Title: Longshanks

Author: Stephen W. Meader

Illustrator: Edward Shenton

Release date: March 4, 2025 [eBook #75520]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, Inc, 1928

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/75520

Credits: Susan E., David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

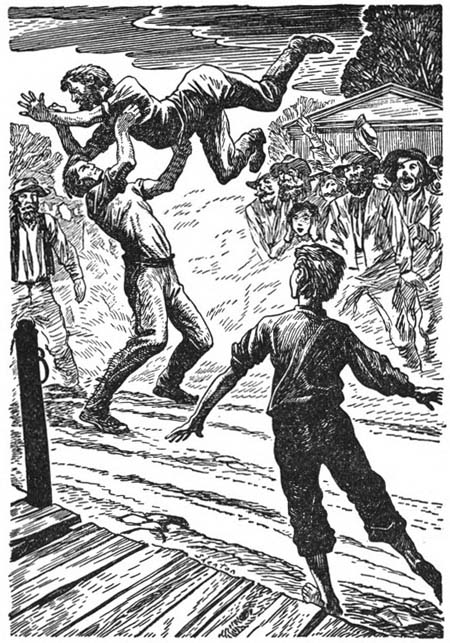

HE LIFTED HIM CLEAR OF THE GROUND

Longshanks

by

STEPHEN W. MEADER

ILLUSTRATED BY

EDWARD SHENTON

HARCOURT, BRACE AND COMPANY, NEW YORK

COPYRIGHT, 1928, BY

HARCOURT, BRACE AND COMPANY, INC.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

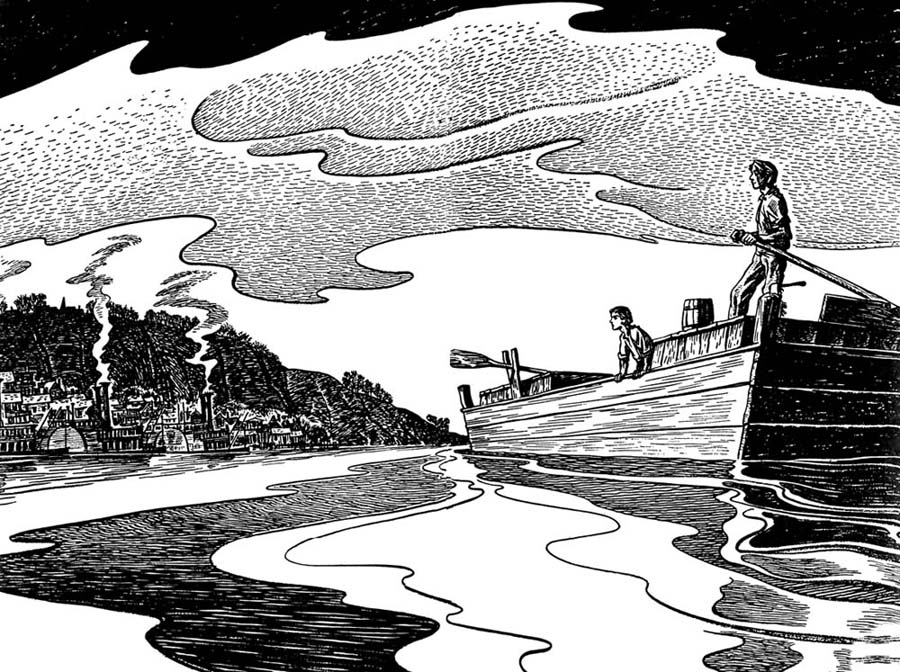

| HE LIFTED HIM CLEAR OF THE GROUND | Frontispiece |

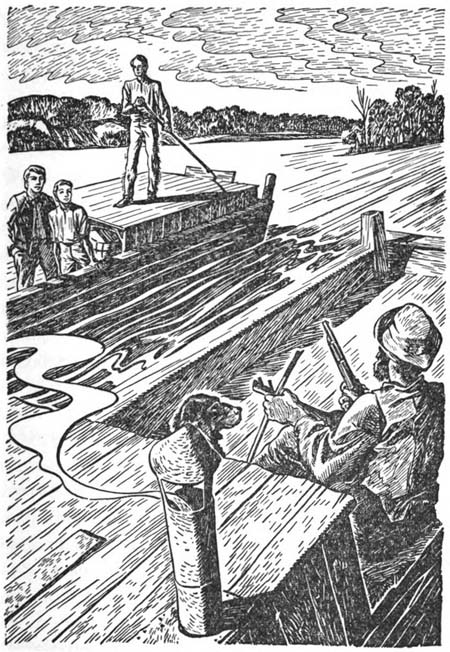

| HE PULLED A PISTOL OUT OF THE BOX | 58 |

| HE COULD SEE THE BEAST ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE POOL | 154 |

| HE SAW THE PRINT OF A NAKED FOOT | 178 |

Down the last long hill into Wheeling Town came the stage, its four lean horses at a canter and its brakes squealing under the heavy foot of Long Bill Mifflin.

The early April sun, which had been promising Spring all day, was gone now, and a chill rose with the dusk from the river. The boy on the seat beside the driver pulled his cloak around him.

“Le’s see, now,” said Long Bill, unwinding the lash of his sixteen-foot whip. “Ye say ye hain’t got no friends in the town, here, but I reckon ye got plenty o’ money. So it ’pears like a public house is the thing. Which one? Well, thar’s three or four good taverns. The one we put up at is the Gin’ral Jackson. Then thar’s the Injun Queen, an’ Burke Howard’s place, only I wouldn’t counsel ye to go thar. Good licker, good beds, an’ bad company. Most all of ’em will be full now, though, with the steamboat leavin’ tomorrow.”

Tad Hopkins thanked the driver for this information and looked down from his perch with[2] interest as the big coach lurched through the ruts of Wheeling’s main thoroughfare. Soon they came to a stop in the yard of the General Jackson Inn. Tad climbed down, pulled his portmanteau out of the great leather “boot” at the back of the coach, said good-by to his comrade of the past two days, and went into the tavern.

“No beds—not even half a bed,” said the inn-keeper with a gesture of finality.

Tad went down the street, jostling his way through crowds of river-men, backwoodsmen, drovers, and traders. Occasionally he passed an elegantly dressed dandy, but for the most part the people he saw were rough and uncouth.

Wheeling, he now realized, was a frontier town of the great West, and he felt a tingle of excitement at the thought that he had come to the gate-way of his adventure.

Finding a place to sleep in this alluring outpost seemed a difficult matter, however. The landlord at the Indian Queen was as short in his refusal of lodgings as the first man had been, and at two other taverns where he inquired Tad was met with the same answer. Then, down close to the river front, he saw a big white-painted frame building with a crude sign that bore the letters “HOTELL.”[3] Lights blazed in the downstairs windows, and a sound of music came from within.

Tad trudged up the steps and entered a large room with a sanded floor. Two fiddlers were scraping away diligently at the farther end of the place, and a crowd of thirty or forty men stood drinking and watching a raggedly dressed old fellow do a buck-and-wing dance.

At one end of the long and busy bar lounged a big, red-haired man in shirt-sleeves. Tad crossed to him.

“Could you put me up for tonight?” he asked.

The man eyed him shrewdly.

“I’ve got a cot in one of the rooms, but it’ll cost ye dear,” he answered at length. “Two dollars for the night. An’ I doubt ye’ve that much money.”

“Yes,” said Tad. “It’s high, but I can pay it.”

“Let’s see your cash,” the other replied coldly.

Tad hesitated a second, then pulled a purse from under his belt. The big handful of Government notes and silver which he held up seemed to satisfy the tavern-keeper.

“Two dollars—in advance,” he said, with a nod. “That’ll cover supper an’ breakfast.”

Tad paid him and was stuffing the purse back[4] into its place when he saw a tall, dark man, who had come up during the conversation and was standing a few feet away, leaning an elbow on the bar. He was a rather handsome fellow of twenty-four or twenty-five, with a sweeping, dark mustache and restless, sharp, black eyes. His clothes, beautifully tailored and expensive, seemed to have been worn a little too long or too carelessly. But it was his hands that Tad noticed first of all. They were white and slim, with extraordinarily long fingers. And on the middle finger of the right hand was a queer-shaped silver ring with a dull green stone.

The man shifted his gaze quickly, as Tad looked up, and the next moment he was ordering a drink from one of the bartenders.

“Here, you, Rufus,” cried the landlord to a negro boy who emerged just then from the kitchen, “take this feller up to Number Four—lively.”

“Yassah, Marse’ Burke,” was the reply, and Tad, hearing the name, remembered the stage-driver’s warning.

“Burke Howard,” he thought. “Yes, that was the name. But I’ve got to sleep somewhere, and at any rate I’ll keep my eyes open.”

The darky led him upstairs to a large, bare[5] room with two beds and a small cot. One of the beds was already occupied by a snoring guest, and the other had a shabby pair of boots beside it. Tad left his satchel under the cot and returned to the lower floor. In the great kitchen just back of the bar he found a long table at one end of which a few river-men were noisily finishing their supper. And sitting down at the other end, he was soon served with hot beef stew and potatoes. The long, cold ride had made him hungry. He did full justice to the meal and arose feeling better. The fiddlers were still playing when he returned to the main room. He watched awhile, then took his cloak and went out of the stuffy atmosphere of the bar into the cool night. A few steps down the hill brought him to the river front, and just below was the big gray shape of a steamboat, tied up at the landing. There were a few lights aboard her, and an occasional rumble of barrels came from the lower deck where sleepy stevedores were loading the last of her cargo for the long voyage down river.

Tad saw a small, lighted office at the landward end of the dock and picked his way through and around the scattered piles of freight till he reached it.

[6]“I want to take passage to New Orleans,” he said to the sour-visaged clerk.

The man continued to write an entry in his book, scowling importantly. Then he cast a slow, scornful glance in the boy’s direction.

“To New Orleans,” he replied, “the fare is forty-five dollars—forty-five—dollars—with yer stateroom an’ meals, that is. I reckon you mean Cincinnati or maybe Louisville, don’t you?”

“No, New Orleans,” Tad repeated patiently and drew forth his wallet. “Here’s fifty. The name is Thaddeus Hopkins of New York.”

Subdued, the clerk gave him his change and his receipt, and Tad climbed the hill once more to Burke Howard’s place with a great sense of being a man of the world.

It was not until a half hour later, when he lay in his cot in the big, dark bedroom at the Inn, that his lonesomeness returned.

The man in the farther bed snored steadily with a purring sound, and Tad could not go to sleep, try as he would. Instead he lay there thinking of the events of the last few days and of the journey ahead of him.

It was amazing to realize that less than a week had passed since he received his father’s letter. Back at the Academy for Young Gentlemen in[7] southern Pennsylvania, where he had spent the last two winters, it had seemed, five days ago, as if the long routine of lessons would never end. And then, one morning, had come the long envelope from New Orleans, addressed in his father’s big, bold hand, and in it had been news!

It was in the breast pocket of his coat now, but he did not need to look at it, for he knew it by heart.

“Dearest Tad,” his father had written:

“I hear from Master Lang that you have been doing well in your work. Otherwise I would hesitate to suggest the plan I have in mind. As it is, I believe there can be no harm to your education in leaving the school before the end of the term.

“I shall be sailing for England in a short time, to look after some business, and it has occurred to me that it would make a pleasant vacation for us both if you were to accompany me. There is now a steam-packet leaving Wheeling every fortnight for the South, and I wish you to make ready as soon as possible, so as to sail by the next vessel, on the sixth of April.

“A draft on my bankers is enclosed, which Master Lang will cash for you, and this should provide ample funds for the journey to New Orleans.

“I am looking forward with great joy to our[8] voyage together, and shall be waiting for you at the levee on the arrival of your steamboat.

“Lovingly, your father,

“Jeremiah Hopkins.

“March 12, 1828.”

Tad’s preparations for departure, watched enviously by the other boys in his form, had filled the next two days. And at daybreak of the third morning he had boarded the Baltimore-to-Wheeling stage.

Crossing the mountains on the great creaking coach, listening to Long Bill Mifflin’s stories and watching the road ahead for signs of the deer and bear and mountain lions that the driver assured him filled the woods—all this had made it a journey he would never forget. And now he was in Wheeling with the mighty river running past, not a hundred yards from his bed, and the steam-packet Ohio Belle waiting to carry him on the long southward slant of nineteen hundred miles to New Orleans.

Tad was genuinely fond of his father, though they had seen little of each other for the past two years. Jeremiah Hopkins was a New York cotton broker of considerable wealth. His interests frequently[9] took him into the South and to Europe, and after Tad’s mother died, he had left the boy in the care of school-masters.

The prospect of a whole long Spring and Summer spent in voyaging with his father made Ted’s heart thump joyfully. He was just drowsing off, with rosy thoughts of the future filling his head, when the door of the room was opened quietly.

A tall figure entered and crossed the room with slow steps, lurching a little as he walked. There was no lamp in the place, but a ray of moonlight, reflected from the wall, lighted the man’s face dimly. As Tad watched, he moved a few paces toward the cot and stood motionless, looking down at the boy with a somber expression as if he were deep in thought. Tad looked up from under lowered lids, pretending to be asleep, and after a moment the figure turned away and went over to the vacant bed. It was the gentleman with the long white fingers he had seen below in the bar.

For some reason he could not quite define, Tad was frightened. Surely there was nothing strange about the man’s actions. A little drunk perhaps, but incidents like that were to be expected in a river-front tavern. He watched him partially undress and tumble into the bed, where presently his[10] snores began to mingle with those of the first sleeper. And not till then did Tad draw a full breath.

Stealthily he felt beneath his pillow for the purse. It was there, safe and sound. He wound the leather thong tightly about his fingers and lay quiet, too much disturbed to sleep.

An hour crept by. Somewhere off in the woods back of the town a fox barked, and hound dogs answered with a frenzy of baying. A tipsy roisterer went past, mouthing a river song. Then gradually the noises of the night subsided, and Tad dropped off to sleep.

Bright April sunshine, streaming in the window of the room, flooded the bare walls with matter-of-fact daylight. It shone in Tad’s eyes, and he woke up with a start.

The steamboat! It left at eight. He reached for his big silver watch under the pillow, and found to his relief that it was only a few minutes after six. At the same time he discovered the purse, still firmly attached to his hand. The terror of the night seemed ludicrous now. He chuckled at his own timidity and began dressing rapidly.

The two other occupants of the chamber were still heavily asleep when Tad doused his face and hands in the wash basin, strapped his traveling-bag, and went out.

In the front bar there was only a single customer—a humorous-faced little Irishman in brass-buttoned blue clothes, who sat beside a table with a glass of hot toddy in one hand and a pipe in the other.

He looked at Tad jovially. “Bedad, an’ it’s glad I am the last barrel is aboard!” he said, quite as if they had known each other for years.

[12]“Are you one of the steamboat men?” the boy asked.

“I am that, lad—first mate of the Ohio Belle, an’ a terrible tired one. We’ve been takin’ cargo for two days an’ nights on end. An’ now I’ve got a half hour ashore while they’re a-gettin’ up steam.”

“Does she sail in half an hour?” asked Tad.

“Or sooner,” replied the Irish mate. “Th’ ould man’s a driver whin his cargo’s once loaded. If it’s breakfast ye’re thinkin’ of, wait and have it aboard with me. I take it ye’re bound down river. I’ve bread and butter and a cold chicken in me locker, and we’ll get coffee from that black son o’ Ham in the galley. The passengers ain’t supposed to begin gettin’ their meals aboard till dinner time. But we’ll have a breakfast, or my name’s not Dennis McCann.”

The plan sounded like a good one to Tad. He waited while the mate finished his glass and paid his score; then, shouldering the bulky portmanteau, he followed him down the hill.

“Ye see,” said McCann, “this steamboatin’ is only a bit of a change like, for me. Me real business is deep-water sailin’, as ye may tell by the roll o’ me legs.”

Already, by twos and threes and singly, people[13] were going aboard. Tad and his companion shouldered through the crowd that had assembled to witness the great event of the week, and crossed the gayly painted gangplank.

Instead of climbing the broad stairway to the deck above, McCann led the boy forward through a narrow alleyway just inside the paddle-box amidships. A blast of heat struck them as they emerged, and Tad found himself facing a row of glowing doors, where sweating darkies fed the boiler-fires with cordwood.

“That’s prime, seasoned hickory,” shouted the mate above the roar of the fires. “Don’t take long to get a head o’ steam with wood like this. But wait till ye see the dirty green stuff they give us down along the lower river.”

They went through another passage where the heat was almost stifling and came out on the forward cargo deck, solidly piled with merchandise. Climbing a steep, ladder-like companionway, they reached the main passenger deck. Higher still, Tad could see the “Texas,” or upper deck, with the pilot-house perched atop, and just aft of it the two tall stacks, with clouds of smoke pouring from them.

“Rest here awhile, me lad,” said McCann, “whiles I rustle that breakfast.”

[14]Tad sat down on his portmanteau, close to the rail, and watched the spectacle below. The passengers made a colorful assemblage. There were plain pioneer folk in linsey-woolsey and butternut cloth, going back to their homesteads in Indiana or Illinois. There were wealthy planters from the cotton States, resplendent in fine raiment and attended by retinues of colored body-servants. Small tradesmen, drovers and the like, from the nearer river towns, made up a fair proportion, and Tad saw two or three lonely-looking hunters in buckskin, with their long rifles and little packs of provisions, bound for the wild western country. One oddly dressed man, with an eyeglass, who was constantly asking questions and jotting down notes in a little book, Tad decided must be an English tourist.

There remained a little group which he found it harder to identify. Three or four men in fashionable frock-coats, their pearl-gray beaver hats cocked at a rakish angle, and clouds of smoke rolling up from their cigars, idled and jested by the landward end of the gangplank. Either they had no luggage, or it was already stowed aboard. Tad did not care for their looks, and he liked them still less when he saw them joined by a companion—the tall, dark fellow whom he had already[15] encountered twice in his brief stay at Wheeling.

The friendly mate returned just then with a steaming pail of coffee and led Tad off to his bunk in the officers’ cabin. Breakfast over, McCann rose and put on his mate’s cap.

“There goes the ‘all ashore’ call,” said he. “I’ll take ye down to the purser, an’ ye can get yer room from him.”

Tad found the stateroom assigned to him and put his bag inside. It was a tiny cubicle with a single bunk, its window opening on the deck far aft. Outside, the boy joined a group of passengers at the rail.

The last hurried arrivals had rushed aboard, and final preparations for departure were now in progress. Negro deck hands stood by the mooring ropes at bow and stern. At a signal from the pilot-house the cables were cast off and the darkies burst into song as they hauled them in and coiled them down.

Bells rang sharply in the engine-room. With a creak and a splash the tall paddle-wheels began to turn, and the steamboat, catching the swift current, swept grandly out into the Ohio. A long, bellowing blast of the whistle bade farewell to the waving throngs astern.

That day and those that followed were full of[16] experiences for Tad. Hour after hour he sat by the rail, or stood on the Texas with his friend the mate, watching the valley unfold. The river was running bank-full, fed by the April freshets; and added to the eight or ten miles an hour of which the steamer was capable, the strong current gave them a speed that seemed almost dizzying.

They shot past dozens of loaded broadhorns and keel-boats, drifting down with a single long steering-oar directing their course. The boatmen would cheer the Ohio Belle or curse her, depending on their humor and whether or not their craft misbehaved when her wash hit them.

Some of these rude arks held all the worldly possessions of a family—homesteaders setting out to conquer the wilderness in Missouri or Iowa. Many of them had chicken coops on their half-decks, and once Tad saw a yoke of red steers chained to a post amidships and watching the water with rolling, frightened eyes.

He tried to imagine what sort of life the people led, aboard those homely, slow-moving boats. Almost he envied the freckled youngster he saw fishing over the side of one weather-beaten broadhorn. If he weren’t going to New Orleans to see his Dad—well, he couldn’t help thinking what a[17] lazy, carefree, interesting voyage one could take in an Ohio River flatboat!

To Tad, raised in the more thickly populated country along the Atlantic seaboard, the forest-covered hills that rolled back from the river as far as the eye could see were satisfyingly wild and mysterious. And yet he was surprised at the feeling of bustle and activity that pervaded the valley.

Little settlements of new log houses were continually appearing along the shore, and in many places sheep and cattle were grazing in freshly cleared pastures. Ferry-boats, rowed by lusty river-men, plied back and forth between the West Virginia and Ohio villages. Trading scows, loaded with calico, tools, and manufactured goods from the East, put in at the farms and hamlets to exchange their merchandise for produce.

“This is a great country, lad—a great country,” Dennis McCann would say. “Some day, belikes, ’twill be almost as great as Ireland!”

Tad watched the pilot spin the huge wheel to left and right, as the Ohio Belle splashed her way down through the shallows. There was plenty of water and fairly easy steering, but the skill of the gray-bearded old keel-boat man in the pilot-house[18] seemed uncanny nevertheless. He could sense a sunken snag farther away than Tad could see a floating one. And he seemed to mind steering at night no more than in the daytime.

They stopped at Marietta and later at Parkersburg that first afternoon, and as darkness fell, the chief pilot came up to relieve his assistant, who had had the wheel most of the day. Tad, before he turned in that night, had the thrill of standing in the pilot-house and watching the old-time river-man take his craft down through the inky blackness, swinging the bends like a race horse.

The little stateroom was clean and comfortable in spite of its tiny size, and the boy slept so soundly that not even the hoarse wail of the whistle awoke him.

The Ohio Belle made a stop of several hours at Cincinnati to load and unload freight the morning of the third day. And again the following forenoon at Louisville there was a long delay.

The weather, which had been fine up till then, turned cloudy with spits of rain that morning, but Tad, as usual, spent his time on deck with the mate. The river was high enough to make the passage of the Falls a possibility, and the Ohio Belle, shallow of draft like all the river steamers, took the white water safely.

[19]The rain increased in the afternoon, and Tad was finally driven inside out of the wet. He had paid very little attention to his fellow passengers on the voyage so far. But now, for something to do, he strolled down the inside passageway to the main saloon. It was just before he reached the cabin companion that he passed a door standing ajar and heard men talking angrily. Suddenly one voice rose to a shout and a chair was pushed back with a violent scraping noise. Then the door opened, and in it, with his back to Tad, stood a tall man in shabby, well-cut clothes. The fellow swayed a little and caught the door-jamb with one hand. With the other he flung a pack of dirty playing-cards back into the room. Then he spoke in a thick, choking voice.

“You’ve cleaned me,” he said. “You’ve got my last cent, curse you! But I’ll be back, and don’t you forget it!” As he turned to leave he almost fell over Tad, and the boy was startled by the look of ferocity on his white, drawn face—a face he knew and had begun to fear.

With long strides the man reached the end of the passage, then checked himself in the act of turning the corner, and glanced back at Tad as if he remembered something. An instant later he was gone.

[20]The other gamblers in the stateroom were silent for a moment after his departure. Then one of them burst into a loud guffaw.

“So he’ll be back, eh!” he cried. “That’s a good ’un. Who’d lend him a plugged nickel on board here?”

They resumed their game, and some one slammed the door shut. Restless, Tad roamed about the interior of the vessel, went down to watch the darkies firing the boilers on the lower deck, watched the Indiana bluffs to the northward slide past in the rain, ate supper with the other cabin passengers, and finally went back to his stateroom. When he had undressed he bolted the door, opened the window a few inches for fresh air, and went to bed. Lulled by the steady beat of the rain, he was soon asleep.

It must have been hours later when he woke, for the downpour had ceased and a gusty wind was blowing. Was it the wind rattling his door that had wakened him? Rubbing his eyes he rose on one elbow and peered over the edge of his bunk. And there, just climbing through the window, was the black, looming figure of a man.

For three or four seconds Tad was too terrified to move. Then he recovered his presence of mind and scrambled up, drawing a deep breath to shout for help. But before he could utter a sound the intruder had dropped, cat-like, to the floor of the stateroom and was on him in a bound.

A powerful hand closed on his windpipe, and a gag of some sort was stuffed into his mouth.

Tad, strong and wiry for his fifteen years, fought back at his tall antagonist savagely, but it was an unequal struggle. With a swift skill that argued previous experience, the prowler pulled a cord from under his coat, and twisting the lad over on his stomach, he caught his wrists in a tight hitch behind him. Half a dozen quick passes of the cord, and Tad lay trussed up on the bunk, helpless as a baby.

Then the man rose leisurely, produced a tinder-box from somewhere, and lit a candle, which he stuck on the lid of the box and set down on the floor. Tad, getting a good look at him for the first time, saw that he was masked. A black handkerchief[22] with holes cut in it covered the whole upper part of his face.

With quick fingers the fellow went through Tad’s clothes, taking his father’s letter, his watch, and a few other trifles, and putting them in his own pocket.

The boy, struggling desperately to get his hands free, had to lie there in anguish and see his treasures taken. At last, as the robber paused, baffled for a moment, Tad felt the knots that held him slip a little. He bent his knees up to loosen the tension between ankles and wrists, and worked his arms cautiously back and forth. One hand slid through, then the other, but he lay still and gave no sign.

The man had opened the portmanteau and was rummaging through it swiftly, but still he did not find what he was after. As he rose, the candle’s beam shone full on his right hand and Tad had a momentary glimpse of a ring—silver, with a dull green stone. It was the gambler from Wheeling, who had seen him open his purse to pay for his lodging. Would he give up the search and leave as he had come? It was a foolish hope. At that very instant the fellow turned and stepped over to the bunk, his slim, sure fingers feeling under the pillow where the purse was hidden.

[23]Tad could restrain himself no longer. With a cry, muffled by the gag, he pulled his arms from behind him and leaped upon the thief. Together they went sprawling across the tiny cabin. The candle was kicked over and extinguished and the struggle went on in the dark. Suddenly the gambler shifted his position, and Tad felt an arm tighten about his head with a grip like a vise. His ears began to sing, and all his senses were numbed by the pain of the head-lock. He was powerless to move. Then he became dimly aware that his antagonist was using his other hand to open the door. A draft of cold air struck him and he was pulled out upon the deck. With a suddenness that gave him no time for terror, he felt himself swung up and outward over the rail. And then, as in a bad dream, he was falling—falling.

The shock of the icy water brought him out of his stupor. For a second or two his whole energy was concentrated on getting back to the air again, for the fifteen-foot drop had plunged him deep. As he came up, choking, he pulled the gag out of his mouth and tried once more to call for help. But the stern of the Ohio Belle had already gone past, and there was nothing around him but watery blackness.

What should he do now? He was a good swimmer,[24] but the water was almost as cold as in winter, and he knew he could not last long in it. The steamer had been running close to the Indiana shore most of the day, and he had been thrown from the starboard side of the vessel. Something told him to try for the north bank. With the river sweeping down upon him at five or six miles an hour, it was easy to keep his sense of direction. He struck out almost at right angles to the current and swam steadily, saving his strength.

The task seemed endless. As far as he could tell, he might still be miles from land, and he was numb with cold. Twice he had such an attack of shivering that he could not take a stroke for several seconds. His short cotton night-shirt was not much of an impediment to swimming, but the trailing cord was still tied fast to one of his feet, and he used up some of his strength in a vain effort to get rid of it.

Some last reserve of pluck kept his arms and legs going despite the achy weariness that was in them. He thought he saw a blacker mass rising in the blackness ahead, but it seemed to draw no nearer, and he lost hope. Then his toe struck something soft that frightened him. He lashed out desperately to get away from it and struck it again. It was mud. He could stand up, half out[25] of water, and wade. The looming bulk ahead of him must be trees. In another minute or two he was crawling up the bank, so nearly exhausted that he seemed hardly able to move, yet filled with an indescribable sense of happiness at being alive.

Another attack of shivers made him realize that he must try to get warm. Rising, he half stumbled, half ran along a sort of path that followed the top of the bank. And a moment later, to his joy, he saw a small cabin set in a clearing ahead of him. Hurrying forward, he approached the front of the shack and was about to rouse its inmates by knocking on the door, when two huge dogs came running around the corner and rushed at him. They growled and snapped so viciously at his bare legs that Tad made a hasty retreat, beating them off with the cord which he had removed from his ankle and was still carrying.

“Hello, the house!” he cried.

But the people inside either could not or would not hear him, and after a moment of hesitation a renewed attack by the dogs caused him to keep on his way westward along the bank. The damp twigs and briars slapped and scratched his naked legs, but he was past paying any attention to such trifles. If only he could find a sheltered corner of[26] some sort where he could curl up and rest without perishing of cold!

The path opened after a while on another clearing, bigger than the first, and he made out the shapes of half a dozen scattered houses off to the right, away from the river. There was something depressing in their silent blackness, and after his experience at the last place, he had little heart to approach them. Instead he followed a deeply rutted road that led forward to the bank of what seemed to be a good-sized creek flowing into the Ohio.

Tad groped his way to the door of a log shanty which stood by the water—a store-house of some kind, he thought. But here again he was disappointed, for a heavy padlock secured the latch.

As he stood there, shivering and desperate, his eye fell on a long, dark bulk beside the landing-stage. It was a boat—a clumsy broadhorn of the kind he had seen drifting down the river.

He drew closer and saw a roofed shelter covering the after part. It looked warm and dry. Surely there could be no harm in resting there until daylight. He would come ashore before the owners appeared, he told himself. And a moment later he was scrambling aboard. There were rough, warm burlap bags and a heavy tarpaulin in the[27] shelter. Shivering, he made a place for himself in a deep, snug corner and pulled the canvas cover about him. After a moment or two his body began to warm the nest, and a heavenly peace seemed to soothe his weariness like a drug. Before another minute passed, he had fallen into a slumber far too deep for dreams.

The song came sifting into Tad’s consciousness pleasantly, to the accompaniment of a snapping, sizzling noise and a most appetizing smell. He opened his eyes and tried to think where he was, but everything was dark around him—dark and strange. He put out a hand and felt bags close by. Then he remembered in a flash all the details of the catastrophe that had brought him there. With a start he sat upright, looking out over the tops of bales and boxes.

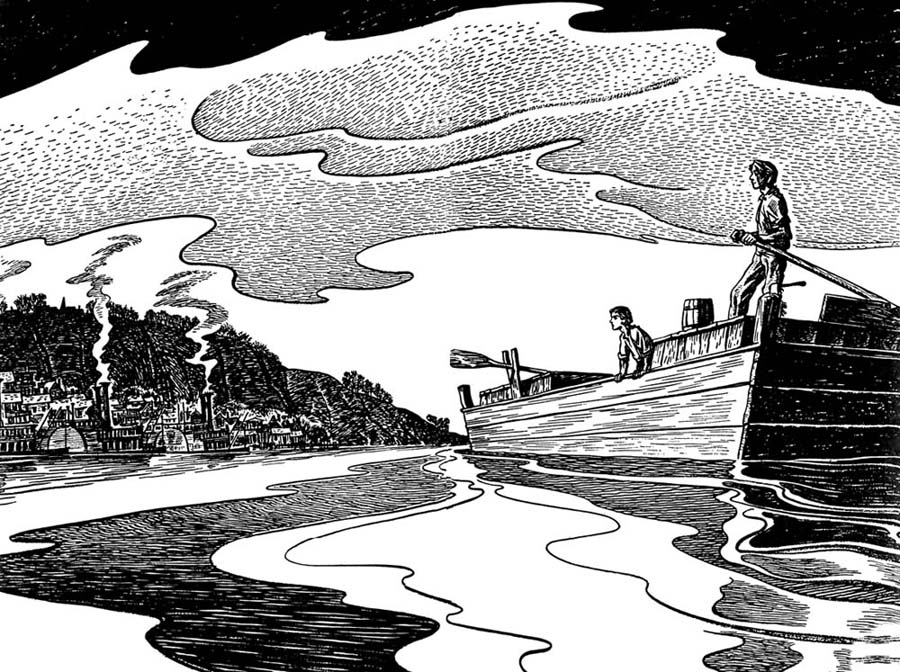

It was not only morning but bright, broad daylight. And the boat was moving. He could see the line of trees on shore marching past. Painfully, for he was very stiff and sore, he changed his position so that he could look out ahead. There in the waist of the broadhorn, just forward of the shelter, was a small fire blazing cheerfully on a rough clay hearth. Over it crouched a young man in a cap and “store clothes,” holding a frying-pan[29] full of bacon, which gave forth the pleasant aroma he had already noticed.

The tuneful cook resumed his song, adding a verse that took his crew on the next stage of their journey, and Tad, looking beyond him, discovered that there was still another person aboard the flatboat. Up on the half-deck, forward, a big, loose-jointed young fellow of nineteen moved back and forth. In each brown fist he gripped the handle of a fifteen-foot sweep-oar trimmed out of an ash sapling, and pulled steadily and powerfully, walking two steps forward and two back at each stroke. He was dressed in a coarse butternut shirt and fringed leather hunting-breeches, which made a quaint contrast to the more pretentious costume of the man by the fire. He was a tremendously tall youngster—as tall as any one Tad had ever seen—and his gaunt, big-featured, homely face, with the quirk of humor at the corners of his mouth, attracted the boy instantly. He had a mop of tousled, rusty-black hair and deep-set gray eyes that were fixed, at that moment, on the Kentucky shore.

The singer’s voice ceased abruptly, and Tad, glancing in his direction, found the man’s eyes looking straight into his own.

“Well, I’ll be tee-totally—” he began, and[30] rose, almost dropping the pan. “Looky here, Abe! Leave go them oars an’ come a-runnin’.”

The young giant in the bows landed amidships in a single long jump.

“What is it? Snakes?” he cried.

For answer the other pointed a finger at Tad, as the boy crawled out of his hiding-place. The look of open-mouthed astonishment on the cook’s face had changed now to one of outraged wrath.

“See here, you—you dirty, thievin’ skunk!” he blustered. “What in the nation do ye think ye’re a-doin’ aboard of our—”

His voice was drowned by a roar of good-natured merriment from his tall companion. And Tad, looking down at himself for the first time, realized what a grotesque appearance he presented. The brief night-shirt he had worn when the gambler entered his stateroom had been torn to ribbons in the fight which followed. And after being covered with mud and further ripped by the briars, it was no longer recognizable as a garment. From head to foot he was smeared with dirt and dried blood, and his hair was matted with twigs.

“All right,” he grinned, “I don’t blame you for laughing, or for thinking I’m a thief, either. But[31] you don’t have to worry. I just crawled in here to sleep last night, and—”

“What do ye mean by makin’ free with other folks’ property?” began the smaller of the two boatmen. The one called Abe put a restraining hand on his shoulder.

“Shut up, Allen,” he said. “Let the boy tell his story. You’re cold, ain’t you, son? Here, wrap yerself up in this.”

Gratefully, Tad pulled around him the heavy blanket which was offered, and proceeded to give them an outline of his adventure, while Allen continued cooking the breakfast.

“Humph!” grunted that individual, still sourly, when Tad had finished. “How much was you robbed of?”

“Not quite two hundred dollars,” answered the boy.

“Ha, ha!” chuckled the doubter. “That’s a likely yarn!”

“Wait a minute, Allen,” Abe interrupted. “I don’t know how much money he had an’ don’t keer. But I do know when a boy’s tellin’ the truth. What’s your name, sonny?”

“Thaddeus Hopkins,” answered the boy. “People generally call me Tad.”

[32]“All right, Tad,” the tall young backwoodsman continued. “I reckon the fust thing you’re interested in is breakfast. After that we’ll see about dressin’ you and make some plans.

“Now, Allen, if the viands are prepared you may serve our frugal repast.”

There was such a comical dignity in his stiff bow as he made the last remark that both his hearers laughed in spite of themselves. Without more ado they attacked the smoking pile of bacon and cornmeal johnny-cake, and Tad thought no food he had ever eaten had tasted quite so good. There had seemed to be a prodigious lot of it when they started, but the giant sweep-oarsman had an appetite quite in keeping with his huge, gaunt frame, and in fifteen minutes the pans were empty.

“Thar,” said Abe as he wiped the last of the bacon grease from his tin plate with a piece of corn-bread, “now maybe we can give some attention to navigatin’ the good ship Katy Roby.”

He winked at Tad as he pronounced the name, and Tad, glancing at Allen, saw him flush with embarrassment and turn quickly to the business of cleaning the breakfast utensils.

Abe looked at both banks, to make sure the broadhorn was drifting on the right course, and[33] rummaged in a pine box under the shelter, astern. From it he pulled forth presently a pair of woolen breeches, worn and shrunken, and a clean white cotton shirt.

“These may fit ye a bit long,” he said to Tad, “but rollin’ up the legs an’ sleeves won’t hurt a thing. Maybe ye’ll grow into ’em.”

Tad was really touched, for he could see that the gangling young boatman had given him his own “best clothes.”

“Thanks,” he said. “That’s mighty good of you. And if you don’t mind, I’m going to wash before I put them on.”

There was a length of new rope for mooring, tied to one of the bow-posts, and when Tad had stripped off his rags he threw the rope over the side and let himself down into the river. In the bright morning sun it felt warmer than the night before, but there was no temptation to stay in long. He scrubbed off as much of the grime as he was able, holding on by one hand, and then clambered back aboard. Five minutes later he was warm, dry, and decently clad, at least according to the simple standards of the river.

“Now, Allen,” said Abe, resting on his oar-handles, “what are we a-goin’ to do with this young rooster?”

[34]Allen was frowning in perplexity.

“Got any folks along this part o’ the river?”

“No,” Tad said. “I don’t know a soul between here and New Orleans. But if you want to put me ashore, I suppose I could get something to do and earn my keep until Father comes for me.”

Abe shook his head. “That don’t seem to me exactly reasonable,” he said. “We’re a-goin’ down to New Orleans ourselves, an’ we could maybe use a spare hand. What d’ye say, Cap’n?”

Allen seemed a trifle dubious. “Think the rations’ll hold out?” he asked.

“Sartin they will,” Abe replied. “We can make it quicker’n we planned, by runnin’ nights sometimes. An’ with a real dead-shot rifleman like you along, we ought to jest about live on b’ar an’ turkey meat, anyhow.”

The other member of the crew was somewhat mollified by these words. “Wal, maybe so,” said he. “I reckon we can’t help ourselves. What can ye do, boy? Cook?”

“I’m sorry,” Tad hesitated, “I—I don’t think I can, but perhaps I could learn.”

“I b’lieve Allen, here, would condescend to give ye a lesson,” put in Abe, seriously.

“Hm,” said Allen. “Can ye ketch fish, or chop wood?”

[35]“I never tried,” answered Tad, “but I’d like to.”

Abe, who had been rowing hard during this questioning, leaned on his oars again.

“Now see here,” he said, “you don’t have to worry about this yere boy. Any youngster with the spunk to wrestle with a robber, an’ be dropped off a steamboat into cold water at midnight, an’ swim across the Ohio River, an’ run three miles, naked, with mean dogs after him—can look out for himself. He’ll be cookin, fishin’, an’ choppin’ wood long ’fore he gits to New Orleans.”

With these words Tad was officially admitted to membership in the crew of the home-made flatboat Katy Roby and set forth on one of the strangest and most interesting adventures that ever befell a fifteen-year-old school boy.

All that fine April day they made steady progress down the swollen river. Part of the time Abe and Allen worked at the oars, adding a mile or two an hour to the speed of the current. Part of the time they loafed in the sun on the half-deck, asking Tad questions about the politer world of the Eastern cities and swapping yarns about their own great frontier country.

“You mean to tell me they all wear shoes in New York?” asked Abe incredulously.

[36]“Yes,” said Tad, “all but a few poor children. I’ve never gone barefoot since I was a baby.”

“Gosh!” the lanky backwoodsman exclaimed. “Look at my feet!” He pulled off his moccasin and showed a sole covered by a single vast callus. “Outside of about five months in winter when I wore hide boots, I never had a shoe on my foot till last year. Pap always figgered it was cheaper to let me grow my own leather,” he added, with the twinkle in his gray eyes that Tad was learning to expect.

Piecing together what the two boatmen told him and what he picked up from their conversation, he learned that Allen Gentry was the son of a merchant living in the settlement at the mouth of Little Pigeon Creek, where Tad had first sought shelter in the flatboat. His father, James Gentry, was the owner of the craft, and was sending Allen to sell the corn, pork, and potatoes which made up its cargo in the great produce market of New Orleans.

Abe, as he himself told Tad, was merely a “hired hand,” sent along to do the heavy work and to “take keer” of Allen. But it was quite apparent that the long-limbed country boy with his quaint humor and his common sense was the real leader of the expedition.

When the lingering spring sunset came, the flatboat was bowling along so merrily that Abe decided to make a long day’s run of it. He left the bow sweeps and stretched his long bulk on the little after deck with the steering-oar under his arm. Allen pulled out a home-made banjo from some mysterious hiding-place and proceeded to strum it softly. His pleasant tenor voice, floating out across the reaches of the river, was joined by a bass bellow from another broadhorn astern, and for several miles they drifted to the mellow harmony of “Skip to My Lou,” “Weevily Wheat,” “Down the Big River,” and “Wabash Gals.”

The afterglow dimmed out of the sky, and bright stars filled it. And Tad, yawning drowsily, was sent to bed. Rolled up in a blanket on the hard deck planks and lulled by the murmur of the river, he slept as soundly as he ever had in his life.

The sun had already risen when he woke, and he was surprised to see the budding branches of a big sycamore overhanging the deck of the flatboat. Abe was up on the bank chopping wood for[38] the breakfast fire, and Allen was casting off the stern mooring-rope which had been fastened around the tree. Tad threw off his blanket, pulled up a bucket of water from over the side, and hastily performed his morning ablutions.

By the time he had finished, the boat was well on its way again.

“Wal, youngster,” chuckled Allen, “how’s this? You awake an’ ready to eat again?”

The truth was, Tad did have a fine appetite for breakfast, and he admitted it with a grin. “I feel as if I ought to work for it first, though,” he said.

“So you can,” Abe put in. “Here’s the ax. S’pose you split some o’ this wood up in nice fine kindlin’, while I go up forrard an’ persuade her a little with the oars.”

Tad, willing enough, picked up the ax and started clumsily to hack away at the chunk of pine. By dint of hard work he managed to split away a cross-grained sliver from one side and was attacking the larger piece again when a smothered choking sound reached his ears. There lay Allen, rolling on the planks and holding his sides with laughter.

In a country where children learned to use an ax almost as soon as they could walk and supplied the house with firewood before they knew their[39] A-B-C’s, the sight of Tad’s awkwardness was enough to provoke any man’s mirth.

But Abe did not laugh. He left his oars and came down to Tad’s side.

“Watch,” he said. “You’ll git the knack of it in no time.” And swinging the ax one-handed, with no apparent effort, he cleft the log cleanly through the center, then into quarters. His arm rose and fell steadily, and in an amazingly short time there was only a neat pile of slender pine splints lying by the hearth.

As they breakfasted, a big keel-boat, piled with farm implements and furniture and with half a dozen lively-looking children swarming over and through everything, steered close to them.

“Movers,” said Allen.

A bearded man with a cross, discontented face appeared at the gunwale of the keel-boat and hailed them.

“Where are we? Can you tell me?” he shouted.

“This is the Ohio River,” Abe replied cheerfully.

“Yes, but whereabouts—what part?” fretted the mover.

“Jest now,” said Abe, considering, “you’re in Indianny. But in five more minutes your bow-end’ll be in Illinois. Thar’s the Wabash, now.”

[40]He pointed to the right bank a mile or so below, and Tad saw a wide river emptying into the Ohio from the north.

The bearded man muttered something that might have been thanks and went back to the tiller of the keel-boat, while Abe resumed his breakfast.

“They’ll make a mighty valuable addition to the population of whatever place they’re a-goin’ to,” he remarked between mouthfuls of johnny-cake.

“Must be Illinois,” put in Allen. “That question sounded jes’ like a ‘Sucker.’”

The latter scornful epithet, Tad discovered, was universally applied by the Hoosiers to their neighbors on the west. Although hundreds of families were moving from Indiana into Illinois every year and the people of the two States were often blood kin to each other, there was a vigorous rivalry that did not always confine itself to calling names.

Something of this feeling Tad was soon to see, for they made a landing at Shawneetown on the Illinois shore, sometime during the forenoon. One of the first things he had asked his new friends was how he might send word of his safety to his father, in New Orleans. And it had been agreed[41] that they should stop at the first town where steamboats touched and mail a letter.

There were no writing materials aboard the Katy Roby. When Abe and Allen had calculations to make, they did it with a burnt stick on the deck planking. So, leaving Allen to guard the flatboat and her cargo, Abe and Tad climbed the muddy hill from the landing-stage and sought a place where paper and ink might be bought. One of the first buildings they reached was a rambling log house with a wide porch in front, which turned out to be a general store. They entered and made their purchases, and Tad started to write his letter, using the head of a barrel for a table. Briefly he described the attempt to put him out of the way and how he had made his escape. Basing his estimate on the average speed of the Katy Roby, he wrote that with good luck they would reach New Orleans within two or three weeks.

He was just signing his name to the message when he heard a commotion of some kind outside. The group of loafers who had been hanging around the door when they entered now left the porch with a clatter of boots. A loud voice was raised tauntingly.

“Wal, you long-legged, slab-sided, lousy[42] Hoosier, want to see how it feels to git thrown?” it asked.

Tad hastily pocketed his letter and went to the door. In the midst of a ring of spectators outside, a big, stocky, river-man was brushing the dirt off his hands, while a crestfallen youth in torn homespun lifted himself out of the mud.

Abe’s long, awkward figure towered above the group of bystanders. Evidently the champion’s invitation had been addressed to him. He strolled forward into the ring. “Don’t keer ’f I do,” he said.

There were roars of laughter from the Illinois men.

“Them leather breeches is to scare off the varmints!” one cried.

“What do they feed you on, Longshanks?” asked another.

“Suckers,” answered Abe, with a grin, and pulled his belt a notch tighter.

The river-man was broad-shouldered and powerful, with short, thick arms like a bear’s. He pounded himself on the chest with a huge fist and roared:

“Here I am! I’m ‘Thick Mike’ Milligan o’ Kaskaskia! I kin drink more likker an’ walk straighter, chaw more terbakker an’ spit less[43] juice, break more noses an’ swaller less teeth, than any man on the rivers. I eat wildcat fer breakfast an’ alligator fer supper. I’m a ragin’ hyena! I’m a terror to snakes! Look out, fer I’m a-comin’!”

As he shouted the last words, he jumped in the air and clapped his heels together. Then with a rush he charged at Abe.

There was nothing awkward about the tall Hoosier now. He took a quick sidewise step, springy as a cat on his moccasined feet. One long arm shot out and caught Milligan by his thick neck, spinning him about so that he dropped on one hand and one knee. The river-man was up in an instant, roaring like a bull. But now he came on more warily, trying to get in close, where he could come to grips with his opponent. Abe, circling and retreating constantly, held him out of reach with those long, sinewy scarecrow arms of his.

The onlookers began to hoot and jeer. “They call that wrastlin’ in Indianny?” yelled one. And another edged close to Abe to trip him.

“Look out!” cried Tad, but his warning was unnecessary. The lanky young flatboatman had seen the movement out of the corner of his eye, and instead of falling over the outthrust foot he[44] suddenly leaped backward, seized the tricky bystander by the collar, and hurled him through the air, straight at Milligan. Then, without the loss of a second, he was after the two of them. Catching the river bully off his balance, he lifted him clear of the ground and slammed him on his back, piling the dazed and gasping meddler on top of him before either could collect his wits.

“Thick Mike” picked himself up angrily, while the crowd howled its desire for the “best two out o’ three falls!”

Abe seemed to have undergone a change. He was mad now—mad clean through—and his gray eyes blazed as he trod lightly forward to meet Milligan’s attack.

The river-man tried a new plan. Waiting till Abe was close, he suddenly plunged in low, hoping to get a crotch-hold and upset the lanky Hoosier. This time Abe wasted no time in dodging. Before the other’s hands were fairly on him, he had seized him with both arms around the middle and whirled him, feet in air, over his shoulder. Milligan landed heavily on the small of his back, and with a panther-like spring Abe was on him, pinning his shoulders flat.

There was no longer a question as to which was[45] the better wrestler, and the stocky Kaskaskia man was the first to admit it. He rose, still a little dizzy from the force of his fall, and shook Abe’s hand.

“They ain’t many kin do that,” he grinned. “How tall air ye, lad?”

“Six foot four,” said Abe.

“An’ how old?”

“Nineteen,” answered the flatboatman.

“Great sufferin’ catfish!” the other exclaimed. “Ye’d oughter be a good-sized feller when ye grow up!”

The crowd of loafers did not seem disposed to take their champion’s defeat quite so good-humoredly. As Abe and Tad went back to the store to post the letter, these hangers-on followed at their heels.

“Huh! Wrastle? Sure he kin. That ain’t nothin’,” said one of them. “But what’d he look like in a real ruckus—knock-down an’ drag-out?”

The tall youth turned on the top step and deliberately rolled up the sleeves of his shirt.

“Listen,” he said, quietly. “One Hoosier to one Sucker ain’t a fair fight. But if any two of ye want to tackle me at once, I’ll be pleased to accommodate. Step right up here, boys.”

His words produced an immediate hush. For a[46] moment he stood there eyeing them scornfully, while they shuffled their feet and looked sheepish. Then he entered the store.

“Come on, Tad,” he said with a wink, “we’ll be a-goin’ now.”

The boy gave his letter to the postmaster, got that worthy’s assurance that he would mail it on the steamboat Nancy Jones, from Louisville, likely to stop at Shawneetown in the next day or two, and followed Abe down the hill.

Allen, who had heard the shouting, was filled with curiosity. “What’d ye see, boys—a fight?” he asked.

“No,” said Abe, “it was jest a demonstration.” And chuckling, he went about the business of getting headway on the boat. Allen, however, was not satisfied till he had got a glowing account of the wrestling bout from Tad.

“That’s right,” he nodded. “This yere Abe is the powerfullest critter ever I see. He kin outrun, outwrastle an’ outfight any man in our country, back home—yes, an’ outtalk any woman. He’s as fast as greased lightnin’ and tougher’n a white oak post.”

It was early afternoon when they passed the broad mouth of a cave on the Illinois bank. Allen, who had once been as far as Paducah on the steamboat,[47] pointed it out and told the gruesome story of the Wilson Gang, a notorious outlaw band which, twenty-five years earlier, had made the cavern its stronghold.

“Thar was more’n a hundred of ’em,” said he, “an’ they used to rob boats an’ travelers all up an’ down the river. They say thar’s a sort o’ chimney goin’ up from that cave into another one over it, an’ after the gang was cleaned out, sixty skeletons of murdered folks was found up in that secret cave.”

Tad gazed at the place in awe as they drifted past. It looked peaceful enough now. The sun slanted brightly across the gray face of the rock, and a flight of twittering swallows darted in and out of the dusky opening.

They fished and talked, sang and whittled, with alternate spells at the oars, all afternoon, and toward sunset sighted a black cloud of smoke beyond the next bend.

“Steamboat comin’,” remarked Abe. A long, mournful whistle-blast came up the river, and they saw a man, at work in a stump-filled clearing, suddenly drop his plow handles and run down to the shore. He leaped in the air, waving his hat frantically as the tall stacks and shining upper works of the craft appeared around the bend.[48] His horses eyed the approaching monster with alarm, snorted, reared, and would have dashed off if the plow had not buried itself and anchored them.

The steamer passed within a dozen yards of the flatboat and they read her name, Amazon, in gilded letters across her paddle-boxes. The big wheels thrashed and churned with a mighty uproar as the vessel forced her way up against the current at all of four or five miles an hour. The foamy wake that rolled out from her paddle-wheels caught the Katy Roby at an awkward angle and made her pitch like a steer. Bracing his feet, Abe pulled on the oars with all his strength to keep the craft from swinging sidewise. A roar of laughter went up from the deck of the Amazon where two or three of the crew were gathered.

“Hold her, bean-pole!” shouted one of them.

Abe dropped the oars, picked up a four-foot stick of firewood, and sent it whirling after the steamer, already many yards away. He threw so hard and so true that the billet bounced off the rail a foot from the fellow’s head, and the steamboat men retreated hastily.

Abe grinned as he handled the sweeps again. “I’m willin’ to take their wash,” he said, “but not their sass.”

[49]That night, when Allen was tuning up his banjo, Tad went aft to lie by the steering-oar with Abe. He looked at the long, easy frame of the backwoods youth and thought of that morning’s wrestling-match.

“Jiminy, but you’re strong!” he said, admiringly.

Abe shifted his position, looking off at the low stars.

“That’s nothin’!” he said gruffly. “I was born big. There’s no credit in that. What I’d like is to be able to sing an’ play the banjo like Allen. I can’t carry a tune any more’n a crow. Or I’d like to go to an academy like you. I bet you’ve read a power o’ books!”

Tad was truthful. “Not such a terrible lot,” he said. “They’ve got a whole library full at school, but when you have to read them, there’s no fun in it.”

“Gee,” murmured Abe, and was silent for a little. Then he turned toward the younger boy, his rugged, homely face serious in the starlight.

“I couldn’t git much schoolin’, back whar we lived on Little Pigeon,” he said. “But I’ve read some—books like the Life o’ Washington, an’ the Fourth Reader an’ the Bible, an’ Æsop’s Fables, an’ the Laws of Indiana, an’ Pilgrim’s Progress,[50] an’ Robinson Crusoe, an’ the Almanac. Guess I’ve read about all the books I could borrow from any one ’round Gentryville.

“’Course I learned to write an’ cipher in the log school. An’ I used to work out the accounts for folks—neighbors—an’ write letters for ’em if they had to send news off. I fixed me up a quill pen out of a turkey-buzzard’s feather, an’ the ink I made out o’ blackberry-briar roots an’ copperas.

“I’d rather have book-learnin’ than all the muscle in the world. They say there’s a new University goin’ to open in Indiana next Fall. If I was rich, maybe I wouldn’t go up thar in a hurry! But I guess I’ll likely stay workin’ ’round on farms an’ boats.”

“I should think you’d want to,” Tad put in. “If I was as big and husky as you, and could do the things you can, I’d never go back to school.”

“Thar,” chuckled Abe, “you’ve put your finger on it. I seem to be a born corn-husker. An’ that’s all right, too. I like an ax. I like to work with an ax, splittin’ rails, buildin’ things. An’ I like to plow, an’ hoe, an’ take care o’ cattle. Only,” he paused, frowning, “some way, that ain’t enough.” And for many minutes thereafter he sat buried in thought, his chin in his hand. Tad, respecting the stern, almost sad expression on the older boy’s[51] face, rose quietly and joined Allen up forward.

Allen finished his song and greeted him. “What’s the matter—Abe got one of his silent spells?” he asked. “Don’t mind him. He’s all right—jes’ shiftless an’ dreamy sometimes.”

And striking a chord or two, he launched into the stanzas of “Old Aunt Phoebe.”

They were peeling potatoes for the noon meal on the fourth day of the flatboat’s voyage when Tad chanced to look off to the southward and stood up suddenly, with an exclamation of wonder. Above the Kentucky bluffs a cloud was rising swiftly—a living cloud of beating wings.

“Pigeons!” said Abe. And Allen, springing to his feet, ran back under the shelter to get his fowling-piece.

The great flight of birds came swiftly. Before Allen could finish loading the long-barreled shotgun, the first of them were winging over—twos and threes and fifties, and then thousands—so many that they seemed to cover the sky. A vast, vibrating hum of wings filled the air.

Allen rammed home his charge and lifted the gun. Taking aim was hardly necessary. He pointed where the flock seemed thickest and fired. At the loud report a sort of eddying movement went through the nearer part of the cloud of birds, but there was no change in the speed or direction of the flight.

Then bodies of dead and wounded pigeons began[53] dropping like feathered hailstones into the river. They sent up little splashes of water. There must have been a dozen at least.

Only one pigeon fell aboard the Katy Roby. Tad picked up the warm, plump body and held it, watching the eyes glaze. The sleek brownish-gray feathers were ruffled, and a shot had carried away part of the long tail.

Allen was grumbling. “One pigeon! I hit plenty, but they all fell in the water. We’d oughter have a dog along to fetch ’em.” He was reloading rapidly while he talked, and raised the gun again, looking for the likeliest place to shoot.

Abe’s voice came from the bows.

“Don’t kill any more of ’em, Allen,” he said with something like a command in his tone. “Spose’n you should git one or two more to fall in the boat. It takes more’n three pigeons to make a meal for this crew. You ain’t jest shootin’ ’em for the fun of it, are you?”

“Well, why not?” replied young Gentry with a scowl. “Thar’s millions an’ millions. Look at ’em!” He waved his arm in a wide arc. “They’re so thick they’re ’most a nuisance.”

“No, sir,” Abe answered. “They never harm crops, do they? An’ they’re pretty, an’ hev a right to live. They’re bein’ killed off too fast as it[54] is. My Pap says when he was a boy in Kaintuck’ there used to be four or five flights every year when the pigeons would make the sun dark for a whole day. You don’t see that now. This flock here is ’most over now. That’s what comes o’ killin’ ’em by the bushel jest for the sport of it.”

Even as he spoke, the rear guard of the flock swept over, leaving the sky clear once more. The dark cloud of beating wings drew away rapidly to the north, and in a moment the only traces of the event were the stiffening body in Tad’s hand and the acrid smell of burnt powder as Allen sulkily set about cleaning his gun.

When dinner was over, the long-legged backwoods boy rose, stretched and climbed to the forward deck. Before picking up the oars he shaded his eyes with his hand and looked away south-westward.

“Boys,” he said, “unless I’m mighty mistook, we’ll pass Cairo an’ be sailin’ down the Mississippi before night.”

“Huh,” snorted Allen, “what do you know ’bout it? This ain’t the headwaters o’ Little Pigeon Creek ye’re a-navigatin’!”

“Reckon I’m as wise an ol’ barnacle as any aboard this packet,” Abe replied with a twinkle. “Whar do you figger us to be, Cap’n Gentry?”

[55]“Wal, le’s see, now,” said Allen. “We sighted Paducah jes’ before noon. Now I fergit how many miles it is from thar, but seems like they told me it was a full day’s run, that time I was down thar I told ye about.”

The argument went on spasmodically for the balance of the afternoon. But Abe, as usual, was right.

An hour after sunset, in the calm blue dusk, they floated out of the Ohio with the broad current of the Mississippi sweeping down in a resistless muddy tide from the northwest. They knew the power of that flood a moment later when another broadhorn, just below them, was caught in an eddy and whirled end for end like a twig in a brook.

Abe pulled with might and main on the starboard oar, and Allen swung the steering-sweep to bring them over toward the Kentucky shore. “We might’s well stay this side whar it ain’t so yaller, long as we kin,” said the big bow-oarsman. “I feel sort o’ more at home in water that might ha’ come down from Little Pigeon.”

They tied up to the Kentucky bank while it was still light enough to find a good mooring-place. Not much singing or hilarity aboard that night. Something of the vast, brooding mystery of the[56] river had got into them. Tad didn’t feel afraid, or even lonesome, exactly. He just wasn’t in a mood for talking. The immense distances, the wildness of the country, the hurrying, watery sounds of the mile-wide flood—perhaps it was none of these, or all of them combined, that weighed down their spirits.

“Spooky, ain’t it?” said Allen, shaking himself uneasily, and he went to his blankets without taking out the banjo.

Tad followed soon and left Abe sitting hunched in dark silhouette against the stars, his big hands gripped around his knees and his eyes on the shadowy line of willows and cottonwoods across the river. He was used to spells of sadness. This one seemed no worse than usual.

Morning made a difference. The sun shone on budding leaves of tender green and sparkled on the dimpling surface of the water. A perfect riot of bird-song filled the air. In the big trees that overhung the mooring-place there must have been hundreds of warblers, finches and song-sparrows, and several times Tad caught the red flash of a cardinal among the branches.

Allen sang and Tad whistled intermittently while they cooked and ate breakfast, and even Abe hummed something that might have been[57] “Turkey in the Straw” and danced a home-made double shuffle on the fore deck, as he cast off.

“Make the most of it, boys,” he laughed. “This is all the Spring we’re a-goin’ to see. By day after tomorrer we’ll ketch up with Summer, at this rate.”

The sun was warm enough that day to give truth to the tall boy’s words. They passed islands where the dogwood, at the height of its bloom, made a white canopy almost to the water’s edge. And in fields along the shore there were bare-footed children running about in calico frocks.

The river did not seem lonesome in daylight. Above and below them they could see busy specks that were keel-boats and barges. They overtook one of these toward noon—a shabby old trading-scow. On its after part was built a little house, or “caboose,” from which a length of rusty stove-pipe projected. And a dingy bit of what had once been bright cotton print waved in tatters at the top of a pole. Despite the forlorn appearance of the craft, cheerful sounds came from it, as the Indiana flatboat drew alongside.

A squat, broad-shouldered old man with a bushy gray beard and merry eyes was sitting on a box, forward of the caboose, scraping away lustily at a backwoods fiddle, and thumping time with[58] one foot on the deck. And sitting facing him, apparently entranced by the hoarse squeaking of the fiddle, was a fine red setter dog.

The old fellow finished his tune with a flourish and swung about on his box.

“Howdy, boys!” he cried. “I’m Moses Magoon o’ the Big Sandy, peaceful trader an’ musician by choice, but a bad ’un when raised. Mebbe you’ve heard o’ these half-horse, half-alligator fellers. I’m one-third horse, one-third alligator, an’ the other third mixed catamount an’ copperhead. What d’ye find yerselves in need of today? I’ve got calico, buttons an’ sewin’ thread, extra fine pantaloons, shoe leather an’ wheaten flour, pots an’ pans, powder an’ lead, candles, salt, nutmegs, an’ red pepper.”

All this had been said in a loud, hearty voice and without any apparent pause for breath. Mr. Magoon was about to continue when Abe interrupted by laying an oar across the bow of the trading-boat and pulling the two craft together, side by side. This maneuver was not to the liking of the setter, which jumped up, growling, teeth bared for action.

“Be still, Fanny,” said the old man quietly. With a dexterous motion he pulled an old-fashioned horse pistol out of the box beneath him and laid it across his knees. At the sight of this weapon, fully eighteen inches long, Abe’s jaw dropped comically.

HE PULLED A PISTOL OUT OF THE BOX

[59]“Hol’ on!” he exclaimed, and hastily withdrew the foot he was about to set aboard the scow. “’Pears like we’d better introduce ourselves, too. We’re the law-abidin’est, softest-spoke flatboat crew betwixt this an’ the Falls o’ the Ohio. We’re two-thirds fishin’ worm an’ three-quarters turtle-dove. All we want’s a chance to trade some good salt pork an’ ’taters fer a pair o’ them extra fine pantaloons—boy size—’bout big enough fer young Tad here. Ef you’ll jes’ put away that blunderbuss an’ explain the purpose of our visit to Miss Fanny, we’ll come aboard an’ do business.”

Magoon’s whiskers parted to display a set of strong, even teeth. He tipped his head back and reared with laughter. “So ye shall,” he said at last, and wiped the tears from his eyes with the back of a weather-browned hand. “Durned ef I ever heerd sech a brag as that on any o’ the rivers,” he chuckled. “But I’ll guar’ntee the fishin’ worms an’ turtle-doves kin take keer o’ theirselves when they hafter.”

He rose, thrust the pistol back into its hiding-place, and limped over to the gunwale with outstretched[60] hand. “Make yerselves to home,” he said.

They lashed the two boats loosely with a length of rope, and Allen stayed aboard the Katy Roby to steer, while Abe and Tad made their purchase. They picked out a pair of serviceable brown homespun breeches from the merchant’s stock, and for them traded two flitches of bacon and a barrel of apples.

Allen, with an eye to the profit of the voyage, started to raise some objection, but Abe merely answered, “I’ll pay fer ’em when I git my wages,” and went on rolling out the barrel.

When the transaction was completed, the genial trader looked up at the sun and whistled. “What about dinner?” he asked. “I’ve got a big catfish here—more’n Fanny an’ me could eat in a week. S’pose I make some hot coals an’ we’ll broil him on a plank.”

The Hoosier crew were in hearty agreement with this idea, and while Abe relieved him at the steering-oar, Allen set about making corn-bread as their share of the feast.

Tad, who had no special chores to perform, stayed aboard the scow and got better acquainted with Magoon and the red setter.

The old river-man had an ingenious sort of[61] Dutch oven built into the wall of the caboose. Adding dry wood to his fire, he soon had a brisk blaze roaring up the chimney. Meanwhile he proceeded to clean and split the catfish, and peg it out on a piece of plank which had evidently been used before for the purpose.

“That pistol,” said Moses Magoon, “my ol’ Pap toted over the mountings from North Caroliny in ’seventy-nine. It’s old an’ rusty an’ ain’t been fired fer fifteen year. ’Tain’t even loaded now, but I keep it handy to persuade some o’ these thievin’ river toughs with.

“I been cruisin’ up an’ down the Mississip’ an’ the Ohio ever since I was a young feller, an’ I’ve run afoul of ’em all, one time or another. Jes’ last week here, a big keel-boat with half a dozen men on deck come up alongside, somethin’ like you did. It was Little Billy, an’ his gang, from up the North Fork o’ Muddy Run, an’ I figgered I was in fer trouble.

“But this yere Little Billy has only got his eye out fer two things—money an’ whisky—an’ I don’t carry neither one of ’em. I let him come aboard an’ look, an’ he never laid hand on any o’ my goods—jes’ as polite as you please. ‘Well,’ says he, ‘long as ye ain’t got no Kaintucky red-eye, what’ll ye take fer the dog?’

[62]“‘Sorry, Mister,’ I says, an’ I was scairt. ‘She ain’t no ways fer sale,’ I says. ‘She’d break her heart an’ die if I let her go.’ An’ Little Billy, he jes’ grins an’ says, ‘Right, I had a good dog myself, once.’ An’ with that he steps back on his keel-boat an’ off they go.

“I had a bad time, couple o’ years back, with Mike Fink—him they call ‘The Snag,’” the old trader went on. “I landed at New Madrid one night an’ went up to the store. When I come back, with my arms full o’ provisions, I see another boat tied up, close above. An’ jest as I was goin’ to step aboard mine, eight or ten men that had been layin’ low under the bank stood up thar in the dark. One of ’em says, ‘All right, stranger, we’ll take keer o’ this,’ an’ he grabs the provisions. Then they march me aboard o’ my own craft an’ tell me to show ’em whar my money is an’ no monkey business. I acted like I was plumb scairt to death—teeth a-chatterin’ an’ knees a-shakin’.

“‘All right,’ I finally whispers, ‘I’ll show ye whar it’s hid, only thar ain’t room fer but two to go in.’

“Mike Fink swings ’round to his gang. ‘Git back on shore, ye lousy varmints!’ he bellers. When they’re all up on the bank, he pulls out his[63] knife an’ holds it in his teeth, an’ I lead the way into the caboose here. It’s a right dark night an’ Mike he strikes a light an’ holds up a candle, while I’m rummagin’ round in the corner. Pretty soon I undo the ketch o’ this leetle trap door down here in the bulkhead, an’ open her up. ‘Whar’s that go?’ says the Snag. ‘That’s my secret hidin-place,’ I says—‘want me to go first, or you?’ An’ I’m still lettin’ on to be tremblin’ so I kin hardly talk.

“‘You,’ says Mike, ‘an’ by the ol’ ’Tarnation I’ll cut you into stewin’ meat if you try any tricks.’

“So I crawls through the hole on my hands an’ knees, an’ waits fer him to follow.”

Magoon opened the little trap door as he spoke, and Tad laughed when he saw a two-foot ledge of deck and then the river beyond it.

“Wal,” the old man went on, “Mike didn’t come through, right off, an’ I tell you I was scairt. ’Twas so durn dark outside, I knew he couldn’t see, but he stayed thar an’ tried to figger if I was up to anything. Finally he says, ‘Bring the money out here in the cabin.’ I’m workin’ at the moorin’-rope all this time, an’ now I make a noise like I’m tuggin’ an’ liftin’. ‘Can’t,’ says I. ‘It’s too heavy!’

[64]“That fetched him, sure ’nough. Here he comes on all fours, with the knife still in his teeth. I gives the rope one last pull an’ it comes away, an’ then ’fore he rightly sees whar he is, I ketches him by the scruff o’ the neck an’ heaves him overboard.

“You can bet I didn’t wait to see whether he was drowned, neither. I give a big shove with the oar an’ got out o’ reach o’ the bank, an’ then I stood by the gunwale with an ax, ready to cut the hands off anybody that tried to swim out an’ climb aboard.

“It must have took Mike a few minutes to crawl out an’ git organized again. Anyhow they never follered me.”

The last part of the story had been told out on the open deck, and Abe and Allen were listening with rapt attention.

“Is that the same Mike Fink they call the ‘Snappin’ Turtle’ up our way?” asked Abe.

“That’s him,” the old man nodded. “He’s called that above the Wabash. Both names is too good fer him. Wal, boys, how’s the dinner comin’ along?”

Tad’s mind was filled with questions about the river pirates, but he postponed asking them long[65] enough to do full justice to the planked catfish. When the meal was over he perched himself on the gunwale of the trading-boat and waited for the grizzled river-man to get his cob pipe going.

“Mr. Magoon,” he said, when the blue smoke-clouds were rising at last, “who do you think is the worst outlaw you ever ran across?”

The old man puffed in silence for a moment. “Reckon the worst I ever see with my personal eyes was ol’ Jericho Wilson o’ the Cave Gang,” he replied at length. “Him an’ Black Carnahan an’ Earless Jake Rogers was a bad bunch. They had more’n a hundred men to back ’em up, an’ kep’ the whole Ohio Valley scairt fer a while. When that posse of up-river hunters wiped ’em out, I know mighty well we all breathed easier.

“But listen to me, boy. Fer real cold-blooded, cutthroat deviltry, nobody on any o’ the rivers kin touch this man John Murrell. He an’ his gang hang out on an island somewhere down beyond Natchez. He started as a gambler, hoss-thief, an’ murderer, but his main trade nowadays is stealin’ niggers. They say he’s killed twenty-eight men himself, an’ gosh knows how many the rest o’ the gang have put away. Mostly he works along the lower river, but once in a while, when things git[66] too hot around the plantations, he stays out o’ sight fer a while, mebbe up the Ohio, or over in Alabama.”

“Did you ever see him?” asked Tad.

“Not me, an’ I hope the day don’t soon come!” said Magoon, fervently. “They tell me he’s a tall, pale-faced sort o’ feller, with dead black hair like a Frenchman. But the chances are you’ll never run afoul of him. He don’t bother with flatboats much. He’s out for bigger game.”

He got up from his box and looked over at the eastern shore, shading his eyes with his hand. Some one on the bank was waving a white cloth to and fro.

“That’s a signal fer me to land,” he said. “The folks along the river know a tradin’-scow by the calico flag, an’ wave to us when they want us.”

Tad got back aboard the Katy Roby, and they cast off the tie-rope.

“Wal, so long, Hoosiers,” said Magoon. “Reckon I won’t see ye again, less’n I ketch ye in New Orleans. Take keer o’ yerselves. Ho, ho! Fishin’ worms an’ suckin’ doves! Heh, heh!” And he was still chuckling over Abe’s words and repeating them to Fanny, the setter, as the two boats drifted apart.

[67]Tad watched the odd little craft until its owner was no longer visible in the distance. Then he looked down at the coarse, homely pantaloons that covered his legs. In spite of himself he could not help a little smile as he thought of the spectacle he would present to one of his carefully attired schoolmates.

Abe saw the smile, and his face lit with pleasure.

“Like ’em, Tad?” he asked.

“You bet,” said Tad stoutly. “But listen, Abe, you oughtn’t to do this for me. How much does Mr. Gentry pay you, anyway?”

“That’s all right,” replied the big backwoodsman, grinning proudly. “I git eight dollars a month an’ my steamboat passage home.”

And with that he vaulted to the fore deck and picked up the oars.

The current set over strongly toward the Kentucky shore that afternoon, and soon they found themselves swinging around the outer side of an immense bend. At noon they had been heading almost due south. By three o’clock they were running northwest, and an hour later they were carried over to the Missouri side as another great sweep began, this time to the left.

“That must be New Madrid,” said Allen. “The river makes a big S, an’ the town lays right in the second bend.”

They saw a settlement of twenty or thirty houses sprawled along the bank, with a white church rising from trees above the landing. The river ran fast around the bend, and Abe had left the oars to man the steering-sweep. “Want to land?” he shouted. “Guess we don’t need nothin’,” said Allen. “After hearin’ what happened to that trader feller at New Madrid I’d jest as leave sleep farther down.”

They shot past the drowsy town and swung southward again with the hurrying brown flood.[69] Instead of the wilderness of willow-clad banks and reedy marshes past which they had been drifting, the Missouri shore stretched away here in broad acres of plowed ground.

At sunset they saw ahead of them a big, white-painted house set among trees on a knoll. A broad, rolling lawn stretched down from it to the river, and there were barns and outbuildings half hidden by shrubbery at the rear. Beyond the expanse of lawn and nearer the river, was a less pretentious house, flanked by a row of trim cabins. There were a dozen or more of these, each with its small garden and a curl of blue smoke coming from the chimney.

“Golly,” said Abe, “ain’t that a pretty layout? S’pose we could git some good clear water here? I’m all clogged up with yaller mud, drinkin’ this river water. Let’s land anyhow.”

He steered inshore and tossed a snubbing-rope over one of the piles at the end of the little landing. When they had made the Katy Roby fast, Abe and Allen went up the path toward the smaller house at the end of the line of cabins.

A big man in riding-boots and a wide-brimmed black hat was sitting on the veranda. He had a long, drooping mustache from which a black cigar protruded at a ferocious angle. Altogether he did[70] not look particularly hospitable. Abe stood awkwardly at the foot of the steps.

“Evenin’,” said he. “I reckon a place as fine an’ handsome as this must have a good well o’ water. Ef it ain’t too much trouble, we’d like to fill up a kaig or two.”

The man got up and took the cigar from his mouth. Under the huge mustache he smiled, and his whole expression grew more friendly.