THE

HELL BOMB

![[Logo]](images/i_title.jpg)

Title: The hell bomb

Author: William L. Laurence

Release date: January 29, 2025 [eBook #75243]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1950

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/75243

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Tim Lindell, Wayne State College and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

![[Logo]](images/i_title.jpg)

Copyright 1950 by The Curtis Publishing Co. Copyright 1950 by William L. Laurence. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper. Manufactured in the United States of America. Published simultaneously in Canada by McClelland & Stewart Limited.

The material in this book falls into two categories: (1) a popular version in terms understandable to the layman of technical data published in scientific literature in this country and abroad, and widely known among scientists everywhere; and (2) technical conclusions reached by deduction based on these published facts and theory, for which I assume the sole responsibility. In doing so, I wish to make it emphatically clear that I have had no access to any classified information on the current hydrogen-bomb program, and also that whatever access I had to H-bomb information during my stay at Los Alamos in the spring and summer of 1945 was strictly limited to the somewhat vague and general discussions carried on there in 1945 and earlier.

I hereby take the opportunity to express my profound appreciation to Dr. James G. Beckerley, Director of Classification, Atomic Energy Commission, Washington, D. C., and to Mr. Corbin Allardice, Director, Public Information Service, of the AEC’s New York Operations Office, for their generous cooperation in clearing this manuscript for publication. It must be strictly understood that any such clearance merely means that the AEC viiihas “no objection to publication” on the grounds of security. It does not in any way vouch for the accuracy or correctness of the book’s contents.

| I | The Truth about the Hydrogen Bomb | 3 | |

| II | The Real Secret of the Hydrogen Bomb | 29 | |

| III | Shall We Renounce the Use of the H-bomb? | 57 | |

| IV | Korea Cleared the Air | 88 | |

| V | A Primer of Atomic Energy | 114 | |

| Appendix: The Hydrogen Bomb and International Control | 149 | ||

| A. | Significant Events in the History of International Control of Atomic Weapons | 151 | |

| B. | The International Control of Atomic Weapons: a Brief History of Proposals and Negotiations | 155 | |

| C. | The Atomic Impasse | 168 | |

| D. | Possible Questions Regarding H-bombs and International Control | 171 | |

“It is most important in our democracy that our government be frank and open with the citizens. In a democracy it is only possible to have good government when the citizens are well informed. It is difficult enough for them to become well informed when the information is easily available. When that information is not available, it is impossible. While there may be some cases in which the information which the citizen needs, in order to make an intelligent judgment of national policy, must be kept secret, so that military potential will not be jeopardized, the present use of secrecy far exceeds this minimum limit. These are the methods of an authoritarian government and should be vigorously opposed in our democracy....

“The citizen must choose insofar as that is possible. Today, if he tries to come to some conclusion about what should be done to increase the national security, the citizen runs up against a high wall of secrecy. He can, of course, take the easy solution and say that these are questions which should be left to the upper echelons of the military establishment to decide. But these questions are so important today, that to leave them to the military men to decide is for the citizen essentially to abrogate his basic responsibility. If, in time of peace, questions on which the future of our country depends are left to any small group, not representative xiiof the people, to decide, we have gone a long way toward authoritarian government.

“The United States has grown to be a strong nation under a constitution which wisely has laid great emphasis upon the importance of free and open discussion. Urged by a large number of people who have fallen for the fallacy that in secrecy there is security, and, I regret, encouraged by many, including eminent scientists, to prophesy doom just around the corner, we are dangerously close to abandoning those principles of free speech and open discussion which have made our country great. The democratic system depends on making intelligent decisions by the electorate. Our democratic heritage can only be carried on if the citizen has the information with which to make an intelligent decision.”

(From a talk on the hydrogen bomb, March 27, 1950, at Town Hall, Los Angeles, by Professor Robert F. Bacher, head of the Physics Department, California Institute of Technology. Professor Bacher served as the first scientific member of the Atomic Energy Commission and was one of the major architects of the atomic bomb at Los Alamos, New Mexico.)

I first heard about the hydrogen bomb in the spring of 1945 in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where our scientists were putting the finishing touches on the model-T uranium, or plutonium, fission bomb. I learned to my astonishment that, in addition to this work, they were already considering preliminary designs for a hydrogen-fusion bomb, which in their lighter moments they called the “Superduper” or just the “Super.”

I can still remember my shock and incredulity when I first heard about it from one of the scientists assigned to me by Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer as guides in the Dantesque world that was Los Alamos, where the very atmosphere gave one the sense of being in the presence of the supernatural. It seemed so fantastic to talk of a superatomic bomb even before the uranium, or the plutonium, bomb had been completed and tested—in fact, even before anybody knew that it would work at all—that I was inclined at first to disbelieve it. Could anything be more powerful, I found myself thinking, than a weapon that, on paper at least, promised to release an explosive force of 20,000 tons of TNT? It was a screwball world, this world 4of Los Alamos, I kept saying to myself, and this was just a screwball notion of my younger scientific mentors.

So at the first opportunity I put the question to Professor Hans A. Bethe, of Cornell University, one of the world’s top atomic scientists, who headed the elite circle of theoretical physicists at Los Alamos. Dr. Bethe, I knew, was the outstanding authority in the world qualified to talk about the subject, since he was the very man who first succeeded in explaining how the fusion of hydrogen in the sun is the source of energy that will make it possible for life to continue on earth for billions of years.

“Is it true about the superbomb?” I asked him. “Will it really be as much as fifty times as powerful as the uranium or plutonium bomb?”

I shall never forget the impact on me of his quiet answer as he looked away toward the Sangre de Cristo (Blood of Christ) mountain range, their peaks turning blood-red in the New Mexico twilight. “Yes,” he said, “it could be made to equal a million tons of TNT.” Then, after a pause: “Even more than a million.”

The tops of the mountains seemed to catch fire as he spoke.

Long before it was discovered that vast amounts of energy could be liberated by the fission (splitting) of the nuclei of a twin of the heaviest element in nature—namely, uranium of atomic mass 235 5(235 times the mass of the hydrogen atom, lightest of all the elements)—scientists had known that truly staggering amounts of energy would be released if one could fuse together four atoms of hydrogen, the first element on the atomic table, into one atom of helium, element number two on that table, which weighs about four times as much as hydrogen. In December 1938—three weeks before the discovery of uranium fission was announced in Germany—Dr. Bethe had published his famous hypothesis about the fusion of four hydrogen atoms in the sun to form helium. This provided the first satisfactory explanation of the mechanism that enables the sun to radiate away in space every second a quantity of light and heat equivalent to the energy content of nearly fifteen quadrillion tons of coal. And while Dr. Bethe was the first to work out the fine details of the process, scientists had been speculating for more than twenty years on the likelihood of hydrogen fusion in the sun as source of the sun’s eternal radiance.

American audiences first heard about hydrogen as the solar fuel in a lecture, on March 10, 1922, at the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia, by Professor Francis William Aston, famous British Nobel-Prize-winning chemist, who even at that early date warned mankind against what he called “tinkering with the angry atoms.” His words on that occasion have a strange prophetic ring, though most of what he said is now known to be wrong. “Should 6the research worker of the future discover some means of releasing this energy [from hydrogen] in a form which could be employed,” he predicted, “the human race will have at its command powers beyond the dreams of scientific fiction, but the remote possibility must always be considered that the energy, once liberated, will be completely uncontrollable and by its violence detonate a neighboring substance. If this happens, all of the hydrogen on earth might be transformed [into helium] at once, and this most successful experiment might be published to the rest of the universe in the form of a new star of extraordinary brilliance, as the earth blew up in one vast explosion.”

By 1945 we had learned that many things were wrong in Professor Aston’s prophecy. It had been definitely established, for example, that it would be impossible to “transform all the hydrogen on earth at once,” no matter how many superduper hydrogen bombs were to be exploded. In fact, we had learned that, under conditions as they exist on earth, we could never use common hydrogen, the element that makes up one ninth by weight of all water, either in a superduper bomb or as an atomic fuel for power. On the other hand, ten years after Dr. Aston’s lecture a new type of hydrogen was discovered to exist in nature. It was found to constitute one five-thousandth part of the earth’s waters, including the water in the tissues of plants and animals. It was shown to have an atomic 7weight of two—double the weight of common hydrogen—and was named deuterium. The nucleus, or center, of the deuterium atom was named the deuteron, to distinguish it from the nucleus of common hydrogen, known as the proton. Deuterium also became popularly known as “heavy hydrogen.” Water containing two deuterium atoms in place of the two atoms of light hydrogen became known as “heavy water.”

The most startling fact learned about deuterium soon after its discovery in 1932 was that it offered potentialities as an atomic fuel, or an explosive, of tremendous energy, provided one condition could be met. This condition was a “match” to light it with. And here was the catch. The flame of this match, it was found, would have to have a temperature of the order of 50,000,000 degrees centigrade, two and a half times the temperature in the interior of the sun.

Oddly enough, the discovery of the principle that made the atomic bomb possible also brought with it the promise that a “deuterium fire” might, after all, be lighted on earth. Early studies had revealed that the explosion of an atomic bomb, if it lived up to expectations, would generate a central temperature of about 50,000,000 degrees centigrade. Here, at last, was the promise of realization of the impossible—the 50,000,000 degree match.

The men of Los Alamos thus knew that if the atomic bomb they were just completing for its 8first test worked as they hoped it would, it could be used as the match to light the deuterium fire. They could build a superduper bomb of a thousand times the power of the atomic bomb by incorporating deuterium in the A-bomb, the explosion of which would act as the trigger for the superexplosion. And they also knew that the deuterium bomb held such additional potentialities of terror, beyond its vastly greater blasting and burning power, that the step from the duper to the super would be just as great as the step from TNT to the duper.

The hydrogen bomb, H-bomb, or hell bomb, as the fusion bomb had become popularly known, thus became a reality in the flash of the explosion of the first atomic bomb at 5:30 of the morning of July 16, 1945, on the New Mexico desert. As the men of Los Alamos, of whom I was at that time a privileged member, watched the supramundane light and the apocalyptic mushroom-topped mountain of nuclear fire rising to a height of more than eight miles through the clouds, they did not have to wait until they checked with their measuring instruments to know that a match sparking a flame of about 50,000,000 degrees centigrade had been lighted on earth for the first time. The size of the fire mountain and the end-of-the-world-like thunder that reverberated all around, told the tale better than any puny man-made instruments.

And there in our midst, as we learned only recently, 9stood a Judas, Klaus Fuchs, a name that “will live in infamy” along with that of other archtraitors of history. By the greatest of ironies, there he was, this spy, standing right in the center of what we believed at the time to be the world’s greatest secret, waiting at that very moment to tell the Russians of our success and how we achieved it. As he confessed five years later, he betrayed to them the most intimate details not only about the A-bomb but about the H-bomb as well—details that he learned as a member of the innermost of inner circles. For, alas, he was a trusted member of the theoretical division, the sanctum sanctorum of Los Alamos. This select group of scientists, behind doubly and triply locked doors, discussed in whispers their ideas about the superduper.

His associates at Los Alamos, who should know, sadly admit that Fuchs made it possible for Russia to develop her A-bomb at least a year ahead of time. It is my own conviction that the information he gave the Russians made it possible for their scientists to attain their goal at least three, and possibly as much as ten, years sooner than they could have done it on their own. Yet, though Fuchs confessed everything he told the Russians, the content of his confession is still kept a top secret from the American people, who sadly need information on one of the greatest problems facing mankind. The reason given is that we cannot 10actually be sure that Fuchs told the Russians all that he says he did, and, if published, his confession might, by his tricky design, give the Russians additional information. Of course, anything is possible for a warped mind such as that of Fuchs. Nevertheless, it seems highly implausible that this traitor, who went to the Russians voluntarily, should withhold any vital information from them for as long as five years. The best evidence that he didn’t is the Russian A-bomb.

Yet some good comes even of the greatest evil. All the circumstantial evidence points to the fact that during the five-year period following the end of the war our work on the hydrogen bomb had stopped completely. The A-bomb was the mightiest weapon in the world, we seem to have reasoned, and it would take Russia many years before she would get an A-bomb of her own. Why spend great efforts on a superbomb?

The shock when Russia exploded her first A-bomb much sooner than we expected, topped by the second shock that Fuchs had handed Moscow all our major secrets on a platter—including, as must be surmised, those of the H-bomb—awakened us to the facts of life. It is no accident that President Truman’s official announcement of the order to build “the so-called hydrogen bomb or superbomb” came within three days of the announcement of Fuchs’s arrest and confession. The President gave his order with full knowledge of 11Fuchs’s confession, which made it evident that the Russians were already at work on the hydrogen bomb and had probably been working on it uninterruptedly since 1945. The tragic prospect is that instead of the Russians catching up with us, it is we who may have to catch up with them.

Five years after the first announcement of the explosion of the A-bomb over Hiroshima, even the most intelligent Americans still have only the vaguest idea about the facts. Yet these facts are within the understanding of the average man. If we keep the earlier analogy of the match in mind, it becomes simple to understand the principles underlying both the A-bomb, now more correctly identified as the “fission bomb,” and the hydrogen bomb, more properly described as the “fusion bomb.”

Our principal fuel is coal, which, as everyone knows, is “bottled sunshine,” stored up in plants that grew about two hundred million years ago. When we apply the small amount of heat energy from a match, the bottled energy is released in the form of light and heat, which we can use in a great variety of ways. The point here is that it requires only the application of a very small amount of energy from a match to release a very large amount of energy that has been stored for millions of years in the ancient plants we know as coal.

Now, during the past half century we discovered that the nuclei, or centers, of the smallest 12units of which the ninety-odd elements of the material universe are made up—units we know as atoms—had stored up within them since the beginning of creation amounts of energy millions of times greater than is stored up by the sun in coal. But we had no match with which to start an atomic fire burning.

Then, in January 1939, came the world-shaking discovery of the phenomenon known as uranium fission. In simple language, we had found a proper “match” for lighting a fire with a twin of uranium, the ninety-second, and last, natural element. This twin is a rare form of uranium known as uranium 235—the figure signifying that it is 235 times heavier than common hydrogen. Doubly phenomenal, the discovery of uranium fission meant that to light the atomic fire, with the release of stored-up energy three million times greater than that of coal and twenty million times that of TNT (on an equal-weight basis) would require no match at all. When proper conditions are met, the atomic fire would be lighted automatically by spontaneous combustion.

What are these proper conditions? In the presence of certain chemical agencies, spontaneous combustion will take place when an easily burning substance, such as sawdust, for example, accumulates heat until it reaches the kindling temperature at which it ignites. The chemical agencies here are the equivalent of a match.

13The requirement to start the spontaneous combustion of uranium 235, and also of two man-made elements named plutonium and uranium 233 (all three known as fissionable materials or nuclear fuels), is just as simple. In this operation you do not need a critical temperature, but what is known as a critical mass. This simply means that spontaneous combustion of any one of the three atomic fuels takes place as soon as you assemble a lump of a certain weight. The actual critical mass is a top secret. But the noted British physicist, Dr. M. L. E. Oliphant, of radar fame, published in 1946 his own estimate, which places its weight between ten and thirty kilograms. If so, this would mean that a lump of uranium 235 (U-235), plutonium, or U-233, weighing ten or thirty kilograms, as the case may be, would explode automatically by spontaneous combustion and release an explosive force of 20,000 tons of TNT for each kilogram undergoing complete combustion. In the conventional A-bomb a critical mass is assembled in the last split second by a timing mechanism that brings together, let us say, one tenth and nine tenths of a critical mass. The spontaneous combustion that followed such a consummation on August 6 and 9, 1945 destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Thus, if we substitute the familiar phrase “spontaneous combustion” for the less familiar word “fission,” we get a clear understanding of what is 14known in scientific jargon as the “fission process,” a “self-multiplying chain reaction with neutrons,” and similar technical mumbo-jumbo. These terms simply mean the lighting of an atomic fire and the release of great amounts of the energy stored in the nuclei of U-235 since the beginning of the universe. The two so-called man-made elements are not really created. They are merely transformed out of two natural heavy elements in such a way that their stored energy is liberated by the process of spontaneous combustion.

Why, one may ask, does not spontaneous combustion of U-235 take place in nature? Why, indeed, has not all the U-235 in nature caught fire automatically long ago? To this also there is a simple answer. Just as in the spontaneous combustion of sawdust the material must be dry enough to burn, so must the U-235. Only in place of the word “dry” we must use the word “concentrated.” The U-235 found in nature is very much diluted with another element that makes it “wet.” It therefore must be separated first, by a very laborious and costly process, from the nonfissionable, or “wetting,” element. Even then it won’t catch fire, and could not be made to burn by any means, until the amount separated (“dried”) reaches the critical mass. When these two conditions—conditions that do not exist in nature—are met, the U-235 catches fire just as sawdust does when it reaches the critical temperature.

15The fact that as soon as a critical mass is assembled the three elemental atomic fuels burst into flame automatically thus puts a definite limit to the amount of material that can be used in the conventional A-bomb. The best you can do is to incorporate into a bomb two fragments, let us say, of nine tenths of a critical mass each. To enclose more than two such fragments would present difficulties that appear impossible to overcome. It is this limitation of size, an insurmountable roadblock put there by mother nature, that makes the basic difference between the A-bomb and the H-bomb.

For, as we have already seen, to light an atomic fire with deuterium it is necessary to strike a match generating a flame with a temperature of about 50,000,000 degrees centigrade. As long as no such match is applied, no fire can start. It thus becomes obvious that deuterium is not limited by nature to a critical mass. A quantity of deuterium a thousand times the amount of the U-235, and hence a thousand times more powerful, can therefore be incorporated in an ordinary A-bomb, where it would remain quiescent until the A-bomb match is struck. Weight for weight, deuterium has only a little more energy content than U-235, so that a bomb incorporating a 1,000 kilograms (one ton) of deuterium would thus have an energy of 20,000,000 tons of TNT.

Here must be mentioned another form of hydrogen, named tritium. It has long ago disappeared 16from nature but it is now being re-created in ponderable amounts in our atomic furnaces. Tritium, the nucleus of which is known as a triton, weighs three times as much as the lightest form of hydrogen. It has an energy content nearly twice that of deuterium. But it is very difficult to make and is extremely expensive. Its cost per kilogram at present AEC prices is close to a billion dollars, as compared with no more than $4,500 for a kilogram of deuterium. A combination of deuterons and tritons would release the greatest energy of all, 3.5 times the energy of deuterons alone. It would reduce the amount of tritons required to half the volume and three fifths of the weight required in a pure triton bomb, thus making the cost considerably lower.

But why bother with such fantastically costly tritons when we can get all the deuterium we want at no more than $4,500 a kilogram, while we can make up the difference in energy by merely incorporating two to three and a half times as much deuterium? Here we are dealing with what is probably the most ticklish question in the design of the H-bomb.

To light a fire successfully, it is not enough merely to have a match. The match must burn for a time long enough for its flame to act. If you try to light a cigarette in a strong wind, the wind may blow out your match so fast that your cigarette will not light. The same question presents itself 17here, but on a much greater scale. The match for lighting deuterium—namely, the A-bomb—burns only for about a hundred billionths of a second. Is this time long enough to light the “cigarette” with this one and only “match”?

It is known that the time is much too slow for lighting deuterium in its gaseous form. But it is also known that the inflammability is much faster when the gas is compressed to its liquid form, at which its density is 790 times greater. At this density it would take only seven liters (about 7.4 quarts) per one kilogram (2.2 pounds), as compared with 5,555 liters for gaseous deuterium. And it catches fire in a much shorter time.

Is this time long enough? On the answer to this question will depend whether the hydrogen bomb will consist of deuterium alone or of deuterium and tritium, for it is known that the deuteron-triton combination catches fire much faster than deuterons or tritons alone.

We were already working with tritium in Los Alamos as far back as 1945. I remember the time when Dr. Oppenheimer, wartime scientific director of Los Alamos, went to a large safe and brought out a small vial of a clear liquid that looked like water. It was the first highly diluted minute sample of superheavy water, composed of tritium and oxygen, ever to exist in the world, or anywhere in the universe, for that matter. We both looked at it in silent, rapt admiration. Though we did not 18speak, each of us knew what the other was thinking. Here was something, our thoughts ran, that existed on earth in gaseous form some two billion years ago, long before there were any waters or any forms of life. Here was something with the power to return the earth to its lifeless state of two billion years ago.

The question of what type of hydrogen is to be used in the H-bomb therefore hangs on the question of which one of the possible combinations will catch fire by the light of a match that is blown out after an interval of about a hundred billionths of a second. On the answer to this question will also depend the time it will take us to complete the H-bomb and its cost. To make a bomb of a thousand times the power of the A-bomb would require a 1,000 kilograms of deuterium at a cost of $4,500,000, or 171 kilograms of tritium and 114 kilograms of deuterium at a total cost of more than $166,000,000,000 at current prices, not counting the cost of the A-bomb trigger. Large-scale production of tritium, however, will most certainly reduce its cost enormously, possibly by a factor of ten thousand or more, while, as will be indicated later, the amount of tritium, if required, may turn out to be much smaller.

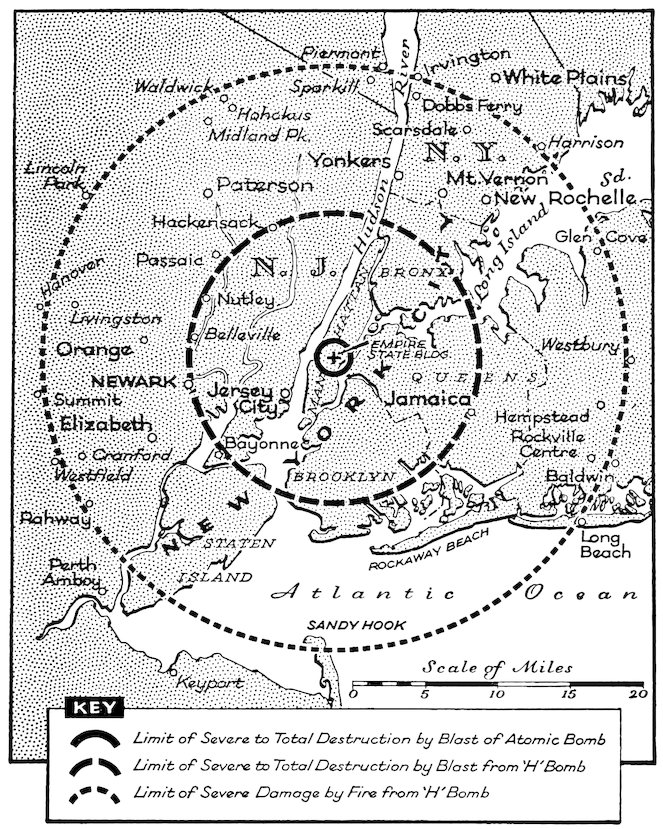

MAP BY DANIEL BROWNSTEIN

19We can thus see that if deuterium alone is found to be all that is required to set off an H-bomb it will be cheap and relatively easy to make in a short time—both for us and for Russia. Furthermore, such a deuterium bomb would be practically limitless in size. One of a million times the power of the Hiroshima bomb is possible, since deuterium can be extracted in limitless amounts from plain water. On the other hand, if sizable amounts of tritium are found necessary, the cost will be much higher and it will take a considerably longer time, since the production of tritium is very slow and costly. This, in turn, will place a definite limit on the power of the H-bomb, since, unlike deuterium, the amounts of tritium will necessarily always be limited. As will be shown later, we are at present in a much more advantageous position to produce tritium than is Russia, so that if tritium is found necessary, we have a head start on her in H-bomb development.

The radius of destructiveness by the blast of a bomb with a thousand times the energy of the A-bomb will be only ten times greater, since the increase goes by the cube root of the energy. The radius of total destruction by blast in Hiroshima was one mile. Therefore the radius of a superbomb a thousand times more powerful will be ten miles, or a total area of 314 square miles. A bomb a million times the power of the Hiroshima bomb would require 1,000 tons of deuterium. Such a super-superduper could be exploded at a distance from an abandoned, innocent-looking tramp ship. It would have a radius of destruction by blast of 100 miles and a destructive area of more than 30,000 20square miles. The time may come when we shall have to search every vessel several hundred miles off shore. And the time may be nearer than we think.

The radius over which the tremendous heat generated by a bomb of a thousandfold the energy would produce fatal burns would be as far as twenty miles from the center of the explosion. This radius increases as the square root, instead of the cube root, of the power. The Hiroshima bomb caused fatal burns at a radius of two thirds of a mile.

The effects of the radiations from a hydrogen bomb are so terrifying that by describing them I run the risk of being branded a fearmonger. Yet facts are facts, and they have been known to scientists for a long time. It would be a disservice to the people if the facts were further denied to them. We have already paid too high a price for a secrecy that now turns out never to have been secret at all.

I can do no better than quote Albert Einstein. “The hydrogen bomb,” he said, “appears on the public horizon as a probably attainable goal.... If successful, radioactive poisoning of the atmosphere, and hence annihilation of any life on earth, has been brought within the range of technical possibilities.”

What Dr. Einstein meant by “radioactive poisoning of the atmosphere, and hence the annihilation 21of any life on earth,” was explained in realistic detail by such eminent physicists as Dr. Bethe, Dr. Leo Szilard, Dr. Edward Teller, and others. All of them may even now be engaged on work on the hydrogen bomb.

Here is how “poisoning of the atmosphere” may result from the explosion of a hydrogen bomb: Tremendous quantities of neutrons, which can enter any substance in nature and make it radioactive, are liberated. In the case of a deuterium bomb, one eighth of the mass used—125 grams per kilogram—is liberated. In the case of a deuteron-tritium bomb, fully one fifth of the mass—200 grams per kilogram—is released, while in a bomb using pure tritium, fully one third of the mass—333 grams per kilogram—is liberated as free neutrons. There are 600,000 billion billion neutrons in each gram, each capable of producing a radioactive atom in its environment. The neutron is one of the two building blocks of the nuclei of all atoms.

These neutrons can be used to make any element radioactive, Professor Szilard and his colleagues point out. It follows that the casing of the bomb could be selected with a view to producing, after the neutrons enter it, an especially powerful radioactive substance. Since each artificially made, radioactive element gives out a specific type of radiation and has a definite life span, after which it decays to one half of its radioactivity, the designer 22of the bomb could rig it in such a way that its explosion would spread into the air a tremendous cloud of specially selected radioactive substances that would give off lethal radiations for a definite period of time. In such a way a large area could be made unfit for human or animal habitation for a definite period of time, months or years.

Take, for example, the very common element cobalt. When bombarded with neutrons, it turns into an intensely radioactive element, 320 times more powerful than radium. Any given quantity of neutrons would produce sixty times its weight in radioactive cobalt. If the bomb contains a ton of deuterium, 250 pounds would come out as neutrons. On the assumption that every neutron enters a cobalt atom, this would produce 7.5 tons of radioactive cobalt. That quantity would give out as much radioactivity as 2,400 tons of radium.

Now, this radioactive cobalt has a half-life of five years, meaning that it loses half of its radioactive power at every five-year period. So after a lapse of that period of time its radioactivity would be equal to 1,200 tons of radium, in ten years to 600 tons, and so on. If used as a bomb-casing it would be pulverized and converted into a gigantic radioactive cloud that would kill everything in the area it blankets. Nor would it be confined to a particular area, since the winds would take it thousands of miles, carrying death to distant places.

23The radioactivity produced by the Bikini bombs was detected within one week in the United States. In that short time the westerly winds swept the radioactive air mass from Bikini, 4,150 miles away, to San Francisco. When it reached our shores, the activity was weak and completely harmless, but it was still detectable. That, by the way, was how we learned that the Russians had exploded their first atomic bomb.

But, in the words of Professor Teller, one of the Los Alamos men who made the preliminary studies on the hydrogen bomb, “if the activity liberated at Bikini were multiplied by a factor of a hundred thousand or a million, and if it were to be released off our Pacific Coast, the whole of the United States would be endangered.” He added that “if such a quantity of radioactivity should become available, an enemy could make life hard or even impossible for us without delivering a single bomb into our territory.”

One limitation to such an attack, Professor Teller points out, is the boomerang effect of these gases on the attacker himself. The radioactive gases would eventually drift over his own country, too. He adds, however, that since these gases have different rates of decay—some faster, some slower—the attacker is in a position to choose those radioactive products best suited to his attack. “With the proper choice he could ensure that his victim would be seriously damaged by them, and 24that they would have decayed by the time they reached his own country.”

“It is not even impossible to imagine,” in the words of Professor Teller, “that the effects of an atomic war fought with greatly perfected weapons and pushed by utmost determination will endanger the survival of man.... This specific possibility of destruction may help us realize more clearly the probable consequences of an atomic war for our civilization and the possible consequences for the whole human race.”

On this point Professor Szilard is much more specific. “Let us assume,” he said at a University of Chicago Round Table, “that we make a radioactive element which will live for five years and that we just let it go into the air. During the following years it will gradually settle out and cover the whole earth with dust. I have asked myself, ‘How many neutrons or how much heavy hydrogen do we have to detonate to kill everybody on earth by this particular method?’ I come up with about fifty tons of neutrons as being plenty to kill everybody, which means about 400 tons of heavy hydrogen” (deuterium).

Now, obviously Professor Szilard was stating the extreme case. He merely called attention to the scientific fact that man now has at his disposal, or soon will have, means that not only could wipe out all life on earth, but could also make the earth itself unfit for life for many generations to come, 25if not forever. Here we have indeed what is probably the greatest example of irony in man’s history. The very process in the sun that made life possible on earth, and is responsible for its being maintained here, can now be used by man to wipe out that very life and to ruin the earth for good.

It is inconceivable that any leaders of men today, or in the near future, would resort to such an extreme measure. But the fact remains that such a measure is possible. And it is by no means unthinkable that a Hitler, faced with certain defeat, would not choose to die in a great Götterdämmerung in which he would pull down the whole of humanity with him to destruction. And who can be bold enough to guarantee that another Hitler might not arise sometime, somewhere, possibly in a rejuvenated Germany making another bid for world domination or total annihilation?

It is more likely, of course, that an attacker, particularly if he is otherwise faced with certain defeat, might choose the less drastic method outlined by Professor Teller, selecting for his weapon a short-lived radioactive element that would have spent itself by the time it reached his shores. If he is the sole possessor of the hydrogen bomb, he may not even have to use it, a threat of its use being sufficient to end the war on terms to his liking. In the face of such a threat, as Professor Szilard pointed out, who would dare take the responsibility of refusing?

26These are the stark, unvarnished facts about the “so-called hydrogen bomb.” They raise many questions to which the American people as a whole will have to find the answer. It is possible, and the odds here are more than even, that the very possession of the hydrogen bomb by both ourselves and Russia will make war unthinkable, since neither side could be the winner. This would be a near certainty if we had the answer to Russia’s Trojan Horse method of taking over nations by first taking over their governments, as was done in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and the Balkan countries. Suppose the Communists take over Italy, then Germany, by the same method. What would we do then? The answer is, of course, that if we wait until “then,” everything would be lost, no matter what we did. It therefore becomes obvious that our very existence may depend on what we do here and now to prevent such an eventuality.

Now that the hydrogen bomb has come out into the open after five years as a super-top secret, the authorities, and particularly the Atomic Energy Commission, may be called upon to answer some embarrassing questions. “Why,” we may ask, “was the work on the hydrogen bomb apparently dropped altogether during the past five years?” According to Professor Bethe, it would take about three years to develop it. This means that, had we 27continued working on it in 1945 and thereafter, we would have had it as far back as 1948. We have thus lost five precious years, our loss being Russia’s gain.

Some scientists and others contend that, because of our great harbor and industrial cities, the hydrogen bomb would be a greater threat to us than to the Soviet, because most Russian cities are much smaller than ours, while her industries are much more dispersed. There may be some truth in this. But on the other hand there are some great advantages on our side. With a strong Navy and good submarine-detecting devices we may have control of the seas and be able to prevent the delivery of the hydrogen bomb by ship or submarine. With a strong Air Force and radar system we could prevent the delivery of hydrogen bombs from the air.

By far the most important advantage the possession of the hydrogen bomb would give us against Russia is its possible use as a tactical weapon against huge land armies. Since they can devastate such large areas, one or two hydrogen bombs, depending on their size, could wipe out entire armies on the march, even before they succeeded in crossing the border of an intended victim. The H-bomb would thus counterbalance, if not completely nullify, the one great advantage Russia possesses—huge land armies capable of overrunning western Europe. The bomb might thus serve 28as the final deterrent to any temptation the Kremlin’s rulers may have to invade the Atlantic Pact countries.

Yet no matter how one looks at it, the advent of the H-bomb constitutes the greatest threat to the survival of the human race since the Black Death.

One is reminded of a dinner conversation in Paris in 1869, recorded in the Journal of the Goncourt brothers. Some of the famous savants of the day were crystal-gazing into the scientific future a hundred years away. The great chemist Pierre Berthelot predicted that by 1969 “man would know of what the atom is constituted and would be able, at will, to moderate, extinguish, and light up the sun as if it were a gas lamp.” (This prophecy has almost come true.) Claude Bernard, the greatest physiologist of the day, saw a future in which “man would be so completely the master of organic law that he would create life [artificially] in competition with God.”

To which the Goncourt brothers added the postscript: “To all of this we raised no objection. But we have the feeling that when this time comes to science, God with His white beard will come down to earth, swinging a bunch of keys, and will say to humanity, the way they say at five o’clock at the salon: ‘Closing time, gentlemen!’”

Can the hydrogen bomb actually be made? If so, how soon? How much will it cost in money and vital materials? Above all, will it, if made, add enough to our security to make the effort worth while?

As was pointed out by Prof. Robert F. Bacher of the California Institute of Technology, one of the chief architects of the wartime atomic bomb and the first scientific member of the Atomic Energy Commission, “since the President has directed the AEC to continue with the development [‘of the so-called hydrogen, or super bomb’] we can assume that this development is regarded as both possible and feasible.” Many eminent physicists believe that it can be made, and the use by the President of the word “continue” suggests that this belief is based on more than theory. No less an authority than Albert Einstein has stated publicly that he regards the H-bomb as “a probably attainable goal.”

On the other hand, there are scientists of high eminence, such as Dr. Robert A. Millikan, our oldest living Nobel-Prize-winner in physics, who doubt whether the H-bomb can be made at all. And there are also those who express the view 30that, while it probably could be made, it would not offer advantages great enough, if any, to justify the cost in vital strategic materials necessary for our security.

Fortunately, facts mostly buried in technical literature make it possible for us to go behind the scientific curtain and look intimately at the reasons for these differences in opinion. More important still, these facts not only provide us with a clearer picture of the nature of the problem but also enable us to make some reasonable deductions or speculations. The scientists directly involved do not feel free to discuss these matters openly, not because they would be violating security, but because of the jittery atmosphere that acts as a damper on open discussion even of subjects known to be non-secret.

We already know that the so-called hydrogen bomb, if it is to be made at all, cannot be made of the abundant common hydrogen of atomic mass one, and that there are only two possible materials that could be used for such a purpose: deuterium, a hydrogen twin twice the weight of common hydrogen, which constitutes two hundredths of one per cent of the hydrogen in all waters; and a man-made variety of hydrogen, three times the weight of the lightest variety, known as tritium. We also know that to explode either deuterium or tritium (also known, respectively, as heavy and superheavy hydrogen) a temperature measured in millions 31of degrees is required. This is attainable on earth only in the explosion of an A-bomb, and therefore the A-bomb would have to serve as the fuse to set off an explosion of deuterium, tritium, or a mixture of the two.

These facts, fundamental as they are, merely give us a general idea of the conditions required to make the H-bomb. All concerned, including Dr. Millikan, fully accept the validity of these facts. But there is one other factor at the very heart of the problem—the extremely short time at our disposal in which to kindle the hydrogen bomb with the A-bomb match. According to statements attributed to him in the press, Dr. Millikan believes that the time is too short; in other words, he seems to be convinced that the A-bomb match will be blown out before we have time to light the fire. Those of opposite view believe that methods can be devised for “shielding the match against the wind” for just long enough to light the fire. As we shall presently see, it is these methods for shielding the match that lead some to doubt whether the game would be worth the candle, or the match, if you will. These honest doubts are based on the possibility that, even if successful, the shielding might exact too high a price in terms of vital materials, particularly the stuff out of which A-bombs are made—plutonium. According to this view, we may at best be getting but a very small return for our investment in materials vitally important in 32war as well as in peace. Even though the price in dollars were to be brought down to a negligible amount.

A closer look at the details of the problem may enable us to penetrate the thick fog that now envelops the subject. We may begin with a quotation from Dr. Bacher, who outlined the principle involved with remarkable clarity. “The real problem in developing and constructing a hydrogen bomb,” he said in a notable address before the Los Angeles Town Hall,

is, “How do you get it going?” The heavy hydrogens, deuterium and tritium, are suitable substances if somehow they could be heated hot enough and kept hot. This problem is a little bit like the job of making a fire at 20 degrees below zero in the mountains with green wood which is covered with ice and with very little kindling. Today, scientists tell us that such a fire can probably be kindled.

Once you get the fire going, of course, you can pile on the wood and make a very sizeable conflagration. In the same way with the hydrogen bomb, more heavy hydrogen can be used and a bigger explosion obtained. It has been called an open-ended weapon, meaning that more materials can be added and a bigger explosion obtained.

The phrase that goes to the very heart of the problem is “very little kindling,” which is another way of illustrating the difficulty of lighting a fire in a high wind when you have only one match. We 33know that to ignite deuterium, by far the cheaper and more abundant of the two H-bomb elements, a temperature comparable to those existing in the interior of the sun, some 20,000,000 degrees centigrade, is necessary. This temperature can be realized on earth only in the explosion of an A-bomb. We also know that the wartime model A-bombs generated a temperature of about 50,000,000 degrees, more than enough to light a deuterium fire. The trouble lies in the extremely short time interval, of the order of a millionth of a second (microsecond), and a fraction thereof, during which the A-bomb is held together before it flies apart. In the words of Professor Bacher, we must make our green, ice-covered wood catch fire in the subzero mountain weather before the “very little kindling” we have is burned up.

The times at which deuterium will ignite at any given temperature, in both its gaseous and its liquid form, are widely known among nuclear scientists everywhere, including Russia, through publication in official scientific literature of a well-known formula, originally worked out by two European scientists as far back as 1929, and more recently improved upon by Professor George Gamow and Professor Teller. By this formula, derived from actual experiments, it is known that deuterium in its gaseous form will require as long as 128 seconds to ignite at a temperature of 50,000,000 degrees centigrade, well above 100,000,000 34times longer than the time in which our little kindling is used up. This obviously rules out deuterium in its natural gaseous form as material for an H-bomb.

How about liquid deuterium? We know that the more atoms there are per unit volume (namely, the greater the density), the faster is the time of the reaction. The increase in the speed of the reaction (in this case the ignition of the deuterium) is directly proportional to the square of the density. For example, if the density, (that is, the number of atoms per unit volume) is increased by a factor of 10, the time of ignition will be speeded up by the square of 10, or 100 times faster. Since liquid deuterium has a density nearly 800 times that of gaseous deuterium, this means that liquid deuterium (which must be maintained at a temperature of 423 degrees below zero Fahrenheit at a pressure above one atmosphere) would ignite 640,000 times faster (namely, in 1/640,000th part of the time) than its gaseous form. Arithmetic shows that the ignition time for liquid deuterium at 50,000,000 degrees centigrade will be 200 microseconds, still 200 times longer than the period in which our kindling is consumed.

The same formula also reveals the time it would take liquid deuterium to ignite at higher temperatures, the increase of which shortens the ignition time. These figures show that the ignition time for liquid deuterium at 75,000,000 degrees centigrade 35is 40 microseconds. At 100,000,000 degrees the time is 30 microseconds; at 150,000,000 degrees, 15 microseconds; and at 200,000,000 degrees on the centigrade scale, about 4.8 millionths of a second. Doubling the temperature speeds up the ignition time for liquid deuterium by a factor of about six.

The problem thus is a dual one: to raise the temperature at which the A-bomb explodes, and to extend the time before the A-bomb flies apart. It is also obvious that if the liquid deuterium is to be ignited at all, it must be done before the bomb has disintegrated—that is, during the incredibly short time interval before it expands into a cloud of vapor and gas, since by then the deuterium would no longer be liquid.

Can we increase the A-bomb’s temperature fourfold to 200,000,000 degrees and literally make time stand still while it holds together for nearly five millionths of a second? To get a better understanding of the problem we must take a closer look at what takes place inside the A-bomb during the infinitesimal interval in which it comes to life.

This life history of the A-bomb is an incredible tale, from the time its inner mechanisms are set in motion until its metamorphosis into a great ball of fire. As explained earlier, the A-bomb’s explosion takes place through a process akin to spontaneous combustion as soon as a certain minimum amount (critical mass) of either one of two fissionable 36(combustible) elements—uranium 235 or plutonium—is assembled in one unit. The most obvious way it takes place is by bringing together two pieces of uranium 235 (U-235), or plutonium, each less than a critical mass, firing one of these into the other with a gun mechanism, thus creating a critical mass at the last minute. If, for example, the critical mass at which spontaneous combustion takes place is ten kilograms (the actual figure is a top secret), then the firing of a piece of one kilogram into another of nine kilograms would bring together a critical mass that would explode faster than the eye could wink—in fact, some thousands of times faster than TNT.

Just as an ordinary fire needs oxygen, so does an atomic fire require the tremendously powerful atomic particles known as neutrons. Unlike oxygen, however, neutrons do not exist in a free state in nature. Their habitat is the nuclei, or hearts, of the atoms. How, then, does the spontaneous combustion of the critical mass of U-235 or plutonium begin? All we need is a single neutron to start things going, and this one neutron may be supplied in one of several ways. It can come from the nucleus of an atom in the atmosphere, or inside the bomb, shattered by a powerful cosmic ray that comes from outside the earth. Or the emanation from some radioactive element in the atmosphere, or from one introduced into the body of the bomb, may split the first U-235 or plutonium atom, knock 37out two neutrons, and thus start a chain reaction of self-multiplying neutrons.

To understand the chain reaction requires only a little arithmetic. The first atom split releases, on the average, two neutrons, which split two atoms, which release four neutrons, which split four atoms, which release eight neutrons, and so on, in a geometric progression that, as can be seen, doubles itself at each successive step. Arithmetic shows that anything that is multiplied by two at every step will reach a 1,000 (in round numbers) in the first ten steps, and will multiply itself by a 1,000 at every ten steps thereafter, reaching a million in twenty steps, a billion in thirty, a trillion in forty, and so on. It can thus be seen that after seventy generations of self-multiplying neutrons the astronomical figure of two billion trillion (2 followed by 21 zeros) atoms have been split.

At this point let us hold our breath and get set to believe what at first glance may appear to be unbelievable. The time it takes to split these two billion trillion atoms is no more than one millionth of a second (one microsecond). If we keep this time element in mind we can arrive at a clear understanding of the tremendous problem involved in exploding an A- or an H-bomb.

And while we are recovering from the first shock we may as well get set for another. That unimaginable figure of two billion trillion atoms represents the splitting (explosion) of no more than one 38gram (1/28th of an ounce) of U-235, or plutonium.

Now, the energy released in the splitting of one gram of U-235 is equivalent in power to the explosive force of 20 tons of TNT, or two old-fashioned blockbusters. Since we know from President Truman’s announcement following the bombing of Hiroshima that the wartime A-bomb “had more power than 20,000 tons of TNT,” it means that the atoms in an entire kilogram (1,000 grams) of U-235 or plutonium must have been split. In other words, after the A-bomb had reached a power of 20 tons of TNT, it had to be kept together long enough to increase its power a thousandfold to 20,000 tons. This, as we have seen, requires only ten more steps. It can also be seen that it is these ten final crucial steps that make all the difference between a bomb equal to only two blockbusters, which would have been a most miserable two-billion-dollar fiasco, and an atomic bomb equal in power to two thousand blockbusters.

With the aid of these facts we are at last in a position to grasp the enormousness of the problem that confronted our A-bomb designers at Los Alamos and is confronting them again today. It can be seen that for a bomb to multiply itself from 20 to 20,000 tons in ten steps by doubling its power at every step, it has to pass successively the stages of 40, 80, 160, 320, and so on, until it reaches an explosive power of 2,500 tons at the seventh step. Yet it still has to be held together for three more 39steps, during which it reaches the enormous power of 5,000 and 10,000 tons of TNT, without exploding.

Here was an irresistible force, and the problem was to surround it with an immovable body, or at least a body that would remain immovable long enough for the chain reaction to take just ten additional steps following the first seventy. There is only one fact of nature that makes this possible, or even thinkable—the last ten steps from 20 to 20,000 tons take only one tenth of a millionth of a second. The problem thus was to find a body that would remain immovable against an irresistible force for no longer than one tenth of a microsecond, 100 billionths of a second.

This immovable body is known technically as a “tamper,” which pits inertia against an irresistible force that builds up in 100 billionths of a second from an explosive power of 20 tons of TNT to 20,000 tons. The very inertia of the tamper delays the expansion of the active substance and makes for a longer-lasting, more energetic, and more efficient explosion. The tamper, which also serves as a reflector of neutrons, must be a material of very high density. Since gold has the fifth highest density of all the elements (next only to osmium, iridium, platinum, and rhenium), at one time the use of part of our huge gold hoard at Fort Knox was seriously considered.

With these facts and figures in mind, it becomes 40clear that an H-bomb made of deuterium alone is not feasible. It is certainly out of the question with an A-bomb of the Hiroshima or Nagasaki types, which generate a temperature of about 50,000,000 degrees, since, as we have seen, it would take fully 200 microseconds to ignite it at that temperature. It is one thing to devise a tamper that would hold back a force of 20 tons for 100 billionths of a second, and thus allow it to build up to 20,000 tons. It is quite another matter to devise an immovable body that would hold back an irresistible force of 20,000 tons for a time interval 2,000 times larger, particularly if one remembers that in another tenth of a microsecond the irresistible force would increase again by 1,000 to 20,000,000 tons. Obviously this is impossible, for if it were possible we would have a superbomb without any need for hydrogen of any kind.

It is known that we have developed a much more efficient A-bomb, which, as Senator Edwin C. Johnson of Colorado has inadvertently blurted out, “has six times the effectiveness of the bomb that was dropped over Nagasaki.” We are further informed by Dr. Bacher that “significant improvements” in atomic bombs since the war “have resulted in more powerful bombs and in a more efficient use of the valuable fissionable material.” It is conceivable and even probable that the improvements, among other things, include better tampers that delay the new A-bombs long enough 41to fission two, four, or even eight times as many atoms as in the wartime models. But since, as we have seen, the ten steps of the final stages require only an average of 10 billionths of a second per step, increasing the power of the new models even to 160,000 tons (eight times the power of the Hiroshima type) would take only three steps, in an elapsed time of no more than 30 billionths of a second. And even if we assume that the improved bomb generates a temperature of 200,000,000 degrees, it would still be too cold to ignite the deuterium during the interval of its brief existence, since, as we have seen, it would take 4.8 microseconds to ignite it at that temperature. In fact, calculations indicate that it would require a temperature in the neighborhood of 400,000,000 degrees to ignite deuterium in the time interval during which the assembly of the improved A-bomb appears to be held together, which, as may be surmised from the known data, is within the range of 1.2 microseconds.

From all this it may be concluded with practical certainty that an H-bomb of deuterium only is out of the question. Equally good, though entirely different, reasons also rule out an H-bomb using only tritium as its explosive element.

There are several important reasons why an H-bomb made of tritium alone is not feasible. The most important by far, which alone excludes it from any serious consideration, is the staggering 42cost we would have to pay in terms of priceless A-bomb material, as each kilogram of tritium produced would exact the sacrifice of eighty times that amount in plutonium. The reason for this is simple. Both plutonium and tritium have to be created with the neutrons released in the splitting of U-235, each atom of plutonium and each atom of tritium made requiring one neutron. Since an atom of plutonium has a weight of 239 atomic mass units, whereas an atom of tritium has an atomic weight of only three, it can be seen that a kilogram, or any given weight, of tritium would contain eighty times as many atoms as a corresponding weight of plutonium, and hence would require eighty times as many neutrons to produce. In other words, we would be buying each kilogram of tritium at a sacrifice of eighty kilograms of plutonium, which, of course, would mean a considerable reduction in our potential stockpile of plutonium bombs.

We would cut this loss by more than half because a kilogram of tritium would yield about two and a half times the explosive power of plutonium. But even this advantage would soon be lost, since tritium decays at the rate of fifty per cent every twelve years, so that a kilogram produced in 1951 would decay to only half a kilogram by 1963. Plutonium, on the other hand, can be stored indefinitely without any significant loss, since it changes 43slowly (at the rate of fifty per cent every twenty-five thousand years) into the other fissionable element, U-235, which in turn decays to one half in no less than nine hundred million years. What is more, plutonium, if the day comes when we can beat our swords into plowshares, will become one of the most valuable fuels for industrial power, the propulsion of ships, globe-circling airplanes, and even, someday, interplanetary rockets. It holds enormous potentialities as one of the major power sources of the twenty-first century. Tritium, on the other hand, can be used only as an agent of terrible destruction. It will yield its energy in a fraction of a millionth of a second or not at all. The only other possible uses it may have would be as a research tool for probing the structure of the atom, and as a potential new agent in medicine, in which it may be used for its radiations.

How much tritium would it take to make an H-bomb 1,000 times the power of the wartime model A-bombs? Since tritium has about 2.5 times the power per given weight of U-235 or plutonium, it would take 400 kilograms (about 1,880 quarts of the liquid form) of tritium to make a bomb that would equal the power of 1,000 kilograms of plutonium. Such a bomb, we can see, would have to be made at the sacrifice of 32,000 kilograms of plutonium. In other words, we would be getting a return, in terms of energy content, of 441,000 kilograms for an investment of 32,000. And we would be losing fully half of even this small return every twelve years.

How many A-bombs would we be sacrificing through this investment? On the basis of Professor Oliphant’s estimate that the critical mass of an A-bomb is between 10 and 30 kilograms, we would sacrifice at least 1,066, and possibly as many as 3,200, if we take the lower figure. And we must not forget that a bomb a thousand times the power will produce only ten times the destructiveness by blast and thirty times the damage by fire of an A-bomb of the old-fashioned variety.

These cold facts make it clear that a tritium bomb, particularly one a thousand times the power of the A-bomb, is completely out of the picture.

But, one may ask, if a deuterium bomb is not possible and a tritium bomb is not feasible, and these are the only two substances that can possibly be used at all, isn’t all this talk about a superbomb sheer moonshine? And if so, how explain President Truman’s directive “to continue” work on it?

To find the answer let us go back for a moment to Dr. Bacher’s man in the mountains, confronted with the problem of lighting a fire with green, ice-covered wood at twenty degrees below zero with “very little kindling.” Obviously the poor fellow would be doomed to freeze to death were it not for one little item he had almost forgotten. Somewhere in his belongings he discovers a container 45filled with gasoline, which increases the inflammability of the wet wood to the point at which it will catch fire with a quantity of kindling that would otherwise be much too small.

Something closely analogous is true with the H-bomb. It so happens that a mixture of deuterium and tritium is the most highly inflammable atomic fuel on earth. It yields 3.5 times the energy of deuterium and about twice the energy of tritium when they are burned individually. Most important of all, the deuterium-tritium mixture, known as D-T, ignites much faster than either deuterium or tritium by themselves. For example, the D-T combination ignites 25 times faster than deuterium alone at a temperature of 100,000,000 degrees, and the ignition time is fully 37.5 times faster than for deuterium at 150,000,000 degrees.

The published technical data show that at a temperature of 50 million degrees the D-T mixture ignites in only 10 microseconds, or 20 times faster than deuterium alone. At 75 million degrees it takes only 3 microseconds, as against 40 for deuterium, while at 100 million degrees it needs only 1.2 microseconds to catch fire, a time, as we have seen, only 0.1 microsecond longer than it took the wartime A-bomb to fly apart. Since the latter held together for 1.1 microseconds at a temperature of about 50 million degrees, it is reasonable to assume that the improved and more efficient models generate a temperature at least twice as high, and that 46this is done by holding them together for about 1.2 microseconds.

It can thus be deduced that the only feasible H-bomb is one in which a relatively small amount of a deuterium-tritium mixture will serve as additional superkindling, to boost the kindling supplied by the improved model A-bomb, for lighting a fire with a vast quantity of deuterium. This, it appears, is the real secret of the H-bomb, which is really no secret at all, since all the deductions here presented are arrived at on the basis of data widely known to scientists everywhere, including Russia. And since it is no secret from the Russians, whom the arch-traitor Fuchs has supplied with the details still classified top secret, the American people are certainly entitled to the known facts, so vitally necessary for an intelligent understanding of one of the most important problems facing them today.

A deuterium bomb with a D-T booster would become a certainty if the temperature of the A-bomb trigger could be raised to 150 million or, better still, to 200 million degrees. At the former temperature the D-T superkindling ignites in 0.38 microseconds; at the higher temperature the ignition time goes down to as low as 0.28 microseconds. Now, the D-T mixture releases four times as much energy as plutonium, and the faster the time in which energy is released, the higher goes the temperature. Since four times as much energy is 47released at a rate four times faster than in the wartime model A-bomb, it is not unreasonable to assume that the temperature generated would be high enough to ignite the green wood in the bomb—its load of deuterium.

How much tritium would be required for the kindling mixture? On this we can only speculate at present. Since the D-T kindling calls for the fusion of one atom of tritium with one atom of deuterium, and the atomic weight of tritium is three as compared with two for deuterium, the weight of the two substances will be in the ratio of 3 for tritium to 2 for deuterium. Thus if the amount to be used for the kindling mixture is to be one kilogram, it will be made up of 600 grams of tritium and 400 grams of deuterium. Since, as we have seen, it would take eighty kilograms of plutonium to produce one kilogram of tritium, we would have to use up only 48 kilograms of plutonium to create the 600 grams, or the equivalent of one and a half to about five A-bombs, according to Dr. Oliphant’s estimate.

But would we need as much as 600 grams of tritium? Such an amount, mixed with 400 grams of deuterium, would yield an explosive power equal to 80,000 tons of TNT, an energy equivalent of 100 million kilowatt-hours. A twentieth part of this amount would still be equal in power to 4,000 tons of TNT, equivalent in terms of energy to 5,000,000 kilowatt-hours. Now one twentieth of 48600 grams, just 30 grams of tritium, could be made at a cost of no more than 2.4 kilograms of plutonium. Thus we would be paying only one twelfth to one fourth of an A-bomb (in addition to the one used as the trigger) to get the equivalent of ten A-bombs in blasting power and of thirty times the incendiary power, which would totally devastate an area of more than 300 square miles by blast and of more than 1,200 square miles by fire.

Would 30 grams of tritium be enough to serve as the superkindling for exploding, let’s say, 1,000 kilograms (one ton) of deuterium? We shall probably not know until we actually try it. It will largely depend on the temperature generated by our more powerful A-bomb models. If it is true, as Senator Johnson informed his television audience, that they have “six times the effectiveness of the bomb that was dropped over Nagasaki” (which, by the way, had more than twice the effectiveness of the Hiroshima model), it is quite possible that their temperature is as high as 150 million, or even 200 million, degrees. In that case, the extra kindling of a 20–30 gram D-T mixture, with its tremendous burst of 5,000,000 kilowatt-hours of energy in 0.28 to 0.38 microseconds (added to the vast quantity already being liberated by the exploding plutonium, or U-235), might well heat the deuterium to the proper ignition temperature and keep it hot long enough for its mass to explode well within 1.2 microseconds. In any case it would 49appear logical to expect that a mixture of 150 grams of tritium and 100 grams of deuterium, which would release an energy equal to that of the Hiroshima bomb, should be able to do the job with plenty of time to spare.

We thus have a threefold answer to the question: Can the H-bomb actually be made? As we have seen, the deuterium bomb is definitely not possible. The tritium bomb is theoretically possible, but definitely not practicable. But a large deuterium bomb using a reasonably small amount of a deuterium and tritium mixture as extra kindling is both possible and feasible.

We now also stand on solid ground in dealing with the questions of cost and of the time it would take us to get into production. With these questions answered, we can then decide whether the H-bomb, if made, will add enough to our security to make the effort worth while.

We know at this stage that the H-bomb requires three essential ingredients. It needs, first of all, an A-bomb to set if off. We have a sizable stockpile of them. It needs large quantities of deuterium. We have built several deuterium plants during the war, and they should be large enough to supply our needs. Since it is extracted from water, the raw material will cost us nothing. The only item of cost will be the electric power required for the concentration process, and this should not be above $100 per kilogram, and probably less. The third vital 50ingredient, tritium, can be made in the giant plutonium plants at Hanford, Washington. Thus it can be seen that all the essential ingredients of the H-bomb, the costliest and those that would take longest to produce, as well as the multimillion-dollar plants required for their production, are already at hand.

This means that as far as the essential materials are concerned, we are ready to go right now. And as for the cost, it would appear to require hardly any new appropriations by Congress, or, at any rate, only appropriations that would be mere chicken feed compared with the five billion we have already invested in our A-bomb program.

The raw material out of which tritium is made is the common, cheap light metal lithium, the lightest, in fact, of all the metals. It has an atomic weight of six, its nucleus consisting of three protons and three neutrons. When an extra neutron invades its nucleus, it becomes unstable and breaks up into two lighter elements, helium (two protons and two neutrons) and tritium (one proton and two neutrons). They are both gases and they are readily separated. And while lithium of atomic weight six constitutes only 7.5 per cent of the element as found in nature (it comes mixed with 92.5 per cent of lithium of atomic weight seven), there is no need to separate it from its heavier twin, since the latter has no affinity for 51neutrons and nearly all of them are gobbled up by the lighter element.

The production of tritium, even in small amounts, will nevertheless be a formidable process. As we have seen, it takes eighty times as many neutrons to produce any given amount of tritium as to produce a corresponding amount of plutonium. Since the lithium will have to compete with uranium 238 (parent of plutonium) for the available supply of neutrons, and since the number of atoms of U-238 per given volume is nearly forty times greater than the number of lithium atoms, the rate of tritium production would be very much slower than that of plutonium. On the other hand, even if it took as much as two hundred times as long to produce a given quantity of tritium, the handicap would be considerably overcome because of the relatively small amounts that may be required. If, for example, we should need only 30 to 150 grams of tritium per bomb, it would take our present plutonium plants only six to thirty times longer to produce these quantities than it takes them to produce one kilogram of plutonium. A hypothetical plant such as the one mentioned in the official Smyth Report, designed to produce one kilogram of plutonium per day, would thus yield 30 grams of tritium in six days.

How much tritium would be needed for an adequate stockpile of H-bombs? Since our primary 52reasons for building it are to deter aggression, to prevent its use against us or our allies, and as a tactical weapon against large land armies, it would appear that as few as twenty-five, or fifty at the most, would be adequate for the purpose. On the basis of the larger figure (assuming 30 to 150 grams of tritium per bomb), it would mean an initial stockpile of only 1.5 to 7.5 kilograms of tritium, which would entail the sacrifice of about 120 to 600 kilograms of plutonium. Once this initial outlay had been made, however, our plutonium sacrifice would be reduced annually to only one twenty-fourth of the original respective amounts—namely, 5 to 25 kilograms a year—just enough to make up for the decay of the tritium at the rate of fifty per cent every twelve years.

One of the major problems to be solved, in addition to the main problem of designing the assembly, arises from the fact that the deuterium and the tritium booster will have to be in liquid form. Liquid hydrogen boils (that is, reverts to gas) at a temperature of 423 degrees below zero Fahrenheit under a pressure of one atmosphere (fifteen pounds per square inch). To liquefy it, it is necessary to cool it in liquid air (at 313.96 below zero F.) while keeping it at the same time under a pressure of 180 atmospheres. To transport it, it must be placed in a vacuum vessel surrounded by an outer vessel of liquid air. This would point to the need of giant refrigeration and storage plants, 53as well as of refrigerator planes for transporting large quantities of liquid deuterium and its tritium spark plug.

Will the H-bomb, if made, add enough to our security to make the effort worth while? We have seen that the required effort may, after all, not be very great. In fact, it may turn out to be a relatively small one, in view of the fact that all the basic ingredients and plants are already at hand and fully paid for. But supposing even that the effort turns out to be much more costly than it now appears? The question we must then ask ourselves is: Can we afford not to make the effort?

It is true, of course, as some have pointed out, that ten or even fewer A-bombs could destroy the heart of any metropolitan city, while only one would be quite enough, as we know, for cities the size of Hiroshima or Nagasaki. But that neglects to take into consideration the fact that one H-bomb concentrates within itself the power of thirty A-bombs to destroy by fire and by burns an area of more than 1,200 square miles at one blow. Nor does it take into consideration the military advantage of delivering the power of a combination of ten and thirty A-bombs in one concentrated package, which would make it a tremendous tactical weapon against a huge land army scattered over many miles, or its possible enormous psychological effect against such an army.

Most important of all, this view grossly minimizes 54the apocalyptic potentialities of the H-bomb for poisoning large areas with deadly clouds of radioactive particles. It is a monstrous fact that an H-bomb incorporating one ton of deuterium, encased in a shell of cobalt, would liberate 250 pounds of neutrons, which would create 15,000 pounds of highly radioactive cobalt, equivalent in their deadliness to 4,800,000 pounds of radium. Such bombs, according to Professor Harrison Brown, University of Chicago nuclear chemist, could be set on a north-south line in the Pacific approximately a thousand miles west of California. “The radioactive dust would reach California in about a day, and New York in four or five days, killing most life as it traverses the continent.”

“Similarly,” Professor Brown stated in the American Scholar, “the Western powers could explode H-bombs on a north-south line about the longitude of Prague which would destroy all life within a strip 1,500 miles wide, extending from Leningrad to Odessa, and 3,000 miles deep, from Prague to the Ural Mountains. Such an attack would produce a ‘scorched earth’ of an extent unprecedented in history.”

Professor Szilard, one of the principal architects of the A-bomb, has estimated, as already stated, that four hundred one-ton deuterium bombs would release enough radioactivity to extinguish all life on earth. Professor Einstein, as we have seen, has publicly stated that the H-bomb, if successful, 55will bring the annihilation of all life on earth within the range of technical possibilities. The question we must therefore ask ourselves is: Can we allow Russia to be the sole possessor of such a weapon?

There can be no question that Russia is already at work on an H-bomb. Like ourselves, she already has the plutonium plants for producing both A-bombs and tritium. She can produce deuterium in the same quantities as we can. In Professor Peter Kapitza she has the world’s greatest authority on liquid hydrogen.