Title: The achievements of Luther Trant

Author: Edwin Balmer

William MacHarg

Illustrator: William Oberhardt

Release date: March 4, 2025 [eBook #75523]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston, MA: Small, Maynard & Company, 1909

Credits: Brian Raiter

William Oberhardt

Boston

Small, Maynard & Company

Copyright, 1909–1910 by Benj. B. Hampton

Copyright, 1910 by Small, Maynard & Company

Except for its characters and plot, this book is not a work of the imagination.

The methods which the fictitious Trant—one time assistant in a psychological laboratory, now turned detective—here uses to solve the mysteries which present themselves to him, are real methods; the tests he employs are real tests.

Though little known to the general public, they are precisely such as are being used daily in the psychological laboratories of the great universities—both in America and Europe—by means of which modern men of science are at last disclosing and defining the workings of that oldest of world-mysteries—the human mind.

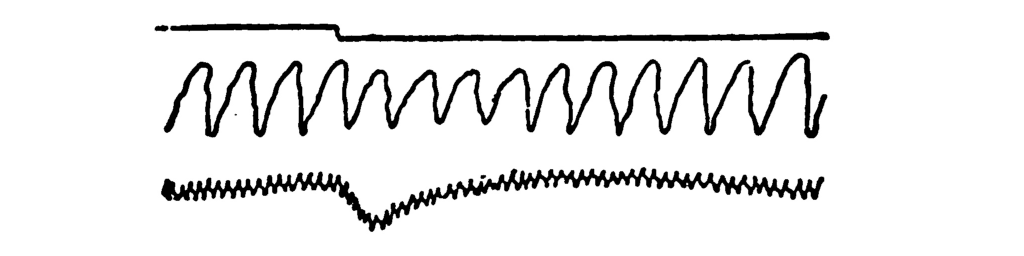

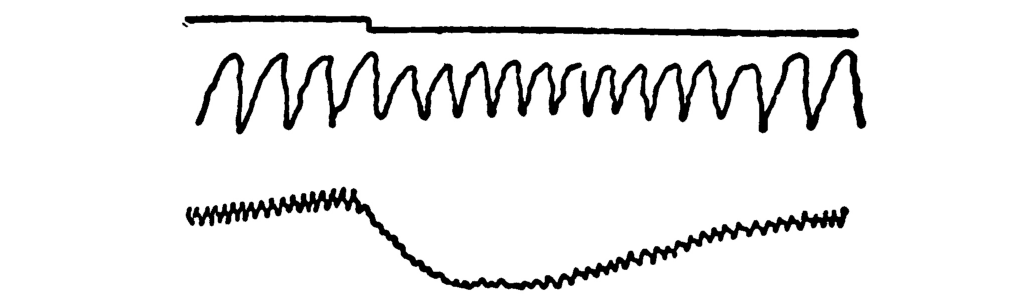

The facts which Trant uses are in no way debatable facts; nor do they rest on evidence of untrained, imaginative observers. Innumerable experiments in our university laboratories have established beyond question that, for instance, the resistance of the human body to a weak electric current varies when the subject is frightened or undergoes emotion; and the consequent variation in the strength of the current, depending directly upon the amount of emotional disturbance, can be registered by the galvanometer for all to see. The hand resting upon an automatograph will travel toward an object which excites emotion, however capable its possessor may be of restraining all other evidence of what he feels.

If these facts are not used as yet except in the academic experiments of the psychological laboratories and the very real and useful purpose to which they have been put in the diagnosis of insanities, it is not because they are incapable of wider use. The results of the “new psychology” are coming every day closer to an exact interpretation. The hour is close at hand when they will be used not merely in the determination of guilt and innocence, but to establish in the courts the credibility of witnesses and the impartiality of jurors, and by employers to ascertain the fitness and particular abilities of their employees.

Luther Trant, therefore, nowhere in this book needs to invent or devise an experiment or an instrument for any of the results he here attains; he has merely to adapt a part of the tried and accepted experiments of modern, scientific psychology. He himself is a character of fiction; but his methods are matters of fact.

The Authors.

“Amazing, Trant.”

“More than merely amazing! Face the fact, Dr. Reiland, and it is astounding, incredible, disgraceful, that after five thousand years of civilization, our police and court procedures recognize no higher knowledge of men than the first Pharaoh put into practice in Egypt before the pyramids!”

Young Luther Trant ground his heel impatiently into the hoar frost on the campus walk. His queerly mismated eyes—one more gray than blue, the other more blue than gray—flashed at his older companion earnestly. Then, with the same rebellious impatience, he caught step once more with Reiland, as he went on in his intentness:

“You saw the paper this morning, Dr. Reiland? ‘A man’s body found in Jackson Park’; six suspects seen near the spot have been arrested. ‘The Schlaack’s abduction or murder’; three men under arrest for that since last Wednesday. ‘The Lawton trial progressing’; with the likelihood that young Lawton will be declared innocent; eighteen months he has been in confinement—eighteen months of indelible association with criminals! And then the big one: ‘Sixteen men held as suspected of complicity in the murder of Bronson, the prosecuting attorney.’ Did you ever hear of such a carnival of arrest? And put beside that the fact that for ninety-three out of every one hundred homicides no one is ever punished!”

The old professor turned his ruddy face, glowing with the frosty, early-morning air, patiently and questioningly toward his young companion. For some time Dr. Reiland had noted uneasily the growing restlessness of his brilliant but hotheaded young aid, without being able to tell what it portended.

“Well, Trant,” he asked now, “what is it?”

“Just that, professor! Five thousand years of being civilized,” Trant burst on, “and we still have the ‘third degree’! We still confront a suspect with his crime, hoping he will ‘flush’ or ‘lose color,’ ‘gasp’ or ‘stammer.’ And if in the face of this crude test we find him prepared or hardened so that he can prevent the blood from suffusing his face, or too noticeably leaving it; if he inflates his lungs properly and controls his tongue when he speaks, we are ready to call him innocent. Is it not so, sir?”

“Yes,” the old man nodded, patiently. “It is so, I fear. What then, Trant?”

“What, Dr. Reiland? Why, you and I and every psychologist in every psychological laboratory in this country and abroad have been playing with the answer for years! For years we have been measuring the effect of every thought, impulse and act in the human being. Daily I have been proving, as mere laboratory experiments to astonish a row of staring sophomores, that which—applied in courts and jails—would conclusively prove a man innocent in five minutes, or condemn him as a criminal on the evidence of his own uncontrollable reactions. And more than that, Dr. Reiland! Teach any detective what you have taught to me, and if he has half the persistence in looking for the marks of crime on men that he had in tracing its marks on things, he can clear up half the cases that fill the jail in three days.”

“And the other half within the week, I suppose, Trant?”

The older man smiled at the other’s enthusiasm.

For five years Reiland had seen his young companion almost daily; first as a freshman in the elementary psychology class—a red-haired, energetic country-boy, ill at ease among even the slight restrictions of this fresh-water university. The boy’s eager, active mind had attracted his attention in the beginning; as he watched him change into a man, Trant’s almost startling powers of analysis and comprehension had aroused the old professor’s admiration. The compact, muscular body, which endured without fatigue the great demands Trant made upon it and brought him fresh to recitations from two hours sleep after a night of work; and the tireless eagerness which drove him at a gallop through courses where others plodded, had led Reiland to appoint Trant his assistant just before his graduation. But this energy told Reiland, too, that he could not hope to hold Trant long to the narrow activities of a university; and it was with marked uneasiness that the old professor glanced sideways now while he waited for the younger man to finish what he was saying.

“Dr. Reiland,” Trant went on more soberly, “you have taught me the use of the cardiograph, by which the effect upon the heart of every act and passion can be read as a physician reads the pulse chart of his patient, the pneumograph, which traces the minutest meaning of the breathing; the galvanometer, that wonderful instrument which, though a man hold every feature and muscle passionless as death, will betray him through the sweat glands in the palms of his hands. You have taught me—as a scientific experiment—how a man not seen to stammer or hesitate, in perfect control of his speech and faculties, must surely show through his thought associations, which he cannot know he is betraying, the marks that any important act and every crime must make indelibly upon his mind—”

“Associations?” Dr. Reiland interrupted him less patiently. “That is merely the method of the German doctors—Freud’s method—used by Jung in Zurich to diagnose the causes of adolescent insanity.”

“Precisely.” Trant’s eyes flashed, as he faced the old professor. “Merely the method of the German doctors! The method of Freud and Jung! Do you think that I, with that method, would not have known eighteen months ago that Lawton was innocent? Do you suppose that I could not pick out among those sixteen men the Bronson murderer? If ever such a problem comes to me I shall not take eighteen months to solve it. I will not take a week.”

In spite of himself Dr. Reiland’s lips curled at this arrogant assertion. “It may be so,” he said. “I have seen, Trant, how the work of the German, Swiss and American investigators, and the delicate experiments in the psychological laboratory which make visible and record the secrets of men’s minds, have fired your imagination. It may be that the murderer would be as little, or even less, able to conceal his guilt than the sophomores we test are to hide their knowledge of the sentences we have had previously read to them. But I myself am too old a man to try such new things; and you will not meet here any such problems,” he motioned to the quiet campus with its skeleton trees and white-frosted grass plots. “But why,” he demanded suddenly in a startled tone, “is a delicate girl like Margaret Lawrie running across the campus at seven o’clock on this chilly morning without either hat or jacket?”

The girl who was speeding toward them along an intersecting walk, had plainly caught up as she left her home the first thing handy—a shawl—which she clutched about her shoulders. On her forehead, very white under the mass of her dark hair, in her wide gray eyes and in the tense lines of her straight mouth and rounded chin, Trant read at once the nervous anxiety of a highly-strung woman.

“Professor Reiland,” she demanded, in a quick voice, “do you know where my father is?”

“My dear Margaret,” the old man took her hand, which trembled violently, “you must not excite yourself this way.”

“You do not know!” the girl cried excitedly. “I see it in your face. Dr. Reiland, father did not come home last night! He sent no word.”

Reiland’s face went blank. No one knew better than he how great was the break in Dr. Lawrie’s habits that this fact implied, for the man was his dearest friend. Dr. Lawrie had been treasurer of the university twenty years, and in that time only three events—his marriage, the birth of his daughter, and his wife’s death—had been allowed to interfere with the stern and rigorous routine into which he had welded his lonely life. So Reiland paled, and drew the trembling girl toward him.

“When did you see him last, Miss Lawrie?” Trant asked gently.

“Dr. Reiland, last night he went to his university office to work,” she replied, as though the older man had spoken. “Sunday night. It was very unusual. All day he had acted so strangely. He looked so tired, and he has not come back. I am on my way there now to see—if—I can find him.”

“We will go with you,” Trant said quickly, as the girl helplessly broke off. “Harrison, if he is there so early, can tell us what has called your father away. There is not one chance in a thousand, Miss Lawrie, that anything has happened to him.”

“Trant is right, my dear.” Reiland had recovered himself, and looked up at University Hall in front of them with its fifty windows on the east glimmering like great eyes in the early morning sun. Only, on three of these eyes the lids were closed—the shutters of the treasurer’s office, all saw plainly, were fastened. Trant could not remember that ever before he had seen shutters closed on University Hall. They had stood open until, on many, the hinges had rusted solid. He glanced at Dr. Reiland, who shuddered, but straightened again, stiffly.

“There must be a gas leak,” Trant commented, sniffing, as they entered the empty building. But the white-faced man and girl beside him paid no heed, as they sped down the corridor.

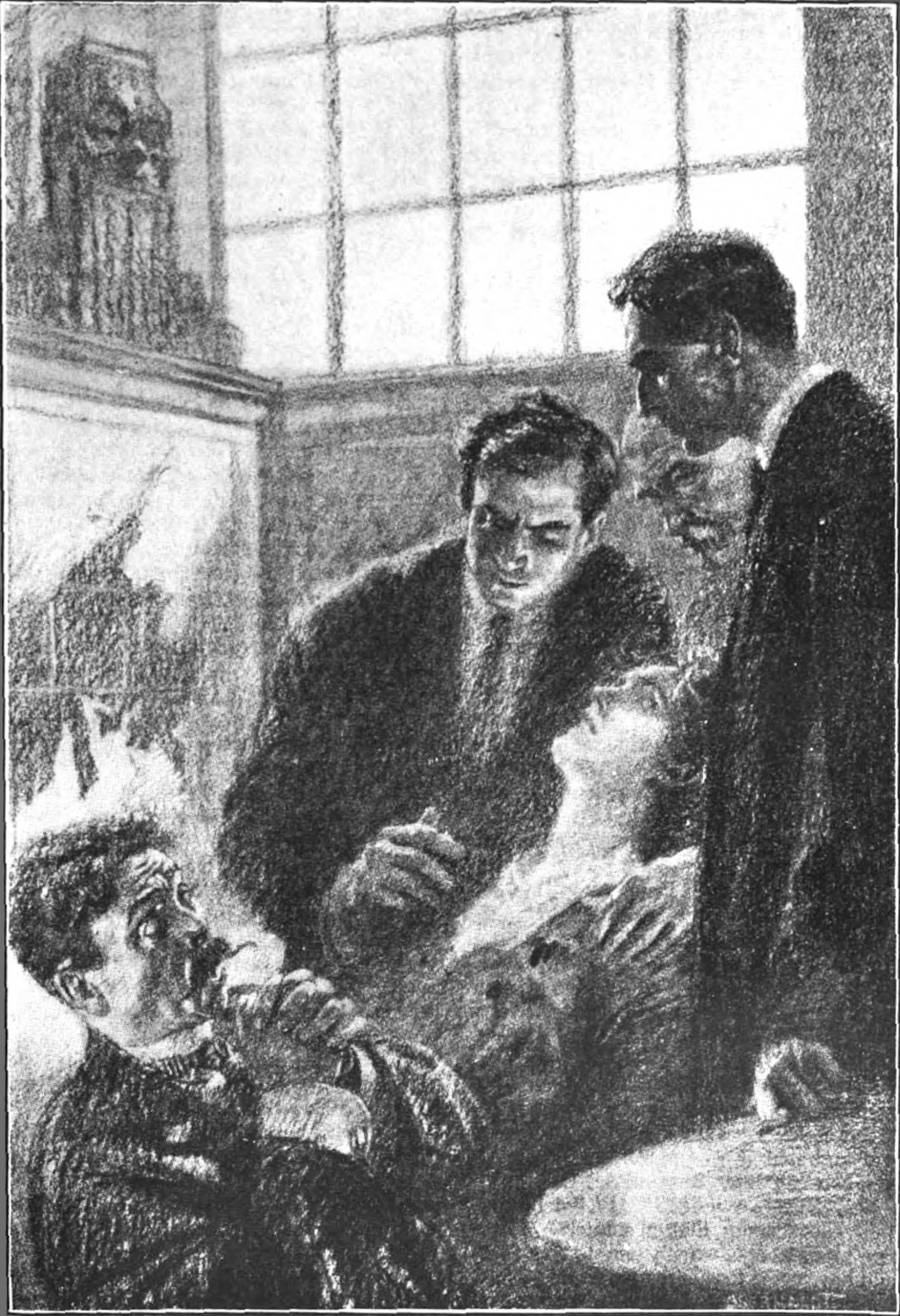

At the door of Dr. Lawrie’s office—the third of the doors with high, ground-glass transoms which opened on both sides into the corridor—the smell of gas grew stronger. Trant stooped to the keyhole and found it plugged with paper. He caught the transom bar, set his foot upon the knob and, drawing himself up, pushed against the transom. It resisted; but he pounded it in, and, as its glass panes fell tinkling, the fumes of illuminating gas burst out and choked him.

“A foot,” he called down to his trembling companions, as he peered into the darkened room. “Some one on the lounge!”

Dropping down, he hurried to a recitation room across the corridor and dragged out a heavy table. Together they drove a corner of this against the lock; it broke, and as the door whirled back on its hinges the fumes of gas poured forth, stifling them and driving them back. Trant rushed in, threw up the three windows, one after the other, and beat open the shutters. As the gray autumn light flooded the room, a shriek from the girl and a choking exclamation from Reiland greeted the figure stretched motionless upon the couch. Trant leaped upon the flat-topped desk under the gas fixtures in the center of the room and turned off the four jets from which the gas was pouring. Darting across the hall, he opened the windows of the room opposite.

As the strong morning breeze eddied through the building, clearing the gas before it, while Reiland with tears streaming from his eyes knelt by the body of his lifelong friend, it lifted from a metal tray upon the desk scores of fragments of charred paper which scattered over the room, over the floor and furniture, over even the couch where the still figure lay, with its white face drawn and contorted.

Reiland arose and touched his old friend’s hand, his voice breaking. “He has been dead for hours. Oh, Lawrie!”

He caught to him the trembling, horrified girl, and she burst into sobs against his shoulder. Then, while the two men stood beside the dead body of him in whose charge had been all finances of this great institution, their eyes met, and in those of Trant was a silent question. Reddening and paling by turns, Reiland answered it, “No, Trant, nothing lies behind this death. Whether it was of purpose or by accident, no secret, no disgrace, drove him to it. That I know.”

The young man’s oddly mismated eyes glowed into his, questioningly. “We must get President Joslyn,” Reiland said. “And Margaret,” he lifted the girl’s head from his shoulder, while she shuddered and clung to him, “you must go home. Do you feel able to go home alone, dearie? Everything that is necessary here shall be done.”

She gathered herself together, choked and nodded. Reiland led her to the door, and she hurried away, sobbing.

While Trant was at the telephone Dr. Reiland swept the fragments of glass across the sill, and closed the door and windows.

Already feet were sounding in the corridors; and the rooms about were fast filling before Trant made out the president’s thin figure bending against the wind as he hurried across the campus.

Dr. Joslyn’s swift glance as Trant opened the door to him—a glance which, in spite of the student pallor of his high-boned face, marked the man of action—considered and comprehended all.

“So it has come to this,” he said, sadly. “But—who laid Lawrie there?” he asked sharply after an instant.

“He laid himself there,” Reiland softly replied. “It was there we found him.”

Trant put his finger on a scratch on the wall paper made by the sharp corner of the davenport lounge; the corner was still white with plaster. Plainly, the lounge had been violently pushed out of its position, scratching the paper.

Dr. Joslyn’s eyes passed on about the room, passed by Reiland’s appeal, met Trant’s direct look and followed it to the smaller desk beside the dead treasurer’s. He opened the door to his own office.

“When Mr. Harrison comes,” he commanded, speaking of Dr. Lawrie’s secretary and assistant, “tell him I wish to see him. The treasurer’s office will not be opened this morning.”

“Harrison is late,” he commented, as he returned to the others. “He usually is here by seven-thirty. We must notify Branower also.” He picked up the telephone and called Branower, the president of the board of trustees, asking him merely to come to the treasurer’s office at once.

“Now give me the particulars,” the president said, turning to Trant.

“They are all before you,” Trant replied briefly. “The room was filled with gas. These four outlets of the fixture were turned full on. And besides,” he touched now with his fingers four tips with composition ends to regulate the flow, which lay upon the table, “these tips had been removed, probably with these pincers that lie beside them. Where the nippers came from I do not know.”

“They belong here,” Joslyn answered, absently. “Lawrie had the tinkering habit.” He opened a lower desk drawer, filled with tools and nails and screws, and dropped the nippers into it.

“The door was locked inside?” inquired the president.

“Yes, it is a spring lock,” Trant answered.

“And he had been burning papers.” The president pointed quietly to the metal tray.

Dr. Reiland winced.

“Some one had been burning papers,” Trant softly interpolated.

“Some one?” The president looked up sharply.

“These ashes were all in the tray, I think,” Trant contented himself with answering. “They scattered when I opened the windows.”

Joslyn lifted a stiletto letter-opener from the desk and tried to separate, so as to read, the carbonized ashes left in the tray. They fell into a thousand pieces; and as he gave up the hopeless attempt to decipher the writing on them, suddenly the young assistant bent before the couch, slipped his hand under the body, and drew out a crumpled paper. It was a recently canceled note for twenty thousand dollars drawn on the University regularly and signed by Dr. Lawrie, as treasurer. But as the young psychologist started to study it more closely, President Joslyn’s hand closed over it and took it from Trant’s grasp. The president himself merely glanced at it; then, with whitening face, folded it carefully and put it in his pocket.

“What is the matter, Joslyn?” Dr. Reiland started up.

“A note,” the president answered shortly. He took a turn or two nervously up and down the room, paused and stared down at the face of the man upon the couch; then turned almost pityingly to the old professor.

“Reiland,” he said compassionately, “I must tell you that this shocking affair is not the surprise to me that it seems to have been to you. I have known for two weeks, and Branower has known for nearly as long—for I took him into my confidence—that there were irregularities in the treasurer’s office. I questioned Lawrie about it when I first stumbled upon the evidence. To my surprise, Lawrie—one of my oldest personal friends and certainly the man of all men in whose perfect honesty I trusted most implicitly—refused to reply to my questions. He would neither admit nor deny the truth of my accusations; and he begged me almost tearfully to say nothing about the matter until the meeting of the trustees to-morrow night. I understood from him that at, or before, the trustees’ meeting he would have an explanation to make to me; I did not dream, Reiland, that he would make instead this”—he motioned to the figure on the couch, “this confession! This note,” he nervously unfolded the paper again, “is drawn for twenty thousand dollars. I recall the circumstances of it clearly, Reiland; and I remember that it was authorized by the trustees for two thousand dollars, not twenty.”

“But it has been canceled. See, he paid it! And these,” the old professor pointed in protest to the ashes in the tray, “if these, too, were notes—raised, as you clearly accuse—he must have paid them. They were returned.”

“Paid? Yes!” Dr. Joslyn’s voice rang accusingly. “Paid from the university funds! The examination which I made personally of his books, unknown to Lawrie—for I could not confess at first to my old friend the suspicions I held against him—showed that he had methodically entered the notes at the amounts we authorized, and later entered them again at their face amounts as he paid them. The total discrepancy exceeds one hundred thousand dollars!”

“Hush!” Reiland was upon him. “Hush.”

The morning was advancing. The halls resounded with the tread of students passing to recitation rooms.

Trant’s eyes had registered all the room, and now measured Joslyn and Dr. Reiland. They had ceased to be trusted men and friends of his as, with the quick analysis that the old professor had so admired in his young assistant, he incorporated them in his problem.

“Who filled this out?” Trant had taken the paper from the hand of the president and asked this question suddenly.

“Harrison. It was the custom. The signature is Lawrie’s, and the note is regular. Oh, there can be no doubt, Reiland!”

“No, no!” the old man objected. “James Lawrie was not a thief!”

“How else can it be? The tips taken from the fixture, the keyhole plugged with paper, the shutters—never closed before for ten years—fastened within, the door locked! Burned notes, the single one left signed in his own hand! And all this on the very day before his books must have been presented to the trustees! You must face it, Reiland—you, who have been closer to Lawrie than any other man—face it as I do! Lawrie is a suicide—a hundred thousand dollars short in his accounts!”

“I have been close to him,” the old man answered bravely. “You and I, Joslyn, were almost his only friends. Lawrie’s life has been open as the day; and we at least should know that there can have been no disgraceful reason for his death.

“Luther,” the old professor turned, stretching out his hands pleadingly to his young assistant, as he saw that the face of the president did not soften, “Do you, too, believe this? It is not so! Oh, my boy, just before this terrible thing, you were telling me of the new training which could be used to clear the innocent and prove the guilty. I thought it braggadocio. I scoffed at your ideas. But if your words were truth, now prove them. Take this shame from this innocent man.”

The young man sprang to his friend as he tottered. “Dr. Reiland, I shall clear him!” he promised wildly. “I shall prove, I swear, not only that Dr. Lawrie was not a thief, but—he was not even a suicide!”

“What madness is this, Trant,” the president demanded impatiently, “when the facts are so plain before us?”

“So plain, Dr. Joslyn? Yes,” the young man rejoined, “very plain indeed—the fact that before the papers were burned, before the gas was turned on or the tips taken from the fixture, before that door was slammed and the spring lock fastened it from the outside—Dr. Lawrie was dead and was laid upon that lounge!”

“What? What—what, Trant?” Reiland and the president exclaimed together. But the young man addressed himself only to the president.

“You yourself, sir, before we told you how we found him, saw that Dr. Lawrie had not himself lain down, but had been laid upon the lounge. He is not light; some one almost dropped him there, since the edge of the lounge cut the plaster on the wall. The single note not burned lay under his body, where it could scarcely have escaped if the notes were burned first; where it would most surely have been overlooked if the body already lay there. Gas would not be pouring out during the burning, so the tips were probably taken off later. It must have struck you how theatric all this is, that some one has thought of its effect, that some one has arranged this room, and, leaving Lawrie dead, has gone away, closing the spring lock—”

“Luther!” Dr. Reiland had risen, his hands stretched out before him. “You are charging murder!”

“Wait!” Dr. Joslyn was standing by the window, and his eyes had caught the swift approach of a limousine automobile which, with its plate glass shimmering in the sun, was taking the broad sweep into the driveway. As it slowed before the entrance, the president swung back to those in the room.

“We two,” he said, “were Lawrie’s nearest friends—he had but one other. Branower is coming now. Go down and prepare him, Trant. His wife is with him. She must not come up.”

Trant hurried down without comment. Through the window of the car he could see the profile of a woman, and beyond it the broad, powerful face of a man, with sandy beard parted and brushed after a foreign fashion. Branower had succeeded his father as president of the board of trustees of the university. At least half a dozen of the surrounding buildings had been erected by the elder Branower, and practically his entire fortune had been bequeathed to the university.

“Well, Trant, what is it?” the trustee asked. He had opened the door of the limousine and was preparing to descend.

“Mr. Branower,” Trant replied, “Dr. Lawrie was found this morning dead in his office.”

“Dead? This morning?” A muddy grayness appeared under the flush of Branower’s cheeks. “Why! I was coming to see him—even before I heard from Joslyn. What was the cause?”

“The room was filled with gas.”

“Asphyxiation!”

“An accident?” the woman asked, leaning forward. Even as she whitened with the horror of this news, Trant found himself wondering at her beauty. Every feature was so perfect, so flawless, and her manner so sweet and full of charm that, at this first close sight of her, Trant found himself excusing and approving Branower’s marriage. She was an unknown American girl, whom Branower had met in Paris and had brought back to reign socially over this proud university suburb where his father’s friends and associates had had to accept her and—criticise.

“Dr. Lawrie asphyxiated,” she repeated, “accidentally, Mr. Trant?”

“We—hope so, Mrs. Branower.”

“There is no clew to the perpetrator?”

“Why, if it was an accident, Mrs. Branower, there was no perpetrator.”

“Cora!” Branower ejaculated.

“How silly of me!” She flushed prettily. “But Dr. Lawrie’s lovely daughter; what a shock to her!”

Branower touched Trant upon the arm. After his first personal shock, he had become at once a trustee—the trustee of the university whose treasurer lay dead in his office just as his accounts were to be submitted to the board. He dismissed his wife hurriedly. “Now, Trant, let us go up.”

President Joslyn met Branower’s grasp mechanically and acquainted the president of the trustees, almost curtly, with the facts as he had found them.

Then the eyes of the two men met significantly.

“It seems, Joslyn,” Branower used almost the same words that Joslyn had used just before his arrival, “like a—confession! It is suicide?” the president of the trustees was revolting at the charge.

“I can see no other solution,” the president replied, “though Mr. Trant—”

“And I might have saved this, at least!” The trustee’s face had grown white as he looked down at the man on the couch. “Oh, Lawrie, why did I put you off to the last moment?”

He turned, fumbling in his pocket for a letter. “He sent this Saturday,” he confessed, pitifully. “I should have come to him at once, but I could not suspect this.”

Joslyn read the letter through with a look of increased conviction. It was in the clear hand of the dead treasurer. “This settles all,” he said, decidedly, and he re-read it aloud:

Dear Branower: I pray you, as you have pity for a man with sixty years of probity behind him facing dishonor and disgrace, to come to me at the earliest possible hour. Do not, I pray, delay later than Monday, I implore you.

James Lawrie.

Dr. Reiland buried his face in his hands, and Joslyn turned to Trant. On the young man’s face was a look of deep perplexity.

“When did you get that, Mr. Branower?” Trant asked, finally.

“He wrote it Saturday morning. It was delivered to my house Saturday afternoon. But I was motoring with my wife. I did not get it until I returned late Sunday afternoon.”

“Then you could not have come much sooner.”

“No; yet I might have done something if I had suspected that behind this letter was hidden his determination to commit suicide.”

“Not suicide, Mr. Branower!” Trant interrupted curtly.

“What?”

“Look at his face. It is white and drawn. If asphyxiated, it would be blue, swollen. Before the gas was turned on he was dead—struck dead—”

“Struck dead? By whom?”

“By the man in this room last night! By the man who burned those notes, plugged the keyhole, turned on the gas, arranged the rest of these theatricals, and went away to leave Dr. Lawrie a thief and a suicide to—protect himself! Two men had access to the university funds, handled these notes! One lies before us; and the man in this room last night, I should say, was the other—” he glanced at the clock—“the man who at the hour of nine has not yet appeared at his office!”

“Harrison?” cried Joslyn and Reiland together.

“Yes, Harrison,” Trant answered, stoutly. “I certainly prefer him for the man in the room last night.”

“Harrison?” Branower repeated, contemptuously. “Impossible.”

“How impossible?” Trant asked, defiantly.

“Because Harrison, Mr. Trant,” the president of the trustees rejoined, “was struck senseless at Elgin in an automobile accident Saturday noon. He has been in the Elgin hospital, scarcely conscious, ever since.”

“How did you learn that, Mr. Branower?”

“I have helped many young men to positions here. Harrison was one. Because of that, I suppose, he filled in my name on the ‘whom to notify’ line of a personal identification card he carried. The hospital doctors notified me just as I was leaving home in my car. I saw him at the Elgin hospital that afternoon.”

Young Trant stared into the steady eyes of the president of the trustees. “Then Harrison could not have been the man in the room last night. Do you realize what that implies?” he asked, whitening. “I preferred, I said, to fix him as Harrison. That would keep both Dr. Lawrie from being the thief and any close personal intimate of his from being the man who struck him dead here last night. But with Harrison not here, the treasurer himself must have known all the particulars of this crime,” he struck the canceled note in his hand, “and been concealing it for—that close friend of his who came here with him. You see how very terribly it simplifies our problem? It was some one close enough to Lawrie to cause him to conceal the thing as long as he could, and some one intimate enough to know of the treasurer’s tinkering habits, so that, even in great haste, he could think at once of the gas nippers in Lawrie’s private tool drawer. Gentlemen,” the young assistant tensely added, “I must ask you which of you three was the one in this room with Dr. Lawrie last night?”

“What!” The word in three different cadences burst from their lips—amazement, anger, threat.

He lifted a shaking hand to stop them.

“I realize,” he went on more quickly, “that, after having suggested one charge and having it shown false, I am now making a far more serious one, which, if I cannot prove it, must cost me my position here. But I make it now again, directly. One of you three was in this room with Dr. Lawrie last night. Which one? I could tell within the hour if I could take you successively to the psychological laboratory and submit you to a test. But, perhaps I need not. Even without that, I hope soon to be able to tell the other two, for which of you Dr. Lawrie concerned himself with this crime, and who it was that in return struck him dead Sunday night and left him to bear a double disgrace as a suicide.”

The young psychologist stood an instant gazing into their startled faces, half frightened at his own temerity in charging thus the three most respected men in the university; then, as President Joslyn eyed him sternly, he caught again the enthusiasm of his reasoning, and flushed and paled.

“One of you, at least, knows that I speak the truth,” he said, determinedly; and without a backward look he burst from the room and, running down the steps, left the campus.

It was five o’clock that afternoon, when Trant rang the bell at Dr. Joslyn’s door. He saw that Mr. Branower and Dr. Reiland had been taken into the president’s private study before him; and that the manner of all three was less stern toward him than he had expected.

“Dr. Reiland and Mr. Branower have come to hear the coroner’s report to me,” Joslyn explained. “The physicians say Lawrie did not die from asphyxiation. An autopsy to-morrow will show the cause of his death. But, at least, Trant—you made accusations this morning which can have no foundation in truth, but in part of what you said you must have been correct; for obviously some other person was in the room.”

“But not Harrison,” Trant replied. “I have just come from Elgin, where, though I was not allowed to speak with him, I saw him in the hospital.”

“You doubted he was there?” Branower asked.

“I wanted to make sure, Mr. Branower. And I have traced the notes, too,” the young man continued. “All were made out as usual, signed regularly by Dr. Lawrie and paid by him personally, upon maturity, from the university reserve. So I have made only more certain that the man in the room must have been one of Dr. Lawrie’s closest friends. I came back and saw Margaret Lawrie.”

Reiland’s eyes filled with tears. “This terrible thing, with her unfortunate presence with us at the finding of her father’s body, has prostrated poor Margaret,” he said.

“I found it so,” Trant rejoined. “Her memory is temporarily destroyed. I could make her comprehend little. Yet she knows only of her father’s death; nothing at all has been said to her of the suspicions against him. Does his death alone seem cause enough for her prostration? More likely, I think, it points to some guilty knowledge of her father’s trouble and whom he was protecting. If so, her very condition makes it impossible for her to conceal those guilty associations under examination.”

“Guilty associations?” Dr. Reiland rose nervously. “Do you mean, Trant, that you think Margaret knows anything of the loss of this money? Oh, no, no; it is impossible!”

“It would at any rate account for her prostration,” the assistant repeated quietly, “and I have determined to make a test of her for association with her father’s guilt. I will use in this case, Dr. Reiland, only the simple association of words—Freud’s method.”

“How? What do you mean?” Branower and Joslyn exclaimed.

“It is a method for getting at the concealed causes of mental disturbance. It is especially useful in diagnosing cases of insanity or mental breakdown from insufficiently known causes.

“We have a machine, the chronoscope,” Trant continued, as the others waited, interrogatively, “which registers the time to a thousandth part of a second, if necessary. The German physicians merely speak a series of words which may arouse in the patient ideas that are at the bottom of his insanity. Those words which are connected with the trouble cause deeper feeling in the subject and are marked by longer intervals of time before the word in reply can be spoken. The nature of the word spoken by the patient often clears the causes for his mental agitation or prostration.

“In this case, if Margaret Lawrie had reason to believe that any one of you were closely associated with her father’s trouble, the speaking of that one’s name or the mentioning of anything connected with that one, must betray an easily registered and decidedly measurable disturbance.”

“I have heard of this,” Joslyn commented.

“Excellent,” the president of the trustees agreed, “if Margaret’s physician does not object.”

“I have already spoken with him,” Trant replied. “Can I expect you all at Dr. Lawrie’s to-morrow morning when I test Margaret to discover the identity of the intimate friend who caused the crime charged to her father?”

Dr. Lawrie’s three dearest friends nodded in turn.

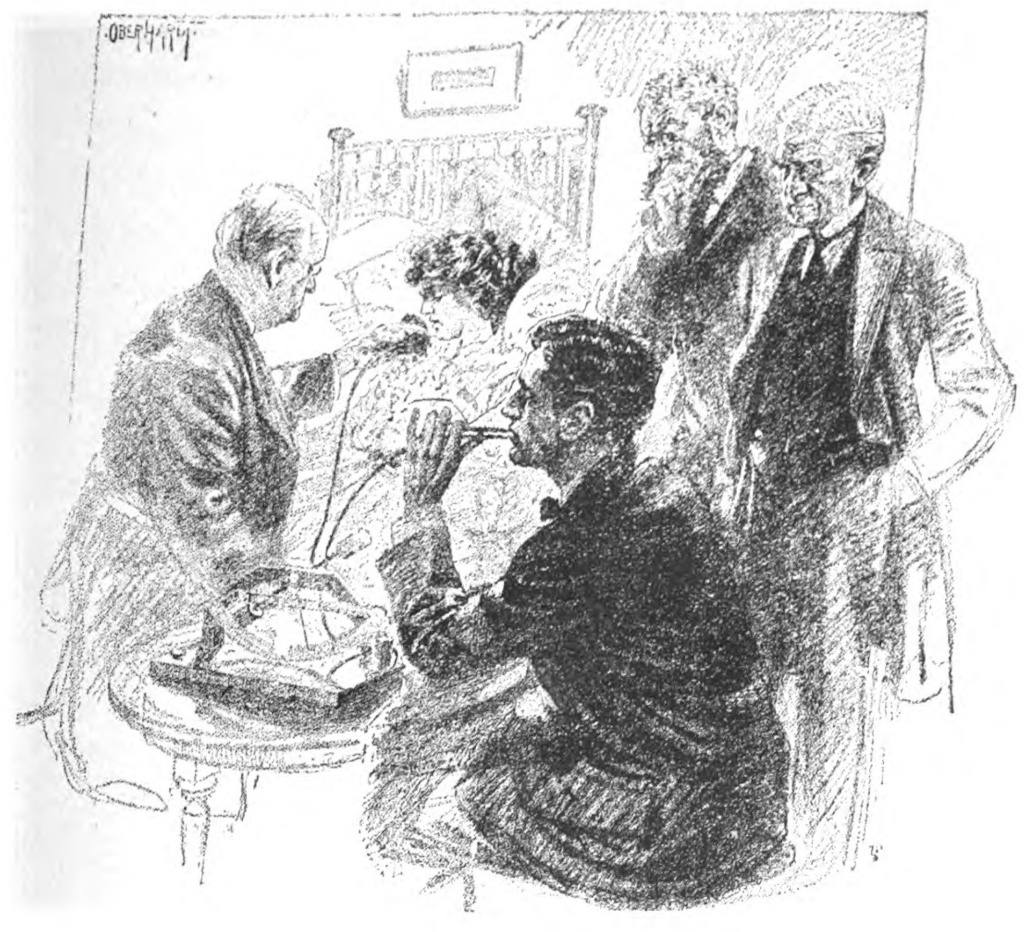

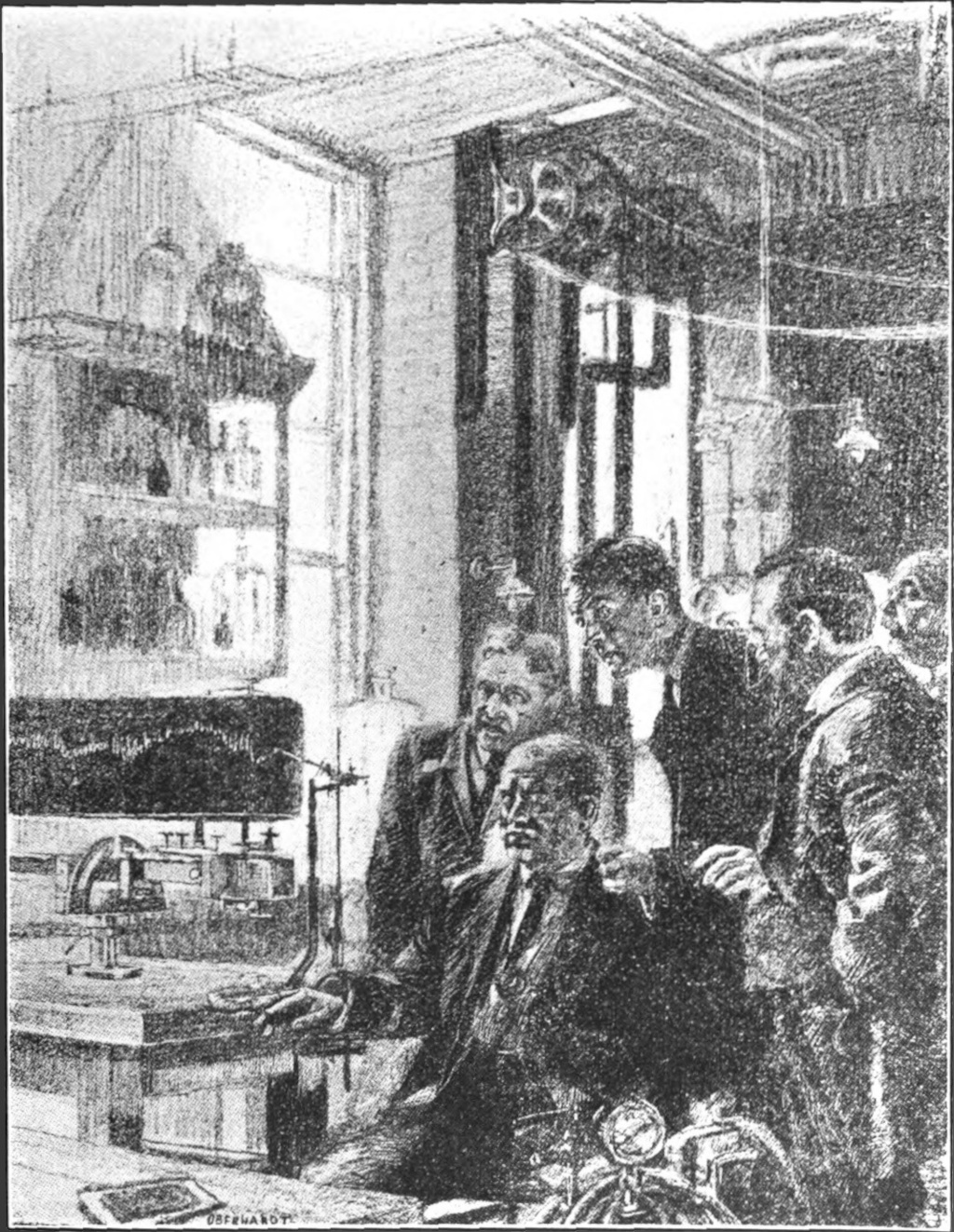

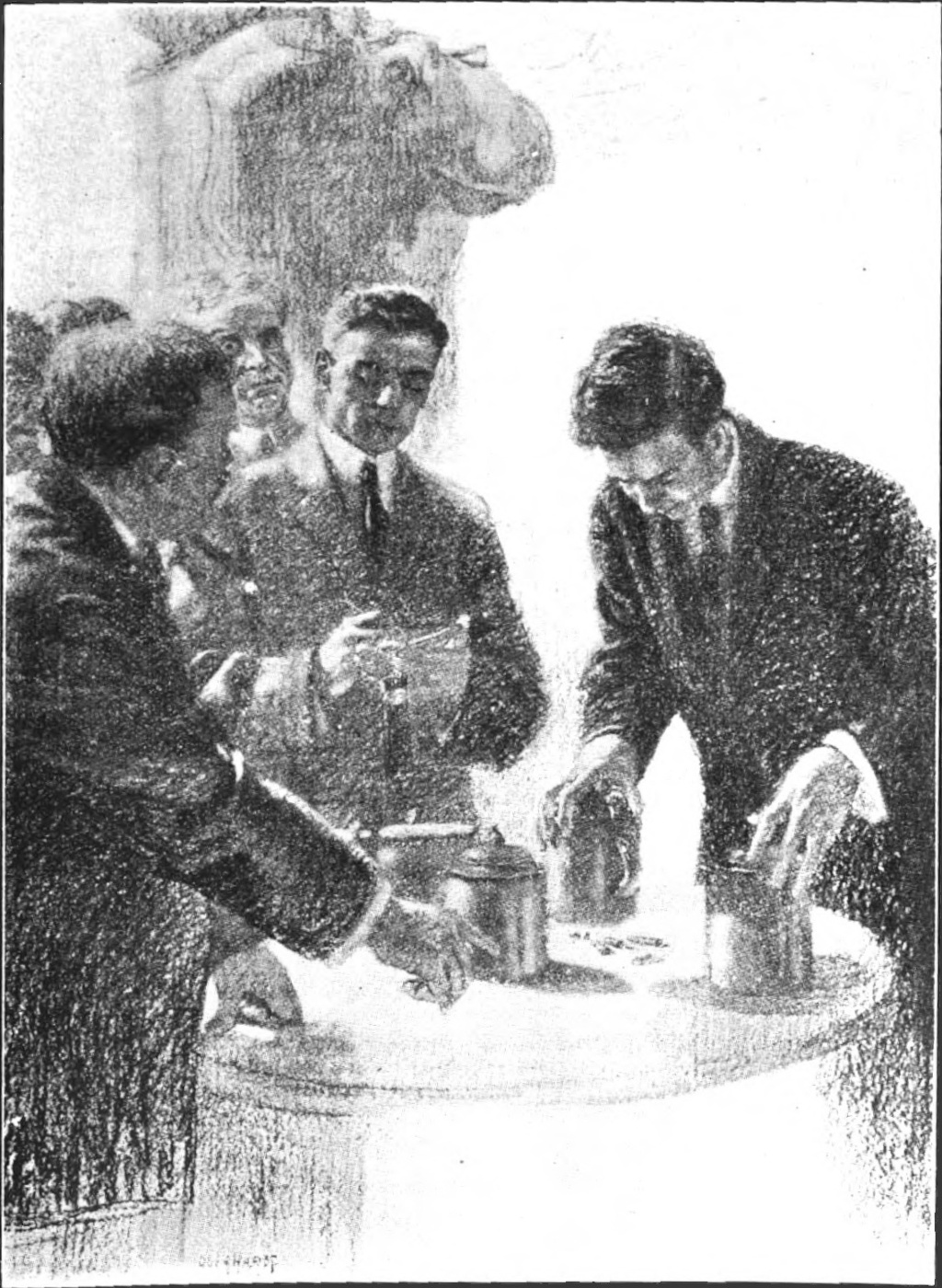

Trant came early the next morning to the dead treasurer’s house to set up the chronoscope in the spare bedroom next to Margaret Lawrie’s.

The instrument he had decided to use was the pendulum chronoscope, as adapted by Professor Fitz of Harvard University. It somewhat resembled a brass dumb-bell very delicately poised upon an axle so that the lower part, which was heavier, could swing slowly back and forth like a pendulum. A light, sharp pointer paralleled this pendulum. The weight, when started, swung to and fro in the arc of a circle; the pointer swung beside it. But the pointer, after starting to swing, could be instantaneously stopped by an electro-magnet. This magnet was connected with a battery and wires led from it to the two instruments used in the test. The first pair of wires connected with two bits of steel which Trant, in conducting the test, would hold between his lips. The least motion of his lips to enunciate a word would break the electric circuit and start swinging the pendulum and the pointer beside it. The second pair of wires led to a sort of telephone receiver. When Margaret would reply into this, it would close the circuit and instantaneously the electro-magnet clamped and held the pointer. A scale along which the pointer traveled gave, down to thousandths of a second, the time between the speaking of the suggesting word and the first associated word replied.

Trant had this instrument set up and tested before he had to turn and admit Dr. Reiland. Mr. Branower and President Joslyn soon joined them, and a moment after a nurse entered supporting Margaret Lawrie. Dr. Reiland himself scarcely recognized her as the same girl who had come running across the campus to them only the morning before. Her whole life had been centered on the father so suddenly taken away.

Trant nodded to the nurse, who withdrew. He looked to Dr. Reiland.

“Please be sure that she understands,” he said, softly. The older man bent over the girl, who had been placed upon the bed.

“Margaret,” he said tenderly, “we know you cannot speak well this morning, my dear, and that you cannot think very clearly. We shall not ask you to do much. Mr. Trant is merely going to say some words to you slowly, one word at a time; and we want you to answer—you need only speak very gently—anything at all, any word at all, my dear, which you think of first. I will hold this little horn over you to speak into. Do you understand, my dear?”

The big eyes closed in assent. The others drew nervously nearer. Reiland took the receiving drum at the end of the second set of wires and held it before the girl’s lips. Trant picked up the mouth metals attached to the starting wires.

“We may as well begin at once,” Trant said, as he seated himself beside the table which held the chronoscope and took a pencil to write upon a pad of paper the words he suggested, the words associated and the time elapsing. Then he put his mouthpiece between his lips.

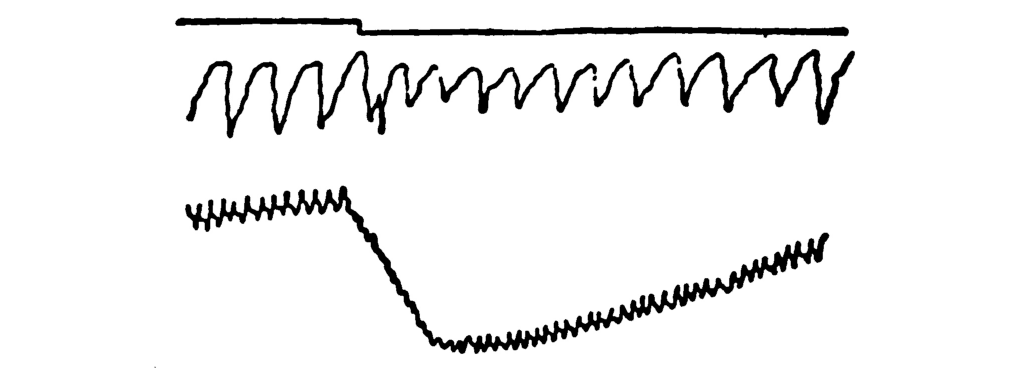

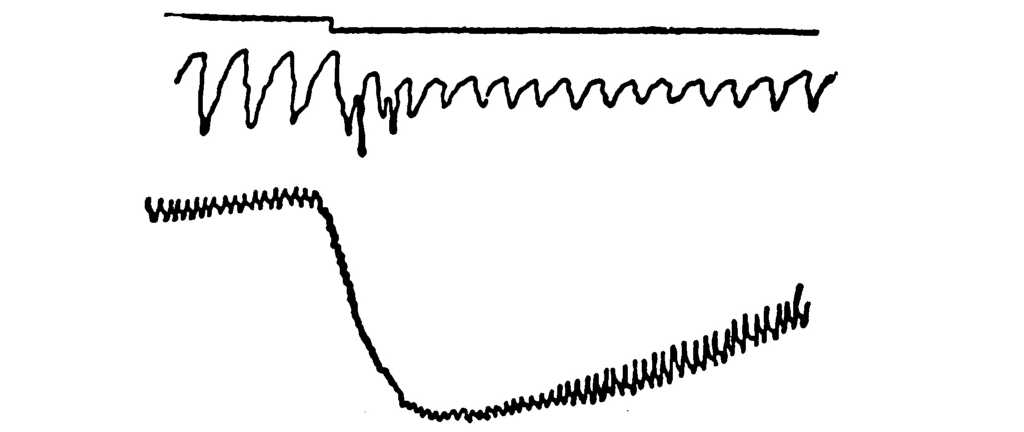

“Dress!” he enunciated clearly. The pendulum, released by the magnet, started to swing. The pointer swung beside it in an arc along the scale. “Skirt!” Miss Lawrie answered, feebly, into the drum at her lips. The current caught the pointer instantaneously, and Trant noted the result thus:

Dress—2.7 seconds—skirt.

“Dog!” Trant spoke, and started the pointer again. “Cat!” the girl answered and stopped it. Trant wrote:

Dog—2.6 seconds—cat.

A faint smile appeared on the faces of Mr. Branower and Dr. Joslyn, but Reiland knew that his young assistant was merely establishing the normal time of Margaret’s associations through words without probable connection with any disturbance in her mind.

“Home,” Trant said; and it was five and two-tenths seconds before he could write “father.” Reiland moved, sympathetically, but the other men still watched without seeing any significance in the time extension. Trant waited a moment. “Money!” he said, suddenly. Dr. Reiland watched the swinging pointer tremblingly. But “purse” from Margaret stopped it before it had registered more than her established normal time for innocent associations.

Money—2.7 seconds—purse.

“Note!” Trant said, suddenly; and “letter” he wrote again in two and six-tenths seconds.

Dr. Joslyn moved impatiently; and Trant brusquely pulled his chair nearer the table. The chair legs rasped on the hard-wood floor. Margaret shivered and, when Trant tried her with the next words, she merely repeated them. President Joslyn moved again.

“Cannot you proceed, Trant?” he asked.

“Not unless we can make her understand again, sir,” the young man answered. “But I think, Dr. Joslyn, if you would show her what we mean—not merely try to explain again—we might go on. I mean, when I say the next word, will you take the mouthpiece from Dr. Reiland and speak into it some different one?”

“Very well,” the president agreed, impatiently, “if you think it will do any good.”

“Thank you!” Trant replaced his mouthpieces. “October!” He named the month just ended. The pointer started. “Recitations!” the president of the university answered in one and nine-tenths seconds.

“Thank you. Now for Miss Lawrie, Dr. Reiland!”

“Steal!” he tried; and the girl associated “iron” in two and seven-tenths seconds.

“Good!” Trant exclaimed. “If you will show her again, I think we can go ahead. Fourteenth!” he said to the president. Joslyn replied “fifteenth” in precisely two seconds and passed the drum back. All watched Miss Lawrie. But again Trant rasped carelessly his chair upon the floor and the girl merely repeated the next words. Reiland was unable to make her understand. Joslyn tried to help. Branower shook his head skeptically. But Trant turned to him.

“Mr. Branower, you can help me, I believe, if you will take Dr. Joslyn’s place. I beg your pardon, Dr. Joslyn, but I am sure your nervousness prevents you from helping now.”

Branower hesitated a moment, skeptically; then, smiling, acquiesced and took up the drum. Trant replaced his mouthpieces.

“Blow!” he said. “Wind!” Branower answered, quietly. Trant mechanically noted the time, two seconds, for all were intent upon the next trial with the girl.

“Books!” Trant said. “Library!” said the girl, now able to associate the different words and in her minimum time of two and a half seconds.

“I think we are going again,” said Trant. “If you will keep on, Mr. Branower. Strike!” he exclaimed, to start the pointer. “Labor trouble,” Branower returned in just under two seconds; and again he guided the girl. For “conceal” she answered “hide” at once. Then Trant tested rapidly this series:

Margaret, conceal—2.6—hide.

Branower, figure—2.1—shape.

Margaret, thief—2.8—silver.

Branower, twenty-fifth—4.5—twenty-sixth.

“Joslyn!” Trant tried an intelligible test word suddenly. He had just suggested “thief” to the girl; now he named her father’s friend, the president of the university. But “friend” she was able to associate in two and six-tenths seconds. Trant sank back and wrote this series without comment:

Margaret, Joslyn—2.6—friend.

Branower, wife—4.4—Cora.

Margaret, secret—2.7—Alice.

Trant glanced up, surprised, considered a moment, but then bowed to Mr. Branower to guide the girl again, saying “wound,” to which he wrote the reply “no,” after four and six-tenths seconds. Immediately Trant made the second direct and intelligible test.

“Branower!” he shot, suggestively, to the girl; but “friend” she was again able to associate at once. As the moment before the president of the trustees had glanced at Joslyn, now the president of the University nodded to Branower. Trant continued his list rapidly:

Margaret, Branower—2.7—friend.

Branower, letter-opener—4.9—desk.

“Father!” Trant tried next. But from this there came no association, as the emotion was too deep. Trant, recognizing this, nodded to Mr. Branower to start the next test, and wrote:

Margaret, father—no association.

Branower, Harrison—5.3—Cleveland.

Margaret, university—2.5—study.

Branower, married—2.1—wife.

Margaret, expose—2.6—camera.

Branower, brother—4.9—sister.

Margaret, sink—2.7—kitchen.

Branower, collapse—4.8—balloon.

“Reiland!” Trant said to the girl at last. It was as if he had put off the trial for his own old friend as long as he could. Yet if anyone had been watching him, they would have noted now the quick flash of his mismated eyes. But all eyes were upon the swinging pointer of the chronoscope which, at the mention of her father’s best and oldest friend in that way, Margaret was unable to stop. One full second it swung, two, three, four, five, six—

The young assistant in psychology picked up his papers and arose. He went to the door and called in the nurse from the next room. “That is all, gentlemen,” he said. “Shall we go down to the study?”

“Well, Trant?” President Joslyn demanded impatiently, as the four filed into the room below, which had been Dr. Lawrie’s. “You act as if you had discovered some clew. What is it?”

Trant was closing the door carefully, when a surprised exclamation made him turn.

“Cora!” Mr. Branower exclaimed; “you here? Oh! You came to see poor Margaret!”

“I couldn’t stay home thinking of you torturing her so this morning!” The beautiful woman swept their faces with a glance of anxious inquiry.

“I told Cora last night something about our test, Joslyn,” Branower explained, leading his wife toward the door. “You can go up to Margaret now, my dear.”

She seemed to resist. Trant fixed his eyes upon her, speculatively.

“I see no reason for sending Mrs. Branower away if she wishes to stay and hear with us the results of our test which Dr. Reiland is about to give us.” Trant turned to the old professor and handed him the sheets upon which he had written his record.

“Now, Dr. Reiland, please! Will you explain to us what these tell you?”

Dr. Joslyn’s hands clenched and Branower drew toward his wife as Reiland took the papers and examined them earnestly. But the old professor raised a puzzled face.

“Luther,” he appealed, “to me these show nothing! Margaret’s normal association-time for innocent words, as you established at the start, is about two and one-half seconds. She did not exceed that in any of the words with guilty associations which you put to her. From these results, I should say, it is scientifically impossible that she even knows her father is accused. Her replies indicate nothing unless—unless,” he paused, painfully, “because she could associate nothing with my name you consider that implies—”

“That you are so close to her that at your name, as at the name of her father, the emotion was very deep, Dr. Reiland,” the young man interrupted. “But do not look only at Margaret’s associations! Tell us, instead, what Dr. Joslyn’s and Mr. Branower’s show!”

“Dr. Joslyn’s and Mr. Branower’s?”

“Yes! For they show, do they not—unconsciously, but scientifically and quite irrefutably—that Dr. Joslyn could not possibly have been concerned in any way with those notes, part of which were due and paid upon the fourteenth of October; but that Mr. Branower has a far from innocent association with them, and with the twenty-fifth of the month, on which the rest were paid!”

He swung toward the trustee. “So, Mr. Branower, you were the man in the room Sunday night! You, to save the rascal Harrison, your wife’s brother and the real thief, struck Dr. Lawrie dead in his office, burned the raised notes, turned on the gas and left him to seem a suicide and a thief!”

For the second time within twenty-four hours, Trant held Dr. Reiland and the president of the university astounded before him. But Branower gave an ugly laugh.

“If you could not spare me, you might at least have spared my wife this last raving accusation! Come, Cora!” he commanded.

“I thought you might control yourself, Mr. Branower,” Trant returned. “And when I saw your wife wished to stay I thought I might keep her to convince even President Joslyn. You see?” he quietly indicated Mrs. Branower as she fell, white and shaking, into a chair. “Do not think that I would have told it in this way if these facts were new to her. I was sure the only surprise to her would be that we knew them.”

Branower bent to his wife; but she straightened and recovered.

“Mr. Branower,” Trant continued then, “if you will excuse chance errors, I will make a fuller statement.

“I should say, first, that since you kept his relationship a secret, this Harrison, your wife’s brother, was a rascal before he came here. Still you procured him his position in the treasurer’s office, where he soon began to steal. It was very easy. Dr. Lawrie merely signed notes; Harrison made them out. He could make them out in erasable ink and raise them after they were signed, or in any other simple way. Suffice it that he did raise them and stole one hundred thousand dollars. When the notes were presented for payment, the matter was laid before you. You must have promised Dr. Lawrie to make up the loss, for he paid the notes and entered the payment in his books. Then the time came when the books must be presented for audit. Lawrie wrote that last appeal to you to put off the settlement no longer. But before the letter was delivered you and Mrs. Branower had hurried off to Elgin to see this Harrison, who was hurt. You got back Sunday evening and read Dr. Lawrie’s note. You went to him; and, unable to make payment, there in his office you struck him dead—”

But Branower was upon him with a harsh cry.

“You devil! You—devil! But you lie! I did not kill him!”

“With a blow? Oh, no! You raised no hand against him. But his heart was weak. At your refusal to carry out your promise, which meant his ruin, he collapsed before you—dead. Do you wish to continue the statement now yourself?”

The wife gathered herself. “It is not so! No!” she forbade, “no!” But Branower turned on President Joslyn a haggard face.

“Is this true?” the president demanded sternly. Branower buried his face in his hands.

“I will tell you all,” he said thickly. “Harrison, as this fellow found out somehow, is my wife’s brother. He has always been reckless, wild; but she—Cora, do not stop me now—loved him and clung to him as—as a sister sometimes clings to such a brother. They were alone in the world, Joslyn. She married me only on condition that I save and protect him. He demanded a position here. I hesitated. His life had been one long scandal; but never before had he been dishonest with money. Finally I made it a condition to keep his relationship secret, and sent for him. I myself first discovered he had raised the notes, weeks before you came to me with the evidence you had discovered that something was wrong in the treasurer’s office. As soon as I found it out, I went to Lawrie. He agreed to keep Harrison about the office until I could remove him quietly. He paid the notes from the university reserve, just raised, upon my promise to make it up. David had lost all speculating in stocks. I could not pay this tremendous amount in cash at once; but the books were to be audited. Lawrie, who had expected immediate repayment from me, would not even once present a false statement. In our argument his heart gave out—I did not know it was weak—and he collapsed in his chair—dead.”

Dr. Reiland groaned, wringing his hands.

“Oh, Professor Reiland!” Mrs. Branower cried now. “He has not told everything. I—I had followed him!”

“You followed him?” Trant cried. “Ah, of course!”

“I thought—I told him,” the wife burst on, “this had happened by Providence to save David!”

“Then it was you who suggested to him to leave the stiletto letter opener in Lawrie’s hand as an evidence of suicide!”

Branower and his wife both stared at Trant in fresh terror.

“But you, Mr. Branower,” Trant went on, “not being a woman with a precious brother to save, could not think of making a wound. You thought of the gas. Of course! But it was inexcusable in me not to test for Mrs. Branower’s presence. It was her odd mental association of a perpetrator with the news of the suspected suicide that first aroused my suspicions.”

He turned as though the matter were finished; but met Dr. Joslyn’s perplexed eyes. The end attained was plain; but to the president of the university the road by which they had come was dark as ever. Branower had taken his wife into another room. He returned.

“Dr. Joslyn,” said Trant, “it is scientifically impossible—as any psychologist will tell you—for a person who associates the first suggested idea in two and one-half seconds, like Margaret, to substitute another without almost doubling the time interval.

“Observe Margaret’s replies. ‘Iron’ followed ‘steal’ as quickly as ‘cat’ followed ‘dog.’ ‘Silver,’ the thing a woman first thinks of in connection with burglary, was the first association she had with ‘thief.’ No possible guilty thought there. No guilty secret connected with her father prevented her from associating, in her regular time, some girl’s secret with Alice Seaton next door. I saw her innocence at once and continued questioning her merely to avoid a more formal examination of the others. I rasped my chair over the floor to disturb her nerves, therefore, and got you into the test.

“The first two tests of you, Dr. Joslyn, showed that you had no association with the notes. The date half of them came due meant nothing to you. ‘October’ suggested only recitations and ‘fourteenth’ permitted you to associate simply the succeeding day in an entirely unsuspicious time. I substituted Mr. Branower. I had explained this system as getting results from persons with poor mental resistance. I had not mentioned it as even surer of results when the person tested is in full control of his faculties, even suspicious and trying to prevent betraying himself. Mr. Branower clearly thought he could guard himself from giving me anything. Now notice his replies.

“The twenty-fifth, the day most of the notes were due, meant so much that it took double the time, before he could drive out his first suspicious association, merely to say ‘twenty-sixth.’ I told you I suspected his wife was at least cognizant of something wrong. It took him twice the necessary time to say ‘Cora’ after ‘wife’ was mentioned. He gave the first association, but the chronoscope registered mercilessly that he had to think it over. ‘Wound’ then brought the remarkable association ‘no’ at the end of four and six-tenths seconds. There was no wound; but something had made it so that he had to think it over to see if it was suspicious. When I first saw that dagger letter opener on Dr. Lawrie’s desk, I thought that if a man were trying to make it seem suicide, he must at least have thought of using the dagger before the gas. Now note the next test, ‘Harrison.’ Any innocent man, not overdoing it, would have answered at once the name of the Harrison immediately in all our minds. Mr. Branower thought of him first, of course, and could have answered in two seconds. To drive out that and think of President Harrison so as to give a seemingly ‘innocent’ association, ‘Cleveland,’ took him over five seconds. I then went for the hold of this Harrison, probably, upon Mrs. Branower. I tried for it twice. The second trial, ‘brother,’ made him think again for five seconds, practically, before he could decide that sister was not a guilty word to give. As the first words ‘blow’ only brought ‘wind’ in two seconds and ‘strike’ suggested ‘labor’ at once, I knew he could not have struck Dr. Lawrie a blow; and my last words showed, indeed, that Lawrie probably collapsed before him. And I was done.”

Dr. Joslyn was pacing the room with rapid steps. “It is plain. Branower, you offer nothing in your defense?”

“There is nothing.”

“There is much. The university owes a great debt to your father. The autopsy will show conclusively that Dr. Lawrie died of heart failure. The other facts are private with ourselves. You can restore this money. Its absence I will reveal only to the trustees. I shall present to them at the same time your resignation from the board.”

He turned to Trant. “But this secrecy, young man, will deprive you of the reputation you might have gained through the really remarkable method you used through this investigation.”

“It makes no difference,” Trant answered, “if you will give me a short leave from the university. As I mentioned to Dr. Reiland yesterday, the prosecuting attorney of Chicago was murdered two weeks ago. Sixteen men—one of them surely guilty—are held; but the criminal cannot be picked among them. I wish to try the scientific psychology again. If I succeed, I shall resign and keep after crime—in the new way!”

Police Captain Crowley—red-headed, alert, brave—stamped into the North Side police station an hour later than usual and in a very bad temper. He glared defiantly at the row of patrolmen, reporters, and busybodies, elbowed aside his desk sergeant without a word, and slammed into his private office. The customary pile of morning papers, flaying him in stinging front-page columns, covered his desk. He glanced them over, grunting; then swept them to the floor and let himself drop heavily into his chair.

“He’s got to be guilty!” The big fist struck the table top desperately. “It’s got to be,” the hoarse voice iterated determinedly—“him!” He had checked the last word as the door swung open, only to utter it more forcibly as he recognized the desk sergeant.

“Kanlan, eh, Ed?” the desk sergeant ventured. “You have him at Harrison Street station again the boys tell me.”

“Yes, we have him.”

“You got nothing out of him yet?”

“No, nothing—yet!”

“But you think it’s him?”

“Who said anything about thinking?” Crowley glanced to see that the door was shut. “I said it’s got to be him! And—it’s got to, whether or no, ain’t it?”

A month before, Randolph Bronson—the city prosecuting attorney for whose unpunished murder Crowley was under fire—had dared to try to break up and send to the penitentiary the sixteen men who formed the most notorious and dangerous gambling “ring” in the city. It grew certain that some of the sixteen would stick at nothing to put the prosecutor out of the way. The chief of police particularly charged Crowley, therefore, to see to Bronson’s safety in the North Side precinct, where the young attorney boarded. But Crowley had failed; for within twelve days of the warning, early one morning, Bronson had been found dead a block from his boarding house—murdered. Crowley had been unable to fix a clew upon a single one of the sixteen. He had confidently arrested them all at once, but after his stiffest “third degree” had to release them. Now, in desperation, he had rearrested Kanlan.

“Sure,” said the desk sergeant, “Kanlan or some one’s got to be guilty soon—whether or no. But if you ain’t got the goods on Kanlan yet, maybe you’d want to talk to a lad that’s waiting in front.”

“Who is he? What does he know?”

“Trant’s his name—from the university, he says. And he says he can pick our man.”

“What is he—student?”

“He says some sort of perfesser.”

“Professor!” Crowley half turned away.

“Not that kind, Ed.” The desk sergeant bent one arm and tapped his biceps. “He’s got plenty of this; and he’s got hair, too”—the sergeant glanced at Crowley’s red head—“as red as any, Cap.”

“Send him in.”

Crowley looked up quickly at Trant when he entered. He saw a young man with hair indeed as thick and red as his own; and with a figure, for his more medium height, quite as muscular as any police officer’s. He saw that the young man’s blue-gray eyes were not exact mates—that the right was quite noticeably more blue than the other, and under it was a small, pink scar which reddened conspicuously with the slightest flush of the face.

“Luther Trant, Captain Crowley,” Trant introduced himself. “For two years I have been conducting experiments in the psychological laboratory of the university—”

“Psycho—Lord! Another clairvoyant!”

“If the man who killed Bronson is one of the sixteen men you suspect, and you will let me examine them, properly, I can pick the murderer at once.”

“Examine them properly! Saints in Heaven, son! Say! that gang needed a stiff drink all round when we were through examining them; and never a word or a move gave a man away!”

“Those men—of course not!” Trant returned hotly. “For they can hold their tongues and their faces, and you looked at nothing else! But while you were examining them, if I, or any other trained psychologist, had had a galvanometer contact against the palms of their hands, or—”

“A palmist, Lord preserve us!” Crowley cried. “Say! don’t ever think we needed you. We got our man yesterday—Kanlan—and we’ll have a confession out of him by night. Sergeant!” he called, as the door opened to admit a man, “do you know what you let in—a palmist!” But it was not the sergeant who entered. “A‑ah! Inspector Walker!”

“Morning, Crowley,” Trant heard the quiet response behind him as he turned. A giant in the uniform of an inspector of police almost filled the doorway.

“Come with me, young man,” he said. “Miss Allison was passing with me outside here and we heard some of what you’ve been saying. We’d like to hear more.”

Trant looked up at the intelligent face and followed. A young woman was waiting outside the door. As the inspector pointed Trant toward a quiet room in the rear of the building, she followed. Inspector Walker fastened the door behind them. The girl had seated herself beside the table in the center, and as she turned to Trant she raised her veil above her brown, curling hair, and pinned it over her hat. He recognized her at once as the girl to whom Bronson had become engaged barely a week before he had been killed. On her had fallen all the horrors as well as the grief of Bronson’s murder, and Trant did not wonder that the shadow of that event was visible in her sweet face. But he read there also another look—a look of apprehension and defiance.

“I was coming in with Inspector Walker to see Captain Crowley,” the girl explained to Trant, “when I overheard you telling him that you think this—Kanlan—couldn’t have killed Mr. Bronson. I hope this is so.”

Trant looked to Walker. “Miss Allison’s father was Judge Allison, the truest man who ever sat on the bench in this city,” Walker responded. “His daughter knows she must not try to prevent us from punishing a man who murders; but neither of us wants to believe Kanlan is the man—for good reasons. Now, what was that you were telling Crowley?”

“I was trying to tell Captain Crowley of a simple test which must prove Kanlan’s guilt or innocence at once, and, if necessary, then find the guilty man. I have been conducting experiments to register and measure the effects and reactions of emotions. A person under the influence of fear or the stress of guilt must always betray signs. A hardened man can control all the signs for which the police ordinarily look; he can control his features, prevent his face flushing noticeably. But no man, however hardened or trained to control himself, can prevent many minute changes which by scientific means are measurable and betray him hopelessly. No man, however on his guard—to take the simplest test—can control the sweat glands in the palms of his hands, which always moisten under emotion.”

“A scared man sweats; that’s so,” Walker assented.

“So psychologists have devised a simple way of registering the emotions shown through the glands in the palms of the hand,” Trant continued, “by means of the galvanometer. I have one in the box I left with the desk sergeant. It is merely a device for measuring the varying strength of an ordinary electric current. The man tested holds in each hand a contact metal wired to the battery. When he grasps them a weak and imperceptible current passes through his body or—if his hands are very dry—perhaps no current at all. He is then examined and confronted with circumstances or objects connected with the crime. If he is innocent, the objects have no significance in his mind, and cause no emotion. His face betrays none; neither can his hands. But if he is guilty, though he still manages to control his face, he cannot prevent the moisture from flowing from the glands in his palms. Understand me; I do not mean an amount of moisture noticeable to the eye, but it is enough to make an electric contact through the metals which he holds—enough to register very plainly upon the galvanometer, whose moving needle, traveling in the scale, betrays him pitilessly!”

The inspector shook his head skeptically.

“I recognize that this is new to you,” said Trant. “But I am telling you no theory. Using the galvanometer properly, we can this morning determine—scientifically and irrefutably—whether or not Kanlan killed Mr. Bronson, and later, if it is not he, which of the others is the assassin. May I try it?”

Miss Allison, more white than before, had risen, and laid her hand upon Trant’s sleeve.

“Oh, try it, Mr. Trant!” she cried. “Try—try anything which can stop them from showing through this gambler, Kanlan, and Mrs. Hawtin that Mr. Bronson—” She broke off, and turned to the inspector. Walker was looking Trant over again. The psychologist faced the police officer eagerly. “I can’t believe it’s Kanlan,” said Walker.

Until now Trant had been impressed chiefly by the huge bulk of the inspector, but as Walker spoke of the gambler whom Crowley, to save his own face, was trying to “railroad” to execution, Trant saw in the inspector something approaching sentimentality. For he was that common anomaly of the police department, an officer born and bred among the criminals he is set to watch.

“I’ll take you to Kanlan,” the inspector granted at last. “As things are going with him, you can’t hurt, and maybe you can help. Everyone knows Kanlan would have put out Bronson; but not—I am certain—that way. I was born in the basement opposite Kanlan’s. If Mr. Bronson had been attacked in broad day, with a detective on each side of him and all of them had been beaten up or killed, I’d have been the first to step over to Kanlan and say, ‘Jake, you’re wanted.’ But Bronson was not caught that way. The man that killed him waited till the house was quiet, until Crowley’s guards were asleep, and then somehow or other—how is a bigger mystery than the murder itself—got him out alone in the street at two o’clock in the morning, and struck him dead from a dark doorway.

“But I’m not taking you to Kanlan only to help save him from Crowley.” Walker straightened suddenly as his eyes met the girl’s. “It’s to help Miss Allison, too. For the only clew Crowley or anyone else has to the man who murdered Bronson is in connection with the means of getting Bronson out of the house that way. Crowley has discovered that a Mrs. Hawtin, whom Kanlan can control through her gambling debts to him, is living a few doors beyond the place where Bronson’s body was found. Crowley claims he can show Mrs. Hawtin was a friend of Bronson’s, and—” The inspector hesitated, glancing at the girl.

“Captain Crowley’s case,” said Miss Allison, finishing, “is based on the charge that after Randolph—Mr. Bronson—had returned to his rooms from seeing me that evening, he went out again two hours later to answer a summons from this—this Mrs. Hawtin. So long as Captain Crowley can convict some one for this crime, they seem to care nothing how they slander and blacken the name of the man who is killed—as little as they care for those left who—love him.”

“I see,” said Trant. His eyes rested a moment upon the inspector, then again upon the girl. It surprised him to feel, as his eyes met hers that short moment, how suddenly this problem, which he had set himself to solve, had changed from a scientific examination and selection of a guilty man to the saving—though through the same science—of the reputation of a man no longer able to defend himself, and the honor of a woman devoted to that man’s memory.

“But before I can examine Kanlan, or help you in any other way, Miss Allison,” he explained gently, “I must be sure of my facts. It is not too much to ask you to go over them with me? No, Inspector Walker,” he anticipated the big police officer’s objection as Walker started to speak, “if I am to help Miss Allison, I cannot spare her now.”

“Please do not, Mr. Trant,” the girl begged bravely.

“Thank you. Mr. Bronson, I believe, was still boarding on Superior Street at a bachelor’s boarding house?”

“Yes,” the girl replied. “It is kept by Mrs. Mitchell, a very respectable widow with a little boy. Randolph had boarded with her for six years. She had once been in great trouble and he was kind to her. He often spoke of how she gave him motherly care.”

“Motherly?” Trant asked. “How old is she?”

“Twenty-seven or eight, I should think.”

“Thank you. How long had you known Mr. Bronson, Miss Allison?”

“A little over two years.”

“Yes; and intimately, how long?”

“Almost from the first.”

“But you were not engaged to him until just the week before his death?”

“Yes; our engagement was not made known till just two days before his—death.”

“Inspector Walker, how long before Mr. Bronson was killed was any of the ‘ring’ likely to put him out of their way?”

“For two weeks at least.”

“It fits Crowley’s case, of course, as well as—any other,” said Trant, thoughtfully, “that two days after the announcement of his engagement was the first time anyone could actually catch him alone. But it is worth noting, inspector. Mr. Bronson called upon you that evening, Miss Allison? Everything was as usual between you?”

“Entirely, Mr. Trant. Of course we both recognized the constant danger he was in. I knew how and why he had to be guarded. His regular man, from the city detail, had been with him all day downtown; and Captain Crowley’s man came with him to our house. Mr. Bronson went back to his boarding house with him precisely at half past ten.”

“He reached the boarding house,” Inspector Walker took up the account, “a little before eleven and went at once to his room. At twelve-thirty the last boarder came in. Crowley’s man immediately chained the front door and made all fast. He went to the kitchen to get something to eat, he says, and may have fallen asleep, though he denies it. However, until after Bronson’s body was found, we have made certain, there was no alarm inside or out.”

“There is no doubt that Mr. Bronson was in the house when it was locked up?”

“None. The last boarder, as he went to his room, saw Bronson sitting at his table going over some papers. He was still dressed but said he was going to bed immediately. An hour and a half later—with no clew as to how he went out, with no discoverable reason for his going out except that given by Crowley—a patrolman found Bronson’s body on the sidewalk a block east of his boarding house. He had been struck in the forehead and killed instantly by a man who must have waited for him in the vestibule of a little electro-plating shop.”

“Must have, inspector?” Trant questioned.

“Yes; he chose this shop doorway because it was the darkest place in the block.”

“At what time was that—exactly?” Trant interrupted. “The papers say the attack was made ten minutes after two o’clock—that the watch in his pocket was broken and stopped by his fall at exactly ten minutes after two. Is that correct?”

“Yes,” the inspector replied. “The watch stopped at 2.10; but, in spite of that, the exact time of the murder must have been nearer two than ten minutes later, for Mr. Bronson’s watch was fast.”

“What?” Trant cried. “You say his watch was fast? I had not heard of that!”

“It was noticed two days ago,” the inspector explained, “that the record shows that the patrolman who found Bronson’s body rang up from the nearest patrol box at five minutes after two. If the attack was made just before, the watch must have been at least ten minutes fast, so we have the time, after all, only approximately.”

“I see.” Trant turned to the girl. “It is strange, Miss Allison, that a man like Mr. Bronson carried an incorrect watch.”

“He did not. It was always right.”

“Was it right that evening?”

“Why, yes. I remember that he compared his time with our clock before leaving.”

Trant leaped up, excitedly. “What? What? But still,” he calmed himself, “whether at two or ten minutes after two, the main question is the same. You, too, Miss Allison, can you give no possible reason why Mr. Bronson might have gone out?”

“I have tried a thousand times in these terrible two weeks to think of some reason, but I cannot. Our house is in a different direction than that he took. The car line to the city is another way. He knew no one in that direction—except Mrs. Hawtin.”

“You knew that he knew her?”

“Of course, Mr. Trant! He had convicted her once for shoplifting, but, like everyone whom his place had made him punish, he watched her afterwards, and, when she tried to be honest, he helped her as he had helped a hundred like her—men and women—though his enemies tried to discredit and disgrace him by accusing him of untrue motives. Oh, Mr. Trant, you do not know—you cannot understand—what shadows and pitfalls surround a man in the position Mr. Bronson held. That is why, though for two years we had known and loved each other, he waited so long before asking me to marry him. I am thankful that he spoke in time to give me the right to defend him now before the world! They took his life; they shall not take his good name! No! No! They shall not! Help me, Mr. Trant, if you can—help me!”

“Inspector Walker!” said Trant tensely, “I understand that all of the sixteen men of the ring claimed alibis. Was Kanlan’s one of the best or the worst?”

The inspector hesitated. “One of the worst,” he replied, unwillingly. “I am sorry to say, the very worst.”

To his surprise, Trant’s eyes blazed triumphantly. “Miss Allison,” said he, quietly and decidedly, “I had not expected till I had tested Kanlan to be able to assure you that he is not guilty. But now I think I am safe in promising it—provided you are sure that Mr. Bronson’s watch was right when he left you that night. And, Inspector Walker, if you are also certain that the murderer waited in the vestibule of that electro-plating shop, it will be soon, indeed, that we can give Crowley a better—or rather a worse—man to send to trial in Kanlan’s place.”

Again Trant was conscious that the giant inspector was estimating not the incomprehensible statement he had made, but Trant himself. And again Walker seemed satisfied.

“When can I go with you to Harrison Street to prove this, inspector?”

“I shall see Miss Allison home, and meet you at Harrison Street in an hour.”

“You will let me know the result of the test at once, Mr. Trant?”

“At once, Miss Allison.” Trant took his hat and dashed from the station.

Harrison Street police station, Chicago, is headquarters of the first police division in the third city of the world. But neither London nor New York, the two larger cities, nor Paris, whose population of two million and a half Chicago is now passing, possesses a police division more complex, diverse, and puzzling in the cosmopolitan diversity of the persons arrested than this first of Chicago.

But from all the dozen diversities brought to the Harrison Street station daily, for two weeks none had challenged in interest the case against Jake Kanlan, the racing man and gambler, rearrested and held for the murder of Bronson. Trant appreciated this as, with his galvanometer and batteries in a suit case, he pushed his way among patrolmen, detectives, reporters, and the curious into the station. But at once he caught sight of the giant inspector, Walker.

“You’re late.” Walker led him into a side room. “I’ve been putting in the time telling Sweeny here,” Walker introduced him to one of the two men within, “and Captain Crowley, how you mean to work your scheme. We’ve been waiting for you an hour!”

“I’m sorry,” Trant apologized. “I have been going over the files of the papers just before and after the murder. And I must admit, Captain Crowley,” Trant conceded, “that Kanlan had as strong a reason as any for wanting Bronson out of the way. But I found one remarkably significant thing. You have seen it?” He pulled a folded newspaper from his pocket and handed it to them. “I mean this paragraph at the bottom of the front page.”

The captain read it eagerly, then leaned back and laughed. “Sure, I saw it,” he derided. “It’s that old Johanson fake, Sweeny—and he thought it was a clew!” The inspector took the paper.

“Threatener of Bronson Breaks Jail” was the heading, and under it was this short paragraph:

James Johanson, the notorious Stockyards murderer, whom City Attorney Bronson sent up for life three years ago, escaped from the penitentiary early this morning and is thought by the officials to be making his way to this city. His trial will be remembered for the dramatic and spectacular denunciation of the Prosecuting Attorney by the convicted man upon his condemnation, and his threat to free himself and “do for” Bronson.

“You see the date of the paper?” said Trant. “It is the five o’clock edition of the evening before Bronson was murdered! Johanson is reported escaped and at once Bronson is killed.”

Crowley snickered patronizingly. “So you thought, before your palmistry, you could string us with that?” he jeered. “You might better have kept us waiting a little longer, young man, and you’d have found out that Johanson couldn’t have done it, for he never escaped. It was a slip of a sneak thief, Johnson, that escaped, and he was on his way back to Joliet before night. The News got the name wrong, that’s all, son.”

“I was quite able to find that out, too, before coming here, Captain Crowley,” Trant said quietly, “both that Johanson never escaped and that all evening papers except the News had the name correctly. Even the News corrected its account in its later edition. And I did not say that Johanson himself had anything to do with it. But either you must claim it a strange coincidence that, within eight hours after a report was current in the city that Johanson had broken out and was coming to murder Bronson, Bronson was actually murdered, or else you must admit the practical certainty that the man waiting to murder Bronson saw this account, and, not knowing it was incorrect, chose that night to kill the attorney, so as to lay it to Johanson.” He picked up his suit case. “But come, let us test Kanlan.”

“I haven’t told Jake what you’re going to do to him,” Walker volunteered, as he led the three to the cells below. Sweeny, at Crowley’s nod, had brought with him a satchel from the upper office.