Title: Christina and the boys

Author: Amy Le Feuvre

Illustrator: Gordon Browne

Release date: February 10, 2025 [eBook #75332]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1906

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

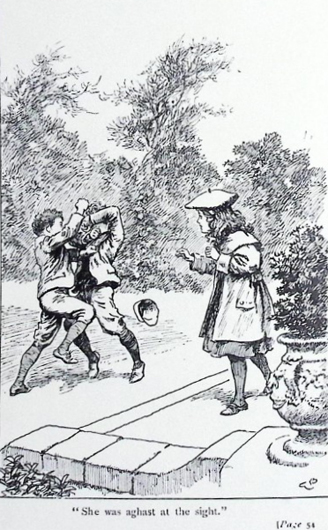

"She was aghast at the sight."

By

AMY LE FEUVRE

Author of "Two Tramps," "Probable Sons," etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY GORDON BROWNE

HODDER AND STOUGHTON

PUBLISHERS LONDON

Printed in 1906

Butler and Tanner, The Selwood Printing Works, Frome, and London

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I. "AND IT MIGHT HAVE BEEN ME!"

CHAPTER II. "FEAR DWELLS NOT HERE"

CHAPTER III. "THEY SAY I'M CODDLING YOU!"

CHAPTER IV. "THE UNITED KINGDOM"

CHAPTER VI. "DEFYING THE HUNT"

CHAPTER VIII. "I WAS MADE RICH TO HELP THE POOR"

CHAPTER X. "HOW COULD I HELP GOING?"

CHAPTER XIII. MISS BERTHA'S BONNET

CHAPTER XIV. "MY DAD IS GOING TO DIE"

CHAPTER XVI. "IT IS ONLY THE SELFISH WHO ARE COWARDS"

CHRISTINA AND THE

BOYS

"AND IT MIGHT HAVE BEEN ME!"

"AND it might have been me!"

Christina's eyes were big with horror as she clasped her tiny hands round her knees, and stared into the fire in front of her.

She was in her father's library: a large dimly-lighted room with books lining the shelves on the walls from top to bottom. It was an afternoon in early autumn; the last rays of the setting sun were stealing in through a stained glass window and colouring the dingy writing-table with red and blue patches. It was a silent, unused room; but it seemed as if it wanted wise spectacled scholars in it, and not a small pale-faced child in a short frock and white frilled pinafore.

Yet she looked as if she were quite at home there, and indeed she was. The library was her ideal of bliss.

Christina's father had been abroad since her mother's death, which took place when she was born. She had been brought up entirely by her old nurse, and though Bracken Towers held innumerable rooms of every sort and size, Christina had been limited to her two nurseries. She lived in them entirely and it was only during the last year that she had made acquaintance with the library.

Mrs. Hallam, the housekeeper, had always seemed to Christina to be the real owner of the house. She was a tall, severe-looking woman, with sharp eyes, and a still sharper tongue. Nurse was the only privileged person who drank tea with her in her private sitting-room. Christina was never allowed in there. Mrs. Hallam made no secret of her dislike to children.

"They either are so forward and unmanageable that they'll be upsetting and spoiling all one's personal possessions, or else they'll sit by as dumb as a dog, and take in all you'll be remarking and repeat it to the first person they come across."

This was her verdict when Nurse one day wanted Christina to accompany her to tea, and she had never tried to take her again.

It was a happy day when Christina found herself in the library. It was the only room that nearly always had a fire, and she had been passing the door when the housemaid was going in to light it.

"Is this Mrs. Hallam's room?" asked the child innocently.

And Emily, the housemaid, had laughed at her.

"Come in and see it. 'Tis your father's wish that it should always be kept well aired. He does set store on his books so! Mr. Tipton says 'tis most vallyble library, and 'tis to keep the books from getting damp we have so many fires."

So Christina had stolen shyly in, and looked with awe and wonder at the treasures it contained. And then from awe she passed to wistful longing, and when Nurse one day said lightly, "If you're a good girl and put every book back where you find it, you can read them," she had joyfully taken advantage of this permission, and had made the library her retreat whenever Nurse was "called away on business" from the nursery.

The books in the library proved an inexhaustible pleasure to the little maiden. There were old books and new books; books with pictures, books without. An illustrated series of Froissart's "Chronicles" kept her entranced for two months, and now, on this particular day, she had seized an old "History of France" and had been following, with breathless interest, the fortunes and fate of Jeanne d'Arc.

She shut her book up with a little shiver when she read of the heroine's shameful death. And there, upon the hearthrug, she was doing what she always did after reading about any heroine of fiction: transferring herself—Christina, aged eight—into the circumstances and position of the heroine.

"And it might have been me!"

Christina had a very big conception of what ought to be done, and a very tremulous and small opinion of her own courage.

Slaughter of any kind was abhorrent to her. The death of a fly on a window pane, a mouse in a trap, or a bird in the garden, was the occasion for a flood of tears and much lamentation. Now she murmured to herself:

"If I had heard the voice, I should have had to get a sword and go; I should have been obliged to lead the soldiers into battle and kill; I should have been wicked if I had said no; and oh, I couldn't, couldn't have done it! And it might have been me!"

Tears began to crowd into her eyes. She shook her curly head, and unclasping her hands, she knelt on the rug, and with closed eyes put up this passionate prayer:

"Please God, never send a voice to me to tell me to fight in battle. I shall be a coward, I shan't be able to do it. O God, never tell me to kill anybody! And oh, please, never turn me into a Joan of Arc!"

After which prayer she dried her eyes and was slightly comforted.

She did not turn again to her book. The tragic fate of the maid of France was too vivid and real to be easily effaced. It was almost a relief when she heard her nurse call her. She trotted upstairs and met her at the nursery door. That good woman had a perturbed look on her round good-tempered face.

"Come in, Miss Tina, and hear what I've got to tell you. Me and Mrs. Hallam have both been struck down by a letter—such news, and so little time to prepare; but we have had rumours, and I always said the master would never come home again till he got a lady to come with him. 'Tis eight years this coming Christmas that your sweet mother was taken, and 'tis not to be wondered at. And now you'll have to prepare yourself to meet your father and a stepmother all at once, and that not a day later than next Saturday. There will be change here at last. Me and Mrs. Hallam have lived so quiet that it has quite upset us; but 'tis only natural and right after all, and I'm not the kind of ignorant, uneducated person to be speaking to you against a second mother. She may be the very one to slip into your mother's shoes, and she may not, but we'll hope for the best."

Christina looked up at her nurse with big eyes.

"I don't understand," she murmured. "Is father coming home?"

"Yes, and he's bringing a new wife, and a room has got to be prepared for a young gentleman; but who or what he is, me and Mrs. Hallam can't make out. Now you be a good girl and stay quiet up here, for I've promised to help Mrs. Hallam in unpacking some of the glass and china, and getting the drawing-room put to rights."

Nurse was bustling away, when Christina called after her imploringly:

"May I go to see Miss Bertha?"

"No. I can't spare any one to take you, and it is too damp and cold for you to be out to-day. Stay in the nursery like a good child."

Nurse was a picture of an old woman. Round and ruddy, with silver hair smoothed under her big cap, she looked the embodiment of health and content. Yet she suffered from many twinges of rheumatism, and had an old-fashioned horror of open air. The nursery was like a hothouse in the winter time, and Christina was consequently delicate, and peculiarly susceptible to cold.

The child stood at the large window when Nurse had left her, and looked out with some wistfulness across the park towards the goal of her desire. It was a tiny cottage, originally one of the park lodges, but owing to the alteration of the drive which once ran past it, was now let to a single lady, and stood in half an acre of ground, railed off from the surrounding park.

Christina heaved a sigh. She breathed hard on the panes of glass, and traced some letters with her finger.

"I'm afraid of fathers and mothers," she acknowledged to herself. "I don't know what they're like. Emily's father isn't kind to her, she says, and I've seen some mothers in the village who slap their little boys. I wish I could tell Miss Bertha."

Suddenly she gave a scream of delight.

"Here she is walking up the drive, and I do believe Dawn is with her! Oh, I hope, I hope they're coming to see me. And I forgot Dawn's father. He is kind; oh, I do hope my father will be like him!"

She was not long left in doubt. A very short time afterwards the nursery door opened, and a little old lady, accompanied by a rosy-cheeked, fair-haired boy; came forward.

"We thought we should find you in, dear," Miss Bertha said, "and as Dawn is spending the day with me, I brought him along."

Christina's pale cheeks became pink with excitement. She and Dawn rushed at each other, Dawn with such impetus that he brought her to the ground.

Christina was too happy to mind her fall. She clung to Miss Bertha.

"Father is coming home with a mother," she announced, and if Miss Bertha showed no surprise, Dawn was stricken dumb.

Miss Bertha slipped off her tweed cloak, and drew up a chair to the fire. She then took Christina on her lap, and Dawn flung himself down on the hearthrug, rolling himself over on his back, and pillowing his curly head on his arms behind it.

"You haven't got a mother," he remarked with dancing eyes. "You and me are just the same."

"I s'pose mothers can be made," said Christina thoughtfully.

"Yes," said Miss Bertha cheerily, "and a very happy thing it is to have a new mother. I heard the rumour, Childie, so I just ran along to tell you what a good thing it will be."

"What will she do?"

Christina's little face looked anxious with care.

"Perhaps what I am doing now. She will talk to you and love you and take care of you."

"Nurse does that."

Christina's tone was a little doubtful.

"Ah! You wait and see!" said Miss Bertha, nodding her head. "Fathers and mothers are like nobody else! If I had mine alive now, how happy I should be!"

There was a little silence, which Dawn broke.

"My mother is alive though we can't see her. She takes care of dad and me. And my toad has lost himself, Tina; and Porky, the big black pig, was killed the day before we came from London. And Miss Bertha's given me some lily bulbs for my garden!"

Christina's eyes shone.

"I wish Nurse would let me garden in winter. She says it's too cold. And oh, Miss Bertha, do you like Joan of Arc?"

The little maid's brain was too full of her heroine to forget her. For the next half-hour the old lady and the children talked of the past, with its superstitions and heroism, and then dark settled down, and Nurse came in, and Christina's friends departed. She watched them wistfully from the window, then she ate her tea, feeling a sense of importance and superiority over her boy friend.

"I'm not going to be alone any more. I shall have a father and mother too, and Dawn won't have so much as me!"

She was full of curiosity over the expected arrivals, but Nurse could give her very little information. When she was in bed, she lay awake picturing her new mother.

"She will be in black velvet with feathers, like the picture in the hall; and she will move very soft, and will speak like Miss Bertha when she reads the Bible; and I—oh, I shall be frightened of them both, and I wish they weren't coming!"

Down went her head under the bedclothes.

The unexpected and unknown always had terrors for Christina. It seemed to overwhelm her now. Two strange people coming to take possession of the great unused rooms downstairs, people who would have full control of her actions; who might be kind, but might equally be cruel; people who would pass her on the stairs, invade her nursery, inhabit the library, and might even forbid her to cross its threshold. At this thought Christina lifted up her voice and wept aloud.

She cried herself to sleep, and was astonished to wake the next morning and find herself looking forward with pleasure to what had been a dreadful nightmare to her the night before.

The morning was bright and sunny. Nurse was in the best of spirits.

"Miss Bertha said she would like to have you over to lunch to-day as we are all so busy, so Connie will walk down with you soon after breakfast. Be a good child, and be ready to come back at three o'clock, for 'tis too cold for you to be out after that."

Christina's cheeks got rosy red. It was going to be a golden day indeed! Nurse so seldom let her out of her sight, and Connie, the nursery maid, could tell such lovely stories!

When she started down the drive—a little bundle of wraps and furs with a Shetland veil over her face to shield her from the wind—she felt as if she never wanted to go back to the nursery again. It was a frosty morning. Connie held her hands tight so that she might not slip, and talked without stopping of the master and mistress so soon returning. There were no stories to-day.

"Indeed, Miss Christina, my head is too full of what's coming. The house will be full of company. Lords and ladies and dooks and duchesses have visited here in times past, so Mrs. Hallam says, and I'm just longin' to catch sight of them. There will be dinner parties and balls, and company every day, and 'tis time this dull old house was shook up."

Christina looked quite scared.

"Will I have to see them all?"

"Yes, you'll be dressed up in your best clothes and go down in the drawing-room, and you'll have to speak pretty to all of 'em; and I hope Nurse will let me go down and fetch you up a time or two, for I shall catch sight o' the dresses and the jools, and hear the music agoing!"

Christina heaved a deep sigh.

"I shall never be able to speak, never!" she ejaculated with a shake of her head.

They reached Miss Bertha's little cottage. She was out in her garden looking at her bed of violets, but greeted Christina warmly, and took her into her sitting-room.

Miss Bertha's sitting-room was a paradise to the lonely child. It was furnished with a bright old chintz, and was crowded with everything that could bring joy to a child's heart. There was a stuffed squirrel under a glass case, some queer china figures on a shelf, ivory chess-men, Indian books with coloured illustrations of natives and animals on rice paper. There was a small cabinet of curiosities from all parts of the world; for Miss Bertha had had a brother who was a sailor, and who used to bring her many a queer treasure. There was a model of a heathen temple, an Indian puzzle box, a Chinese doll, a stuffed snake, and some bottled scorpions. Christina was never tired of looking at them all.

Connie took off her walking things and then departed.

Miss Bertha stirred the fire into a bright blaze, produced some knitting, and then prepared herself to listen. All children laved her because she let them talk, and though Christina was shy and silent as a rule, Miss Bertha enjoyed her full confidence.

"What is a coward, Miss Bertha?"

The old lady's keen eyes looked at the child before she replied:

"One who has no courage."

"Is it wicked to be a coward? Because I'm pretty sure I'm one."

Miss Bertha shook her head at her.

"I haven't seen any signs of it, Childie. There are different kinds of cowardice and different kinds of courage. Tiny girls like you are naturally not so fearless as boys. I would rather be afraid of the dark myself than afraid to speak the truth. It is cowardly to tell a lie."

"I haven't any courage," said Christina pitifully, with a quivering under-lip. "If I heard a voice like Joan of Arc did, I should put my fingers in my ears and not listen to it. I couldn't have ridden into battle as she did! I'm afraid of everything, Dawn says I am, and every day I get more things to be afraid of. I'm—I'm afraid of father and mother!"

Her voice faltered. She slipped down from her chair and buried her face in Miss Bertha's black merino gown.

Miss Bertha stroked the soft curly head tenderly.

"That fear won't last long. It is only because they are strangers. Don't think too much about your fears, they are mostly shadows."

"Dawn says a coward ought always to be kicked."

Miss Bertha laughed outright.

Christina raised her head with big tearful eyes. "Oh, please, Miss Bertha, why did God make me a coward? I'm sure I've always been one ever since I was a tiny baby."

"No, darling, God never made you a coward; and if you think you are not as brave as you ought to be, ask Him to make you brave."

Christina dried her eyes, and jumping up clasped her arms round Miss Bertha's neck.

"It wouldn't be too difficult for God, would it?" she asked, hope dawning in her eyes.

"No, it would be quite easy. Shall we ask Him now to take away all fear of meeting your father and mother?"

Miss Bertha was the only person who talked to Christina about good things. She seemed to live so close to God herself that she brought every one she knew close to Him too. Christina's nurse often wondered at the knowledge her little charge seemed to have of God and of His love and power. She was not a religious person herself, but as a matter of duty heard Christina say her morning and evening prayers, and on Sunday afternoons would read her a chapter out of the Bible. Beyond this she never went, and Christina looked upon Miss Bertha as the only one who could solve her childish perplexities and religious difficulties. For the little girl was a thinker beyond her years, and her brain was far stronger than her body.

She was quite accustomed to Miss Bertha's custom of getting down upon her knees at any moment of the day to speak to the One whom she loved and followed; and now, as the grey and golden heads were bowed together, Christina's burden disappeared. She jumped up almost joyfully.

"And now, please, Miss Bertha, may I have your dear little Chinese doll to nurse?"

She was a child again for the time, and her merry chatter and laughter brought a corresponding light and gladness into the face of her old friend.

"FEAR DWELLS NOT HERE"

LUNCH was had in the tiny dining-room on the other side of the passage. Christina, accustomed to her simple nursery menage, always enjoyed her midday meal with Miss Bertha. She was peculiarly susceptible to pretty things. Miss Bertha's fine linen damask tablecloth, the quaint old sugar bowls and salt cellars in their crimson glass and cut silver mounts, the old-fashioned silver, and the pretty flowers that always graced her table, delighted Christina quite as much as the roast chicken and apple tart, and the ripe pears that followed afterwards.

"When I grow up," she announced, "I shall have just such a house as this, Miss Bertha, and I shall have Nurse for my maid like your Lucy."

"Ah, I shall wish you a fuller house than mine," said Miss Bertha; with a little laugh and shake of her head. "It is very quiet and monotonous to live by yourself. When I was a young thing, I remember thinking that I never could do it, and, as each one of my relations began to leave me, I always prayed that I might be the next to go."

"To go where?" asked Christina with big eyes.

Miss Bertha pointed with a smiling face out of the window up to the blue sky.

Christina looked awed, and her friend said quickly:

"I am not so impatient now. This world is a nice place, Childie, and if you have no family or relations, you can have friends, and there are always some to be helped along the way."

"Like you help me and Dawn," said Christina gravely.

"Ah, there is Dawn! I told him I should bring you to see him after lunch. His aunt Rachael has gone away for the day. So we will go at once."

Christina was wrapped up in her walking things, and very soon she was trotting along the road with the old lady. They did not go into the village with its square-towered church and thatched cottages, but turned up a lane with high banks on each side, and in at a white gate and up an untidy-looking drive.

"Ah," said Miss Bertha, shaking her head. "Here is work that would keep Dawn out of mischief; he could take up every one of these leaves, and sweep the paths."

"And I could help him," said Christina with shining eyes.

It was a queer irregular house they came to, partly built of wood, partly stone. The wooden porch and low roof was covered with a leafless vine with long untidy tendrils and branches. It had evidently not been pruned for years. The front door stood partly open. Inside was a square hall with an open wood fire. In a big armchair drawn up before it lounged Dawn's father smoking. He was on his feet in an instant when he saw his visitors, and welcomed them with a bright smile and slow measured voice.

"Now, I'm sure you didn't come to see me, but my Will-o'-the-wisp; and where he is, I haven't the faintest conception!"

"We are disturbing you," said Miss Bertha; "let us go through the garden; he will be out, not in, I expect."

"I would come with you, but I've got a painting fit on, and am back to my studio after this pipe has been smoked. Ah! Here he is!"

Dawn came flying in with rumpled curls and rosy cheeks, but his face and hands were as black as a chimney-sweep's.

"Oh, Tina, come on! Such a lovely bonfire I've made at the bottom of the garden! Dad gave me three old canvases and I'm getting all the rubbish I can find. It's Hallowe'en, and Aunt Rachael told me what the Scotch people do, and if we're sweethearts, we must jump through the fire together; as you're Scotch you must do it. Come on and try, and don't mind the smoke, it only makes you dirty!"

Christina was divided between fascination and horror, and Miss Bertha took hold of her hand encouragingly.

"We will come and look on, but my jumping days are over, and I don't think yours have begun."

Out into the garden they went, and it was a scene of autumn desolation, for weeds and thorns seemed to be choking all else. Dawn's flying feet hardly touched the ground, and at the very end of the lawn, he pointed with triumph to the bonfire. He certainly was collecting rubbish: a three-legged chair, an old broom, a wooden bucket without a bottom, an old saddle, a piece of frayed carpet, and a variety of smaller articles were all waiting to be sacrificed.

Christina watched him dancing round, and her colour came and went. She squeezed Miss Bertha's hand.

"And Joan of Arc was in the middle. They burnt her!" she exclaimed under her breath.

"Come on, Tina, jump across with me; don't funk it."

Dawn took hold of her hand.

Christina drew a long breath, made a step forward, then burst into tears.

"I can't! I can't! I'm a coward!"

"I'm not a coward," said Miss Bertha briskly, "but I can't jump across! Look here, Dawn, don't you know that at this time of year bonfires are made to burn leaves and dry sticks, and not chairs and tables! Get your wheelbarrow and spade and sweep up your garden paths; Christina will help you. Pile the leaves on your bonfire and all the weeds you can find. You will be tidying up your place, and having some fun into the bargain. I want to see a sick child in the cottage next to you. I shan't be gone long, and then I am going to take Christina home. Make the most of your time."

"Do try one little jump!" urged Dawn, when Miss Bertha had disappeared. "Just see me! It's quite easy."

"No," said Christina; "I know I should tumble down and be burnt up in the middle, and I couldn't be burnt!"

"You wouldn't be. What a pity it is that you are a girl! You're never up to any games. Let's come and get the leaves!"

"But I love to play games," asserted poor Christina: "I make up lovely ones in my own head, and wish you were with me to play with me; but jumping through a fire isn't the only game to play!"

"No," said Dawn, running to an old shed and bringing out a wheelbarrow; "we'll make up an end to the babes in the wood. You go and lie down on the path over there and cover yourself over with leaves. And I'll be the wicked uncle, and will come along to get some leaves for my—my pigs, and then I'll find your dead body, and will be very frightened, and then will take you along to burn you, and the heat of the fire will make you come alive, and then you must jump up and point your finger at me, and I'll be so frightened, that I shall tumble back into my own fire, and be burnt to a cinder myself."

"And then," added the more merciful Christina, "just before you burn, I'll drag you out, and you'll fall down on your knees and say you're sorry for all your sins, and then I'll forgive you, and we'll go and look for my brother, who isn't dead either!"

This game was carried out, and the paths did not receive much attention in consequence. But when it was over Dawn began to talk:

"We're painting another picture."

"What's it about?"

"Red and yellow leaves in a wood, and a little old man with sticks coming through it. I was the little man. I put on dad's greatcoat. I'm first-rate in the picture."

"How clever your dad is!"

A sigh followed.

"I wonder if my father paints pictures?"

"I'm sure he doesn't."

"What will he do all day?"

"He'll ride a horse and smoke a pipe and read a newspaper," said Dawn with serious conviction.

"And mother?"

"She'll—I don't know about mothers. Aunt Rachael helps to cook the dinner and mends our clothes and makes jam. She made some apple jam out of our garden yesterday! Come in and taste some!"

To think was to act with Dawn. He dropped his broom and dashed away to the house. Christina followed him.

"Aunt Rachael gave me some skimmings in a saucer. I believe I left it in dad's room. Come on, and we'll find it."

Without any ceremony Dawn flung open the door of his father's studio. His father was standing before his big canvas, painting earnestly. He did not look round or speak till Dawn had seized hold of his saucer of jam. Then he turned and smiled at Christina.

"When are you going to let me put you into a picture?" he asked.

Christina's cheeks became crimson, but she did not speak.

"She says she couldn't have you stare at her, dad. Tina is very shy, like my black rabbit Loo was. Loo would shake all over when I took hold of her, and she never left off shaking till she died. Put your finger in, Tina, and lick it. I've got no spoon. It's just scrumptious!"

"You'll find a spoon in my cupboard," said Dawn's father.

And Christina the next minute was sitting down on a rug with her small friend, sharing his delicious compound.

"So your father is coming back," Dawn's father, Mr. O'Flagherty, said after a pause.

"And Tina doesn't know what he's like, but we hope he'll be something like you," said Dawn eagerly.

His father shook his head and went on painting.

"I expect he'll be nice," said Christina loyally.

"Fathers are always nice, aren't they, Jack-in-the-box? It's their children who are the tyrants and taskmasters; the poor fathers have a sad time of it, but they never complain; not even when a year's work is spoilt in one moment by a meddlesome imp applying the wrong varnish!"

Dawn put his saucer of jam down and flung himself upon his father with tearful eyes.

"I've told you thousands of times how sorry I was. I did mean to help you, dad; you know I did! I begged you to give me a thrashing; but I've helped you with some of your pictures, haven't I? Oh, I wish you wouldn't make me keep remembering that varnish! I wish you had had a girl like Tina instead of a boy like me!"

His father put his brush in his mouth, and for a minute rested his hand on the curly head that was burrowing itself into his coat pocket.

"You're my plague and joy, sonny, and as necessary to me as my paint is! Now be off with you. I hear Miss Bertha calling."

"I hope my father will speak to me like that," said Christina, as they left the room.

"Dad and I are very old friends," Dawn responded quaintly. "We've learnt to understand each other."

All the way home Christina turned over these words in her mind.

"If my father isn't old friends with me, we can be new ones perhaps. I hope, oh, I do hope he will like me!"

When Miss Bertha left her at the door of her home, she said to her softly:

"I am going to give you a nice little verse, Childie, to think of when you get frightened of people and of things. It is this:

"'What time I am afraid, I will trust in Thee.'"

Christina repeated it over to herself as she climbed the nursery stairs. She met Nurse with a glad light in her eyes.

"I've had the most lovely day, Nurse, and I don't think I shall mind very much my father and mother coming home."

"Mind!" exclaimed Nurse aghast. "I should think you oughtn't to mind, indeed! A little girl ought to be full of happiness at the very thought!"

The eventful day came. Christina wandered up and down the house rejoicing in the blazing fires and cheerful rooms. To her, before, her home had been a puzzle and a mystery. There had been so many locked doors and darkened rooms; rooms that even in the light of day were shrouded with linen coverings. Now all was changed. Curtains were drawn aside; coverings taken away; the silver and china and pictures delighted and astonished the child. She watched the gardeners fill the big hall with flowering plants; she looked on whilst Mrs. Hallam arranged flowers in every room: flowers which had come from the greenhouses, into which Christina had never been allowed to go.

"Why, Nurse!" she exclaimed drawing a long breath. "We have more pretty things than Miss Bertha has!"

And Nurse laughed outright at the comparison.

Dusk set in, and the travellers had not arrived. Christina had her tea, and sat expectantly at the nursery window; but when eight o'clock came, Nurse insisted upon putting her to bed.

"They'll not be here now till nearly ten o'clock. They must have missed the train."

And Christina did not know whether she was glad or sorry that the meeting was deferred. She was too tired with the excitement of the day to keep awake, and slept soundly till she was roused by Nurse the next morning.

"Have they come, Nurse; what are they like? Did they come to see me when I was asleep?"

"No," said Nurse a little reluctantly; "but your father asked if you were well. 'Twas just a bustle and confusion from the time they arrived. I was glad that you had not waited up."

Nurse's face was rather gloomy. Christina's spirits sank at once.

"Shall I have to go and see them before I have my breakfast?"

"No, indeed. They'll sleep late themselves, and won't want to be disturbed. No, you must wait till you're sent for, my dearie."

Nurse was very silent through breakfast; but Christina's quick ears caught the unusual stir of feet and voices through the house. She was in a fever of unrest and of fear, and when breakfast was cleared away, and Nurse had left her alone, she sat down on a low chair by the fire, and with clenched hands repeated over and over to herself:

"'What time I am afraid, I will trust in Thee.'"

And then suddenly the door burst open, and like a small whirlwind a young girl swept in.

"There! I am right after all, and this is the nursery! Phew! What a heat! It's like a hothouse. Why there she is! Now, you small girl, let me look at you! They have so laughed at me for having a ready-made daughter. You aren't very big, that's one comfort! What is your name? How old are you? And what do you think of me? Can't you stand up? Come over to the window and let me have a look at you! But we'll have some air first, I can't breathe in such an atmosphere. No wonder you're such a white-faced creature!"

Talking without a pause, Christina's new stepmother flung open the nursery window, and Christina recoiled instinctively as the blast of cold air met her.

"Your nurse is one of the coddling sort, I can see! Now, I've been brought up in the fresh air, and I shall try if I can't make you as hardy as myself. I shall see that you're not kept in a glass case any longer. Now, aren't you pleased to see me? Dear me! I wish Puggy was here!"

Christina looked up into the laughing girlish face bent over her. Her stepmother was in a short tweed coat and skirt, and looked like an overgrown schoolgirl. Her hair, which was a pretty golden-brown, was drawn back from a decidedly fresh attractive face. Rosy cheeks, blue eyes and a mouth that was never anything but smiling, completed the picture. Christina's fears disappeared at once.

"Yes," she said smiling in return. "I think I shall like you to be my mother."

"You queer little soul! I can tell you I didn't like the idea of a stepdaughter at all, but I was told that I should have no bother, for your nurse had you entirely in her charge. And I love children if they're no bother—ah, here is your nurse!"

She turned to meet Nurse's look of horror at the open window.

"No, don't shut it, Nurse; you have this room ever so much too warm. Look at this child's pale cheeks!"

"Miss Christina has a cold, and is very delicate ma'am. You must excuse me if I act contrary to your wishes!"

Nurse banged down the wide window sash with no very gentle hand.

Christina's young stepmother laughed in her face.

"You are a foolish woman," she said; "not fit to have the charge of a child!"

Then humming a song she sauntered out of the room, and Nurse sat down in her easy chair and began to cry.

"And if this is the beginning, what will be the end!" she sobbed. "And 'tis the same all over the house; but there, Miss Tina, don't you mind what a foolish old woman says. I'm not fit to have the charge of you."

Christina stood on the hearthrug not knowing what to say. She was relieved when Connie came in and asked Nurse to go to Mrs. Hallam, who wanted her.

"I think my mother won't be unkind," said Christina to herself with a wise little shake of her head, "but I should like to see my father."

She waited for some time in the empty nursery, and then, weary of her own company, determined to slip down to the library and read a book.

Very softly she crept downstairs, and was relieved to meet no one on the way; the library was empty. Christina climbed up on the steps, and took out the volume of French History that she was last reading. Then she sat down on the hearthrug, and in a few minutes had forgotten all about her father and mother. Outside surroundings had faded away; she was living inside her book.

Suddenly a voice made her start.

"Is this Christina?"

She jumped up in fright, for there, standing before her, stood her father. Very tall, and very big he seemed to her. His dark eyes were fixed upon her, and though she could not see his mouth for the heavy moustache that concealed it, it seemed to her that he was looking displeased.

"Yes," she said trying hard to be brave; "oughtn't I to be here?"

Her father drew her to him, and placing one hand under her chin raised her face to his, then he stooped and did what her stepmother had not done—he kissed her.

"And is this where you hide yourself?" he asked. "Are you fond of books?"

"I love them!" Christina answered with glowing eyes.

Her father smiled.

"And so do I, so we shall be friends at once."

He sat down, and took her on his knee.

In a few minutes Christina was chatting unreservedly to him, asking him innumerable questions about things that had puzzled her.

"What do these words mean that are stamped across all your books? Nurse doesn't know, do you?"

"It is our family motto. Don't you know it? It means this in English: 'Fear dwells not here.' The Maclahans have neither been better or worse than most folks, but right back to the first annals of their history, no cowardly deed has been done by them. They have not known what fear is."

There was silence, then very timidly from Christina:

"And I'm a Maclahan?"

"Yes," said her father heartily, "and though you're not very grand yet, either in looks or size, you must grow up a brave courageous woman, or you will be the first to disgrace your family."

Christina drew a long breath, but said nothing for some minutes; then she asked:

"And have all the little girl Maclahans been brave always?"

"Let us come and look at some of them," said her father; and he led her to the long picture gallery that wound round the house.

Christina had sometimes been there with Nurse, and had vaguely wondered who all the grand ladies and gentlemen were. It had never entered her head that they were in any way connected with her. Now she looked up at them eagerly and curiously. Her father knew them all by name, he could remember their different histories. Christina looked at and admired the men, but it was the women about whom she asked most.

"And they were really little girls like me, and always brave, father? They never felt afraid of anything?"

"Do they look as if they feared anybody or anything?" her father returned, a little triumph in his tone.

And Christina shook her head decidedly.

"No, they look so straight and high."

"And that is the look of a Maclahan," said her father. "Hark, I hear your—your mother calling!"

He left her. Christina's little soul was perturbed and miserable. She went back to the nursery and did some thinking by the nursery fire, then she laboriously traced out in big pencil letters, on a sheet of white paper, "Fear dwells not here," and pinned it to the wall over the mantelpiece. After that, she walked up and down the room holding her head as high as she could, and practising with patience and care the kind of look she fancied was upon the faces of the ladies in the picture gallery.

"If only," she murmured; "if only that was not our motto! Oh, if father only knew, if he only guessed—what would he do with me!"

She shut her eyes, and pictured in the olden days a castle, and all the household gathered round the gates. Soldiers were marching out guarding a prisoner, one who had disgraced her family by an act of cowardice, one who was to be banished outside for ever, whose picture in the gallery was to be taken down and burnt: the coward herself, sent out into the cold strange world to perish with hunger, disowned, cast out by her family! Some Spartan tales that she had read helped her to picture this scene with great reality. Then she tried to adapt it to her own day. What would happen if one day she brought disgrace upon the whole family by her fears?

Poor little Christina! Her vivid imagination made her very miserable, and Nurse wondered when dinner time came that she seemed to have no appetite.

"THEY SAY I'M CODDLING YOU!"

"WE will have a walk this afternoon," said Nurse; "the sun is coming out."

"Shall I see father and mother again to-day, do you think?"

"I can't tell you," said Nurse a little shortly.

But as Christina went out on to the terrace an hour afterwards she came upon her father and mother just starting for a ride. Two beautiful horses were being held by the grooms in readiness, and their restless antics caused Christina to eye them nervously.

Mrs. Maclahan was making her husband fasten her glove for her, but directly she noticed Christina, she turned towards her.

"Now, Herbert, look at this child. Isn't she like a little old woman in all those wraps? Come here, Christina—it is a mouthful of a name! I shall call you Tina. Have you ever been on horseback? Never? Then the sooner you learn to ride the better. Hold Damon steady, Barker! There! Up you go! Now, how do you feel?"

Before Christina knew where she was, she found herself on the big chestnut. Her stepmother's strong arm had tossed her up as easily as if she had been a doll.

The little girl's heart beat hard and fast, and every vestige of colour left her cheeks. But catching sight of her father's pleased smile, she sat erect, and with determined lips murmured to herself Miss Bertha's verse.

Nurse began to expostulate, but Mrs. Maclahan cut her short.

"Afraid? Nonsense, she must learn to ride! Now, Barker, lead her down to the lodge; I will mount there. Take hold of the reins, Tina; that's right! Herbert, ride with her; I will walk."

Poor Christina in agony clutched hold of the reins. Her head swam, there was a buzzing noise in her ears. No one had any idea how the nervous child suffered, but not a word did she utter.

Once her father laid his hand on her as she swayed from side to side.

"Hold yourself up, little woman, or you will fall. I must get you a small pony, then there will be no fear. Are you enjoying it?"

Christina was absolutely mute. Every step was torture, but how could she confess that she was afraid? She was a Maclahan she kept assuring herself. It seemed years before the lodge was reached, and then Barker gently lifted her down.

For a moment Christina looked up at her father pitifully.

"I didn't fall," she said; and she fainted dead away.

There was confusion then. Her father carried her into the lodge, and Nurse rushed forward forgetting her respectful manner in the excitement of the moment.

"My poor child! Oh, 'tis a cruel shame, when she's afraid of as much as a fly—and as to horses—the very looks of them are a terror to her! I've known children made imbeciles for life for less than this, and her heart not strong! 'Tis enough to kill her; likely enough we shall never get her round!"

"Go back to the house, you fussy old woman, unless you can control yourself!"

Mrs. Maclahan spoke sharply, for she was vexed at the result of her thoughtless, good-natured act. She pushed Nurse away, and was the first to speak to her little stepdaughter when the colour returned to her face and she opened her eyes.

"There! Now you're all right, aren't you? Are you given to this kind of thing?"

Christina struggled to her feet, and looked vaguely round.

"Let her go to her nurse," said her father quickly; "I fear she's very delicate."

Mrs. Maclahan shrugged her shoulders.

"She is being made so. The sooner a change is made in the nursery the better. She'll be all right now. Come along, Herbert; we shall never get off. You won't be such a little goose again, will you, Tina?"

She mounted the chestnut and rode away; and Christina walked back to the house with Nurse, feeling shaky and still confused.

Nurse petted and comforted her, and when she saw that she was quite herself again, left her on the nursery sofa whilst she went to Mrs. Hallam's room to talk over the "new mistress."

That day seemed a long one to Christina. She felt as if she were in disgrace. Neither her father or mother came near her, but after the nursery tea was over, Nurse had a message brought to her that she was to go to Mrs. Maclahan. She came back with tears in her eyes, and informed the child that she was going to leave her.

Christina could not and would not believe it.

"I couldn't live, Nurse, without you!" she assured her passionately.

"They say I'm coddling you, and you must be made hardy and strong. They think every child is cut out in the same pattern. Your stepmother is one for fresh air and sport, so she says, and she's going to take you in hand herself. Me, who has nursed you through your teething and vaccination and that terrible attack of whooping-cough, and been a mother and nurse rolled in one for eight years! Me to be turned away with a month's notice, like the kitchen-maid!"

Nurse put her head down into her apron and sobbed bitterly.

Christina gazed at her in horrified wonder. Her little soul rose in protest against such a sentence. Without a thought of fear, with hot cheeks and flashing eyes, she dashed down the stairs into the room that she knew had been prepared for her stepmother. She found her there writing letters, and her father was dictating to her as she wrote.

"Nurse is not to be sent away!" Christina exclaimed.

Had a thunderbolt fallen out of a mild spring shower of rain, Mrs. Maclahan could not have been more astonished; but Christina was too excited to note anything.

"I can't have Nurse leave me! I would rather you left me," she passionately went on. "I will do anything if you let Nurse stop! She doesn't coddle me and make me afraid! I will ride that big horse every day, I will do sport if you teach me, I will do everything you want; but I love her, I love her, and she mustn't leave me!"

She stood there with crimson cheeks and heaving breast, then catching her father's eye, she flung herself upon him with a passion of tears:

"I will be a Maclahan! I'll never, never, never be afraid any more, father, if you let Nurse stay with me!"

"I have seen no signs of fear in you yet," said her father, laughing. "Why, Ena, did you think this white-cheeked, demure-faced baby carried such a tempestuous little heart within her? I think we must come to some arrangement with poor Nurse."

"I'm afraid," said Mrs. Maclahan with a short little laugh, as she went on writing her letters, and did not glance at Christina—"I am afraid that the child has expressed the case quite clearly. It is a question of Nurse's departure or mine! I am quite convinced that both of us will not be able to live in the same house."

"Come along with me to the library, Christina; I found a book to-day that I think you would like."

And before she could say another word, Christina found herself carried off by her father to her favourite room.

"Now," he said, placing before her an old red leather volume, "these are some old Norse legends, translated more than three hundred years ago, and the pictures are very quaint."

Christina was entranced at once. Sad to say, she forgot poor Nurse, and when her father saw her thoroughly engrossed in her book, he left her, and went back to discuss her nursery education with his wife.

When Christina met Nurse again that evening that good woman was calm and collected, and said with as much dignity as she ever showed towards her little charge:

"I was upset, dearie, but we'll say no more at present about my going. I shan't be off next week, nor the week after."

Christina said no more, but when she was in bed her troubles, that always seemed very heavy then, returned to her.

A new nurse was far more to be dreaded than a new father and mother.

"Oh," she sighed, "I wish I could see Miss Bertha! She would comfort me, I know she would." Then the remembrance of Miss Bertha's text came to her:

"'What time I am afraid, I will trust in Thee.'"

The very saying it over seemed to soothe her. She fell asleep with the words upon her lips.

The next day her mother came into the nursery at eleven o'clock, and told Nurse to get her little stepdaughter ready to go out with her.

Christina's eyes were big with fear, until she looked across to her paper over the mantelpiece.

"Do you think I shall be put on the horse again Nurse?" she asked timidly.

"No," said Nurse shortly; "I don't think you will."

The little girl heaved a sigh of relief. She met her mother in the hall, who laughed when she saw her.

"Take off that veil, child! This fresh, bright morning air won't get a chance of getting near those white cheeks! Now come along; we are going for a brisk walk."

They started down the avenue at a quick pace, and Christina had to trot to keep up with her stepmother's swinging strides. It did her good, for it prevented her from feeling the cold, and the colour slowly crept into her cheeks.

"Now tell me," said Mrs. Maclahan in that quick, imperious tone of hers, "Have you been shut up in this way all your life? Have you had no children to play with, no outdoor games or exercises?"

"There is Dawn!" said Christina eagerly. "Oh, I should like to play more with Dawn. He hardly ever comes to me, and it's too long a walk for Nurse to go to him."

"Dawn! What a queer name! Who is he? What is he?"

"He's a boy; he's always called that because his father painted a picture of him and called it Dawn. He painted three pictures, and called them Dawn and Day and Dusk. Dawn's real name is Avril, but he hates being called that, and his father calls him by ever so many names: Will-o'-the-wisp and Jack-in-the-box, and lots of others."

"He sounds interesting. Tell me about the pictures. I love them. If he was Dawn, who was Day and Dusk? Did you ever see the pictures? Were they in the Academy?"

"Oh, yes. Dawn is always telling me they were. Day was the blacksmith; he is a young man and wants to marry Connie, only she says his face is too dirty. And Dusk was old Mr. Green, who used to be a cobbler, but he's nearly blind now, and Miss Bertha goes to read to him every Saturday."

"Take me to see Dawn now. It is a dear little name, and if he is a nice boy, he shall come to play with you every day. I have a small brother who is coming here for his holidays. In fact, I meant to have brought him here yesterday, for there is an outbreak of fever at his school, but he is staying in London for a few days with one of my sisters. He will soon shake you up and keep you lively!"

Christina was too shy to assure her stepmother that she did not want to be shaken up, but she quickened her steps joyfully in the direction of Dawn's home, and then suddenly, down the road in front of them, he came tearing along, his curly hair flying in the wind.

He took off his hat and waved it frantically when he caught sight of Christina.

"I'm running away!" he cried out. "Running for my life. Dad has gone to London, and Aunt Rachael has a headache, and I've eaten all cook's mince pies for Sunday, and she's after me with a broom!"

"Ah," said Mrs. Maclahan, "this is a boy after my own heart! Come for a walk with us, and then you shall come back to tea with Tina!"

Dawn looked up at her with laughing assurance.

"You're Tina's new mother, aren't you? I like you awfully. If you will talk to that old Nurse and tell her Tina won't get into mischief, I'll come and spend every day with her. I don't go to school when we live in the country. Dad and I vegetate, and rest our brains, and then we go back to London, and I'm at lessons all day long. I'm awfully glad dad is doing a country picture that makes him come here. I'd like to stay here always!"

The walk that Christina dreaded turned out a very happy one. Dawn chattered on as freely to Mrs. Maclahan as he did to Christina alone. They went up as far as the breezy common, and here Christina shivered and caught her breath, and tried to shield herself behind her mother, for the wind was bitter, and seemed to be trying to get into her bones.

Mrs. Maclahan noticed her reluctance to face the wind, but made her do it.

"I've been brought up hardily, and I shall bring you up so too! I should think cold water baths would be a good thing for you!"

Tears came into poor Christina's eyes. She felt tired and cold, and longed for Nurse's arms and the nursery fire. The thought of a cold bath seemed the last straw. Dawn looked at her comically. Then he turned his cheeky little face up to Mrs. Maclahan.

"You're a Spartan mother," he remarked. "Tina and me have played at being Spartans. We killed a doll of hers; we beat her and then we drowned her and then we burnt her; and Tina cried the whole time, but she had to do it, for the doll had told a lie and was a coward, and we wanted to teach her that she was to fear nothing!"

"You did it all," said Christina in a trembling voice. "You made out she was a coward, I didn't say so. And it was no good teaching her not to be a coward when she was dead!"

"Christina is always afraid that she's a coward herself," observed Dawn cheerfully; "but I don't know that she is. She's frightened, but she doesn't funk! As long as you don't funk, it doesn't matter about being frightened, does it?"

Christina's cheeks got crimson. Her stepmother glanced at her.

"I dare say we have walked far enough," she said. "I must profit by your experience, Dawn. I must remember that Tina won't funk, but I hope I shall cure her of being frightened."

They turned back, and when they reached the gates of Christina's home, Dawn held out his hand.

"I won't come in, after all, to-night," he said rather grandly. "I funk some persons sometimes. Christina's nurse and our cook are not quite my friends."

"I should never run away from women," said Mrs. Maclahan.

Dawn's eyes twinkled.

"Yes you would, if you were panting for a run! Any excuse would make you. And Aunt Rachael's head will be better and she'll be looking for me: and I promised dad I would be a good boy to her!"

He danced off down the road, singing as he went.

Christina climbed the stairs to the nursery, feeling as if her legs would hardly move any more.

"Oh, Nurse," she exclaimed, pushing open the nursery door, "can't I go to bed? I think I'm too tired to stay up!"

Nurse fussed over her at once, but wisely persuaded the tired child to stay where she was and have some dinner. And when it was over, Christina began to feel refreshed and rested. She did not see either of her parents again that day. They dined very late, and did not come in from their ride till just before dinner.

In a few days' time, the house seemed to settle down into its new routine. Christina was visited in her nursery by her mother, but these visits were dreaded both by the nurse and child, for they heralded the opening of windows, and much advice about the advantages of fresh air and light clothing, which Nurse especially resented. Mr. Maclahan occasionally came across his little daughter in the library. He allowed her to wander in and out as she had been in the habit of doing; otherwise she never went downstairs, and was never summoned to go into the drawing-room at any time.

It was a happy day for the child when she saw Miss Bertha again. She met her out of doors one day, and upon the old lady offering to take her home for half an hour, Nurse had willingly consented, as she had some errands to do in the village.

"I will walk up to the house with her, Nurse, so you need not call for her."

Miss Bertha had noticed the wistful longing in Christina's eyes, and when they were alone the little girl poured out such a flood of talk that the old lady felt quite bewildered.

"Take your time, Childie; tell me everything from the beginning; I can wait to hear it. I shan't run away."

So Christina told her everything from the beginning, and Miss Bertha listened with interest.

"And has my text helped you, Childie?"

"Oh yes, it has, Miss Bertha, ever so many times. I'm so glad it doesn't say I'm not to be frightened, because I am, and I can't help it, and when I was on mother's horse I was terribly frightened, but I said:

"'I will trust in Thee,'

"and I asked God to hold me tight on and keep me from falling off, and He did it. I never fell, and I know I should have if I hadn't asked God. And, Miss Bertha, isn't it a dreadful thing that our motto should be 'Fear dwells not here'? Oh, Miss Bertha, what shall I do to make myself a proper Maclahan? I ought to be as brave as a lion, and when father finds out about me, I don't know what he'll say! And Nurse is going to leave me, and mother startles me. She smiles and she's never said anything cross, but she makes me shiver when she comes into the room, and she's going to make me hard, she says. She says I want plenty of cold water and fresh air, and she's going to get me a governess who will teach me 'nasticks: do you know what they are? I'm frightened of it all. The only thing I like is that I can play with Dawn as much as I like, but he hasn't come near me, though mother said he could!"

Then Miss Bertha was able to get her word in.

"Dawn has been in bed two days—nothing much the matter with him: he ate too many mince pies, and drank a bottle of vinegar in mistake for currant wine. He has been well punished for his greediness, I am glad to say; but he will be round to see you as soon as his aunt lets him out. Why, my dear Childie, most of your fears are groundless! Your mother will never be unkind to you. Nurse has brought you up in an old-fashioned way, and your mother wants to bring you up in the new-fashioned way. I met your mother yesterday for the first time, and she talked to me about you. She wants to see you stronger, and perhaps you will be all the better for some of her alterations. I am sorry that Nurse is going, but you are getting old enough to do regular lessons now, and a governess will be most kind and nice I expect. You have nothing to make yourself unhappy about."

Christina was silent; then she took hold of Miss Bertha's hand, and laid her soft little cheek upon it.

"I know you love me," she said; "and if you think it is best for me, I won't be afraid!"

Miss Bertha stopped. They were in her garden now, and for one minute she raised her face in silence to the open sky above her, then she bent down and kissed the earnest child by her side:

"Christina, my darling child, say those very words you have uttered to God in your morning and evening prayers. Say them over and over again to Him when troubles and doubts and fears crowd round you. Say to Him softly and reverently:

"'I know You love me; and if You think it is best for me, I won't be

afraid!'"

Christina was awed by the solemnity in Miss Bertha's tone, and when she looked up at her, she saw tears were in her eyes.

She did not speak, but she could not forget the lesson taught, and though she was long in learning it, she remembered it to the end of her life.

"THE UNITED KINGDOM"

"AND is he coming to-day? Really to-day? And will he be about as old as we are? How scrumptious!"

"His name is Puggy; and Blanche, mother's maid, says he's a terror!"

Christina's eyes were round as she gave Dawn this information.

"How jolly! Has he been sent away from school? Why is he coming before the holidays?"

"His school has got scarlet fever. He is just as old as you Dawn, but mother says he's quite different to you."

"Should think so!" said Dawn in tones of scorn. "There's no one like me in the world, dad says so!"

"I wonder," said Christina meditatively, "if there's a little girl just like me anywhere."

"Dad says God never makes a duplicate anywhere; isn't that a lovely long word, and I learnt another yesterday. It was volatile: it means me, but it isn't very nice. Dad called me a volatile elf, so I pelted him with chestnut skins in the garden till he told me what it meant. Why is he called Puggy? It sounds like a pug-dog."

"I asked father, and he laughed. 'It suits him because he's pugnacious,' he said."

"That's another breather! What does it mean?"

Christina shook her head.

"I keep thinking of Blanche's words, 'a terror.' I expect he'll be a terror to me."

"Now," said Dawn, shaking his fist in her face, "you think of your motto, and don't you dare to talk of any one being a terror to you. And if he is, you bring him along to me, and I'll fight him!"

"Oh," said Christina, "you never would! That would be awful! I always thought it so wicked to fight, but mother does, so I suppose it's what she calls 'sport'!"

"Your mother fight?"

Dawn looked very puzzled. He was in the garden with Christina, and tired with running about, they were now taking a rest on the top of a low wall in the kitchen garden.

"Yes," said Christina with a grave nod; "mother and a lot of ladies all fought each other with sticks in a field at the bottom of the lawn over there. They were fighting for a ball, and they all tried to hit each other. I ran away, because I couldn't bear to look at them."

"Oh, you goose! That was a game of hockey. They weren't hitting each other, only the ball. You really ought to learn some games, Tina; you don't know anything at all!"

"It frightened me," pursued Christina. "I've never seen ladies play at games like that!"

"You wait till this boy comes, then we'll do an awful lot of things; oh, I wish I could stay to see him! Do you think I could run off to the station and see him arrive? What train does he come by?"

"Mother is going to meet him herself; she said she would. I think it's at four o'clock."

"I'll be there then," said Dawn, "and I think I'll leave you now. Good-bye."

He was away like the wind, and Christina, feeling it very dull to be in the garden alone, went indoors. She was full of curiosity over the new arrival, but as usual her fears were uppermost.

"There are so many happenings!" she told herself gravely. "I never shall get to like them. And a strange boy is worse than a strange nurse, or a strange father and mother!"

She was sitting at her nursery tea when Puggy made his appearance. Her stepmother led him forward:

"This is my baby brother, Tina. He does not look a baby, does he? You must be very good friends. He will help you to eat up that plate of bread and butter very quickly. Now, Puggy, be on your best behaviour remember; and when you are in the nursery, do what Nurse tells you."

Puggy was a short, sturdy boy, only half a head taller than Christina herself. His hair was closely cropped, and it was of a reddish tinge. Blue eyes, a very round mouth and snub nose and freckled face, these belonged to Puggy, and his name seemed to suit him.

He sat down to the table in utter silence. Christina looked across the table at him very fearfully. Mrs. Maclahan had left the room, and Nurse began to pour out a cup of very weak tea.

The children's eyes met, then Puggy winked his eye knowingly at Christina. The colour flow into her cheeks, what was she to do? She could not wink back, and she was too shy to speak.

Nurse broke the silence.

"What is your name, my dear?"

"Puggy."

"You were not christened Puggy."

"Wasn't I? I don't remember being at my christening. I s'pose I was there."

Then his round lips widened into a smile.

"My proper name is John Durward, but you are to call me Master Puggy always."

Nurse looked at him sternly, but said nothing; then Puggy addressed Christina:

"You'll have to call me Uncle Puggy."

Christina's eyes became round with wonder. This astonishing statement made her forget her shyness.

"I didn't know little boys could be uncles."

"Oh, can't they! And their nieces have to do what they tell them, always!"

"But you're not a proper uncle. You didn't belong to me when—when I was born."

Puggy looked taken aback. He appealed to Nurse.

"Isn't a fellow uncle to his sister's child?"

Nurse smiled.

"You are no relation to Miss Tina, leastways only a step-uncle."

"Well, that's good enough."

He nodded across at Christina triumphantly.

There was not much more talk between them till after tea, and then somehow or other Christina's shyness melted away, and she found herself talking to Puggy as she talked to Dawn. She told him all about her little playfellow; she showed him her toys and games; and he in his turn waxed confidential.

"I'd like to know that fellow. I believe I saw him at the station; there was a boy with a mop of hair who stared at me as if I were a gorilla. I'll teach him manners when I see him! Look here, just come over the house with me. I want to know my way about."

"But," said Christina feebly, "I don't know my way properly. All the rooms have been locked up till father came home."

"Come on, and let's find them out now. We must do something. It's too slow in this old nursery!"

Christina looked round to ask permission of Nurse, but she had disappeared. So feeling as if she were going into a strange country, she followed the enterprising Puggy out on the landing, and they commenced their investigations. The corridors were long, and some rooms were still locked up, but they peeped into a good many, and at last found themselves before an old arched door at the very end of the upper corridor. One of the under housemaids appeared from the back stairs, and looked quite astonished when she saw the children. Christina spoke to her.

"We want to go through this door Ann, may we?"

"Oh, lawks, Miss Tina! That's up to the turret room that has a ghost. I never goes by that door after dark if I can help it!"

Christina's cheeks blanched, she shrank back. Puggy danced up and down with delight.

"Hurrah for the ghost! Come on, we'll rout him out, and the door isn't locked!"

"Don't you go up those steps, there's a good child, Miss Tina."

Puggy had swung the door open, and a winding stone staircase disclosed itself to them.

"I'm sure we'd better not go," said Christina, looking at the dusky steps with horror.

"Who's the ghost?" demanded Puggy valiantly.

"I dunno. It's just some one that walks about the room there and makes a noise. Mr. Tipton has heard it often. He sleeps in the room there, close to the staircase."

"Let us wait till to-morrow," suggested Christina.

But Puggy was bent on going up the steps that moment, and would have dragged his shrinking little companion after him if a call from Mrs. Maclahan had not stopped him.

Christina hailed the appearance of her stepmother with relief and delight.

"Why, what on earth are you doing here?" she asked, as she came up to them.

Puggy explained, and his sister laughed merrily.

"A ghost! What nonsense! And Tina believes it from the look in her eyes! Come down to the library both of you. We're having tea there, and your father wants to see you, Tina. We'll ask him about the ghost. To-morrow you can explore the house as much as you like."

So down to the library they went, and the blazing fire and the cosy tea that Mr. and Mrs. Maclahan were enjoying did much to drive away Christina's fresh fears.

"No," said Mr. Maclahan, taking hold of his small daughter and perching her on his knee; "we have no ghosts in this house I am glad to say. I used to have the turret room at the top of those stairs as my den as a boy, and if you think well, Ena dear, we will turn it over to these children now."

"I think it would be a capital idea. I fancy Puggy is too much like me to care to be long in that ill-ventilated nursery."

Christina did not know whether to be glad or sorry that she was to be introduced to the unknown room; but Puggy was enthusiastic. He turned to her father with a comic look of perplexity on his face.

"Please what am I to call you? Herbert, like Ena does?"

"No," his sister said sharply. "If we give you an inch you'll take an ell. You have no respect for anybody!"

Puggy smiled radiantly.

"It isn't my fault!" he said. "You made him my brother, I didn't; and Tina ought to call me uncle! May I call him the 'Squire' like the porters did at the station?"

"Yes," said his sister; "and mind you're a good boy, and don't lead Tina into scrapes."

"You won't be such a reader now you have some one to play with," said Mr. Maclahan, addressing his little daughter.

Christina looked round the room thoughtfully. "I like books best," she said, "and Dawn will play with Puggy."

"No," said her stepmother quickly. "Games are better than books for you, Tina, and I shall see that you have them. But Dawn can come over here every day if he chooses. I like that boy!"

The very next morning being bright and sunny, Christina was turned out into the garden to play with Puggy, and they had not been out a quarter of an hour before Dawn made his appearance. He came with bulging pockets, and produced for Puggy's edification first a white mouse, then a mechanical motor-car, and then a bag of nuts.

"I know all about you," he said, shaking back his curls. "Tina has told me, and I've come to look round with you. Do you like mice? This one is a darling! When he isn't in my pocket, I carry him on my head inside my cap. Dad brought me such a jolly motor-car. You can light it with real oil and it goes like the wind. Like to see it? Here are some nuts for you, Tina."

They were good friends at once, and so full of fun and spirits that Christina's laugh rang out again and again, yet before very long, the first sign of dissent between them arose.

"Tina, go into the house and fetch me my knife. I left it on the nursery table."

It was Puggy who spoke, and his tone was peremptory. He added, as Christina obediently walked away: "That's the good of girls to fetch and carry. They're good for nothing else."

He wanted to impress Dawn with his manliness, but Dawn knew better. He flushed up at once.

"Dad says only cannibals and savages make girls work for them, gentlemen never do; at least Englishmen don't!"

"You don't call yourself an Englishman, do you? I heard my sister say this morning that your father was a poor Irish artist. You're a Paddy, that's what you are!"

"A Paddy can be a gentleman!" retorted Dawn, springing up from the ground where he had been playing with Nibble his mouse, and pocketing the little creature in furious haste.

Puggy laughed scornfully.

"Paddies are always beggars. They live with pigs and chickens in bog cabins. I know all about them. We have two Paddies at my school. One tells lies, and the other never washes!"

"And what are you? A brag and a bully!"

Dawn's cheeks were scarlet, his eyes flashing fire. Puggy made a dash at him, and the next moment both boys were fighting. Jackets were tossed aside, sleeves tucked up, and if Puggy hit away with dogged persistence, Dawn perplexed him by his many sided onslaughts: dancing here and there, he was never in the same place for a second, and they were in the very thick of it when poor little Christina came back from her errand.

She was aghast at the sight. Both boys were bleeding, but neither gave way. After one despairing cry, she fled into the house, and burst in upon her father and stepmother, who were in the library.

"They're killing each other! Stop them! Oh, do come quick!"

Mrs. Maclahan laughed at the horror in her tones.

"Fighting, I suppose," she said. "I knew Puggy would be at it. Leave them alone, Tina. It's only the first go off! They'll be the better friends after it."

"But!" gasped Christina. "They're hurting each other! It's so wicked to fight, oh, do stop them!"

Her father rose and looked at his wife humorously.

"My dear, Christina has not your constitution, and I'm not fond of fights. Puggy must learn to control himself. Come along, Tina. Where are these young combatants?"

Christina led him into the garden breathlessly.

"Dawn has never fought any one before, I'm sure he hasn't, and oh! They're hurting each other so!"

When they arrived on the scene, the boys were rolling over on the ground; Dawn was undermost, but if his body was getting the worst of it, his spirit was unbroken; and when Mr. Maclahan's stern voice broke in upon them, and they both rose to their feet, he exclaimed, "We'll have another round!"

"That you won't! Puggy, is this the way you treat your visitor? Shake hands and be friends, and remember that I never allow fights in my house or grounds."

Neither of the boys was unwilling to make peace; but Christina stood beside them sobbing bitterly.

"Oh," she cried, "you're both so hurt! How could you hurt each other so!"

"Pooh!" said Puggy, marching off to the house with a black eye, a bleeding nose and bruised knuckles. "What sillies girls are to make such a fuss!"

Dawn looked up at Mr. Maclahan with his irrepressible twinkle. His face was damaged too, and a bump on his forehead stood out as big as a pigeon's egg.

"I've been fighting for my country," he said, "and for a girl. Dad will not scold me!"

Later on, when the boys had washed and anointed their wounds, Mrs. Maclahan came out to talk to them. She turned to her husband when he joined them, saying laughingly:

"Do you know this small trio represent the United Kingdom? Your small daughter is Scotch by birth, and may I say by her stern morality? Dawn is a veritable Paddy, and my pugnacious brother a thorough little John Bull. I hope they will do each other good."

From that day Mrs. Maclahan always alluded to the children as the "United Kingdom." They liked the idea and never lost sight of it in their games. After that first fight, Dawn and Puggy were the best of friends; Christina followed them everywhere, and though she admired Puggy's pluck and determination and his perseverance in carrying through anything he attempted, however hard it proved to be, her heart remained faithful to her sunny-tempered, easy-going boy friend, Dawn.

Puggy was soon introduced to Miss Bertha.

At first he was inclined to be indifferent to her.

"Old ladies are such fidgets!" he said.

But Dawn and Christina attacked him with such violence for saying a slighting word of their best friend that he collapsed, and after one visit to the tiny house and a tea such as all boys love, he confided to them that Miss Bertha was a "proper brick," and her house was "ripping."

"And how are things going, Childie," Miss Bertha asked Christina, just before she left her.

"Oh, I like Puggy," the little girl responded brightly. "I'm never dull now, we do such a lot of things; but Nurse is soon going away, that's the most dreadful thing!"

Miss Bertha smiled.

"Your 'dreadful things' are not so dreadful when they come. Can't you trust God about that?"

Christina looked wistful.

"I am trying not to be afraid. I keep saying my text over and over, and it does help me."

"Of course it does. I think you ought to be a very happy little girl."

And Christina went home thinking that she was.

TWO HIGHWAYMEN

IT was a wet afternoon. Dawn arrived in the nursery at three o'clock, and shook the rain off his curls and overcoat like a Newfoundland dog.

"I told dad I was coming along to cheer you two up. I thought it would be a good day for hide and seek indoors."

"No," said Puggy promptly, "we're going up to the turret room. It has been cleaned out for us, and we're going to take any furniture up that we like."

Dawn cut a caper.

"I'll help you to pick and choose," he said. "Shall we have any pictures from this room?"

"Ah," said Christina, hurriedly going to her toy cupboard and producing a brown paper parcel. "You'll never guess what this is! Father gave it to me this morning. He had it framed for me, and it's our motto, and I'm going to hang it up on our wall up there. It means the same as that!"

She pointed to her piece of paper still pinned to the nursery wall with the words "Fear dwells not here!"

Dawn looked at it attentively.

"Well," he said, thumping his chest vigorously. "I can say 'Fear dwells not here!' but you can't, Tina. You're such a one for being frightened!"

"No," said Christina humbly, "I shall always be frightened inside me, I'm afraid, but I'm trying not to be frightened outside and I'm getting better."

"Come on and don't gas so!" exclaimed Puggy.

And all three children made their way to the turret door.

The stone stairs were steep and wound round and round. Dawn, who was ahead of the other two, suddenly sat down and had an inspiration.

"Listen!" he said. "This is just like the steps the pilgrims go up on their knees for their sins. Wasn't it Martin Luther who was crawling up one day when he was trying to be good? Some chap like that, I know, Aunt Rachael read to me about him. Let's try it. We're half-way up now, but it doesn't matter, we'll do the rest of the steps on our knees, it's so good to do penance sometimes!"

"But won't it be difficult?" asked Christina doubtfully.

"It'll be as easy as pat," said Puggy, "see me do it!"

But he found it more awkward than he thought. In a few minutes Dawn gave up trying it.

"It's too slow!" he said. "Besides I haven't been wicked enough to-day to do penance! It's splendid for you, Tina. You ought to do penance whenever you feel in a funk, you'd soon cure yourself."

"I'm not going to give up once I'm started," said Puggy, puffing and panting as he struggled on. "You never do anything unless it's easy, Dawn!"

Christina struggled on also, until she looked down at her knees.

"I believe a hole is coming in my stocking," she asserted.

"It hurts me dreadfully. I wish I had on knickerbockers like you. I shall give up!"

Puggy was the only one, who finished his self-appointed task.

"There!" he said. "I'm jolly glad that's done. And I shan't try it again. Now for our den!"

It was a dear little room with windows all round it. There was a cupboard, chair and table: on the wall hung a rusty sword.

Puggy took it down and brandished it in the air. "This will keep off robbers and spies, Tina! We'll cut their heads off directly they appear."

"You must have a password," suggested Dawn; "or one dark night you might out off a friend's head by mistake."

"We'll have 'Come if you dare.' We'll always keep the door locked, and only us three will know what it is, so no one else will ever be let in."

"Supposing if Nurse were to come up," suggested Christina.

"She would be a spy, so we should cut her head off."

"No, but really I mean."

"Well, we shouldn't unlock to her!"

"And father and mother!"

"Oh, they wouldn't come. We should have to be true to our rights. We couldn't let them in. Don't you go supposing things, that's so like a girl!"

Christina subsided. She went and stood at the window.

"I can see Dawn's house," she remarked; "and such a long way! It looks so small. Come and look."

"Why!" said Dawn. "You'll be able to signal to me. We'll have three flags like the railway men have. If you hang out a red flag, it'll mean stop away. You must never put that out unless you're both out for the day and then I shan't come over. The green flag you must hang out when you're up here by yourself, Puggy, and the white when Tina is, and when you're both here you must hang out the two flags!"

"And if we want you in a great hurry?" asked Christina.