Title: Panama to Patagonia

The Isthmian Canal and the west coast countries of South America

Author: Charles M. Pepper

Release date: October 30, 2024 [eBook #74660]

Language: English

Original publication: Chicago: A.C. McClurg & co, 1906

Credits: Peter Becker, Neil Mercer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Panama to Patagonia

[p. iv]

The Isthmian Canal

And the West Coast Countries of South America

By

Charles M. Pepper

Author of “Tomorrow in Cuba”

With Maps and Illustrations

Chicago

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1906

[p. v]

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1906

Entered at Stationers’ Hall

Published March 24, 1906

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

[p. vi]

THIS BOOK IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED

TO

My Wife

KITTIE ROSE PEPPER

AND TO

My Daughter

NORITA ROSE PEPPER

COMRADES IN MANY TRAVELS

[p. vii]

MY purpose in this work is to consider and describe the effect of the Panama Canal on the West Coast countries of South America from the year 1905. At this period its construction by the United States may be said to have begun. If my own deep conviction that this influence makes powerfully for their industrial development and their political stability be an illusion, the pages which follow may afford the disbelievers grounds for pointing out wrong premises or false conclusions. “We doubt” long has been the dogma of the North American and the European in everything relating to the permanency of progress in the Spanish-American Republics. “I believe” is yet only the creed of the individual. A huge material fact obtruding itself may secure a listening ear from the doubters. The Canal obtrudes.

The severely practical Northern mind finds itself in a brain-fog with reference to the Southern Continent. Speculative reasoning regarding new forces of civilization does not appeal to it. It wants the concrete circumstances. Now the Canal is not an abstraction. The industrial and commercial energies which it wakens are not abstractions. The interoceanic waterway is a national undertaking, but it shows the way to individual enterprise. More than the gates of chance are[p. viii] opened to American youth. They are the gates of opportunity. Consequently the need of knowledge.

The number of recent books relating to the history of South America seems to indicate a demand for this knowledge in its primary form. They open the path for a volume which may be limited more strictly to industrial, fiscal, and political information. For that reason, while not overlooking the historical element in the institutions and governmental systems, I have not thought it necessary to consider them chronologically from the colonial epoch or even from the era of independence.

The effort to divorce economic and social forces from places and peoples in order to analyze a principle usually is so barren that I have not attempted it. Places have their significance, and people are the human material. Customs and institutions are only understood properly in their environment. So many excellent descriptive works have been written about South America that I have sought to subordinate these features; yet since the information applies to localities something about them could not entirely be omitted. Moreover, I have that abounding faith which leads me to look forward to the time when the engineering marvels of the Canal construction may prove enough of a magnet to draw thither the travelled American who would know what his country is doing and who, once on the Isthmus, will be likely to continue down the West Coast with a view to determining the relative attractions of the noble Andes and the Alps. Yet I have made no attempt to preserve the[p. ix] form of continuous narrative. The treatment of the subject does not demand it.

To South American friends who may be offended at the frankness or the bluntness of the views expressed, a word may be communicated. The confidences extended me while on an official mission widened my own vision of the aspirations of their public men. At the same time they conveyed the idea that the economic evolution to which all look forward will come more swiftly if reactionary tendencies are combated more openly and aggressively. Opinions on the policy of the United States being uttered with freedom, I have not thought it necessary to adopt the apologetic attitude in regard to other Republics. In seeking the constructive elements in the national life and character of the South American countries, it has been with the undisguised hope that the contact and the impact of North American character may be a reciprocal influence.

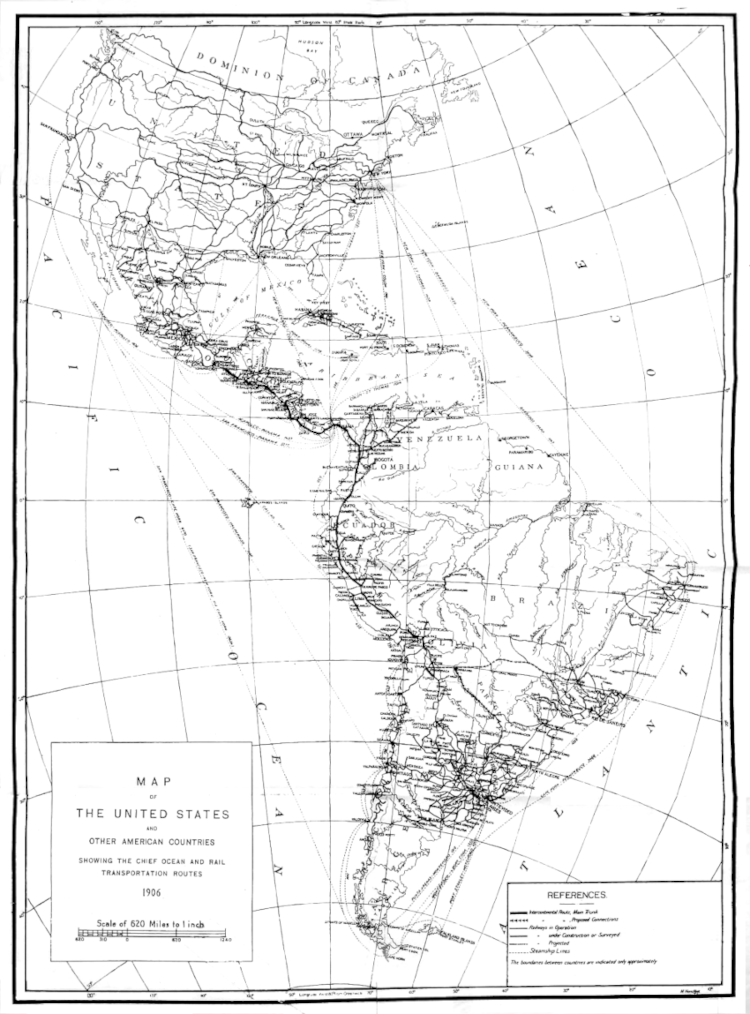

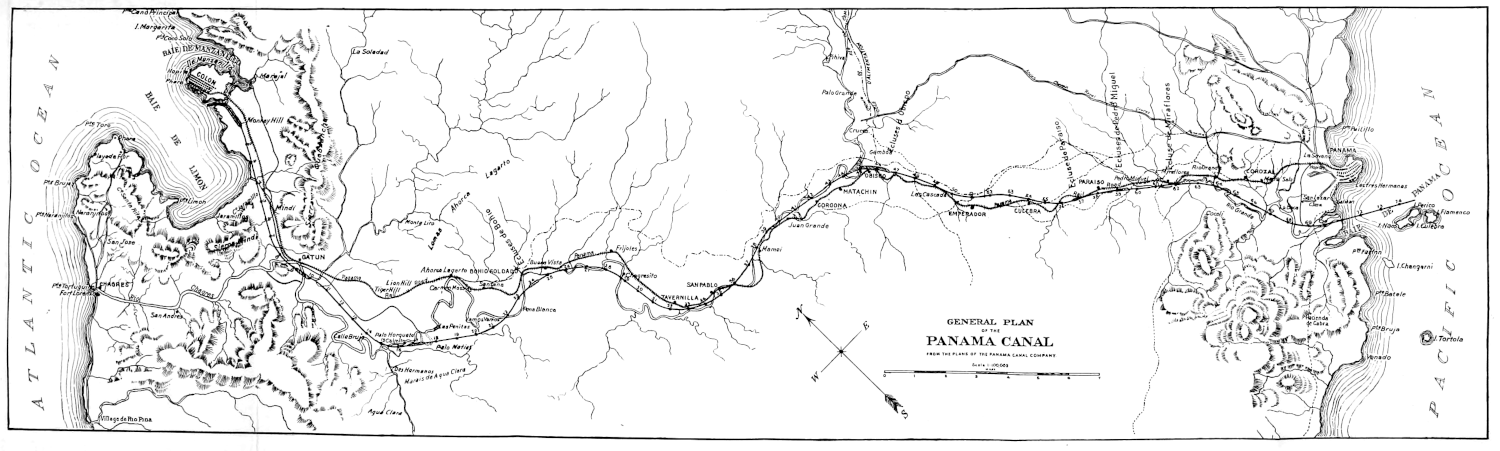

Acknowledgment of material for the general map, which amplifies that of the permanent Pan-American Railway Committee, is due its chairman, Hon. H. G. Davis, whose faith in the future relation of the United States to the other American countries is an example to the generation which will share the benefits both of the Canal and of railroad construction.

C. M. P.

Washington, D. C.

January, 1906.

[p. xi]

| CHAPTER I | |

| ECONOMIC EFFECT OF THE CANAL | Page |

| Philosophic Spanish-American View—Henry Clay’s Mistaken Population Prophecy—The Andes Not a Canal Limitation—Intercontinental Railway Spurs—Argentina and the Amazon as Feeders—Centres of Cereal Production—Crude Rubber—Atlantic and Pacific Traffic—Growth of West Coast Commerce—North and South Trade-wave—Distances via Panama, Cape Horn, and the Straits of Magellan—Waterway Tolls and Coal Consumption—Ecuador and Peru—Bolivia and Chile—Isthmian Railroad Rates—Value of United States Sanitary Authority—American Element in New Industrial Life | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| TRAVEL HINTS | |

| Adopting Local Customs—Value of the Spanish Language—Knowledge of People Obtained through Their Speech—English in Trade—Serviceable Clothing in Different Climates—Moderation in Diet—Coffee at its True Worth—Wines and Mineral Waters—Native Dishes—Tropical Fruits—Aguacate and Cheremoya Palatal Luxuries—Hotels and Hotel-keepers—Baggage Afloat and Ashore—Outfits for the Andes: Food and Animals—West Coast Quarantines—Money Mediums—The Common Maladies and How to Treat Them | 21 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| THE ISTHMUS OF PANAMA | |

| Canal Entrance—Colon in Architectural Transformation—Unchanging Climate—Historic Waterway Routes—Columbus and the Early Explorers—Darien and San Blas—East and West Directions—Life along the Railway—Chagres River and Culebra Cut—Three Panamas—Pacific Mouth of the Canal—Functions of the Republic—Natural Resources—Agriculture[p. xii] and Timber—Road-building—United States Authority on the Zone—Labor and Laborers—Misleading Comparisons with Cuba—The First Year’s Experience | 37 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| A GLIMPSE OF ECUADOR | |

| Tranquil Ship Life—Dissolving View of Panama Bay—The Comforting Antarctic Current—Seeking Cotopaxi and Chimborazo—Up the Guayas River—Activity in Guayaquil Harbor—Old and New Town—Shipping via the Isthmus and Cape Horn—Chocolate and Rubber Exports—Railway toward Quito—A Charming Capital—Cuenca’s Industries—Cereals in the Inter-Andine Region—Forest District—Minerals in the South—Population—Galapagos Islands—Political Equilibrium—National Finances | 57 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| PERUVIAN SHORE TOWNS | |

| Pizarro’s Landing-place at Tumbez—Last Sight of the Green Coast—Paita’s Spacious Bay—Lively Harbor Scenes—An Interesting and Sandy Town—Its Climatic and Other Legends—Future Amazon Gateway—Sugar and Rice Ports—Eten and Pacasmayo—Transcontinental Trail—Cajamarca—Chimbote’s Naval Advantages—Supe’s Attractions—Ancon’s Historic Treaty—Callao’s Excellent Harbor—Importance of the Shipping—Customs Collections—Pisco’s Varied Products—Rough Seas at Mollendo—Bolivian and Peruvian Commerce for the Canal | 73 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| LIMA AND THE CORDILLERAS | |

| Pleasing Historic Memories—Moorish Churches and Andalusian Art—Pizarro’s Remains in the Cathedral—Transmitted Incidents of the Earthquake—The Palace, or Government Building—General Castilla’s Humor—Decay of the Bull-fight—Cultured Society of the Capital—Foreign Element—San Francisco Monastery—Municipal Progress—Chamber of Commerce—A Trip up the Famous Oroya Railway—Masterwork of Henry Meiggs—Heights and Distances—Little Hell—The Great Galera Tunnel—Around Oroya—Railroad to Cerro de Pasco Mines—American Enterprise in the Heart of the Andes | 89 |

| CHAPTER VII[p. xiii] | |

| AREQUIPA AND LAKE TITICACA | |

| Capital of Southern Peru—Through the Desert to the Coast—Crescent Sand-hills—A Mirage—Down the Cañon—Quilca as a Haven of Unrest—Arequipa Again—Religious Institutions—Prevalence of Indian Race—Wool and Other Industries—Harvard Observatory—Railroading over Volcanic Ranges—Mountain Sickness at High Crossing—Branch Line toward Cuzco—Inambari Rubber Regions—Puno on the Lake Shore | 109 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| THE REGIONS AND THEIR RESOURCES | |

| Topography a Key to Economic Resources—Coast, Sierra, and Montaña—Cotton in the Coast Zone—Piura’s High Quality—Lima and Pisco Product—Prices—Increase Probable—Sugar-cane as a Staple—Probability of Growth—Rice as an Export and an Import—Irrigation Prospects—Mines in the Sierra—Geographical Distribution of the Deposits—Live-stock on the High Plains—Rubber in the Forest Region—Iquitos on the Amazon a Smart Port—Government Regulations for the Gum Industry | 123 |

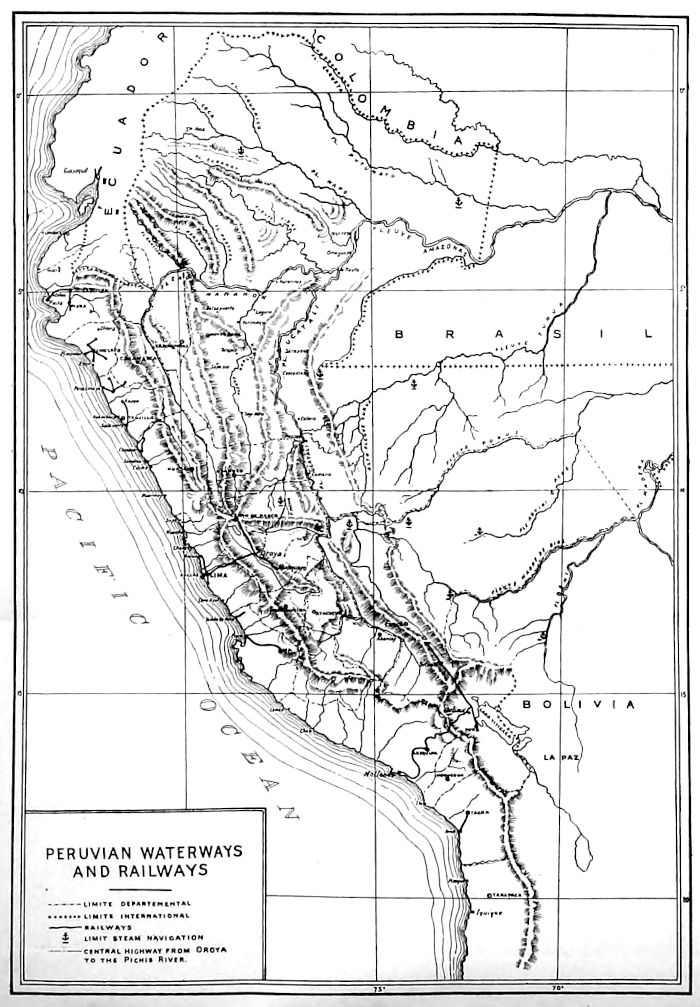

| CHAPTER IX | |

| WATERWAYS AND RAILWAYS | |

| Importance of River System—Existing Lines of Railroads—Pan-American Links—Lease of State Roads to Peruvian Corporation of London—Unfulfilled Stipulations—Law for Guaranty of Capital Invested in New Enterprises—Routes from Amazon to the Pacific—National Policy for Their Construction—Central Highway, Callao to Iquitos—The Pichis—Railroad and Navigation—Surveys in Northern Peru—Comparative Distances—Experiences with First Projects—Future Building Contemporaneous with Panama Canal | 137 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| THE PEOPLE AND THEIR INCREASE | |

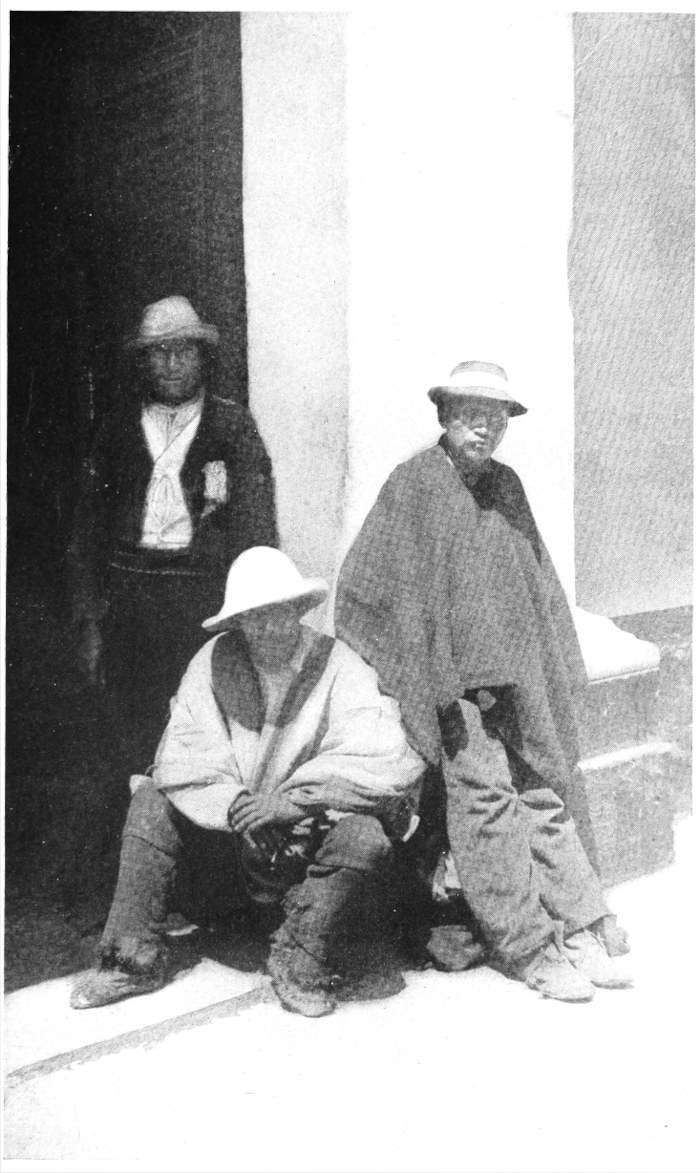

| Density of Population in Time of the Incas—Three Million Inhabitants Now Probable—Census of 1876—Interior Country[p. xiv] Not Sparsely Populated—Aboriginal Indian Race and Mixed Blood—Fascinating History of the Quichuas—Tribal Customs—Superstition—Negroes and Chinese Coolies—Immigration Movements of the Future—Wages—European Colonization—Cause of Chanchamayo Valley Failure—Climatic and Other Conditions Favorable—An Enthusiast’s Faith | 151 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| PERU’S GROWING STABILITY | |

| Seeds of Revolution Running Out—Educated Classes Not the Sole Conservative Force—President Candamo’s Peacemaking Administration—Crisis Precipitated by his Death—Triumph of Civil Party in the Choice of his Successor—President Pardo’s Liberal and Progressive Policies—Growth in Popular Institutions—Form of Peruvian Constitution and Government—Attitude of the Church—Rights of Foreigners—Sources of Revenue—Stubborn Adherence to Gold Standard—Interoceanic Canal’s Aid in the National Development | 164 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| ALONG COAST TO MAGELLAN STRAITS | |

| Arica, the Emerald Gem of the West Coast—Memorable Earthquake History—A Future Emporium of Commerce for the Canal—Iquique the Nitrate Port—Value of the Trade—Antofagasta’s Copper Exports—Caldera and the Trans-Andine Railway to Argentina—Valparaiso’s Preëminence among Pacific Ports—Extensive Shipping and Execrable Harbor—Plans for Improvement—No Fear of Loss from the Interoceanic Waterway—Coal and Copper at Lota—Concepcion and Other Towns—Rough Passage into the Straits—Cape Pillar—Punta Arenas, the Southernmost Town of the World—Trade and Future | 180 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| LIFE IN THE CHILEAN CAPITAL | |

| Railway along Aconcagua River Valley—Project of Wheelright, the Yankee—Santiago’s Craggy Height of Santa Lucia—A Walk along the Alameda—Historic and Other Statues—The Capital a Fanlike City—Public Edifices—Dwellings of the Poor—Impression of the People at the Celebration of[p. xv] Corpus Christi—Some Notes on the Climate—Habits and Customs—“The Morning for Sleep”—Independence of Chilean Women—Sunday for Society—Fondness for Athletic Sports—Newspapers an Institution of the Country | 201 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| NITRATE OF SODA AN ALADDIN’S LAMP | |

| Extensive Use of Nitrates as Fertilizers—Enormous Contributions to Chilean Revenues—Résumé of Exportations—Description of the Industry—How the Deposits Lie—Iodine a By-product—Stock of Saltpetre in Reserve—The Trust and Production—Estimates of Ultimate Exhaustion—A Third of a Century More of Prosperous Existence—Shipments Not Affected by Panama Canal—Copper a Source of Wealth—Output in Northern Districts—Further Development—Coal—Silver Mines Productive in the Past—Prospect of Future Exploitation | 217 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| CHILE’S UNIQUE POLITICAL HISTORY | |

| National Life a Growth—Anarchy after Independence—Presidents Prieto, Bulnes, Montt, Perez—Constitution of 1833—Liberal Modifications—The Governing Groups—Civil War under President Balmaceda—His Tragic End—Triumph of his Policies—Political System of To-day—Government by the One Hundred Families—Relative Power of the Executive and the Congress—Election Methods Illustrated—Ecclesiastical Tendencies—Proposed Parliamentary Reforms—Ministerial Crises—Party Control | 232 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| PALPITATING SOCIAL QUESTIONS | |

| Existence of the Roto Discovered—Mob Rule in Valparaiso—Indian and Caucasian Race Mixture—Disquieting Social Phenomena—Grievances against the Church—Transition to the Proletariat—Lack of Army and Navy Opportunity—Not Unthrifty as a Class—Showings of Santiago Savings Bank—Excessive Mortality—Need of State Sanitation—Discussion of Economic Relation—Changes in National Tendencies—Industrial Policies to Placate the Roto | 248 |

| CHAPTER XVII[p. xvi] | |

| CHILE’S INDUSTRIAL FUTURE | |

| Agricultural Possibilities of the Central Valley—Its Extent—Wheat for Export—Timber Lands of the South—Wool in the Magellan Territory—Grape Culture—Mills and Factories—Public Works Policy—Longitudinal and Other Railway Lines—Drawbacks in Government Ownership—Trans-Andine Road—Higher Levels of Foreign Commerce—Development of Shipping—Population—Experiments in Colonization—Internal and External Debt—Gold Redemption Fund—Final Word about the Nitrates | 262 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| WAYFARING IN BOLIVIA—THE ROYAL ANDES | |

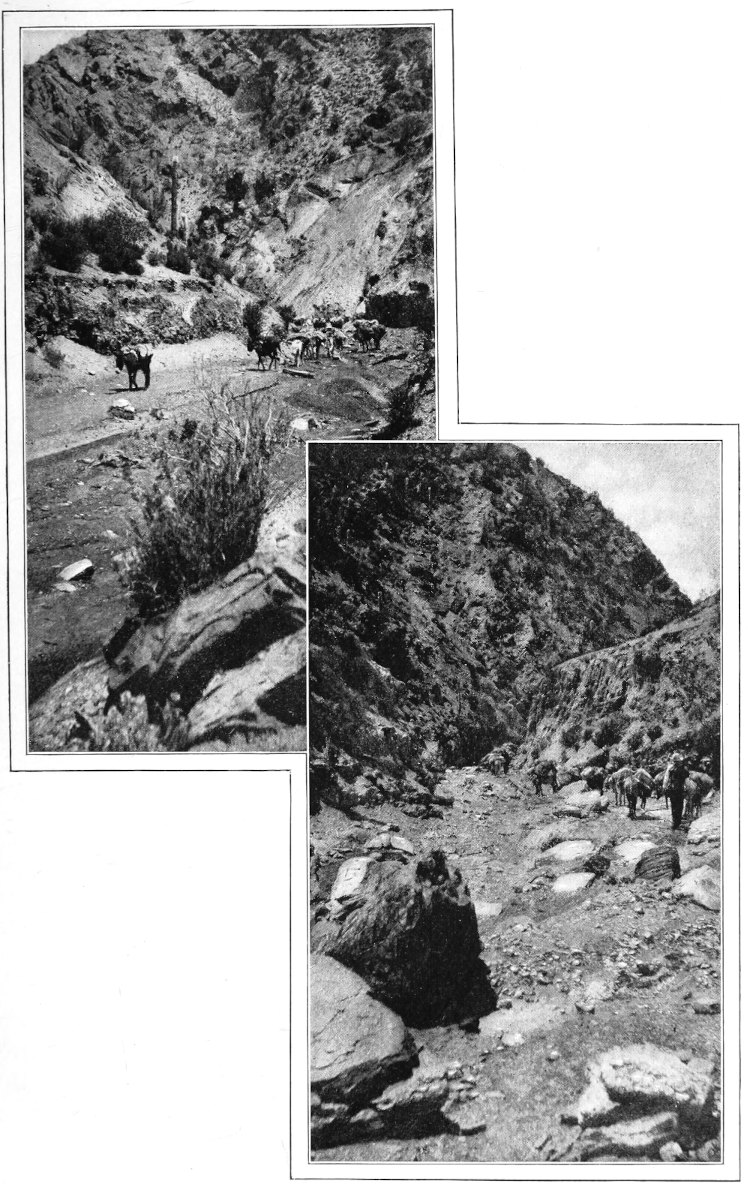

| Old Spanish Trail from Argentina—Customs Outpost at Majo—Sublime Mountain View—Primitive Native Life—Sunbeaten Limestone Hills—Vale of Santa Rosa—Tupiza’s People and Their Pursuits—Ladies’ Fashions among the Indian Women—Across the Chichas Cordilleras—Barren Vegetation—Experience with Siroche, or Mountain Sickness—Personal Discomforts—Hard Riding—Portugalete Pass—Alpacas and Llamas—Sierra of San Vicente—Uyuni a Dark Ribbon on a White Plain—Mine Enthusiasts—Foreign Consulates | 278 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| WAYFARING IN BOLIVIA—THE CENTRAL PLATEAU | |

| A Hill-broken Table-land—By Rail along the Cordillera of the Friars—Challapata and Lake Poöpo—Smelters—Spanish Ear-marks in Oruro—By Stage to La Paz—Fellow-passengers—Misadventures—Indian Tombs at Caracollo—Sicasica a High-up Town, 14,000 Feet—Meeting-place of Quichuas and Aymarás—First Sight of the Famed Illimani Peaks—Characteristics of the Indian Life—Responsibility of the Priesthood—Position of the Women—Panorama of La Paz from the Heights—The Capital in Fact—Cosmopolitan Society | 297 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| THE MEXICO OF SOUTH AMERICA | |

| Depression and Revival of Mining Industry—Bolivia’s Tin Deposits and Their Extension—Oruro, Chorolque, Potosi, and[p. xvii] La Paz Districts—Silver Regions—Potosi’s Output through the Centuries—Pulacayo’s Record—Mines at Great Heights—Trend of the Copper Veins—Corocoro a Lake Superior Region—Three Gold Districts—Bismuth and Borax—Bituminous Coal and Petroleum—Tropical Agriculture—Some Rubber Forests Left—Coffee for Export—Coca and Quinine—Cotton | 313 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| BOLIVIAN NATIONAL POLICY | |

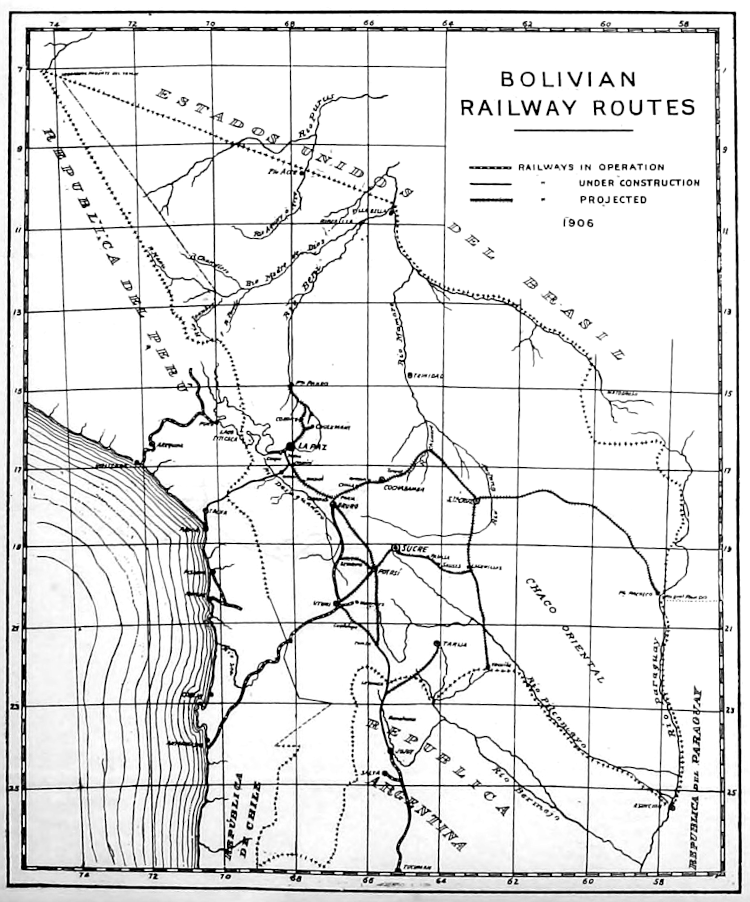

| Panama Canal as Outlet for Mid-continent Country—Railways for Internal Development—Intercontinental Backbone—Proposed Network of Lines—Use Made of Brazilian Indemnity—Chilean Construction from Arica—Human Material for National Development—Census of 1900—Aymará Race—Wise Governmental Handling of Indian Problems—Immigration Measures—Climatic Variations—Political Stability—General Pando’s Labors—Status of Foreigners—Revenues and Trade—Commercial Significance of Treaty with Chile—Gold Legislation—A Canal View | 331 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| NEW BASIS OF THE MONROE DOCTRINE | |

| John Quincy Adams’ Advice—Canning’s Trade Statesmanship—Lack of Industrial and Commercial Element—Excess of Benevolent Impulse—Forgotten Chapters of the Doctrine’s History—The Ecuador Episode—President Roosevelt’s Interpretation—Diplomatic Declarations—Spectres of Territorial Absorption—Change Caused by Cuba—Progress of South American Countries—European Attitude on Economic Value of Latin America—German and English Methods—Proximity of Markets to United States Trade Centres—Conclusion | 351 |

| APPENDIX—Hydrographic Tables of Distances | 373 |

| INDEX | 379 |

| TABLES | 399 |

[p. xix]

| Page | |

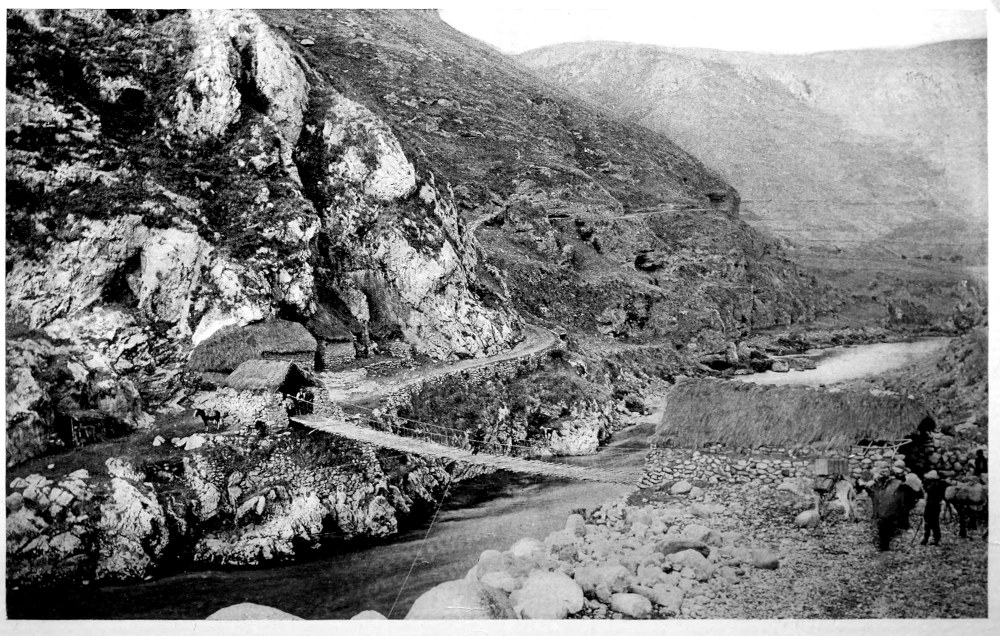

| A Mountain Bridge | Frontispiece |

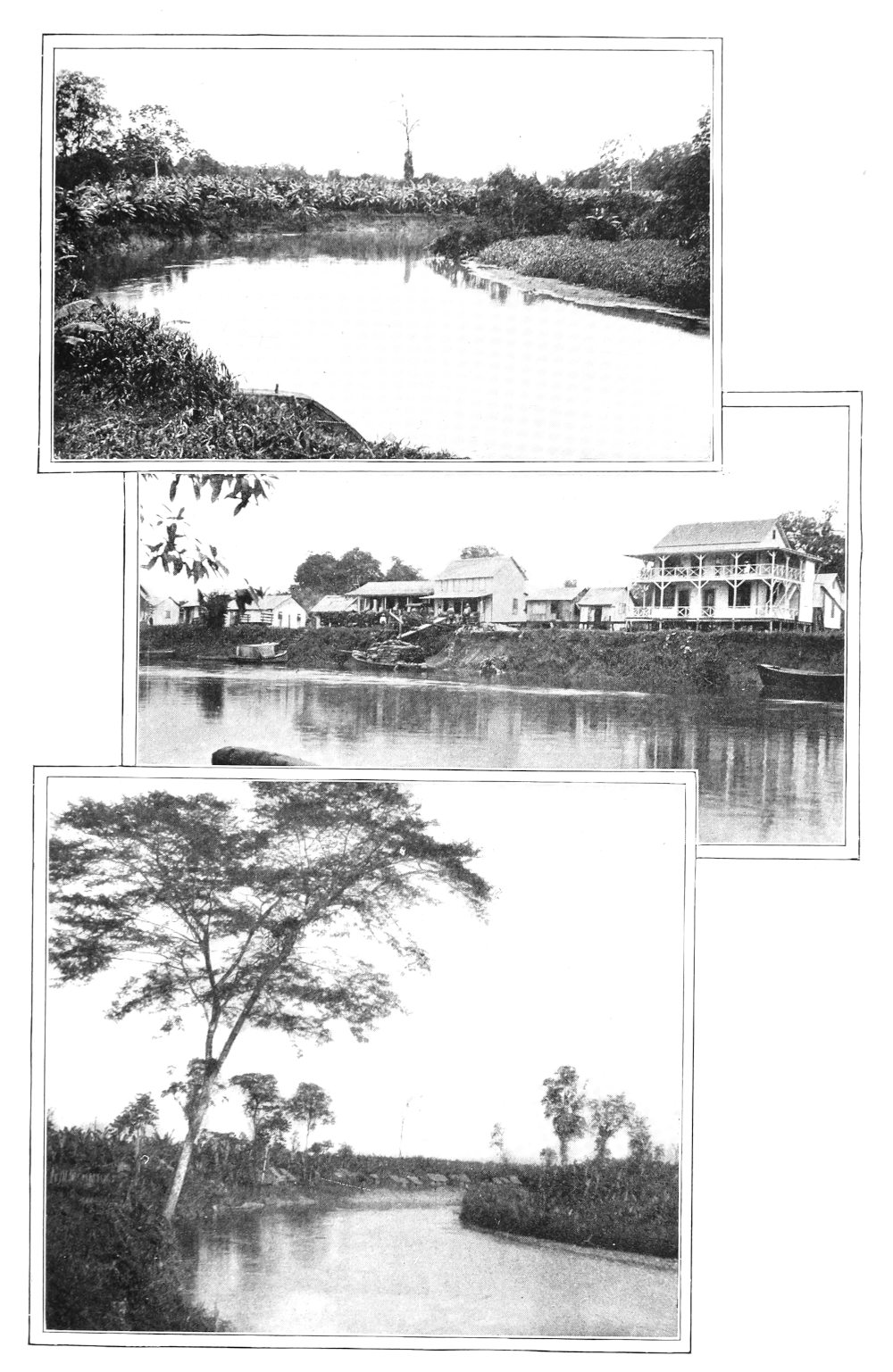

| Scene on the Chagres River | 10 |

| Swamp Section of the Canal | 10 |

| The Atlantic Entrance to the Canal | 10 |

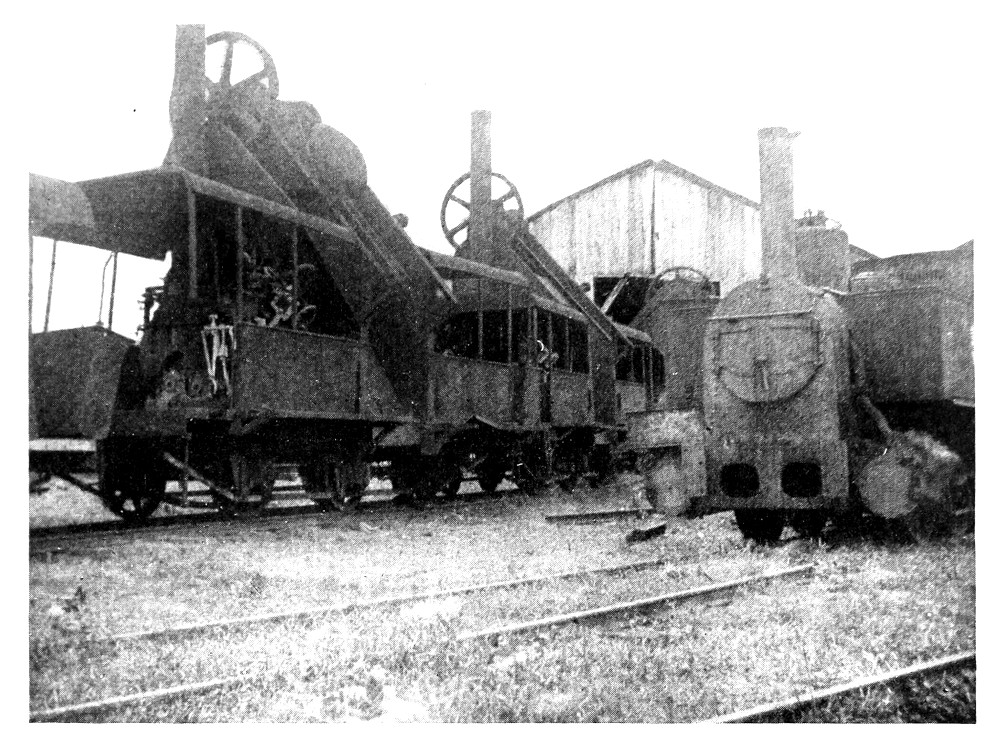

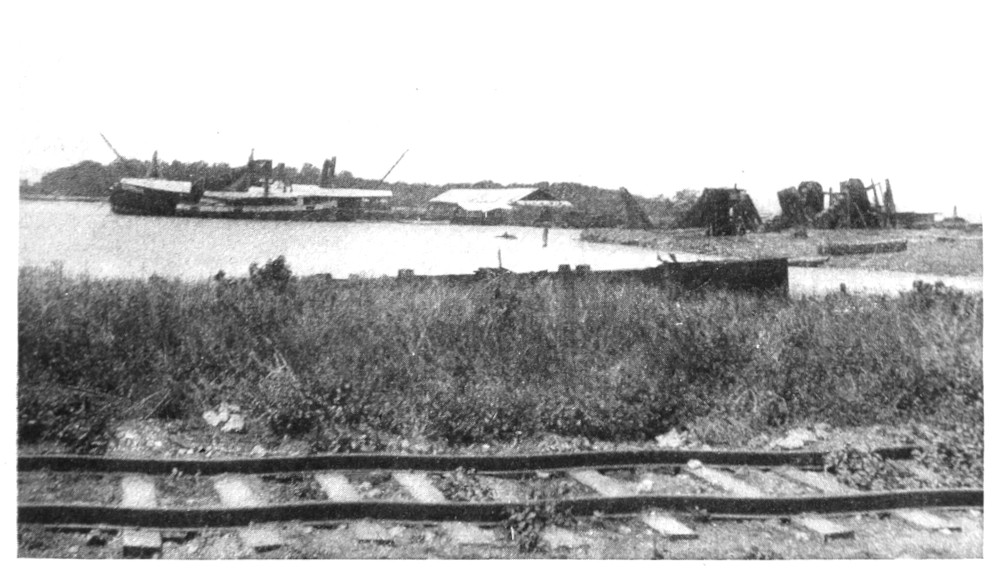

| Abandoned Machinery—Two Views | 18 |

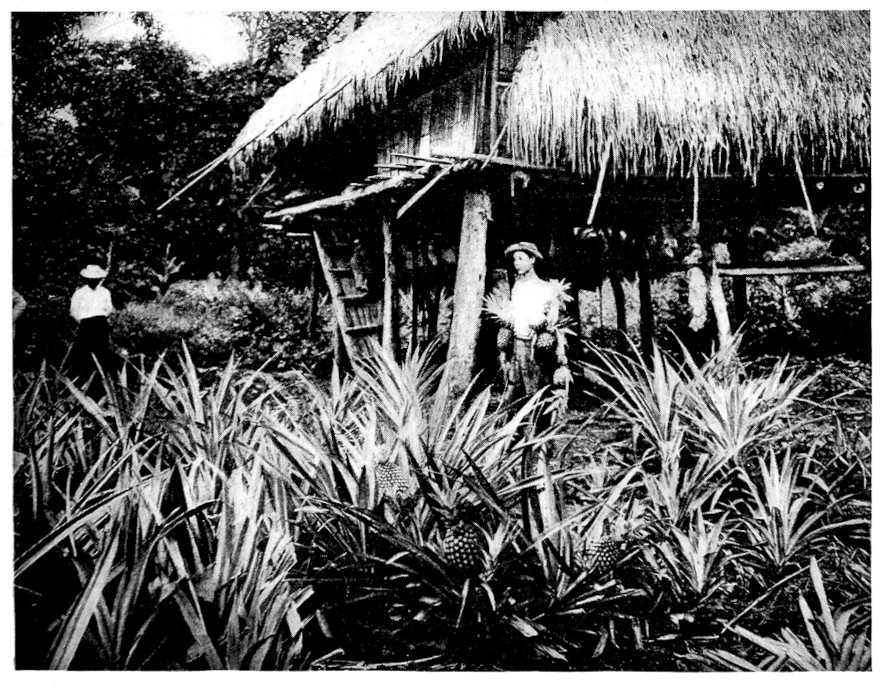

| Pineapple Garden | 28 |

| Banana Grove | 28 |

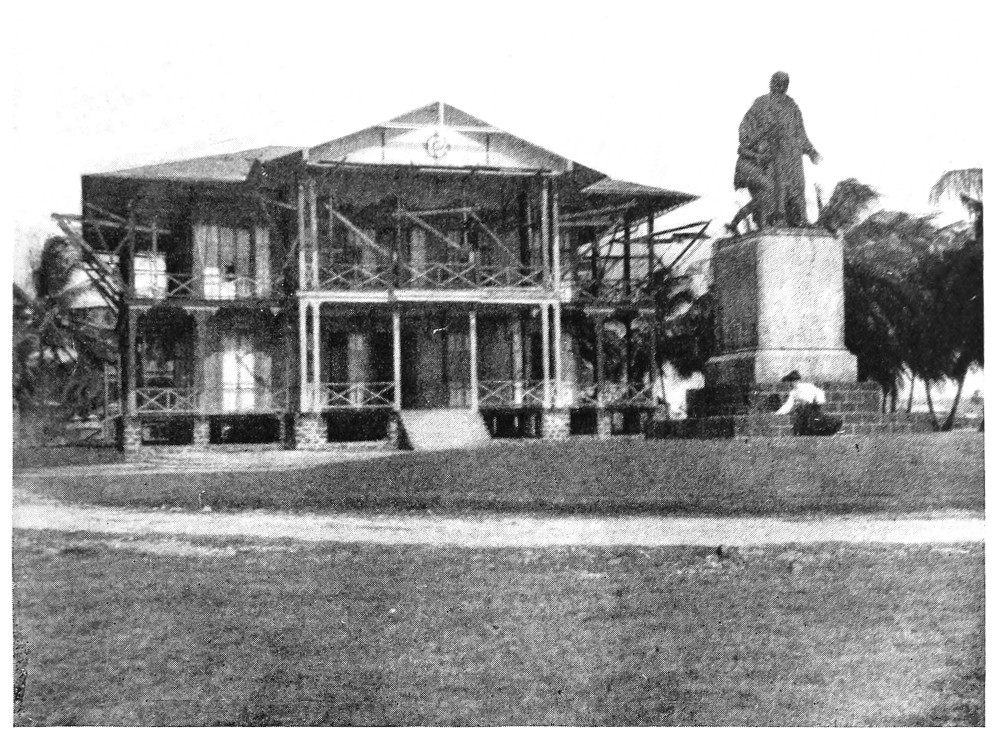

| The De Lesseps House, Colon | 44 |

| Caribbean Cocoa Palms | 44 |

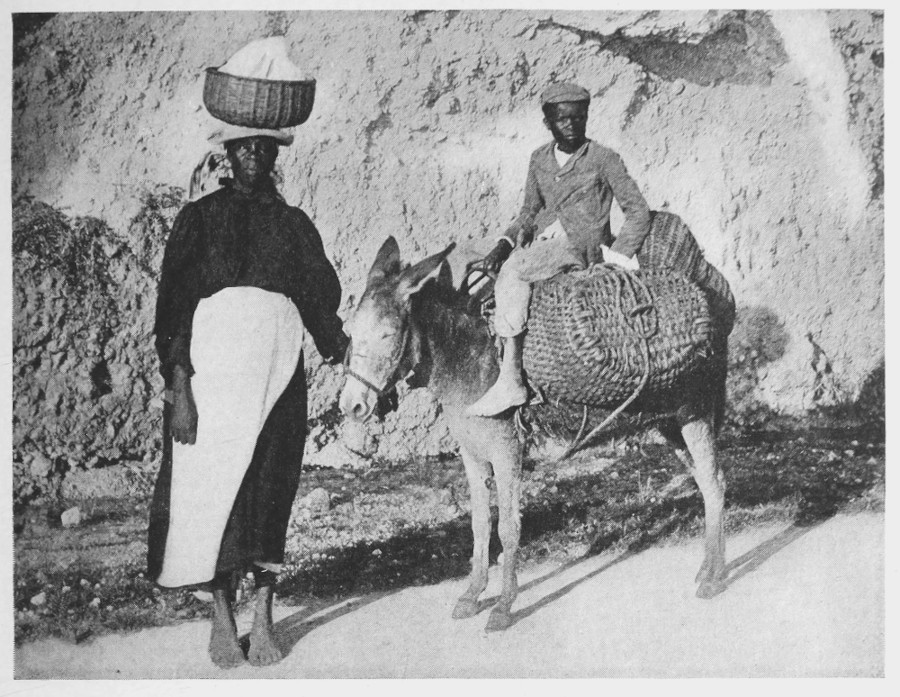

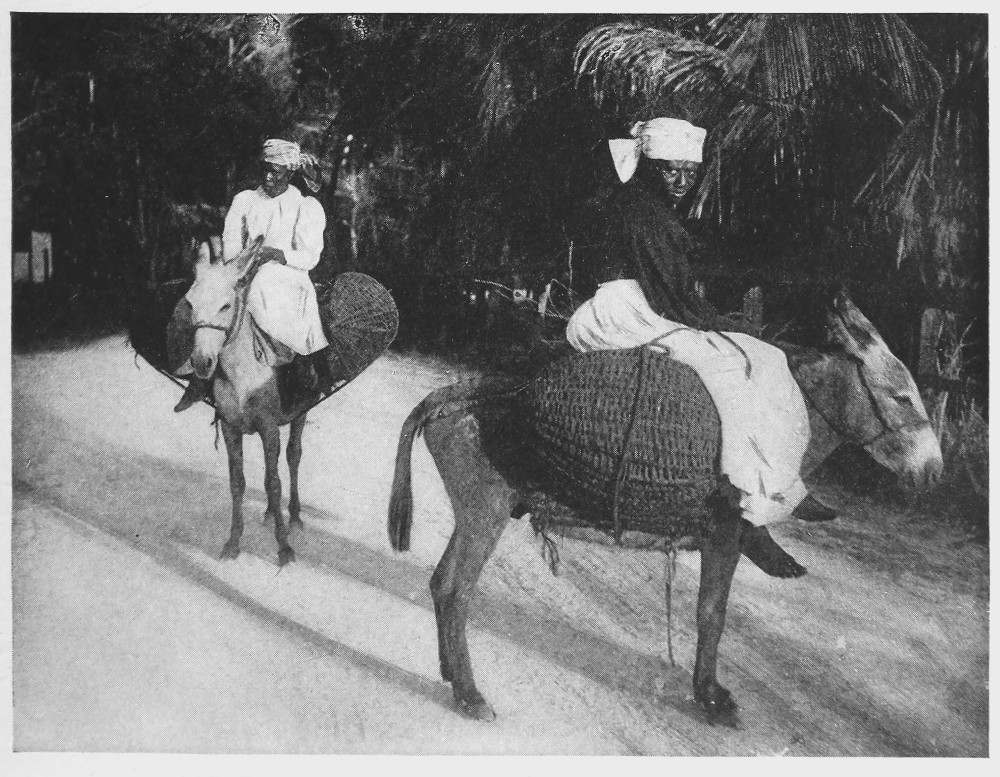

| Panama Natives from the Swamp Country | 50 |

| Panama Natives from the Mountains | 50 |

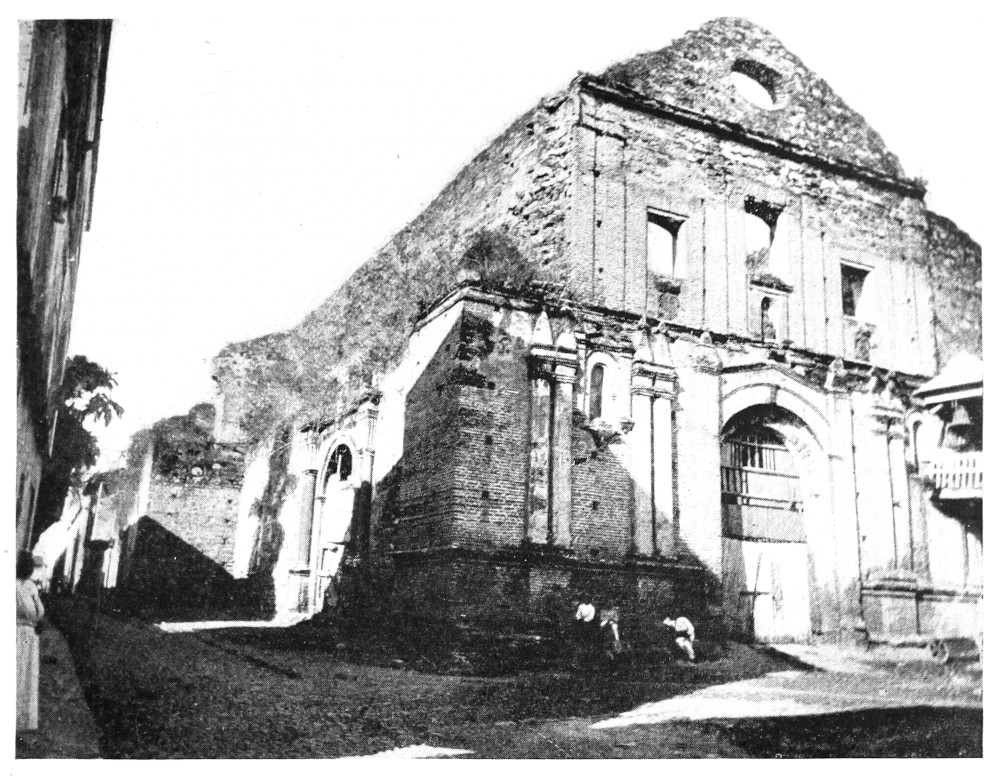

| Ruins at Panama—Two Views | 54 |

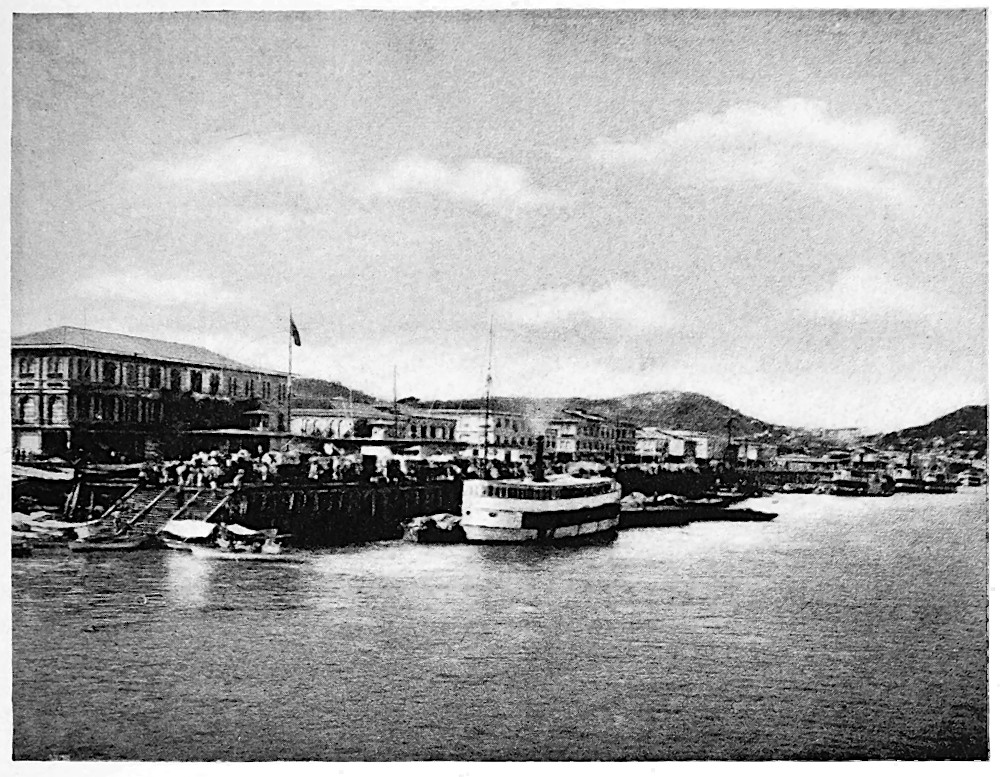

| The Waterfront at Guayaquil | 60 |

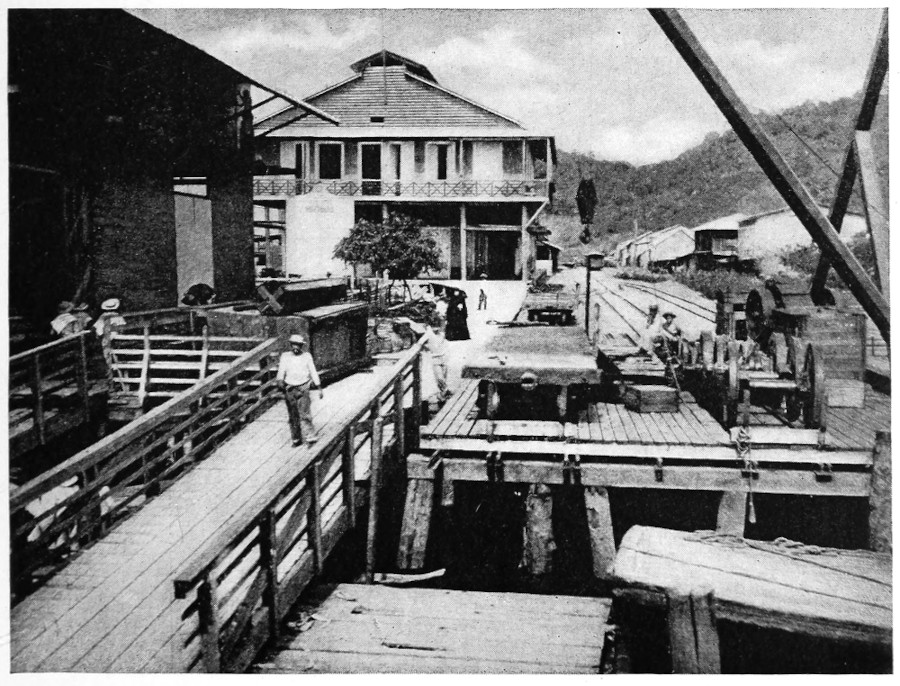

| The Wharf at Duran | 60 |

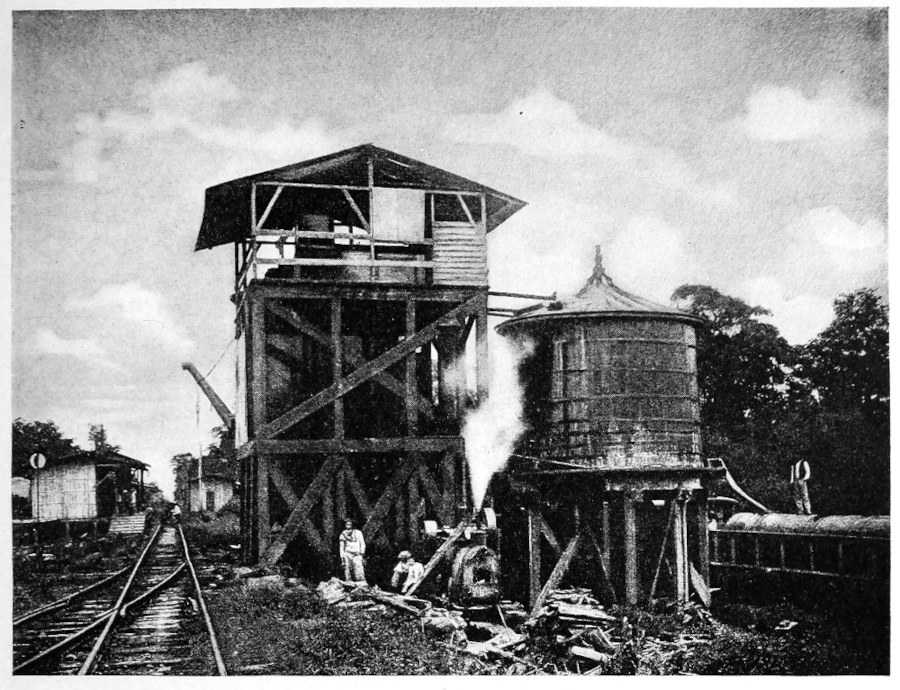

| Weed-killer Plant, Guayaquil and Quito Railway | 64 |

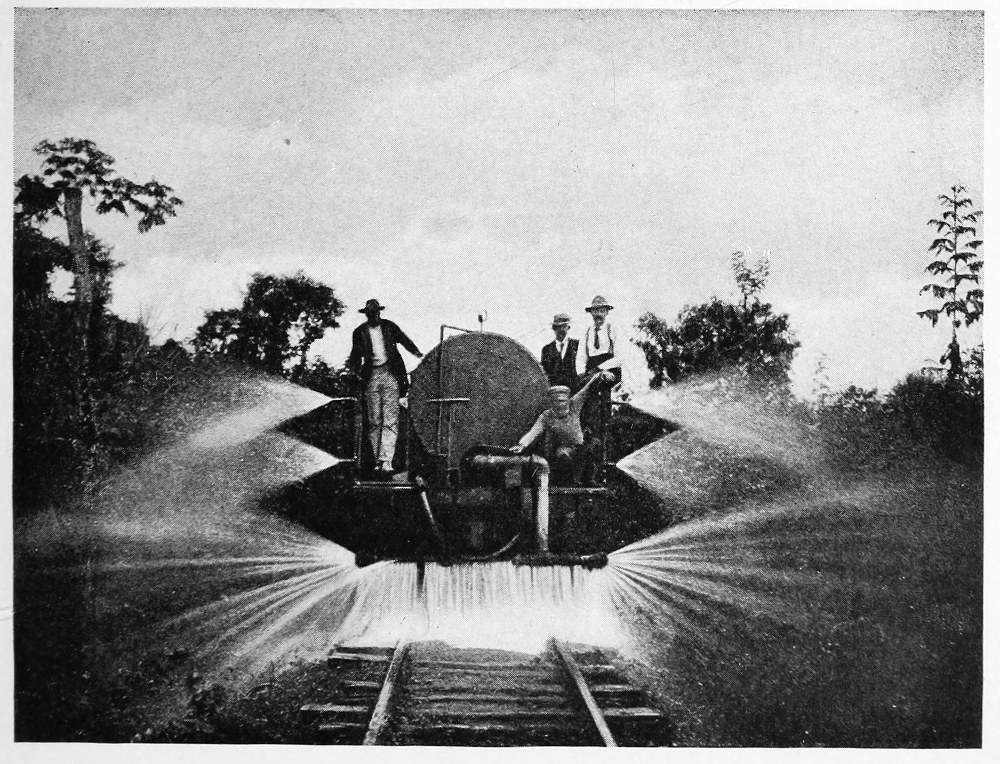

| Railway Spraying Cart | 64 |

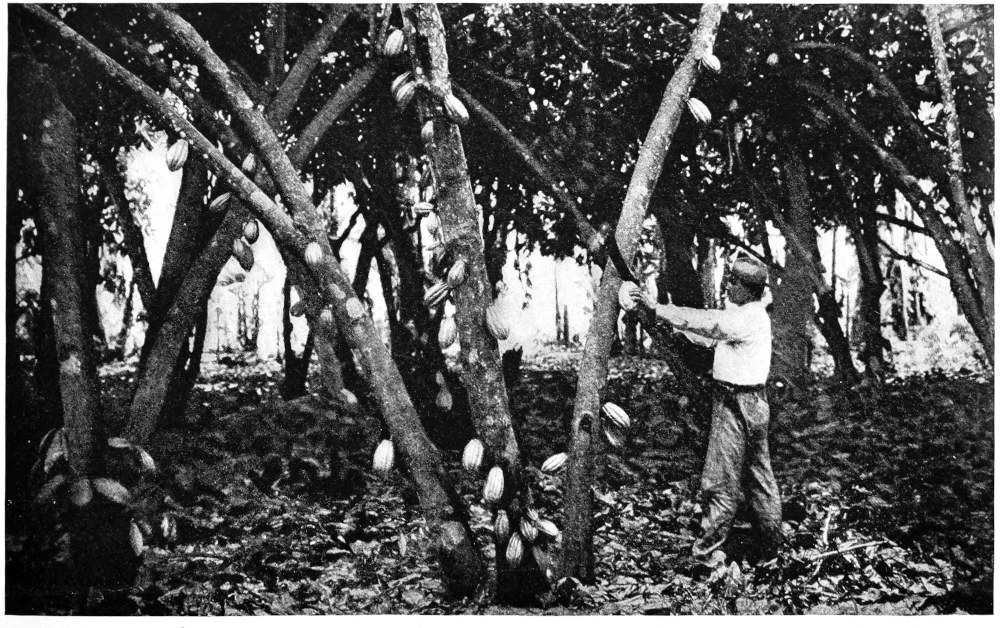

| Cacao Trees | 70 |

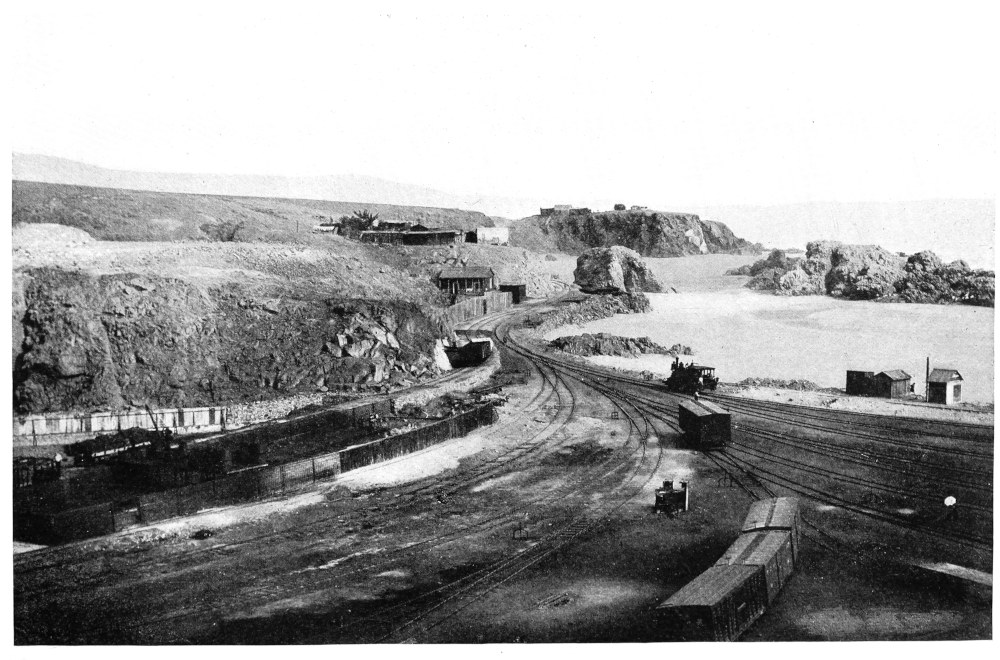

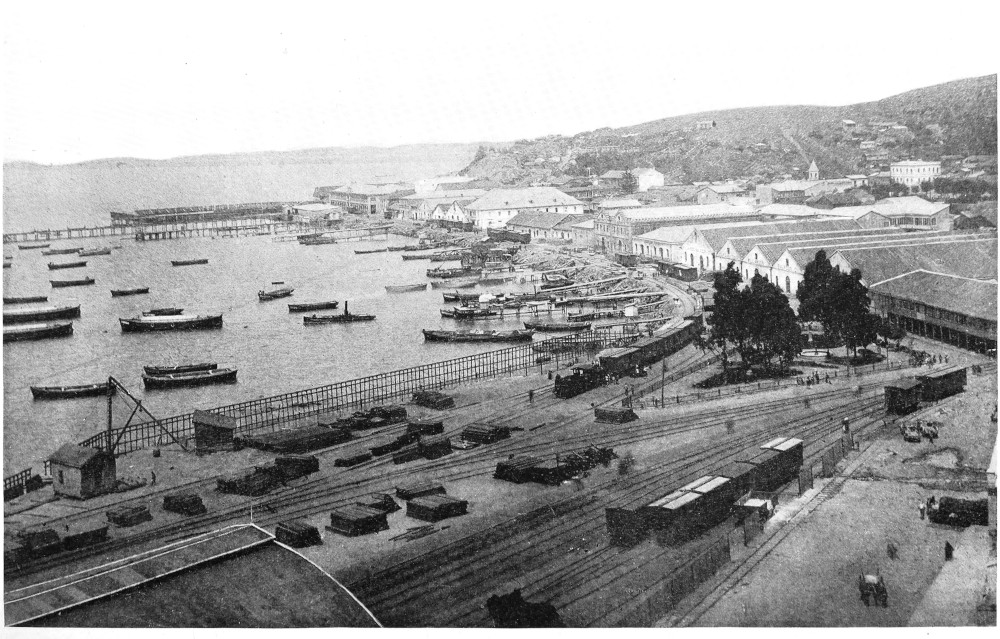

| View of Mollendo Harbor and Railway Yards | 86 |

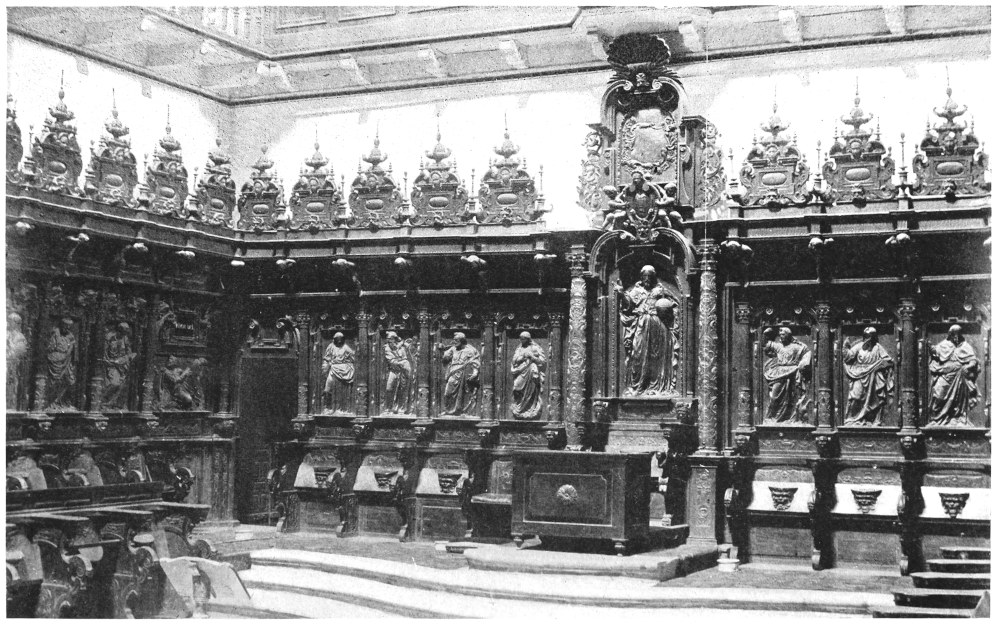

| Interior of Cathedral, Lima | 92 |

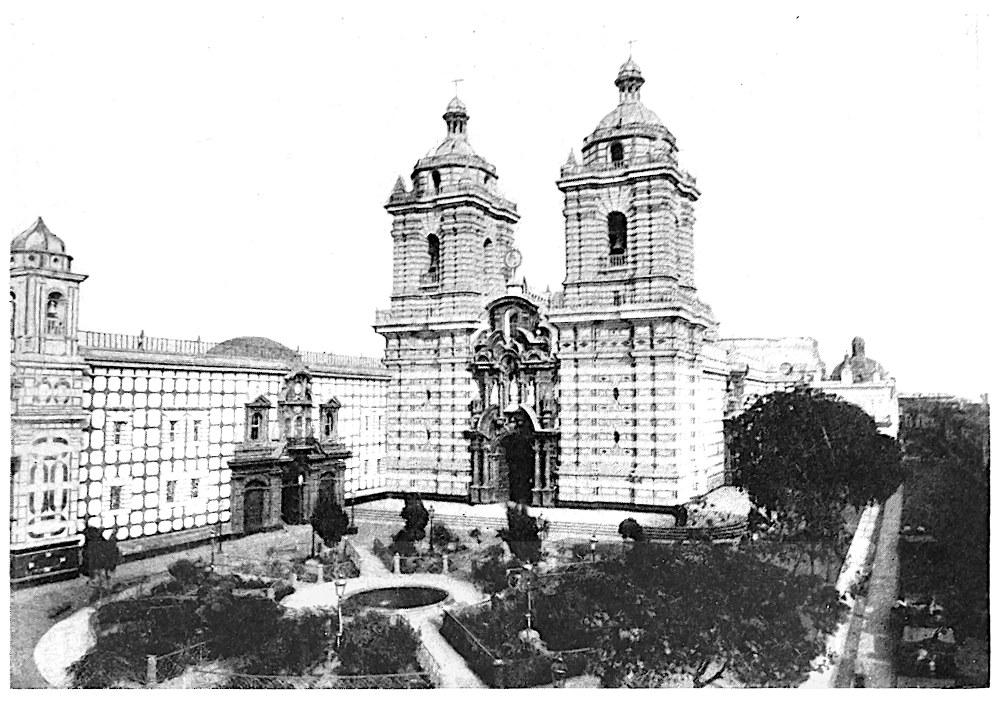

| Church of San Francisco, Lima | 94 |

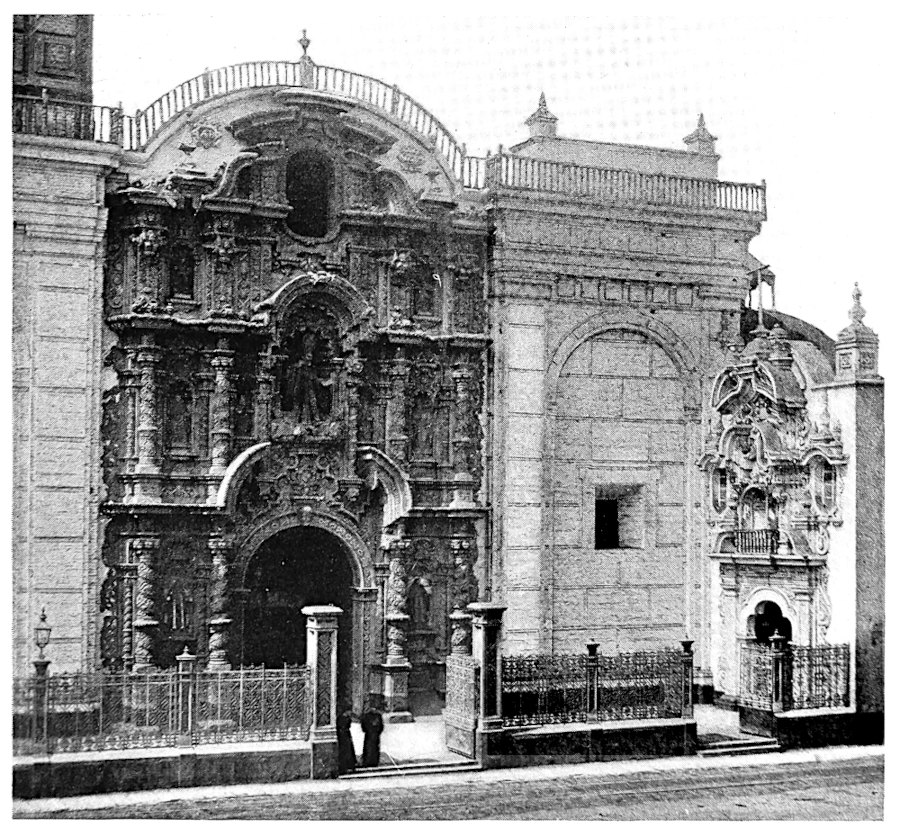

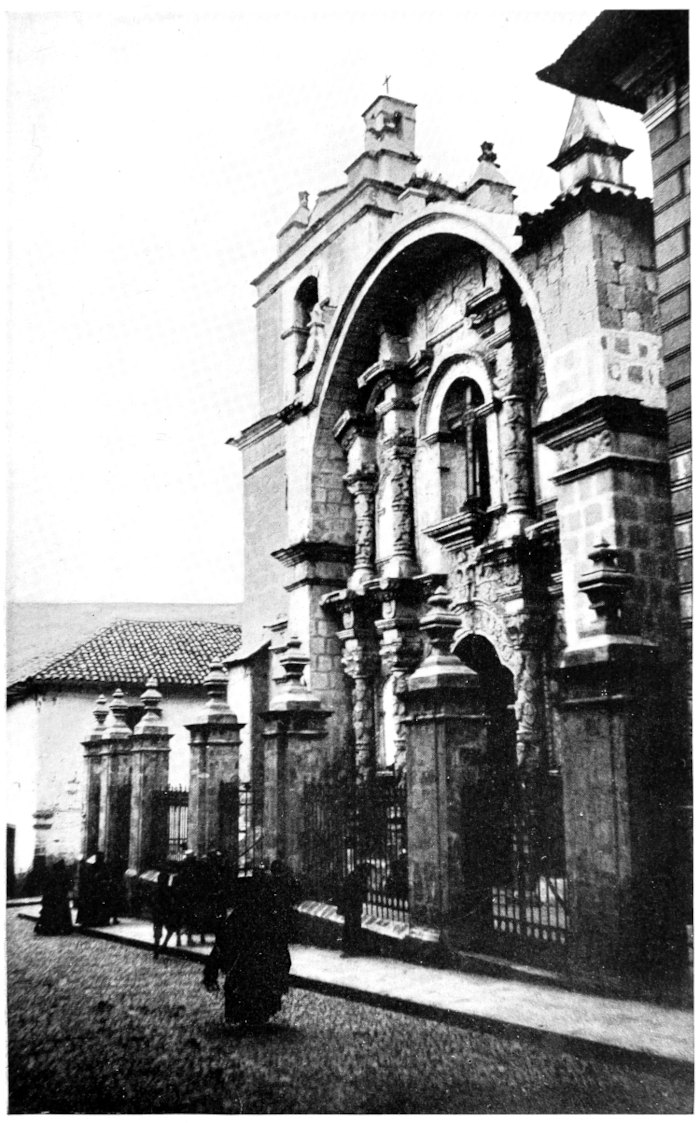

| Church of San Augustin, Lima | 94 |

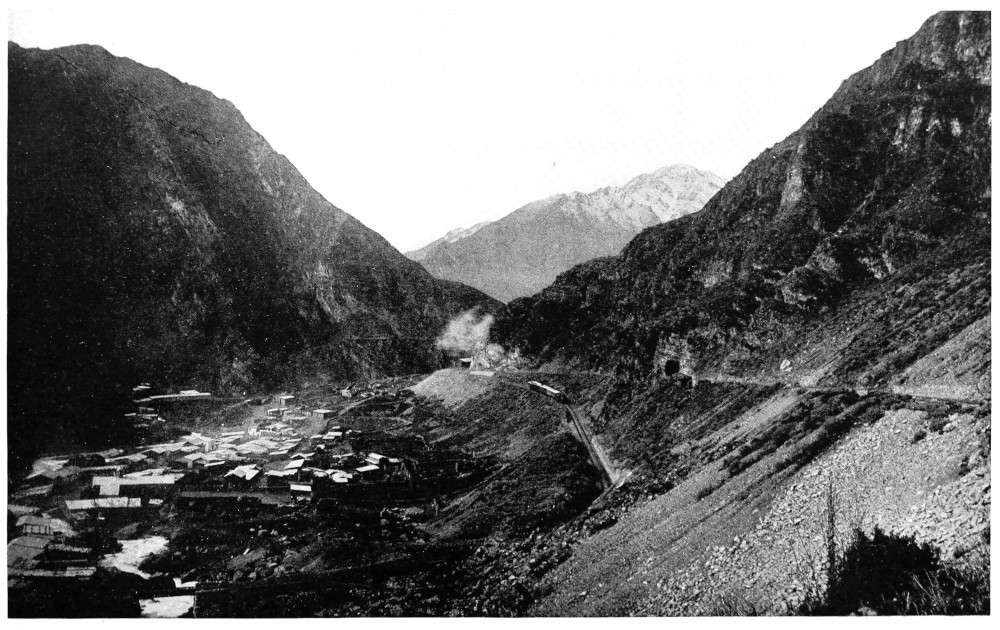

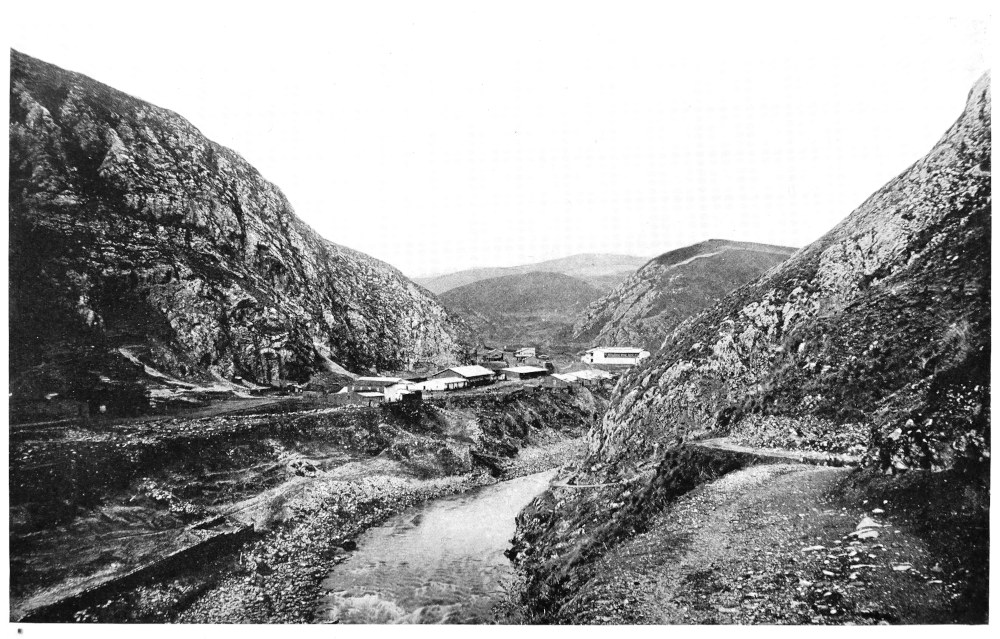

| Scene on the Oroya Railway, Chicla Station | 98 |

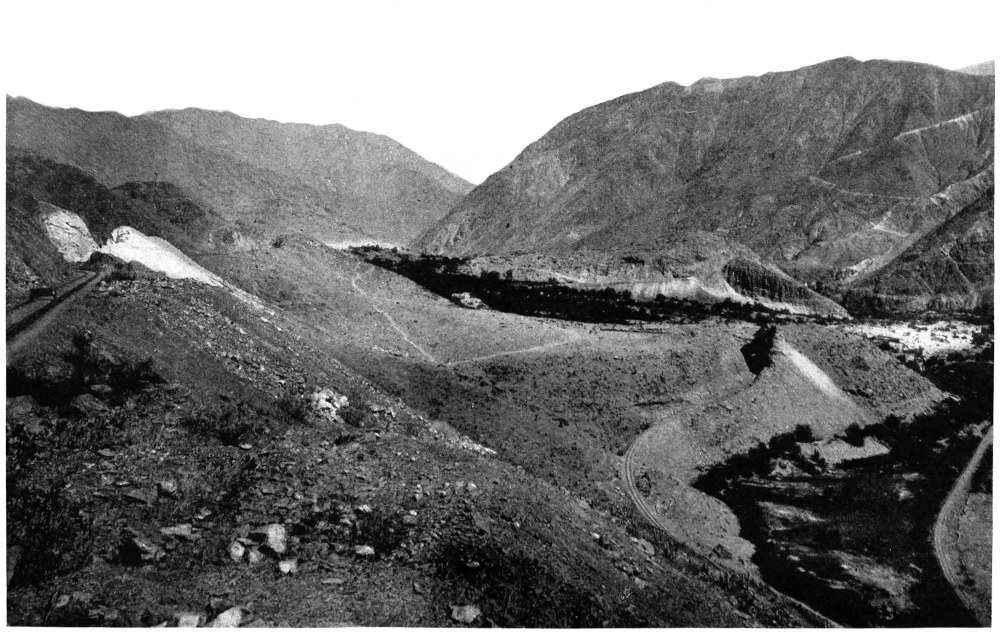

| Scene on the Oroya Railway, San Bartolomew Switchback and Grade[p. xx] | 102 |

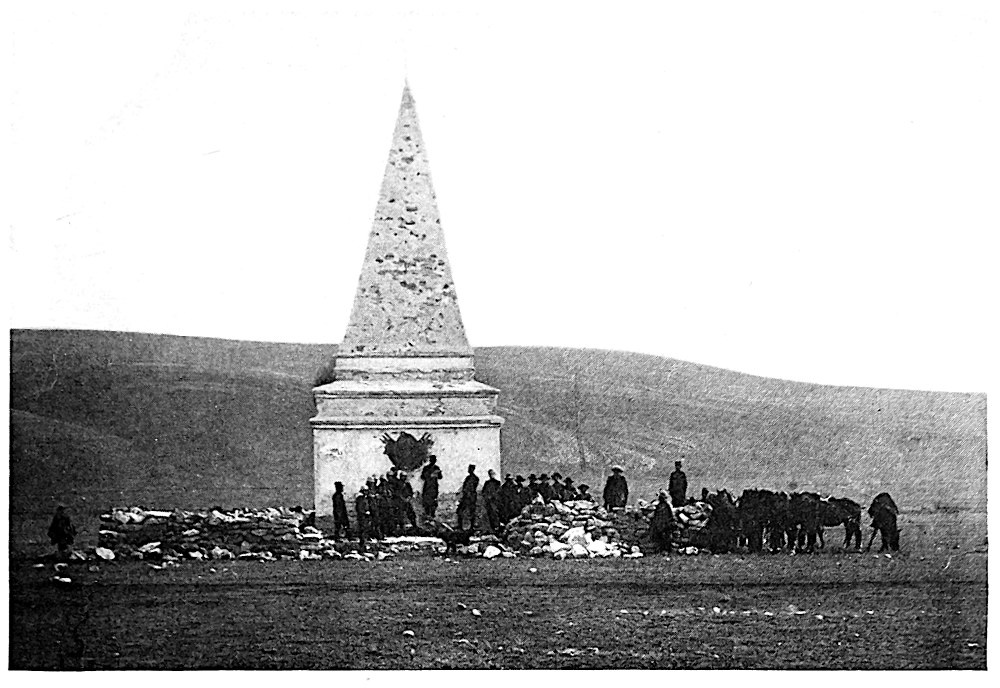

| Pyramid of Junin | 106 |

| Independence Monument, Lima | 106 |

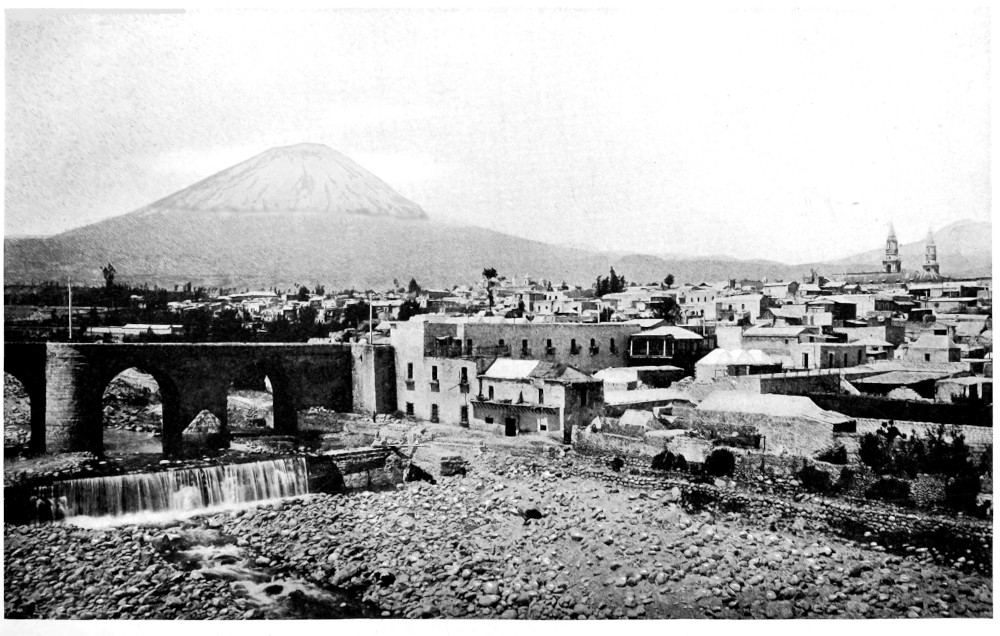

| View of Arequipa and the Crater of El Misti | 114 |

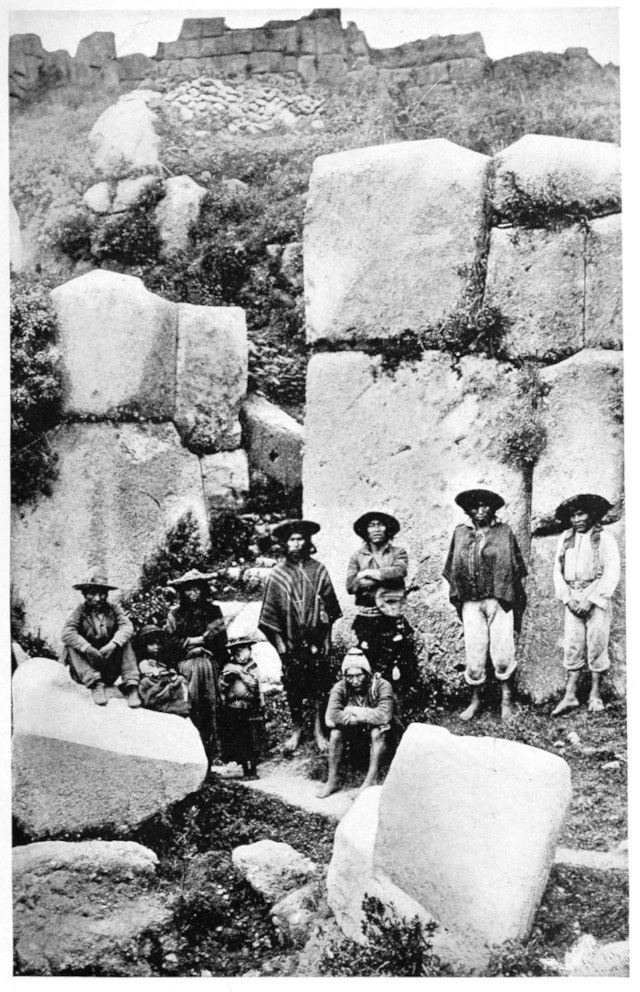

| Ruins of an Inca Fortress at Cuzco | 120 |

| A Farmhouse in the Forest Region | 130 |

| View of Oroya, the Inter-Andine Crossroads | 142 |

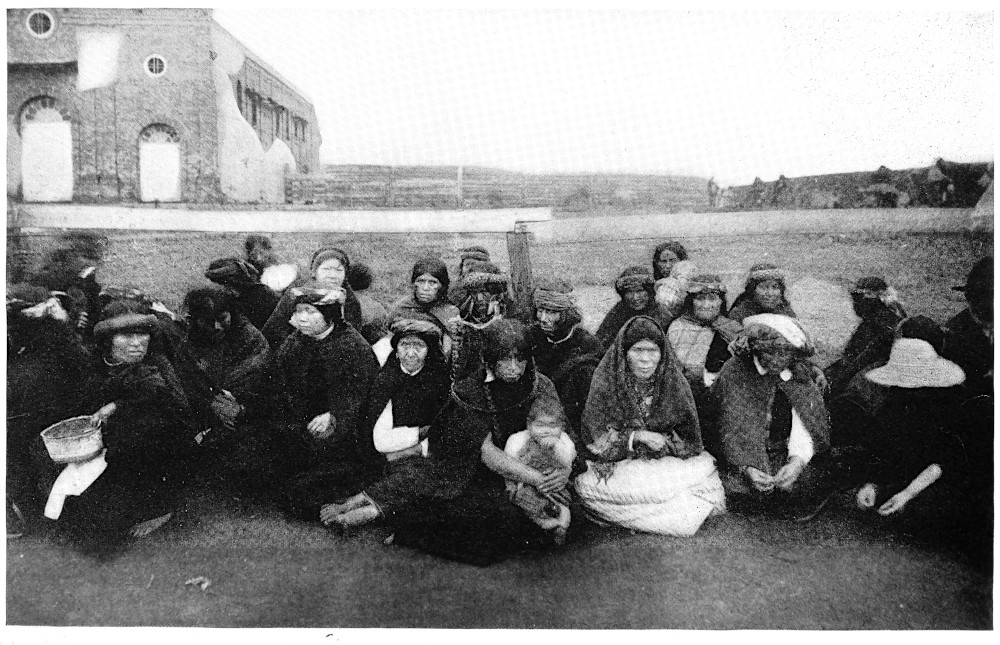

| Group of Peruvian Cholos | 154 |

| Portrait of José Pardo, President of Peru | 170 |

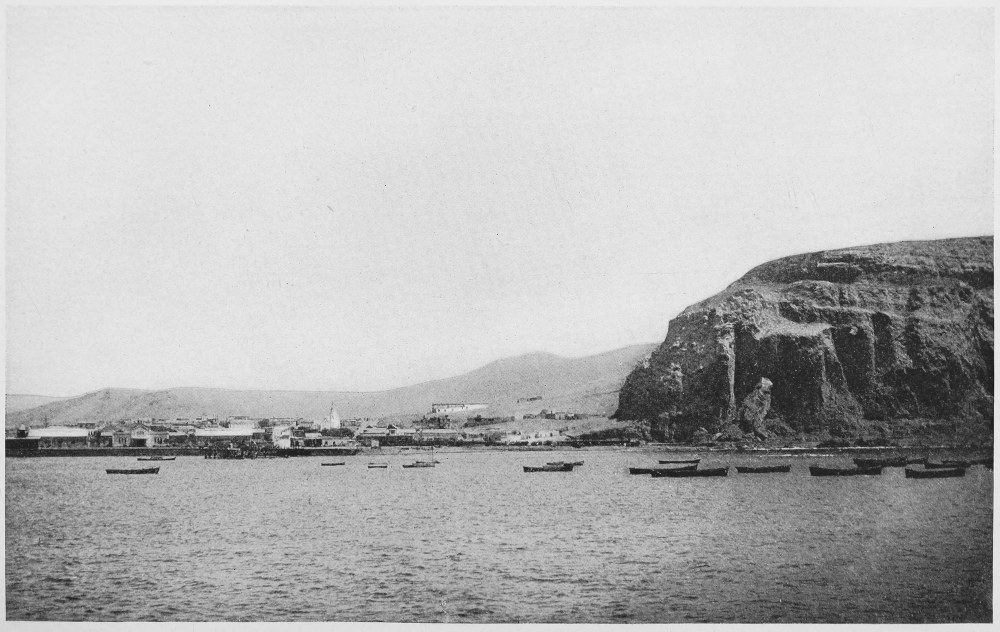

| View of Arica | 182 |

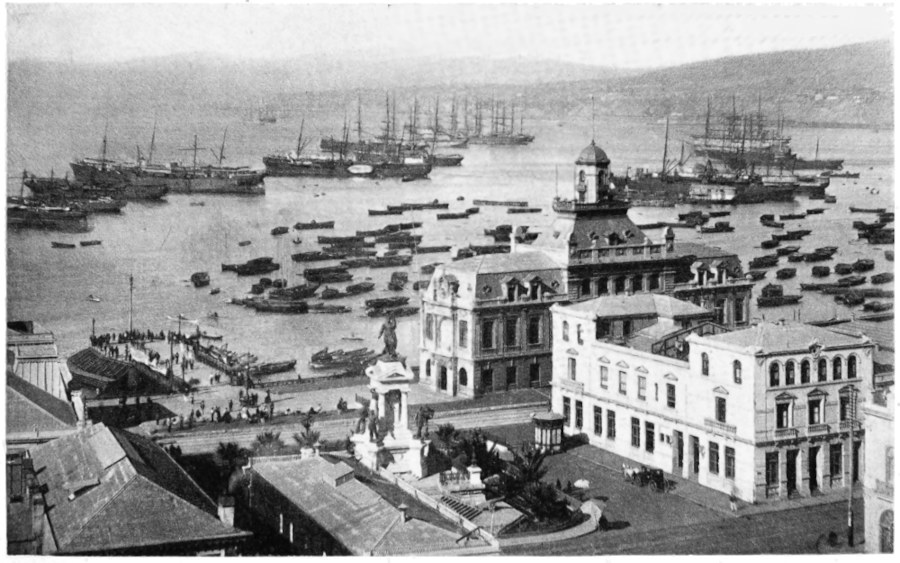

| Scene in the Harbor of Valparaiso, showing the Arturo Prat Statue | 190 |

| View of Talcahuano | 194 |

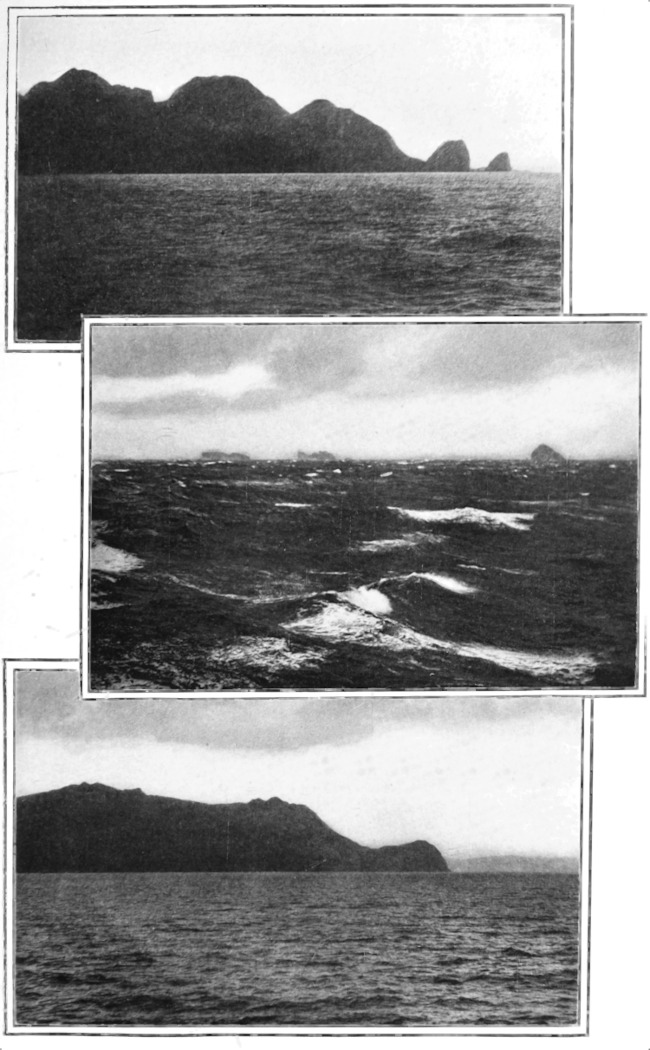

| Scenes at the Straits of Magellan; Cape Pillar, the Evangelist Islands, and Cape Froward | 198 |

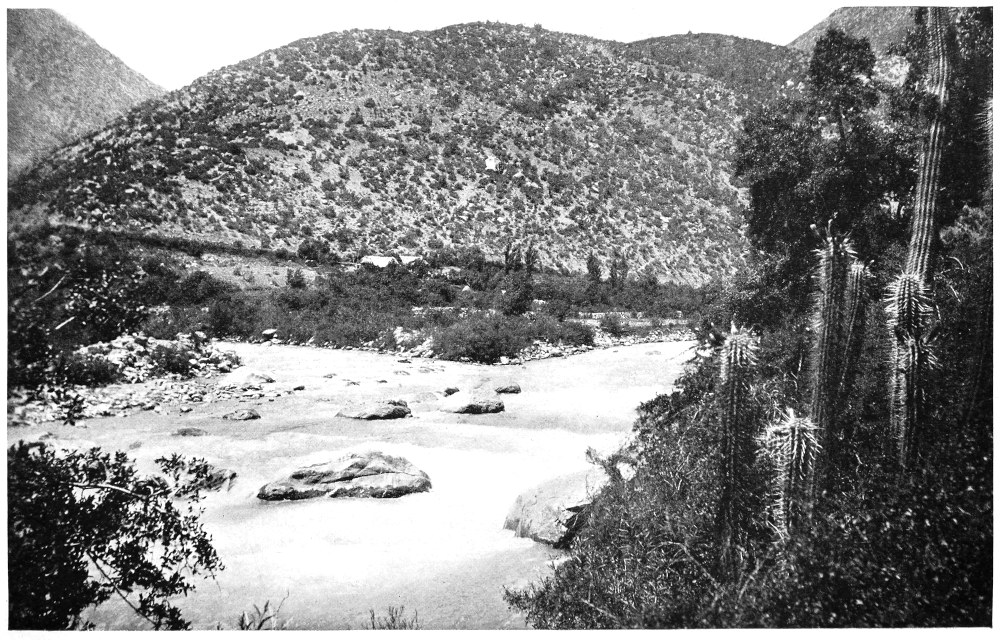

| Scene on the Aconcagua River | 202 |

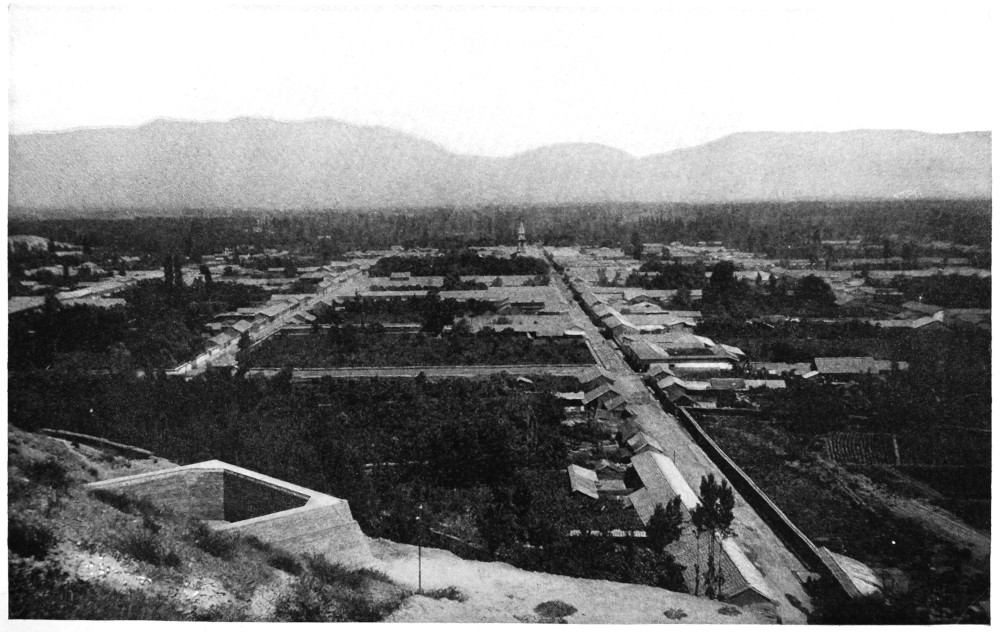

| View of Los Andes | 210 |

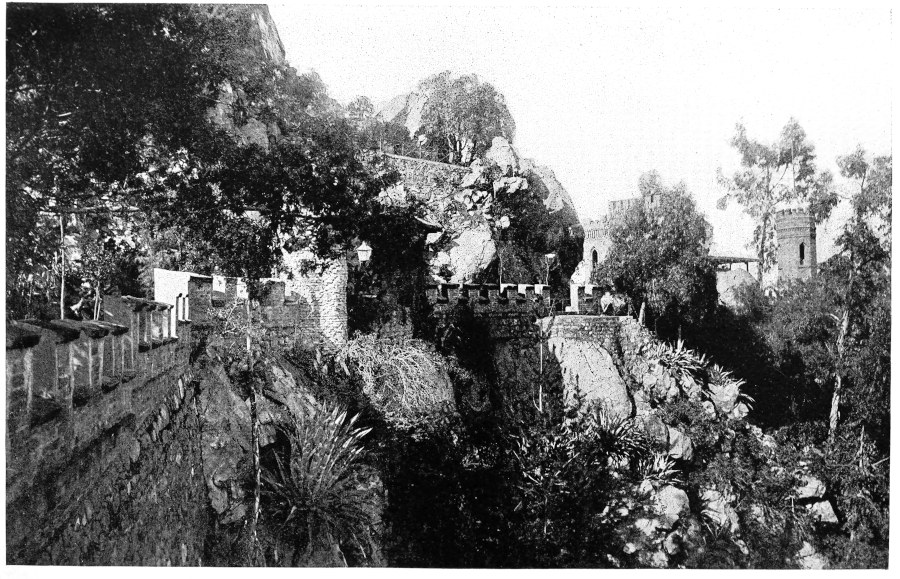

| The Roman Aqueduct on Santa Lucia, Santiago | 214 |

| Group of Araucanian Indian Women | 250 |

| “Christ of the Andes” | 270 |

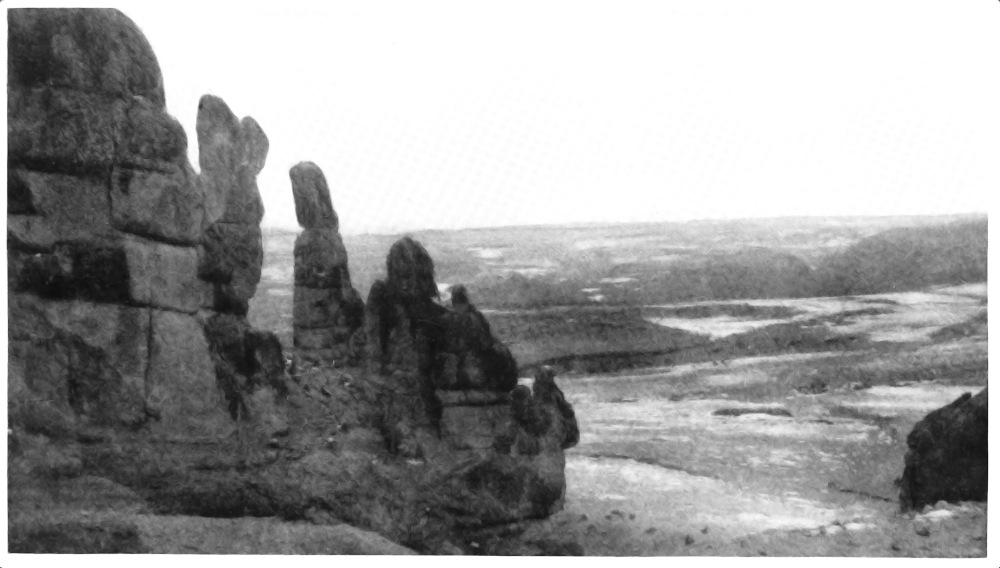

| Sandstone Pillars near Tupiza | 286 |

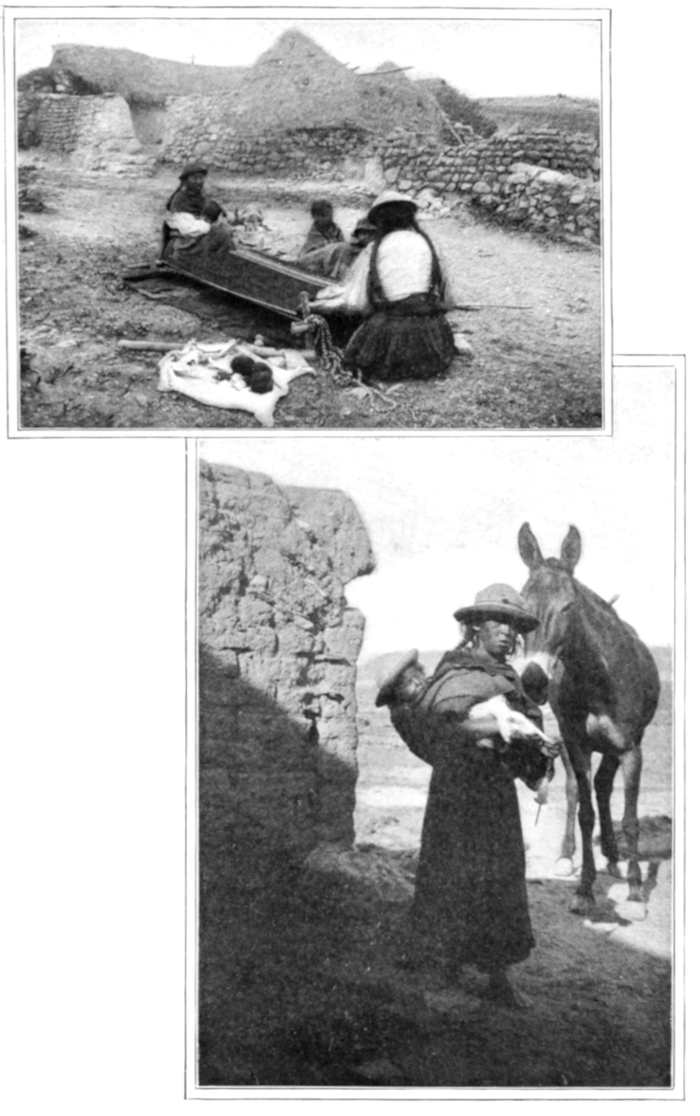

| Bolivian Indian Women Weaving | 292 |

| Aymará Indian Woman and Child | 292 |

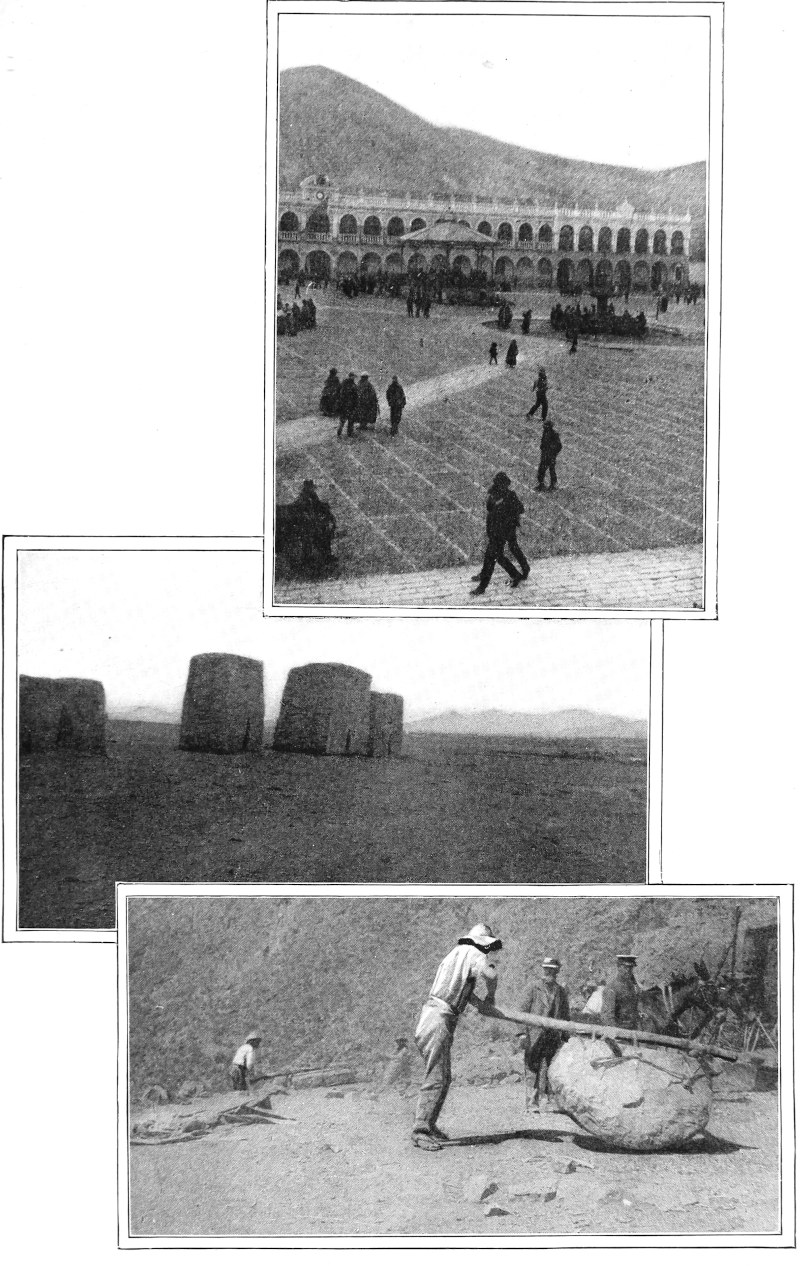

| Scene in the Plaza at Oruro | 302 |

| Ancient Tombs at Caracollo | 302 |

| Primitive Methods of Tin-crushing | 302 |

| A Drove of Llamas on the Pampa | 306 |

| View of the Cathedral, La Paz | 310 |

| Gathering Coca Leaves in the Yungas—Two Views | 328 |

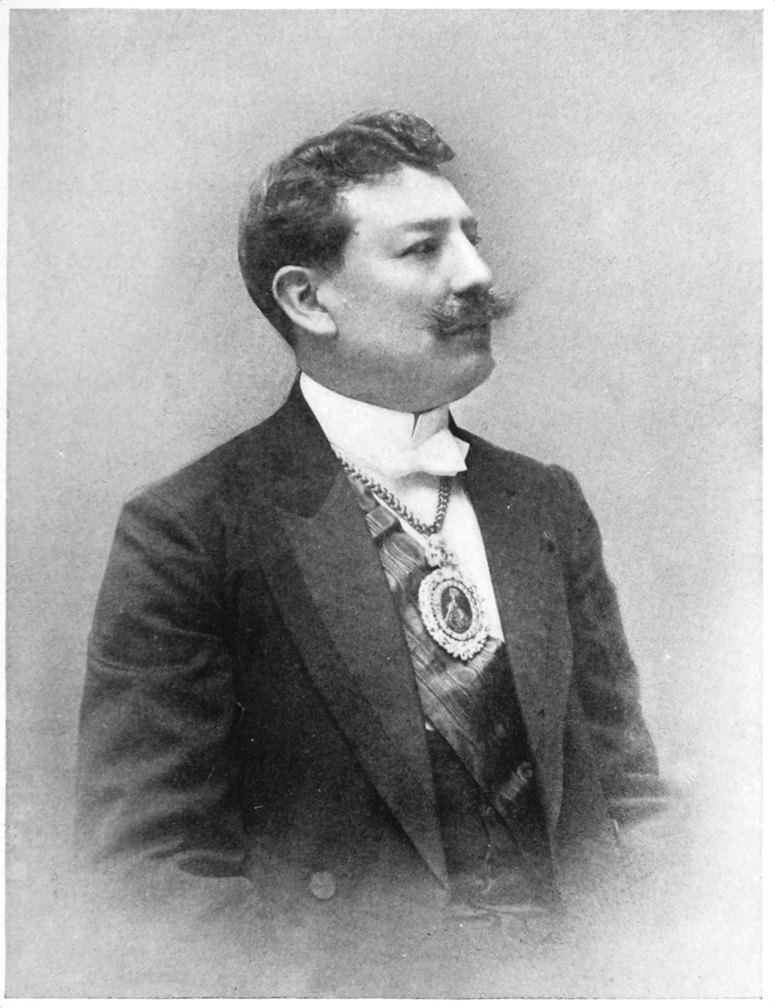

| Portrait of Ismael Montes, President of Bolivia | 344 |

[p. xxi]

| Page | ||

| I. | The United States and other American Countries—Transportation Routes | 2 |

| II. | General Plan of the Panama Canal | 38 |

| III. | Peruvian Waterways and Railways | 138 |

| IV. | Bolivian Railway Routes | 334 |

[p. 1]

PANAMA TO PATAGONIA

ECONOMIC EFFECT OF THE CANAL

Philosophic Spanish-American View—Henry Clay’s Mistaken Population Prophecy—The Andes Not a Canal Limitation—Intercontinental Railway Spurs—Argentina and the Amazon as Feeders—Centres of Cereal Production—Crude Rubber—Atlantic and Pacific Traffic—Growth of West Coast Commerce—North and South Trade-wave—Distances via Panama, Cape Horn, and the Straits of Magellan—Waterway Tolls and Coal Consumption—Ecuador and Peru—Bolivia and Chile—Isthmian Railroad Rates—Value of United States Sanitary Authority—American Element in New Industrial Life.

THE effect of the Panama Canal on the West Coast industrial development and the reciprocal influence of this South American progress on the waterway are economic facts. The citizen of the United States who would know the subject in a wider range than the mere gratification of his patriotic impulses and his national pride, should turn to the study of commercial geography, the potential political economy of unexploited natural resources. The European statesman, jealously watchful of trade conditions in the New World and the causes which modify them, will follow these channels without suggestion.

[p. 2]

Whether the digging of the Canal take ten, fifteen, or twenty years, does not affect its industrial value. The Spanish-American, with his inherited inertia and his lack of initiative, in waiting for to-morrow would be content if the work consumed half a century. What Humboldt prophesied of the Southern Continent as the seat of future civilization, what Agassiz predicted of the Andean and the Amazon populations, he is sure now will be realized. He even reverts to his favorite method of comparing the square miles of Belgium with the square miles of his own South American country, whichever one it may be, and exhibits the latter’s possibilities for the human race by explaining the number of people it can sustain when it shall have as many inhabitants to the square mile as has Belgium. Yet while he believes that the destiny of the Southern Continent is at the threshold of realization, Yankee impatience only would amuse him. Since the interoceanic waterway and all its benefits are to be, what matter a few years? Time, says the Castilian proverb, is the element. This philosophic Latin view may serve as a curb to fault-finding if the construction work on the Canal seems to halt while the engineering obstacles are studied and experiments are made in order to determine the best means to overcome them.

But though the Spanish-American, who is of the race that controls the West Coast countries of South America, is patient in his waiting for ultimate results, he does not fail to grasp the immediate effect. All the processes of the economic evolution unroll before his mental vision. For Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Chile, and Bolivia, the standard already has been set,[p. 3] and the goal towards which they must work has been fixed. Their national policies and their commercial and industrial growth at once come under the stimulus of the waterway. “The Panama Canal,” said the leader of public thought in one of the Republics, “will precipitate our commercial evolution.” It is the spring from which will gush the streams of immigration.

In the present volume I shall have little to say of Colombia, for though the Isthmus of Panama is the reception-room of that country, the Canal is to be considered jointly with relation to the Caribbean and the Pacific shores. I include Bolivia because, while as a political division it is not ocean-bordering, geographically it is a Pacific coast country on account of its outlet through Chilean and Peruvian seaports.

Population in South America is not marked by periods of phenomenal increase. Henry Clay, in his generous pleas for the recognition of the struggling Republics, was led in the warmth of his imagination to foresee the day when they would have 72,000,000 and we would have 40,000,000 inhabitants. The population of the United States was then less than 10,000,000. Clay spoke when the resources of the Louisiana Purchase were still distrusted by many conservative public men, and long before Daniel Webster had delivered his celebrated philippic against the Oregon region as a worthless area of deserts and shifting sands. Mindful of the slow growth in the Southern Hemisphere, I make no predictions of sudden leaps, but merely seek to indicate what proportion of the present and future inhabitants comes within the sphere of the Canal.

[p. 4]

The population of western Colombia and of Ecuador, Peru, Chile, and Bolivia is approximately 11,000,000, dwelling chiefly along the seacoast. It has been assumed that only this long slope of almost continuous mountain wall from Panama to Patagonia is subject to the direct influence of the Canal, and that the barrier of the Andes makes all the rest of the South American continent dependent on Atlantic outlets. The assumption is presumptuous. It is based on an unflattering lack of geographical knowledge and on a complete ignorance of political and economic conditions.

The primary mistake is in considering the Coast Cordilleras as the principal chain. The great rampart of the Andes in places is hundreds of miles across. Productive plains and fertile valleys lie on the western side of the Continental Divide as well as on the Atlantic slope. Besides, there are many bifurcations of these lofty ranges which must be pierced toward the Pacific. The mineral belt with its incalculable wealth, after centuries only partially exploited, has its basis of profitable production and export by means of the water transport of the Pacific. And greatest of all the facts is the certainty that railways will bore through the granite ramparts in a westerly direction. The central spine or backbone of the Intercontinental or Pan-American trunk line is not all a dream, and from its links spurs will shoot out toward the Pacific. It would have been as reasonable to imagine that the Rocky Mountains could forever shut in the region between them and the Sierra Nevadas, barring all outlet to the Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico, as to suppose that the Pacific Ocean from Panama south is[p. 5] everlastingly restricted to the fringe of coast for its commerce. This is in the industrial sense and aside from the reasons of national polity which by railway enterprises on the part of the various governments are causing the Andes to disappear.

The grain fields and pastures of Argentina lie close to the Pacific. How close? Within less than 200 miles. The pampas of the western and northwestern provinces are from 500 to 1,200 miles distant from the Atlantic seaboard. The pressure of the agricultural population is westward. A generation—perhaps a decade—will bring it to the slopes of the Andes. The first railway to join the Atlantic and the Pacific, that from Buenos Ayres to Valparaiso, will be completed by means of a spiral tunnel long before vessels are propelled through the Canal.

But Valparaiso is far south, so far that, in the opinion of some authorities, it is the limit of the Canal radius. Let this be granted momentarily while the map is scanned. Place the thumb on the Chilean port of Caldera, 400 miles north of Valparaiso; the index finger on Tucuman, and the middle finger on Cordoba. The lines forking from these Argentine cities forecast the next chapter of railway expansion. Let it be known also that Nature, in kindly mood, has formed a saddle in the mountain range in this section, and that engineering surveys of routes through the depression are the basis of projects which only await a larger agricultural area under cultivation in order to become railway enterprises with an assured commercial basis. Both Cordoba and Tucuman will be in rail communication with the Pacific coast some years before the waterway is finished. Nor are these the only[p. 6] trans-Andine lines in prospect. They serve the purposes of illustration, so that a description of the others may be omitted. I cite the first two in order that it may be known there is an Argentine relation to the Canal, and a highly important one as to population and as to the exports and imports which are the foundation of maritime and rail traffic.

If this suggestion is new and strange, I follow it by a more startling proposition. As one result of the Panama Canal, a measure of Amazonian commerce will flow to and from the Pacific.

To begin with, there is the nearness. By several trans-Andine routes the navigable affluents of the Amazon are less than 300 miles from the coast. Steamships of 800 tons navigate as far as Yurimaguas on the Huallaga River, which was the historic route of the Spaniards over the Continental Divide. Steam vessels also go up the Marañon from Iquitos, 425 miles to the Falls of Manserriche, which by several practicable railway routes are within less than 400 miles of the Bay of Paita. Minor Peruvian ports below Paita are able to offset its shipping advantages by shorter trails. Not more than 225 miles of difficult railway construction are necessary to open to a large section of the vast Amazon region the commerce of Callao, Peru’s chief port.

In relation to the Amazon as a feeder, it has to be recognized that the Andes form a greater obstacle than in Argentina, and that the river basins will be populated much more slowly and never so densely as the Argentine pampas and sierras. But the mighty stream is within the sphere of the Canal, as I shall have occasion to explain more fully in subsequent chapters.[p. 7] For the present purpose a single illustration, perhaps fanciful, will answer.

It may seem a far cry from the 200,000 telephones used by the farmers of Indiana, the trolleys which tangle their way through that State, and the automobiles and bicycles which traverse the country roads, to the gum forests of South America. But the world’s hunger for crude rubber is a growing one. Bicycles, the infinite variety of motors, electric lighting, and telephones, all demand more of this article; and the 55,000 tons, which was substantially the world’s production in 1905, is insufficient for future needs. This increasing demand will stimulate the rubber production of an extensive region in northeastern Peru, and Peru has imperative reasons of national policy for wanting to turn that traffic down her own rivers, and across and over the Andes to the Pacific, instead of letting it flow out through Brazilian territory. Iquitos, the centre of this commerce, is 2,300 miles up the Amazon from Para, and Para is 3,000 miles from New York, a total of 5,300 miles by the all-water route. By river and future rail Iquitos is, at the furthest, 800 miles from Paita, and Paita, via Panama, is a little short of 3,100 miles from New York; so that the total distance is less than 4,000 miles. New Orleans by the isthmian route is within 3,300 miles of the Peruvian rubber metropolis.

Instead of the Pacific commerce being limited to the seashore strip after the Panama Canal is dug, the view which receives attention in South America is the probable influence of the waterway in diverting traffic from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Trade may not be turned upstream, and commerce is slow to leave established lines of transportation, but trade-waves are not[p. 8] so fixed as isothermal lines. They may show variations until the current finds its natural course to the newer markets created.

I do not mean from this to infer that the aggregate commerce of the Atlantic coast countries of South America will be lessened by the Panama Canal. Tropical Brazil, for an indefinite period, will continue to supply the bulk of the coffee consumed, and the maritime movement will follow the existing courses of navigation. Temperate Brazil, the Argentine Republic, and Uruguay will develop as the granary and the grazing-ground of the world in proportion as the United States consumes its own wheat and beef. Their exports increase with the widening of the market for these staple products. Political economists and crop statisticians have been slow to perceive that the extension of the area of agricultural cultivation and the growth of population in this great cereal region depend more on the ability of Europe to take the surplus grain, beef, and mutton than on the demands for home consumption. Public men, especially in the Argentine Republic, in their measures for encouraging immigration also have neglected to take into account this overshadowing economic factor. But it explains why during certain periods immigration has been almost stationary, while at other periods the incoming of settlers for the field and farm has been a rushing one. As a natural balance, therefore, for the diversion of traffic to the Pacific coast through the agency of the artificial waterway, the Atlantic slope has the certainty of steadily growing exports of agricultural products.

As regards Argentina, the coming railways to the Pacific, of which I have made mention, mean that a[p. 9] quantity of the cereals, wool, and hides will find their outlet by these routes; and a larger volume of the exchange for them—farm tools, cottons and woollens, mineral oils, and miscellaneous merchandise—will obtain the cheaper and shorter transit through the Canal and down the West Coast. Thus, without damage to the Atlantic commerce, the Pacific coast traffic will form a larger proportion in the total of South American commerce than in the past. This is especially true with reference to the United States. The trade-wave north and south may be accounted one of the phenomena of international intercourse. It is not tidal, but a brief comparison shows its growing volume. In 1894 Argentina took from the United States goods to the value of $4,863,000, and sent in return products worth $3,497,000. In 1904 the exports were $10,751,000, and the imports $20,702,000, and in the following year they were increasing.

The commercial relation of the West Coast countries may better be exhibited by tabulation in the following form:

| Exports to United States[1] | Imports from United States | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1894 | 1904 | 1894 | 1904 | |

| Chile | $3,536,000 | $10,685,000 | $2,272,000 | $4,880,000 |

| Peru | 491,000 | 3,008,000 | 591,000 | 3,961,000 |

| Ecuador | 816,000 | 2,347,000 | 761,000 | 1,354,000 |

| Total | $4,843,000 | $16,040,000 | $3,624,000 | $10,195,000 |

| 1 See Foreign Commerce of the United States, Annual Review, 1904. | ||||

[p. 10]

Here, within the extremes of the eleven years, is an increase in the foreign commerce between the West Coast countries named and the United States from $8,467,000 to $26,235,000 as measured by the annual volume. The growth continued in the subsequent twelvemonth. It is a forcible illustration of the north and south trade-wave movement. Under the further stimulus of the Canal for industrial development and commercial growth the contribution to traffic for the waterway will be not inconsiderable.

An analysis of the West Coast foreign commerce for a given year shows it to have exceeded $211,000,000, with a rising tendency. The intercoast trade, which is included under the foreign head, may be placed at $11,000,000 to $12,000,000. There is left, therefore, approximately $200,000,000 of international traffic for Europe and the United States.

If the international traffic were to remain stationary, the amount that would be diverted from the Cape Horn or the Magellan route through the Canal would be important, but the overshadowing element in the waterway as an economic factor is the certainty of an increase in the foreign trade. The marked feature of the West Coast countries in recent years is the growth in consumptive capacity as shown by the imports, for the increase in population has not been large. Oriental trade may be diverted from other channels through the Canal, but western South American commerce may look for growth in volume on account of internal development of the countries which are tributary to it. In this view it may be doubted whether the estimate that 75 per cent of the Canal traffic will be between ports north of the same parallels of latitude will prove[p. 11] correct. The north and south trade-waves may be watched for an indication of the proportion of waterway freight that will go south, keeping in mind that New York is almost on a direct line north of the western South American ports.

These West Coast markets may be studied with reference to the shortening of distance. We may take the fact that from Colon to New York is 1,981 miles, and from Colon to New Orleans 1,380 miles; add the 48 miles of future waterway and then make our comparisons of the ports along the coast—Guayaquil, Callao, Valparaiso—with the distance through the Straits of Magellan or around Cape Horn. We also may figure on the national policy of the United States, which will not be to treat the Canal as strictly a commercial proposition. The fixing of the toll rates is not near enough to furnish the basis of definite calculation any more than is the possibility of estimating the total prospective tonnage each year, though the guesses have ranged from 300,000 to 10,500,000 tons.

The steamers which ply between New York, Hamburg, or Liverpool and the Pacific coast ports vary from 3,000 to 6,500 tons. That hardly may be taken as the measure of carrying capacity of the major part of the vessels which will pass through the Canal, but on such a basis the estimate may be made of the saving in coal consumption, and the radius within which it will be cheaper to use the Canal than to double Cape Horn or thread the difficult and dangerous passage through the Straits. For New Orleans, Mobile, and the other Gulf ports, the element of distance is not comparative, because heretofore no direct maritime[p. 12] movement between them and the West Coast of South America has been maintained. With the waterway once open the whole Mississippi Valley becomes the beneficiary. Nor does the talk of carrying coal and other cargoes from Pittsburg through Panama to Patagonia without breaking bulk appear fantastic.

Variations in the steamers’ courses are responsible for the differences in the tables of distances usually given, but they are not important.[1] The relation in nautical miles of the chief shipping-ports on the West Coast to trade centres may be set forth as follows:

| Miles | |

|---|---|

| New York to Colon | 1,981 |

| Colon to Panama | 48 |

| Panama to Guayaquil | 835 |

| “ “ Paita | 1,052 |

| “ “ Callao | 1,569 |

| “ “ Mollendo | 1,928 |

| “ “ Arica | 2,161 |

| “ “ Iquique | 2,267 |

| “ “ Antofagasta | 2,418 |

| “ “ Valparaiso | 3,076 |

1 See Appendix for tables of the Hydrographic Office of the United States Navy.

This brings Valparaiso within 5,100 miles of New York by way of Panama; but with the omission of all the intervening ports except Iquique, Callao, and Guayaquil, it would be less than 5,000 miles. By way of the Straits the distance from Valparaiso is usually accounted 9,000 miles, touching at Montevideo and the Brazilian ports. When the Straits are avoided and Cape Horn is doubled, from the Cape to Pernambuco is 3,468 miles, and from Pernambuco to New York 3,696 miles. Either by the Straits or around the Cape the total is almost twice the distance via Panama.

Colon is 4,720 miles from Liverpool, and the relative advantages of the West Coast ports between Valparaiso and Panama may be calculated in the[p. 13] proportion of their respective distances. From Valparaiso to Liverpool via Panama is 7,600 to 7,800 miles according to the vessel’s schedule of wayports on the Pacific. From Valparaiso to Liverpool, through the Straits of Magellan, is 9,800 miles, touching at the Falkland Islands, and about 300 miles shorter by omitting them.

For Hamburg the saving in distance by the isthmian route may be placed at 2,400 miles. Proceeding north from Valparaiso, the loss by Cape Horn is in inverse proportion. Fifteen hundred miles north of Valparaiso is the central Peruvian port of Callao, which therefore has 3,000 miles’ gain in distance by Panama to Hamburg instead of by Cape Horn.

I have given these general figures before reciting details on the maritime commerce of the various countries. They show how the economic value of the Canal to them is primarily a question of subtraction,—the difference between the coal needed on the longer sea voyage and the Canal tolls. But the question of the return cargo also enters into the calculation and is distinctly in favor of the waterway, as is also that of the duration of maritime insurance.

No statistics are available which show the commerce of the western departments of Colombia; and the unsettled state of that country for years past gives no index of what its potential traffic may be. But the valley of Cauca in its variety of agricultural and mineral resources is a kingdom in itself. It is a future commercial feeder to the Canal.

The foreign trade of Ecuador amounted in the latest available year to $19,000,000.[2] Substantially all of it[p. 14] constitutes what might be called light freight, and a part of it now goes across the Isthmus by transshipment. Yet the portion which follows the longer route around Cape Horn or through the Straits is not small. The traffic flows through Guayaquil as in a single stream. Guayaquil, by way of Panama, is 2,864 miles from New York and 2,263 miles from New Orleans; by the Cape Horn route it is 11,470 miles to New York. The entire foreign commerce of Ecuador in the future is for the Panama Canal, except the excess which follows up the coast to San Francisco and beyond.

2 Statistics obtained by New York Chamber of Commerce for 1904.

The foreign commerce of Peru may be placed above $40,000,000 annually.[3] The bulk of the traffic is now via the Straits of Magellan and Cape Horn. From Callao to New York, by way of Cape Horn, is 10,700 miles. By way of Panama it is 3,600 miles, only a little longer than from New York to San Francisco or from New York to Mexico City by the transcontinental railroad lines. In reference to Peru, it also is to be noted that the heaviest exports are from the ports north of Callao. Sugar is the largest marine freight in quantity, and this comes from Salaverry and other ports fully 500 miles north. Much of this raw sugar is now carried around Cape Horn, though some of it is left at the Chilean ports to be refined for the West Coast consumption. When the Canal is opened, with the exception of this Chilean traffic, all the raw sugar of Peru will be shipped through it to New Orleans, New York, or Liverpool.

3 Estimated on the basis of the calendar year 1904, when the total was $41,000,000, according to the report of the British Consul General.

Through the port of Mollendo, 360 miles south of Callao, come the ores, the metals, and the wools,[p. 15] both of southern Peru and of Bolivia. Some of the minerals may continue their course around the Horn, and also the guano which Peru in the future may export, but not all of these cargoes will find the longer route cheaper. All the wools will take the shorter route. Some wool is sent up the coast and transshipped across the Isthmus by the railways. This method is also followed in the shipment to Liverpool of some of the raw cotton raised in southern Peru. The whole of this light freight is traffic for the interoceanic waterway.

Bolivian commerce finds its outlet and inlet, chiefly through Chilean and Peruvian seaports, to the amount of $18,000,000 a year. Small as this is, the bulk of it follows the Cape Horn and Magellan routes, though some of the European merchandise is imported on the Atlantic slope through Argentina. The silver and copper ores are transported principally through the port of Antofagasta, which is 650 miles north of Valparaiso. For the mineral freights, Canal tolls may neutralize the advantage of the shortened distance via Panama to Liverpool, or may not compensate for the lessened coal consumption. But whether they do or not, the general merchandise from England and from Germany, not being bulky, will have the shorter course and probably the cheaper one on the return voyage through the Canal.

But Antofagasta, though of growing importance, is not likely to be indefinitely the chief port of export for Bolivia. The building of a railway from the great central plateau to Arica makes it certain that the copper output of Bolivia, much of the tin, and part of the silver product in time will be shipped through[p. 16] that port, while it will be a natural inlet for imported merchandise. Arica is so close to Mollendo—only 233 miles—that with regard to distances it may be considered on the same basis. The mineral and other internal developments, which are to fix the industrial status of Bolivia and which I shall have occasion to discuss in subsequent chapters, have a very direct relation to the facilities that will be afforded by the isthmian waterway.

Formerly it was thought that Chile would be seriously harmed by the Panama Canal. In the commercial sense this supposition does not bear scrutiny. Chile’s foreign trade is approximately $130,000,000 annually, with a tendency to reach $150,000,000. By far the heaviest proportion of this commerce is the shipments of the nitrates of soda or saltpetre fertilizers. Iquique is the principal shipping-point. The sailing-ships are the cheapest carriers for these bulky cargoes, and tolls based on tonnage may make it unprofitable to transport a large portion of them through the interoceanic channel. There is also the other consideration that the vessels which bring coal to the Chilean ports from Australia and from Newcastle secure their return cargoes of nitrates. These fertilizers being a natural monopoly, Chile will have the benefit of the industry, and the Panama Canal in no way can lessen this traffic. In its permanent effect the waterway can have little influence on the nitrates, because the deposits will be worked out not many years after its completion. Within a third of a century, or forty years at the furthest, the exhaustion of the saltpetre beds will have begun, and the cargoes of fertilizers will be lessening before[p. 17] that time.[4] In any aspect of the broad future of the Canal and its effect on the West Coast, the nitrates of Chile need not be considered as an influencing factor.

4 See Chapter XIV, Nitrate of Soda.

But it may be said that until the interoceanic canal is actually open these subjects are too remote to call for immediate consideration. This view does not hold when analysis is made of the swift recognition of its effect by South American countries. There are present-day influences which are clear enough to be taken into account.

For the entire West Coast there is at once a beneficial result in having the Canal an enterprise of the United States government. This is the equal treatment which must be accorded all the steamship companies in transshipping freight over the Panama Railway. The line was operated in the interest of the transcontinental railroads to prevent competition. Under this arrangement little regard was shown for the traffic from the coast south of Panama. The result of the control of the isthmian railway line by the transcontinental roads was against encouraging the steamship lines to seek to increase their freight between Valparaiso and the intervening ports to Panama for transshipment, because the Panama Railway exacted what it pleased.[5] With the stock of the company vested in[p. 18] the United States, hereafter all traffic agreements must be made on the basis of equality. This is a very important factor in the tendency of the West Coast countries to mould their national policies for industrial development and commercial expansion. It enables them to enjoy some of the benefits of the Canal without waiting for its completion. It means more shipping from the year 1906 on.

5 In the memorial presented in 1905 to the United States government by the diplomatic representatives of various South American Republics, asking for fair treatment in Panama railroad rates, these statements were made:

It may be calculated that the most distant ports of our respective Republics are from New York, 4,500 miles, via Panama. From those same ports to New York there is a distance of over 11,000 miles, via Magellan; and, nevertheless, the transportation by this last route and the transportation by steamer from our ports to Europe, are on an average from 25 to 30 per cent cheaper than our commerce with New York via Panama.

The Peruvian sugar pays, by the Isthmus, 30 shillings sterling a ton, and 23 shillings sterling a ton via Magellan.

The cacao of Guayaquil, via Panama, pays to Europe from 52 to 58 shillings a ton, and to New York 65 to 68 shillings a ton.

From Hamburg shipments of rice from India are constantly being made to Ecuador, via Panama, at the rate of from 30 to 33 shillings sterling per ton of 2,240 pounds, or, say, from $7.50 to $8 per ton; while the same article from New York pays at the rate of $0.60 per 100 pounds, or, say, $13.20 per ton,—an overcharge of almost 75 per cent. Twelve coal-oil stoves, which in New York, free-on-board, cost from $45 to $48, pay on the coast of Ecuador and of Peru 30 and 37½ cents, respectively, per cubic foot, or, say, $19.20 to $21, which represents 42.66 per cent upon the cost price. The same article bought in Germany would pay a freight of from $6.40 to $6.75.

An international good also comes from the presence of the United States on the Isthmus in the capacity of a sanitary authority. It will not be hampered, as at home, by state quarantine systems. The example of what it is doing at Panama will be of immense benefit to all the ports south to Valparaiso. Its resources and its assistance will be at the disposal of the various governments which may seek its aid. With them power is centralized, and they will be able to coöperate effectually. The International Sanitary Bureau, with headquarters in Washington, for which provision was made by the Pan-American Conference held in Mexico, may[p. 19] become a vital force through this means. Epidemics and plagues, of which the most malignant is the yellow fever, may never be entirely wiped out, but that their area can be restricted and their ravages infinitely lessened will be demonstrated by a few years’ experience. Commerce will be immensely the gainer, and the trade of the West Coast may look for a steady and natural growth in proportion as the epidemic diseases of the seaports are controlled.

The influence of the gold standard of Panama will be helpful to commerce, though it will not in itself cause the several Republics which are on a silver or a paper basis to change to gold. But they will be benefited by being neighbors to financial stability. Uniformity of exchange will be promoted, and the inconveniences of travellers will be lessened. The fact that the currency of the United States is legal tender in the Panama Republic will help merchants and shippers at home, who heretofore have had to make their transactions entirely on the basis of the English pound sterling or the French franc.

In an outline of the general subject some attention should be paid to the inevitable overflow of energy and capital after they once become engaged in building the waterway and in supplementary projects. No one who understands the constructive American character doubts that the capitalists and contractors enlisted in the work will fare forth to seek other fields. It happens that coincident with the beginning of the Canal construction by the United States, the West Coast countries are entering upon definite policies of harbor and municipal improvements and other forms of public works, including railway building. There[p. 20] is also the new era of the mines. The industrial impulse is one of the immediate economic effects of the Canal. It appeals to the American spirit. It will find a quickening response. In subsequent chapters I therefore venture to indicate its field of activity, with such suggestions as may be of practical worth.

[p. 21]

TRAVEL HINTS

Adopting Local Customs—Value of the Spanish Language—Knowledge of People Obtained through Their Speech—English in Trade—Serviceable Clothing in Different Climates—Moderation in Diet—Coffee at its True Worth—Wines and Mineral Waters—Native Dishes—Tropical Fruits—Aguacate and Cheremoya Palatal Luxuries—Hotels and Hotel-keepers—Baggage Afloat and Ashore—Outfits for the Andes: Food and Animals—West Coast Quarantines—Money Mediums—The Common Maladies and How to Treat Them

TO live as they live; to travel as they travel;—that is about all there is to living and travelling in South America and on the Isthmus.

All the customs will not be adopted by Northerners, nor all the habits followed. More comfort will be demanded and more cleanliness. But the general fact holds that the people living in any country have acquired by experience the knowledge of what is required by climatic and other conditions in regard to food, drink, dress, shelter, and recreation. There is reason for all things, even for the adobe tomb dwellings of the aboriginal Indians of Bolivia, or the mid-day siesta of the busy merchant of Panama.

First of all, it is desirable to know the language. Spanish is the idiom of South America, with the exception of Brazil. At the outset let me say that the chance traveller who wants to go down the coast or[p. 22] even take an occasional trip into the interior can get along with his stock of English. In all the seaport towns are English-speaking persons, merchants or others. On the ships English is as common as Spanish, and in some of the obscurest places the tongue of Chaucer may be heard. In one of the most out-of-the-way and utterly forsaken little holes on the coast, I found the local official who was sovereign there teaching his boy arithmetic in English. He had been both in England and in the United States, and while his own prospects now were bounded by the horizon of the cove and the drear brown mountain cliffs that shut it in, he was determined that his son should have a wider future. There are also many young South Americans who have been educated in the United States and some of whom are met at almost inaccessible points in the interior.

I state this so that no one who contemplates a journey may be turned away from it by any supposed difficulty in getting along through inability to speak the prevailing idiom. He can do very well. Yet with all his faculties of observation alert he will miss much through his ignorance of the readiest mode of conveying and receiving thought. To know any country it is necessary to know the people, and the people are only known through the medium of their speech. Their customs are better understood, their limitations are appreciated, and their strivings for something better, if they have any, are interpreted sympathetically. The paramount local topic becomes a living theme into which the visitor can enter understandingly and add to his stock of knowledge.

Let me say, also, that wherever trade is, there is the[p. 23] English language, and as commerce grows it will spread. The terse English business letter is the admiration of the Latin-American merchant. Yet there is no wilder notion than that trade will advance itself without the knowledge of the language of the country into which it is pushing. Many native mercantile houses have English-speaking clerks, or occasionally a member of the firm knows the idiom. But the commercial traveller from the United States who does not speak Spanish never will compete with his German rival who talks trade in all known tongues.

This, in brief, is the commercial situation as to the English language. The business man who waits for Spanish America to come within its sphere as the world language, will not achieve success in this generation.

For those who look forward to a future in South America, either in trade or in industrial enterprises, there is only one word of advice to be given: that is, to learn Spanish and to learn it at once. Diffident as the North American is about foreign tongues and badly as he speaks any language except his own, there is little reason why his self-distrust or his contempt for other nationalities should keep him from acquiring Spanish. “It is pronounced as written and is written as pronounced.” Colloquially it is the easiest of tongues to master. Since every letter is sounded and is always pronounced the same, there is no trouble with the syllables and there are no such difficult sounds as the German umlaut or the French “en.” The high-sounding expressions, while they seem very formal and complicated, are quickly acquired, and the habit of thinking of the greetings of the day and similar commonplace topics in the strange tongue comes[p. 24] more easily than is imagined. With practice any fairly persistent person can get enough of Spanish to avoid the cumbersome process of thinking in English and then translating his thoughts. A vocabulary of 2,000 words is an ample one for the purposes of every-day life.

The oaths need not be learned. The English expletives are expressive enough not to need translation, and they lack the suggestive obscenity of the Spanish objurgations. It is good to learn “Caramba!” in all the tones and inflections and to stop there.

The phrase-book may be studied without ridicule, and every opportunity be taken for putting its precepts to the test. I do not mean from this to indicate that a thorough knowledge of Spanish can be gained in such manner, or that the Yankee ever will master the noble and stately literary language of Cervantes, Calderon, and Lope de Vega. He will not need to use the literary language. If he have a chance to secure his first training in Bogota or Lima, that will be an unusual advantage, for it is in those capitals that the purest Spanish of the New World is spoken. But this is not necessary, and if it be his misfortune to learn the rudiments through an uneducated Chilean or Argentine source, even that harsh and choppy Spanish will be understood. By all this I mean the practical tool of the tongue in common use, and not the melodious Castilian that may be desirable in polite society.

It is a very decided advantage to know enough of the written language to read the newspapers, an occasional book by a native author, the steamship schedules, the railway time-tables, the proclamations and[p. 25] official decrees, and the advertising posters. All serve their purpose to the man who has business or who would be in touch with his surroundings. It is true that in the interior the Indian tribes adhere to their own dialects and the majority of South American Indians do not understand Spanish. But the officials everywhere speak it, and in the Indian villages there is a head man, or cacique, who knows the idiom of the master race. If they are not familiar with Spanish, the sounds of English are even more strange to them.

Dress for sea voyages is easily determined, but clothing for land and sea is a more difficult question. My own experience, and I think it is the experience of other travellers, has been that woollens are the most serviceable in all climates. In the cold regions they are essential. In the tropics, when loosely woven, they are comfortable. Where the pure wool is disagreeable to the wearer, a mixture of cotton in the garment may serve. Flannels are the best protection against an overheated body and quick changes of temperature. These hints apply to all places, all times, and all conditions.

For the rest, although the Anglo-Saxon newcomer sometimes assumes otherwise, the people of all the West Coast cities are civilized and accustomed to the usages of polite society. Men wear the conventional dress suit, or traje de etiqueta, on formal occasions. The six o’clock rule does not hold in Spanish-American countries. Official functions, weddings, and similar social gatherings call for the dress suit as early as ten o’clock in the morning. But the visitor in this matter may consult his own convenience to some extent,[p. 26] regardless of local customs. The professional classes, doctors and lawyers especially, have a habit of upholding their dignity by wearing the tall hat and the frock coat in the hottest seasons. It is rather a tradition than a requirement of good breeding. The traveller may ignore it without losing social caste.

In the matter of eating and drinking moderation is a rule which slowly impresses itself on foreigners. As to drinking, the Englishman on the West Coast has not yet learned temperance. He absorbs vast quantities of brandy and soda, or of whiskey and water, with the soda or water always in infinitesimal amounts. He has his excuse for it,—the loneliness of his exile, the climate, and so forth. But he also has a counter-irritant for the drink habit in his fondness for the manly outdoor sports which he practises as regularly as at home.

French wines may be procured anywhere in South America, but it is not always well to trust the labels. A fair native wine is made in Peru, and Chile produces an unusually good article. If the quality of the claret is not quite equal to Medoc, it is good enough for any one except a connoisseur. English ales also are to be had, and of recent years bottled St. Louis or Milwaukee beer can be obtained at all the larger places. I have found St. Louis beer up in the Cerro de Pasco mining regions of Peru. All of the countries have local breweries, but Americans do not like the brew.

Mineral waters, which are to be had everywhere, in time come to pall on the palate. They may be alternated with the wines or other beverages satisfactorily. There is a native drink called chicha, a[p. 27] distillation of corn fermented in lye, which is refreshing and strengthening and tastes like fresh cider. The subjects of the Incas refreshed the Spanish conquerors with this drink. It is celebrated in song,—“O nectar sabroso.” Yet a word of warning—to enjoy chicha a second time and other times, make no inquiry and take no thought of how it is prepared. Always imbibe it from a gourd.

The aboriginal thirst of the Indians and also of the mestizos, or half-breeds, is for raw alcohol. This thirst is satisfied by the aguardiente, or cane rum. It demoralizes the native population, and is a curse with which the governments are unable to cope. When the rum cannot be obtained, some other form of alcoholic spirits is provided.

The Continental custom as to meals obtains both in the tropical parts of the West Coast and in the colder climates, as in Bolivia and Chile. There is simply breakfast, or the mid-day meal, and dinner. In the morning coffee and rolls—or with most of the Spanish-Americans, coffee and cigarettes—are the sole refreshment which is expected to carry one through till noon. Americans, however, usually procure fruit and eggs. Coffee-making and coffee-drinking are arts unknown to the Yankee. Travel in South America is a liberal and much-needed education in this respect.

The almuerzo, or mid-day breakfast, is fully as substantial a meal as the six or seven o’clock dinner. Both begin with soup and fish, the best of the latter being the corbina. At the breakfast eggs invariably are served, and usually rice. The latter is prepared as a vegetable with rare art, retaining the form and whiteness of the grain. Meat courses, beginning with[p. 28] the fowl, follow in procession, and a salad always may be had.

The Spaniard and his descendants in South America approach roast pig as reverently as Charles Lamb did. For them it is a poem. A very good dish transplanted from Spain is called the puchero, and is something like a New England boiled dinner, having a variety of vegetables cooked with the meats which are its foundation.

In the interior, where reliance has to be had on the Indian population, the standard dish is the chupé, though it bears different names. This is a rich soup, highly seasoned by dried red peppers, with plenty of vegetables, and with a meat stock as the basis. Sometimes the meat is the vicuña or llama, sometimes goat, sometimes mutton, and once in a while beef. It is wholesome and satisfying. The only caution to be observed is not to see its preparation by the Indian women.

Two luxuries among the fruits of the tropics make oranges, bananas, and pineapples seem commonplace. These are the alligator pear and the cheremoya. The Northern appetite cloys at the preserved sweets which the tropical palate demands, but it never loses the enjoyment of these fruits. The alligator pear (Guanabanus Persea) in the West Indies and in Mexico goes by the name of aguacate or avocat. In South America it is called the palta. It is eaten as a salad, and French genius never concocted a delicacy equal to this natural appetizer.

The aguacate looks like a small squash rather than a pear. It has a kernel, or hard stone, as big as the fist. The flanks are laid open, the stone removed,[p. 29] and the fruit is ready to serve in its own dressing. Some prefer it with just a pinch of salt. Others add a touch of pepper. Many like a little vinegar with the salt and pepper, and a few even prefer a regular French dressing with oil, though that is apt to spoil the natural flavor. Epicures like it with sugar and lemon juice. The aguacate is one of the undisguised palatal blessings of the tropics and the semi-tropics. It should be sought after and insisted on at every occasion. The imported fruit loses the poetic savor. The most careful packing and tenderest care cannot preserve its delicate taste. I tried it once in bringing some from Honolulu to San Francisco. They looked well, but something was lacking in the taste. A similar experience between Jamaica and New York was the reward for my efforts. I was convinced after these experiments that the aguacate is one of the real luxuries which it pays to go abroad in order to enjoy. Young persons who travel will be interested in knowing that it is said to germinate the tender sentiment.

The cheremoya is not unlike the pawpaw of the temperate climates. The fibre is harder and not so juicy. But the fruit is very rich, so rich that the palate does not crave much. A mouthful lingers like the dream of the poet. The cheremoya is called the anona in Cuba. Several varieties of it differ from one another only in the delicacy and richness of the flavor. Cracked ice is the complement of the fruit. They should be introduced to each other an hour before serving.

A delusion which the adventuring North American should get rid of is that no decent hotels are found on the West Coast and in the interior. Everywhere are[p. 30] passable ones and in some of the cities exceptionally good ones. In the ordinary coast towns they are not much more than stopping-places, yet almost invariably an excellent breakfast or dinner can be obtained. As to the lodging conveniences the old Spanish tradition still obtains that a place to sleep in is all that is called for, and clean linen and similar comforts should not be demanded by the traveller who is moving on. But even in this respect improvements are being made.

Most of the hotel-keepers are of foreign nationality,—French, Germans, Italians, and Spaniards. It is rare to find anything of a higher grade than an inn kept by a native. The best hotels are those under the control of the Frenchmen, and when a choice is to be made they should be given the preference, for there is not only good eating but cleanliness and some consideration for the conveniences of life. A Frenchman keeps the hotel at La Paz in Bolivia, and it is a good one. Another passably fair house of entertainment in the same place is kept by a Russian. At the mining-town of Oruro a North American of German descent provides excellent accommodations. In the remote town of Tupiza in the fastnesses of the Andes, where of all places one would hardly look for a foreigner, I found a Slav hotel-keeper and a decent kind of a resting-place. The proprietor was from one of the Danubian provinces. In Lima a very well appointed hotel is managed by an Italian. In Santiago the best one is under the control of a Frenchman.

In the interior palatial inns are not to be expected, though a young French mining engineer who came out telegraphed along the Andes trail which he was[p. 31] to follow to have room with bath reserved for him. The telegram is still shown. Such inns as exist are called tambos. Even in the poorest of these, while the lodging is wretched, a good meal usually can be had.

The practice obtains nearly everywhere of charging separately for the lodging, but in some of the larger cities the hotels now are conducted on the American plan. The visitor is apt to be puzzled by the annexes. Naturally he assumes that the annexes to a hotel are part of it, but usually they are separate and under a distinct management. In Valparaiso there are a Hotel Colon and a Hotel Colon Annex, a block or two apart and altogether different. In Santiago are the Hotel Oddo and the Annex to the Oddo, and so on. This causes confusion, and the traveller should make inquiry in advance so as to know where he is going. While the sanitary conveniences in most of the hotels are poor, improvements are being made, and there is something of an approach to the demands of civilization.

A simple rule as to baggage holds good. Take as little as practicable and pack it as conveniently as possible. That means a good deal of loose luggage; but since trunks are charged by weight and very few of the railroads make any allowance for free baggage, it is desirable to have one’s belongings arranged so that they can be piled up around him. One soon becomes accustomed to this and to providing himself with an armful of rugs and blankets.

Railroad fares are about one-third less than in the United States. The accommodations are not luxurious, but they are fair. Night trips are unknown.[p. 32] Chile is the only country on the West Coast which provides a through night train with a sleeper. This is on the line between Santiago and Talca.

An addition to the regular expense of travel is that for embarkation and disembarkation. It is not covered in the steamship ticket, and since, with few exceptions, in the different ports the vessels do not go to wharves of their own or put their passengers ashore in lighters, each makes his choice of the small boats and pays the bill. These charges are not high, yet in the course of a long voyage they mount up, and it always is desirable to make the bargain with the boatman in advance.

For travel in the Andine regions it is necessary to provide one’s own outfit. For those who have to go about much it is not practicable to have their own pack and riding animals, though occasionally a mining engineer will keep a pair of horses or mules and transport them from place to place. Usually the mules and burros, or donkeys, have to be hired. In every case it is advantageous to own the montura, or saddle, and other accoutrements, with especial regard to the capacity of the saddle-bags. Though in the United States the McClellan is the favorite for hard travelling, Americans engaged in mining or in exploration work in the Andes prefer the Mexican saddle. A mining company in southern Peru after various trials discarded everything except Mexican saddles, and had these made especially in San Francisco. In my own experience I found them the most comfortable.

The petacas, or leather trunks, are used by all the South Americans. These are small, and a pair of them balance nicely on either side of the pack animal. Yet[p. 33] during a long mountain journey I managed to transport an ordinary trunk. The Andean mule is bred in northern Argentina. It is not the society pet that is its cousin of the United States Army, and it will carry a burden of two hundred pounds in the upper altitudes.

A supply of canned goods and similar provisions is essential, for it is not possible to rely solely on such wayfaring entertainment as may be had at the Indian huts, even when the trip is short enough to keep within the limits of human habitation. Charqui, or jerked beef, is the mainstay of the stomach for a long journey, but dried mutton sometimes may be had, and is less likely to become unpalatable. Chuni, the dried and frozen potato which nourishes the Bolivian Indians, has nutritive virtues, but palatability is not one of them.

The chief problem in mountain travelling is fodder for the animal rather than food for the man. In the valleys and part way up the punas, or table-lands, fresh alfalfa may be had. But in the higher sierras this is lacking, and it is necessary to carry a stock of barley. In some places where barley can be raised it runs to straw and does not mature into the grain, so that the local supply is not to be depended on.

A hammock is useful in the forest regions. A tent and other camping outfit are sometimes desirable, yet where it is possible to keep within the range of population it is better to risk shelter in the Indian huts, the traveller carrying his own blankets or sleeping-bag. A Western frontiersman or miner has little difficulty in outfitting for the Andean regions.

The quarantine is one of the serious annoyances[p. 34] of travel on the West Coast, though the interruption which it causes often is exaggerated. At times one may have to postpone a landing or a departure because of the restriction, and in that case there is nothing to be done but go on to the next open port and wait in patience. The regulations of the different governments are similar, though they are not always enforced with discretion and common-sense. Yet they are no more severe than the regulations of New Orleans or other Southern ports of the United States. Their purpose of self-protection is justifiable. The objection is that the application of the measures taken is unreasonable. The steamship companies insist on the exaction of charging the passengers an extra sum for the time in which the vessel is held in quarantine.

So many sorts of money are in circulation that it is impossible for the traveller not to lose through exchange. The United States dollar is known well enough, but it has not yet made its way down the coast sufficiently to insure being taken for its full worth. Letters of credit and bank drafts would better be in English money, for the banks and exchange houses insist on counting the $5 gold piece as equal only to the pound sterling, or $4.85. It will take some years for the full result of the Panama money system to be felt on the West Coast, though ultimately that will help to extend the use of United States currency.

A calculation is made every quarter by the United States Mint of the value of the coins representing the monetary units of the various Latin-American countries. This serves as an index of values, though in actual transactions it cannot always be insisted upon.[p. 35] The universal coin on the West Coast is the Peruvian sol, equal to 48½ cents gold. It is the size of the American silver dollar. Since Peru has the gold standard and coins a Peruvian pound called the inca, exactly the weight and fineness of the English pound sterling, there is no fluctuation. Ten soles make a pound. For local purposes along the coast the Peruvian sol is therefore the best medium of exchange.

I have left for separate consideration the subject of the diseases incident to West Coast travel and residence. Their mention frightens. Why, I do not know.

Pneumonia and typhoid in the temperate climates cause greater ravages than tropical diseases in their field, nor is malaria in its manifold manifestations limited to a given area. Fever and ague in the United States, calentura in the West Indies, terciana in the forest regions of the Andes,—it all is essentially the breakbone fever. Quinine and calomel remain the tonic preventives. Tropical dysentery is to be guarded against by common-sense in diet. The social vices bring their inexorable penalty more swiftly than in the North, but their remedy is the moral prophylactic. Yellow fever, since the demonstration of the mosquito as the active agent in its propagation, is losing its terrors, but its avoidance comes under the sphere of epidemic quarantines rather than of individual measures. The exceptional conditions which will prevail on the Isthmus during the Canal construction and the exceptional means adopted to combat disease are not to be taken as representative of the West Coast. Yet the benefit of this experience will be great. But whether along the coast, on the plateaus of the Andes,[p. 36] or in the tropical valleys, one general rule is more valuable than a medicine chest. It is that of a healthy, fearless mind which does not magnify ordinary ailments and which keeps its poise in the shadow of more serious illness.

[p. 37]

THE ISTHMUS OF PANAMA

Canal Entrance—Colon in Architectural Transformation—Unchanging Climate—Historic Waterway Routes—Columbus and the Early Explorers—Darien and San Blas—East and West Directions—Life along the Railway—Chagres River and Culebra Cut—Three Panamas—Pacific Mouth of the Canal—Functions of the Republic—Natural Resources—Agriculture and Timber—Road-building—United States Authority on the Zone—Labor and Laborers—Misleading Comparisons with Cuba—The First Year’s Experience.

WHEN the Caribbean is restive, restless is the voyager. After tossing in misery one April night I peered through the port-hole of the steamer’s cabin at what seemed a cluster of swinging lanterns dipping into the sea. They were the lights of Colon. The vessel was riding at anchor to await the morning hour when the approach to the quays could be made.

Daybreak unfolded through the mist, disclosing green foliage ridges and broken forest-clad hills sloping to a shallow bowl. This circular basin is the island of Manzanillo. The town lies as in the bottom of a saucer. Colon is not a harbor in the usual sense, for the curving Bay of Limon which it fringes is an open roadstead. The improvements by the United States will make it a commercial haven.

For all the years to come the blue horizon will be swept by the eager eye of the traveller for the Canal[p. 38] entrance. Seen from the ship’s deck, it is like the smooth surface of a sluggish river, broad and open. The artistic instinct of the French engineers found expression even in the prosaic work of earth excavation. They planted a village in the midst of cocoanut groves, and the palm-thatched cottages charm the eye. The bronze group of Columbus and the Indian, Empress Eugenie’s gift, allegorical of the enlightenment of the New World, may be seen through glasses, while the showy residence built for De Lesseps is discerned.