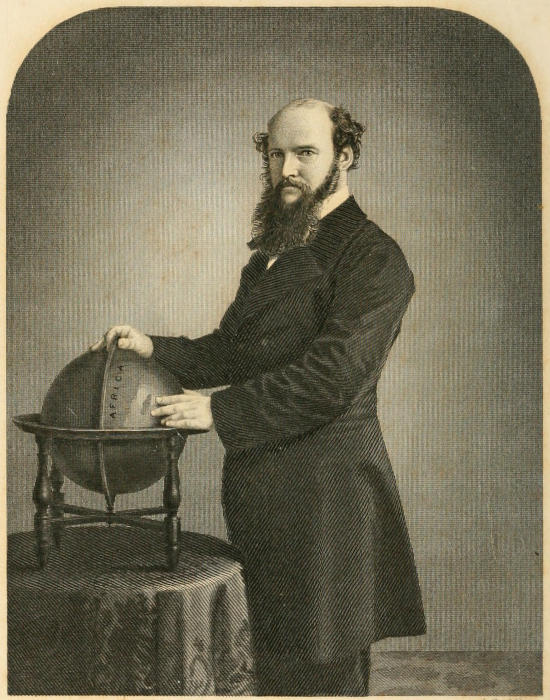

J. Saddler.

LYONS Mc. LEOD, F.R.G.S.

&c. &c.

London: Hurst & Blackett, 1860.

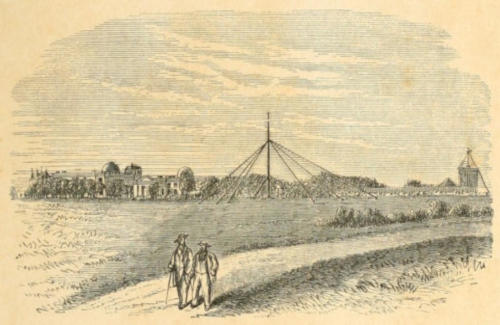

Title: Travels in Eastern Africa, volume 1 (of 2)

with the narrative of a residence in Mozambique

Author: Lyons McLeod

Release date: November 3, 2024 [eBook #74675]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Hurst and Blackett, 1860

Credits: Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

J. Saddler.

LYONS Mc. LEOD, F.R.G.S.

&c. &c.

London: Hurst & Blackett, 1860.

TRAVELS IN EASTERN AFRICA;

WITH

THE NARRATIVE OF A RESIDENCE IN

MOZAMBIQUE.

BY

LYONS McLEOD, Esq., F.R.G.S.,

HONORARY FELLOW OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

AND OF THE METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY, MAURITIUS

LATE H.B.M. CONSUL AT MOZAMBIQUE.

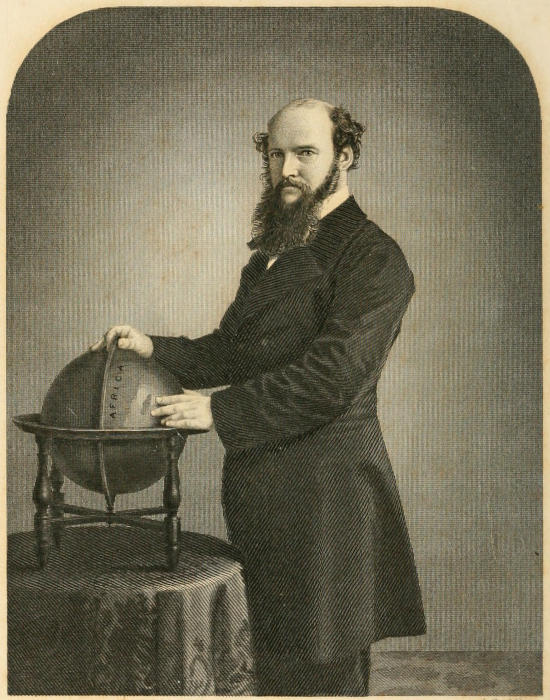

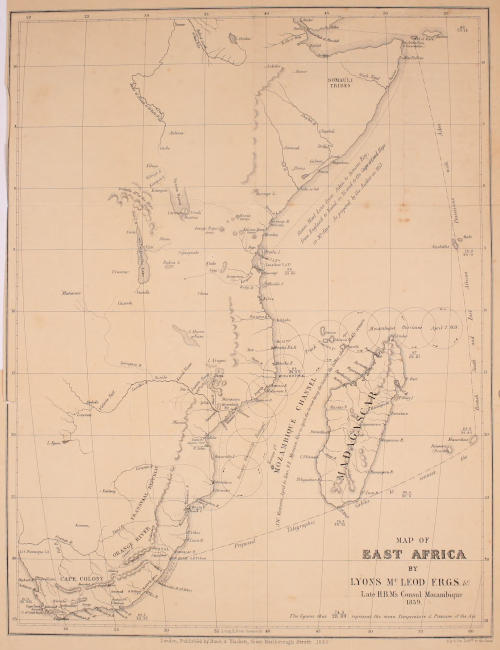

THE ROYAL OBSERVATORY, CAPE OF GOOD HOPE.

“Ethiopia shall soon stretch out her hands unto God.”—Psalm LXVIII. v. 31.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

HURST AND BLACKETT, PUBLISHERS,

SUCCESSORS TO HENRY COLBURN,

13, GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET.

1860.

The right of Translation is reserved.

Gentlemen,

Impressed with the conviction that, from the most remote time, Civilization and Christianity have been best promoted by Commerce, which binds rival nations in the bonds of Peace, I respectfully dedicate this work to the Mercantile portion of my countrymen, in the hope that by their united efforts, Slavery may be made to disappear from the continent of Africa, through the establishment of commercial relations, especially with that rich portion of its coast and the neighbouring Ethiopian Archipelago, including the fertile island of Madagascar, described in the following pages.

I have the honor to be, Gentlemen,

Your most obedient and humble Servant,

THE AUTHOR.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The “Ireland”—W.S.L. Postal-line—Mr. Jenkins—The Author Discovers that he is Styled a “Government”—The General’s Quarters—Proceed to Sea—Accident in the Saloon—Total Darkness in the “Lower Regions”—Spittoons and Safety Lamps—The Gale—Put Back to Plymouth—Ten Passengers Leave the “Ireland.” | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Departure from Plymouth—Reflections on Leaving England—Cabin Attendants—Live Stock—Mr. Jenkins and “the Pure Element”—N.E. Trades—Red Atlantic Dust—Short Allowance of Water—Viewing the “Line”—The Southern Cross—A Lady Navigator—“Fire! Fire!”—The Maniac—Arrival at the Cape | 25 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| W.S.L., Worst Steam-Line—Table Mountain—The Table-cloth is Spread—Pic-nic to Constantia—Careless Smoking—Cape Wines—The “Ireland” Proceeds to India—Melancholy Forebodings—Midnight Alarm in Simon’s Bay—The Cape Observatory | 49[vii] |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Table Bay—Breakwater to be Built—Harbour of Refuge—Policy of Sir George Grey—Proposal for Carrying the Mail to the Cape by way of Aden—Discovery of Coal on the Zambesi—Its Effects on the Future of South and East Africa—Absence of Trees at Cape Town—Climate of the Cape | 67 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Further Detention at the Cape—Arrival of the “Frolic” from Mozambique—“John of the Coast”—New Naval Commander-in-Chief—Storm at the Cape—Courage of Cape Boatmen—Destruction of Shipping in Table Bay—Embark in the “Hermes”—Coast of Kaffraria—Well Watered and Beautiful Country | 87 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Arrive at Natal—The Bar—Proposed Harbour of Refuge—Wharves in the St. Lawrence—Railroad at Natal—D’Urban—Port Natal Harbour—Verulam—Pieter-Maritzburg—Slave Ship off Port Natal—The Havannah Slavers—Chamber of Commerce—Natal Waggon—“Daft Jemmy” | 100 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Present State of Natal—Physical Formation—Succession of Terraces—Products most suitable for Each—Labour Required for Natal—Development and Prosperity of Free Labour Colonies—The Destruction of the Slave Trade—Climate of Natal—“Shall we Retain our Colonies?” | 130[viii] |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Port St. Lucia—Zulu Country—Panda—Delagoa Bay—Its Unhealthiness; Causes Examined—Lourenço Marques—Dutch Fort—Tembe and Iniack—British Territory—Fecundity of Boer Females—Products—Transvaal Republic—Mineral Wealth—Future of the Country | 147 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Appearance of the Coast to the North of Delagoa Bay—Facility of Shipping Slaves—Slavers’ Signals—Rivers Lagoa and Inhampura—Cape Corrientes—“Sail, ho!”—The Chase—“Zambesi”—Ex-Governor Leotti—A Slaver Clears from Cardiff—Inhambane—Products—Mineral Wealth | 180 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Kingdom of Mocoranga—Kotba for the Soudan of Cairo—Sultan of Kilwa—Kingdom of Algarves—Remains of Ancient Cities—Inscriptions not Deciphered—Zimboë Bruce—Sofala, the Ancient Ophir—Productions—The Manica Gold Mines—Surrounding Region Adapted for Europeans—Industry of the Natives—The Priests Rob the Jewels from the Image of the Blessed Virgin | 204 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| The River Zambesi—Luavo Mouths—Killimane—River Shire—Valley of the Shire Abounding in Elephants—How Salt is Made on the Zambesi—From the Ocean to Kaord Vasa Navigable at all Seasons—Water Rises Sixty Feet in Narrows of Lupata—Access to the Cazembe Territory by the Zambesi—Three Seams of Coal Discovered—Products | 225[ix] |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Angoxa—Its History—Perfidious Conduct of the Portuguese—Effects of British Interference—Wholesome Dread which the Portuguese have of the Imâm of Muskat—Visit of the Sultan of Angoxa to Johanna—Invites a British Merchant to Trade with him—Seizure of the British Brig “Reliance” | 245 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Arrival at Mozambique—Interview with the Governor-General—Saluting the Consular Flag—Description of the Consul’s House on the Mainland—Portuguese Rosa—Cruelty of the Portuguese Towards their Slaves—“Flog until he will Require no More!”—Irrigation and Native Labour | 258 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Brief Historical Sketch of the Portuguese on the East Coast of Africa—Description of Mozambique—Its Position as an Emporium for Commerce—Its Restoration, like that of Alexandria, possible—Fort San Sebastian—Churches and Chapels—Palace of the Governor-General—Wharf—Population—Society | 279 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Slave-Trade under the French Flag—Vessels Employed—How Fitted and Provisioned—Price Paid for Slaves by the French—Ceremony of Engaging the “Labourers”—How Treated at Réunion—Dhows Employed, and Horrors of the Traffic—Statement of the Captain of a French Trading Vessel—Statement of the Supercargo of an American Trading Vessel—Revolt of Slaves on Board of a French Brig, and Massacre of the Crew—How the Slaves are obtained in the Interior of Africa—The Natives Rise en masse—Feelings of the Natives towards British Consul and Family—The “Zambesi” assisting the “Minnetonka” to obtain Slaves | 303 |

The “Ireland”—W.S.L. Postal-line—Mr. Jenkins—The Author Discovers that he is Styled a “Government”—The General’s Quarters—Proceed to Sea—Accident in the Saloon—Total Darkness in the “Lower Regions”—Spittoons and Safety Lamps—The Gale—Put Back to Plymouth—Ten Passengers Leave the “Ireland.”

On the 6th December, 1856, I embarked, with my wife, on board the Royal Mail Screw Steamer “Ireland,” for the Cape of Good Hope, en route to Mozambique, to which place I had been appointed as Her Majesty’s Consul.

Externally, the “Ireland” was what sailors call a very “tidy craft.” She was about 1,000 tons burthen; long, low, and rakish; having three[2] masts and one funnel, and what is called a stump bowsprit. As she was fitted with a screw propeller, she was devoid of those great protuberances called paddle-boxes, which in a steamer so materially (to my eye) destroy the symmetry of the hull of the vessel, which, in this case, was built of iron, and painted entirely black.

Flying at the mizen peak was the well known ensign of Old England, the field of which appeared to me unusually disfigured by the talismanic letters, W.S.L., in a glaring yellow colour, begrimed by soot.

On asking the meaning of those letters, I was told that they were the initials of an M. P., who had not only sufficient interest to obtain the contract for carrying the mail in a line of very slow steamers, but who was held in such dread by a venerable body of old gentlemen sitting behind the sign of the “Sea Horses,” in Whitehall, known as the Board of Admiralty, that the M. P., W.S.L., was permitted to place the initials of his name on the national ensign, without being subjected to the usual fines and penalties inflicted on those similarly offending. Others told me[3] that W.S.L. stood for the “worst steam line,” but this I looked upon as the invention of some disappointed mail contractor.

Such was the “Ireland” externally; and, as she was at anchor in the beautiful little west-country harbour of Dartmouth, which boasted W.S.L. for its representative in the House of Commons, the saucy craft might well say, “I am monarch of all I survey.”

Arriving alongside of the “Ireland,” about one hour before her advertised time of sailing, in a small steamer full of fellow passengers, which had brought us some miles down the little river Dart, we imagined that there would be every accommodation for our reception; but, on the contrary, we found that we were not supposed to come near her for some imaginary time, which they on board could not name to us. All that we learned was, that the numerous barges then alongside of her, full of coals, had to be cleared of their cargoes before the passengers were allowed on board. To our repeated applications to be permitted alongside, we were told to return to the shore; and as it was raining very heavily, the man who[4] was steering the small steamer, put her helm up and made for the land; however, this being done without the consent of the passengers, they soon took matters into their own hands, and compelled the small craft to dash alongside, causing considerable damage to the coal-barges. Exposed to a volley of abuse, some of the most adventurous of the gentlemen scrambled on board, and we were actually compelled to appeal to the commander of the vessel before we could get the ladies on the deck of the “Ireland.”

It appears that we had unfortunately arrived alongside of the vessel at the cabin dinner-hour, and were exposed to all this inconvenience at the whim of the chief officer and the head steward; the former of whom wished to clear the coal-barges, and the latter to save himself the trouble of laying a few more plates on the table.

No sooner were we on board of this passenger ship than we found ourselves rudely pushed about, and, after having been driven round the wet deck with pigs, sheep, and poultry, with considerable difficulty we threaded our way through hampers, water-casks, coals, &c., to the cabin saloon.

This was an elegant apartment, decorated with gold and green, having at the further end a grate and marble mantel-piece; but as the chimney led to the screw propeller, of course, the first time a fire was lighted, the saloon and cabins were deserted in consequence of the smoke, which made one almost fancy that the ship was on fire; so it turned out to be for ornament and not for use.

Observing the state of confusion in which everything was on board this first-class passenger ship—being an old traveller—as soon as the ladies were placed in shelter from the rain, which was coming down in a most pitiless manner, I returned to the deck to look after my luggage, when I found that the chief officer had ordered the small steamer to return to the shore with the luggage of all those passengers who had succeeded in reaching the deck of the “Ireland,” contrary to his wishes. This officer, who was promised a command in the W.S.L. Line of Steamers on his return to England, took upon himself to mark the passengers who had so offended him, and during the passage he had to be admonished by the commander for his marked rudeness to some[6] of the ladies, as well as the gentlemen who had acted contrary to his wishes on the occasion referred to. On an application being made to the commander, the small steamer was ordered alongside, and we recovered our luggage.

Returning to the saloon, we found considerable commotion among the lady passengers, as it was discovered that the “ladies’ saloon” had been appropriated for the use of a family.

To my inquiry for my cabin or state-room, the head steward replied, “You’re a government passenger, sir—you must go below; your cabin is the aftermost one but one, on the starboard side of the lower deck. That’s the way, sir! down that ladder.” With considerable difficulty I descended a ladder which received many a blessing from the passengers during the voyage. Arrived at the bottom of the shaft (for I can liken the descent only to that into a coal mine), I found myself in a dark, dismal locality, always afterwards denominated the “lower regions.” Here were squalling babies, fighting stewards, swearing sailors, and discontented everybodies.

On asking if there was any one there to point[7] out the cabins, a voice answered from a distance, “Why the d—l do you not come with that water? I will not get a bit of dinner this night;” while another one exclaimed, “I’ll break your head if you do not hurry and bring me a light?” Even the children in this dismal place appeared to be bent on doing harm, and were engaged in combat with each other, or struggling with their weary and discontented nurses.

After making good use of my lungs, a queer-looking, red-headed, one-eyed individual, in shirt sleeves, made his appearance, carrying in his hand a tin spittoon, on the rim of which was the miserable remains of a purser’s dip, by the flickering light of which I was examined from head to foot. Cautiously approaching, the stranger welcomed me on board, and requested me to make myself “quite at home.”

To my inquiry, “Who are you?” he replied:—“It’s all right, sir; you’ll know me before long. On shore they call me ‘Mr. Jenkins,’ but on board this thing I am called the ‘bed-room steward.’ However, here we are for the voyage, sir, and we must make the best of it.”

I asked “Mr. Jenkins” to show me my cabin, when he inquired what my name was. Having satisfied my interrogator on this point, he exclaimed:—

“Oh, you’re a government; come this way, sir.”

To my inquiry what he meant by calling me a “government,” Mr. Jenkins replied, “You’ll see directly, sir!”

Following this extraordinary being through a labyrinth of boxes, hampers, deal boards, carpenter’s tools, and carpet-bags, we arrived at the door of a cabin, seizing the handle of which, Mr. Jenkins cautioned me not to be disappointed, and gently opened it. Being in the after part of the ship, I expected to find a small cabin, but not the miserable dog-hole now revealed to me. It was barely six feet in length, and its extreme breadth scarcely five feet.

To my exclamation that “there must be some mistake!” Mr. Jenkins replied:—

“No, sir; he never makes mistakes! You see, sir, you’re a ‘government,’ as I told you before, and that is why he has given you this cabin.”

After some exercise of patience and temper, I[9] learned from Mr. Jenkins that he meant W.S.L., and that the term a “government” applied to myself, referred to my being a government passenger, a certain number of whom are carried by all steamers belonging to lines which have a contract for carrying the mails.

To my observation that I was surprised that W.S.L. was not afraid to treat the government passengers in such a shameful manner, by putting them into cabins which he could not possibly let to any other passengers, Mr. Jenkins stated that “W.S.L. was not afraid of any government, that he hated all ‘governments,’ and when he got them on board of his ships he always served them in that way.”

To this I could only remark, on more minutely examining the cabin, that it was a most disgraceful place to put a lady into. Jenkins, ever ready with an answer, immediately replied:—

“You see, sir, all ‘governments’ are supposed to be gentlemen—‘governments’ are not supposed to be married.”

“But surely, Jenkins, there must be some better cabin than this still vacant?”

“No, sir, not one; take my advice and make the best of it. You see, sir, outside here in the steerage we have little enough room at any time, but, considering we are bound to a hot climate, it will be stifling in a fortnight’s time—well, the Admiralty insist upon his taking the full number of ‘governments’ with him this voyage. Well, he has already let all the cabins and got paid for them; the consequence is that for one of ‘the governments’ he has ordered this ‘structure’ to be built. Just come and look at it, sir.”

Following my loquacious friend, I managed at last to reach the hatchway close to which the carpenters were elevating what Jenkins had termed a “structure,” to be adapted into a sleeping cabin for a gentleman, as I afterwards found, six feet in height.

Asking for an explanation of this stoppage to the ventilation of the “lower regions,” Jenkins, ever ready to explain his part of this passenger ship, exclaimed:—

“This, sir, is what I wish particularly to point out to you; the men employed upon it call it the ‘general’s quarters,’ the children call it ‘Punch’s[11] house,’ and I call it the ‘structure.’ Have you any interest, sir, with the Board of Trade?”

“What makes you ask such a question?”

“Don’t be offended, sir; I have put that question to every ‘government’ that has come on board of this ship.”

“If I was a ‘government,’ I would stop this ship—that ‘structure’ is sure to cause fever and death.”

Leaving Mr. Jenkins gazing on the “structure,” I hurried on deck and found my way into the saloon, where I explained the state of things below to my wife. I found that some ladies who had preceded us in their arrival on board, and who, like us, were government passengers, had already made her acquainted with the very inferior accommodation to which we were condemned for the voyage.

The ladies retired early that evening, for the greater number of them had travelled a considerable distance during the day; but what with the hammering kept up all night by the carpenters, the straw pillows, and the miserable coffins of berths, on comparing notes the next morning, it[12] was found that but few among the passengers, male or female, slept during the first night on board the “Ireland.”

On examining the “structure” the next morning, we perceived that it had visibly increased its dimensions during the night, thereby excluding light and air. Jenkins talked in a despairing tone of the “Board of Trade,” and occasionally alluded to the “Emigration Commissioners,” but despite this the “structure,” accompanied by, if possible, increasing noise, progressed, greatly to the amusement of the little boys, and to the annoyance of all adults.

After breakfast we were told that the vessel would not be ready for sea before two days, and some of the passengers and myself went on shore in search of carpenters to fit up our cabins. In my cabin, the dimensions of which I have already given, there were two sleeping berths, the lower of which it was impossible for one to lie in, much less to sleep there; and this vessel was going to cross the equator twice during her outward voyage.

Such meagre accommodation would not have[13] been permitted in an emigrant vessel; and here was a mail steamer, under the pretence of being a first-class ship, obtaining passengers from the old established Indian traders, who were paying higher passage money than by those ships, and sixty passengers were crowded into a space where there was barely accommodation for half that number.

With the aid of a carpenter from the shore, the upper berth was enlarged, but with the lower one it was found impossible to do anything without curtailing the already small standing room. It was therefore turned into a receptacle for carpet-bags, and I made my mind up to sleep on the floor for the passage to the Cape of Good Hope.

With an outlay of about three pounds sterling on our state-room, it was made tenantable; and it was calculated that the passengers had expended about one hundred pounds on fittings in their cabins, or state-rooms, which ought to have been there on their arrival on board the “Ireland.”

Evening came, and there was no cessation to the hammering which had been going on ever[14] since we scrambled on board. The carpenters were to be employed another night in completing the “general’s quarters,” or, as the children would insist upon calling it, “Punch’s house.” It was therefore determined, by those whose unfortunate lot it was to have their state-rooms in the “lower regions,” to remain in the saloon all night, as it was quite impossible to sleep with the hammering and shouting carried on below, accompanied, as it would be, by the thrilling tones of the interesting little darlings who had hitherto displayed very bellicose dispositions.

About eleven o’clock, we asked the head steward to furnish us with some supper; firstly, because we were really hungry; and, secondly, because we were all good-humouredly putting up with the great inconvenience of remaining in the saloon, instead of retiring to our cabins, we thought, and very naturally too, that some supper would have enabled us to pass the time more agreeably.

The steward appeared quite bewildered at our asking such a thing, and replied “that suppers were not allowed.” But we were not to be put[15] off with this reply. The passengers whose state-rooms led out of the saloon determined that their friends belonging to the “lower regions” should have some refreshments, and soon produced from their state-rooms innumerable delicacies, which had been laid in for the voyage. While enjoying this pic-nic, the unhappy steward, who foresaw in this demonstration the future violation of the rules and regulations of the W.S.L. Line of Steamers, without a moment’s notice, put the lights out, and left us in utter darkness. Some of the young folks proposed a serenade, to which all willingly gave their consent, and in this agreeable manner another hour was passed.

At midnight the steward again made his appearance, and informed us that we were too noisy, and that we must disperse.

Under these circumstances, there was nothing to be done but to go below. Bidding our hospitable friends in the saloon state-rooms “pleasant dreams and sweet repose,” we descended the ladder leading to the “lower regions,” and formed ourselves into a committee of inspection on the “general’s quarters,” where we found a[16] young indigo planter, of five years of age, was in possession of the premises, where he insisted upon rehearsing, even at that early hour, certain portions of Punch, much to the amusement of the carpenters working at the expense of W.S.L., and of some young Scotch cadets bound to India, who, even at that early period of the voyage, began to look upon young Frank Indigo as a “fearfu’ laddie.”

The whole of that night there was a continuation of hammering, shouting, singing, whistling, and crying. And thus another sleepless night was passed; and we were all glad when daylight dawned, and we repaired to the steamer’s dirty deck.

On the afternoon of the 8th, preparations were made for going to sea; and about 5 P.M., Captain Bully, the agent of the W.S.L. Line of Steamers, came on board, and informed the commander of the “Ireland” that he must proceed to sea at once.

The steam was up, and, although thick clouds were seen banking up in the south west, the scud flying fast to the north east over our heads, the[17] sea-birds, with their alarming cries, flying inland, and the mercury in the barometer falling rapidly, Captain Bully said these indications were “all nonsense,” and that we would have fine weather; besides, if the mails were detained any longer, W.S.L. would be fined; and that therefore we must go to sea, after which he had nothing to do with us. Accordingly, at 6 P.M., we passed from the snug little harbour of Dartmouth into the English Channel, to breast a gale of whose approach even the ducks and geese on board the ship were sensible.

As soon as we got into the Channel, we found it was blowing fresh, with a heavy cross sea from the south west. The engines were weak, and, although the screw propeller made a great deal of noise, it did very little work.

In two hours’ time all the passengers were obliged to retire to their state-rooms, with the exception of a few old tars, myself being numbered among the latter.

As the night advanced the wind grew louder, the sea more boisterous, and the straining and creaking of the ship, together with those mysterious[18] noises which are heard in a new vessel, increased.

In the “lower regions” we were entirely in darkness, and it appeared impossible to procure a light in the state-rooms.

In the middle of this melancholy state of affairs, a fearful crash was heard in the saloon, which conveyed the impression to those below that something serious had happened. The report was immediately circulated in the “lower regions” that the marble mantel-piece had been carried away, killing three of the gentlemen in the saloon. When the accident occurred, I happened to be in the saloon, and was fortunate in saving one gentleman from seriously injuring himself. The fact was that the seats or benches running along the saloon-tables were secured to the deck by large screws, which, being made of inferior metal, or imperfectly cast, snapped off during one of the heavy rolls of the vessel; the consequence was that all those persons seated on the bench which gave way were precipitated with some considerable violence against the side cabins, suffering more or less injury. The second[19] officer and two of the passengers were a good deal hurt, the officer being carried to his cabin.

As I sat at the end of the table, near the marble mantel-piece, until the real circumstances of the case were known, it was supposed by many that I was one of those injured, and, on descending to the “lower regions,” I found my wife, who is a great sufferer at sea, almost dead with terror. For, it appears, she heard those outside of her cabin say that three of the gentlemen were killed. This accident had such an effect upon her nervous system, that she did not recover from it for the whole voyage.

On asking Mr. Jenkins the cause of his portion of the ship being in darkness, he replied that “the candles sent on board were too large for the lamps in the state-rooms, and that it was impossible for one man to cut them down fast enough.”

Jenkins had no one to help him, his ordinary assistants having to yield to the “mal de mer,” and he was at his wit’s end what to do to keep the place lighted. Fertile in invention, on this occasion a most amusing idea came to his[20] aid. In the earlier part of the day he had come across some dozens of tin spittoons, which had been sent on board the vessel, by a mistake, for some other articles of more importance. Jenkins bethought him of these useless implements, and having tried one of the offending candles, he found that it would just fit into the spittoon, and he at once decided upon saving himself the trouble of reducing the candles by placing them in the spittoons. Accordingly, on a bed-room candle-stick being asked for, Jenkins handed one of these spittoons, with a candle in it, accompanied by a polite bow and a bland smile, as if he was supplying the latest fashion of safety-lamp. It was afterwards suggested to Jenkins, by a lady, that if the candles were held in hot water they might be evenly reduced to any diameter; while, at the same time, there would be a considerable saving of the material, which Jenkins might turn into money on getting into harbour. The hint was taken, and the passengers were not compelled to use a spittoon for a bed-cabin candle-stick.

There was little sleep in the “Ireland” that[21] night, what with the noise below, the rolling and pitching of the ship, the screams of the affrighted children, the rushing of feet upon deck, the noise of the steam, and the screw-propeller—all occasionally hushed in the howling of the tempest. Still the “Ireland” had to breast the sea, and it would be no common gale that would induce her determined commander to put back.

About four o’clock the next morning, we were disturbed by a noise which made every one in the afterpart of the vessel, below the upper deck, imagine, for a moment, that the ship had struck a rock, so violent was the shock given to the frame of the vessel.

On inquiry, it was ascertained that one of the extra water-tanks carried on deck, not having been lashed, had got adrift; and, after having first nearly unshipped the funnel, it brought up against the bulwark, where it injured the side of the vessel considerably.

So slight a cause creating so violent a shock gave us but a poor opinion of the frame of the ship, which we found was built by contract.

The storm continued with that loud howling of the wind, and sharp whistling among the shrouds, which betokened the increase of the gale; while, occasionally, the vessel would descend into the sea as if she were overburdened, and anon a mighty sea would strike, arresting her in her progress, and making her shake from stem to stern.

At five o’clock the close-reefed topsails were blown into ribbons, the storm staysail was torn to shreds, and the engines, unassisted by canvas, soon gave indications of their weakness. It was found that the machinery was totally unfit to drive the vessel in the face of the gale and sea with which she had to contend. As day dawned, there was every prospect of an increase of the gale, and the prudent commander determined to seek shelter while yet the engines were not disabled. Hardly had we bore up for Plymouth, when the gale increased, and, by the rapid falling of the barometer, we had reasons for believing that the most dangerous part of the revolving storm passed very near to us.

As soon as we were at anchor under shelter in[23] the magnificent breakwater at Plymouth, the passengers began to make their appearance in the saloon, and it was then discovered that there were not seats for many of them at the table; in consequence of which, and the general discontent at the arrangements on board, ten of the passengers left the ship.

This created some vacancies in the state-rooms leading out of the saloon, and as I was obliged to go on by that mail, I insisted upon having one of the vacant state-rooms, by which means we left the “lower regions.” All the fixtures which we had put up for our comfort were removed to our new quarters, and the ladies on board said that my wife’s cabin was the most comfortable in the vessel, which I thought was not saying much for it.

During our late cruise, many of the ladies who had embarked without their husbands fared very badly. Mrs. R., with two children and a nurse, passengers to Mauritius, from the hour she came on board, on the eve of our departure from Dartmouth, until her husband stepped on deck at Plymouth, to take herself and little ones on[24] shore, had not tasted anything with the exception of a little cold water taken from a can in her cabin, which was so strong of paint that it made herself and her children quite ill. Of course this lady and her family did not return to the “Ireland” after landing at Plymouth, nor would any of her friends sail again in any vessel having W.S.L. connected with her.

Soon after our arrival at Plymouth, we had a warm invitation from our friends on shore to renew our late visit. We got a good ducking while reaching the shore in one of the Plymouth boats; but this and our past dangers were soon forgotten in the affectionate greetings and smiling welcomes of our kind friends. But this was not to last long, for the next day, as we were sitting down to an early Sunday dinner, a carriage drove up to the door, with a note from the Captain of the “Ireland,” telling us that he was going to start immediately; so, once more taking a hasty farewell of our hospitable friends, we found ourselves again on board the “Ireland.”

Departure from Plymouth—Reflections on Leaving England—Cabin Attendants—Live Stock—Mr. Jenkins and “the Pure Element”—N.E. Trades—Red Atlantic Dust—Short Allowance of Water—Viewing the “Line”—The Southern Cross—A Lady Navigator—“Fire! Fire!”—The Maniac—Arrival at the Cape.

It was a beautiful Sunday evening when we again embarked in the “Ireland.” The gale had been succeeded by a calm which lent enchantment to the view of the rich and varied scenery of Plymouth harbour. Evening was closing in, and anon from the shore might be heard the bells of the churches and chapels calling on man to praise his Maker.

The steam was up, the passengers were all embarked, the latest mail-bags had just arrived, so that the “Ireland” once more moved into the[26] English Channel. This time the “Channel of Old England” was as still as a mill-pond, and mirrored the bright stars of the firmament as the busy steamers glided about with their red and green lights, warning each other of danger.

Many an eye was cast on the receding shores of that loved island, never to gaze upon it more. Many sad hearts were sighing for homes never to be visited again.

Of the numerous passengers pacing that deck, and thinking of those who would miss them at the accustomed hearths, as the long winter evenings set in, how few were destined to return to the homes they loved so well!

Some of the brave men who talked so lightly then, and tried to cheer the drooping spirits of their fair companions, were to be sorely tried in a distant clime, and to fall gloriously struggling to retain India for the land of their birth.

Wives going to their longing husbands were destined never to meet them—or only in danger and in death.

Longing hearts were then on the way to be wedded to those whose plight had been trothed[27] many years before, and now, having earned independence, invited their young loves to share it.

Girls blooming into womanhood, bound for their unknown journey in the East, were soon to find rest in death.

The majority of the passengers were journeying to India, then on the eve of rebellion. Loving wife, gallant soldier, blooming maiden, and almost lisping childhood, were destined to take their part in that awful tragedy, the acts of which may never be told.

Not one-fourth part of the passengers in the “Ireland” on that voyage are now living; and even of the survivors, some have been sorely tried, as the pages of this book will reveal. But I must not anticipate.

I have travelled much, but I have never met with a party of ladies who had such a strong presentiment of coming evil. Many and many a time have some of those, who are now no more, expressed their dread, not only of proceeding in the vessel, but even of going to India; although they were then on the way to those they loved best on earth.

In a few days we had all shaken into our places, and, despite sundry inconveniences, we were determined to be happy, and that goes a long way in this world, both on shore and afloat, to render unhappy mortals as we are contented with our lot.

It is true that the stewardess, being too fond of the “cratur” in her coffee, the ladies dispensed with her services as much as possible; and that the servants being altogether inadequate in number for the work which they had to perform, the greater part of the attendance at table fell upon the gentlemen passengers, who, to stop the daily occurrence of the soup being poured over the ladies, kindly offered their services during dinner time.

These cabin assistants, or incumbrances, eventually drove the head steward out of his mind. On going to sea, the poor man found that the cabin-servants had never been in a vessel before, having shipped on board for the purpose of learning their duty, with which understanding they were paid accordingly, at the rate of ten shillings per month, and to pay for their own breakages.

The balance these men would have to receive on the pay-day would indeed be very trifling, for they were always breaking. One poor youth, who had not got his “sea legs,” fell down and broke thirteen dishes at once, and as for plates, they appeared to be broken by dozens.

The live stock placed on board at Dartmouth was the admiration of every one; and yet, from there not being one man expressly to look after the stock, fowls, ducks, and geese disappeared very quickly, literally dying in the coops from starvation and want of water. At last the gentlemen passengers, as a matter of precaution, made a point of examining the stock every morning, in order that they might see those thrown overboard which had died during the previous night.

On one occasion I recollect seeing eleven dead geese thrown overboard; and from this neglect a vessel that was most liberally found, on starting from England, for the entire voyage to India, ran short of everything before she arrived at the Cape of Good Hope.

The ladies were without a bath during the whole voyage, although there was a comfortable[30] bath-room on board; owing to the pump not being properly fitted, the bath could only be filled once a day, during the time of washing the decks before breakfast. To overcome this difficulty, the stewardess very coolly proposed that a certain number of the ladies should bathe in the same water each day; a proposition which of course found no seconder in those most interested, and in consequence only one lady could enjoy the luxury of a bath per diem.

It was found that 2,000 gallons of fresh water had been destroyed, by letting the salt water run into the tank while washing decks. This water, being impossible to drink, was set aside for washing water, to be used in the cabins. Jenkins thought that pure salt water was equally as good for washing the body, and therefore supplied the cabins with the “pure element,” while he disposed of that which was brackish to those who were glad to pay him for the same.

Soon after we had entered the North East Trade Wind, and more especially when passing the Cape de Verde Islands, the atmosphere assumed that hazy appearance so remarkable during the blowing[31] of the Harmattan winds on the west coast of Africa. But on the present occasion I did not experience that dryness of the air of which one is made so sensible during a Harmattan wind. When at the river Gambia, some years previous, the feeling caused by the dryness of the Harmattan wind was, although generally pleasant and very bracing, at times painful; the skin being dried up and wrinkled, and a general feeling, on the surface of the body, as if suffering from an attack of acute rheumatism. The teeth were affected as if one had been using some very strong acid in the mouth, and the bones of the head and face were slightly painful; and yet I am inclined to think that these were not rheumatic affections.

During the prevalence of these winds, I have frequently seen the furniture split, and articles which were veneered considerably damaged; the veneering in some cases being curled up like dried sheets of paper. Books left closed on the table at night would be found on the following morning completely opened, and each leaf standing up as if it had been highly stiffened with[32] gum. At such times glass tumblers would break, apparently of their own accord; and I have known one slight tap given to a tumbler made of blown-glass, not only to break it, but, as if by sympathy, others remotely placed in different parts of the room.

When in the latitude of the Cape de Verde Islands on former occasions, at about this season of the year, and with the same hazy appearance, I have succeeded in obtaining some of the red Atlantic dust which is found to fall upon the rigging and decks of vessels. This dust was supposed for a long time to be carried by the north-east trade wind from the desert of Africa into the Atlantic; but it has been shown more recently, by Professor Ehrenberg, to consist, in great part, of infusoria with siliceous shields, and of the siliceous tissue of plants. Although many species of infusoria peculiar to Africa are known to Professor Ehrenberg, he has, I believe, found none of those in this Red Atlantic Dust examined by him. But, on the other hand, he has discovered in it two species hitherto known to him as living only in South America. At the season when this dust is[33] so very plentiful in the air about the Cape de Verde Islands, the valley of the Orinoco is dry; and as the strong winds which sweep at that period of the year, over the valley of the Orinoco, are known to blow towards the Southern Andes, at the time when much vapour is condensed on that chain, and strong ascending currents of air are thereby created, it is held by writers on the Trade Winds, that this dust is carried to the eastward by an upper current of air, which again naturally falls to the earth, where the lower, or north-eastern, current commences.

In accordance with the above theory, Lieutenant Maury, of the United States Navy, concludes, with much apparent confidence, that this Red Atlantic Dust comes originally from South America; and it is even stated that it is carried by the south-west or upper current over Africa, and that some of this dust has even reached Germany and other parts of Europe.

It certainly is one of the most interesting phenomena of nature, throwing great light on the aërial currents, and one of which there are too many attesting witnesses to cause it to be doubted.[34] This Red Atlantic Dust has often fallen on ship’s decks, when even one thousand miles distant from the African coast, and at points upwards of 1500 miles distant from each other in a north and south direction; showing over what an immense area of the Atlantic this phenomenon may be observed.

I can easily believe that vessels have run on shore, owing to the obscurity of the atmosphere, in this part of the ocean, for I have observed that large vessels were hardly visible at the distance of a mile from this cause; and navigators must have suffered great anxiety from the difficulty of making good observations at this, our winter season, in those latitudes.

After an experience of seven years on the West Coast of Africa, I have no hesitation in stating that the feeling of a Harmattan wind is very different from that of the north-east trade in the region just referred to.

On approaching the Equator, we were informed that some more of the drinking water was damaged, that the passengers were, in consequence, placed upon an allowance of one pint of[35] water each per diem, and that we were to take charge of this allowance ourselves. The water was placed at the cabin-doors at six o’clock in the morning; and from the time we were put on short allowance of water, there was very little sleep on board of the ship after four o’clock in the morning; for every one was on the look-out, and, if one did not open the door of one’s cabin and seize the water the moment it was placed there, it disappeared immediately;—there was no redress, and no more water to be had until the next morning.

Under these circumstances the children, of course, asked for more water than before; and young Frank Indigo recommended his companions to eat ham, bacon, in fact anything salt, “because then, you know, they must give you water.”

The weather was getting warmer every hour, while we had the gratification of knowing that the liquids were decreasing rapidly; after the tenth day at sea, there was not a bottle of soda-water on board the “Ireland,” bound to Calcutta, in the hot season.

On crossing the Equator, there were great[36] inquiries for old Father Neptune, but the captain thought it was judicious to bribe him not to visit the “Ireland,” as the ceremony of shaving so many young ladies would have created quite a scene. So we found ourselves in another hemisphere without the occurrence of anything more amusing than the old trick of an aged tar exhibiting the “line” through a battered telescope; and the day was pretty well spent before the younger passengers discovered that the old wag had been inducing them to look at a thread of a spider’s web instead of the Equator. The first visit to the Ocean reveals such mysteries that the human mind is prepared to entertain great absurdities as sublime truths.

From the time of passing the Cape de Verde Islands, the younger ladies had taken considerable interest in the Southern Cross. It was really a beautiful sight, as we proceeded rapidly to the south, under the power of steam, to see some of these fair maidens, night after night, sitting on the deck, gazing in silent admiration on the glorious firmament, spangled with the starry hosts.

Some of these fair girls had not been out of[37] England before; and one, I remember well, had never seen the Ocean until she beheld it in its fury from the deck of the “Ireland,” when we made our first start from England. Those who have visited the Southern Hemisphere, and seen the emblem of Christianity standing alone in the heavens, pointing to the South Pole, may imagine the effect of this glorious panorama on the minds of these young girls.

The eye looks in vain for another constellation to rest upon; it is to the glorious revolving Cross that the Southern Hemisphere is indebted for its celestial beauty; and I have never been able to look upon it without thinking what must have been the feelings of Bartholomew Diaz, of Vasco de Gama, and their followers, who, as they bent their way to the dark pole, perceived this emblem of their faith dominant in the South:—

The ladies never appeared tired of asking questions relative to the heavens; every book treating on astronomy, which could be discovered on board the vessel, was eagerly examined; and those gentlemen who were privileged to be present at the “star meetings” found both instruction and rational amusement, while some who had only studied the heavens before in a cursory manner, or even with scientific objects, were really surprised at the practical knowledge acquired by the young ladies in a few evenings.

One of these young ladies, and she was by no means a “blue stocking,” informed us that her brother, who was a naval officer, had explained to her how both the Great Bear, in the north, and the Southern Cross, in the south, might be used for correcting the variation of the compass. When called upon one evening, with the compass before her, she very clearly pointed out how, with the Pole Star in the northern hemisphere, the variation of the needle may be ascertained within tolerable limits.

A few evenings afterwards, on coming on deck, after tea, the Southern Cross was observed standing nearly upright, but inverted; that is to say,[39] approaching its lower culmination. The same young lady held a plumb line, made of a bullet and silken thread, before her eye, until the two extreme stars of the Cross came to the meridian, nearly pointing out the true south, by which our fair navigator read off the variation of the needle very correctly.

After this, I happened to state that both the Great Bear and the Southern Cross were clocks in the heavens for the use of those inhabiting the torrid zone, and each of them served the same purpose for the inhabitants of their own hemispheres. I was immediately called upon to explain my statement, and induced to give the following account of the manner of telling the hour by the Southern Cross:—

There can be little difficulty in remembering that, at the southern winter solstice, on the 21st of June, the right ascension of the sun is six hours; at the northern autumnal equinox, on the 21st of September, twelve hours; at the southern summer solstice, on the 21st of December, eighteen hours; and at the northern vernal equinox, on the 21st of March, twenty-four hours, very nearly: consequently[40] we may say that the daily increase of the right ascension of the sun, the whole year round, is, on an average, almost four minutes.

If, therefore, I wish to know the sun’s right ascension on the 1st of July, I recollect that at the last solstice, on the 21st of June, it was six hours. From this date to the 1st of July, ten days will have elapsed, which, multiplied by the daily increase, four minutes, makes its accumulation forty minutes, which, added to the six hours of right ascension attained by the sun on the 21st of June, gives a right ascension of six hours, forty minutes, on the day proposed.

Having obtained the right ascension of the sun, I have only to subtract that from the mean right ascension of the two antarctic pointers, α and γ Crucis, which being twelve hours, nineteen minutes, may easily be remembered.

“Do I make myself understood, ladies?”

“Oh, yes!”

“On the present occasion we have to subtract six hours, forty minutes, from twelve hours, nineteen minutes: which will leave five hours, thirty-nine minutes.”

“Exactly so!”

“And that five hours, thirty-nine minutes, is P.M. time, when the Southern Cross will be upright on the meridian, on the day proposed, viz., the 1st of July.”

“Well! this is Christmas Eve; what time was the Southern Cross on the meridian?”

“At the southern solstice, on the 21st of December, the right ascension of the sun was eighteen hours; from that date to the present, three days have elapsed.”

“Yes—quite right.”

“That will make the right ascension of the sun to-day, eighteen hours, twelve minutes; but how can we subtract that from twelve hours, nineteen minutes?”

“A very correct question; you must increase the right ascension of the pointers, in this and similar cases, by twenty-four hours, making it thirty-six hours, nineteen minutes, from which subtracting the right ascension for to-day, will give eighteen hours, twelve minutes, the time of the upper culmination of the Cross, counting from yesterday at noon, as you added twenty-four[42] hours to the right ascension of the pointers; consequently the Cross was upright at twelve minutes past six o’clock this morning, and nearly twelve hours afterwards, it was at its lower culmination, when you saw our fair navigator correct the variation of the compass by it.”

In this way the Southern Cross became an object of great admiration to the ladies, and they were soon able to estimate the time from it in any position.

The passengers in general made themselves agreeable to each other, and therefore many of our discomforts were made light of. This was not the case in other vessels belonging to the W.S.L. Line, and hence the disagreeable scenes which took place on board of them.

The ladies formed themselves into singing classes, under the direction of one of the reverend gentlemen passengers. Some of the gentlemen gave us their experience as travellers. One medical man gave us a lecture on the eye, and other subjects. Another young friend favoured us with an account of his ascent of the Nile, as far as Kartun. In this manner the day was got[43] through, while in the evening, when tired of dancing, we gathered round the Captain on the poop, and there spent a pleasant hour or two in listening to some tale from him, or a song from the ladies.

The “Bill of Fare,” in consequence of the destruction of our poultry from sheer neglect, became beautifully less; and, indeed, after the first fortnight, no dish left the table with anything on it—a pretty clear proof that the table was not well supplied. About the same time puddings were discontinued, in consequence of the head steward having thrown a dish containing an uncooked pudding at the baker’s head. This placed the baker on the doctor’s list, and stopped fresh bread for the cabin. All these trials were very severe on the children, of whom there were an unusual number on board. Still we all had some delicacies for the voyage, and these were cheerfully divided among the little ones.

At last the drinking water got very bad, the pint allowed to us being really as thick as the coffee, and looking very much like a dose of rhubarb, from the immense quantity of iron rust[44] which it contained. It became so bad that it was impossible to drink without filtering it through blotting paper, an interesting occupation, which engaged the gentlemen’s attention for some hours per diem. Here was another instance of neglect, the water-tanks having been filled without being cleaned. The officers of the ship said that they had never heard of white-washing the tanks inside with lime, to keep the water pure, and that the rust was always left in the tanks to purify their contents. I thought, after this, that a man might learn something new every day.

Our usual amusements began to tire us, and the increasing discomforts made us all long for the Cape of Good Hope, for we were becoming very discontented with the vessel, and began to give our feelings expression; when one day, while at lunch, where every one looked as if a little change of scene would do him good, there was a sudden cry of “Fire!—the ship’s on fire!”

“Oh, where?—where?”

For a moment there was a scene of confusion, easier to imagine than to describe—

The Captain was at his post immediately; and it was soon discovered that the head of the main-mast was on fire.

The ship was at the time under steam, and all the sails were furled, it being a dead calm. The funnel was too close to the main-mast; and, as the vessel steamed ahead, there not being a breath of air, of course the smoke and heat from the funnel struck the main-mast and set it on fire.

The energetic exertions and cool example of the commander were not lost upon his subordinates, who ably seconded him. The chief officer greatly distinguished himself; as, indeed, did all the officers. The spars and burning rigging falling on some hay placed on the main hatchway, caused a blaze and considerable smoke, which made us imagine at one time that the ship was on fire in the main hold; but fortunately this was not the case.

The steam being up, we soon had a good supply of water from the engine-room, by means of a small auxiliary engine, called a “donkey engine,” I suppose from the fact of its making a braying noise like that much-abused animal.

Water was got aloft, and poured over the sails, many of the men, as well as the chief officer, working on the hot-iron crosstrees at the mast-head, in the thick stifling smoke from the funnel, at the risk of their lives.

For some short time there was considerable fear that the fire would master us; but by the strenuous exertions of all, and the meritorious efforts of the crew, the fiery element was subdued. The only damage suffered was the loss of two sails, which were entirely burned, and the head of the main mast seriously charred.

In the middle of the fire, one of the gentlemen passengers, who had become deranged, and was in consequence confined to his cabin, finding his keeper absent, and alarmed by the confusion in the Saloon, rushed into it, among the ladies, with only one garment on him, and a large carving-knife in his hand. I need not say that the Saloon was instantly cleared.

At this moment the position of the ladies was anything but pleasant: a fire raging on deck, from which they did not know how soon they would be called upon to escape by the boats of[47] the ship, which could not have held half the persons on board; and in the Saloon a raging maniac brandishing a large knife, by which he kept the cabin clear against all comers, and at the same time confined the ladies to their state-rooms.

As soon as the fire was got under, attention was turned to the disarming and securing of the poor maniac, when the “general” proposed getting his sword, and cutting the poor creature down; but younger heads and kinder hearts overruled this.

Some of the gentlemen promised to assist the doctor; and, having taken their stations, gradually closed on the poor sufferer; while the surgeon, conversing with his patient, and keeping him under the influence of his calm eye, approached and disarmed him. He was then easily secured, and confined in his cabin, until so much improved that, on approaching the Cape, he was allowed to roam about the decks, molesting no one. How different might have been his fate had violence been used to him during the temporary absence of reason!

Thankful, indeed, were we that the fire did not take place at night; in the consequent confusion, what accidents might not have happened? But He in whose “hands our times are” suited our trial to our means.

I observed that all were more contented with the ship after this exciting scene; but, nevertheless, we were exceedingly glad when, ten days after escaping from this great danger, we arrived in Table Bay, and anchored off Cape Town, the capital of the colony, grateful to that Merciful Providence who had led us so far safely on our journey.

W.S.L., Worst Steam Line—Table Mountain—The Table-cloth is Spread—Pic-nic to Constantia—Careless Smoking—Cape Wines—The “Ireland” Proceeds to India—Melancholy Forebodings—Midnight Alarm in Simon’s Bay—The Cape Observatory.

At noon of the last day in the month of January, 1857, the “Ireland” cast anchor in Table Bay, which was crowded with vessels of all sizes and under every flag. Even the national ensign of England, with the three talismanic letters, W.S.L., in glaring yellow, was seen flying at the mizen-peak of a steamer, recognized as the “England,” a sister ship to the “Ireland,” and belonging to the same line, well known at the Cape of Good Hope as the “worst steam line” which has yet called at[50] that great turning point in the navigation between the East and the West.

Immediately on our anchoring, some of the passengers of the “England” came on board, who informed us that they were on the way to Europe, and that, between Mauritius and the Cape, they had fallen in with the tail-end of a hurricane, which had placed them in considerable danger, but that, having repaired damages, they were going to start for England in a few hours’ time. Many of our passengers seized the opportunity to convey to their friends the intelligence of their safe arrival as far as the Cape of Good Hope.

Of course there was a comparison of “notes” as to the state of these two vessels, and we found that we were not worse off than the passengers on board our sister ship. We afterwards learned, from persons residing at the Cape, who had come in the “England” on her outward voyage, that previous to their arrival at Cape Town, they ran entirely out of drinking water, and that, on their making the harbour, they had to telegraph to the signal staff to send them water, by which means a water-tank was sent to them before their[51] arrival. They had a large number of soldiers on board on that occasion, and it was stated that the military officers had to take matters in their own hands as far as the discipline of the stewards was concerned.

Fortunately, these two vessels were commanded by gentlemanly, considerate officers, and their tact and temper kept the discontent within reasonable bounds. With another vessel, belonging to the same line, matters took a different course, and on her arrival at the Cape of Good Hope the passengers were obliged to bind the commander to keep the peace towards them for the remainder of the voyage. The commander of the “Ireland” used his best endeavours to make the passage from England in thirty-five days; but we were forty-three days on the voyage, and would have been longer had we not been favoured by slants of wind, which, under ordinary circumstances, we could not have expected on the route adopted. The real fact was that the vessels were not fitted with sufficiently powerful machinery, and the space which ought to have been devoted to fuel was appropriated for cargo.

On arriving at Table Bay, our attention was drawn to a beautiful phenomenon of nature, by which Cape Town is supplied with water, and of which the following is a brief description:—

Table Mountain, under which Cape Town is built, is the terminus of a ridge of high land which covers a considerable portion of the promontory of the Cape of Good Hope. The side of this mountain, facing the north-west, and immediately behind the town, is perpendicular, and about 4000 feet in height. From the basin of Table Bay, during that portion of the twenty-four hours in which the air is warmer than the water, there is a considerable evaporation, which saturates the warm air overhanging the basin. The air, saturated with this moisture, rising to the edge of the cliff or summit of Table Mountain, meets with a cold polar current of air in the form of the prevalent south-east wind, by which it is immediately condensed into a cloud, and then precipitated on the ridge in the shape of dew or rain, according to the relative difference of temperature of the two currents of air. Thence, falling down the face or perpendicular side of the mountain,[53] this deposit of dew or rain forms a stream of cool sparkling water, which affords an abundant supply to the 30,000 inhabitants of Cape Town, and the numerous ships that make this their port of call. From the harbour this white cloud appears as if ever pouring over the edge of the ridge, and never able to attain its object, the foot of the mountain. When dense, so as to entirely cover the top of Table Mountain, it is the precursor of a storm; so that, when bad weather is expected, it is usual to say that “the table-cloth is spread.”

While engaged in looking at this beautiful phenomenon of nature, the increasing size of the table-cloth on the mountain warned us of the coming storm, and hastened us in our efforts to reach the shore. As there were a number of ladies and children on board the vessel having no gentlemen to assist them, and all anxious to reach the shore, after a passage during which they had suffered considerable privations, my wife made an offer of my services to provide accommodation for them at Cape Town, and render them any little assistance during their short stay in harbour. Accordingly our party was soon formed; a large[54] shore-boat was provided, and we found ourselves on shore at Cape Town, and assembled at the custom-house, where the ladies had to remain until accommodation was provided for them. In consequence of there being so many vessels in harbour, the hotels, which are remarkably good, were full. After some little difficulty, always to be encountered in a strange town where one does not know one street from another, we succeeded in discovering two houses in which our large party could be accommodated as boarders, and where we were rendered very comfortable during our stay. The following day was devoted to viewing the town, already so often described, when the younger ladies discovered that they had left England without “quite a number” of little trifles which afforded them an opportunity of parting with their pin-money, and at the same time drawing a comparison of the value of “trifles” in England and in her Colonies. In the evening we had a visit from the young gentlemen passengers, when we were asked to join a pic-nic, to see one of the wine-producing estates. Preliminaries were soon arranged, and on the next morning a private[55] omnibus (if I may use such an expression), with four beautiful horses, made its appearance at the door of our boarding-house. The hour was early, five in the morning, and this was supposed to afford an excuse for sundry performances on a key bugle, which hastened our departure, and considerably disturbed the neighbourhood. Adding our contribution to the already large supplies of edibles on the omnibus, and with the ladies comfortably seated inside, and the gentlemen on the outside, away we started for Constantia, the well-known estate of the hospitable family of the Vanreenans.

The gale, which had been blowing since our arrival, was at an end; the rain which had fallen had laid the red dust on the roads, which is the subject of great annoyance to the residents. The morning was cool, the air bracing and exhilarating to the spirits. Nature appeared to have put on her most smiling aspect to welcome us to this portion of her domain. And, in short, it was one of those charming mornings, so prevalent at the Cape, when the better nature of man will rise with the song of the birds in gratitude to the Divine Maker of all.

So sudden and so great a change from the confinement and discomfort of a vessel had a corresponding effect on us all; and, as the fleet horses dashed along, we fully enjoyed the scenes of quiet beauty, and the picturesque views which the road to Constantia revealed to us in that sunny morning.

There was not a disagreeable person in the party; all the agreeables had been gathered together, and the contrary natures had been excluded. The jest and quick repartee followed each other in rapid succession; all were smiles, and sorrow and sadness appeared to have lost their existence for that day.

Strange that we had been so long together, and had not until that morning learned the better part of each other’s nature. How many surprises there were that day! Some learned that they were related by family ties, others that they were close neighbours in “the Old Country,” and all that from that day forth they felt interested in each other’s career.

Arrived at Constantia, we found the whole of those persons engaged on the estate in great commotion,[57] for here, in this lovely spot, the frightful element “Fire,” from which we had so lately escaped, had been doing considerable destruction; and, although the fire had been overcome, it was not known how soon it might break out again.

It appeared that the fire originated from one of the natives employed on the estate having carelessly thrown away the ashes of his pipe; these smouldered for a time, and the vegetation at that season being dry, when once inflamed, soon created an alarming conflagration, which rapidly assumed gigantic proportions, threatening to destroy all the surrounding estates. Fortunately the heavy rain of the previous night had somewhat arrested the progress of the fire, but, as the sun rose and the vegetation dried, it required constant vigilance to prevent the fire breaking out again.

In this state of things, of course our happy party could not think of intruding on these good people in their distress. But being politely offered the use of the grounds, we outspanned our horses, procured water, milk, and eggs, and, having[58] some good housewives among the party, we enjoyed a most comfortable breakfast of our own providing.

The day was spent in rambling over the country, and making ourselves somewhat acquainted with the wine-growing of the colony. We were informed that the vine, from the grapes of which the delicious Constantia wine is produced, will only grow upon this estate, from which it derives its name, and only on certain portions of it where the soil is said to be of a quality peculiar to a few localities of this district.

The grape with which the wine is coloured is grown in a part of the estate set aside for that purpose, and appeared to us dryer and more stony than other localities.

The Cape, or South African, wines have been received with considerable favour in the English market, and are recommended in all our hospitals for their purity and absence of spirit.

The export of wine from the Cape has increased from 106,067 gallons, in 1854, to 797,092 gallons, in 1857; and during that period, in consequence[59] of the failure of the grape in Europe, the price of the wine has increased three-fold;—a cask of Cape wine, which could be purchased formerly in England for eighteen pounds, now fetching fifty-four pounds sterling.

At the present moment, I am inclined to think that the merchants give too high a price to the producers to enable us to benefit to the extent that we should in England from the large supplies of wine which we may obtain from the Cape. But now that roads through newly-discovered mountain passes are opening up new districts suitable for the production of wine, such as the Oudts horn, and many others, the increased supply will naturally decrease its cost in the market.

There is an earthy taste in the South African wines, which greatly reduces their value; as this is not inherent to the grape, but simply the effect of the red dust of the district with which the grapes are covered, more attention in the manufacture of the wines will obviate this objection, and place them in that position in the markets of Europe to which their intrinsic merit entitle them.

After passing a most agreeable day, we returned[60] to Cape Town, as the shades of evening were closing in, and night was about to spread her mantle over the forest of masts floating in Table Bay.

In two days afterwards the “Ireland” was away on her course to India, bearing with her those who were to take part in the great Indian drama. The merry-hearted whip, who handled the ribbons so gracefully; the mother, with her loving children; the maidens, with their mirthful laughter; the soldier, with his gallant bearing; the beardless boys, panting for glory and this world’s renown, who joined us on that festive day at Constantia—where are they?

Foremost amongst the stormers of Lucknow the soldiers fell; the merry-hearted whip died, homeward bound, from the effects of his fearful wounds; the mother, after watching over her babes through dangers worse than death, arrived in safety at Calcutta, then drooped and died. The maidens—one, the loveliest of them all, was seized with cholera on her arrival in India; her beauty vanished and her spirit fled—some are wedded, while others perished—ask not how.

On landing at Cape Town, I had made inquiries[61] for the Naval Commander-in-chief, and was informed that Commodore Trotter was up the Mozambique Channel. In the absence of the chief, I applied to the officer in charge of the naval station, when I found that, although orders had been sent out to the Cape, at the request of the Foreign Office, to forward me to my Post in one of Her Majesty’s ships, no definite steps had been taken for that purpose.

When the Admiralty orders for the conveyance of Her Majesty’s Consul for Mozambique to his Post, in a ship of war, reached Simon’s Town, it appears there was, at that time, the miserable remains of a vessel lying in the harbour, which, in former times, did duty as a tender to the ship of the senior officer, but, owing to her being unseaworthy, she had been condemned. As the orders were imperative, it was supposed that an officer of some standing, commanding a large steamer, would have to convey me to Mozambique; as the steamer in question, from her great expenditure of coals, was worse than useless on the Cape station, to which all the coals used have to be carried from England at a great[62] expense. This steamer was a remarkably good sailor, and might have been usefully employed under canvas, in the Mozambique Channel, instead of lying, month after month, at Simon’s Bay doing nothing.

The Mozambique Channel is looked upon as one of the most unhealthy stations in the world; and, therefore, it is but natural that a naval officer, who has arrived at a position on the Navy List, where he knows that seniority will alone advance him, should hesitate to go to a part of the world where he is likely to make a vacancy. On the return of the Commodore, the destination of the large steamer was pretty well indicated, and, therefore, it was suggested that the old condemned schooner “Dart” should be fitted out to take the Consul to Mozambique, and, by her imposing appearance in that port, awe the slave-dealers of Eastern Africa.

Accordingly, a lieutenant and a party of men were ordered on board the “Dart;” her old sails were bent, and with the assistance of some coils of rope, a few buckets of tar, two or three pounds of putty, and the expenditure of a pot or two[63] of black paint, all supplied by order from Her Majesty’s Dockyard at Simon’s Town, the “Dart” began to look quite smart. The loftier spars were put in their places, the lighter yards thrown across, the masts nicely stayed, the yards squared, ropes hauled taut—long, low, and rakish; with a blue ensign abaft, and a long blue pennant at the mast head, she looked “quite the thing.”

Many smiled at the “Consul’s Yacht” (as I was told they called the “old Dart done up”); some shook their heads, and ventured to doubt if the Consul would ever reach his Post in her, and all were on the look out for the arrival of the “Ireland,” when suddenly, one night, there was heard, over the harbour of Simon’s Town, a cry of distress proceeding from the “old Dart done up.” “Help! help! for heaven’s sake, the Consul’s Yacht is sinking.” Immediately, the boatswain’s mate’s whistles were heard on board of all the men-of-war in the harbour. “Away there, boat’s crews—away, there, away!” “Hurry up, lads; that d—d thing of paint and putty is going down at her anchors!!”

By the exertions of those on board, pumping and baling with buckets, the “old Dart” was kept afloat until the men-of-war’s boat towed her into shallow water, when she was again dismantled, being pronounced not even fit for a “Consul’s Yacht.”

This, I found, was the only step that had been taken towards forwarding me to my Post, where the slave-trade, in its most revolting form, was carried on without a hope of being checked, but by my intervention as the British Consul.

As a large amount of specie was expected from England, which would have to be carried by one of Her Majesty’s ships from Simon’s Bay to Algoa Bay, the large steamer was compelled to remain for this important service, and Her Majesty’s Consul for Mozambique was detained at the Cape of Good Hope for more than five months, the greater portion of which time three steam-ships of war were lying in Simon’s, or Table, or Algoa Bay. To those who may not be initiated in the subject of the carriage of specie, I ought to explain that the Captains of Her Majesty’s ships receive a certain per centage[65] on all specie carried by the vessel which they command; while, for carrying Consuls, and other public servants, they receive only a fairly remunerative amount of table-money to compensate them for any expense they may have been put to in entertaining their guest.

When head money for pirates was found to be a premium for murder, it was very properly abolished. Similarly, let us hope that freight-money for the carriage of gold and silver will no longer be an inducement to the neglect of the public service.

As the movements of the squadron at the Cape were wrapt in the most sublime mystery, it was quite impossible to anticipate the distant period when one of Her Majesty’s ships could be placed at my disposal.

Under these circumstances, finding that my future movements were in nubibus, I resolved to take time by the forelock. Having made the acquaintance of Mr. Thomas Maclear, F.R.S., the Astronomer Royal for the Cape of Good Hope, and, through the courtesy of the Honorable Mr. Field, Collector of the Customs,[66] being allowed to take my scientific instruments out of the Custom House, I had my magnetic instruments conveyed to the Royal Observatory, where Mr. Maclear, with that generous aid which he is always ready to afford in the cause of science, had a room placed at my disposal. Lodgings were procured near the Observatory, and many agreeable hours were passed by my wife and myself in the society of Mr. and Mrs. Maclear, and their amiable and highly intelligent family, whose unvarying kindness and attention to us, while resident at the Cape, will never be forgotten.

Table Bay—Breakwater to be Built—Harbour of Refuge—Policy of Sir George Grey—Proposal for Carrying the Mail to the Cape by way of Aden—Discovery of Coal on the Zambesi—Its Effects on the Future of South and East Africa—Absence of Trees at Cape Town—Climate of the Cape.

Since the Portuguese voyagers, Bartholomew Diaz and Vasco de Gama, rounded the Cape of Good Hope, and opened to the commerce of Europe, by way of the Southern Ocean, the rich and still undeveloped countries of the East, what magnificent ships of war, and fleets of merchantmen—chartered with the good, the fair, and the brave—have sailed past that Cape of Tempests, finding, in the midst of that stormy sea, no haven of rest from the gale, no harbour of refuge from the hurricane!

During the four hundred years which have passed since the gorgeous panorama of the East was made known to Europe by the immortal actors in the Portuguese Era of Conquest, what numbers of human beings have perished, what untold riches have been engulphed around that stormy headland!

On the great ocean route from Europe to India, if we except Port Louis, in the Island of Mauritius, there is not one harbour containing dry docks, and the necessary accommodation for repairing in security the hulls of the immense merchant fleets, of sailing and steam-ships, which are for ever ploughing the watery waste which lies between the East and the West. That such a great necessity should so long have existed, at such an important turning point of navigation as that of the Cape of Good Hope, can only be accounted for by the great natural difficulties to be overcome in the formation of a harbour of refuge having the necessary capabilities to supply the wants of the large amount of shipping passing the Cape.

Lying in a great line of commerce and navigation,[69] and, from the recent rapid development of internal communication by the construction of roads, which will be immediately followed by railroads, already commenced, it requires only a judicious expenditure of money, rendering Table Bay a safe, accessible, and quiet harbour, to make Cape Town a port of great wealth, an emporium for the East and the West, and the outlet for the rich and varied productions of Southern Africa. From time to time projects have been set on foot for this purpose, but it has been reserved for the era of Colonial Self-Government to introduce a plan, magnificent in conception, practicable in details, and incalculable in results, for the purpose of rendering Table Bay a safe harbour at all times and seasons.

The principal wants which will be supplied by this great undertaking are:—

1st. A harbour easy of access, and safe at all times and seasons for the commerce between the East and the West.

2nd. A refuge for vessels repairing and refitting; and—

3rd. A naval station for the purpose of protecting[70] the navigation to India, China, and Australia in time of war.