Copyright 1908 by George Barrie & Sons

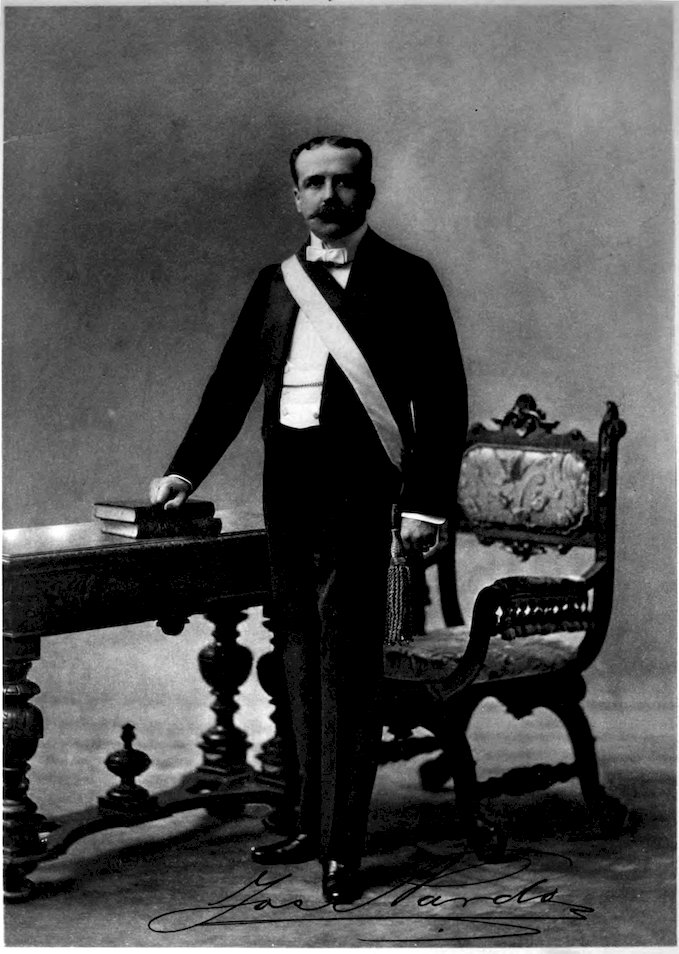

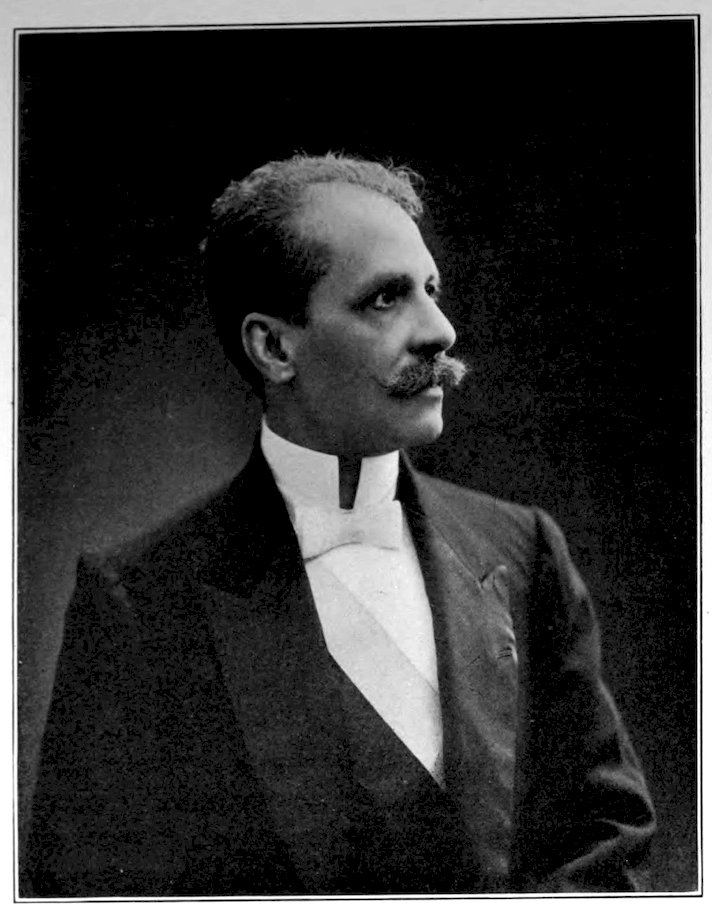

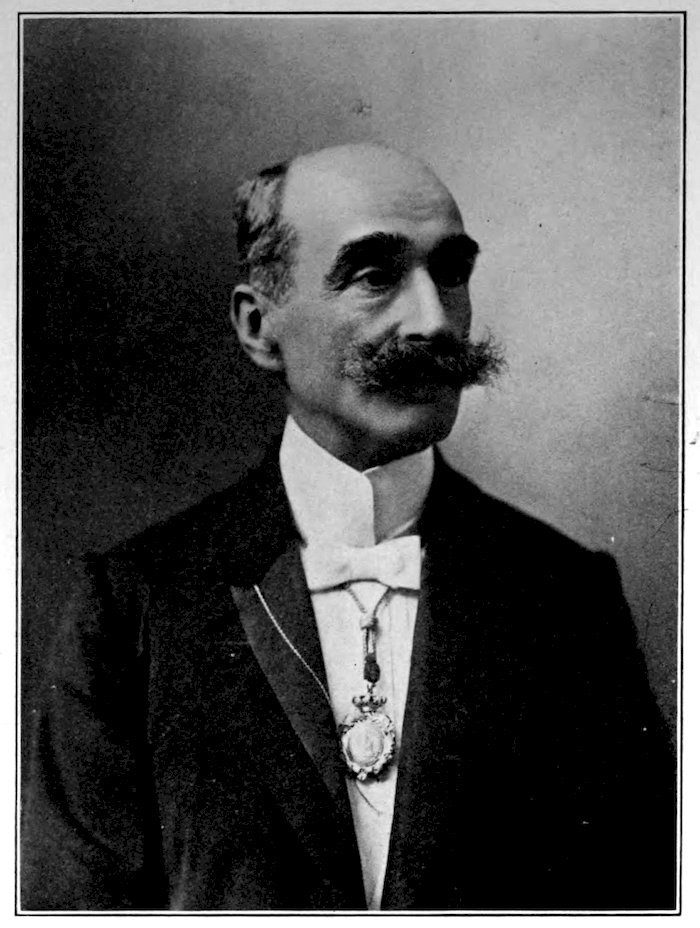

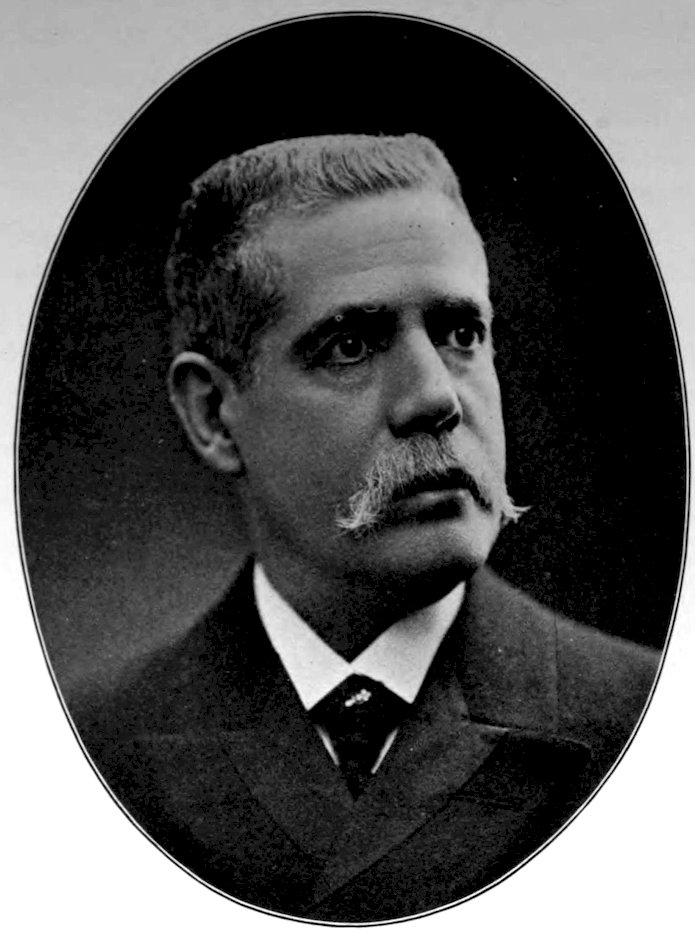

HIS EXCELLENCY Dr. JOSÉ PARDO

PRESIDENT

OF THE PERUVIAN REPUBLIC

Title: The old and the new Peru

A story of the ancient inheritance and the modern growth and enterprise of a great nation

Author: Marie Robinson Wright

Release date: January 4, 2025 [eBook #75033]

Language: English

Original publication: Philadelphia: George Barrie & Sons, 1908

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/75033

Credits: Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Copyright 1908 by George Barrie & Sons

HIS EXCELLENCY Dr. JOSÉ PARDO

PRESIDENT

OF THE PERUVIAN REPUBLIC

![[Logo]](images/i_007.jpg)

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| DEDICATION | 5 |

| LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | 9 |

| INTRODUCTION | 13 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| ANCIENT PERU—PRE-INCAIC MONUMENTS | 17 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| THE RISE OF THE CUZCO DYNASTY | 35 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| THE VAST EMPIRE OF THE INCAS | 53 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| THE SPANISH DISCOVERY AND INVASION UNDER PIZARRO | 65 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| THE CONQUEST OF PERU | 77 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| THE REIGN OF THE VICEROYS | 93 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| THE CHURCH IN COLONIAL DAYS | 113 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| THE OVERTHROW OF SPANISH AUTHORITY | 127 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| PERU UNDER REPUBLICAN GOVERNMENT | 145 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| THE ADMINISTRATION OF PRESIDENT JOSÉ PARDO | 163 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| THE POLITICAL ORGANIZATION OF THE REPUBLIC | 177 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| THE CITY OF THE KINGS AND ITS BEAUTIFUL SUBURBS | 187 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| PERUVIAN HOSPITALITY AND CULTURE | 203 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| THE NATIONAL LIBRARY—PERUVIAN WRITERS—PAINTING AND ILLUSTRATIVE ART | 217 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| THE OLDEST UNIVERSITY IN AMERICA—MODERN SCHOOLS OF PERU | 233 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| THE BENEVOLENT SOCIETIES OF PERU | 247 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| AREQUIPA—THE MISTI-HARVARD OBSERVATORY | 255 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| A GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF THE COUNTRY | 269 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| THE WEALTH OF THE GUANO ISLANDS | 283 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| CALLAO, THE CHIEF SEAPORT OF PERU—STEAMSHIP LINES | 291 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| AGRICULTURE AND IRRIGATION ON THE COAST | 301 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| TRUJILLO AND THE CHICAMA VALLEY | 313 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| THE COTTON FIELDS OF PIURA | 327 |

| 8 | |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| VINEYARDS AND ORCHARDS OF THE SOUTHERN COAST REGION | 335 |

| CHAPTER XXV | |

| TACNA AND ARICA | 343 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | |

| MINES OF THE SIERRA AND OTHER REGIONS | 351 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | |

| THE OROYA RAILWAY, THE HIGHEST IN THE WORLD | 367 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | |

| A TRIP OVER THE SOUTHERN ROUTE—NEW RAILWAYS AND PUBLIC ROADS | 377 |

| CHAPTER XXIX | |

| PASTURE LANDS OF THE PLATEAU—THE ALPACA AND THE VICUÑA OF PUNO | 389 |

| CHAPTER XXX | |

| CUZCO, THE ANCIENT INCA CAPITAL | 397 |

| CHAPTER XXXI | |

| THE MONTAÑA AND ITS PRODUCTS—THE RUBBER LANDS OF LORETO | 407 |

| CHAPTER XXXII | |

| IQUITOS, THE CHIEF PERUVIAN PORT OF THE AMAZON | 417 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII | |

| NAVIGATION AND EXPLORATION ON THE AMAZON WATERWAYS | 425 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | |

| FOREIGN INTERESTS IN PERU—IMMIGRATION AND COLONIZATION | 431 |

| CHAPTER XXXV | |

| FINANCIAL AND COMMERCIAL PROGRESS—MANUFACTURING INDUSTRIES | 439 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI | |

| THE PASSING OF THE OLD PERU—ITS LEGACY TO POSTERITY—THE DESTINY OF THE NEW PERU | 451 |

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| HIS EXCELLENCY DR. JOSÉ PARDO, PRESIDENT OF THE PERUVIAN REPUBLIC | Fronts. |

| THE COAT-OF-ARMS OF PERU | Title page |

| GIRDLE FOUND IN THE CEMETERY OF PACHACÁMAC | 17 |

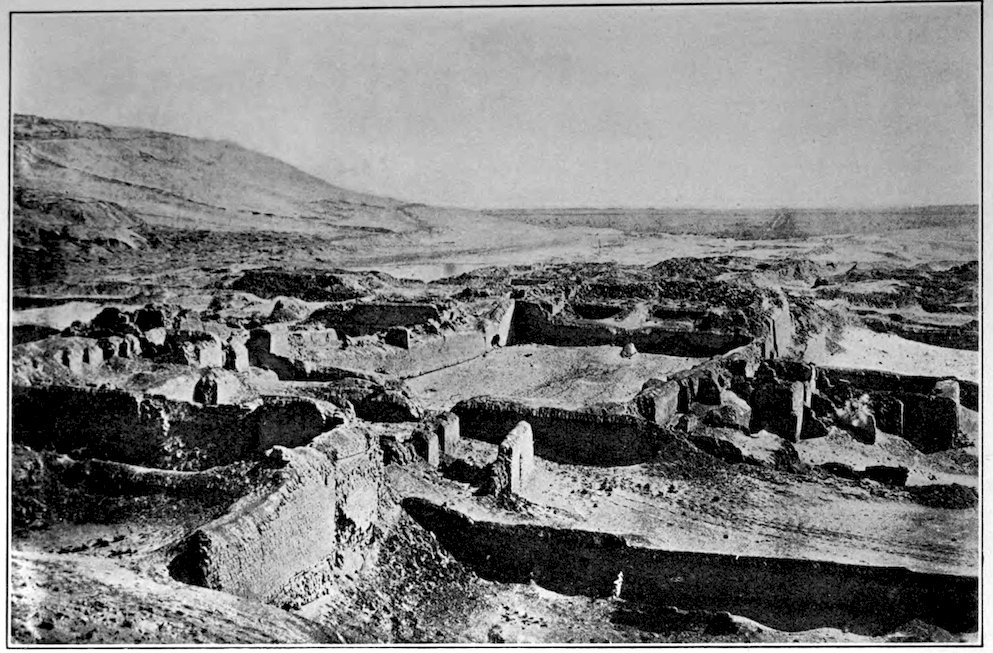

| SOUTHWESTERN PART OF PACHACÁMAC VIEWED FROM THE NORTH | 18 |

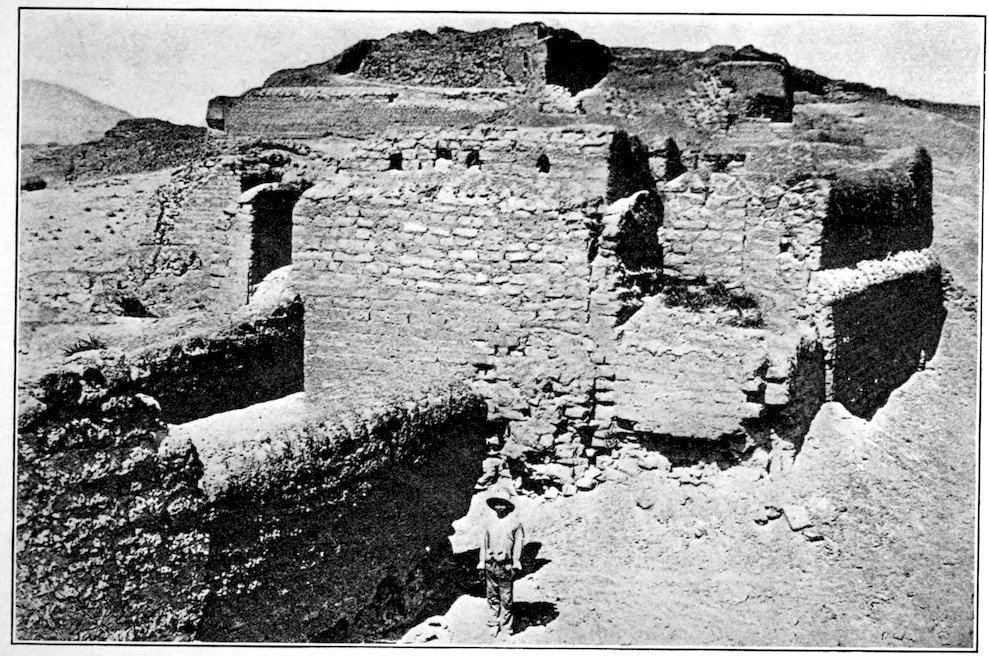

| ENTRANCE TO THE PRINCIPAL PALACE OF PACHACÁMAC | 19 |

| THE EASTERN STREET OF PACHACÁMAC | 20 |

| TERRACES OF THE SOUTHEAST FRONT OF PACHACÁMAC, WITH CEMETERY OF SACRIFICED WOMEN | 21 |

| A VIEW OF THE SUN TEMPLE OF PACHACÁMAC, SHOWING NICHED WALLS | 22 |

| RUINS OF THE CONVENT, PACHACÁMAC | 23 |

| HUACAS FROM THE GRAVES OF PACHACÁMAC | 24 |

| PRE-INCAIC POTTERY FROM PACHACÁMAC | 25 |

| CURIOUS SYMBOLS OF PACHACÁMAC WORSHIP | 26 |

| FAÇADE OF THE PALACE OF CHAN-CHAN, NEAR TRUJILLO | 27 |

| CARVED TERRACES OF THE PALACE OF CHAN-CHAN | 28 |

| ANIMAL CARVINGS ON THE WALLS OF CHAN-CHAN | 29 |

| RUINS OF CHAN-CHAN | 30 |

| MORTUARY CLOTH WITH SYMBOLIC EMBLEMS | 31 |

| FOUND IN THE BURIAL PLACE OF PACHACÁMAC | 32 |

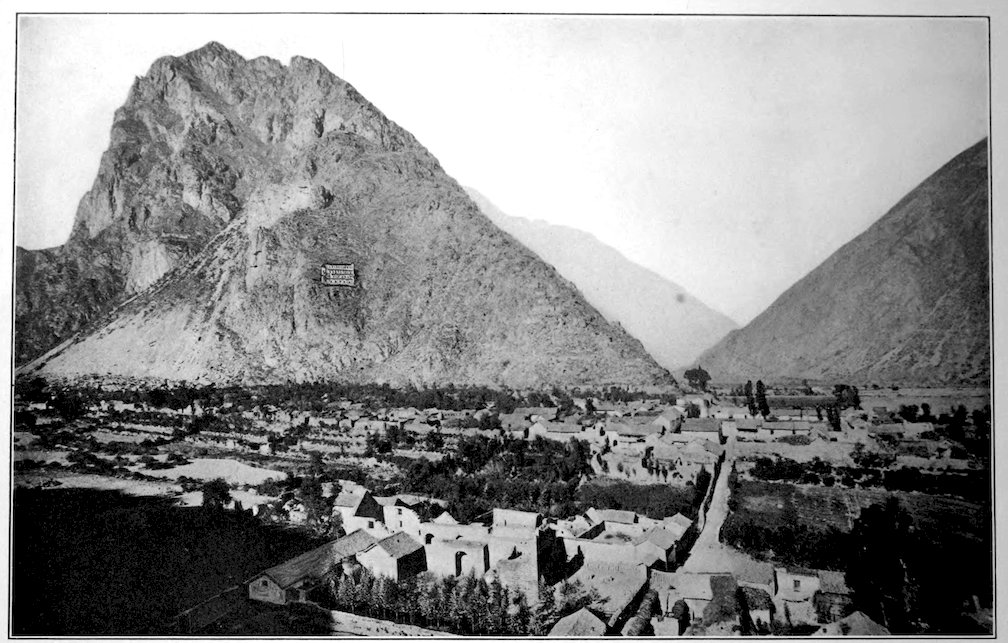

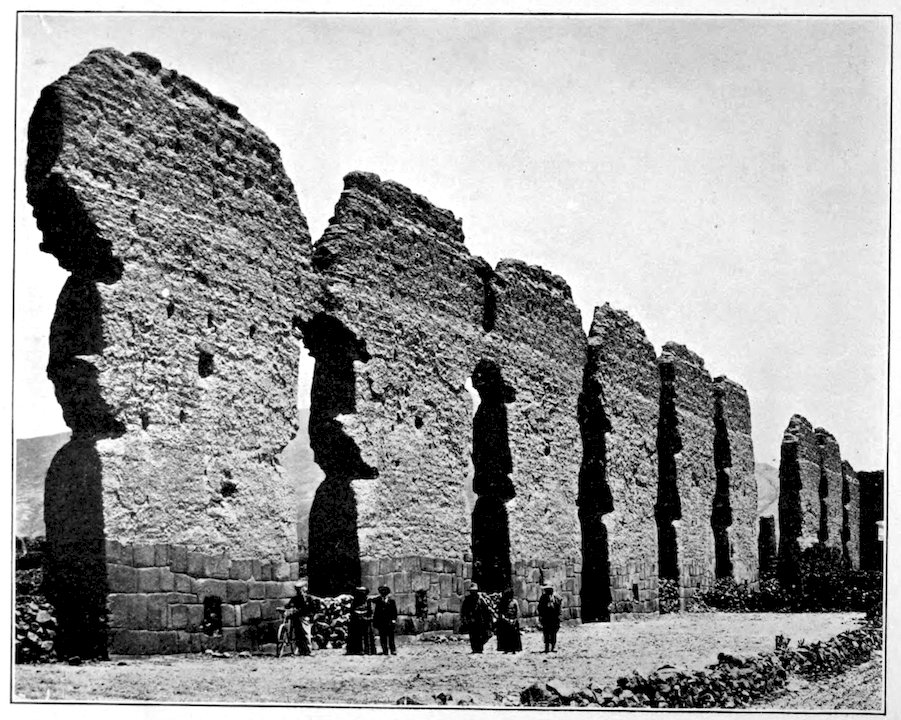

| OLLANTAYTAMBO, ONCE THE FAVORITE RESIDENCE OF THE INCAS | 34 |

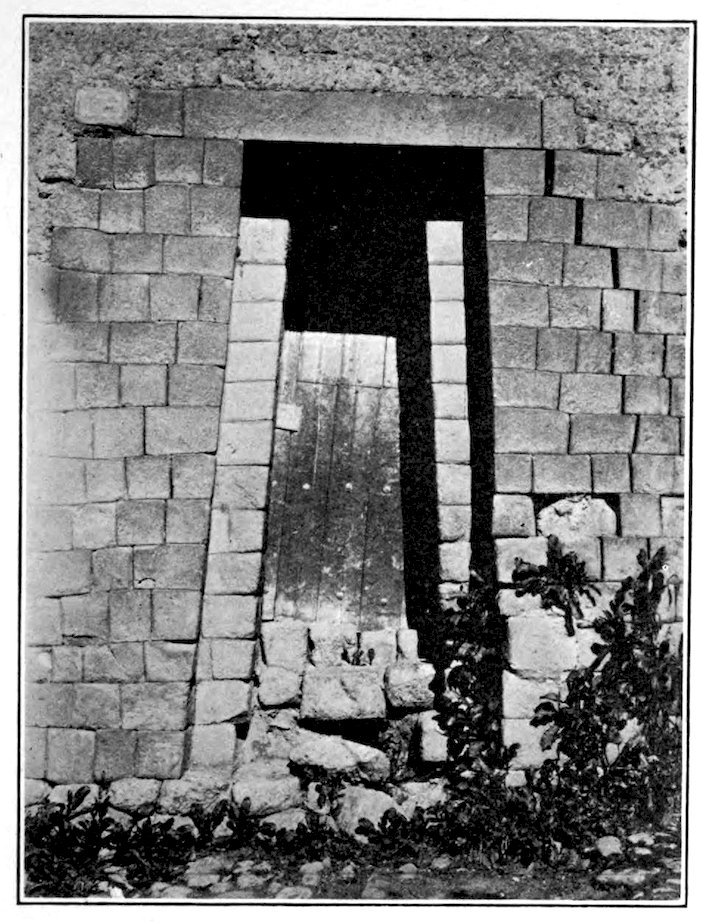

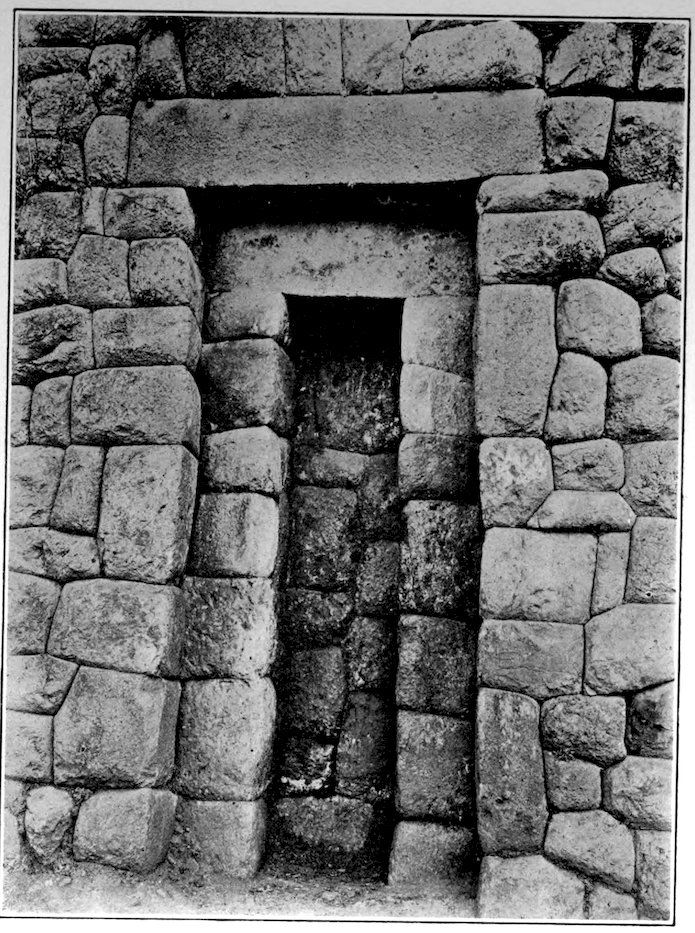

| AN INCAIC DOORWAY | 35 |

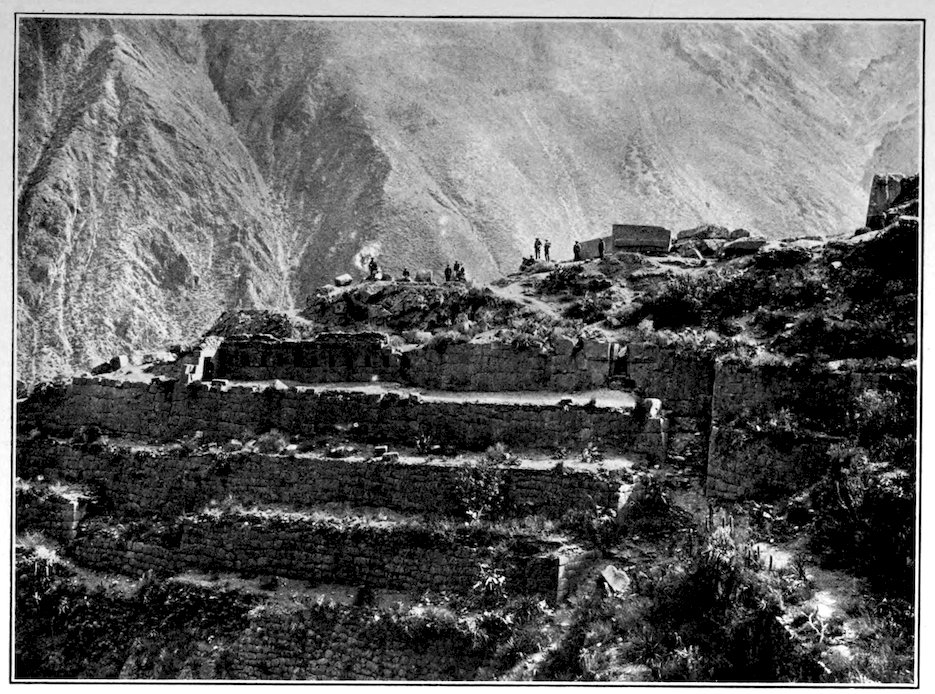

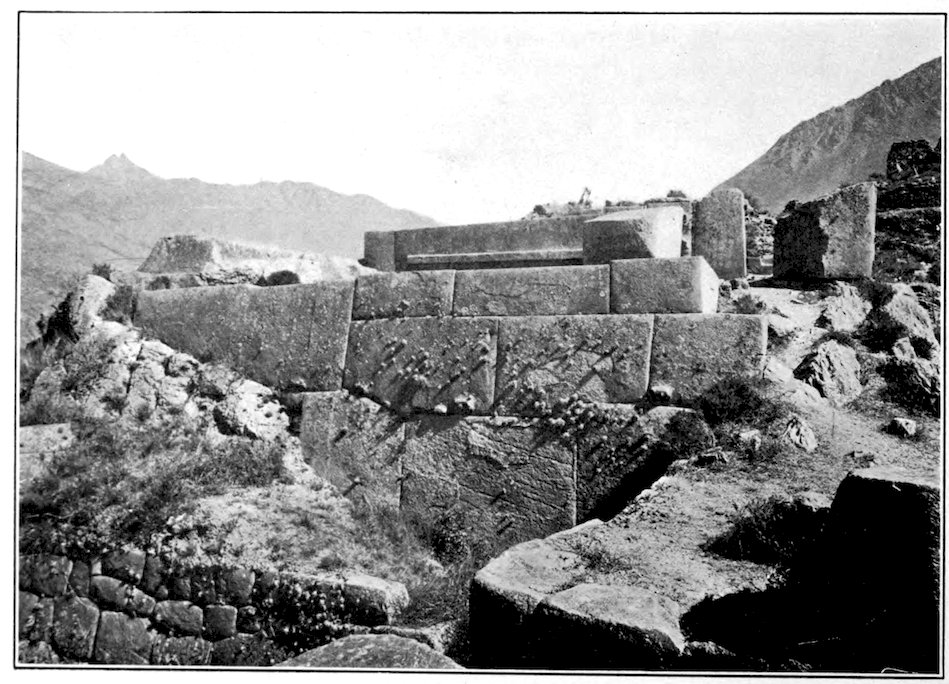

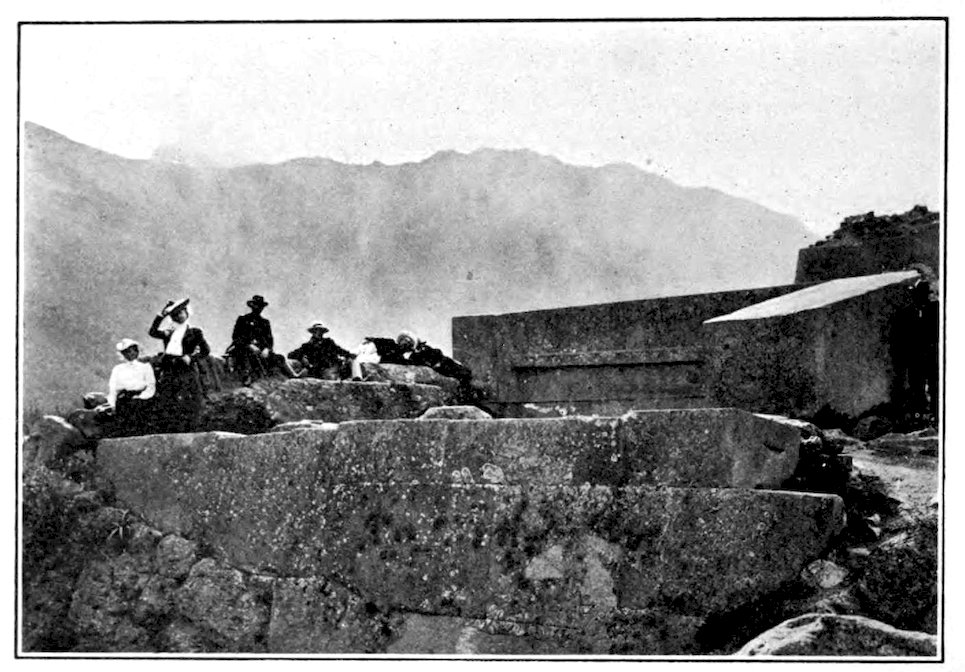

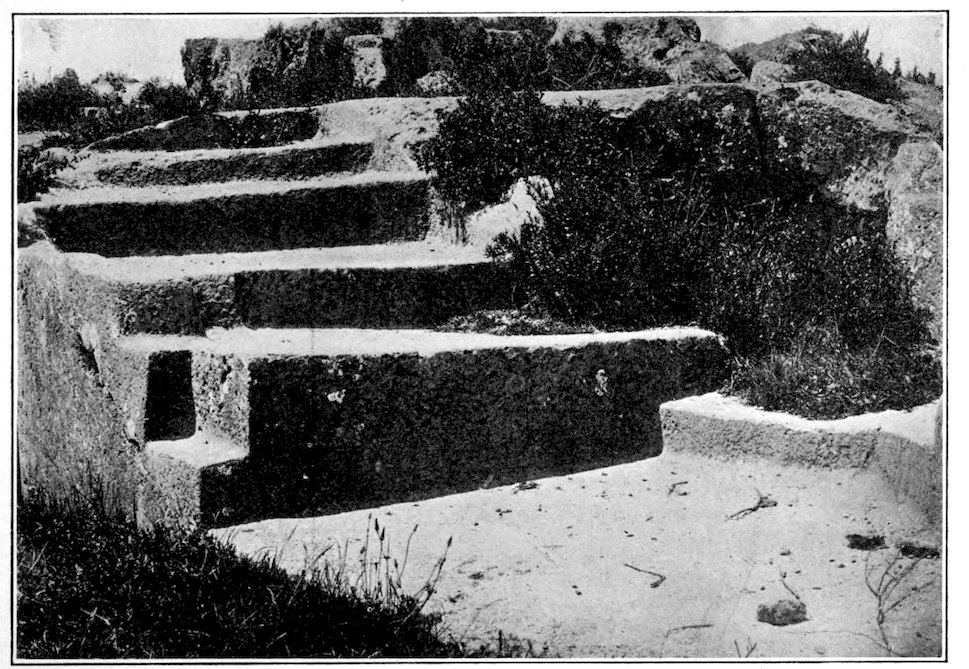

| TERRACE OF THE INCA’S PALACE, OLLANTAYTAMBO | 37 |

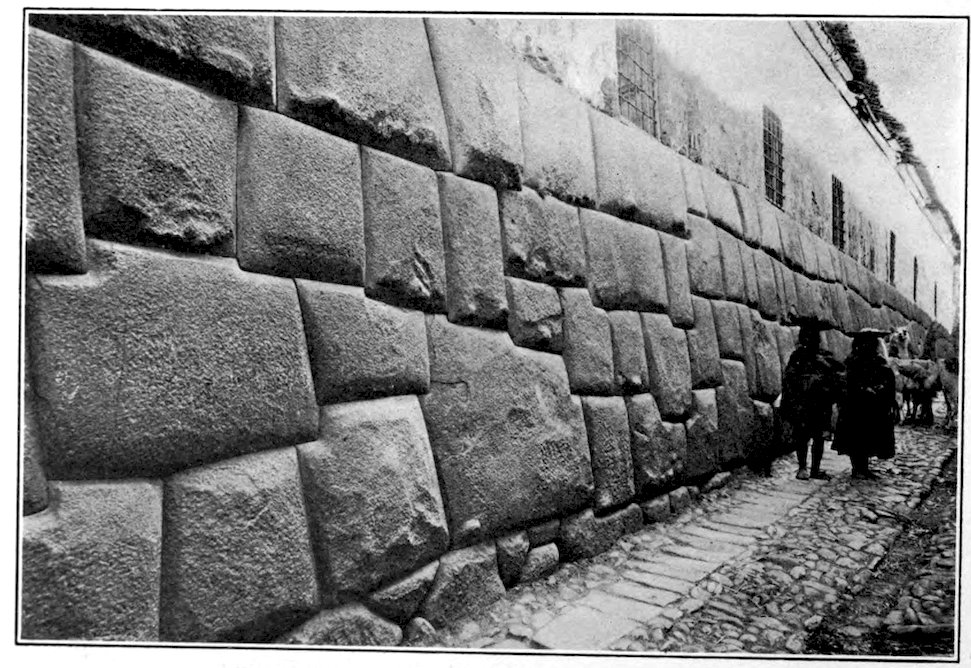

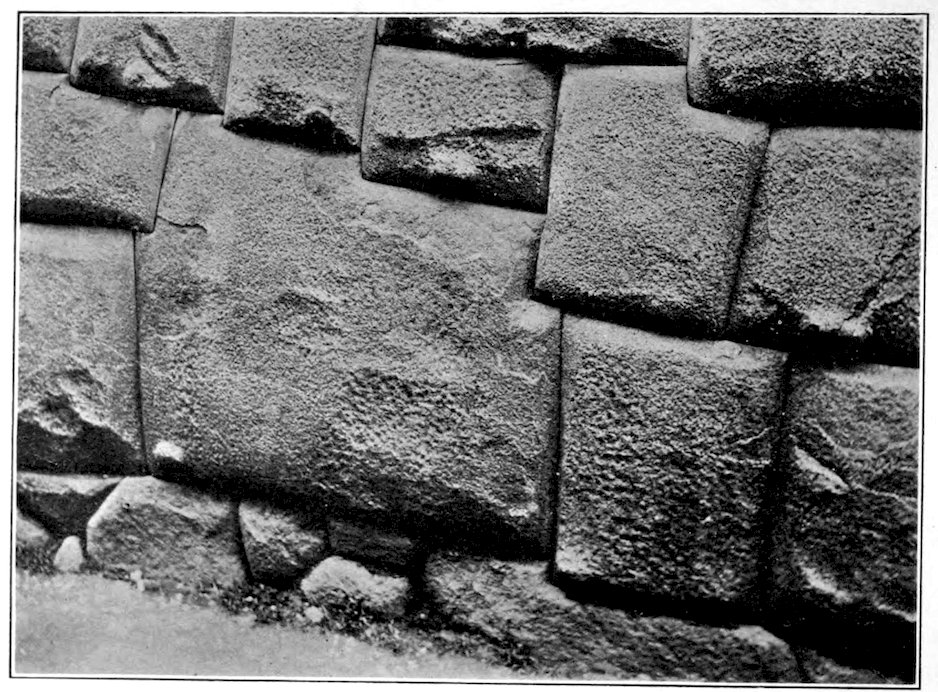

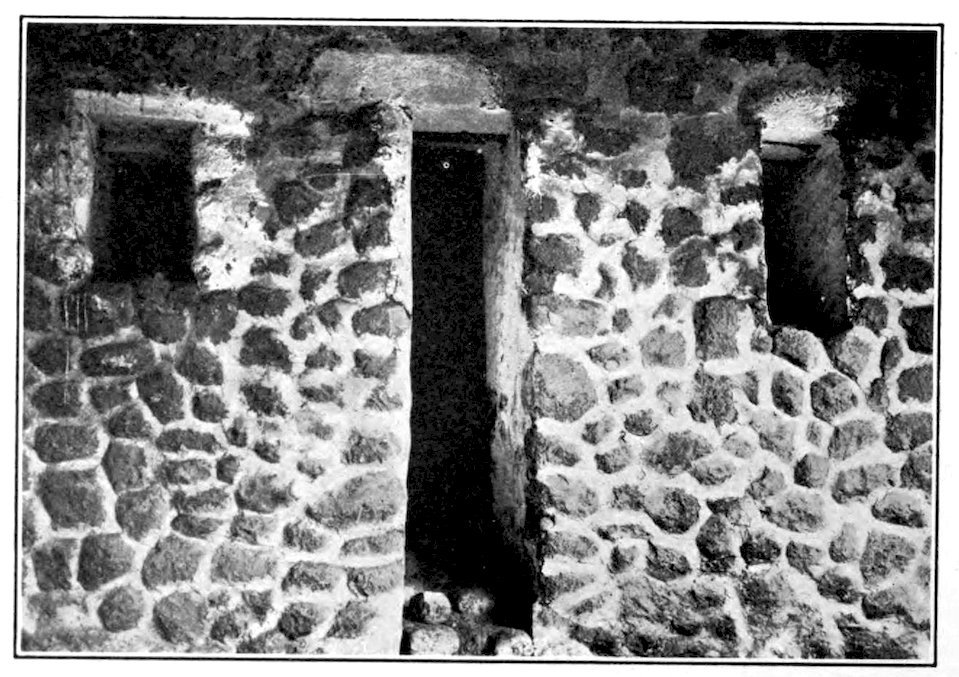

| WALL OF THE PALACE OF ONE OF THE INCAS, CUZCO | 38 |

| RUINS OF THE PALACE OF MANCO-CCAPAC, CUZCO | 39 |

| NICHE IN THE FAÇADE OF THE PALACE OF MANCO-CCAPAC | 41 |

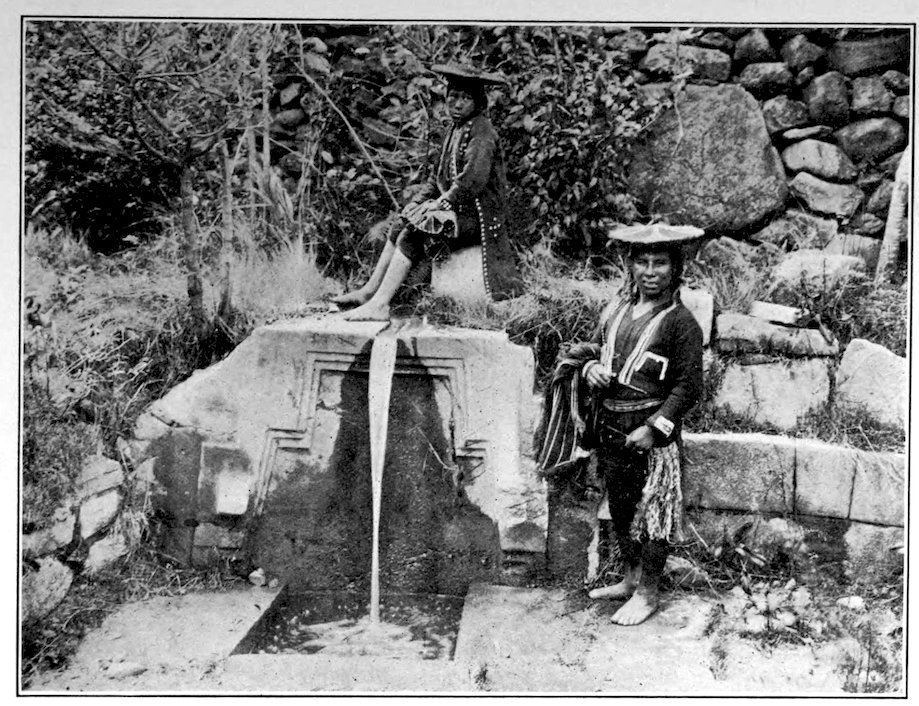

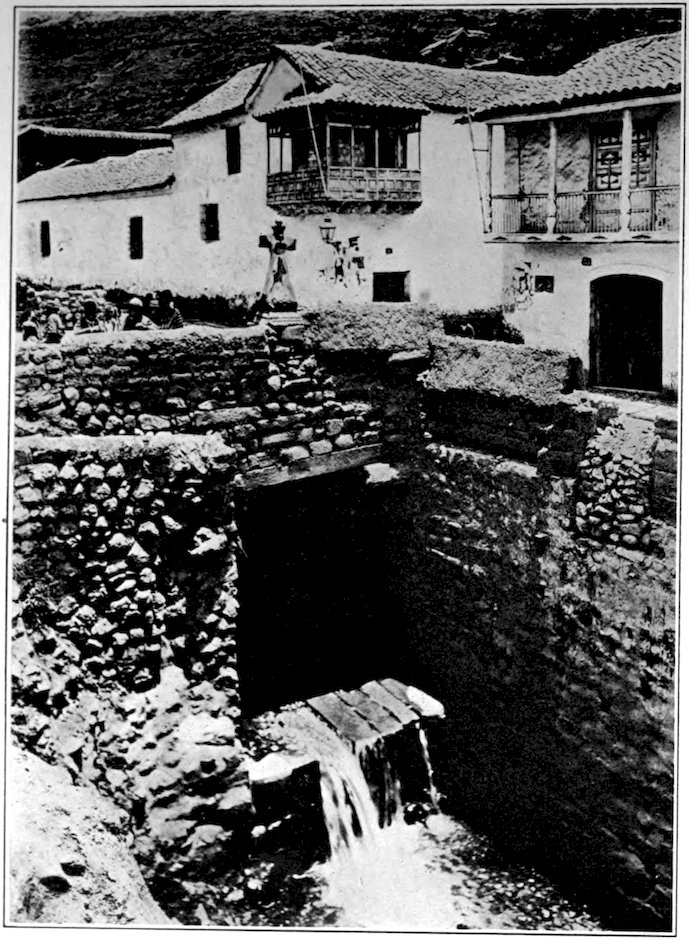

| INCA FOUNTAIN AT CUZCO | 43 |

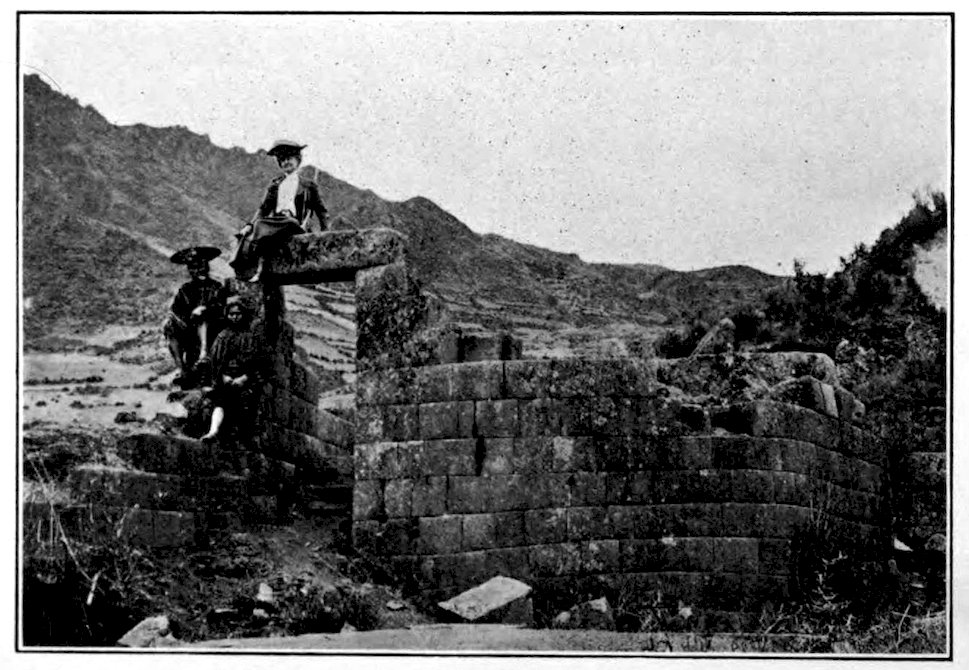

| RUINS AT OLLANTAYTAMBO | 44 |

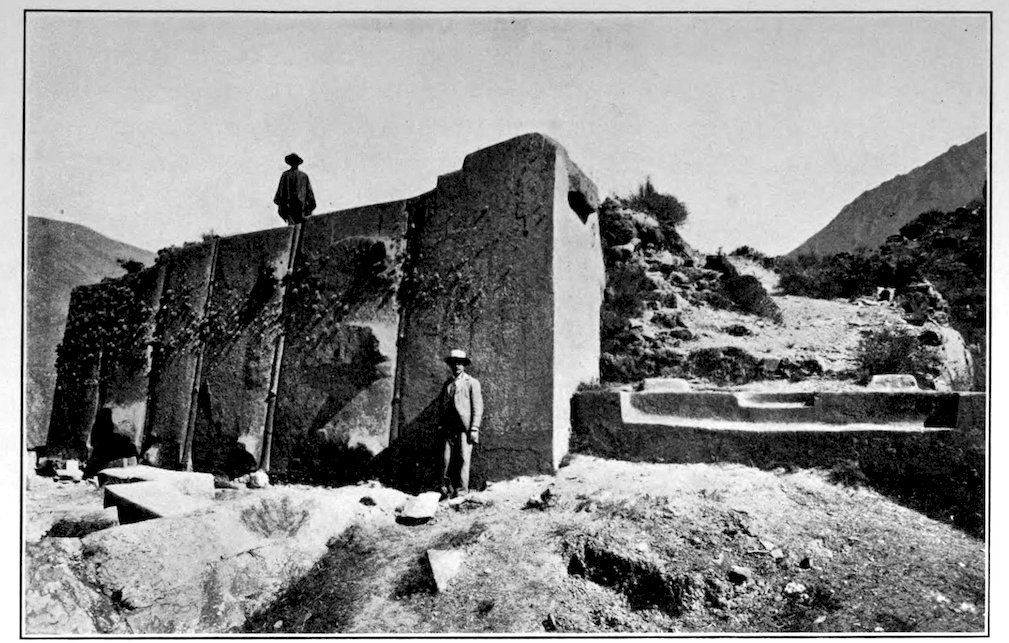

| STONE WALLS OF THE PALACE OF OLLANTA, OLLANTAYTAMBO | 45 |

| RUINS OF THE TEMPLE OF THE INCA VIRACOCHA, NEAR CUZCO | 46 |

| SEATS FROM WHICH THE INCA AND HIS SUITE VIEWED THE SACRIFICES | 47 |

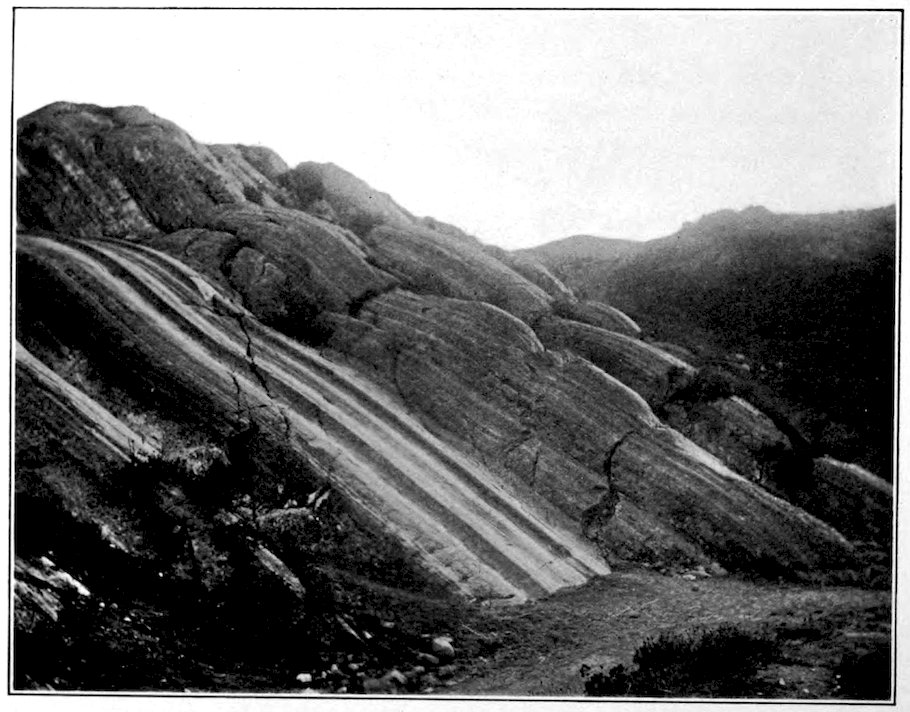

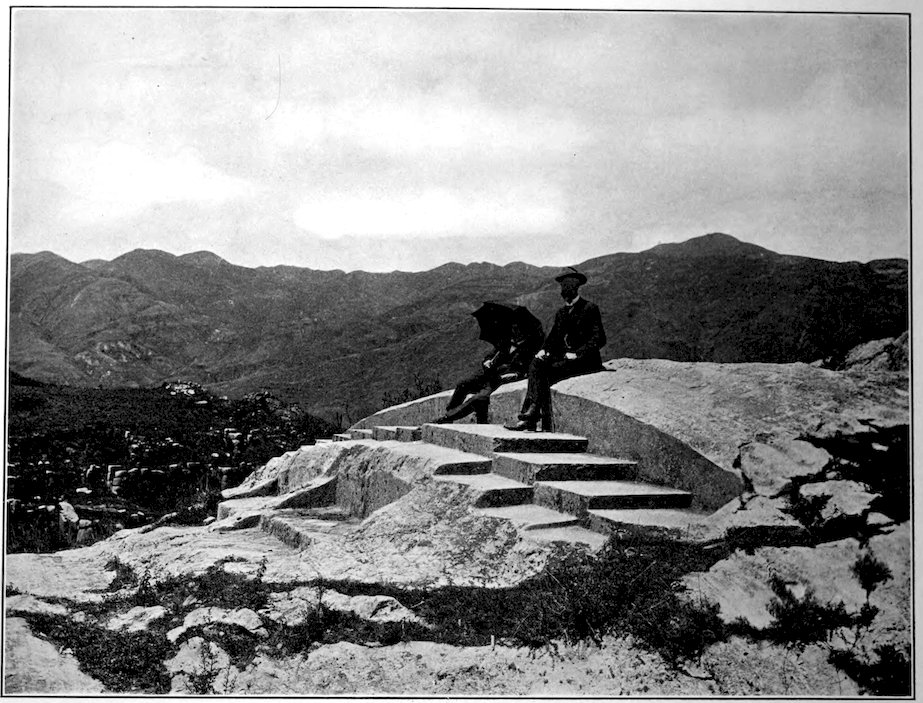

| THE RODADERO, CUZCO, SITE CHOSEN FOR RUNNING CONTESTS OF THE HUARACU | 48 |

| FOREIGN TOURISTS AT OLLANTAYTAMBO | 50 |

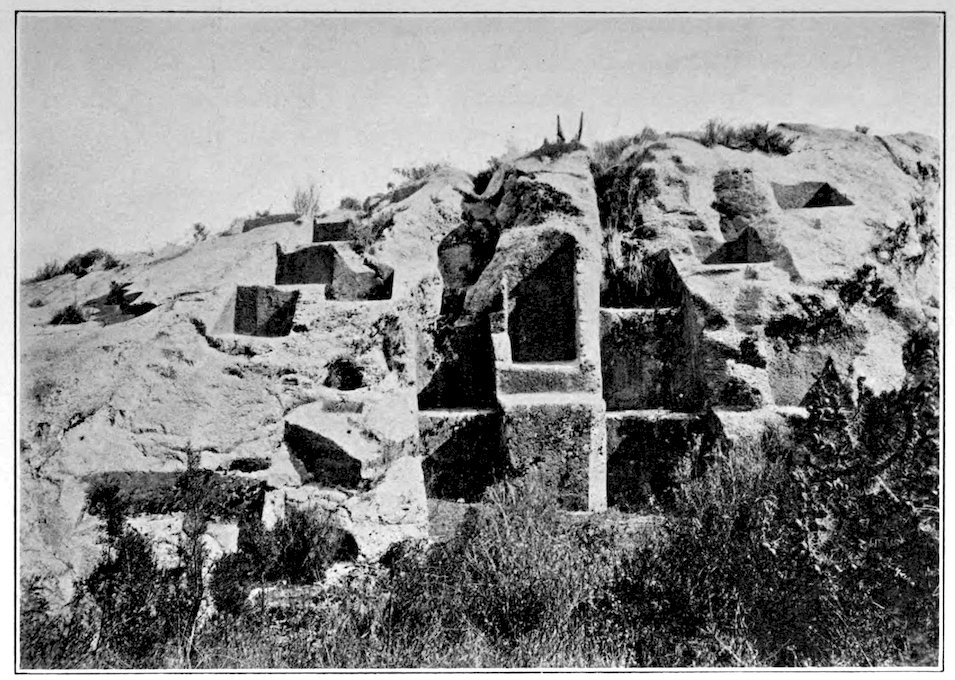

| INCA OBSERVATORY, INTI-HUATANA, AT PISAC, NEAR CUZCO | 52 |

| CORNER-STONE OF AN ANCIENT FORTRESS, CUZCO | 53 |

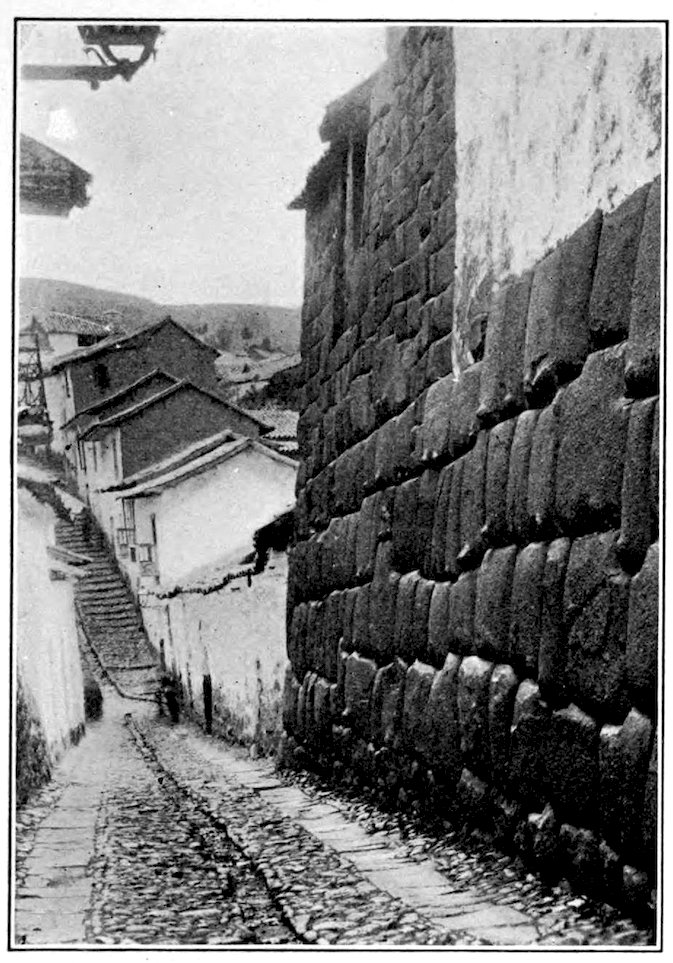

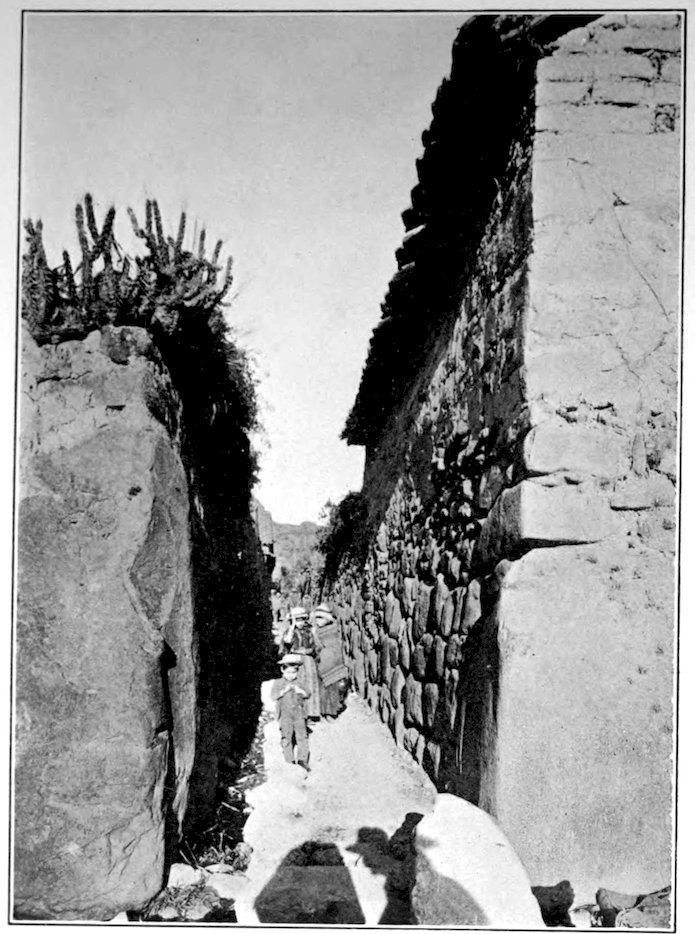

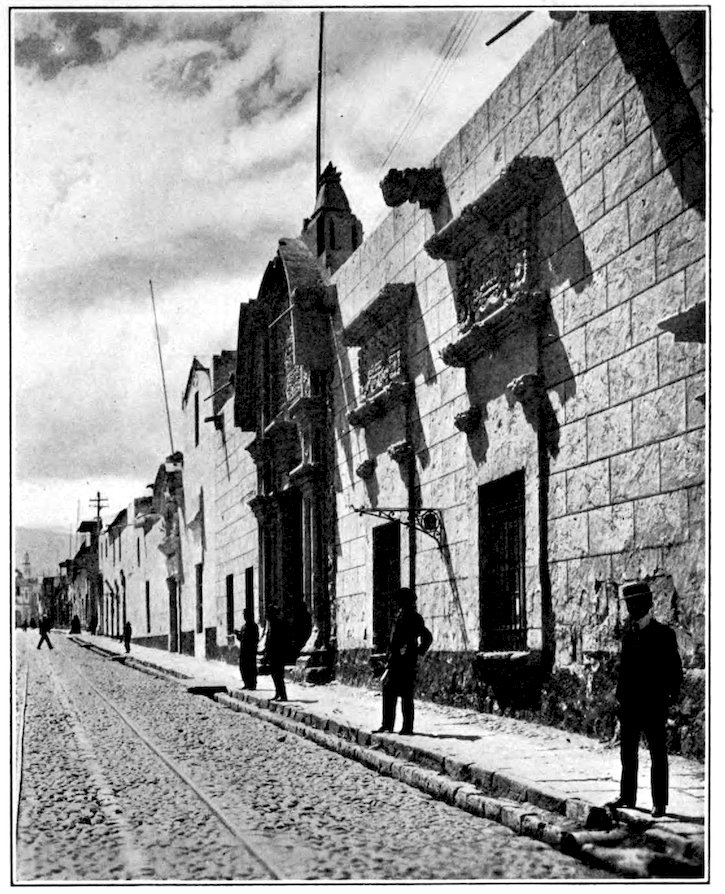

| ANCIENT STREET OF CUZCO, SHOWING INCAIC WALLS | 55 |

| PRINCIPAL HALL OF THE INCA OBSERVATORY, INTI-HUATANA | 57 |

| SHOWING THE TWELVE-ANGLE STONE, RUINS OF CUZCO | 58 |

| THE INCA’S BATH, OLLANTAYTAMBO | 59 |

| THE HOUSE OF THE SERPENTS, CUZCO | 61 |

| DOORWAY OF THE OBSERVATORY, INTI-HUATANA | 62 |

| THE INCA’S THRONE, OVERLOOKING THE CITY OF CUZCO | 64 |

| ANCIENT STREET OF CUZCO | 65 |

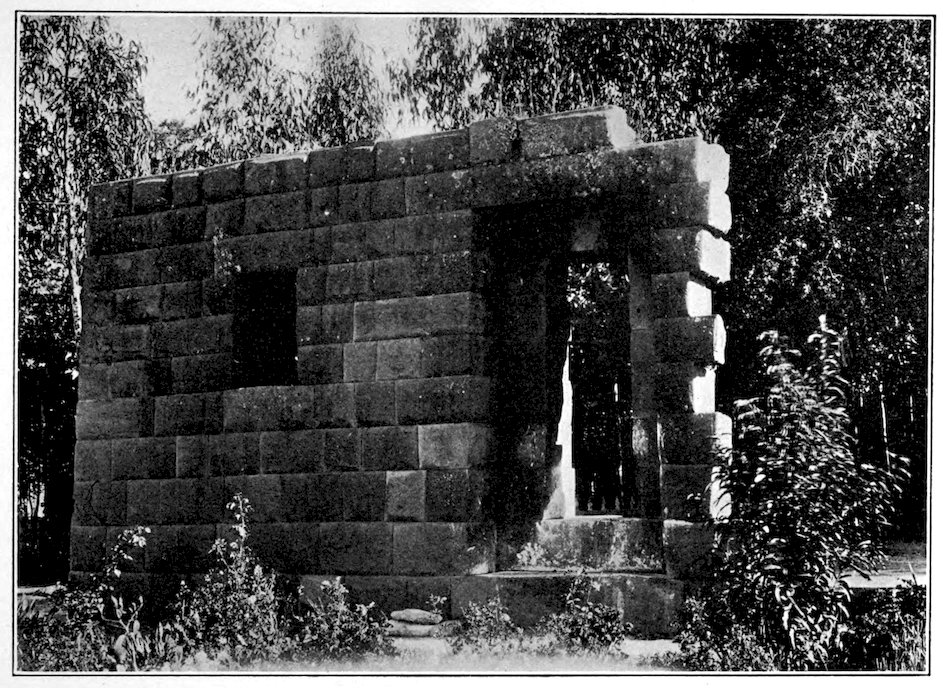

| RUINS OF AN INCA’S PALACE | 67 |

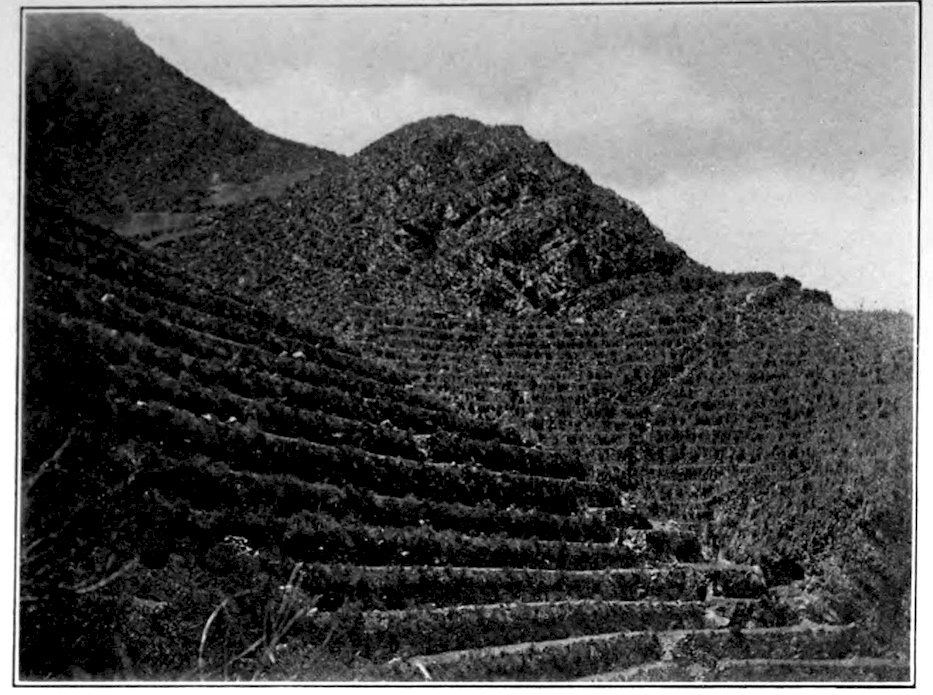

| THE ANDENES, OR ARTIFICIAL TERRACES, CULTIVATED UNDER THE INCAS | 68 |

| SEATS CUT IN SOLID STONE, AT KENKO, NEAR CUZCO | 69 |

| ANCIENT BRIDGE OF SANTA TERESA, CUZCO | 70 |

| AN INCAIC STREET, CUZCO | 72 |

| ENTRANCE TO AN INCAIC HOUSE | 74 |

| THE DEATH OF ATAHUALLPA. FROM A PAINTING BY THE PERUVIAN ARTIST LUIS MONTERO | 76 |

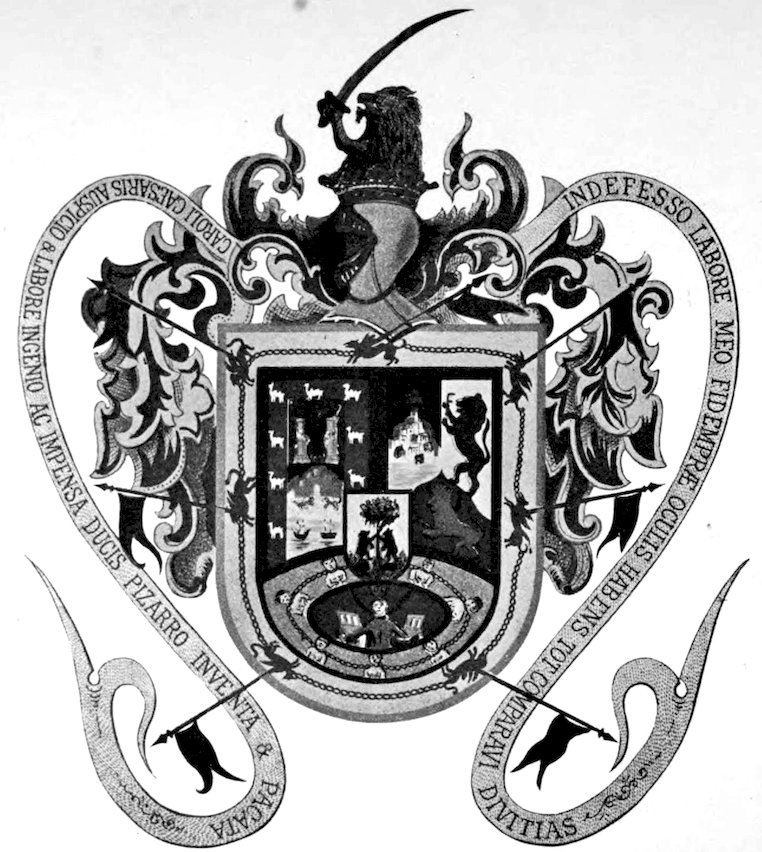

| COAT-OF-ARMS OF PIZARRO GRANTED BY CHARLES V. IN HONOR OF THE DISCOVERY OF PERU | 77 |

| FRANCISCO PIZARRO, CONQUEROR OF PERU AND FOUNDER OF LIMA | 79 |

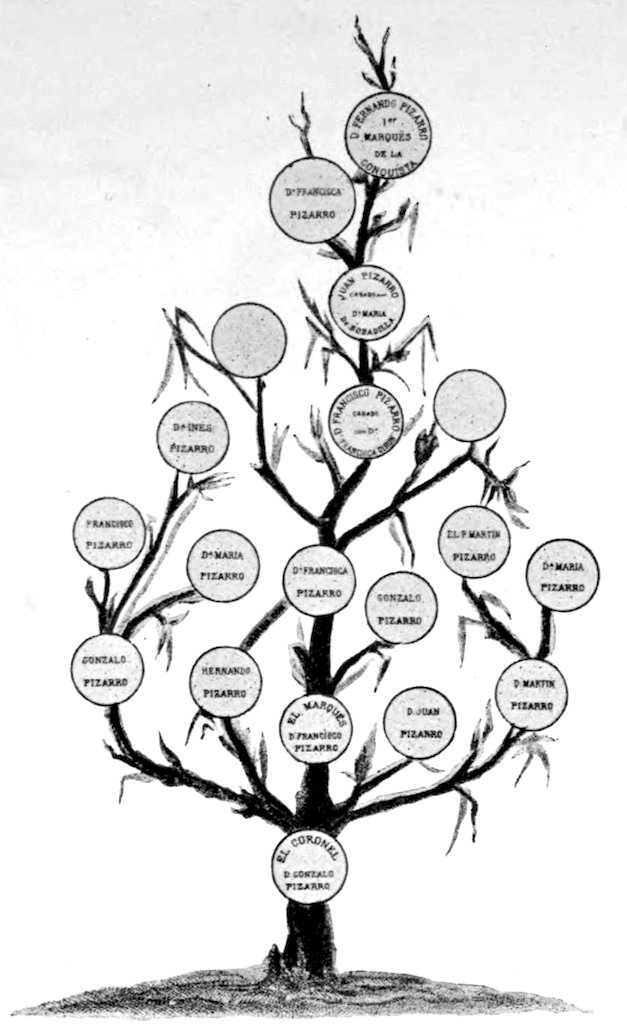

| GENEALOGY OF FRANCISCO PIZARRO, CONQUEROR OF PERU | 81 |

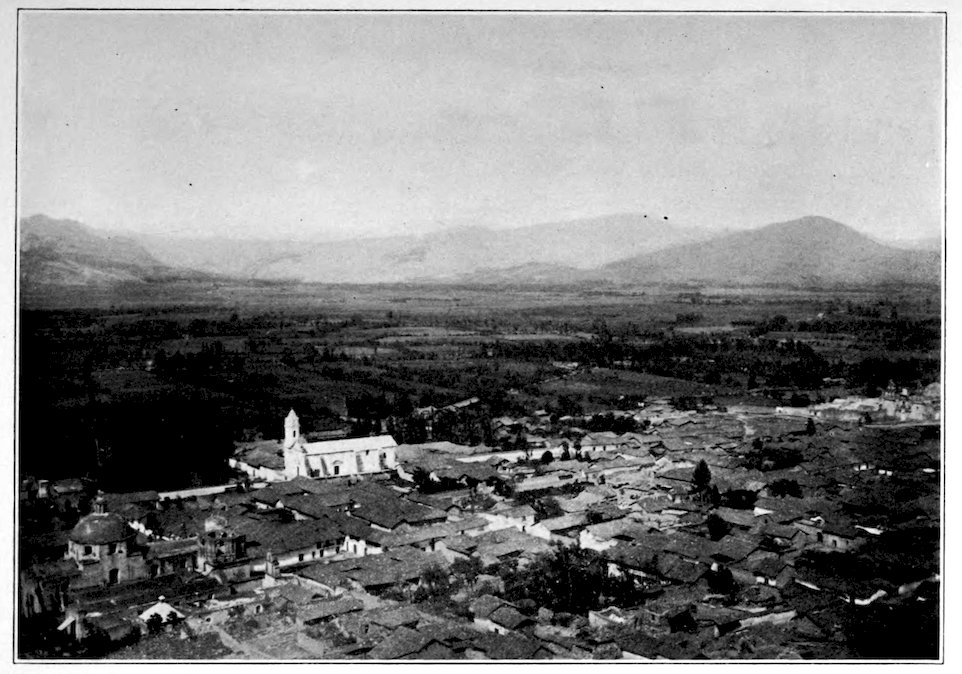

| CAJAMARCA, WHERE ATAHUALLPA WAS SEIZED AND EXECUTED BY PIZARRO’S ORDER | 83 |

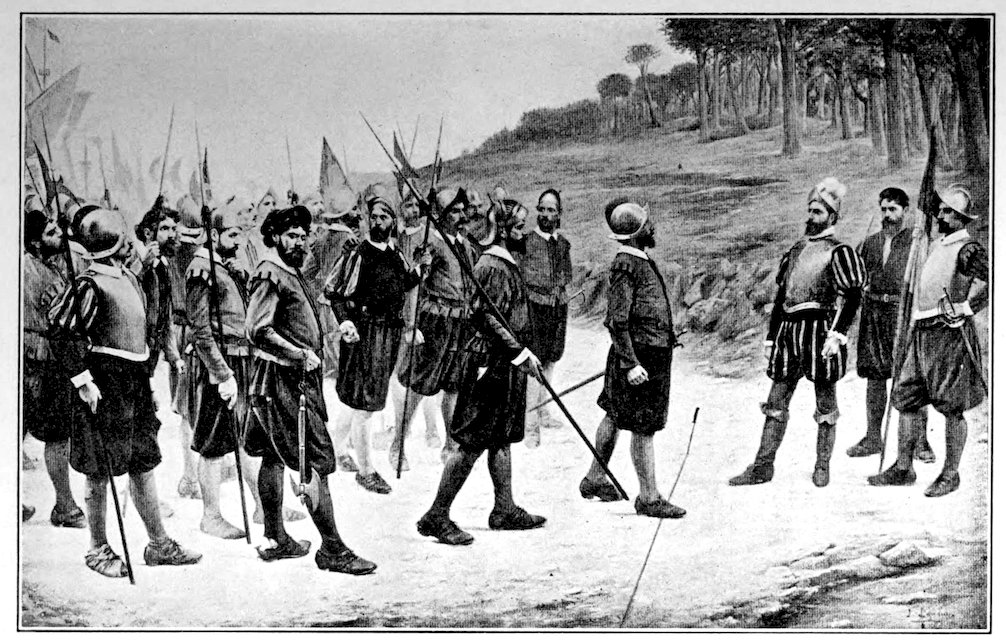

| PIZARRO ON THE ISLAND OF GALLO. FROM A PAINTING BY JUAN O. LEPIANI | 85 |

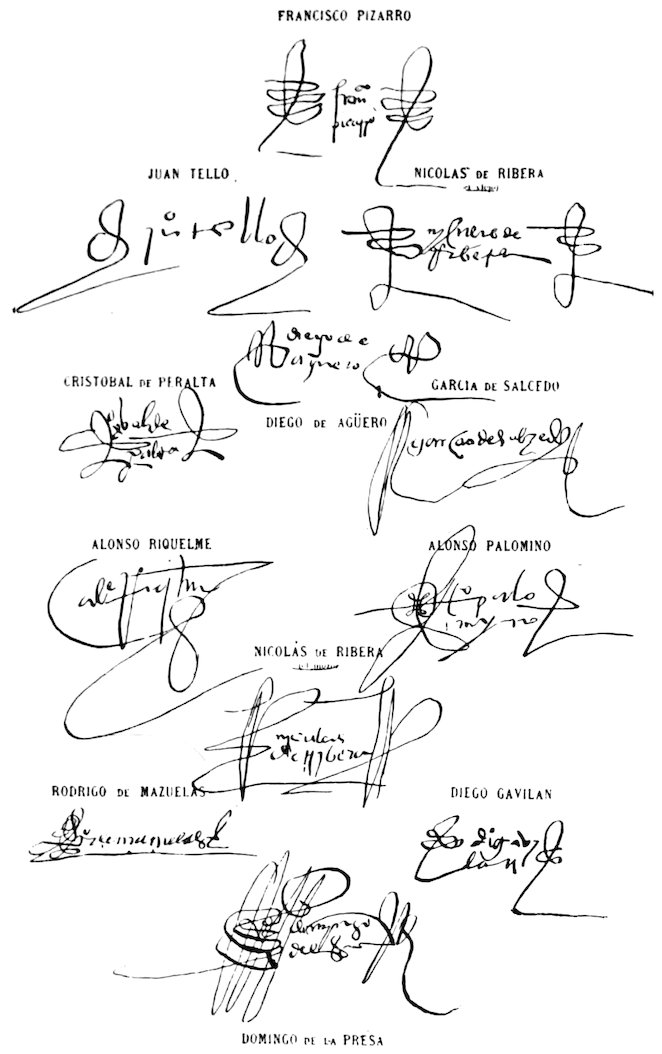

| AUTOGRAPHS OF THE FIRST OFFICIALS WHO GOVERNED LIMA WITH PIZARRO | 86 |

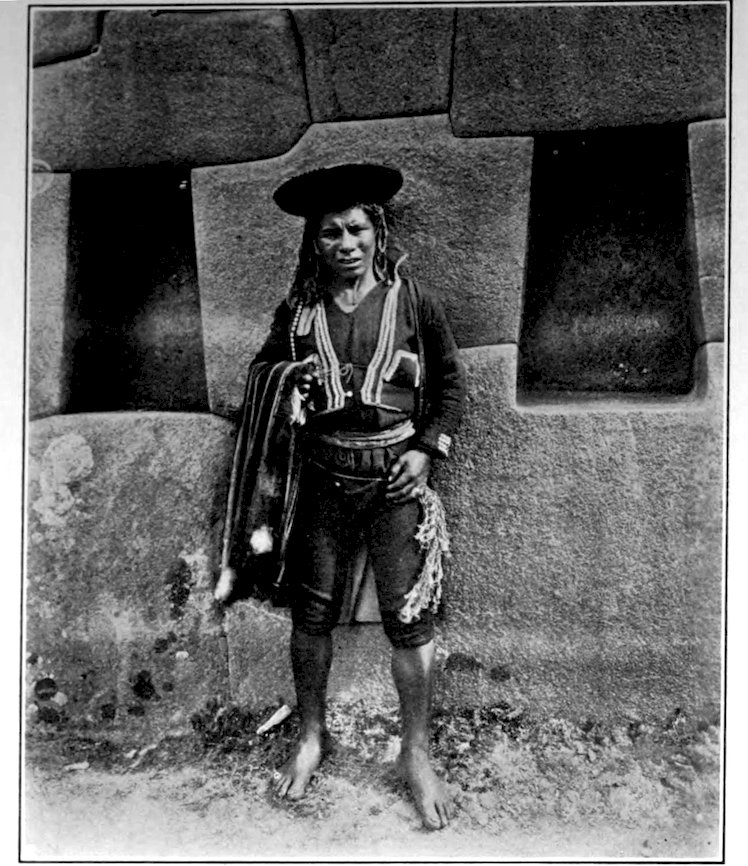

| A DESCENDANT OF THE CONQUERED INCA | 88 |

| COAT-OF-ARMS GRANTED PIZARRO BY CHARLES V. AFTER THE CONQUEST OF CUZCO | 90 |

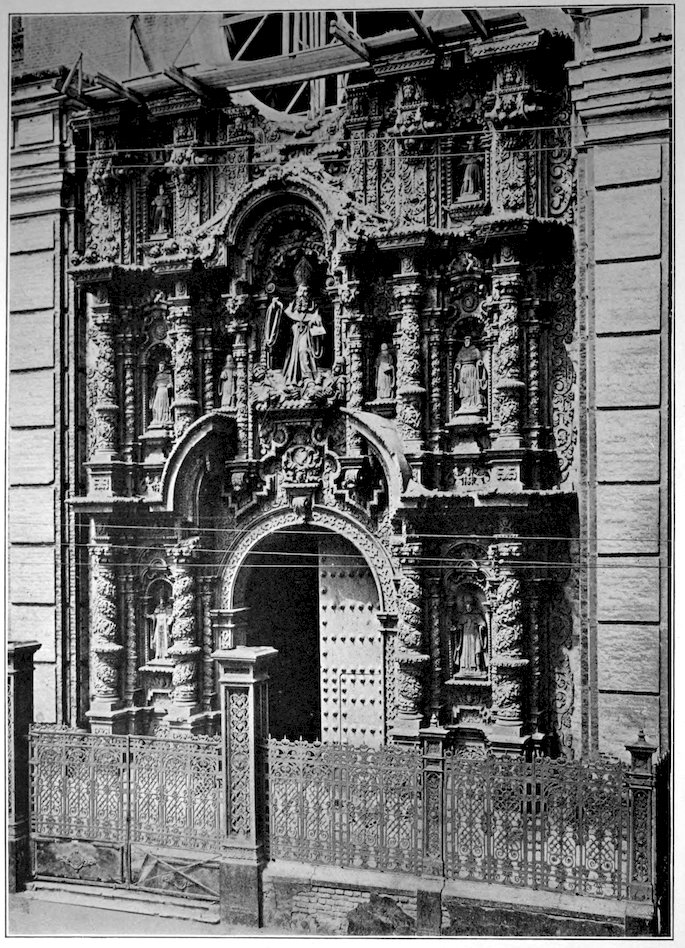

| FAÇADE OF SAN AGUSTIN CHURCH, LIMA, SHOWING ELABORATE CARVING OF COLONIAL DAYS | 92 |

| THE FIRST COAT-OF-ARMS BESTOWED ON LIMA BY CHARLES V. | 93 |

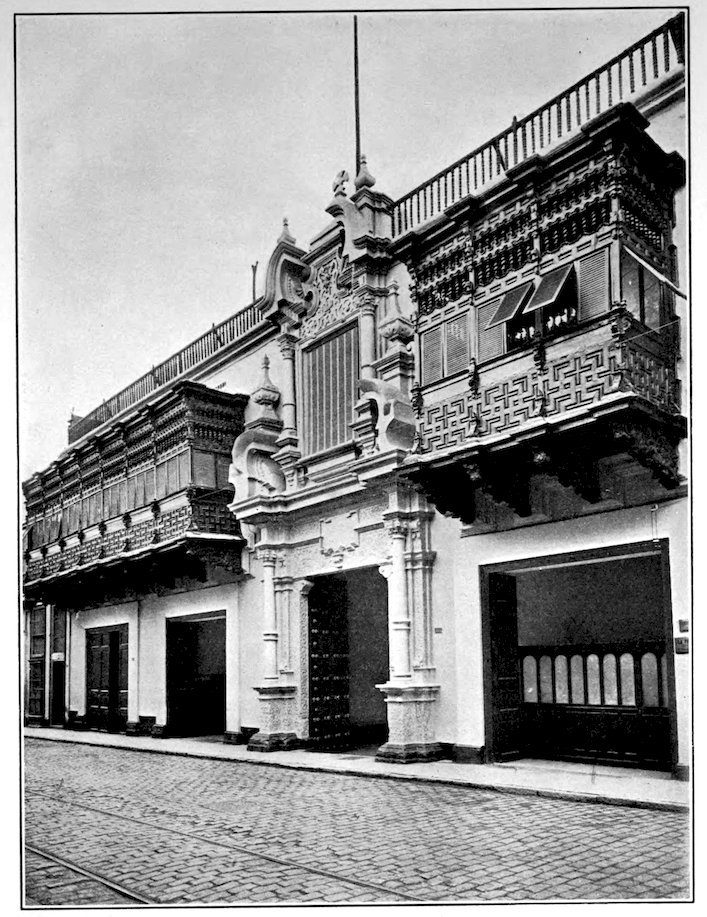

| LIMA RESIDENCE OF THE MARQUIS OF TORRE-TAGLE DURING THE VICEREGAL PERIOD, SHOWING “MIRADORES,” OR BALCONIES | 95 |

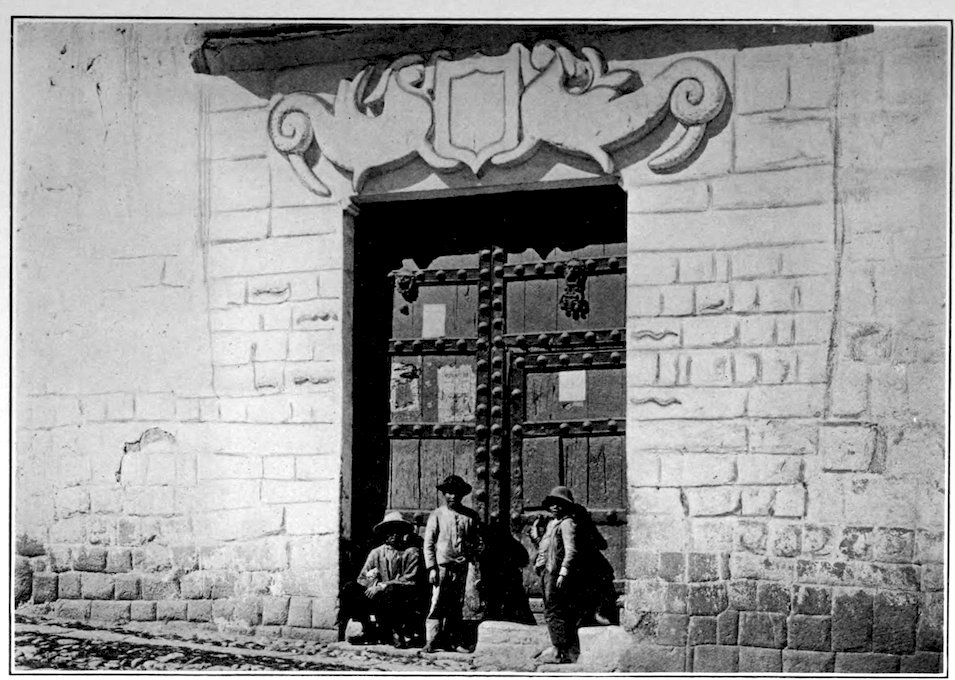

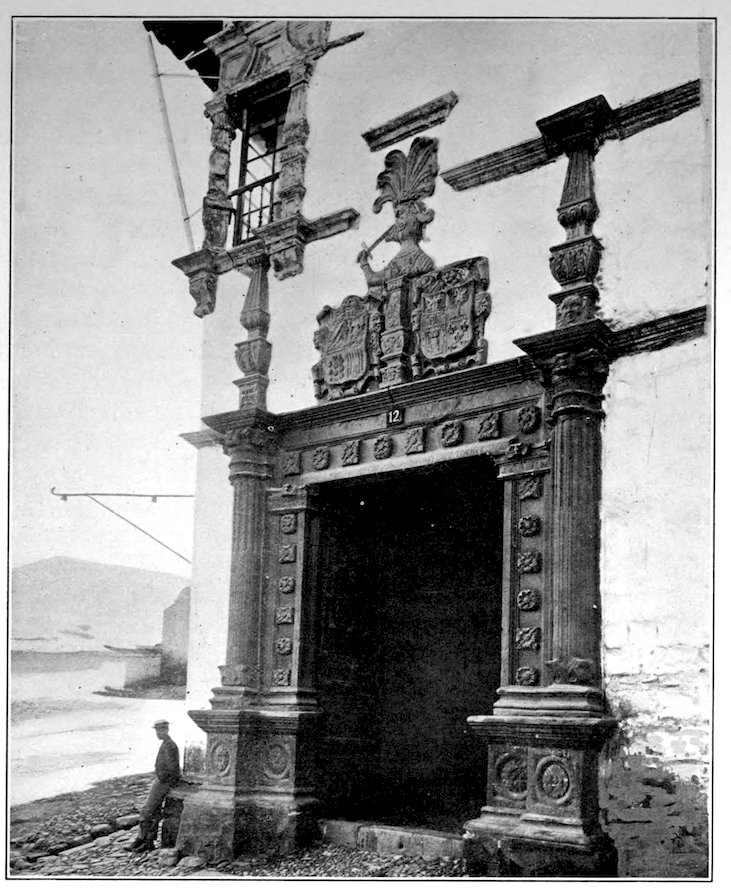

| DOORWAY OF A COLONIAL PALACE IN CUZCO, PERIOD FOLLOWING THE CONQUEST | 97 |

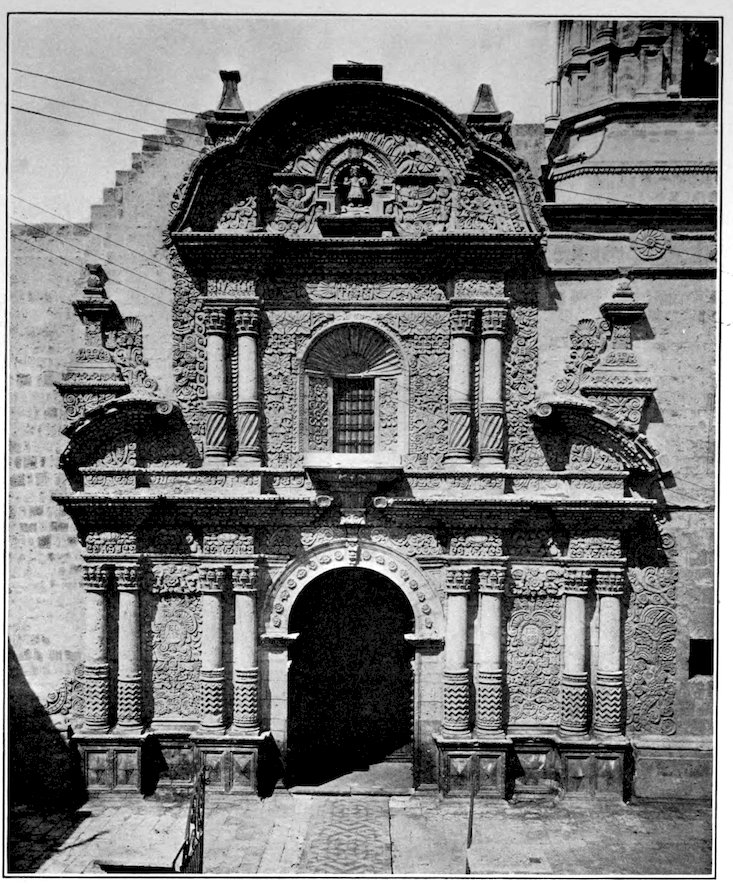

| CHURCH OF THE COMPAÑIA, AREQUIPA, SHOWING EXQUISITE HAND CARVING | 99 |

| THE KEY OF THE CITY OF LIMA | 102 |

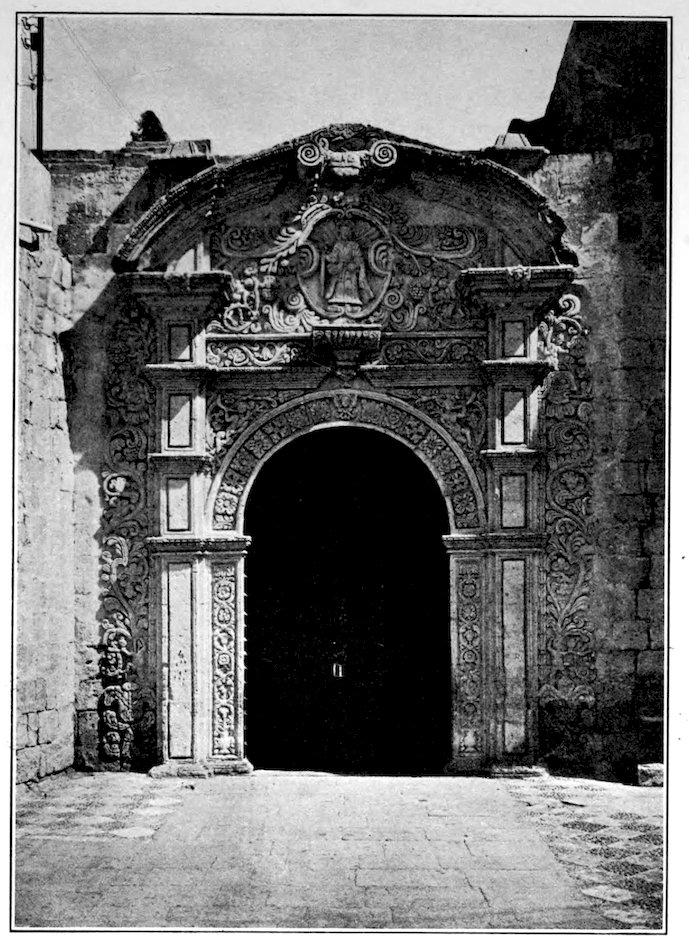

| DOORWAY OF A CHURCH IN AREQUIPA, BUILT DURING THE COLONIAL PERIOD | 103 |

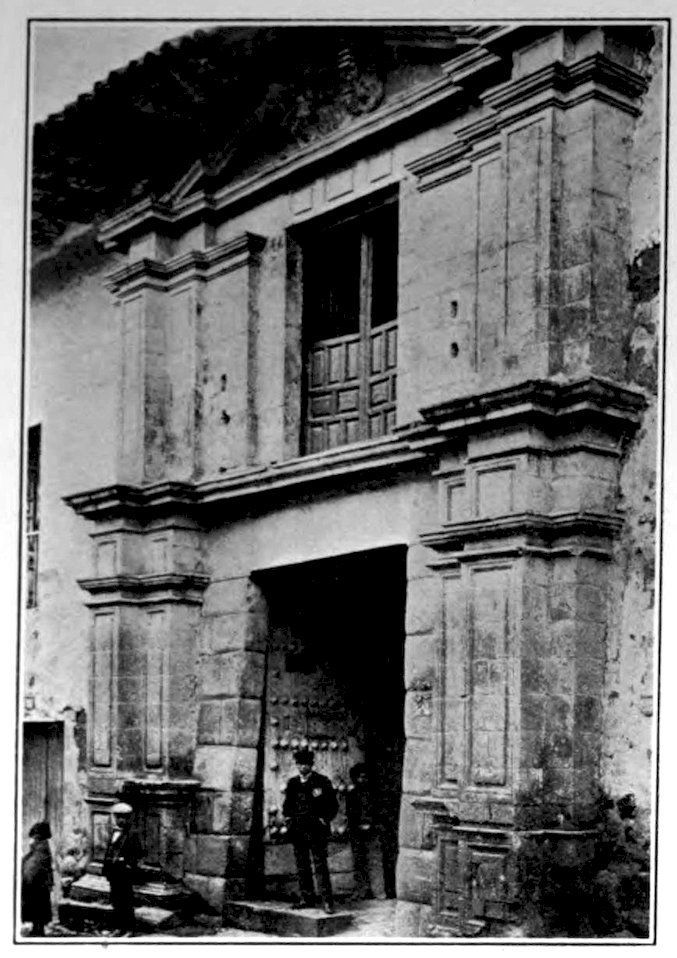

| ENTRANCE TO A COLONIAL INN, CUZCO | 106 |

| ONE OF THE COLONIAL PALACES OF AREQUIPA, BUILT TWO CENTURIES AGO | 107 |

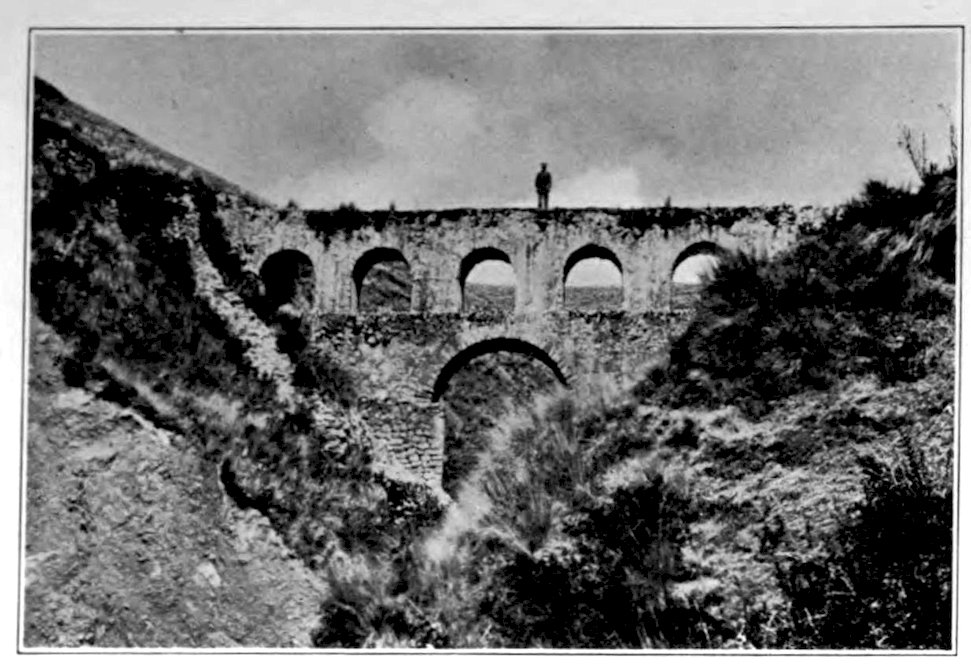

| 10A COLONIAL AQUEDUCT | 108 |

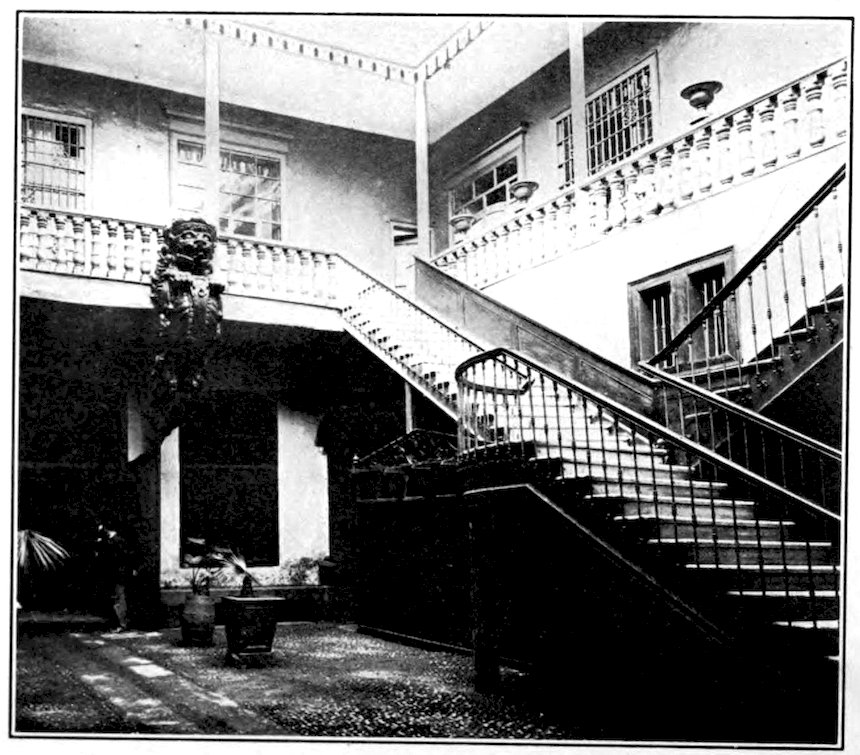

| PATIO OF A COLONIAL HOUSE, LIMA | 110 |

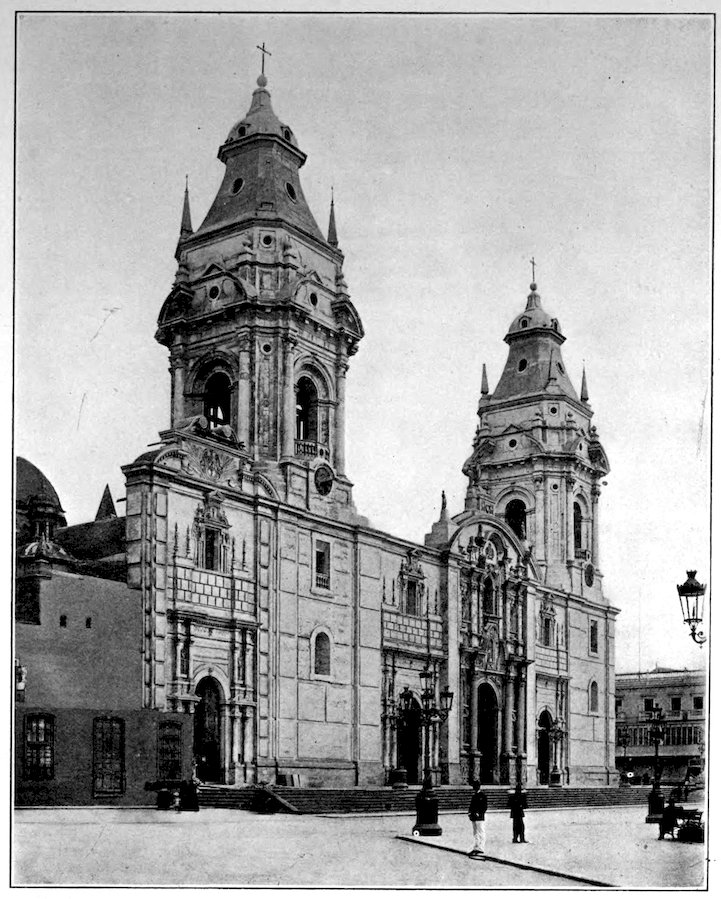

| THE CHOIR AND ALTAR OF THE CATHEDRAL OF LIMA—THE ALTAR OF SOLID SILVER | 112 |

| ARMS OF THE CATHEDRAL OF LIMA | 113 |

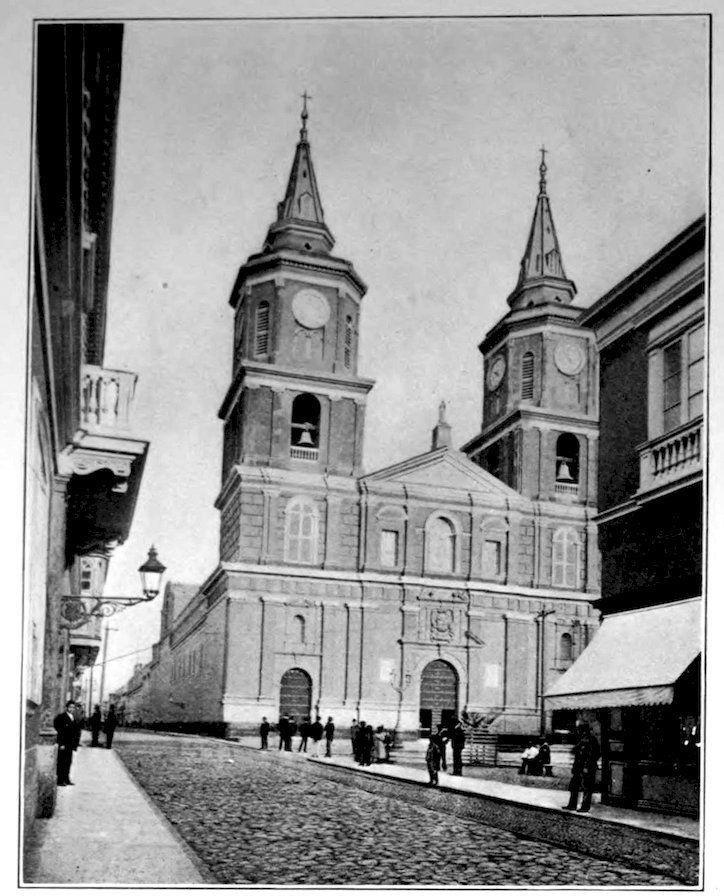

| THE CATHEDRAL, LIMA | 115 |

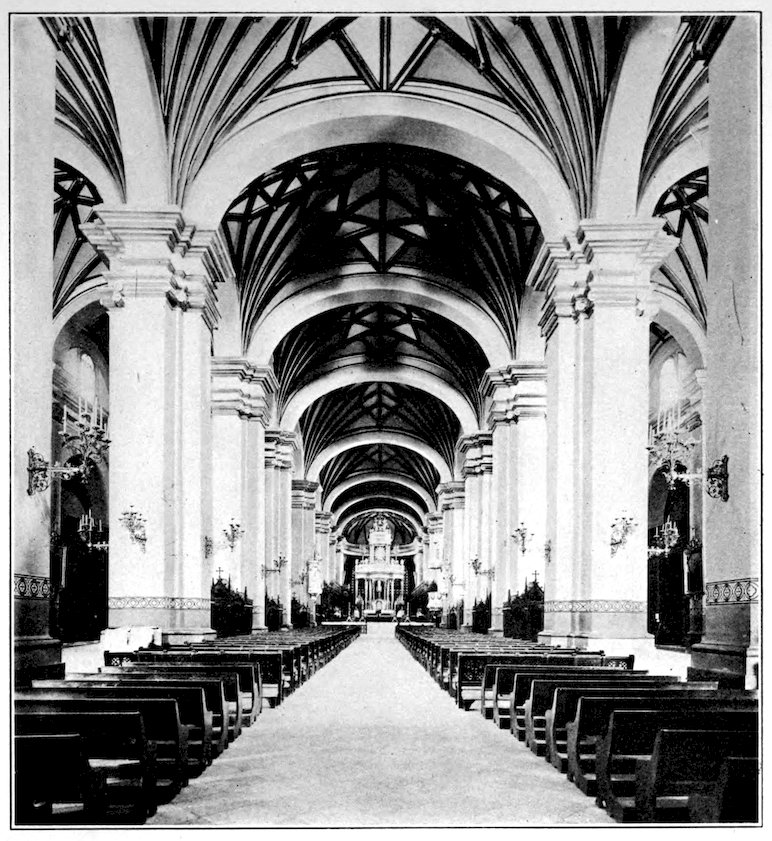

| INTERIOR OF THE CATHEDRAL, LIMA | 117 |

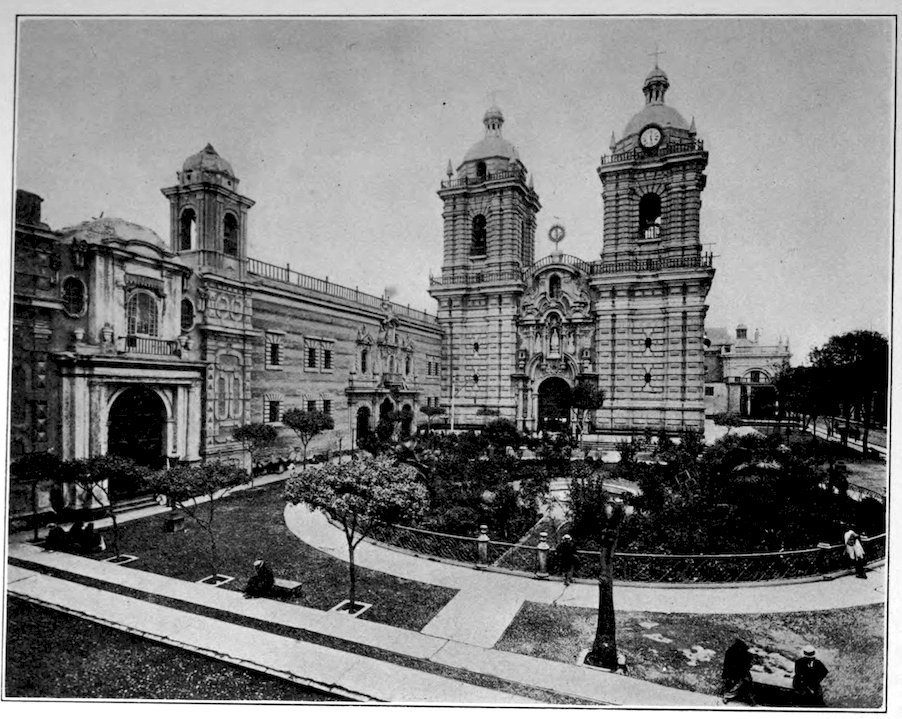

| CHURCH AND PLAZUELA OF SAN FRANCISCO, LIMA | 118 |

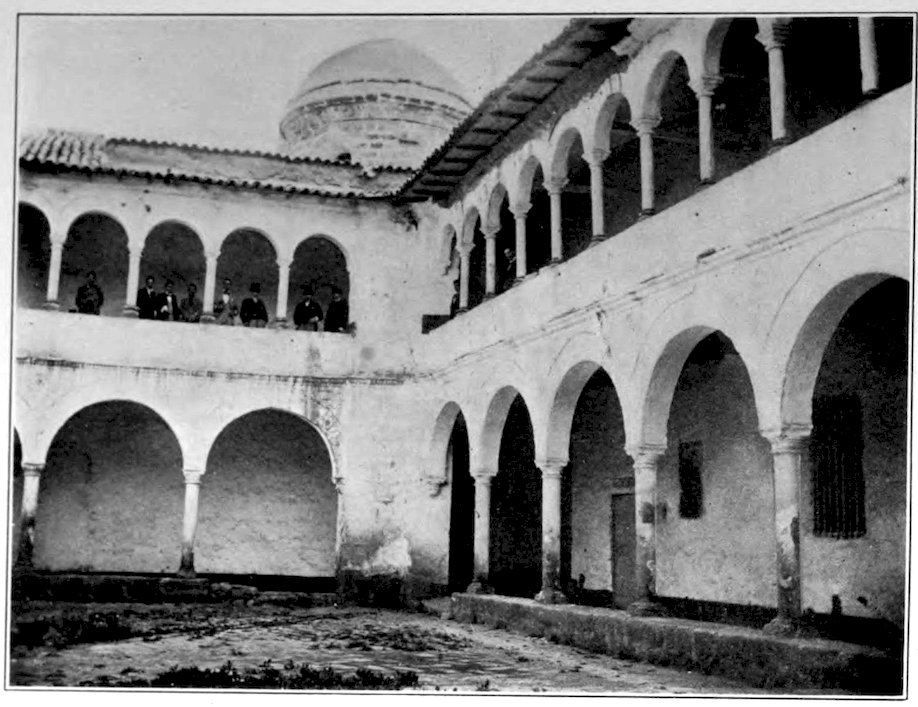

| CONVENT OF SANTO DOMINGO, CUZCO, BUILT ON THE FOUNDATIONS OF THE TEMPLE OF THE SUN | 119 |

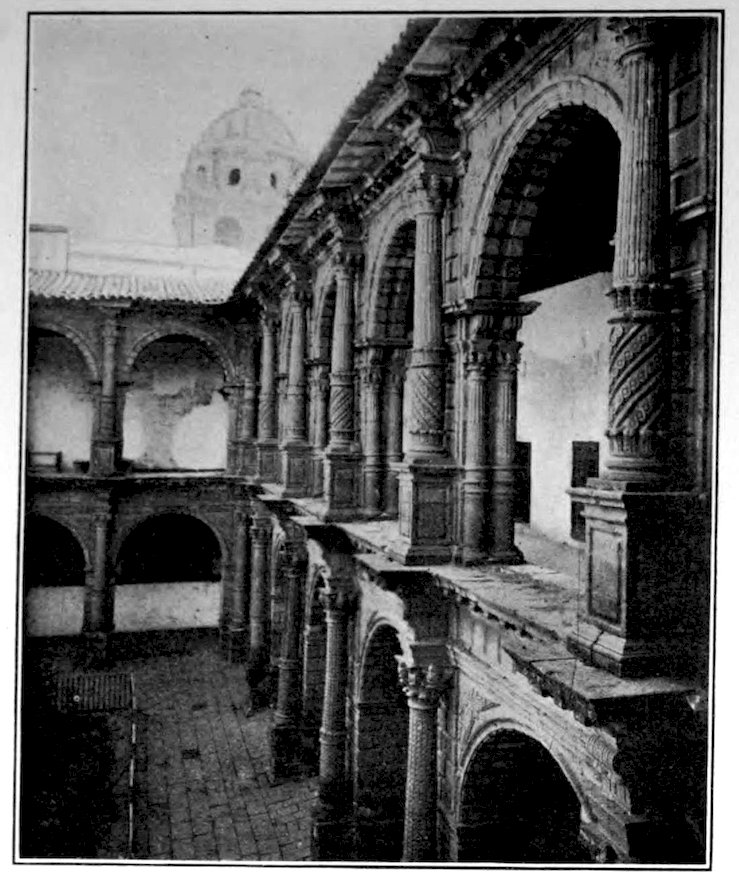

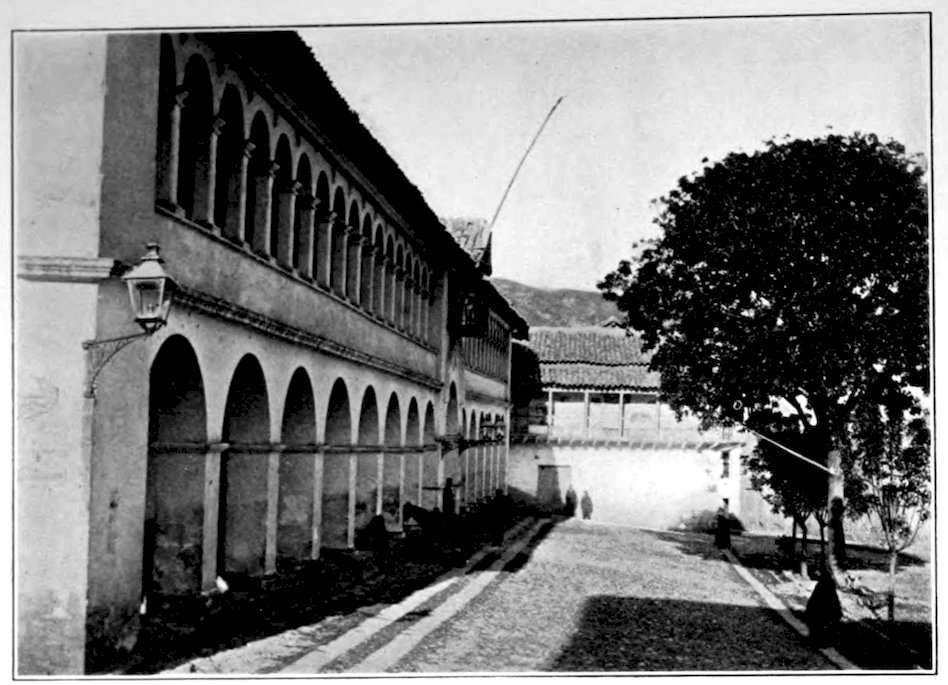

| CLOISTER OF LA MERCED, CUZCO | 120 |

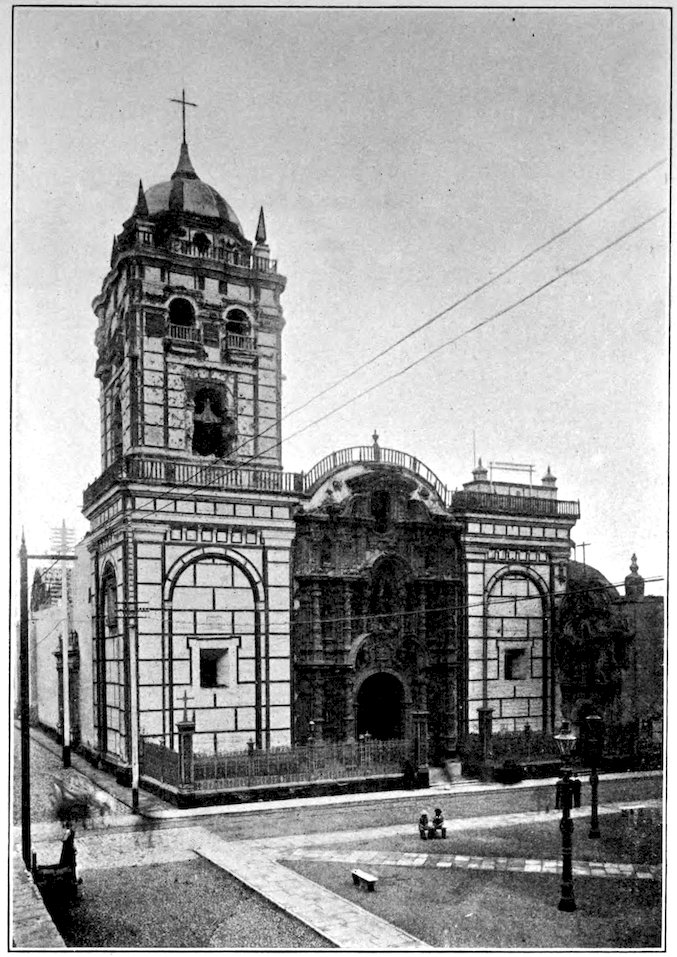

| CHURCH OF SAN AGUSTIN, LIMA | 121 |

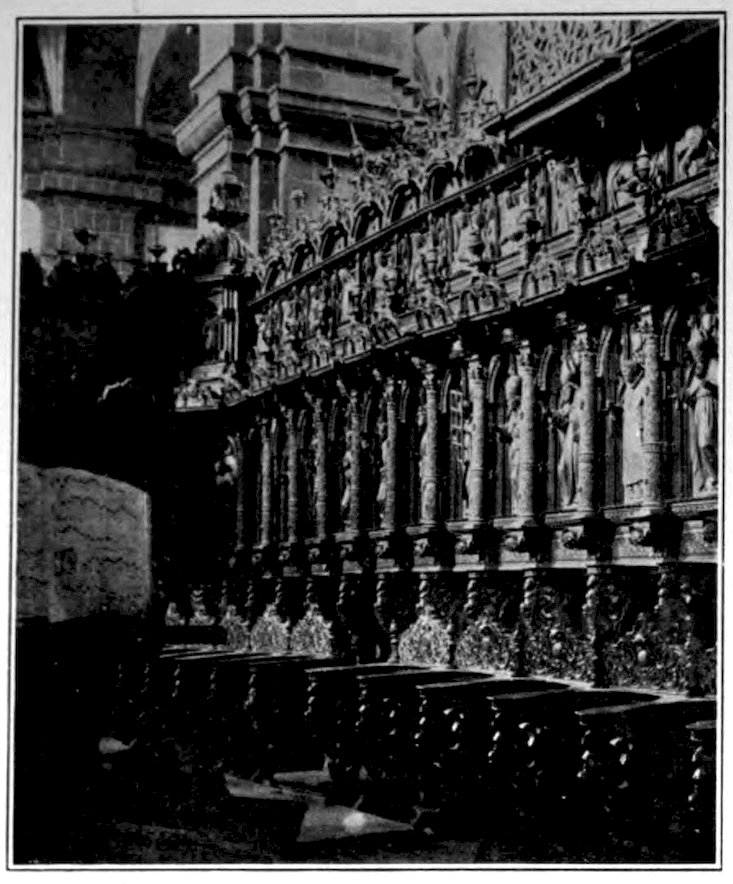

| CHOIR OF THE CATHEDRAL OF CUZCO | 122 |

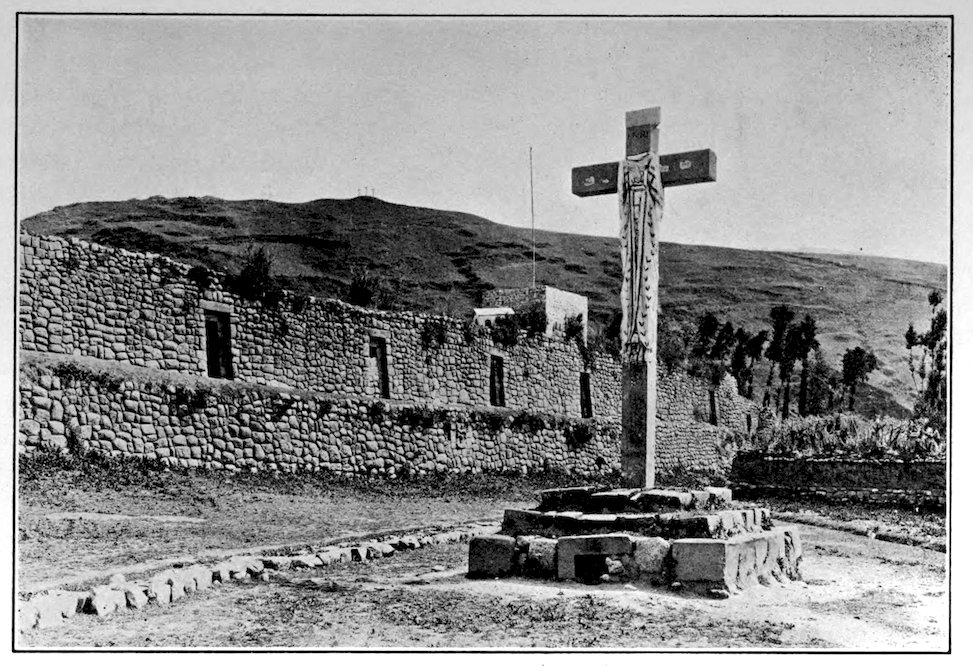

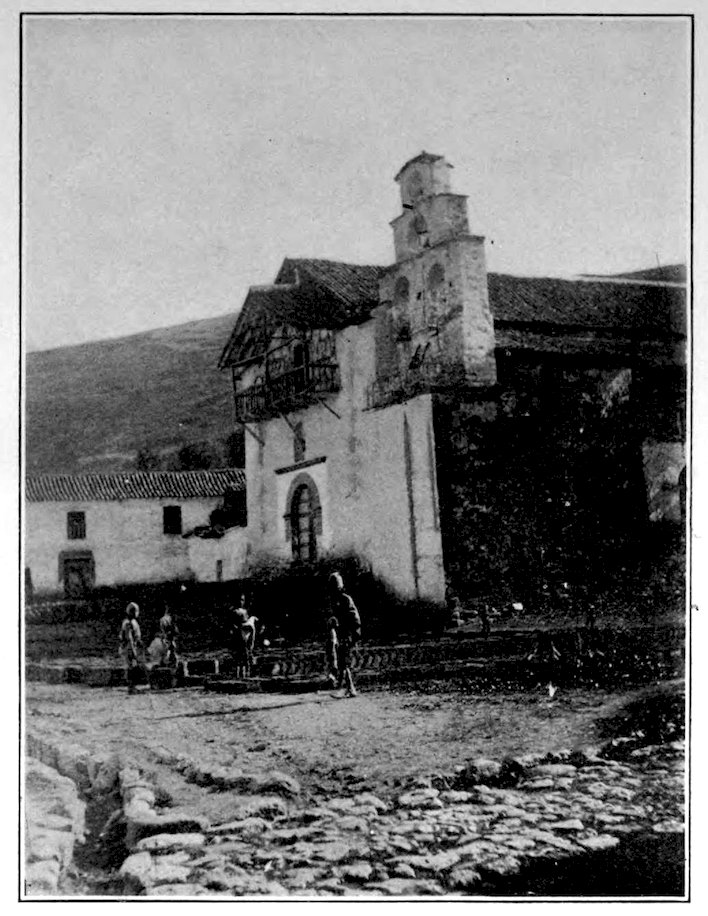

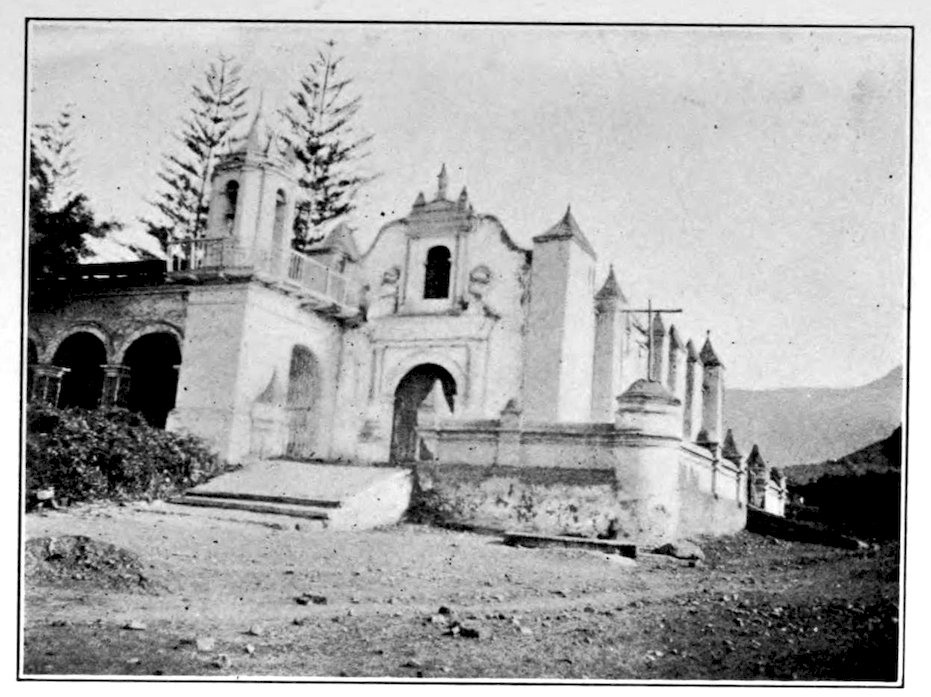

| OLD CHURCH AT URCOS | 123 |

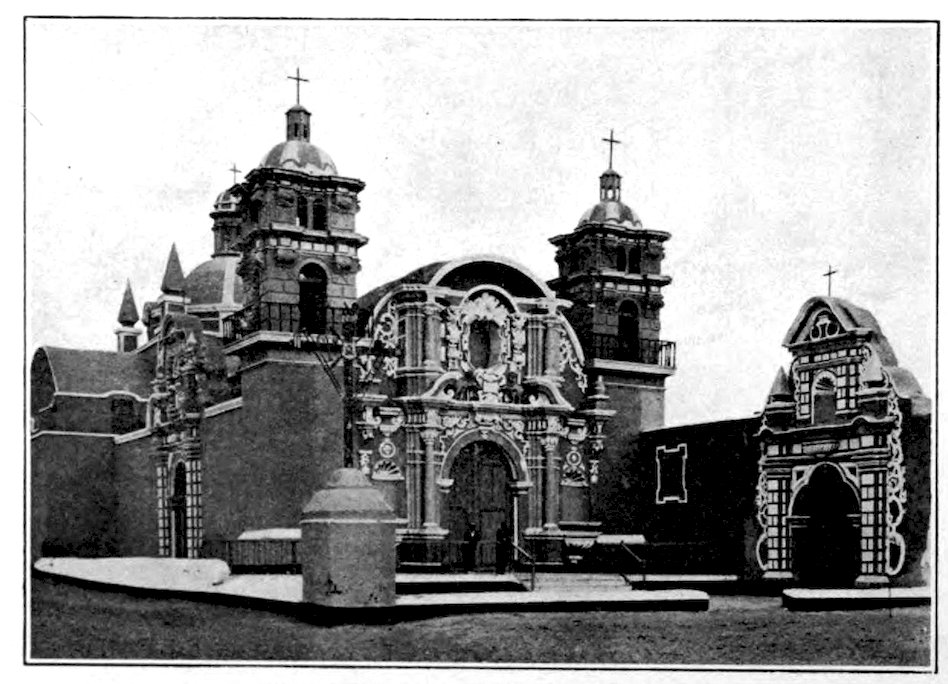

| CHURCH OF THE COMPAÑIA AT PISCO | 124 |

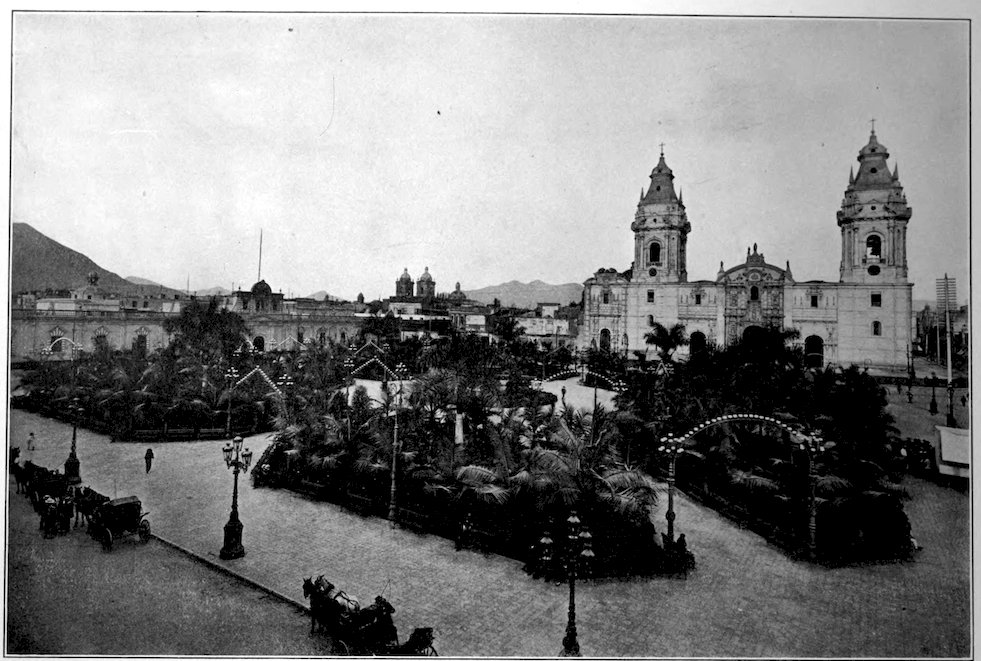

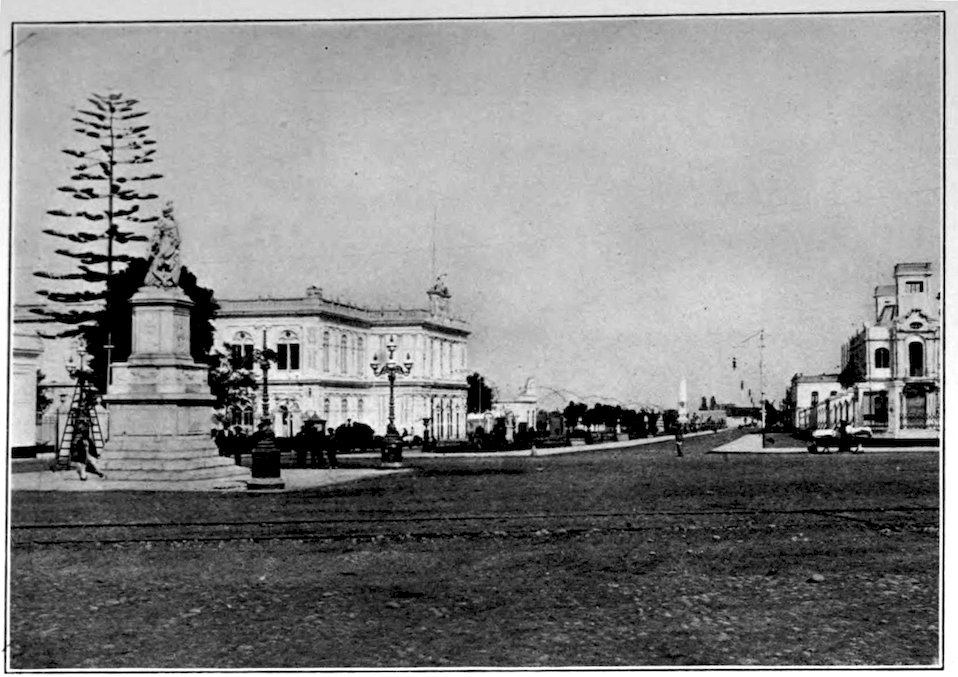

| PLAZA DE ARMAS, THE PRINCIPAL PUBLIC SQUARE OF LIMA | 126 |

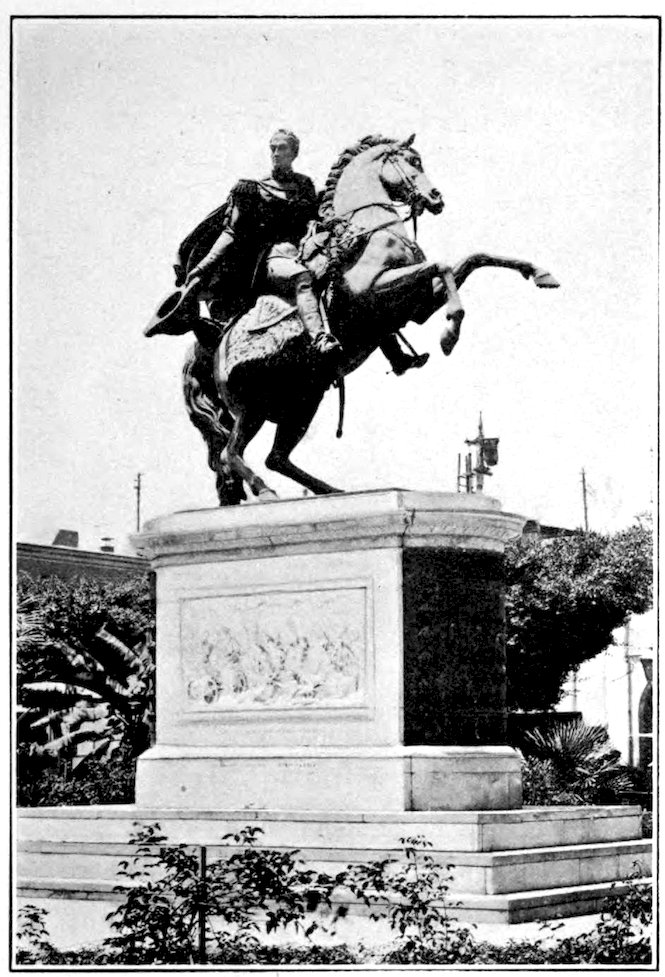

| STATUE OF BOLIVAR, LIMA | 127 |

| PLAZA OF THE INQUISITION, LIMA | 129 |

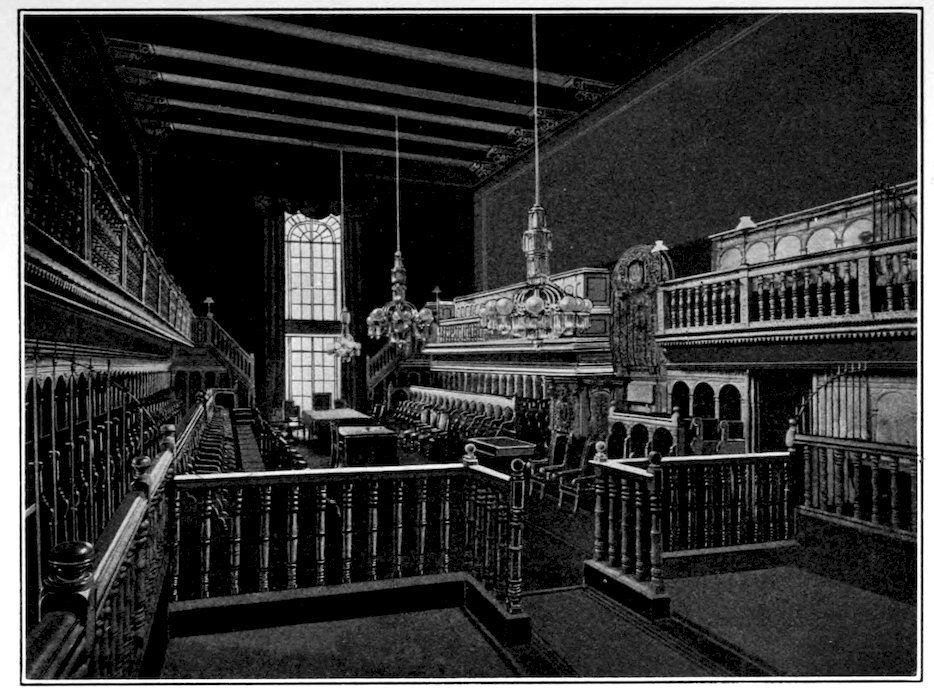

| THE SENATE CHAMBER, LIMA | 133 |

| CHAMBER OF DEPUTIES, LIMA | 135 |

| THE HISTORICAL PALACE OF THE VICEROYS, LIMA | 139 |

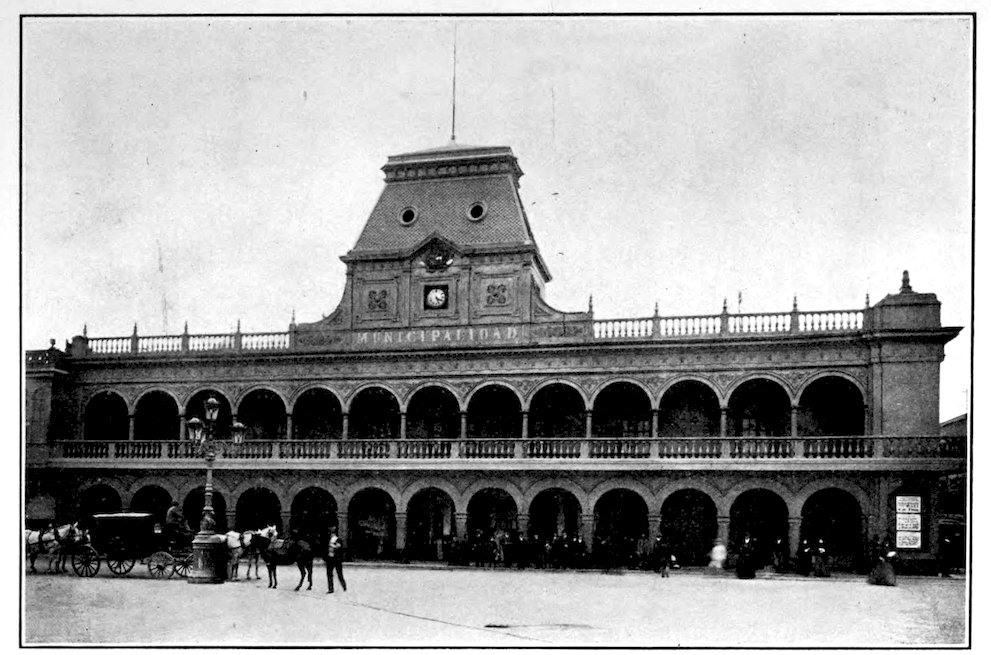

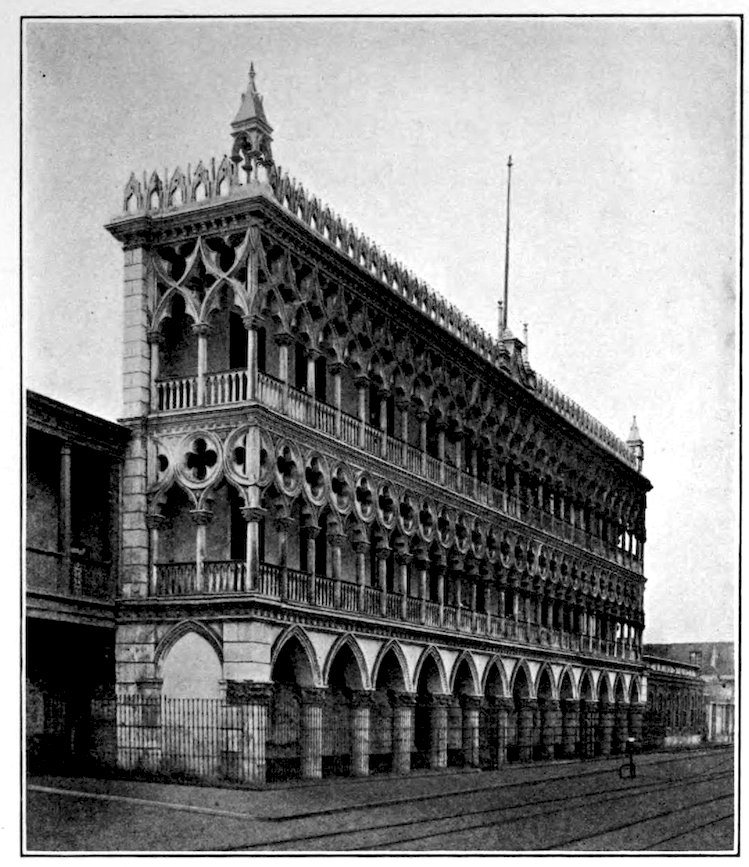

| THE MUNICIPAL PALACE, LIMA | 141 |

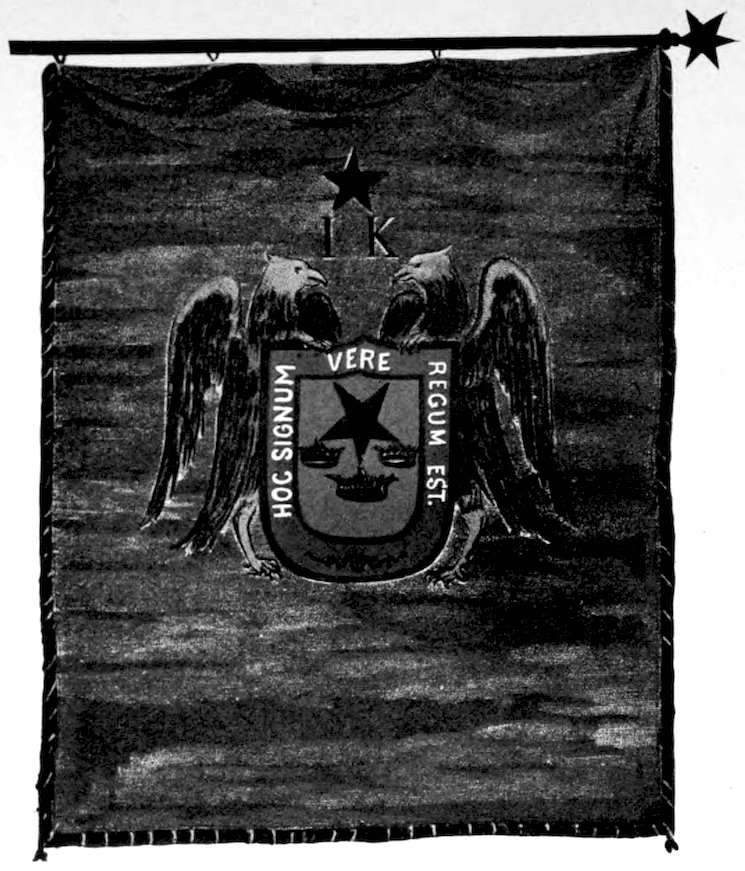

| ARMS OF PERU AT THE TIME OF THE INDEPENDENCE | 144 |

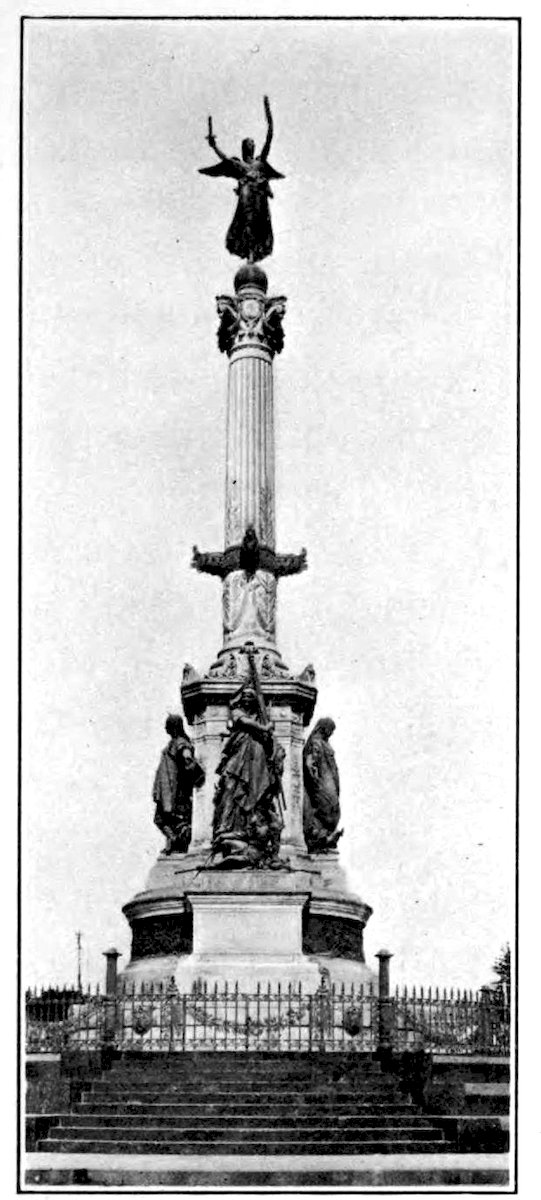

| MONUMENT DOS DE MAYO | 145 |

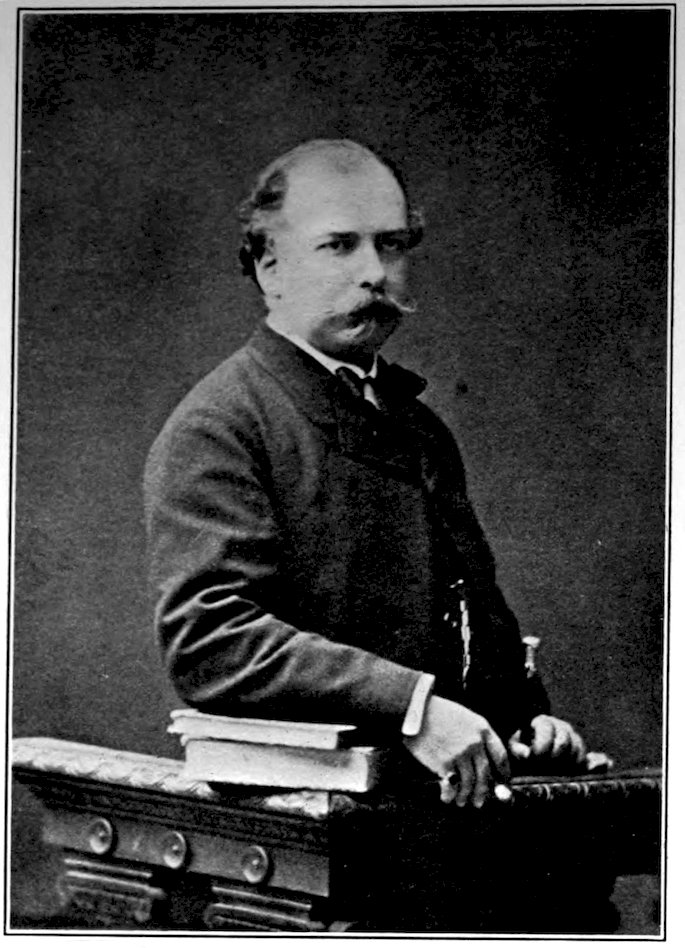

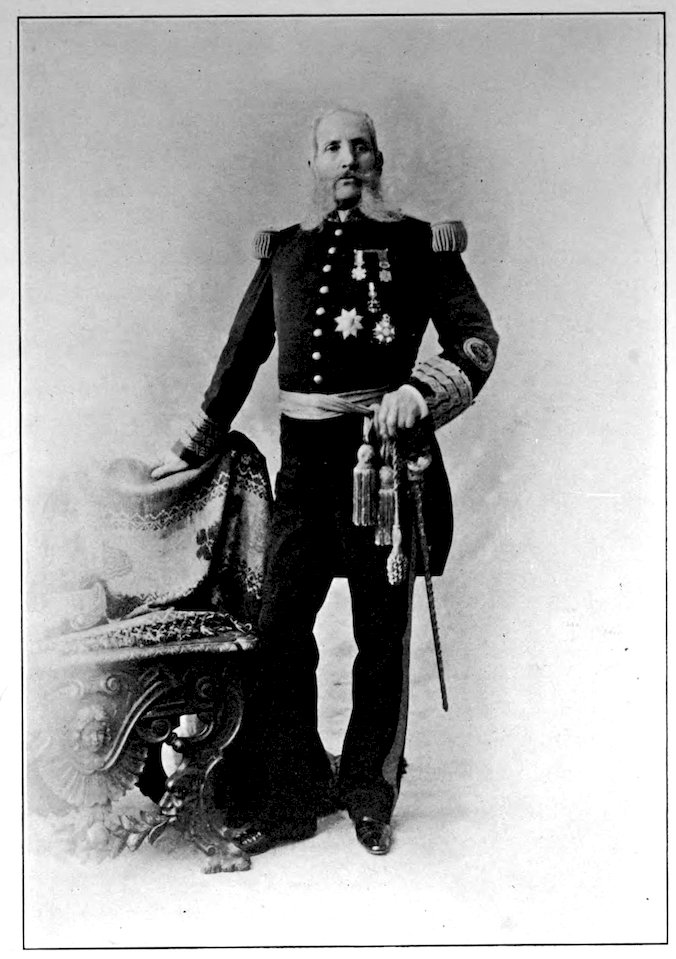

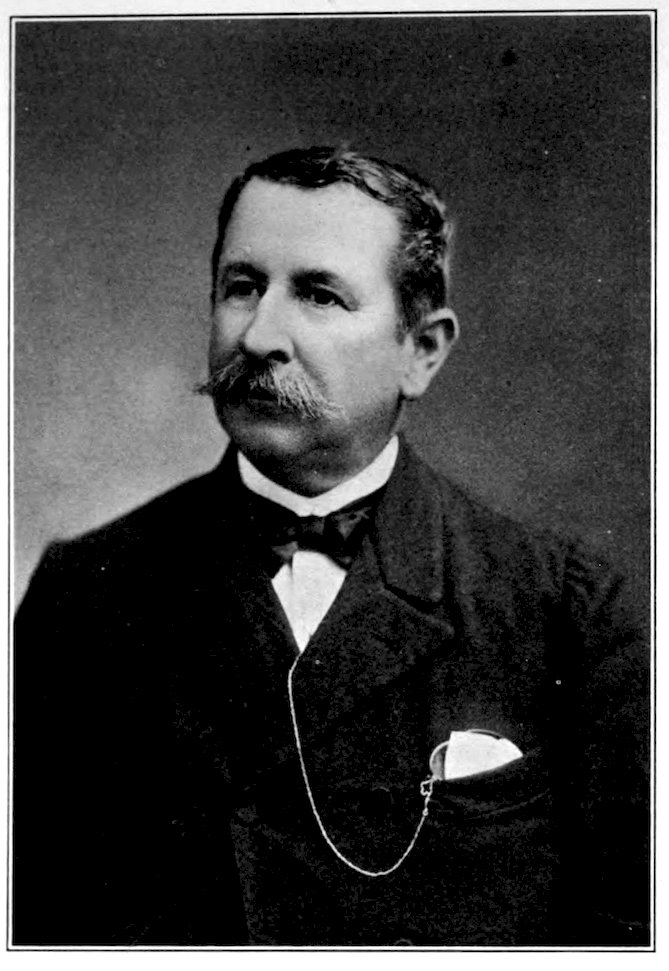

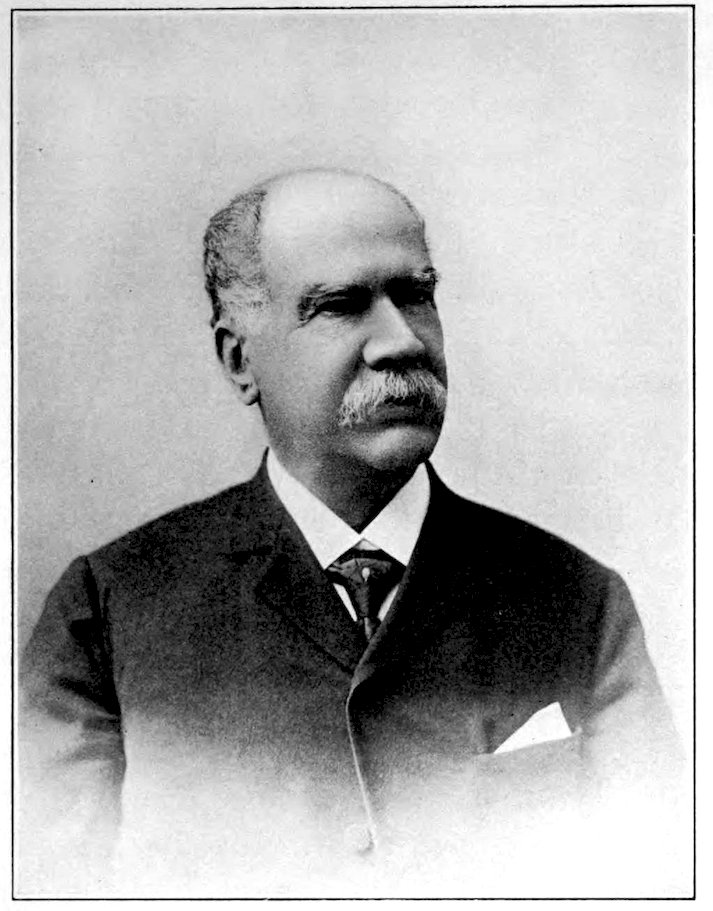

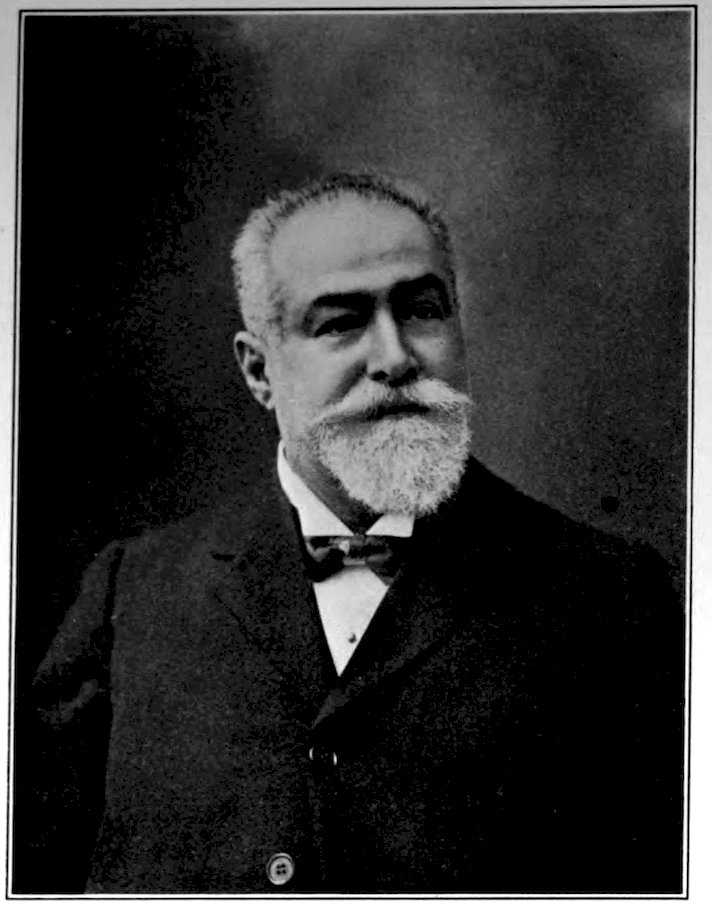

| DON MANUEL PARDO, THE FIRST CIVIL PRESIDENT OF PERU | 148 |

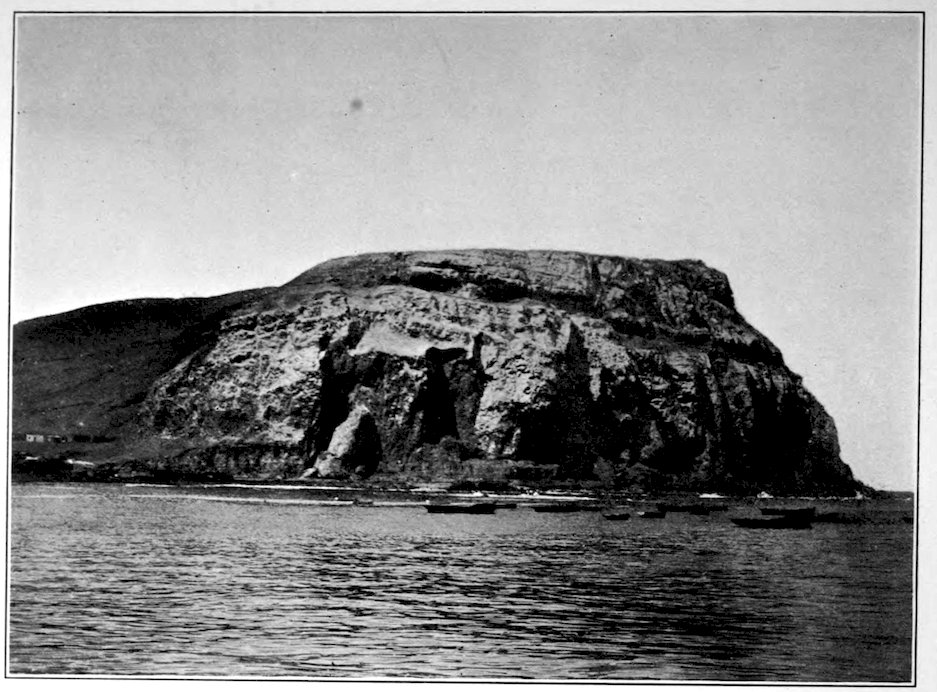

| THE MORRO OF ARICA | 150 |

| DON MANUEL CANDAMO—ELECTED PRESIDENT OF PERU 1903, DIED 1904 | 152 |

| GENERAL ANDRÉS CÁCERES, PRESIDENT OF PERU, 1886–1890 AND 1894–1895 | 155 |

| SCENE ON BOARD A PERUVIAN WARSHIP | 158 |

| COAT-OF-ARMS OF PERU | 160 |

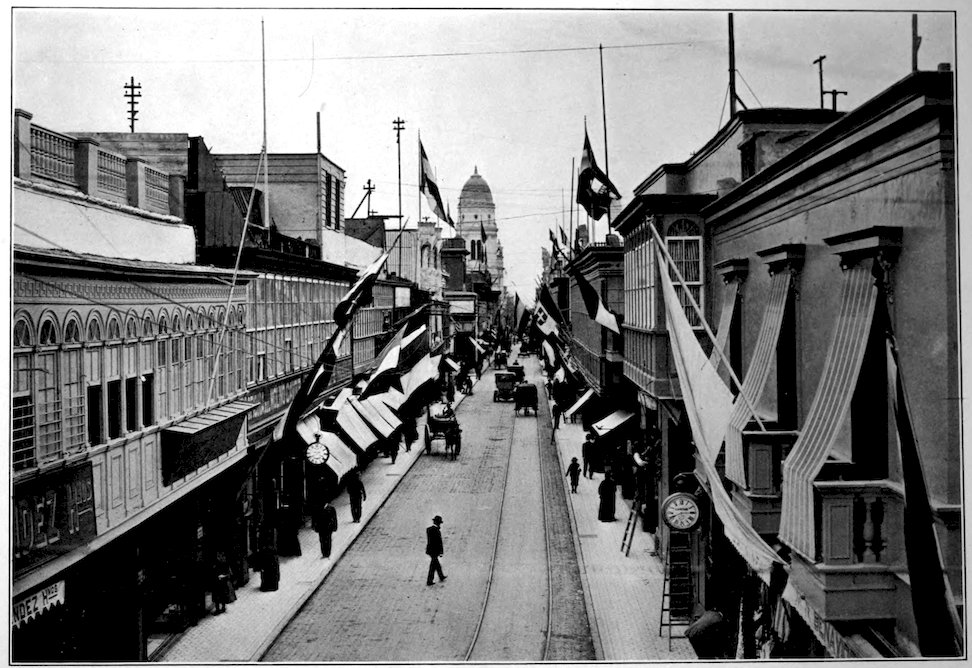

| ONE OF THE PRINCIPAL STREETS OF LIMA, DECORATED ON A NATIONAL HOLIDAY | 162 |

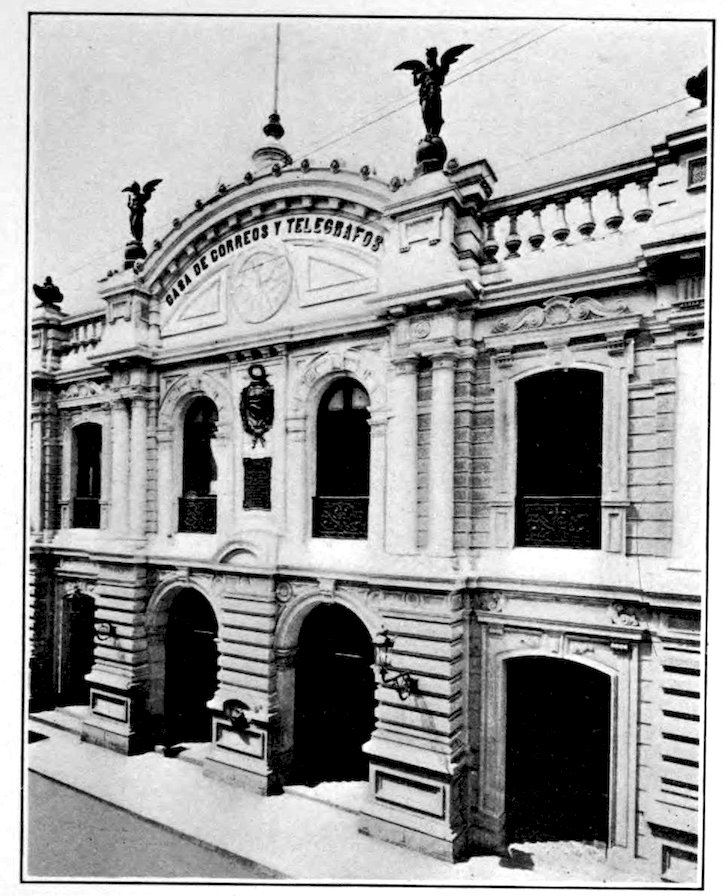

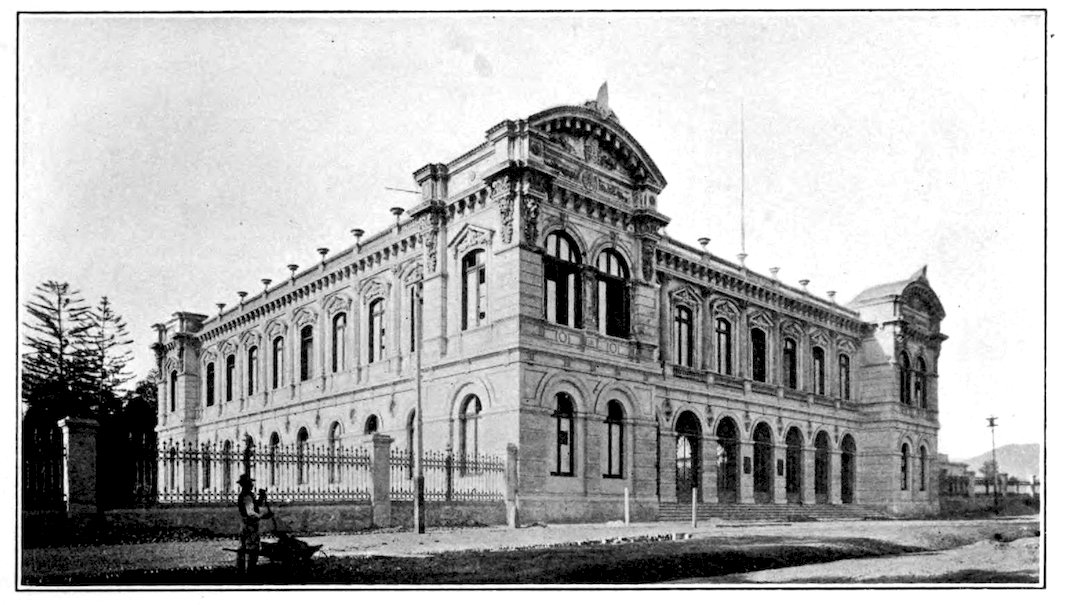

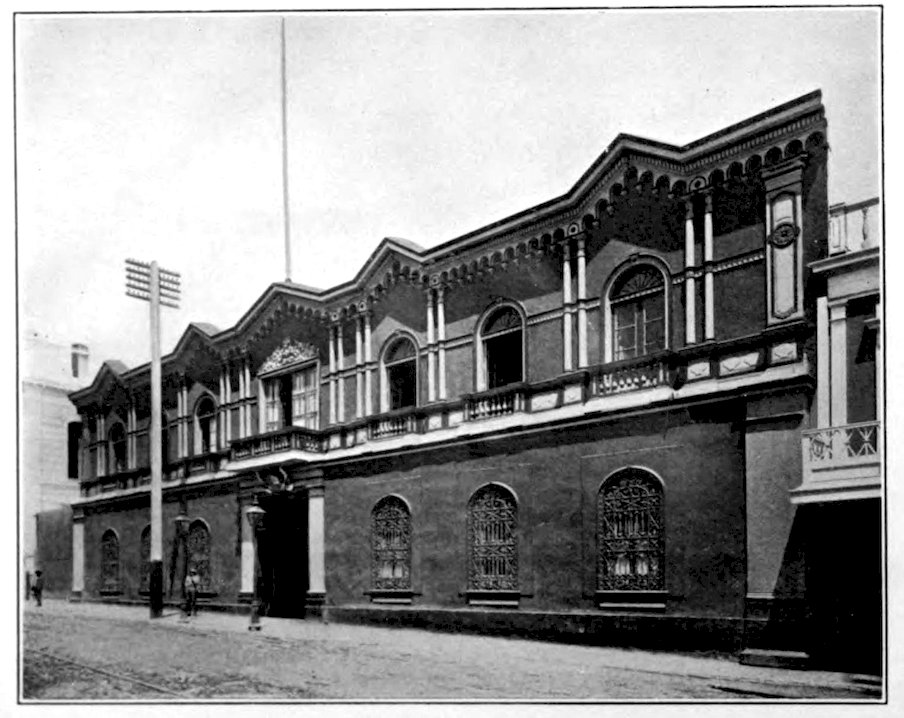

| POST OFFICE, LIMA | 163 |

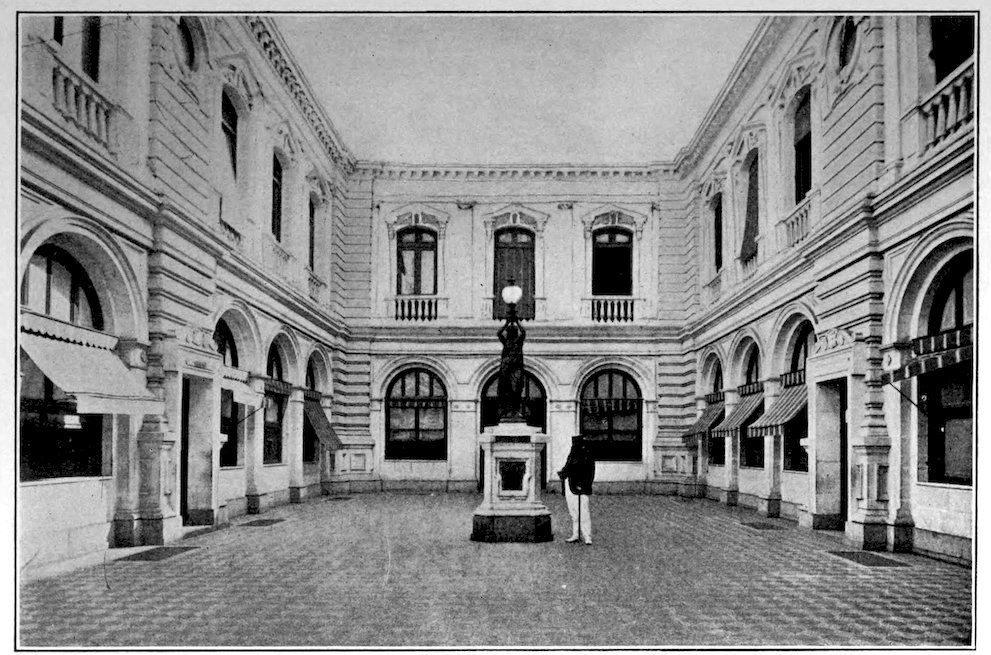

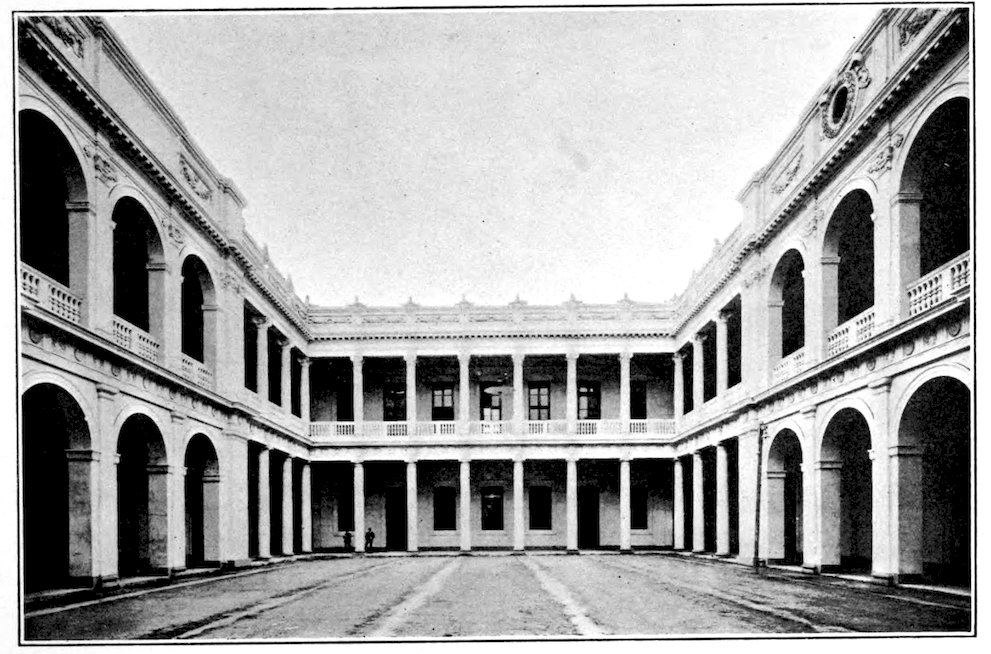

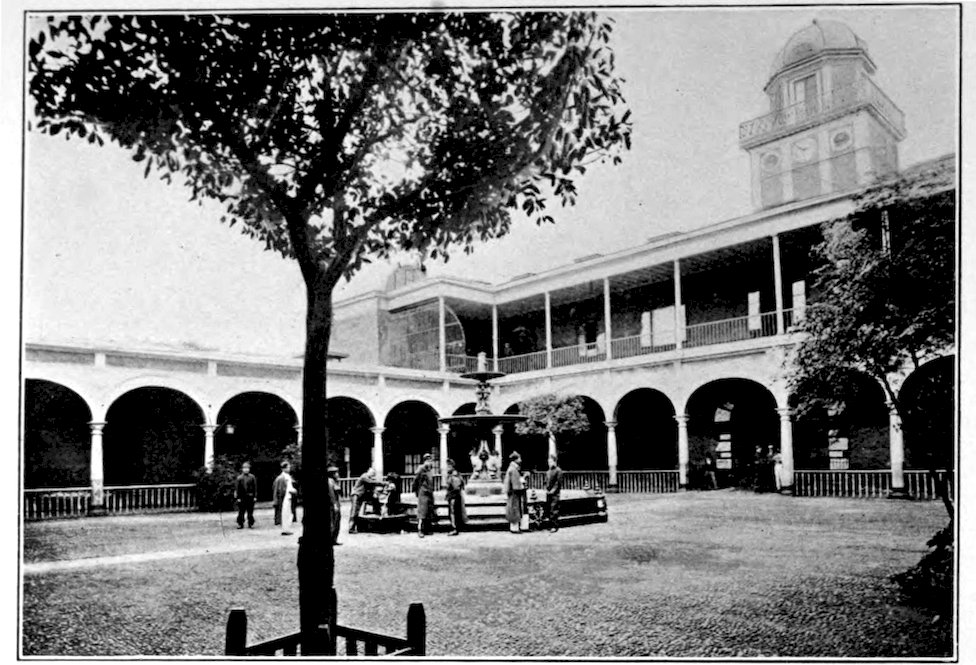

| PATIO OF THE POST OFFICE, LIMA | 165 |

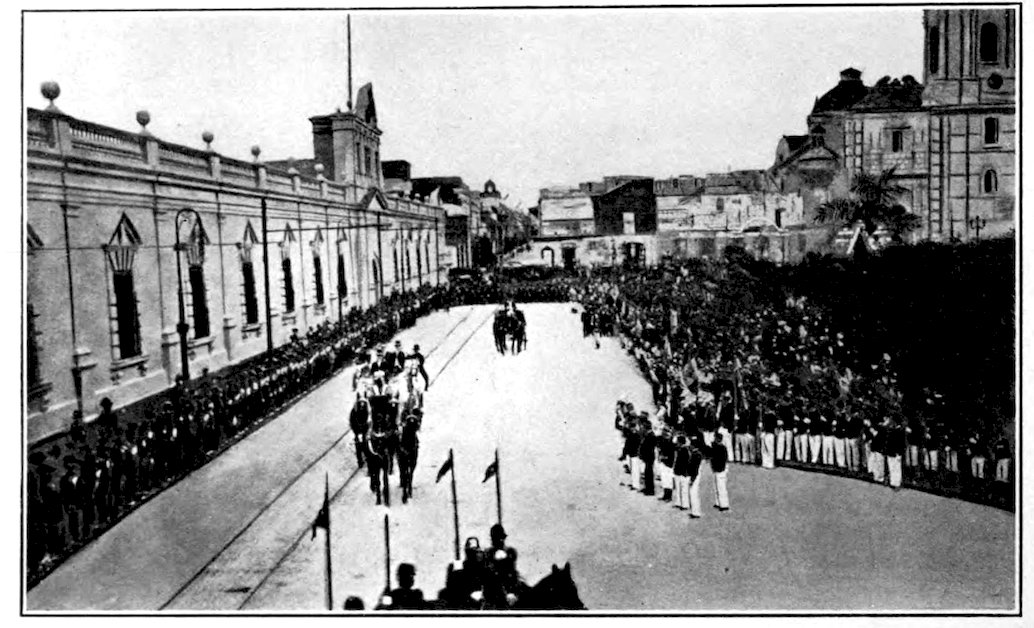

| THE PRESIDENT’S COACH LEAVING THE GOVERNMENT PALACE FOR THE HOUSE OF CONGRESS | 166 |

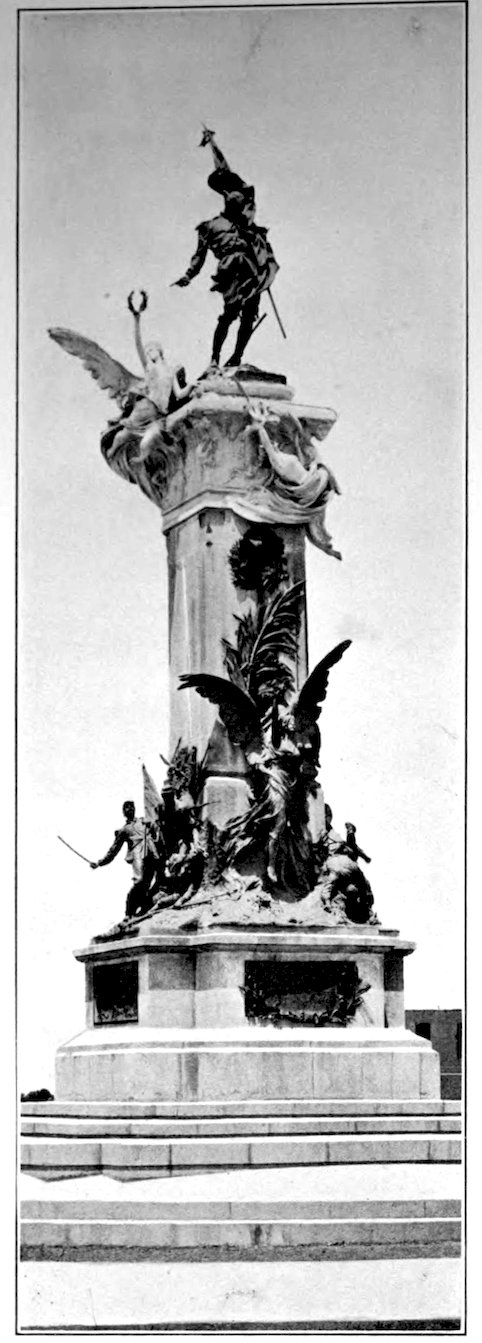

| MONUMENT TO BOLOGNESI | 168 |

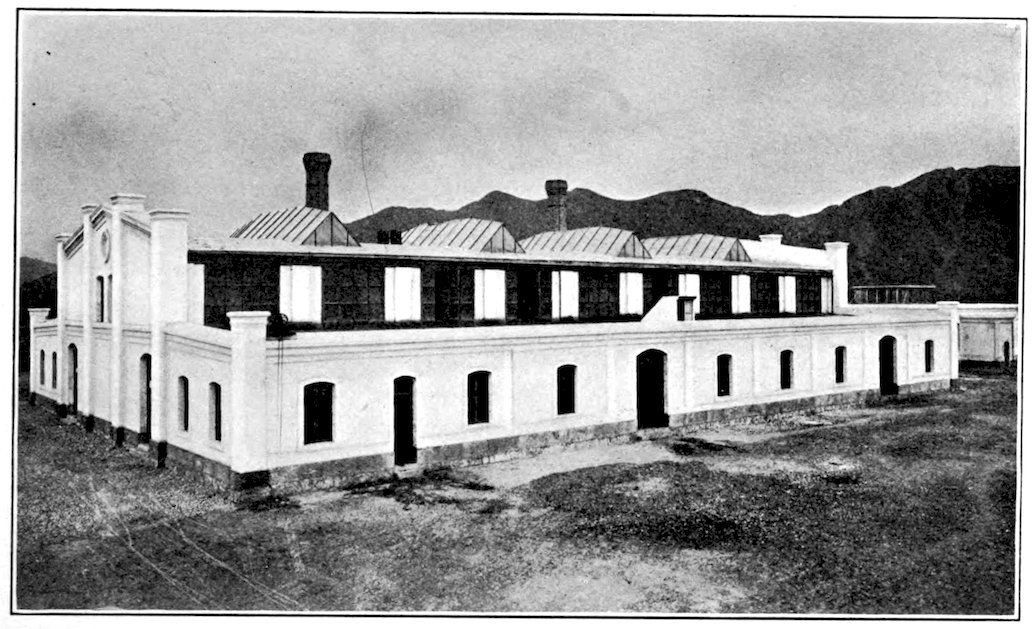

| THE WAR ARSENAL, LIMA | 169 |

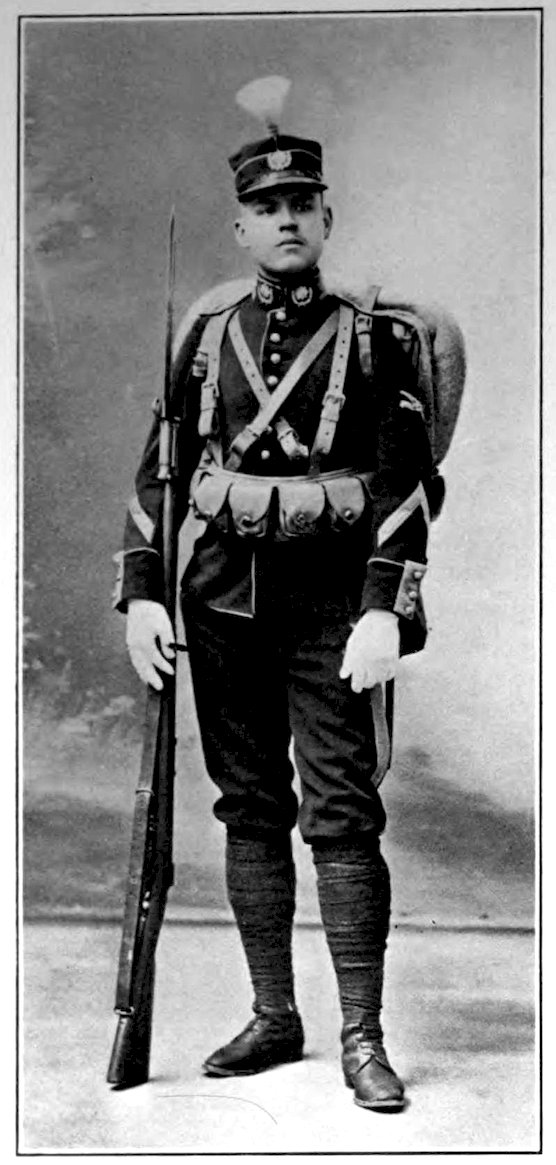

| INFANTRY UNIFORM, PERUVIAN ARMY | 170 |

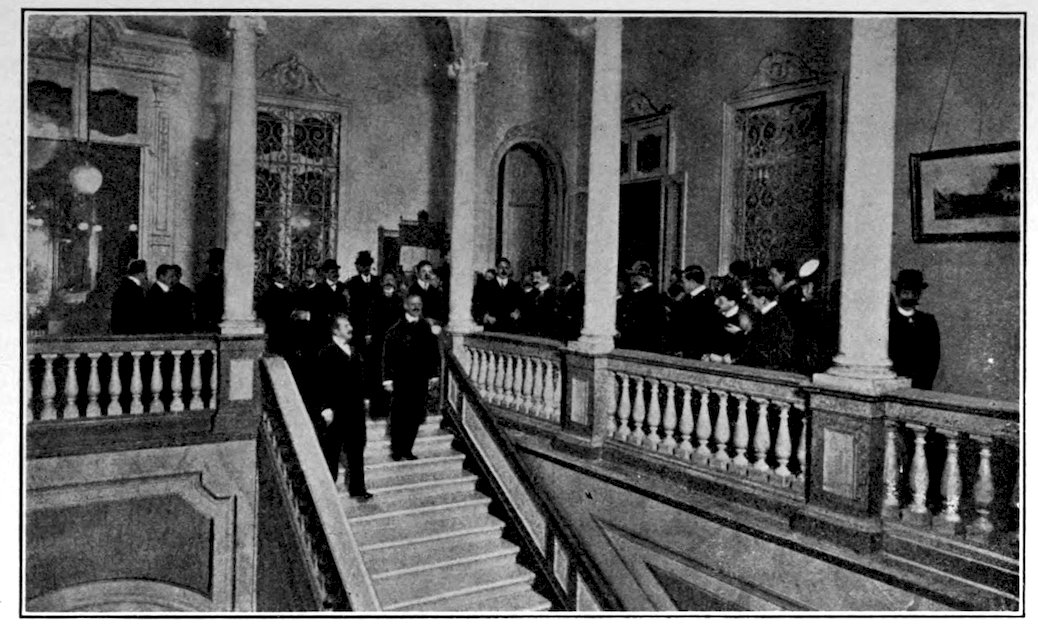

| MR. ROOT AT THE NATIONAL CLUB, LIMA | 171 |

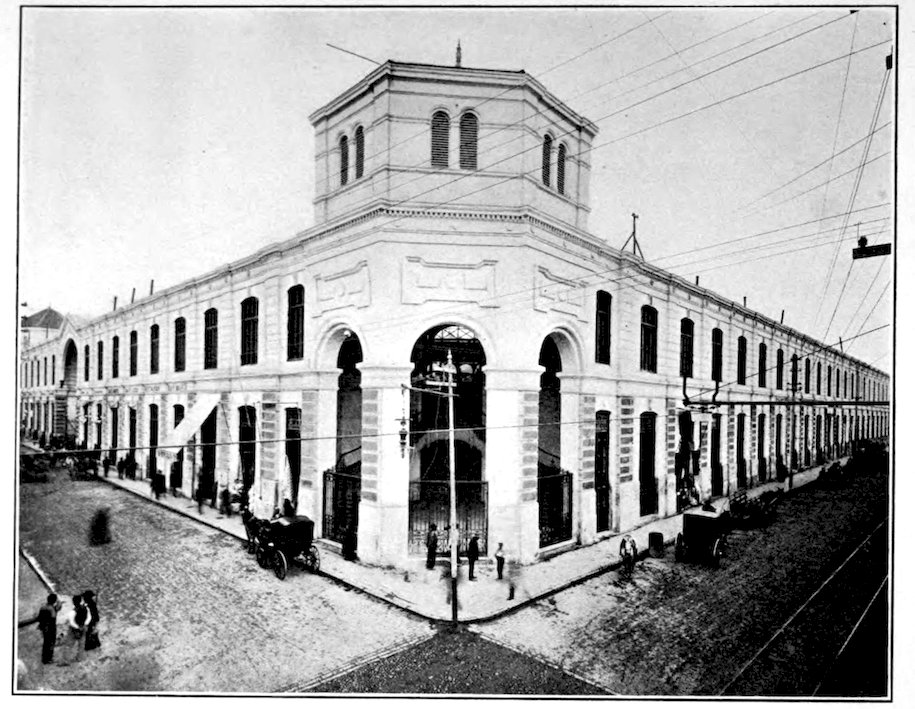

| THE CENTRAL MARKET, LIMA | 172 |

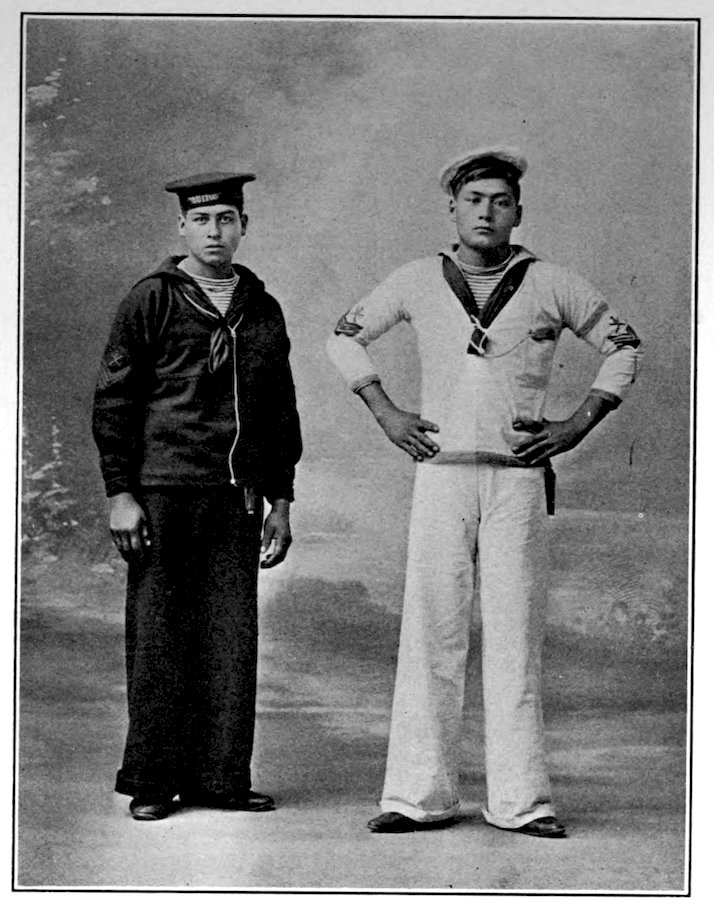

| PERUVIAN MARINES | 173 |

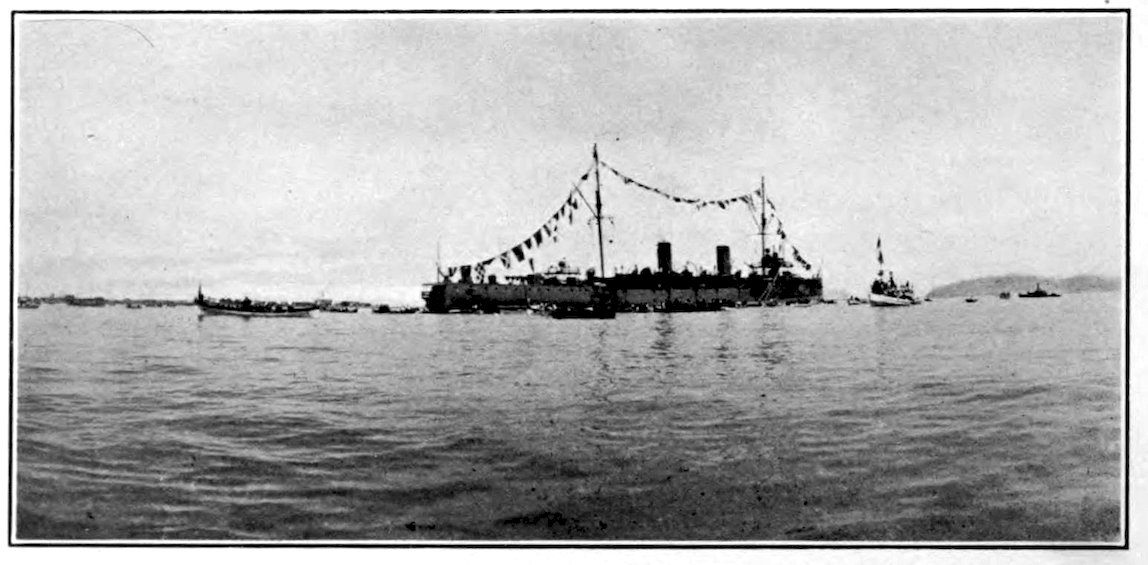

| THE PERUVIAN IRONCLAD GRAU, IN THE HARBOR OF CALLAO | 174 |

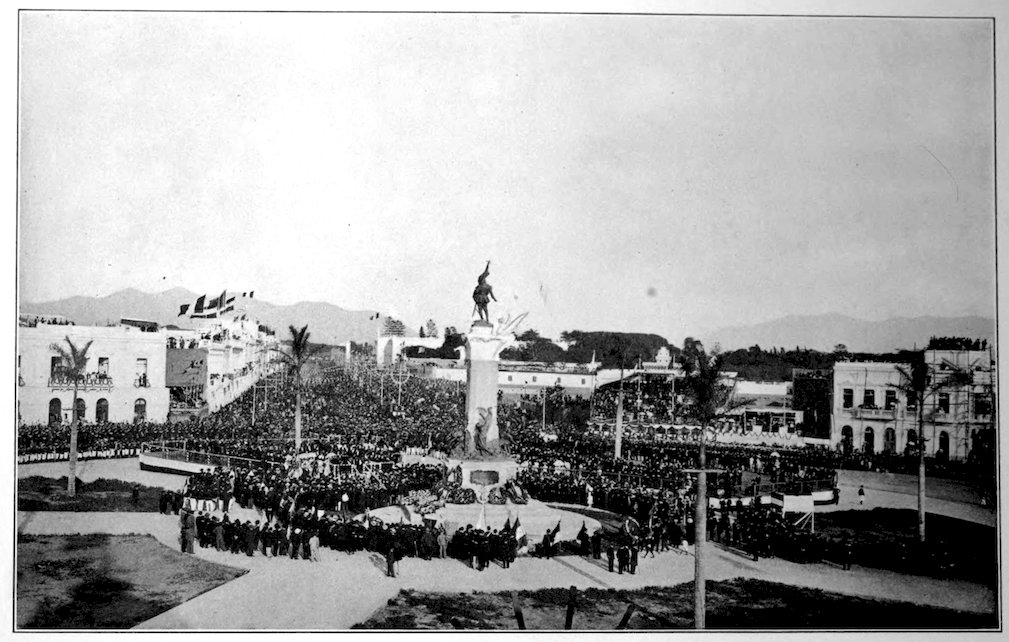

| THE UNVEILING OF BOLOGNESI’S STATUE IN LIMA | 176 |

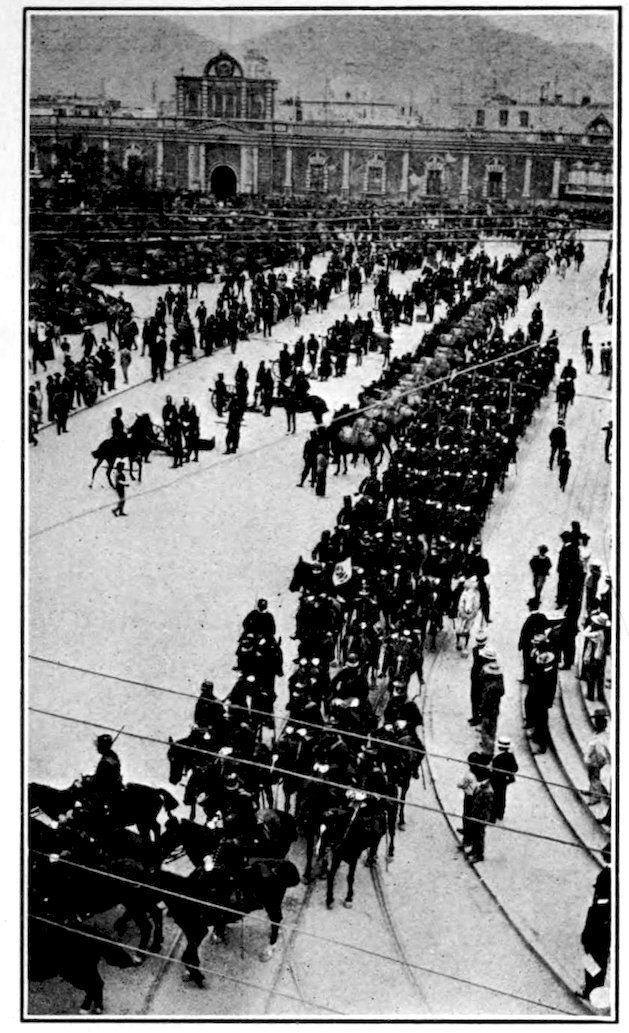

| A REVIEW OF THE TROOPS, LIMA | 177 |

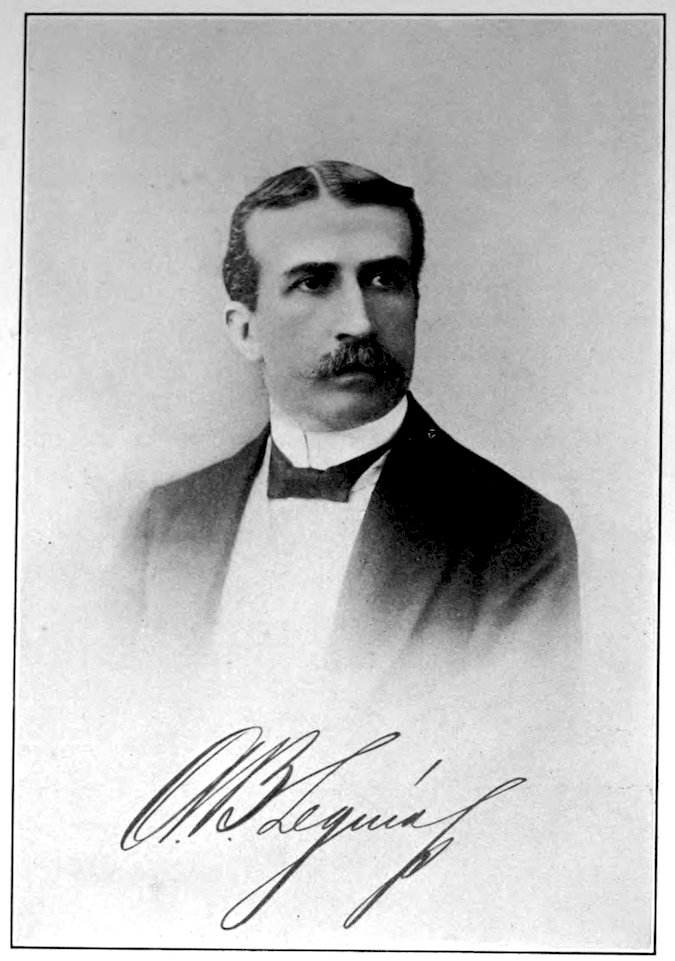

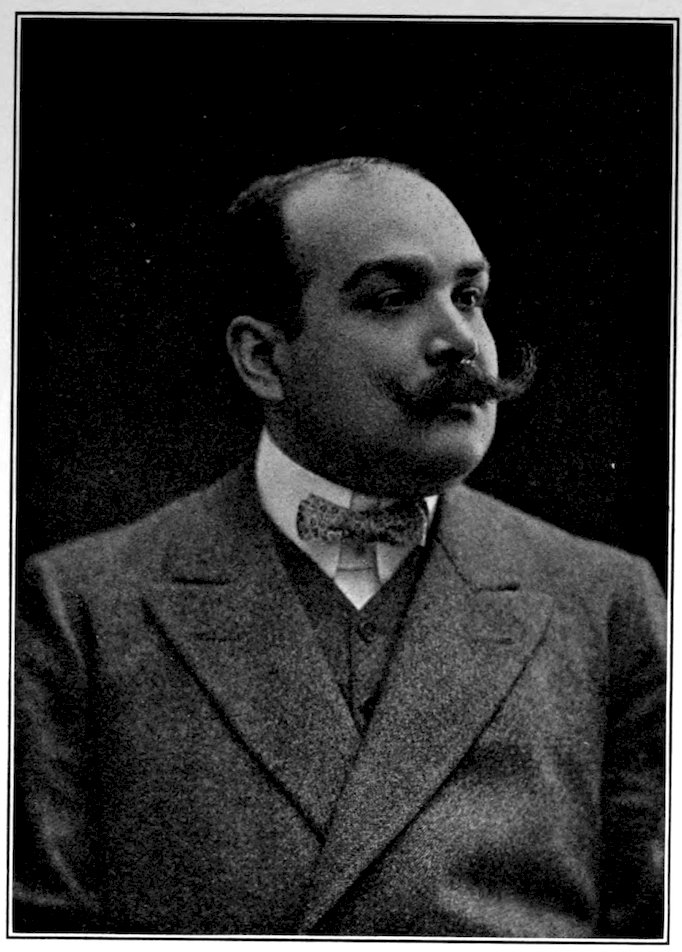

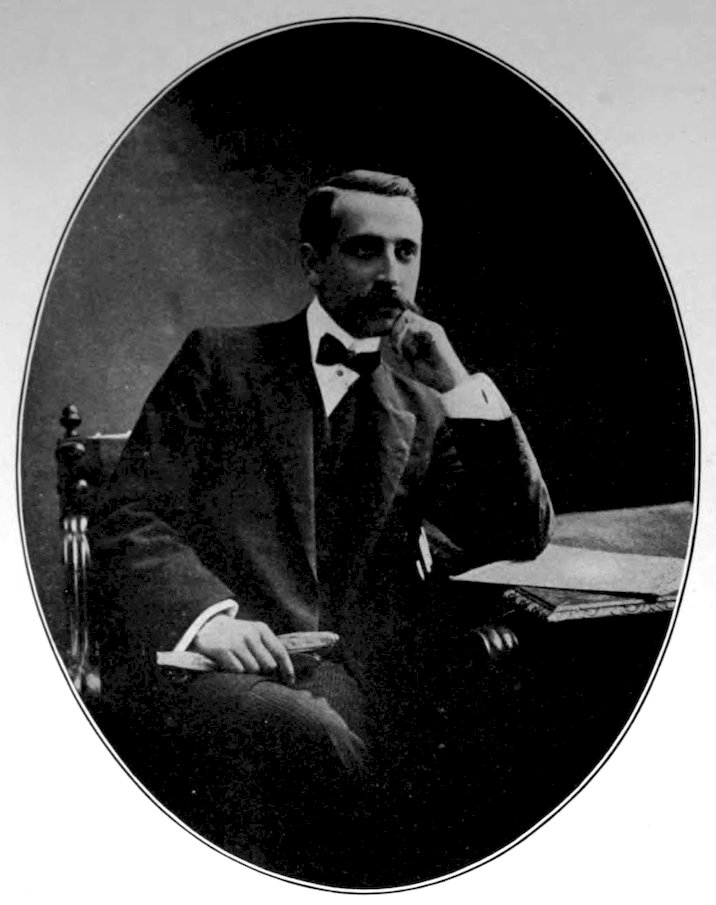

| HIS EXCELLENCY DR. AUGUSTO B. LEGUIA, ELECTED PRESIDENT OF PERU 1908–1912, TO BE INAUGURATED SEPTEMBER 24, 1908 | 178 |

| DR. EUGENIO LARRABURE Y UNÁNUE, ELECTED VICE-PRESIDENT FOR TERM 1908–1912 | 179 |

| THE MILITARY SCHOOL, CHORILLOS | 180 |

| DR. SOLÓN POLO, MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS IN PRESIDENT JOSÉ PARDO’S CABINET | 181 |

| DR. CARLOS WASHBURN, PRESIDENT OF DR. PARDO’S CABINET | 182 |

| THE MINT, LIMA | 183 |

| REVIEW OF ARTILLERY TROOPS, LIMA | 184 |

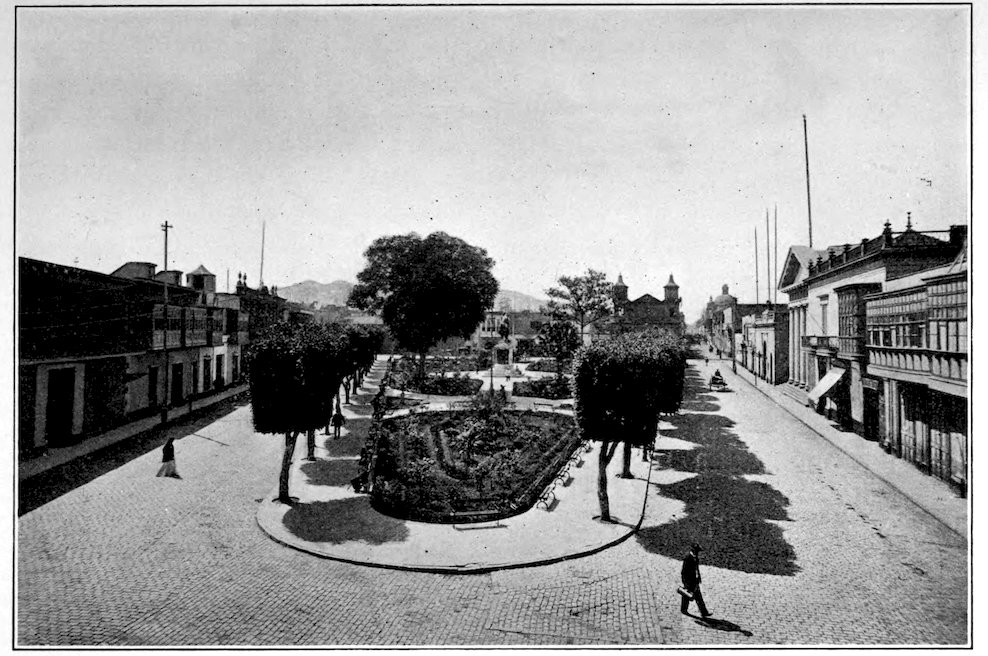

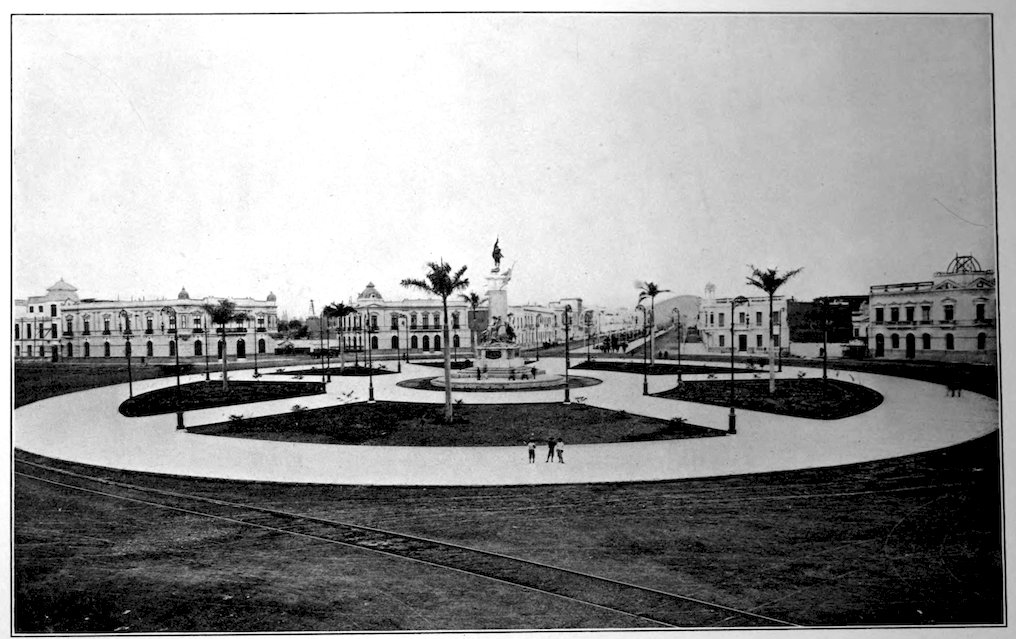

| BOLOGNESI CIRCLE, PASEO COLÓN, LIMA | 186 |

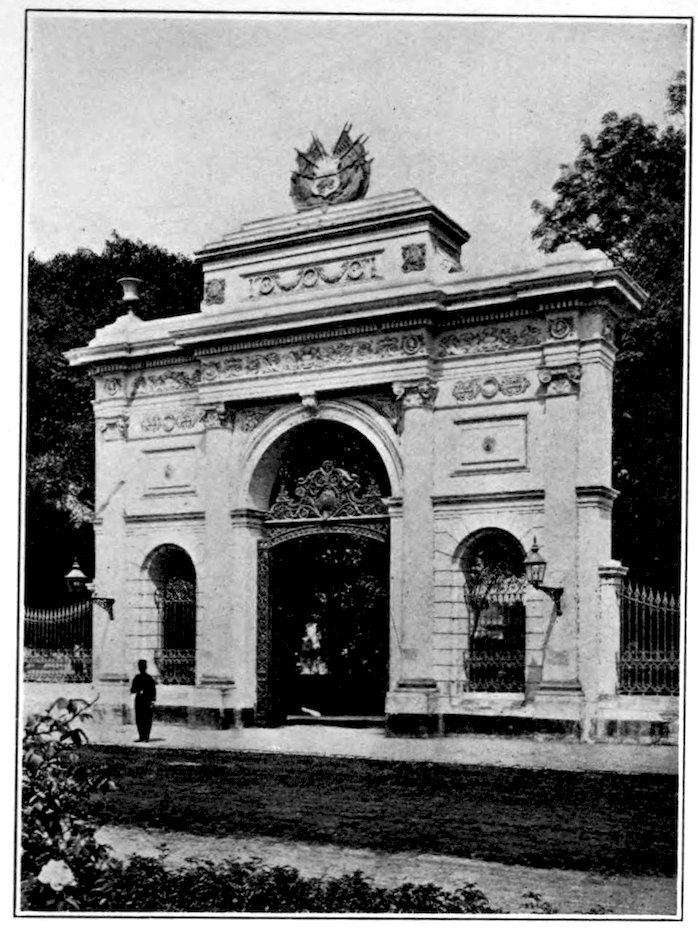

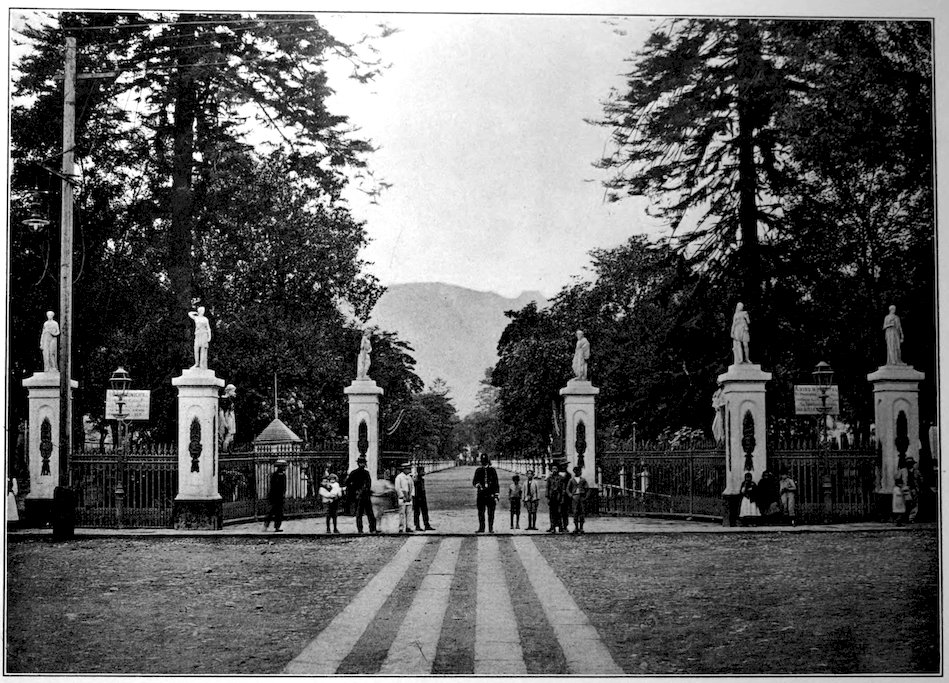

| ENTRANCE TO MUNICIPAL PARK | 187 |

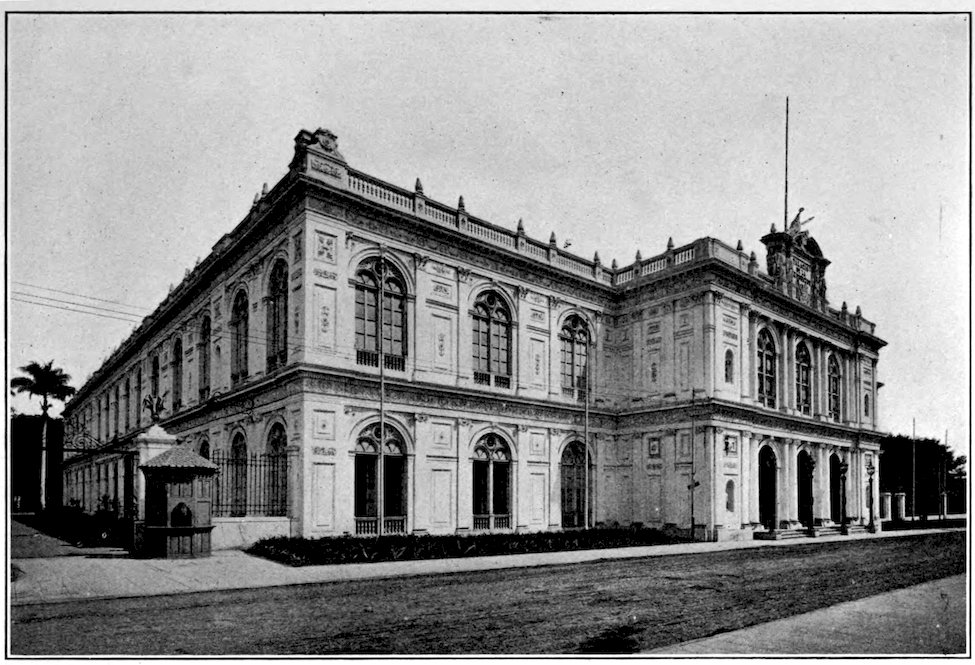

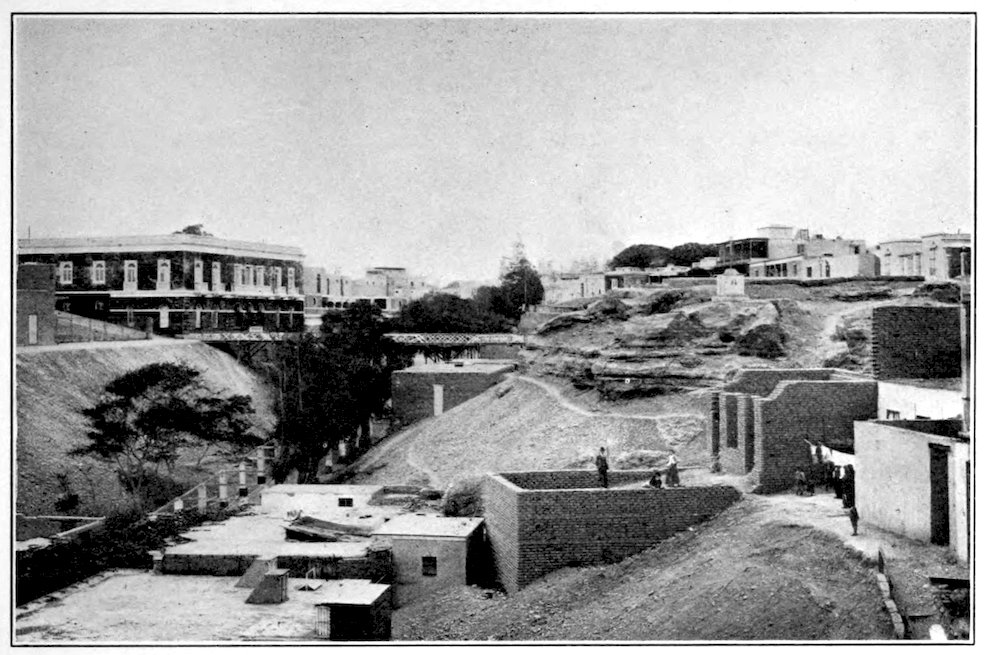

| THE NATIONAL MUSEUM, LIMA | 189 |

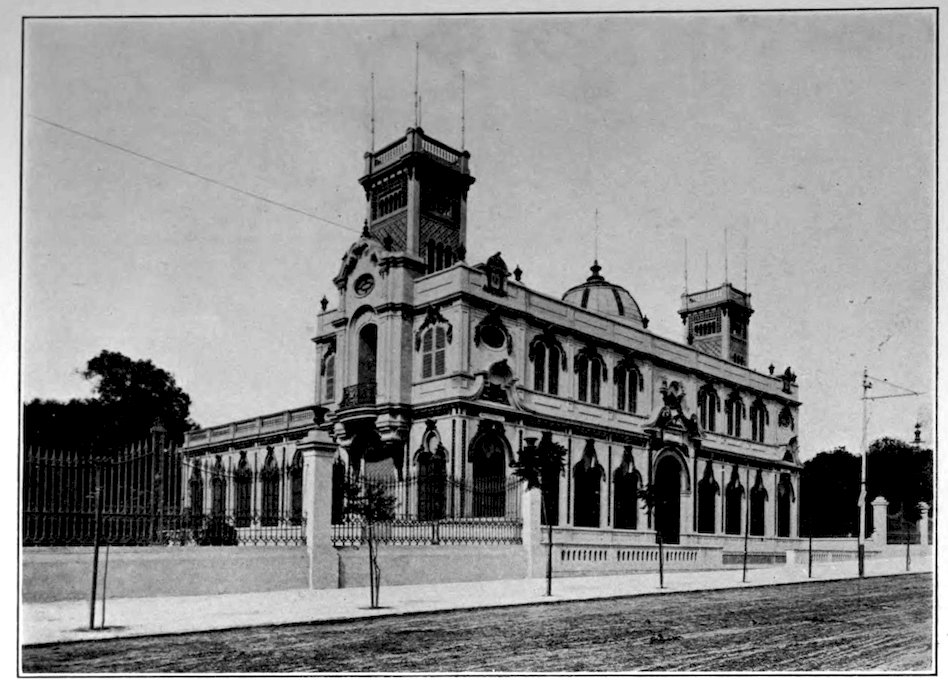

| THE MUNICIPAL INSTITUTE OF HYGIENE | 190 |

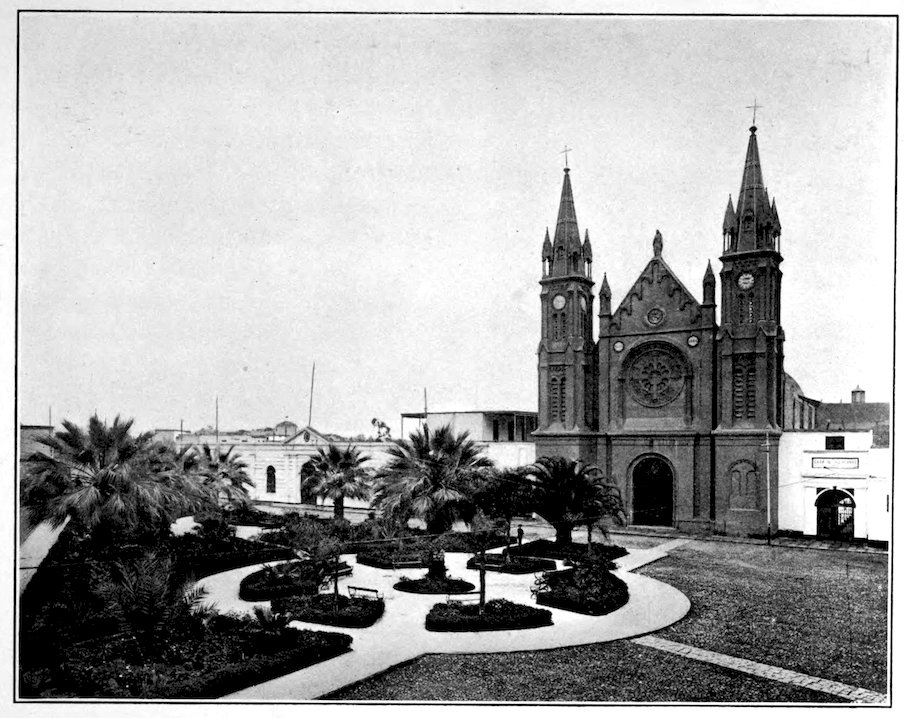

| PLAZUELA DE LA RECOLETA | 191 |

| STATUE OF COLUMBUS IN THE PASEO COLÓN | 192 |

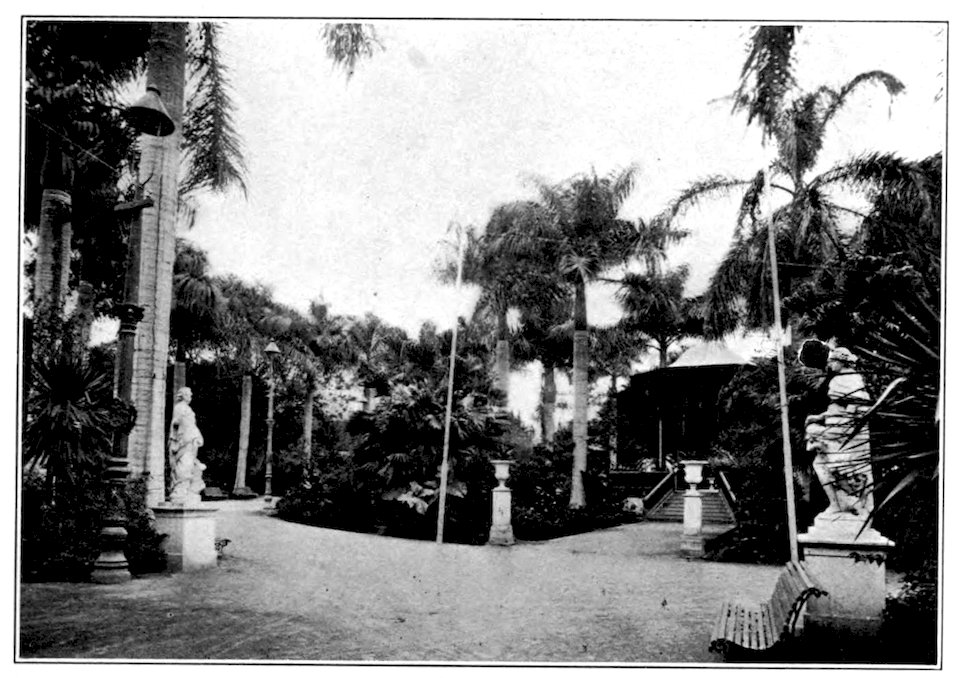

| KIOSK OF PALMS, EXPOSITION PARK | 193 |

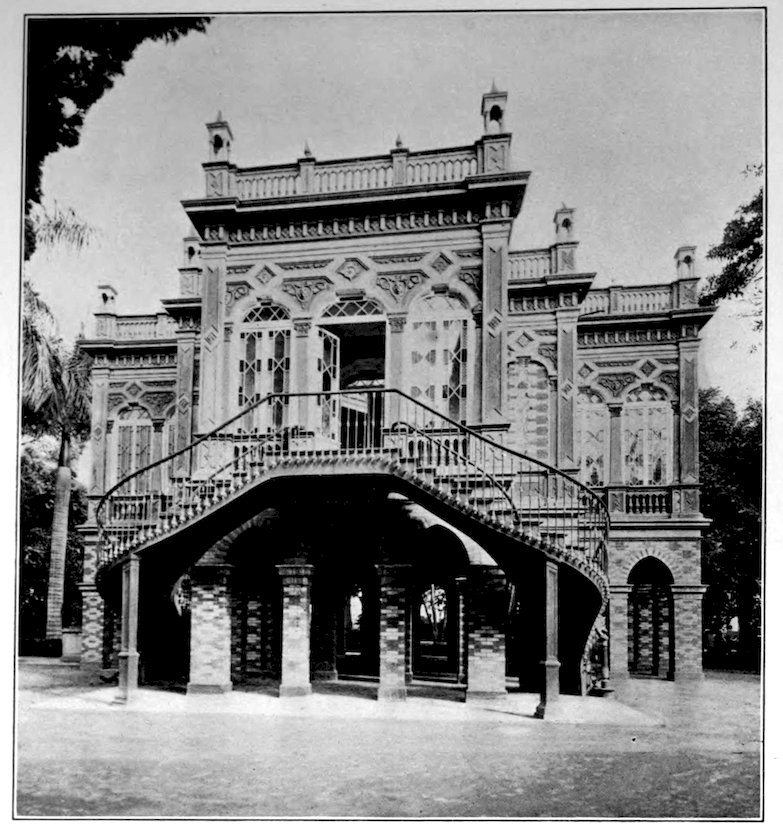

| PAVILION IN EXPOSITION PARK | 194 |

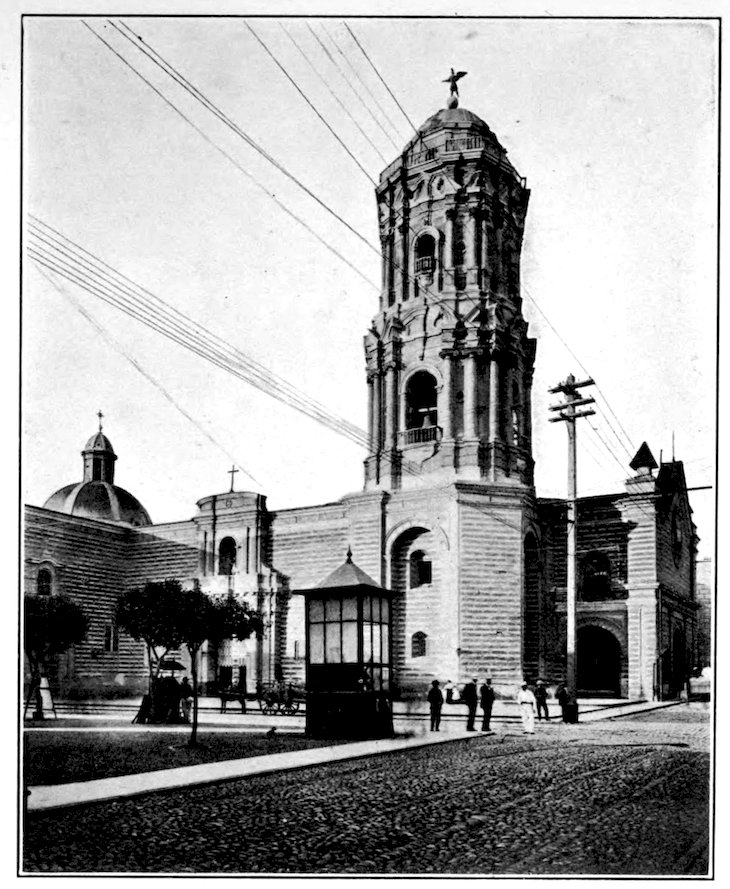

| CHURCH OF SANTO DOMINGO | 195 |

| SAN PEDRO, THE FASHIONABLE CHURCH OF LIMA | 196 |

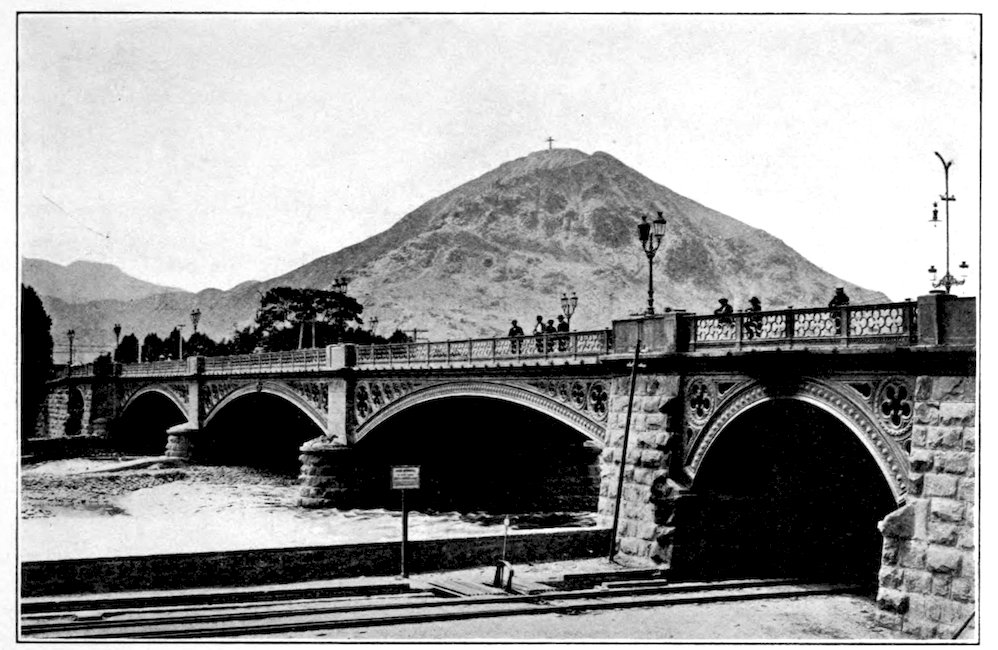

| THE BALTA BRIDGE OVER THE RIMAC RIVER | 197 |

| PASEO COLÓN—THE FAVORITE DRIVEWAY OF LIMA | 198 |

| THE PRESENT STANDARD OF LIMA, AS MODIFIED IN 1808 | 200 |

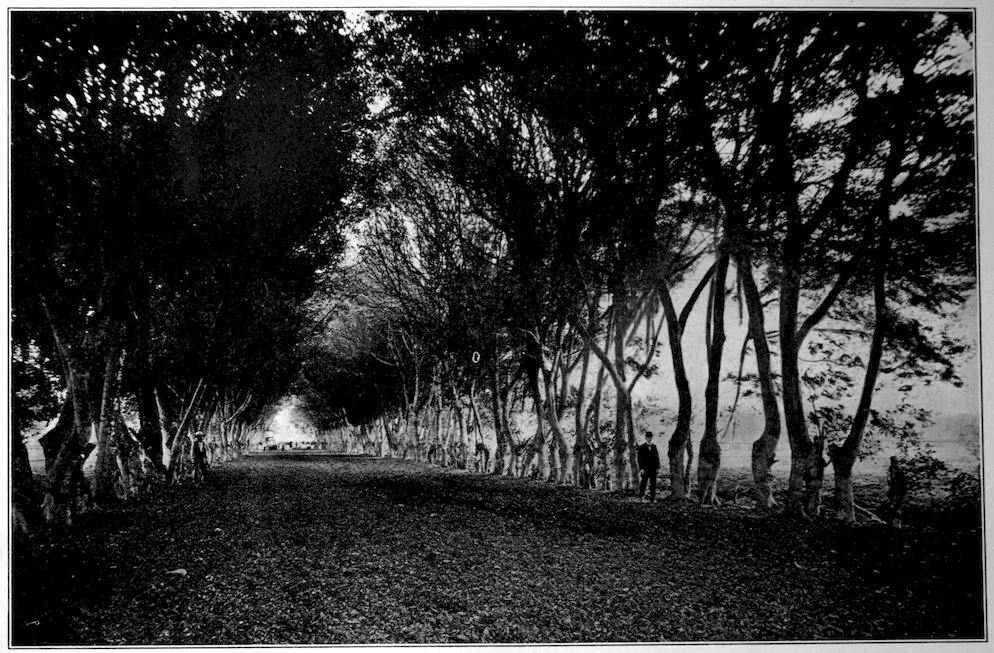

| A PICTURESQUE SUBURBAN DRIVEWAY, LIMA | 202 |

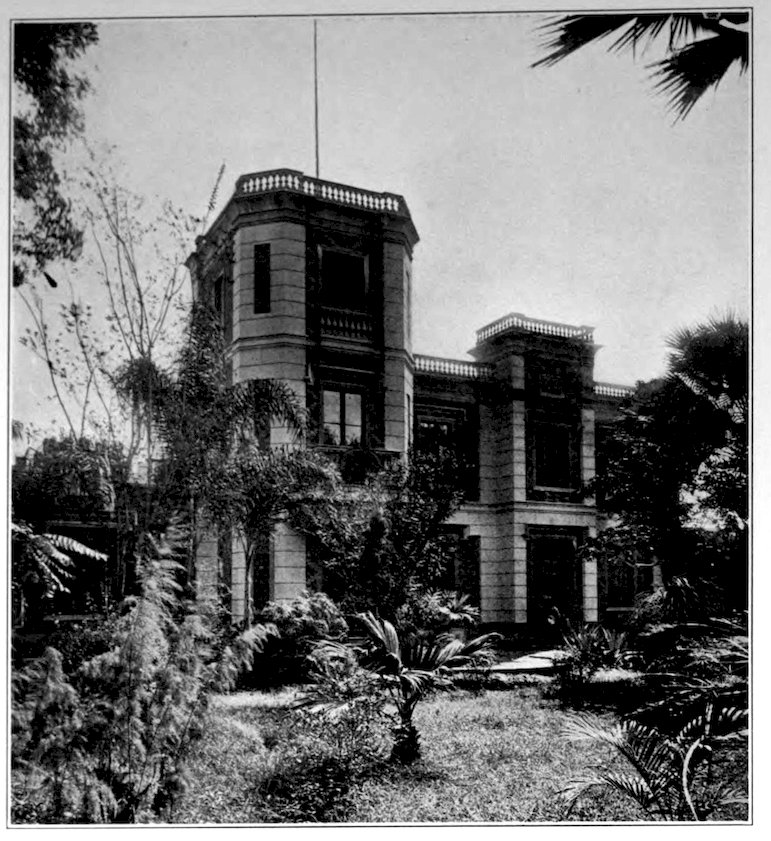

| A MODERN PRIVATE RESIDENCE OF LIMA | 203 |

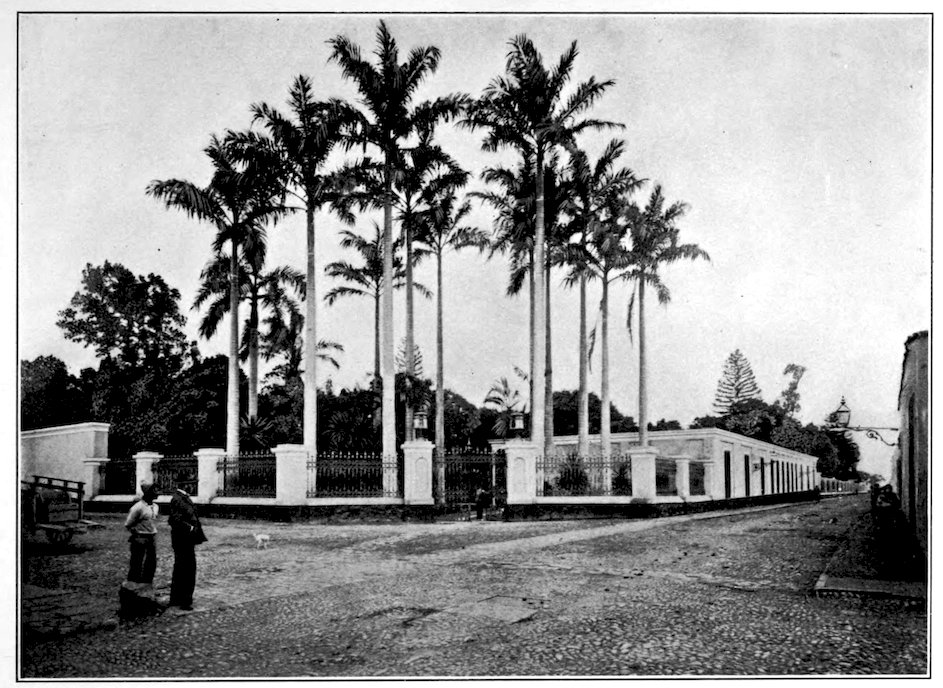

| ENTRANCE TO THE BOTANICAL GARDEN, LIMA | 205 |

| GRAND STAND OF THE JOCKEY CLUB, LIMA | 206 |

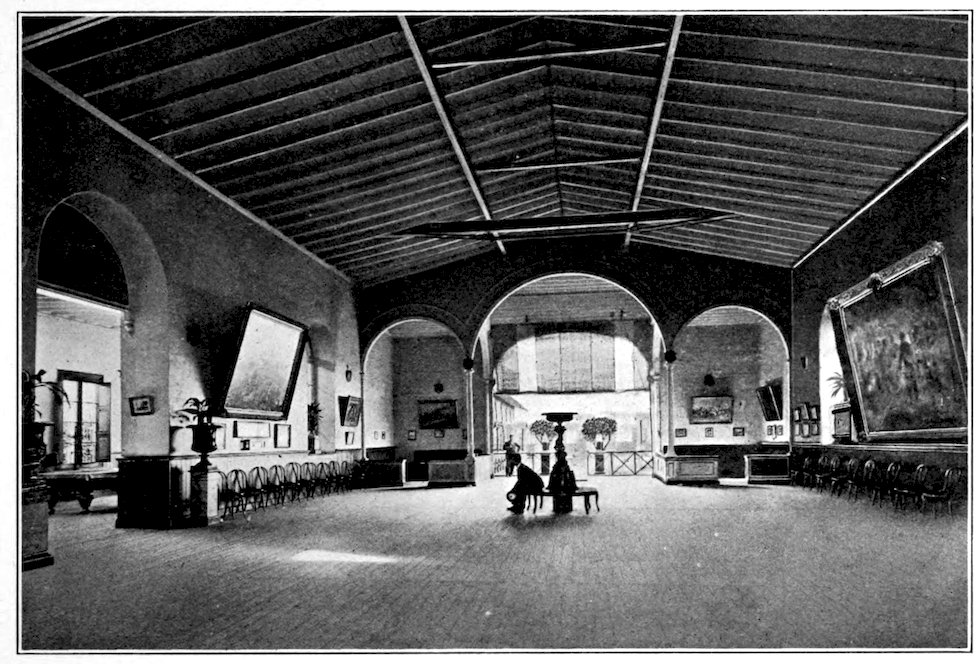

| PRINCIPAL HALL OF THE INTERNATIONAL REVOLVER CLUB, LIMA | 207 |

| THE AMERICAN LEGATION AT LIMA | 208 |

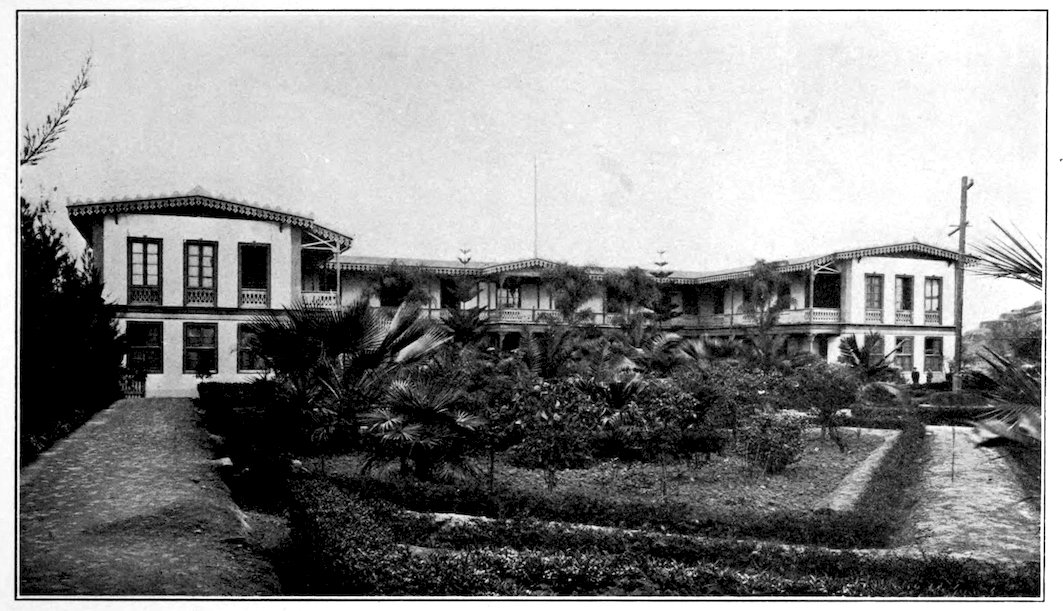

| BARRANCO, A SEASIDE SUBURB OF LIMA | 209 |

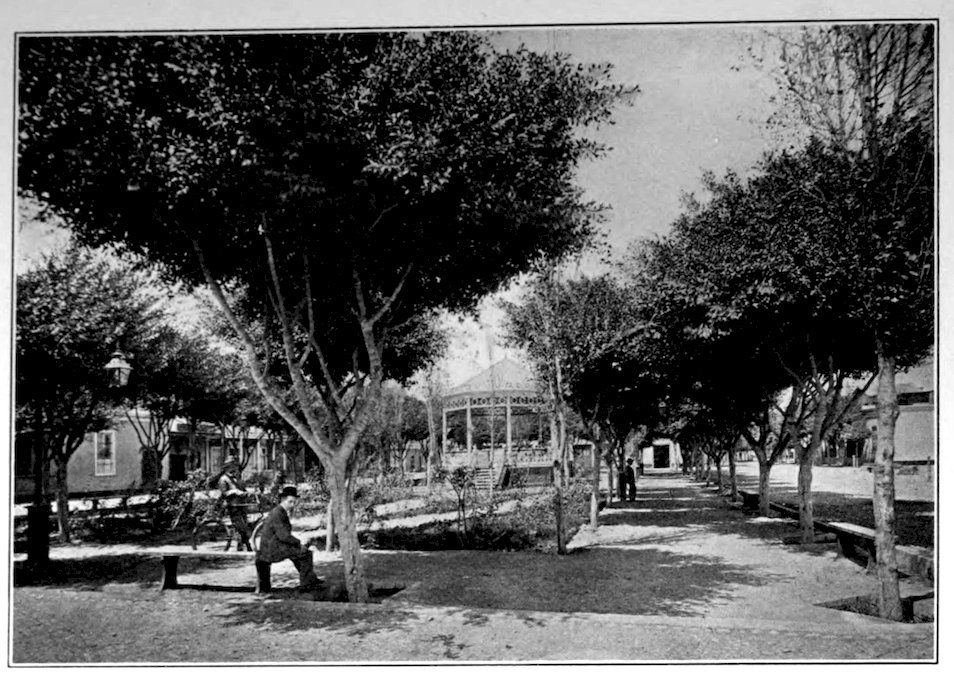

| PARK AT BARRANCO | 210 |

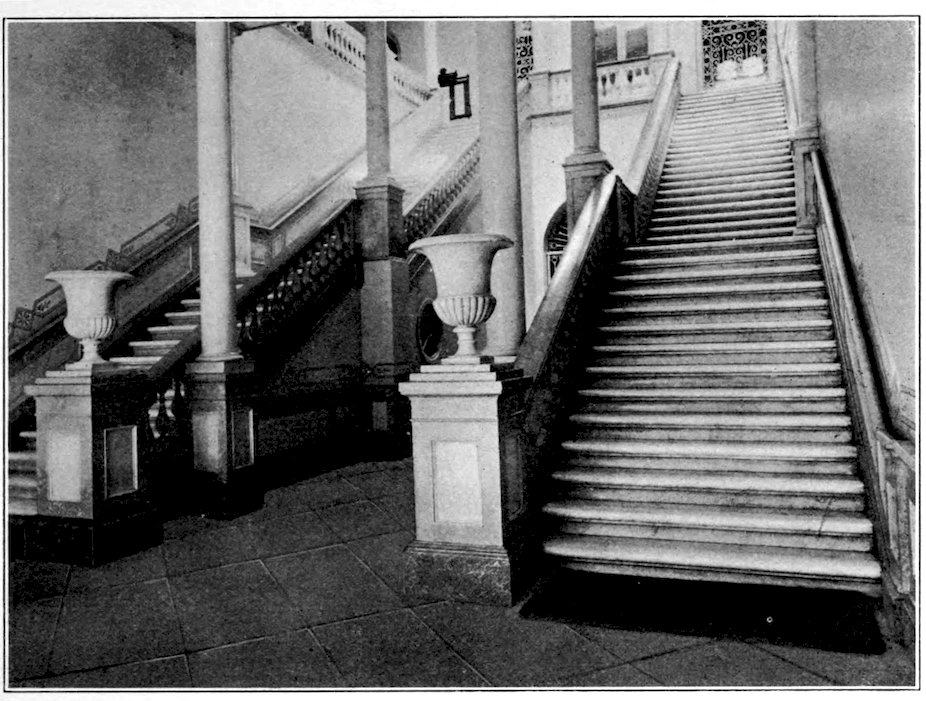

| STAIRWAY OF THE NATIONAL CLUB, LIMA | 211 |

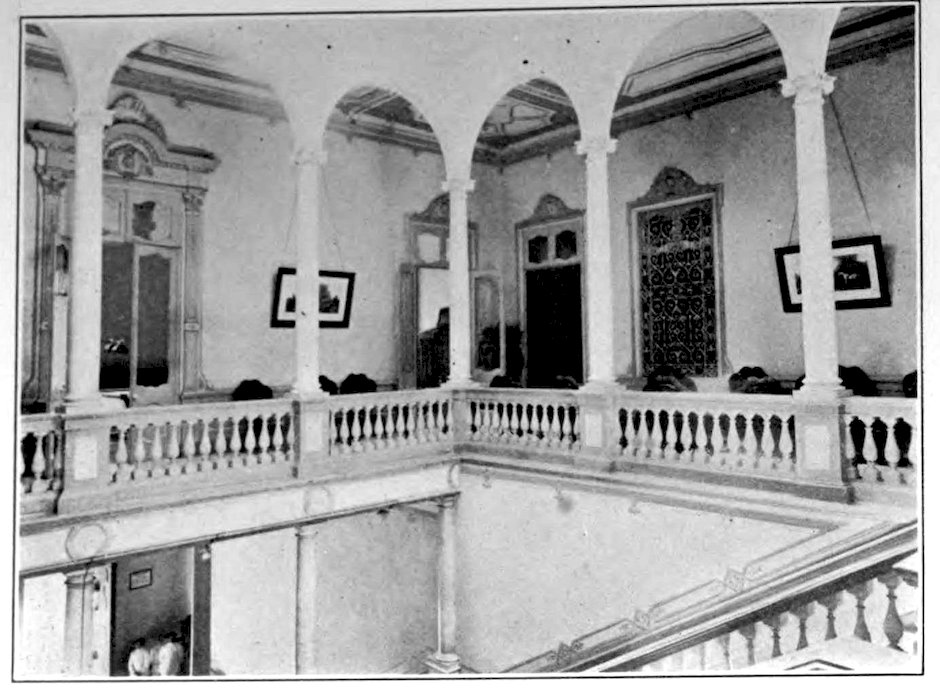

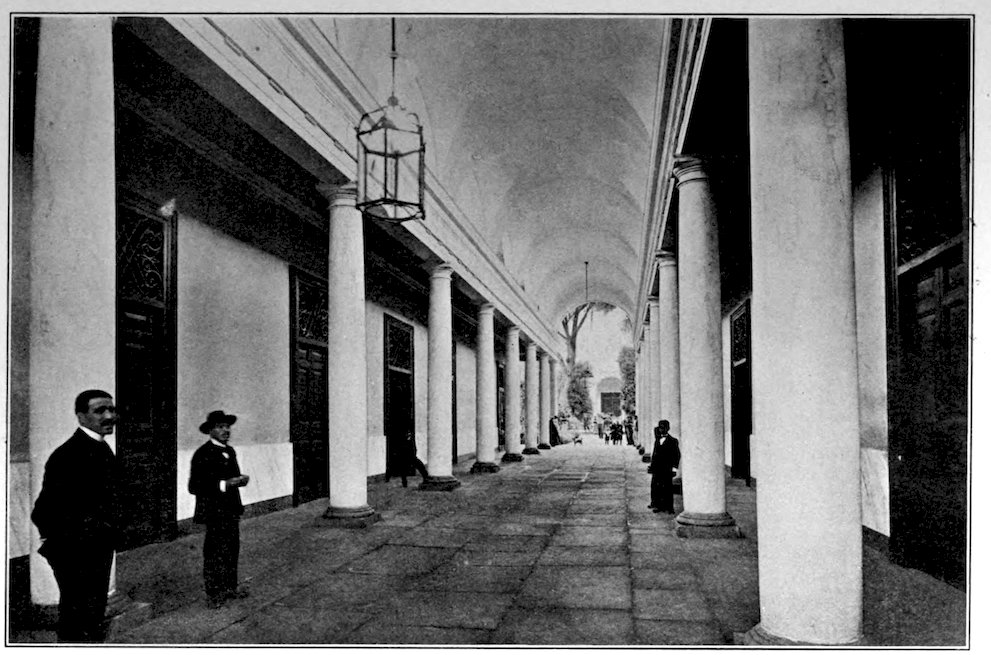

| MAIN CORRIDOR OF THE NATIONAL CLUB, LIMA | 212 |

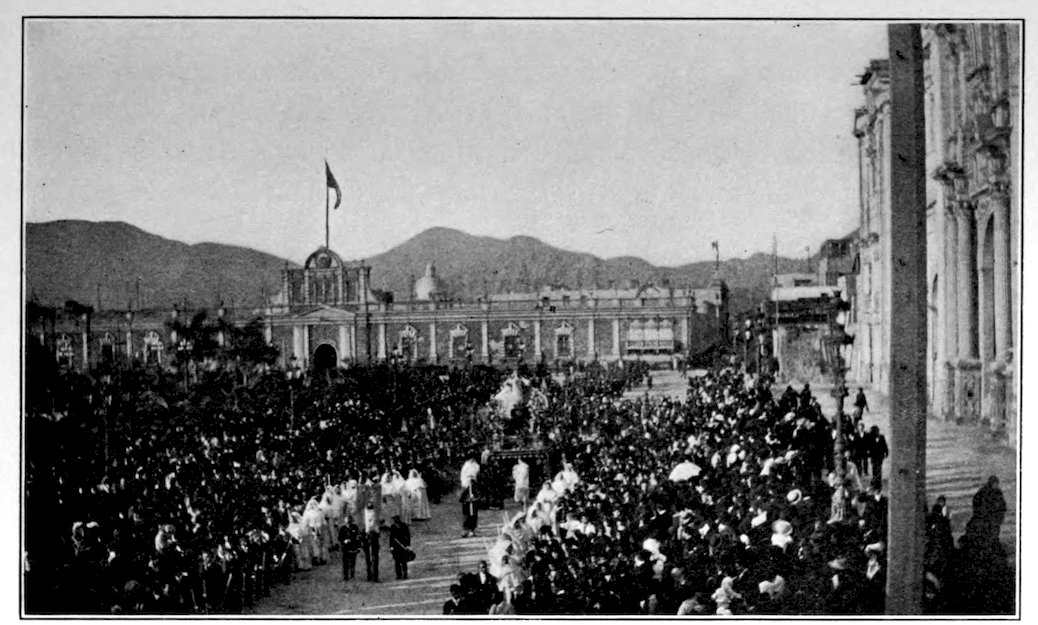

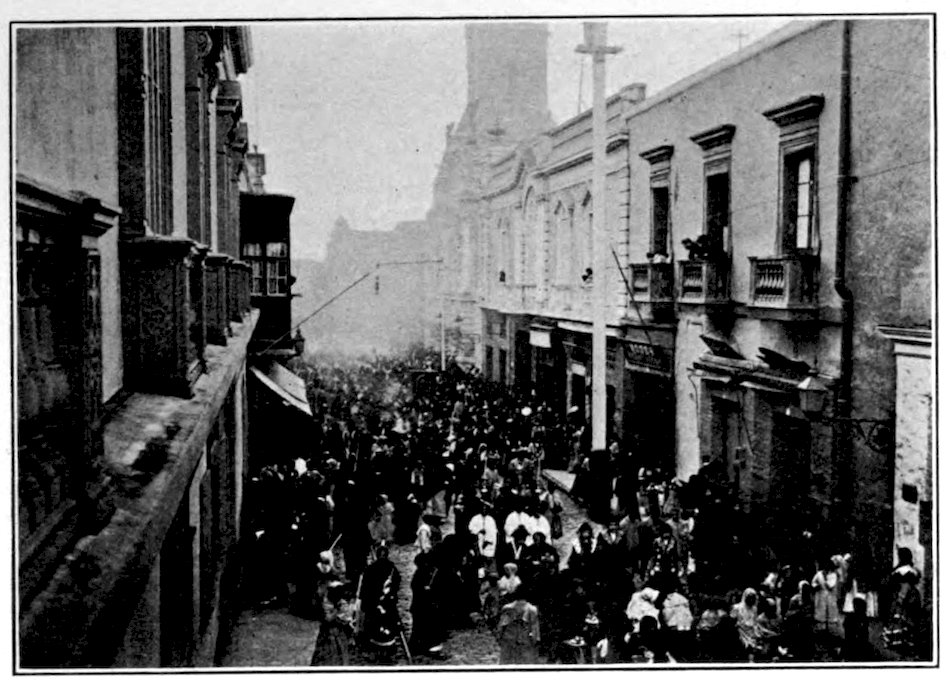

| ANNUAL PROCESSION IN HONOR OF SAINT ROSE OF LIMA | 213 |

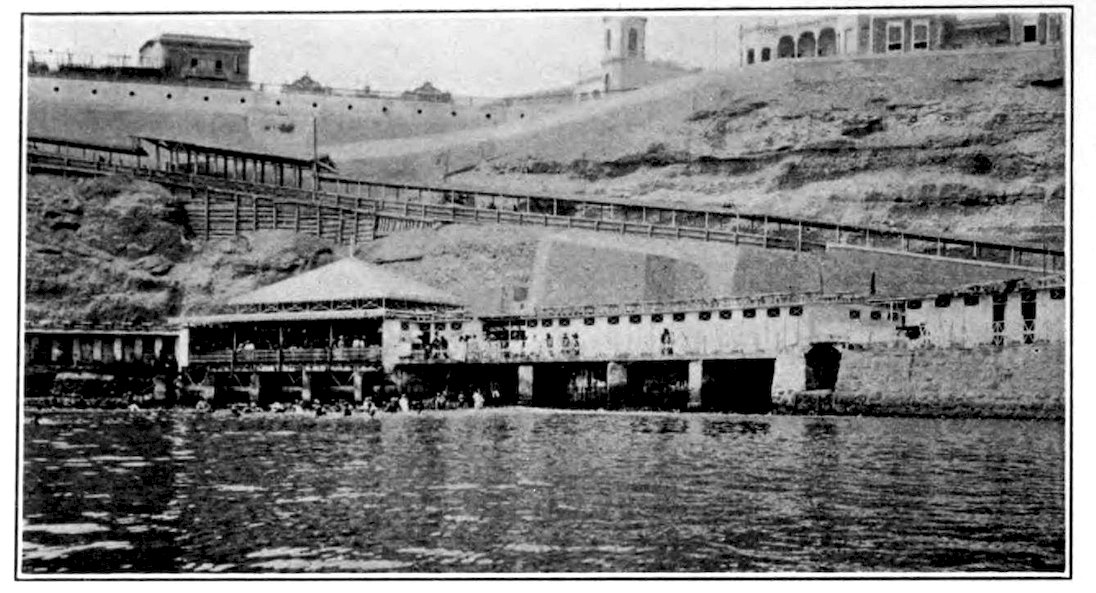

| ROAD TO THE BEACH, CHORILLOS | 214 |

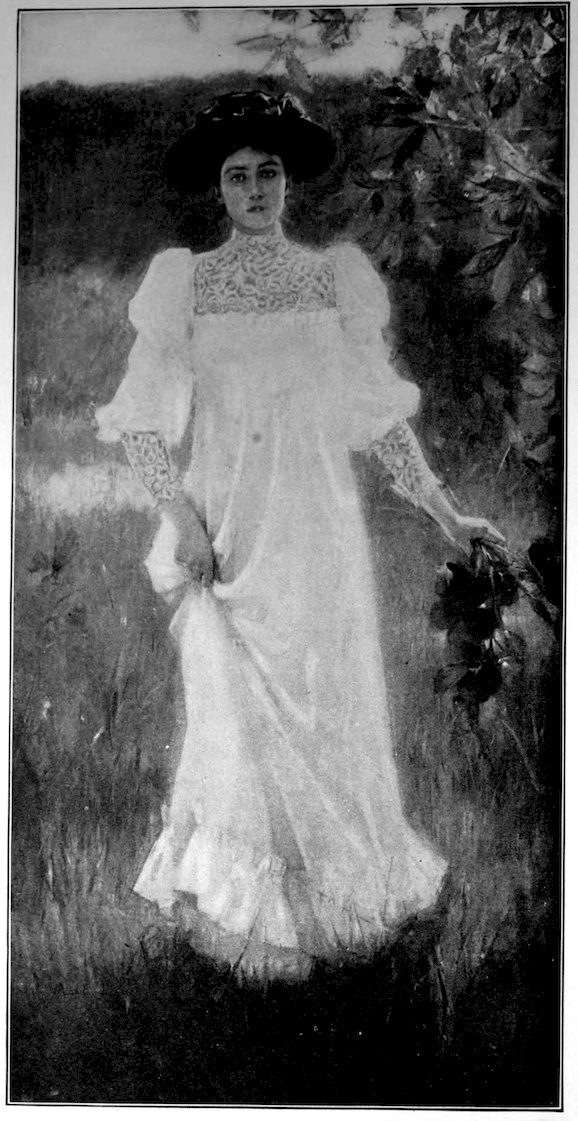

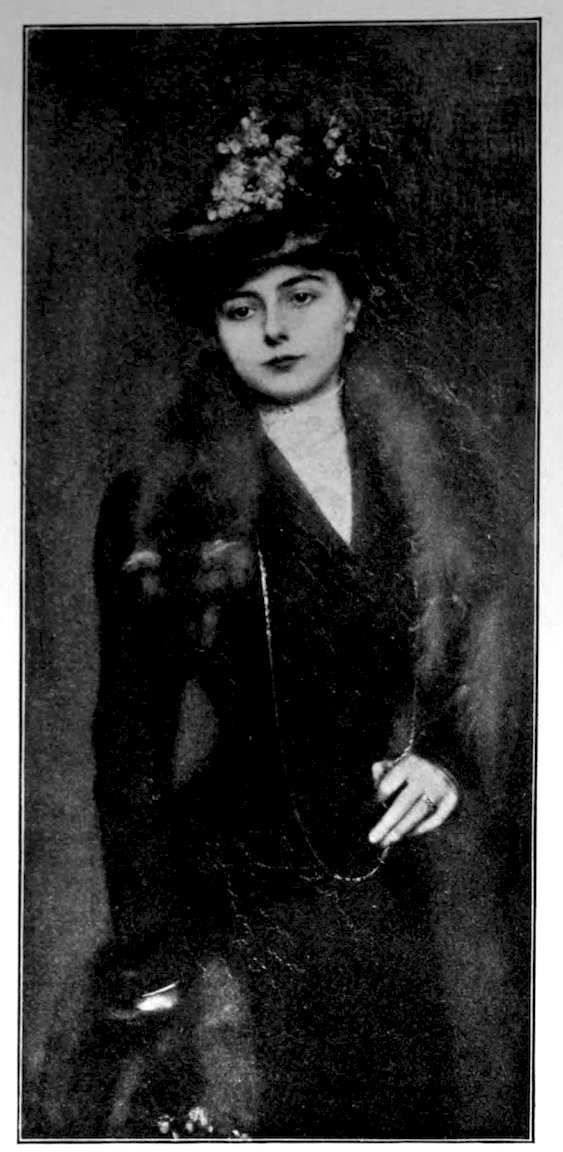

| PORTRAIT. BY ALBERT LYNCH | 216 |

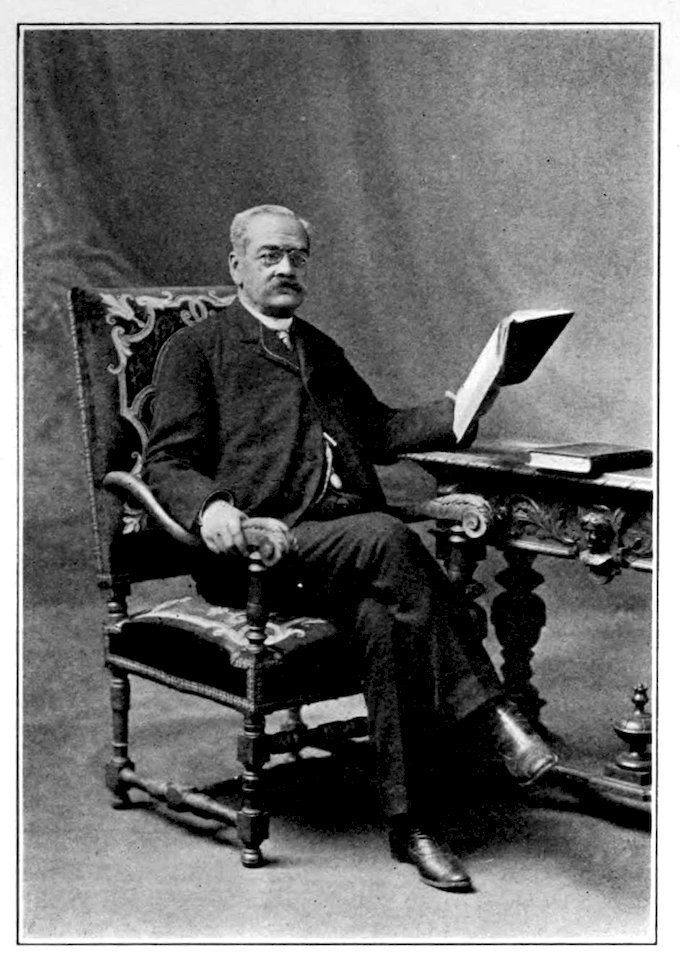

| DR. RICARDO PALMA, DIRECTOR OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY, LIMA | 217 |

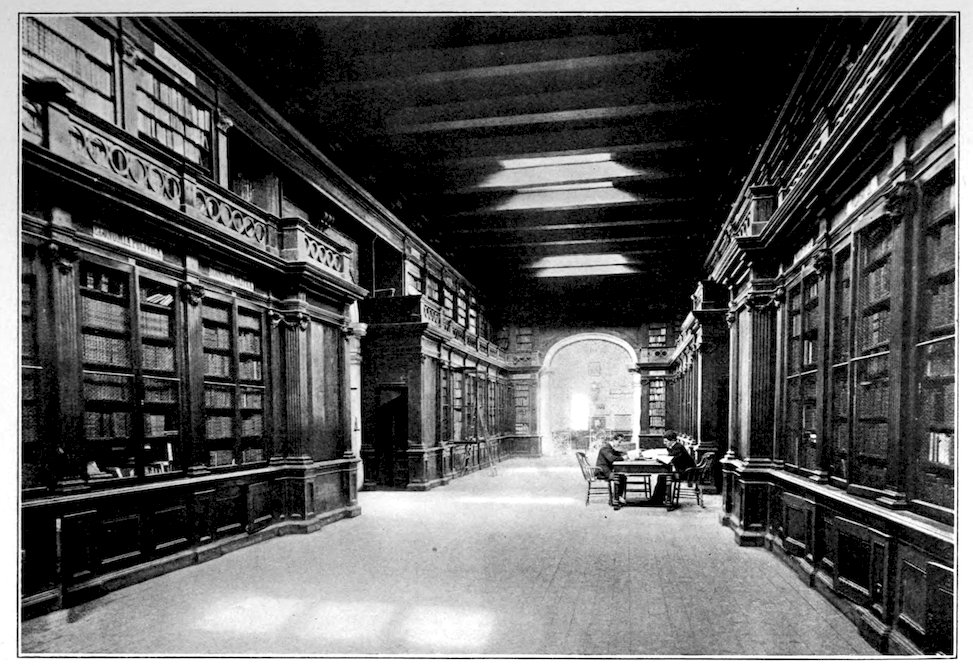

| INTERIOR OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY, LIMA | 219 |

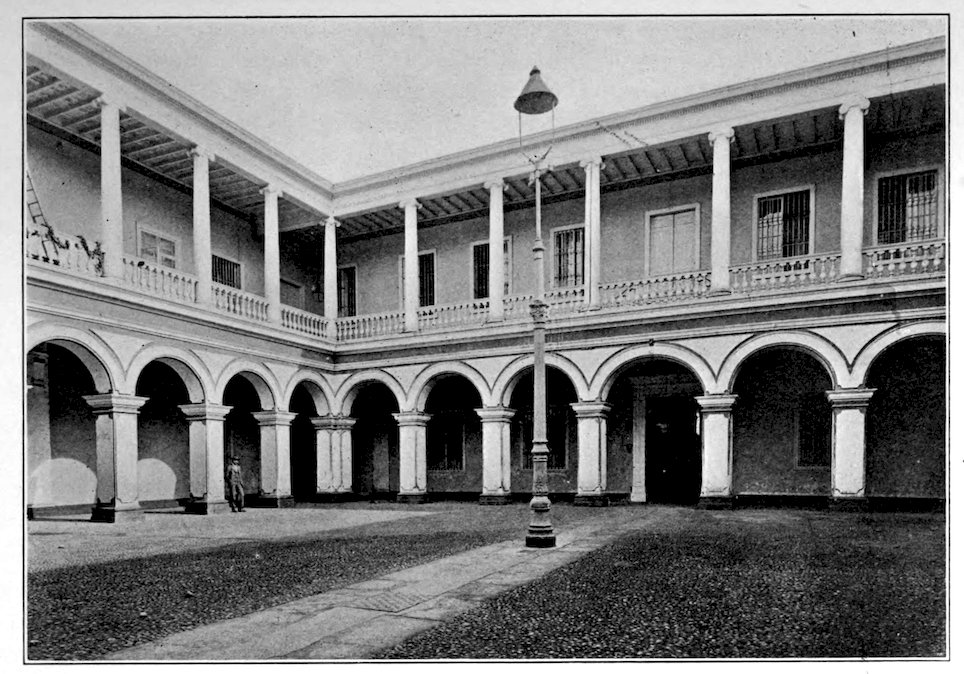

| PATIO OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY, LIMA | 221 |

| DR. JOSÉ ANTONIO MIRÓ QUESADA, THE NESTOR OF THE PERUVIAN PRESS | 224 |

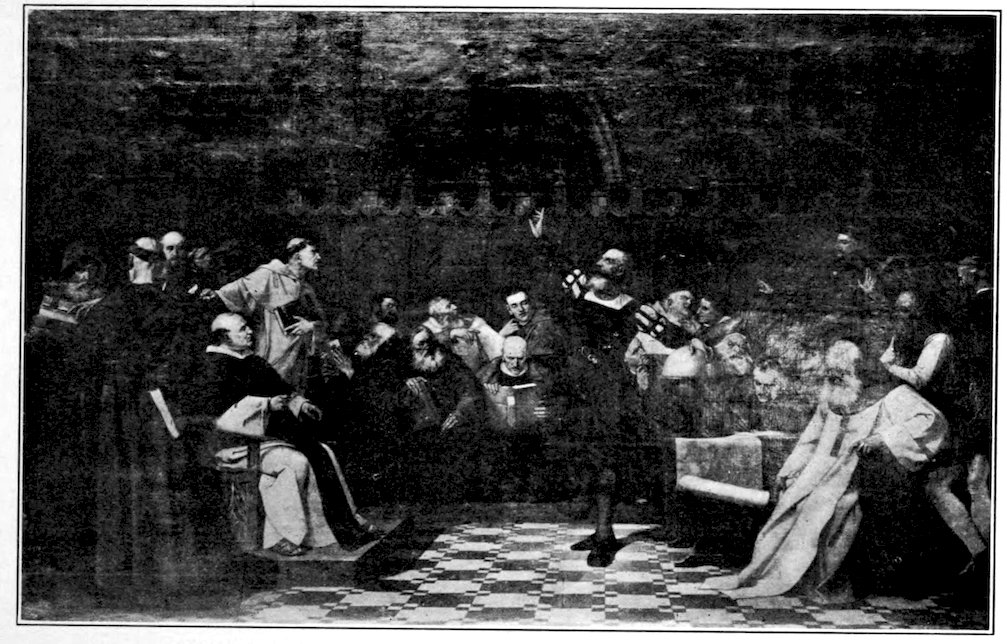

| COLUMBUS BEFORE THE UNIVERSITY OF SALAMANCA, BY IGNACIO MERINO | 225 |

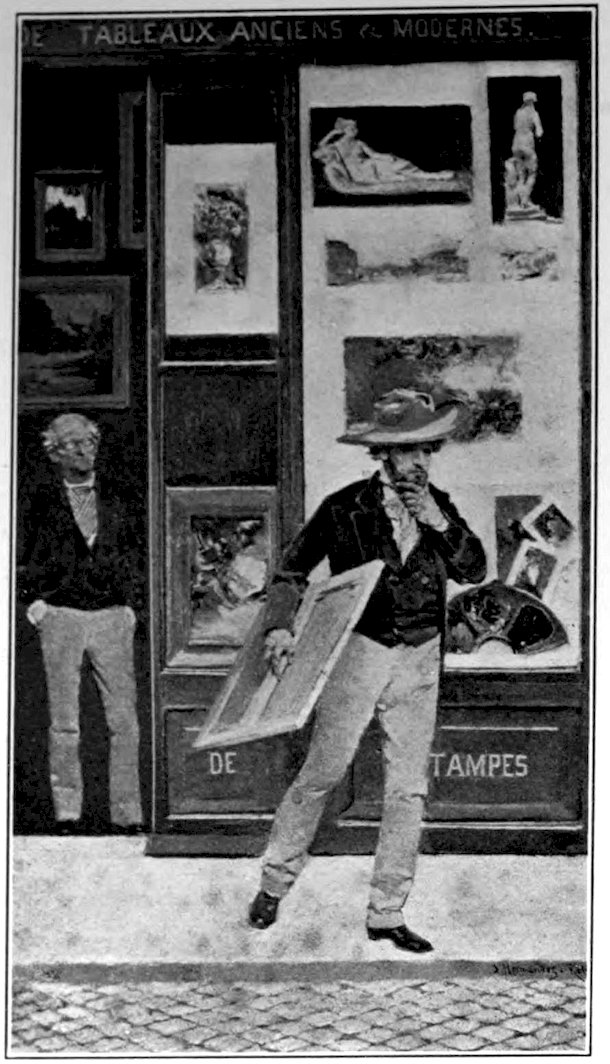

| THE DISILLUSION OF THE ARTIST. BY DANIEL HERNANDEZ | 226 |

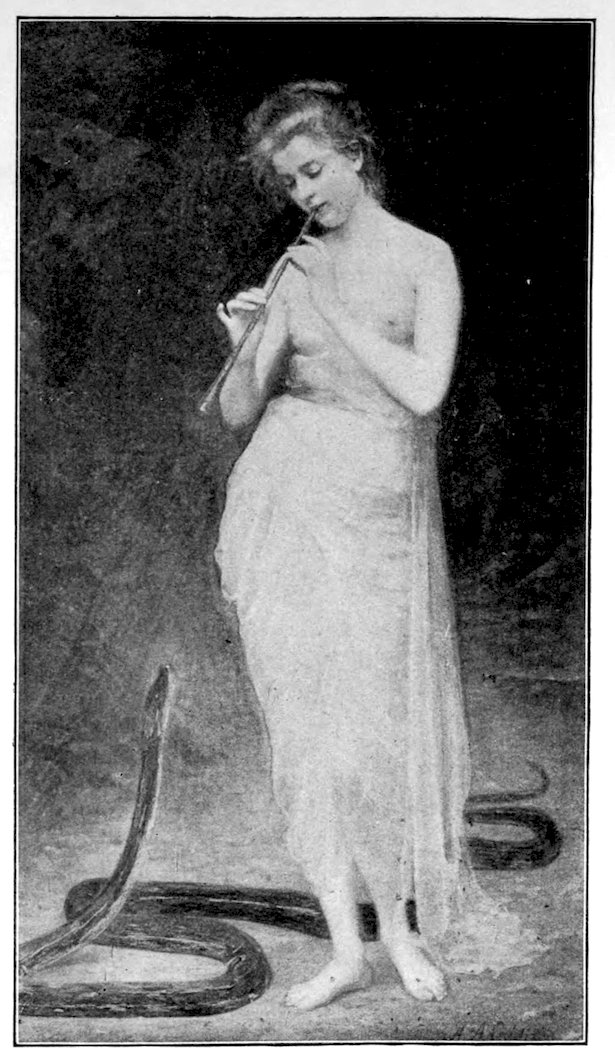

| THE CHARMER. BY ABELARDO ALVAREZ CALDERON | 227 |

| UNE PARISIENNE. BY ALBERT LYNCH | 228 |

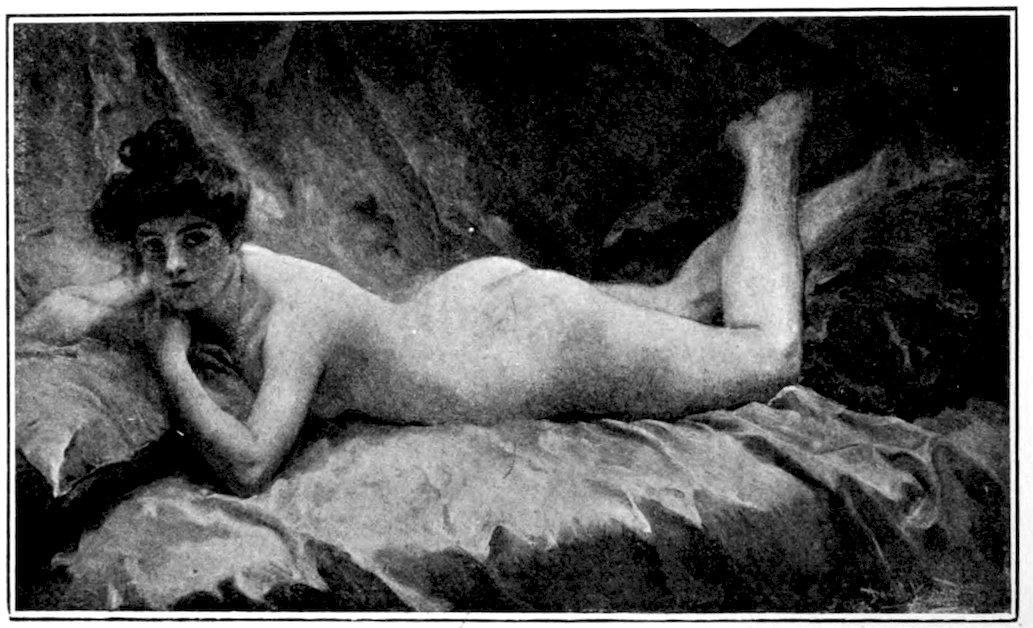

| DOLCE FAR NIENTE. BY DANIEL HERNANDEZ | 230 |

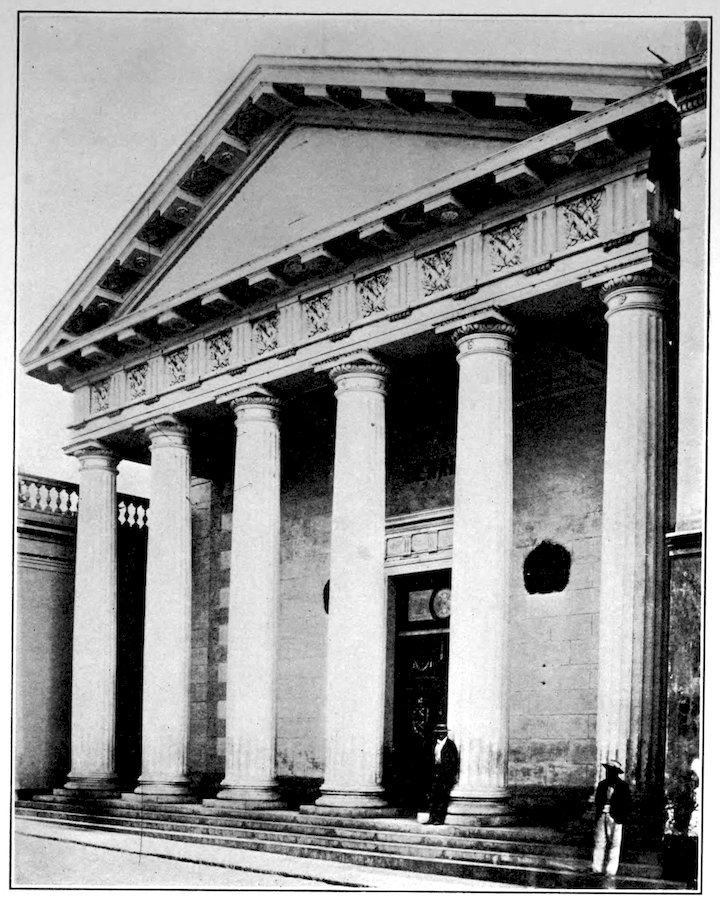

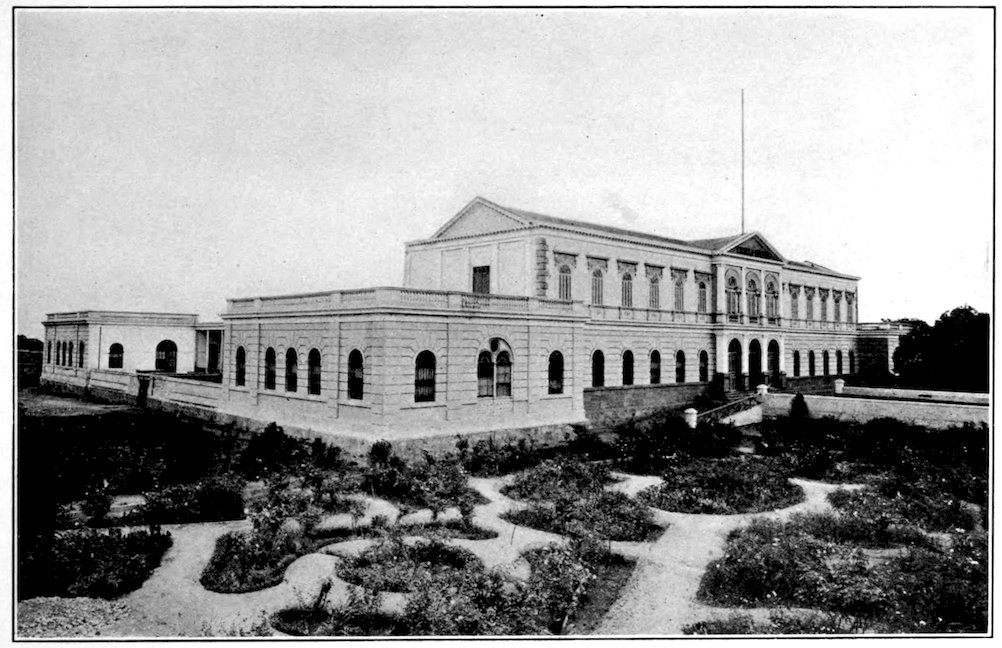

| UNIVERSITY OF SAN MARCOS, LIMA | 232 |

| DR. LUIS F. VILLARÁN, RECTOR OF THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN MARCOS | 233 |

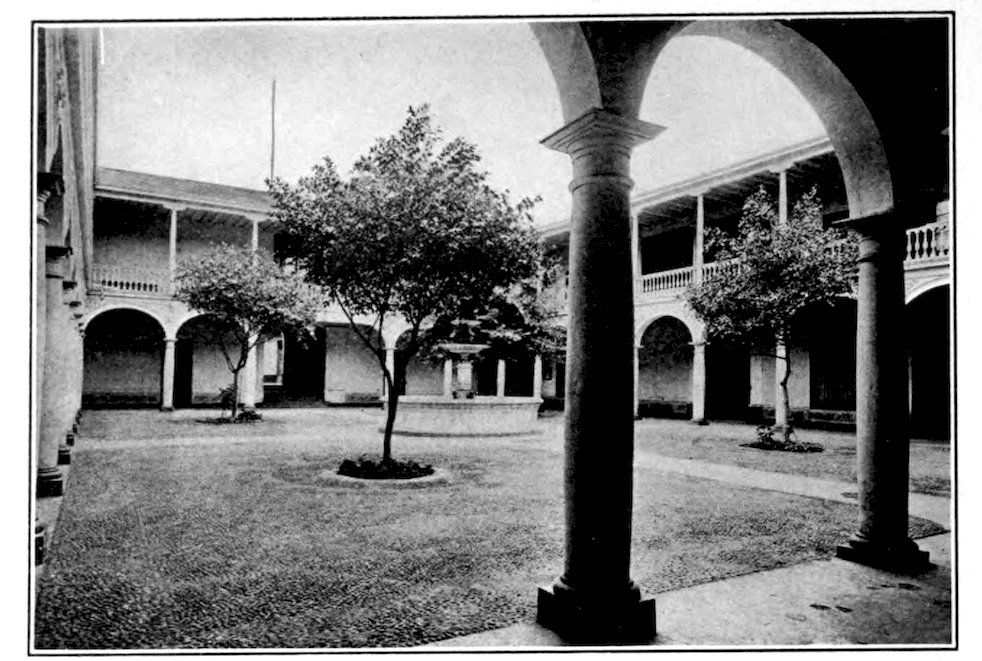

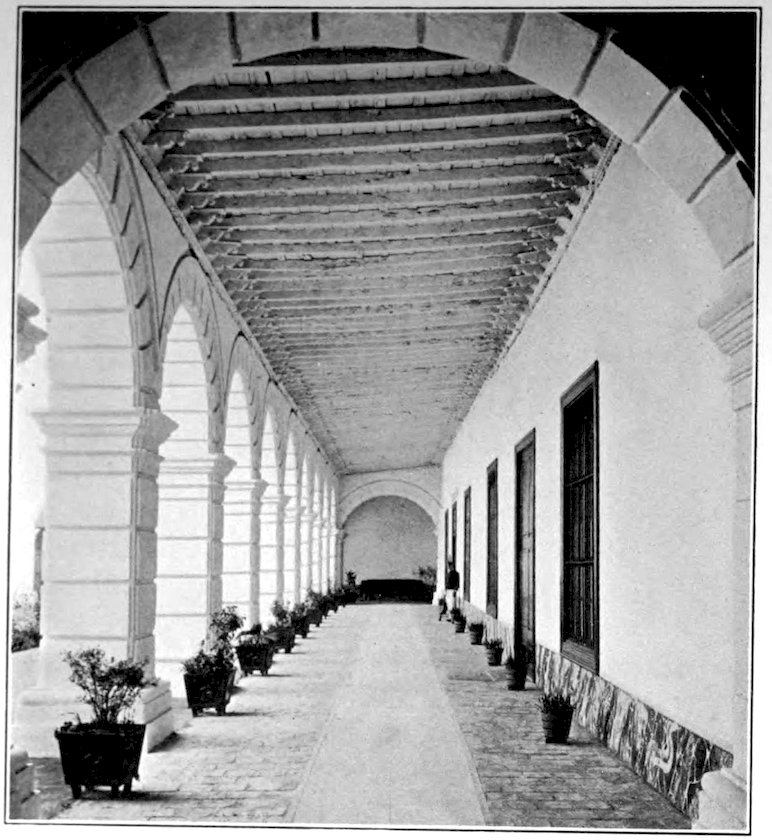

| CLOISTER OF THE NATIONAL COLLEGE OF GUADALUPE, LIMA | 235 |

| DR. MANUEL BARRIOS, DEAN OF THE FACULTY OF MEDICINE, LIMA | 236 |

| THE FACULTY OF MEDICINE, LIMA | 237 |

| DR. JAVIER PRADO Y UGARTECHE, DEAN OF THE LITERARY FACULTY, UNIVERSITY OF SAN MARCOS | 238 |

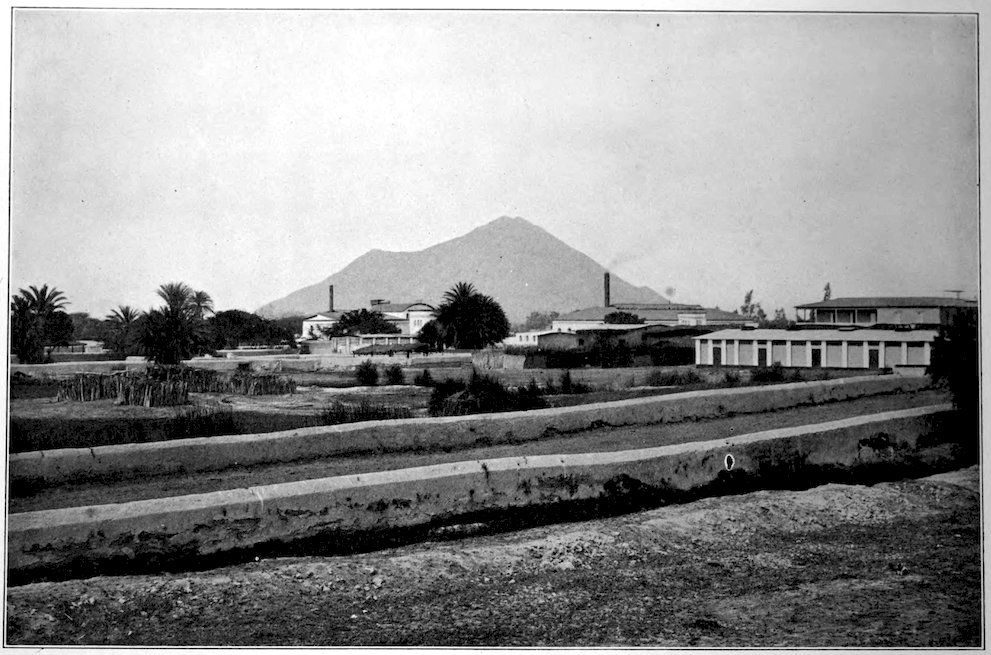

| THE NATIONAL SCHOOL OF AGRICULTURE, LIMA | 239 |

| THE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND TRADES, LIMA | 241 |

| THE SCHOOL OF ENGINEERS, LIMA | 242 |

| THE COLLEGE OF LAW, LIMA | 244 |

| ALAMEDA DE LOS DESCALZOS, LIMA | 246 |

| STREET SCENE ON THE FEAST DAY OF LA MERCED, LIMA | 247 |

| OFFICES OF THE BENEVOLENT SOCIETY, LIMA | 249 |

| HOSPITAL DOS DE MAYO, LIMA | 251 |

| MILITARY HOSPITAL, LIMA | 252 |

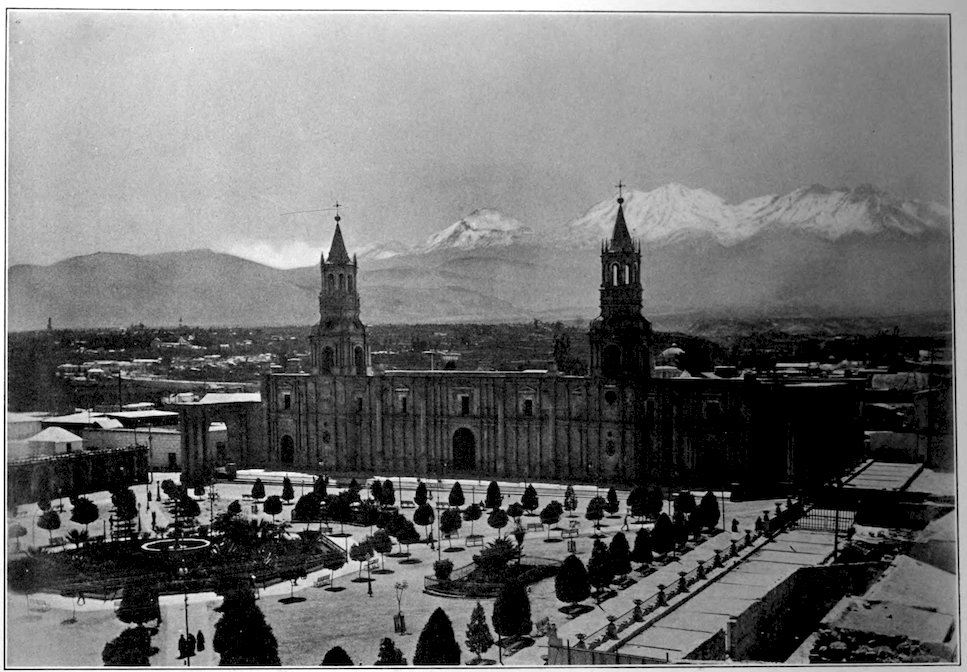

| THE CATHEDRAL, AREQUIPA | 254 |

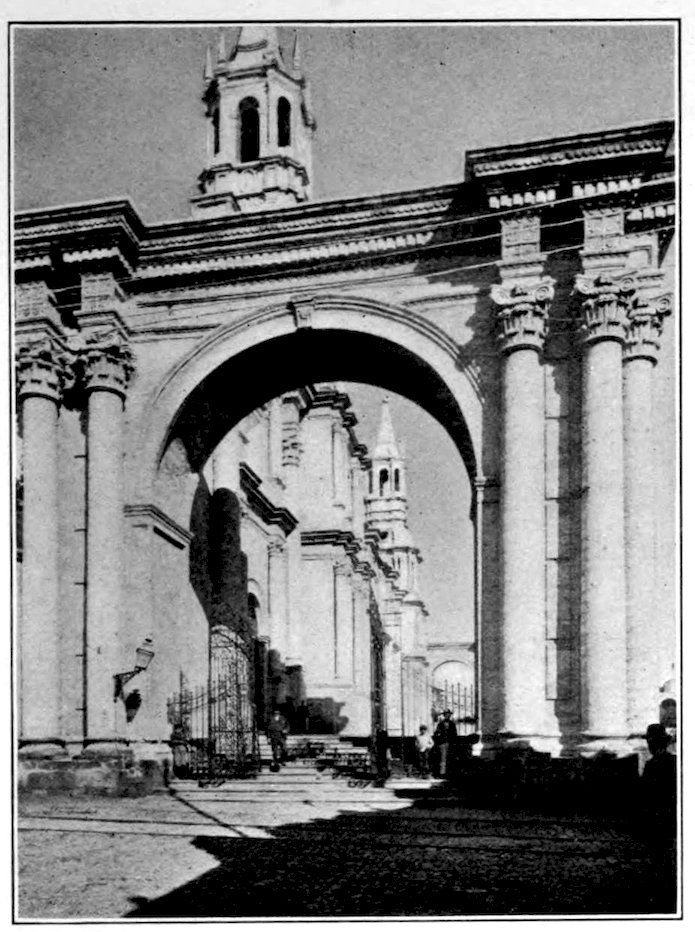

| ARCH AT THE ENTRANCE TO THE CATHEDRAL, AREQUIPA | 255 |

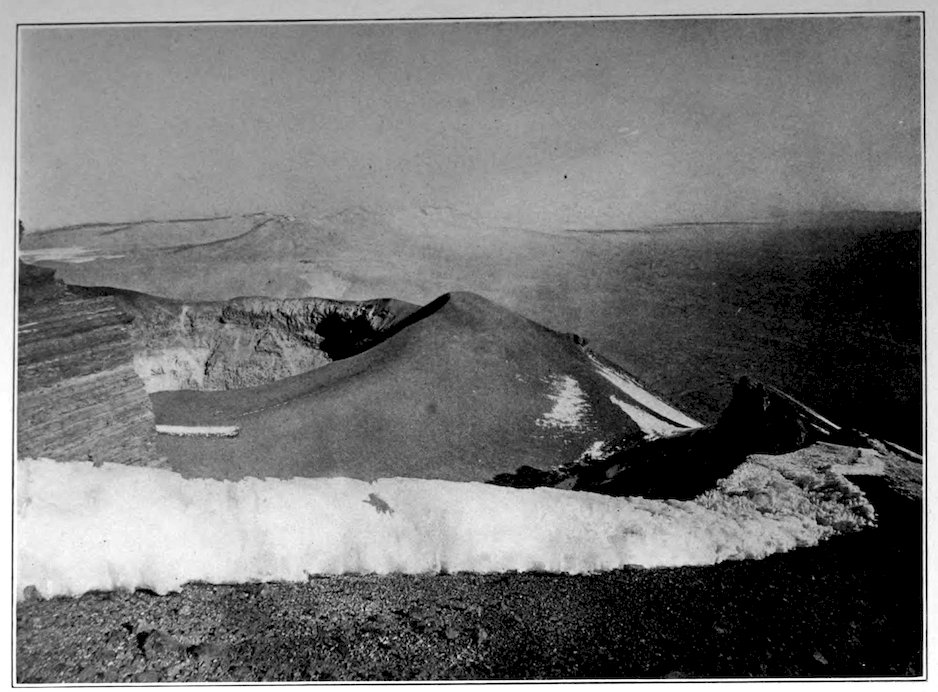

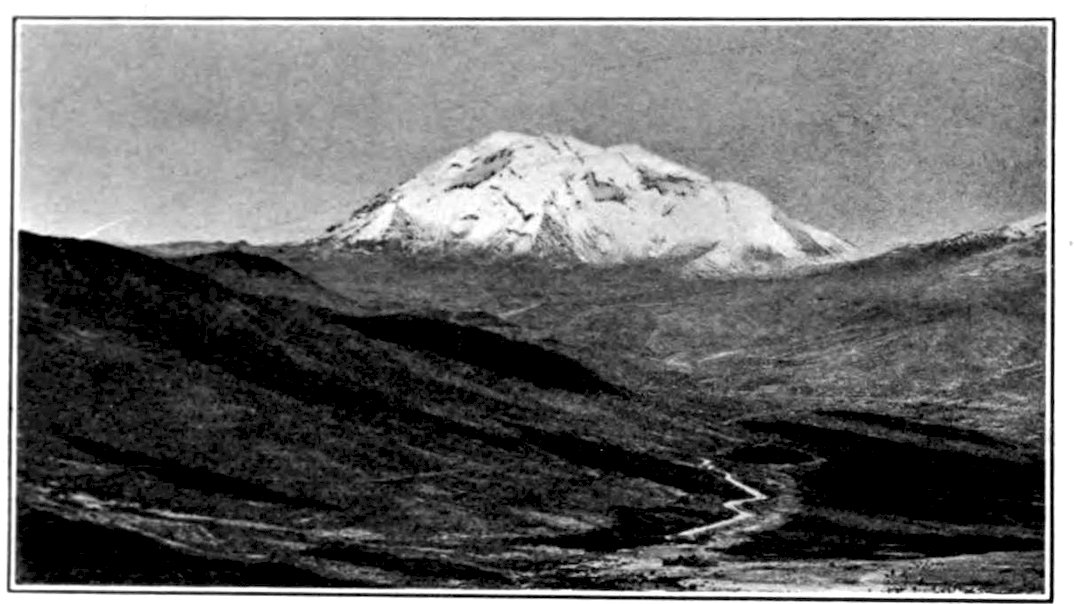

| 11THE CRATER OF THE MISTI | 256 |

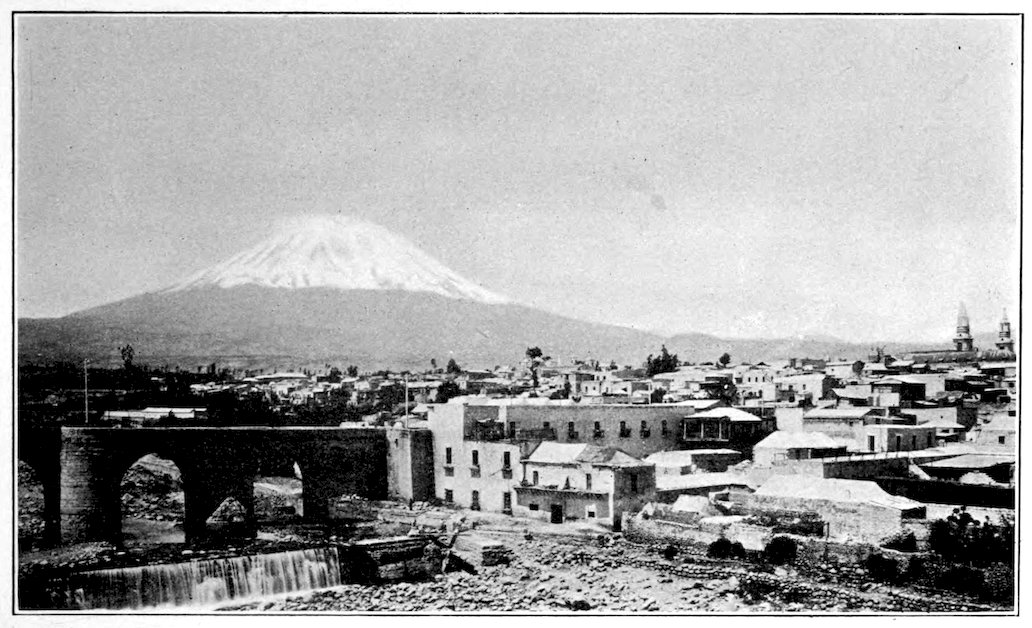

| AREQUIPA AND THE MISTI | 257 |

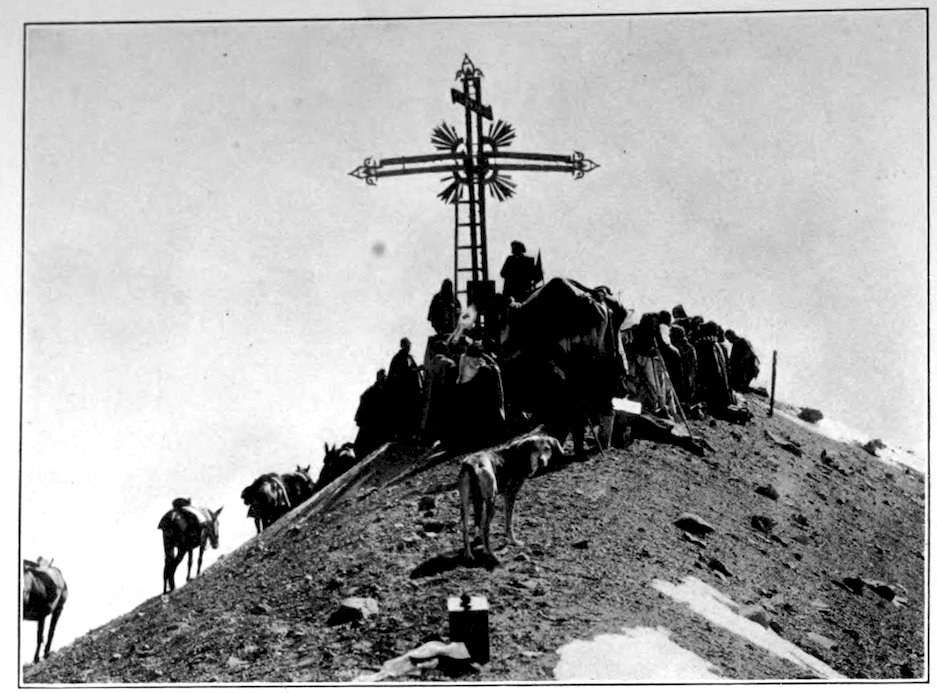

| A CELEBRATION OF MASS ON THE SUMMIT OF THE MISTI | 258 |

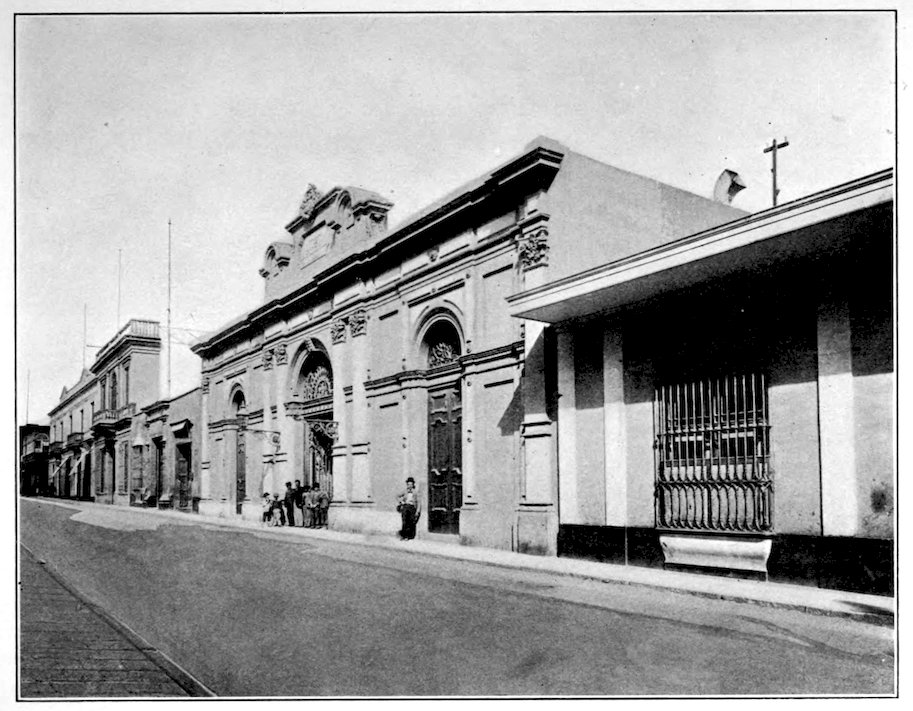

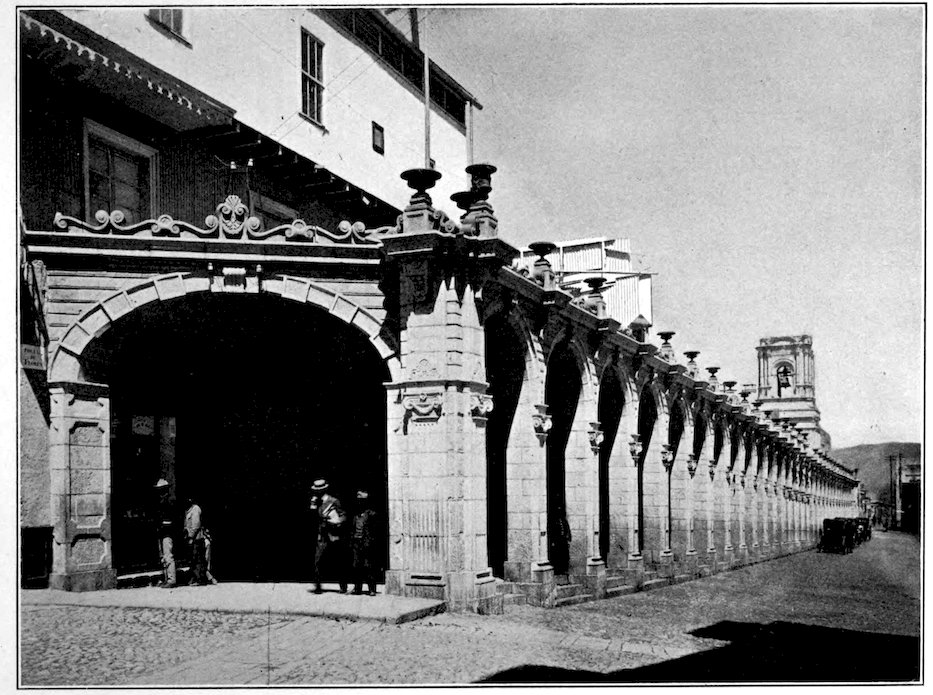

| LOS PORTALES, AREQUIPA | 259 |

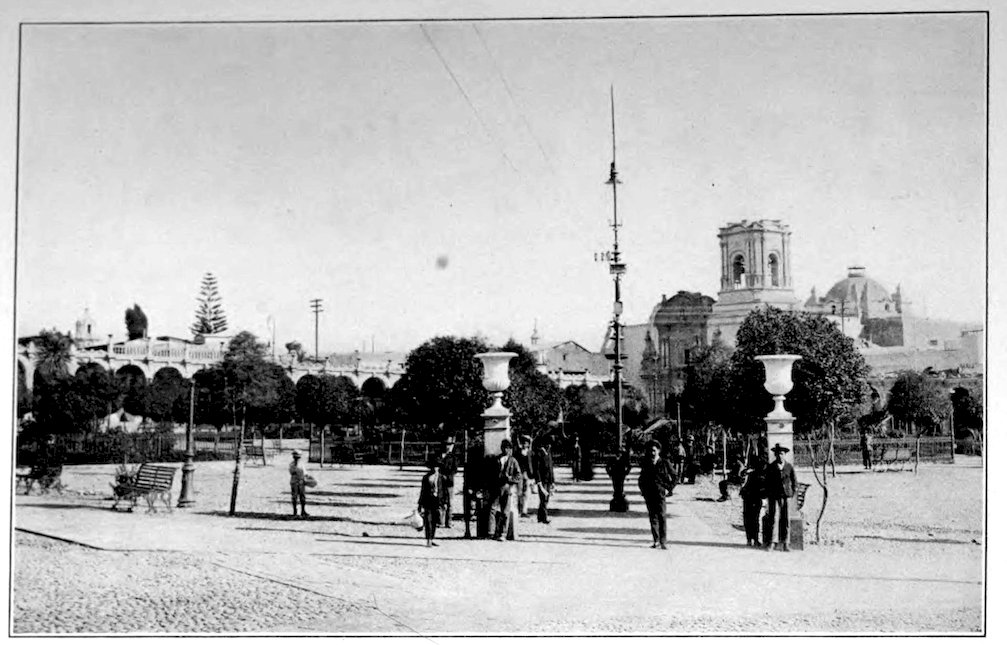

| PLAZA DE ARMAS, AREQUIPA | 260 |

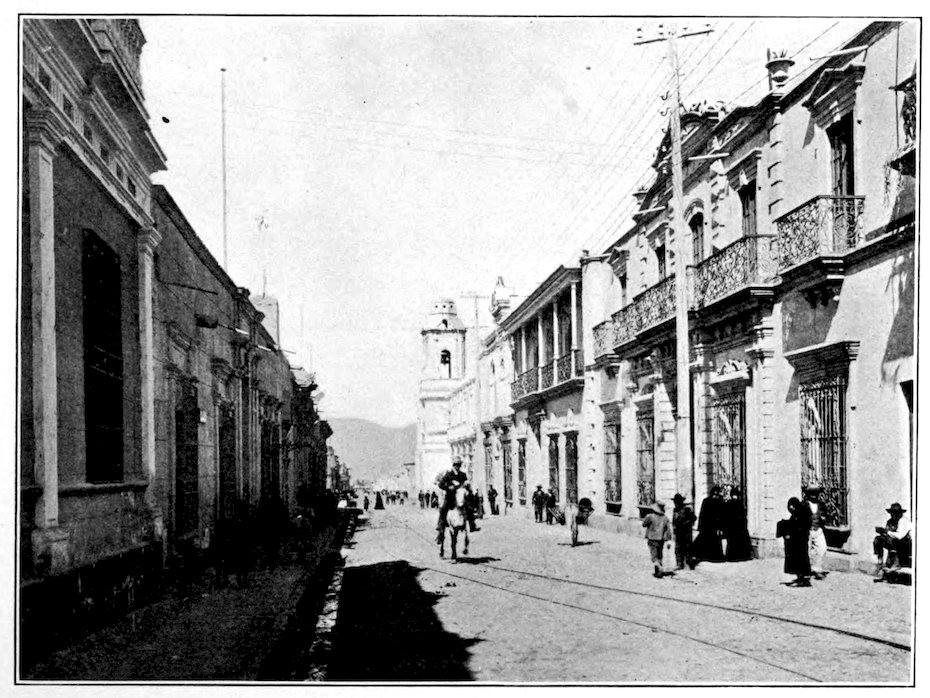

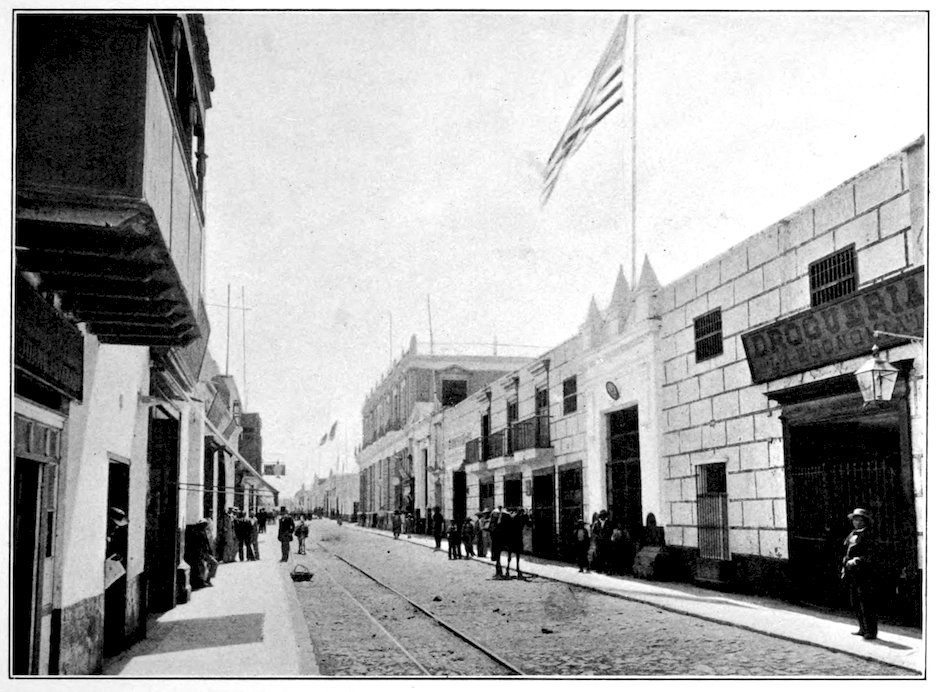

| STREET SCENE, AREQUIPA | 261 |

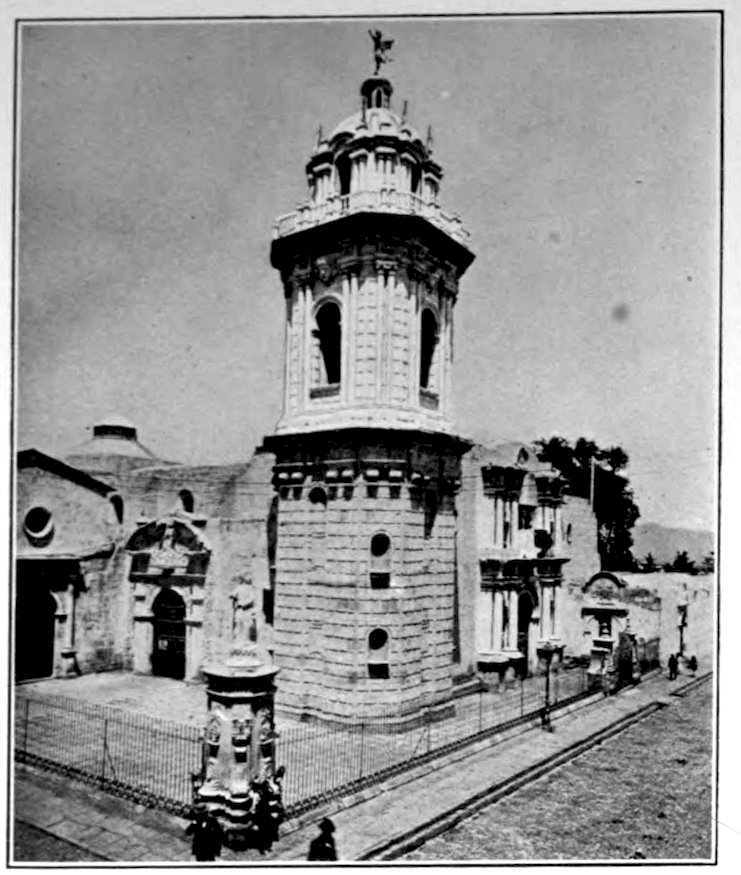

| CHURCH OF SANTO DOMINGO, AREQUIPA | 262 |

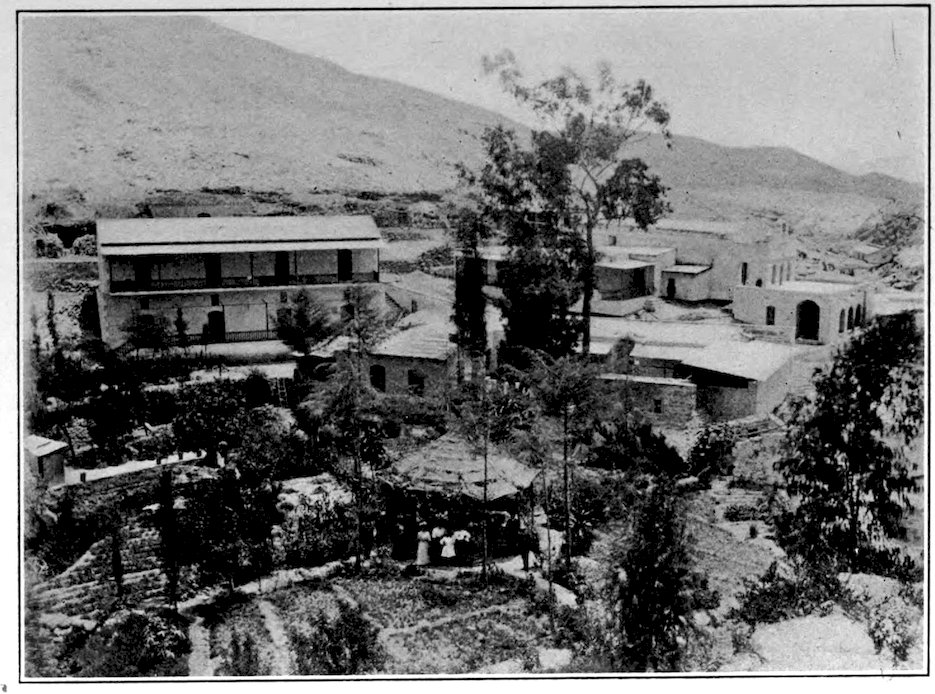

| GENERAL VIEW OF THE BATHS OF YURA | 263 |

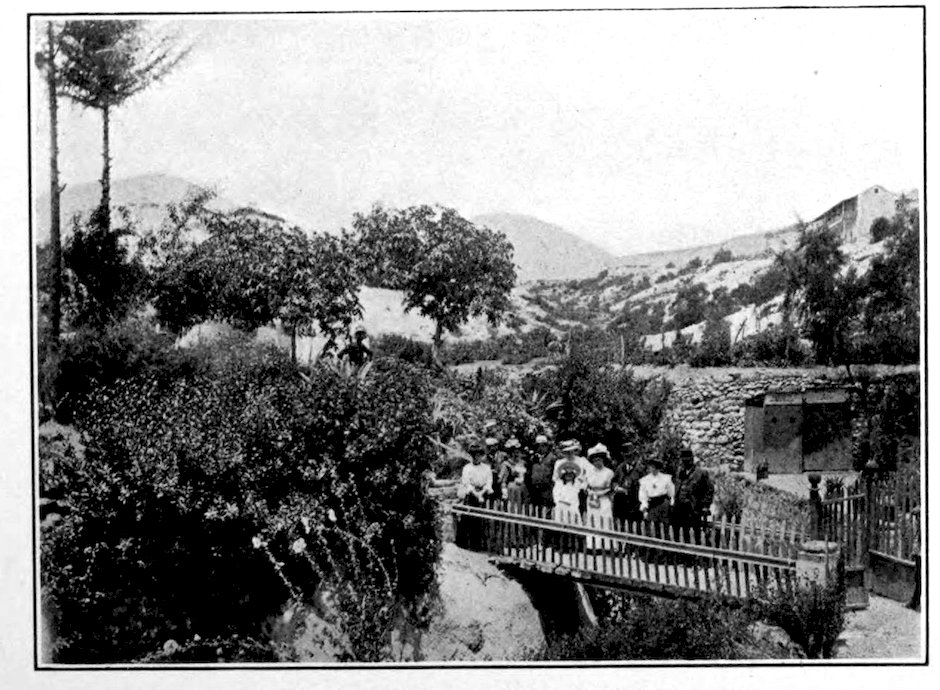

| AT THE BATHS OF YURA, AREQUIPA | 263 |

| BOLOGNESI PARK, AREQUIPA | 264 |

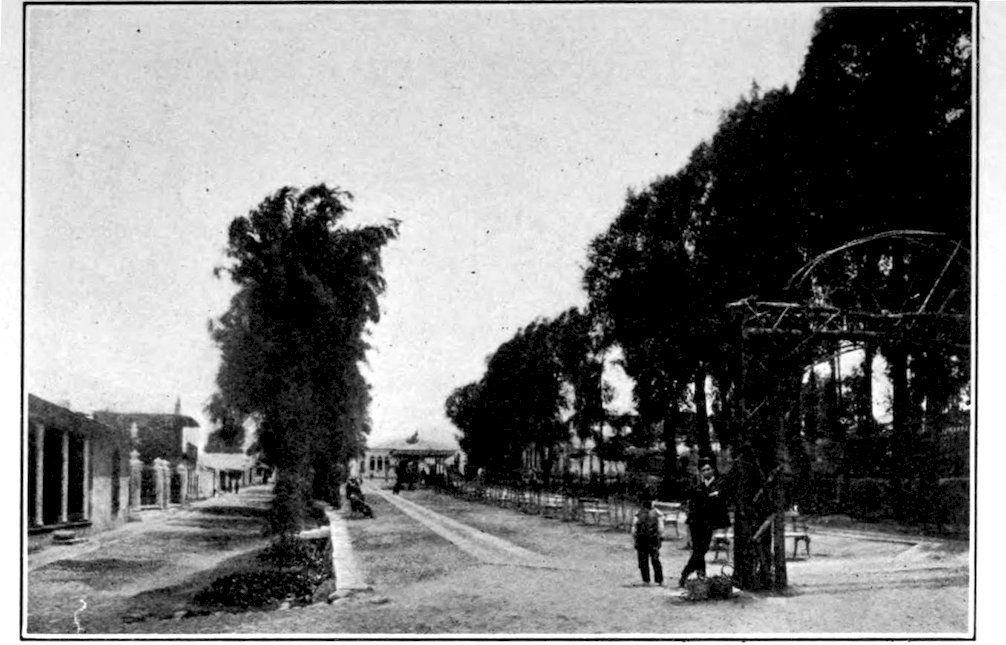

| AVENIDA DE TINGO, AREQUIPA | 265 |

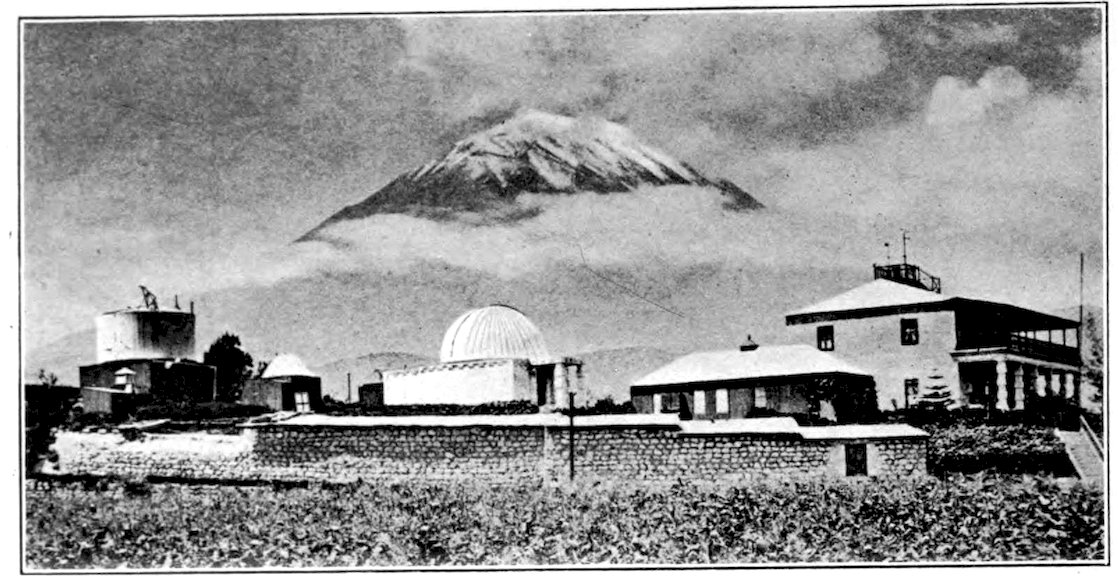

| HARVARD OBSERVATORY AT AREQUIPA | 266 |

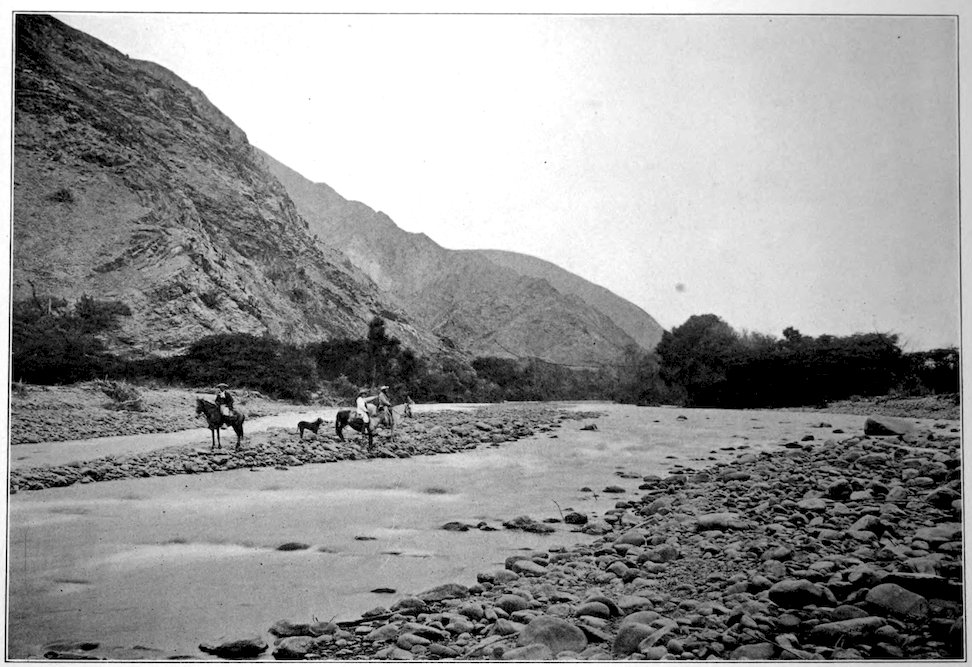

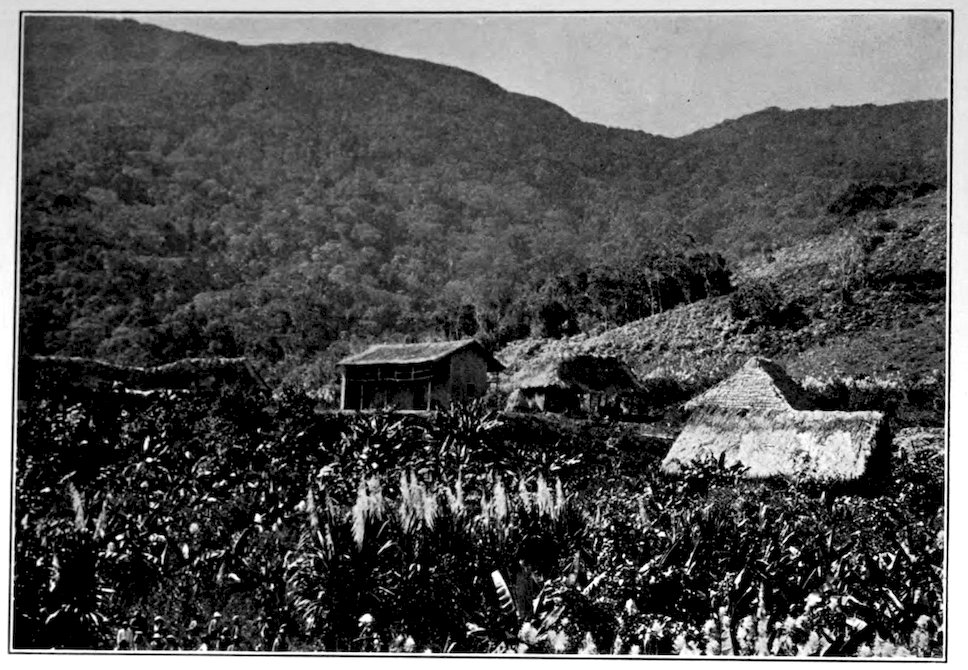

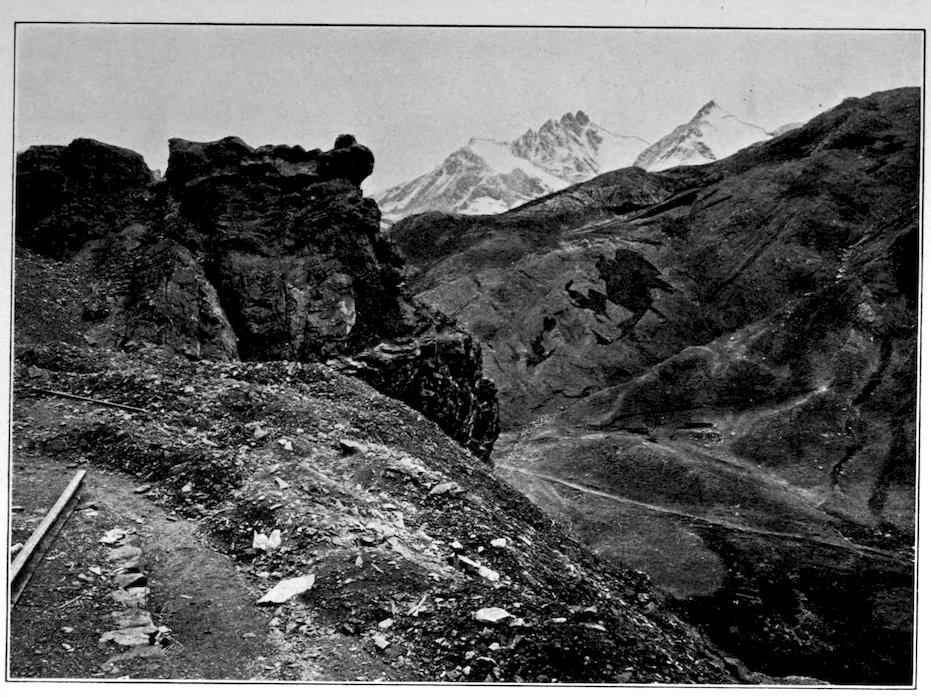

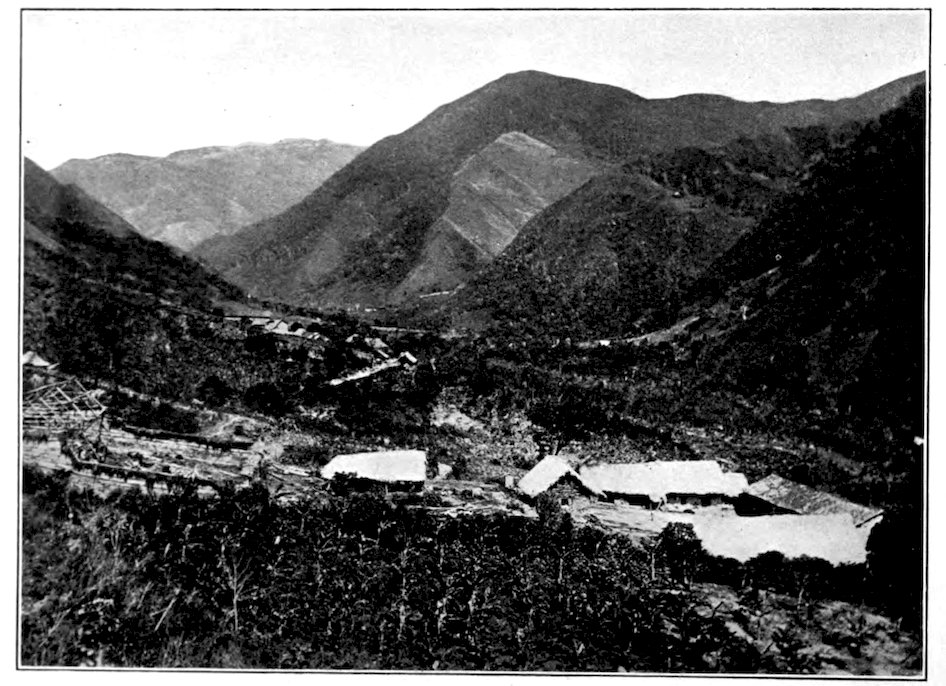

| CHANCHAMAYO, ON THE EASTERN SLOPE OF THE SIERRA | 268 |

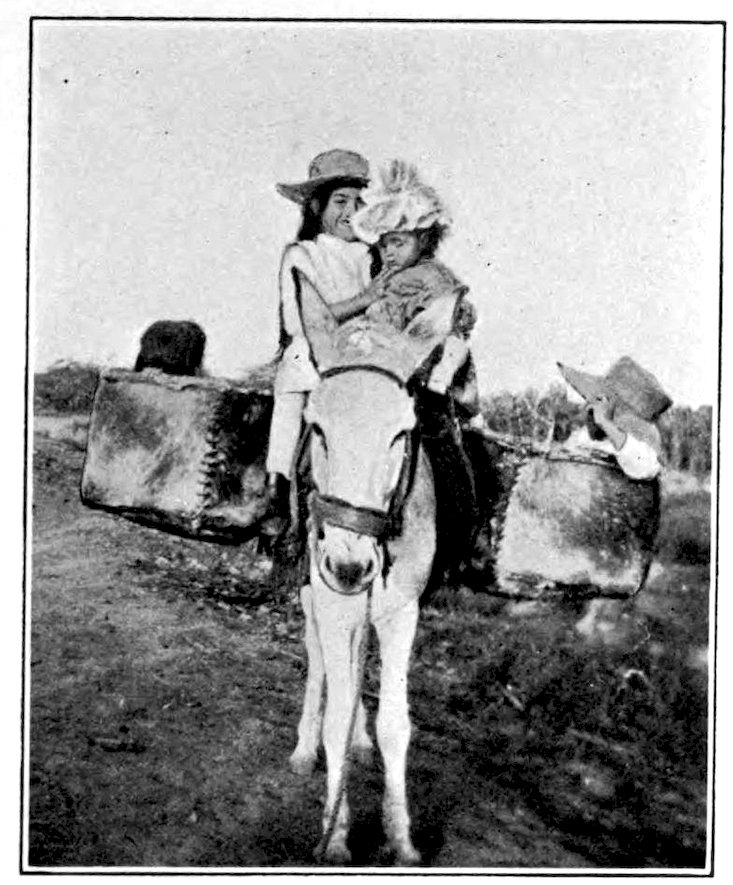

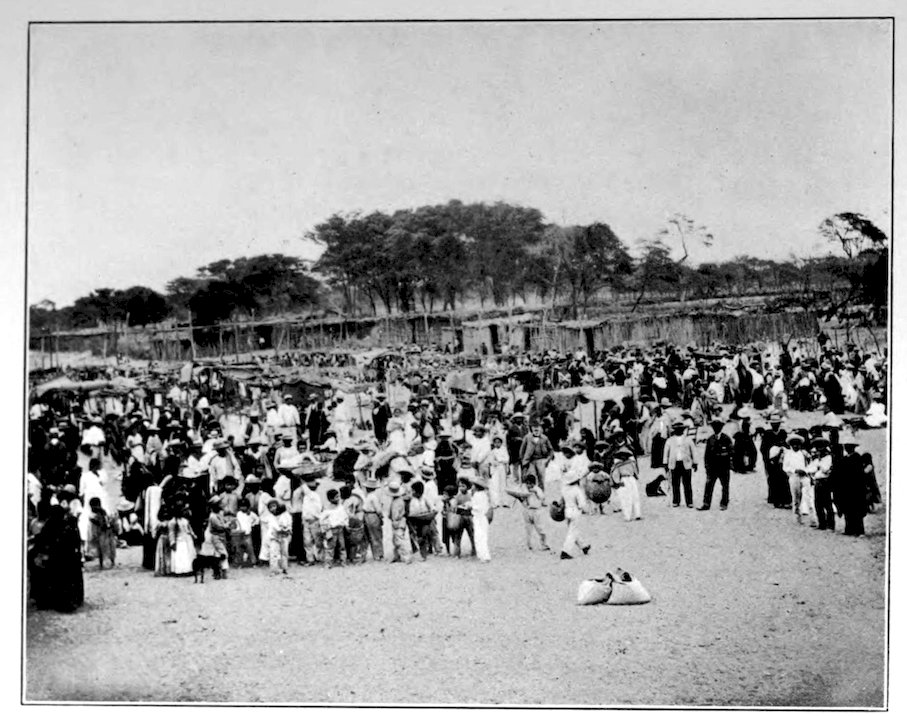

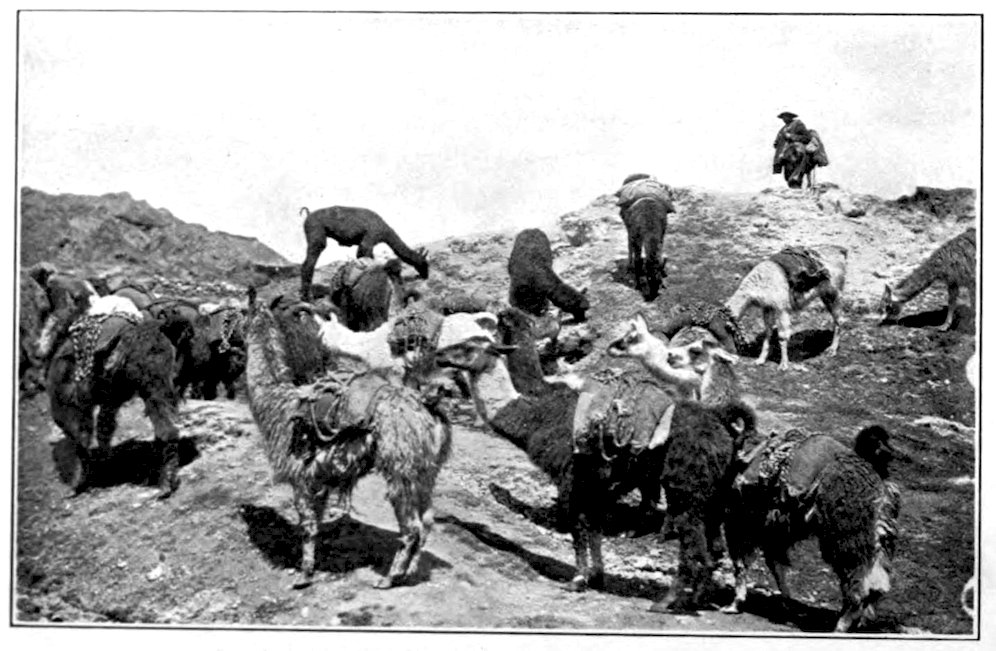

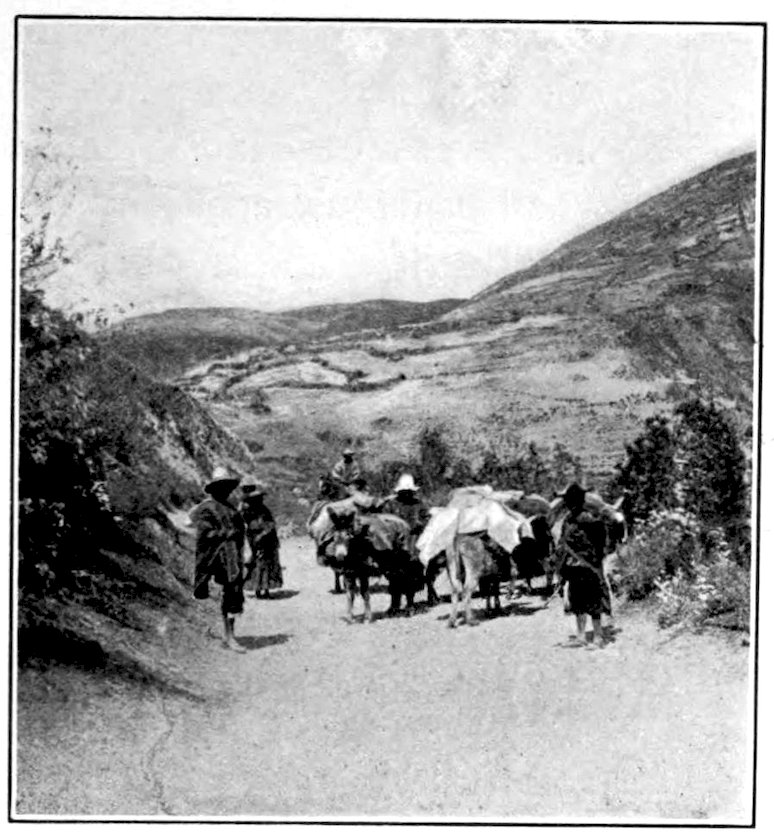

| ON THE WAY TO MARKET | 269 |

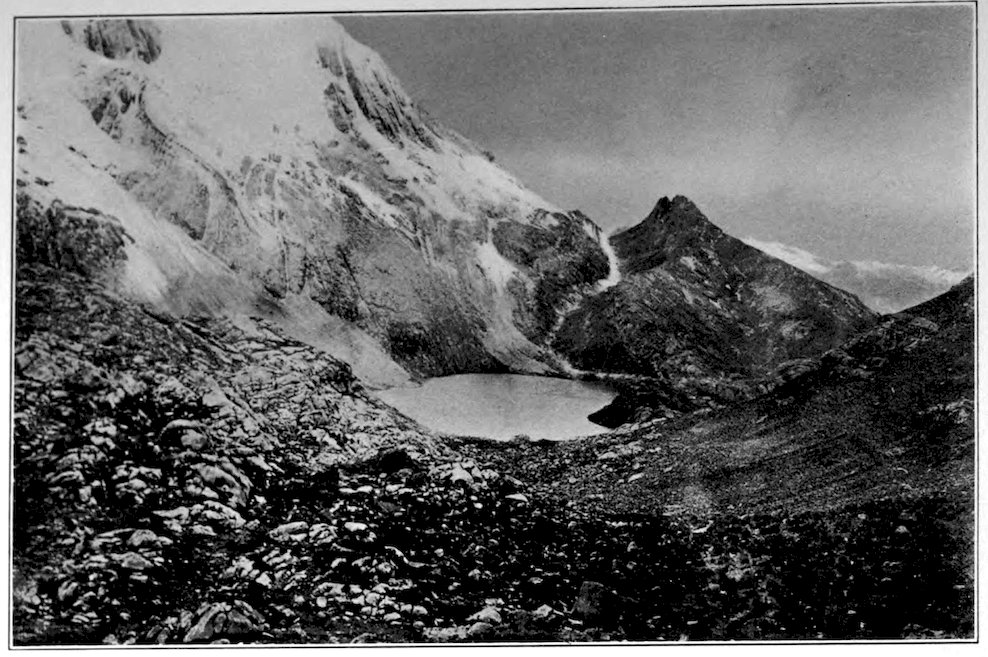

| LAKE OF LA VIUDA, IN THE HIGH SIERRA | 270 |

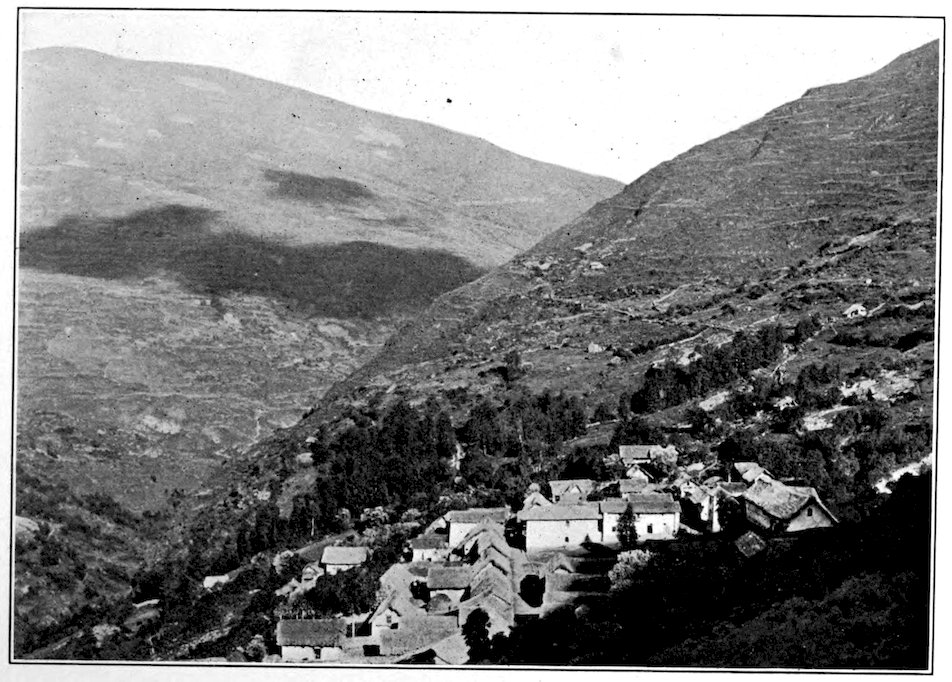

| IN THE VALLEY OF ABANCAY | 271 |

| SCENE ON THE TUMBES RIVER | 272 |

| MONZON VALLEY, IN THE HUALLAGA REGION | 273 |

| ANCÓN, A COAST RESORT NEAR CALLAO | 274 |

| THE BELL ROCK OF ETEN | 275 |

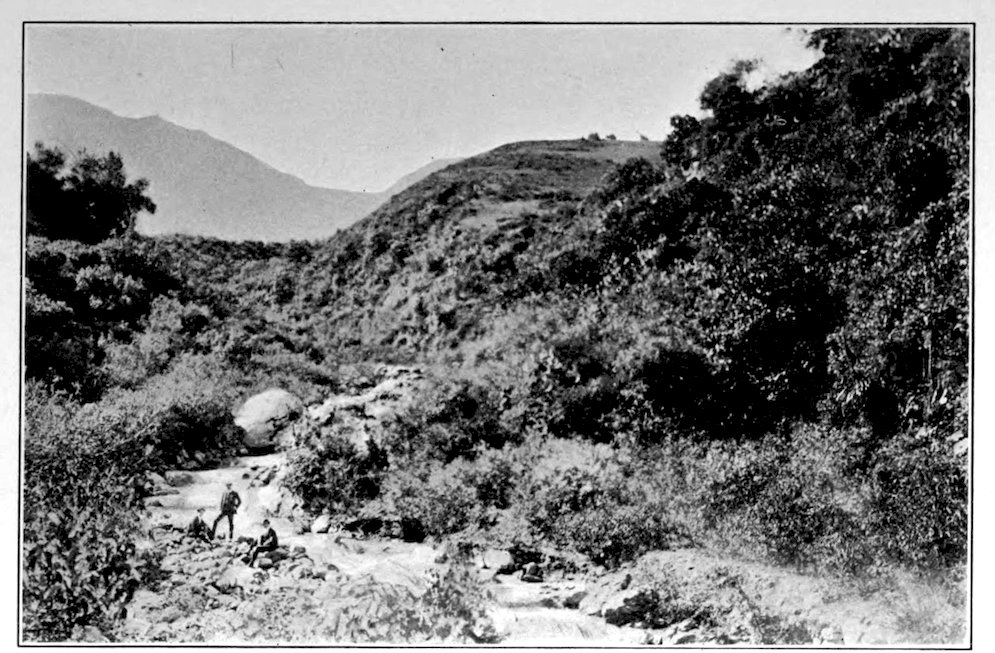

| QUEBRADA SANTA ROSA, ANCASH DEPARTMENT | 276 |

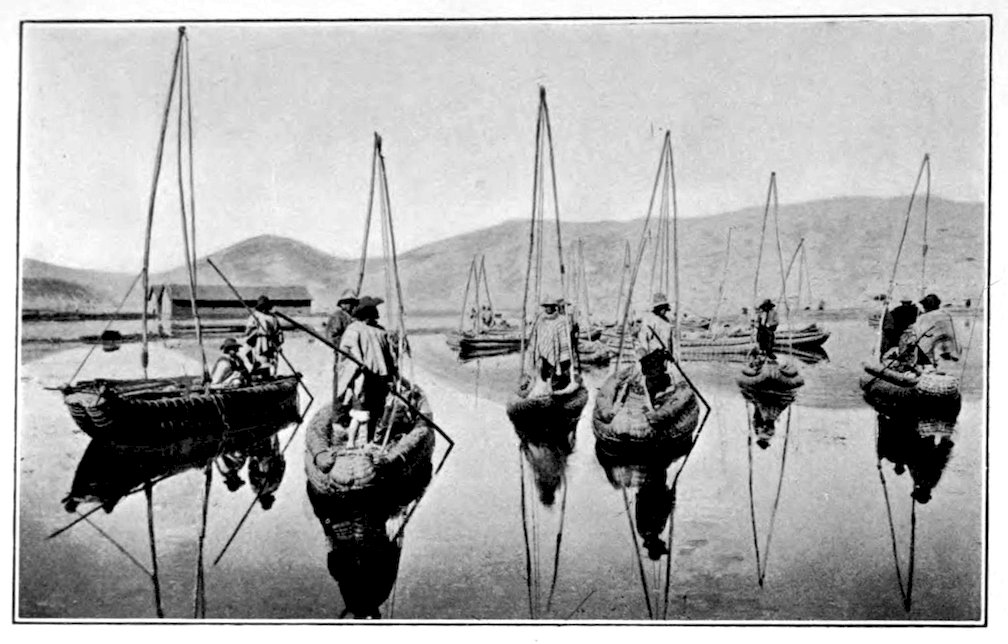

| NATIVE BOATMEN ON LAKE TITICACA | 278 |

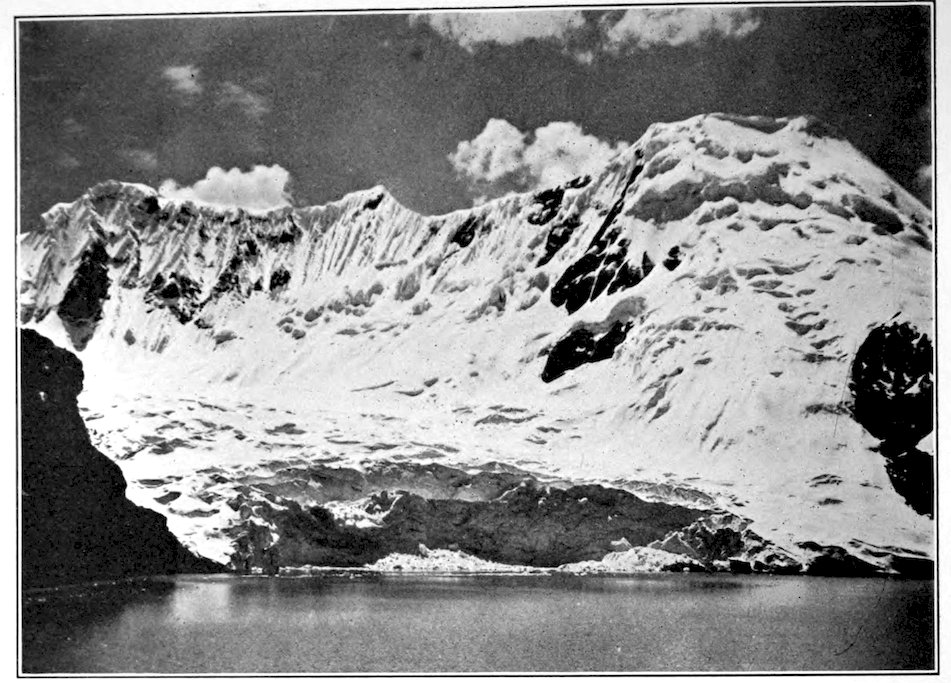

| A LAKE AMONG THE GLACIERS OF YAULI | 280 |

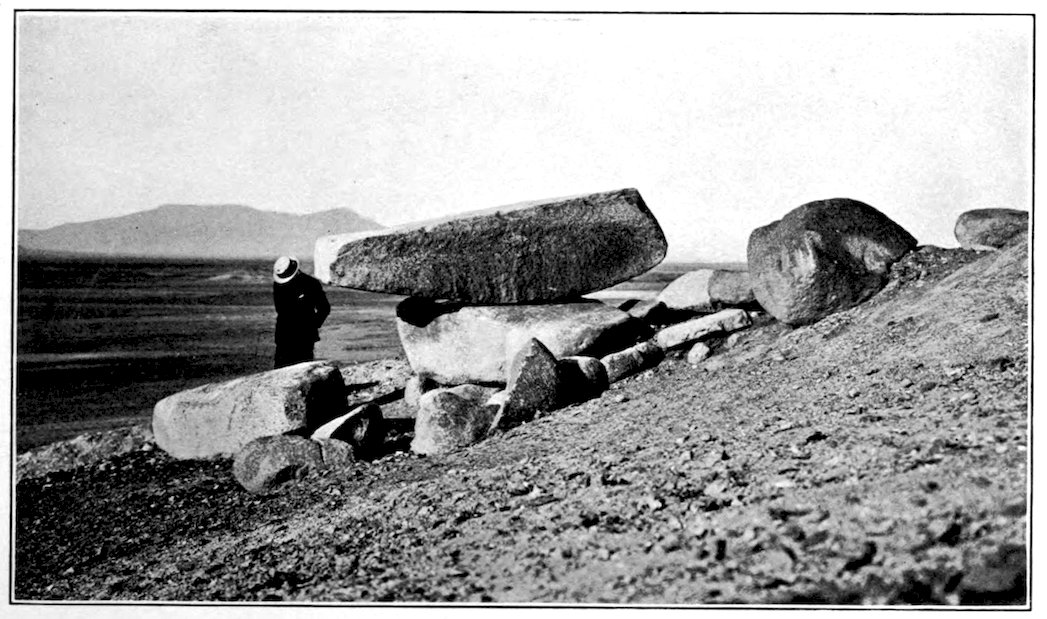

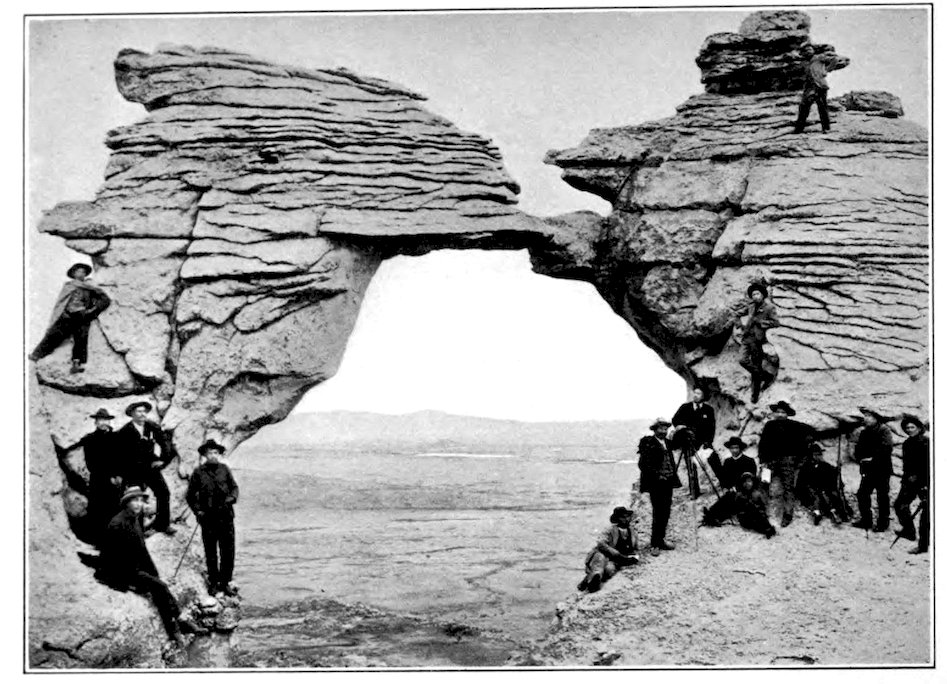

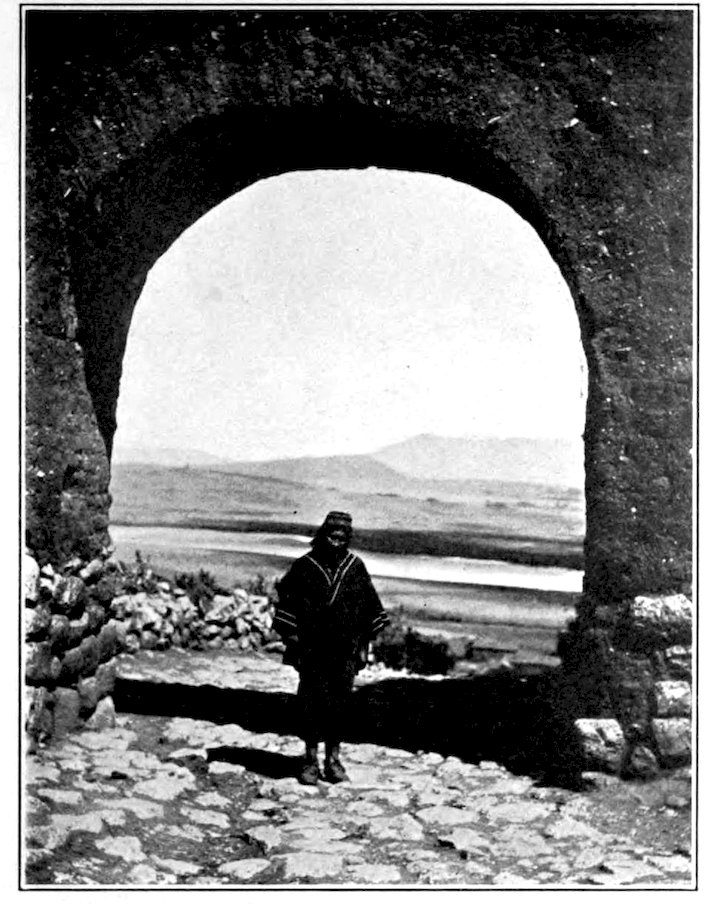

| NATURAL ARCH OF STONE AT HUANCANE, NEAR LAKE TITICACA | 282 |

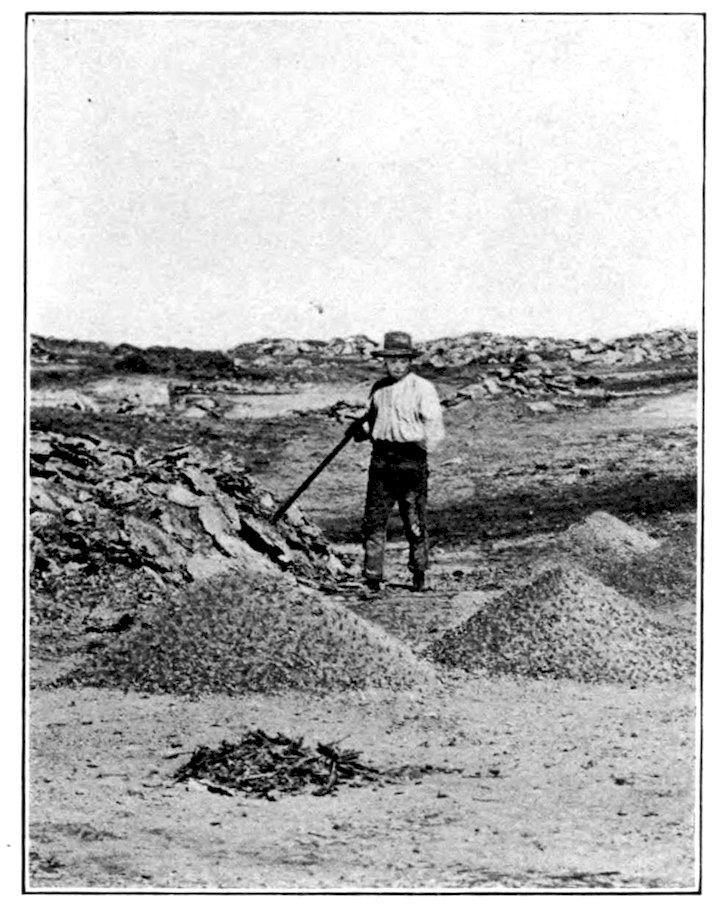

| PREPARING GUANO FOR SHIPMENT | 283 |

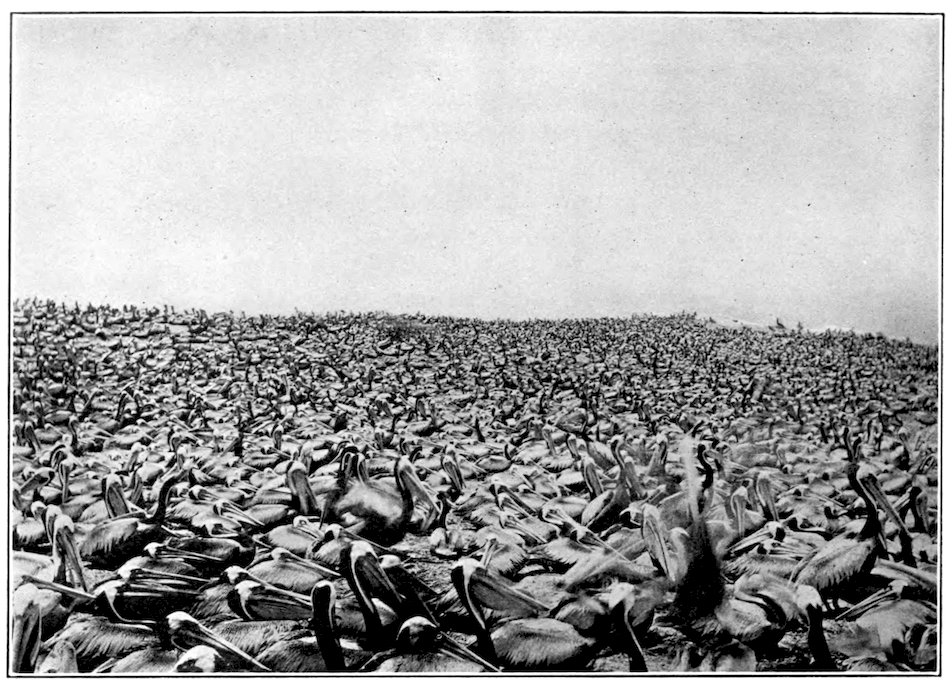

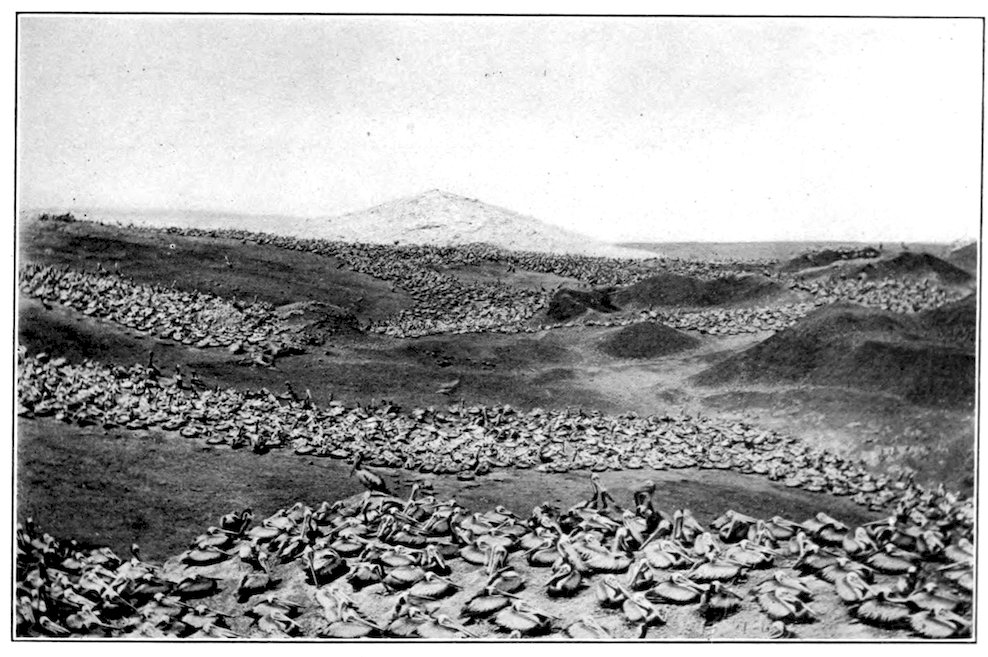

| THE HOUR OF SIESTA FOR THE GUANO BIRDS | 284 |

| THE PELICAN AT HOME | 285 |

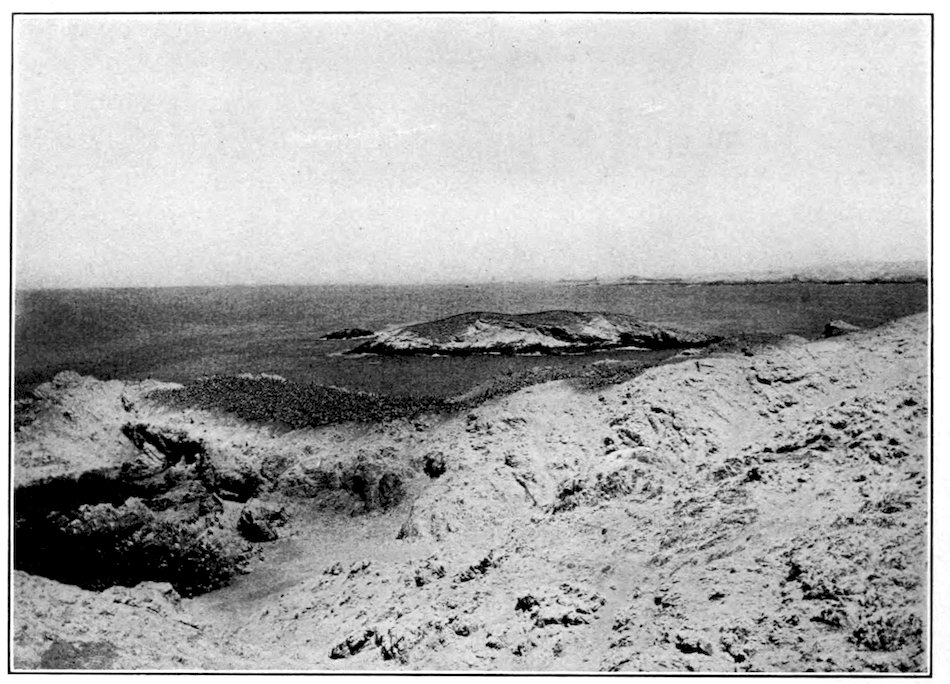

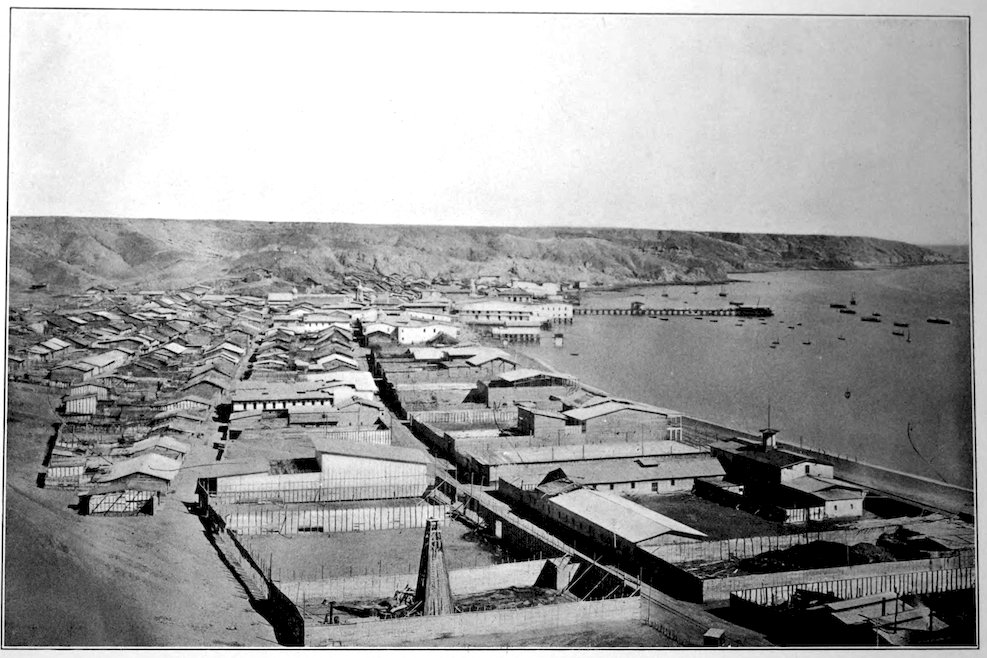

| GUANO ISLANDS OF LOBOS DE TIERRA | 286 |

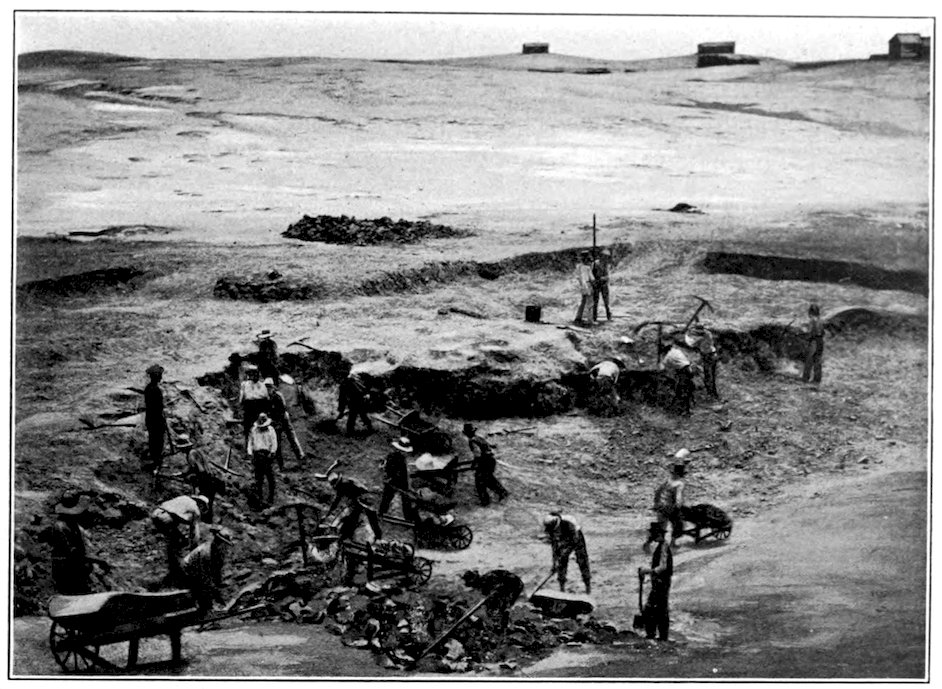

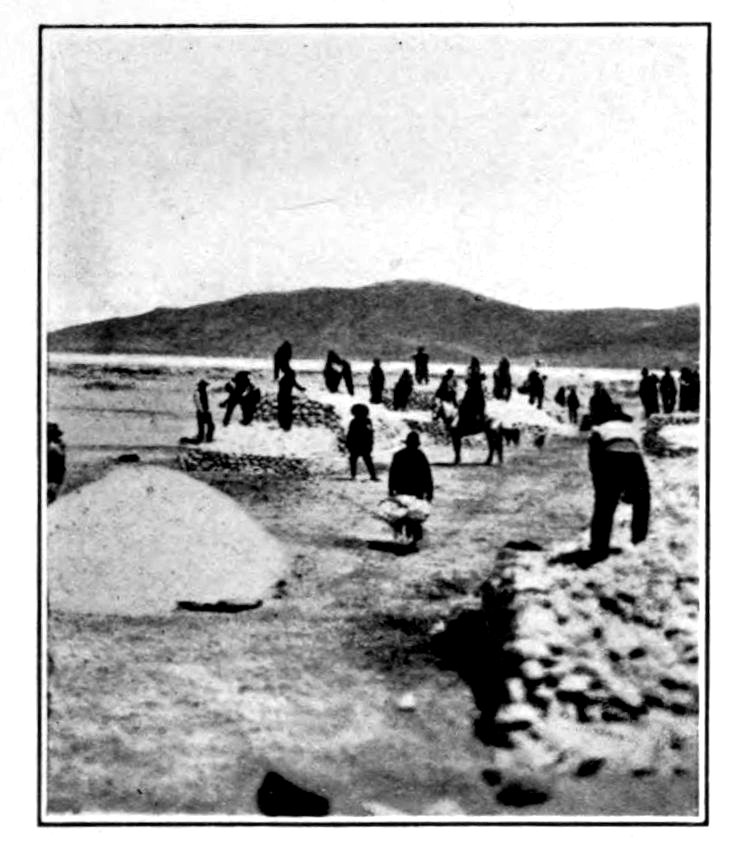

| DIGGING GUANO ON THE CHINCHA ISLANDS | 287 |

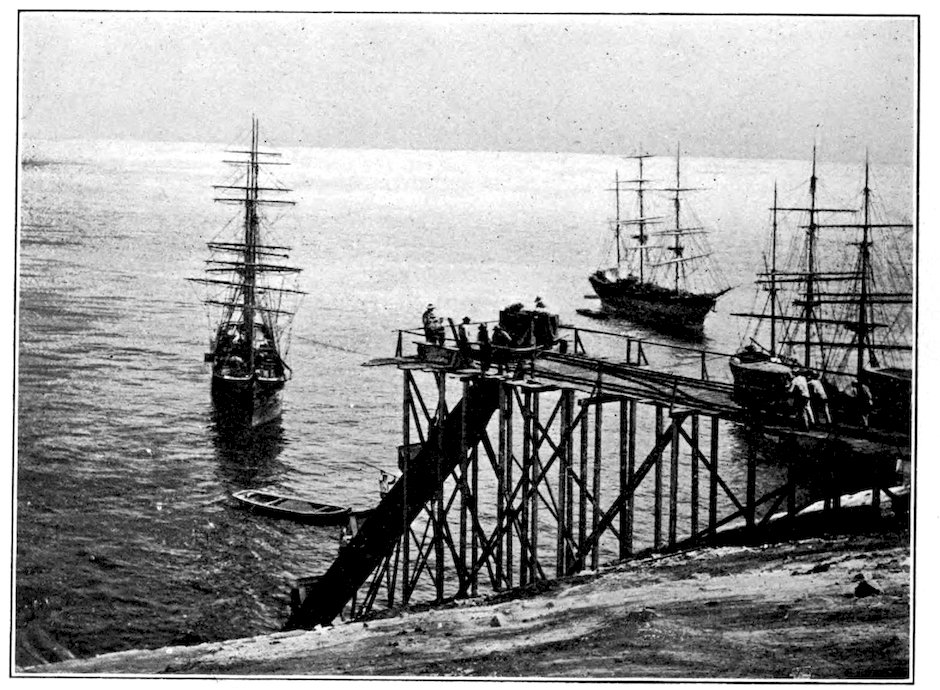

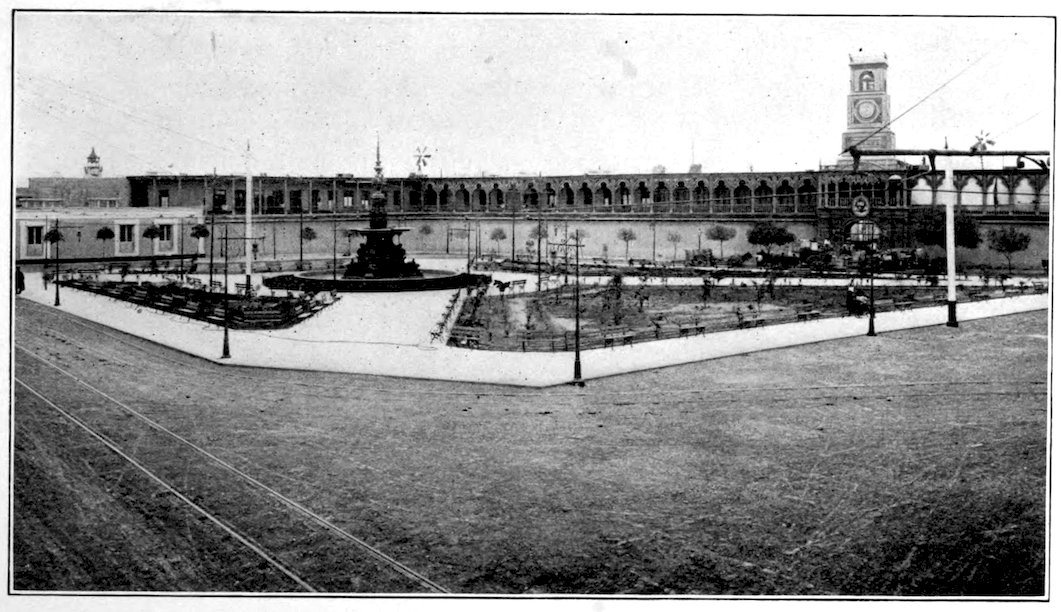

| A GUANO PORT, CHINCHA ISLANDS | 288 |

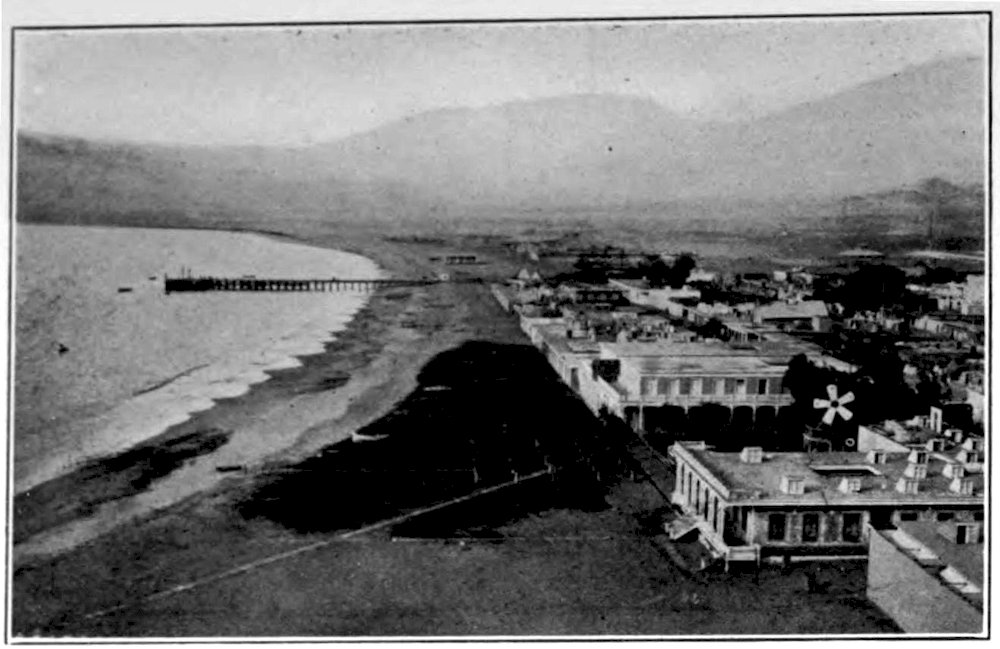

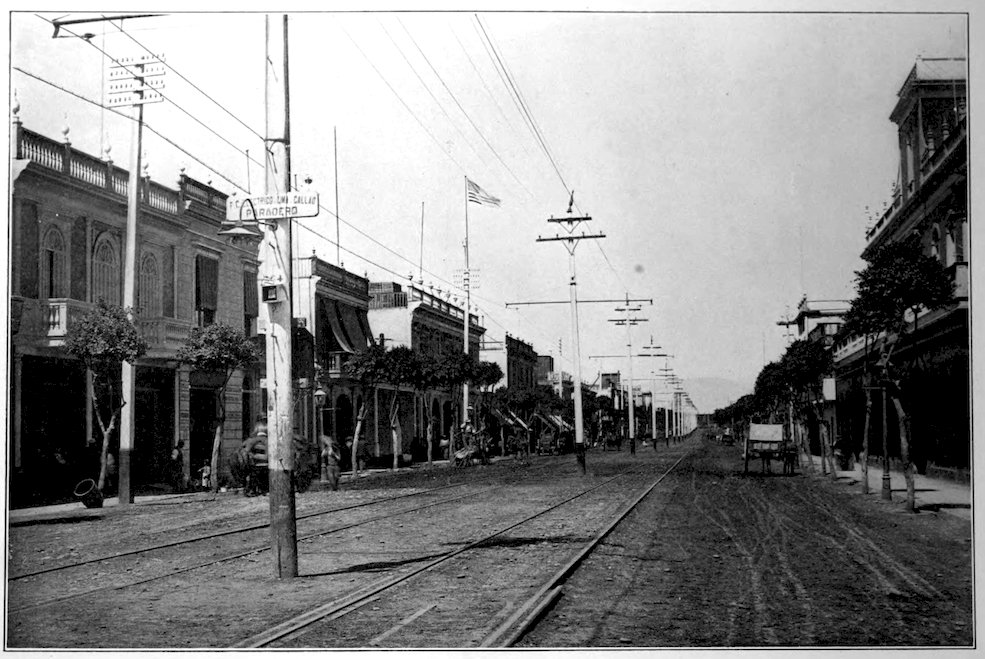

| CALLE DE LIMA, CALLAO | 290 |

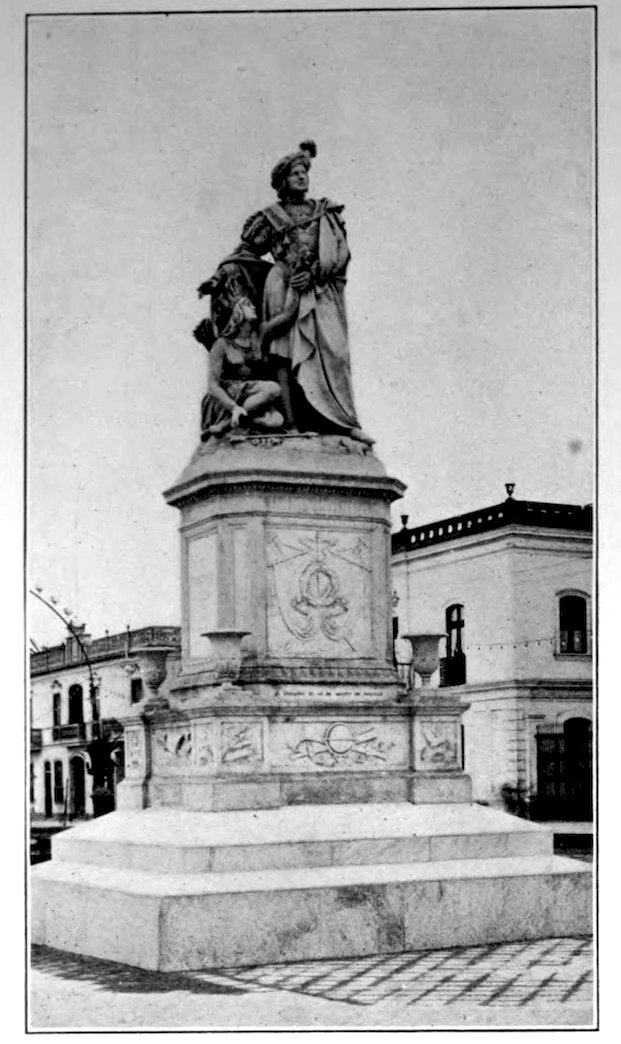

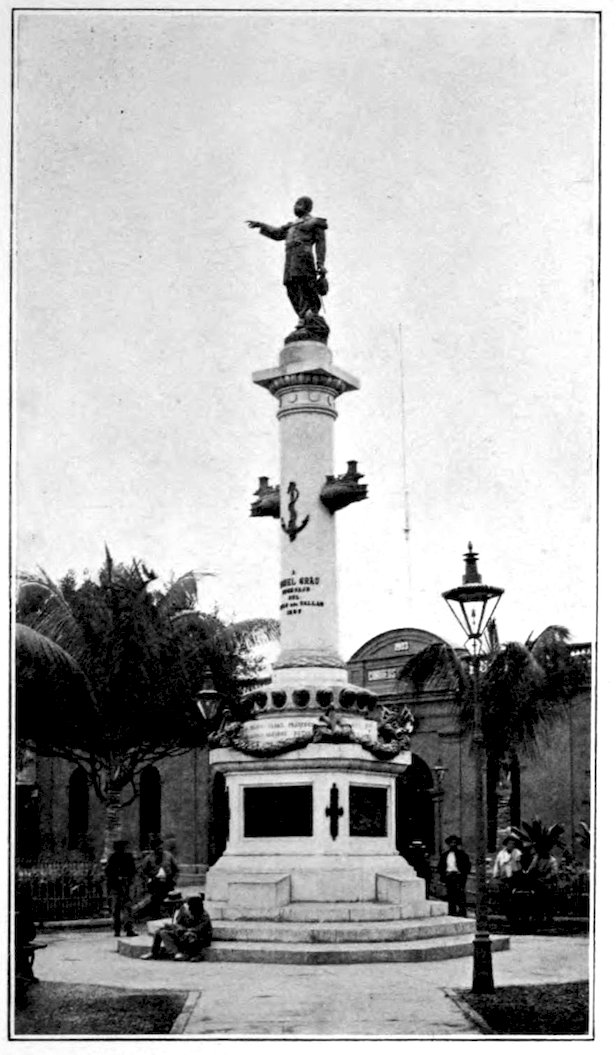

| MONUMENT TO ADMIRAL GRAU, CALLAO | 291 |

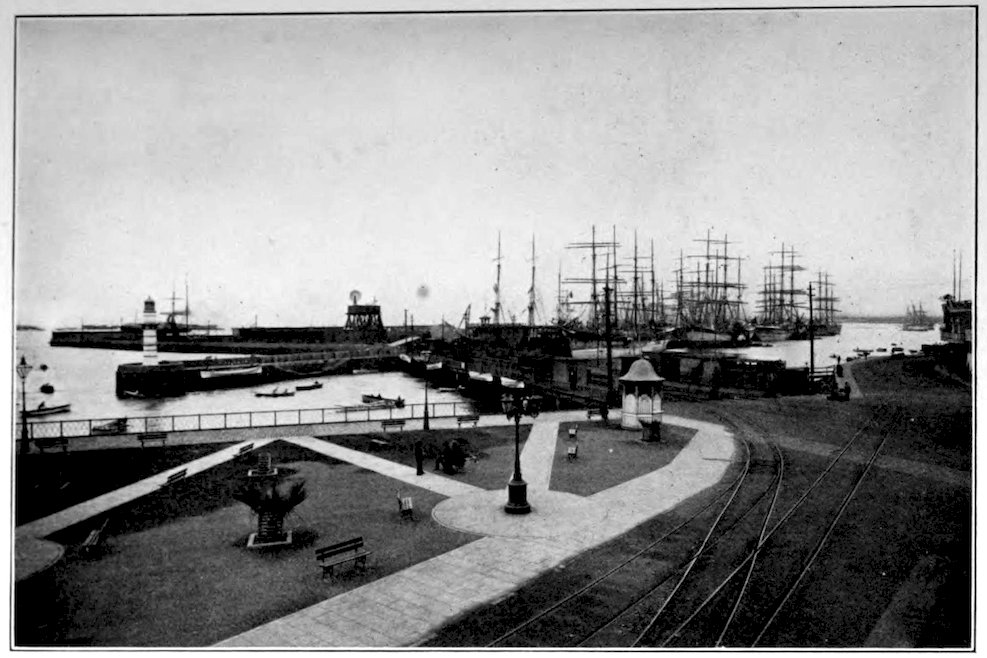

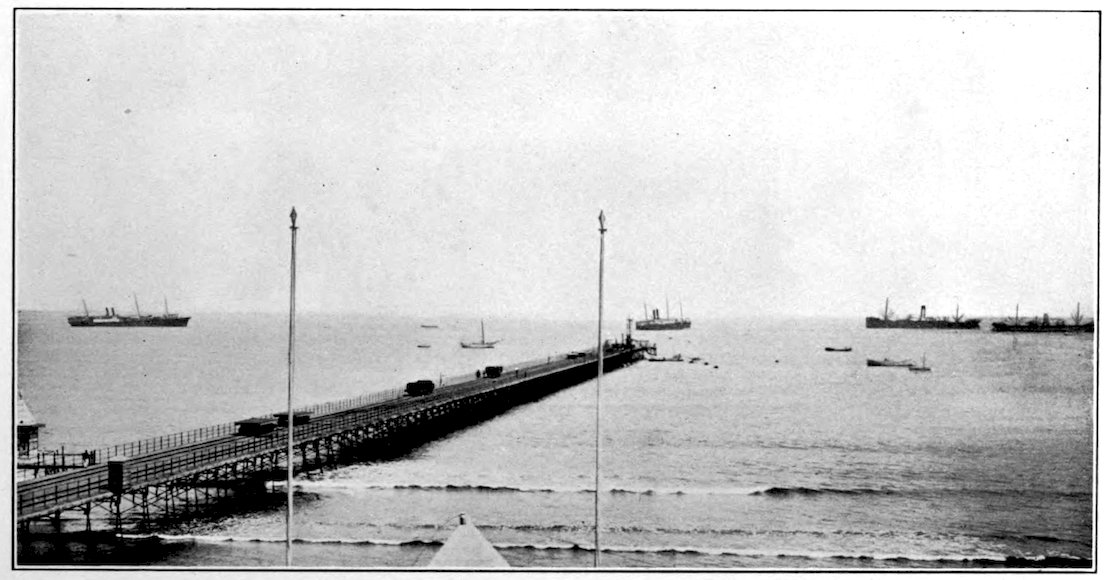

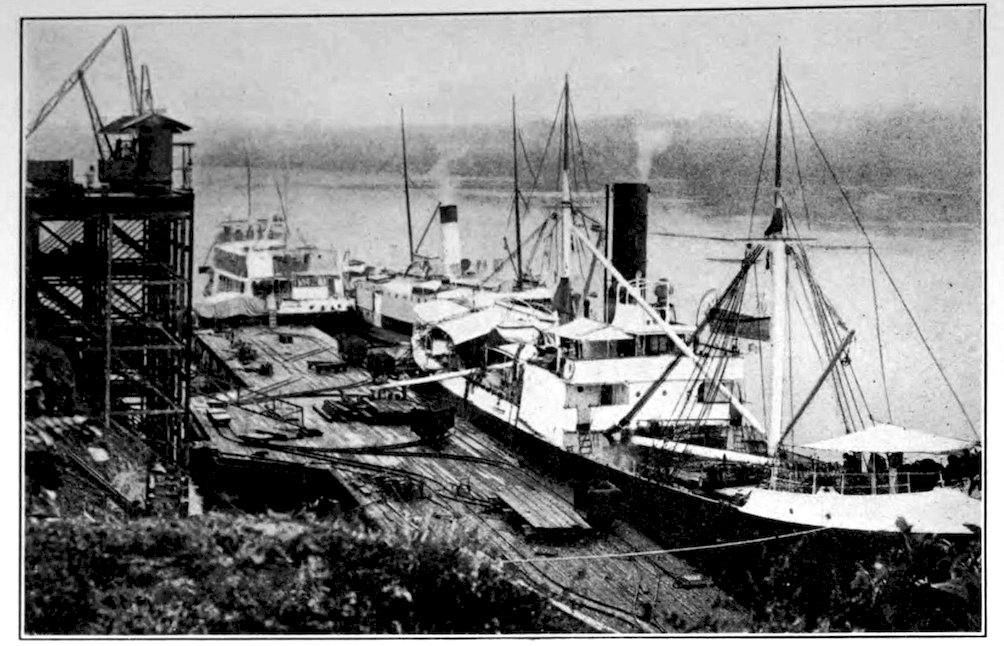

| THE DOCKS AT CALLAO | 292 |

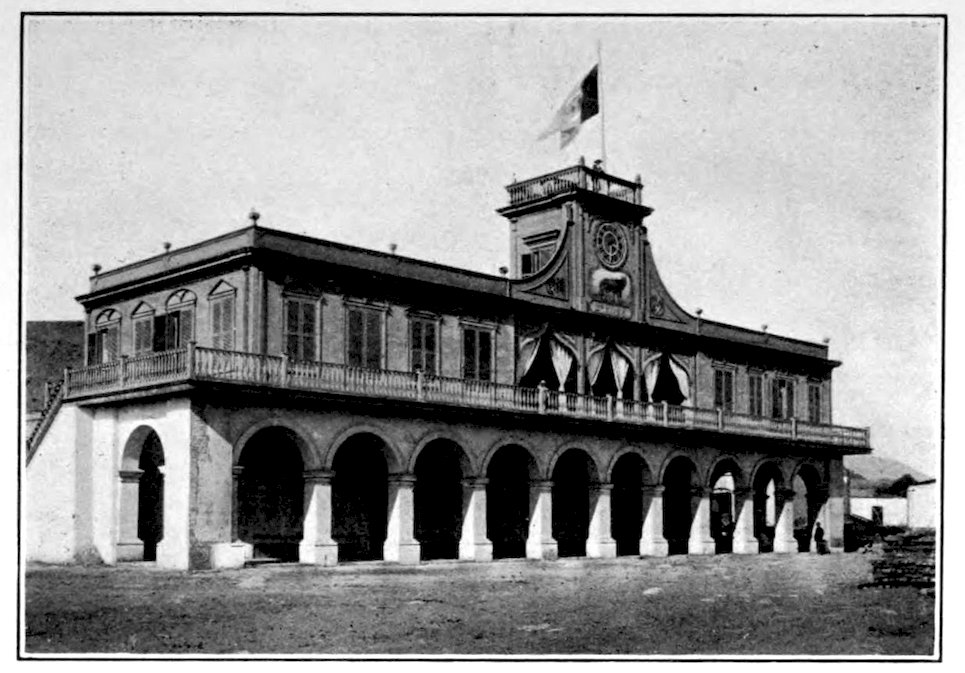

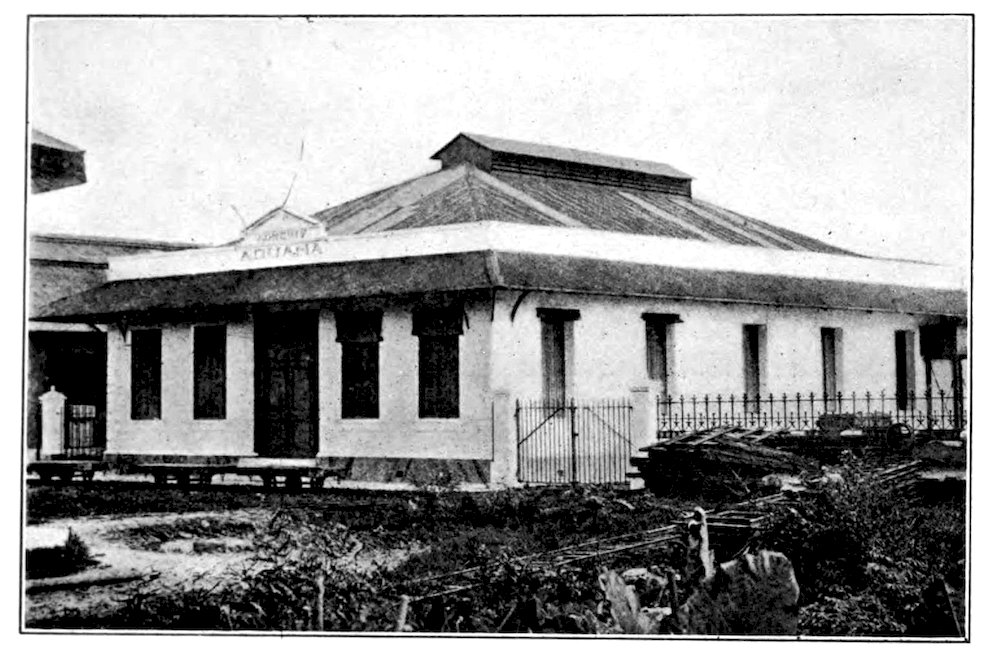

| THE CUSTOM HOUSE, CALLAO | 293 |

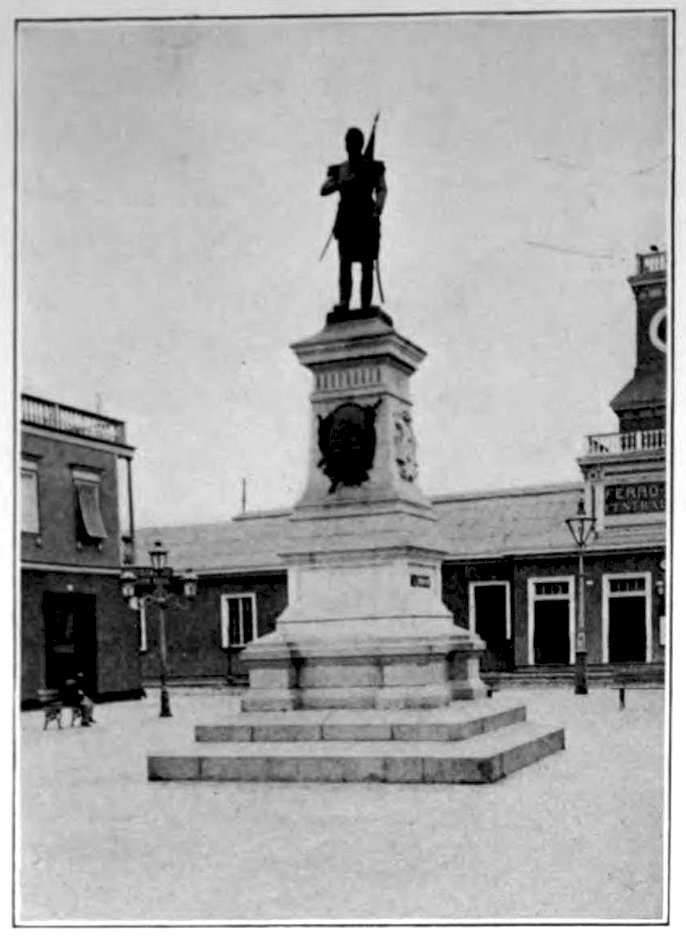

| STATUE OF THE LIBERATOR, CALLAO | 294 |

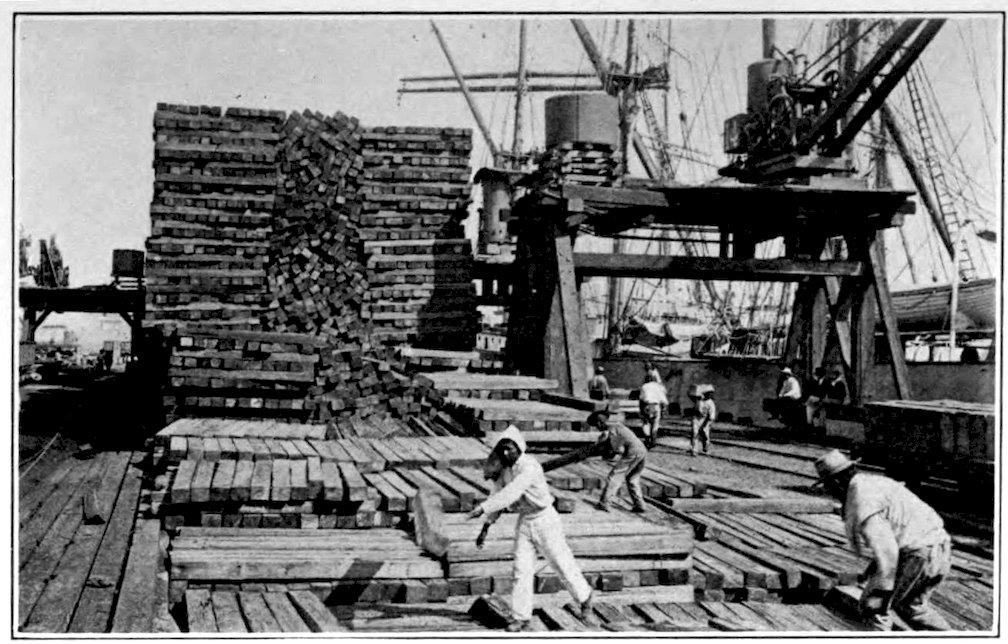

| UNLOADING LUMBER AT CALLAO | 295 |

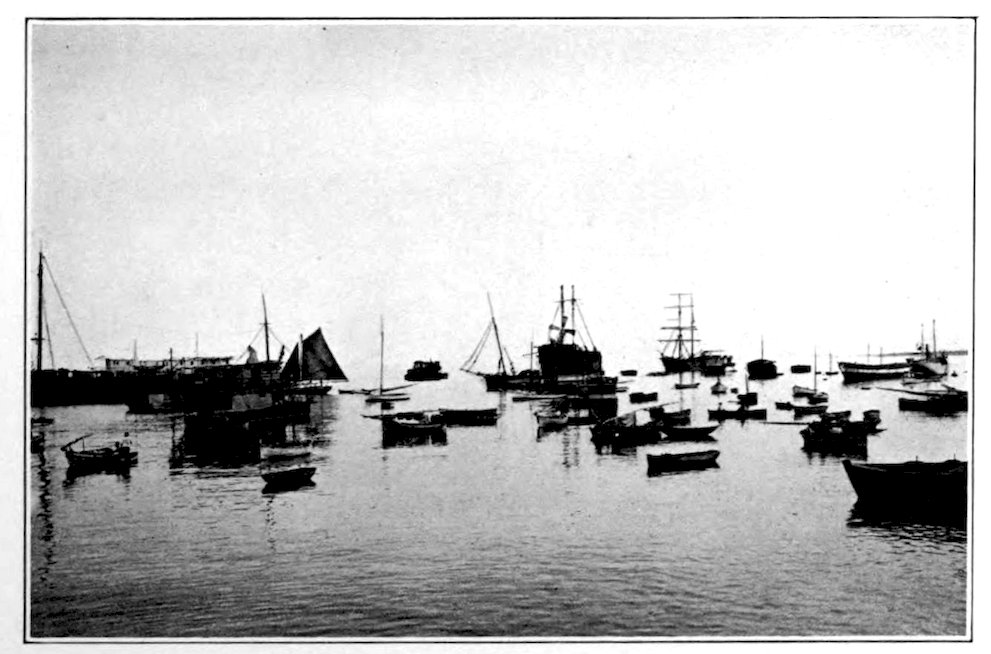

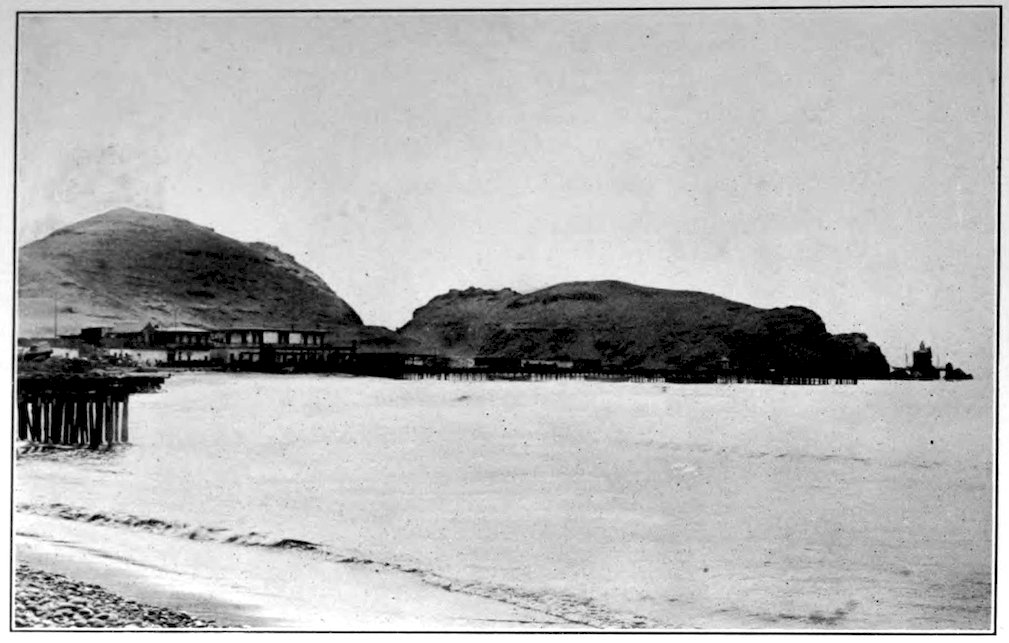

| CALLAO HARBOR | 295 |

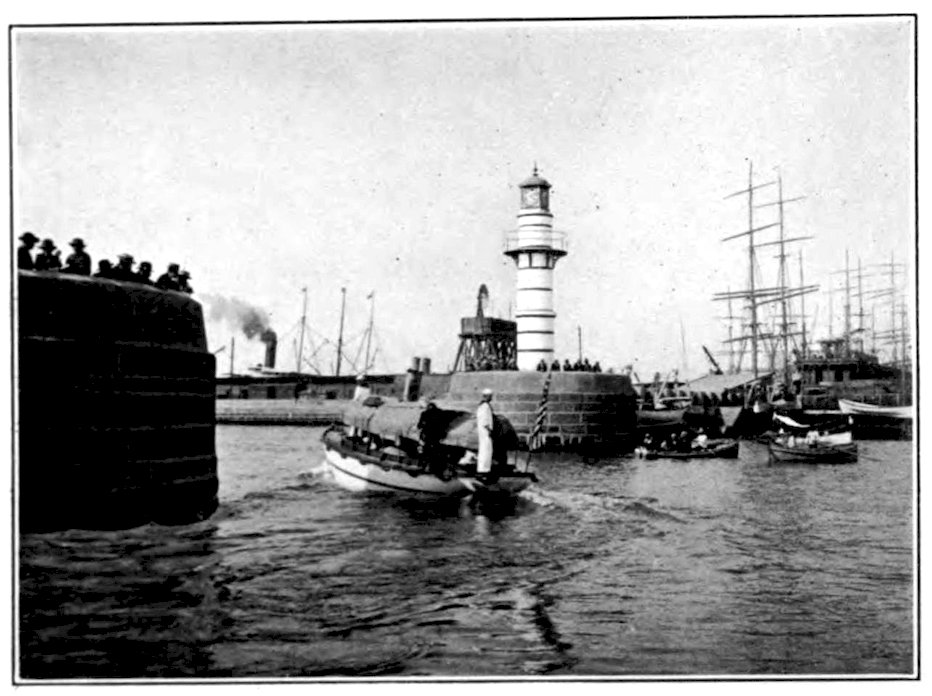

| PIER OF THE ARSENAL, CALLAO | 296 |

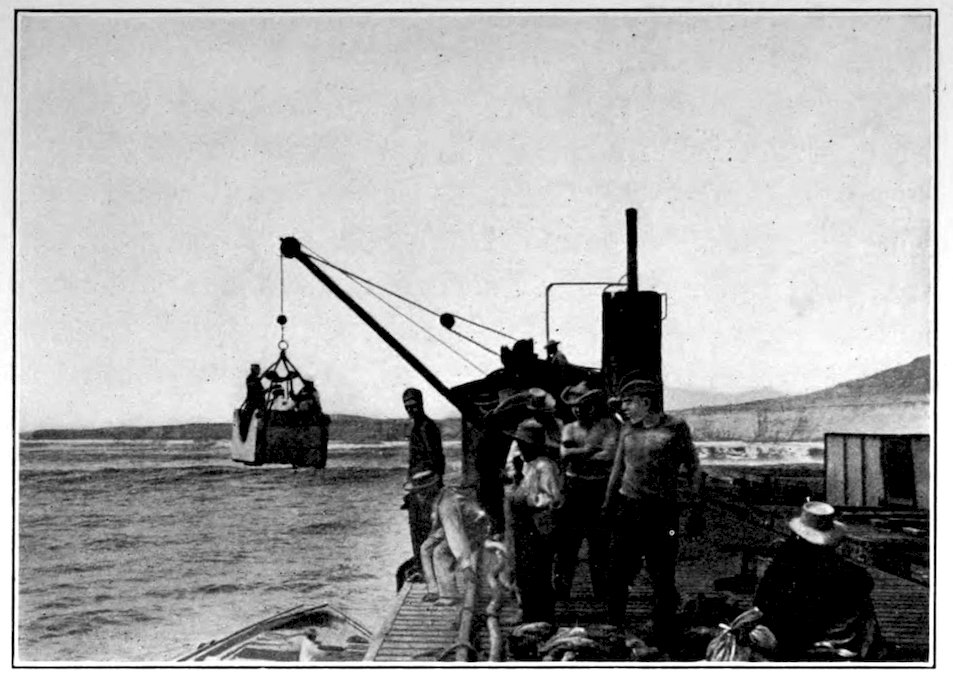

| PASSENGERS LANDING AT ETEN FROM A STEAMER OF THE PACIFIC LINE | 297 |

| PREFECTURE, CALLAO | 298 |

| A TYPICAL HACIENDA OF THE COAST REGION | 300 |

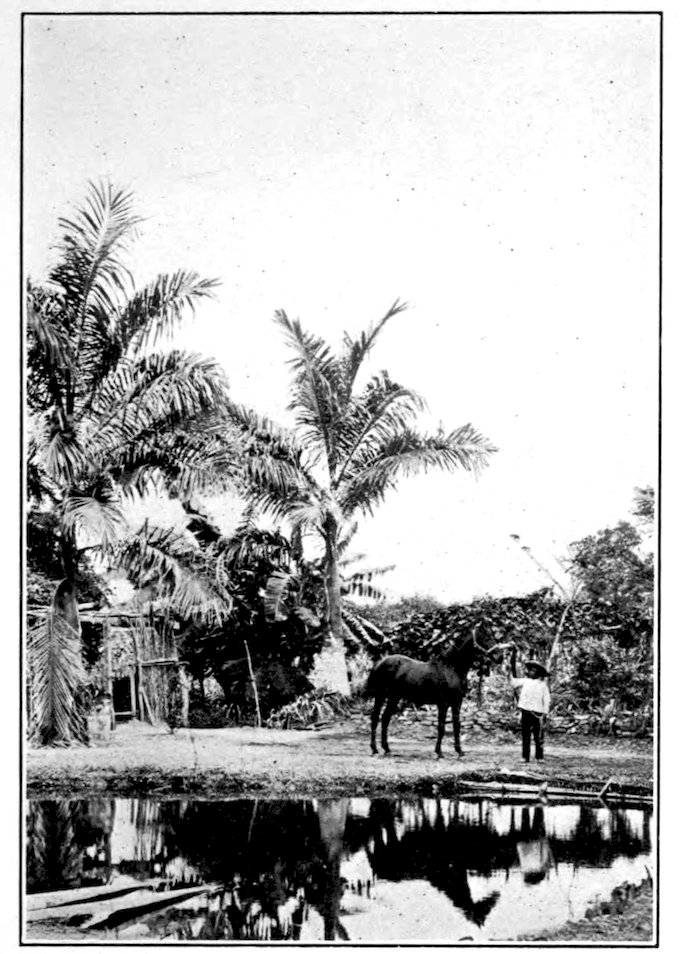

| PICTURESQUE GARDEN ON A RICE PLANTATION | 301 |

| IRRIGATING CANAL ON A PIURA PLANTATION | 302 |

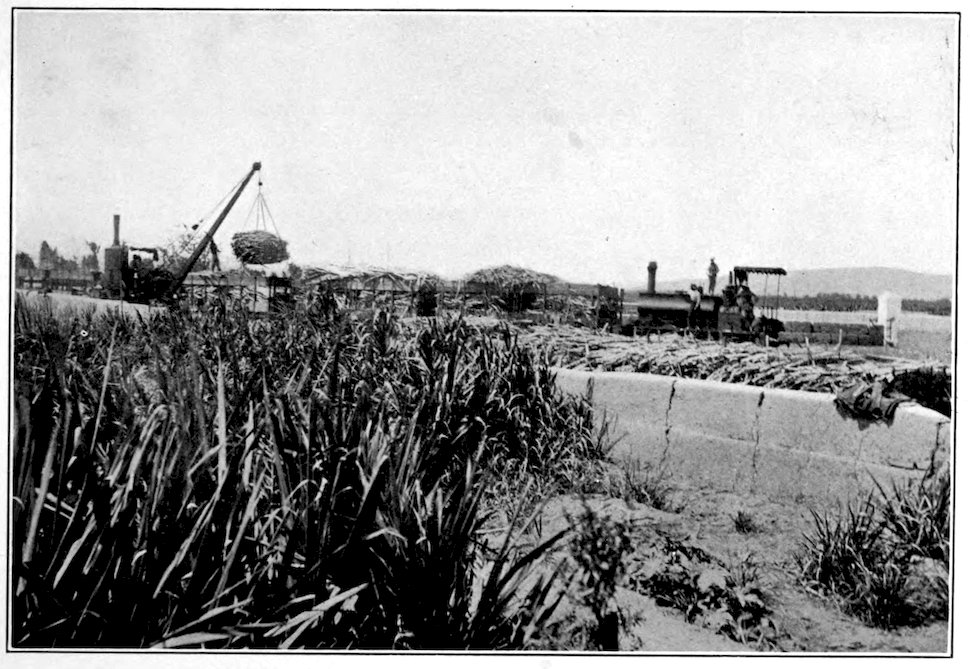

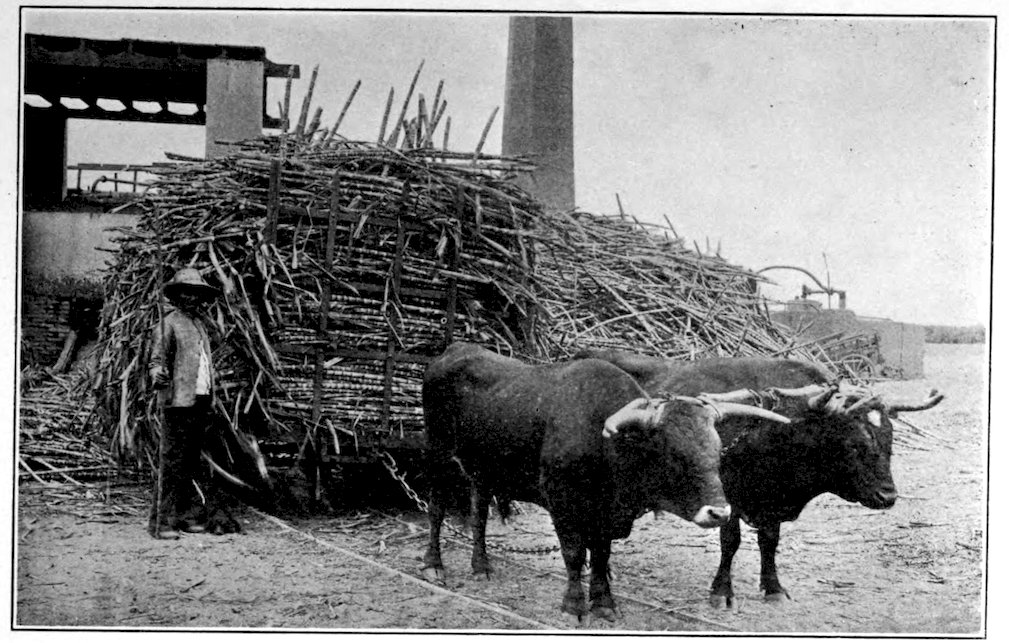

| LOADING SUGAR-CANE, SANTA BARBARA PLANTATION, CAÑETE | 303 |

| PIER AND WAREHOUSES OF THE BRITISH SUGAR COMPANY, LIMITED, AT CERRO AZUL | 304 |

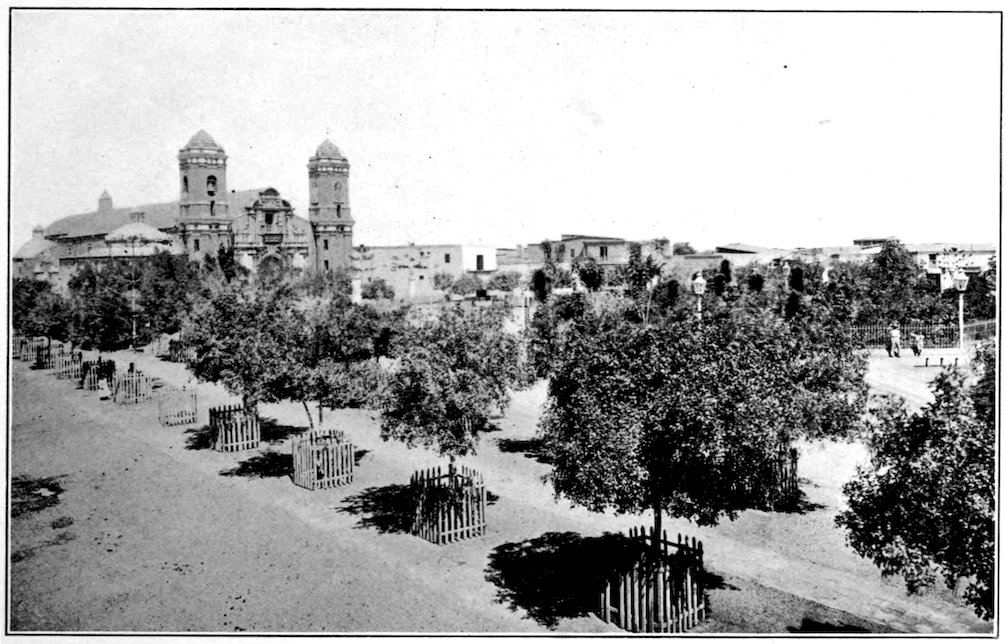

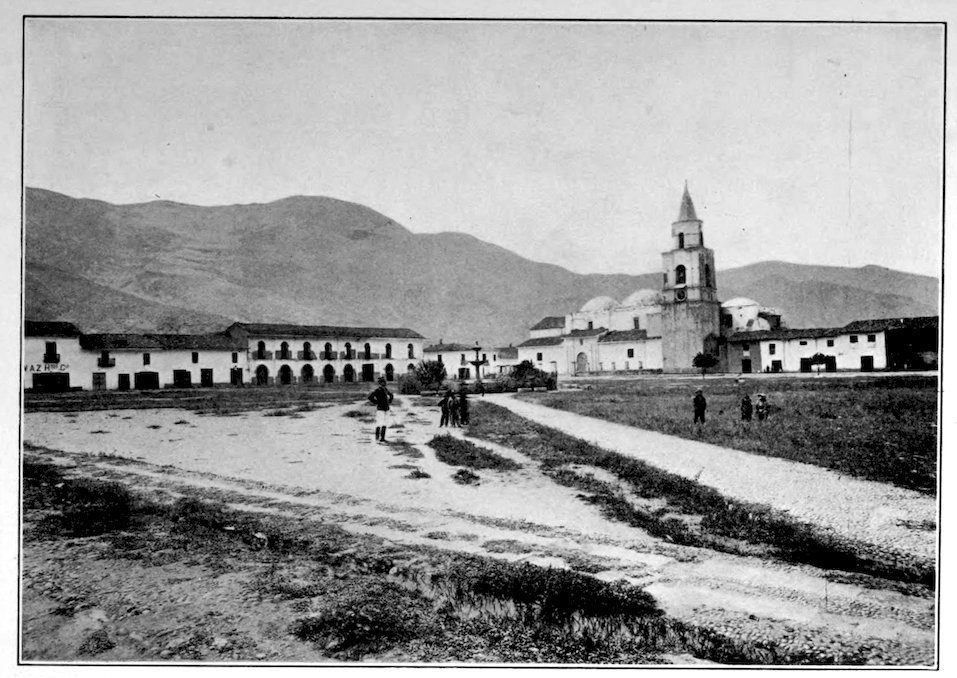

| FERREÑAFE, A FLOURISHING CENTRE OF THE RICE INDUSTRY | 305 |

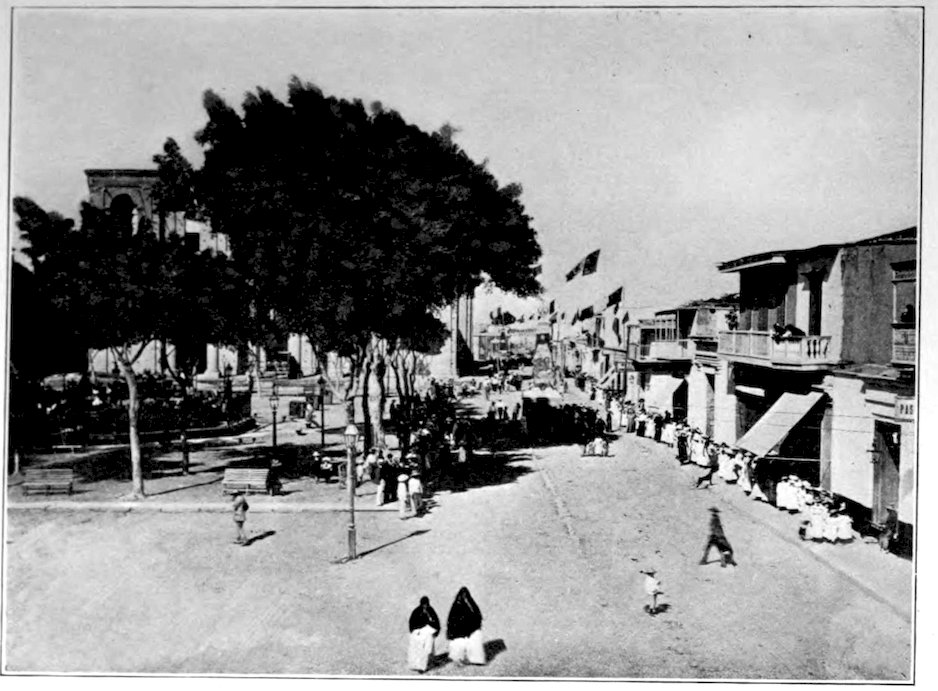

| A HOLIDAY IN CHICLAYO | 306 |

| WORKMEN ON A COAST PLANTATION | 307 |

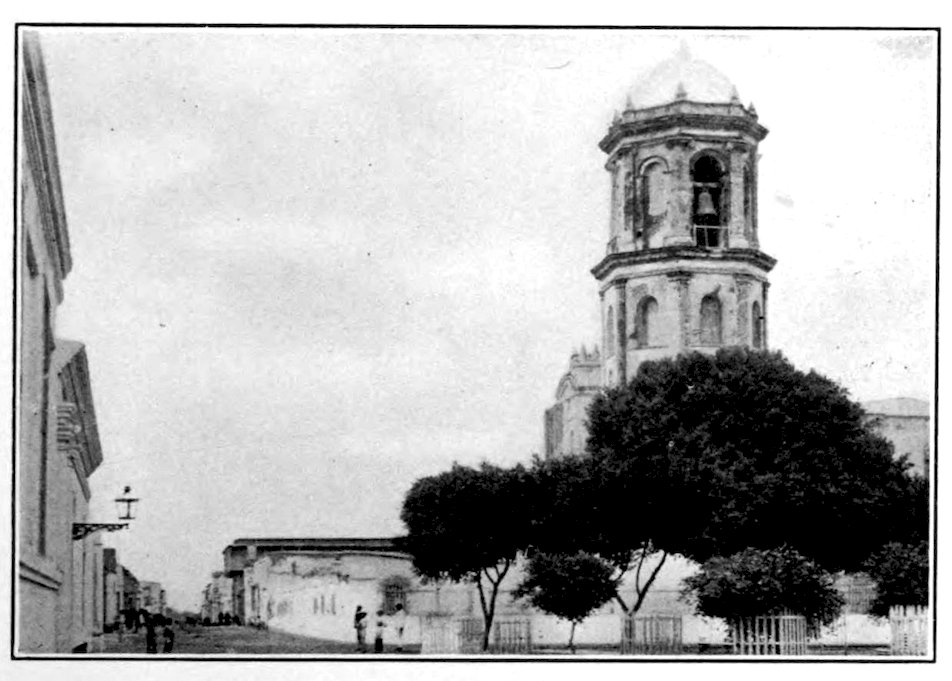

| STREET AND OLD CHURCH OF LAMBAYEQUE | 307 |

| PATAPO, DEPARTMENT OF LAMBAYEQUE | 308 |

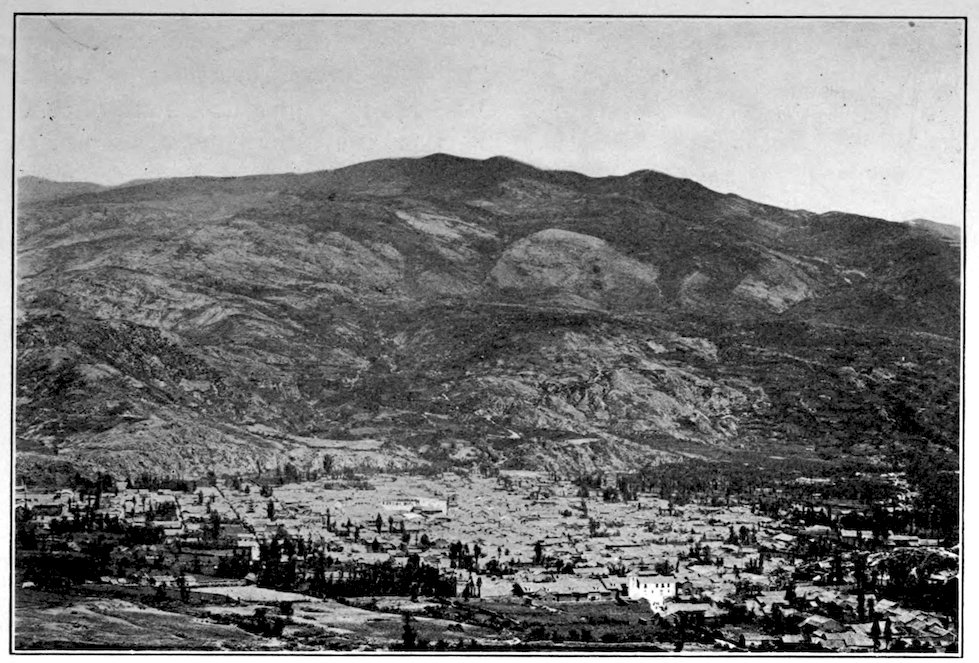

| HUARAZ, CAPITAL OF THE DEPARTMENT OF ANCASH | 309 |

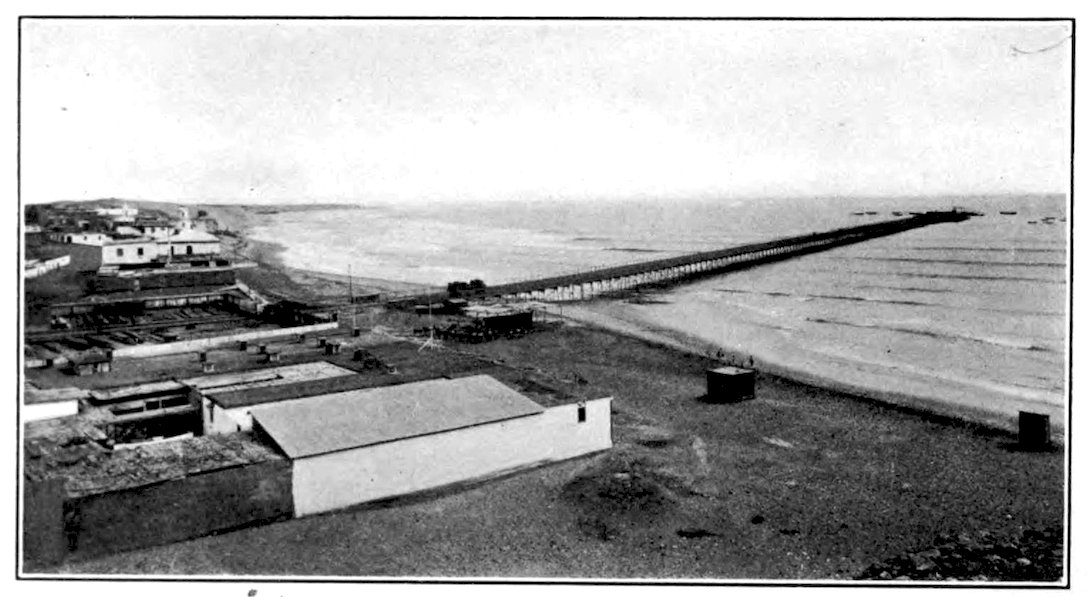

| PORT OF PACASMAYO | 310 |

| THE CHICAMA RIVER, DEPARTMENT OF LA LIBERTAD | 312 |

| HUACO DEL SOL, TRUJILLO | 313 |

| GALLERY OF THE PALACE OF JUSTICE, TRUJILLO | 314 |

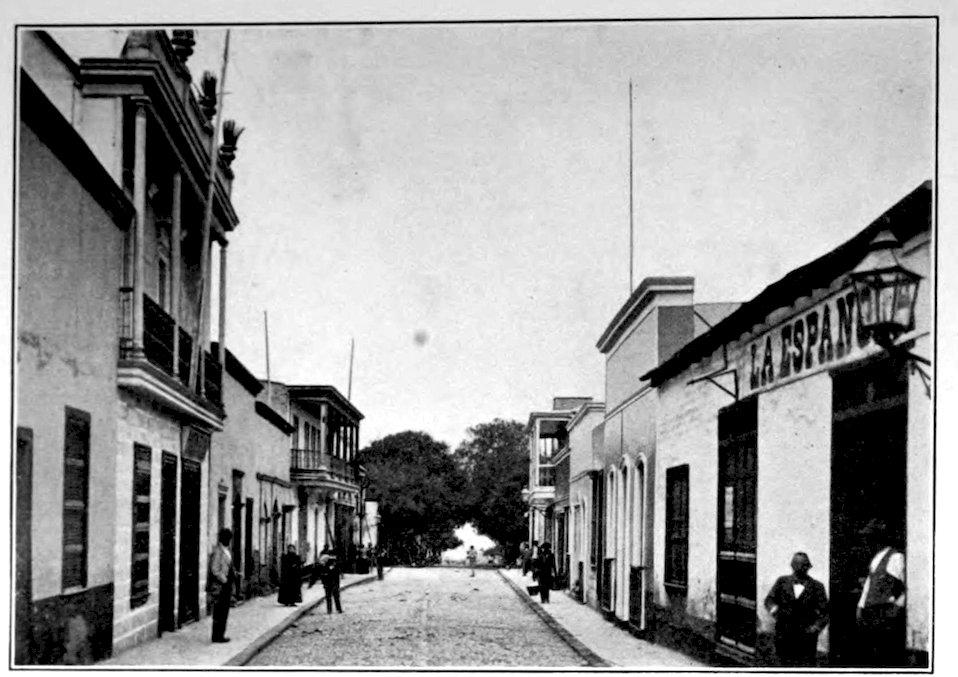

| CALLE DEL COMERCIO, TRUJILLO | 315 |

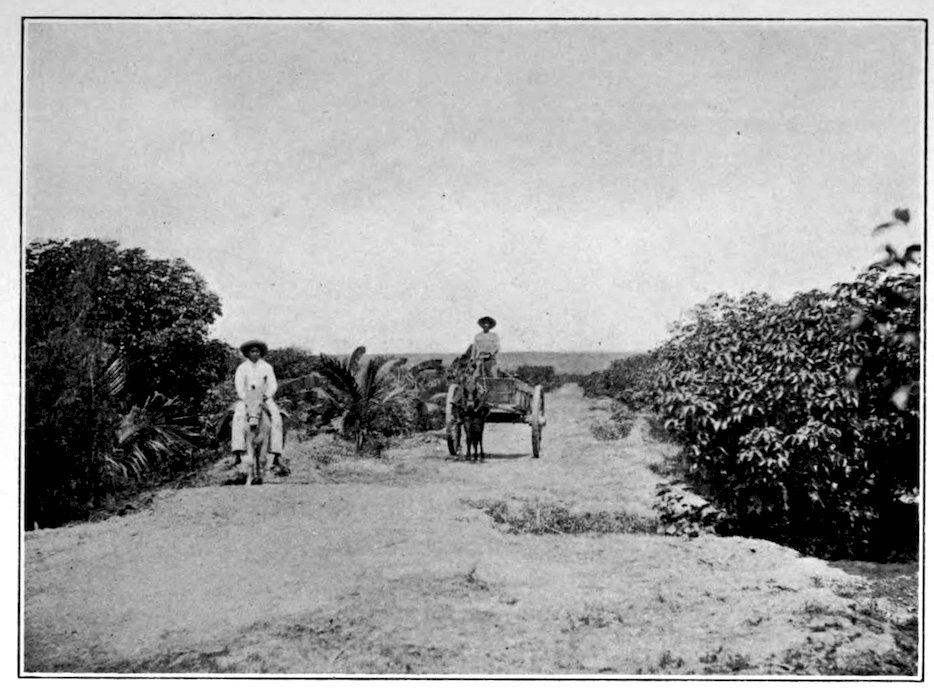

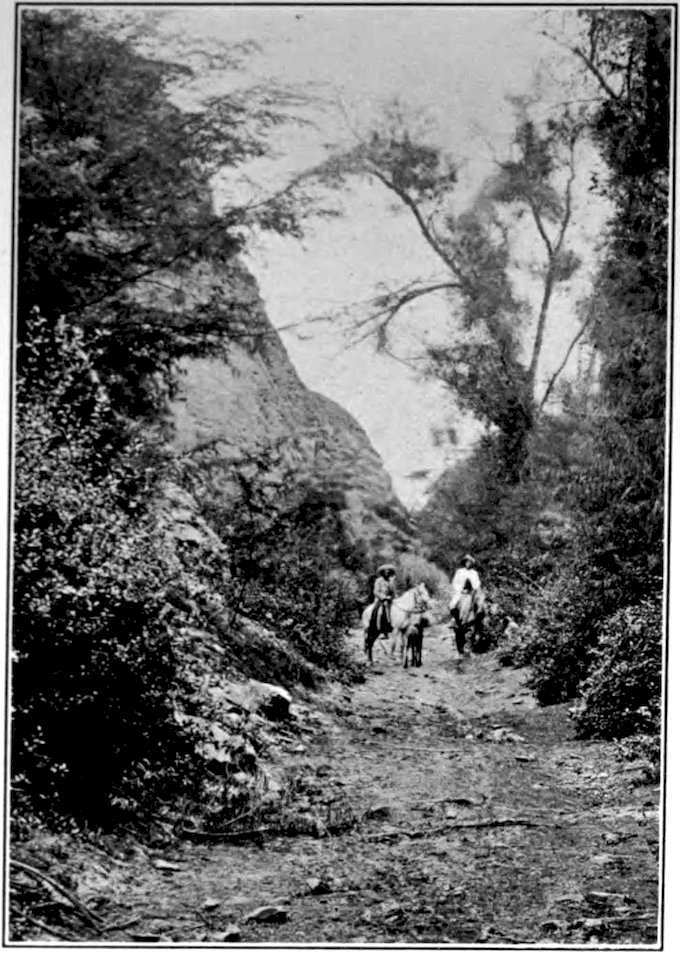

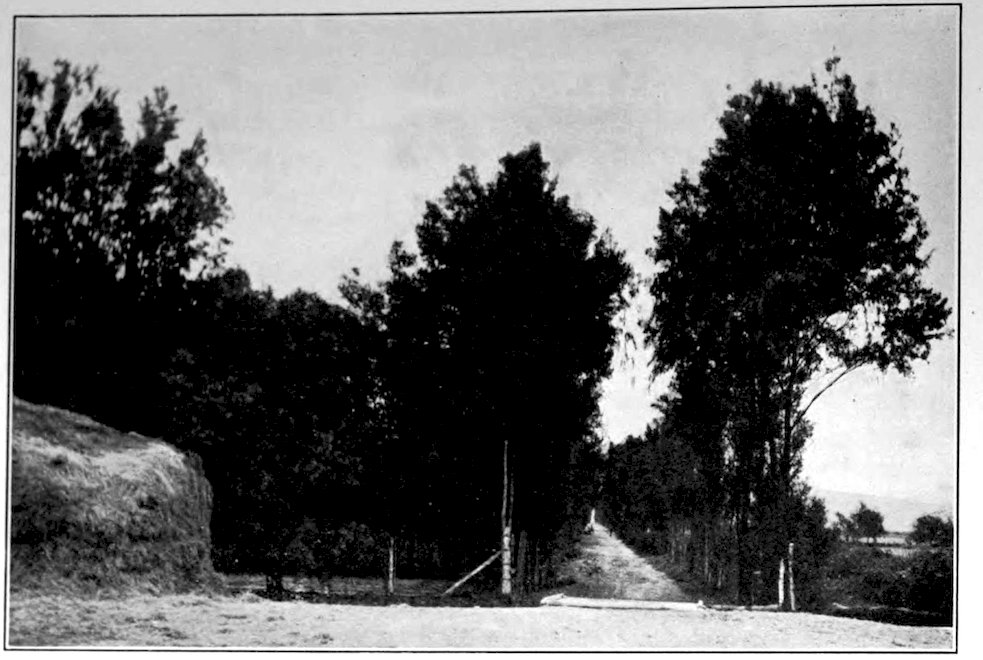

| PICTURESQUE ROAD THROUGH A SUGAR ESTATE | 316 |

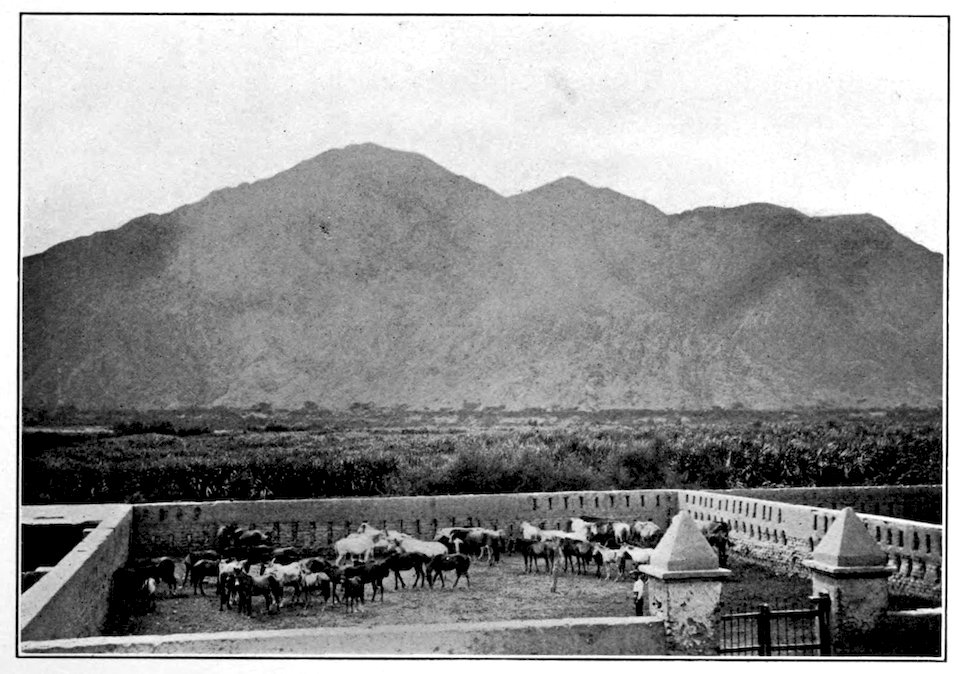

| A CORRAL ON A SUGAR ESTATE, CHICAMA VALLEY | 317 |

| A LOAD OF CANE READY FOR THE FACTORY | 319 |

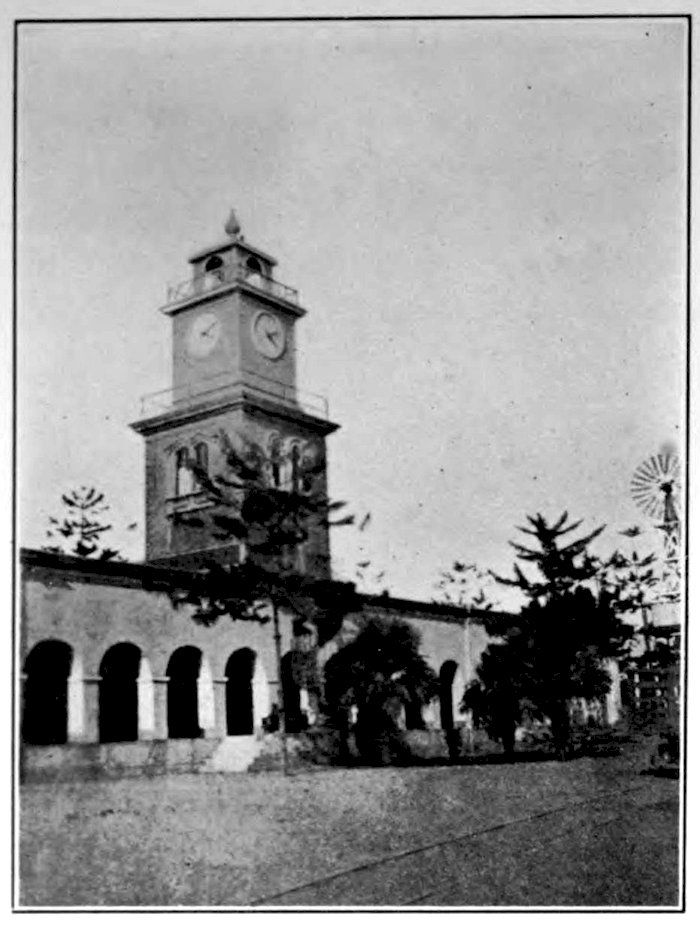

| MAIN ENTRANCE TO A SUGAR HACIENDA NEAR TRUJILLO | 320 |

| THE CHAPEL OF A HACIENDA AT GALINDO | 321 |

| PARK OF LA LIBERTAD, TRUJILLO | 322 |

| ADMINISTRATION HOUSE OF A SUGAR ESTATE IN THE CHICAMA VALLEY | 323 |

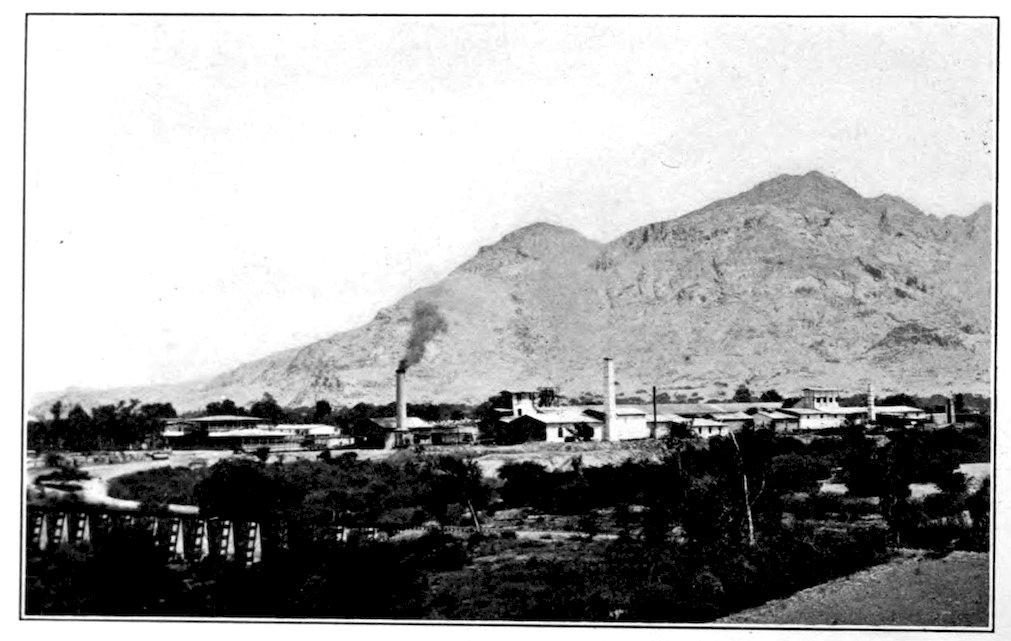

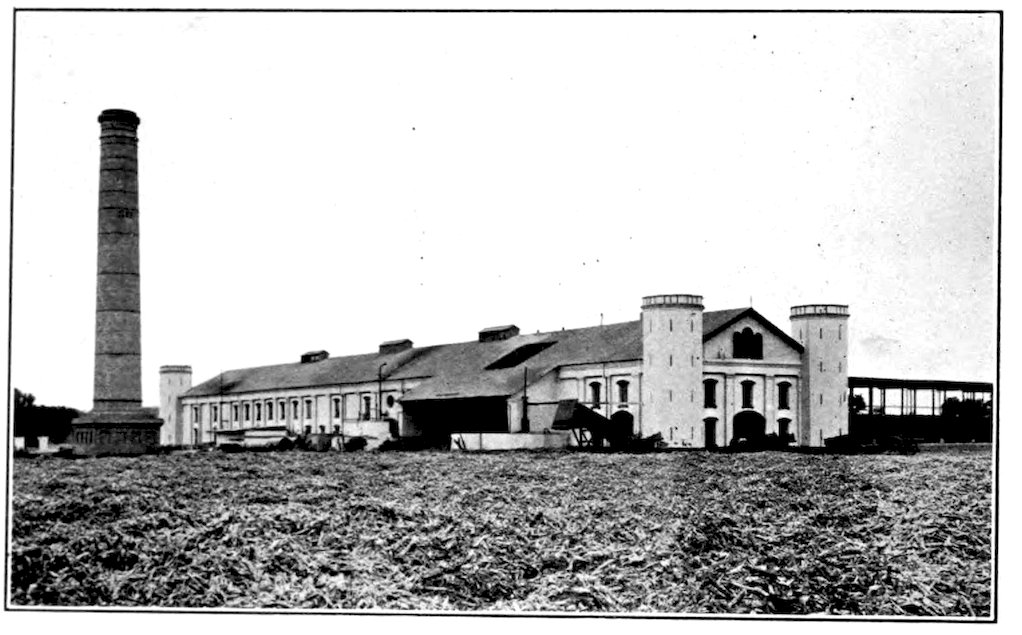

| A SUGAR FACTORY OF THE CHICAMA VALLEY | 324 |

| PAITA, THE CHIEF SHIPPING PORT FOR PERUVIAN COTTON | 326 |

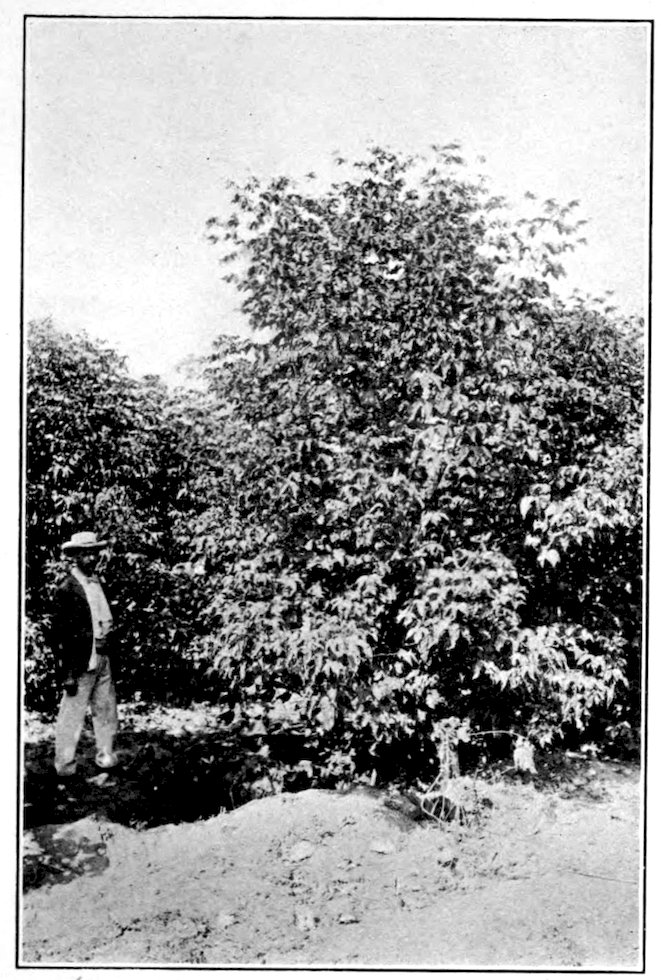

| A COTTON PLANT ON A PIURA PLANTATION | 327 |

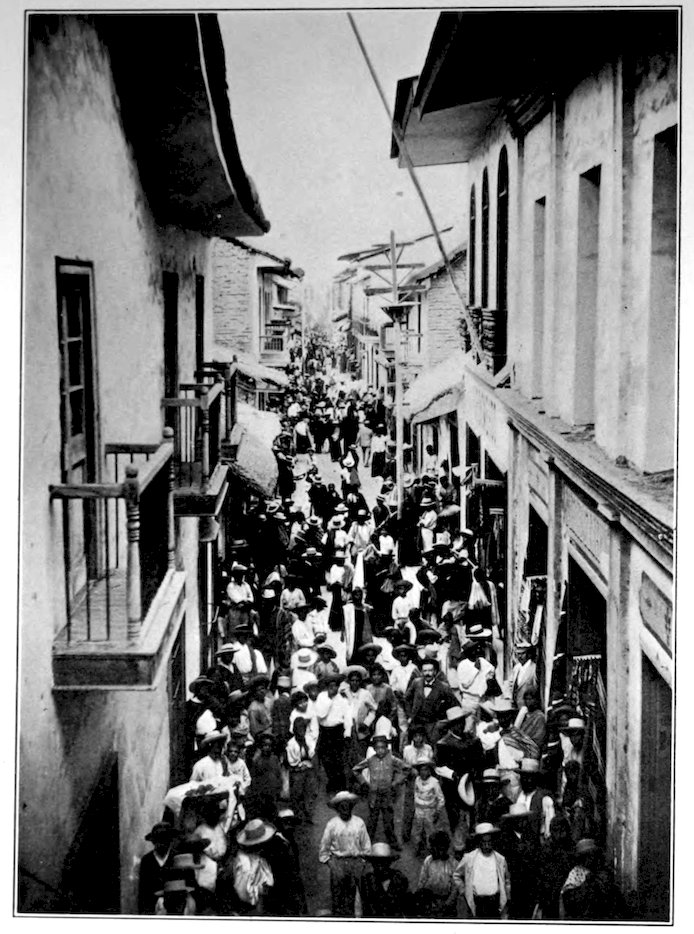

| A BUSY THOROUGHFARE OF CATACAOS | 328 |

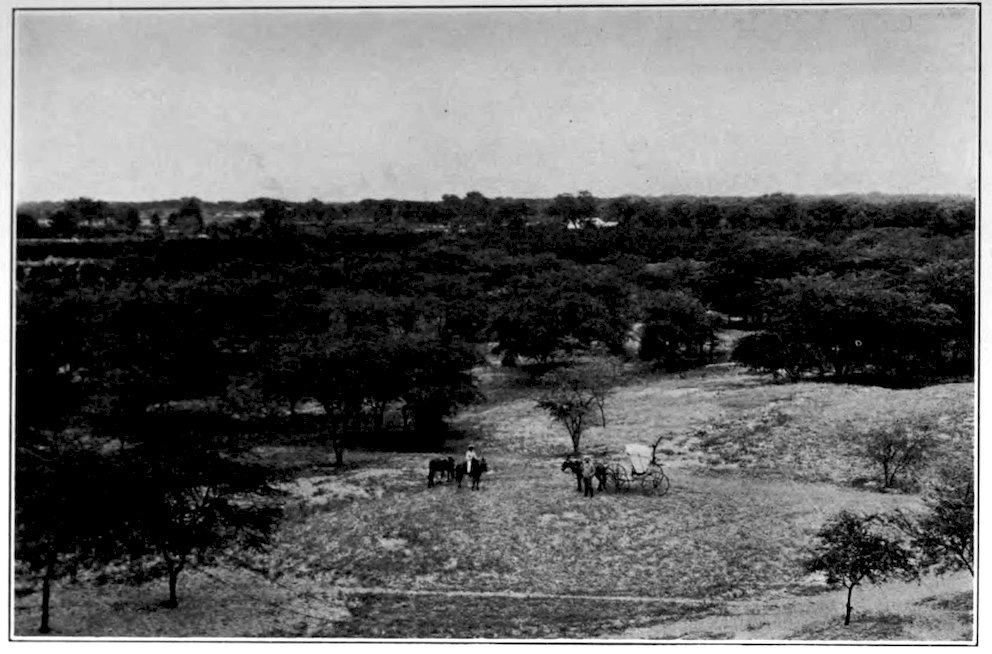

| ALGARROBA TREES ON A PIURA PLANTATION | 330 |

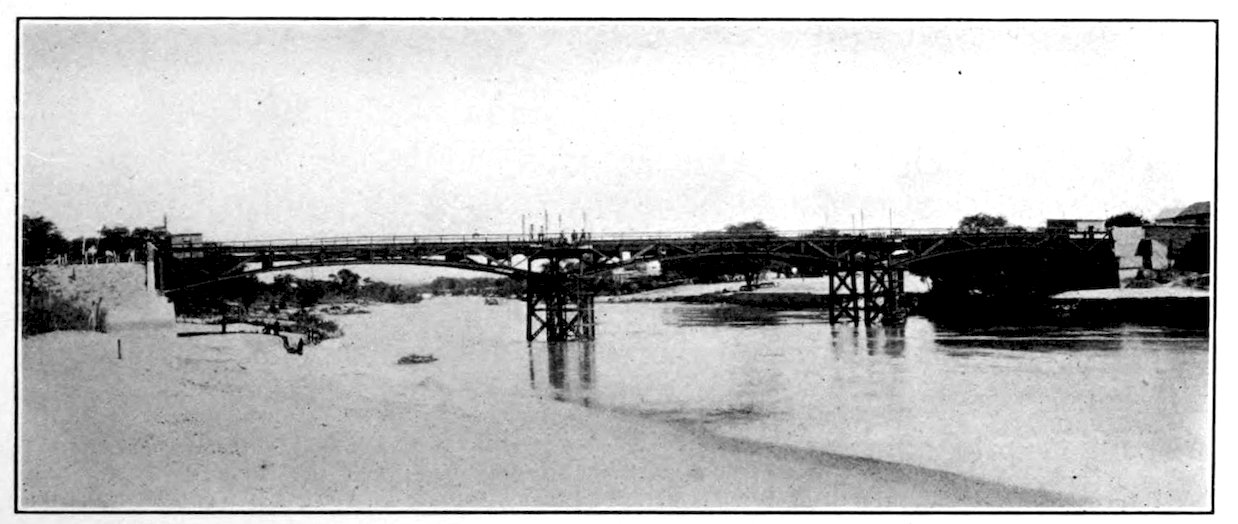

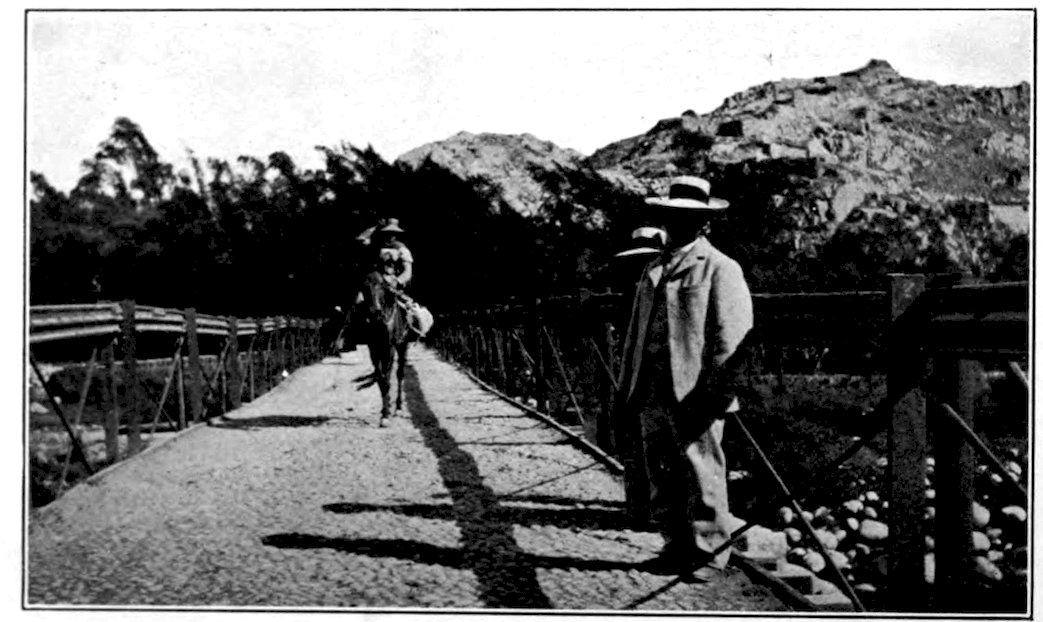

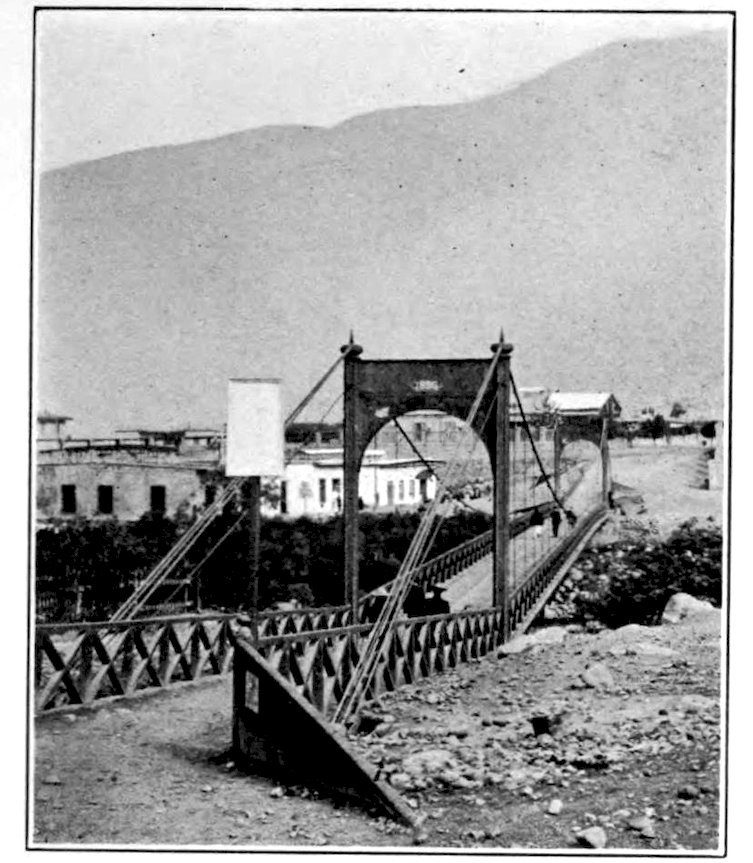

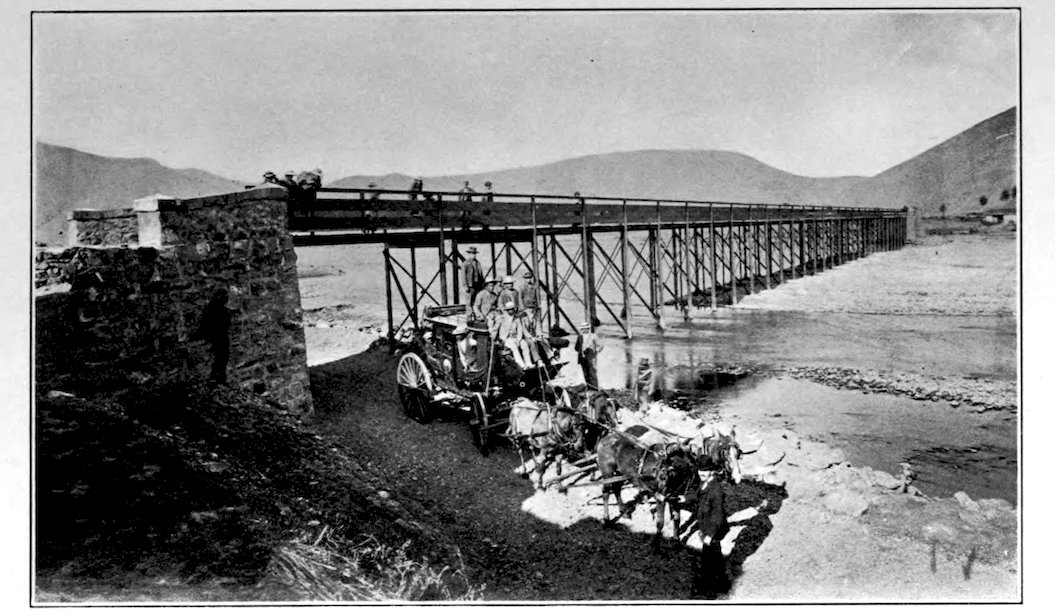

| IRON BRIDGE OVER THE PIURA RIVER | 331 |

| THE MARKET PLACE AT CATACAOS | 332 |

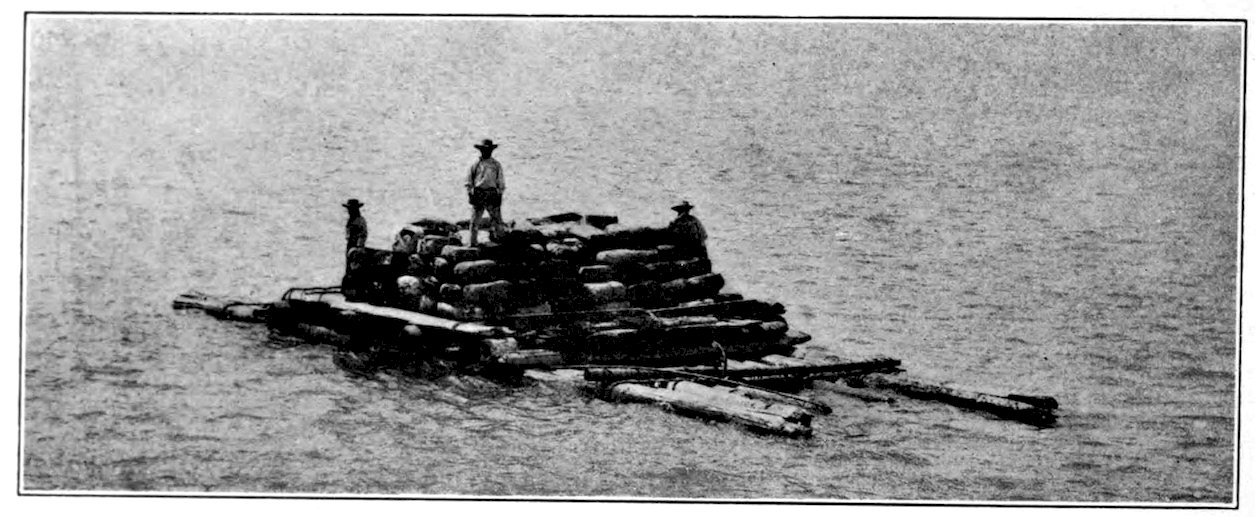

| A “BALSA” LOADED WITH FREIGHT, PAITA | 334 |

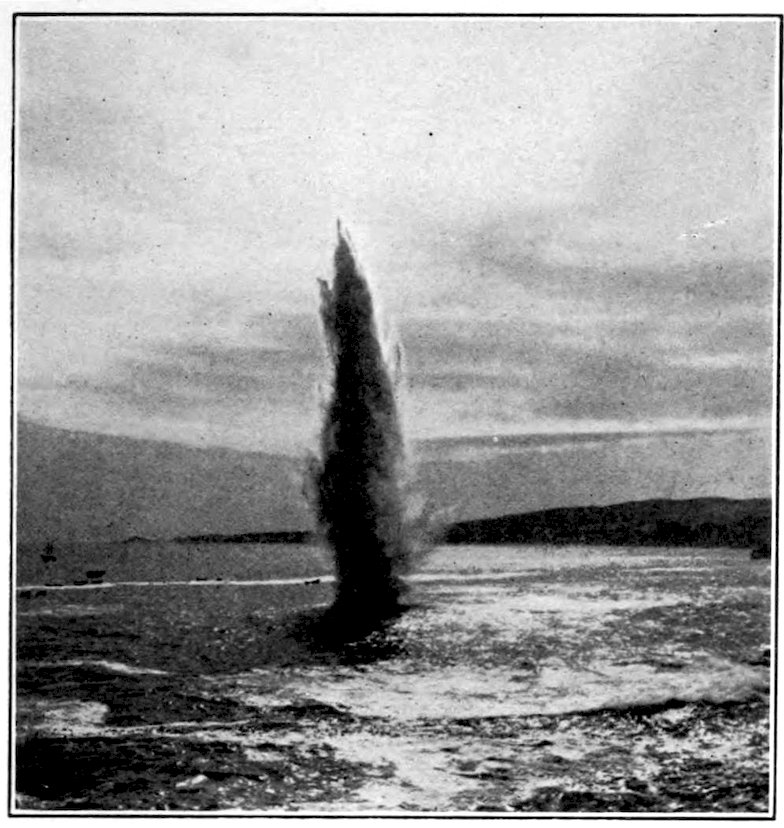

| SUBMARINE BLASTING OFF MOLLENDO | 335 |

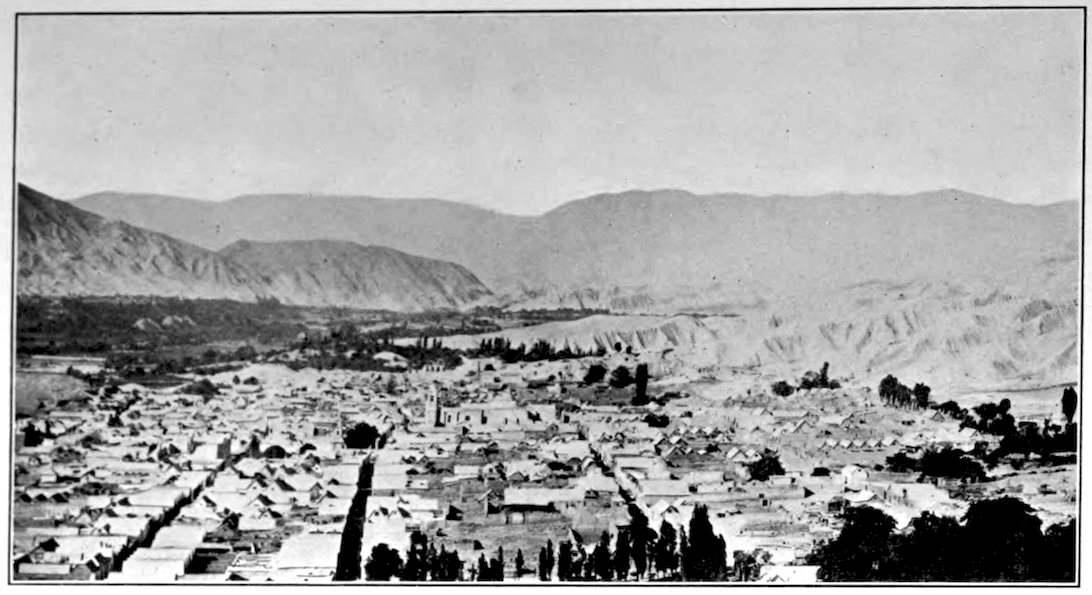

| MOQUEGUA, A WINE-GROWING CENTRE OF THE SOUTHERN COAST REGION | 336 |

| THE LANDING PIER OF THE PORT OF PISCO | 337 |

| AVENUE OF WILLOW TREES ON A SOUTHERN COAST HACIENDA | 338 |

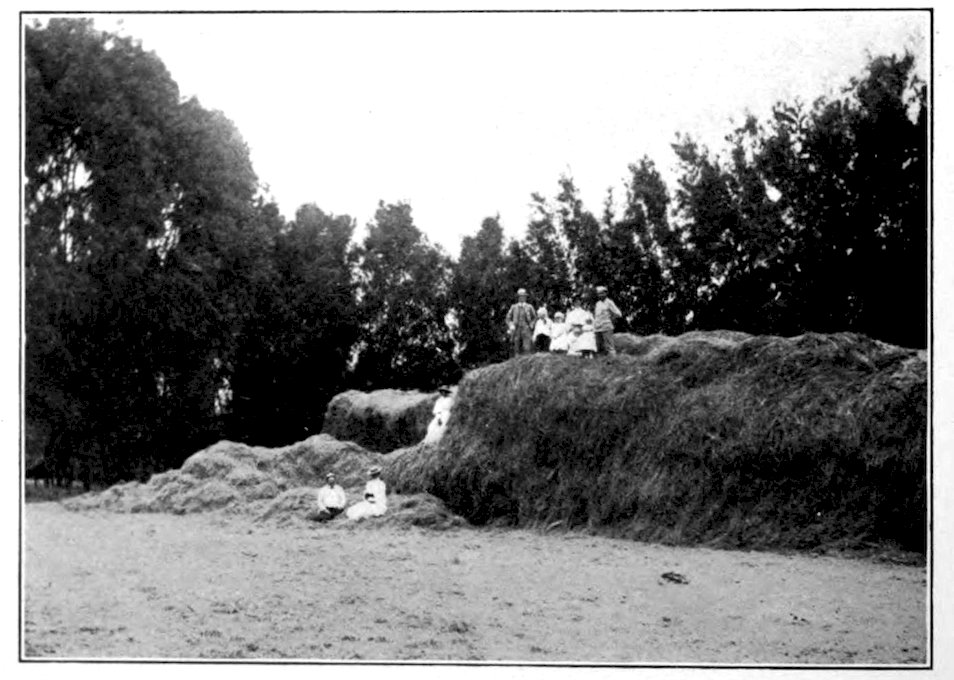

| HARVESTING ALFALFA ON THE FRISCO HACIENDA, NEAR MOLLENDO | 338 |

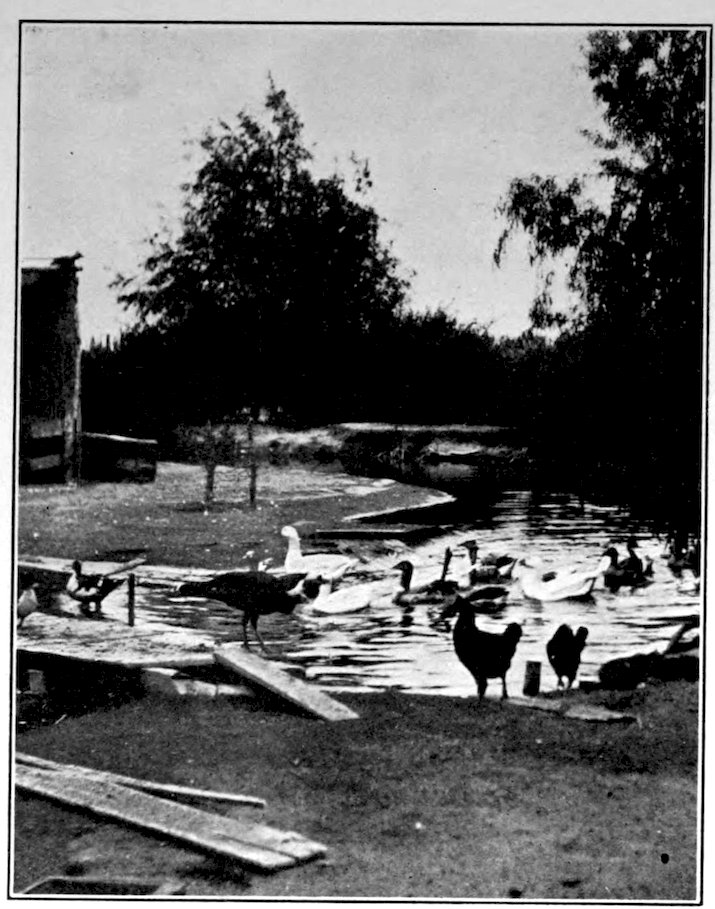

| SCENE ON A POULTRY FARM IN SOUTHERN AREQUIPA | 339 |

| A MILK VENDER ON HER WAY TO MARKET | 340 |

| THE SAMA VALLEY, TACNA | 342 |

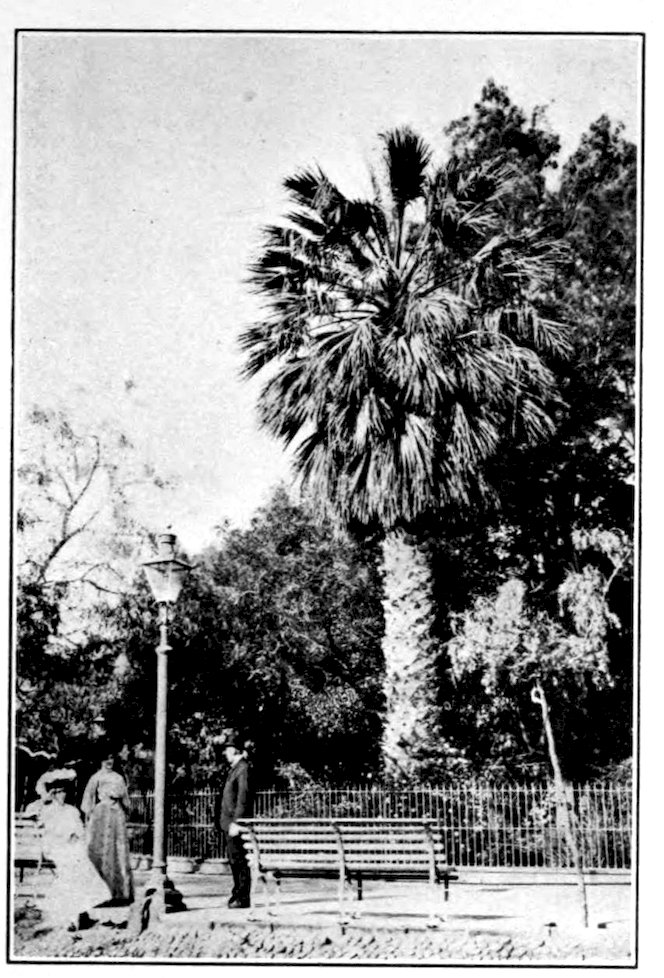

| A VENERABLE PALM OF TACNA | 343 |

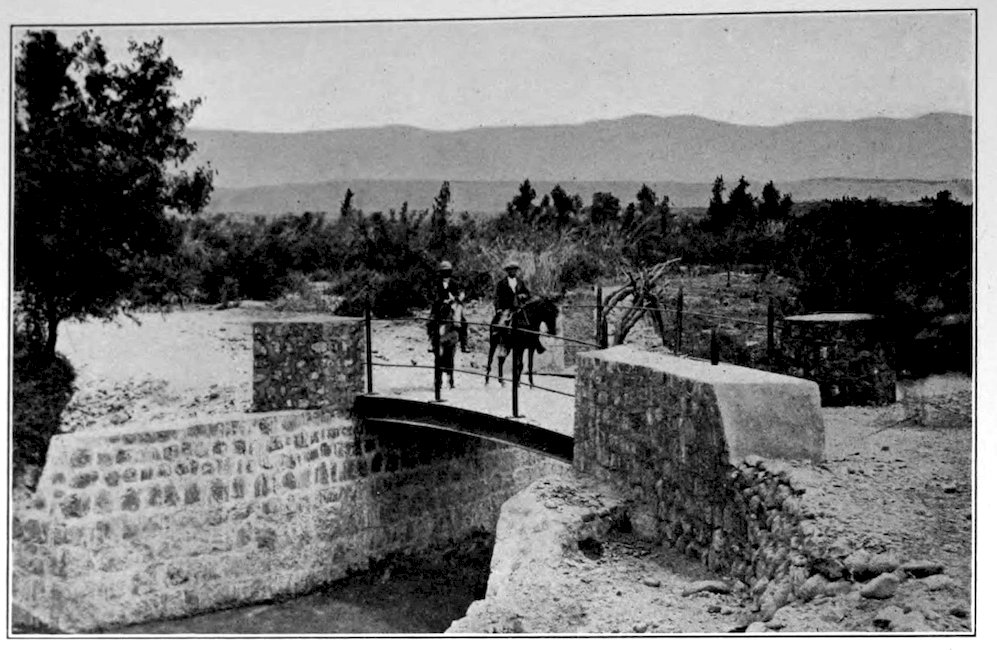

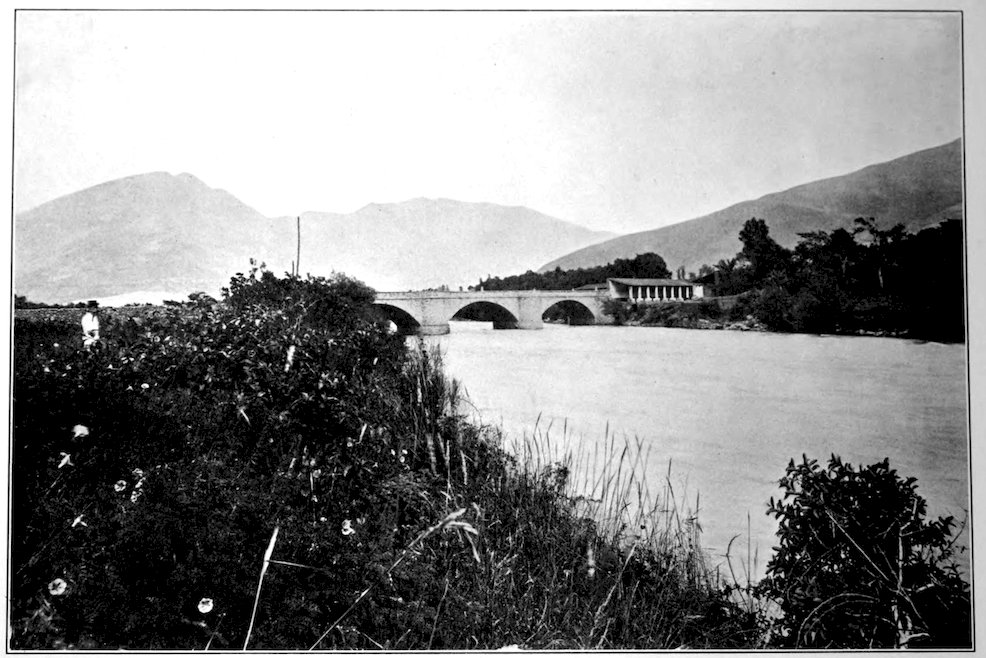

| BRIDGE ACROSS THE SAMA RIVER, PROVISIONAL BOUNDARY BETWEEN PERU AND CHILE | 344 |

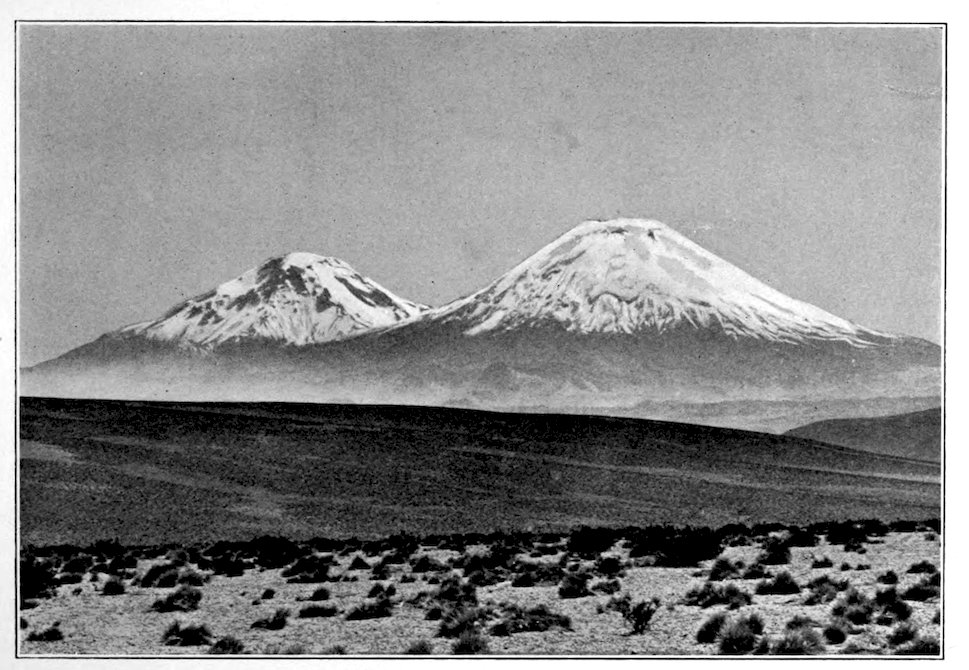

| SNOW PEAKS ON THE BOLIVIAN BORDER, TACNA | 345 |

| CALLE SAN MARTIN, NEAR PARK ENTRANCE, TACNA | 346 |

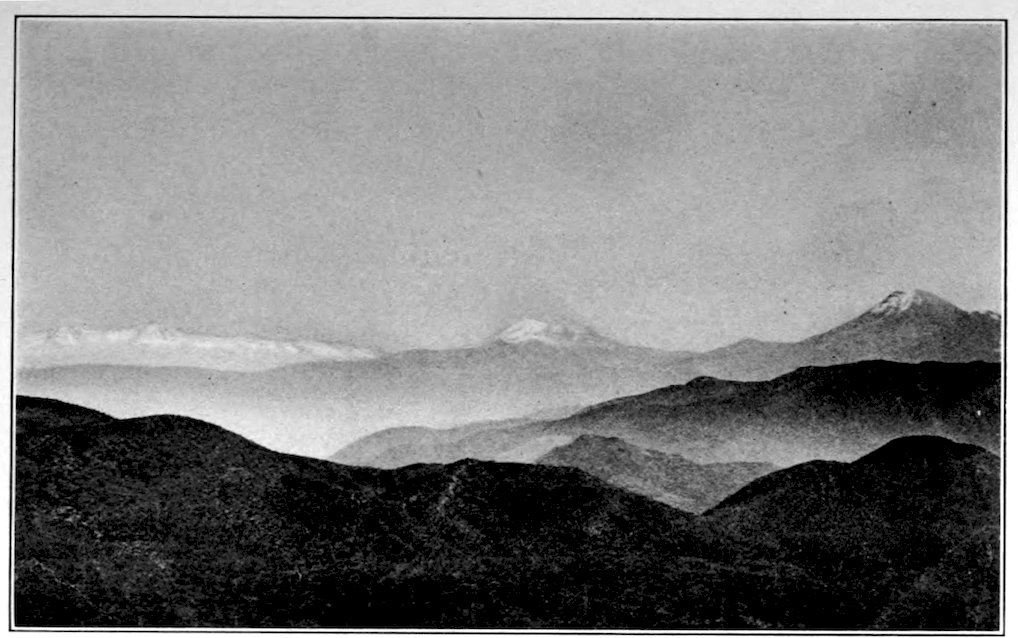

| VIEW OF THE SUMMIT OF THE SIERRA, TACNA | 347 |

| EL CHUPIQUIÑA, AN EXTINCT VOLCANO IN TACNA | 348 |

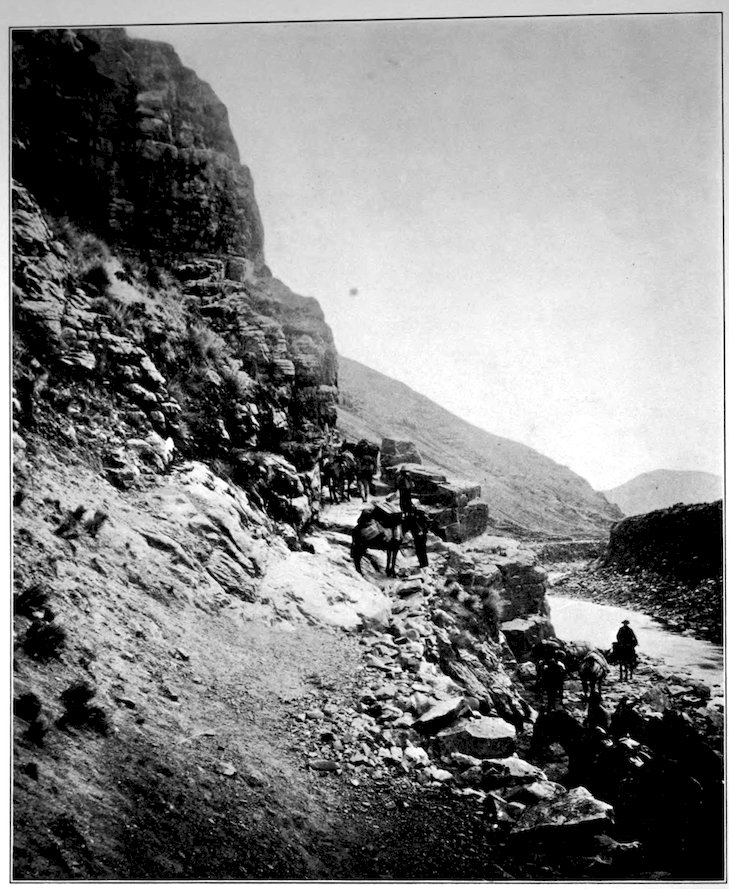

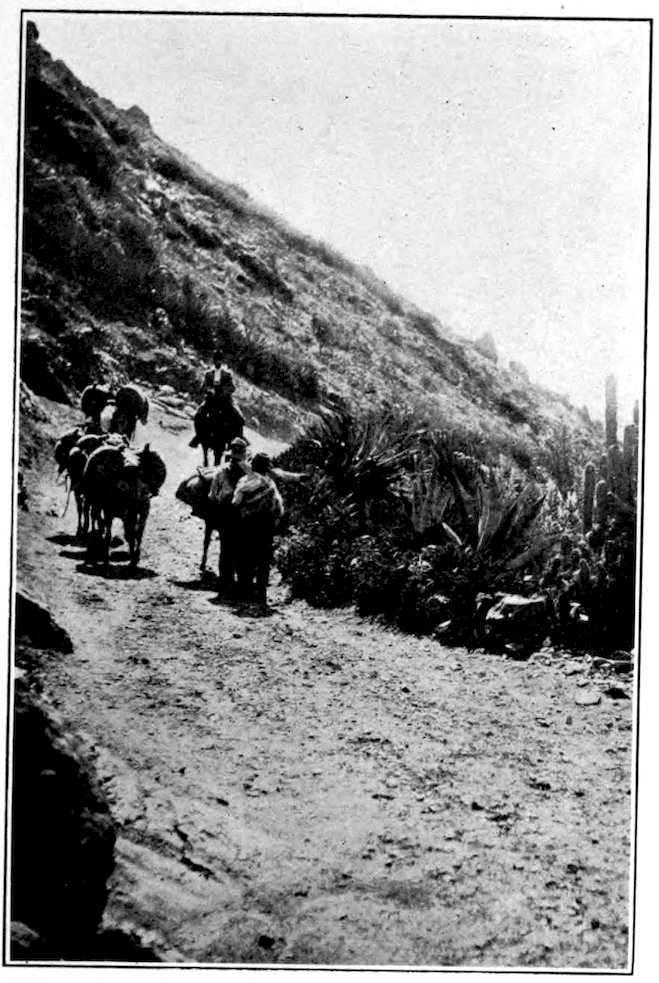

| A GOLD TRAIN EN ROUTE FROM SANTO DOMINGO TO TIRAPATA WITH BULLION IN BARS | 350 |

| SCENE AT THE BORAX MINES OF AREQUIPA | 352 |

| HUÁNUCO | 353 |

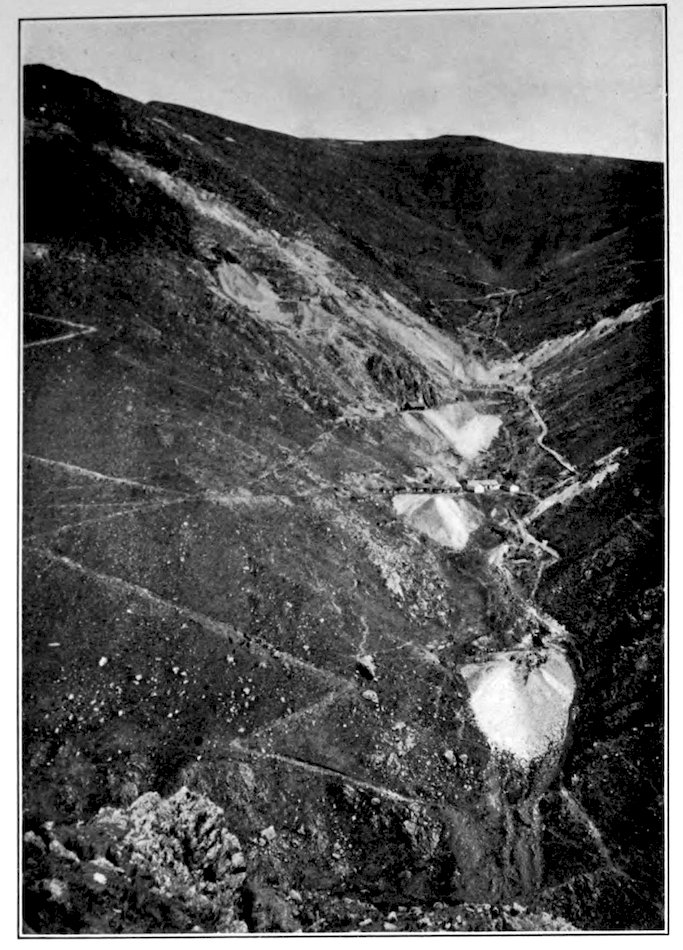

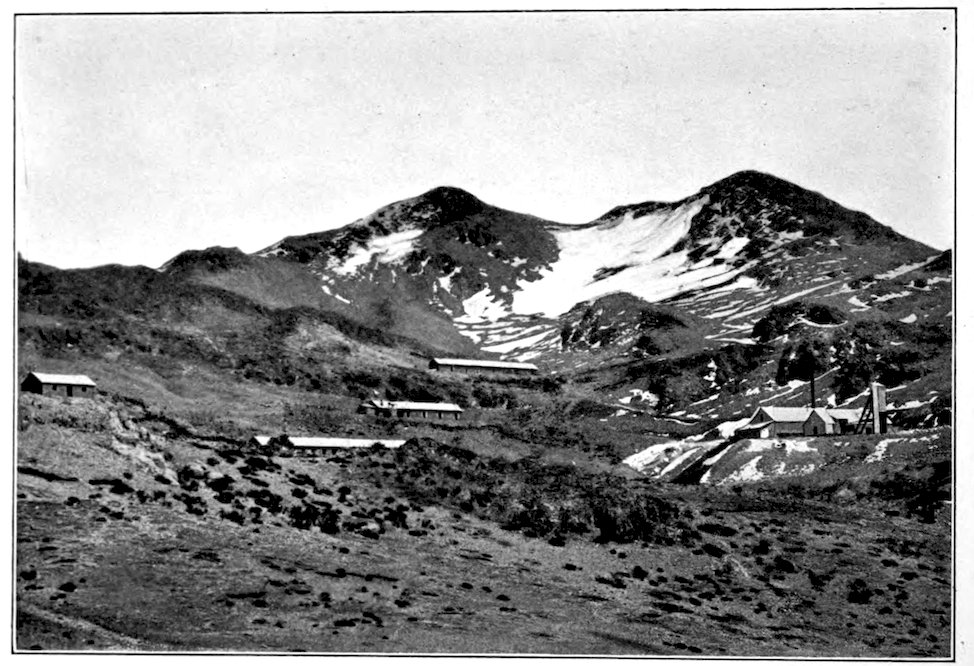

| CAILLOMA MINES, ALTITUDE SEVENTEEN THOUSAND FEET, DEPARTMENT OF AREQUIPA | 354 |

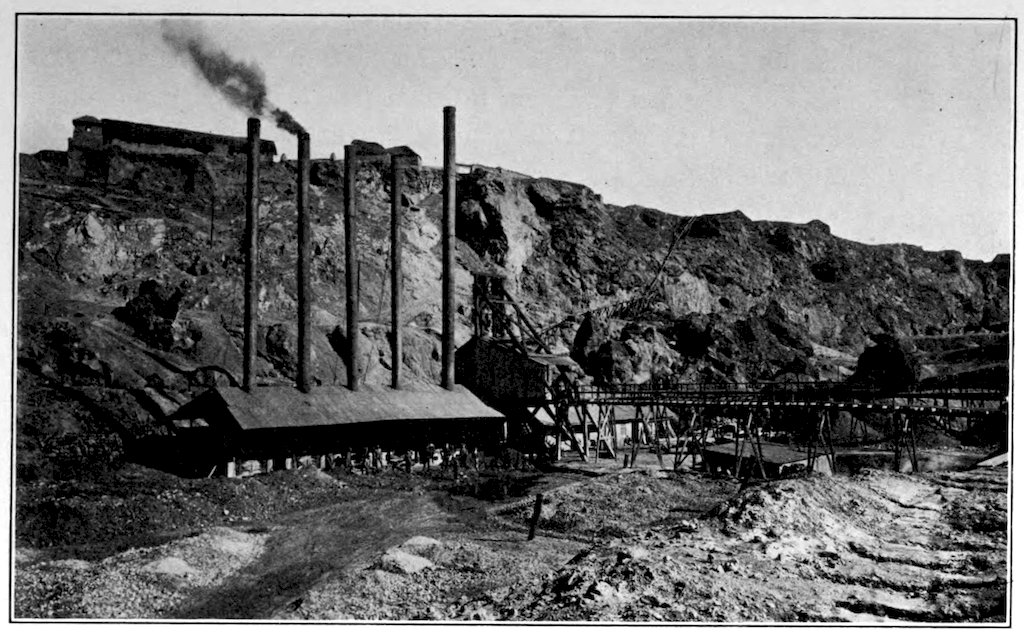

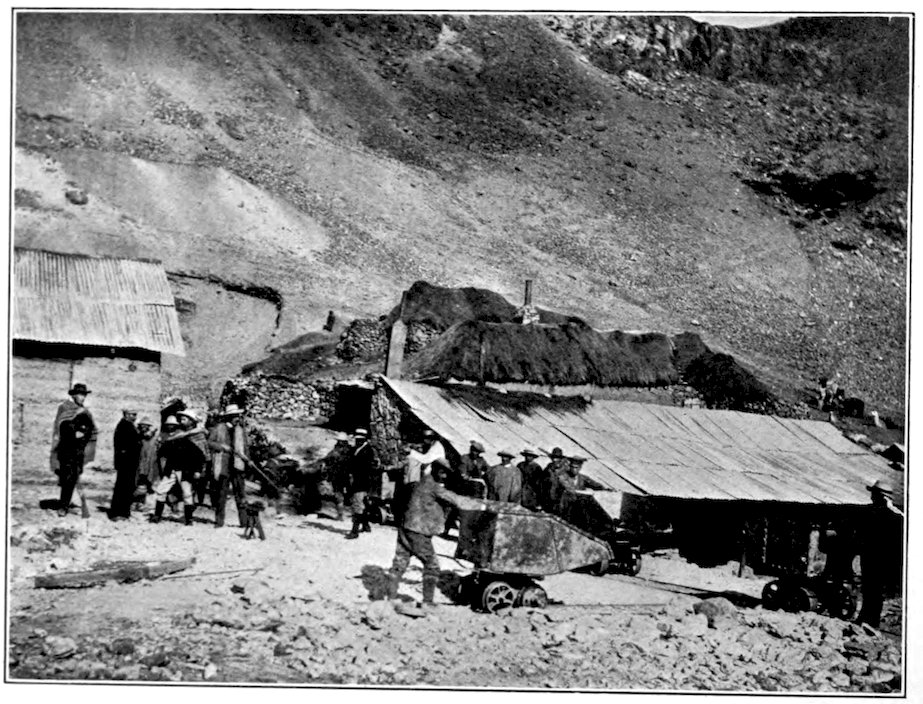

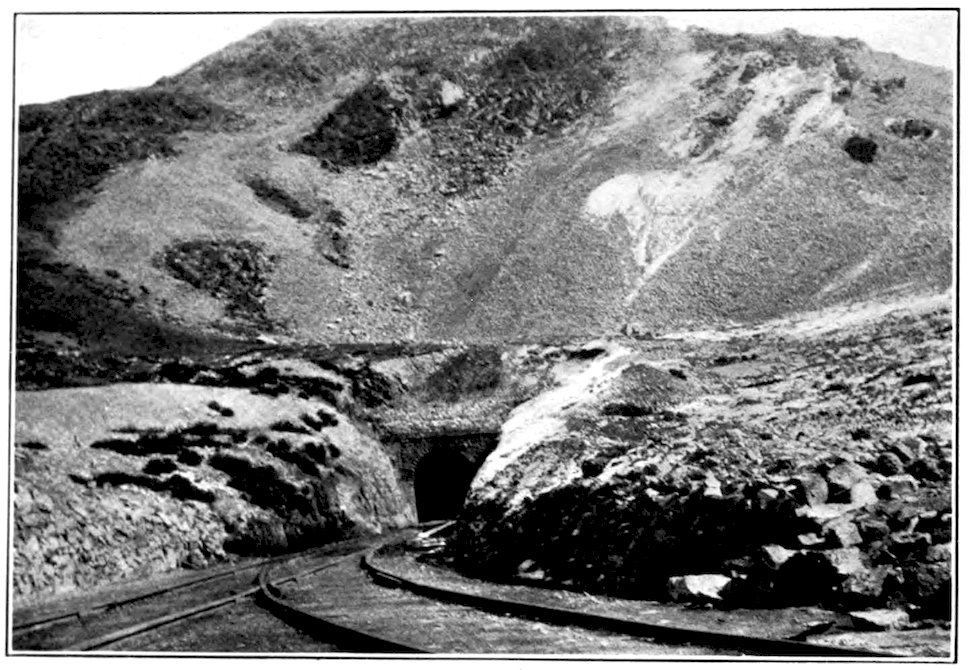

| CARMEN SHAFT, CERRO DE PASCO MINES | 355 |

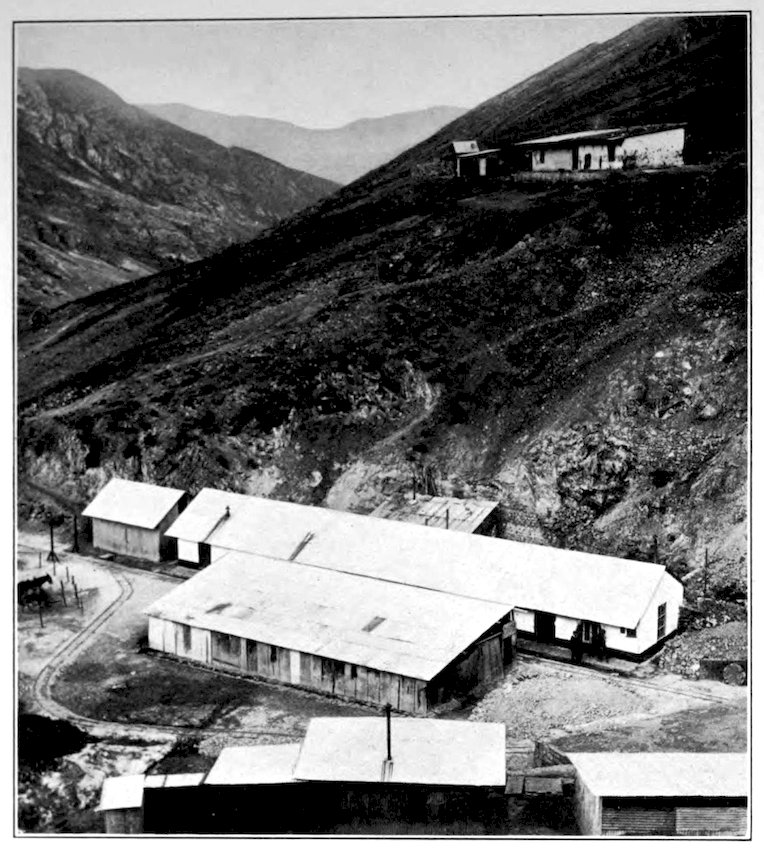

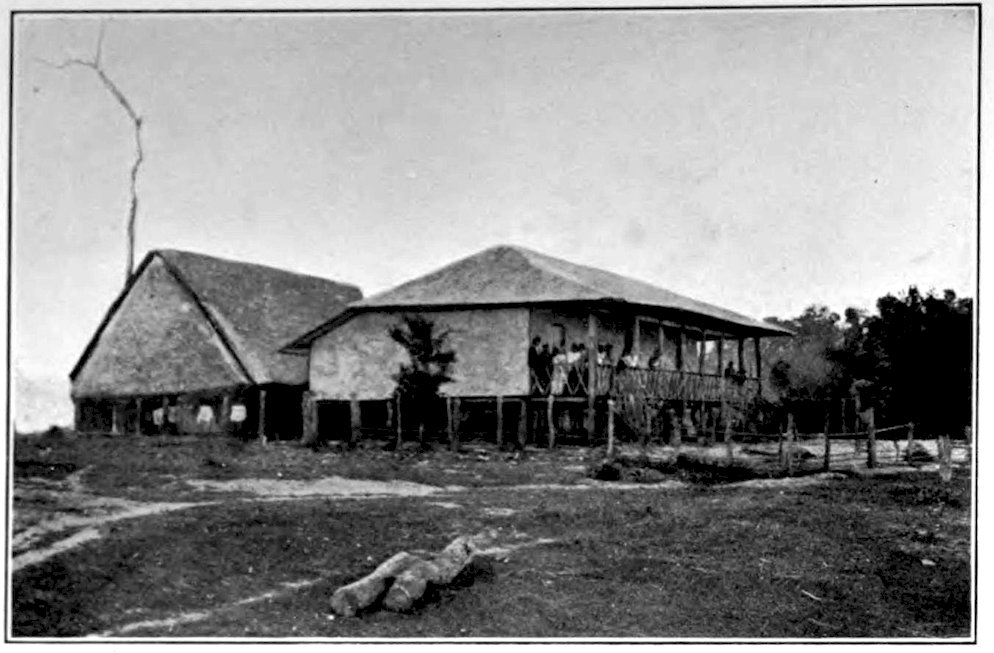

| THE INCA MINING COMPANY’S OFFICE AT SANTO DOMINGO, BUILT OF MAHOGANY | 356 |

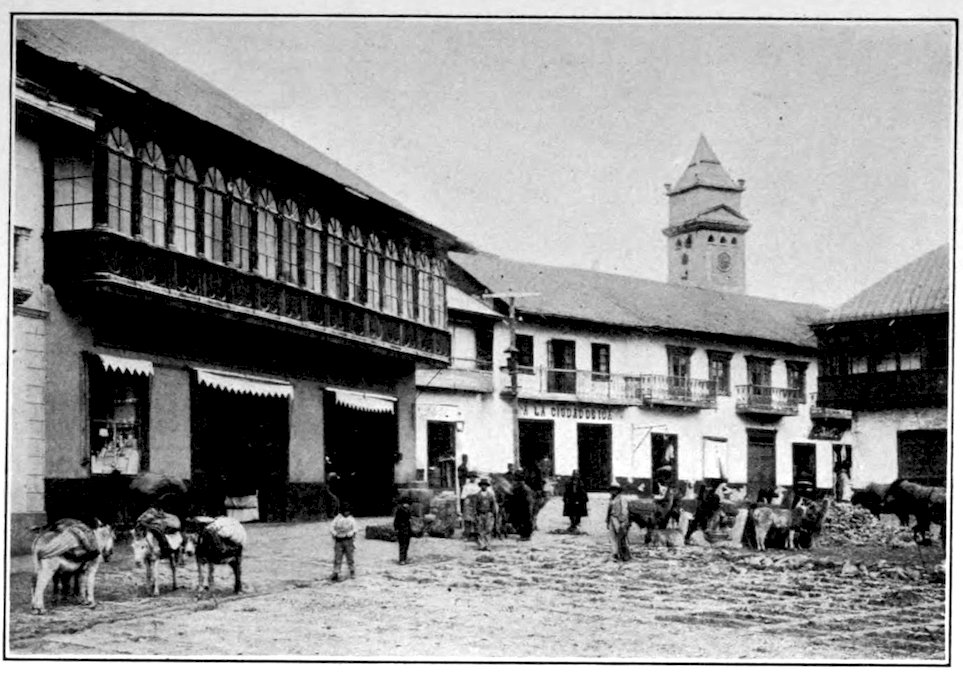

| THE MAIN STREET OF CERRO DE PASCO | 357 |

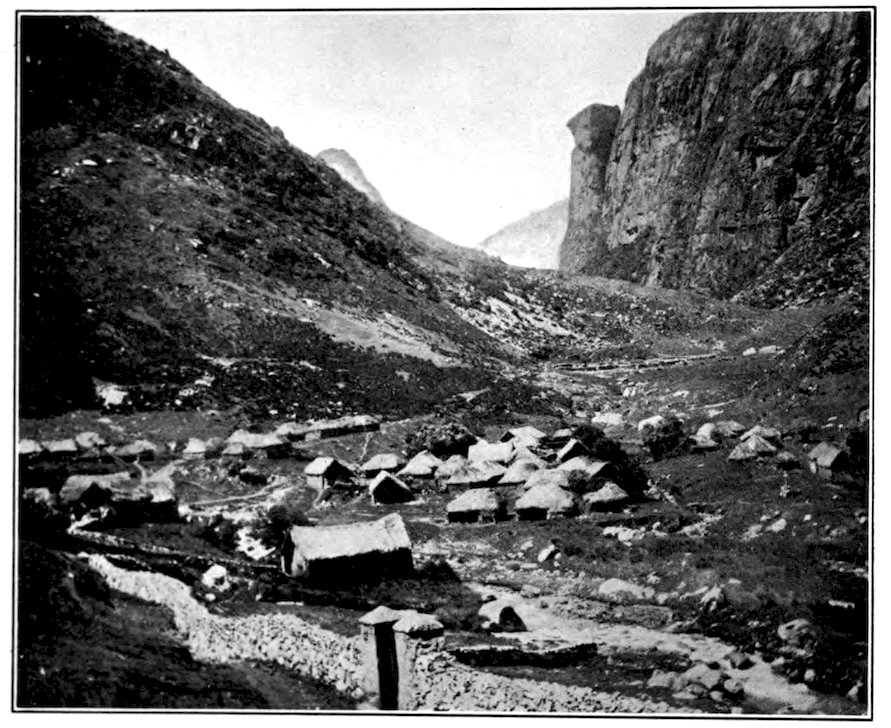

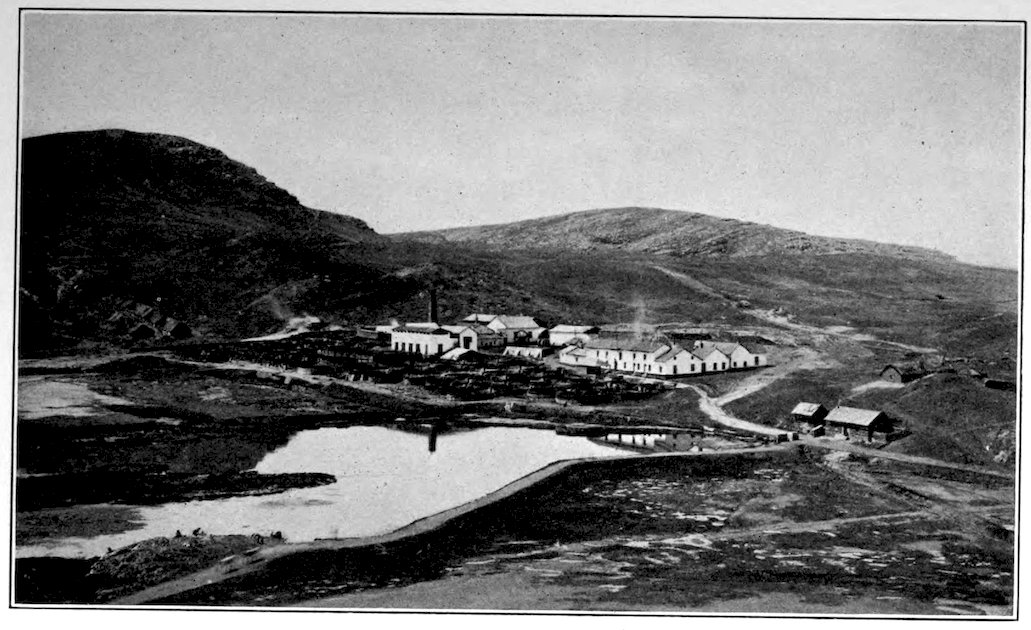

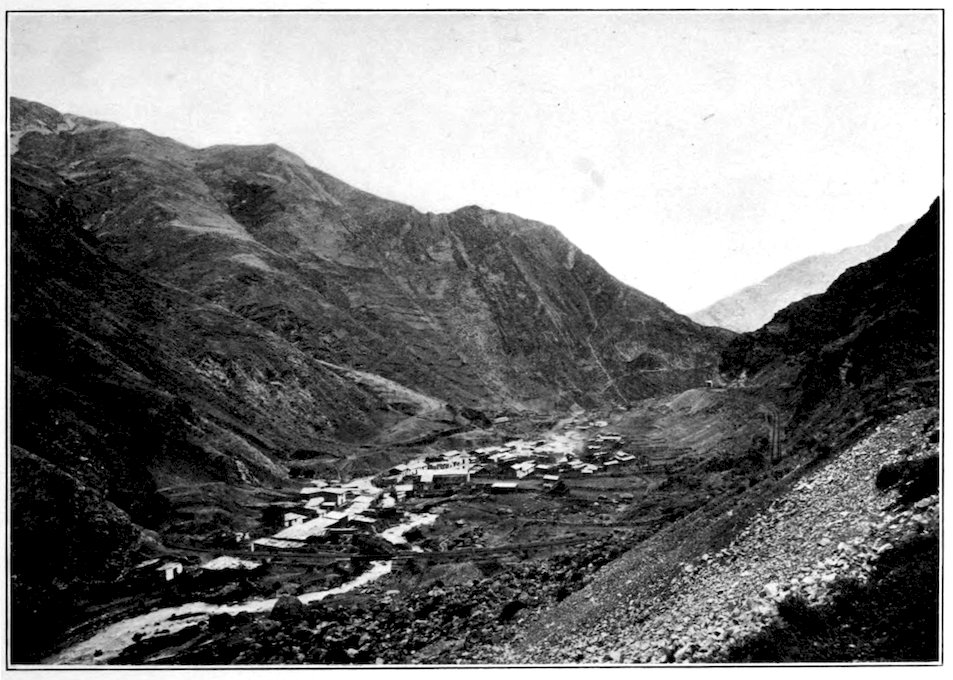

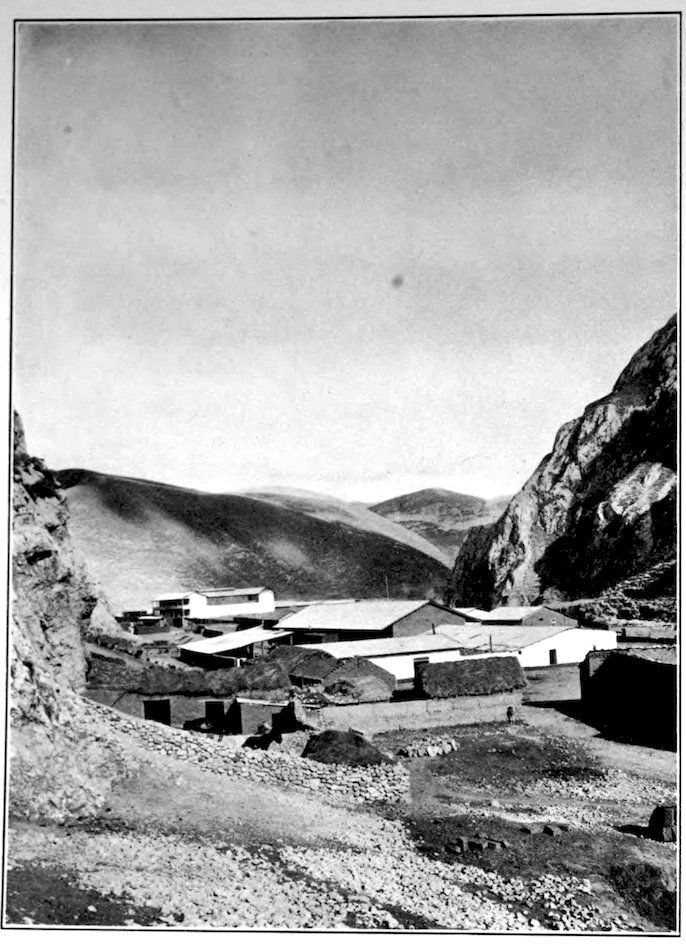

| A MINING TOWN OF THE PUNA | 358 |

| LLAMAS AND DONKEYS AWAITING CARGO AT CERRO DE PASCO | 359 |

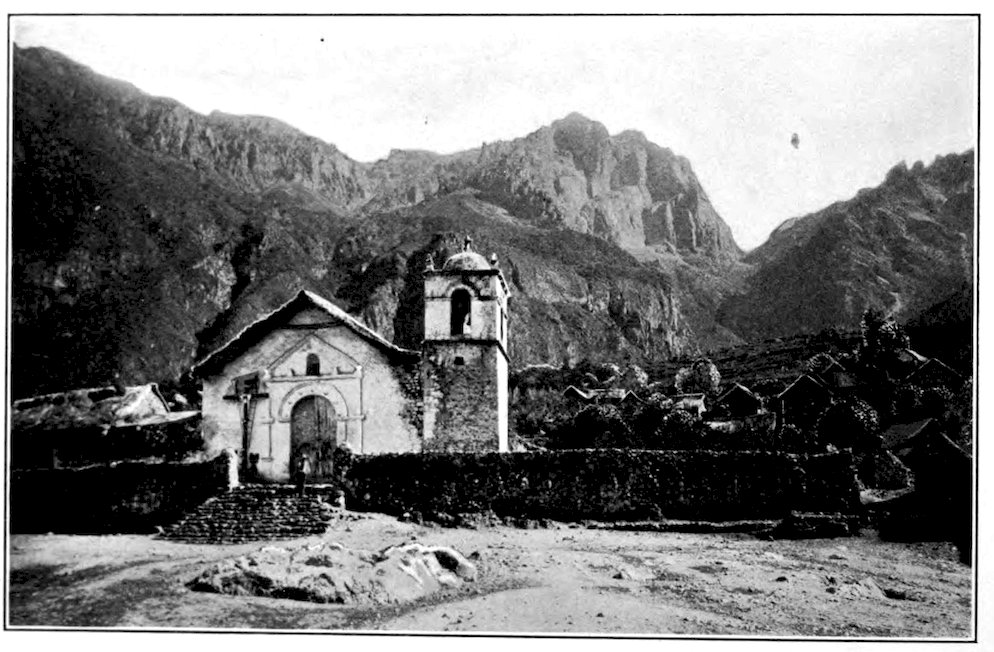

| OLD CHURCH IN THE MINING TOWN OF CAILLOMA | 360 |

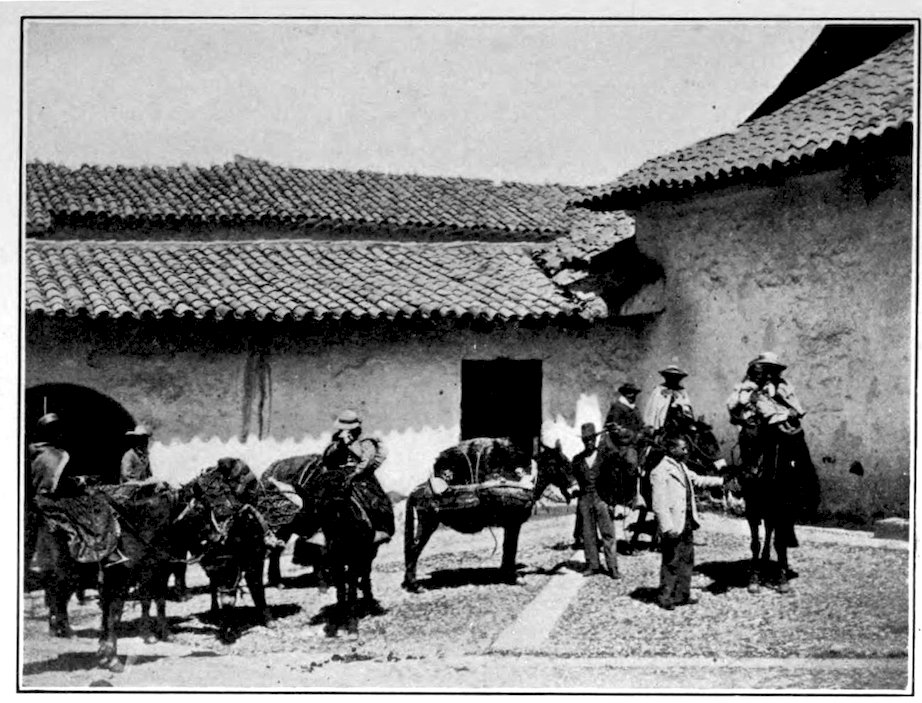

| MINERS ARRIVING AT AN INN IN THE SIERRA | 361 |

| SAN JULIAN MINE, CASTROVIRREINA | 362 |

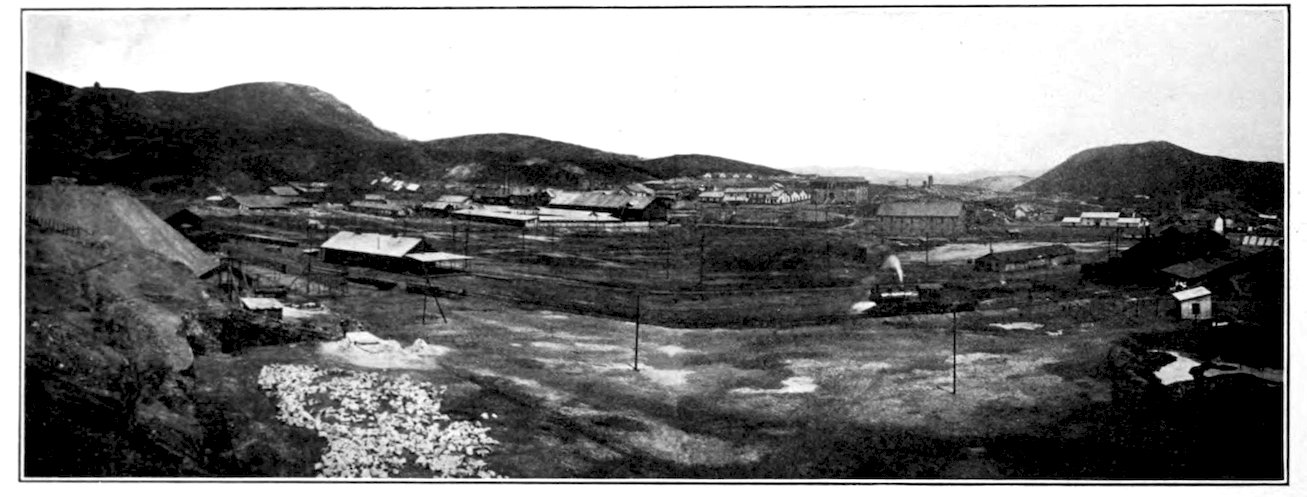

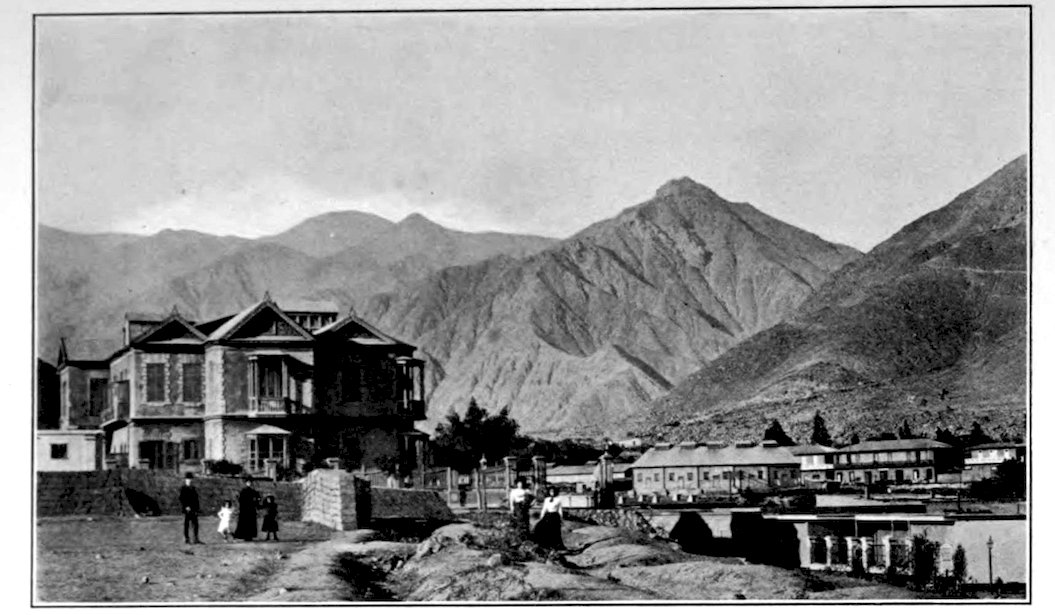

| THE MINING TOWN OF CASAPALCA, DEPARTMENT OF LIMA | 363 |

| HEADQUARTERS OF THE CERRO DE PASCO MINING COMPANY AT CERRO DE PASCO | 364 |

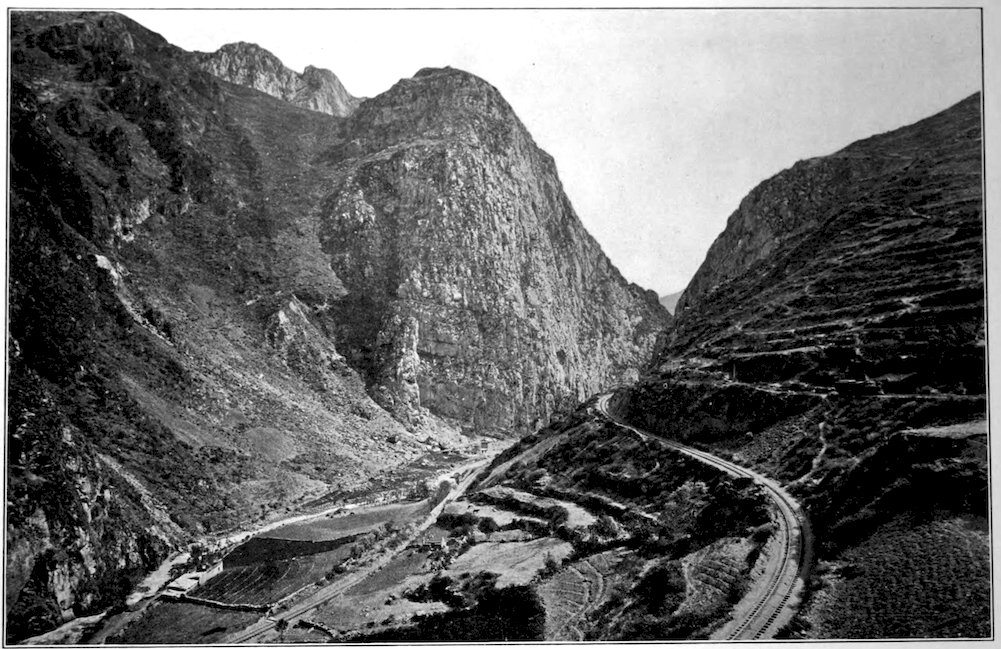

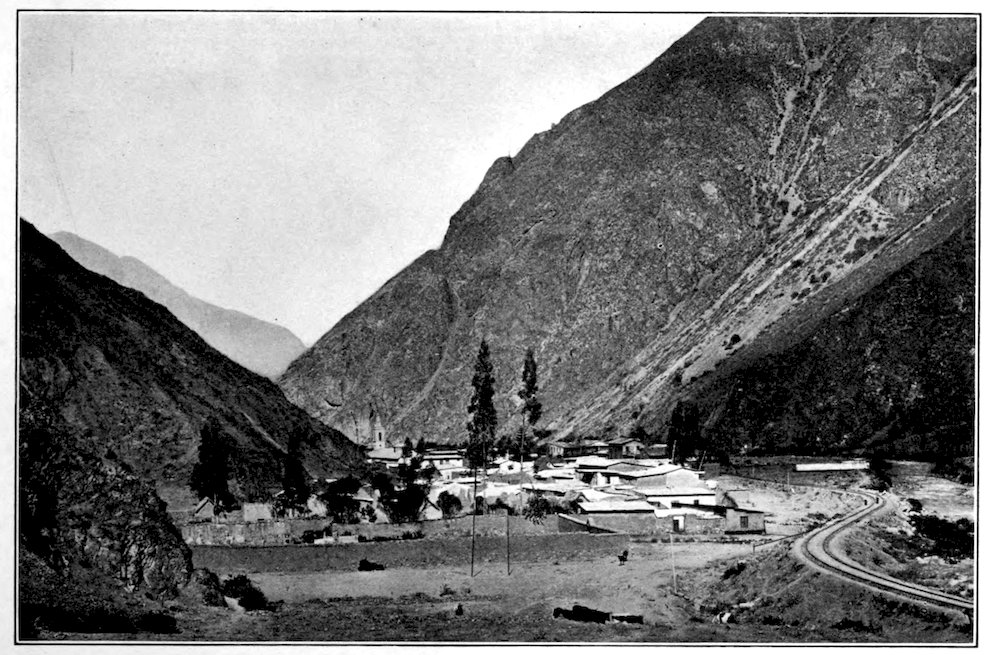

| THE PICTURESQUE CURVE OF SAN BARTOLOMÉ, OROYA ROUTE | 366 |

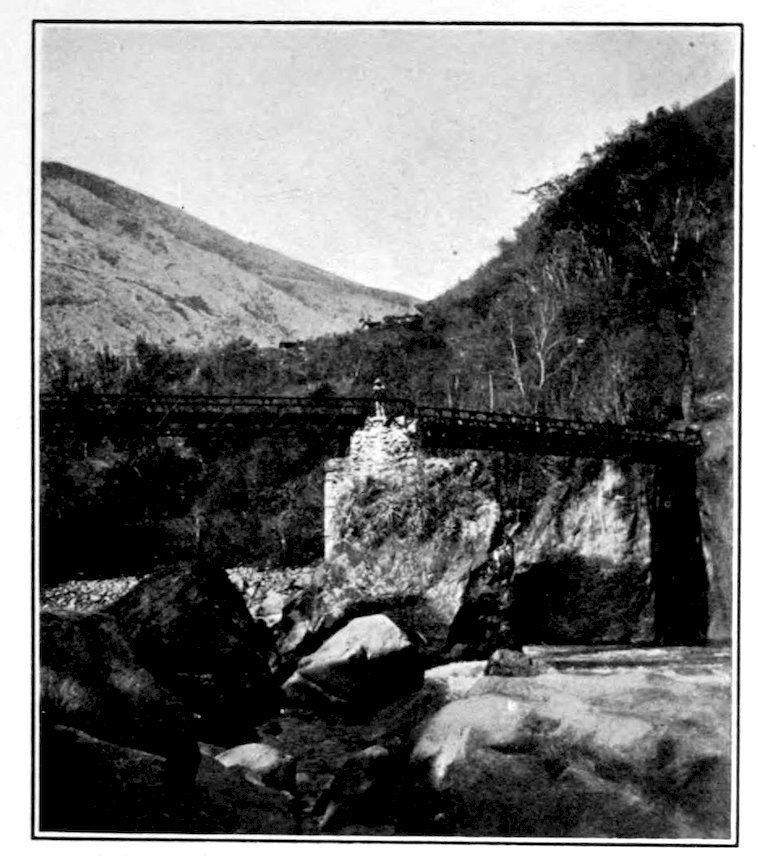

| CHOSICA BRIDGE, OROYA ROUTE | 367 |

| CHOSICA, A HEALTH RESORT ON THE OROYA ROUTE | 368 |

| MATUCANA, EIGHT THOUSAND FEET ABOVE THE SEA, OROYA ROUTE | 369 |

| RAILWAY STATION IN THE SIERRA, OROYA ROUTE | 370 |

| CHILCA, A MINING TOWN ON THE OROYA ROUTE | 371 |

| OROYA | 372 |

| 12GALERA TUNNEL, HIGHEST POINT ON THE OROYA RAILWAY, NEARLY SEVENTEEN THOUSAND FEET ABOVE THE SEA | 374 |

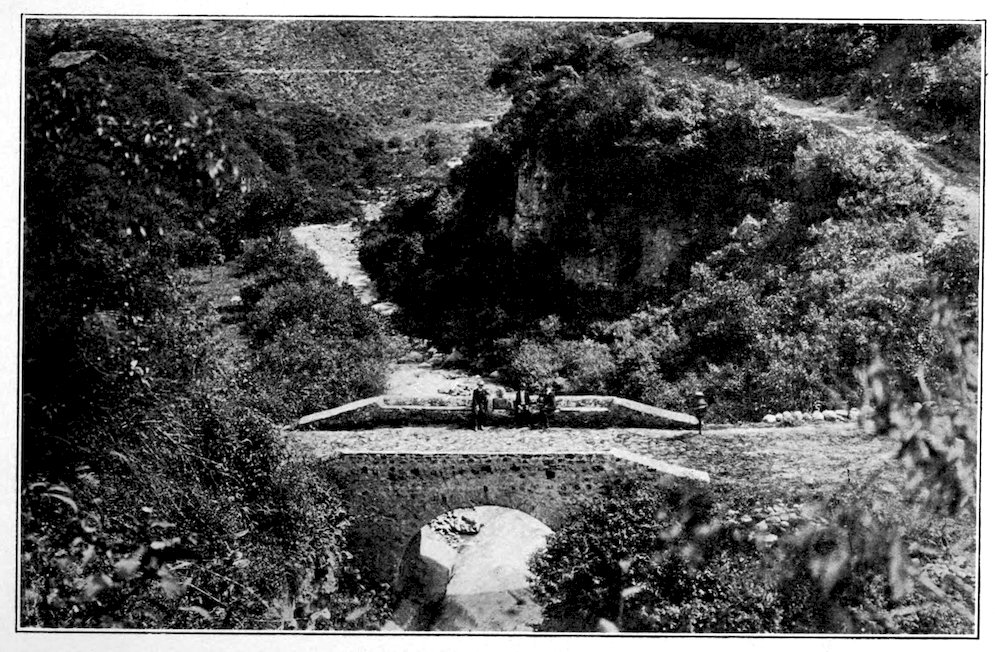

| STONE ROADWAY ACROSS THE HUALLAGA RIVER, IN HUÁNUCO | 376 |

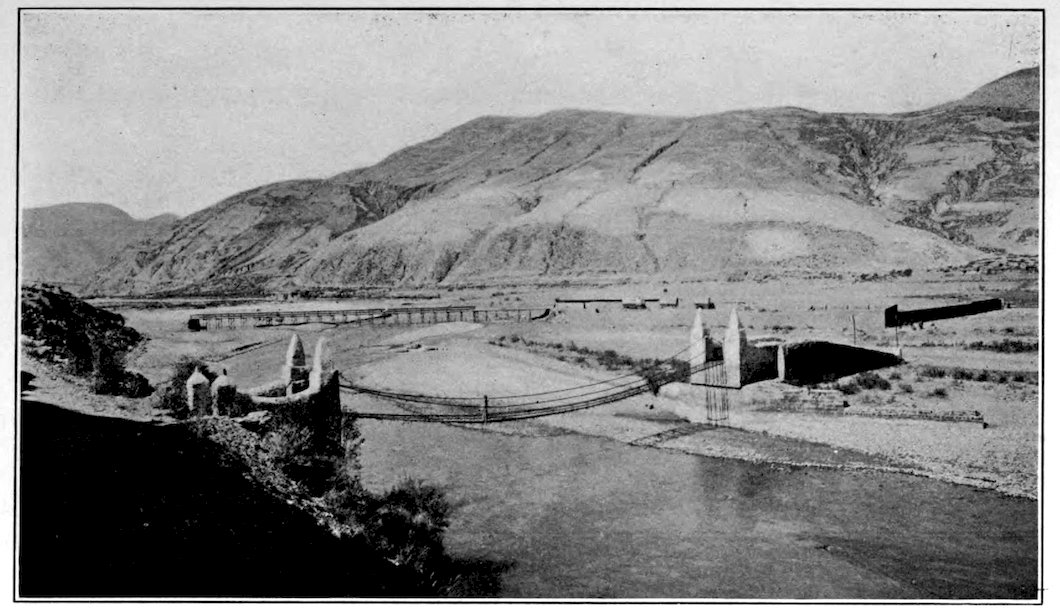

| IRON BRIDGE OVER THE URUBAMBA RIVER | 377 |

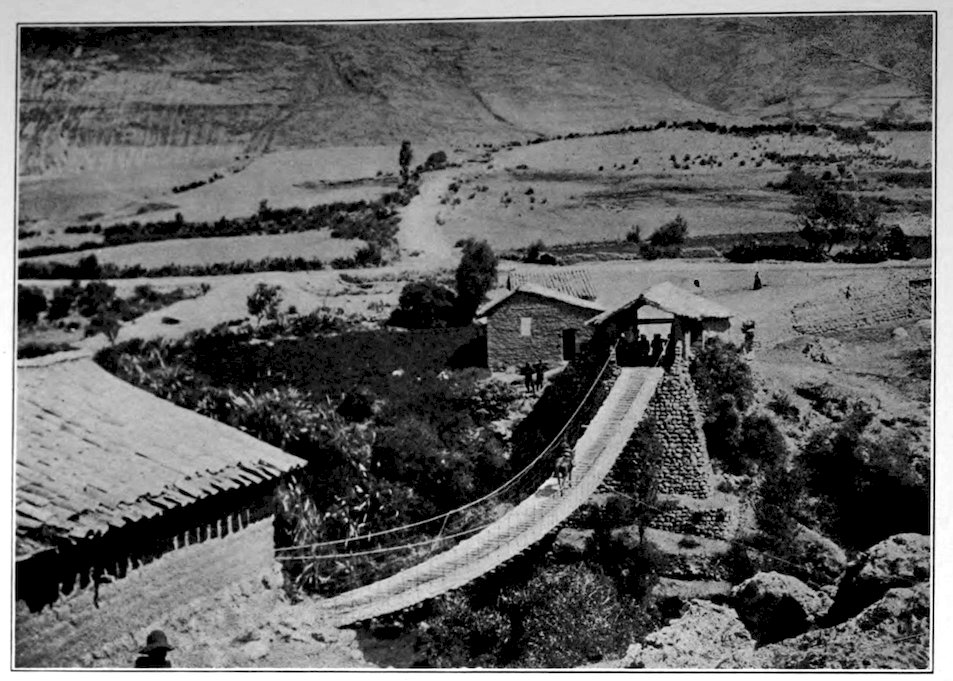

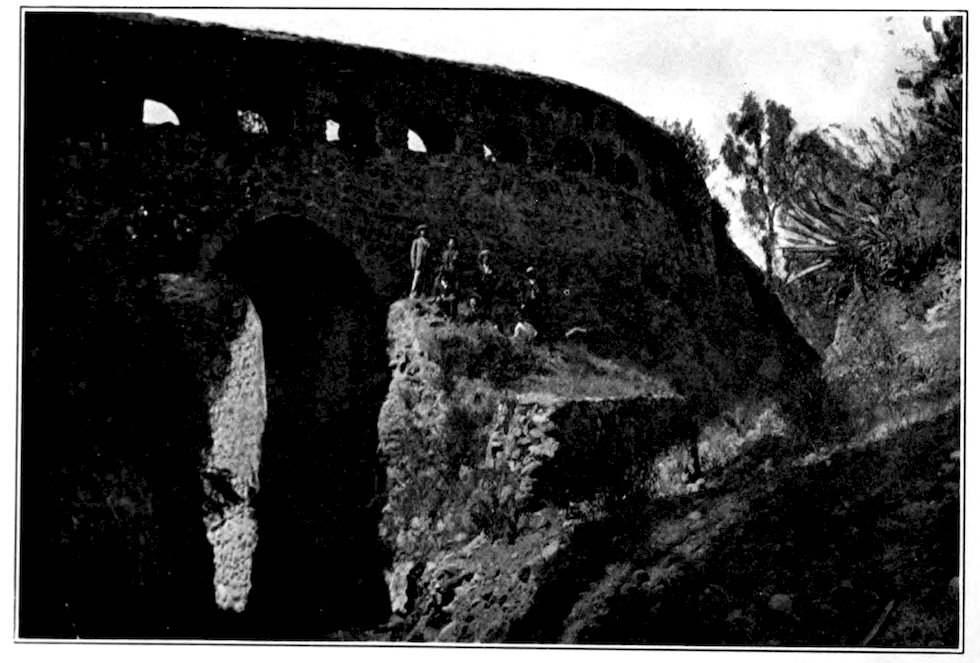

| ANCIENT SUSPENSION BRIDGE ON THE ROAD FROM HUANCAYO TO CAÑETE | 378 |

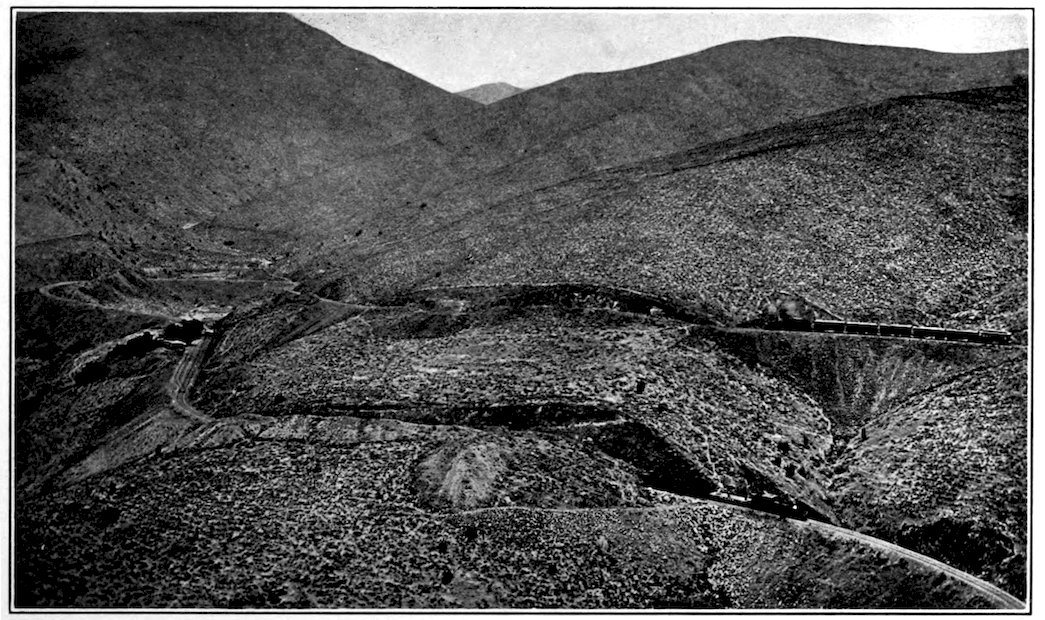

| RAILWAY UP THE SIERRA FROM MOLLENDO TO AREQUIPA | 379 |

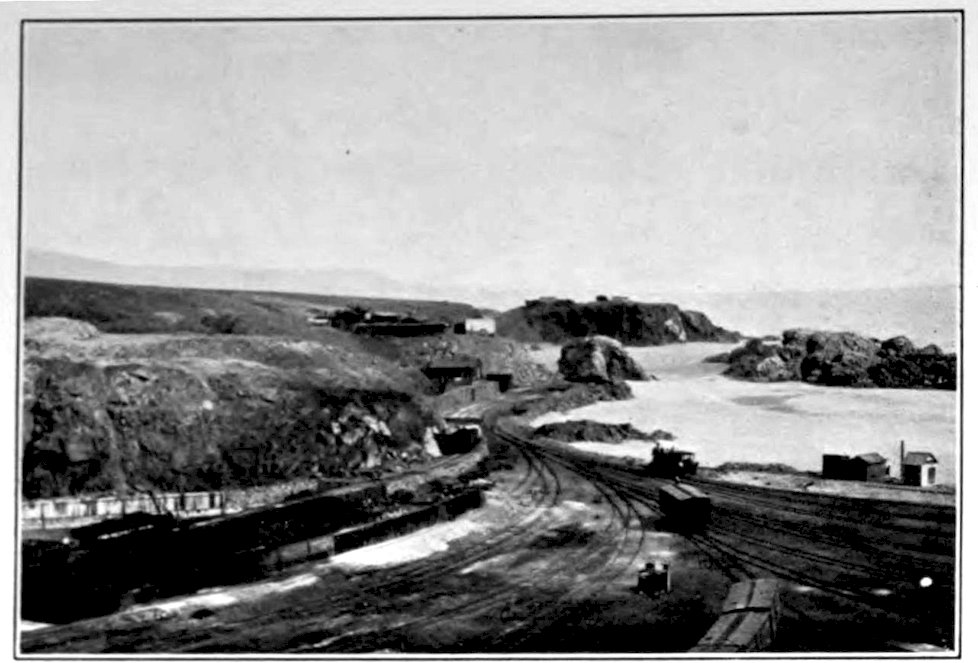

| MOLLENDO, TERMINUS OF THE SOUTHERN RAILWAY | 380 |

| THE TOWN OF MOLLENDO | 380 |

| NEW RAILWAY BRIDGE AND OLD COACH ROAD BETWEEN SICUANI AND CUZCO | 381 |

| ANCIENT VIADUCT SOTOCCHACA, AYACUCHO | 382 |

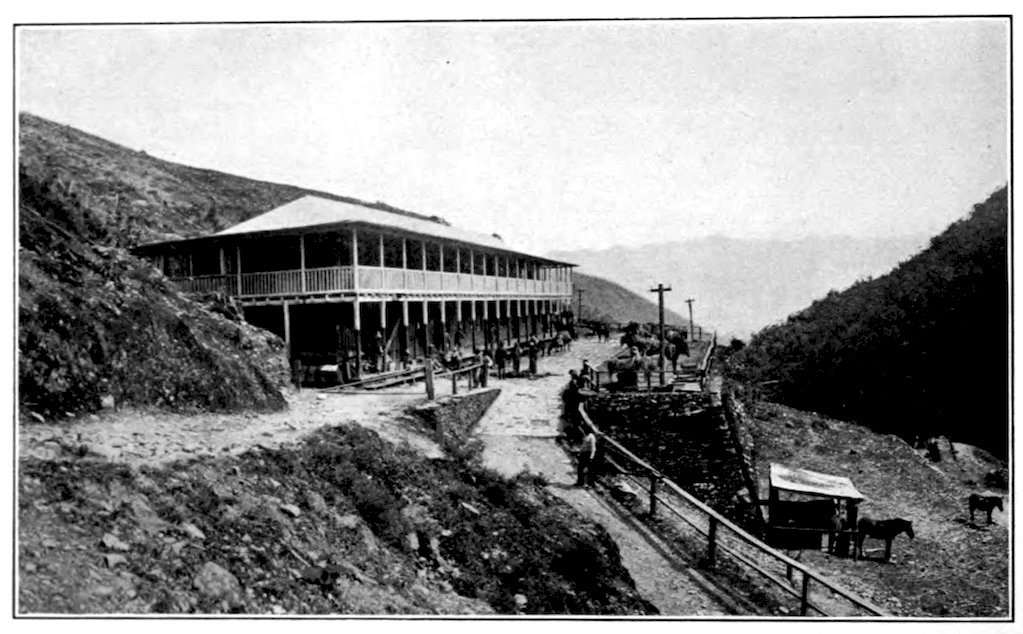

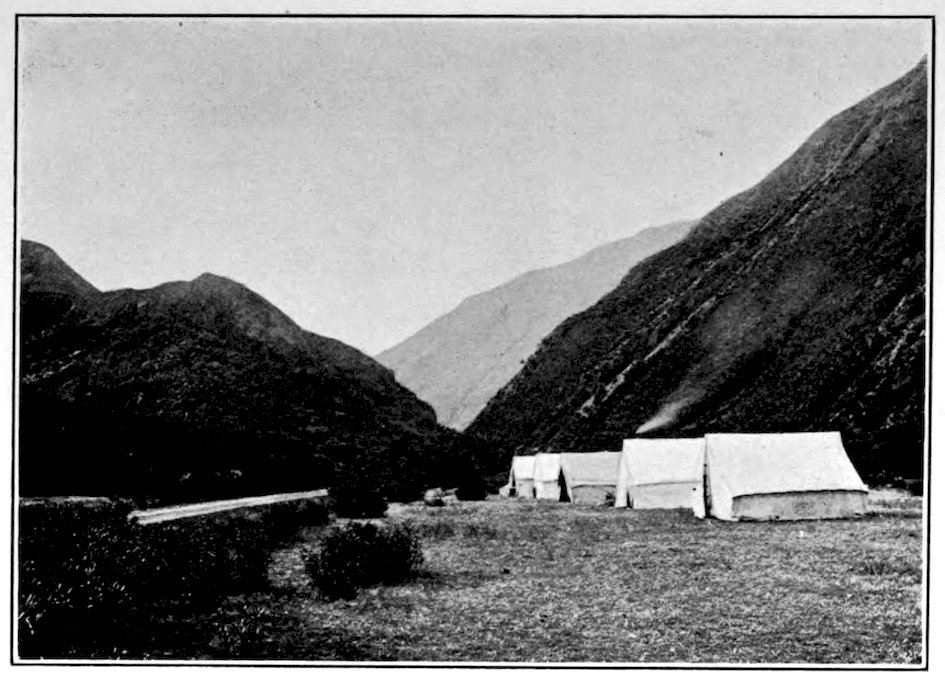

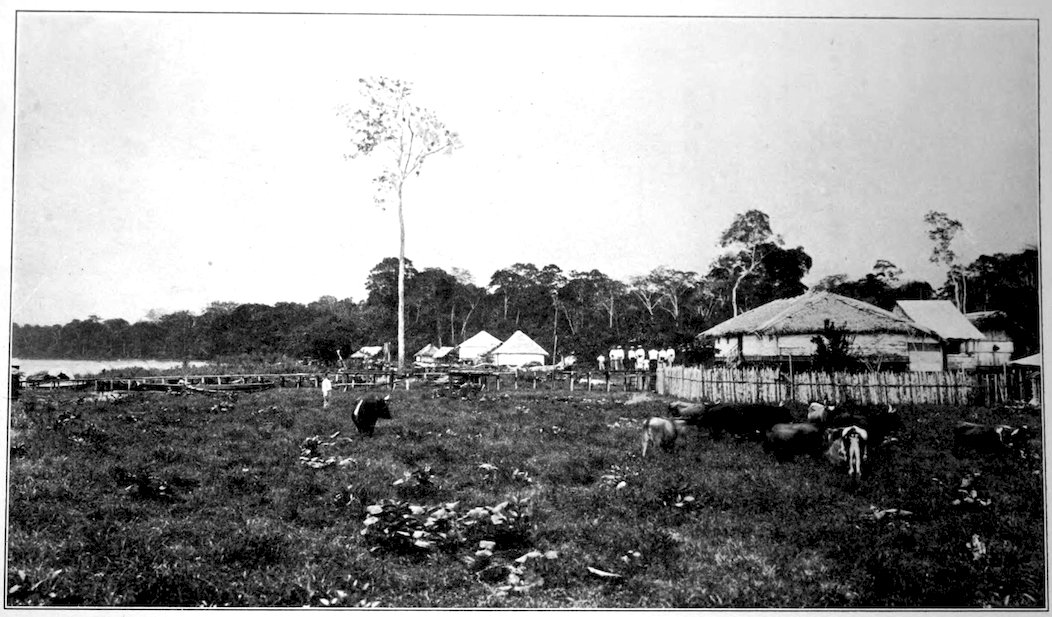

| RAILWAY ENGINEERS’ CAMP ON THE LINE BETWEEN CHECCACUPE AND CUZCO | 383 |

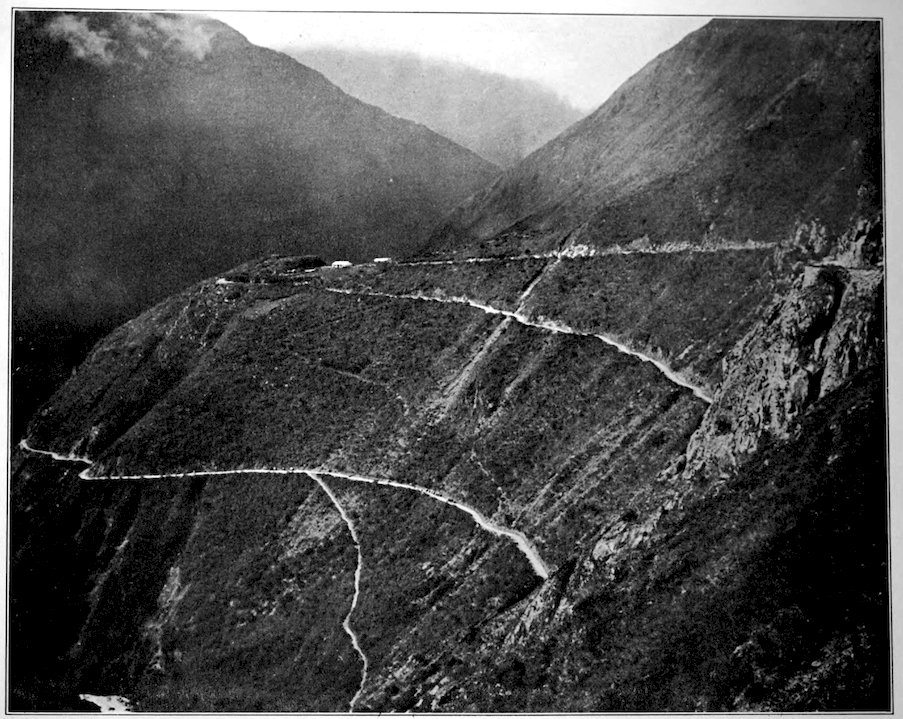

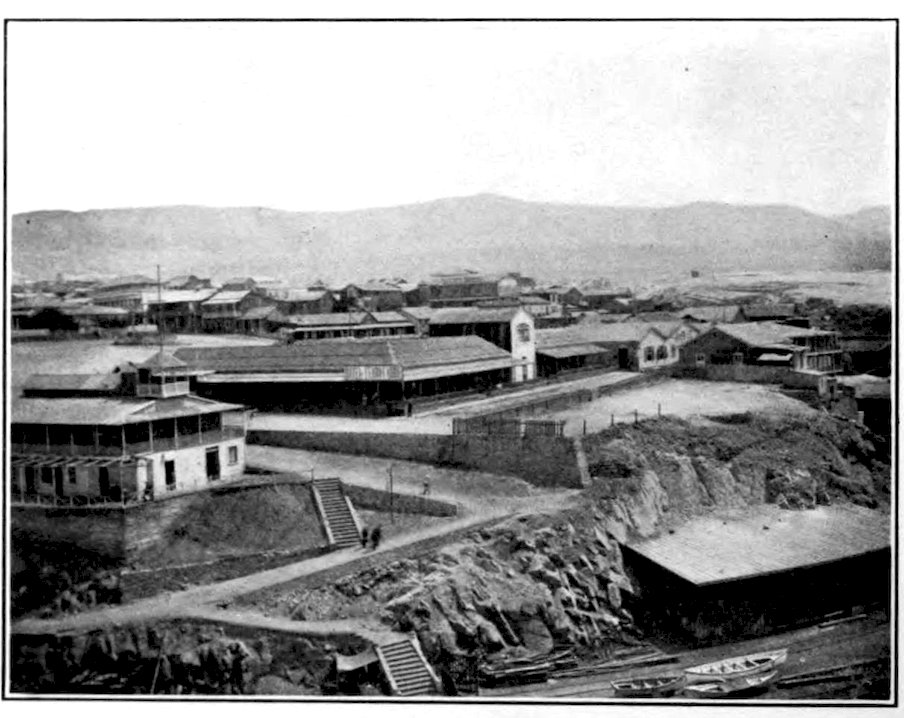

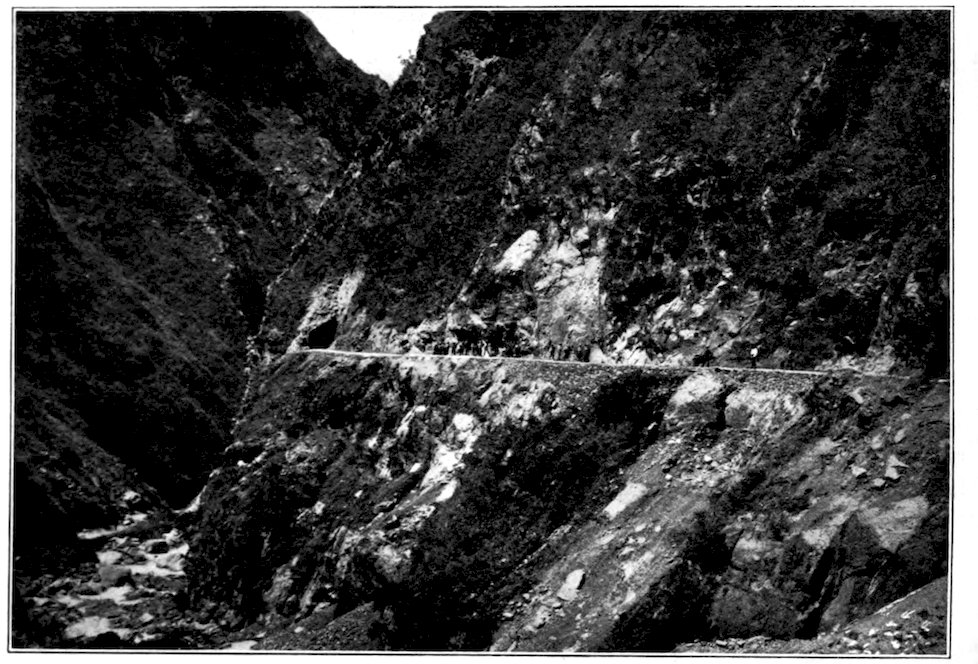

| HIGHWAY BETWEEN THE SIERRA AND THE MONTAÑA, IN THE DEPARTMENT OF JUNÍN | 384 |

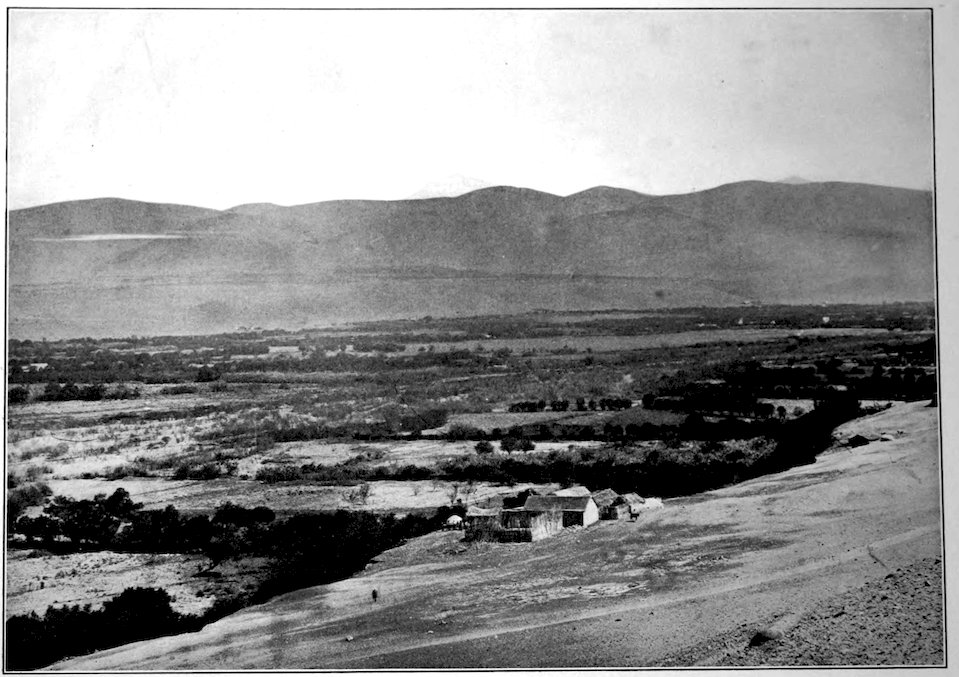

| VIEW OF THE VALLEY BETWEEN SICUANI AND CUZCO, SOUTHERN ROUTE | 385 |

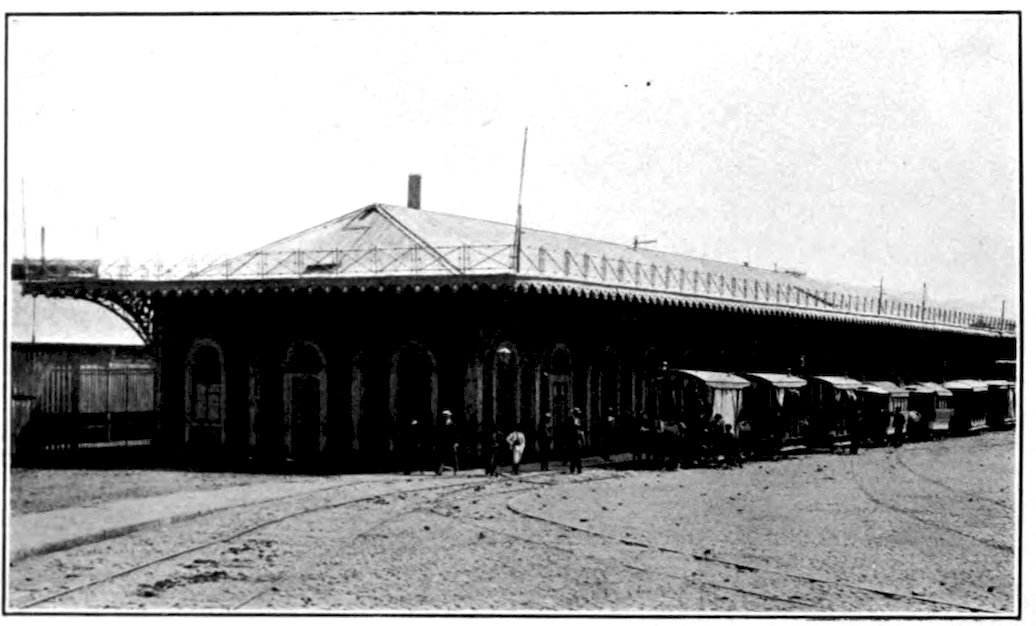

| SOUTHERN RAILWAY STATION, AREQUIPA | 386 |

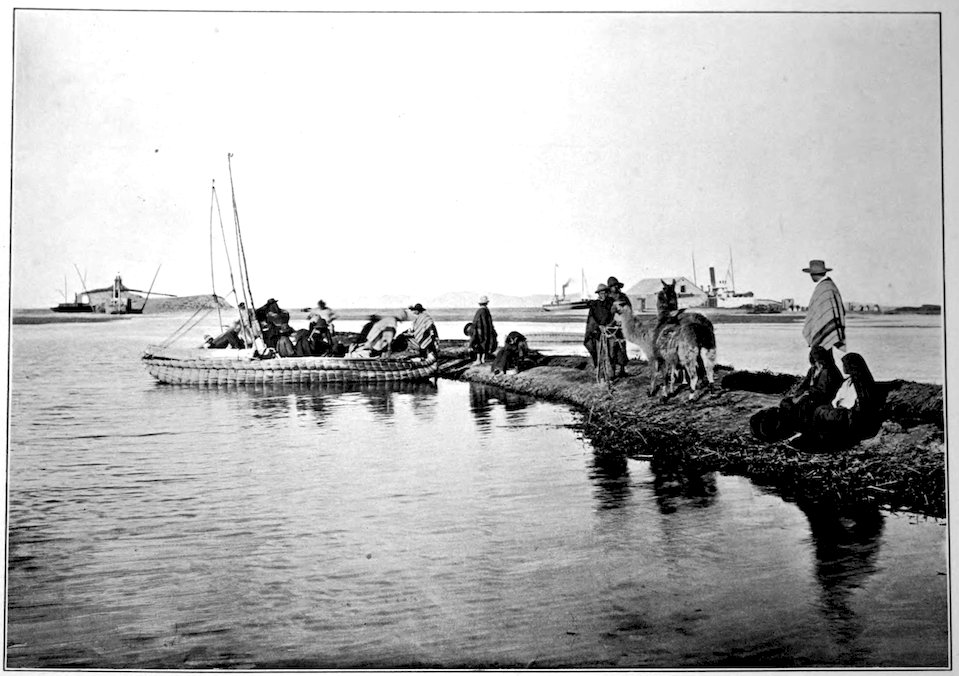

| LLAMAS OF PUNO EMBARKING ON A BALSA, LAKE TITICACA | 388 |

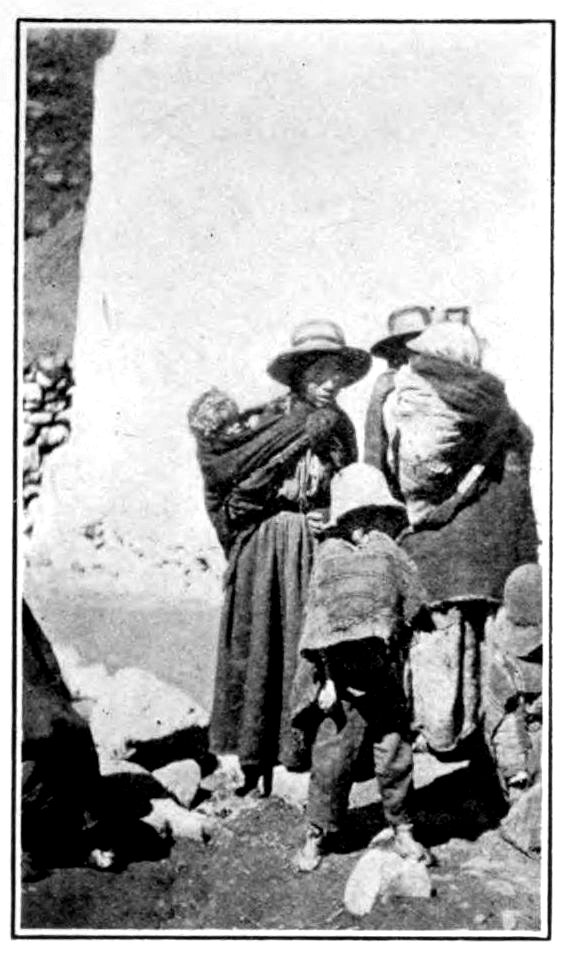

| A NATIVE FAMILY OF THE PUNA | 389 |

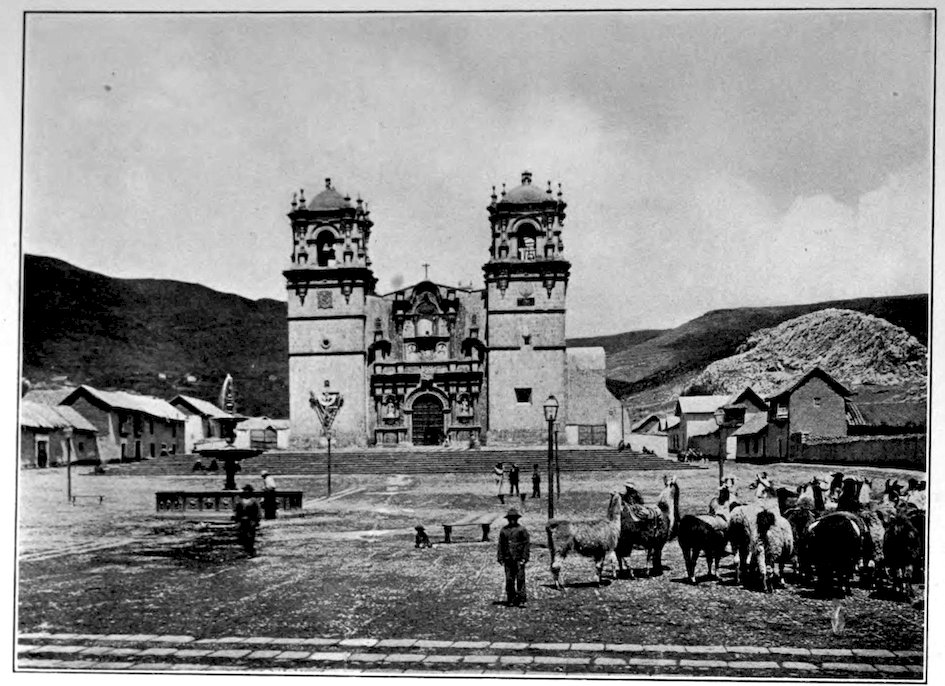

| THE PRINCIPAL PLAZA OF PUNO | 390 |

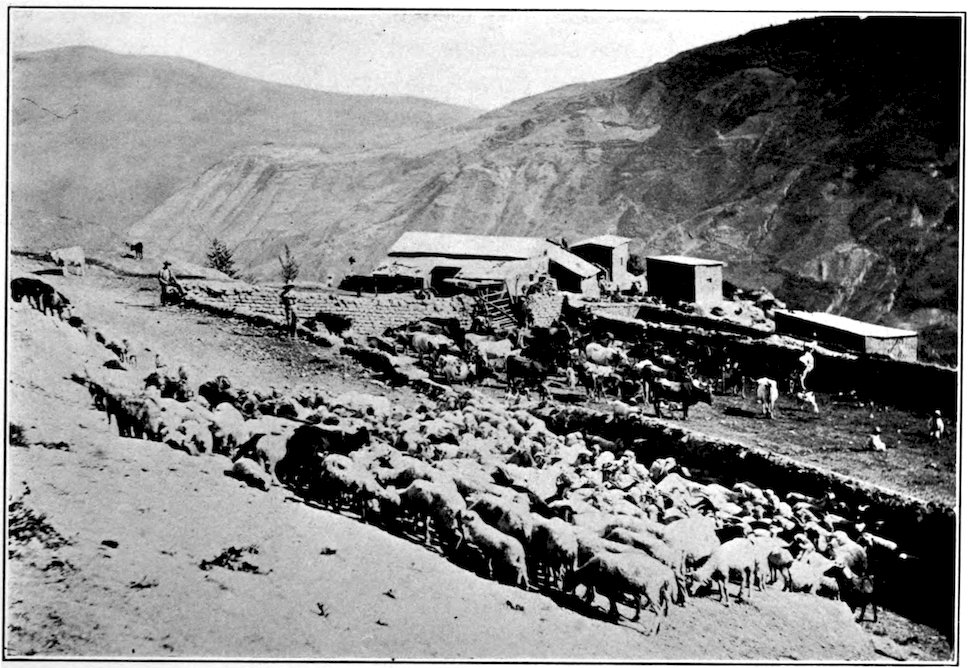

| SHEEP ON THE PASTURES OF ANCASH | 391 |

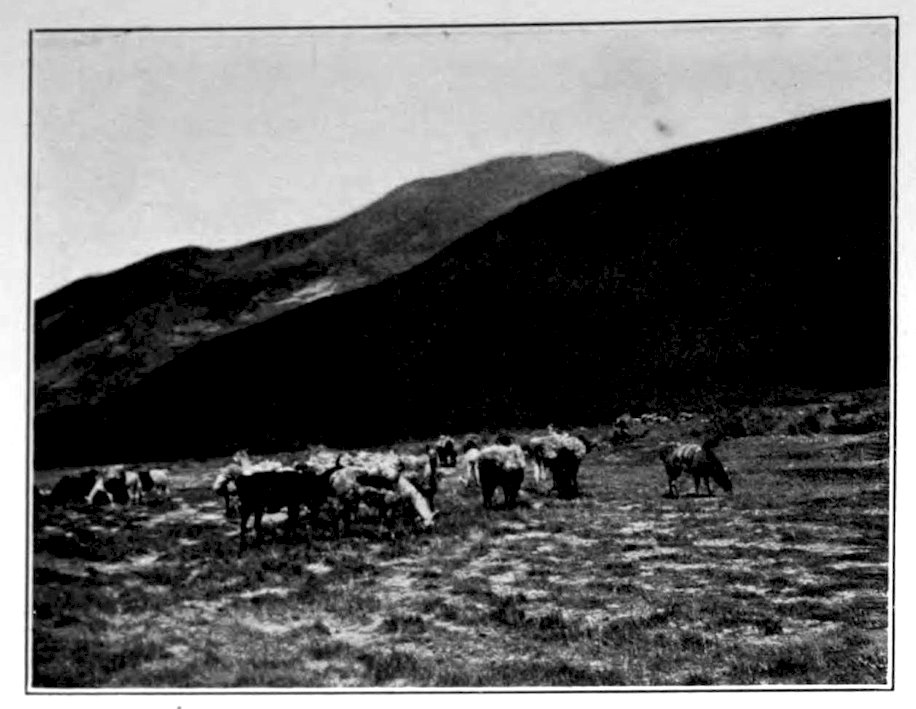

| LLAMAS GRAZING ON THE PUNA | 392 |

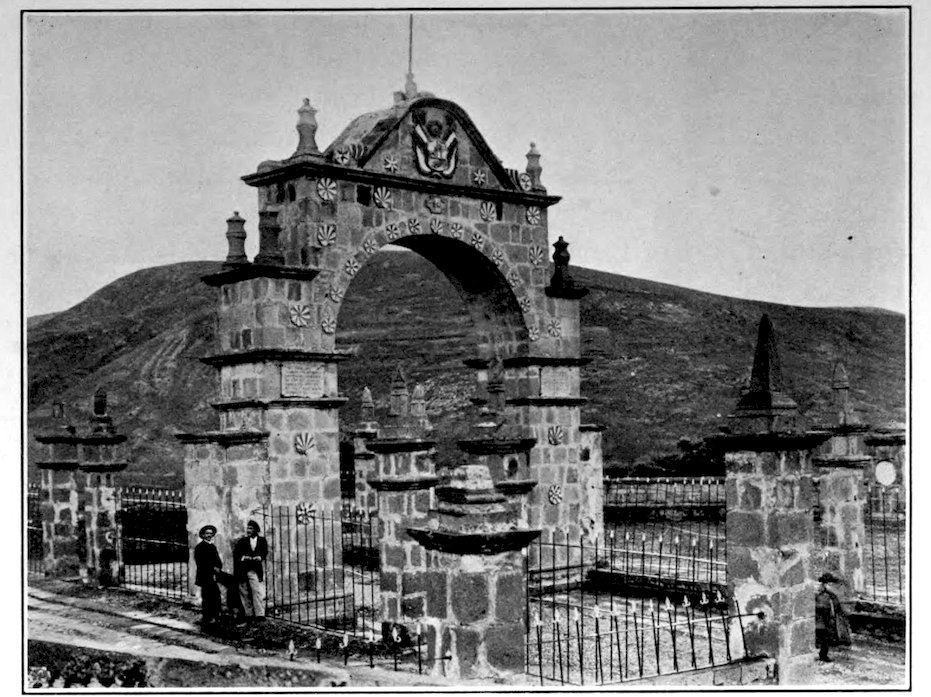

| ARCHED GATEWAY OF PUNO | 393 |

| LLAMAS—SHOWING ONE RECENTLY SHEARED | 394 |

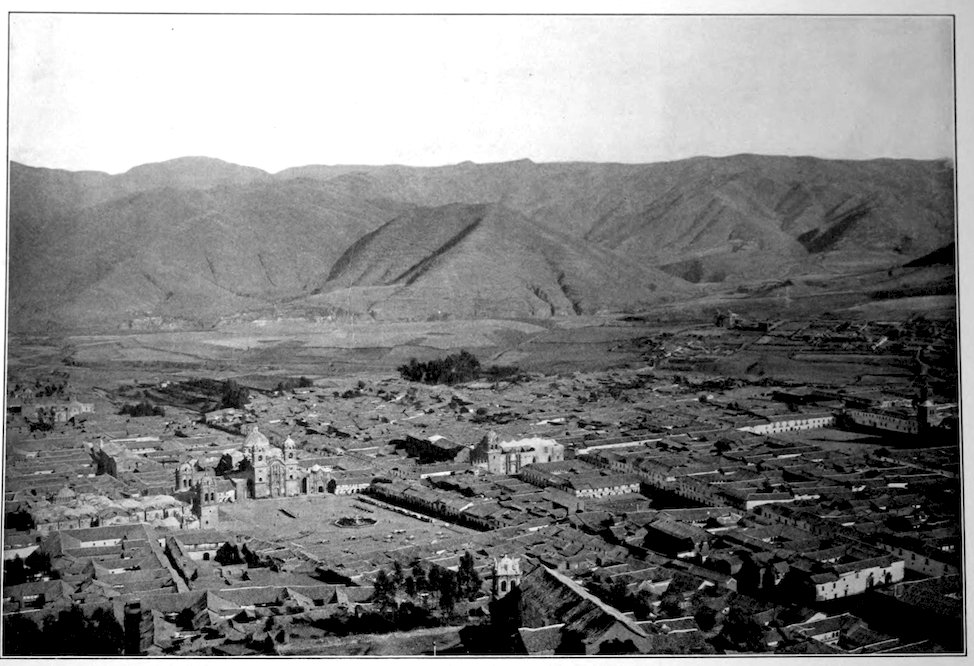

| CUZCO, THE ANCIENT CAPITAL OF THE INCAS’ EMPIRE | 396 |

| ANCIENT ADOBE ARCHWAY NEAR CUZCO | 397 |

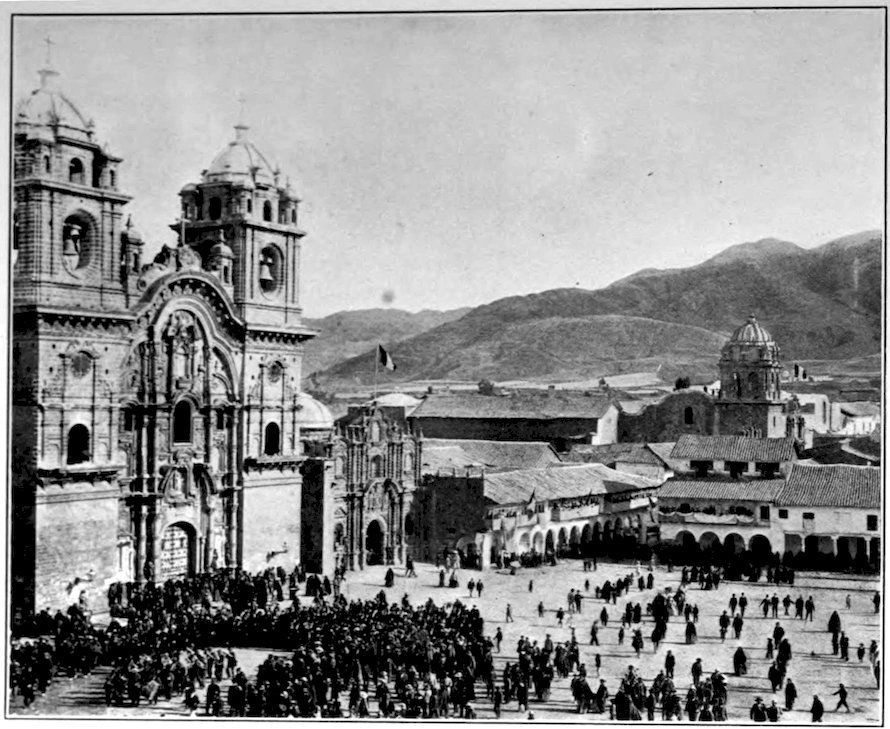

| A FEAST DAY CELEBRATION, SHOWING THE UNIVERSITY AND THE JESUITS’ CHURCH, CUZCO | 398 |

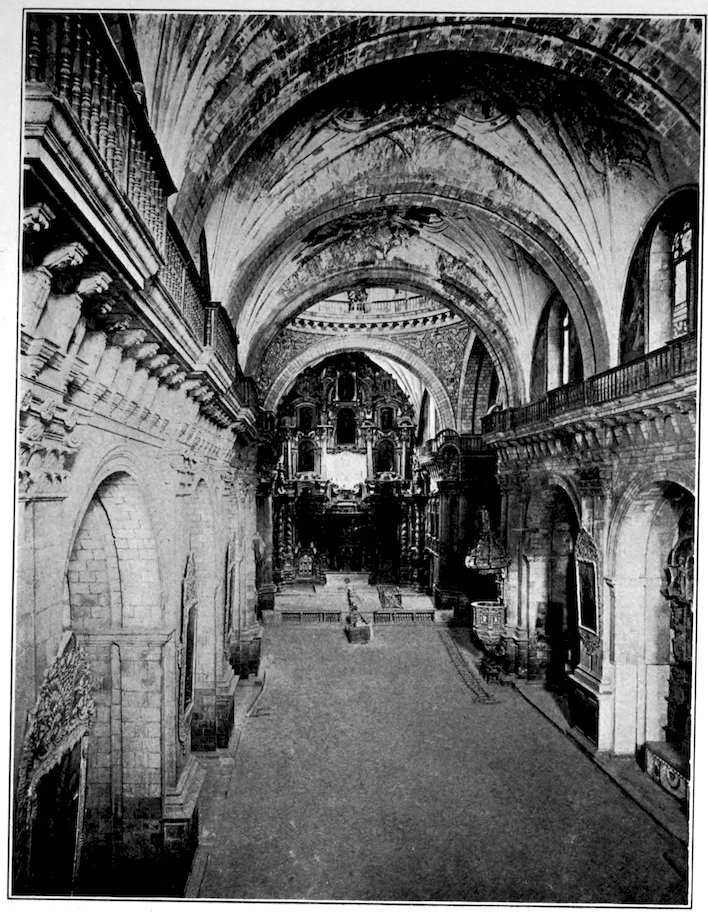

| INTERIOR OF THE JESUITS’ CHURCH, CUZCO | 399 |

| THE PREFECTURE, CUZCO | 400 |

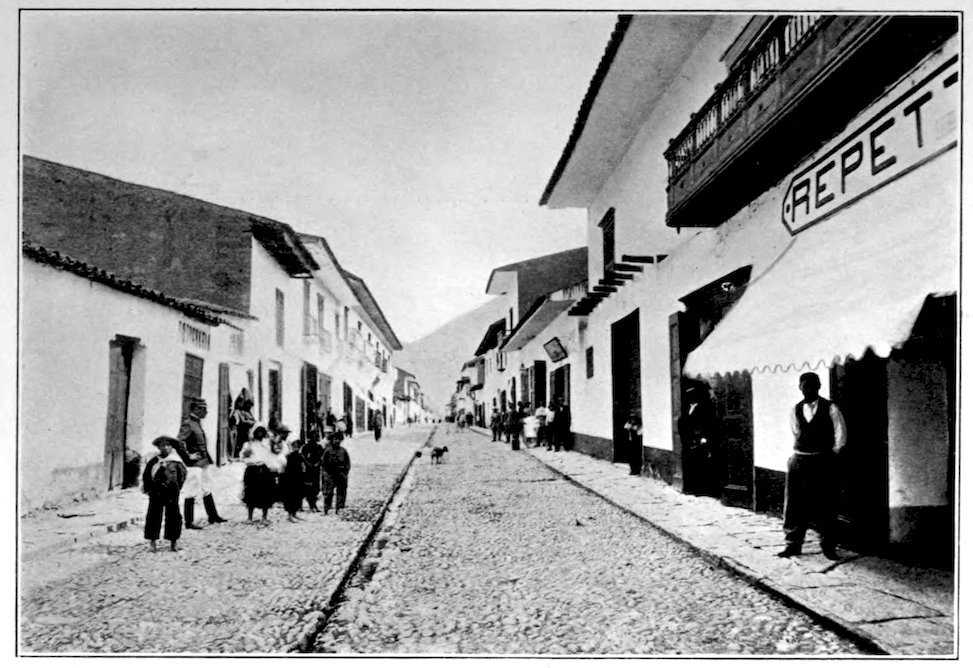

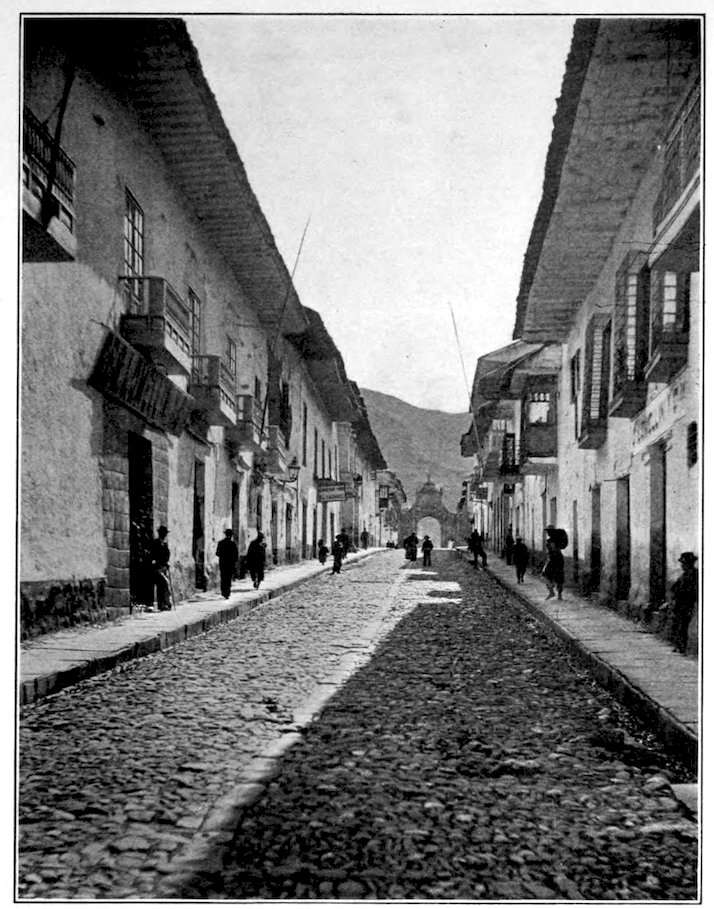

| CALLE MARQUEZ, CUZCO | 401 |

| THE UNIVERSITY OF CUZCO | 402 |

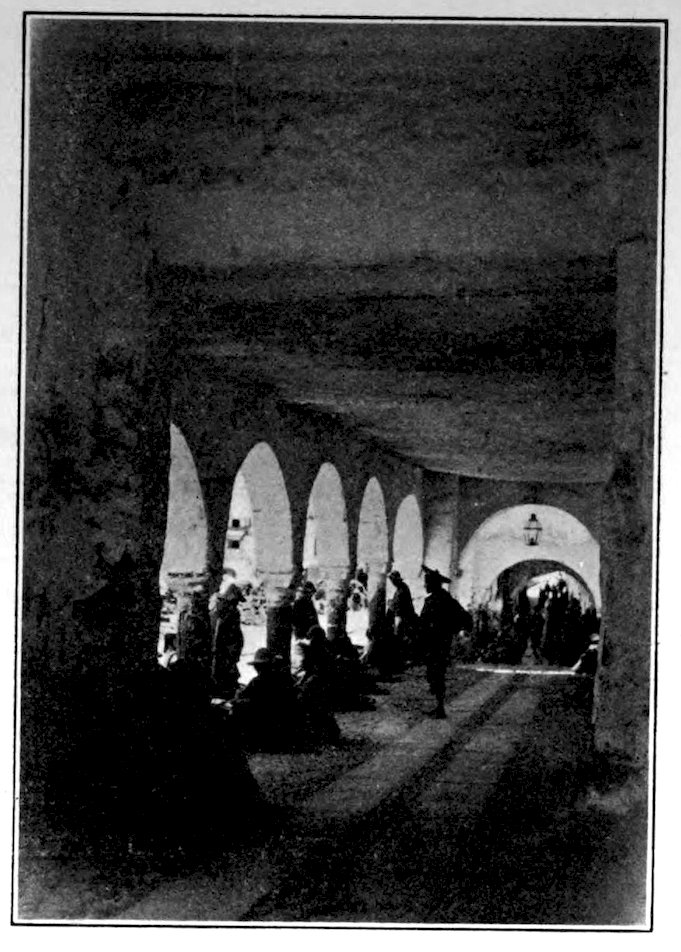

| VENDERS IN THE ARCADE, CUZCO | 403 |

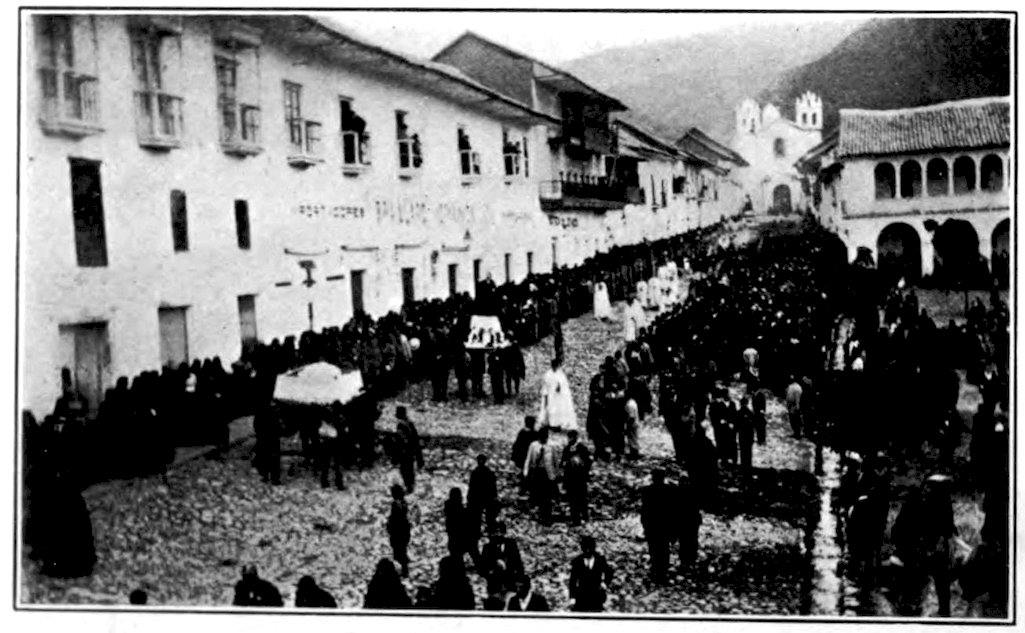

| A RELIGIOUS PROCESSION IN CUZCO | 404 |

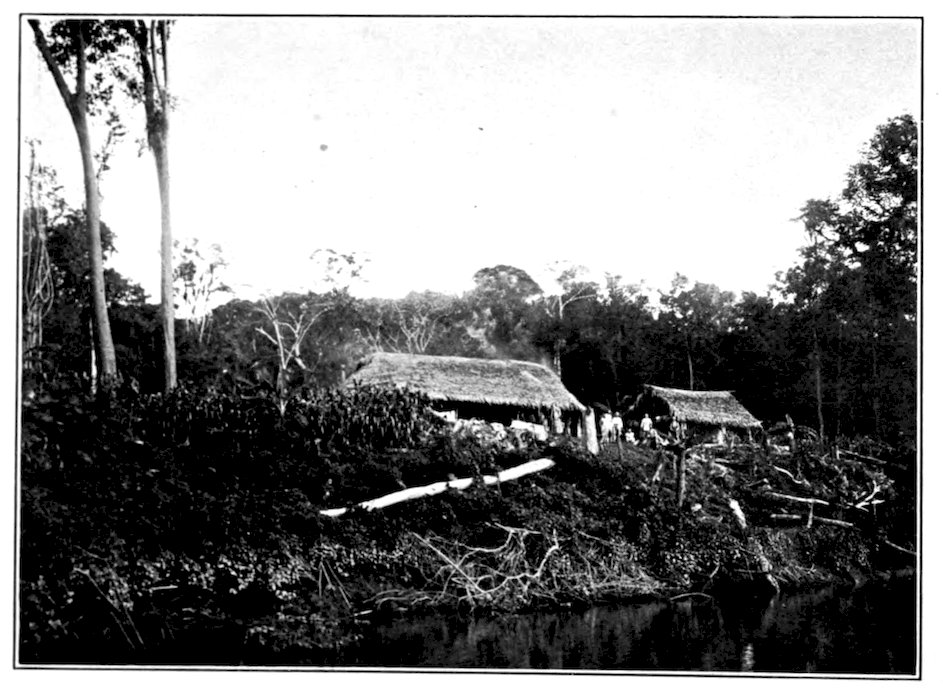

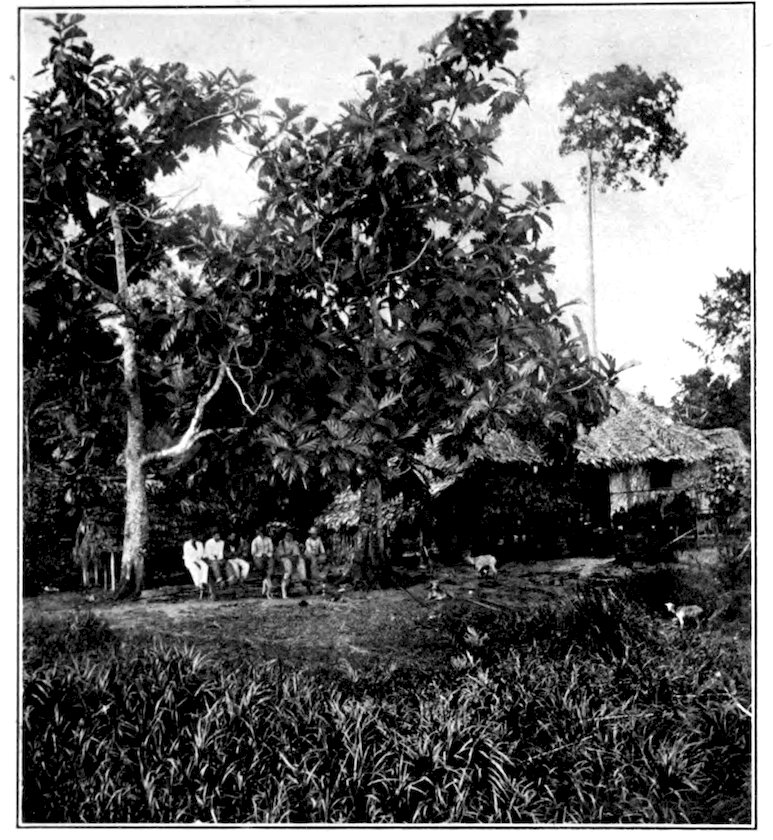

| A RUBBER ESTABLISHMENT IN THE DEPARTMENT OF LORETO | 406 |

| INDIANS CARRYING COCA TO MARKET | 407 |

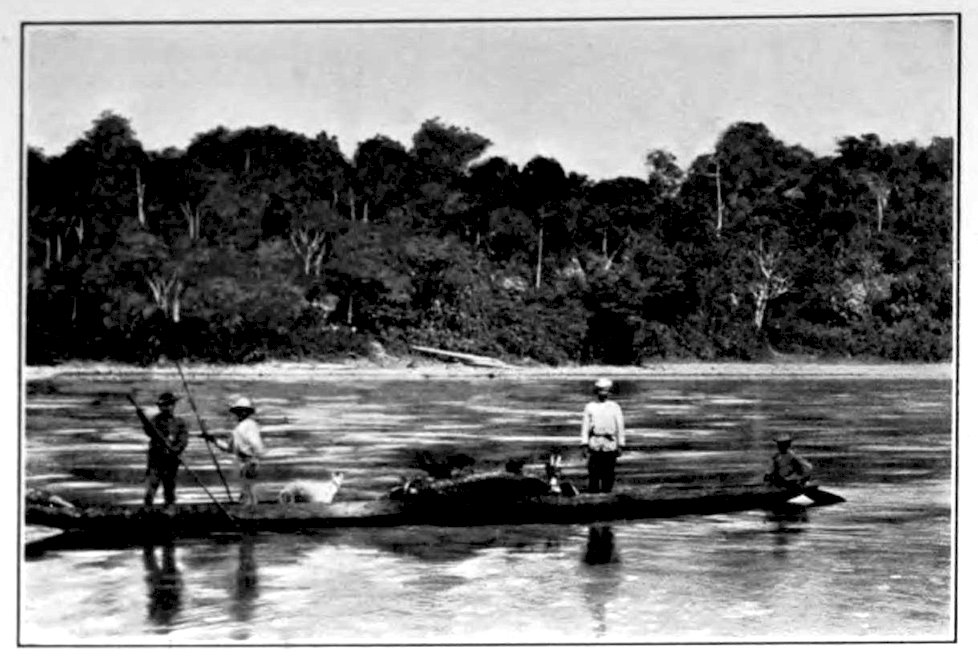

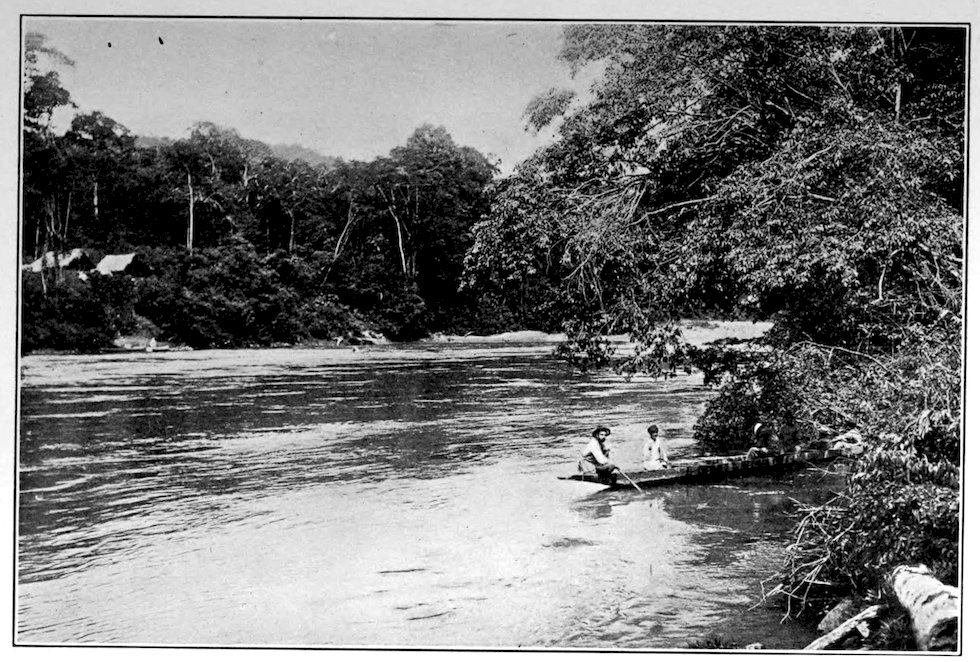

| CANOEING ON THE HUALLAGA RIVER | 408 |

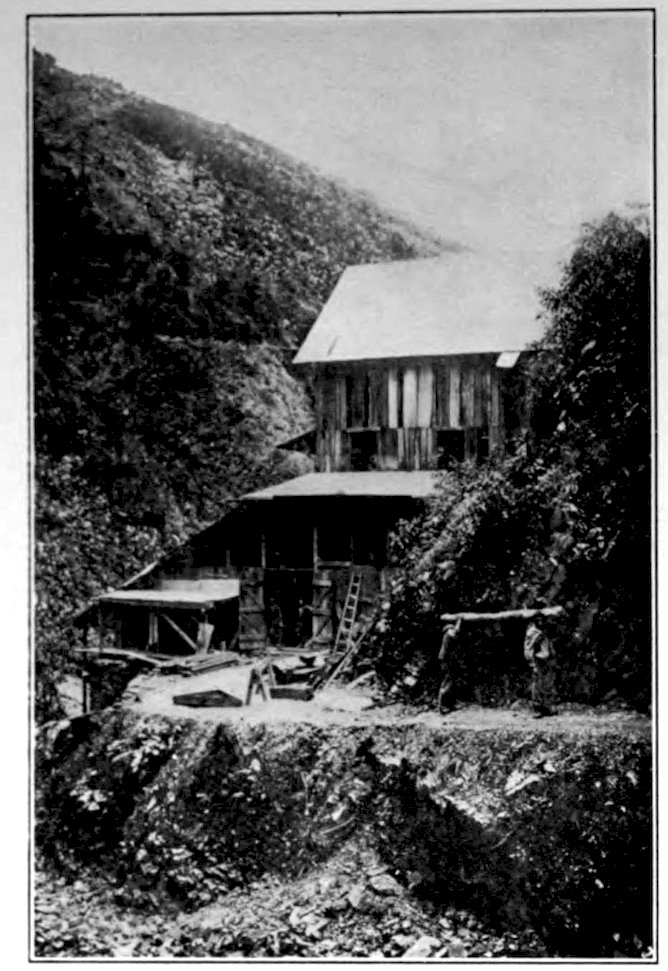

| SHIPYARD AT ASTILLERO, WHERE THE INCA MINING COMPANY’S FIRST STEAMER WAS BUILT | 409 |

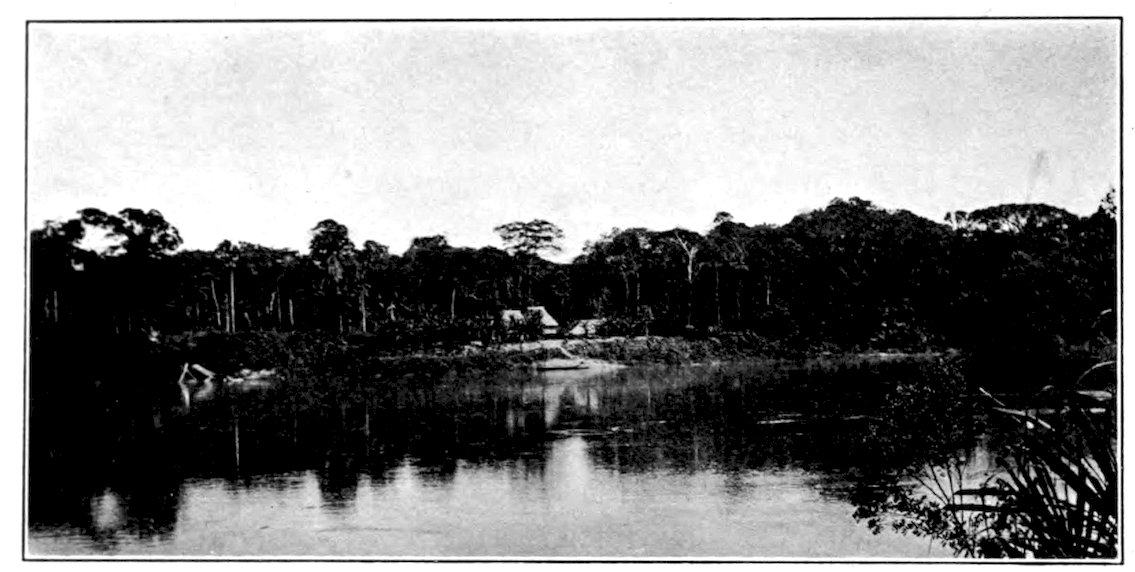

| CHICAPLAYA, IN THE HEART OF THE MONTAÑA | 410 |

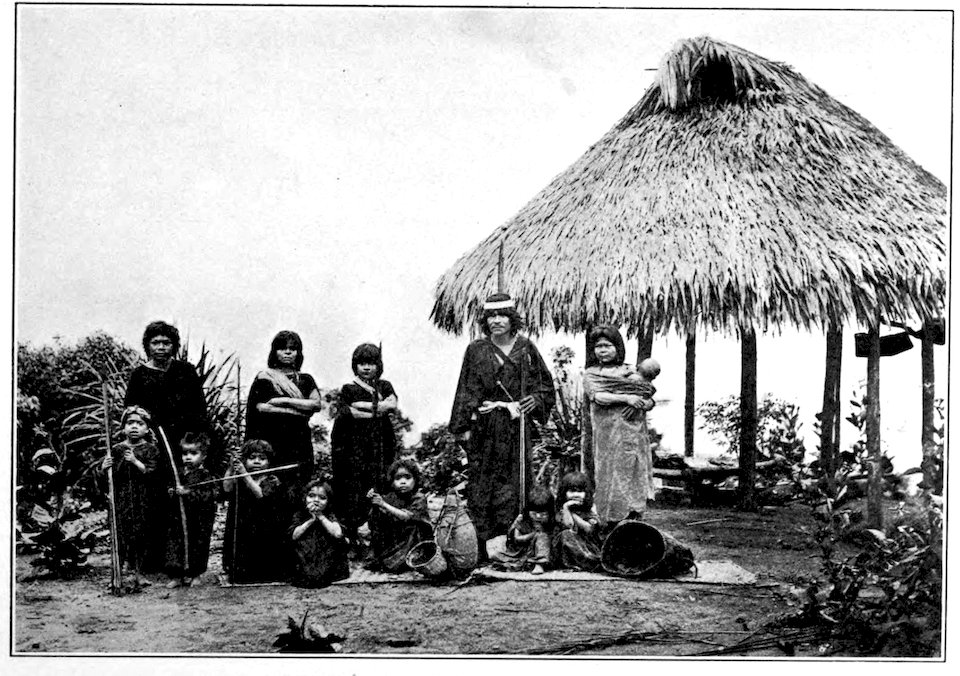

| CHUNCHO INDIANS OF THE PENEDO VALLEY | 411 |

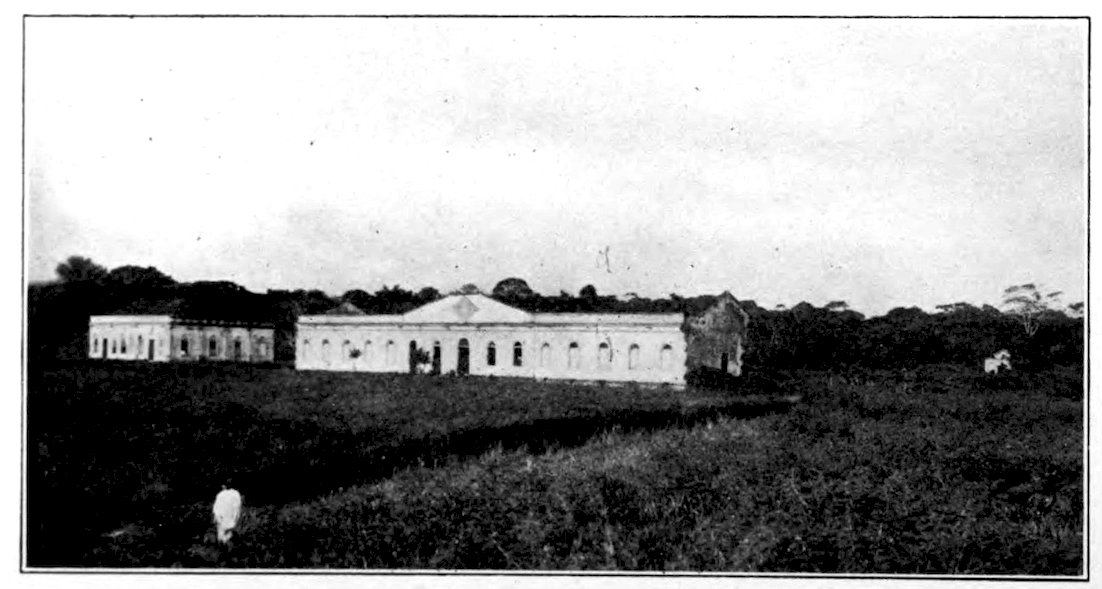

| MASISEA, THE FIRST WIRELESS TELEGRAPH STATION BUILT BETWEEN PUERTO BERMUDEZ AND IQUITOS | 412 |

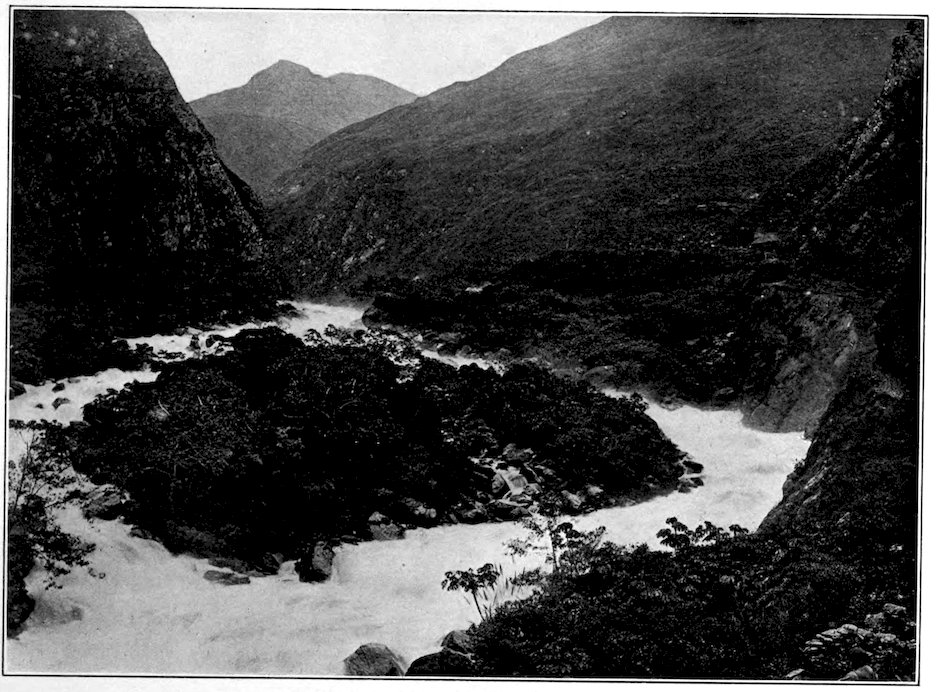

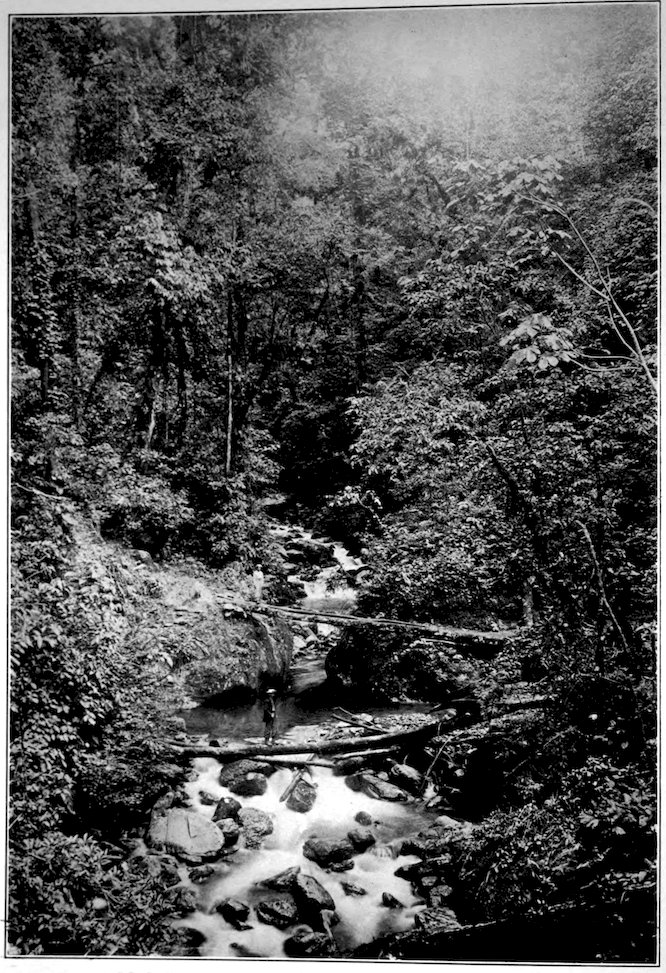

| A TURBULENT TRIBUTARY OF THE MADRE DE DIOS RIVER | 413 |

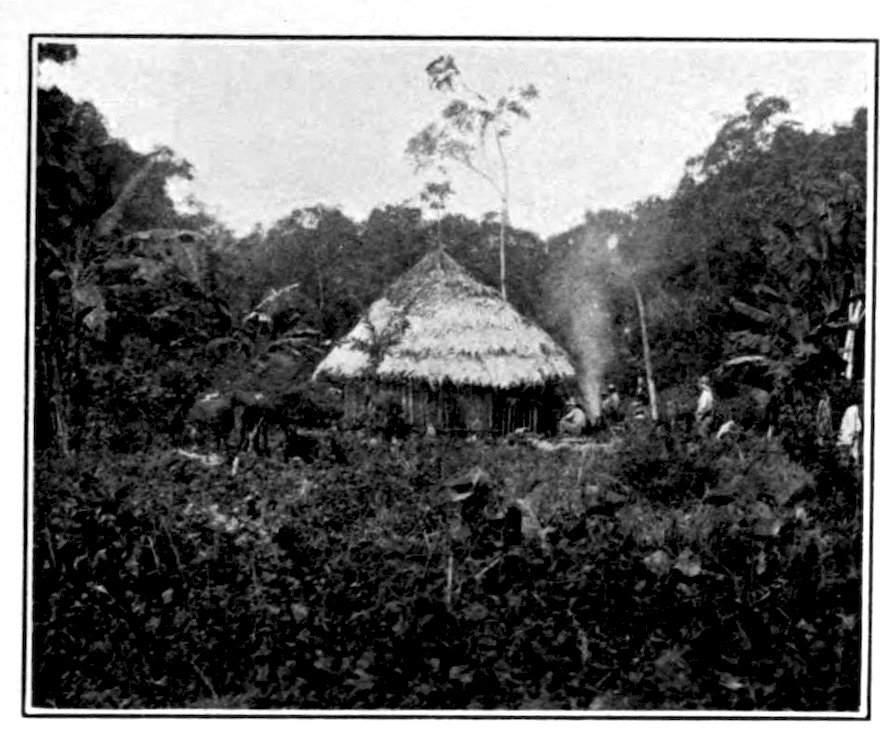

| A RUBBER CAMP IN THE MONTAÑA | 414 |

| RAPIDS ON THE TAMBOPATA RIVER | 414 |

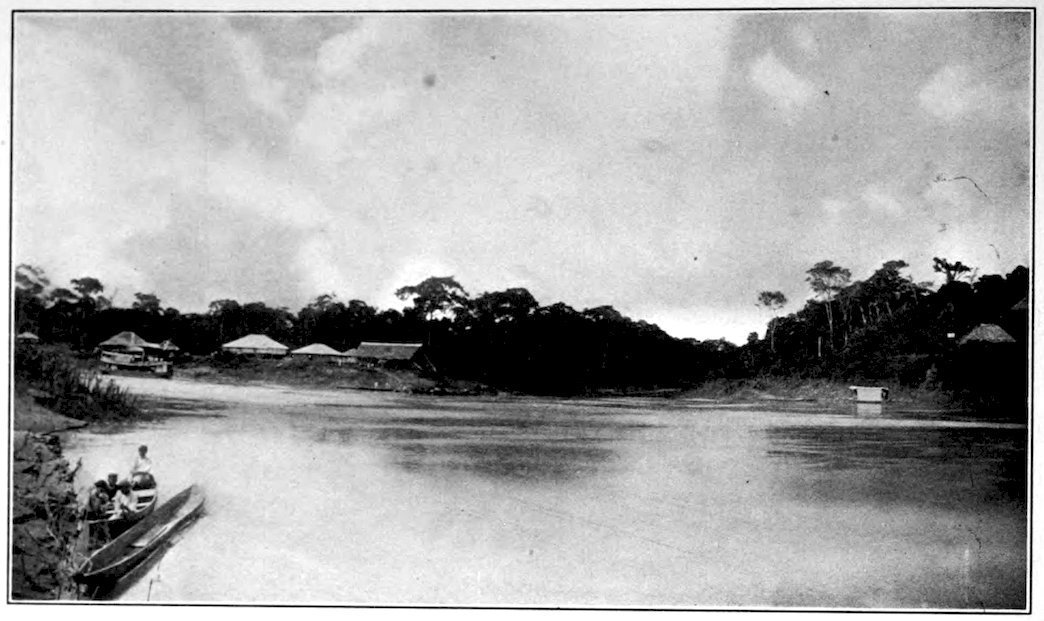

| A TYPICAL SCENE ON THE WATERWAYS OF THE UPPER AMAZON | 415 |

| SCENE ON THE MADRE DE DIOS RIVER NEAR MALDONADO | 416 |

| HOSPITALITY IN THE RUBBER COUNTRY | 417 |

| THE BOOTH PIER, IQUITOS | 418 |

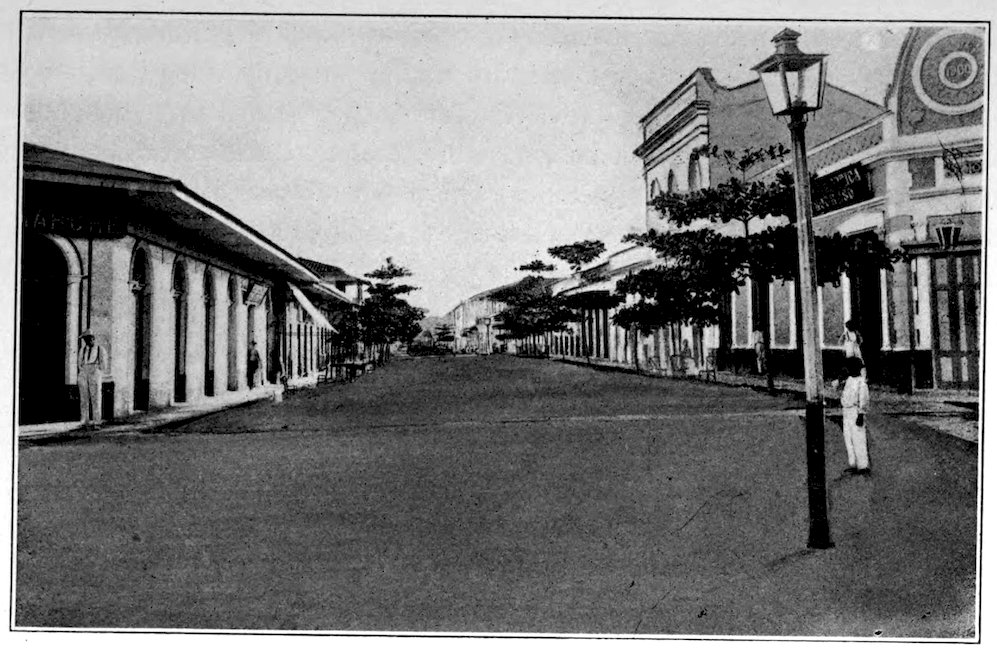

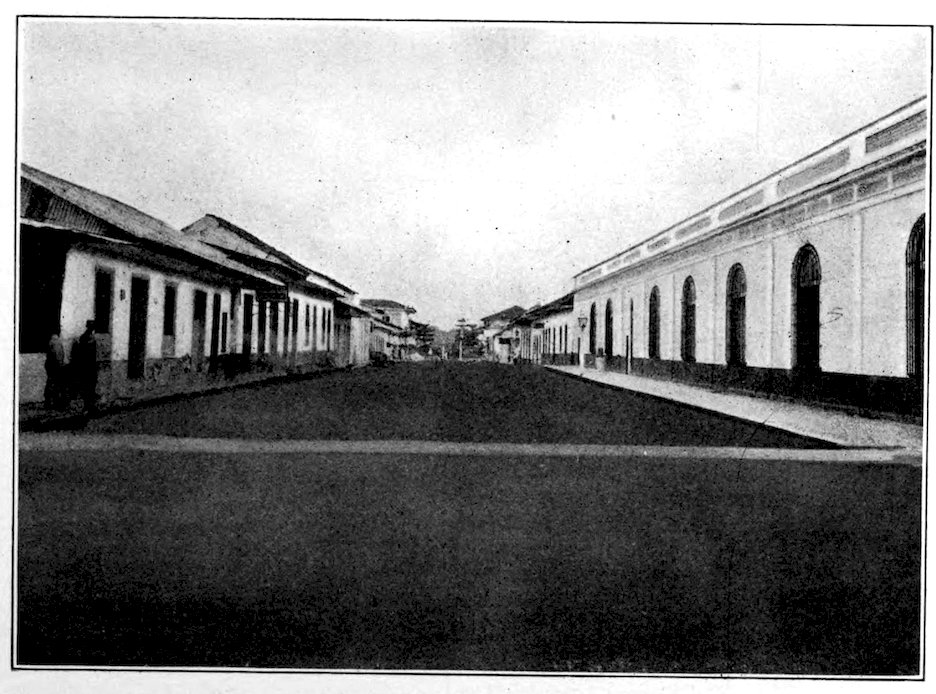

| ONE OF THE PRINCIPAL STREETS OF IQUITOS | 419 |

| CALLE DE MORONA, IQUITOS | 419 |

| RIVER SCENE NEAR IQUITOS | 420 |

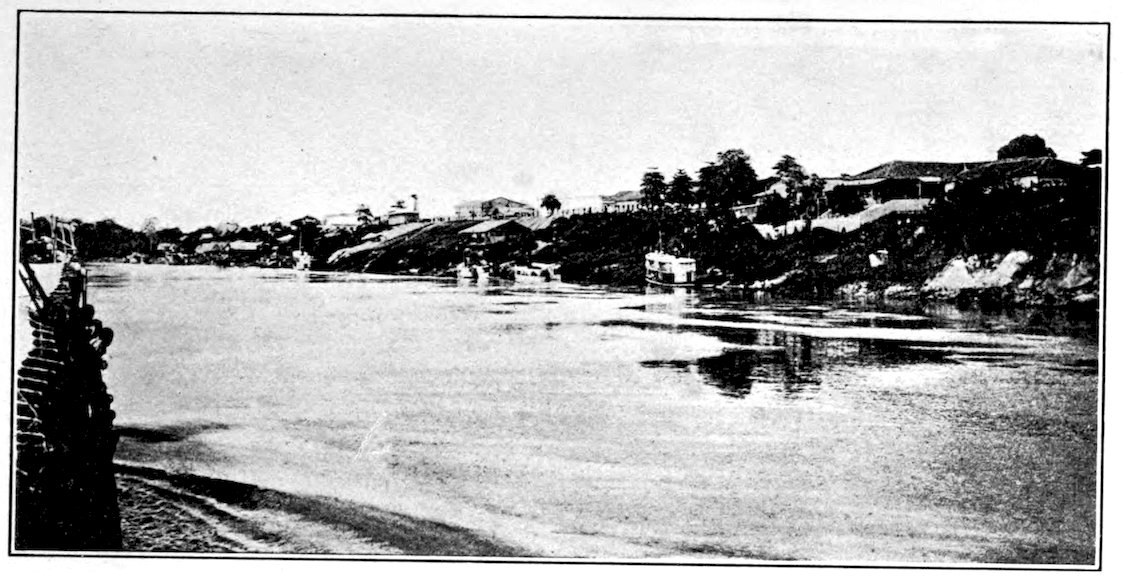

| A VIEW OF IQUITOS FROM THE RIVER | 421 |

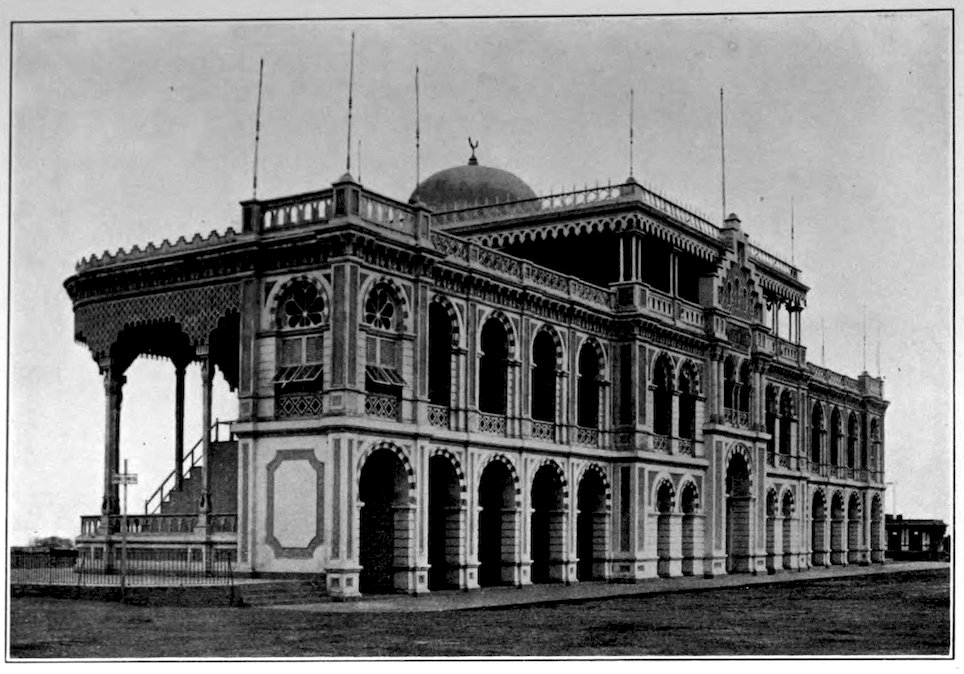

| THE CUSTOM HOUSE AT IQUITOS | 422 |

| A ROAD THROUGH THE VIRGIN FOREST TO PUERTO BERMUDEZ | 424 |

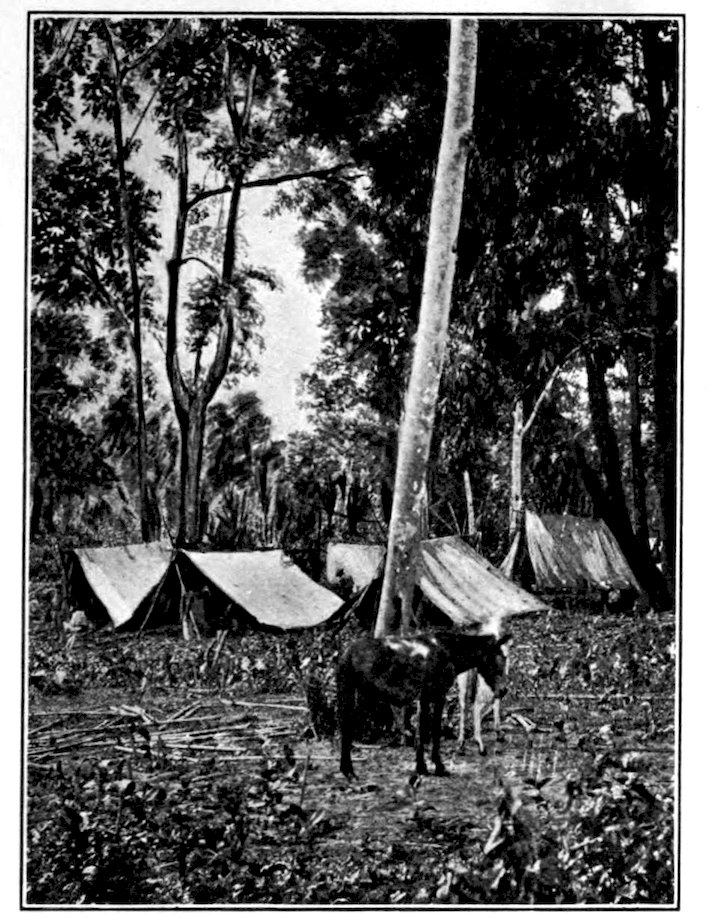

| AN ENGINEERS’ CAMP AT PUERTO BERMUDEZ ON THE PICHIS RIVER | 425 |

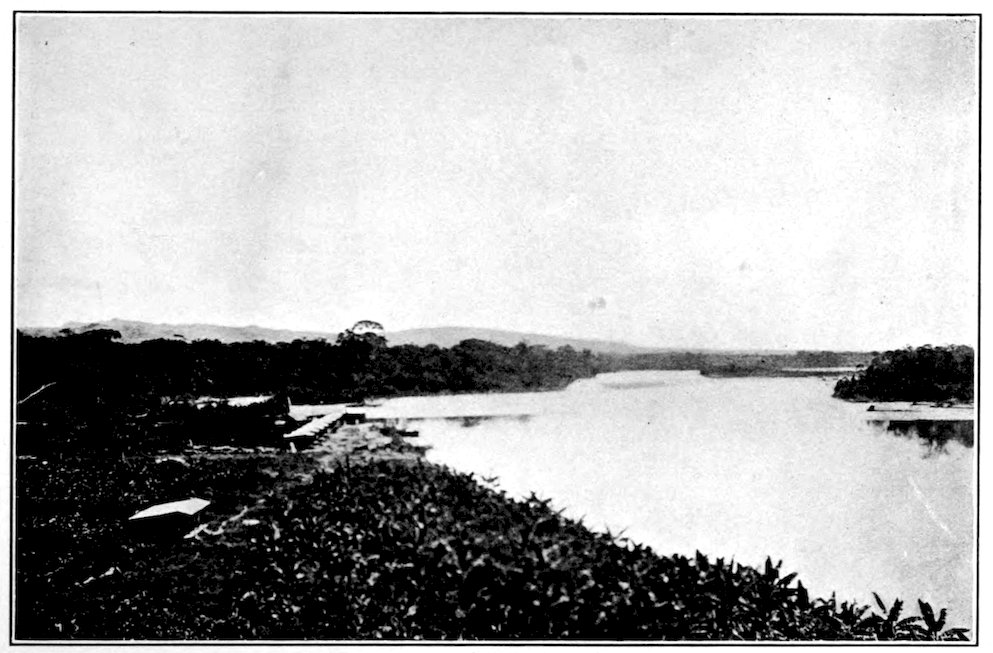

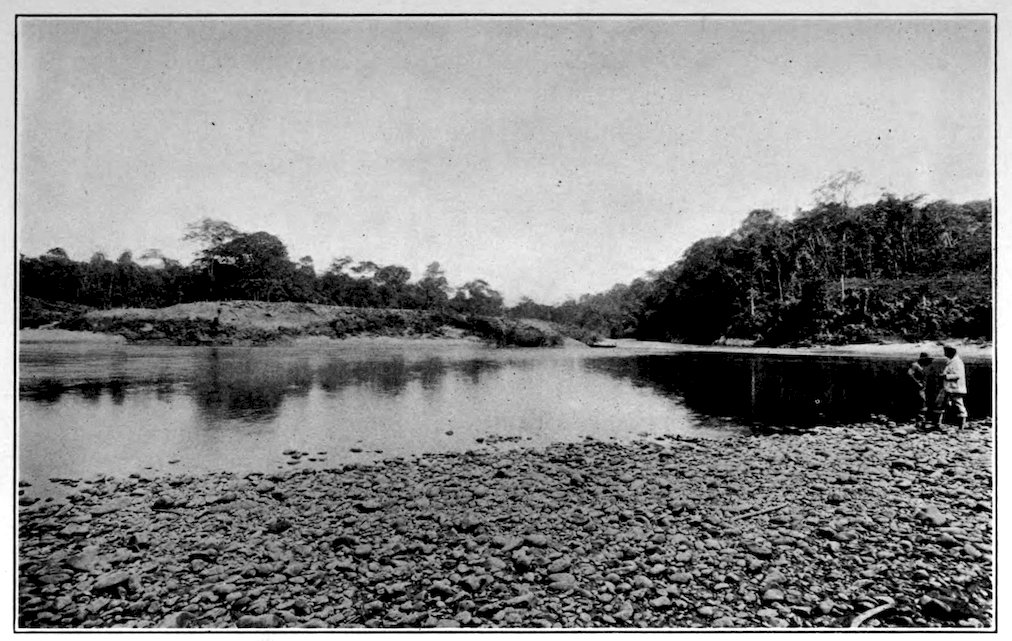

| THE CONFLUENCE OF THE CHUCHURAL AND PALCAZU RIVERS | 427 |

| PUERTO CLEMENT | 428 |

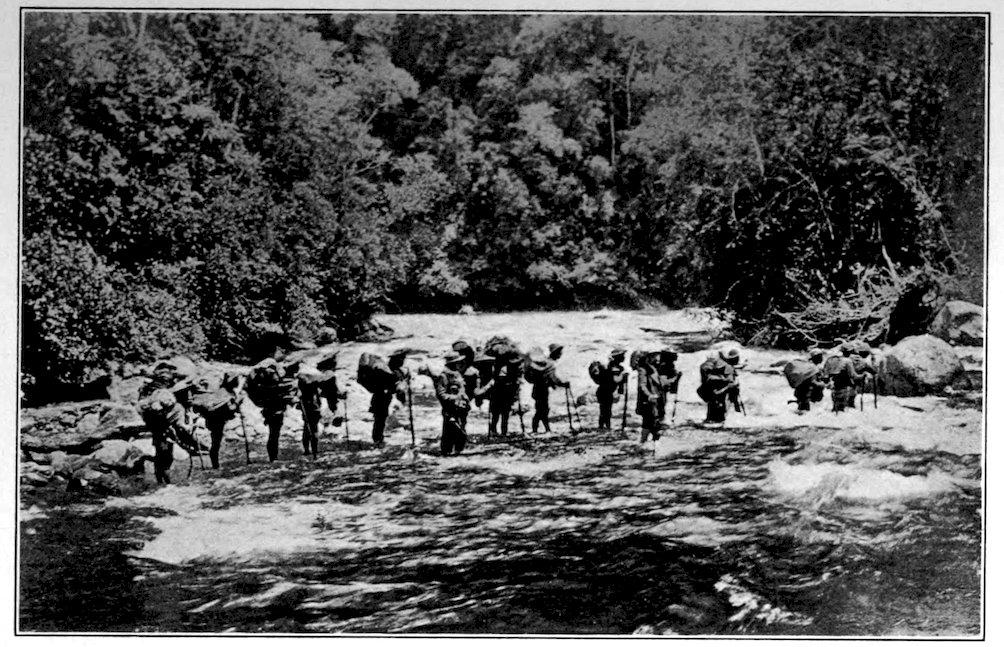

| FORDING THE INAMBARI RIVER | 429 |

| TABATINGA, ON THE FRONTIER BETWEEN PERU AND BRAZIL | 430 |

| COLONISTS OF THE SIERRA | 431 |

| IN THE HEART OF THE MINING REGION | 433 |

| A FOREIGN COLONY IN THE RUBBER COUNTRY | 434 |

| A FERTILE VALLEY FOR COLONIZATION IN THE APURIMAC REGION | 435 |

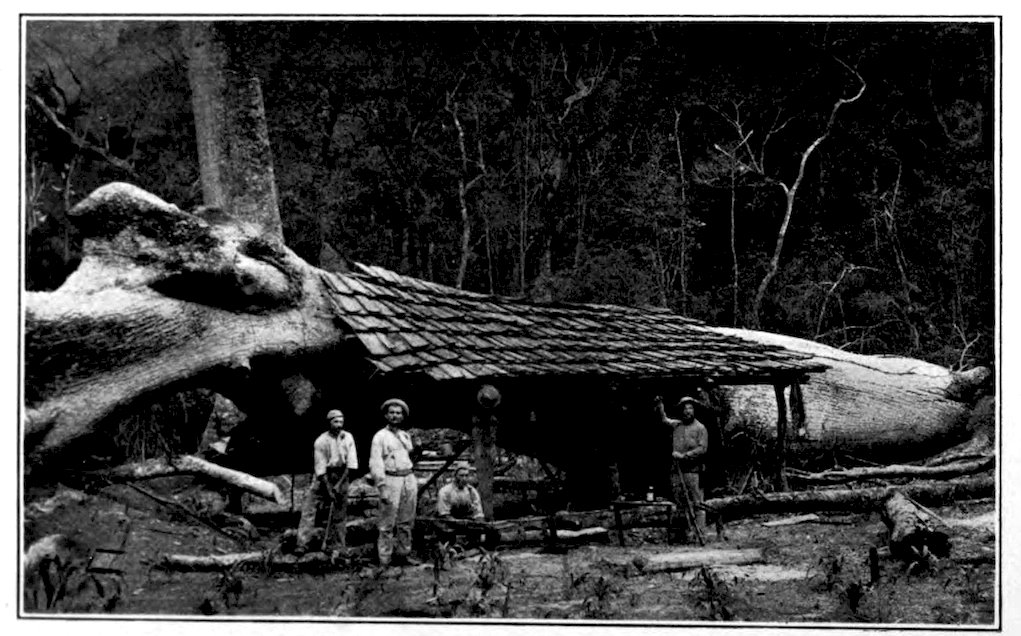

| AN INGENIOUS PROSPECTOR’S HOUSE IN THE FOREST | 436 |

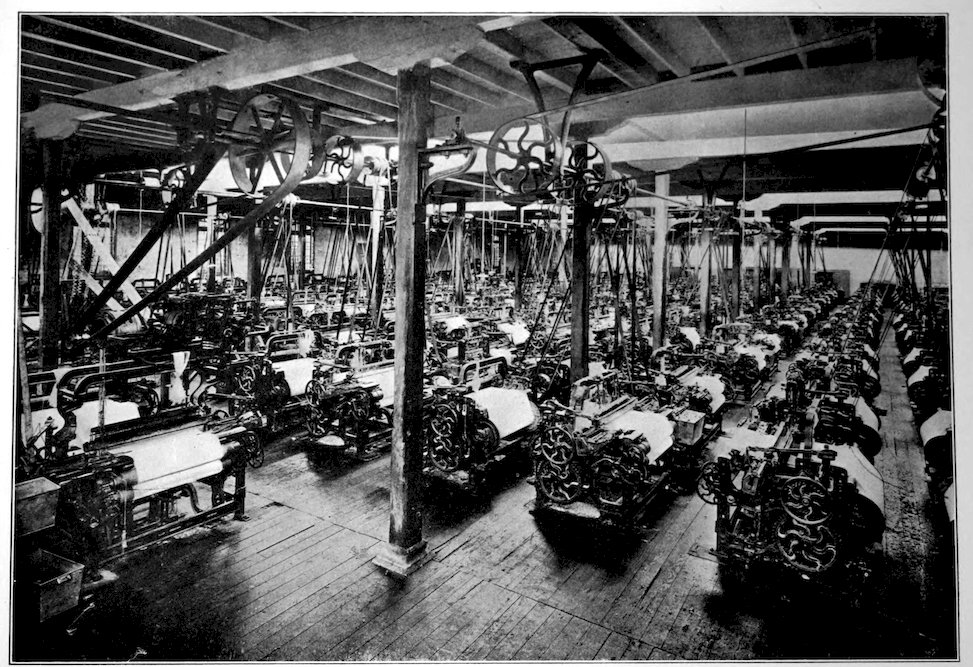

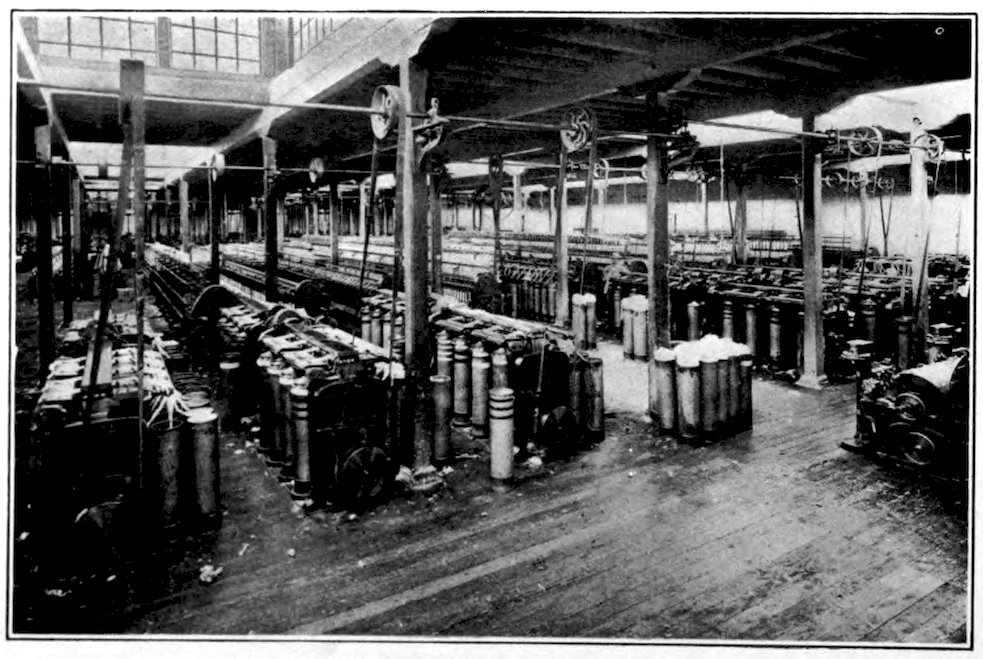

| THE VICTORIA COTTON MILLS, LIMA | 438 |

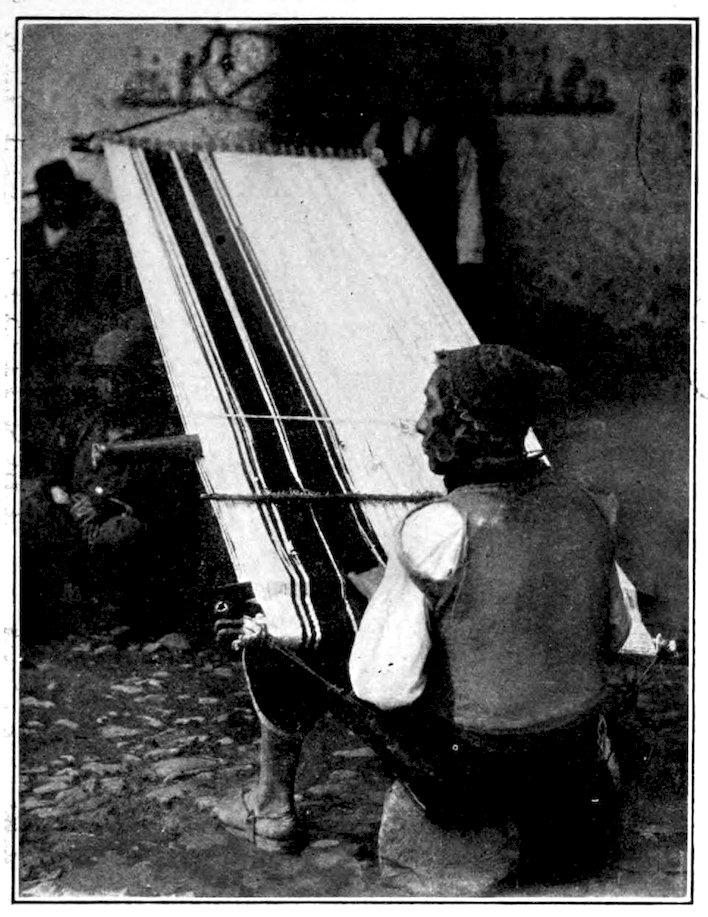

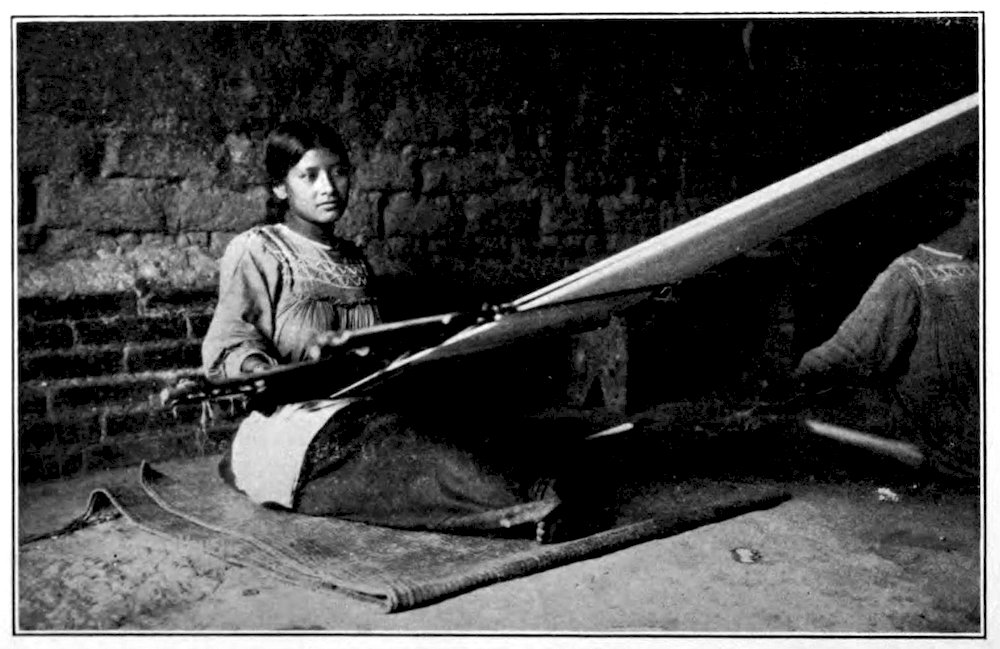

| AN INDIAN WEAVING THE PONCHO | 439 |

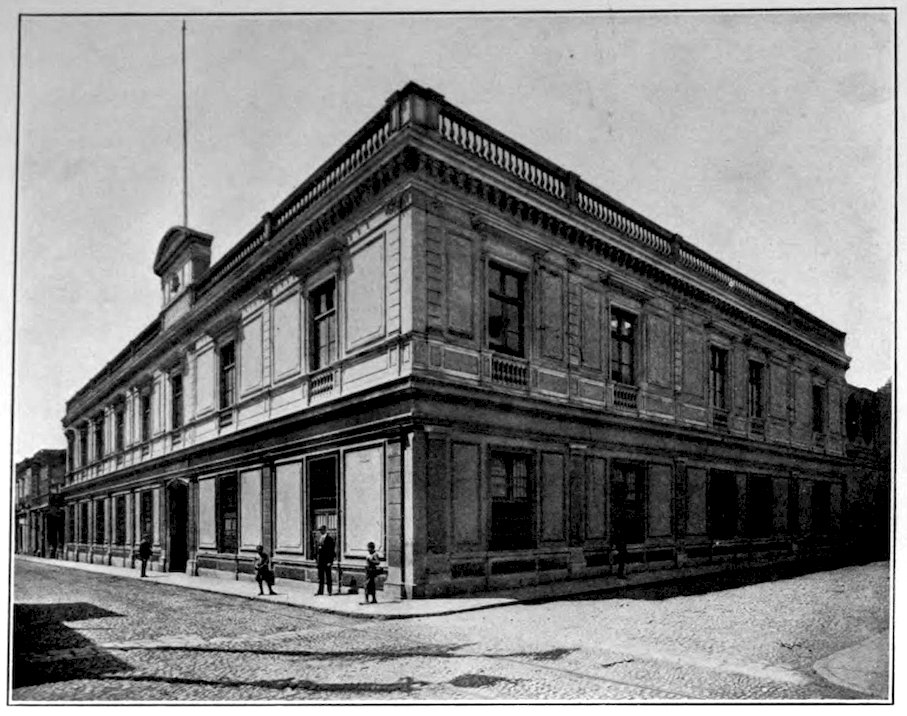

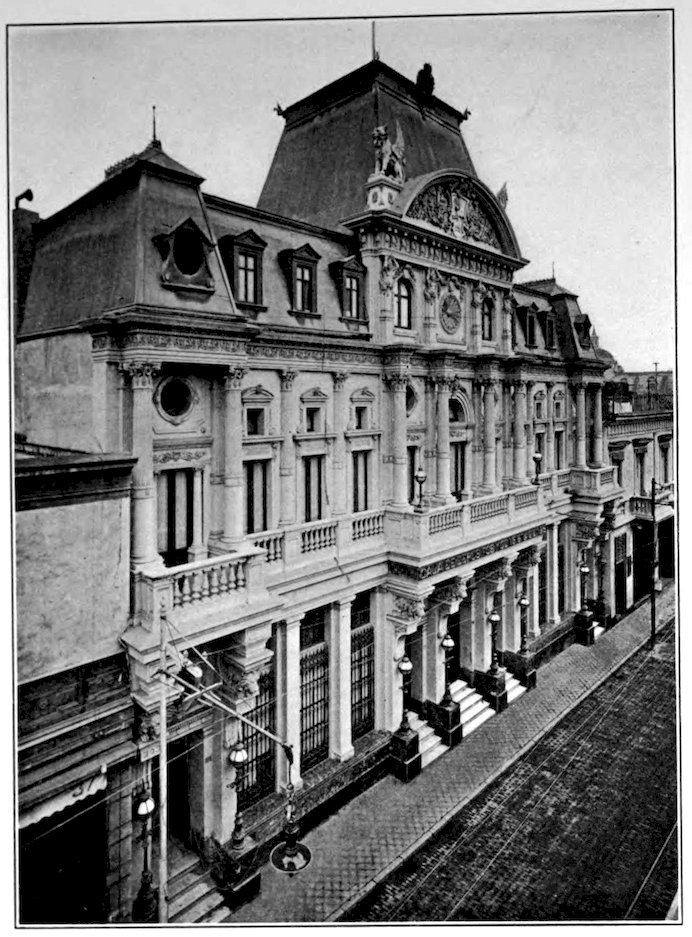

| THE LIMA SAVINGS BANK | 442 |

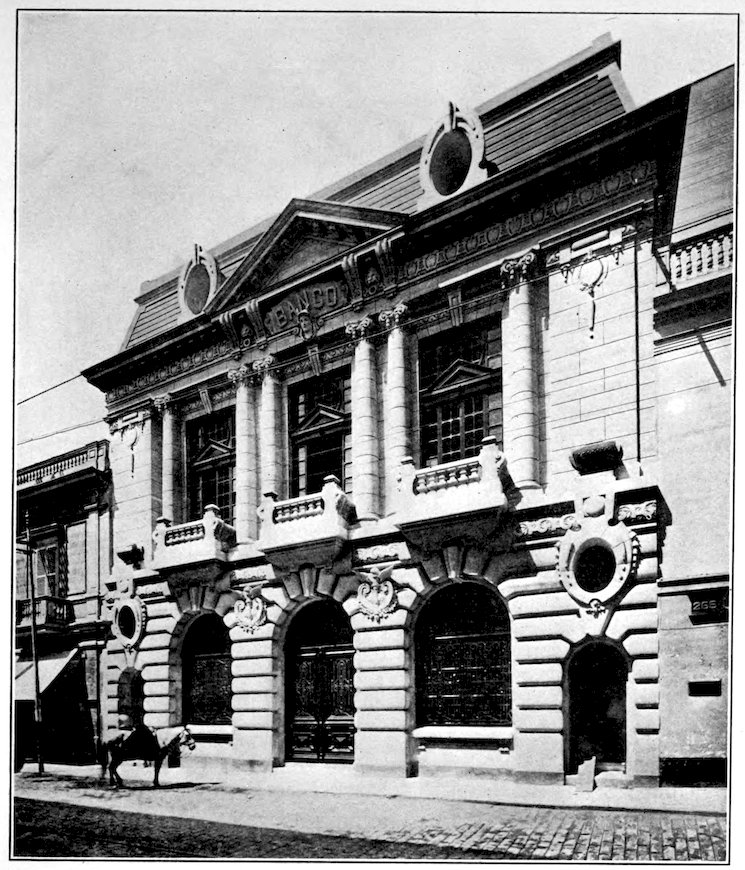

| THE BANCO POPULAR, LIMA | 443 |

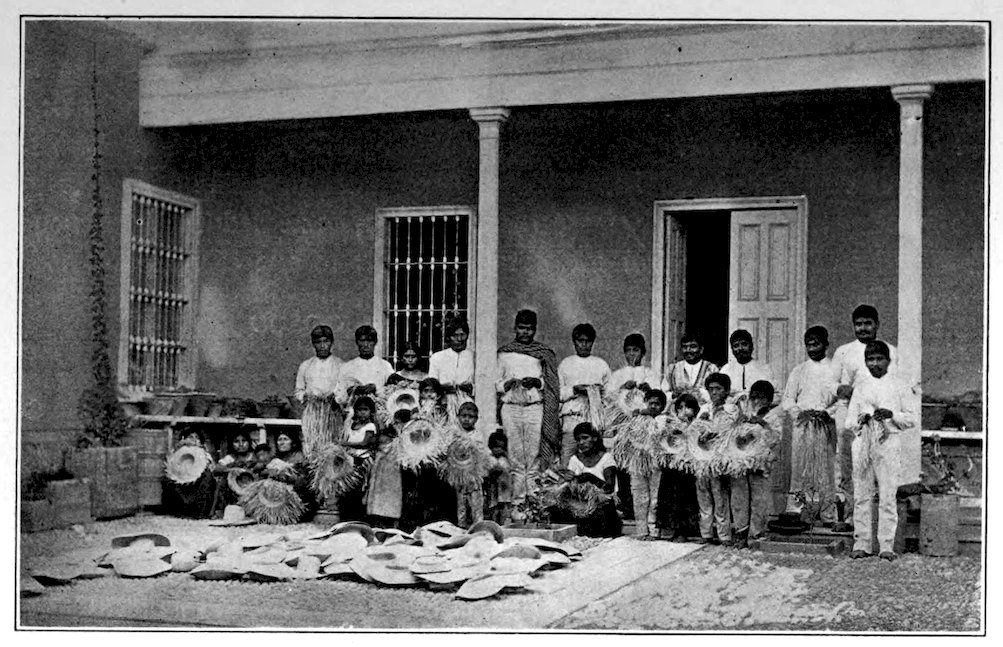

| A NATIVE INDUSTRY OF THE COAST REGION | 445 |

| A COCAINE FACTORY IN THE MONZON VALLEY | 446 |

| THE ITALIAN BANK, LIMA | 448 |

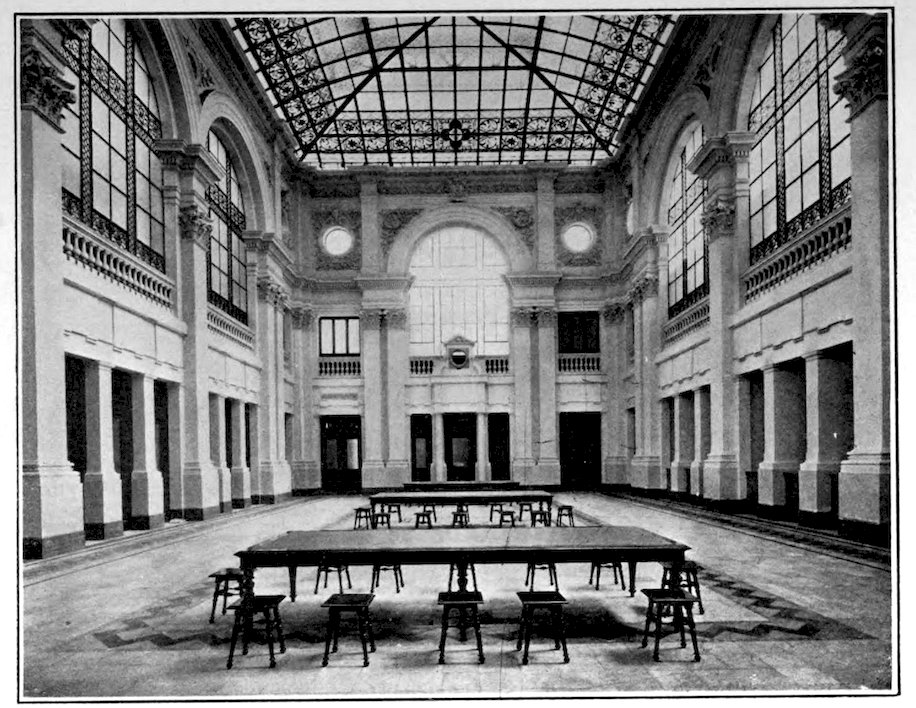

| VESTIBULE OF THE BANK OF LONDON AND PERU, LIMA | 449 |

| PERUVIAN COTTON IN THE FACTORY | 450 |

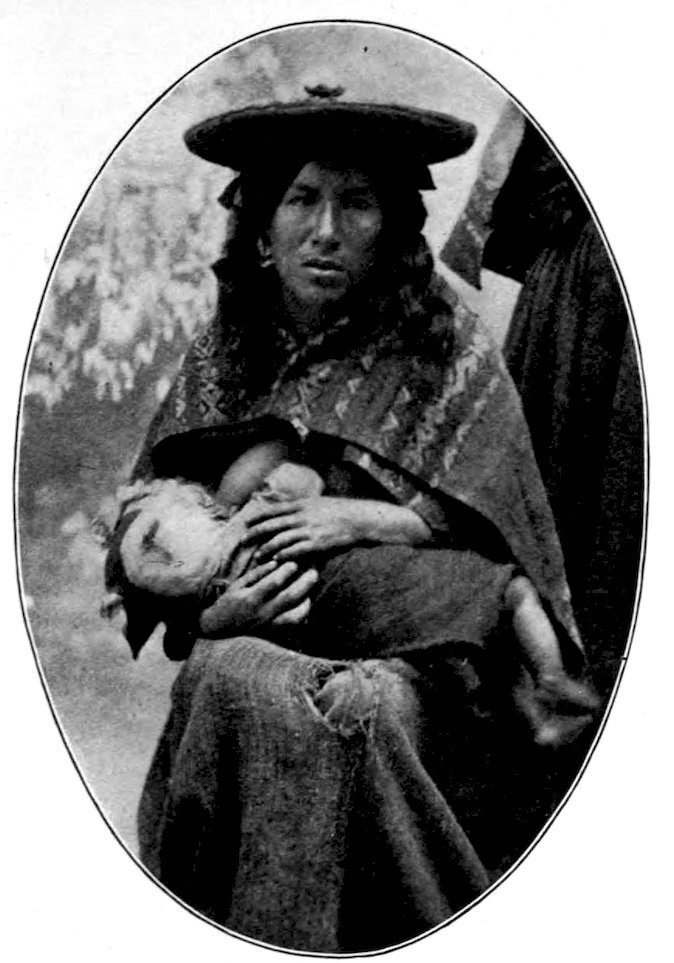

| A QUICHUA MOTHER | 451 |

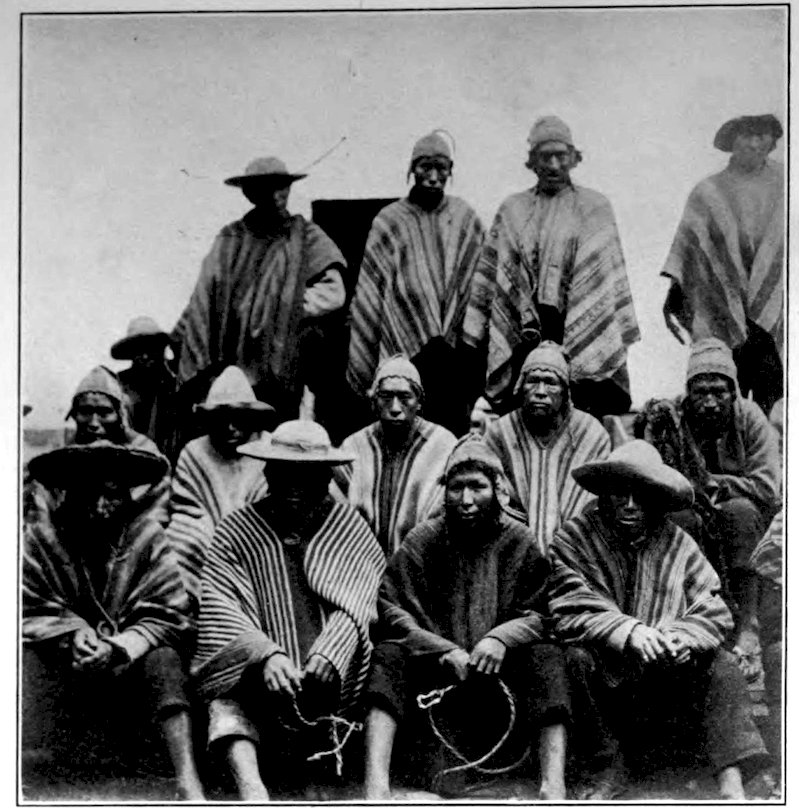

| DESCENDANTS OF THE INCAS’ SUBJECTS | 452 |

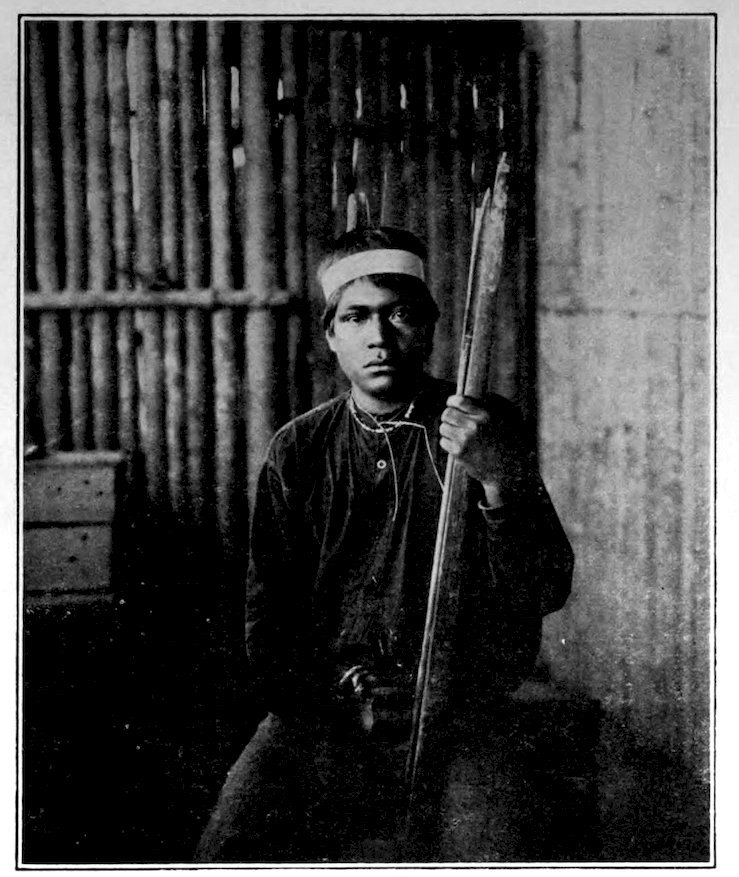

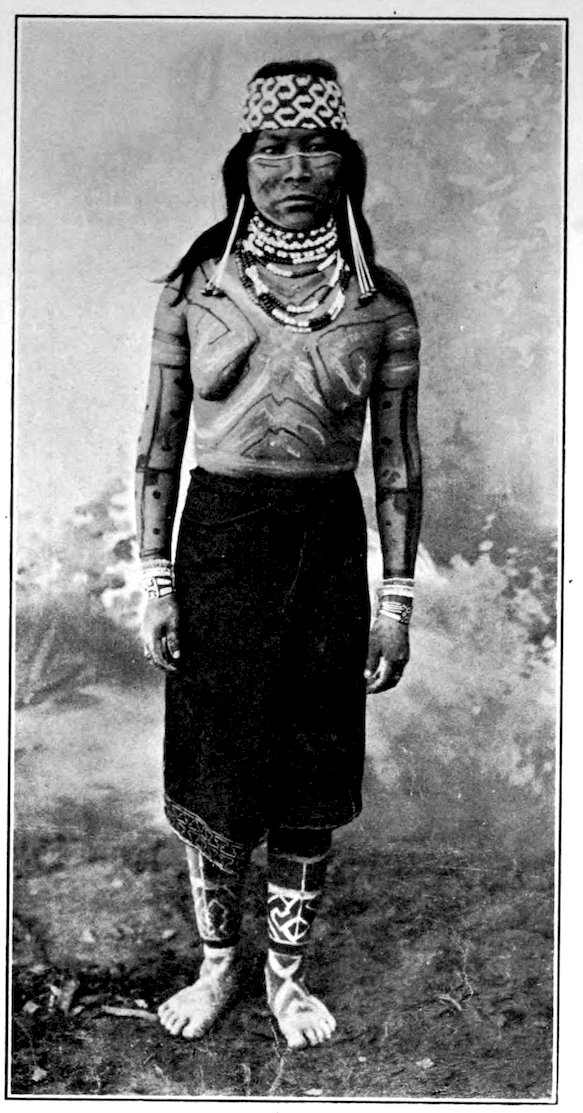

| A TYPE OF THE AMAZON INDIAN | 453 |

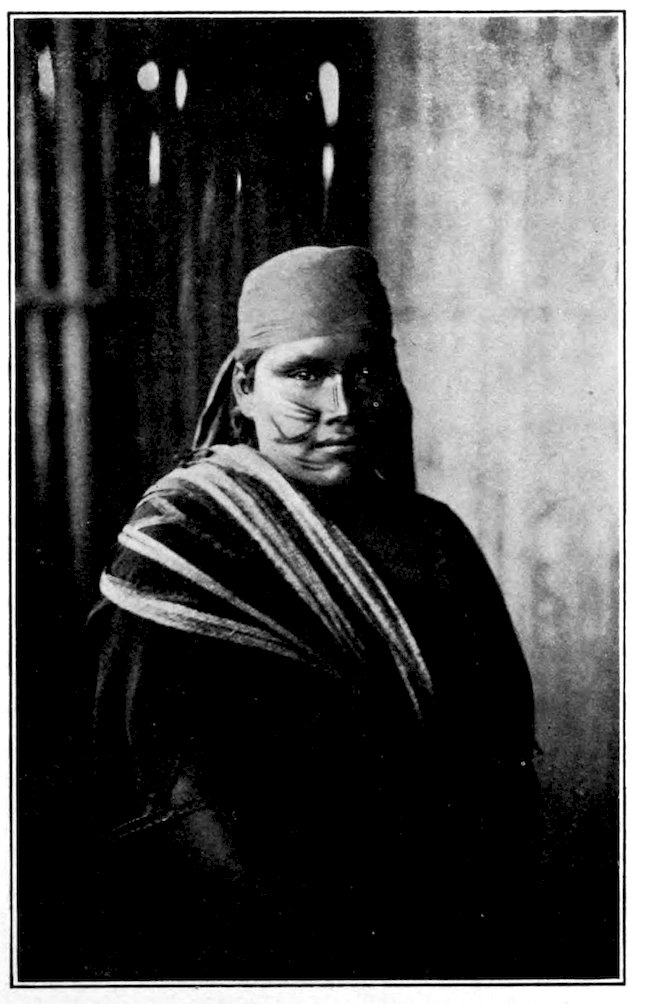

| THE SCION OF A NOBLE FAMILY OF THE FOREST | 453 |

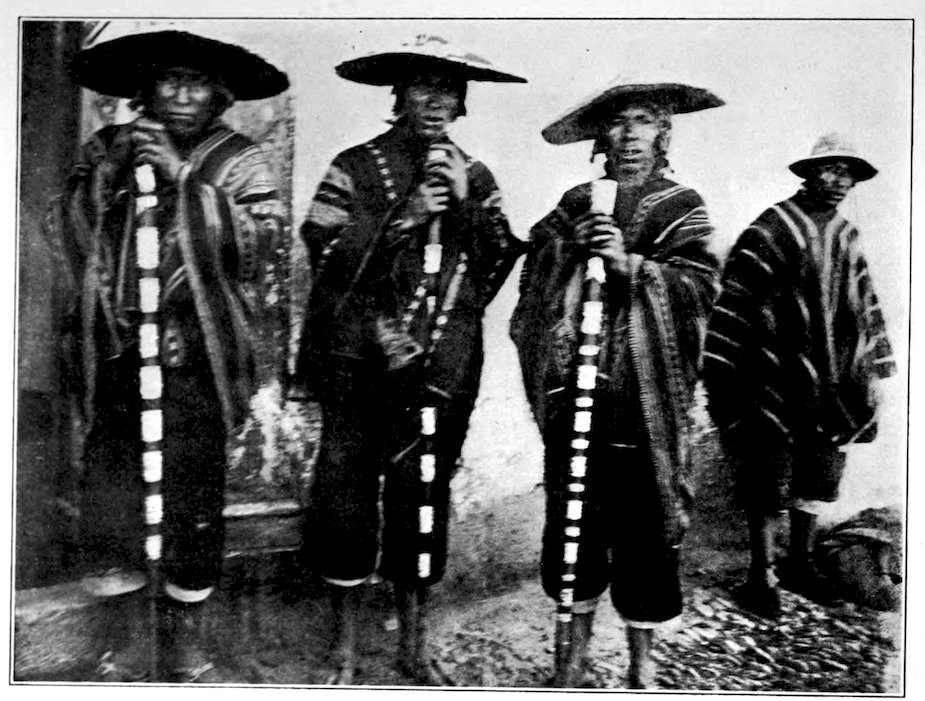

| ALCALDES, WITH VARAS, THE INSIGNIA OF THEIR AUTHORITY | 454 |

| AN INDIAN WOMAN OF LORETO | 455 |

| A NATIVE WEAVER, CHICLAYO | 456 |

| MAP OF PERU | Facing 456 |

Universally known as a land of untold antiquity, of fascinating romance and marvellous traditions, Peru may be considered, from the standpoint of history, the most interesting of all the South American countries. The revelations of scientific research are daily adding to the record of its glory in the remote past, when the Incas and their predecessors ruled with theocratic sway over a large part of the continent and lived in barbaric splendor at Cuzco, at Chan-Chan, or at some other of the great pre-Columbian capitals, the ruins of which to-day excite the admiration of archæologists and the enthusiasm of sightseers. The literature of the country, also, is constantly revealing new phases of the national life as it existed in ancient times, and especially in the more recent period of the Spanish viceroyalty. Unlimited wealth, easily acquired through the labor of the conquered race in the rich mines of the sierra during colonial days, led to the greatest extravagance, though at the same time it provided ample means for travel and study, the benefits of which became apparent in the fine culture of the people—a culture which has left its impress on succeeding generations of Peruvians, giving them the reputation they enjoy to-day of being essentially a gentle and polished nation.

But, although scientific investigation and literary skill have added much within recent years to what was already more or less generally known about Peru, and the land of the Incas and the viceroys has been made a more charming subject than ever before as regards its antiquity and romance, yet the Peru of to-day, the real Peru, has received comparatively little attention from writers and travellers, and is still almost an unknown country to the average reader. The purpose of the present volume is to present a passing glimpse of the Old Peru—the whole story of which can only be told in many volumes—and to give a faithful description of the progress and development that are evident in every feature of the national life as reflected in the social, political, industrial, and commercial institutions of the New Peru. The prosperous future of Peru is assured by the patriotism, energy, and enterprise that are apparent in every feature of the national life, and it is certain that the present century will see the wealth and greatness of the country increased beyond 14anything dreamed of in the days of the Incas and the viceroys. The spirit that won the national independence and successfully established republican institutions lives to-day, and is working for the ascendancy of the noblest ideals of the race.

In the preparation of this work, I found that the knowledge I had previously gained through close association with the people of Latin America during more than fifteen years’ journeying in these countries was of the greatest advantage. Travelling in Peru was more like visiting among friends than studying the manners and customs of a foreign people, and the uniform kindness and hospitality everywhere shown me made my experience in this beautiful land one of constant pleasure and of enduring memory. I sincerely appreciate the great assistance rendered me in securing information from government sources, from the public libraries and from many kind friends in every part of Peru, and I take this opportunity of expressing my thanks, from my heart. It is impossible to live in Peru without learning to love the country and its people, and while I have tried to allow no partiality to influence my judgment in writing this book, I cannot do otherwise than present to the reader what I found most interesting in my own study of the Old and the New Peru.

Philadelphia, September 20, 1908.

GIRDLE FOUND IN THE CEMETERY OF PACHACÁMAC.

The historian of the Conquerors who described the newly discovered Peru as “the Ophir of the Occident” gave it a name which modern research proves to have been singularly appropriate. Not only in wealth, but in antiquity, this interesting country is comparable to the fabled land of the East from which the emissaries of King Solomon brought so many luxuries to please the taste of their royal master. There are eminent writers and students of the records of ancient times who are of the opinion that the famous Ophir of the Bible was no other than ancient Peru, and that the Phœnicians—those intrepid navigators of past ages—visited its shores and were the founders of its earliest civilization.

But speculation as to the origin of the ancient Peruvians covers such an extensive field that almost every writer on the subject has a distinct opinion; and every nation of the Orient has been supposed, by one authority or another, to have laid the foundation of Peruvian culture. The most popular theory gives to China the credit of introducing the earliest civilization on the American continent; and in support of this belief many parallels are drawn between the Mongolians and the primitive races of the New World in their traditions, customs, and, particularly, the similarity of their features. In some parts of the coast district of Peru, the indigenes do not speak Quichua, as do the descendants of the Incas’ people, but have a language which is said to be easily understood by the Chinese; and there is, apparently, a close analogy between the ancient creeds of the coast Indians and Chinese worship. According to several authorities, the traditional heroes of Peruvian and Mexican civilization were Buddhist priests. In this 18connection it is worthy of mention that some of the huacas which have been taken from ancient cemeteries on the coast, bear a marked resemblance to the well-known idols of Buddhist worship. The name huaca is given to all consecrated relics in these ancient burials, including the corpse and its wrappings, as well as the innumerable articles of household and personal use, ornaments and food, interred therewith. The custom of placing maize and other edibles in the grave, and (as has been found in some cases) of putting a coin in the mouth of the deceased, affords proof that these ancients believed in a future life. Most of the interments were made in huge mounds, called huacas, built of sun-dried bricks, or, in the earliest periods, of round balls of mud.

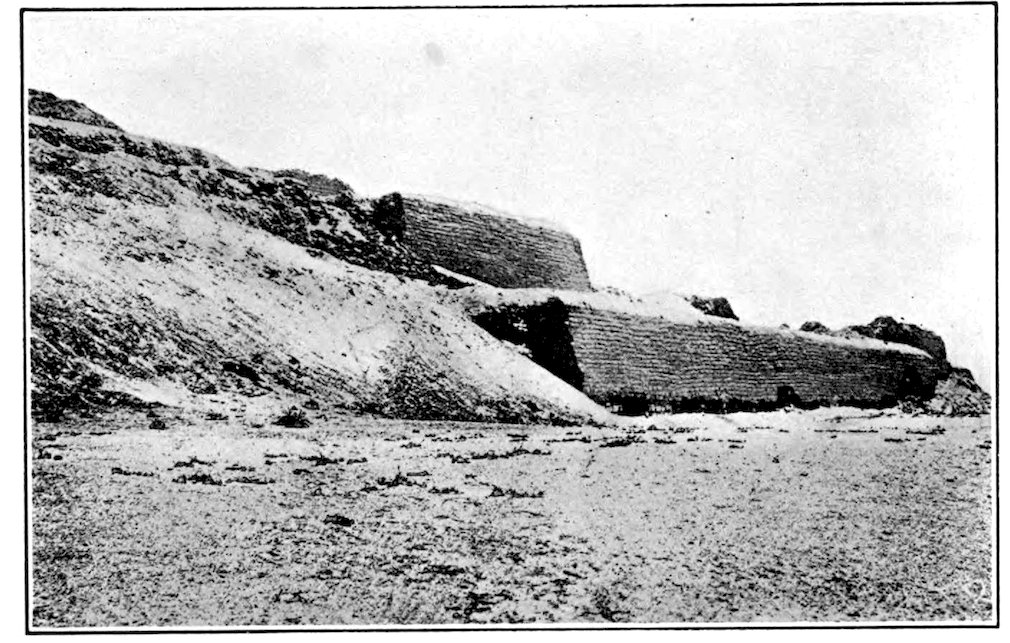

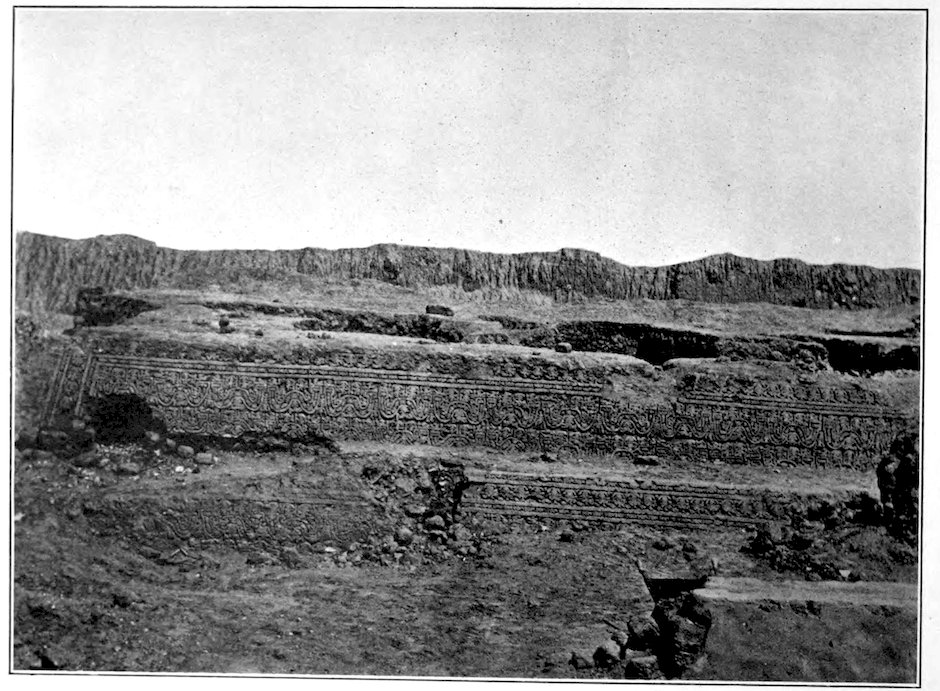

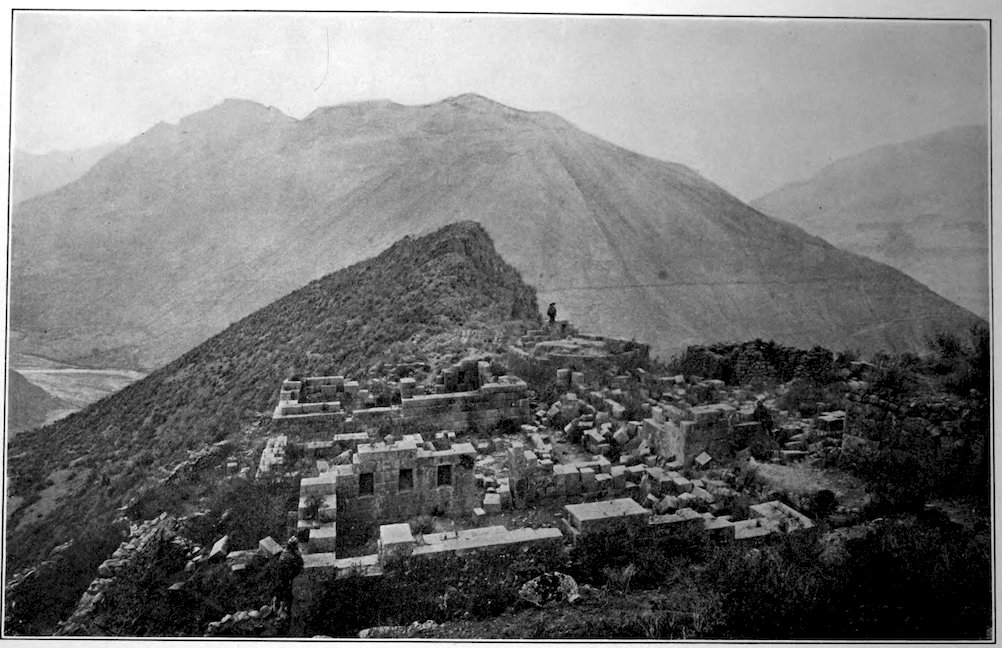

SOUTHWESTERN PART OF PACHACÁMAC. VIEWED FROM THE NORTH.

From whatever source Peru derived its earliest culture, everything indicates that at some period, probably at various times during the early ages, immigrants arrived in the country from Asiatic shores. The most eminent authorities, among them the Peruvian scholars Dr. Pablo Patron, Dr. Larrabure y Unanue, and others who have made a scientific study of the antiquity of their country, agree in the belief that there were several early immigrations to Peru from China and Japan. A few even accept the theory that the origin of the advanced races who first peopled the ancient world of the West is to be traced to a 19lost “Atlantis” and a submerged “Lemuria,” supposed to have been great continents in a past age, whose inhabitants, rivalling the ancient Egyptians in culture, lived in close communication with America, and gave it the basis of its earliest civilization. Conservative scholars are disposed to give little attention to purely speculative theories, and prefer to seek the solution of the problem by the most practical methods.

It is to the honor of Peru that the government, recognizing the importance of exploring its great treasure-store of antiquities in the interest of modern knowledge, is directing a systematic effort to penetrate the veil of mystery which envelopes the remote past of the country and its people. Dr. Max Uhle, an eminent authority on Peruvian archæology, is now occupied in the work of excavating and classifying Peruvian antiquities in accordance with modern scientific methods. The facts so far accumulated from reliable archæological data point to an antiquity of at least three thousand years, and may indicate a much more remote period of culture.

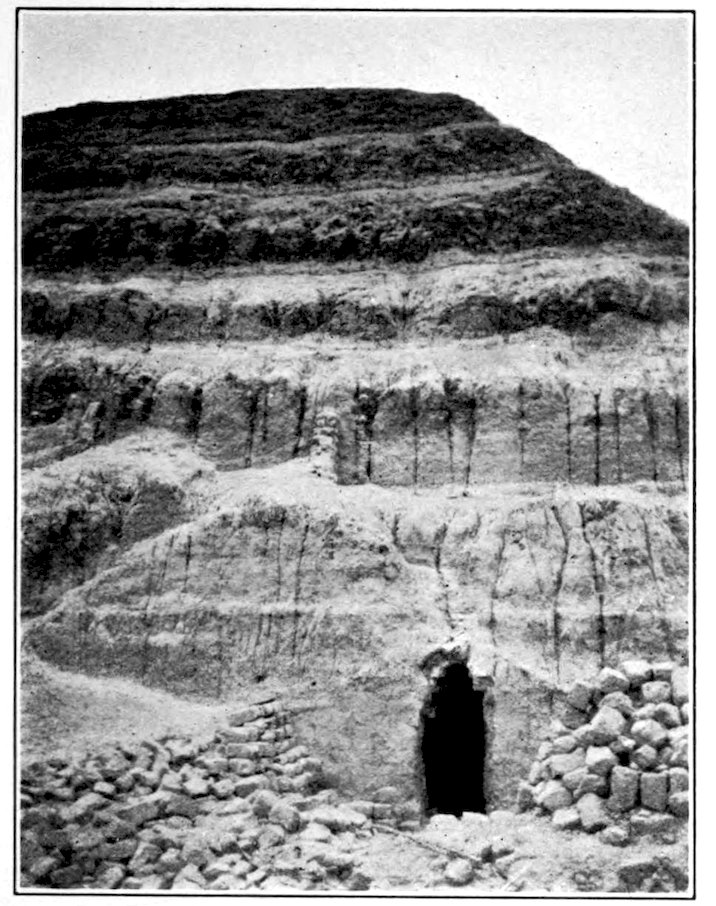

ENTRANCE TO THE PRINCIPAL PALACE OF PACHACÁMAC.

Long ages before the New World was discovered by Europeans, and centuries before the Incas established their wonderful empire, Peru was the home of a mighty race, or of successive races, whose dominion extended at some time over a great part of tropical America. The records of their advancement still exist in the stupendous 20ruins of their sacred temples and in the objects of art and evidences of culture found in their burial mounds.

Like the various nations of the Orient, these ancients of the New World had their ambitious struggles for supremacy one against another, their periods of great prosperity and power,—sometimes arriving at the height of despotic rule over all contemporaries,—and their time of decline before the ascendancy of a more potent rival. The record of changes wrought in successive periods, and of influences resulting from communication between the inhabitants of widely separated regions, is written in their monuments and in the huacas of their cemeteries, and furnishes the key to the chronology of prehistoric Peru, possibly to all American antiquity.

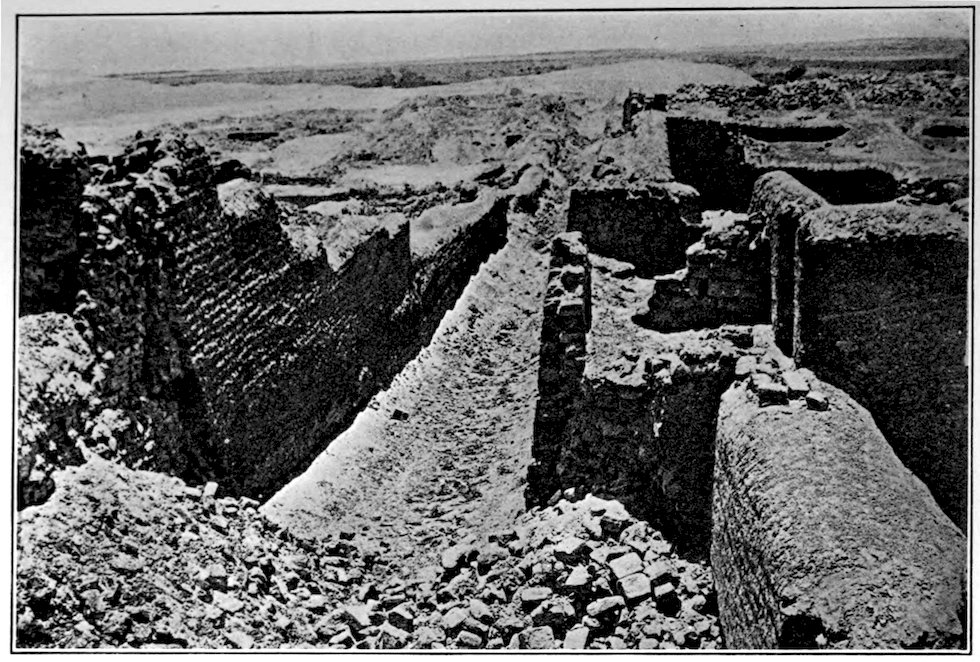

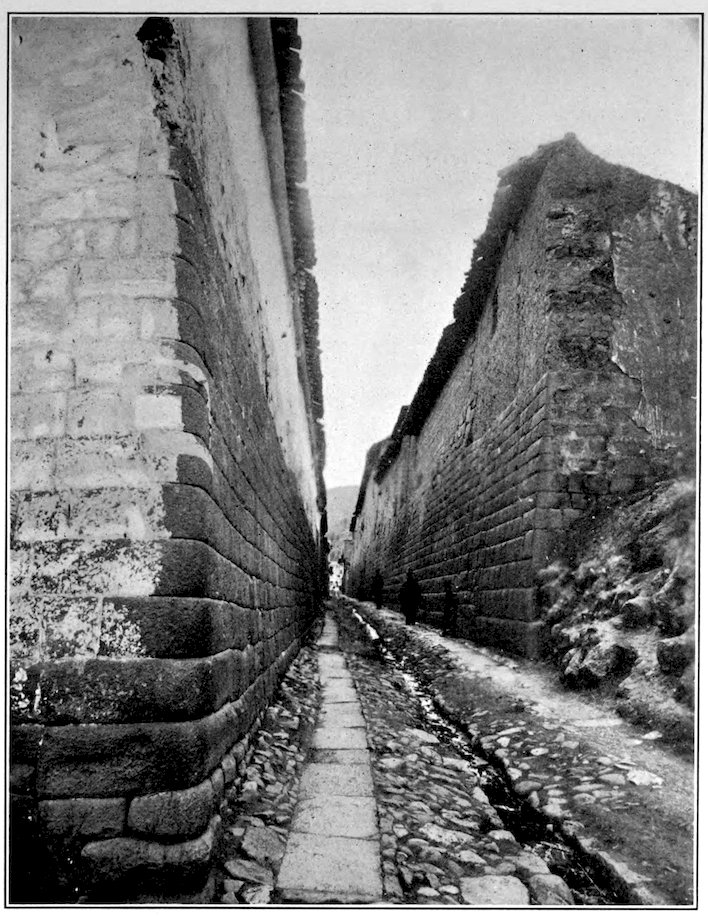

THE EASTERN STREET OF PACHACÁMAC.

Interesting ruins abound in every part of Peru, from the environs of the capital to the most remote districts of the frontier. Within a few hours’ ride of Lima are situated the ancient necropolis of Ancón and the temple of Pachacámac, where recent excavations have brought to light many interesting prehistoric relics. In no other land do the same conditions exist as in Peru, where the archæologist has advantages in the pursuit of his investigations which the countries of the ancient Egyptians, Babylonians, and Greeks do not afford. Here it is possible to study, at first hand, many of the customs that prevailed 21long before the advent of the Spaniards, as they are still practised in the sierra, where the same feast days have been observed from time immemorial, the same methods of spinning and weaving are followed to-day as in prehistoric ages, the picturesque and brilliantly colored costumes of their ancestors are yet in vogue among the indigenes, and even a few of the wonderful dyes, which excel in permanence those of the best European markets, are made to-day by these children of an ancient race, as they were by their forefathers in centuries past.

The most ancient civilization in Peru of which traces have been found up to the present time was developed in the coast region, around Nasca and Ica in the southern district and near Trujillo in the north; and the traveller whose interest in antiquities induces him to pay a visit to this country can see some of the most remarkable ruins on the American continent without the inconvenience of making a long and fatiguing overland journey, as the ocean steamers of the South Pacific call at ports in the immediate neighborhood of extensive ruins of prehistoric cities. Along the coast may also be seen shell mounds and other fragments of a primitive age, showing that in a very remote period the inhabitants subsisted almost entirely on sea food; though nothing has been found to indicate that these people were in any way related to the races that attained, at a later date, such a high degree of culture as that represented in the monuments, potteries, and particularly in the textiles, of Nasca, Pachacámac, and Trujillo. The textiles of ancient Peru are marvellous in quality, design, and coloring, and are the especial delight and admiration of the archæologist.

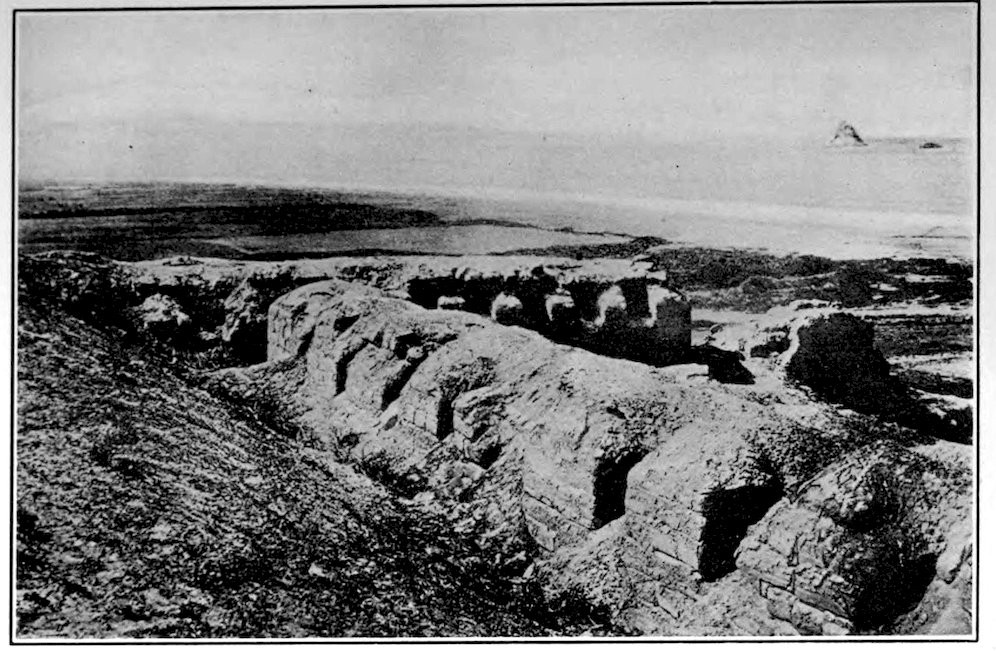

TERRACES OF THE SOUTHEAST FRONT OF PACHACÁMAC, WITH CEMETERY OF SACRIFICED WOMEN.

A VIEW OF THE SUN TEMPLE OF PACHACÁMAC, SHOWING NICHED WALLS.

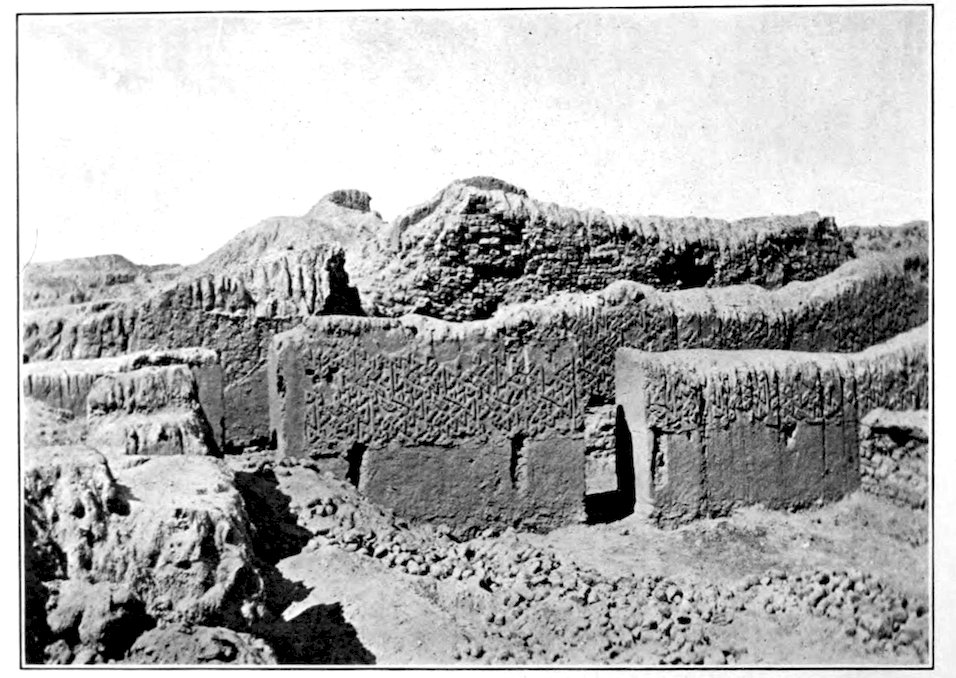

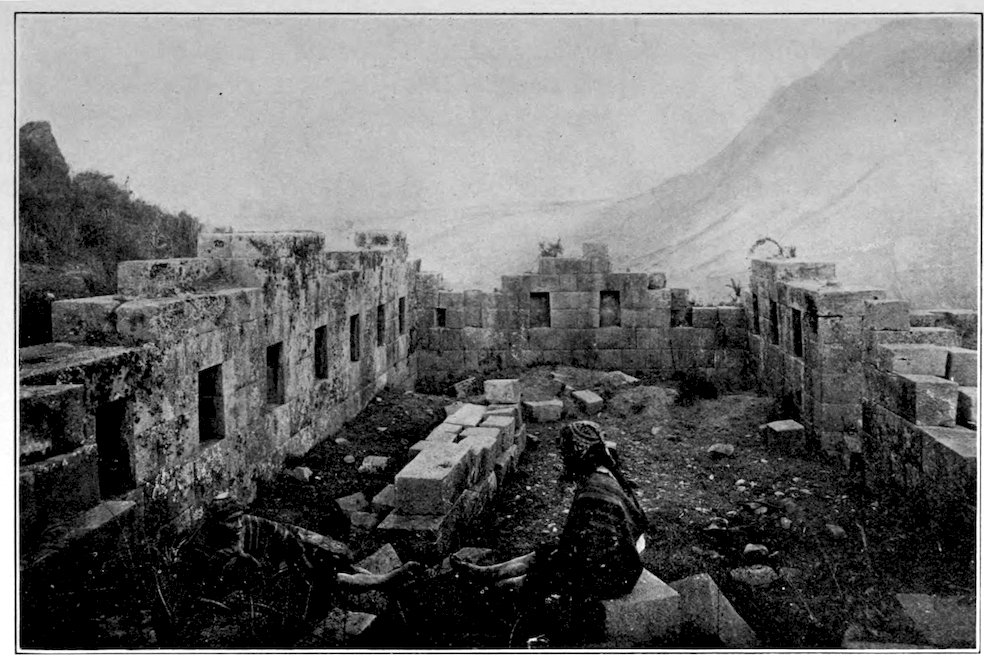

Pachacámac, situated about twenty-five miles south of Lima, in the valley of Lurin, overlooking the sea, is, in some respects, the most interesting prehistoric monument of Peru. Nearly all travellers who visit Lima spend a day among these crumbling walls and burial mounds. The first part of the journey to Pachacámac lies across the Rimac valley, which is itself famous in ancient legends as the site of a wonderful temple dedicated to the oracle “Rimac,” the name signifying “one who speaks.” The remains of this great edifice—once almost as celebrated for splendor and riches as that of Pachacámac—are still to be seen just outside of Lima. Between the valleys of Rimac and Lurin, a desert waste of sand extends, known as the Tablada de Lurin; it is a welcome relief when this part of the ride is over and the green meadows of Lurin appear in view, though even the desert has its unspeakable charm. Several hills rise two or three hundred feet above the level of the desert, and among these hills the ancient city of Pachacámac was located. The area within the outer walls that enclose the ruins measures nearly three miles in length by two in breadth, the chief interest being centred in the space occupied by the walls of the temple erected to the god Pachacámac. It was while excavating in these ruins a few years ago that Dr. Uhle made the discoveries which laid the foundation for a new classification of Peruvian antiquities, in accordance with the evidences of successive periods of culture. Previous to that time, all the objects taken from Peruvian cemeteries and placed on exhibition in the museums of Europe and North America, were arranged in a manner to give the impression that they represented various phases of one continuous period of culture. Carved monoliths, mummies, and vessels of gold, silver, and pottery, were disposed of with no more definite clue to their origin than was afforded by a statement of the locality from which they had been taken and the circumstances and date of their excavation. A scientific exploration of the ruins of Pachacámac has revealed the fact that its great temple outlasted several successive ages of culture, and that its other edifices were constructed at later periods, the Incas having built a Temple of the Sun and a convent for the Virgins of the Sun close to the ancient shrine of Pachacámac, whose name signifies 23“The Creator of the World.” The temple of the “Creator God” has undergone many changes. Excavations show that the original edifice was destroyed long centuries ago, whether by earthquake or in a mighty conflict with a rival people is not known, and that a cemetery at its base was buried in the débris. A larger temple was afterward erected on the same site, immediately over the earlier edifice, the terraces of the later structure covering the débris under which the older cemetery was located. The burial place of the larger temple, as well as that of the original building, was found to be filled with graves, the worshippers of Pachacámac having come to this shrine as the Mohammedans flocked to Mecca centuries later, feeling that they had gained the greatest of all blessings if they could but be buried within the sacred city. It is estimated that thirty thousand of the faithful were interred in the cemetery of Pachacámac. An examination of the huacas found in the various strata of these ruins shows the influence of five separate periods on the culture of this region, and has enabled the archæologist to determine the antiquity of Pachacámac relative to that of other ancient ruins, such as those of Tiahuanaco in Bolivia and the more recent edifices of Incaic origin. It is regarded as certain that the oldest temple of Pachacámac represents an earlier period than does Tiahuanaco, though the latter antedates by many centuries the monuments of Inca civilization. The art displayed in the shape and design of some of the vessels taken from the cemetery of Pachacámac bears a resemblance, in the earlier period, to that seen in the huacas of Tiahuanaco, and, in its latest expression, to the art of the Incaic civilization; this would seem to indicate that at least three successive cultures dominated the whole of ancient Peru, with long periods of transition intervening, when the country was divided and governed by numerous races of more or less advanced culture.

RUINS OF THE CONVENT, PACHACÁMAC.

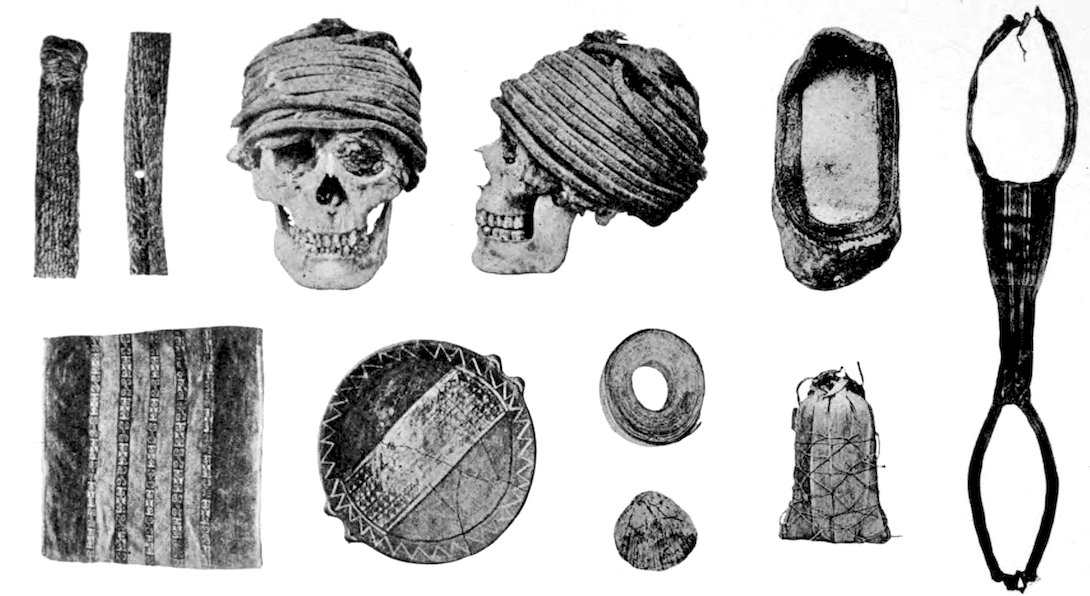

HUACAS FROM THE GRAVES OF PACHACÁMAC.

PRE-INCAIC POTTERY FROM PACHACÁMAC.

Why did the ancient Peruvians choose, as the site of one of their greatest temples, a strip of arid plain, when a vast region lay before them, presenting every variety of blessing which a bountiful Nature and beneficent Providence could bestow upon a favored land? This question is suggested not only as one contemplates the ruins of Pachacámac, but also in the presence of the temple and monoliths of Tiahuanaco. Was it that fear was the directing impulse, and a desire to propitiate an evil deity was stronger than the inspiration to adore a beneficent and beloved creator? In a land of snow-capped mountains, unfathomable cañons, and varied climate, where stupendous evidences of an omnipotent power were constantly present to impress the imagination of a primitive people, and the changes wrought by Nature were sometimes sudden and disastrous, as in the case of earthquakes and tidal waves, it is not strange that, as is seen in India, where similar conditions prevailed, the dawning intelligence of a primitive race was apparently dominated by fear rather than love in the exercise of its religion. An explanation of the choice of locality for the temple of Pachacámac is afforded by the following legend, the origin of which is said to be very ancient. The distinguished author of the archæological treatise Pachacámac relates the story: “In the beginning of the world there was no food for a man and a woman whom the god Pachacámac had created. The man starved, but the woman survived. One day, as she was searching among the thorn bushes for roots with which to stay her hunger, she lifted up her eyes to the sun and with tears and lamentation cried: ‘Beloved Creator of all things! Why hast thou brought me into the light of this world if I am to die of hunger and want? Oh, that thou hadst not created me out of nothing, or hadst suffered me to die immediately on entering the world, instead of leaving me alone in it without children to succeed me, poor, cast down, and sorrowful! Why, O Sun, having created us, why wilt thou let us perish? And if thou art the Giver of Light, why art thou so niggardly as to refuse me my nourishment? Thou hast no pity and heedst not the sorrow of those whom thou hast created only to their misery. Cause heaven to slay me 25with lightning or earth to swallow me, or give me food, for thou, Almighty One, hast made me!’ The sun, touched with pity, descended to her and bade her give up her fears and hope for comfort, for she would soon be delivered from the cause of her trouble. One day, while she was wearily searching for roots, she became impregnated with his rays and bore a son after four days. But Pachacámac, who was the son of the Sun, was angry with the woman for having worshipped his father and for having borne him a son in defiance of himself; he seized the newborn demigod and cut him to pieces. In order, however, that the woman should not suffer for lack of food, he sowed the dismembered parts of the boy, and the harvest was a bountiful one; from the teeth grew corn; from the ribs and bones sprang the yucca and other roots; from the flesh appeared vegetables and fruits. Since that time, men have known no more want, and they owe this abundance of food to Pachacámac. But the mother mourned for her child and appealed again to the Sun. Again the Sun was moved to pity and he commanded her to bring him the umbilical cord of the murdered child; into it he put life, and gave her another son, whom she called Wichama, who grew strong and powerful and, when a young man, set out to travel like his father, the Sun. But as soon as Wichama left his mother, Pachacámac slew her and caused the birds to devour her, all but the hair and bones, which he concealed near the shore. Then Pachacámac created men and women who were to take possession of the earth, and he set up Curacas and Caciques to rule over them. But when Wichama, returning, found that his mother had been slain, he was in a terrible rage, and commanded her bones to be brought to him; these he joined together and he brought her back to life. The two then planned revenge against Pachacámac, who, rather than struggle with his second brother, threw himself into the sea from the spot where his temple now stands. When Wichama saw his enemy escape from him, he was in a fury of rage and with the breath of his nostrils he set fire to the air and scorched the fields. He accused the inhabitants of having aided Pachacámac and besought his father to turn them to stone. His request was granted, but both the Sun and Wichama repented of this terrible deed, and caused the petrified Curacas and Caciques to be set up and worshipped, some on the shore and others in the sea, where they still stand as rocks and reefs.” The same authority interprets the story as a myth of 26the Seasons, describing the phenomena of nature, as annually repeated in the climate of the coast land. The description of climatic conditions shows, as the most characteristic feature, the annually repeated struggle of the vegetation of the valley, which depends entirely on artificial irrigation, against the scorching heat of the sun. The former is personified in the god Pachacámac. The Sun, with whom Pachacámac carries on his struggle, represents the solar year; the first solar son, whom Pachacámac kills, represents possibly the spring sun before the rising of the highland rivers, when the season of fruitfulness begins; the scattering of the teeth and bones of the murdered son produces the fertility of the soil. The woman who bears a son to the Sun god is the year; from a needy but toil-free life in the wilderness, Pachacámac leads her to a life of care and toil, such as cultivation of the fields requires; still grieving over the death of her first son, she is given Wichama, the autumn and winter Sun, with whom Pachacámac enters into a struggle. The woman grows old as does the year; Pachacámac kills her—as the year ends with the harvest. After the ingathering of the harvest and the autumnal decrease of the rivers, Pachacámac is unable to resume the struggle; his flight into the ocean to escape Wichama corresponds to the protecting cover of dense fogs which every winter overspread the parched fields. The Sun hero wreaks his vengeance on the fields of the fog region which even in winter are exposed to the arid sun.

CURIOUS SYMBOLS OF PACHACÁMAC WORSHIP.

FAÇADE OF THE PALACE OF CHAN-CHAN, NEAR TRUJILLO.

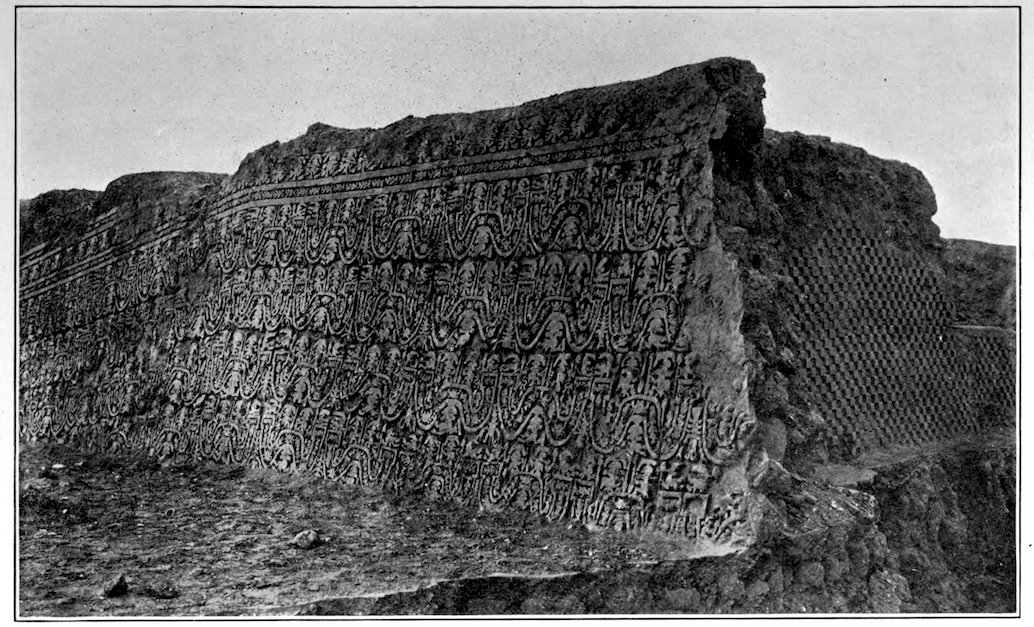

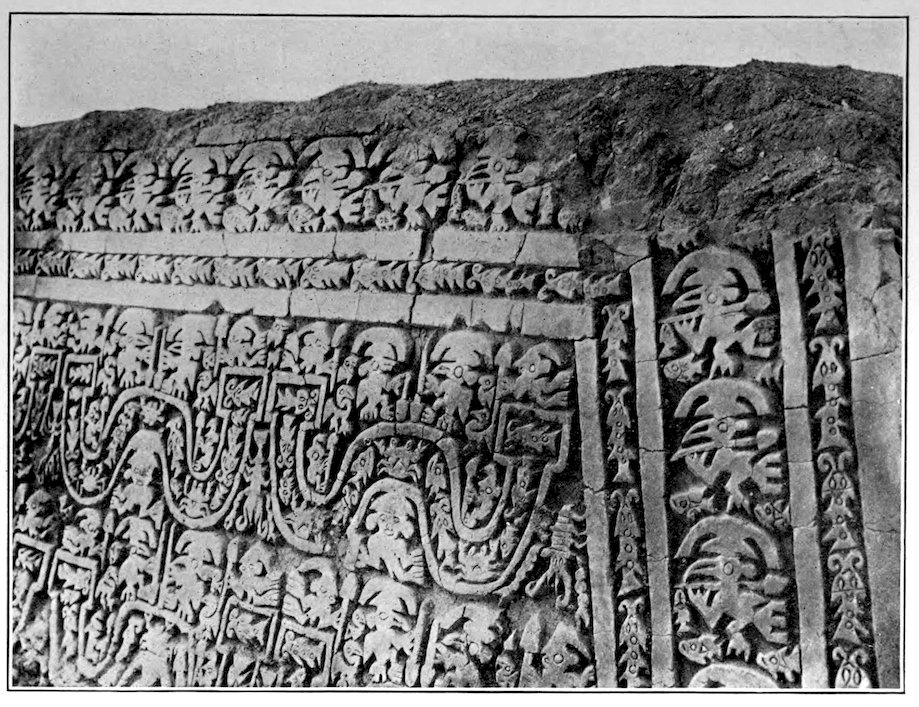

Mythical legends are related of three principal deities that were worshipped by the ancient Peruvians. Of these, an important place is given to the great god Con, who, according to tradition, was invisible, possessing “no bones, nerves, or extremities,” and who “travelled with the swiftness of spirits.” He levelled the sierras, filled up the cañons, and covered the earth with fruits and everything necessary for the sustenance of men and women, so that they might enjoy abundance. But, unappreciative of their blessings, the people of the coast gave themselves up to all manner of evil and forgot their benefactor. Con, indignant over their corruption, transformed them into black cats and other ill-favored animals, denied them the blessing of rain, and changed their happy and fruitful land into an arid desert. According to the same legend, Pachacámac, restored fertility to the earth and created a new race of men, the ancestors of the present Indians. Besides Con and Pachacámac, there was also the mighty Viracocha, the god of the deluge, who rose from the waters of Lake Titicaca, made the heavens and the earth, and, before creating the light of day, peopled the earth with its first inhabitants. These were afterward changed to stone because of their disobedience; but in order that the darkness should disappear and Peru be peopled, Viracocha appeared again—this time with followers—and created the sun and the stars and formed models of the future Peruvians; the images, representing men, women, and children, he distributed throughout the different provinces. He then sent his followers to 28the different regions to animate these models, which was done by the invocation, “Arise and people this earth, which is barren and solitary! Thus commands Viracocha, who is the creator of the world!” In response to these words the images became possessed of life and appeared on the mountains, in the valleys, beside the rivers, everywhere. A few beings, created to fulfil a special destiny, were animated by Viracocha himself, and as soon as they recognized their creator, they erected a temple of worship in his honor. The Spanish historian, Sebastian Lorente, who relates the legends of Con, Pachacámac, and Viracocha in his interesting and valuable work on Peru, impressed by the evident relation existing between the three great deities, infers that in ancient Peru there were three principal centres of population and culture,—the coast, the sierra, and the Titicaca plateau. These centres did not arrive at the height of their power contemporaneously, nor were they necessarily related to one another, though the influence of each one is seen, in some degree, in the development of all three. A distinct, and undoubtedly a very ancient, architecture prevails in the temples, palaces, and pyramids of the coast, unidentified either with that of the interior valleys or of the high plateau. The magnificent ruins of Chimu culture, as seen in the great walls of Chan-Chan, which measure from twenty to thirty feet in height, and show wonderful designs and stucco work on their surface, as well as the monuments of an earlier people, as seen at Huaca del Sol, near Moche, and the temple Pachacámac, are of a different character from the edifices of Huánuco Viejo in the sierra, of Sacsahuaman at Cuzco, and of the pillars and round tower (Pelasgian style) in Puno; while these latter ruins bear little relation in construction to the cyclopean edifices of Tiahuanaco, in Bolivia, the centre of what is sometimes called the Aymará culture.

CARVED TERRACES OF THE PALACE OF CHAN-CHAN.

ANIMAL CARVINGS ON THE WALLS OF CHAN-CHAN.

Aside from their scientific importance, the antiquities of Peru are interesting to travellers because they have many features that appeal to one’s imagination and love of mystery. They lie out of the beaten track of the sightseer, who journeys annually, guide-book in hand, to gaze on the ruins of their Egyptian and Pelasgian contemporaries in the Old World. But they possess the greater fascination of the unsolved problem, made doubly attractive by apparently innumerable “clues,” which stimulate the imagination and tempt one to construct independent theories as to their origin and antiquity. Karnak and the Pyramids may be no more ancient than Nasca; certainly the Sphinx is not nearly so great an enigma as are the huacas of Trujillo and Ancón cemeteries; and there is nothing in 30Oriental antiquities that quite resembles the mummies taken out of one of these mysterious burial mounds.

RUINS OF CHAN-CHAN.

The method of preparing the ancient Peruvian corpse for burial was unique, though it cannot be couriered artistic, as, at first sight, the huaca looks like a large sack well filled and bound around with a network of ropes. The process of unwrapping, which is a long one, reveals the corpse in a sitting posture, with the arms clasping the knees and the head bent over. Sometimes the swathings are of finely woven vicuña cloth, and ornaments of gold and silver are hung on the corpse, beautiful and costly vases and various other articles of value being placed beside it. From a study of these articles it has been possible to learn, to some extent, what the mode of life was among these ancient people, and many of the huacas have furnished data of the greatest importance. Fine textiles, woven in curious designs, are found in most of the cemeteries; but in those of greatest antiquity no textiles appear, and this fact affords a clue to their great age also, as buried textiles have been found to outlast periods of fifteen hundred years. The nitrous nature of the soil in which these burials have taken place accounts for the wonderful preservation of the mummies, which are really desiccated corpses. The burial of the poor was a simple ceremony and in some cases consisted merely in depositing the corpse in a grave in the sand; though, always, the treasures of the departed were placed beside them, and it is not unusual to find tools, household utensils, and articles of personal adornment scattered over the arid fields. The 31great plain of Chimu, near Trujillo, which covers a territory twelve miles long by six miles broad on the northern bank of the Moche River, and which was so rich in buried treasure when the Spaniards first began to plunder its temple, palaces, and burial ground, that the king’s fifth of the gold taken out amounted, in 1576, to ten thousand ounces, is literally strewn with human skulls, pieces of pottery, and other huacas. The cemetery of Ancón has apparently inexhaustible treasures, and excursion parties seldom return to Lima after a visit to its graves without bringing trophies of their outing in the form of prehistoric relics.

MORTUARY CLOTH WITH SYMBOLIC EMBLEMS.

The contemplation of the ancient ruins of Peru stirs the imagination and brings before the mental vision pictures of these people of a forgotten past, with many fanciful ideas of their appearance and their origin, of the lives they led, the religion they practised, and the predominating social features of their civilization. Were they “a white and bearded race” as some of the legends tell? Or did the natives emerge out of barbarism and advance in culture, at first, unaided by outside influences? Were the conditions in ancient Peru as favorable for the evolution of human culture as those of ancient India and Egypt? One would like to know, in reference to the ancient edifices, whose crumbling ruins are still wonderful after the lapse of ages, who built them, and what the elaborate picture writings on their walls mean to tell us. It is said that the pre-Incaic people used hieroglyphics, but that the knowledge of this art was lost or prohibited by the Incas. Their civilization also gives evidence, in the ornamented pottery, the carvings of intricate design, and the fine workmanship of their gold and silver vessels, that its art surpassed, in technique and imagination, the productions of later prehistoric periods. In the earliest ages two closely related civilizations existed in the coast region of Peru, one of them centred around Trujillo 32and the other in the vicinity of Nasca and Ica, and, fine as they were, there is nothing similar to them in later cultures. The southern form is especially notable for the perfection of shape and decoration of its pottery, the freedom and breadth of its style; while the northern form is more distinguished by the harmony and greatness of its development. Gold, silver, and copper abounded and were wrought into manifold shapes; gold was cast and chased, soldered with copper and silver, or used as plating over copper and inlaid with turquoises; mosaic was also known. This culture was followed by that of the Tiahuanaco, which in the course of centuries declined and was forgotten, until the appearance of the Incas, who became the heirs of all the cultures which had preceded theirs in Peru.

FOUND IN THE BURIAL PLACE OF PACHACÁMAC.

OLLANTAYTAMBO. ONCE THE FAVORITE RESIDENCE OF THE INCAS.

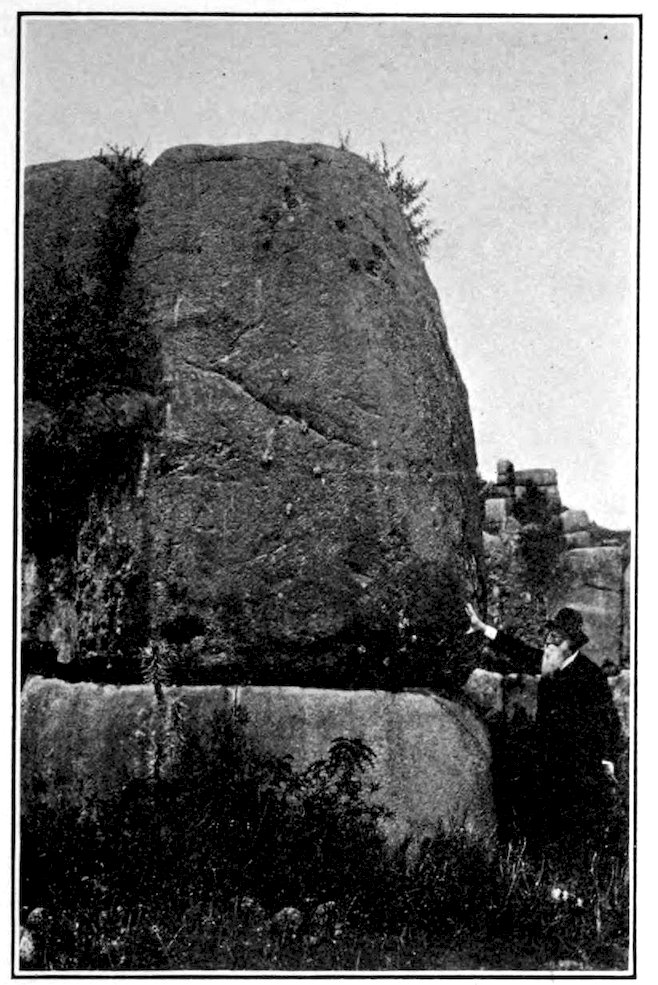

AN INCAIC DOORWAY.

Throughout the annals of history there is found no parallel to the extraordinary character and development of the great empire of the Incas, whose glory and splendor attained such supremacy and shone with such lustre, under a benign though despotic sovereignty, as to eclipse all earlier culture in pre-Columbian America. Whatever may have been the heritage which the Children of the Sun received from their predecessors, they carefully avoided giving it any importance in their records. The Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, who wrote the history of his people more than half a century after the Conquest, says that this rich and mighty monarchy was founded in the midst of barbarism and degradation and developed in all its magnificence through the divine direction of noble princes, who derived their power from heaven alone, and who were both the spiritual and the temporal rulers of the people, by right of their celestial origin.

A romantic charm envelopes the fame of the Incas and their brilliant court, their spectacular religion with its temples prodigally ornamented with gold and silver, and, above all, their own royal personality, so impressive in the dignity and sanctity of heaven-born greatness. One must even confess to resentment when meddlesome scholars seek to take away any of the prestige of these picturesque Conquerors of the Andes in favor of an earlier race, or of successive races, whose identity is lost in a mist of fable and legend, and 36who can present no such fascinating pageant to our imagination as do the heroes of Cuzco, with their mythical genealogy, the fame of their refined theocracy, and the prowess of their splendid legions. After all, it has not yet been proved that the lords of Cuzco were not of the same race and origin as the authors of the most ancient civilization of Peru, and, even, of all America. Scholars who have studied the language, customs, and monuments of the ancient Peruvians, find what is evidently a parent influence making itself felt through all the changing conditions of successive periods, and in spite of seemingly foreign and unrelated cultures that have appeared in various localities during the course of the ages. The two languages which are most generally spoken by the Indians throughout the territory formerly included in the Incas’ dominion—the Aymará and the Quichua—are apparently derived from a common stock. May it not be true that the people who spoke these languages, and to whom are credited the monuments of Tiahuanaco and Cuzco, were the heirs of a common ancestry, and that their progenitors were the authors of the earliest culture in Peru?

Out of the confusion of many legends that are related by the Indians to account for the origin of the Incas’ empire, the one which is best known, and most generally approved, because of the poetic beauty of the conception, tells us that the Sun, the creator of mankind, through compassion for the deplorable degradation of the world, sent two of his children, Manco-Ccapac and Mama Ocllo, to regenerate humanity and to teach the arts of civilized life. The celestial pair, who were not only brother and sister, but husband and wife, appeared first on an island in the midst of Lake Titicaca, and from this point they set forth on their benevolent mission. Lake Titicaca is supposed to have been chosen as the place of departure because, since it was the first to receive the rays of the sun when Viracocha dispersed the darkness, it was fitting that the first messengers of the light of civilization should also appear on its sacred island. They carried a rod of gold about two feet long and of the thickness of a man’s finger, having received from their father, the Sun, instructions to establish themselves in the place where the rod should sink into the earth at the first stroke. In the cerro of Huanacaure the golden rod was buried out of sight as soon as it struck the soil, and here was founded the great empire of the Incas,—“Inca” meaning “lord,”—which was to flourish and extend its dominion from the northern border of the present republic of Ecuador to the south of Chile and from the Pacific Ocean to the eastern valleys of the Andean chain, covering a territory of more than a million square miles, and giving protection to at least ten million faithful and industrious subjects, obedient to the Inca’s laws.

TERRACE OF THE INCA’S PALACE, OLLANTAYTAMBO.

According to a tradition, which Sebastian Lorente gives us, Manco-Ccapac was the son of a curaca, or chief, of Pacaritambo, in the Apurimac valley, a youth so beautiful that he was called “the son of the Sun.” He was left an orphan at an early age, and the fortune-tellers easily persuaded him that he was of celestial origin. At eighteen or twenty years of age the boy entered on his great mission. A humble orator, he erected an altar to Huanacaure, the principal idol of his forefathers, which the Incas never after failed to invoke in time of danger. With a few followers he established his dominion, attracting some by promises and forcing others by threats, while he fascinated the masses by his magnificent personality. He wore a tunic embroidered in silver, on his breast glistened a disk of gold, jewels adorned his arms, and gorgeous plumes formed his headdress. By various means he succeeded in gaining command over his compatriots, who served his ambition and obeyed his laws. There is something reasonable and matter-of-fact about this tradition which inclines one to think that it may have foundation in truth. It is seen that Manco-Ccapac worshipped the principal idol of his forefathers, which shows that his plan was to incorporate in the new religion the most venerated beliefs of the people, and not to antagonize them by an iconoclastic policy; he set up his government in Cuzco, where the inhabitants were by nature docile and easily disciplined; he appeared at the psychological moment when Peru was ready for a new cult and a new system of laws; and, also, he was dowered with extraordinary gifts, looked like a king, and was thoroughly acquainted with the character of his people. There can be no doubt that Manco-Ccapac was a native of the country, whether he came originally from the Titicaca plateau and was of Aymará descent, as some authorities claim, or had his birthplace in the valley of the Apurimac and spoke the language of the Quichuas, the people “of the green valleys” as the word 38Quichua signifies. It is said that the Incas themselves spoke neither Aymará nor Quichua, but a language unknown to the people and not allowed to be spoken by anyone but royalty.

WALL OF THE PALACE OF ONE OF THE INCAS, CUZCO.

The dynasty founded by Manco-Ccapac at Cuzco is generally believed to have dated from the twelfth century. All the genealogies furnished by historians are more or less incomplete, limiting to thirteen or fourteen, at most, the number of monarchs who reigned during that long period of four hundred years. The list of Incas given by Garcilaso de la Vega, and regarded as the most reliable, contains the names of thirteen Princes of the Sun. Most of the authorities of importance name Manco-Ccapac as the founder of the Empire of the Incas, with Mama Ocllo as Coya, or Empress; though opinion is greatly divided as to their origin and the date of their imperial accession. One well-known historian of the Conquest, Montesinos, places the period of the first appearance of this royal line in the sixth century after the Deluge. It is related that, during that remote age, there arrived in Cuzco a family of four couples who civilized this region. The eldest of the four brothers, having gained possession of the territory, divided it into four portions, or suyos, from which it took the name of Tahuantinsuyo, “the kingdom of the four regions.” The territory to the south was called Collasuyo, to the west Cuntisuyo, to the north Chinchasuyo, and to the east Antisuyo. The youngest brother afterward secured command of the kingdom and became the first of a line of princes who governed Peru up to the time of the Spanish Conquest. The most interesting feature of this tradition is the division of the rule of these monarchs into three great dynasties, of which the first was that of the Pirhuas (from pyru, meaning 39“fire,” apparently indicating that they were fire-worshippers), the second, that of the Amauttas, or wise men, and the third the Inca dynasty. The first of the Pirhuas founded the city of Cuzco in the name of Viracocha, “the Supreme Being,” and one of his successors built a great temple in Cuzco (perhaps Sacsahuaman, which is believed to antedate the Inca period), while another ruler of the same royal line is credited with having reformed the calendar, built public roads and established severe rules in religion. One of these kings, the record says, “died while repressing an invasion of depraved people from the plains.” The Amauttas made many wise laws, reformed the calendar and the religion of Viracocha, organized the military forces of the kingdom and repelled the Chimus of the plains. During the reign of the last of the Amauttas, we are told, “was fulfilled the fourth sun of the Amauttas, and there took place a great invasion of ferocious tribes who attacked the kingdom in different parts, obliging the sovereigns of Cuzco to flee to the grottos of Tamputoko for four hundred years, during which they lost their literature and a great part of the Amautta culture; the advent of the Incaic dynasty restored the power of the royal line, and made Cuzco again the centre of a great and beneficent civilization.” In the light of modern research, which is continually causing a revision of former ideas regarding the origin and antiquity of the Peruvian empire, the story of the three dynasties appears to be more than “the mere fable” which it has been designated by some modern writers on the subject. It particularly appeals to one as a solution of the problem of the Incas’ origin, since every feature of Incaic civilization proves it to be of native character, even though the predecessors of the “third dynasty” may have arrived from foreign shores.

RUINS OF THE PALACE OF MANCO-CCAPAC, CUZCO.

40Manco-Ccapac, or, as his name would be written in English, Manco the Great, occupies a position in among the heroes of the world’s history not inferior to the exalted pedestal on which we have placed the founders of empires in the Old World. He possessed the same rare gifts of bold judgment and fearless initiative which belonged to Alexander the Great, to Charlemagne, and to other sovereigns who have been “Great” because they have known both the strength and the weakness of their people, and by conciliating the one and dominating the other, have made themselves masters and leaders of mankind. Had Manco-Ccapac not thoroughly understood the conditions existing at the time when he entered on his mission, and had he not possessed judgment, tact, and the dominant qualities of leadership to enable him to win a host of followers, even his upright character and his humanitarian purpose would not have proved sufficient to ensure the wonderful success which he achieved in founding an empire more extensive than ancient Rome, and as rich as the fabled monarchies of the Orient. Throughout the Inca’s realm the principles of honesty, industry, and justice were inculcated in every subject from his cradle, the moral duties of a good Peruvian being embodied in the Quichua motto of the nation: Ama sua, Ama aqquella, Ama llula, which translated literally means, “Not a thief, Not idle, Not a cheat.” It is a form of salutation among the Indians of Cuzco to this day, the response being Ccampas Ginallattac! “The same to you!”

The record of historical events, as they occurred throughout the long reign of the Inca dynasty, was preserved only by a system of quipus, or knotted cords, the art of writing being unknown to the Incas, or, according to some authorities, prohibited by law. Only the Quipucamayos, the authorized guardians of the quipus, were able to decipher them. This career was considered one of great honor, and instruction therein was given in all the provinces, under the direction of the Amauttas, the Savants of the empire. The chief archives of the state were preserved in Cuzco, where an immense collection of quipus was found by the invading Spaniards, who destroyed the greater part of them, without having them interpreted. As a consequence, the information secured by the historians of the Conquest and by writers of later date, relative to the genealogy and history of the Incas is necessarily incomplete and, no doubt, inaccurate; though the descriptions of the appearance, laws, customs, and national development of the people of Tahuantinsuyo may be considered as generally faithful and reliable.

According to the genealogy given by Garcilaso de la Vega, the first Inca, Manco-Ccapac, was succeeded by Sinchi Rocca, a peaceful and prudent ruler, who is said to have taken the first census of his kingdom, and is credited by some authorities with having made the division of the empire into the four regions previously named; though, according to Cieza de Leon, one of the most reliable authors, these names were applied to four great highways which extended from Cuzco to the extreme limits of the empire, northward, eastward, southward, and westward. In any case, the Incas built broad and level roads, from six to 41eight feet wide, and in the mountain regions, where they skirted the steep slopes of the Andean range, they were prevented from wearing away by the construction of stone embankments; on the plains, the highway was indicated, as in many countries at the present day, by guide posts at intervals along its course. Also, tambos, or inns, were built at the distance of a day’s journey apart, and here the traveller could always find shelter for the night. The third Inca, Lloque Yupanqui, conquered the Canas, a powerful people of Ayaviri and Pucará, after a struggle which depopulated their settlements, and forced the emperor to introduce mitimaes, or colonists, to replace them. He also subjugated the Collas of the present department of Puno.

NICHE IN THE FAÇADE OF THE PALACE OF MANCO-CCAPAC.

It was during the reign of the fourth Inca, Maita-Ccapac, that the power and genius of the imperial monarchs began to extend its influence as never before, and greater pomp and magnificence than had previously been known attended the coronation and other ceremonials honored by the sacred and royal presence of the Inca.

Following the course of training required of every heir to the Inca throne, Maita-Ccapac had, when a youth, passed through the Huaracu, a ceremonial of the greatest importance, and one in which all the young Inca nobles of his own age—the title of Inca being borne by every descendant of Manco-Ccapac through the male line—participated, after having been trained in the same military exercises as the royal prince. A description of the Huaracu is interesting as showing that these people had an institution not unlike that of mediæval chivalry in Europe: From his earliest years, the hereditary prince was given into the care of the Amauttas, to be taught science and religion, especially the latter, as the Inca was the highest spiritual authority on earth; great attention was also paid to the military training, as it was desirable that, not only in wisdom but in military skill, the prince 42should excel all contemporaries. At sixteen years of age, the young heir, Maita-Ccapac, and his companions, following the sacred custom of their race, were submitted to a public test, supervised and directed by elderly and distinguished Inca nobles, which included trials of ability in athletics such as wrestling, jumping, running, besides sham battles, which were held as a trial of valor, and were so severe that many of the youths were wounded and a few killed. The royal prince had not shown the least fear nor evidence of fatigue, though put to the very limit of endurance; “for,” he said, “if I am afraid of the shadow of a combat, how shall I be able to meet the enemy in real warfare?” These exercises lasted for thirty days, during which the prince slept on the ground, went barefooted and dressed simply, thus showing his sympathy with the poorest of his future subjects. The tests concluded, the order of knighthood was conferred by the Inca emperor, father of Maita-Ccapac, all the young nobles who had taken part in the exercises kneeling with the royal heir, one after another, while the emperor pierced their ears with the yauri, a kind of gold needle made for the purpose, which remained in the ears until the hole was large enough to permit the insertion of the earrings peculiar to the Incas; these were not hung from the ears but were placed in the pierced opening, and replaced from time to time by rings of larger circumference, until, as in the case of Maita-Ccapac, the cartilage of the lobe was so stretched that it touched the shoulder. After this ceremony the greatest of the Inca nobles placed on the feet of the royal heir the sandals of his particular order; a scarf of similar significance to the toga virilis of the Romans was wound around his waist, and his head was adorned with a wreath of flowers,—to indicate that clemency and goodness should adorn the character of the valiant warrior,—while evergreen, intertwined with the flowers, symbolized the eternal endurance of such virtues. A fillet of finest vicuña wool was bound around his head, and a yellow masca paicha, a kind of fringe, also woven of vicuña wool, was added to this headdress, falling over the brows. The yellow masca paicha was the peculiar insignia of the heir-apparent. As soon as this ceremony was concluded, all the Inca nobles knelt before the prince and rendered him homage as their sovereign. From this time, he was entitled to take his seat among the advisers of his father, so that he might be initiated into the art of governing and become familiar with politics and administration. Being recognized as of age, and the heir to the throne, he was given command of his father’s armies and was entitled to display the royal standard of the rainbow in his military campaigns.

The coronation of Maita-Ccapac was the occasion of grand pageants, continued fiestas, and a brilliant display of royal magnificence. We are told that he “was crowned with a blue masca paicha and wore a tunic of white and green, dotted with crimson butterflies.” His royal robe was made of finest vicuña wool and was ornamented with gold and precious stones. The headdress of all Inca emperors was particularly distinguished by two feathers which were placed upright in the front of the encircling llautu, or fillet; these feathers were plucked from the wing of the sacred bird Cori-quenca, a species of gull, black and white in color, one feather being taken from the right wing of the male and the other from the left 43wing of the female, to adorn the royal crown. These birds may still be seen in the vicinity of Lake Vilcanota, near Cuzco.

INCA FOUNTAIN AT CUZCO.

An invincible warrior, Maita-Ccapac extended the power of the empire to the remote borders of Collasuyo (now Bolivia) and beyond the Apurimac to Arequipa and Moquegua. His name is connected with one of the most notable works achieved in the history of the mediæval world, as he is said to have been the author of the method and plans used, by his command, in the construction of the first suspension bridge ever built. Over this bridge, which was swung across the Apurimac River, he passed with an army of twelve thousand men, making an easy conquest of the enemy, who were struck with awe in the presence of such a wonderful feat. A second bridge, built by one of the successors of Maita-Ccapac, is still to be seen near the site of the original construction. Many of the andenes, of which traces are to be observed to-day in various parts of the country, were also constructed during the reign of Maita-Ccapac, though the origin of these terraced farms on the mountain side is placed by some authorities back in pre-Incaic times. The andenes were so named from Anti, a province east of Cuzco, and were formed by building stone walls on the mountain sides, at short distances one above the other from the base to the summit, and filling the enclosed space with fertile soil, some of it being mixed with guano from the Chincha Islands, as the Incas knew the fertilizing value of this deposit and made general use of it in their agriculture. A tradition of the time of the fourth Inca relates that the loyal subjects in one of the provinces built a grand palace of copper in which to entertain Maita-Ccapac and his Coya when they visited that part of the kingdom; and, though this story is 44no doubt a fable, yet it is certain that mining made great progress during this reign. It is marvellous that, with only the primitive means at their command, without iron, powder, or machinery, these people extracted gold both from quartz and placer mines, and obtained silver, tin, and copper as well. The metal was smelted in small furnaces and then emptied into moulds; the beautiful ornaments which were made for the adornment of the temples and palaces and for the Inca’s wear, afford a proof of the remarkable ingenuity of these primitive artifices. The successor of Maita-Ccapac, Inca-Ccapac Yupanqui, “the Avaricious,” did not achieve great fame, though he spent the greater part of his reign in subduing turbulent subjects in various parts of the kingdom. He was a miser, and ordered that all who died should be interred with their gold and jewels, his object being to secure this treasure later for the royal coffers.

RUINS AT OLLANTAYTAMBO.

Inca Rocca, the sixth monarch of the royal house of Cuzco, was one of its greatest warriors and most renowned statesmen. The fame of his conquests spread to the most remote regions, and the wisdom of his administration was no less widely known and admired. Everywhere great palaces were reared to display the grandeur of his imperial house, and it was decreed that, at his death, all the vast treasures collected for their adornment should be used to ornament his tomb and for the service of his family; his successors followed his 45example, and the brilliancy of the Inca’s court increased with each subsequent reign. He founded schools for the education of the nobility under the direction of the Amauttas, though the children of the common people were not admitted, because, according to his view, it was enough for them to learn the trade of their fathers. He was, however, very solicitous for the welfare and protection of all his subjects, and made strict laws that punished with death homicides, incendiaries, and thieves.

STONE WALLS OF THE PALACE OF OLLANTA, OLLANTAYTAMBO.