Title: Balbus; or, the future of architecture

Author: Christian Augustus Barman

Release date: January 25, 2025 [eBook #75202]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd, 1926

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/75202

Credits: Produced by Tim Lindell, Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

BALBUS

For the Contents of the Series see the end of the Book

OR

THE FUTURE OF ARCHITECTURE

BY

London:

KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO., Ltd.

New York: E. P. Dutton & Co.

The same Author has also written:

Printed in Great Britain by

MACKAYS LTD., CHATHAM

It is often maintained that there is a similarity between architecture and dress in that both are applied as a covering, the one to the individual human body, the other to the body politic. But there is one thing that those who point to this similarity are not always careful to bear in mind, namely that it is precisely in their relation to this human content that the arts of architecture and dress differ most widely. The bodies of adult men and women are distinguished from one another only by a few small variations of colour and proportion. Of so little consequence are these departures from the universal norm that fashion experts are freely permitted to disregard their effect, and usually content themselves with saying that “trousers are worn narrower” and that “gowns are of pastel shades of mousseline and chiffon.” Having, in such observations as these, momentarily exhausted the subject of sartorial growth, they can do nothing but await the next measurement, the next material, that its[6] guiding spirits may decree. What would they say, however, if they were asked to discuss the toilet of a greyhound, a turkey-cock or a hippopotamus, and compare it with the vesture appropriate to human beings? Would not the historian of clothes become deeply embarrassed at such an enlargement of his field of vision, at the sudden appearance of such a multiplicity of forms? Yet the scope and variety of his subject would still be as nothing beside the scope of architectural history, and the variety of the architectural forms that it is the task of this history to register, and anatomize, and trace back severally to their origin. For while the origin of sartorial form is to be discerned in the fixed and unchanging outline of the human body, the origin of architectural form must be looked for in the infinite diversity of the social organism and in the sweeping and rapid changes into which this organism is for ever being thrown. Of all architectural movements there is none, therefore, so irresistible in its progress or so expansive in its effect as that which owes its existence to a social movement. In the construction of the first circular cathedral window on the one hand, and Sir William Chambers’ experiments in Oriental design on the other, we have two typical events[7] in the history of architectural form whose influence upon the course of this history has been far less profound than that, let us say, of the publication of Rousseau’s Emile or the repeal of the laws forbidding the exportation of machinery. Had not the very fact of Balbus building become an index to the social condition of the commonwealth? Thus any change in the state of society may accelerate building or retard it, and may likewise alter the whole subject or content of a particular province of building; while events of a purely architectural origin and significance most often leave a record that is only skin-deep.

But whether the movement be deep or shallow, local or enlarged, the historian has to consider it with just the same degree of care. While we expect him to give no part of his subject more than its due, on the other hand we insist that the ancillary and the fleeting shall be recorded side by side with the chief and lasting things. We do not, however, usually ask this of the prophet, and even were we to do so he would not be able to satisfy us without incurring intolerable risks. For the progress of an art is like the dual movement of the sea, which is actuated by wind and tide in mysterious combination; and between these two forces there[8] is this great difference, that the one will, after some little study, make itself known in advance, but none but an ill-guided or a mendacious prophet would attempt to foretell the other. Tide and current are important enough when we have to construct a picture of past and present movement, but in our anticipation of the future they are our only guides. In architecture as in dress the position of the prophet is the same: he cannot safely predict any new forms save those that are moulded by the human entity these forms invest. The shrewdest observer of fashion would be at a loss to give the precise length for the masculine waistcoat of five years hence. Tell him, however, that about that time there will be a large demand for reefer suits from the New Forest ponies, and he will describe the design of these suits with considerable accuracy. And in architecture no less we must content ourselves with seizing upon social movements already at work, and may form our estimate of future growth only by projecting these movements into the architectural plane, and there working out their architectural equivalent.

There are some, unfortunately, among prophets and historians alike who remain wholly or partly blind to this important[9] truth, and who claim that an occasional gust of wind is all that ever disturbs the architectural waters upon which they keep observation. According to them, there has been no movement of greater consequence than are the ripples on a stagnant pool, nor do they encourage us to expect any such movement in the future. Architecture and dress are treated exactly alike by these imperfect observers, and the favourite topics of sartorial conversation invariably reappear when architecture becomes the subject of their talk. These topics are dimension and material, and it may be worth while to consider for a moment in what manner they are sometimes able to intrude into what would appear to be a serious discussion of architectural form.

Everybody has heard it said at one time or another that the skyscraper is the building of to-morrow, and will soon lord it over the streets of every great city. Such a prophecy is about as likely to be fulfilled as a prophecy concerning the length of a garment. The size of a building is a matter by no means devoid of interest, but there is very little to help us in making a forecast of that size, and very little point in attempting it. Yet whole buildings have been erected on the strength of such a forecast. It is not[10] surprising that such buildings have afterwards involved their owners in heavy pecuniary losses, losses far heavier, indeed, than would ever be sustained by a racehorse backer working on a similar method. Nor is there even the semblance of a reason why size should be dignified with the name of style, and a change of size be spoken of as though it were tantamount to the creation of a new formal entity. A tall building might be continued upwards until it reached the stars, and still we should be unable to describe it as a new architectural expression, an innovation in the domain of artistic form. The Edgware Road might, for that matter, have its architectural configuration carried on as far as Newcastle in the shape in which it runs into Oxford Street, but we should not thereby be entitled to hold it up as the latest thing in street design. The topless towers of Ilium were something new in the size of towers only, and not in tower design properly speaking, just as the endless street of Edgware would be a new thing in the size of streets only, and not in street design. The same confusion lurks in the statement that certain industrial structures put up to store large quantities of water, coal, grain and similar commodities exhibit the modern spirit more strikingly than any[11] other kind of building. What, one may reasonably ask, is the difference between a coal-scuttle and a coal store, between a bucket of water and a tank of water, between a bottle of beer and a vat of beer? No doubt it is a novel experience to come upon a coal-scuttle fifty feet high, its bottom shaped like a cloud-burst, or a bin of barley large enough to hold two thousand tons. But is not the difference the same as the difference between the short street and the long street, between the four-storey building and the forty-storey building? We once more observe a difference of size merely; it is the shilling against the pound, the seven horse-power car against the seventy horse-power one. We have chosen to make these things larger than we have hitherto deemed it convenient to have them, and who shall say what size we may make them to-morrow?

Beside this deluded belief in the importance of dimension we may often observe an equally fruitless concentration on material. The architectural forms of the future, we are told, will be determined by the new material of which it appears likely that this architecture may be built. One could just as reasonably say that an orchestral performance is determined by such sounds as a haphazard collection of[12] instruments is likely of its own accord to emit. Nothing could be farther from the truth. In the present state of civilization the notes played by the musicians upon their instruments are determined by the composer’s score; the engine of a car is determined by the work that will be required of it; the knowledge and skill of our doctors are determined by the enactments of the General Medical Council; and the materials used in building are determined by the kind of building that the architect is asked to put up. In another age these things may have been slightly otherwise, but here and now they usually conform to this rule. In another age the materials with which you built, like the horse you rode, the cheese you ate, the doctor who attended you in sickness, were no doubt conditioned by your exact situation upon the earth’s surface, but to-day they are not so conditioned. To-day the industrial order of society has achieved all but the completest liberty to manufacture such materials as it may think suitable, and to carry these materials to whatever place may be chosen for their employment. A modern building may draw its substance from the clayfields of France, Spain and Belgium, the forests of Finland and Canada, the tar-impregnated rocks of Switzerland, the granite-quarries[13] of Ireland and Sweden, and yet betray in not a single line that it is anything but English in descent and urban in quality. At no time in history has form been dependent upon material, though it may have been influenced by it to a greater or lesser degree, and in our own age the autonomy of form is more firmly established than it has been in any other age of which we are aware. It is hardly necessary to add that to try and foretell the future acceptance of a material would be even more futile and more hazardous than the attempt to foretell the future acceptance of a dimension. If we cannot determine the size that will be given to the buildings of to-morrow, we know at any rate what is the range of possible sizes from which a choice will have to be made. The range of possible materials, however, may be fixed with no more accuracy or finality than the range of possible propulsive strengths of our future explosives, or the range of ether movements susceptible of being perceived or recorded by man. The progress of modern invention shows no sign of becoming retarded as yet, and only when its end draws within sight is there a likelihood that we may be able to foretell its next and ultimate stage, and lay down the limits of its achievement.

But if we are unable to discover what[14] will be the size of the buildings of to-morrow, and of what materials these buildings will be constructed, we may console ourselves with the thought that the whole field of architecture proper remains open for us to explore at will. We have, for example, but to regard with some care those social movements which are likely to suscitate a similar movement in architecture, and the course of this architectural movement will gradually become disclosed to us. Two such social movements will here be selected and their immediate architectural consequences followed out. The first of these is the emancipation of modern woman, which has produced a new type of building in which the strongest architectural impulse of the past and the highest architectural excellence of the past are both conspicuously absent. The other is the determined fight that is to-day being put up in order to prevent the complete paralysis of street traffic in the great towns of Europe, and, more particularly, of the United States of America. The effect of this struggle is to substitute for the old impulse and the old excellence a new impulse and a new excellence, both of an inferior order, but of considerable interest nevertheless.

The question may arise whether architectural[15] creation can be the result of more than one kind of human impulse. Do not all buildings erected by man, it may be asked, owe their origin to the same unchanging desire, though the fruits of that desire may be many and various? The answer is that there are, indeed, two distinct forces at work, two separate impulses which, though most often acting in combination, yet are neither similar in nature nor of equal importance. We have only to look from Westminster Abbey to the Cenotaph in Whitehall to realize that these two buildings are distinguished by a profound difference of meaning and of intention. Let us take the greatest possible difference and reduce it to its simplest aspect. It is (we may say) the business of the architect to design buildings. But he may set up round about his buildings a number of lesser objects such as bridges, parapets, columns, fountains, and others suchlike. How do these two kinds of structure compare? Are they different in size only, and would the Cenotaph, if it were enlarged to the size of Westminster Abbey, become a work of architecture commensurable with the Abbey? Of course, it would not, for the simple reason that the Abbey has an inside. Now, it is not by chance that the words outer and inner have become, in all[16] languages, the recognized metaphorical equivalents of body and soul. The usage is one that has occasionally been condemned by students of the logic of language, but it rests upon a perfectly sound foundation in that it appeals to an experience of universal validity, an experience which, let it be noted, is derived from architecture, and from architecture alone. A building is the only thing that you may both look into and look out of, both extraspect and introspect, and having learnt from the art of building thus to regard the human mind from two sides, as it were, we should at all times be careful to distinguish this dual aspect in buildings also. Now, in whatever manner we may describe these two views and the difference between them, this much is certain: that the greatest and most enduring qualities in architecture are those that reside in the design and arrangement of the internal spaces of a building, of those enclosing forms that are, in the last resort, the only justification of that building.

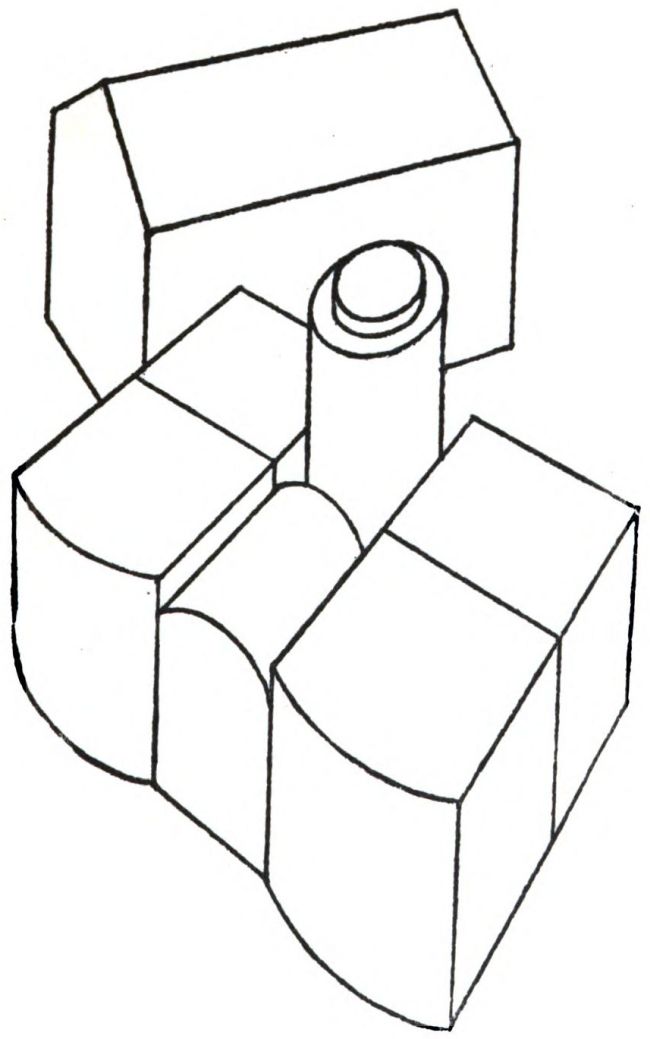

The idea is familiar to the architect, if not perhaps in the very words I have used, but he has not shown himself eager to let the layman into the secret. How many of us have not been puzzled by the mysterious significance attaching to the[17] word plan, and the still more mysterious aspect of the thing itself? What is there in a plan (for something there must be) that gives it this supremacy among all the possible representations of a building? A building worthy of the name of great architecture, so a simple answer might run, is invariably composed of a succession of spaces or cells. In this it resembles the human body, which is made up of just such a series—the cranial, thoracic and abdominal cavities, as we call them—with, in addition, the mechanical attachments of the limbs. And in buildings, as in the human body, the first essentials of beauty are to be found in the shape, disposition, and junction of this sequence of cells. These are the important facts about a building that are more fully revealed in a plan than in any other kind of drawing. We now know why an architect always hastens to record his ideas in the form of a plan—provided, of course, that his subject is indeed an arrangement of inhabitable cells. Sir Edwin Lutyens did not begin by sketching out the plan of his Cenotaph, but he cannot have found anything except a plan of much use in recording his ideas for his great war memorials at Verdun and Arras, a multicellular disposition, each of them, of great richness and delicacy.

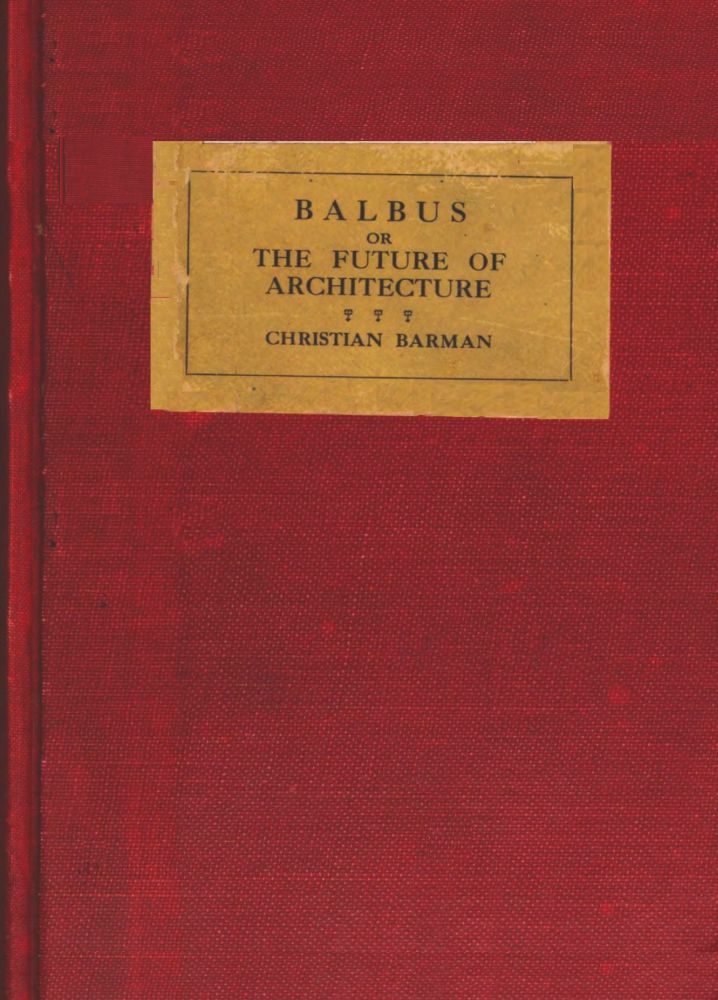

A pair of internal casts, illustrating the development of the architectural cell group. Above, a one-room dwelling-house. Below, a typical small house of the Regency period. The first floor has been removed, but the elliptical staircase-well with its lantern-light is shown complete. The front is double-bayed and the vestibule has a vaulted ceiling.

Let us consider for a moment how this disposition has in the course of time come about and how it has attained to its present complexity. There follows, upon cave and tent, the one-roomed cottage, so distant in spirit from the modern house, and yet persisting everywhere beside it. Under its single roof the tenants sleep, cook, eat; the very farmyard animals were once admitted to its shelter, as the camel and donkey are to-day admitted to the Egyptian fellah’s hut. One by one, however, this rudimentary dwelling puts forth cells as need sharpens and opportunity comes: the cattle are expelled to one side, the kitchen hearth to another, the beds to a third; cellar, larder, toolhouse follow. New cells have fastened themselves to the older ones; the house has become an organized collocation of parts; in it are found the elements of a plan. But, though organized, it remains haphazard in arrangement, what one of Jane Austen’s characters derisively calls “a scrambling collection of low single rooms, with as many roofs as windows.” Its growth is piecemeal and experimental, undirected, almost blind. It does not, however, remain so for ever, for man is an animal that learns by all that it does. In time these same elements, once scattered, will be measured[21] and composed together into a house by the prescient mind of one who will henceforth be known as an architect. A greater coherence, a greater orderliness, is gradually but surely acquired, and from the growing power of large and orderly planning there spring the ultimate achievements of architecture that are the pride of our race. Town hall, palace, theatre, church, all these proceed from this same skill in the fashioning of cells and in the gathering of them into a reasoned whole, into a plan.

A typical church of the Italian mid-Renaissance with one large and four smaller domes. This diagram and those on p. 19 represent not the exterior of the building but the interior space, its walls and ceilings removed, and regarded from outside as a solid, on the same principle as that which governs the design of the celestial globe.

To fashion, to gather; but at whose command? It is not for the architect to decide what cells there shall be; cells of what size, dedicated to what purpose, combined in what numbers. The architect is a servant only, and these things are the business of his master. It is when the master fails to attend to them that we get a building without a content, without a soul: a building that is admitted to the realm of architecture only on sufferance, since there is nothing to give its cells any particular shape, or to suggest or enforce any particular disposition of these cells. This is the typical building of to-day and to-morrow, and among the various agencies that have helped to bring it forth the freedom of modern woman is certainly the first, and is probably the most important also. There are, in addition, several causes of social instability that affect architecture in one way or another, and each of them helps to render modern building more uncertain, more indeterminate, or, as a biologist might say, more clearly lacking in morphological differentiation. On the formal side also (as contrasted with the functional) two lesser influences may be noted in passing. One is that astonishing manifestation of anti-æsthetic enthusiasm which has continued in more than one guise ever since the beginning of civilized society, but which to-day gains an added strength in that it has its source in the very stronghold of art itself. It is to be feared that Marinetti’s advice to use the altar of art as a spittoon has not been altogether neglected by architects, though their fellow artists may have taken it rather more deeply to heart. The other external influence is more subtle but no less active. It has been pointed out that only in a plan can the chief virtues of great architecture be adequately represented. It is a significant fact that the chief vehicle of architectural information to-day, the most popular means of recording architectural excellence, is the photograph, not the plan, of which it is the direct opposite. The photograph expresses all that the[25] plan leaves unsaid; it ignores all save a small remnant of the major qualities registered in the plan, and this remnant it twists and falsifies to a degree which renders its testimony worse than valueless. We have still to be shown the photograph that, representing the interior of a room, will convey a modicum of reliable information concerning the shape of that room. For in looking at a room through a photograph we are, be it remembered, looking at it through a small hole in a box. These two factors then have, in so far as they enter into contact with architectural form, been clearly disruptive in their effect, but the influence which must next engage our attention is an incomparably deeper one.

It is exactly half a century since the feminist movement began upon the career whose triumphant finish coincided with the great Peace of Versailles. There was in this country no feminist agitation worth speaking of, until the signal was given by the Reform Bill of 1876. In the very same year the late John Wanamaker, who had for some time been in business in Philadelphia as a dealer in men’s and boys’ clothing, discovered that women seemed prepared to do a certain amount of shopping on their own account. He[26] opened a new department, which became the foundation of his later successes. Where men had walked rapidly in and out, mindful only of the tie or the pair of boots they had come to buy, a long procession of women wound its way from counter to counter, dismayed by the many omissions in their shopping list, and grateful to find how easily these omissions were to be repaired. The small band of women workers marching to victory was followed by an army of shoppers a hundred times more numerous, and of such energy and enterprise that men’s clothing departments were everywhere incorporated into their already extensive domain. The allegiance of the whole body of women must have been coveted for some time, for even in the early years of the nineteenth century the big west-end drapers would clothe an eligible debutante in their choicest productions, generously relying upon her to find a husband who could afford to pay her bills. But though the bait was ready, its opportunity had still to be found, and when the feminist movement at last provided it the large drapers’ store leapt forward, and the two revolutions went on together in a simultaneous advance. The first act of public violence was committed by the adherents of feminism in 1909, and as the[27] stones went crashing through the windows of the Government offices in Whitehall, the newly erected windows of Mr. Gordon Selfridge became the cynosure of the more pacific among feminine eyes. It will be necessary later on to consider the influence of modern woman from other angles of view, but we may be sure that from none of these has it been more potent or more remarkable, for as a consumer of wealth she is transforming the design of our buildings more thoroughly than is clear even to-day.

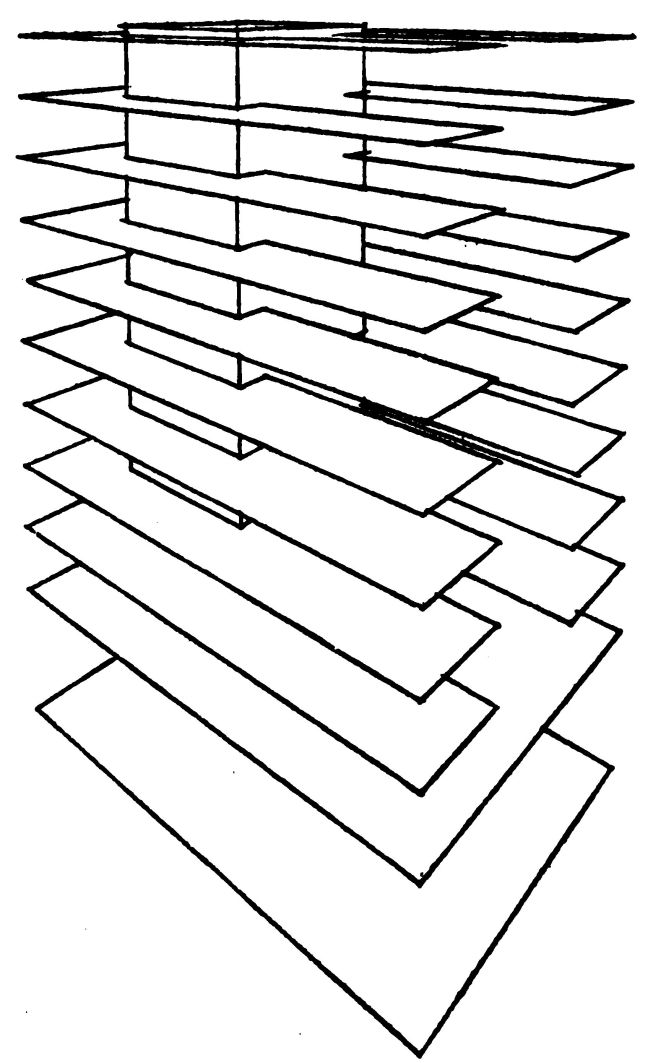

Very few years elapse before the large new drapery store assumes the characteristic form that will gradually impose itself upon many of our other buildings. It is realized almost at once that no external wall must cut off the ground floor of the building from the pavement of the street, for the business can only succeed if the undreamt-of collection of goods is amply and seductively displayed to the feminine passer-by. For some time experiments were made (notably by the Leonhard Tietz stores in Germany) with buildings clothed in glass from top to bottom, but, though German architects are still toying with the idea, the familiar stretches of undivided glass are nowadays applied to the ground floor only. Inside the buildings, however, no walls are wanted[28] at any point, on any of the floors, and there we find large open spaces offering no obstruction to the view, and allowing counters and show-cases to be moved backwards and forwards with the capricious tides of fashion. No longer is the building composed of an expressive sequence of definitely formed cavities; there is only layer upon layer of formless space, tier upon tier of vacant sites, along which the hundred specialized departments may pitch their glittering booths. It no more resembles a piece of major architecture than does a market-place covered with awnings and sunshades. It has become, in fact, a flight of hanging market-places piled one upon the other, rising high into the air, and delving many yards into the ground.

The constituent parts of this type of building are fourfold. There are the floors themselves; and there are the props necessary to support these floors. There is the covering, opaque or transparent, in which the top and sides are wrapped to protect the contents from the weather. Lastly, there is the private road which runs through the building from top to bottom. This road belongs to the modern composite type about which a little more still requires to be said. Let us here but observe that, reared on end and pointing[29] upward, it allows visitors to ride or walk from one level to another, while at the same time it contains within itself the numerous pipes and conduits through which water, heat and electrical energy are delivered to each floor, and the sewage carried away from it and discharged into the public drain.

Part of a modern commercial building, divested of its outer wall curtain and with the supporting metal framework removed. The U-shaped floor-platforms are, as it were, threaded on the vertical road, in which are contained the lifts and stairways and the various kinds of conduits. (Woolworth Building, New York, by Cass Gilbert.)

The new eviscerated architecture, once invented by the builder of the drapery store for his regiments of feminine customers, did not take long to gain a very considerable following. Indeed, it could not have had a more auspicious place of origin. As the bee carries the pollen from flower to flower, so the no less indefatigable draper carried the seeds of this architecture into the streets of every town of importance. We need only remind ourselves of the manner in which he is pressing forward to-day in the West End of London, transmuting with golden wand the whole of Regent Street, large portions of Oxford Street, and a great deal of Kensington and Bayswater, into something very rich and, as I have tried to show, not a little strange. Richest of all, perhaps, is the colonnade in Oxford Street whose relation to the rest of London is the relation between the majestic bulk of a transatlantic liner and the diminutive proportions of the fleet of tugboats that surrounds her. The modern drapery store is as large as it is ubiquitous, and its wealth and power are consonant with these outward signs of importance. The Wanamaker store, of which I have already spoken, provides an interesting example of the eminence to which these establishments have to-day attained. Everybody is aware of the interest displayed by publications such as the Daily Mail in the building and equipment of the suburban home, an interest which it would appear not unprofitable for them to indulge. The New York Wanamaker store, however, opened in October, 1925, a great and fascinating exhibition devoted exclusively to the future development of the city of New York. The first, to my knowledge, of its kind to be held anywhere, such an exhibition argues a sense of responsibility, a foresight, courage and public spirit that would be hard to parallel in any kind of business. Most of all, of course, it points to a very considerable degree of affluence, for the exhibition itself was accompanied by a wide and intensive publicity campaign in the New York Press. A commercial house that can afford to take such pains towards the popularizing of architectural and town-planning development schemes may claim to be a fairly important institution and an opulent[33] patron of the arts. Both the importance and the opulence have been conferred upon the drapery store by the emancipated women of to-day.

The possibilities of open-floor design for all kinds of building were, then, abundantly exhibited and widely perceived. From shop and factory the new device spread to the office block, whose claim to be in the modern movement is not usually admitted unless it consists of the same succession of shelf-like floors suspended round a central road. Schools and universities have already subscribed to the principle of unformed and undivided space. An appeal recently issued on behalf of the University of Pittsburg opens with the statement that 14,460,000 cubic feet of space are required for the University to discharge its normal functions. I cannot forbear to mention that one of the objects of the new buildings is (so the appeal goes on to tell us) to commemorate “the achievers of Pittsburg” and to testify to their “records of tonnage production.” The idea of perpetuating Pittsburg tonnage production in 14,460,000 cubic feet of University is not without a pleasing logic of its own.

And what of the house and home? Are we to meet there, too, with the same[34] undefined vacuity, the same absence of internal form? Already a Dutch architect has built a house with nothing inside its four outer walls except an upper floor to which an open stairway gives access. The upper and lower floors are subdivided by means of movable screens, which enable the owner to arrange his rooms according to the fancy of the moment, and, I suppose, to adjust his houseroom to the measure of his hospitality. This is, of course, how houses are mostly constructed in Japan, but it should be remembered that, though the Japanese house is built entirely without walls, whether internal or external, it yet exhibits the utmost complexity and formal refinement in the general lines of its design. The plan is there, though only its skeleton is permanent, and wall-divisions are made movable for another reason than that which is causing them to vanish from our Western buildings. Moreover, the Japanese house is of one storey only, and if the open floor is likewise to establish itself for good in our own domestic architecture, it will probably be restricted with us also to the one-storey dwelling, to bungalow and town flat. But even in these the outer walls and windows will, of course, remain—at any rate until we acquire the hardy[35] constitution of the Japanese, to whom a paper screen is sufficient protection in all weathers.

The breakdown of the principal architectural impulse is complete the moment the function of a building is expressed in an undifferentiated mass of cubic feet. It is at this moment that the second great movement, the movement which is to substitute a new external impulse for the old internal one, first becomes manifest. This movement springs, it will be recalled, from the threatened failure of our communications, a failure which is due, however, to no deficiency in these communications themselves, but to the vast and unequal overcrowding of modern cities. And the great increase of our populations that is the principal achievement of the nineteenth century presents three aspects, each one of which requires at this point to be carefully borne in mind.

First, the growth of population was not uniformly distributed, but went on far more swiftly in the great towns of Europe and America than it did throughout the countryside. Thus, while the population of England and Wales increased by about 90 per cent. between 1861 and 1921, the corresponding advance for London was about 133 per cent., while Berlin and New York went up by 500 and 600 per[36] cent. respectively. The difference, however, is a diminishing one, having been far greater throughout the second half of the nineteenth century than it is to-day. Our English urban population, for example, grew during the decade 1870–1880 at a rate which was nearly 200 per cent. in excess of the rate of growth of the rural population. The first decade of the present century shows an excess in the urban rate over the rural of only 10 per cent.

Our second observation is this: that during the time when it was at its highest point, the rate of growth of the urban population rose too rapidly for the concomitant growth of building to keep pace with it. The result was that the growth of building fell into arrears, and that such arrears still in part remain to be made good to-day. As the inhabitants became more numerous so the shortage of houses became more acute, until at last an ugly and even dangerous congestion of human beings began everywhere to show itself. This congestion would never have existed if the rate of building had been equal to the rate of growth of the population; swift as it was, the rate of building could never become swift enough. A similar condition, though due to a different cause, prevailed after the great Fire of London,[37] when Wren himself was driven to denounce the ill effects that flowed from “the mighty demand for the hasty works of thousands of houses at once.” Now, it is a commonplace that the growth of building may proceed in two directions, but it is not always realized that the two kinds of growth must proceed together, that each has its appointed function which the other is powerless to discharge. The growth of a town outward at its periphery is necessary, and the upward growth of its central region is also necessary. The first was the chief concern of the town-planning of yesterday and to-day, which unfortunately failed to carry out its appointed task. The second is likely to become the chief concern of the town-planning of the immediate future. Let us hope that it may be more fortunate.

These two growths are identical in one respect. Each of them remains, like all forms of growth known to science, entirely normal and beneficial so long as it is correctly regulated. We know that the growth of different parts of our body is regulated by means of chemical substances known as hormones, and that where certain hormones are lacking, or present in excess, we get the dwarf and the giant, goitre and cretinism. When it happens to the builders of a city that, in[38] the happy phraseology of a seventeenth-century pamphlet, “the Magistrate has either no power or no care to make them build with any uniformity,” they at once become the agents of a growth that is just as abnormal, just as obnoxious, as these physiological ones. It would seem, as the nineteenth century has taught us, that the power of regulating architectural growth begins to fail when that growth exceeds a certain measure of speed and urgency. Clearly, as the rate of growth increases, so the regulating power must also increase if it is to retain an effective control over building, for if it fails to increase in a similar ratio its influence must come to an end. This is what has happened all too often. Nor, haphazard and ungracious as the growth of building has been throughout the whole of Western civilization, has it anywhere been more irregular than at those points where it has moved most swiftly, and where the demands of the expanding population have reached the utmost severity of pressure. We are often told that New York is a city of high buildings. It is nothing of the kind: it is a moderately low city disfigured by a few high buildings only. Not more than one building in every thousand in the Manhattan Island district, famous for its skyscrapers,[39] exceeds twenty storeys in height. Nor should it be forgotten that the average height of buildings in New York is exactly the same as that obtaining in London, and rather less than the height of buildings in Paris. But while the upward growth of the two European cities has by no means been uniform and harmonious, it has not attained to the astonishing irregularity that receives such unmerited praise from English visitors to New York. It is the irregularity that is of consequence, and the source of this irregularity lies, on the one hand, in the sharp and unequally resisted strain put upon building by its effort to overtake the rate of increase of population, and, on the other, in the complete or partial breakdown of proper civic control, and the renunciation of the civic standard in building.

The third fact that has to be recorded in connection with the growth of our populations is a curious one. While the growth of building merely tended to become proportionate to the growth of the population, it was necessary that the means of communication should increase at a much faster rate. The more people there were, the more often and the more rapidly these people were compelled to move about from one place to another. Thus, while the inhabitants of Europe and[40] America multiplied, let us say, like the interest gathering upon a fixed capital sum, the movement of these inhabitants, of their various belongings, their food and drink, the materials and products of their labour, the waste left over from their individual and corporate metabolism, all this movement grew in scope, volume and swiftness in the manner of compound interest, or like a snowball enlarging itself into an avalanche. It is impossible in these pages to examine this mysterious law in any detail, but an example of its working may perhaps be given. It was stated just now that during the sixty years 1861–1921 the population of England and Wales increased by about 90 per cent., or, roughly, from twenty millions to thirty-eight. Many figures might be quoted to illustrate the growth of communications during the same period, but those yielded by the Post Office, at whose enterprising hands this growth took origin, will be enough for our purpose. We find, then, that the annual postal revenue of this country had, in the year 1921, increased to forty-five millions from four millions in 1861, an advance of 1025 per cent. If this is the rate at which our communications must expand, no wonder the London traffic authorities complain that the more facilities they[41] are able to provide, the greater becomes the demand made upon those facilities. Startling as the Post Office figures may seem, if we could as readily estimate the growth of the total movement along our roads, including not only pedestrian and vehicular traffic, but the transmission of water, fuel, and sewage, and of written and spoken messages as well, we should find the growth yet more considerable. Nor should we be surprised at the long, heroic struggle of nineteenth-century scientists and legislators to perfect this great and complicated thing, the modern road, or marvel to see them extend it hither and thither, and guard it from encroachments, and level and straighten out its trajectory, and search out a firm foundation for it, and render its surface hard and impervious, and dry it, clean it, illuminate it, and at last equip it for the automatic distribution of water and fuel, and for a continuous scavenging of all our towns.

It is this remarkable achievement of civilized man that to-day threatens to become ineffective. No sooner had the growth begun than it became clear that a keen rivalry between buildings and roads was inevitable, and further that unless the balance between these two were jealously maintained, the result to the road, so[42] necessary to the life of our civilization, would be disastrous. The first half of the nineteenth century saw the passing of innumerable private Acts connected with roadmaking, and in 1848 the famous Public Health Act set up a considerable national machinery, since improved and extended by many later measures. The Public Health Act has, in point of fact, two objects. While the more important of these is to ensure the quick, safe and efficient development of the roads, the Act was also designed to ensure that the growth of new buildings should not, in its headlong speed, fall below a decent standard of strength, comfort and cleanliness. But all this time the road remains the special care of the authorities, for, while in their capacity of building controllers they merely inspect and sanction such work as is being done by private enterprise, they themselves undertake the making and mending of roads with increasing pertinacity. Nor would their work have shown the smallest sign of failure were it not for the abnormal and unregulated growth of our large cities, a growth which has now reached a stage at which the roadmaker must assume a measure of control if the traffic in our streets is to continue in motion.

The control of buildings is no new[43] thing. In addition to the measures enacted to safeguard the integrity of the road-space we have had, for several centuries, the right to protest against a building being put up for a purpose that may be considered noxious. Not only has this right been enforced directly by means of legislation, but the State has made itself responsible for seeing that such undertakings as are entered into between landowner and tenant are carried out to the letter. If anyone proposed to erect a poison-gas factory in Grosvenor Square, his neighbours would have immediate power to restrain him, while a fruiterer’s shop could only be expelled if its owner were found to violate the conditions under which the land is granted. The law, however, upholds such conditions, and by these two means manages to exercise a considerable measure of user control, as it is now commonly called. Now, zoning is, by its very name, a comprehensive system of user control of this same kind. In so far, however, as it merely forbids the erection of a certain class of building in a stated zone, it can scarcely be said to influence architectural form. The true architectural importance of zoning lies in the fact that, the town-planner having failed adequately to control the height of buildings, it places in[44] the hands of the roadmaker “emergency” powers enabling him to control their capacity.

He cannot, however, hope to do this justly and usefully without paying due regard to the use or function of each building at the same time that he inquires into its capacity, and this dual control is in fact the peculiar object of the roadmaker in his quality of zoning controller. Let me give an example of how he goes to work. It has been calculated by the committee which is preparing the development plan for the New York region that one mile of theatres is the cause of a daily traffic movement of 36,000 vehicles. The corresponding figure for a street of suburban shops is only one-fourth as high, while a mile of factories of ordinary size is responsible for a mere 600 vehicles. On the other hand, the rapid development of labour-saving machinery is daily increasing the output of modern factories, and has, during the last seven years, more than doubled the amount per worker of goods traffic going in and out of the average American workshop. In addition to the moving vehicles, the stationary ones, too, require to be considered, though a time is no doubt approaching when the parking of cars on public ground will be forbidden in most large towns. The worst aspect of[45] this subsidiary problem is, of course, presented by places of amusement, whose audiences are acquiring the motor-car habit even more rapidly than the community as a whole. Not many years will elapse before American theatre and concert audiences habituate themselves to the motor-car to the exclusion of any other vehicle, and when this condition has been reached the mile of theatres already referred to will require a strip of land over a hundred feet wide along its entire length, in order to make room for the lines of waiting cars. Fortunately the motor-car has not yet attained such wide patronage in our own country, but anyone who will stroll down the narrow streets on the west side of Shaftesbury Avenue, say between the hours of eight and ten, on a week-day night, must conclude that with us also the difficulties are fast growing acute.

What is the solution to this knot of related problems? We can only reach it if we calculate the capacity of each building, multiply this figure by its traffic-producing coefficient, and then set this figure against the capacity of the surrounding streets. Difficult as these computations may appear, they yet are entirely feasible. Upon them is founded the science of zoning, a science which is as yet so imperfectly understood by the[46] majority of us that it has been necessary to describe its origin and purpose in some detail. We may now go on to ask what is likely to be its effect on the architecture of the immediate future. The answer is one which may appear to contradict itself. Devised for the purpose of protecting the street from the undue growth of its buildings, the zoning ordinance must tend before all else to encourage the growth in size of the average individual building, and to grant it a measure of formal autonomy which will rapidly destroy the few remaining vestiges of coherent street design.

A height restriction, such as those in force in England, is founded upon a conception of civic order, but it may in addition have one of three practical objects. It may be designed to prevent unstable construction, or to ensure that the surrounding area is not unduly darkened, or to allow a jet of water to sweep over the roof in an outbreak of fire. The zoning ordinance is concerned with none of these things. Its object is to regulate capacity alone, and this it does by drawing an inclined line upward from the centre of the street, thus fixing an angle within which the outline of the building is forced to remain. Now, it is in the first place to be observed that[47] rapidly sloping walls are as impracticable as they are unsightly in buildings of great height. It follows that the ordinance may best be complied with by breaking up the façade into receding vertical planes, each separated from the next by a narrow terrace. And the larger is the site occupied by a building thus falling back along a fixed angle, the higher this building will be allowed to reach, for in a triangle of which the angles remain constant the height will vary as the base. In the second place, a building measuring more than, say, sixty or seventy feet in depth will require an open area to provide it with an adequate supply of light and air. In a skyscraper of the old-fashioned type it was the custom to place this area at the centre of the building, which became a quadrangular box, encircling the four sides of a deep central void. But it is at its centre that a building erected under the zoning ordinance is allowed to reach its maximum height. To give up this part, more valuable than any other, for the necessary area would of course be folly, and the area is, in consequence, placed where the sacrifice of useful volume will be smallest, that is to say, at the periphery of the building, in such a manner as to lie open to the street.

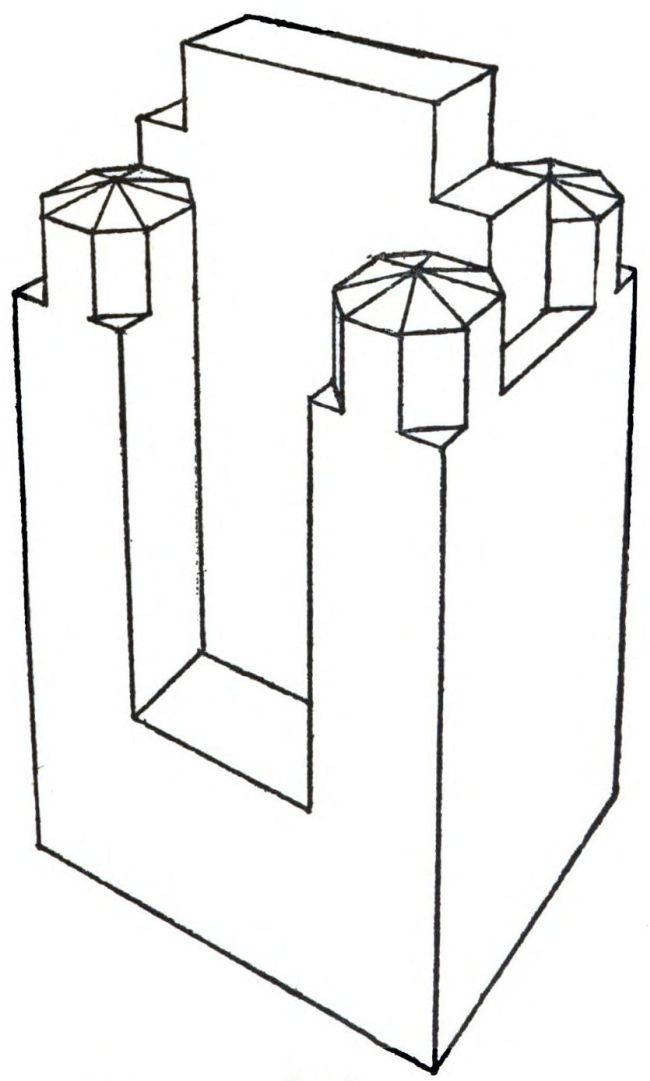

A zoned building, consisting of an H-shaped arrangement of parallelepipeds with two external areas. The influence of the American zoning law is visible in the upper part only. It accounts for the stepping-back of the central block and the octagonal tower that surmounts each corner. (Fraternity Clubs Building, New York, by Murgatroyd and Ogden.)

A building erected under the zoning ordinance will, therefore, occupy as much ground as its promoter is able to buy with borrowed money, and will, wherever possible, spread itself over the entire area of a city block, so that it is bounded by a street on all four sides. Its outline will, in addition, present two striking characteristics. It will rise on all sides in a succession of receding stages gathered at the summit in a central tower-like mass which, provided its area does not exceed a prescribed limit, may itself escape the restraining influence and rise unhindered. And while at each corner the street wall itself is brought to the full height permissible under the ordinance, the central part of each façade will be recessed so as to form one or several open courts or areas. At the moment of writing, London is about to witness the completion of its first building designed along these lines. Why the American zoning regulations should have been made to govern the design of the new Devonshire House building in London is not excessively clear, but this interesting piece of work does at any rate provide a valuable illustration of the laws of growth to which American architecture will in future be subject. For this reason it is by far the most interesting and the most characteristically modern of our large new buildings.[51] There is just now a curious tendency to describe as modern a small number of structures whose windows are treated in accordance with a short-lived æsthetic fashion of thirty years ago. Devonshire House furnishes proof that architecture is able to be more modern than that, for here the new zoning ordinance is, for the first time in London, shown actively at work.

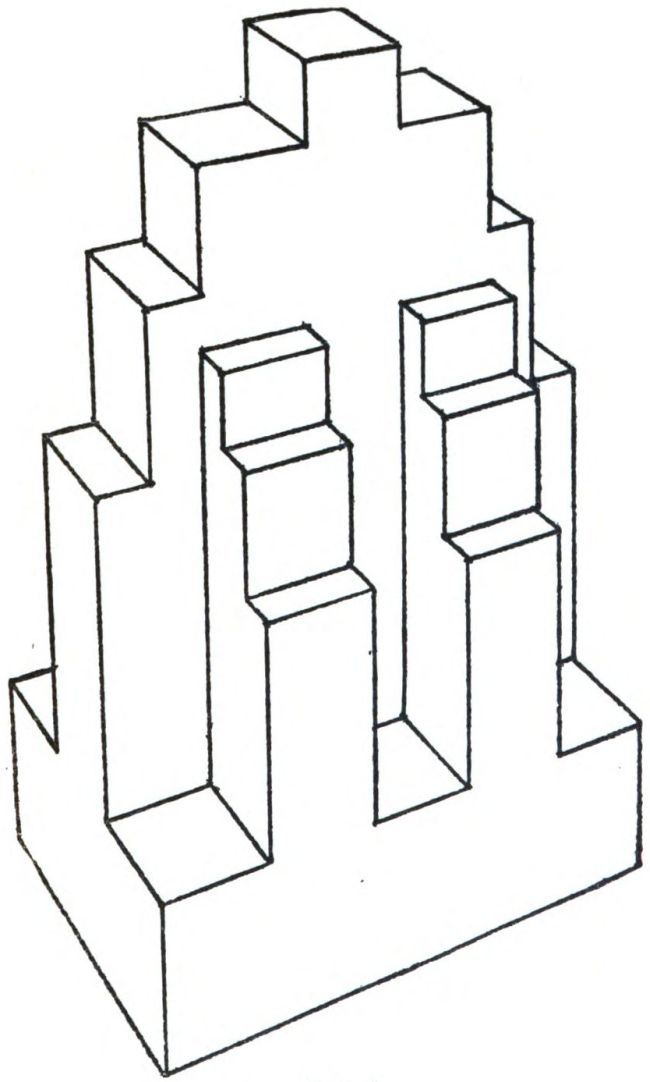

A zoned building, more recent than the last, showing the American zoning law in full operation. The central parallelepiped here runs across the two others, thus forming six external areas separated by six buttress-like projections. Each of these projections is stepped back in obedience to the zoning law. (Bell Telephone Building, St. Louis, by Russell and Crowell.)

We may now see why it was remarked that zoning had substituted a new architectural impulse for the governing impulse of internal form to which we owe the major masterpieces of architecture. A zoned building can never be a masterpiece in the same sense as these. You cannot compare a zoned building to Chartres Cathedral, any more than you can compare a suit of clothes to a paper-weight. The form of the one is dictated by something working from inside outwards, while the form of the other is the result of an agency working upon the surface from without. The paper-weight may be as beautiful in its way, but its beauty does not arise, as the beauty of clothing arises, from its power to invest the human form with an apt, expressive and dignified integument. In the same manner the zoned building may be beautiful, but not with the beauty of the greatest architecture, which consists in the fashioning of a dwelling-place, human or divine, in such a manner as to guard and delight those who enter into it. The zoned building is, I repeat, like the University of Pittsburg, a matter of cubic feet piled up around a private road. Any new formal impulse that may control its growth resides in the street without; any new formal excellence it may exhibit has for its origin the directing authority of this street. But in spite of the inferior quality of its products, it is easy to see that the zoning ordinance holds out a considerable promise to the architecture of the future, supplying a fresh and vigorous motive in the place of an older that is rapidly failing, and setting up the authority of reason where caprice alone now rules.

Before we leave this subject, a word may perhaps be added concerning the limitations of this method of control. It clearly cannot be applied everywhere with equally pleasing results. A town or a district in which the streets run at right angles to one another will show it at its best, for there, and there only, will it be possible for the defining lines to meet with any degree of regularity. London buildings, too, have sometimes to conform to a stipulated angle, though for another[55] reason than those of New York. But the irregularity of our streets, and the narrowness of most of our building frontages, have caused these controlling angles to become a source of grotesque heterogeneity and ugliness instead of allowing them to establish a new kind of order. Nor should our town be one containing sites excessively large, or have some of its streets so narrowly spaced as to produce sites that are sensibly smaller than the average. The larger area will permit of too great a building height, the smaller of too little, and it would appear necessary that the “street block” should, in addition to a regular outline, observe an approximate equality of size also. Founded upon these two equalities, the zoning ordinances proceed to build up an equality of height, of content, which in its turn begets yet another that is the guarantee of their ultimate success. For nothing will prosper in America that does not pay, and fortunately zoning has been found to pay, and to pay very handsomely. The “realtors” of the big American towns did not take long to discover that, while the building of a skyscraper must enhance the value of the surrounding land, this enhancement is considerably greater where the growth is controlled than where it is left free to[56] congest, and stifle, and darken, as in the licence of nineteenth-century New York. To the neighbouring landowner an unregulated skyscraper, if it pointed to a new opportunity, was at the same time an evil and a discouragement, for, if all buildings simultaneously went up to those same heights, would they not mutually destroy one another? The zoning ordinance has thus become a part of the republican policy of the United States, under which a competitive society is made to bring forth numbers rather than eminence, and watches over these its children with democratic solicitude.

We have examined with some care the evolution of wheeled traffic and the changes its multiplication must inevitably bring about in the appearance of our streets. Is not flying, it may be asked, always described as the locomotion of the future, and is not the shape of our buildings likely to reflect so important a development? The first part of this question would take us beyond the scope of the present essay, but the answer to the second part may perhaps form the subject of a digressive paragraph. One might reasonably say that the design of a building is likely to respond to the needs of aerial traffic in three ways only, but not in any way that is likely to be of great[57] consequence. The first possibility is that a building may be required providing means whereby aeroplanes are enabled to make a safe landing on its roof. A flat roof of ample dimensions thus becomes necessary, and yet we have seen that one of the effects of the zoning ordinance is to break up the roof surface of a building into a series of narrow ledges. A building upon the top of which it is desired to bring an aeroplane to land will, therefore, in those places where zoning prevails, need to be conspicuously low. Possibly a roof may here and there be projected outward beyond the walls of a building, an expedient whose drawbacks are such that it is unlikely to be often adopted. In any case it will be necessary to provide an entrance to the building from this roof, but there is nothing very new about that. The second possibility is that the aeroplane may have to be lowered from the roof of the building to the street level. The easiest way of making this descent is (to quote from a newspaper advertisement of the great Wanamaker exhibition to which I have referred) by “corkscrewing down the exterior of the building.” One of the great mural cartoons included (side by side with a Ford “family aeroplane”) in this exhibition shows an enormous cylindrical tower, encircled by[58] a descending spiral, very much like a corkscrew in appearance. This tower is not, however, an ordinary city building, but, reaching high above the concourse of these, a special structure surmounted by a mooring mast for dirigibles. Happily the building has yet to be designed that will, while giving shelter, however unworthy, to human beings, wrap itself in a broad fire-escape for the convenience of corkscrewing aeroplanes. And there is, on the whole, no ground for supposing that our urban architecture will at any time pay so exorbitant a regard to the advance of the aeroplane as to transform itself in this manner.

But it will be remarked that aerial travel is bound to call into being a number of buildings of a special kind, devoted to this one purpose alone. May we expect such buildings to be as novel and as eminently characteristic as the Wanamaker cartoon would appear to suggest? It is difficult to believe that among them there will be anything more unusual than the dirigible hangar, which is already a familiar sight, and which, to do it justice, has a peculiar interest in that it is the only modern building whose purpose contains an unanswerable argument for a roof vaulted throughout its entire breadth. The hangar built at Orly by the French[59] engineer Freyssinet is perhaps the example best known in this country; if it is not, it certainly deserves to be. But though the rounded shape of a balloon clearly demands a vaulted roof, there is no reason why such roofs should not be used elsewhere, as they have in fact been used for many centuries; and in his Utrecht Post Office the Dutch architect Crouwel has given us a building that, stripped of its great clock and its counters and other furnishings, might easily be mistaken by a wandering dirigible for its accustomed lair. Striking though the appearance of the Orly hangar may be found, it would scarcely be fair to attribute its success to the peculiar function it so efficiently discharges. And if this is all that the dirigible balloon is likely to do for architecture, what shall we say of the aeroplane? It would appear that only when practising the movement described by our American friends as “corkscrewing” will the aeroplane need the help of the architectural innovator. Till then we must remain content to see it inhabit a structure hardly distinguishable from the coach-house of our forbears.

The prospect opened to us by aerial locomotion is limited, for no matter how high our winged vehicles may one moment soar, they cannot approach the[60] earth without losing much of their glamour and strangeness. Let us turn instead to the far more considerable factor which came before us at the beginning of this essay. The emancipation of modern woman was there glanced at in only one of the three aspects of which the two others have still to be regarded. We saw how, as a consumer of wealth, she has been instrumental in withdrawing the art of building from the light of its central inspiration, and depriving it of the most highly treasured of its resources. As a producer of wealth, her influence has perhaps been less momentous, but it is by no means to be disregarded, for the modern dwelling-house exhibits the fruits of it in almost every detail of planning and equipment. So profound are the changes it has suffered that a medium-sized house, built, say, three generations ago, and left in its original state, presents almost insuperable difficulties to the housewife of to-day. Its cavernous succession of kitchens and larders, its monumental boiling ranges, its numberless stairs and endless dim passages, all of these things must fall into desuetude, unless a regiment of muscular girls and women is enlisted to maintain order among them. We all know how in the leisurely age of our[61] great-grandmothers a house was much more loosely, more vaguely planned, with nothing resembling the meticulous precision that is brought to bear upon it to-day. It was not necessary in those days to measure the distance the housewife had to walk in order to put the dinner on the table, for the walk was one which she was never called upon to take. There was no need to place a roomy and well-ventilated linen-cupboard close to the principal bedrooms, for the bedroom linen might be kept anywhere and fetched from anywhere without inflicting appreciable hardship upon the housewife. But wide though the gulf may be that divides the modern house from that of the early nineteenth century, the novelty of the former would not be nearly so apparent were it not for the much broader gulf by which it is divided from that of a generation later. During the second half of the century the romantic revival was scattering over the country a number of houses whose unpracticalness was so gigantic that they could only strike the beholder completely dumb. The labyrinth at Knossos being at that time still undiscovered, these structures are generally presumed to derive from the cathedrals and dungeons of the Middle Ages. It is by comparison with these preposterous[62] inventions that the post-war house stands out in a yet more appealing and more individual light. Instead of losing purpose and definition, like the typical city building, it has gained vastly in both these qualities, and it has gained because, from being the scene of the housewife’s activities, it has become her instrument and ally, and sometimes (it must be admitted) her accomplice even.

The next step, indeed, has already been taken. It is possible even now to watch the modern residence gradually assuming the properties of a machine. At the beginning of the last century nine-tenths of the cost of a house went into the structure, while the remaining tenth paid for its fixtures and equipment. Nowadays we spend almost as much on drains and plumbing, on baths and closets, on bedroom lavatory basins supplied with hot water, on central heating, electric light, telephones and suchlike, as we spend on the building of the house. So remarkable has been this development that an American writer has prophesied a period when houses will be given away free with the plumbing. It is doubtful whether such munificence will ever become a commercial possibility, but the prophecy contains more than a modicum of truth. We may reasonably expect to see all[63] but the most indispensable furniture done away with in the small house of to-morrow, while its walls, ceilings, and doors will assume a blankness and roundedness that has hitherto been thought needful only in the operating chambers of our hospitals. In order still to reduce the housewife’s labours, the apartments will be brought together in those vast blocks that are meeting with such strenuous opposition from private householders in the United States, an opposition to which the zoning authorities have almost invariably given every support. What is the reason for this opposition? It is that a new apartment house will (in the words of a recent American Court pronouncement) “increase the fire hazard” of the district upon which it intrudes, and will be “creative of noises from autos, taxis, milk wagons, drays, etc., in a locality where peace and quiet now prevail; it will obstruct light and air, and sooner or later it will bring with it the immoralities which always attend the building of such structures.” The list of its potential misdeeds goes on, but I have quoted at sufficient length to show what are the conditions to be expected when the house is supplanted by large, noisy, and efficient machines, which none but the richest and the poorest may altogether elude.

Is it inevitable that they will be so supplanted? The displacement is steadily going on, and the scope and rapidity of the process must depend upon the eagerness with which modern woman sets herself to pluck the fruits of liberty that are now so compliantly brought within her reach. It should be borne in mind, however, that the mechanization of the house is inspired by a purpose diametrically opposite to that entertained by the pioneers of modern methods in industry. The triumph of the powerloom over the handloom was conditioned by its ability to produce so many more yards of material than the handloom could be made to yield. But while the machine was introduced into the industrial world in order to multiply the products of labour, the object of the modern house is to diminish the necessity for labour. By exchanging the handloom for the powerloom the weaver could, while still taking the same amount of trouble, produce a greater result, but when the modern housewife moves into a labour-saving flat her object is by taking considerably less trouble to produce the same result as before. How and where she spends the hours of leisure thus acquired is a question which does not bear upon our present argument, except in so far as this leisure[65] has enabled her to raise the drapery store to the exalted place it occupies to-day, and by this means to divert the trend of modern architecture in the direction which we have just been following.

It is, then, largely by virtue of her new position as a producer that the woman of to-day has become able to exercise such a signal influence in her quality of consumer of wealth. But from both these points of view we may perceive her acting immediately upon the main architectural current, while, if we consider her from the conjugal point of view, her influence will show itself only in the flow of the tributary stream which is conveniently described as decoration. It is a regrettable fact that the decorative arts in England had, until they suddenly came within this influence, shown not the smallest sign of vitality since Soane and Nash translated the Attic enthusiasm of Shelley, Landor and Winckelmann into stone and stucco. Learned though he may have been, there can be no doubt that John Soane was as genuinely moved by the masterpieces of Greek decoration as Shelley by the large and authentic voices of Plato and Æschylus. The modern decorator, however, who ransacks the storehouse of history from Robert Adam to the caves of prehistoric man, is never animated by[66] better instincts than those of the merchant adventurer, and often enough by worse. Of a creative impulse he is completely innocent. And what are we to say of the teaching of Ruskin, who followed upon the heels of these great men, except that it was calculated to impart a knowledge not so much of decoration as of botany, while its temper was wholly inimical to such pleasure as might yet be taken here and there in decorative skill? Stifled by the tedious pullulation of Ruskin’s “natural forms,” this pleasure appears to be awakening once more, and it is to modern woman that we must look for the cause of this awakening.

A convenient way of picturing the change of outlook that has led to this revival is to compare two familiar works of nineteenth-century fiction separated by a generation or two. Gautier’s Mademoiselle de Maupin contains long passages redolent of that nature-worship which made Wordsworth a best-seller and which inspired our Ruskin to discard the principles of decorative design in favour of those derived from the study of plant growth. Innumerable landscapes are presented to us in this book, many of them bathed in moonlight of the most impeccable romantic quality. Country mansions, pleasure-pavilions, creeper-clad[67] cottages, all these are concealed beneath a dense mass of verdure, their existence briefly hinted at, while the sinuous paths by which they may be approached are made the subject of the closest description, together with the trees, shrubs, creepers, herbs and mosses which form their setting. Such power of attention as remains in the reader is skilfully directed upon the subject of feminine apparel, to the treatment of which the author brings a sympathy and animation almost equal to those with which he approaches the vegetable kingdom. But the apartments through which his characters move, the walls and furniture against which their forms, so exquisitely clad, stand disclosed to the reader, receive as little thought as the exterior of the buildings, so that it is impossible for us to say what they are like. As soon as the men and women cross the threshold of a house, an impenetrable mist descends upon their surroundings. Alas, there was no one to take any interest in even the most delightful of the houses or rooms, and we are left to reconstruct them for ourselves, aided only by our knowledge of a few authentic remains.

In Zola’s Nana we have a complete antithesis to this fatigue, this chlorosis of the decorative faculty. The adornment[68] of her immediate setting has with this famous character become a consuming passion. Her intuitive artistic knowledge, her manifold inventiveness, never cease to astonish the architects and decorators who work at her bidding. Nor, in her brief but triumphant career through the world of vice, does she once tire of devising fresh schemes of decoration, schemes which Zola himself appears to regard with an enthusiasm approaching that of his heroine. As she pauses at last on the brink of financial ruin, this passion for decoration flares up with an almost hysterical intensity. It is then that she dreams of “un prodige, un éblouissement ... un lit comme il n’en existait pas, un trône, un autel ... en or et en argent repoussés, pareil à un grand bijou.” To the end her preoccupation maintains its firm hold upon her, for through it alone it was that she could gain her mysterious ascendancy over the minds and the senses of men. “Jamais elle n’avait senti si profondément la force de son sexe,” remarks Zola as he shows her to us happily contemplating the scenes of prodigious elegance that she had established around her. Such is the change of attitude which nineteenth-century society must somehow have witnessed before it could be so brilliantly[69] recorded in writing. It is a similar change that has infused new life into modern decoration.

The question may present itself whether to connect this movement with Zola’s unfortunate heroine is not to detract from its merit or importance. That must remain entirely a matter for individual judgment. I will here but remark that, in borrowing their light from the constellation of unhappy spirits in which Nana shone so vividly, the decorative arts are only imitating the example set throughout Europe and America by the art of feminine dress, and that whatever is said of one of these arts applies to the other also. But this superficial resemblance is not the only thing that unites decoration with dress, for the modern movement in decoration cannot be better described than as an enlargement of the old and more immediate business of personal adornment. Both currents spring from a common source, and if the younger of them will always remain in some respects apart from its sartorial companion, grown with the centuries into a venerable historic stream, we yet have reason to be thankful that the arid waste of decoration is being watered again, however fitfully.

What is it that has turned the decorator of to-day into a kind of transcendent[70] costumier? I here have room to hint at a couple of reasons only. In the first place, it should be remembered that while the avowed ideal of masculine clothing is to render its wearers inconspicuous by causing them all to look alike, the ideal of feminine clothing is to give an appearance of strangeness and singularity. Now, nothing could accord more happily with our mechanical civilization than the masculine ideal; nothing, on the other hand, could come into more violent and more disappointing conflict with it than the feminine. Modern industry does not discriminate; it holds out to both sexes the same opportunities for acquisition, it heaps upon both the same monotonous profusion of manufactured goods. A hat, a mantle, a gown, is no sooner devised than a million others of the selfsame pattern pour in steady streams into every corner of the world. A startling colour cannot be affected by someone eager to achieve distinction of appearance without multiplying more rapidly than the budding green in Mr. Wells’ Time Machine. Provincial visitors to the West End of London are astonished at the number of well-dressed women they see about the streets, and profess themselves unable to distinguish between a duchess and a shop-assistant, while Londoners who[71] tread for the first time the pavements of Paris or New York find themselves similarly baffled. Thanks to the ceaseless activities of the large drapers’ store (supported by the admirable enterprise of artificial silk manufacturers) no woman to-day, however penurious, need deny herself any of those elegant accessories that were the crowning luxury of her ancestors. But, pleasing as this facility may be to the multitude, is it to be imagined that the more fortunate or ambitious can look upon it with the same satisfaction? Assuredly not, for they have even invoked the law of copyright in their attempt to resist it.

In drawing our conclusions from this spectacle of unwelcome equality it is useful also to bear in mind the relation between the female and the male populations of Western Europe. During the last half century the excess of women in this country has, roughly speaking, doubled in proportion to the total number of inhabitants of both sexes. The effect of a fixed and constant inequality may be neutralized by a series of adjustments in the social structure, but when the inequality threatens to increase fourfold in the course of a century the pressure it engenders is not so easily relieved. One of the most distressing sights to be met[72] with in Paris to-day is the large number of coloured and mostly negroid males that is gradually being assimilated by the white population. There are some even who predict that France will soon have become a bi-coloured republic. Should this unpleasant prophecy be realized, the present excess of white females will no doubt go a long way to account for the change. Whether or not this excess has done anything to stimulate the new movement in decoration it is, of course, impossible to say with certainty, but our surmise receives the strongest confirmation from the fact that in the United States of America, alone among modern countries in this respect, the modern decorative movement appears to be awakening no response at all. For in that country alone the male population exceeds the female by a surplus that is increasing at almost exactly the same rate as our own female surplus is increasing.

The new movement has been described as an enlargement of the art of dress, an affinity which those who visited the 1925 Paris Exhibition of Decorative Art will be ready enough to acknowledge. Among the most skilful of the exponents of the movement is M. Maurice Dufrène, and no one could wish for a more complete expression[73] of its main characteristics than his Chambre de Dame, shown at the 1925 exhibition along with other apartments by the same artist. Wherever one may turn in this room, one’s eye rests upon long sinuous curves whose rise and fall is as the billowing of an exquisite garment. The richness and amplitude of its lines recall nothing so much as the famous liquefaction that the silk frock of Herrick’s Julia would undergo, more particularly while the poet watched her in the act of walking. The dressing-table undulates round its absent mistress with a softness of movement that causes one to think of a fur or a cloak, while in the distance, framed in a background of streaming silver, the bed rolls lazily like a magic carpet suspended on the breeze. The cushions and lampshades have the appearance of intimate garments too pertly displayed. From an elongated hollow in the ceiling, fringed with curling foam, a golden light descends with studied moderation upon the skin of a giant polar bear, the canine adjunct enlarged and architecturalized, its muzzle caught in the loops of a heavy rope of silver. Everybody said the room was a distinguished success, and this, in so far as it served to enhance a brilliant though imaginary personality, it indubitably was.

The chief manifestation of the new movement, however, lies not so much in its forms as in the teguments wherein those forms are clothed. They are invariably of the greatest succulence. Soft, smooth, evenly or sharply luminous, they answer one another like the modulated textures of the dressmaker’s products. Even metallic surfaces are made to play their dull or glittering part in the combination, for there is nothing, as Baudelaire wrote in one of his poems, that provides so telling a foil to the warmth of woven materials as “l’énivrante monotonie du métal, du marbre et de l’eau.” It is only fit, therefore, that among the most successful of all these designers should be the metalworker Edgar Brandt, whose fame has securely established itself even on the other shore of the Atlantic. To infuse with profound feminine charm the design of a metal grille or an ornamental chandelier may appear difficult, but this is what M. Edgar Brandt has succeeded in doing; nor could we ask for a more striking testimony to the strength and singleness of the impulse from which this modern movement in decoration derives than we may find in his triumphant enlistment of such unlikely aids as these. The proper place and[75] function of his work, of which I will not attempt a detailed description, is as unmistakable as the work itself. Only the other day a candidate for an academic prize in architecture introduced an imitation of it into a design for a bank building. Of course, he had to be rebuked on behalf of the prize committee, happily through the person of that witty and scholarly critic, Mr. H. S. Goodhart-Rendel. The particular manner of design he had chosen, the designer was told, should be confined to “the surroundings of beautiful and expensive women.” Its nature could not have been more succinctly defined.