Title: Dreamikins

Author: Amy Le Feuvre

Release date: January 7, 2025 [eBook #75057]

Language: English

Original publication: London: The R. T. S. Office, 1918

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/75057

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

ANNETTE FOUND DREAMIKINS FAST ASLEEP IN A WHEELBARROW

BY

AMY LE FEUVRE

AUTHOR OF

"A LITTLE LISTENER," "JILL'S RED BAG,"

"ROBIN'S HERITAGE," ETC.

FANCY and Truth go hand in hand.

How can a "Grown-up" understand!

A Giant faith in a tiny soul;

And a love of fun make up the whole.

LONDON: THE R.T.S. OFFICE

4 BOUVERIE STREET, E.C.4

MADE IN GREAT BRITAIN

TO

MY LITTLE NIECE AND GODCHILD

VYVIAN

CONTENTS

CHAP.

VII. FREDA AND DAFFY IN TROUBLE

DREAMIKINS

The Little Door

FREDA and Daffy stood on the edge of a Great Discovery.

Have you ever done it? Then you will know how they felt; how their small hearts were thumping loudly; how to the tips of their toes and fingers they were trembling with that wonderful joyful excitement of the unknown in front of them.

They were just two small girls, very slim, with long legs and short frocks—holland frocks—smocked across their chests, and they wore limp sunburnt straw hats which kept the sun out of their eyes, for it was a very hot day in June.

Freda was the elder of the two; she had red-golden hair, which was plaited in a long pigtail, and a freckled face, blue eyes, and a delicate little mouth and nose, with a very round determined chin. She was always intensely earnest in everything that she did; untiring in schemes that would unite pleasure with usefulness—as, when she locked Purling, the old butler, into his pantry, and left him there for an hour, she told Daffy it would be so good for him to be obliged to sit still and rest, for he had told her how his legs ached going up and down stairs; and when Nurse had asked her how she could take pleasure in being so naughty, she retorted:

"If it rests Purling and pleases me, those are two good things, not naughty, that I've done!"

Daffy was very fair and fragile-looking. She had a way of dancing along on the tips of her toes, and darting here and there like a bright dragon-fly, and seemed to grown-up people as if she tried just to keep out of their reach. She had a little pale face and soft flaxen hair. Her eyes were brown, with heavy fringed lashes. She was rarely unhappy, and treated most things that happened to her in a very calm unruffled way. Freda was hot-tempered, but nothing upset Daffy's sweetness of outlook. She was always ready to follow Freda's lead.

The children had only just come to live in their father's big country house, which had been let for some years, and they could not remember staying in it before, as they were quite tiny children when they had done so. Their home was in London. Their father had been a busy politician, but now had volunteered for the War, and had gone out to Egypt in the Yeomanry. Their mother loved town and was always busy, either entertaining company in her own house or enjoying it elsewhere. The children saw very little of her.

They had all had whooping-cough, and though now quite well, the doctor advised their mother to send them into the country for the summer; and as the Hall was empty, the tenant having gone to the War, Mrs. Harrington sent them there in charge of their old nurse.

Freda and Daffy were delighted with their country home, but a lot of things about it puzzled them.

It was now about three o'clock in the afternoon. They had explored every corner in the big gardens surrounding the house. A short time before, they had wandered along a straight path in a belt of fir-wood, which had led them, after a long walk, up to a brick wall and a closed door. The door had evidently not been opened for years; ivy had grown over it. Of course they immediately wanted to know what was on the other side. The keyhole was filled with rust and dirt. With the help of a small pocket-knife Freda cleared it out, then she applied one of her blue eyes to it and uttered a low cry of ecstasy.

"Oh, Daffy, it's a garden—a lovely one! Oh, such roses! Such flowers!"

"Let me look."

But Daffy had to wait for some minutes before she had her turn at the keyhole.

"I see a white rabbit on the grass," she said. "Oh, Freda, it's an enchanted garden! Does it belong to us?"

"It ought to," said Freda, looking at the door with sadness. "This is our door, Daffy. It has no business to be locked away from us."

"But it's a long way from the house."

"That doesn't matter a bit. The lodge gate is miles away, but it belongs—"

"Shall we climb over the wall?"

Both children looked up at the old wall above them—a wall that was fully ten feet high.

"No; but we can follow the wall along till we come to another door. There must be one for people to get in and out. Come on!"

Through the fir plantation they went, keeping as close to the wall as they could, though there was a mass of briers and undergrowth for some distance along that prevented them touching it. Eventually they squeezed through some wire railings and got out into the open park. Here a grass-grown ditch was the only obstacle between them and the wall.

"What a big garden it must be inside!" sighed Daffy.

And then it was that Freda came upon the Great Discovery, and she gave a little scream as she did so. It was a little green-painted wooden door only about three feet high. It was on the other side of the ditch. In a moment both children were over the ditch trying to turn the handle, and, to their joy and delight, it turned. There was no lock or bolt, and after a little tugging and pushing they got it open.

"It's like the door in 'Alice in Wonderland!'" gasped Freda. "Oh, look, Daffy, look! There's somebody there!"

They were kneeling down now with beating hearts. Both heads were close together, and eyes taking in all that there was to be seen. A garden indeed, with a cool green lawn, and rose-covered arches, and flowers of every colour crowding each other out of the beds. In the distance, a low, grey house with striped green-and-white sun-blinds, and under a shady tree on the lawn a man in a low hammock chair. He was smoking. He had cushions under his head, and his feet were resting on a long stool; but he had an easel in front of him, and he was either painting or drawing.

"Daffy, let's crawl through! We must! We'll go and ask him who he is."

To speak was to act with Freda. She crammed her battered hat down on her head and crawled through the little door, Daffy following her. Then they stood up and advanced along the gravel path.

"This is an adventure!" whispered Daffy.

But Freda, with eager shining eyes, sped along without a word. The man was too engrossed with his occupation to look up, and it was only when Freda spoke that he turned wondering eyes upon them.

"Did you leave the door open on purpose? Did you expect us to find it one day? And will you tell us why it is so little? Is it for the fairies?"

The man had kind eyes; they saw that at once. He was no ogre or gloomy hermit. But he looked ill, and they saw that crutches were by his side.

"Ah," he said, "that's my secret, But I didn't have it made for you."

"Why is the gate locked, the proper gate belonging to us?" asked Freda.

Daffy had quietly glided round to the back of his chair.

"Oh!" she said, in her soft little voice. "What a darling little fairy girl! She's swinging from an apple-tree bough, Freda. Come and see!"

Freda stepped up closer.

"So she is! Who is she?"

"She's my Dreamikins."

"Is she a real little girl, or just a paper one?"

"She's as real as they're made. What a pity she wasn't here to see you crawling through that little door?"

"Did you see us?"

"Yes, but I pretended not to, so that I shouldn't scare you away."

"Oh, we were much too excited to go back, much!"

"Much!" echoed Daffy from behind. "We never do go back when we're finding out things."

"May we sit down and talk to you?" asked Freda; but she dropped down on the grass as she spoke. "We're simply dying to talk to somebody sensible. I s'pose you know we live the other side of your wall."

The man nodded.

"I guess that. Now we'll play the game properly. You must tell me about yourselves and I'll tell you about ourselves. Who will begin?"

"You," cried both the little girls at once.

So he began:

"My name is Fibo. That is what Dreamikins calls me, and if we're going to be friends you can call me so too."

"But you weren't christened Fibo?" said Freda.

"I was christened Augustus Arnold. Do you like that better?"

"Why does she call you Fibo?" inquired Daffy.

She had been dancing up and down lightly on her toes; now she stood still, and regarded the strange man gravely.

"Dreamikins and I have a way of naming our friends as we like; and I was Mephibosheth to her—'lame on both feet,' but we shortened it to Fibo."

Daffy's eyes were full of pity.

"Tell us more," demanded Freda.

He waved his hand behind him.

"There's my house, and it's run by Mr. and Mrs. Daw and their daughter Carrie. And Drab the cat, and Grinder the dog, and Whiskers the white rabbit are my family; and I came here ten years ago."

"But Dreamikins—isn't she your family?" asked Freda.

He shook his head.

"She has a father and mother, and a home at Brighton and another in Scotland, and this is her other home, and the one she likes best. Dreamikins' mother is my sister. Now you know all about me."

"And we'll tell you about ourselves," said Freda eagerly. "We come from London, but we don't like it very well, because Dad is in Egypt, and Mums is doing all kinds of things in London that she never used to do before the War. And we got the whooping-cough, and Mums thinks we are too pale, so we've come down here to run wild, she says; but of course Nurse stops us doing that."

"Did you ever have a nurse?" demanded Daffy suddenly.

"Didn't I! What an old dear she was too!"

"Fancy having a nurse you could call an old dear!"

Freda looked quite shocked.

"Our nurse is the most important person in the whole world. If the King and Queen were to tell her they wanted to see us, she would say:

"'Not to-day, Your Majesty. When I see fit I will let you know.'"

Daffy gave a little chuckle.

"That's Nurse's favourite saying, 'When I see fit!' She's much more proud than kings and queens are."

"Yes," Freda went on; "so, you see, Nurse has brought us down here, and Purling, and Cook, and a few of the others have come too. Mr. Fibo, what is a 'purse-proud rich'?"

"A rich person who is proud of the money in his purse."

Freda nodded.

"Of course! That ridic'lous, disgusting boy who rides the butcher's horse had an argyment with me yesterday. I was sitting on the park wall when he came by, and my legs was—were on the road side, you know. He said we were that. Why, Daffy and me have never been rich in our lives! Why, I've only sevenpence and a farthing in my purse now; and how much have you, Daffy?"

"Fourpence halfpenny," said Daffy promptly; "and a penny belongs to the missionary box—I mean it has to go there."

"Why, Mr. Fibo, he said something about our big house; but it isn't our house at all! Daffy and me live in just a bit of it. The front stairs aren't ours even! Purling says we're not to go near them. We can't slide down the banisters or tobogg on a tea-tray down the stairs. You see, it's like this. Dad and Mums are to have all the big rooms downstairs when they come, and till then they're locked up. The bedrooms along the big passage belong to the housemaids. They say they won't have us messing up their rooms. Old Purling lives in the pantry—that's his part of the house; Mrs. Stilton has all the kitchen part of the house, and her dear little sitting-room, which she keeps us out of. And Daffy and me—we just have our day-nursery and our night-nursery, and the back stairs to go up and down. We're quite poor, you see. Only two rooms to live in, and those really belong to Nurse, she says. We haven't a single bit of room our very own."

"Except the corner," said Daffy, with twinkling eyes, "and the punishment chair."

"Have you ever sat in a chair," questioned Freda, turning her eager little face towards Fibo, "which is so small in the seat and high in the legs that you can't bend your back a tiny inch or you'll fall off?"

Fibo threw back his head and laughed aloud.

"We had one in our nursery when I was a boy. It was an heirloom then. I didn't think one was in existence now."

"Nurse found it in the nursery here. She sucked her lips when she saw it. She always sucks her lips when she's pleased. And we have to sit on it for half an hour when we're punished."

"I see that you are very unhappy children," said Fibo gravely; but his eyes were smiling in spite of his grave face.

Daffy pirouetted on her toes.

"We love it here," she said, "because we can be out of doors all day finding adventures."

"Like you," put in Freda—"you and this garden and the little door."

"Please let us see your pictures," said Daffy, stealing a little nearer to the invalid's chair.

He put down his hand and took up a portfolio from the grass.

"I'll show you what I have. They're going into a book very soon."

"Do you make books?"

"No, only the pictures in them."

They hung over his chair in rapt enjoyment of all he showed them. There were fairies dancing and playing hide-and-seek amongst beautiful flowers, lying asleep under ferns and toadstools, climbing along a rainbow to get the pot of gold at the other end, and tickling children's cheeks with their tiny fingers as they lay asleep in their cots. There were dogs and cats, all going through wonderful adventures; and in nearly every picture there was a reproduction of Dreamikins. Daffy eagerly looked out for her, and when he turned over a sheet which showed her standing bareheaded with hair flying in the wind on the top of a hill, and hands stretched out upwards, Daffy exclaimed:

"I like that. Oh, I wish I had a picture like that! What is she doing?"

Fibo pointed to words printed underneath:

"I don't like earth, I want heaven!"

"Did she really say that?" asked Freda wonderingly.

"Yes, when her mother had punished her for running away."

Fibo smiled at the recollection as he spoke. Then he put the sketch into Daffy's hand.

"You can have it if you want it. This is only a copy. I have the original."

Daffy took the picture with a radiant face, then, with a quick little dart, she bent her head and kissed, as lightly as a butterfly might, the back of Fibo's right hand.

"That is my 'thank you' to the hand that did it!" she said.

Freda's gaze had wandered away from the sketches to the flowers.

"What lovely flowers you have! It looks like an enchanted garden. We have no flowers like these. Does Dreamikins pick them when she comes to stay with you?

"Yes; she knows all their histories, and which of them the fairies love best."

"Ah," said Daffy, with her cooing little laugh, "you believe in fairies! So do Freda and me, since we saw 'Peter Pan' in London, and I used to before when I was quite a baby. Nurse doesn't. She doesn't believe in any of the nice things, only in doses of medicines, and punishment, and bringing us up like 'little ladies' and 'good Christians.' I hate ladies and Freda hates good Christians, so Nurse and we argify about them."

"Oh, but I believe—heart and soul—in good Christians," said Fibo, leaning his head back and looking at Daffy with a kind smile; "what I don't believe in, are bad ones!"

"But I 'spect your good Christians are nicer than Nurse's. Why, I shouldn't wonder if you were one yourself!"

"Will Freda hate me if I am? But I can truthfully say I'm not a good one, only I have a try, and a hard try too, in that direction."

"How did you hurt your legs?" asked Freda quickly, wishing to change the conversation. "We want to know such a lot of things, and if we don't go back soon Nurse will be coming after us."

"Oh, how could she?" chuckled Daffy. "Why, I'm sure that Fibo made a little door like that on purpose to keep out nurses."

"Well now, I'll tell you about it. First about my legs. They were shot in the Boer War—that was before you were born, so, you see, I've had plenty of time to get accustomed to do without them. I came down to live here with my sister after my smash up, and then she got married and went away, and I liked my garden so much that I stayed on here."

"All alone?" said Daffy, with pity in her eyes.

"I wasn't very long alone. My sister soon brought Dreamikins to me, and she spends part of every year now with me. My sister promised me that I should share Dreamikins before she came into this world. She did not like leaving me to get married, but now she doesn't like leaving her husband to come and see me, and that's quite proper, you know. Well now, about the little door. Of course Dreamikins made me make it. She wanted to go out adventure-seeking in your park, and didn't want her nurse to come after her. So we made it nice and small."

"How lovely!" cried Freda. "But isn't it funny that Dreamikins should want to get out of this lovely garden when we want to get into it! When is she coming to see you again? Soon?"

"Not very soon."

"Then will you have us instead of her, and let us come in and out whenever we like?"

"Whenever you like," Fibo said at once.

"I'm afraid we shall have to be going," Freda said uneasily. "It will be tea-time. It always is tea-time when we want to enjoy ourselves."

"Run along, and get Nurse in a good temper, and then tell her where you've been. Everything must be above-board!"

The children said good-bye. Daffy danced backwards down the path, kissing her hand to him, then he called out:

"Pick a flower to take away with you, and give it to Nurse from me."

Freda stooped over a pink rose-bush.

"I'll pick the very biggest, and we'll make Nurse keep it on the table where we can smell it."

Daffy flitted from bed to bed, unable to make a selection. At last she picked a white Madonna lily.

Then they called out their thanks, and crept through the little green door. When they were once outside, they ran as fast as they could back to the house, and as they ran, Freda said:

"We've made a friend, Daffy,—quite a new one,—and we'll have him all the time we're here. I think it's been splendid!"

"Yes," said Daffy breathlessly; "if Nurse lets us keep him. But we can tell her that he's a grown-up, and won't lead us into mischief. And he's a cripple, and I believe Nurse's sister's husband's cousin is a cripple, so she ought to feel sorry."

A maid was ringing the big tea-bell out of the nursery window. They panted up the stairs, and Nurse met them at the nursery door.

"Where have you been all this time? Jane, make them tidy for tea at once. Master Bertie is ready."

She was fat and comfortable looking. In sickness or trouble, Nurse's lap was a perfect haven; but she had old-fashioned ideas of training children, and her training was Spartan-like in its severity.

Freda and Daffy were soon back in the nursery. It was a pleasant-looking room when the sun shone in at the windows. It was large and square, with dark oak-panelled walls and a low ceiling. Three windows looked into the park, and they had a view of the little village beyond clustering round an old square-towered church. Nurse was sitting in her big chair behind the tea-tray. The table was round. Bertie was in his high chair next Nurse. Freda and Daffy slipped into their chairs, then both held out their flowers to Nurse. Their faces were anxious as they did it. So much depended upon how she received their news!

The Tea-Party

"A VERY nice gentleman gave us these to give you, Nurse," said Freda.

"He's so ill, poor man!" sighed Daffy. "Just like your relation, Nurse. He made me think of him."

"Have you been worrying Mr. Trimmer?" asked Nurse, taking the rose from Freda's hand and sniffing it thoughtfully.

Mr. Trimmer was the head gardener. The children shook their heads.

"Oh dear no! Mr. Trimmer isn't without legs, and he chases us away from the greenhouses whenever he sees us," said Daffy. "Smell my lily, Nurse. He told us to choose any flower we liked for you."

"Now just speak up straight, and tell me what you've been doing."

Nurse eyed them sternly.

They told their story breathlessly, each interrupting the other in their anxiety to appease Nurse's gathering wrath.

"You mean to tell me you pushed yourselves into a strange garden, and spoke to a strange gentleman without any one's permission? Where do you get your forwardness, I wonder! In my day children would have died rather than behaved so."

Freda and Daffy were silent. Nurse scolded on, and then Daffy looked at her very sweetly:

"A poor, sick soldier, all alone, Nurse! And he has a little niece he loves, and she isn't there to comfort him, and he loves good Christians, and tries to be one himself. We told him you tried to make us into them, and he sent you these flowers, and hopes you'll let us go to see him again. I think you'd like him very much if you saw him, and I know he'd like you. And this is his little niece!"

Daffy held out her precious sketch.

Nurse took it, put on her spectacles, and read the words underneath:

"I don't like earth, I want heaven!"

"You see how good she is," put in Daffy persuasively.

Nurse gave a kind of grunt. Bertie, who had been silently listening to the conversation, now spoke.

"Me see, Nurse; me see the 'lickle girl."

"There, my lambkin, look!"

Nurse held it out to him with softened voice.

"I'll say this much, he's a clever painter. He'll be Captain Arnold, that took the Dower House some years back."

"What's the Dower House? And why has it a gate into our garden?"

"Why, it belongs to your father, of course. His mother lived and died there—your grandmother that was; but as it won't be wanted for a long time yet 'twas let. There was a Miss Arnold; your mother visited her."

"She's married. Oh, Nurse, if Mums knows them, I'm sure we may go and see him."

"Him! Is that the way to speak of a gentleman?"

"Then does the house really belong to father?" questioned Freda. "What does he want two houses for?"

"When Master Bertie grows up, bless his soul! and brings his wife here,—your father being no longer here,—then the Dower House would be ready for your mother to live in!"

"But, Nurse, how interessing!" exclaimed Freda eagerly. "Where would we live—with Bertie or with Mums?"

"You'd go with your mother, of course. This is your brother's house, not yours, if anything happened to your father. But there! Dear knows why I'm talking in such fashion. We'll hope that your father will live to a ripe old age. There's no call to be talking of his death!"

Nurse relapsed into silence. Freda's busy brain worked away.

"Why should Bertie live here and not us?" she demanded presently. "He's much littler than us!"

"He's a boy, and the heir," said Nurse importantly; "you're only girls."

Freda pouted, then she made a grimace at Bertie across the table, and he returned it promptly.

But Daffy's eyes were shining.

"Oh, think of it, Freda! One day we shall live in that lovely garden, and Bertie will be outside! We must let him come in and see us sometimes through the little door. And we shall keep dozens of white rabbits, and pick flowers whenever we like. I'd much rather live there than here, wouldn't you?"

"Yes, much; only, then, what will Fibo do?"

"We mustn't send him away. Oh, I'm sure we shall all squeeze in together beautifully. We must tell him about it and see what he says."

"But it won't happen for ever so long," said Freda regretfully; "and how awful of us wanting it to, for Nurse says Dad will have to die to let us live there."

Daffy looked horrified. Then with a bound she came back to the subject in hand.

"So, Nurse, if we're very good, can we go into that garden again? He wants us to come; he said whenever we like we could come to him."

"You'll go nowhere and see nobody unless you're asked properly and I'm with you," said Nurse sharply.

Freda and Daffy looked at each other with agonised eyes, but said no more. When tea was over, Nurse said she was going to take them for a walk. And in half an hour's time the three children were walking sedately along the country road which led to the village.

Freda and Daffy, walking a little in advance of Nurse, were able to talk together without being overheard.

"I shall write him a letter, Daffy, and ask him to write to Nurse and ask us."

"Or a wire," suggested Daffy joyfully. "Mums always asks people to tea by wires or the telephone."

"We haven't a telephone here, but there's a post office in the village. Oh, Daffy, could one of us creep in and send a wire?"

"It's a lot of money, Freda. Wouldn't a letter do?"

"Better still," said Freda excitedly; "we'll send a message—we'll get somebody to take a message. We'll find some one when we get to the village. Nurse said she was going to buy some stamps."

So, full of hope, the little girls walked on, and the village was soon reached. The post office was next to the general shop, and when Nurse went into the post office, Freda asked if she and Daffy could buy some sweets next door. Nurse gave the required permission, and they dashed in. Daffy produced her purse and began choosing her sweets; Freda eagerly turned to the stout smiling woman behind the counter.

"Do you send any of your loaves or tea or veg'tables to the Dower House?"

"Yes, dearie, very often. Mrs. Daw has all her soap and soda and such-like from us. My Willie is going up this evening with a tin of paraffin."

"Oh, please, will you get him to take a message from us to—to—is he Captain Arnold?"

"Yes, that's his name, poor gentleman. Such a pleasant-spoken gent he be, too!"

"Oh, please," went on Freda, with feverish haste, "could you give me a little piece of paper and pencil, just to write the message on?"

"Surely I will, and my Willie will take it with the greatest pleasure."

Paper and pencil were produced. Freda wrote laboriously:

"Plese ask Nurse perlitely to let us come and see you, but not her,

she wants to come with us. And we wood like to come to morowe.—FREDA and

DAFFY."

They had plenty of time to do what they wanted, for Nurse liked a little gossip sometimes, and Mrs. Vidler at the post office was an old friend of hers.

They came out of the shop delighted with their success. Daffy had two pennyworth of mixed sweets, and Freda, who was always just, gave her a penny from her own purse as her share of the purchase.

"Now he'll write a proper invitation, and Nurse will have to say 'Yes.'"

They were very happy for the rest of that evening, and when the postman came to the house the next morning, and Jane brought up a letter for Nurse, they looked at each other with shining eyes. How quick and prompt he had been! Nurse read her letter through in silence. They anxiously waited for her to speak, but when she did, it was to scold Bertie for spilling his milk, and the little girls were afraid to ask her any questions.

"If she gets cross she won't let us go," said Freda; "we'll be as good as gold till dinner-time."

"If we can," said Daffy doubtfully.

In London they had had two hours' lessons every morning with a daily governess; but to have nothing to do here, and knowing that their mother expected them to "run wild," was the way, they felt, to lead them into scrapes.

Nurse turned them all three into the garden after breakfast, but told them not to go out of sight of the house.

"What shall we play at?" asked Daffy.

Freda was never at a loss for games. Red Indians, pirates, gipsies, bandits had all served their turn. Now, when war was on, German spies, escaped prisoners, submarines, and air machines were what interested them most. The result was that, an hour later, Nurse came out to find Daffy up an oak-tree near the shrubbery, the oak being her flying machine. Freda was dragging a big sack down to the pond, but Bertie, inside the sack, was howling and kicking, and so gave the show away. When Nurse freed him, she found him covered with red earth, and her wrath was great.

"He's a spy. I didn't know the sack was dirty. I got it from the potting shed. He went out of sight of the house when he was hiding. Daffy went up in her flying machine and told me where to find him."

"I won't be dwowned!" shouted Bertie. "And you was smothercating me!"

Nurse called Daffy down from the tree. She had torn her frock, and had a large hole in the knee of her stocking.

"You would try the patience of Job," said Nurse, marching them up into the nursery. "It seems quite impossible for you to play as little ladies should. You make Master Bertie as naughty as yourselves. I shall have to give him a bath, and you will both sit for half an hour on your chairs for punishment."

The punishment chairs were placed in opposite corners of the nursery, and Freda and Daffy took possession of them with their faces towards the wall.

Freda was hot and angry, and kicked her legs to and fro. Daffy was absolutely unruffled.

"Never mind, Freda," she said comfortingly, when Nurse had left the room, "we had a glorious game. And I've left my handkercher up in my air machine, so I shall have to go up and get it as soon as ever I get off this chair. Oh, don't you wish we could live up in trees like the birds? I do."

"I should like to see Nurse having to climb a tall fir-tree every night to get to her nest," said Freda, with malice in her tone. "And I should like her nest to be made of holly. It would serve her right!"

Daffy chuckled with laughter.

"And now, of course," Freda went on gloomily, "she won't let us go and see Fibo this afternoon. Nothing could have turned out worse. I don't know why our games always do!"

"It's Satan, I suppose," said Daffy placidly. "Nurse says it's him who makes us get into scrapes."

Then they were silent. The nursery seemed oppressively warm this morning. Presently Nurse returned. Jane was with Bertie.

"I don't really think I shall let you go now," said Nurse. "I've had an invitation for you to go to tea with Captain Arnold this afternoon, and if you had been good—"

A wail from both chairs interrupted her.

"It isn't as if we really had made up our minds to be wicked," pleaded Freda. "Dirt and holes aren't wicked, and we didn't mean them to come on us!"

"And we're being punished now, Nurse. You can't punish us twice the same day for the same thing!"

"Stop argufying at once," said Nurse sternly. "I punish you for your good, not because it pleases me. Why can't I turn you out into the garden without your rampaging about like wild beasts, and tearing and destroying everything you possess!"

"If you let us go to tea with Captain Arnold, we promise to come home cleaner than when we went!" Freda rashly asserted.

Nurse gave a sniff.

"That you couldn't do, if you pass through my hands before you go."

The little girls were silent. They fancied Nurse was relenting, and wisely sat still on their chairs without even kicking their feet till their half-hour was up.

When dinner-time came, Nurse told them she was going to let them go; and at four o'clock two daintily dressed little maidens in soft white silk frocks and shady straw hats walked sedately along by Nurse's side to the Dower House.

There was no hope of being allowed to crawl in at the entrancing little door to-day. They went down the avenue, out by the lodge gates, along the road until they came to some high green wooden gates in the big wall. Then they walked up a short broad drive with shrubberies on each side, and reached the front of the house.

A pleasant-looking maid opened the door.

"I have brought the young ladies," said Nurse, in a very superior tone, "and I hope they will behave nicely as they should. I will send the nurserymaid for them at seven o'clock. That is the time mentioned."

Then she went away, and the children crossed a wide hall with a black beam across it, and to this beam was suspended a child's swing.

"Dreamikins!" whispered Daffy as she passed.

Then they went through a glass door to the garden, and found Fibo expecting them. He was in his chair under the trees, but he was not drawing; he was smoking his pipe and reading a newspaper. He greeted them with a smile.

"Very pleased to see you. The letter worked all right, didn't it?"

"Yes," said Freda. "It was very nearly a miss though, for we got our clothes in a mess this morning. It's so impossibly difficult to keep clean if you're enjoying yourself."

"We must all try hard this afternoon, or you won't be allowed to come and see me again."

The little girls' tongues wagged fast, they seemed to have so much to tell him—all about the Dower House one day becoming their home, and how Bertie was going to turn them out.

"I can't imagine him daring to do it," said Daffy reflectively. "Why, he's so small, we can do anything to him now. He quite looks up to us, and of course we make him do whatever we tell him. I don't see how he'll ever be so beastly as to tell Mums and us to go out of the house."

"I shouldn't worry about that. Perhaps you'll be queens in castles of your own by that time."

"Yes," said Freda eagerly, with shining eyes; "that's just it. Anything—anything might happen. Such crowds of beautiful things are in front of us!"

"My next beautiful thing is to see Dreamikins," said Daffy softly. "When do you think she'll come?"

"Ah!" said Fibo. "I've heard. One day next week; then we'll have a golden time."

"What day?"

"That's her secret. I am never told. We get ready for her, and she just walks in and surprises me. We always do it like that."

"How lovely! And does she come by herself?"

"Annette brings her."

"Who's Annette?"

"Her nurse. She's French. Dreamikins is very fond of her. Her mother thought she would learn French from her, but I am afraid Annette is too fond of English. She speaks it very well."

Freda and Daffy looked a little awed.

"Mums has a French maid, but we don't like her, and Nurse doesn't either. She says she's a heathen. She goes to Mass!"

"You aren't painting pictures to-day," Daffy said, rather reprovingly.

"No; I'm giving my hands a rest. I'm looking at pictures, and not painting them."

Daffy gazed into his eyes reflectively.

"I wonder what pictures you're looking at," she said. "You seem looking at the sky. Don't you often wish we could get nearer to heaven?"

"No; it's best to be a good way off. It would be like a hungry child gazing through the window into a baker's shop."

"But I should like to do that," said Freda quickly, "because if you can't get things, the next best thing is to pretend you have them; and sometimes in London, when Nurse let us, Daffy and me would pretend to have a feast outside a cake shop. I would ask her to taste some cakes, and she would offer me some tarts, and we would say how they tasted; and really, sometimes I fancied they were right inside my mouth."

Fibo nodded in a very understanding way. Daffy was gazing up into the sky. Then she gave an angelic smile.

"Freda and I used not to like heaven much; God used to frighten us. But we're much fonder of Him now, aren't we, Freda?"

"Yes, since last Sunday."

Freda's eyes began to twinkle. Then she gave a little chuckle.

"We went to church in the morning, Fibo. May we tell you? It was very hot and long, and nothing interessing until the Psalms came. And then I found out one of Nurse's big mistakes. She always hushes us when we're near a church, or saying our prayers, or anywhere near God. You know what I mean? She makes out that God likes us to be whispering; and on Sunday we have to be so quiet that it quite tires us out. It's the longest day that was ever made. Well, we and the clergyman were saying the Psalms, one against the other, and he began, 'Sing we merrily unto God our strength, make a cheerful noise.' Now the Psalms are quite true, aren't they? They're in the Bible."

Fibo nodded. Freda was speaking with breathless eagerness.

"So I told Daffy about it when we got home, and she wouldn't quite believe it. So she got her Bible and found the Psalms, to see if I was right, and somehow she didn't find the same verse, but she found a better one still. It was, 'Make a joyful noise unto the Lord—make a loud noise.'"

She paused.

"Well?" said Fibo inquiringly.

"Well, we did it! We shut the nursery door and we did it! We did all three—the cheerful noise, and the joyful noise, and the loud noise. And Nurse was downstairs; but, of course, she came up, and she was furious! We told her God had told us to do it, and He liked it, and we've been glad ever since that He does; but Nurse made out it was all wrong. Now she can't go against the Bible."

Daffy's face was twinkling all over.

"We did do it!" she said. "We yelled and stamped and shouted. I'm sure we must have been heard from one end of heaven to the other!"

"I wish I'd been there," said Fibo.

"You aren't shocked at noise, are you? Does Dreamikins like to make a noise?"

"Sometimes."

They went on talking, and then tea was brought out under the trees; and Drab, a soft grey cat, and Grinder, a fox-terrier, and Whiskers, the white rabbit, joined them. The little girls thought it was the most delicious tea they had ever eaten, the cakes were so fresh, and there were strawberries and cream; and after it was over, Grinder and Drab and Whiskers all had a gambol together upon the lawn. Of course Freda and Daffy joined them; and when they were all rolling about on the grass together, Fibo took out his sketch-book, and made a rapid sketch of them. He wrote underneath it, "My Tea-party," and when Freda and Daffy saw it they were delighted.

"But promise you'll never show it to Nurse. She would think it awful of us!"

"I think I shall have to talk to Nurse. Is it her legs, do you think, that make her want yours to be as stiff as they are? Or is it her head? What a pity she couldn't have a bit of her altered! Like this!"

Then he drew Nurse's heavy body, with a little, laughing, curly head on the top of it; and then her head, on a tiny, short-frocked child's body, and the child was dancing.

"Which nurse of these two would you like best?" he asked.

The children were enchanted. But after a minute or two, Daffy said gravely:

"I think p'raps Nurse had better be left as she is. I shouldn't like that laughing, curly head when I had a pain; and if she had those dancing legs, how quick she would run after us when we didn't want her to!"

"Yes," said Fibo, smiling; "I think God knew how to make a nurse when He did it. We can't improve upon her."

When Jane came for them they were very loath to go.

Freda said anxiously:

"You don't think that we asked ourselves to tea, did you? We never thought of that; only we were despairing that we should never see you again."

"And we hope," said Daffy softly, "that Nurse will let us come and see you our own way another day, through that dear little door. It's such an adventure!"

"And then we won't have our best frocks on, and can romp all over the place," added Freda.

Fibo assured them they could come through that door any day and every day they liked; and they walked home with Jane, feeling that a very good time was in front of them.

Dreamikins Arrives

FIBO let his newspaper drop on the grass with a little sigh. It was hard to read of the big War raging in Flanders, and to know the need of every man in England to be taking his part in it, and yet to feel himself out of it all. "Might as well be dead," he muttered, and then he shook his head at his discontented self.

It was a very hot afternoon, and he had a headache. Grinder lay on his side panting, with his tongue well out; he was half-asleep. Suddenly every hair bristled on his back, and he darted off to the house.

"Hears the advent of his enemy, the butcher boy," Fibo said to himself languidly.

Was it the pattering of leaves from the tree above that he heard behind him? Suddenly two soft little velvet arms were round his neck. A warm rose-bud of a mouth was kissing his ear.

"Here I are, Fibo!"

Such a light and gladness came into Fibo's face. In another moment he had dragged his small niece round where he could see her.

Dreamikins was always a pretty sight. To-day her golden curls, her fair dainty face with its big blue eyes and long-curled black lashes, her graceful little figure in its dainty white muslin hat and frock, and her white socks and shoes, seemed in his eyes to shine with extra glory.

"You're just in time," Fibo said gravely, "to save your Uncle Fibo from turning into a growling grizzly bear."

"I'm never just too late, are I?" said Dreamikins, dancing up and down before him in ecstasy.

Dreamikins' grammar was shocking; her uncle never tried to improve it.

"Any news?" asked Fibo carelessly.

That was the question Dreamikins always liked to be asked when she had been away from him.

Her eyes looked big and solemn. She clasped her two tiny hands, pressing her finger-tips together, as she did when in terrible earnest about anything.

"The news this time is good, Fibo. You'll be surprised to hear that Blacky left me, 'bout two weeks ago. I felt quite alone and mis'able, and then God gave me a darling little angel Cherubine. She plays with me all day long, and whispers all night, unless I'm asleep, you know. And she helps me to be good, you know. I told her how Blacky helped me to be wicked. I reely got quite tarred of fighting, fighting him all day long; and Cherubine doesn't put anything wicked into my head at all."

"Then my naughty scamp is no more, and I have an angel niece," said Fibo, looking at her reflectively. "I should think Annette doesn't know herself."

"Well, I aren't exackly an angel yet—not like Cherubine. Would you like to speak to her, Fibo? She's rather shy, and she gene'lly gets behind me."

Fibo had made acquaintance with a good many personalities who accompanied Dreamikins upon her visits to him. The first one was Old Man Sol. When Dreamikins was three she talked about him. He seemed rather a harmless old soul, but a great comfort to Dreamikins. She sometimes called her nurse after she had been put into her cot at night, because Old Man Sol wanted to be kissed, or tucked up tighter. She always talked hard to him, and he always helped her in her games. By and by he faded away, and a shadowy, indescribable Pollybill took his place. Dreamikins was absolutely happy with this creation of hers.

"Is it a she or a he?" Fibo asked one day.

"It isn't neither," said Dreamikins triumphantly.

"Oh, an 'it,' is it?"

But Dreamikins shook her head. "Pollybill is only Pollybill, and nuffin else at all. I call Pollybill 'you.'"

"What does 'you' look like?"

"Pollybill has a kitty's eyes, big and round, no cloves, only soft hair, and can be very little and very big, just what I want. And Pollybill always says 'Yes' to me, never 'No.'"

Dreamikins could describe this individual no better, and Fibo was rather glad when Pollybill departed. Then came two or three fairies and sprites, but none of them ever stayed with her long. Blacky was a Pixie. He had a long innings, and Dreamikins found him a lovely scapegoat for all her mischievous propensities.

"I 'sure you it was Blacky made me do it. He pushed me into it, and I foughted him till I was tarred out."

She had brought Blacky with her to Fibo on her last visit, and he was glad to think that he had gone for good.

"I'm very glad to welcome you to my house, Cherubine," said Fibo quite gravely, "and I hope you're going to make a long stay with us."

Dreamikins put her head on one side as if listening to somebody.

"She says she likes me so much, Fibo, that she's going to stay with me till she takes me to heaven."

"I hope that you and she will grow old together, then," said Fibo.

Dreamikins looked quite shocked.

"Oh, Fibo dear, angels never grow! I'll tell you a little more about her. Mummy told me I had a guardian angel, so she said I didn't want any of my 'make ups.' Mummy doesn't unnerstand like you; she always calls them 'make ups.' So I thought about it a lot, and God told me He wanted me to be good. It makes Him so uncomfor'ble when I'm naughty. So I asked Him didn't He think He could send me a darling little angel to take care of me, instead of the grave grown-up one that always hangs over children in beds. I asked Him to try to do it, because I must have somebody to play with. And He said He'd lend me Cherubine. And she came down, and tucked her wings under my pillow, and kissed me, and we sleeps together, and when I wake she wakes. And now, please, may I show her Whiskers? And oh, Fibo dear, are you very glad to see us?"

"Yes, I truly am; and I have a surprise for you. I can keep secrets as well as you."

Dreamikins danced up and down on her toes.

"Tell us. We're simply dying to hear!"

"I have two real little girls for you to play with."

"Oh, Fibo!"

Dreamikins stopped dancing. She could hardly believe such good news.

"Where? Whose are they?"

"They're not in my pocket," said Fibo, laughing; "but one fine afternoon your little door opened, and in they crawled from the park."

"Real little girls?"

"Real. They're bigger than you; and they live in the old Hall."

"In the big shut up house? And what's their names?"

"I call them E.E. and B.B.—Elusive Elf and Busy Brain."

Dreamikins nodded approvingly. Then she promptly seated herself on her uncle's knees.

"Now," she said, with raised finger, "begin at the very first beginning, and tell me all about them."

Fibo meekly obeyed her. They were talking hard when Annette appeared to ask if Dreamikins would come in to tea.

"I'm going to have it with Fibo."

"But there's an egg for you," said Annette—"a little brown egg produced only this morning by Madame Daw from the fat white hen. She has eaten nothing—not a little morsel, Captain—since her early breakfast. Her tongue only loves to talk, never to eat."

Dreamikins knitted her brows, then she grandly waved Annette away.

"The egg can come here," she said; "I'm not going to the egg."

Fibo looked at Annette, then at Dreamikins.

"Cherubine," he said slowly, "will you take Dreamikins in to her tea? I'm not having mine till an hour later, and her body wants some food if her brain does not."

Dreamikins opened her lips, then shut them tightly. She slipped off her uncle's knee.

"Just this once," she said, "I'll go; but Cherubine lives without eating, and she needn't try to make me."

"But you always eat when you come here," said Fibo cheerfully. "And to-morrow we'll have tea in the garden together, and perhaps we'll have B.B. and E.E."

"You're a very C.O.," said Dreamikins, laughing, and then she danced away to the house. Fibo and she had many names they called each other, and C.O. meant Cunning Ogre.

So the next day Freda and Daffy received an invitation to tea. It came in a big envelope, and inside was a sketch of Dreamikins dancing up and down.

"The pleasure of Miss Freda's and Miss Daffy's company is requested

at four o'clock upon the Dower House lawn.

"R.S.V.P.

"N.B.C."

"What does 'N.B.C.' mean?" questioned Nurse, looking at the note suspiciously through her spectacles.

Freda responded promptly:

"No best clothes! Fibo hates best clothes, and so do we. He's very fond of 'N.B.C.'"

"Dreamikins has come," said Daffy, with shining eyes. "The postman told me she came yesterday. Nurse, can we ask Dreamikins to tea one day? We must ask her back."

"'Tis to be hoped she's not so queer as her name," said Nurse grimly. "If she be proper behaved I won't go against it."

Freda and Daffy were punctual to the moment. They were obliged to go round the front way, for Nurse accompanied them to the door; but Dreamikins had been watching for them and came running to meet them. She did not seem afraid of Nurse's grimness, but held out her small hand.

"How do you do? Will you come to tea too? Are you the governess?"

"I'm the young ladies' nurse," said Nurse, in her grand tone. But she was rather pleased at being taken for a governess.

"No, I'll not come in, thank you; and, Miss Freda and Miss Daffy, you're to be good children, and I shall expect you back at seven. Jane will come for you."

She turned away and left them.

Dreamikins stood confronting them for a moment in silence. Then she smiled seraphically:

"Cherubine and me like you awfully much. Do you think you shall like us?"

"Fibo said we would," said Daffy cautiously; but Freda caught hold of Dreamikins' hand.

"If you can play pretence games we'll just love you," she said with enthusiasm.

Dreamikins led them out into the garden, and for the next hour they played together. Fibo said he wanted to read, and he would talk to them later. When tea came out under the shady trees, the three little girls seemed quite tired and exhausted enough to enjoy the rest.

"We've been through the door into the Wilderness," said Dreamikins, "we've hunted boars and tigers, and rescued just a few Ogre's prisoners. And I can run the fastest, but Freda is the strongest, and Daffy can jump the highest."

They all chattered together as if they had been friends all their lives.

Once Dreamikins got grave.

"We didn't have any soldier fighting, Fibo. Mummy made me promise not to be playing that. And Cherubine cries when people hurt each other. She says they never hurt each other in heaven. They don't even scratch the skin on their knees when they tumble down."

"I suppose they don't have stones," said Daffy thoughtfully.

"The stones are quite soft and velvety," said Dreamikins quickly; "and sometimes you can eat them; they're sweets, you know."

"That's fairyland," objected Freda. "The Bible doesn't say anything about sweets."

"No; the streets are paved with gold," said Daffy.

"Nice to slide along on," said Dreamikins contentedly.

Her uncle laughed.

"Oh, you Babes!" he exclaimed.

Dreamikins admonished him with her small finger.

"Don't be a P.D., Fibo. We're not babes—not in the least!"

"What's a P.D.?" asked Daffy curiously.

"Proud Dog!" said Dreamikins. "He's always a P.D. when he calls me a 'Babe.'"

Then she said with a sudden change of tone:

"And now let's talk about the War, Fibo. Cherubine is just having a nice little nap, so we needn't mind her feelings."

"Anything but that, Dreamikins," said her uncle gravely. "I thank God daily you little ones are kept in peace and safety."

"We don't talk about it much," said Freda. "Nurse says horrors are not for nurseries. But Daffy and me want to know what will happen if everybody kills everybody. Who'll be the soldiers then?"

"God won't let all the peoples be killed," said Dreamikins. "It will crowd up heaven so all at once, and make it so stuffy!"

Freda and Daffy were not yet accustomed to Dreamikins' speeches. They stared at her in wonder. Then Daffy ventured to put her right.

"Do you think heaven is a little place? It stretches and stretches like elastic, and the more people go in the bigger it gets."

Dreamikins' blue eyes looked past Daffy as if she had not heard her.

"And of course if all the men did get killed, the women would go and finish the War, wouldn't they, Fibo? Mummy would—she wants to be there now, and I'd get a lovely gun and go with her."

"Oh, you modern child! Leave the War alone," said her uncle. "Let us talk of Whiskers, or Pixies, or anything but the Bad Bit of Life which is with us."

"Tell us one of your stories—not a arrygory, because I have to find the meaning, and it spoils it."

So the little girls settled down, and Fibo told them a wonderful, nonsensical story about a fat giant with a cough, who was afraid of his wife and tried to hide his wicked deeds from her, only his cough always betrayed him. And they listened breathlessly, and when he had finished, Freda gave a long sigh.

"You are a beautiful story-teller. I could listen all night."

"Yes," said Dreamikins proudly; "Fibo has got a big bump in his head, he says, which is bigger than other people's, and a little fairy lives inside it who whispers these stories to him. Sometimes she goes to sleep, and he can't wake her, and then he says he can't make up stories by himself, which is a pity."

"Dreamikins is exhausting in her demands," said Fibo. "The more she hears the more she wants to hear. My poor tongue aches with its constant wagging."

When seven o'clock came, and Jane appeared, Freda gave a groan.

"I could stay here for ever; couldn't you, Daffy?"

Daffy nodded.

"Yes, even if we had nothing to eat," she said.

And Fibo looked at her with his funny little smile.

"That's a great compliment to Dreamikins and me," he said.

Dreamikins was already arranging in a rapid whisper with Freda a time of meeting in the park the next day.

"I shall come through the little door," she said, "and we'll all go wild; shall we?"

Then she added impressively:

"I shall tell Cherubine she mustn't stop us before it's really time."

"What do you mean?" asked Freda.

"Well, before we're really wicked. You see, she has to keep me good. God sent her to do it."

"Oh!"

Freda looked doubtful. Then her brow cleared.

"She hasn't anything to do with Daffy and me. She can't stop us."

Dreamikins looked at her thoughtfully, but said no more. They kissed each other, and the sisters walked home feeling they had a new friend.

The Return Visit

"IT'S too bad, she won't come!"

Freda stood at the nursery window with Daffy. Their noses were flattened against the panes, and they were gazing disconsolately down the beech avenue.

It was raining fast, softly, persistently, and it did not mean to stop, even though Dreamikins had been asked to tea, and it was now four o'clock. Tea was laid on the round table in the nursery. Freda and Daffy had inspected it very critically when Nurse was out of the room washing Bertie's face and hands and putting him into a clean holland suit in honour of the occasion.

There was a big currant cake in the centre of the table, some strawberry jam, and a large plate of cut bread-and-butter.

"I should like one of Mum's teas," said Daffy, with a sigh, "with sangwiches, and hot tea-cakes, and sugar-iced cakes, and chocolates. I would like Dreamikins to think we had very nice teas."

"And tea in the garden is so much nicer than in a room," sighed Freda.

"But she wouldn't have tea in the garden to-day," said Daffy.

Then they went to the window to watch for her coming. It was Nurse who told them she was sure she would not come, and now they had begun to believe it.

Bertie came up to them, and stretched up on tiptoes to see too.

"There's a b'llella!" he suddenly announced.

And, sure enough, his quick eyes had discovered the big umbrella first. It was waving about rather uncertainly, and two tiny legs and feet were underneath it.

"She's coming, Nurse! And all by herself Dreamikins is allowed to come out to tea alone."

They rushed out of the room and down the stairs to meet her. They found her in the front hail, and Purling, the old butler, was taking her wet umbrella from her.

"She's come in at the front door!" said Daffy, in awed tones.

Dreamikins looked up at them with her radiant smile.

"Did you come all by yourself?" asked Freda.

Dreamikins opened her lips quickly, then shut them tight, and waited quite a moment before she spoke.

"I was just going to say 'Yes,'" she said. "I wanted to say it, but Cherubine pinched me, so I knew I mustn't. Annette brought me to the gate and then I got her to leave me."

"Where did Cherubine pinch you?" asked Daffy curiously.

"Oh, just inside my heart," Dreamikins answered airily. "She gets in there and does what she likes."

Then she kissed her friends rather solemnly, and followed them upstairs to the nursery without saying another word.

Nurse welcomed her quite kindly. Dreamikins in a clean white frock, and her best manners, brought a smile to Nurse's lips.

Bertie hastened up to shake hands. He was very excited over this new visitor, and was ready to be friends with her at once.

Very soon they were sitting round the tea-table. Shyness had suddenly descended upon Freda and Daffy. It was Dreamikins who did most of the talking—Dreamikins and Nurse.

"I think," Dreamikins said, looking at Nurse with one of her sweetest smiles, "that I shall call you H.D. Do you mind if I do?"

"Why H.D.?" demanded Nurse.

"It means something to me," Dreamikins replied. "I always like calling people by letters. I call Mummie D.Q. Not when she scolds me, though—never then!"

She shook her curls with vigour as she spoke. Then she condescended to explain.

"D.Q. means Darling Queen," she said.

Freda and Daffy began to guess under their breath what H.D. meant, but Dreamikins would not tell them. She went on calmly:

"You see, I can't call you Nurse, because you aren't my nurse. I gave up nurses when I was quite little; they changed so often, and Mummie and me got quite tarred of them."

"I hope you weren't a very troublesome little girl," said Nurse sternly. "Children who have no nursery are always spoilt and unruly. I am sorry for their mothers, but all the best families keep their children in the nursery till they go to school."

"Did you have a nurse?" asked Dreamikins.

But Nurse changed the conversation.

When tea was over, Jane cleared away the tea, and Nurse and she left the nursery for a short time. Then the children's tongues ran fast.

"Show me your house; it's such a big one. Let us play hide-and-seek in the passages."

"Nurse won't let us. We can never do anything nice. What is H.D.?"

"Haughty Dragon," said Dreamikins, laughing gaily. "Fibo and I always call people H.D.'s who look like your nurse does. Oh, we must play hide-and-seek. I'll go and ask her."

Away darted Dreamikins, peeping into every room and dancing up and down the passages as if it were all a game. She found Nurse, and actually coaxed the permission she wanted out of her.

"It's a wet afternoon, and if you promise not to spoil or disarrange anything, you can do it," said Nurse.

Then followed a lovely hour. Freda and Daffy and even Bertie were as excited and happy as their little guest. At last the time came when Dreamikins could not be found. Every corner and cupboard in the few rooms in which they were allowed to hide were ransacked. The passages with their queer corners were searched again and again, and the children came to Nurse in the nursery with troubled faces.

"We're quite tired out," said Freda gloomily, "and we think she's climbed up one of the chimneys and got on to the roof."

Nurse bestirred herself.

"She's a mischievous child, I fear. There's such daring in her eye; but it won't do for her to come to harm here."

So Nurse went from room to room, and then at the end of one of the passages thought of a little door which led into the cistern-room. There were steps up inside, and on these steps was a white hair ribbon.

Nurse got agitated, and called aloud, and a weak little voice answered her:

"I'm nearly drownded, but Cherubine is keeping me up."

Sure enough, in the big cistern, drenched to the skin, Dreamikins was clinging with her hands to the top; her feet were on a tiny ledge that mercifully was inside, or the big cistern would indeed have drowned her. She had clambered in, taken off her shoes and stockings, and imagined that the water was not very deep.

"I was so hot, I wanted to paddle. I thought it was a little pond, and then I splashed down ever so far, but I got up again and held on tight and screamed, and I've screamed away all my voice, but Cherubine helped me."

She was certainly exhausted with her wetting and with fright. Nurse got her out with a stern set face, and carried her off to the night-nursery, where she changed all her clothes, gave her a hot drink, and then took her back to her little friends.

"Now, none of you are to leave this room," she said. "It's a mercy we haven't had a death in this house, and it isn't this child's fault that we haven't!"

Dreamikins sat still for five minutes whilst she explained to the others how she had come to be found in such a situation.

"I thought I was going to be drownded, and I asked God to send me a better angel, for Cherubine was too small to help me. But she just managed it, till the H.D. came. And now what shall we play at?"

They settled down to a game of marbles on the nursery floor. But very soon they tired of their game and began to talk again.

"Why do you live in such a big empty house?" questioned Dreamikins.

"Because Dad and Mums are in London," said Freda, "and there's nobody to fill their part of the house."

"I could get some people to fill it," said Dreamikins thoughtfully.

"What kind?" asked Daffy. "We shouldn't take anybody into our house, you know."

"It doesn't really belong to us at all," said Freda hastily. "Bertie will have it one day, and turn us out."

Bertie stared with his round eyes at his sister.

"I won't turn you out," he said. "I couldn't. You're so strong."

Dreamikins' eyes were gazing away into space. She said slowly:

"Fibo and I read a very interessing story in the Bible last night when I went to bed. It was about the good people who are turned into sheep, and the wicked who turn into goats. Goats don't live in heaven—only sheep. And if you want to be a proper sheep you have to do some differcult things. They're differcult for children; grown-up people could do them easily, but I've been thinking we really ought to begin some of them in case we die quickly. I shouldn't like to find myself a goat all of a sudden."

Freda and Daffy were not so fond of Bible stories as Dreamikins seemed to be. They looked bored, and Dreamikins was quick to notice it.

"Now, you just listen to me," she said, with upraised finger, "and I'll tell you what we've got to do. We've got to do six things, and if we do them to the proper people, Jesus will count it that we've done it to Him. Fibo explained it beautifully; he always does. We must give meat to somebody who's hungry, and drink to somebody who's thirsty, and take into our houses a stranger. That's what made me begin to think of it. Fancy how many strangers you could take in this big house! And we must visit somebody who's sick, and somebody who's in prison, and we must give a poor, naked, ragged beggar some clothes."

"We couldn't do it possibly," said Freda emphatically.

But Daffy's eyes began to shine.

"Oh yes, we could; it would be beautiful!" she said.

Dreamikins put her arms round her and hugged her.

"You and me will begin it, and then Freda will, too," she said. "We must. Cherubine will help. She thinks we ought to."

The little heads got close together. Nurse was sewing by the window, so they talked in whispers.

And then, all too soon, Jane appeared, saying that "Miss Broughton's maid" had arrived to take her home.

Dreamikins was very reluctant to go, but Nurse produced her clothes all beautifully dried, and Annette came upstairs to wait upon her.

"Ah, Miss Emmeline, you be always in trouble. What a peety!" exclaimed Annette, when she was told of Dreamikins' escapade.

Dreamikins smiled up at her.

"I 'sure you it's no trouble to me, none at all!" she said, with the greatest composure.

She hugged Freda and Daffy warmly, kissed Bertie, shook hands very politely with Nurse, and trotted off. They watched from the window her little figure tripping down the drive. Annette was holding a big umbrella over her.

"I'm not at all sure whether she's a fit playmate for you," said Nurse, with a shake of her head. "If she leads you into worse mischief than the two of you are generally up to, the house won't hold you all!"

Freda and Daffy said nothing, but presently they began to discuss Dreamikins together.

"She seems so ridicklously good," said Freda; "I never heard anybody speak about God as she does. Of course, Cherubine is a make up, but she believes it, and now she makes out we must do all this or we shan't please God. I never think about pleasing God at all. Nurse would say we never could. He's so awfully holy and far away."

"Yes; she's good," said Daffy slowly, "but she isn't proper and stupid like some good children are. And I think there'll be a lot of fun about being these Bible sheep. She gets a lot of fun out of being good."

"Yes; but she doesn't do it because of that. She really loves Jesus Christ—she told me so. I almost wish I did, but I don't."

Daffy made no answer. She thought a great deal more than Freda did, and some of her thoughts were serious.

"We'll try and take a stranger in as soon as ever we can," said Daffy. "It will be most exciting! We'll smuggle him in by one of the windows downstairs, or else Nurse will make a row."

"It might be a 'her,'" said Freda; "we don't know who it will be yet."

"It must be somebody who wants a night's lodging—some poor beggar. We see some going along the roads when we are out."

"I wonder if Dreamikins will find somebody before we do. She has no horrid nurse keeping her from doing things she wants."

"A H.D.," said Daffy, with twinkling eyes. "We'll call her H.D. to ourselves, Freda; she'll never know."

They began to wonder when they would see Dreamikins again. Their days seemed dull without her, but Nurse determined that they should not meet too often. She was distrustful of Dreamikins; there was something in her joyous face and free easy manner that touched on insubordination. And then something happened that put Dreamikins out of her head. A letter came one morning from Mrs. Harrington, and it brought sad news. The children's father had been killed by a Turkish shell in Mesopotamia.

When Nurse broke the news to the children, her voice shook. Freda and Daffy would not believe it.

"Dad killed, Nurse! Oh, he can't be! It's a mistake. He can't possibly be dead!"

"What does Mums say?"

"She's coming down this week. Dear heart alive! What shall we all do? The master—so young and hearty—but there, this War be takin' all the best! He had no need to volunteer as he did!"

Freda and Daffy crept into a corner of their nursery and cried a little. Nurse was crying easily and almost happily; tears hurt and choked Freda. She was horribly ashamed of them, and struggled to overcome them. Daffy felt she ought to cry harder than she did. She loved her father, but could not yet take in what his loss would mean. They had never seen very much of him; he had always been so busy, but sometimes he would take them to the Zoo or to Madame Tussaud's or to the Pantomime, and then the hours were golden.

"Shall we go on living here?" she asked Freda. "Perhaps Mums will take us back to London."

"Oh, I hope not. Oh, Daffy, do you remember what Nurse said? It has come to pass, and we never thought it would."

"About this being Bertie's house if Dad died? Yes, I remember."

Daffy spoke soberly, but Freda's eagerness carried her on.

"Of course if it's Bertie's house now he can give us leave to do anything we like, and it will be quite easy to put strangers up for the night. Nurse could say nothing at all, nothing. We'll ask Bertie now."

Bertie was pulled into the corner which Freda and Daffy always retired to when they had important business on hand. It was the corner which was farthest from Nurse's chair, and from her quick ears, which often heard more than they were meant to do.

"Bertie, this is your house now. You'll give us leave to have one of the bedrooms to do what we like with, won't you?"

Bertie stared at his sister with round eyes.

"Is it mine own house? Why is it?" he asked.

"Because dear Dad is dead, and he has left it to you."

"But I don't want Dad to be deaded. It makes Nurse cry."

"It makes me cry too," said Freda, gulping down a lump in her throat; "but God has done it, so there's nothing to say. And this is very important. It has to do with God. He wishes us to do it, and we want a bedroom, Daffy and me."

"What must I do?" asked Bertie meekly.

"Make him write it on paper," said Daffy, "like one of our story-books. Don't you remember a man left a little girl—Helen her name was—all his money and a big house, and he wrote it on a bit of paper?"

"I'll write it," said Freda quickly. "We'll do it at once, in case we might be stopped."

So a piece of paper was found, and a black stump of pencil, and Freda wrote in her best round copy-book writing:

"I give to Freda and Daffy one of my bedrooms in this house for

somebody that God wants to stay here."

And then they told Bertie he must sign his name. He had great trouble in doing this, but they stood over him till it was done, and then Freda folded up the paper and put it into a small box of hers which locked.

"Now," she said to Bertie, "this paper is a secret, and you mustn't tell Nurse."

"I haven't been a naughty boy?" questioned poor Bertie, who always connected secrecy with misdoings.

"You've been a 'markably good boy," said Freda approvingly; and Bertie ran back to his brick-building with great content. "Now we'll have to get the room ready," said Freda triumphantly, "and then we'll find the stranger."

"But we mustn't do anything just now," said Daffy, who generally checked Freda's rapid plans. "It won't be proper. Look at Nurse. She's still crying! And we're forgetting to cry ourselves."

So they sat quietly in their corner, and began to talk about their father, and then they felt more and more miserable, and more tears fell. When Jane came in they felt pleased to hear her say to Nurse:

"The poor children! How they feel it! 'Twill be comfort for us to have the Mistress down. 'Tis a terrible blow, sure enough!"

Feeding the Hungry

MRS. HARRINGTON did not come down to her children for some days. When she arrived she was in deep black, and she brought the family lawyer with her. She did not see much of her children, but then she never had. She cried a little over them the first evening of her arrival, then she began to discuss their clothes with Nurse.

"I will have no black frocks. Keep them in their holland and white ones, and give them black sashes and ribbons, and put a black ribbon round their hats. That is all that is necessary."

"As long as we are in the country, I suppose, ma'am," said Nurse, with rather a shocked face.

"I am not going to have you back in town for some time. I am going to let our town house, but I will talk to you about this later on."

Nurse looked rather dismayed, but she said nothing.

This was all that the children heard. They were pleased at the idea of staying on in the country, and now that Nurse was more occupied with their mother, and less in the nursery, they enjoyed greater liberty. Jane was very good-natured, and was not particular about their behaviour. When she went out walking with them they could do pretty well as they liked. One afternoon they met Dreamikins with her maid. She welcomed them with rapture.

"I've been longing to see you. Cherubine and me feel quite dull. Fibo told me your daddy was dead. Are you very sad?"

"Of course we are," said Daffy. "We've cried gallons, and all the house is miserable, and everybody wears black dresses but us; it's a shame!"

"Do you like black frocks? Why?"

"Because they don't show the dirt," said Freda promptly. "We hoped Mums would give us some, but she won't."

"I s'pose you've been too miserable to think of being sheep."

"No-o," said Freda slowly; "we've laid plans for the stranger's bedroom, but it isn't ready yet."

"Mine is," said Dreamikins, with pride. "I maded the bed myself. I asked Fibo if I might get a bedroom ready for a visitor, and he said 'Yes.' Fibo nearly always says 'Yes,' he is such an A.M."

"What's that?"

"Angel Man. I always call him that when he is special kind. I've come out this morning to hunt about for a stranger, but I can't find one; not even a little one. Everybody we've met lives about here."

"We might do some of the other things first," said Daffy thoughtfully.

"But the stranger is the most exciting," said Freda. "I'm longing to meet him."

And then as they were walking along the lane talking eagerly somebody came towards them. It was a man, and he was in dusty clothes, and he limped. He carried an old sack across his shoulder, and one of his boots was tied round his foot with a handkerchief.

In a moment the three little girls darted towards him.

Dreamikins reached him first.

"Would you like to sleep at our house to-night?" she asked him breathlessly.

"No, at ours," shouted Freda and Daffy together.

He looked at them surlily.

"Garn with yer games!" he said; and he pushed past them, but Dreamikins laid her soft little hand on his arm.

"You must listen—we'll make you. It isn't a game; it's real sober truth. If you don't want us to take you in, p'raps you're hungry, or thirsty. Are you?"

Then the old tramp stopped.

"Yes," he said, "I be fair longin' for a drink. Have ye a copper, little leddies?"

But Dreamikins shook her head. "We must give it to you ourselves, and I reached you first, so I'll do it."

Freda and Daffy looked rebellious. But Dreamikins turned upon them with her sweetest smile.

"You won't mind, will you? I'll just go and get him a glass of milk. I'll take him to our house and give it to him. You see, my house is nearer than yours."

Before Freda and Daffy could offer any objections she had turned the corner of the lane with the tramp.

Annette, who had been talking to Jane, now hurried up.

"Ah, Miss Emmeline!" she exclaimed. "Where is it now that cheeld has gone? Away with a beggar? What a life I lead!"

She ran after her little charge, and Freda and Daffy were following, when Jane stopped them, and insisted upon going another way.

"'Tisn't time to be turning back to the village yet. Come, Miss Freda, we're going to the wood where the nuts are. You let them go and fight their own battles. We'll go on where we meant to go."

Jane gained her point after some disputing; but Daffy whispered:

"We'll go and see Dreamikins this afternoon when we're playing in the garden, and we'll go through the little door."

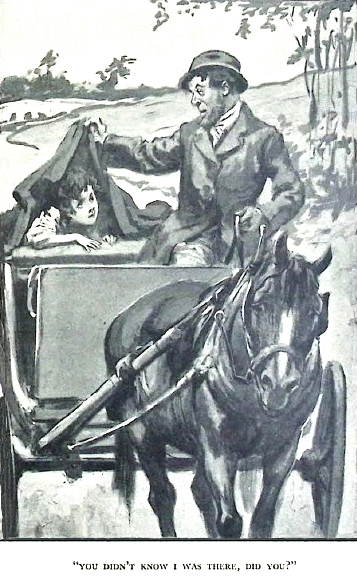

FREDA AND DAFFY POUNCED UPON HIM IMMEDIATELY

"I mean to be first next time," said Freda. "Dreamikins will take every one away from us if we don't take care."

For the first time they felt rather angry with their little friend; but they were very curious to know whether she had given the strange man a drink or not.

"The thing for us to do is to be ready for everything out of doors," said Freda, with decision. "We must have food and drink in our pockets, and give them to the very first beggar we see."

"I wish it wasn't beggars we have to look for; they're so dirty and rude," said Daffy discontentedly.

But on their way home fortune seemed to favour them. They came across a little boy with a white face and ragged coat sitting in the hedge. His feet were bare, and he was clutching a bundle which rested on his knees. Freda and Daffy pounced upon him immediately.

"Are you thirsty?"

"Hungry, are you?"

"Sick?"

"Do you want a nice bed to-night to go to sleep on?"

The boy looked at them with rather frightened eyes, and didn't speak.

"Who are you, and where do you live?" asked Freda, trying to speak more quietly. "You must be quick and answer, because Jane will be interfering, so make haste."

The boy jerked his thumb back over his shoulder.

"My feyther be on his rounds. He've gone over to them there 'ouses to mend their pots and pans."

"Is he a tinker?"

The boy nodded.

"And are you very poor? Wouldn't you like us to give you something to eat and drink?"

Another nod, but the boy's face brightened, and he looked up at them expectantly.

Alas, Jane came up.

"Now, Miss Freda, Nurse don't allow you to speak to tramps, I know."

"He isn't a tramp," said Freda indignantly; "his father is a tinker. We have a picture in our book 'Tim the Tinker.' They're kind of gipsies, and he's a very nice little boy."

Daffy bent her head near the stranger child.

"Come up to the Hall this afternoon at three o'clock, and wait behind the big tree in front of the house," she whispered.

Freda heard the whisper and approved. Very often whilst she hotly disputed with Nurse, Daffy quietly went and did the thing they wanted to do.

Jane found no difficulty in getting them to come home. Freda and Daffy walked on sedately in front of her. They talked eagerly in low tones, and made plans for the good of the small wayfarer.

They were turned out in the garden as usual, after their nursery dinner. Both Freda and Daffy had managed to secrete some meat, and Freda had added a piece of currant pudding, which she put in her pocket. Daffy had got a medicine bottle filled with clean water. They made their way to the grand old cedar in the centre of the lawn, and there sat down to wait for their visitor. Bertie was trundling his wheelbarrow along the gravel path. He was filling it with small stones as he went.

"We shall do better than Dreamikins," said Daffy. "And the Bible says a cup of cold water, not milk, is the thing to be given. I remember Nurse reading it to us long ago, so I've got a cup in my pocket too."