Title: Horse-hoeing husbandry

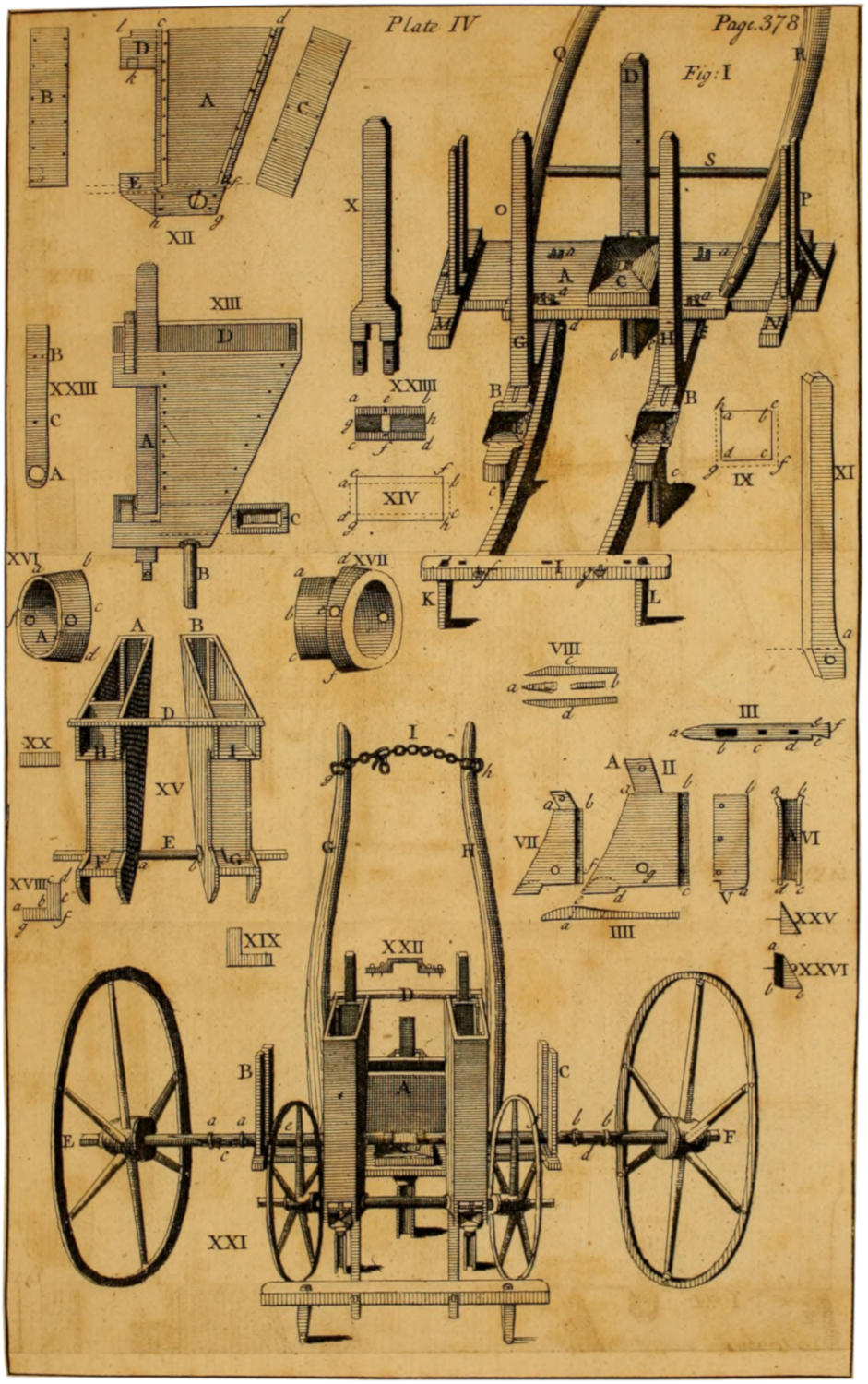

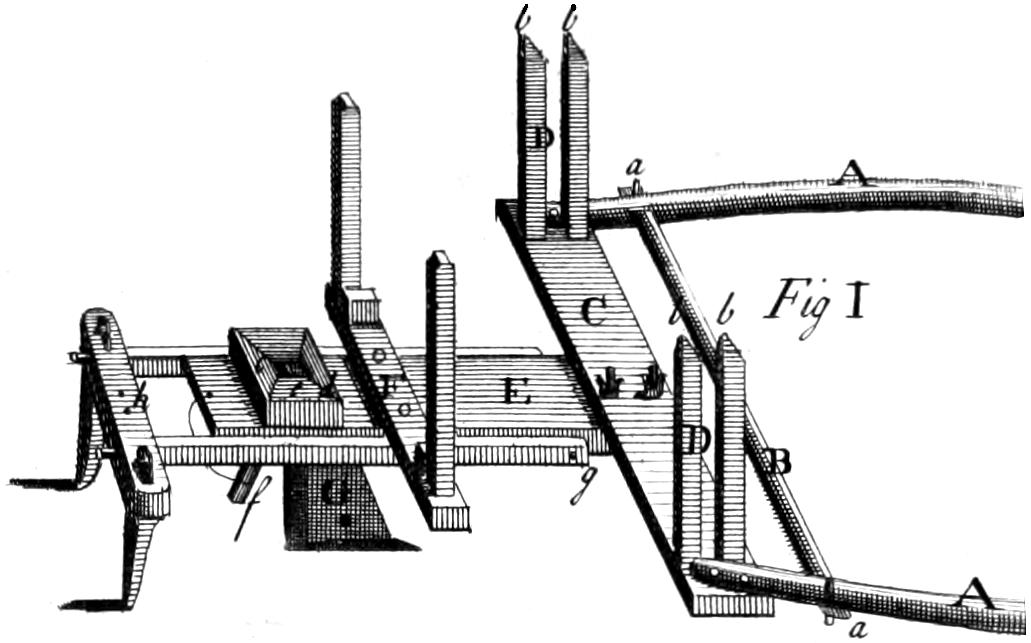

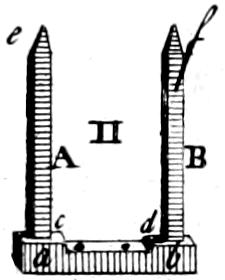

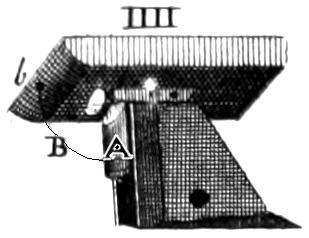

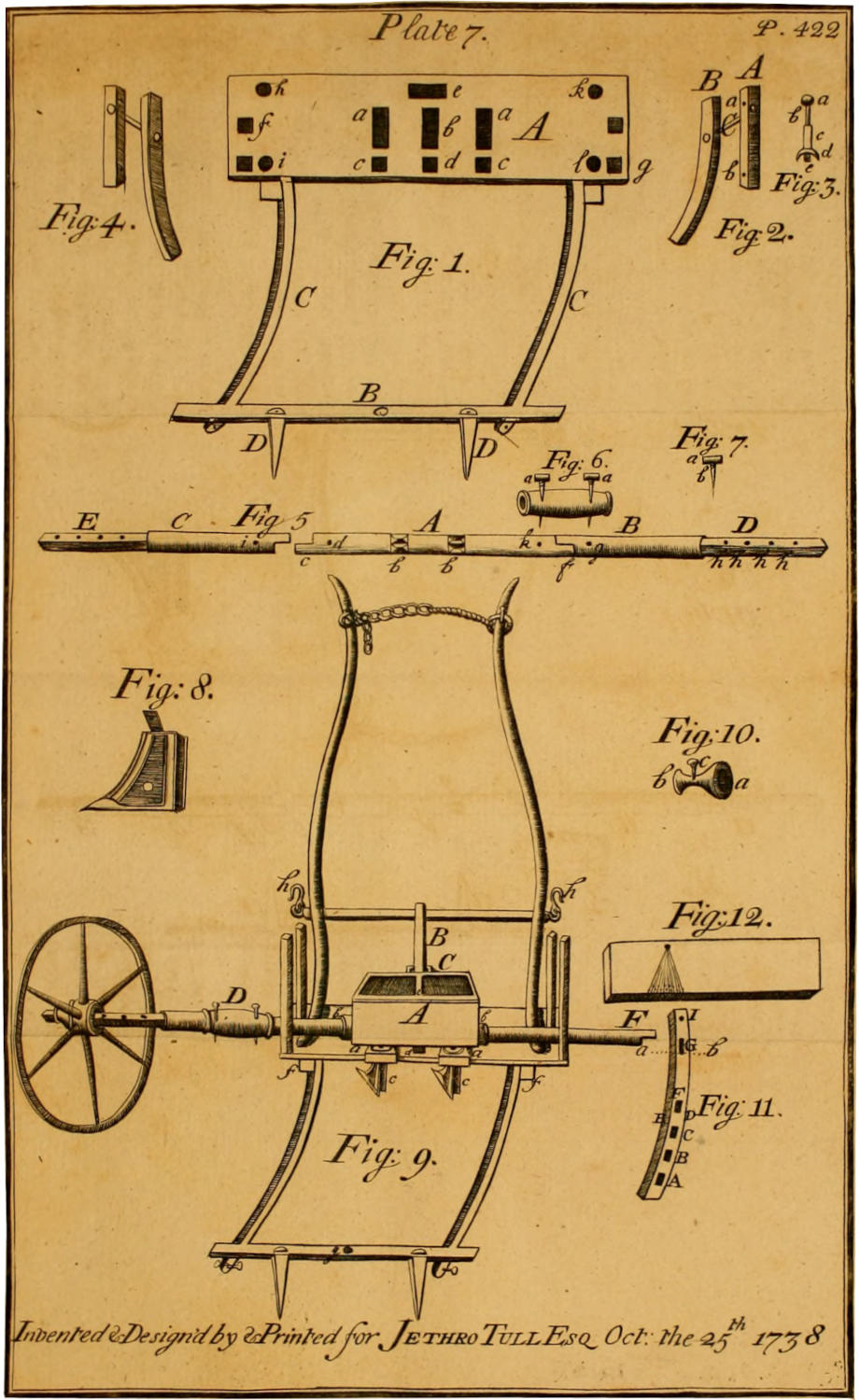

or, an essay on the principles of vegetation and tillage. Designed to introduce a new method of culture; whereby the produce of land will be increased, and the usual expence lessened. Together with accurate descriptions and cuts of the instruments employed in it.

Author: Jethro Tull

Release date: November 14, 2024 [eBook #74741]

Language: English

Original publication: London: A. Millar, 1762

Credits: Peter Becker, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

OR,

An ESSAY on the PRINCIPLES

OF

Vegetation and Tillage.

Designed to introduce

A New Method of Culture;

WHEREBY

The Produce of Land will be increased, and the

usual Expence lessened.

Together with

Accurate Descriptions and

Cuts of the Instruments

employed in it.

By JETHRO TULL, Esq;

Of Shalborne in Berkshire.

The Fourth Edition, very carefully Corrected.

To which is prefixed,

A New PREFACE by the Editors, addressed to all concerned in Agriculture.

LONDON:

Printed for A. Millar, opposite to Catharine-street

in the Strand.

M.DCC.LXII.

[iii]

As

Mr. Tull’s Essay on Horse-hoeing

Husbandry has been published some

Years, it may be presumed that

the World hath by this time

formed some Judgment of his Performance;

which renders it the less necessary for the Editors

of this Impression to say much concerning

it. For every Man who has attended to the

Subject, and duly considered the Principles

upon which our Author’s Method of Culture

is founded, is an equal Judge how far his Theory

is agreeable to Nature: Though it is but

too true, that few have made sufficient Experiments

to be fully informed of its Worth.

As

Mr. Tull’s Essay on Horse-hoeing

Husbandry has been published some

Years, it may be presumed that

the World hath by this time

formed some Judgment of his Performance;

which renders it the less necessary for the Editors

of this Impression to say much concerning

it. For every Man who has attended to the

Subject, and duly considered the Principles

upon which our Author’s Method of Culture

is founded, is an equal Judge how far his Theory

is agreeable to Nature: Though it is but

too true, that few have made sufficient Experiments

to be fully informed of its Worth.

How it has happened, that a Method of Culture, which proposes such Advantages to those who shall duly prosecute it, hath been so long neglected in this Country, may be matter of Surprize to such as are not acquainted with the Characters of the Men on whom the Practice thereof depends; but to those who know them thoroughly it can be none. For it is certain that very few of them can be prevailed on to alter their usual Methods upon any Consideration; though they are convinced that their[iv] continuing therein disables them from paying their Rents, and maintaining their Families.

And, what is still more to be lamented, these People are so much attached to their old Customs, that they are not only averse to alter them themselves, but are moreover industrious to prevent others from succeeding, who attempt to introduce any thing new; and indeed have it too generally in their Power, to defeat any Scheme which is not agreeable to their own Notions; seeing it must be executed by the same Sort of Hands.

This naturally accounts for Mr. Tull’s Husbandry having been so little practised. But as the Methods commonly used, together with the mean Price of Grain for some Years past, have brought the Farmers every-where so low, that they pay their Rents very ill, and in many Places have thrown up their Farms; the Cure of these Evils is certainly an Object worthy of the public Attention: For if the Proprietor must be reduced to cultivate his own Lands, which cannot be done but by the Hands of these indocile People, it is easy to guess on which Side his Balance of Profit and Loss will turn.

This Consideration, together with many others which might be enumerated, hath induced the Editors to recommend this Treatise once more to the serious Attention of every one who wishes well to his Country; in hopes that[v] some may be prevailed upon, by regard either to the public Good or their own private Interest, to give the Method here proposed a fair and impartial Trial: For could it be introduced into several Parts of this Country by Men of generous Principles, their Example might, in time, establish the Practice thereof, and bring it into general Use; which is not to be expected by any other means.

It is therefore to such only, as are qualified to judge of a Theory from the Principles on which it is founded, that the Editors address themselves, desiring they will give this Essay another Reading with due Attention: and at the same time they beg leave to remind them how unfit the common Practisers of Husbandry are to pass Judgment, either on the Theory or Practice of this Method; for which Reason it is hoped that none will be influenced by such, but try the Experiment themselves with proper Care.

As a Motive to this, it is to be observed that, although the Method of Culture here proposed has made little Progress in England, it is not like to meet with the same Neglect abroad, especially in France; where a Translation of Mr. Tull’s Book was undertaken, at one and the same time, by three different Persons of Consideration, without the Privity of each other: But afterwards, Two of them put their Papers into the Hands of the Third, Mr. Du Hamel du Manceau, of the Royal Academy of Sciences at Paris, and of[vi] the Royal Society at London; who has published a Book, intituled, A Treatise of Tillage on the Principles of Mr. Tull. The ingenious Author has indeed altered the Method observed by Mr. Tull in his Book; yet has very exactly given his Principles and Rules: But as he had only seen the First Edition of the Horse-hoeing Husbandry, so he is very defective in his Descriptions of the Ploughs and Drills, which in that were very imperfect, and were afterwards amended by Mr. Tull in his Additions to that Essay.

One of our principal Reasons for taking Notice of this Book is, to shew the Comparison this Author has made between the Old Method of Husbandry and the New. By his Calculation the Profits arising from the New, are considerably more than double those of the Old. For, according to him, the Profits of Twenty Acres of Land for Ten Years, amount, at 10d. ¹⁄₂ per Livre,

| l. | s. | d. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| By the Old Method, to 3000 Livres, or | 131 | 5 | 0 | } | Sterling. |

| By the New Method, to 7650 Livres, or | 334 | 13 | 9 | ||

which makes a prodigious Difference in favour of the latter. As this Computation was made by one who cannot be supposed to have any Prejudice in favour of Mr. Tull’s Scheme, it will naturally find more Credit with the Public than any Comparison made by Mr. Tull himself, or by such as may have an Attachment to his Principles.

[vii]

It may probably be expected, that the Editors should take Notice of such Objections as have been made, either to Mr. Tull’s Theory or Practice; but we do not know any that in the least affect his Principles: They stand uncontroverted: Nor are there any to the Practice, which may not be equally urged against every Sort of Improvement. One of the principal which have come to our Knowlege is, its being impracticable in common Fields, which make a great Part of this Country, without the Concurrence of every one who occupies Land in the same Field. But doth not this equally affect the Old Husbandry? For every such Person is obliged to keep the Turns of plowing, fallowing, &c. with the other Occupiers; so that if any of them were inclinable to improve their Lands, by sowing Grass-seeds, or any other Method of Culture, they are now under the same Difficulties as they would be, were they to practise Mr. Tull’s Method. Therefore this is rather to be lamented as a public Misfortune, than to be brought as an Objection to the Practicableness of that Method. Others object, that the introducing this Sort of Husbandry is unnecessary, seeing the Improvements which are made by Grass-seeds are so considerable; besides, that the Returns made by the Fold and the Dairy, being much quicker than those of Grain, engage the Farmer to mix Plowing and Grazing together. But when this is duly considered it[viii] can have no sort of Weight: for is it not well known that, in those Farms where the greatest Improvements have been made by Grass-seeds, the Quantity of Dressing required for the Arable Land often runs away with most of the Profit of the whole Farm? especially when the Price of Grain is low. And if this be the Situation of the most improved Farms, what must be the Case of those which chiefly consist of Arable Land; where most of the Dressing must be purchased at a great Price, and often fetched from a considerable Distance? Add to this the great Expence of Servants and Horses, unavoidable in Arable Farms; and it will appear how great the Advantages are which the Grasier hath over the plowing Farmer. So that it is much to be wished, the Practice of mixing the Two Sorts of Husbandry were more generally used in every Part of the Kingdom; which would be far from rendering Mr. Tull’s Method of Culture useless; seeing that, when it is well understood, it will be found the surest Method to improve both.

For although Mr. Tull chiefly confined the Practice of his Method to the Production of Grain (which is a great Pity), yet it may be extended to every Vegetable which is the Object of Culture in the Fields, Gardens, Woods, &c. and perhaps may be applied to many other Crops, to equal, if not greater Advantage, than to Corn.

[ix]

In the Vineyard it has been long practised with Success; and may be used in the Hop-Ground with no less Advantage. For the Culture of Beans, Peas, Woad, Madder, and other large-growing Vegetables; as also for Lucern, Saintfoin, and the larger Grasses; we dare venture to pronounce it the only Method of Culture for Profit to the Farmer; seeing that, in all these Crops, one Sixth Part of the Seeds now commonly sown will be sufficient for the same Quantity of Land, and the Crop in Return will be much greater; which, when the Expence of Seeds is duly considered, will be found no small Saving to the Farmer.

Nor should this Method of Culture be confined to Europe: for it may be practised to as great Advantage in the British Colonies in America, where, in the Culture of the Sugar-Cane, Indigo, Cotton, Rice, and almost all the Crops of that Country, it will certainly save a great Expence of Labour, and improve the Growth of every Plant, more than can be imagined by such as are ignorant of the Benefit arising from this Culture. And should the Subjects of Great Britain neglect to introduce this Method into her Colonies, it may be presumed our Neighbours will take care not to be blameable on this Head; for they seem to be as intent upon extending every Branch of Trade, and making the greatest Improvements of their Land, as we are indifferent to both: So that, unless a contrary Spirit be soon exerted, the Balance of[x] Trade, Power, and every other Advantage, must be against us.

There have been Objections made by some to Mr. Tull’s Method, as if it were practicable only on such Lands as are soft and light, and not at all on stiff and stony Ground. That it hath not been practised on either of these Lands in England we are willing to grant; but we must not from thence infer that it is impossible to apply it to them. For the Hoe-Plough has been very long used in the Vineyards in many Countries, where the Soil is stronger, and abounds with Stones full as much as any Part of this Country. However, though the Use of this Plough may be attended with some Difficulties upon such Land, for Wheat, or Plants of low Growth, whose Roots may be in Danger of being turned out of the Ground, or their Tops buried by the Clods or Stones; yet none of the larger-growing Plants are subject to the same Inconveniencies. Besides, the stronger the Soil is, the more Benefit will it receive from this Method of Culture, if the Land be thereby more pulverized; which will certainly be the Consequence, where the Method laid down by Mr. Tull is duly observed.

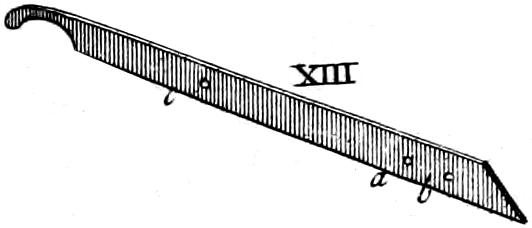

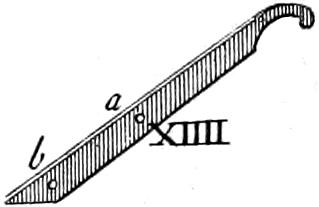

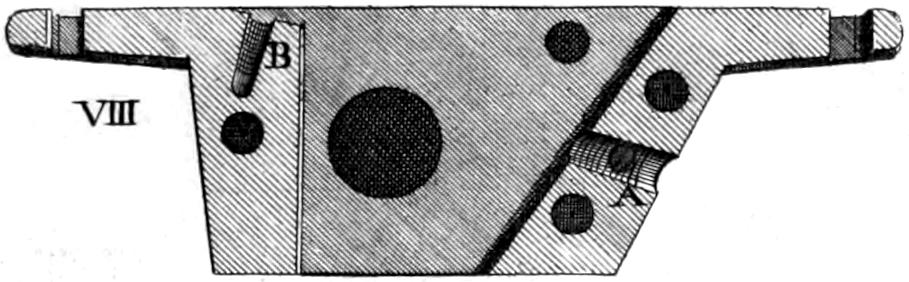

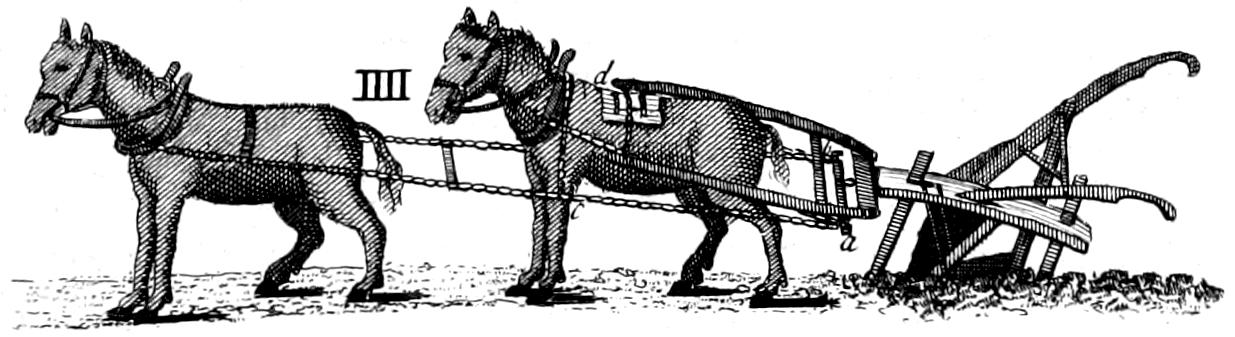

But as most Instruments, in their First Use, are attended with some Difficulty, especially in the Hands of such as are indocile, the Hoe-plough has been complained of, as cumbersome and unwieldy to the Horse and Ploughman. But perhaps this arises chiefly from the Unwillingness of[xi] the Workmen to introduce any new Instrument: Indeed, seeing little is to be expected from those who have been long attached to different Methods, the surest Way to promote the Use of it, is to engage young Persons, who may probably be better disposed, to make the Trial at their first entering into Business; and then a little Use will make it easy. It is proper to observe here, that the Swing-plough, which is commonly used in the deep Land about London, will do the Business of the Hoe-plough in all Ground that is not very strong, or very stony; and that where it is so, the Foot-plough, made proportionably strong, will completely answer all Purposes. But it must be remembered, that when these are used to hoe Corn, the Board on the Left Hand of the Plough, answering the Mould-Board, must be taken off; otherwise so much Earth will run to the Left Side, as to injure the Crop when it is low.

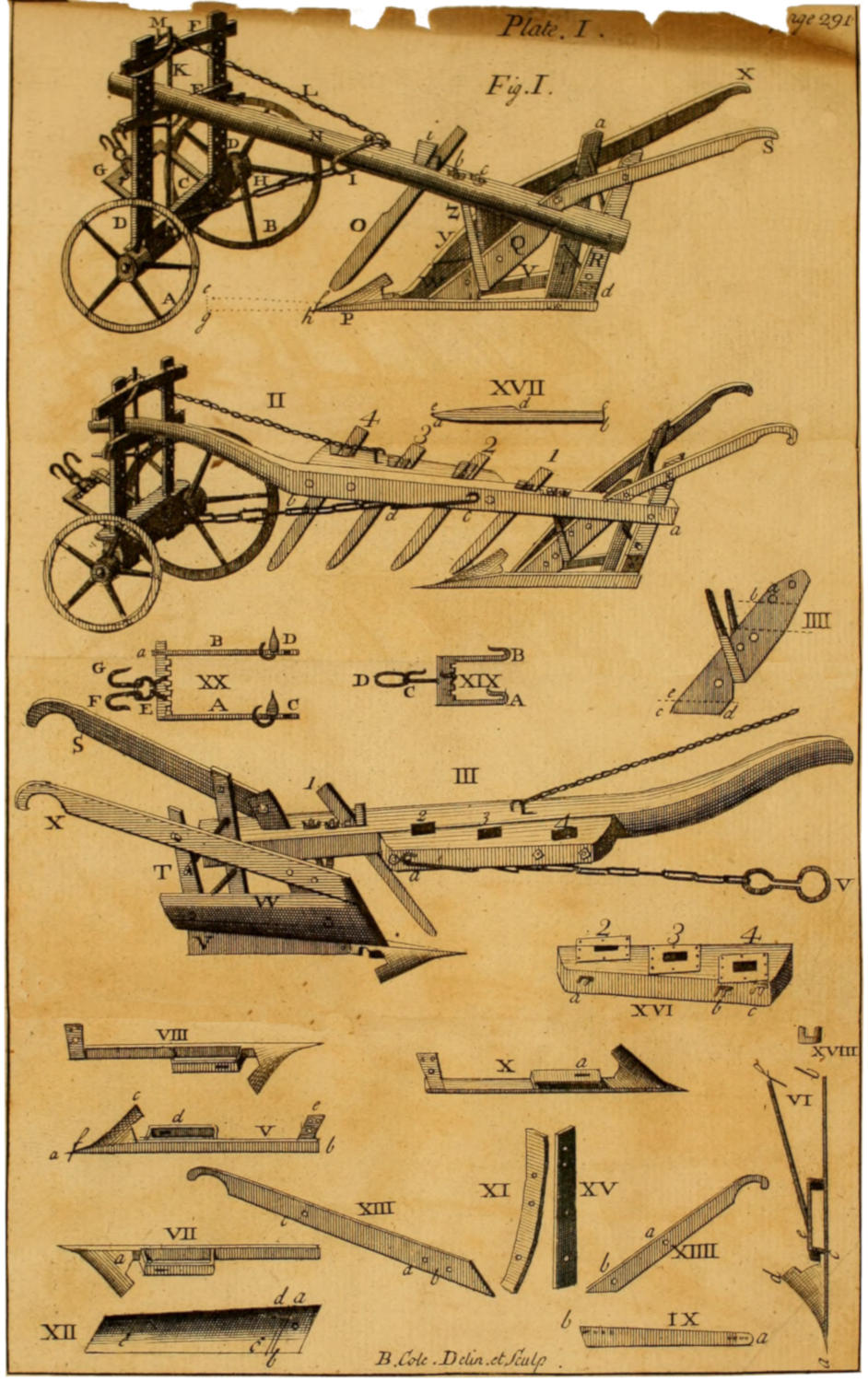

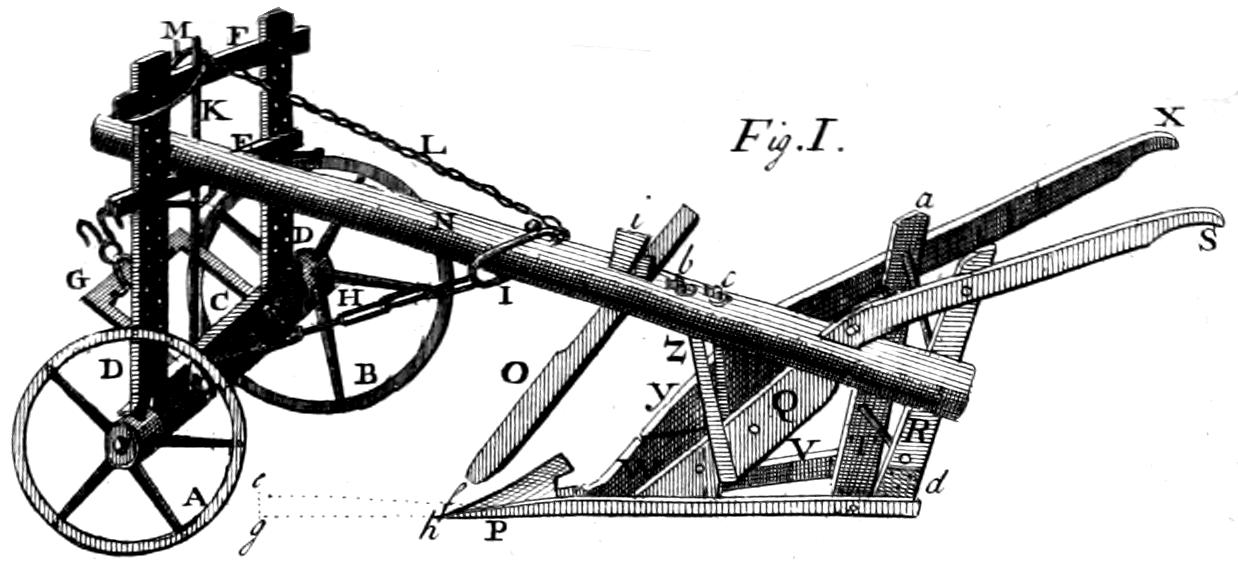

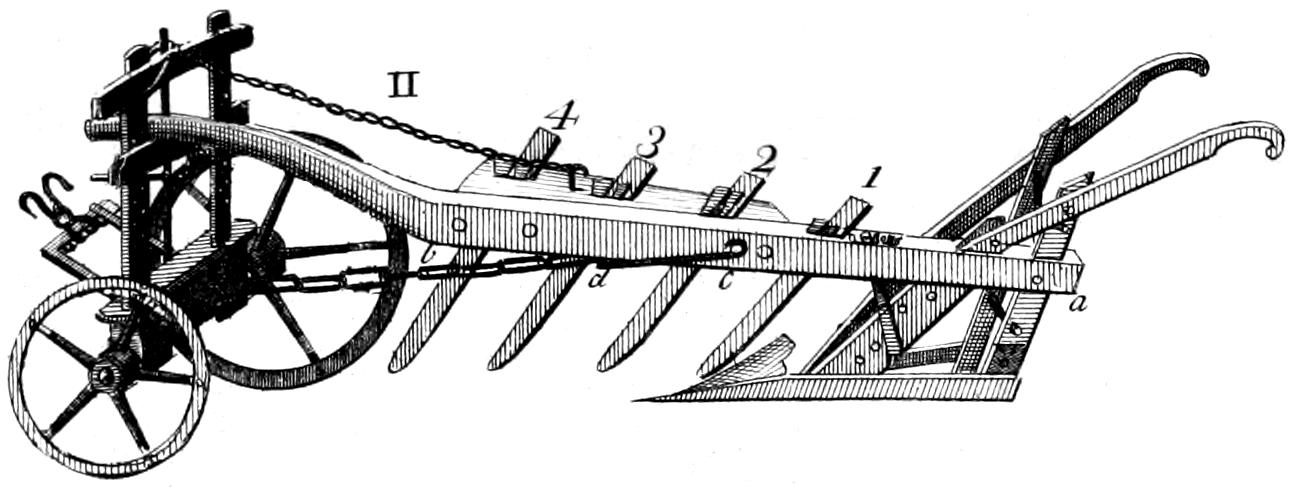

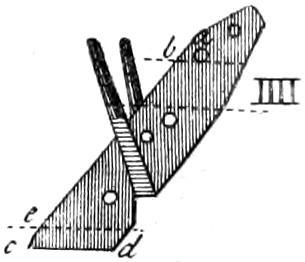

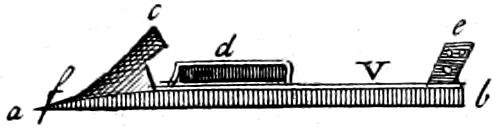

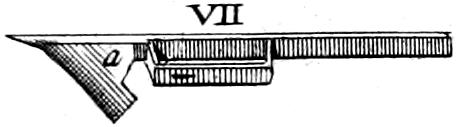

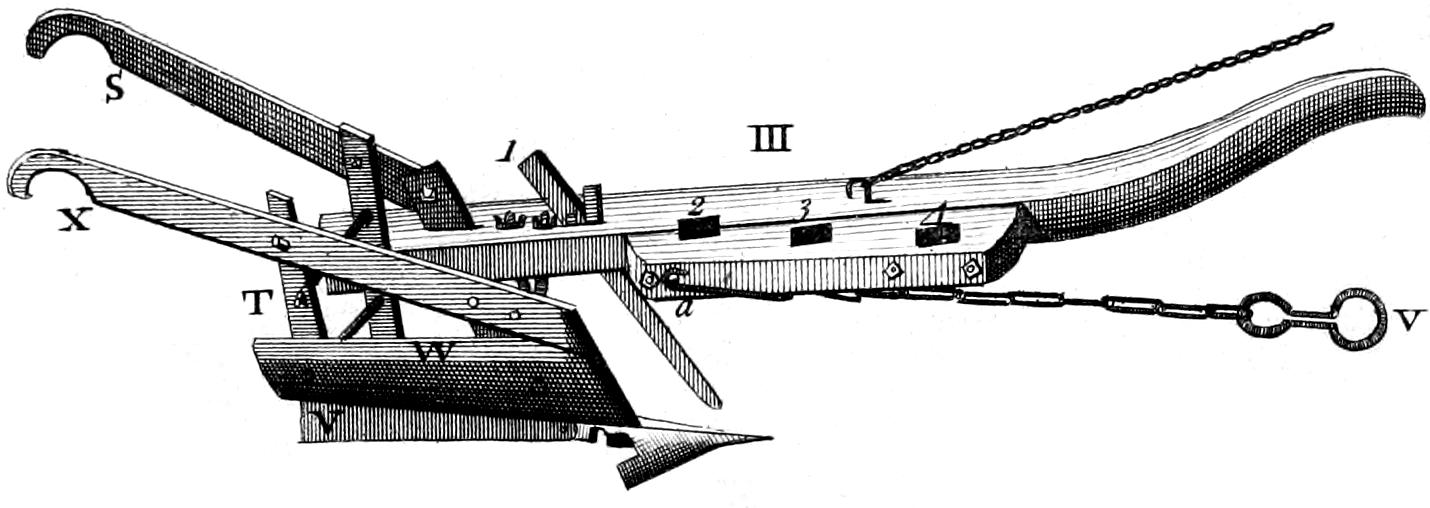

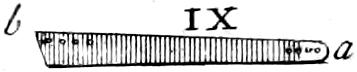

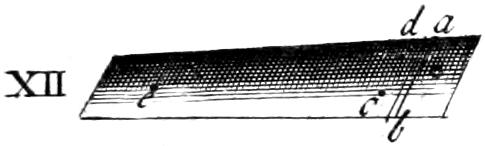

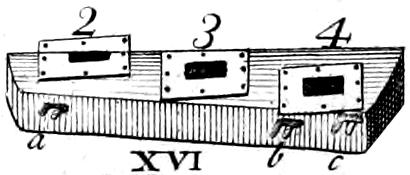

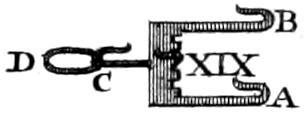

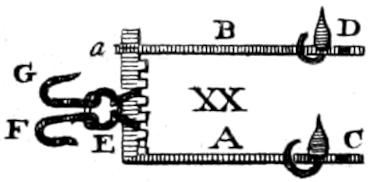

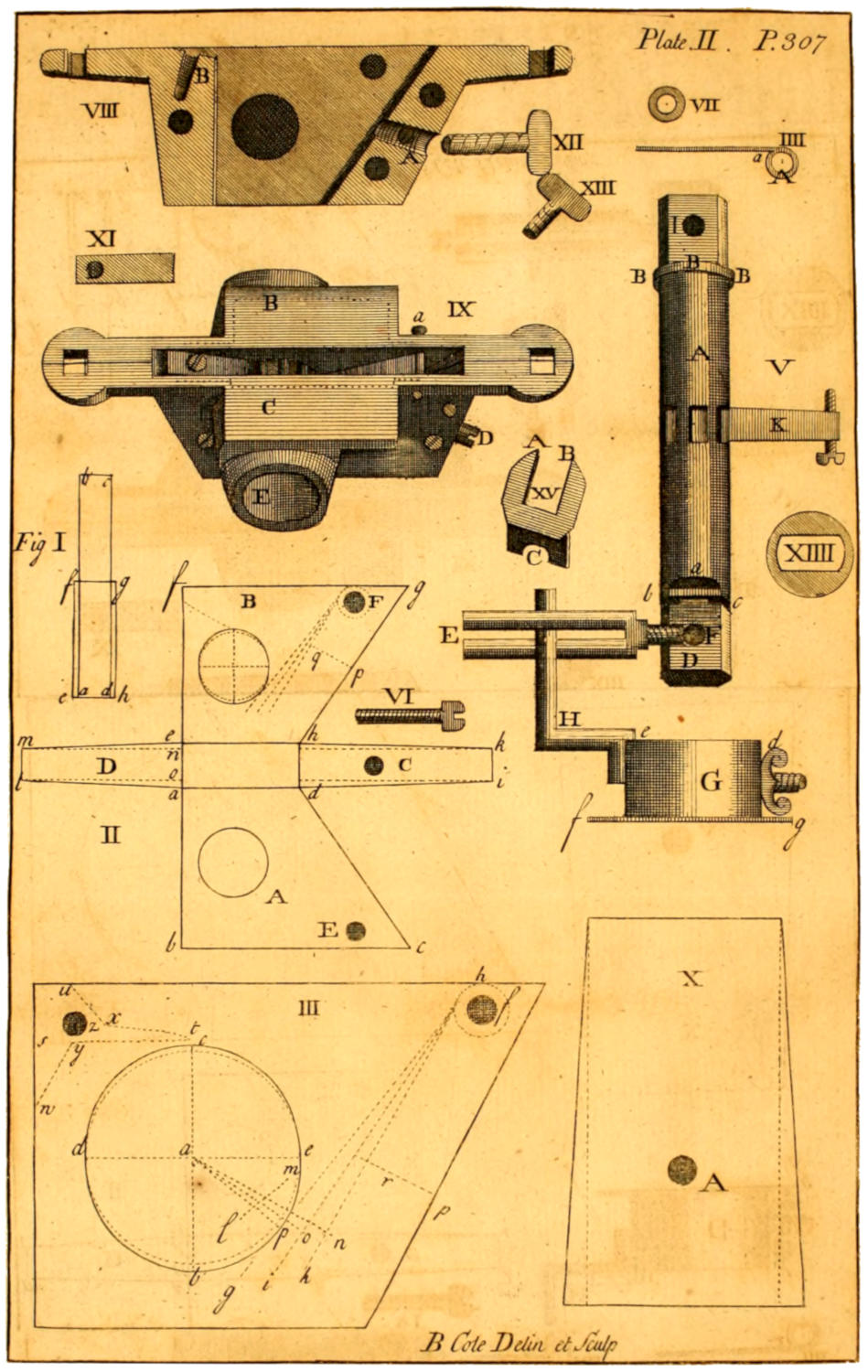

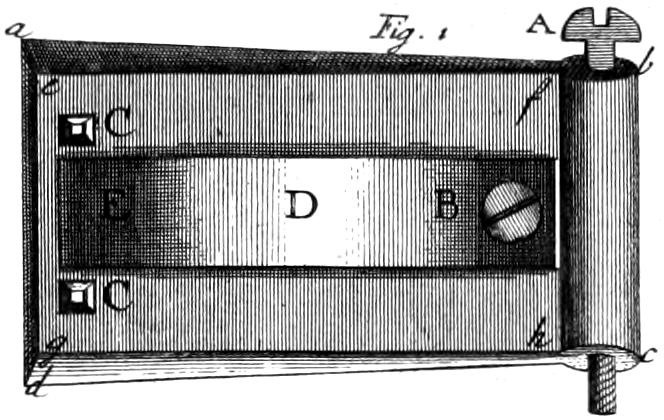

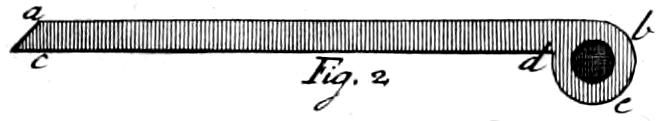

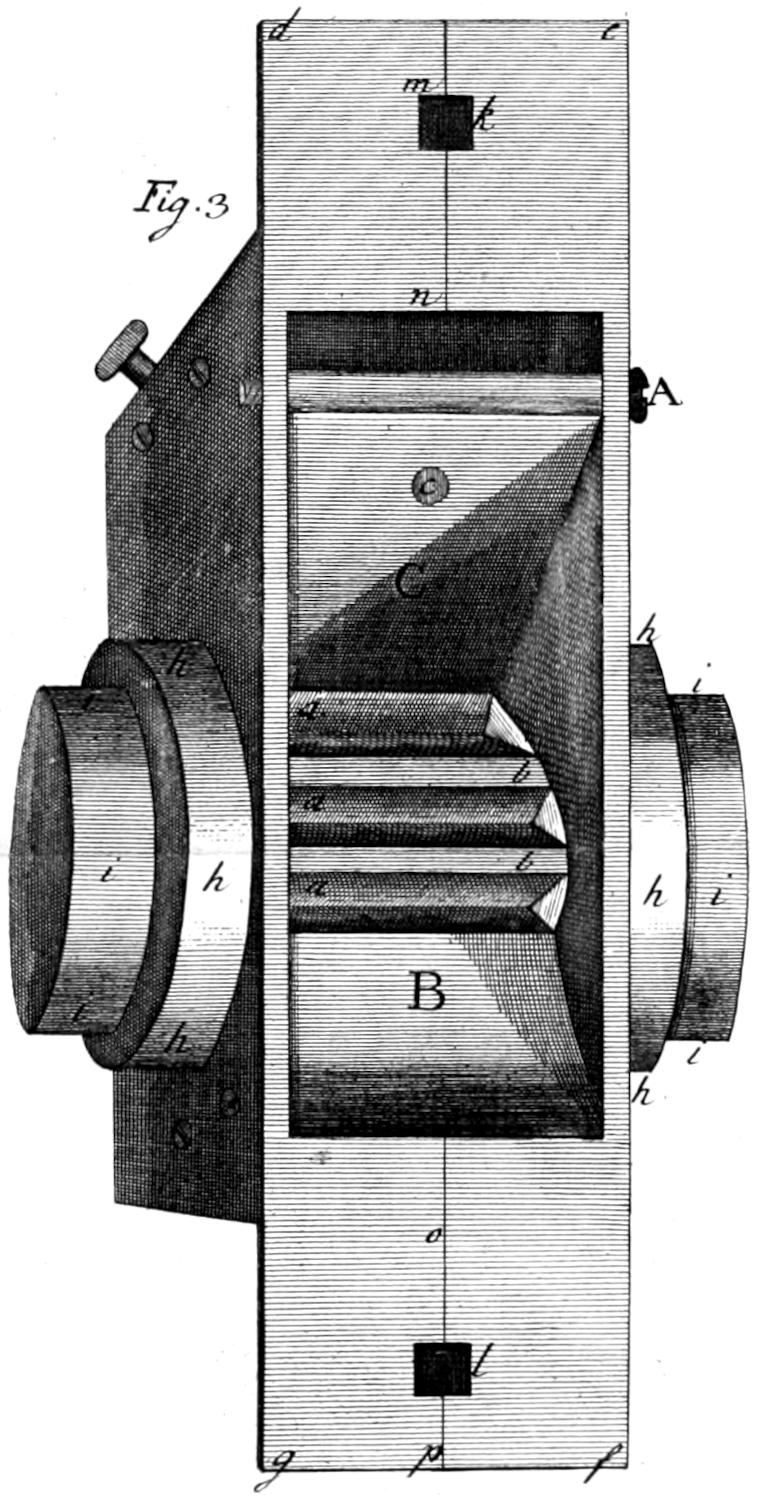

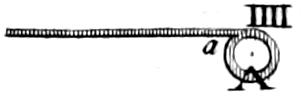

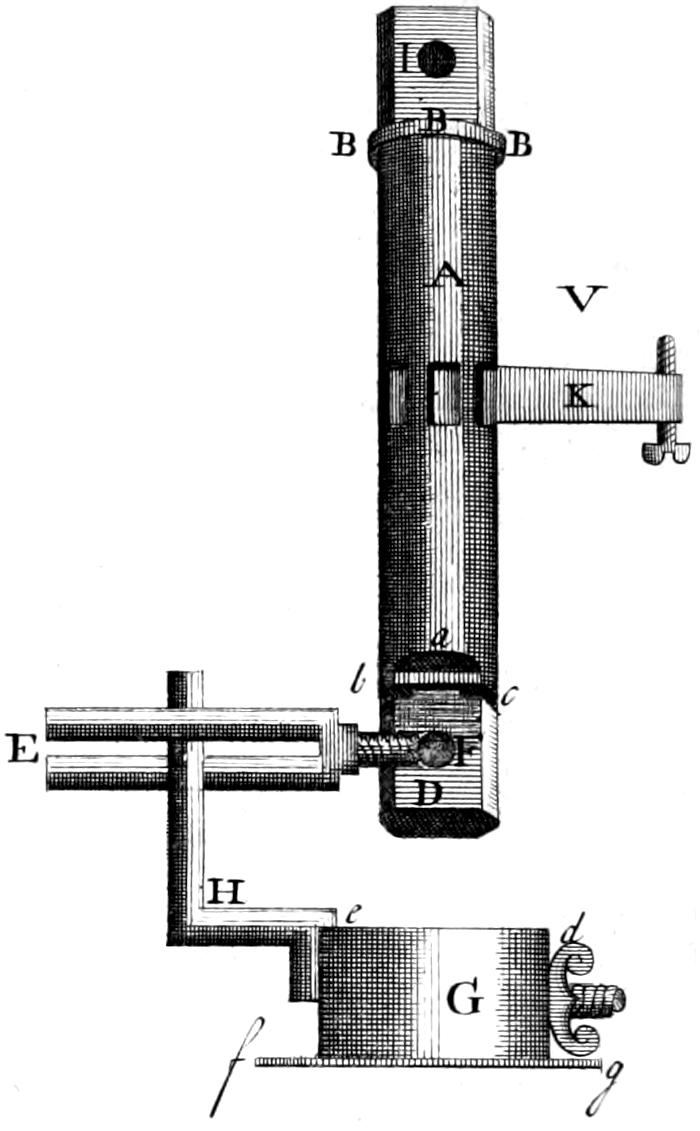

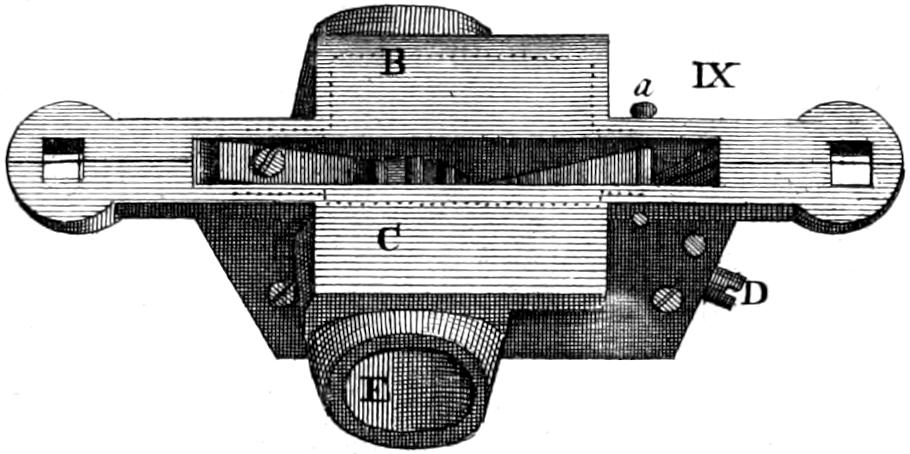

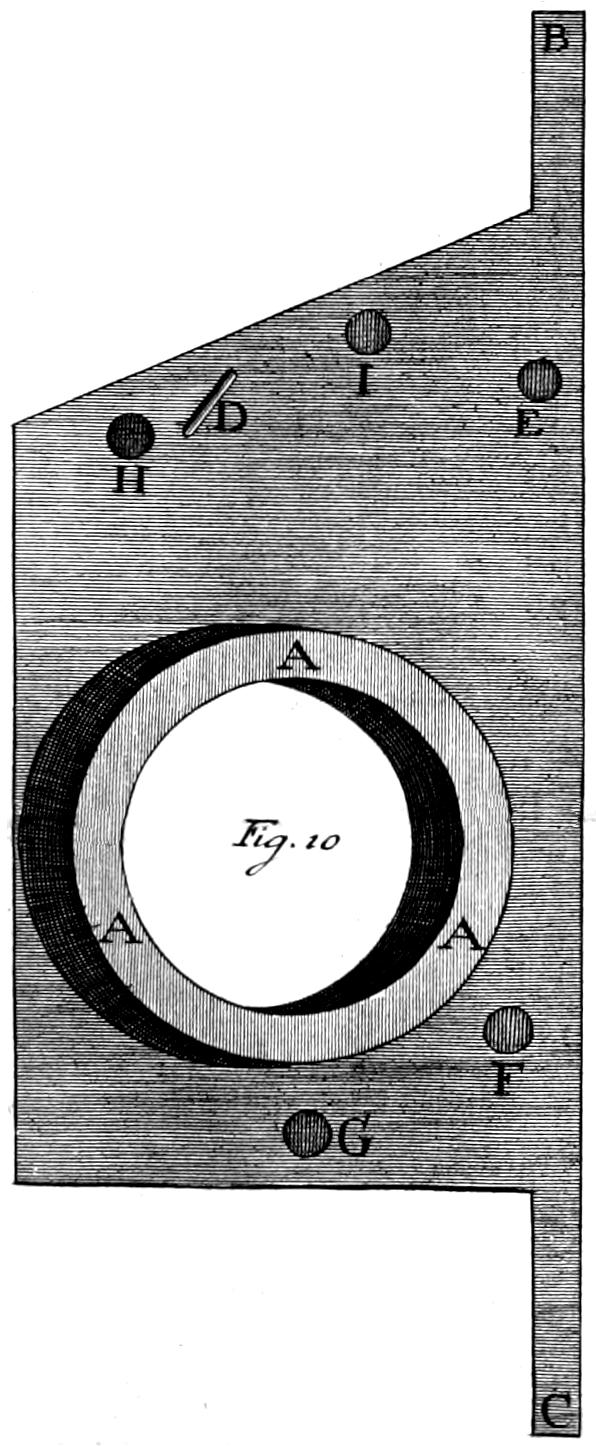

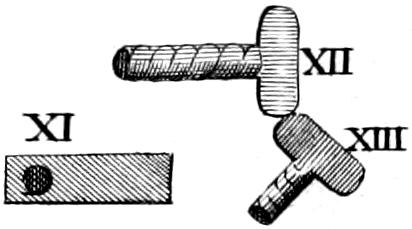

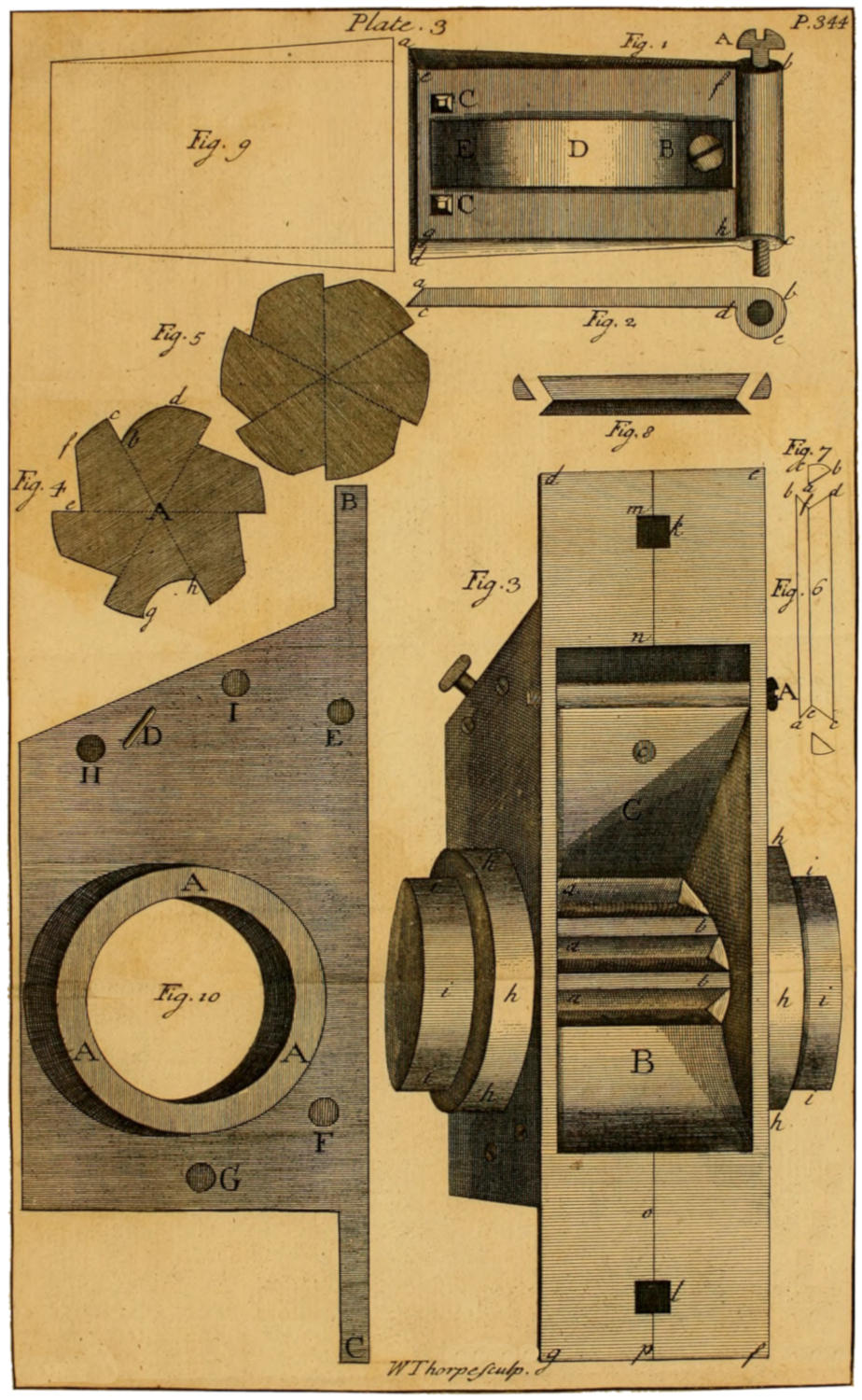

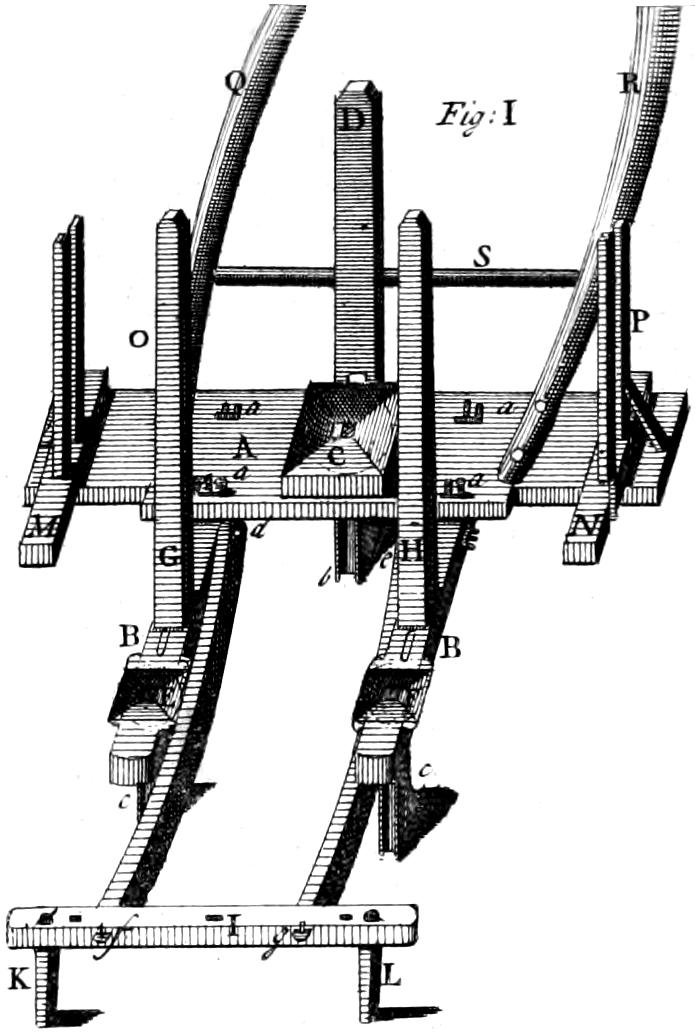

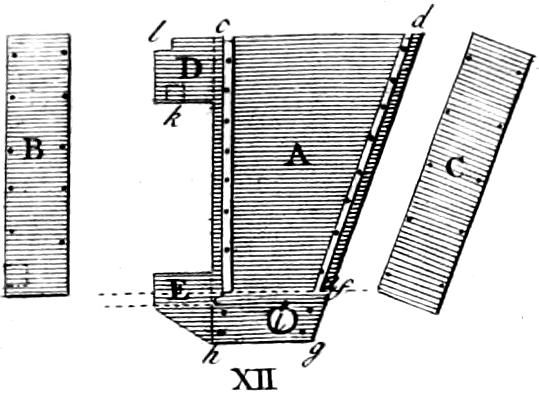

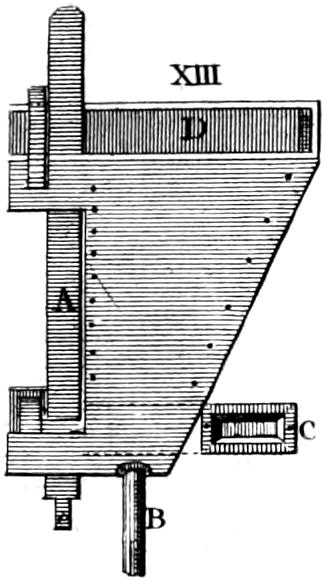

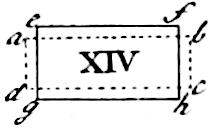

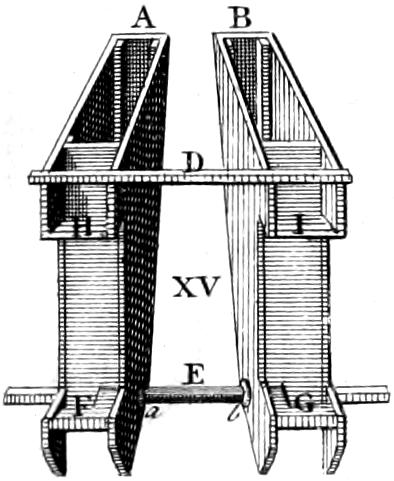

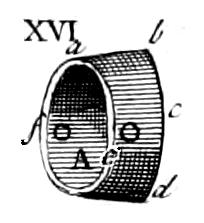

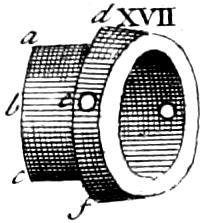

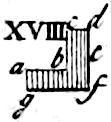

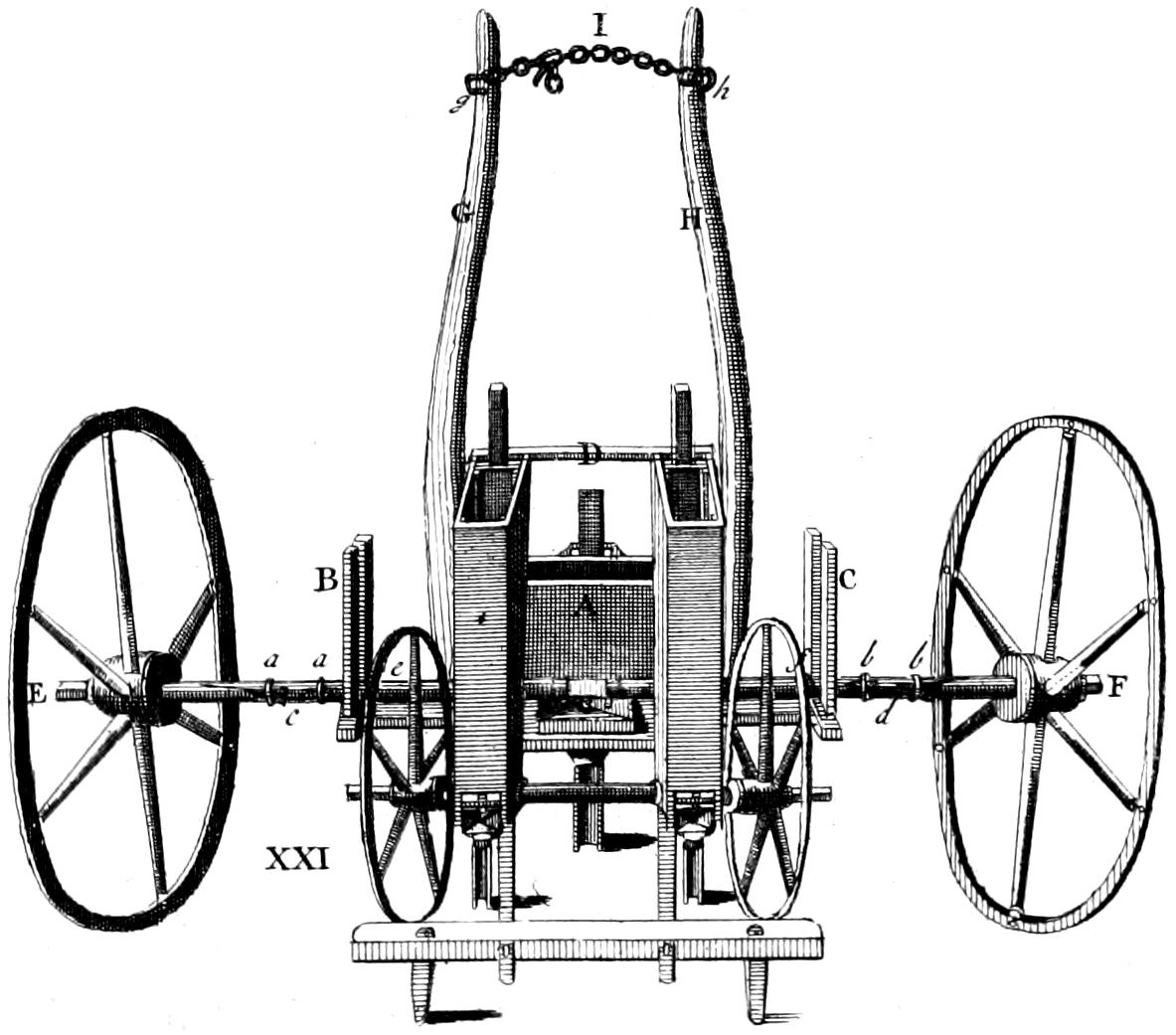

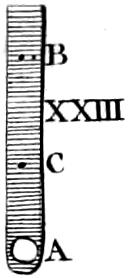

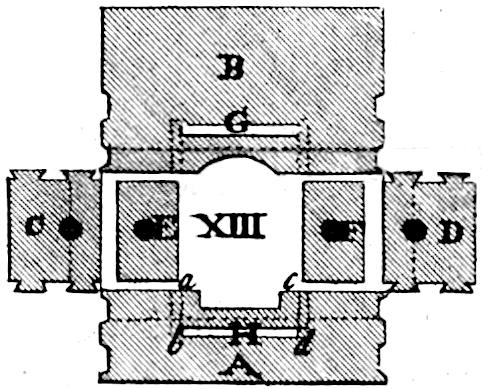

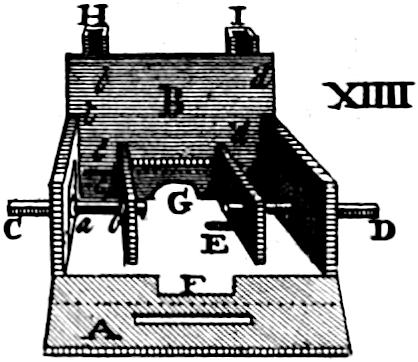

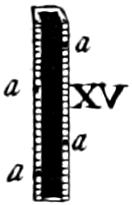

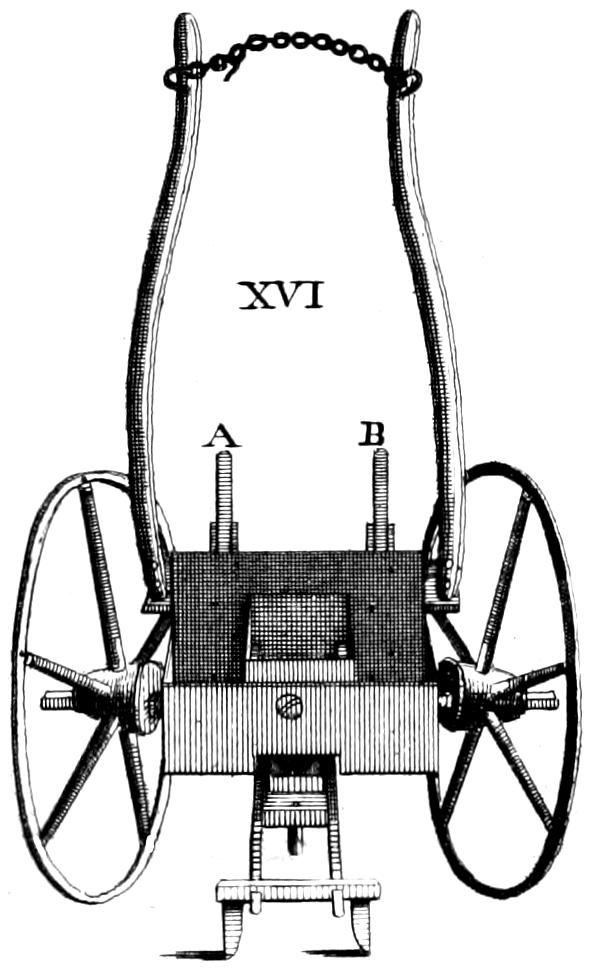

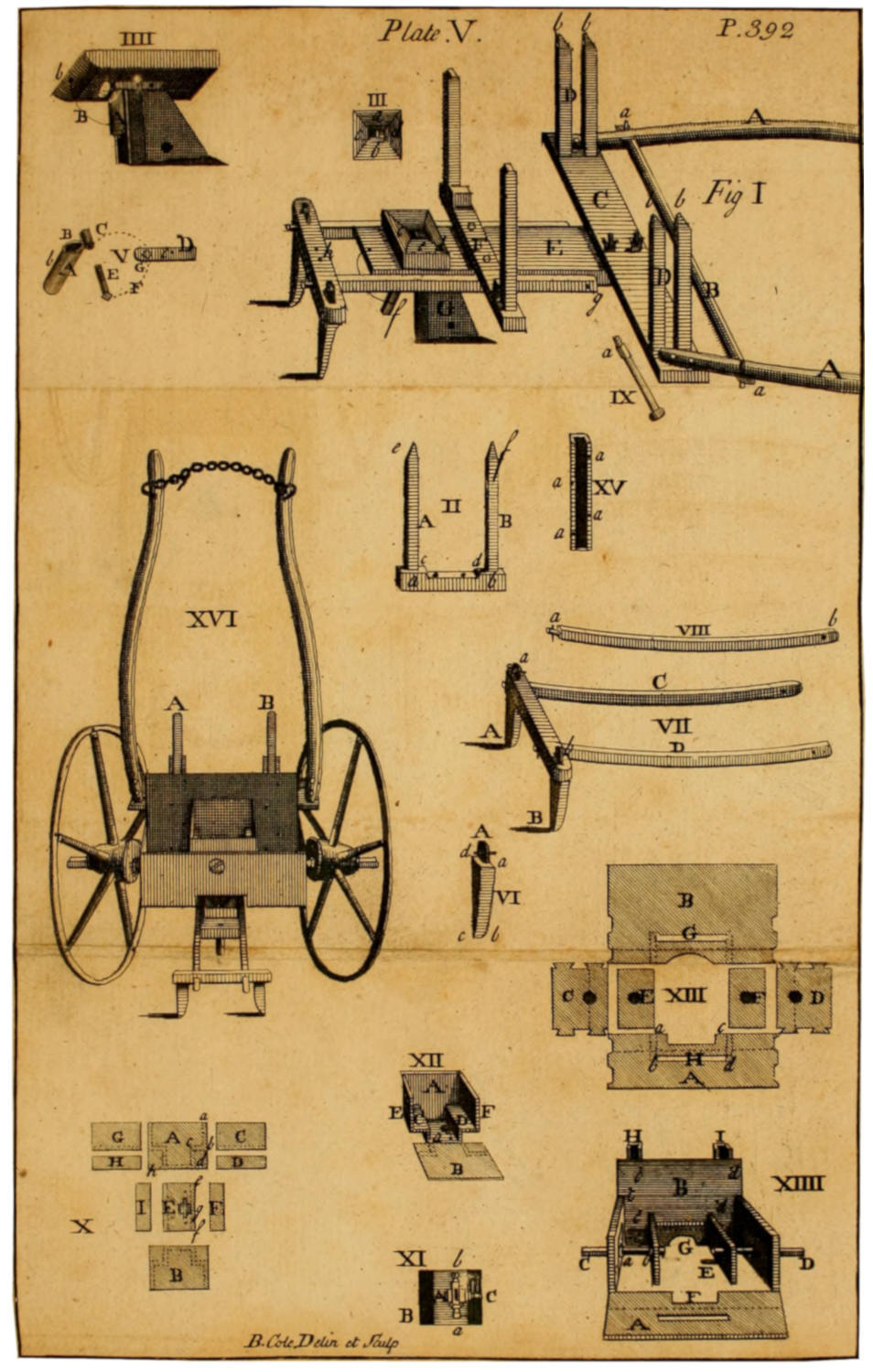

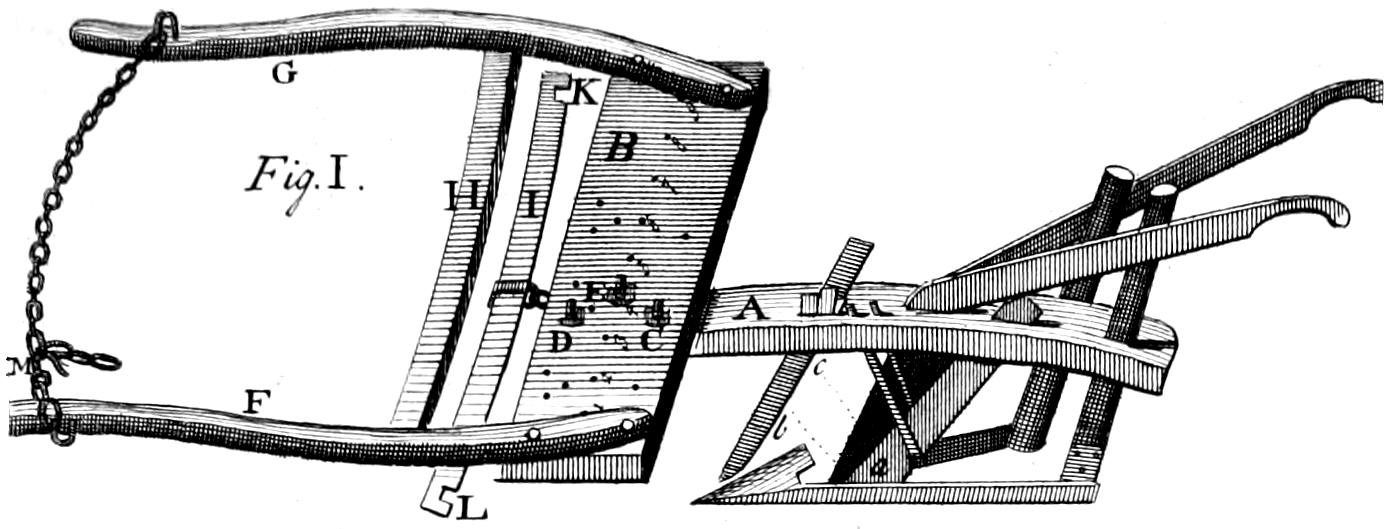

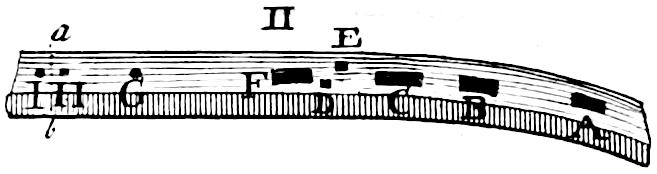

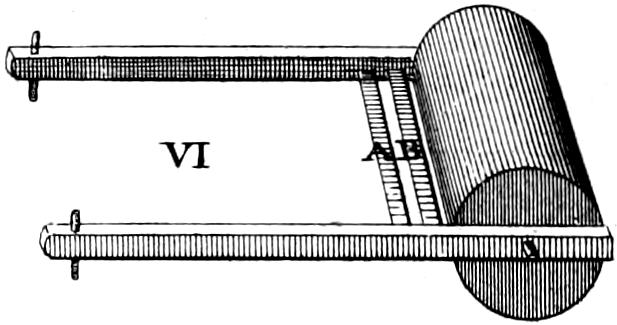

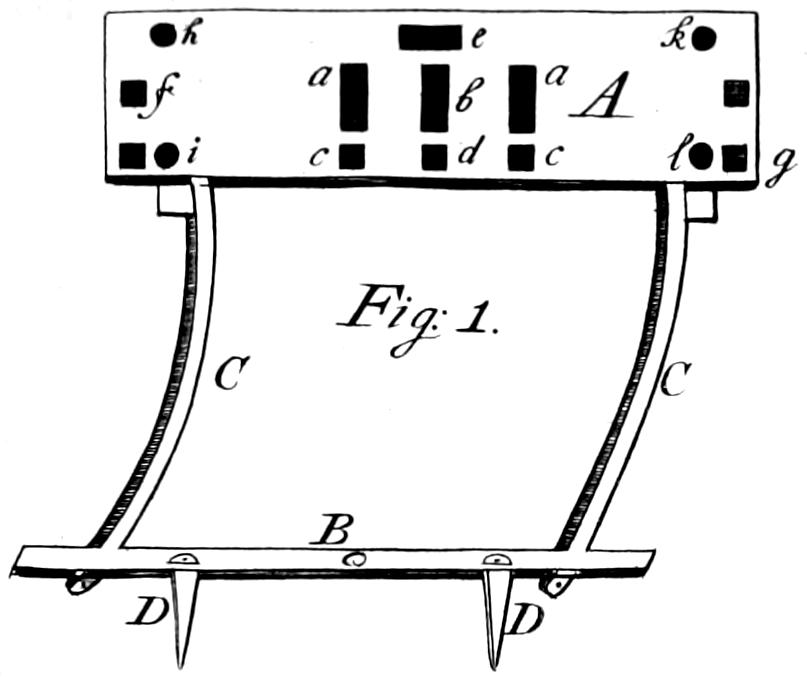

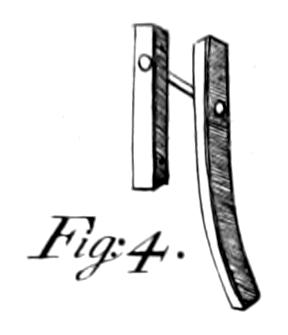

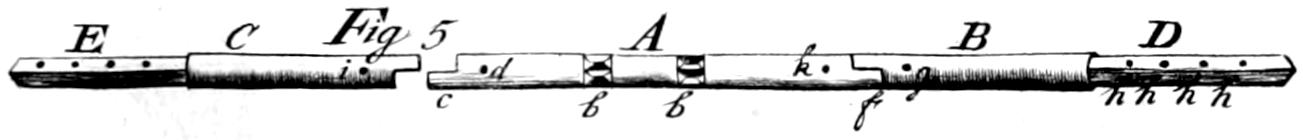

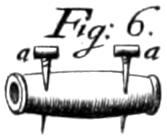

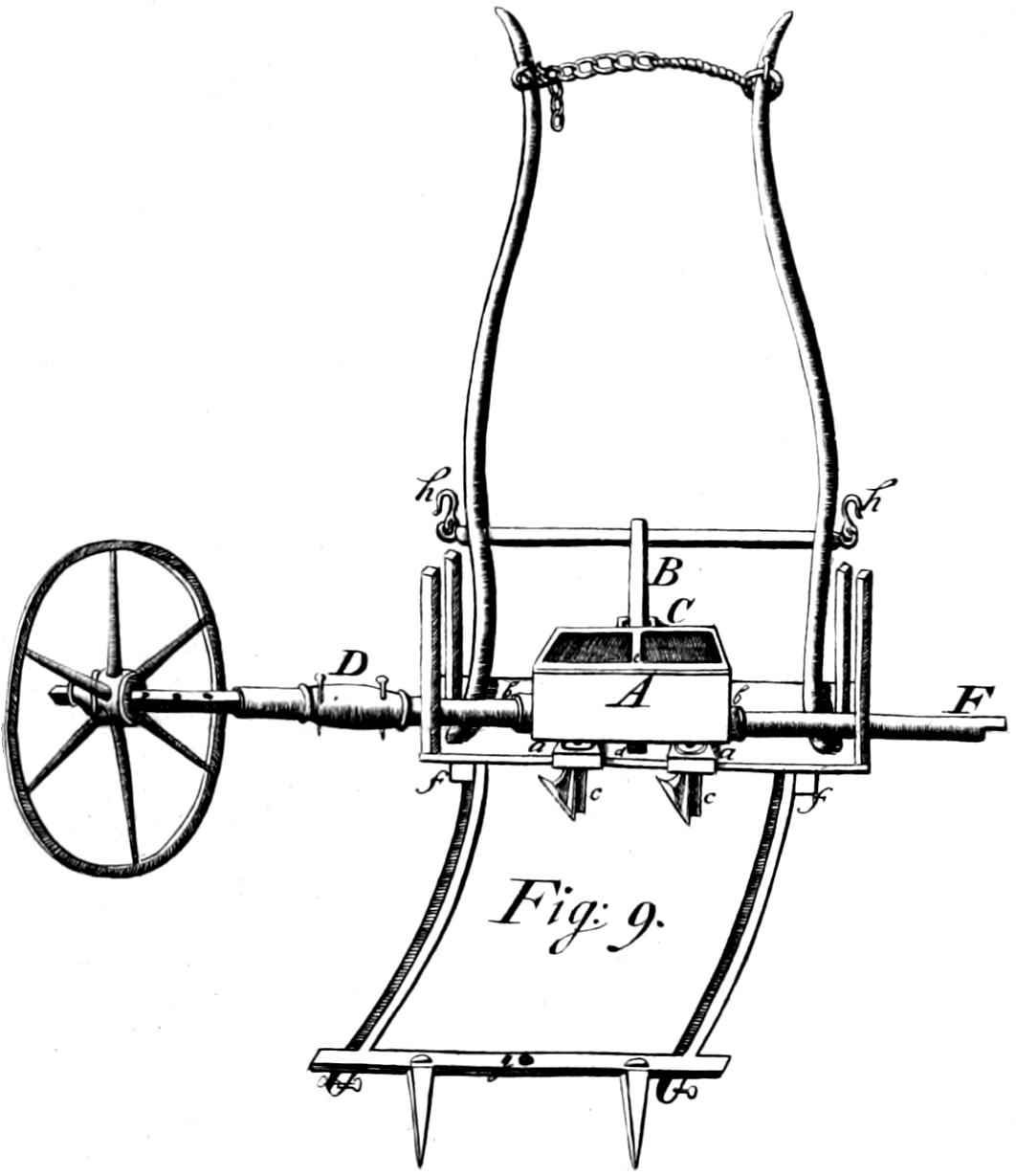

The Drills are excellent Instruments; yet we imagine them capable of some farther Improvement. Parallel Grooves, at about an Inch asunder, round the Inside of the Hopper, would shew the Man who follows the Drill, whether or no both Boxes vent the Seed equally. By an Hitch from the Plank to the Harrow, the latter may be lifted to a proper Height, so as not to be in the Way when the Ploughman turns at the Headland. Two light Handles on the Plank, like those of the common Plough, would[xii] enable the Person who follows the Drill to keep it from falling off the Middle of the Ridge. It may also be useful, in wet Weather, to double the Drills; by which means Two Ridges may be sown at the same time, the Horse going between them: For the Planks of Two Drills, each Plank having one of the Shafts fixed to it, may be joined End for End by Two flat Bars of Iron, one on each Side, well secured by Iron Pins and Screws; and, by corresponding Holes in the Planks and Bars, the Distance between the Drills may be altered, according to the different Spaces between the Ridges.

The Alterations made by the Editors of this Impression are little more than omitting the controversial Parts of the Book, which were judged of no Service to the Reader, as they no-ways affected the Merits of Mr. Tull’s Principles.

But as he endeavoured to recommend his Theory by drawing a Comparison between the Old Method of Culture and the New, so we beg leave to annex a Computation of the Expence and Profit of each; for which we are obliged to a Gentleman, who for some Years practised both in a Country where the Soil was of the same Nature with that from whence Mr. Tull drew his Observations, viz. light and chalky. And we chuse to give this the rather, as it comes from one who has no Attachment to Mr. Tull’s Method, farther than that he found it answer in his Trials. We appeal to[xiii] Experience, whether every Article in this Calculation is not estimated in favour of the Common Husbandry; whether the Expence be not rated lower than most Farmers find it, and the Crop such as they would rejoice to see, but seldom do, in the Country where this Computation was made.

In the New Husbandry every Article is put at its full Value, and the Crop of each Year is Four Bushels short of the other; tho’, in several Years Experience, it has equalled, and generally exceeded, those of the Neighbourhood in the Old Way.

An Estimate of the Expence and Profit of Ten Acres of Land in Twenty Years.

| I. In the Old Way. | ||||||

| First Year, for Wheat, costs 33l. 5s. viz. | l. | s. | d. | l. | s. | d. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Plowing, at 6s. per Acre | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Second and Third Ditto, at 8s. per Acre | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Manure, 30s. per Acre | 15 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 22 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Two Harrowings, and Sowing, at 2s. 6d. per Acre | 1 | 5 | 0 | |||

| Seed, three Bushels per Acre, at 4s. per Bush. | 6 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Weeding, at 2s. per Acre | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Reaping, Binding, and Carrying, at 6s. per Acre | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 11 | 5 | 0 | ||||

| 33 | 5 | 0 | ||||

| Second Year, for Barley, costs 11l. 6s. 8d. viz. | ||||||

| Once Plowing, at 6s. per Acre | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Harrowing and Sowing, at 1s. 6d. per Acre, | 0 | 15 | 0 | |||

| Weeding, at 1s. per Acre | 0 | 10 | 0 | |||

| Seed, 4 Bushels per Acre, at 2s. per Bushel | 4 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Cutting, Raking, and Carrying, at 3s. 2d. per Acre | 1 | 11 | 8 | |||

| Grass-Seeds, at 3s. per Acre | 1 | 10 | 0 | |||

| 11 | 6 | 8 | ||||

| 44 | 11 | 8 | ||||

| Third and Fourth Years, lying in Grass, cost nothing: So that the Expence of Ten Acres in Four Years comes to 44l. 11s. 8d. and in Twenty Years to | 222 | 18 | 4 | |||

| First Year’s Produce is half a Load of Wheat per Acre, at 7l. | 35 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Second Years Produce is Two Quarters of Barley per Acre, at 1l. | 20 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Third and Fourth Years Grass is valued at 1l. 10s. per Acre | 15 | 0 | 0 | |||

| So that the Produce of Ten Acres in Four Years is | 70 | 0 | 0 | |||

| And in Twenty Years it will be[xv] | 350 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Deduct the Expence, and there remains clear Profit on Ten Acres in 20 Years by the Old Way | 127 | 1 | 8 | |||

| II. In the New Way. | ||||||

| First Year’s extraordinary Expence is, for plowing and manuring the Land, the same as in Old Way | 22 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Plowing once more, at 4s. per Acre | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Seed, 9 Gallons per Acre, at 4s. per Bushel | 2 | 5 | 0 | |||

| Drilling, at 7d. per Acre | 0 | 5 | 10 | |||

| Hand-hoeing and Weeding, at 2s. 6d. per Acre | 1 | 5 | 0 | |||

| Horse-hoeing Six times, at 10s. per Acre | 5 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Reaping, Binding, and Carrying, at 6s. per Acre | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| The standing annual Charge on Ten Acres is | 13 | 15 | 10 | |||

| Therefore the Expence on Ten Acres in Twenty Years is | 275 | 16 | 8 | |||

| Add the Extraordinaries of the First Year, and the Sum is | 297 | 16 | 8 | |||

| The yearly Produce is at least Two Quarters of Wheat per Acre, at 1l. 8s. per Quarter; which, on Ten Acres in Twenty Years, amounts to | 560 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Therefore, all things paid, there remains clear Profit on Ten Acres in Twenty Years by the New Way | 262 | 3 | 4 | |||

[xvi]

So that the Profit on Ten Acres of Land in Twenty Years, in the New Way, exceeds that in the Old by 135l. 1s. 8d. and consequently is considerably more than double thereof: an ample Encouragement to practise a Scheme, whereby so great Advantage will arise from so small a Quantity of Land, in the Compass of a Twenty-one Years Lease; One Year being allowed, both in the Old and New Way, for preparing the Ground.

It ought withal to be observed, that Mr. Tull’s Husbandry requires no Manure at all, tho’ we have here, to prevent Objections, allowed the Charge thereof for the first Year; and moreover, that tho’ the Crop of Wheat from the Drill-plough is here put only at Two Quarters on an Acre, yet Mr. Tull himself, by actual Experiment and Measure, found the Produce of his drilled Wheat-crop amounted to almost Four Quarters on an Acre: And, as he has delivered this Fact upon his own Knowlege, so there is no Reason to doubt of his Veracity, which has never yet been called in question. But that we might not be supposed to have any Prejudice in favour of his Scheme, we have chosen to take the Calculations of others rather than his, having no other View in what we have said, than to promote the Cause of Truth, and the public Welfare.

The Wheat and Turnep Drill-Boxes, or the Drill-Plough complete, mentioned in this Treatise, may be had at Mr. Mulford’s in Cursitor-street, Chancery-lane, London.

[1]

Since the most immediate Use of

Agriculture, in feeding Plants, relates

to their Roots, they ought to be treated

of in the first Place.

Since the most immediate Use of

Agriculture, in feeding Plants, relates

to their Roots, they ought to be treated

of in the first Place.

Roots are very different in different Plants: But ’tis not necessary here to take notice of all the nice Distinctions of them; therefore I shall only divide them in general into two Sorts, viz. Horizontal-Roots, and Tap-Roots, which may include them all.

All have Branchings and Fibres going all manner of ways, ready to fill the Earth that is open.

But such Roots as I call Horizontal (except of Trees) have seldom any of their Branchings deeper than the Surface or Staple of the Earth, that is commonly mov’d by the Plough or Spade.

The Tap-Root commonly runs down Single and Perpendicular[1] reaching sometimes many Fathoms below.

[1]In this manner descends the first Root of every Seed; but of Corn very little, if at all, deeper than the Earth is tilled.

These first Seed-Roots of Corn die as soon as the other Roots come out near the Surface, above the Grain: and therefore this first is not called a Tap Root; but yet some of the next Roots that come out near the Surface of the Ground, always reach down to the Bottom of the pulveriz’d Staple; as may be seen, if you carefully examine it in the Spring time; but this first Root in Saint-foin becomes a Tap Root.

This (tho’ it goes never so deep) has horizontal ones passing out all round the Sides; and extend to several Yards Distance from it, after they are by their[2] Minuteness, and earthly Tincture, become invisible to the naked Eye.

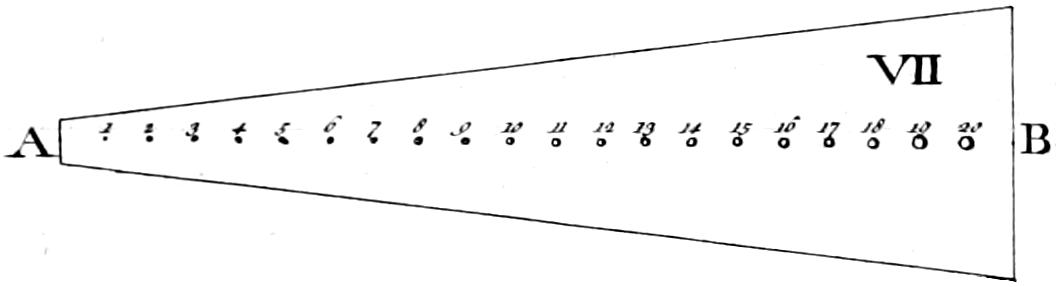

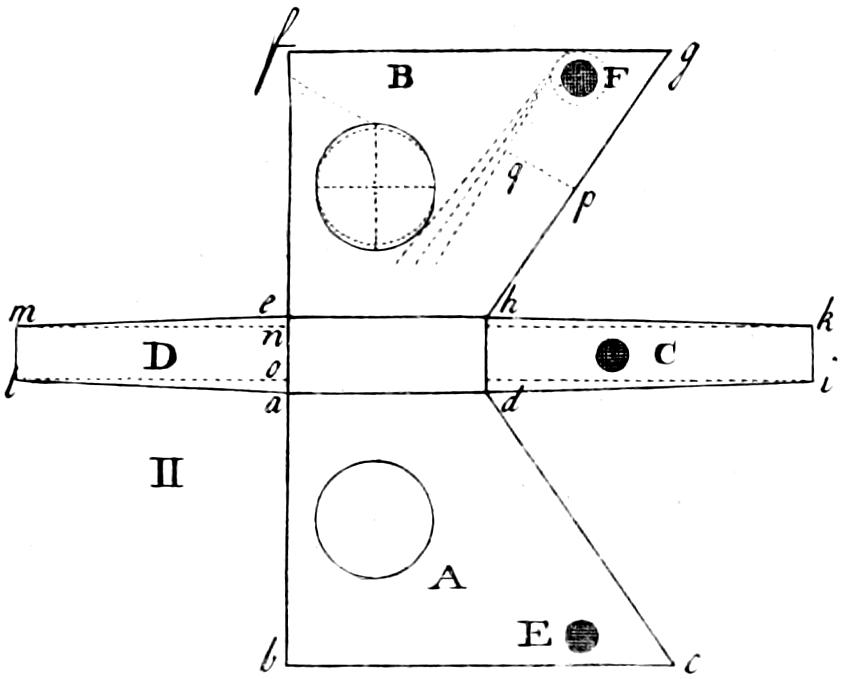

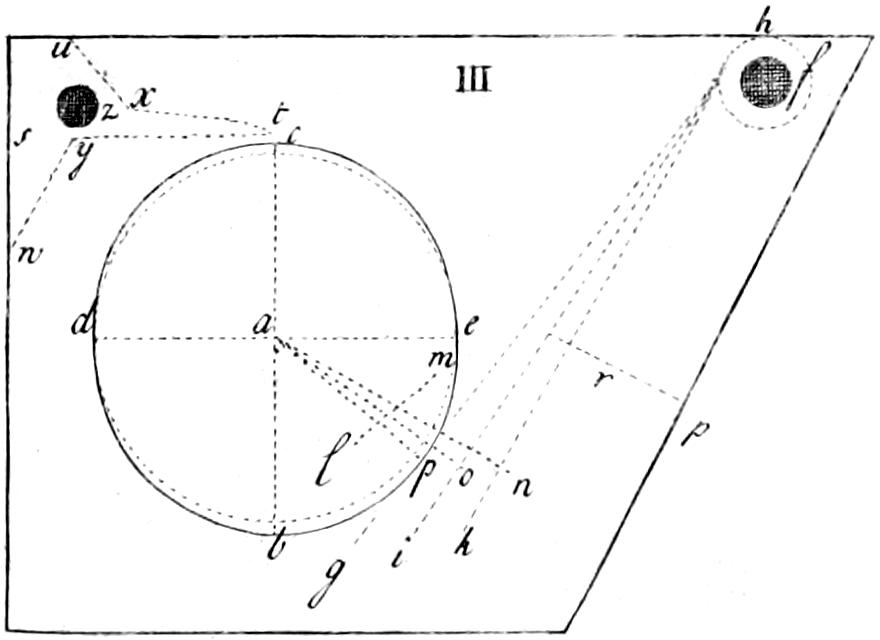

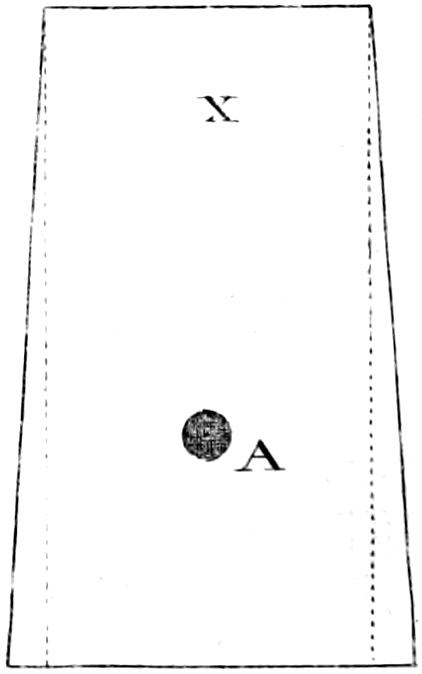

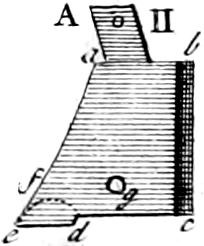

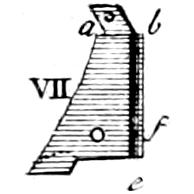

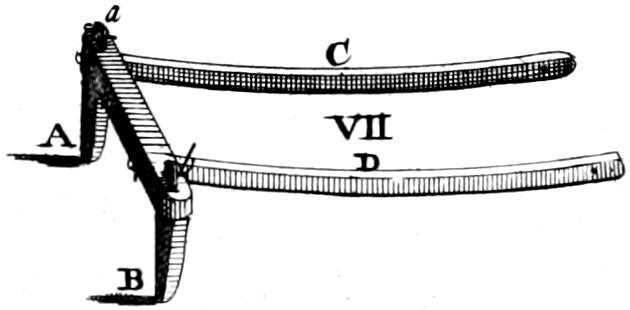

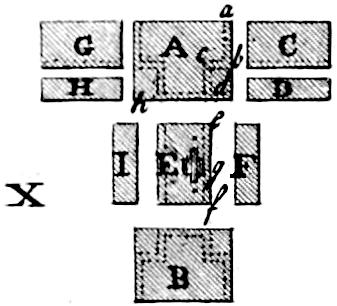

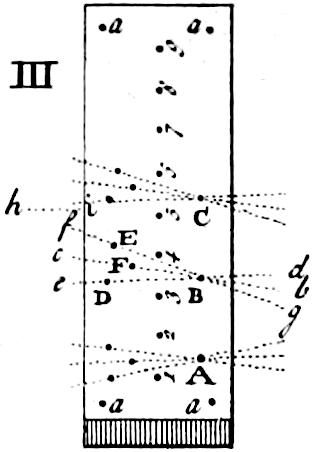

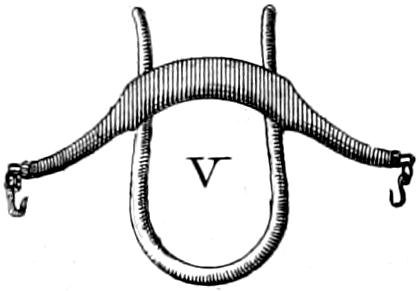

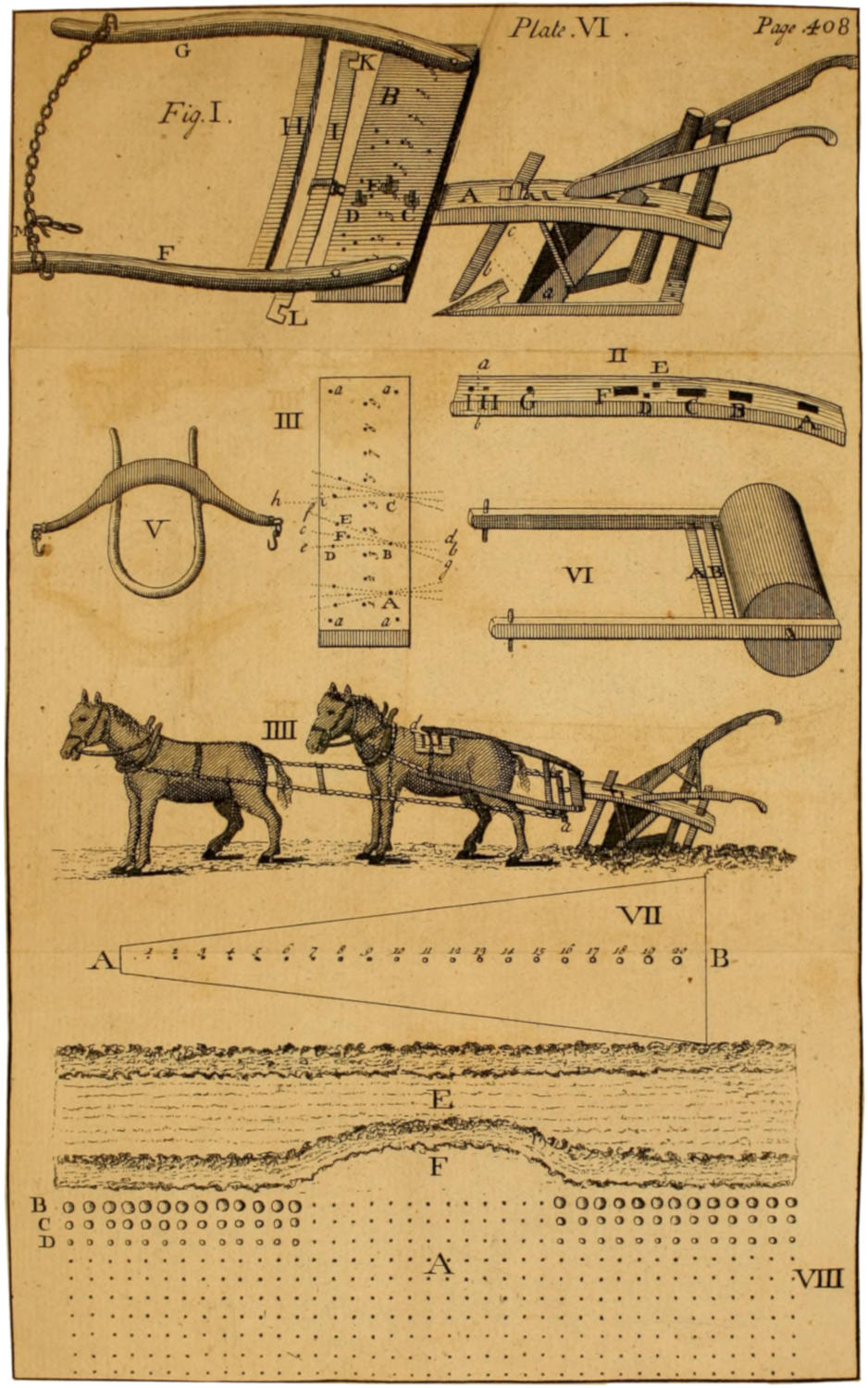

Pl. 6. Fig. 7. Is a Piece or Plot dug and made fine in whole hard Ground, the End A 2 Feet, the End B 12 Feet, the Length of the Piece 20 Yards; the Figures in the middle of it are 20 Turneps, sown early, and well ho’d.

The manner of this Hoing must be at first near the Plants, with a Spade, and each time afterwards, a Foot farther Distance, till all the Earth be once well dug; and if Weeds appear where it has been so dug, hoe them out shallow with the Hand-Hoe. But dig all the Piece next the out Lines deep every time, that it may be the finer for the Roots to enter, when they are permitted to come thither.

If these Turneps are all gradually bigger, as they stand nearer to the End B, ’tis a Proof they all extend to the Outside of the Piece; and the Turnep 20 will appear to draw Nourishment from six Feet Distance from its Centre.

But if the Turneps 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, acquire no greater Bulk than the Turnep 15, it will be clear, that their Roots extend no farther than those of the Turnep 15 does; which is but about 4 Feet.

By this Method the Distance of the Extent of Roots of any Plant may be discover’d.

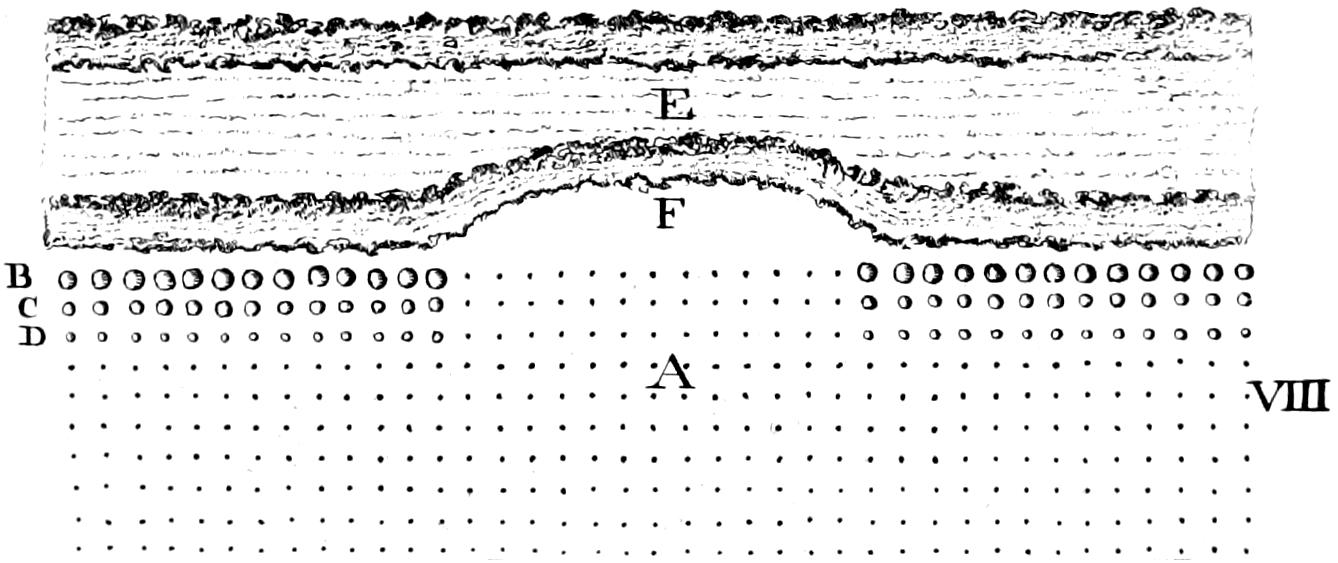

What put me upon this Method was an Observation of two Lands (or Ridges) drill’d with Turneps in Rows, a Foot asunder, and very even in them; the Ground, at both Ends, and one Side, was hard and unplow’d; the Turneps not being ho’d, were very poor, small, and yellow, except the Three outside Rows, B, C, D, which stood next to the Land (or Ridge) E, which Land being plow’d and harrow’d, at the time the Land A ought to have been ho’d,[3] gave a dark flourishing Colour to these three Rows; and the Turneps in the Row D, which stood farthest off from the new-plow’d Land E, received so much Benefit from it, as to grow twice as big as any of the more distant Rows. The Row C, being a Foot nearer to the new-plow’d Land, became twice as large as those in D; but the Row B, which was next to the Land E, grew much larger yet[2].

[2]A like Observation to this on the Land E, has been made in several Turnep Fields of divers Farmers, where Lands adjoining to the Turneps have been well tilled; all the Turneps of the contiguous Lands that were within three or four Feet, or more, of the newly pulveriz’d Earth, received as great, or greater increase, in the Manner as my Rows B C D did; and what is yet a greater Proof of the Length of Roots, and of the Benefit of deep Hoing, all these Turneps have been well Hand-ho’d; which is a good Reason why the Benefit of the deep Pulveration should be perceivable at a greater Distance from it than mine, because my Turneps, not being hoed at all, had not Strength to send out their Roots through so many Feet of unpulveriz’d Earth, as these can through their Earth pulveriz’d by the Hoe, tho’ but shallowly.

This Observation, as ’tis related to me (I being unable to go far enough to see it myself) sufficiently demonstrates the mighty Difference there is between Hand-hoing and Horse-hoing.

F Plate 6. is a Piece of hard whole Ground, of about two Perch in Length, and about two or three Feet broad, lying betwixt those two Lands, which had not been plow’d that Year; ’twas remarkable, that during the Length of this interjacent hard Ground, the Rows B, C, D, were as small and yellow as any in the Land.

The Turneps in the Row D, about three Feet distant from the Land E, receiving a double Increase, proves they had as much Nourishment from the Land E, as from the Land A, wherein they stood; which Nourishment was brought by less than half the Number of Roots of each of these Turneps.

In their own Land they must have extended a Yard all round, else they could not have reach’d the Land E, wherein ’tis probable these few Roots went[4] more than another Yard, to give each Turnep as much Increase as all the Roots had done in their own Land.

Except that it will hereafter appear, that the new Nourishment taken at the Extremities of the Roots in the Land E, might enable the Plants to send out more new Roots in their own Land, and receive something more from thence.

The Row C being twice as big as the Row D, must be suppos’d to extend twice as far; and the Row B, four times as far, in proportion as it was of a Bulk quadruple to the Row D.

A Turnep has a Tap-Root, from whence all these Horizontal Roots are deriv’d.

And ’tis observable; that betwixt these two Lands there was a Trench, or Furrow, of about the Depth of nine or ten Inches, where these Roots must descend first, and then ascend into the Land E: But it must be noted, that some small Quantity of Earth was, by the Harrowing, fall’n into this Furrow, else the Roots could not have pass’d thro’ it.

Roots will follow the open Mould[3], by descending[5] perpendicularly, and mounting again in the same manner: As I have observ’d the Roots of a Hedge to do, that have pass’d a steep Ditch two Feet deep, and reach’d the Mould on the other side, and there fill it; and digging Five Feet distant from the Ditch, found the Roots large, tho’ this Mould was very shallow, and no Roots below the good Mould.

[3]A Chalk-Pit, contiguous to a Barn, the Area of which being about 40 Perch of Ground, was made clean and swept; so that there was not the Appearance of any Part of a Vegetable, more than in the Barn’s Floor: Straw was thrown from thence into the Pit, for Cattle to lie on; the Dung made thereby was haled away about three Years after the Pit had been cleansed; when, at the Bottom of it, and upon the Top of the Chalk, the Pit was covered all over with Roots, which came from a Witch-Elm, not more than Five or Six Yards in Length, from Top to Bottom, and which was about Five Yards above, and Eleven Yards from the Area of the Pit; so that in three Years the Roots of this Tree extended themselves Eight times the Length of the Tree, beyond the Extremities of the old Roots, at Eleven Yards Distance from the Body: The annual-increased Length of the Roots was near Three times as much as the Height of the Tree.

I’m told an Objection hath been made from hence against the Growth of a Plant’s being in proportion to the Length of its Roots; but when the Case is fully stated, the Objection may vanish. This Witch-Elm is a very old decay’d Stump, which is here called a Staggar, appearing by its Crookedness to have been formerly a Plasher in an old White-thorn Hedge wherein it stands: It had been lopped many Years before that accidental Increase of Roots happened; it was stunted, and sent out poor Shoots; but in the third Year of these Roots, its Boughs being most of them horizontally inclined, were observed to grow vigorously, and the Leaves were broad, and of a flourishing Colour; at the End of the third Year all these Roots were taken away, and the Area being a Chalk-Rock lying uncovered, round the Place where the Single Root, that produced all these, came out of the Bank, no more Roots could run out on the bare Chalk, and the Growth of the Boughs has been but little since.

Wheat, drill’d in double Rows in November, in a Field well till’d before Planting, look’d yellow, when about Eighteen Inches high; at Two Feet Distance from the Plants, the Earth was Ho-plow’d, which gave such Nourishment to ’em, that they recovered their Health, and changed their sickly Yellow, to a lively Green Colour.

So in an Orchard, where the Trees are planted too deep, below the Staple or good Mould, the Roots, at a little Distance from the Stem, are all as near the upper Superficies of the Ground, as of those Trees, which are planted higher than the Level of the Earth’s Surface.

But the Damage of planting a Tree too low in moist Ground is, that in passing thro’ this low Part, standing in Water, the Sap is chill’d, and its Circulation thereby retarded.

One Cause of Peoples not suspecting Roots to extend to the Twentieth Part of the Distance which in reality they do, was from observing these Horizontal-Roots, near the Plant, to be pretty taper; and if they did diminish on, in proportion to what they do[6] there, they must soon come to an End. But the Truth is, that after a few Inches, they are not discernibly taper, but pass on to their Ends very nearly of the same Bigness; this may be seen in Roots growing in Water, and in some other, tho’ with much Care and Difficulty.

In pulling up the aforemention’d Turneps, their Roots seem’d to end at few Inches Distance from the Plants, they being, farther off, too fine to be perceiv’d by ordinary Observation.

I found an extreme small Fibre on the Side of a Carrot, much less than a Hair; but thro’ a Microscope it appear’d a large Root, not taper, but broken off short at the End, which it is probable might have (before broken off) extended near as far as the Turnep Roots did. It had many Fibres going out of it, and I have seen that a Carrot will draw Nourishment from a great Distance, tho’ the Roots are almost invisible, where they come out of the Carrot itself.

By the Piece F Plate 6. may be seen, that those Roots cannot penetrate, unless the Land be open’d by Tillage, &c.

As Animals of different Species have their Guts bearing different Proportions to the Length of their Bodies; so ’tis probable, different Species of Plants may have their Roots as different. But if those which have shorter Roots have more in Number, and having set down the means how to know the Length of them in the Earth, I leave the different Lengths of different Species to be examin’d by those who will take the Pains of more Trials. This is enough for me, that there is no Plant commonly propagated, but what will send out its Roots far enough, to have the Benefit of all the ho’d Spaces or Intervals I in the following Chapters allot them, even tho’ they should not have Roots so long as their Stalks or Stems.

[7]

And this great Length of Roots will appear very reasonable, if we compare the Largeness of the Leaves (which are the Parts ordain’d for Excretion) with the Smalness of the Capillary Roots, which must make up in Length or Number what they want in Bigness, being destin’d to range far in the Earth, to find out a Supply of Matter to maintain the whole Plant; whereas the chief Office of the Stalks and Leaves is only to receive the same, and to discharge into the Atmosphere such Part thereof as is found unfit for Nutrition; a much easier Task than the other, and consequently fewer Passages suffice, these ending in an obtuse Form; for otherwise the Air would not be able to sustain the Stalks and Leaves in their upright Posture: but the Roots, tho’ very weak and slender, are easily supported by the Earth, notwithstanding their Length, Smalness, and Flexibility.

Plants have no Stomach, nor Oesophagus, which are necessary to convey the Mass of Food to an Animal: Which Mass, being exhausted by the Lacteals, is eliminated by way of Excrements, but the Earth itself being that Mass to the Guts (or Roots) of Plants, they have only fine Recrements, which are thrown off by the Leaves.

In this, Animal and Vegetable Bodies agree, that Guts and Roots are both injured by the open Air; and Nature has taken an equal Care, that both may be supply’d with Nourishment, without being expos’d to it. Guts are supply’d from their Insides, and Roots from their Outsides.

All the Nutriment (or Pabulum) which Guts receive for the Use of an Animal, is brought to them; but Roots must search out and fetch themselves all the Pabulum of a Plant; therefore a greater Quantity of Roots, in Length or Number, is necessary to a Plant, than of Guts to an Animal.

All Roots are as the Intestines of Animals, and have their Mouths or Lacteal Vessels opening on their outer[8] spongy Superficies, as the Guts of Animals have theirs opening in their inner spongy Superficies.

The Animal Lacteals take in their Food by the Pressure that is made from the Peristaltic Motion, and that Motion caus’d by the Action of Respiration, both which Motions press the Mouths of the Lacteals against the Mass or Soil which is within the Guts, and bring them into closer Contact with it.

Both these Motions are supply’d in Roots by the Pressure occasion’d by the Increase of their Diameters in the Earth, which presses their Lacteal Mouths against the Soil without. But in such Roots as live in Water, a Pressure is constantly made against the Roots by the Weight and Fluidity of the Water; this presses such fine Particles of Earth it contains, and which come into Contact with their Mouths, the closer to them.

And when Roots are in a till’d Soil, a great Pressure is made against them by the Earth, which constantly subsides, and presses their Food closer and closer, even into their Mouths; until itself becomes so hard and close, that the weak Sorts of Roots can penetrate no farther into it, unless re-open’d by new Tillage, which is call’d Hoing.

When a good Number of Single-Mint Stalks had stood in Water, until they were well stock’d with Roots from their two lower Joints, and some of them from three Joints, I set one in a Mint-Glass full of Salt Water; this Mint became perfectly dead within three Days.

Another Mint I put into a Glass of fair Water; but I immers’d one String of its Roots (being brought over the Top of that Glass into another Glass of Salt-water, contiguous to the Top of the other Glass: This Mint dy’d also very soon.

Of another (standing in a Glass of Water and Earth till it grew vigorously) I ty’d one single Root into a Bag, which held a Spoonful of dry Salt, adjoining to[9] the Top of the Glass, which kill’d this strong Mint also. I found that this Salt was soon dissolv’d, tho’ on the Outside of the Glass; and tho’ no Water reach’d so high, as to be within Two Inches of the Joint which produc’d this Root: The Leaves of all these were salt as Brine to the Taste.

Of another, I put an upper Root into a small Glass of Ink, instead of a Bag of Salt, in the Manner above-mention’d; this Plant was also kill’d by some of the Ink Ingredients. The Blackness was not communicated to the Stalk, or Leaves, which inclin’d rather to a yellowish Colour as they died, which seem’d owing to the Copperas.

I made a very strong Liquor with Water, and bruised Seeds of Wild-Garlick, and, filling a Glass therewith, plac’d the Top of it close to the Top of another Glass, having in it a Mint, two or three of whose upper Roots, put into this stinking Liquor, full of the bruised Seeds, and there remaining, it kill’d the Mint in some time; but it was much longer in dying than the others were with Salt and Ink. It might be, because these Roots in the Garlick were very small, and did not bear so great a Proportion to their whole System of Roots, as the Roots, by which the other Mints were poison’d, did to theirs.

When the Edges of the Leaves began to change Colour, I chew’d many of them in my Mouth, and found at first the strong aromatic Flavour of Mint, but that was soon over; and then the nauseous Taste of Garlick was very perceptible to my Palate.

I observ’d, that when the Mint had stood in a Glass of Water, until it seem’d to have finish’d its Growth, the Roots being about a Foot long, and of an earthy Colour, after putting in some fine Earth, which sunk down to the Bottom, there came from the upper Joint a new Set of white Roots, taking their Course on the Outside of the Heap of old Roots downwards, until they reach’d the Earth at the Bottom; and then, after[10] some time, came to be of the same earthy Colour with the old ones.

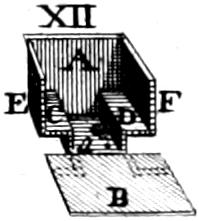

Another Mint being well rooted from Two Joints, about Four Inches asunder; I plac’d the Roots of the lower Joint in a deep Mint-Glass, having Water at the Bottom, and the Roots of the upper Joint into a square Box, contriv’d for the Purpose, standing over the Glass, and having a Bottom, that open’d in the Middle, with a Hole, that shut together close to the Stalk, just below the upper Joint; then laying all these upper Roots to one Corner of the Box, I fill’d it with Sand, dry’d in a Fire-shovel, and found, that in one Night’s time, the Roots of the lower Joint, which reach’d the Water at the Bottom of the Glass, had drawn it up, and imparted so much thereof to those Roots in the Box above, that the Sand, at that Corner where they lay, was very wet, and the other three Corners dry. This Experiment I repeated very often, and it always succeeded as that did.

And for the same Purpose I prepar’d a small Trough, about two Foot long, and plac’d a Mint-Glass under each End of the Trough; over each Glass I plac’d a Mint, with half its Roots in the Glass, the other half in the Trough: The Mints stood just upon the Ends of the Trough. Then I cover’d these Roots with pulveriz’d Earth, and kept the Glasses supply’d with Water; and as oft as the white fibrous Roots shot thro’ the Earth, I threw on more Earth, till the Trough would hold no more; and still the white Fibres came thro’, and appear’d above it; but all seem’d (as I saw by the Help of a coarse Microscope) to turn, and when they came above-ground, their Ends enter’d into it again. These two Mints grew thrice as large as any other Mint I had, which were many, that stood in Water, and much larger than those which stood in Water with Earth in it: They being all of an equal Bigness when set in, and set at the same time. Tho’ these two, standing in my Chamber, never had[11] any Water in their Earth, but what those Roots, which reach’d the Water in the Glasses, sent up to the Roots, which grew in the Trough. The vast Quantity of Water these Roots sent up, being sufficient to keep all the Earth in the Troughs moist, tho’ of a thousand times greater Quantity than the Roots which water’d it, makes it probable, that the Water pass’d out of the Roots into the Earth, without mixing at all with the Sap, or being alter’d to any Degree. The Earth kept always moist, and in the hot Weather there would not remain a Drop of Water in the Glasses, when they had not been fresh supply’d in two Days and one Night; and yet these Roots in the Glasses were not dry’d, tho’ they stood sometimes a whole Day and Night thus in the empty Glasses. These two Mints have thus liv’d all one Summer.

Tho’ the Vessels of Marine Plants be some ways fortify’d against the Acrimony of Salt, as Sea-fish are, yet the Mints all shew, that Salt is poison to other Plants.

The Reason why the Salts in Dung, Brine, or Urine, do not kill Plants in the Field or Garden, is, that their Force is spent in acting upon, and dividing the Parts of Earth; neither do these Salts, or at least any considerable Quantity of them, reach the Roots.

I try’d Salt to many Potatoes in the Ground being undermin’d, and a few of their Roots put into a Dish of Salt-water, they all died sooner or later, according to their Bigness, and to the Proportions the Quantity of Salt apply’d did bear to them.

By the Mints it appears, that Roots make no Distinctions in the Liquor they imbibe, whether it be for their Nourishment or Destruction; and that they do not insume what is disagreeable, or Poison to them, for lack of other Sustenance; since they were very vigorous, and well fed in the Glasses, at the time when the most inconsiderable Part of their Number[12] had the Salt, Garlick, and Ink offer’d to them.

The sixth Mint shews, that when new Earth is apply’d to the old Roots, a Plant sends out new Roots on Purpose to feed on it: And that the more Earth is given it, the more Roots will be form’d, by the new Vigour the Plant takes from the Addition of Earth. This corresponds with the Action of Hoing; for every time the Earth is mov’d about Roots, they have a Change of Earth, which is new to them.

The seventh Mint proves, that there is such a Communication betwixt all the Roots, that when any of them have Water, they do impart a Share thereof to all the rest: And that the Root of the lower Joint of this Mint had Passages (or Vessels) leading from them, through the Stalk, to the Roots of the upper Joint; tho’ the clear Stalk (through which it must have pass’d) that was betwixt these two Joints, was several Inches in Length.

This accounts for the great Produce of long tap-rooted Plants, such as Lusern and St. Foin, in very dry Weather: for the Earth at a great Depth is always moist. It accounts also for the good Crops we have in dry Summers, upon Land that has a Clay Bottom; for there the Water is retain’d a long time, and the lower Roots of Plants which reach it, do, like those of this Mint, send up a Share to all the higher Roots.

If those Roots of a Plant, which lie at the Surface of the Ground, did not receive Moisture from other Roots, which lie deeper, they could be of no Use in dry Weather. But ’tis certain, that if this dry Surface be mov’d or dung’d, the Plant will be found to grow the faster, tho’ no Rain falls; which seems to prove, both that the deep Roots communicate to the shallow a Share of their Water, and receive in Return from them a Share of Food, in common with all the rest of the Plant, as in the Mints they did.

[13]

The two last Mints shew, that when the upper Roots have Moisture (as they had in the Earth in the Trough, carried thither first by the lower Roots) they impart some of it to the lower, else these could not have continu’d plump and fresh, as they did for 24 Hours in the empty Glass. And I have since observed them to do so, in the cooler Season of the Year, for several Weeks together, without any other Water, than what the upper Roots convey’d to them, from the moist Earth above in the Trough[4]. I know not what Time these Roots might continue to be supply’d thus in the hot Weather, because I did not try any longer, for fear of killing them.

[4]’Tis certain, that Roots and other Chyle Vessels of a Plant have a free Communication throughout all their Cavities, and the Liquor in them will run towards that Part where there is least Resistance; and such is that which is the most empty, whether it be above or below; for there are no Valves that can hinder the Descent or Ascent of Liquor in these Vessels, as appears by the growing of a Plant in an inverted Posture.

But it must be noted, that the Depth of the Glass protected the Roots therein from the Injury of the Motion of the free Air, which would have dry’d them, if they had been out of the Glass.

In this Trough is shewn most of the Hoing Effects; viz. That Roots, by being broken off near the Ends, increase their Number, and send out several where one is broken off.

That the Roots increase their Fibres every time the Earth is stirr’d about them.

That the stirring the Earth makes the Plants grow the faster.

Leaves are the Parts or Bowels of a Plant, which perform the same Office to Sap, as the Lungs of an Animal do to Blood; that is, they purify or cleanse it of the Recrements, or fuliginous Steams, received in the Circulation, being the unfit Parts of the Food; and perhaps some decay’d Particles, which fly off the[14] Vessels, through which Blood and Sap do pass respectively.

Besides which Use, the Nitro-aerous Particles may there enter, to keep up the vital Ferment or Flame.

Mr. Papin shews, that Air will pass in at the Leaves, and out thro’ the Plant at the Roots, but Water will not pass in at the Leaves; and that if the Leaves have no Air, a Plant will die; but if the Leaves have Air, tho’ the Root remain in Water in vacuo, the Plant will live and grow.

Dr. Grew, in his Anatomy of Plants, mentions Vessels, which he calls, Net-work, Cobweb, Skeins of Silk, &c. but above all, the Multitude of Air-Bladders in them, which I take to be of the same Use in Leaves, as the Vesiculæ are in Lungs. Leaves being as Lungs inverted, and of a broad and thin Form; their Vesiculæ are in Contact with the free open Air, and therefore have no need of Trachea, or Bronchia, nor of Respiration.

The chief Art of an Husbandman is to feed Plants to the best Advantage; but how shall he do that, unless he knows what is their Food? By Food is meant that Matter, which, being added and united to the first Stamina of Plants, or Plantulæ, which were made in little at the Creation, gives them, or rather is their Increase.

’Tis agreed, that all the following Materials contribute, in some manner, to the Increase of Plants; but ’tis disputed which of them is that very Increase or Food. 1. Nitre. 2. Water. 3. Air. 4. Fire. 5. Earth.

[15]

I will not mention, as a Food, that acid Spirit of the Air, so much talk’d of; since by its eating asunder Iron Bars it appears too much of the Nature of Aqua Fortis, to be a welcome Guest alone to the tender Vessels of the Roots of Plants.

Nitre is useful to divide and prepare the Food, and may be said to nourish Vegetables in much the same Manner as my Knife nourishes me, by cutting and dividing my Meat: But when Nitre is apply’d to the Root of a Plant, it will kill it as certainly as a Knife misapply’d will kill a Man: Which proves, that Nitre is, in respect of Nourishment, just as much the Food of Plants, as White Arsenick is the Food of Rats. And the same may be said of Salts.

Water, from Van-Helmont’s Experiment, was by some great Philosophers thought to be it. But these were deceived, in not observing, that Water has always in its Intervals a Charge of Earth, from which no Art can free it. This Hypothesis having been fully confuted by Dr. Woodward, no body has, that I know of, maintain’d it since: And to the Doctor’s Arguments I shall add more in the Article of Air.

Air, because its Spring, &c. is as necessary to the Life of Vegetables, as the Vehicle of Water is; some modern Virtuosi have affirm’d, from the same and worse Arguments than those of the Water-Philosophers, that Air is the Food of Plants. Mr. Bradley being the chief, if not only Author, who has publish’d this Phantasy, which at present seems to get Ground, ’tis fit he should be answer’d: And this will be easily done, if I can shew, that he has answer’d this his own Opinion, by some or all of his own Arguments.

His first is, that of Helmont, and is thus related in Mr. Bradley’s general Treatise of Husbandry and Gardening, Vol. I. p. 36. ‘Who dry’d Two hundred Pounds of Earth, and planted a Willow of Five Pounds Weight in it, which he water’d with[16] Rain, or distill’d Water; and to secure it from any other Earth getting in, he covered it with a perforated Tin Cover. Five Years after, weighing the Tree, with all the Leaves it had borne in that Time, he found it to weigh One hundred Sixty-nine Pounds Three Ounces; but the Earth was only diminish’d about two Ounces in its Weight.’

On this Experiment Mr. Bradley grounds his Airy Hypothesis. But let it be but examined fairly, and see what may be thence inferr’d.

The Tin Cover was to prevent any other Earth from getting in. This must also prevent any Earth from getting out, except what enter’d the Roots, and by them pass’d into the Tree.

A Willow is a very thirsty Tree, and must have drank in Five Years time several Tuns of Water, which must necessarily carry in its Interstices a great Quantity of Earth (probably many times more than the Tree’s[5] Weight, which could not get out, but by the Roots of the Willow.

[5]The Body of an Animal receives a much less Increase in Weight than its Perspirations amount to, as Sanctorius’s Static-Chair demonstrates.

Therefore the Two hundred Pounds of Earth not being increased, proves that so much Earth as was poured in with the Water, did enter the Tree.

Whether the Earth did enter to nourish the Tree, or whether only in order to pass through it (by way of Vehicle to the Air), and leave the Air behind for the Augment of the Willow, may appear by examining the Matter of which the Tree did consist.

If the Matter remaining after the Corruption or Putrefaction of the Tree be Earth, will it not be a Proof, that the Earth remained in it, to nourish and augment it? for it could not leave what it did not first take, nor be augmented by what pass’d through it. According to Aristotle’s Doctrine, and Mr. Bradley’s[17] too, in Vol. I. pag. 72. “Putrefaction resolves it again into Earth, its first Principle.”

The Weight of the Tree, even when green, must consist of Earth and Water. Air could be no Part of it, because Air being of no greater specific Gravity than the incumbent Atmosphere, could not be of any Weight in it; therefore was no Part of the One hundred Sixty-nine Pounds Three Ounces.

Nature has directed Animals and Vegetables to seek what is most necessary to them. At the Time when the Fœtus has a Necessity of Respiration, ’tis brought forth into the open Air, and then the Lungs are filled with Air. As soon as a Calf, Lamb, &c. is able to stand, it applies to the Teat for Food, without any Teaching. In like manner Mr. Bradley remarks, in his Vol. I. pag. 10. ‘That almost every Stem and every Root are formed in a bending manner under Ground; and yet all these Stems become strait and upright when they come above-ground, and meet the Air; and most Roots run as directly downwards, and shun the Air as much as possible.’

Can any thing more plainly shew the Intent of Nature, than this his Remark does? viz. That the Air is most necessary to the Tree above ground, to purify the Sap by the Leaves, as the Blood of Animals is depurated by their Lungs: And that Roots seek the Earth for their Food, and shun the Air, which would dry up and destroy them.

No one Truth can possibly contradict or interfere with any other Truth; but one Error may contradict and interfere with another Error, viz.

Mr. Bradley, and all Authors, I think, are of Opinion, that Plants of different Natures are fed by a different Sort of Nourishment; from whence they aver, that a Crop of Wheat takes up all that is peculiar to that Grain; then a Crop of Barley all that is proper to it; next a Crop of Pease, and so on, ’till each has drawn off all those Particles which are proper[18] to it; and then no more of these Grains will grow in that Land, till by Fallow, Dung, and Influences of the Heavens, the Earth will be again replenish’d with new Nourishment, to supply the same Sorts of Corn over again. This, if true (as they all affirm it to be), would prove, that the Air is not the Food of Vegetables. For the Air being in itself so homogeneous as it is, could never afford such different Matter as they imagine; neither is it probable, that the Air should afford the Wheat Nourishment more one Year, than the ensuing Year; or that the same Year it should nourish Barley in one Field, Wheat in another, Pease in a Third; but that if Barley were sown in the Third, Wheat in the First, Pease in the Second, all would fail: Therefore this Hypothesis of Air for Food interferes with, and contradicts this Doctrine of Necessity of changing Sorts.

I suppose, by Air, they do not mean dry Particles of Earth, and the Effluvia which float in the Air: The Quantity of these is too small to augment Vegetables to that Bulk they arrive at. By that way of speaking they might more truly affirm this of Water, because it must be like to carry a greater Quantity of Earth than Air doth, in proportion to the Difference of their different specific Weight; Water, being about 800 times heavier than Air, is likely to have 800 times more of that terrestrial Matter in it; and we see this is sufficient to maintain some Sort of Vegetables, as Aquatics; but the Air, by its Charge of Effluvia, &c. is never able to maintain or nourish any Plant; for as to the Sedums, Aloes, and all others, that are supposed to grow suspended in the Air, ’tis a mere Fallacy; they seem to grow, but do not; since they constantly grow lighter; and tho’ their Vessels may be somewhat distended by the Ferment of their own Juices which they received in the Earth, yet suspended in Air, they continually diminish in Weight (which is the true Argument of a Plant) until they grow to[19] nothing. So that this Instance of Sedums, &c. which they pretend to bring for Proof of this their Hypothesis, is alone a full Confutation of it.

Yet if granted, that Air could nourish some Vegetables by the earthy Effluvia, &c. which it carry’d with it[6]; even that would be against them, not for them.

[6]This is meant of dry Earth, by its Lightness (when pulveriz’d extremely fine) carried in the Air without Vapour: For the Atmosphere, consisting of all the Elements, has Earth in it in considerable Quantity, mix’d with Water; but a very little Earth is so minutely divided, as to fly therein pure from Water, which is its Vehicle there for the most Part.

They might as well believe, that Martins and Swallows are nourish’d by the Air, because they live on Flies and Gnats, which they catch therein; this being the same Food, which is found in the Stomach of the Chameleon.

If, as they say, the Earth is of little other Use to Plants, but to keep them fix’d and steady, there would be little or no Difference in the Value of rich and poor Land, dung’d or undung’d; for one would serve to keep Plants fix’d and steady, very near, if not quite as well as the other.

If Water or Air was the Food of Plants, I cannot see what Necessity there should be of Dung or Tillage.

4. Fire. No Plant can live without Heat, tho’ different Degrees of it be necessary to different Sorts of Plants. Some are almost able to keep Company with the Salamander, and do live in the hottest Exposures of the hot Countries. Others have their Abode with Fishes under Water, in cold Climates: for the Sun has his Influence, tho’ weaker, upon the Earth cover’d with Water, at a considerable Depth; which appears by the Effect the Vicissitudes of Winter and Summer have upon subterraqueous Vegetables.

Tho’ every Heat is said to be a different Degree of Fire; yet we may distinguish the Degrees by their different Effects. Heat warms; but Fire burns: The first helps to cherish, the latter destroys Plants.

[20]

5. Earth. That which nourishes and augments a Plant is the true Food of it.

Every Plant is Earth, and the Growth and true Increase of a Plant is the Addition of more Earth.

Nitre (or other Salts) prepares the Earth, Water and Air move it, by conveying and fermenting it in the Juices; and this Motion is called Heat.

When this additional Earth is assimilated to the Plant, it becomes an absolute Part of it.

Suppose Water, Air, and Heat, could be taken away, would it not remain to be a Plant, tho’ a dead one?

But suppose the Earth of it taken away, what would then become of the Plant? Mr. Bradley might look long enough after it, before he found it in the Air among his specific or certain Qualities.

Besides, too much Nitre (or other Salts) corrodes a Plant; too much Water drowns it; too much Air dries the Roots of it; too much Heat (or Fire) burns it; but too much Earth a Plant never can have, unless it be therein wholly buried; and in that Case it would be equally misapply’d to the Body, as Air or Nitre would be to the Roots.

Too much Earth, or too fine, can never possibly be given to Roots; for they never receive so much of it as to surfeit the Plants, unless it be depriv’d of Leaves, which, as Lungs, should purify it.

And Earth is so surely the Food of all Plants, that with the proper Share of the other Elements, which each Species of Plants requires, I do not find but that any common Earth will nourish any Plant.

The only Difference of Soil[7] (except the Richness) seems to be the different Heat and Moisture it[21] has; for if those be rightly adjusted, any Soil will nourish any Sort of Plant; for let Thyme and Rushes change Places, and both will die; but let them change their Soil, by removing the Earth wherein the Thyme grew, from the dry Hill down into the watry Bottom, and plant Rushes therein; and carry the moist Earth, wherein the Rushes grew, up to the Hill; and there Thyme will grow in the Earth that was taken from the Rushes; and so will the Rushes grow in the Earth that was taken from the Thyme; so that ’tis only more or less Water that makes the same Earth fit either for the Growth of Thyme or Rushes.

[7]As I have said in my Essay, That a Soil being once proper to a Species of Vegetables, it will always continue to be so; it must be supposed, that there be no Alteration of the Heat and Moisture of it; and that this Difference I mean, is of its Quality of nourishing different Species of Vegetables, not of the Quantity of it; which Quantity may be alter’d by Diminution or Superinduction.

So for Heat; our Earth, when it has in the Stove the just Degree of Heat that each Sort of Plants requires, will maintain Plants brought from both the Indies.

Plants differ as much from one another in the Degrees of Heat and Moisture they require, as a Fish differs from a Salamander.

Indeed Misletoe, and some other Plants, will not live upon Earth, until it be first alter’d by the Vessels of another Plant or Tree, upon which they grow, and therein are as nice in Food as an Animal.

There is no need to have Recourse to Transmutation; for whether Air or Water, or both, are transform’d into Earth or not, the thing is the same, if it be Earth when the Roots take it; and we are convinced that neither Air nor Water alone, as such, will maintain Plants.

These kind of Metamorphoses may properly enough be consider’d in Dissertations purely concerning Matter, and to discover what the component Particles of Earth are; but not at all necessary to be known, in relation to the maintaining of Vegetables.

[22]

Cattle feed on Vegetables that grow upon the Earth’s external Surface; but Vegetables themselves first receive, from within the Earth, the Nourishment they give to Animals.

The Pasture of Cattle has been known and understood in all Ages of the World, it being liable to Inspection; but the Pasture of Plants, being out of the Observation of the Senses, is only to be known by Disquisitions of Reason; and has (for ought I can find) pass’d undiscover’d by the Writers of Husbandry[8].

[8]When Writers of Husbandry, in discoursing of Earth and Vegetation, come nearest to the Thing, that is, the Pasture of Plants, they are lost in the Shadow of it, and wander in a Wilderness of obscure Expressions, such as Magnetism, Virtue, Power, Specific Quality, Certain Quality, and the like; wherein there is no manner of Light for discovering the real Substance, but we are left by them more in the Dark to find it, than Roots are when they feed on it: And when a Man, no less sagacious than Mr. Evelyn, has trac’d it thro’ all the Mazes of the Occult Qualities, and even up to the Metaphysics, he declares he cannot determine, whether the Thing he pursues be Corporeal or Spiritual.

The Ignorance of this seems to be one principal Cause, that Agriculture, the most necessary of all Arts, has been treated of by Authors more superficially than any other Art whatever. The Food or Pabulum of Plants being prov’d to be Earth, where and whence[9] they take that, may properly be called their Pasture.

[9]By the Pasture is not meant the Pabulum itself; but the Superficies from whence the Pabulum is taken by Roots.

This Pasture I shall endeavour to describe.

[23]

’Tis the inner or (internal) Superficies[10] of the Earth; or which is the same thing, ’tis the Superficies of the Pores, Cavities, or Interstices of the divided Parts of the Earth, which are of two Sorts, viz. Natural and Artificial.

[10]This Pasture of Plants never having been mentioned or described by any Author that I know of, I am at a loss to find any other Term to describe it by, that may be synonymous, or equipollent to it: Therefore, for want of a better, I call it the inner, or internal Superficies of the Earth, to distinguish it from the outer or external Superficies, or Surface, whereon we tread.

Inner or internal Superficies may be thought an absurd Expression, the Adjective expressing something within, and the Substantive seeming to express only what is without it; and indeed the Sense of the Expression is so; for the Vegetable Pasture is within the Earth, but without (or on the Outsides of) the divided Parts of the Earth.

And, besides, Superficies must be joined with the Adjective Inner (or Internal) when ’tis used to describe the Inside of a thing that is hollow, as the Pores and Interstices of the Earth are.

The Superficies, which is the Pasture of Plants, is not a bare Mathematical Superficies; for that is only imaginary.

By Nature, the whole Earth (or Soil) is composed of Parts; and, if these had been in every Place absolutely joined, it would have been without Interstices or Pores, and would have had no internal Superficies, or Pasture for Plants: but since it is not so strictly dense[11], there must be Interstices at all those Places where the Parts remain separate and divided.

[11]For were the Soil as dense as Glass, the Roots or Vegetables (such as our Earth produces) would never be able to enter its Pores.

These Interstices, by their Number and Largeness, determine the specific Gravity (or true Quantity) of every Soil: The larger they are, the lighter is the Soil; and the inner Superficies is commonly the less.

The Mouths, or Lacteals, being situate, and opening, in the convex Superficies of Roots, they take their Pabulum, being fine Particles of Earth, from the Superficies of the Pores, or Cavities, wherein the Roots are included.

[24]

And ’tis certain, that the Earth is not divested or robb’d of this Pabulum, by any other Means, than by actual Fire, or the Roots of Plants.

For, when no Vegetables are suffer’d to grow in a Soil, it will always grow richer. Plow it, harrow it, as often as you please, expose it to the Sun in Horse-Paths all the Summer, and to the Frost of the Winter; let it be cover’d by Water at the Bottom of Ponds, or Ditches; or if you grind dry Earth to Powder, the longer ’tis kept exposed, or treated by these or any other Method possible (except actual Burning by Fire); instead of losing, it will gain the more Fertility.

These Particles, which are the Pabulum of Plants, are so very minute[12] and light, as not to be singly attracted to the Earth, if separated from those Parts to which they adhere[13], or with which they are in Contact (like Dust to a Looking-Glass, turn it upwards, or downwards, it will remain affixt to it), as these Particles do to those Parts, until from thence remov’d by some Agent.

[12]As to the Fineness of the Pabulum of Plants, ’tis not unlikely, that Roots may insume no grosser Particles, than those on which the Colours of Bodies depend; but to discover the greatest of those Corpuscles, Sir Isaac Newton thinks, it will require a Microscope, that with sufficient Distinctness can represent Objects Five or Six hundred times bigger, than at a Foot Distance they appear to the naked Eye.

My Microscope indeed is but a very ordinary one, and when I view with it the Liquor newly imbibed by a fibrous Root of a Mint, it seems more limpid than the clearest common Water, nothing at all appearing in it.

[13]Either Roots must insume the Earth, that is their Pabulum, as they find it in whole Pieces, having intire Superficies of their own, or else such Particles as have not intire Superficies of their own, but want some Part of it, which adheres to, or is Part of the Superficies of larger Particles, before they are separated by Roots. The former they cannot insume (unless contained in Water); because they would fly away at the first Pores that were open: Ergo they must insume the latter.

[25]

A Plant cannot separate these Particles from the Parts to which they adhere, without the Assistance of Water, which helps to loosen them.

And ’tis also probable, that the Nitre of the Air may be necessary to relax this Superficies, to render the prolific Particles capable of being thence disjoin’d; and this Action of the Nitre seems to be what is call’d, Impregnating the Earth.

Since the grosser Vegetable Particles, when they have pass’d thro’ a Plant, together with their moist Vehicle, do fly up into the Air invisibly; ’tis not likely they should, in the Earth, fall off from the Superficies of the Pores, by their own Gravity: And if they did fall off, they might fly away as easily before they enter’d Plants, as they do after they have pass’d thro’ them; and then a Soil might become the poorer[14] for all the Culture and Stirring we bestow upon it; tho’ no Plants were in it; contrary to Experience.

[14]But we see it is always the richer by being frequently turned and exposed to the Atmosphere: Therefore Plants must take all their Pabulum from a Superficies of Parts of Earth; except what may perhaps be contained in Water fine enough to enter Roots intire with the Water.

It must be own’d, that Water does ever carry, in its Interstices, Particles of Earth fine enough to enter Roots; because I have seen, that a great Quantity of Earth (in my Experiments) will pass out of Roots set in Rain-water; and tis found that Water can never be, by any Art, wholly freed from its earthy Charge; therefore it must have carry’d in some Particles of Earth along with it: But yet I cannot hence conclude, that the Water did first take these fine Particles from the aforesaid Superficies: I rather think, that they are exhal’d, together with very small Pieces to which they adhere, and in the Vapour divided by the Aereal Nitre; and, when the Vapour is condens’d, they descend with it to replenish[26] the Pasture of Plants; and that these do not enter intire into Roots, neither does any other of the earthy Charge that any Water contains; except such fine Particles which have already pass’d thro’ the Vegetable Vessels, and been thence exhal’d.

This Conjecture is the more probable, for that Rain-Water is as nourishing to Plants set therein as Spring-Water, tho’ the latter have more Earth in it; and tho’ Spring-water have some Particles in it that will enter intire into Roots, yet we must consider, that even that Water may have been many times exhal’d into the Air, and may have still retain’d a great Quantity of Vegetable Particles, which it received from Vegetable Exhalations in the Atmosphere; tho’ not so great a Quantity as Rain-water, that comes immediately thence.

These, I have to do with, are the Particles which Plants have from the Earth, or Soil; but they have also fine Particles of Earth from Water, which may impart some of its finest Charge to the Superficies of Roots, as well as to the Superficies of the Parts of the Earth[15] which makes the Pasture of Plants.

[15]If Water does separate, and take any of the mere Pabulum of Plants from the Soil, it gives much more to it.

Yet it seems, that much of the Earth, contain’d in the clearest Water, is there in too large Parts to enter a Root; since we see, that in a short time the Root’s Superficies will, in the purest Water, be cover’d with Earth, which is then form’d into a terrene Pasture, which may nourish Roots; but very few Plants will live long in so thin a Pasture, as any Water affords them. I cannot find one as yet that has liv’d a Year, without some Earth have been added to it.

And all Aquatics, that I know, have their Roots in the Earth, tho’ cover’d with Water.

The Pores, Cavities, or Interstices of the Earth, being of two Sorts, viz. Natural and Artificial; the[27] one affords the Natural, the other the Artificial Pasture of Plants.

The natural Pasture alone will suffice, to furnish a Country with Vegetables, for the Maintenance of a few Inhabitants; but if Agriculture were taken out of the World, ’tis much to be fear’d, that those of all populous Countries, especially towards the Confines of the frigid Zones (for there the Trees often fail of producing Fruit), would be oblig’d to turn Anthropophagi, as in many uncultivated Regions they do, very probably for that Reason.

The artificial Pasture of Plants is that inner Superficies which is made from dividing the Soil by Art.

This does, on all Parts of the Globe, where used, maintain many more People than the natural Pasture[16]; and in the colder Climates, I believe, it will not[28] be extravagant to say, ten times as many: Or that, in Case Agriculture were a little improved (as I hope to shew is not difficult to be done), it might maintain twice as many more yet, or the same Number, better.

[16]The extraordinary Increase of St. Foin, Clover, and natural Grass, when their Roots reach into pulveriz’d Earth, exceeding the Increase of all those other Plants of the same Species (that stand out of the Reach of it) above One hundred Times, shew how vastly the artificial Pasture of Plants exceeds the natural. A full Proof of this Difference, (besides very many I have had before) was seen by two Intervals in the middle of a poor Field of worn-out St. Foin, pulveriz’d in the precedent Summer, in the manner describ’d in a Note on the latter Part of Chap. XII. relating to St. Foin. Here not only the St. Foin adjoining to these Intervals recover’d its Strength, blossom’d, and seeded well, but also the natural Grass amongst it was as strong, and had as flourishing a Colour, as if a Dung-heap had been laid in the Intervals; also many other Weeds came out from the Edges of the unplow’d Ground, which must have lain dormant a great many Years, grew higher and larger than ever were seen before in that Field; but above all, there was a Weed amongst the St. Foin, which generally accompanies it, bearing a white Flower; some call it White Weed, others Lady’s Bedstraw: Some Plants of this that stood near the Intervals, were, in the Opinion of all that saw them, increased to a thousand Times the Bulk of those of the same Species, that stood in the Field three Feet distant from such pulveriz’d Earth.

Note, These Intervals were each an Hundred Perch long, and had each in them a treble Row of Barley very good. The Reason I take to be this, That the Land had lain still several Years after its artificial Pasture was lost; whereby all the Plants in it having only the natural Pasture to subsist on, became so extremely small and weak, that they were not able to exhaust the Land of so great a Quantity of the (vegetable) nourishing Particles as the Atmosphere brought down to it.

And when by Pulveration the artificial Pasture came to be added to this natural Pasture (not much exhausted), and nothing at all suffered to grow out of it for above Three Quarters of a Year, it became rich enough, without any Manure, to produce this extraordinary Effect upon the Vegetables, whose Roots reached into it. How long this Effect may continue, is uncertain: but I may venture to say, it will continue until the Exhaustion by Vegetables doth over-balance the Descent of the Atmosphere, and the Pulveration.

And what I have said of any one Species of Plants in this Respect may be generally apply’d to the rest.

The natural Pasture is not only less than the artificial, in an equal Quantity of Earth; but also, that little consisting in the Superficies of Pores, or Cavities, not having a free Communication[17] with one another, being less pervious to the Roots of all Vegetables, and requiring a greater Force to break thro’ their Partitions; by that Means, Roots, especially of weak Plants, are excluded from many of those Cavities, and so lose the Benefit of them.

[17]None of the natural Vegetable Pasture is lost or injured by the artificial; but on the contrary, ’tis mended by being mix’d with it, and by having a greater Communication betwixt Pore and Pore.

But the artificial Pasture consists in Superficies of Cavities, that are pervious to all Manner of Roots, and that afford them free Passage and Entertainment in and thro’ all their Recesses. Roots may here extend to the utmost, without meeting with any Barricadoes in their Way.

The internal Superficies, which is the natural Pasture of Plants, is like the external Superficies or[29] Surface of the Earth, whereon is the Pasture of Cattle; in that it cannot be inlarg’d without Addition of more Surface taken from Land adjoining to it, by inlarging its Bounds or Limits.

But the artificial Pasture of Plants may be inlarg’d, without any Addition of more Land, or inlarging of Bounds, and this by Division only of the same Earth.

And this artificial Pasture may be increas’d in proportion to the Division of the Parts of Earth, whereof it is the Superficies, which Division may be mathematically infinite; for an Atom is nothing; neither is there a more plain Impossibility in Nature, than to reduce Matter to nothing, by Division or Separation of its Parts.

A Cube of Earth of One Foot has but Six Feet of Superficies. Divide this Cube into Cubical Inches, and then its Superficies will be increas’d Twelve times, viz. to Seventy-two Superficial Feet. Divide these again in like Manner and Proportion; that is, Divide them into Parts that bear the same Proportion to the Inches, as the Inches do to the Feet, and then the same Earth, which had at first no more than Six Superficial Feet, will have Eight hundred Sixty-four Superficial Feet of artificial Pasture; and so is the Soil divisible, and this Pasture increasable ad Infinitum.

The common Methods of dividing the Soil are these; viz. by Dung, by Tillage, or by both[18].

[18]For Vis Unita Fortior.

All Sorts of Dung and Compost contain some Matter, which, when mixt with the Soil, ferments therein; and by such Ferment dissolves, crumbles,[30] and divides the Earth very much: This is the chief, and almost only Use of Dung: For, as to the pure earthy Part, the Quantity is so very small, that, after a perfect Putrefaction, it appears to bear a most inconsiderable Proportion to the Soil it is design’d to manure: and therefore, in that respect, is next to nothing.

Its fermenting Quality is chiefly owing to the Salts wherewith it abounds; but a very little of this Salt applied alone to a few Roots of almost any Plant, will (as, in my Mint Experiments, it is evident common Salt does) kill it.

This proves, that its Use is not to nourish, but to dissolve; i. e. Divide the terrestrial Matter, which affords Nutriment to the Mouths of Vegetable Roots.

It is, I suppose, upon the Account of the acrimonious fiery Nature of these Salts, that the Florists have banish’d Dung from their Flower-Gardens.

And there is, I’m sure, much more Reason to prohibit the Use of Dung in the Kitchen-Garden, on Account of the ill Taste it gives to esculent Roots and Plants, especially such Dung as is made in great Towns.

’Tis a Wonder how delicate Palates can dispense with eating their own and their Beasts Ordure, but a little more putrefied and evaporated; together with all Sorts of Filth and Nastiness, a Tincture of which those Roots must unavoidably receive, that grow amongst it.

Indeed I do not admire, that learned Palates, accustom’d to the Goût of Silphium, Garlick, la Chair venee, and mortify’d Venison, equalling the Stench and Rankness of this Sort of City-Muck, should relish and approve of Plants that are fed and fatted by its immediate Contact.

People who are so vulgarly nice, as to nauseate these modish Dainties, and whose squeamish Stomachs[31] even abhor to receive the Food of Nobles, so little different from that wherewith they regale their richest Gardens, say that even the very Water, wherein a rich Garden Cabbage is boil’d, stinks; but that the Water, wherein a Cabbage from a poor undung’d Field is boil’d, has no Manner of unpleasant Savour; and that a Carrot, bred in a Dunghill, has none of that sweet Relish, which a Field-Carrot affords.

There is a like Difference in all Roots, nourish’d with such different Diet.

Dung not only spoils the fine Flavour of these our Eatables, but inquinates good Liquor. The dung’d Vineyards in Languedoc produce nauseous Wine; from whence there is a Proverb in that Country, That poor People’s Wine is best, because they carry no Dung to their Vineyards.

Dung is observ’d to give great Encouragement to the Production of Worms; and Carrots in the Garden are much worm-eaten, when those in the Field are free from Worms.

Dung is the Putrefaction of Earth, after it has been alter’d by Vegetable or Animal Vessels. But if Dung be thoroughly ventilated and putrefy’d before it be spread on the Field (as I think all the Authors I have read direct) so much of its Salts will be spent in fermenting the Dung itself, that little of them will remain to ferment the Soil; and the Farmer who might dung One Acre in Twenty, by laying on his Dung whilst fully replete with vigorous Salts, may (if he follows these Writers Advice to a Nicety) be forced to content himself with dunging one Acre in an Hundred.