Title: A royal smuggler

or, The adventures of two boys in the Indian Archipelago

Author: William Dalton

Illustrator: Carl Werntz

Release date: September 28, 2024 [eBook #74489]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: M. A. Donohue & Co, 1902

Credits: Aaron Adrignola, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

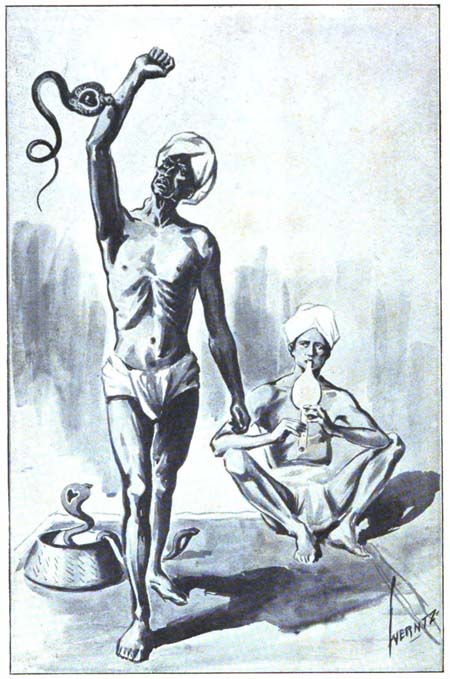

IN AN INSTANT IT HAD FIXED ITS FANGS UPON THE OLD MAN’S ARM.

Or THE ADVENTURES OF

Or THE ADVENTURES OF

TWO BOYS IN THE INDIAN

ARCHIPELAGO

BY

WILLIAM DALTON,

CHICAGO:

M. A. Donohue & Co.

Copyrighted 1902

By THOMPSON & THOMAS

| Chapter | I. | An Important Letter | 7 |

| Chapter | II. | A Great Calamity | 22 |

| Chapter | III. | Our Uncle’s Last Will and Testament | 41 |

| Chapter | IV. | The Robbery and Abduction of Marie | 53 |

| Chapter | V. | We Run Away and Take Service with “Nest-hunters” | 65 |

| Chapter | VI. | We Set Out on our Voyage | 90 |

| Chapter | VII. | The old Head-man, the “Strong One,” the “Handsome One,” the “Weak One” | 107 |

| Chapter | VIII. | We Descend into the Nest-caves | 121 |

| Chapter | IX. | My Adventures in the Nest-caves | 137 |

| Chapter | X. | I Recognize the Nest-Robbers | 152 |

| Chapter | XI. | A Search for a Mare’s-Nest | 164 |

| Chapter | XII. | We Bite the Biters, but are Overhauled by a Dutch Cruiser | 174 |

| Chapter | XIII. | We Sell our Nests, are Taken Prisoners, but Outwit our Captors | 190 |

| Chapter | XIV. | History of our Captain, his Hatred of the Dutch | 214 |

| Chapter | XV. | Adventures with a big Snake and a Man-eater | 223 |

| Chapter | XVI. | We Pick up a Chinese Storyteller, who Sends us to Sleep | 236 |

| Chapter | XVII. | We are Hoodwinked by the Chinese, who Robs us of our All | 249 |

| Chapter | XVIII. | Adventures in Bali | 261 |

| Chapter | XIX. | We Visit the Capital of Blilling, and Witness some Widow-burning | 276 |

| Chapter | XX. | We Return to the Coast, and hear of an old Enemy | 298 |

| Chapter | XXI. | The Wen-necked Hunchback, and his Revelations to Prabu | 310 |

| Chapter | XXII. | We Join a Tiger-hunt, but narrowly Escape Poisoning, and Escape to our Island | 321 |

| Chapter | XXIII. | A Fight; a Great Peril and a Timely Rescue | 333 |

| Chapter | XXIV. | We Land at Mojopahit, and are Imprisoned as Rebels | 348 |

| Chapter | XXV. | Through Woods and Wilds | 366 |

| Chapter | XXVI. | We Hunt Tigers, and Discover some old Acquaintances | 377 |

| Chapter | XXVII. | And Last, Containing a Tolerably Happy Ending | 389 |

A ROYAL SMUGGLER.

“News from Uncle Adam!” cried my brother Martin, as the maid, one morning, placed upon the breakfast-table a letter, bearing a foreign postmark; and the words are still fresh in my memory, for that epistle influenced the fates of my father, brother, and myself. It was addressed to our parent, in reply to one he had sent to Batavia, some twelve months before.

“My dear brother Claud,” it ran, “I have received yours, containing the sad intelligence of the death of your poor wife, and the almost simultaneous loss of your fortune, through the failure of that rogue of a banker. I will not, however, waste time in words of condolence, but at once proceed to business. Well, you are poor—I am rich; you have no occupation—I have too much. You are young—I am getting old; for there are many years’ difference in our ages. Thus, in more ways than one, we may assist each other. I can help you with money, and you can help[8] brother Adam by employing your energies in his commercial affairs out here in Batavia. But, as deeds are better than words, I herewith inclose a draft, and beg that you will, with all convenient speed, take passage for yourself and my two nephews for this island.

“Yours, my dear brother, lovingly,

“Adam Blake.

“P.S.—I am sorry to add, that I cannot offer you and the boys a home in my house, as I am no longer a lonely man, my chief reason for marrying again being for the sake of my dear little Lip-lap, your niece.”

“Won’t it be a jolly voyage! How good of Uncle Adam!” cried Martin.

“A second wife,” murmured my father, sadly, as if pondering upon his own bereavement.

“I wonder,” said I, “what our cousin is like, and why Uncle calls her Lip-lap—Lip-lap, what can it mean?”

“A nickname given to the children of Americans born in Java, Claud,” answered my father.

“Queer,” said my brother. “But it is no matter what they call her so that she is pretty—I like pretty girls.”

“All of which we shall discover when we reach Java,” replied our father. “But now, boys, get you to your lessons, while I go to make inquiries about a ship.”

“I say, Claud, won’t it be jolly? Father will be rich again, and we shall grow up to be great merchants,[9] like Uncle Adam, and have a cousin, too,” said Martin, merrily; but as the thought passed through his mind that the death of our dear mother had been caused chiefly by our father’s misfortunes, he burst into tears. “Oh! why did God take from us poor dear mamma? Why didn’t this letter come ever so many months ago, and she would have lived!”

Heaven knew that I had felt our loss as deeply as my brother; but for his sake, for the sake of my father, who had never smiled since her death, and who trembled at a word or a thing that brought it fresh again to his memory, I had struggled to suppress any sign of emotion at the chance mentioning of her name. Then, throwing my arms around his neck, I said (I believe with tears in my own eyes):

“Martin, it is wicked to be ever recurring to our loss, when you know how it shocks our father. Remember, mamma is in heaven, and happy.”

“I know it is wicked, but I cannot help it—I won’t help it—I never will stop talking of dear mamma!” and the passionate boy ran from the sitting-room into our sleeping-chamber, and, throwing himself upon the bed, sought relief in a good cry.

Since our mother’s death, such outbreaks of grief had been common with my warm-hearted but impulsive brother. Our uncle’s letter, however, produced a good effect upon his mind, by directing his thoughts to the active, perhaps adventurous, life which seemed before us. But unfortunately we had to wait six months before we could get a ship—a loss of time[10] that, as will be seen hereafter, materially influenced our future. Taking into account this delay, the six months for the coming of the letter, and a similar period for our outward voyage, it will be seen that a year and a half elapsed between the penning of our uncle’s invitation and our anchoring in the roadstead of Batavia. What unexpected events, what misfortunes, may happen in eighteen months! and they did happen.

Ominous, indeed, of misfortune was the night of our arrival in the island. It was the latter end of October, the period of the monsoons. My brother and I were well-nigh frightened to death, most assuredly we never expected to reach the land, for the elements were at war. The sea rose in mountainous heights; the horizon was spread with vast sheets of livid flame; the thunder shook both heaven and earth; and the wind, as it rushed inland in its fury, uprooted the largest trees, and toppled down the huts of peasants and the warehouses of the merchants in the lower town. It was a mercy, indeed, that even the great pier which forms the harbor of Batavia should have escaped.

The hurricane, however, although terrible in its fury, was but of short duration; for by daybreak we were enabled to moor the vessel alongside the pier, and also to procure a messenger, whom my father at once dispatched to advise his brother of our arrival.

“If that is Batavia, it is a queer, dirty hole,” said Martin, shrugging his shoulders, as he stood gazing[11] upon the bamboo huts of the poor natives, the warehouses of the Dutch merchants, and the thousands of bales of goods, covered with tarpaulin, which seemed to block up and render the roadways impassable.

“Right, lad,” said the captain, who was standing near my brother; “it is a queer, dirty hole. Moreover, it is worse than it seems, for, after sunset, the vapors and putrid exhalations, arising from the decaying vegetable and animal matter in the marshes, where you see yonder mangroves, render it poisonous to Americans.”

“And we have to live there,” said Martin, with a shudder. “Yet,” he added, thoughtfully, “it can’t kill everybody, for Uncle Adam has lived in it many years.”

“Not so, my lad. Like the other American merchants, your uncle quits this place every evening at six o’clock, for his home in the upper town in yonder mountain, where you will find large streets, a healthy atmosphere, the Government-house and offices, the theatre, and the grand residences of the principal colonists.”

“That is good news,” said I, for I had been as nervous as my brother at the prospect of having to live in such a wretched place as the town before us; “but,” I added, “where is the Chinese city, for I have heard that those people abound in Java?”

“Ay, my man, the Chinese swarm in Java, as in every island of the Indian Archipelago where money is to be made. Their town, however, or campong, as[12] they term it, is situated upon the other side of the mountain, in a spot almost as unwholesome as this.”

At this moment we saw our messenger, accompanied by another native, come along the quay toward the ship. But as the latter will prove no unimportant personage in my narrative, I will describe his appearance. Taller in stature than the majority of his diminutive race, he was yet far shorter than the average height of Americans; his complexion was a light brown; his eyes full, black, and piercing; his hair not luxuriant, like many of the Asiatic races, but yet not so scanty as most of the men of Java. He was well set, and his limbs strong and muscular, as if he had been trained among the fishing or hunting tribes. His dress consisted of a pair of thin cotton drawers and colored sarong, or long plaid-like scarf, which was thrown across the shoulder, and brought around the waist, so as to form a sash or girdle, from which was suspended the kris, or creese, a weapon without which no Indian islander of whatever rank is ever seen; and but that his upper teeth were filed and blackened, he would have been accounted among Americans a man of no mean personal appearance.

“He is a slave, or servant of your uncle’s,” said my father. “Say,” he added, impatiently, as the man trod the deck, “bring you letter or message from the counselor Van Black?”

“My master,” he replied, bending his body forward, while at the same time he raised his hands with the palms joined before his face, until the thumbs touched[13] his nose, “I bring no letter, no message; but yet a carriage awaits upon the quay, to convey your honor to the house of the counselor Van Black, where, I am bidden to say, you and your sons will find a welcome.”

“No message, no letter!” repeated my father, in surprise. “It is strange that, after a parting of so many years, Adam came not himself to welcome us. Tell me, man,” he added, “how fares it with your master and his family? Are they in health?”

“The family,” replied the native, emphasizing the word, and making another obeisance, “are as well as their best friends would wish them. But, craving your pardon, Prabu is charged to convey the noble stranger and his sons to the upper town; to do that, and nothing more. He is a servant, and must obey.”

“Astounding! What can be the meaning of this?” replied my father, thoughtfully; but finding it was of no use to further question Prabu, as he had called himself, he said, turning to us two boys, “Come, lads, let us follow this fellow, for the sooner we reach my brother’s house the sooner we shall be free from suspense.”

“Our uncle is ill—too ill to come or write; but fearing to alarm you, has forbidden this man to open his lips,” said Martin, offering the best explanation of Prabu’s taciturnity.

“I fear so, indeed,” replied my father. “The greater reason, then, that we should hasten to him; so forward, my sons.”

[14]I had also my own fears, and an explanation to offer, but as they passed through my mind, a chilling sensation at my heart seemed to freeze the words, ere they could escape my lips, and so I followed in silence to a great, clumsy, old Dutch coach, with four Java ponies, that was awaiting us on the quay.

Now, the road from the lower to the upper town is steep and narrow. Thus, on our way we should have been amused by the opportunity the ascent gave us of looking at the surrounding scenery, so new to us, and the multitude of quaintly-dressed people of all ranks, on foot and in all descriptions of vehicles, who were proceeding to their places of business in the wretched city we had just quitted; but a species of melancholy foreboding seemed to have seized upon us, which obscured our eyes, turned our thoughts inwardly, and reined in our tongues, for neither spoke, until the carriage stopped before the courtyard of a large, flat-roofed mansion in the upper town.

Perceiving that the gates stood open, my father, who could no longer bridle his impatience, descended from the carriage, telling us to follow. As we did so, Martin, touching me on the shoulder, and speaking for the first time since we had entered the vehicle, said:

“This is very queer, Claud. What do you make of it?”

“Martin, I have a foreboding that something is wrong, very wrong; calamity is in store for us; the storm, upon our arrival last night, was ominous. Besides, to my thinking, mystery is seated upon the mahogany-colored[15] countenance of that fellow Prabu. Look, even now how he is straining his glittering eyes after us.”

“Pooh, pooh, Claud, don’t croak; you make a fellow shiver,” replied my brother.

By this time we overtook our father, at the portico of the mansion. Here the mystery was heightened, for no uncle stood there to welcome his relatives, but in his place a head servant, or groom of the chamber, who, calling my father by name, invited us to follow him; but now, losing all patience, he rudely seized the man by the shoulder, exclaiming:

“Say, fellow, is my brother, your master, sick, that I see him not here to welcome us?”

“Sir,” replied the servant, evasively, “my lady awaits you.”

So saying, he threw open the doors of a large and luxuriously furnished apartment, ushering us into the presence of a lady of dignified demeanor, but who seemed almost lost amid a pile of velvet cushions upon which she was reclining, and instantly the mystery was solved, our forebodings realized, for she was attired in widow’s weeds.

“Great heaven!” exclaimed my father, “can it be possible, then, that my brother is——”

“Alas! no more,” said the lady, rising and taking his hand. “It is scarcely three months since my poor husband died of the fever.” Then, in soft, purring tones, like those of a cat, she added, “It was the will of God; we may not repine. You will pardon me, my[16] brother, that I forebade my servants to give you this sad news; but, out of respect to my late husband’s memory, I desired to be the first to break to you the sorrowful intelligence, at the same time to bid you and your sons welcome to this house.” Then, seeing that our father’s heart was too full of grief to reply, she said, as she folded my brother and me, one after the other, in her arms:

“These, then, are my charming nephews? Let me embrace you, dear boys. You are noble fellows, and shall find as good a home in this house as if your poor, dear uncle had been saved to us.”

“Madam, my sister,” replied my father, “your conduct towards us has been kind and thoughtful, still my grief is too keen and new; craving your pardon, I would be alone for a time.”

“It would have been unpardonable, my brother, had I not foreseen this desire,” she replied, striking a small Chinese gong suspended from the ceiling. “Go,” she said to the servant who answered the summons, “conduct my brother and his sons to the rooms prepared for them.”

The apartments to which we were conducted were situated in another wing of the building, upon the ground floor, and consisted of two bedrooms and a large sitting-room. They all had French windows opening into the grounds, and had evidently been carefully and thoughtfully prepared for our reception. Leaving our parent to give full vent to his grief, for the death of a brother to whom he had been passionately[17] attached, we boys (who had never known our uncle, and could not, therefore, so keenly feel his loss) went to our own chamber, which, by the way, was of ample size, and fitted up as both sitting and bedroom.

“I am so sorry for poor, dear uncle, though we never saw him,” said Martin, as soon as we were alone.

“I am more sorry for our father, Martin. I fear that this fresh stroke of misfortune, coming so soon after our dear mother’s death, will utterly destroy his already weak health.”

“Nay, Claud, we boys must be his support. Then, you know, it must be consoling even to him to find our new aunt so kind and thoughtful.”

“New aunt!” I repeated; then, looking cautiously round, and first listening to hear if footsteps were at hand, I said, in a whisper, “Do you know, Martin, I don’t like that woman.”

“Don’t you, though,” he replied, with a look of astonishment. “But why?”

“Well, I don’t know, but I don’t. You remember the lines poor mother used to repeat to us——

“Claud,” replied my brother, “I am beginning to be afraid of you; you are like a witch. But—but,” he added, “this is foolish; it is wicked; for she is a relation—at least, a kind of a one, you know—and[18] you have no reason to dislike her. But isn’t she pretty, though?”

“Pretty! Well, so is a tigress, so is a serpent, and she reminds me of both; she puts me in mind of the portrait in that French story-book we used to read at home, of the woman who poisoned so many husbands—just the same plump figure, raven hair, pale skin, dark eyes, that seem to mean everything, under an effort to look as if they meant nothing, and soft hands; then her embrace was as mock as a play-actor’s, nothing real in it, and her kiss like that of Judas.”

“Hang it, Claud, it’s a shame; be quiet, you shall say no more!” exclaimed my brother, placing his hand upon my mouth. And in truth I did feel a little ashamed of this warm expression of opinion upon so short an acquaintance; nevertheless, I believed in it at the time, and, moreover, that night dreamt that all I had said had come true. But then, you know, there is not much in dreams; at least, it is foolish to place reliance upon them.

After this conversation, neither spoke for some time. At length the silence was broken by Martin. “Claud,” said he, “I wonder how much money our uncle has left to father?”

“Not much, I fear, if our new aunt had any part in making his will.”

“Oh! bother; drop talking of her. It’s a great shame if he hasn’t, though, after coming all this way by his own invitation.”

“Well, we shall soon know all about the will, I dare[19] say,” said I, a little shocked that my brother should so soon speak of money affairs; and Martin understood and felt hurt at my thoughts, for he answered:

“It is for our father, who is ill, and has had so much trouble, that I want the money, Claud, not myself; for I am strong and healthy, and, if necessary, shall be able to get my living somehow—for instance, as a clerk, a messenger, a hunter, or anything, you know, out here, where white men are valuable.”

“But you, Martin, are only a boy.”

“And I should like to know whether a white boy is not as good as two mahogany-colored men?” he replied, boastfully.

“Hush! we have been watched—listened to!” for although I had said nothing about it to Martin, I had, several times, while we had been conversing, heard a rustling in the shrubbery, just outside the glass door of our room. Hitherto, I had taken but little notice, but now I distinctly heard a cough.

“Come along, then, and let us unearth the sly fox,” whispered Martin; and the next minute we were standing by a shrubbery near the window. Having listened patiently for some time, and heard nothing but the humming of birds and insects, Martin whispered:

“It was fancy only.”

“Then it was a very pretty fancy, too, for there it is,” I replied, as at that moment I detected the eye of the listener who had alarmed us, sparkling through the leaves and branches; and the next instant I had gently dragged forth one of the prettiest little girls[20] I had ever seen—tall and graceful in figure, with long, flowing, golden locks; a fair complexion, tinted with red, but just then mounting with crimson blushes; fine blue eyes, and dimpled cheeks—indeed, a little fairy—yes, a fairy, although she was attired in deep mourning.

“Oh! don’t; you hurt my arm!” she exclaimed, half pettishly, half smiling, as she struggled to escape from my grasp.

“We won’t let you go; we don’t often catch real live fairies,” said Martin. “Besides, you have half killed us with fright.”

“For shame,” she replied, “for two great boys to be frightened by a little girl like me.”

“You know a mouse may frighten an elephant, if the elephant hears a strange noise and doesn’t know that it is caused by a mouse.”

“Well, then,” she replied, “I am sorry I have frightened you both; but I am sure I could not help it; it was that nasty cough.”

“But how came you to be hiding in the shrubs? Was it to listen to what we were talking about? for certainly you must have heard all we said.”

“Yes, oh! yes; that is, all you said,” here she whispered, “about her. It was very wicked, but I won’t tell; not I—that I won’t. But,” she added, “I couldn’t help hearing, as I was in the shrubbery.”

“But what brought you there?” I asked.

“To get a peep at my two new cousins, of course. I have heard so much about you from poor, dear papa,[21] and have so long expected you to come, that when she wouldn’t let me stay in the room, when you came this morning, I cried my eyes out—at least, almost—and then——”

“And then what?” asked Martin.

“Why, I came here by myself, determined to have a peep at you both, and uncle, too, if I could. But hush!” she exclaimed, placing a finger upon her lips, “I must go; I heard My Lady calling for me. She must not know that I have been here; pray don’t tell her, or I shall be punished for disobedience;” and in an instant she had flitted out of sight.

“So that is our cousin,” said Martin, when we had returned to our room. “What a pretty girl!”

“Yes,” said I; “and so amiable, that she makes up for our queer-tempered looking new aunt.”

“After all, Claud, I begin to think you are right about ‘My Lady,’ as they call her. What a shame to punish a nice girl like that for anything!” replied Martin.

And now I have told all that is worth telling of our first day in the upper town of Batavia.

To my father, in his then feeble state of health, the news of his brother’s death proved so great a shock, that he was unable to leave his room for a whole week. During that time, however, our aunt behaved most affectionately, not only to the invalid and his boys, but, I may add, to our pretty cousin Marie, her step-daughter, with whom we were now permitted to associate on the most cousinly terms; and, although this did not metamorphose my dislike into love for her, it had a great effect upon my poor father,—so great, indeed, that, with a delicacy of feeling quite in accordance with his nature, he awaited a full week after his recovery before he would broach the subject of his late brother’s will. Doubtlessly he each day expected that she herself would open up the matter, but in this he was disappointed; therefore he, one afternoon, but in a spasmodic manner, as if to get the words from his lips as speedily as possible, begged permission to see a copy of the will; but, vexatiously enough, as she was about to reply, the servant announced, “Mynheer Ebberfeld.”

My father looked annoyed; I started in my chair,[23] for eyes never rested upon a more ill-favored man. “My lady,” however, seemed pleased at his coming, for, after introducing him as the principal notary of Batavia, and a councilor, she said:

“My dear brother, Mynheer Ebberfeld’s coming at this moment is most fortunate; for, as he drew up my late dear husband’s will, he is the most fitting person to explain its provisions.”

“Your pardon, madam; your pardon, sir,” replied the notary, with a low bow, and a simper upon his sinister countenance, “but this hour, and this presence, is scarcely fitting, nay, most inopportune, for business matters; let me, therefore, crave your patience until to-morrow, and then we will together scan the pages of the precious document itself. In the meantime, let me assure you that you will find its contents by no means unsatisfactory to yourself and sons.”

“Nay, mynheer, my brother is naturally anxious to become acquainted with the will, so I pray you let not etiquette deny him that satisfaction,” said “my lady,” with one of her most amiable smiles.

“Not so,” interposed my good-natured father; “since Mynheer Ebberfeld deems the time, place, and presence improper, I by no means desire him to proceed; to-morrow will be time sufficient.”

“Thanks, mynheer, for your concession; a European gentleman I felt would be too chivalrous to refuse so reasonable a suggestion,” replied Ebberfeld.

Of the young people of the family, I alone had been present during the foregoing conversation; but, at its[24] close, the urbane notary, with amiable earnestness, begged and obtained permission of the lady to invite, “for that day only,” as the playbills have it, Marie, as well as my brother, to a seat at the dinner table.

“The society of young people,” said he to my father, “makes me feel a boy again; it is a passion with me to see them happy. I delight in contributing my poor share towards their amusement. Thus, my lad,” he added, addressing me, “knowing that you have just arrived from America, I ordered a serpent-charmer to exhibit his tricks in the grounds after dinner; that is, if I have madame’s permission;” and the genial smile with which he asked, and “my lady” bowed her acquiescence to this scheme for our benefit, for an instant made me think I had been positively wicked in feeling a repugnance at first sight to two such amiable personages.

The dinner was served in a gorgeously decorated pavilion in the grounds at the back of the mansion; and, in addition to roast and boiled meats, after the Dutch fashion, consisted of a variety of Javanese fish, and a large dish of that famous bird’s-nest soup, of which the Chinese have a proverb: “That if the spirit of life were departing from the nostrils, and the odor of this nest-soup were to salute them, the spirit would reanimate the clay, knowing there is no luxury in Paradise to compare with it.”

Assuredly, Mynheer the notary must have agreed cordially with the proverb, for he devoured it with the gusto of a gourmand, and was unceasing in his efforts to press it upon us.

[25]“My lady,” he said, suddenly putting down his spoon, “may I, nay, stretching a point, I will presume to compliment you upon your cook and purveyor. This soup is deliciously compounded; the nests must have been of the purest white—in short, perfection. May I ask from whence you procured them?”

“By means of my slave Prabu; his family are nest-hunters, chiefly in the employ of the Chinese merchants of the Campong. Permit me,” she added, “the pleasure of sending a basket of them to your house.”

“Madam,” replied the notary, bending his neck so forward, that he seemed about to stand upon his head in his own soup-dish, “you will merit, aye, and may command, too, my eternal gratitude; it will be as supplying my table with a dish from Paradise.”

I felt shocked at this speech, for it sounded in my ears like blasphemy, and all about a mere voluptuous relish, by far too glutinously rich for a stomach like mine, which had been accustomed only to plain, invigorating food.

This dish, so precious in the far East, is compounded of—first, the nest of the swallow (Hirundo esculenta), which, when dissolved, is like a brown jelly or melted glue, the sinews of deer, the feet of pigs, the fins of young sharks, and the brawny part of a pig’s head, all mixed together with plover’s eggs, mace, cinnamon, and red pepper.

“Pray let me help you to some of this most delicious of earthly delicacies, this soup of Paradise,” said the epicure, to my father and brother, both of whom had[26] already exhibited their disgust at the precious mixture. My father politely declined. As for Martin, he spoke plainly:

“Thank you, no; I don’t like the nasty mess; but I just should like to go upon one expedition with this Prabu and his brother nest-hunters, wouldn’t you, Claud?”

“All in good time, young gentlemen, you will grow to idolize this rare dish,” said Ebberfeld; adding in his oily tones, “As for nest-hunting, for which you express such a desire, with your worthy parent’s permission, I will undertake to find you an opportunity; for a love of enterprise is a good sign in the young.”

“Thanks, it will be rare sport,” replied Martin.

After the dinner, we removed to a large tent erected upon a spacious lawn, to witness the tricks of the snake-charmer. Martin, Marie, and I sat upon the grass, our seniors on couches upon the opposite side of the tent.

There were two performers—the snake-charmer, an old man, who, once seen, could never be forgotten, for not only had he a huge hump upon his back, but a wen upon his neck, so large, that it seemed to be outgrowing his head, which it pushed upon his right shoulder; the other was his attendant, a boy, rather good-looking than otherwise, for a Javanese peasant.

Marie, having frequently witnessed this man’s performance, looked on now with nonchalance, but Martin and I strained our eyes to the utmost, towards a large box which the old man began to open, as soon as[27] the boy commenced playing upon a native fife or flute. At the sound of the instrument, the lid of the box being now removed, the hooded head of a spectacled snake raised its crest about a foot above the side, at first languidly, though gracefully, and as if listening to the music; but when the boy played a more lively air, the beautiful reptile moved its head and neck fantastically, as if endeavoring to keep time. After some five minutes, the old man, baring one of his arms, knelt by the side of the box, when, I supposed at the time, because the boy happened to discontinue the music, the neck of the reptile became swollen, and in an instant it had fixed its fangs upon the man’s arm.

Up jumped Martin, crying, “The poor old man will be killed!” and in another second he would have grasped the snake; but simultaneously Marie seized his hands, and, with a strength lent to her by terror alone, dragged him back.

“Foolish cousin!” she exclaimed; “had you approached one step nearer the cobra, you would not have lived out the day.”

A cobra! How my heart sickened at the name. That beautiful snake was, then, the reptile of whose deadly bite I had heard and read so much.

As for Martin, ever fearless of harm to himself when another was in danger, he struggled to escape from Ebberfeld, who had now come to the assistance of our cousin, exclaiming frenzily:

“The poor old man will be killed, I tell you. See, the blood is pouring from his arm! Drive away the snake!”

[28]“Foolish boy,” replied mynheer; “remain where you are; that old man is the cobra’s master. It is by these tricks he lives. What is play to him would be death to you.”

This explanation quieted my brother, and made him laugh; but speedily our attention was turned in another direction: our brave cousin, overcome by her exertions or terror at my brother’s narrow escape, had swooned.

“How vexatious!” cried our aunt. “Go,” she added to Prabu, the slave, who had just entered the tent with some message, “carry the foolish girl to her maid.”

What a feeling arose in my heart at these words. As for Martin, with flashing eyes, he said, savagely, “Foolish—she is not foolish; she is as brave and good as an angel. It is you who are wicked.”

“Martin!” exclaimed our father, sternly, reproachfully; and although in a storm of passion, habitual obedience to a beloved parent at once silenced my brother. Better, perhaps, had he been permitted to give vent to his almost justifiable wrath, for feelings akin to hatred seized upon his heart, never to be removed; but, then, in his behalf, I must admit that other matters arose afterwards to fan the flame.

This mishap broke up the party, but, most vexatiously to my brother and me, our father, taking us to his own apartments, detained us with him the rest of the day, for fear that Martin, while in his angry mood, should come in contact with “my lady.” “For with your aunt, Martin,” he said, “I would not now trust[29] you alone. Your hasty temper would probably lead you into some disrespectful act, that might be of material injury to your future prospects, for as yet we know not to what extent she may have power over us all. To-morrow I shall not be so ignorant, for then I intend to examine my poor brother’s will.”

“Bother the will and the money, too,” replied Martin, hastily, “if they are to prevent a fellow from defending those who have saved his life. Besides, father, I want to know whether cousin Marie has recovered.”

“Well, well, my dear boy, you are a noble fellow, but with a temper that may get you into difficulties if not kept in check. As for your cousin, rest contented; she is well by this time. It was only a fainting-fit.”

“But, father, I want to know that, or I sha’n’t sleep a wink.”

“Tut, tut!” replied my father. “Rest contented till the morning; but now get you to your own room, for it is time all honest people were in bed.”

We obeyed, but not to sleep; our minds were too full of the event of the day, our anxiety too great about our cousin. For an hour or two, indeed, till darkness (which comes so suddenly in the East) had set in, we sat pondering, when Martin said, “I won’t go to bed until I know whether our cousin has recovered, and that’s flat.”

“But how are we to find out?”

“I will tell you, Claud. Marie’s room is in the other wing, just above the verandah; her window is within a yard of the fig-tree, and overlooks the garden. Let us go there. I will ascend the tree.”

[30]“Well, and what then?” I asked.

“Why, I will throw some pebbles at the panes. If she is well, it will arouse her; she will show herself, and I shall be satisfied.”

“I don’t half like the plan,” said I; “we may frighten her into another fainting-fit.”

“Well, look here, Claud. All I want to know is, whether you will go with me.”

“Suppose I say no.”

“Then I will go by myself, that’s all.”

“Very well, then, we will go together.”

The night was of pitchy darkness; so far, so good. We could creep by the very walls without being observed, should any inmate still be about. Having reached the fig-tree, Martin began to make its ascent; but the trunk was so smooth, and the lowest branch so high, that it was beyond his reach. To remedy that difficulty, however, I stood against the tree, while he clambered on to my shoulders, and by that means just managed to grasp the first branch. As soon as I felt myself relieved from his weight, I began to tremble (I am a bit of a coward, or, at least, compared with Martin, a little nervous), in fear that a false step, or the rustling of the leaves, might arouse some restless sleeper; and he did make a false step, and, by so doing, such a noise, that I felt certain we should be discovered; but he persevered, and when he had reached the branch nearly level with our cousin’s window, as had previously been arranged between us, he signalized the same by dropping a few pebbles upon my head.[31] Then, with a beating heart, I listened. Pat, pat, pat, against the panes went three pebbles, but no answer. Others were then thrown, but still no answer. A third time he pebbled the panes, and successfully, for I could distinctly hear the French windows open. “Marie is aroused at last,” I muttered; but no! if so, Martin would have spoken; but for a few minutes there was a dead silence; then (oh, didn’t I feel as if I should like to have shrunk down within my own shoes), I heard our aunt’s voice calling to a slave to bring lights. How provoking! my brother, after all, had mistaken our aunt’s room for Marie’s. What would be the consequences? surely they would detect him when the lights came? or if not, believing thieves were about the premises, would arouse the household; then, not daring to call to him, I despaired. Fortunately, however, not losing his presence of mind, the next minute he had slidden quietly down the smooth trunk.

“Bother!” he whispered in my ear. “What a muff I must have been to have made such a mistake! But come, Claud, let us hide among the bushes, and perhaps they will think we were old Boreas.”

For a short time we stood stock-still among the shrubs and trees; then, believing our aunt had recovered from her alarm, we moved, creeping softly, in an opposite direction to the house, so that, should any person or persons be on the lookout, we might escape them; but by so doing, in those large and intricately laid out grounds, after an hour’s ramble we had literally lost ourselves.

[32]“What shall we do now?” asked my brother, coming to a dead halt.

“Remain where we are till daybreak, when there will be light enough to show us the way back to our room,” said I.

“All right, old fellow,” he replied, coolly; “we have no alternative; in the meantime, let us make ourselves at home;” and he threw himself at full length upon a piece of green sward.

“Stay, Martin,” I said; “there is a glimmer yonder; surely it cannot be a glow-worm.”

“A glow-worm,” he repeated; “nonsense! It is the light from a lantern. Queer! who can be there at this time? let us see.”

As we approached the light, we found it proceeded from a small grotto-like hut, which we perceived to be within a few yards of the window of our room.

“This is lucky, for we know where we are; but before we go in, let us see what’s doing at this time of night; something wrong, I am sure. Stay,” he added, as we reached the walls; “can’t you hear voices?”

Martin was right; we could hear voices, very distinctly, too, and in anger; one was that of the slave, Prabu, the other the old snake-charmer’s.

“Well, well, old man,” Prabu was saying, in reply to something the other man had said, but which we had not heard; “you have explained why I find you in the grotto, but if my lady has condescendingly permitted you to remain here, it was not good that you should keep a light through the night to frighten honest people out of their wits.”

[33]“Worthy Prabu, I am old, and require luxuries that the young, strong and handsome, like thyself, find not necessary.”

“It may be so; yet, Huccuck, thou art more than suspected of being a rogue; still, if the light helps thee to keep the venomous reptiles in your box from escaping, it may remain; but as you value your liberty, get thee hence before daybreak, for such are my lady’s orders.”

So saying, to our great relief, the slave quitted the hut. Having allowed him sufficient time to get beyond earshot, we found our way to our own room, when, notwithstanding our heroic resolutions not to close our eyes till we had seen or heard of Marie, we were speedily in the arms of Somnus.

“Claud! Claud! old fellow, awake; get up, there is such a to-do!” cried Martin, early the next morning, at the same time that he pulled one of my ears.

“Bother, don’t,” I replied, only half-awakened, but wholly vexed at being disturbed.

“That brute of a snake has escaped from its box and the old hunchback.”

“It is no concern of ours. Serves old Huc—what’s his name?—right, for not being more careful.” And I turned round to sleep again.

“But it is a concern of ours, and may serve us wrong, or any one else in whose room or way it may happen to come. For shame, Claud! get up! See, I am more than half-dressed.”

Now fully aroused, for he had tugged at both ears,[34] I jumped out of bed; and, hastily putting on my clothes, ran into the grounds with my brother. There was indeed “a to-do,” as Martin had called it.

The hunchback, moaning and wailing for the loss of his dear friend and companion, the partner in his means of obtaining a livelihood, and around or near to him the servants and slaves of the household, males and females, armed with garden implements, sticks—anything, indeed, upon which they could place their hands. Terror-stricken, and every now and then looking behind, as if they expected to find the reptile at their very heels, they were listening to the tale of the serpent’s escape, or offering advice as to the means of its recapture. Prabu came up a minute after us, and seeing that, while all were talking, not one seemed inclined to act, he cried to the men:

“Dogs and sons of dogs, stand not here like frightened curs! distribute yourselves about the grounds; search every corner; examine every hole and bush.” But still none moved until “my lady,” coming forward and stamping her foot upon the earth, cried angrily, “Get ye gone; do as you are bid. The man who kills the reptile shall have the weight of its head in gold.”

At this the poltroons scampered off, all but Prabu and the hunchback, who, addressing the lady in piteous, whining tones, cried, “Not kill, dear lady; not kill. You would not deprive a wretched old man of his daily rice.”

“Get you gone, wretch! join in the search; and, mark me, heartily shall you be punished if, through[35] your carelessness, harm happens to any one in this house.”

“Come, Martin,” said I, “let us look for a stick or a fork, and help to find the reptile.”

“Not so, boys; it is needless that you should incur danger. Get you back into the house.”

“True, aunt,” said Martin; “but let us to our father’s room.”

“No, no!” exclaimed “my lady,” with a start of alarm; but, recalling her words quickly, she continued, “Yes, to your father’s room, if you will; but better to your own, for he is ill, and it will be cruel to disturb him.”

“My lady, I will search all the rooms which open into the grounds; the reptile may have crept into one of them,” said Prabu.

Those words frightened me. “Then our father’s first, good Prabu,” I said; “for he sleeps with his door open.”

In another minute, without ceremony, we had passed through the French windows of our father’s sleeping-room. The bed was at the other end, and our parent, covered with a mosquito curtain, appeared to be sleeping undisturbed by the hubbub.

“Thank heaven, our father is safe!” I exclaimed; but scarcely had the words left my lips, when I stumbled—nay, fell—putting forth one hand to save myself. Imagine my horror to find it upon the cold, clammy skin of the reptile. It lifted its crest, and put forth its fang with a hiss; but, luckily, Prabu was at[36] my heels: for, as the hiss issued from its jaws, his glittering creese at one blow divided its head from its body. But an instant after I envied the reptile its death-wound. A wild, prolonged shriek from Martin proclaimed the saddest incident of my life. Our parent was dead.

“The poor Sahib! my poor young master!” cried Prabu, looking upon the bed. “It is the cobra’s bite.”

“No, not dead! say not dead, good Prabu! Send for a doctor; my father may have swooned; he cannot be dead!” I cried, giving way to the wildest grief.

But my brother’s conduct surprised me. He, so passionate, so impulsive, after his first outburst of agony, said not a word. For a few minutes he stared wildly in our parent’s face, then, throwing himself upon the body and embracing him, he prayed of him to awake; but, seeming to have realized the truth, he exclaimed, “My father has been murdered! I will kill that hunchback!” and snatching the creese out of Prabu’s hand, he darted off towards the spot where we had left the snake-charmer; but the fellow had fled, mysteriously fled. Almost bereft of his senses by grief, Martin rushed into the presence of our aunt.

“Wicked woman!” he exclaimed, “it is you who have killed my father.”

“Hush! hush! my dear boy,” she replied, kindly, affectionately, taking his hand and drawing him towards her; “you must not say such words; but I wonder not, for this great calamity has well-nigh deprived me of my senses. It is terrible, very terrible;[37] but, my dear boy, you must not give way to this wild grief, it will kill you. Come, come,” and she ran her soft white hand through his chestnut locks. Still, notwithstanding her affectionate manner, apparent grief at my father’s death, her expressed indignation at the hunchback, and the large sum she offered for his apprehension (although, except for carelessness, for what crime he was to be apprehended I could not imagine), she did not succeed in winning our love. Nay, even if we had not at the first entertained a kind of instinctive dislike to her, we, who had been brought up under the eye of an American mother, could never have been brought to respect, not to say love, “my lady.” Her habits, her behavior to her slaves and servants, were repugnant to our feelings. Of these habits and ways the reader may judge from the following sketch of the class of which she was to the full a representative:—

“The lip-lap ladies, i. e., natives of Batavia, are of a listless and lazy temperament, not quitting their beds till about half-past seven or eight o’clock (a late hour in the East). They spend the forenoon in laughing, talking, and playing with their female slaves, who, perhaps, a few minutes afterwards, they will have whipped most unmercifully for the merest trifle. The greater portion of the day, attired in a cool, airy dress, they lounge upon sofas or sit upon the ground, with their legs crossed under them, chewing betel—a habit with which, like most Indian women, they are infatuated. Not content with this, they masticate the[38] Java tobacco, which evil practice encrimsons the saliva, and in time fringes their lips with a black border, and causes their teeth to become black; the great excuse for the use of the betel being that it purifies the mouth, and preserves them from the toothache. To do them justice, these ladies are really not deficient in powers of understanding, and would become very useful members of society, endearing wives and good mothers, if they were but kept from familiarity with the slaves in their infancy, and educated under the immediate eye of their parents, who should be assiduous to inculcate in their tender minds the principles of true morality and polished manners. But, alas! the parents are far from taking such a burdensome task upon themselves. As soon as the child is born, they abandon it to the care of a female slave, by whom it is reared, till it attains the age of nine or ten years. These nurses, being most frequently but one remove above brutes in intellect, instil into the minds of their charges prejudices and superstitions, which, increasing as they grow to maturity, seem to stamp them rather as the progeny of half-witted, mischievous slaves, than of civilized beings.

“In common with most of the women in India, they are excessively jealous of their husbands and of their female slaves; and upon the slightest pretext, they will have these poor bondswomen whipped with rods and beaten with rattans till they sink down before them nearly exhausted. Among other methods of torturing, they make the poor girls sit before them in[39] such a posture that they can pinch them with their toes, with such cruel ingenuity that they faint away from excess of pain. Yet are these lip-lap ladies much sought after by the Dutch colonists for wives; for as soon as one of them becomes a widow, and the body of her husband is interred (which is generally done the day after his decease), she has immediately a number of suitors.

“Their dress is very light and airy. They have a piece of cotton cloth wrapped round the body, and fastened under the arms next to the skin; over it they wear a jacket and a chintz petticoat, which is all covered by a long gown, or kabay, as it is called, which hangs loose; the sleeves come down to the wrists, where they are fastened close, with six or seven little gold or diamond buttons. When they go out in state, or to a company where they expect the presence of a lady of a councilor of India, they put on a very fine muslin kabay. They all go with their heads uncovered. The hair, which is perfectly black, is worn in a wreath, fastened with gold and diamond hair-pins, which they call a condé. In the front, and on the sides of the head, it is stroked smooth, and rendered shining by being anointed with cocoa-nut oil.

“They are particularly partial to this head-dress, and the girl who can arrange their hair the most to their liking is the chief favorite among their slaves. On Sundays they sometimes dress in the European style, with stays and other fashionable incumbrances, which, however, they do not like at all, being accustomed[40] to an attire so much looser and more pleasant in this torrid clime.

“When a lady goes out, she has usually four or more female slaves attending her, one of whom bears her betel-box. They are sumptuously adorned with gold and silver, and this ostentatious luxury the Indian ladies carry to a very great excess.

“The title of ‘My lady’ is given exclusively to the wives of councilors of India. The ladies are very fond of riding through the streets of the town in their carriages in the evening. Formerly, when Batavia was in a more flourishing condition, they were accompanied by musicians; but this is little customary at present—no more than rowing through the canals that intersect the town in little pleasure-boats: and the going upon these parties, which were equally enlivened by music, was called orangbayen.”

I must now, as rapidly as possible, sketch the events of two years—events that led to our becoming wanderers in the wilds of Java. Well, about a month after our father’s funeral, the notary, Ebberfeld, read to us the will. By that testament, Uncle Adam had divided his fortune, including money, merchandise, houses—indeed, everything he had possessed—into two portions; the one to go absolutely to his daughter Marie, upon her reaching the age of twenty-one, the second to be divided equally between the widow and his brother. It was also willed that should Marie die unmarried, and the widow be survivor, that her portion should go to the latter. Further, ran the document, “Should my brother outlive my wife, then her share shall go to him; or, in the event of his demise, to his sons: but if my wife outlive my brother and his sons, Claud and Martin, then the portion of the latter shall pass absolutely to her.” It was further willed, that should our father die before the youngest of us boys reached the age of twenty-one, then the widow was to become our guardian.

“Uncle has been very good to us, Claud,” said Martin,[42] the first moment we were alone after hearing the will read; “but I would rather be my own master without the money, than be under her guardianship, and have twice as much.”

“Why, Martin, I thought that, like me, you had begun to like our aunt?”

“Well, not to like her, but not to dislike her so much. However, that is neither here nor there; we sha’n’t be under her guardianship, but under that of Ebberfeld.”

“Nonsense, Martin! what can he have to do with us?”

“Everything, for he will marry her, and so be her master and ours.”

“How could you dream of such a thing, Martin?”

“I did not dream it, Claud. Is it probable that I should dream of such a man at all? Nevertheless, I know it. Prabu told me so.”

“Worse and worse,” said I, laughing. “Is it likely a slave should be acquainted with his mistress’s private affairs?”

“Yes!” replied my brother, triumphantly; “and for a very good reason. ‘My lady’ has promised him his liberty papers upon the day of her marriage. Now, will you believe it?”

There was no reason I should not believe it, for our aunt would not be the first widow who had married again; but so unpalatable was the idea of being under Ebberfeld’s guardianship, that I tried to disbelieve it. It mattered but little, however, what I believed or disbelieved,[43] for married they were, within a month after that conversation; and from the time of that ceremony we dated the two most miserable years of our lives.

Mynheer Ebberfeld, the oily-tongued notary, the patron of young people, proved to be a domestic tyrant of the first water. His word was law, and a Draconic law, too, to all but “my lady” and, strange to say, Prabu. Of the first he was very proud; for although her father was a Dutchman, she was descended by the mother’s side from the Susunans, or ancient sovereigns of Java, and cousin-german to a rich Japanese pangeran, or prince. Himself a half-caste, Mynheer had hitherto, although very rich, been held but in small esteem by the colonists; his marriage, however, rendered him so important in his own estimation, that he became the most arrogant man in the island. But arrogant, exacting, avaricious, tyrannical as he was, Prabu seemed to care but little for him—nay, with such nonchalance did the freed slave treat both master and mistress (for he was still, after a manner, in their service), that at times I used to think he was in possession of some secret that placed them in his power.

To Marie, my brother, and me, this man was more hateful for his tyranny to his slaves, than for any overt acts to ourselves. But I will relate a tragedy that occurred within the first twelve months of his marriage through his brutality, and you may then judge for yourselves the kind of man we had for guardian.

Ebberfeld possessed an estate some ten miles from[44] the upper town. Upon this was a family of slaves, consisting of a man, his wife, and three children, all natives of Bugis, one of the wildest of the Indian islands. The man, although of a race noted for its ferocity, had ever been hard-toiling, docile, and gentle, and, moreover, passionately attached to his wife and children. It was the latter most amiable passion that caused the poor fellow’s ruin, for he became goaded to madness by the wanton cruelty of Ebberfeld to those dear relatives. Unable to witness this brutality any longer, he ran “a muck” among those he so dearly loved, resolved to release them from their sufferings—that is, he slew mother and children with his creese; then, throwing the weapon into a neighboring canal, he ran till he met two Dutch merchants, to whom he surrendered himself, begging that they would kill him.

Now, such is the spirit of revenge, the impatience of restraint, and the repugnance to submit to insults, in the breasts of all the Indian islanders, that these “mucks,” or murders, are of frequent occurrence; and if the perpetrator survive, he is invariably punished with a disgraceful death; but in this case, the Governor-General not only pardoned the poor fellow, in consideration of the fearful provocation he had had, but severely reprimanded Ebberfeld for his wanton cruelty, and, moreover, deprived him of an office of importance to which he had recently been appointed. Deeply resenting the pardoning of a slave that had caused him so great a loss, and perhaps more so the deprivation of[45] his appointment, Mynheer took to courses which led to his ultimate ruin, and that is why I have related this tragedy. But a few words about this peculiar form of revenge, which, although unknown to other people, is yet universal in the Indian islands.

“To run a muck,” says Dr. Johnson, “signifies to run madly, and attack all that we meet.” “A muck” among the Indian islanders means, generally, an act of desperation, in which the individual or individuals devote their lives, with few or no chances of success, for the gratification of their revenge. Sometimes it is confined to the individual who has offered the injury; at other times it is indiscriminate, and the enthusiast, with a total aberration of reason, assails the guilty and the innocent. On other occasions, again, the oppressor escapes, and the muck consists in the oppressed party’s taking the lives of those dearest to him, and then his own, that, as in the instance of Ebberfeld’s slave, they and he may be freed from some insupportable oppression and cruelty.

The most frequent mucks, by far, are those in which the desperado assails indiscriminately friend and foe, and in which, with disheveled hair and frantic look, he murders or wounds all he meets without distinction, until he be himself killed, falls exhausted by loss of blood, or is secured by the application of certain forked instruments, with which experience has suggested the necessity of opposing those who run a muck, and with which, therefore, the officers of police are always furnished. One of the most singular circumstances attending[46] these acts of criminal desperation is the apparently unpremeditated, and always the sudden and unexpected, manner in which they are undertaken. The desperado discovers his intention neither by his gestures, his speech, nor his features; and the first warning is the drawing of the creese, the wild shout which accompanies it, and the commencement of the work of death. In 1814, a chief of Celebes surrendered himself to the British and a party of their allies headed by a chief. He was disarmed and placed under a guard, in a comfortable habitation, and the hostile chief kept him company during the night. His creese was lying on a table at a little distance from him. About twelve o’clock at night, while engaged in conversation, he suddenly started from his seat, ran to his weapon, and, having possessed himself of it, attempted to assassinate his companion, who, having superior strength, returned a mortal stab.

The retainers of the prisoner, who were without, hearing what was going on within, attacked those of the friendly chief and the European sentinels with great courage, and would have mastered them, had not the officer of the guard rushed out with his drawn sword, and overpowered those who were engaged with them. When he entered the apartment where the chiefs were, he found the captive chief expiring, leaning on the arm and supported by the knee of his opponent, who, with his drawn dagger over him, waited to give, if necessary, an additional stab.

In the year 1812, the very day on which the fortified[47] palace of the Sultan of Java was stormed, a certain petty chief, a favorite of the dethroned Sultan, was one of the first to come over to the conquerors, and was active, in the course of the day, in carrying into effect the successful measures pursued for the pacification of the country. At night he was, with many other Javanese, hospitably received into the spacious house of the chief of the Chinese, and appeared to be perfectly satisfied with the new order of things. The house was protected by a strong guard of Sepoys. At night, without any warning, but starting from his sleep, he commenced havoc, and before he had lost his own life, killed and wounded a great number of persons, chiefly his countrymen, who were sleeping in the same apartment.

Now, to Mynheer, as to all arrogant, overbearing men, honor and position were as the breath of life to his nostrils. Thus, the loss of his appointment made him morose and taciturn, and for hours together he would sit communing with himself, like one meditating some deep-laid scheme.

Then, strange to relate, Prabu seemed to have been taken into his confidence; for they would occasionally sit together in close conference in the library. Again, the twain would disappear for a week or two at a time—Prabu, as he would tell us, to go “nest-hunting” on his own account for the Chinese merchants of the Campong, and Ebberfeld to accompany him, for the love of the excitement and the benefit of his health.

“Yes,” said my brother, after having heard this,[48] “it is all very well for Prabu to tell us that story; but it is fudge. It is my opinion they are hatching some conspiracy against the Government.”

“Well,” I replied, “that is a very romantic explanation of the mystery, at all events;” but then I did not, of course, believe anything so improbable, for, although there could be little doubt that our guardian was bad enough for anything, I did not give him credit for brains or pluck enough to take so high a flight in his wickedness; neither did Martin any longer entertain that belief when, one day, that grandee, the Javanese pangeran, or prince, came to our house to remain on a few weeks’ visit, and for a very good reason. His mahogany-colored highness was on terms of amity with the Dutch Government; for, although the latter had deprived him of sovereign power, as an equivalent they paid him a large annual stipend, and permitted him to retain his estates as proprietor.

“There can be little doubt,” I said, “that the Prince would like to exterminate the conquerors of his race, and, like his ancestors, establish barbaric rule over the island; but, then, it is not possible, and he is not mad enough to attempt impossibilities. It would be to resign the substance for the shadow.”

“True, Claud; but then, if there be truth in history, vanity, revenge, and ambition have caused many a man to give up his one bird in hand for a chance of catching the two in the bush.”

“But look you, brother Martin; it is no business of ours, and I vote we don’t bother ourselves about it.”

“Agreed,” replied Martin.

[49]Now we both honestly intended to keep to this agreement, and to trouble our heads with our own affairs alone; but fate would have it otherwise.

A few days after the foregoing conversation, as my brother and I were sitting at our studies in the apartment which had been originally our father’s, but which we had occupied since his death, Marie came running into the room with tears in her eyes, and looking the very picture of terror.

“Cousin Claud! cousin Martin!” she cried, “that wicked, wicked man!”

“What is the matter, Marie? why are you so frightened?” asked Martin.

“Enough to make one frightened—that bad man is going to kill us all—you, Claud, and poor me.”

“Nonsense, Marie. Kill us, indeed! What for?” said I, laughing.

“To get the money my father left us in his will. You know it goes to her, if we all die first.”

“This is indeed foolish, you silly girl,” said Martin. “What can he want with our money? Why, he is as rich as Crœsus.”

“Oh!” she replied, “that is no matter; he wants more than he has of his own, and that grand but wicked-looking Prince wants it, too. But listen, and I will tell you how I found it all out. You must know,” she added, in whispered tones, “that Cæsar” (a favorite dog) “and I were having a game of romps, when suddenly he scampered into Mynheer Ebberfeld’s private garden, which, you know, he has forbidden[50] either of us to enter. Well, not dreaming that Mynheer was there, indeed, quite thoughtlessly, I ran after Cæsar, and found myself close to the pavilion before I knew where I was. Then, hearing two voices—those of the Prince and Mynheer—I could not help going near, quite near, to the woodwork—”

“And listening,” said Martin. “Had you forgotten the fate of Bluebeard’s wives?”

“Oh! I am coming to something quite as bad,” she replied. “The Prince, I suppose, must have been asking for money, for I heard Mynheer tell him that he had already either mortgaged or sold nearly all his private property, and he did not think he could supply any more. ‘But,’ said the Prince, ‘old Adam Black must have left a very large fortune; for he was one of the richest men in Java.’ ‘True,’ answered Mynheer; ‘but one half is left to the chit (“fancy now his calling me a chit!” she interposed, angrily) of a girl, his daughter; the other half he divided between my wife and the father of the two boys, his nephews.’”

“Well, well, go on, Marie,” said I, now all curiosity.

“Then the Prince said, quite coolly, ‘Well, Mynheer, have not you, in right of your wife, as the guardian of these youngsters, any control over the money?’ ‘None, Prince,’ replied Mynheer. ‘True,’ he added; ‘were the girl in legal possession of her fortune, we might make her marry your highness.’”

“The rogue!” exclaimed Martin.

“Yes, cousin, that was a pretty speech, wasn’t it?”[51] she said; “but don’t interrupt me. Well, to this the Prince made some scornful reply about he, a descendant of the ancient Susunans, marrying a Dutch trader’s daughter, the whole of which I did not catch; and the moment after he said, ‘But in the event of the death of this girl and the boys, Mynheer, to whom would the money go?’ ‘To my wife; but that, in fact, means your humble servant, for she is as warmly interested in the success of our plans as your highness and myself,’ he replied. ‘In that case, the difficulty lies in a nutshell, which may be easily cracked,’ replied the Prince. But after that I could hear no more, for they spoke in whispers; but I have no doubt they were hatching some plot to kill us all three.”

“Nonsense, Marie,” I said; “they are bad men, but would not dare kill us. Why, it would be murder.”

“I don’t know about not daring!” cried Martin. “It is, at all events, fortunate that we are now on our guard; but, Marie, did you hear no more—nothing that might give us a clue to their mysterious doings?”

“Be careful, Martin,” I interposed; “mention no names, you may be overheard.” But my caution was too late; for scarcely had Marie uttered the words, “Yes, yes, I know their wicked designs,” than Mynheer himself stalked through the opened windows into the room, and, taking her by the arm, said, sternly, “Come, girl, come, what falsehoods are you telling? what mischief are you three hatching together?”

“She is telling no falsehood; as for mischief, it is more likely to be you who are hatching it than Marie!” exclaimed Martin, savagely.

[52]“Silence, boy, or I will have you punished,” replied Mynheer, fiercely; and without another word he left, taking our cousin with him.

“That man overheard all Marie told us,” I said.

“I pray Heaven no, Claud,” replied my brother. “If he did, many will be the days ere we shall be permitted to see her again, except, at least, in his or her presence. I tell you, brother,” he added, “if it were not for leaving Marie in Ebberfeld’s power, I should vote for at once laying our heads together to run from here.”

“I am of the same opinion; but where could we go?” said I.

“Anywhere. To the sea, to the woods, or, if Prabu would take us with him, ‘nest-hunting.’”

A fortnight had elapsed since Mynheer had taken Marie from our room. His Javanese highness had left about a week, and we had been kept from both sight and speech with our cousin, an exclusion that much vexed us. It was night, and my brother and I, while undressing for bed, were speculating as to the possibility of eluding our guardian’s vigilance.

“I tell you what, Claud,” said Martin, as he stepped into bed, “I will see Marie, if I die for it—aye, and talk to her, too.”

“A brave resolution; but how? We have been making the effort a whole fortnight, and as yet have not even discovered in what part of the house she is confined.”

“Let me sleep upon it, and I will tell you in the morning,” replied Martin, and not another word could I get from him, so I also endeavored to “sleep upon it;” but after a couple of hours, finding that I was still restless, and my eyes would not keep closed, I arose, and, as it was a bright moonlight night, determined to stroll about the grounds. Scarcely, however, had I stepped out, than I fancied I could hear footfalls, and[54] the murmuring of whispering voices. Alarmed, for, whoever they were, they could not be there for any honest purpose, I crept into the shrubbery, where we had first discovered Marie, and from thence, by the light of the moon, saw four half-naked natives, each with a glittering creese by his side, approaching the window; but guess my astonishment when, in the one who was evidently their leader, I recognized the hunchback snake-charmer, the man whom my brother and I both regarded as the cause of our father’s death. My first impulse was to rush forward and seize the fellow by the throat, my second to shout to Martin; but an instant’s reflection showed me that either would be an act of madness, and I determined to raise an alarm only in the event of their attempting to harm my brother.

Then I began to ponder what could be their object—perhaps to murder or kidnap us boys; for Marie’s story about Ebberfeld, and the advantages he would derive from our death, was vivid in my memory. But no; they were ordinary vulgar robbers, without the least embellishment of romance, for the repulsive little wen-necked hunchback, taking a handful of earth from a bag suspended round his neck, threw it scatteringly into the room. “Good,” he said to his companions; “it fell upon their beds; they will sleep till the morning.”

It was by that act I knew them to be only common robbers, for in Java those worthies entertain a superstition that if a quantity of earth from a newly-opened[55] grave be thrown into the rooms, and, if possible, upon the beds of the inmates of the house they intend to plunder, a death-like sleep will ensue, from which no noise, however great, can awaken them, at least until they have effected their nefarious purpose; but, curiously enough, not only the robbers, but the robbed, have firm faith in the efficacy of this application of grave earth.

Having thus, as it were, propitiated the god of silence and other supernatural authorities favorable to burglary, I had the satisfaction of seeing them steal stealthily from the doorway. At once I resolved, by awakening my brother, to prove the impotency of the charm, but the cunning hunchback, having either less faith in the spell than his brethren, or questioning its powers upon two lads of American birth, suddenly retraced his steps, bringing with him one of his men. Stationing this fellow upon the stone steps, he said:

“Crouch down here, To-ki, and keep thy cat-like eyes upon yonder beds. I fear not the potency of the earth, but should some demon, adverse to our purpose, arouse them, thou hast a creese that can send them into the soundest of slumbers.”

In reply to this cool command, which made my teeth chatter, the amiable Chinese replied:

“Thy will shall be done, oh! mighty Huccuck; the words of the ruler of demons are law to his slave;” and down he crouched, fixing his mischievous, glaring, oblique eyes, upon my brother’s bed. But his back was towards me.

[56]How vexatious was this turn in affairs! To attempt to pass the man unarmed as I was would be sheer madness, yet without so doing I could neither awaken my brother nor alarm the household; still, it was consoling that I had learned the hunchback’s name—the knowledge might be of service in the future.

For some time I stood, pondering what course to take, and upon the probable consequences of the burglary, and I must admit that I was unkind enough to care but very little about any loss Ebberfeld might sustain.

But Marie! the rogues might slay her, or worse—for such had happened before—kidnap, and sell her into slavery in one of the other islands. The fear of so terrible a fate determined me to awaken Martin at all risks. But how? Well, I remembered that I had a pistol bullet in my pocket. True, if it alighted upon his face, it might give him an unpleasant blow, but what was that in comparison with Marie’s safety? And so the leaden messenger hit its mark, and at the same moment I threw myself upon Mr. To-ki, who, in his wondrous surprise, called upon his god Fo to save him from the demon who had seized and robbed him of his creese. To secure the latter had, of course, been my main object. Aroused by the bullet, my brother gave a sharp cry, and began to rub his eyes.

“Get up, Martin, get up,” I cried, “there are robbers in the house; bring a sheet or a curtain to secure this fellow!”

“All right,” he replied, now fully awakened; and in[57] another minute we had twisted, rope-like, a mosquito curtain, and bound the arms and legs, indeed the whole body, of our friend To-ki, as if we had been preparing him for a mummy. Then, having secured him to the bedstead, my brother hastily put on his clothes, and we ran into the garden. There was a small ax lying upon a seat; catching this up, Martin said:

“Clutch your creese tight, and we’ll make our way into the Prince’s apartments, for it is there we shall find Marie.”

By this time, notwithstanding the grave earth, the servants were aroused. Seeing one, our cousin’s maid, scampering towards us, we asked where her young mistress was confined.

“Alas! alas! the hour I was born,” she cried; “they have taken her away.”

“Taken her away!” exclaimed Martin, seizing the girl by the wrist. “Say, who has taken her away?”

“The robber, the hunchback, the snake-charmer.”

“This is Ebberfeld’s doing!” he cried, wildly; “let us to his room, Claud.”

But imagine our surprise upon reaching that worthy’s chamber, which immediately adjoined our aunt’s, to find him in a position similar to that in which we had just left Mr. To-ki, bound hand and foot, and secured to one of the legs of a massive ebony bedstead. There was this difference only, and that excited a certain suspicion in my mind, the cords were so comparatively loose that a man of his strength might, at least so I thought, have easily released himself.

[58]“My boys, my boys,” he whined, “thank God you are safe. Uncut these cords; it may yet be time to secure the thieves. But your aunt, your cousin, are they safe?”

“Do you not know that our cousin Marie has been carried away?” said my brother, as he cut the cords.

“Boy,” he replied, now with his old savageness of manner, “I know nothing, except that I was suddenly awakened by three men, who placed me in the position from which you have just released me. But,” he added, “lose no time; arouse the slaves and servants, and we may yet be able to prevent the rogues from quitting the town.”

We required no second command, and in a few minutes members of the Ebberfeld household were scampering in every direction. But it was fruitless, for, although the city police were aroused and made every search, no clue could be obtained of the depredators, nor, alas! of Marie; and to add to the mystery, even the Chinese whom we had so tightly bound, and from whom we might have obtained some information, managed to escape. In a sentence, it was a clever robbery—so clever, that it marked an epoch in the minds of the Dutch colonists of Batavia.

The authorities, however, did not let the matter rest there, for so great was the consternation of the inhabitants of the upper town, at the abduction of so considerable a personage as the heiress of their late respected councilor Van Black, that early the next morning they sent a party of police to explore the[59] neighboring mountains, as the most likely place for the robbers to have taken refuge. With this party went Mynheer Ebberfeld, clamorously declaring that if it cost him his fortune and life he would rescue his stolen ward. Both Martin and I begged permission to accompany him, but the affectionate man replied that he and his wife had already suffered so great a loss that they would not risk a still greater; “for who knows,” he said, “whether we may not have to encounter an armed band?”

“Well, and suppose we do; don’t you think we can fight for Marie?” said Martin. But he was only snubbed for his forwardness.

Five anxious days and sleepless nights were we kept in suspense as to the fate of our cousin, and, to do our aunt justice, she at least seemed to share our grief. Imagine, therefore, our sensations when, on the morning of the sixth, we heard Ebberfeld’s berlin rattling across the courtyard. In an instant we ran to my lady’s sitting-room, knowing that he would at once go there. Mynheer was standing, sadly, gloomily, with his hand resting upon the back of the sofa, upon which his wife was sitting, and looking as dismal as himself, for he had hastily imparted to her the gist of his news.

“Our cousin, have you news of her, Mynheer?” we asked.

“Alas! yes.”

“Why alas? Is it bad? What is it?” exclaimed Martin.

[60]“My dear lads,” he said, in his most oily tone, and with the mock sorrow of a hired mute upon his countenance, “you will never see poor Marie again; she is in heaven.”

We stood as if dumb with amazement.

“The villains,” he continued, “it is supposed, finding themselves pursued, and fearing that the incumbrance of their prisoner would insure their capture, slew the poor, dear girl, and threw her body into the nearest stream.”

“It is false! I don’t believe it!” cried Martin; whereupon I expected Mynheer would have fallen into a passion, and told us no more; but, not noticing the offensive words, he added, “That, although there was some little difficulty at first in recognizing the features, as when found life must have been extinct two days”—a long period in such a climate—“from the clothes, a locket, ring, watch, and the purse found upon her, there was not the least doubt as to her identity.”

“Strange,” observed Martin, thoughtfully, skeptically, “that robbers should not have taken such valuables.”

“Most wonderful!” replied Mynheer, quickly; “but it is supposed that, in their haste and fear of being captured, they overlooked the trinkets. But it matters not,” he added, in a whining tone; “would that they had taken them, aye, and all I possess, had they but saved the poor dear child’s life. It is sad, most sad!”

“For us,” said my brother, fiercely, “it is sad—worse than our own deaths; but for you, Mynheer—”

[61]“It is a calamity that has cut me to the heart,” interposed our guardian.

“It may be so, or it may not,” said my brother, adding defiantly, but deliberately, and with a searching glance into the notary’s face, as if to watch the effect the words would produce, “but, Mynheer, you will find a consolation in her fortune. Now you will be able to give the Prince more money.”

In an instant I placed myself between them, for I thought Mynheer would then and there have felled him to the ground. He turned deathly pale, his features were contorted into a demoniacal expression, his right hand was clenched and uplifted.