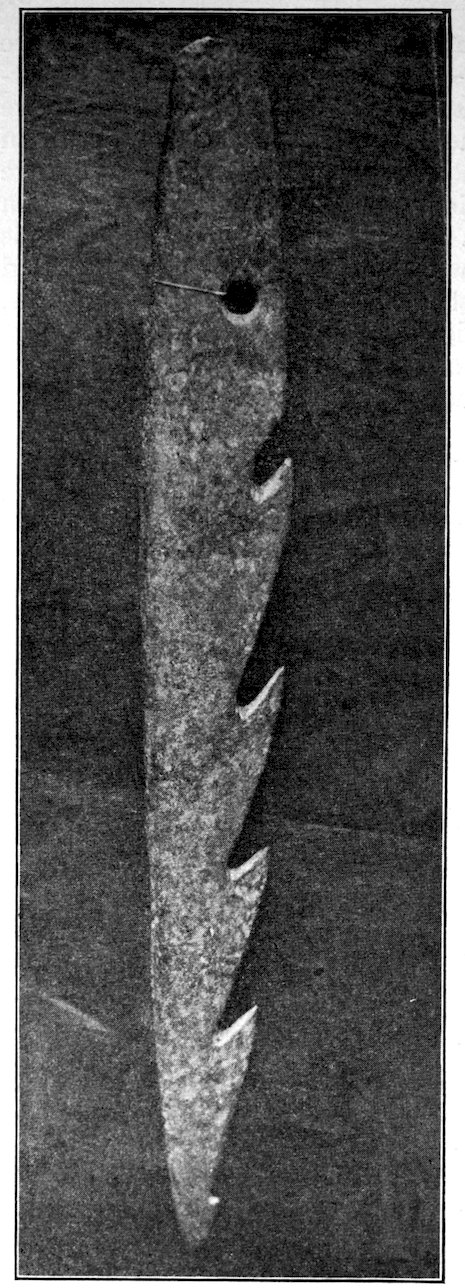

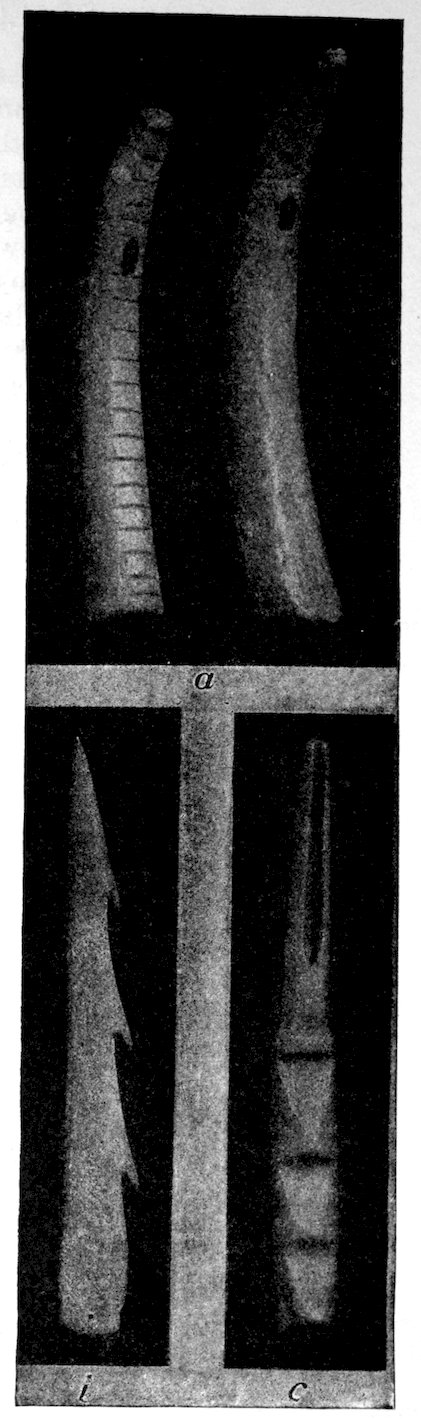

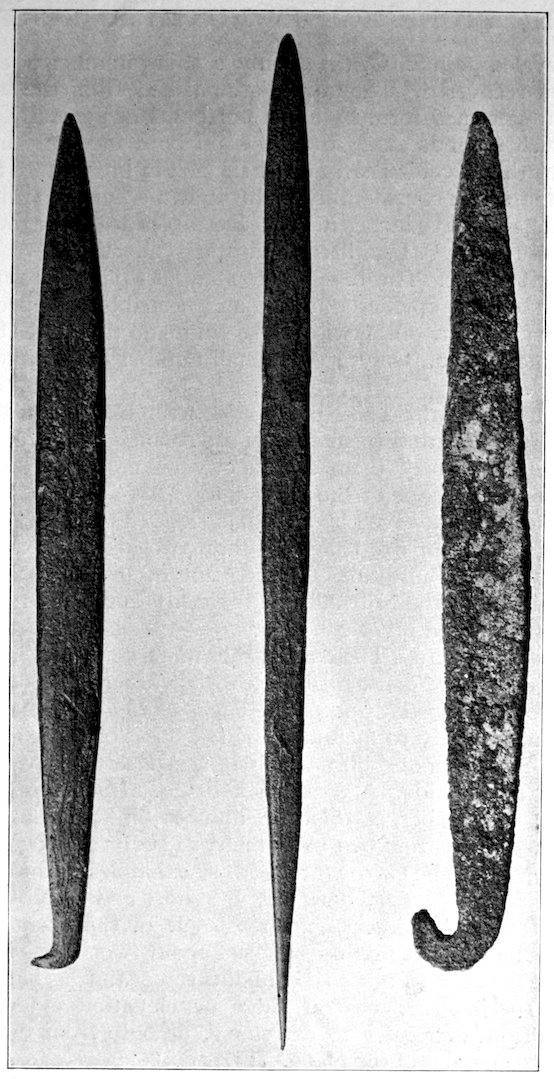

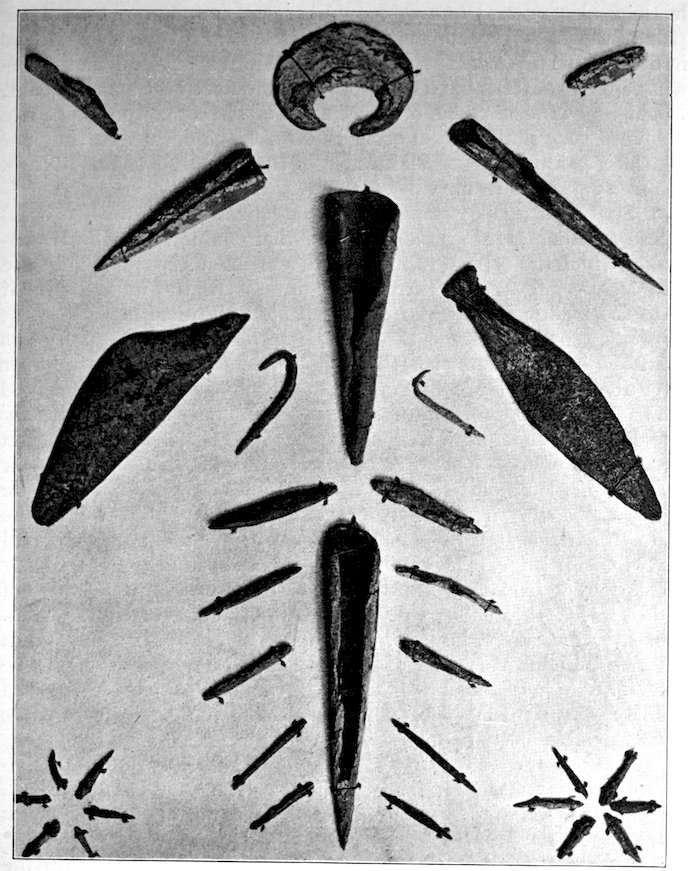

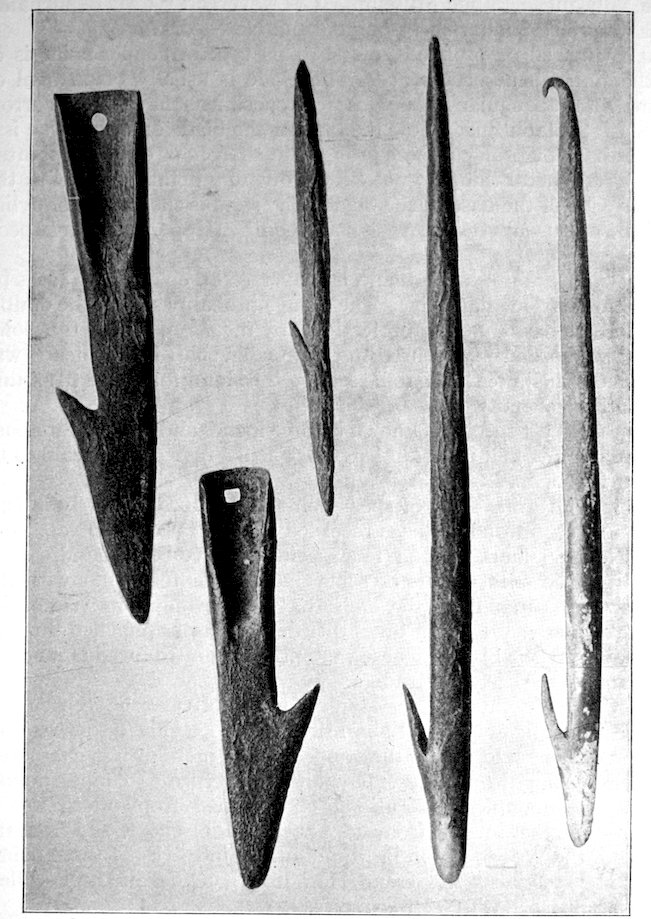

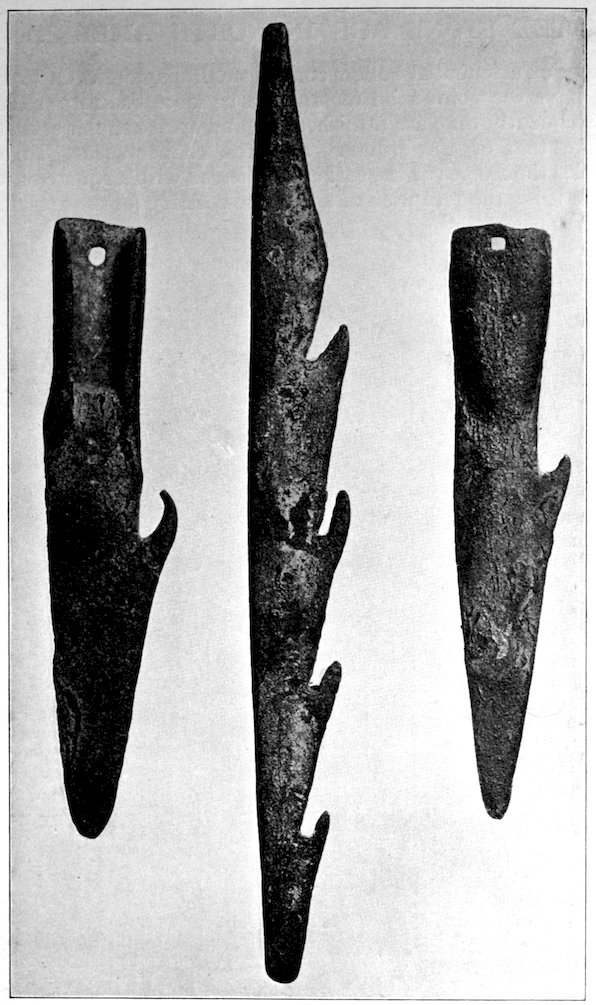

| Harpoon-points | 214 | |

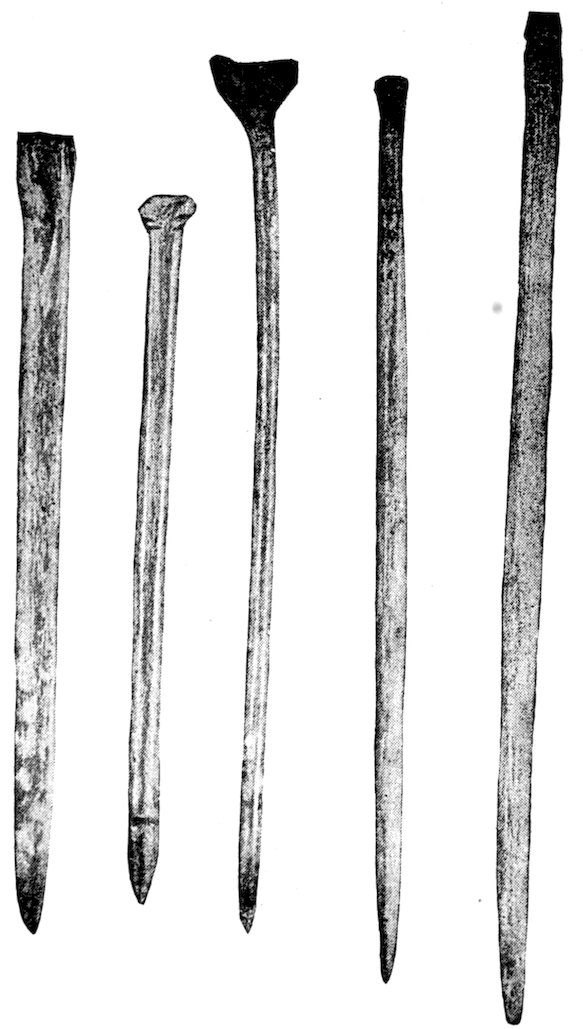

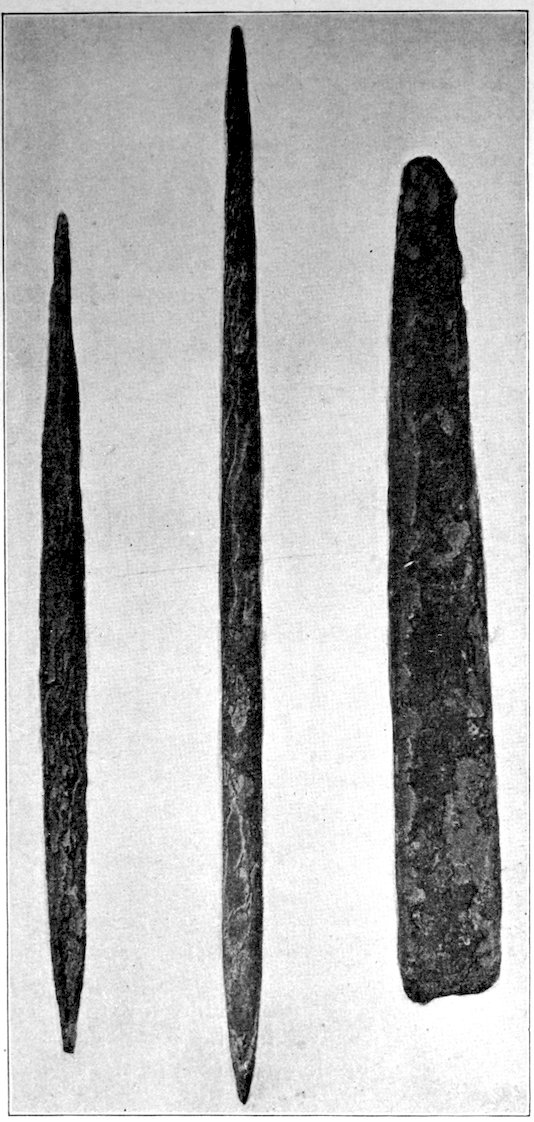

| Pikes and punches | 216 | |

| Awls and drills | 219 | |

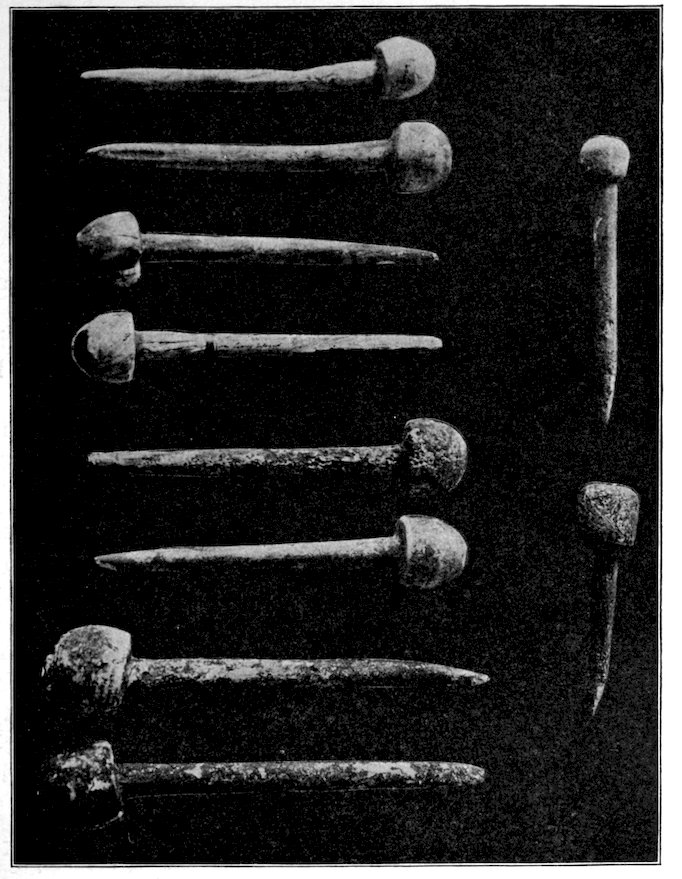

| Spikes | 220 | |

| Needles | 221 | |

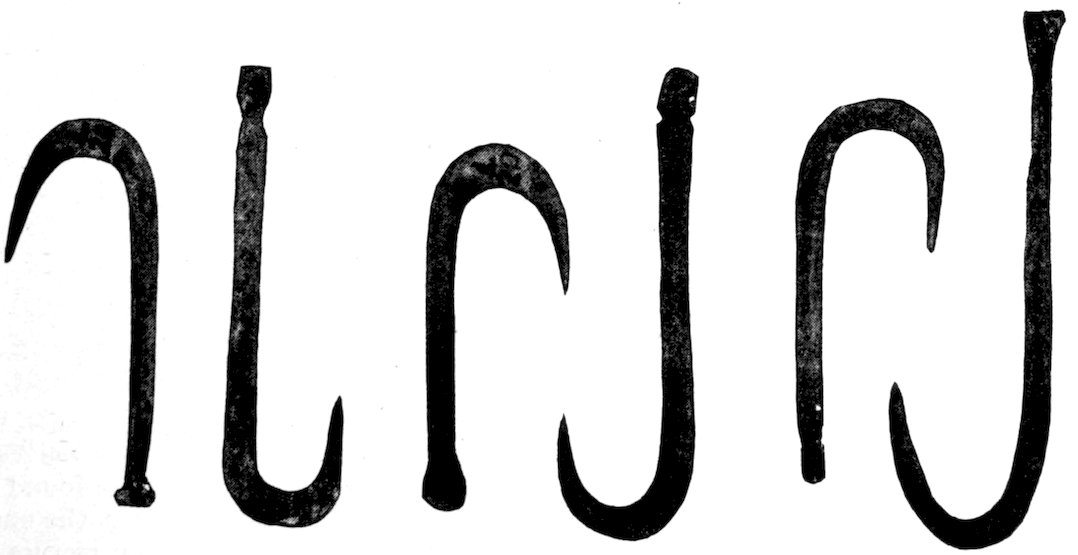

| Fish-hooks—peculiar implements | 222 | |

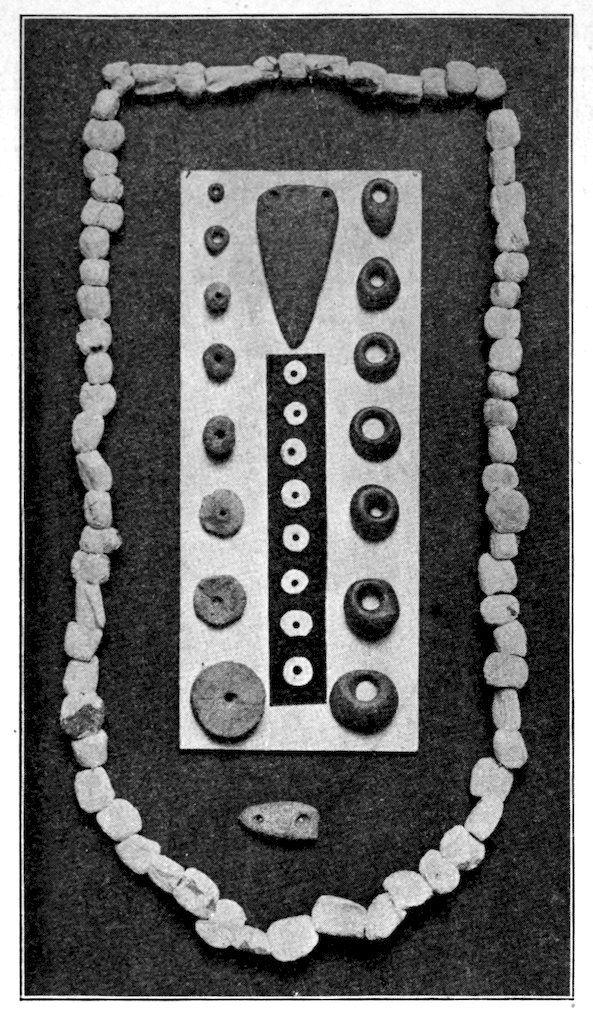

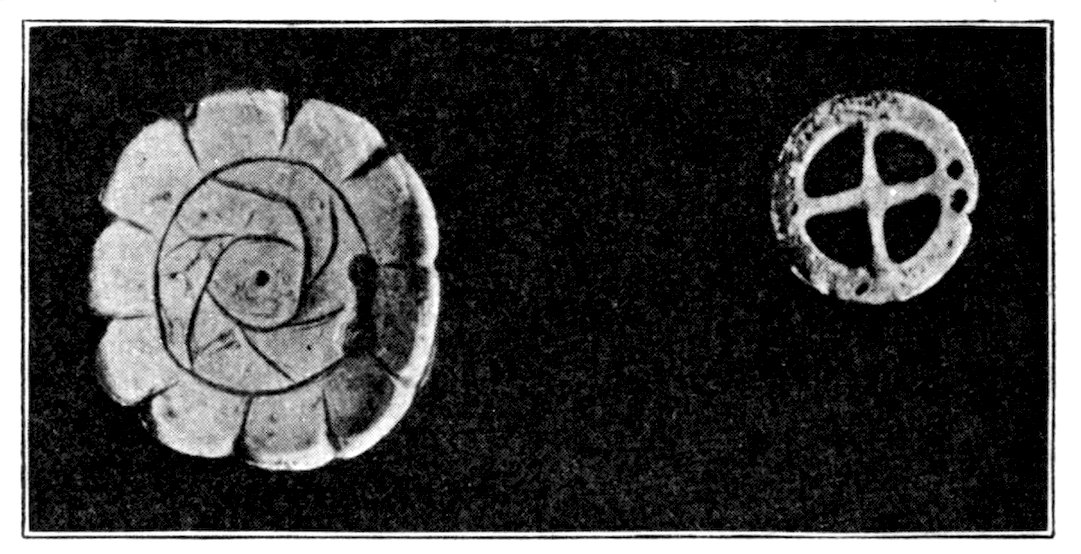

| Banner-stones—beads | 224 | |

| Bangles | 225 | |

| Finger-rings—ear-rings | 226 | |

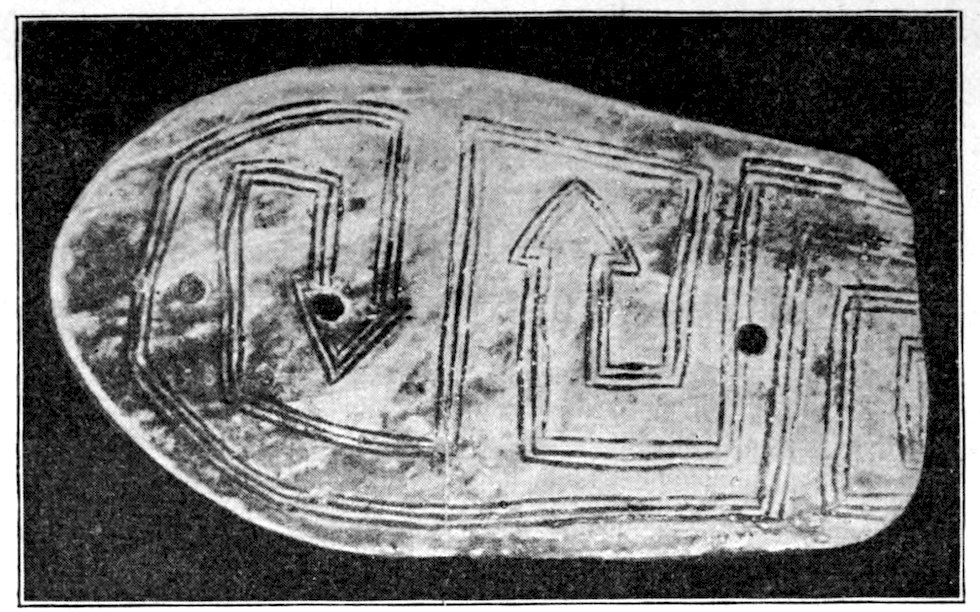

| Ear-spools or ear-plugs—gorgets and pendants | 227 | |

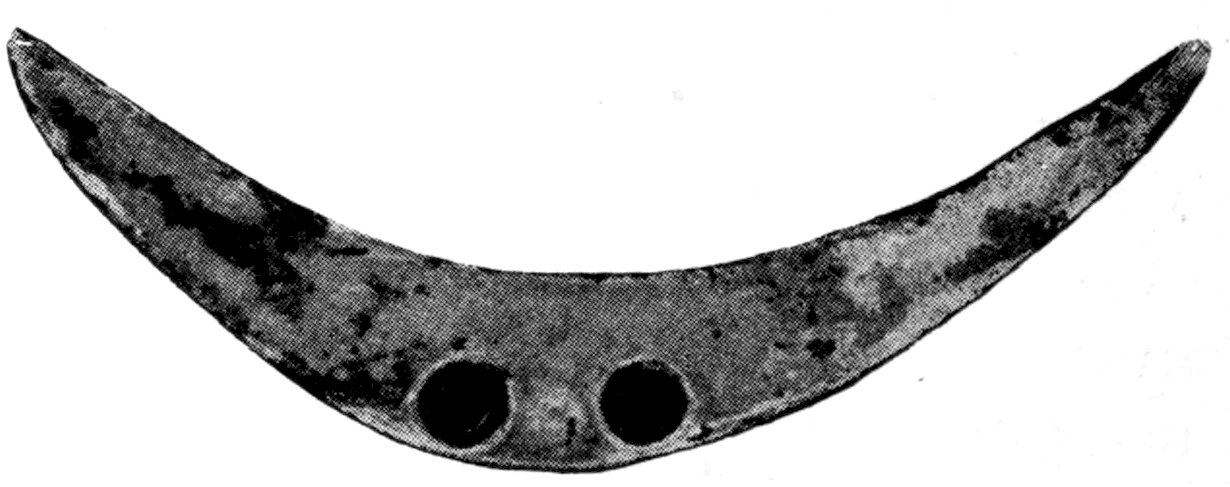

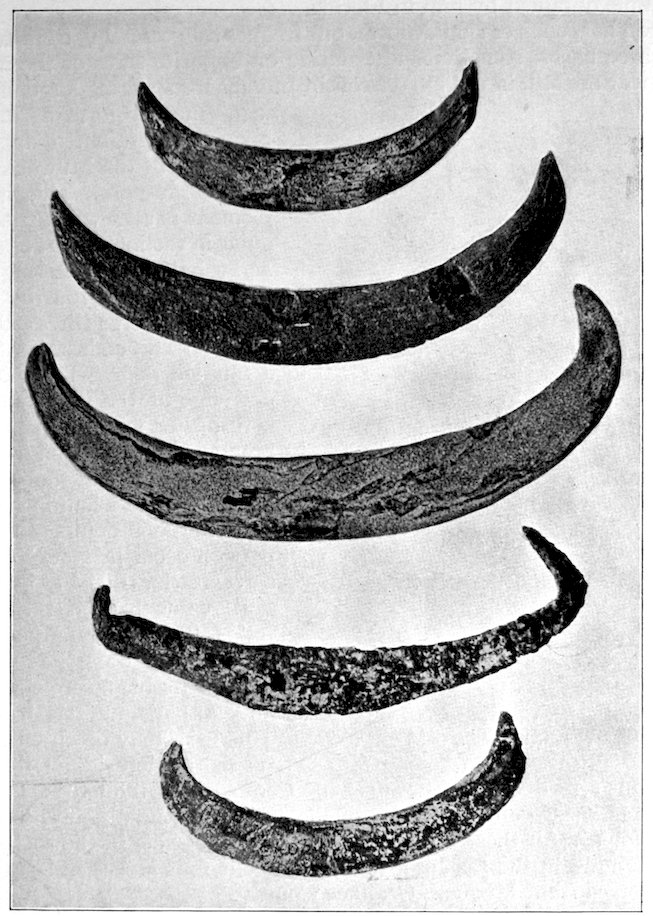

| Crescents | 228 | |

| Other ornaments | 230 | |

| vi | ||

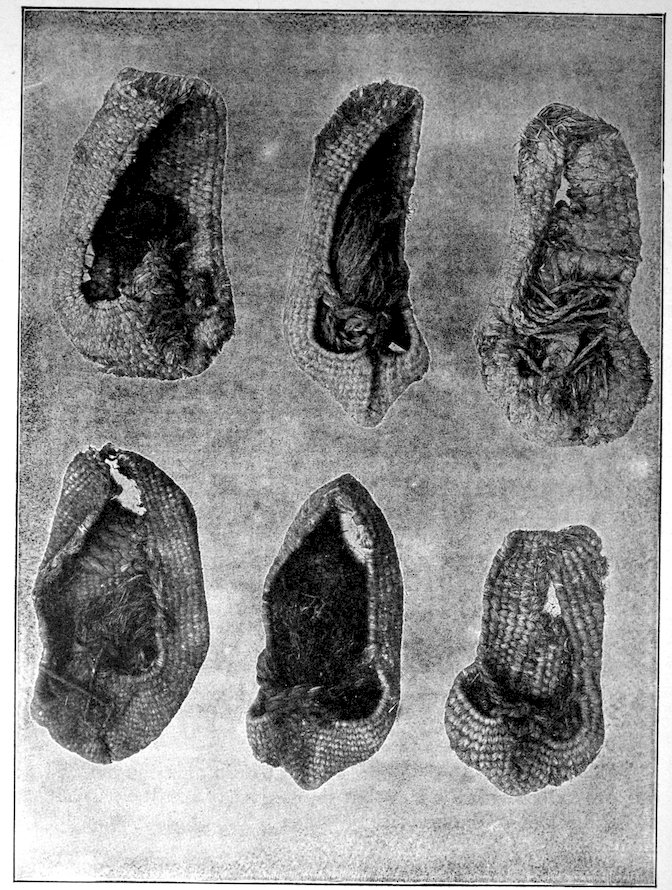

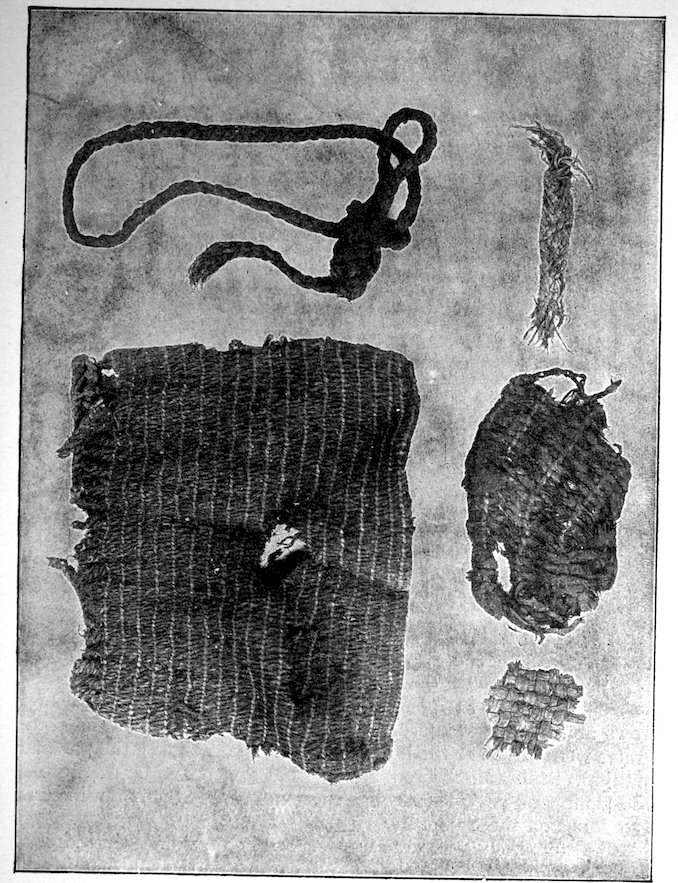

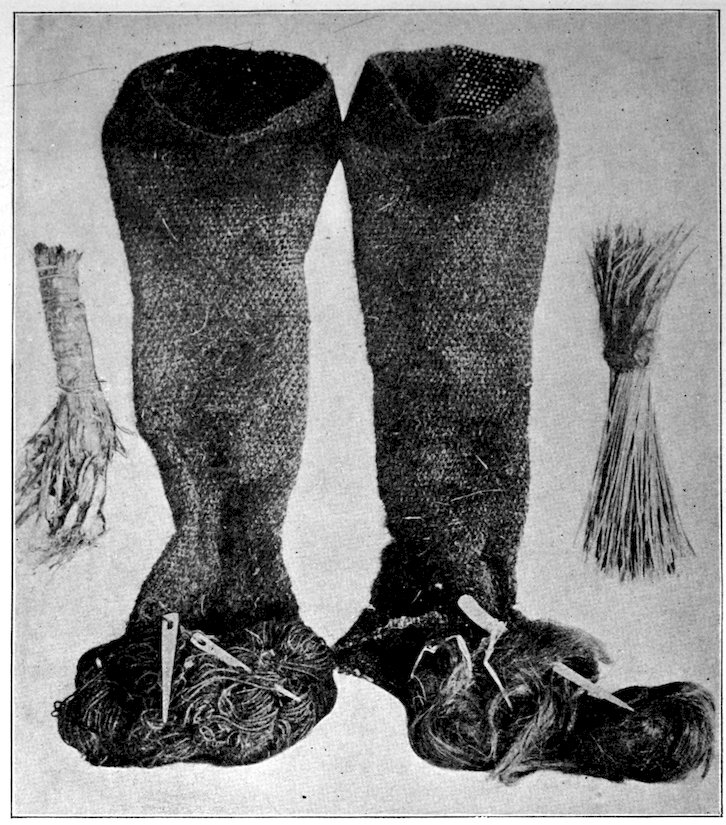

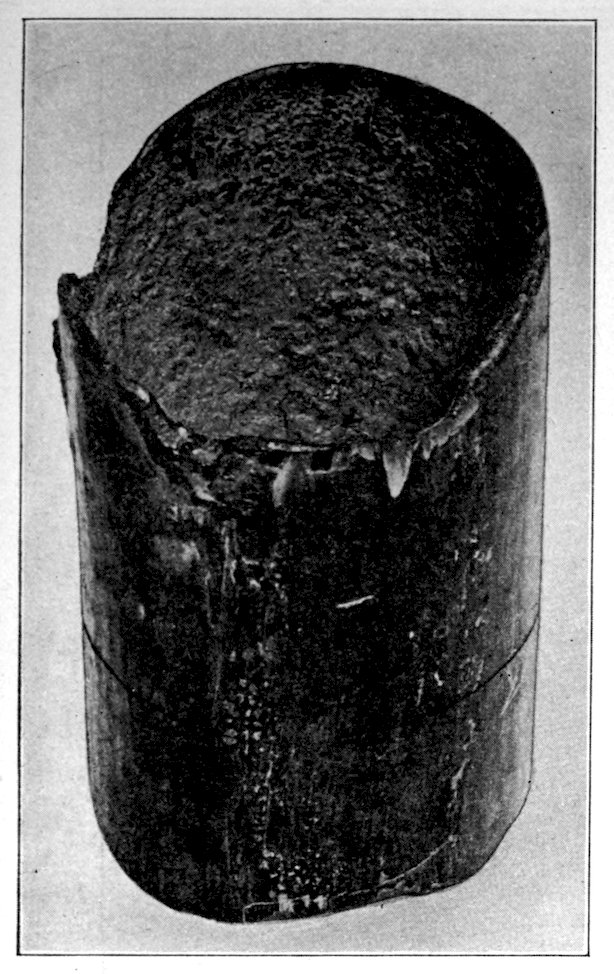

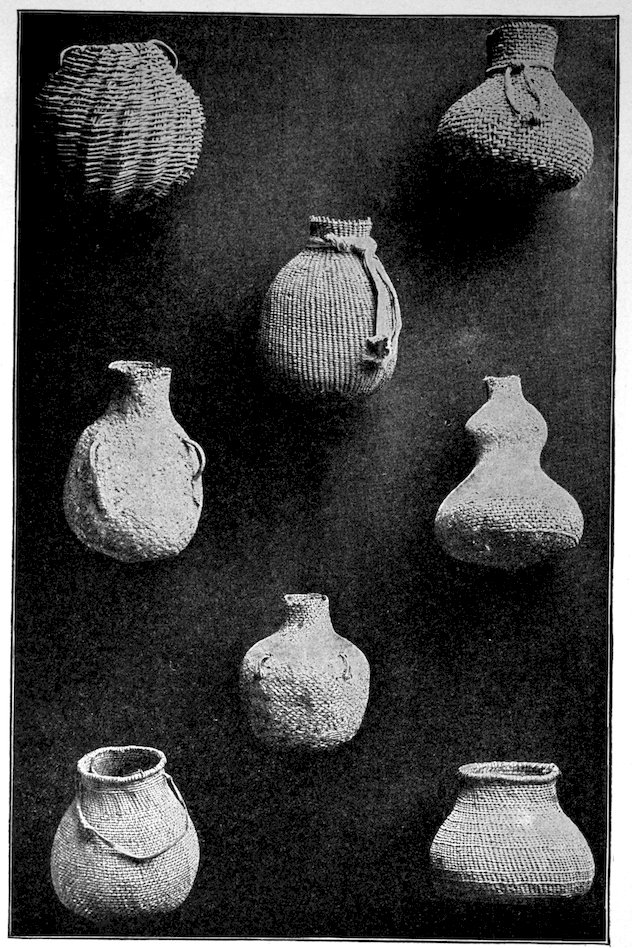

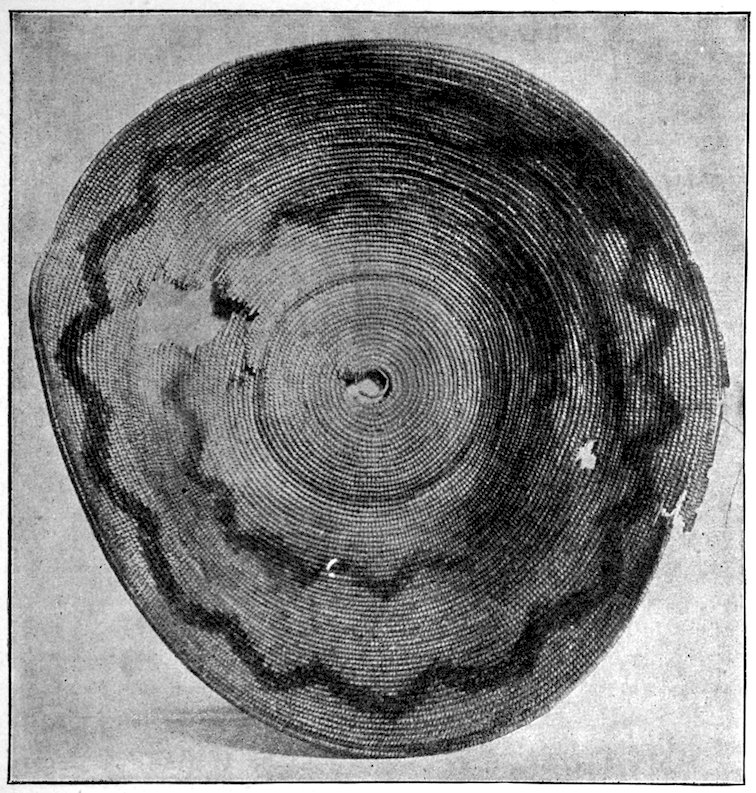

| XXXI. | Textile Fabrics | 235 |

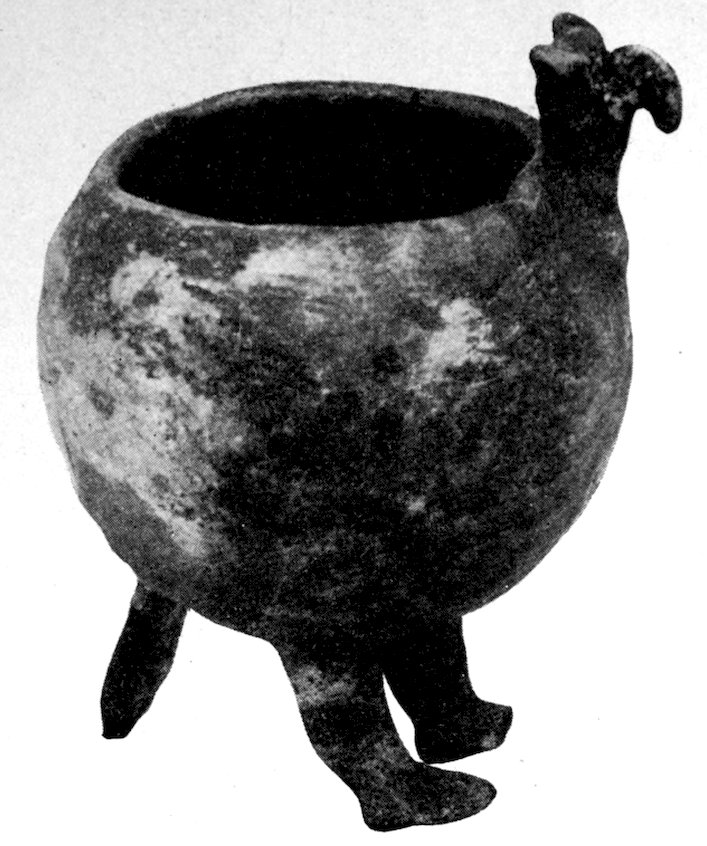

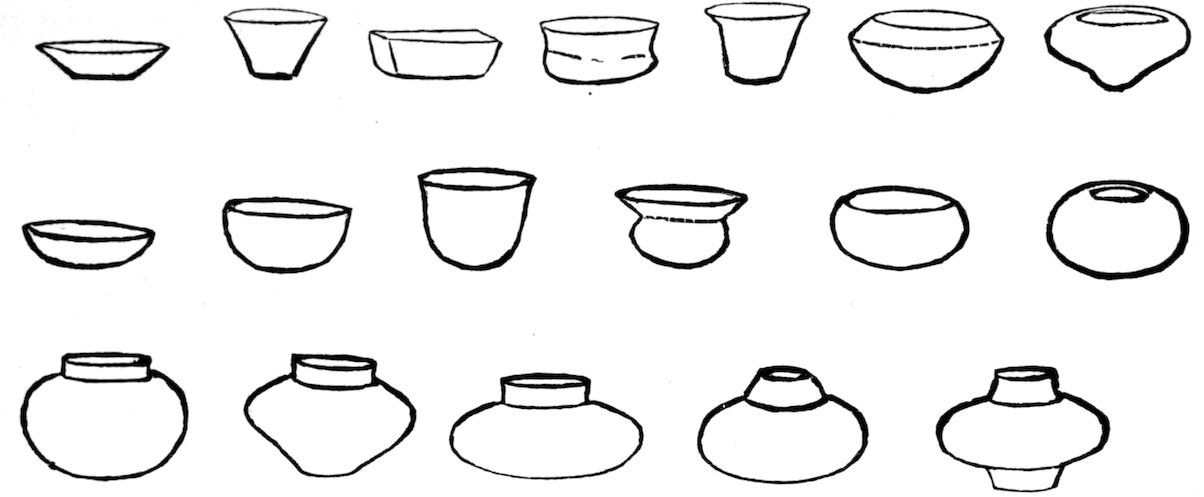

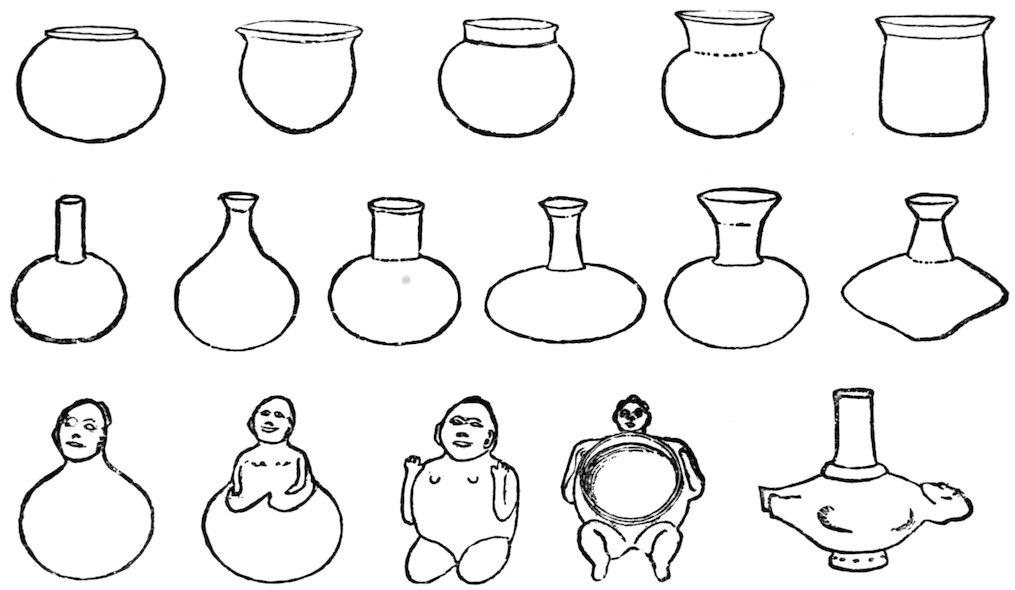

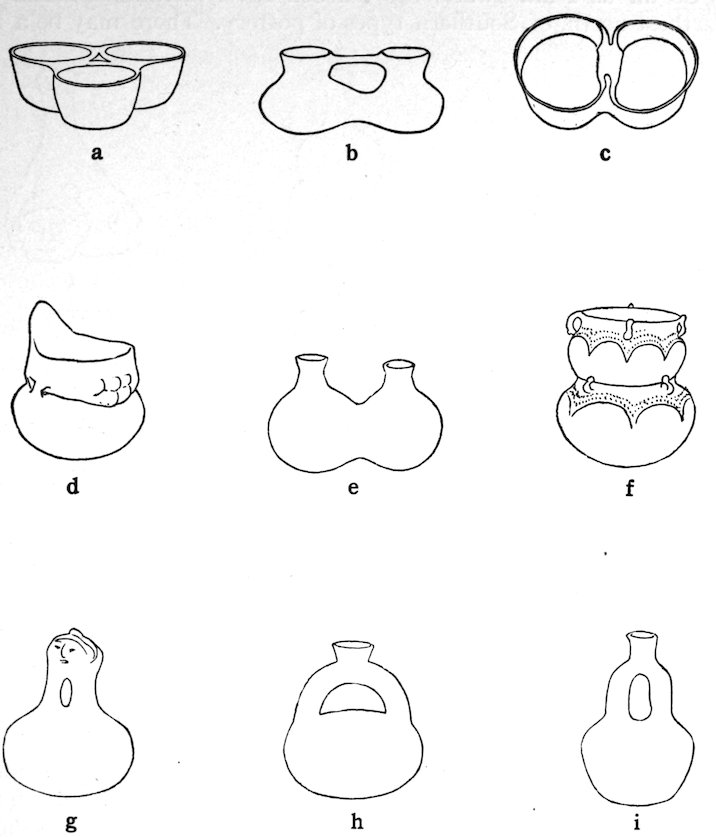

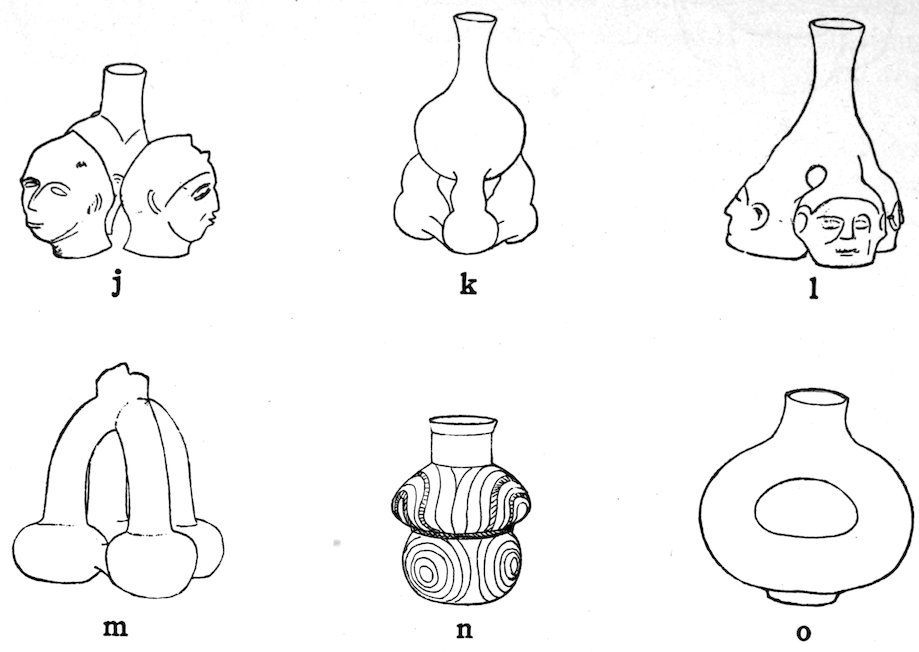

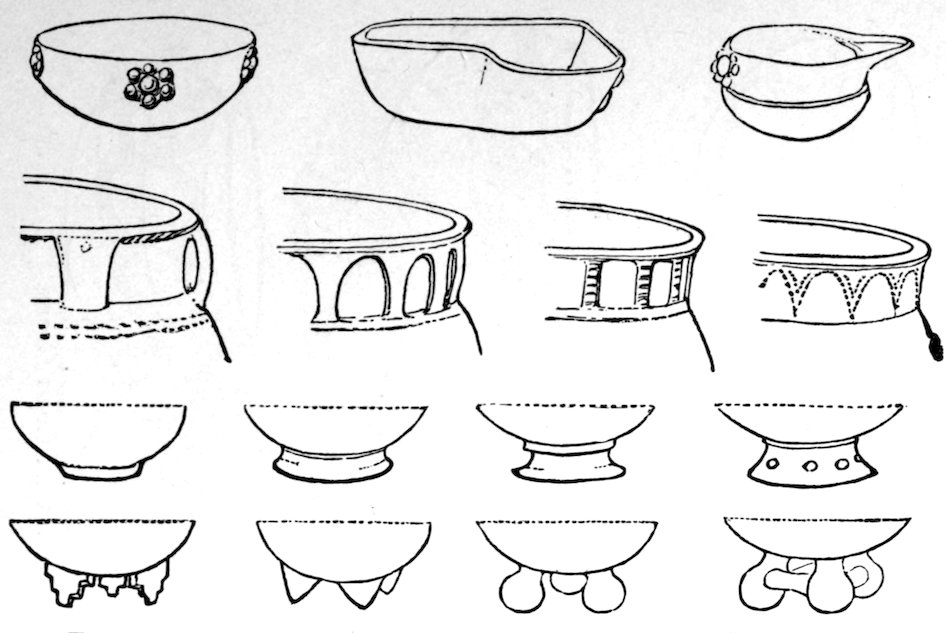

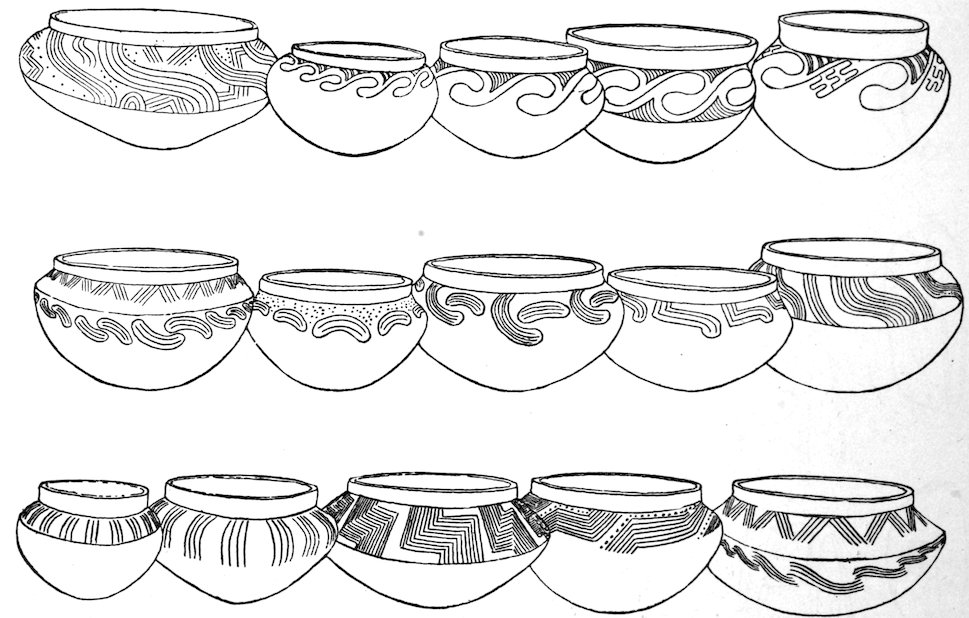

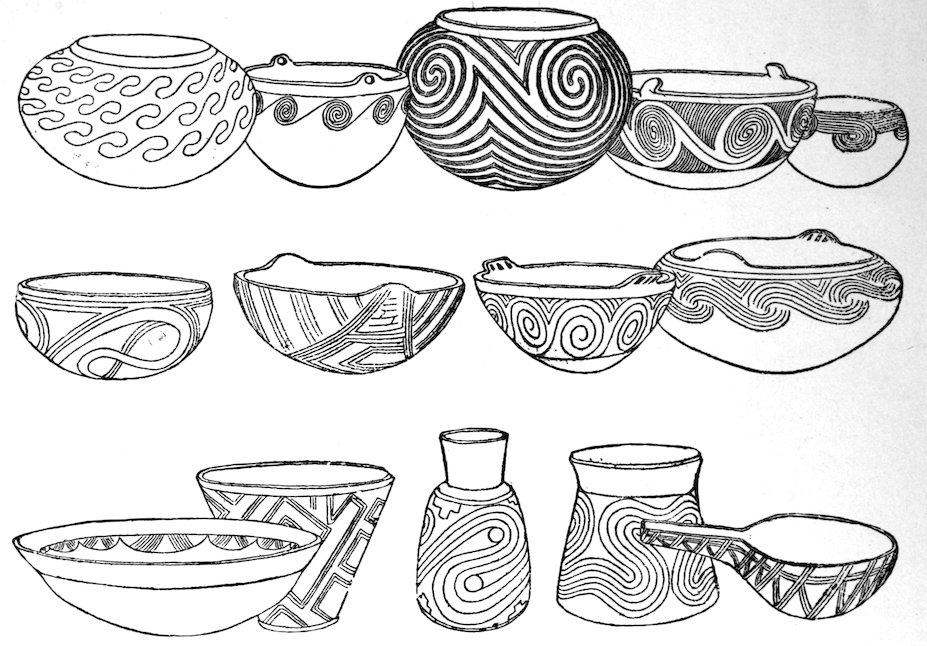

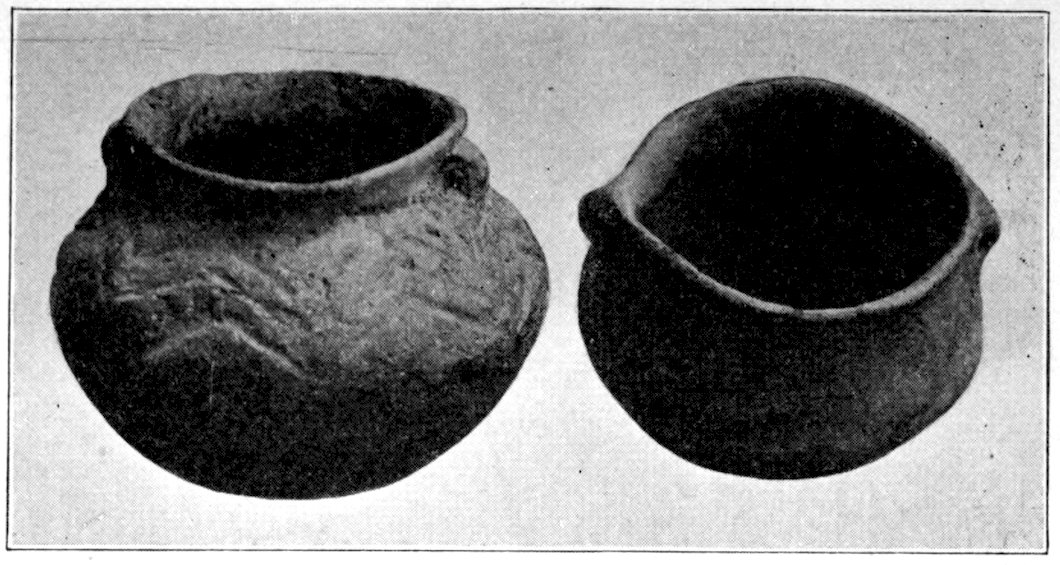

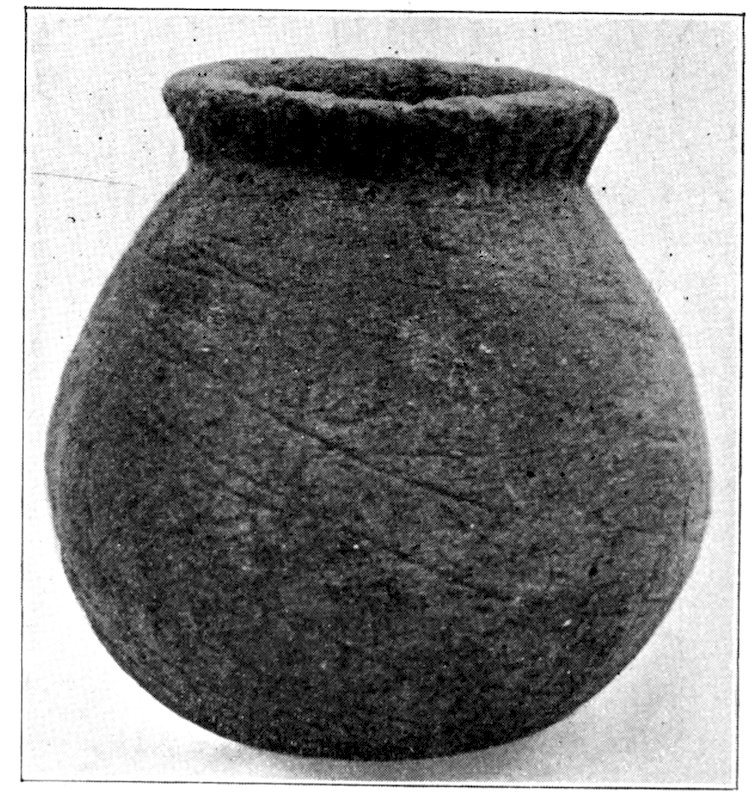

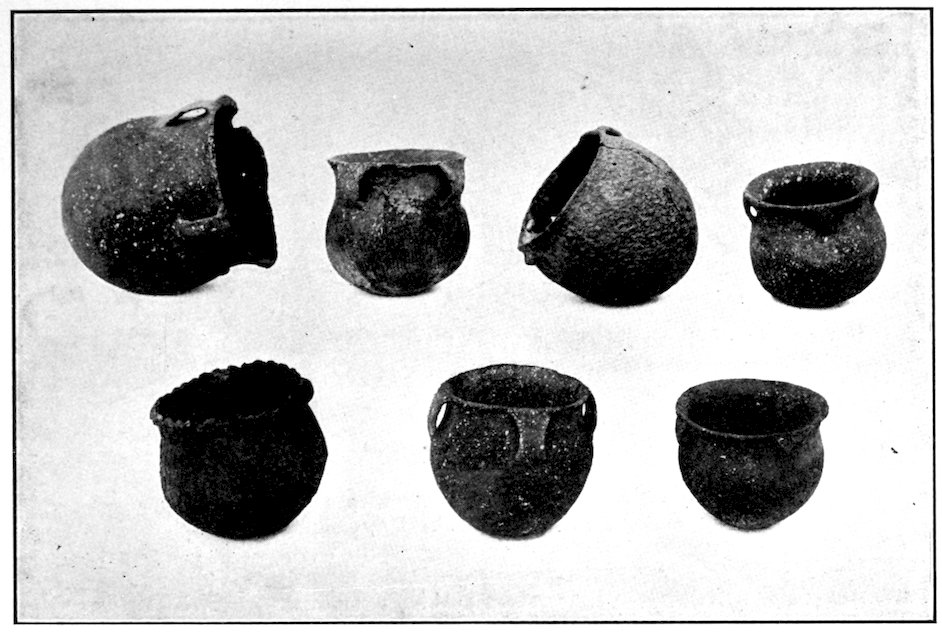

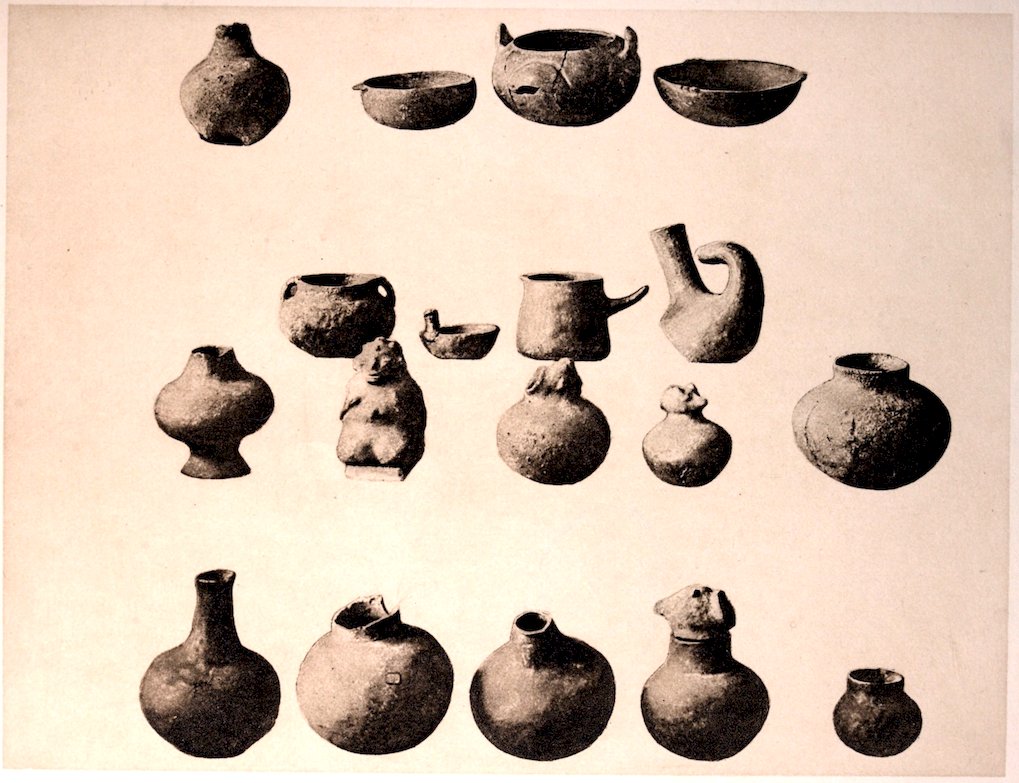

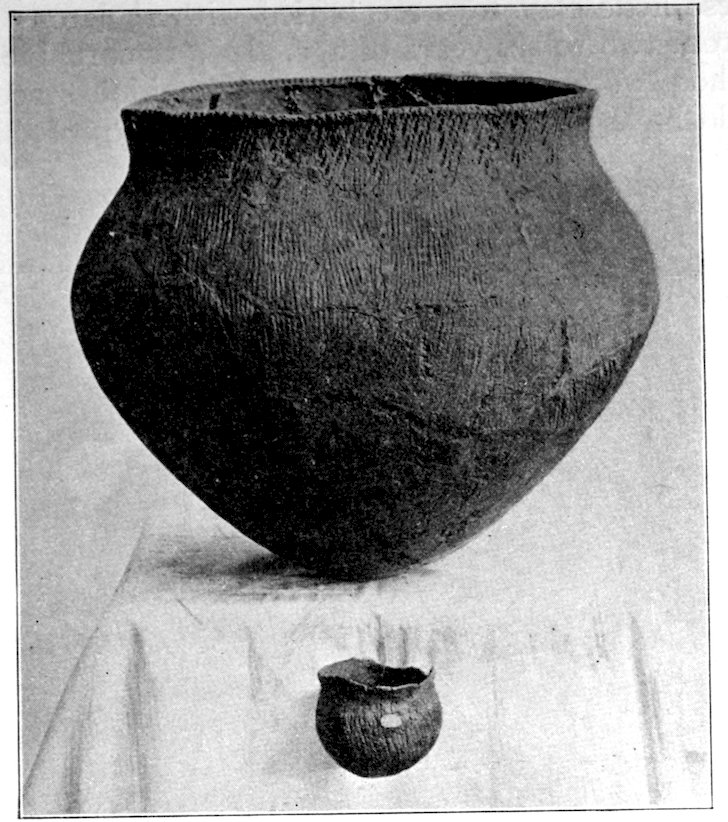

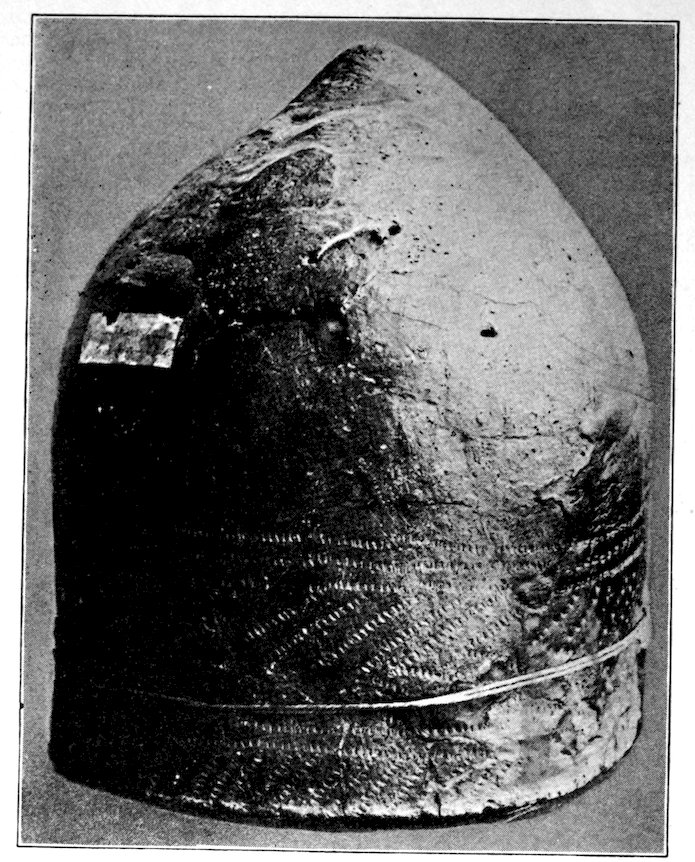

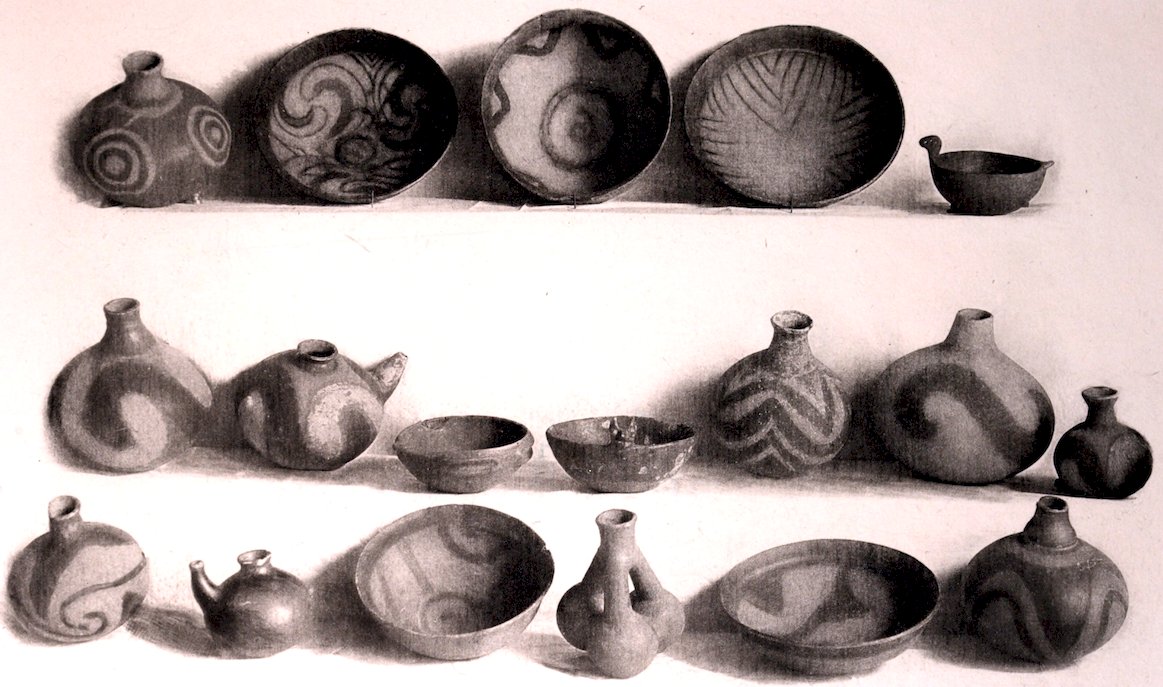

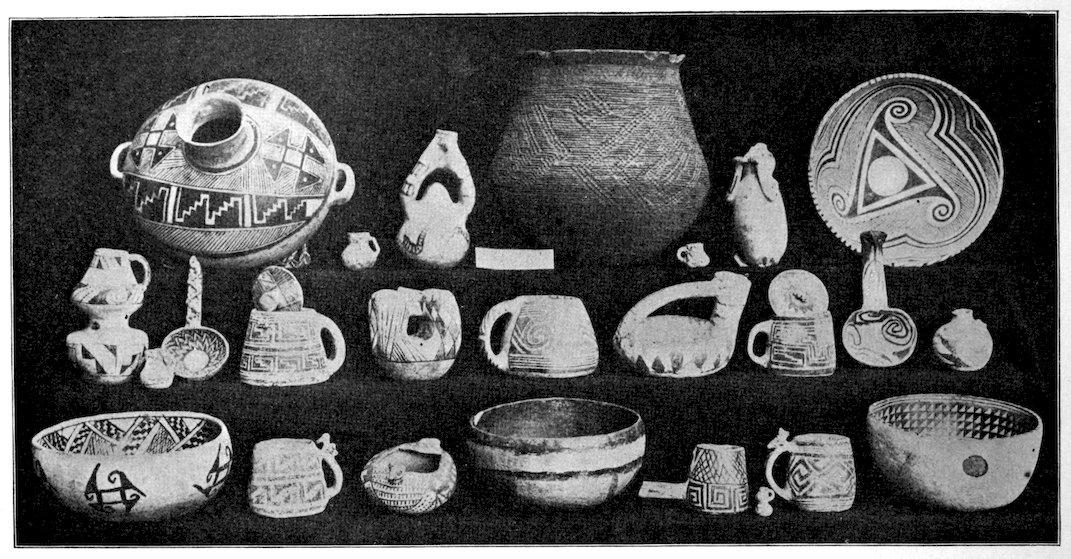

| XXXII. | Pottery of the United States | 247 |

| XXXIII. | Hematite Objects | 295 |

| XXXIV. | Miscellaneous Objects | 308 |

| XXXV. | The Stone Age in Eastern Canada, Utah, and Dakota | 330 |

| Eastern Canada | 330 | |

| The Plains of western and central Canada | 333 | |

| The stone age in Utah | 336 | |

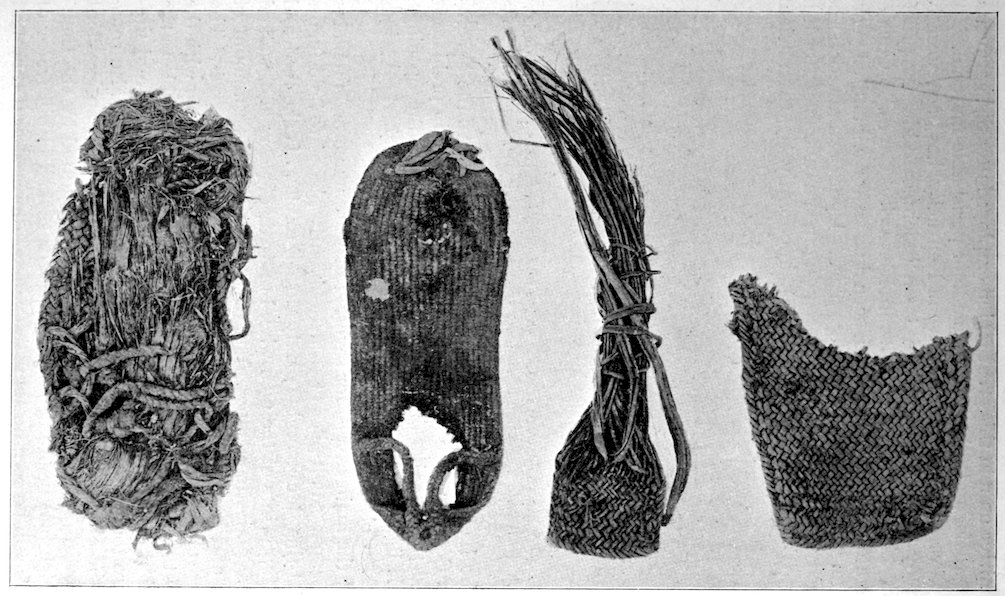

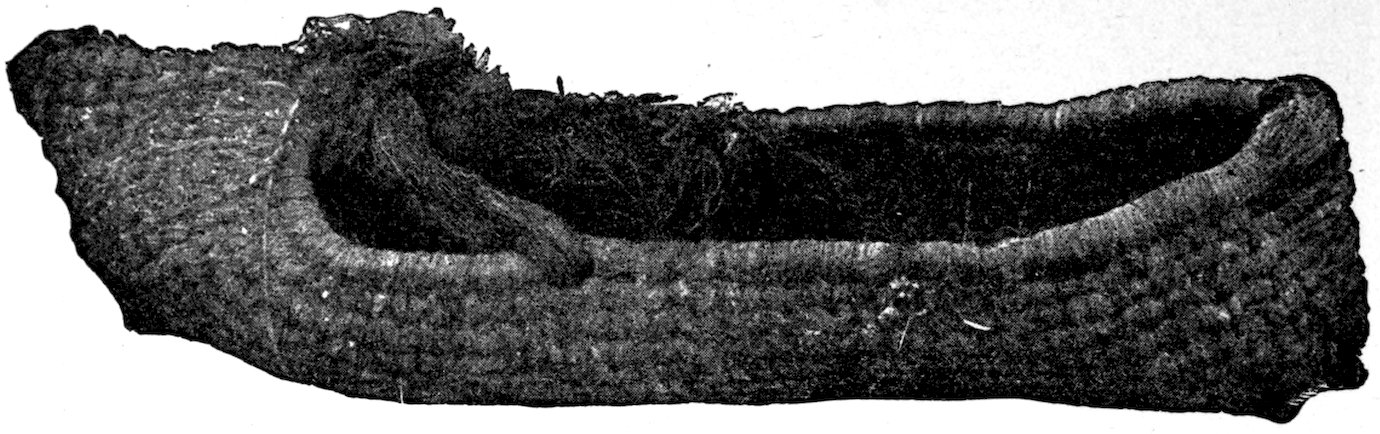

| Objects made of wood | 336 | |

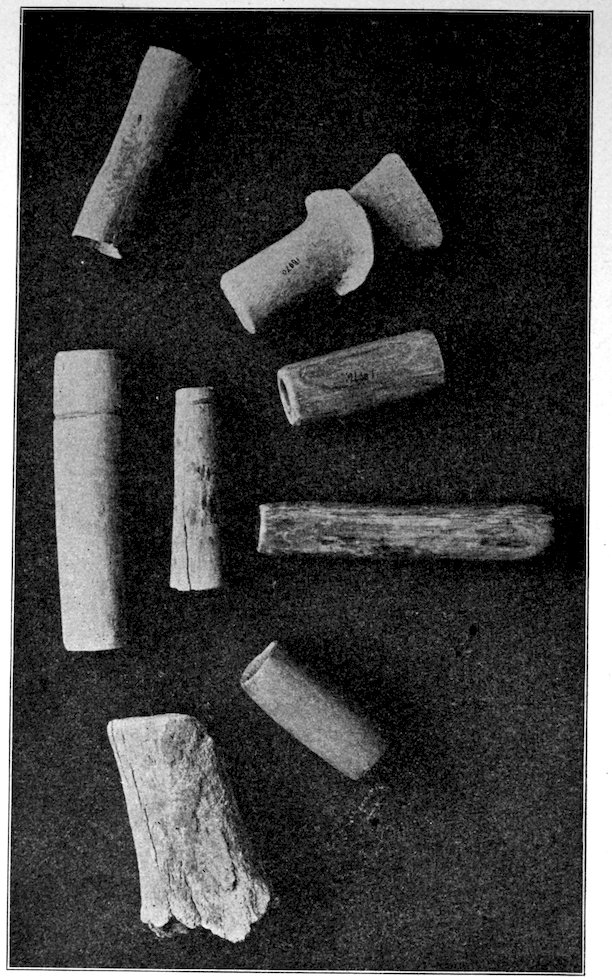

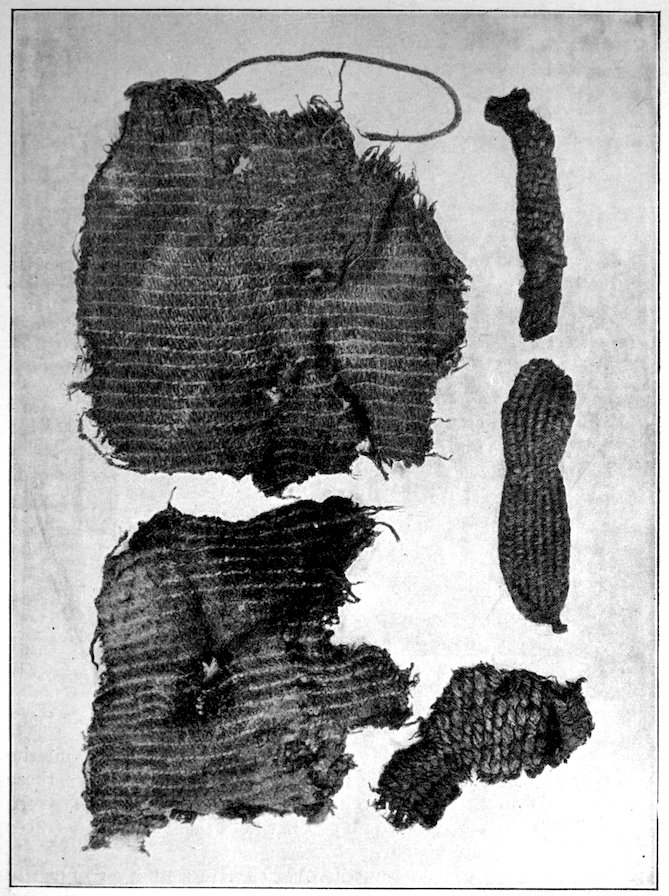

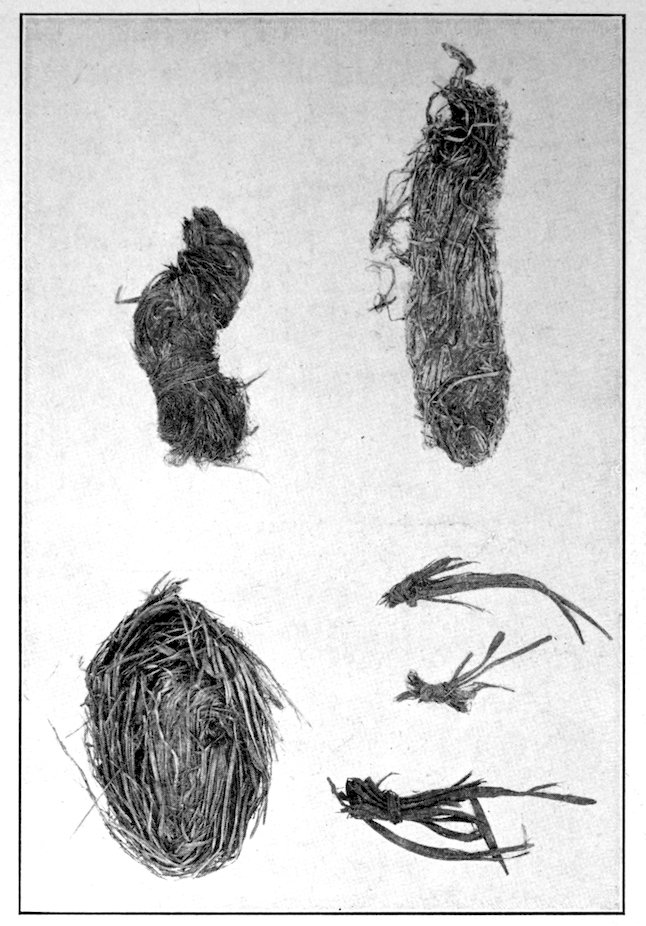

| Textiles; feather objects; bone objects | 337 | |

| Objects made from teeth; shell objects; stone objects; pottery objects | 338 | |

| The stone age in Dakota | 339 | |

| Hide and bark | 339 | |

| Objects made from deer antlers; bone objects; shell objects | 340 | |

| Stone objects | 341 | |

| Objects of copper; of pottery; of unbaked clay | 342 | |

| XXXVI. | Conclusions | 344 |

| The population in prehistoric times | 344 | |

| The stone age in historic times | 348 | |

| The antiquity of man in America | 350 | |

| Adaptation to conditions | 354 | |

| Art in ancient times and modern art | 355 | |

| XXXVII. | Conclusions | 357 |

| The ancient culture-groups | 357 | |

| The stone-age point of view | 363 | |

| Field study needed | 365 | |

| Bibliography | 369 | |

| Index | 411 |

Aboriginal man traced all sorts of figures on the rocks and occasionally on the surfaces of flat ornaments and ceremonials. Not only did he make pictures on shell gorgets and on birch bark, but he also carved complete figures.

I have not made a special chapter for pictographs and picture writings, but have dismissed them from this work, save with here and there a reference. However, they represent stone-age pictorial art. Dr. Fewkes, Mr. Cushing, Dr. Garrick Mallory and others have given us numerous papers on picture writings, pictographs, painted and sculptured symbols. Garrick Mallory’s report on the sign language among the American Indians was published in the Eleventh Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology and covers four hundred pages. This treats extensively of picture writings and pictographs. He portrayed the attempts of stone-age man at expressing his thoughts. He had not arrived at a written language save in Mexico and Central America. In North America he was in the advanced stone age. But he was very skillful in his pictographs and in his carvings of human, animal, bird, reptile, and fish figures. It has occurred to me that he first made rude scratches on flat surfaces, on wigwam sides, on trees, on rocks near trails.

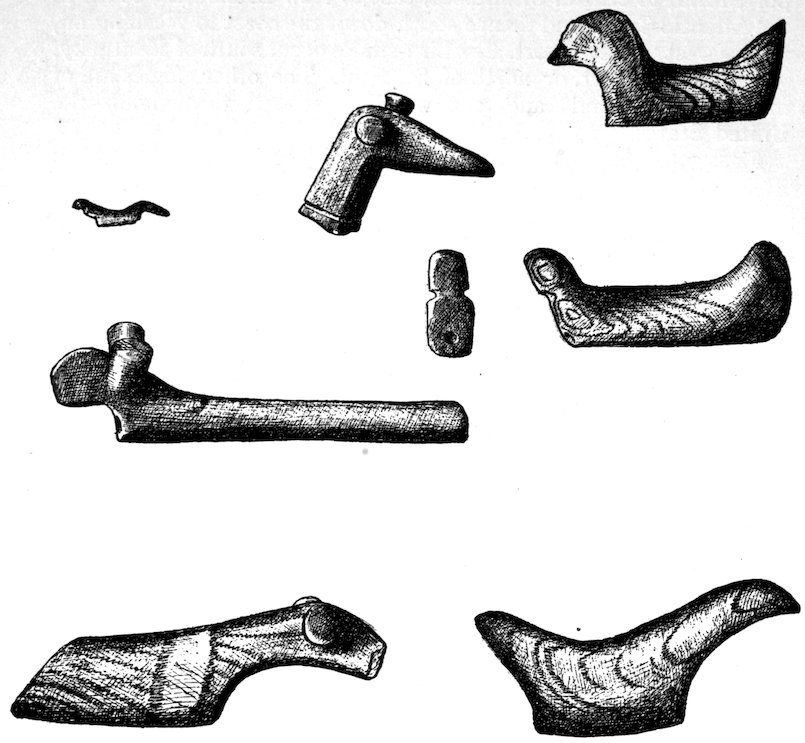

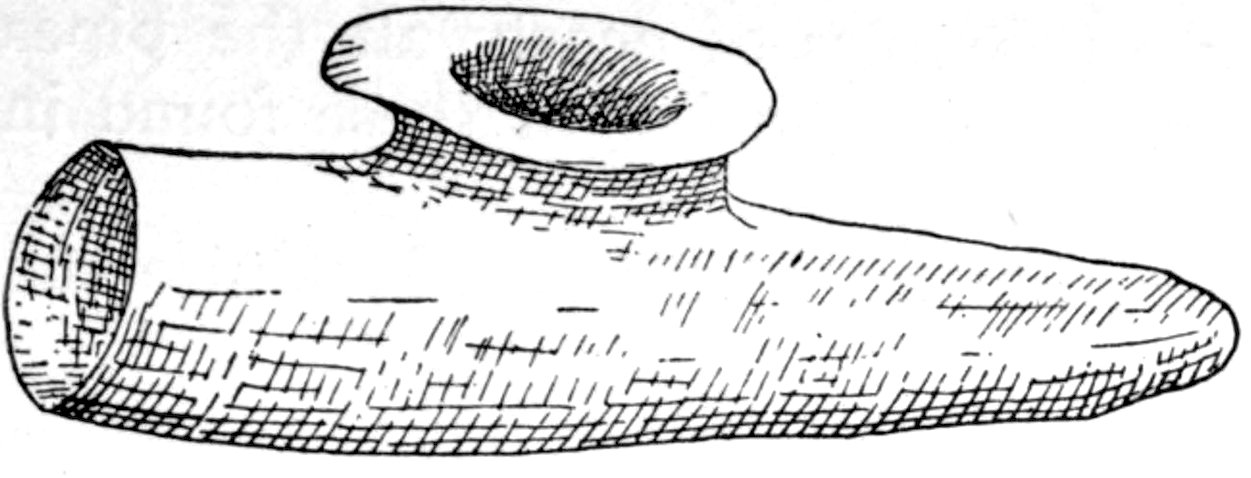

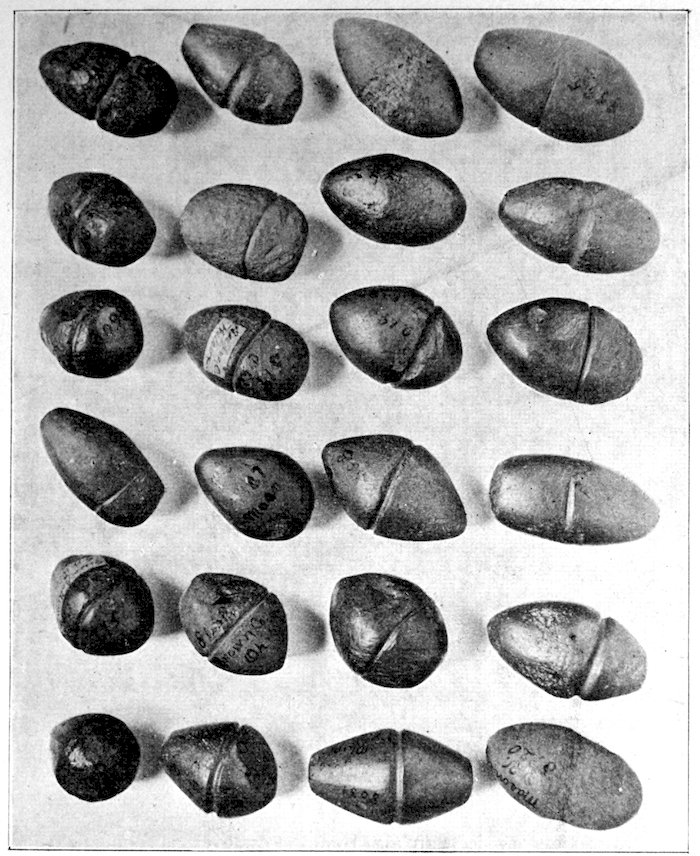

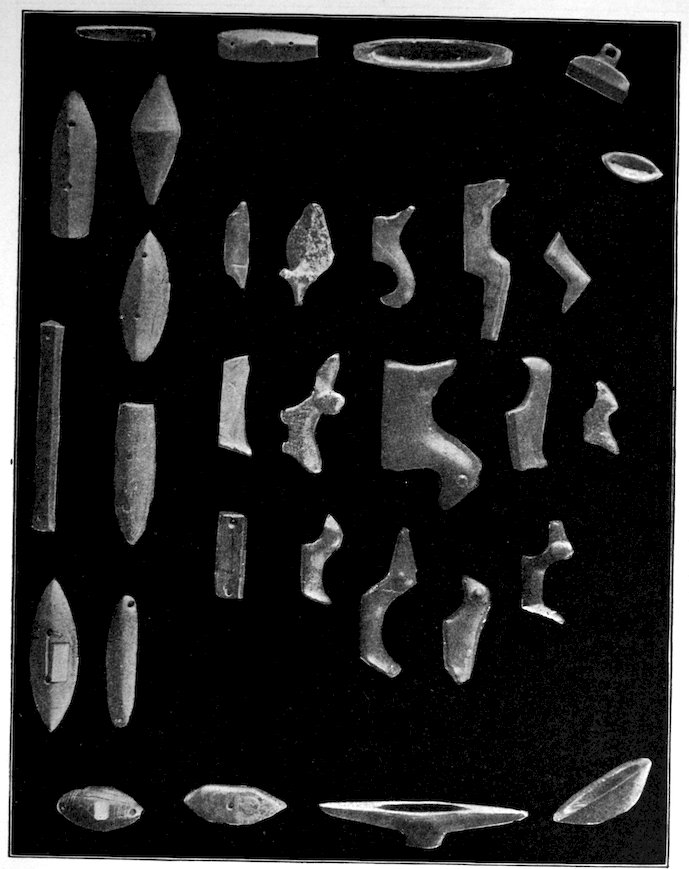

Fig. 399. (S. 2–3.) Unfinished bird-stones. Localities: Ohio, Indiana, Michigan. Phillips Academy collection.

Fig. 400. (S. 1–1.) Unfinished bird-stone. Collection of Emily Fletcher, Westford, Massachusetts.

Fig. 401. (S. 2–3.) Unfinished bird-stone. Phillips Academy collection.

It is significant that the Plains tribes and all the natives who did not construct mounds or earthworks, natives that had not reached the stage of barbarism but were still savages, made no effigies of consequence. The effigies carved in catlinite, and observed among tribes west of the Mississippi during the historic period, seem to have been inspired by a knowledge of the superior arts of the white people. We find that while the roving tribes of the Plains painted various battle and hunting scenes on their tents and shields, yet they were inferior in art as compared with the Pueblo, the Cliff-Dweller, or the Mound-Building peoples. It is also significant, and I shall speak of it at greater length in my Conclusions, that the native American was so little influenced in his art by some life-forms. I have never seen an effigy of a mountain, a tree, a plant, or a flower. The modern Ojibwa Indians design flowers in their bead-work. The ancient Ojibwa did not. The native American did not seem to have been impressed by plant-life or inanimate 4objects. Occasionally, he scratched a trail or a tipi on an ornament, and some of the pictographs in various portions of the United States show wigwams, trails, etc. But while there are numerous examples of carvings in stone, shell, and bone of animals, birds, fish, and reptile life, we search in vain for carvings of the other things I have mentioned. The highest art is found where the largest villages, or the most numerous mounds or cliff-houses, were located. In small mound groups, or areas where the population was not sedentary, the art is very crude. Throughout the areas where the culture is highest, notably Alabama, Georgia, Wisconsin, Tennessee, Arkansas, Missouri, Ohio, and Illinois, we find these large mound groups referred to, all of which proves that the people lived long enough in one place to develop an art.

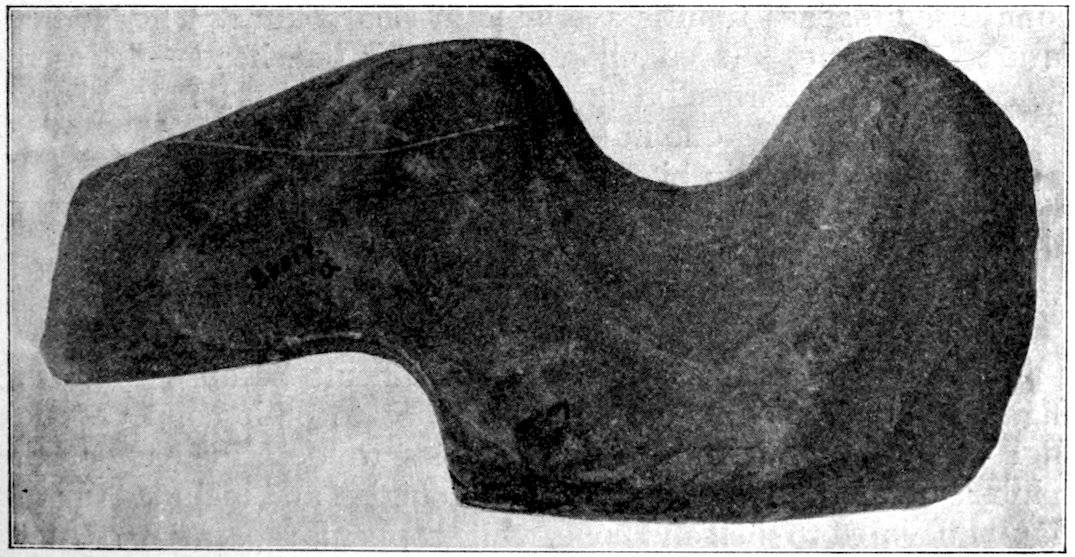

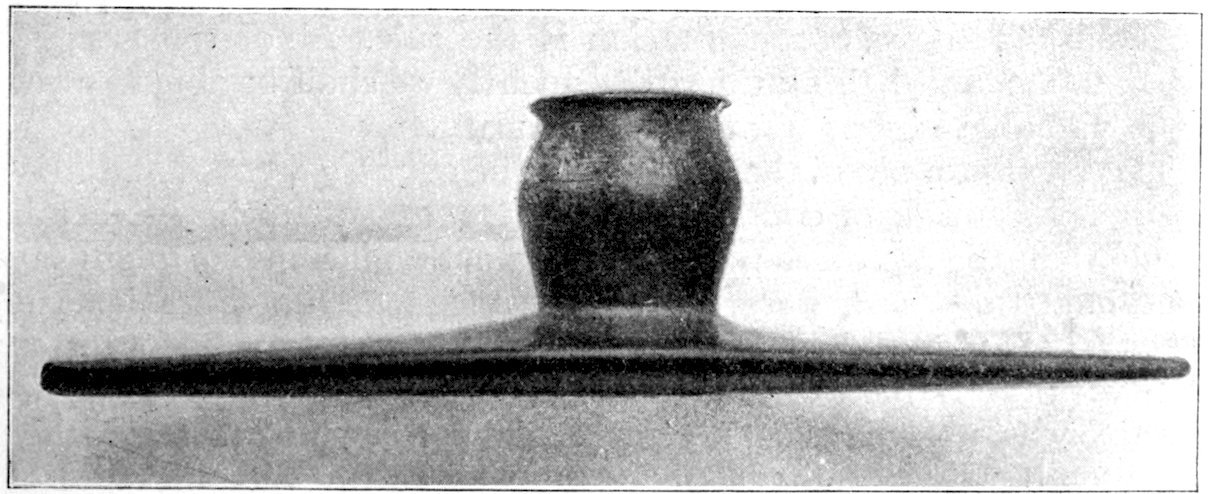

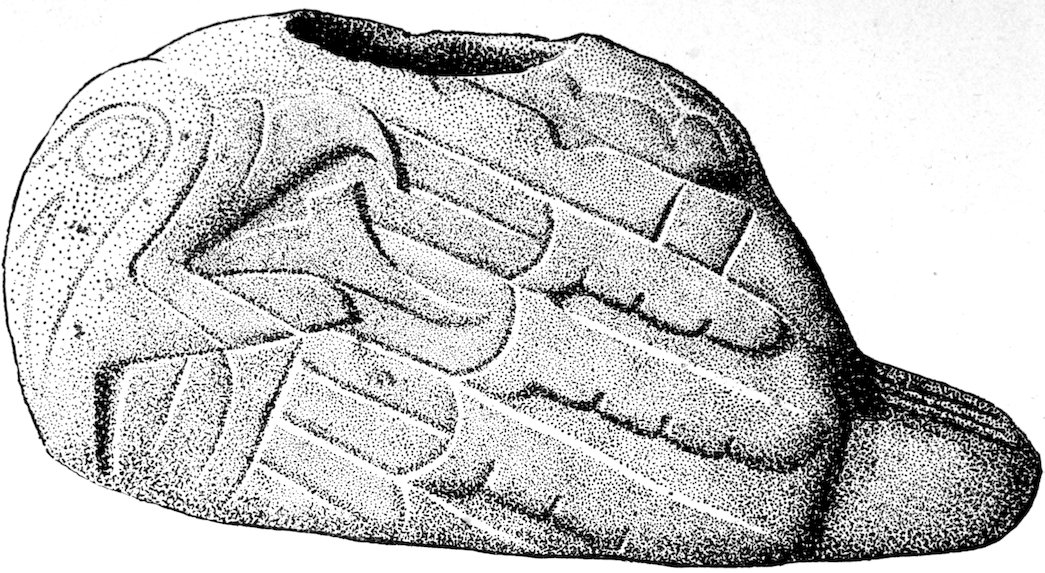

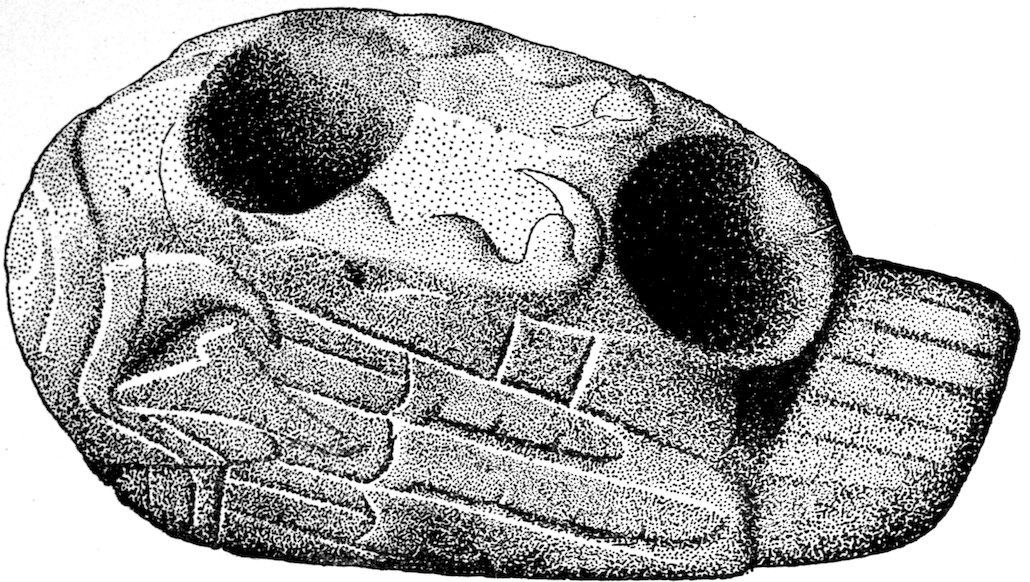

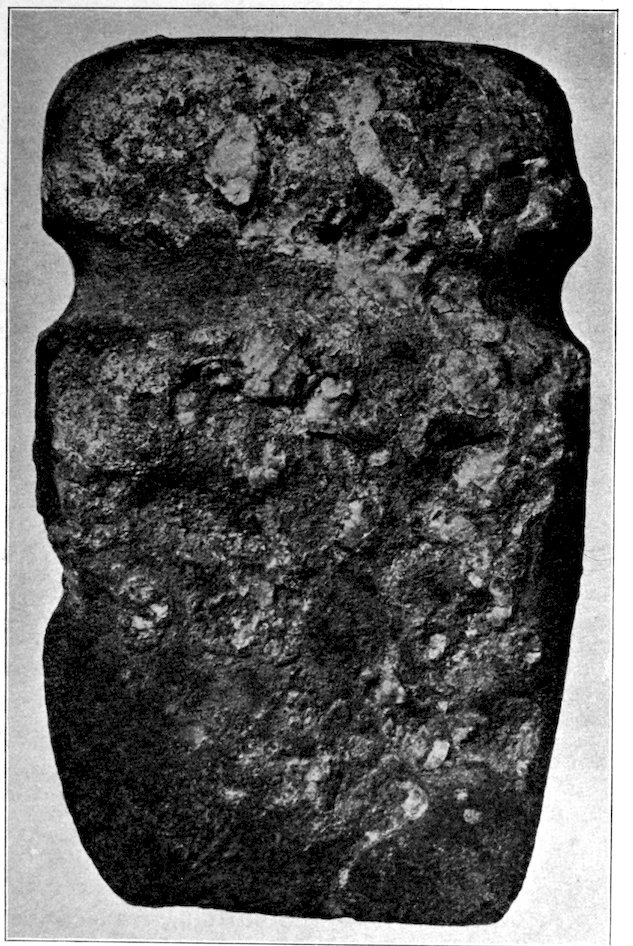

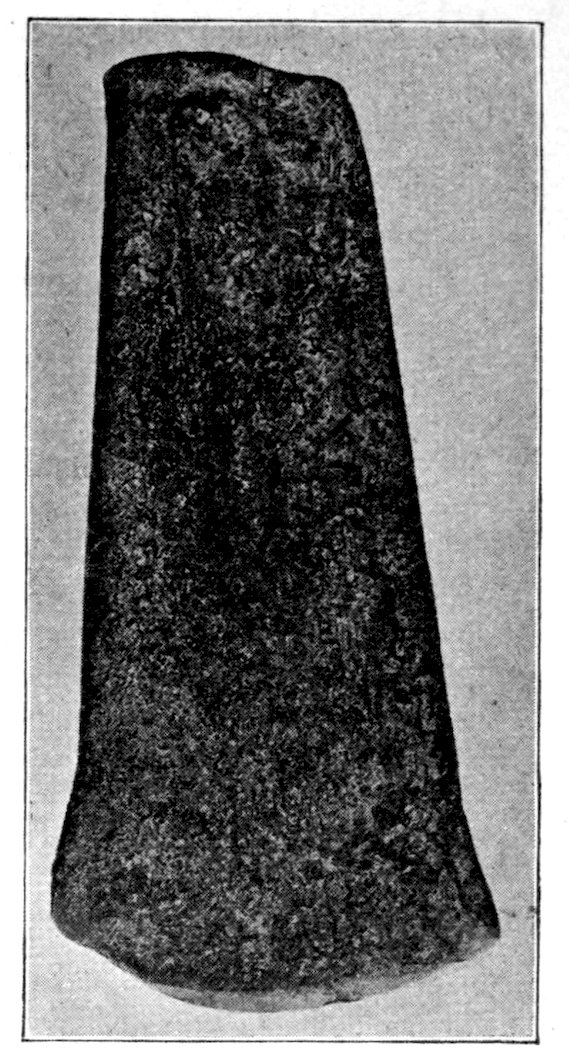

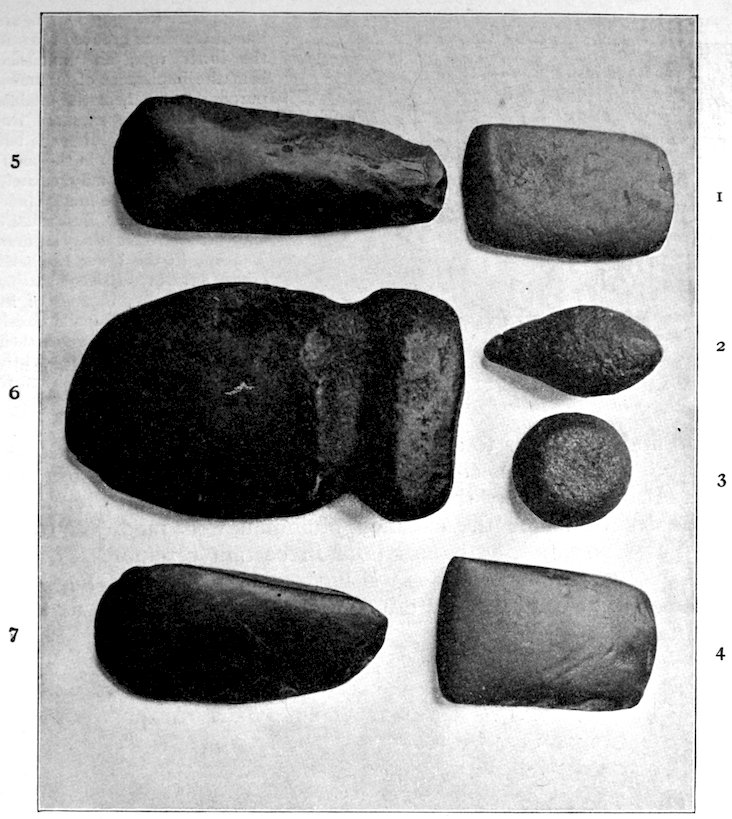

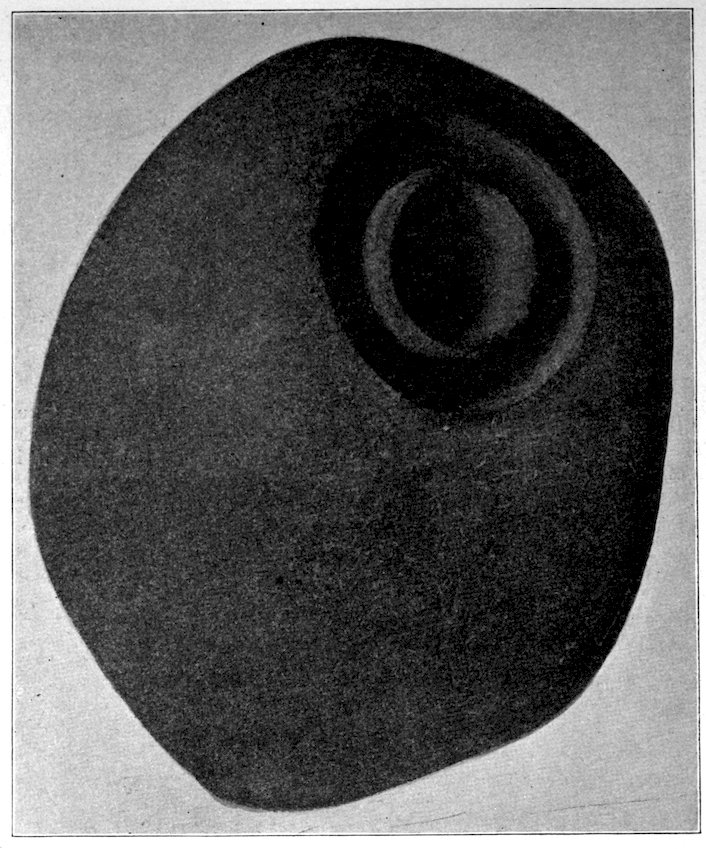

Fig. 402. (S. 1–1.) Central Ontario, Canada. Provincial Museum collection.

This art we see in the carved effigies. To study them in detail requires more space than is available in this volume. The Nomenclature Committee placed all effigies under one head—“Resemblances to known forms.” Under that general head I have placed:

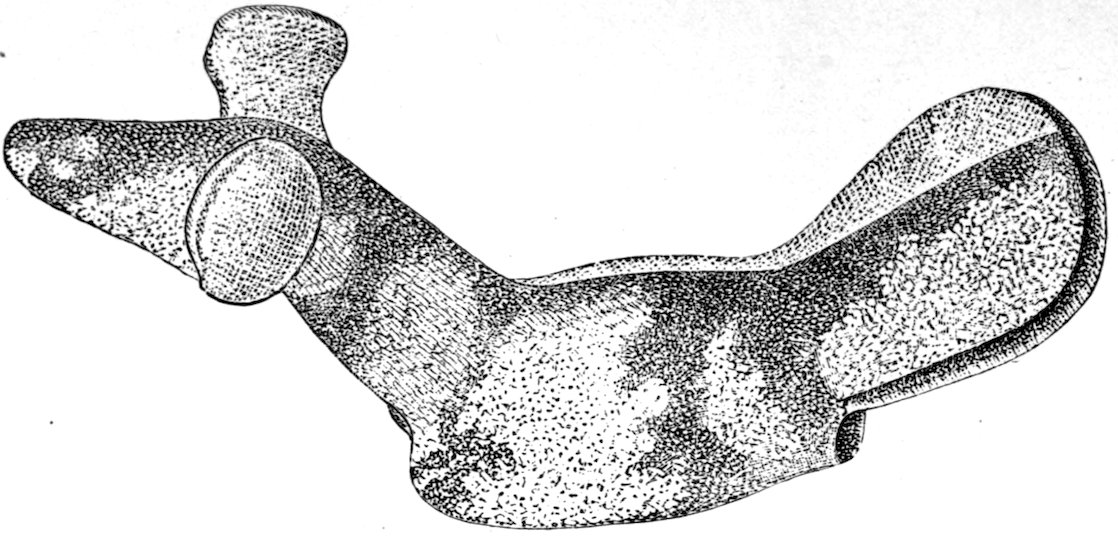

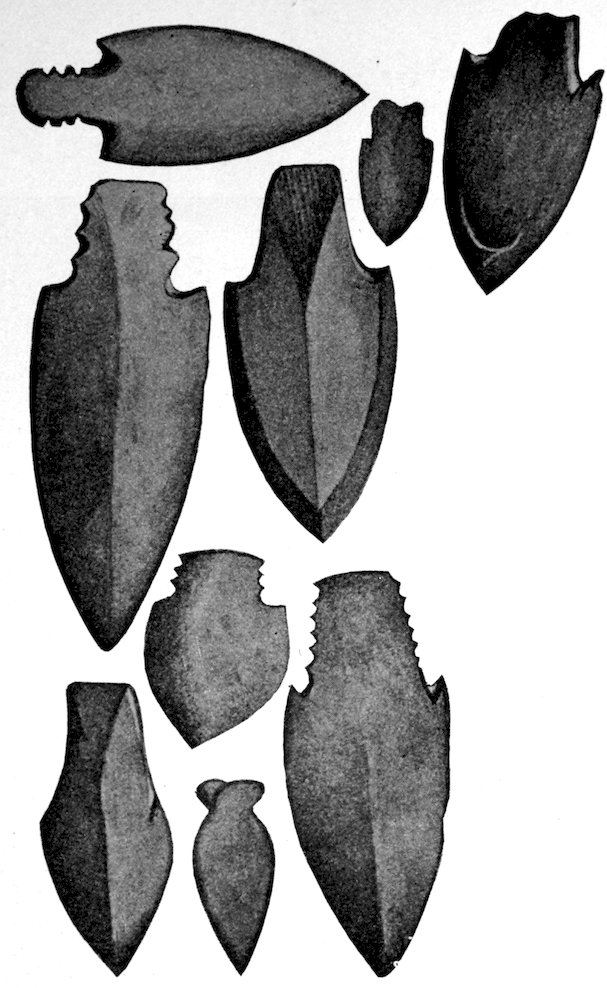

The classification made is rendered difficult because there are effigies in bone, shell, clay, and stone, not to omit copper. Such effigies as were drilled and used as pipes are described under the chapter devoted to pipes. The bone effigies are included in the chapter devoted to shell and bone, while copper is separately treated. Yet there remains, after treating more or less completely of these 5various divisions, a large class of stone objects which are not pipes, or tools, or dishes, and which I have thought best to include by themselves. The largest division in effigies is the so-called bird- or saddle-stone which is found between the following lines: Davenport, Iowa, to central Minnesota, east to New Brunswick, south to the Atlantic Coast, and thence south down the coast to Washington, thence west to Davenport. Few bird-stones occur south of Kentucky, west of Davenport, or north of St. Paul. The other effigies are of multitudinous kinds and are widely scattered throughout the United States.

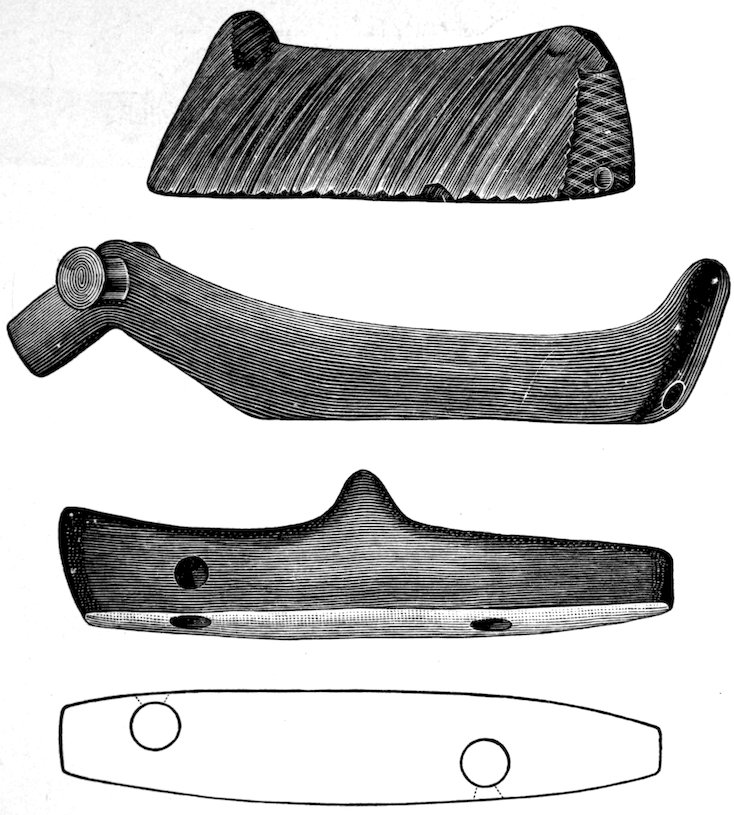

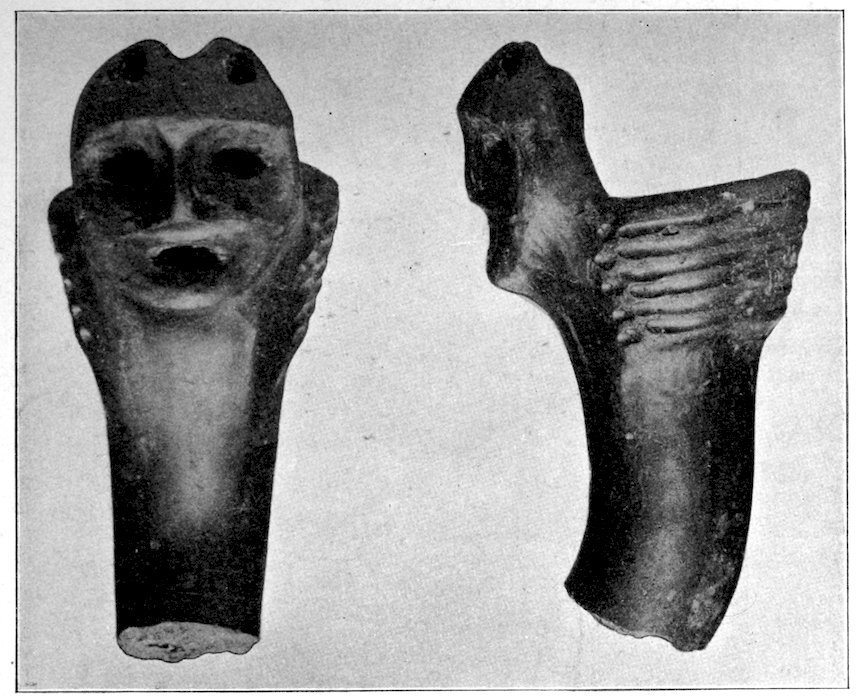

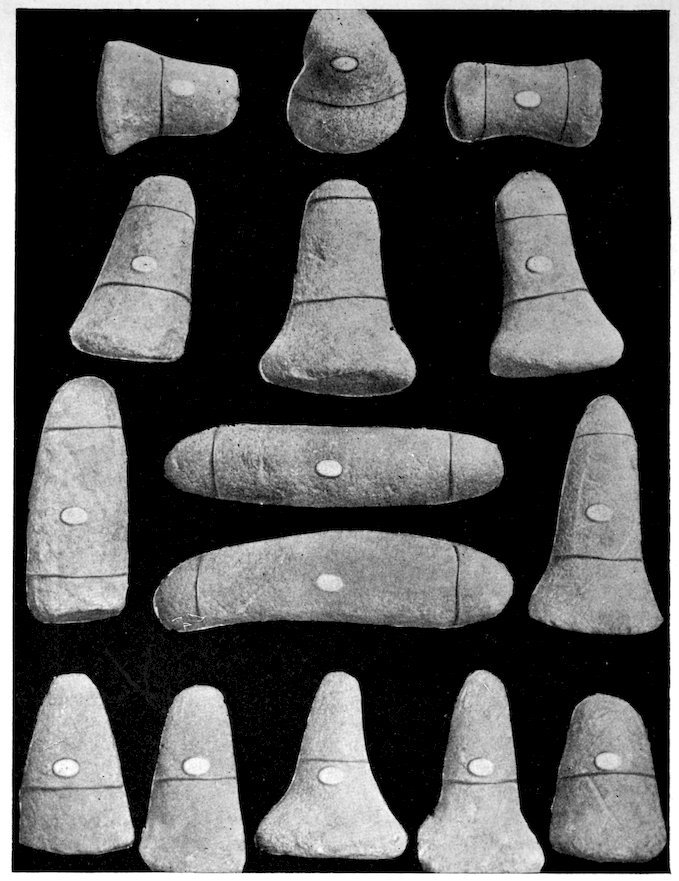

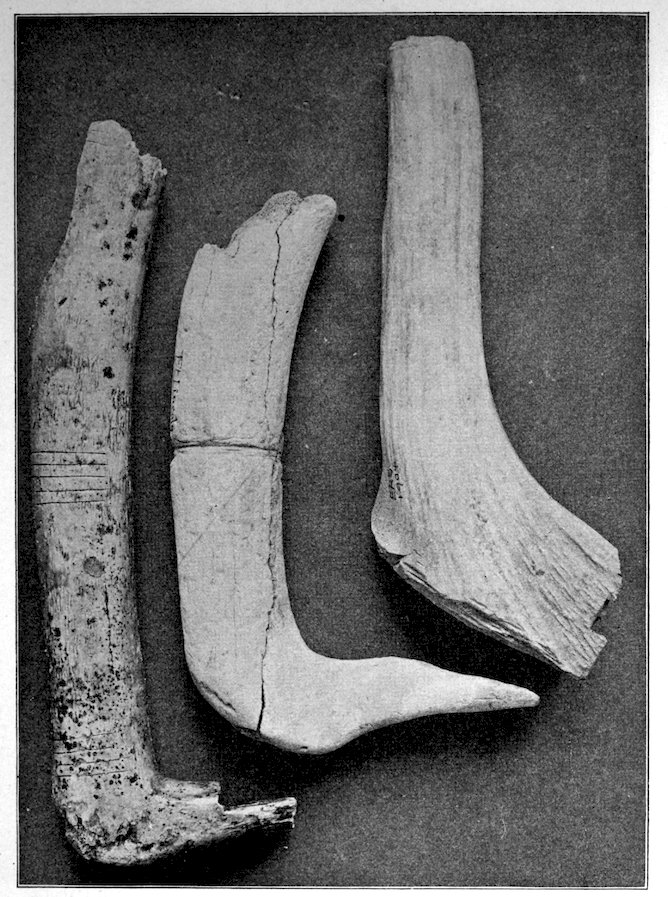

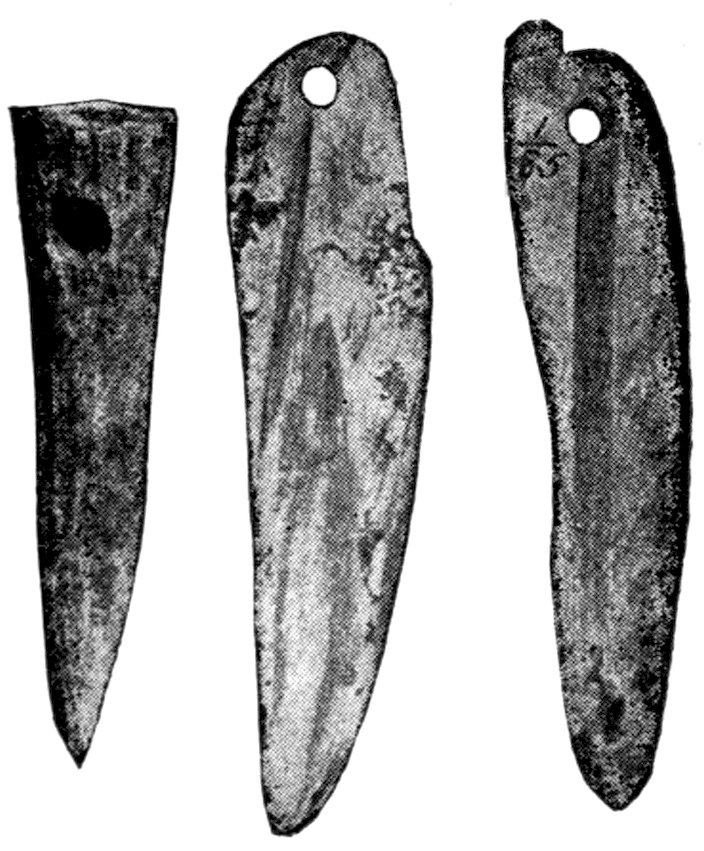

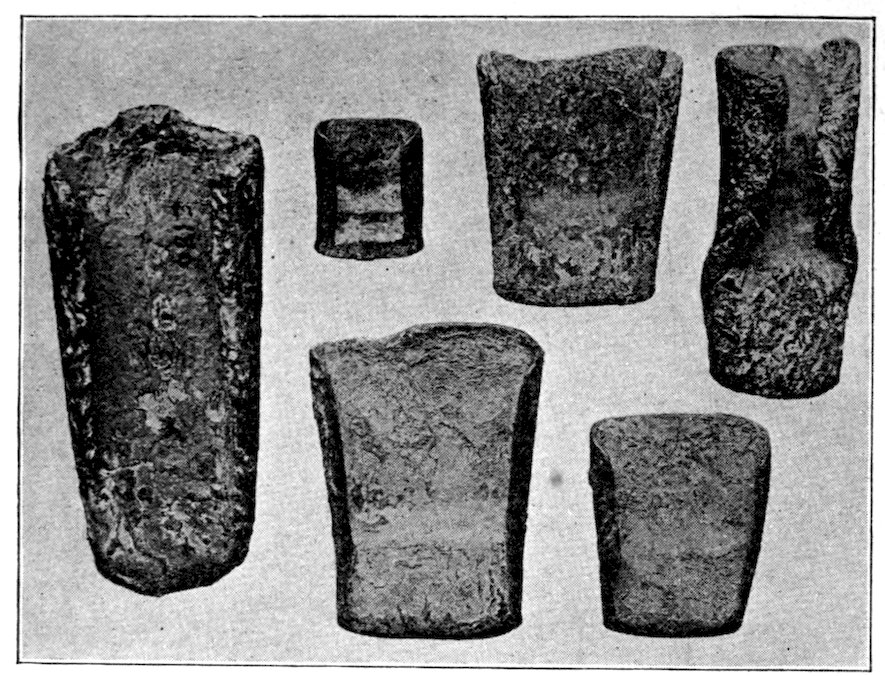

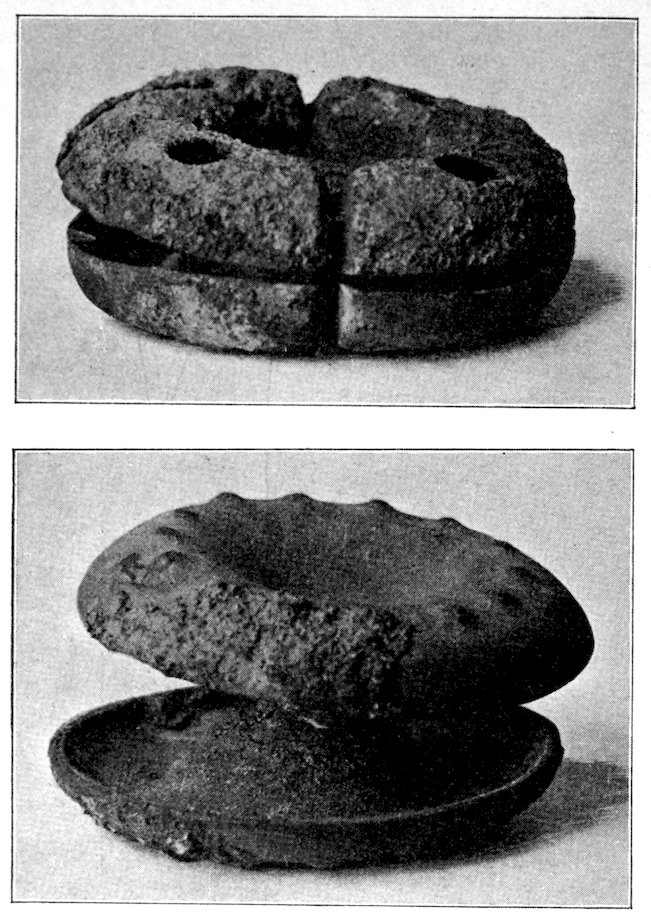

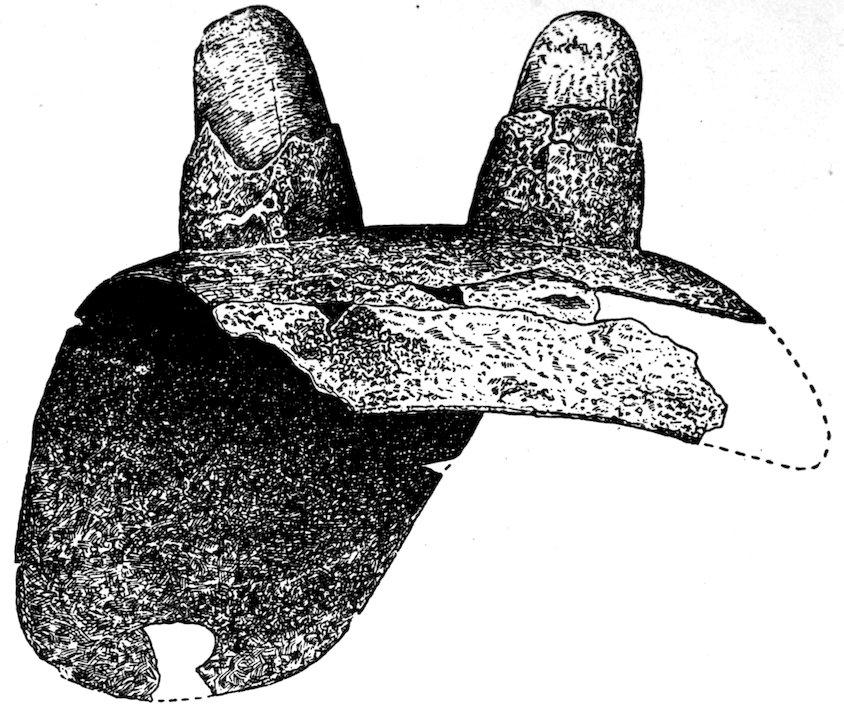

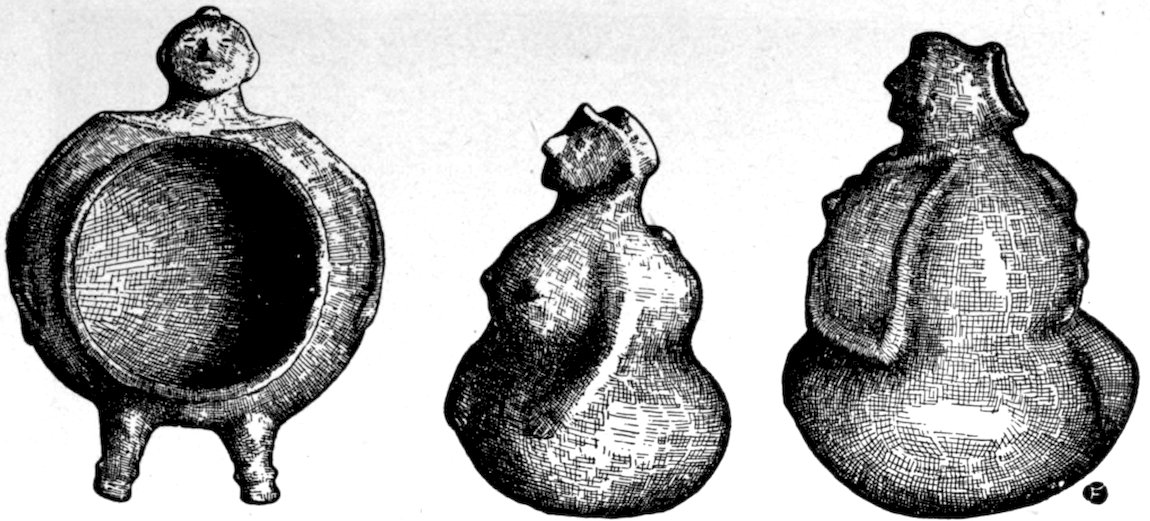

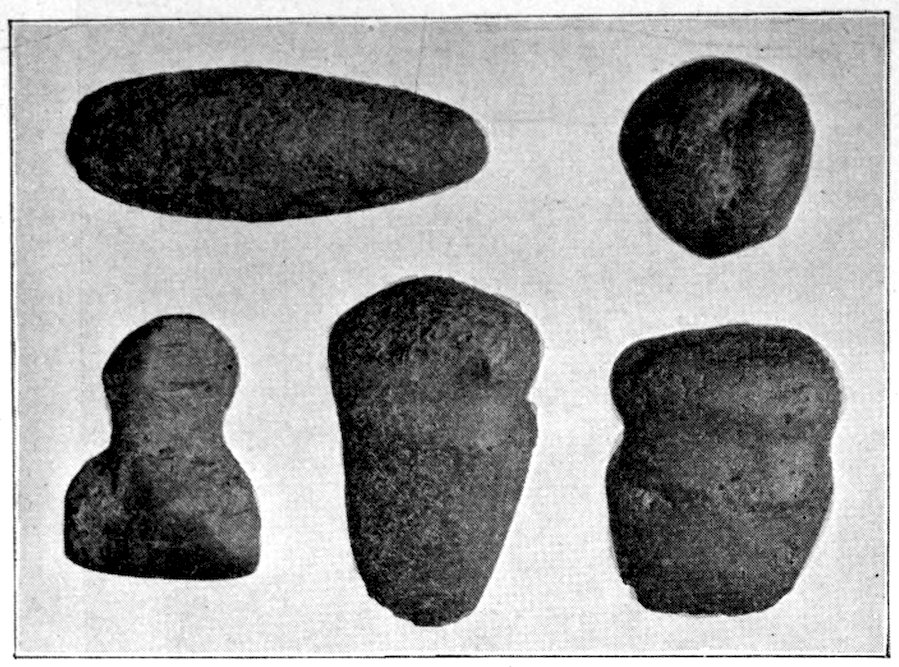

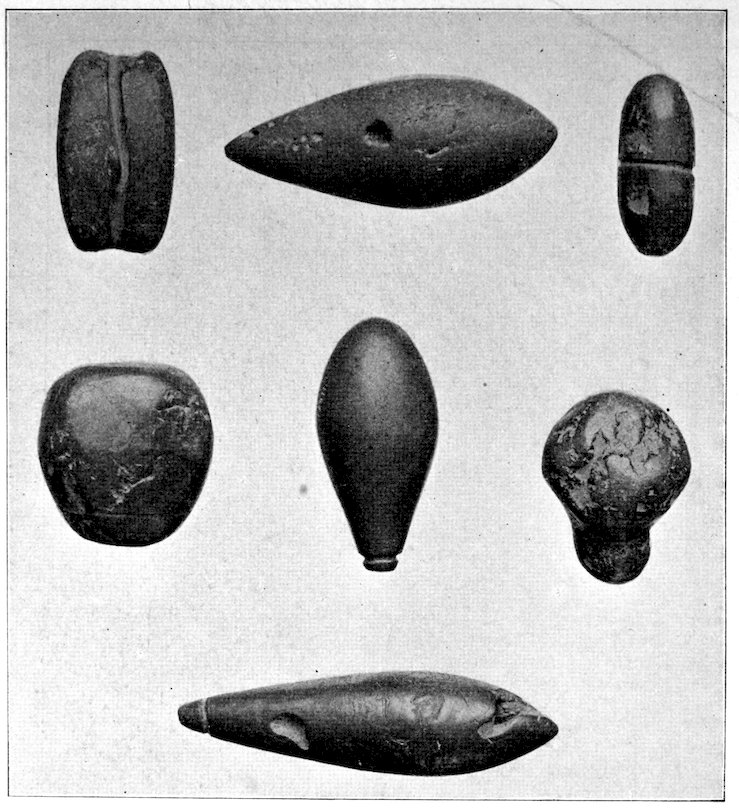

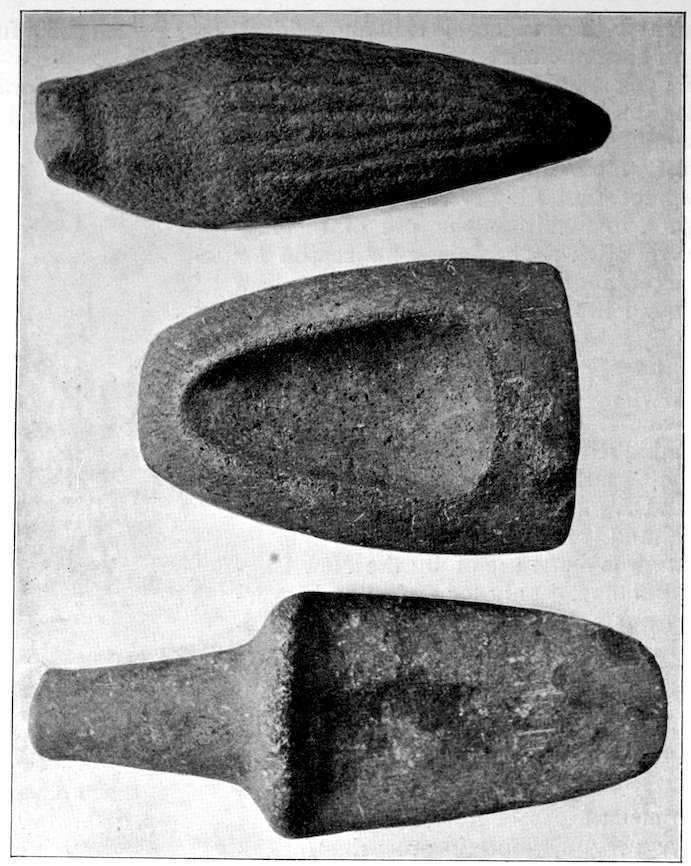

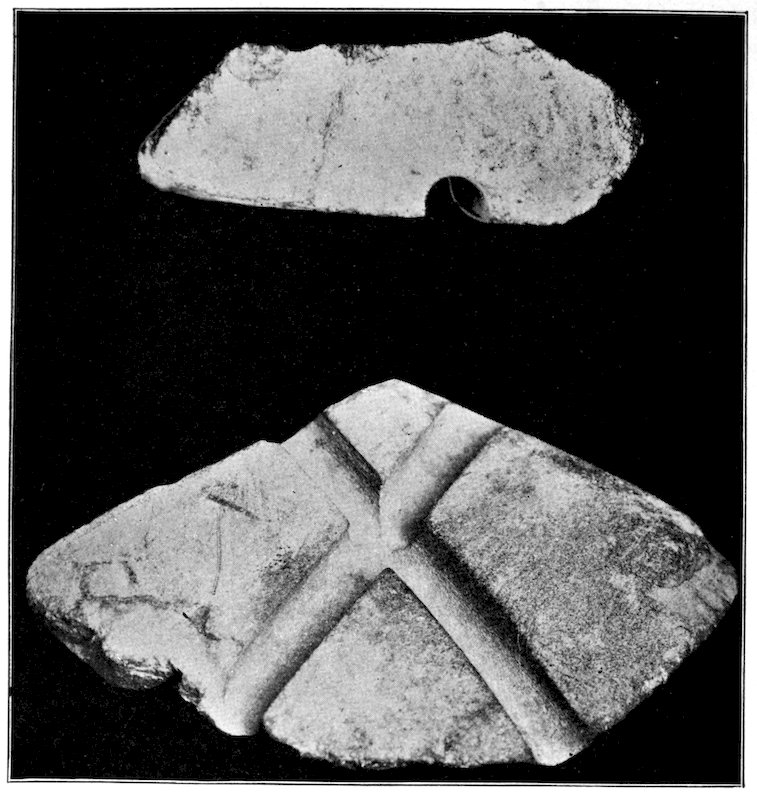

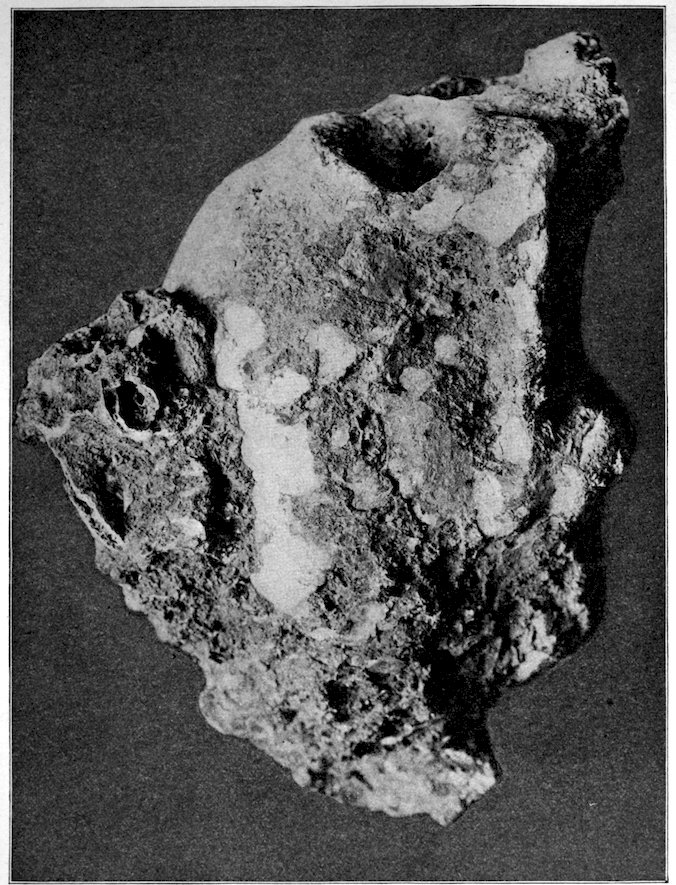

Fig. 403. (S. 1–1 and 1–2.) These three problematical forms are from the Provincial Museum collection, Ontario, Canada. The upper one is from central Ontario. The base view of the lower specimen is also shown.

Fig. 404. (S. 1–2.) Andover collection.

Fig. 405. (S. 1–4.) W. A. Holmes’s collection, Chicago.

8Figs. 399, 400, 401, and the central object in Fig. 269 are all unfinished bird-stones. It was difficult for me to procure these, but after some years of correspondence they were obtained.

The specimens clearly show the work of the hand-hammer. Fig. 401 and the upper right-hand specimen in Fig. 399 have been pecked into shape and the grinding-polishing process was well under way when the specimen was set aside, or lost.

Fig. 406. (S. about 1–3.) Collection of Leslie W. Hills, Fort Wayne, Indiana.

In collecting numbers of these unfinished bird-stones, my object was to prove that these slender, delicate objects did not indicate European knowledge or influence, but were wrought after much labor from ordinary stone by prehistoric man. None of them show 9the marks of steel cutting-tools. Fig. 400 is the roughest one and yet the ears or eyes stand out in relief. Fig. 399 is interesting in that it shows three on which the result of pecking and battering is in evidence. The one to the left, lower row, has been pecked, and ground, and was in process of being polished when the work ceased.

Fig. 407. (S. 1–2.) Collection of Leslie W. Hills, Fort Wayne, Indiana.

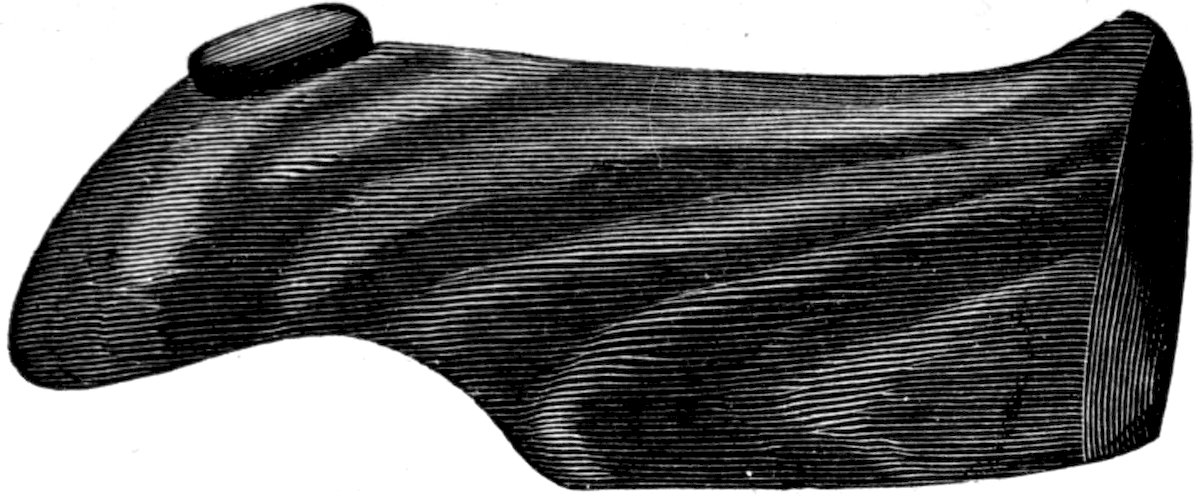

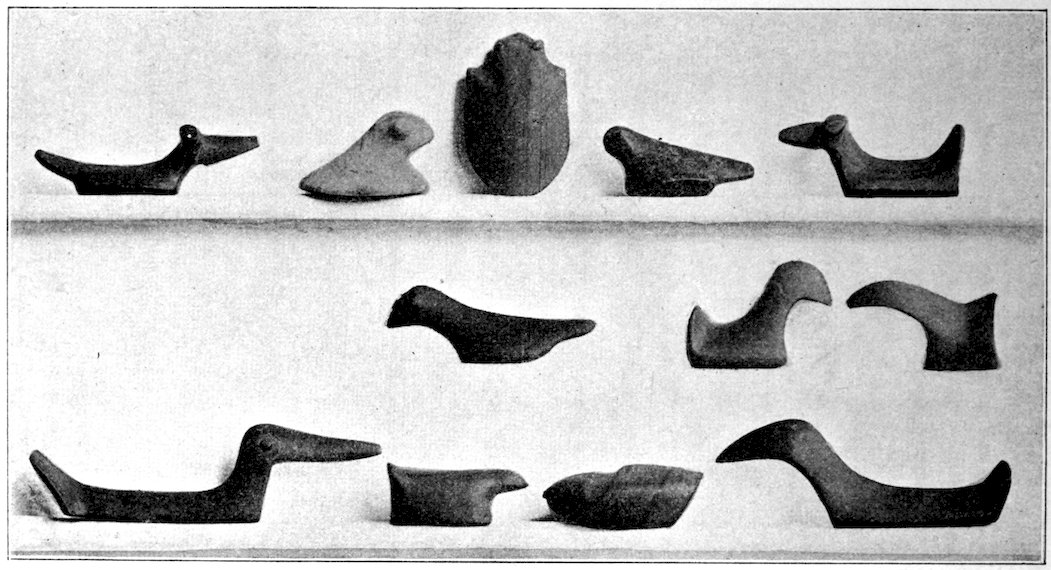

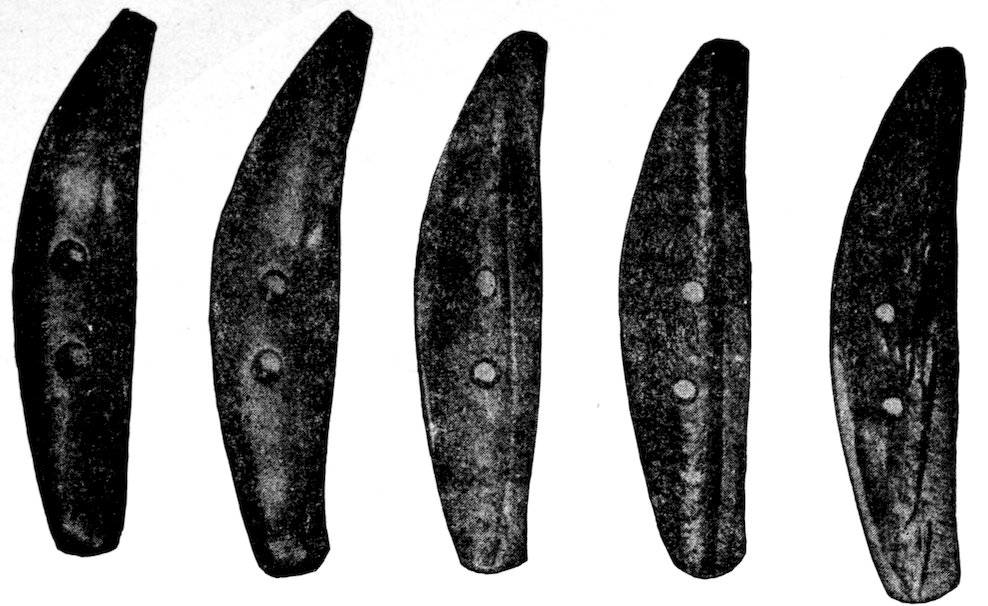

Fig. 401, Andover collection, found in Ohio, is a large bird-stone about five inches in length. The marks of the flint cutting-tool or of the hard grained rubbing-stone, which cut the softer surface of the slate, are still apparent. Fig. 404 presents various bird-stones, both rare and common forms, with and without ears. These are found long and slender, short and thick, almost as low as the bar-amulet, 10and also so high that they merge into other effigies. Six bird-stones from the collection of Mr. Leslie W. Hills of Fort Wayne, Indiana, are shown in Fig. 407.

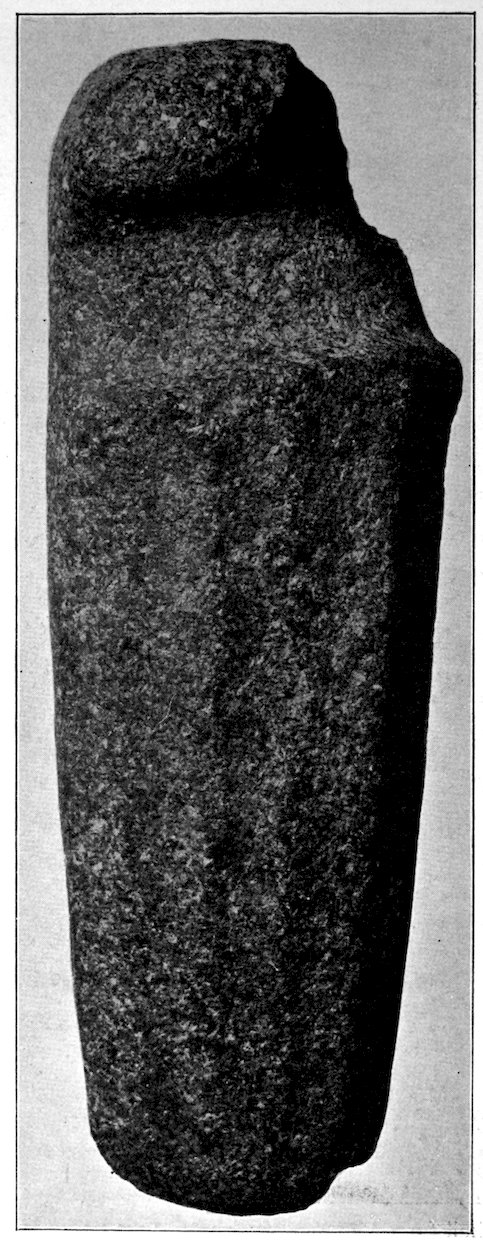

Fig. 408. (S. 3–5.) “This specimen is from western New York. It is made in the form of a bird which from the number of similar specimens have given the name to this class. The eyes are represented by great protuberances, which must have greatly increased the difficulty of manufacture. It is made from a boulder or large piece, and while the material is hard, it is not rough but rather fragile. It could not be chipped like flint nor whittled like soapstone, but must have been hammered or pecked into shape and afterwards ground to its present form, then polished until it is as smooth as glass. A consideration of the conditions demonstrates the difficulty of making this object and the dexterity and the experienced working required.”[1] Material: diorite with feldspar crystals. Smithsonian collection. Otis M. Bigelow’s collection, Baldwinsville.

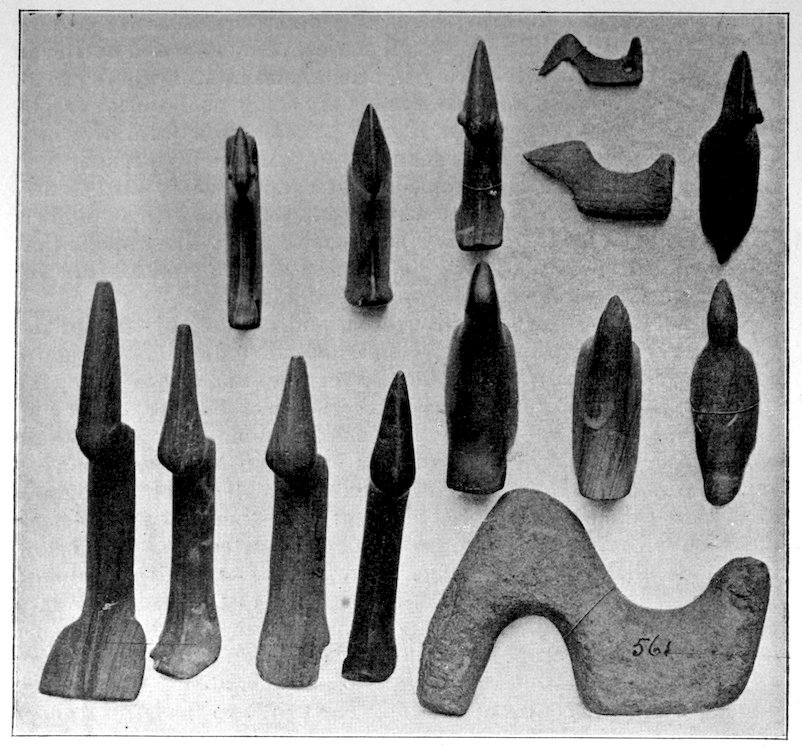

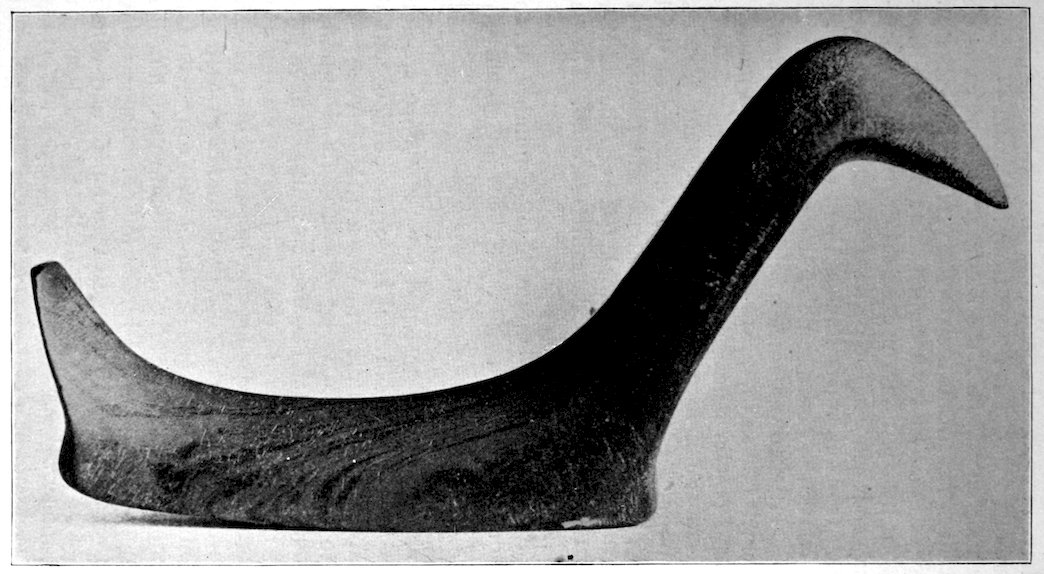

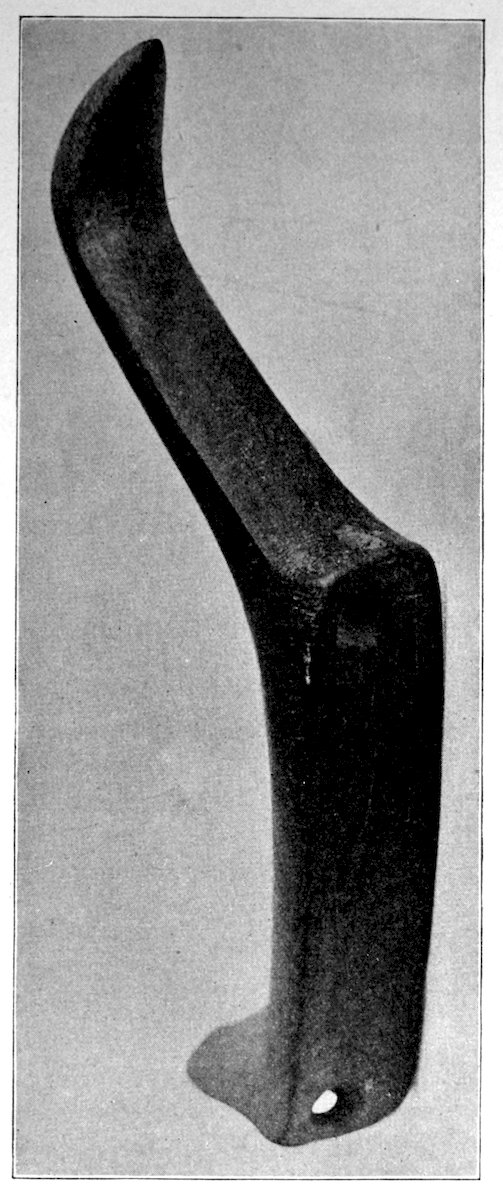

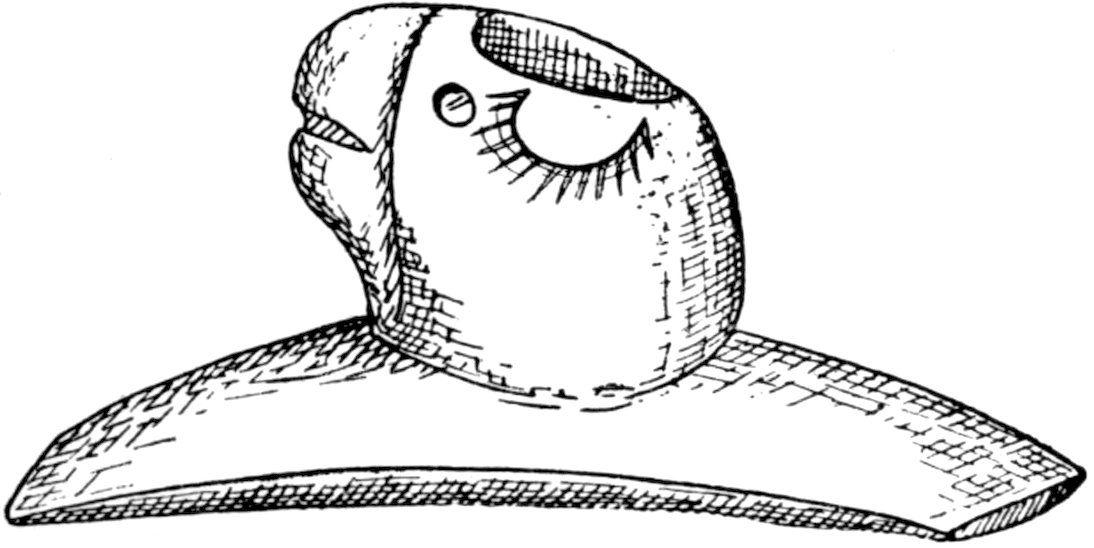

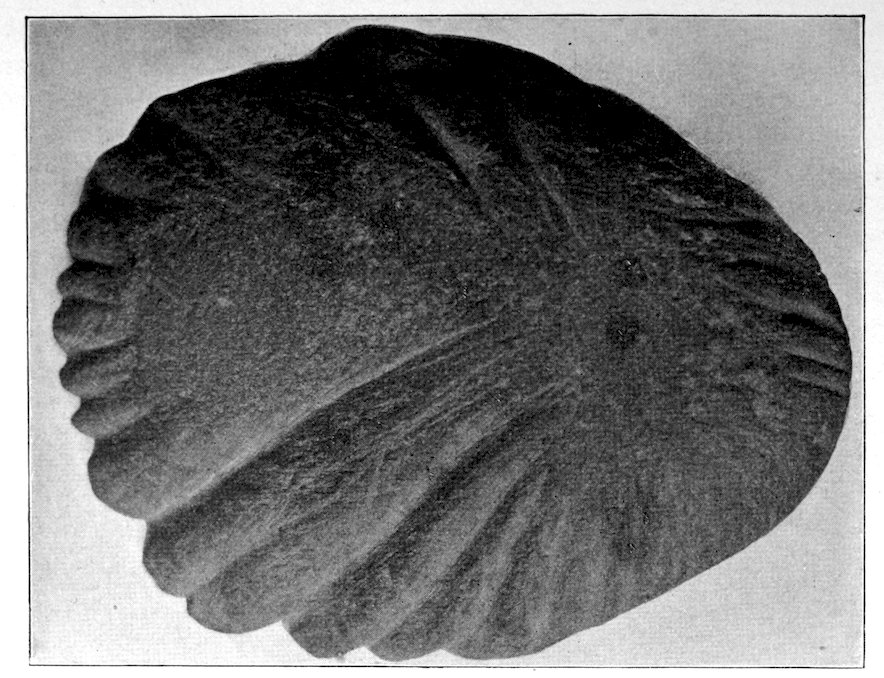

The bird-stones with projection on either side, which by some are called ears, and by others eyes, are quite frequently found in the eastern United States, and Canada. An unusual one is illustrated in Fig. 402, this having one button-shaped knob on the top of the head. Figs. 406 and 409 from the collection of Mr. Hills illustrate bird-stones about one third size, from various portions of Indiana, Ohio, and Canada; an unfinished one in Fig. 409 (number on its side 561) is interesting in that the bill or nose is unusually long, the head high, and the body quite short. One beautiful specimen owned by Mr. George Little of Xenia, Ohio, is illustrated in Fig. 410, and the specimen is turned in Fig. 411 so that the perforations are visible. The neck of this is unusually long. It will be observed that all of these bird-stones have flat bases; none of the bases are round.

In Figs. 404 to 411 are presented bird-stones, Class I, divisions A and B. Naturally, there are more of plain bird-stones (A) than 11those with large projecting ears, or elaborate heads. It will be observed that the width of the tail varies, being long and narrow in some, short and slightly flaring in others, and in still others broad, or fan-shaped. Sometimes the eye is very small, as in the lower left-hand specimen, Fig. 405. Or it may be sunken, several of which are shown in Fig. 409. But usually it is worked in high relief.

There are presented, all told, in this chapter, sixty bird-stones. It would be possible for me to present ten times this number. There are included in the series numbers of effigy-like objects that might not be classed by other observers as bird-stones. For instance, the central specimen, top row, of Fig. 405.

The bird-stones are very interesting and unique objects and the range in them is considerable. Sometimes they are almost square, as is seen in the central specimen, lower row, Fig. 405. Again, the head is a prominent feature, as is observed in the lower one in Fig. 409, and the body is of secondary consideration. A group of these stones from the Andover collection is shown in Fig. 404. The very small bird-stone in the upper row to the left is half size of the original, as are the others. This is the smallest bird-stone, the genuineness of which is beyond question, brought to my attention. Just below it is a peculiarly straight effigy from Tennessee, which is almost bar-amulet in shape, and marks the merging of the bird-stone into the bar-amulet. Fig. 408 is an expanded-wing type of unusual beauty. Fig. 405, from the collection of W. A. Holmes, Chicago, shows typical bird-stones, with an unusual one, almost like a frog, and shown in the centre at the top. Next to it to the left is a short stone, hardly bird-like in character, of which a few have been found in the United States. Fig. 403, from the collection in the Provincial Museum, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, presents at the top a stone as much bar-amulet as bird in character, and also a stone at the bottom in the centre of which is worked a projection or knob.

Fig. 412, from the Reverend William Beauchamp’s collection, is somewhat different from ordinary bird-stones, although it is included under that class. In 1899 I issued a bulletin, “The Bird-Stone Ceremonial,” which is now out of print. It illustrated fifty-three bird-stones. Since that time Mr. Charles E. Brown has published a study of bird-stones.[2] This is an excellent review.

Dr. Thomas Wilson once made a statement[3] concerning bird-stones, and I quote one of his paragraphs: “The United States 12National Museum possesses many of these specimens. While they bear a greater resemblance to birds than anything else, yet scarcely any two of them are alike and they change in form through the whole gamut until it is difficult to determine whether it is a bird, a lizard, or a turtle, and finally the series ends in a straight bar without pretense of presenting any animal.”

Fig. 409. (S. about 1–3.) Collection of Mr. Leslie W. Hills, Fort Wayne, Indiana.

The range of material is from Huronian slate or shale to red sandstone, granite, and porphyry. Usually the stone from which they are made is banded or contains spots of color. They are either red, gray, or brown, with variations. Sometimes feldspathic granite, diorite, and porphyritic-feldspar are made use of. Dr. William Beauchamp gives a very good description of some fifteen bird-stones.[4] I have reproduced none of the illustrations he gives, but as his text is timely, I quote at length from his paper:—

Fig. 410. (S. 1–1.) Collection of George Little, Xenia, Ohio.

14“The theories about their use seem fanciful, as some certainly are. Two writers assert that they were worn by married or pregnant women only, and many have accepted this statement. Others think they were worn by conjurors, or fixed on the prows of canoes. It is enough to say that some of the perforations are not adapted to any of these uses. It seems better to class them with the war and prey or hunting gods of the Zuñis, some of which they resemble. In that case the holes, of whatever kind, would have given a firm hold on the thongs which bound the arrows to the amulet, a matter of importance in an irregular figure.

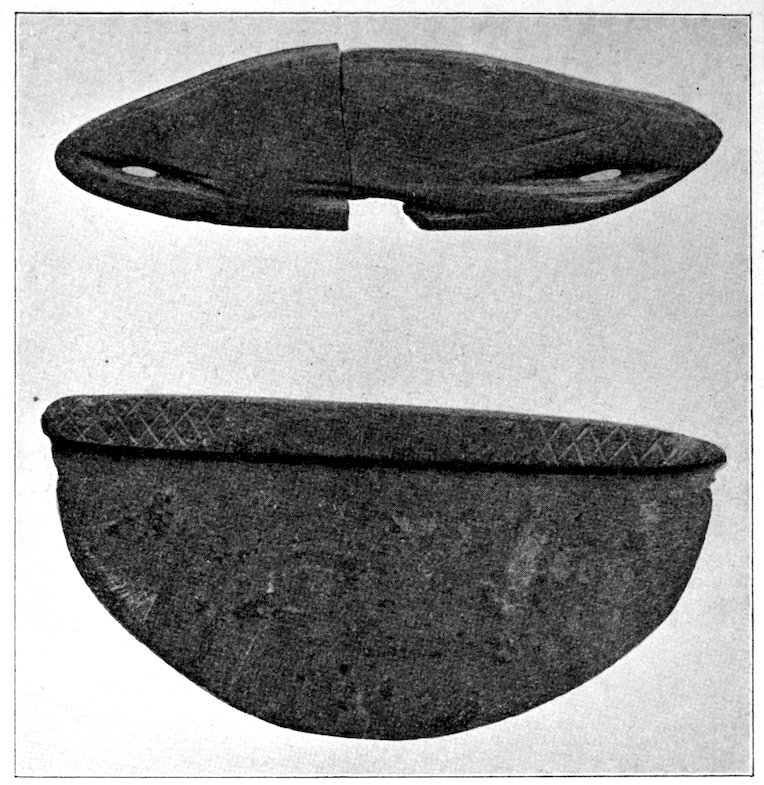

“These perforations form the most important feature. The amulet may be but a simple bar, but to each end of the base is a sloping hole, bored from the end and base and meeting. To this necessary feature may be added a simple head or tail, and there may also be projecting ears. None of these are essential. They are but appropriate or tasteful accessories.

“Two notable collections contain a large number of amulets. In the Canadian collection at Toronto there are about fifty bird-amulets.”

Dr. Beauchamp mentions Mr. Douglass’s seventy specimens in the American Museum of Natural History collection, and also refers to the rarity of bar-amulets in Western New York:—

“They were variable in material as well as form, although most commonly made of striped slate. Perhaps full half have projecting ears, when of the bird-form. In the wider forms, usually of harder materials, there are often cross-bars on the under side, in which the perforations are made. Occasionally these are not entirely enclosed, yet are without signs of breakage. This seems to prove that these were not intended as means of attaching them to any larger object, on which they would rest, but rather for fastening articles upon them, as in the Zuñi amulets already mentioned, and which were illustrated by Mr. Frank H. Cushing, in the Second Report of the Bureau of Ethnology. On comparison a general resemblance to these will be seen, and in a few cases it is quite striking. That they were used in this way, rather than in those suggested by others, 15is a reasonable conclusion which gains strength with fuller study. As a class they belong to the St. Lawrence basin.”

Fig. 411. (S. 1–1.) Side view of Fig. 410.

Mr. Gerard Fowke and Professor David Boyle should be quoted upon this subject. Mr. Fowke says:[5]

Fig. 412. (S. 1–1.) Rev. William Beauchamp’s collection. From Michigan.

“Stone relics of bird-form are quite common north of the Ohio River, but are exceedingly rare south of that stream. [He illustrates the same specimen figured by Dr. Wilson.]

“According to Gilman,[6] the bird-shape stones were worn on the head by the Indian women, but only after marriage. Abbott quotes Colonel Whittlesey to the effect that they were worn by Indian women to denote pregnancy, and from William Penn that when the squaws were ready to marry they wore something on their heads to indicate the fact.

Fig. 413. (S. 1–4.) Peabody Museum, Cambridge.

“Jones[7] quotes from De Bry that the conjurors among the Virginia Indians wore a small black bird above one of their ears as a badge of office.”

Professor Boyle[8] says: “Although for convenience known as bird-amulets—most of them being apparently highly conventionalized bird-forms—now and again one sees specimens that are not suggestive of birds, whatever else they may have been intended to symbolize. In some instances there has not been any attempt to imitate eyes even by means of a depression, but in the majority of cases the eyes are enormously exaggerated, and stand out like buttons on a short stalk, fully half an inch beyond the side of the head. In every finished specimen the hole is bored diagonally through the middle of each end of the base, upwards and downwards. If merely for suspension when being carried, one hole would be sufficient, but the probability is that these were intended for fastening the ‘amulets’ to some other object, but what, or for what purpose, is not known.

“It has been suggested that these articles ... were employed in playing a game; that they are totems of tribes or clans; and that they were talismans in some way connected with the hunt for waterfowl. They are, at all events, among the most curious and highly finished specimens of Indian handicraft in stone found in this part of America, and the collection of them in the Provincial Archæological Museum is said to be the best that has been made.”

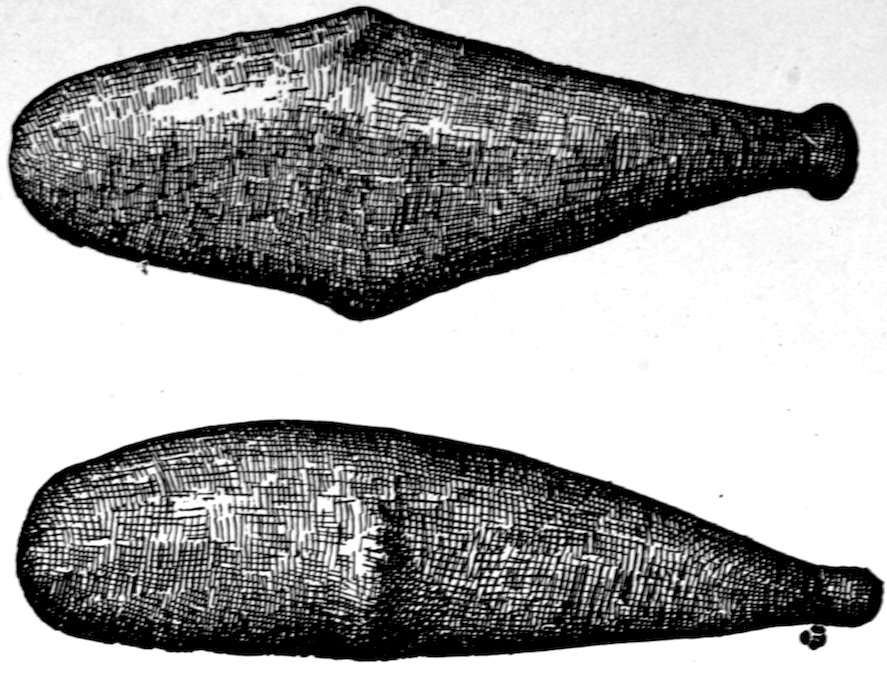

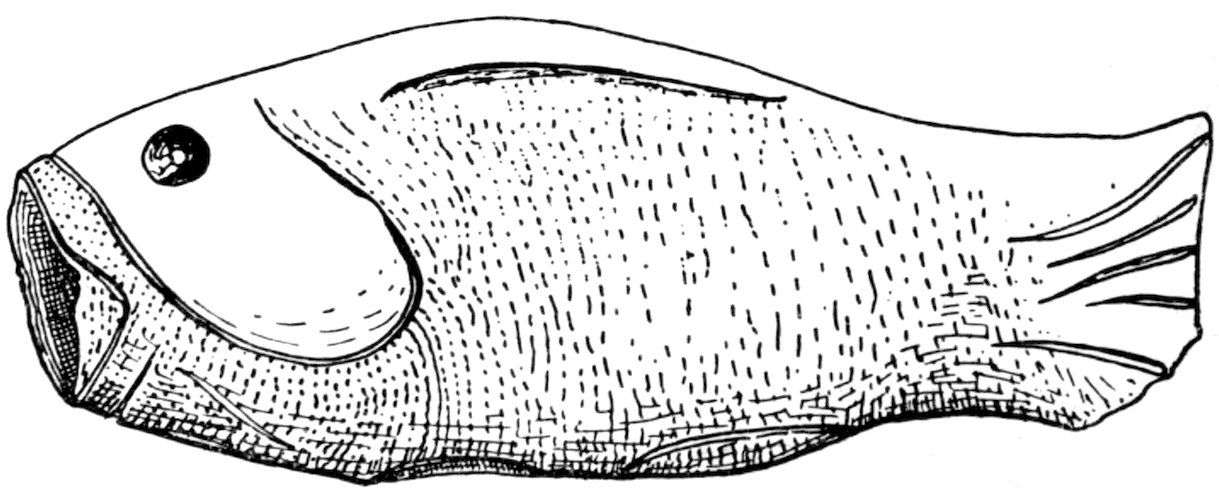

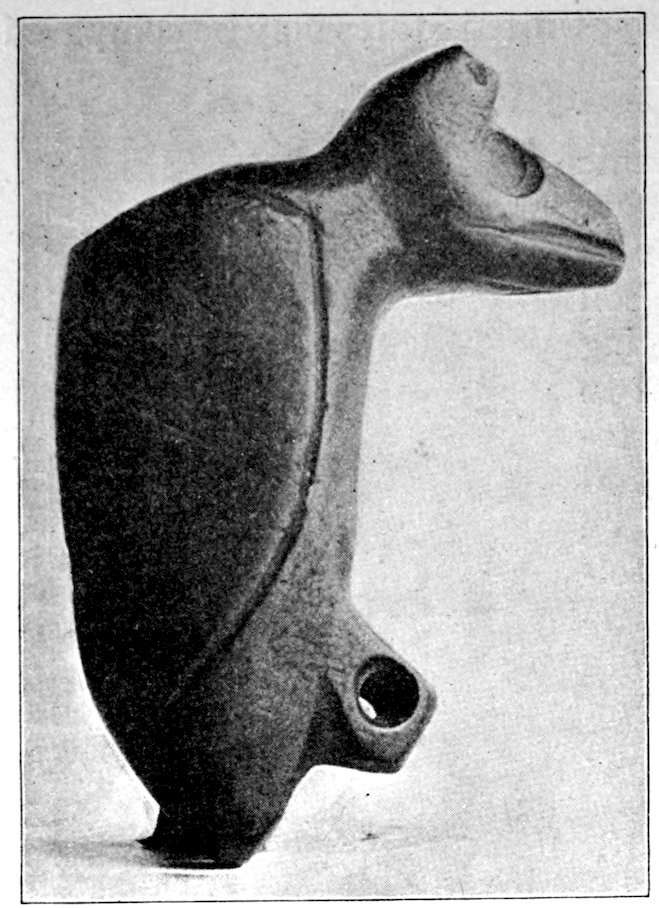

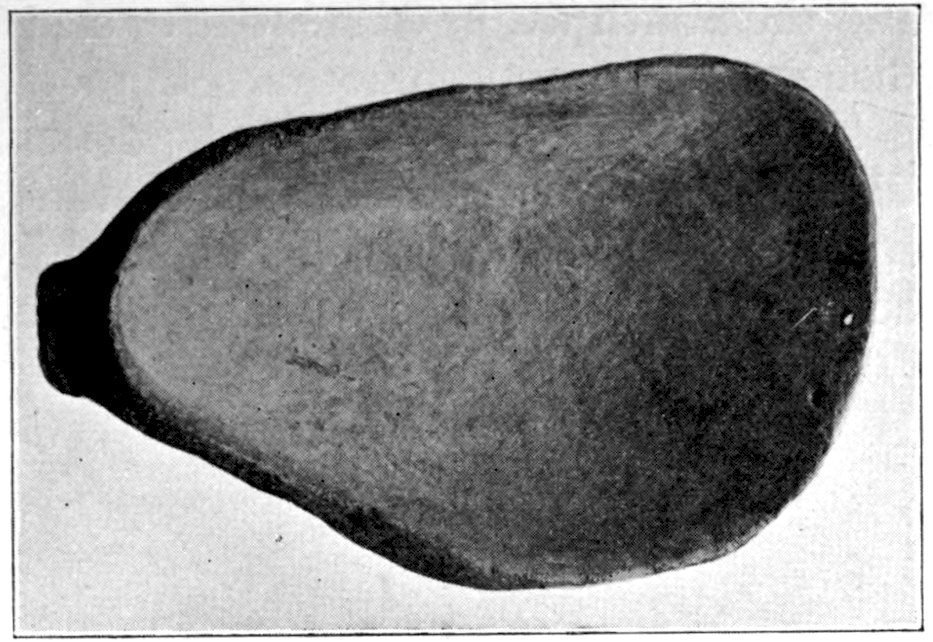

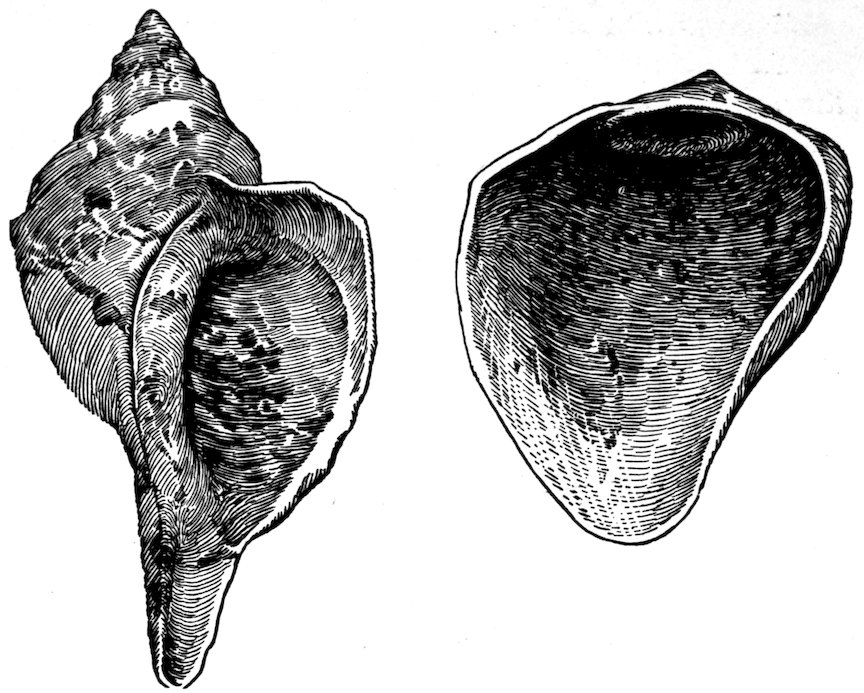

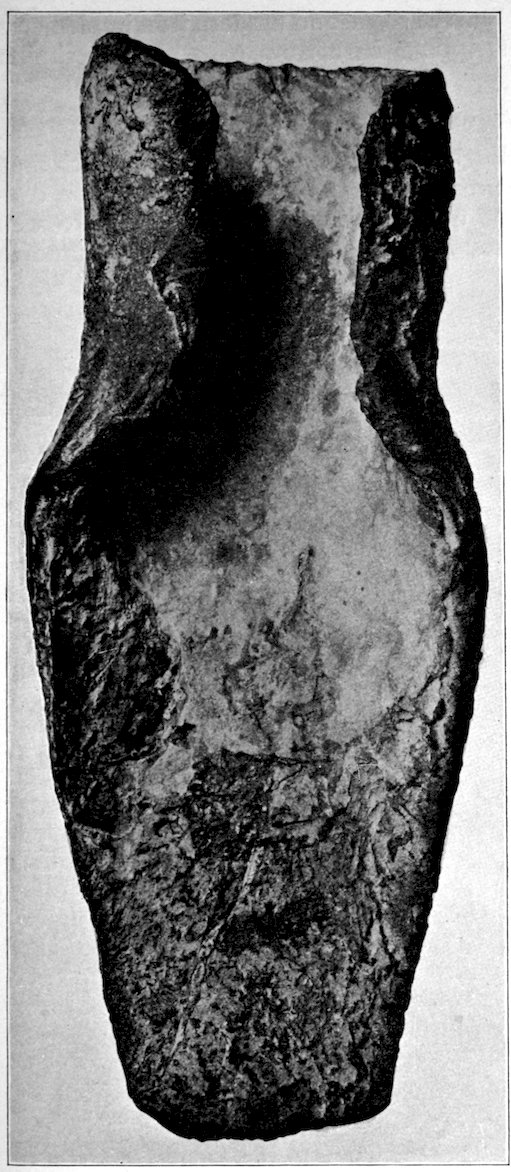

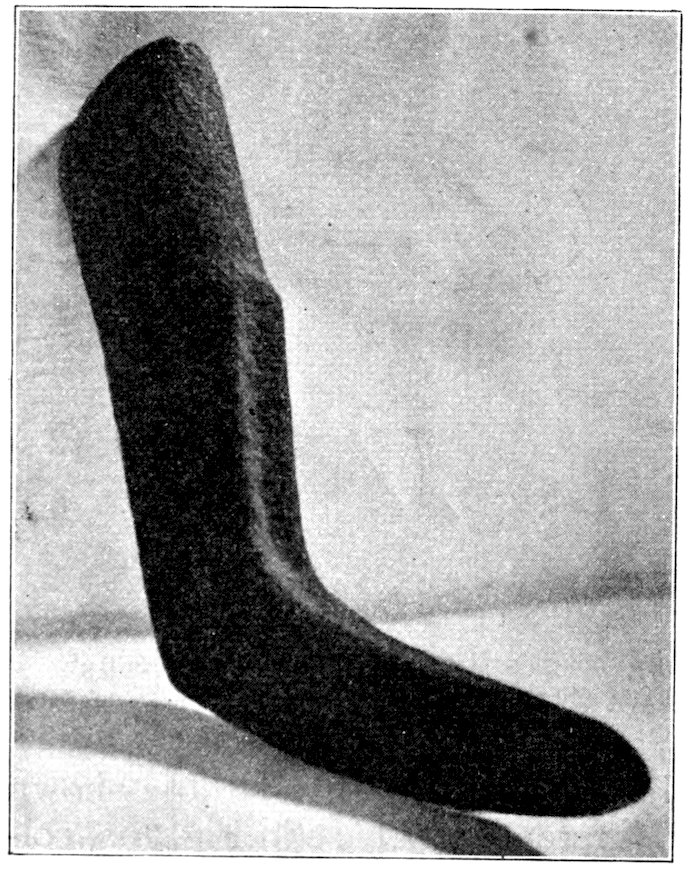

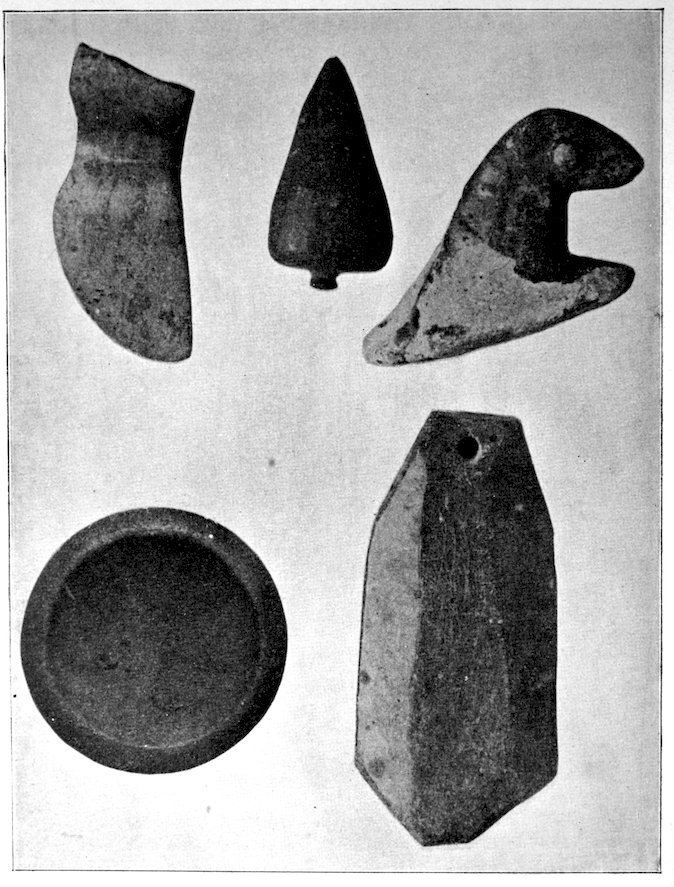

Fig. 414. (S. 3–8.) Effigy of a whale. Andover collection. This stone was found near Fall River, Massachusetts. It appears to be an effigy of a whale. Numbers of rude effigies, more or less whale-like in character, are found along the Atlantic seaboard in Connecticut and Massachusetts. Doubtless the whale would excite wonder in the minds of aborigines—hence the effigies.

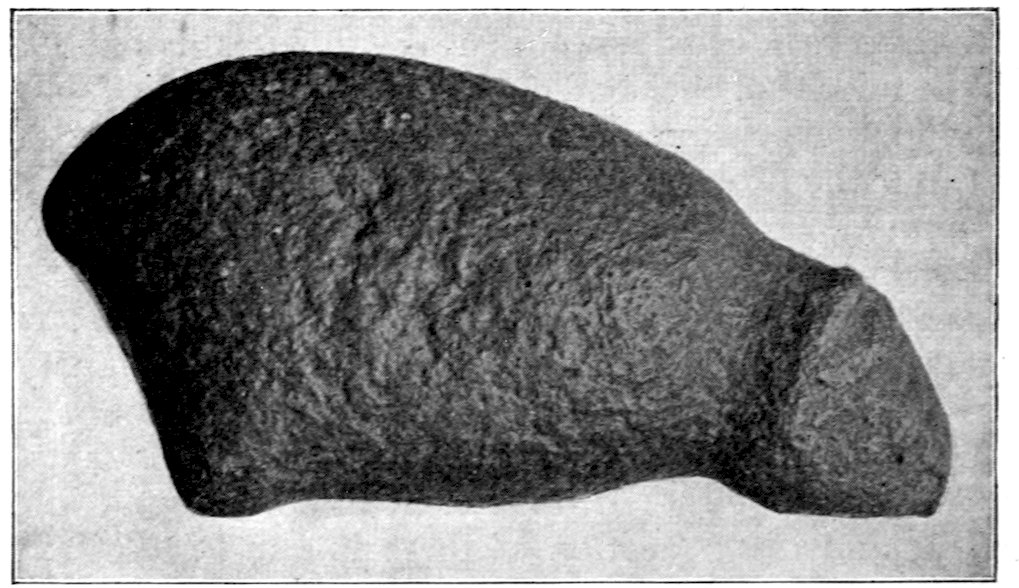

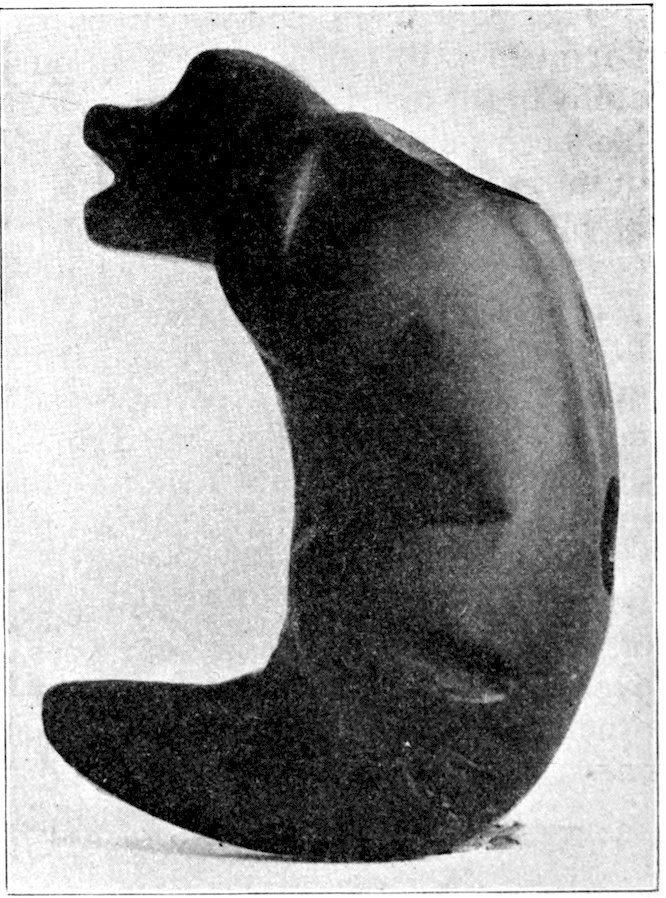

Fig. 415. (S. 1–2.) Bear effigy. Found near the corner of Essex and Boston Streets, Salem, Massachusetts, in 1830.

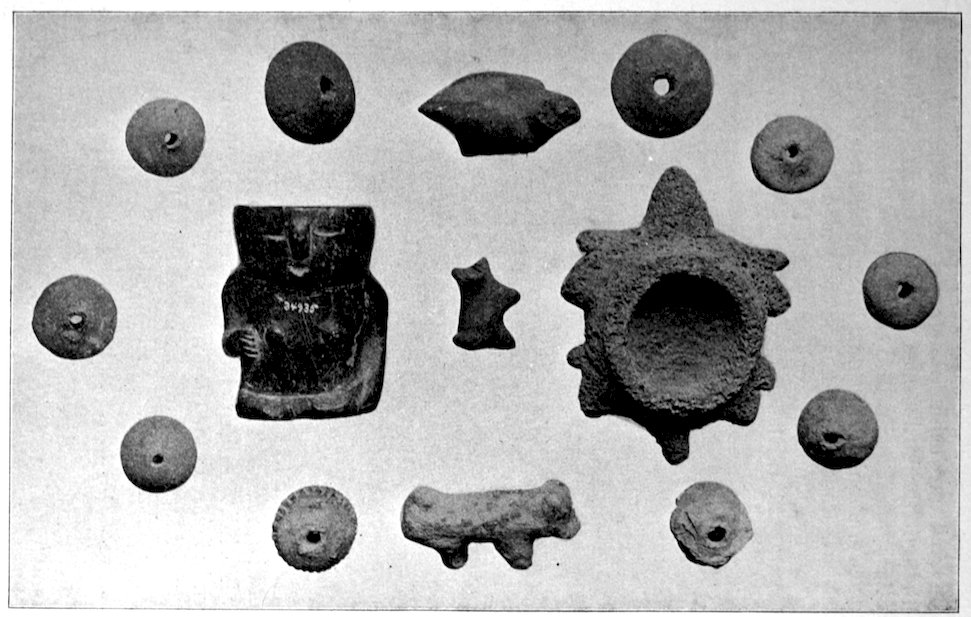

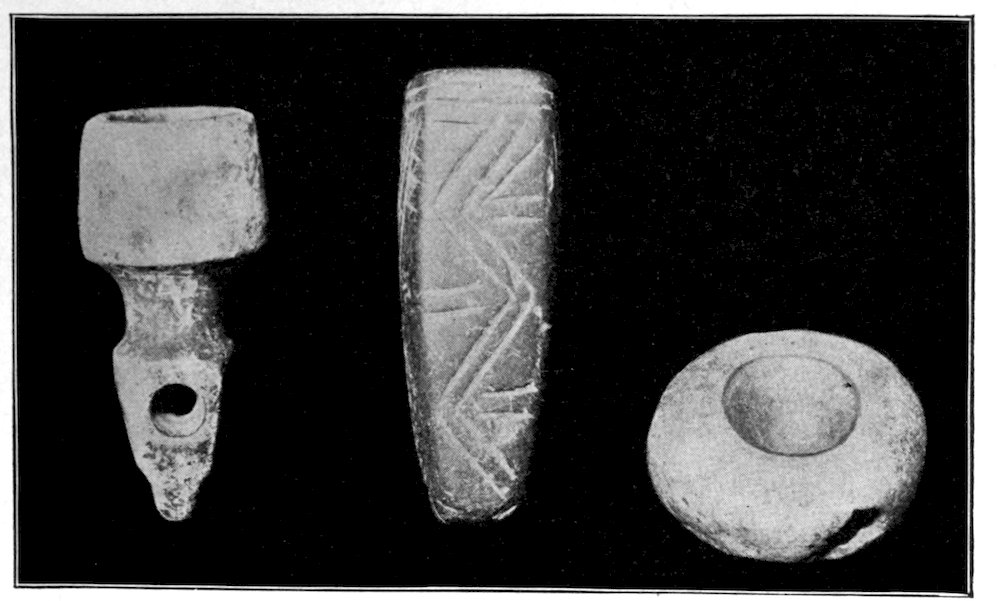

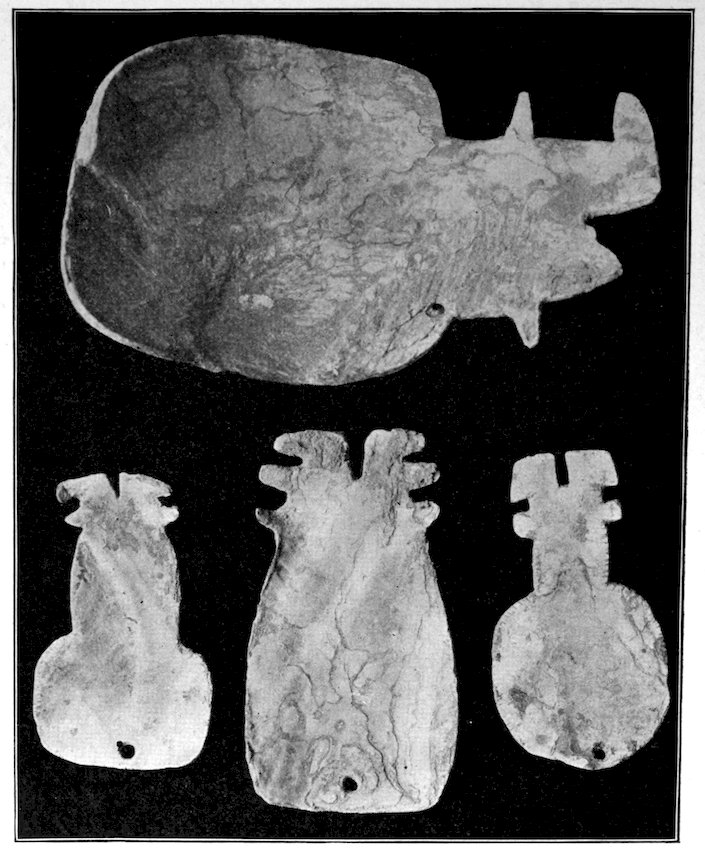

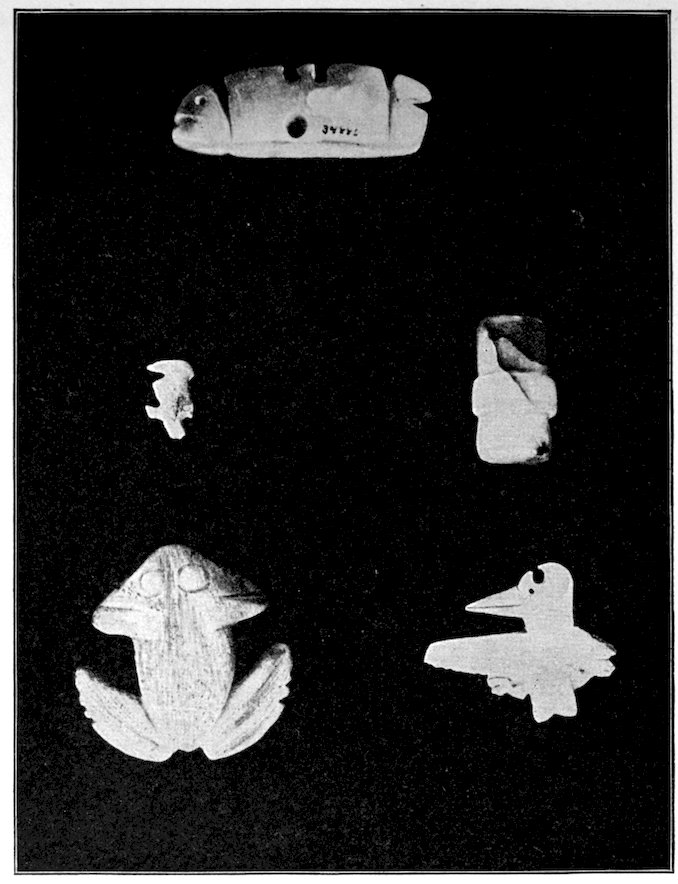

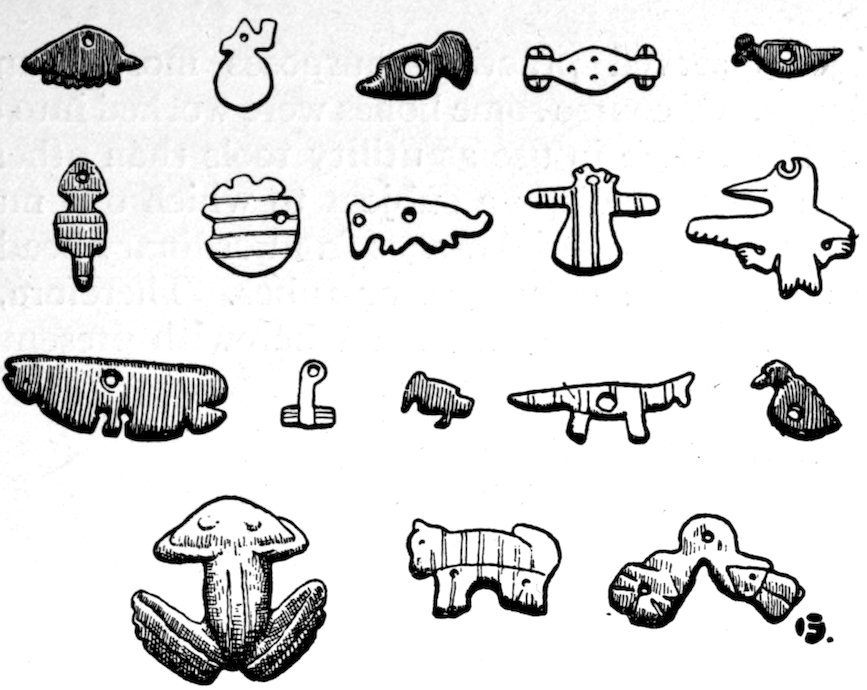

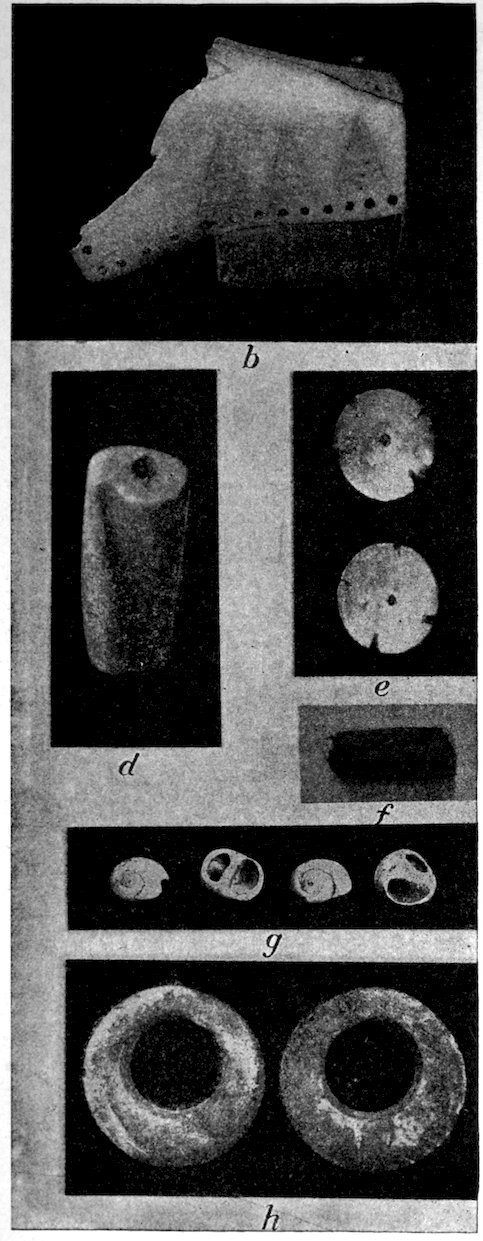

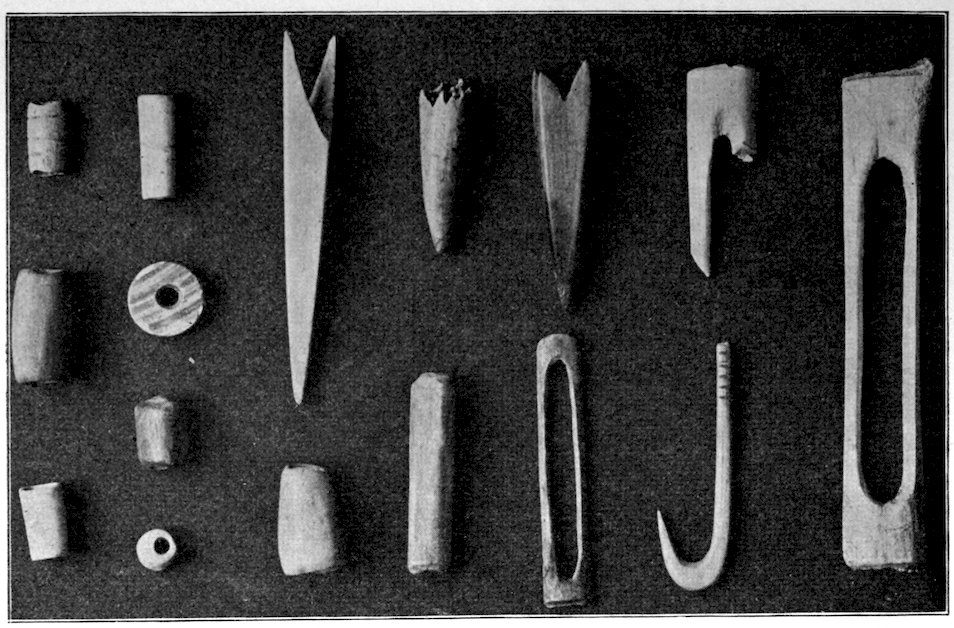

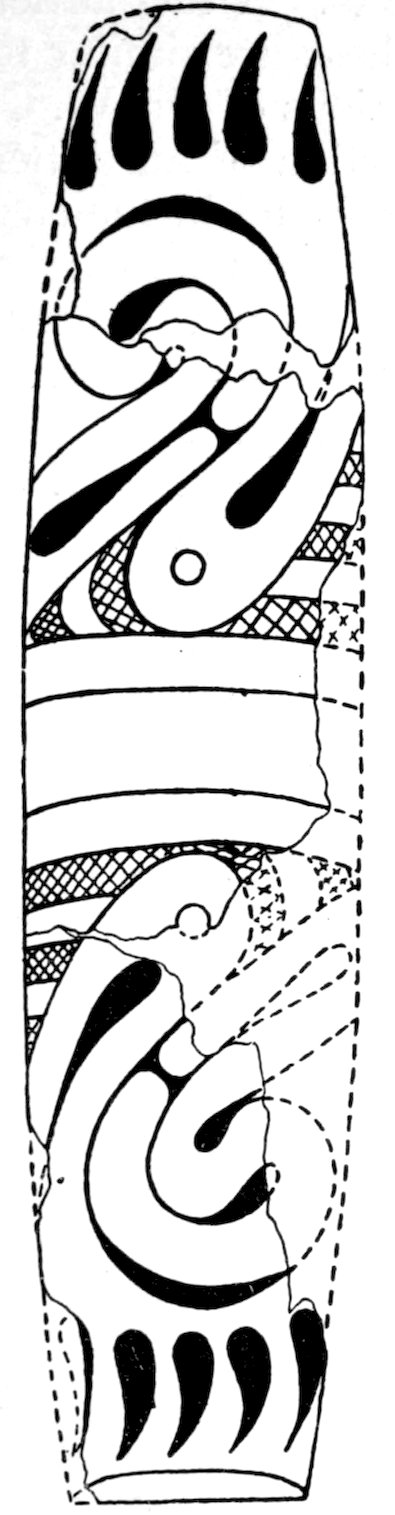

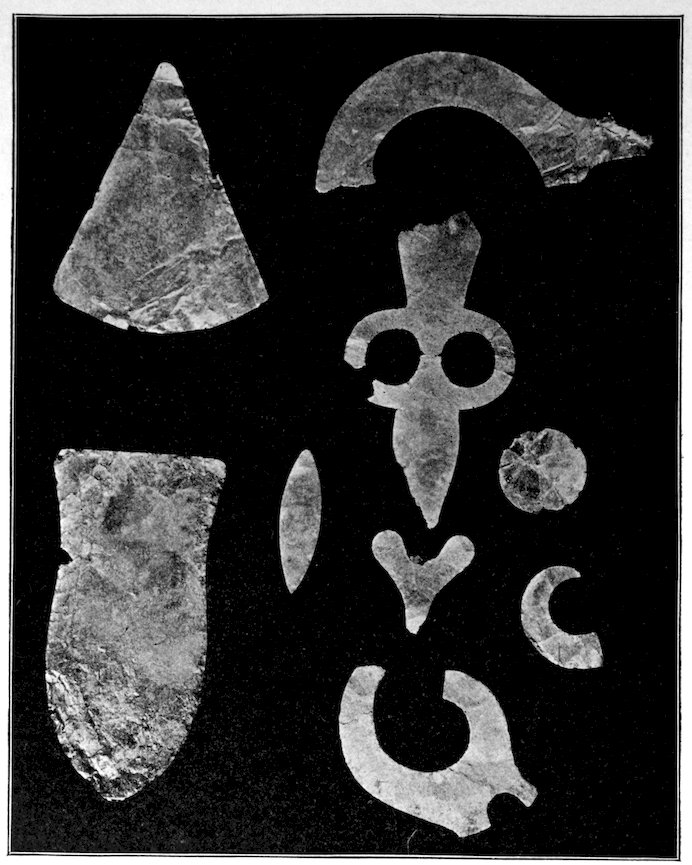

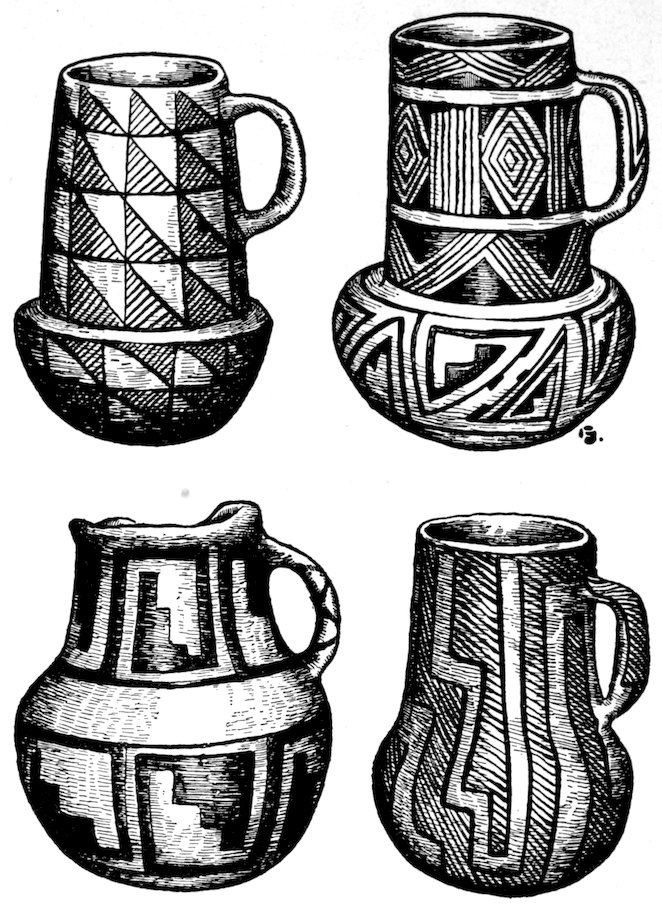

Fig. 416. (S. 1–3.) Group of various objects from ruins near Phœnix, Arizona. Phillips Academy collection.

20Professor Boyle speaks of the bar-amulet after treating of bird-stones, but he does not class them as the same kind of ceremonials.

Frank Hamilton Cushing illustrated bird-stones and flat tablets, and he thought the bird-stones were tied on flat tablets and these worn on the head. I inclined to that opinion when I published “The Bird-Stone Ceremonial,” but now I do not believe this, for the reason that most bird-stones could not be conveniently tied to flat tablets.

Fig. 417. (S. 1–1.) Phillips Academy collection.

That they are found in regions where there are many mounds used to be stated, but this is hardly correct. They have never been found in a mound, and I do not know of an instance where they have been found in graves. They occur more in northern Ohio, Canada, and New York State than elsewhere except Michigan and Wisconsin. I firmly believe that they were not made and used by mound-building tribes but antedate the mound-building period. As to the exact purpose of these things I leave others to judge.

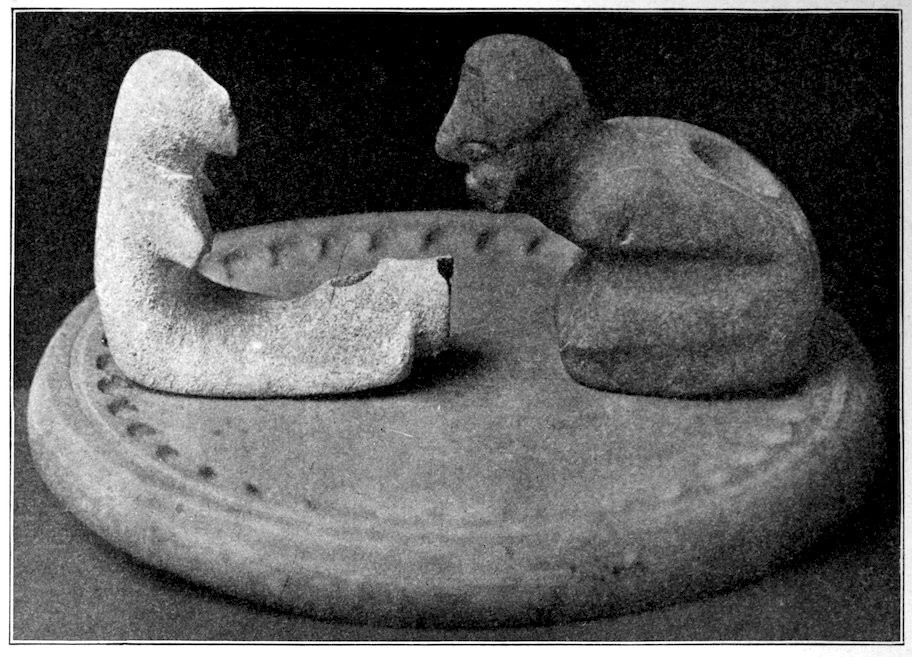

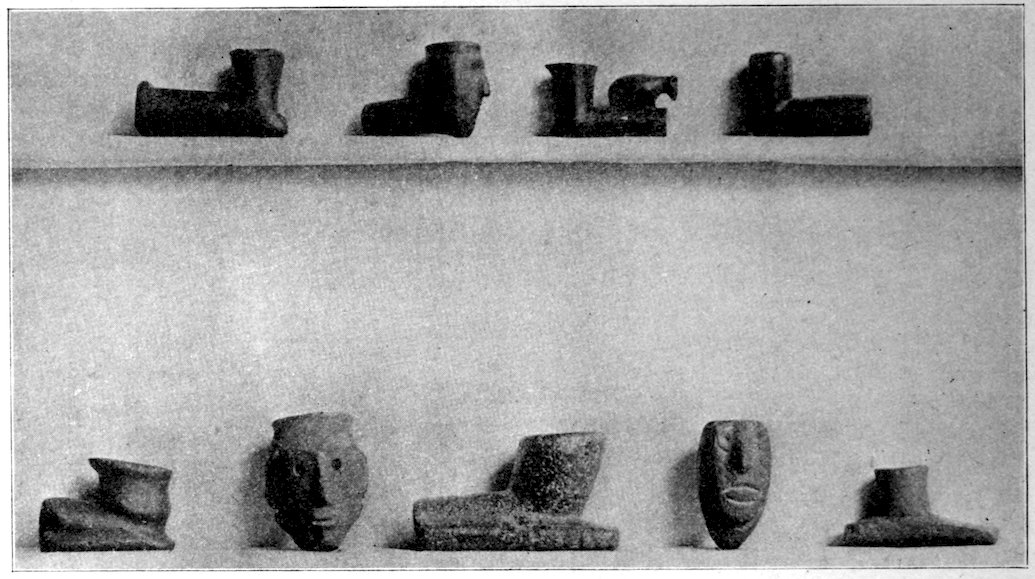

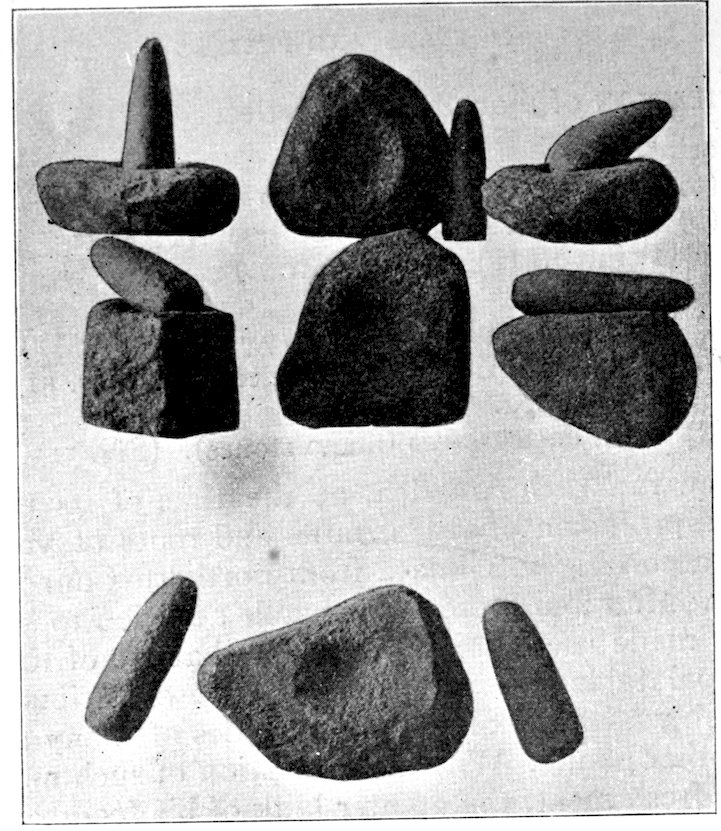

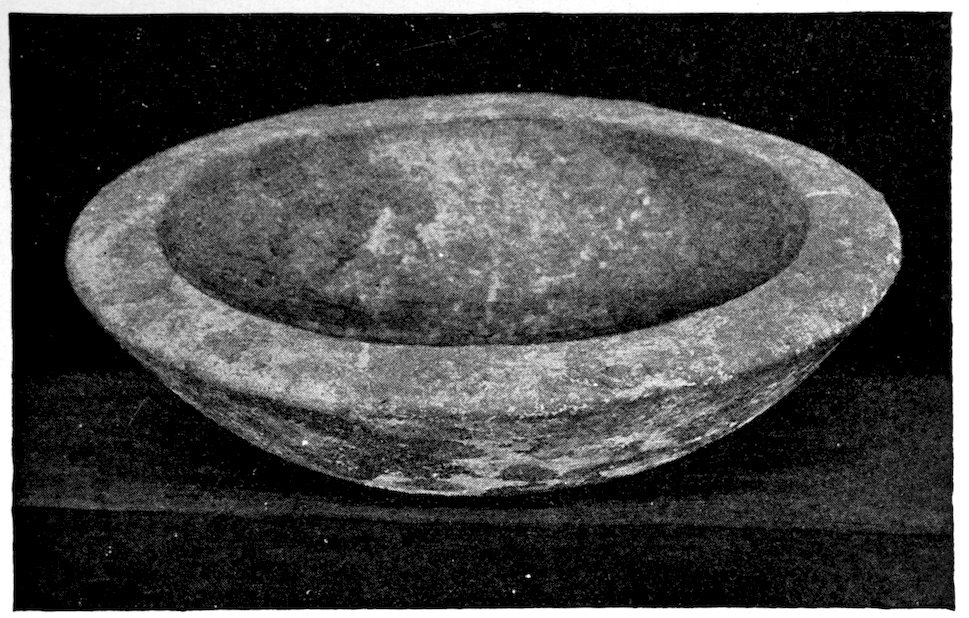

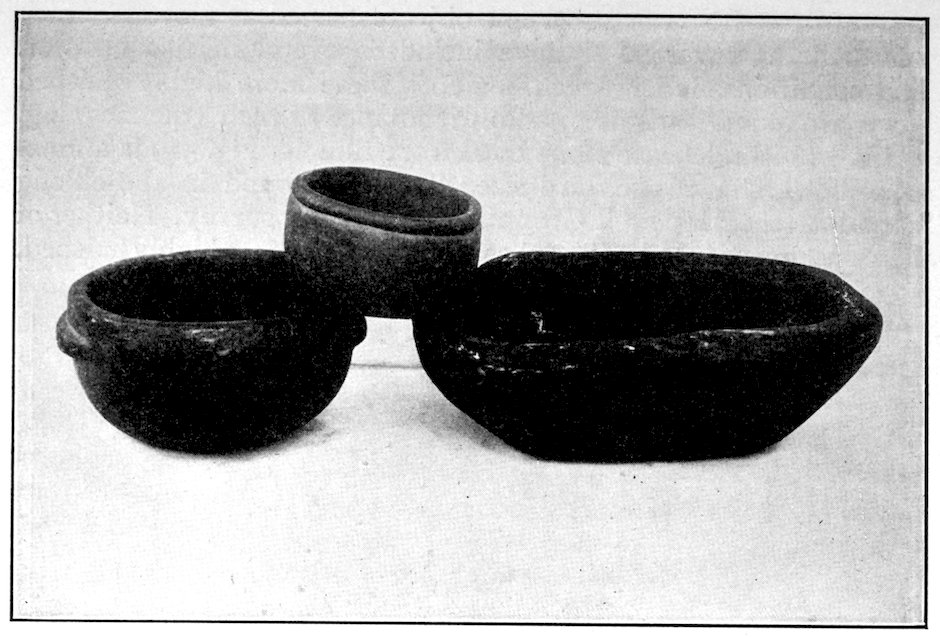

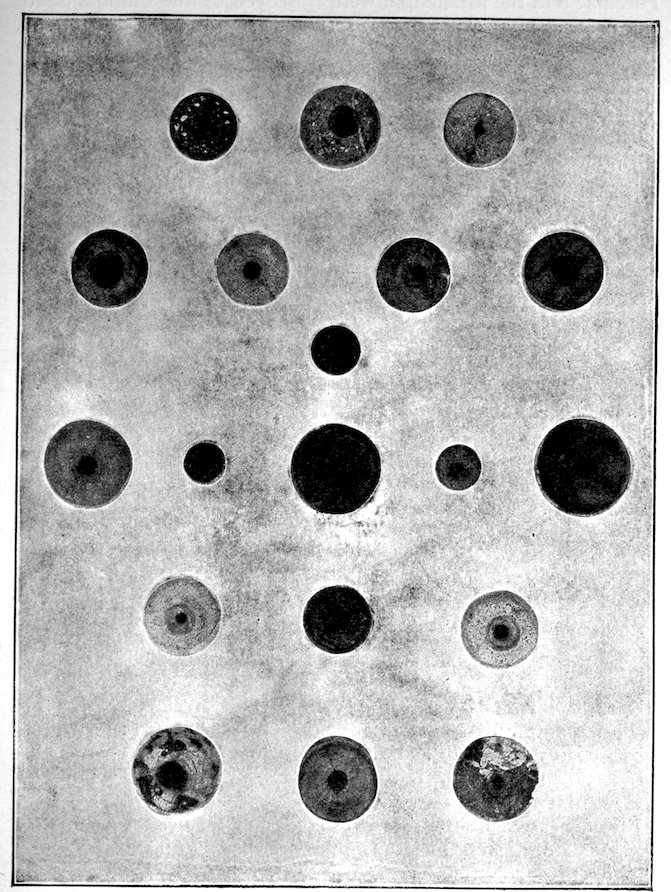

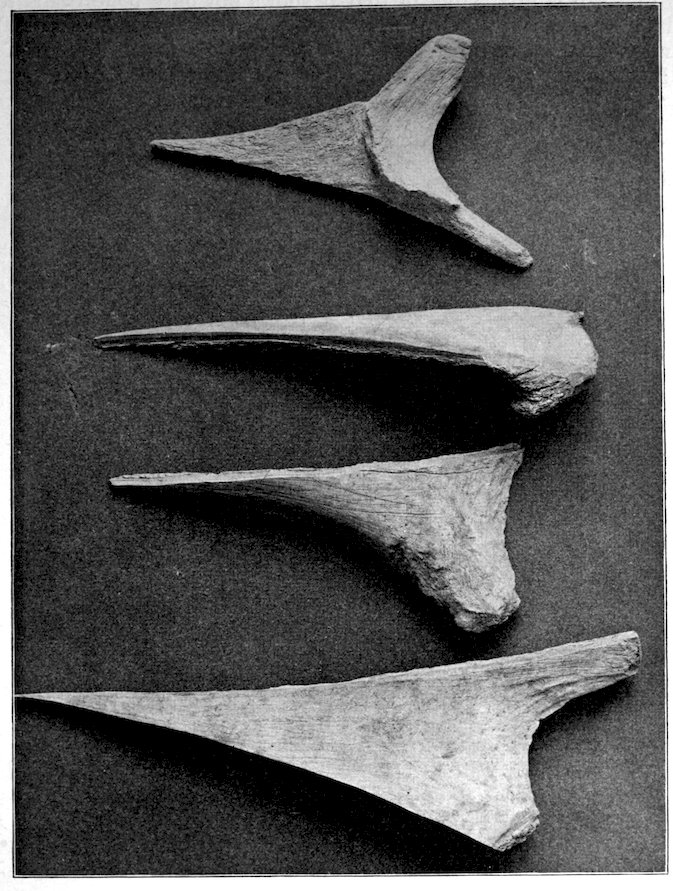

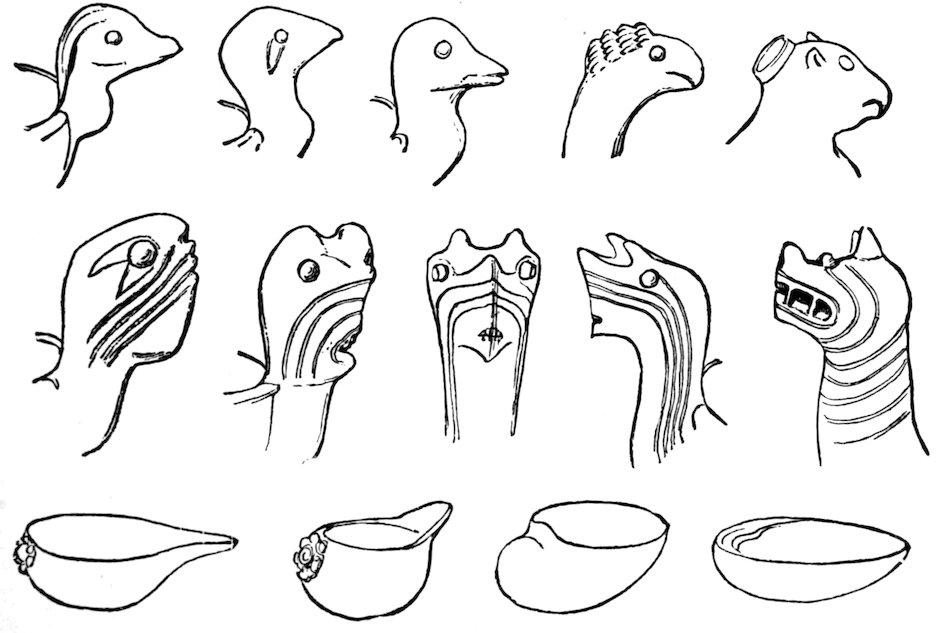

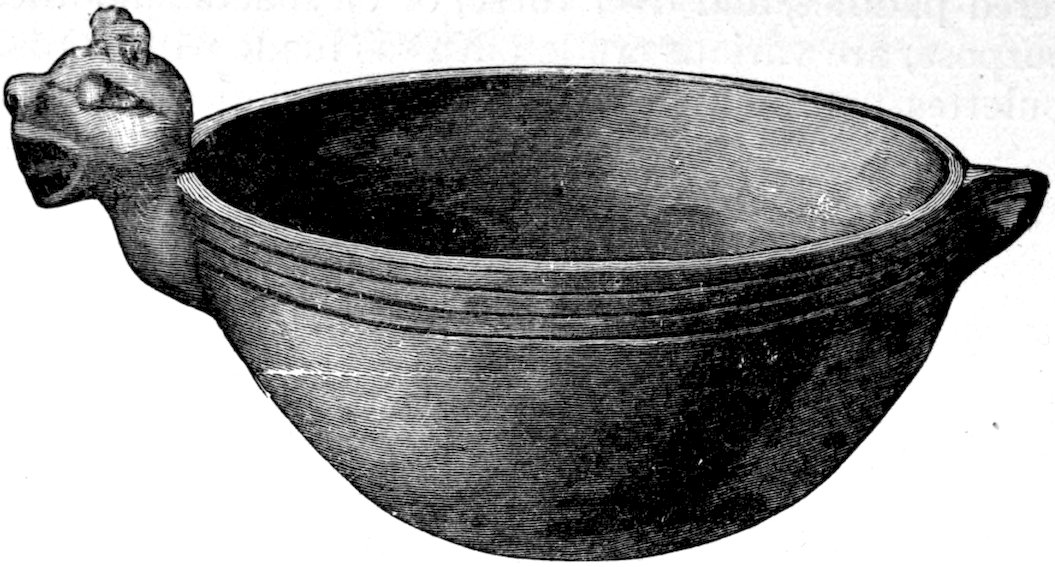

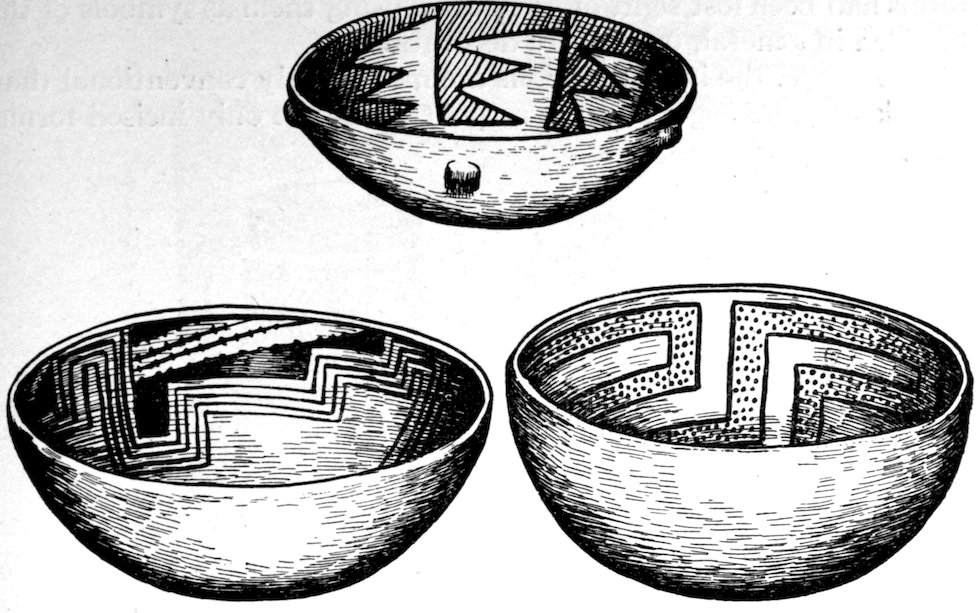

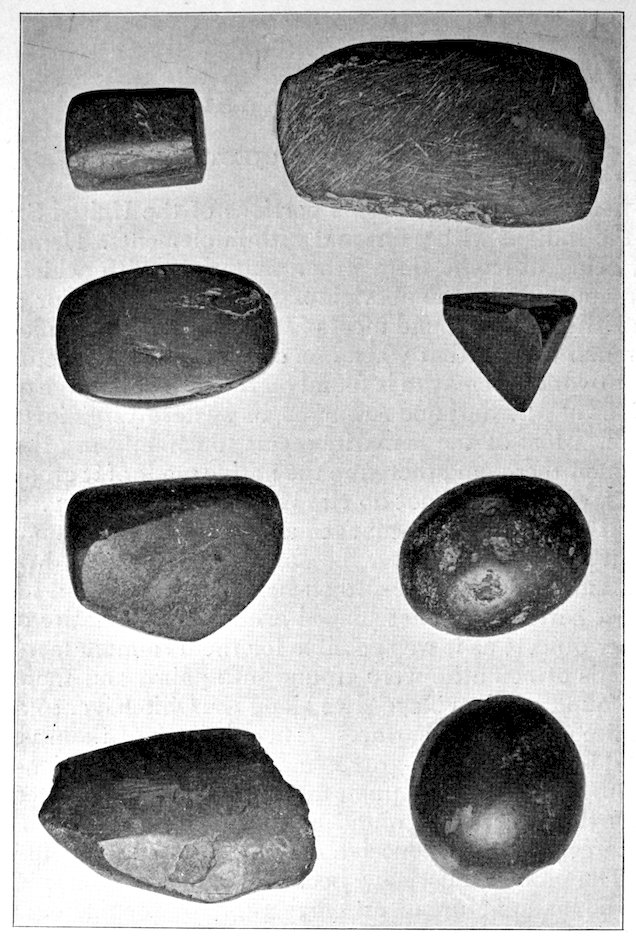

There are many crude effigies, many grotesque sculptures found in this country. There are also stones that are in the border-lands between highly developed problematical forms and effigies. Fig. 413 presents a group of these from the Peabody Museum at Cambridge, Massachusetts. The upper row appears to be whale effigies. In the lower row are small stone bowls or paint-cups.

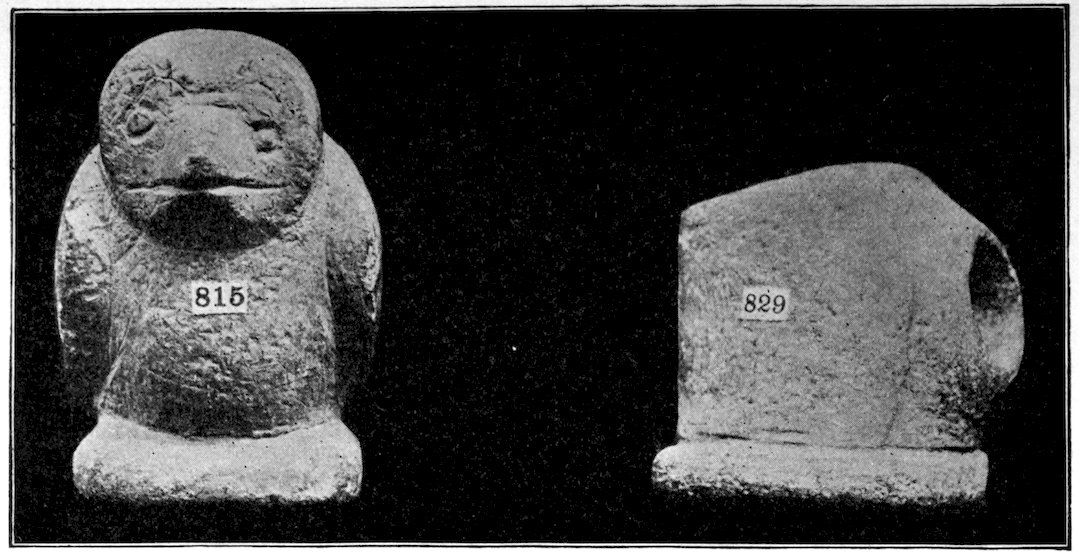

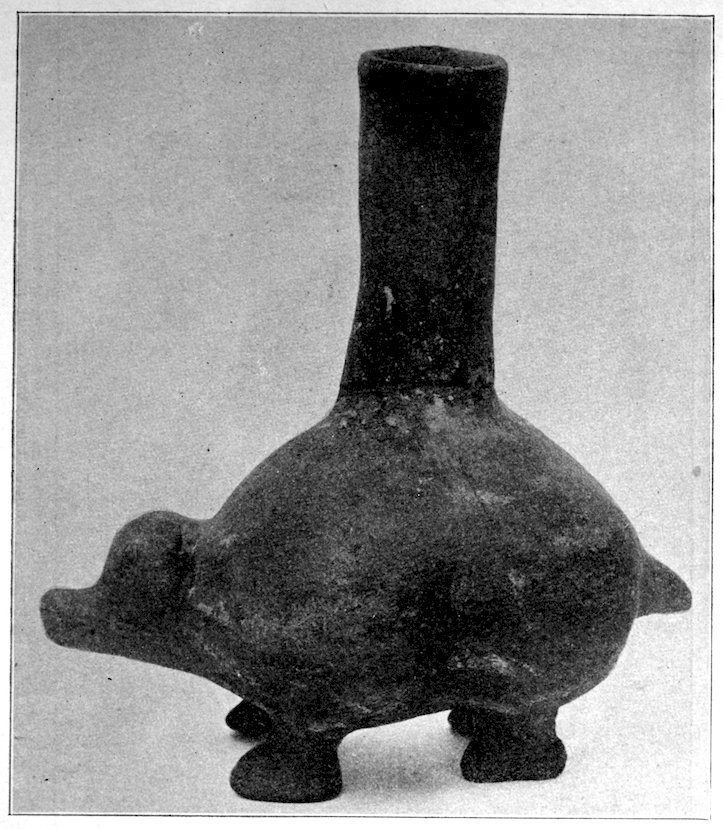

Fig. 418. (S. 1–2.) shows four peculiar stones from the Salt River Valley, Arizona. The one in the lower left-hand corner illustrates an armadillo; in the upper right-hand corner, an owl. The others are unknown effigies. These Arizona specimens are all of volcanic tufa, and are typical of the region. Large numbers were found by Mr. Cushing during his explorations of the ruins of the Salt River Valley, and something like a hundred were dug up by me for Mr. Peabody when I visited the region. The purpose of these is unknown.

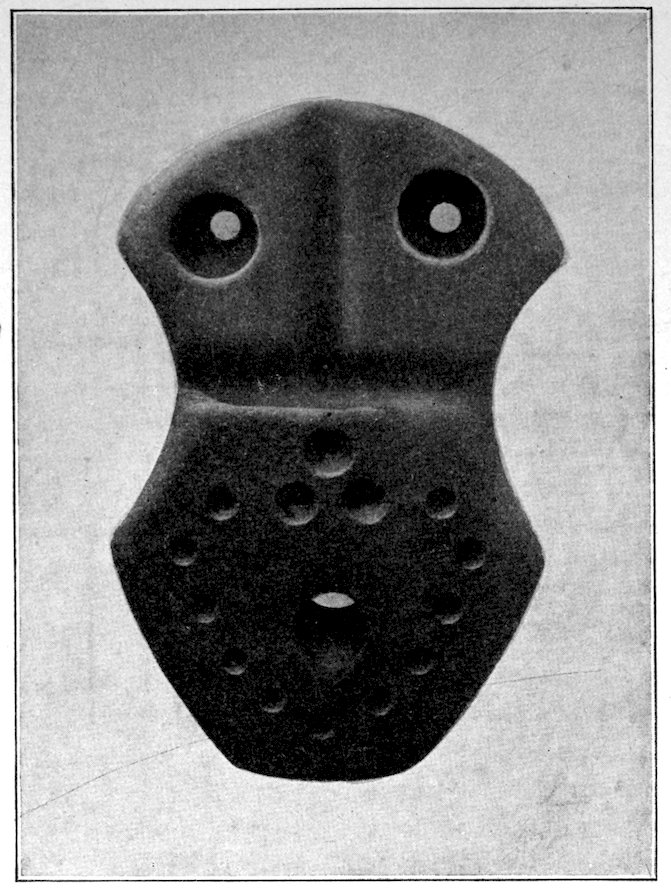

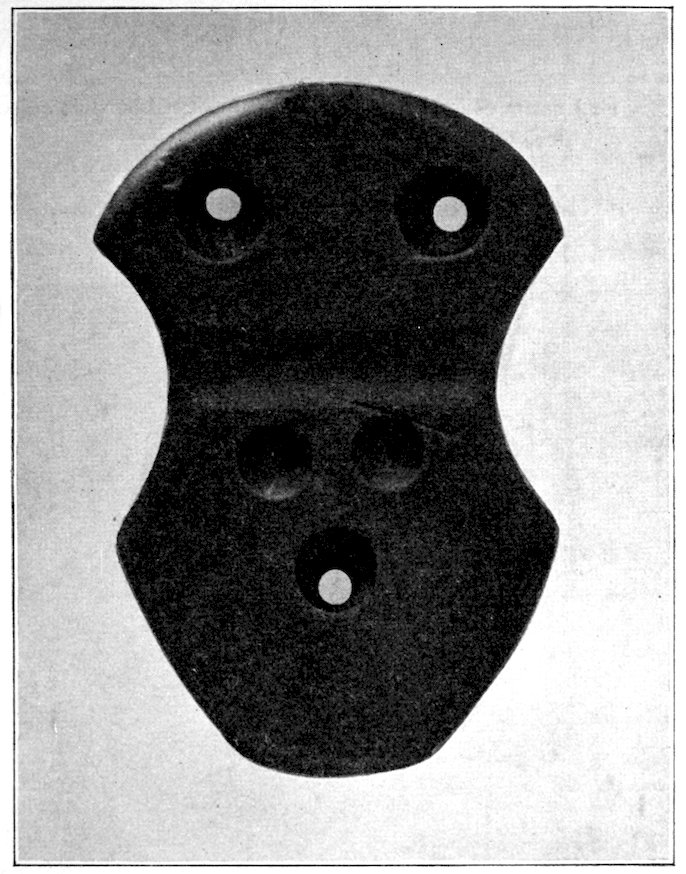

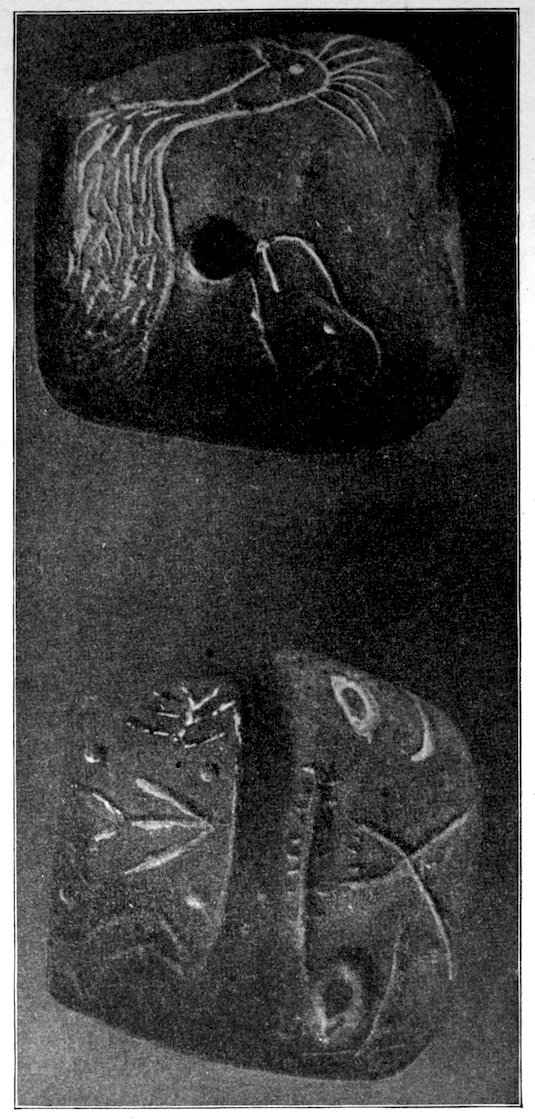

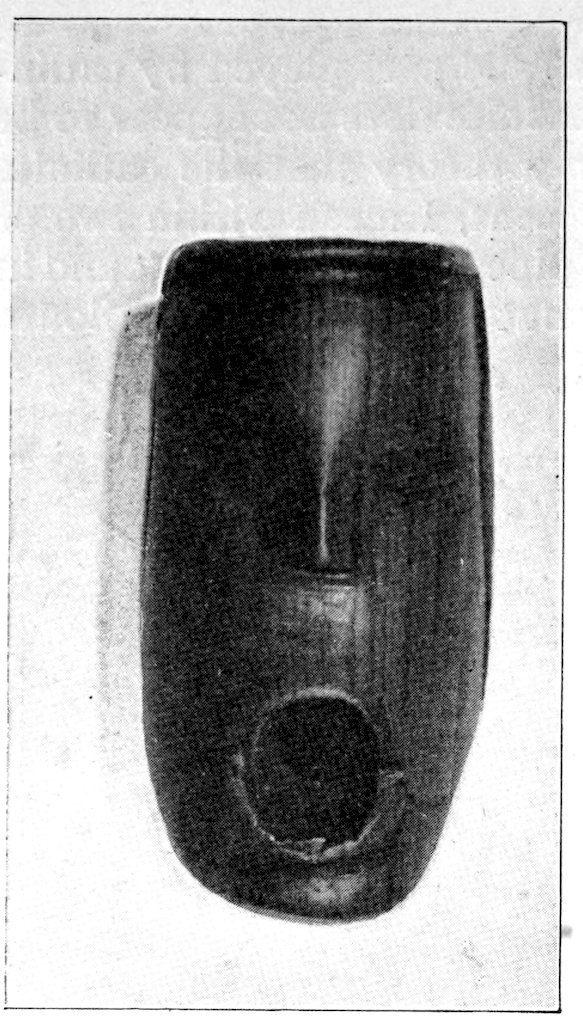

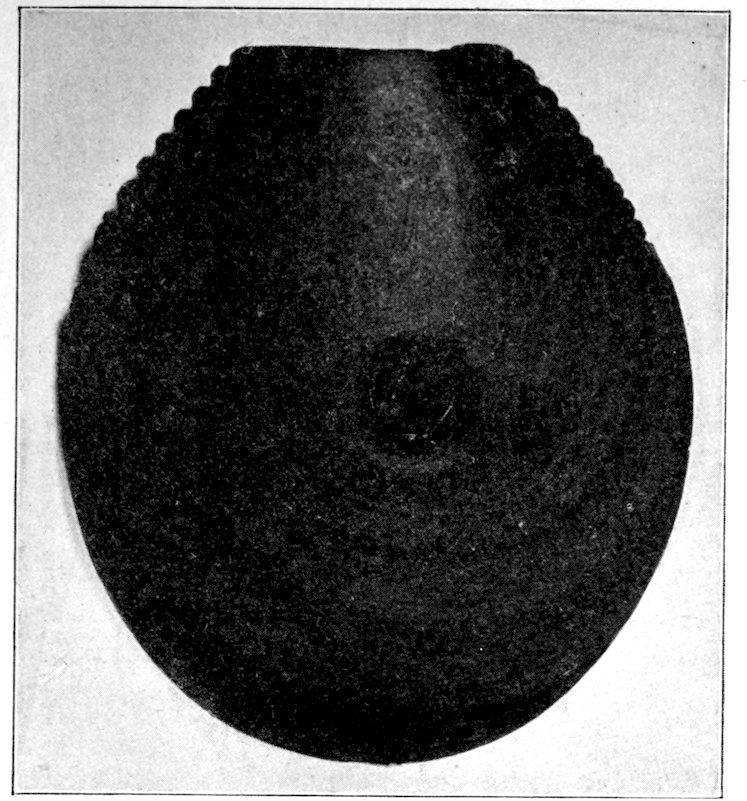

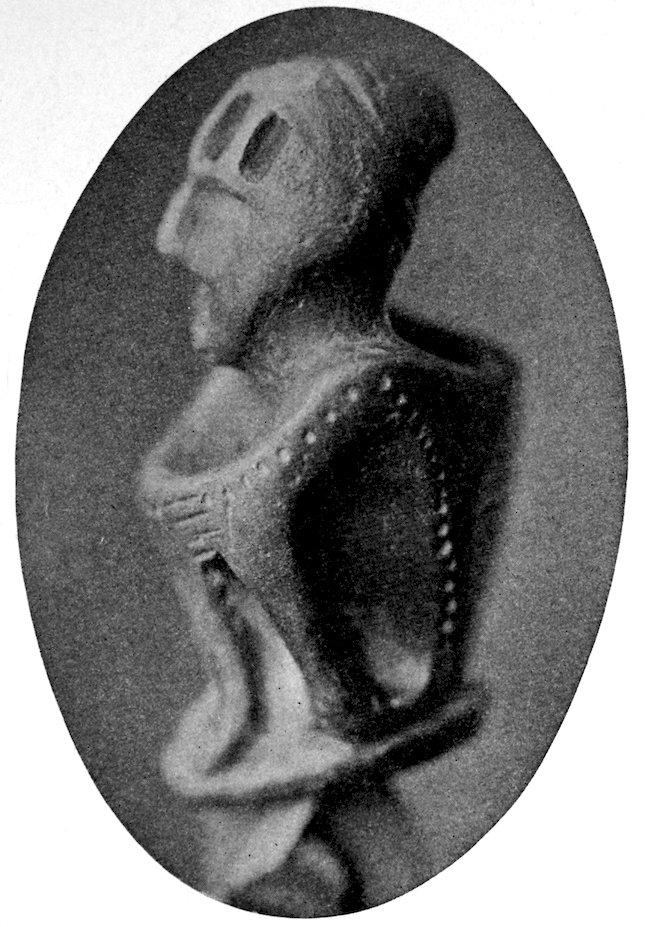

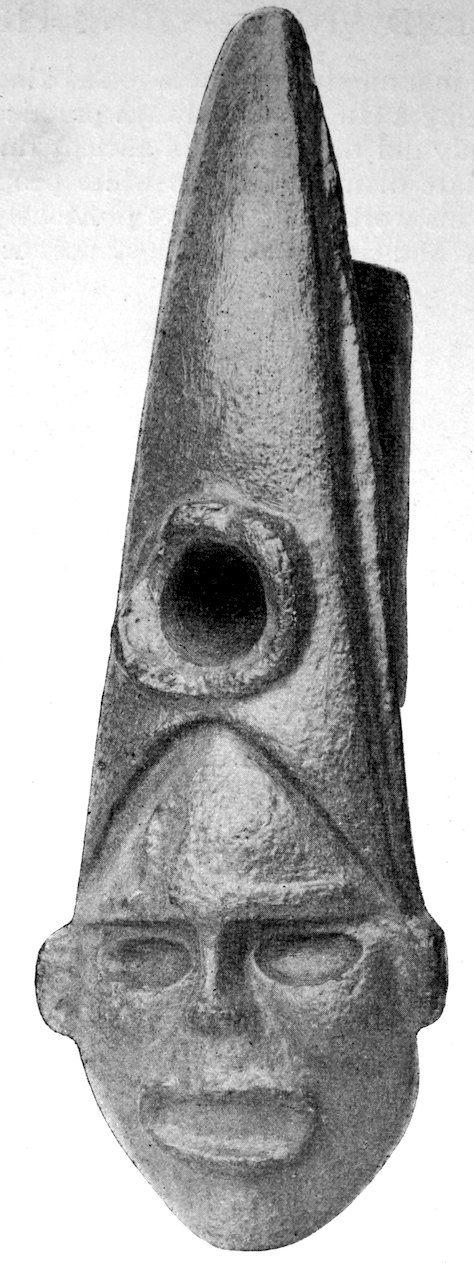

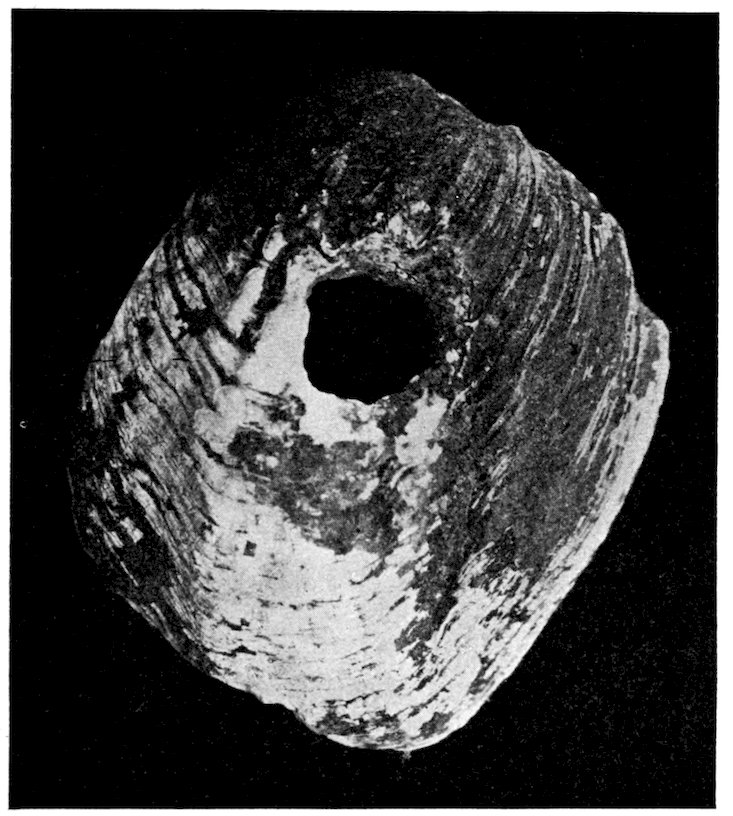

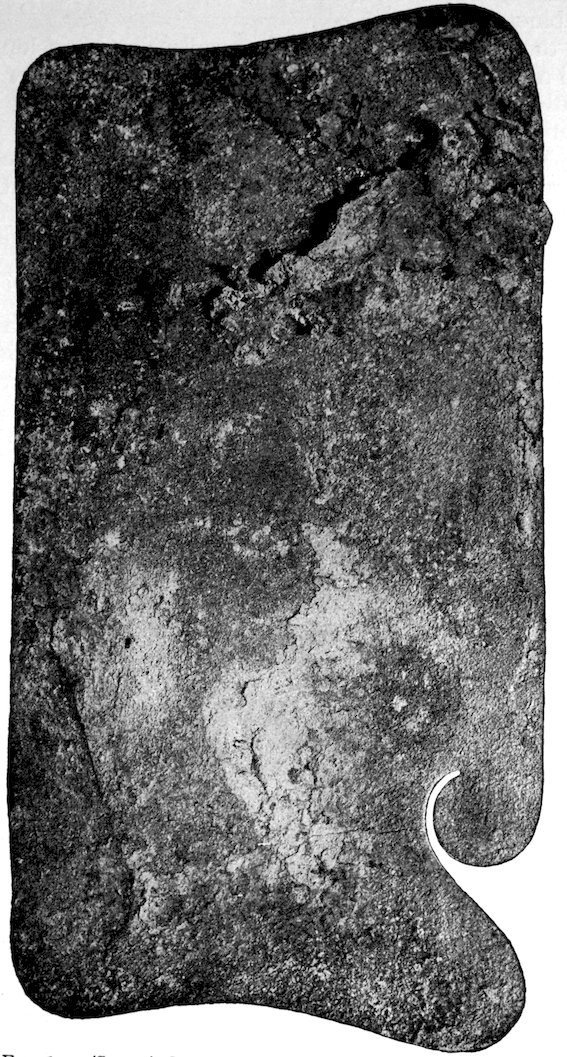

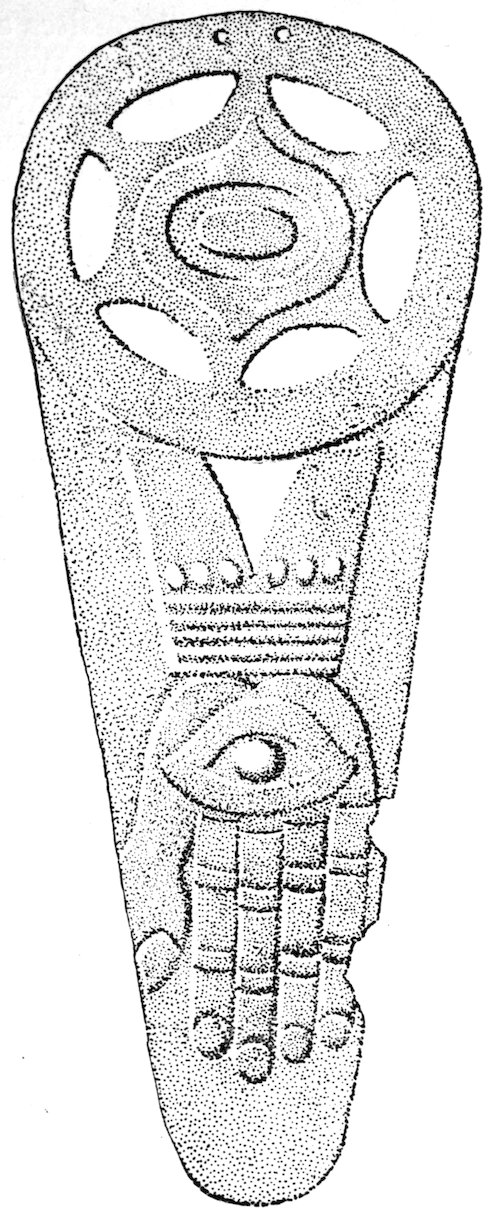

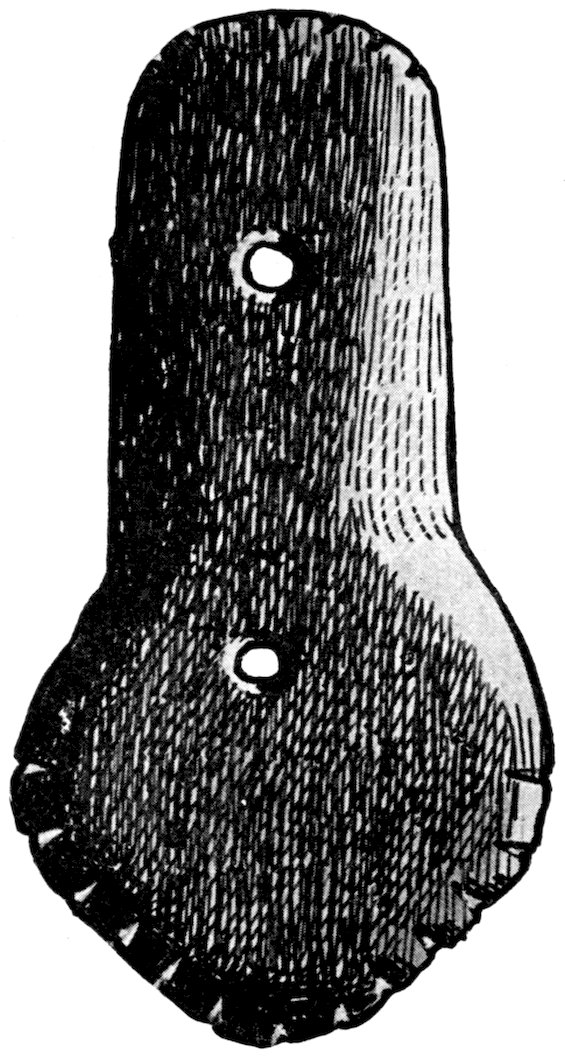

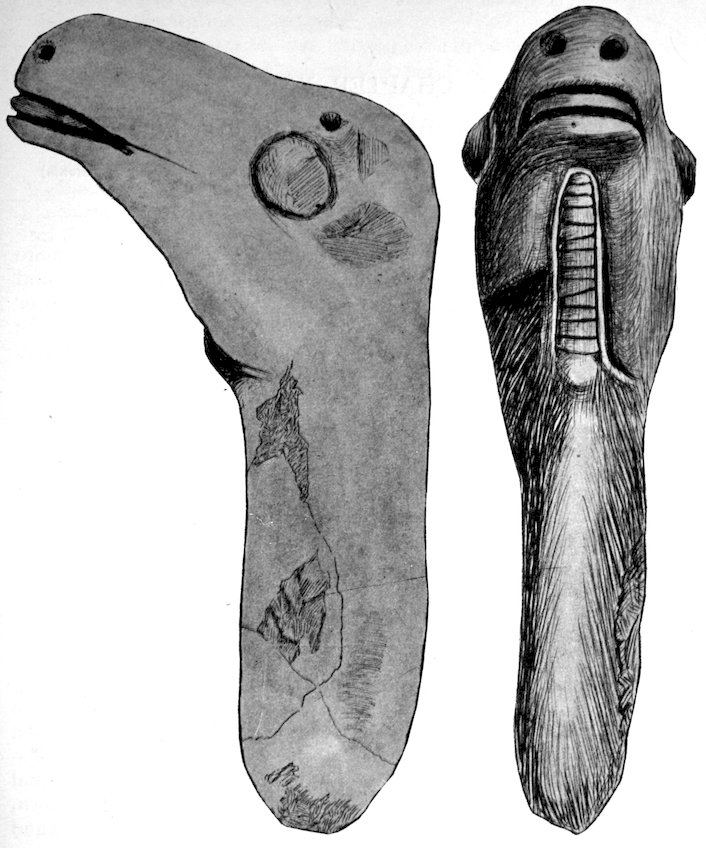

Fig. 419. (S. 1–1.) Front view of the “Owl Ornament,” found in a grave at Fort Ancient, Ohio, 1882. Collection of the Ohio State University. One of the first specimens collected by W. K. Moorehead at Fort Ancient. Material, graphite slate.

Few finer problematical forms have been found. There are two grooves on the face and back of this object. One runs from the top down about an inch and one half, intersecting the other. In the angles formed by these two grooves are two perforations extending through the stone and drilled from each side. At the bottom is an oval-shaped hole on the face extending through. This latter perforation does not exhibit an oval shape from the rear, but presents a round appearance. Around this oval-shaped depression are fourteen holes, each drilled about one eighth of an inch deep. They present the form of an arrow-head, or a heart. On the reverse side are two holes above the oval perforations which are not drilled through the stone, and which lie just under the horizontal groove. The remarkable part of this stone is that the symbol, three, occurs on it in three places—on the face twice and on the reverse once.

23Quite a number of these whale and other effigies have been found in New England; but effigy-work in stone, the making of art-forms from life, was more general in the South and Southwest than in New England, where, indeed, effigy animals are exceedingly rare.

Fig. 415 illustrates an effigy of a bear. This was found in Salem during excavations for a cellar and is in the Peabody Museum of that city.

Mr. L. C. Deming, Ft. Wayne, Indiana, owns a peculiar effigy in stone about six inches in height. Just what it represents I am unable to state, as the ancient workman’s sculpture is crude.

Fig. 420. (S. 1–1.) The “Owl Ornament,” rear view.

Fig. 421. (S. 1–1.) Salem collection. This shows a grooved bar-like object at the bottom, and a curious effigy pendant above.

Fig. 422. (S. 1–3.) W. E. Bryan’s collection, Elmira, New York.

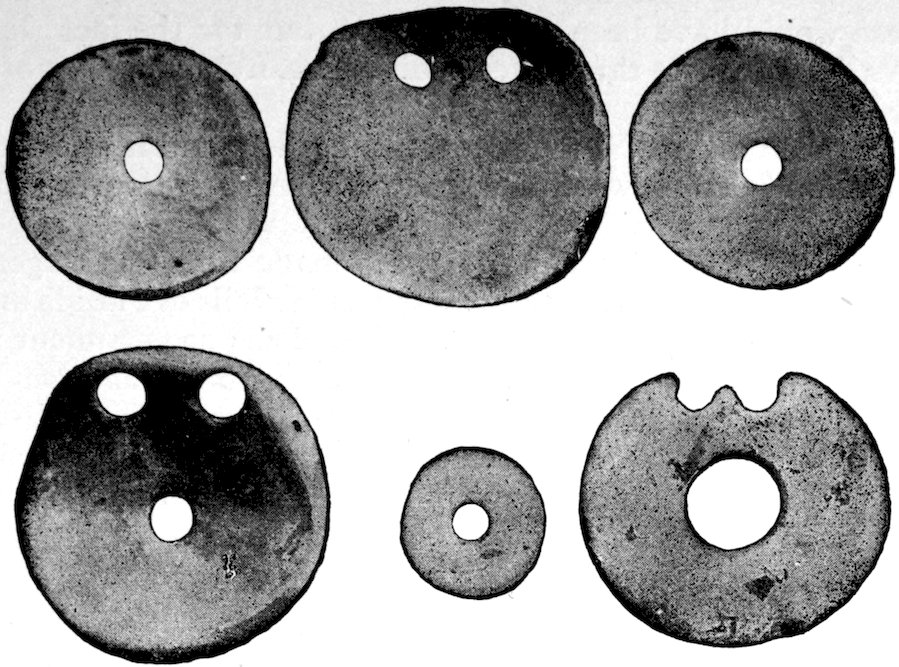

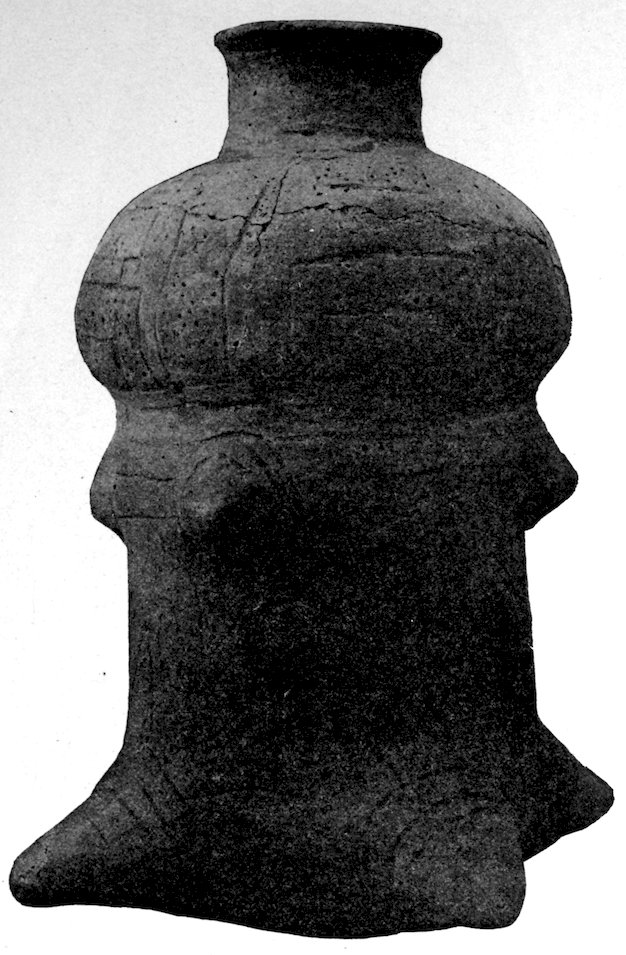

25Fig. 416 shows a number of spindle-whorls to which reference has been made elsewhere. These are made of clay, hard baked. In the lower centre is a stone idol found in a large ruin at Mesa, Arizona. It is made of hard redstone. There is a little depression in the top of the head half an inch in depth. Near the top is a curious animal effigy with eight legs. This is made of fine-grained lava and has a depression in the centre about one and one half inches in diameter.

Fig. 423. (S. 1–1.) From a mound near South Carrollton, Kentucky. Presented to the Phillips Academy Museum, by F. G. Hilman, New Bedford, Massachusetts.

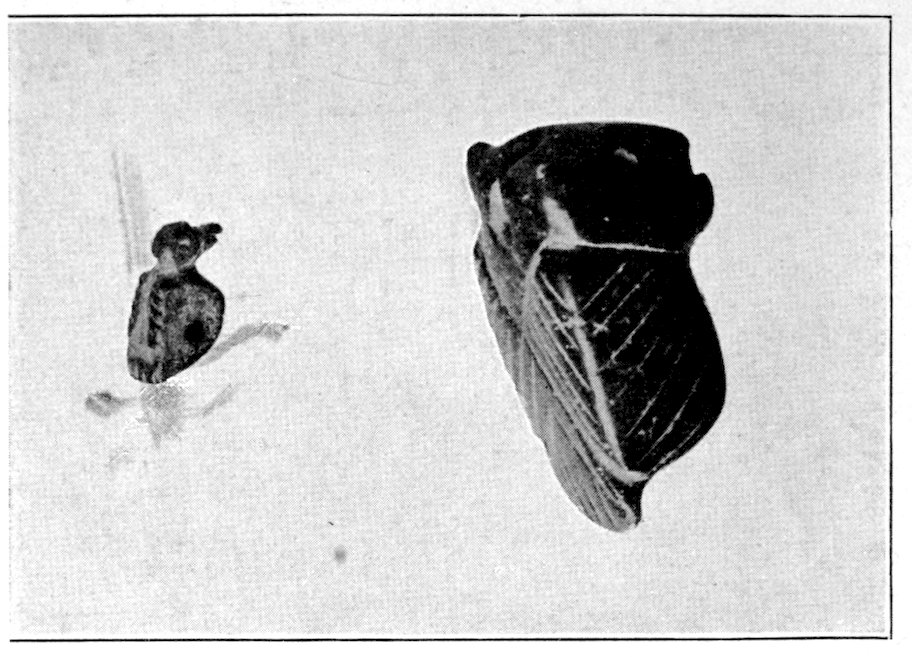

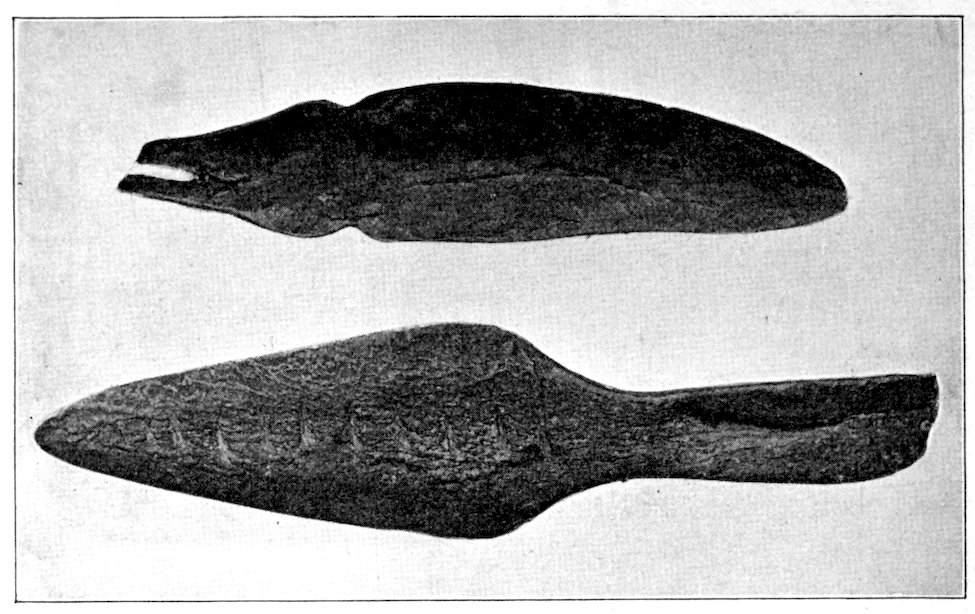

Fig. 417 illustrates two effigies, full size, of black onyx, each typifying a bird. These are very finely carved and were found in southern Arizona in a ruin, by the expedition sent there by Mr. R. S. Peabody, 1897–98.

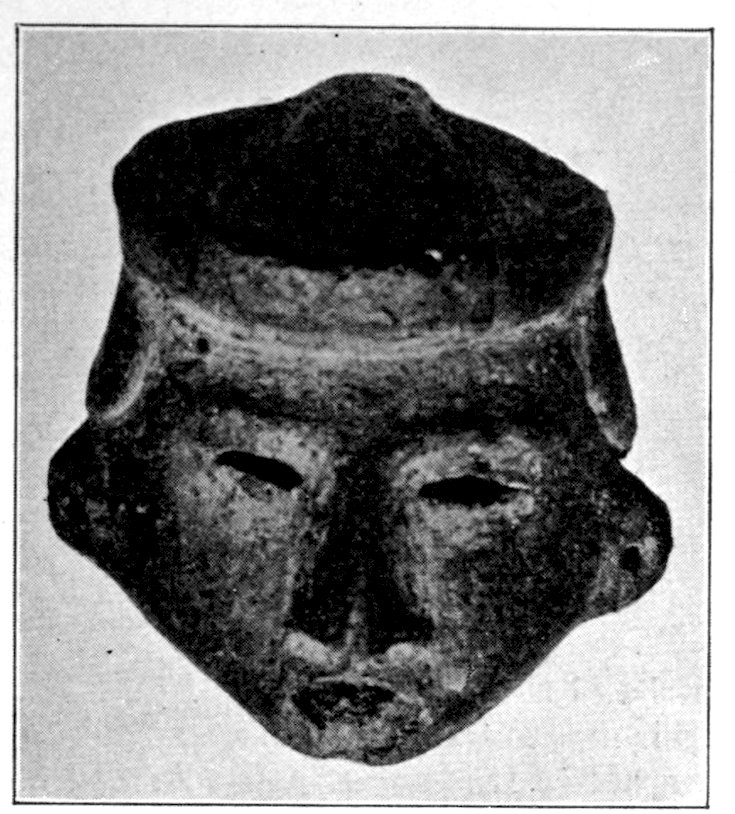

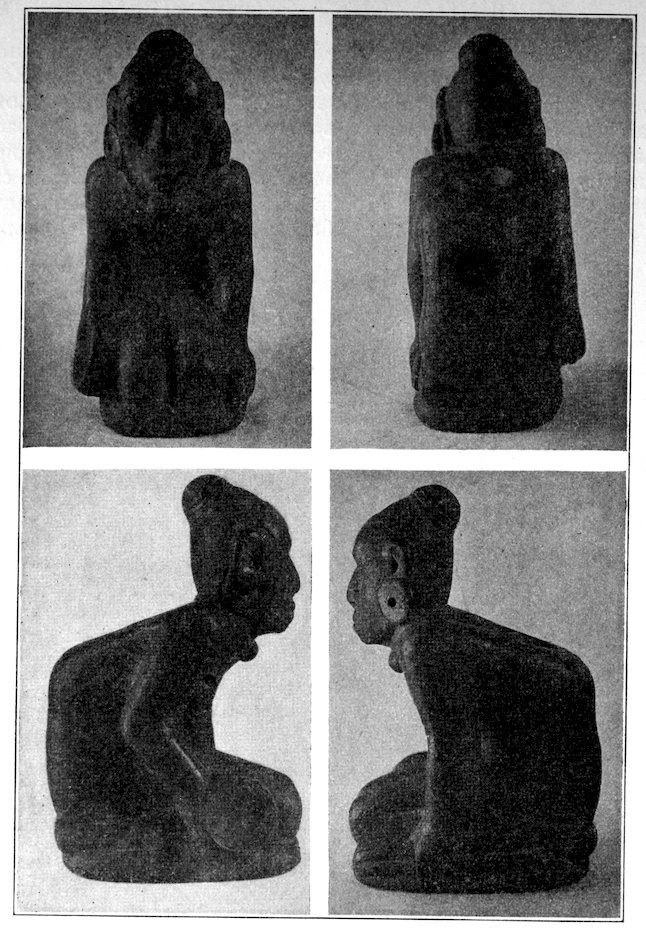

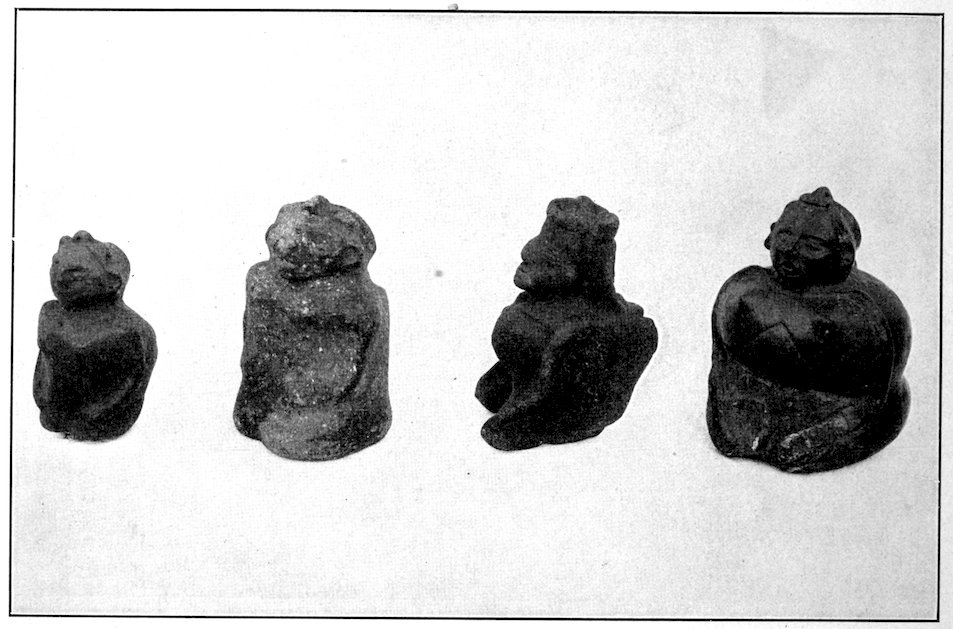

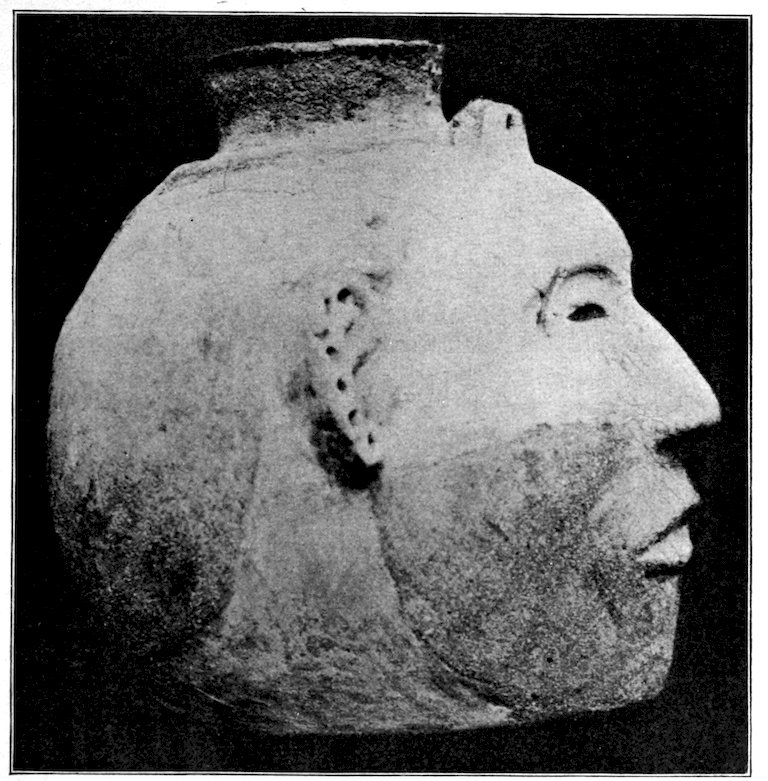

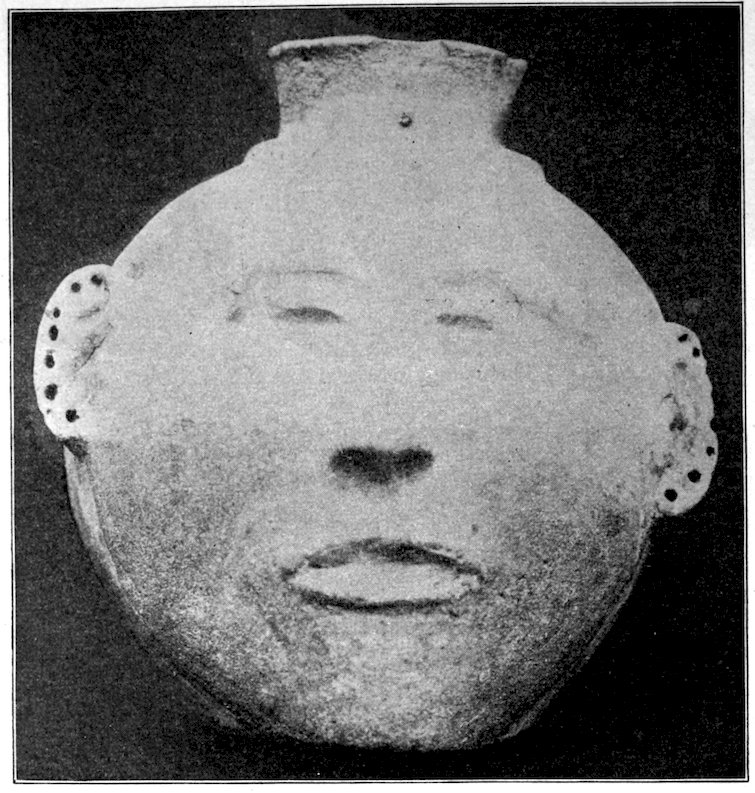

The human form was frequently indicated in stone by the Indians. These sculptures range from very crude delineations, which I have not shown, to the first steps in more ambitious work, such as is exhibited in Fig. 422. This stone head was found near Elmira, New York, by Mr. Ward E. Bryan. The original was seven or eight inches in length. It is cut out of fine-grained sandstone. On the back are curious lines and dots as shown in the figure. The face shown is much cruder than that in Fig. 423. That face is of the peculiar type known as “Mound-Builder.” I have referred to this resemblance elsewhere. Inspection of Fig. 499 in the pipe series, found by Professor Mills at Adena, in the Scioto Valley, Ohio, and 26of the idol, Fig. 426, and some of the effigy pottery, will acquaint readers with this curious, strongly marked, Mound-Builder type of feature. Other examples are to be seen in books treating of American archæology.

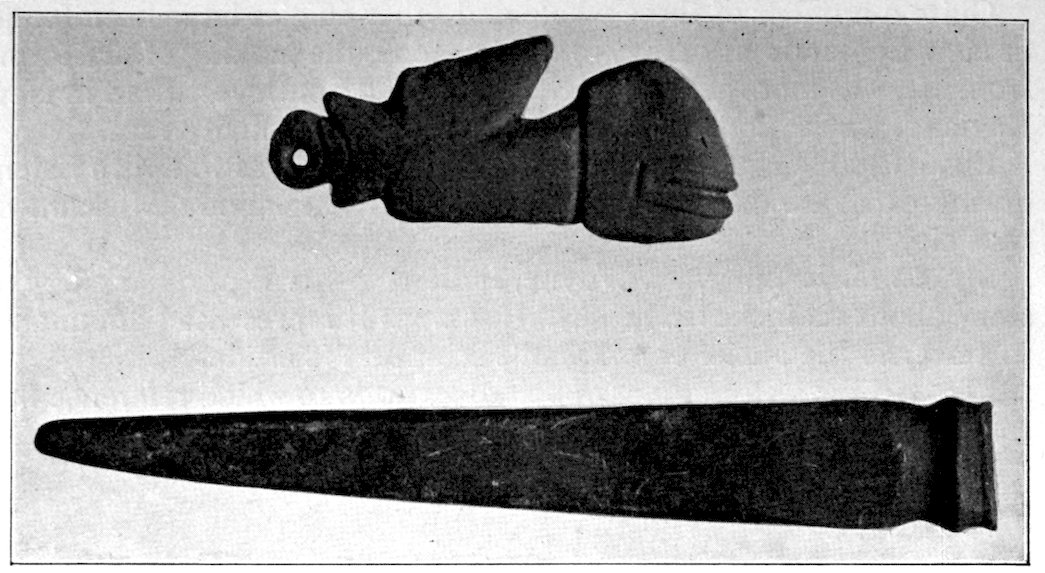

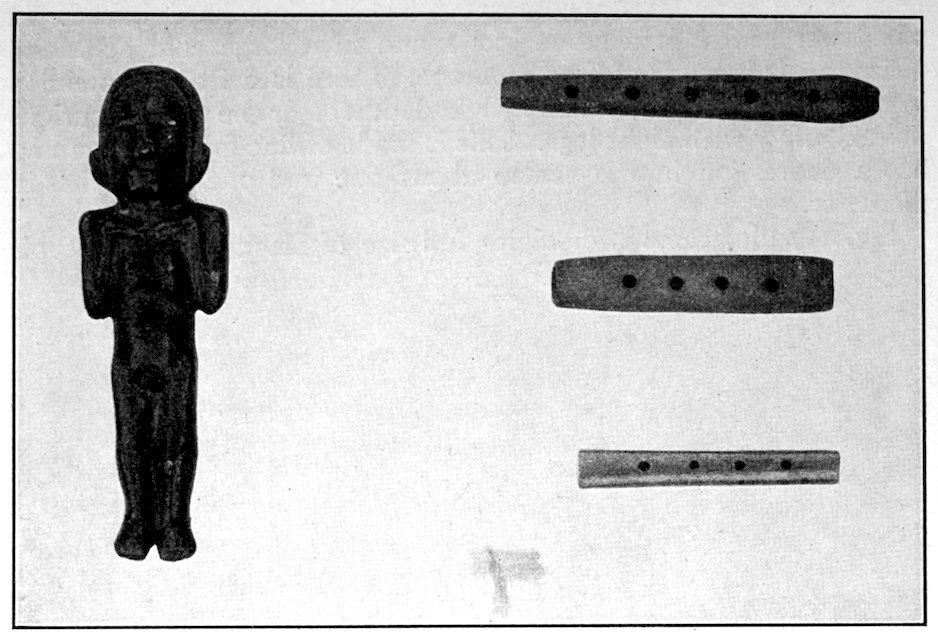

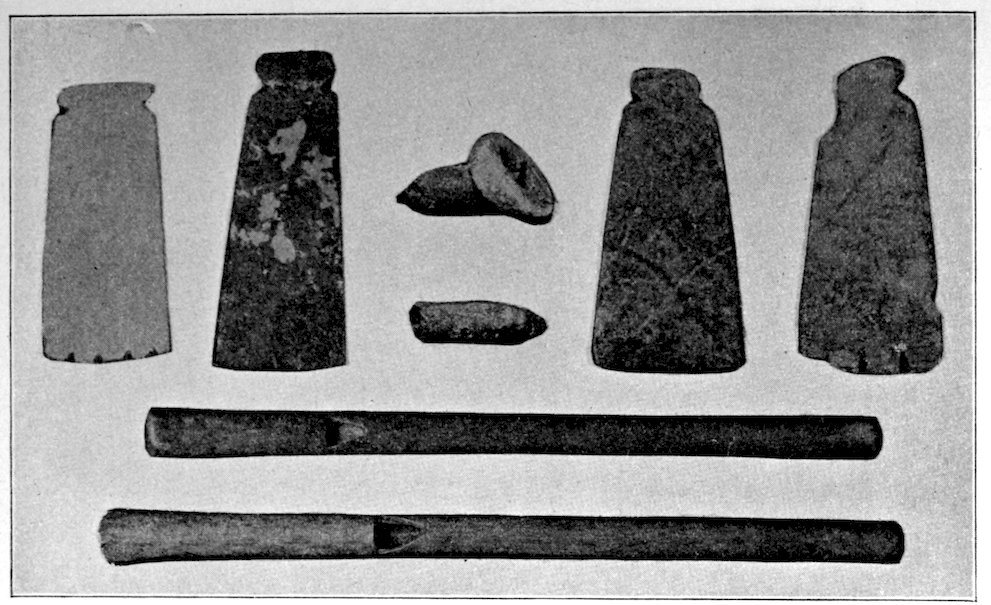

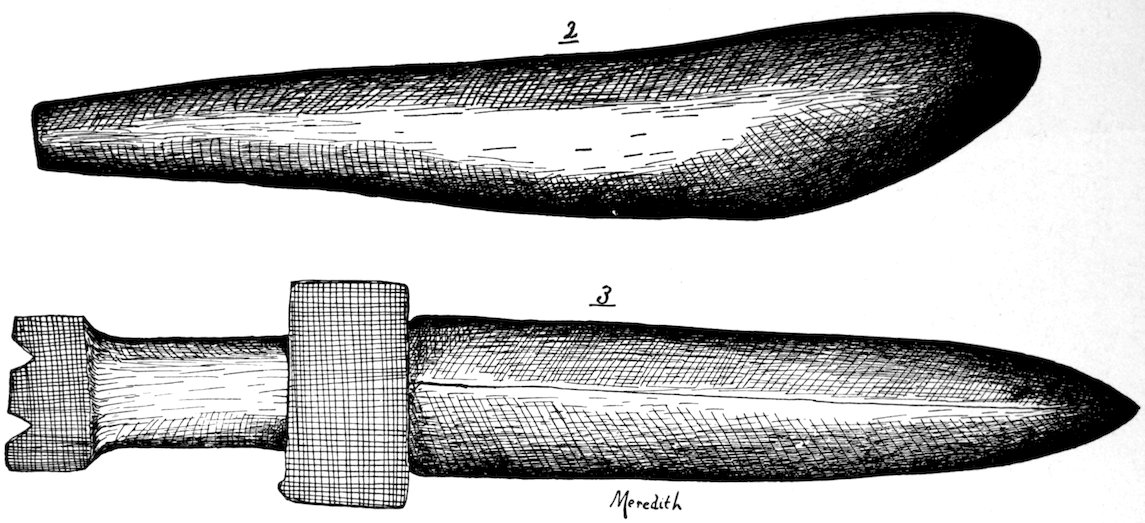

Fig. 424. (S. 1–4.) An idol and three flutes. B. H. Young’s collection.

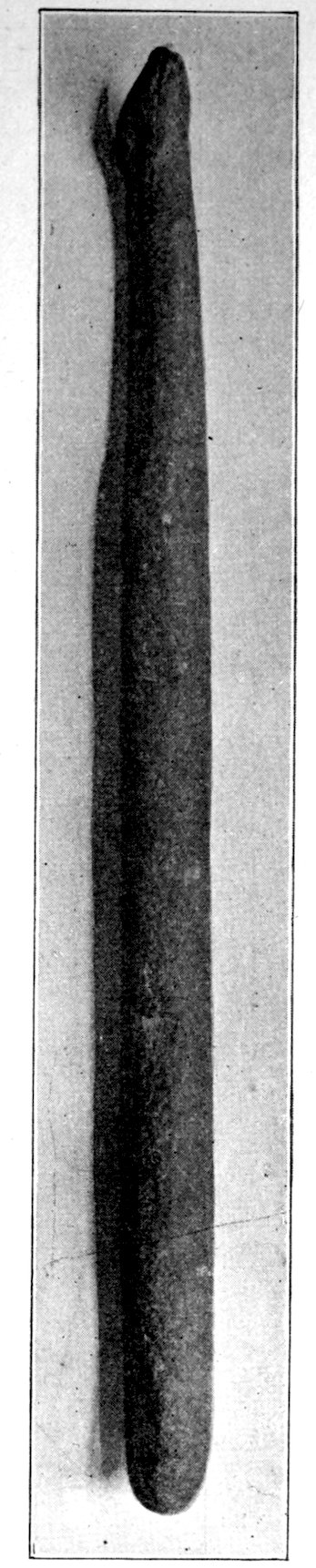

The long flute at the top is made of slate. The head is an imitation of a serpent’s head. It has five holes regularly spaced. It is evident that a small block of wood was placed in the mouth to lessen the wind space.

The central one is of stone, open at both ends, with four holes.

The smallest one, of bone, is open at both ends.

On each of these instruments from seven to nine different sounds can be made.

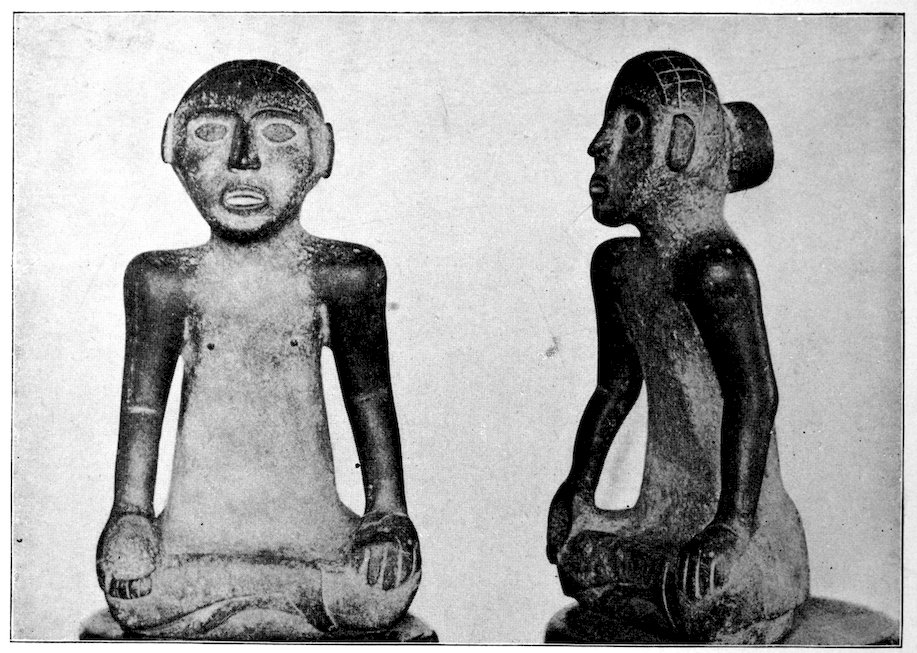

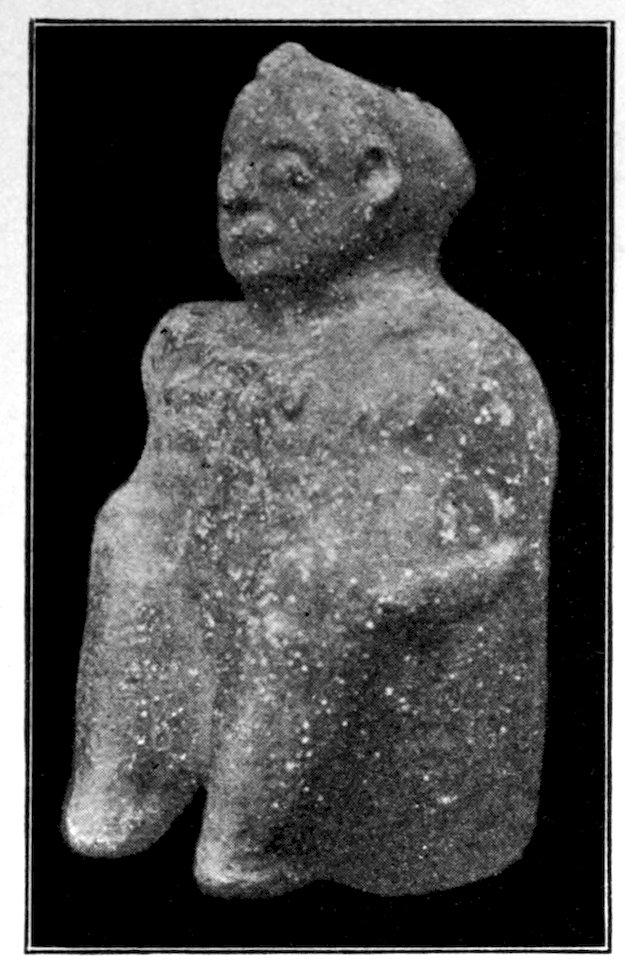

The idol was found in Tennessee, near the Kentucky line. It is made of dark steatite, and is unique in representing the full human form.

The idol presented in Fig. 426 is a remarkable effigy. Not a few of these have been found near the Etowah Group of mounds in Georgia. All such idols have either been found in graves or on the sites of Southern villages, where population was considerable. I never knew of them being found in a mound, although there may have been such discoveries.

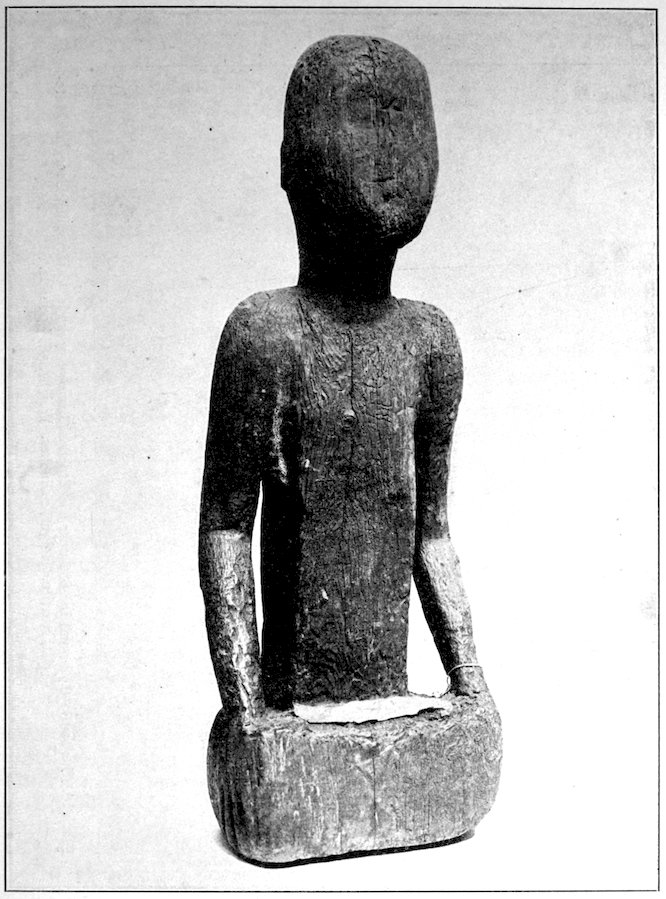

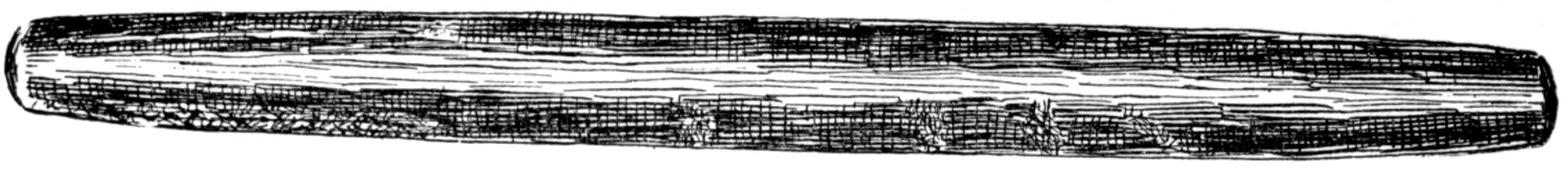

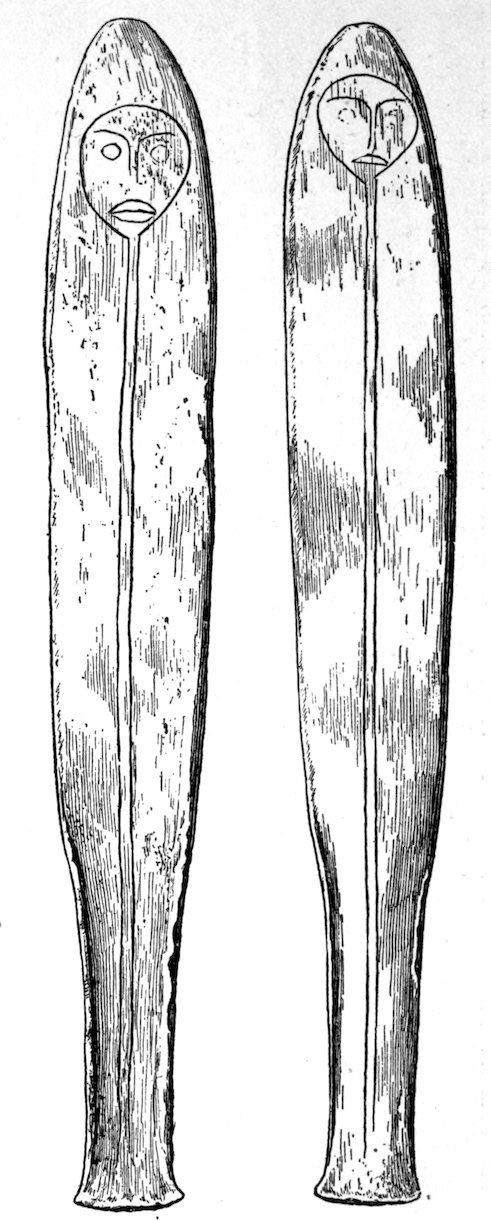

Fig. 425. (S. 1–3.) B. H. Young’s collection. Wooden image found many years ago in Bell County, Kentucky, near Middlesboro, in a cave by a turkey-hunter. It is made of yellow pine, and is of form similar to the stone effigies found in Kentucky. The ears are pierced for ear-rings, and the wrists grooved for bracelets.

Fig. 426. (S. about 1–6.) Found in 1886 near the Etowah Group of mounds, Cartersville, Georgia. Material, steatite. Height, 21 inches. Weight, 56½ pounds.

Previous to the discovery of America, that strange custom of smoking was confined to the New World natives. There have been some vague references to inhaling of smoke by other ancient peoples elsewhere in the world. But these are still in the realm of doubt. Certain it is that the burning of tobacco, dried leaves, bark, etc., in stone, bone, clay, or copper receptacles was not known to any considerable number of men before Columbus set out upon his uncertain voyage, on an unknown sea.

There is an extensive literature dealing with pipes and smoking customs of America, and it is unfortunate that I am unable to produce more than a portion of what has been said by the early travelers, and later scholars and others, regarding this peculiar custom. However, there are two important publications accessible to all readers. The first was published by Mr. Joseph D. McGuire.[9] Mr. McGuire illustrates his paper with two hundred and thirty-one figures and five plates. The other paper was written by Mr. George A. West and contains seventeen plates and two hundred and three figures.[10] Mr. McGuire made a study of pipes and smoking customs throughout the United States; Mr. West, of the St. Lawrence basin and particularly Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota, and Canada. These two publications will give readers abundant material for consideration, and because of their excellence, I have made this somewhat lengthy reference to them.

In addition to the monographs cited, there are numerous shorter articles scattered throughout various publications and reports. These will be found if readers refer to the Bibliography.

In the following pages, I follow the classifications made by Messrs. McGuire and West with very few changes. These must both stand 30as the best that have appeared on the subject up to the present time.

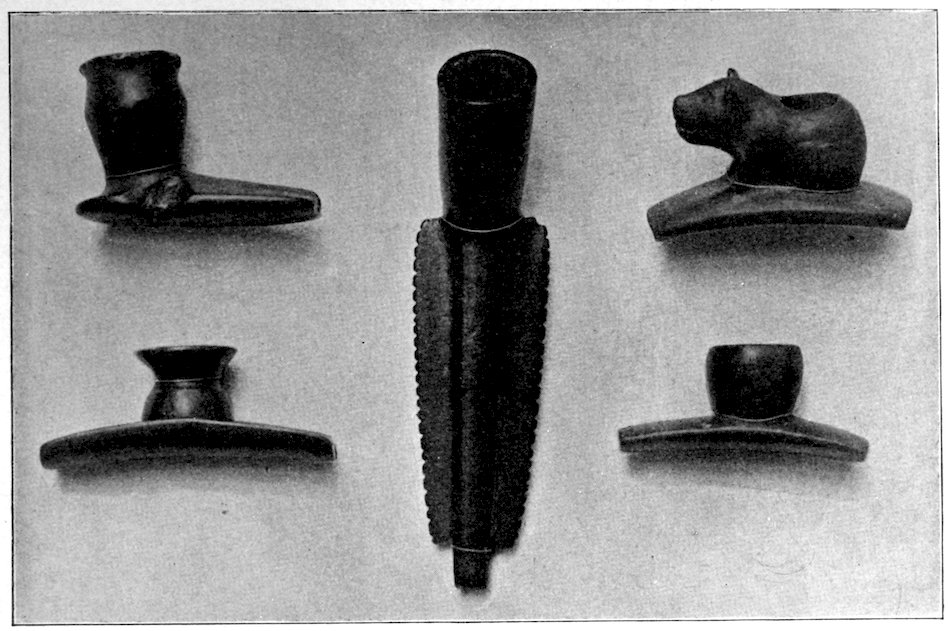

Fig. 427. (S. 1–1.) Stone pipe-bowl made of catlinite. Collection of the University of Toronto, Ontario. Found by Henry Montgomery in a mound in western Manitoba.

Since Mr. McGuire’s paper was published there have been large additions to pipe collections in the museums and private collections. As to the number of pipes in the Smithsonian, American Museum, Peabody Museum, and others, I do not know, but one might venture the opinion that each of these three institutions have at the least fifteen hundred or two thousand pipes scattered throughout the collections; and the smaller museums in proportion. Professor W. C. Mills informs me that there are two hundred and forty pipes in the exhibit under his charge at Columbus, comprising collections owned by the Ohio State University and the Ohio Archæological and Historical Society. They are divided as follows: Monitor, twenty-eight; effigy, forty; tubular, twenty-four; miscellaneous, one hundred and forty-eight. In the Andover collection there are about one hundred and seventy pipes.

There are two large private collections of pipes in America. Mr. John A. Beck of Pittsburg owns about eighteen hundred pipes of various kinds from the United States and Canada. Mr. George A. West reports that there are six hundred in his possession.

Pipes, from their very nature, were probably more highly prized among our aborigines than any other articles. The pipe was sacred, and it was not until Europeans, with their superior civilization, took up the smoking custom, that it became a habit and totally lost its original significance.

It is quite likely that pipes were more generally exchanged among tribes than other artifacts. Possibly, one should except copper, but I am not even sure of that. We find Northern forms South, Eastern types West, and a general indication that aboriginal barter or trade in pipes was extensive.

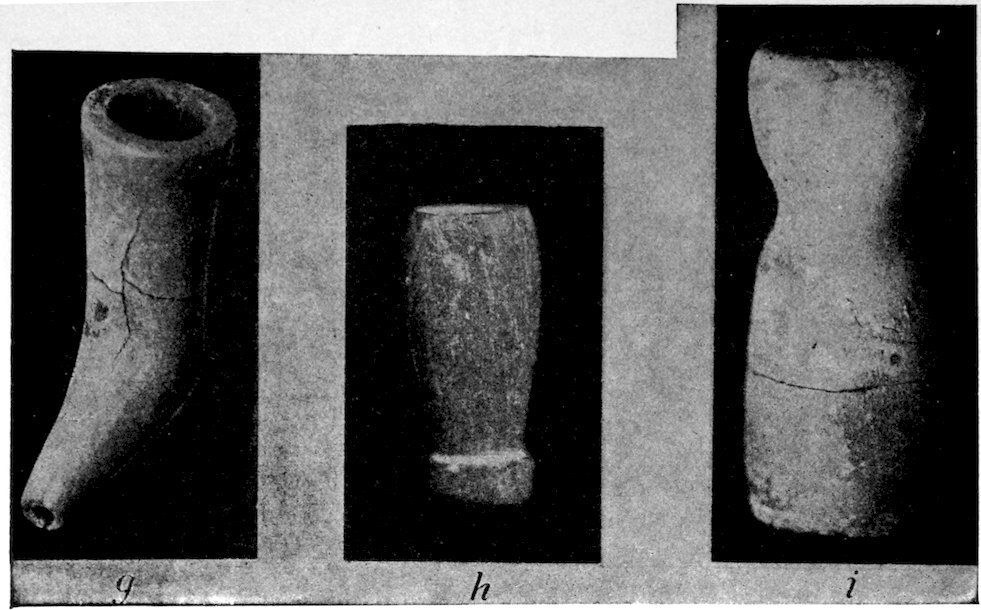

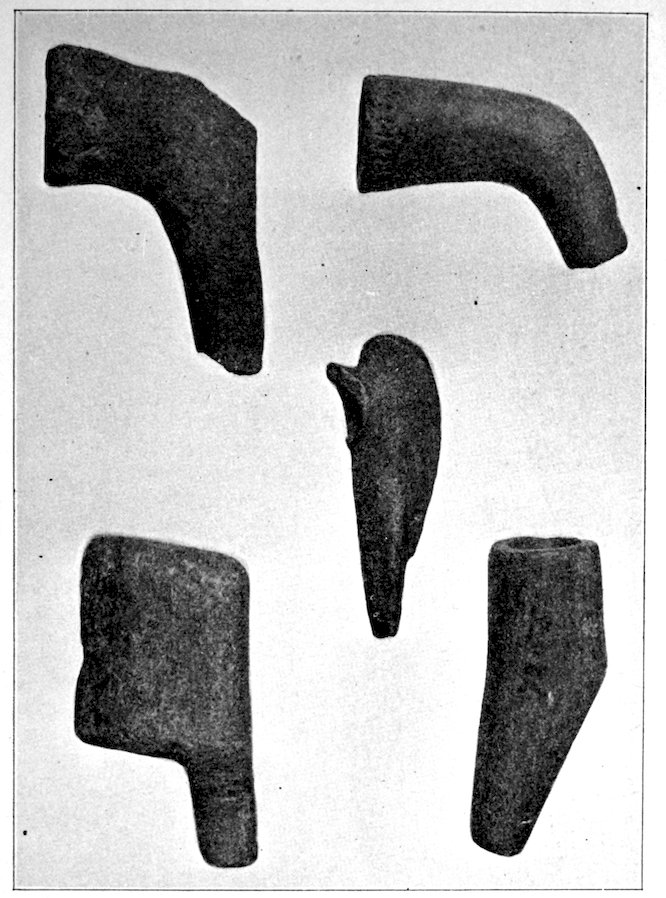

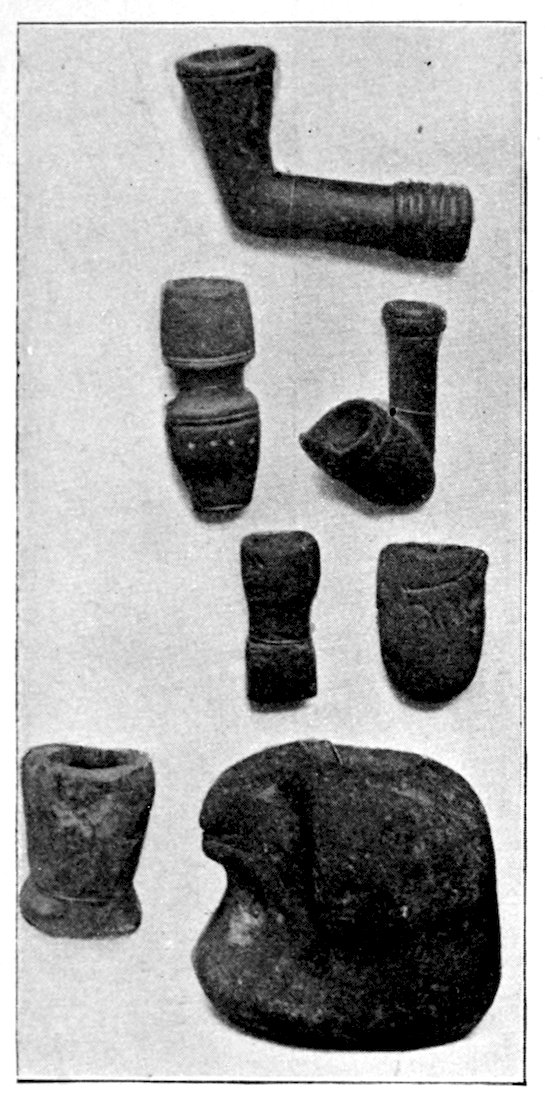

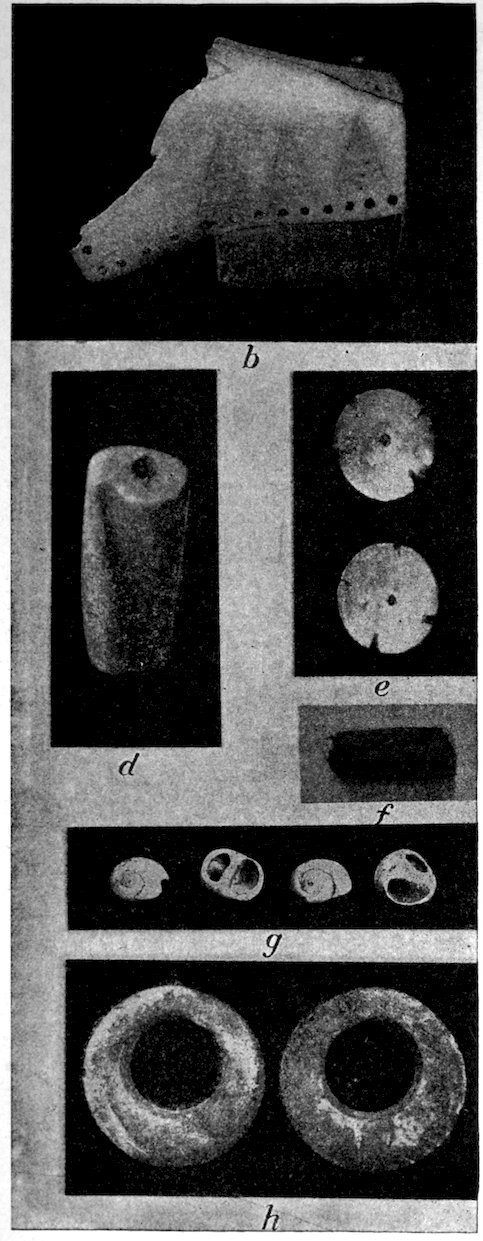

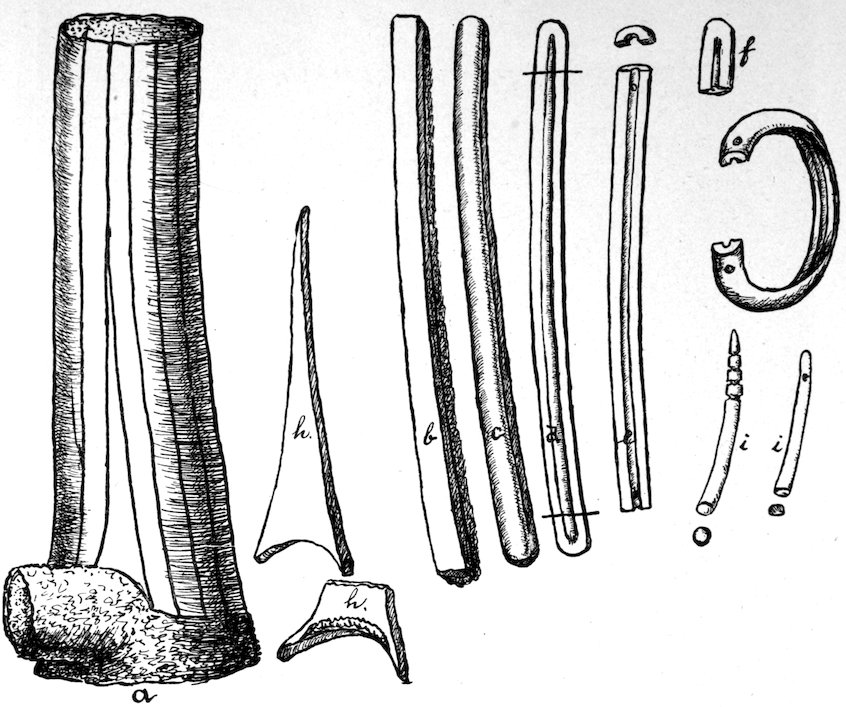

Fig. 428. (S. about 1–2.) Pipes from North Dakota mounds. Explorations of Henry Montgomery. (a) Pipe-bowl of catlinite. (b) Piece of catlinite pipe-bowl which had been cut off before burial. (c) Catlinite pipe, 2¼ inches in length. (d) Large bowl of catlinite pipe, 10¼ inches long; from Ramsey County. (e) Catlinite pipe-bowl found with the piece of pipe shown in (b). (f) Pipe-bowl made from deer antler; length, about 4 inches. (g) Clay pipe, bent; length, 5 inches; found in burial-pit in Benson County. (h) Catlinite pipe-bowl, 1½ inches long. (i) Straight bowl of clay pipe; length, 2¾ inches; found in burial-pit in Ramsey County. (See Fig. 429.)

Fig. 429. (S. about 1–2.) Pipes from North Dakota mounds. Described under Fig. 428. (American Anthropologist, vol. 8, no. 4, plate 33.)

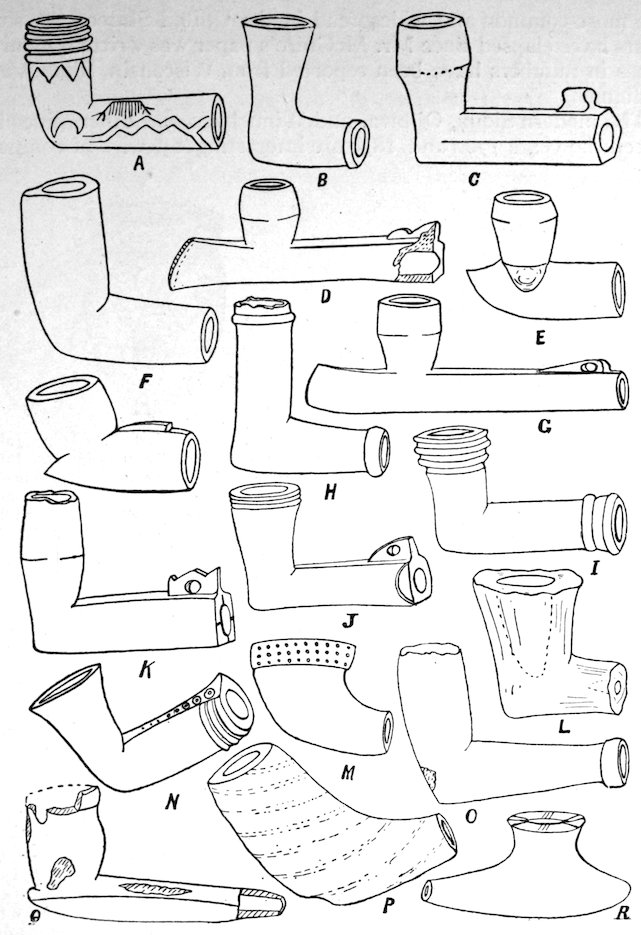

No one save Mr. J. D. McGuire has attempted to group these objects. In his classification, Mr. McGuire presented four plates in which he showed the distribution of fifteen types of pipes. I have followed his numbers, but instead of presenting a map, have named states or localities, from which these were taken.

Fig. 430. (S. 1–1.) Earthenware pipe. Found near Lake Champlain. Collection of the University of Vermont.

Fig. 431. (S. 1–1.) Conoidal tube pipe. Collection of G. A. West, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Sheboygan County, red catlinite.

This table will serve as a beginning, but it is incomplete. Many pipes of 34the types mentioned by Mr. McGuire are found in other sections than those named by him.

Fig. 432. (S. a little over 1–3.) Found in a mound on Long Island, Tennessee River, Jackson County, Alabama. Collection of J. T. Reeder, Michigan.

The names of some pipes may not be familiar to all of my readers. I therefore repeat Mr. McGuire’s list of fifteen pipe-types, and state opposite each, the numbers of figures illustrating that particular type.

The fifteen types of pipes described by Mr. McGuire are illustrated in this chapter under the following figure numbers:—

Certain areas are characterized by particular forms of pipes, and in regions where the population was more dense, several types of pipes are usually found, thus indicating that they were taken from one region to another.

Fig. 433. (S. 1–2.) Collection of S. Van Rensselaer, Newark, New Jersey.

Fig. 434. (S. 1–2.) Pottery pipes from Simcoe and Durham counties, Ontario, Canada. Toronto University collection. Characteristic of northern central Ontario.

37One fact stands out prominently with reference to these pipes, and it is that any one who is familiar with conditions under which pipes are found can distinguish the prehistoric from the modern in most instances. Of course there are exceptions. Many modern pipes show the marks of steel tools, whereas the ancient forms do not. Certain specimens appear to those who have done a great deal of field work as ancient, whereas others do not. This is not merely a matter of opinion. I have found it very difficult, during my lifetime, to make those observers who have no intimate knowledge of field conditions realize the importance of this statement. There is no convenient formula whereby one may explain to a skeptic, how one specimen appears old and another does not. I shall consider this subject at greater length in the Conclusions.

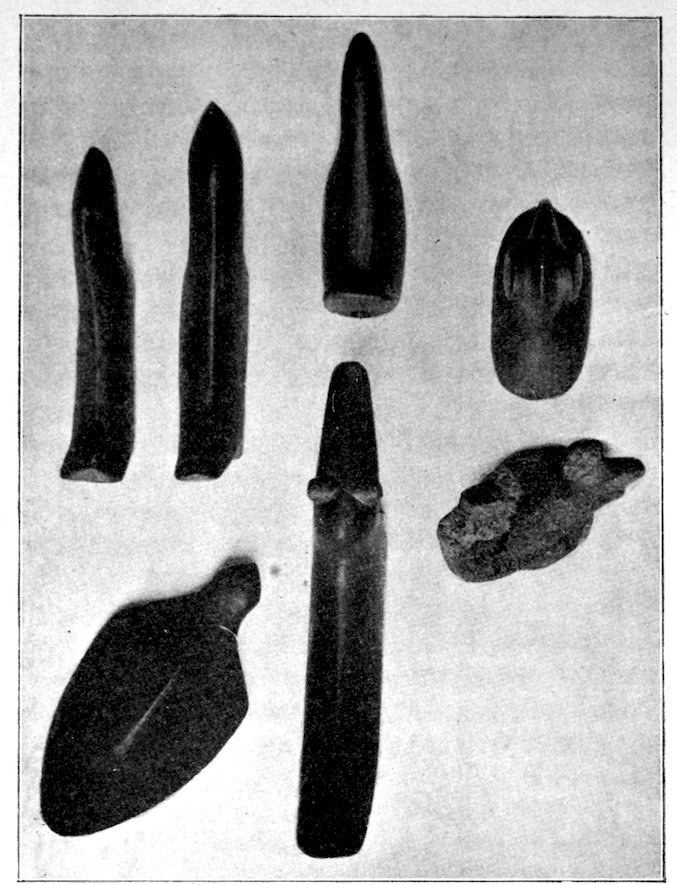

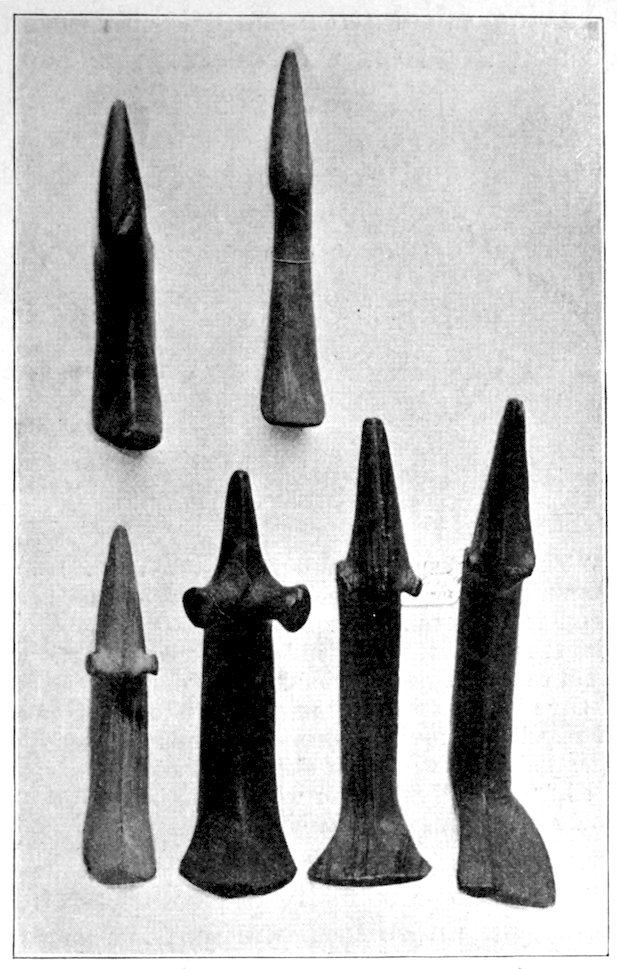

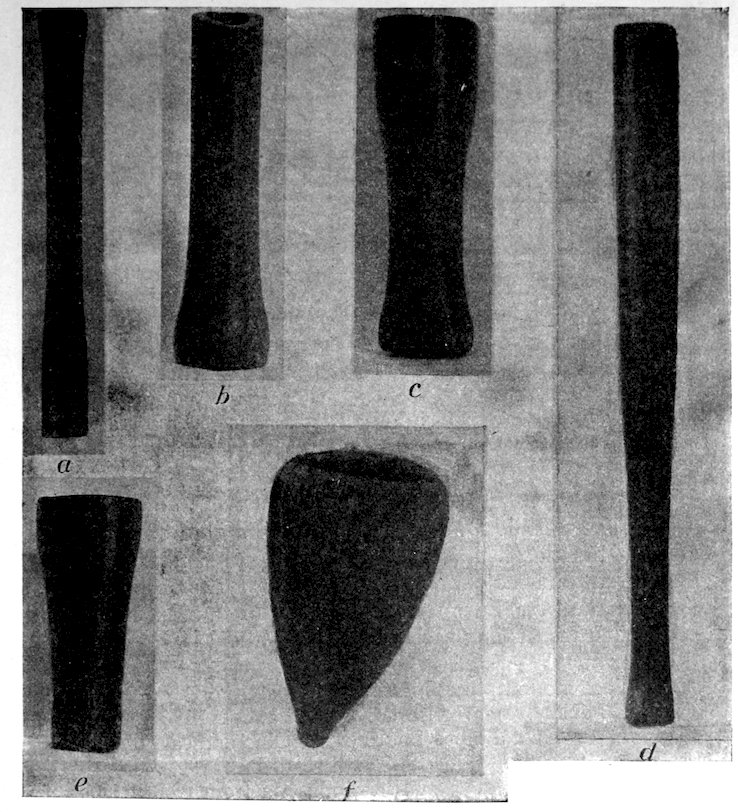

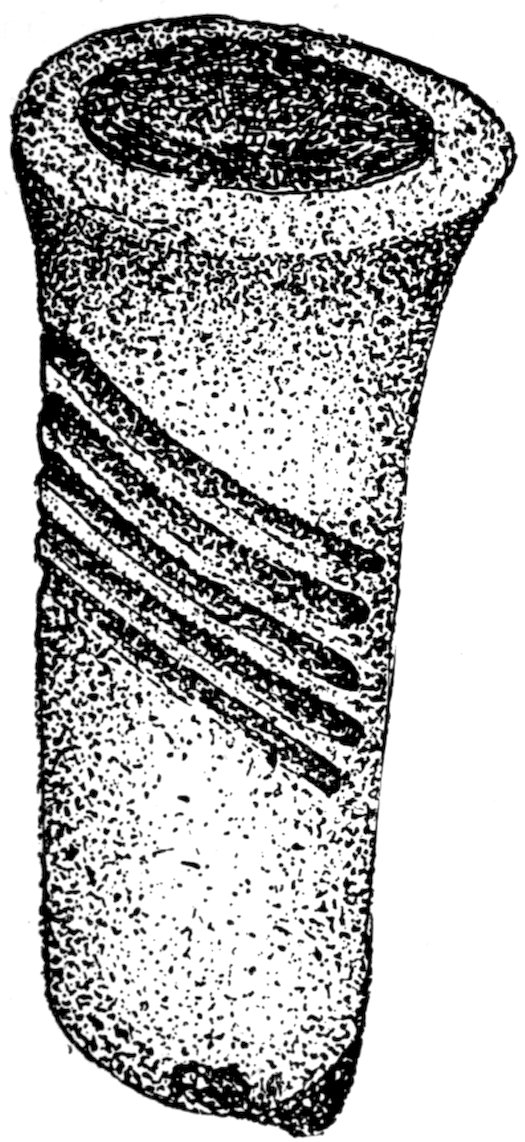

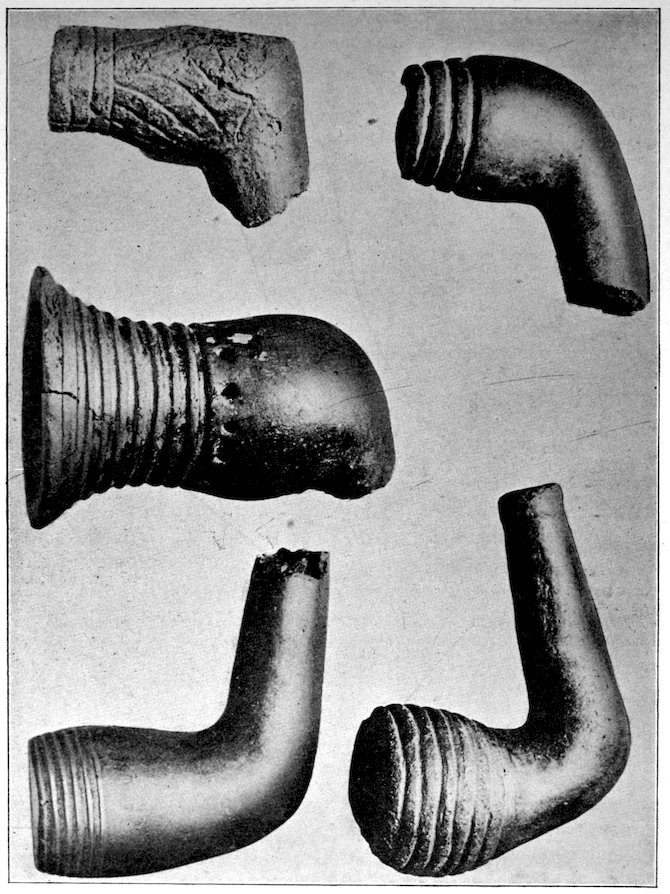

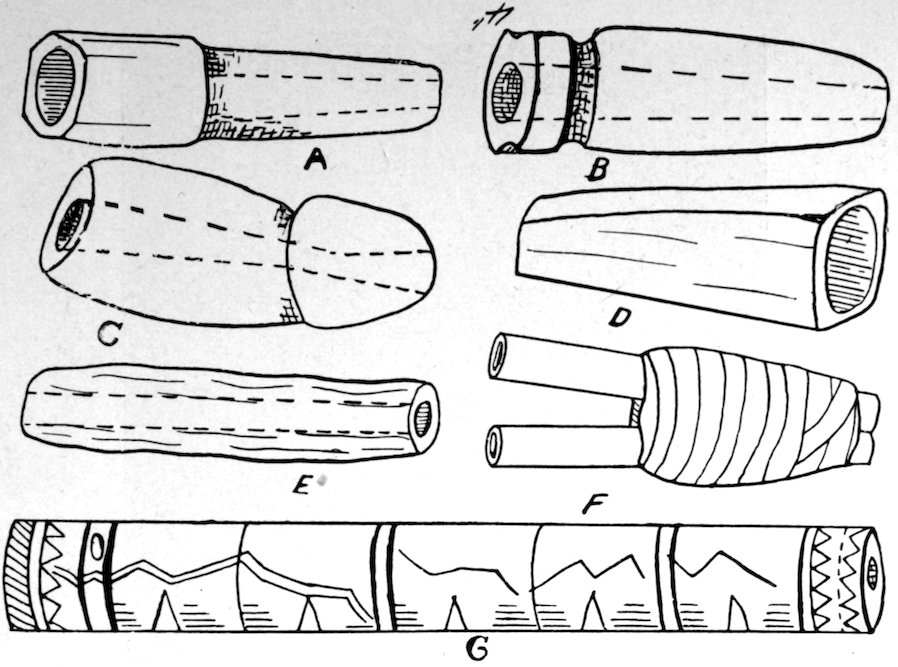

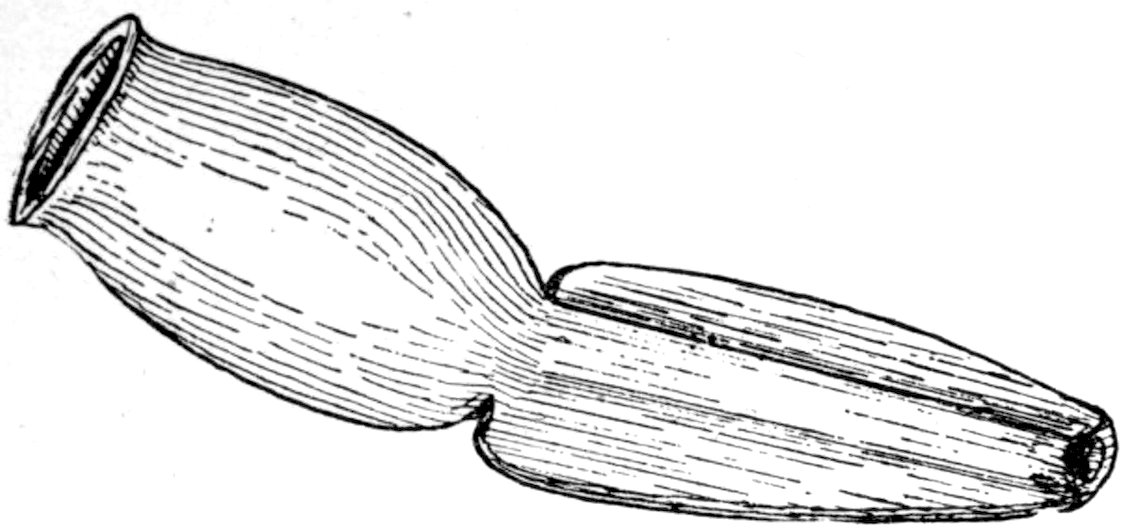

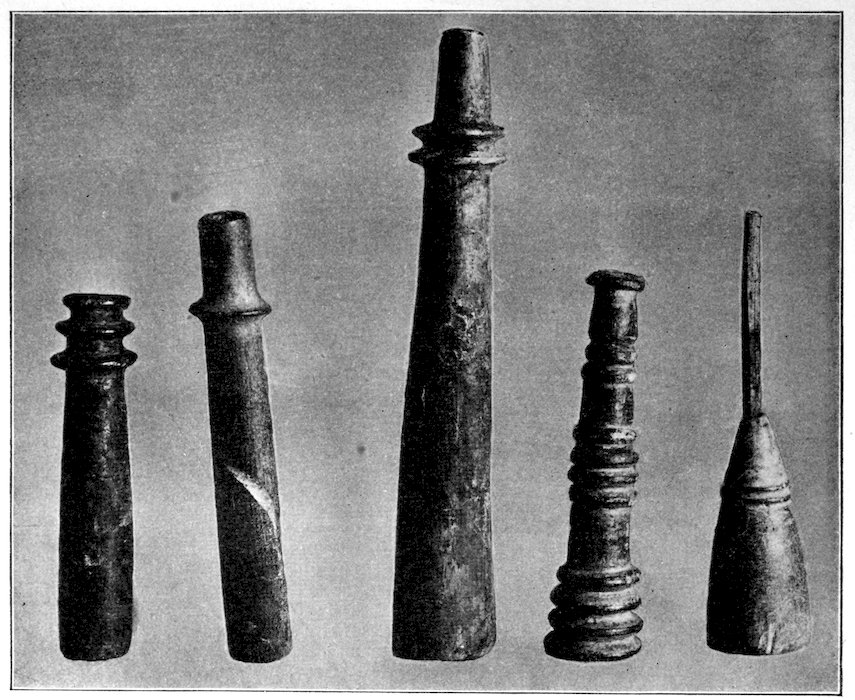

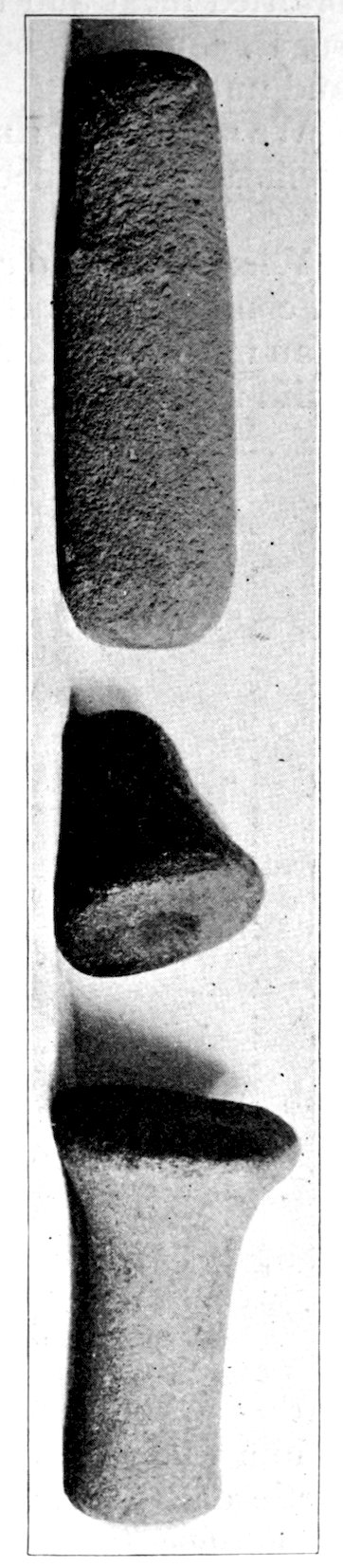

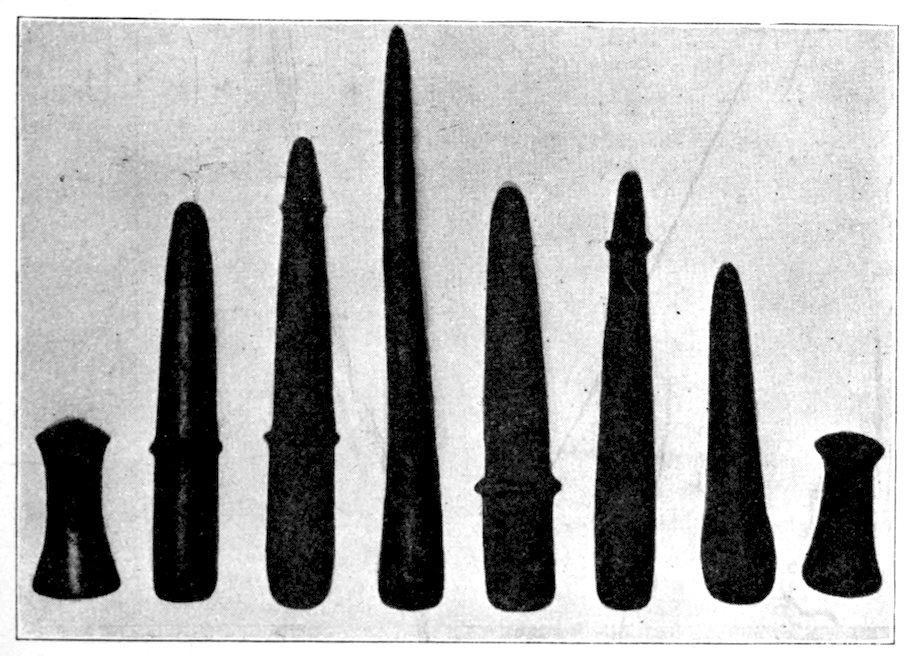

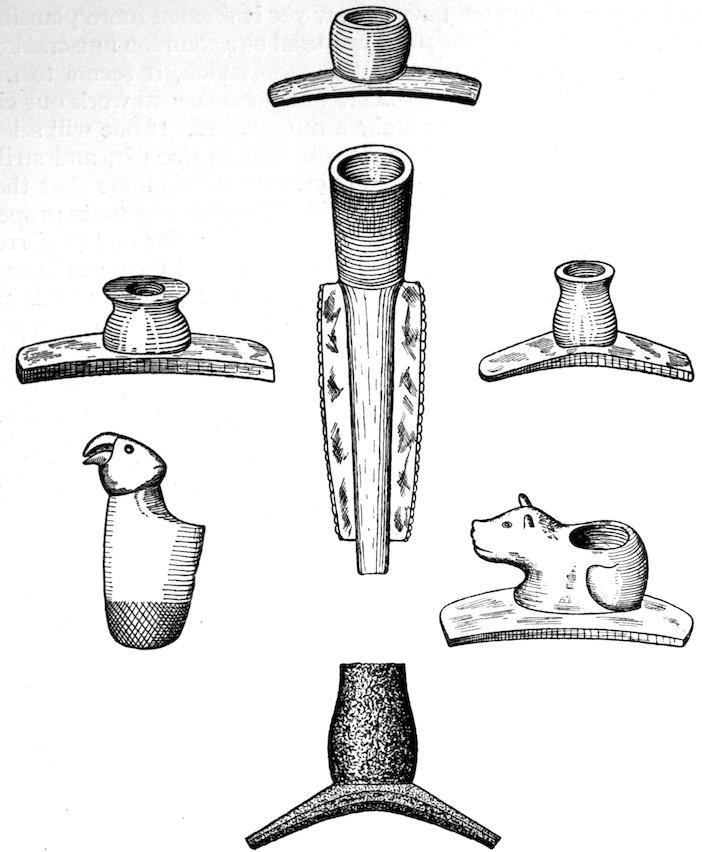

Fig. 435. Peculiar tube pipes. Collection of G. A. West, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Tubular and trumpet-like pipes are shown in Figs. 427–28, and 430. These are considered to be earliest forms. More complicated tubes are observed in Fig. 435. Mr. West described these in his paper, previously cited.

Various remarks offered here and there on the pages of this chapter may be taken to represent my conclusions as to pipes. I have not offered a summary at the end of the chapter, preferring to state pertinent observations, suggested by the figures illustrating pipes, as they occur.

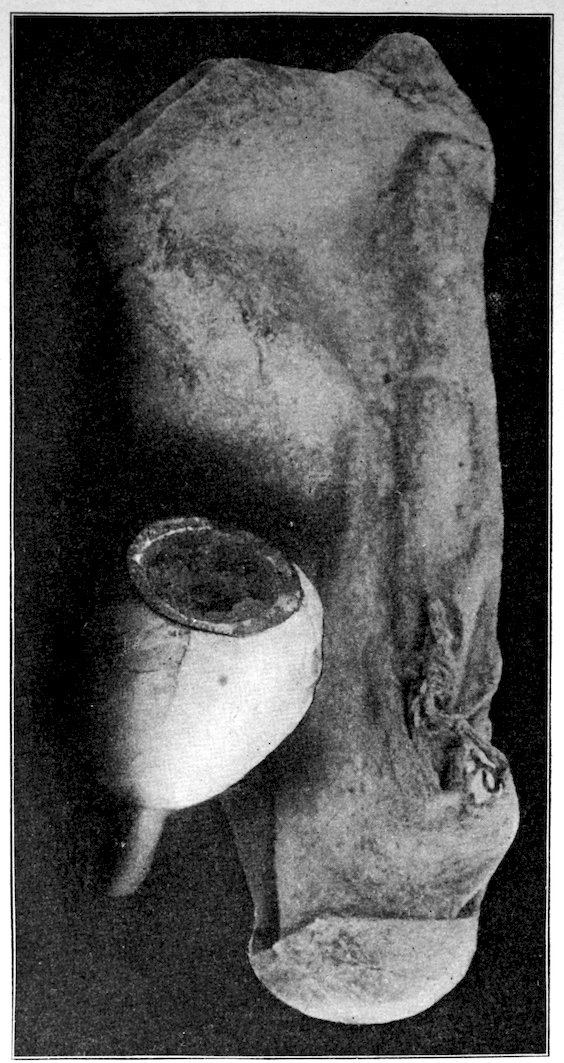

Fig. 436. (S. 2–3.) Onyx pipe-bowl with wooden stem. From cave-house ruins in San Juan County, Utah, February, 1894. The pipe lies against a fragmentary skin covering or robe. Henry Montgomery, Toronto, Ontario.

Fig. 437. (S. 1–2.) Diminutive Siouan pipes. Collection of G. A. West, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

40Of the fifteen types named by Mr. McGuire, the tubular, rectangular, and slightly curved pipe (of the forms shown in Fig. 433), are most common and widespread in the United States. As some years have elapsed since Mr. McGuire’s paper was written, monitor pipes in numbers have been reported from Wisconsin, Illinois, and Indiana.

Fig. 438. (S. 1–2.) Peculiar stone pipe. Collection of H. M. Whelpley, St. Louis, Missouri.

Fig. 439. (S. 1–2.) Vase-shaped pipe. John Weber’s collection. “Found by Mr. John Weber, in Killare, Juneau County, Wisconsin, in 1895, is of a pinkish-colored stone, and exhibits on its two opposite faces etched figures of some animal, possibly a lizard. The figure is after a sketch furnished by Mr. W. H. Elkey.”

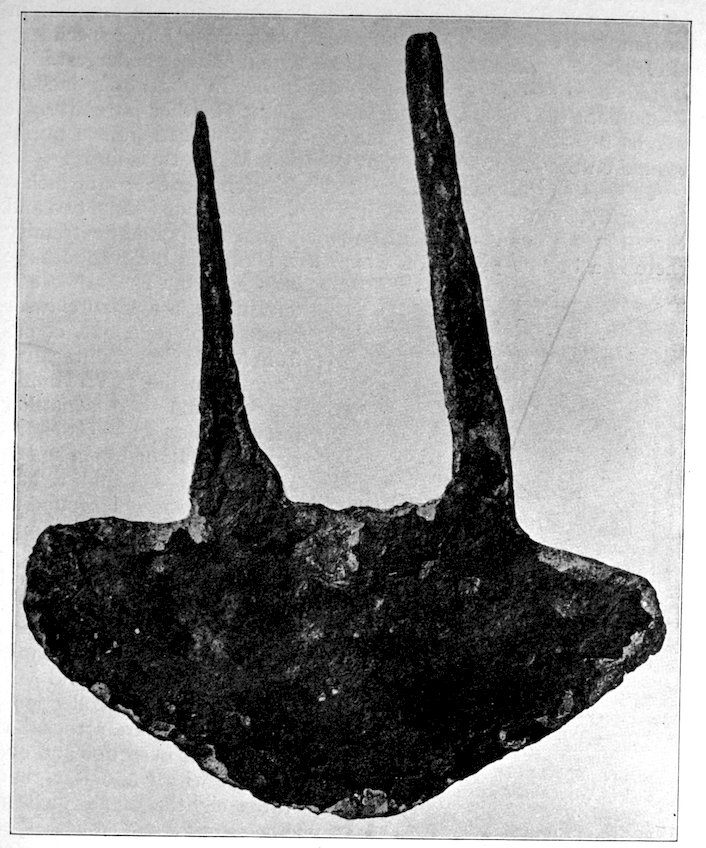

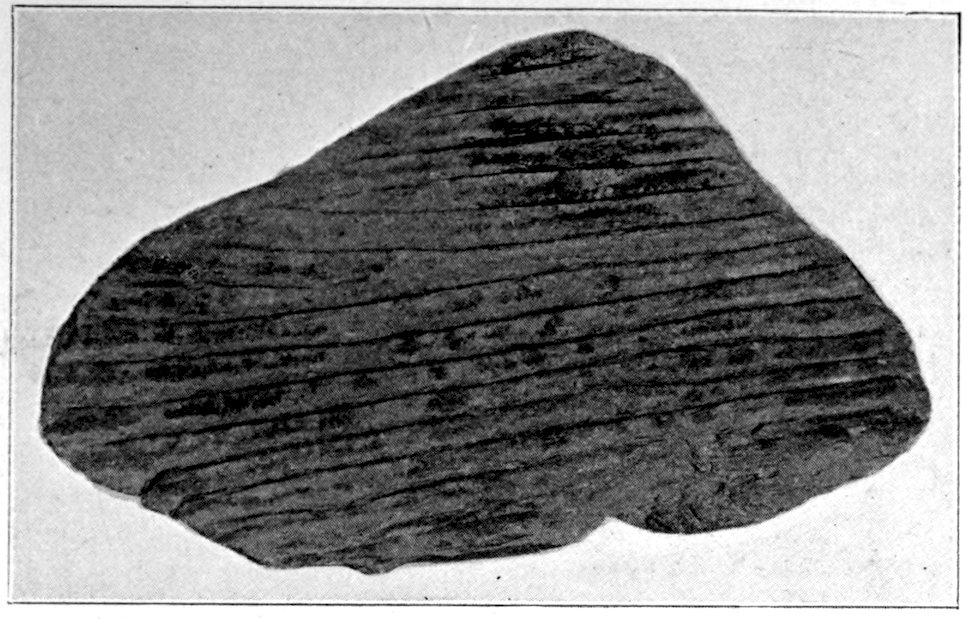

Fig. 440. (S. 2–3.) Double conoidal pipe. J. P. Schumacher’s collection. “A very attractive example, from Brown County, Wisconsin, is of dark sandstone, nearly 4 inches long, 2½ inches high, 3 inches wide, and oval in shape with a flat base. Its stem and bowl cavities are each fully an inch in diameter at the surface, and are placed at right angles to each other. This pipe was evidently pecked into shape, both bowl and stem holes being made by the same process.”

The modern Sioux, Ojibwa, and Winnebago and other pipes between the years 1700 and 1850 are interesting by way of comparison. 41Mr. West[11] wrote a few paragraphs concerning them, which I quote.

“No pipe was ever regarded by the American aborigine with greater reverence and respect than the calumet. It was used in the ratification of treaties and alliances; in the friendly reception of strangers; as a symbol in declaring war or peace, and afforded its bearer safe transport among savage tribes. Its acceptance sacredly sealed the terms of peace, and its refusal was regarded as a rejection of them.

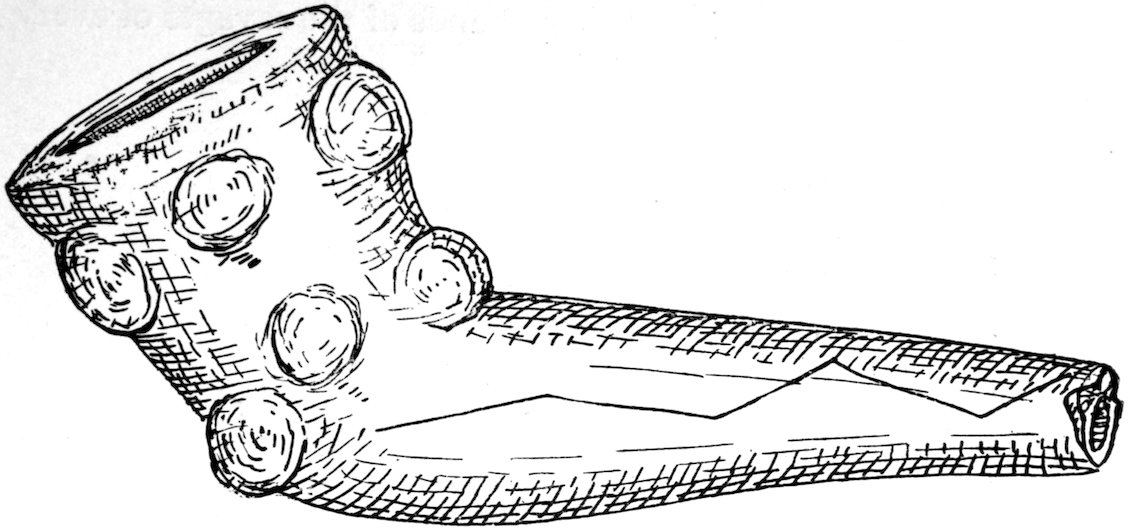

Fig. 441. (S. 1–2.) Black pottery pipe. Collection of G. A. West, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. “This is a type of Southern mound pipe taken from a mound in Pepin County, Wisconsin. It is well tempered with shell, contains eight knobs or coffee-bean protuberances about the bowl, and the stem is ornamented on one side by a zigzag line, probably intended to represent the emblem of lightning. This pipe is 3¼ inches long, and the only one of its kind so far found in this state.”

“Calumets made of steatite, limestone, sandstone, and granite, are often found, but a large majority of them are made of catlinite, a compact clay slate, named after Mr. George Catlin, who lived for many years among the Indians, and to whom great credit is due for his many portraits and other paintings true to aboriginal life. The color of catlinite is usually cherry red, often mottled and shading into ash, grey, or black. This material was quarried by the Indians in several places in Minnesota, Iowa, South Dakota, Missouri, and in Barron County, Wisconsin. Specimens of ‘pipestone’ are 42sometimes secured from the glacial drift. Pipes of catlinite are not necessarily of modern make. Examples have been found, over a wide area, in Indian mounds and graves. In 1880 a broken pipe of this material was found by Ole Rasmussen, in the town of Farmington, Waupaca County, while digging a well, eighteen or twenty feet below the surface. The material has been known, under different names, ever since the Discovery.

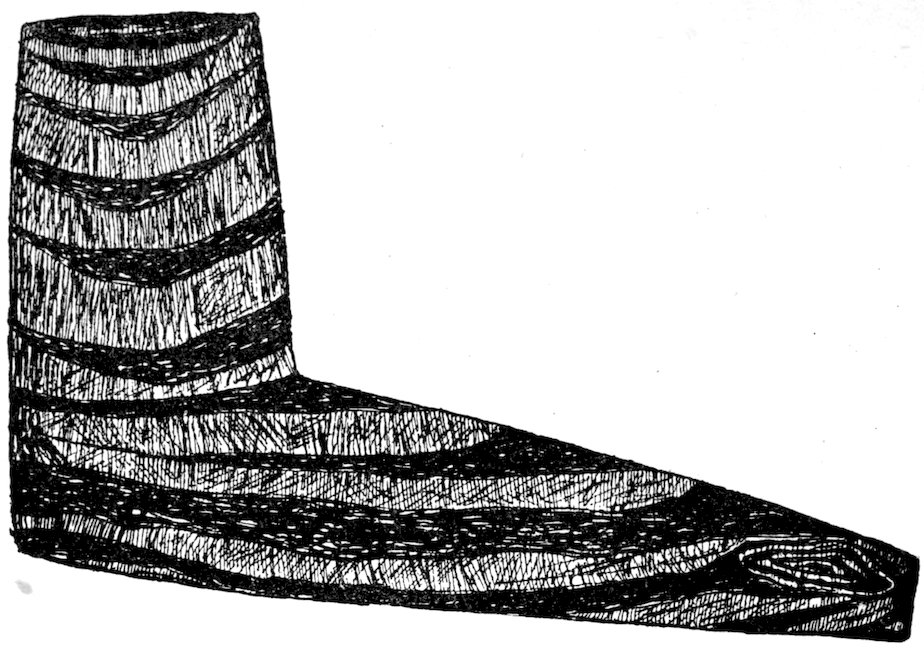

Fig. 442. (S. 1–1.) A pipe of banded slate from the collection of Albert L. Addis, Albion, Indiana. Pipes of slate are not wanting, and they are usually either rounded or angular. It is seldom that the banded slate is worked into pipe effigies.

“Catlin, who in 1835 visited the pipestone quarries of Minnesota, had previously found catlinite ‘in the hands of the savages of every tribe, and nearly every individual in the tribe has his pipe made of it.’ After a visit to the famous quarries, Catlin concludes as follows: ‘From the very numerous marks of ancient and modern diggings or excavations, it would appear that this place has been for many centuries resorted to for the redstone; and from the great number of graves and remains of ancient fortifications in its vicinity, it would seem, as well as from their actual traditions, that the Indians have long held this place in high superstitious estimation; also it has been the resort of different tribes who have made their regular pilgrimages here to renew their pipes.’”[12]

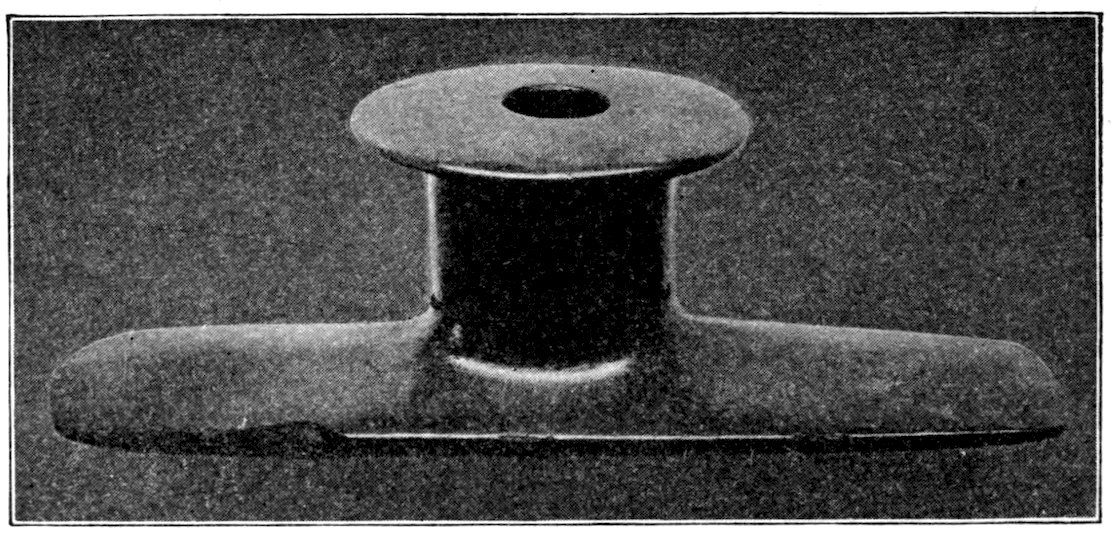

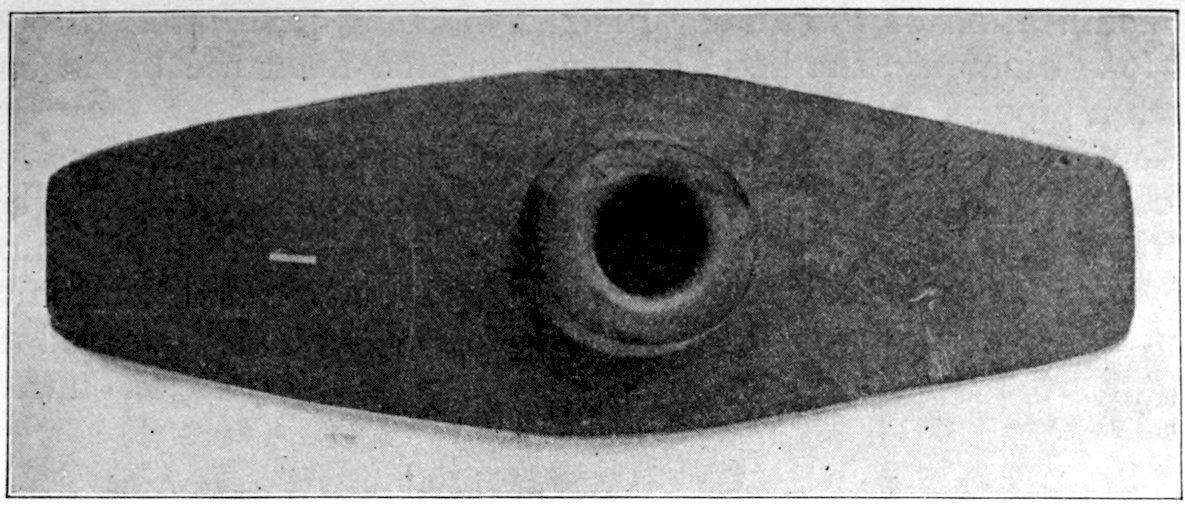

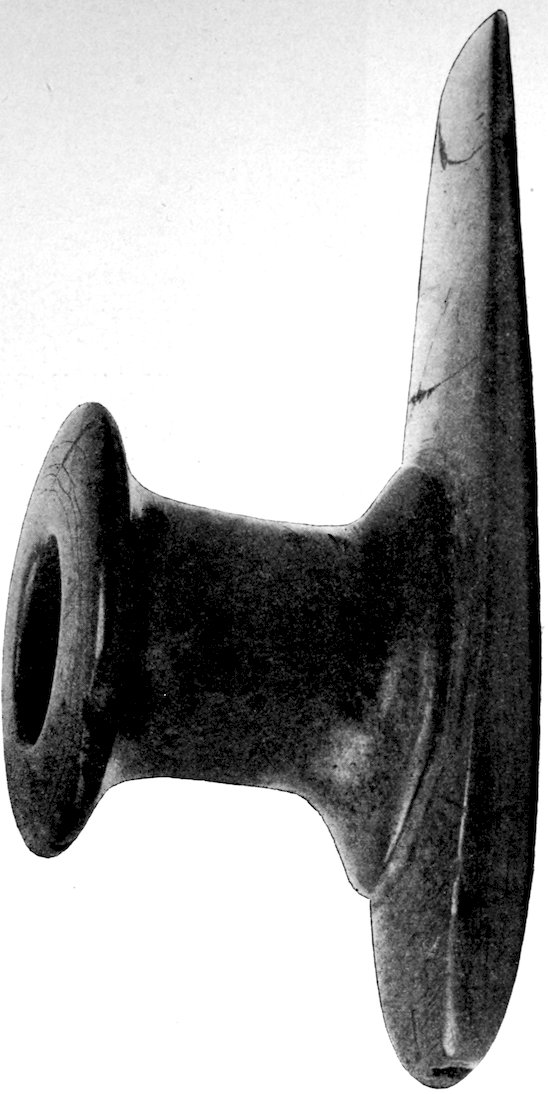

Fig. 443. (S. 4–5.) Handled disc pipe. Collection of G. A. West, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. A rare old specimen found in a mound near Delavan, Walworth County, Wisconsin, of greenish-colored limestone, the color probably due to copper stains.

Fig. 444. (S. 1–2.) Type of monitor pipe. Collection of G. A. West, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. “Found near Buffalo Creek, Nelson County, Virginia; of dark schist, is 5 inches long. It has an alate stem, running the length of the centre of which is a pronounced ridge. The largest specimen of this type so far encountered is probably a ‘Great Pipe,’ having a bowl 8 inches long, being upward of 17 inches in total length, which was found in a mound in Marion County, Kentucky.”

Fig. 445. (S. 4–5.) Short-base monitor pipe. Collection of S. D. Mitchell. This specimen was “found in the town of Aurora, Marquette County, Wisconsin, is of drab slate, 2½ inches long, the end broken away, base rounded, and is ornamented near the stem end on each side by three deep grooves. A second example of the same shape in G. A. West’s collection, found by Mr. August Bartle, in the town of Scott, Sheboygan County, Wisconsin, in 1901, is of drab steatite. The top of its bowl is ornamented by four sets of cross-lines, of three lines each. The bowl cavities in each pipe are irregularly conical in shape.”

44In Kentucky and Tennessee, as well as southern Ohio, where the population was dense, there are examples of nearly all the pipes except the Iroquois and the catlinite. The few of these found in that region must be set down as strays.

Fig. 446. (S. 1–2.) Five tubular pipes, from the collection of James A. Barr, Stockton, California.

The study of several specimens illustrated by both McGuire and West and the comparison of the fifteen figures presented in “The Stone Age” will acquaint readers with the distribution of forms and types. The striking thing in all this, and it may be verified by inspection of any large mound collection, is that the types shown in Figs. 435, 437, 439, and 465 are usually surface finds and may be distinguished from specimens found in mounds and from various village-sites.

Fig. 447. (S. 1–1.) Handled disc pipe. H. P. Hamilton’s collection.

Fig. 448. (S. 1–1.) Collection of Leslie W. Hills, Fort Wayne, Indiana. From Kosciusko County, Indiana.

Fig. 449. (S. 2–5.) Straight-base monitor pipe, Logan collection, Beloit College. “It was ploughed up in an early day by Mr. L. Craigs, on Section 30, Eagle Township, Richland County, is of drab steatite and finely polished. It is 9 inches long, 2¾ inches wide at the base, 3 inches across the flange of the bowl, with the bowl cavity ¾ inch in its greatest diameter, and made with a tubular drill. This is certainly one of the finest examples of the straight-base monitor pipe as yet found in Wisconsin.”

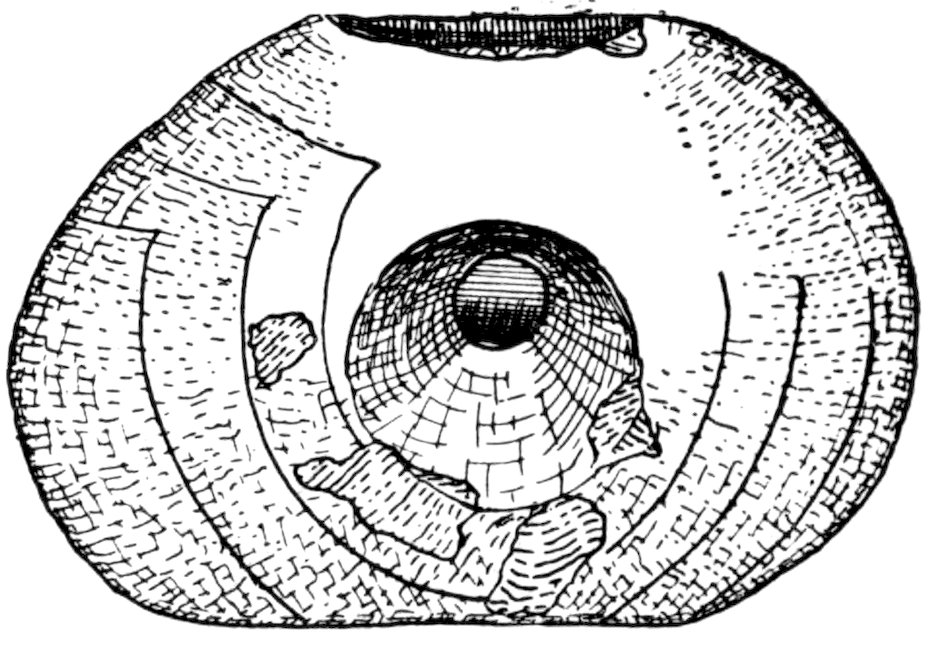

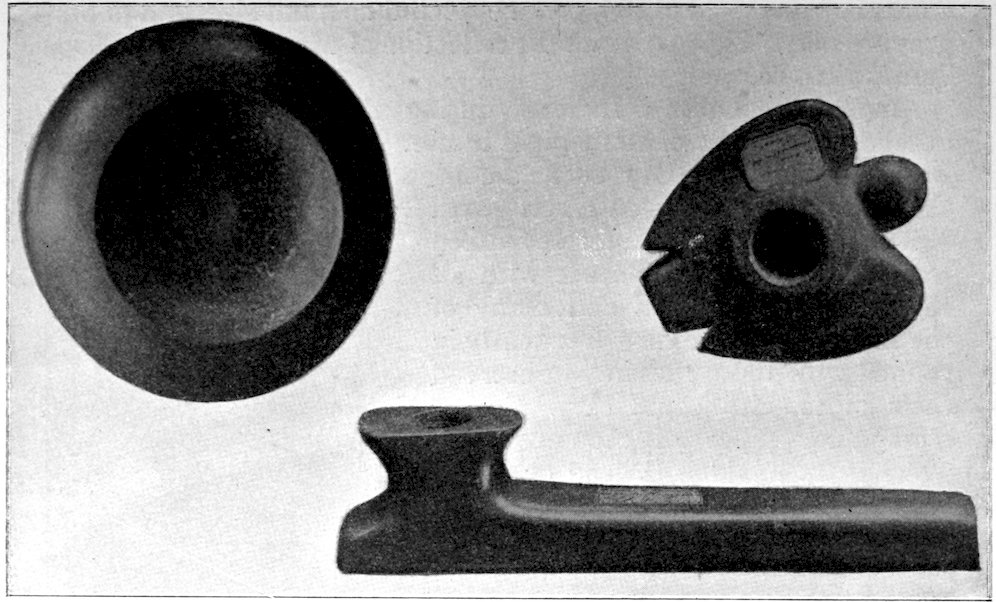

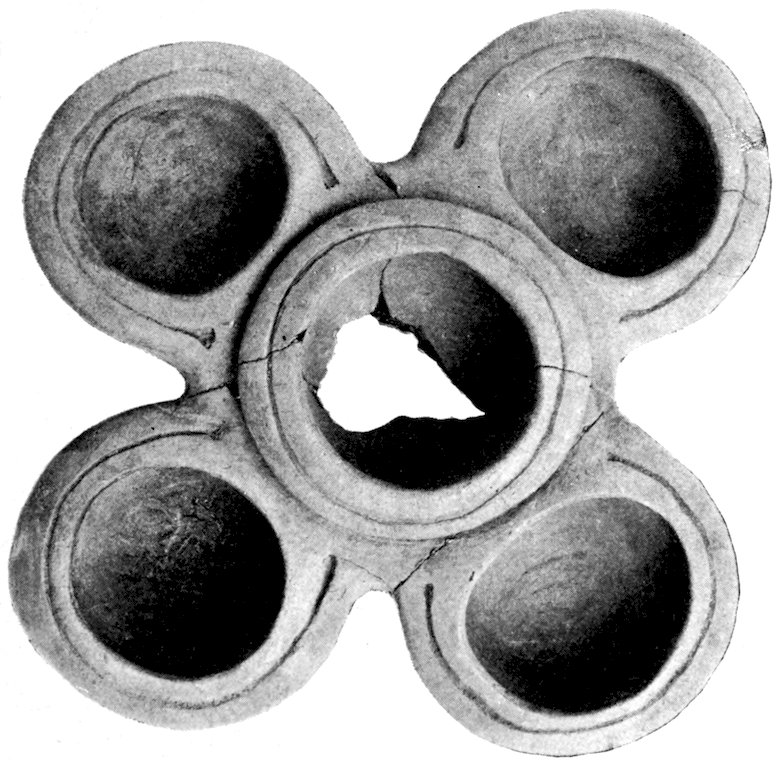

Fig. 450. (S. 1–1.) This figure shows the top view of pipe shown in Fig. 451, and is from the collection of Albert L. Addis, Albion, Indiana. Found in northern Indiana.

Mr. West has kindly permitted me to reproduce portions of his valuable paper on pipes, and I am sorry that space is insufficient to quote his descriptions of the numerous figures he has loaned me. Referring again to the Siouan pipes (Fig. 437), it requires no skill to distinguish these modern forms from the more ancient. Many of the pipes shown in that figure will apply to other living tribes as well as the Sioux.

Fig. 451. (S. 1–1.) Collection of A. L. Addis, Albion, Indiana.

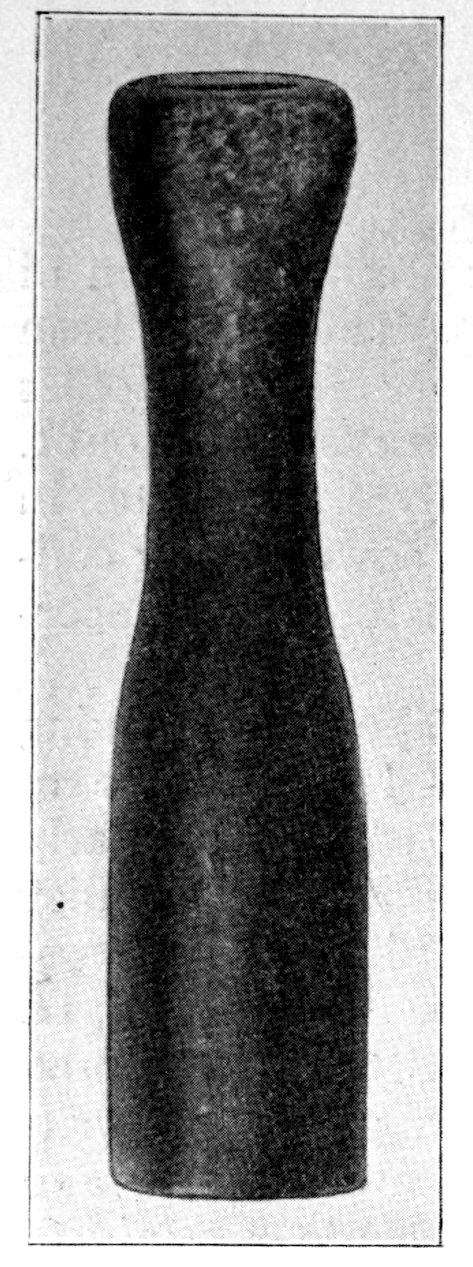

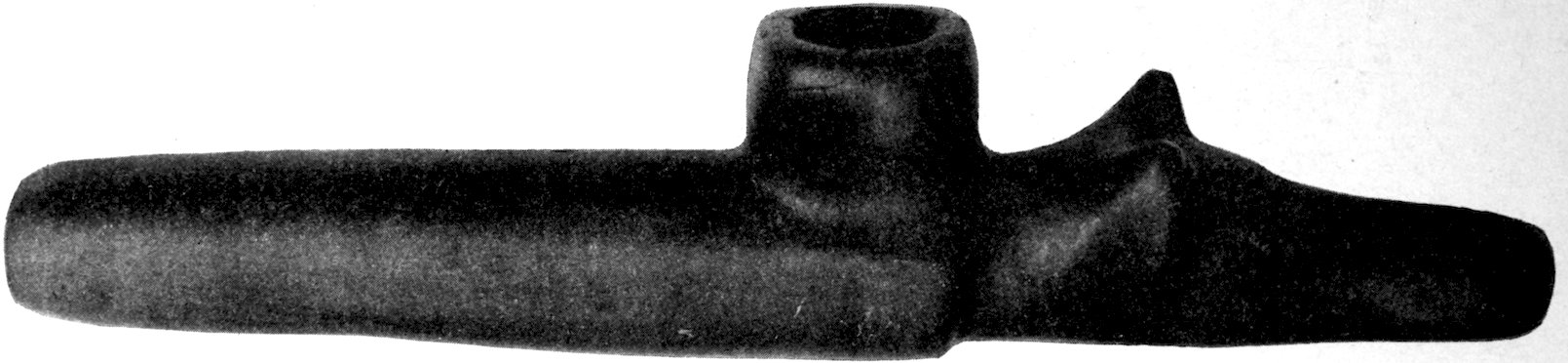

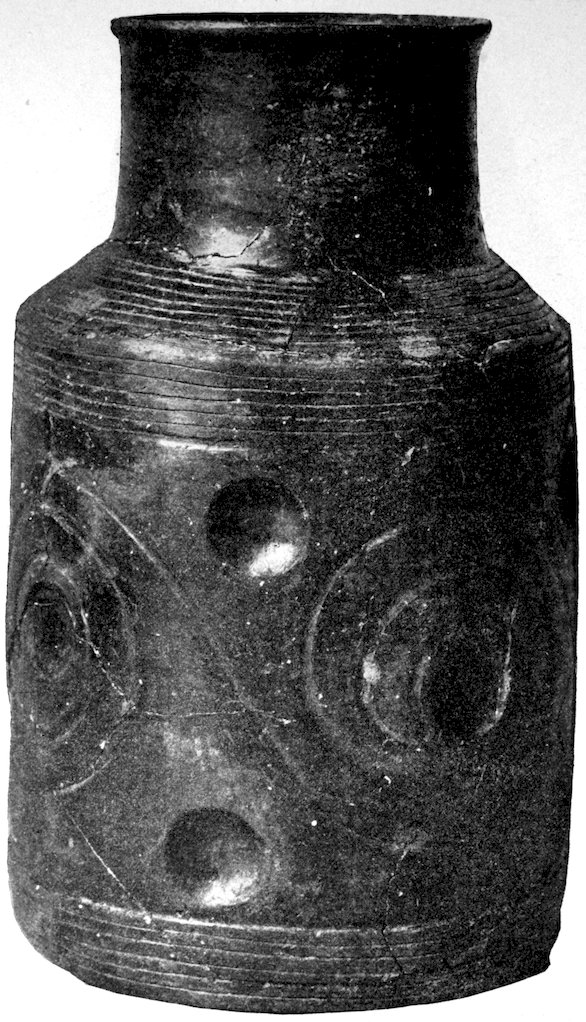

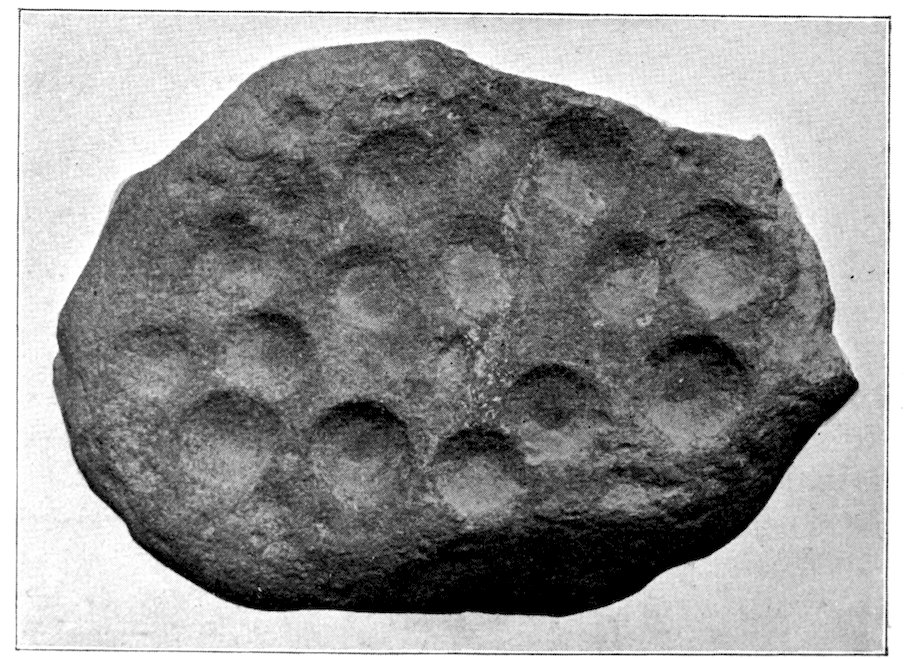

One may suppose that the tubular pipe soon developed into other forms. That is, of course, taking it for granted that the tubular pipe is the first form. Modifications of the tube tending toward the rectangular are often met with, which seems to bear out this theory. Be that as it may, we have in Fig. 438 a pipe from Dr. Whelpley’s collection, oval in outline, curiously ornamented with circular depressions, and which is hardly of the tubular class, but seems to be 48a modification of the same. Instead of being perforated through its long diameter, the bowl is about an inch from the broad end. Such a pipe as this is of rare occurrence.

It will be seen from an inspection of either Mr. West’s or Mr. McGuire’s papers, as well as through a study of any museum collection, or of the various figures presented in this section, that pipes on which there are carvings or decorations, or pipes made in imitation of life-figures, are quite as frequently found as plain and unornamented pipes. Why so much skill should be employed on these pipes, whereas the flat surfaces of slate gorgets and ornaments could have been more easily decorated, is a problem. This may, however, be accounted for by the sacred significance accorded to the pipe by the savage, for it was used in all ceremonial performances, in the declaration of war and peace, and was among his most treasured possessions. It is very seldom that we find markings or tracings on any of these stone gorgets or ceremonial forms, yet on the pipes, as remarked above, ornamentation is the rule. All of this is significant to me, and I think that subsequently we shall be able to draw some valuable lessons from this peculiarity.

Fig. 452. (S. about 1–3.) Large, platform pipe from a burial. Length, 5⅕ inches. W. C. Mills’s explorations.

The Northern pipes, the pipes from the country west of the Mississippi, excepting of course the calumets, appear to be smaller as a rule than the Southern pipes, or the mound pipes. One might say that many of these were individual and sometimes emblematic pipes rather than council pipes. It must, however, not be forgotten that with the Indians of the Great Lakes region especially, all significance was attached to the stem and its ornamentation rather than to the bowl. Fig. 437 shows the well-known Siouan types of pipes of that people from the time of their migration to what is now known as Wisconsin. It is therefore possible that some of the pipes of this place are several centuries old, while others are distinctly of modern make.

Fig. 453. (S. 1–3.) Collection of Leslie W. Hills, Fort Wayne, Indiana.

Fig. 454. (S. 1–1.) This is a straight-base monitor pipe from the collection of George A. West. It is made of greenish steatite and was found in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin. It is a beautiful specimen.

Fig. 455. (S. 1–1.) Collection of George Little, Xenia, Ohio.

51There has been some discussion as to the part played by catlinite in aboriginal trade or exchange. Catlinite does not appear to be as old as other stones. It has been my theory that the catlinite quarry was of recent discovery. By recent, I mean within two or three thousand years or less. Catlinite pipes are frequently found in the mounds and graves of Wisconsin, but not in those of the South in any considerable numbers.

Fig. 456. (S. 1–1.) Collection of H. E. Towns, Fond du Lac, Wisconsin.

Fig. 457. (S. 1–1.) This pipe was ploughed up five miles east of Delaware, Ohio. Collection of Frank L. Grove, Delaware, Ohio.

In fact their occurrence there is very rare, yet they are found in great numbers in modern graves, in village-sites where tribes have lived in the historic period. This in itself is significant.

Fig. 458. (S. 1–1.) Found about four miles north of Pierceton, Indiana. Collection of W. F. Matchett, Pierceton, Indiana.

Fig. 459. (S. 1–5.) University of Vermont collection.

Fig. 446 shows five tubular pipes from California, collection of Professor James A. Barr. These are all specialized forms, and somewhat different in the method of treatment, being highly polished and ornamented by rings carved in relief.

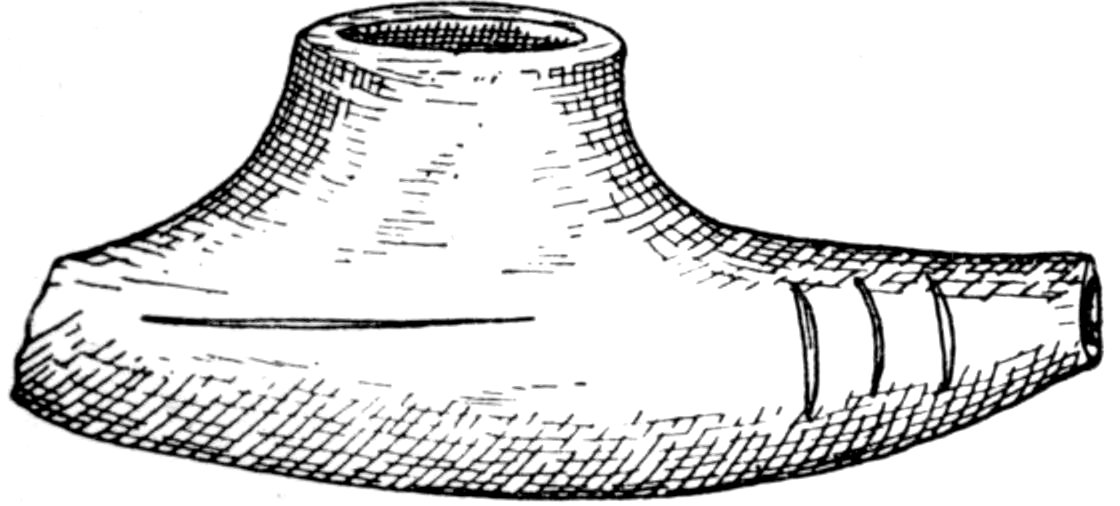

The disc pipe is placed in a class by itself by Mr. McGuire. We have six of these at Andover, all from graves at the mouth of the Wabash, southern Indiana. One of these is shown in Fig. 447. Mr. West remarks as follows regarding this type of pipe:—

“The disc pipe, in the writer’s opinion, is an old type, and was in use by the aborigines of this country long before the coming of the whites. Authorities, however, differ as to this conclusion. General Gates P. Thruston suggests that the stem holes of the disc pipe being funnel-shaped, it may safely be regarded as an old type.

“Mr. J. D. McGuire writes: ‘The shape is so suggestive of the jewsharp, an instrument used extensively in trade with the Indians, as to indicate that the pipe itself is modeled after the form of this 53primitive musical instrument, even though the file marks, so common on many of the pipes, are absent from those coming under the writer’s observation.’

Fig. 460. (S. 1–3.) Collection of L. W. Hills, Fort Wayne, Indiana.

“A careful study of the several forms of this type convinces the author that it was not modeled after the jewsharp. Of the twenty-eight examples in the author’s collection, when examined with a powerful glass, all exhibited innumerable marks and scratches, that could have been made by the use of a piece of sandstone or flake of flint. In no case were file marks found.

“Mr. McGuire states: ‘Finding them of catlinite so far from the quarries would indicate that they are of no great age.’ If Mr. McGuire’s conclusion is correct, aboriginal barter and trade could not have been carried on between distant tribes until within a comparatively 54recent date, an abundance of evidence to the contrary notwithstanding.”[13]

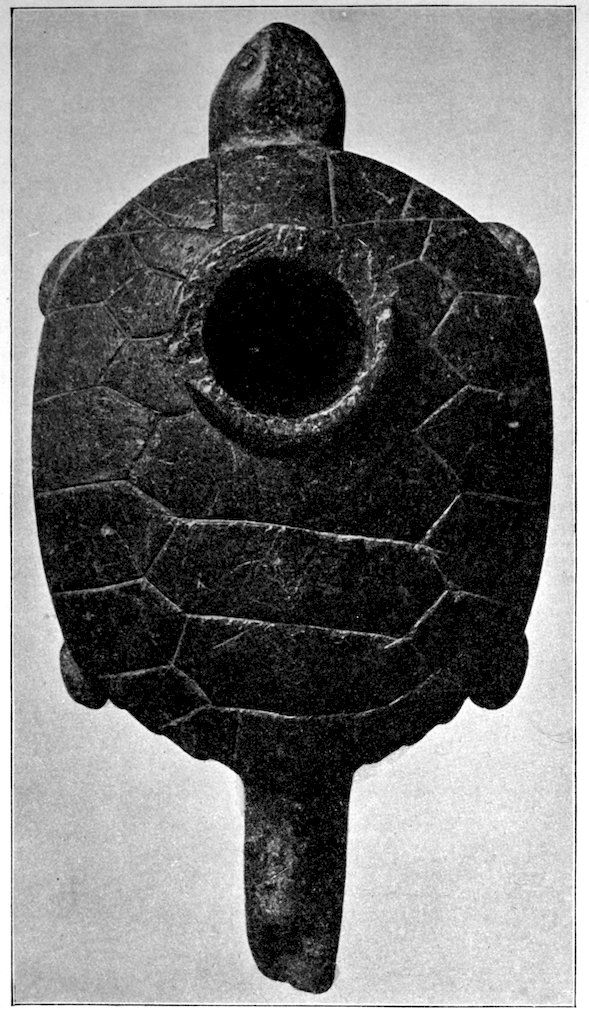

Fig. 461. (S. 1–1.) Turtle pipe found at Pierceton, Indiana. Front view. Collection of W. D. Matchett, Peirceton, Indiana.

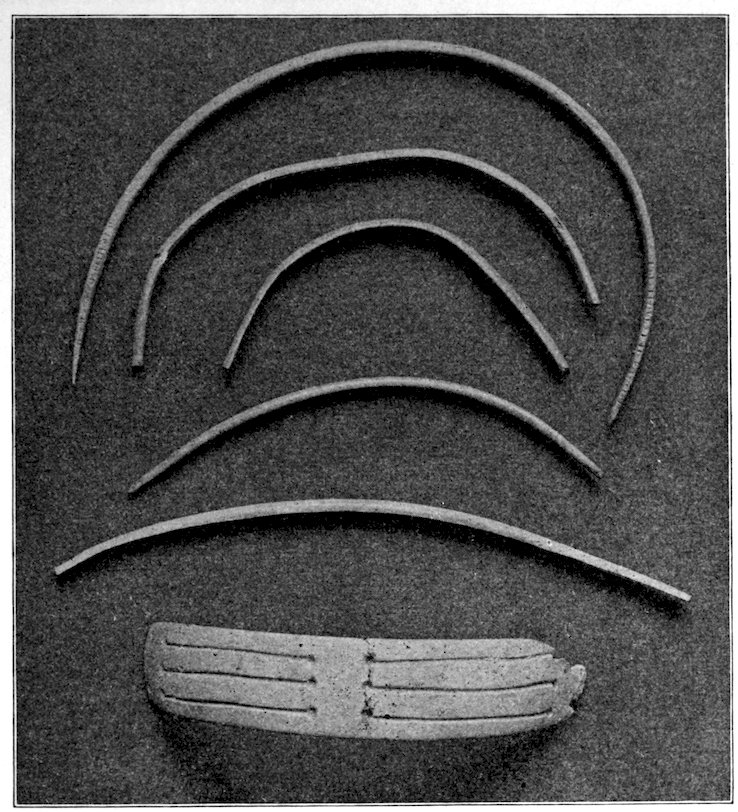

“Fig. 447, found at Baldwin’s Mills, Waupaca County, the largest handled disc pipe so far found in Wisconsin, is of beautiful dark red catlinite with pink flecks. Its bowl is five inches long, terminating in a handle shaped like the blade of a hatchet, with what would be the cutting edge ornamented with three notches. The disc is 3½ inches wide and so thin that the distance through from the face of the disk to the outer side of the bowl is but three fourths of an inch. The stem hole has the characteristic curve and its interior is nicely polished. Both stem and bowl holes appear to have been started with a stone drill and enlarged with a wooden drill used in conjunction with sand. Under a glass this specimen 55shows innumerable scratches, but none of these appear to have been made by the use of metal tools. The same can be said of eleven handled disc pipes in the author’s collection.” Mr. West has a record of one hundred and four disc pipes found in Wisconsin.

Fig. 462. (S. 1–1.) Rear view of Fig. 461.

The fact that these disc pipes are frequently made of catlinite leads me to believe that they are not as old as other forms; yet there seems to be no evidence of their use after the advent of white man.

The pipe with the curved base and monitor pipes are closely related. These are found throughout the entire Mississippi Valley, and are especially numerous in Illinois, to West Virginia and from southern Wisconsin to southern Tennessee. Many beautiful specimens have been taken from mounds and graves, particularly from the mounds. In Figs. 449–53, I show five of these. Perhaps the most beautiful ones have been found in the mounds of the Scioto Valley, Ohio.

Fig. 463. (S. 1–3.) Group of pipes from various localities in the Mississippi Valley.

(a) Scioto County, Ohio.

(b) Ross County, Ohio.

(c) Pipe made from a whale’s tooth, Alaska.

(d) Scioto County, Ohio.

(e) Miami County, Ohio.

(f) Scioto County, Ohio.

(g) Scioto County, Ohio.

(h) Wabash Cemetery, Indiana.

(i) Hancock County, Ohio.

(j) Silver Creek, Morgantown, North Carolina.

(k) Grovetown, Georgia.

57Just how this peculiar form originated, no man may know. It was the favorite among the prehistoric peoples. A few examples found in use among historic tribes are very poor imitations of the old forms, and cannot compare in workmanship and beauty of finish with such as are removed from the mounds of the Middle West and the South.

Fig. 464. Three pipe-bowls. Collection of Henry Montgomery, Toronto, Ontario.

Left. Pipe-bowl made of sandstone. From near Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Length, 2¾ inches.

Centre. Pipe-bowl made of limestone. From Markham, Ontario. Length, 3 inches.

Right. Pipe-bowl made of white quartzite. Found by Henry Montgomery in Simcoe County, Ontario. About one third actual size.

Beginning with Fig. 449 and continuing to Fig. 453, and from Fig. 471 through Fig. 500, I present a series of pipes, all of which are decorated either by incised lines or by likenesses of animals, birds, or human beings, carved in relief. These may be taken as typical of any large series of pipes in a public museum, and represent the height of pipe-making art.

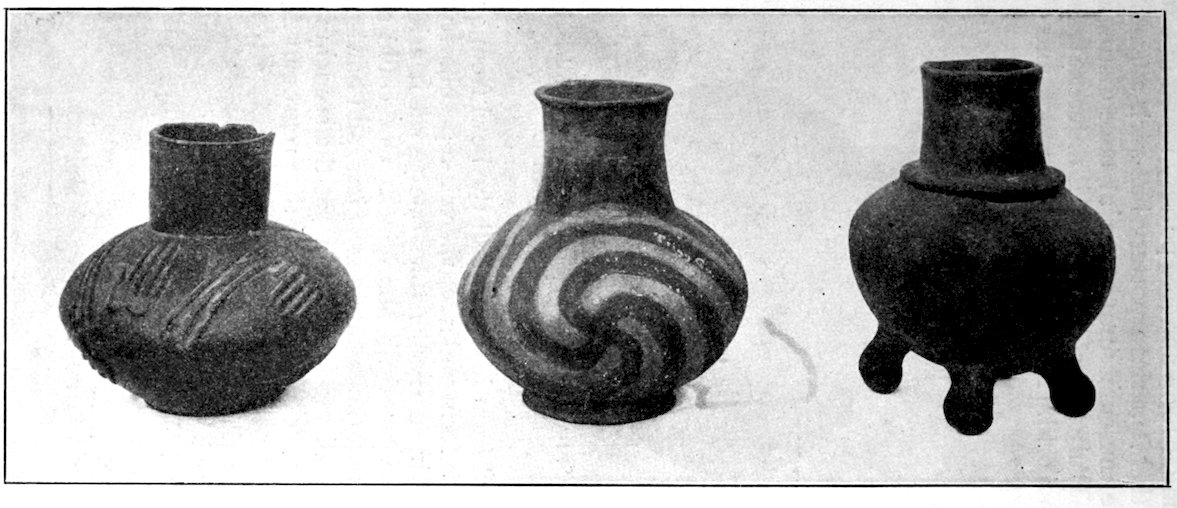

As previously remarked, the decoration seems to be the essential thing in pipes. The idea of the maker was to portray something on the pipe or to have the pipe stand for more than a mere receptacle in which tobacco was smoked. No other conclusion is possible when we consider the high percentage of decorated and ornamented pipes, and the surprising number of pipes worked into effigies. Fig. 469 is a very clumsy pipe at best, and the decorations on it may not indicate age. Examples such as this are not wanting, and there are a great many in collections. Contrasted with this rough specimen is Fig. 455, which is also decorated but is worked less crudely.

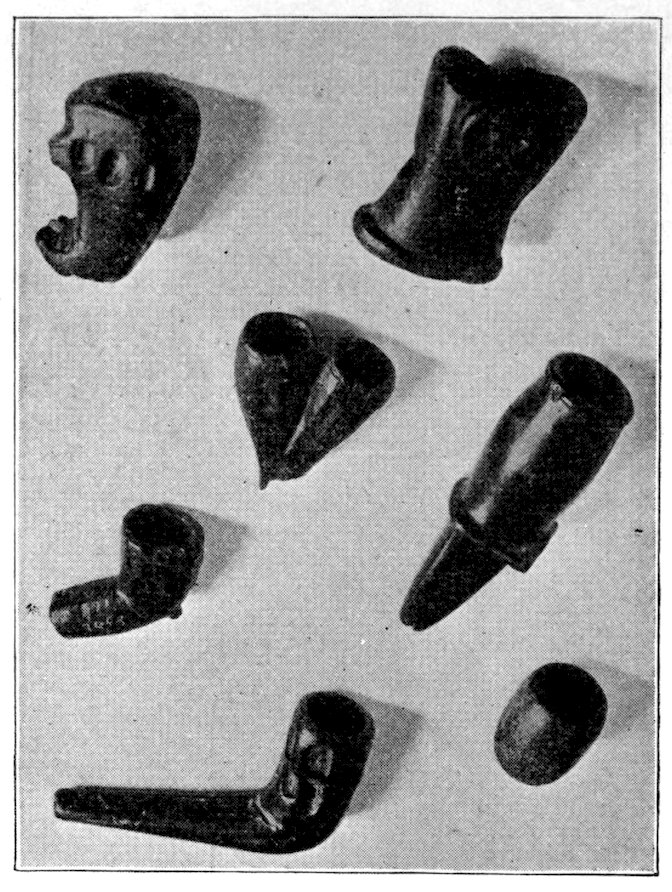

Fig. 465. (S. 1–1.) Collection of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences, Buffalo, New York. Typical Iroquois pipes. These are fine examples of Iroquois art and were found in western New York, where the Iroquois culture was high. From graves at Grand Island, New York.

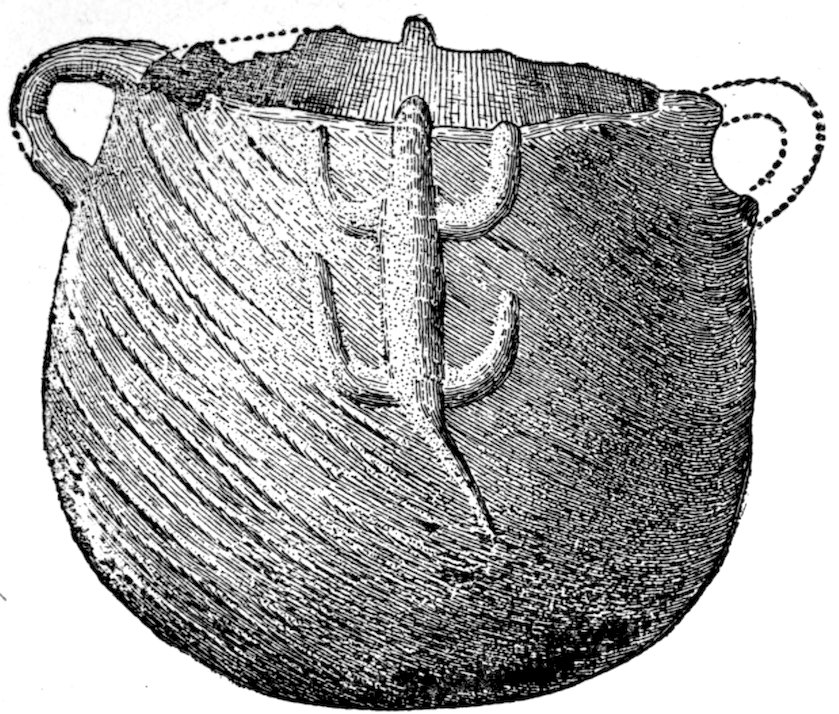

Fig. 466. (S. 1–3.)

From a stone grave, Wofford Farm, Hurricane Mills, Humphrey County, Tennessee. Material: red and brown clay.

Collection of J. T. Reeder, Houghton, Michigan.

Fig. 467. (S. 1–1.)

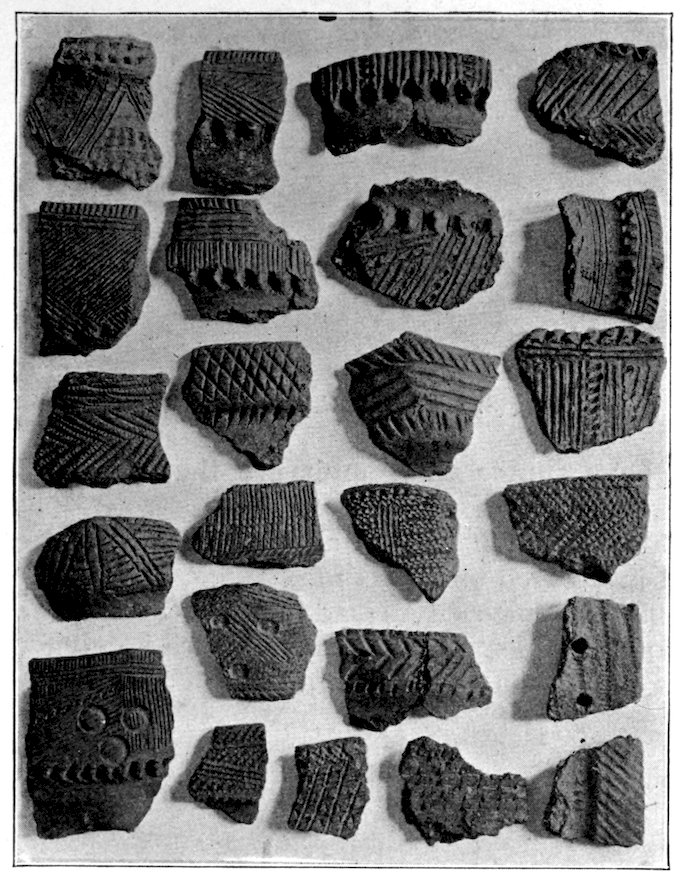

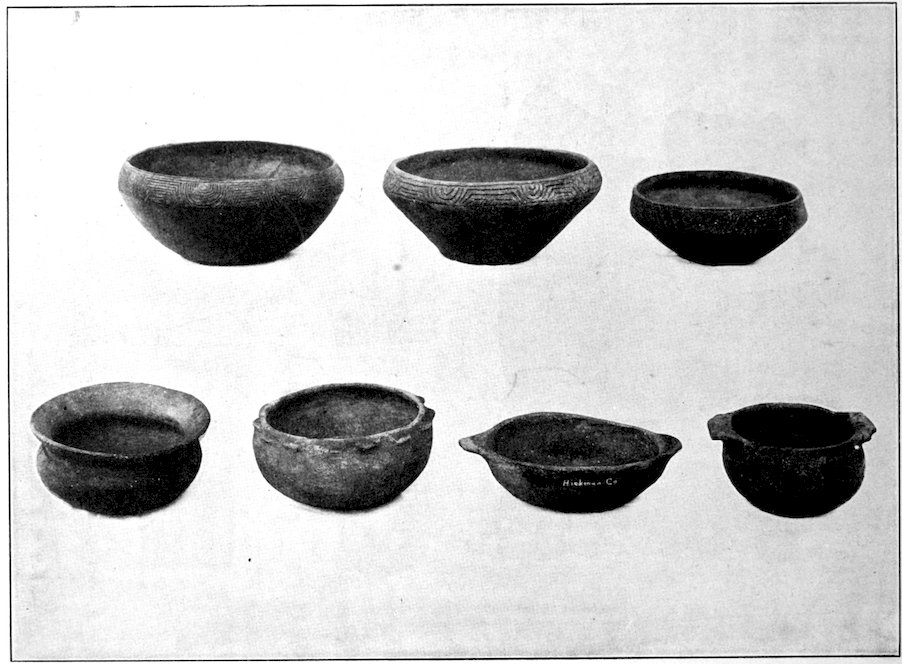

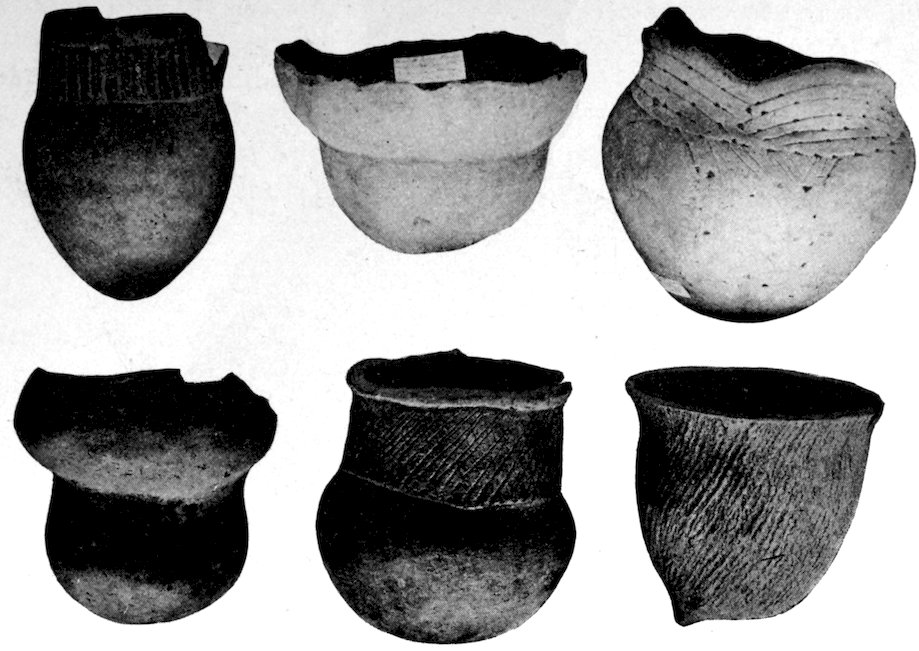

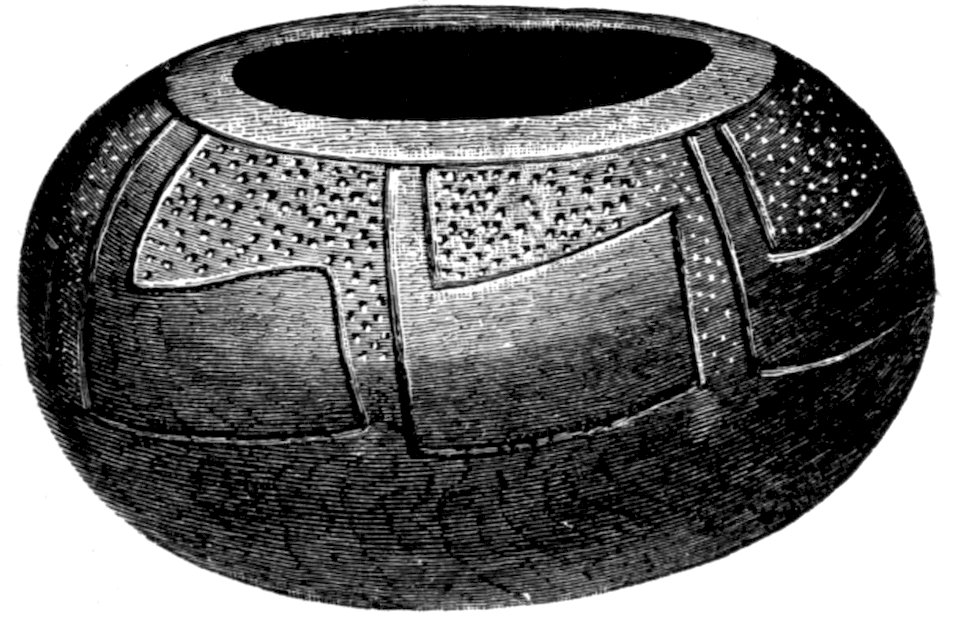

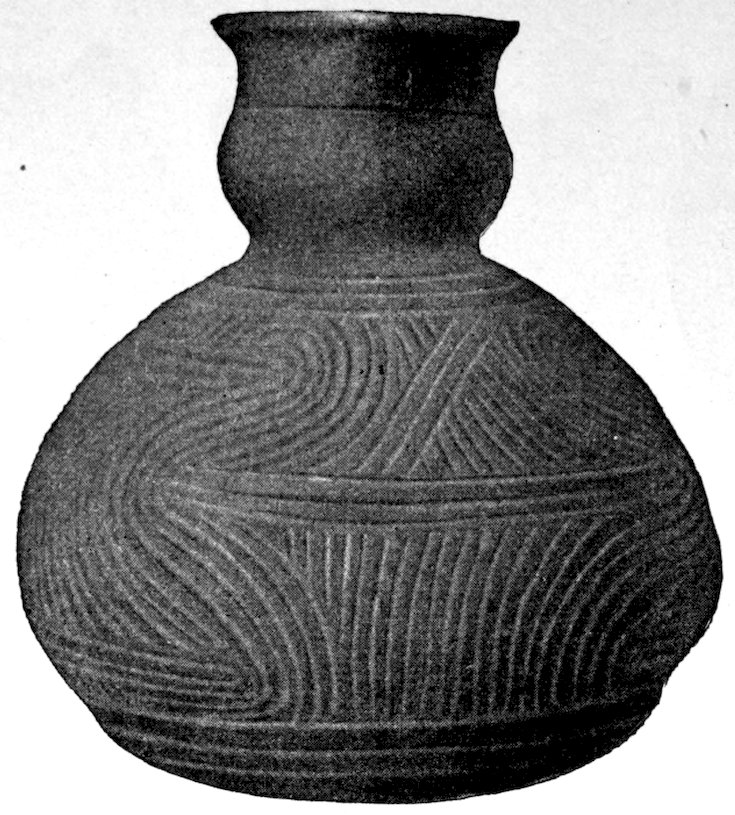

Greenstone pipe found in Tennessee. Apparently an Iroquois type of pipe. This is a rare form.

From the collection of W. B. Rhodes, Danville, Pennsylvania.

Fig. 468. (S. 2–3.) New York State Museum collection, Albany, New York. Human effigy and human bird-pipes from Iroquois sites in northwestern New York. Both of these sculptures are unusually fine examples of art in pipe-working, for the greater part of Iroquois pipes are plainer.

Fig. 469. Pottery pipe with human face; the stem part broken off. Simcoe County, Ontario, Canada. Toronto University Museum.

The human sculpture of the priest on the altar at Palenque, so frequently illustrated, illustrates an individual either blowing or drawing smoke through a tube. The tube is ornamented with bands, and appears to be larger at one end. It is a straight and not a curved pipe. I have always thought that this interesting figure from ancient Palenque typified what the pipe meant to the more cultured American tribes. There is a vast difference between the use of the pipe as portrayed in that sculpture, and the degeneration of the smoking ceremony as it appears to-day among modern tribes. We have in this figure the ancient shaman in full regalia; the elaboration with which the slab is wrought, and the fact that it was part of the sacred altar at Palenque, are significant.

Fig. 470. New York State Museum collection, Albany, New York. The New York State Museum contains many fine specimens of early Iroquois make. The upper figure to the right, with long stem, is gracefully curved.

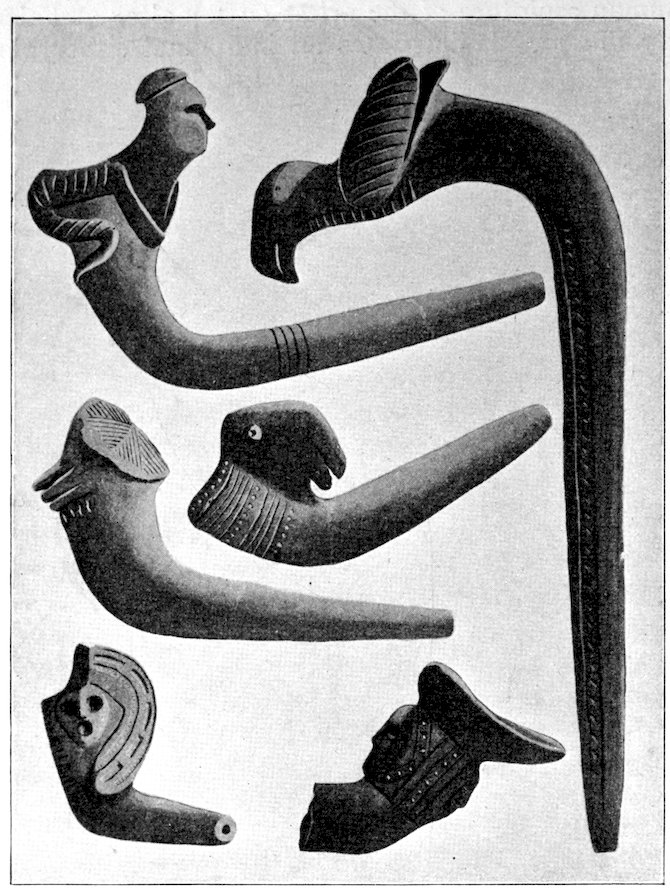

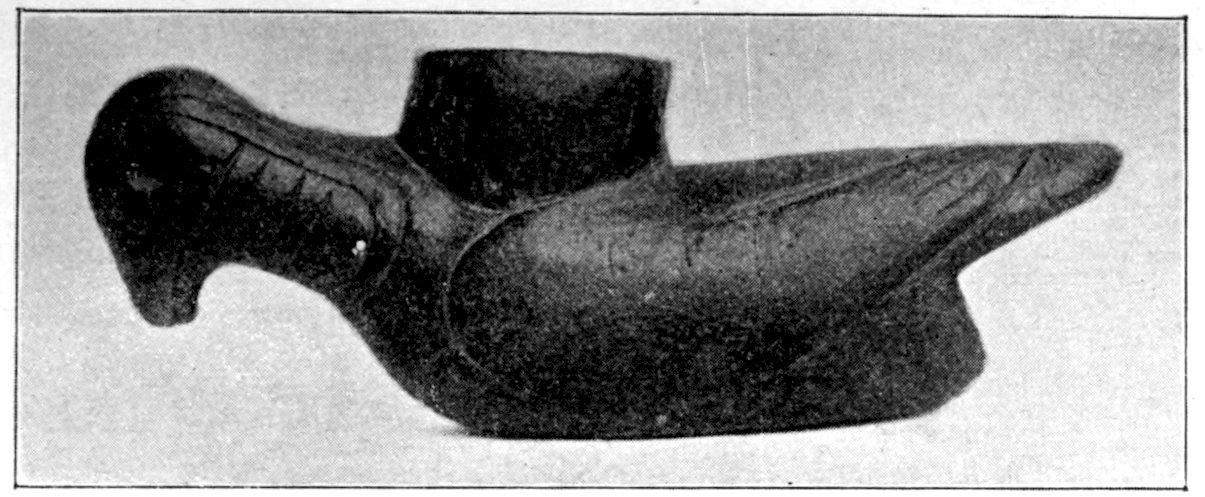

Fig. 471. (S. 1–1.) Collection of Leslie W. Hills, Fort Wayne, Indiana. This is the form of bird effigy most frequently found. That is, it is not common, but more of this type are found in the Mound-Builder country than other bird-forms.

We have no such sculptures in the Mississippi Valley, but we have altar mounds in which effigy and monitor pipes were buried. I have never found a crude pipe in an altar mound and I do not think that either Squier and Davis or Professor Mills ever found an example of crude art in an altar mound. This refers to original interments, on the base-line—not to intrusive burials. Everything indicates that the pipes in use in pre-Columbian times were of two kinds, the small, individual pipes, and the large council pipes, or those made use of at important functions either religious or tribal, being characteristic. I have never observed the mark of any steel or iron tool on a mound pipe in the Ohio Valley.

Fig. 472. (S. 1–2.) This form of pipe is rare in Wisconsin. But a few mouth-pipes with curved bases have been found in the St. Lawrence region. It may have been obtained by trade in the South. Collection of J. G. Pickett.

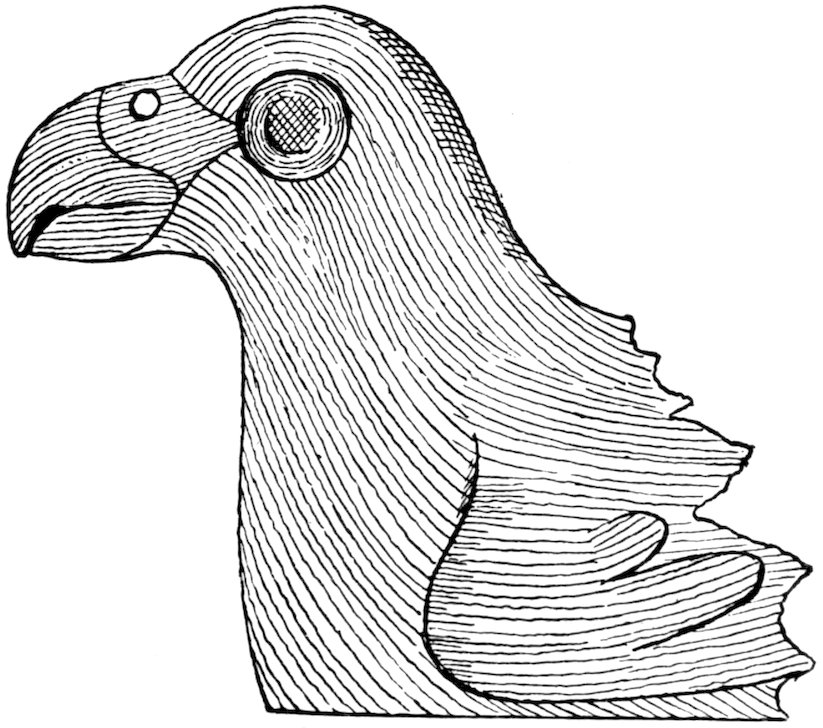

Fig. 473. (S. 1–2.) Collection of A. J. Powers, Mt. Vernon, Iowa. Eagle pipe, Georgia. This remarkable pipe has been described several times in various publications. It is a beautiful specimen.

65Whether smoking was discovered through accident, or developed from the use of the straight tube in the hands of the priests, is something we may never be able to determine with accuracy.

While the effigy pipes required particular skill in their manufacture, yet some of the tubular, rectangular, and disc pipes, although unornamented, are wrought skillfully and brought to a high finish, and the surfaces polished until almost as smooth as glass.

Fig. 474. Collection of Leslie W. Hills, Fort Wayne, Indiana. A group of beautiful mound pipes from Indiana, Kentucky, and Tennessee. None of these can be considered modern.

I have often thought that a careful catalogue of all pipes in our large museums, with a detailed statement as to where each was found, would be of great value, and enable us to prepare accurate tables as to these and their significance and age. In this connection it is to be regretted that greater care has not been at all times exercised in securing complete data relative to aboriginal pipes and other artifacts deposited in museums and private collections, for without this a specimen however interesting is of little value in solving archæological problems.

Fig. 474 A. (S. 2–3.) Front and rear view of pipe from Trigg County, Kentucky. Hard, compact, dark reddish stone. B. H. Young’s collection.

67The bird seems to have been the favorite sculpture, yet there are frequent portrayals of the frog. I present three of them, all of sandstone, in Figs. 485 and 486, and a beautiful one, full size, in a photogravure plate, Fig. 500, from the collection of Mr. F. P. Graves, Doe Run, Missouri.

Fig. 475. (S. about 1–1.) Slate pipe, bird effigy. Collection of Mrs. Nellie Gowthrop, Camden, Michigan.

Among the Ojibwa Indians, during the summer of 1909, I observed a number of stone pipes in use. An excellent opportunity was afforded to study such among these Indians, as I was on White Earth Reservation, Minnesota, for seventeen weeks, and came in contact with all the full blood Indians and many of the mixed bloods. Being frequently in council with these Indians, I observed their pipes with some care. Except rectangular pipes of Siouan types, which were inlaid with lead or silver, most of the pipes were exceedingly crude and far inferior in every way to the ancient forms. Few Indians owned inlaid pipes. The major part of all the pipes I observed were common egg-shaped bowls without stem which were fitted with the common cane or wooden stem, such as are sold in stores at a penny each. Others were rectangular and unornamented. Two in use by old medicine-men, one smoked by a Cree woman, and several others were purchased by me and placed in the Andover collection.

As these Ojibwa are all in possession of steel tools, one would suppose that their pipes would be well made. But on the contrary, the art of making pipes has degenerated among them.

While there are tubular pipes in California, they do not occur in great numbers, and, as has been remarked, other types of pipes are either very scarce or entirely absent.

It seems to me that among our American aborigines the finest art existed previous to contact with European civilization. The finest sculptures on exhibition in our museums come from sites which appear to be prehistoric. To him who is skeptical and does not believe these statements, I suggest that he inspect modern Iroquoian, Siouan, Ojibwa, and Cherokee pipes, and compare them with the ancient forms such as have been taken from mounds and graves in southern Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee.

Fig. 476. (S. about 1–3.) Collection of J. T. Reeder, Houghton, Michigan. Locality, Tennessee. Materials: soapstone, slate, and quartz.

Fig. 476 A. (S. about 1–3.) Collection of J. T. Reeder, Houghton, Michigan. Locality, North Carolina. Material, soapstone.

Fig. 476 B. (S. 3–4.) Steatite, Barbour County, Kentucky. From a mound on Stoner’s Creek. B. H. Young’s collection, Louisville, Kentucky.

Fig. 476 C. (S. 1–2.) This beautiful little pipe is of a type occasionally found in Pennsylvania and the Carolinas. It may not be prehistoric. At any rate, it is an interesting specimen. Collection of Dudley A. Martin, Duboistown, Pennsylvania.

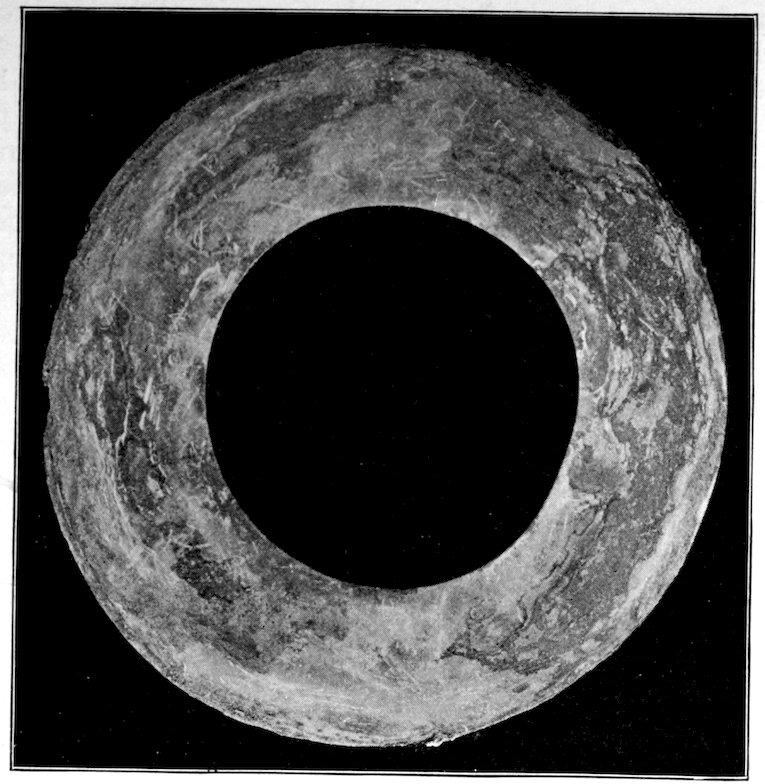

Most of these tubular pipes are much larger at one end than the other, corresponding to the bowl, which is more highly developed in later forms. There is one in the Andover collection that was obtained from the Hupa Indians of California about fifty years ago by an early settler. The stem is round, made of redwood, and a stone ring surrounds the bowl. The tobacco would of necessity have to be packed tightly when one smoked such a pipe, unless, as has been reported, the smoker lay upon his back.

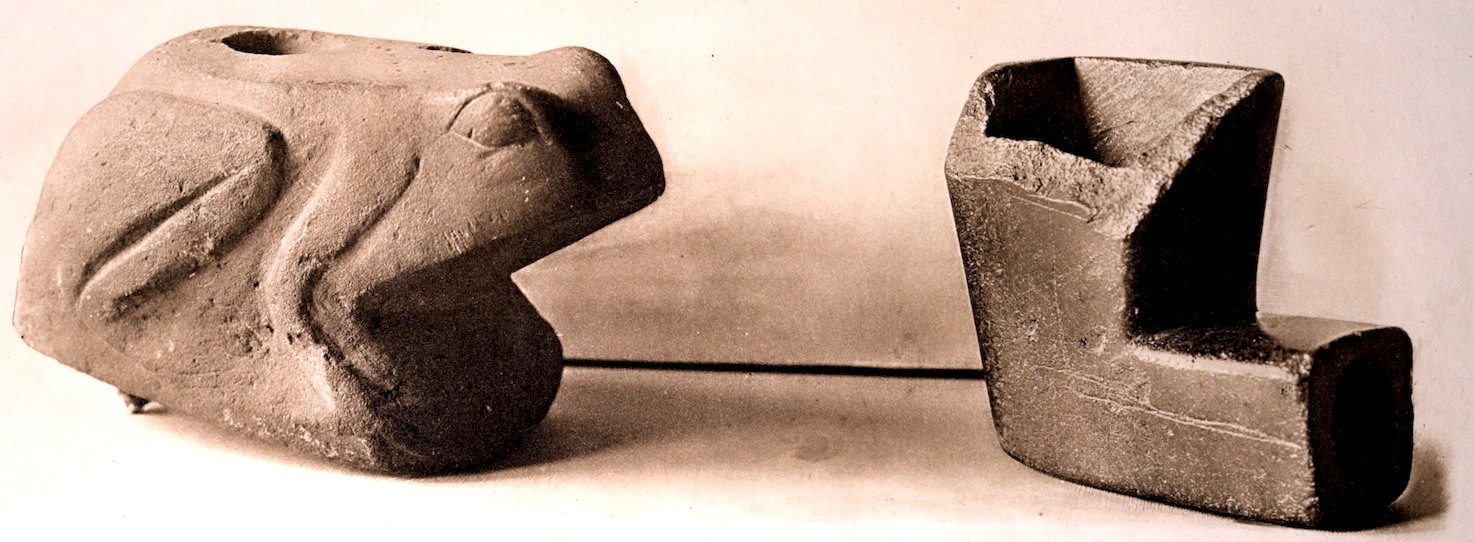

Fig. 457 is a roughly outlined and unfinished effigy pipe, which when complete was intended to represent the head of some animal. In this we have evidence of the method of work 70on the part of the maker. Instead of the hand-hammer it would appear that a cutting-tool had been used. He had begun to rim out the bowl on the top of the head, but the stem hole is not yet in evidence.

Fig. 477. (S. 1–1.) Eagle pipe. Clarence B. Moore. A superb pipe of limestone representing an eagle. “This pipe, 4.6 inches in length, carved with great spirit, is a worthy exemplar of the prehistoric art of Moundville. The bird is represented on its back, the head swung around to one side with the beak open and tongue extended. Incidentally, it may be said that the ‘hump’ shown on the tongue by the native artist, though somewhat exaggerated, is not imaginary, as may be proved upon examination of an eagle. It may be that this pipe, showing as it does the eagle lying on its back, its legs and claws on the belly, represents the dead bird. By pulling out the tongue of a dead eagle one would be certain to notice the ‘hump’; hence the examination of a dead bird would have sufficed so far as correct rendering on the pipe was concerned. On the other hand, the ‘hump’ on the tongue is plainly shown on pottery from Moundville, where the eagle’s head is erect and the bird is evidently represented as alive.”

It is in the effigy pipes themselves as a class that we see the greatest skill and care manifested in the manufacture of these strange objects. This does not, however, mean that all effigy pipes are models of the carver’s art, as many of them show poor workmanship. In other words, the art in pipes is no exception to the rule of art elsewhere. There were those who understood their business and produced masterpieces, and there were those who produced just the opposite. There may be a totally different method of treatment in representing the same creature, as for instance Figs. 468 and 470 showing the Iroquois treatment of human and bird forms in life; 71and the Southern Mound-Builder, Figs. 473, 474 A, 499, illustrating birds and men. The Iroquois and the Plains tribes made pipes more nearly like our modern pipes of to-day. The bowl was round or angular, and the stem long and tapering, or angular. Excellent examples from the Buffalo collection are shown in Fig. 465.

Fig. 477 A. (S. 1–1.) Eagle pipe. Clarence B. Moore. “Several experts who have charge of eagles in captivity inform us that under certain circumstances the ‘hump’ on the tongue is visible on the living bird. Possibly the aboriginal artist at Moundville was familiar with the characteristics on eagles through the possession there of captive birds—a custom observed among the Zuñi of New Mexico at the present time.

“Owing to slight disintegration of the stone at that part of the pipe where the head is, the details of the carving are somewhat indistinct, but by holding the pipe in a suitable light all the details of the head are still distinguishable. A wing is represented on each side. The legs, beginning at the tail, which extends outward, rise upward and forward, the feet and talons resting on the belly and embracing the orifice of the bowl. The opening for the stem is immediately above the tail.”[14]

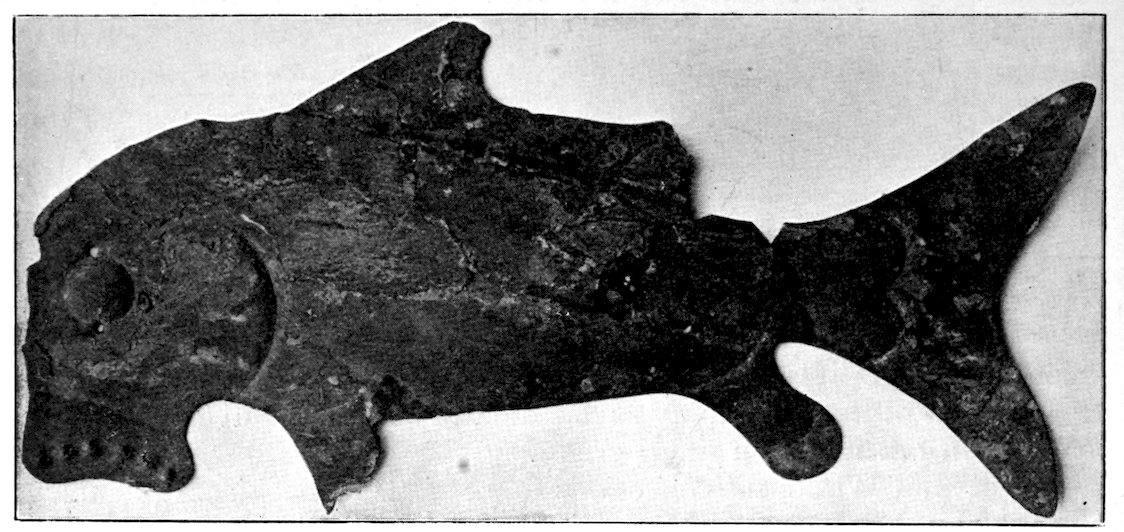

Fig. 478. (S. 1–1.) Handled pipe. This figure “represents one of the oldest handled pipes that has come under the writer’s observation. This interesting specimen was taken from a burial-mound, on the Nicholai farm, Big Bend, Waukesha County, Wisconsin, in July, 1902, by Mr. La Fayette Ellerson. With it was found a curved-base mound pipe.” From the collection of G. A. West, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

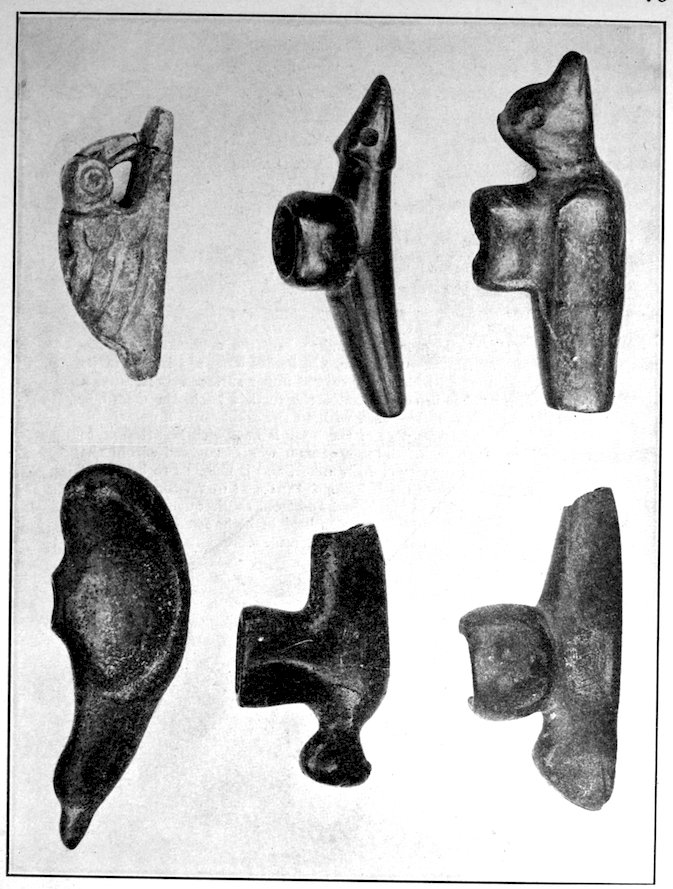

Fig. 478 A. (S. 1–2.) Handled pipe. “Found by Mr. O. S. Ludington, near Prairie du Chien, of red sandstone, formed, mainly by the pecking process, into the shape of a fish, and is 5½ inches long, 2½ inches wide, and 1 inch thick. Its bowl cavity is three fourths of an inch across, the stem hole nearly as large, and both are cone-shaped, having been made with a stone drill. This specimen is not worked down smooth, nor does it exhibit file marks.” From the collection of G. A. West, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

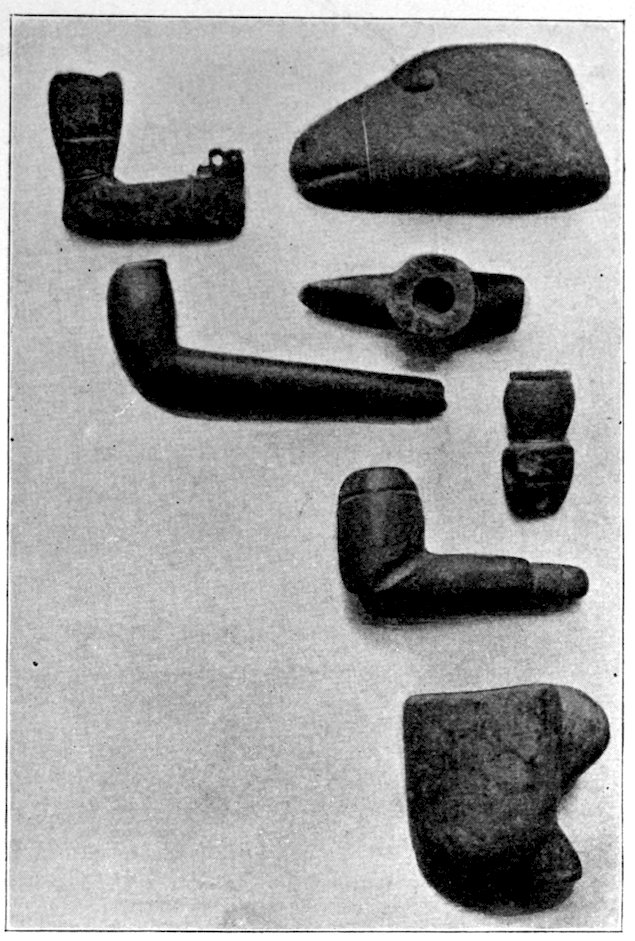

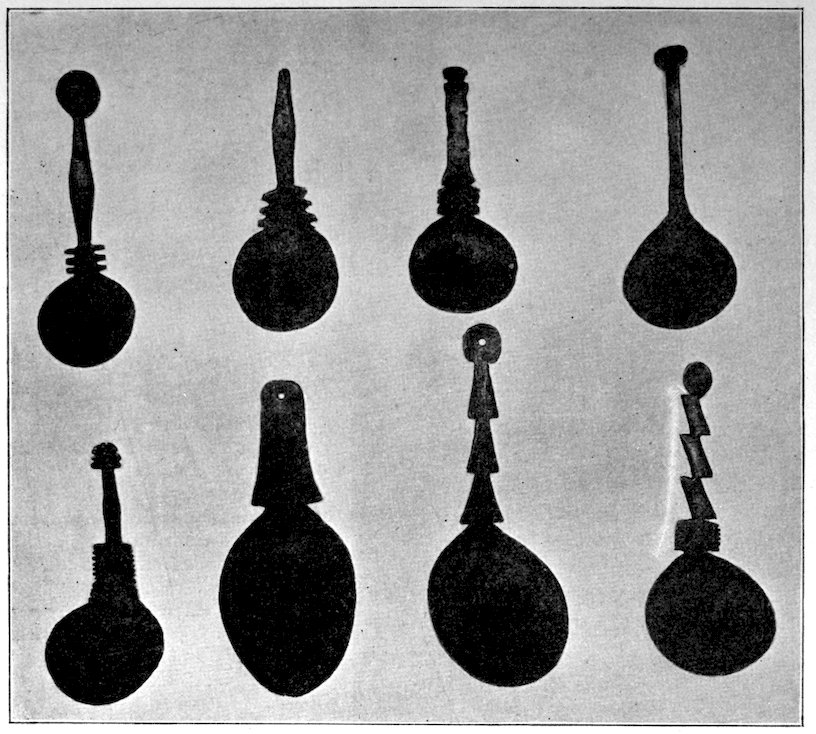

Fig. 479. (S. 1–3.) Six interesting effigy pipes from the collection of Bennett H. Young, Louisville, Kentucky.

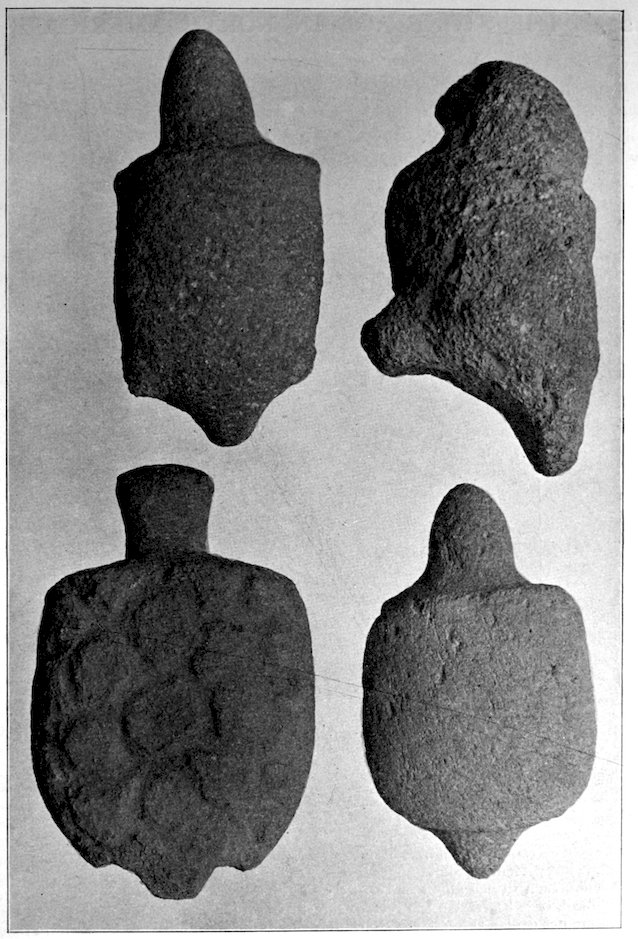

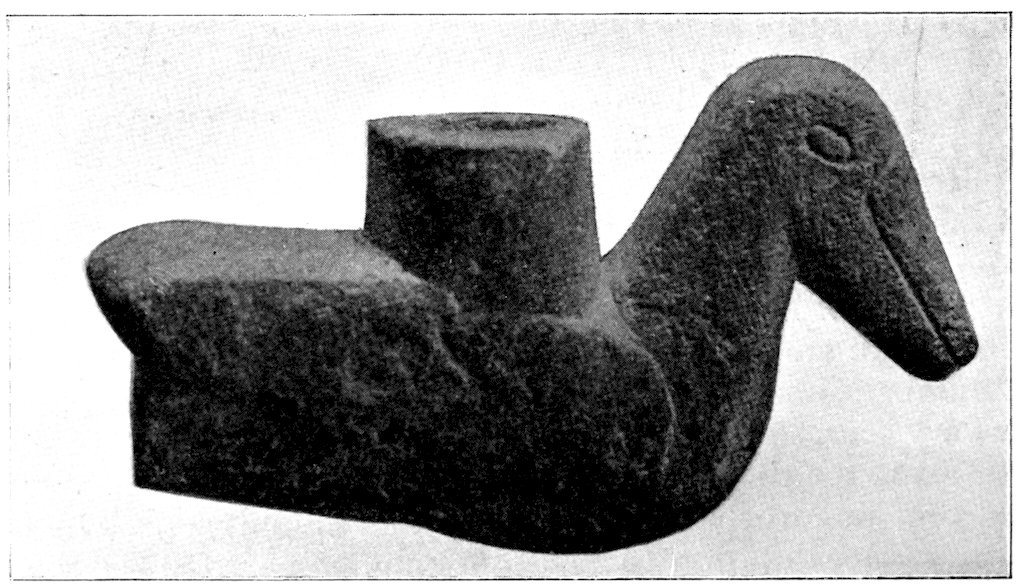

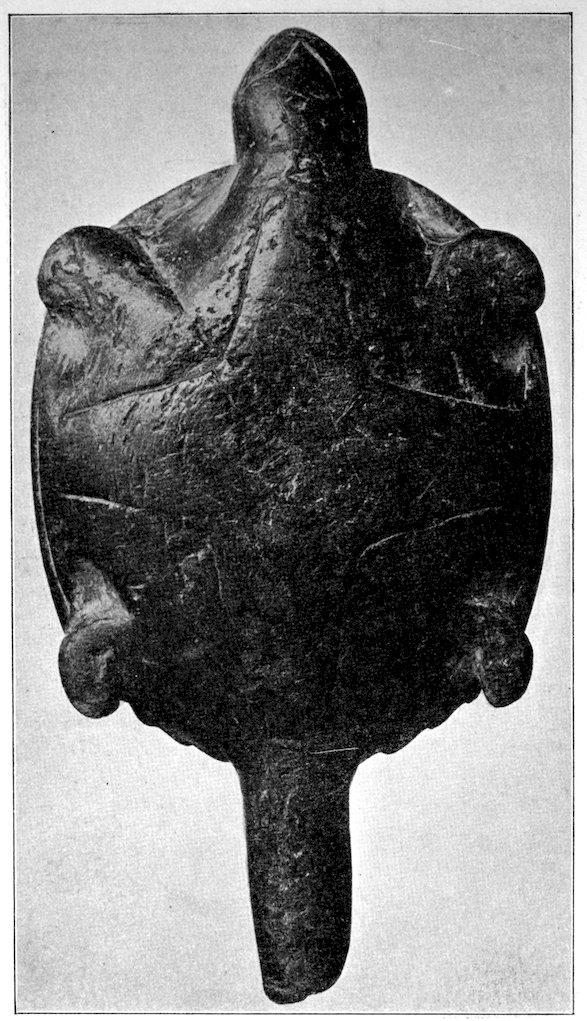

Fig. 479 A. Turtle pipe. Milwaukee Museum collection. This figure “is of grayish-brown steatite, 3¼ inches long, 2¼ inches in its greatest width, and with a finely carved upper surface representing a turtle. The bowl is in the centre of the turtle’s back, the stem hole is small, and was doubtless used without the addition of a detachable mouthpiece. The lower part of the body is flat, with no attempt to form either legs or tail.” This specimen was discovered within the southern limits of the city of Milwaukee, and is believed to be one of two ceremonial pipes of turtle-form, so far found in Wisconsin. “The turtle was an emblem of the Sioux, and from the frequent occurrence of its shell in graves must have been held in high esteem by the Indians; yet representations of it in stone are exceedingly rare.”

Fig. 480. (S. 1–1.) Effigy pipe, Hopewell Group.

Fig. 481. (S. 1–1.) Turtle pipe found near Burnett, Dodge County, Wisconsin. Milwaukee Public Museum collection.

Fig. 481 A. (S. 1–1.) Another view of Fig. 481.

77The Iroquois pipes and pipes characteristic of the Plains, pipes classified by Mr. McGuire and Mr. West as Micmacs, and other modern pipes, are scattered quite generally throughout north, central, and eastern United States. It is good that Mr. McGuire has given us so careful a distribution of pipes as is set forth in his fifteen divisions. The student of archæology must distinguish between the pipes from the old burial-places and those that are apparently modern. The prehistoric cultures and the modern cultures of our American aborigines here in the United States may be compared with those of Europe; where on one site we might find Roman weapons or implements, those of early Germanic tribes associated with the Roman, and beneath all of these, those of the stone-age type. But if the soil had been disturbed, through digging on the part of people subsequent to these epochs, stone-age objects, together with those of Roman and Germanic occupations, might be found associated together. It follows, therefore, that here in America, when we find modern catlinite pipes and rectangular stone pipes on a village-site or beneath the surface, these may represent different epochs or cultures. These cultures may or may not be separated by hundreds of years.

There are many complications to be taken into consideration, in our study of the distribution of pipes. As has been pointed out, rude pipes are quite as likely to have been made by modern Indians as by prehistoric people.

It does not follow, because the type of pipes recognized as Iroquoian in character is widespread north of the Ohio Valley and Canada, that all pipes in that region were made by the tribes of this stock.

The Iroquois overran the entire territory north of the Ohio and east of the Scioto. We know that they overwhelmed the Eries, Hurons, and others, whose art was quite different.

Fig. 482. (S. 1–2.) Oolitic limestone pipe, Hart County, Kentucky. Highly polished, a beautiful specimen. Collection of Bennett H. Young. These long effigy pipes of this type are to be found in the Smithsonian and American Museum collections. An example in the G. A. West collection, found in Ohio, is 14 inches long.

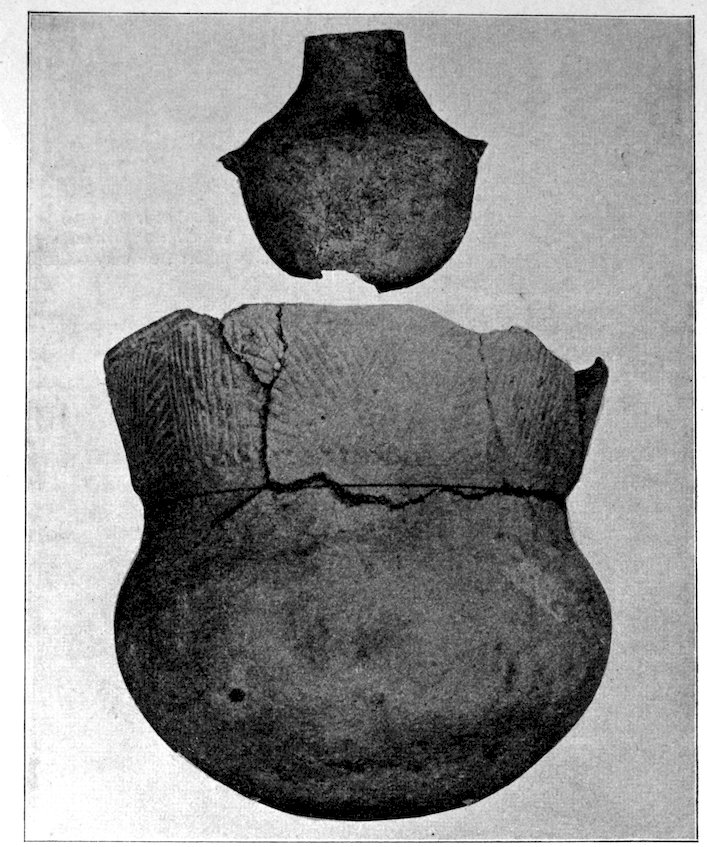

Fig. 483. (S. 1–1.)

From ossuary in the Township of Manvers, County of Durham, Ontario, Canada.

Collection of J. G. Ogle D’Olier, Rochester, New York.

Fig. 484. (S. 1–1.)

From ossuary in the Township of Manvers, County of Durham, Ontario, Canada.

Collection of J. G. Ogle D’Olier, Rochester, New York.

Fig. 485. (S. 2–3.) Beautiful effigy pipe of a frog found in a grave at Waynesville, Ohio, overlooking the Miami River. Secured by W. K. Moorehead, 1889. Now in the Ohio State University Museum, Columbus.

Fig. 486. (S. 1–2.) Frog pipe. From village-site at the mouth of Bush Creek, Adams County, Ohio.

As I have remarked, these Iroquoian pipes are easily distinguished from other forms; they are not found in the ancient burial-places of the Mississippi Valley. The beautiful mound and grave pipes from the Ohio Valley, the middle South, and the far South, shown in Figs. 474, 477 A, 485 to 491, 494, 496, and 499, are not only of ancient lineage, but show no mark of steel tools, and do not appear to have been inspired by European civilization. On the other hand, many of the pipes referred to do appear to have been suggested by a knowledge of European art. Some of the best effigy pipes, the monitor or platform pipes, were not made of stone, but of a fine grade of fire-clay. There are also effigies in pipes of terra-cotta. In answering a letter requesting information, Professor W. C. Mills, under date of April 27, 1910, said concerning the pipes in his collection: “Of the platform pipes, ten are fire-clay, of the effigy pipes, fifteen are fire-clay, and of the tubular pipes, twenty are fire-clay. The fire-clay pipes were never burned, but were 80cut from original pieces of clay. Twenty of the miscellaneous pipes are made of potter’s clay.”

Fig. 487. (S. 2–3.) An interesting human effigy found in northern Ohio, now in the collection of the Ohio State University, Columbus.

The bird is much in evidence as a prehistoric sculpture. In fact, there are more bird-pipes than any other life-form. This at once suggests the famous “Thunder Bird,” so famous in Indian mythology in America. Yet if it is true that these effigies are not totemic, as relating to tribes, but stand for “Thunder Birds,” it is curious that so many different kinds of birds should have been represented. There are the hawk, eagle, crow, woodcock, duck, woodpecker, paroquet, and others. Examine Fig. 474 A. It is one of the best sculptures presented in this chapter. Compare this beautiful carving with the following bird-pipes, Figs. 470, 471, 473, 476, 477, 480, where possible readers are advised to visit some public museum or consult a library and study the illustrations of bird-pipes. The range is considerable. Even in so brief space as is afforded in this chapter, it will be observed that it was the intention of the ancient people to represent not one kind of bird but many. The statement frequently made, that it is impossible in some instances to determine just what species of bird was intended, is true. But we have no difficulty in distinguishing between the duck, the eagle, the owl, or the crow, although the different kinds of ducks, or of hawks, might not be differentiated accurately.

Fig. 488. (S. 1–1.) Effigy pipe of limestone. A remarkable effigy pipe found by Mr. Moore in one of the mounds at Moundville, Alabama. This group of mounds has furnished some remarkable specimens in stone and clay.

Mr. West says of the so-called handled pipes:—

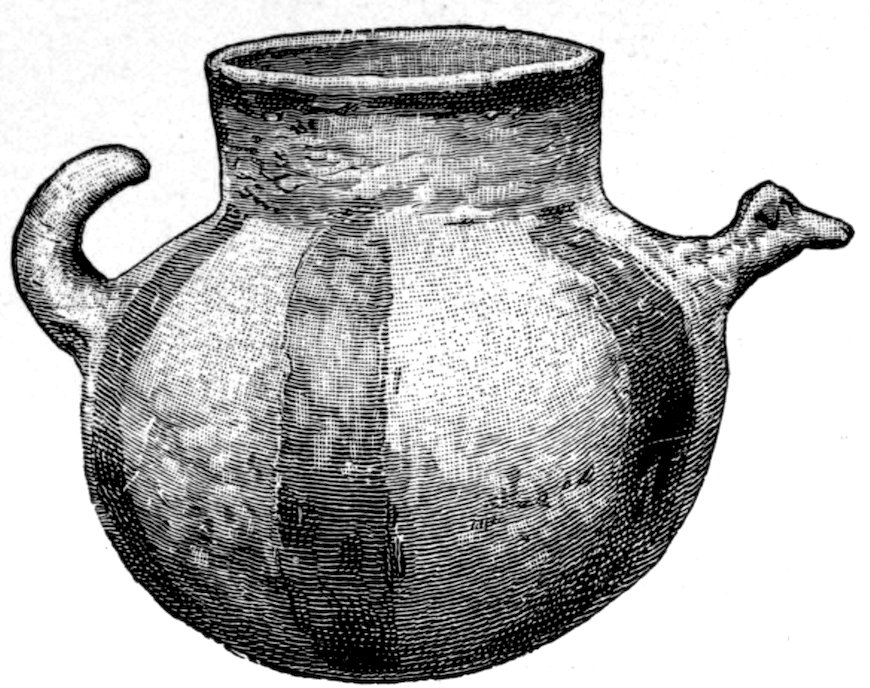

“In this class the author has placed a small number of very interesting pipes which are provided with an elongated base or handle, by which they were held or supported; and in most examples with a short mouthpiece also. Some are without the latter feature, and were probably furnished with a short stem of wood or bone. They differ considerably as to general shape and manner of ornamentation. A few have the bowls artistically carved to represent the head of a human being, a fish, or an animal.

“A small number of similar pipes have been described from other sections of the United States. Twenty-two examples have been 82found in Wisconsin, no two of which are of exactly the same pattern. No theory of their authorship among the Wisconsin or other Indians has as yet been advanced. Even though originally limited to one tribe, so convenient a form of pipe is sure to have been copied by individuals belonging to others.

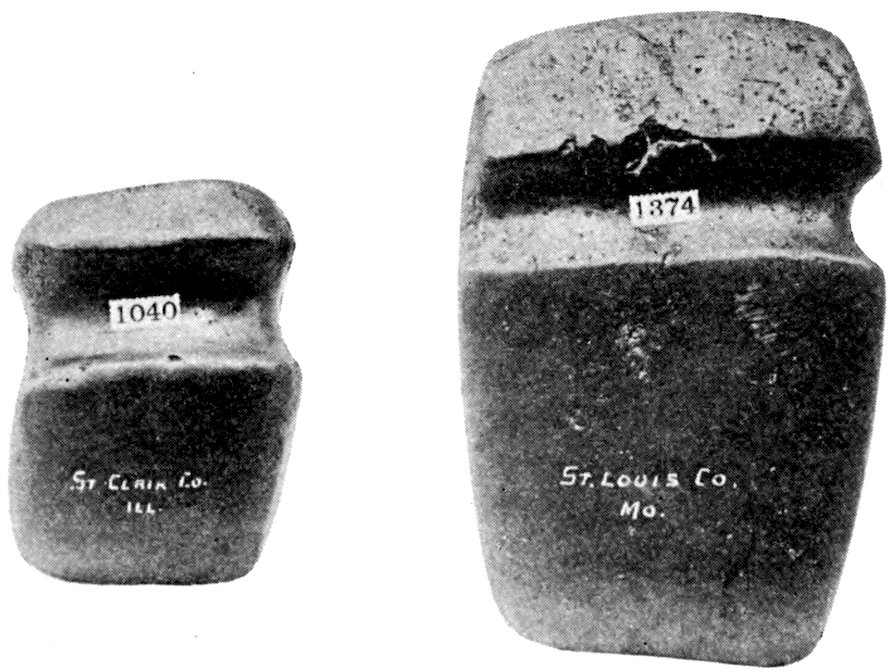

Fig. 489. (S. 2–3.) These pipes were found together in a small mound, a short distance south of St. Louis, Missouri. Collection of H. M. Braun, East St. Louis, Illinois.

Fig. 490. (S. 2–3.) Human effigy pipe, from a grave in the Willis Cemetery, Hopkinsville, Kentucky. Phillips Academy collection.

“Authorities who have written on the subject, seem to regard this type of pipe as modern. Some of the Wisconsin finds contain no marks of metal tools, are unpolished, and have all indications of being prehistoric, while others are new in appearance, finely polished and show evidence of the use of metal tools in their manufacture.”[15]

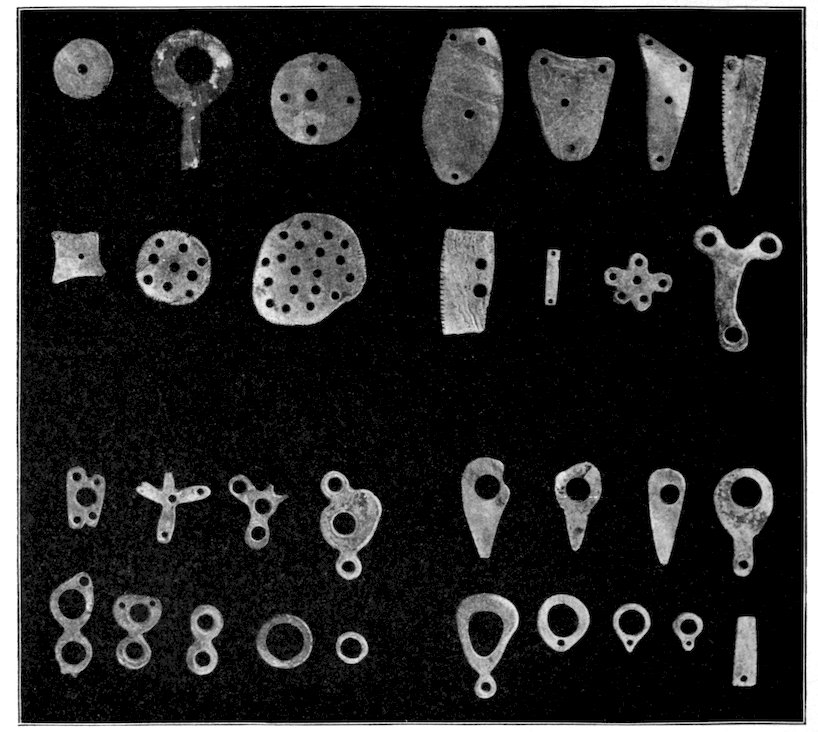

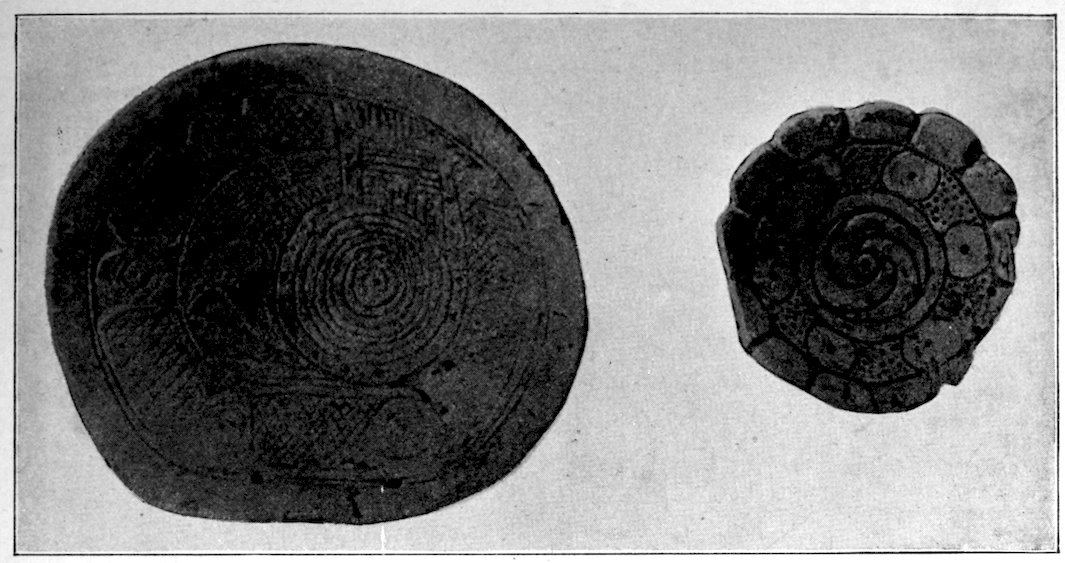

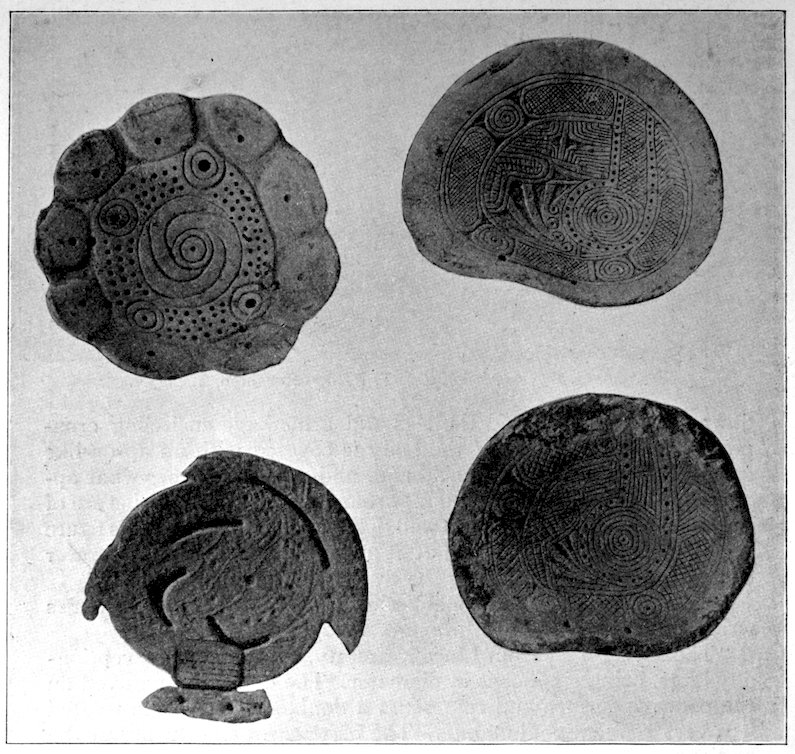

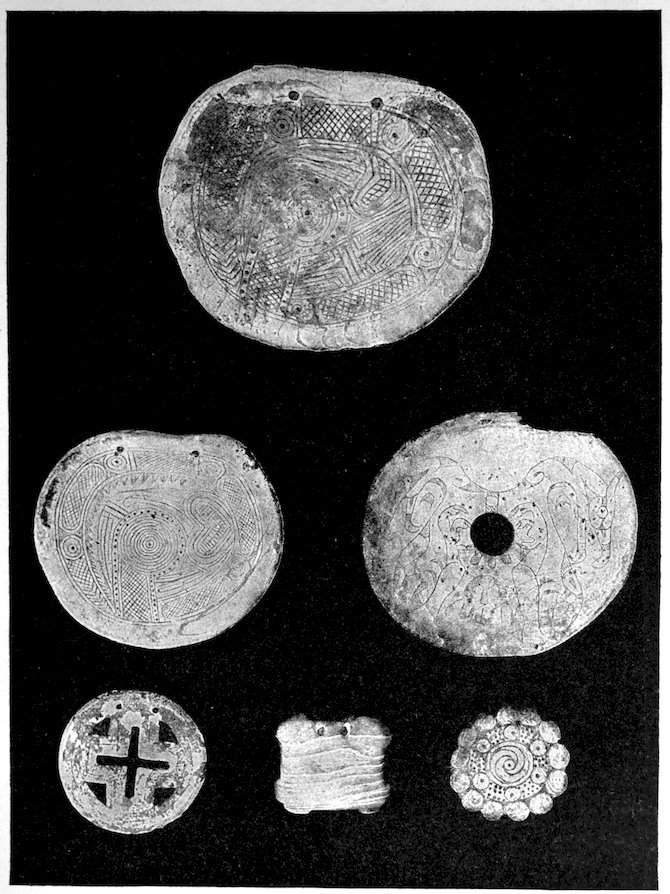

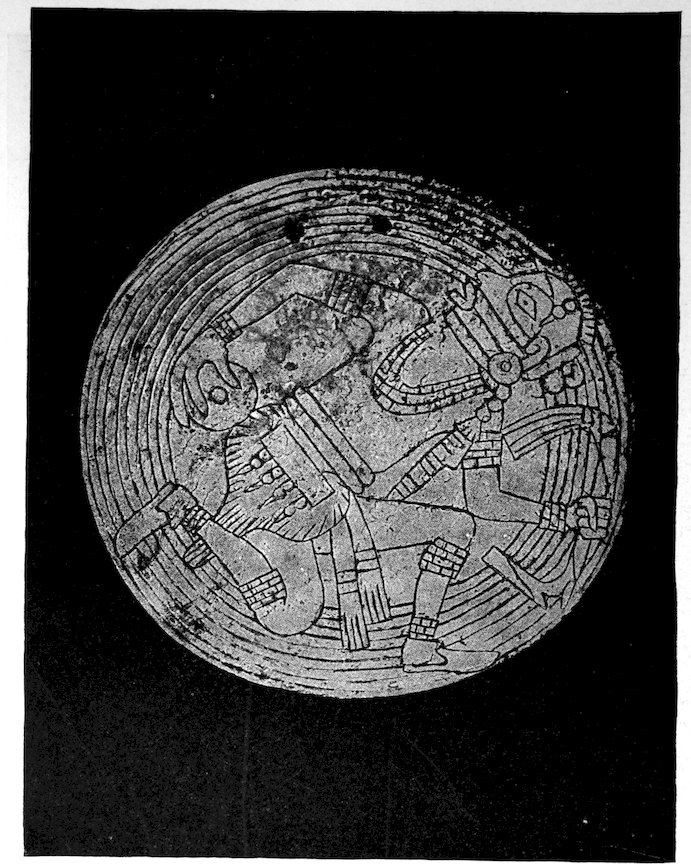

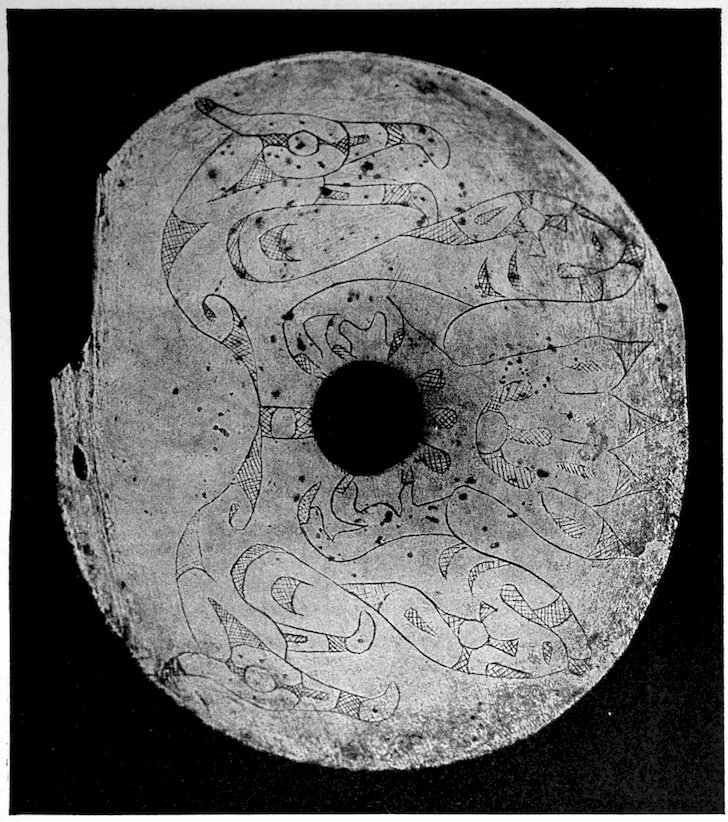

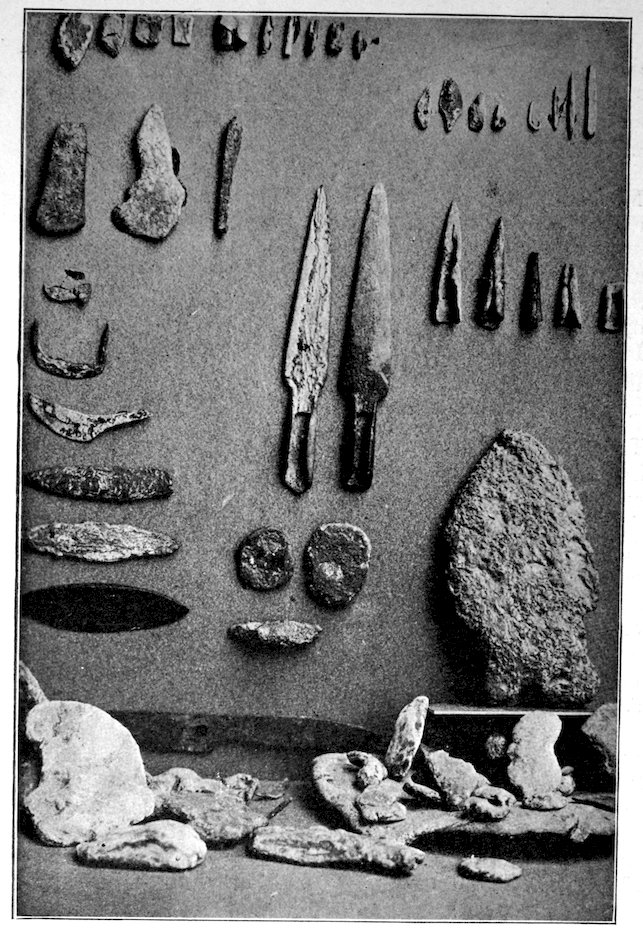

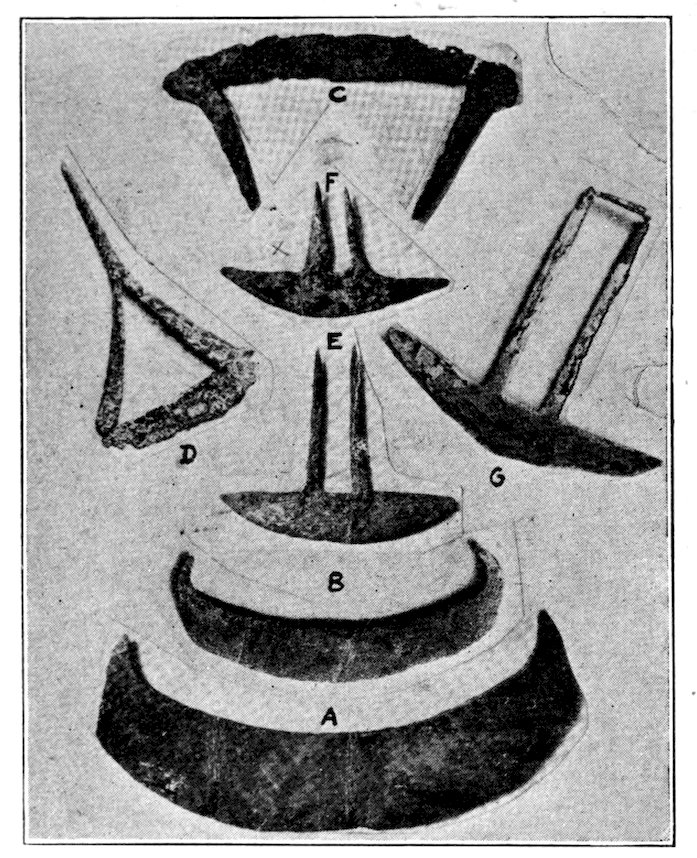

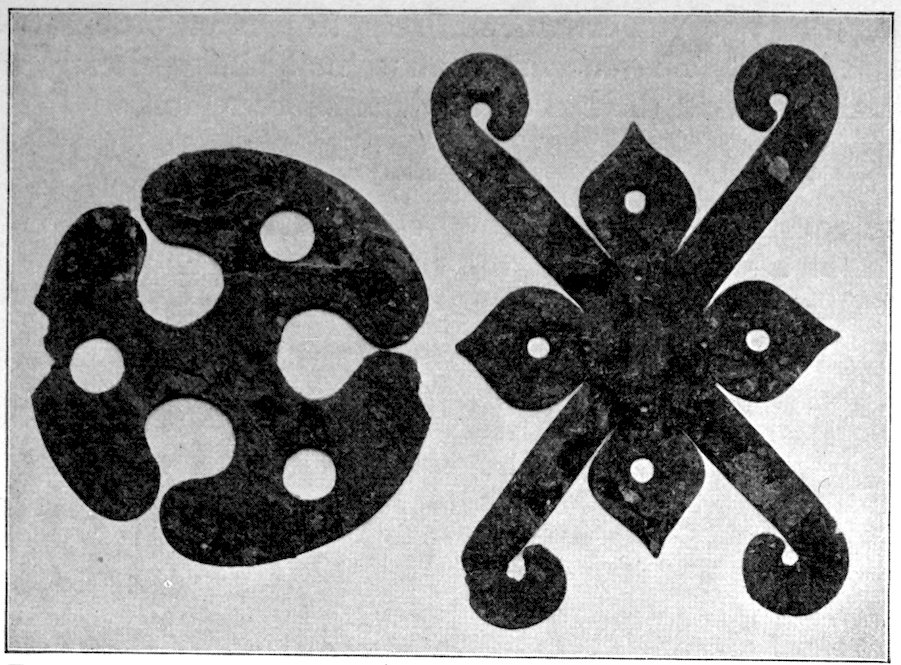

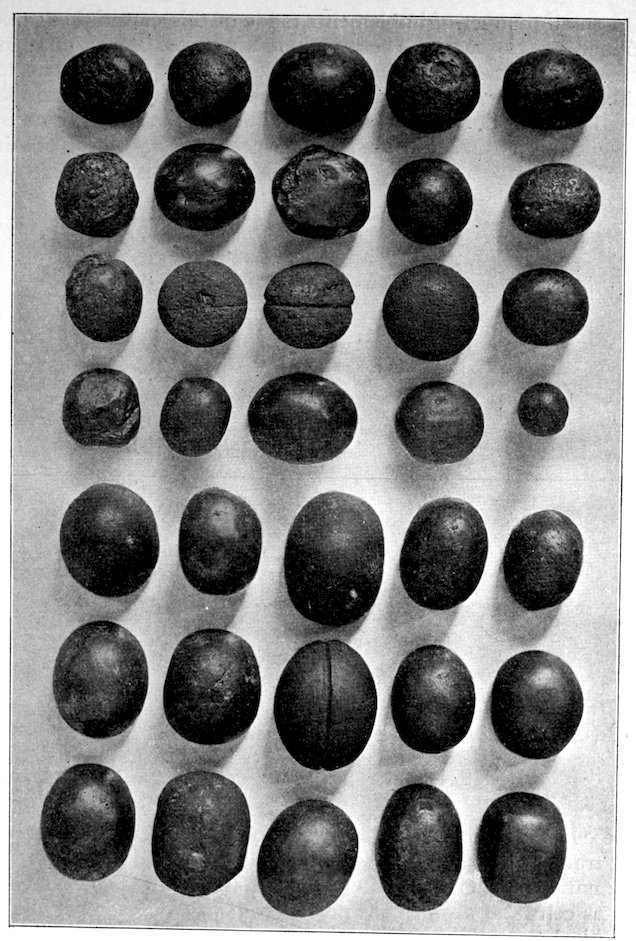

Fig. 491. (S. 3–5.) The discs and the effigy pipes were found in 1904 by W. W. Almond while ploughing on a farm near Menard’s Mound, about eight miles from Arkansas Post. It would appear that these were buried together in a cache, and covered with a layer of pottery. These will be described more fully under Conclusions, chapters XXXVI, XXXVII.

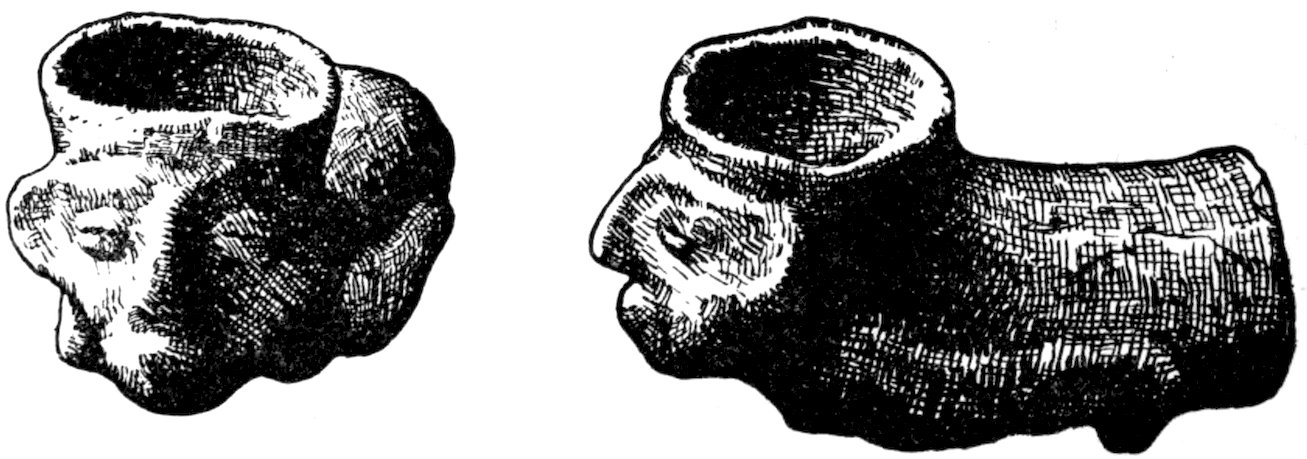

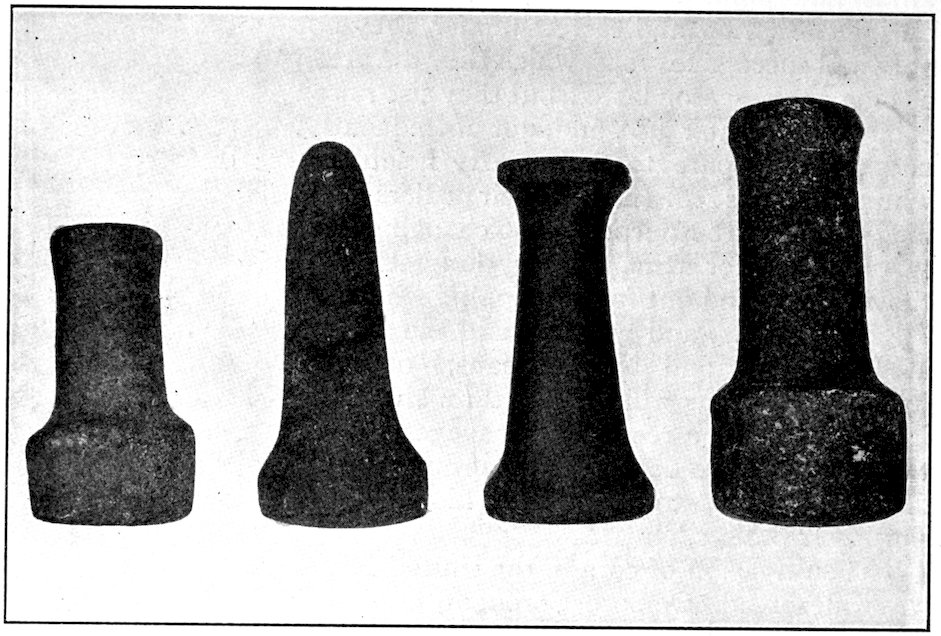

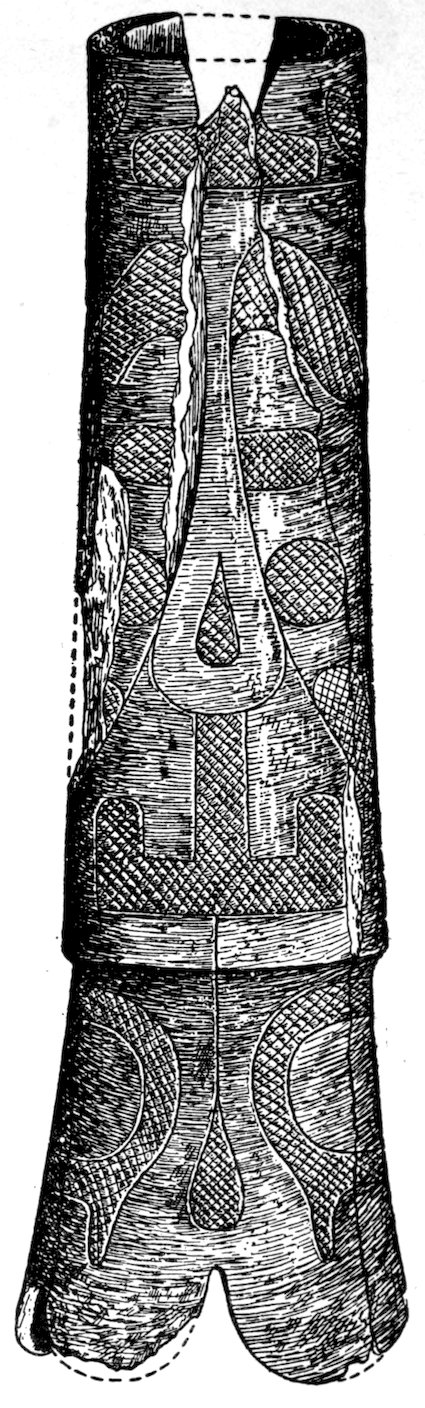

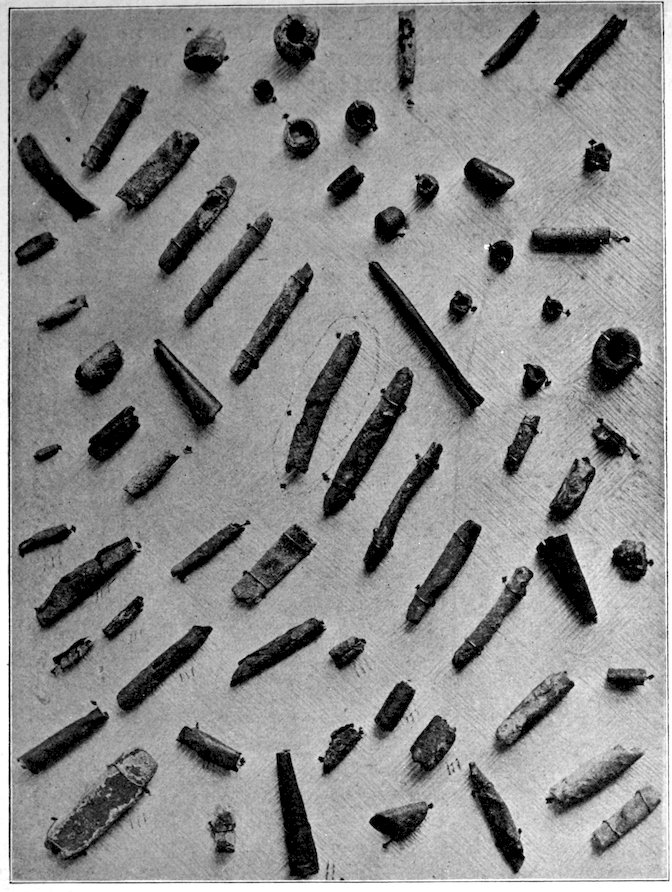

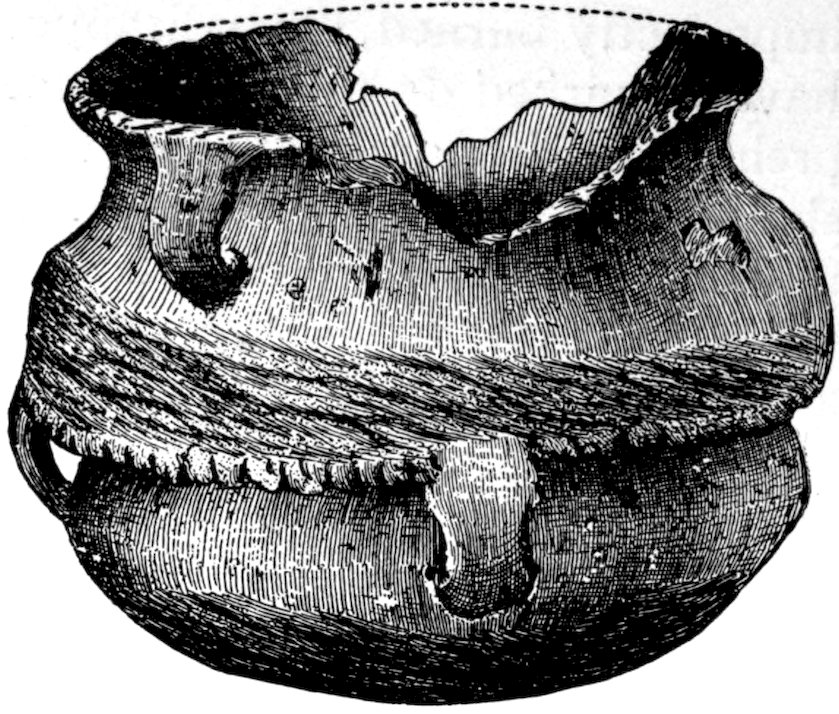

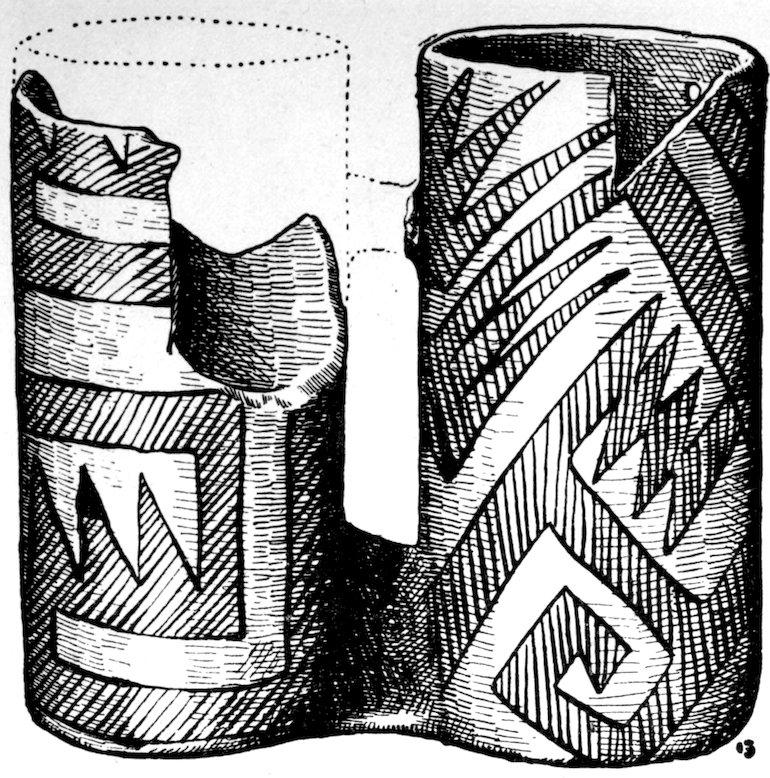

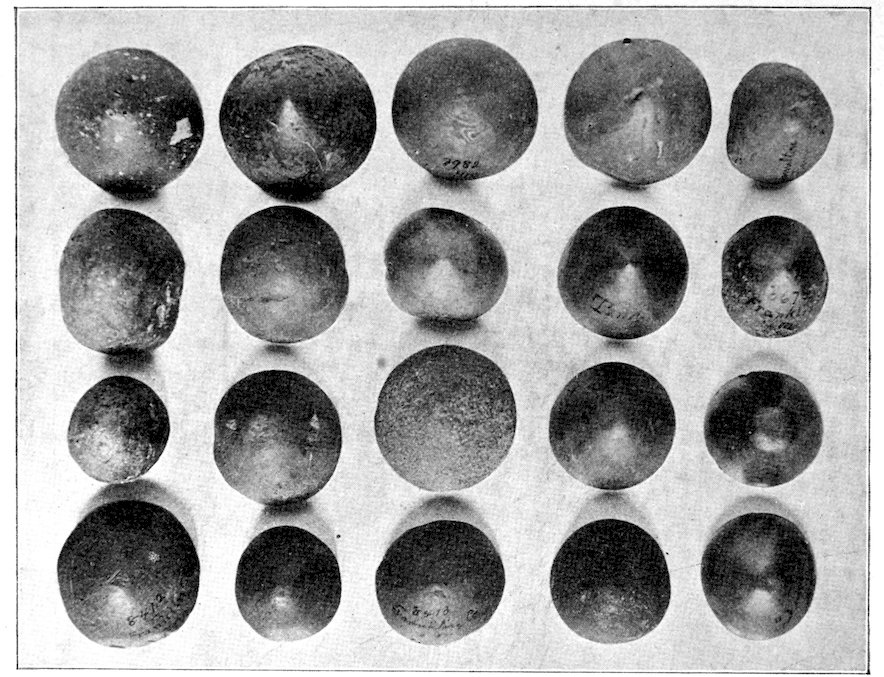

Fig. 492. (S. 4–5.) Collection of W. C. Herriman, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Figs. 492 and 493 present two views of a pipe of the ordinary clay material. The bowl is behind the head, passing down the region of the back. The unique feature of this pipe is that when shaken it gives evidence of a hollow sound in the head with several small, hard particles which distinctly rattle. These have never been investigated and their nature is not known.

Fig. 493. (S. 4–5.) Side view of Fig. 492.

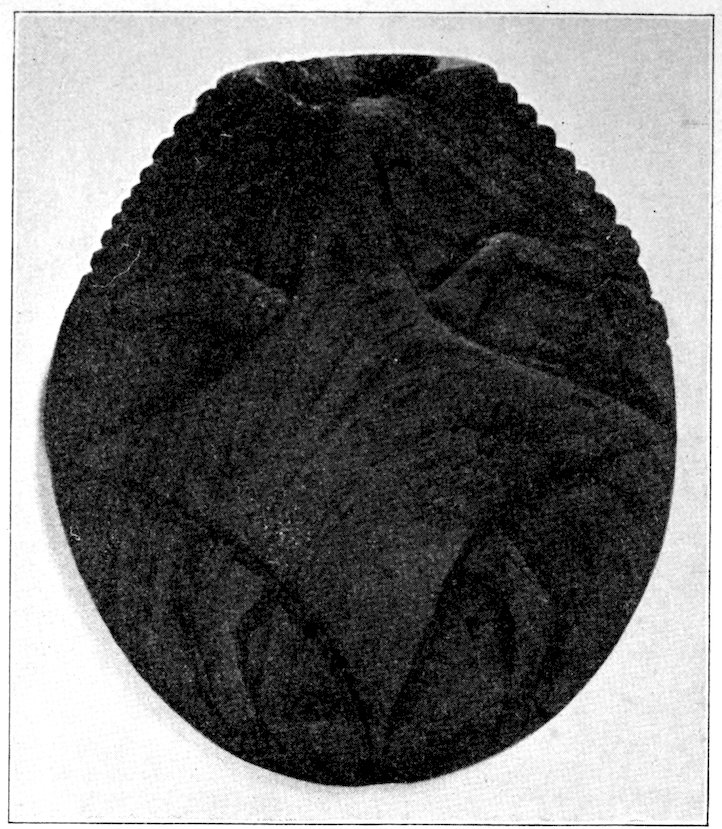

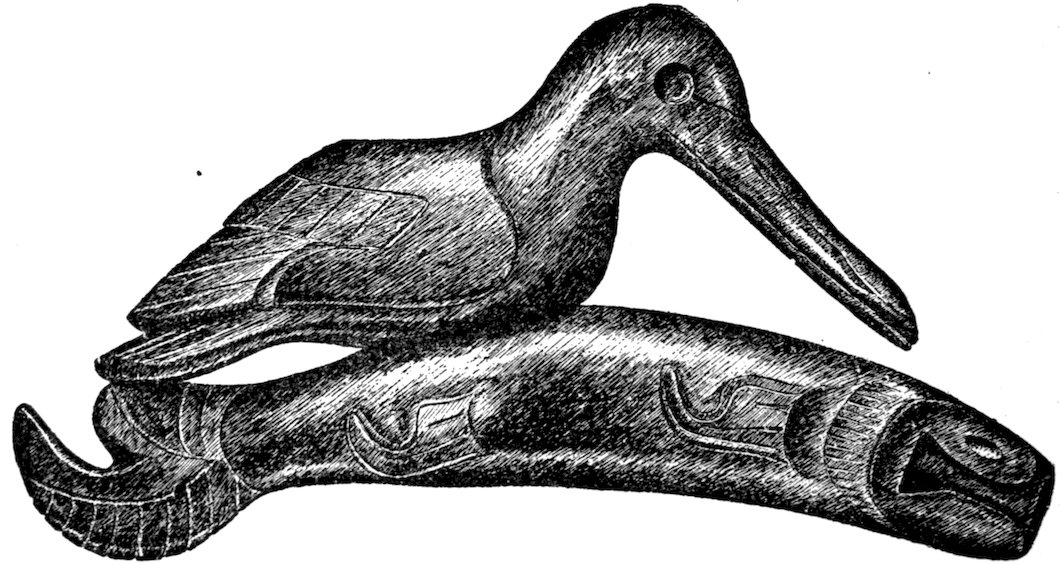

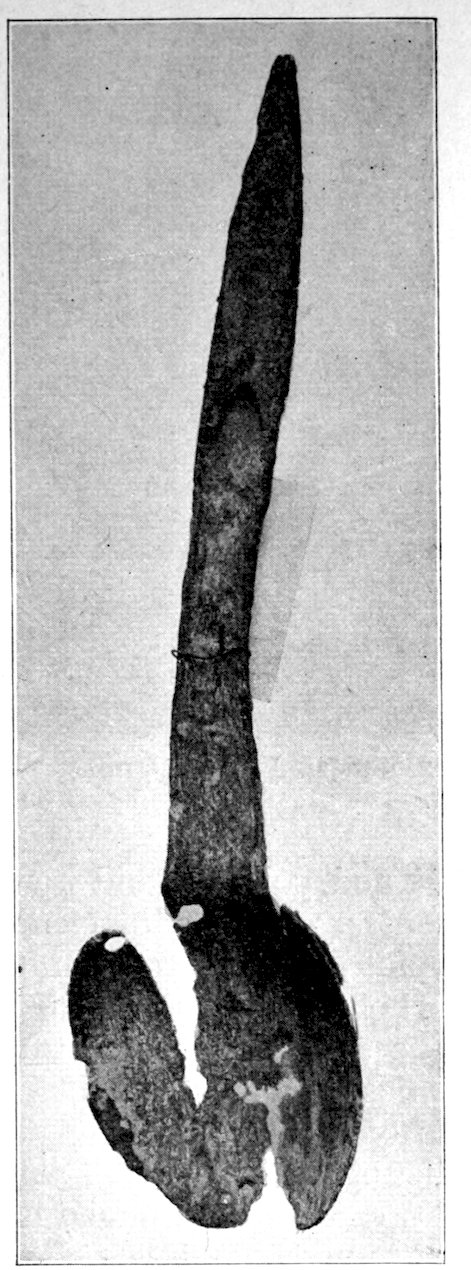

Fig. 480 is a remarkable carving in graphite slate. This was found by me on the altar of the effigy mound, Hopewell Group, Ross County, Ohio, during the course of explorations, August 1901–March 1902. The pipe represents a woodcock resting on the back of a grotesque fish. The bird is true to life, the fish is not. No pipe found by Squier and Davis in the famous Mound City Group exceeded this in its beautiful artistic lines and skill evinced in manufacture. With this pipe were thousands of pearl beads, copper ear ornaments, obsidian blades, and other remarkable objects, all of which are foreign to Ohio. The pipe, together with the other objects, is exhibited in the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago.

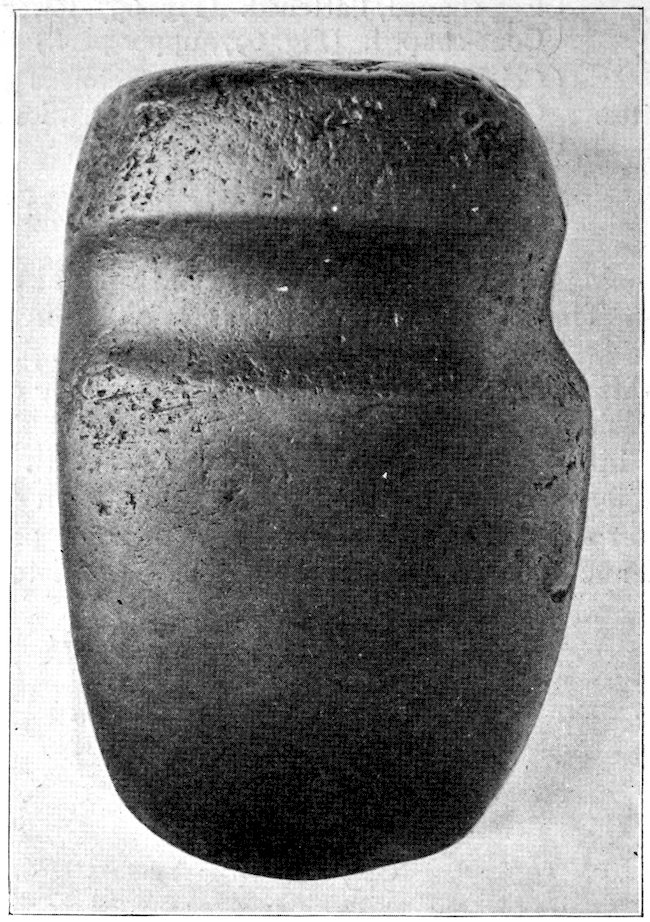

Fig. 494. (S. about 2–7.) Collection of H. M. Whelpley, St. Louis, Mo. Found near Muskogee, Ind. Ter. Color, terra-cotta; size, eight and one half inches high by five and one half inches anterio-posterior, by four and one eighth inches wide; weight, five pounds. The discoidal in the right hand measures one and three fourths by five eighths inches. Each of the two sticks in the left hand are four and one eighth inches long. Earrings, one by three eighths inch; bead under chin, three fourths by three eighths inch.

Fig. 495. (S. 1–6.) Collection of W. A. Holmes, Chicago, Illinois.

In Figs. 481 and 481 A, I present front and rear views of an effigy pipe from Wisconsin, now in the Milwaukee Public Museum. This is one of the finest examples of mound pipe found in 88the North. An inspection of the two figures will acquaint readers with the fact that the top and bottom of the pipe represent two kinds of reptilia. Prof. S. A. Barrett, who kindly furnished this and some other photographs for me, explains this peculiarity as follows:

Fig. 496. (S. 1–2.) Collection of Leslie W. Hills, Fort Wayne, Indiana. The effigy to the left is a remarkable and interesting pipe, of hard black stone, and was found in Ohio.

“In sending you the information concerning specimens, there is one point that I overlooked, and that is the difference between the carapace and the plastron of the turtle pipe. It is an interesting fact that the carapace of this specimen is that of a terrapin, while the plastron is carved after the fashion of the snapping turtle.”

Fig. 497. (S. 1–1.) Portrait pipe. Collection of G. A. West, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. This figure was dug from a grave at East Jacksonport, Door County, Wisconsin, over which was an old pine stump 30 inches in diameter, by Mr. L. K. Erkskin, from whom it was secured by Mr. W. H. Elkey, for Mr. G. A. West. This pipe is of compact flinty limestone and most skillfully carved into a resemblance of the head and face of a frowning Indian. Both bowl and stem excavations are conical in shape, and were evidently made with stone drills.

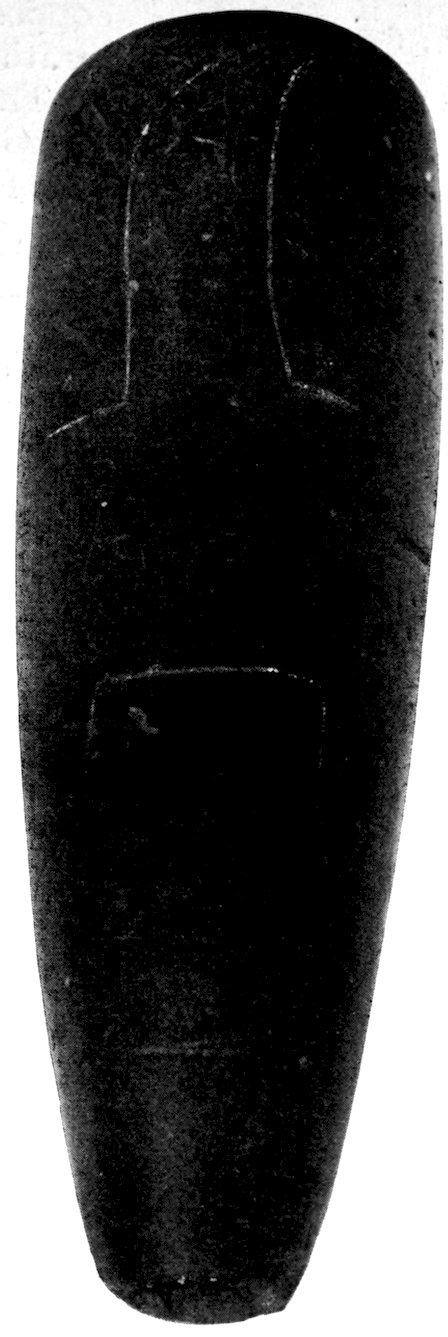

I have referred in a number of places to smoking as a ceremony. In addition to being a rite, it was always practiced for medicinal purposes. Not only did the Indians in ancient times inhale fumes in order to alleviate distress, but the white people did likewise. Mr. McGuire, in his work which I have previously quoted, makes this perfectly clear and cites numerous instances as to the supposed curative property of tobacco. I quote one of his paragraphs[16] concerning the truly remarkable material gathered by Mr. Bragg:—