Title: The Donovan chance

Author: Francis Lynde

Illustrator: Thomas Fogarty

Release date: December 7, 2024 [eBook #74848]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1920

Credits: Produced by Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

THE DONOVAN CHANCE

BY

ILLUSTRATED BY

THOMAS FOGARTY

NEW YORK

1921

Copyright, 1921, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Copyright, 1920, by The Sprague Pub. Co.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | The Bug and the Elephant | 1 |

| II | In Tourmaline Canyon | 25 |

| III | A Breach of Discipline | 51 |

| IV | “The Old Man of the Mountain” | 71 |

| V | At Tunnel Number Two | 93 |

| VI | Bull Peak and the Crawling Shale | 110 |

| VII | The Uninvited Special | 130 |

| VIII | A Fellow Named Jones | 152 |

| IX | “Gangway!” | 173 |

| X | The Winning Goal | 195 |

Engine 331, the biggest mountain passenger-train puller on the Nevada Short Line, was a Pacific-type compound, with a bewildering clutter of machinery underneath that made a wiper’s job a sort of puzzle problem; the problem being to get the various gadgets clean without knocking one’s head off too many times against the down-hanging machinery. Larry Donovan, mopping the last of the gadgets as the shop quitting-time whistle blew, called it a day’s work, flung down his handful of oily waste and crawled out of the concrete pit.

Grigg Dunham, fireman of the 246, which was standing next door to the 331, leaned out of his cab window.

“’Lo, Blackface!” he grinned. “Time to go home and eat a bite o’ pie.”

Larry’s return grin showed a mouthful of well-kept teeth startlingly white in their facial setting of grime. Normally he was what you might call a strawberry blonde, with lightish red hair that curled and crinkled discouragingly in spite of a lot of wetting and brushing, and a skin, where it wasn’t freckled or sunburned, as[2] healthily clear as a baby’s; but wiping black oil and gudgeon grease from the under parts of a locomotive would make a blackamoor out of an angel—for the time being, at least.

“I’m going after that piece of pie as soon as I can wash up,” he told Dunham; and a minute later he was stripping off his overalls in the round-house scrub room.

Thanks to a good bath and a change from his working clothes it was an altogether different looking Larry who presently left the round-house to go cater-cornering up the yard toward the crossing watchman’s shanty at Morrison Avenue. One thing his hard-earned High School course—just now completed—had taught him was to be really chummy with soap and water, and another was to leave the shop marks behind him when the quitting whistle blew—as a good many of his fellow workers on the railroad did not. Big and well-muscled for his age, it was chiefly his cheerful grin that stamped him as a boy when he looked in upon his father at the crossing shanty.

“Ready, Dad?” he asked; and the big, mild-eyed crossing watchman, whose empty left sleeve showed why he was on the railroad “cripple” list, nodded, took down his coat from its hook on the wall and joined his son for the walk home.

“Well, Larry, lad, how goes the new job by this time?” John Donovan asked, after the pair had tramped in comradely silence for a square or two.

Larry was looking straight ahead of him when he replied:

“I’m going to tell you the truth, Dad; I’m not stuck on it—not a little bit.”

The crossing watchman shook his big head in mild disapproval.

“You’ve done fine, Larry; pulling yourself through the school by the night work in the shops. But it’s sorry I am if it’s made you ashamed of a bit of black oil.”

“It isn’t that; you know it isn’t, Dad. The black oil doesn’t count.”

“Well, what is it, then?”

“It’s—er—oh, shucks! I just can’t tell, when you pin me right down to it. I don’t mind the work or getting dirty, or anything like that; and I do like to fool around engines and machinery. I guess it’s just what there is to look forward to that’s worrying me. I’ll be wiping engines for a few months, and then maybe I’ll get a job firing a switching engine in the yard. A year or two of that may get me on a road engine; and if I make good, a few years more’ll move me over to the right-hand side of the cab.”

“Good enough,” said John Donovan. “What’s wrong with that?”

“Nothing—except that the last boost will be the end of it; you know it will, Dad. It’s mighty seldom that a locomotive engineer ever gets to be anything else, no matter how good an engineer he is. Right there I’ll stop; and I’ve been sort of asking myself if I’m going to be satisfied to stop.”

Again John Donovan made the sign of disapproval.

“’Tis too many high notions the school’s been putting into your head, Larry, boy,” he deprecated. “You’d be forgetting that your father was an engineer before you—till the old ’69 went into the ditch and gave me this”—moving the stump in the empty sleeve.

“No, I’m not forgetting, Dad; not for a single minute,” Larry broke in quickly. “You’ve made the best of your chance—and of everything. And I want to do the same. Maybe I am doing it in the round-house; I can’t think it out yet. But I mean to think it out. There are Kathie and Jimmie and Bessie and little Jack; they’ve got to have their chance at the schools, too, the same as I’ve had mine.”

“And you’ll give it to them, Larry, if I can’t. With even a fireman’s pay you could help.”

“I know,” said Larry; and at this point the little heart-to-heart talk slipped back into the comradely silence and stayed there.

Larry ate supper with the family that evening as usual, but he said so little, and was so evidently preoccupied, that his mother asked him if he wasn’t feeling well. The talk with his father on the way home had been his first attempt to put the vague stirrings inside of him into spoken words, and the natural consequence was that he was trying to make the stirrings take some sort of definite and tangible shape. Of course they refused utterly to do anything so reasonable as that—which is the way that all ambitious stirrings have in their early stages—and the result was to make him thoughtful and tongue-tied.

So the table chatter went on through the meal without any help from him, and he found himself listening with only half an ear when his father told of a perfectly hair-raising escape an automobile full of people had had on his crossing during the day. Kathryn, who was fifteen, was the only one besides the mother to notice Larry’s preoccupation, and when he came down-stairs after supper to go out, she was waiting at the front door for him.

“What is it, Larry?” she asked. “Did something go twisty with you to-day?”

“Not a thing in the wide world, Kathie,” he denied, calling up the good-natured grin and laying an arm in brotherly fashion across her shoulders.

“But you’re not going back to work to-night?”

“Not me,” he laughed, cheerfully reckless of his grammar now that his school-days were over. “I’m just going out to walk around the block and have a think; that’s all.”

“What about?”

“Oh, I don’t know; everything, I guess. Don’t you worry about me. I’m all right.” And to prove it he went off whistling and with his hands in his pockets.

The after-supper stroll, which was entirely aimless as to its direction, led him first through the quiet streets of the “railroad colony.” In its beginnings Brewster had been strictly a railroad town; but now it had become the thriving metropolis of Timanyoni Park; a city in miniature, with electric lights and power furnished by the harnessed river, with some manufacturing, and with an irrigated wheat and apple-growing country around it to take the place of the cattle ranges which had preceded the coming of the railroad.

Now, though Larry’s stroll was aimless, as we have said, that is, in any conscious sense of having a definite destination, there was just one direction it was almost bound to take. Born and bred in a railroad atmosphere, it was second nature for him to drift toward the handsome, lava-stone building which served the double purpose of the Nevada Short Line’s passenger station and general office headquarters.

The long concreted approach platform running down[6] from the foot of the main street offered itself as a cab rank for the station; and as Larry traversed it, still deep in the brown study, General Manager Maxwell’s smart green roadster cut a half circle in the turning area, whisked accurately into its parking space between two other cars, and the fresh-faced young fellow who had played at first base on the Brewster High School nine in the winning series with Red Butte, climbed out and hailed the brown-studier.

“Hullo, Curly!” he called, using the school nickname which Larry had long since come to accept merely because he had never been able to think up any way of killing it off. “What are you doing down here at this time o’ night?”

“‘Time o’ night’ happens to be time of the early evening,” Larry corrected; adding: “One thing I’m not doing is joy-riding in a green chug-wagon.”

“Tag,” said the general manager’s son good-naturedly. “Neither am I. Father has a conference of some sort on with the bosses. I don’t know what’s up, but I suppose it’s all this anarchist talk that’s been going around and stirring things up. He ’phoned me up home a little while ago and told me to drive down and wait for him.”

“Anarchist talk?” said Larry; “I haven’t heard any.”

“Oh, it’s just that little bunch of trouble-makers over on the west end. You remember reading in the papers how they spoiled a lot of work in the shops and raised Cain generally. The court over in Uintah County sent three of them to prison last week for sabotage and the others have threatened to get square with the company for prosecuting them. That’s all.”

Larry caught step with the former first baseman as they walked on toward the station building.

“Is this all you’re going to do this vacation, Dick?” he asked; “drive down to the offices once in a while to take your father home in the car?”

“Not on your sweet life!” was the laughing reply. “What I’m going to do is tied up in a sort of secret, but I guess it’ll be all right to tell you. The company is going to build a road up the Tourmaline to the Little Ophir gold field, and—this is the secret part of it—we’re going to try to beat the Overland Central to it. I’m to go out with the surveying party, or rather the construction party, as a sort of roustabout, chain-bearer—anything you like to call it.”

The difference between Dick Maxwell’s prospects and his own gave Larry Donovan the feeling of having been suddenly wrapped in a wet blanket. In a flash he saw a panorama picture of Dick’s summer; the free, adventurous life in the mountain wilds, the long days crammed full of the most interesting kind of work, the camp fire at night in the heart of the immensities, and, more than all, the chance to be helping to do something that was really adding to the sum of the world’s riches. Wiping grease from tired machinery wasn’t to be spoken of in the same day with it. Yet Larry was game; he wouldn’t share the wet blanket with the lucky one.

“That’s simply bully!” he said; “first lessons in engineering, eh?”

“Y-yes; maybe: but it ought to be you, Larry, instead of me. You’ve got the head for it, and the math., and all the rest of it. Have you gone to work in the round-house as you said you were going to?”

“Yep,” said Larry, and he tried to say it as a workingman would have said it. “I had to make up my mind one way or the other. It was either the round-house or an apprenticeship in the back shop.”

“Wouldn’t the apprenticeship have been better?”

“Nope; nothing at the end of that alley but maybe a foreman’s job.”

“And maybe a master-mechanic’s,” Dick Maxwell put in.

“Not much!” Larry scoffed. “Might have put that sort of stuff over in our grandfather’s days—they did put it over then. But you can’t do it now. Look at our own superintendent of Motive Power—Mr. Dawson; he’s a college man—has to be; and so is every single one of the division master-mechanics. It’s all very well to talk about climbing up through the ranks, Dick, and I guess now and then a fellow does do it by working his head off. But it’s the education that counts.”

“I guess that’s so, too,” was the half reluctant reply. “But how about the ‘promosh’ from where you are now in the round-house, Larry?”

“From where I am now I can count on getting an engine to run some day, if I’ll be good—and if I live long enough. That’s a step higher than a shop foremanship—at least, in wages.”

By this time they had passed through the station archway that ran through the first story of the railroad building and were out upon the broad, five-track train platform.

“Let’s tramp a bit,” said Dick. “They’re still drilling over that conference in the trainmaster’s office and goodness only knows when they’ll be through.”

The tramping turned itself into a sort of sentry-go up and down the long platform; and to go with it there was a lot of talk about things as they are, and things as they ought to be. Since he couldn’t talk freely at home—at least to anybody but Kathryn, and she, after all was said, was only a girl—Larry opened his mind to the fellow with whom, among all his late classmates, he had been most chummy.

“I don’t know; it looks as if a fellow never does know, until it’s everlastingly too late, Dick; but I shouldn’t wonder if I’m not taking that ‘line of the least resistance’ that Professor Higgins used to be always talking about. I guess I could make out to go to college this fall and grind my way through somehow, even without much money; in fact I’m sure I could if I should set my head on it. But then there are the home folks. Dad’s got about all he can carry, and then some; and Kathie and the others are needing their boost for the schooling—they’ve got to have it. I’ll leave it to you, Dick: has a fellow in my fix any right to drop out for four solid years—just when the money he can earn is needed most?”

It was too deep a question for Dickie Maxwell and he confessed it. What he didn’t realize was that it was made a lot deeper for him because he had never known how much brain or brawn, or both, it takes to roll up the slow, cart-wheel dollars in this world. He hadn’t had to know, because his father, in addition to being the railroad company’s general manager, was half-owner in one of the best-paying gold mines in the near-by Topaz range. True, Mr. Richard Maxwell was democratic enough to put his son into an engineering party for the[10] summer, but that didn’t mean that the wages that Dick might earn—or the wages he might get without specially earning them—would make any real difference to anybody.

As the two boys tramped up and down the platform and talked, the stir around them gradually increased. Train gates and grilles were as yet unknown in Brewster, and intending travelers, with their tickets bought and their baggage checked, were free to wander out upon the platform to wait for their train—which they mostly did.

Dick Maxwell held his wrist watch up to the light of one of the masthead electrics. The “Flying Pigeon” from the west was almost due; but Number Eleven, the time freight from the east, had not yet pulled in, as they could see by looking up through the freight yard starred with its staring red, yellow and green switch lights.

“Eleven is going to miss making her time-card ‘meet’ here with the ‘Pigeon’ if she doesn’t watch out,” said the general manager’s son, who knew train schedules and movements on the Short Line much better than he did some other and—for him, at least—more necessary things.

“That will just about break Buck Dickinson’s heart,” Larry predicted. “Only day before yesterday I heard him bragging that since they gave him the big new 356 Consolidated he hadn’t missed a ‘meet’ in over two months.”

Again Dick looked at his watch.

“If the ‘Pigeon’s’ on time he has only thirteen minutes left,” he announced; and then: “Hullo!—what’s that?”

“That” was a small white spot-light coming down through the freight yard from the east. It was too little[11] for an engine headlight—and too near the ground level. Somewhere up among the yard tracks it stopped; the switch lamp just ahead of it flicked from yellow to red; the little headlight moved on a few yards; and then the switch signal flicked back to yellow.

Larry Donovan laughed.

“I ought to know what that thing is, if you don’t,” he offered. “It’s Mr. Roadmaster Browder’s gasoline inspection car—‘The Bug,’ as they call it. I’d say he was taking chances; coming in that way just ahead of a time freight.”

“A miss is as good as a mile,” Dick countered. “He’s in, and side-tracked and out of the way, and that’s all he needed. There goes his light—out.”

As he spoke the little spot-light blinked out, and as the two boys turned to walk in the opposite direction an engine headlight appeared at the western end of things, coming up the other yard from the round-house skip. Since Brewster was a locomotive division station, all trains changed engines, and the boys knew that this upcoming headlight was carried by the “Flying Pigeon’s” relief; the engine that would take the fast train up Timanyoni Canyon and on across the Red Desert.

Half a minute later the big passenger flyer trundled up over the outside passing-track with a single man—the hostler—in the cab. At the converging switches just west of the station platform the engine’s course was reversed and it came backing slowly in on the short station spur or stub-track to come to a stop within a few yards of where Larry and the general manager’s son were standing.

“The 331,” said Larry, reading the number. “She[12] ought to run pretty good to-night. I put in most of the afternoon cleaning her up and packing her axle-boxes.”

Dick Maxwell didn’t reply. Being a practical manager’s son, he was already beginning to acquire a bit of the managerial point of view. What he was looking at was the spectacle of Jorkins, the hostler, hooking the 331’s reversing lever up to the center notch, and then dropping out of the engine’s gangway to disappear in the darkness.

“That’s a mighty reckless thing to do, and it’s dead against the rules,” Dick said; “to leave a road engine steamed up and standing that way with nobody on it!”

“Atkins and his fireman will be here in a minute,” Larry hazarded. “And, anyway, nothing could happen. She’s hooked up on the center, and even if the throttle should fly open she couldn’t start.”

“Just the same, a steamed-up engine oughtn’t to be left alone,” Dick insisted. “There’s always a chance that something might happen.”

Now in the case of the temporarily abandoned 331 something did happen; several very shocking somethings, in fact; and they came so closely crowding together that there was scarcely room to catch a breath between them.

First, a long-drawn-out whistle blast announced the approach of the “Flying Pigeon” from the west. Next, the waiting passengers began to bunch themselves along the inbound track. Dickie Maxwell, managerial again, was growling out something about the crying necessity for station gates and a fence to keep people from running wild all over the platform when Larry grabbed[13] him suddenly, exclaiming, “Who is that—on the ’Thirty-one?”

What they saw was a small, roughly dressed man, a stranger, with a bullet-shaped head two-thirds covered by a cap drawn down to his ears, snapping himself up to the driver’s step in the cab of the 331. In a flash he had thrown the reversing lever into the forward motion and was tugging at the throttle-lever. A short car-length away down the platform, fat, round-faced Jerry Atkins and his fireman were coming up to take their engine for the night’s run to Copah. They were not hurrying. The “Flying Pigeon” was just then clanking in over the western switches, and the incoming engine must be cut off and taken out of the way before they could run the 331 out and back it in to a coupling with the train. And since the two enginemen were coming up from behind, the high, coal-filled tender kept them from seeing what was going on in the 331’s cab.

But the two boys could see, and what they saw paralyzed them, just for the moment. The bullet-headed stranger was inching the throttle-valve open, and with a shuddering blast from the short stack the wheels of 331 began to turn. An instant later it was lumbering out around the curving stub-track and as it lurched ahead, somebody, invisible in the darkness, set the switch to connect the spur-track with the main line.

Dick Maxwell gasped.

“Who is that man at the throttle?” he demanded; but before there could be any answer they both saw the man hurl himself out of the right-hand gangway of the moving machine, to alight running, and to vanish in the nearest shadows. Then they knew.

“The anarchists!—they’re going to wreck her!” yelled Larry. “Come on!” and then they both did just what anybody might have done under the stinging slap of the first impulse, and knowing that a horrifying collision of the runaway with the over-due fast freight couldn’t be more than a few short minutes ahead: they started out to chase a full-grown locomotive, under steam and abandoned, afoot!

It was the fact that the 331 was a “compound” that made it seem at first as though they might be able to catch her. Compound engines are the kind designed to take the exhaust steam from one pair of cylinders, using it over again in the second pair. But to get the maximum power for starting a heavy train there is a mechanism which can be set to admit the “live” steam from the boiler into both pairs of cylinders; and the 331 was set that way when the wrecker opened the throttle. As a consequence the big passenger puller was choking itself with too much power, and so was gaining headway rather slowly.

“He’s left her ‘simpled’—we can catch her!” Larry burst out as they raced over the cross-ties in the wake of the runaway. “We—we’ve got to catch her! Sh-she’ll hit the time freight!”

It was all perfectly foolish, of course; but perfectly human. If they could have taken time to think—only there wasn’t any time—they would have run in exactly the opposite direction; back to the despatcher’s office where a quick wire alarm call to the “yard limits” operator out beyond the eastern end of the freight yard might have set things in motion to shunt the wild engine[15] into a siding, and to display danger signals for the incoming freight train.

But nobody ever thinks of everything all at once; and to Larry and his running mate the one thing bitingly needful seemed to be to overtake that lumbering Pacific-type before it could get clear away and bring the world to an end.

They were not more than half-way up through the deserted freight yard before they both realized that even well-trained, base-running legs and wind were not good enough. Dick Maxwell was the first to cave in.

“W-we can’t do it!” he gurgled—“she’s gone!”

It was at this crisis that Larry Donovan had his inspiration; found himself grappling breathlessly with that precious quality which makes the smashed fighter get up and dash the sweat out of his eyes and fight again. The inspiration came at the sight of the roadmaster’s transformed hand-car which had been fitted with a gasoline drive, standing on the siding where its late users had left it.

“The Bug—Browder’s motor car!” he gasped, leading a swerving dart aside toward the new hope. “Help me push it out to the switch—quick!”

They flung themselves against the light platform car, heaved, shoved, got it in motion, and ran it swiftly to the junction of the siding with the main track. Here, tugging and lifting a corner at a time (they had no key with which to unlock the switch, of course,) they got it over upon the proper pair of rails. Another shove started the little pop-popping motor and they were off, with Larry, who as a night helper in the shops the[16] winter before had worked on the job of transforming the hand-car and installing the engine in it, at the controls.

By the time all this was done the runaway had passed the “yard limits” signal tower and was disappearing around the first curve in the track beyond. Neither of the boys knew anything about the speed possibilities in the “Bug,” but they soon found that it could run like a scared jack rabbit. Recklessly Larry depressed the lever of the accelerator, trusting to the lightness of the car to keep it from jumping as it squealed around the curves, and at the first mile-post they could see that they were gaining upon the wild engine, which was still choking itself with too much power.

“Another mile and we’ll get there!” Dick Maxwell shouted—he had to shout to make himself heard above the rattle and scream of the flying wheels; “another mile, if that freight’ll only——”

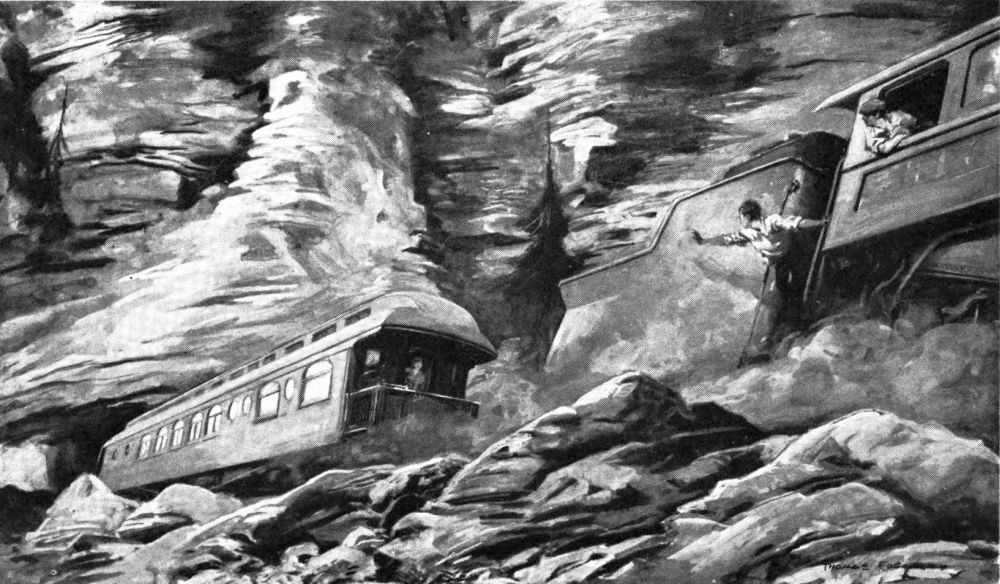

There was a good reason why he didn’t finish whatever it was that he was going to say. The two racing machines, the beetle and the elephant, had just flicked around a curve to a long straight-away, and up ahead, partly hidden by the thick wooding of another curve, they both saw the reflection from the beam of a westbound headlight. The time freight was coming.

It was small wonder that Dickie Maxwell lost his nerve for just one flickering instant.

“Stop her, Larry—stop her!” he yelled. “If we keep on, the smash’ll catch us, too!”

But Larry Donovan was grimly hanging on to that priceless gift so lately discovered; namely, the gift which enables a fellow to hang on.

“No!” he yelled back. “We’ve got to stop that runaway.[17] Clamp onto something—I’m giving her all she’s got!”

It was all over—that is, the racing part of it was—in another half-minute. As the gap was closing between the big fugitive and its tiny pursuer, Larry shouted his directions to Dick.

“Listen to me, Dick: there’s no use in two of us taking the chance of a head-ender with Eleven. When we touch I’m going to climb the ’Thirty-one. As I jump, you shut off and reverse and get back out of the way, quick! Do you hear?”

The Brewster High School ex-first-baseman heard, but he had a firm grip on his nerve, now, and had no notion of heeding.

“I won’t!” he shouted back. “Think I’m going to let you hog all the risk? Not if I know it!”

Circumstances, and the quick wit of one Larry Donovan, cut the protest—and the double risk—as the poor dog’s tail was cut off; close up under the ears. As the motorized hand-car surged up under the “goose-neck” coupling buffer on the rear of the 331’s tender, Larry did two separate and distinct things at the same instant, so to speak; snapped the motor car’s magneto spark off and so killed it, and leaped for a climbing hold on the goose-neck.

With his hold made good he permitted himself a single backward glance. True to form, the Bug, with its power cut off, was fading rapidly out of the zone of danger. Larry gathered himself with a grip on the edge of the tender flare, heaved, scrambled, hurled himself over the heaped coal and into the big compound’s cab and grabbed for the throttle and the brake-cock handle.

There wasn’t any too much time. After he had shut off the steam and was applying the air-brakes with one hand and holding the screaming whistle open with the other, the headlight of the fast freight swung around the curve less than a quarter of a mile away. As you would imagine, there was also some pretty swift work done in the cab of the freight engine when Engineer Dickinson saw a headlight confronting him on the single track and heard the shrill scream of the 331’s whistle.

Luckily, the freight happened to be a rather light train that night—light, that is, as modern, half-mile-long freight trains go—and the trundling flats, boxes, gondolas and tank-cars, grinding fire under every clamped wheel, were brought to a stand while there was yet room enough, say, to swing a cat between the two opposed engines. Explanations, such as they were, followed hastily; and the freight crew promptly took charge of the situation. The Bug was brought up, lifted off the rails, carried around, and coupled in to be towed instead of pushed; and then Dickinson’s fireman was detailed to run the 331 back to Brewster, with the freight following at a safe interval.

Larry and Dick Maxwell rode back in the cab of 331, Larry doing what little coal shoveling was needed on the short run. When the big Pacific-type, towing the transformed hand-car, backed through the freight yard and edged its way down to the passenger platform, there was an excited crowd waiting for it, as there was bound to be. News of the bold attempt at criminal sabotage had spread like wildfire, and the two criminals—the one who had started the locomotive, and the other who had set the[19] outlet switch for it—had both been caught before they could escape.

Larry Donovan, dropping his shovel, saw the crowd on the station platform and knew exactly what it meant; or rather, exactly what was going to happen to him and Dick when they should face it. Like most normal young fellows he had his own special streak of timidity, and it came to the fore with a bound when he saw that milling platform throng.

With a sudden conviction that it would be much easier to face loaded cannon than those people who were waiting to yell themselves hoarse over him and Dickie Maxwell, he slid quickly out of the left-hand gangway before the 331 came to a full stop, whisked out of sight around an empty passenger-car standing on the next track, and was gone.

It was still only in the shank of the evening when he reached home. A glance through the window showed him the family still grouped around the lamp in the sitting-room. Making as little noise as possible he let himself into the hall and stole quietly up-stairs to his room. Now that the adventure was over there were queer little shakes and thrills coming on to let him know how fiercely he had been keyed up in the crisis.

After a bit he concluded he might as well go to bed and sleep some of the shakiness off; and he already had one shoe untied when somebody tapped softly on his door.

“It’s only me—Kathie,” said a voice, and he got up to let her in. One glance at the sort of shocked surprise in his sister’s pretty eyes made him fear the worst.

“Mr. Maxwell has just sent word for you to come to[20] his office, right away,” was the message that was handed in; and Larry sat on the edge of his bed and held his head in his hands, and said, “Oh, gee!”

“What have you been doing to have the general manager send for you at this time of night?” Kathie wanted to know. The question was put gently, as from one ready either to sympathize or congratulate—whichever might be needed.

“You’ll probably read all about it in the Herald to-morrow,” said Larry, gruffly; and with that he tied his shoe string and found his cap and went to obey the summons.

It is hardly putting it too strongly to say that Larry Donovan found the six city squares intervening between home and the headquarters building a rather rocky road to travel as he made his third trip over the same ground in a single evening. The timidity streak was having things all its own way now, and he thought, and said, he’d rather be shot than to have to face what he supposed he was in for—namely, the plaudits of a lot of people who would insist upon making a fuss over a thing that was as much a bit of good luck as anything else.

But, as often happens, if you’ve noticed it, the anticipation proved to be much worse than the reality. Reaching the railroad headquarters-station building he found that the “Flying Pigeon” had long since gone on its way eastward, the crowd had dispersed, and there was nobody at all in the upper corridor of the building when he passed through it on his way to the general manager’s suite of rooms at the far end.

Still more happily, after he had rather diffidently let himself in through the ante-room, he found only the[21] square-shouldered, grave-faced general manager sitting alone at the great desk between the windows. There was a curt nod for a greeting; the nod indicating an empty chair at the desk end. Larry sat on the edge of the chair with his cap in his hands, and the interview began abruptly.

“You are John Donovan’s son, aren’t you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“H’m; so you’re the fellow who was with my Dick. What made you run away and go home after you got back with the 331?”

Larry grinned because he couldn’t help it, though it was a sort of lesé majesté to grin in the presence of the general manager.

“I—I guess it was because I was afraid of the crowd,” he confessed.

“Modest?—or just bashful?”

“J-just scared, I guess.”

The barest shadow of a smile flickered for an instant in the general manager’s shrewd gray eyes.

“I don’t know as I blame you so much for that,” he commented. Then: “Dick tells me that you are wiping engines in the round-house. Did you pick out that job for yourself?”

“N-not exactly,” Larry managed to stammer. “I was through school and had to go to work at something. I guess I just took the first thing I could find.”

“Well, do you like it? Is it what you want to do?”

Larry somehow found his courage returning.

“No, sir; it isn’t,” he said baldly.

“Why isn’t it?”

Stumblingly and most awkwardly, as it seemed to him[22] when he recalled it afterward, Larry blurted out some of his half-formed ambitions, and the conditions which were handcuffing them; the desire to get on in the world without knowing just how it was to be accomplished.

“If Dad hadn’t been crippled,” he finished; “if he could have gone on getting an engineer’s pay, things would be different. But as it is—well, I guess you can see how it is, Mr. Maxwell. I’m the oldest.”

The general manager heard him through without breaking in, and at the end of the story he was looking aside out of one of the darkened windows.

“You may not realize it,” he said, without looking around, “but you did a mighty brave thing to-night, boy. Dick has told me all about it; how it was your idea to take the roadmaster’s gasoline inspection car for the chase; how you kept on when he would have given up; how you drove him back at the last and wouldn’t let him share the risk which you took alone.”

Larry felt that this was too much. He had time for the sober second thought now, and he saw how all of the danger might have been avoided.

“I’m sort of ashamed of myself, Mr. Maxwell,” he said sheepishly. “The ’Thirty-one wasn’t going very fast; she was ‘simpled’ and was choking herself. If, instead of chasing her, we had run up to the despatcher’s office, they could have caught her all right at ‘yard limits’.”

“That doesn’t cut any figure,” was the sober reply. “The main thing is that you did what you set out to do—stopped that runaway engine. Results are what count. You didn’t think of the easy thing to do, but you did think of something that worked. For that the company[23] is indebted to you. How should you like to have the debt paid?”

“We didn’t do it for pay,” Larry protested.

“I know that,”—curtly. “Just the same, you have earned the pay. What would you like? Don’t be bashful twice in the same evening.”

Thus adjured, Larry took his courage in both hands and gripped it so hard that if it had had a voice it must have yelled aloud.

“I—I’d like to have a job this summer where I could earn enough money to count for something at home, and where I could have a chance to learn something and get ahead.”

Again the grave-eyed “big boss” was looking out of the darkened window.

“Tell me just what the job would be—if you could have your choice,” he said quietly.

For one flitting instant Larry thought of the engineering party that was going to the Tourmaline, and what a perfectly rip-roaring good time he could have with Dick if he should be along; but so he dismissed that picture before it should get too strong a hold.

“I guess I’m not picking and choosing much,” he made shift to say. “I’ll do anything you tell me to, Mr. Maxwell.”

“But that wouldn’t be paying the company’s debt. If you’ve got it in you to make good, you shall have the kind of job to give you the opportunity,” said the general manager, adding: “That is, of course, if your father approves.”

Larry leaned forward anxiously.

“Would it be—would it be to go on wiping engines?” he made bold to ask, rather breathlessly.

He couldn’t be sure, but he thought there was just a hint of a twinkle in the grave gray eyes to go with Mr. Maxwell’s reply.

“That wouldn’t be much of a reward—to make you foreman of engine-wipers: you’d probably earn that for yourself in course of time. I said you might have the kind of job you wanted most. Dick has been telling me of your talk just before the 331 was stolen. Next Monday morning you and he will both go out with the Tourmaline Canyon construction force—to do whatever Mr. Ackerman, the chief of construction, may want you to do; always providing your father approves. Your pay will be something better than you are at present getting in the round-house. That’s all; run along, now, and talk it over with your father and mother.”

And Larry ran, treading upon air for the space of six city squares. For now, you see, he had been given his chance—which was all that a Donovan could ask.

Timanyoni Park, ringed in all the way around by mountain ranges, is a valley shaped something like a big oval clothes-basket, with the long way of the basket running north and south, and a ridge of watershed hills cutting it in two in the other direction.

The southern half of the Park is about all that the average traveler ever sees of it, because the main line of the Nevada Short Line runs through that part of it; and if you should ask Mr. A. Traveler what about it, he would probably tell you that it is a fine farming country with big wheat fields and beautiful apple orchards—all irrigated, of course—and a thriving little city called Brewster lying somewhere in the middle of it.

That would all be true enough of what the passing tourist sees, but north of the watershed hills is the West that you read about. With the exception of one mining-camp—Red Butte—and a single railroad track—the Red Butte branch of the Short Line—skirting its western edge, that half of the clothes-basket is a jumbled wilderness of wooded hills just about as Nature left it. And slicing a half-moon out of these northern hills, the Tourmaline, a quick-water mountain stream, a goodish-sized little river in the volume of water it carries, enters through a rugged canyon, dipping into the valley basket a little to[26] one side of the northern handle, let us say, and dodging out again a few miles farther on to find its way to the Colorado River.

The time—our time—for getting a first glimpse of the Tourmaline Canyon is the middle of a June forenoon; bright sunshine, a sky so blue that it almost hurts your eyes to look up at it, the air so crisp and sweet and clean as to make it a keen joy just to be alive and breathing it.

To right and left, as we look up the canyon, gray granite cliffs, seamed and weathered into all sorts of curious shapes, shut in a narrow gorge at the bottom of which the swift mountain torrent roars and rumbles and thunders among the boulders in its bed. On the left the canyon wall drops sheer to the water; but on the right there is a shelving, sliding bank of loose rock at the foot of the cliff. Along this bank two workmanlike young fellows, wearing the corduroys and high lace-boots of the engineers, are making their way slowly up-stream, scanning every foot of the shelving talus ledge as they cover it.

“Gee! Some fierce old place to build a railroad, I’ll tell the world!” said Dick Maxwell, the lighter-built of the two, clawing for footholds on the steep bank. “Find anything yet, Larry?”

“Nothing that looks like a location stake,” was the answer. “I guess we’ll have to back-track a piece and measure the distance up from that last one we found.”

“Aw’ right,” said Dick, with a little groan for the effort loss; “give me the end of the tape and I’ll do the back-flip,” and with the ring of the steel tape-line in hand he crawled back along the shelving slide. “Got[27] you!” he called out, when the last-discovered stake was reached; and Larry, holding the tape case, marked the hundred-foot point and began to search again for the stake which ought to be there and didn’t show up.

Five years earlier, when gold was first discovered at the headwaters of the Tourmaline, the railroad company had surveyed a line up the canyon and some twenty miles of track had been laid eastward from Red Butte. Later, the gold excitement had died down, and the Tourmaline Extension, something less than half completed, was abandoned.

But now new gold discoveries had been made and “Little Ophir” had leaped, overnight, as one might say, into the spot-light—which is a way that gold discoveries have of doing. A stirring, roaring mining-camp city had sprung up on the site of the old workings at the canyon head, and the building of the railroad extension was once more under way. For Little Ophir was without railroad connections with the outside world, and the canyon of the Tourmaline afforded the only practicable route by which a railroad could reach it.

Early in June a big construction force had been mobilized at Red Butte and the work of refitting and extending the track already laid was begun. Out ahead of the graders and track-layers an engineering party, under Mr. Herbert Ackerman, chief of construction, was reëstablishing the line of the old survey; and it was in this party that the general manager’s son, Dick, and Larry Donovan, son of the Brewster crossing watchman, were the “cubs.”

On the morning in question the two boys had been sent up the canyon ahead of the main party to find and mark the stakes of the former survey so that they could[28] be readily located by the transitmen who were following them. For several miles it had been plain sailing. In the lonely wilderness there had been nothing to disturb the stakes, and in the high, dry, mountain atmosphere but few of them had rotted away. But now, in the most difficult part of the gorge, the trail seemed to be lost.

“Haven’t found it yet?” Dick asked, coming up from the tape-holding.

“Not a single sign of it. Here’s the hundred-foot point,” and Larry dug his boot heel into the shale.

“Let’s spread out a bit,” Dick suggested. “It must be right around here somewhere.”

Accordingly, they separated, and in a scattering of boulders a little farther on, Larry found the stake—or at least, a stake. He was on his knees before it when Dick came up to say:

“Hullo! got it at last, have you?” And then, as with a sudden shock of surprise: “Why, say, Larry—that isn’t one of our old stakes! It’s a brand new one!”

It was; so new that it looked as if it might have been driven that very forenoon. The stakes they had been finding hitherto were all browned and weathered, as they were bound to be since they had been driven five years before. But this one was unmistakably new, with the mark, “Sta.162-50” in blue chalk plainly to be read. Moreover, it had been planted between two stones in a place where nobody would be likely to find it unless he knew exactly where to look for it.

“See here, Dick,” said Larry, scowling down at the discovery, “I don’t ‘savvy’ this. It doesn’t look a little bit good to me.”

“You said a whole earful then, Larry. You don’t[29] suppose any of our men have been up here ahead of us putting in new stakes, do you?”

Larry shook his head.

“We’d have known about it if they had. We’ve been passing all the transit crews each morning as we came out.”

Dick stooped and read the blue chalk markings.

“‘Sta.162-50’ means fifty feet beyond Station One Hundred and Sixty-two. And Station One-sixty-two would be sixteen thousand two hundred feet beyond some given starting point; that’s a little over three miles. We haven’t any starting point three miles back. Our stations are all numbered from Red Butte.”

Again Larry frowned and shook his head.

“Three miles would take it below the mouth of the canyon—just about down to our present camp. Say, Dick—it’s up to us to get busy on this thing. I don’t like the look of it. Here; you hold the tape on this stake and stop me at fifty feet,” and he took the ring end and scrambled on up the canyon.

“You’ve got it,” Dick announced, when the fifty-foot mark ran out of the leather case. Then: “What do you find?”

“Nothing, yet,” was the answer; and Dick proceeded to reel in the steel ribbon, walking on up to Larry as he wound.

“Nothing” seemed to be right. The fifty-foot point was in the heart of a little thicket of aspens. Carefully they searched the grove, looking behind every boulder. But there was no stake to be seen.

Though they were both Freshman—new to the engineering game, they had already learned a few of the first[30] principles. For example, they knew that staked “stations” in a survey were usually 25, 50 or 100 feet apart, according to the nature of the ground. Therefore, fifty measured feet from the point they had just left should have landed them either at Station 162 or Station 163, according to the direction in which the survey had been made. But apparently it hadn’t.

It was Dickie Maxwell who presently solved the mystery, or part of it. Crawling upon his hands and knees among the little aspens, he was halted by the sight of a bit of fine copper wire twisted about the trunk of one of the trees. A closer inspection revealed four knife-blade cuts in the bark; two running crosswise and half-way around the tree and the other two up and down on opposite sides of the trunk to complete a semi-cylindrical parallelogram.

“Come here, Larry!” he called; and when Larry had crept into the thicket: “See that wire and those marks?”

Larry saw and got quick action. Whipping out his pocket knife and cutting the thread-fine wire, he stuck the point of the blade into one of the up-and-down cracks. At the touch a section of the bark came off like the lid of a box, and under it, carved in the clean white surface of the heart wood, was the legend, “Sta.163.” Dick sat back on his heels.

“Larry, you old knuckle-duster, it’s rattling around in the back part of my bean that we’ve found something,” he remarked, with the cherubic smile that had more than once helped him to dodge a richly deserved reprimand in his school days. “Can you give it a name to handle it by?”

Larry Donovan, sitting on a rock, propped his square[31] chin in his cupped hands and lapsed into a brown study. He was a rather slow thinker, unless the emergency called for swift action, but he usually battered his way through to a reasonably logical conclusion in the end.

“You remember that rumor we heard before we left Brewster,” he said; “about the Overland Central planning to get a railroad into Little Ophir ahead of us?”

Dick nodded, and Larry went on.

“I was just thinking. The only way to reach Little Ophir with a railroad track is up this canyon; and from what we’ve seen of the canyon this far, you’d say that there isn’t room for more than one railroad in it, wouldn’t you?”

“Wow!” said Dick, springing to his feet; “you sure said a whole mouthful that time, Larry! But see here—we located this canyon line first, years ago. If this is an O. C. survey that we’ve found, they’re cutting in on us! Let’s hike back and tell Mr. Ackerman, right away. We oughtn’t to lose a minute!”

Now haste was all right, and, in the circumstances, was doubtless a prime factor in whatever problem was going to arise out of the clash between the two railroad companies. But along with his Irish blood—which wasn’t Irish until after you’d gone back three or four generations—Larry Donovan had inherited a few drops of thoughtful Scotch.

“Hold on, Richard, you old quick-trigger; let’s make sure, first,” he amended. “Maybe we can trace these markers and find out where they lead to. When we make our report we want something more than a wild guess to put in it—not?”

The tracing, which took them back down-canyon,[32] proved to be a regular detective’s job. Great pains had evidently been taken to hide all the markings of the strange survey. At each fifty measured feet they stopped and searched; hunted until they found what they were looking for. Sometimes it was a stake driven down level with the surface of the ground and covered with a flat stone. In another place the marks would be on a boulder, with another stone stood up in front of them to hide them.

Roughly speaking, the newer survey paralleled the older, fairly duplicating it in the narrower parts of the gorge, where there was room for only a single line of track; which meant, as Larry pointed out, that the first builders to get on the ground would have a monopoly of all the room there was. As they went on, the chase grew more and more exciting, and they began to speculate a bit on the probabilities.

“If this is an Overland Central line it must come in from the north, somewhere,” Dick argued. “To do that, it will have to cross the Tourmaline to get over to our side of things. We must watch out sharp for that crossing place.”

So they watched out, making careful book notes of each freshly discovered set of marks as they went along. Luckily, their chief had early made them study the abbreviations used by the engineers in stake marking; “P.I.,” point of intersection of a curve, “C—4.6,” a cutting of four and six-tenths feet, “F—2,” a fill of two feet, and so on. These figures Larry was copying into his note-book as they occurred on the various stakes; and finally, squarely opposite the mouth of what appeared to be a blind branch gulch coming into the main canyon[33] from the north side, they found one of the carefully hidden stakes with this on it: “Tang. W.3-S.,P.I.,N.12-W.”

“Now what under the sun does all that mean?” Dick queried. Then: “Oh, I know part of it. ‘Tang.’ means ‘tangent.’ But what would you make out of ‘W.3-S.’?”

Larry made a quick guess.

“Maybe it is a compass bearing; ‘west, three degrees south.’ How would that fit?”

Dick laid his pocket compass on top of the stake, and after the swinging needle had come to rest, took a back sight in the direction of the nearest up-canyon station.

“That’s just about the ticket,” he announced. “Allowing for the compass variation, it’s a little south of west. The next is ‘P.I.’—that means that it marks the intersection of a curve. Now for the ‘N.13-W.’ Say! that’s another compass bearing. Hooray! Got you now, Mr. Right-of-way thief. Right here’s where you’re going to cross the——”

He was looking over at the opposite gulch as he spoke, and his jaw dropped.

“Gee, Larry!” he exclaimed; “they can’t get a railroad in through that place over there. That’s nothing but a pocket gulch. You can see the far end of it from here!”

Once more Larry Donovan sat down and propped his chin in his hands. This time he was trying to recall all he had ever known or heard of the geography of the region lying to the north.

“Anywhere along about here would do,” he decided at length; adding: “For a place for them to break in, I mean. Burnt Canyon ought to be between twenty-five and thirty miles straight north of us, and the O. C. has[34] a branch already built to the copper mines in Burnt Canyon. That gulch over across the creek is about where you’d look for them to come out if they’re building south from the copper mines.”

“But they can’t come out there!” Dick protested. “Can’t you see that there isn’t any back door to that pocket?”

There certainly didn’t look to be. The opposite gulch was narrow and quite thickly wooded, and from any point of view they could obtain, it seemed to end abruptly against forested cliffs at its farther extremity. On the other hand, there were the stake markings pointing plainly and directly across at it.

“What’s your notion, Dick?” Larry asked, after another thoughtful inspection of the surroundings. “What’d we better do next?”

“I’ll say we ought to hurry right back to camp and report to Mr. Ackerman.”

“Maybe you’re right; but I sort of hate to go in with only half a report like this. I’d like to explore that gulch over yonder first.”

“Granny! Why, Larry! you can explore it from here—every foot of it!”

“It looks that way, I’ll admit. Yet you can’t be sure at this distance. Here’s my shy at it: you go on back to camp and tell Mr. Ackerman what we’ve found, so far, and I’ll hunt me up a place to cross the river and go dig into that gulch a little. It’s sort of up to me, you know, Dick. Your father took me out of the round-house wiping job and gave me my chance to make good on this one. And I shan’t be making good all the way through if I stop here.”

Whereupon, Dickie Maxwell argued. Besides carrying a cherubic smile for the staving off of deserved reprimands, he owned a streak of pertinacious obstinacy that was hard to down. Moreover, with the evidence of his own two good eyes to back him up, he was fully persuaded that an exploration of the pocket gulch, either singly or collectively, would be just so much time and effort thrown away.

Larry didn’t argue; he merely held out. So, at the end of it Dick grinned and gave in, saying, “Oh, well, you old stick-in-the-mud—if you’ve got to go dig into that gulch before you can get another good night’s sleep, let’s mog along and have it over with.”

“But you needn’t go,” Larry put in.

“Sure Mike I will, if you do. Pitch out and find your ferry, or your ford, or whatever it is that you’re going to cross the river on.”

The crossing of the fierce little river presented somewhat of a problem. One glance at the torrent slashing itself into spindrift among the boulders was enough to convince even the tenderest of tenderfoots that wading the stream was out of the question.

“I’ve got it,” said Larry. “We’ll hike back up-stream to where we saw those big stones lying in the river. We can make three bites of it there.”

It was a rough and rugged quarter of a mile up-canyon to the place of the big stones. Two great boulders, each large enough to fill an ordinary sitting-room and figuring as prehistoric shatterings from the cliffs above, lay in an irregular triangle in the stream bed. The leaps from one to another of these over the split-up torrent were a bit unnerving to contemplate and Dick shook his head.

“You’re long-legged enough to do it, Larry, but I’m afraid I can’t,” he said. “If we could make a bridge of some kind——”

Larry was willing enough to go on the exploring expedition alone, but he was unwilling to leave Dick behind for a mere physical obstacle. Releasing the small stake-ax that he carried in his belt, he hacked down a little pine-tree standing near and trimmed the branches. “It won’t be much better than a tight-rope,” he grinned, “but we’re neither of us very high-shy.”

Handling it together, they heaved the trimmed pine across to the first boulder and Larry tested it.

“Safe as a clock,” he announced. “Come on.”

Dick balanced himself across, and then they pulled the tree over and bridged the second chasm with it. This crossing made, the third proved to be nothing more than an easy jump to the northern stream bank, and a few minutes later they had covered the down-stream distance to the gulch mouth and were entering the pocket.

They stopped and looked around. Even at this nearer view of it the blind gorge appeared to be nothing but a blind.

“What do you say now,” Dick laughed. “Are you satisfied?”

“Not yet,” said Larry. “Take a little time off, if you like, and rest your face and hands while I walk up to the head of this thing.”

“Oh, no; I’m still with you,” was the joshing retort; and together they began an exploration of the pocket.

Even after they had found the astounding outcome the illusion as seen from the opposite side of the river was perfect. A hundred yards from its apparent end they[37] still would have declared that the gulch stopped abruptly against a solid cliff. But upon taking a few steps to the left they found that what seemed to be the end of the pocket was merely a jutting spur of the mountain completely concealing an extension of the gorge which went winding its way beyond, deep into the heart of things. And at the turn into this extension they found another of the new, blue-chalk-marked location stakes; in plain sight, this one, with no attempt having been made to conceal it like those on the other bank of the river.

“I’m It,” Dick acknowledged, laughing again, but at himself this time. “You can put it all over me when it comes down to sheer, unreasonable thoroughness, old scout, I give you right. But how about it now? Do we chase back with the news?”

“Still and again, not yet,” Larry demurred. “That report we’re going to make to Mr. Ackerman oughtn’t to stop short off in the middle of things. Maybe these stakes don’t mean anything but a preliminary survey; the O. C. just sort of feeling the ground over to see what they could do if they wanted to. But taking it the other way round, maybe it’s the real thing—the working lay-out. What if they’ve already been building down sneak-fashion from Burnt Canyon? What if they should happen to be right around the next twist in this crooked gully, ready to make a swift grab for the river crossing and our right-of-way in the canyon?”

Dick groaned in mock despair.

“I see,” he lamented. “You won’t be satisfied until you’ve walked me ten or thirteen miles on the way to Burnt Canyon. All right; let’s go. I’m the goat.”

At that they pushed on up the crooked gulch and for a time it seemed as if Dickie Maxwell were going to have the long end of the argument. True, they were still finding the location stakes at regular intervals, but that didn’t necessarily mean that they were going to find anything else.

It was possibly a mile back from the gulch’s mouth, and in the very heart of the northern mountain range, that they made the great discovery. As they tramped around the last of the crooking gulch elbows the scene ahead changed as if by magic. The crooking elbow proved to be the gateway to an open valley surrounded by high mountains on all sides save that to the north.

Over the hills in the northern vista a newly constructed wagon road wound its way—they could tell that it was new by the freshness of the red clay in the cuts and fills; and in the middle of the valley ... here was what made them gasp and duck suddenly to cover in a little groving of gnarled pines. Spread out on the level were stacks of bridge timbers, great piles of cross-ties, neat rackings of steel rails, wagons, scrapers, a portable hoisting engine—all the paraphernalia of a railroad construction camp!

“Gee-meny Christmas!” Dick ejaculated under his breath, and that expressed it exactly. Here was the advanced post of the enemy, with everything in complete readiness for the forward capturing dash into Nevada Short Line territory.

It seemed to be the exactly fortunate moment for a hurried retreat and the sounding of a quick alarm in the home camp on the Tourmaline; but now Larry Donovan’s[39] streak of ultimate thoroughness came again to the front.

“Nothing like it,” he objected to Dick’s frantic urgings in favor of the retreat; “let’s make it a knock-out while we’re about it. We want to be able to tell Mr. Ackerman the whole story when we go back; how much material they’ve got here, and all that.”

Oddly enough, the little valley, with its wealth of stored material and tools and machinery, seemed to be utterly deserted as they entered it. They saw no signs of life anywhere; there was not even a watchman to stop them when they crept cautiously up to the material piles and took shelter among them.

“Quick work now, Dick!” Larry directed. “You take the dimensions of those bridge sticks and count ’em while I’m counting the ties and rails!” and they went at it, “bald-headed,” as Dick phrased it in telling of it afterward, like a couple of fellows figuring against time on a tough problem on examination day. And since there is said to be nothing so deaf as an adder, neither of them heard a sound until a gruff voice behind them said:

“Well, how about it? Do they check out to suit you?”

At the gruff demand they jumped and spun around as if the same string had been tied to both of them; started and faced about to find a big, bearded giant in a campaign hat and faded corduroys looking on with a grim smile wrinkling at the corners of a pair of rather fierce eyes.

“Murder!” said Dick in a stifled whisper; and Larry didn’t say even that much. For now they both saw what they had failed to see from the down-valley point[40] of view; namely, a collection of roughly built shacks half hidden in a grove of pines, with a number of men moving about among them.

“Spies, eh?” remarked the big man who had accosted them; then, with the smile fading slowly out of the eye-wrinkles: “Who sent you two kids up here?”

“Nobody,” Larry answered shortly.

“Ump!” grunted the giant. “Just doing a bit of Sherlocking on your own account, are you? I suppose you belong to Herb Ackerman’s outfit, don’t you?”

Larry made no reply to this; and Dick, taking his cue promptly, was also silent.

“No sulking—not with me!” growled the big man harshly. “I can make you talk if I want to. How many men are there in your outfit, and whereabouts are they working now?”

Larry’s square jaw set itself like that of a bull-dog that had been told to let go and wouldn’t.

“You’ll have to find that out for yourself,” he snapped.

The inquisitor held out a hand.

“Give me that note-book!” he commanded.

Now Larry Donovan’s methodical manner of thinking applied only to crises where there was plenty of time. But at this curt demand thought and action were simultaneous. With a quick jerk he flipped the incriminating note-book over the demander’s head. Naturally, the man dodged; and Larry saw the note-book alight and hide itself—as he had hoped it might—on top of a high pile of the stacked cross-ties.

“So that’s the way you’re built, is it?” rasped the big man, angered, doubtless, by the fact that he had dodged something that hadn’t been thrown at him. “We’ll take[41] care of you two cubs, all right! Get a move on—up to the shacks!”

Actuated by a common impulse, they both stole a quick glance down the valley, measuring the chances for a mad dash for freedom. The man saw the glance and stepped aside to bar the way.

“None of that!” he growled. “Get on up to the shacks!”

There seemed to be nothing for it but an ignominious surrender, so they tramped away, with their captor keeping even pace with them a step behind. They were halted before one of the shacks, a long, one-storied building which they took to be the camp commissary or store-house. It was; but one end of it was partitioned off for another purpose; and after the padlocked door at this end had been opened and they were shoved into the semi-darkness of the interior, they found themselves stumbling over tools of all descriptions—picks, shovels, crowbars, screw-jacks, blocks and tackle, coils of rope.

“Huh!” said Dick, “their tool-house.” And then they sat down on a pair of the rope coils to consider the state of the nation.

“My fault,” was Larry’s first word. “If we had turned back when you wanted to——”

“Cut it,” Dick broke in. “We needed the stuff we were after—if we could only have gotten away with it. What do you reckon they’ll do with us?”

“Your guess is as good as anybody’s,” Larry said, with a wry smile. “The one thing they’re not going to do, if they can help it, is to let us carry the news of this thing back to our camp. And that’s just the one thing we must do, if it takes a leg.”

They had plenty of time in which to consider ways and means. Immediately deciding that nothing could be done or attempted in daylight, they wore out the long afternoon plotting and planning—to mighty little purpose.

Their prison was a makeshift, to be sure, but it was pretty effective. There were no windows; what little light they had came through the unbattened cracks in the walls. There was but the one door, and that was padlocked on the outside. And while there were plenty of excellent tools for digging a tunnel, the heavy plank floor securely nailed down made that expedient impossible.

For hours they were completely ignored. Nobody came near their end of the building, and apparently there were no camp activities of any kind going on outside. Larry guessed at the explanation, which proved to be the right one.

“Those men we saw are only the Overland Central engineering party,” he hazarded. “They’re waiting for their working force to come in from somewhere up the line. That is why everything is so quiet.”

In the plotting and planning they soon discovered that their tool-room prison was partitioned off at the end of the commissary or store. Through the cracks in the partition they could see into the other part of the building. It appeared to be locked up and deserted, and was half filled with canned stuff, sides of salt meat stacked up, a lot of hams in their canvas covers, a wagon-load or two of flour in sacks, barrels of potatoes and cabbages—provisions of all sorts.

“If we could only get through this partition some[43] way,” Dick suggested, “the rest of it would be easy—with half a dozen windows to choose from.”

They had been gradually working down to this through the afternoon; like the man, who, after looking in all the likely places for his lost cattle, began to look in the unlikely ones; and being the mechanical member of the partnership, Larry set his wits at work. The partition was built of up-and-down planks spiked to two-by-fours at the bottom, in the middle and at the top. The two-by-fours were on their side of the wall, and while daylight remained, Larry made a careful inspection of the different planks, one by one, to ascertain if they were all nailed solidly.

His search was finally rewarded. One of the planks was not nailed quite home, or perhaps it had warped a bit after the nailing was done. Anyway, there was a little crack between it and the two-by-fours; and with a pick taken from the tool pile Larry cautiously pried the board loose at the bottom and in the middle, leaving it hanging by the two nails at the top. Then—the Donovan thoroughness coming into play again—he bent the projecting nails flat so that the board could be pulled back into place until the time should come for it to be pushed aside.

“Somebody might happen to come into the storeroom and see it bulged out,” was the explanation he gave Dick while he was twisting and toiling over the nails. “I don’t mind jamming my fingers a little. There’s no use sweating your head off making a chain, and then leaving one link in it so it will pull in two at the first jerk.”

With the way of escape to the larger room thus provided,[44] they waited to see what would happen at suppertime. Much to their relief, the thing they were hoping for did happen. A little past sunset the door was opened and a substantial camp supper was thrust in to them. After that, there was another wait for darkness; and when they were able to see the stars through the wall cracks they swung the hanging plank aside and squeezed through the narrow slit into the store-room.

Here they had to grope and feel their way among the piled-up stores, and once Dick stumbled and fell over a box of the canned stuff, falling, luckily, upon a heap of sacked flour and thus saving the crash that might have betrayed them. Down at the farther end of the building the ruddy light of a camp fire was shining through the cracks, and toward this flickering beacon they made their way cautiously.

Through the wall cracks they could both see and hear. The members of the Overland Central’s advance engineering party were sitting about the fire, talking and smoking, and the two boys soon heard enough to tell them that Larry’s guess had been right; the engineers were waiting for the arrival of the construction crew.

Since it was still too early to make any further move towards an escape, Larry and Dick settled themselves, each at his spying crack. For what seemed to them an interminable time the circle around the fire remained unbroken; and when the men finally began to drop out of it they went only one or two at a time to the bunk shack on the opposite side of the camp area.

None the less, since all things mundane must have an end, there did come a time at last when there were only two of them left; the big chief and another whom[45] the boys took to be the boss bridge-builder. It was the bridge-man who said:

“About them two kids you caught this afternoon; what are you goin’ to do with ’em?”

“Been thinking about that,” said the giant. “It won’t do to let them go back to Ackerman and spill the beans. What we’ve got to do is to let Ackerman come on with his transitmen and get past the mouth of the gulch, going up. Then, before his graders come along, we can cut in behind him and grab the canyon before he catches on. Besides, we’ll have the advantage of being between him and his working force.”

“But you can’t very well keep the kids here,” the other man objected. “They’ll be missed and looked for.”

“No; we won’t keep ’em here; we’ll send ’em up to Burnt Canyon with the teams going back to-morrow. We can hold ’em on some sort of a trespass charge until the job is put across. And about their being missed: that’s up to Ackerman. If there’s any worrying to be done, we’ll let George do it.”

“Do you know who the boys are?”

“No; but I have a sneaking notion that one of them is General Manager Maxwell’s son.”

“Sufferin’ Mike!” said the bridge-man; “and you’d take a chance lockin’ him up?”

The big chief chuckled.

“There’ll be a row kicked up about it, I suppose, and Mr. Richard Maxwell’ll be pretty hot under the collar. But everything’s fair in love or war—or in business. We’ve got to have that canyon right-of-way. Finished your pipe? All right; we’ll turn in. This waiting game makes me as sleepy as a house cat in daytime.”

But the bridge-builder had another word to add and he added it.

“If these boys belong to Ackerman’s party—and I s’pose there’s no doubt of that—it won’t do to let ’em get loose. Are they safe, in that tool-house?”

“As safe as a clock. There’s only the one door, and I’ve told Mexican Miguel to take his blankets and make himself a shake-down for the night just outside of it. He’ll hear ’em if they make any stir. But they won’t. Being boys, they’ll sleep like a couple of logs.”

After the two men had gone across to the bunk house the boys still waited, though now it was with impatience curdling the very blood in their veins, since they realized that every minute was precious if the canyon steal was to be prevented. Again and again Dick’s excitement yelled for action, but each time Larry pulled him down with a “Not yet,” until at length Dick was sure it must be nearly midnight.

When Larry finally gave the word they crept to a window on the side of the building opposite that which faced the camp area, pulled out its single fastening nail, slid the sash, and in a jiffy they were out under the stars and free. Careful to the last, Larry turned and softly closed the window after they were out, “Just so the first man up in the morning won’t know that we’re gone,” he whispered. “It’s pinching me now that such minutes as we can save even that way are going to count.”

“Which way do we go?” Dick asked, being completely turned around in the darkness.

“Not any way, until after I’ve got that note-book of mine,” said Larry the thorough; adding: “I hope the big[47] chief didn’t go back to look for it after we were locked up.”

Treading as lightly as story-book Indians, they stole around the commissary building, and at the tool-room end of it they had a glimpse of the sleeping sentinel stretched out before the padlocked door. A quick little run took them to the material piles, and Larry climbed to the top of the cross-tie stack and was overjoyed when he found his note-book lying just where it had lodged.

They had a glimpse of the sleeping sentinel stretched out before the padlocked door

“Now we’re on our way,” he announced, scrambling down; and the stumbling retreat in the darkness was begun.

It seemed to both of them that they had blundered along for uncounted miles before they heard the welcome thunder of the Tourmaline growling among its boulders in the main canyon. Arrived at the gulch mouth, however, they hardly knew which way to go. Up-stream there were the big boulders and the pine-tree bridge, but tight-rope work over a boiling mountain torrent in the dark of the moon didn’t appeal much to either one of them.

“No,” said Larry; “we can’t risk that, and, besides, it would take us just that much out of our way. It’s down-stream for us, and we’ll have to take a chance on finding some way to cross.”

Deciding thus, they turned to the right and clawed their way down the canyon. It was a stiff job in the darkness, and there were spots where the canyon cliffs leaned in so far that they had to wade in the edge of the torrent; but they hurried on and finally came out of the mountain hazards and into the foot-hills, where the going was easier and they could make better time.

At that moment the big construction camp, where Chief Engineer Ackerman had his headquarters, was two good miles below the mouth of Tourmaline Canyon. Luckily, the railroad grade at this particular point was closely paralleling the river, so when the two boys came opposite the camp they had no difficulty in locating it. A few lusty shouts aroused the camp, and some of the men turned out and backed a wagon into the stream, and thus the two Marathon runners were ferried across.

Three brief minutes in the tent of the chief sufficed for the giving of the alarm, and Larry’s heart swelled with—well, not exactly with envy, perhaps, but at any rate with eager emulation and the hope that he, too, might some day rise to such heights of efficiency, when he saw how quickly the chief grasped the situation and how capably he met it.

A few quietly given orders to his assistants and to the foremen crowding to the tent flap started the checkmating move, which was simple enough now that the warning had been given. With every man in the well-disciplined force falling into line, the graders were sent forward at once to take immediate possession of the threatened point in the canyon, the obvious counter-move being to have the Short Line grade established and occupied before the Overland Central could make its capturing dash across the river.

After the orders had been given and the men were hustling the preparations for the forward move, Chief Ackerman turned to the pair of leg-weary scouts.

“You fellows have done well—mighty well—for a[49] couple of first-year cubs,” he said in hearty commendation. “Now go ahead and tell me all about it.”

Larry let Dick do the telling, contenting himself with producing the note-book with its carefully penciled record. As in the chase of the runaway engine, when there was credit to be given, Dickie Maxwell did the square thing.

“If you make any report of this to headquarters, Mr. Ackerman,” he wound up, “I wish you fix it so as to put Larry in where he belongs. He made me go on when I thought it wasn’t any sort of use. If it hadn’t been for him we wouldn’t have had anything to report but that survey on this side of the river, and——”

“Oh, let up, will you?” Larry growled in sheepish confusion. “You talk a heap too much, Dick, when you get started.” And then to the chief, in still more confusion: “I hope you won’t do anything that Dick says, Mr. Ackerman. He was in it just exactly as much as I was. He knows it, too, but he’s always throwing off that way on me.”

Mr. Ackerman smiled and didn’t say what he would or would not do. But a few days later, after the report had gone to the headquarters in Brewster, General Manager Maxwell tossed the chief’s opened letter across his office desk to his brother-in-law, Mr. William Starbuck, who happened to be with him at the moment.

“You see what Ackerman says,” he remarked. “It seems that we have won the first round in the tussle for the right-of-way in Tourmaline Canyon, and that we owe the winning chiefly to that Donovan boy—you remember him; son of John Donovan the crippled locomotive[50] engineer. I told the boy he’d have to show what was in him if we gave him a chance on the new work, and he seems to be doing it. There’s good timber in that Donovan stock.”

“What do you reckon these O. C. people will do, Larry, when they find that we’ve got ahead of them in the canyon?”

“Huh?” came a yawning grunt from the opposite tent cot. Then: “Good goodness! can’t you let a fellow sleep for a few minutes?”

“A few minutes? It’s ten o’clock, and I’ll bet we’re the only two people left in this camp—unless the other one is the mess cookee!”

“Ah-yow!” gaped the sleeper, turning upon his back and stretching his arms over his head. “I feel as if I’d been up three nights hand-running, and then some. Ten o’clock, did you say?”

“Yep, and five minutes after. I guess Mr. Ackerman gave orders to let us sleep—to pay for the hiking we did yesterday and last night. But you haven’t told me yet what you think the O. C. bunch will do, now that we’ve pushed our grading force up and got ahead of them at the place where they were fixing to cross the river.”

Before Larry could answer the tent flap was pulled open and a well-built young fellow about two years their senior stuck his face in and grinned good-naturedly at them.

“Now then, lazyheads!” was his greetings; “’bout ready to turn out and wash your face and hands?”

“We’re thinking about it,” said Dick. “But just why, in particular—if you don’t mind telling us?”

“Oh, nothing; only the chief said I might persuade you to help me. We’re running the wires up to connect with the new ‘front,’ and I’m needing a couple of bell-hops.”

“Bell-hops nothing!” Dick scoffed. “You’re ’way off. We’re the pulchritudinous—that’s a good word; stick it down in your note-book—we are the pul-chri-tu-di-nous little do-whichits of this outfit. Haven’t you heard what we did last night?”