Combination Dresser and Washstand

Title: Hospital housekeeping

Author: Charlotte A. Aikens

Release date: January 8, 2025 [eBook #75063]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Del T. Sutton, 1906

Credits: The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

By

CHARLOTTE A. AIKENS

Late Director Sibley Memorial Hospital, Washington, D. C.; Late

Superintendent of Iowa Methodist Hospital, Des Moines;

Superintendent of Columbia Hospital, Pittsburg;

Former Associate Editor The National

Hospital Record

SECOND EDITION

Detroit, Mich.

DEL T. SUTTON

1910

Copyright 1906

by

DEL T. SUTTON

In the preparation of this volume, three classes of readers have been in mind: the trained nurse who, without practical experience in hospital management, finds herself in charge of a hospital, small or large; the practical woman who, having had no opportunity for special training, has upon her the responsibility of the direction of the domestic affairs of an institution; and the lady member of the hospital board of managers who, in the discharge of the duties of her position, becomes responsible to the public for the proper government of institutional affairs. It was thought that the latter, especially, might, through the use of this volume, secure a better grasp of the details of hospital housekeeping as a whole than is possible without some such aid. The ability to see all around a situation, to view the institution as a whole, is essential to good management. As a rule, such ability comes only by experience. Especial pains have been taken to make the volume thoroughly practical, and to present clearly and concisely lessons learned in actual dealing with, and close study of, the questions discussed. The greater portion of the contents of the volume have already seen the light of day in the columns of the National Hospital Record. Since their appearance in that journal, the papers have been carefully revised, and much new and important matter added. For assistance in preparation, the author has been under great obligation to a number of hospital superintendents, who have furnished [Pg 8] information as to methods, and to contemporary writers, especially on the subject of dietetics. Special mention should be made of the works of W. Gilman Thompson, M. D., Mrs. Ellen H. Richards, I. Burney Yeo, M. D., Sir Henry Burdett, and of the literature of the United States Department of Agriculture. To Miss Emma Lynch, who, as hospital matron, has been for several years associated with the author in institutional work, special thanks are due for valuable assistance. Many practical suggestions have been gleaned from the papers given at the annual conventions of the Association of Hospital Superintendents. To the writers of these papers the author expresses grateful appreciation. Many of the electrotypes used for illustration have been kindly furnished by courtesy of the business firms whose names accompany them. These have been introduced because they were deemed essential to a clear understanding of the subject on the part of such readers as may not be familiar with the use of such appliances. So far as the author is aware, no attempt has previously been made to discuss the subject of hospital housekeeping as a whole. As a pioneer in the field, the book doubtless has many defects. If it proves of practical value to even a small number of those for whose assistance it was prepared, it will have justified its existence.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

Hospital housekeeping is intensely practical business. If it is to be successfully and satisfactorily conducted, it demands that the housekeeper be a woman of no inferior or uncertain attainments. All the elements that make for success in home housekeeping, and many more, are needed in a hospital. There must be breadth of vision, the qualities of an organizer, the ability to deal with large problems, a keen sense of justice, and the executive force needed to manage, without fear, fuss or favor, the various classes of people that touch the housekeeper’s realm. Many a man who is a success in managing a village store would utterly fail when placed in charge of even one section of a great department store. And the same may be said of the average woman in hospital housekeeping. Apart from the special knowledge of the business, that comes only by diligent study, accurate observation and experience—never by accident—the housekeeper needs special qualities of mind and heart. Indeed, special qualifications are needed by every one whose life work is to be wrought out in an institution. A hospital or any institution that has to deal with infirm, aged or unfortunate members of society, is no place for a person of strong racial [Pg 14] antipathies. It is no place for the tale-bearer or the gossip, nor for the person who has a grudge against fate and feels she has never received justice. It is no place for the person who is discouraged, or who assumes the air of a martyr, and leads a crushed life, bemoaning the fact that her highest motives and best efforts are never appreciated. Those who would live happily in an institution must be prepared to be misunderstood, and fortified against discouragement from that source. Sympathy with the aims of the institution is a primary qualification. No one should enter an institution as a worker, and especially as head of a department, who is not prepared to have her interests centered in the people for whose benefit the institution was brought into existence. Ability to see things from more than one standpoint, to work comfortably with different classes of people, an infinite capacity for detail, and systematic business habits—these are a few of the qualities that should characterize the woman who undertakes to manage the domestic affairs of a hospital. It need hardly be mentioned that she needs a healthy body and a strong constitution.

The hospital housekeeper needs, if anyone needs it, reliability of judgment, and poise of soul. If she is to control others, she must know how to control herself. The ability to reprimand without arousing antagonism must be hers. She should endeavor to cultivate the feeling of personal responsibility in all over whom she has authority, and to make them understand that the success of an institution depends not on perfection of equipment, nor in numbers, but in thorough co-ordination of the work in all the departments, and faithful service on the part of all.

They should know that a lack of punctuality or carelessness in one department disturbs the working of the entire system. The influence of [Pg 15] the kitchen and laundry is felt throughout the entire institution. Skillful management consists not alone in the ability to attend to the apparently important affairs with ease, but in never losing sight of the minor details. Nothing is so large as to be of paramount importance, nothing so small as to be considered immaterial, where human lives are concerned.

To define the exact limits of the housekeeper’s province is impossible, as institutions vary so greatly in size and in the number of officers. Local conditions always influence the situation. One lone woman may have to manage the domestic affairs of an institution, superintend its entire business, including its nursing, manage its bookkeeping, do the work of an interne in emergencies, and act in various other capacities, that readily suggest themselves to those who are acquainted with life in a small hospital. In another institution her province may be limited entirely to the purely domestic affairs, the purchase and preparation of food, care of linen, the cleaning, and the management of those who work in these departments. In either instance, the responsibility is great. To meet this responsibility without being oppressed by its weight, requires that the working force be completely organized, the work definitely divided and assigned. There should not be a square inch of the building for which someone is not directly responsible for its good order and cleanliness. Real success in management, however, does not alone consist in the work going on as it should while the housekeeper is there to direct and supervise. Her own health and efficiency demand that she have recreation and rest, and, as a matter of fact, depend on her not being always there. Her skill and generalship of the situation will be shown in the fact that, whether present or absent, the routine of the work is not noticeably interrupted. In every institution there should be some individual who is [Pg 16] sufficiently acquainted with her methods to assume control and carry on the system in her absence.

In addition to the mastery of the details of the practical work, the hospital housekeeper must know how to give an account of her stewardship to those who have a right to demand it. The business side of hospital work, that which has to do with dollars and cents, is one of her many duties that has special importance. It is one of the corner-stones in the hospital foundation, and however much the housekeeper may dislike the tedious work of adding and subtracting, and reckoning, and itemizing, if she is a faithful steward of trust funds, she will give it due attention. The weak point in a great many hospitals is the looseness of methods of accounting. Frequently the board of managers are not sufficiently impressed with their responsibility to plan and demand a system of bookkeeping that will furnish plain facts in a shape that will be easily grasped; and it is not to be wondered at that the housekeeper is, if not careless, then not sufficiently careful for her books to be of any value as institutional records.

The busy housekeeper needs a simple method of accounting that is at once comprehensive and easy to handle. A simple, convenient form for a general expense book is here shown. One page can be devoted to each week’s or month’s expenditures and the use of such method makes the annual financial statement an easy matter to arrange. It is not claimed that this is the best method for a general expense account; it is one method—a simple, workable method.

In addition to this the use of a small day book will be necessary, which will show on the left-hand page the money received and on the other side the disbursements for the day. For this an ordinary blank book that has spaces ruled for dates, items, dollars and cents, will be sufficient. In this each day will be recorded the article purchased, the date and the cost. Periodically this itemized account is gone over, the articles grouped under the several heads and copied in the general expense book. [Pg 17]

GENERAL HOSPITAL

| Receipts and Expenditures from ___________ to ___________ | ||||

| RECEIPTS | ||||

| Balance on hand .... 1st, 190... | ||||

| Received from ....................... | ||||

| Received from ....................... | ||||

| Received from ....................... | ||||

| Received from other sources .... | ||||

| EXPENDITURES | ||||

| Meat | ||||

| Fish | ||||

| Butter | ||||

| Flour, bread and meal | ||||

| Milk | ||||

| Water supply | ||||

| Ice | ||||

| Potatoes and vegetables | ||||

| Groceries and provisions not | ||||

| above enumerated | ||||

| Soap and cleaning appliances | ||||

| Fuel | ||||

| Gas, oil and light | ||||

| Bedding and general house | ||||

| furnishings | ||||

| Nurses’ uniforms | ||||

| Other training school expenses | ||||

| Advertising, printing, stationery, | ||||

| postage | ||||

| Repairs | ||||

| Stationary furnishings | ||||

| Contingencies | ||||

[Pg 18] An “order book” should contain an account of all orders given, the quantity, cost, date ordered, date received. An ordinary blank-book may be ruled with columns for each of these entries, and the month and year. This furnishes information that is valuable from several standpoints. If the housekeeper is suddenly called away, it is easy to turn to for a list of the firms patronized, or to find the usual amounts ordered, and is valuable for comparison and reference from month to month and year to year. All dealers’ checks sent with goods should be preserved, for comparison with the itemized monthly account, before indorsing it for payment.

In the matter of the hospital inventory, various forms may be adopted, according to the purposes for which the inventory is intended. It may be a simple list of the furnishings of the hospital, made up without any special plan, and with or without the value or cost of the article attached. In case of loss by fire, this inventory might have special value as an insurance record. Such books should of course be kept in the safe, with other documents and articles of value.

As convenient as any way of keeping a hospital inventory, is to have the contents of the building arranged under the heads of the rooms for which the articles were purchased. The kitchen, storerooms, diet kitchens, offices, reception rooms, wards, private rooms, etc., all have stationary furniture especially for them, and for purposes of reference it will be most convenient to list this in connection with [Pg 19] the room containing it. If the value of each article is attached a recapitulation will show at a glance the total value of the hospital furnishings.

Once each year, at least, the housekeeper should make a business of finding out the average cost per day of feeding her hospital family, and the average cost of feeding one patient. This knowledge is valuable not alone for statistics, but for her own satisfaction. It should give confidence in her administration, or show whether there is a weakness that might be corrected.

“There is nothing in a hospital small enough to be careless about,” is a remark frequently heard in hospital corridors. It is important for the housekeeper to bear in mind that, although oft quoted, this statement happens to be true. Perhaps no one thing will produce a more lasting impression on a casual visitor than the manner in which he is received at the front entrance. Two trained nurses who spent a couple of days in visiting hospitals in an eastern city related the following experience: At hospital number one the door was opened by a very untidy-looking, irrepressible colored boy, who seemed to feel it his duty to do the gallant thing according to his ideas of gallantry. After an entirely unnecessary speech, his concluding remarks were that he would just love to go through the hospital with them, but he “ain’t got no time,” and he guessed he’d have to ask Dr. —— to go with them. At hospital number two, no one specially seemed to be in charge of the door, and, after repeated rings, a resident physician, who, judging from his hair and general appearance, had been napping, came rushing through the hall—the door was open—getting into his coat by the time he reached the door. The climax was reached at hospital number three, which was a maternity hospital, an adjunct of a large city hospital. Here the door was opened by a colored woman in the last stages of pregnancy. At hospital number four a pert maid, none too tidy, was on [Pg 21] duty at the front entrance. Her distinguishing feature seemed to be that she “didn’t know.” At hospitals five and six, the persons in charge knew what was expected, and did the proper thing, but the varied experiences served to show the laxity that exists in that one particular.

The careful hospital housekeeper will see to it that the person in charge of the main entrance knows his business and is reliable and courteous. He need not know all the business of the institution, but he should know enough to answer questions properly and when to be silent. If no special uniform is provided, he should be neatly and quietly attired. Parcels, telegrams, messages, are constantly being delivered for the inmates, and he should be responsible for them until they are delivered to the nurse in charge. Letters should be placed in a locked box, the key to be held by some reliable person who will see to their distribution. Mail for the patients should not be given to the inmates direct, but to the nurse in charge, and some nurse should always be in charge. Carelessness at this point may result in an important letter or message not being delivered, or delivered at a time when it is specially important that the patient’s mind be free from disturbance or intrusion of any kind. Complaints are frequently made, of large hospitals especially, that boxes of flowers sent to patients have been thrown carelessly into a parcel room, and not delivered at all, or delivered after their beauty and fragrance had gone. If the person at the door is careless about matters of that kind, he will be just as likely to be careless about more serious things. A temporary substitute at the door should always be arranged for when the porter is obliged to be absent, even for a few minutes.

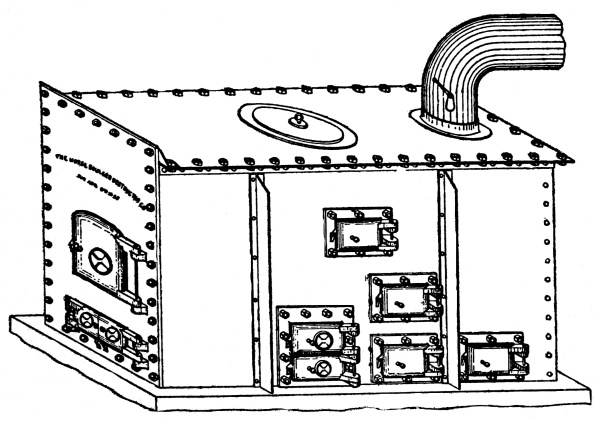

In all apartments intended for the use of patients some degree of [Pg 22] uniformity should be observed in the furnishings, though this may easily be carried to extremes. These rooms vary in size and price, but the essentials for all are the same. The chief thought should be to have the furnishings suitable, sensible and restful. Dainty white enameled furniture for hospital rooms is rapidly replacing that of darker hue and adds greatly to the attractiveness of the hospital. For [Pg 23] the average room a combination dresser and washstand is preferable to cumbering the room with two separate pieces of furniture. These have the essential features of the dresser, in that they provide a mirror and drawers, and of the washstand by having a towel rack and cupboard. In any case, small dressers are preferable to large ones. Every private room should have its own wash bowl and pitcher, soap dish, mug, receptacle for toilet brush, water bottle and drinking glass. The bed should be placed so that the nurse can have access to it on three sides. The woven-wire springs should be warranted not to sag in the middle.

Combination Dresser and Washstand

Blankets, on account of the frequent washings, should not be all wool, nor too heavy. For warmth it is better to depend on light blankets than on any form of “comforter.”

Rugs may be as bright and handsome as the hospital can purchase. The cheap wool rugs that are everywhere displayed for sale are a poor investment. The most satisfactory rugs are those made to order of tapestry Brussels, or when it can be afforded, the more expensive grade of Brussels or velvet. For small rooms three widths are usually sufficient and these made without border are not an expensive rug. For larger rooms a border is preferable, but in any case such rugs are economical and serviceable.

Long lace curtains should have no place in a hospital. They are always getting in the way and being torn, always collecting dust and always an obstacle to the view and to ventilation. At best they are a nuisance, an unnecessary expense and serve no useful purpose. Soft, plain white sash curtains are the only suitable curtains for the hospital window. Provision should be made for looping them back if the patient desires it, and most patients have a longing desire to see out of doors. [Pg 24]

A comfortable, roomy rocker, with arms and without any “squeaks,” is indispensable in the private room.

If large enough, the room should also have a couch. It makes an agreeable change from the bed during convalescence. The common couches with elevated head are most unsatisfactory. No patient can lie on an inclined plane for any length of time in comfort. When it becomes necessary for a nurse to sleep in the patient’s room when on “special duty” these couches are an abomination. No nurse could ever get up feeling really rested, after trying to sleep on such a couch. The best hospital couch is that styled sometimes “the den couch.” The bed is flat, a full six feet by two, and the headboard being at right angles, effectually prevents the pillows from slipping off. Such a couch can be made as comfortable as a bed, combining both beauty and utility. They can be made to order by any firm that manufactures couches or beds. When covered with the best grade of pantasote these couches cost usually from fifteen dollars upward and when covered with leather from thirty dollars upward. They are the only kind of hospital couches it pays to invest in.

HOSPITAL COUCH

INVALID TABLE

A straight-back chair, a wardrobe for the patient’s clothing, a movable screen and a small table or two, complete the essentials in the modern sick room. The newest hospital tables are of iron and glass and may be had in different sizes. An invalid’s table that will extend over the bed is a luxury much appreciated by the patient, especially during convalescence. Plenty of pillows is another luxury that will add to the patient’s comfort. A small pillow or two to tuck around the patient, in places where a little warmth or support is desired, is a sensible addition to the ordinary furnishing of the sick room. Half a dozen will be none too many. [Pg 26]

The best finish for the walls of the private room is a coat of oil paint. They can then be subjected to periodical cleaning without being defaced. The shades should be soft and delicate and restful. A pretty shade of greenish blue is a delight to most eyes. On the wisdom of pictures in a sick room, opinion is divided. Some would banish them as unnecessary, and because they afford a lodging place for dust and disease germs. Others would introduce them to banish the monotony and relieve the walls of the bare effect. If used at all, pictures should be carefully selected, and have plain wooden frames, that will not be injured by disinfectants. To many patients the illuminated scripture texts on the walls are a comfort, and few, even of those who in health have no use for such things, object to them when sick. The custom of making memorial rooms, picture galleries or museums where the memory of benefactors is enshrined, is to be condemned. A simple plate on the wall or on the door is sufficient. More than this is unwise and in bad taste. The craze for memorials has reached a point that is embarrassing in many hospitals, and the time must surely come when doctors and hospital officers will interfere, and protest against having the patient forever gazing into the countenance of some member of the family of the benefactor of the institution.

As soon as possible after a patient has left the room, it should undergo a thorough cleaning. Every article but the stationary furnishings should be removed. Carelessness about this matter sometimes proves very embarrassing. Drawers, cupboards, and wardrobes should be washed with a solution of bichloride of mercury. The windows should be cleaned and fresh sash curtains put on. The walls should be brushed, the floor cleaned, the mattress disinfected, the bed clothing washed and all utensils thoroughly aired. If the last occupant was afflicted [Pg 27] with a communicable disease, the mattress should be subjected to steam sterilization.

Fumigation of the rooms periodically is necessary to ensure the safety of the coming patients. Formaldehyde for fumigation purposes has largely superseded sulphur. When the room is ready for fumigation, the windows should be closed, the drawers of the furniture opened, all chinks stopped, the keyhole stopped with cotton, and the room left closed for twenty-four hours. It may then be opened, and, when thoroughly aired, is again ready for occupancy. The sheet method of fumigation, using a pint of formaldehyde to every 1,000 cubic feet of air-space, has been thoroughly tested and proven reliable. The drug is simply poured on the sheet, which is hung over a line in the room to be disinfected, which has been prepared as above directed. It should be remembered that formaldehyde has little or no power of penetration, and for this reason all possible surfaces of materials to be disinfected should be exposed.

In the daily cleaning, the work should be so divided throughout the entire hospital that the regular morning cleaning can be accomplished in a comparatively short time, leaving special cleaning to be completed later in the day. In order to accomplish this, it may be necessary to employ special cleaners by the hour. This does away with the necessity of providing meals and lodging for a large force of cleaners.

By nine o’clock in the morning the halls and stairs should be in order, front steps and walks cleaned, wards swept and dusted and the whole interior presenting a neat appearance. “Dust in a hospital is not only dust, but danger.” Domestic cleanliness and hospital cleanliness are [Pg 28] quite different terms. The hospital housekeeper owes it to the public and to the sick whom she serves to keep the wards and rooms in the best condition for the promotion of health.

On the hardwood floors a soft hair brush will raise less dust than the ordinary broom. Wet tea leaves should be sprinkled whenever obtainable. The dust should be taken up frequently. The ward floors, unless polished, should be washed every day. It is well to change the water often and not use it too freely. Special attention needs to be given to corners. After each meal it will be necessary to brush up the crumbs.

The dusting is even more important than the sweeping, and must be done with great thoroughness and care. Each patient in the hospital is helping to make the atmosphere impure by throwing off disease germs. Dried particles of pus, blood and excreta, lint from blankets and bedding, scales of epithelium and other matter, more or less dangerous, are flying about in the air and being deposited on ledges, skirting boards, window sills, bedstead rails and the various parts of furniture. To bring in a feather duster or a dry cloth and attempt to dust, is simply to flap the dust from one place only to have it settle in another. It results in a more equal distribution of the dust, but it is not dusting. Dusting is removing dust, and the only way that can be done effectually is by the use of a damp cloth, to which the particles will adhere. Furniture that will be injured by that kind of dusting is out of place in a hospital. Special attention needs to be given to dusting under radiators and in obscure nooks where dust will accumulate if not looked into daily.

The bath rooms, toilet rooms and lavatories also need constant supervision, and ought to be as carefully cleaned and ventilated as any [Pg 29] part of the hospital. Indeed, special pains are needed if they are to be free from bad odors. Disinfectants should be used freely in these places at least once a week, and any evidence of imperfect drainage promptly reported and attended to. A good disinfectant for this purpose is the one known as the “American Standard,” made by dissolving six ounces of chloride of lime in a gallon of water. For cleaning bath tubs kerosene is recommended. It is a wise precaution to constantly keep posted over closets and sinks a notice prohibiting the throwing of matches, hair and insoluble material into them. More than one plumber’s bill has been caused by a careless maid emptying her bar of soap from her scrubbing pail into the closet. In fact, so common is that occurrence that a careful housekeeper has invented a device for holding the soap, thus preventing such accidents, and also the waste caused by leaving the soap in the water. This device is a tin box about eight inches long by four inches wide and four inches deep in front and six at the back. On the back are two pieces of wire bent over to fasten the box to the outside of the scrubbing pail. These can be made by any tinsmith at a very small cost, and will hold a cake of soap and a cake of sapolio. They will save many times their cost in a year.

It is in the hospital ward that the major portion of routine hospital work is accomplished, and where the nurses who will have much of the responsibility of the hospital work of the future will be trained in habits of accuracy and neatness, in proper systems of ward work and good hospital housekeeping. Inasmuch as the number of hospital officers varies with the size and demands of the hospital, it should be understood that for the purposes of these papers the hospital housekeeper combines the position of superintendent of nurses and matron—the plan that is generally conceded to be productive of the greatest degree of harmony. In all but small hospitals, competent assistants in both the nursing and domestic departments will be needed, but the authority and responsibility of affairs domestic should be centered in one woman. Whatever may be the opinion of hospital trustees on that point, no one who has lived for a year in a hospital where the superintendent of nurses and the matron were equal in authority, and pulling in opposite directions, will sigh for a repetition of the experience.

The architecture of the hospital ward, and the general plans of the building, will have not a little influence in creating difficulties for the housekeeper and in adding to, or lessening, the burdens of the nursing staff.

Tiled floors and walls are ideal for wards, but too expensive for every hospital to have. Even five feet of tiling on ward walls is greatly to [Pg 31] be desired. Denied that luxury, as many hospitals are, the next best thing is to have the walls finished in cement or hard plaster, which, if well coated with enamel paint, will admit of thorough cleansing and disinfection.

Heavy moulding and sharp corners which afford a lodging place for dust and germs should not be there. The ceilings should be high, and ample air-space provided for the number of patients for which the ward is designed. The ventilating shafts, windows and radiators should be arranged with reference to the proposed location of the ward beds. When the hospital housekeeper can manage it, each ward will have its own linen room, with abundance of linen. It adds no small item to the number of miles a nurse is obliged to walk each day, if every time she needs a clean sheet, towel or gown she has to walk half the length or the whole length of a long hall to get it.

A little forethought and consideration for the nurse’s part in the hospital economy, in arranging the plans of the building, would result in at least avoiding unnecessary labor for those who will have no small part in carrying out the humane designs of the hospital.

Of equal importance is it to have a “clothes chute” on every floor, connecting with the sorting room in the basement. This will render unnecessary large receptacles for soiled linen. The storing of quantities of soiled bed and body linen in the vicinity of the hospital ward for even a few hours can never be anything else but injurious. The atmosphere cannot be pure while soiled linen is there to give off its impure odors. Very dirty linen should be rolled in a separate bundle. Pins should be removed and disinfection attended to before being sent to the laundry. Clothing belonging to patients should be plainly marked [Pg 32] with the owner’s name. In most cases it will prove more satisfactory to all concerned for the hospital to decline to be responsible for laundering articles of personal wear for any patient. There is always danger of their being lost or torn.

The ward beds should be of uniform height and style and well coated with enamel paint. In buying beds several important points are to be considered. If beds are offered which require two men, and a hammer, and a box of bolts and a wrench, to get them adjusted, they should not be considered, even if listed at a dollar each. They are dear at any price, when one considers the prices that prevail in the labor market, the strain on human patience, and the fuss that the moving of such a bed to another room or ward entails. It is a mistake, too, to buy beds without inquiring the length. Six-foot patients are not uncommon, and these find it very distressing when put in a bed that is too short. The bed should be at least six feet four inches in length.

In all hospital beds, there should be some kind of bar at the foot, that will keep the mattress from slipping down. Some hospitals have attempted to remedy this defect in beds by having boards sawed and placed as foot boards, but these are unsightly, and if the right kind of bed is bought such makeshifts will not be necessary. Before ordering a quantity of beds, it is well to get a trial bed, and thus be sure of the quality of mesh in the wire mattress, and that other details are satisfactory. No beds without back rests should be purchased, for in the majority of cases a back rest will be necessary. Separate back rests must be purchased and stored when not in use, and these are rarely as satisfactory as when attached to the bed.

It is well, also, to look closely into the plan of the back rest. Some [Pg 33] have a round iron rod across the lower edge If such a thing is there, a sensitive, nervous patient will discover that rod, and worry till she or it is removed.

In ordering beds it is wise always to state the height from the ground that is desired, or low beds may be sent. About twenty-four or twenty-six inches is the usual height desired. It is possible to secure beds that can be adjusted to any desired height. The disadvantage of such beds is the difficulty of adjustment so that each corner will be exactly as high as the other corners. Each one must be measured, and the moving of the wire mattress up and down on the legs of the bed, makes it impossible to keep the enamel on the legs.

By all means hospital beds should have castors, and care should be exercised to see that these castors are so constructed and adjusted that they will not fall out every time the bed is moved. There is a great difference in castors and in their durability.

For the general wear and tear of a hospital, the cotton-felt mattress is giving better satisfaction than the hair mattress, and it is somewhat less expensive. It is a good plan to have a few pads made of bed ticking thickly inlaid with cotton batting. These should be made the same size as the bed, with rings at the corners to secure them. For very filthy or unconscious patients these pads are desirable, as they can be washed and boiled as often as necessary. A couple of these pads makes a bed as comfortable as a mattress.

The mattress should be carefully protected by a rubber sheet securely fastened at the corners. Every nurse thinks she knows how to make a bed before she goes to a hospital for training, but as a matter of fact very few do. It is sometimes a difficult thing for the nurse to learn, but it is one of the most important of the early lessons in ward work. [Pg 34] The appearance of the ward beds, and the way in which they are made, is a good index to the character of the nurse in charge. If the spread is on crooked, the open ends of the pillow covers pointing in opposite directions, and the bed has the loose appearance of having been thrown together without method, one may naturally expect the general work of the nurse to be slipshod and unreliable. It is well to teach nurses to stand at the ward door occasionally, and take a critical survey of the ward, noting down the things out of order. A nurse who is watchful in observing signs of disorder in her ward may naturally be expected to be a careful observer of signs of disease.

Order, which is said to be Heaven’s first law, should be one of the first laws of ward work. Even the height of the curtains of the windows add to or detract from the appearance of the ward. The beds should be an equal distance apart and in a straight line. The head of the bed should never be used as a drying-place for wash cloths or towels, nor as a hook on which to hang bath robes and wrappers.

Aseptic ward tables of iron and glass are now being used in some hospitals, but it is doubtful if their use will ever be general. They answer some of the purposes of a ward table, but not all. Even very poor patients prefer to have their own combs and toilet articles, their own handkerchiefs and stationery, their own books and flowers. If some place is not provided for these numerous small things, which the average patients find it necessary to have close by, they will inevitably resort to stowing their “things” under the mattress—a custom not to be tolerated by the neat housekeeper. Good housekeeping requires that in a hospital, as elsewhere, a place be provided for everything and everything be kept in its place. Until the proper [Pg 35] aseptic ward table is invented and offered at a reasonable price, the small wooden locker, well coated inside and out with enamel paint, will continue to be used. These lockers can be made to order for a very moderate price, usually from three to five dollars each. They should be about 20 inches in width, 30 inches from the floor, 14 inches deep, and mounted on castors. The drawer should be about 4 inches deep and there should be a shelf in the lower part. A daily inspection of bedside lockers is necessary, or apple cores, fruit peelings, remnants of food, and refuse of various kinds will accumulate. All cupboards and linen rooms should have daily attention, and should be in such perfect order that the doors may be thrown open at any time for inspection without embarrassing the nurse in charge.

The outer garments of the patient and those not needed during illness should be taken charge of by the nurse on the entrance of the patient, and the list recorded in a book provided for the purpose in every ward. Each article should be labelled, and placed in the locker in the general clothes room, and the number of the locker noted with the list of clothing in the record book. An accurate and uniform system of clothes records throughout the hospital should be insisted on. Unless this is done confusion when the nurses’ places are changed will be inevitable. Carelessness in this duty on the part of a nurse has resulted in no small discomfiture to the hospital officers. Clothing has been mislaid and not found for weeks after the patient has left the hospital, and the whole institution has been branded with negligence by the patient and his friends. All the kindness received, and the most skillful professional treatment, will often be lost sight of, if, through the carelessness of a nurse, the hospital is unable to render [Pg 36] to the patient the clothing entrusted for safe-keeping. Money or valuables should never be kept either in private room or hospital ward, but sent to the office to be deposited in the safe.

Though many well-regulated hospitals have a medicine cabinet in every ward, the custom does not generally prevail, nor is it desirable that it should. The less a patient knows, sees or thinks of medicine, except the dose intended for him at the time, the better. The custom of hanging clinical records over the foot or at the head of the bed is another custom that might better be abandoned, even though it be very convenient for the nurse. Patients are only too prone to meditate upon and discuss their symptoms, in spite of all efforts to induce them to trust themselves entirely to doctors and nurses, and cease questioning and worry. Some sympathizing friend or convalescent patient may be depended upon to keep them informed when an unpleasant symptom is recorded. This will occur in spite of all rules and vigilance. It is not easy under any circumstances to keep ward patients from discussing their ailments and symptoms. Especially is this true in women’s wards. In men’s wards the newspapers are read, the political situation is discussed, city improvements and occurrences are talked about, all sorts of subjects occupy the time of those who are able to talk, but a different state of things entirely prevails in the women’s wards. What they get to eat, how they feel, and the nurses and doctors furnish the general topics there. To have a clinical record to gossip about might divert attention from the nurses and doctors, but even these long-suffering individuals would willingly sacrifice themselves as a topic of conversation rather than have the patients read the records and constantly discuss their symptoms. [Pg 37]

The tendency in modern hospitals is in favor of smaller wards, as affording better facilities for proper classification and separation of patients. A nurses’ utility room adjoining every large ward or located conveniently near two or three small wards, where medicines, clinical records, supply charts and blanks, order books and the memorandum books necessary for ward work are kept, is a much appreciated convenience in some hospitals. Opening off this room is the ward diet kitchen, where the refrigerator and food supplies for the ward are kept, and the facilities for quick preparation of special diets for individual patients.

A much needed adjunct to a hospital ward is an isolation or “quiet” room, to which a patient whose presence is offensive to the other occupants of the ward may be removed. Whenever possible, a dying patient should be separated from the other patients in the ward. Gruesome tales that are disgraceful have been told of patients passing out of life in full view of the other occupants of the ward, without even the measure of privacy a screen affords. It is a melancholy comfort to relatives and friends to be with the patient in his last hours, and this cannot be permitted in a ward without confusion and discomfort to other patients. When planning a ward for the care of the sick or the poor, the object, of course, is the saving of lives, but people will die in hospitals in spite of the best skill and care, and the poor man is surely entitled to a quiet place to die in. There is much in hospital life to blunt the sensibilities of those who live in such institutions constantly. Familiarity with suffering and death robs them of mystery and awe, but it should never be allowed to detract from the reverent care of the dying and dead. “Put yourself in his place,” is a good rule to observe in dealing with even the most unworthy of Adam’s sons. [Pg 38]

The ease with which the routine work of the ward goes on will depend largely on proper facilities and a proper system. There should be a regular order for the work of the day—a time for bed making, a time for sweeping and dusting and washing the ward floors, a time for the daily cleaning of the bath rooms and toilet rooms and refrigerators and cupboards. Interruptions may be expected, but unless a routine order of work is established the cleaning will be executed in haphazard style. Neither nurses nor maids can be depended on to use their judgment in such matters. If left to plan their work, they will probably be found sweeping their wards when the doctors are ready to begin their dressings, and the time for other things will depend on their ideas of the importance of the various duties. The habit of doing things quickly and thoroughly should be formed by every one who has any responsibility of the routine work of a hospital, where everything should move with clock-work precision. So much time can be wasted by lack of system, or in talking or dawdling. The untidy habit of leaving glasses or utensils dirty till a sufficient quantity has accumulated to make it a necessity to wash them, should never be tolerated.

It ought not to be necessary to mention the necessity of plenty of tools and the right kind of tools for ward work—plenty of basins, and syringes, and dressing pans, and instruments, and drinking-cups, and medicine glasses, and the thousand and one little things that go to make up the complete furnishings of the hospital ward. But, as a matter of fact, many nurses go through their course of training hampered by a lack of facilities for proper work. One set of instruments for dressing is provided, where several are needed at the same time; insufficient [Pg 39] linen to keep the beds and their occupants clean is the rule, and so on indefinitely.

On the other hand, head nurses and hospital housekeepers lament over the carelessness of nurses and the constant destruction of hospital appliances. Just what course to pursue with the girl who every few days puts a rubber catheter or rectal tube or nozzle on to boil, and lets it burn up; who pours boiling drinks into glass tumblers, and thereby keeps up a constant breakage; who leaves hypodermic needles without wires, and finds them useless when needed again; who breaks medicine glasses and fails to report the accident, till the head nurse finds her measuring medicine with a spoon; who puts the thermometer into the mouths of delirious patients or children, and goes away and forgets it; who lets the sterilizer boil dry; who puts glass syringes and appliances in unsafe places, and returns to find them broken—just what course to pursue to correct these destructive tendencies is an ever-recurring problem to the hospital housekeeper. Nurses who are most careful and conscientious in carrying out the doctor’s orders, and in their duties to the patients, frequently lack that fine sense of honor regarding their duty to the hospital and the care of materials. A deposit for breakage is now demanded in some hospitals when a nurse enters for training. If this is not done the nurse should be made to replace articles destroyed and to pay for repairs that are rendered necessary by her carelessness.

Proper economy in the use of hospital goods is an important lesson for nurses to learn early in their career, and one which will demand frequent emphasis throughout their course. Gas stoves are left burning when not in use, and help to swell the gas bill. Milk is left out of the ice-box, and quickly becomes unfit for use. Materials of various [Pg 40] kinds that could be utilized are thrown away. The destruction or waste of one article seems a very trivial affair, but in the aggregate such trivial affairs amount to hundreds of dollars in the course of a year. The cost of rubber sheets alone is an important item in ward expenses. The best will soon crack if folded when not in use. If loops of tape are fastened to the corners and the sheets hung against a closet wall when not in use, they will be found to last twice as long.

Plenty of screens in a hospital ward is a necessity to proper nursing. The poor appreciate privacy and refinement and delicacy as much as many of their wealthier neighbors, and they have a right to such privacy as a screen affords. The timid, frightened little woman who has just been admitted, and who shrinks from the gaze of everybody, ought to be screened off till the first awful feeling of strangeness wears away. The patient who is critically ill needs also to be screened. The general work of the ward requires the constant use of screens. One screen for every two beds is not too many for the necessities of the average ward. One of the most practical and altogether desirable ward screens is made of a wooden frame, white enameled, covered on both sides with white oilcloth. A set of clothes-bars, from four and a half to five feet high, makes a very satisfactory frame, that is large and yet light enough for one nurse to handle.

A fair equipment for a ward of twenty beds would be:

The linen room is one of the very important parts of the institution. Demands will be made on it almost every hour, and, if the hospital is to do proper work, it must be equal to the demands. As well expect a carpenter to construct a building without tools as expect nurses to do conscientious work without a sufficient supply of bed and body linen to keep their patients in proper condition. Lack of knowledge on the part of the managers as to the amount of supplies necessary, rather than a lack of money, is accountable for the shortage of linen in many hospitals. An important part of the housekeeper’s duties is to know what supplies are on hand, and keep the board informed as to the needs. Time, and tact, and perseverance in educating them as to what is absolutely necessary for proper work, will do much to correct such defects in hospital management. It is difficult for the laity, who are perhaps accustomed to having bedding changed in their homes but once a week, and then sometimes allowing for but one clean sheet for each bed, to appreciate that a constant changing of beds goes on in a hospital, both day and night, and that economy is out of the question. A hospital can really afford to be extravagant in the matter of linen. That is one point, and perhaps the only one, in which lavish expenditure will really redound to the good of the hospital. Better cut down expense in a dozen other ways than to give rise to the criticism that the hospital has not sufficient linen to keep its patients and its beds in proper [Pg 44] condition. Cleanliness may be next to godliness in most circumstances, but no hospital can afford to let cleanliness take second rank with any other virtue. In fact, if want of cleanliness in the care of the beds or patients be noted, very grave doubts as to the godliness of the management will surely arise, be the professions in that direction never so loud.

The amount of linen required per bed will depend somewhat on the character of the work done in the hospital. Where only acute cases are handled, and emergency work is done, the supply must needs be greater, as the average number of patients entirely confined to bed will be greater. Six pairs of sheets and pillow covers for each bed is a fair amount to begin with. That number of sheets is often needed for one patient in a day, but taking the average patient in the average ward, that amount will usually be sufficient, even to provide for the extra demand in special cases. A half-dozen draw sheets for each bed in the ward are also necessary. Six face towels and four bath towels per bed is a fair estimate. Two spreads for each bed and two pairs of blankets will be sufficient for the ordinary ward, but a few extra blankets should be provided for each ward, for the use of patients who require extra heat. This estimate is based on the supposition that linen sent to the laundry Monday morning will be returned at the latest by Wednesday morning following. Every well equipped hospital has its supply of gowns for the use of any patient who needs them or cares to use them. They are best made to order of firm bleached muslin, without trimming of any kind. For ease in management they should be open all the way and should fasten in the back. Tape fastenings will be found most satisfactory, as buttons are constantly torn off in the mangle. [Pg 45]

The linen room should be really a room—not a closet. Special cupboards or closets for each ward or department will be needed, but the general linen room has special needs that do not apply to the ward closets. Plenty of light is a necessity. A work-table, a sewing machine, and a gas stove on which an iron may be heated, should be in it, besides the shelves and cupboards needed for the hospital linen supply. To this room new linen should be sent to be marked.

It will be found that a uniform system of marking linen will save time in sorting. Sheets may be marked on the wrong side at the corner of the top end, pillow covers an inch above the hem close to the seam, towels in the corner of one end just above the hem, table-napkins and tray cloths diagonally across the corner. Blankets and spreads may be marked by a tape sewn diagonally across the corner.

The person in charge of the linen room will be expected to keep the linen in repair and to account for every piece that passes through her hands. It is very important to have a systematic method of accounting for linen that will enable the housekeeper to know the amount on hand, and to discover if linen is lost. It matters not whether the washing is done on the hospital premises or sent to a commercial laundry, some system of accounting is necessary unless the housekeeper is willing for a constant depletion of blankets, sheets, towels, etc., to go on without her knowledge. Where a public laundry is patronized the importance of this matter is evident. When hundreds of towels and sheets are sent in at once, it is not unusual for linen to be taken from the large quantity to supply missing articles in the list of other [Pg 46] customers who had sent smaller amounts, from which, if articles were missing, it would be quickly discovered. The housekeeper of a certain institution relates the following incident bearing on this point: The linen of the institution was sent to a public laundry, and for some time she had been missing towels, though the laundry always claimed to return the proper number. Finally the manager of the institution happened into a barber shop and accidentally discovered there a pile of the institution towels. Inquiry revealed the fact that the barber kept strict account of his towels and the laundry had to return the number sent or pay for them. The barber cared nothing whose mark was on the towels if he got as many as he sent. A laundry employee had been in the habit of substituting linen from large institutions to make up the required number from smaller lots, and thus the problem of the missing linen for that institution was solved. The inexperienced housekeeper may perhaps settle down into the belief that of course the linen sent to the hospital laundry is safe since it does not leave the premises. If all servants and everybody about the establishment were tried and true and trustworthy, through and through, it might be safe, but in these days of possible degeneracy and certain uncertainty in the servant class, it is wise to trust implicitly but few, and to keep an eye on those.

Another point that needs some emphasis is that the housekeeper or her assistant—not the nurses or the servants—must decide when linen is to be discarded. Well-worn or torn linen should not be sent to the wards. A special drawer, marked “Discarded Linen,” should be in the general linen room, and into this the one who sorts linen can lay aside what in her judgment is unfit for wear or beyond mending. But the housekeeper should reserve for herself the privilege of deciding when an article is [Pg 47] to be used as old linen. Unless this rule is rigidly enforced, a reckless extravagance will be the result. Good towels will be used as dusters or as scouring cloths. Sheets that might have been utilized in some other way will be torn up and used as cleaning cloths, and a constant depletion of the supply will go on without the housekeeper’s knowledge. Many a housekeeper who has assumed charge of a hospital that had been previously managed without a system of linen accounting has found it one of the most difficult of her tasks to check the tendency to appropriate the hospital towels, sheets and pillow covers for cleaning purposes. Constant vigilance in that direction for months was needed to impress the household that the haphazard, loose way of handling linen was a thing of the past.

Every careful hospital housekeeper has found the necessity of a special closet, for the storing of extra linen of all kinds for times of special emergency. It is poor management to have the full supply in circulation at one time. Attention to this emergency closet will save embarrassment many times. What could be more embarrassing than to have a patient injured in an accident, brought in grimy and dirty, and not have a clean gown to put on him? And yet that very thing has happened when the hospital housekeeper has failed to anticipate the emergency.

Sheets that are worn thin in the center may be doubled and stitched together for draw sheets, and in that way will last for months. The ends of bath towels can be hemmed for wash cloths. Squares of linen from partly worn tray-cloths and napkins may often be fringed for doilies for ward medicine trays. The training in economy in supplies, and in methods of utilizing material that would otherwise be wasted, is an important part of the nurse’s training that will benefit her through life. [Pg 48]

The nurses, too, in their use of hospital linen, are responsible in no small measure for its appearance. Blood-stains and various other stains can be readily washed out when the stain is fresh. Every nurse should be taught that it is her duty to remove such stains as far as possible by a preliminary soaking and washing before being sent to mingle with other clothing in the laundry. A little salt in the water will hasten the process. If such matters were thoroughly impressed on each nurse, as a part of her duty in her hospital training, there would be fewer complaints of nurses in private practice needing an extra maid to wait on them. Stains from certain oily dressings are exceedingly difficult to remove. In fact, in the general washing it is practically impossible to thoroughly efface such stains. A little care in managing, and, as far as possible, keeping one set of sheets for cases requiring such dressing, will prevent the whole ward supply from being stained. The oldest linen should be specially set apart for such cases.

Where a regular maid is in charge of the linen room, she can usually, in addition to the general care of the linen, make up new material. The cutting of new goods is a matter for the housekeeper’s personal supervision. Each new lot of linen that is laid on the shelves for general use should be added to her inventory. Under the heading of “Discarded Linen” in her linen account book, she can mark each piece she lays aside as old linen, and by reckoning up each month the new linen that is added, and the discarded linen, can readily keep account of the amount in general use. In buying linen for a hospital it is questionable economy ever to buy cheap material. Towels and spreads should always be without fringe. [Pg 49]

In placing linen on the shelves of a general linen room some method will be found advantageous. If the rule is to lay towels and pillow covers on the shelves in piles of twenty, sheets and spreads and gowns in piles of a dozen, it is but the work of a few minutes to take an inventory of the contents of the linen room. If, in buying linen, the housekeeper has taken pains to secure glass towels with some distinctive pattern or coloring, it will be easy to keep the kitchen, diet kitchen and ward glass towels in separate piles. Red and white check toweling for the kitchen, blue and white check for the diet kitchen, and plain white toweling with a single stripe on the edge, for the ward glass towels, is a distinction easy to secure in any place. Face towels for patients can be secured with red border and for nurses and officers with blue.

Each nurse should be instructed to bring with her two laundry bags—one to be kept in her room to receive soiled linen, the other to be sent to the sorting room, to remain till the clean clothes are returned in it. A list of the articles contained should be pinned to each bag to facilitate the sorting of the clean clothes and for reference. It is needless to state that all nurse’s clothing should be marked with her full name. Initials may be sufficient marking in a home, but are useless in a hospital. If it can be brought about (and it can by insisting on it), it will be found that a uniform system of marking nurses’ clothing will be a great saving of time in sorting. To have a pile of thirty or forty nightdresses to sort and put in bags, and find no two marked in the same place, making it necessary to unfold every garment and look it over on all sides to find the mark, is an unnecessary trial and waste of time for whoever has the sorting to do. If each garment were marked on the under side of the front, which is [Pg 50] usually folded on top, to sort them would be an easy matter. To return clothing without being washed, when the nurse has not marked it properly, is the only way to teach nurses, who are habitually careless in their marking.

Printed laundry lists should be furnished for the sorting room, duplicate lists of each lot of clothes sent to the laundry being made. One list goes to the head laundress, the other is retained in the sorting room for reference.

HOUSEKEEPER’S LINEN ACCOUNT BOOK

| Date | Supplies Purchased | Supplies Received | Value | Remarks |

Perhaps no part of the hospital housekeeper’s domain will call for a greater expenditure of her energy and patience than the laundry. Though out of sight, its results are always in evidence, and failure in the laundry means that every part of the work of the establishment is handicapped. There may be abundance of linen to meet the needs of the hospital, and yet if constant supervision over the work of the laundry is not exercised, three-fourths of the linen supply may at times be found piled in the laundry, the linen room shelves empty, and the nurses flying hither and thither on borrowing expeditions when a clean towel is called for.

A wise philosopher has said, “Every man is as lazy as he dares to be,” and the average laundry employee is like the rest of the world in that respect. Few of them love the work for the work’s sake, and if the weekly wage is not sufficiently large to be attractive, they will be lazy and neglect their work if they have opportunity.

A competent manager for the laundry is essential for successful work, especially in a large institution. This person should know how to manage his staff of helpers so as to secure the best possible service, and should have a knowledge of the needs of the institution where his own department is concerned, and of the work that is important to be done without delay. Good common sense in arranging the time when the [Pg 52] different parts of the work should be done, will prevent much trouble in any laundry. Nurses’ clothing and articles not in constant demand, that are returned but once a week, can be laid aside to make way for the things in constant demand. When once a competent manager is secured, the buying of supplies may be safely entrusted to him.

But, unfortunately for the hospital housekeeper, few except the larger hospitals can afford the luxury of a skilled manager for the laundry. A head laundress is the nearest they can approach to such a luxury, and even that much needed individual is often out of reach. In many cases the hospital housekeeper, in addition to her other duties, has really to take the place of manager of the laundry.

Where several laundresses are employed, and none are fitted for directing the work of others, it is a wise provision for the housekeeper to personally divide the work and assign it, and have each laundress responsible to her. The servant problem has assumed such an acute form that it requires delicate handling in any household, and where the character of the work is as important as that of the hospital laundry, every possible tendency to friction should be avoided.

Let laundry workers understand fully what their hours of work shall be, and that they are expected to be in their places promptly at the hour. Explain the importance of having the supplies for the wards and operating rooms constantly kept up to the mark, and also the linen for the trays. Prohibit visitors during working hours. It is always better to make such prohibitions when engaging help rather than wait for some occasion to call it forth. The occasion will certainly come unless it is anticipated and prevented. Make some provision for them to do their [Pg 53] own personal washing, and let it be plainly understood they are not to take in washing from other sources to increase their income. That is sometimes tried and carried on very successfully, if it is found that the laundry has not careful supervision. If it is not desirable for their own washing to be done in connection with the hospital, then a time must be arranged for it.

Where the laundresses are mothers of families, as is often the case, this point is worth mentioning at the time of engagement. Their washing must be done—the question is, when and where. It is better to have a plain understanding about the matter than to have them attempt a course of deception. Feed the laundresses well and arrange for them to make a cup of tea or coffee between meals if they want it. The work is hard and exhausting, and they cannot put their best into it if they are hungry. Take an interest in their health and see that their minor ailments are attended to when necessary. Arrange for an afternoon off at least once in two weeks. They have little matters of business to attend to, and they need the recreation as much as other people. Arrange to visit the laundry at least every day—twice a day if possible, and not always at the same hour. Commend their work and their promptness when there is room for it. A word of appreciation will often do more to inspire them to better service than a severe rebuke. When they have worked overtime in some unusual rush, do not forget to mention your appreciation of it. Then see that they have proper things to work with. It is impossible to have satisfactory service if proper facilities are not provided. [Pg 54]

The housekeeper, where no manager of the laundry is employed, will have the purchasing and giving out of supplies and should have an idea of how much is needed for each week’s work. Provide a good quality of soap and starch. The cheaper grades are almost always more expensive owing to the additional amount necessary for the work. The better grade of starch will produce better finished work. See that the vessels used for starching are well cleansed after use. Know something about the methods used in starching. If collars, cuffs and belts are not stiff, inquire the reason. To produce a proper stiffness, the starch should be used as hot as can be borne by the hand, and well rubbed in. Clothing that is starched should be put to dry as soon as the starching is completed. If left around in baskets the articles will inevitably come out discolored. It is well to give a list of the articles requiring starching rather than trust to their judgment. Aprons and coats for the operating room that are to be put in the sterilizer need no starching, while other aprons and coats must be starched. They will not know the difference if they are not told.

If the clothes are streaked with blue, make some inquiries into the washing process. It may be the clothes have not been rinsed thoroughly free from soap. They should pass through at least two rinsing waters (three is better) to free them from soap. The first rinsing water should be quite hot. The bluing should be done in plenty of water, so that every part of the garments may be under water. In preparing the bluing water see that the blue is dissolved in a separate pail before being put into the vessel in which the articles are to be blued. In mixing the bluing water, it is easy for parts of the vessel to become deeply stained with the strong bluing solution, which will be rubbed into the clothes and leave streaks. When plenty of soda is used to soften the water there will be less trouble with black specks from the soap. Impress on them the fact that the nurses’ uniforms and colored [Pg 55] shirt waists are not to be boiled. If the uniforms are thoroughly soaked over night in a strong salt solution they will retain the color better. When uniforms are dried in the open air see that they are hung wrong side out.

Special care needs to be used in washing blankets. They should be dealt with separately and gotten through with quickly. The suds should be quite hot and a little ammonia added. The rinsing should be in water of the same temperature and they should be dried in the open air.

Whenever possible have all the hospital clothes dried in the open air. No drying room, however well constructed, can compare with nature’s process of drying by fresh air and sunshine. The best method of bleaching is by the use of the sun rays while the clothes are wet. However, in planning for laundry work, it is never wise to depend entirely on open air drying. An artificial dryer is a necessity where promptness is required. Quick drying is essential to good work. Where bad work is done, the trouble is oftener in the washing than in the drying.

In planning for the ironing much may be done to facilitate the work. Little labor-saving devices can be introduced which will increase the amount of work done in a day. Ironing boards of special shapes, and for special purposes, and tables of various designs can be had for a trifle and will result in a saving of time and more finished work. A box of thin pine boards with a hinge cover and with perforations in the sides is a convenient receptacle for storing dampened clothing waiting to be ironed. See that they have proper irons for the different parts of their work and that they have wax to use as needed. Supply unbleached muslin for ironing sheets or the hospital sheets will be found covering the ironing boards. Instruct them to keep their ironing sheets clean. [Pg 56] Well-finished work cannot be produced on a dirty ironing sheet.

Let the laundresses understand that bad work will not be accepted, and they will not send it. Bad work that was passed in the linen room has often caused embarrassment in the operating room. As far as possible, have a routine order for laundry work, and expect the laundresses to comply. If they understand that clothing sent from the wards on Tuesday morning must be returned to the wards not later than Thursday morning, they can arrange to have it done, while if no limit is set for the clothes to be in the laundry, the haphazard results will be constantly felt in the wards.

Have a method of folding linen and insist on that method being followed. It is impossible to have neat-looking shelves in the linen room if no uniformity be observed about folding in the laundry.

Then see that the work rooms are kept clean. It is useless to expect clean linen unless the laundry and its furnishings are kept in proper condition. The woodwork and windows and floors should be as scrupulously clean as any other part of the hospital. But they will not be kept so unless a time is set for the cleaning, and someone sees that it is done.

Greasy towels or clothes, from the kitchen, pantries and bake rooms, should either be entirely washed by those who use them, or have a preliminary washing before being sent to the laundry. Such articles cannot be washed with any other clothing; a special suds must be gotten ready and time spent that would have counted for more if spent on other work.

A false economy in planning a hospital often results in a space entirely inadequate being set apart for the laundry. As the general work of the hospital increases it is then found impossible to meet the [Pg 57] demands, and recourse has to be had to the public laundry—always an expensive arrangement. Another common mistake, is to place the laundry in the basement, where lack of light and air is always a hindrance to good work. Whenever possible, the laundry should be located in a separate building, where plenty of light and air and sunshine can penetrate, and where there is room to separate the clothing while in its different processes and proper work can be done. All clothing should be well aired and thoroughly dry before it leaves the laundry, so that it may immediately be placed on the shelves for use.

It is difficult to give an accurate estimate regarding the cost of installation and operation of a laundry plant, as conditions vary greatly. A list of the articles required for a plant capable of doing the work of a sixty-bed hospital is appended. In preparing this list the elimination, so far as possible, of all expensive features, has been attempted. A laundry plant, like nearly everything else, can be figured on in various ways, and at largely varying cost, so that, with different machines, a plant with the same amount of machinery will cost three times as much as another of practically equal capacity and actual working value. It is well, therefore, before purchasing a plant, to be thoroughly informed regarding the actual needs of a hospital, the various makes and grades of machines, cost of operating, etc.

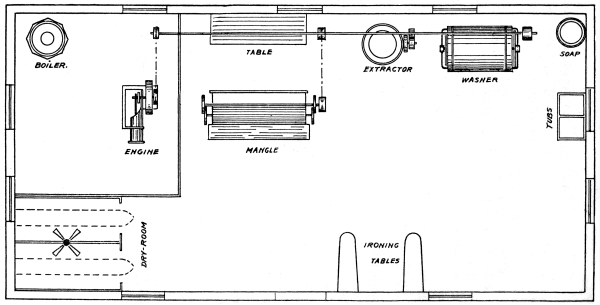

A very serviceable laundry equipment for a hospital of fifty to sixty patients, is made up as follows: [Pg 58]

One 12 h. p. vertical boiler, complete with suitable injector and regular boiler trimmings.

One 6 h. p. horizontal engine, complete with all engine trimmings, and a sight feed lubricator.

One 36 × 30 wood washer.

One 20-inch solid curb extractor, countershaft attached.

One 40-gallon galvanized steel soap tank, with circular boil pipe.

One sectional dry room, arranged to handle plain or fancy clothes, and complete with three metal trucks, ventilating fan, etc.

One 66-inch steam mangle.

One 30-inch reversible body ironer.

Two ironing tables.

One truck tub.

This outfit will cost about $1,100 to $1,200, including pipes, pipe fittings, valves, shafting, etc., and will require a floor space of about 24 × 48 feet. The accompanying diagram gives a good idea of an economical arrangement of such a plant.

In one institution having about one hundred patients, a plant similar to this is used. All the work is done with two women and one man, the man looking after the power and the washing. If the hospital employs a man who can look after the power for two or three days in a week, the cost for help may be reduced.

Where the laundry work of a hospital runs up to $750 or $1,000 a year, there are but few instances where a direct financial saving will not be effected by the hospital operating its own laundry plant. [Pg 59]

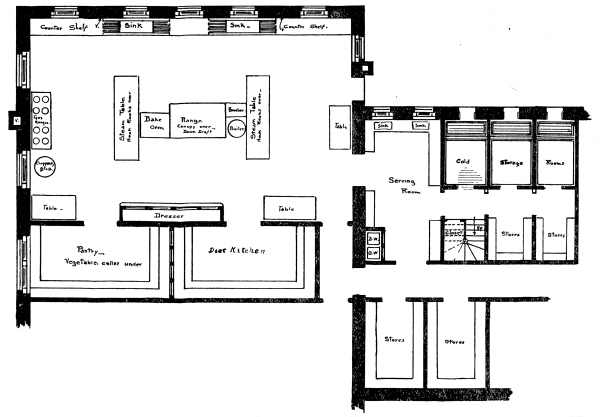

With the advance in science, and a better knowledge of things desirable and things avoidable in hospital construction, a gradual change is taking place in institutions designed for the care of the sick. Perhaps in no department have greater changes taken place than in the construction of the modern hospital kitchen. Instead of being located in the basement, where odors from cooking were diffused throughout the whole building, and where absence of light invited the accumulation of dirt, the kitchen is now located in the top story, or, if the hospital be built on the cottage plan, in a separate building. In deciding on the location, one thought should be prominent—the possibility of conveying cooked food without delay to those for whom it is prepared. With proper facilities for keeping food hot, this important point is not difficult of accomplishment.

Wherever the kitchen is located, it should be large, light and thoroughly ventilated. Proper care in planning and construction will insure the installation of vent flues and ducts to carry off smoke and odors, as soon as generated. As far as possible, the interior of the kitchen and its furnishings should be constructed of non-absorbent material. Those who have had experience with cement floors claim for them that they are splendidly absorbent of grease, exceedingly difficult to cleanse, and liable to crack, thereby furnishing crevices [Pg 61] for the deposit of dirt of all kinds. Therefore, in a hospital designed to be thoroughly sanitary, cement floors will have no place. Tile seems to be the material that gives the most general satisfaction for kitchen floors and walls. A white vitrified tile, laid on a heavy foundation, having the joints between the tiles carefully sealed with cement, gives perhaps the nearest to the ideal kitchen floor yet attained. If the floor is constructed so as to slope gently toward a drain properly trapped and protected, the cleaning will be facilitated. The side walls and ceiling of glass tile, with the corners well rounded, gives a surface that is not only bright and beautiful, but thoroughly sanitary. Such a finish will endure the most severe cleaning without injury. Wood mouldings, that invite the deposit of dust, will of course be avoided.

The sinks in the hospital should be placed at sufficient distance from the walls, so as to be accessible on all sides.

A hygienic outfit for the hygienic kitchen is of course essential, but sometimes more difficult to secure than is the sanitary room. Dressers and drawers for the accommodation of the kitchen utensils must be provided, and in these things crevices and angles and dark corners and all sorts of complications of this character seem unavoidable. If these cabinets could be of metal, all angles and corners done away with by the finishing with curves, the shelves loose fitting and easily removable, it would be a decided advance in kitchen arrangements. The drawers could be made in the same way, the emphasis being on the point “easily removable.” Thus constructed, the person in charge would find it easier to remove them than to undertake to clean them while in position.

Architects say, that in hospitals where steam boilers and engines for supplying power for elevators, electric lights, laundries, etc., are in [Pg 62] use, arrangements should be made to utilize for cooking the large amount of exhaust steam, that ordinarily goes to waste. When this is done, ashes, smoke and their attendant ills can be avoided. The hospital may then be not only “a thing of beauty,” but “a joy forever,” and the drudgery of that department greatly reduced.

Through the courtesy of Mr. W. J. Palmer, architect, of Washington, D. C., we are able to present drawings for a hospital kitchen embodying most of the features above mentioned. The drawings were designed for a kitchen located on the ground floor in a separate building, but with a few changes could be easily adapted to a kitchen located on the top floor. The range is located in the center of the room, with steam tables on each side to keep the cooked food hot. A gas range is provided and a chopping block, tables and dressers are arranged conveniently for work. On one side is a small pantry, which leads to the vegetable cellar beneath, and adjoining it is the main diet kitchen. At one end is the serving room, where the food is divided and dispatched to the wards. Leading from the serving room is a hall, off which on one side are the cooling rooms, and on the other side storerooms for staple supplies. If the kitchen be on the top floor, a cooling room on that floor, sufficient at least to care for one day’s provisions, will be necessary, having the main cooling rooms located on the main floor or in the basement.