Title: Travels to Tana and Persia

A narrative of Italian travels in Persia, in the 15th and 16th centuries

Author: Giosofat Barbaro

Ambrogio Contarini

Editor: Baron Henry Edward John Stanley Stanley

Translator: Eugene Armand Roy

William Thomas

Release date: February 4, 2025 [eBook #75292]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Burt Franklin, 1873

Credits: Turgut Dincer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note

These are old texts, and part of their value includes preserving them as written with all of their inconsistencies intact. That said, some probable printing errors were identified and fixed; these are listed at the end. In addition, word spacing and punctuation have been amended without further note. The listed errata have NOT been fixed, again in the interest of preserving the original.

WORKS ISSUED BY

The Hakluyt Society.

TRAVELS TO TANA AND PERSIA,

BY BARBARO AND CONTARINI.

A NARRATIVE OF ITALIAN TRAVELS IN PERSIA,

IN THE 15TH AND 16TH CENTURIES.

FIRST SERIES. NO. XLIX-MDCCCLXXIII

TRAVELS

TO

TANA AND PERSIA,

BY

JOSAFA BARBARO

AND

AMBROGIO CONTARINI.

TRANSLATED FROM THE ITALIAN BY

WILLIAM THOMAS, CLERK OF THE COUNCIL TO EDWARD VI,

AND BY

S. A. ROY, ESQ.

AND EDITED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY

LORD STANLEY OF ALDERLEY.

BURT FRANKLIN, PUBLISHER

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

Published by

BURT FRANKLIN

514 West 113th Street

New York 25, N. Y.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED BY THE HAKLUYT SOCIETY

REPRINTED BY PERMISSION

Printed in U.S.A.

| The Right Hon. Sir DAVID DUNDAS, President. | ||

| Admiral C. R. DRINKWATER BETHUNE, C.B. | } | Vice-Presidents. |

| Major-General Sir HENRY C. RAWLINSON, K.C.B., D.C.L., F.R.S., Vice-Pres.R.G.S. | } | |

| W. A. TYSSEN AMHURST, Esq. | ||

| Rev. GEORGE P. BADGER. | ||

| JOHN BARROW, Esq., F.R.S. | ||

| Vice-Admiral COLLINSON, C.B. | ||

| Captain COLOMB, R.N. | ||

| W. E. FRERE, Esq. | ||

| EGERTON VERNON HARCOURT, Esq. | ||

| JOHN WINTER JONES, Esq., F.S.A. | ||

| R. H. MAJOR, Esq., F.S.A., Sec.R.G.S. | ||

| Sir W. STIRLING MAXWELL, Bart. | ||

| Sir CHARLES NICHOLSON, Bart., D.C.L. | ||

| Vice-Admiral ERASMUS OMMANNEY, C.B., F.R.S. | ||

| Rear-Admiral SHERARD OSBORN, C.B., F.R.S. | ||

| The Lord STANLEY of Alderley. | ||

| EDWARD THOMAS, Esq., F.R.S. | ||

| The Hon. FREDERICK WALPOLE, M.P. | ||

CLEMENTS R. MARKHAM, Esq., C.B., F.R.S., Sec.R.G.S. Honorary Secretary.

The volume herewith given to the members of the Hakluyt Society, contains six narratives by Italians, of their travels in Persia about the time of Shah Ismail. Mr. Charles Grey, who has translated and edited four of these travels, having accompanied Sir Bartle Frere to Zanguibar, has been unable to finish the printing of his book, and the correction of his proofs has been entrusted to me. As all these travellers were almost contemporaries, and as they refer to one another, the council have thought it best to give them to members in one single volume.

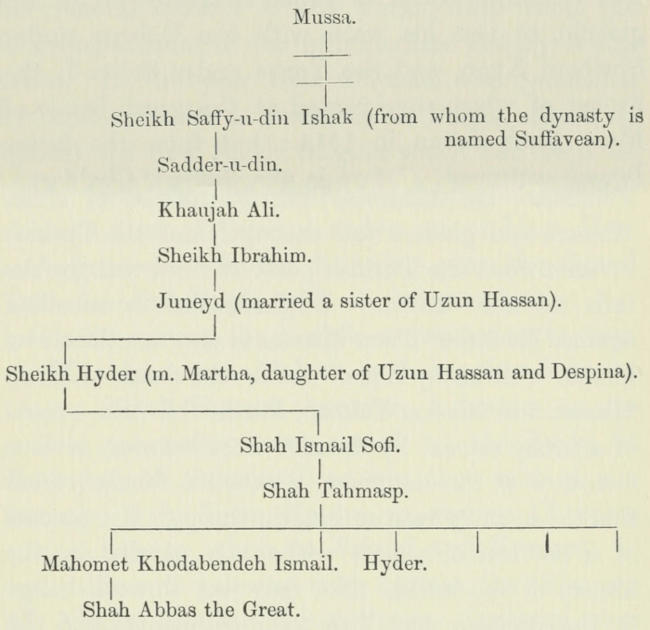

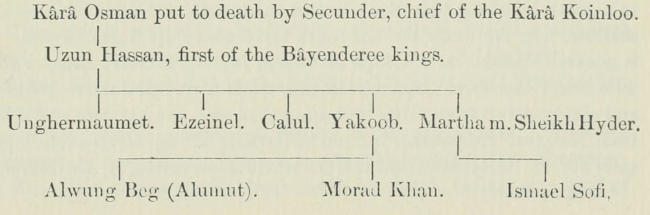

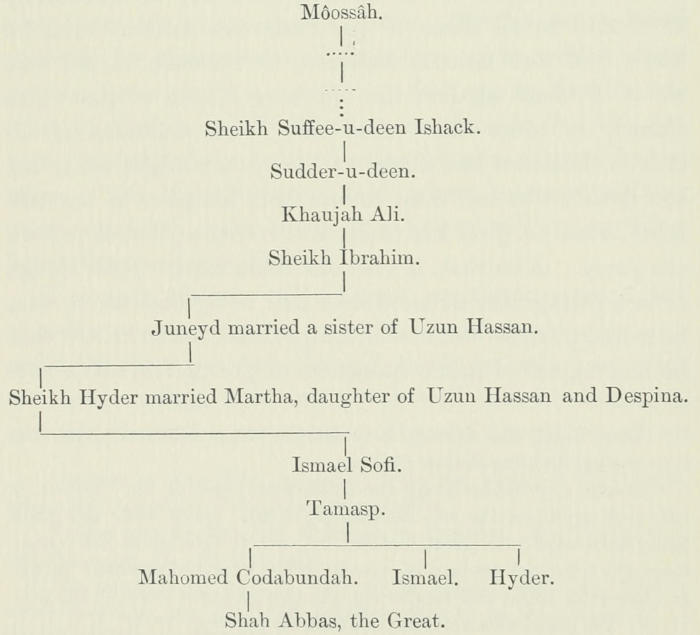

Shah Ismail, or Ismail Sufy, is the chief personage in this volume; he found Persia in disorder, and reunited it; he revived the Persian nationality, and very much increased the division which existed between Persia and the rest of the Mussulman States; a division or schism which has been erroneously called religious, but which originally was national and political, and, as revived and augmented by Shah Ismail, entirely national. The feelings which animated the earlier Persians to reject the first three caliphs, were the national repulsion of the Persians to their Arab conquerors, and a preference for hereditary[vi] succession instead of popular election. Shah Ismail took advantage of these national sentiments and dynastic traditions, without which Persia, overrun as it was by Turkish tribes, would have merged into the Ottoman Empire. Shah Ismail did his work so effectually, that Nadir Shah was unable to undo it, and was assassinated for attempting it; and, though the greater part of the Persian population and the reigning dynasty at this day speak Turkish as their own language, yet they are as Persian in feeling as the Persian inhabitants of Shiraz and Isfahan.

Of the Italian travellers and envoys, whose narratives are here given, Josafa Barbaro is the most interesting personage: but none of them attract the same interest which attaches to Varthema, or to the Portuguese and Spanish travellers and voyagers of the same period.

The travels of Barbaro and Contarini have long been ready for publication, but have been delayed hitherto, for want of an editor. The work was undertaken by Sir Henry Rawlinson and Lord Strangford, but the former had not time to attend to it, and the latter died before he had really commenced it.

The translation of Contarini was done by Mr. Roy of the British Museum, who also made a translation of Josafa Barbaro, and a question arose whether Mr. Roy’s translation, or the quaint old translation of William Thomas, should be published by the Society. I decided in favour of Thomas’ translation, partly in deference to what I knew was the opinion in its[vii] favour of Lord Strangford, on account of its interest as English of the time of Edward VI, shewing much better orthography than that current at a later period (Fanshaw’s translation of Camoens for instance), and partly on account of the interest which attaches (especially to members of the Hakluyt Society) to Mr. Thomas and his unfortunate end.

Chalmers’ Biography tells us that Mr. William Thomas was a learned writer of the sixteenth century, and was born in Wales, or was at least of Welsh extraction, and was educated at Oxford. Wood says, that a person of both his names was in 1529 admitted a bachelor of Canon Law, but does not say that it was this person. In 1544, being obliged to quit the kingdom on account of some misfortune, he went to Italy, and in 1546 was at Bologna, and afterwards at Padua; in 1549 he was again in London, and on account of his knowledge of modern languages, was made clerk of the council to King Edward VI, who soon after gave him a prebend of St. Paul’s, and the living of Presthend, in South Wales. According to Strype, he acted very unfairly in procuring the prebend, not being a spiritual person; and the same objection undoubtedly rests against his other promotion. On the accession of Queen Mary, he was deprived of his employment at Court, and is said to have meditated the death of the Queen; but Ball says it was Gardiner whom he formed a design of murdering. Others think that he was concerned in Wyatt’s rebellion. It is certain, that for some of these charges he was committed to the Tower in 1553, together[viii] with William Winter and Sir Nicholas Throgmorton. Wood says, “He was a man of a hot fiery spirit, had sucked in damnable principles, by his frequent conversations with Christopher Goodman, that violent enemy to the rule of women. It appears that he had no rule over himself, for about a week after his commitment he attempted suicide, but the wound not proving mortal, he was arraigned at Guildhall, May 9th, 1553, and hanged at Tyburn on the 18th.”

Chalmers gives the following list of his works:—

1. “The History of Italy.” Lond. 1549, 1561, 4to.

2. “The Principal Rules of the Italian Grammar, with a Dictionary for the better understanding of Boccace, Petrarch, and Dante.” Ibid. 1550, 1561, 1567, 4to.

3. “Le Peregrynne, or, a defence of King Henry VIII to Aretine, the Italian poet.” MSS. Cott., Vesp. D 18, in Bodl. Library. This, Wood says, was about to be published in the third volume of Brown’s “Fasciculus.”

4. “Common Places of State,” written for the use of Edward VI. MS. Cotton.

5. “Of the Vanity of the World.” Lond. 1549, 8vo.

6. “Translation of Cato’s speech, and Valerius’s answer; from the 4th Decade of Livy.” Ibid. 1551, 12mo.

He also made some translations from the Italian, which are still in manuscript.

Mr. Thomas might have rendered further service to letters, instead of mixing himself up in conspiracies, had he received a favourable answer to an application which he made to Cecil, to be sent at the expense of the Government to Italy. A copy of his letter to Cecil, taken from the original at the Record Office, here follows:—

To the right honorable Sʳ William Cecill Knight one of the King’s Mag. twoo principall Secretaries.

Sʳ myne humble comᵉndacons remembered According to yoʳ pleasʳᵉ declared unto me at my departure I opened to my L of Pembroke the consideracon of the warde which you procured for yoʳ Sister wherein he is the best contented man that may be and made me this answer that though he wrote at his friends request yet he wrote unto his friende to be considered as it might be wᵗʰ yoʳ owne comoditie and none otherwise ffor if he had knowen so much before as I tolde him he wolde for nothing have troubled yᵒ wᵗʰ so unfriendly a request Assuring yoᵘ faithfully that I who have knowen him a good while never sawe him more bent to any man of yoʳ degree than I perceave he is unto yoᵘ and not without cause he thanketh yoᵘ hertily for yoʳ newes yoᵘ sent him And Sʳ whereas at my departure we talked of Venice considering the stirre of the worlde is nowe like to be very great those waies I coulde finde in myne hert to spende a yere or two there if I were sent I have not disclosed thus much to any man but to yoᵘ nor entende not to do. wherefore it may please yoᵘ to use it as yoᵘ shall thinke good Howe so ever it be yoʳ may be sure to commande me as the least in yoᵘ house. And so I humbly take my leave. ffrom Wilton the xiiijᵗʰ of August 1552.

Yoʳˢ assuredly to thuttermost

Willm Thomas.

From the following extracts from the indictment, and other records of his trial, taken from the Record Office, it will be seen that he did conspire against[x] Queen Mary, and not only, as Ball supposes, against Gardiner.

Report of Deputy Keeper of the Public Records, iv, p. 248.

Pouch Nᵒ. xxx in the Record Office contains a file of 11 membranes, relating to the Trial and conviction of William Thomas for high treason. The Indictment found against him at Guildhall, dated 8 May, 1 Mary, 1554, charges that, he hearing of the proposed marriage between the Queen and Philip, Prince of Spain, had a discourse with one Nicholas Arnolde, late of London, Knight, as to the manner in which such marriage could be prevented or impeded, upon which the said William Thomas put various arguments against such marriage in writing, and afterwards, to wit 21 December, 1 Mary, at London, in the parish of Sᵗ Alban, in the ward of Cripplegate, the said William Thomas compassed and imagined the death of the Queen.

And afterwards, on the 22ᵈ December, in order to carry his wicked intentions into effect, he went into the house of the said Sir Nicholas, in the parish of Sᵗ. Bartholomew the Less, in the ward of Farringdon Without, and there had a traitorous discourse with the said Nicholas, to the following effect:—“Whether were it not a good ‘devise’ to have all these perils that we have talked of, taken away with very little bloodshed, that is to say, by killing of the Queen. I think John Fitzwilliams might be persuaded to do it, because he seems by his countenance to be so manly a man, that he will not refuse any peril that might come to his own person, to deliver his whole native country from so many and so great dangers, as be offered thereunto, if he might be made to understand them”; which words the said Sir Nicholas, afterwards, viz., 24 December, at London, in the parish of Sᵗ. Anne, in the ward of Aldersgate, repeated to James Croftes, Knight, one of the conspirators with Sir Thomas Wyatt, a traitor who had been attainted for levying war against the Queen, whereof the said James Croftes was also attainted.

And the said William Thomas, not contented with the before-mentioned treasons, in order more fully to fulfil such his imaginations, 27 December, went from London to Devonshire, to a place called Mount Sautrey, then inhabited by Peter Caro, Knight, with which Peter Caro, an abominable traitor, the said William Thomas had a traitorous conference and consultation, and then and there aided the said Peter Caro; and afterwards, to wit, 4 February, fled from Mount Sautrey, from county to county, in disguise, not knowing where to conceal himself; and yet he did not desist from sending seditious bills and letters to his friends, declaring his treasonable intentions, in order that he might induce them to join him in his treasons.

Membrane I, Wednesday, 9 May, 1 Mary, London.

Record of Sessions, held at Guildhall, before the said Sir Thomas Whyte, and his fellows setting forth.

1 May, 1 Mary, London—Special Commission of Oyer Terminer.

8 May, 1 Mary, London—Indictment as before mentioned.

William Thomas, being brought to the bar by the Constable of the Tower, pleads Not Guilty.

Venire, awarded instanter.

Verdict, Guilty.

Judgment as usual in cases of High Treason.

Execution at Tyburn.

Record delivered into Court, by William, Marquis of Winchester, on Monday next, after the Octaves of the Holy Trinity, 1 Mary.

TO THE KINGS MOST EXCELLENT MAᴵᴱ.

Whan I consider the state of foreyn cuntreys, and do compare this yoʳ Ma’ˢ realme to the rest of the worlde as well for justice and civilitie as for wealth and commodities, I do so much reioice in my cuntrey that as I do yelde contynuall and most hertie thanks unto God for His goodness unto us that are born in it, so I wishe all other Englishemen to do, seeing that nombers there be who, puffed up wᵗʰ wealthe, wote not why they whyne. For undoubtedly if the whole worlde were divided into ix partes, as the quarter of the spheare is into nynetie degrees, and that viii of those ix partes shulde be iudged to be evill cuntreys, the ixth parte only remaining good, this realme of Englande must needes be taken into that one good parte for all respects. The heat is never extreame, and the colde seldome fervent, because we are little further than mydde waye between the sunne and the northe. We have grayne of all kindes necessarie, fyshe, fowle, and fleshe, and some fruites. The sea environeth the cuntrey, to serve us both for carieng out of our owne habundance, and also for fetching of strange comodities hither, in such sort as beside the nedeful we wante nothing to serve us for pleasʳᵉ. Our justice cannot be amended if the faulte be not in the ministers. The subiects are the King’s children, and not sklaves, as they be otherwheare. And finally oʳ civilitie is great, and wolde be p’fict if some mennes barbarousenes did not nowe and then corrupt[2] it. So that wᵗhout affection me seemeth, I may by good reason advaunce my cuntrey for goodness to be one of the best p’ts of that ixᵗʰ parte if it shulde be divided againe. For the better proof whereof to thentent it may appeare what barbarouse people are in other regions, what wante of good foode they have, what miserable lyves they leade, what servitude and subiection they endure, what extremities of heate and colde they suffer, what sup’stitions they folowe, and what a nombre of other inconveniences do hange upon them, the least whereof is ferre from us.

I have thought good to translate out of the Italian tonge this litell booke, written by a Venetian of good fame and memorie, who hath travailed many yeres in Tartarie and Persia, and hath had greate experience of those p’tes, as he doth sufficiently declare, which I determined to dedicate unto yoʳ Maᵗⁱᵉ as vnto him that I knowe is most desirouse of all vertuouse knowledge. Trusting to God yoᵘ shall longe lyve and reigne a most happie king over a blessed countrey, most humbly beseeching yoʳ highnes to accept this poore newe yeres gift, being the worke of myne owne hande, as a token of the faithfull love that I am bounde to beare vnto yoᵘ as well naturally as through the speciall goodnesse that I have founde in yoᵘ.

Yoʳ Maᵗˢ most bounden Servant,

Willm. Thomas.

[Here beginne the things that were seene and herde by me, Josaphat Barbaro, citizen of Venice, in twoo voiages that I made thone vnto Tana and thother into Persia.]

Thearthe (as the geometricians by evident reasons do prove) is as little in respect of the firmament, as a pricke made in the middest of the circumference of a circle; whereof by reason that a great parte is either covered wᵗʰ water or else intemperate by excesse of heat or colde, that parte which is inhabited is by a great deale the lesser parte. Nevertheles, so little is the power of man, that fewe have been founde that have seene any good porc̃on of it, and if I be not deceaved, none at all that hath seene the whole. In our time those that have seene some parte most com̄only are merchauntmen or maryners, in which two exercises from the beginneng vnto this daie my Lordes and fathers the Venetians have beene and are so excellent that I believe they may verylie be called the principall. For syns the decaie of the Romaine estate (that sometime ruled over all) this inferior worlde hath been so divided by diversitie of languages, customes and religion, that the greatest parte of this little that is enhabited shulde have been unknowen, if the Venetian merchandise and marinership had not discovered it. Amongst whom, if there be any that have seene ought at this daye, I may reaken myself one: seeing I have spent all my yoʷthe and a great parte of myne age in ferre cuntries, amongst barbarouse people and men wᵗhout civilitie, much different in all things from our customes, wheare I have proved and seene many things that, bicause they be not vsed in our parties, shulde seem fables to them (as who[4] wolde saie) that were never out of Venice. Which in dede hath been the cause that I have not much forced either to write or to talke of that that I have seene.

Neverthelesse, being constrayned through the requeste of them that may com̄ande me, and considering that things which seeme more incredible than these are writen in Plinio Solino, Pomponio Mela, Strabone, Herodoto, Diodoro, Dionisio Halicarnasseo, and others of late as Marco Paulo, Nicolo Conte, our Venetians, and John Mandevile thenglisheman: and by other last of all as Pietro Quirini, Aluise da Mosto, and Ambrogio Contarini, me thought I coulde no lesse do than write the things that I have seene to the honor of God that hath preserved me from infinite dangers and to his contentac̃on that hath required me; the rather for their proffitt that in tyme to com̄e shall happen to travaile into the ꝑties wheare I have beene, and also for the com̄oditie of oʳ noble citie in case the same shulde hereaftre have occasion to sende those waies. Wherfore I shall divide my woʳke into twoo partes. In the first wherof I shall declare my voiage vnto Tana, and in the seconde myne other voiage into Persia, and speake little of the perills and trowbles that I endured, myself.

The yere of oʳ Lorde mccccxxxvi I beganne my voiage towardes Tana, wheare for the most parte I contynewed the space of xvi yeres, and have compassed all those cuntreys as well by sea as by lande not only wᵗʰ diligence, but in maner curiousely.

The plaine cuntrey of Tartarie to one that were in the middest thereof hath on theast the ryver of Ledil, on the west and northwest parte Polonia, on the northe Russia, and on the sowthe partes towards the sea called Mare Maggiore, the regions of Alania, Cumania, and Gazaria. All which places do confyne upon the sea called Tabacche; and to thentent I be the better vnderstanded, I shall declare it partely by the costes of the Sea Maggiore, and partely by[5] Lande to the ryver called Elice, which is within xl miles of Capha: and passing that ryver it goeth towards Moncastro, wheare the notable ryver of Danube renneth. From which place forwardes I woll speake of nothing because those places are familiar and knowen well enough.

The cuntrey of Alania is so called of the people Alani, which in their tonge they call As. These have been Christen men, and were chased awaie and destroied by the Tartares.

In that region are hills, ryvers, and plaines: wheare are to be seene an infinite nombre of little hills forced in signe or steede of sepultures, and on the toppe of everie of them a great stone wᵗʰ an hole: wherein standeth a crosse of one peece made of an other stone.

In one of these little hilles we were ꝑsuaded there shulde be hidden a great treasure. For in the tyme that Mr. Pietro Lando had beene consule at Tana, there came one named Gulbedin from El Cairo, wheare he had learned of a Tartarien woman that in one of these little hylles called Contebe,[1] the Alani had hidden a great treasᵉ. And for proofe thereof the woman had given this man certein tokens as well of the hill as of the grounde. So that this Gulbedin entreprised to make certein holes or pittes like wells into this hill in divers places; and having so contynued the space of twoo yeers he died: whereby it was iudged that only for lacke of habilitie he coulde not bringe this treasure to light. Wherefore vij of us merchant men being togither in Tana on Saint Catherines night the yere 1437, fell in reasoning howe this matter might be brought to passe. The names of those merchants were Francesco Cornaro, brother vnto Jacomo Cornaro of the banke, Catarino Contarini, who afterwards vsed to Constantinople. Giovan Barbarigo sonne vnto Andrea of Candia. Giovan da Valle, that died master of the fooyste in the Lake of Garda, and that with certein other Venetians the yere 1428 went vnto Derbenthe wᵗʰ a[6] fooyste that he had made, and there by appointment of the Lorde of that place, spooyled certein shipps that came from Strana, which was a marveilouse acte. Moises Bon, sonne to Alessandro of Judecca, Bartolomeo Rosso, a Venetian, and owner of the house in Tana that we were in at that tyme, and I the vijᵗʰ. In effect three of this companie having beene at the place before, ꝓsuaded the rest that the thinge was faisible, so that we agreed and bound ourselfs both by othe and by writing, made by Catarino Contarini, the copie whereof I have yet to shewe, to go digge this hill; whereupon the matter being thus concluded, we hired cxx men to go wᵗʰ us for that purpose, vnto whom we gave three ducates a peece for the moonthe. And about viij daies aftre we vij wᵗʰ oʳ cxx men departed from Tana, wᵗʰ stuff, vittaills, weapons, and instruments necessarie, which we caried vpon those zena that they use in Russia, and went vp the ryver on the yse, so that the next daie we arryved at the place, for it standeth neere the ryver, and about lx miles distant from Tana. This little hyll is lᵗⁱᵉ paces high and is plaine above, on which plaine is an other little hill like a round bonett, compassed about wᵗʰ a stone so large that ij men a fronte may walke on the bryme, and this little hill is xii paces high. The hill bylowe was round as if it had been made wᵗʰ a compasse, and was lxxx paces by diameter.

After all things were readie we beganne to cutt and digge on the plaine of this greater hill, which is the beginneng of the little hill, entending to make a large waie to enter into the botome: but the earthe was so harde frozen that neither wᵗʰ mattockes nor yet wᵗʰ pickaxes we coulde well break it. Nevertheles, after that we were a little entred we founde thearthe softer, so that we wrought meetely well that daie. But whan we retoʳned the next morneng we founde thearthe so harde frozen that we were constraigned to forgoo our enterprise, and to retoʳne vnto Tana; determyneng nevertheles to com̄e thither again an other tyme.

About thende of Marche we retoʳned thither by boates and litle vessells wᵗʰ cl men, which beganne to digge of newe. So that in xxij daies we made a waie of lx paces longe, viij paces brode, and x paces high. Nowe shall yoᵘ hear wonders and things almost incredyble.

We founde all things as it had been tolde us before, which putt vs in the more compforte of the rest. So that the hope of finding of this treasure made vs that had hyred the laborers to carie the barowes better than they: and I myself was master of making of the barowes. The great wonder was that first next vnto the grasse thearthe was blacke. Than next vnto that all was coles, but this is possible, for having willowes enough there by, they might easilie make fyre on the hill. Vnder this were asshes a spanne deep—and this is also possible; for having reades there by which they might burne, it was no great matter to make asshes. Then were there rynds of Miglio an other spanne deepe, and bicause it may be said that that they of the cuntrey lyved wᵗʰ bread made of Miglio, and saved the ryndes to bestowe in this place, I wolde faine knowe what proportion of miglio wolde furnishe that quantitie to cover such an hill of so great a breadth wᵗʰ the onlie ryndes thereof for a spanne deepe? Under this an other spanne deepe were skales of fishe as of carpes and such other. And bicause it may be saied that in the ryver there are carpes and other fishe enough whose skales wolde suffise to cover such an hill, I referre it vnto the reader’s iudgment wheather this thinge either be possible or like to be trewe: and yet do I tell it for trewe. And do consider besides that he which caused this sepulture to be made being named Indiabu, mynding to vse all these ceremonies which ꝑchaunce were used in those daies, did thinke on it longe before: and made all these things to be gathered and laied togither by some processe of tyme.[2]

Thus having cutt in and finding hitherto no treasʳᵉ, we determyned to make ij trenches into the great hill of iiij paces in breadeth and height. This doon we founde a white harde earthe into the which we made steppes to carie up the barrowes by. And so being entred v. paces deeper we founde in the botome certein vessels of stone, some of them wᵗʰ asshes, some wᵗʰ coles, some emptie and some full of fishe back bones. We founde also v or vi beadestones as bigge as oranges made of bricke and covered wᵗʰ glasse such as in the marke of Ancona they used to plaie wᵗʰall. We founde also halfe the handle of a little ewer of sylver, made with an adders hedde on the toppe. Finally in the passion week theast winde beganne to blowe so vehemently that it raysed thearthe wᵗʰ the stoanes and cloddes that had been digged and threwe them so in the workemens faces that the blowdde folowed. Wherfore we determined to leave of and to prove no further; which we did on the Easter Monday after.

This place was before called the caves of Gulbedin, but after our digging there it hathe beene called the cave of the Franchi, and is so called vnto this daie. For the worke that we did in those few daies is so great, that it seemeth a m men coulde skarsalie have done it in so shorte a tyme. And yet we had no certaintie of this treasure, but (as we coulde learne), if there be any treasʳᵉ the cause why it shulde be hidde there was that Indiabu Lorde of the Alani hearing that Themꝓoʳ of the Tartares came against hym; for hydeng of his treasure feigned to make his sepulture after their custome, and so conveigheng thither secretlie that which seemed him good, he afterwardes caused this litell hill to be made upon it. The faith of Macomett beganne to take place amonge the Tartariens about an Cᵗʰ yeres past. In dede some of them were Macomettanes before, but everie man was at his libertie to believe what hym best liked; so that some worshipped ymags of woode, and of ragges, which[9] they carried on their carts about with them. The beginneng of Macometts faith was in the tyme of Hedighi capitaigne of the people of Sidahameth Can Emperoʳ of Tartarie. This Hedighi was father vnto Naurus, of whom we shall speake at this present.

There reigned in the champaignes of Tartarie the yere 1438 an emperoʳ called Vlumahumeth Can, that is to saie, the great Macomett emperoʳ, who, having alreadie reigned certein yeres, and being in the champaignes towards Russia wᵗʰ his Lordo[3] (that is to saie, his people), had this Naurus as his capitaigne, sonne vnto Hedighi before named, by whose meanes Tartarie was constreigned to receave the faith of Macomett. Betwene this Naurus and Thempoʳ, there happened such a discorde, that Naurus wᵗʰ such people as wolde folowe him left him, and went towards the river Ledil vnto Chezimameth, that is to say Litle macomett, one of the bloudde of thother emperor, and there agreed wᵗʰ both their forces to go against Vlumahumeth. Wherevpon they tooke their waie by Citerchan into the champaignes of Tumen, and coming about by Circassia they went towards the ryver Tana, and towards the golfe of the sea called Tabacche, which, with the ryver of Tana, were both frozen. And bicause their people was great and their beasts innumerable, therefore it behoved them to go the more at large to thentent they that went before shulde not destroie the grasse, and other such thinges as served for the refresshing of them that came aftre. So that the formost of this people and cattaill were at a place called Palastra whan the hindermost were at a place called Bosagaz (which signifieth grayye woodde), on the river of Tana, the distance between which two places is cxx myles, which space of grounde this foresaid people occupied, though in dede they were not all apt to travaile.

We had newes of their cōmyng iiij moonthes before. But[10] a moneth before this Lordes arryvall there beganne to cōme towardes the Tana certain skowltes, being younge men, iij or iiij on horsebacke, eche of them wᵗʰ a spare horse in hande. Those that came into Tana were called before the consule and well entreated. But whan they were examyned whither they went and what was their busynes, they answered they were yonge men that went about for their passetyme, and more coulde not be had of them. And they never taried passing an howre or twoo, but that they goon againe, and so it contynewed daylie, saving their nombre did somewhat more and more encrease. But whan this Lorde was wᵗhin v or vi ioʳneys of Tana than they begane to come by xxv and lᵗⁱᵉˢ togither, well armed and in good ordre, and as he drewe nearer they encreased by the hundrethes.

At length he came himself, and was lodged in an auncient Moschea, wᵗhin an arrowe shoot of Tana. Incontinently the consule determined to send him presents, and sent him a Nouena, an other to his moother, and an other to Naurus, capitaigne of the armie. Nouena is called a present of nyne divers things, as who wolde saie sylkes, skarlette and other such to the numbre of ix. For such is the maner of presenting the Lordes of those ꝑties. So there was caried vnto hym breade, wyne made of honye, ale and other divers things, to the nombre of ix: and I was appointed to go wᵗʰ all. Being thus entered into the Moschea, we founde the Lorde lyeng on a carpett, leanyng his hedde vnto Naurus, he himself being of the age of xxij, and Naurus xxv. Whan I had presented the things that we brought, I recōmended the towne, wᵗʰ the people, vnto him, and telled him that they were all at his cōmandement: wherevpon he answered wᵗʰ most gentle woordes, and aftre looking towardes me beganne to laughe and to clappe his handes togither, saieng, beholde what a towne is this, wheare as iij men have but iij eyes, which he saied, bicause Buran Taiapietra,[11] our Turcimanno, had but one eye; Zuan Greco, the consules servant, one other eye; and he that caried the wyne of honye likewise but one. And than we tooke oʳ leave, and departed.

And bicause some woll skarse thinke it likely that, as I have saied, the skowltes shulde go by iiij, by x, xx, and xxx, through those plaines x, xv, and sometime xx ioʳneys before the people; constrewing whareof they might lyve. I answere that every of them which so departe from the people carieth wᵗʰ him a bottell, made of a goates skynne, full of meale of the grayne called miglio, made in past wᵗʰ a litle honye, and hath a certain litle dishe of woodde, so that whan he misseth to take any wylde game (whereof there is great store in those champaignes which they can well kyll, specially wᵗʰ their bowes) than taketh he a litle of this meale, and putting a litle water vnto it maketh a certein potion, of the which he feedeth. For whan I have asked some of them what thinge they lyve vpon in the champaigne, they have asked me again, Why do men die for hunger? as who wolde saie, If I may have wherewᵗʰ sleightlie to susteigne the lief, it suffiseth me. And, in dede, they passe their lyves well enough wᵗʰ herbes and rootes and such other as they can gett, so they wante not salte. For, if they lacke salte, their mowthes woll so swell and fester that some of them die thereof: and in that case they cōmonly fall into the fluxe.

But to retoʳne wheare we lefte, whan this Lorde was departed than this people wᵗʰ their cattaill folowed. First, heardes of horses by lx-c.cc, and more in an hearde. Aftre them folowed heardes of camells and oxen, and aftre them heards of small beastes, which endured for the space of vi daies, that as ferre as we might kenne wᵗʰ oʳ eyes the champaigne, every waie was full of people and beasts folowing on their waie. And this was only the first parte; whereby it is to be considered what a much greater nombre shulde be in the myddle parte. We stood on the walles (for we kept[12] the gates shutt), and thevening we were weerie of looking, for the moltitude of these people and beasts was such that the dyameter of the plaine which they occupied seemed a Paganea of cxx myles. This is a Greeke woorde that I learned in Morea, being in a gentleman’s house that brought an c plowemen in wᵗʰ him: every one of them wᵗʰ a staffe in his hande. The maner of this people was, that they went in ordre a rowe, one distant from an other an c paces, strikeng on the arthe wᵗʰ their stafes, and sometime throwing fooʳthe a woʳde to raise the game, for the which the hunters and fawkeners, some on horsebacke and some on foote, wᵗʰ their hawkes and dogges, waited whereas they thought best; and whan their tyme came lett their hawkes flee or their dogges renne, as the game required. And amongest the other game that thei hunted there were ꝑtriches and certain other birdes that we call hethecockes, which are shorttailed like an henne, and holde up their heades like oʳ cockes, being almost as great as pecocks, which they resemble altogether in coloʳ, saving in the tayle. And, by reason that Tana standeth between litle hills and hath many diches for x miles compasse, as ferre as wheare the olde Tana hath beene, therefore a great nombre of these fowle and game fledde amongst those litle hilles and valeys for succoʳ; insomuch that about the walls of Tana and wᵗhin the diches were so many pertriches and hethecockes that all those places seemed rich mennes poultries. The boies of the towne tooke some of them and solde them twoo for an aspre, which is viij baggatims of ours a peece. There was a freere at that tyme in Tana called freere Thermo, of Saint Frauncs order, who (wᵗʰ a birdeng nett, making of ij cereles one great and stickeng it out on a croked poll wᵗhout the walls) tooke x and xx at a tyme, and with the selling of them gate so much mooney as bought him a litell boye, Circasso, which he named Pertriche, and made him a freere: and all the night they of the towne wolde leave their wyndowss[13] open wᵗʰ a certain light in it to allure the fowle to flee vnto it. Sometimes the hartes and other wilde beastes wolde renne into the houses and in such nombres, that almost it is not to be belieued: but that happened not neere vnto Tana.

From the plaine through which this people passed, it did well appeare that their nombre was very great, and so many that at a certain place called Bosagaz, wheare I had a fissheng place about xl miles from Tana, the fisshers telled me that they had fisshed all the wynter, and had salted a great quantitie of Moroni and Cauiari, and that certain of this people cōmyng thither had taken all their fishe, aswell freshe as salte, and all their Cauiari, and all their salte, which was as bigge as that of Sieniza, in such wise that there was not a crome of salte to be founde after they were goon. Thei brake also the pipes and barells, and tooke the barell stafes wᵗʰ them, perchaunce to trym̄e their cartes withall. And further, they brake iij litle mylles there made to grynde salte, only for covetousenes of that litle yron that was in the myddest of them. But that which was doon to me was cōmon to all other. For Zuan da Valle, who had a fisshing there also, hearing of this lordes cōmyng, digged a great diche, and putt therein about xxx barrells of cauiari and to the entent it shulde not be ꝑceaued, when he had covered wᵗʰ earth again, he burned woodde upon it: but it availed not, for they founde it and left not a iote thereof.

This people carie wᵗʰ them innumerable cartes of twoo wheeles higher than ours be, which are closed wᵗʰ mattes made of reades, and ꝓte covered wᵗʰ felte, parte wᵗʰ clothe, if they apꝓteigne vnto men of estimacōn. Some of these cartes carie their houses vpon them which are made on this wise. They take a cercle of tymber, whose dyameter is a pase and an halfe, crossed wᵗhin fooʳthe wᵗʰ other halfe cercles: betwene the which they bestowe their mattes of reade, and than is it covered wᵗʰ felte or cloth, according to the[14] habilitie of the person. So that whan they lodge they take downe these howses to lodge in.

Two daies after that this Lorde was departed, certain of the towne of Tana came vnto me, willing me to go to the walles, wheare one of the Tartares taried to speake wᵗʰ me. I went thither and founde one that tolde me howe Edelmugh, the Lordes brother-in-lawe, was not ferre of, and desired (if I coulde be so contented) to entre vnto the towne and to be my ghest. I asked licence of the consule, which being obteigned, I went to the gate and receaued him in wᵗʰ iij of his companye. For the gates were all this while kept shutt. I had him to my hawse and made him good cheare, specially wᵗʰ wyne, which pleased him so well that he taried twoo daies wᵗʰ me: and being disposed to departe entreated me to go wᵗʰ him, for he was become my brother; and, wheare as he went, I might go saufely; and so spake some what to the merchaunts, whereof there was none there, but that he wondered at it.

So, being determined to go wᵗʰ him, I tooke wᵗʰ me twoo Tartariens of the towne on foote: rode on horsebacke myself, and about the iijᵈᵉ howre of the daie sett forwarde. But he was so dronke that the bloudde ranne out of his nose; and whan I wolde ꝓsuade him not to drynke so much, he wolde make mowes like an ape, saieng, Lette me drynke; whan shall I finde eny more of this?

By the waie, it behoved vs to passe a ryver which was frozen over; and being alighted, I endeavored myself to go wheare the snowe was on the yse. But he who was overcome wᵗʰ wyne, going wheareas his horse ledde him, chaunced on the yse in divers placs wheare no snowe was, by reason whareof the horse was nowe up, nowe downe, aftre which sorte he contynewed the thirde parte of an howre. Finallie, being passed that river, we came to an other water, and passed it, wᵗʰ much a doo, aftre the like maner: so that, being wearied, he rested him wᵗʰ certain of the people that[15] lodged there: wheare we taried all that night, as yll provided, as may be thought. The next morneng we rode fooʳthe, though not so lustylie as we had done the daie before, and when we weare passed an other arme of the foresaid ryver: following the waie that the people travailed (which were over all as a meyny of ants) wᵗhin two daies ioʳney, we approached vnto the place, wheare the Lorde himself was: and there was my conductoʳ much honored of all men, and fleshe, breade and mylke, wᵗʰ other like things given him: so that we wanted no meate. The next daie folowing coveting to see howe this people rode, and what order they obserued in their things, I did see so many wonders, that if I wolde ꝓticulerlie write them, I shoulde make a great volume.

We went to the Lordes lodging, whom we founde vnder a pavilion wᵗʰ innumerable people about him. Of the which those that desired audience kneeled all separate one from an other, and had left their weapons a stones caste off ere they came to their Lorde. Vnto some of them the Lorde spake, and demaunding what they wolde, he alwaies made a signe to them wᵗʰ his hande that they shulde arise. Whereupon they wolde arise, but not approache eight paces more till they kneeled againe: and so neerer and neerer till they had audience.

The justice that is vsed throughout their campe is verie soddaine, aftre this maner: Whan a difference groweth betwene partie and partie, and wordes multiplied (not aftre the maner of oʳ quarters, for these do vse no violence), thei both or moo (if they be moo) arise and go what waie they thinke good: and to the first man of any estimacōn that they meete they saie: Master, do vs right, for we here are in controversie, wherevpon he tarieth and heareth what both ꝑties can saie: determyneng therevpon what he thinketh best wᵗhout further writing, and what so ever he determineth is accepted wᵗhout any contradiction. For vnto these iudgements many[16] ꝓsons assemble, vnto whom he that maketh the determīacōn saieth yoᵘ shal be all witnesses, with which kinde of iudgements the campe is continually occupied. And if any like difference happen by the waie they observe the verie same ordre.

I did see on a daie (being in this Lordo) a treene[4] dishe overwhelmed[5] on thearthe: vnder the which I founde a litle loofe baken: and demaunding of a Tartarien that was by me, What thinge it was, he answered, It was putt there for Hibuch-Peres, that is to wete for the Idolatrers. Why, qᵈ I, are there Idolatrers amongst this people? O, oh, qᵈ he, that there be enough, but they are verie secret.

To nombre the people surely, in my iudgement, it was impossible; but to speake according to myne estimacōn, I believe, vndoubtedly, that in all the Lordo whan they came togither there were not so fewe as ccc thousand ꝑsons. This I saie because Vlu Mahumeth had also parte of the Lordo, as it hath been rehearsed before.

The hablemen are verie valiaunt and hardie, in such wise that some of them for their excellencie are called Tulubagator, which signifieth a valiaunt foole: being a name of no lesse reputacōn amongst them than the sernames of wisedome or beaultie wᵗʰ vs, as Peter, ec., the wiseman, Paule, ec., the goodly man. These haue a certein preemynence that all things they do (though partely it be against reason) are rekened to be well doon: because that proceading of valiauntnes it seemeth to all men that they do as it best becometh them. Wherefore there be many of them that in feates of armes esteeme not their lyves, feare no perill, but stryke on afore to make waie wᵗhout reason: so that the weake harted take cowraige at them and become also very valiaunt. And this sername, to my seemyng, is verie convenient[17] for them: bicause I see none that deserueth the name of a valiaunt man, but he is a foole in dede.[6] For, I pray yoᵘ, is it not a folie in one man to fight against iiij? Is it not a madnes for one wᵗʰ a knyfe to dispose himself to fight against divers that haue sweardes? Wherefore to this purpose I shall write a thinge that happened on a tyme while I was at Tana.

Being one daie in the streate, there came certein Tartariens into the towne, and saied that in a litle woodde not past iii miles of there were about an cᵗʰ horsemen of the Circasses hidden, entending to make a roade even to the towne, as they were wonte to do. At the hearing whereof I happened to be in a fletchers shoppe, wheare also was a Tartarien merchaunt that was cōme thither wᵗʰ semenzina, who, as soone ahe hearde this, rose vp and saied, why go we not to take them? howe many horses be they? I answered, an c. Well, said he, we are five, and howe many horses woll yoᵘ make? I answered, xl. O, qᵈ he, the Circasses are no men, but women: let us go take them. Wherevpon, I went to seeke Mr. Frauncs, and tolde him what this man had saied. And he, alwaies laugheng, folowed me, asking me wheather my hert serued me to go. I answered yea; so that we tooke oʳ horses and ordeyned certein men of ours to come by water. And about noone we assaulted these Circasses, being in the shadowe, and some of them on sleepe, but by mishappe a litle before oʳ arryvall, our trumpett sowned: by reason wheʳof many of them had tyme to eskape. Nevertheles, we killed and tooke about xl of them. But to the purpose of these valiaunt fooles, the best was that this Tartarien wolde needes have had us folowe them still to take them: and seeing no man offer unto it, ranne aftre those that were eskaped himself alone, crieng Noi[18] mahe torna.[7] And about an howre after retoʳned lamenting wonders much that he coulde take never a one of them. Beholde, wheather this were a madnesse or no, for if iiij of them had retoʳned they might haue hewen him to peecs, for the which whan we reproved him, he laughed vs to skorne. The skowtes here before menc̃oned that came before the campe vnto Tana, went alwaies before the campe into viij costes to descrie if there were daungier any waie.

As soone as the Lorde is lodged, incontinently they vnlade their baggaige, leaving large waies betweene their lodgings. If it be in the wynter the beastes are so many that they make wondrefull mooyre: and if it be in som̄er spreading much dust. Incontinently, aftre they haue untrussed their baggaige they make their ovens roste and booyle their fleshe: and dresse it wᵗʰ mylke, butter, and cheese, and most com̄only they are not wᵗhout some venyson, or wilde fleshe, specially redde deere. In this armie are many artisanes, as clothiers, smythes, armorers, and of all other craftes and things that they neede. And if it shulde be demaunded wheather they go, like the Egiptians oʳ no?[8] I answer, no. For (saving that they are not walled about) they seeme verie great and faire cities. And to this purpose, as I retoʳned on a tyme to Tana, on the gate whereof was a very faire towre, I saied vnto a Tartarien marchānt that was in my companie: who earnestly behelde this towre, howe thinkest thoᵘ, is not this a faire thinge? But he, smiling, againe answered, he that is afearde buyldeth towres: wherein me seemeth he said trewly.

And because I have spoken of merchaunt men, retoʳneng to my purpose of the armie, I saie there be alwaies merchauntes which carie their wares divers waies though they passe wᵗʰ the Lordo, entending to go otherwheare. These[19] Tartariens are good fawkeners, have many jerfaulcones, and their flight is much to the Cammeleons, which is not vsed wᵗʰ vs.[9] They hunte the harte and other great beastes also. These hawkes they carie on their fistes, and in the other hande they haue a crowche:[10] which, whan they be weerie, they leane their hande vpon. For one of these hawkes is twise as bigge as an egle. Sometimes there passeth over the armie a flocke of gheese, to the which some of the campe shoote certein croked arrowes vnfeathered, which, in the ascending, hurle abowt breaking all that is in their waie, neckes, leggs, and whinges: and sometyme there passe so many that it seemeth the ayre is full of them: and than do the people showte and crie wᵗʰ so extreame a noyse, that the gheese astonied wᵗhall do fall downe. And bicause I am entered into talking of byrdes, I shall here rehearse one thinge that I thinke notable. Rideng through this Lordo, on the banke of a litle ryver, I founde a man that seemed of reputacōn talking wᵗʰ his serūnt, who called me vnto him and made me alight, demaunding of me wheareabouts I went. I answered as the case required, wherevpon, looking aside, I ꝑceaued beside him iiij or v tesells:[11] on the which were certein lynettes; he furthew cōmaunded one of his serūnts to take one of those lynetts: who tooke two threades of his horsetayle, made a snare which he putt on the tasells, and streight waie tooke a lynett, which he brought to his master, who furthwᵗʰ did bidde hym dresse it: so that the serūnt tooke him, quickely pulled him, made a broche of woode, rosted him and retoʳned wᵗhall vnto his mʳ, who tooke it in his hande, and beholding me, said: I am not nowe,[20] whereas I may shewe the that honoʳ and courtesie that thoᵘ mearitest, but of such as I haue that God hath sent me we wolde make mearie; and so tooke the linett in his hande, brake it in three partes, gave me one, eate an other himself: and the iijᵈᵉ, which was verie litle, he gave vnto him that tooke it. What shall I saie of the great and innumerable moltitude of beastes that are in this Lordo? Shall I be believed? But, be as it be may, I haue determyned to tell it. And, beginneng at the horses, I saie there be many horsecorsers which take horses out of the Lordo and carie them into divers places: for there was one Carauana that came into Persia er I deꝑted thense, which brought iiij thousand of them; whereof ye neede not to mervaile, for if yoᵘ were disposed in one daie to bie a thousande or ijᵐˡ horses yoᵘ shulde finde them to sell in this Lordo, for they go in heardes like sheepe, and as they go, if you saie to the owner I woll haue an cᵗʰ of these horses he hath a staffe wᵗʰ a coller on thende of it, and is so connyng in that feate that it is no sooner spoken, but he hath streight cast the coller about the horse necke, and drawen him out of the hearde: and so by one and one which he lyst, and as many as yoʷ bidde him. I have divers tymes mett these horsecorsers on the waie wᵗʰ such a nombre of horses as haue covered the champaigne, that it seemed a wonder. The countrey breedeth not verie good horses, for they be litell, haue great bealies, and eate no provander: and whan thei be brought into Persia the greatest praise yoᵘ can give them is, that they woll eate provander: wᵗhout the which they woll not endure any laboʳ to the purpose. The seconde sorte of their beastes is oxen, which are verie faire and great, and such a nombre wᵗʰall, that they serve the shambles of Italie, being sent by the waie of Polonia, and some throwgh Valacchia into Transilvania, and so into Allemaigne, from whense they are brought into Italie. The thirde sorte of beasts that they have are camells of twoo bonches, great and rowghe, which[21] they carie into Persia, and there sell them for xxv ducats a peece: whereas they of theast haue but one bonche, are litle, and be solde for x ducats a peece. Their iiijᵗʰ kinde of beasts are sheepe, which be unreasonable great, longe legged, longe woll, and great tayles, that waie about xijˡ a peece. And some such I haue seene as haue drawen a wheele aftre them, their tailes being holden vp. Whan for a pleasʳᵉ they haue been put to it, with the fatt of which tayles they dresse all their meates and serueth them in steede of butter, for it is not clammye in the mowthe.

I wote not who wolde verifie this, that I shall saie nowe[12] if he haue not seene it. For it may well be demaunded whereof shulde so great a nombre of people lyve travaileng thus every daie! wheare is the coʳne they eate? wheare do they gett it? To the which, I that haue seene it, do answere on this wise. About the mooneth of Februarie they make proclamac̃ons throughout the Lordo, that he which woll sowe shall prepare his things necessarie against the mooneth of Marche, to sowe in such a place. And such a daie of that mooneth they must take their waie thitherwards. This doon, they that are mynded to sowe prepare themselfs, and being agreed togither, lading their seede on cartes[13] wᵗʰ such cattaill as their busynes require, togither wᵗʰ their wiefs and children or parte of them they go to the place appointed, which most cōmonly passeth not ij ioʳneys from the place of the Lordo wheare the crie is made. And there do they eare, sowe, and tarie, till they haue furnisshed that they came for, which doon they retoʳne to their Lordo.

Thempoʳ, wᵗʰ the Lordo, doth this meane while, as the mother is wonte to do wᵗʰ her children. For whan she letteth them go plaie she ever keepeth her eye on them, and[22] so doth he never departe from these plowemen iiij ioʳneys, but compasseth about them nowe here, nowe there, till the corne be rype, and yet when it is ripe he goeth not thither wᵗʰ his Lordo, but sendeth those that sowed it and those that mynded to bye of it wᵗʰ their cartes, oxen, and camells, and those other things that they need; even as they do at their village.

Thearthe is fertile, and bringeth fooʳthe lᵗⁱᵉ busshells wheate for one of seede: and their busshell is as great as the Padouane. And of Miglio they haue an c for one; and sometimes thei haue so great plentie that they leaue no small quantitie in the feelde. To this purpose I shall tell yoᵘ, There was a sonnes sonne of Vlumahumeth, who, having ruled certein years, fearing his cousyn Cormayn that dwelled on the other side of the ryver of Ledil, to thentent he wolde not loose such a parte of his people as must haue goon to this tyllaige, which they coulde not haue doon wᵗhout their manifest perill, he wolde not suffer them to sowe in the space of xj yeres. All which tyme they lyved of fleshe, mylke, and other things. Nevertheles, they had alwaies in their tavernes a little meale and panico: but that was verie deere. And whan I asked them howe they did, they wolde answer that they had fleshe; and yet, for all that, he at leingth was driven awaie by his said cousin. Finallie, Vlumahumeth, of whom we spoke afore, whan Zimahumeth was arryved neere vnto his confines, seeing himself unhable to resist, lefte his Lordo and fledde wᵗʰ his children and others, by reason whereof Zimahumeth became emperoʳ of all the people: and went to wards the ryver of Tana in the mooneth of June, and passed the same about ij daies ioʳney above Tana wᵗʰ all that nombre of people, their cartes, and cattaill: a mervailouse thinge to believe, but more wonderfull to beholde. For they passed all wᵗhout any rumoʳ, and as saufe as if they had goon by lande. Their maner of passaige is this. They that are of the most substanciall sende of their folkes afore, who make[23] certein zattere[14] of drie woode, whereof there is plentie alonge the ryver. They also make certein bondells of softe reades, which they putt vnder their zattere and vnder their cartes, and so tye the same to their horses, who swymeng over the ryver (guyded by certein naked men) passe the hole companie aftre this maner. About a mooneth aftre, rowing vp the water towarde a certein fissheng place, I mett wᵗʰ so many zatteres and bondells comyng downe the water (which this people had lett go), that we coulde skarselie passe, and besids that I did see so many zatteres and bondells on the banks, that it made me to wonder. And whan we arrived at the fissheng place we founde that these had doon much woʳse there than those that I haue writen of before. And bicause I woll not forget my freends yoᵘ shall vnderstande that Edelmulgh, the empoʳˢ brother in lawe before named, came unto Tana, and his sonne wᵗʰ him, and soddainelie embraced me, saieng, here I haue brought the my sonne, and incontinently tooke a cassacke from his sonnes backe and putt it vpon me, wherewᵗʰ he gave me also viij sklaves of the nation of Rossia, saieng, this is parte of the praye that I haue taken in Rossia. In recompence whereof I presented him wᵗʰ convenient things again, and so he taried wᵗʰ me ij daies. Some there be that, departing from others, thinking never to meete again, do easylie forgett their amitie, and so vse not those curtesies that they ought to vse: wherein, by that litle experience that I haue had, me seemeth they do not well. For, as the saieng is, mountaignes shall never meate, but men may. In my retoʳneng out of Persia wᵗʰ the Ambassadoʳ of Assambei,[15] willing to passe through Tartarie, and so through Polonia to cōme to Venice (though at that time I went not through that waie), it chaunced me to be in companie of divers Tartarien merchaunts of whom I enquired[24] for this Edelmulg, and learned by signes of the phisonomie, and by the name, that he which was given me by the father, as those Tartariens than telled me, was great wᵗʰ thempoʳ. So that if we had goon further we must needes haue fallen into his handes. In which cace I am assured I shulde haue had no lesse good cheere of him, than as I haue made both to him and his father, but who wolde haue belieued that xxxvᵗⁱᵉ yeres aftre in so ferre distant cuntreys a Tartarien shulde haue mett wᵗʰ a Venetian? An other thinge I woll rehearse even to the same purpose. The yere 1455, being in a vinteners seller in the Rialto, as I ꝑvsed the seller in thone end of the same, I ꝑceaued twoo men tyed in chaynes, which, by their countenaunce, me thought shulde be Tartariens. I asked who they were, and they answered that they had been sklaves of the Catelaines, and that, fleing awaie, in a litle bote, they were taken by this vyntener, wherevpon I went incontinently to the Signori di Notte, and declared this matter, who by and by sent officers thither, brought them to the coʳte, and in the vinteners presence delivered them, putteng him to his fyne. Thus I gate them loosed, and had them home to my house, and askeng them what they were and of what cuntrey; thone of them answered, he was of Tana, and had been serunt to Cazadahuch, whom I had knowen well, for he was thempoʳˢ customer over all things that came vnto Tana; so that, regarding him more advisedly, me seemed to remembre his face, for he had been many tymes in my house. I asked him what was his name. He answered, Chebechzi, which signifieth a bulter of meale. And whan I had well behelde him, I saied vnto him, doest thoᵘ knowe me? He answered, no. But, as soone as I mentioned Tana and Jusuph (for so they called me there), he fell to thearthe, and wolde haue kissed my feete: saieng vnto me, thoʷ hast saved my lief twies, and this is thone of them, for being a sklave I rekened myself deade, and thother was whan Tana was on fyre,[25] thoʷ madest an hole in the wall, through the which so many creatures escaped, amongest whom was I and my mʳ both. And it is true, for whan Tana was sett on fyre, I made an hole in the wall forneagaint a certein grounde wheare many persons were assembled: through the which there issued aboue xl, and amongest them this felowe and Cazadahuch. I kept these twoo Tartariens in my house about twoo moonethes, and when the shippes departed towardes Tana I sent them home. Wherefore, I saie that departeng one from an other, wᵗʰ opinion never to retoʳne into those ꝑties againe, no man ought to forgett his amitie as though they shuld never meete, for there may happen a thousande things that, if they chaunce to meete againe, he that is most hable shall haue neede of his succoʳ that can do least. Nowe, to retoʳne vnto the things of Tana. I woll describe it by the west and northwest, costing the sea of Tabacche to the going fooʳthe on the lefte hande, and aftre some parte of the sea called Maggiore, even to the Province named Mengleria. Departing than from Tana about the foresaid coste of the sea, iij joʳneys wᵗhin lande, I founde a region called Chremuch, the lorde whereof is named Biberdi, which signifieth given to God; he was sonne vnto Chertibei, that signifieth twelve Lorde. He hath many villaiges vnder him, which at a neede woll make a thousand horses, faire champaignes, many good woodes, and ryvers plentie. The principall men of this region lyve by robbing on those plaines and speciallie on the roberie of the carouanes that go from place to place. They are well horsed, valiaunt men, and subtill witted, but not verie gryme of visaige. They haue corne enough, fleshe, and honye, but no wyne. Beyonde these are cuntreys of divers languages, though not much different one from an other; that is to witt, Elipehe, Tatarcosia, Sobai, Cheuerthei,[16] As Alani, of whom I haue spoken here before. And these renne alongest even vnto Mengleria[17] for the space[26] of xij ioʳneys. Mengleria confyneth wᵗʰ Caitacchi, which are neere the mountaigne Caspio, and wᵗʰ parte of Giorgiana, and wᵗʰ the sea Maggiore, and wᵗʰ the mountaigne that passeth through Circassia, and hath on thone side a ryver called Phaso that compasseth it and falleth into the sea Maggiore. The Lorde of this province, named Bendian, hath two walled townes on the foresaid sea, one called Vathi and an other Seuastopoli, and besides that divers other piles and stronge houses. The cuntrey is all stonie and barayn, wᵗhout any kinde of grayne, saving panico. Salte is brought vnto them out of Capha. They make a litle cloth, but it is both course and naught: and they arr beastly people. For proof whereof, being in Vathi (where one Azolin Squarciafigo, a Genowaie, arryved in companie of a Paranderia of Turks that went thither wᵗʰ us from Constantinople), there was a yonge woman stode in her doore vnto whom this Genowaie saied Surina patro ni cocon? which is, mistres is the good man wᵗhin? meaneng her husbande. She answered, Archilimisi, that is to witt, he woll cōme anon. Whereupon he swapped her on the lippes and shewed her vnto me, saieng, beholde what faire teethe she hath: and so shewed me her breast and toouched her teates, which she suffered wᵗhout moving. Afterwardes, we entred into her house, and sate us downe, and this Azolin fayneng to haue vermyn about him beckened on her to searche him: which she did verie diligentlie and chastely. This, meane while, the good man came in, and my companion put his hande in his purse, and saied Patron tetari sica, which is as much to saie as, mʳ, hast thoʷ any mooney? Wherevnto he made a countenaunce that he had none about him: and so he tooke him a fewe aspres, wᵗʰ the wᶜh he went streight to bye some vittaills. Within a while after, we went through the towne to sporte vs, and this Genowaie did every wheare after the maner of that cuntrey what pleased him wᵗhout reproche of any man, whereby it may appeare weather they be beastly people or[27] no, and therefore the Genowaies that practise in those ꝑties vse for a proverbe to saie, Thoʷ art a Mongrello, whan they arr disposed to saie thoᵘ art a foole. And nowe, bicause I haue saied that Tartari signifieth mooney, I haue thought good to declare that Tetari properlie signifieth white, and by this they understande syluer mooney, which is white, for the Greeks also call it aspri, wᶜh signifieth white, the Turkes Akcia, which signifieth white and in Venice in tyme past, and yet to this present we haue mooney called Bianchi, in Spaigne also they haue mooney called Bianche. Whereby it may appeare howe many nacōns agree in their languaige to call one thinge by one maner of name.

Retoʳning backe to the Tana, I do passe the ryver wheare Alama was, as I haue saied before, and so discurre by the sea of Tabacche, on the right hande, going fooʳthe even to the Isle of Capha, wheare is a straict of the lande that knitteth the Ile wᵗʰ the mayne lande, liek vnto that of Morea, which is called Zuchala. There are verie great salt springes, that of itself being dried woll become ꝓficte salte. Costeng this ilande, first on the sea Tabacche is the cuntrey named Cumania, of the people Cumani. After that is the hedde of the isle wheare Capha standeth, in the same place wheare Gazzaria hath been. And yet to this daie the Pico, that is to saie, the yarde wherewᵗʰ they measure at Tana, and in all those ꝑties is called Pico de Gazzaria. The champaigne of this Ile of Capha is vnder the Tartariens domynion, who haue a Lorde called Vlubi, sonne of Azicharei. They are a good nombre of people hable at a neede to make iij or iiijᵐᵗ horses; they haue twoo places walled, but not stronge, thone whereof is called Sorgathi, which they also called Incremin, that signifieth a forteresse; and thother Cherchiarde, which signifieth xl placs. In this ilande, first at the mowthe of the sea Tabacche, is a place called Cherz, which we call Bosphoro Cimerio; next to that is Capha, Saldaia, Grasui, Cymbalo, Sarsona, and Calamita. All at[28] this present vnder the great Turke, of the which I neede to saie no more, bicause they are knowen well enough. And yet me thinketh it necessarie to declare the losse of Capha, as I learned it of one Antony da Guasco, a Genowaie, who was present there, and fledde by sea into Giorgiana, and from thense into Persia, the same tyme that I happened to be there, to thentent it may be knowen aftre what maner this place is fallen into the Turks hands. In that tyme there was a Tartarien Lorde in the Champaigne named Emimachbi, who had yerely of them of Capha a certein tribute as the custome of the cuntrey there is. Betweene him and them of Capha there happened variaunce, insomuch that the Consule of Capha, being a Genowaie, determined to sende vnto thempoʳ of Tartarie for some one of the bloudde of this Eminachbi, by whose favoʳ he thought it possible to expell Eminachbi out of his astate. And having therevpon sent a shippe vnto Tana wᵗʰ an ambassadoʳ, this ambassadoʳ went into the Lordo and there obteigned of thempoʳ one of the bloudde of this Eminachby, named Menglieri, promiseng to conduct him to Capha, and that if the towne wolde not accept this appointement than to sende Menglieri backe again. Eminachbi, mistrusteng this matter, sent an ambassadoʳ vnto Ottomanno, promiseng him that if he wolde sende an armie by sea to assaulte the towne he would assault it by lande, and so shulde Capha be the Turkes. Ottomanno being desirouse thereof sent his armie, and in shorte space gate the towne, in the which Menglieri was taken, and sent to Ottoman̄o, who kept him in prison many yeres. Not longe after Eminachbi, through the Turks yll conversac̃on, repenting him of giveng the towne to Ottomanno, prohibited the passaige of all vittailles into the towne, by reason whereof they had so great skarsetie of corne and fleshe that they rekened themselfs in maner besieged. Wherevpon the Turke was ꝓsuaded that if he sent Menglieri to Capha, keeping him wᵗhin the towne in curteise[29] warde, the towne shulde haue plentie: for Menglieri was welbeloued of the people wᵗhout. And so Ottomanno did; so that, as soone as it was knowen that he was arrived, incontinently the towne had plentie of all things, for he was also beloued of the townesmen. This man thus remaineng in curteise warde went wheare he wolde wᵗhin the towne; and one daie amongest other, there happened a game of shooting for a prise. The maner wheʳof is, they honge on certein polles sett vp like a galowes, a boll of sylver tied only wᵗʰ a fyne threede. Those nowe that shall shoote for the prise shoote thereat wᵗʰ forked arrowes and arr on horsebaike, and first must gallopp vnder the gallowes, so that being in his full carier passed a certein space, he turneth his bodie and shooteth backewarde, the horse galoping still awaywarde, and he that after this sorte cutteth the threede wynneth the game. Menglieri, findeng occasion vpon this to escape, appointed an c horsemen (wᵗʰ whom he had intelligence before) to hide themselfs the same daie in a litell valey not ferre from the towne, and fayneng to renne for the game he made awaie to his companie; wherevpon the force of all the whole iland folowed him: by reason whereof, he being waxed stronge, went to Surgathi, a towne vi miles from Capha, and took it, and so having slayne Eminachbi, made himself Lorde of all those places. The yere folowing he determined to go towards Citerchan,[18] a place xvi ioʳneys distant from Capha, vnder the domynion of one Mordassa[19] Can, who in that tyme was wᵗʰ his Lordo vpon the ryver of Ledil. He fought wᵗʰ him, tooke him and tooke his people from him: a great parte whereof he sent into the Ile of Capha, and so aboade the wynter on that ryver. At which tyme, by chaunce, there was an other Tartarien Lorde lodged a fewe ioʳneys of, who, hearing that he wyntered there, whan the ryver was frozen came on him soddainely, assaulted him, and discompfited[30] him, and so recovered Mordassa that had been kept prisoner. Menglieri being thus discompfited, retoʳned vnto Capha in yll ordre. And Mordassa, wᵗʰ his Lordo, came the next springe even to Capha, and made certein roades to the dammaige of the ilande. But, seing he coulde not haue the towne yelden vnto him, he toʳned backe. Nevertheles, I was enformed that he was making of a newe armye to com̄e againe into the ilande and to chace Menglieri awaie, as it proved after in dede; but hereof sprange a false rumoʳ, through thignorance of them that vnderstande not whereof the warre amongest these Lordes proceadeth, not knowing what difference is betwene the great Can and Mordassa Can. For they, hearing that Mordassa Can made a newe armie to retoʳne vnto the ilande, bruted that the great Can shulde come by Capha, awaie against Ottomanno, purposeng by the waie of Moncastro to entre into Valachia, into Hungarie; and so, wheareas Ottomanno was behinde the ilande of Capha, which standeth on the sea Maggiore is Gothia, and aftre that Alania, which goeth by the ilande towardes Moncastro, as I have saied before.

The Gothes speake dowche, which I knowe by a dowcheman, my serūnt, that was wᵗʰ me there: for they vnderstode one an other well enough, as we vnderstande a furlane[20] or a florentine.

Of this neighboʳhode of the Gothes and Alani, I suppose the name of Gotitalani to be deryved, for Alani were first in this place. But than came the Gothes and conquered these cuntreys, myngleng their name wᵗʰ the Alani, and so being myngled togither called themselfs Gotitalani, who, in effect, folowe all the Greekish fac̃ons, and so also do the Circassi.

And bicause we haue spoken of Tumen and Cithercan, thinking good to write the things there woʳthie of memorie, we saie that going from Tumen east northeast about vij[31] ioʳneys, is the ryver Ledil, whereon standeth Cithercan, which at this p’nt is but a litle towne in maner destroied; albeit, that in tyme passed it hath been great and of great fame. For, before it was destroied by Tamerlano, the spices and silke that passe nowe through Soria came to Cithercan, and from thense to Tana, wheare vj or vij galeys only were wonte to be sent from Venice to fetche those spices and silkes from Tana; so that, at that tyme, neither the Venetians nor yet any other nacion on this side of the sea costes, vsed merchaundise into Soria. The ryver Ledil is great and large, and falleth into the Sea of Bachu about xxvᵗⁱᵉ myles distant from Cithercan, and as well in that ryver as in the sea arr innumerable fisshes taken.

That sea yeldeth much salte, and yoʷ may saile vp that ryver by ioʳneys almost as ferre as Musco, a towne of Rossia. And they of Musco come yerely wᵗʰ their boates to Cithercan for salte. There arr many ilandes and woodes on this ryver, some of which ilandes conteigne xxx myles in cōpasse. In these woodes arr great trees growing, which, being made holowe, serue for boates of one peece, so bigge that thei woll carie viij or x horses at a tyme and as many men. Passing this ryver and going east northeast towards Musco, keeping the rivers side xv ioʳneys continuallie, arr innumerable people of the Tartariens, but toʳneng plaine northeast yoʷ arryve at the confines of Rossia, at a litle towne called Risan, which appertaigneth to a brother in lawe of John Duke of Rossia, and there they be all Christians aftre the ryte of the Greekes. This countrey is verie fertyle of corne, fleshe, honye, and divers other things: and their drynke is called Bossa,[21] which signifieth ale. There arr also many woodes and villages, and so passing a litle further yoʷ com̄e to a citie called Colona. The one and other of both which townes arr fortified wᵗʰ woodde, whereof also they buylde their houses, bicause there is small quantitie of stone to be[32] founde thereabouts. Three ioʳneys from thense is the said towne of Musco, wheare the forenamed John Duke of Rossia dwelleth, throwgh the middest of which towne renneth the most noble ryver of Musco, and hath certein bridge over it: and, as I believe, the towne tooke his name of the ryver. The castell is on a litell hyll environed about wᵗʰ woodes. The habundance that they haue of corne and fleshe may well be cōmprehended by this, that they sell not their fleshe by weight, but by the eye; and surely they have iiijˡ for a marchetto. Yoʷ shall haue lxx hennes for a ducat, and a goose for iij marchetti. But the colde is so fervent in that cuntrey that the ryvers are frozen. In the wynter arr brought thither hogges, oxen, and other beastes, readie flayne, and sett vpright on foote as harde as stones, and in such nombre that he who wolde bye twoo hundred in a daie may haue them there. But they woll not be cutt, for they arr harde as marble till they be brought into the stufes. As for fruictes, they haue none, saving a fewe apples and nuttes and litle wylde nuttes.

Whan thay be disposed to travaile, specially any longe ioʳneys, they go in the wynter, for than is it frozen over all: and by reason thereof good travaileng, saving that it is colde, and than do they carie what they lyst with great ease vpon those sani which serue them as cartes serue vs and oʳ parties, we call them Tranoli. But in the som̄er they darr not in maner go fooʳthe of their doores, for the vnreasonable mooyre and moltitude of stingeng flies which com̄e fooʳthe of so many great woodes as they haue about them: the greatest parte whereof is vnhabitable. They haue no grapes, but make them wyne of honye, and some make ale of miglio, in thone and other whereof they putt hoppes, which giveth a taste that maketh a man as doonye[22] or dronken as the wyne.

Furthermore, me seemeth it not convenient to forgett the provisions that their foresaid duke made to brydle such[33] dronkardes, as throʷgh their dronkenesse neglected the woʳking and doing of many things which shulde haue been proffitable for them. He made a crye that they shulde make neither ale nor wyne of honye, nor use hoppes in any thinge, and by this meane hath reduced them to good lyving, which hath contynued nowe for the space of xxvᵗⁱᵉ yeres. In tyme passed[23] the Rossians paied trybute to Themꝓoʳ of Tartarie, but nowe they haue subdued a towne called Cassan (which, in oʳ tonge, signifieth a cawldron[24]), that standeth on the ryver Ledil, on the lefte hande as yoʷ go towards the Sea of Bachu, v ioʳneys from Musco. This is a towne of great merchaundise. From whense cometh the most parte of the furres that are caried to Musco and into Polonia, Prusia, and Flandres, which furres come out of the Northe and Northeast, from the regions of Zagatai and Moxia, northerne cuntreys enhabited by Tartariens, that for the most parte arr idolatrers; and so also be the Moxii. And bicause I haue had some experience of the things of the Moxii, therefore I entende to speake somewhat of their faith and maners, as I haue learned.

At a certein tyme of the yere they vse to take a horse: which they laie alonge on the plaine. His iiij feete bounden to iiij stakes, and his heade to an other. This doon, cometh one wᵗʰ bowe and arrowes; and, standing a convenient distance of, shooteth towardes the hert so often, till he haue killed him. And whan the horse is thus deade they flaye him and make a bottell of his hide, vsing with the fleshe certein ceremonies: which, nevertheles, they eate at leingth. Than they stufe the hyde so full of strawe, that it seemeth hole again; and in every of his legges putt a pece of woodde; and so sett him afoote againe, as though he were on lyve. Finally, they go to a great tree and thereof cutt such a boowe as they thinke best, and thereof make a skaffolde[34] whereon they sett this horse standing, and so woʳship him. Offering sables, armelynes,[25] menyver,[26] martrons, and foxes, which they hange on the same tree, even as we offer up candells. By reason whereof the trees there are full of such furres. This people, for the more parte, lyve of fleshe, and the greatest parte thereof wilde fleshe: and fishe they haue also in those ryvers. Nowe that I haue spoken of the Moxij I haue no more to saie of the Tartariens, saving that those which be Idolatrers worship Images that they carie on their cartes, though some there be that vse daylie to woʳship that beast that they happen first to meete whan they go fooʳthe of their doores. The duke also hath subdued Novgroth, which in oʳ tonge signifieth ix[27] castells, and is a verie great towne, eight ioʳneys distāt from Musco, northweast: which before tyme, was governed by the people; being men wᵗhout reason and full of heresies. Nevertheles, by litle and litle they arr nowe brought to the Catholike faith. For some belieue in dede, and some belieue not; but they lyve nowe wᵗʰ reason and haue justice mynistred amongst them.