Title: Among the camps

or, Young people's stories of the war

Author: Thomas Nelson Page

Illustrator: W. A. Rogers

William Ludwell Sheppard

Release date: March 8, 2025 [eBook #75553]

Language: English

Original publication: New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1891

Credits: David E. Brown and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BY THOMAS NELSON PAGE.

| ELSKET AND OTHER STORIES. 12mo, | $1.00 |

| NEWFOUND RIVER. 12mo, | 1.00 |

| IN OLE VIRGINIA. 12mo, | 1.25 |

| THE SAME. Cameo Edition. With an etching by W. L. Sheppard. 16mo, | 1.25 |

| AMONG THE CAMPS. Young People’s Stories of the War. Illustrated. Sq. 8vo, | 1.50 |

| TWO LITTLE CONFEDERATES. Illustrated. Square 8vo, | 1.50 |

| “BEFO’ DE WAR.” Echoes of Negro Dialect. By. A. C. Gordon and Thomas Nelson Page. 12mo, | 1.00 |

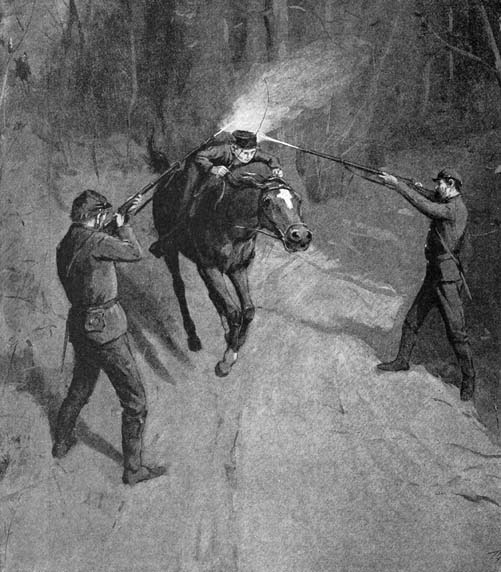

“HALT!” BANG, BANG, WENT THE GUNS IN HIS VERY FACE.

AMONG THE CAMPS

OR

YOUNG PEOPLE’S STORIES OF THE WAR

BY

THOMAS NELSON PAGE

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1891

Copyright, 1891, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Press of J. J. Little & Co.

Astor Place, New York

To Her:

My acknowledgments are due to Messrs. Harper & Brothers and to Mr. A. B. Starey, the Publishers and the Editor of HARPERS’ YOUNG PEOPLE, in which Magazine I had the pleasure of having these stories, with the accompanying illustrations, first appear.

T. N. P.

| A Captured Santa Claus | Page | 1 |

| Kittykin, and the Part She Played in the War | “ | 41 |

| “Nancy Pansy” | “ | 65 |

| “Jack and Jake” | “ | 115 |

| “Halt!” Bang, bang, went the Guns in His very Face | Frontispiece | |

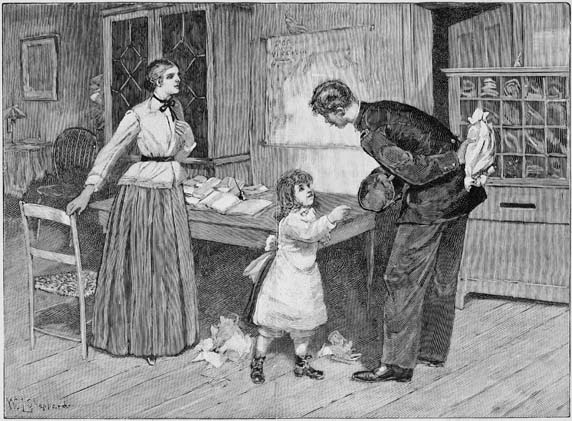

| Colonel Stafford opens the Bundle | Page | 11 |

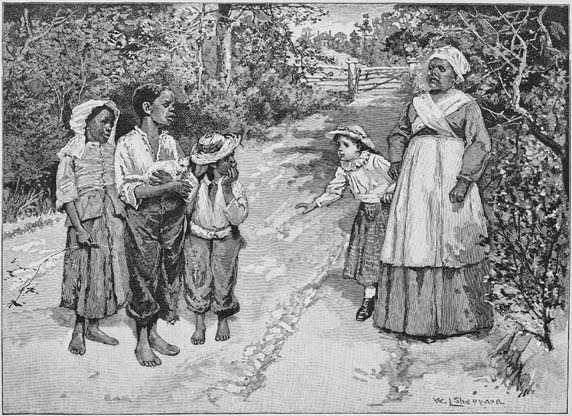

| “What You Children gwine do wid dat little Cat?” asked Mammy, severely | “ | 40 |

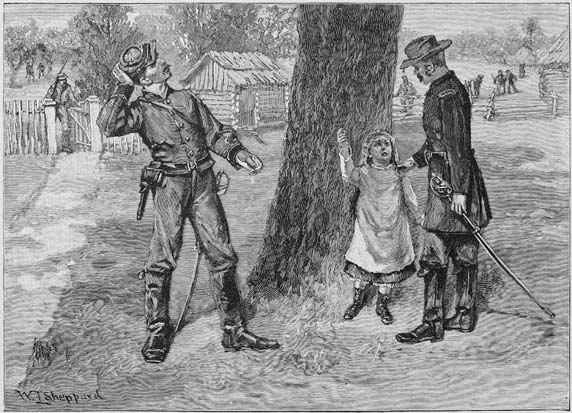

| “I Want My Kittykin,” said Evelyn | “ | 54 |

| Nancy Pansy clasped Harry closely to Her Bosom | “ | 77 |

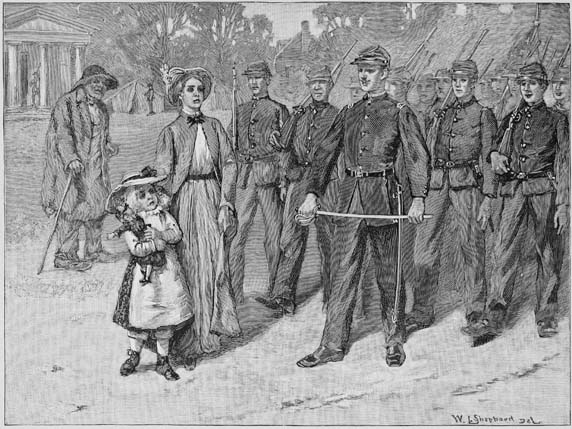

| She ran up to Him, putting up Her Face to be Kissed | “ | 91 |

| He drew Them Plans of the Roads and Hills and big Woods | “ | 123 |

| Jack made a running Noose in the Rope and tried to throw it over the Horse’s Head | “ | 139 |

HOLLY HILL was the place for Christmas! From Bob down to brown-eyed Evelyn, with her golden hair floating all around her, every one hung up a stocking, and the visit of Santa Claus was the event of the year.

They went to sleep on the night before Christmas—or rather they went to bed, for sleep was long far from their eyes,—with little squeakings and gurglings, like so many little white mice, and if Santa Claus had not always been so very punctual in disappearing up the chimney before daybreak, he must certainly have been caught; for by the time the chickens were crowing in the morning there would be an answering twitter through the house, and with a patter of little feet and subdued laughter small white-clad figures would steal through the dim light of dusky rooms and passages, opening doors with sudden bursts, and shouting “Christmas gift!” into darkened chambers, at still sleeping elders, then scurrying away in the gray light to rake open the hickory embers and revel in the exploration of their crowded stockings.

[2]Such was Christmas morning at Holly Hill in the old times before the war. Thus it was, that at Christmas 1863, when there were no new toys to be had for love or money, there were much disappointment and some murmurs at Holly Hill. The children had never really felt the war until then, though their father, Major Stafford, had been off, first with his company and then with his regiment, since April, 1861. Now from Mrs. Stafford down to little tot Evelyn, there was an absence of the merriment which Christmas always brought with it. Their mother had done all she could to collect such presents as were within her reach, but the youngsters were much too sharp not to know that the presents were “just fixed up”; and when they were all gathered around the fire in their mother’s chamber, Christmas morning, looking over their presents, their little faces wore an expression of pathetic disappointment.

“I don’t think much of this Christmas,” announced Ran, with characteristic gravity, looking down on his presents with an air of contempt. “A hatchet, a ball of string, and a hare-trap isn’t much.”

Mrs. Stafford smiled, but the smile soon died away into an expression of sadness.

“I too have to do without my Christmas gift,” she said. “Your father wrote me that he hoped to spend Christmas with us, and he has not come.”

“Never mind; he may come yet,” said Bob encouragingly. (Bob always was encouraging. That was why he was[3] “Old Bob.”) “An axe was just the thing I wanted, mamma,” said he, shouldering his new possession proudly.

Mrs. Stafford’s face lit up again.

“And a hatchet was what I wanted,” admitted Ran; “now I can make my own hare-traps.”

“An’ I like a broked knife,” asserted Charlie stoutly, falling valiantly into the general movement, whilst Evelyn pushed her long hair out of her eyes, and hugged her baby, declaring:

“I love my dolly, and I love Santa Tlaus, an’ I love my papa,” at which her mother took the little midget to her bosom, doll and all, and hid her face in her tangled curls.

[4]

THE holiday was scarcely over when one evening Major Stafford galloped up to the gate, his black horse Ajax splashed with mud to his ear-tips.

The Major soon heard all about the little ones’ disappointment at not receiving any new presents.

“Santa Tlaus didn’ tum this Trismas, but he’s tummin’ next Trismas,” said Evelyn, looking wisely up at him, that evening, from the rug where she was vainly trying to make her doll’s head stick on her broken shoulders.

“And why did he not come this Christmas, Miss Wisdom?” laughed her father, touching her with the toe of his boot.

“Tause the Yankees wouldn’ let him,” said she gravely, holding her doll up and looking at it pensively, her head on one side.

“And why, then, should he come next year?”

“Tause God’s goin’ to make him.” She turned the mutilated baby around and examined it gravely, with her shining head set on the other side.

“There’s faith for you,” said Mrs. Stafford, as her husband asked, “How do you know this?”

[5]“Tause God told me,” answered Evelyn, still busy with her inspection.

“He did? What is Santa Claus going to bring you?”

The little mite sprang to her feet. “He’s goin’ to bring me—a—great—big—dolly—with real sure ’nough hair, and blue eyes that will go to sleep.” Her face was aglow, and she stretched her hands wide apart to give the size.

“She has dreamt it,” said the Major, in an undertone, to her mother. “There is not such a doll as that in the Southern Confederacy,” he continued.

The child caught his meaning. “Yes, he is,” she insisted, “’cause I asked him an’ he said he would; and Charlie——”

Just then that youngster himself burst into the room, a small whirlwind in petticoats. As soon as his cyclonic tendencies could be curbed, his father asked him:

“Well, what did you ask Santa Claus for, young man?”

“For a pair of breeches and a sword,” answered the boy, promptly, striking an attitude.

“Well, upon my word!” laughed his father, eying the erect little figure and the steady, clear eyes which looked proudly up at him. “I had no idea what a young Achilles we had here. You shall have them.”

The boy nodded gravely. “All right. When I get to be a man I won’t let anybody make my mamma cry.” He advanced a step, with head up, the very picture of spirit.

“Ah! you won’t?” said his father, with a gesture to prevent his wife interrupting.

[6]“Nor my little sister,” said the young warrior, patronizingly, swelling with infantile importance.

“No; he won’t let anybody make me ky,” chimed in Evelyn, promptly accepting the proffered protection.

“On my word, Ellen, the fellow has some of the old blood in him,” said Major Stafford, much pleased. “Come here, my young knight.” He drew the boy up to him. “I had rather have heard you say that than have won a brigadier’s wreath. You shall have your breeches and your sword next Christmas. Were I the king I should give you your spurs. Remember, never let any one make your mother or sister cry.”

Charlie nodded in token of his acceptance of the condition.

“All right,” he said.

[7]

WHEN Major Stafford galloped away, on his return to his command, the little group at the lawn gate shouted many messages after him. The last thing he heard was Charlie’s treble, as he seated himself on the gate-post, calling to him not to forget to make Santa Claus bring him a pair of breeches and a sword, and Evelyn’s little voice reminding him of her “dolly that can go to sleep.”

Many times during the ensuing year, amid the hardships of the campaign, the privations of the march, and the dangers of battle, the Major heard those little voices calling to him. In the autumn he won the three stars of a colonel for gallantry in leading a desperate charge on a town, in a perilous raid into the heart of the enemy’s country, and holding the place; but none knew, when he dashed into the town at the head of his regiment under a hail of bullets, that his mind was full of toyshops and clothing stores, and that when he was so stoutly holding his position he was guarding a little boy’s suit, a small sword with a gilded scabbard, and a large doll with flowing ringlets and eyes that could “go to sleep.” Some of his friends during that year had charged the Major with growing miserly, and rallied him upon hoarding up his[8] pay and carrying large rolls of Confederate money about his person; and when, just before the raid, he invested his entire year’s pay in four or five ten-dollar gold pieces, they vowed he was mad.

The Major, however, always met these charges with a smile. And as soon as his position was assured in the captured town he proved his sanity.

The owner of a handsome store on the principal street, over which was a large sign, “Men’s and Boys’ Clothes,” peeping out, saw a Confederate major ride up to the door, which had been hastily fastened when the fight began, and rap on it with the handle of his sword. There was something in the rap that was imperative, and fearing violence if he failed to respond, he hastily opened the door. The officer entered, and quickly selected a little uniform suit of blue cloth with brass buttons.

“What is the price of this?”

“Ten dollars,” stammered the shopkeeper.

To his astonishment the Confederate officer put his hand in his pocket and laid a ten-dollar gold piece on the counter.

“Now show me where there is a toyshop.”

There was one only a few doors off, and there the Major selected a child’s sword handsomely ornamented, and the most beautiful doll, over whose eyes stole the whitest of rose-leaf eyelids, and which could talk and do other wonderful things. He astonished this shopkeeper also by laying down another gold piece. This left him but two or three more of[9] the proceeds of his year’s pay, and these he soon handed over a counter to a jeweller, who gave him a small package in exchange.

All during the remainder of the campaign Colonel Stafford carried a package carefully sealed, and strapped on behind his saddle. His care of it and his secrecy about it were the subjects of many jests among his friends in the brigade, and when in an engagement his horse was shot, and the Colonel, under a hot fire, stopped and calmly unbuckled his bundle, and during the rest of the fight carried it in his hand, there was a clamor that he should disclose the contents. Even an offer to sing them a song would not appease them.

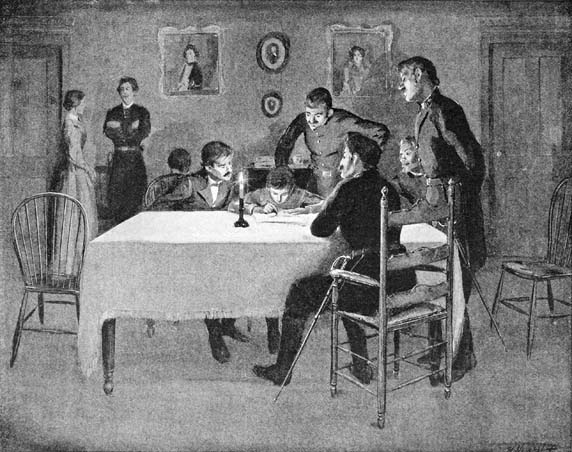

The brigade officers were gathered around a camp-fire that night on the edge of the bloody field. A Federal officer, Colonel Denby, who had been slightly wounded and captured in the fight, and who now sat somewhat grim and moody before the fire, was their guest.

“Now, Stafford, open the bundle and let us into the secret,” they all said. The Colonel, without a word, rose and brought the parcel up to the fire. Kneeling down, he took out his knife and carefully ripped open the outer cover. Many a jest was levelled at him across the blazing logs as he did so.

One said the Colonel had turned peddler, and was trying to eke out a living by running the blockade on Lilliputian principles; another wagered that he had it full of Confederate bills; a third, that it was a talisman against bullets, and[10] so on. Within the outer covering were several others; but at length the last was reached. As the Colonel ripped carefully, the group gathered around and bent breathlessly over him, the light from the blazing camp-fire shining ruddily on their eager, weather-tanned faces. When the Colonel put in his hand and drew out a toy sword, there was a general exclamation, followed by a dead silence; but when he took the doll from her soft wrapping, and then unrolled and held up a pair of little trousers not much longer than a man’s hand, and just the size for a five-year-old boy, the men turned away their faces from the fire, and more than one who had boys of his own at home, put his hand up to his eyes.

One of them, a bronzed and weather-beaten officer, who had charged the Colonel with being a miser, stretched himself out on the ground, flat on his face, and sobbed aloud as Colonel Stafford gently told his story of Charlie and Evelyn. Even the grim face of Colonel Denby looked somewhat changed in the light of the fire, and he reached over for the doll and gazed at it steadily for some time.

[11-12]

COLONEL STAFFORD OPENS THE BUNDLE.

[13]

DURING the whole year the children had been looking forward to the coming of Christmas. Charlie’s outbursts of petulance and not rare fits of anger were invariably checked if any mention was made of his father’s injunction, and at length he became accustomed to curb himself by the recollection of the charge he had received. If he fell and hurt himself in his constant attempt to climb up impossible places, he would simply rub himself and say, proudly, “I don’t cry now, I am a knight, and next Christmas I am going to be a man, ’cause my papa’s goin’ to tell Santa Claus to bring me a pair of breeches and a sword.” Evelyn could not help crying when she was hurt, for she was only a little girl; but she added to her prayer of “God bless and keep my papa, and bring him safe home,” the petition, “Please, God, bless and keep Santa Tlaus, and let him come here Trismas.”

Old Bob and Ran too, as well as the younger ones, looked forward eagerly to Christmas.

But some time before Christmas the steady advance of the Union armies brought Holly Hill and the Holly Hill children far within the Federal lines, and shut out all chance of their being reached by any message or thing from their[14] father. The only Confederates the children ever saw now were the prisoners who were being passed back on their way to prison. The only news they ever received were the rumors which reached them from Federal sources. Mrs. Stafford’s heart was heavy within her, and when, a day or two before Christmas, she heard Charlie and Evelyn, as they sat before the fire, gravely talking to each other of the long-expected presents which their father had promised that Santa Claus should bring them, she could stand it no longer. She took Bob and Ran into her room, and there told them that now it was impossible for their father to come, and that they must help her entertain “the children” and console them for their disappointment. The two boys responded heartily, as true boys always will when thrown on their manliness.

For the next two days Mrs. Stafford and both the boys were busy. Mrs. Stafford, when Charlie was not present, gave her time to cutting out and making a little gray uniform suit from an old coat which her husband had worn when he first entered the army; whilst the boys employed themselves, Bob in making a pretty little sword and scabbard out of an old piece of gutter, and Ran, who had a wonderful turn, in carving a doll from a piece of hard seasoned wood.

The day before Christmas they lost a little time in following and pitying a small lot of prisoners who passed along the road by the gate. The boys were always pitying the prisoners and planning means to rescue them, for they had an idea that they suffered a terrible fate. Only one certain case[15] had come to their knowledge. A young man had one day been carried by the Holly Hill gate on his way to the headquarters of the officer in command of that portion of the lines, General Denby. He was in citizen’s clothes and was charged with being a spy. The next morning Ran, who had risen early to visit his hare-traps, rushed into his mother’s room white-faced and wide-eyed.

“Oh, mamma!” he gasped, “they have hung him, just because he had on those clothes!”

Mrs. Stafford, though she was much moved herself, endeavored to explain to the boy that this was one of the laws of war; but Ran’s mind was not able to comprehend the principles which imposed so cruel a sentence for what he deemed so harmless a fault.

This act and some other measures of severity gave General Denby a reputation of much harshness among the few old residents who yet remained at their homes in the lines, and the children used to gaze at him furtively as he would ride by, grim and stern, followed by his staff. Yet there were those who said that General Denby’s rigor was simply the result of a high standard of duty, and that at bottom he had a soft heart.

[16]

THE approach of Christmas was recognized even in the Federal camps, and many a song and ringing laugh were heard around the camp-fires, and in the tents and little cabins used as winter quarters, over the boxes which were pouring in from home. The troops in the camps near General Denby’s headquarters on Christmas eve had been larking and frolicking all day like so many children, preparing for the festivities of the evening, when they proposed to have a Christmas tree and other entertainments; and the General, as he sat in the front room in the house used as his headquarters, writing official papers, had more than once during the afternoon frowned at the noise outside which had disturbed him. At length, however, late in the afternoon, he finished his work, and having dismissed his adjutant, he locked the door, and pushing aside all his business papers, took from his pocket a little letter and began to read.

As he read, the stern lines of the grim soldier’s face relaxed, and more than once a smile stole into his eyes and stirred the corners of his grizzled moustache.

The letter was scrawled in a large childish hand. It ran:

[17]

“My Dearest Grandpapa: I want to see you very much. I send you a Christmas gift. I made it myself. I hope to get a whole lot of dolls and other presents. I love you. I send you all these kisses.... You must kiss them.

“Your loving little granddaughter,

“Lily.”

When he had finished reading the letter the old veteran gravely lifted it to his lips and pressed a kiss on each of the little spaces so carefully drawn by the childish hand.

When he had done he took out his handkerchief and blew his nose violently as he walked up and down the room. He even muttered something about the fire smoking. Then he sat down once more at his table, and placing the little letter before him, began to write. As he wrote, the fire smoked more than ever, and the sounds of revelry outside reached him in a perfect uproar; but he no longer frowned, and when the strains of “Dixie” came in at the window, sung in a clear, rich, mellow solo, he sat back in his chair and listened:

sang the beautiful voice, full and sonorous.

When the song ended, there was an outburst of applause, and shouts apparently demanding some other song, which was refused, for the noise grew to a tumult. The General rose[18] and walked to the window. Suddenly the uproar hushed, for the voice began again, but this time it was a hymn:

Verse after verse was sung, the men pouring out of their tents and huts to listen to the music.

sang the singer to the end. When the strain died away there was dead silence.

The General finished his letter and sealed it. Carefully folding up the little one which lay before him, he replaced it in his pocket, and going to the door, summoned the orderly who was just without.

“Mail that at once,” he said.

“Yes, sir.”

“By the way,” as the soldier turned to leave, “who was that singing out there just now? I mean that last one, who sang ‘Dixie,’ and the hymn.”

“Only a peddler, sir, I believe.”

The General’s eyes fixed themselves on the soldier.

“Where did he come from?”

[19]“I don’t know, sir. Some of the boys had him singing.”

“Tell Major Dayle to come here immediately,” said the General, frowning.

In a moment the officer summoned entered.

He appeared somewhat embarrassed.

“Who was this peddler?” asked the commander, sternly.

“I—I don’t know—” began the other.

“You don’t know! Where did he come from?”

“From Colonel Watchly’s camp directly,” said he, relieved to shift a part of the responsibility.

“How was he dressed?”

“In citizen’s clothes.”

“What did he have?”

“A few toys and trinkets.”

“What was his name?”

“I did not hear it.”

“And you let him go!” The General stamped his foot.

“Yes, sir; I don’t think—” he began.

“No, I know you don’t,” said the General. “He was a spy. Where has he gone?”

“I—I don’t know. He cannot have gone far.”

“Report yourself under arrest,” said the commander, sternly.

Walking to the door, he said to the sentinel:

“Call the corporal, and tell him to request Captain Albert to come here immediately.”

In a few hours the party sent out reported that they had[20] traced the spy to a place just over the creek, where he was believed to be harbored.

“Take a detail and arrest him, or burn the house,” ordered the General, angrily. “It is a perfect nest of treason,” he said to himself as he walked up and down, as though in justification of his savage order.

“Or wait,” he called to the captain, who was just withdrawing. “I will go there myself, and take it for my headquarters. It is a better place than this. I cannot stand this smoke any longer. That will break up their treasonable work.”

[21]

ALL that day the tongues of the little ones at Holly Hill had been chattering unceasingly of the expected visit of Santa Claus that night. Mrs. Stafford had tried to explain to Charlie and Evelyn that it would be impossible for him to bring them their presents this year; but she was met with the undeniable and unanswerable statement that their father had promised them. Before going to bed they had hung their stockings on the mantelpiece right in front of the chimney, so that Santa Claus would be sure to see them.

The mother had broken down over Evelyn’s prayer, “not to forget my papa, and not to forget my dolly,” and her tears fell silently after the little ones were asleep, as she put the finishing touches to the tiny gray uniform for Charlie. She was thinking not only of the children’s disappointment, but of the absence of him on whose promise they had so securely relied. He had been away now for a year, and she had had no word of him for many weeks. Where was he? Was he dead or alive? Mrs. Stafford sank on her knees by the bedside.

“O God, give me faith like this little child!” she prayed again and again. She was startled by hearing a step on the front portico and a knock at the door. Bob, who was working[22] in front of the hall fire, went to the door. His mother heard him answer doubtfully some question. She opened the door and went out. A stranger with a large bundle or pack stood on the threshold. His hat, which was still on his head, was pulled down over his eyes, and he wore a beard.

“An’, leddy, wad ye bay so koind as to shelter a poor sthranger for a noight at this blissid toim of pace and goodwill?” he said, in a strong Irish brogue.

“Certainly,” said Mrs. Stafford with her eyes fixed on him. She moved slowly up to him. Then, by an instinct, quickly lifting her hand, she pushed his hat back from his eyes. Her husband clasped her in his arms.

“My darling!”

When the pack was opened, such a treasure-house of toys and things was displayed as surely never greeted any other eyes. The smaller children, including Ran, were not awaked, at their father’s request, though Mrs. Stafford wished to wake them to see him; but Bob was let into the secrets, except that he was not permitted to see a small package which bore his name. Mrs. Stafford and the Colonel were like two children themselves as they “tipped” about stuffing the long stockings with candy and toys of all kinds. The beautiful doll with flaxen hair, all arrayed in silk and lace, was seated, last of all, securely on top of Evelyn’s stocking, with her wardrobe just below her, where she would greet her young mistress when she should first open her eyes, and Charlie’s little blue[23] uniform was pinned beside the gray one his mother had made, with his sword buckled around the waist.

Bob was at last dismissed to his room, and the Colonel and Mrs. Stafford settled themselves before the fire, hand in hand, to talk over all the past. They had hardly started, when Bob rushed down the stairs and dashed into their room.

“Papa! papa! the yard’s full of Yankees!”

Both the Colonel and Mrs. Stafford sprang to their feet.

“Through the back door!” cried Mrs. Stafford, seizing her husband.

“He cannot get out that way—they are everywhere; I saw them from my window,” gasped Bob, just as the sound of trampling without became audible.

“Oh! what will you do? Those clothes! If they catch you in those clothes!” began Mrs. Stafford, and then stopped, her face growing ashy pale. Bob also turned even whiter than he had been before. He remembered the young man who was found in citizen’s clothes in the autumn, and knew his dreadful fate. He burst out crying. “Oh, papa! will they hang you?” he sobbed.

“I hope not, my son,” said the Colonel, gravely. “Certainly not, if I can prevent it.” A gleam of amusement stole into his eyes. “It’s an awkward fix, certainly,” he added.

“You must conceal yourself,” cried Mrs. Stafford, as a number of footsteps sounded on the porch, and a thundering knock shook the door. “Come here.” She pulled him[24] almost by main force into a closet or entry, and locked the door, just as the knocking was renewed. As the door was apparently about to be broken down, she went out into the hall. Her face was deadly white, and her lips were moving in prayer.

“Who’s there?” she called, tremblingly, trying to gain time.

“Open the door immediately, or it will be broken down,” replied a stern voice.

She turned the great iron key in the heavy old brass lock, and a dozen men rushed into the hall. They all waited for one, a tall elderly man in a general’s fatigue uniform, and with a stern face and a grizzled beard. He addressed her.

“Madam, I have come to take possession of this house as my headquarters.”

Mrs. Stafford bowed, unable to speak. She was sensible of a feeling of relief; there was a gleam of hope. If they did not know of her husband’s presence—But the next word destroyed it.

“We have not interfered with you up to the present time, but you have been harboring a spy here, and he is here now.”

“There is no spy here, and has never been,” said Mrs. Stafford, with dignity; “but if there were, you should not know it from me.” She spoke with much spirit. “It is not the custom of our people to deliver up those who have sought their protection.”

[25]The officer removed his hat. His keen eye was fixed on her white face. “We shall search the premises,” he said sternly, but more respectfully than he had yet spoken. “Major, have the house thoroughly searched.”

The men went striding off, opening doors and looking through the rooms. The General took a turn up and down the hall. He walked up to a door.

“That is my chamber,” said Mrs. Stafford, quickly.

The officer fell back. “It must be searched,” he said.

“My little children are asleep in there,” said Mrs. Stafford, her face quite white.

“It must be searched,” repeated the General. “Either they must do it, or I. You can take your choice.”

Mrs. Stafford made a gesture of assent. He opened the door and stepped across the threshold. There he stopped. His eye took in the scene. Charlie was lying in the little trundle-bed in the corner, calm and peaceful, and by his side was Evelyn, her little face looking like a flower lying in the tangle of golden hair which fell over her pillow. The noise disturbed her slightly, for she smiled suddenly, and muttered something about “Santa Tlaus” and a “dolly.” The officer’s gaze swept the room, and fell on the overcrowded stockings hanging from the mantel. He advanced to the fireplace and examined the doll and trousers closely. With a curious expression on his face, he turned and walked out of the room, closing the door softly behind him.

“Major,” he said to the officer in charge of the searching[26] party, who descended the steps just then, “take the men back to camp, except the sentinels. There is no spy here.” In a moment Mrs. Stafford came out of her chamber. The old officer was walking up and down in deep thought. Suddenly he turned to her: “Madam, be so kind as to go and tell Colonel Stafford that General Denby desires him to surrender himself.” Mrs. Stafford was struck dumb. She was unable to move or to articulate. “I shall wait for him,” said the General, quietly, throwing himself into an arm-chair, and looking steadily into the fire.

[27]

AS his father concealed himself, Bob had left the chamber. He was in a perfect agony of mind. He knew that his father could not escape, and if he were found dressed in citizen’s clothes he felt that he could have but one fate. All sorts of schemes entered his boy’s head to save him. Suddenly he thought of the small group of prisoners he had seen pass by about dark. He would save him! Putting on his hat, he opened the front door and walked out. A sentinel accosted him surlily to know where he was going. Bob invited him in to get warm, and soon had him engaged in conversation.

“What do you do with your prisoners when you catch them?” inquired Bob.

“Send some on to prison—and hang some.”

“I mean when you first catch them.”

“Oh, they stay in camp. We don’t treat ’em bad, without they be spies. There’s a batch at camp now, got in this evening—sort o’ Christmas gift.” The soldier laughed as he stamped his feet to keep warm.

“Where’s your camp?” Bob asked.

“About a mile from here, right on the road, or rather right on the hill at the edge of the pines ’yond the crick.”

[28]The boy left his companion, and sauntered in and out among the other men in the yard. Presently he moved on to the edge of the lawn beyond them. No one took further notice of him. In a second he had slipped through the gate, and was flying across the field. He knew every foot of ground as well as a hare, for he had been hunting and setting traps over it since he was as big as little Charlie. He had to make a detour at the creek to avoid the picket, and the dense briers were very bad and painful. However, he worked his way through, though his face was severely scratched. Into the creek he plunged. “Outch!” He had stepped into a hole, and the water was as cold as ice. However, he was through, and at the top of the hill he could see the glow of the camp-fires lighting up the sky.

He crept cautiously up, and saw the dark forms of the sentinels pacing backward and forward wrapped in their overcoats, now lit up by the fire, then growing black against its blazing embers, then lit up again, and passing away into the shadow. How could he ever get by them? His heart began to beat and his teeth to chatter, but he walked boldly up.

“Halt! who goes there?” cried the sentry, bringing his gun down and advancing on him.

Bob kept on, and the sentinel, finding that it was only a boy, looked rather sheepish.

“Don’t let him capture you, Jim,” called one of them; “Call the Corporal of the Guard,” another; “Order up the[29] reserves,” a third; and so on. Bob had to undergo something of an examination.

“I know the little Johnny,” said one of them.

They made him draw up to the fire, and made quite a fuss over him. Bob had his wits about him and soon learned that a batch of prisoners were at a fire a hundred yards further back. He therefore worked his way over there, although he was advised to stay where he was and get dry, and had many offers of a bunk from his new friends, some of whom followed him over to where the prisoners were.

Most of them were quartered for the night in a hut before which a guard was stationed. One or two, however, sat around the camp-fire, chatting with their guards. Among them was a major in full uniform. Bob singled him out; he was just about his father’s size.

He was instantly the centre of attraction. Again he told them he was from Holly Hill; again he was recognized by one of the men.

“Run away to join the army?” asked one.

“No,” said Bob, his eyes flashing at the suggestion.

“Lost?”

“No.”

“Mother whipped you?”

“No.”

As soon as their curiosity had somewhat subsided, Bob, who had hardly been able to contain himself, said to the Confederate major in a low undertone:

[30]“My father, Colonel Stafford, is at home, concealed, and the Yankees have taken possession of the house.”

“Well?” said the major, looking down at him as if casually.

“He cannot escape, and he has on citizen’s clothes, and—” Bob’s voice choked suddenly as he gazed at the major’s uniform.

“Well?” The prisoner for a second looked sharply down at the boy’s earnest face. Then he put his hand under his chin, and lifting it, looked into his eyes. Bob shivered and a sob escaped him.

The major placed his hand firmly on his knee. “Why, you are wringing wet,” he said, aloud. “I wonder you are not frozen to death.” He rose and stripped off his coat. “Here, get into this;” and before the boy knew it the major had bundled him into his coat, and rolled up the sleeves so that Bob could use his hands. The action attracted the attention of the rest of the group, and several of the Yankees offered to take the boy and give him dry clothes.

“No, sir,” laughed the major; “this boy is a rebel. Do you think he will wear one of your Yankee suits? He’s a little major, and I’m going to give him a major’s uniform.”

In a minute he had stripped off his trousers, and was helping Bob into them, standing himself in his underclothes in the icy air. The legs were three times too long for the boy, and the waist came up to his armpits.

“Now go home to your mother,” said the major, laughing[31] at his appearance; “and some of you fellows get me some clothes or a blanket. I’ll wear your Yankee uniform out of sheer necessity.”

Bob trotted around, keeping as far away from the light of the camp-fires as possible. He soon found himself unobserved, and reached the shadow of a line of huts, and keeping well in it, he came to the edge of the camp. He watched his opportunity, and when the sentry’s back was turned slipped out into the darkness. In an instant he was flying down the hill. The heavy clothes impeded him, and he stopped only long enough to snatch them off and roll them into a bundle, and sped on his way again. He struck the main road, and was running down the hill as fast as his legs could carry him, when he suddenly found himself almost on a group of dark objects who were standing in the road just in front of him. One of them moved. It was the picket. Bob suddenly stopped. His heart was in his throat.

“Who goes there?” said a stern voice. Bob’s heart beat as if it would spring out of his body.

“Come in; we have you,” said the man, advancing.

Bob sprang across the ditch beside the road, and putting his hand on the top rail of the fence, flung himself over it, bundle and all, flat on the other side, just as a blaze of light burst from the picket, and the report of a carbine startled the silent night. The bullet grazed the boy’s arm, and crashed through the rail. In a second Bob was on his feet. The picket was almost on him. Seizing his bundle, he dived into[32] the thicket as a half-dozen shots were sent ringing after him, the bullets hissing and whistling over his head. Several men dashed into the woods after him in hot pursuit, and a couple more galloped up the road to intercept him; but Bob’s feet were winged, and he slipped through briers and brush like a scared hare. They scratched his face and threw him down, but he was up again. Now and then a shot crashed behind him, but he did not care for that; he thought only of being caught.

A few hundred yards up, he plunged into the stream, and wading across, was soon safe from his pursuers. Breathless, he climbed the hill, made his way through the woods, and emerged into the open fields. Across these he sped like a deer. He had almost given out. What if they should have caught his father, and he should be too late! A sob escaped him at the bare thought, and he broke again into a run, wiping off with his sleeve the tears that would come. The wind cut him like a knife, but he did not mind that.

As he neared the house he feared that he might be intercepted again and the clothes taken from him, so he stopped for a moment, and slipped them on once more, rolling up the sleeves and legs as well as he could. He crossed the yard undisturbed. He went around to the same door by which he had come out, for he thought this his best chance. The same sentinel was there, walking up and down, blowing his cold hands. Had his father been arrested? Bob’s teeth chattered, but it was with suppressed excitement.

[33]“Pretty cold,” said the sentry.

“Ye—es,” gasped Bob.

“Your mother’s been out here, looking for you, I guess,” said the soldier, with much friendliness.

“I rec—reckon so,” panted Bob, moving toward the door. Did that mean that his father was caught? He opened the door, and slipped quietly into the corridor.

General Denby still sat silent before the hall fire. Bob listened at the chamber door. His mother was weeping; his father stood calm and resolute before the fire. He had determined to give himself up.

“If you only did not have on those clothes!” sobbed Mrs. Stafford. “If I only had not cut up the old uniform for the children!”

“Mother! mother! I have one!” gasped Bob, bursting into the room and tearing off the unknown major’s uniform.

[34]

TEN minutes later Colonel Stafford, with a steady step and a proud carriage, and with his hand resting on Bob’s shoulder, walked out into the hall. He was dressed in the uniform of a Confederate major, which fitted admirably his tall, erect figure.

“General Denby, I believe,” he said, as the Union officer rose and faced him. “We have met before under somewhat different circumstances,” he said, with a bow, “for I now find myself your prisoner.”

“I have the honor to request your parole,” said the General, with great politeness, “and to express the hope that I may be able in some way to return the courtesy which I formerly received at your hands.” He extended his hand and Colonel Stafford took it.

“You have my parole,” said he.

“I was not aware,” said the General, with a bow toward Mrs. Stafford, “until I entered the room where your children were sleeping, that I had the honor of your husband’s acquaintance. I will now take my leave and return to camp, that I may not by my presence interfere with the joy of this season.”

[35]“I desire to introduce to you my son,” said Colonel Stafford, proudly presenting Bob. “He is a hero.”

The General bowed as he shook hands with him. Perhaps he had some suspicion how true a hero he was, for he rested his hand kindly on the boy’s head, but he said nothing.

Both Colonel and Mrs. Stafford invited the old soldier to spend the night there, but he declined. He, however, accepted an invitation to dine with them next day.

Before leaving, he requested permission to take one more look at the sleeping children. Over Evelyn he bent silently. Suddenly stooping, he kissed her little pink cheek, and with a scarcely audible “Good-night,” passed out of the room and left the house.

The next morning, by light, there was great rejoicing. Charlie and Evelyn were up betimes, and were laughing and chattering over their presents like two little magpies.

“Here’s my sword and here’s my breeches,” cried Charlie, “two pair; but I’m goin’ to put on my gray ones. I ain’t goin’ to wear a blue uniform.”

“Here’s my dolly!” screamed Evelyn, in an ecstasy over her beautiful present. And presently Bob and Ran burst in, their eyes fairly dancing.

“Christmas gift! It’s a real one—real gold!” cried Bob, holding up a small gold watch, whilst Ran was shouting over a silver one of the same size.

That evening, after dinner, General Denby was sitting by[36] the fire in the Holly Hill parlor, with Evelyn nestled in his lap, her dolly clasped close to her bosom, and in the absence of Colonel Stafford, told Mrs. Stafford the story of the opening of the package by the camp-fire. The tears welled up into Mrs. Stafford’s eyes and ran down her cheeks.

Charlie suddenly entered, in all the majesty of his new breeches, and sword buckled on hip. He saw his mother’s tears. His little face flushed. In a second his sword was out, and he struck a hostile attitude.

“You sha’n’t make my mamma cry!” he shouted.

“Charlie! Charlie!” cried Mrs. Stafford, hastening to stop him.

“My papa said I was not to let any one make you cry,” insisted the boy, stepping before his mother, and still keeping his angry eyes on the General.

“Oh, Charlie!” Mrs. Stafford took hold of him. “I am ashamed of you!—to be so rude!”

“Let him alone, madam,” said the General. “It is not rudeness; it is spirit—the spirit of our race. He has the soldier’s blood, and some day he will be a soldier himself, and a brave one. I shall count on him for the Union,” he said, with a smile.

Mrs. Stafford shook her head.

A few days later, Colonel Stafford, in accordance with an understanding, came over to General Denby’s camp, and reported to be sent on to Washington as a prisoner of war. The General was absent on the lines at the time, but was[37] expected soon, and the Colonel waited for him at his headquarters. There had been many tears shed when his wife bade him good-by.

About an hour after the Colonel arrived, the General and his staff were riding back to camp along the road which ran by the Holly Hill gate. Just before they reached it, two little figures came out of the gate and started down the road. One was a boy of five, who carried a toy sword, drawn, in one hand, whilst with the other he led his companion, a little girl of three, who clasped a large yellow-haired doll to her breast.

The soldiers cantered forward and overtook them.

“Where are you going, my little people?” inquired the General, gazing down at them affectionately.

“I’m goin’ to get my papa,” said the tiny swordsman firmly, turning a sturdy and determined little face up to him. “My mamma’s cryin’, an’ I’m goin’ to take my papa home. I ain’ goin’ to let the Yankees have him.”

The officers all broke into a murmur of mingled admiration and amusement.

“No, we ain’ goin’ let the Yankees have our papa,” chimed in Evelyn, pushing her tangled hair out of her eyes, and keeping fast hold of Charlie’s hand for fear of the horses around her.

The General dismounted.

“How are you going to help, my little Semiramis?” he asked, stooping over her with smiling eyes.

[38]“I’m goin’ to give my dolly if they will give me my papa,” she said, gravely, as if she understood the equality of the exchange.

“Suppose you give a kiss instead?” There was a second of hesitation, and then she put up her little face, and the old General dropped on one knee in the road and lifted her in his arms, doll and all.

“Gentlemen,” he said to his staff, “you behold the future defenders of the Union.”

The little ones were coaxed home, and that afternoon, as Colonel Stafford was expecting to leave the camp for Washington with a lot of prisoners, a despatch was brought in to General Denby, who read it.

“Colonel,” he said, addressing him, “I think I shall have to continue your parole a few days longer. I have just received information that, by a special cartel which I have arranged, you are to be exchanged for Colonel McDowell as soon as he can reach the lines at this point from Richmond; and meantime, as we have but indifferent accommodations here, I shall have to request you to consider Holly Hill as your place of confinement. Will you be so kind as to convey my respects to Mrs. Stafford, and to your young hero Bob, and make good my word to those two little commissioners of exchange, to whom I feel somewhat committed? I wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.”

“WHAT YOU CHILDREN GWINE DO WID DAT LITTLE CAT?” ASKED MAMMY, SEVERELY.

KITTYKIN played a part in the war which has never been recorded. Her name does not appear in the list of any battle; nor is she mentioned in any history as having saved a life, or as having done anything remarkable one way or the other. Yet, in fact, she played a most important part: she prevented a battle which was just going to begin, and brought about a truce between the skirmish lines of the Union and the Confederate troops near her home which lasted several weeks, and probably saved many lives.

There never was a kitten more highly prized than Kittykin, for Evelyn had long wanted a kitten, and the way she found her was so delightfully unexpected.

It was during the war, when everything was very scarce down in the South where Evelyn lived. “We don’t have any coffee, or any kittens, or anything,” Evelyn said one day to some soldiers who had come to her home from their camp, which was a mile or so away. You would have thought[42] from the way she put them together that kittens, like coffee, were something to have on the table; but she had heard her mamma wishing for coffee at breakfast that morning, and she herself had long been wanting a kitten. Indeed, she used to ask for one in her prayers.

Evelyn had no fancy for anything that, in her own words, “was not live.” A thing that had life was of more value in her eyes than all the toys that were ever given her. A young bird which, too fat to fly, had fallen from the nest, or a broken-legged chicken, which was too lame to keep up with its mother, had her tenderest care; a little mouse slipping along the wainscot or playing on the carpet excited her liveliest interest; but a kitten, a “real live kittykin,” she had never possessed, though for a long time she had set her heart on having one. One day, however, she was out walking with her mammy in the “big road,” when she met several small negro children coming along, and one of them had a little bit of a white kitten squeezed up in his arm. It looked very scared, and every now and then it cried “Mew, mew.”

“Oh, mammy, look at that dear little kittykin!” cried Evelyn, running up to the children and stroking the little mite tenderly.

“What you children gwine do wid dat little cat?” asked mammy, severely.

“We gwine loss it,” said the boy who had it, promptly.

“Oh, mammy, don’t let them do that! Don’t let them[43] hurt it!” pleaded Evelyn, turning to her mammy. “It would get so hungry.”

A sudden thought struck her, and she sprang over toward the boy, and took the kitten from him, which instantly curled up in her arms just as close to her as it could get. There was no resisting her appeal, and a minute later she was running home far ahead of her mammy, with the kitten hugged tight in her arms. Her mamma was busy in the sitting-room when Evelyn came rushing in.

“Oh, mamma, see what I have! A dear little kittykin! Can’t I have it? They were just going to throw it away, and lose it all by itself;” and she began to jump up and down and rub the kitten against her little pink cheek, till her mother had to take hold of her to quiet her excitement.

Kittykin (for that was the name she had received) must have misunderstood the action, and have supposed she was going to take her from her young mistress, for she suddenly bunched herself up into a little white ball, and gave such a spit at Evelyn’s mamma that the lady jumped back nearly a yard, after which Kittykin quietly curled herself up again in Evelyn’s arm. The next thing was to give her some warm milk, which she drank as if she had not had a mouthful all day; and then she was put to sleep in a basket of wool, where Evelyn looked at her a hundred times to see how she was coming on.

Evelyn never doubted after that that if she prayed for a thing she would get it; for she had been praying all the time[44] for a “little white kitten,” and not only was Kittykin as white as snow, but she was, to use Evelyn’s words, “even littler” than she had expected. There could not, to her mind, be stronger proof.

As Kittykin grew a little she developed a temper entirely out of proportion to her size; when she got mad, she got mad all over. If anything offended her she would suddenly back up into a corner, her tail would get about twice as large as usual, and she would spit like a little fury. However, she never fought her little mistress, and even in her worst moments she would allow Evelyn to take her and lay her on her back in the little cradle she had, or carry her by the neck, or the legs, or almost any way except by the tail. To pull her tail was a liberty she never would allow even Evelyn to take. If she was held by the tail her little pink claws flew out as quick as a wink and as sharp as needles. Evelyn was very kind to Kittykin, however, and was careful not to provoke her, for she had been told that getting angry and kicking on the floor, as she herself sometimes did when mammy wanted to comb her curly hair, would make an ugly little girl, and of course it would have the same effect on a kitten.

Fierce, however, as Kittykin was, it soon appeared that she was the greatest little coward in the world. A worm in the walk or a little beetle running across the floor would set her to jumping as if she had a fit, and the first time she ever saw a mouse she was far more afraid of it than it was of her. If it had been a rat, I am sure that she would have died.

[45]One day Evelyn was sitting on the floor in her mother’s chamber sewing a little blue bag, which she said was her work-bag, when a tiny mouse ran, like a little gray shadow, across the hearth. Kittykin was at the moment busily engaged in rolling about a ball of yarn almost as white as herself, and the first thing Evelyn knew she gave a jump like a trap-ball, and slid up the side of the bureau like a little shaft of light, where she stood with all four feet close together, her small back roached up in an arch, her tail all fuzzed up over it, and her mouth wide open and spitting like a little demon. She looked so funny that Evelyn dropped her sewing, and the mouse, frightened half out of its little wits, took advantage of her consternation to make a rush back to its hole under the wainscoting, into which it dived like a little duck. After holding her lofty position for some time, Kittykin let her hairs fall and lowered her back, but every now and then she would raise them again at the bare thought of the awful animal which had so terrified her. At length she decided that she might go down; but how was she to do it? Smooth though the mahogany was, she had, under excitement, gone up like a streak of lightning; but now when she was cool she was afraid to jump down. It was so high that it made her head swim; so, after walking timidly around and peeping over at the floor, she began to cry for some one to take her down, just as Evelyn would have done under the same circumstances.

Evelyn tried to coax her down, but she would not come;[46] so finally she had to drag a chair up to the bureau and get up on it to reach her.

Perhaps it was the fright she experienced when she found herself up so high that caused Kittykin to revenge herself on the little mouse shortly afterward, or perhaps it was only her cat instinct developing; but it was only a short time after this that Kittykin did an act which grieved her little mistress dreadfully. The little mouse had lived under the wainscot since long before Kittykin had come, and it and Evelyn were on very good terms. It would come out and dash along by the wall to the wardrobe, under which it would disappear, and after staying there some time it would hurry back. This Evelyn used to call “paying visits;” and she often wondered what mice talked about when they got together under the wardrobe. Or sometimes it would slip out and frisk around on the floor—“just playing,” as Evelyn said. There was a perfect understanding between them: Evelyn was not to hurt the mouse nor let mammy set a trap for it, and the mouse was not to bite Evelyn’s clothes—but if it had to cut at all, was to confine itself to her mamma’s. After Kittykin came, however, the mouse appeared to be much less sociable than formerly; and after the occasion when it alarmed Kittykin so, it did not come out again for a long time. Evelyn used to wonder if its mamma was keeping it in.

One day, however, Evelyn was sewing, and Kittykin was lying by, when she suddenly seemed to get tired of doing nothing, and began to walk about.

[47]“Lie down, Kittykin,” said her mistress; but Kittykin did not appear to hear. She just lowered her head, and peeped under the bureau, with her eyes set in a curious way. Presently she stooped very low, and slid along the floor without making the slightest noise, every now and then stopping perfectly still. Evelyn watched her closely, for she had never seen her act so before. Suddenly, however, Kittykin gave a spring, and disappeared under the bureau. Evelyn heard a little squeak, and the next minute Kittykin walked out with a little mouse in her mouth, over which she was growling like a little tigress. Evelyn was jumping up to take it away from her when Kittykin, who had gone out into the middle of the room, turned it loose herself, and quietly walking away, lay down as if she were going to sleep. Then Evelyn saw that she did not mean to hurt it, so she sat and watched the mouse, which remained quite still for some time.

After a while it moved a little, to see if Kittykin was really asleep. Kittykin did not stir. Her eyes were fast shut, and the mouse seemed satisfied; so, after waiting a bit, it made a little dash toward the bureau. In a single bound Kittykin was right over it, and had laid her white paw on it. She did not, however, appear to intend it any injury, but began to play with it just as Evelyn would have liked to do; and, lying down, she rolled over and over, holding it up and tossing it gently, quite as Evelyn sometimes did her, or patting it and admiring it as if it had been the sweetest little mouse in the world. The mouse, too, appeared not to mind it the least[48] bit; and Evelyn was just thinking how nice it was that Kittykin and it had become such friends, and was planning nice games with them, when there was a faint little squeak, and she saw Kittykin, who had just been petting the little creature, suddenly drive her sharp white teeth into its neck.

Evelyn rushed at her.

“Oh, you wicked Kittykin! Aren’t you ashamed of yourself?” she cried, catching her up by the tail and shaking her well, as the best way to punish her.

Just then her mamma entered. “Oh, Evelyn, why are you treating kitty so?” she asked.

“Because she’s so mean,” said Evelyn, severely. “She’s a murderer.”

Her mamma tried to explain that killing the mouse was Kittykin’s nature; but Evelyn could not see that this made it any the less painful, and she was quite cool to Kittykin for some time.

The little mouse was buried that evening in a matchbox under a rose-bush in the garden; and Kittykin, in a black rag which was tied around her as a dress, was compelled, evidently much against her will, to do penance by acting as chief mourner.

[49]

KITTYKIN was about five months old when there was a great marching of soldiers backward and forward; the tents in the field beyond the woods were taken down and carried away in wagons, and there was an immense stir. The army was said to be “moving.” There were rumors that the enemy was coming, and that there might be a battle near there. Evelyn was so young that she did not understand any more of it than Kittykin did; but her mother appeared so troubled that Evelyn knew it was very bad, and became frightened, though she did not know why. Her mammy soon gave her such a gloomy account, that Evelyn readily agreed with her that it was “like torment.” As for Kittykin, if she had been born in a battle, she could not have been more unconcerned. In a day or two it was known that the main body of the army was some little way off on a long ridge, and that the enemy had taken up its position on another hill not far distant, and Evelyn’s home was between them; but there was no battle. Each army began to intrench itself; and in a little while there was a long red bank stretched across the far edge of the great field behind the house, which Evelyn was told was “breastworks” for the[50] picket line, and she pointed them out to Kittykin, who blinked and yawned as if she did not care the least bit if they were.

Next morning a small squadron of cavalry came galloping by. A body of the enemy had been seen, and they were going to learn what it meant. In a little while they came back.

“The enemy,” they said, “were advancing, and there would probably be a skirmish right there immediately.”

As they rode by, they urged Evelyn’s mamma either to leave the house at once or to go down into the basement, where they might be safe from the bullets. Then they galloped on across the field to get the rest of their men, who were in the trenches beyond. Before they reached there a lot of men appeared on the edge of the wood in front of the house. No one could tell how many they were; but the sun gleamed on their arms, and there was evidently a good force. At first they were on horseback; but there was a “Bop! bop!” from the trenches in the field behind the house, and they rode back, and did not come out any more. Next morning, however, they too had dug a trench. These, Evelyn heard some one say, were a picket line. About eleven o’clock they came out into the field, and they seemed to have spread themselves out behind a little rise or knoll in front of the house. Mammy’s teeth were just chattering, and she went to moaning and saying her prayers as hard as she could, and Evelyn’s mamma told her to take Evelyn[51] down into the basement, and she would bring the baby; so mammy, who had been following mamma about, seized Evelyn, and rushed with her down-stairs, where, although they were quite safe, as the windows were only half above the ground, she fell on her face on the floor, praying as if her last hour had come. “Bop! bop!” went some muskets up behind the house. “Bang! bop! bang!” went some on the other side.

Evelyn suddenly remembered Kittykin. “Where was she?” The last time she had seen her was a half-hour before, when she had been lying curled up on the back steps fast asleep in the sun. Suppose she should be there now, she would certainly be killed, for the back steps ran right out into the yard so as to be just the place for Kittykin to be shot. So thought Evelyn. “Bang! bang!” went the guns again—somewhere. Evelyn dragged a chair up to a window and looked. Her heart almost stopped; for there, out in the yard, quite clear of the houses, was Kittykin, standing some way up the trunk of a tall locust-tree, looking curiously around. Her little white body shone like a small patch of snow against the dark brown bark. Evelyn sprang down from the chair, and forgetting everything, rushed through the entry and out of doors.

“Kitty, kitty, kitty!” she called. “Kittykin, come here! You’ll be killed! Come here, Kittykin!”

Kittykin, however, was in for a game, and as her little mistress, with her golden hair flying in the breeze, ran toward[52] her, she rushed scampering still higher up the tree. Evelyn could see that there were some men scattered out in the fields on either side of her, some of them stooping, and some lying down, and as she ran on toward the tree she heard a “Bang! bang!” on each side, and she saw little puffs of white smoke, and something went “Zoo-ee-ee” up in the air; but she did not think about herself, she was so frightened for Kittykin.

“Kitty, kitty! Come down, Kittykin!” she called, running up to the tree and holding up her arms to her. Kittykin might, perhaps, have liked to come down now, but she could no longer do so; she was too high up. She looked down, first over one shoulder, and then over the other, but it was too high to jump. She could not turn around, and her head began to swim. She grew so dizzy, she was afraid she might fall, so she dug her little sharp claws into the bark, and began to cry.

[53-54]

“I WANT MY KITTYKIN,” SAID EVELYN.

[55]Evelyn would have run back to tell her mamma (who, having sent the baby down-stairs to mammy, was still busy up-stairs trying to hide some things, and so did not know she was out in the yard); but she was so afraid Kittykin might be killed that she could not let her get out of her sight. Indeed, she was so absorbed in Kittykin that she forgot all about everything else. She even forgot all about the soldiers. But though she did not notice the soldiers, it seemed that some of them had observed her. Just as the leader of the Confederate picket line was about to give an order to make a dash for the houses in the yard, to his horror he saw a little girl in a white dress and with flying hair suddenly run out into the clear space right between him and the soldiers on the other side, and stop under a tree just in the line of their fire. His heart jumped into his mouth as he sprang to his feet and waved his hands wildly to call attention to the child. Then shouting to his men to stop firing, he walked out in front of the line, and came at a rapid stride down the slope. The others all stood still and almost held their breaths for fear some one would shoot; but no one did. Evelyn was so busy trying to coax Kittykin down that she did not notice anything until she heard some one call out:

“For Heaven’s sake, run into the house, quick!”

She looked around and saw the gentleman hurrying toward her. He appeared to be very much excited.

“What on earth are you doing out here?” he gasped, as he came running up to her.

He was a young man, with just a little light mustache, and with a little gold braid on the sleeves of his gray jacket; and though he seemed very much surprised, he looked very kind.

“I want my Kittykin,” said Evelyn, answering him, and looking up the tree, with a little wave of her hand, towards where Kittykin still clung tightly. Somehow she felt at the moment that this gentleman could help her better than any one else.

Kittykin, however, apparently thought differently about[56] it; for she suddenly stopped mewing; and as if she felt it unsafe to be so near a stranger, she climbed carefully up until she reached a limb, in the crotch of which she ensconced herself, and peeped curiously over at them with a look of great satisfaction in her face, as much as to say, “Now I’m safe. I’d like to see you get me.”

The gentleman was stroking Evelyn’s hair, and was looking at her very intently, when a voice called to him from the other side:

“Hello, Johnny! what’s the matter?”

Evelyn looked around, and saw another gentleman coming toward them. He was older than the first one, and had on a blue coat, while the first had on a gray one. She knew one was a Confederate and the other was a Yankee, and for a second she was afraid they might shoot each other, but her first friend called out:

“Her kitten is up the tree. Come ahead!”

He came on, and looked for a second up at Kittykin, but he looked at Evelyn really hard, and suddenly stooped down, and putting his arm around her, drew her up to him. She got over her fear in a minute.

“Kittykin’s up there, and I’m afraid she’ll be kilt.” She waved her hand up over her head, where Kittykin was taking occasion to put a few more limbs between herself and the enemy.

“It’s rather a dangerous place when the boys are out hunting, eh, Johnny?” He laughed as he stood up again.

[57]“Yes, for as big a fellow as you. You wouldn’t stand the ghost of a show.”

“I guess I’d feel small enough up there.” And both men laughed.

By this time the men on both sides began to come up, with their guns over their arms.

“Hello! what’s up?” some of them called out.

“Her kitten’s up,” said the first two; and, to make good their words, Kittykin, not liking so many people below her, shifted her position again, and went up to a fresh limb, from which she again peeped over at them. The men all gathered around Evelyn, and began to talk to her, and both she and Kittykin were surprised to hear them joking and laughing together in the friendliest way.

“What are you doing out here?” they asked; and to all she made the same reply:

“I want my Kittykin.”

Suddenly her mamma came out. She had just gone down-stairs, and had learned where Evelyn was. The two officers went up and spoke to her, but the men still crowded around Evelyn.

“She’ll come down,” said one. “All you have to do is to let her alone.”

“No, she won’t. She can’t come down. It makes her head swim,” said Evelyn.

“That’s true,” thought Kittykin up in the tree, and to let them understand it she gave a little “Mew.”

[58]“I don’t see how anything can swim when it’s as dry as it is around here,” said a fellow in gray.

A man in blue handed him his canteen, which he at once accepted, and after surprising Evelyn by smelling it—which she knew was dreadfully bad manners—turned it up to his lips. She heard the liquid gurgling.

As he handed it back to its owner he said: “Yank, I’m mighty glad I didn’t shoot you. I might have hit that canteen.” At which there was a laugh, and the canteen went around until it was empty. Suddenly Kittykin from her high perch gave a faint “Mew,” which said, as plainly as words could say it, that she wanted to get down and could not.

Evelyn’s big brown eyes filled with tears. “I want my Kittykin,” she said, her little lip trembling.

Instantly a dozen men unbuckled their belts, laid their guns on the ground, and pulled off their coats, each one trying to be the first to climb the tree. It was, however, too large for them to reach far enough around to get a good hold on it, so climbing it was found to be far more difficult than it looked to be.

“Why don’t you cut it down?” asked some one.

But Evelyn cried out that that would kill Kittykin, so the man who suggested it was called a fool by the others. At last it was proposed that one man should stand against the tree and another should climb up on his shoulders, when he might get his arms far enough around it to work his way up. A stout fellow with a gray jacket on planted himself[59] firmly against the trunk, and one who had taken off a blue jacket climbed up on his shoulders, and might have got up very well if he had not remarked that as the Johnnies had walked over him in the last battle, it was but fair that he should now walk over a Johnny. This joke tickled the man under him so that he slipped away and let him down. At length, however, three or four men got good “holds,” and went slowly up one after the other amid such encouraging shouts from their friends on the ground below as: “Go it, Yank, the Johnny’s almost got you!” “Look out, Johnny, the Yanks are right behind you!” etc., whilst Kittykin gazed down in astonishment from above, and Evelyn looked up breathless from below. With much pulling and kicking, four men finally got up to the lowest limb, after which the climbing was comparatively easy. A new difficulty, however, presented itself. Kittykin suddenly took alarm, and retreated still higher up among the branches.

The higher they climbed after that, the higher she climbed, until she was away up on one of the topmost boughs, which was far too slender for any one to follow her. There she turned and looked back with alternate alarm and satisfaction expressed in her countenance. If the men stirred, she stood ready to fly; if they kept still, she settled down and mewed plaintively. Once or twice as they moved she took fright and looked almost as if about to jump.

Evelyn was breathless with excitement. “Don’t let her jump,” she called, “she will get kilt!”

[60]The men, too, were anxious to prevent that. They called to her, held out their hands, and coaxed her in every tone by which a kitten is supposed to be influenced. But it was all in vain. No cajoleries, no promises, no threats, were of the least avail. Kittykin was there safe, out of their reach, and there she would remain, sixty feet above the ground. Suddenly she saw that something was occurring below. She saw the men all gather around her little mistress, and could hear her at first refuse to let something be done, and then consent. She could not make out what it was, though she strained her ears. She remembered to have heard mammy tell her little mistress once that “curiosity had killed a cat,” and she was afraid to think too much about it so high up in the tree. Still when she heard an order given, “Go back and get your blankets,” and saw a whole lot of the men go running off into the field on either side, and presently come back with their arms full of blankets, she could not help wondering what they were going to do. They at once began to unroll the blankets and hold them open all around the tree, until a large circle of the ground was quite hidden.

“Ah!” said Kittykin, “it’s a wicked trap!” and she dug her little claws deep into the bark, and made up her mind that nothing should induce her to jump. Presently she heard the soldiers in the tree under her call to those on the ground:

“Are you ready?”

And they said, “All right!”

[61]“Ah!” said Kittykin, “they cannot get down, either. Serves them right!”

But suddenly they all waved their arms at her and cried, “Scat!”

Goodness! The idea of crying “scat” at a kitten when she is up in a tree!—“scat,” which fills a kitten’s breast with terror! It was brutal, and then it was all so unexpected. It came very near making her fall. As it was, it set her heart to thumping and bumping against her ribs, like a marble in a box. “Ah!” she thought, “if those brutes below were but mice, and I had them on the carpet!” So she dug her claws into the bark, which was quite tender up there, and it was well she did, for she heard some one call something below that sounded like “Shake!” and before she knew it the man nearest her reached up, and, seizing the limb on which she was, screwed up his face, and—Goodness! it nearly shook the teeth out of her mouth and the eyes out of her head.

Shake! shake! shake! it came again, each time nearly tearing her little claws out of their sockets and scaring her to death. She saw the ground swim far below her, and felt that she would be mashed to death. Shake! shake! shake! shake! She could not hold out much longer, and she spat down at them. How those brutes below laughed! She formed a desperate resolve. She would get even with them. “Ah, if they were but—” Shake! sha— With a fierce spit, partly of rage, partly of fear, Kittykin let go, whirled suddenly, and flung herself on the upturned face of the man next beneath[62] her, from him to the man below him, and finally, digging her little claws deep in his flesh, sprang with a wild leap clear of the boughs, and shot whizzing out into the air, whilst the two men, thrown off their guard by the suddenness of the attack, loosed their hold, and went crashing down into the forks upon those below.

The first thing Evelyn and the men on the ground knew was the crash of the falling men and the sight of Kittykin coming whizzing down, her little claws clutching wildly at the air. Before they could see what she was, she gave a bounce like a trap-ball as high as a man’s head, and then, as she touched the ground again, shot like a wild sky-rocket hissing across the yard, and, with her tail all crooked to one side and as big as her body, vanished under the house. Oh, such a shout as there was from the soldiers! Evelyn heard them yelling as she ran off after Kittykin to see if she wasn’t dead. They fairly howled with delight as the men in the tree, with scratched faces and torn clothes, came crawling down. They looked very sheepish as they landed among their comrades; but the question whether Kittykin had landed in a blanket or had hit the solid ground fifty feet out somewhat relieved them. They all agreed that she had bounced twenty feet.

Why Kittykin was not killed outright was a marvel. One of her eyes was a little bunged up, the claws on three of her feet were loosened, and for a week she felt as if she had been run through a sausage mill; but she never lost any of her[63] speed. Ever afterward when she saw a soldier she would run for life, and hide as far back under the house as she could get, with her eyes shining like two little live coals.

For some time, indeed, she lived in perpetual terror, for the soldiers of both lines used to come up to the house, as the friendship they formed that day never was changed, and though they remained on the two opposite hills for quite a while, they never fired a shot at each other. They used instead to meet and exchange tobacco and coffee, and laugh over the way Kittykin routed their joint forces in the tree the day of the skirmish.

As for Kittykin, she never put on any airs about it. She did not care for that sort of glory. She never afterward could tolerate a tree; the earth was good enough for her; and the highest she ever climbed was up in her little mistress’s lap.

[64]

“NANCY PANSY” was what Middleburgh called her, though the parish register of baptism contained nothing nearer the name than that of one Anne, daughter of Baylor Seddon, Esq., and Ellenor his wife. Whatever the register may have thought about it, “Nancy Pansy” was what Middleburgh called her, and she looked so much like a cherub, with her great eyes laughing up at you and her tangles blowing all about her dimpling pink face, that Dr. Spotswood Hunter, or “the Old Doctor,” as he was known to Middleburgh, used to vow she had gotten out of Paradise by mistake that Christmas Eve.

Nancy Pansy was the idol of the old doctor, as the old doctor was the idol of Middleburgh. He had given her a doll baby on the day she was born, and he always brought her one on her birthday, though, of course, the first three or four which he gave her were of rubber, because as long as she was a little girl she used to chew her doll after a most cannibal-like fashion, she and Harry’s puppies taking turn[66] and turn about at chewing in the most impartial and friendly way. Harry was the old doctor’s son. As she grew a little older, however, the doctor brought her better dolls; but the puppies got older faster than Nancy Pansy, and kept on chewing up her dolls, so they did not last very long, which, perhaps, was why she never had a “real live doll,” as she called it.

Some people said the reason the old doctor was so fond of Nancy Pansy was because he had been a lover of her beautiful aunt, whose picture as Charity giving Bread to the Poor Woman and her Children was in the stained-glass window in the church, with the Advent angel in the panel below, to show that she had died at Christmas-tide and was an angel herself now; some said it was because he had had a little daughter himself who had died when a wee bit of a girl, and Nancy Pansy reminded him of her; some said it was because his youngest born, his boy Harry, with the light hair, who now commanded a company in the Army of Northern Virginia, was so fond of Nancy Pansy’s lovely sister Ellen; some said it was because the old doctor was fond of all children; but the old doctor said it was “because Nancy Pansy was Nancy Pansy,” and looked like an angel, and had more sense than anybody in Middleburgh, except his old sorrel horse Slouch, who, he always maintained, had sense enough to have prevented the war if he had been consulted.

Whatever was the cause, Nancy Pansy was the old doctor’s boon companion; and wherever the old doctor was,[67] whether in his old rattling brown buggy, with Slouch jogging sleepily along the dusty roads which Middleburgh called her “streets,” or sitting in the shadiest corner of his porch, Nancy Pansy was in her waking hours generally beside him, her great pansy-colored eyes and her sunny hair making a bright contrast to the white locks and tanned cheeks of the old man. His home was just across the fence from the big house in which Nancy Pansy lived, and there was a hole where two palings were pulled off, through which Nancy Pansy used to slip when she went back and forth, and through which her little black companion, whose name, according to Nancy Pansy’s dictionary, was “Marphy,” just could squeeze. Sometimes, indeed, Nancy Pansy used to fall asleep over at the old doctor’s on the warm summer afternoons, and wake up next morning, curiously enough, to find herself in a strange room, in a great big bed, with a railing around the top of the high bedposts, and curtains hanging from it, and with Marphy asleep on a pallet near by.

“That child is your shadow, doctor,” said Nancy Pansy’s mother one day to him.

“No, madam; she is my sunshine,” answered the old man, gravely.