Title: The perfume of the lady in black

Author: Gaston Leroux

Illustrator: Simont

Release date: January 31, 2025 [eBook #75258]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Brentano's, 1909

Credits: Aaron Adrignola, Laura Natal, Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

The Perfume of the Lady in Black

By GASTON LEROUX

Author of “The Mystery of the Yellow Room”

NEW YORK

BRENTANO’S

1909

Copyright, 1909, by

BRENTANO’S

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | WHICH BEGINS WHERE MOST ROMANCES END | 9 |

| II | IN WHICH THERE IS QUESTION OF THE CHANGING HUMORS OF JOSEPH ROULETABILLE |

24 |

| III | THE PERFUME | 31 |

| IV | EN ROUTE | 45 |

| V | PANIC | 60 |

| VI | THE FORT OF HERCULES | 83 |

| VII | WHICH TELLS OF SOME PRECAUTIONS TAKEN BY JOSEPH ROULETABILLE TO DEFEND THE FORT OF HERCULES AGAINST THE ATTACKS OF AN ENEMY |

102 |

| VIII | WHICH CONTAINS SOME PAGES FROM THE HISTORY OF JEAN-ROUSSEL-LARSAN BALLMEYER |

126 |

| IX | IN WHICH OLD BOB UNEXPECTEDLY ARRIVES | 135 |

| X | THE EVENTS OF THE ELEVENTH OF APRIL | 157 |

| XI | THE ATTACK OF THE SQUARE TOWER | 205 |

| XII | THE IMPOSSIBLE BODY | 216 |

| XIII | IN WHICH THE FEARS OF ROULETABILLE ASSUME ALARMING PROPORTIONS |

228 |

| XIV | THE SACK OF POTATOES | 248 |

| XV | THE SIGHS OF THE NIGHT | 266 |

| XVI | THE DISCOVERY OF AUSTRALIA | 274 |

| XVII | OLD BOB’S TERRIBLE ADVENTURE | 288 |

| XVIII | HOW DEATH STALKED ABROAD AT NOONDAY | 297 |

| XIX | IN WHICH ROULETABILLE ORDERS THE IRON DOORS TO BE CLOSED |

311 |

| XX | IN WHICH ROULETABILLE GIVES A CORPOREAL DEMONSTRATION OF THE POSSIBILITY OF THE “BODY TOO MANY” |

320 |

| EPILOGUE | 357 |

| Facing Page | |

| Rouletabille had hidden himself in the shadow of a pillar |

14 |

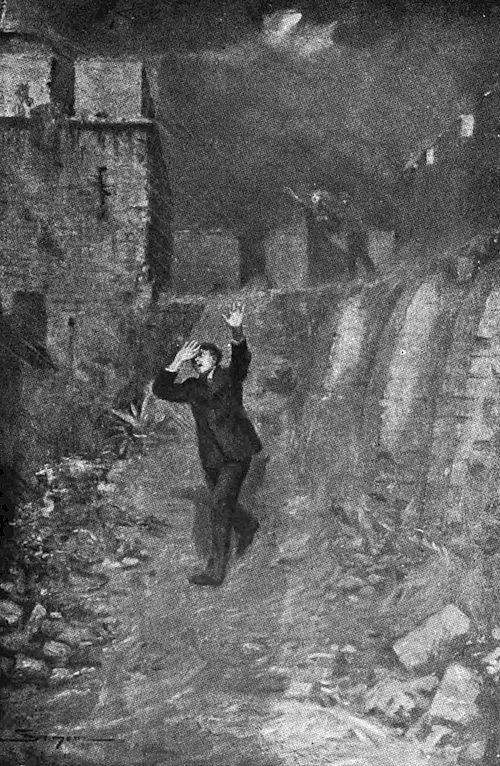

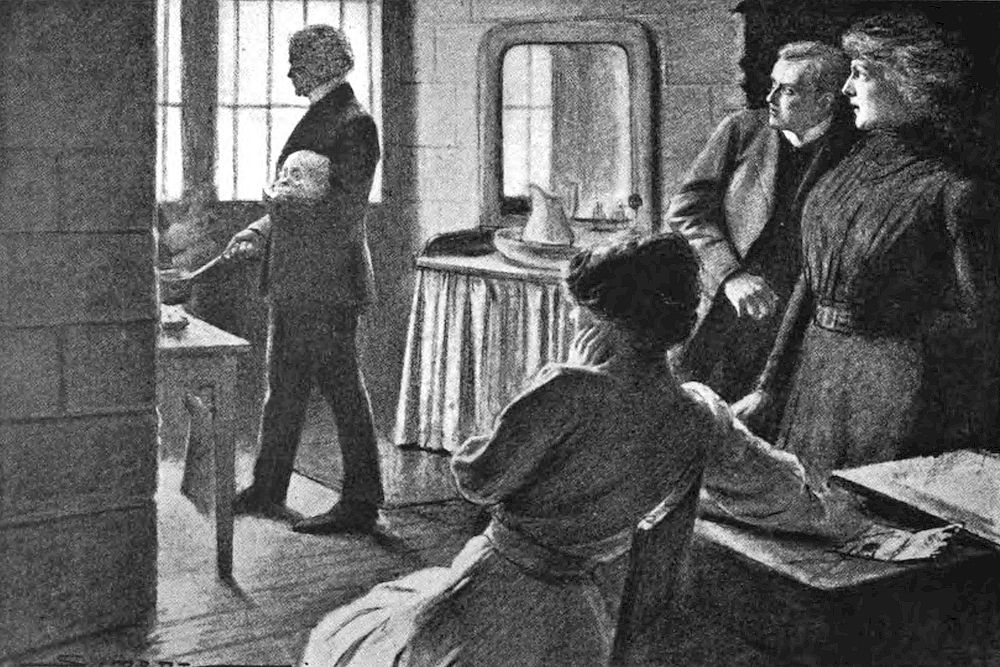

| He stood erect, wrapped in the rags of a long coat which hung about his legs, bareheaded and barefooted |

52 |

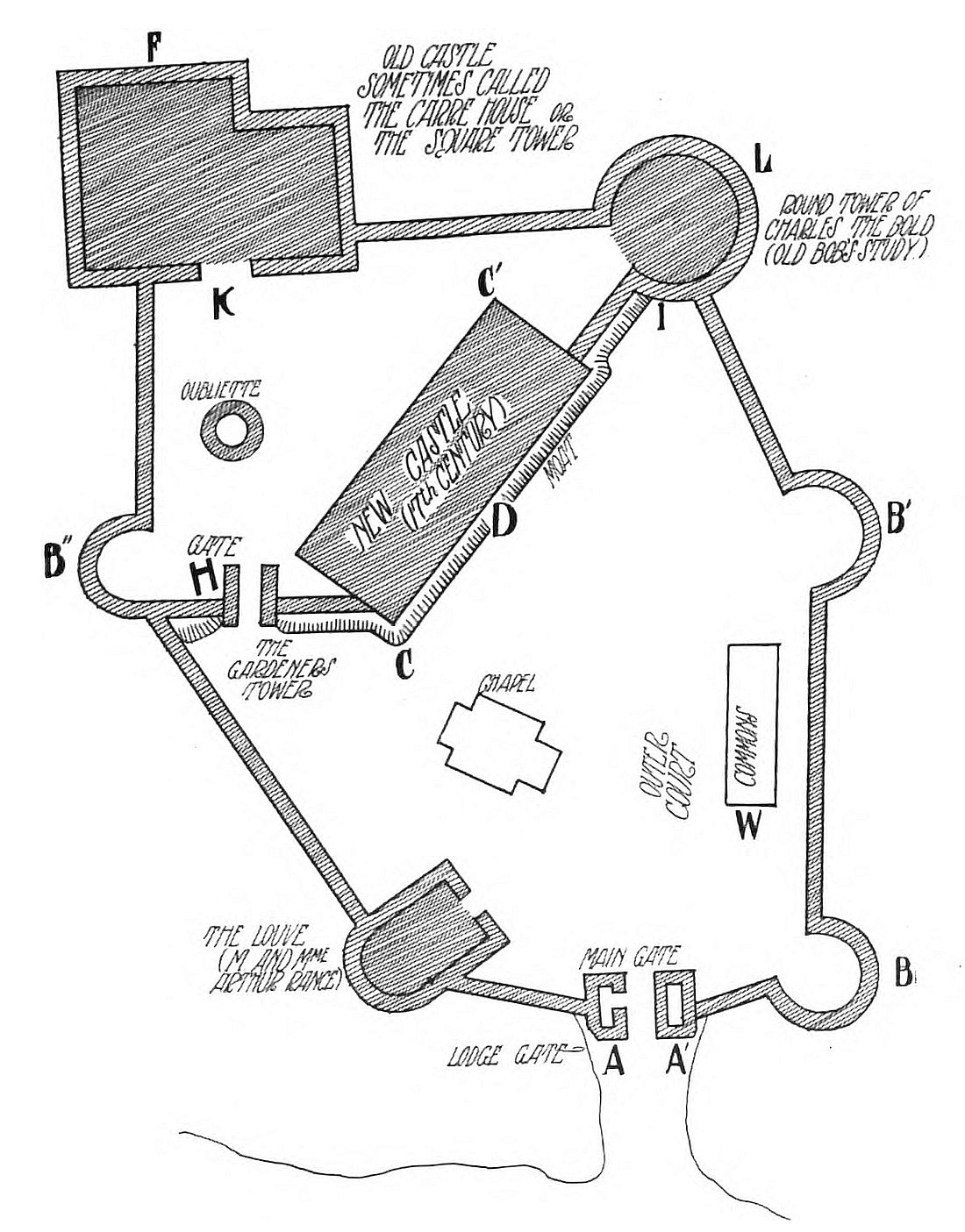

| The Plan of the Fort of Hercules | 87 |

| The Fort of Hercules | 90 |

| It made us nervous and restless to look at each other, seated around the table, mute, leaning forward, wearing our black spectacles, behind which it was as impossible to read our eyes as our thoughts |

167 |

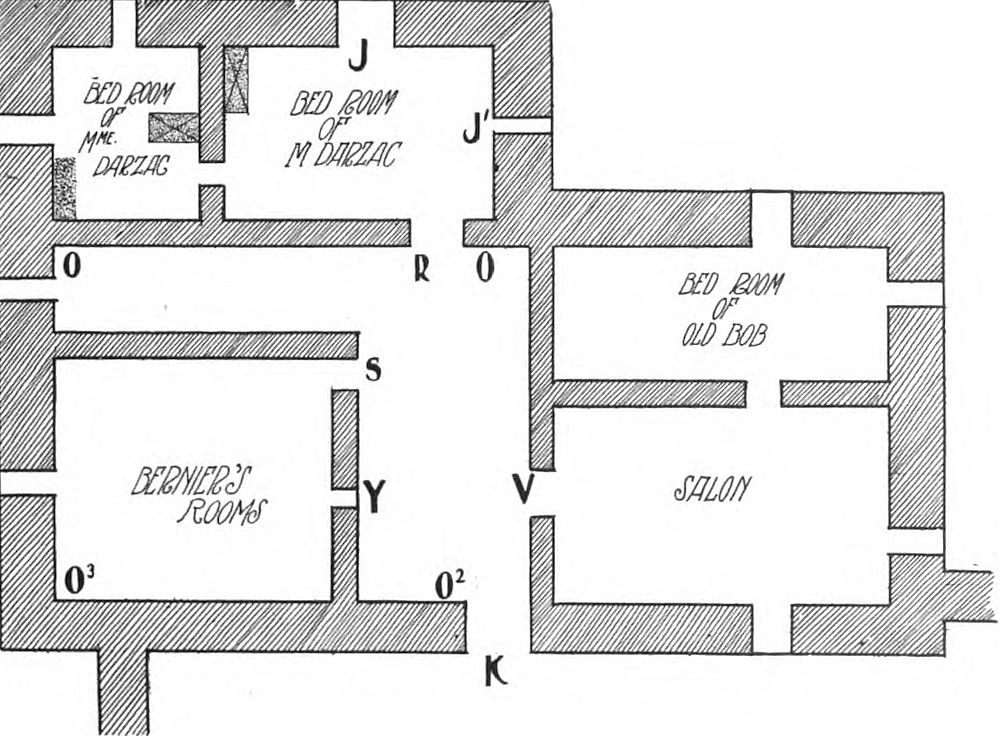

| The Plan of the inhabited floor of the Square Tower |

183 |

| He fled from us and rushed further into the night, shrieking aloud, “The perfume of the Lady in Black! The perfume of the Lady in Black!” |

203 |

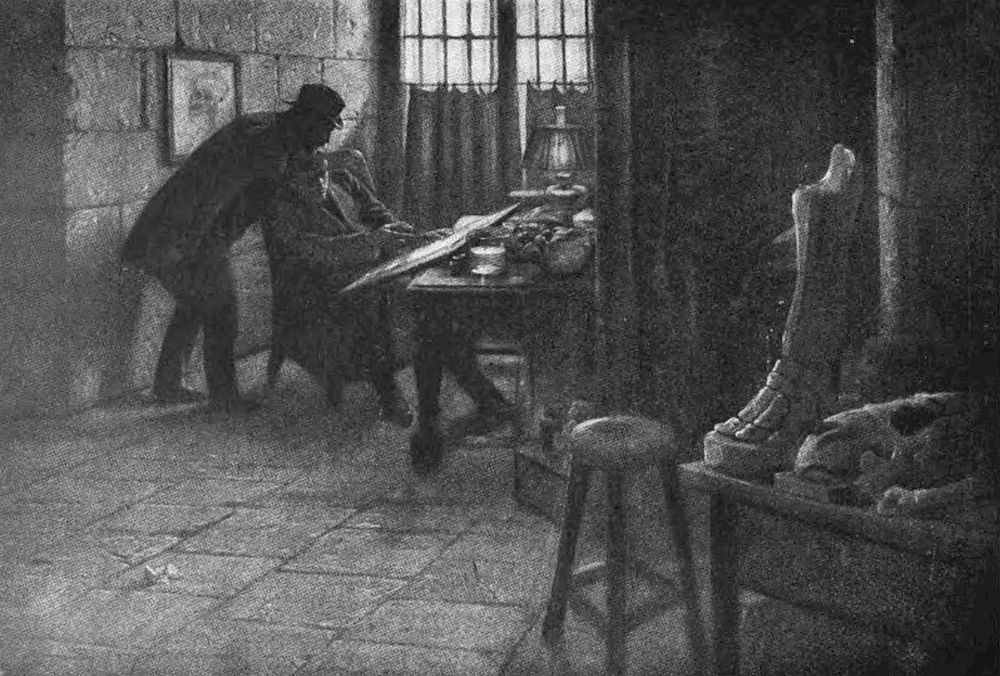

| His eyes seemed glued to his drawing. They never moved from the paper |

234 |

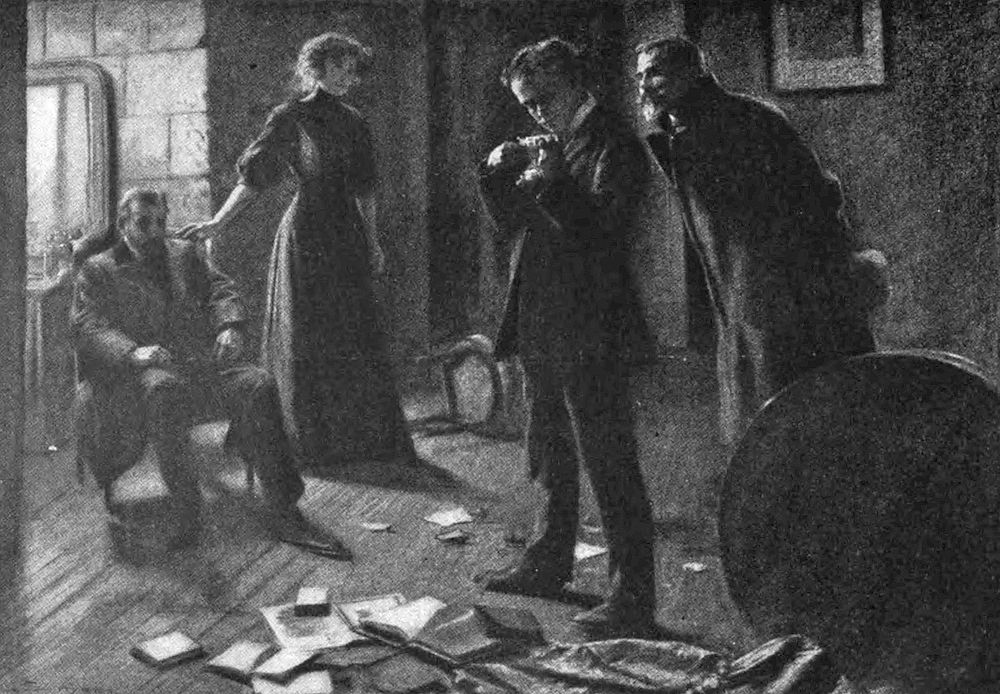

| Rouletabille examined the barrel of Darzac’s revolver and then compared the weapon with the other which he held |

242 |

| It was Bernier! It was Bernier who lay there, the death rattle in his throat and a stream of blood flowing from his breast |

302 |

| Ah! That profile standing out darkly from the depths of the embrasure, lighted up by the red glow of the setting sun |

332 |

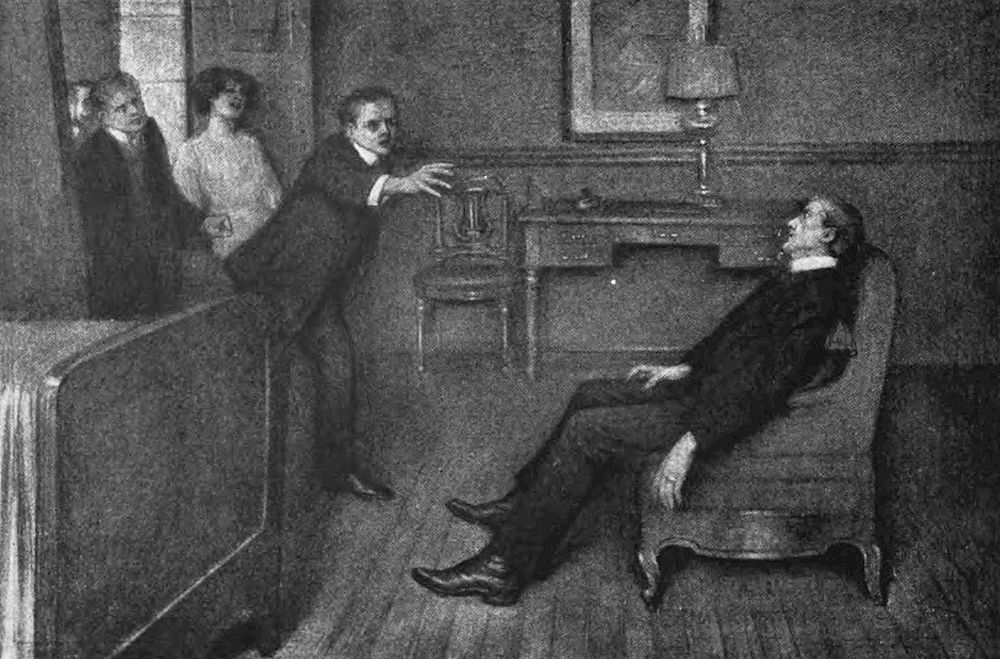

| Rouletabille advanced toward him: “Larsan,” he said, “Larsan, do you give yourself up?” But Larsan did not reply |

352 |

[Pg 9]

The marriage of M. Robert Darzac and Mlle. Mathilde Stangerson took place in Paris, at the Church of St. Nicolas du Chardonnet, on April 6th, 1895, everything connected with the occasion being conducted in the quietest fashion possible. A little more than two years had rolled by since the events which I have recorded in a previous volume—events so sensational that it is not speaking too strongly to say that an even longer lapse of time would not have sufficed to blot out the memory of the famous “Mystery of the Yellow Room.”

There was no doubt in the minds of those concerned that, if the arrangements for the wedding had not been made almost secretly, the little church would have been thronged and surrounded by a curious crowd, eager to gaze upon the principal personages of the drama which had aroused an interest almost world wide and the circumstances of which were still present in the minds of the sensation-loving public. But in this isolated little corner of the city, in this almost unknown parish, it was easy enough to maintain the utmost privacy. Only a few friends of M. Darzac and Professor Stangerson, on whose discretion [Pg 10] they felt assured that they might rely, had been invited. I had the honor to be one of the number.

I reached the church early, and, naturally, my first thought was to look for Joseph Rouletabille. I was somewhat surprised at not seeing him, but, having no doubt that he would arrive shortly, I entered the pew already occupied by M. Henri-Robert and M. Andre Hesse, who, in the quiet shades of the little chapel, exchanged in undertones reminiscences of the strange affair at Versailles, which the approaching ceremony brought to their memories. I listened without paying much attention to what they were saying, glancing from time to time carelessly around me.

A dreary place enough is the Church of St. Nicolas du Chardonnet. With its cracked walls, the lizards running from every corner and dirt—not the beautiful dust of ages, but the common, ill-smelling, germ-laden dust of to-day—everywhere, this church, so dark and forbidding on the outside, is equally dismal within. The sky, which seems rather to be withdrawn from than above the edifice, sheds a miserly light which seems to find the greatest difficulty in penetrating through the dusty panes of unstained glass. Have you read Renan’s “Memories of Childhood and Youth?” Push open the door of St. Nicolas du Chardonnet and you will understand how the author of the “Life of Jesus” longed to die, when as a lad he was a pupil in the little seminary of the Abbe Duplanloup, close by, and could only leave the school to come to pray in this church. And it was in this funereal darkness, in a scene which seemed to have been painted only for mourning and for all the rites consecrated to sorrow, that the marriage of Robert Darzac and Mathilde [Pg 11] Stangerson was to be solemnized. I could not cast aside the feeling of foreboding that came over me in these dreary surroundings.

Beside me, M. Henri-Robert and M. Andre Hesse continued to chat, and my wandering attention was arrested by a remark made by the former:

“I never felt quite easy about Robert and Mathilde,” he said—“not even after the happy termination of the affair at Versailles—until I knew that the information of the death of Frederic Larsan had been officially confirmed. That man was a pitiless enemy.”

It will be remembered, perhaps, by readers of “The Mystery of the Yellow Room,” that a few months after the acquittal of the Professor in Sorbonne, there occurred the terrible catastrophe of La Dordogne, a transatlantic steamer, running between Havre and New York. In the broiling heat of a summer night, upon the coast of the New World, La Dordogne had caught fire from an overheated boiler. Before help could reach her, the steamer was utterly destroyed. Scarcely thirty passengers were able to leap into the life boats, and these were picked up the next day by a merchant vessel, which conveyed them to the nearest port. For days thereafter, the ocean cast up on the beach hundreds of corpses. And among these, they found Larsan.

The papers which were found carefully hidden in the clothing worn by the dead man, proved beyond a doubt his identity. Mathilde Stangerson was at last delivered from this monster of a husband to whom, through the facility of the American laws, she had given her hand in secret, in the unthinking ardour of girlish romance. This wretch, whose real name, according to court records, was Ballmeyer, and who had married [Pg 12] her under the name of Jean Roussel, could no longer rise like a dark shadow between Mathilde and the man whom she had loved so long and so well, without daring to become his bride. In “The Mystery of the Yellow Room,” I have related all the details of this remarkable affair, one of the strangest which has ever been known in the annals of the Court of Assizes, and which, without doubt, would have had a most tragic denouement, had it not been for the extraordinary part played by a boy reporter, scarcely eighteen years old, Joseph Rouletabille, who was the only one to discover that Frederic Larsan, the celebrated Secret Service agent, was none other than Ballmeyer himself. The accidental—one might almost say “providential”—death of this villain, had seemed to assure a happy termination to the extraordinary story, and it must be confessed that it was undoubtedly one of the chief factors in the rapid recovery of Mathilde Stangerson, whose reason had been almost overturned by the mysterious horrors at the Glandier.

“You see, my dear fellow,” said M. Henri-Robert to M. Andre Hesse, whose eyes were roving restlessly about the church, “you see, in this world, one can always find the bright side. See how beautifully everything has turned out—even the troubles of Mlle. Stangerson. But why are you constantly looking around you? What are you looking for? Do you expect anyone?”

“Yes,” replied M. Hesse. “I expect Frederic Larsan.”

M. Henri-Robert laughed—a decorous little laugh, in deference to the sanctity of the surroundings. But I felt no inclination to join in his mirth. I was an hundred leagues from foreseeing the terrible experience which was even then approaching us; but when I recall that [Pg 13] moment and seek to blot out of my mind all that has happened since—all those events which I intend to relate in the course of this narrative, letting the circumstances come before the reader as they came before us during their development—I recollect once more the curious unrest which thrilled me at the mention of Larsan’s name.

“What’s the matter, Sainclair?” whispered M. Henri-Robert, who must have noticed something odd in my expression. “You know that Hesse was only joking.”

“I don’t know anything about it,” I answered. And I looked attentively around me, as M. Andre Hesse had done. And, indeed, we had believed Larsan dead so often when he was known as Ballmeyer, that it seemed quite possible that he might be once more brought to life in the guise of Larsan.

“Here comes Rouletabille,” remarked M. Henri-Robert. “I’ll wager that he isn’t worrying about anything.”

“But how pale he is!” exclaimed M. Andre Hesse in an undertone.

The young reporter joined us and pressed our hands in an absent-minded manner.

“Good morning, Sainclair. Good morning, gentlemen. I am not late, I hope?”

It seemed to me that his voice trembled. He left our pew immediately and withdrew to a dark corner, where I beheld him kneel down like a child. He hid his face, which was indeed very pale, in his hands, and prayed. I had never guessed that Rouletabille was of a religious turn of mind, and his fervent devotion astonished me. When he raised his head, his eyes were filled with tears. He did not even try to hide [Pg 14] them. He paid no attention to anything or anyone around him. He was lost completely in his prayers, and, one might imagine, in his grief.

But what could be the occasion of his sorrow? Was he not happy at the prospect of the union so ardently desired by everyone? Had not the good fortune of Mathilde Stangerson and Robert Darzac been in a great measure brought about by his efforts? After all, it was perhaps from joy, that the lad wept. He rose from his knees, and was hidden behind a pillar. I made no endeavor to join him, for I could see that he was anxious to be alone.

And the next moment, Mathilde Stangerson made her entrance into the church upon the arm of her father, Robert Darzac walking behind them. Ah, the drama of the Glandier had been a sorrowful one for these three! But, strange as it may seem, Mathilde Stangerson appeared only the more beautiful, for all that she had passed through. True, she was no longer the beautiful statue, the living marble, the ancient goddess, the cold Pagan divinity, who, at the official functions at which her father’s position had forced her to appear, had excited a flutter of admiration whenever she was seen. It seemed, on the contrary, that fate, in making her expiate for so many long years an imprudence committed in early youth, had cast her into the depths of madness and despair, only to tear away the mask of stone, which hid from sight the tender, delicate spirit. And it was this spirit which shone forth on her wedding day, in the sweetest and most charming smile, playing on her curved lips, hiding in her eyes, filled with pensive happiness, and leaving its impress on her forehead, polished like [Pg 15] ivory, where one might read the love of all that was beautiful and all that was good.

Rouletabille had hidden himself in the shadow of a pillar.

As to her gown, I must acknowledge that I remember nothing at all about it, and am unable even to say of what color it was. But what I do remember, is the strange expression which came over her visage when she looked through the rows of faces in the pews without seeming to discover the one she sought. In a moment she had regained her composure, and was mistress of herself once more. She had seen Rouletabille behind his pillar. She smiled at him and my companions and I smiled in our turn.

“She has the eyes of a mad woman!”

I turned around quickly to see who had uttered the heartless words. It was a poor fellow whom Robert Darzac, out of the kindness of his heart, had made his assistant in the laboratory at the Sorbonne. The man was named Brignolles, and was a distant cousin of the bridegroom. We knew of no other relative of M. Darzac whose family came originally from the Midi. Long ago he had lost both father and mother; he had neither brother nor sister, and seemed to have broken off all intercourse with his native province, from which he had brought an eager desire for success, an exceptional ability to work, a strong intellect, and a natural need for affection, which had satisfied itself in his relations with Professor Stangerson and his daughter. He had also as a legacy from Provence, his native place, a soft voice and slight accent, which had often brought a smile to the lips of his pupils at the Sorbonne, who, nevertheless, loved it as they might have loved a strain of music, which made the necessary dryness of their studies a little less arid.

[Pg 16]

One beautiful morning, in the preceding spring, and consequently a year after the occurrences in the yellow room, Robert Darzac had presented Brignolles to his pupils. The new assistant had come direct from Aix, where he had been a tutor in the natural sciences, and where he had committed some fault of discipline which had caused his dismissal. But he had remembered that he was related to M. Darzac, the famous chemist, had taken the train to Paris, and had told such a piteous tale to the fiancé of Mlle. Stangerson, that Darzac, out of pity, had found means to associate his cousin with him in his work. At that time, the health of Robert Darzac had been far from flourishing. He was suffering from the reaction following the strong emotions which had nearly weighed him down at the Glandier and at the Court of Assizes; but one might have thought that the recovery, now assured, of Mathilde, and the prospect of their marriage would have had a happy influence both upon the mental and physical condition of the professor. We, however, remarked on the contrary, that from the day that Brignolles came to him—Brignolles, whose friendship should have been a precious solace, the weakness of M. Darzac seemed to increase. However, we were obliged to acknowledge that Brignolles was not to blame for that, for two unfortunate and unforeseen accidents had occurred in the course of some experiments, which would have seemed, on the face of them, not at all dangerous. The first resulted from the unexpected explosion of a Gessler tube, which might have severely injured M. Darzac, but which only injured Brignolles, whose hands were badly scarred. The second, which might have been extremely grave, happened through the explosion of a tiny [Pg 17] lamp against which M. Darzac was leaning. Happily, he was not hurt, but his eyebrows were scorched, and for some time after his sight was slightly impaired, and he was unable to stand much sunlight.

Since the Glandier mysteries, I had been in such a state of mind that I often found myself attaching importance to the most simple happenings. At the time of the second accident I was present, having come to seek M. Darzac at the Sorbonne. I myself led our friend to a druggist and then to a doctor, and I (rather dryly, I own) begged Brignolles, when he wished to accompany us, to remain at his post. On the way, M. Darzac asked why I had wounded the poor fellow’s feelings. I told him that I did not care for Brignolles’ society, for the abstract reason that I did not like his manners, and for the concrete reason, on this special occasion, that I believed him to be responsible for the accident. M. Darzac demanded why I thought so, and I did not know how to answer, and he began to laugh—a laugh that was quickly silenced, however, when the doctor told him that he might easily have been made entirely blind, and that he might consider himself very lucky in having gotten off so well.

My suspicions of Brignolles were, doubtless, ridiculous, and no more accidents happened. All the same, I was so strongly prejudiced against the young man that, at the bottom of my heart, I blamed him for the slow improvement in M. Darzac’s physical condition. At the beginning of the winter Darzac had such a bad cough that I entreated him to ask for leave of absence and to take a trip to the Midi—a prayer in which all his friends joined. The physicians advised San Remo. He went thither, and a week later he wrote us that he felt much better—that it seemed [Pg 18] to him as though a heavy weight had been lifted from his breast. “I can breathe here,” he wrote. “When I left Paris, I seemed to be stifling.”

This letter from M. Darzac gave me much food for thought, and I no longer hesitated to take Rouletabille into my confidence.

He agreed with me that it was a most peculiar coincidence that M. Darzac was so ill when Brignolles was with him and so much better when he and his young assistant were separated. The impression that this was actually the fact was so strong in my mind that I would on no account have permitted myself to lose sight of Brignolles. No, indeed. I verily believe that if he had attempted to leave Paris, I should have followed him. But he made no such attempt. On the contrary, he haunted the footsteps of M. Stangerson. Under the pretext of asking news of M. Darzac, he presented himself at the house of the Professor almost every day. Once he made an effort to see Mlle. Stangerson, but I had painted his portrait to M. Darzac’s fiancée in such unflattering terms, that I had succeeded in disgusting her with him completely—a fact on which I congratulated myself in my innermost soul.

M. Darzac remained four months at San Remo, and returned home at the end of that time almost completely restored to health. His eyes, however, were still weak, and he was under the necessity of taking the greatest care of them. Rouletabille and myself had resolved to keep a close watch on Brignolles, but we were satisfied that everything would be right when we were informed that the long-deferred marriage was to occur almost immediately and that M. Darzac would take his wife away [Pg 19] on a long honeymoon trip far from Paris—and from Brignolles.

Upon his return from San Remo, M. Darzac had asked me:

“Well, how are you getting on with poor Brignolles? Have you decided that you were wrong about him?”

“Indeed, I have not,” was my response.

And Darzac turned away, laughing at me, and uttering one of the Provencal jests which he affected when circumstances allowed him to be gay, and which found on his lips a new freshness since his visit to the Midi had accustomed him again to the accents of his childhood.

We knew that he was happy. But we had formed no real idea of how happy he was—for between the time of his return and the wedding day we had had few chances to see him—until we beheld him walking up the aisle of the church, his face fairly transformed. His slight erect figure bore itself as proudly as though he were an Emperor. Happiness had made him another being.

“Anyone could guess that he was a bridegroom!” tittered Brignolles.

I left the neighborhood of the man who was so repulsive to me, and stepped behind poor M. Stangerson, who stood through the entire ceremony with his arms crossed on his breast, seeing nothing and hearing nothing. I was obliged to touch him on the shoulder when all was over to arouse him from his dream.

As they passed into the sacristy, M. Andre Hesse heaved a deep sigh.

“I can breathe again,” he murmured.

“Why couldn’t you breathe before, my friend?” asked M. Henri-Robert.

[Pg 20]

And M. Andre Hesse confessed that he had feared up to the last moment that the dead man would reappear.

“I can’t help it,” was the only response he would make when his friend rallied him. “I cannot bring myself to the idea that Frederic Larsan will stay dead for good.”

And now we all—a dozen or so persons—were gathered in the sacristy. The witnesses signed the register, and the rest of us congratulated the newly wedded pair. The sacristy was yet more dismal than the church, and I might have thought that it was on account of the darkness that I could not perceive Joseph Rouletabille, if the room had not been so small. But, assuredly, he was not there. Mathilde had already asked for him twice, and M. Darzac requested me to go and look for him. I did so, but returned to the vestry without him. He had disappeared from the church.

“How strange it is!” exclaimed M. Darzac. “I can’t understand it. Are you sure that you looked everywhere? He may be in some corner dreaming.”

“I looked everywhere, and I called his name,” I told him.

But M. Darzac was still not satisfied. He wanted to look through the church for himself. His search was better rewarded than mine, for he learned from a beggar, who was sitting in the porch with a tambourine, that Rouletabille had left the church a few minutes before and had been driven away in a hack. When the bridegroom brought this news to his wife, she appeared to be both pained and anxious. She called me to her side and said:

“My dear M. Sainclair, you know that we are to take the train in two hours. Will you hunt up our little friend and bring him to me, and [Pg 21] tell him that his strange behaviour is grieving me very much?”

“Count upon me,” I said.

And I began a wild goose chase after Rouletabille. But I appeared at the station without him. Neither at his home, nor at the office of his paper, nor at the Cafe du Barreau, where the necessities of his work often called him at this hour of the day, could I lay my hand on him. None of his comrades could tell me where I might chance to find him. I leave you to think how unwillingly I turned my steps in the direction of the railroad station. M. Darzac was greatly disturbed, but as he had to look after the comfort of his fellow travellers (for Professor Stangerson, who was on his way to Mentone, was to accompany his daughter and her husband to Dijon, changing cars there, while the Darzacs continued their trip to Culoz and Mt. Cenis), he asked me to break the bad news to his bride. I performed the commission, adding that Rouletabille would, without doubt, present himself before the train started. At these words, Mathilde began to cry softly, and shook her head:

“No—no!” she whispered. “It is all over. He will never come again.”

And she stepped into the railway carriage.

It was at this point that the insufferable Brignolles, seeing the emotion of the newly-made bride, whispered again to M. Andre Hesse, “Look! Look! Hasn’t she the eyes of a maniac? Ah, Robert has done wrong. It would have been better for him to wait.” M. Hesse gave him a disdainful glance, and bade him be silent.

I can still see Brignolles as he spoke those words, and can recall as vividly as though it were yesterday the feeling of horror with [Pg 22] which he inspired me. There was no longer any doubt in my mind that he was an evil and a jealous man, and that he would never forgive his relative for having placed him in a position which might be considered subordinate. He had a yellow face and long features that looked as if they had been drawn down from forehead to chin. Everything about him seemed to diffuse bitterness and everything about him was long. He had a long figure, long arms, long legs and a long head. However, to this general rule of length, there were exceptions—the feet and the hands. He had extremities small and almost beautiful.

After having been so rudely silenced for his malicious words by the young lawyer, Brignolles immediately took offense and left the station, after having paid his respects to the bride and bridegroom. At least, I believe that he left the station, for I did not see him again.

There was three minutes yet before the departure of the train. We still hoped that Rouletabille would appear, and we looked across the quay, thinking once or twice that we saw the form of our young friend approaching, among the hurrying throng of travellers. How could it be that he would not advance, as we were so used to seeing him, in his quick, boyish fashion, rushing through the crowd, paying no heed to the cries and protestations that his method of pushing his way usually evoked while he seemed to be hurrying faster than any one else? What could he be doing that detained him?

Already the doors were closed. The bell on the engine began to sound its first slow strokes, and the calls of hack drivers began to arise: “Carriage, Monsieur? Carriage?” And then the quick last word which gave the signal for the departure. But no Rouletabille. We were all [Pg 23] so grieved, and, moreover, so surprised, that we remained on the platform, looking at Mme. Darzac, without thinking to wish her a pleasant journey. Professor Stangerson’s daughter cast a long glance upon the quay, and, at the moment that the speed of the train began to accelerate, certain now that she was not to see her “little friend” again, she threw me an envelope from the car window.

“For him,” she said.

And almost as though moved by an irresistible impulse, her face wearing an expression of something that resembled terror, she added in a tone so strange that I could not help recalling the horrible speeches of Brignolles:

“Au revoir, my friends—or adieu.”

[Pg 24]

In returning alone from the station I could not help feeling some surprise at the singular sensation of sadness which oppressed me, and of the cause of which I had not the least idea. Since the affair at Versailles, with the details of which my existence had become so strangely intermingled, I had enjoyed the closest intimacy with Professor Stangerson, his daughter, and Robert Darzac. I ought to have been completely happy on the day of this wedding, which seemed in every way so satisfactory. I wondered whether the unexplained absence of the young reporter did not account in some measure for my strange depression. Rouletabille had been treated by the Stangersons and by M. Darzac as their deliverer. And especially since Mathilde had left the sanitarium, in which, for several months, her shattered nervous system had needed and received the most assiduous care—since the daughter of the famous professor had been able to understand the extraordinary part which the boy had played in the drama that, without his help, would inevitably have ended in the bitterest grief for all those whom she loved—since she had read by the light of her restored reason the short-hand reports of the trial, at which Rouletabille appeared at the last moment like some hero of a miracle—she had surrounded the youngster with an affection little less than maternal. She [Pg 25] interested herself in everything which concerned him; she begged for his confidence; she wanted to know more about him than I knew, and, perhaps, more even than he knew himself. She had shown an unobtrusive but strong curiosity in regard to the mystery of his birth, of which all of us were ignorant, and on which the young man had kept silence with a sort of savage pride. Although he fully realized the tender friendship which the poor soul felt for him, Rouletabille maintained his reserve and in his dealings with her affected a formal politeness which astonished me, coming from the boy whom I had known so exuberant, so whole-hearted, so strong in his likes and dislikes. More than once I had mentioned the matter to him, and he had answered me in an evasive manner, laying great stress, however, upon his sentiments of devotion for “a lady whom he esteemed beyond anyone in the world, and for whom he would have been ready to sacrifice his all, if fate or fortune had given him anything to sacrifice for anyone.” He would take strange whims at such times. For instance, after having made, in my presence, a promise to take a holiday and remain all day with the Stangersons, who had rented for the summer (for they did not wish to live at the Glandier again) a pretty little place at Chennevieres, on the borders of the Marne, and after having shown an almost childish joy at the prospect, he suddenly and without any reason refused to accompany me. And I was obliged to set out alone, leaving him in his little room, in the corner of the Boulevard St. Michel and the Rue Monsieur-le-Prince. I wished as I departed that he might experience as much pain as I knew that he would cause Mlle. Stangerson. One Sunday, she, vexed at the [Pg 26] lad’s behavior, made up her mind to go with me to his den in the Latin Quarter, and surprise him.

When we reached his lodgings, Rouletabille, who had answered our knock with an energetic “Come in,” sat working at a little table. He arose as we entered, and turned so pale that we believed that he was about to fall in a faint.

“Good heavens!” cried Mlle. Stangerson, hastening toward him. But he was quicker than she, and before she reached the table on which he leaned, he had thrown a cover over the papers which were spread over the surface, hiding them entirely.

Mathilde had, of course, noticed the action. She paused in amazement.

“We are disturbing you,” she said.

“Oh, not at all,” replied Rouletabille. “I have finished my work. I will show it to you sometime. It is a masterpiece—a piece in five acts, for which I am not able to find the denouement.”

And he smiled. Soon he was again entirely master of himself, and made us a hundred droll speeches, thanking us for having come to cheer him in his solitude. He insisted on inviting us to dinner, and we three ate our evening meal in a Latin Quarter restaurant—Foyot’s. It was a happy evening. Rouletabille telephoned for Robert Darzac, who joined us at dessert. At this time M. Darzac was not ill, and the amazing Brignolles had not yet made his appearance in Paris. We played like children. That summer night was so beautiful in the solitude of the Luxembourg!

Before bidding adieu to Mlle. Stangerson, Rouletabille begged her pardon for the strange humor which he evinced at times, and accused himself of being at bottom a very disagreeable person. Mathilde kissed [Pg 27] him and Robert Darzac put his arm affectionately around the lad’s shoulders. And Rouletabille was so moved that he never uttered a word while I walked with him to his door; but at the moment of our parting, he pressed my hand more tenderly than he had ever done before. Poor little fellow! Ah, if I had known! How I reproach myself in the light of the present for having judged him with too little patience!

Thus, sad at heart, assailed by premonitions which I tried in vain to drive away, I returned from the railway station at Lyons, pondering over the numerous fantasies, the strange caprices of Rouletabille during the last two years. But nothing that entered my mind could have warned me of what had happened, or still less have explained it to me. Where was Rouletabille? I went to his rooms in the Boulevard St. Michel, telling myself that if I did not find him there, I could, at least, leave Mme. Darzac’s letter. What was my astonishment when I entered the building to see my own servant carrying my bag. I asked him to tell me what he was doing and why, and he replied that he did not know—that I must ask M. Rouletabille.

The boy had been, as it turned out, while I had been seeking him everywhere (except, naturally, in my own house), in my apartments in the Rue de Rivoli. He had ordered my servant to take him to my rooms, and had made the man fill a valise with everything necessary for a trip of three or four days. Then he had directed the man to bring the bag in about an hour to the hotel in the “Boul’ Mich.”

I made one bound up the stairs to my friend’s bed chamber, where I found him packing in a tiny hand satchel an assortment of toilet [Pg 28] articles, a change of linen and a night shirt. Until this task was ended, I could obtain no satisfaction from Rouletabille, for in regard to the little affairs of everyday life, he was extremely particular, and, despite the modesty of his means, succeeded in living very well, having a horror of everything which could be called bohemian. He finally deigned to announce to me that “we were going to take our Easter vacation,” and that, since I had nothing to do, and the Epoch had granted him a three days’ holiday, we couldn’t do better than to go and take a short rest at the seaside. I made no reply, so angry was I at this high-handed method, and all the more because I had not the least desire to contemplate the beauties of the ocean upon one of the abominable days of early spring, which for two or three weeks every year makes us regret the winter. But my silence did not disturb Rouletabille in the least, and taking my valise in one hand, his satchel in the other, he hustled me down the stairs and pushed me into a hack which awaited us before the door of the hotel. Half an hour later, we found ourselves in a first-class carriage of the Northern Railway, which was carrying us toward Trepot by way of Amiens. As we entered the station, he said:

“Why don’t you give me the letter that you have for me?”

I gazed at him in amazement. He had guessed that Mme. Darzac would be greatly grieved at not seeing him before her departure, and would write to him. He had been positively malicious. I answered:

“Because you don’t deserve it.”

And I gave him a good scolding, to which he interposed no defense. He did not even try to excuse himself, and that made me angrier than [Pg 29] ever. Finally, I handed him the letter. He took it, looked at it and inhaled its fragrance. As I sat looking at him curiously, he frowned, trying, as I could see, to repress some strong feeling. But he could no longer hide it from me when he turned toward the window, his forehead against the glass, and became absorbed in a deep study of the landscape. His face betrayed the fact that he was suffering profoundly.

“Well?” I said. “Aren’t you going to read the letter?”

“No,” he replied. “Not here. When we are yonder.”

We arrived at Trepot in the blackest night that I remember, after six hours of an interminable trip and in wretched weather. The wind from the sea chilled us to the bone and swept over the deserted quay with weird sounds of lamentation. We met only a watch-man, wrapped in his cloak and hood, who paced the banks of the canal. Not a cab, of course. A few gas jets, trembling in their glass globes, reflected their light in the mud puddles formed by the falling rain. We heard in the distance the clicking noise of the little wooden shoes of some Trepot woman who was out late. That we did not fall into a huge watering trough was due to the fact that we were warned by the hoofs of a stray horse, which passed that way to drink. I walked behind Rouletabille, who made his way with difficulty in this damp obscurity. However, he appeared to know the place, for we finally arrived at the door of a queer little inn, which remained open during the early spring for the fishermen. Rouletabille demanded supper and a fire, for we were half starved and half frozen.

“Ah, now, my friend,” I said, when we were settled after a fashion. “Will you condescend to explain to me what we have come to look for in [Pg 30] this place, aside from rheumatism and pneumonia?”

But Rouletabille, at this moment, coughed and turned toward the fire to warm his hands again.

“Oh, yes,” he answered. “I am going to tell you. We have come to look for the perfume of the Lady in Black.”

This phrase gave me so much to think about that I scarcely slept at all that night. Besides, the wind howled continuously, sending its wails over the water, then swallowing itself up in the little streets of the town as if it were entering corridors. I heard someone moving about in the room next to mine, which was occupied by my friend; I arose and tried his door. In spite of the cold and the wind, he had opened the window, and I could see him distinctly waving kisses toward the shadows. He was embracing the night.

I closed the door again and went quietly back to bed. Early in the morning I was awakened by a changed Rouletabille. His face was distorted with grief as he handed me a telegram which had come to him at the Bourg, having been forwarded from Paris, in accordance with the orders that he had left.

Here is the dispatch:

“Come immediately without losing a minute. We have given up our trip to the Orient, and will join M. Stangerson at Mentone, at the home of the Rances at Rochers Rouges. Let this message remain a secret between us. It is not necessary to frighten anyone. You may pretend that you are on your vacation, or make any other excuse that you like, but come. Telegraph me general delivery, Mentone. Quickly, quickly, I am waiting for you. Yours in despair—Darzac.”

[Pg 31]

“Well!” I cried, leaping out of bed. “It doesn’t surprise me!”

“You never believed that he was dead?” demanded Rouletabille, in a tone filled with an emotion that I could not explain to myself, for it seemed greater even than was warranted by the situation, admitting that the terms of M. Darzac’s telegram were to be taken literally.

“I never felt quite sure of it,” I answered. “It was too useful for him to pass for dead to permit him to hesitate at the sacrifice of a few papers, however important those were which were found upon the victim of the Dordogne disaster. But what is the matter with you, my boy? You look as though you were going to faint. Are you ill?”

Rouletabille had let himself sink into a chair. It was in a voice which trembled like that of an old man that he confided to me that, even while the marriage ceremony of our friends was going on, he had become possessed with a strong conviction that Larsan was not dead. But after the ceremony was at an end, he had felt more secure. It seemed to him that Larsan would never have permitted Mathilde Stangerson to speak the vows that gave her to Robert Darzac if he were really alive. Larsan would only have had to show his face to stop the marriage; and, however dangerous to himself such an act might have been, he would not, the [Pg 32] young reporter believed, have hesitated to deliver himself up to the danger, knowing as he did the strong religious convictions of Professor Stangerson’s daughter, and knowing, too, that she would never have consented to enter into an alliance with another man while her first husband was alive, even had she been freed from the latter by human laws. In vain had everyone who loved her attempted to persuade her that her first marriage was void, according to French statute. She persisted in declaring that the words pronounced by the priest had made her the wife of the miserable wretch who had victimized her, and that she must remain his wife so long as they both should live.

Wiping the perspiration from his forehead, Rouletabille remarked:

“Sainclair, can you ever forget Larsan’s eyes? Do you remember, ‘The Presbytery has not lost its charm or the garden its brightness?’”

I pressed the boy’s hand; it was burning hot. I tried to calm him, but he paid no attention to anything I said.

“And it was after the wedding—just a few hours after the wedding, that he chose to appear!” he cried. “There isn’t anything else to think, is there, Sainclair? You took M. Darzac’s wire just as I did? It could mean nothing else except that that man has come back?”

“I should think not—but M. Darzac may be mistaken.”

“Oh, M. Darzac is not a child to be frightened at bogies. But we must hope—we must hope, mustn’t we, Sainclair, that he is mistaken? Oh, it isn’t possible that such a fearful thing can be true. Oh, Sainclair, [Pg 33] it would be too terrible!”

I had never seen Rouletabille so deeply agitated, even at the time of the most terrible events at the Glandier. He arose from his chair and walked up and down the room, casting aside any object which came in his way and repeating over and over: “No, no! It’s too terrible—too terrible!”

I told him that it was not sensible to put himself in such a state merely upon the receipt of a telegram which might mean nothing at all, or might be the result of some delusion. And there, too, I added, that it was not at this time, when we needed all our strength and fortitude, that we ought to give way to imaginary fears which were particularly inexcusable in a lad of his practical temperament.

“Inexcusable! I am glad you think so, Sainclair.”

“But, my dear boy, you frighten me. What is there you know that you have not told me?”

“I am going to tell you. The situation is horrible. Why didn’t that villain die?”

“And, after all, how do you know that he is not dead?”

“Look here, Sainclair—Don’t talk—Be quiet, please—You see, if he is alive, I wish to God that I were dead!”

“You are crazy. It is if he is alive that you have all the more reason to live to defend that poor woman.”

“Ah, that is true! That is true! Thanks, old fellow! You have said the only thing that makes me want to live. To defend her! I will not think of myself any longer—never again.”

And Rouletabille smiled—a smile which almost frightened me. I threw [Pg 34] my arm around him and begged him to tell me why he was so terrified, why he spoke of his own death and why he smiled so strangely.

Rouletabille laid his hand on my shoulder, and I went on:

“Tell your friend what it is, Rouletabille. Speak out. Relieve your mind. Tell me the secret that is killing you. I would tell you anything.”

Rouletabille looked down and steadily into my eyes. Then he said:

“You shall know all, Sainclair. You shall know as much as I do, and when you do, you will be as unhappy as I am, for you are kind and you are fond of me.”

Then he straightened back his shoulders as though he had already cast off a burden and pointed in the direction of the railway.

“We shall leave here in an hour,” he said. “There is no direct train from Eu to Paris in the winter: we shall not reach Paris until 7 o’clock. But that will give us plenty of time to pack our trunks and take the train that leaves the Lyons station at nine o’clock for Marseilles and Mentone.”

He did not ask my opinion on the course which he had laid out. He was taking me to Mentone, just as he had brought me to Trepot. He was well aware that in the present crisis I could refuse him nothing. Besides, he was in such a state of mental strain that even if he had wished it, I should scarcely have left him. And it was not hard for me to accompany him, for we were just beginning our long vacations, and my affairs were so arranged that I felt entirely at liberty.

“Then we are going to Eu?” I inquired.

[Pg 35]

“Yes: we will take the train from there. It will scarcely take half an hour to drive over.”

“We shall have spent only a little time in this part of the country,” I remarked.

“Enough, I hope—enough for me to find what I am looking for.”

I thought of the perfume of the Lady in Black, but I kept silence. Had he not said that he was going to tell me everything? He led me out to the jetty. The wind was still blowing a gale, and we were almost taken off our feet. Rouletabille stood for an instant as if lost in thought, closing his eyes as if in a dream.

“It was here,” he said, “that I last saw her.”

He looked down at the stone bench beside which we were standing.

“We were sitting there. She held me to her heart. I was a very little fellow, even for nine years old. She told me to stay there—on this bench—and then she went away, and I never saw her again. It was night—a soft summer evening—the evening of the distribution of prizes. She had not assisted at the distribution, but I knew that she would come that night—that night full of stars and so clear that I hoped every moment that I would be able to distinguish her face. But she covered it with her veil and breathed a heavy sigh. And then she went away. And I have never seen her since.”

“And you, my friend?”

“I?”

“Yes, what happened to you? Did you sit on the bench for very long?”

“I would have—but the coachman came to look for me and I went in.”

“Where?”

[Pg 36]

“Into the school.”

“Is there a boarding school at Trepot?”

“No, but there is one at Eu—I went to the school at Eu.”

He motioned me to follow him.

“We will go there,” he said. “I can’t talk here. There is too much of a storm.”

In another half hour we were at Eu. At the foot of the Rue des Marroniers our carriage rolled over the pavements of the big, cold, empty place, as the coachman announced his arrival by cracking his whip, filling the dead town with the noise of the snapping leather.

Soon we heard the sound of a bell—that of the school, Rouletabille told me—and then everything was quiet again. We alighted and the horse and carriage stood motionless upon the street. The driver had gone into a saloon. We entered the cool shades of a high Gothic church which faced upon the square. Rouletabille cast a glance at the castle—a red brick structure, crowned with an immense Louis XIII roof—a mournful facade which seemed to weep over the glory of departed princes. The young reporter gazed sorrowfully at the square battlements of the City Hall, which extended toward us the hostile lance of its soiled and weather-beaten flag; at the Cafe de Paris; at the silent houses; at the shops and the library. Was it there that the boy had bought those first new books for which the Lady in Black had paid?

“Nothing has changed.”

An old dog, colorless and shaggy, upon the library steps, stretched [Pg 37] himself lazily on his frozen paws.

“Cham! Cham!” called Rouletabille. “Oh, I remember him well. It is Cham—it is my old Cham.”

And he called him again, “Cham! Cham!”

The dog got upon his feet, turned toward us, listening to the voice that called him. He took a few steps, wagged his tail, and stretched himself out in the sun again.

“He doesn’t remember me,” said Rouletabille sadly.

He drew me into a little street which had a steep down grade, and was paved with sharp pebbles. As we went down the hill he took my hand and I could feel the fever in his. We stopped again in front of a tiny temple of the Jesuit style, which raised in front of us its porch, ornamented with semicircles of stone, the “reversed consoles” which are the characteristic features of an architecture which contributed nothing to the glory of the Seventeenth Century. After having pushed open a little low door, Rouletabille bade me enter, and we found ourselves inside a beautiful mortuary chapel, upon the stone floor of which were kneeling, beside their empty tombs, magnificent marble statues of Catherine of Cleves and Guise le Balafre.

“The college chapel,” whispered Rouletabille.

There was no person in the chapel. We crossed the room hastily. On the left wall, Rouletabille tapped very gently a kind of drum, which gave out a queer, muffled sound.

“We are in luck!” he said. “Everything is going well. We are inside the college and the concierge has not seen me. He would surely have remembered me.”

“What harm would that have done?”

[Pg 38]

Just at that moment a man with bare head and a bunch of keys at his side passed through the room and Rouletabille drew me into the shadow.

“It is Pere Simon. Ah, how old he has grown! He is almost bald. Listen: this is the hour when he goes to superintend the study hour of the younger boys. Everyone is in the class room at this time. Oh, we are very lucky! There is only Mere Simon in the lodge—that is, if she is not dead. At any rate, she can’t see us from here. But wait—here is Pere Simon back again!”

Why was Rouletabille so anxious to hide himself? Decidedly, I knew very little of the lad whom I believed that I knew so well. Every hour that I had spent with him of late had brought me some new surprise. While we were waiting for Pere Simon to leave us a clear field once more, Rouletabille and I managed to slip out of the chapel without being seen, and hid ourselves in the corner of a tiny garden, laid out in the middle of a stone court, behind the shrubbery of which we could, leaning over, contemplate at our leisure the grounds and buildings of the school. Rouletabille hung on to my arm as though he were afraid of falling. “Good Heavens!” he murmured, in a voice broken with emotion. “How things are changed! They have torn down the old study where I found the knife and the leather hangings where the money was hidden have, doubtless, been destroyed. But the chapel walls are just the same. Look, Sainclair: lean over the hedge. That door that opens in the rear of the chapel is the door of the infant class room. But never, never did I leave that class room so gladly, even in my happiest play hours, as when Pere Simon came to fetch me to the parlor where the [Pg 39] Lady in Black was waiting for me. Ah—suppose that they have destroyed the parlor!”

And he cast a quick look toward the building behind him.

“No—no: it is all right—beside the mortuary. There is the same door at the right through which she came. We shall go there as soon as Pere Simon is out of the way.”

And he set his teeth.

“I believe that I am going crazy!” he said with a short laugh. “But I can’t help my feelings. They are stronger than I. To think that I am going to see the parlor—where she waited for me! I had been living only in the hope of seeing her, and after she had gone, although I had promised to be good and sensible, I fell into such a despondent state that after each of her visits, they feared for my health. They were only able to save me from utter prostration by telling me that if I fell ill they would not let me see her any more. So from one visit to another, I had her memory and her perfume to comfort me. Never having seen her dear face distinctly, and being so weak that I was ready to swoon with joy every time she pressed me to her heart, I lived less with her image than with the heavenly odor. Often on the days after she had come and gone, I would escape from my comrades during the recreation hours and steal to the parlor, and when I found it empty, I would draw deep breaths of the air which she had breathed and remain there like a little devotee, and leave with a heart filled with the sense of her presence. The perfume which she always used and which was indissolubly associated in my mind with her, was the most delicate, the most subtle, and the sweetest odor I have ever known, and I never [Pg 40] breathed it again in all the years which followed until the day I spoke of it to you, Sainclair. You remember—the day we first went to the Glandier?”

“You mean the day that you met Mathilde Stangerson?”

“That is what I mean,” responded the lad in a trembling voice.

(Ah, if I had known at that moment that Professor Stangerson’s daughter, as the result of her first marriage in America, had had a child, a son, who would have been, if he had lived, the same age as Rouletabille, perhaps I would have at last comprehended his emotion and grief, and the strange reluctance which he showed to pronounce the name of Mathilde Stangerson there at the school, to which, in the past, had come so often the Lady in Black!)

There was a long silence, which I finally broke.

“And you have never known why the Lady in Black did not return?”

“Oh!” cried Rouletabille. “I am sure that she did return. It was I who was not here.”

“Who took you away?”

“No one: I ran away.”

“Why? To look for her?”

“No—no! To flee from her—to flee from her, I tell you, Sainclair. But she came back—I know that she came back.”

“She may have been broken hearted at not finding you.”

Rouletabille raised his arms toward the sky and shook his head.

“I don’t know—how can I know? Ah, what an unhappy wretch I am! But, [Pg 41] hush, Sainclair! Here comes Pere Simon! Now, he’s gone again. Quick—to the parlor!”

We were there in three seconds. It was a commonplace room enough, rather large, with cheap white curtains in front of the shadeless windows. It was furnished with six leather chairs placed against the wall, a mantel mirror, and a clock. The whole appearance of the place was sombre.

As we entered the room, Rouletabille uncovered his head with an appearance of respect and reverence which one rarely assumes except in a sacred place. His face became flushed, he advanced with short steps, rolling his travelling cap in his hands as if he were embarrassed. He turned to me and said in low tones—far lower than he used in the chapel:

“Oh, Sainclair, this is it—the parlor. Feel how my hands burn. My face is flushed, is it not? I was always flushed when I came here, knowing that I should find her. I used to run. I felt smothered—I do now. I was not able to wait. Oh, my heart beats just as it used when I was a little lad! I would come to the door—right here—and then I would pause, bashful and shamefaced. But I would see her dark shadow in the corner: she would take me in her arms and hold me there in silence, and before we knew it, we were both weeping, as we clung together. How dear those meetings were. She was my mother, Sainclair. Oh, she never told me so: on the contrary, she used to say that my mother was dead, and that she had been her friend. But she told me to call her Mamma—and when she wept as I kissed her, I knew that she really was my mother. See—she always sat there in the dark corner, and she came always at [Pg 42] nightfall, when the parlor had not yet been lit up for the evening. And every time she came, she would place on the window sill a big, white package, tied with pink cord. It was a fruit cake. I have loved fruit cake ever since, Sainclair!”

The poor lad could no longer contain himself. He rested his arms on the mantel and wept like a little child. When he was able to control himself a little, he raised his head and looked at me with a sad smile. And then he sank into a chair as though he were tired out. I had not had the heart to say one word to him during his reminiscences. I knew well that he was not talking with me, but with his memories.

I saw him draw from his breast the letter which he had placed there in the train, and tear it open with trembling fingers. He read it slowly. Suddenly his hand fell, and he uttered a groan. His flushed face grew pallid—so pallid that it seemed as though every drop of blood had left his heart. I stepped toward him, but he waved me away and closed his eyes. He looked almost as though he were sleeping. I walked across the room, moving as softly as one does in the chamber of death. I looked up at the wall, where hung a heavy wooden crucifix. How long did I stand gazing on the cross? I have no idea. Nor do I know what we said to someone belonging to the house, who came into the parlor. I was pondering with all my strength of concentration on the strange and mysterious destiny of my friend—on this mysterious woman who might or might not have been his mother. Rouletabille had been so young in those school days. He longed so for a mother, that he might have imagined that he had found one in his visitor. Rouletabille—what other name did we know him by? Joseph Josephin. It was without doubt under that name [Pg 43] that he had pursued his early studies here. Joseph Josephin, the queer appellation of which the editor of the Epoch had said to him, “It is no name at all!” And now, what was he about to do here? Seek the trace of a perfume? Revive a memory—an illusion? I turned as I heard him stir. He was standing erect and seemed quite calm. His features had taken on the serenity which comes from assurance of victory.

“We must go now, Sainclair. Come, my friend.”

And he left the parlor without even looking back. I followed him.

In the deserted street, which we regained without meeting anyone, I stopped him by asking anxiously:

“Well—did you find the perfume of the Lady in Black?”

He must have seen that all my heart was in the question and that I was filled with an ardent desire that this visit to the scenes of his childhood might have brought a little peace to his soul.

“Yes,” he said, very gravely. “Yes, Sainclair, I found it.”

And he handed me the letter from Professor Stangerson’s daughter.

I looked at him, doubting the evidence of my own senses—not understanding, because I knew nothing. Then he took my two hands and looked into my eyes.

“I am going to confide a secret to you, Sainclair—the secret of my life, and perhaps some day the secret of my death. Let what will come, it must die with you and me. Mathilde Stangerson had a child—a son. He is dead—is dead to everyone except to the two of us who stand here.”

[Pg 44]

I recoiled, struck with horror under such a revelation. Rouletabille the son of Mathilde Stangerson! And then suddenly I received a still more violent shock. In that case, Rouletabille must be the son of Larsan.

Oh, I understood now, all the wretchedness of the boy. I understood why he had said this morning: “Why did he not die? If he is living, I wish to God that I were dead!”

Rouletabille must have read my thoughts in my eyes, and he simply made a gesture which seemed to say, “And now you understand, Sainclair.” Then he finished his sentence aloud. The word which he spoke was “Silence!”

When we reached Paris we separated, to meet again at the train. There, Rouletabille handed me a new dispatch, which had come from Valence, and which was signed by Professor Stangerson. It said, “M. Darzac tells me that you have a few days’ leave. We should all be very glad if you could come and spend them with us. We will wait for you at Arthur Rance’s place, Rochers Rouges—he will be delighted to present you to his wife. My daughter will be pleased to see you. She joins me in kindest greetings.”

Just as the train was starting, a concierge from Rouletabille’s hotel came rushing up and handed us a third dispatch. This one was sent from Mentone, and signed by Mathilde. It contained two words: “Rescue us.”

[Pg 45]

Now I knew all. As we continued on our journey, Rouletabille related to me the remarkable and adventurous story of his childhood, and I knew, also, why he dreaded nothing so much as that Mme. Darzac should penetrate the mystery which separated them. I dared say nothing more—give my friend no advice. Ah, the poor unfortunate lad! When he read the words “Rescue us,” he carried the dispatch to his lips, and then, pressing my hand, he said: “If I arrive too late, I can avenge her, at least.” I have never heard anything more filled with resolution than the cold determination of his tone. From time to time a quick movement betrayed the passion of his soul, but for the most part he was calm—terribly calm. What resolution had he taken in the silence of the parlor, when he sat motionless and with closed eyes in the shadow of the corner where he had used to see the Lady in Black?

While we journeyed toward Lyons, and Rouletabille lay dreaming, stretched out fully dressed in his berth, I will tell you how and why the child that he had been ran away from school at Eu, and what had happened to him.

Rouletabille had fled from the school like a thief. There was no need to seek for another expression, because he had been accused of stealing. This was how it happened.

[Pg 46]

At the age of nine, he had already an extraordinarily precocious intelligence, and could arrive easily at the solution of the most perplexing problems. By logical deductions of an almost amazing kind, he astonished his professor of mathematics by his philosophical method of work. He had never been able to learn his multiplication tables, and always counted upon his fingers. He would usually get the answers to the problems himself, leaving the working out to be done by his fellow pupils, as one will leave an irksome task to a servant. But first, he would show them exactly how the example ought to be done. Although as yet ignorant of the rudiments of algebra, he had invented for his own personal use a system of algebra carried on with queer signs, looking like hieroglyphics, by the aid of which he marked all the steps of his mathematical reasoning, and thus he was able to write down the general formulæ so that he alone could interpret them. His professor used proudly to compare him to Pascal, discovering for himself without knowledge of geometry, the first propositions of Euclid. He applied his admirable faculties of reasoning to his daily life, as well as to his studies, using the rules both materially and morally. For example, an act had been committed in the school—I have forgotten whether it was of cheating or talebearing—by one of ten persons whom he knew, and he picked out the right one with a divination which seemed almost supernatural, simply by using the powers of reasoning and deduction, which he had practiced to such an extent. So much for the moral aspect of his strange gift, and as for the material, nothing seemed more simple to him than to find any lost or hidden object—or even a stolen one. It was in the detection of thefts especially that he displayed a wonderful resourcefulness, as if nature, in her wondrous fitting [Pg 47] together of the parts that make an equal whole, after having created the father a thief of the worst kind, had caused the son to be born the evil genius of thieves.

This strange aptitude, after having won for the boy a sort of fame in the school, on account of his detection of several attempts at pilfering, was destined one day to be fatal to him. He found in this abnormal fashion a small sum of money which had been stolen from the superintendent, who refused to believe that the discovery was due only to the lad’s intelligence and clearness of insight. This hypothesis, indeed, appeared impossible to almost everyone who knew of the matter, and, thanks to an unfortunate coincidence of time and place, the affair finished up by having Rouletabille himself accused of being the thief. They tried to make him acknowledge his fault; he defended himself with such indignation and anger that it drew upon him a severe punishment. The principal held an investigation and a trial, at which Joseph Josephin was accused by some of his youthful comrades in that spirit of falsehood which children sometimes possess. Some of them complained of having had books, pencils, and tablets stolen at different times, and declared that they believed that Joseph had taken them. The fact that the boy seemed to have no relatives, and that no one knew where he came from, made him particularly likely, in that little world, to be suspected of crime. When the boys spoke of him, it was as “that thief.” The contempt in which he was held preyed upon him, for he was not a strong child at best, and he was plunged in despair. He almost prayed to die. The principal, who was really the most kind hearted of [Pg 48] men, was persuaded that he had a vicious little creature to deal with, because he was unable to produce an impression on the child, and make him comprehend the horror of what he had done. Finally, he told the lad that if he did not confess his guilt, it had been decided not to keep him in the school any longer, and that a letter would be written to the lady who interested herself in him—Mme. Darbel was the name which she had given—to tell her to come after him.

The child made no reply and allowed himself to be taken to his little room, where he had been kept a prisoner. Upon the morrow he had disappeared. He had run away. He had felt that the principal, to whose care he had been entrusted during the earliest years of his childhood (for in all his little life he could remember no other home than the school), and who had always been so kind to him, was no longer his friend, since he believed him guilty of theft. And he could see no reason why the Lady in Black would not believe it, too—that he was a thief. To appear as a thief in the sight of the Lady in Black! He would far rather have died.

And he made his escape from the place by climbing over the wall of the garden at night. He rushed to the canal, sobbing, and, with a prayer, uttered as much to the Lady in Black as to God Himself, threw himself in the water. Happily, in his despair, the poor child had forgotten that he knew how to swim.

If I have reported this passage in the life of Rouletabille at some length, it is because it seems to me that it is all important to the thorough comprehension of his future. At that time, of course, he was ignorant that he was the son of Larsan. Rouletabille, even as a child [Pg 49] of nine years, could not without agony harbor the idea that the Lady in Black might believe him to be a thief, and thus, when the time came that he imagined—an imagination too well founded, alas!—that he was bound by ties of blood to Larsan, what infinite misery he experienced! His mother, in hearing of the crime of which he had been accused, must have felt that the criminal instincts of the father were coming to light in the son, and, perhaps—thought more cruel than death itself—she may have rejoiced in believing him dead.

For everyone believed him dead. They found his footsteps leading to the canal, and they fished out his cap. How had he lived after leaving the school? In a most singular fashion. After swimming to dry land and making up his mind to fly the country, the lad, while they were searching for him everywhere in the canal and out of it, devised a most original plan for travelling to a distance without being disturbed. He had not read that most interesting tale, The Stolen Letter. His own invention served him. He reasoned the thing out, as he always did.

He knew—for he had often heard them told by the heroes themselves—many stories of little rascals who had ran away from their parents in search of adventures, hiding themselves by day in the fields and the wood, and travelling by night—only to find themselves speedily captured by the gendarmes, or forced to return home because they had no money and no food, and dared not ask for anything to eat along the road which they followed, and which was too well guarded to admit of their escape if they applied for aid. Our little Rouletabille slept at night like everyone else, and travelled in broad daylight, without hiding himself. But, after having dried his garments (the warm weather was [Pg 50] coming on, and he did not suffer from cold), he tore them to tatters. He made rags of them, which barely covered him, and begged in the open streets, dirty and unkempt, holding out his hands and declaring to passers-by that if he did not bring home any money his parents would beat him. And everyone took him for some gypsy child, hordes of which constantly roamed through the locality. Soon came the time of wild strawberries. He gathered the fruit and sold it in little baskets of leaves. And he assured me, in telling the story, that if it had not been for the terrible thought that the Lady in Black must believe that he was a thief, that time would have been the happiest of his life. His astuteness and natural courage stood him well in stead through these wanderings, which lasted for several months. Where was he going? To Marseilles. This was his plan:

He had seen in his illustrated geography views of the Midi, and he had never looked at those pictures without breathing a sigh and wishing that he might some day visit that enchanted country. Through his gypsy-like manner of living, he had made the acquaintance of a little caravan load of Romanies, who were following the same route as himself, and who were journeying to Ste. Marie’s of the Sea to render homage to a new king of their tribe. The lad had an opportunity to render them some small service, and finding him a pleasant, well-mannered little fellow, these people, not being in the habit of asking everyone whom they met for his history, desired to know nothing more about him. They believed that, on account of ill treatment, the child had run away from some troop of wandering mountebanks, and they invited him to travel [Pg 51] with them. Thus he arrived in the Midi.

In the neighborhood of Arles, he separated himself from his travelling companions, and at last came to Marseilles. There was his paradise! Eternal summer—and the port.

The port was the favorite resort of all the gamins of the locality, and this fact was the greatest safeguard for Rouletabille. He roamed over the docks as he chose, and served himself according to the measure of his needs, which were not great. For example, he made of himself an “orange fisher.” It was at the time that he exercised this lucrative calling that, one beautiful morning upon the quay, he made the acquaintance of M. Gaston Leroux, a journalist from Paris, and this acquaintance was destined to have such an influence upon the future of Rouletabille that I do not consider it out of place to transcribe here in full the article in which the editor of Le Matin recorded that first memorable interview.

THE LITTLE ORANGE FISHER.

As the sun, piercing through the cloudless heavens, struck with its ardent rays the golden robe of Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde, I descended toward the quay. The scene which met my eyes was one which was worth going far to see. Townfolk, sailors and workmen were moving about, the former idly looking on, while the others tugged at the pulleys and drew up the cables of their vessels. The great merchant vessels glided like huge beasts of burden between the tower of St. Jean and the fort of St. Nicholas, caressing the sparkling waters of the Old Port in their onward motion. Side by side, shoulder to shoulder, the smaller barks seemed to hold out their arms to each other, to throw aside their veils of mist and to dance upon the water. Beside them, tired with the long journey, worn out from ploughing for so many days and nights over unknown seas, the heavy laden East Indiamen rested [Pg 52] peacefully, lifting their great, motionless sails in rags toward the skies.

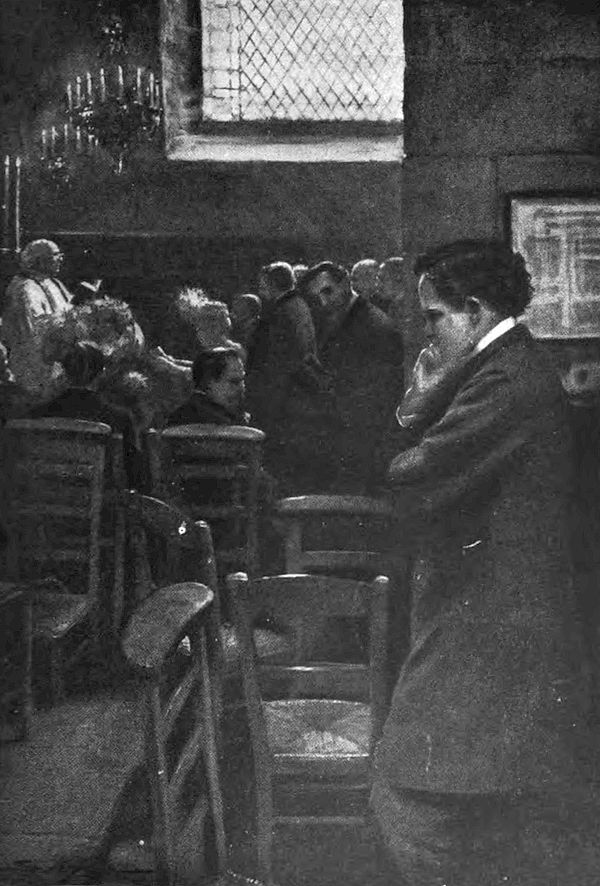

My eyes, sweeping swiftly over the scene through the forest of masts and sails paused at the tower which commemorated the fact that it was twenty-five centuries since the children of Ancient Phœnicia first cast anchor upon this happy shore, and that they had come by the water ways of Ionia. Then my attention returned to the border of the quay, and I perceived the little orange fisher.

He was standing erect, clad in the rags of a man’s coat which hung down almost to his feet, bareheaded and barefooted, with blonde curly locks and black eyes, and I should think that he was about nine years old. A string passed around his shoulder supported a big sailcloth sack. His left hand rested on his waist and his right hand held a stick three times as tall as himself, which was surmounted by a little wooden hook. The child stood motionless and lost in thought. When I asked him what he was doing there, he told me that he was an orange fisher.

He seemed very proud of being an orange fisher and did not ask me for a penny, as the little vagabonds of the neighborhood are accustomed to demand toll of every bystander. I spoke to him again, but this time he made no answer, for he was too intent on watching the water. On one side of us was the beautiful steamer Fides, in from Castellmare and on the other a three masted schooner from Genoa. Further off were two ships loaded with fruits which had just arrived from Baleares that morning, and I saw that they were spilling a part of their cargo. Oranges were bobbing up and down upon the water and the light current sent them in our direction. My “fisher” leaped into a little canoe, came quickly to the vessel, and, armed with his stick and hook, waited. Then he began his gathering. The hook on his stick brought him one orange, then a second, a third and a fourth. They disappeared in the sack. The boy gathered a fifth, jumped upon the quay and tore open the golden fruit. He plunged his little teeth in the pulp and devoured it in an instant.

“You have a good appetite.” I told him.

“Monsieur,” he replied, flushing slightly as he spoke, “I don’t care for any food but fruit.”

“That is a very good diet,” I replied as gravely as he had spoken. “But what do you do when there are no oranges?”

“I pick up coal.”

He stood erect, wrapped in the rags of a long coat which hung about his legs, bareheaded and barefooted.

And his little hand, diving into the sack, brought out an enormous piece of coal.

[Pg 53]

The orange juice had rolled down his chin to his coat. The coat had a pocket. The little fellow took a clean handkerchief from this pocket and carefully wiped both chin and coat. Then he proudly put the handkerchief back.

“What is your father’s work?” I asked.

“He is poor.”

“Yes, but what does he do?”

The orange fisher shrugged his shoulders.

“He doesn’t do anything, he is poor.”

My inquiries into his family affairs did not seem to please him. He turned away from the quay and I followed him. We came in a moment to the “shelter,” a little square of sea which holds the small pleasure yachts—the neat little boats all polished wood and brass, the neat little sailors in their irreproachable toilettes. My ragamuffin looked at them with the eye of a connoisseur and seemed to find a keen enjoyment in the spectacle. A new yacht had just been launched and her immaculate sail looked like a white veil against the blue sky.

“Isn’t it pretty?” exclaimed my little companion.

The next moment he fell over a board covered with fresh tar and when he picked himself up, he looked with dismay at the stain on his coat which seemed to be his proudest possession. What a disaster! He looked as if he could have burst into tears. But quick as thought he drew out his handkerchief and rubbed and rubbed the spot, then he looked at me piteously and said:

“Monsieur, are there any other stains? Did I get anything on my back?”

I assured him that he had not, and with an expression of satisfaction, he put the handkerchief back in his pocket once more.

A few steps further on, upon the walk which stretches in front of the red and yellow, and blue houses, the windows of which are brave with wares of many kinds, we found an oyster stand. Upon the little tables were displayed piles of oysters in their shells, and flasks of vinegar.

When we passed by the oyster stand, as the fish appeared fresh and appetizing, I said to the orange fisher.

“If you cared for anything to eat except fruit, I might ask you to have some oysters with me.”

His black eyes glistened and we sat down together to eat our oysters. The merchant opened them for us while we waited. He started to bring us vinegar, but my companion stopped him with an imperious gesture. [Pg 54] He opened his bag carefully and triumphantly produced a lemon. The lemon, having been in close contact with the bit of coal, might have passed for black itself. But my guest took out his handkerchief and wiped it off. Then he cut the fruit and offered me half, but I like oysters without other flavor, so I declined with thanks.

After our luncheon we went back to the quay. The orange fisher asked me for a cigarette and lighted it with a match which he had in another pocket of his coat.

Then, the cigarette between his lips, puffing rings toward the sky like a man, the little creature threw himself down on the ground and with his eyes fixed upon the statue of Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde, took the very pose of the boy who is the most beautiful ornament of the Brussels tower. He did not lose a line of the attitude, and seemed very proud of the fact and apparently desired to play the part exactly.

Upon the following day Joseph Josephin met M. Gaston Leroux once more upon the quay, and the man handed him a newspaper which he carried in his hand. The boy read the article pointed out to him, and the journalist gave him a bright new 100-sous piece. Rouletabille made no difficulties about accepting it, and seemed to even find the gift a natural one. “I take your money,” he said to Gaston Leroux, “because we are collaborators.” With his hundred sous he bought himself a fine new bootblack’s box and installed himself in business opposite the Bregaillon. For two years he polished the boots of those who came to eat the traditional bouillabaisse at this hostelry. When he was not at work, he would sit on his box and read. With the feeling of ownership which his box and his business had brought him, ambition had entered his mind. He had received too good an education and had been too well instructed in rudimentary things not to understand that if he did not himself finish what others had begun for him, he would be deprived of the best chance which he had of making for himself a place in the [Pg 55] world.

His customers grew interested in the little bootblack, who always had on his box some work of history or mathematics, and a harness maker became so attached to him that he took him into his shop.

Soon Rouletabille was promoted to the dignity of working in leather, and was able to save. At the age of sixteen years, having a little money in his pocket, he took the train for Paris. What did he intend to do there? To look for the Lady in Black.