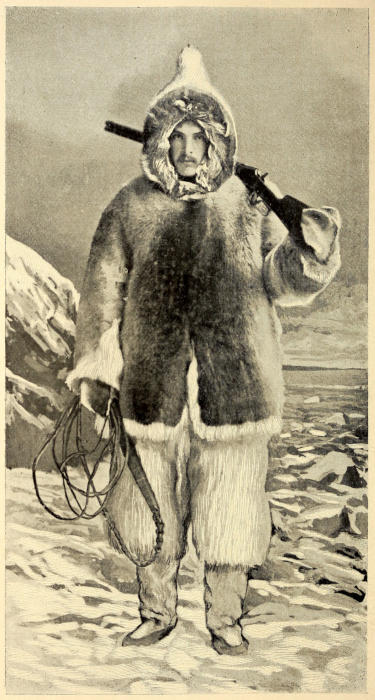

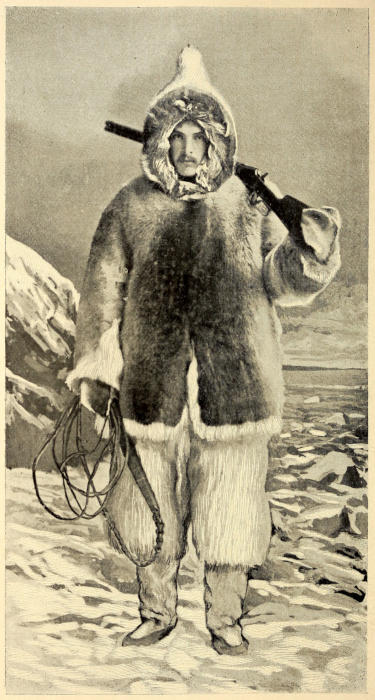

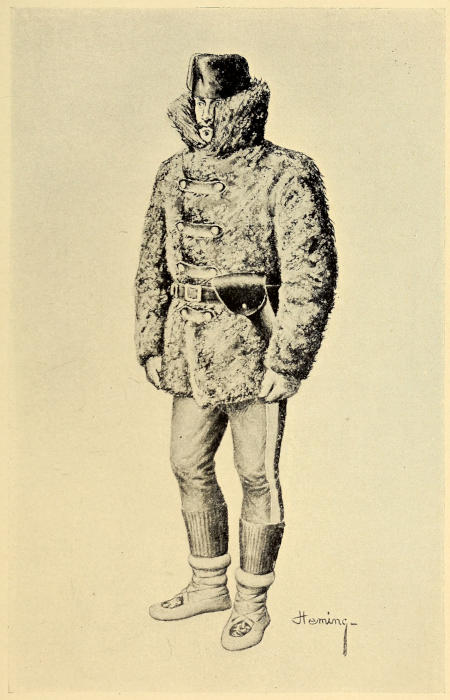

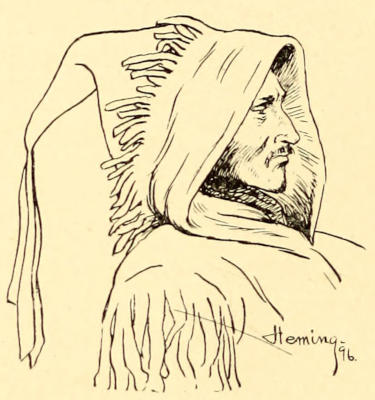

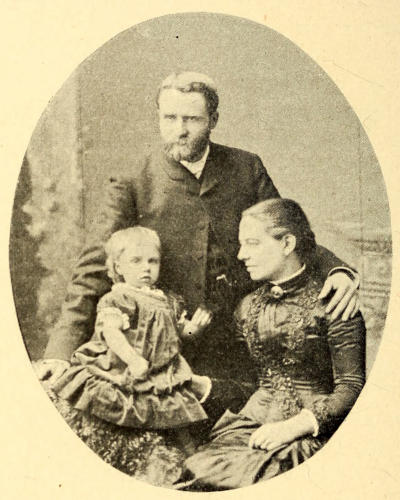

J. W. TYRRELL.

(In Eskimo costume.)

Title: Across the sub-Arctics of Canada

A journey of 3,200 miles by canoe and snowshoe through the Barren Lands

Author: J. W. Tyrrell

Illustrator: Arthur Heming

Release date: January 22, 2025 [eBook #75178]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Dodd, Mead and Co, 1898

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/75178

Credits: Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

J. W. TYRRELL.

(In Eskimo costume.)

ACROSS THE SUB-ARCTICS

OF CANADA

A JOURNEY OF 3,200 MILES BY CANOE

AND SNOWSHOE THROUGH THE

BARREN LANDS

BY

J. W. TYRRELL, C.E., D.L.S.

INCLUDING A LIST OF PLANTS COLLECTED ON THE EXPEDITION,

A VOCABULARY OF ESKIMO WORDS, A ROUTE MAP

AND FULL CLASSIFIED INDEX

With Illustrations from Photographs taken on the

Journey, and from Drawings by

ARTHUR HEMING

NEW YORK:

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY.

1898

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Toronto to Athabasca Landing | 7 |

| II. | Down the Athabasca | 19 |

| III. | Running the Rapids | 36 |

| IV. | Chippewyan to Black Lake | 49 |

| V. | Into the Unknown Wilderness | 70 |

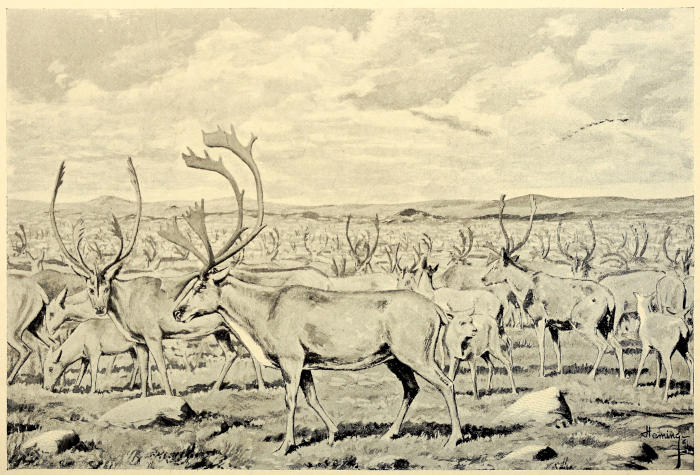

| VI. | The Home of the Reindeer | 80 |

| VII. | A Great Frozen Lake | 90 |

| VIII. | On the Lower Telzoa | 102 |

| IX. | Meeting with Natives | 114 |

| X. | The Eskimos | 127 |

| XI. | Customs of the Eskimos | 147 |

| XII. | Down to the Sea | 172 |

| XIII. | Adventures by Land and Sea | 181 |

| XIV. | Polar Bears | 189 |

| XV. | Life or Death? | 199 |

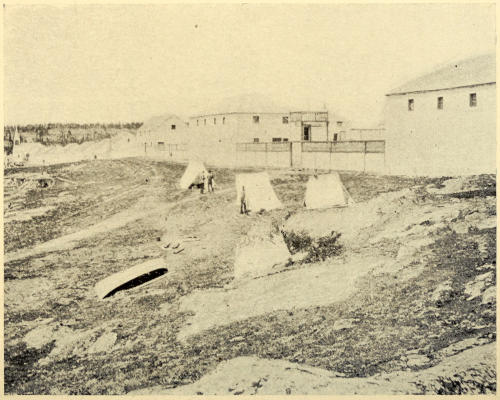

| XVI. | Fort Churchill | 210 |

| XVII. | On Snowshoes and Dog-Sleds | 219 |

| XVIII. | Crossing the Nelson | 229 |

| XIX. | Through the Forest and Home Again | 240 |

| APPENDIX | ||

| I. | Plants Collected on the Expedition | 251 |

| II. | Eskimo Vocabulary of Words and Phrases | 273 |

| PAGE | |

| J. W. Tyrrell | Frontispiece |

| J. Burr Tyrrell | 8 |

| Our Canoemen | 11 |

| Hudson’s Bay Company’s Traders | 13 |

| A Hudson’s Bay Company’s Interpreter | 15 |

| A Pioneer of the North | 16 |

| Indians of the Canadian North-West | 18 |

| Trooper, N.-W. Mounted Police, in Winter Uniform | 26 |

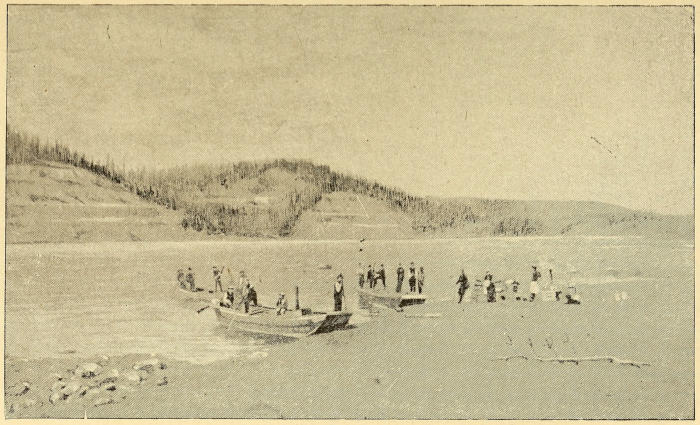

| Landing of Scows above Grand Rapid | 29 |

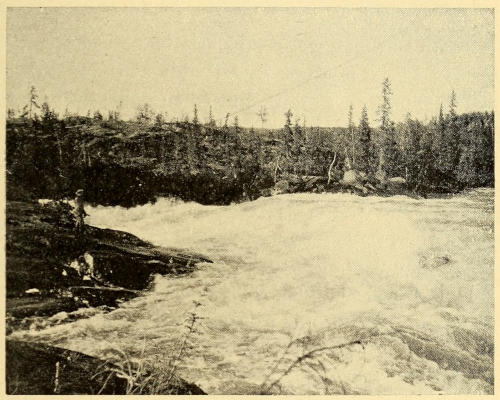

| Grand Rapid, Athabasca River | 31 |

| English-Chippewyan Half-Breed | 32 |

| Neck Developed by the Tump-Line | 35 |

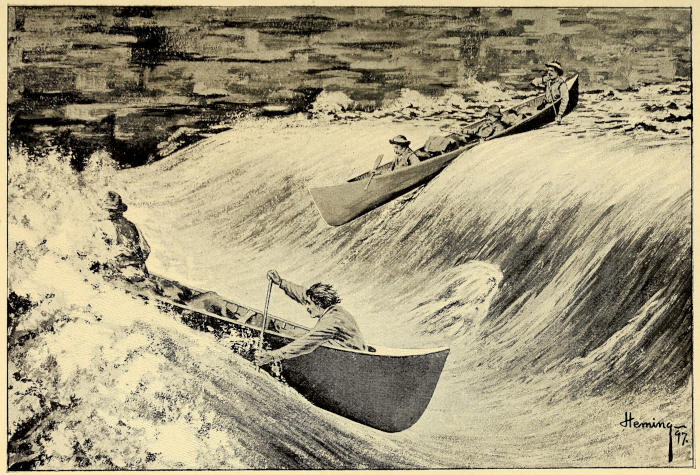

| Shooting the Mountain Rapid, Athabasca River | 40 |

| Store, Fort McMurray | 41 |

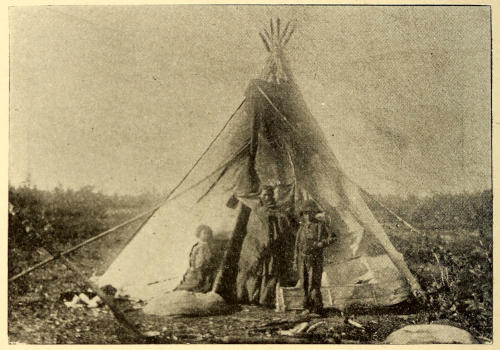

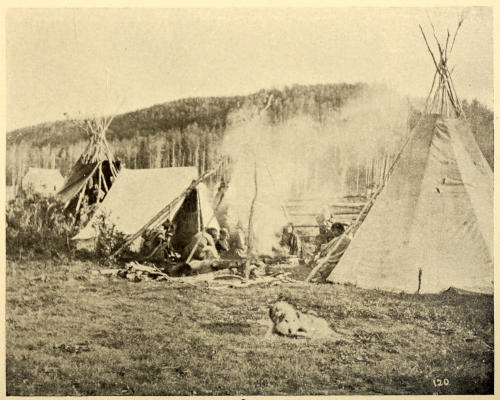

| Chippewyan Camp | 42 |

| Starving Cree Camp, Fort McMurray | 44 |

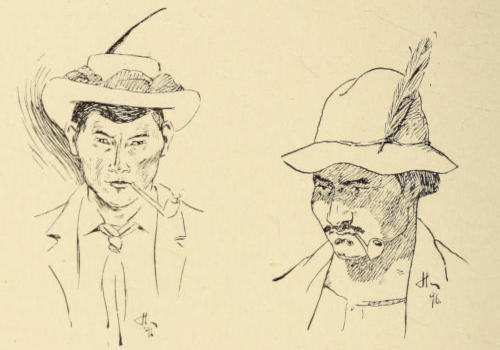

| A Dandy of the North. A Voyageur | 46 |

| An English-Cree Trapper | 48 |

| Fort Chippewyan | 50 |

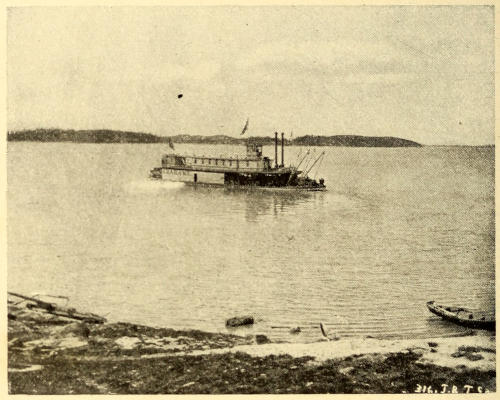

| Steamer “Grahame” | 52 |

| Landing on North Shore, Lake Athabasca | 56 |

| A Typical Northland Father | 59 |

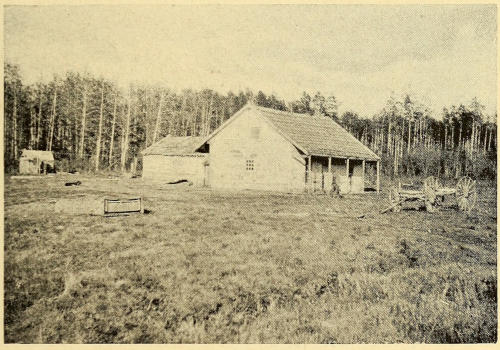

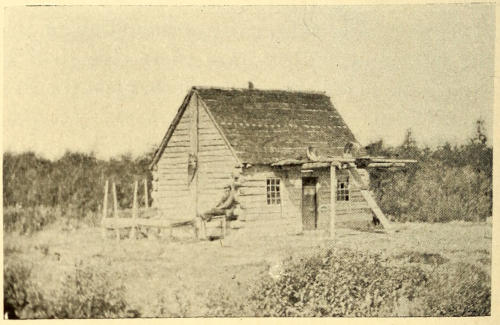

| Indian Log House | 64 |

| Cataract, Stone River | 65 |

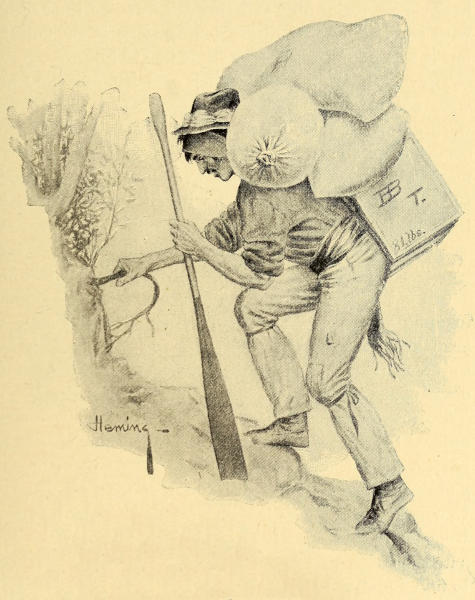

| A Difficult Portage | 67 |

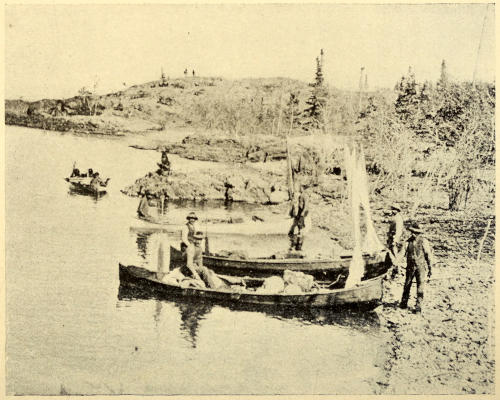

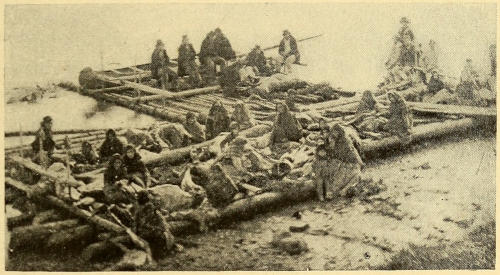

| Indian Rafts Loaded with Venison | 69 |

| A. R. C. Selwyn, C.M.G., F.R.S. | 74 |

| Scotch-Cree Half-Breed | 79[vi] |

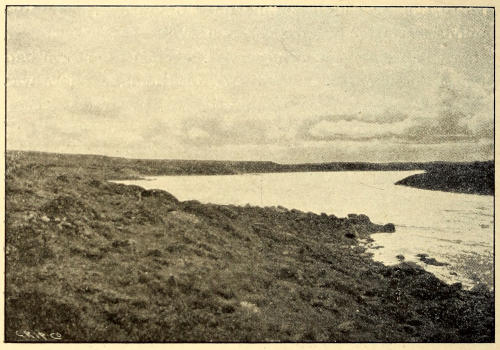

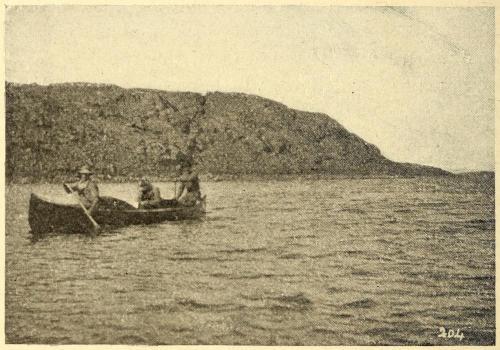

| Telzoa River | 82 |

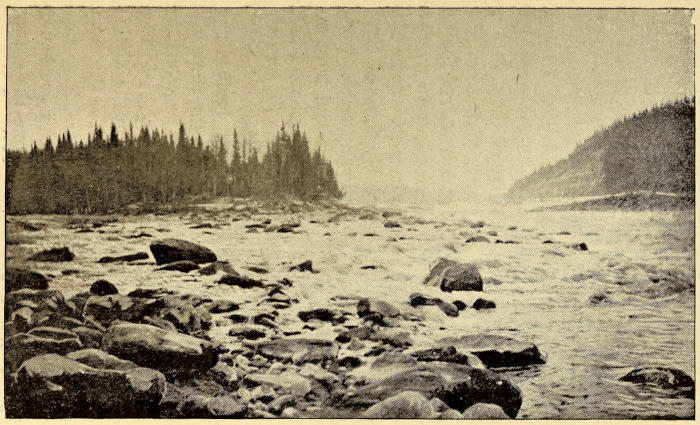

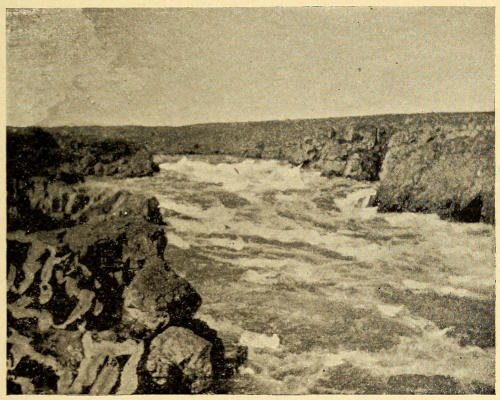

| Rapids, Telzoa River | 83 |

| Herd of Reindeer | 85 |

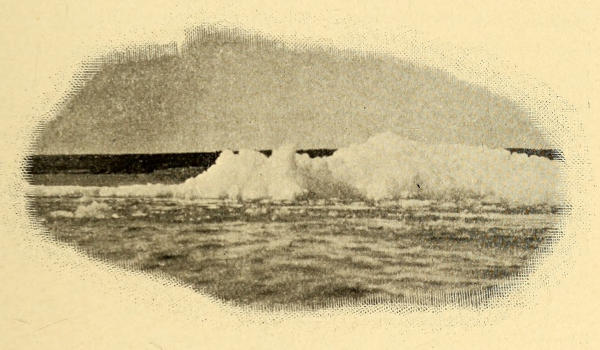

| Ice on the Shore of Markham Lake | 91 |

| Tobaunt Lake | 94 |

| French-Cree Half-Breed | 101 |

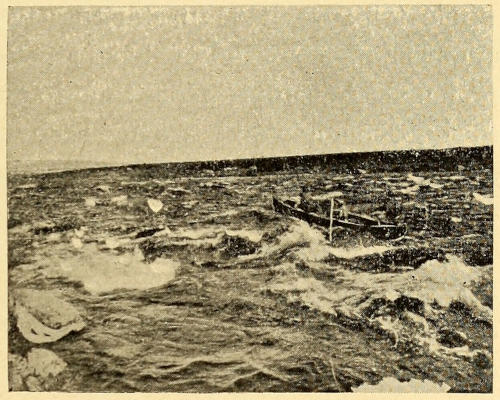

| Rapids on the Lower Telzoa | 103 |

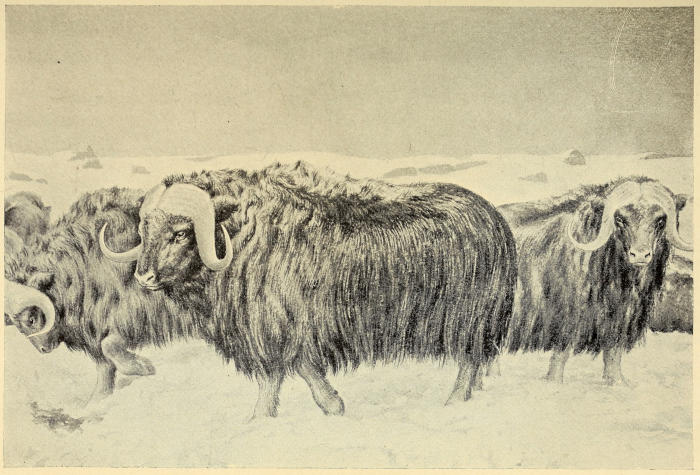

| Musk Oxen | 104 |

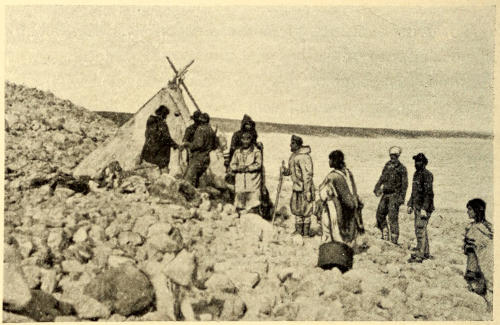

| Eskimo “Topick,” Telzoa River | 106 |

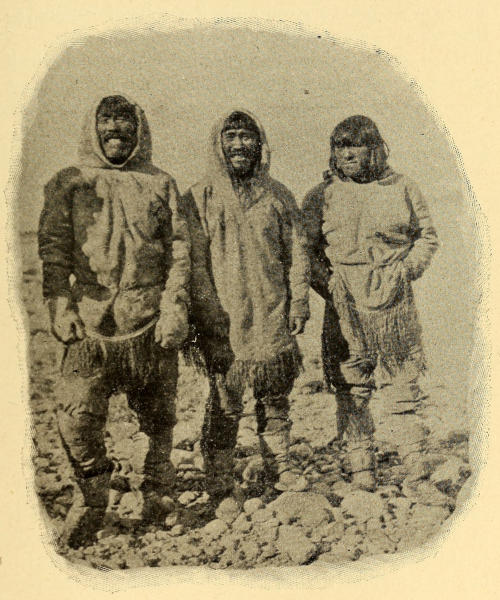

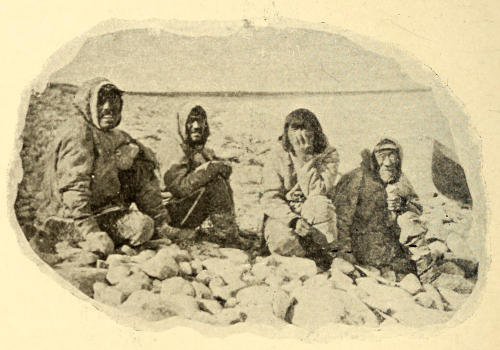

| Eskimo Hunters | 121 |

| Group of Eskimos | 122 |

| Icelandic Settler | 125 |

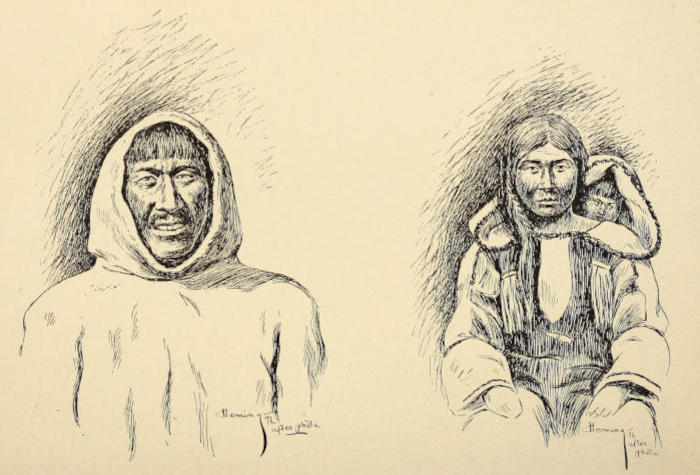

| An Eskimo. Eskimo Woman | 126 |

| Half-Breed Hunter with Wooden Snow-Goggles | 134 |

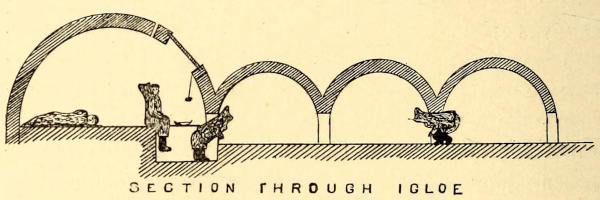

| Section Through Igloe | 136 |

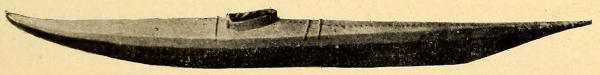

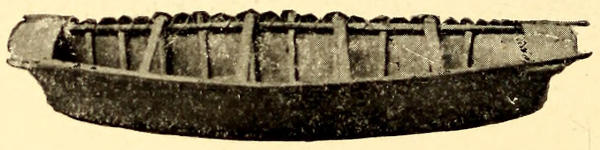

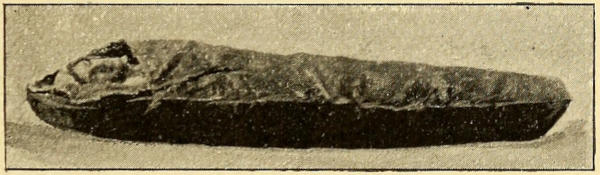

| Eskimo Kyack | 141 |

| Eskimo Oomiack | 142 |

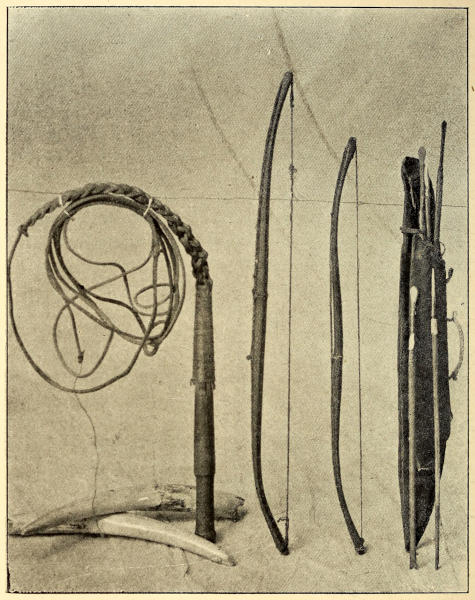

| Dog-Whip, Walrus Tusks and Bows and Arrows | 146 |

| Harpoons, Lances and Spears | 154 |

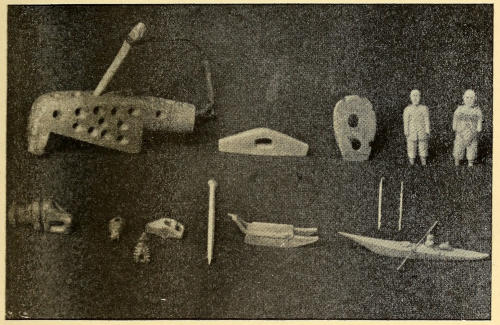

| Eskimo Games and Toys | 163 |

| Half-Breed Boy | 180 |

| Blackfoot Boy | 188 |

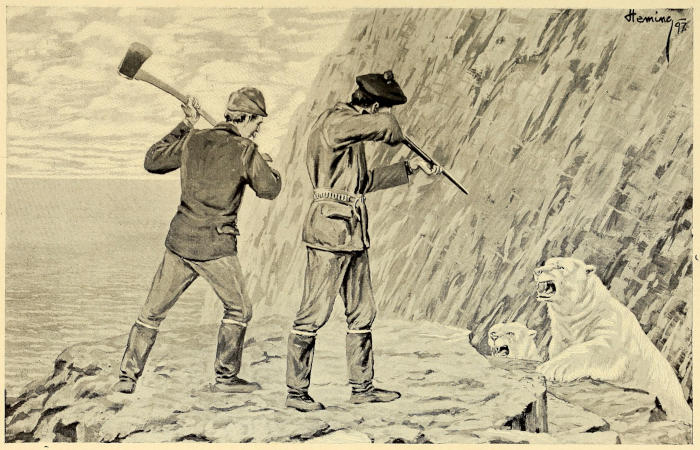

| Encounter With Polar Bears | 196 |

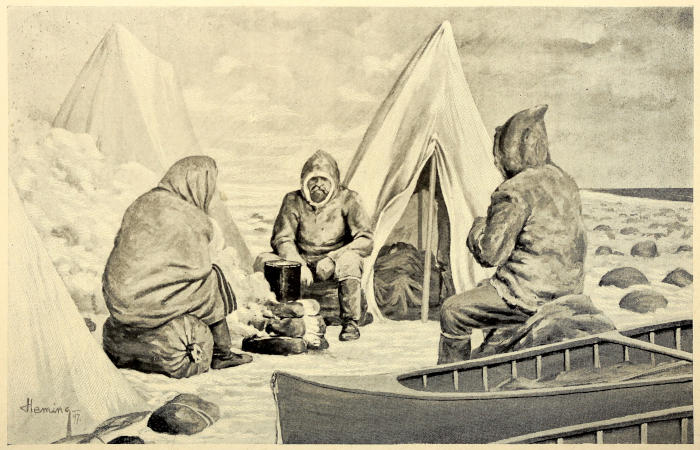

| The Last of Our Provisions | 199 |

| French Salteaux Girl | 209 |

| Rev. Joseph Lofthouse and Family | 212 |

| Ruins of Fort Prince of Wales | 216 |

| Ice-Block Grounded at Low Tide | 218 |

| N.-W. M. P. “Off Duty” | 228 |

| Half-Breed Dog-Driver | 229 |

| Hudson’s Bay Company’s Store, York Factory | 238 |

| Red-Deer Cow-Boy | 239 |

| Dog-Train and Carryall | 240 |

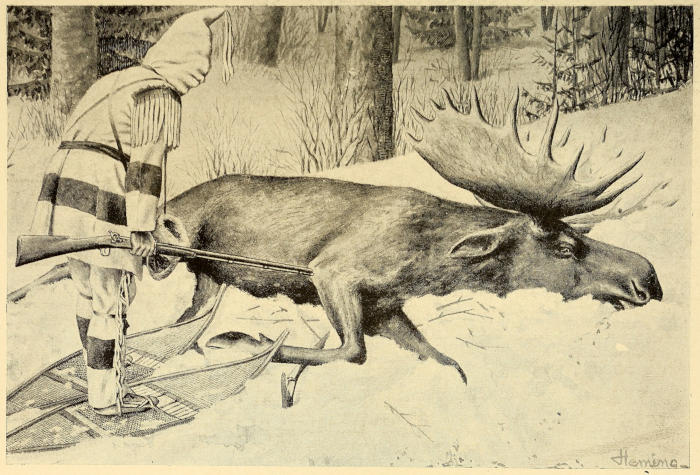

| Cree Hunter’s Prize | 250 |

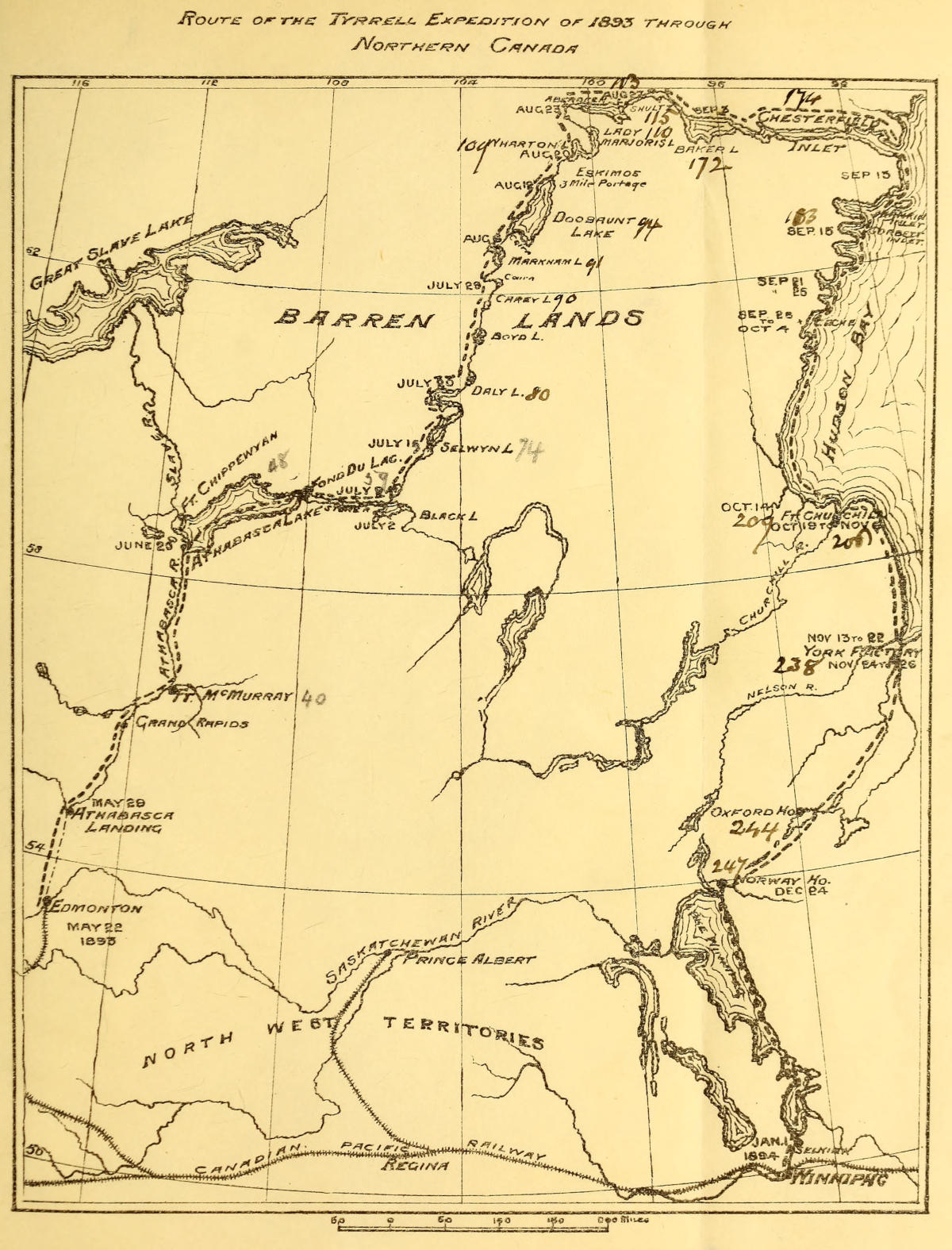

Route of the Tyrrell Expedition of 1893 through Northern Canada

On the morning of the 10th of May, 1893, in response to a telegram from Ottawa, I took train at Hamilton for Toronto, to meet my brother, J. Burr Tyrrell, of the Canadian Geological Survey, and make final arrangements for a trip to the North.

He had been authorized by the Director of that most important department of the Canadian Government to conduct, in company with myself, an exploration survey through the great mysterious region of terra incognita commonly known as the Barren Lands, more than two hundred thousand square miles in extent, lying north of the 59th parallel of latitude, between Great Slave Lake and Hudson Bay. Of almost this entire territory less was known than of the remotest districts of “Darkest Africa,” and, with but few exceptions, its vast and dreary plains had never been trodden by the foot of man, save that of the dusky savage.

During the summer of 1892 my brother had obtained some information concerning it from the Chippewyan Indians in the vicinity of Athabasca and Black Lakes,[8] but even these native tribes were found to have only the vaguest ideas of the character of the country that lay beyond a few days’ journey inland.

In addition to this meagre information, he had procured sketch maps of several canoe routes leading northward toward the Barren Lands. The most easterly of these routes commenced at a point on the north shore of Black Lake, and the description obtained of it was as follows: “Beginning at Black Lake, you make a long portage northward to a little lake, then across five or six more small ones and a corresponding number of portages, and a large body of water called Wolverine Lake will be reached. Pass through this, and ascend a river flowing into it from the northward, until Active Man Lake is reached. This lake will take two days to cross, and at its northern extremity the Height of Land will be reached. Over this make a portage until another large lake of about equal size is entered. From the north end of this second large lake, a great river flows to the northward through a treeless country unknown to the Indians, but inhabited by savage Eskimos. Where the river empties into the sea we cannot tell, but it flows a great way to the northward.”

From the description given, it appeared that this river must flow through the centre of the unexplored territory, and thence find its way either into the waters of Hudson Bay or into the Arctic Ocean. It was by this route we resolved to carry on the exploration, and, if possible, make our way through the Barren Lands.

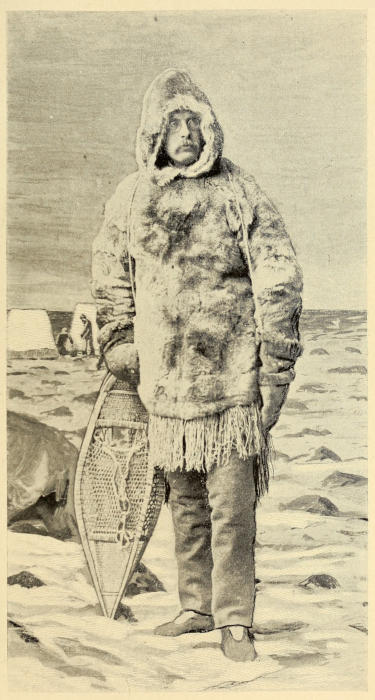

J. BURR TYRRELL.

(Leaving Fort Churchill.)

One of the first and most important preparations for the journey was the procuring of suitable boats, inasmuch as portability, strength and carrying capacity[9] were all essential qualities. These were obtained from the Peterboro’ Canoe Company, who furnished us with two beautiful varnished cedar canoes, eighteen feet in length, and capable of carrying two thousand pounds each, while weighing only one hundred and twenty pounds. Arrangements had also been made to have a nineteen foot basswood canoe, used during the previous summer, and two men in readiness at Fort McMurray on the Athabasca River.

Four other canoemen were chosen to complete the party, three of them being Iroquois experts from Caughnawaga, Quebec. These three were brothers, named Pierre, Louis and Michel French. Pierre was a veteran canoeman, being as much at home in a boiling rapid as on the calmest water. For some years he had acted as ferryman at Caughnawaga, and only recently had made a reputation for himself by running the Lachine Rapids on Christmas day, out of sheer bravado. His brother Louis had won some distinction also through having accompanied Lord Wolseley as a voyageur on his Egyptian campaigns; while Michel, the youngest and smallest of the three, was known to be a good steady fellow, boasting of the same distinction as his brother Louis.

The other man, a half-breed named John Flett, was engaged at Prince Albert, in the North-West. He was highly recommended, not so much as a canoeman, but as being an expert portager of great experience in northern travel, and also an Eskimo linguist.

The two men, James Corrigal and François Maurice, who through the kindness of Mr. Moberly, the officer of the Hudson’s Bay Company at Isle-à-la-Crosse, were[10] engaged to meet us with a third canoe at Fort McMurray, were also western half-breeds, trained in the use of the pack-straps as well as the paddle, and were a pair of fine strong fellows. Thus it was arranged to combine in our party the best skill both of canoemen and portagers.

Our reasons for not employing the Indians from Lake Athabasca were, that these natives had on nearly all previous expeditions proved to be unreliable. Such men as we had engaged, unlike these Indians, were free from any dread of the Eskimos, and as we advanced soon became entirely dependent on us as their guides. Besides, they were more accustomed to vigorous exertion at the paddle and on the portage than the local Indians, who are rather noted for their proficiency in taking life easy.

Next in importance to procuring good boats and canoemen was the acquisition of a complete set of portable mathematical instruments, but after some difficulty these, too, were obtained. The following is a list of them: One sextant with folding mercurial horizon, one solar compass, two pocket compasses, two prismatic compasses, one fluid compass, two boat logs, two clinometers, one aneroid barometer, a pair of maximum and minimum thermometers, one pocket chronometer, three good watches, a pair of field-glasses, an aluminum binocular, and a small camera. These, though numerous, were not bulky, but they comprised a part of our outfit over which much care had to be exercised throughout the journey. A bill of necessary supplies was also carefully made out, and the order for them forwarded to the Hudson’s Bay Company’s store at Edmonton, with instructions to have them freighted down the Athabasca River to Fort Chippewyan, on Lake Athabasca, as early as possible.

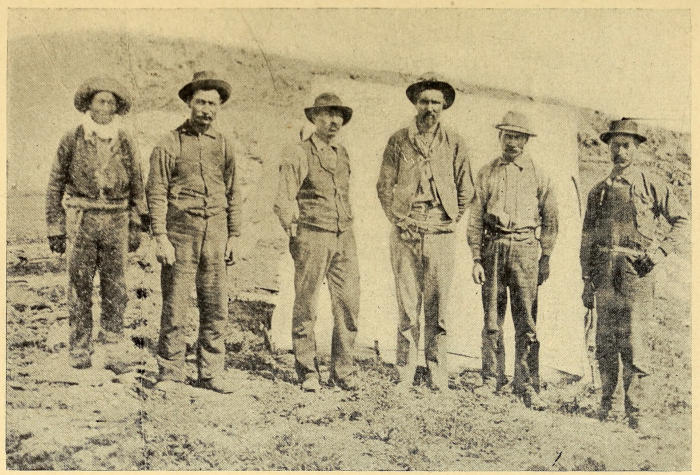

OUR CANOEMEN.

François Maurice. Pierre French. John Flett. Jim Corrigal. Michel French. Louis French.

The above and a hundred and one other preparations having been completed, my brother and I bade farewell to our homes, and on the 16th of May boarded the North Bay evening express at Toronto. The journey was not begun without the stirring of tender emotions, for to me it meant separation, how long I knew not, from my young wife and baby boy five months old, and to my brother it meant separation from one too sacred in his eyes to mention here.

Once aboard the train we made ourselves as comfortable as possible for a five days’ ride. I do not propose to weary my readers with a detailed account of the long run across continent by rail, as it is not reckoned a part of our real journey; in passing I will merely make the briefest reference to a few of the incidents by the way.

It was not until after many delays between North Bay and Fort William on the Canadian Pacific Railway, owing chiefly to the disastrous floods of that year, which inundated the track for long distances, washed it out at several points and broke one of the railway bridges, that we arrived at Winnipeg, the capital of the Province of Manitoba. Upon reaching the city it was found that our canoes, which had been shipped to Edmonton some time previously, had not yet passed through. After considerable telegraphing they were located, and it was found that they would arrive on the following day. In consequence of this and other business to be transacted with the Commissioner of the Hudson’s Bay Company, we were obliged to remain here for a day. During our[13] brief stay we were warmly greeted by many friends, and were most kindly entertained at Government House by the late Lieutenant-Governor, Sir John Schultz, and Lady Schultz, to whom we were indebted for the contribution to our equipment of several articles of comfort.

HUDSON’S BAY COMPANY’S TRADERS.

The next day we bade our Winnipeg friends good-bye and took the C. P. R. train for the West. The route lay through vast areas of the most magnificent agricultural country, as a rule level and unbroken, save by the innumerable and ancient but still deep trails of the buffalo. Little timber was observed, excepting in isolated patches and along the river valleys, and for the most part the land was ready for the plough. Passing through many new but thriving towns and settlements by the way, we arrived early on the morning of the 22nd at the busy town of Calgary, pleasantly situated in the beautiful[14] valley of the South Branch of the Saskatchewan River, and just within view of the snow-clad peaks of the Rocky Mountains. From Calgary our way lay toward the north, via the Edmonton Branch of the C. P. R., and after a stay of only a few hours we were again hurrying onward. On the evening of the same day, in a teeming rain, we reached Edmonton, the northern terminus of the railway.

Edmonton is a town situated on both banks of the North Branch of the Saskatchewan, and at this time was in a “booming” condition, particularly upon the southern bank. Many large business houses were being erected, and property was selling at stiff prices. Edmonton is chiefly noted for its lignite mines, which are worked to a considerable extent, and produce coal of very fair quality. The seams are practically of unlimited extent, and are easily accessible in many places along the river banks. Gold is also washed from the sands in paying quantities, while the town is surrounded by a fair agricultural and grazing country. Petroleum, too, has been discovered in the vicinity, and indications are that in the near future Edmonton will be a flourishing city.

The older part of the town is situated on the north side of the river, and communication is maintained by means of an old-fashioned ferry, operated by cables and windlass. As the Hudson’s Bay Company’s stores and offices from which our supplies were to be forwarded are situated on the north side, we crossed over on the ferry, and engaged rooms at the Jasper House. Upon enquiry we were gratified to find that the supplies and men, excepting the two who were to meet us later, had all arrived in safety. Our provisions, which were to be[15] freighted down as far as Lake Athabasca by the Hudson’s Bay Company, had not yet gone, but were already being baled up for shipment. The completion of this work, which was done under the supervision of my brother and myself, together with the making up of accounts and transaction of other business, occupied several days. But by the morning of the 27th of May our entire outfit, loaded upon waggons, set off on the northward trail leading to Athabasca Landing, a small trading-post situated one hundred miles distant on the banks of the great Athabasca River.

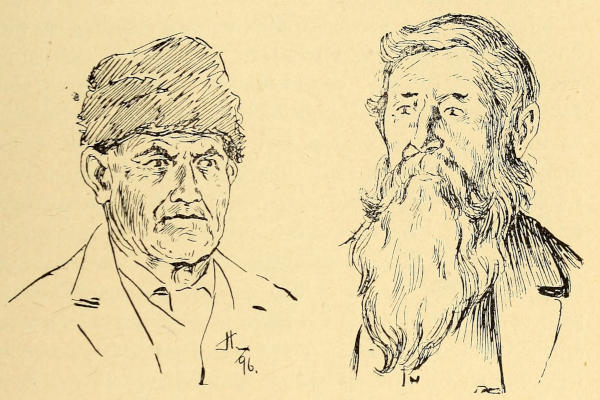

A H. B. C. INTERPRETER.

Two days later, being Monday morning, my brother and I, accompanied by a driver only, started out in a light vehicle in rear of the outfit. The weather was showery, and the trail in many places very soft. Occasionally deep mud-holes were encountered, bearing evidence of the recent struggles of the teams of our advance party, but as we were travelling “light,” we had little difficulty in making good progress. Later in the day the weather cleared, permitting us to enjoy a view of the beautiful country through which we were passing. As to the soil, it was chiefly a rich black loam, well covered, even at this early season, between the clumps of poplar scrub, by rich prairie grass. A few settlers were already in the field, and had just built or were building[16] log cabins for themselves on one side or other of the trail. A little farther on our way the country became more hilly, the soil more sandy, and covered by the most beautiful park-like forests of jack-pine. Many of the trees were as much as fifteen inches in diameter, but the average size was about eight.

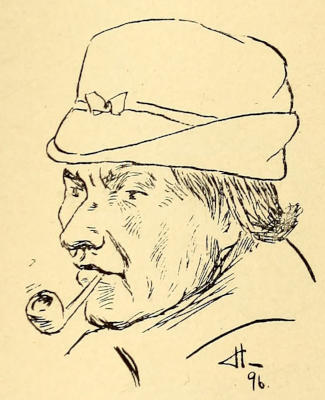

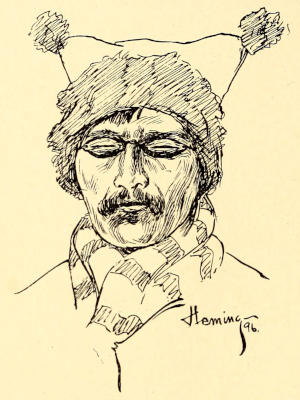

A PIONEER OF THE NORTH.

(Drawn from life by Arthur Heming.)

After passing through some miles of these woods we again emerged into more open country, wooded alternately in places by poplar, spruce and jack-pine. About nine o’clock that evening, when half-way to the Landing, we reached the Height of Land between the two great valleys of the Saskatchewan and Athabasca rivers. Here, upon a grassy spot, we pitched our first camp. As the night was clear no tents were put up, but, after partaking of some refreshment, each man rolled up in his blanket and lay down to sleep beneath the starry sky. We rested well, although our slumbers were somewhat broken by the fiendish yells of prairie wolves from the surrounding scrub, and the scarcely less diabolical screams of loons sporting on a pond close by. An effort was made to have the latter nuisance removed, but any one who has ever tried to shoot loons at night will better understand than I can describe the immensity of the undertaking.

About nine o’clock on the evening of the 30th of May we arrived at Athabasca Landing, only a few hours after the loads of supplies, which we were glad to find had all come through safely.

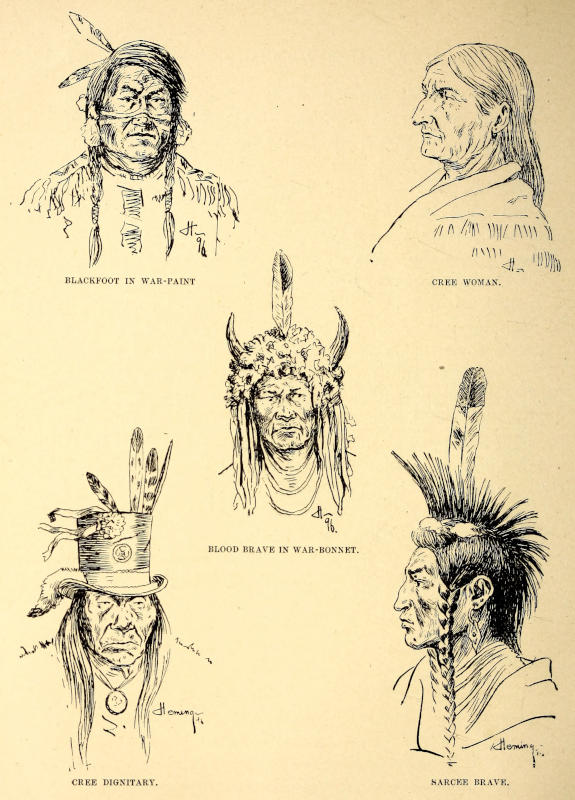

INDIANS OF THE CANADIAN NORTH-WEST.

BLACKFOOT IN WAR-PAINT. CREE WOMAN. BLOOD BRAVE IN WAR-BONNET. CREE DIGNITARY. SARCEE BRAVE.

(Drawn from life by Arthur Heming.)

The town of Athabasca Landing consists in all of six log buildings, picturesquely set in the deep and beautiful valley of one of the greatest rivers of America. Though not of imposing size, it is nevertheless an important station of the Hudson’s Bay Company, being the point from which all supplies for the many northern trading-posts along the Athabasca and Mackenzie rivers are shipped, and the point at which the furs from these places are received. In order to provide for this shipping business, the Company has a large warehouse and wharf.

It is a fact I think not very well known, that from this place up stream for about one hundred miles and down for fifteen hundred miles to the Arctic Ocean, this great waterway, excepting at two rapids, is regularly navigated by large river steamers, owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company and employed in carrying supplies for their posts and the furs which are secured in trade. Because of these two impassable rapids the river is divided into three sections, necessitating the use of three steamers, one for each section. Goods are transported from one boat to the other over the greater part of the rapids by means of scows, but for a short[20] distance, at the Grand Rapid, by means of a tramway built for the purpose.

As we had previously ascertained, the steamer Athabasca was due to leave the Landing on her down-stream trip on or about the 1st of June, so, taking advantage of the opportunity, we shipped the bulk of our stuff to Fort Chippewyan, situated about three hundred and fifty miles down the river on Lake Athabasca. Everything excepting the canoes and provisions sufficient to take us to Chippewyan was loaded upon the steamer. Letters were written and sent back to Edmonton by the drivers, and on the evening of the last day of May we launched our handsome “Peterboroughs” in the great stream, and commenced our long canoe voyage.

The arrangement of the party was as follows: My brother occupied a central position in one canoe, and I a corresponding place in the other. As steersman he chose the eldest of the Iroquois, Pierre, with Michel as bowman. The remaining Iroquois, Louis, took the steering paddle of my canoe, and John, the western man, occupied the bow. Thus were our little crafts manned, each person, including my brother and myself, being provided with a broad maple paddle. Our loads being light, we were in good speeding condition. Just after launching we met some native Indians in their bark canoes, and by way of amusement and exhibition of speed paddled completely around them in the current, much to their amazement. Then with farewell salute, and the stroke of our paddles timed to the song of the canoemen, we glided swiftly down the stream.

As the start had been made late in the afternoon, not many miles were passed before it became necessary to[21] look for a camping place. The banks of the river, formed of boulder clay, were very high, and good landings were scarce. In places the mud on the shore was soft and deep, but about seven o’clock a landing was effected and camp pitched for the night. At this time only two small tents were used, an “A” tent for the canoemen and a wall tent, affording a little more head room, for ourselves. The banks being well wooded with white and black poplar, spruce and birch, plenty of fuel was available. A fire was soon kindled and our evening meal prepared, in the cooking of which John was given the first opportunity of distinguishing himself. He was assisted by little Michel, who proved to be a very good hand. Having some bread and biscuits in stock, baking was not yet a necessity.

The weather now being fair and cool, and the great pest of camp life, the mosquito, not having yet arrived, our experience at this time was most enjoyable. It was the season of spring, and the sweet perfume of the Balm of Gilead, so abundant in the valley of the Athabasca, permeated the air. The leaves on many of the trees were just opening, so that everywhere the woods presented a remarkable freshness and brilliancy of foliage. These were our environments at the commencement of the canoe voyage, and at our first camp on the banks of the Athabasca. How different were they to be at the other end of the journey!

On the morning of the 1st of June camp was called early, and we continued on our way. As we glided down stream a succession of grand views passed, panorama-like, before us. The banks were high, towering in some places three, four or five hundred feet above the river;[22] here abrupt and precipitous, consisting of cut banks of stratified clay; in other places more receding, but by a gradual slope rising, beneath dense foliage, to an equal elevation.

At this season of the year the water being high and the current swift, we made good time, covering a distance of sixty miles for the first full day’s travel. About noon on the 2nd, having reached a narrow part of the river, very remarkable massive walls of ice were found upon either bank, some distance above the water’s edge. These walls were of irregular thickness, and from eight to ten feet in height; but the most striking feature about them was that they presented smooth vertical faces to the river, although built of blocks of every shape and shade from clear crystal to opaque mud. They extended thus more or less continuously for miles down the river, and had the appearance of great masonry dykes. The explanation of their existence is doubtless as follows: Earlier in the season the narrowness of the channel had caused the river ice to jam and greatly raised the water level. After a time, when the water had reached a certain height and much ice had been crowded up on the shores, the jam had given way and caused the water to rapidly lower to a considerable extent, leaving the ice grounded above a certain line. Thus the material for the wall was deposited, and the work of constructing and finishing the smooth vertical face was doubtless performed by the subsequent grinding of the passing jam, which continued to flow in the deeper channel. After the passing of the first freshet, and the formation of these great ice walls, the water had gradually lowered to the level at which we found it.

Late in the afternoon the first rapid of the trip was sighted, but the water being high we had no difficulty in running it. In the evening camp was made on a beautiful sandy beach. During supper-time we had a visit from an old Cree Indian, who came paddling up the river in a little bark canoe. Of course he landed at our camp, for it is a principle strictly observed by every Indian to lose no opportunity of receiving hospitalities, and in accordance with his ideas of propriety, refreshments were given him. He received them as those of his race usually receive all favors, as no more than his right, and without a smile or the least visible expression of pleasure, seated himself by the fire to enjoy them.

On the following morning the great walls of ice, which we had been passing for miles, began to disappear as the channel of the river became wider. At about 9.30 we reached a place known as the Rapid of the Jolly Fool. It is said to have received its name from the fact that at one time an awkward canoeman lost his life by allowing his canoe to be smashed upon the most conspicuous rock in the rapid. We wasted no time examining it, as it was reported to be an easy one, but keeping near the left bank, headed our little crafts into the rushing waters. We had descended only a short distance, and were turning a bend in the stream, when, a little ahead of us, my brother noticed moving objects on the shore. One of the men said they were wolves, while others maintained they were bears, but my brother getting his rifle in readiness, cut the discussion short by demanding silence. As we swept swiftly down with the current, the objects were seen to be a moose deer and her calf. Having no fresh meat on hand, these new-found acquaintances were hailed[24] as “well met.” Not until our canoes had approached within about one hundred and fifty yards did the old moose, standing in the shallow water near the river bank, appear to notice us. Then, apparently apprehending danger, but without alarm, she turned toward the shore, and, followed by her calf, walked up the bank towards the woods. As she did so my brother fired from his canoe, wounding her in the hind-quarters. I then fired, but struck the clay bank above the animal’s head, and in attempting to fire again the shell stuck in my rifle, making it impossible for me to reload. Just as the moose was disappearing into the woods my brother fired again, and inflicted a body wound; but in spite of all away went the deer.

As our canoes were thrust ashore I succeeded in extracting the shell from my rifle, and leaving some of the men in charge of the canoes, my brother and I gave chase. The trail of blood was discovered on the leaves, but it led into such a jungle of fallen timber and thicket that it was no easy matter to follow. Scouts were sent out on either side, while with our rifles we followed the trail, running when we were permitted, jumping logs that came in the way, and clambering over or through windfalls that the moose had cleared at a bound. Presently through the leafy thicket we had a glimpse of our prey. Bang went both rifles and away bounded the moose with two more slugs in her body.

We were now pretty badly winded, but being anxious to complete the work we had undertaken, the chase was kept up. We knew from the wounds already inflicted that the capture was only a matter of physical endurance on our part, and we were prepared to do our best. More[25] than once the trail was lost in the windfalls and jungle, but at length, getting another side view, I shot her through the heart, bringing the noble beast with a thud to the ground. Nothing had been seen of the calf since the beginning of the hunt, but going back to the shore to get assistance, I found that the men had captured and made it a prisoner beside the canoes. Taking charge of the captive myself, I sent the men into the woods to skin the deer and “pack” the meat out to shore. The little calf, which I held by the ear, was very young, and not at all wild. Indeed, though I let go my hold, the little creature did not care to go away, but kept on calling for its mother in such a pitiful way that it made me heartily sorry for having bereft it. After the space of an hour or so my brother and the men returned, well loaded with fresh meat and a fine moose-hide. The meat was placed in sacks and stowed away in the canoes, but the hide being heavy and of little value to us, was placed on a big stone in the sun to dry and await the ownership of the first Indian who should pass that way.

As it was now nearly noon, it was decided to take dinner before re-embarking, and while the cooks were devoting their attention to bannocks and moose-steaks my brother and I were debating as to what we should do with the calf. We had not the heart to deliberately shoot it, but were unable to take it with us alive, as we would like to have done. Through a suggestion of one of the men a happy alternative was decided on. Other moose were doubtless in the vicinity, so that the calling of the calf would likely attract some of them, and in the event of this taking place it was said that the little moose would attach itself to another female. With the hope[26] that such kind fortune would befall it, my brother, after having taken its photograph, led it away by the ear into the shelter of the woods, and there left the little creature to its fate.

During the afternoon of the same day, the head of the Grand Rapid of the Athabasca, situated just 165 miles below the Landing, was reached. Here we met a detachment of the Mounted Police, in charge of Inspector Howard; and as it was late in the day, and Saturday evening, it was decided to pitch camp. The police camp was the only other one in the neighborhood, so the first question which suggested itself was: What possible duty could policemen find to perform in such a wild, uninhabited place? The answer, however, was simple. The place, though without any settled habitation, is the scene of the transhipment of considerable freight on its way to the various trading-posts and mission stations of the great Mackenzie River District. The river steamer Athabasca, belonging to the Hudson’s Bay Company, was now daily looked for with its load from the Landing. Mission scows, loaded with freight for Fort Chippewyan and other points, were expected, and free-traders’ outfits were liable to arrive at any time. It was for the purpose of inspecting these cargoes and preventing liquor from being carried down and sold for furs to the Indians, that Inspector Howard and his detachment were stationed here.

TROOPER, N.-W. MOUNTED POLICE, IN WINTER UNIFORM.

From the Grand Rapid, down stream for about eighty miles to Fort McMurray, the river is not navigable for steamers, and so all goods have to be transported over this distance by scows built for the purpose. The head of the Grand Rapid is thus the northern steamboat[27] terminus for the southern section of the river. The whole distance of eighty miles is not a continuous rapid, but eleven or twelve more or less impracticable sections occur in it, so that no great length of navigable water is found at any place. As its name suggests, the Grand Rapid is the main rapid of the river, and has a fall of seventy or eighty feet. This fall occurs mostly within a distance of half a mile, though the total length of the rapid is about four times that. The upper part is divided by a long narrow island into two channels, and it is through these comparatively narrow spaces that the cataract rushes so wildly. Above and below the island, the river may with great care be navigated by the loaded scows, but the water upon either side is so rough that goods cannot be passed down or up in safety. The method of transportation adopted is as follows: About a mile above the island, at the head of the rapid, the steamer Athabasca ties up to the shore. There she is met by a number of flat-bottomed boats or scows capable of carrying about ten tons each, and to these the boat’s cargo is transferred. When loaded the scows are piloted one by one to the head of the island in the middle of the river, where a rough wharf is built, and to it all goods are again transferred, whence they are carried to the lower end of the island by means of a tramway. The unloaded scows, securely held with ropes by a force of men on the shore, and guided with poles by a crew on board, are then carefully lowered down stream to the foot of the island, where they again receive their loads. Accidents frequently happen in passing down the unloaded scows, for the channel (the eastern one always being chosen) is very rough and[28] rocky. From the foot of the island in the Grand Rapid the scows are then floated down the river, with more or less difficulty, according to the height of water, through the long succession of rapids to Fort McMurray, where they are met by the second steamer, the Grahame, which receives their freight and carries it down the river to Fort Chippewyan on Lake Athabasca, and thence onward to Fort Smith, on Great Slave River, where a second transhipment has to be made over about sixteen miles of rapids. From the lower end of these rapids the steamer Wrigley, under the command of Captain Mills, takes charge of the cargo and delivers it at the various trading-posts along the banks of the Mackenzie River, for a distance of about twelve hundred miles, to the Arctic Ocean.

But to return to our camp at the head of the Grand Rapid. Inspector Howard and his men proved to be interesting companions. I soon discovered, to my surprise, that the Inspector was a cousin of my wife’s, and that I had met him in former years in Toronto. Meeting with even so slight an acquaintance in such a place was indeed a pleasure; and in justice to the occasion a banquet, shall I call it, was given us, at which moose-steak and bear-chops cut a conspicuous figure. In conversation with the Inspector some information was obtained regarding the character of the rapids now before us, and all such was carefully noted, since none of our party had ever run the Athabasca. We had with us the reports of William Ogilvie, D.L.S., and Mr. McConnell, who had descended the river and published much valuable information regarding it, but even they could not altogether supply the place of a guide. We were putting great confidence in the skill of our Iroquois men at navigating rapids, and now in the succeeding eighty miles of the trip there would be ample opportunity of testing it.

LANDING OF SCOWS ABOVE GRAND RAPID.

On the morning following our arrival at the Grand Rapid, being the 4th of June, a number of mission scows, loaded with goods for Chippewyan and other mission stations, arrived. As they appeared, following each other in quick succession around a bend in the river, each boat manned by its wild-looking crew of half-naked Indians, all under the command of Schott, the big well-known river pilot, who is credited by Mr. Ogilvie with being the fastest dancer he has ever seen, they drew in towards the east bank, and one after the other made fast to the shore. The boats were at once boarded by Inspector Howard and his men, and a careful search made for any illegal consignments of “firewater.” Liquor in limited quantities is allowed to be taken into the country when accompanied by an official permit from the Lieut.-Governor of the Territories, but without this it is at once confiscated when found. Out of deference to those for whom these cargoes were consigned, I had better not say whether a discovery was made on this occasion or not. When confiscations are made, however, the find is, of course, always destroyed. The news of the arrival of the scows was welcomed by us, not because of anything they brought with them, but because we expected to obtain directions from Schott regarding the running of the many rapids in the river ahead, and the transport of the bulk of our canoe loads to Fort McMurray, below the rapids. After some consideration, rather less than most Indians require to take, these matters were arranged with Schott, and all but our instruments, tents, blankets and three or four days’ provisions were handed over to him.

GRAND RAPID, ATHABASCA RIVER.

On the evening of the 4th, the steamer Athabasca also put in an appearance, and made fast to the shore a little above the scows. Grand Rapid was no longer an uninhabited wilderness, but had now become transformed into a scene of strange wild life. Large dark, savage-looking figures, many of them bare to the waist, and adorned with head-dresses of fox-tails or feathers, were everywhere to be seen. Some of them, notably those of the Chippewyan tribe, were the blackest and most savage-looking Indians I had ever seen. As it was already nearly night when the last of them arrived by the steamer, the work of transhipping was left for the morning. In the dark woods the light of camp-fires began soon to appear, and around them the whole night long the Indians danced and gambled, at the same time keeping up their execrable drum music.

ENGLISH-CHIPPEWYAN HALF-BREED.

At daylight the next morning the overhauling of cargoes was commenced. One by one the scows were loosened and piloted down the middle of the rapid to the wharf at the head of the island. Here they were unloaded, and after being lightened, were lowered down[33] through the boiling waters by means of lines from the shore and the assistance of poles on board, to again receive their loads at the foot of the island. Two or three scows were also similarly engaged in transporting the cargo of the steamer, of which our supplies formed part, and, much to our annoyance, there was considerable delay on account of having to repair the tramway across the island. We were informed that the Grahame could not now reach Chippewyan before the 20th of June, which would be ten days later than we had expected to be able to leave that place. However, we could only accept the inevitable, and try to make the best use of the time.

While Schott and his crews were thus engaged with their transport, our own men were not idle. They had been told that the rapid would have to be portaged, as no canoeman would venture to run it; but having walked down the shore and themselves examined the river, the Iroquois asked and obtained permission to run it by taking one canoe down at a time. Schott and his Indians thought them mad to try such a venture, but seeming to have every confidence in their own abilities, we determined to see what they could do. John gladly chose the work of portaging along the rough boulder shore and over precipitous rocks in preference to taking a paddle, but the three Iroquois took their places, Louis in the bow, Michel in the middle, and old Pierre in the stern. As the three daring fellows pushed off from the shore into the surging stream, those of us who gazed upon them did so with grave forebodings. They had started, and now there was nothing to do but go through[34] or be smashed upon the rocks. Their speed soon attained that of an express train, while all about them the boiling waters were dashed into foam by the great rocks in the channel. Presently it appeared as if they were doomed to be dashed upon a long ugly breaker nearly in mid-stream; but no! with two or three lightning strokes of their paddles the collision was averted. But in a moment they were in worse danger, for right ahead were two great rocks, over and around which the tumbling waters wildly rushed. Would they try the right side or the left? Only an instant was afforded for thought, but in that instant Pierre saw his only chance and took it—heading his canoe straight for the shoot between the rocks. Should they swerve a foot to one side or the other the result would be fatal, but with unerring judgment and unflinching nerve they shot straight through the notch, and disappeared in the trough below. Rising buoyantly from the billows of foam and flying spray, they swept on with the rushing waters until, in a little eddy half-way down the rapid, they pulled in to the shore in safety. They were all well soaked by the spray and foam, but without concern or excitement returned for the second canoe. In taking this down a valise of stationery and photographic supplies, inadvertently allowed to remain in the canoe, got a rather serious wetting, but as soon as possible its contents were spread out upon the smooth clean rocks to dry. Past the remainder of the rapid a portage was made and camp pitched at the foot. While our Iroquois were thus occupied, Schott and his men had been hard at work running down their scows and had[35] been unfortunate enough to get one of them stranded on a big flat rock in the middle of the rapid. Had it not been for the timely assistance of our party and the generalship of old Pierre, he would probably never have gotten it off. As it was, the accomplishment of the task occupied our united energies for several hours.

NECK DEVELOPED BY THE TUMP-LINE.

Before leaving the Grand Rapid several good photographs of it were obtained, and then on the morning of the 7th of June, bidding adieu to Inspector Howard, and leaving our supplies in the freighters’ hands, we started down the river for Fort McMurray. The first object of special interest passed was a natural gas flow, occurring on the left bank about fifteen miles below the Rapid. At this place a considerable volume of gas is continually discharging, and may be seen bubbling up through the water over a considerable area, as well as escaping from rifts in the bank. The gas burns with a hot pale blue flame, and is said to be used at times by boatmen for cooking purposes. Eight or ten miles farther down stream came the Brûle Rapids, the first of the long series, and though they might easily have been run, we did not try it, as my brother wished to remain on shore for some time to collect fossils. Meanwhile our stuff was portaged, and without difficulty the empty canoes run down to the foot of the rapids, where camp was made. Just at this place commence the wonderful tar sand-beds of the Athabasca, extending over an enormous area. These certainly present a very striking appearance. During warm weather, in many places, the faces[37] of the river banks, from three to five hundred feet in height, presents the appearance of running tar, and here and there tar wells are found, having been formed by the accumulation of the viscid tar in natural receptacles of the rock. Thus collected it has been commonly made use of by workmen in the calking of the scows on the river.[1]

Sixteen miles farther down, the Boiler Rapid, so called from the fact that in 1882 a boiler intended for the steamer Wrigley was lost in it, was successfully run on the following day, and early in the afternoon the third rapid was reached. In attempting to run it on the left side, we found, after descending perhaps half-way, that there were too many rocks in the channel ahead, and therefore an effort was made to cross to the right side, which looked to be clearer. My brother’s canoe, steered by old Pierre, avoided all rocks and was taken successfully across, but mine was not so fortunate. In attempting to follow, we struck a large rock in mid-channel, but happily the collision occurred in such a way that my canoe was not seriously damaged. It was merely whirled end for end in the current and almost filled with water, though not quite sufficiently to sink us. Leaving the two Indians to pull for the shore, I seized a tin kettle and lost no time in dashing out some of the water. After a sharp struggle we managed to land. Of course all we had in the canoe—instruments, blankets, provisions and clothing—was soaked, and it was therefore necessary to unload and turn everything out.[38] My brother, seeing that something had happened, went ashore also, and with his men returned to assist us. The weather was fine, and our goods soon became sufficiently dry to allow us to re-embark.

An examination having been made of the rapid below, a short run was made down and then across to the opposite side, where we landed, and, because of the extreme shallowness of the channel and the many rocks that showed ominously above the surface, the canoes were lowered for the remaining half mile with the lines. The whole length of this rapid is perhaps a mile and a half, and it is sometimes designated as two, the Drowned and Middle Rapids. Following these in quick succession, at intervals of from two to ten miles, we passed through the Long Rapids, which occasioned no difficulty; then the Crooked Rapids, well named from the fact that they occur at a very sharp U shaped bend in the river, around which the current sweeps with great velocity. Just below this the Stony Rapid was passed, and then in turn the Little and Big Cascades, both of which are formed by ledges of limestone rock, about three feet high, extending in more or less unbroken lines completely across the river.

At the Big Cascade a portage of a few yards had to be made, and below this, smooth water was found for a distance of eight or nine miles, until the head of the Mountain Rapid was reached. Judging from the name that this would be a large one, we decided to go ashore to reconnoitre. For a considerable distance the rapid was inspected, but no unusual difficulty appearing, we resolved to go ahead. About a mile farther on, a bend occurred in the rapid, and so high and steep[39] were the banks that only with great difficulty could we see the river beyond. As far as the bend, though the current was swift, there appeared to be but few rocks near the left bank, and plenty of water. We therefore decided to go ashore at that point, if necessary, and examine the stream beyond.

As we proceeded the stream became fearfully swift and the waves increasingly heavy. At the speed we were making the bend was soon reached, but just beyond it another bluff point came in view. We would have gone ashore to make a further inspection, but this was impossible, as the banks were of perpendicular or even overhanging walls of limestone. So alarmingly swift was the current now becoming that we eagerly looked for some place on the bank where a landing might be made, but none could be seen. Retreat was equally impossible against the enormous strength of the river; all we could do was to keep straight in the current. My brother’s canoe, steered by old Pierre, being a little in advance of my own, gave me a good opportunity of seeing the fearful race we were running. Suspicions of danger were already aroused, and the outcome was not long deferred. As we were rounding the bluff, old Pierre suddenly stood up from his seat in the stern, and in another instant we likewise were gazing at what looked like the end of the river. Right before us there extended a perpendicular fall. We had no time for reflection, but keeping straight with the current, and throwing ourselves back in the canoes in order to lighten the bows we braced ourselves for the plunge, and in a moment were lost to sight in the foaming waters below. But only for an instant. Our light cedars, though partly filled by the[40] foam and spray, rose buoyantly on the waves, and again we breathed freely. It was a lucky thing for us that the canoes were not loaded, for had they been they never would have floated after that plunge, but would have disappeared like lead in the billows. We afterwards found we had taken the rapid in the very worst spot, and that near the right side of the river we might have made the descent free of danger. Without a guide, however, such mistakes will sometimes occur in spite of every precaution.

Poor John, my bowman, was badly unstrung as a result of this adventure, and declared that he did not want to shoot any more waterfalls; and for that matter, others of us were of much the same mind. One more small rapid, the Moberly, completed the series, and then for a few miles we enjoyed calm water until, toward evening, we reached Fort McMurray.

SHOOTING THE MOUNTAIN RAPID, ATHABASCA RIVER.

This settlement, containing in all five small log buildings—a warehouse, a store, the traders’ dwelling and two Indian houses—is situated on a cleared tongue of land formed by the junction of the Clear Water River with the Athabasca, and is about two hundred and fifty miles below the Landing. The site of the post is at an elevation of forty or fifty feet above the water, but in the immediate background, and on both banks of the river, the ground rises abruptly, and is covered by a thick growth of poplar, spruce and birch trees. At the time of our arrival two parties of Indians, one Cree and the other Chippewyan, occupying in all a dozen or more lodges, were encamped at the place, and were to be seen in groups here and there idly putting in the time, while everywhere their mangy canines skulked and prowled[41] about, seeking what they might devour—old moccasins, pack straps, etc., apparently being their favorite dainties.

STORE, FORT McMURRAY.

Naturally, our first inquiry upon arriving at the Fort was whether or not our two men and canoe from Isle-à-la-Crosse had arrived; but the appearance of an upturned “Peterborough” on the shore soon answered the question, and a few minutes later two stout half-breeds made their appearance, and informed us they were the men who had been sent by Mr. Moberly to meet us. My brother had expected the two men who had accompanied him on his trip of the previous year, but they having been unable to come, these two, Jim Corrigal and François Maurice, had been engaged in their stead. Jim was a man of middle age, tall and of muscular frame; while his companion was probably not more than twenty years of age, and in appearance rather short and of heavy build. Jim spoke English fairly[42] well, though Cree was his tongue; but François, while speaking only very broken English, could converse in French, Cree and Chippewyan, his knowledge of the last making him subsequently very useful as an interpreter.

CHIPPEWYAN CAMP.

Our party, consisting of eight men, with three canoes, was now complete, and thus assembled, the cleanest available ground remote from Indian lodges was chosen, and camp pitched to await the arrival of the four hundred pounds of supplies left with Schott at Grand Rapid. We soon found we were not the only ones waiting, and that anxiously, for the arrival of the scows from the south. The entire population then at Fort McMurray was in a state of famine. Supplies at the[43] post, having been insufficient for the demand, had become exhausted, and the Indians who had come in to barter their furs were thus far unable to obtain food in exchange, and were obliged, with their families, to subsist upon the few rabbits that might be caught in the woods. We were also out of supplies, but now the scows were hourly expected. Expectations, however, afforded poor satisfaction to hungry stomachs, and no less than five days passed before these materialized. In the meantime, though we were not entirely without food ourselves, some of the natives suffered much distress. At one Cree camp visited I witnessed a most pitiable sight. There was the whole family of seven or eight persons seated on the ground about their smoking camp-fire, but without one morsel of food, while children, three or four years old, were trying to satisfy their cravings at the mother’s breast. We had no food to give them, but gladdened their hearts by handing around some pieces of tobacco, of which all Indians, if not all savages, are passionately fond.

In addition to the unpleasantness created by lack of provisions, our stay at Fort McMurray was attended with extremely wet weather, which made it necessary to remain in camp most of the time, and to wade through no end of mud whenever we ventured out.

On the evening of the 14th the long-looked-for scows with the supplies arrived. It will readily be imagined we were not long in getting out the provisions and making ready a supper more in keeping with our appetites than the meagre meals with which we had for several days been forced to content ourselves. The cause of delay, as Schott informed us, was the grounding of some of the boats in one of the rapids, in consequence of which the cargoes had to be removed by his men, and carried on their shoulders to the shore, the boats then freed, lowered past the obstruction, and reloaded. Such work necessarily entails considerable delay, and is of a slavish character, as all hands have to work in the ice-cold water for hours together.

STARVING CREE CAMP, FORT McMURRAY.

Receiving again our four hundred pounds of supplies from Schott, we lost no more time at Fort McMurray, but at seven o’clock next morning the little expedition, consisting now of eight men and three canoes, pushed out into the river, and with a parting salute sped away with the current, which being swift, and our canoemen fresh, enabled us in a short time to place many miles between us and the Fort. At five o’clock in the evening, having then descended the river a distance of about sixty miles we were delighted to meet the steamer Grahame on her up-stream trip from Fort Chippewyan to McMurray to receive the goods brought down the rapids by the scows. The steamer, being in charge of Dr. McKay, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s officer from Chippewyan, who had been informed of our expedition, was at once brought to a stand in the river, and we were kindly invited on board. When I commenced to clamber up the steamer’s deck, whose hand should be offered to assist me but that of an old friend and fellow-shipmate for two years in Hudson Straits, Mr. J. W. Mills. The acquaintance of Dr. McKay and of the Bishop of Athabasca, who happened to be on board, was also made, and with right genial companions an hour quickly and very pleasantly passed. Mr. Mills, who was attired in the uniform of a steamboat captain, had lately been[46] appointed to the command of the steamer Wrigley, plying on the lower section of the river below Fort Smith, to which place he was to be taken by the Grahame on her return trip from Fort McMurray. Before parting company, the Doctor promised to meet us again at Chippewyan on the 19th inst., and after this short meeting, and many parting good wishes, as well as blessings from the Bishop, we resumed our separate ways.

A DANDY OF THE NORTH. A VOYAGEUR.

Notwithstanding the hour’s delay, and the fact that rain fell all day, we made the very good run of seventy-two miles. As we swept along with the winding river, the most beautiful and varied scenes were continually presented. The banks, though not so high as above Fort McMurray, were bold and thickly draped with spruce and poplar woods. Taking advantage of the[47] discovery of some straight spruce saplings, we landed as night approached, and a number of our men were sent to select a few for the purpose of making good tent-poles, to take the place of the rough ones we had been using. Besides spruce and other varieties of timber, balsam trees, the last seen on the northward journey, were found at this camp.

On the morning of the 16th, though the weather continued showery and a strong head wind had set in, we were early on our way, for we were anxious to reach Chippewyan a day or two before the return of the Grahame, that we might rate our chronometer and make all necessary preparations for a good-bye to the outermost borders of civilization. In descending the Athabasca we were making no survey of the course, nor any continuous examination of the geological features of the district, but were chiefly concerned in getting down to Chippewyan, where we were to receive our full loads of supplies, and from which place our work was really to begin. Despite the unpleasantness of the weather, therefore, our canoes were kept in the stream and all hands at the paddles, and by nightfall another stretch of about sixty miles was covered. We had now reached the low flat country at the delta of the river, where its waters break into many channels, but still a strong current was running, and this we were glad to find continued until within a distance of six or eight miles from the lake. Some parts of the river were much obstructed by drift-wood grounded upon shoals; the banks, too, were low and marshy, and landing-places difficult to find. Several flocks of wild geese were seen, but none secured.

During the morning of the 17th some gun-shots were heard not far distant across the grassy marsh, and turning our canoes in that direction we soon met several bark canoes manned by Chippewyan Indian hunters. François, being the only man in our party who could understand or talk with them, was much in demand, and he was instructed to ask them the shortest way through the delta towards Chippewyan. Indian like, he entered into conversation with the strangers for ten minutes or so, doubtless chiefly about their wives and daughters, and then with a wave of the hand said, “We go dis way.” So that way we went, and by three o’clock in the afternoon found ourselves in the open waters of Lake Athabasca. Two hours later we had crossed the end of the Lake and drawn up our canoes on the rocky shore in front of Fort Chippewyan. It was Saturday evening, and the distance travelled thus far since launching the canoes, was, according to Mr. Ogilvie, 430 miles. As we were already aware, Dr. McKay, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s agent, was not at the Fort, but we were received by the assistant trader, Pierre Mercredie, a half-breed, and shown to a camping-ground in front of the Fort, or otherwise on Main Street of the town. During the evening we had the pleasure of meeting Mrs. McKay and her children, and also Mr. Russell, an American naturalist, who was sojourning at this place on his way down the Mackenzie River.

AN ENGLISH-CREE TRAPPER.

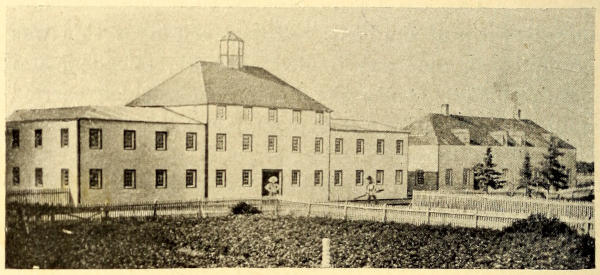

Fort Chippewyan is an old and important trading-post of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Before many of our Canadian and American cities came into existence, Chippewyan was a noted fur-trading centre. From here—or rather from a former site of the post, a few miles distant—Alexander Mackenzie (afterwards Sir Alexander) started, in 1789, on his famous journey down the great river which now bears his name. About the beginning of the present century the post was moved to the position it now occupies on the rocky northern shore of the west end of the Lake.

The Fort consists of a long row of eighteen or twenty detached log buildings, chiefly servants’ houses, connected by a high strong wooden fence or wall, so as to present an unbroken front to the water, behind which, in a sort of court, are situated the Factor’s dwelling and two or three other good-sized log buildings. At the west end of the row stands an Episcopal Mission church and the Mission house, which at the time of our visit was occupied by Bishop Young, the see of whose diocese was formerly here, but since removed to Fort Vermilion, some 270 miles distant on the Peace River. Within easy sight, a short distance farther west, across a little bay, the Roman Catholic Mission church, and various buildings connected therewith, are situated. This mission is a large and flourishing one, and is the see of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Athabasca. All the buildings of Chippewyan are neatly whitewashed, so that, particularly from the front, it presents a most striking appearance. At the back of the Fort, between the rocky hills, plenty of small timber for house-building and firewood is found, and over at the Catholic Mission a little farm is cultivated, and many luxuries in the way of root vegetables obtained from it.

FORT CHIPPEWYAN.

The staple food, however, for both man and dogs (which latter are important members of the community) is fish, several varieties of which are caught in abundance in the lake close at hand. One or two whitefish, according to size, is the usual daily allowance for a dog.

In the north the dog takes the place which the horse occupies in the south, and it is a very interesting sight to see the canine population of the town, perhaps thirty or forty in all, receiving their daily meal. They are called together by the ringing of a large bell, erected for the purpose at all Hudson’s Bay Company posts. At the first stroke all dogs within reach of the sound spring to their feet and scamper off to the feeding place, where they find a man in charge of their rations. Forming round in a circle, each dog waits for the portion thrown to him, which he at once trots away with to enjoy in some quiet retreat. Occasional snarls and fights take place, but it is astonishing to see how orderly Chippewyan dogs are able to conduct themselves at a common mess.

The day after our arrival at the Fort being Sunday, we[52] had our last opportunity for several months of attending Divine service, and were privileged to listen to an excellent sermon preached by His Lordship Bishop Young. Some of our men, being Roman Catholics, were able to avail themselves of the opportunity of attending mass as well, and of receiving a parting blessing from the priest.

STEAMER “GRAHAME.”

The next day being the 19th, the date on which Dr. McKay had promised to rejoin us at the Fort, his return with the Grahame was eagerly looked for. We had made all the preparations for departure that could be made until he and our supplies should arrive. During the afternoon a strong breeze sprang up from the east, raising a heavy sea, and it was not until sunset that the belated steamer tied up to the wharf. She had had[53] a rough passage, so rough that the Doctor declared it was the last time he would ever be a passenger on her in such water, a not unwise resolution, for the steamer, top-heavy and drawing only about three feet of water, was not unlikely to roll over in rough weather.

With the return of the Doctor, Captain Mills and the Captain of the Grahame, we now formed a merry party, and spent a pleasant evening at the Doctor’s house. Captain Mills and I talked over old-time adventures in Hudson Straits, and recalled many incidents from our mutual experiences in the north in bygone days. But as the Doctor had determined to leave again with the steamer on the following day for the Great Slave Lake river posts, there was no time to be lost in social pleasures. In compliance with my brother’s request, sent by letter some months previously, Dr. McKay had engaged the best available Indian guide to accompany us from this place through Lake Athabasca and as far beyond as he knew the country. With the success of this arrangement we were greatly pleased, as it was desirable that as little time as possible should be lost in seeking trails and river routes. The guide’s name was Moberly—a Christian name, though borne by a full-blooded Chippewyan Indian, who, before we were through with him, proved himself to be anything but a Christian. He was acquainted with our route for about one hundred miles to the northward from Black Lake, and even in this distance his services, we thought, would likely save us several days.

The next morning the Fort was a scene of hurry and bustle. Goods were landed from the steamer, cordwood taken on board, and much other business attended to.[54] I took charge of our own supplies, and checked each piece as it was brought ashore. Our chest of tea was the only article that had suffered from the effects of frequent transhipment. It had been broken open and a few pounds lost, but the balance—about sixty pounds—had been gathered up and put in a flour bag. Before noon everything was safely landed on the shore, and it formed a miscellaneous pile of no small extent. Following is a list of the articles: “Bacon, axes, flour, matches, oatmeal, alcohol, tin kettles, evaporated apples, apricots, salt, sugar, frying-pans, dutch oven, rice, pepper, mustard, files, jam, tobacco, hard tack, candles, geological hammers, baking powder, pain killer, knives, forks, canned beef—fresh and corned—tin dishes, tarpaulins and waterproof sacks.” Besides the above, there were our tents, bags of dunnage, mathematical instruments, rifles and a box of ammunition. The total weight of all this outfit amounted at the time to about four thousand pounds.

A sail-boat which my brother had used in 1892, and which was in good condition, rode at anchor before the Fort, and for a time it was thought we would have to make use of this as far as the east end of the lake to carry all our stuff. Moberly, the guide, particularly urged the necessity of taking the big boat, for his home was at the east end of the lake, and he had a lot of stuff for which he wished to arrange a transport, but as we were not on a freighting tour for Moberly, and as we found by trial that everything could be carried nicely in the canoes, we decided to take them only. At this the guide became sulky, and thought he would not go. His wife and two daughters, who were to accompany[55] him as far as their home, tried to persuade him, but Indian-like he would not promise to do one thing or the other. At last we told him to go where he chose, as we were in no way dependent on him, but knew our own way well enough.

As arranged, the Grahame steamed away during the afternoon, for the Great Slave River, with Dr. McKay, Captain Mills and Bishop Young on board, but our own start was deferred until the next morning, and in the meantime home letters were written, for a packet was to go south from here about the 16th of July.

On the morning of the 21st of June, the whole outfit being snugly stowed in the three canoes, our party set out on the eastward course. Old Moberly, the guide, was also on hand with his family and big bark canoe. The morning was beautifully fair and calm; all nature seemed to be smiling. But soon the smile became a frown. The east wind, as if aroused by our paddles, began to stir himself, and before long made things unpleasant enough, coming not alone but with clouds of mist and rain. Though we could make but slow progress, we persisted in travelling until 9.30 p.m., when, having made about twenty-four knots, we pitched camp in a little sandy bay, worthy to be remembered because of the swarms of mosquitos which greeted us on landing. We had been reminded of the existence of these creatures at Chippewyan and at former camps, but here it was a question of the survival of the fittest. Mosquito nets, already fixed to our hats, had to be drawn down and tightly closed, and mosquito oil or grease smeared over the hands.

LANDING ON NORTH SHORE, LAKE ATHABASCA.

The whole north shore of the lake, being bold and rocky, and consisting chiefly of Laurentian gneiss, is of little geological interest except at a few points, which will be spoken of as they are reached. The south shore, which was examined by my brother in 1892, was found to be of entirely different character, low and flat, and its rocks cretaceous sandstones. The chief varieties of timber observed as we passed along were spruce, white poplar and birch, and with these, though of small size, the country was fairly well covered.

Our second day on the lake was even less successful than the first, for though we made a start in the morning, we were soon obliged to put to shore by reason of the roughness of the water and a strong head-wind. At noon we succeeded in getting our latitude, which was 59° 6′ 32″ N.

About six o’clock that evening, shortly after our second launch, we met a party of Indians in their bark canoes, sailing with hoisted blankets before the wind. There were quite a number of them, and as they bore down towards us they presented a picturesque and animated scene. Moberly was some distance in the rear, but François was on hand to interpret, and as we met a halt was made. The first and most natural question asked by the Indians was, “Where are you going?” “To h—,” was François’ prompt but rather startling reply. In order that we might have an opportunity of securing information about the country (not that to which François had alluded, however), it was decided that we should all go ashore and have some tea; so our course was shaped for the nearest beach, a mile or so away. Upon landing we found that some of these Indians were men of whom Dr. McKay had spoken as[58] being shrewd, intelligent fellows. From one old hunter in particular, named Sharlo, we obtained interesting sketch-maps of canoe routes leading northward from Lake Athabasca. Of course tea and tobacco had been served out before such information was sought, for no man of any experience would think of approaching an Indian for the purpose of obtaining a favor without first having conferred one. Our object accomplished, canoes were again launched, and the struggle with the east wind was renewed. Though we travelled until 10.30 at night we made only 16.4 knots during the day, as indicated by the boat’s log; and then in the mouth of the Fishing River we found a sheltered nook in the thick woods for a camping-ground.

The next day, the high wind continuing and rain falling freely, the lake was too rough for us to venture out. A collection of all the many varieties of plants occurring in the vicinity was carefully made. Nets were set out, and some fine fish taken; trolls were also used with fair success, and with my revolver, much to the amusement of the party, I shot and killed some distance under water a fine large pike. A few geese were seen also, but none could be secured.

A TYPICAL NORTHLAND FATHER.

On the following morning, though it was still raining, the wind had fallen, and we were able to go ahead. Because of the wet we had great difficulty in using our surveying instruments and in making notes. During the forenoon while ashore at Cypress Point, a long sand-beach timbered with jack-pine woods, and extending a mile or more out into the lake, we observed a sail not far ahead. A sail-boat in these waters was an unusual sight, but on this occasion we were able to guess[59] its meaning. It was Mr. Reed with his party returning from Fort Fond du Lac (now a small winter post only) to Chippewyan with the last winter’s trade. We had been told we would likely meet him on the lake, and here he came before the breeze in his big York boat. As he approached and sighted us he made in to where we were, and ran his boat on the sand beach. Besides Mr. Reed, the young trader, there were with him two French priests returning from their season’s labor among the Indians. One of them, now an old man, had spent the greater part of his life in mission work in this district, and was about laying down his commission, to be succeeded by his younger companion. As it was nearly noon, our men were instructed, though it was raining heavily, to kindle a fire and prepare lunch for the party. Beneath some thick fir-trees a shelter was found, and the tea being made and lunch laid out on the ground, we all seated ourselves about, and spent a delightful half-hour together. But to us every hour was precious, and without further delay we wished each other God-speed, and continued our courses. By nightfall the log-reading showed our day’s travel to be thirty-two knots, equivalent to about thirty-seven miles. So far we had been fortunate in finding comfortable camping[60] grounds. With a guide who knew the shore we should be expected to do so, but with a guide such as ours, who was commonly several miles behind, his connection with the party made little difference, excepting in the consumption of “grub.”

Three more days passed, and despite the unfavorable weather, seventy miles of shore-line were surveyed. Then a discovery of some interest was made. Just east of the Beaver Hills we found a veritable mountain of iron ore, and that of the most valuable kind, hæmatite. Coal to smelt it is not found in the vicinity, though there is plenty of wood in the forest. The shore of this part of the lake was very much obscured by islands, upon the slopes of which the remains of the last winter’s snow banks could still be seen.

We made an early start on the morning of the 18th, breaking camp at five o’clock, but before we had made any distance a fog settled over the lake so dense that we could not see ten yards from the canoes. For some time we groped along in the darkness, every little while finding our way obstructed by the rocky wall of some island or point of land, and finally, meeting with a seemingly endless shore, we were obliged to wait for the weather to clear. All hands landed and climbed the precipitous bank, with a view to discovering something about the locality, but all was obscurity. Toward noon the fog lifted, and we were able to make out our position, which was on the mainland and north of Old Man Island. On this point we observed a solitary grave, and near by the remains of an old log house. As to who had been the occupant of this solitary hut, or whose remains rested in the lonely grave, we knew not, but[61] their appearance on this uninhabited shore made a realistic picture of desolation and sadness.

On the morning of the 29th of June, high west winds and heavy rain were again the order of the day, but venturing out, we made a fast run before the wind and reached the Fort in a heavy sea. Fond-du-Lac is a fort only in name, and consists in all of two or three small log shanties and a little log mission church, situated on a bare, exposed sandy shore, without any shelter from the fierce winter storms which hold high carnival in this country six or seven months of the year. Having already met the white residents of Fond-du-Lac on the lake, most of their houses, few though they were, were locked up or deserted. Two or three Indians and their families were living at the place, and with one of them letters were left with a hope that they might be taken safely to Chippewyan, and thence forwarded by the Hudson’s Bay Company’s autumn packet to Edmonton. This was undoubtedly the last chance, though only a chance, of sending any news to our friends until we should return to civilization.

From Fond-du-Lac eastward the lake is quite narrow, having much the appearance of a broad river. It is only five miles in width, but extends a distance of fifty miles. On the south shore could be seen a large group of Indian lodges, and at this camp was the home of our guide. It was here that his family were to be left, so we all went across to the Indians’ encampment. Moberly now appeared to be very indifferent as to whether or not he should go any farther with us. Indeed he seemed more inclined to remain with his friends, for to accompany us meant more exertion for[62] him than he was fond of. Various reasons were given why he must remain at this place; but after much parleying, and the offer of liberal inducements, he promised to secure a companion canoeman, and follow our track in the morning. With this understanding we parted, and proceeded along the south shore until evening, when, finding an inviting camping-ground in the open jack-pine wood, we went ashore, while the cooks soon prepared supper, with us the principal meal of the day.

So far our fare had been exceedingly good, for it had been the policy to dispose of luxuries as soon as possible, in order to reduce the weight of the loads on the portages. Our limited stock of canned fruits was, therefore, used with a free hand at first.

June closed with a bright, clear and unusually calm day, which was also marked by the absence of mosquitos and black flies. Under these unusual circumstances, at noon-hour, an event transpired which was seldom repeated during the remaining part of our journey, viz., the taking of a bath.

Just as lunch was ready we were again joined by Moberly and his companion, an old Indian named Bovia. We were glad, if not a little surprised, to see them, for we had a suspicion that the guide had no serious intention of keeping his promise. During the afternoon, however, as before, his canoe lagged far behind, not so much because of his inability to keep up with us, as because of his serene indifference and laziness. The paddles used by him and his comrade were like spoons as compared with our broad blades, and the position of old Bovia, as he pulled with one elbow resting on the gunwale of his canoe, was most amusing. By this way of[63] travelling it was very evident that the guides were going to be a drag rather than a help to us, so it was resolved that before proceeding farther a definite understanding must be arrived at.

Beside the evening camp-fire, accordingly, the matter was broached to the Indians. They were told plainly that if they were to continue with us they would be required to go in advance and show us the way as far as they knew the route, and further, that they would be expected to assist in portaging our stuff whenever that might become necessary. In consideration of this, as already agreed upon, they were to receive their board and eighty skins ($40.00) per month, upon their return to Chippewyan. This arrangement was accepted as being satisfactory to them, and it was hoped that it might result satisfactorily to ourselves.

During the morning of the 1st of July, with a little Union Jack flying at the bow of my canoe, we arrived at the east end of the lake, and concluded a traverse, since leaving Chippewyan, of 210 miles. Here at the extremity of the lake we found several Indian families living, not as is usual, in their “tepees” or skin-covered lodges, but in substantial log huts. One of these, we learned, was the property of our brave Moberly, and in front of it he and old Bovia deliberately went ashore, drew up their canoe, and seated themselves upon the ground beside some friends.

Their action at once struck us as suspicious, but presently they made an open demand for a division of our bacon, flour, tea and tobacco. Some pieces of tobacco and a small quantity of tea had already been given, but any further distribution of the supplies was[64] declined. At this Moberly became very angry, and said he would go with us no farther, and not another foot would he go. From the first his quibbling, unreliable manner, characteristic of the tribe to which he belonged, had been most unsatisfactory, and now having received board for himself and his family in journeying homeward, besides a month’s pay in advance, he had resolved to desert us. There was no use in trying to force him to continue with us against his inclinations, nor could we gain anything by punishing him for his deception, though punishment he richly deserved. He was given one last opportunity of deciding to go with us, but still refusing, we parted company with him without wasting strong language, which he could not have understood.

INDIAN LOG HOUSE.