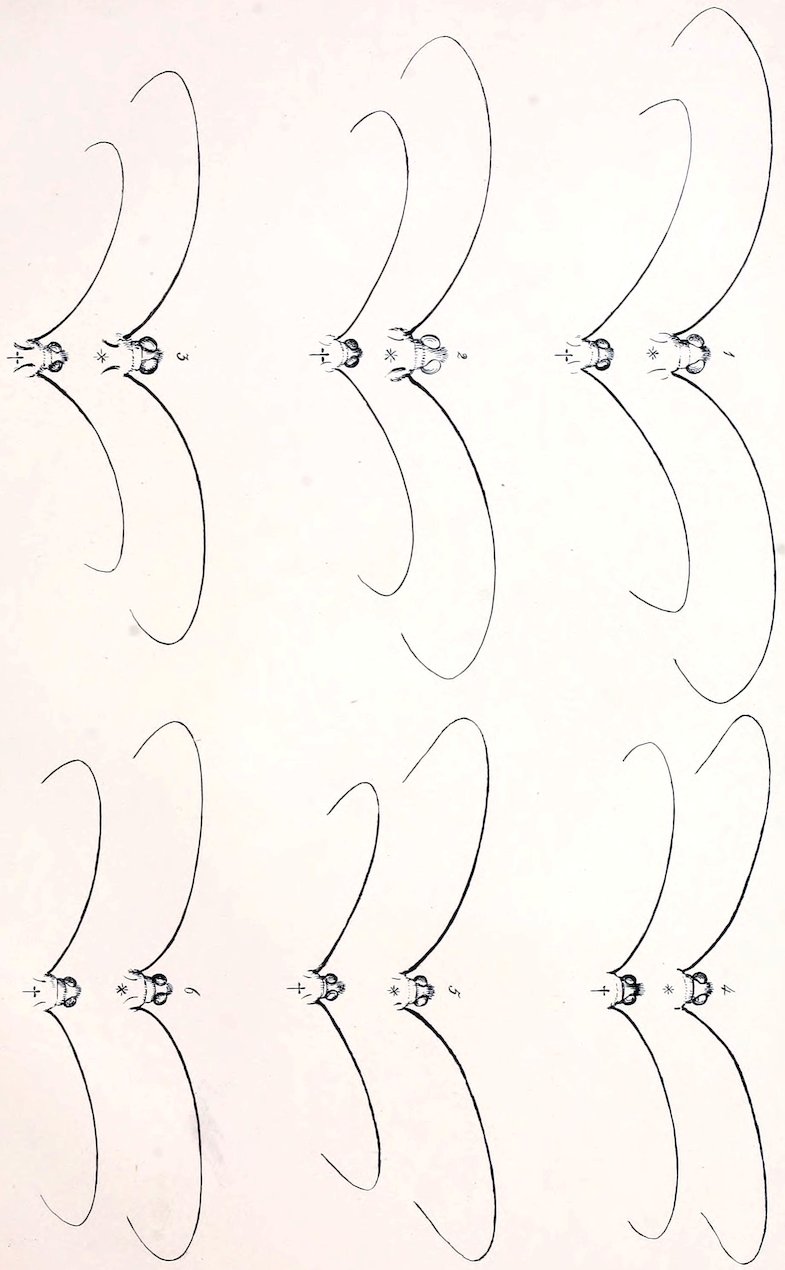

Fig. 1.

Anal valves of O. Amphrisius.

Title: On the phenomena of variation and geographical distribution as illustrated by the Papilionidæ of the Malayan region

Author: Alfred Russel Wallace

Release date: December 11, 2024 [eBook #74871]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Linnean Society of London, 1865

Credits: Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

When the naturalist studies the habits, the structure, or the affinities of animals, it matters little to which group he especially devotes himself; all alike offer him endless materials for observation and research. But, for the purpose of investigating the phenomena of geographical distribution and of local or general variation, the several groups differ greatly in their value and importance. Some have too limited a range, others are not sufficiently varied in specific forms, while, what is of most importance, many groups have not received that amount of attention over the whole region they inhabit, which could furnish materials sufficiently approaching to completeness to enable us to arrive at any accurate conclusions as to the phenomena they present as a whole. It is in those groups which are and have long been favourites with collectors that the student of distribution and variation will find his materials the most satisfactory, from their comparative completeness.

Preeminent among such groups are the diurnal Lepidoptera or Butterflies, whose extreme beauty and endless diversity have led to their having been assiduously collected in all parts of the world, and to the numerous species and varieties having been figured in a series of magnificent works, from those of Cramer, the contemporary of Linnæus, down to the inimitable productions of our own Hewitson. But, besides their abundance, their universal distribution, and the great attention that has been paid to them, these insects have other qualities that especially adapt them to elucidate the branches of inquiry already alluded to. These are the immense development and peculiar structure of the wings, which not only vary in form more than those of any other insects, but offer on both surfaces an endless variety of pattern, colouring, and texture. The scales with which they are more or less completely covered imitate the rich hues and delicate surfaces of satin or of velvet, glitter with metallic lustre, or glow with the changeable tints of the opal. This delicately painted surface acts as a register of the minutest differences of organization,—a 2shade of colour, an additional streak or spot, a slight modification of outline continually recurring with the greatest regularity and fixity, while the body and all its other members exhibit no appreciable change. The wings of Butterflies, as Mr. Bates has well put it[1], “serve as a tablet on which Nature writes the story of the modifications of species;” they enable us to perceive changes that would otherwise be uncertain and difficult of observation, and exhibit to us on an enlarged scale the effects of the climatal and other physical conditions which influence more or less profoundly the organization of every living thing.

1. See ‘The Naturalist on the Amazons,’ 2nd edit. p. 412.

A proof that this greater sensibility to modifying causes is not imaginary may, I think, be drawn from the consideration that while the Lepidoptera as a whole are of all insects the least essentially varied in form, structure, or habits, yet in the number of their specific forms they are not much inferior to those orders which range over a much wider field of nature, and exhibit more deeply seated structural modifications. The Lepidoptera are all vegetable-feeders in their larva-state, and suckers of juices or other liquids in their perfect form. In their most widely separated groups they differ but little from a common type, and offer comparatively unimportant modifications of structure or of habits. The Coleoptera, the Diptera, or the Hymenoptera, on the other hand, present far greater and more essential variations. In either of these orders we have both vegetable- and animal-feeders, aquatic, and terrestrial, and parasitic groups. Whole families are devoted to special departments in the economy of nature. Seeds, fruits, bones, carcases, excrement, bark, have each their special and dependent insect tribes from among them; whereas the Lepidoptera are, with but few exceptions, confined to the one function of devouring the foliage of living vegetation. We might therefore anticipate that their population would be only equal to those of the sections of the other orders that have a similar uniform mode of existence; and the fact that their numbers are at all comparable with those of entire orders, so much more varied in organization and habits, is, I think, a proof that they are in general highly susceptible of specific modification.

The Papilionidæ are a family of diurnal Lepidoptera which have hitherto, by almost universal consent, held the first rank in the order; and though this position has recently been denied them, I cannot altogether acquiesce in the reasoning by which it has been proposed to degrade them to a lower rank. In Mr. Bates’s most excellent paper on the Heliconidæ[2], he claims for that family the highest position, chiefly because of the imperfect structure of the fore legs, which is there carried to an extreme degree of abortion, and thus removes them further than any other family from the Hesperidæ and Heterocera, which all have perfect legs. Now it is a question whether any amount of difference which is exhibited merely in the imperfection or abortion of certain organs, can establish in the group exhibiting it a claim to a high grade of organization; still less can this be allowed when another group, along with perfection of structure in the same organs, exhibits modifications peculiar to it, together with the possession of an organ which in the remainder of the order is altogether wanting. This is, however, the position of the Papilionidæ. The perfect insects possess two characters quite peculiar to them. Mr. 3Edward Doubleday, in his ‘Genera of Diurnal Lepidoptera,’ says, “The Papilionidæ may be known by the apparently four-branched median nervule and the spur on the anterior tibiæ, characters found in no other family.” The four-branched median nervule is a character so constant, so peculiar, and so well marked, as to enable a person to tell, at a glance at the wings only of a butterfly, whether it does or does not belong to this family; and I am not aware that any other group of Butterflies, at all comparable to this in extent and modifications of form, possesses a character in its neuration to which the same degree of certainty can be attached. The spur on the anterior tibiæ is also found in some of the Hesperidæ, and is therefore supposed to show a direct affinity between the two groups; but I do not imagine it can counterbalance the differences in neuration and in every other part of their organization. The most characteristic feature of the Papilionidæ, however, and that on which I think insufficient stress has been laid, is undoubtedly the peculiar structure of the larvæ. These all possess an extraordinary organ situated on the neck, the well-known Y-shaped tentacle, which is entirely concealed in a state of repose, but which is capable of being suddenly thrown out by the insect when alarmed. When we consider this singular apparatus, which in some species is nearly half an inch long, the arrangement of muscles for its protrusion and retraction, its perfect concealment during repose, its blood-red colour, and the suddenness with which it can be thrown out, we must, I think, be led to the conclusion that it serves as a protection to the larva by startling and frightening away some enemy when about to seize it, and is thus one of the causes which has led to the wide extension and maintained the permanence of this now dominant group. Those who believe that such peculiar structures can only have arisen by very minute successive variations, each one advantageous to its possessor, must see, in the possession of such an organ by one group, and its complete absence in every other, a proof of a very ancient origin and of very long-continued modification. And such a positive structural addition to the organization of the family, subserving an important function, seems to me alone sufficient to warrant us in considering the Papilionidæ as the most highly developed portion of the whole order, and thus in retaining it in the position which the size, strength, beauty, and general structure of the perfect insects have been generally thought to deserve.

2. Transactions of the Linnean Society, vol. xxiii. p. 495.

The Papilionidæ are pretty widely distributed over the earth, but are especially abundant in the tropics, where they attain their maximum of size and beauty and the greatest variety of form and colouring. South America, North India, and the Malay Islands are the regions where these fine insects occur in the greatest profusion, and where they actually become a not unimportant feature in the scenery. In the Malay Islands in particular the giant Ornithopteræ may be frequently seen about the borders of the cultivated and forest districts, their large size, stately flight, and gorgeous colouring rendering them even more conspicuous than the generality of birds. In the shady suburbs of the town of Malacca two large and handsome Papilios (Memnon and Nephelus) are not uncommon, flapping with irregular flight along the roadway, or, in the early morning, expanding their wings to the invigorating rays of the sun. In Amboyna and other towns of the Moluccas, the magnificent Deiphobus and Severus, and occasionally even the azure-winged Ulysses, frequent similar situations, fluttering about the orange-trees and flower-beds, or 4sometimes even straying into the narrow bazaars or covered markets of the city. In Java the golden-dusted Arjuna may often be seen at damp places on the roadside in the mountain districts, in company with Sarpedon, Bathycles, and Agamemnon, and less frequently the beautiful swallow-tailed Antiphates. In the more luxuriant parts of these islands one can hardly take a morning’s walk in the neighbourhood of a town or village without seeing three or four species of Papilio, and often twice that number. No less than 120 species of the family are now known to inhabit the Archipelago, and of these ninety-six were collected by myself. Twenty-nine species are found in Borneo, being the largest number in any one island, twenty-three species having been obtained by myself in the vicinity of Sarawak; Java has twenty-seven species; Celebes and the Peninsula of Malacca twenty-three each. Further east the numbers decrease, Batchian producing seventeen, and New Guinea only thirteen, though this number is certainly too small, owing to our present imperfect knowledge of that great island.

In estimating these numbers I have had the usual difficulty to encounter, of determining what to consider species and what varieties. The Malayan region, consisting of a large number of islands of generally great antiquity, possesses, compared to its actual area, a great number of distinct forms, often indeed distinguished by very slight characters, but in most cases so constant in large series of specimens, and so easily separable from each other, that I know not on what principle we can refuse to give them the name and rank of species. One of the best and most orthodox definitions is that of Pritchard, the great ethnologist, who says, that “separate origin and distinctness of race, evinced by a constant transmission of some characteristic peculiarity of organization,” constitutes a species. Now leaving out the question of “origin,” which we cannot determine, and taking only the proof of separate origin, “the constant transmission of some characteristic peculiarity of organization,” we have a definition which will compel us to neglect altogether the amount of difference between any two forms, and to consider only whether the differences that present themselves are permanent. The rule, therefore, I have endeavoured to adopt is, that when the difference between two forms inhabiting separate areas seems quite constant, when it can be defined in words, and when it is not confined to a single peculiarity only, I have considered such forms to be species. When, however, the individuals of each locality vary among themselves, so as to cause the distinctions between the two forms to become inconsiderable and indefinite, or where the differences, though constant, are confined to one particular only, such as size, tint, or a single point of difference in marking or in outline, I class one of the forms as a variety of the other.

I find as a general rule that the constancy of species is in an inverse ratio to their range. Those which are confined to one or two islands are generally very constant. When they extend to many islands, considerable variability appears; and when they have an extensive range over a large part of the Archipelago, the amount of unstable variation is very large. These facts are explicable on Mr. Darwin’s principles. When a species exists over a wide area, it must have had, and probably still possesses, great powers of dispersion. Under the different conditions of existence in various portions of its area, different variations from the type would be selected, and, were they completely isolated, would soon become distinctly modified forms; but this process is checked by the dispersive powers 5of the whole species, which leads to the more or less frequent intermixture of the incipient varieties, which thus become irregular and unstable. Where, however, a species has a limited range, it indicates less active powers of dispersion, and the process of modification under changed conditions is less interfered with. The species will therefore exist under one or more permanent forms according as portions of it have been isolated at a more or less remote period.

What is commonly called variation consists of several distinct phenomena which have been too often confounded. I shall proceed to consider these under the heads of—1st, simple variability; 2nd, polymorphism; 3rd, local forms; 4th, coexisting varieties; 5th, races or subspecies; and 6th, true species.

1. Simple variability.—Under this head I include all those cases in which the specific form is to some extent unstable. Throughout the whole range of the species, and even in the progeny of individuals, there occur continual and uncertain differences of form, analogous to that variability which is so characteristic of domestic breeds. It is impossible usefully to define any of these forms, because there are indefinite gradations to each other form. Species which possess these characteristics have always a wide range, and are more frequently the inhabitants of continents than of islands, though such cases are always exceptional, it being far more common for specific forms to be fixed within very narrow limits of variation. The only good example of this kind of variability which occurs among the Malayan Papilionidæ is in Papilio Severus, a species inhabiting all the islands of the Moluccas and New Guinea, and exhibiting in each of them a greater amount of individual difference than often serves to distinguish well-marked species. Almost equally remarkable are the variations exhibited in most of the species of Ornithoptera, which I have found in some cases to extend even to the form of the wing and the arrangement of the nervures. Closely allied, however, to these variable species are others which, though differing slightly from them, are constant and confined to limited areas. After satisfying oneself, by the examination of numerous specimens captured in their native countries, that the one set of individuals are variable and the others are not, it becomes evident that by classing all alike as varieties of one species we shall be obscuring an important fact in nature, and that the only way to exhibit that fact in its true light is to treat the invariable local form as a distinct species, even though it does not offer better distinguishing characters than do the extreme forms of the variable species. Cases of this kind are the Ornithoptera Priamus, which is confined to the islands of Ceram and Amboyna, and is very constant in both sexes, while the allied species inhabiting New Guinea and the Papuan Islands is exceedingly variable; and in the island of Celebes is a species closely allied to the variable P. Severus, but which, being exceedingly constant, I have described as a distinct species under the name of Papilio Pertinax.

2. Polymorphism or dimorphism.—By this term I understand the coexistence in the same locality of two or more distinct forms, not connected by intermediate gradations, and all of which are occasionally produced from common parents. These distinct forms generally occur in the female sex only, and the intercrossing of two of these forms does not generate an intermediate race, but reproduces the same forms in varying proportions. I believe it will be found that a considerable number of what have been classed as 6varieties are really cases of polymorphism. Albinoism and melanism are of this character, as well as most of those cases in which well-marked varieties occur in company with the parent species, but without any intermediate forms. Under these circumstances, if the two forms breed separately, and are never reproduced from a common parent, they must be considered as distinct species, contact without intermixture being a good test of specific difference. On the other hand, intercrossing without producing an intermediate race is a test of dimorphism. I consider, therefore, that under any circumstances the term ‘variety’ is wrongly applied to such cases.

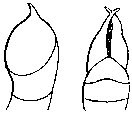

The Malayan Papilionidæ exhibit some very curious instances of polymorphism, some of which have been recorded as varieties, others as distinct species; and they all occur in the female sex. Papilio Memnon, L., is one of the most striking, as it exhibits the mixture of simple variability, local and polymorphic forms, all hitherto classed under the common title of varieties. The polymorphism is strikingly exhibited by the females, one set of which resemble the males in form, with a variable paler colouring; the others have a large spatulate tail to the hinder wings and a distinct style of colouring, which causes them closely to resemble P. Coon, a species of which the sexes are alike and inhabiting the same countries, but with which they have no direct affinity. The tailless females exhibit simple variability, scarcely two being found exactly alike even in the same locality. The males of the island of Borneo exhibit constant differences of the under surface, and may therefore be distinguished as a local form, while the continental specimens, as a whole, offer such large and constant differences from those of the islands that I am inclined to separate them as a distinct species—P. Androgeus, Cr. We have here, therefore, distinct species, local forms, polymorphism, and simple variability, which seem to me to be distinct phenomena, but which have been hitherto all classed together as varieties. I may mention that the fact of these distinct forms being one species is doubly proved. The males, the tailed and tailless females, have all been bred from a single group of the larvæ, by Messrs. Payen and Bocarmé, in Java, and I myself captured in Sumatra a male P. Memnon, L., and a tailed female P. Achates, Cr., “in copulâ.”

Papilio Pammon, L., offers a somewhat similar case. The female was described by Linnæus as P. Polytes, and was considered to be a distinct species till Westermann bred the two from the same larvæ (see Boisduval, ‘Species Générales des Lépidoptères,’ p. 272). They were therefore classed as sexes of one species by Mr. Edward Doubleday, in his ‘Genera of Diurnal Lepidoptera,’ in 1846. Later, female specimens were received from India closely resembling the male insect, and this was held to overthrow the authority of M. Westermann’s observation, and to reestablish P. Polytes as a distinct species; and as such it accordingly appears in the British Museum List of Papilionidæ in 1856, and in the Catalogue of the East India Museum in 1857. This discrepancy is explained by the fact of P. Pammon having two females, one closely resembling the male, while the other is totally different from it. A long familiarity with this insect (which, replaced by local forms or by closely allied species, occurs in every island of the Archipelago) has convinced me of the correctness of this statement; for in every place where a male allied to P. Pammon is found, a female resembling P. Polytes also occurs, and sometimes, though less frequently than on the continent, another female closely resembling the male; while 7not only has no male specimen of P. Polytes yet been found, but the female (Polytes) has never yet been found in localities to which the male (Pammon) does not extend. In this case, as in the last, distinct species, local forms, and dimorphic specimens have been confounded under the common appellation of varieties.

But, besides the true P. Polytes, there are several allied forms of females to be considered, namely, P. Theseus, Cr., P. Melanides, De Haan, P. Elyros, G. R. G., and P. Romulus, L. The dark female figured by Cramer as P. Theseus seems to be the common and perhaps the only form in Sumatra, whereas in Java, Borneo, and Timor, along with males quite identical with those of Sumatra, occur females of the Polytes form, although a single specimen of the true P. Theseus, Cr., taken at Lombock would seem to show that the two forms do occur together. In the allied species found in the Philippine ♀Islands (P. Alphenor, Cr., P. Ledebouria, Eschsch., ♀ P. Elyros, G. R. G.) forms corresponding to these extremes occur along with a number of intermediate varieties, as shown by a fine series in the British Museum. We have here an indication of how dimorphism may be produced; for let the extreme Philippine forms be better suited to their conditions of existence than the intermediate connecting links, and the latter will gradually die out, leaving two distinct forms of the same insect, each adapted to some special conditions. As these conditions are sure to vary in different districts, it will often happen, as in Sumatra and Java, that the one form will predominate in the one island, the other in the adjacent one. In the island of Borneo there seems to be a third form; for P. Melanides, De Haan, evidently belongs to this group, and has all the chief characteristics of P. Theseus, with a modified coloration of the hind wings. I now come to an insect which, if I am correct, offers one of the most interesting cases of variation yet adduced. Papilio Romulus, L., a butterfly found over a large part of India and Ceylon, and not uncommon in collections, has always been considered a true and independent species, and no suspicions have been expressed regarding it. But a male of this form does not, I believe, exist. I have examined the fine series in the British Museum, in the East India Company’s Museum, in the Hope Museum at Oxford, in Mr. Hewitson’s and several other private collections, and can find nothing but females; and for this common butterfly no male partner can be found except the equally common P. Pammon, a species already provided with two wives, and yet to whom we shall be forced, I believe, to assign a third. On carefully examining P. Romulus, I find that in all essential characters,—the form and texture of the wings, the length of the antennæ, the spotting of the head and thorax, and even the peculiar tints and shades with which it is ornamented,—it corresponds exactly with the other females of the Pammon group; and though, from the peculiar marking of the fore wings, it has at first sight a very different aspect, yet a closer examination shows that every one of its markings could be produced by slight and almost imperceptible modifications of the various allied forms. I fully believe, therefore, that I shall be correct in placing P. Romulus as a third Indian form of the female P. Pammon, corresponding to P. Melanides, the third form of the Malayan P. Theseus. I may mention here that the females of this group have a superficial resemblance to the Polydorus group, as shown by P. Theseus having been considered to be the female of P. Antiphus, and by P. Romulus being arranged next to P. Hector. There is no close affinity between 8these two groups of Papilio, and I am disposed to believe that we have here a case of mimicry, brought about by the same causes which Mr. Bates has so well explained in his account of Heliconidæ, and which thus led to the singular exuberance of polymorphic forms in this and allied groups of the genus Papilio. I shall have to devote a section of my paper to the consideration of this subject.

The third example of polymorphism I have to bring forward is Papilio Ormenus, Guér., which is closely allied to the well-known P. Erechtheus, Don., of Australia. The most common form of the female also resembles that of P. Erechtheus; but a totally different-looking insect was found by myself in the Aru Islands, and figured by Mr. Hewitson under the name of P. Onesimus, which subsequent observation has convinced me is a second form of the female of P. Ormenus. Comparison of this with Boisduval’s description of P. Amanga, a specimen of which from New Guinea is in the Paris Museum, shows the latter to be a closely similar form; and two other specimens were obtained by myself, one in the island of Goram and the other in Waigiou, all evidently local modifications of the same form. In each of these localities males and ordinary females of P. Ormenus were also found. So far there is no evidence that these light-coloured insects are not females of a distinct species, the males of which have not been discovered. But two facts have convinced me this is not the case. At Dorey, in New Guinea, where males and ordinary females closely allied to P. Ormenus occur (but which seem to me worthy of being separated as a distinct species), I found one of these light-coloured females closely followed in her flight by three males, exactly in the same manner as occurs (and, I believe, occurs only) with the sexes of the same species. After watching them a considerable time, I captured the whole of them, and became satisfied that I had discovered the true relations of this anomalous form. The next year I had corroborative proof of the correctness of this opinion by the discovery in the island of Batchian of a new species allied to P. Ormenus, all the females of which, either seen or captured by me, were of one form, and much more closely resembling the abnormal light-coloured females of P. Ormenus and P. Pandion than the ordinary specimens of that sex. Every naturalist will, I think, agree that this is strongly confirmative of the supposition that both forms of female are of one species; and when we consider, further, that in four separate islands, in each of which I resided for several months, the two forms of female were obtained and only one form of male ever seen, and that about the same time M. Montrouzier in Woodlark Island, at the other extremity of New Guinea (where he resided several years, and must have obtained all the large Lepidoptera of the island), obtained females closely resembling mine, which, in despair at finding no appropriate partners for them, he mates with a widely different species,—it becomes, I think, sufficiently evident that this is another case of polymorphism of the same nature as those already pointed out in P. Pammon and P. Memnon. This species, however, is not only dimorphic, but trimorphic; for, in the island of Waigiou, I obtained a third female quite distinct from either of the others, and in some degree intermediate between the ordinary female and the male. The specimen is particularly interesting to those who believe, with Mr. Darwin, that extreme difference of the sexes has been gradually produced by what he terms sexual selection, since it may be supposed to exhibit one of 9the intermediate steps in that process which has been accidentally preserved in company with its more favoured rivals, though its extreme rarity (only one specimen having been seen to many hundreds of the other form) would indicate that it may soon become extinct.

The only other case of polymorphism in the genus Papilio, at all equal in interest to those I have now brought forward, occurs in America; and we have, fortunately, accurate information about it. Papilio Turnus, L., is common over almost the whole of temperate North America; and the female resembles the male very closely. A totally different-looking insect both in form and colour, Papilio Glaucus, L., inhabits the same region; and though, down to the time when Boisduval published his ‘Species Général,’ no connexion was supposed to exist between the two species, it is now well ascertained that P. Glaucus is a second female form of P. Turnus. In the ‘Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Philadelphia,’ Jan. 1863, Mr. Walsh gives a very interesting account of the distribution of this species. He tells us that in the New England States and in New York all the females are yellow, while in Illinois and further south all are black; in the intermediate region both black and yellow females occur in varying proportions. Lat. 37° is approximately the southern limit of the yellow form, and 42° the northern limit of the black form; and, to render the proof complete, both black and yellow insects have been bred from a single batch of eggs. He further states that, out of thousands of specimens, he has never seen or heard of intermediate varieties between these forms. In this interesting example we see the effects of latitude in determining the proportions in which the individuals of each form should exist. The conditions are here favourable to the one form, there to the other; but we are by no means to suppose that these conditions consist in climate alone. It is highly probable that the existence of enemies, and of competing forms of life, may be the main determining influences; and it is much to be wished that such a competent observer as Mr. Walsh would endeavour to ascertain what are the adverse causes which are most efficient in keeping down the numbers of each of these contrasted forms.

Dimorphism of this kind in the animal kingdom does not seem to have any direct relations to the reproductive powers, as Mr. Darwin has shown to be the case in plants, nor does it appear to be very general. One other case only is known to me in another family of my eastern Lepidoptera, the Pierulæ; and but few occur in the Lepidoptera of other countries. The spring and autumn broods of some European species differ very remarkably; and this must be considered as a phenomenon of an analogous though not of an identical nature[3]. Araschnia prorsa, of Central Europe, is a striking example of this alternate or seasonal dimorphism. Mr. Pascoe has pointed out two forms of the male sex in some species of Coleoptera belonging to the family Anthribidæ, in seven species of the two genera Xenocerus and Mecocerus (Proc. Ent. Soc. Lond., 1862, p. 71); and no less than six European Water-beetles, of the genus Dytiscus, have females of two forms, the most common having the elytra deeply sulcate, the rarer smooth as in the males. The three, and sometimes four or more, forms under which many Hymenopterous insects (especially Ants) occur must be considered as a related phenomenon, though here each form is specialized to a distinct function in the economy of the species. Among the higher animals, 10albinoism and melanism may, as I have already stated, be considered as analogous facts; and I met with one case of a bird, a species of Lory (Eos fuscata, Blyth), clearly existing under two forms, since I obtained both sexes of each from a single flock.

3. Among our nocturnal Lepidoptera, I am informed, many analogous cases occur; and as the whole history of many of these has been investigated by breeding successive generations from the egg, it is to be hoped that some of our British Lepidopterists will give us a connected account of all the abnormal phenomena which they present.

The fact of the two sexes of one species differing very considerably is so common, that it attracted but little attention till Mr. Darwin showed how it could in many cases be explained by what he termed sexual selection. For instance, in most polygamous animals the males fight for the possession of the females, and the victors, always becoming the progenitors of the succeeding generation, impress upon their male offspring their own superior size, strength, or unusually developed offensive weapons. It is thus that we can account for the spurs and the superior strength and size of the males in Gallinaceous birds, and also for the large canine tusks in the males of fruit-eating Apes. So the superior beauty of plumage and special adornments of the males of so many birds can be explained by supposing (what there are many facts to prove) that the females prefer the most beautiful and perfect-plumaged males, and that thus slight accidental variations of form and colour have been accumulated till they have produced the wonderful train of the Peacock and the gorgeous plumage of the Bird of Paradise. Both these causes have no doubt acted partially in insects, so many species possessing horns and powerful jaws in the male sex only, and still more frequently the males alone rejoicing in rich colours or sparkling lustre. But there is here another cause which has led to sexual differences, viz. a special adaptation of the sexes to diverse habits or modes of life. This is well seen in female Butterflies (which are generally weaker and of slower flight), often having colours better adapted to concealment; and in certain South American species (Papilio torquatus) the females, which inhabit the forests, resemble the Æneas group, which abound in similar localities, while the males, which frequent the sunny open riverbanks, have a totally different coloration. In these cases, therefore, natural selection seems to have acted independently of sexual selection; and all such cases may be considered as examples of the simplest dimorphism, since the offspring never offer intermediate varieties between the parent forms.

The distinctive character therefore of dimorphism is this, that the union of these distinct forms does not produce intermediate varieties, but reproduces them unchanged. In simple varieties, on the other hand, as well as when distinct local forms or distinct species are crossed, the offspring never resembles either parent exactly, but is more or less intermediate between them. Dimorphism is thus seen to be a specialized result of variation, by which new physiological phenomena have been developed; the two should therefore, whenever possible, be kept separate[4].

4. The phenomena of dimorphism and polymorphism may be well illustrated by supposing that a blue-eyed, flaxen-haired Saxon man had two wives, one a black-haired, red-skinned Indian squaw, the other a woolly-headed, sooty-skinned negress—and that instead of the children being mulattoes of brown or dusky tints, mingling the separate characteristics of their parents in varying degrees, all the boys should be pure Saxon boys like their father, while the girls should altogether resemble their mothers. This would be thought a sufficiently wonderful fact; yet the phenomena here brought forward as existing in the insect-world are still more extraordinary; for each mother is capable not only of producing male offspring like the father, and female like herself, but also of producing other females exactly like her fellow-wife, and altogether differing from herself. If an island could be stocked with a colony of human beings having similar physiological idiosyncrasies with Papilio Pammon or Papilio Ormenus, we should see white men living with yellow, red, and black women, and their offspring always reproducing the same types; so that at the end of many generations the men would remain pure white, and the women of the same well-marked races as at the commencement.

3. Local form, or variety.—This is the first step in the transition from variety to species. 11It occurs in species of wide range, when groups of individuals have become partially isolated in several points of its area of distribution, in each of which a characteristic form has become segregated more or less completely. Such forms are very common in all parts of the world, and have often been classed as varieties or species alternately. I restrict the term to those cases where the difference of the forms is very slight, or where the segregation is more or less imperfect. The best example in the present group is Papilio Agamemnon, L., a species which ranges over the greater part of tropical Asia, the whole of the Malay archipelago, and a portion of the Australian and Pacific regions. The modifications are principally of size and form, and, though slight, are tolerably constant in each locality. The steps, however, are so numerous and gradual that it would be impossible to define many of them, though the extreme forms are sufficiently distinct. Papilio Sarpedon, L., presents somewhat similar but less numerous variations.

4. Coexisting variety.—This is a somewhat doubtful case. It is when a slight but permanent and hereditary modification of form exists in company with the parent or typical form, without presenting those intermediate gradations which would constitute it a case of simple variability. It is evidently only by direct evidence of the two forms breeding separately that this can be distinguished from dimorphism. The difficulty occurs in Papilio Jason, Esp., and P. Evemon, Bd., which inhabit the same localities, and are almost exactly alike in form, size, and coloration, except that the latter always wants a very conspicuous red spot on the under surface, which is found not only in P. Jason, but in all the allied species. It is only by breeding the two insects that it can be determined whether this is a case of a coexisting variety or of dimorphism. In the former case, however, the difference being constant and so very conspicuous and easily defined, I see not how we could escape considering it as a distinct species. A true case of coexisting forms would, I consider, be produced, if a slight variety had become fixed as a local form, and afterwards been brought into contact with the parent species with little or no intermixture of the two; and such instances do very probably occur.

5. Race, or subspecies.—These are local forms completely fixed and isolated; and there is no possible test but individual opinion to determine which of them shall be considered as species and which varieties. If stability of form and “the constant transmission of some characteristic peculiarity of organization” is the test of a species (and I can find no other test that is more certain than individual opinion), then every one of these fixed races, confined as they almost always are to distinct and limited areas, must be regarded as a species; and as such I have in most cases treated them. The various modifications of Papilio Ulysses, P. Peranthus, P. Codrus, P. Eurypilus, P. Helenus, &c., are excellent examples; for while some present great and well-marked, others offer slight and inconspicuous differences, yet in all cases these differences seem equally fixed and permanent. If, therefore, we call some of these forms species, and others varieties, we introduce a purely arbitrary distinction, and shall never be able to decide where to draw the line. The races of Papilio Ulysses, L., for example, vary in amount of modification from the scarcely differing New Guinea form to those of Woodlark Island and New Caledonia, but 12all seem equally constant; and as most of these had already been named and described as species, I have added the New Guinea form under the name of P. Penelope. We thus get a little group of Ulyssine Papilios, the whole comprised within a very limited area, each one confined to a separate portion of that area, and, though differing in various amounts, each apparently constant. Few naturalists will doubt that all these may and probably have been derived from a common stock; and therefore it seems desirable that there should be a unity in our method of treating them: either call them all varieties or all species. Varieties, however, continually get overlooked; in lists of species they are often altogether unrecorded; and thus we are in danger of neglecting the interesting phenomena of variation and distribution which they present. I think it advisable, therefore, to name all such forms; and those who will not accept them as species may consider them as subspecies or races.

6. Species.—Species are merely those strongly marked races or local forms which, when in contact, do not intermix, and when inhabiting distinct areas are generally believed to have had a separate origin, and to be incapable of producing a fertile hybrid offspring. But as the test of hybridity cannot be applied in one case in ten thousand, and even if it could be applied, would prove nothing, since it is founded on an assumption of the very question to be decided—and as the test of separate origin is in every case inapplicable—and as, further, the test of non-intermixture is useless, except in those rare cases where the most closely allied species are found inhabiting the same area, it will be evident that we have no means whatever of distinguishing so-called “true species” from the several modes of variation here pointed out, and into which they so often pass by an insensible gradation. It is quite true that, in the great majority of cases, what we term “species” are so well marked and definite that there is no difference of opinion about them; but as the test of a true theory is, that it accounts for, or at the very least is not inconsistent with, the whole of the phenomena and apparent anomalies of the problem to be solved, it is reasonable to ask that those who deny the origin of species by variation and selection should grapple with the facts in detail, and show how the doctrine of the distinct origin and permanence of species will explain and harmonize them. It has been recently asserted by a high authority that the difficulty of limiting species is in proportion to our ignorance, and that just as groups or countries are more accurately known and studied in greater detail the limits of species become settled[5]. This statement has, like many other general assertions, its portion of both truth and error. There is no doubt that many uncertain species, founded on few or isolated specimens, have had their true nature determined by the study of a good series of examples: they have been thereby established as species or as varieties; and the number of times this has occurred is doubtless very great. But there are other and equally trustworthy cases in which, not single species, but whole groups have, by the study of a vast accumulation of materials, been proved to have no definite specific limits. A few of these must be adduced. In Dr. Carpenter’s ‘Introduction to the Study of the Foraminifera,’ he states that “there is not a single specimen of plant or animal of which the range of variation has been studied by the collocation and comparison of so large a number of specimens as have passed under the review of Messrs. Williamson, Parker, Rupert Jones, and myself, in our studies of the 13types of this group;” and the result of this extended comparison of specimens is stated to be, “The range of variation is so great among the Foraminifera as to include not merely those differential characters which have been usually accounted SPECIFIC, but also those upon which the greater part of the GENERA of this group have been founded, and even in some instances those of its ORDERS” (Foraminifera, Preface, x). Yet this same group had been divided by D’Orbigny and other authors into a number of clearly defined families, genera, and species, which these careful and conscientious researches have shown to have been almost all founded on incomplete knowledge.

5. See Dr. J. E. Gray “On the Species of Lemuroids,” Proc. Zool. Soc. 1863, p. 134.

Professor DeCandolle has recently given the results of an extensive review of the species of Cupuliferæ. He finds that the best-known species of oaks are those which produce most varieties and subvarieties, that they are often surrounded by provisional species; and, with the fullest materials at his command, two-thirds of the species he considers more or less doubtful. His general conclusion is, that “in botany the lowest series of groups, SUBVARIETIES, VARIETIES, and RACES are very badly limited; these can be grouped into SPECIES a little less vaguely limited, which again can be formed into sufficiently precise GENERA.” This general conclusion is entirely objected to by the writer of the article in the ‘Natural History Review,’ who, however, does not deny its applicability to the particular order under discussion, while this very difference of opinion is another proof that difficulties in the determination of species do not, any more than in the higher groups, vanish with increasing materials and more accurate research.

Another striking example of the same kind is seen in the genera Rubus and Rosa, adduced by Mr. Darwin himself; for though the amplest materials exist for a knowledge of these groups, and the most careful research has been bestowed upon them, yet the various species have not thereby been accurately limited and defined so as to satisfy the majority of botanists.

Dr. Hooker seems to have found the same thing in his study of the Arctic flora. For though he has had much of the accumulated materials of his predecessors to work upon, he continually expresses himself as unable to do more than group the numerous and apparently fluctuating forms into more or less imperfectly defined species[6].

6. In his paper on the “Distribution of Arctic Plants,” Trans. Linn. Soc. xxiii. p. 310, Dr. Hooker says:—

“The most able and experienced descriptive botanists vary in their estimate of the value of the ‘specific term’ to a much greater extent than is generally supposed.”

“I think I may safely affirm that the ‘specific term’ has three different standard values, all current in descriptive botany, but each more or less confined to one class of observers.”

“This is no question of what is right or wrong as to the real value of the specific term; I believe each is right according to the standard he assumes as the specific.”

Lastly, I will adduce Mr. Bates’s researches on the Amazons. During eleven years he accumulated vast materials, and carefully studied the variation and distribution of insects. Yet he has shown that many species of Lepidoptera, which before offered no special difficulties, are in reality most intricately combined in a tangled web of affinities, leading by such gradual steps from the slightest and least stable variations to fixed races and well-marked species, that it is very often impossible to draw those sharp dividing-lines which it is supposed that a careful study and full materials will always enable us to do.

These few examples show, I think, that in every department of nature there occur instances of the instability of specific form, which the increase of materials aggravates 14rather than diminishes. And it must be remembered that the naturalist is rarely likely to err on the side of imputing greater indefiniteness to species than really exists. There is a completeness and satisfaction to the mind in defining and limiting and naming a species, which leads us all to do so whenever we conscientiously can, and which we know has led many collectors to reject vague intermediate forms as destroying the symmetry of their cabinets. We must therefore consider these cases of excessive variation and instability as being thoroughly well established; and to the objection that, after all, these cases are but few compared with those in which species can be limited and defined, and are therefore merely exceptions to a general rule, I reply that a true law embraces all apparent exceptions, and that to the great laws of nature there are no real exceptions—that what appear to be such are equally results of law, and are often (perhaps indeed always) those very results which are most important as revealing the true nature and action of the law. It is for such reasons that naturalists now look upon the study of varieties as more important than that of well-fixed species. It is in the former that we see nature still at work, in the very act of producing those wonderful modifications of form, that endless variety of colour, and that complicated harmony of relations, which gratify every sense and give occupation to every faculty of the true lover of nature.

The phenomena of variation as influenced by locality have not hitherto received much attention. Botanists, it is true, are acquainted with the influences of climate, altitude, and other physical conditions in modifying the forms and external characteristics of plants; but I am not aware that any peculiar influence has been traced to locality, independent of climate. Almost the only case I can find recorded is mentioned in that repertory of natural-history facts, ‘The Origin of Species,’ viz. that herbaceous groups have a tendency to become arboreal in islands. In the animal world, I cannot find that any facts have been pointed out as showing the special influence of locality in giving a peculiar facies to the several disconnected species that inhabit it. What I have to adduce on this matter will therefore, I hope, possess some interest and novelty.

On examining the closely allied species, local forms, and varieties distributed over the Indian and Malayan regions, I find that larger or smaller districts, or even single islands, give a special character to the majority of their Papilionidæ. For instance: 1. The species of the Indian region (Sumatra, Java, and Borneo) are almost invariably smaller than the allied species inhabiting Celebes and the Moluccas; 2. The species of New Guinea and Australia are also, though in a less degree, smaller than the nearest species or varieties of the Moluccas; 3. In the Moluccas themselves the species of Amboyna are the largest; 4. The species of Celebes equal or even surpass in size those of Amboyna; 5. The species and varieties of Celebes possess a striking character in the form of the anterior wings, different from that of the allied species and varieties of all the surrounding islands; 6. Tailed species in India or the Indian region become tailless as they spread eastward through the archipelago.

Having preserved the finest and largest specimens of Butterflies in my own collection, and having always taken for comparison the largest specimens of the same sex, I believe that the tables I now give are sufficiently exact. The differences of expanse of wings 15are in most cases very great, and are much more conspicuous in the specimens themselves than on paper. It will be seen that no less than fourteen Papilionidæ inhabiting Celebes and the Moluccas are from one-third to one-half greater in extent of wing than the allied species representing them in Java, Sumatra, and Borneo. Six species inhabiting Amboyna are larger than the closely allied forms of the northern Moluccas and New Guinea by about one-sixth. These include almost every case in which closely allied species can be compared.

| PAPILIONIDÆ. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Species of the Moluccas and Celebes (large). | Closely allied species of Java and the Indian region (small). | ||

| Expanse. inches. |

Expanse. inches. |

||

| Ornithoptera Helena (Amboyna) | 7·6 | O. Pompeus | 5·8 |

| O. Amphrisius | 6·0 | ||

| Papilio Macedon (Celebes) | 5·8 | P. Peranthus | 3·8 |

| P. Philippus (Moluccas) | 4·8 | ||

| P. Blumei (Celebes) | 5·4 | P. Brama | 4·0 |

| P. Alphenor (Celebes) | 4·8 | P. Theseus | 3·6 |

| P. Gigon (Celebes) | 5·4 | P. Demolion | 4·0 |

| P. Deucalion (Celebes) | 4·6 | P. Macareus | 3·7 |

| P. Agamemnon, var. (Celebes) | 4·4 | P. Agamemnon, var. | 3·8 |

| P. Eurypilus (Moluccas) | 4·0 | P. Jason | 3·4 |

| P. Telephus (Celebes) | 4·3 | ||

| P. Ægisthus (Moluccas) | 4·4 | P. Rama | 3·2 |

| P. Miletus (Celebes) | 4·4 | P. Sarpedon | 3·8 |

| P. Androcles (Celebes) | 4·8 | P. Antiphates | 3·7 |

| P. Polyphontes (Celebes) | 4·6 | P. Diphilus | 3·9 |

| Leptocircus Curtius (Celebes) | 2·0 | L. Meges | 1·8 |

| Species inhabiting Amboyna (large). | Allied species of New Guinea and the North Moluccas (smaller). | ||

| Papilio Ulysses | 6·1 | P. Penelope | 5·2 |

| P. Telegonus | 4·0 | ||

| P. Polydorus | 4·9 | P. Leodamas | 4·0 |

| P. Deiphobus | 6·8 | P. Deiphontes | 5·8 |

| P. Gambrisius | 6·4 | P. Ormenus | 5·6 |

| P. Tydeus | 6·0 | ||

| P. Codrus | 5·1 | P. Codrus, var. papuensis | 4·3 |

| Ornithoptera Priamus, ♂ | 8·0 | Orn. Poseidon, ♂ | 7·0 |

The differences of form are equally clear.

Papilio Pammon everywhere on the continent is tailed in both sexes. In Java, Sumatra, and Borneo, the closely allied P. Theseus has a very short tail, or tooth only, in the male, while in the females the tail is retained. Further east, in Celebes and the South Moluccas, the hardly separable P. Alphenor has quite lost the tail in the male, while the female retains it, but in a narrower and less spatulate form. A little further, in Gilolo, P. Nicanor has completely lost the tail in both sexes.

Papilio Agamemnon exhibits a somewhat similar series of changes. In India it is always tailed; in the greater part of the archipelago it has a very short tail; while far east, in New Guinea and the adjacent islands, the tail has almost entirely disappeared.

16In the Polydorus-group two species, P. Antiphus and P. Diphilus, inhabiting India and the Indian region, are tailed, while the two which take their place in the Moluccas, New Guinea, and Australia, P. Polydorus and P. Leodamas, are destitute of tail, the species furthest east having lost this ornament the most completely.

| Western species, tailed. | Eastern species (closely allied), less tailed. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Papilio Pammon (India) | tailed. | P. Thesus (islands) | very short tail. |

| P. Agamemnon, var. (India) | tailed. | P. Agamemnon, var. (islands) | not tailed. |

| P. Antiphus (India, Java) | tailed. | P. Polydorus (Moluccas) | not tailed. |

| P. Diphilus (India, Java) | tailed. | P. Leodamas (New Guinea) | not tailed. |

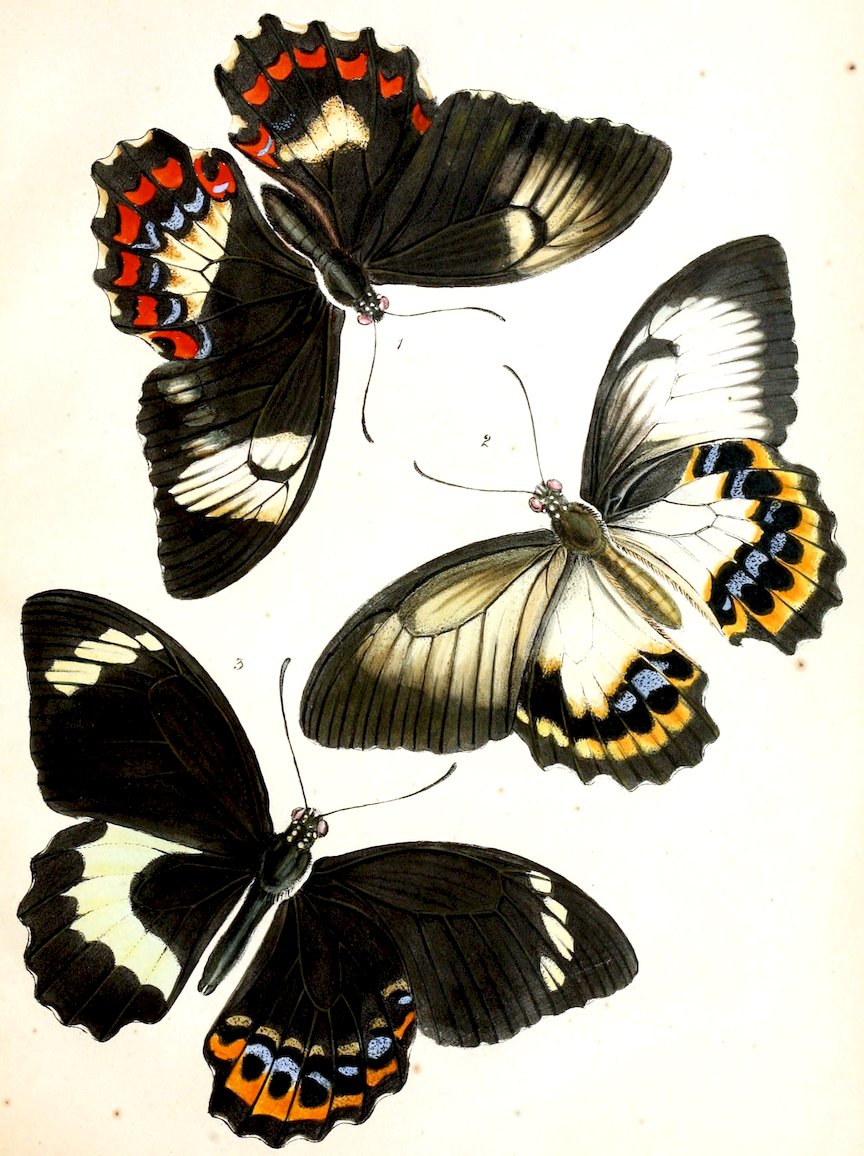

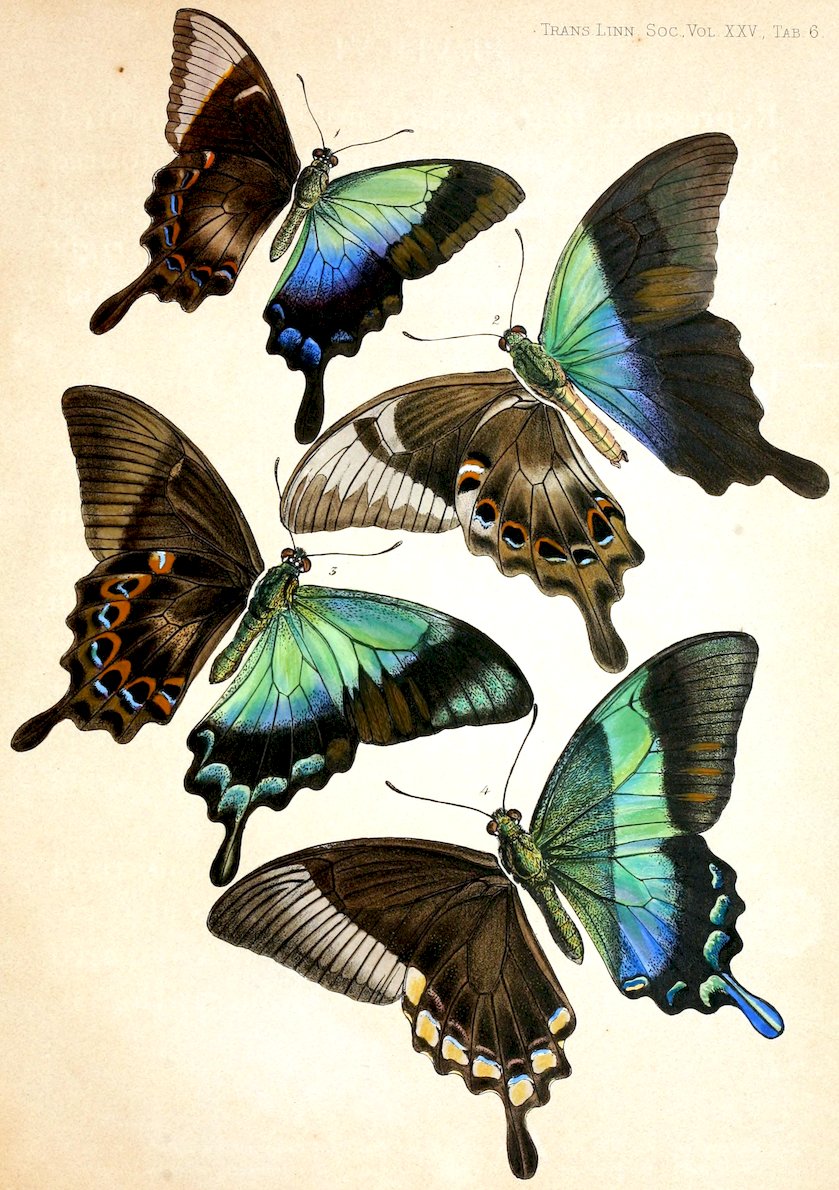

The most conspicuous instance of local modification of form, however, is exhibited in the island of Celebes, which in this respect, as in some others, stands alone and isolated in the whole archipelago. Almost every species of Papilio inhabiting Celebes has the wings of a peculiar shape, which distinguishes them at a glance from the allied species of every other island. This peculiarity consists, first, in the upper wings being generally more elongate and falcate; and secondly, in the costa or anterior margin being much more curved, and in most instances exhibiting near the base an abrupt bend or elbow, which in some species is very conspicuous. This peculiarity is visible, not only when the Celebesian species are compared with their small-sized allies of Java and Borneo, but also, and in an almost equal degree, when the large forms of Amboyna and the Moluccas are the objects of comparison, showing that this is quite a distinct phenomenon from the difference of size which has just been pointed out.

In the following Table I have arranged the chief Papilios of Celebes in the order in which they exhibit this characteristic form most prominently. (See Plate VIII.)

| Papilios of Celebes, having the wings falcate or with abruptly curved costa. | Closely allied Papilios of the surrounding islands, with less falcate wings and slightly curved costa. | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | P. Gigon, n. s. | P. Demolion (Java). |

| 2. | P. Telephus, n. s. | P. Jason (Sumatra). |

| 3. | P. Miletus, n. s. | P. Sarpedon (Moluccas, Java). |

| 4. | P. Agamemnon, var. | P. Agamemnon, var. (Borneo). |

| 5. | P. Macedon, n. s. | P. Peranthus (Java). |

| 6. | P. Ascalaphus. | P. Deiphontes, n. s. (Gilolo). |

| 7. | P. Hecuba, n. s. | P. Helenus (Java). |

| 8. | P. Blumei. | P. Brama (Sumatra). |

| 9. | P. Androcles. | P. Antiphates (Borneo). |

| 10. | P. Rhesus. | P. Aristæus (Moluccas). |

| 11. | P. Theseus, var., ♂. | P. Thesus, ♂ (Java). |

| 12. | P. Codrus, var. | P. Codrus (Moluccas). |

| 13. | P. Encelades. | P. Leucothoë (Malacca). |

It thus appears that every species of Papilio exhibits this peculiar form in a greater or less degree, except one, P. Polyphontes, Bd., allied to P. Diphilus of India and P. Polydorus of the Moluccas. This fact I shall recur to again, as I think it helps us to understand something of the causes that may have brought about the phenomenon we are considering. Neither do the genera Ornithoptera and Leptocircus exhibit any traces of this peculiar form. In several other families of Butterflies this characteristic form reappears in a few species. In the Pieridæ the following species exhibit it distinctly:—

| 17 | |||

| 1. | Eronia tritæa | compared with | Eronia Valeria (Java). |

| 2. | Iphias Glaucippe, var. | „ „ | Iphias Glaucippe (Java). |

| 3. | Pieris Zebuda | „ „ | Pieris Descombesi (India). |

| 4. | P. Zarinda | „ „ | P. Nero (Malacca). |

| 5. | P., n. s. | „ „ | P. Hyparete (Java). |

| 6. | P. Hombronii | have the same form, but are isolated species. | |

| 7. | P. Ithome | ||

| 8. | P. Eperia, Bd. | compared with | P. Coronis (Java). |

| 9. | P. Polisma | „ „ | P., n. s. (Malacca). |

| 10. | Terias, n. s. | „ „ | P. Tilaha (Java). |

The other species of Terias, one or two Pieris, and the genus Callidryas do not exhibit any perceptible change of form.

In the other families there are but few similar examples. The following are all that I can find in my collection:—

| Cethosia Æole | compared with | Cethosia Biblis (Java). |

| Junonia, n. s. | „ „ | Junonia Polynice (Borneo). |

| Limenitis Limire | „ „ | Limenitis Procris (Java). |

| Cynthia Arsinoë, var. | „ „ | Cynthia Arsinoë (Java, Sum., Born.). |

All these belong to the family of the Nymphalidæ. Many other genera of this family, as Diadema, Adolias, Charaxes, and Cyrestis, as well as the entire families of the Danaidæ, Satyridæ, Lycænidæ, and Hesperidæ, present no examples of this peculiar form of the upper wing in the Celebesian species.

The facts now brought forward seem to me of the highest interest. We see that almost all the species in two important families of the Lepidoptera (Papilionidæ and Pieridæ) acquire, in a single island, a characteristic modification of form distinguishing them from the allied species and varieties of all the surrounding islands. In other equally extensive families no such change occurs, except in one or two isolated species. However we may account for these phenomena, or whether we may be quite unable to account for them, they furnish, in my opinion, a strong corroborative testimony in favour of the doctrine of the origin of species by successive small variations; for we have here slight varieties, local races, and undoubted species, all modified in exactly the same manner, indicating plainly a common cause producing identical results. On the generally received theory of the original distinctness and permanence of species, we are met by this difficulty: one portion of these curiously modified forms are admitted to have been produced by variation and some natural action of local conditions; whilst the other portion, differing from the former only in degree, and connected with them by insensible gradations, are said to have possessed this peculiarity of form at their first creation, or to have derived it from unknown causes of a totally distinct nature. Is not the à priori evidence in favour of the assumption of an identity of the causes that have produced such similar results? and have we not a right to call upon our opponents for some proofs of their own doctrine, and for an explanation of its difficulties, instead of their assuming that they are right, and laying upon us the burthen of disproof?

Let us now see if the facts in question do not themselves furnish some clue to their 18own explanation. Mr. Bates has shown that certain groups of butterflies have a defence against insectivorous animals, independent of swiftness of motion. These are generally very abundant, slow, and weak fliers, and are more or less the objects of mimicry by other groups, which thus gain an advantage in a freedom from persecution similar to that enjoyed by those they resemble. Now the only Papilios which have not in Celebes acquired the peculiar form of wing belong to a group which is imitated both by other species of Papilio and by Moths of the genus Epicopeia, West. This group is of weak and slow flight; and we may therefore fairly conclude that it possesses some means of defence (probably in a peculiar odour or taste) which saves it from attack. Now the arched costa and falcate form of wing is generally supposed to give increased powers of flight, or, as seems to me more probable, greater facility in making sudden turnings, and thus baffling a pursuer. But the members of the Polydorus-group (to which belongs the only unchanged Celebesian Papilio), being already guarded against attack, have no need of this increased power of wing; and “natural selection” would therefore have no tendency to produce it. The whole family of Danaidæ are in the same position: they are slow and weak fliers; yet they abound in species and individuals, and are the objects of mimicry. The Satyridæ have also probably a means of protection—perhaps their keeping always near the ground and their generally obscure colours; while the Lycænidæ and Hesperidæ may find security in their small size and rapid motions. In the extensive family of the Nymphalidæ, however, we find that several of the larger species, of comparatively feeble structure, have their wings modified (Cethosia, Limenitis, Junonia, Cynthia), while the large-bodied powerful species, which have all an excessively rapid flight, have exactly the same form of wing in Celebes as in the other islands. On the whole, therefore, we may say that all the butterflies of rather large size, conspicuous colours, and not very swift flight have been affected in the manner described, while the smaller-sized and obscure groups, as well as those which are the objects of mimicry, and also those of exceedingly swift flight, have remained unaffected.

It would thus appear as if there must be (or once have been) in the island of Celebes, some peculiar enemy to these larger-sized butterflies which does not exist, or is less abundant, in the surrounding islands. Increased powers of flight, or rapidity of turning, was advantageous in baffling this enemy; and the peculiar form of wing necessary to give this would be readily acquired by the action of “natural selection” on the slight variations of form that are continually occurring. Such an enemy one would naturally suppose to be an insectivorous bird; but it is a remarkable fact that most of the genera of Fly-catchers of Borneo and Java on the one side (Muscipeta, Philentoma), and of the Moluccas on the other (Monarcha, Rhipidura), are almost entirely absent from Celebes. Their place seems to be supplied by the Caterpillar-catchers (Graucalus, Campephaga), of which six or seven species are known from Celebes and are very numerous in individuals. We have no positive evidence that these birds pursue butterflies on the wing, but it is highly probable that they do so when other food is scarce[7]. However this may be, the fauna of Celebes is undoubtedly highly peculiar in every department of which we have 19any knowledge; and though we may not be able to trace it satisfactorily, there can, I think, be little doubt that the singular modification in the wings of so many of the butterflies of that island is an effect of that complicated action and reaction of all living things upon each other in the struggle for existence, which continually tends to readjust disturbed relations, and to bring every species into harmony with the varying conditions of the surrounding universe.

7. Mr. Bates has suggested that the larger Dragon-flies (Æshna, &c.) prey upon butterflies; but I did not notice that they were more abundant in Celebes than elsewhere.

But even the conjectural explanation now given fails us in the other cases of local modification. Why the species of the western islands should be smaller than those further east,—why those of Amboyna should exceed in size those of Gilolo and New Guinea—why the tailed species of India should begin to lose that appendage in the islands, and retain no trace of it on the borders of the Pacific, are questions which we cannot at present attempt to answer. That they depend, however, on some general principle is certain, because analogous facts have been observed in other parts of the world. Mr. Bates informs me that, in three distinct groups, Papilios which on the Upper Amazon and in most other parts of South America have spotless upper wings obtain pale or white spots at Para and on the Lower Amazon; and also that the Æneas-group of Papilios never have tails in the equatorial regions and the Amazons valley, but gradually acquire tails in many cases as they range towards the northern or southern tropic. Even in Europe we have somewhat similar facts; for the species and varieties of butterflies peculiar to the island of Sardinia are generally smaller and more deeply coloured than those of the mainland, and Papilio Hospiton has lost the tail, which is a prominent feature of the closely allied P. Machaon.

Facts of a similar nature to those now brought forward would no doubt be found to occur in other groups of insects, were local faunas carefully studied in relation to those of the surrounding countries; and they seem to indicate that climate and other physical causes have, in some cases, a very powerful effect in modifying specific form, and thus directly aid in producing the endless variety of nature.

I may state that I can adduce facts perfectly analogous to these from other families of Lepidoptera, especially the Danaidæ; but as the greater part of the species are still undescribed, I can only now assert that similar phenomena do occur there.

I need scarcely say that I entirely agree with Mr. Bates’s explanation of the causes which have led to one group of insects mimicking another (Trans. Linn. Soc. vol. xxiii. p. 495). I have, therefore, only now to adduce such illustrations of this curious phenomenon as are furnished by the Eastern Papilionidæ, and to show their hearing upon the phenomena of variation already mentioned. As in America, so in the Old World, species of Danaidæ are the objects which the other families most often imitate. But, besides these, some genera of Morphidæ and one section of the genus Papilio are also less frequently copied. Many species of Papilio mimic other species of these three groups so closely that they are undistinguishable when on the wing; and in every case the pairs which resemble each other inhabit the same locality.

The following list exhibits the most important and best-marked cases of mimicry which occur among the Papilionidæ of the Malayan region and India:—

| 20 | |||

| Mimickers[8]. | Species mimicked. | Common habitat. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Danaidæ. | |||

| 1. | Papilio paradoxa, Zink., ♂ | Euplœa Midamus, Cr., ♂ | Sumatra, &c. |

| —— ——, ♀ | —— ——, ♀ | ||

| 2. | —— ——, West. | E. Rhadamanthus | Sumatra, &c. |

| 3. | P. Caunus, | E., sp. | Borneo. |

| 4. | P. Thule, Wall. | Danais sobrina, Bd. | New Guinea. |

| 5. | P. Macareus, Godt. | D. Aglaia, Cr. | Malacca, Java. |

| 6. | P. Agestor, G. R. G. | D. Tytia, G. R. G. | Northern India. |

| 7. | P. idæoides, Hewits. | Hestia Leuconoë, Erichs. | Philippines. |

| 8. | P. Delessertii, Guér. | Hestia, sp. | Penang. |

| Morphidæ. | |||

| 9. | P. Pandion, Wall., ♀ | Drusilla bioculata, Guér. | New Guinea. |

| Papilio (Polydorus- and Coon-groups). | |||

| 10. | P. Pammon, L. (Romulus, L.), ♀ | Papilio Hector, L. | India. |

| 11. | P. Theseus, Cr., var., ♀ | P. Antiphus, Fab. | Sumatra, Borneo. |

| 12. | P. Theseus, Cr., var., ♀ | P. Diphilus, Esp. | Sumatra, Java. |

| 13. | P. Memnon, var. Achates, ♀ | P. Coon, Fab. | Sumatra. |

| 14. | P. Androgeus, var. Achates, ♀ | P. Doubledayi, Wall. | Northern India. |

| 15. | P. Œnomaus, God., ♀ | P. Liris, God. | Timor. |

8. The terms “mimicry” and “mimickers” have been objected to on the ground that they imply voluntary action on the part of the insects. This appears to me of little importance compared with the advantages of convenience, flexibility, and expressiveness which they undoubtedly possess, especially as the whole theory propounded by the originator of the term in this sense excludes all idea of voluntary action. The only approximately synonymous words, not implying will, are resemblance, similarity, and likeness; and it is evident that none of these can be applied intelligibly under the variety of forms required, and to which Mr. Bates’s expression so readily lends itself in the terms mimic, mimickers, mimicry, mimicked. Add to this the inconvenience of changing a term which, from the interest and wide discussion of the subject, must be already very generally understood, and I think it will be admitted that nothing would be gained by altering it, even if a better word were pointed out, which has not yet been done.

We have therefore fifteen species or marked varieties of Papilio which so closely resemble species of other groups in their respective localities, that it is not possible to impute the resemblance to accident. The first two in the list (Papilio paradoxa and P. Caunus) are so exactly like Euplœa Midamus and E. Rhadamanthus on the wing, that, although they fly very slowly, I was quite unable to distinguish them. The first is a very interesting case, because the male and female differ considerably, and each mimics the corresponding sex of the Euplœa. A new species of Papilio which I discovered in New Guinea resembles Danais sobrina, Bd., from the same country, just as Papilio Macareus resembles Danais Aglaia in Malacca, and (according to Dr. Horsfield’s figure) still more closely in Java. The Indian Papilio Agestor closely imitates Danais Tytia, which has quite a different style of colouring from the preceding; and the extraordinary Papilio idæoides from the Philippine Islands must, when on the wing, perfectly resemble the Hestia Leuconoë of the same region, as also does the P. Delessertii, Guér., imitate an undescribed species of Hestia from Penang. Now in every one of these cases the Papilios are very scarce, while the Danaidæ which they resemble are exceedingly abundant—most of them swarming so as to be a positive nuisance to the collecting entomologist by continually hovering before him when he is in search of newer and more varied captures. Every garden, every roadside, the suburbs of every village are full of them, indicating 21very clearly that their life is an easy one, and that they are free from persecution by the foes which keep down the population of less favoured races. This superabundant population has been shown by Mr. Bates to be a general characteristic of all American groups and species which are objects of mimicry; and it is interesting to find his observations confirmed by examples on the other side of the globe.

The remarkable genus Drusilla, a group of pale-coloured butterflies, more or less adorned with ocellate spots, is also the object of mimicry by three distinct genera (Melanitis, Hyantis, and Papilio). These insects, like the Danaidæ, are abundant in individuals, have a very weak and slow flight, and do not seek concealment, or appear to have any means of protection from insectivorous creatures. It is natural to conclude, therefore, that they have some hidden property which saves them from attack; and it is easy to see that when any other insects, by what we call accidental variation, come more or less remotely to resemble them, the latter will share to some extent in their immunity. An extraordinary dimorphic form of a female Papilio has come to resemble the Drusillas sufficiently to be taken for one of that group at a little distance; and it is curious that I captured one of these Papilios in the Aru Islands hovering along the ground, and settling on it occasionally, just as it is the habit of the Drusillas to do. The resemblance in this case is only general; but this form of Papilio varies much, and there is therefore material for natural selection to act upon so as ultimately to produce a copy as exact as in the other cases.

The eastern Papilios allied to Polydorus Coon and P. Philoxenus, form a natural section of the genus resembling, in many respects, the Æneas-group of South America, which they may be said to represent in the East. Like them, they are forest insects, have a low and weak flight, and in their favourite localities are rather abundant in individuals; and like them, too, they are the objects of mimicry. We may conclude, therefore, that they possess some hidden means of protection, which makes it useful to other insects to be mistaken for them.

The Papilios which resemble them belong to a very distinct section of the genus, in which the sexes differ greatly; and it is those females only which differ most from the males, and which have already been alluded to as exhibiting instances of dimorphism, which resemble species of the other group.

The resemblance of P. Romulus to P. Hector is, in some specimens, very considerable, and has led to the two species being placed to follow each other in the British Museum Catalogues and by Mr. E. Doubleday. I have shown, however, that P. Romulus is probably a dimorphic form of the female P. Pammon, and belongs to a distinct section of the genus[9].

9. See Plate II. fig. 6.

The next pair, P. Theseus, Cr., and P. Antiphus, Fab., have been united as one species both by De Haan and in the British Museum Catalogues. The ordinary variety of P. Theseus found in Java almost as nearly resembles P. Diphilus, Esp., of the same country. The most interesting case, however, is the extreme female form of P. Memnon (P. Achates, Cr.)[10], which has acquired the general form and markings of P. Coon, an insect which differs from the ordinary male P. Memnon, as much as any two species differ which can be chosen in this extensive and highly varied genus; and, as if to show that this resemblance is not accidental, but is the result of law, when in India we find a species closely allied to 22P. Coon, but with red instead of yellow spots (P. Doubledayi, Wall.), the corresponding variety of P. Androgeus (P. Achates, Cram., 182, A, B,) has acquired exactly the same peculiarity of having red spots instead of yellow. Lastly, in the island of Timor, the female of P. Œnomaus (a species allied to P. Memnon) resembles so closely P. Liris (one of the Polydorus-group), that the two, which were often seen flying together, could only be distinguished by a minute comparison after being captured.

10. See Plate I. fig. 4.

The last six cases of mimicry are especially instructive, because they seem to indicate one of the processes by which dimorphic forms have been produced. When, as in these cases, one sex differs much from the other, and varies greatly itself, it may happen that occasionally individual variations will occur having a distant resemblance to groups which are the objects of mimicry, and which it is therefore advantageous to resemble. Such a variety will have a better chance of preservation; the individuals possessing it will be multiplied; and their accidental likeness to the favoured group will be rendered permanent by hereditary transmission, and, each successive variation which increases the resemblance being preserved, and all variations departing from the favoured type having less chance of preservation, there will in time result those singular cases of two or more isolated and fixed forms bound together by that intimate relationship which constitutes them the sexes of a single species. The reason why the females are more subject to this kind of modification than the males is, probably, that their slower flight, when laden with eggs, and their exposure to attack while in the act of depositing their eggs upon leaves, render it especially advantageous for them to have some additional protection. This they at once obtain by acquiring a resemblance to other species which, from whatever cause, enjoy a comparative immunity from persecution.

This summary of the more interesting phenomena of variation presented by the eastern Papilionidæ is, I think, sufficient to substantiate my position, that the Lepidoptera are a group that offer especial facilities for such inquiries; and it will also show that they have undergone an amount of special adaptive modification rarely equalled among the more highly organized animals. And, among the Lepidoptera, the great and pre-eminently tropical families of Papilionidæ and Danaidæ seem to be those in which complicated adaptations to the surrounding organic and inorganic universe have been most completely developed, offering in this respect a striking analogy to the equally extraordinary, though totally different, adaptations which present themselves in the Orchideæ, the only family of plants in which mimicry of other organisms appears to play any important part, and the only one in which striking cases of polymorphism occur; for such we must consider to be the male, female, and hermaphrodite forms of Catasetum tridentatum, which differ so greatly in form and structure that they were long considered to belong to three distinct genera.

Although the species of Papilionidæ inhabiting the Malayan region are very numerous, they all belong to three out of the nine genera into which the family is divided. One of the remaining genera (Eurycus) is restricted to Australia, and another (Teinopalpus) to the Himalayan Mountains, while no less than four (Parnassius, Doritis, Thais, and Sericinus) are confined to Southern Europe and to the mountain-ranges of the Palæarctic region.