Title: Australia, New Zealand and some islands of the South seas

Australia, New Zealand, Thursday island, the Samoas, New Guinea, the Fijis, and the Tongas

Author: Frank G. Carpenter

Release date: September 24, 2024 [eBook #74473]

Language: English

Original publication: Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1924

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/74473

Credits: Alan, Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

CARPENTER’S

WORLD TRAVELS

Familiar Talks About Countries

and Peoples

WITH THE AUTHOR ON THE SPOT AND

THE READER IN HIS HOME, BASED

ON THREE HUNDRED THOUSAND

MILES OF TRAVEL

OVER THE GLOBE

“READING CARPENTER IS SEEING THE WORLD”

IN AUSTRALIA

The “great white continent” in the midst of the teeming coloured races of the Orient, our Anglo-Saxon cousins are building a new empire of the Pacific.

CARPENTER’S WORLD TRAVELS

Australia, New Zealand, Thursday Island,

The Samoas, New Guinea, The Fijis,

and the Tongas

BY

FRANK G. CARPENTER

LITT.D., F.R.G.S.

WITH 126 ILLUSTRATIONS

FROM ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS

GARDEN CITY NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1924

COPYRIGHT, 1924, BY

FRANK G. CARPENTER

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES

AT

THE COUNTRY LIFE PRESS, GARDEN CITY, N. Y.

First Edition

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

IN THE publication of this volume on my travels in Australia, New Zealand, and the South Seas, I wish to thank the Secretary of State for letters which have given me the assistance of our official representative in the countries visited. I thank also the Secretary of Agriculture and our Secretary of Labour for appointing me an Honorary Commissioner of their Departments in foreign lands. Their credentials have been of great value, making accessible sources of information seldom opened to the ordinary traveller.

To the officials of the Commonwealth of Australia and the Dominion of New Zealand I desire to express my thanks for exceptional courtesies which greatly aided me in my investigations.

I would also thank Mr. Dudley Harmon, my editor, and Miss Ellen McBryde Brown and Miss Josephine Lehmann, my associate editors, for their assistance and coöperation in the revision of notes dictated or penned by me on the ground.

While nearly all of the illustrations in Carpenter’s World Travels are from my own negatives, those in this book have been supplemented by photographs from the official collections of the State and Commonwealth governments of Australia, the Dominion of New Zealand, and the United States Department of Commerce.

F. G. C.

[Pg vii]

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Just a Word before We Start | 1 |

| II. | The Giant of the South Seas | 3 |

| III. | Queensland | 10 |

| IV. | A Crown of Gold and a Cross of Cactus | 19 |

| V. | The Metropolis of the Antipodes | 24 |

| VI. | Walks about Sydney | 31 |

| VII. | The Land of the Golden Fleece | 37 |

| VIII. | In the Great Wool Market | 42 |

| IX. | Life on the Sheep Stations | 47 |

| X. | Rabbits and Dingoes | 56 |

| XI. | Water for Thirsty Lands | 62 |

| XII. | Melbourne | 72 |

| XIII. | In the Marts of the City | 80 |

| XIV. | The State-owned Railways | 85 |

| XV. | Gold Diggings in Creek and Desert | 95 |

| XVI. | A White Workers’ Continent | 104 |

| XVII. | The Three “R’s” in Australia | 113 |

| XVIII. | The Aborigines | 120 |

| XIX. | Kangaroos and Dancing Birds | 129 |

| XX. | Australia as Our Customer | 137 |

| XXI. | Tasmania | 144[Pg viii] |

| XXII. | The Pearl Fisheries of Thursday Island | 152 |

| XXIII. | Australia’s Island Wards | 159 |

| XXIV. | Across the Tasman Sea to Wellington | 165 |

| XXV. | The Dominion of New Zealand | 170 |

| XXVI. | “Social Pests” | 178 |

| XXVII. | The Women of the Dominion | 186 |

| XXVIII. | A Country without a Poorhouse | 194 |

| XXIX. | Where the Working Man Rules | 202 |

| XXX. | On the Government Railways | 213 |

| XXXI. | The Yellowstone of New Zealand | 220 |

| XXXII. | The Maoris | 227 |

| XXXIII. | Mutton and Butter for London Tables | 236 |

| XXXIV. | Some Freaks of Nature | 246 |

| XXXV. | American Goods in New Zealand | 255 |

| XXXVI. | The Fijis and the Tongas | 263 |

| XXXVII. | The Samoas | 273 |

| See the World with Frank G. Carpenter | 282 | |

| Index | 287 |

[Pg ix]

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

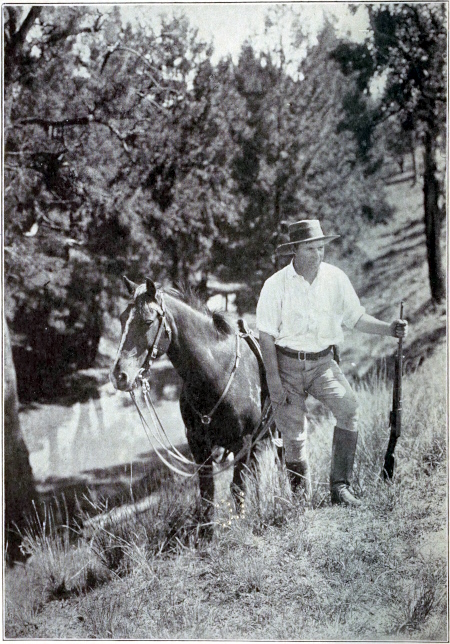

| In the “Great White Continent” | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

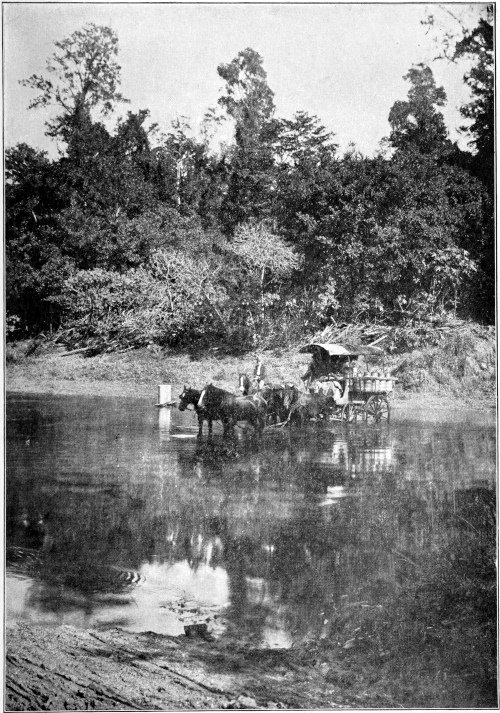

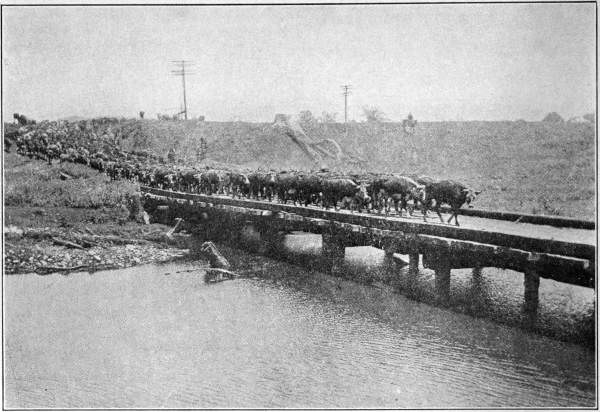

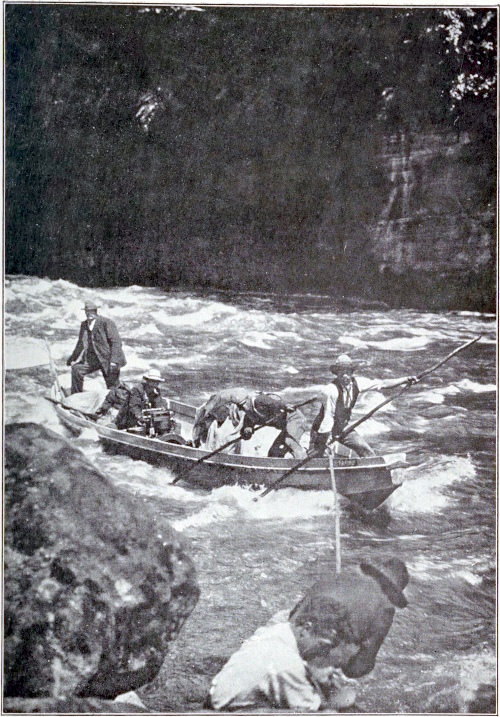

| Crossing the Murray River | 2 |

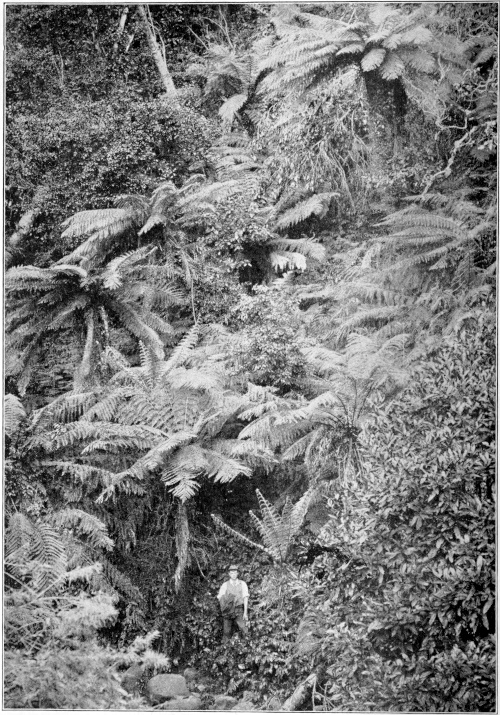

| The giant tree ferns | 3 |

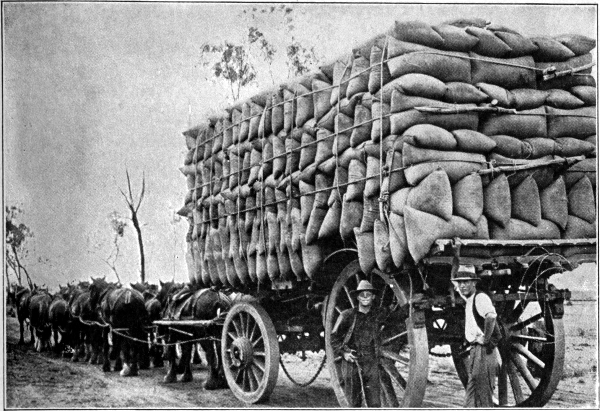

| Wheat going to market | 6 |

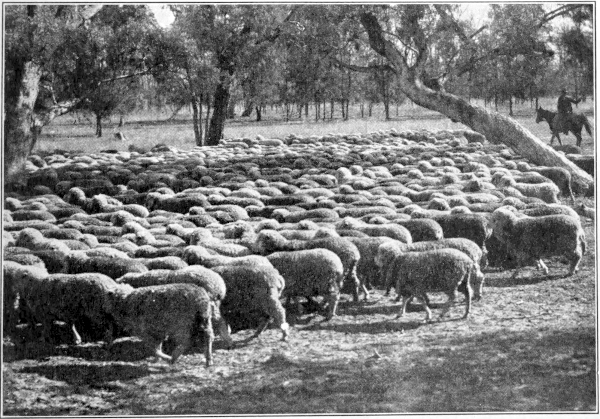

| Wool for half the world | 6 |

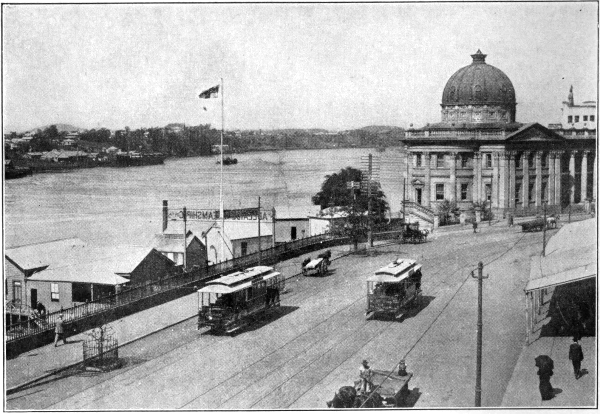

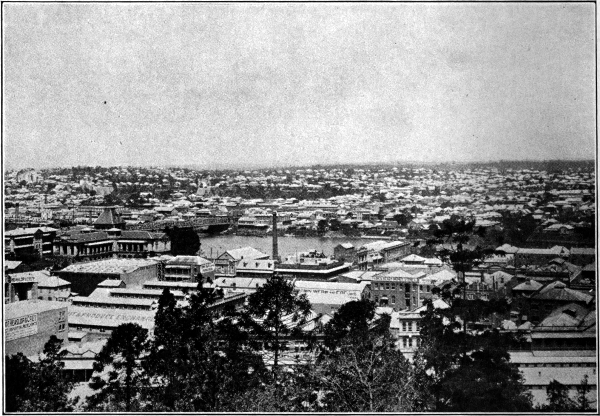

| On the Brisbane water front | 7 |

| The Brisbane River | 7 |

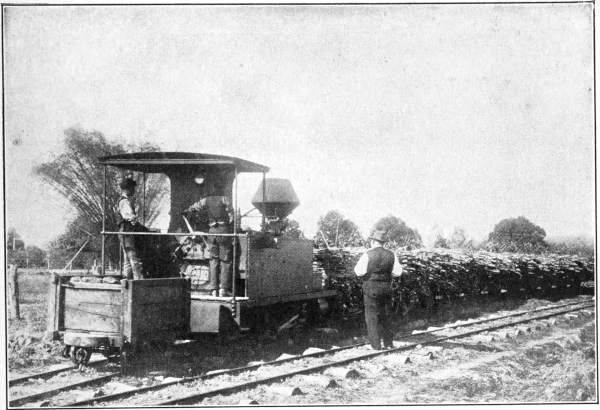

| Queensland sugar | 14 |

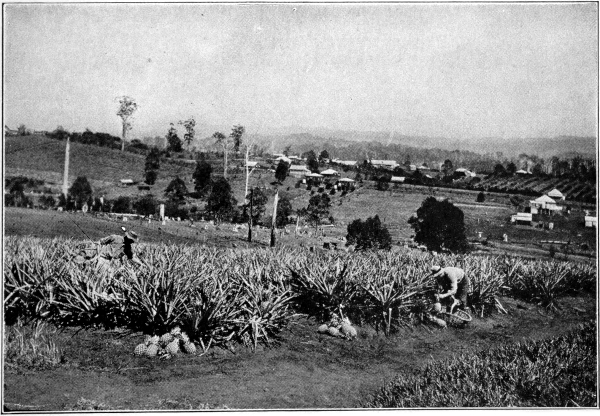

| Pineapples | 14 |

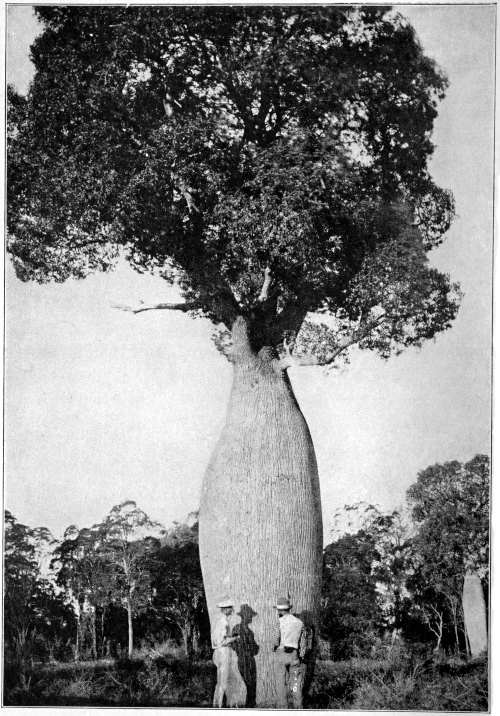

| Bottle trees | 15 |

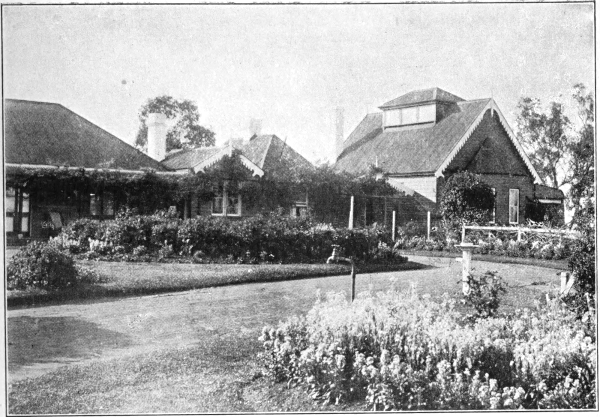

| A settler’s home | 18 |

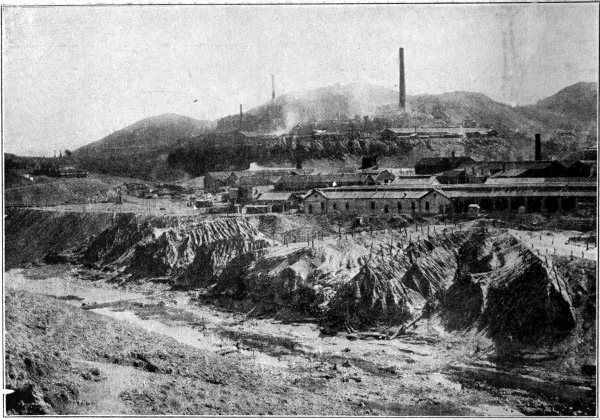

| The hill of gold and copper | 19 |

| The sapphire mines | 19 |

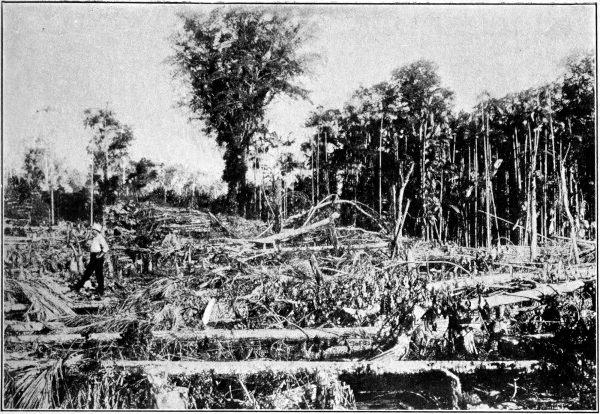

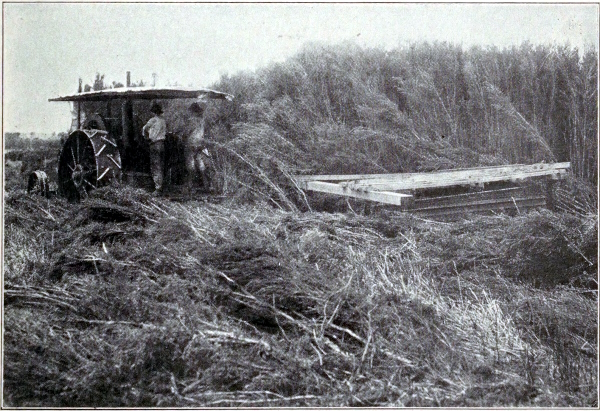

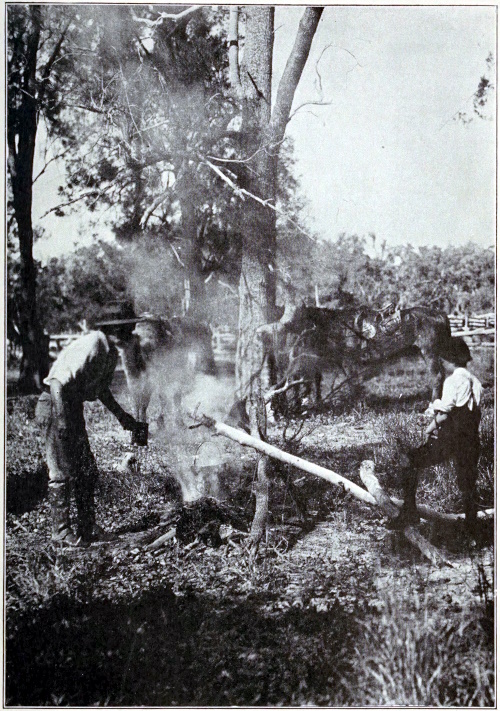

| Clearing off the scrub | 22 |

| How the farmers live | 22 |

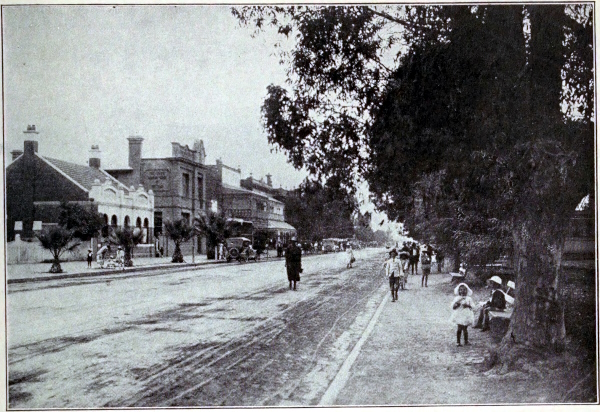

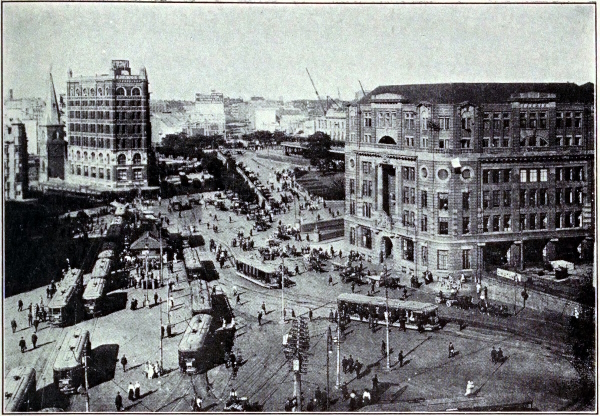

| Down town in Sydney | 23 |

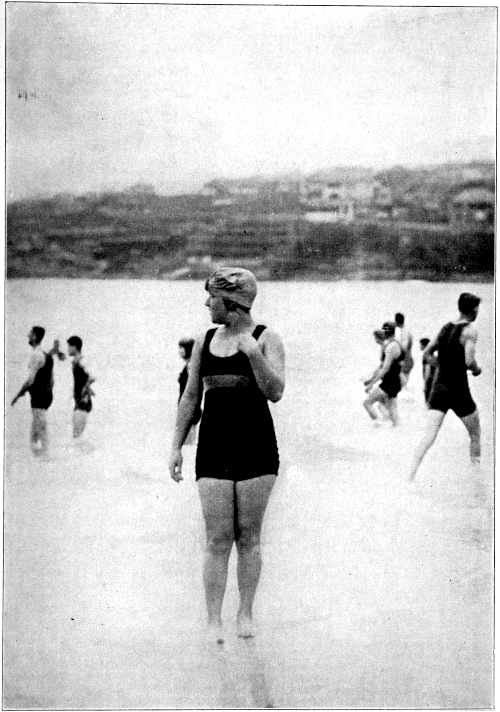

| At Bondi Beach | 30 |

| Airplane view of Sydney harbour | 31 |

| Manly Beach | 31 |

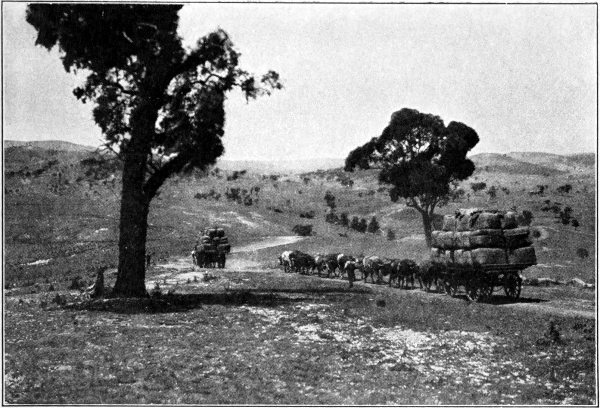

| Hauling the wool clip to market | 38 |

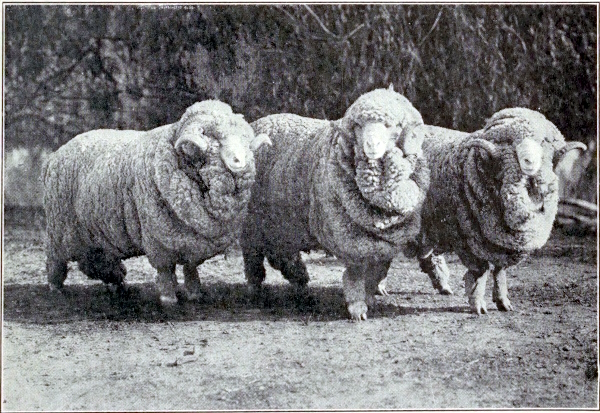

| Some champion Merinos | 38 |

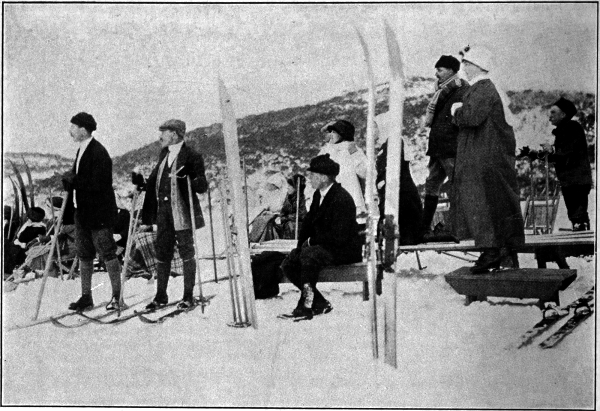

| Winter sports on Mount Kosciusko | 39 |

| Skating amid the green | 39 |

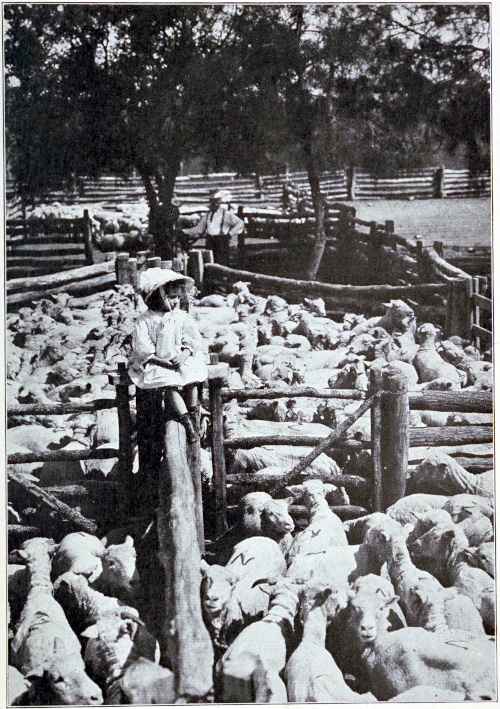

| In the sheepfold | 46 |

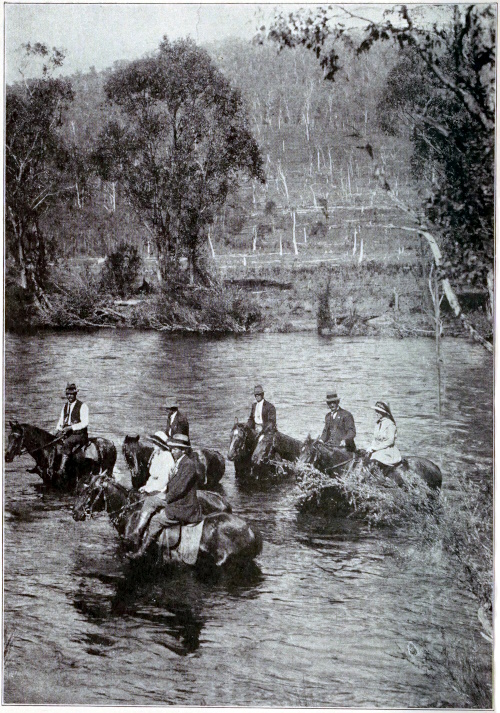

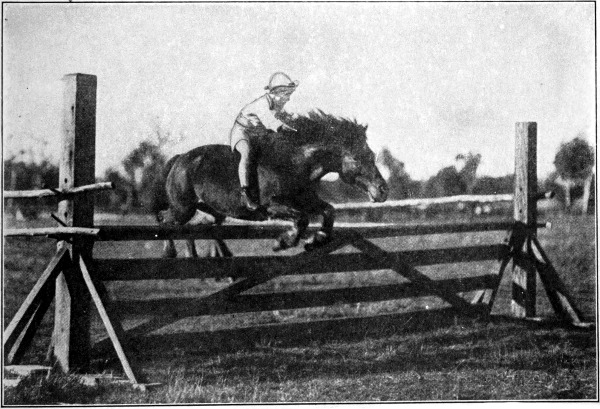

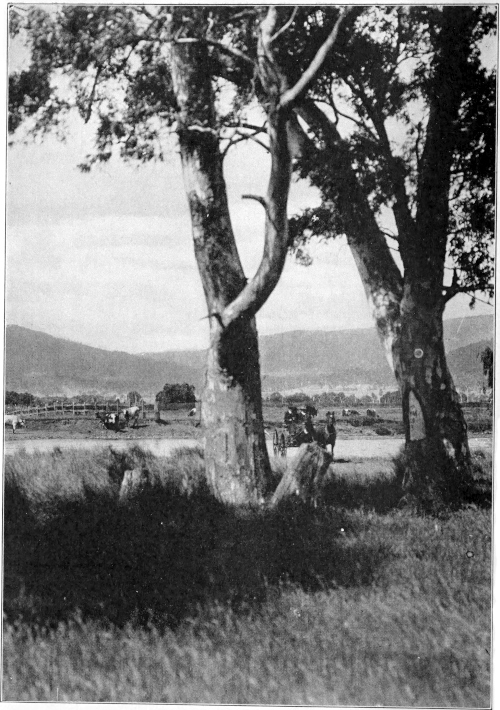

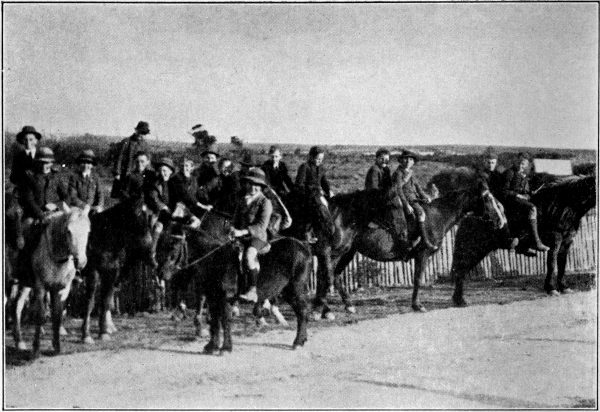

| To a tea party on horseback | 47[Pg x] |

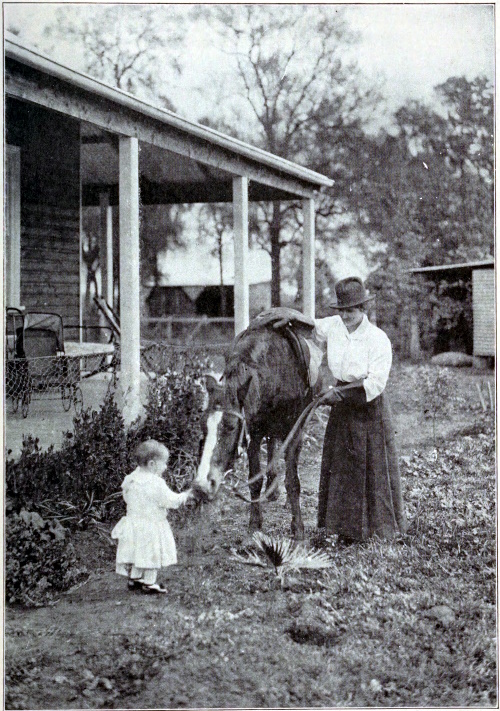

| Home life on a sheep station | 50 |

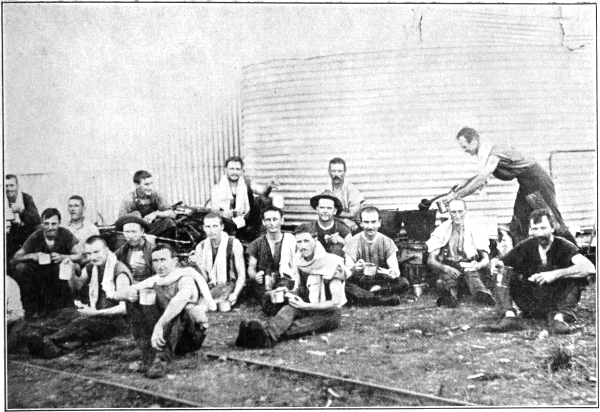

| The sheep shearers | 51 |

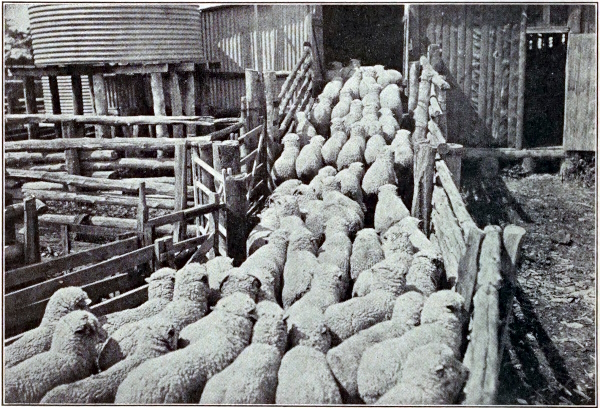

| Sheep about to lose their wool | 51 |

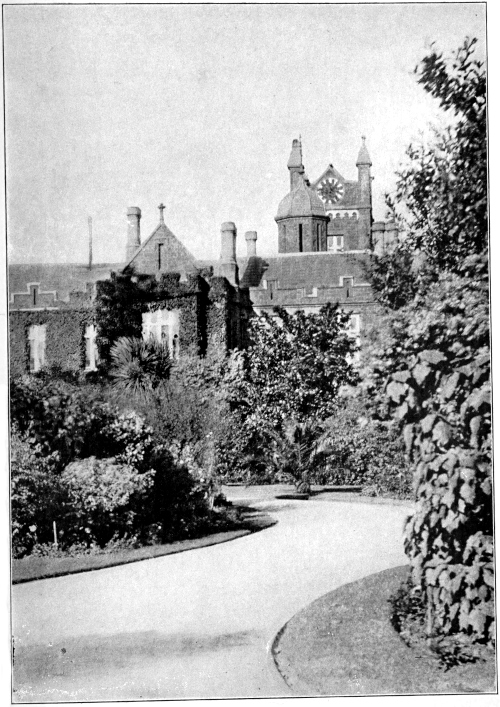

| Home of a station manager | 54 |

| Boys who grow up on horseback | 54 |

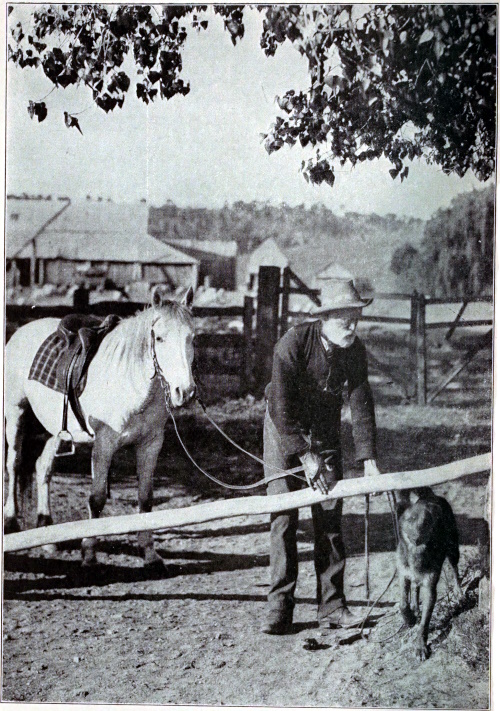

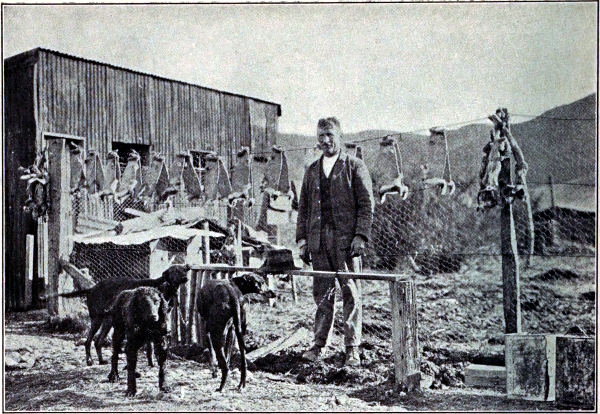

| The boundary rider | 55 |

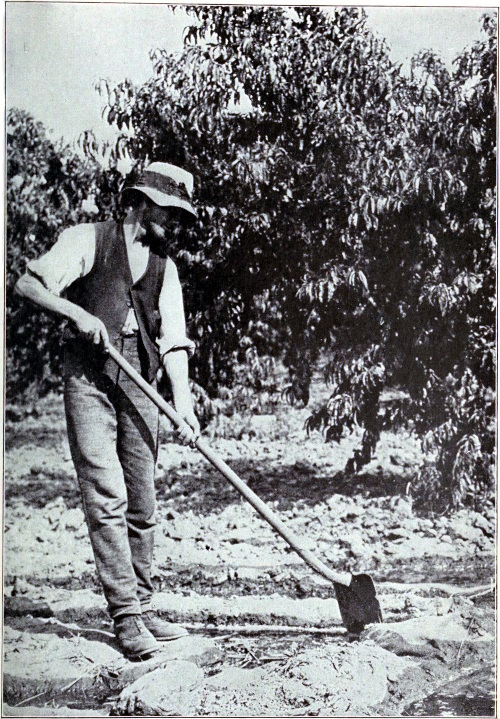

| Irrigating orchard | 62 |

| Rabbit fences | 63 |

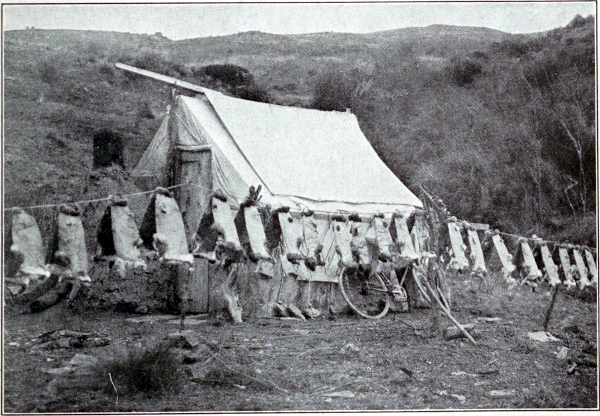

| Packing rabbit skins for export | 63 |

| A city on the reclaimed lands | 66 |

| Breaking down the scrub | 66 |

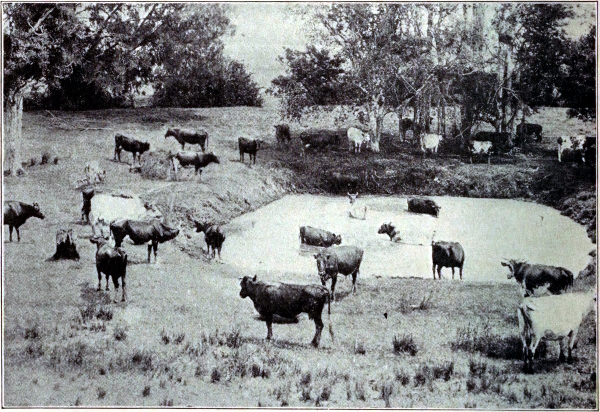

| Rescuing cattle from the drought | 67 |

| How water is saved | 67 |

| “Boiling the billy” | 70 |

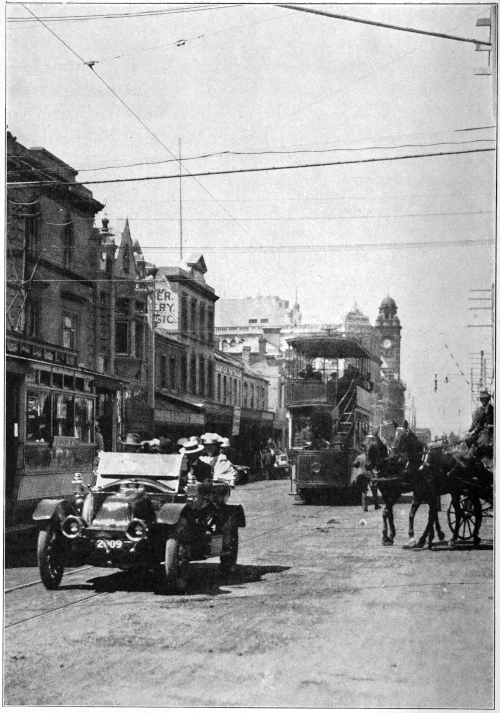

| Collins Street, Melbourne | 71 |

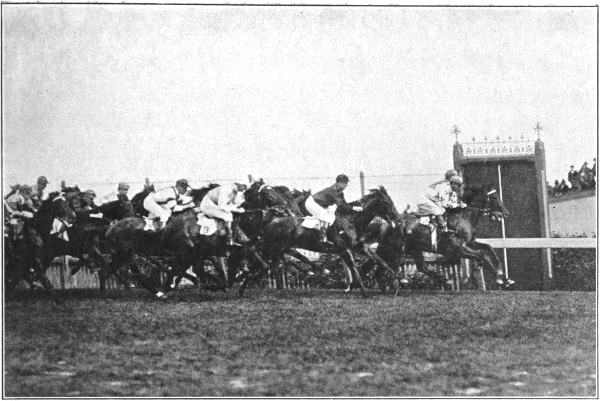

| At the race track | 78 |

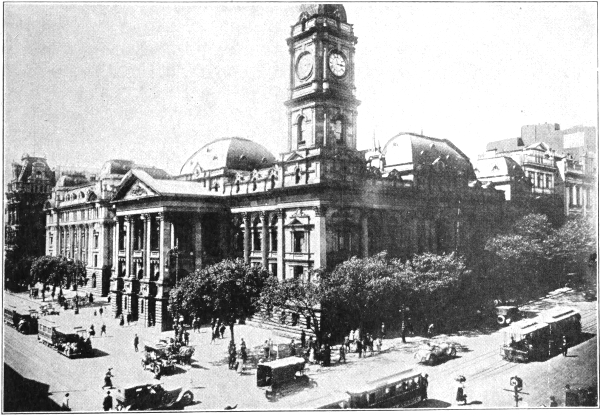

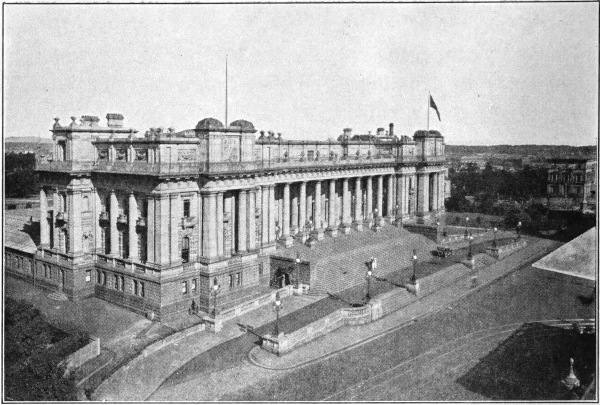

| Melbourne city hall | 78 |

| The Parliament House | 79 |

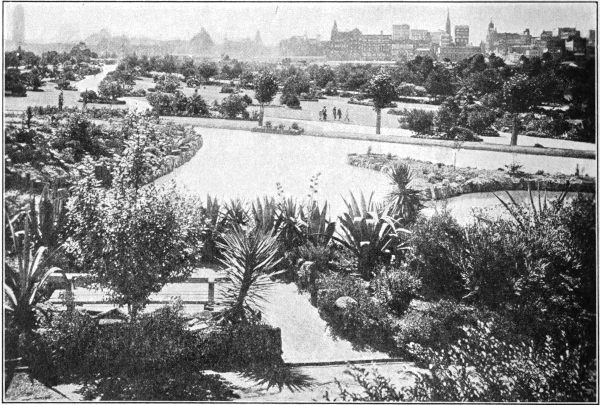

| Alexandra Gardens | 79 |

| Logging in the eucalyptus forest | 86 |

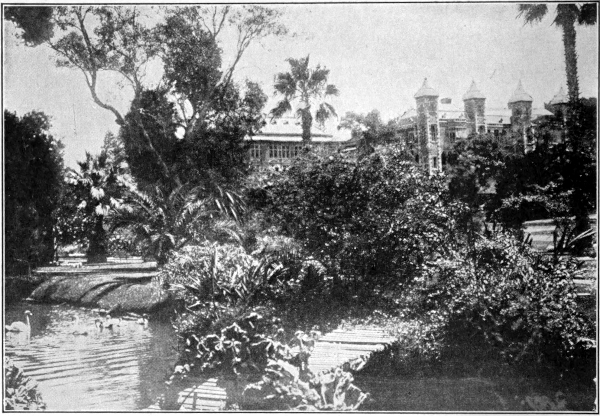

| The Governor’s house at Perth | 87 |

| Moving the wheat crop | 87 |

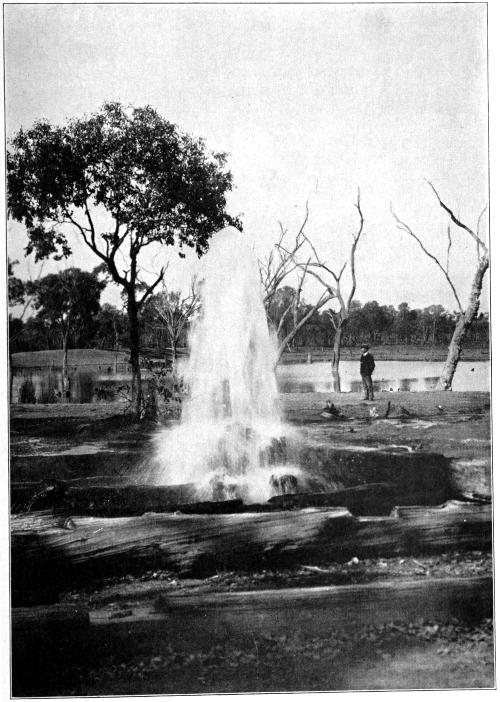

| An artesian bore | 94 |

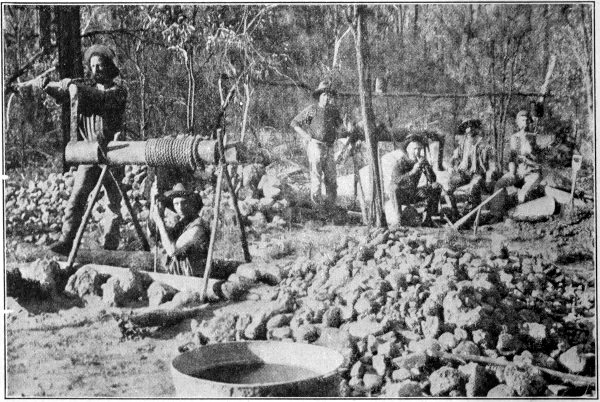

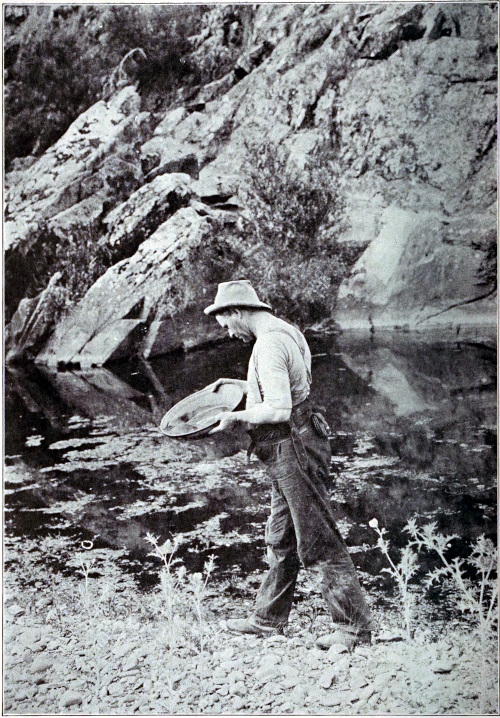

| Panning gold | 95 |

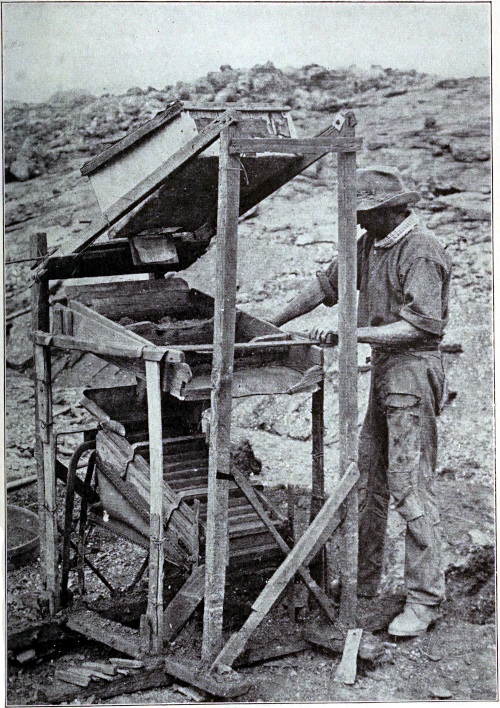

| The dry-blow process | 98 |

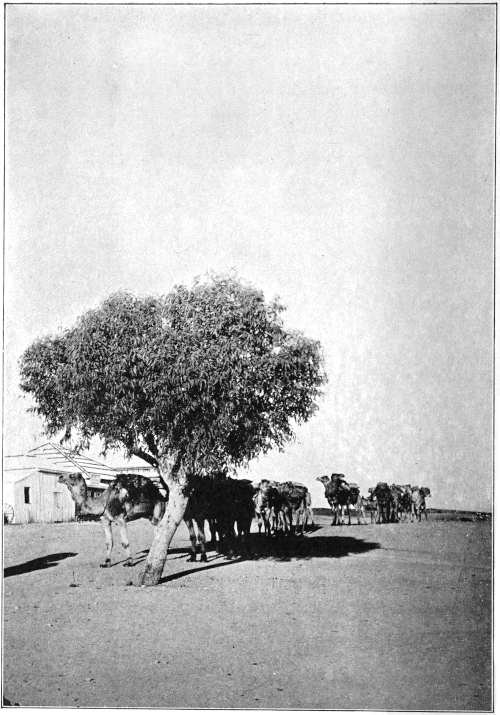

| A camel train | 99 |

| The sheep-shearers’ “smoker” | 102 |

| The leather workers | 102 |

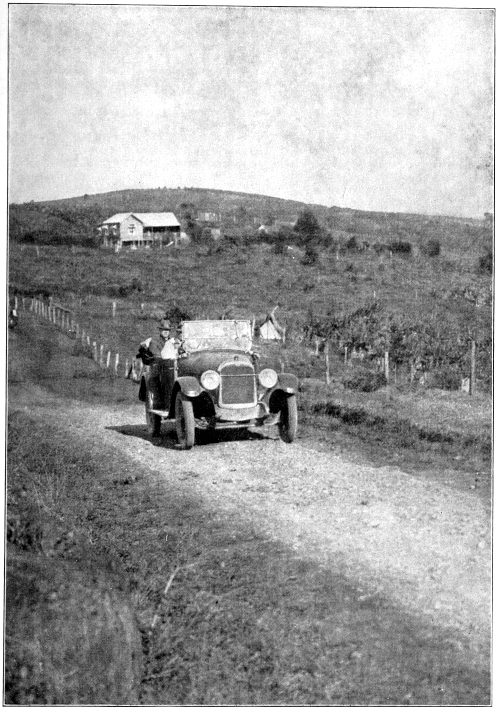

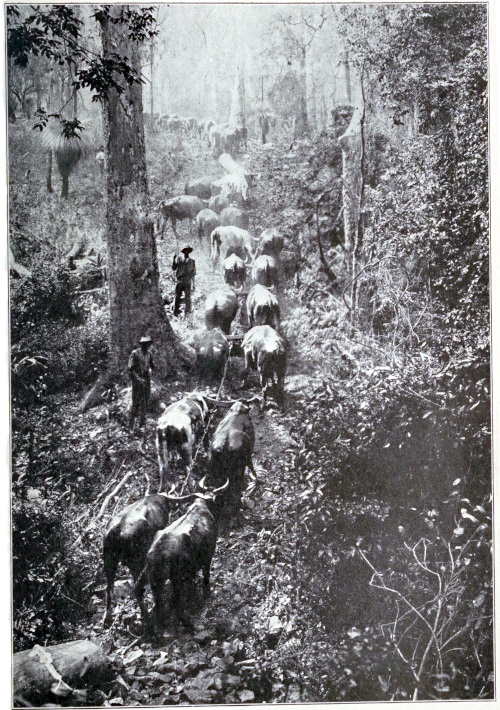

| The drive across country | 103 |

| Immigrants landing | 110 |

| Girls learning to keep house | 111[Pg xi] |

| The grammar school at Melbourne | 114 |

| How some children get to school | 115 |

| Where farm wives go to school | 115 |

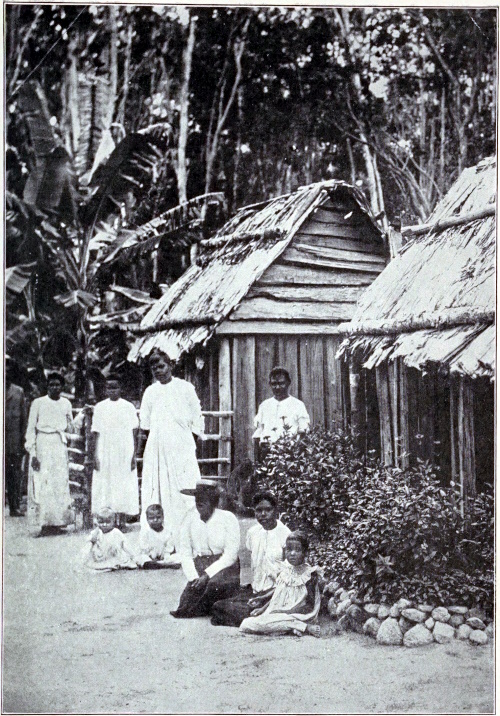

| Half-civilized aborigines | 118 |

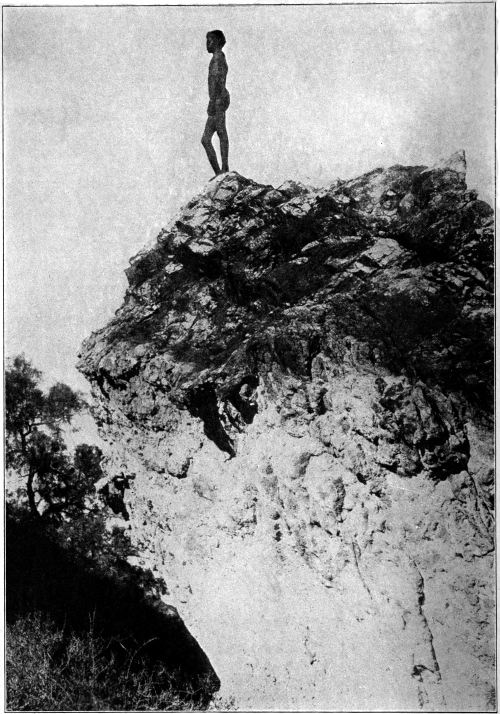

| The aborigines of the wilds | 119 |

| Turkey shooting by airplane | 126 |

| Kangaroo | 127 |

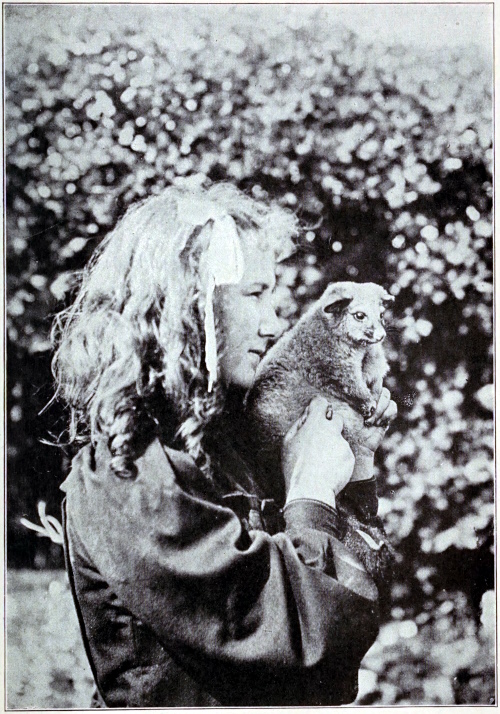

| The Australian opossum | 130 |

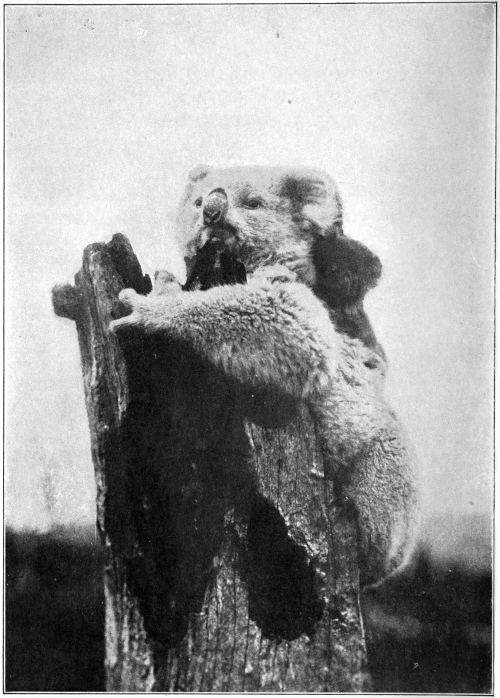

| Mother bear and her baby | 131 |

| In Sydney’s business district | 134 |

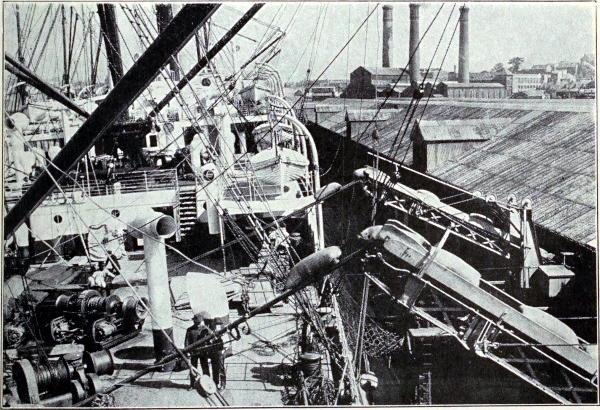

| Loading wheat for export | 134 |

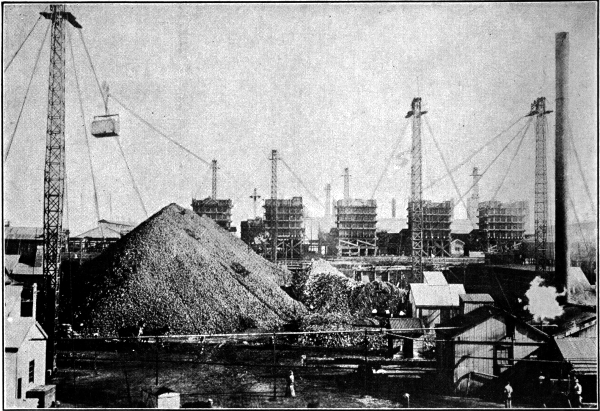

| American machinery in Australian mines | 135 |

| Motor picnics in American cars | 135 |

| The stripper harvester | 142 |

| An Illinois harvester in Australia | 142 |

| In Hobart, Tasmania | 143 |

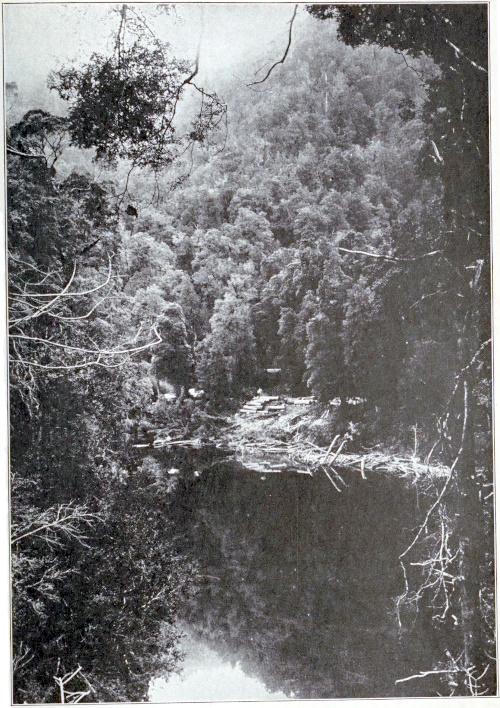

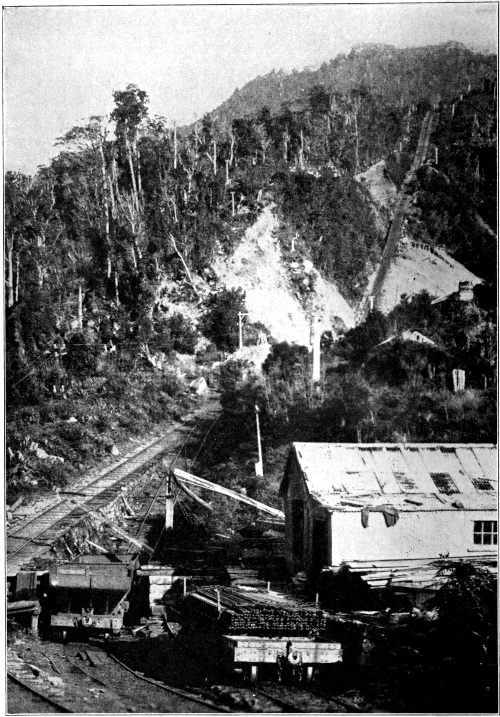

| Logging on a Tasmanian river | 146 |

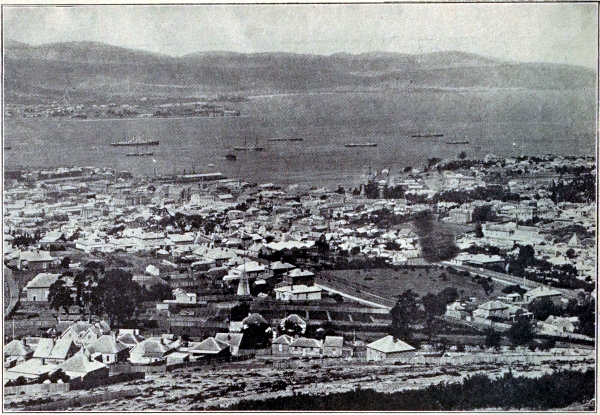

| Hobart and Derwent River | 147 |

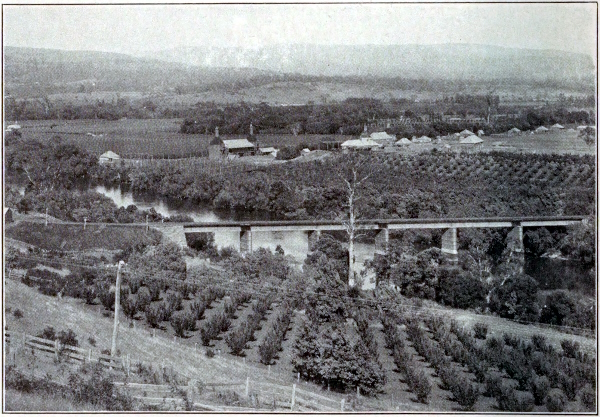

| Orchards of the “Apple Isle” | 147 |

| Thursday Island | 150 |

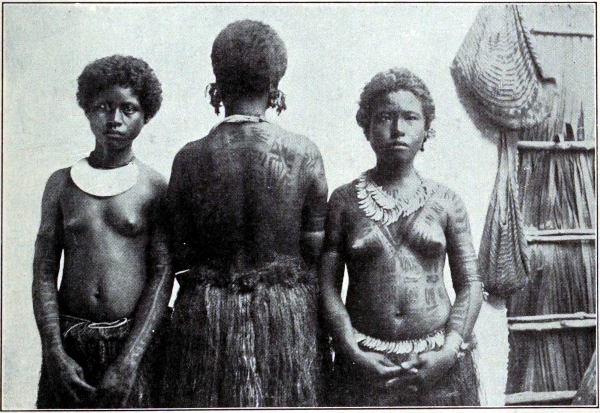

| Tattooed South Sea Island belles | 150 |

| Opening the pearl oyster | 151 |

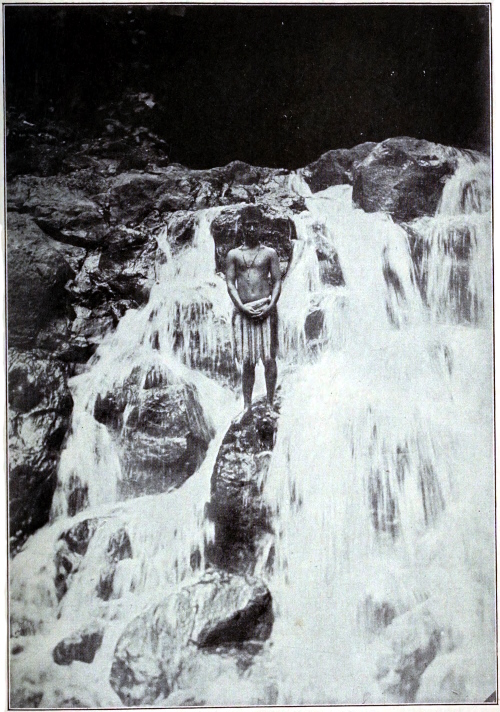

| South Sea Islander | 158 |

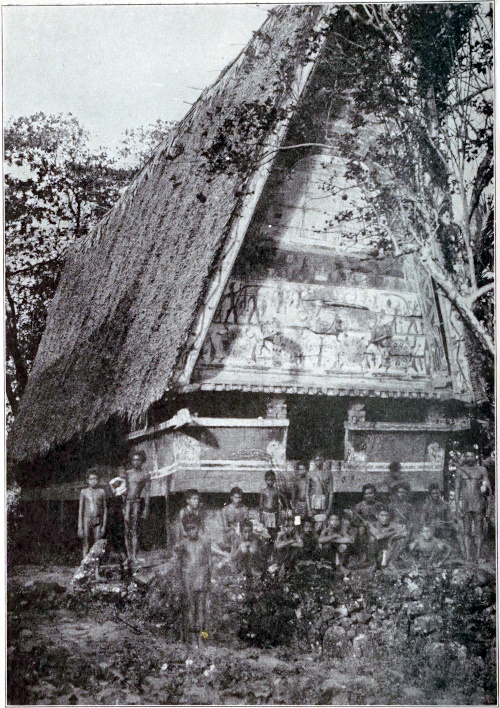

| A village house | 159 |

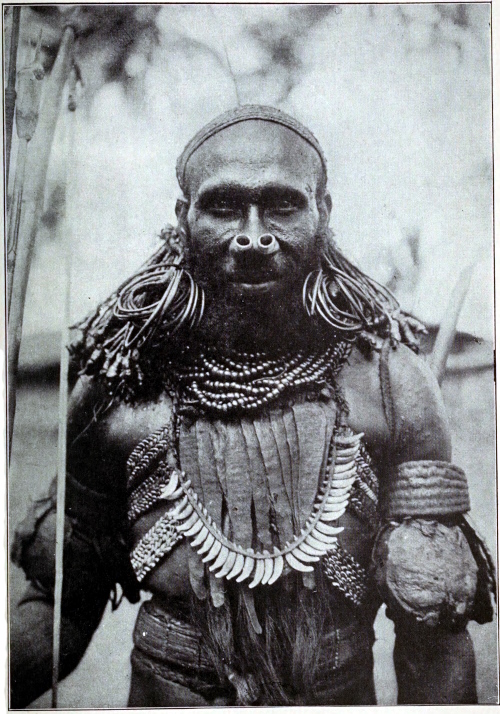

| A South Sea warrior | 162 |

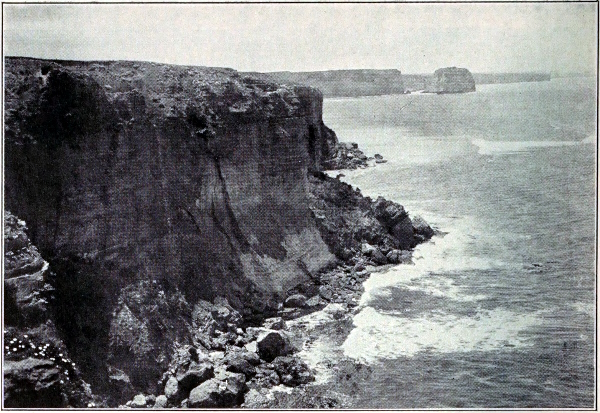

| On the shores of the Tasman Sea | 163 |

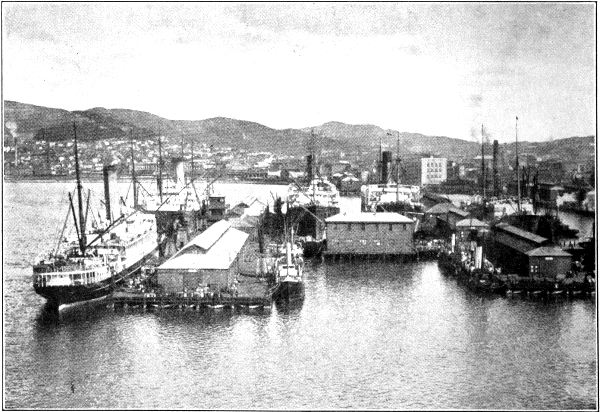

| Wellington harbour | 163 |

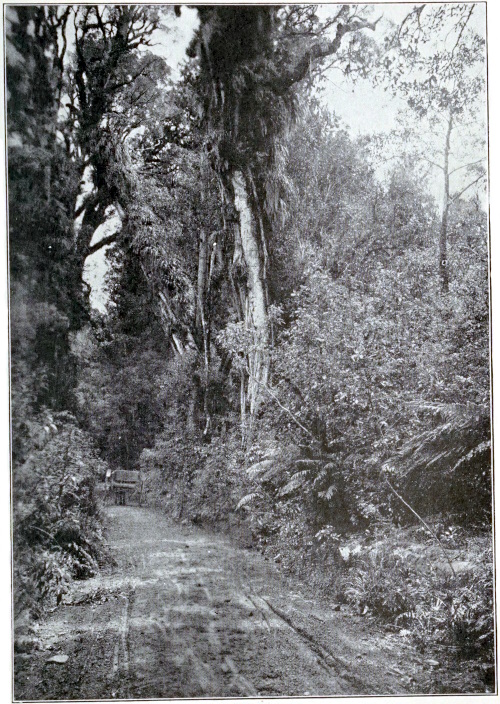

| A New Zealand forest | 170 |

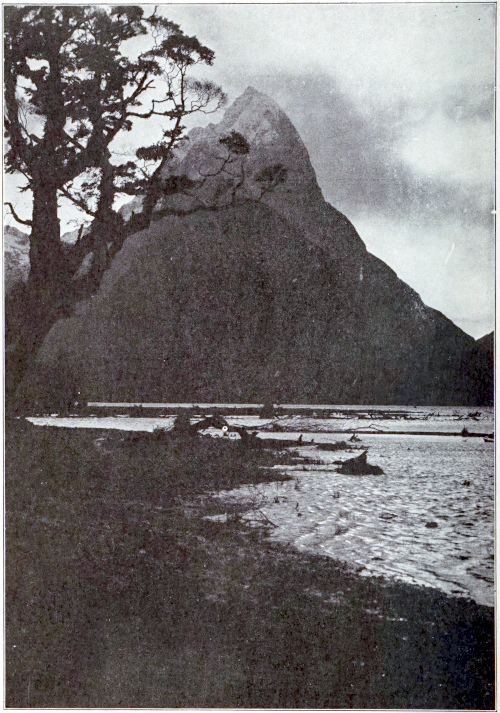

| The beautiful coast of South Island | 171 |

| Potential water power | 178 |

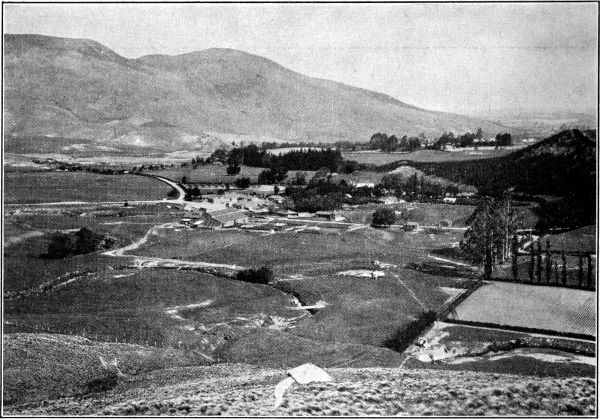

| A New Zealand farm | 179[Pg xii] |

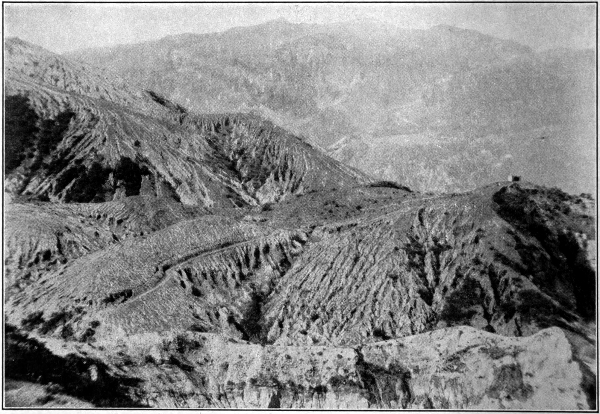

| The crater of Mount Tarawera | 179 |

| Developing new crops | 182 |

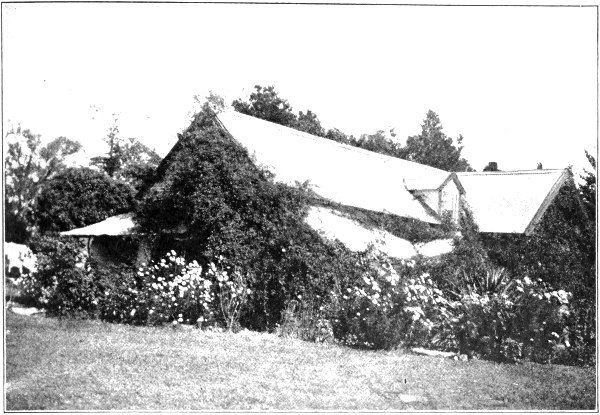

| A settler’s home site | 183 |

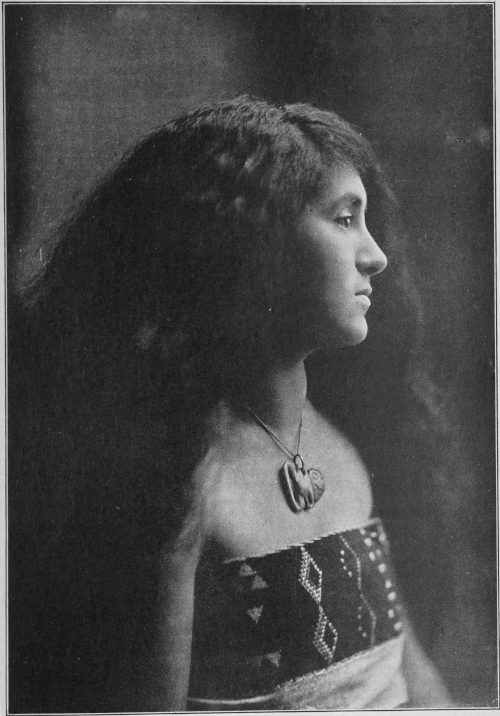

| A Maori belle | 190 |

| Women hop pickers | 191 |

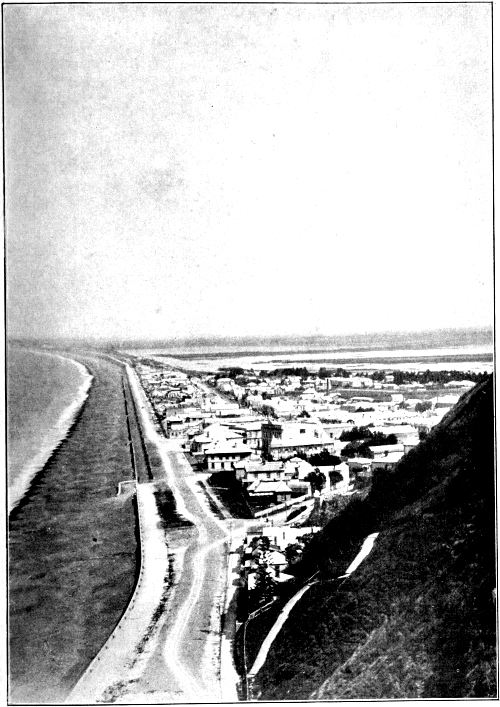

| Beach at Napier | 198 |

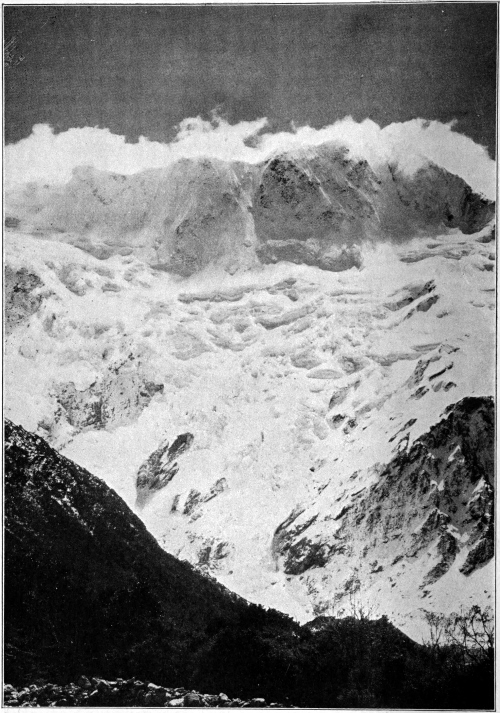

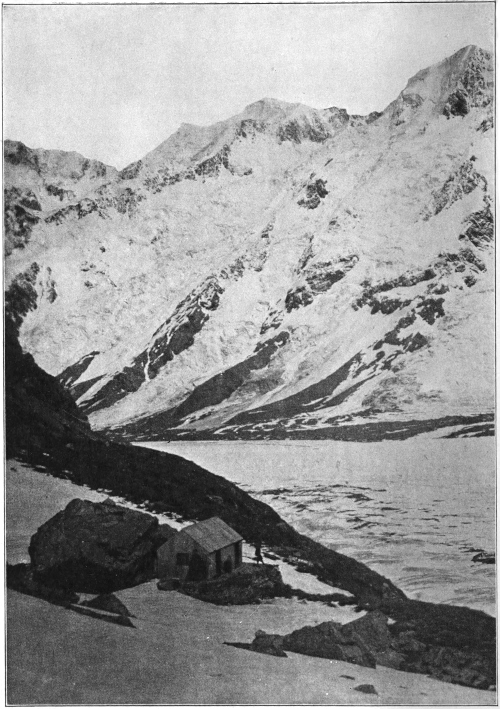

| The great Tasman glacier | 199 |

| Christmas roses | 206 |

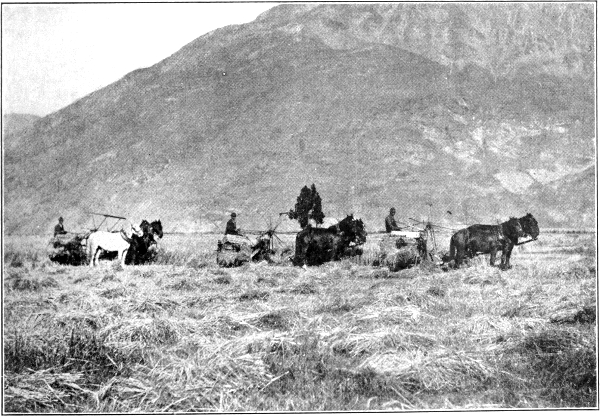

| The wheat harvest | 206 |

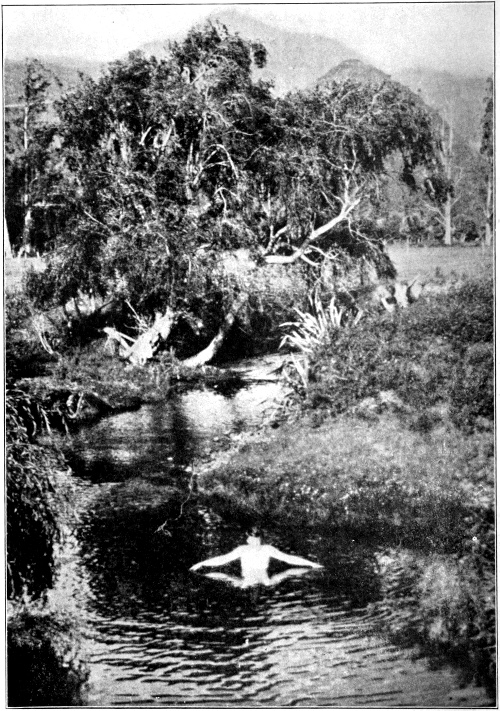

| The New Zealander’s favourite sport | 207 |

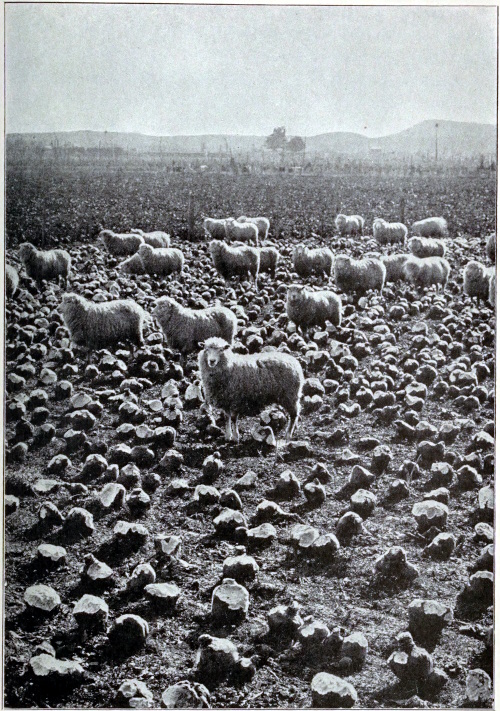

| Sheep in a turnip field | 214 |

| A private railroad | 215 |

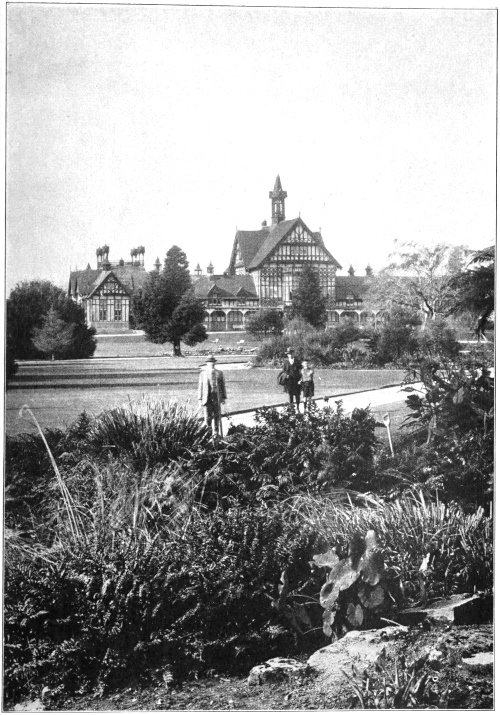

| At the Yellowstone of New Zealand | 222 |

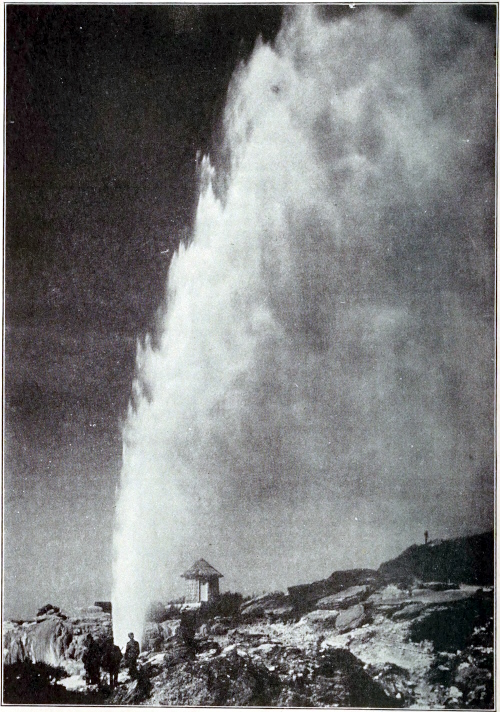

| Wairoa geyser | 223 |

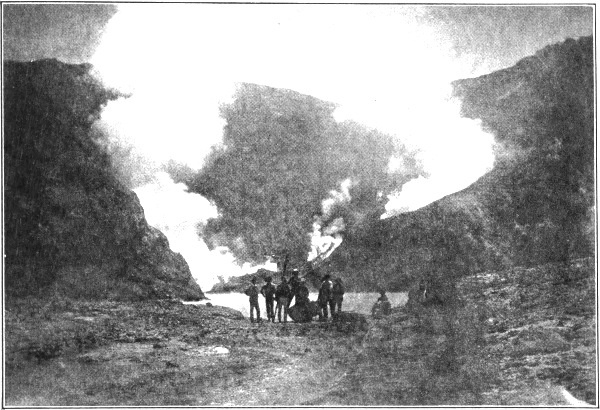

| The hot sulphur pit of White Island | 226 |

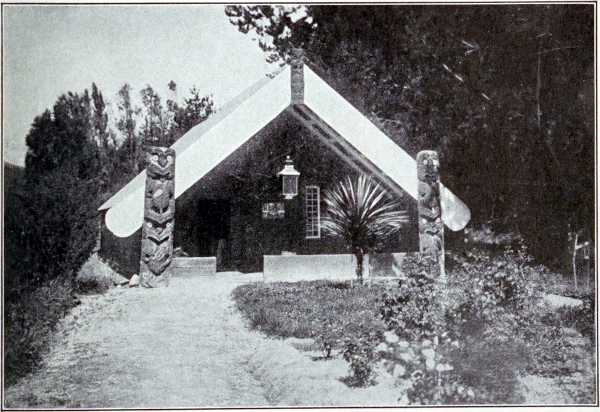

| Maori house at Lake Taupo | 226 |

| Poi dance | 227 |

| Natural fireless cookers | 227 |

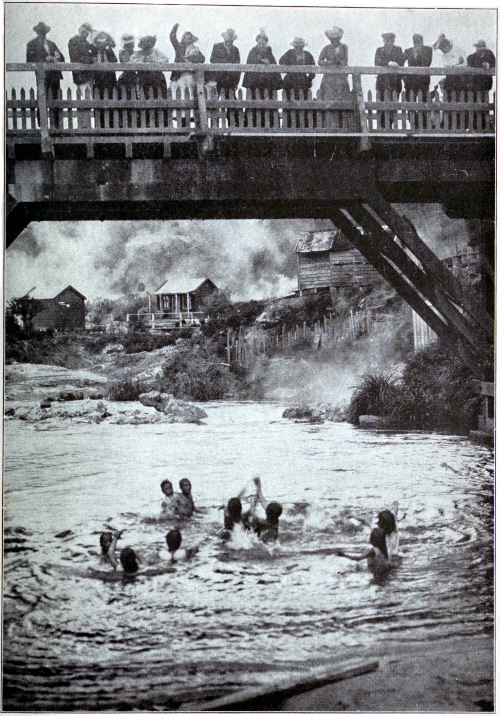

| Bathers in the hot pools | 230 |

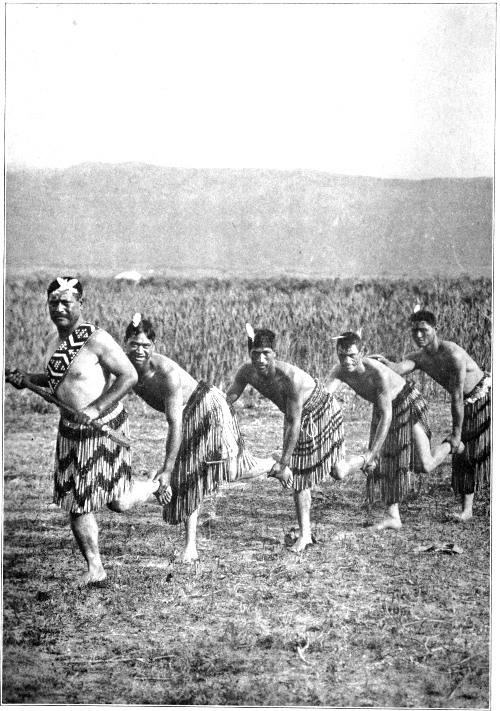

| The Maori haka | 231 |

| Grading butter for export | 238 |

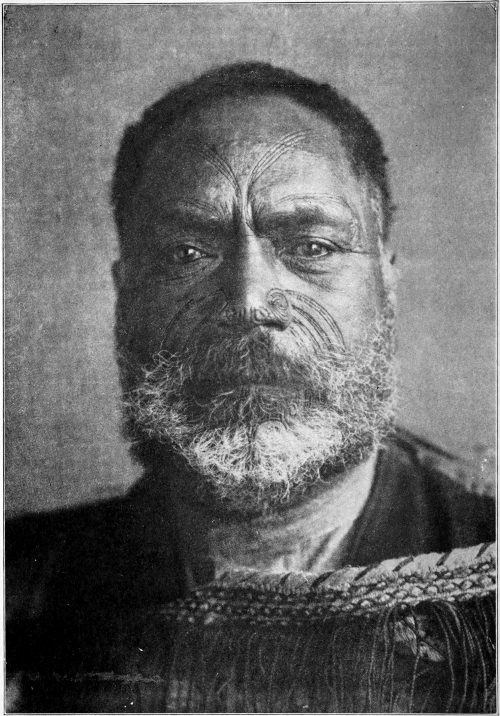

| The dying art of tattooing | 239 |

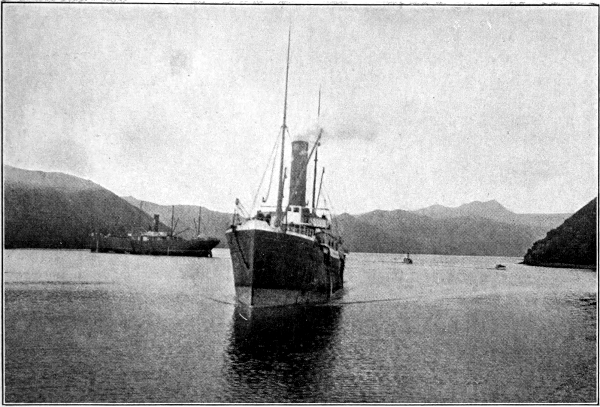

| A New Zealand harbour | 242 |

| The rabbit trappers’ catch | 242 |

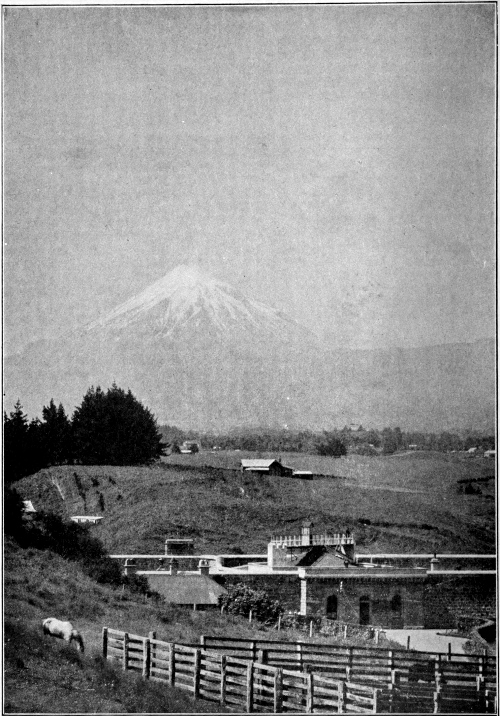

| Mount Egmont | 243 |

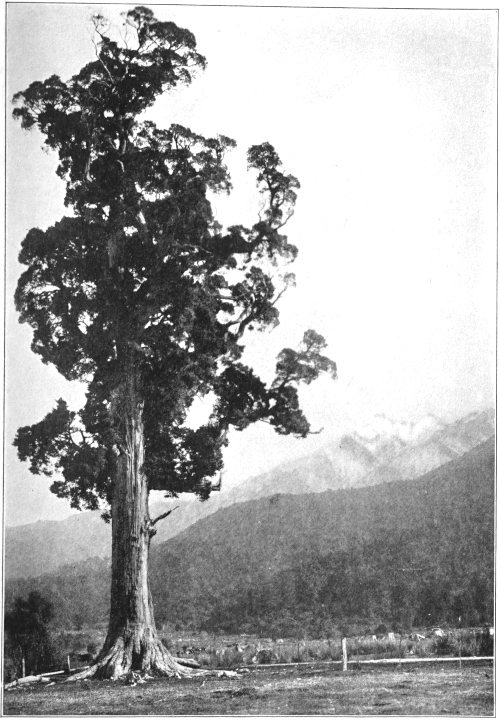

| The totara tree | 246 |

| On Mount Cook | 247 |

| Kauri gum mines | 254 |

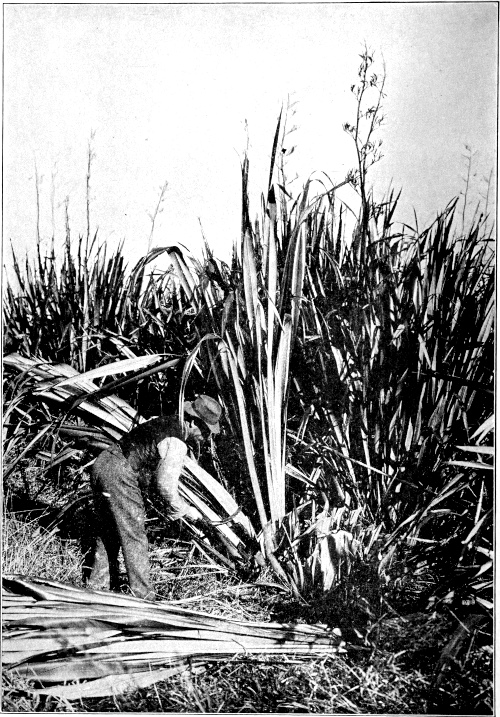

| New Zealand flax | 255 |

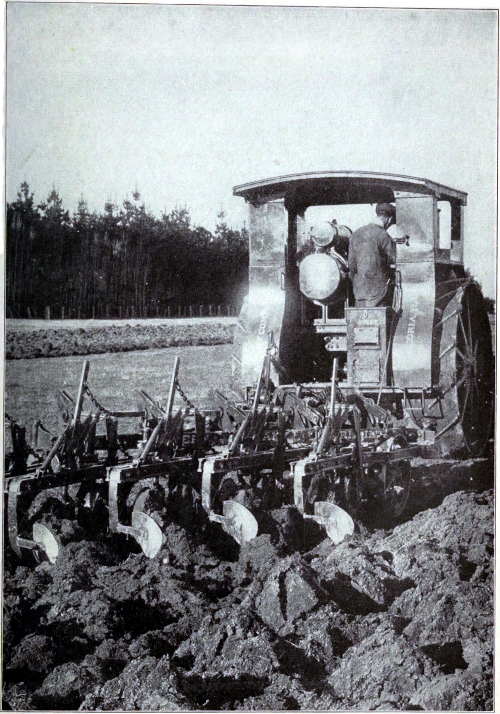

| Farming with tractor and gang ploughs | 258 |

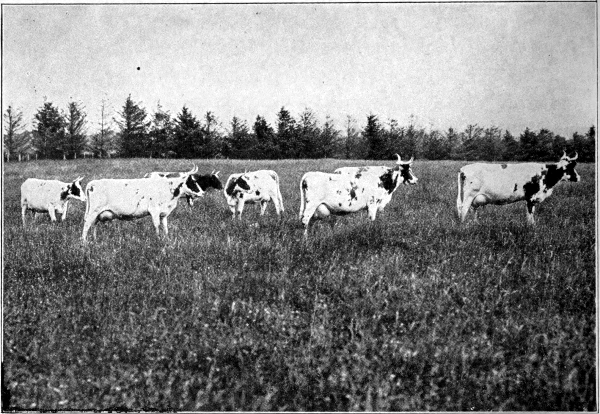

| A dairy herd | 259[Pg xiii] |

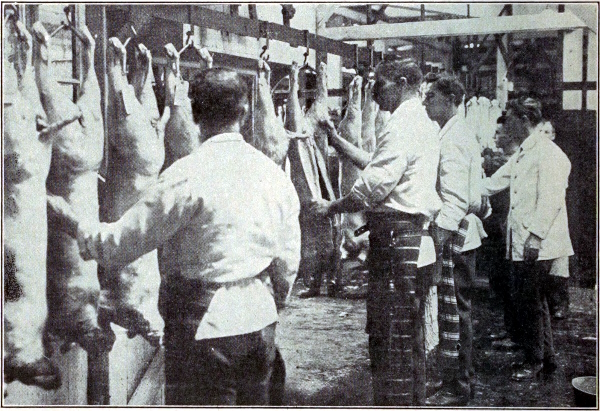

| London’s mutton chops | 259 |

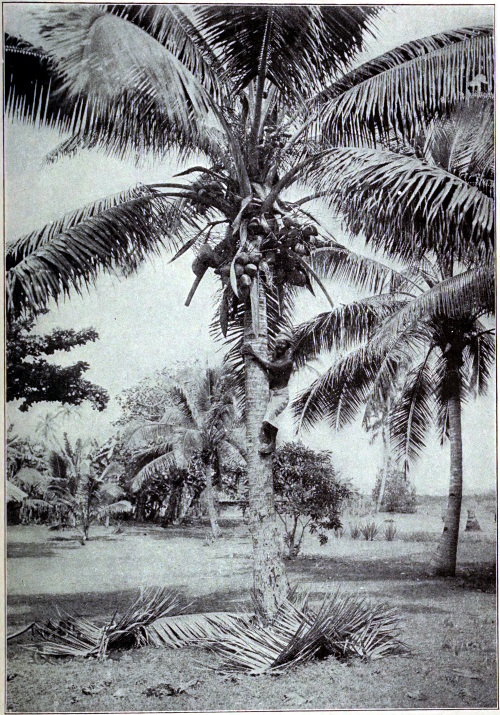

| Gathering coconuts | 262 |

| Tree nursery on a rubber plantation | 263 |

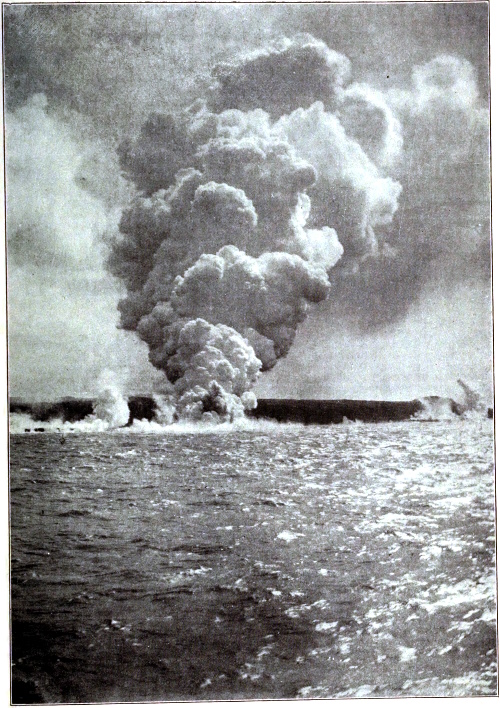

| Savaii in eruption | 270 |

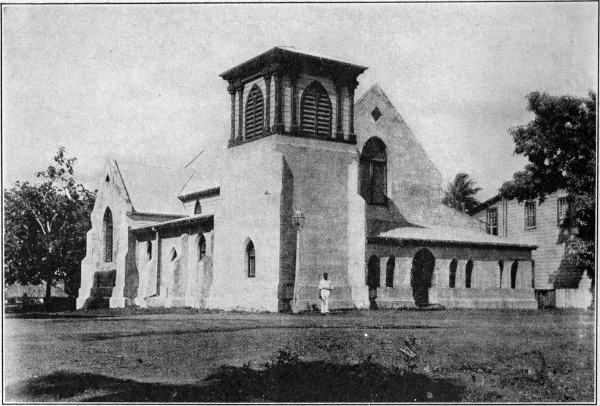

| Native church at Apia | 271 |

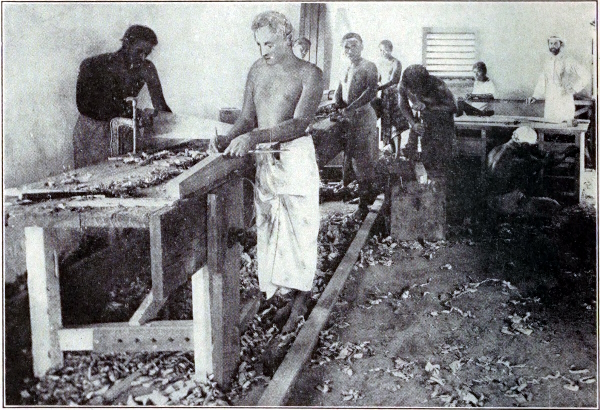

| Native mission school | 271 |

| A Samoan beauty | 274 |

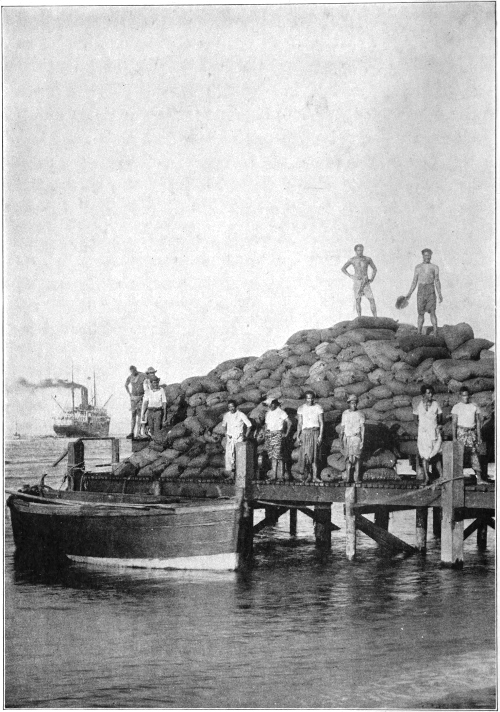

| Copra ready for shipment | 275 |

[Pg 1]

AUSTRALIA, NEW ZEALAND

AND

SOME ISLANDS OF THE SOUTH SEAS

JUST A WORD BEFORE WE START

STARTING on a trip to Australia gives one for the moment the feeling expressed in Kipling’s lines. The “Never-Never Land,” as it is called, is so far away, the voyage is so long, and thoughts of the to-be-discovered continent are so full of dreary anticipation! The vast stretches of desert, the monotonous reaches of forests where the trees shed their bark and the silence is broken only by the harsh cry of the “laughing jackass,” or kookooburra bird, the fearful dryness, and the awful heat—these things of which one reads so much in the books about the country do not make pleasant pictures in the mind of the traveller.

One can go to Australia in three weeks on a comfortable steamer from Seattle, San Francisco, or Vancouver; my own trip, however, was taken after a long, hot stay in the Philippines and a leisurely drifting from there past Borneo and down the coast of Cochin-China to Singapore and[Pg 2] Java. At Batavia I caught a little tramp steamer bound for the East on a route passing through the Dutch East Indies to Torres Strait, Thursday Island, and New Guinea, and thence going southward inside the Great Barrier Reef to Brisbane in Queensland.

The itinerary looked interesting, the voyage venturesome, and as I walked on board my heart sang. A day or so later it wept. The meat was atrocious, the bread soggy, the rancid butter oil, and the water lukewarm and bitter. As a whole, my fellow voyagers were no better than the food. For the most part they were a motley crowd of dirty Hindoos and Malays, with the flotsam and jetsam, blacks, browns, and whites found scattered throughout the islands.

Moreover, two of our Moslem passengers developed a fever, which led to our being quarantined at some of the ports. We were twenty-five long days on the Equator, and it was only when the cool breezes off the Barrier Reef blew new ozone into our lungs that life again seemed worth the living.

But from the day I landed in Brisbane and started off on my journeyings in the “lonely continent” to the day on which I once more turned my face toward home I had no regrets that I had come. Australia was full of surprises and of interest for me; the beauties of New Zealand and the air of its mountains soon drove the evil out of my soul and put new life into my bones. I decided that here was a case where the desire “for to admire and for to see” that had sent me off to the other side of the world had done some good to me after all. I trust that you, too, may be glad that I went and that I have set down here the story of what I saw.

The few rivers of Australia are short and mostly unnavigable. In summer many of the streams dry up entirely or form a series of detached pools. The one big river system is the Murray, on the eastern side of the continent.

In some dense Australian wilds are towering tree ferns such as disappeared from the rest of the earth before the Coal Age and are now seen elsewhere only in the fossilized remains of prehistoric times.

[Pg 3]

THE GIANT OF THE SOUTH SEAS

THE Australians say their country is the biggest thing south of the Equator, and what I have seen here makes me think that they are right. Australia is as big as the United States without Alaska, twenty-five times larger than Great Britain and Ireland, fifteen times the size of France, and three fourths as large as all Europe.

It is a country of magnificent distances, being longer from east to west than the distance from New York to Salt Lake, and wider from north to south than from New York to Chicago. By the fastest trains, Brisbane is thirty-six hours from Sydney, and Sydney is eighteen hours from Melbourne. It takes three days and eighteen hours to make the trip by rail from Melbourne on the southeast to Perth on the southwest coast.

Australia is also a land great in its resources. Since gold was discovered there in 1851, it has produced five billion dollars’ worth of the precious metal. Gold has been found all over the continent—in the mountains, on the farms, and in the sands of the deserts. Yet the greater part of the country has never been prospected, vast areas have not even been explored, and new gold mines may be discovered any day. It is known that the continent contains great quantities of iron, and tin has been extensively mined. There is coal in every state and the deposits of[Pg 4] New South Wales, the only ones that have been well surveyed, are estimated to contain more than one billion tons. The coal beds of the state of Queensland are believed to be inexhaustible. Silver, too, is found in all the states, and the Broken Hill mines of New South Wales are among the richest of the world.

More important than its mineral wealth, however, are the pastoral and agricultural riches of Australia. Enormous flocks of sheep pasture on the sweet grasses of thousands upon thousands of her acres. She produces some of the best wool on earth and exports a quarter of a billion dollars’ worth annually. Her wheat lands produce enough for the needs of her five and a half million people and furnish one hundred million bushels for export. It is estimated that with close settlement she can raise one billion bushels, or sufficient to feed a population of one hundred and fifty millions. Dairying is now one of the largest of her industries and sixty million dollars’ worth of Australian butter goes overseas every year.

In Australia there are great fertile tracts of land, but there are also vast areas of desert. The well-watered eastern part of the continent is rolling and hilly for about one hundred and fifty miles back from the coast. West of this region lies the country of plains, the first part of which is a belt of prairie lands three hundred miles wide, where there are fine sheep and cattle ranches and wheat and fruit farms. Here, too, is the only real river system of Australia, the Murray-Darling. Near the western border of the plains is the salt Lake Eyre sunk in a depression below sea level. Beyond Lake Eyre, extending almost across the continent to within three hundred miles of the west coast, and to within about the same distance from the[Pg 5] ocean on the north and south, is the Great Desert. This has an estimated area of eight hundred thousand square miles, or about one fourth of all Australia. Except in the southwest corner, where gold is mined, there are said to be less than one thousand white people in this arid waste. The air is so dry that one’s fingernails become as brittle as glass, screws come out of boxes, and lead drops out of pencils. I am told there are six-year-old children living in this region who have never seen a drop of rain.

Australia is a land of strange things as well as big ones—queer plants, queer animals, and aborigines who are the most backward members of the human race. There are lilies that reach the height of a three-story house, trees that grow grass, and other trees whose trunks bulge out like bottles. In the dense “bush” are mighty eucalyptus trees rising two hundred feet high. They shed their bark instead of their foliage, and the leaves are attached to the stems obliquely instead of horizontally. There are towering tree ferns such as disappeared from the rest of the earth before the Coal Age and are now seen elsewhere only in the fossilized remains of prehistoric times.

Two thirds of the animals of Australia, like its famous kangaroo, are marsupials; that is, the females have pouches in which they carry their young. Except for the opossum, and the opossum rat of Patagonia, marsupials occur nowhere else. Stranger than the kangaroo, stranger even than Australia’s wingless bird, the emu, is the platypus, which is found only on this island continent. It has a bill like a duck’s, fur like a seal’s, and a pouch like that of a kangaroo. It is equally at home on the land and in the water. It lays eggs, yet it is a mammal; though a[Pg 6] mammal it has no teats, but nourishes its young by means of milk that exudes through pores into its pouch.

As for the natives, when William Dampier, the first Englishman to land on the shores of Australia, came here in 1699, he described the aborigines as “the miserablest people in the world, with the unpleasantest looks and the worst features of any people I ever saw. Setting aside their human shape, they differ little from brutes.” Whence these natives came and how long they had been on their island continent none knows. All agree, however, that the bushman, or blackfellow, as he is generally called, is the lowest form of man. Throughout uncounted years he has made no progress. He is without history and without tradition. Contact with civilization kills him. The aborigines of Australia are a dying race, numbering now a scant fifty thousand.

For centuries after the rest of the world was making history, Terra Australis, or the South Land as it was called, was also a terra incognita, a land unknown. This does not seem strange when one considers how isolated it is. It is so far from the other land masses of the globe that it deserves its name of the “lonely continent.” It is eighteen hundred miles from Asia, forty-five hundred miles from Africa, and more than six thousand miles from the west coast of North America. Even New Zealand, which on the map looks so close to it, is twelve hundred miles away. It takes the best Pacific steamers nineteen days to go from Sydney to San Francisco, and for the fastest mail boats it is a five-weeks’ voyage from any Australian port to Liverpool.

Australia produces enough wheat for her 5,250,000 people, and has 100,000,000 bushels for export. With close settlement, it is estimated that she can raise 1,000,000,000 bushels, or sufficient for 150,000,000 people.

Half the world is kept warm with wool from the flocks of sheep pastured on tens of thousands of Australia’s acres. She produces some of the best wool on earth, and exports more than any other country.

Fifty years ago Brisbane was a village, and before that a British convict colony. To-day it is the fourth city in size in the Commonwealth, and the capital of the progressive state of Queensland.

Brisbane is cut in two by the Brisbane River, a wide stream navigated by ocean vessels, which come here for cargoes of frozen beef, wool, and grain.

When the United States was an infant among the independent nations of the earth, the history of Australia began.[Pg 7] And just here the story of the “lonely continent” is linked with our own. There were a number of persons in the American colonies who remained loyal to the King throughout the Revolutionary War. When independence was won they found this country an uncomfortable place in which to stay. So it was planned by the British to make Australia a new home for the American “Loyalists.” This scheme failed, but another took its place. In colonial days the British had used America as a dumping place for undesirable citizens, especially political prisoners, and had sent them across the Atlantic at the rate of one thousand a year. Now that this human riffraff could no longer be shipped to us it was decided to transport them to Australia. Accordingly, in 1788 a thousand convicts were landed at Sydney Cove, and this was the beginning of the British occupation of the great South Land.

One hundred and thirteen years after that initial settlement there came into being the Commonwealth of Australia. In the birth year of the present century, the half dozen different Australian colonies, some as widely separated as any parts of our own country, became a federated union of the six states of Queensland, Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia, West Australia, and Tasmania. Before this these states had quarrelled frequently over matters of trade and internal development, and each had gone its way without regard for its neighbours. With federation, the tariff barriers between them were removed, common policies were agreed upon, and all joined hands in the determination to work together to create a new nation of white men within the British Empire.

Besides the six states, there are the Northern Territory, the Federal Territory, and the territories of Papua and[Pg 8] New Guinea. The Northern Territory is the tropical area of some half a million square miles ceded by the state of South Australia to the central government. The Federal Territory corresponds nearly to our District of Columbia; for it is the nine hundred and forty square miles set aside for Canberra, the new capital of the Commonwealth. During the erection of the necessary buildings at Canberra, the capital remains at Melbourne. The territory of Papua, or British New Guinea, is the southeastern part of the island of New Guinea and is administered by officials nominated by the Governor-General of Australia. The Territory of New Guinea consists of those lands formerly embraced in German New Guinea, which Australia governs under a mandate from the League of Nations.

In many ways the constitution of the Commonwealth is like ours. Each of the states has its separate government, with great latitude in the management of its own affairs. The British Crown appoints a Governor-General for the whole Commonwealth, but his authority is merely nominal and the real executive power is in the hands of the Premier of Australia and his nine ministers. The Prime Minister is the leader of the majority of the Federal Parliament of which he and his cabinet must be members.

Parliament consists of a Senate and a House, organized much like our own Congress. The Senators are elected for six years and the representatives for three, but under certain conditions the House may be dissolved by the Governor-General before the three-year term is up. There are seventy-six representatives elected in proportion to population, and thirty-six senators, six from each state. Senators and representatives get the same salaries, each receiving five thousand dollars a year. It is provided that[Pg 9] no member of Parliament can hold office if he has been bankrupt and failed to pay his debts, and if he takes benefit, whether by assignment or otherwise, of any bankruptcy law during his term of office his seat will at once become vacant. He cannot have any interest in any company trading with the government, nor can he take pay for other services rendered to the government. The state governments are organized like that of the Commonwealth, each having its premier, who is the leader of the majority in the state Parliament.

Following the World War many countries experienced political upheavals and radical ventures in government. But it was in Australia years earlier that a working-man’s party first gained control of a national government. As we go about in the several states of the Commonwealth we shall find many evidences of the part played in public affairs by the labour unions. They have frequently held a majority in state legislatures, but are especially anxious to dominate the federal Parliament so that they may put their ideas into effect on a wholesale scale. Woman suffrage, adopted in Australia almost without opposition, has added strength to the labour element, for it is generally agreed that nearly every workingman’s wife goes to the polls, while many of the women of the well-to-do classes stay at home.

[Pg 10]

QUEENSLAND

MOST travellers from our hemisphere first set foot on the Australian continent at Sydney, the biggest seaport of the country and the seventh city in size in the whole British Empire. I first stepped out upon its mainland at Brisbane, which lies five hundred miles north of Sydney and is the capital of the state of Queensland.

In coming down the coast from Thursday Island and Torres Strait I had one of the wonder trips of the world, for my way lay inside the Great Barrier Reef.

Imagine a chain of coral as long as from New Orleans to Chicago. Let the chain be composed now of atolls, great coral walls encircling lagoons, now of long coral ridges, and now of gardens of the beautiful red, white, and pink flowers fashioned by these insects of the seas. Such is the Great Barrier Reef, which extends along the whole eastern coast of Australia northward to Torres Strait. For the most part it is only from five to fifteen miles from the mainland although in one place it is a hundred miles off shore. At times we were close to the coast, and again were moving along near huge rings of coral that seemed to float on the green sea. Some of the atolls had vegetation upon them, their round basins being circled with coconut trees, while others, seen only at low tide, were stony and bare.

[Pg 11]

The air was wonderfully clear and the sky a heavenly blue. The few clouds made big patches of dark blue velvet on the dreary gray of the Australian mountains. The sea was as smooth as a mill pond. We were feeling our way along through a wide canal, one side of which was walled with the cliffs of Australia and the other by this masonry of countless millions of coral polyps. Our steamer had to go cautiously, for under the smooth waters were treacherous spurs and peaks of coral ready to rip holes in her side. Our captain kept a sharp lookout for brown waters, which mean bars, or green, which indicate coral, and steered a course through the deep blue of the safe passage. Among navigators the shallows between Cape York and New Guinea have the reputation of being the worst waters in the world. Some of the ship captains boast that they can smell the coral in the dark, just as those of our transatlantic liners declare that they can smell the ice of the bergs that drift down from the North.

Such cautious sailing began to get on the nerves of some of the passengers and I think all of us were glad when our steamer turned into Moreton Bay, the outer harbour of Brisbane. We approached a low shore of sandy dunes and beaches rising gradually into rolling hills thick with trees. Slowly we entered the mouth of the wide Brisbane River, up which we travelled for several hours. As our steamer went on through the murky water, we could look over the side and see masses of jelly fish, transparent mushrooms of bright violet, tossed this way and that by the waves from the ship. The banks were low and covered with bushes. Along the way there were meat-freezing plants, each surrounded by little houses roofed with galvanized iron, the homes of the workmen.

[Pg 12]

As we kept on, the country on each side of the river became more hilly, and when we reached Brisbane I found it a place of as many gulleys as Kansas City. Most of the town lies on the right bank of the river. There are many pretty villas, and rising high above them is the Queensland Parliament House.

After a lenient examination by the customs officials, I drove to my hotel through streets not unlike those of an American town. They were paved with wood instead of brick or asphalt. The stores reminded me of ours at home, and the size of the buildings surprised me.

Brisbane, the capital of the second largest of the six states of Australia, has more than two hundred thousand people, and is the fourth city in size on the continent. During the last half century it has had a phenomenal growth. Less than seventy-five years ago it was taken away from the neighbouring colony of New South Wales and became the capital of Queensland. At first it grew but slowly, for it was handicapped by having been the site of the Moreton Bay Settlement, a colony for the worst of the convicts sent over from England. When it began to get on its feet a terrible flood swept away so many of the houses in the low-lying sections that it was believed the town would never recover. Yet it took a new lease of life, and to-day it is hard to realize that, fifty years ago, it was only a village with less than one thousand inhabitants.

The public buildings were planned with an eye to the needs of the future. The State Treasury would do credit to our own capital at Washington. The Law Courts cost nearly two hundred thousand dollars, and the Parliament Building half a million. In George Street is a splendid palace which houses the Lands Office, and the Public[Pg 13] Library is a striking piece of Italian architecture. On a steep cliff above the big-domed custom house rises the Cathedral of St. John, considered the finest Gothic structure in all Australasia.

Talking with the Queenslanders it is easy to see that they think theirs is the coming state of Australia. They say the good lands of Victoria have long since been taken up, that New South Wales is fairly well developed, and that such large areas of South Australia and West Australia are desert that those states can never support a great population. Queensland has two slogans: One claims that it is “a paradise for willing workers,” and the other that it is “the richest unpeopled country in the world.” The state has vast tracts of arid land, which it expects to reclaim by artesian wells. It has already redeemed from the desert a country more than twice as large as the state of New York, having discovered that most of the great area beyond the coastal range is underlaid with subterranean lakes and streams, which will furnish water for stock. The cultivated acreage is growing every year. Enough pastures for seventeen million sheep are now in use, and the state has already nearly twice as many sheep as any other division of Australia.

Queensland might be called “The Newest England” of these British south lands. It is a principality in itself. It comprises the northeastern quarter of the Australian continent; from north to south it is as long as from Washington to Omaha, and from east to west about as wide as from Washington to Chicago. It is three times as big as France, and twelve times the size of England and Wales.

The upper half of Queensland is not far from the Equator[Pg 14] and raises cotton, sugar, tobacco, and all sorts of tropical fruits. Bananas do so well that one of its nicknames is the “Banana State.” Scrub lands cleared at a cost of about ten dollars an acre can be planted without ploughing and will produce fruit in a twelvemonth. Fifteen tons of pineapples to the acre is not an unusual crop, and pines weighing from fourteen to sixteen pounds have been grown. The factories for canning this fruit that have been started with the aid of the government may some day compete with the great pineapple canneries of Hawaii.

A great advantage of the fruit-growing business in Australia, as in South America, is the difference in seasons in the Northern and Southern hemispheres. Being south of the Equator, the fruits ripen at a time of year when European and North American markets offer the best prices, and refrigeration and fast boats are already landing Queensland fruits on our winter tables.

Australia usually raises enough sugar to supply her own needs, and ninety per cent of her crop is produced in tropical Queensland. Sugar cane was first grown here about 1865, and in the early days the plantations were worked with coloured labour brought in from the South Sea islands. Later on it was decided to send the “blacks” home, and keep the resources of the state for white men exclusively. From the standpoint of the growers, this was a real sacrifice, and the Commonwealth government is now doing everything possible to stimulate sugar production. At one time it paid bonuses on sugar produced by white men, but these have been given up. Now the government buys the entire crop outright and controls its refining and sale. The cane is crushed in Queensland, but is refined by the big Colonial Sugar Refining Company in Melbourne[Pg 15] and Sydney. Under the government monopoly the consumer pays about twelve cents a pound. Importation of sugar by private individuals or companies is forbidden, and whenever the Queensland crop falls below three hundred thousand tons the government imports enough to meet the requirements.

Australia has her sugar bowl in Queensland, which produces nearly enough cane to supply the entire population. It is one of the few places in the world where the crop is grown without coloured labour.

When it is snowing in New York, the Queensland fruit grower is gathering his pineapples. They are raised on land leased from the government with the privilege of purchase on easy terms.

On the elevated sandstone plains of interior Queensland grows the queer bottle tree. One’s general impression of Australian forests is their total unlikeness to anything elsewhere.

In the southern part of the state are the Darling Downs, four million acres of the richest soil on the continent. Here the average rainfall is more than thirty inches a year, and almost everywhere artesian water may be had within a few feet of the surface. Since they were first settled in 1840 the Downs have been the home of prosperity. To-day they roll away in orchards and green fields, dotted here and there with herds of fat dairy cattle, and checkered with chocolate squares of ploughed lands. I am told that some of the soil is too rich to raise wheat until it has been farmed a few years. In some places it produces one hundred and ten bushels of corn to the acre, and on a number of farms two crops are raised every year. A great deal of money is made in alfalfa, which grows very rank. Often as many as nine crops are cut in one year, each yielding from one to two tons per acre. On the best land it is not uncommon for a man to get a hundred dollars per acre annually out of alfalfa. As a general thing the farming is carelessly done, and but little fertilizer is used. The seeds are merely sown and the crop is reaped.

The principal city on the Downs is Toowoomba, two hundred miles west of Brisbane and two thousand feet above sea level. It serves as a playground and health resort for the people of Brisbane and elsewhere in the hot lowlands. Throughout the year the climate is temperate and bracing, and in June and July, the coolest months of the year, there[Pg 16] are often frosty mornings here and fires are welcome at night.

Toowoomba is also the unofficial capital of the rich farming district of the Downs. Its streets are generally full of men who have ridden in from the country to talk sheep, wool, grapes, wheat, or timber, or to seek amusement after their hard work in the fields. Its pretty homes are surrounded by gardens of English flowers and hawthorne hedges and rows of weeping willow trees. I have seen many weeping willows along the streams of Australia, and the people say that all are the descendants of slips brought from the island of St. Helena. In the old days ships bound for Australia used to stop for water at the place of Napoleon’s exile and the outgoing colonists provided themselves with willow cuttings to be planted in their new homes.

Queensland’s great need is more people. In this huge state, capable of supporting a population of many millions, there are less than eight hundred thousand, or only about one person to every square mile. I have before me an advertisement of the Acting-Registrar General declaring that the two necessities of the state are “increased production and increased population” and offering inducements in the way of cheap lands on easy terms to “the industrious in every walk of life.”

Throughout Australia land transfers are made under what is called the Torrens Title, a system which has spread to Canada, to England, and to other countries of Europe, and has been adopted by the United States for the Philippines and Hawaii. Ohio also has adopted it, and others of our states are using it in modified forms. By this system the landowner registers his property with the[Pg 17] land office, receiving a duplicate certificate of title. If later he wishes to sell he hands over the certificate to the purchaser, who has the sale registered at the land office, where the facts of the transaction are entered on the original certificate. If the owner puts a mortgage on the property the terms are recorded with the Registrar. The certificate therefore always contains the name of the owner, a description of the land, and a statement of all liens and encumbrances. No title searching is necessary, and by the payment of a small fee at the Registrar’s office, anybody can find out all about a given piece of land. The Torrens System and the secret ballot are two big ideas that we owe to our Australian cousins.

For many years a thorn in the flesh of the small farmers and workingmen of Queensland was the fact that, by special legislation, big lease holders of the public lands paid lower rents per acre than the holders of small tracts. The Land Act Bill of 1915, framed to remedy this condition, was passed by the lower house of the state Parliament but was rejected by the upper chamber, or Legislative Council. The Council was at that time composed of thirty-seven members appointed nominally by the Crown, but really by the Queensland Prime Minister and his Cabinet. They could hold office for life, and no limit was placed on their number. As constituted in 1915, the Council had only two representatives of labour and the rest of its members were conservatives, many of them moneyed men determined to guard their own interests. On the other hand, the seventy-two members of the Legislative Assembly are elected by the people for three-year terms. The Land Act Bill was passed by the next Assembly and again rejected by the Council. Then the[Pg 18] government stepped in to see that the will of the people was carried out. It appointed enough new members known to favour the act to swamp the conservatives in the Council, and the bill at once became law. So enlarged, the Council, with its majority in absolute accord with that in the lower house, became a mere rubber stamp for the legislation passed by the Assembly, and even approved the bill ending its own existence.

The government of Queensland is sometimes criticized as a patriarchal institution for coddling the people. Both town and country make all sorts of demands on it to serve their interests. They tell a story of one official who, exasperated by a deputation of farmers, burst out with this:

“You ask the government to do everything. I am surprised that you do not demand that we furnish milk for your babies.”

Queensland, the northern half of which lies just south of the Equator, is sometimes called the “Banana State,” because of the success of settlers in growing that fruit in the newly cleared lands.

The farmer who owned the hill now known as Mount Morgan sold it to prospectors for five dollars an acre. It has since yielded gold worth $125,000,000 besides vast quantities of copper.

In the Anakie gold fields of western Queensland mining sapphires is a well established industry, with an output worth about one hundred thousand dollars a year. The lemon or orange tinted stones are the most prized.

[Pg 19]

A CROWN OF GOLD AND A CROSS OF CACTUS

QUEENSLAND is one of the gold states of Australia. It is especially noted for Mount Morgan, perhaps the richest gold mine of the world. This mountain is twenty-four miles from the city of Rockhampton, on the coast north of Brisbane. It has already produced more than one hundred and twenty-five million dollars’ worth of gold, and paid more than fifty million dollars in dividends. The original fourteen owners invested only a few hundred pounds.

The mountain belongs to a low range of hills not far from the coast. It was part of a farm owned by a man named Gordon, who had fenced it in and was using it for pasturage. One night Gordon was visited by two brothers named Morgan, who were prospecting. The Morgans stayed overnight, and Gordon told them he thought there was copper on his farm as he had noticed green and blue stains in the rocks. The next day he took the prospectors to the mountain, and when they left they carried away samples. A few days later they came back and offered him five dollars an acre for the property. He was glad to sell, and for this price the Morgans bought one of the richest mining properties ever known. To get money to work the mine they sold a half interest to three men in Rockhampton for ten thousand dollars. With this they[Pg 20] experimented, and finally discovered that the ore could be worked by the chlorination process. The result was that they and their associates soon became millionaires.

Since then the works have expanded until a town has grown up at the foot of the mountain. There are great mills, in which more than two thousand men are employed. The mine has continued to pay big dividends, but these now come from copper rather than from gold. For, when the gold began to grow scarce, apparently inexhaustible supplies of copper were found underneath the deposits of the more precious metal.

Some people think that there may be other gold deposits in the neighbourhood equally as rich as those of Mount Morgan. However that may be, it is a fact that twenty miles from the city a little boy one day found a nugget worth ten thousand dollars.

Rockhampton is a city of twenty thousand founded on the gold and copper mines. It is now growing as a centre of the dairying and mixed farming interests fast developing in the surrounding country. The town, which has the Tropic of Capricorn running through one of its streets, is built some thirty miles inland on a steamy valley of the Fitzroy River. It is cut off by a high range of hills from the ocean breezes. Even in June, the coolest month of the year, the thermometer goes above eighty degrees Fahrenheit, and in February the mercury often rises to one hundred and sixteen. In the early gold-mining days the Britishers who came out to get rich and toiled in the heat nicknamed the place the “City of the Three S’s”—Sin, Sweat, and Sorrow. Nevertheless, it is a growing town full of business.

Three hundred miles northwest of Rockhampton is the[Pg 21] town of Charters Towers, the centre of another big gold field a few miles back of the seaport of Townsville. The gold at the “Towers” was discovered in 1872 by three prospectors, who took out millions of dollars’ worth in a short time. The principal mining is quartz, some of the workings being very deep. As at Mount Morgan, copper mining is carried on profitably along with the gold mining. Another field is that of Gympie, where, it is said, the boys used to pick up grains of gold in the streets after a rain, sometimes getting as much as half an ounce a day. In that town one man found a nugget worth eleven hundred dollars.

So far, Queensland has produced nearly half a billion dollars’ worth of gold, and mines are still being worked throughout a large area, although the cream of the known deposits has been skimmed off.

There are also deposits of lead, as well as of iron, bismuth, and silver. Iron is found in all sections, and in one district there are little mountains of iron ore. Mt. Leviathan, a hill two hundred feet high, is said to be composed of pure magnetic iron. In the long tongue of York Peninsula, which Queensland thrusts up toward Torres Strait, there are tin deposits over a wide area. Tin is found also in the southern part of the state.

Some of the finest Australian opals come from western Queensland. That region has a long belt of opal-bearing country, extending from a point near the Gulf of Carpentaria across the southern border of the state and into New South Wales. The opals are brought into Brisbane by the handful and sold at low prices. Many of the opal miners are sheep-shearers, who hunt for the stones in the off season. The gems are found in quartz and in[Pg 22] sandstone, from six inches to thirty feet below the surface. The Queensland black opal brings big prices in Paris, London, and New York. It is not really black but a mixture of rich colours, with iridescent green and violet prevailing. Deep down in its heart is a living spark of flame, which has given it also the name of the “fire opal.”

About two hundred miles west of Rockhampton are the Anakie gem fields which are studded with sapphires. Stones to the value of nearly one hundred thousand dollars are produced there every year. The best of them are of the clear lemon and orange tints which have become especially popular with the jewellers of Paris.

So much for Queensland’s crown of gold studded with gems. Her cross is the greenish-gray cactus, which has ruined vast areas of rich agricultural lands. I have heard different stories about how prickly pear came to Australia. Some say John Macarthur, who was such a benefactor to the country through his introduction of the Merino sheep from Spain, is responsible for it. Perhaps he had seen the cactus hedges used in the thickly settled Mediterranean countries to separate small holdings and thought they would be a good thing for the gardens and paddocks of the Australian settlers. It is even said that the first prickly-pear plant was sent to the Downs carefully wrapped in cotton wool and packed in a sealed box. Now, for mile upon mile the traveller sees only an impenetrable thicket of this spiny, gray-green vegetation, growing right up to the settlers’ front doors. It is stated that the plant covers more than fifteen million acres of Queensland, or an area nearly twice that of Rhode Island.

When an Australian speaks of clearing the land of “scrub” he does not refer to a mere matter of brush and saplings, but to what we would consider a dense forest of full-grown trees.

In the cattle country of southern Queensland the farm houses are one-story frame bungalows, roofed with corrugated iron and often set up on iron piles to keep out the wood-devouring ants.

An American dropped from an airplane into Martin Place, Sydney, would feel very much at home. Many of the newer buildings are of our skyscraper type, while the street is filled with motor cars made in the States.

The state government sent a Prickly-Pear Commission on an eighteen-months’ tour around the world in the[Pg 23] effort to find some parasite or disease with which to destroy the pear. It has offered great rewards to any chemist who finds a specific against it, and year by year different methods of extermination are tried out. So far, however, no cheap and infallible way has been found. Uprooting or cutting is useless, unless every single leaf is burned. Squirting a solution of arsenic and soda into each leaf by means of a “pear gun” has proved effective in the case of small growing plants, but this is too slow and expensive on such an overwhelming proposition as fifteen million acres. The remedy probably lies in the closer settlement of the country and the principle of every man’s keeping his own dooryard clean.

[Pg 24]

THE METROPOLIS OF THE ANTIPODES

I AM in Sydney, the fastest-growing city of Australia and the commercial metropolis of this part of the world. People who look upon the island continent as a big desert surrounded by a strip of pasture should come to Sydney. They will find here a city that will open their eyes. It has now about the population of St. Louis or Boston, but it seems to have twice as much business as any place of the same size in the United States. Situated south of the Equator and about the same distance from it as Louisiana, it lies in the centre of the most populous part of Australia, and just where goods can most easily come in for distribution over a vast territory. Sydney is the capital and distribution point for the two million people of New South Wales, a state the size of Texas and Indiana combined. These two million are the richest people of a country with a per-capita wealth of $1,624 or, at five to the family, eighty-one hundred dollars per family.

I know one man who has a million acres of land, and I could hardly throw a stone in the business part of Sydney without striking the holder of five thousand acres and more. There are men here who have a million sheep, and many who own flocks of tens of thousands. Australia has no Fords or Rockefellers. Rarely does any one leave an estate worth above five million dollars. On the other[Pg 25] hand, the wealth is more evenly divided than in the United States, and the workers live much more comfortably than their brothers in Europe. Everywhere on the streets of Sydney I see signs of well-being. There are no patched clothes, and in fact there is no poverty as we know it.

Of all the big cities south of the Equator, I like Sydney best. Especially do I like the people here. Buenos Aires has a population of more than a million and a half, but it is a succotash of Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish ingredients, with a mixture of Indian, English, German, and French. Rio de Janeiro has a million and a quarter inhabitants, sprinkled with so much African blood that one can hardly tell where the white ends and the black begins. Moreover, as in other cities of South America, most of the people are wretchedly poor.

Here the faces are all English, Irish, and Scotch, or, what is better, pure Australian. The Australians are finer looking than their British cousins. They are taller, straighter, and better-formed. Six feet is not an uncommon height for either men or women. The latter are Amazons. Many of them are slender and they tower above me like so many giantesses. They are sometimes called “cornstalks,” because they spring up so rapidly and grow so tall.

Its magnificent harbour and the enterprise of its people have made Sydney the New York of Australia. The city does business with all the world. It is the terminus of a dozen great steamship lines connecting the continent with Europe, Asia, Africa, and North and South America. To-day there are tramps in the harbour from Cape Town, ships from China and Japan, fast vessels from France,[Pg 26] and big steamers from England. One American passenger line connects Sydney with San Francisco, and three others carry freight to and from our Pacific and Atlantic coasts. The Commonwealth Line, which now operates a number of Australian government-owned ships of steel and wood, has a regular service from Sydney to London via the Suez Canal. Besides being linked up with all the great ports of the world, Sydney is a centre of trade along the coast and with the countless islands of the South Seas.

The commerce here is enormous. The wool shipments alone have a value of something like sixty million dollars a year, and there is a large export of grain, coal, and meat. Considering the number of the population, the imports are very heavy. Although New South Wales has not so many people as Chicago, it buys three hundred and sixty million dollars’ worth of goods from foreign countries every year, and most of them come in through Sydney.

In beauty and commercial advantages, Sydney harbour equals the Bay of Naples, the harbour of Rio de Janeiro, or the famous waters about Constantinople on the Bosporus. At its entrance, which is not more than a mile wide, great rocks rising to more than half the height of the Washington Monument form a natural gateway. No matter how stormy the ocean outside, when a steamer passes the Heads, it finds quiet waters. It enters a winding lake or stream, with hundreds of bays, inlets, and creeks studded with islands and walled with wooded hills. The harbour has an area of twenty-two square miles of water held in a rock-bottomed basin. There is a reef in the fairway, but since it runs parallel with the direction of[Pg 27] incoming and outgoing vessels, it is an advantage rather than a drawback, for it divides the harbour into two deep-sea channels. There are no large rivers depositing sand and silt to be dredged out. At the Heads the water is eighty feet deep, and at the wharves it is from thirty to fifty feet. The ships come right into the town, so that one can step ashore, walk three minutes, and be in the business section.

Since coming here I have climbed to the top of the Public Works Building for a bird’s-eye view of the city. This building is on the harbour in almost the centre of the town. Standing upon it one can see the great ocean steamers landing goods at the quays, the ships entering and leaving, and the little tugs and ferries moving this way and that.

Looking over the city I noticed that its buildings cut the skyline like the teeth of a broken saw, one now and then extending for many stories above its neighbours. There are indeed three Sydneys—the fast-disappearing city of the early governors, with its gabled cottages and brick houses; the Sydney of a later time with the ugly architecture of the Victorian era; and the modern, up-to-date Sydney, which reminds me of an American city. It has buildings of the skyscraper type, though not so high as ours. Many of the houses are built of yellow sandstone taken from local quarries.

Sydney covers a large area. Its streets wind about like those of Boston, and it is facetiously said that the place was originally laid out by a bullock driver with a boomerang. The city is noted for its excellent wooden pavements, which, according to our consul here, will last for ten years without repairs. Some time ago part of the[Pg 28] pavement of George Street, upon which are some of the chief business houses, was taken up. The blocks were as good as when laid eleven years before, save that they had been worn down about one fourth of an inch. These blocks are of eucalyptus wood dipped in boiling tar and laid on a foundation of cement. They are fitted as closely as a parquet floor, and are so smooth that three-ton loads can be hauled over them by one horse. Paving blocks of the Australian eucalyptus are now used by some cities of Europe.

One of the most interesting rides I have had in Australia was my trip from Brisbane to Sydney. This takes one through the better parts of the states of Queensland and New South Wales. The road-bed is smooth and the cars are about like those of the United States except that there are no Pullmans until the boundary of New South Wales is reached. There is no baggage checking system such as ours, although the traveller is given a receipt for his trunks. The first-class car in which I rode was divided into compartments with cushioned benches under the windows.

The scenery on this trip is worth noticing. A part of the way is over mountains and across rolling grazing lands. Some of the ride was through forests of eucalyptus trees, always and in all their numerous varieties called “gums” by the Australians. The leaves of the trees seemed to me to hang down as though in mourning and most of them had lost half their bark. The old bark was black and hung in long streamers down the trunks like dishevelled hair, while the new bark, white or silver-gray, looked very pretty by contrast.

In some places there were groves of dead trees. They[Pg 29] had been ringed with the axe to kill them for clearing and stood stark and gray without leaves or bark. In the glare of the bright sun their limbs looked like clean and well-polished bones. A dead Australian forest is a veritable skeleton forest, the deadest-looking thing in nature. Where the trees have been felled the stumps are perfectly white, the logs lying on the ground are white, and the whole makes one think of a bone yard.

When we passed over the Darling Downs we travelled for miles across green fields as flat as a floor surrounded by wire fences, which enclosed great flocks of fat sheep and herds of sleek cattle. On the ploughed lands the soil was as black as that of the Nile Valley and the dark ground looked soft and velvety in the brilliant sunlight. We crossed tracts each of a hundred acres and more of luxuriant alfalfa, and again went through fields where the green blades of wheat were just poking their tips up through the dark earth. Where a stream had made a deep cut I could see that the rich top soil was many feet in depth.

There were but few farm outbuildings, no big barns, and no farmhouses of any great size. The homes were one-story cottages of wood painted yellow and roofed with galvanized iron. In spite of Australia’s huge forests, wood is still expensive and galvanized iron is largely used. Most of the houses had big round iron tanks on their porches to catch the rain from the roofs. Many had galvanized iron chimneys, and a few were built entirely of this material, which is imported from England.

I noticed that some of the cottages were set high up on iron piles capped by iron saucers with rims turned down, in the same way that the American farmer protects his[Pg 30] granary from the rats. The upturned saucers are used to keep out the white ants which will devour almost any wood or leather they can get hold of. In tropical Queensland the piles have another advantage; for they permit a circulation of air under the houses, cooling the floors.

Bondi Beach, near Sydney, is the resort of thousands. Though sometimes accused of overdoing it, the devotion of the Australians to outdoor pleasures has helped make them a healthy, vigorous people.

The water traffic of Sydney harbour centres at the Circular Quay, where all the ferries dock, and the street-car lines converge. The ferry system is one of the largest and most efficient in the world.

On the narrow neck of land separating Sydney harbour from the ocean is Manly Beach, which divides honours with Bondi as a place for surf bathing. On the hills some of the wealthy business men have their mansions.

[Pg 31]

WALKS ABOUT SYDNEY

COME with me for a walk through the city of Sydney. The sun is hot, but the porticoes of iron and glass, built out over the sidewalks, will protect us from its rays. We stroll by great stores with fine window displays, and find we can buy almost anything here that is to be had in New York. The prices are marked in pounds, shillings, and pence. Some of the department stores sell several million dollars’ worth of goods annually and employ from five hundred to one thousand clerks. Such stores do a big mail-order business with the people on the sheep stations and farms of the “back blocks.”

One feature of Sydney is the numerous arcades that are cut through from one street to another and lined with stores. They are ceiled with glass, paved with tiles, and decorated with tropical plants and flowers. They are delightful quarters in which to shop during the heat of the day.

The principal artery of the business section is Circular Quay, where the many ferries to the suburbs move in and out with their thousands going to and from work. The main streets of the down-town district lead to it. On Macquarie Street is the entrance to the Government House, where the governor of New South Wales resides. This thoroughfare was named for a stern old administrator[Pg 32] of colonial times who used convict labour to put up the Parliament House and other buildings, many of which are still in use. Pitt and King streets are lined with handsome stores and office buildings. Above Circular Quay are great concrete wheat elevators with a capacity of six million bushels, which were erected not long ago under American supervision.

Sydney has big insurance buildings, bank buildings, excellent clubs, and many hotels. The two largest hotels are the Australia and the Wentworth, which have the features of the best American and European houses. The prices are about the same as in the United States, though at first they seem cheaper. The extras make up the difference. There are small hotels in every block, but most of these are merely saloons, or public houses, with a room or so for rent to conform to the law providing that liquor shall be sold only at places offering board and lodging as well as drinks.

There are some splendid public buildings. Take the town hall, for example. It is a magnificent stone structure in the heart of the city, containing a pipe organ, which is the largest south of the Equator, and a hall seating five thousand people. Some years ago the city of Melbourne bought what was then the largest organ in Australia. But Sydney was, of course, bound to beat Melbourne, and bought a bigger one. Her organ cost eighty-five thousand dollars, and has several thousand pipes.

Other fine structures are the Public Works office and the buildings of the various state departments. On George Street is the Victoria Market, put up at enormous expense to serve the whole city. But it did not succeed[Pg 33] and has now been turned into offices. Throughout the city and suburbs are a number of well-regulated municipal markets.

In the down-town section is the office of the Sydney Bulletin, the most widely read paper in the Commonwealth. This bright pink weekly has been called a “cross between the London Punch and the New York Nation,” for its contents are both grave and gay. But it also has a flavour peculiarly its own. For one thing, it is so full of slangy phrases that outsiders almost need a glossary to understand some of its paragraphs. In it “Bananaland” may stand for Queensland; “Apple Isle” for Tasmania; the “Ma State” for New South Wales; “Fog Land” for Great Britain; the “Big Smoke” for London. Under the heading of “Aboriginalities” are paragraphs from correspondents throughout the country on matters relating to Australian place names, natural history, strange customs, and the like. The tone of the paper is often flippant, and, so the conservatives say, even irreverent and disloyal.

Nevertheless, the Bulletin is doing much toward building up an Australian literature, for its encouragement and prompt checks have kept going many a struggling young poet or journalist. It is the chief literary and dramatic paper of the country, and its so-called “red page” always carries able book reviews and criticisms. Politically, it is independent, although it inclines more to the Labour than to the Liberal view. Still, it does not hesitate at times to publish editorials denouncing the Labour leaders. It is Australian of the Australians, and is read in the towns and cities, in the scorching northern mining camps, in the remotest sand plains of[Pg 34] the west, and in the isolated sheep stations of the “bush.”

Sydney has as good lungs as any city of Europe. It is noted for its extensive park system. Moore Park contains more than three hundred and fifty acres, Centennial Park five hundred and fifty acres, and there are also the cricket fields, race courses, and fair grounds. One of the best zoos of the world is at Taronga Park on the north side of the harbour. Here cages have been largely dispensed with, and the animals are given as nearly as possible their native conditions and surroundings. The Botanical Gardens are on the spot where the early convicts raised their vegetables.

Sixteen miles south, of Sydney is the National Park, which contains more than thirty-three thousand acres, most of them covered with virgin forest. Convenient to the city there are also a number of sandy beaches where “surfing,” swimming, and fishing are enjoyed. At the Manly and Bondi beaches “surfing” is especially popular. It is the sport of expert swimmers, who throw themselves on boards on which the incoming waves dash them to shore. The pastime is borrowed from the South Sea Islanders and is especially adapted to the heavy surf of the Sydney beaches.

The most interesting park in all Australia is the Domain. It is in the centre of Sydney and has magnificent trees, velvety lawns, and walks and drives of every description. The park is accessible to everyone; there are no signs to keep off the grass, and babies and grown-ups play and stroll upon it.

Every Sunday afternoon the Domain becomes the forum of the people. Any one who wishes to preach or pray or[Pg 35] talk politics has a right to set up his pulpit on the grass and toot for hearers. No one questions his doctrines, and he may say what he pleases. There are at least a score or more of such speakers here every Sunday, each with a crowd about him. There are lightning calculators, labour agitators, Socialists, preachers of every gospel and every creed, phrenologists and beggars, faith healers and cranks of all sorts.

The crowd is a good-natured one, made up of all classes, but with working people in the majority. When I visited the Domain the other Sunday, there were at least twenty-five thousand persons there. I paused for a time at each group. The first was gathered about a lightning calculator, who talked a blue streak as his hand danced over a blackboard, stopping only at intervals to sell books explaining how to learn the higher mathematics in three lessons. The next speaker was a temperance orator. He was criticizing the rich men and the officials of the city and denouncing the saloons. Beyond him was a Socialist, who demanded heavier taxes from the rich and a general division of property, and farther on was a Negro, who was preaching the end of the world in a marked Yankee accent. At another place a Salvation Army band was led by a woman with a sweet singing voice and a complexion as fair as that of a baby.

About fifty feet from this crowd I saw a walking hospital in charge of a woman called “the Good Samaritan.” The old lady had thirteen invalids, each of whom was terribly afflicted. They were of all ages, from babies to threescore and ten—some lame, some halt, and some blind. They sat about in chairs on the grass while the Good Samaritan in their midst showed their sores and deformities[Pg 36] to the crowd and begged money for their support. She had a carpet laid at her feet and upon this the charitably inclined cast their pennies and sixpences.

Near by was a blind man with a cracked voice and a fiddle, who sang and sawed for money, and farther over an orator haranguing about the big captains of industry in America. They were, he said, enslaving the Yankee labouring men, and would in time probably come over to place the yoke of bondage on the workers of Australia.

All this discussion in the different parts of the park went on without commotion or trouble; every one said what he pleased and none bothered about what anybody said.

Leaving the Domain, I walked back to the hotel, noticing the queer signs by the way. One was “Lollies for Sale.” It was over the door of a confectioner’s store where all sorts of candies were displayed. “Lollies” is the popular word here for candies, and between the acts at the theatres boys go about through the audience calling out “Lollies, ladies! Lollies, gents! Does any one want a box of fine fresh lollies?” So, I suppose, America is indebted to Australia for its “lollipops.”

[Pg 37]

THE LAND OF THE GOLDEN FLEECE

THERE were large flocks in the days of the patriarchs, when Abraham and Lot had to separate to get new grazing grounds. It is written that King Solomon sacrificed one hundred and twenty thousand sheep when he dedicated the Temple at Jerusalem, and we know that Mesha, King of Moab, gave Jehoram, King of Israel, one hundred thousand lambs as tribute. We have read also of Job’s “cattle upon a thousand hills.” The sheep kings of those days must have had immense farms, but they were nothing in comparison with those of Australia. In the state of Victoria there are six sheep stations of more than one hundred thousand acres each; in New South Wales are nearly two hundred of like area, and Queensland has ranches so extensive that one will support upward of one hundred and forty thousand sheep. In the whole Commonwealth there are eighteen estates carrying more than one hundred thousand head each.

Yet, even at that, there are old timers who consider these farms small. In the early days, when land was taken up in great parcels at less than nominal rates, there were men who acquired tracts the size of the state of Rhode Island. James Tyson, one of the most noted of the stock kings, owned three million acres and died worth twenty millions of dollars, an unheard-of fortune at that time.[Pg 38] Samuel McCaughey, who came to Australia practically penniless in 1856, when sheep raising was on the decline because of the gold fever, picked up blocks of land and bought flocks of sheep until he finally had one million head, owned a million acres outright, and leased a million or so besides. At one shearing he clipped a million and a quarter pounds of wool.

Nowadays the tendency is away from these enormous holdings. With a view to getting more people on the land, all the state governments have done something toward their reduction. Moreover, closer settlement frequently means greater production from the land, for the smaller holdings are not generally devoted to sheep alone, but are used for wheat growing, dairying, and other farming as well. In districts where at one time a property of two hundred thousand acres was thought not too large to provide for one man and his family, five thousand acres is now considered a good pastoral proposition. Sometimes a five-thousand-acre farm, well cultivated and improved, pays better than two hundred thousand acres did in the past.

The sheep ranches used to be merely wild lands, where flocks were grazed on the hills and valleys with a few shepherds to watch them. The present sheep stations are more like farms. The land is fenced in great fields, or paddocks, of eight hundred acres or more. Some contain several thousand acres, and single paddocks may have from two to twenty thousand sheep. Our American consul at Sydney tells me of one station he visited, which had wire fencing enough to reach from New York to San Francisco, enough roads to make a highway from New York to Baltimore, and enough employees to populate a [Pg 39]good-sized town. I have travelled over other stations quite as large, and I have been amazed at the vast extent of the fencing.

In the great “back blocks,” where sheep ranches of 100,000 acres are common, it takes days and even weeks for the bullock drivers and their teams to get the wool clip to the nearest railroad.

The Australian sheep men have brought the Merino to its highest perfection and doubled the weight of its average fleece since the breed was first introduced.

Though the snowfall is confined to a few isolated areas, the slopes of Mount Kosciusko, which is more than seven thousand feet high and the loftiest peak on the continent, are the scenes of real winter sports.

Even about the winter’s ice on the mountain lakes of Victoria the trees are as green as in the spring, for the eucalyptus sheds its bark instead of its leaves and makes the country an “evergreen land.”

In the state of New South Wales, where I am now writing, practically all its thirty-four million sheep are kept in fenced paddocks. There are thousands of miles of wire netting put up to keep out wild dogs and rabbits. Millions of dollars have been invested in buildings, and the salary list of a great station may be as long as that of a department store. Sheep raising is by no means a cheap business and to make it pay everything must be carefully managed.

It costs from fifteen to twenty thousand dollars a year to run even a good-sized station and there are some ranches on which the annual expenses mount up to hundreds of thousands of dollars. Of late years wages have steadily increased, until the men are now paid from five to nine dollars a week with board and lodging. Each man receives weekly about twelve pounds of meat, ten pounds of flour, and a quarter of a pound of tea, as well as other rations, so that every big farm must keep a store and a warehouse. Even the smaller stations have a dozen or more men in ordinary times, and at shearing season the hands are numbered by scores. Then there is the land itself, which, when taken in tracts of tens of thousands of acres, costs the purchaser or tenant a large sum of money. The rates for leases are different in the several states, but in all there are farms paying annual rents of thousands of dollars.

The ranchers are called “squatters,” which in Australia is not a disparaging term, as with us. It was first applied to those who settled on unoccupied lands, and then to those leasing vast tracts from the government at nominal rentals.[Pg 40] Since these men often grew to be rich, the title became a complimentary one and it is now applied to stock-owners and graziers generally.

The squatters are Jasons who have won a splendid Golden Fleece. Of the five hundred and fifty million sheep in the world, Australia has around eighty million, or more than any other country. Russia, Argentina, and South Africa come next, in the order named. Australia’s yearly wool production runs to between six and seven hundred million pounds and her annual wool exports have been bringing her the sum of two hundred and fifty million dollars. Wool is her greatest single source of wealth. Her sheep also furnish exports of frozen mutton that in good years have increased her income by twenty-five million dollars. The annual exports of sheepskins are sometimes worth fifteen million dollars, and sausage casings, made of the intestines of sheep and lambs, are sent overseas to the value of five hundred thousand dollars.

During my stay here I have attended Sydney’s annual sheep show. There were hundreds of fine animals from every part of Australia. More than half of them were entered in the fine-wool class, and the rest were fat sheep raised for mutton. Every sheep at the show was worth several hundred dollars, and some were valued at thousands. Among the latter was the ram that took first prize. It was a great barrel-shaped bale of wool with a pair of big horns at one end of it. The wool lay on the ram in folds and rolls, the skin apparently wrinkling itself in order that the animal might hold more. His ears were entirely hidden by the wool, which also came out three inches over the eyes, leaving only small holes for the[Pg 41] ram to see through. I poked my finger into the fleece and could just touch the skin. The wool hung down in great bunches on the belly and the legs were covered clear to the hoofs. On the outside the fleece was of a dirty white colour, but when I pulled it apart I could see it was of a rich creamy white. The strands were spiral and springy and very fine.

The Australian farmers pay more for blooded sheep than do those of any other country. It is not uncommon for a well-bred ram to sell for five thousand dollars and one has even brought more than thirty thousand dollars.

The hundreds of sheep men at the show looked much like a crowd of Yankee business men. They were all landholders, and many had farms which would be considered principalities in the United States, but some of which are looked upon as quite small here. For instance, at the dinner closing the event I asked whether the vice-president of the show had a large station. The reply was that he had not, for his holdings comprised only about sixty-five thousand acres. Another man pointed out to me owns two hundred thousand acres and another has half a million acres, all fenced.

[Pg 42]

IN THE GREAT WOOL MARKET

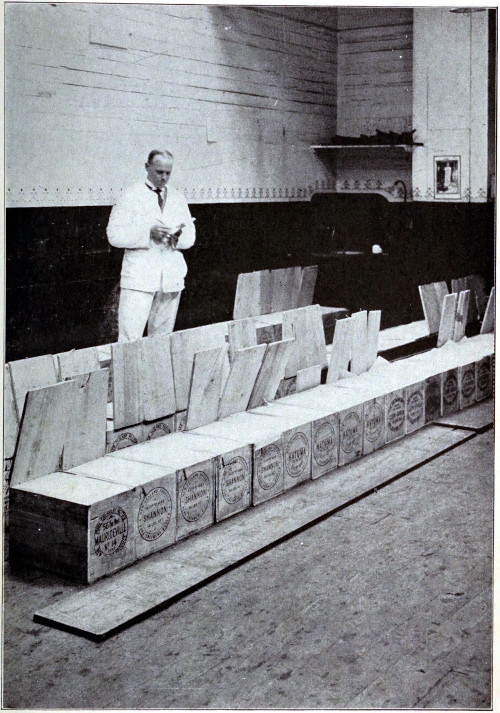

SYDNEY is the chief wool market of Australia. It annually ships hundreds of millions of pounds to Europe, Japan, and the United States, and it has some of the largest wool warehouses on the globe. Let us take a walk through one of them. We are in a great room covering many acres. It is roofed with glass and upon its floors are thousands of bales of wool, each as high as your shoulder and marked with the name of the station from which it came. All are wrapped in yellow bagging, but the tops are open and the white wool seems to have burst forth and to be pouring out upon the floor.

In parts of the warehouse are mountains of wool which have been taken out of the bales, and in other places men are repacking the wool for shipment. Thrust your hand into one of the piles. Now look at it! It shines as though it were coated with vaseline and your cuff is soiled with the grease; for this is unscoured wool, just as it came from the sheep’s back.

All of the Australian wool clip is sold at auction, and the sales are attended by wool buyers from England, continental Europe, the United States, and Japan. We see many of them in the Sydney warehouses dressed in overalls and linen coats to protect their clothes from the greasy wool. They go from bale to bale, taking notes of each[Pg 43] man’s stock, in order that they may know how much to offer when it is put up at the Sydney Wool Exchange.

The Exchange is near the wharves in the heart of the city. It is a long, narrow room, much like a chapel, with an auctioneer’s desk like a pulpit in one end of it. The various wholesale dealers or commission merchants are allotted different days on which they may auction off their stock, and on those days the buyers come to bid. As many as ten thousand bales are sometimes sold in one day, and single sales will foot up as much as three quarters of a million dollars. Cable reports are received as to the prices in the great wool markets over the world, and the excitement rises and falls with the quotations.

I had a chat with one of the largest wool dealers. He told me that some years ago almost all the wool of Australia was shipped by the squatters direct to London, and there resold and reshipped. At present the greater part of the product is shipped to commission agents at the Australian ports, to which the textile-manufacturing countries send their buyers.