Title: Lost Gip

Author: Hesba Stretton

Release date: November 20, 2024 [eBook #74763]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Henry S. King and Co, 1873

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

LOST GIP has been reprinted from

THE DAY OF REST.

One Penny Weekly. Price Sixpence in Monthly

Parts, with an Informational Number.

FRONTISPIECE.

BY

HESBA STRETTON

AUTHOR OF

"JESSICA'S FIRST PRAYER," "LITTLE MEG,"

"THE DOCTOR'S DILEMMA," ETC., ETC.

———————

SIX ILLUSTRATIONS.

———————

Eleventh Thousand.

LONDON:

HENRY S. KING AND CO.

65, CORNHILL, AND 12, PATERNOSTER ROW.

———

1873.

[All Rights reserved.]

CONTENTS.

———————

CHAPTER XI. AN AWAKENED CONSCIENCE

CHAPTER XIII. JOHNNY'S SUNDAY SUIT

CHAPTER XVIII. LEAVING THE OLD HOME

LOST GIP.

———————

GIP'S FIRST BREATH.

GOING along one of the back streets of the East End of London on a sultry summer day is by no means a pleasant or refreshing walk. The middle of the street is narrow, and the kennels bordering the side pavements are usually choked up with refuse thrown out from the dwellings on either hand. Heaps of rotting fruit, potato-parings, and decaying cabbage-leaves lie about the causeways, to be eagerly turned over and over in search of a prize by half-famished children, whose only anxiety, during the summer months, is to satisfy, if possible, the hunger always gnawing at them.

There is no sweet scent in the air—no freshness; what scents there may be, are the very reverse of sweet. The sun smites down upon the closely built houses and dirty pavement and un-watered street, till fever seems to follow in the trail of the sultry days. At each end of such streets there generally stands a busy spirit-vault, which carries on a thriving trade; for the dry air makes every one athirst, and the door swings to and fro incessantly with the stream of men, women, and children passing in and out.

But at the back of these thoroughfares, there lie close alleys and courts, where the heat is still more unbearable. No current of air runs through them; and they are so shut out of sight that those who live in them feel no shame, and no fear of being seen by any one less wretched than themselves. There is a dead level of misery and degradation. The dirt becomes more loathsome, and the diseases bred by it more deadly. Half the children born in them die before they have lived out their twelve months of misery. Only those who are singularly strong, or are specially cared for by their mothers, live into the second year. Babies' funerals are so frequent they excite no notice, except that of the children who have survived the common fate, and who follow the little coffin to the end of their own alley, leaving it there, to be carried away into some dim region, of which they know nothing. As for the mothers, the greater portion of them seem to have lost their natural love for their little ones, and are glad to be rid of a care which would have made their lives a still heavier burden to them.

It was in one of these close, pent-up alleys that a boy was idling, one hot summer noonday, about the door of a small dwelling in the corner farthest from the street,—a poor house, like all the rest, with more panes of brown paper in its windows than of glass. The four rooms of it, two on each floor, were tenanted by as many families, with their lodgers. There seemed to be a little excitement within, and several women were bustling about, and could be seen through the open door going up and down the staircase. At that time of the day there were but few men about the yard; for most of them were costermongers, and were away at work. But the alley was tolerably well filled with almost naked children, playing noisily in the open gutter, or fighting with one another with still louder noise.

The boy joined none of them, but looked on with an absent and anxious face, from time to time peeping in through the open door, or listening intently to every sound in the room at the top of the crazy staircase. All at once he heard a feeble wailing cry; and the tears started into his eyes, why he did not know, but he brushed them off his face hastily, and kept his head turned away, lest anybody should see them.

"Sandy!" shouted a woman's voice from the stairhead. "Sandy, give us your jacket to wrap the baby in."

If it had been the depth of winter, he would have stripped off his ragged jacket willingly for the new baby. He had a passion for young helpless creatures, and he had nursed and tended two other babies before this one, and had seen them both fade away slowly, and die in this unwholesome air.

He did not care much for his mother; how could he, when he seldom saw her sober? But the babies were very precious to him; dearer even than the mongrel cur he had contrived to keep in secret for a long time, but which had been taken from him because he could not pay the duty. There was no duty upon babies;—Sandy remembered that joyfully. The police would take no inconvenient notice of this new little creature. He might carry it about with him, and play with it, and teach it all sorts of pretty tricks, with no danger of losing it.

"Is it a gel or a boy?" he asked eagerly from the woman, who hurried downstairs for his jacket.

"A little gel!" she answered. "A reg'lar little gipsy, with black eyes, and black hair all over its head."

"Let me have her as soon as you can," urged Sandy, rubbing his hands, and dancing upon the doorstep, to let off a little of his pleasurable excitement.

He stole round the costermonger's barrow, sat down on

one of the baskets, and then peeped at the new little face.

"You can have her d'reckly," said the woman; "it's as hot as an oven everywhere to-day."

"I'll come for her," replied Sandy, following her up to the door.

In a few minutes a small bundle was handed out to him, wrapped in his old jacket; and he trod softly and cautiously downstairs, with it in his arms.

He was at a loss for some secluded corner, where he could look at his new treasure; for he did not wish to have all the brawling, shouting children in the alley crowding about him, as he knew they would be in an instant, if he sat down on the doorstep with that mysterious little bundle on his lap. A rapid glance showed him a costermonger's barrow reared on one end in a corner, with a basket or two on the ground. He stole round it, and sat down on one of the baskets; then, slowly opening the jacket, peeped at the new little face.

How was it that the tears dimmed his eyes again? The recollection of Tom and little Vic, lying now in their tiny coffins deep down in the ground, came back so vividly to him, that he could not see this baby for crying. He knew it was a bad thing to do, and he was angry with himself, and dreadfully afraid of any one finding it out, yet for a minute or two, he could not conquer it. But after rubbing his eyes diligently with the sleeve of the jacket, he found them clear enough to look carefully at his prize.

A thorough gipsy, no doubt of that. Eyes as black as coal, and the little head all covered with the blackest hair. She lay quite content in his arms, looking seriously up into his face, as if she could really see it, and wanted to make sure what sort of a brother he was going to be to her. Sandy puckered up his features into a broad smile, whistled to her softly, put his finger into her small mouth, and trotted her very gently on his knee.

The baby was "as good as gold;" she did not cry, and so betray their hiding-place. But her black solemn eyes never turned away from their gaze at Sandy's face.

"Oh! I wish there were somebody as could keep it alive for me!" thought Sandy, sorrowfully.

He had a vague notion that there was some one, somewhere, who could save the new-born baby from dying, as Tom and little Vic had died. In the streets he had seen numbers of rich babies, who did not want for anything, and whose cheeks were fat and rosy, not at all like the puny, wasted babies in the alley. But how it happened, whether it was simply because they were rich, or because there was somebody who could keep them alive, and cared more for them than for the poor, he could not tell. He had often watched them with longing eyes, and knew how pretty they looked in their blue or scarlet cloaks and white hoods, and he wished now with all his heart that he could find some one who would keep little Gipsy alive for him. He called the baby Gipsy to himself and others, and no one in the alley took any trouble to give her another name. What was the good of registering a baby that was sure to be dead in a short time?

Sandy's mother was up and about her business again in a few days. She earned her living, when she took the trouble to earn it, by going about as a costermonger, as most of her neighbours did. When she had enough strength of mind to save four or five shillings from the spirit-vault at the corner of the street, she would hire a barrow for a week, and lay in a stock of cheap fruit and vegetables, and Sandy would go with her to push it. But that was very occasionally; it was seldom that her strength of mind did not fail before the temptation of another and another dram.

Then Sandy was thrown upon his own resources, and gained a very scanty supply for his wants by selling fusees near the Mansion House, or any other crowded spot, where one in a thousand of the passers-by might see him, and by chance patronize him. Often, when there was no baby at home, he did not go there for weeks, but slept wherever he could find a shelter—in an empty cart, or under a tarpaulin; even without a shelter, if this could not be had.

If his mother came across him during these spells of wandering, the only proof of relationship she manifested was her demand for any and all of the halfpence he might have in his possession, and her diligent search among his rags for them. It was only when there was a baby that Sandy went home as regularly as the night fell, carrying with him a sticky finger of some cheap sweetmeat, which contained almost more of poison than of sugar.

Gip was left to his care even more than the other babies. By this time his mother had become too inveterate a drunkard to take much interest in her. Now and then she would bear her off in her arms to the spirit-vault, and come reeling back with her, to Sandy's great alarm. But in general she took no notice of Gipsy, and left the boy to tend her as well as he could. It was a good thing for the baby. Sandy carried her out of the foul air into the broader and opener streets, often lingering wistfully at a baker's window till he got a wholesome crust for her to nibble at.

His jacket continued to be almost the only clothing she had, and as the winter came on, he shivered with cold, till his benumbed arms could scarcely hold her. But that he bore without a murmur, for who was there to complain to? He had never known a friend to whom he could go and say, "I am hungry, and cold, and almost naked."

He had never heard that it had once been said, "Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these My brethren, ye have done it unto Me."

Was it possible that Sandy could be one of the least of these His brethren?

There was, however, this great and last difficulty in Sandy's case. If any one had clothed him, doing it in remembrance of their Lord, his mother would have immediately pawned the clothes, and spent the money in the spirit-vault.

———◆———

GIP'S HOME.

WHETHER Gip was naturally stronger than Tom and little Vic, or whether Sandy had learned by experience how to take better care of her, she outlived the first fatal twelve months, and bid fair to struggle through another year. It is true, she was pinched and stunted, her poor little arms were thin, and her face was sallow, with great black eyes in it, usually very solemn, but ready to twinkle merrily upon Sandy. She had been fed with more gin than milk: Sandy could only recollect twice or three times that she had had a draught of sky-blue milk given to her by a kindly woman, who now and then spared them a bit of bread.

But her teeth were coming, which would be a help to her, if he could find anything for them to eat; and he watched their growth with much delight, often nursing her as she cried and moaned all night long upon his knees, while the mother was unconscious in a drunken sleep. Gipsy was growing cunning, too, and caught quickly at the pretty tricks which the other babies had died too soon to learn.

Now that she held out a promise to live, he began to wonder how she would grow up, and what he should do with her when she was a big girl. Anything would be better than being like their mother! If he could only find some way of getting on himself, that he might help Gip when she was growing up!

Small chance was there for Sandy to get on. His cares and duties were increasing fast; and with them, the urgent need for earning more money in one way or another. Gip wanted more food; and before long, his old jacket, which she wore, would be falling into shreds, to say nothing of his own ragged and tattered condition. He made himself very troublesome about the Mansion House, and other places, by pursuing gentlemen, and beseeching them to buy a box of fusees. More than once he had been handed over to the police, who had given him a not unfriendly cuff on the ears, and bade him be off about his business.

What was his business but to provide for himself and Gip, and by one means or another snatch up enough food to keep them alive? Unfortunately, there was a second branch of business—to buy now and then some old thing in Rag Fair, without which he would not be allowed to wander about the streets, and would be compelled to remain at home and starve. Sandy was sometimes on the very verge of despair; but at the worst, times would mend a little. His mother, in her drunken forgetfulness, would let fall a sixpence, or once even a shilling; and Sandy's quick eyes would see it, and his quick fingers would seize it, like a fortune. Or one of the neighbours would give him a day's work at pushing a barrow, paying him sixpence for it, with some small potatoes or frost-bitten turnips into the bargain, at the end of the long day. Then Gip and he would make quite a feast.

"Where are I to go, Gip?" he asked one day, after the police had been more than usually hard upon him. "Where are I to go, and what are I to do? Go about your bis'ness, eh? Well! suppose I ain't got no bis'ness? And I ain't likely to have no bis'ness anywheres, as I can see. I don't know what you and me was born for. They'll begin to tell you to go about your bis'ness as soon as ever you can run in the streets."

Gip looked shrewdly back at him with her bright black eyes, as if she understood the difficulty, but could not help him out of it. She could talk a little by this time, and could manage to get down to the entrance of the alley, and watch for him coming home, till she saw him, and then toddle to meet him, with such tottering steps—for her thin little legs bent under her weight—that Sandy's heart would throb fast with the fear lest she should fall. Sometimes she did fall; and with a shout that made all who heard it turn to look at him, he would dash forward, and pick her up in his arms before she had time to scream.

Gip could trot, too, beside her mother, holding on by her tattered skirt, as the woman dragged her slipshod feet down to the nearest spirit-vault. She swore at the child sometimes, but more often she took her inside, and poured the last drop or two of her glass of gin down Gip's throat, when her grimaces and antics made all around her laugh loudly, as though the puny creature's excitement was a source of great mirth. Gip was learning the road to the spirit-vault readily, and would make her way there herself, when she was tired of playing in the gutter with the other children, and wanted to find her mother; for she was too heavy now for Sandy to carry her out with him, and she was too young to run by his side as he tried to sell fusees along the streets.

Sandy returned home one evening very low and down-hearted. It had been a rainy day, and nobody had stopped in their hurried tramp about their business to look at his damp fusee boxes. They were completely soaked, though he had done his best to keep them covered under his jacket. But then he was quite wet through himself, and the water was dripping from his thick, uncombed hair, and trickling coldly down his face and neck. Night had set in; yet still the rain fell in torrents, driven along the streets by a strong westerly wind. The light from the lamps glistened in pools of water lodging on the pavement, through which he splashed heedlessly with his bare feet. The pipes that drained the roofs leaked, and poured down in waterfalls upon him, as he hurried along, keeping close to the houses for as much shelter as they could give.

Gip could not be waiting and watching for him such a night as this; and it was very well she could not, for he had brought nothing for her—positively nothing—not even one of the stale buns which he begged for her sometimes. It was harder than anything else, worse than the rain, to think that perhaps she would be forced to go to sleep hungry—crying for food, while he had none to give her.

No; Gip was not at the corner. He looked closely into the doorway, where she often sat, as he passed, and felt his heart sink a little lower, as if he were disappointed not to find her there.

For once the alley was quiet and deserted; not a creature who had a home was out that night. Two or three of the windows twinkled dimly with the light of a candle in the room within, and so helped him to avoid the gutter, where the water was running as noisily as a brook. But the room where his mother lived was all blank and dark—not a gleam of light in it, either of fire or candle.

He lifted the latch, and went in, calling softly in the darkness, "Gip! Little Gip!"

Not a sound answered him; Gip's dear shrill voice was silent. Perhaps she was still with her mother in the spirit-vault. Or, perhaps, she was only keeping quiet in fun; for it was one of her pretty tricks to hide, and be as still as a mouse when he came in, while he pretended to search for her everywhere: in their empty cupboard, and under their mother's bed, and even up the chimney, as if Gip could be there! till she would break out suddenly into a burst of laughter, and run at him from her fancied hiding-place, where he had seen her all the time.

Sandy stole carefully across the dark room to the candle, which stood in the neck of a bottle on the chimney-piece, and tried to strike a light with some of his damp fusees. But they sputtered and glimmered only for an instant, leaving him in the darkness of the quiet and perhaps empty room.

But at length he succeeded in getting a match to burn long enough to light the candle. He could see at a glance everything in the small bare room. There was his mother's old flock bed on the floor; and there was his mother herself lying upon it in a dead sleep, her face swollen and red, and her ragged gown drawn over her; for long since the only blanket and old counterpane had gone to the pawnbroker's shop, and there was no chance of their being redeemed.

But was Gip there? Sandy could see plainly enough there was no little Gip under his mother's gown, or beside her on the bed. She was not there; she was not anywhere in the room. He stood motionless in his bewilderment; his eyes wandering round the bare walls, and his heart beating painfully. If little Gip was not at home, where could she be?

He could not bear his pain and dread long. He ran to his mother's side, and shook her roughly by the shoulder, shouting as loudly as he could in her ear.

But she was almost like one dead. It was hard work to awake her, and still harder to bring her to her senses. She lifted herself up in bed, and struck at him; but Sandy slipped out of her way.

Once again, at a safe distance, where he was quite out of reach, he shouted his question at her.

"Where's Gip?" he cried. "Mother, what have you done with my little Gip?"

"Gip?" repeated his mother, in her thick, drunken voice, "Gip? I lost her; couldn't find her anywheres. She's somewhere."

That was all. Sandy's mother fell back again on the bed, and sank into her deep sleep.

Little Gip was lost.

———◆———

LOST IN LONDON.

FOR a minute or two Sandy stood still again, bewildered and motionless, as at first, staring at the place where Gip ought to have been by her mother's side, and hardly able to believe that he should not see her white little face looking up suddenly from among the rags, and hear her cry,—

"Here little Gip are, Dandy!"

The wind and rain beat against the window, and soaked through the paper that covered most of the panes. Down in the alley there was an unusual stillness. All at once he fancied he could hear Gip crying and wailing in the storm, and could see her toddling with her naked feet on the wet stones, with her damp hair hanging over her little face. What a many streets there were in London, with so many turnings! and Gip was lost among them, wandering about alone in the rain and the wind and the darkness, trying to find Sandy, and crying for him to come and carry her home again. He felt as though his heart would break at the mere thought of it.

It was only for a minute or two that Sandy lingered, for there was no time to lose. Then he crept very cautiously towards his sleeping mother, and felt carefully in her pocket. No; she had not come home till every penny was spent; neither had he a penny in the world.

But he carried away with him his stock of fusees; for he had made up his mind during that minute or two, that as soon as he found little Gip, he would bear her off to some distant part of London, and go home no more to their drunken mother. He felt almost triumphant when this plan crossed his mind, in spite of his deep distress. Gip would soon be old enough now to run by his side, and when she was tired, he would carry her; and they would live together in any hole or corner. He knew several, where, if he put Gip next to the wall, and lay outside himself, perhaps she would not feel the rain and cold so very much. Some of the other fusee boys would help him when they were in luck, and he would help them in his turn. One thing he was resolved upon—he would never go back to his mother again, never!

He went slowly down into the quiet alley, still hoping he might hear Gip cry from some dark corner.

He called to her, at first softly, then more and more loudly, until some of the neighbours opened their doors or windows, and asked what was the matter, and why he was making that row?

"Mother's been and lost Gip," he answered, catching at the hope that perhaps she was safely lodged in one of their dwellings; "is there anybody as has seen her? It is a awful night, fit to drown the cats as are out of doors, and she's sich a little gel. Mother's dead drunk, and doesn't know a word about her. Hasn't anybody seen little Gip?"

The women chattered to one another across the narrow alley about Nancy Carroll and her drunkenness, but not one of them knew anything of Gip, except that she had been seen with her mother going down into the street a little before dark. One or two hinted that maybe she had been made away with as a trouble, and Sandy's blood ran chill at the mere thought of such a terrible thing.

"No, no!" he cried. "Nobody 'ud have the heart to do that; she's sich a pretty little gel. No, no! Mother 'ud never do sich a thing as that; she'd be good to her at times, she would, when she were herself; and little Gip wasn't never a trouble."

"Drink 'ill make Nancy Carroll do anything!" said a sharp-voiced woman, who prided herself upon not getting drunk oftener than once a week, and then upon a Sunday, when business was slack.

Sandy did not linger to discuss the dreadful question with her; he was only the more eager to be off, and prove the suspicion false, by finding Gip somewhere. Tucking up his stock-in-trade, by which he was to support Gip and himself, as securely as he could under his jacket, he turned away, and ran down the dark archway into the street.

But once there, which way was he to turn—to the right hand or the left? In the alley this perplexity had not troubled him, for there were not two directions where Gip could wander. There were spirit-vaults which his mother frequented at each end of the street. Every way there stretched around him a tangled network of streets, with lanes and alleys and courts crossing one another, extending for hundreds of miles. True, little Gip could not have wandered very far off as yet, for she was too small and weakly; but if Sandy chose one direction, perhaps she would be paddling away just in the opposite one, and every step he took would set them farther and farther apart.

First of all, he went to both of the spirit-vaults, which were crowded this wet night, and searched in every corner, asking the busy assistants behind the counters if they had seen a little girl all alone. But she was not there, and there was nothing else to guide him to her. Yet a choice had to be made, and trusting himself to his luck, Sandy set off running as fast as he could through the now deserted streets, peeping into every doorway with his quick, searching eyes, and shouting "Gip! Gip!" up every archway and passage where she might have found shelter, if she had had sense enough.

It was a miserable night, one that Sandy could never forget, if he lived to be a hundred years old. The rain came down pitilessly, and the gusts of wind tore past him, blowing open his tattered clothes, as to force a way for the cold rain to beat against his bare skin. But his dread for Gip made him almost unconscious of his own wretchedness and weariness and hunger. She had no shoes, had little Gip, or a bonnet, or a jacket; nothing but a worn-out cotton frock, which he had picked up very cheaply in Rag Fair; so cheap and worn that his mother had not found it worth while to sell it again.

To think of Gip out in this rain and wind was agony to him; and he could very well bear the smaller misery of being wet and chilled to the bone himself. Along the silent streets, over crossings, round corners, Sandy pressed on at the top of his speed, resting now and then to take breath on a doorstep for a short minute or so, until the eastern sky grew grey and the clouds overhead were no longer black, and the morning came, and all the great city woke up slowly; but yet he had not found Gip. She was lost still.

As the streets filled, he knew his chance of seeing or hearing her would be very small. But he could not give up the search. It seemed as if he could not live without little Gip. Why to lose her in this way would be a hundred times worse than to see her lying dead in her small coffin, like the other babies, and watch the lid nailed over her peaceful face, and follow her with quiet tears to the cemetery a long way off; where the ground swallowed them up, and there was an end of them! They would never be cold, or famished, or beaten any more. Why had not Gip died rather than this dreadful misfortune happen to her? He would never give up seeking for her until he found out whether she was living or dead.

———◆———

LOST IN JERUSALEM.

FOUR days after this, Sandy was still seeking his lost Gip, but with a forlorn and despairing heart. Never until now had London seemed so big to him; never before had he felt how crowded it was with people, all strangers to him; many of them, as it appeared, enemies to him. He did not know a single friend among them. There were a few fusee boys who were good to him when they were in luck, but they did not altogether approve of Sandy's plan, that he should do nothing but search for Gip, whilst they worked to feed him. There had been some hard words already spoken to him about it; and Sandy could see close at hand that even these old comrades would forsake him.

It was Sunday afternoon; but that did not make much difference to him, except that the streets were clearer again, and there was a better chance of seeing Gip. It was quieter, too, with less rattle of wheels, and she could hear him if he shouted to her. The day was fine, and the low autumn sun was shining behind the smoke and the mist. Sandy had lost his eager step and searching look; and though to find Gip was still all he lived for, he was sauntering along with languid feet and an aching heart.

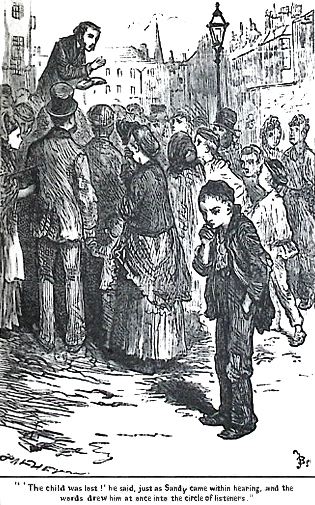

Sunday had had its pleasures, even for him, in former days. He had carried Gip often on to London Bridge, where the fresh air from the river had blown about them, and made her laugh many a time. He was on his way thither now; but by-and-by he saw a cluster of people gathered in an open space, and he quickened his footsteps, for always in a little crowd like this there would be some small figure about the size of Gip, which made him fancy for a moment that he had found her.

There was a chair in the centre of the knot set against a wall, and a young man stood upon it, speaking in a clear and very earnest voice. His face was pleasant, and his bright eyes seemed to single out every face among those around him.

"The child was lost!" he said,

just as Sandy came within hearing, and the

words drew him at once into the circle of listeners.

"The child was lost!" he said, just as Sandy came within hearing, and the words drew him at once into the circle of listeners. "The child was lost; only think of that! He was with them when they left the city in the morning; He had walked along the streets with them, talking to His mother and father. Then they lost sight of Him; but they thought, 'He is gone with some of our neighbours' children;' and they went on their way without feeling any trouble.

"But when the night came, and they were going to have supper at the inn, Mary would say to her husband, 'Have you seen Jesus?' She would say it quite calmly, never thinking that He was lost. 'Have you seen Jesus?'

"And most likely he would answer, 'No, but He is sure to be with the other children; I will go and call Him.'

"But He was not with the other children. Then they became frightened, and they went from one to another among their friends and relations, asking, 'Do you know where our son Jesus is? We have lost Him!'

"Everybody answered them, 'No: He was with us this morning when we left the city; but it is a long time since we saw Him.'

"It was night then, and they could not return to the city before the morning came. Do you think Mary slept that night? Do you suppose she could lie down peacefully, and close her eyes, and forget her great and sudden trouble? Oh, no! She would be wondering where her lost child was, where he was sleeping, and if he were hungry and homeless in the great city they had left, or perhaps wandering about in the fields and woods outside, with no place to lay His head. She watched for the morning, and at the very first glimmer of light she was on her feet, ready to run all the way back to the city.

"And all the way back they would ask every one they met, 'Have you seen our son Jesus of Nazareth?'

"Those who did not know them would say, 'Tell us what your son is like.'

"Then Mary did her best to describe Him as exactly as she could; for she knew every look upon His face, and every tone of His voice. But very likely the clearest thing she could say, the thing most people would know Him best by, would be, 'He wears a little coat which I made myself, and it is all in one piece, without seam, woven from the top throughout.'

"Most folks see clothes plainer than faces. But she did not get any news of Jesus before they reached the city.

"They wandered up and down the streets, seeking everywhere for the child Jesus. They sought Him sorrowing, sorrowing. Think what it would be to lose your child, perhaps the only one you had, in this great city of London; never to know where it had wandered, or whose hands it had fallen into; by night not to know whether it was sleeping under any shelter, and by day not to know whether any one was giving it bread to eat."

"Why, that's like me and Gip!" cried Sandy, pushing through the circle to get closer to the speaker, and listening with all his might, lest he should miss a single word.

"At last," he continued, "Mary said suddenly, 'How foolish we are! When we were here with our boy, we went scarcely anywhere but to the Temple, and that was where Jesus always liked best to go. Let us look for Him there.'

"So they went up to the Temple, where Jesus loved most to go; and there they found Him! Try to think how all this sorrow was turned in a moment into great joy; and how, as they were going home to Nazareth with their child, their hearts would dance for very gladness, whenever their eyes fell upon Him.

"And now Jesus, who was a lost child then, is seeking us, who are all like lost children, wandering away from the house and home of God, our Father. You know you are a long way off from God; you have lost your way, and do not know how to get home to Him again. We are like foolish little children, who follow some show along the streets till they lose sight of the way back, and can only wander on and on, farther and farther away, till in time, if they are not found, they will forget all about their old home, or that they ever had one.

"Have you forgotten your home with God? Or do some of you wish and long to get back to Him? Well, God has sent Jesus to seek for you, and to show you the way back. He is seeking for you now, as Mary sought for Him sorrowing; and if He find you, all His sorrow will be turned into great joy. He will be satisfied for all the sore pain you have given Him.

"You cannot see Him, you cannot hear His voice; but He is here amongst us, close beside us. I am speaking for Him, because you can hear my voice, and see my face. And I say to every one of you, Jesus Christ is seeking you, is calling to you. Are you willing to be found? That is the question. He cannot force you to go home. Do you wish to have a home with God?

"Lost, are you? Yes, you are lost. Some of you in drunkenness, perhaps; some of you in thieving: all of you are lost in sin and misery. But I have this message for every one of you:

"'Jesus is come to seek and to save those who are lost.'

"You have only to speak to Him, to call to Him, as a lost child calls to its mother, and He will save you."

Sandy did not miss a word; though he could not understand them all, simple as they were. There was a hymn sung, and a short prayer uttered, and then the small congregation melted away, and Sandy strolled on to London Bridge. He turned aside then, into one of the abutments, and stood leaning over the parapet, as if he were watching the river beating and whirling against the great pillars below him. The water was flecked with light from the setting sun, but he saw neither the river nor the sky. His mind was full to bewilderment of new ideas. His brain was pondering over this story of a Child who had been once lost like Gip, but who was now seeking those who were lost. A person whom nobody could see, but who went up and down the streets always to take people home to God. Could not this Jesus help him to find little Gip?

"You was lost once yourself," he said, speaking half aloud without knowing it; "and you was found again all right. When you're goin' about lookin' for folks now, maybe you'll come across little Gip, and please to take care of her for me."

"Who are you speaking to?" asked a voice as quiet as his own, close beside him.

Sandy turned round quickly, and almost angrily, ashamed of having been overheard.

Behind him stood a boy of his own height, supported upon crutches, with a face as wan and pinched as little Gip's. But there was a pleasant smile in his eyes as he gazed straight into Sandy's face. His clothes were shabby, but warm, and he had a red woollen comforter round his neck, and worsted gloves on his hands. He seemed almost a gentleman to the ragged and barefoot boy, who was about to steal away, half shy and half angry, when the stranger stretched out his hand to stop him, and, in doing so, dropped one of his crutches. He would have fallen on the hard stone pavement, if Sandy had not caught him in his arms.

———◆———

A NEW FRIEND.

"WE are to be friends, you see," said the lame boy, cheerfully, as Sandy set him to lean against the parapet, while he picked up the crutch. "I thought I should never catch you, though I have been following you as fast as ever I could all the way from the place where Mr. Mason was preaching. You liked his sermon, didn't you? I saw you listening as if you'd never heard anything like that before; and it's every word true, and more. I thought I'd like to ask you how you liked it; and when you turned in here, I caught up with you. Now would you mind telling me who it was you were speaking to, half aloud?"

The lame boy's voice was frank, and his face was lighted up with a friendly smile, such as Sandy had never met before. He could not shut up his heart against him. Besides, he had been longing to speak to some one about little Gip; somebody who would neither jeer at him nor be angry with him, as the other fusee boys were. Yet he felt shy still, and his brown face grew crimson, and his tongue stammered, as he once more leaned over the parapet, and gazed down at the eddying of the water under the arch, with his head turned away from the stranger.

"I were talkin' to Him as that gentleman spoke of," he said, in a very low tone, "Him as were lost Himself when He were a little child; lost in the streets, you know. The gentleman said now he were growed up. He do always walk up and down the streets lookin' fur folks as were lost. So I were arskin' Him to take care of my little Gip, if He come across her."

"Who's little Gip?" asked the gentle cheery voice at his side.

"Oh! she's my little gel!" cried Sandy, laying his head down on the stone coping, but doing his best to speak calmly. "Mother's little gel, you know; and mother got drunk last Tuesday, that night it rained cats and dogs, and lost Gip somewheres; and I've been lookin' for her ever since everywhere, pokin' into every corner as I can think on; and I begin to be afeard as Gip's dead!"

It had been hard work for Sandy to say all this; but when he came to the word dead, his voice was choked, and the sobs he had kept down broke out vehemently. He felt the strange boy's arm stealing round his neck; and so astonished was he, that his sobbing ceased, and he held his breath to listen to what he was saying.

"If little Gip is dead," he whispered, "she is gone to heaven, to be with the Lord Jesus, and she can never, never be hungry, or cold, or lost again. There are thousands and thousands of little children there, all good, and happy, and safe; and He loves them so! Nothing can ever hurt them again, because He is always taking care of them. If little Gip is dead, she must be with the Lord Jesus."

"I didn't know that," murmured Sandy. "I don't know nothin'. I don't know as my little Gip is dead. I'd rather have her than let Him have her. She were so fond of me; and I could make her happy, I could; and keep her safe. I never see Him as you speak of, or heard tell of Him afore now. Gip didn't know Him any more than me, and she'd be a deal happier with me; and wherever she is, she'll fret for Sandy, as used to give her peppermint and candy, and carry her to look at the pretty shops. If Lord Jesus finds her, He ought to give her up to me again; for it isn't Him as has nursed her, and took care of her ever since she were born."

Sandy's shyness had worn off whilst he spoke out his mind; and now he faced the lame boy with an expression of indignation, almost of angry defiance, at the thought that anybody had a greater claim to Gip, or could make her happier than he.

The stranger looked somewhat saddened and perplexed; but he kept his hand on Sandy's shoulder, to prevent him from running away from him.

"I wish you would come and talk to mother about it," he said, after a pause. "She's had three children that are dead, and she says they are happier than they could have been with her. If little Gip is not dead, mother will know what to do, and how to set about finding her, for she's the cleverest woman in all London; and I'll help you to search for her. I'm not strong enough to work; but when it is a fine day like this, I can get about on my crutches, and go farther than you'd think. I call them my wings. Yes, I'll search for little Gip, as well as you, if you'll come along with me, and tell mother."

Sandy hesitated a little. Compared with him, the lame boy was so grand that he scarcely dared go home with him; but there was the hope of getting advice and help in seeking Gip, and he could not lose any chance. He watched the stranger getting himself balanced on his crutches with a new and tender sense of pity, and the very feeling that he could so easily run away from him kept him closer at his side. He would have walked behind him, but the boy did not seem to understand that.

"Keep close to me," he said; "I want to talk to you. My name is John Shafto, and we live in the place I'm taking you to. Tell me what your name is, and where you live, while we are going along. See! I can get on with my wings as fast as you, unless you run."

He was keeping up with Sandy quite easily, his white face turned towards him full of eager interest and friendliness. Sandy had never seen a face or heard a voice like his.

"My name's Sandy Carroll, sir," he answered, pressing nearer to John Shafto, for all his reserve had melted away like frost in the sunshine, "and mother's called Nance Carroll. She's never anythink else but drunk. If she's sober a bit of a mornin', it don't last longer than she can get a few coppers. I was a-gettin' afeard little Gip 'ud take to it, for mother 'ud give her drops of gin and such like; but now she's lost, I don't know what 'll become of her. Maybe it 'ud be better for her to die, and go to that place you spoke of, only I don't see how she's to get in. If I'd known of it before, I'd have tried to get Tom and little Vic took in, but it's too late now. They're buried and done for, I s'pose."

He spoke very regretfully, for he had been fond of Tom and little Vic, though they were nothing to Gip, who had lived to learn the pretty tricks he could teach her. Yet he was grieved to think that perhaps he could have managed to get these babies taken into a good place, where they would never be hungry or cold again, if he had only known of it.

"If Tom and little Vic are dead," answered John Shafto, "they are gone to heaven. Every little child goes there when it dies."

"I know nothin' about it!" said Sandy. "Tell me all you know."

"Mother knows more than I do," he replied; "let us make haste to her."

It was not long before they reached the house, which lay at the back of a small chapel, and in a corner of a little square grave-yard, where the grass grew rank and dark over the mounds, in spite of the smoke and soot falling upon it from the chimneys around. There was no other dwelling in the yard, but the blank high walls of some workshops enclosed it. Nor was there any symptom of the turf having been dug up for years, and the head-stones of the graves were black with smoke. All was quiet, and dark, and gloomy the sun could hardly shine into it at midday, and now it was evening. But it was very peaceful and still, hushed away from the great turmoil and bustle of the city, though it lay in the very heart of it.

Sandy lowered his voice when they turned into the grave-yard, and crossed it by a path paved with flat stones, which bore the names of persons long since dead and forgotten.

At the back of this grave-yard, in a corner where a sharp eye might by chance see it from the street, stood a little low old-fashioned house of two storeys, if the upper floor could be called a storey, when it was not more than seven feet high in the pitch of the roof, with two dormer windows in the front. On the ground-floor there was a large shop window, with a very dingy hatchment in the centre, and above it a bunch of funeral plumes, brown with age. On one side of the hatchment hung a card, framed in black, with "Funerals performed!" on it. Whilst in the opposite pane was another card, displaying the words, "Pinking done here."

One of the three large panes had been broken, and a stiff placard was pasted over it, to keep out the wind and rain. The old house looked as if it were skulking in the corner of the grave-yard to hide its poverty and decay; keeping out of sight as much as it could, yet forced to show itself a little, that those who dwelt in it might have a chance of earning a scanty living.

"This is mother," said John Shafto.

John Shafto's crutches seemed to tap more loudly on these flat gravestones than on the common flags in the streets; and before he and Sandy reached the house, the shop door was opened from within. A rosy, cheerful, motherly-looking woman, with blue ribbons in her cap, stood in the doorway as they drew near to it. So strange and odd and out of place she seemed beside the broken window and gloomy hatchment, that even Sandy felt a strange sensation of surprise.

Her voice, too, when she said, "Johnny!" was cheerful, and as she kissed the lame boy fondly, Sandy stood by, staring at her with wide-open eyes.

"This is mother!" said John Shafto.

"And who have you brought home with you, Johnny?" she asked, holding out her hand to Sandy, as if she did not see his poor rags and dirty skin.

He did not know what to make of it; but she took his hand in hers, and gave it a warm, hearty clasp.

"He's lost his little sister in the streets last Tuesday," said John Shafto; "and I've brought him home to ask you what we must do, mother. You'll be sure to think of something. Now then, Sandy, you come in and sit down, and tell mother all about it."

He led the way into the house, and Mrs. Shafto gave Sandy a friendly push to follow him before her.

Inside the shop, on the counter, lay a little coffin, about the size that would fit Gip; and Sandy paused for an instant to look into it, as if, perhaps, he might see Gip's dear face and tiny limbs lying for ever at rest in it. But it was empty. And keeping down a sob which rose in his throat, he passed on into a small kitchen behind the undertaker's shop.

———◆———

MRS. SHAFTO.

IT was a very bright cosy little kitchen, with a clear fire burning in the grate, and not a single pinch of ashes on the hearth. The grate was an old-fashioned one, with well-brushed hobs, and two balls of steel on each side the fire, which glistened and sparkled like silver in the dancing flames. A polished brass warming pan hanging against the wall was bright enough to see one's face in. The floor was quarried with deep rich red tiles; and in a wide recess near the chimney stood a large cupboard, looking almost half the size of the room, and as if it promised plenty and to spare within it. In the warmest corner there was an easy-chair, with arms and back well padded, and covered with patchwork; and a pair of slippers lay on the warm hearth before it.

There was not much daylight; for the window opened upon a narrow passage between two of the high buildings which overshadowed the small grave-yard, and only a strip of sky could be seen beyond their tall roofs. But one did not miss the daylight whilst the fire burned so clearly, and Mrs. Shafto's beaming face smiled upon every one who came within sight of her. Her face was better than the sun, at least in John Shafto's eyes.

"Father's not come home?" he said, glancing at the empty easy-chair.

"No, Johnny, it's not time yet," she answered, placing a chair in the very front of the fire for Sandy, and bidding him put his cold bare feet on the shining fender. He dared not look her in the face yet; but he could not help watching her when she was not looking at him.

"First of all," she said, "we must have something to eat. Eating before talking is my rule, Johnny."

Sandy watched her with hungry eyes as she went to the cupboard, and cut two slices from a loaf, one large, thick, and substantial, the other thin and delicate, but both well spread with treacle. It took him quite by surprise to have the large slice given to himself, and the little one to John Shafto. This was treatment he could not understand, nor could he speak about it. All he could do was to sit still in blissful silence, feeling the glow of the pleasant fire through all his veins; and discovering how hungry he had been by the delight of devouring his substantial slice of bread.

"Now, then!" said Mrs. Shafto, when he had eaten the last crumb. She had seated herself in a low wooden rocking-chair, opposite to the easy-chair in the corner, and was looking at Sandy with kindly eyes, as if she had known him a long while, and was an old friend of his.

He felt as if he could tell her anything, and could never wish to hide a thing from her. With great eagerness, he told her all his story about little Gip. While John Shafto listened, nodding from time to time, as having heard most of it before.

Mrs. Shafto also shook her head now and then, and cried, "Well, well, poor fellow! poor little Gipsy!"

Until Sandy's heart grew warm, and almost happy, with her sympathy, before he ended all he had to say.

"Poor little Gip!" repeated Mrs. Shafto, wiping the tears from her eyes. "Have you looked for her in every place that she'd be likely to be, Sandy?"

"Ay!" said Johnny. "When Jesus was lost, you know, His mother began to think where He'd most likely go to, and she found Him in the Temple. Where do you think little Gip would go when she found herself lost?"

"She'd know of nowhere but the gin-shop," answered Sandy; "mother never took her nowhere else. There were two gin-shops where mother gets drunk, and I did go there."

Mrs. Shafto's face had a cloud upon it for a minute or two, and he heard her say as if to herself—"Poor little baby!"

"Mother's quite lost when she's in drink," continued Sandy, sadly; "it 'ud be no good to ask her if she rec'lects anythink. All she'd know is as she lost little Gip somewhere. I've not been nigh her again, for I can't bear to see her now she's been as bad as that. I didn't think as she could ever be as bad as that."

"But she's your own mother," said Mrs. Shafto, softly.

Sandy raised his eyes, which had been staring gloomily into the glowing embers, to look at her. Johnny had drawn his chair close up to hers, and laid his head down on her shoulder, and put his arm round her waist. What made him feel so, he could not tell, but all at once, he wished in the very bottom of his heart that he could love his mother like that; he wondered how she could be so very different from Mrs. Shafto.

"Perhaps," she went on, in the same soft, gentle tone, "little Gip found her way home the very next morning; I think it is very likely she did, and now she's watching for you, and fretting after you, and wondering where you are. What are you going to do, Sandy?"

He had started to his feet, and sprung to the door; but he stopped for a moment as she spoke to turn round, and answer, in breathless haste,—

"I'm goin' to run home," he said; "p'raps it's like what you say. Little Gip's there, p'raps. Oh! why didn't I think of that afore?"

"Stay one minute, Sandy," cried Mrs. Shafto, "while I put on my bonnet, and I'll go with you; and we'll bring Gip here, and all have tea together, if father isn't at home. Johnny 'ud love to see little Gip, wouldn't you Johnny?"

"I should love it dearly," he answered; "and I'll get tea ready whilst you're away. Be sure you come back, Sandy; I'm so sorry for you, I can't say how sorry. But perhaps some day your mother will become good, and be like my mother."

Across Sandy's mind there glanced a happy thought of his mother, with a bright, cheerful face, and wearing blue ribbons in her white cap, like Mrs. Shafto; and of a kitchen like this, with its clean floor, and comfortable chairs, and warm fire. But it all vanished away in an instant; and he fancied he could see her instead, with her red and swollen face, dressed in dirty rags, and lying in a drunken sleep upon the floor. That was his mother, and little Gip's!

It was not long before he was walking away at a brisk pace beside Mrs. Shafto, in the direction of the alley where little Gip had been born. Mrs. Shafto had a good deal to say to him as they paced along about himself and Gip. If they did not find her at home, she said, she would speak to her husband about it. He was a very learned man, and could give as good advice as anybody she knew; and perhaps, if he felt well enough, he would go with him to the police-stations, and make inquiries there about the missing child.

Sandy had never thought of going to the police, whom he looked upon as his and Gip's natural enemies, with no interest in them, except to cuff him and order him about his business when he was too pressing in trying to sell his fusees. He was very doubtful whether they would not cuff him if he went troubling them about little Gip; but Mrs. Shafto talked in so hopeful a strain that he felt his spirits rise as if he were sure of finding her when they reached the alley.

They did reach it at last: and Sandy rushed up the stairs, and tried to lift the latch of their old room. But the door was fast locked, and no shrill little voice answered him, when he called Gip through the keyhole, in the hope that her mother had left her there for safety. His spirits sank again. There was no key in the lock, so it must have been fastened from the outside. They descended the dirty, creaking staircase again, Mrs. Shafto keeping her skirts well from the wall; and Sandy knocked at the door of the neighbour who lived in the front room on the ground-floor.

The man who opened it greeted him with a low, jeering laugh.

"Come arskin' after your mother, eh?" he said. "Well! she's gone, and a good riddance, I say. She was always a tearin' and a stormin' up and down the alley, till there wasn't a moment's peace and quietness. All women is averse to peace and quiet; but I never see one like Nance Carroll for blusterousness. She were larfed at so about losin' her baby as she couldn't bear it, and she made off on Friday. The key's here, but there's nothink left in the room but the bed, and that goes to the landlord. Have I seen little Gip? No, no. She's at the bottom of the river long ago, I bet. Babies aren't lost like that, you know, if they haven't been made quiet. It were high time for your mother to make off, for the police were beginnin' to poke their noses up this alley; and arskin' some very ill-convenient questions."

"Do you think the poor little creature has been made away with?" enquired Mrs. Shafto, with a faltering voice.

The man winked, and nodded significantly; half smiling at her ignorance of human nature, as he closed the door in their faces.

Sandy sat down on the lowest step of the staircase, and hid his face in his hands, rocking, himself to and fro.

Mrs. Shafto stood by, in silence, for a minute or so; and then she laid her hand gently on his rough head.

"Come home, Sandy," she said; "come home with me, and have tea with my Johnny."

"She's my mother, you know," whispered Sandy, hoarsely, "just like you're Johnny's mother; and I rec'lect her kissin' of me once when I were a little chap. I don't want to think she could kill little Gip!"

"No, no," answered Mrs. Shafto; "she never could, I'm sure. It's not in a mother's nature; and who should know how a mother feels better than me, when I've had four, and lost them all, save Johnny? Come home with me, Sandy; and we'll talk it over with Johnny and Mr. Shafto."

———◆———

A SAD SIGHT.

MRS. SHAFTO and Sandy were leaving the alley, disappointed and cast down, when a policeman, who seemed to be lying in wait for them, crossed the street, and laid his hand firmly on the lad's shoulder. Sandy writhed and struggled, but he could not set himself free from the strong grip. A knot of people, principally the inhabitants of the alley, gathered round quickly, and Mrs. Shafto's rosy face grew pale and frightened.

"What has the boy been doing?" she ventured to ask the policeman; for she was hemmed in by the crowd, and could not escape and start away home, as in the first moment of terror she wished to do.

"He's been doing nothing that I know of just now," answered the policeman; "but we want him at the station for a few minutes; and I must take care he doesn't give me the slip. Slippery as eels all this sort are."

"Can I go with him?" she asked again. "I'm very sorry for the boy; and my son Johnny will never rest till he knows what's become of him."

"Are you any relation of his?" enquired the man, looking inquisitively at her decent dress and her face, so different from the women who were crowding about them.

"No," she said: "I never saw him till about an hour ago, when Johnny brought him home to our house. But I came here with him to look for his mother and his little sister, who has been lost all the week; and now his mother is gone away, and not left word where he could find her. Poor boy!"

"Don't you know anything about your mother?" asked the policeman, tightening his hold upon Sandy's arm.

"I've never set eyes on her since last Tuesday night," answered Sandy, earnestly. "She'd been and lost my little Gip, and I swore I'd never go nigh her again till I'd found out Where Gip was. It's my little Gip I wants, not her."

"Should you know Gip if you saw her again?" asked the man.

"Know Gip!" repeated Sandy; but his voice failed him before he could say any more. Know Gip! Why! he knew every little black tangled curl on her head; every funny little look upon her face; every tone of her voice, whether laughing or crying. Know Gip! There was not anything else in the world he knew so well, not even hunger and cold; his own little Gip, whom he had nursed and tended from the very hour she was born!

"Come along with me, then," said the policeman, in a gruff, but not unkindly tone: "it's not far to the station, and maybe I can show you Gip."

There was no need to grasp Sandy firmly now; he would have followed the policeman faithfully to any spot in London. Mrs. Shafto could scarcely keep pace with them, so rapidly did they walk. She could not spare breath to utter a single word; and neither of the other two spoke. Sandy's heart was too full for speech; and the policeman closed his lips tightly, as if no power on earth, except his superintendent, could open them.

Mrs. Shafto was not quite sure she was doing what her husband would like; but she could not bear the idea of Johnny's deep disappointment if she lost sight of Sandy, and they never knew any more about him and lost Gip. Breathless and panting, she reached the entrance of the police station, just as Sandy was vanishing through an inner door.

"You can't go in there, ma'am," said a man, just within the entrance.

"It's a friend of the lad's," called back the policeman; "let her come on."

She found Sandy already standing in front of a high desk, over which appeared the head of an inspector, who was rapidly asking him questions, as if eager to get through the business, about his mother: where she lived, how she got her living, how often she was drunk, how many children she had had, and what they had died from.

"Was she kind to you and Gip?" he enquired, with his sharp eyes fastened on the boy.

"Not partic'ler," answered Sandy; "she'd knuckle me in the streets, and search me for coppers if she thought I'd got any. She weren't partic'ler kind, you know."

"Did you ever hear her threaten to get rid of her baby?"

"She'd swear at me and Gip when she were in drink," said Sandy, "and wish we was all dead and buried, but she weren't a partic'ler bad mother. I know them as has worse. If she hadn't lost little Gip, I'd not say a word again' her, sir. It was all drink as did it. Nobody couldn't be cruel to little Gip, such a good little thing she were, and so pretty."

"Tell me what Gip was like," said the inspector.

Sandy hesitated and stammered. He could see Gip before his eyes now; but how could he tell what she was like? He had not any words in which he could describe her; and he had never thought of her in that way.

"She were pretty," he answered, pausing between each word, "very pretty and good; and she'd such funny ways. She were like nobody but Gip, sir."

"Not like yourself, I suppose," said his examiner.

"I don't know what I are like," replied Sandy, looking down at his rough big hands and feet; "I don't think Gip were a bit like me."

"How old was she?"

"She were three year old last summer," he said; "mother were sellin' ripe cherries the day afore Gip were born; that I'm sure of, sir."

"Davis," said the inspector, "take the boy to see the body."

But Sandy did not move when the policeman came forward. He caught hold of the edge of the desk, to save himself from falling, and looked round the room with wild, terrified eyes; eyes that saw nothing which was before them. Everything had faded from his sight, and he saw only little Gip's pretty face mocking at him on every side. What was it the inspector had said? Take him to see the body. He knew well enough what that meant. He was not so ignorant as not to know that all the young children who perished in the streets and alleys about his house did not die simply from illness and bad air and unwholesome food. Often he had heard whispers going about from mouth to mouth that such and such a child had been made away with. But now those words seemed to burn in his brain as if he had never known of such things. He had put away angrily such a thought about his mother and little Gip, when the neighbours had hinted at it. And now she was lying, somewhere close at hand, dead! Not only dead, but murdered! No one touched him, no one spoke to him. His terror-stricken face kept all around him silent for a minute or two.

"Sandy! Sandy!" cried Mrs. Shafto, being the first to speak, and putting her arm round him as she might have done to her own lame son, "my poor dear boy! Perhaps it isn't Gip, after all. Nobody knows that it's Gip. Come with me to look at her. And if it should be Gip, I'll tell you where her soul is gone. It 'ill be nothing but her poor little body here; but Gip 'ill be gone to heaven, where Jesus is. You know nothing about it yet; but I can tell you. Come and see, and then I'll tell you all about it."

"Ay! I'll go," said Sandy, catching her by the arm, and walking with unsteady steps, for he felt sick and giddy. "Take us to see if it's my little Gip."

They passed on without another word, following the policeman down a long narrow passage, to a room, the door of which was locked. Sandy heard the grating of the key as it turned in the wards, and the opening of the door; but he did not dare to lift up his eyes. He held back for a moment, turning away his head, and shrinking as if he could not cross the door-sill. At last he looked in. The policeman had lit one jet of gas just above a long, narrow table; and underneath the bright light lay a small still figure, about the size of Gip, with a covering thrown over it. The man quietly turned down the covering, and in a gentle tone called Sandy to come in, and look at the dead little face.

Mrs. Shafto led him across the floor, whispering that she could tell him where Gip was really gone to, and that she was happier than he could think. Sandy's eyes had grown so dim again that he could see nothing clearly. There was such a haze before them, that the tiny face and little quiet form all seemed in a mist. Mrs. Shafto could see it plainly,—the pinched, worn features, a child's face, with the suffering look of a woman's; but it was at rest now, and at peace, with all the trouble ended, and all the suffering ceased. Her tears fell fast; and she bent over the dead child, and kissed it tenderly.

That awoke Sandy, who stood beside her and it as if in some dreadful dream. He rubbed his bedimmed eyes, and looked closely, though shudderingly, at the little child.

"Why, it's not my Gip at all!" he cried. "She'd black hair, and she were like a gipsy, not a bit like this little gel. No; that isn't Gip!"

He could hardly keep himself from breaking out into laughter, and dancing about the bare, empty room in this sudden deliverance from his agony of dread. But a second glance at the dead face sobered him. What this child was, his little Gip might be somewhere—a terrible thought, which would haunt him all his life long, if he could not find her.

They returned to the inspector's office, for Sandy to declare that the child found was not his lost sister; and after being warned that the police would have an eye upon him, he was allowed to go away in the care of Mrs. Shafto, who had voluntarily given her address, and promised that she also would keep her eye upon the homeless lad.

———◆———

MR. SHAFTO.

SANDY had no desire to slip away from the friendly guardianship of Mrs. Shafto. Her words had strengthened the new hope in his heart, that the grave was not the end of those children he had seen buried in it, and he wished to learn more about this strange and good news. He kept close beside her, though she seemed less inclined to talk to him than when they were going to look for his mother. She could not trust herself to speak, for her heart was full of the sad and terrible sight she had just left.

Mrs. Shafto was also a little anxious about Sandy, who followed her so closely, as closely as a stray and homeless dog might have done, and for whom she had undertaken a kind of responsibility. Though they were not as miserable and degraded as the people she had been seeing, they were very poor, she and her husband; so poor that, but for her own hard and incessant work as a needlewoman, they would often have to go without sufficient bread to eat.

What was she to do with this great, growing lad out of the streets, as wild and ignorant as a young savage; a thief very probably; with no spark of good in him, except his love for his little sister? She knew very well that her husband would grudge any help given to Sandy if it deprived him of the least comfort, or demanded of him any self-denial. But she could not endure the thought of thrusting him away, uncomforted and unhelped, into the open street, with no sort of home to find refuge in. She could not treat a dog so; and of how much more worth was this boy than a dog! Besides, it was Johnny who had found him first, and brought him home—her lame lad, who seemed to know so well what Christ would have him do, and how to tread gladly in his Lord's steps. She could not go back to the house, and tell him she had cast off Sandy, and left him in the great wilderness of London.

On went Mrs. Shafto, still sadly and in silence, across the square grave-yard, and through the gloomy shop, with its small coffin open on the counter—a coffin that would have just fitted the dead baby she had kissed. Sandy followed her, his bare feet making no sound upon the floor; but he stopped at the door of the kitchen, for there was a strange person there—not his new friend, Johnny Shafto.

This person was a tall lanky man, about forty-five years old, whose thin long legs were stretched quite across the hearth, as though no one else needed to sit by the fire. He was lolling in the comfortable padded chair in the best corner, his hands hanging idly from his wrists, and his arms from his shoulders, as if he never had done and never could do one hearty task of work. His face was narrow and gloomy, with straight hair falling over it; and his head drooped as if he found it too much trouble to hold it upright. He looked up lazily as Mrs. Shafto went in, and spoke to her with a fretful voice.

"What a time you've been," he said, "gadding about on a Sunday evening on other people's business, and I've been wanting my tea this half-hour. Nobody asked me to stay at the school; I suppose they think nothing of me for being an undertaker, without any business either. If I had a thriving trade, and kept a mourning coach or two, it would be a different thing. They never seem to remember that I'm a Shafto, and my grandfather was their minister in his time. If my father had done his duty by me, they would have been ready enough, every one of them, to invite me to tea. Where have you been to, Mary?"

She was hastily taking off her bonnet and shawl before getting the tea ready, and now both her face and voice quivered as she answered.

"I've been seeing a sad sight," she said; "Johnny will have told you about the poor boy that has lost his sister? Well, him and me have been to a police station—a place I was never in before, and we've seen a poor dear dead little creature, no bigger than my Mary when she was taken from me; a poor murdered baby, and I cannot get the sight out of my head."

"You've got such a poor head," said Mr. Shafto, "always running on other folks. I dare say you never thought of mentioning that your husband was an undertaker, and had a coffin he could sell cheaply, and would bury it as reasonably as anybody in London; now did you?"

"I never thought of it," she answered.

"That's just what I say," he continued, triumphantly; "you never do remember things useful, when we've a child's coffin in stock. Why don't you shut that door?"

Mrs. Shafto stepped back to the doorway, and whispered to Sandy to sit down in the dark shop for a few minutes, till tea was ready. Then she shut him out of the bright little kitchen, and went softly up to her husband, speaking in a voice lower and unsteadier than usual.

"Dear John," she said, coaxingly, "it was our Johnny that brought yonder poor lad to our house. He's taken such a fancy to him, it would grieve him sorely if we turned our backs upon him. Maybe Johnny won't be spared to us much longer; and I could never forgive myself if I'd hurt him about anything. Besides, don't you remember, John—you that are such a scholar yourself, and your grandfather minister at the chapel—how the King says, when the Last Day is come, that He counts all we do for these poor creatures of His as if it were done to Him? It looks as if God had brought this boy and Johnny together, and we must not set ourselves against anything He does."

"Where is the boy?" enquired Mr. Shafto.

"He's in the shop, in the dark. I'd light the gas, and give him something to eat there, if you think he's not fit company for us. But it's not pleasant to eat among coffins and plumes. And, dear! dear! how ever shall we be fit company for angels? Though my Johnny 'ill be fit for them, I know; only I'm afraid I shall never be."

"I suppose you'll have your own way," grumbled Mr. Shafto.

"But I want it to be your way too, my dear, fully and freely," she continued, patiently. "I want you to feel, when Sandy's eating our morsel of bread, that he's here in the place of the Lord Jesus. I'm sorry I never thought to say my husband was an undertaker, and would bury the baby reasonably. I know I'd have made it a pretty shroud, poor thing! But that's past and gone; and you must forgive me, John. Why, that's rhyme I've made, you hear. Ah! you're a great scholar, and I don't mind your laughing at me. I may call Sandy in, and put him in a corner where you needn't see him, if you like, for Johnny's sake, you know?"

"Well, he may come in," said Mr. Shafto, dropping his head down again, and stretching out his legs still farther across the warm hearth.

Mrs. Shafto opened the door quietly, and called Sandy in a whisper, placing a chair for him in a corner, as much as possible out of sight of her husband, who did not appear to take any notice of the boy. But he groaned aloud several times, causing Sandy to start nervously, for his mind had been over-strained, and his body was faint with excitement and fatigue. Mr. Shafto's groans seemed to betoken some new and dreadful calamity, and Sandy could scarcely keep himself from bursting into a vehement fit of crying.

But it was not long before tea was ready, and Mrs. Shafto went to the foot of a staircase, which wound like a corkscrew up to the two low rooms in the roof. She called "Johnny!"

And the next moment the tap, tap of a pair of crutches sounded on the floor; and John Shafto came down the crooked staircase slowly and laboriously, till he reached the last step, and his pale face and dazzling eyes peered in at them from the darkness. It was a radiant face, unlike any that Sandy had ever seen, with a happy smile upon it, as though he had learned some great secret, and could never more be overwhelmed by sorrow.

"Where is Sandy?" he asked, for his eyes could not see him in the sudden light. "Have you found little Gip, mother?"

"Not yet, Johnny," she answered, cheerfully; "there's Sandy. Go and sit by him, dear heart; and he'll tell you about what we've been doing."

John Shafto sat down by Sandy, with his hand through his arm, ready to listen eagerly to all he could tell him, asking him questions, and talking about little Gip in his low pleasant voice. Until Sandy felt that, even if little Gip were lost, he would have another friend who would love him, and whom he could love. They whispered together till bed-time, forming plans for seeking and finding poor lost Gip.

That night, after Mr. Shafto had gone to bed, Mrs. Shafto made up a place for Sandy to sleep on the kitchen hearth, with an old mattress and a brown moth-eaten velvet pall out of the shop, which had not been in use for years. It made so grand and magnificent a bed, that Sandy was almost afraid to lie down upon it, and could scarcely believe it was not all a dream.

Once when he awoke, before the fire had quite burned out, and saw the polished warming pan twinkling, and the steel balls glittering in the dim light, he sat up to rouse himself, and think where he could be. Then the remembrance of the lame boy's tender face and pleasant voice came back to him, and he went to sleep again with a strange sense of peace at the thought of the new friend he had found.

———◆———

SEEKING THE LOST.

But when the morning came, and Mrs. Shafto went to rouse Sandy, and kindle the kitchen fire, what was her surprise and disappointment to find that he was gone! The mattress had been dragged into a corner, and the pall roughly folded up, and laid upon it, but there was no other trace of the guest who had been made so comfortable by her last night.

John looked exceedingly grave and troubled, though he did not put his anxiety into words. Only Mr. Shafto, when he came down to a late breakfast after the fire had burned up well, and the room was warm, displayed some triumph; and declared, with more energy than was usual to him, that the lad was a rogue and a thief, no doubt, and they would find he had not gone off without carrying some plunder with him. Nothing, however, was missing from the kitchen; and there was no plunder in the shop, except a few rusty plumes, and the hatchment, with its faded painting, in the window.

Yet it was a sad day for John Shafto and his mother, though Sandy was not proved to be a thief. Their hearts had warmed so to the desolate boy, and they had felt so keen a sympathy with him about little Gip that this desertion pained them to the quick. John Shafto, as he lay awake all the early part of the night, had pondered over every possible means of tracing the lost child; and had prayed to God, with intense earnestness, that she might be found. He had felt so comforted by these prayers and ponderings, that he had made haste to get up in the morning to talk to Sandy; and not only to talk, but to set off in search himself upon his crutches, as soon as he could learn anything by which he might know little Gip if he saw her. Now all this was over. Sandy was gone, without a word to his new friend. A great blank fell upon John Shafto, as though all his love had been thrown back upon him carelessly and ungratefully.

Very slowly the hours of that autumn day passed by. John Shafto limped along some of the back slums near his own home, gazing with fresh interest and attention at the starved and puny children playing about the doors and in the gutters. There had never seemed such swarms of them before, nor so much sadness in their lives. He saw them fighting with one another for a crust of mouldy bread or the rind of an orange: the strongest always gaining the victory over those younger or weaker. He heard little children, who could hardly speak, stammering out bad words, which had no meaning for them, but which showed what the sin was of those about them. Now and then a baby looked at him over the shoulder of a drunken mother, who was entering or leaving a gin-palace.

Because his heart was full of little Gip, he saw all these things as he had never seen them before. Two or three times he had called to a child moping alone, as if it were an entire stranger to the other children about it, but none of them had answered to the name of Gip. At length he went home, heartsick and very sorrowful.

Mrs. Shafto had been sewing away busily whilst Johnny was absent, fretted by her husband's persistent fears that Sandy had carried something off with him, and by his slow, lazy search through all the shelves and drawers which the boy might have rifled. Several times he fancied something was missing, and would not let her rest until she put down her work, and found what he was moaning over as gone. She was in very low spirits herself. It was so odd of the boy, she thought; he had seemed to cling so much to her last night. Could it be that he was afraid of her promise at the police station, that she would keep her eye upon him? Did he suppose she meant to make a sort of prisoner of him? If Sandy tried to keep out of their way, there was very little chance that either she or Johnny would come across him again. London was too wide a place for that.