Footnotes have been collected at the end of the text, and are

linked for ease of reference.

In Volume 1 of this work, the editor provided a section of ‘Addendum and

Corrigiendum’, with errata of the following volumes, include this one.

The errata for Volume 2 have been copied from that volume for

straightfoward reference, and are included in the transcribers’s

endnotes.

Stage directions, except for entrances, can be:

- in-line

- in the middle of a line and delimited with ‘[ ]’,

- end of line

- right-justified on the same line where there is room, with only the leading ‘[’,

- next line

- right-justified on the following line, where there is insufficent room, with a hanging

indent.

The same convention is followed here. Since this version is somewhat wider than the

original, most directions are on the same line as the speech.

Entrances were centered and separated slightly from lines above and below. This

is rendered here as a full blank line.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered

during its preparation.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

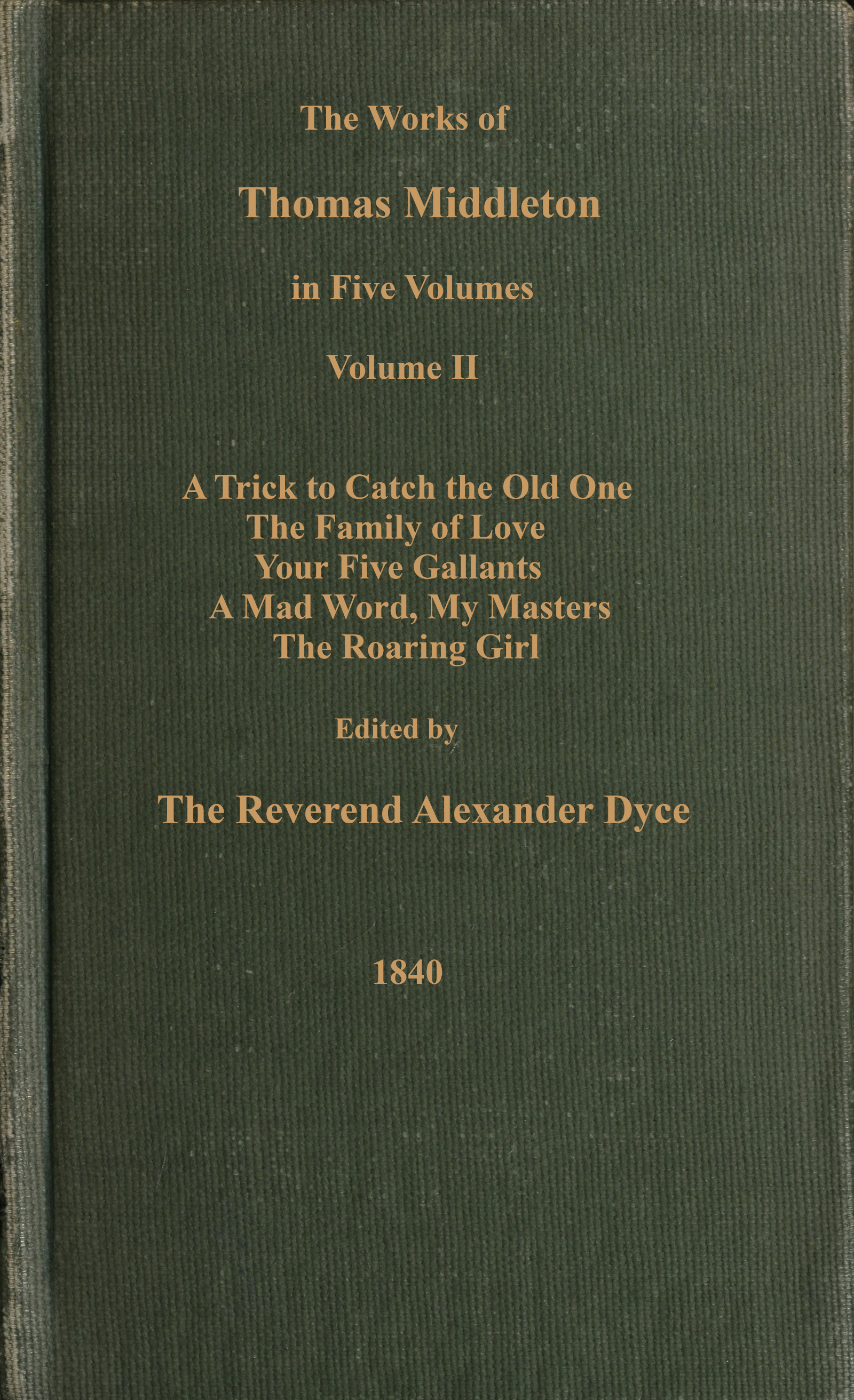

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

I

THE WORKS

OF

THOMAS MIDDLETON.

- A TRICK TO CATCH THE OLD ONE.

- THE FAMILY OF LOVE.

- YOUR FIVE GALLANTS.

- A MAD WORLD, MY MASTERS.

- THE ROARING GIRL.

IILONDON:

PRINTED BY ROBSON, LEVEY, AND FRANKLYN,

46 St. Martin’s Lane.

THE WORKS

OF

THOMAS MIDDLETON,

Now first collected,

WITH

SOME ACCOUNT OF THE AUTHOR,

AND

NOTES,

BY

THE REVEREND ALEXANDER DYCE.

IN FIVE VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

LONDON:

EDWARD LUMLEY, CHANCERY LANE.

1

A TRICK

TO CATCH THE OLD ONE.

3A Tricke to Catch the Old-one. As it hath beene often in

Action, both at Paules, and the Black-Fryers. Presented before

his Maiestie on New-yeares night last. Composde by T. M.

At London Printed by G: E. and are to be sold by Henry Rockytt,

at the long shop in the Poultrie vnder the Dyall. 1608. 4to.

Second ed., 1616. 4to.

This drama (which Langbaine not undeservedly calls “excellent”)

is reprinted in the 5th vol. of A Continuation of

Dodsley’s Old Plays, 1816.

A Trick to catch the Old One was licensed by Sir George

Bucke, 7th Oct. 1607: see Chalmers’s Suppl. Apol. p. 201.

- Witgood.

- Lucre, his uncle.

- Hoard.

- Onesiphorus Hoard, his brother.

- Limber,

Kix,[1]

Lamprey,

Spichcock, friends of Hoard.

friends of Hoard.

- Dampit.

- Gulf.

- Freedom, son to Mistress Lucre.

- Moneylove.

- Host.

- Sir Launcelot.

- Creditors.

- Gentlemen.

- George.

- Drawer.

- Boy.

- Scrivener.

- Servants, &c.

- Courtesan.

- Mistress Lucre.

- Joyce, niece to Hoard.

- Lady Foxstone.

- Audrey, servant to Dampit.

SCENE (except during the first two scenes of act i.),

London.

5A TRICK

TO CATCH THE OLD ONE.

ACT I. SCENE I.

A Street in a Country Town.

Wit. All’s gone! still thou’rt a gentleman, that’s

all; but a poor one, that’s nothing. What milk

bring[2] thy meadows forth now? where are thy

goodly uplands, and thy down lands? all sunk into

that little pit, lechery. Why should a gallant pay

but two shillings for his ordinary[3] that nourishes

him, and twenty times two for his brothel[4] that

consumes him? But where’s Long-acre?[5] in my

uncle’s conscience, which is three years’ voyage

about: he that sets out upon his conscience ne’er

finds the way home again; he is either swallowed

in the quicksands of law-quillets, or splits upon the

piles of a præmunire; yet these old fox-brained

6and ox-browed uncles have still defences for their

avarice, and apologies for their practices, and will

thus greet our follies:

He that doth his youth expose

To brothel, drink, and danger,

Let him that is his nearest kin

Cheat him before a stranger:

and that’s his uncle; ’tis a principle in usury. I

dare not visit the city: there I should be too soon

visited by that horrible plague, my debts; and by

that means I lose a virgin’s love, her portion, and

her virtues. Well, how should a man live now

that has no living? hum,—why, are there not a

million of men in the world that only sojourn upon

their brain, and make their wits their mercers;

and am I but one amongst that million, and cannot

thrive upon’t? Any trick out of the compass of

law[6] now would come happily to me.

Cour. My love!

Wit. My loathing! hast thou been the secret

consumption of my purse, and now comest to undo

my last means, my wits? wilt leave no virtue in

me, and yet thou ne’er the better?

Hence, courtesan, round-webb’d tarantula,

That dry’st the roses in the cheeks of youth!

Cour. I’ve

[7] been true unto your pleasure; and all your lands

Thrice rack’d, were

[8] never worth the jewel which

I prodigally gave you, my virginity:

Lands mortgag’d may return, and more esteem’d,

But honesty once pawn’d, is ne’er redeem’d.

7Wit. Forgive: I do thee wrong

To make thee sin, and then to chide thee for’t.

Cour. I know I am your loathing now; farewell.

Wit. Stay, best invention, stay.

Cour. I that have been the secret consumption of

your purse, shall I stay now to undo your last means,

your wits? hence, courtesan, away!

Wit. I prithee, make me not mad at my own

weapon: stay (a thing few women can do, I know

that, and therefore they had need wear stays), be

not contrary: dost love me? Fate[9] has so cast it

that all my means I must derive from thee.

Cour. From me? be happy then;

What lies within the power of my performance

Shall be commanded of thee.

Wit. Spoke like

An honest drab, i’faith: it may prove something;

What trick is not an embryon at first,

Until a perfect shape come over it?

Cour. Come,

[10] I must help you: whereabouts left you?

8I’ll proceed:

Though you beget, ’tis I must help to breed.

Speak, what is’t? I’d fain conceive it.

Wit. So, so, so: thou shalt presently take the

name and form upon thee of a rich country widow,

four hundred a-year valiant,[11] in woods, in bullocks,

in barns, and in rye-stacks; we’ll to London, and

to my covetous uncle.

Cour. I begin to applaud thee; our states being

both desperate, they are soon resolute: but how

for horses?

Wit. Mass, that’s true; the jest will be of some

continuance. Let me see; horses now, a bots on

’em! Stay, I have acquaintance with a mad host,

never yet bawd to thee; I have rinsed the whoreson’s

gums in mull-sack many a time and often:

put but a good tale into his ear now, so it come

off cleanly, and there’s horse and man for us, I

dare warrant thee.

Cour. Arm your wits then

Speedily; there shall want nothing in me,

Either in behaviour, discourse, or fashion,

That shall discredit your intended purpose.

I will so artfully disguise my wants,

And set so good a courage on my state,

That I will be believ’d.

Wit. Why, then, all’s furnished.[12] I shall go nigh

to catch that old fox mine uncle: though he make

but some amends for my undoing, yet there’s some

comfort in’t, he cannot otherwise choose (though it

be but in hope to cozen me again) but supply any

hasty want that I bring to town with me. The

9device well and cunningly carried, the name of a

rich widow, and four hundred a-year in good earth,

will so conjure up a kind of usurer’s love in him

to me, that he will not only desire my presence,—which

at first shall scarce be granted him, I’ll keep

off a’ purpose,—but I shall find him so officious to

deserve, so ready to supply! I know the state of

an old man’s affection so well: if his nephew be

poor indeed, why, he lets God alone with him;

but if he be once rich, then he’ll be the first man

that helps him.

Cour. ’Tis right the world; for, in these days,

an old man’s love to his kindred is like his kindness

to his wife, ’tis always done before he comes

at it.

Wit. I owe thee for that jest. Begone: here’s

all my wealth; prepare thyself, away. I’ll to mine

host with all possible haste; and with the best art,

and most profitable form, pour the sweet circumstance

into his ear, which shall have the gift to

turn all the wax to honey. [Exit Courtesan.]—How

no[w]? O, the right worshipful seniors of our

country!

Enter Onesiphorus Hoard,

Limber,

and Kix.

[13]

Ones. H. Who’s that?

10Lim. O, the common rioter; take no note of

him.

Wit. You will not see me now; the comfort is,

Ere it be long you will scarce see yourselves.

[Aside; and exit.

Ones. H. I wonder how he breathes; has consum’d all

Upon that courtesan.

Lim. We have heard so much.

Ones. H. You’ve

[14] heard all truth. His uncle and my brother

Have been these three years mortal adversaries:

Two old tough spirits, they seldom meet but fight,

Or quarrel when ’tis calmest:

I think their anger be the very fire

That keeps their age alive.

Lim. What was the quarrel, sir?

Ones. H. Faith, about a purchase, fetching over

a young heir. Master Hoard, my brother, having

wasted much time in beating the bargain, what did

me old Lucre, but as his conscience moved him,

knowing the poor gentleman, stept in between ’em,

and cozened him himself.

Lim. And was this all, sir?

Ones. H. This was e’en it, sir; yet, for all this,

I know no reason but the match might go forward

betwixt his wife’s son and my niece: what though

there be a dissension between the two old men, I

see no reason it should put a difference between

the two younger; ’tis as natural for old folks to

fall out, as for young to fall in. A scholar comes

a-wooing to my niece; well, he’s wise, but he’s

poor: her son comes a-wooing to my niece; well,

he’s a fool, but he’s rich.

Lim. Ay, marry, sir.

11Ones. H. Pray, now, is not a rich fool better

than a poor philosopher?

Lim. One would think so, i’faith.

Ones. H. She now remains at London with my

brother, her second uncle, to learn fashions, practise

music; the voice between her lips, and the

viol[15] between her legs, she’ll be fit for a consort

very speedily: a thousand good pound is her portion;

if she marry, we’ll ride up and be merry.

Kix. A match, if it be a match. [Exeunt.

SCENE II.

Another Street in the same Town.

Enter Witgood, meeting Host.

Wit. Mine host!

Host. Young master Witgood!

Wit. I have been laying[16] all the town for thee.

Host. Why, what’s the news, bully Had-land?

Wit. What geldings are in the house, of thine

own? answer me to that first.

Host. Why, man, why?

Wit. Mark me what I say: I’ll tell thee such

a tale in thine ear, that thou shalt trust me spite of

thy teeth, furnish me with some money wille nille,

and ride up with me thyself contra voluntatem et

professionem.

Host. How? let me see this trick, and I’ll say

thou hast more art than a conjurer.

Wit. Dost thou joy in my advancement?

12Host. Do I love sack and ginger?

Wit. Comes my prosperity desiredly to thee?

Host. Come forfeitures to a usurer, fees to an

officer, punks to an host, and pigs to a parson desiredly?

why, then, la.

Wit. Will the report of a widow of four hundred

a-year, boy, make thee leap, and sing, and dance,

and come to thy place again?

Host. Wilt thou command me now? I am thy

spirit; conjure me into any shape.

Wit. I ha’ brought her from her friends, turned

back the horses by a slight;[17] not so much as one

among her six men, goodly large yeomanly fellows,

will she trust with this her purpose: by this light,

all unmanned, regardless of her state, neglectful of

vain-glorious ceremony, all for my love. O, ’tis

a fine little voluble tongue, mine host, that wins a

widow!

Host. No, ’tis a tongue with a great T, my boy,

that wins a widow.

Wit. Now, sir, the case stands thus: good mine

host, if thou lovest my happiness, assist me.

Host. Command all my beasts i’ th’ house.

Wit. Nay, that’s not all neither: prithee, take

truce with thy joy, and listen to me. Thou knowest

I have a wealthy uncle i’ th’ city, somewhat the

wealthier by my follies: the report of this fortune,

well and cunningly carried, might be a means to

draw some goodness from the usuring rascal; for

I have put her in hope already of some estate that

I have either in land or money: now, if I be found

true in neither, what may I expect but a sudden

breach of our love, utter dissolution of the match,

and confusion of my fortunes for ever?

13Host. Wilt thou but trust the managing of thy

business with me?

Wit. With thee? why, will I desire to thrive in

my purpose? will I hug four hundred a-year, I

that know the misery of nothing? Will that man

wish a rich widow, that has ne’er a hole to put his

head in? With thee, mine host? why, believe it,

sooner with thee than with a covey of counsellors.

Host. Thank you for your good report, i’faith,

sir; and if I stand you not in stead, why then let

an host come off hic et hæc hostis, a deadly enemy

to dice, drink, and venery. Come, where’s this

widow?

Wit. Hard at Park-end.

Host. I’ll be her serving-man for once.

Wit. Why, there we let off together: keep full

time; my thoughts were striking then just the

same number.

Host. I knew’t: shall we then see our merry

days again?

Wit. Our merry nights—which ne’er shall be more seen. [Aside.]

[Exeunt.

SCENE III.

Enter[19] Lucre and Hoard quarrelling; Lamprey,

Spichcock, Freedom, and Moneylove, coming

between to pacify them.

Lam. Nay, good master Lucre, and you, master

Hoard, anger is the wind which you’re both too

much troubled withal.

14Hoa. Shall my adversary thus daily affront[20] me,

ripping up the old wound of our malice, which

three summers could not close up? into which

wound the very sight of him drops scalding lead

instead of balsamum.

Luc. Why, Hoard, Hoard, Hoard, Hoard,

Hoard! may I not pass in the state of quietness

to mine own house? answer me to that, before

witness, and why? I’ll refer the cause to honest,

even-minded gentlemen, or require the mere indifferences

of the law to decide this matter. I got

the purchase, true: was’t not any man’s case? yes:

will a wise man stand as a bawd, whilst another

wipes his nose[21] of the bargain? no; I answer no

in that case.

Lam. Nay, sweet master Lucre.

Hoa. Was it the part of a friend—no, rather of

a Jew;—mark what I say—when I had beaten

the bush to the last bird, or, as I may term it, the

price to a pound, then, like a cunning usurer, to

come in the evening of the bargain, and glean all

my hopes in a minute? to enter, as it were, at the

back door of the purchase? for thou ne’er camest

the right way by it.

Luc. Hast thou the conscience to tell me so

without any impeachment to thyself?

Hoa. Thou that canst defeat thy own nephew,

Lucre, lap his lands into bonds, and take the extremity

of thy kindred’s forfeitures, because he’s

a rioter, a wastethrift, a brothel-master,[22] and so

15forth; what may a stranger expect from thee but

vulnera dilacerata, as the poet says, dilacerate

dealing?

Luc. Upbraidest thou me with nephew? is all

imputation laid upon me? what acquaintance have

I with his follies? if he riot, ’tis he must want it;

if he surfeit, ’tis he must feel it; if he drab it, ’tis

he must lie by’t: what’s this to me?

Hoa. What’s all to thee? nothing, nothing;

such is the gulf of thy desire and the wolf of thy

conscience: but be assured, old Pecunius[23] Lucre,

if ever fortune so bless me, that I may be at leisure

to vex thee, or any means so favour me, that I

may have opportunity to mad thee, I will pursue it

with that flame of hate, that spirit of malice, unrepressed

wrath, that I will blast thy comforts.

Luc. Ha, ha, ha!

Lam. Nay, master Hoard, you’re a wise gentleman——

Hoa. I will so cross thee——

Luc. And I thee.

Hoa. So without mercy fret thee——

Luc. So monstrously oppose thee——

Hoa. Dost scoff at my just anger? O, that I

had as much power as usury has over thee!

Luc. Then thou wouldst have as much power as

the devil has over thee.

Hoa. Toad!

Luc. Aspic!

Hoa. Serpent!

Luc. Viper!

16Spi. Nay, gentlemen, then we must divide you

perforce.

Lam. When the fire grows too unreasonable hot,

there’s no better way than to take off the wood.

[Exeunt Lamprey and Spichcock, drawing off

Lucre and Hoard different ways: manent[24]

Freedom and Moneylove.

Free. A word, good signior.

Mon. How now, what’s the news?

Free. ’Tis given me to understand that you are

a rival of mine in the love of mistress Joyce, master

Hoard’s niece: say me ay, say me no?

Mon. Yes, ’tis so.

Free. Then look to yourself, you cannot live

long: I’m practising every morning; a month

hence I’ll challenge you.

Mon. Give me your hand upon’t; there’s my

pledge I’ll meet you. [Strikes him, and exit.

Free. O, O! what reason had you for that, sir,

to strike before the month? you knew I was not

ready for you, and that made you so crank:[25] I am

not such a coward to strike again, I warrant you.

My ear has the law of her side, for it burns

horribly. I will teach him to strike a naked face,

the longest day of his life: ’slid, it shall cost me

some money but I’ll bring this box into the

chancery. [Exit.

17

SCENE IV.

Host. Fear you nothing, sir; I have lodged her

in a house of credit, I warrant you.

Wit. Hast thou the writings?

Host. Firm, sir.

Wit. Prithee, stay, and behold two the most

prodigious rascals that ever slipt into the shape of

men; Dampit, sirrah, and young Gulf his fellow-caterpillar.

Host. Dampit? sure I have heard of that

Dampit?

Wit. Heard of him? why, man, he that has lost

both his ears may hear of him; a famous infamous

trampler of time; his own phrase. Note him well:

that Dampit, sirrah, he in the uneven beard and

the serge cloak, is the most notorious, usuring,

blasphemous, atheistical, brothel-vomiting rascal,

that we have in these latter times now extant;

whose first beginning was the stealing of a masty[26]

dog from a farmer’s house.

Host. He looked as if he would obey the commandment[s]

well, when he began first with stealing.

Wit. True: the next town he came at, he set

the dogs together by th’ ears.

Host. A sign he should follow the law, by my

faith.

Wit. So it followed, indeed; and being destitute

of all fortunes, staked his masty against a

noble,[27] and by great fortune his dog had the day:

how he made it up ten shillings, I know not; but

18his own boast is, that he came to town but with

ten shillings in his purse, and now is credibly worth

ten thousand pound.

Host. How the devil came he by it?

Wit. How the devil came he not by it? If you

put in the devil once, riches come with a vengeance:

has been a trampler of the law,[28] sir; and

the devil has a care of his footmen. The rogue

has spied me now; he nibbled me finely once,

too:—a pox search you! [Aside.]—O, master

Dampit!—the very loins of thee! [Aside.]—Cry

you mercy, master Gulf; you walk so low, I promise

you I saw you not, sir.

Gulf. He that walks low walks safe, the poets tell us.

Wit. And nigher hell by a foot and a half than the rest of his fellows.— [Aside.

But, my old Harry!

Dam. My sweet Theodorus!

Wit. ’Twas a merry world when thou camest to

town with ten shillings in thy purse.

19Dam. And now worth ten thousand pound, my

boy. Report it; Harry Dampit, a trampler of

time, say, he would be up in a morning, and be

here with his serge gown, dashed up to the hams

in a cause; have his feet stink about Westminster

Hall, and come home again; see the galleons, the

galleasses,[29] the great armadas of the law; then

there be hoys and petty vessels, oars and scullers

of the time; there be picklocks of the time too;

then would I be here; I would trample up and

down like a mule: now to the judges, May it

please your reverend honourable fatherhoods; then to

my counsellor, May it please your worshipful patience;

then to the examiner’s office, May it please

your mastership’s gentleness; then to one of the

clerks, May it please your worshipful lousiness,—for

I find him scrubbing in his cod-piece; then to the

hall again, then to the chamber again——

Wit. And when to the cellar again?

Dam. E’en when thou wilt again: tramplers of

time, motions of Fleet Street, and visions of Holborn;[30]

here I have fees of one, there I have fees

of another; my clients come about me, the fooliaminy

and coxcombry of the country: I still trashed[31]

20and trotted for other men’s causes; thus was poor

Harry Dampit made rich by others’ laziness, who,

though they would not follow their own suits, I

made ’em follow me with their purses.

Wit. Didst thou so, old Harry?

Dam. Ay, and I soused ’em with bills of charges,

i’faith; twenty pound a-year have I brought in

for boat-hire, and I ne’er stept into boat in my

life.

Wit. Tramplers of time!

Dam. Ay, tramplers of time, rascals of time,

bull-beggars![32]

Wit. Ah, thou’rt a mad old Harry!—Kind master

Gulf, I am bold to renew my acquaintance.

Gulf. I embrace it, sir. [Exeunt.

ACT II. SCENE I.

Luc. My adversary evermore twits me with my

nephew, forsooth, my nephew: why may not a

virtuous uncle have a dissolute nephew? What

though he be a brotheller, a wastethrift, a common

surfeiter, and, to conclude, a beggar, must sin in

him call up shame in me? Since we have no part

in their follies, why should we have part in their

infamies? For my strict hand toward his mortgage,

that I deny not: I confess I had an uncle’s

pen’worth; let me see, half in half, true: I saw

neither hope of his reclaiming, nor comfort in his

being; and was it not then better bestowed upon

21his uncle than upon one of his aunts?—I need not

say bawd, for every one knows what aunt stands

for in the last translation.

Now, sir?

Ser. There’s a country serving-man, sir, attends

to speak with your worship.

Luc. I’m at best leisure now; send him in to

me.

[Exit Servant.

Enter Host disguised as a serving-man.

Host. Bless your venerable worship.

Luc. Welcome, good fellow.

Host. He calls me thief[33] at first sight, yet he

little thinks I am an host. [Aside.

Luc. What’s thy business with me?

Host. Faith, sir, I am sent from my mistress,

to any sufficient gentleman indeed, to ask advice

upon a doubtful point: ’tis indifferent, sir, to whom

I come, for I know none, nor did my mistress direct

me to any particular man, for she’s as mere a

stranger here as myself; only I found your worship

within, and ’tis a thing I ever loved, sir, to be despatched

as soon as I can.

Luc. A good, blunt honesty; I like him well.

[Aside.]—What is thy mistress?

Host. Faith, a country gentlewoman, and a

widow, sir. Yesterday was the first flight of us;

but now she intends to stay till a little term business

be ended.

Luc. Her name, I prithee?

Host. It runs there in the writings, sir, among

her lands; widow Medler.

22Luc. Medler? mass, have I ne’er heard of that

widow?

Host. Yes, I warrant you, have you, sir: not

the rich widow in Staffordshire?

Luc. Cuds me, there ’tis indeed; thou hast put

me into memory: there’s a widow indeed! ah, that

I were a bachelor again!

Host. No doubt your worship might do much

then; but she’s fairly promised to a bachelor

already.

Luc. Ah, what is he, I prithee?

Host. A country gentleman too; one whom

your worship knows not, I’m sure; has spent

some few follies in his youth, but marriage, by my

faith, begins to call him home: my mistress loves

him, sir, and love covers faults, you know: one

master Witgood, if ever you have heard of the

gentleman.

Luc. Ha! Witgood, sayst thou?

Host. That’s his name indeed, sir; my mistress

is like to bring him to a goodly seat yonder; four

hundred a-year, by my faith.

Luc. But, I pray, take me with you.[34]

Host. Ay, sir.

Luc. What countryman might this young Witgood

be?

Host. A Leicestershire gentleman, sir.

Luc. My nephew, by th’ mass, my nephew! I’ll

fetch out more of this, i’faith: a simple country

fellow, I’ll work’t out of him. [Aside.]—And is that

gentleman, sayst thou, presently to marry her?

Host. Faith, he brought her up to town, sir;

has the best card in all the bunch for’t, her heart;

and I know my mistress will be married ere she

23go down; nay, I’ll swear that, for she’s none of

those widows that will go down first, and be married

after; she hates that, I can tell you, sir.

Luc. By my faith, sir, she is like to have a

proper gentleman, and a comely; I’ll give her

that gift.

Host. Why, does your worship know him, sir?

Luc. I know him? does not all the world know

him? can a man of such exquisite qualities be hid

under a bushel?

Host. Then your worship may save me a labour,

for I had charge given me to inquire after

him.

Luc. Inquire of him? If I might counsel thee,

thou shouldst ne’er trouble thyself further; inquire

of him of no more but of me; I’ll fit thee.

I grant he has been youthful; but is he not now

reclaimed? mark you that, sir: has not your mistress,

think you, been wanton in her youth? if

men be wags, are there not women wagtails?

Host. No doubt, sir.

Luc. Does not he return wisest that comes home

whipt with his own follies?

Host. Why, very true, sir.

Luc. The worst report you can hear of him, I

can tell you, is that he has been a kind gentleman,

a liberal, and a worthy: who but lusty Witgood,

thrice-noble Witgood!

Host. Since your worship has so much knowledge

in him, can you resolve[35] me, sir, what his

living might be? my duty binds me, sir, to have

a care of my mistress’ estate; she has been ever

a good mistress to me, though I say it: many

wealthy suitors has she nonsuited for his sake;

24yet though her love be so fixed, a man cannot tell

whether his non-performance may help to remove

it, sir: he makes us believe he has lands and

living.

Luc. Who, young master Witgood? why, believe

it, he has as goodly a fine living out yonder,—what

do you call the place?

Host. Nay, I know not, i’faith.

Luc. Hum—see, like a beast, if I have not

forgot the name—pooh! and out yonder again,

goodly grown woods and fair meadows: pax[36] on’t,

I can ne’er hit of that place neither: he? why,

he’s Witgood of Witgood Hall; he, an unknown

thing!

Host. Is he so, sir? To see how rumour will

alter! trust me, sir, we heard once he had no

lands, but all lay mortgaged to an uncle he has

in town here.

Luc. Push,[37] ’tis a tale, ’tis a tale.

Host. I can assure you, sir, ’twas credibly reported

to my mistress.

Luc. Why, do you think, i’faith, he was ever so

simple to mortgage his lands to his uncle? or his

uncle so unnatural to take the extremity of such a

mortgage?

Host. That was my saying still, sir.

Luc. Pooh, ne’er think it.

Host. Yet that report goes current.

Luc. Nay, then you urge me:

Cannot I tell that best that am his uncle?

Host. How, sir? what have I done!

25Luc. Why, how now! in a swoon, man?

Host. Is your worship his uncle, sir?

Luc. Can that be any harm to you, sir?

Host. I do beseech you, sir, do me the favour

to conceal it: what a beast was I to utter so

much! pray, sir, do me the kindness to keep it

in; I shall have my coat pulled o’er my ears, an’t

should be known; for the truth is, an’t please

your worship, to prevent much rumour and many

suitors, they intend to be married very suddenly

and privately.

Luc. And dost thou think it stands with my

judgment to do them injury? must I needs say the

knowledge of this marriage comes from thee? am

I a fool at fifty-four? do I lack subtlety now, that

have got all my wealth by it? There’s a leash of

angels[38] for thee: come, let me woo thee speak

where lie they?

Host. So I might have no anger, sir——

Luc. Passion of me, not a jot: prithee, come.

Host. I would not have it known, sir,[39] it came

by my means.

Luc. Why, am I a man of wisdom?

Host. I dare trust your worship, sir; but I’m

a stranger to your house; and to avoid all intelligencers,

I desire your worship’s ear.

Luc. This fellow’s worth a matter of trust.

[Aside.]—Come, sir. [Host whispers to him.] Why,

now thou’rt an honest lad.—Ah, sirrah, nephew!

Host. Please you, sir, now I have begun with

your worship, when shall I attend for your advice

upon that doubtful point? I must come warily

now.

26Luc. Tut, fear thou nothing;

To-morrow’s evening shall resolve the doubt.

Host. The time shall cause my attendance.

Luc. Fare thee well. [Exit Host.]—There’s

more true honesty in such a country serving-man

than in a hundred of our cloak companions:[40] I

may well call ’em companions, for since blue coats

have been turned into cloaks,[41] we can scarce know

the man from the master.—George!

Geo. Anon, sir.

Luc. List hither: [whispers] keep the place

secret: commend me to my nephew; I know no

cause, tell him, but he might see his uncle.

Geo. I will, sir.

Luc. And, do you hear, sir?

Take heed you use him with respect and duty.

Geo. Here’s a strange alteration; one day he

must be turned out like a beggar, and now he must

be called in like a knight. [Aside, and exit.

Luc. Ah, sirrah, that rich widow!—four hundred

a-year! beside, I hear she lays claim to a

title of a hundred more. This falls unhappily that

he should bear a grudge to me now, being likely

to prove so rich: what is’t, trow,[42] that he makes

me a stranger for? Hum,—I hope he has not so

much wit to apprehend that I cozened him: he

27deceives me then. Good heaven, who would have

thought it would ever have come to this pass! yet

he’s a proper gentleman, i’faith, give him his due,

marry, that’s his mortgage; but that I ne’er mean

to give him: I’ll make him rich enough in words,

if that be good; and if it come to a piece of money,

I will not greatly stick for’t; there may be hope

some of the widow’s lands, too, may one day fall

upon me, if things be carried wisely.

Now, sir, where is he?

Geo. He desires your worship to hold him

excused; he has such weighty business, it commands

him wholly from all men.

Luc. Were those my nephew’s words?

Geo. Yes, indeed, sir.

Luc. When men grow rich, they grow proud too,

I perceive that; he would not have sent me such

an answer once within this twelvemonth: see what

’tis when a man’s come to his lands! [Aside.]—Return

to him again, sir; tell him his uncle desires

his company for an hour; I’ll trouble him but an

hour, say; ’tis for his own good, tell him: and,

do you hear, sir? put worship upon him: go to, do

as I bid you; he’s like to be a gentleman of worship

very shortly.

Geo. This is good sport, i’faith. [Aside, and exit.

Luc. Troth, he uses his uncle discourteously

now: can he tell what I may do for him? goodness

may come from me in a minute, that comes

not in seven year again: he knows my humour;

I am not so usually good; ’tis no small thing that

draws kindness from me, he may know that and[43]

28he will. The chief cause that invites me to do him

most good, is the sudden astonishing of old Hoard,

my adversary: how pale his malice will look at

my nephew’s advancement! with what a dejected

spirit he will behold his fortunes, whom but last

day he proclaimed rioter, penurious makeshift,

despised brothel-master![44] Ha, ha! ’twill do me

more secret joy than my last purchase, more precious

comfort than all these widow’s revenues.

Re-enter George, shewing in Witgood.

Now, sir?

Geo. With much entreaty he’s at length come,

sir.

[Exit.

Luc. O, nephew, let me salute you, sir! you’re

welcome, nephew.

Wit. Uncle, I thank you.

Luc. You’ve a fault, nephew; you’re a stranger here:

Well, heaven give you joy!

Wit. Of what, sir?

Luc. Hah, we can hear!

You might have known your uncle’s house, i’faith,

You and your widow: go to, you were to blame;

If I may tell you so without offence.

Wit. How could you hear of that, sir?

Luc. O, pardon me!

’Twas

[45] your will to have kept it

[46] from me, I perceive now.

Wit. Not for any defect of love, I protest, uncle.

Luc. O, ’twas unkindness, nephew! fie, fie, fie.

Wit. I am sorry you take it in that sense, sir.

Luc. Pooh, you cannot colour it, i’faith, nephew.

29Wit. Will you but hear what I can say in my

just excuse, sir?

Luc. Yes, faith, will I, and welcome.

Wit. You that know my danger i’ th’ city, sir,

so well, how great my debts are, and how extreme

my creditors, could not out of your pure judgment,

sir, have wished us hither.

Luc. Mass, a firm reason indeed.

Wit. Else, my uncle’s house! why, ’t had been

the only make-match.

Luc. Nay, and thy credit.

Wit. My credit? nay, my countenance: push,[47]

nay, I know, uncle, you would have wrought it so

by your wit, you would have made her believe in

time the whole house had been mine.

Luc. Ay, and most of the goods too.

Wit. La, you there! well, let ’em all prate what

they will, there’s nothing like the bringing of a

widow to one’s uncle’s house.

Luc. Nay, let nephews be ruled as they list,

they shall find their uncle’s house the most natural

place when all’s done.

Wit. There they may be bold.

Luc. Life, they may do any thing there, man,

and fear neither beadle nor somner:[48] an uncle’s

house! a very Cole-Harbour.[49] Sirrah, I’ll touch

thee near now: hast thou so much interest in thy

widow, that by a token thou couldst presently send

for her?

Wit. Troth, I think I can, uncle.

Luc. Go to, let me see that.

Wit. Pray, command one of your men hither,

uncle.

30Luc. George!

Geo. Here, sir.

Luc. Attend my nephew. [Witgood whispers

to George, who then goes out.]—I love a’ life[50] to

prattle with a rich widow; ’tis pretty, methinks,

when our tongues go together: and then to promise

much and perform little; I love that sport a’

life, i’faith: yet I am in the mood now to do my

nephew some good, if he take me handsomely.

[Aside.]—What, have you despatched?

Wit. I ha’ sent, sir.

Luc. Yet I must condemn you of unkindness,

nephew.

Wit. Heaven forbid, uncle!

Luc. Yes, faith, must I. Say your debts be

many, your creditors importunate, yet the kindness

of a thing is all, nephew: you might have sent me

close word on’t, without the least danger or prejudice

to your fortunes.

Wit. Troth, I confess it, uncle; I was to blame

there; but, indeed, my intent was to have clapped

it up suddenly, and so have broke forth like a joy

to my friends, and a wonder to the world: beside,

there’s a trifle of a forty pound matter toward the

setting of me forth; my friends should ne’er have

known on’t; I meant to make shift for that myself.

Luc. How, nephew? let me not hear such a

word again, I beseech you: shall I be beholding[51]

to you?

Wit. To me? Alas, what do you mean, uncle?

31Luc. I charge you, upon my love, you trouble

nobody but myself.

Wit. You’ve no reason for that, uncle.

Luc. Troth, I’ll ne’er be friends with you while

you live, and[52] you do.

Wit. Nay, and you say so, uncle, here’s my

hand; I will not do’t.

Luc. Why, well said! there’s some hope in thee

when thou wilt be ruled; I’ll make it up fifty,

faith, because I see thee so reclaimed. Peace;

here comes my wife with Sam, her t’other husband’s

son.

Enter Mistress Lucre and Freedom.

Wit. Good aunt.

Free. Cousin Witgood, I rejoice in my salute;

you’re most welcome to this noble city, governed

with the sword in the scabbard.

Wit. And the wit in the pommel. [Aside.]—Good

master Sam Freedom, I return the salute.

Luc. By the mass, she’s coming, wife; let me

see now how thou wilt entertain her.

Mis. L. I hope I am not to learn, sir, to entertain

a widow; ’tis not so long ago since I was one

myself.

Wit. Uncle——

Luc. She’s come indeed.

Wit. My uncle was desirous to see you, widow,

and I presumed to invite you.

Court. The presumption was nothing, master

Witgood: is this your uncle, sir?

Luc. Marry am I, sweet widow; and his good

uncle he shall find me; ay, by this smack that I

32give thee [kisses her], thou’rt welcome.—Wife, bid

the widow welcome the same way again,

Free. I am a gentleman now too by my father’s

occupation, and I see no reason but I may kiss a

widow by my father’s copy: truly, I think the

charter is not against it; surely these are the

words, The son once a gentleman may revel it, though

his father were a dauber; ’tis about the fifteenth

page: I’ll to her.

[Aside, then offers to kiss the Courtesan, who repulses him.

Luc. You’re not very busy now; a word with

thee, sweet widow.

Free. Coads-nigs! I was never so disgraced

since the hour my mother whipt me.

Luc. Beside, I have no child of mine own to

care for; she’s my second wife, old, past bearing:

clap sure to him, widow; he’s like to be my heir,

I can tell you.

Court. Is he so, sir?

Luc. He knows it already, and the knave’s

proud on’t: jolly rich widows have been offered

him here i’ th’ city, great merchants’ wives; and

do you think he would once look upon ’em? forsooth,

he’ll none: you are beholding[53] to him i’ th’

country, then, ere we could be: nay, I’ll hold a

wager, widow, if he were once known to be in

town, he would be presently sought after; nay,

and happy were they that could catch him first.

Court. I think so.

Luc. O, there would be such running to and

fro, widow! he should not pass the streets for ’em:

he’d be took up in one great house or other presently:

faugh! they know he has it, and must

33have it. You see this house here, widow; this

house and all comes to him; goodly rooms, ready

furnished, ceiled with plaster of Paris, and all

hung about[54] with cloth of arras.—Nephew.

Wit. Sir.

Luc. Shew the widow your house; carry her

into all the rooms, and bid her welcome.—You

shall see, widow.—Nephew, strike all sure above

and[55] thou beest a good boy,—ah! [Aside to Witgood.

Wit. Alas, sir, I know not how she would take it!

Luc. The right way, I warrant t’ye: a pox, art

an ass? would I were in thy stead! get you up,

I am ashamed of you. [Exeunt Witgood and Courtesan].

So: let ’em agree as they will now: many

a match has been struck up in my house a’ this

fashion: let ’em try all manner of ways, still there’s

nothing like an uncle’s house to strike the stroke

in. I’ll hold my wife in talk a little.—Now, Jenny,

your son there goes a-wooing to a poor gentlewoman

but of a thousand [pound] portion: see my

nephew, a lad of less hope, strikes at four hundred

a-year in good rubbish.

Mis. L. Well, we must do as we may, sir.

Luc. I’ll have his money ready told for him

again[56] he come down: let me see, too;—by th’

mass, I must present the widow with some jewel, a

good piece of[57] plate, or such a device; ’twill hearten

her on well: I have a very fair standing cup; and

a good high standing cup will please a widow above

all other pieces. [Exit.

Mis. L. Do you mock us with your nephew?—I

have a plot in my head, son;—i’faith, husband, to

cross you.

34Free. Is it a tragedy plot, or a comedy plot,

good mother?

Mis. L. ’Tis a plot shall vex him. I charge

you, of my blessing, son Sam, that you presently

withdraw the action of your love from master

Hoard’s niece.

Free. How, mother?

Mis. L. Nay, I have a plot in my head, i’faith.

Here, take this chain of gold, and this fair diamond:

dog me the widow home to her lodging,

and at thy best opportunity fasten ’em both upon

her. Nay, I have a reach: I can tell you thou art

known what thou art, son, among the right worshipful,

all the twelve companies.

Free. Truly, I thank ’em for it.

Mis. L. He? he’s a scab to thee: and so certify

her thou hast two hundred a-year of thyself, beside

thy good parts—a proper person and a lovely.

If I were a widow, I could find in my heart to have

thee myself, son; ay, from ’em all.

Free. Thank you for your good will, mother;

but, indeed, I had rather have a stranger: and if I

woo her not in that violent fashion, that I will

make her be glad to take these gifts ere I leave

her, let me never be called the heir of your body.

Mis. L. Nay, I know there’s enough in you, son,

if you once come to put it forth.

Free. I’ll quickly make a bolt or a shaft on’t.[58]

[Exeunt.

35

SCENE II.

Enter Hoard and Moneylove.

Mon. Faith, master Hoard, I have bestowed

many months in the suit of your niece, such was

the dear love I ever bore to her virtues: but since

she hath so extremely denied me, I am to lay out

for my fortunes elsewhere.

Hoa. Heaven forbid but you should, sir! I ever

told you my niece stood otherwise affected.

Mon. I must confess you did, sir; yet, in regard

of my great loss of time, and the zeal with which

I sought your niece, shall I desire one favour of

your worship?

Hoa. In regard of those two, ’tis hard but you

shall, sir.

Mon. I shall rest grateful: ’tis not full three

hours, sir, since the happy rumour of a rich

country widow came to my hearing.

Hoa. How? a rich country widow?

Mon. Four hundred a-year landed.

Hoa. Yea?

Mon. Most firm, sir; and I have learnt her

lodging: here my suit begins, sir; if I might but

entreat your worship to be a countenance for me,

and speak a good word (for your words will pass),

I nothing doubt but I might set fair for the widow;

nor shall your labour, sir, end altogether in thanks;

two hundred angels[59]——

Hoa. So, so: what suitors has she?

Mon. There lies the comfort, sir; the report of

her is yet but a whisper; and only solicited by

36young riotous Witgood, nephew to your mortal

adversary.

Hoa. Ha! art certain he’s her suitor?

Mon. Most certain, sir; and his uncle very industrious

to beguile the widow, and make up the

match.

Hoa. So: very good.

Mon. Now, sir, you know this young Witgood

is a spendthrift, dissolute fellow.

Hoa. A very rascal.

Mon. A midnight surfeiter.

Hoa. The spume of a brothel-house.

Mon. True, sir: which being well told in your

worship’s phrase, may both heave him out of her

mind, and drive a fair way for me to the widow’s

affections.

Hoa. Attend me about five.

Mon. With my best care, sir. [Exit.

Hoa. Fool, thou hast left thy treasure with a thief,

To trust a widower with a suit in love!

Happy revenge, I hug thee! I have not only the

means laid before me, extremely to cross my adversary,

and confound the last hopes of his nephew,

but thereby to enrich my state, augment my revenues,

and build mine own fortunes greater:

ha, ha!

I’ll mar your phrase, o’erturn your flatteries,

Undo your windings, policies, and plots,

Fall like a secret and despatchful plague

On your secured comforts. Why, I am able

To buy three of Lucre; thrice outbid him,

Let my out-monies be reckoned and all.

Enter Three of Witgood’s Creditors.

First C. I am glad of this news.

37Sec. C. So are we, by my faith.

Third C. Young Witgood will be a gallant again

now.

Hoa. Peace. [Listening.

First C. I promise you, master Cockpit, she’s a

mighty rich widow.

Sec. C. Why, have you ever heard of her?

First C. Who? widow Medler? she lies open to

much rumour.

Third C. Four hundred a-year, they say, in

very good land.

First C. Nay, take’t of my word, if you believe

that, you believe the least.

Sec. C. And to see how close he keeps it!

First C. O, sir, there’s policy in that, to prevent

better suitors.

Third C. He owes me a hundred pound, and I

protest I ne’er looked for a penny.

First C. He little dreams of our coming; he’ll

wonder to see his creditors upon him. [Exeunt Creditors.

Hoa. Good, his creditors: I’ll follow. This makes for me:

All know the widow’s wealth; and ’tis well known

I can estate her fairly, ay, and will.

In this one chance shines a twice happy fate;

I both deject my foe and raise my state. [Exit.

38

ACT III. SCENE I.

Enter Witgood and Three Creditors.

Wit. Why, alas, my creditors, could you find no

other time to undo me but now? rather your malice

appears in this than the justness of the debt.

First C. Master Witgood, I have forborne my

money long.

Wit. I pray, speak low, sir: what do you

mean?

Sec. C. We hear you are to be married suddenly

to a rich country widow.

Wit. What can be kept so close but you creditors

hear on’t! well, ’tis a lamentable state, that

our chiefest afflictors should first hear of our fortunes.

Why, this is no good course, i’faith, sirs:

if ever you have hope to be satisfied, why do you

seek to confound the means that should work it?

there’s neither piety, no, nor policy in that. Shine

favourably now: why, I may rise and spread again,

to your great comforts.

First C. He says true, i’faith.

Wit. Remove me

[60] now, and I consume for ever.

Sec. C. Sweet gentleman!

Wit. How can it thrive which from the sun you sever?

Third. C. It cannot, indeed.

Wit. O, then, shew patience! I shall have enough

To satisfy you all.

39First C. Ay, if we could

Be content, a shame take us!

Wit. For, look you;

I am but newly sure yet to

[61] the widow,

And what a rend might this discredit make!

Within these three days will I bind you lands

For your securities.

First C. No, good master Witgood:

Would ’twere as much as we dare trust you with!

Wit. I know you have been kind; however, now,

Either by wrong report, or false incitement,

Your gentleness is injured: in such

A state as this a man cannot want foes.

If on the sudden he begin to rise,

No man that lives can count his enemies.

You had some intelligence, I warrant ye,

From an ill-willer.

Sec. C. Faith, we heard you brought up a rich

widow, sir, and were suddenly to marry her.

Wit. Ay, why there it was: I knew ’twas so:

but since you are so well resolved[62] of my faith toward

you, let me be so much favoured of you, I

beseech you all——

All. O, it shall not need, i’faith, sir!——

40Wit. As to lie still awhile, and bury my debts

in silence, till I be fully possessed of the widow;

for the truth is—I may tell you as my friends—

All. O, O, O!——

Wit. I am to raise a little money in the city,

toward the setting forth of myself, for mine own

credit and your comfort; now, if my former debts

should be divulged, all hope of my proceedings

were quite extinguished.

First C. Do you hear, sir? I may deserve your

custom hereafter; pray, let my money be accepted

before a stranger’s: here’s forty pound I received

as I came to you; if that may stand you in any

stead, make use on’t. [Offers him money, which

he at first declines.] Nay, pray, sir; ’tis at your

service. [Aside to Witgood.

Wit. You do so ravish me with kindness, that

I am[63] constrain’d to play the maid, and take it.

First C. Let none of them see it, I beseech you.

Wit. Faugh!

First C. I hope I shall be first in your remembrance

After the marriage rites.

Wit. Believe it firmly.

First C. So.—What, do you walk, sirs?

Sec. C. I go.—Take no care, sir, for money to

furnish you; within this hour I’ll send you sufficient.

[Aside to Witgood.]—Come, master Cockpit,

we both stay for you.

Third C. I ha’ lost a ring, i’faith; I’ll follow

you presently: [exeunt First and Second Creditors]—but

you shall find it, sir; I know your youth

and expenses have disfurnished you of all jewels:

41there’s a ruby of twenty pound price, sir; bestow

it upon your widow. [Offers him the ring, which

he at first declines.]—What, man! ’twill call up her

blood to you; beside, if I might so much work

with you, I would not have you beholding[64] to

those bloodsuckers for any money.

Wit. Not I, believe it.

Third C. They’re a brace of cut-throats.

Wit. I know ’em.

Third C. Send a note of all your wants to my

shop, and I’ll supply you instantly.

Wit. Say you so? why, here’s my hand then,

no man living shall do’t but thyself.

Third C. Shall I carry it away from ’em both,

then?

Wit. I’faith, shalt thou.

Third C. Troth, then, I thank you, sir.

Wit. Welcome, good master Cockpit. [Exit

Third Creditor.]—Ha, ha, ha! why, is not this

better now than lying a-bed? I perceive there’s

nothing conjures up wit sooner than poverty, and

nothing lays it down sooner than wealth and

lechery: this has some savour yet. O that I had

the mortgage from mine uncle as sure in possession

as these trifles! I would forswear brothel at noonday,

and muscadine and eggs at midnight.

Court. [within] Master Witgood, where are you?

Wit. Holla!

Court. Rich news!

Wit. Would ’twere all in plate!

Court. There’s some in chains and jewels: I

am so haunted with suitors, master Witgood, I

know not which to despatch first.

42Wit. You have the better term,

[65] by my faith.

Court. Among the number

One master Hoard, an ancient gentleman.

Wit. Upon my life, my uncle’s adversary.

Court. It may well hold so, for he rails on you,

Speaks shamefully of him.

Wit. As I could wish it.

Court. I first denied him, but so cunningly,

It rather promis’d him assured hopes,

Than any loss of labour.

Wit. Excellent!

Court. I expect him every hour with gentlemen,

With whom he labours to make good his words,

To approve you riotous, your state consum’d,

Your uncle——

Wit. Wench, make up thy own fortunes now;

do thyself a good turn once in thy days: he’s rich

in money, movables, and lands; marry him: he’s

an old doating fool, and that’s worth all; marry

him: ’twould be a great comfort to me to see thee

do well, i’faith; marry him: ’twould ease my conscience

well to see thee well bestowed; I have a

care of thee, i’faith.

Court. Thanks, sweet master Witgood.

Wit. I reach at farther happiness: first, I am

sure it can be no harm to thee, and there may

happen goodness to me by it: prosecute it well;

let’s send up for our wits, now we require their

best and most pregnant assistance.

Court. Step in, I think I hear ’em. [Exeunt.

43Enter Hoard and Gentlemen, with the Host as Servant.

Hoa. Art thou the widow’s man? by my faith,

sh’as a company of proper men then.

Host. I am the worst of six, sir; good enough

for blue coats.[66]

Hoa. Hark hither: I hear say thou art in most

credit with her.

Host. Not so, sir.

Hoa. Come, come, thou’rt modest: there’s a

brace of royals;[67] prithee, help me to th’ speech

of her.

[Gives him money.

Host. I’ll do what I may, sir, always saving

myself harmless.

Hoa. Go to, do’t, I say; thou shalt hear better

from me.

Host. Is not this a better place than five mark

a-year standing wages? Say a man had but three

such clients in a day, methinks he might make a

poor living on’t; beside, I was never brought up

with so little honesty to refuse any man’s money;

never: what gulls there are a’ this side the world!

now know I the widow’s mind; none but my young

master comes in her clutches: ha, ha, ha!

[Aside, and exit.

Hoa. Now, my dear gentlemen, stand firmly to me;

You know his follies and my worth.

First G. We do, sir.

Sec. G. But, master Hoard, are you sure he is

not i’ th’ house now?

Hoa. Upon my honesty, I chose this time

44A’ purpose, fit: the spendthrift is abroad:

Assist me; here she comes.

Now, my sweet widow.

Court. You’re welcome, master Hoard.

Hoa. Despatch, sweet gentlemen, despatch.—

I am come, widow, to prove those my words

Neither of envy sprung nor of false tongues,

But such as their

[68] deserts and actions

Do merit and bring forth; all which these gentlemen,

Well known, and better reputed, will confess.

Court. I cannot tell

How my affections may dispose of me;

But surely if they find him so desertless,

They’ll have that reason to withdraw themselves:

And therefore, gentlemen, I do entreat you,

As you are fair in reputation

And in appearing form, so shine in truth:

I am a widow, and, alas, you know,

Soon overthrown! ’tis a very small thing

That we withstand, our weakness is so great:

Be partial unto neither, but deliver,

Without affection, your opinion.

Hoa. And that will drive it home.

Court. Nay, I beseech your silence, master Hoard;

You are a party.

Hoa. Widow, not a word.

First G. The better first to work you to belief,

Know neither of us owe him flattery,

Nor t’other malice; but unbribed censure,

[69]So help us our best fortunes!

[70]45Court. It suffices.

First G. That Witgood is a riotous, undone man,

Imperfect both in fame and in estate,

His debts wealthier than he, and executions

In wait for his due body, we’ll maintain

With our best credit and our dearest blood.

Court. Nor land nor living, say you? Pray, take heed

You do not wrong the gentleman.

First G. What we speak

Our lives and means are ready to make good.

Court. Alas, how soon are we poor souls beguil’d!

[Aside to Gent.

Sec. G. And for his uncle——

Hoa. Let that come to me.

His uncle[’s] a severe extortioner;

A tyrant at a forfeiture; greedy of others’

Miseries; one that would undo his brother,

Nay, swallow up his father, if he can,

Within the fathoms of his conscience.

First G. Nay, believe it, widow,

You had not only match’d yourself to wants,

But in an evil and unnatural stock.

Hoa. Follow hard, gentlemen, follow hard.

Court. Is my love so deceiv’d? Before you all

I do renounce him; on my knees I vow [Kneeling.

He ne’er shall marry me.

Wit. [looking in] Heaven knows he never meant it! [Aside.

Hoa. There, take her at the bound. [Aside to Gent.

46First G. Then, with a new and pure affection

Behold yon gentleman; grave, kind, and rich,

A match worthy yourself: esteeming him,

You do regard your state.

Hoa. I’ll make her a jointure, say. [Aside to Gent.

First G. He can join land to land, and will possess you

Of what you can desire.

Sec. G. Come, widow, come.

Court. The world is so deceitful!

First G. There ’tis deceitful,

Where flattery, want, and imperfection lie;

[71]But none of these in him: push!

[72]Court. Pray, sir——

First G. Come, you widows are ever most backward

when you should do yourselves most good;

but were it to marry a chin not worth a hair now,

then you would be forward enough. Come, clap

hands, a match.

Hoa. With all my heart, widow. [Hoard and Courtesan shake hands.]—Thanks, gentlemen:

I will deserve your labour, and [to Courtesan] thy love.

Court. Alas, you love not widows but for wealth!

I promise you I ha’ nothing, sir.

Hoa. Well said, widow,

Well said; thy love is all I seek, before

These gentlemen.

Court. Now I must hope the best.

Hoa. My joys are such they want to be express’d.

Court. But, master Hoard, one thing I must

47remember you of, before these gentlemen, your

friends: how shall I suddenly avoid the loathed

soliciting of that perjured Witgood, and his tedious,

dissembling uncle? who this very day hath appointed

a meeting for the same purpose too;

where, had not truth come forth, I had been

undone, utterly undone!

Hoa. What think you of that, gentlemen?

First G. ’Twas well devised.

Hoa. Hark thee, widow: train out young Witgood

single; hasten him thither with thee, somewhat

before the hour; where, at the place appointed,

these gentlemen and myself will wait the opportunity,

when, by some slight[73] removing him from

thee, we’ll suddenly enter and surprise thee, carry

thee away by boat to Cole-Harbour,[74] have a priest

ready, and there clap it up instantly. How likest

it, widow?

Court. In that it pleaseth you, it likes[75] me well.

Hoa. I’ll kiss thee for those words. [Kisses her.]—Come, gentlemen,

Still must I live a suitor to your favours,

Still to your aid beholding.

[76]First G. We’re engag’d, sir;

’Tis for our credits now to see’t well ended.

Hoa. ’Tis for your honours, gentlemen; nay, look to’t.

Not only in joy, but I in wealth excel:

No more sweet widow, but, sweet wife, farewell.

Court. Farewell, sir.

[Exeunt Hoard and Gentlemen.

Wit. O for more scope! I could laugh eternally!

Give you joy, mistress Hoard, I promise

your fortune was good, forsooth; you’ve fell upon

wealth enough, and there’s young gentlemen enow

can help you to the rest. Now it requires our

wits: carry thyself but heedfully now, and we are

both——

Host. Master Witgood, your uncle.

Wit. Cuds me! remove thyself awhile; I’ll

serve for him.

[Exeunt Courtesan and Host.

Luc. Nephew, good morrow, nephew.

Wit. The same to you, kind uncle.

Luc. How fares the widow? does the meeting hold?

Wit. O, no question of that, sir.

Luc. I’ll strike the stroke, then, for thee; no more days.

[77]

Wit. The sooner the better, uncle. O, she’s

mightily followed!

Luc. And yet so little rumoured!

Wit. Mightily: here comes one old gentleman,

and he’ll make her a jointure of three hundred a-year,

forsooth; another wealthy suitor will estate

his son in his lifetime, and make him weigh down

the widow; here a merchant’s son will possess

her with no less than three goodly lordships at

once, which were all pawns to his father.

Luc. Peace, nephew, let me hear no more of

49’em; it mads me. Thou shalt prevent[78] ’em all.

No words to the widow of my coming hither. Let

me see—’tis now upon nine: before twelve, nephew,

we will have the bargain struck, we will,

faith, boy.

Wit. O, my precious uncle! [Exeunt.

SCENE II.

Hoa. Niece, sweet niece, prithee, have a care to

my house; I leave all to thy discretion. Be content

to dream awhile; I’ll have a husband for thee

shortly: put that care upon me, wench, for in

choosing wives and husbands I am only fortunate;

I have that gift given me.

[Exit.

Joy. But ’tis not likely you should choose for me,

Since nephew to your chiefest enemy

Is he whom I affect: but, O, forgetful!

Why dost thou flatter thy affections so,

With name of him that for a widow’s bed

Neglects thy purer love? Can it be so,

Or does report dissemble?

How now, sir?

Geo. A letter, with which came a private charge.

Joy. Therein I thank your care. [Exit George.]—I know this hand—

[Reads] Dearer than sight, what the world reports of

me, yet believe not; rumour will alter shortly: be

50thou constant; I am still the same that I was in love,

and I hope to be the same in fortunes.

Theodorus Witgood.

I am resolv’d:

[79] no more shall fear or doubt

Raise their pale powers to keep affection out. [Exit.

SCENE III.

Enter Hoard,

Gentlemen,[80] and Drawer.

Dra. You’re very welcome, gentlemen.—Dick,

shew those gentlemen the Pomegranate there.

Hoa. Hist!

Dra. Up those stairs, gentlemen.

Hoa. Hist, drawer!

Dra. Anon, sir.

Hoa. Prithee, ask at the bar if a gentlewoman

came not in lately.

Dra. William, at the bar, did you see any gentlewoman

come in lately? Speak you ay, speak

you no.

[Within.] No, none came in yet but mistress

Florence.

Dra. He says none came in yet, sir, but one

mistress Florence.

Hoa. What is that Florence? a widow?

Dra. Yes, a Dutch widow.[81]

51Hoa. How?

Dra. That’s an English drab, sir: give your

worship good morrow. [Exit.

Hoa. A merry knave, i’faith! I shall remember

a Dutch widow the longest day of my life.

First G. Did not I use most art to win the widow?

Sec. G. You shall pardon me for that, sir; master

Hoard knows I took her at best ’vantage.

Hoa. What’s that, sweet gentlemen, what’s that?

Sec. G. He will needs bear me down, that his

art only wrought with the widow most.

Hoa. O, you did both well, gentlemen, you did

both well, I thank you.

First G. I was the first that moved her.

Hoa. You were, i’faith.

Sec. G. But it was I that took her at the bound.

Hoa. Ay, that was you: faith, gentlemen, ’tis right.

Third G. I boasted least, but ’twas I join’d their hands.

Hoa. By th’ mass, I think he did: you did all well,

Gentlemen, you did all well; contend no more.

First G. Come, yon room’s fittest.

Hoa. True, ’tis next the door. [Exeunt.

Enter Witgood, Courtesan, Host, and Drawer.

Dra. You’re very welcome: please you to walk

up stairs; cloth’s laid, sir.

Court. Up stairs? troth, I am very[82] weary,

master Witgood.

Wit. Rest yourself here awhile, widow; we’ll

have a cup of muscadine in this little room.

52Dra. A cup of muscadine? You shall have the

best, sir.

Wit. But, do you hear, sirrah?

Dra. Do you call? anon, sir.

Wit. What is there provided for dinner?

Dra. I cannot readily tell you, sir: if you

please you may go into the kitchen and see yourself,

sir; many gentlemen of worship do use to do

it, I assure you, sir.

[Exit.

Host. A pretty familiar, prigging[83] rascal; he

has his part without book.

Wit. Against you are ready to drink to me,

widow, I’ll be present to pledge you.

Court. Nay, I commend your care, ’tis done

well of you. [Exit Witgood.]—’Las,[84] what have

I forgot!

Host. What, mistress?

Court. I slipt my wedding-ring off when I

washed, and left it at my lodging: prithee, run; I

shall be sad without it. [Exit Host.]—So, he’s

gone. Boy.

Boy. Anon, forsooth.

Court. Come hither, sirrah; learn secretly if

one master Hoard, an ancient gentleman, be about

house.

Boy. I heard such a one named.

Court. Commend me to him.

53Re-enter Hoard and Gentlemen.

Hoa. Ay, boy,

[85] do thy commendations.

Court. O, you come well: away, to boat, begone.

Hoa. Thus wise men are reveng’d, give two for one. [Exeunt.

Re-enter Witgood and Vintner.

Wit. I must request

You, sir, to shew extraordinary care:

My uncle comes with gentlemen, his friends,

And ’tis upon a making.

[86]Vin. Is it so?

I’ll give a special charge, good master Witgood.

May I be bold to see her?

Wit. Who? [t]he widow?

With all my heart, i’faith, I’ll bring you to her.

Vin. If she be a Staffordshire gentlewoman, ’tis

much if I know her not.

Wit. How now? boy! drawer!

Vin. Hie!

Boy. Do you call, sir?

Wit. Went the gentlewoman up that was here?

Boy. Up, sir? she went out, sir.

Wit. Out, sir?

Boy. Out, sir: one master Hoard, with a guard

of gentlemen, carried her out at back door, a pretty

while since, sir.

Wit. Hoard? death and darkness! Hoard?

Host. The devil of ring I can find.

Wit. How now? what news? where’s the widow?

Host. My mistress? is she not here, sir?

Wit. More madness yet!

Host. She sent me for a ring.

Wit. A plot, a plot!—To boat! she’s stole away.

Host. What?

Enter Lucre and Gentlemen.

Wit. Follow! inquire old Hoard, my uncle’s adversary.

[Exit Host.

Luc. Nephew, what’s that?

Wit. Thrice-miserable wretch!

Luc. Why, what’s the matter?

Vin. The widow’s borne away, sir.

Luc. Ha? passion of me!—A heavy welcome, gentlemen.

First G. The widow gone?

Luc. Who durst attempt it?

Wit. Who but old Hoard, my uncle’s adversary?

Luc. How!

Wit. With his confederates.

Luc. Hoard, my deadly enemy?—Gentlemen, stand to me,

I will not bear it; ’tis in hate of me;

That villain seeks my shame, nay, thirsts my blood;

He owes me mortal malice.

I’ll spend my wealth on this despiteful plot,

Ere he shall cross me and my nephew thus.

Wit. So maliciously!

Luc. How now, you treacherous rascal?

Host. That’s none of my name, sir.

Wit. Poor soul, he knew not on’t!

Luc. I’m sorry. I see then ’twas a mere plot.

Host. I trac’d ’em nearly——

Host. And hear for certain

They have took Cole-Harbour.

[88]Luc. The devil’s sanctuary!

They shall not rest; I’ll pluck her from his arms.—

Kind and dear gentlemen,

If ever I had seat within your breasts——

First G. No more, good sir; it is a wrong to us

To see you injur’d: in a cause so just

We’ll spend our lives but we will right our friends.

Luc. Honest and kind! come, we’ve

[89] delay’d too long:

Nephew, take comfort; a just cause is strong.

Wit. That’s all my comfort, uncle. [Exeunt all

but Witgood.] Ha, ha, ha!

Now may events fall luckily and well:

He that ne’er strives, says wit, shall ne’er excel.

[Exit.

SCENE IV.

A Room in Dampit’s House.

Dam. When did I say my prayers? In anno

88, when the great armada was coming; and in

anno 89,[90] when the great thundering and lightning

56was, I prayed heartily then, i’faith, to overthrow

Poovies’ new buildings; I kneeled by my great

iron chest, I remember.

Aud. Master Dampit, one may hear you before

they see you: you keep sweet hours, master Dampit;

we were all a-bed three hours ago.

Dam. Audrey?

Aud. O, you’re a fine gentleman!

Dam. So I am, i’faith, and a fine scholar: do

you use to go to bed so early, Audrey?

Aud. Call you this early, master Dampit?

Dam. Why, is’t not one of clock i’ th’ morning?

is not that early enough? fetch me a glass of fresh

beer.

Aud. Here, I have warmed your nightcap for

you, master Dampit.

Dam. Draw it on then. I am very weak truly:

I have not eaten so much as the bulk of an egg

these three days.

Aud. You have drunk the more, master Dampit.

Dam. What’s that?

Aud. You mought, and[91] you would, master

Dampit.

Dam. I answer you, I cannot: hold your

prating; you prate too much, and understand

too little: are you answered? Give me a glass

of beer.

57Aud. May I ask you how you do, master

Dampit?

Dam. How do I? i’faith, naught.

Aud. I ne’er knew you do otherwise.

Dam. I eat not one pen’north of bread these two

years.[92] Give me a glass of fresh beer. I am not

sick, nor I am not well.

Aud. Take this warm napkin about your neck,

sir, whilst I help to make you unready.[93]

Dam. How now, Audrey-prater, with your scurvy

devices, what say you now?

Aud. What say I, master Dampit? I say nothing,

but that you are very weak.

Dam. Faith, thou hast more cony-catching[94] devices

than all London.

Aud. Why, master Dampit, I never deceived you

in all my life.

Dam. Why was that? because I never did trust thee.

Aud. I care not what you say, master Dampit.

Dam. Hold thy prating: I answer thee, thou

art a beggar, a quean, and a bawd: are you answered?

Aud. Fie, master Dampit! a gentleman, and

have such words?

Dam. Why, thou base drudge of infortunity,

thou kitchen-stuff-drab of beggary, roguery, and

cockscombry, thou cavernesed quean of foolery,

knavery, and bawdreaminy, I’ll tell thee what, I

will not give a louse for thy fortunes.

Aud. No, master Dampit? and there’s a gentleman

comes a-wooing to me, and he doubts[95] nothing

but that you will get me from him.

58Dam. I? If I would either have thee or lie with

thee for two thousand pound, would I might be

damned! why, thou base, impudent quean of foolery,

flattery, and coxcombry, are you answered?

Aud. Come, will you rise and go to bed, sir?

Damp. Rise, and go to bed too, Audrey? How

does mistress Proserpine?

Aud. Fooh!

Dam. She’s as fine a philosopher of a stinkard’s

wife, as any within the liberties. Faugh, faugh,

Audrey!

Aud. How now, master Dampit?

Dam. Fie upon’t, what a choice of stinks here

is! what hast thou done, Audrey? fie upon’t, here’s

a choice of stinks indeed! Give me a glass of fresh

beer, and then I will to bed.

Aud. It waits for you above, sir.

Dam. Foh! I think they burn horns in Barnard’s

Inn. If ever I smelt such an abominable

stink, usury forsake me. [Exit.

Aud. They be the stinking nails of his trampling

feet, and he talks of burning of horns. [Exit.

ACT IV. SCENE I.

An Apartment at Cole-Harbour.[96]

Enter Hoard, Courtesan, Lamprey, Spichcock, and Gentlemen.

First G. Join hearts, join hands,

In wedlock’s bands,

59Never to part

Till death cleave your heart.

[To Hoard] You shall forsake all other women;

[To Courtesan] You lords, knights, gentlemen, and yeomen.

What my tongue slips

Make up with your lips.

Hoa. [kisses her] Give you joy, mistress Hoard: let the kiss come about. [Knocking.

Who knocks? Convey my little pig-eater

[97] out.

Luc. [within] Hoard!

Hoa. Upon my life, my adversary, gentlemen!

Luc. [within] Hoard, open the door, or we will force it ope:

Give us the widow.

Hoa. Gentlemen, keep ’em out.

60Lam. He comes upon his death that enters here.

ᚠLuc. [within] My friends, assist me!

Hoa. He has assistants, gentlemen.

Lam. Tut, nor him nor them we in this action fear.

Luc. [within] Shall I, in peace, speak one word with the widow?

Court. Husband, and gentlemen, hear me but a word.

Hoa. Freely, sweet wife.

Court. Let him in peaceably;

You know we’re sure from any act of his.

Hoa. Most true.

Court.[98] You may stand by and smile at his old weakness:

Let me alone to answer him.

Hoa. Content;

’Twill be good mirth, i’faith. How think you, gentlemen?

Lam. Good gullery!

Hoa. Upon calm conditions let him in.

Luc. [within] All spite and malice!

Lam. Hear me, master Lucre:

So you will vow a peaceful entrance

With those your friends, and only exercise

Calm conference with the widow, without fury,

The passage shall receive you.

Luc. [within] I do vow it.

Lam. Then enter and talk freely: here she stands.

Enter Lucre, Gentlemen, and Host.

Luc. O, master Hoard, your spite has watch’d the hour!

You’re excellent at vengeance, master Hoard.

61Hoa. Ha, ha, ha!

Luc. I am the fool you laugh at:

You are wise, sir, and know the seasons well.—

Come hither, widow: why is it thus?

O, you have done me infinite disgrace,

And your own credit no small injury!

Suffer mine enemy so despitefully

To bear you from my nephew? O, I had

Rather half my substance had been forfeit

And begg’d by some starv’d rascal!

Court. Why, what would you wish me do, sir?

I must not overthrow my state for love:

We have too many precedents for that;

From thousands of our wealthy undone widows

One may derive some wit. I do confess

I lov’d your nephew, nay, I did affect him

Against the mind and liking of my friends;

[99]Believ’d his promises; lay here in hope

Of flatter’d living, and the boast of lands:

Coming to touch his wealth and state, indeed,

It appears dross; I find him not the man;

Imperfect, mean, scarce furnish’d of his needs;

In words, fair lordships; in performance, hovels:

Can any woman love the thing that is not?

Luc. Broke you for this?

Court. Was it not cause too much?

Send to inquire his state: most part of it

Lay two years mortgag’d in his uncle’s hands.

Luc. Why, say it did, you might have known my mind:

I could have soon restor’d it.

Court. Ay, had I but seen any such thing perform’d,

Why, ’twould have tied my affection, and contain’d

62Me in my first desires: do you think, i’faith,

That I could twine such a dry oak as this,

Had promise in your nephew took effect?

Luc. Why, and there’s no time past; and rather than

My adversary should thus thwart my hopes,

I would——

Court. Tut, you’ve been ever full of golden speech:

If words were lands, your nephew would be rich.

Luc. Widow, believe’t,

[100] I vow by my best bliss,

Before these gentlemen, I will give in

The mortgage to my nephew instantly,

Before I sleep or eat.

First G. [friend to Lucre] We’ll pawn our credits,

Widow, what he speaks shall be perform’d

In fulness.

Luc. Nay, more; I will estate him