![[The image of the bookcover is unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: California illustrated

including a description of the Panama and Nicaragua routes

Author: J. M. Letts

Release date: November 12, 2024 [eBook #74730]

Language: English

Original publication: NYC: William Holdredge, Publisher, 1852

Credits: Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

INCLUDING

A DESCRIPTION

OF THE

PANAMA AND NICARAGUA ROUTES.

BY

A RETURNED CALIFORNIAN.

New York:

WILLIAM HOLDREDGE, PUBLISHER,

NO. 140 FULTON STREET.

1852.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1852,

BY J. M. LETTS,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court for the Southern District of New York.

E. O. JENKINS, PRINTER AND STEREOTYPER,

No. 114 Nassau Street, New York.

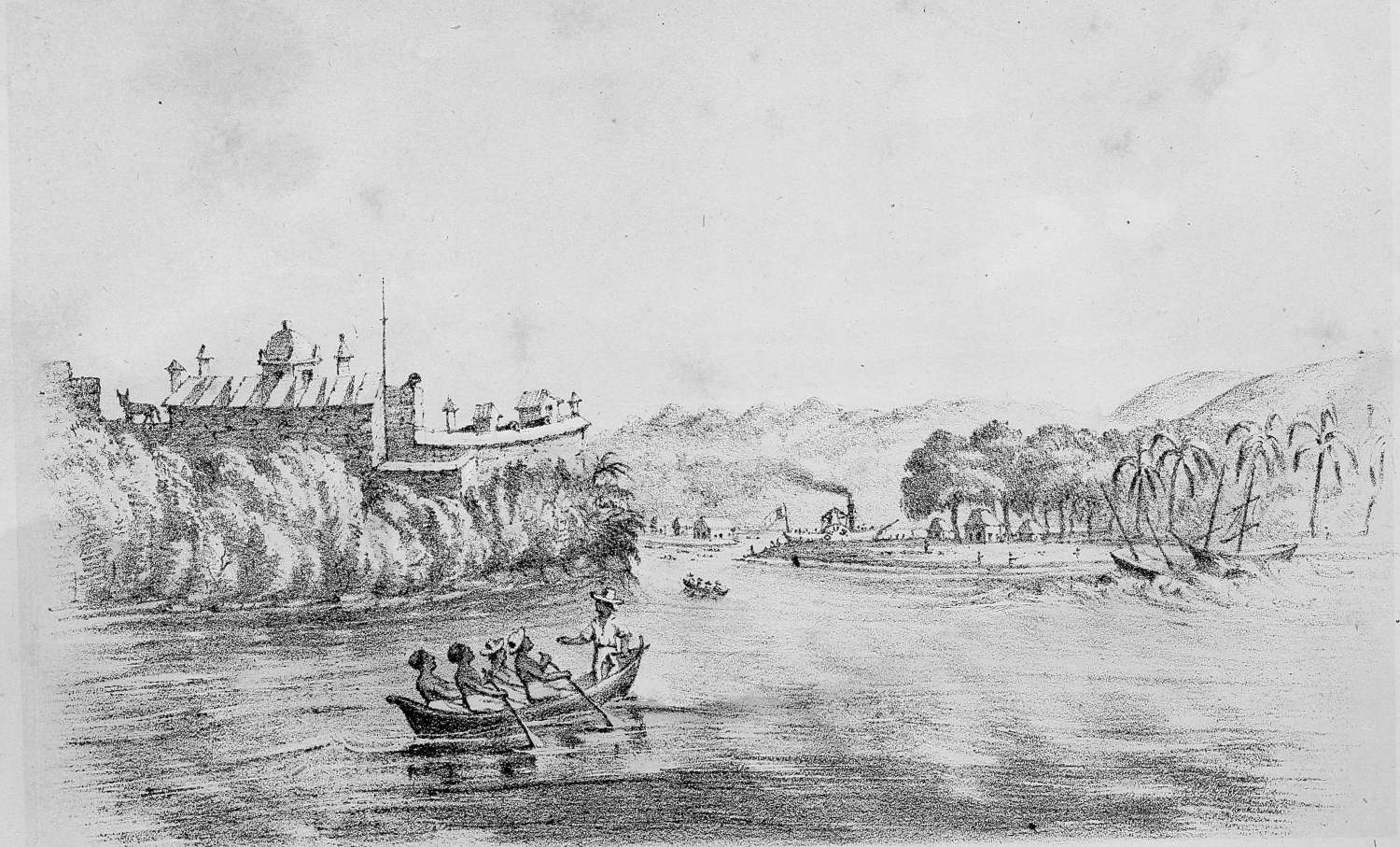

TO

OF

Wood Lawn, Staten Island,

THIS JOURNAL

IS

Most Respectfully Dedicated,

BY

THE AUTHOR.

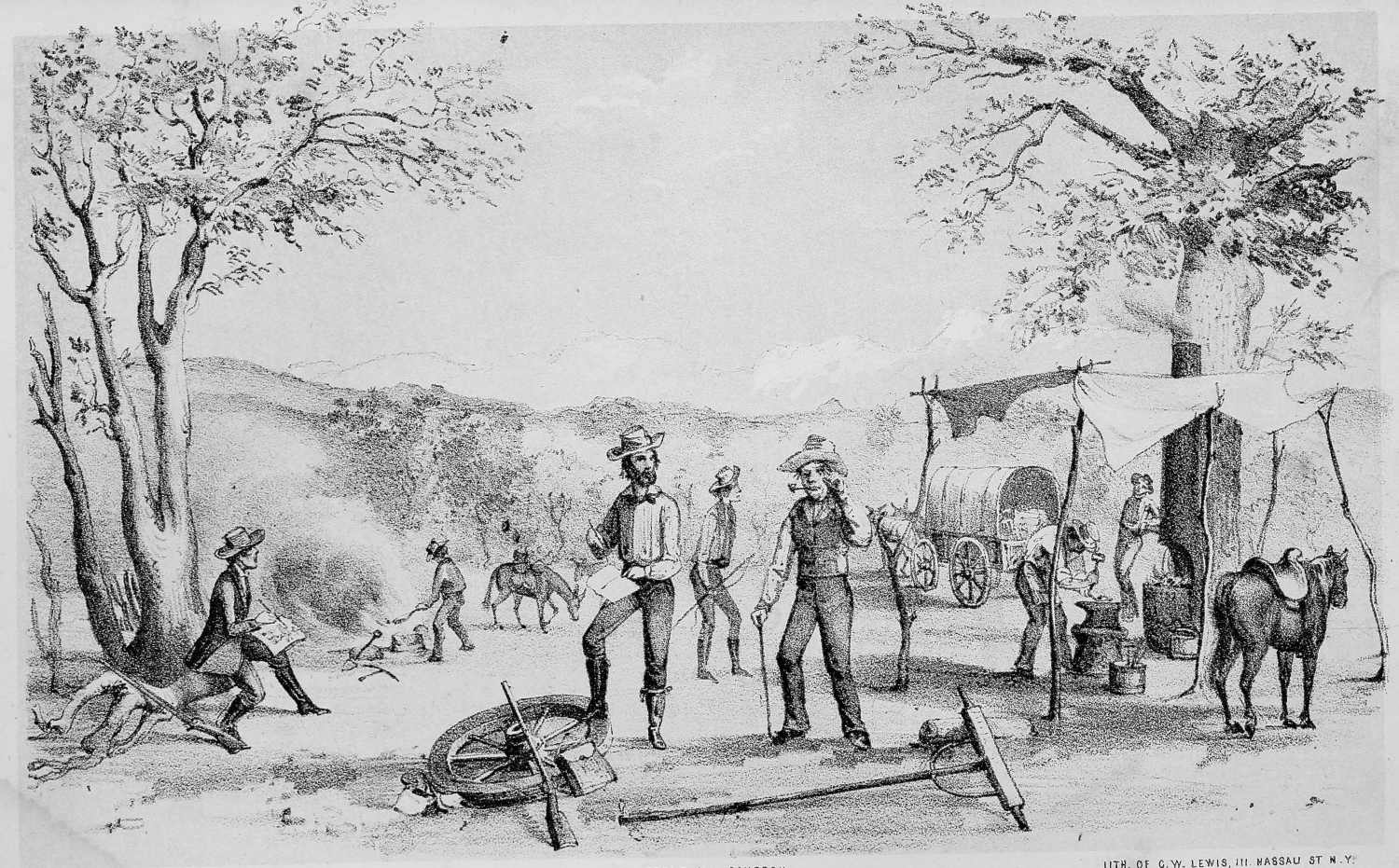

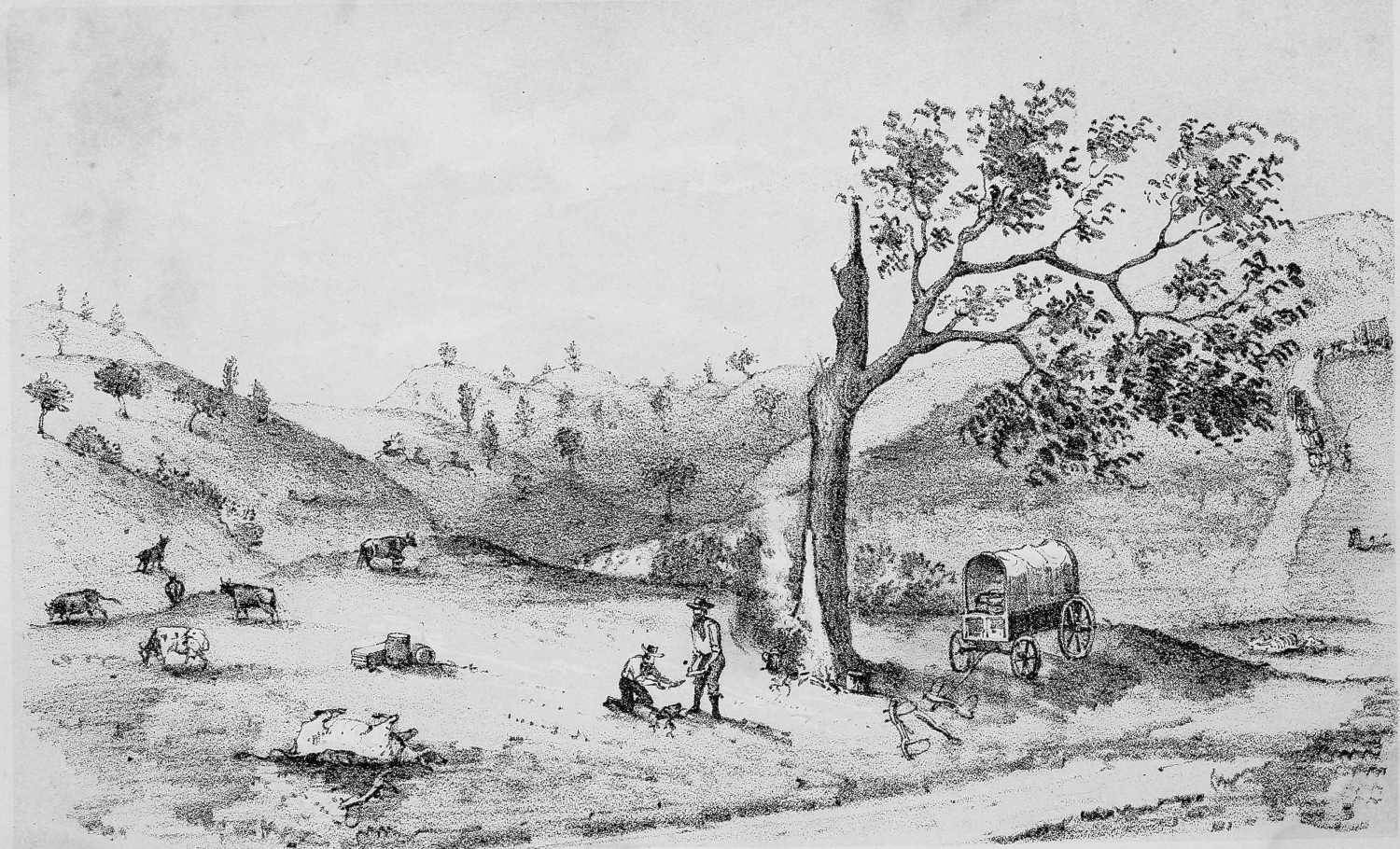

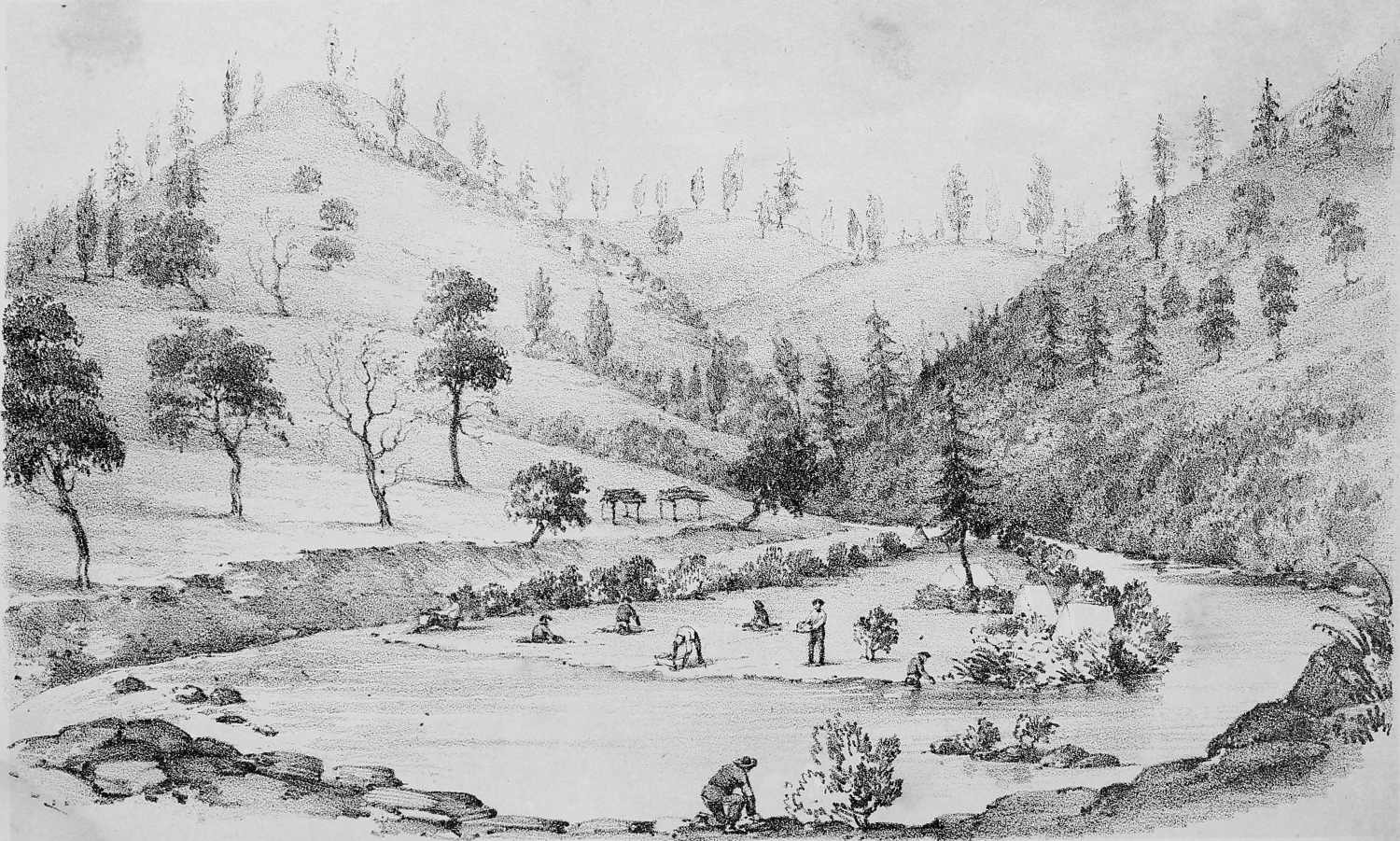

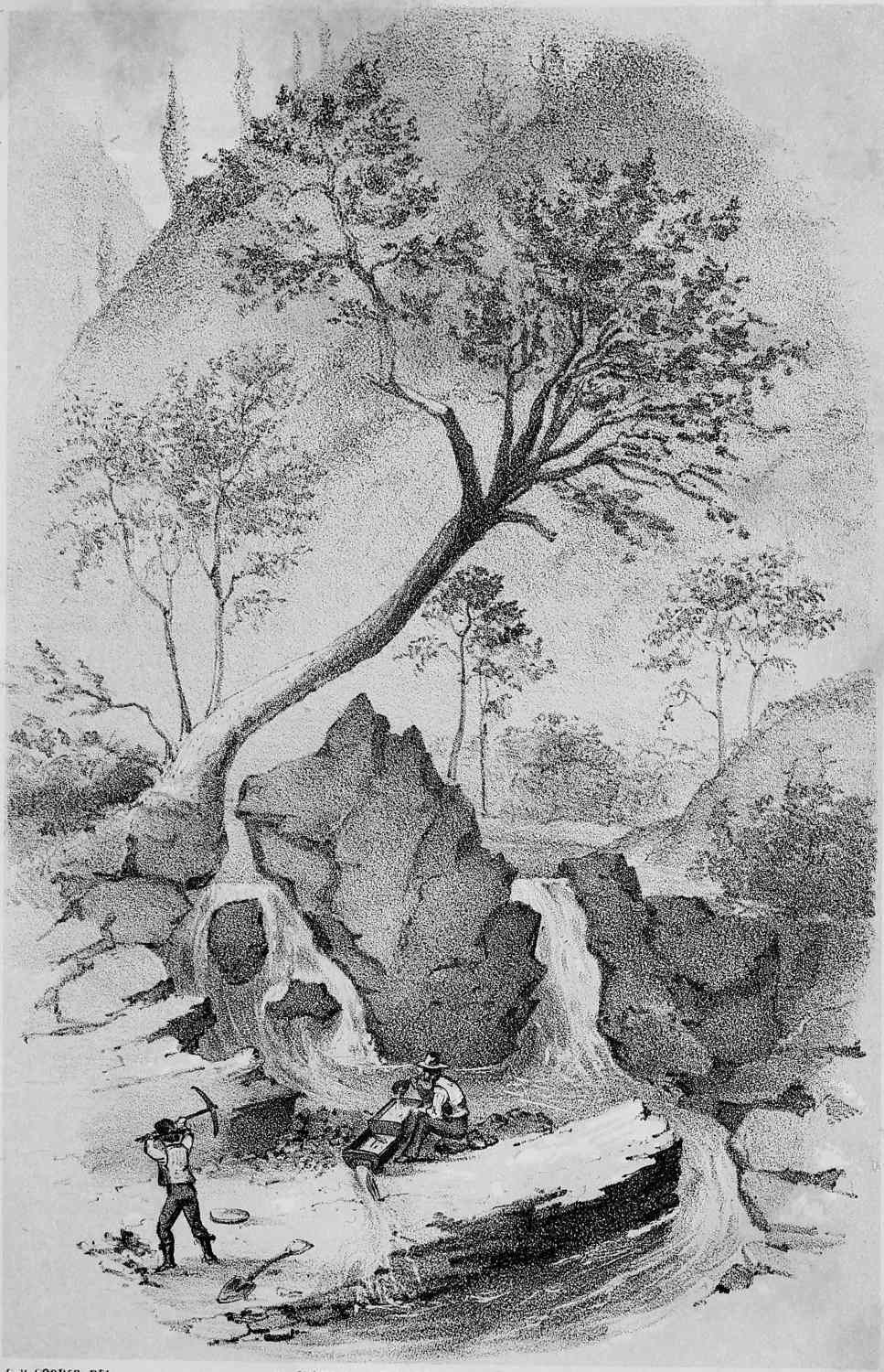

I have, in these pages, endeavored to convey a correct impression, I have stated such facts only as I knew to be facts, and interspersed them with incidents that fell under my own observation. A season’s residence in the mineral regions enabled me to obtain a correct interior view of life in California. The illustrations are truthful, and can be relied upon as faithfully portraying the scenes they are designed to represent. They were drawn upon the spot, and in order to preserve characteristics, even the attitudes of the individuals represented are truthfully given. The first part of this volume is written in a concise manner, with a view to brevity, as the reader is presumed to be anxious to make the shortest possible passage to the Eldorada.

THE AUTHOR.

| Page | |

| CHAPTER FIRST.—Sail from New York—Our Pilot leaves us—Land recedes from View—Sea-Sickness—A Whale—Enter the Gulf Stream—Encounter a Gale—Enter the Tropic of Cancer—“Land, ho!”—Caycos and Turk’s Islands—St. Domingo—Cuba—Enter the Caribbean Sea—Sporting—Sunday—Standing in for the Port of Chagres—Beautiful Scene—Drop Anchor, | 9 |

| CHAPTER SECOND.—Natives and “Bungoes”—Crescent City arrives—We sail into the mouth of the River—Prepare for a Fight—Fashions and Fortifications—An honest Alcalde—Non-fulfillment of Contracts, | 13 |

| CHAPTER THIRD.—First Attempt at Boat building—Excitement on “’Change”—A Launch and Clearance—The Crew—A Mutiny—Quelled—Poor Accommodations—A Night in Anger—An Anthem to the Sun—Nature in Full Dress, | 16 |

| CHAPTER FOURTH.—Breakfast—Primitive Mode of Life—Meet the Orus—Mutiny and Rain—A Step backward—Encampment—A fortified and frightened Individual—Sporting—Mosquitos, | 20 |

| CHAPTER FIFTH.—First Rapid—An Unfortunate Individual—A Step Backward—Several Individuals in a State of Excitement—Tin Pans not exactly the thing—A Breakfast Extinguished—Sporting—Monkey Amusements—A Flash in the Pan—Two Feet in our Provision Basket—Poverty of the Inhabitants and their Dogs—Arrival at Gorgona, | 23 |

| CHAPTER SIXTH.—Customs and Dress of the Nobility—A Suspicious Individual—Journey to Panama—A Night Procession—A wealthy Lady in “Bloomer”—An Agreeable Night Surprise—“Hush” on Horseback—Captain Tyler shot—A Mountain Pass at Night—Thunder Storm in the Tropics, | 27 |

| CHAPTER SEVENTH.—Panama—Cathedral and Convents—Religious Ceremonies—Amalgamation—Fandango, | 33 |

| CHAPTER EIGHTH.—Bay of Panama—Islands—Soldiers—Arrival of $1,000,000 in Gold and Silver—A Conducta—“Bungoes” “up” for California—Wall Street Represented—Sail for San Francisco—Chimborazo—Cross the Equator—A Calm—A Death at Sea, | 37 |

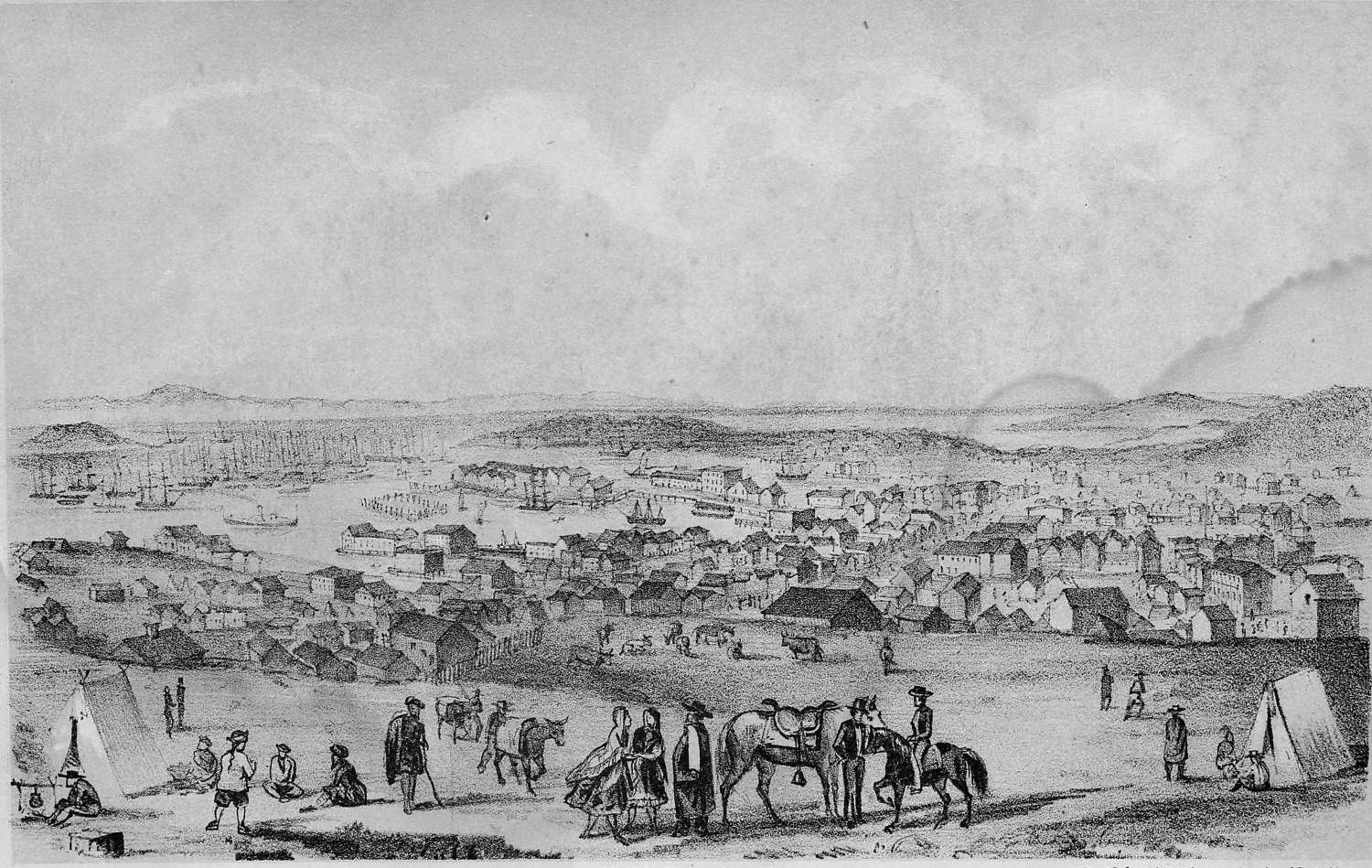

| CHAPTER NINTH.—Stand in for San Francisco—Indications of Land—The Coast—Enter the “Golden Gate”—Inner Bay—San Francisco—Lumps of Gold—Notes of Enterprise—Surrounding Scene—Gambling, | 44 |

| CHAPTER TENTH.—The “Hounds”—Villainy—Indignation Meeting—Vigilance Committee, | 51 |

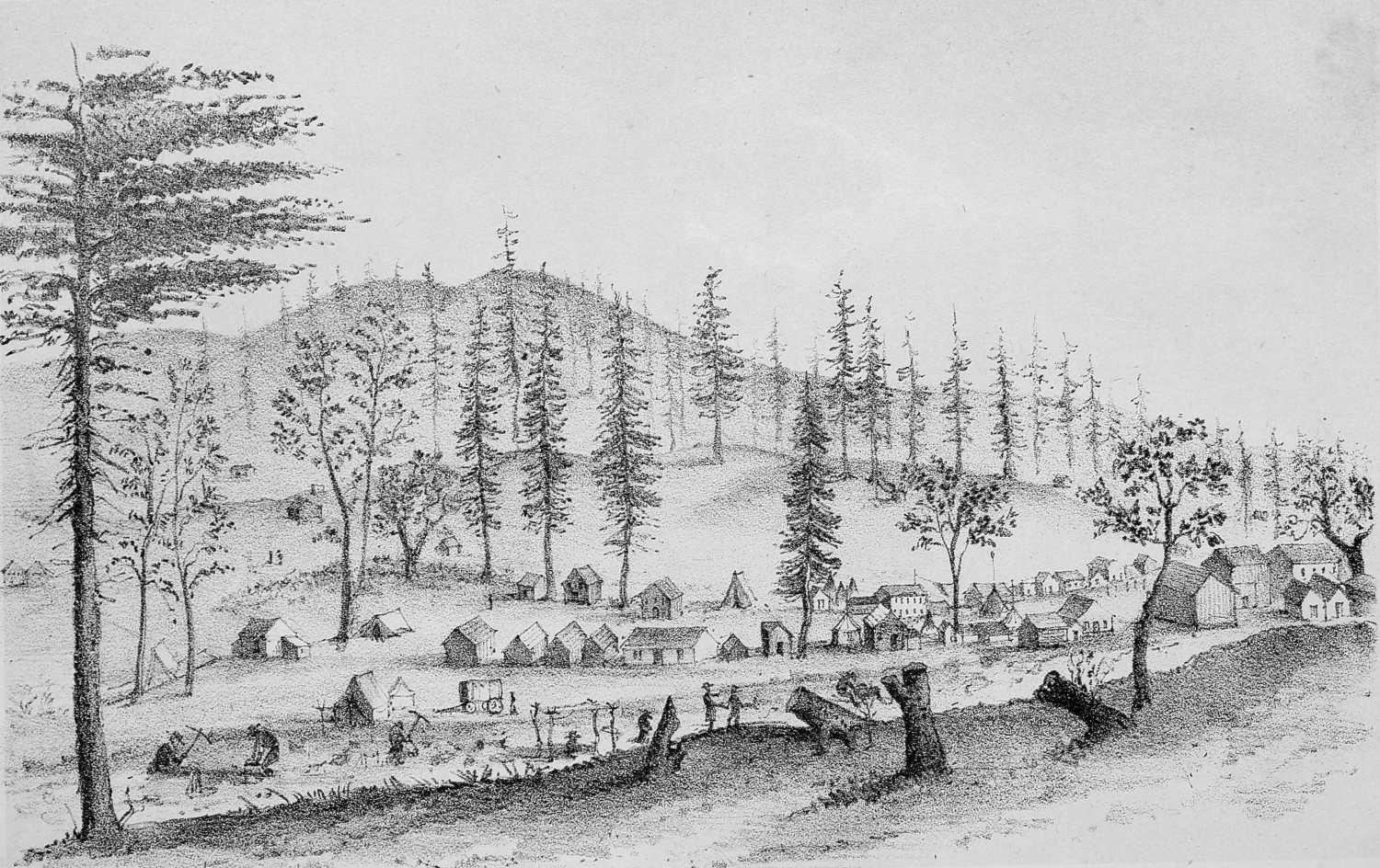

| CHAPTER ELEVENTH.—Start for the Mineral Regions—Banks of the Sacramento River—Shot at—Gold versus Mica—Sutterville—Primitive Mode of Life—Sacramento City—An Individual who had “seen the Elephant,” | 56 |

| CHAPTER TWELFTH.—Sutter’s Fort—A Herd of Cattle—“Lassoing”—Rio de los Americanos—A Disappointed Hunter—A Californian Serenade—A Mule and his Rider—Parting Company—Thirst—Serenades supported by Direct Taxation—Sierra Nevada, | 63 |

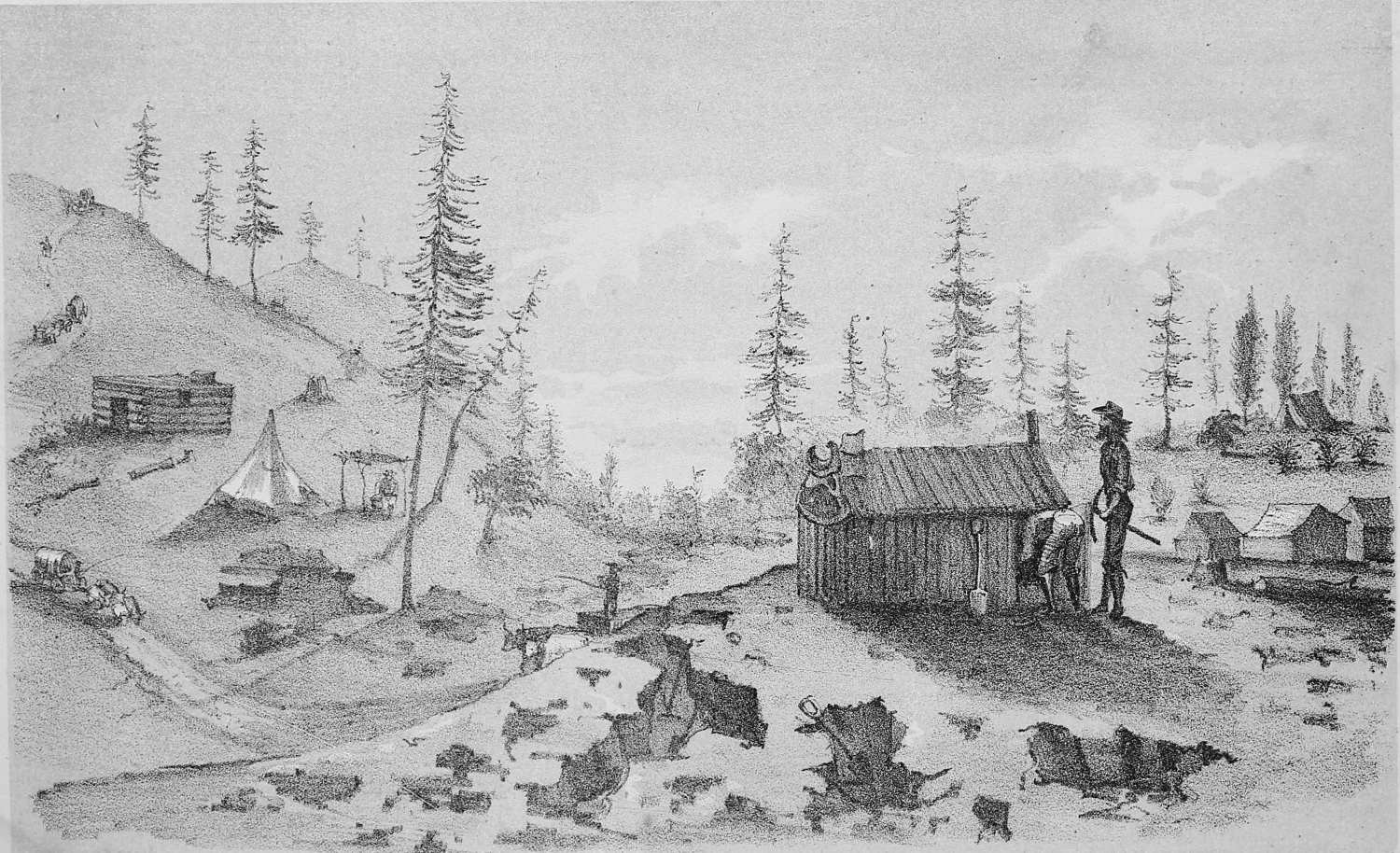

| CHAPTER THIRTEENTH.—Venison—First View of the Gold Regions—Surrounding Scenery—“Mormon Bar”—A Pocket—My Machine in Motion—Certainty of Success—First Dinner—“Prospecting”—A Good “Lead”—Disappointed Miners—A New Companion—A Higher Point on the River—Volcanoes—Snowy Mountain—Auburn—Lonely Encampment, | 70 |

| CHAPTER FOURTEENTH.—A Sea Captain as Cook—A Herd of Deer—Return to Mormon Bar—Keeping House—Our Machine in Motion—$1,500 in One Hour—An Elopement—Wash Day—Sporting—Prospecting—Discovery of Gold—Excitement—Fatigue—The Cakes “hurried up”—Incentives to Exertion—Canalling a Bar, | 80 |

| CHAPTER FIFTEENTH.—Start for Sacramento City—The “Niagara Co.”—Frederick Jerome—A Love Chase—Heroine under a Blanket—Suspicious Boots—Part of a Lady’s Hat found—A Ball—Arrival at Sacramento City—Poor Accommodations—Return to the Interior—A Chase—A New York Merchant—Beals’ Bar—Embark in Trade—A Mountaineer—Indian {vi}Characteristics, | 87 |

| CHAPTER SIXTEENTH.—The Mormons—The attempted Murder of Gov. Boggs—Canalling Mormon Bar—False Theories in reference to Gold Deposits—Influence of Amasa Lyman, “the Prophet”—Exciting Scene—Jim returns—A Monte Bank “Tapped”—Jim’s Advent at Sacramento City, | 95 |

| CHAPTER SEVENTEENTH.—False Reports and their Influences—Daily Average—Abundance of Gold—Original Deposit—“Coyotaing”—Sailors—Their Success and Noble Characteristics—Theatrical Tendencies—Jack in the After-Piece—Miners on a “Spree”—The Wrong Tent, | 101 |

| CHAPTER EIGHTEENTH.—Arrivals—Preparation for the Rainy Season—New Discoveries—Coloma—Gamblers versus Bayonets—“Hangtown”—Public Executions—Fashionable Entertainments—Wild Cattle—Dangerous Sporting—Murdered Indians—The Wrongs they suffer, | 107 |

| CHAPTER NINETEENTH.—Canalling operations—Unsuccessful Experiments—Coffee-Mills and Gold Washers—Formation of Bars—Gold removed from the Mountains during the Rainy Season—Snow on the Mountains, and its Dissolution—Rise and Fall of the River—Stock Speculations—Quicksilver Machines—Separation of Gold and Quicksilver—Individual Enterprise—Incentives to Exertion—Expenses, | 113 |

| CHAPTER TWENTIETH.—Commotion in the Political Elements—California a State—Slavery Prohibited—Political Campaign, and the Rainy Season—Speech of a Would-be-Governor—Enthusiasm and Brandy—Election Districts—Ballot-Boxes and Umbrellas—Miners in a Transition State—Preparations for the Rainy Season—Primitive Habitations—Trade Improving—Advent of the Rainy Season—Its Terrific Effects—Rapid Rise of the River—Machines destroyed—Arrivals—My Store and Bed—A Business Suit—Distressing Groans—The Bottle a Consolation—Several Strange Specimens of Humanity cooking Breakfast—The Scurvy—A Death, | 118 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-FIRST.—Dangerous Navigation—A Trip over the Falls—A Night from Home—Sailor Hospitality—Scarcity of Provisions—A Hazardous Alternative—A Wayward Boy—Preparations for leaving the Interior—Distribution of Effects—Our Traveling Suit—Start for San Francisco—Farewell—Three Individuals under a Full Head of Steam—Arrival at the “Half-Way Tent”—Poor Accommodations—A Morning Walk and Poor Breakfast—Wading Lagoons—Wild Geese—Arrival at the American River—Our Toilet, and entry into Sacramento City, | 123 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-SECOND.—A Dry Suit—Restaurants—Waiters and Champagne-Two Individuals “Tight”—A $10 Dinner—Monte Banks and Mud—Gambling and its Results—Growth of Sacramento City—Unparalleled Prosperity—A Revulsion and its Cause—The Flood, | 130 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-THIRD.—Sail for San Francisco—A Fleet—Mud—Prosperity—Ships and Storehouses—Buoyant Seas—Shoals in Business—Revulsion and Fire—Their Consequences—Sail for Santa Barbara—The Town—Dexterous Feat by a Grizzly Bear—Fashions—Sail for St. Lucas—Porpoises and Sea Fowls—Their Sports—Approach the town—Peculiar Sky—Caverns in the Sea—Cactus—Beautiful Sea Shells—Sail for Acapulco—Magnificent Scenery—Volcanos and Cascades—Volcanos at Night—Eternal Snow, | 134 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-FOURTH.—Acapulco—The Tree of Love—Bathing and Females—A Californian in a Tight Place—Earthquakes—Sail for Realejo—Volcano Viejo—Its Devastating Eruption—Realejo and Harbor—A Cart and its Passengers—A Wall-street Financier fleeced—Chinandega—Its beautiful Arbors—Bathing—Preparing Tortillos—Leon—Its magnificence and desolation—Don Pedro Vaca and Family, | 142 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-FIFTH.—A Problem in Mathematics worked out with a Cane—Pueblo Nueva—Cultivating the Acquaintance of a Horse—Looking for the Rider—An “Old Salt” stuck in the Mud—Uncomfortable Night’s Rest—Nagarotes—Lake Leon and the surrounding Volcanos—Matares—Delightful Country—Managua—Don Jose Maria Rivas—Nindaree—Ruins of a Volcano—A Long Individual in Spurs—A Dilemma—One of my Horse’s Legs in motion—A Boy in a Musical Mood—Entry into Massaya—Bloomerism, | 151 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-SIXTH.—Massaya—The Carnival—Female Labors—Gourds—Maidens consigned to a Volcano—A Donkey “non est”—Ox versus Donkey—Same Medicine prescribed—Lake Nicaragua—Grenada—A “Priest” in a Convent—“Our” Horse—A Group of Islands—Cross the Lake—Mr. Derbyshire’s Plantation—Breakfast—Bullocks stepping on Board—Sail for San Carlos—Magnificent Scene—A Hymn of Thanks—A Mountain City—Gold Mines—Arrival at San Carlos—Custom House Regulations repudiated, | 157 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVENTH.—Passage down the San Juan River—Castilian Rapids—The “Director”—Arrival at San Juan—Boarded by a Posse of Negroes—British Protectorate—Philanthropy of Great Britain—Her Magnanimous and Disinterested Conduct towards the Nations of the Earth—Nicaragua graciously remembered—A Hunt for a Sovereign—A Full-Grown King Discovered—His Diplomacy—Invincibility—Amusements and Coronation—His First Pair of Pantaloons—Hail “King of the Mosquito Coast”!!!—All hail, Jamaca I.!!!—“Hear! hear!!!” | 163 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHTH.—Sail for Home—Pass the “Golden Gate”—Sad Condition {vii}of the Passengers—Graves at the Base of the Snowy Mountains—Land Recedes—Luxuries on Board—A Death and Burial—Another Death—Whales and Porpoises versus Serpents of Fire—Thunder Storm—Death of Dr. Reed—Three Dead Bodies found on Board—The Scurvy—Five of the Passengers Insane—Evils of the Credit System—A Cultivated Mind deranged—Memory lost—Its Cause—The Victim upon the Verge of Death—Harpooning Porpoises—Exciting Sport, | 169 |

| CHAPTER TWENTY-NINTH.—Cloud and Clipperton Islands—Whales, Sharks, Porpoises, and Dolphins—A Shark captured—Shark Steak—“Caudle Lecture”—Death of Samuel B. Lewis—A Calm—Foot Races by the Ship’s Furniture—Passenger Peculiarities—Short of Provisions—“’Bout Ship”—First of January—Its Luxuries at Sea—A Tame Sea Fowl—A Passenger Dying—A Shark—A delightful Evening Scene—A Death—Burial at Sea by Candle Light—A Turtle navigating the Ocean—His suspicious conduct—A written Protest against the Captain—Cocus Island—Capturing “Boobies,” | 175 |

| CHAPTER THIRTIETH.—Intense Heat—Human Nature as exhibited by the Passengers—Danger, not apprehended—A Tattler—A “Dutch Justice”—“Long Tom Coffin”—A Quaker Hat—An Individual running Wild—His Oaths, Depredations, Musical Accomplishments, Showman Propensities, and Pugilistic Developments—“Blubber,” Buckskin, and “The Last Run of Shad”—A capsized Whale Boat—Thrilling Sensation—Harpoon used—A Shark—“Land ho!”—Gulf of Panama—South American Coast—“Sail ho!”—Dolphin for Dinner—A Whale—A Terrific Gale—Our Sails and Spars carried away, | 180 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY-FIRST.—Bay of Panama—Its Beauties—Tropical Fruits—The City in sight—Excitement on Board—Appearance of the City—Her Ruins—Preparations to Drop Anchor—“Stand by!”—“Let go the Anchor!”—Farewell to the Sick—A Perilous Ride on the Back of an Individual—On Shore—First Dinner—Nothing left—An Individual feeling comfortable—Panama Americanized—A Moonlight Scene viewed from a Brass “Fifty-Six”—A Dilapidated Convent as seen at Night—Church Bells—Burning the Dead—Exposure of the Desecrated Remains—Sickening and Disgusting Sight—Infants cast into Pits—The Rescue of their Souls requiring a Gigantic Effort on the part of the Church—A Catacomb—“Eternal Light”—Ignorance of the Mass—Peerless Characteristics, | 184 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY-SECOND.—A Nun—Fandango—Marriage Engagement broken—Start for Gorgona—Our Extreme Modesty—Sagacity of the Mule—Sleep on my Trunk—A Dream—An Alligator with a Moustache—Infernal Regions—Demons—An Individual with Long Ears, and a Mule in Boots—Falling out of Bed—Funeral Procession—Gorgona—Start for Chagres—Our Bungo Full—Spontaneous Combustion, almost—“Poco Tiempo”—Lizards for Dinner—The Hostess—Gatun—Music of the Ocean—Arrival, | 190 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY-THIRD.—Chagres, its Growth—Getting on board the Empire City—Magnificent Steamer—Gold Dust on board—Steamers Alabama, Falcon, Cherokee, and Severn—My friend Clark arrives on board—Preparations for Starting—Our Steamer makes her First Leap—“Adios”—Caribbean Sea—Heavy Sea on—Jamaica—Port Royal—Kingston—“Steady!”—Beautiful Scene—Orange Groves—People flocking to the Shore—Drop Anchor—The Town—General Santa Anna’s Residence—“Coaling up”—Parrot Pedler in a Dilemma, | 196 |

| CHAPTER THIRTY-FOURTH.—Our Wheels revolve—The Natives of the Island Extinct—The Wrongs they have suffered—The Island once a Paradise—San Domingo, her Mountains—Cuba—A Shower Bath Gratis—“Sail ho!”—Caycos Island and Passage—Turtle for Dinner—A Sermon—Gallant Conduct of our Steamer—We ship a Sea—A Spanish Vessel in Distress—Our Tiller Chains give way—A Knife and Fork in search of Mince Pies—Gulf Stream—Water-Spouts—“Light Ship”—Sandy Hook—Anxiety—Sight of New York—Feelings and Condition of the Passengers—A Sad Fate—Aground—A new Pilot—Again under weigh—Near the Dock—Death—Man Overboard—Make Fast—At Home—One Word to those about to embark, | 201 |

| Constitution of the State of California, | 207 |

PANAMA AND NICARAGUA ROUTES.

SAIL FROM NEW YORK—OUR PILOT LEAVES US—LAND RECEDES PROM VIEW—SEA-SICKNESS—A WHALE—ENTER THE GULF STREAM—ENCOUNTER A GALE—ENTER THE TROPIC OF CANCER—“LAND, HO!”—CAYCOS AND TURK’S ISLANDS—ST. DOMINGO—CUBA—ENTER THE CARIBBEAN SEA—SPORTING—SUNDAY—STANDING IN FOR THE PORT OF CHAGRES—BEAUTIFUL SCENE—DROP ANCHOR.

Dear reader:—If you have visited California, you will find nothing in these pages to interest you; if you have not, they may serve to kill an idle hour. On the 27th of January, 1849, having previously engaged passage, I had my baggage taken on board the bark “Marietta,” lying at Pier No. 4, East River, preparatory to sailing for Chagres, en route to California. It was 9, A.M. A large concourse of friends and spectators had collected on the pier to witness our departure, and after two hours of confusion and excitement, we let go our hawser—and, as we swung around into the stream, received the last adieus of our friends on shore. We were taken in tow by a steam-tug, and were soon under way, our bowsprit pointing seaward. We occupied our time, while running down the bay, in writing notes to our friends, our pilot having kindly volunteered to deliver them. We passed Forts Hamilton and Diamond at 1, P.M., and at three had made Sandy Hook. Our pilot’s boat, which had been laying off, came along side to receive him; we gave our last thoughts into his charge, and bade him adieu.{10}

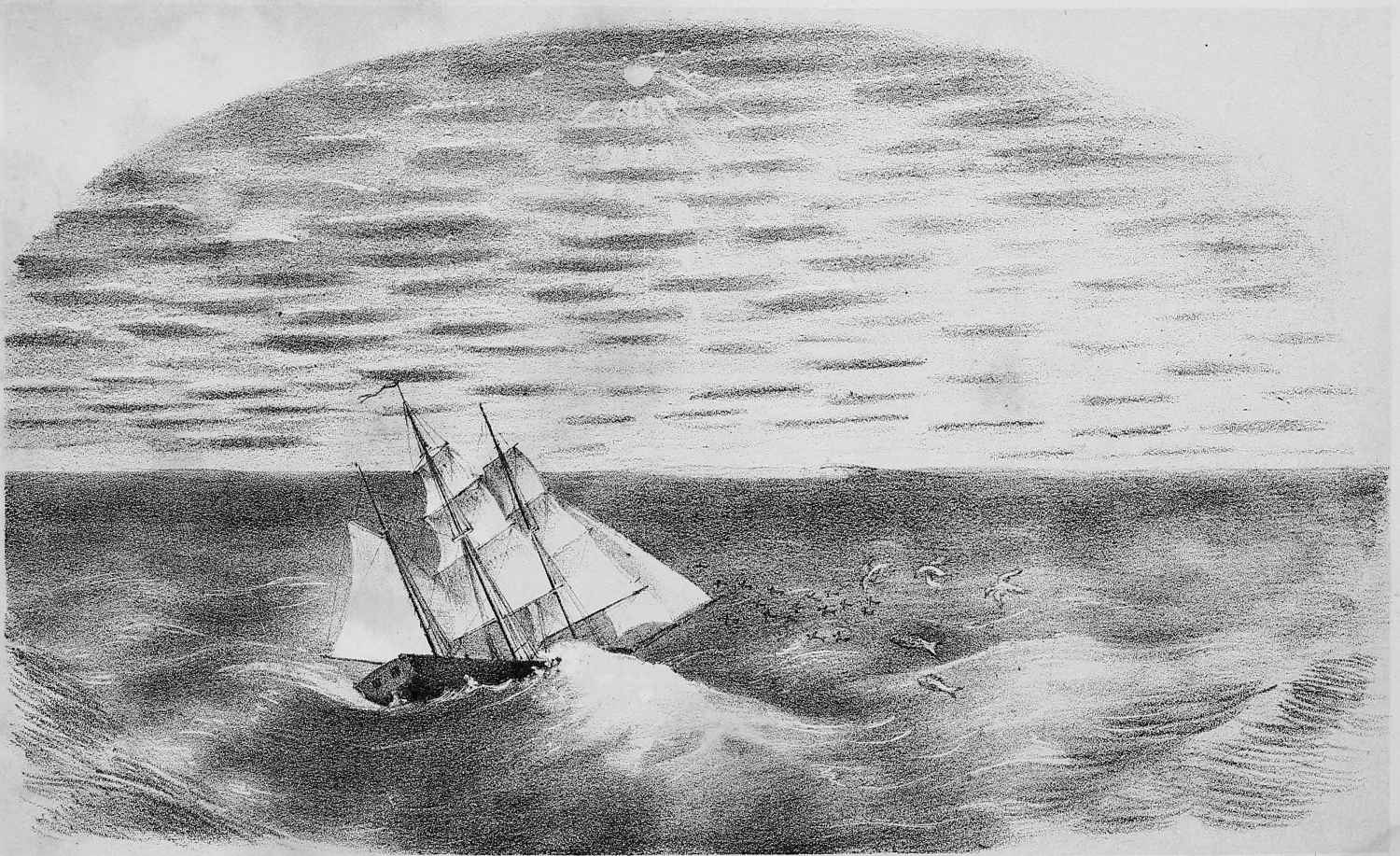

We had now passed Sandy Hook, and putting our helm down, we stood away to the South. The wind being light, we bent on studding sails, and were soon making our course at the rate of five knots. The excitement had now subsided; and, as the hills were fast receding, we were most painfully admonished that we were leaving home and friends. We soon sunk the highest points of land below the horizon, and felt that we were fairly launched upon the ocean, and that we were traveling to a scene of adventure, the result of which no one could divine. We felt that sinking of spirit one only feels on such occasions; and, at this particular time, clouds as dark as night hung in the horizon of the future. Night came on, and with it a stiff breeze, creating a heavy sea. This caused most of the passengers to forget their friends, and bestow their undivided care upon themselves.

For some cause, at this particular juncture, the passengers were affected with peculiar sensations, mostly in the region of the stomach. They did not think it was sea-sickness. Whatever the cause may have been, the effect was most distressing. It assumed an epidemic form. The symptoms were a sickening sensation and nausea at the stomach; the effect, distressing groans and copious discharges at the mouth. The captain felt no alarm; said he had had similar cases before on board his ship. The night was spent in the most uncomfortable manner imaginable. Many of the passengers, too sick to reach their berths, were lying about on deck, and at every surge would change sides of the vessel. All being actuated by the same impulse, performed the same evolutions.

With the dawn of the 28th, the wind lulled, and our canvas was again spread to a three knot breeze. At noon we took our first observation, and at evening passed a ship, although not within speaking distance. The dawn of the 29th is accompanied by a seven-knot breeze, and we stand away on our course with all sail set. At 3 P.M., we were saluted by a whale, and at 4 entered the Gulf Stream. We here first observe luminous substances in the water, which at night appear like an ocean of fire. During the night it blew a gale, and we ran under double-reefed topsails, with mainsail furled. 30th. Leave the Gulf Stream, the wind blowing a terrific gale. We are tossed about on moun{11}tainous waves, and all sick. 31st. All sail set, and running six knots; dolphins and porpoises playing about the ship. We are again saluted by a whale.

1st Feb. Pleasant; all appear at table; enter the trade winds; hoist studding-sails; lovely day; 4, P.M., mate catches a dolphin, and brings him on deck. 2d. Calm summer day. 3d. All on deck; extremely pleasant. 4th. Sunday; pleasant; pass a ship; fine breeze; throw the log; are running eight knots. 5th. Pass through schools of flying-fish, one of which flies on board. We enter the tropic of Cancer. A flock of black heron are flying through the air; we take an observation; are eighty miles from Caycos and Turk’s Island; making for the Caycos passage. 7th. 5, P.M. The captain discovers land from the mast-head, and we are cheered with the cry of “Land, Ho!” We pass around Caycos Island, and through the passage; and on the morning of the 8th, are in sight of St. Domingo, sixty miles distant. It looms up from the horizon like a heavy black cloud. 9th. Pass the island of Cuba, and on the 10th enter the Caribbean Sea. We passed near the island of Nevassa, a small rocky island, inhabited only by sea-fowl. They mistaking our vessel for a fowl of a larger species, came off in flocks, until our rigging was filled, and the sun almost obscured. They met with a foul reception. There were eighty passengers on board, all armed. They could not resist the temptation, but wantonly mutilated the unsuspecting birds, many of which expiated with their lives the crime of confiding in strangers. One would receive a charge of shot, with which it would fly back to the island, uttering the most unharmonious screeches, when a new deputation would set off for us, many of them destined to return to the island in the same musical mood. Fortunately, we were driven along by the breeze, and they returned to their homes, and have, no doubt, spent many an evening around the family hearth, speculating upon the peculiar sensations experienced on that occasion. The enthusiasm of the passengers did not immediately subside, but they spent the afternoon in shooting at targets.

11th. Thermometer standing at 80°. We are carried along with a three-knot breeze; our ship bowing gracefully to the undulations of the sea. It being Sunday, home presents itself vividly to our imagination. 13th. Standing in for the coast of{12} New Grenada; at 6 P.M., the captain cries out from the mast-head, “Land Ho!” We shorten sail, and on the morning of the 14th are standing in for the port of Chagres.

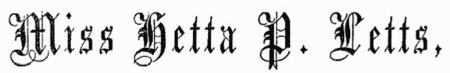

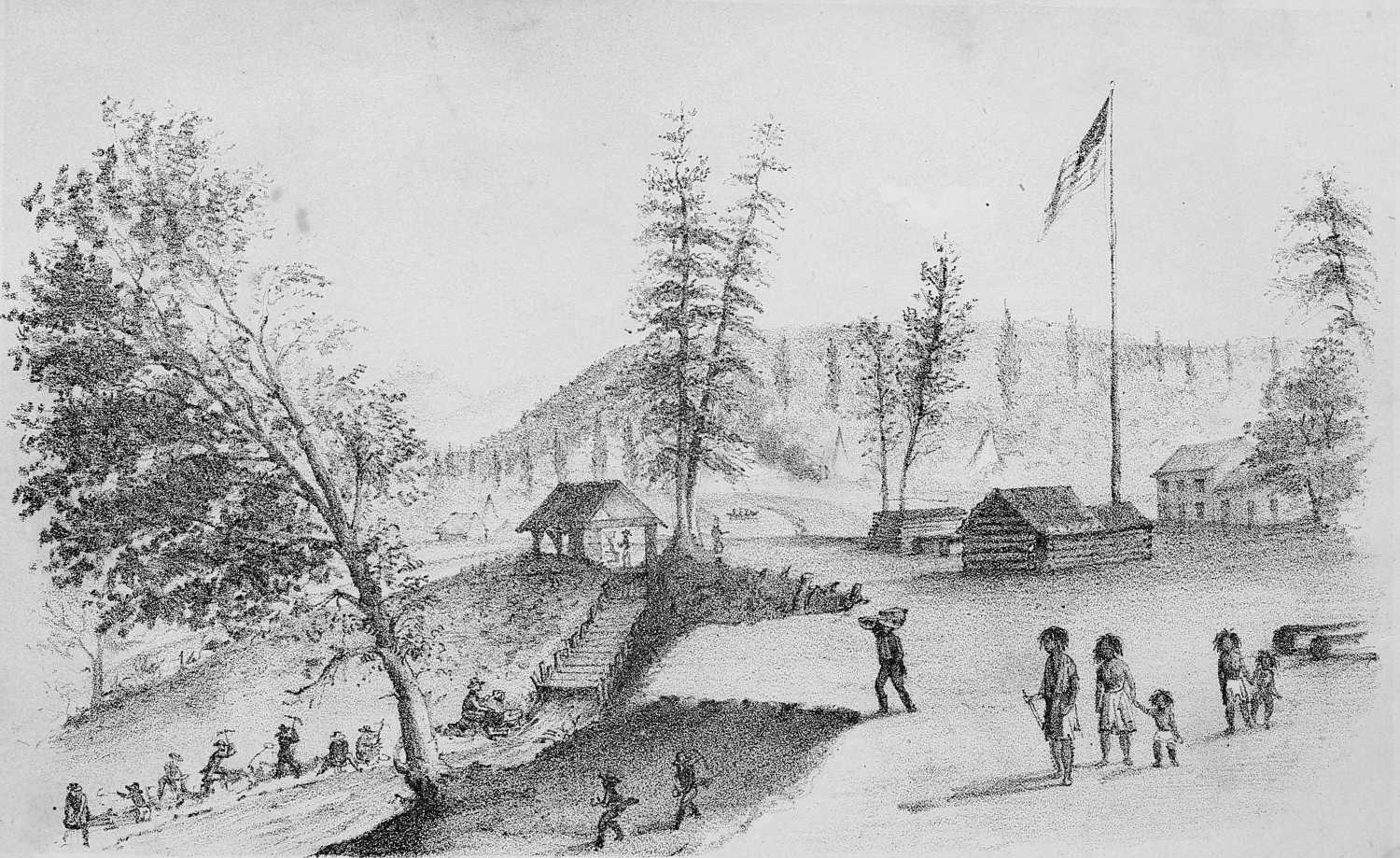

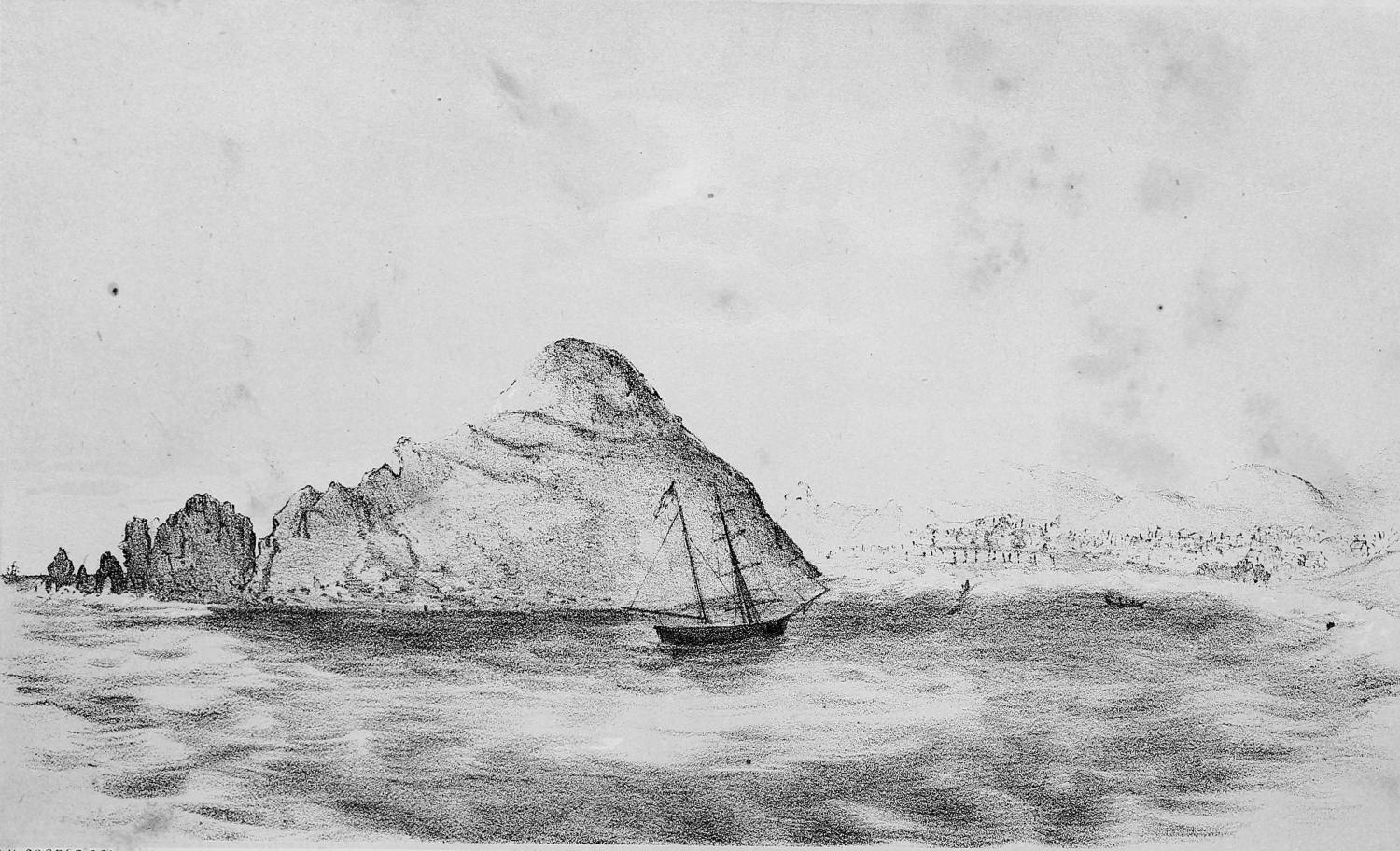

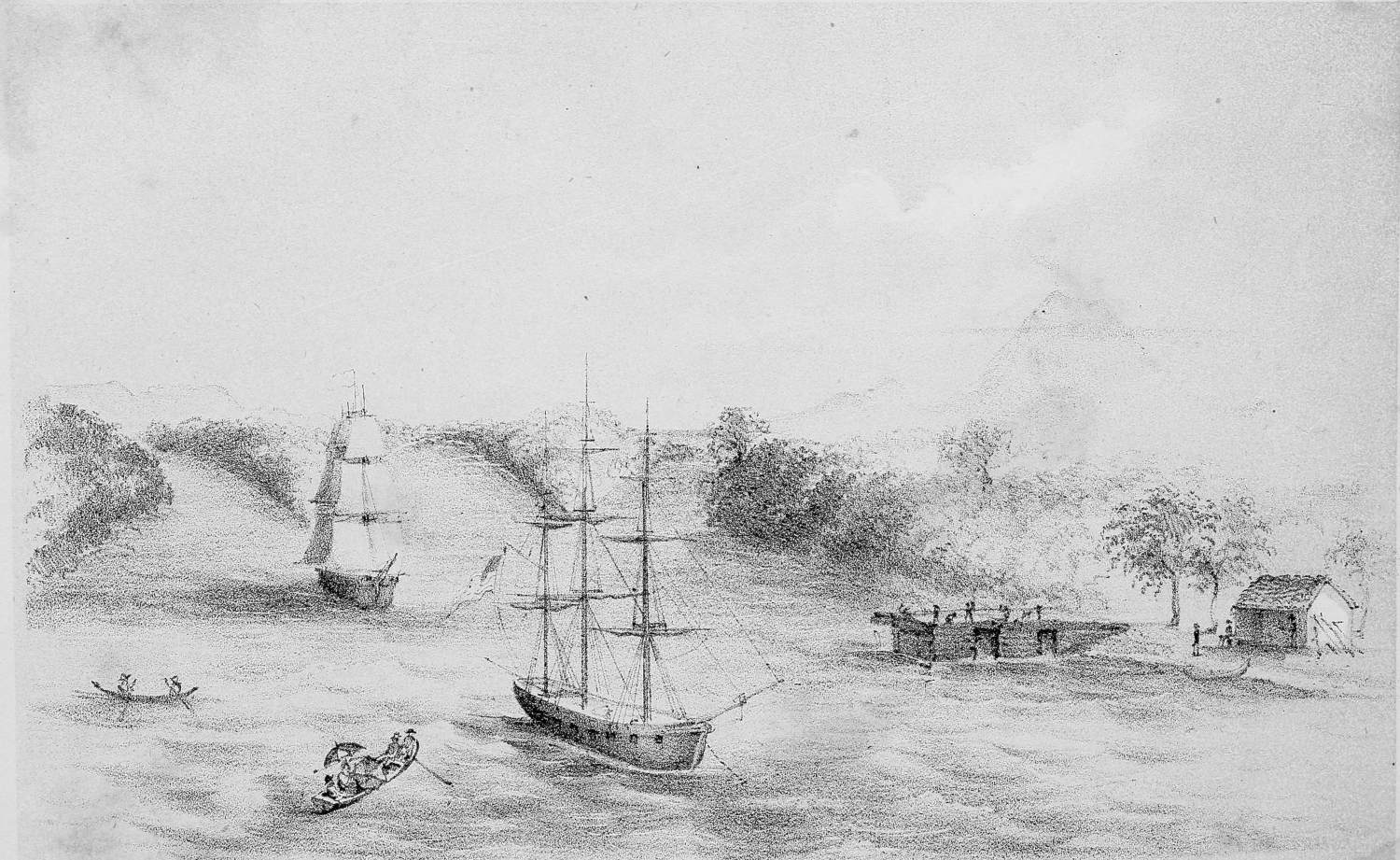

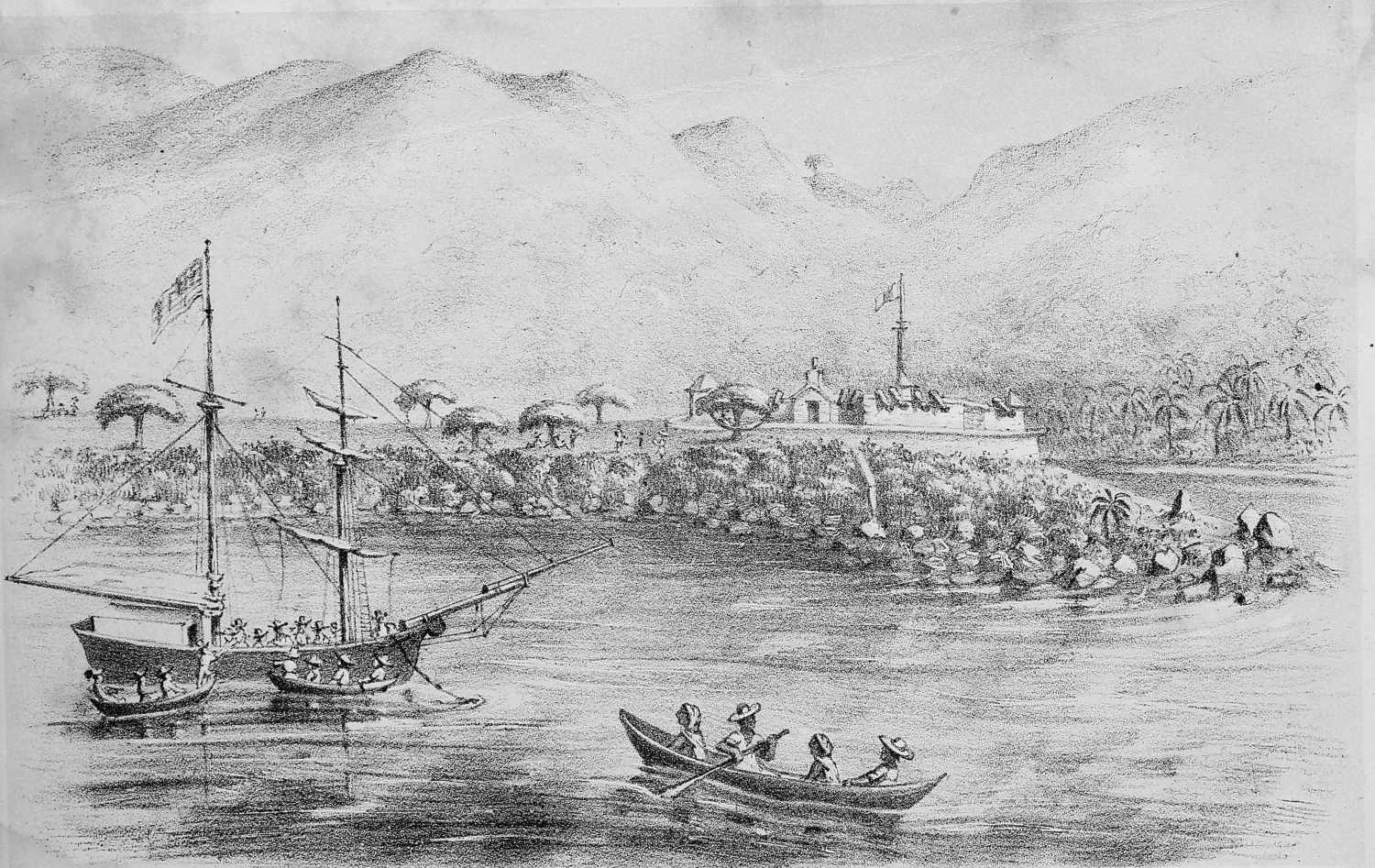

A most beautiful scene is spread out before us; we are making directly for the mouth of the river, the left point of the entrance being a bold, rocky promontory, surmounted by fortifications. (See Plate). The coast to the left is bold and rocky, extending a distance of five miles, and terminating in a rocky promontory, one of the points to the entrance of Navy Bay, the anticipated terminus of the Panama railroad. The coast to the right is low, stretching away as far as the eye can reach. In the background is a succession of elevations, terminating in mountains of considerable height, the valleys, as well as the crests of the hills, being covered with a most luxuriant growth of vegetation, together with the palm, cocoa-nut, and other tropical trees of the most gigantic size. As we neared the port, we passed around the steamer Falcon, which had just come to anchor, and passing on to within half a mile of the mouth of the river, we rounded to, and let go our anchor.{13}

NATIVES AND “BUNGOES”—CRESCENT CITY ARRIVES—WE SAIL INTO THE MOUTH OF THE RIVER—PREPARE FOR A FIGHT—FASHIONS AND FORTIFICATIONS—AN HONEST ALCALDE—NON-FULFILLMENT OF CONTRACTS.

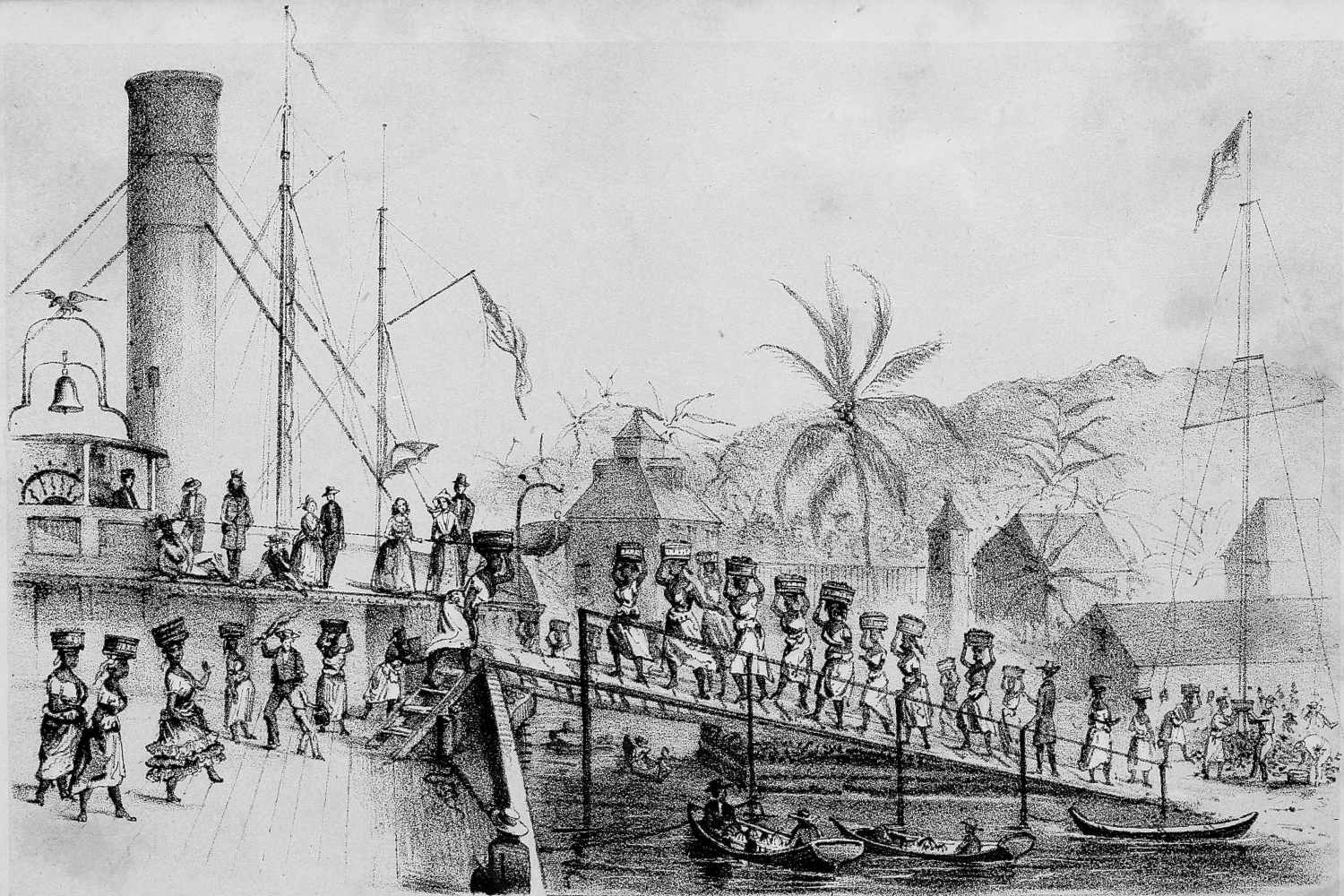

Our attention was first attracted to the natives who were rowing off to us in “bungoes,” or canoes of immense size, each manned by eight, ten, or twelve natives, apparently in a state of nudity. Their manner of propelling their craft was as novel as their appearance was ludicrous. They rise simultaneously, stepping up on a high seat, and, uttering a peculiar cry, throw themselves back on their oars, and resume their former seats. This is done with as much uniformity as if they were an entire piece of machinery. In the afternoon the Crescent City came to anchor, together with several sailing vessels, bringing, in all, about one thousand passengers.

We remained outside until the 17th, when we weighed anchor and passed into the mouth, making fast to the right bank, now called the American side of the river. We found an abundance of water in the channel, but at the entrance several dangerous rocks. As this coast is subject to severe northers, it is an extremely difficult port to make. The steamers still anchor some two miles out. We found several vessels near the mouth, beached and filled.

It was amusing to see the passengers preparing to make their advent on land. It is well understood that no one started for California without being thoroughly fortified, and as we had arrived at a place, where, as we thought, there must be, at least, some fighting to do, our first attention was directed to our armor. The revolvers, each man having at least two, were first overhauled, and the six barrels charged. These were put in our belt, which also contained a bowie knife. A brace of smaller{14} pistols are snugly pocketed inside our vest; our rifles are liberally charged; and with a cane in hand, (which of course contains a dirk), and a slung shot in our pockets, we step off and look around for the enemy.

We crossed the river to Chagres, which consists of about thirty huts constructed of reeds, and thatched with palm-leaves, the inhabitants, the most squalid set of beings imaginable. They are all good Catholics, but do not go to the Bible for the fashions. There are fig-leaves in abundance, yet they are considered by the inhabitants quite superfluous, they preferring the garments that nature gave them, sometimes, however, adding a Panama hat.

We visited the fortifications, which were in a dilapidated state, the walls fast falling to decay. The only sentinels at the time of our visit, were three goats and two children. (See Plate.) It has a commanding position, and has been a work of much strength, but the guns are now dismounted, and the inhabitants ignorant of their use. In returning from the fort, we crossed a stream where a party of ladies were undressing for a bath, i. e., they were taking off their hats. We passed on, and after viewing the “lions,” returned to our vessel, not very favorably impressed with the manners or customs of the town.

We had contracted with the Alcalde for canoes to carry us up the river. The steamboat Orus, then plying on the river, having contracted to take up the Falcon’s passengers, had offered an advanced price, and secured all the canoes, including ours. Our Alcalde had been struck down to the highest bidder, and I will here say that, although many charges have been brought against the New Grenadians, they have never been accused of fulfilling a contract, especially if they could make a “real” by breaking it. We did not relish the idea of remaining until the canoes returned, as Chagres had the name, (and it undoubtedly deserved it,) of being the most unhealthy place in Christendom. Many of our passengers had their lives insured before starting, and there was a clause in each policy, that remaining at Chagres over night would be a forfeiture.

The trunks of the steamers’ passengers, particularly those of the Crescent City, were landed on the bank of the river, while their owners were endeavoring to secure passage up. The

“bungoes” had all gone up with the Orus. There were left two or three small canoes, and the scenes of competition around these were exciting, and often ludicrous in the extreme. Now a man would contract for passage for himself and friend, and while absent to arrange some little matter preparatory to a start, some one would offer the worthy Padrone (captain) a higher price, when he would immediately put the trunks of the first two on shore, and take on board those of the latter, together with their owners, and shove out into the stream. Now the first two would appear, with hands filled with refreshments for the voyage, and begin to look around for their boat. In a moment their eyes fall upon their trunks, and the truth flashes across their imagination. Now the scene of excitement begins. The boat is ordered to the shore, it don’t come, and they attempt to wade out to it. The first step convinces them of the impracticability of this expedient, as they sink into the mud to their necks. Revolvers are flourished, but they can be used by both parties, consequently are not used at all.{16}

FIRST ATTEMPT AT BOAT BUILDING—EXCITEMENT “ON ’CHANGE”—A LAUNCH AND CLEARANCE—THE CREW—A MUTINY—QUELLED—POOR ACCOMMODATIONS—A NIGHT IN ANGER—AN ANTHEM TO THE SUN—NATURE IN FULL DRESS.

We saw but one alternative, which was, to construct a boat ourselves, and work it up the river. Upon this we decided, and purchasing the temporary berths of our vessel, soon had a boat on the stocks, 6 feet by 19, and in three days it was afloat at the side of the “Marietta,” receiving its freight. We called it the “Minerva,” and she was probably the first American-bottom ever launched at this port. A misfortune here befel me which I will relate somewhat minutely, as it was undoubtedly the cause of the death of a party concerned. In going out one morning to assist in the construction of the boat, I left my vest, which had a sum of money sewed up in the upper side pocket, in my berth, covered in such a manner I thought no one could discover it. I did not give it a thought during the day, but on going to my berth in the evening, I noticed the covering had been disturbed, and as my room-mates were in the habit of helping themselves to prunes, from a box in my berth, I imagined they had discovered and taken care of it. I was the more strongly impressed that this was the case from the fact that they had frequently spoken of my carelessness. I immediately saw them; they had seen nothing of it. Watches were stationed and the ship searched, but no trace of the money. A person who had had access to the cabin on that day for the first time was strongly suspected, but no trace of the money found. Our suspicions, however, were well founded, as the sequel will show. The passengers very kindly offered to make up a part of the loss, but as I had a little left I most respectfully declined its acceptance. We had about 3000 lbs. of freight and nine persons,

and at 2 P.M., 22d Feb., gave the word, “let go,” run up our sail, and as it was blowing a stiff breeze from the ocean, glided rapidly along up the river, our worthy captain, Dennison, and his accomplished mate, Wm. Bliss, of the “Marietta,” calling all hands on deck, and giving us three times three as we parted, to which adios we responded with feeling hearts. Now, as there is a straight run of three miles, a fair wind, and nothing to do but attend to our sail and tiller, we will take a survey of craft and crew. We are freighted with trunks, shovels, pick-axes, India-rubber bags, smoked ham, rifles, camp-kettles, hard-bread, swords and cheese. Our crew, commencing at the tallest, (we had no first officer,) consisted of two brothers, Dodge, young men of intelligence and enterprise; the eldest a man of the most indomitable perseverance, the younger of the most unbounded good humor, both calculated to make friends wherever they go, and to ride over difficulties without a murmur. They had associated with them three Germans, Shultz, Eiswald, and Hush. Shultz was a young man of energy, fond of music, a good singer, gentlemanly and companionable; Eiswald, full of humor and mirth, extracting pleasure from every incident, always at his post, a fine companion and good navigator; Hush, was a small man, with exceedingly large feet; he appeared to be entirely out of his element; he was disposed to do all he could, but his limbs would not obey him; his arms appeared to be mismated; his legs, when set in motion, would each take an opposite direction, and his feet were everywhere, except where he wanted to have them. We were quite safe when he was still, but when set in motion we found him a dangerous companion. Mr. Russ, a young lawyer of New York, Mr. Cooper, an artist, also of New York, a man of energy, perseverance and genius, and one of the most efficient men of the party. Mr. Beaty, an elderly man, extremely tall and slender, and very moral and exemplary in his habits; being in feeble health, he was to act as cook for the voyage. Ninthly and lastly, myself, an extremely choleric young man, of whom delicacy forbids me to say more.

We have now arrived at the bend of the river, and as here is a spring of excellent water, we make fast and fill our water-keg. Water is obtained here for the vessels in port, by sending up{18} small boats. It can be obtained in any quantity, and a more lovely place cannot well be conceived of. After adjusting our baggage preparatory to manning our oars, we again shoved out into the stream. We manned four oars, consequently kept a reserve. We were all fresh and vigorous, and, being much elated with the novelty of our voyage, resolved to work the boat all night. It was already quite dark, but with the aid of a lamp we kept on our course. The river here was walled up on either side by gigantic trees, their branches interchanging over our heads, almost shutting out the stars. Sometimes the branches stretching out but little above the surface of the river, were filled with water fowls, the white heron presenting a strange and most striking appearance. They would start with fright at our approach, striking wildly in the dark with their wings; some would find secure resting-places on the more elevated branches, while others would settle down through the dense foliage to the margin of the river. Innumerable bats, attracted by our light, were flitting along the surface of the river, but aside from these all nature appeared to be hushed in sleep.

We moved along with much spirit until about eleven o’clock, when there were symptoms of disaffection. Some were weary, others sleepy; some declared they would work no longer, others that the boat should not stop. We had all the premonitory symptoms of a mutiny. It was suggested that we should uncork a bottle of brandy, which was accordingly done, and it was soon unanimously declared that our prospects had never appeared so flattering. I am sure our boat was never propelled with such energy. I am not prepared to say that the brandy didn’t have an influence. We moved along rapidly for an hour when we had a relapse of the same disaffection. We resolved to stop; but we were in a dilemma. We had left home under the impression that the Chagres river was governed by alligators and anacondas, assisted by all the venomous reptiles in the “whole dire catalogue,” consequently, to run to the shore was to run right into the jaws of death, which we did not care to do at this particular time. We pulled along until we came in contact with a limb, which stretched out over the surface of the river, to which we made fast. After detailing two of the party as a watch, we stowed ourselves away as best we could. I was{19} in a half-sitting posture—my feet hanging outside the boat, my back coming in contact with the chime of our water-keg. I tried for some time to sleep, but in vain. I tried to persuade myself that I was at home in a comfortable bed, just falling into a doze, but my back was not to be deceived in that way; and after spending two hours in my uncomfortable position, I got up. I found that my companions had been as badly lodged as myself, and all as anxious to man the oars. We were soon under way, and soon the approaching day was proclaimed by the incessant howl of the animal creation, including the tiger, leopard, cougar, monkeys, &c., &c., accompanied by innumerable parrots and other tropical birds. All nature seemed to be in motion. The scene is indelibly impressed upon my memory. The trees on the margin of the river were of immense size, clothed to their tops with morning-glories and other flowers of every conceivable hue, their tendrils stooping down, kissing the placid bosom of the river. Birds of the most brilliant plumage were flying through the air, in transports of joy. All nature seemed to hail the sun with bursts of rapture. Everything appeared to me so new and strange. My transition from a northern winter to this delightful climate, seemed like magic, and appeared like a scene of enchantment, like the dawning of a new creation.{20}

BREAKFAST—PRIMITIVE MODE OF LIFE—MEET THE “ORUS”—MUTINY AND RAIN—A STEP BACKWARDS—ENCAMPMENT—A “FORTIFIED” AND FRIGHTENED INDIVIDUAL—SPORTING—MOSQUITOS.

We moved along until the sun had ascended the horizon, when we made fast to the shore and took breakfast. Being somewhat fatigued, we remained until after dinner. We were visited here by two native men and a little boy, all dressed in black, the suits that nature gave them. They were cutting poles with big knives or machets; they had brought their dinner with them, which consisted of a piece of sugar-cane, a foot in length.

We again manned our oars and worked our boat until about sunset, when we drew along shore at a pleasant point designing to encamp. Some of the party were anxious to gain a higher point on the river, and we again pushed out. As we were gaining the middle of the stream, a canoe turned the point containing two boys; they immediately cried out, “vapor! vapor!” (steamboat, steamboat,) and before we could reach the shore, the “Orus” came dashing around the point, throwing her swell over the sides of our boat, and we were near being swamped. This caused great consternation and excitement, which soon subsided, and we were again under way. We were, however, destined not to end our day’s journey, without additional difficulties. We worked an hour without finding a suitable place to spend the night. Those having proposed stopping below, now strongly demurred to going on, and after an eloquent and spirited discussion, it was decided by a majority vote, that we should run back. It commenced to rain about this time, and we returned in not the most amiable mood.

We erected an india rubber tent on shore and, laying our{21} masts fore and aft, threw our sail over it as a protection to the boat; and, after supper, detailed our watch, when another attempt was made to sleep. Mr. Hush and myself, were on the first watch. I took my station in the boat, but there being a strange commotion in the water, and the sides of the boat not being very high, Mr. H. preferred the shore. He armed himself with a brace of revolvers, and one of horse pistols, a bowie-knife, a large German rifle and broad sword, and stepped on shore. The night was extremely quiet, and at ten o’clock it ceased to rain. Nothing was heard except the peculiar whistle of a bird, which much resembled that of a school boy. The river, however, was in a constant agitation, which we presumed to be caused by alligators rushing into schools of fish.

At 12, Mr. H. thought he heard a strange noise in the forest, approaching the encampment, and in a few minutes uttering a most unearthly yell, he jumped for the boat. His feet hanging a little “too low on the edge,” caught under a root, and he brought up in the river. This being full of alligators, only added to his fright, and the precise time it took him to get out, I am unable to say.

The morning was again hailed by universal acclamation, and after an early breakfast we resumed our voyage. We had a pleasant run during the day, stopping frequently to secure pheasants, pigeons, toucans, parrots, &c. The latter are not very palatable, but we were not disposed to be fastidious, and every thing we shot, except alligators, went into the camp-kettle. Late in the afternoon we met a bungo, the natives pointing to a tree, the top of which was filled with wild turkeys. We pulled along under the tree, discharged a volley, and succeeded in frightening them to another. Having a carbine charged with shot, I brought one to the ground. I climbed up the bank, but found the forest impenetrable. The under growth was a dense chaparal, interlaced with vines, every shrub and tree armed with thorns. I, however, with my machet, reached the turkey. There being a sandy beach near, we resolved to encamp for the night; and while we were pitching our tent, Mr. B. dressed and cooked our turkey.

We were here attacked by the most ravenous swarm of musquitos it was ever my lot to encounter. We had promised{22} ourselves a comfortable night’s rest, but it was like most of the promises one makes himself. We entered the campaign with the greatest zeal; but before morning, would have been glad to capitulate on any terms. The morning dawned as it only dawns within the tropics. Being Sunday we resolved to rest, and called our place of encampment, Point Domingo.{23}

FIRST RAPID—AN UNFORTUNATE INDIVIDUAL—A STEP BACKWARDS—SEVERAL INDIVIDUALS IN A STATE OF EXCITEMENT—TIN PANS NOT EXACTLY THE THING—A BREAKFAST EXTINGUISHED—SPORTING—MONKEY AMUSEMENTS—A “FLASH IN THE PAN”—TWO FEET IN OUR PROVISION BASKET—POVERTY OF THE INHABITANTS AND THEIR DOGS—ARRIVAL AT GORGONA.

Monday morning, having an early breakfast, we were again under way. We shot several alligators, and at 10, A.M., arrived at the first rapid. We uncorked a bottle of brandy and prepared for hard work. As Mr. Hush did not help work the boat, (it was not safe to give him a pole) it was suggested that he should walk. We commenced the ascent, and after an hour of hard labor, gained the summit. We drew up along shore, and Mr. H. attempted to jump on board. His feet, as usual, taking the wrong direction, he stumbled and caught hold of an India rubber bag for support, which not being securely fastened, went overboard. The current being strong it passed rapidly down, and there was no alternative but to follow it with the boat. We soon found ourselves going with the greatest velocity, down the rapid we had just toiled so hard to ascend. We overtook the bag at the foot, and making fast to the shore, we held a very animated colloquy, which was embellished with an occasional oath by way of emphasis. Mr. H. suspected that he was the subject of our animadversions, but there was nothing said.

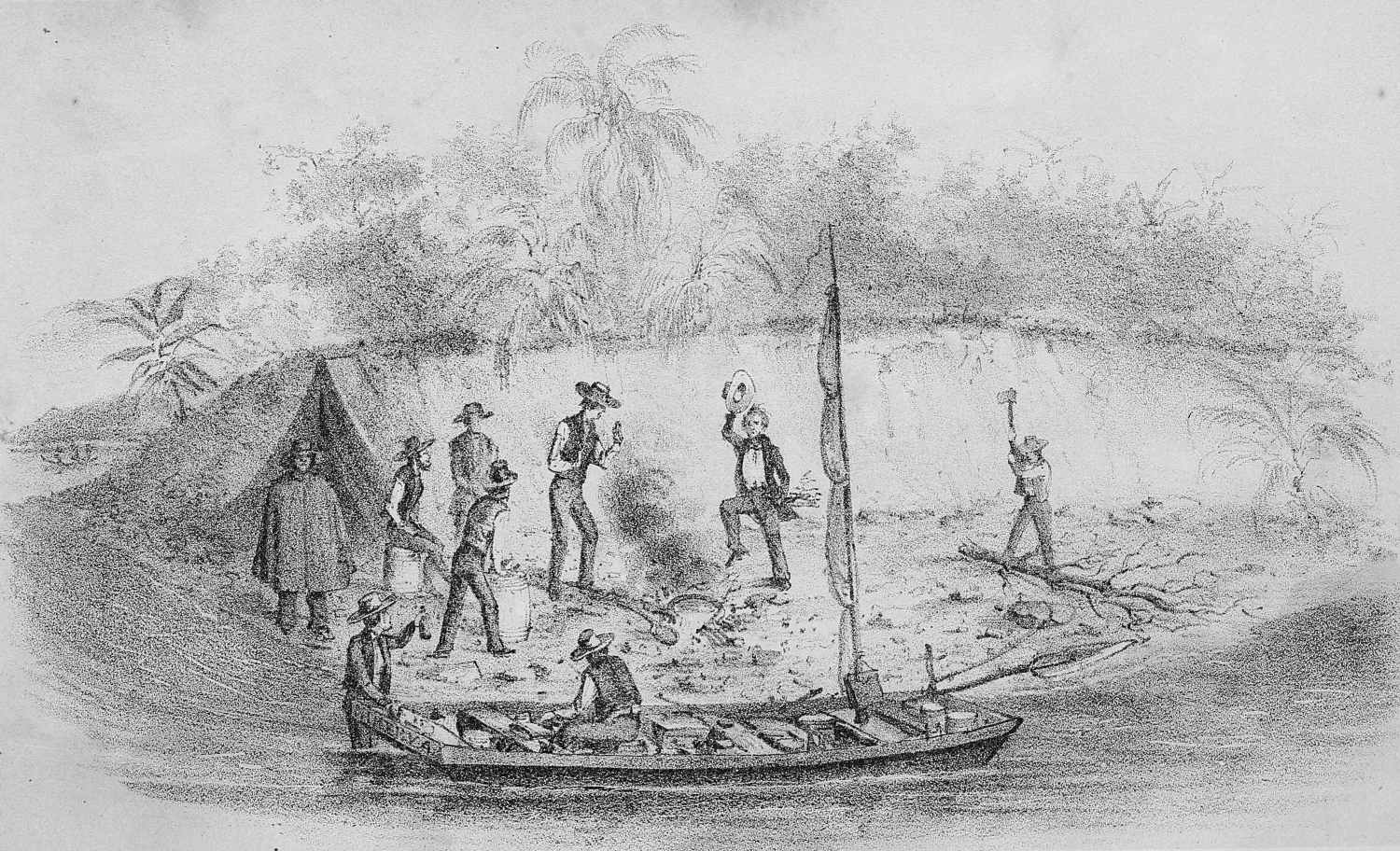

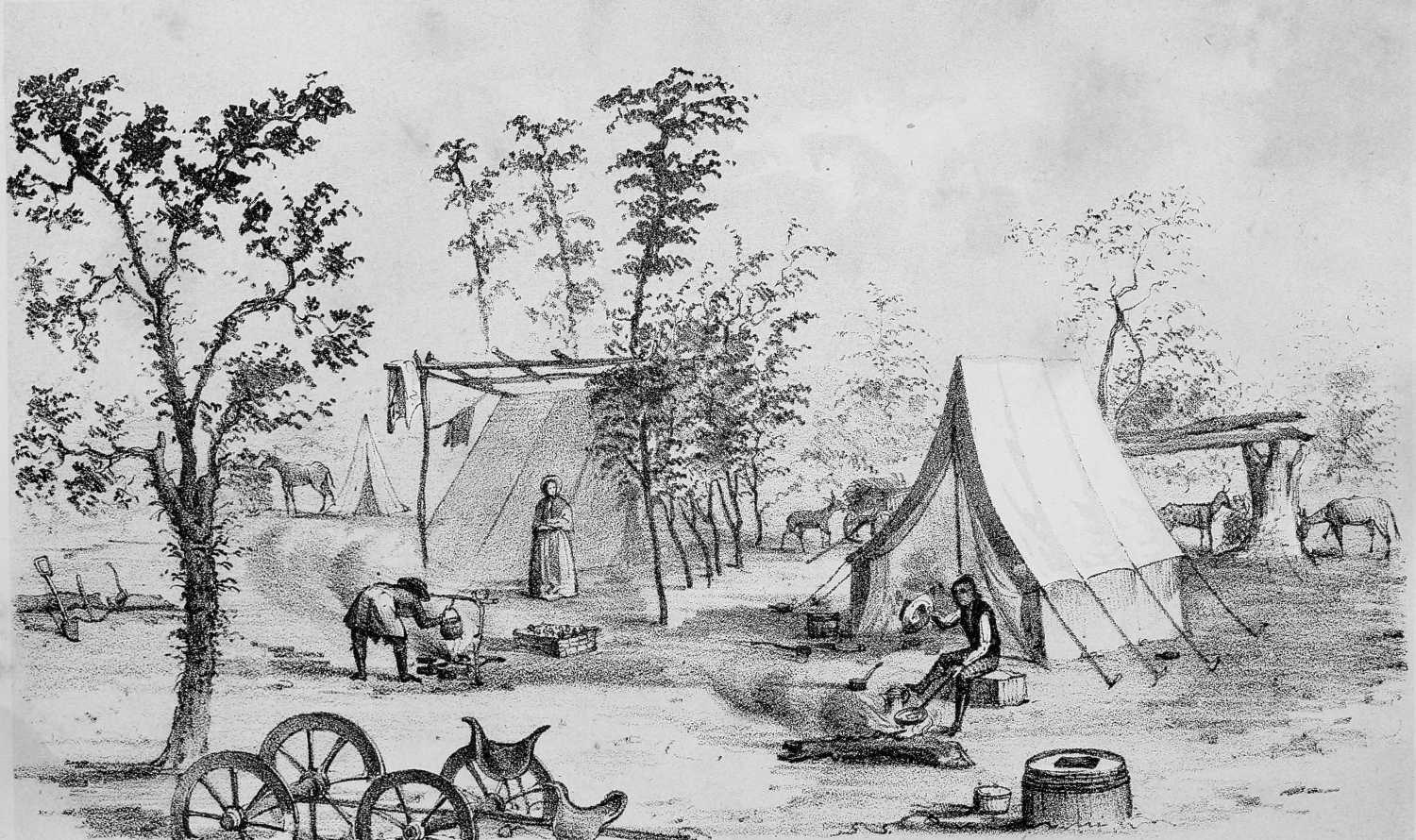

We again ascended the rapid, and worked on until rain and night overtook us. We were obliged to encamp on an unpleasant rocky shore, and cook supper in the rain. We passed an uncomfortable night; and in the morning it was still raining in torrents. We were furnished with India rubber ponchos and were making preparations to start while Mr. Cooper and Mr. Beaty were preparing breakfast. It was difficult to get{24} fuel, and still more difficult to make it burn. They however succeeded in kindling the fire. We usually boiled our coffee-water in the camp-kettle, but this being full of game, we filled a large tin pan with water, and placed it over the fire, supported by three stones. The ham was frying briskly by the fire, our chocolate dissolving, and every thing going on swimmingly, when one of the stones turned, capsizing the tin pan, putting out every particle of fire, and filling the chocolate and ham with ashes. (See plate.) Mr. Cooper was frantic with rage, doffing his hat, throwing the ham into the river, kicking over the chocolate cup, cursing every thing in general, and tin pans in particular, while Mr. Beaty, with a most rueful countenance, clasped his hands, exclaiming, “Oh! my!!!”

Mr. Dodge came to the rescue, and we had a warm breakfast, and were soon under way. At ten, the sun came out, and we had a pleasant run, using our sail. We encamped in a delightful place on the left bank of the river, and had a comfortable night’s rest. When we awoke in the morning, the air was filled with parrots, toucans, tropical pheasants, etc. Our guns were immediately brought into requisition, and we soon procured a full supply, including seven pheasants. One of the party and myself finding a path that had been beaten by wild beasts resolved to follow it, and penetrate more deeply into the forest. After going some distance we heard a strange noise, which induced my companion to return. Being well armed I proceeded on, and soon came upon a party of monkeys taking their morning exercise. There were about twenty of them, in the top of a large tree. The larger ones would take the smaller and pretend they were about to throw them off; the little ones, in the mean time, struggling for life. There was one very large one, with a white face, who appeared to be doing the honors of the occasion, viz., laughing when the little ones were frightened. If I had been within speaking distance of his honor, I would have informed him that his uncouth laugh had diminished the audience on the present occasion by at least one half. I did not break in upon their sports, but, following the path, soon found myself at a bend of the river.

A native was passing, who informed me that there were turkeys on the other side. I stepped into his canoe, and in a

moment we were climbing the opposite bank. When within shooting distance I raised my gun; it missed fire, and the turkeys flew away, the native exclaiming “mucho malo.” We recrossed, and I soon reached the encampment. Our game was cooked, and the party ready to embark. We shoved out, but, unfortunately, Hush had forgotten his bowie knife. We floated back, he ascended the bank, and succeeded in finding it. In returning, he found it difficult to reach the boat; the bank being quite abrupt, he, however, determined to jump, and, after making a few peculiar gyrations with his arms, he did jump, and landed both feet in our provision basket, breaking several bottles, and in his effort to extricate himself kicked the basket overboard. He would have followed it, had it not been for timely assistance.

The day was excessively hot, the river rapid, and our progress slow. In the after part of the day, we passed a rancho where there were a few hills of corn, the first sign of industry we had seen along the river. One can hardly conceive of a country susceptible of a higher cultivation. They have a perpetual summer; tropical fruits grow spontaneously; they have the finest bottom lands for rice, tobacco, cotton, corn, or sugar plantations perhaps on this continent; yet, with the exception of a very little corn and sugar, nothing is cultivated. The enterprise of the States would make the country a paradise.

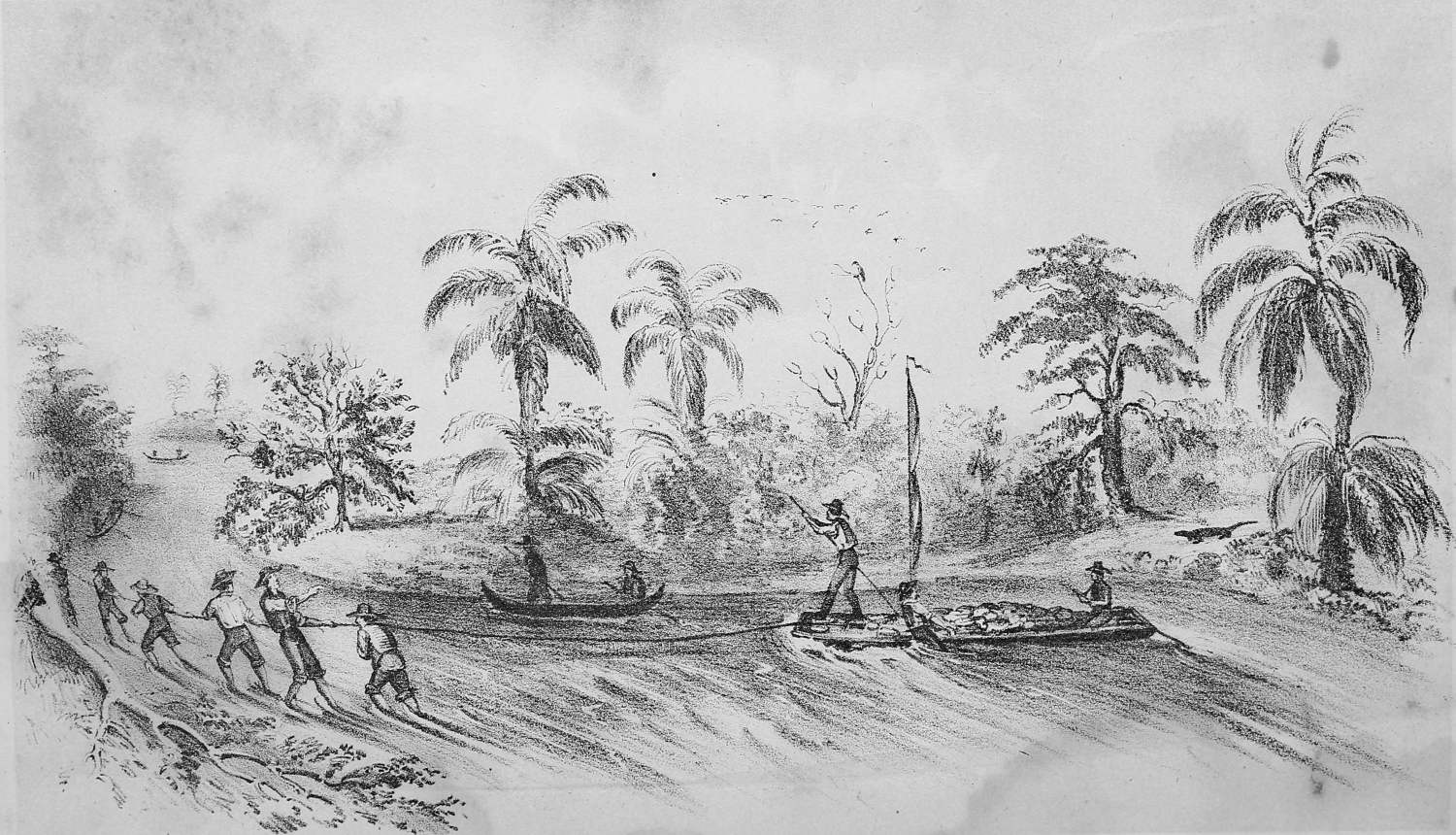

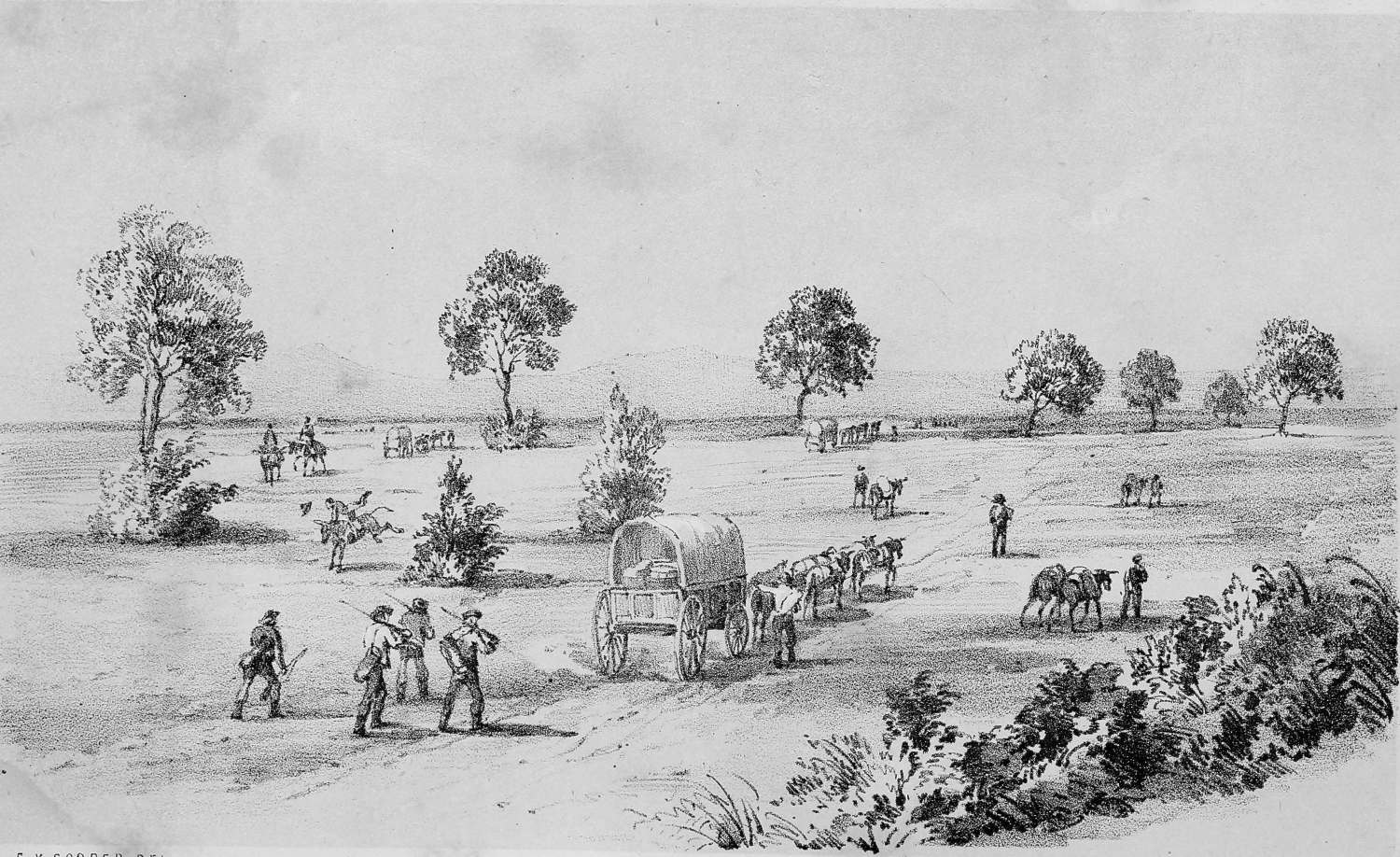

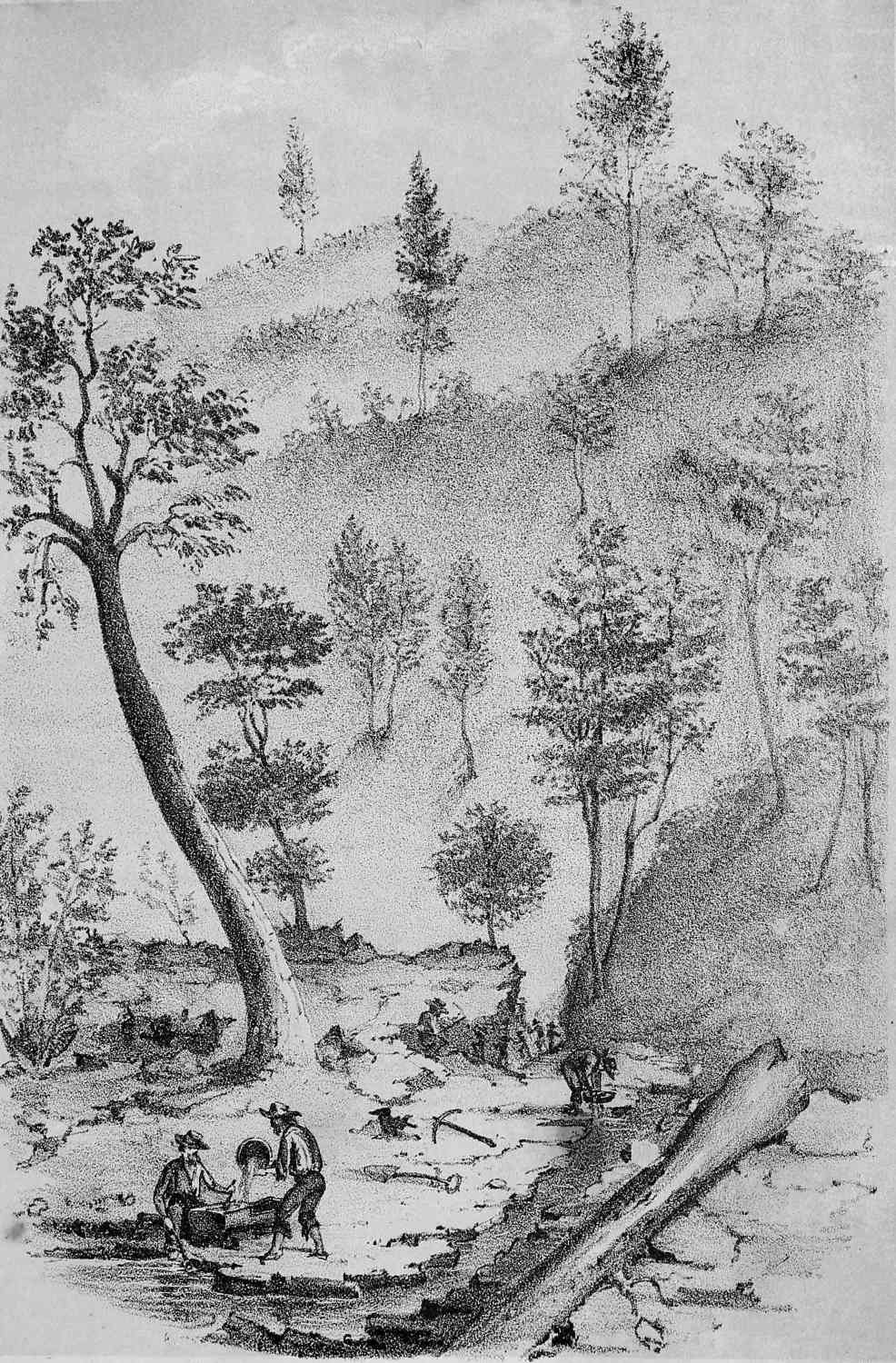

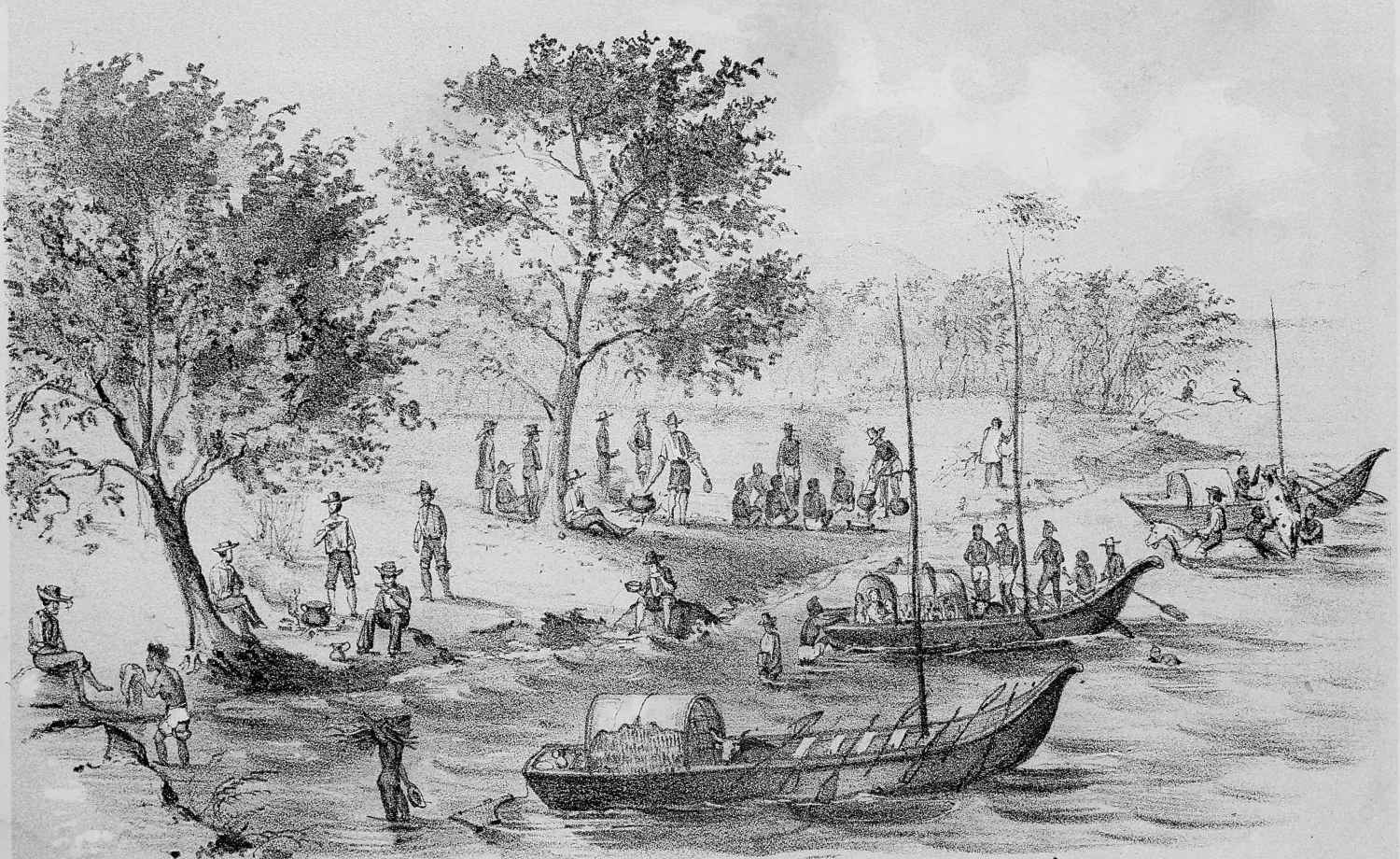

We encamped at night where the river had a peculiar bend, forming a horse-shoe, and one of the most delightful spots I ever saw. I selected it for my own use—as a rice and sugar plantation—but have not yet had the title examined. In the middle of the night a canoe passed down in which was the man suspected of having borrowed my vest. He spoke to one of our party, said he was on his way to Chagres, on business, but would return to Gorgona immediately. We took an early start in the morning, and at nine stopped at a rancho to purchase cigars. Such a squalid family I never saw. There were three women, two or three young ladies, and half a dozen children—none of them were dressed, excepting a little boy who had on a checked palm leaf hat. We asked for cigars, they had none, but would make some for us, “poco tiempo,” (little time). We couldn’t wait. We were much struck with{26} the appearance of the dog, which was so poor that, in attempting to bark at us, it turned a summerset. We were now not far from Gorgona, and exerted every nerve to reach our destination. At noon, while at dinner, a young native approached us from the forest, and proposed to help work the boat up to Gorgona. As he was a tall, athletic young fellow, and didn’t charge anything, we accepted his proposition, and gave him his dinner. We were now six miles from Gorgona, and with the aid of our native there was a prospect of arriving in good time. The river was shallow, with frequent rapids, and, although our boat drew only nine inches water, we were frequently obliged to get out and tow it up. (See Plate). Your humble servant is standing on the bow of the boat with a long pole. Cooper is “boosting” at the side. Hush is doing duty—the first on the rope. Dodge is in a passion and in the act of addressing some emphatic remark to gentlemen on board. Natives are seen in their canoes, and just above, seated on the limb of a tree, is a monkey who appears to be looking on enjoying the scene. As we passed under the tree he came down upon one of the lower branches, and seemed disposed to take passage. An alligator is seen on the bank below, and in the air innumerable parrots. The noise of these is one of the annoyances of this country, their screeching incessant and intolerable. Late in the afternoon we arrived within half a mile of Gorgona, which was behind a bend of the river, where our native wished to land. We soon passed the bend, when the town was in full view, and in a few moments our labors were at an end. Our friends had felt some solicitation for us. Seven days was an unusual passage at this season of the year, and if they had wished to effect an insurance on us it is doubtful whether it could have been done in Gorgona at the usual rates.

CUSTOMS AND DRESS OF THE NOBILITY—A SUSPICIOUS INDIVIDUAL—JOURNEY TO PANAMA—A NIGHT PROCESSION—A WEALTHY LADY IN “BLOOMER”—AN AGREEABLE NIGHT SURPRISE—“HUSH” ON HORSE BACK—CAPTAIN TYLER SHOT—A MOUNTAIN PASS AT NIGHT—THUNDER STORM IN THE TROPICS.

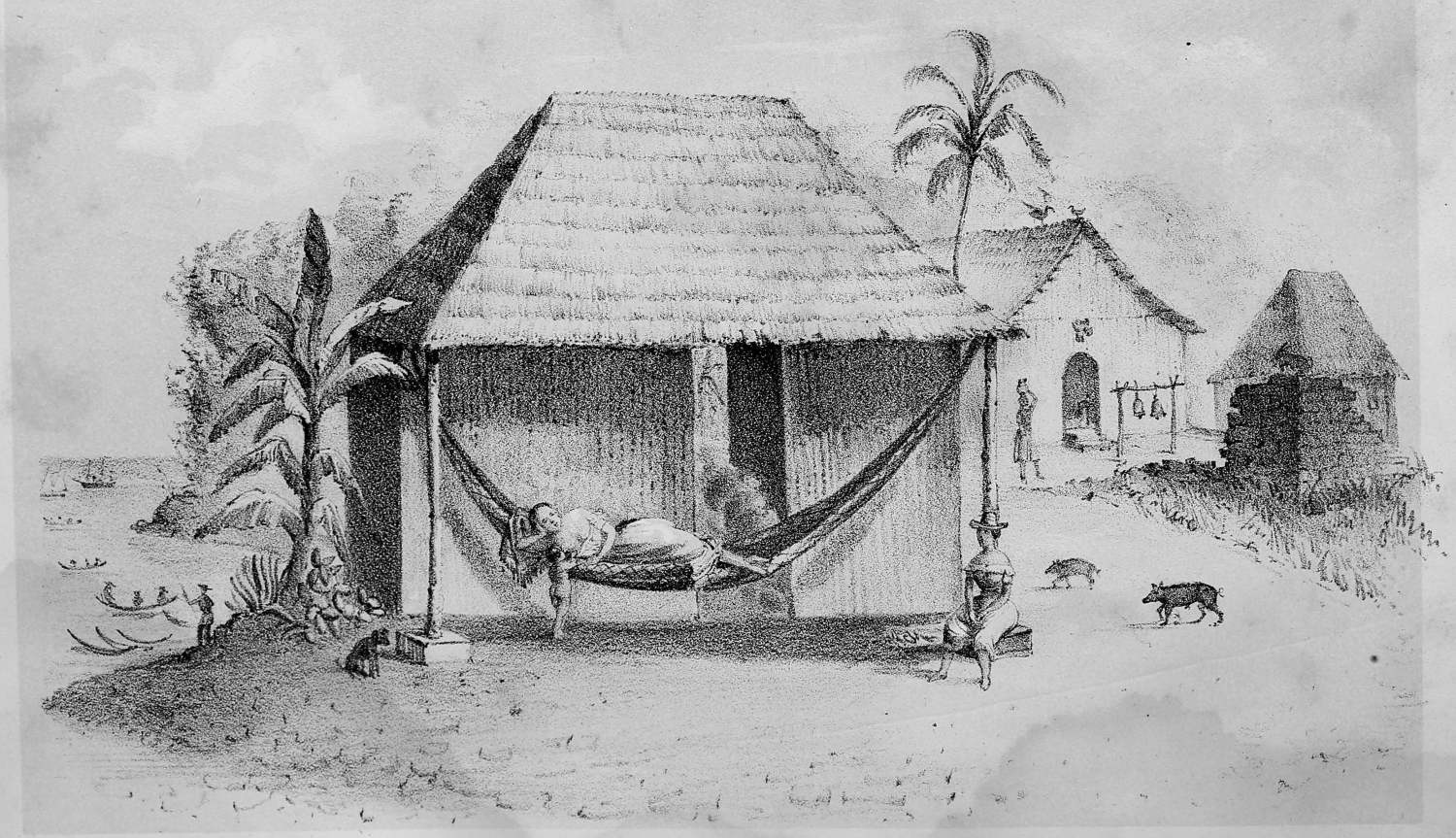

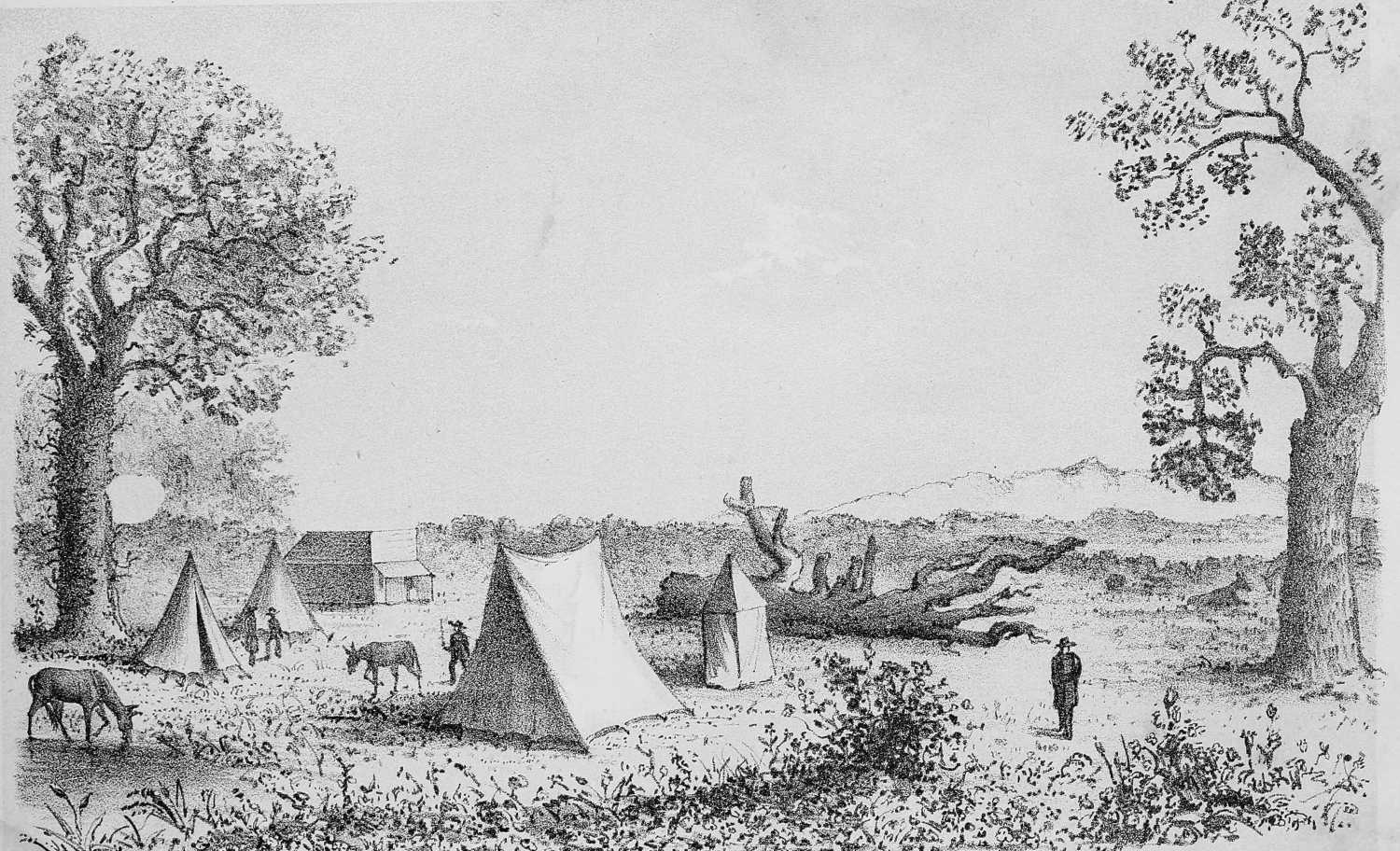

The town is pleasantly situated about fifty feet above the level of the river, and contains some eight hundred inhabitants. At the time of our arrival, there were about five hundred Americans encamped in the town. The buildings are mostly constructed of reed, thatched with palm-leaf. (See Plate). A hammock is slung under the eave of one of these houses, occupied by the mother, in the act of administering to the wants of a little one; an open countenanced dog is near, as if waiting to relieve the child, a señora is shelling corn, and a hog is looking on, one foot raised, in readiness to obey the first summons.

The people dress, as in Chagres, with the addition, in some cases, of half a yard of linen and a string of beads. The Alcalde and his lady were generally well dressed; but, as strange as it may appear, they were always accompanied in their morning walks by their son, a lad of fourteen, his entire costume consisting of a Panama hat. In the evening of the day of our arrival, we observed our worthy boatman making himself familiar around the American tents. Soon the police were on the alert, and we were informed that he was one of the most notorious thieves in the country. He had landed back, thinking it safer to come into town at night. We had our baggage carried up, and were soon residents of the American part of the town. I was here put in possession of facts which strengthened my suspicions of the individual who passed down the river on the previous night; and, in the sequel, instead of returning to Gorgona, he, on his arrival at Chagres, hired a native to carry{28} him to a vessel that was about to sail for New Orleans, and in attempting to climb on board he missed his footing, fell into the water and was drowned. His hat came to the surface, but his body was never recovered.

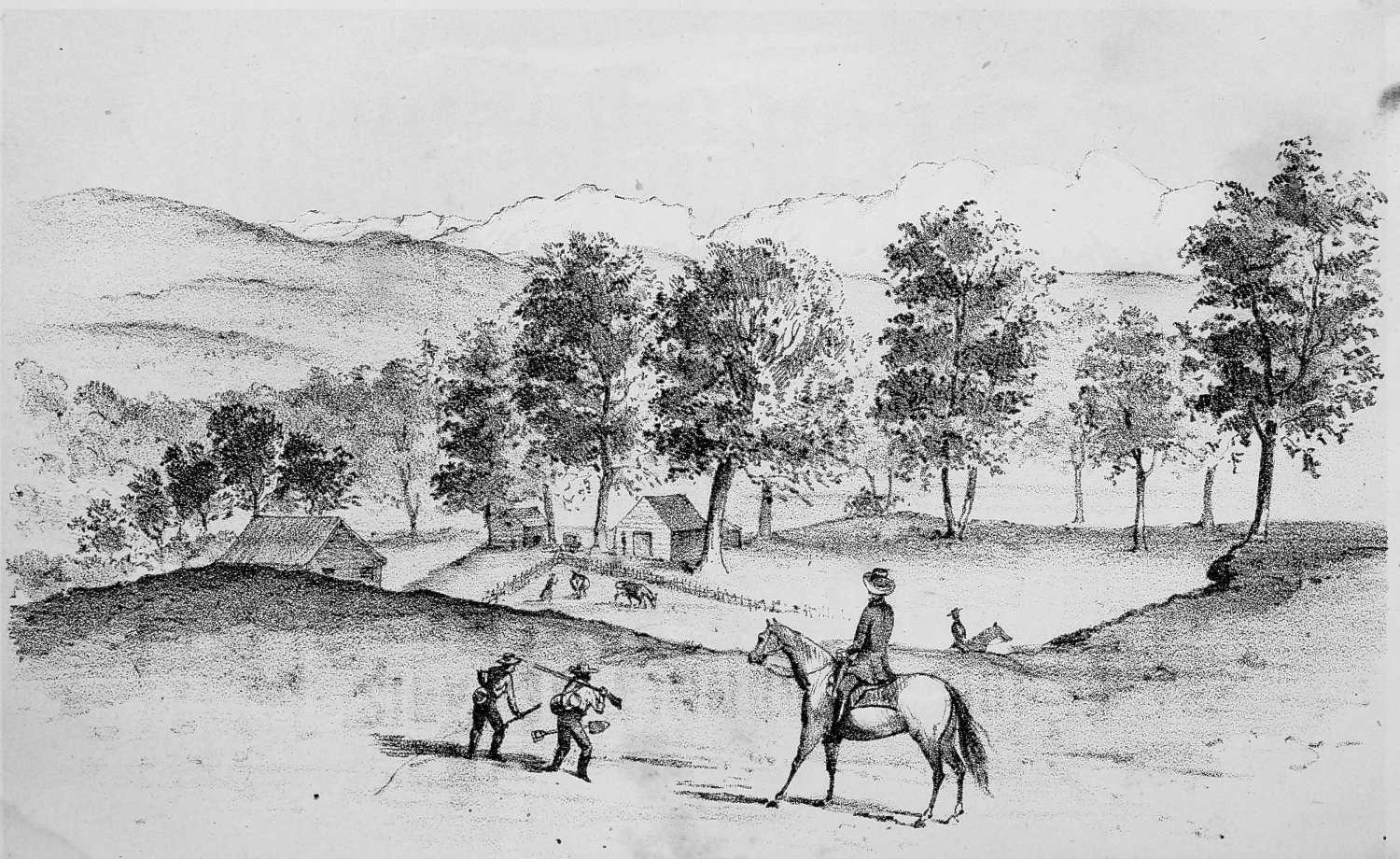

There was, at this time, no means of conveyance from Panama to San Francisco, and people preferred remaining, and consuming their provisions in Gorgona, to paying exorbitant prices to have it transported to Panama. After remaining some days I purchased a horse, and started for Panama, twenty-five miles distant.

It is a pleasant ride across, being a succession of mountains and valleys, each valley containing a spring-brook of the purest water. Two miles out of Gorgona you enter a mule path running through a dense forest, the branches interchanging overhead, forming an arbor sufficiently dense to exclude the sun. You sometimes pass through gullies in the side of the mountain, sufficiently wide at the bottom to admit the mule and his rider, and looking up, you find yourself in a chasm with perpendicular sides, twenty feet in depth, into which the sun has never shone. Here, as in all Spanish countries, are numerous crosses, marking the resting-place of the assassin’s victim. When within three miles, the country opens, disclosing to the view the towers of the cathedral, indicating the location of Panama. The balance of the road is paved with cobble stones, the work of convicts, who are brought out in chain-gangs. One mile out, you cross the national bridge, a stone structure of one arch; here is also an extensive missionary establishment, now in ruins. When within half a mile of the wall of the city, you pass a stone tower, surmounted by a cross. You are now in the suburbs of the city. The street is paved, and on either side are ruins, some of considerable extent, having been costly residences, with highly cultivated gardens attached. You pass a plaza, on one side of which is an extensive church. You now enter between two walls, which gradually increase in height, as you approach the gate, until, crossing a deep moat which surrounds the city, they are joined to the main wall.

On entering the gate the first thing that presents itself is a chapel, where you are expected to return thanks for your safe arrival. I rode through, put my horse in the court-yard of the

“Washington House,” took supper, surveyed the town, and retired. At about three in the morning, I was aroused by a strange noise. On going to the window I saw a procession of nuns and priests passing through the street, escorted by a band of music. They presented a strange appearance. The priests were dressed in black robes and tights, wearing black hats with broad brims, rolled up and fastened to the crown; the nuns, with white scarfs passing over the head and sweeping the round, each carried a lighted taper, presenting the appearance of a procession of ghosts. They would all join in chanting some wild air, when the band would play the chorus. Nothing could be more impressive than such a scene as this. Aroused from sleep at the dead of night, by such wild strains, uttered in such impassioned tones, as if pleading for mercy at the very gates of despair. They seemed like doomed spirits, wandering about without a guiding star, under the ban of excommunication.

I rose early in the morning, bathed in the Pacific, and after breakfast mounted for Gorgona, where I arrived in the evening. I went to a rancho, half a mile distant, for sugar-cane for my horse. I was waited upon by the proprietress who accompanied me to the cane-field, and used the machet with her own hands. After cutting a supply for the horse, she presented me with a piece for my own use, which I found extremely palatable. This lady is one of the most extensive landholders in New Grenada, and one of the most wealthy. She lived in a thatched hovel, the sides entirely open, with the earth for a floor. Her husband was entirely naked, and seemed to devote his attention to the care of the children, of whom there were not less than a dozen, all dressed like “Pa.” She dressed in “Bloomer,” i. e., she wore a half-yard of linen, and a palm-leaf hat. My horse was stolen during the night. I went to the Alcalde next morning, offered him $5 reward, and before night I was obliged to invest another real in sugar-cane for my worthy animal. Money here is a much more effectual searcher than eyes, particularly for stolen horses.

After remaining a few days I again started for Panama. It was after noon, and after riding some distance my horse was taken sick. I stopped until evening, when I again mounted, but was soon obliged to dismount and prepare for spending the{30} night in the woods. It was quite dark, and as I was taking the saddle off my horse five very suspicious-looking natives came up, and were disposed to be inquisitive. To rid myself of them, I told them I expected a “companiero.” They left with apparent reluctance. After kindling the fire, fearing they might renew their visit, I put caps on my revolver, preparatory to loading it. As I was in the act of so doing my horse startled, looked wildly about, and, in a moment, I heard footsteps approaching. As they drew near, I thought they were in boots, and consequently Americans. I cried out, “Americano?” They immediately called my name. My surprise and pleasure can well be imagined as I recognized the voices of the Dodges, Shultz, Eiswald, and Hush.

After mutual congratulations we prepared supper, and were soon seated around the fire, recalling the incidents of our voyage up the river. The elder Dodge was lying on a trunk near the fire, and late in the evening, as the muleteer was attempting to drive the horses back, one of them took fright, wheeled about, and in attempting to jump over the trunk, his forefeet came in contact with Dodge, knocking him off, and planting his hind feet into his back. We were struck with horror, supposing him dead, but after straightening him up, and washing his face and head, he was able to speak. He was still in a critical condition, and we were obliged to attend him during the night. The next morning, after a long hunt for our horses, we rode a short distance to an American tent, and leaving the Dodges and company, I rode on to Panama. The next day Mr. Dodge arrived, in a very feeble state of health, but eventually recovered.

In a few days I returned to Grorgona, and sold the “Minerva.” She was drawn up into town, inverted, making the roof of the “United States Hotel,” the first framed building erected in Gorgona. On my way back to Panama, as I had got about half way through, I was surprised at meeting Mr. Hush. He informed me that he did not think Panama a healthy place, and that he was on his return to the States. He sat on his horse with a good deal of ease, his feet appearing to have on their best behavior. He could not get them into the stirrups, still they appeared to go quietly along by the sides of the horse. Why he thought Panama unhealthy, was a mystery to some. I am{31} not prepared to say that his party ever insinuated anything of the kind. In the after part of the day, I was over taken by Maj. Sewall, lady, and suite. They descended the mountain, and as they were about to cross the brook at its base, Capt. Tyler, one of the party, dismounted, and as he was crossing over, a double-barrelled gun accidentally discharged within four feet of him, he receiving the entire charge in his hip. This caused the greatest consternation. The Capt. having Mrs. Sewall’s child in his arms, it was feared it had received a part of the charge. This fortunately did not prove to be the case. The Capt. was immediately stripped, the wound dressed, and through the kind assistance of the Engineering corps of the Panama Railroad, who were encamped near, a litter was constructed, and he was taken through to Panama on the shoulders of the natives.

I was detained until the sun had disappeared behind the mountain, and it was with some difficulty my horse found his way. I ascended the next mountain, and in attempting to descend, lost my way. I dismounted, and after a long search, found the gully through which it was necessary to pass. There was not a ray of light—it was the very blackness of darkness—and on arriving at the end of the gully, I was again obliged to dismount, and after groping about for half an hour, found what I presumed to be the path. My horse was of a different opinion. The matter was discussed—I carried the “point.” After riding a short distance, he stopped, and on examining the path, I found that it dropped abruptly into a chasm twenty feet in depth. My horse now refused to move in any direction, which left no alternative but to encamp. I succeeded in finding canebrake, which I cut for him, and spreading out my India rubber blanket, using my saddle as a pillow, I stretched myself out for the night. A most profound stillness reigned through the forest. All nature seemed to be hushed in sleep. Occasionally a limb would crack, struggling with the weight of its own foliage, and once, not far distant, a gigantic tree, a patriarch of the forest, came thundering to the ground. A slight breeze passed mournfully by, as if sighing its requiem, and again all was still.

This solemnity was painfully ominous. There appeared to be something foreboding in the very solemnity that reigned. If{32} I ever realized the companionship of a horse, it was on this occasion; and I believe it was reciprocal, for when I would speak to him, he would neigh, and seem to say, “I love you, too.”

In the middle of the night I was attracted by the barking of a monkey, which very much resembled that of a dog. This called to mind home, and caused many a bright fancy to flit through my imagination. I was soon, however, drawn from my reverie by the low muttering of distant thunder, portending an approaching deluge, which, in this climate, invariably follows. It grew near, and was accompanied by the most vivid flashes of lightning. This revealed to me my situation. I was on the side of the mountain, at the base of an almost perpendicular elevation, which was furrowed by deep gullies, giving fearful token of approaching devastation. Very near was a gigantic palm-tree, the earth on the lower side of which appeared to have been protected by it. I removed my saddle and blanket, and my horse, asking to accompany me, was tied near. The lightning grew more vivid, and the thunder, as peal succeeded peal, caused the very mountains to quake. The clouds, coming in contact with the peaks, instantaneously discharged the deluge, which, rushing down, carried devastation in its track. The sight was most terrific. By the incessant flashes I could see the torrents rushing down, chafing, foaming, and lashing the sides of the mountains, as if the furies were trying to vie with each other in madness. In an hour the rage of the elements had ceased, the thunder muttering a last adieu, fell back to his hiding place, and again all was still. My blanket had protected me from the rain; and if I am ever on a committee to award premiums for valuable inventions, Mr. Goodyear will be at the head of my list. I slept until morning, when I had an opportunity of viewing the devastation of the night. I mounted, and at 10 o’clock arrived at Panama.

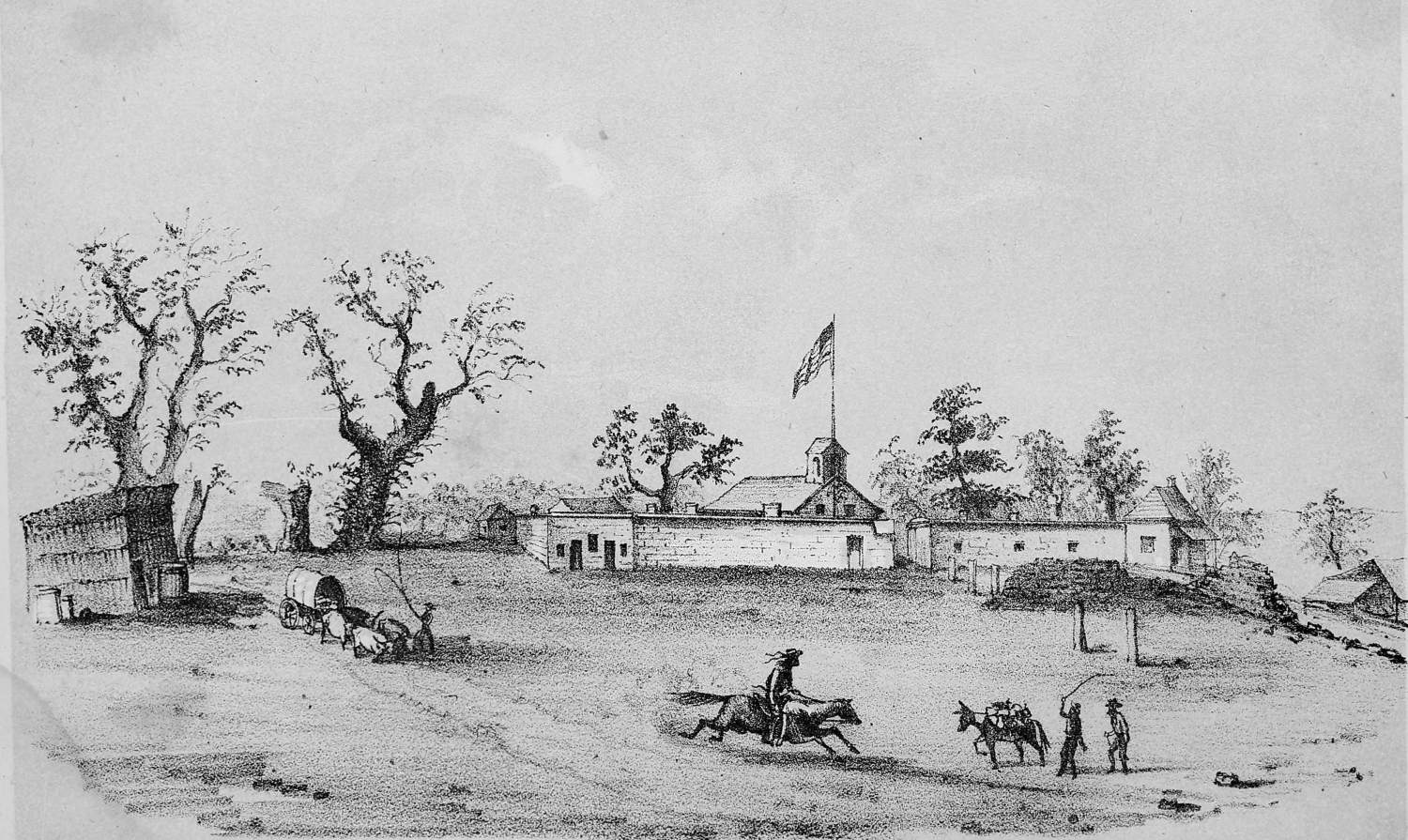

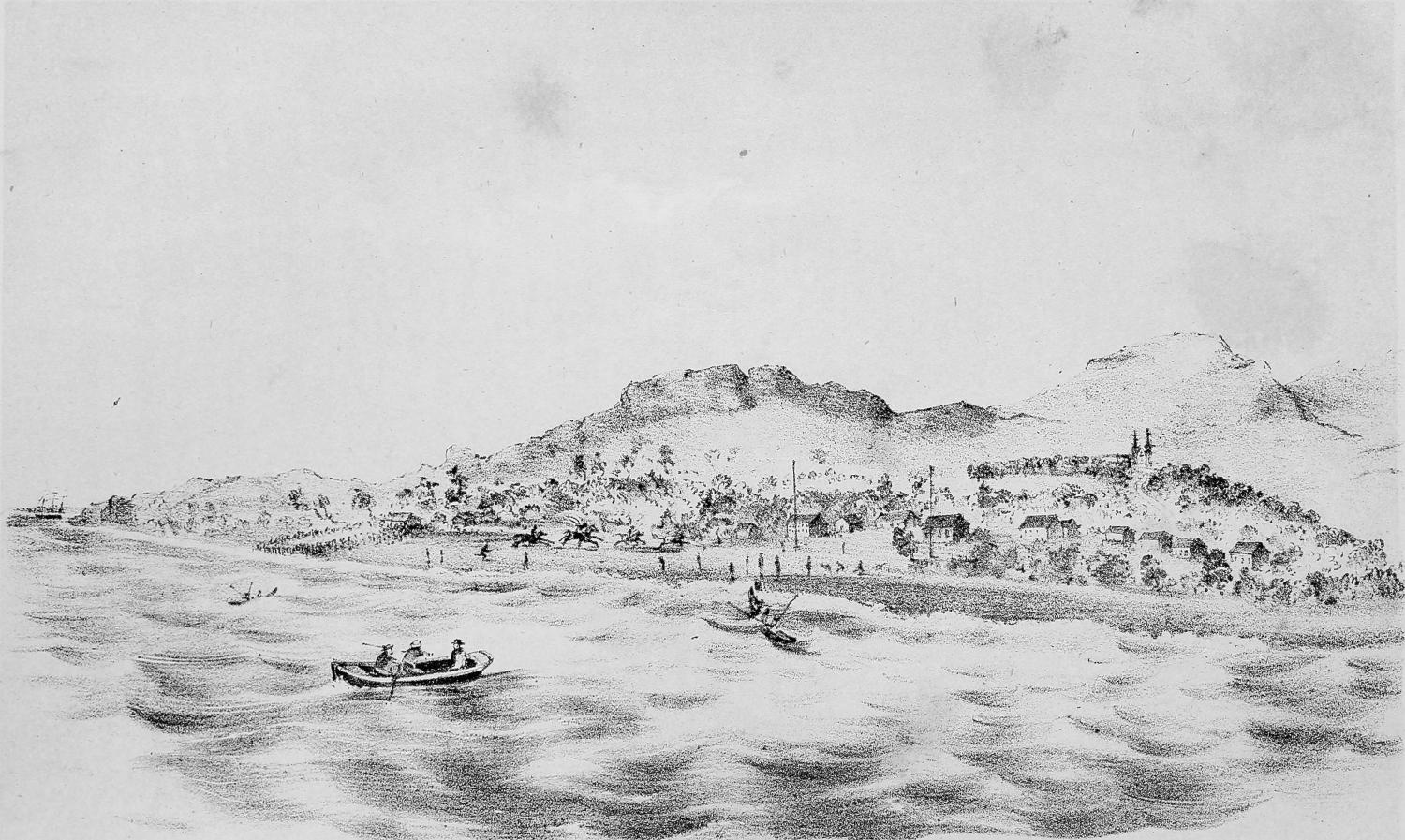

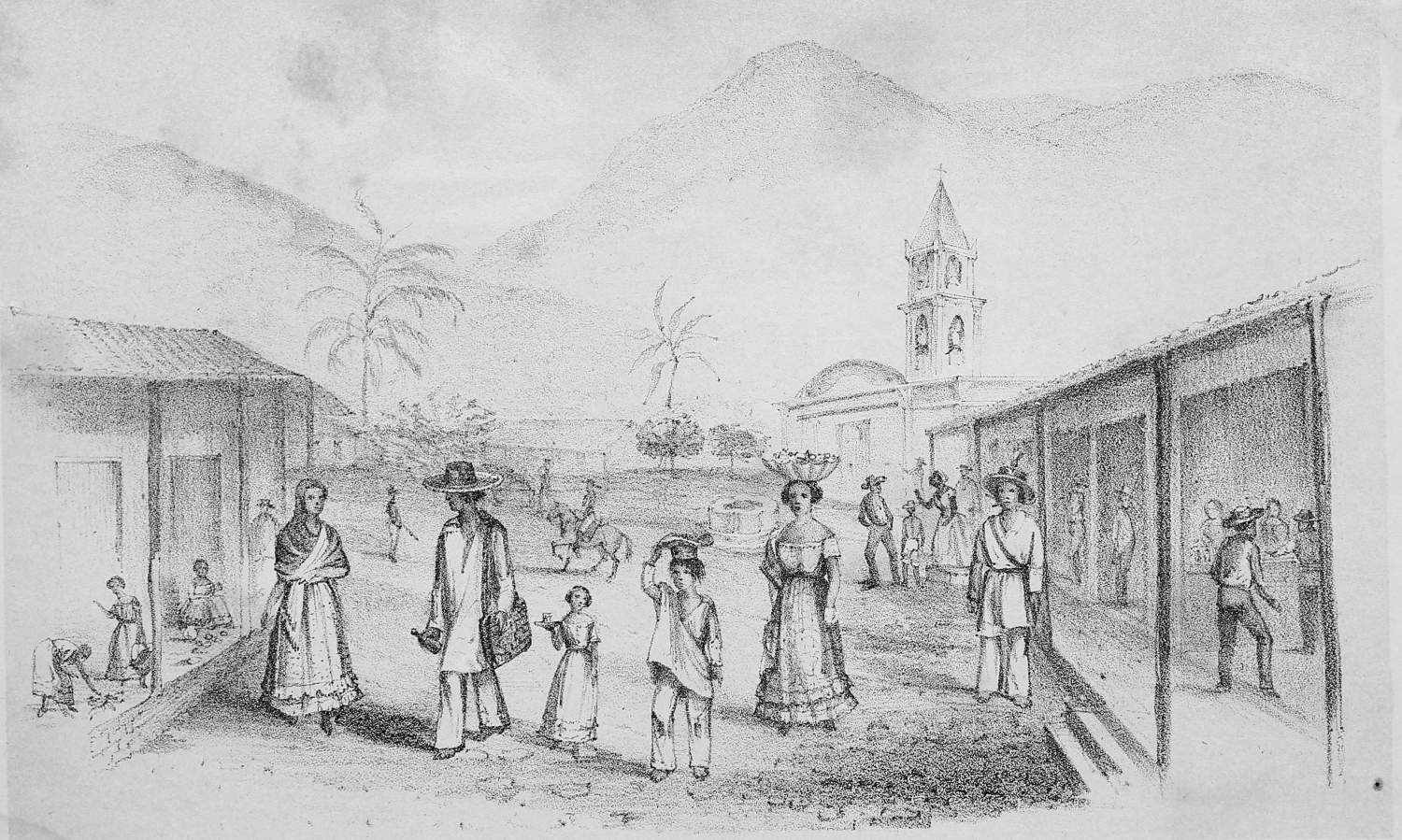

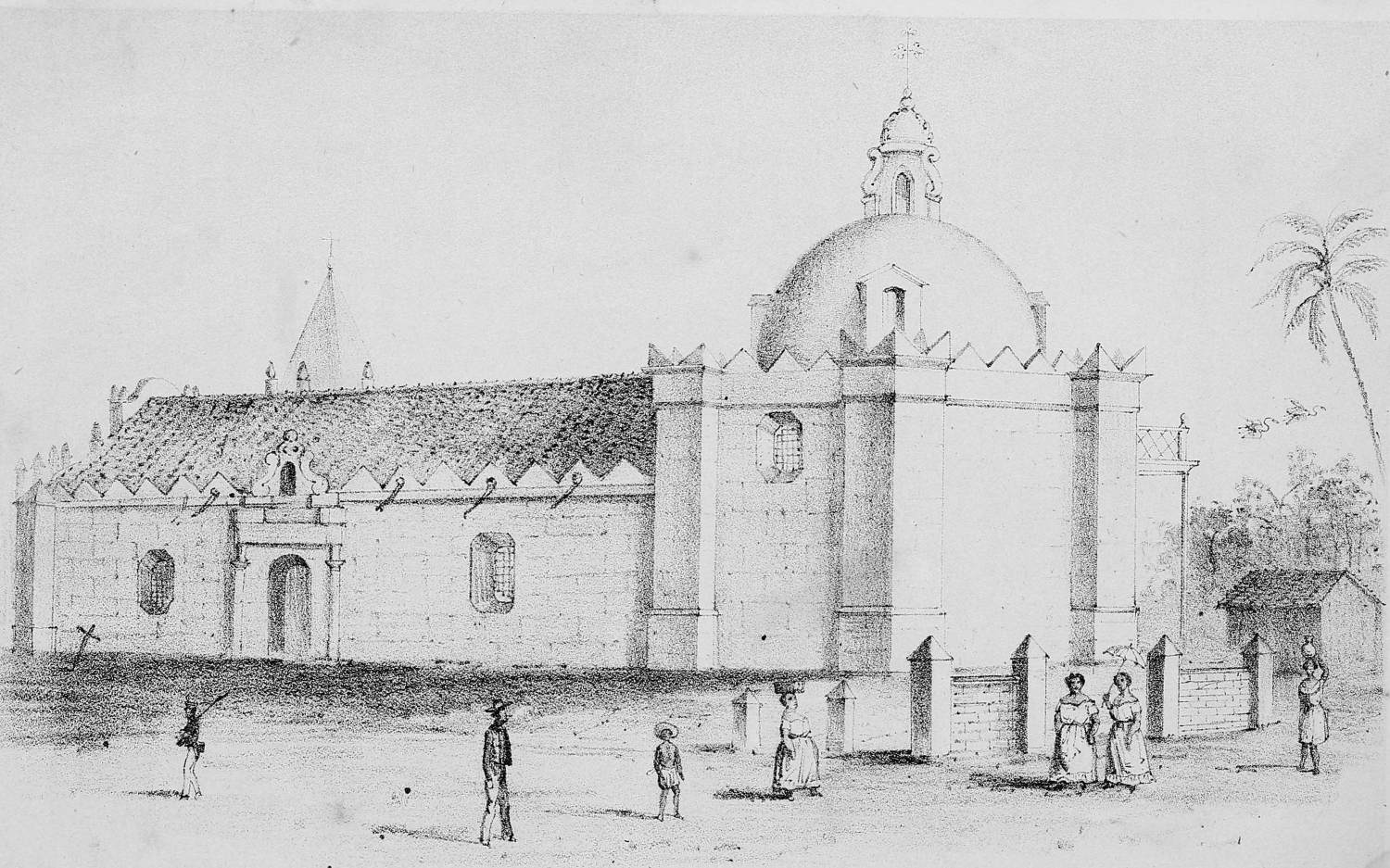

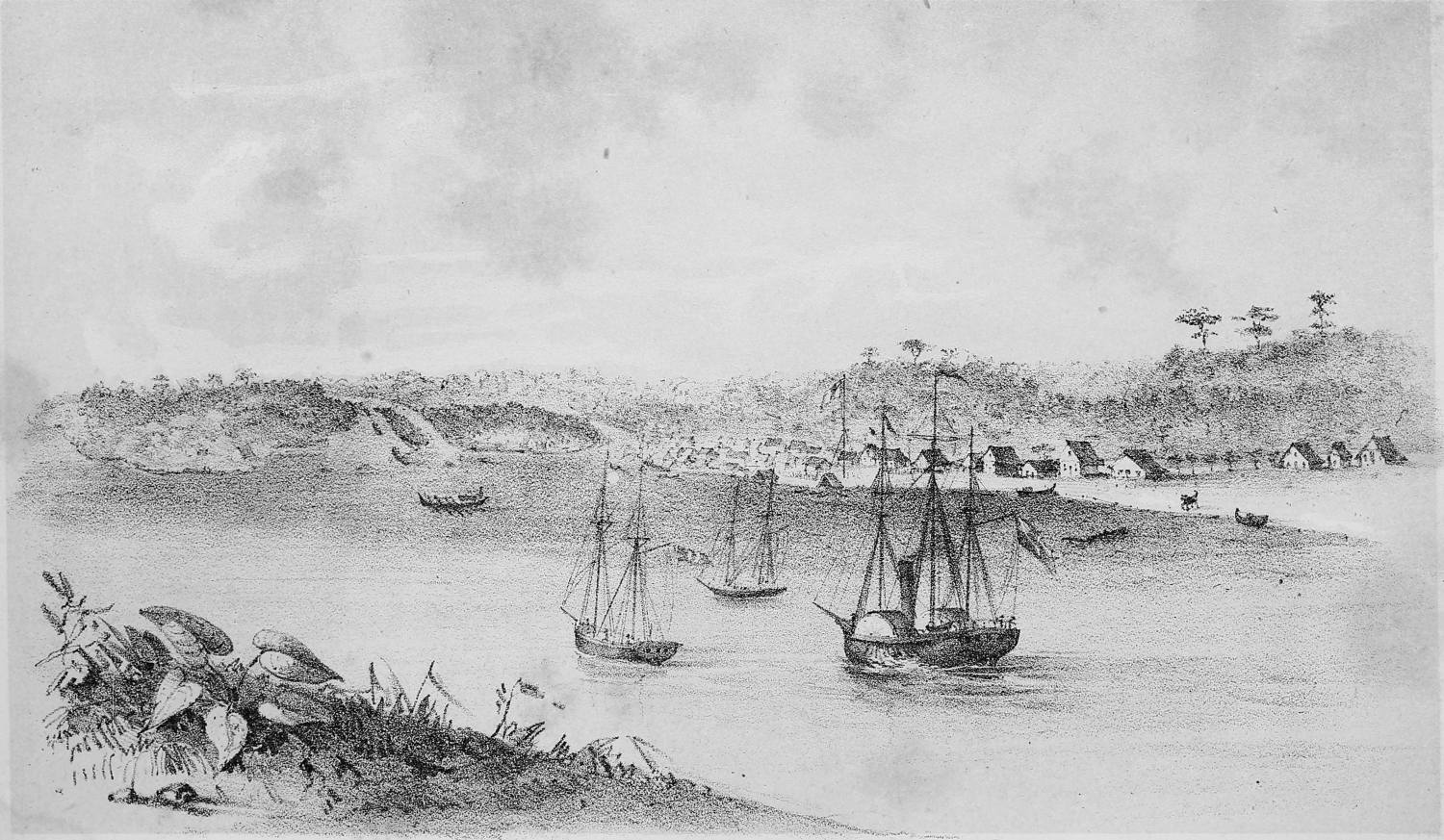

Panama, under the Spanish dominion, was a city of twelve thousand inhabitants, and was the commercial mart of the Pacific. The old city having been destroyed by buccaneers, the present site was selected. The military strength of the city is a true index to the state of the country at the time of its construction; and its present condition a lamentable commentary on the ruthless spirit that has pervaded the countries of South America. The number and extent of the churches and monasteries are a monument to the indomitable zeal and perseverance for which the Catholic Church has been justly celebrated. Old Panama is seven miles distant. An ivy-grown tower is all that remains to mark the spot. The city is inclosed by a wall of much strength, outside of which is a deep moat. It has one main and one side entrance by land, and several on the water-side. The base of the wall on the water-side is washed by the ocean at flood tide, but at the ebb the water recedes a mile, leaving the rocks quite bare. There was formerly a long line of fortifications, but at present the guns are dismounted, excepting on an elbow of the wall, called the “battery.” (See Plate.) In the centre of the town is the main plaza, fronting which is the cathedral, the government house, and the prison. (See Plate.) Here is seen a “Padre,” walking with a señorita; an “hombre,” mounted on a donkey, with a large stone jar on each side, from which he serves his customers with water; a “chain-gang” of prisoners, carrying bales of carna, guarded by a barefooted soldier. And still further to the left is a sentinel watching the prison. I will here state, that most of the Panama hats that are made here, are manufactured in this prison.{34}

The principal avenues, running parallel, are “Calle San Juan de Dio,” “Calle de Merced,” and “Calle de Obispo.” There are numerous extensive churches, the principal one being the cathedral. This is a magnificent structure, and of colossal dimensions. In the end fronting the plaza are niches, in which are life-size statues of the twelve Apostles, of marble. It has two towers, the upper sections of which are finished with pearl. The interior was furnished without regard to expense. It is now somewhat dilapidated, but still has a fine organ. The convent, “La Mugher,” is an extensive edifice, being 300 feet in length. The roof of most parts has fallen in, and the walls are fast falling to decay. The only tenant is a colored woman who has a hammock slung in the main entrance. She has converted the convent into a stable, charging a real a night for a horse or mule—they board themselves; they, however, have the privilege of selecting their own apartments. It encloses a large court, in which there are two immense wells, and numerous fig, and other fruit trees. There is a tower still standing on one end of the building, without roof or window; it has, however, several bells still hanging. The convent of “San Francisco,” is also an extensive structure, in a dilapidated state; one part of it is still tenanted by nuns. It has a tower with bells still hanging. These buildings, as well as all the buildings of Panama, are infested by innumerable lizards, a peculiarity of the city that first strikes the stranger. They are harmless, but to one unaccustomed to seeing them, are an unpleasant sight.

The people here, as in all catholic countries, are very attentive to religious rites and ceremonies, and almost every day of the week is ushered in by the ringing of church and convent bells. The ringing is constant during the day; and people are seen passing to and from church, the more wealthy classes accompanied by their servants, bearing mats, upon which they kneel on their arrival. Almost every day is a saint’s day, when all business is suspended to attend its celebration.

Good Friday is the most important on the calendar. All business is suspended, all attend church during the day, and at night they congregate en masse in the plaza in front of one of the churches outside the walls. Inside the church, held by a native in Turkish costume, is an ass, mounted on which is a

life-size wax figure of the Saviour. There are also life-size figures of Mary, St. Peter, St. Paul, and St. John, each mounted on a car, and each car illuminated by one hundred tapers, which are set in candelabras of silver, and borne by sixteen men. Incense is burned, a chant is sung accompanied by the organ, and at the ringing of a small bell, all rise from their knees; the bell rings again, and the procession moves. The ass is first led out, followed by the figures of Mary and the Apostles in order; next, the band of music and the procession follows, which is illuminated by innumerable tapers. They move toward the main gate, all joining in the chant. The passage of the first of the procession through the gate, is announced by the simultaneous discharge of rockets which illumine the very heavens. The discharging of rockets is continued, and, after passing through the principal streets, they return to the church and deposit the images. They again return to the city, seize an effigy of Judas Iscariot and after hanging it up by the neck, cut it down and burn it. The celebration closes with the usual night procession of nuns and priests. These celebrations and processions are conducted with the greatest solemnity, the people all engaging in them as if they thought them indispensable to salvation.

The priests are quite ultra in their dress, wearing a black silk gown, falling below the knee, black silk tights, patent-leather shoes, fastened with immense silver buckles, a black hat, the brim of the most ungovernable dimensions, rolled up at the sides and fastened on the top of the crown. Their zeal in religion is equalled only by their passion for gaming and cock-fighting. It appears strange to see men of their holy calling enter the ring with a cock under each arm, gafted for the sanguinary conflict, and, when the result is doubtful, enter into a most unharmonious wrangle, with the faithful under their charge.

The citizens of Panama are composed of all grades of color, from the pure Sambo, (former slaves or their descendants,) to the pure Castilian. The distinctive lines of society are not very tightly drawn. At the fandangoes all colors are represented, and a descendant of Spain will select, as a partner, one of the deepest dye. In this hot climate the waltz or quadrille soon throws all parties into a most profuse perspiration, which causes that other{36} characteristic of the African race to manifest itself. I would recommend my American friends to select partners of the lighter color, as I am not prepared to say the odor is altogether pleasant. The order of the evening is to fill the floor; the music and dance commence; when a gentleman gives out, another takes his partner, and so on, until it is time for refreshments. The ladies never tire.

BAY OF PANAMA—ISLANDS—SOLDIERS—ARRIVAL OF $1,000,000 IN GOLD AND SILVER—A CONDUCTA—“BUNGOES” “UP” FOR CALIFORNIA—WALL STREET REPRESENTED—SAIL FOR SAN FRANCISCO—CHIMBORAZO—CROSS THE EQUATOR—A CALM—A DEATH AT SEA.

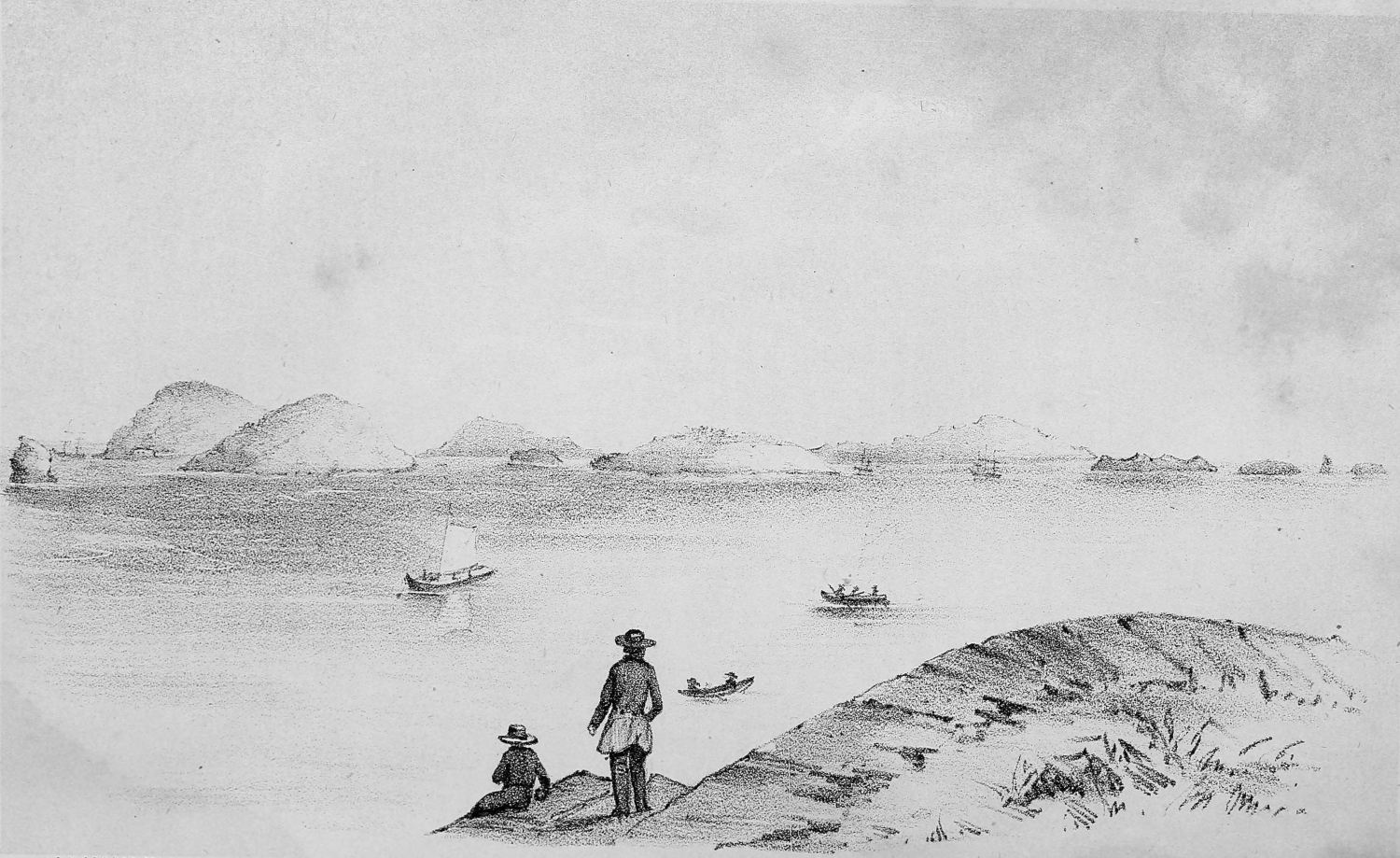

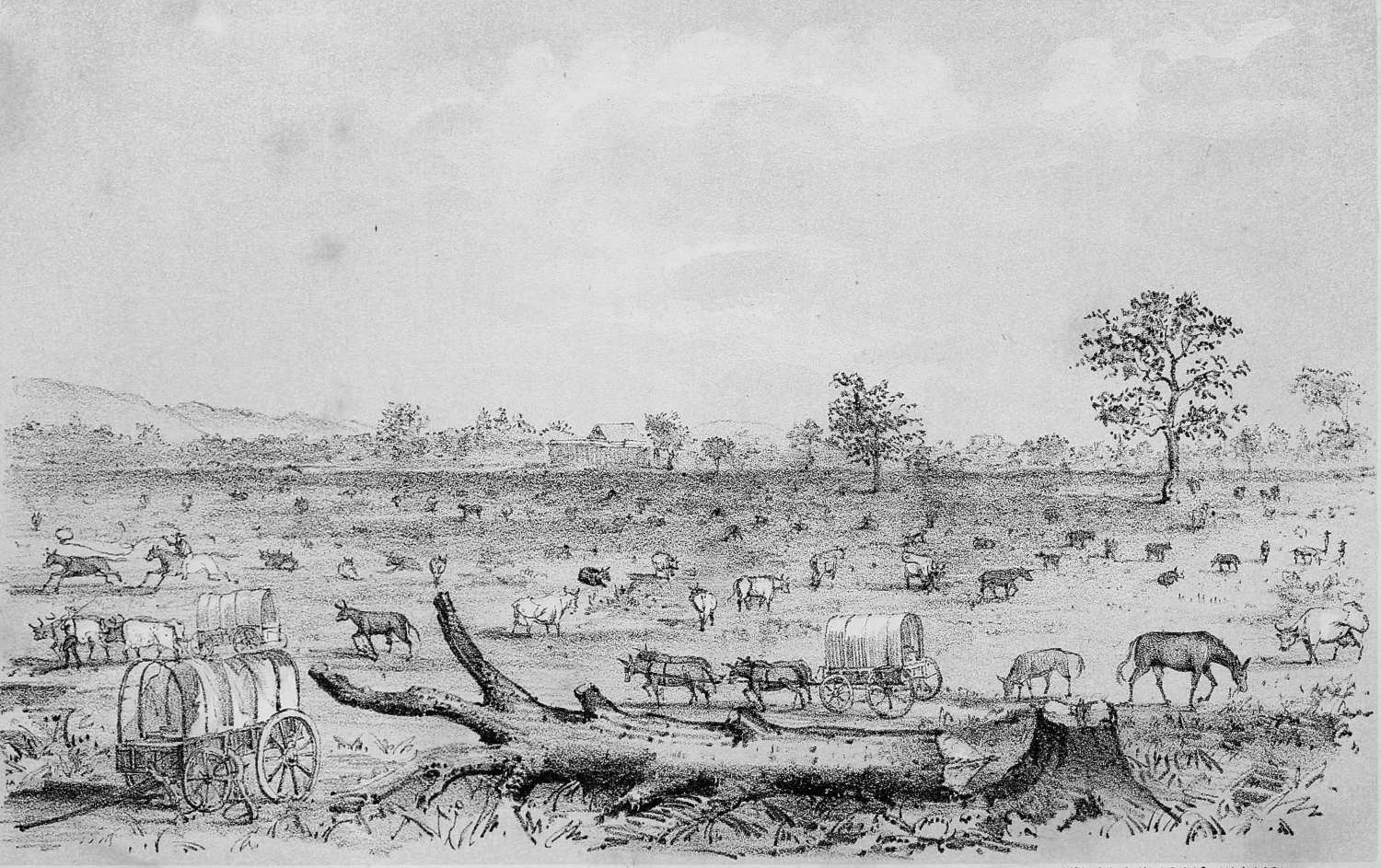

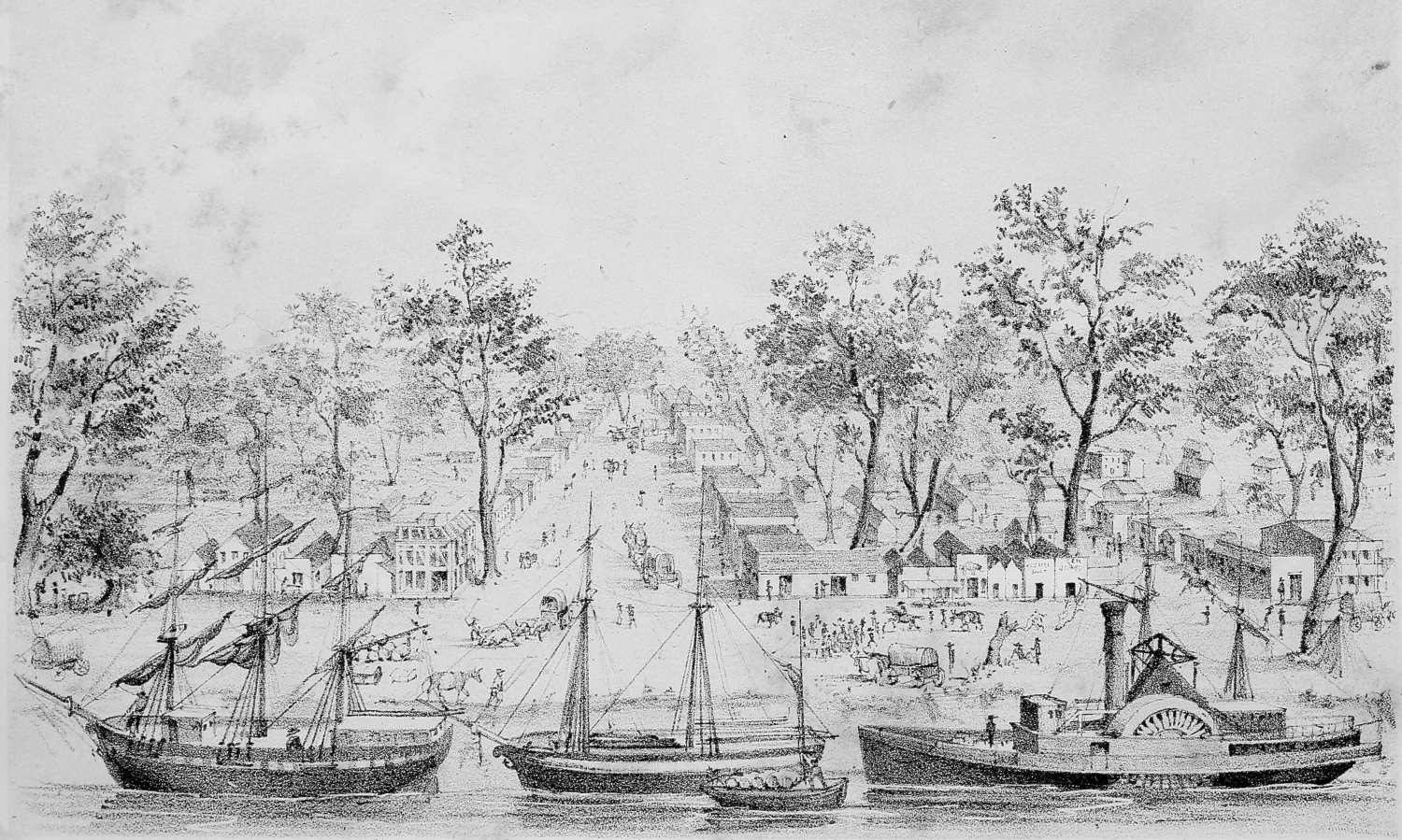

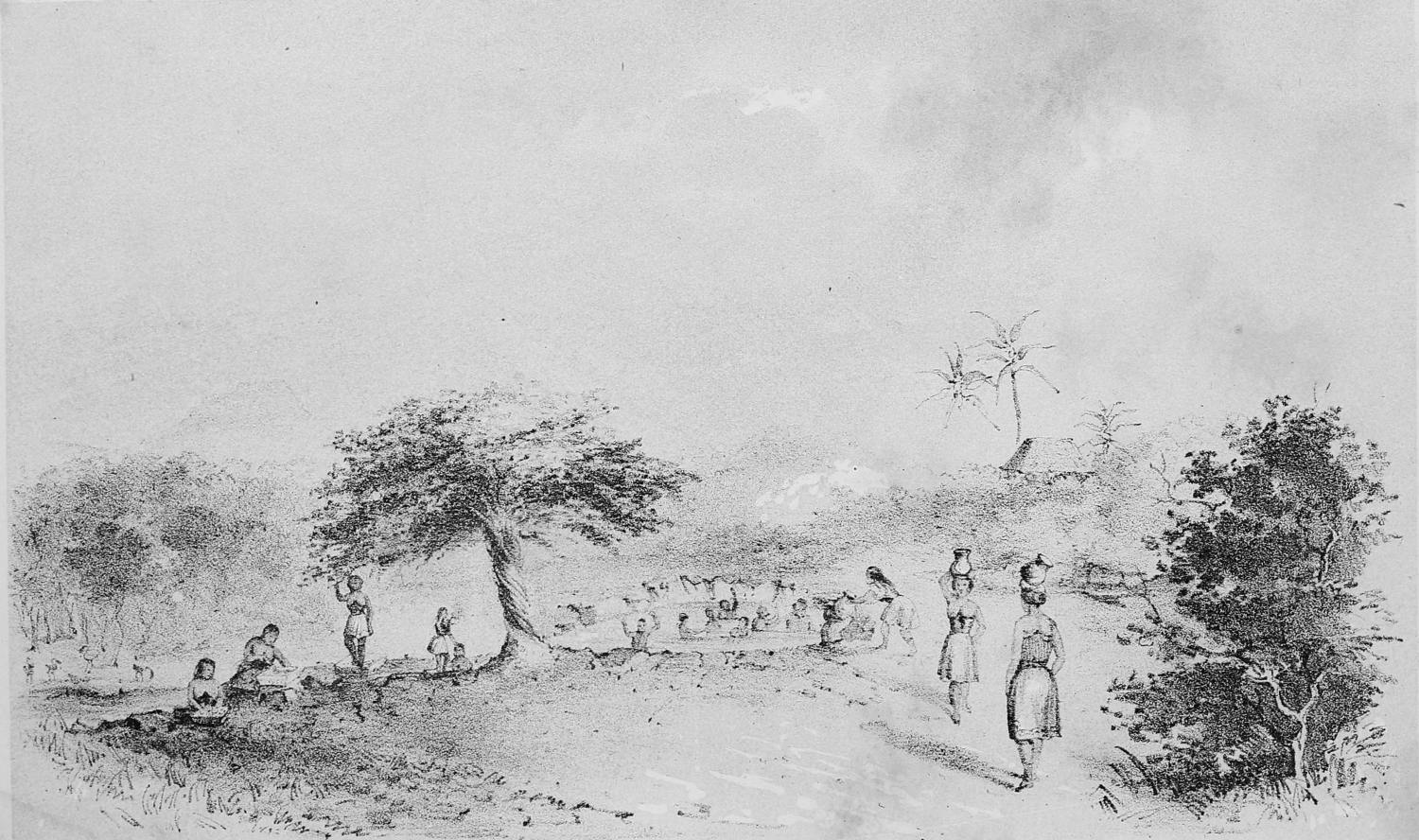

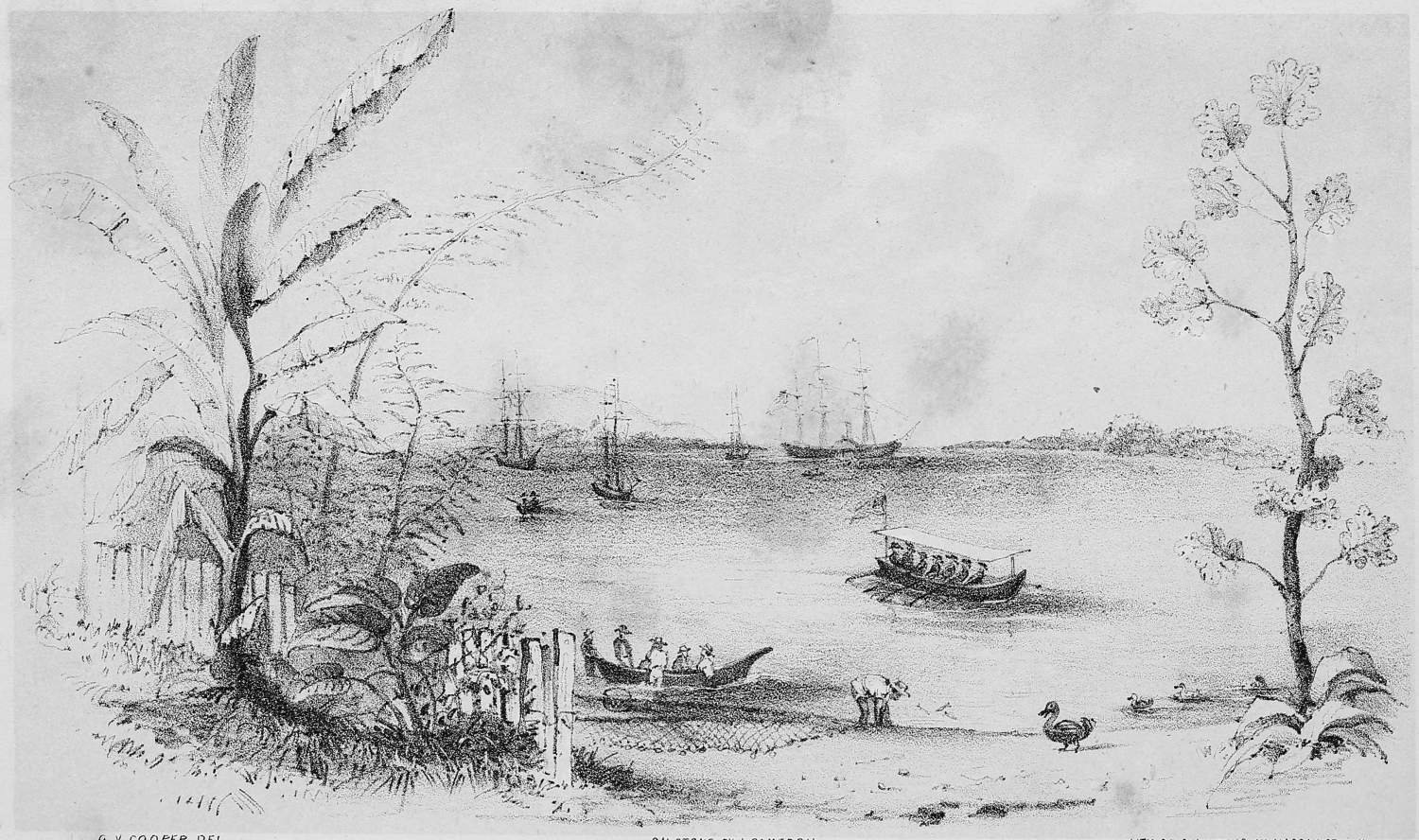

In the bay of Panama (called the “Pearl Archipelago,” from the numerous pearls obtained in its waters,) there are innumerable islands, all of great fertility, supplying the city with vegetables, tropical fruits, eggs, fowls, &c. (See Plate.) It is, from these islands vessels are supplied with provisions and water, the latter being obtained at Toboga, one of the largest of the group. A more enchanting scene than is presented from the higher points of these islands, cannot be imagined. The bay as placid as a mirror, Panama in full view, with mountains rising in the background. Looking along down the coast of South America, you see a succession of lofty mountains, some by their conical peaks proclaiming their volcanic origin, some still clouded in smoke, giving token of the fierce struggle that is going on within. Still farther to the right the bay opens into the broad Pacific; that little ripple that is now running out, will go on gathering strength, until it breaks upon the shores of the “Celestial Empire.” Still farther to the right, a tower, shrouded in ivy, seems weeping over the tomb of a city.

In the background mountain succeeds mountain, until the last is buried in clouds. Ships and steamers are lying quietly at anchor; numerous islands are blooming at your feet, clothed with tropical fruits, growing and ripening spontaneously. Nature reigns supreme, the hand of man has not marred her perfection; if his rude habitation is sometimes seen, it is nestling quietly in the bosom of some grove planted by the hand of Nature, interlaced by vines, their tendrils entwining, forming an arbor over his head, and presenting fruit and wine at{38} his door. It seems a paradise. It would seem that man might be happy here. He has not to care for to-morrow, but to partake of the bounties of nature as they are presented. But, alas! man spends his life struggling for the thousand phantasies his own diseased imagination has engendered, while nature has placed happiness within his reach, and only asks contentment on the part of the recipient of her bounties.

The markets of Panama, as well as the retail trade in other departments, are under the supervision of females. They are generally well supplied with every variety of fruit from the islands, together with eggs, fowls, &c. The beef and pork are sold by the yard. Beef is cut in thin strips and dried in the sun; this is packed or sewed up in skins, and is an article of export from many of the South American Republics. The inhabitants have a great passion for “fighting-cocks.” There is not a house that is not furnished with from one to a dozen. They generally occupy the best aparments, and, on entering a house, your first salutation is from “chanticleer,” he having a strange propensity to do the loud talking. They also venerate the turkey-buzzard, with which the city is sometimes clouded. They are the carrion bird of the south, and no doubt good in their place, but the most loathsome of all the feathered tribe.

The citizens of Panama, as well as of other tropical countries, have the happy faculty of devoting most of their time to the pursuit of pleasure, i.e., they divide time between business and pleasure, giving to the latter a great predominance. Before the innovations made by “los Americanos,” stores were open from 9 to 10 A.M., and 4 to 5 P.M., the balance of the day was spent in smoking, drinking coffee, chocolate, or cocoa, gambling, cock-fighting, attending church, or wooing sleep in hammocks. The city is generally healthy, yet at some seasons of the year, is subject to fevers of a malignant type. It has been visited several times by that scourge the cholera, which swept off many of its inhabitants, and, at one time, seemed destined to depopulate the country. The priests clad themselves in sackcloth, and devoted every moment to the rites of the church, burning incense and invoking the patron saint of the city to stay the ravages of the disease. The vaults in which the dead{39} are deposited, are a succession of arches in mason-work, resembling large ovens. When one of these is full it is closed up, and the adjoining one filled.

The city has a small garrison of soldiers, their only duty being to guard the prison, and conduct prisoners out in chain-gangs to labor, paving the streets, repairing the walls, carrying goods, &c. A gang will be seen in front of the cathedral, in the accompanying plate. The appearance of the under-officers, is ludicrous in the extreme. They are seen parading the streets with an air of authority, in full uniform, and barefooted.

Soon after my arrival at Panama, one of the British steamers came in from Valparaiso with $1,000,000 in gold and silver. This was deposited in front of the custom-house, and guarded during the night by soldiers; and, in the morning, packed on mules, preparatory to crossing the Isthmus. It required thirty-nine mules to effect the transportation. A detachment of nine first started, driven by a single soldier, armed with a musket, and barefooted. The second, third, and fourth detachments started at intervals of half an hour, each guarded like the first. The mules were driven in droves, without bridle or halter. The route being through an unbroken forest of twenty-five miles, it would seem a very easy matter to rob the “conducta.” But, strange to say, although $1,000,000 per month, for several years, has passed over the route, no such attempt has ever been made. In the immediate vicinity, and overlooking the city, is a mountain called “Cerro Lancon,” which was once fortified by an invading foe, from which the city was bombarded and taken. On the summit a staff is now seen, from which the stars and stripes float proudly in the breeze. This was erected by the Panama Railroad Company, to point out, during the survey, the location of the city.

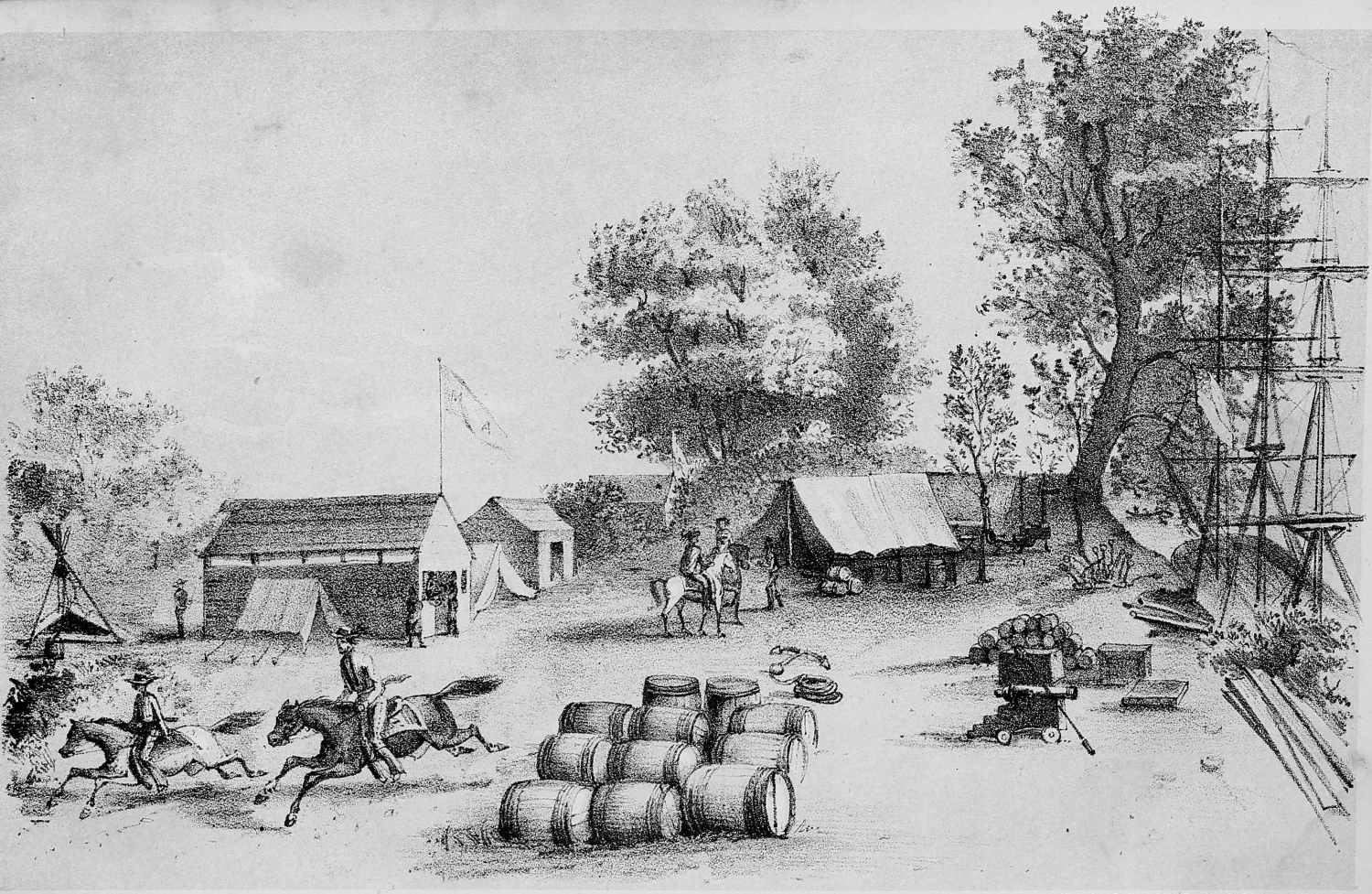

Great anxiety was felt by the Americans at Panama to proceed on to California. The sun had passed overhead, and was settling in the north, indicating the approach of the rainy season. Many were sick of the fever, many had died, which added to the general anxiety. Many had procured steamer tickets before leaving home. The steamers had passed down to San Francisco, been deserted by their crews, and were unable to return, and there were no seaworthy vessels in port. The indomitable go-a-head-ativeness of the Yankee nation could not{40} remain dormant, and soon several “bungoes” were “up” for California. Schooners of from thirteen to twenty-five tons, that had been abandoned as worthless, were soon galvanized, by pen and type, into “the new and fast sailing schooner.” These were immediately filled up at from $200 to $300 per ticket, passengers finding themselves. In the anxiety to get off, a party purchased an iron boat on the Chagres River, carried it across to Panama on their shoulders, fitted it out, and sailed for California. The first “bungo” that sailed, after getting out into the bay some three or four miles, was struck by a slight flaw of wind, dismasted, and obliged to put back for repairs. This caused a very perceptible decline in “bungo” stocks. Many took passage in the British steamer for Valparaiso, in hopes to find conveyance from that port. The passengers of one of “the fast sailing schooners” when going on board, preparatory to sailing, found that the owners, in their zeal to accommodate their countrymen, had sold about three times as many tickets as said vessel would carry. Instead of allowing fourteen square feet to the man, as the law requires, they appear to have taken the exact-dimensions of the passengers, and filled the vessel accordingly. The passengers refused to let the captain weigh anchor, and sent a deputation on shore to demand the return of their money; but lo! the disinterested gentlemen were “non est inventus.” After a long search, they succeeded in finding one of the worthies, and notwithstanding his disinterested efforts in behalf of the public, he was locked up. The captain fearing personal violence, left the vessel privately, and for several days was nowhere to be found. The passengers, however, entered into a compromise with themselves, the first on the list going on board. The mate informed the captain and they were soon under way. The owner, who had been so persecutingly locked up, having formerly been an operator in Wall street, resolved to slight the hospitalities of the city, and took his leave when the barefooted sentinel wasn’t looking.

One circumstance that added much to the annoyance of our detention was, that the letters from our friends were all directed to San Francisco, and were then lying in the letter-bags at Panama, but not accessible to us. I felt this annoyance most sensibly. I would have given almost any price for one word of{41} intelligence from home. On returning one evening from Gorgona I was informed by Mr. Pratt, my room-mate, that a gentleman had called during my absence with a letter. I left the supper table to go in search of him; some one knocked at the door; and imagine my surprise and pleasure as Mr. D. Trembley, an old acquaintance from New York was ushered into the room. He had letters for me dated two months subsequent to my departure. He was accompanied by his brother, and I had the pleasure of making the passage up the Pacific in their company.

The prospect, at this time, of getting passage to California was extremely doubtful, and many returned to the States. During the latter part of April, however, several vessels arrived in port, and were “put up” for San Francisco. I had sent to New York for a steamer ticket—which was due, but there being no steamer in port, and being attacked with the fever, I was advised to leave at the earliest possible moment. I secured passage in the ship “Niantic,” which was to sail on the 1st of May. On the morning of that day bungoes commenced plying between the shore and ship, which was at anchor some five miles out, and at 4 P.M., all the passengers were on board. The captain was still on shore, and there was an intense anxiety manifested. Many had come on board in feeble health; some who had purchased tickets had died on shore; many on board were so feeble that they were not expected to live. I was one of the number; we all felt that getting to sea was our only hope, and all eyes were turned toward shore, fearing the captain might be detained. At half-past five his boat shoved off, when all on board were electrified. As he neared the ship all who were able prepared to greet him, and some, whose lungs had been considered in a feeble and even precarious state, burst out into the most vociferous acclamations. The captain mounted the quarter-deck and sung out, “Heave ahead,” when the clanking of the chain and windlass denoted that our anchor was being drawn from its bed. At half-past six the “Niantic” swung from her moorings, and was headed for the mouth of the “Gulf of Panama.” Again the shouts were deafening. No reasonable politician could have wished a greater display of enthusiasm, and a nominee would consider his election quite{42} certain, whose pretensions were backed up by two hundred and forty pairs of such lungs. We had a light breeze and moored slowly out—the lights of the city gradually settling below the horizon. As we passed the islands an occasional light would appear and immediately vanish. Soon all nature was shrouded in darkness, and with the exception of an occasional creaking of the wheel, and a slight ripple at the prow, everything was still.

In the morning we were running down along the coast of South America, the captain wishing to cross the equator, in order to fall in with the trade winds. We passed along very near the coast, having the Andes constantly in view, some of the peaks towering up, their heads buried in the blue ether of Heaven.