Title: By beach and bog-land

Some Irish stories

Author: Jane Barlow

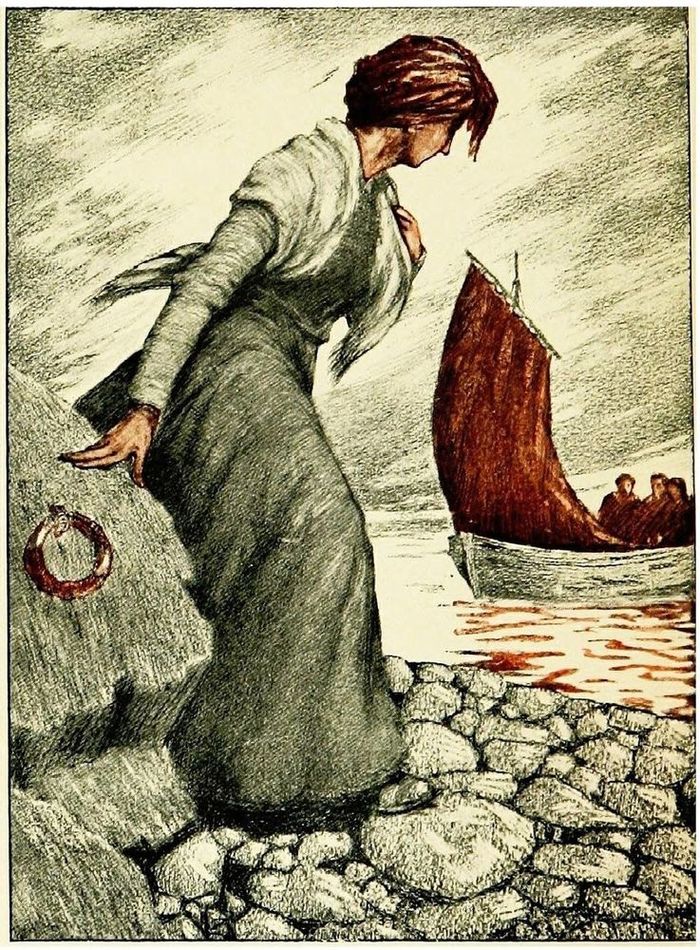

Illustrator: Paul Henry

Release date: April 8, 2025 [eBook #75823]

Language: English

Original publication: London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1905

Credits: the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Crown 8vo, Cloth, 6s.

THE WIZARD’S KNOT. By William Barry.

THE LOST LAND. By Julia M. Crottie.

NEIGHBOURS: Being Annals of a Dull Town. By Julia M. Crottie.

London: T. FISHER UNWIN.

BY BEACH AND

BOG-LAND

SOME IRISH STORIES

BY

JANE BARLOW

With a Frontispiece by Paul Henry

LONDON

T. FISHER UNWIN

Paternoster Square

MCMV

All Rights Reserved

[Pg vii]

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| In the Winding Walk | 1 |

| A Money-crop at Lisconnel | 31 |

| The High Tide and the Man-Trappers | 55 |

| The Foot-Sticks of Slughnatraigh | 73 |

| Old Isaac’s Biggest Haul | 101 |

| The Wrong Turning | 117 |

| Crazy Mick | 141 |

| Widow Farrell’s Wonderful Age | 149 |

| The Hins’ Housekeeper | 175 |

| Two Pair of Truants | 189 |

| Their New Umbrellas | 209 |

| A Small Practice | 225 |

| A Lingering Guest | 247 |

| Loughnaglee | 261 |

| Moriarty’s Meadow | 269 |

| Delayed in Transmission | 285 |

| For Company | 295 |

[Pg 1]

By Beach and Bog-land

When people go away from Clonmalroan, they go away, as a rule, very thoroughly. Their absence is an absence more complete than that of other persons from other places less out of the world and behind the times. Once any traveller’s departing form has been beheld pass round the turn in the deep-banked boreen, or watched dwindle into a speck on the straight road streaking the wide bog-land, the chances are that little news of him will reach his former neighbours, till some day that same speck is espied growing into human shape again along that same road, and acquaintances remark to each other in the course of conversation: “And so big Pat Byrne”—to put case—“is afther comin’ home wid himself.”

For Clonmalroan is but meagrely provided with the means of communication, and its[Pg 2] inhabitants are mostly ill able to make use even of those which it possesses. It is as yet untouched by the wonderful thread of wire, which has put a running-string through the web of human lives—puckered up in a moment from Hong Kong to Cambridge—and the shining metals with their rush and roar, still halting many miles short of it, are lamely prolonged by the wheel tracks of the jiggeting side-car with a slenderly filled mail-bag on the well. The letters it brings are commonly brief and obscure, the difficult product of certainly no excessive ease in composition. They convey little more than an intimation of continued existence led among surroundings only mistily imagined by readers whose own journeying has lain within the radius of a day’s tramp. Beyond that limit everything is vague and dim, a mysterious region from whence the absentee seems not so very much more likely to reappear than do those who have been seen off with a wake and a keen. Not that such returns even as these are by any means unheard of at Clonmalroan. Would the friends of Michael Larissy, who duly waked and buried him three years ago, aver that they have never set eyes on him since? Or ask anybody, almost, in the parish, why he wouldn’t take half a crown to be crossing after nightfall that bridge over the Rosbride River near Sallinbeg, where a poor tinker-woman was swept away and drowned in a flood some few autumns back. Then, everybody knows that several of the Denny family have[Pg 3] “walked.” Therefore the assertion: “It was himself or his ghost,” is not regarded as containing a very unequally balanced hypothesis, especially if “himself” has been supposed away sojourning in those unknown and imperfectly reported lands.

But there came one autumn when far and far away from Clonmalroan began to happen events which had such a heart-burning interest for many of its people that some news of them did penetrate the densest barriers of ignorant resourcelessness. Mere sparks, perhaps, as it were blown from some huge conflagration, whose distant flames make only a sullen glare behind a smothering smoke-fog. Yet a spark may blacken a body’s home over her head, or sear the sight out of her eyes. A great war was thundering and lightening across wide seas, under alien skies: a war which in no way behoved Clonmalroan, and which might have stormed itself out, little heeded there, had it not been for the circumstance that Pat and Micky and their brethren are “terrible lads for goin’ an’ listin’,” and that the regiment they had for the most part joined was understood to be “up at the forefront of everythin’.”

After a while, moreover, it was not those wild, irresponsible boys alone that this lurid cloud engulfed in threatening glooms. The reserves were called out, people said, at first without any clear notion of what the phrase might signify, but soon perceiving too plainly how it meant that men whose soldiering days were long past and nearly[Pg 4] forgotten, except just the little pension, must now break the ties they had peaceably formed and once more set forth campaigning. Murtagh O’Connor, of Naracor, had to leave a wife and five children on his bit of a holding “in a quare distraction,” his friends reported, “for when he was killed, what could happen them but the Union?” And many another household on that countryside had to consider the same woeful question.

So all round and about Clonmalroan there came to be an intense craving for the latest war intelligence. Never had newspapers been in such request. At Donnelly’s bar the Freeman and the Independent were as badly tattered as strips of ill-preserved papyri by the end of an evening’s reading. The Widdy Gallaher “would be walkin’ wild about the country the len’th of the day,” folk said, “for the sight of a one. Be raison,” they added, “of her two sons.” And another illiterate and sceptical old Mrs Linders for similar reasons “was tormintin’ everybody to read her out every word there would be on the paper, even if they tould her ’twas only the market prices.” The elders, indeed, were often at a disadvantage in this way, owing to the inferior educational arrangements under which their generation had risen. Big Brian O’Flaherty, who had an independent and ambitious spirit, demeaned himself to set about learning the alphabet from that little spalpeen, Larry M‘Crilly, in hopes of subsequently reading his news “and no thanks to anybody.” But Larry was impatient and sarcastic, and Big[Pg 5] Brian slow-witted and irascible, so the course of lessons one day ended abruptly with “a clout on the head” to the taunting teacher. With more modest aspirations old John Connellan got the schoolmaster to print for him, “the way it would be on the paper,” the name of Private Patrick Connellan; and he might be seen on many a cold day sitting out on the rimy grass bank before his dark door, for the sake of the light, and comparing with this scrap the unintelligible lines of the Independent. It was very slow, puzzling work, since the columns were many and lengthy, and his eyes none of the best. Old John seldom could retain the loan of the wide sheets long enough to assure himself completely that his grandson’s name was happily absent from them. For no news was certainly the best that could be looked for from the papers. What, indeed, was likely to happen a lad save one of those casualties which were so briefly recorded. “Och, woman dear, they’re sayin’ at Donnelly’s that there’s a terrible sight of officers kilt on the Freeman to-day, so there’ll prisently be a cruel big list of the rank and file. God be good to us all, woman dear—and poor Micky and the rest. I’m wonderin’ will they be apt to print it to-morra.”

Thus the winter, always at Clonmalroan a season when cares and losses are rife, was beyond its wont harassed and haunted by fear and sorrow. The calling away on active service of the Captain from the Big House was one of its incidents that[Pg 6] tended to deepen the general depression. His stalwart form and sturdy stride and off-hand greeting were missed going to and fro, and much commiseration was directed to “poor Lady Winifred, and she not so long married, the crathur, left all alone by herself up at the Big House.”

It was only comparatively speaking a big house at all, though it made some architectural pretensions with its pillared front and porch and balustraded roof. Its lower windows looked out of a spacious hall, and a few ill-proportioned sitting-rooms; upstairs rambling passages and wide-floored lobbies cramped the uncomfortable bedchambers. Disrepair prevailed within and without, ranging from the rough work of wind and weather to the minuter operations of mouse and moth. Even at its best, all had been ugly and inconvenient enough. Nevertheless to become mistress thereof Lady Winifred had not merely left a far statelier and more luxurious establishment, but had quitted it under a cloud of disapproval, with an assurance that she was taking a long step down in the world. For her Captain was a person so impecunious and impossible, with such an unsuccessful past career, and such unsatisfactory future prospects, that nobody could imagine what she saw in him, and everybody thought the worse of her for seeing it,[Pg 7] whatever it might be. The marriage was just not discountenanced and forbidden outright, but most austere visages were turned upon it, and the wedding, Lady Astermount’s maid declared, “couldn’t have been quieter if an affliction had occurred in the family only the previous week.”

Notwithstanding that inauspicious send-off, however, Captain and Lady Winifred O’Reilly passed a surprisingly pleasant year at this shabby old house of his among the bog-lands. Lonesome and monotonous are the bog-lands, and creep up very close to the Big House; but it stands set in a miniature glen of its own, with a wreath of shrubberies around it, and during the months after they arrived the O’Reillys busied themselves much about additional trees and evergreens, wherewith to screen their domain more effectually from the dreary outlook and roughly sweeping winds in the years that were to come. Many improvements, too, had to be made in neglected plots of garden ground, where the Captain looked at geraniums and pansies and carnations through another person’s eyes, until at last he saw something in them himself, and learned with extreme pride to call them by their proper names. This lore gave him more pleasure on the whole than he had ever derived from his familiarity with the colours worn by jockeys or stamped on playing cards, studies which had hitherto engrossed a larger share of his attention. His wife and he diversified their gardening with long rides together on steeds not[Pg 8] expensively high bred. Clonmalroan opinion waxed somewhat critical when the pair came trotting by. Her ladyship, they said, didn’t look the size of a wren perched on that big, rawny baste of a chestnut, with an ugly, coarse gob of a head on him too, and the brown mare was something slight for his Honour, who must ride well up to fourteen stone. But the riders themselves were satisfied with their mounts.

Their contentment had showed no signs of waning in that mild November weather, with its pearl-white mists and wafted odour of burning weeds, when the likelihood of his going out loomed up suddenly on their horizon. The certain news came one morning, while they were working away near the back gate, where their small bog stream flows under steep banks, on which they had designed a plantation of rhododendrons. In the black peat soil these thrive amain, and by next June would have lit a many-hued glow in the shadowy little glen. Lady Winifred tried hard not to see that this interruption of their labours was to the Captain scarcely such an unmitigated calamity as to herself. Her recognition of the fact made her feel doubly desolate; not that there was more difference in their sentiments than had to be in the nature of things, or than left him otherwise than miserable at their parting. She tried further to go on with the plantation, as he would no doubt return in time to see it in blossom; but she was relieved when a spell of bad weather presently set in and let her[Pg 9] stay indoors. Yet indoors it seemed as if the whole solitude of the great bog had pressed into the empty house. All day it said, wherever she went, upstairs or downstairs, one word to vex her: Gone. But at night she had various fortunes in dreams good and evil.

And every morning at breakfast, in the low, broad-windowed bookroom, she sat opposite to the Captain’s place, just as usual, except that the place was empty. She chose that seat because from it she could watch for old Christy Denny coming by from Salinbeg post-office with the mail-bag. That window looked out on a small lawn, bounded by a shrubbery through which a path ran leading round a corner of the house to the front door. The laurel bushes straggled into frequent gaps, so that between them the approach of a passer-by could be fitfully descried. And any morning might bring the letter for her, the foreign letter. To think of how it was perhaps in those very moments journeying towards her in the battered old brown bag made her so hungry and thirsty that she sometimes forgot to pour out her tea, or cut the over-large loaf. Nor was she always disappointed. Every now and then a letter did come, and in its re-reading she would find a refuge through the terrors of the day, as in a flattering dream by night. All the while, indeed, she knew that she was in a fool’s paradise: that, being so many weeks old, it could give her no assurance of its writer’s safety. The hands that had folded its sheets might ere now have grown cold beside some[Pg 10] far-off stream, where geysers of deadly hail broke out rattling on the hills, and the wide air was as full of murderous stings as a swamp of sweltering venom. She might more rationally rely upon the newspapers with their flashed tidings. But these she never dared open herself, and she could not forbear to hang her hopes upon that delusive correspondence.

One midwinter morning she came down to breakfast with her heart set more than ever eagerly upon the arrival of old Christy. Partly because she had not had a letter for longer than usual, and partly because it was Saturday, and on Sunday no mail comes in Salinbeg. This last was of course no reason at all for expecting a letter; but it did seem to her almost improbable that Fate could intend such harshness as to make her wait two whole days and nights before she could begin hoping again. So she looked out of the window with shining eyes, and set about crumbling the bread on her plate before she had tasted a bit, and thought Christy was late before he had well started on his two-mile trudge. It was hard weather, and on the corner of lawn she looked into lay a sprinkling of frozen snow; only a sprinkling; she had seen it whiter last June with daisies spread to the sun. But the frost was keen, as she would have felt by the air blowing through the open window if she had been at leisure to consider anything except the possibility of their bringing the sound of footsteps on the hardened path.

[Pg 11]

Old Christy was late really, and she listened in vain. When at length he did come, she saw him first, a shadow moving along within the still shadow of the laurels. Just opposite to the window a gap in them made a ragged arch, and Lady Winifred knew that if Christy had anything special for her he would come through the opening and straight across the grass to her, instead of following the path round the house to the hall door. For a minute, a half-happy minute of doubt, she watched him nearing the fateful place, fearful, hopeful, blindly impatient, and then—stunned. Old Christy had gone past the gap, hurrying a little it seemed, as if he wished to get out of sight. This in fact he did. “Sure now, the mistress’s face is all eyes these times,” he said to Mrs Keogh in the kitchen, “and lookin’ at me they do be like as if she thought bad of me not bringin’ her aught. But bedad if she could see to the bottom of me heart, she’d know it’s sorry I am I haven’t got somethin’ for her at the bottom of th’ ould bag. Troth would she so;” and Mrs Keogh replied: “Ah, sure it’s frettin’ she is; goodness may pity the crathur, she’s frettin’. And doesn’t ait what would fatten a sparrow. It’s my belief she’ll do no good.”

The mistress did not appear to be fretting as she sat without motion, and still gazed out over the lawn. Though its aspect was quite unchanged, it had become a grave wherein her hope, newly slain, must lie buried until the sun had set and risen, and again set and risen. Even by the[Pg 12] uncertain measure of years, the mistress was very young yet, and otherwise younger still, so that the edges of the experiences which make up life had not been worn smooth for her, to expedite their slipping past. A whole day looked nearly as interminable to her as to a small child, who gets out of bed with no clear prospect of ever getting into it again. And now her own bedtime lay beyond more than twelve leaden-footed hours, so early was this desolate, sunny morning. It seemed late, however, to some of her neighbours, who were keeping round eyes on her movements, and considered her as tardy as she had been thinking Christy. Perhaps a chirp or a rustle may have reached and prompted her unawares, or perhaps she merely acted from habit, but by-and-by she got up and scattered her plateful of crumbs upon the rimy window ledge, where they lay like a little drift of discoloured snow. As she strewed them she said to herself bitterly towards Fate, and ruthfully towards fellow-victims: “Why should the birds go hungry because I have no letter?” and she was careful to shut down the window sash, lest the sleek black cat should, according to custom, lurk ambushed within to pounce upon a preoccupied prey. Then she stood aside, half hidden by the faded crimson curtain, and looked out at nothing with a cold ache in her heart.

The small birds arrived in headlong haste. Some of them were almost pecking before the window closed. For the frost’s tyranny had[Pg 13] made of not a few among them desperate characters, fluttering with reckless enterprise. Even a scutty wren ventured out of cover, and advanced along the ledge in a dotted line of tiny hops, scarcely less smooth than a mouse’s run. A robin redbreast alighting brought a gleam of colour something brighter than a withered beech leaf and duller than a poppy petal. Two tomtits in comic motley suits disputed with tragic audacity the claims of all their biggers—thrushes, blackbirds, finches and sparrows. The whole party twittered and fluttered and wrangled together, blithe and pugnacious, but the spreader of the feast gave no heed to any of its incidents. She smiled neither at the abrupt gobblings of the large golden bill, nor at the absurd defiances of the blue-and-yellow dwarfs. Her act of charity seemed to have gained her nothing. Then all at once, at some caprice of panic, the assembled birds whisked themselves down from the window-stool into the gravel walk below. Each one of them bore off in his beak a breadcrumb which looked like a little white envelope, and gave him the appearance of a letter-carrier. The sudden movement caught Lady Winifred’s attention, and she was struck by the fantastic resemblance. But at the same moment she remembered keenly how she had been reft of her hope for that day and the next; and immediately, as if the frost at her heart were broken up, she saw the mock letters through a rain of tears. She had not foregone her recompense after all.

[Pg 14]

Near the back gates of Lady Winifred’s Big House, the Widdy Connor’s very little one makes a white dot on the edge of the black bog-land that winds away towards Lisconnel. She lived in it quite alone after her son Terence had listed on her, which he did one winter when times were hard and work was scarce. Everybody almost concurred in the opinion that there “wasn’t apt to be such another grand-lookin’ soldier in the regiment as young Terry Connor, or in an army of regiments bedad.” For Terry’s good looks and good nature and athletic prowess were celebrated round and about Clonmalroan. Six foot three in his stockings, and not a lad to stand up to him at the wrestling; there wasn’t another as big a man in the parish, unless it might be the Captain.

But, of course, it was not in the nature of things that anyone else should equal the extravagant pride and pleasure in those pre-eminent qualities evinced by Terry’s mother. She made a show of herself over him, according to the view entertained by some matrons with smaller sons; and now and then, when the widow had exceeded unusually in vaingloriousness, one of them might be heard to predict that, “she’d find she’d get none the better thratement from him for cockin’ him up wid consait; little enough he’d be thinkin’ of[Pg 15] her, or mindin’ what she bid him.” The widow for her part always declared that “the only thing he’d ever done agin her in his life was listin’; and that he’d never ha’ thought of if the both of them hadn’t been widin to-morra mornin’ of starvation.” And perhaps the affliction which that step caused her was not so very far from being made amends for by her exulting delight in the splendour of his martial aspect when he came over to visit her on furlough in his scarlet with green facings beautiful to behold. One of those carping critics declared to goodness after Mass, that she had come into chapel with him “lookin’ as sot up as if she was after catchin’ some sort of glittery angel flyin’ about wild, and had a hold of him by the wing.”

But then at that time the regiment was safely quartered at Athlone, a place no such terribly long way off, and known to have been actually visited by ordinary people. It was a woefully different matter when the Connemaras were sent off on active service to strange lands about which all one’s knowledge could be summed up in the words “furrin” and “fightin’”—words of limitless fear. Then it was that retribution might be deemed to have lighted upon her inordinate vanity about her son’s conspicuous stature. For this now became a source of special torment, as threatening to make him the better mark, singling him out for peculiar peril.

“And you’ll be plased to tell him, Mr Mulcahy,” she dictated to the schoolmaster, who[Pg 16] was also cobbler and scribe at Clonmalroan, “that whatever he does he’s not to be runnin’ into the forefront of the firin’, and he a head and shoulders higher than half of the lads. He’d be hit first thing. God be good to us. Bid him to be croochin’ down back of somethin’ handy. Or if there was ne’er a rock or a furze bush on the bit of bog, he might anyway keep stooped behind the others. But if he lets them get aimin’ straight at him, he’s lost.”

Mr Mulcahy, who was stirring up the sediment of his lately watered ink, received these suggestions about conduct in the field with decided disapproval. “Bedad now, Mrs Connor,” he said, “there’d be no sinse in tellin’ him any such things. For in the first place he wouldn’t mind a word of it, and in the next place—goodness may pity you, woman, but sure you wouldn’t be wishful to see him comin’ back to you after playin’ the poltroon, and behavin’ himself discreditable?”

“Troth and I would,” said Mrs Connor. “If he was twinty poltroons. All the behavin’ I want of him’s to be bringin’ himself home. Who’s any the betther for the killin’ and slaughterin’? The heart’s weary in me doubtin’ will I ever get a sight of him agin. That’s all I’m thinkin’ of, tellin’ you the truth, and if I said anythin’ diff’rint it ’ud be a lie.”

“He might bring home a trifle of honour and glory, and no harm done,” Mr Mulcahy urged. But Mrs Connor said: “Glory be bothered”; and[Pg 17] in the end he only so far modified his instructions as to substitute for her more detailed injunctions a vague general order to “be takin’ care of himself.”

It may perhaps be considered another righteous judgment upon this most un-Spartan mother, that while these precautions of hers were entirely neglected, little of the honour and glory which she had flouted did attend the fate of her Terry. He was shot through the lungs by a rifle posted a mile or two distant from the dusty hillock on which he dropped, and where he lay gasping and choking for what seemed to him a vastly long time, before the night fell suddenly dark and cold, and not to pass away. As this particular casualty was not discovered till the next morning, his name did not appear on the list which Barny Keogh spelled over to the Widdy Connor a few days later, and at the end of which she said fervently: “Thanks be to the great God. There’s no sign of himself in it.” But on the very next evening, a half line in the Freeman ran: “Add to Killed: Private T. Connor;” and when Peter Egan down below at Donnell’s read it out by chance, the widdy, listening, felt as if she had just wakened up into a dim sort of nightmare. All the more she felt so, because everybody round her was saying: “May the Lord have mercy on his soul,” as if anybody could believe that Terry had really become to them a subject for such pious ejaculations. So she hurried back through the wide spaces of the bleak March gloaming to[Pg 18] her little, silent house, where she shut herself in to sleep off her dream. But it woke up with her in the grey of the early dawning.

Lady Winifred’s Captain was killed about the same time as Terry Connor, and, like him, without anything specially glorious in the circumstances of his death. Rather the contrary. The occasion of it was a minor disaster to the arms of his side—a check, a reverse—over which it could not be but that someone had blundered. In point of fact a highly-distinguished General, dictating a draft report of the same to his discreet Secretary, had expressed an opinion that the regrettable incident had been brought about by want of judgment on the part of the commanding officer, the late Captain O’Reilly, when the younger man coughed significantly, and casually remarked: “Ah, O’Reilly—he married one of Lord Astermount’s daughters—the third, I think, Lady Winifred, a little fair girl. Her people didn’t like the match at all, I believe, but still—” His chief appeared scarcely to notice the observation: but Captain O’Reilly’s want of judgment was not mentioned in despatches.

When their world came to an end for the widow, Lady Winifred O’Reilly, and the widow, Katty Connor, the bog-land was just beginning to turn springwards, and everything on it stirred under[Pg 19] the strengthening sunshine. Round about the Big House the birds, who now despised breadcrumbs because other food wriggled abundantly in the dewy grass, sang much and gleefully in the fresh mornings, and through the long golden light as it ebbed off the lawn. But Lady Winifred, looking out no more for letters, sought a refuge from it all in the bookroom, which was a dusky brown place in the brightest hours. There she sat on the floor in a corner before a far-stretching row of Annual Registers, and read them volume by volume. She had chosen this course of study just as she might have chosen the top of an adjacent rubbish heap in a suddenly surging flood. Steadily through she read them without skipping—History of Europe—Chronicle—State Papers—Characters—Useful Projects, even when they included the specification of Dr Higgen’s patent for a newly-invented water cement or stucco—Poetry, even when it was by the Laureate William Whitehead. That is to say, her eyes travelled down and down the double columns where the faded ink was less distinct than the damp stains which mottled the margin. It may be doubted whether they conveyed many thoughts to her brain, but they blocked the way to others. One of the most definite impressions she received was a feeling of resentment towards those persons who were recorded to have lived a hundred years and upwards in full possession of all their faculties.

One showery afternoon in the last days of May,[Pg 20] Lady Winifred was interrupted in the middle of the events of the year 1783 by the entrance of Rose Ahern, the housemaid, who came to take leave of her. Rose, who was now summoned home to tend an invalided mother, had lived longer at the Big House than its mistress, and often remarked these times that “anybody’d be annoyed to see her mopin’, and the two of them that gay and plisant together only a half twelve-month back.” On this occasion, having repeatedly said: “So good-bye to you kindly, me lady, and may God lave your Ladyship your health,” she continued inconsistently to linger in her place, making small sounds and movements designed to attract attention. But Lady Winifred had reverted to her volume twenty-six, and was inaccessible to any save point-blank address. At last Rose went almost to the door, and turned round to say: “I beg your pardon, me lady—beggin’ your Ladyship’s pardon—but what colour might the Master’s uniform be, me lady? None of us ever seen his Honour wearin’ it, it so happens.”

“It was scarlet, I believe,” Lady Winifred said, continuing to look at the pages. “Oh, yes, scarlet.”

“There now, didn’t I tell Thady so?” said Rose. “And he standin’ me out ’twas blue it was, the way it couldn’t ha’ been him we seen; and declarin’ ’twas apter to be poor Terry Connor, thinkin’ of his mother. But sure it’s a good step to her house from[Pg 21] where we seen him—whoever he was—last night.”

“Saw him last night,” Lady Winifred said, looking up (“And indeed now,” Rose averred afterwards, “’twas like openin’ a crack of a window—her eyes shinin’ out of the dark corner”). “Oh, Rose, what are you saying?”

“’Deed, then, maybe I’m talkin’ like a fool, me lady,” said Rose, “and you’ve no call to be mindin’ me. Only when I was seein’ me brother Thady down to the back gate last night, there was somebody in a red coat at the far end of the Windin’ Walk, there was so, and a big man too. And this mornin’ I heard several sayin’ there did be a soldier seen in it this while since of an evenin’. But sorra a one’s stoppin’ anywheres next or nigh Clonmalroan. It’s the quare long step he’s apt to have come—between us and harm. And I dunno what should be bringin’ poor Terry Connor there, instead of to his own little place; but the poor Master always had a great wish for the Windin’ Walk. Many a time have I seen him meself smokin’ up and down it, before ever he got married; and last year he was a dale in it along with yourself, me lady, lookin’ after the wee bushes plantin’—beggin’ your Ladyship’s pardon. And all the while very belike it might ha’ been just a shadow under the moonlight; only red it was, that’s sartin. But people do be talkin’ foolish, your Ladyship. And may God lave your Ladyship your health. It was as like as not to be nothin’ at all.”

[Pg 22]

“Oh, very likely,” Lady Winifred said, indifferently, “nothing at all.”

But that evening she left the house once more. She had intended to wait until dusk, but its slow oncoming wore out her patience, and there were still rich gleams and glows receding among the furthest tree trunks when she stole forth into the open air. It breathed freshly fragrant on her, after her many weeks in the mouldering mustiness of the bookroom, and the blackbirds were singing with notes clear as the gathering dews and mellow as the westering light. The season was now the late autumn of spring, when most blossoms are falling, though the young leaves are yet in their first luminous green. On the lawn the laburnums and thorn bushes stood with their outlines enamelled on the grass in gold and pearl and pink coral. Along the shaded avenue and shrubbery paths lay softly drifts of dimmer blossoms and blossom dust, in faint ambers and russets and crimsons. But the white plumes of the Guelder roses were still glimmering ghostly above her head as she went by, and some of the firs were studded all over with little pale-yellow tapers like wild Christmas trees.

Lady Winifred was going towards the back gate, and presently came where the Winding Walk, under a dense canopy of evergreens, runs[Pg 23] parallel with the avenue, on the right hand, and on the left within hearing of the fretted, rocky stream in the bit of a glen below. Once between the screening laurels and junipers, you could see, however, only up and down short curves of the waving path. About midway in it was a rustic wooden seat, niched in a recess of the shrubs, and Lady Winifred intended to sit down there and wait and watch. But when she reached it, she found it already occupied by someone who had also been watching, as was clearly seen in the look that leaped forward to meet the newcomer, and at sight recoiled again. In this tall woman, with a black shawl over frosted dark hair, Lady Winifred recognised the Widow Connor concerning whom, ages ago, before the days of the Annual Registers, she half remembered to have heard about the loss of a soldier son. The older widow was rising up with many apologies for the boldness of slipping in there, never thinking any of the family would be coming out; and she would have gone away, but the other hastened to sit down beside her, and kept a hand on her shawl. “I won’t stay myself unless you do,” said Lady Winifred. “I only came out because it was so warm,” she explained, as she had been explaining to herself, “and such a fine evening.”

“Tellin’ you the truth, me lady,” said the Widdy Connor, “me poor Terry himself would sometimes be smokin’ a pipe in here of an evenin’ when there was nobody about. I was tellin’ him[Pg 24] he’d a right to not be makin’ so free—but sure, after all, he done no harm. There’s great shelter under the shrubberies when the weather does be soft—and be the same token, we do be gettin’ a little shower this minyit, me lady; that’s what’s rustlin’ in the laves. So ’twould be nathural enough if Terry was mindin’ the place. But trespassin’ or annoyin’ the family now, he’d never be intendin’. Just comin’ of an odd evenin’ he might be, the way he used. Anyhow Paudeen Nolan and Jim M‘Kenna was positive ’twas him they seen, and they all goin’ home from the hurley match. The other lads said diff’rint; but that Anthony Martin’s a big stookawn, and his brother’s as blind as the owls. Nor I wouldn’t go be what Rose Ahern says—”

“Rose has very good sight,” said Lady Winifred.

“Ah, then you’re after hearin’ the talk, me lady?” said the widow. “Faix now, they’d no call to be tellin’ you wrong, and bringin’ you out under the wet for nothin’, to get your death of cold. Because Terry it was, whatever they may say. But there’s wonderful foolishness in people. For some of them says they wouldn’t believe any such a thing; so what woula they believe at all? And more of them says it’s a bad sign for anybody to be walkin’ that way. And what badness is there in it, if a lad would be takin’ a look at a place he had a likin’ for, and where he might get a chance of seein’ his frinds? And it’s the quare sort of unluckiness ’twould be for one of[Pg 25] them to git a sight of him, if ’twas only goin’ by, and ne’er a word out of him. That’s what I was sayin’ this mornin’ to ould Theresa Joyce. For says she to me: ‘It’s unlucky,’ says she. ‘And you’d do betther to be wishin’ he’d bide paiceable wherever he is, till yourself comes along to him,’ says she. But it’s aisy for Theresa Joyce to be talkin’, and she as ould as a crow. She can’t be livin’ any great while longer, so I was sayin’ to her; and it’s somethin’ else she’d be wishin’ if she’d no more age on her than meself. Sure I was reckonin’ up, me lady, accordin’ to things that happint, and at the most I can make it I’m short of fifty years. That’s lavin’ a terrible long time to be contintin’ oneself in.”

“And I’m twenty,” said Lady Winifred.

“Well, now the Lord may pity you, and may goodness forgive me,” the widow said compunctiously as if she had somehow been an accomplice of this cruel fate, and were all at once smitten with remorse. She seemed to ponder for a while deeply, and at last said: “If be any odd chance it isn’t Terry after all, and only the Captain—I won’t be grudgin’ it to her; no, the crathur, I will not.”

Thereupon silence continued long between the two watchers, and nothing befell them except that their blackness was gradually softened into the shadows as cobweb-coloured dusk enmeshed them.

Then there came a moment when the older woman saw the younger start, and, quivering[Pg 26] like a bough after it has bent to a waft of wind, look fixedly in one direction. “In the name of God, do you see anythin’, me lady?” Widdy Connor whispered, and as she spoke she saw too. For a small rent in the straggling laurel on their right made a spy-hole, which brought within view a curve of the Winding Walk near its gate end, many yards away, and there, moving and glimpsing in the twilight, from which it seemed to have absorbed the last lingering brightness, went a gleam of scarlet. It was coming towards the seat, and the faces turned that way looked as if a white moonbeam had fallen across them. Almost immediately branches rustled close by, and out into the path a girl hooded with a fawn-coloured shawl stepped warily on the left hand, and stood poising herself for a swift dart past the recess, unintercepted if not unobserved. Lady Winifred could not have noticed the leap of an ambushed tiger; but her companion sprang up and caught the girl by the wrist. “Norah Grehan,” said the widow. “And who at all are you watching for this night? Me son Terry was spakin’ to ne’er a girl, I well know. He’d have told me, so he would. Who are you lookin’ to see?”

“Och, Mrs Connor, ma’am, lave go of me,” the girl said, twisting her arm and struggling. “And don’t let on to anybody that you seen me, or there’ll be murdher. It’s Jack M‘Donnell that’s waitin’ for me below there. He that listed about Christmas, and now they’re sendin’ him to the war. He and me are spakin’ this good while[Pg 27] back, unbeknownst, be raison of me father makin’ up a match for me wid some other man; I dunno who he is, but I won’t have him, not if he owned all the bastes that ever ran on four legs. So I do be slippin’ across the steppin’-stones of an evenin’ for to get a word with Jack, that comes over the bog from the dear knows how far beyant Lisconnel. And if they knew up at the farm I’d be kilt.”

“And maybe the best thing could happen you,” said the widow.

“Ah, don’t say so, woman dear. He’ll be comin’ back one of these days for sure, a corporal maybe, or a sargint, with lave to marry. And he’s plannin’ to conthrive for me to be livin’ wid his mother’s sisther in Sligo till then, the way they won’t get me married on him while he’s gone—no fear. He’ll be tellin’ me about it to-night—and bedad there he is whistlin’ to me. Ah, let me go, Mrs Connor; but whisht, like a good woman,” said the girl, wrenching herself free, and speeding away between the half visible dark foliage.

Then Lady Winifred, who had heard the last part of this colloquy, got up also and said: “I think I’ll go home now. It’s a very pleasant evening, but the air feels rather cold.”

“’Deed now you’d a right to not be out under the rain, wid nothin’ on the head of you, me lady, but the little muslin cap,” said the widow, and added as Lady Winifred went: “And, troth, it’s the cruel pity to see the likes of her wearin’ any[Pg 28] such a thing, ay indeed is it. Nora Grehan and Jack M‘Donnell, sure now the two of them’s at the beginnin’, and she’s at the endin’. But there’s an endin’ in every beginnin’, and maybe, plase God, there’s a beginnin’ in every endin’.”

Lady Winifred, meanwhile, was not pitying herself. As she walked slowly back to her empty Big House, along paths odorous with the rain whose drops began to pierce their leafiest roofs, she felt again a stunned disappointment, only vaguer and more chilling than the overdue letter had caused her. And there were no little birds about now to mock her into keener consciousness. After all, things were just as they had been when she set out, no worse surely, and how could they be better, except in a dream? But a dream she might have before to-morrow came, and brought back her long day in the brown bookroom with the companionship of the Annual Registers. There were still so many unread of the dusty volumes, clasped with blackish cob-webs, made ghastly now and then by the shrivelled skeleton of the dead spinster. She need not yet consider what she should do when they were all finished.

As the Widdy Connor went towards her little silent house, she was saying to herself: “Jack M‘Donnell bedad! Sure the height of him isn’t widin the breadth of me hand of Terry; everybody knows that. It’s my belief ’twasn’t Jack they seen that time at all. They couldn’t ha’ mistook him for Terry, the tallest lad in this[Pg 29] counthryside.... And says I to Theresa Joyce: ‘The heart of me did be leppin’ up wid pride every time I’d see him have to stoop his head, comin’ in to me at our little low door. But it’s lower his head’s lyin’ now,’ says I, ‘low enough it’s lyin’,’ And says she to me: ‘If ’twas ever so low, the heart of you’ll be leppin’ up twice as high wid joy and plisure,’ says she, ‘the next time you behould him.’ But, ah sure, it’s aisy talkin’. I’ll see him come stoopin’ in at it no more.”

[A dramatised version of this story will be found in the author’s volume: “Ghost Bereft, with Other Stories and Studies in Verse,” published by Messrs Smith & Elder.]

[Pg 31]

The Widow M‘Gurk flung down a black sod into the midst of the blossom-like pink-and-white embers and ashes on her hearth with a shock that splashed up vivid sparks in all directions, causing a pair of long-legged, panic-stricken chickens to fly higher, far less nimbly, and seek refuge from the startling shower among the rafters overhead. Her action was symbolical, for as she performed it she said: “It’s gone; there’s the whole of it. And you might as well be holdin’ your tongue till you’ve got somethin’ raisonable to say.” As a matter of fact, her niece, Minnie Walsh, had not been making any observations; but Mrs M‘Gurk had some excuse for indiscriminate censoriousness just then, seeing that she referred to the loss of nothing less than what she called “the greatest chance ever she got in her life’s len’th.” Perhaps that rather long length had really been not more productive of great chances than is usual in the lives of people who dwell on the bog-lands at Lisconnel. Yet her neighbours were disposed to consider that she had enjoyed a somewhat full share of good luck. They all[Pg 32] remembered, for instance, the handsome legacy of half a dozen half-crowns that had once come to her from the States, and some of them would say when discussing her affairs: “And she widout a crathur to be thinkin’ of only herself.” This latter circumstance could, of course, be otherwise stated as the fact that “she had not a soul belonging to her in the wide world to be doing e’er a hand’s turn for her”; and when she was first left a childless widow, many years ago, that view had predominated. It still prevailed among most of the older inhabitants, whose children were grown up, and capable of lending a helping hand, sometimes from across the western foam; but they of a younger generation, whose long families were as yet the “burden” which the Gaelic sorrowfully calls them, would speak of her loneliness in a tone implying: “It’s well to be her.” In this opinion the widow’s proudly independent spirit helped to confirm them, her habit being to pose as a prosperous person, resentful of any sympathy which appeared incongruous with that attitude, while she adopted an extension of the principle: “Tell thou never thy foe that thy foot acheth,” in this respect treating everyone impartially as an enemy. Here, however, was a quite exceptional occurrence, upon the cruel unluckiness of which the most stoical pride could scarcely be imagined to forbear exclaiming. It came about thus.

Early in the summer, Mrs M‘Gurk’s portly yellowish hen had hatched her a clutch of eggs[Pg 33] with such singular success that not one of the whole baker’s dozen failed to produce its chick, and had brought them up so discreetly and warily that all, save the solitary victim of a bright-eyed hawk’s swooping pounce, had come securely to a more profitable fate. Mrs M‘Gurk, furthermore, had obtained remarkably good prices—as much, sometimes, as eighteenpence a couple—for them down beyond in the town, and the consequence was that, after paying her rent at Michaelmas, and buying several parcels of tea for distribution as well as for her own use, she found herself one day possessed of two shillings, which she had no immediate occasion to spend. Now it happened that she was at this time entertaining as a guest her niece’s daughter, Minnie Walsh, who had been visiting some relations away over beyond Moyallen, and found her great-aunt’s cabin a convenient halting-place on her journey back to her home near the town of Ballytrave. Her father’s cousin, Peter M‘Gonigal, had promised to pick her up in his cart, which would be passing within a mile or so of Lisconnel on its return from leaving a couple of calves over at Letter-french; and Peter’s own destination being within an easy walk of the long-car from Ardlesh to Ballytrave, Minnie’s route lay smooth and clear. All the while she stayed at Lisconnel she kept on counting the days until she could set off, less from impatience to rejoin her domestic circle than because of a wonderful festival which was in prospect at Ballytrave. It would even be grander, she[Pg 34] had heard tell, than the ones last autumn, and everybody had said that the like of them nobody had ever beheld—play-acting, and dancing, and the beautiful music, with a roomful of fiddlers and pipers, and a couple of big harps that were like a fairy wind through the trees, and the songs that would make you wish you couldn’t tell what, and think you were come just near to getting it somehow. And the whole of them in Gaelic, too, the very same way, people said, that they did be in the old ancient times. She wouldn’t miss it for anything at all.

Minnie Walsh was generally a silent, quiet girl, but when she spoke of this Feish, she brightened up out of a dulness which made her enthusiasm the more striking by contrast. Its glow was caught by her hearers, and often gave a livelier turn to assemblies of the neighbours, whether on the swarded edges of the bog, basking in long, honey-coloured sunbeams, or gathered closer, on rough-hewn stools and benches, about a less distant hearth-fire. Mention of the jigs and rinca-fadhas would set the young folk dancing, and their elders’ memories were stirred into another sort of activity, producing fragments of half-forgotten ditties, and familiar phrases long disused. For Lisconnel had hardly any Irish speakers in those days except Pat Ryan’s very old mother, who so seldom said anything, that her language might indeed be a matter of conjecture. She pricked up her ears one evening upon hearing her son exchange certain guttural greetings with Joe Sheridan,[Pg 35] and she suddenly declaimed in her corner a long Gaelic ballad, relating the adventures of a Princess, a Giant, and an enchanted steed, which seemed but gibberish to some of her audience, and to the rest would have seemed so, only that it being a widely spread folk-tale, they were able to guide themselves through it by the clues of a word or name recognised here and there. At the end of it, Widow M‘Gurk sighed profoundly with a regretful satisfaction, and said: “Sure now the sound of it does me heart good. It must be a matter of fifty year since ould Kit Maher would be singin’ the very same at me poor father’s house away in Asherclogher. But, bedad, if I got a sight of a one of them reels, Minnie says is to be in it, I’d consait I was a little girsheach again, I would so.”

“And why wouldn’t you come see them?” said her grand-niece. “Me mother was biddin’ me many a time to be bringing you along, and me cousin Peter’d take the two of us just as ready as one; and he could drop you here on his way back in a couple of days as handy as anythin’.”

“Them two shillin’s I have saved would just pay me car fare goin’ and comin’,” said her great-aunt, “supposin’ I was fine fool enough to think of such a thing.”

It was from this doubtful beginning that Mrs M‘Gurk’s resolve to attend the Ballytrave Feish sprang and rapidly matured. Everything helped it on. Minnie Walsh, desirous of company on her formidable day-long journey, coaxed and[Pg 36] cajoled, the neighbours athirst for even vicarious variety and excitement, encouraged and urged her, and above all her own wishes took her by the hand. It would be one while, she said to herself, before she got such another chance; you might think it had all happened on purpose. Her pitaties finished lifting, and her turf well saved, just at the time when a cart was going and coming that way, and she so far beforehand with the world that, as she reasoned, the journey wouldn’t cost her a penny. So the expedition was speedily determined upon, and her plans approached the brink of accomplishment without a check.

The possibility of the whole project, however, was for the time being compressed into the shape of two current coins, those marvellous seeds from which most heterogeneous crops are raised at all seasons; and since so much hinged upon her possession of them, “Sure now Mrs M‘Gurk was the very foolish woman”—as neighbours repeatedly pointed out to her—“to go put her two shillings into a pocket with a hole in it.” Yet that was exactly what she did one unlucky afternoon. She had been in the act of transferring them from a little lustre jug on the dresser to an old patchwork bag, when sounds of barking and bleating made her apprehend that the Sheridans’ young collie was molesting her kid, tethered on a grassy strip beside the bog stream. Whereupon she had slipped the shillings into her pocket, and ran down to the rescue. And, alas, as she was recrossing the stepping-stones, she had put her[Pg 37] hand into that pocket and discovered there only one shilling and a hole very amply large enough to account for the absence of the other. From the first it seemed a sadly hopeless case. The bit of ground on which the shilling must have been dropped was, indeed, of limited extent, not many yards square; but the rough surface, shagged with tangled tussocks, furzes, heather clumps, and marsh greenery, mocked at the quest for a thing so small, and she had moreover passed the black mouths of two or three bog-holes, which might have irretrievably swallowed it up. Mrs M‘Gurk almost despaired on the spot, though she groped wildly till she was too stiff for longer stooping. But when the news of her loss spread, there was no lack of volunteers to carry on the search. A party of them, including representatives from nearly all the half-score houses of the hamlet, were to be seen at any day-lit hour diligently employed. The children especially found it a fascinating new pastime, and, fired as much by a spirit of emulation as by several promises of a halfpenny, threw themselves into the pursuit with ardent zeal and supple joints. Yet the widow drew little or no comfort from the sight of their energy. She said they might all as well be looking for it to come tumbling down out of the stars, the way Crazy Mick was looking for his wife and childer that died on him. Her neighbours’ other attempts at consolation were equally unsuccessful, Mrs Doyne’s being perhaps the most complete failure. A person of invariably dark forebodings,[Pg 38] she now suggested that if Mrs M‘Gurk had gone, she might have been very apt to lose her life. Them long cars were terrible dangerous things. Or else the playhouse at Ballytrave might be going on fire, and everybody in it burning to ashes—the Lord have mercy on them. She was reading of that same happening on the paper not so long ago. And it would be a deal worse than losing a shilling, or two shillings, for that matter. Mrs M‘Gurk replied that if some she could name lost all the sinse they ever had, it would make no great differ; and strode indignantly away from the group of bucket-filling women, while Judy Sheridan said apologetically: “The crathur’s annoyed. Sure her heart was set on gettin’ the jaunt.”

The mishap had necessarily brought the whole scheme to an end. For as she no longer possessed the price of her return fare, how would she ever get home again to her cabin on the knock-awn’s side, her field-fleck, her turf-stack, her few hens and her old kid—all her worldly wealth? “’Deed then, ma’am, ’twould be like slammin’ a door wid the handle on the wrong side of you,” Mrs Rafferty reluctantly agreed, when talking over the disaster with her. Mrs Rafferty was to have had the kid’s milk during Mrs M‘Gurk’s absence, in return for boiling the few hens their bit of food, and the arrangement had seemed to her so advantageous that she regretted its collapse on personal grounds. But regrets, interested or otherwise, were alike futile; and now on the day but one[Pg 39] before she should have been starting, Mrs M‘Gurk, shaking off the last twining tendril of withered hope, had gloomily faced the worst.

Having thus summarily mended her fire and snubbed her grand-niece, the Widow M‘Gurk went out of doors again, in pursuit of a white chicken, which she had espied astray at a dangerous distance when she was fetching in her turf. It gave her a long and exasperating chase over the bog before it would be captured, and as she tramped back heavily with it under her shawl, she commented to herself that the only thing she wondered at was how it had contrived not to get lost on her too. The golden beams that slanted to her from a fiery scaffolding in the west dazzled her sight, and made her stumble over stocks and stones, but in her mind she beheld nothing except the eclipse of her bit of pleasure darkening with its shadow her whole horizon. Yet at this very moment Minnie Walsh, with sunshine and glee brightening her fair hair and blue eyes, was watching at the house-door for its unforeseeing mistress, whom she greeted with: “It’s found, Aunt Bridget; glory be to goodness, it’s found.”

“Och, don’t be romancin’,” Mrs M‘Gurk said, while the chicken screeched in her excited grasp. “Who was it?” she shouted jubilantly as she mounted the steep little footpath.

“Ould Mr Rafferty brought it just after you goin’ out,” Minnie explained, as they bustled in together; “he got it down below.” And, sure enough, there on the smoke-darkened deal table[Pg 40] gleamed a silver shilling. Mrs M‘Gurk seized it eagerly, as if grasping a friend’s hand, and then—dashed it down with a rap on the table again, pressed under a wrathful thumb. “The ould liar,” she said bitterly, “the ould liar,” and closed a mouth whose grimness was mutely very eloquent. Minnie stared at her with a pink and white face of disappointed perplexity. “Is it lettin’ on to you he was that this is me own shillin’ he’s after findin’ yonder?” Mrs M‘Gurk said, “and it wid the new pattron of the Queen on it, in the little quare crown, and 1889 on it as plain as print, when me own one’s wore that thin an smooth, you’d say she hadn’t a hair on her head, let alone anythin’ else, and 1861 just dyin’ off it. It’s fools he was makin’ of you and me.... And what’s this, to goodness?” she continued, catching sight of another coin on the table, “a sixpenny bit it is—and where might that come from, if you plase?”

“Sure, Mrs Fahy it was come wid that a little while ago,” Minnie said with much diffidence; “she said she was just after pickin’ it up on the very same place where you lost the shillin’, and she had the notion it might ha’ been two sixpennies you dropped; and says I to her I well knew it was not. But says she to me it wasn’t hers anyway, and she’d lave it wid you on chance. So I couldn’t forbid her.”

“The schamin’ thief,” said Mrs M‘Gurk, “and yourself was the quare stronseach. Just let her wait aisy till I tell her what I think of herself and her impidence and her dirty sixpennies.” In the[Pg 41] meanwhile she relieved her feelings by hurling away the white chicken from beneath her plaid shawl, and hunting it to its roosting-place among the rafters of the inner room, whither she followed it.

Minnie stood looking out at the front door. She was cast down by the repudiation of the shilling, which had once more shattered her hopes of a travelling companion, and she perceived that her great-aunt considered her in some degree to blame for an offence whose nature she did not clearly understand. This made her view with misgivings the approach of another visitor, who now came quickly up the footpath. It was no acquaintance of hers, a tall thin girl, with a baby on her arm, and so poor-looking, even for Lisconnel, that Minnie thought her errand would be some request. But when a slender brown hand opened to disclose several dark “coppers,” Minnie was not much surprised to hear: “I’m after findin’ these four pennies down below, so I thought I had a right to be bringin’ them up here, in case it was some of the money Mrs M‘Gurk is after losin’ out of her pocket.”

“It is not,” said Minnie, “by any manner of manes. She lost nothin’ only a shillin’. You might be takin’ them away, if you plase, and thank you kindly, for it’s annoyed me aunt is.” She tried to intercept the girl, who slipped past her and laid the money on the table. “Ah, now, don’t be lavin’ them there,” said Minnie in a whisper, “she’s inside in the room this minyit, ragin’. Or,[Pg 42] at all events, tell her yourself, the way she won’t be blamin’ me for lettin’ you. For she’s torminted already wid people bringin’ her the wrong things. I’ll call her out to you.” The girl, however, said: “Ah! not at all,” and ran swiftly away.

While Minnie stood doubting whether or no to pursue her with the pennies, Mrs M‘Gurk’s voice came through the inner door: “What talk was that you had wid Joanna Crehan, and what brought her trapesin’ up here?”

“She’s after findin’—” Minnie began to reply deprecatingly, but a peremptory injunction cut her short.

“Sling it out to her then, and bid her not throuble herself to be comin’ next or nigh my place again,” Mrs M‘Gurk shouted, with an evident desire to be overheard.

Before Minnie could have taken any steps towards executing this delicate commission, a little gossoon bolted into the house, and the jingle of something in his hand was hardly needed to apprise her of his business. “It’s entirely too bad, and so it is,” she grumbled to herself, slipping out at the door. “I’ll just go and sit the other side of the hill for a while, till they’ve done pickin’ up pinnies and shillin’s down below. Plase goodness it ’ill soon be too dark now to see a stim. But bedad there must ha’ been a quare dale of money dropped on that one little small bit of ground. I wonder how it happened at all.”

Minnie, whose imaginative powers were limited, could descry no probable explanation; but she[Pg 43] pondered over it among the furze bushes, until the September dusk fell so greyly over their fairy golden lamps of blossoms that she thought she might safely venture back. When she went indoors she saw her great-aunt standing by the table, on which several additional coins seemed to have been deposited—more pennies, and, Minnie thought, another shilling; but the fire-light flickered on them uncertainly, and the expression of her great-aunt’s countenance was a warning notice to questioners. Mrs M‘Gurk surveyed them in silence for a few moments longer, and then she swept them together with the side of her hand, more contemptuously than if they had been potato skins. “Just wait, me tight lads,” she said, “and I’ll larn yous to be litterin’ up me house wid your ould thrash.”

Joanna Crehan, the girl who had left the four pennies, returned with the baby, her youngest brother, to their dwelling, which is a bit down the road on the right hand, coming into Lisconnel from Duffclane, and was the Quigleys’ before they emigrated. It stands on a flat slab of bare stone, which floors it evenly enough, and a low bank quilted with heather gives it a little shelter at the back, but it fronts the widest sweep of the bog-land just over the way. The rim of fine-textured sward is such a frequent playing and lounging[Pg 44] place for its tenants, that their feet wear many equally bare brown patches, which grow rapidly in size during the drier summer months, and shrink slowly all the rest of the year. They were at their largest this evening, and the little Crehans were using one of them for a game of marbles, while Mrs Crehan and her second eldest daughter sat knitting on a big boulder, and her elder son lay in its long shadow neither asleep nor awake. Joanna handed her the baby, and took from her the knitting-needles with their dangling grey woollen leg, an exchange in which she acquiesced half-contentedly, being divided between her wish to continue “Mike the crathur’s” sock and to welcome “Patsy the crathur’s” greeting grin. “Where was you off to wid him?” she said to Joanna. “I never seen sight of you goin’.”

“I went to bring Mrs M‘Gurk me fourpence towards her shillin’,” said Joanna. “How many stitches had I a right to keep on me back needle?”

“Your four pinnies to Mrs M‘Gurk?” said her mother, “and what in the name of fortune bewitched you to go do such a thing as that?”

“She’s distracted losin’ it,” said Joanna, “and I’d liefer than forty fourpinnies she had it back.”

“The divil’s cure to the both of yous then,” said Mrs Crehan, “and is that all the nature you have in you? To be slinkin’ out of the house wid your pinnies to her that’s nothin’ to us good or bad, and your poor brother settin’ off to-morra to the strange place, wid ne’er a halfpenny to put in his pocket, and yourself the only one of us that[Pg 45] has a brass bawbee to our names, or the dear knows it’s not begrudin’ him we’d be.”

“And I thought you and Mike was always so wonderful great,” put in Nannie Crehan, taking up the recital of her sister’s delinquencies, “lettin’ on you were kilt if anybody said a word agin him. And to take and give away the fourpence from him, to ould Widdy M‘Gurk, that’s as apt as not to throw them in your face. And I thought—”

“Did you ever by chance think that you hadn’t a great dale of wit?” said Joanna; “not that you need throuble yourself to be tellin’ anybody.”

Mike got up and sauntered off towards a group of people at a little distance, while silence fell on his mother and sisters, who this evening lacked spirits for vivacious altercation. Joanna sat gazing blankly across the vast floor of the bog, as it lifted up against the fading fires of the west; every minute its dark rim extinguished some bright embers. She felt intensely miserable. It was the hardest grip of the unhappiness that had been pressing on her heart almost ever since the moment a few days ago when she had seen Mike set his foot on something shining silverly from under a dandelion leaf on the bog there below the knock-awn, where they all were looking for Mrs M‘Gurk’s lost shilling.

In obedience to his warning frown she had suppressed an ecstatic shriek, supposing that he had some plan of his own about the method of announcing his find, and she had presently seen him slip it secretly into his pocket. Never would[Pg 46] she have imagined that he did not intend to restore it; but as time slipped by, this dreadful suspicion was forced upon her. For Mike made no sign, and when she asked him about it in private, at first answered evasively, but finally told her to “hould her fool’s gab, and quit meddlin’.” The mere possibility filled her with wrath and dismay. She had always thought so much of Mike, and she had never heard tell of anybody belonging to them behaving in such a manner. What made it worse was that Mike would be travelling off next day by himself all the way to the county Roscommon, where his uncle had got him farm work. He had never left home before, and only the strong propulsion of adverse circumstances, including a father bedridden half the year, would now have thrust him out. For Mike, long the only grown son in a flock of girls, was an important and cherished possession among the Crehans, not to be parted with lightly. Everybody agreed that none of them made such a fool of him as his eldest sister Joanna, and she had indeed taken his going sadly to heart. She had fretted much over the poverty which would oblige him to start almost penniless, as after providing him with the indispensable footgear, not a spare farthing remained in the establishment except a dwindled remnant of the shilling which Mary had earned last Easter by doing jobs for Mrs O’Neill down beyond Duffclane.

But though this had been bad enough, infinitely worse was it to think of his setting forth into the wide world laden with that guilty coin. It was[Pg 47] apt to bring ill-luck on him, she felt. And anyhow it was “no thing to go do,” a phrase wherein she acknowledged the supremacy of that law which a more philosophical mind than hers had marvelled at under the starry heavens. Various minor ingredients helped to embitter her distress. Wounded pride and affection, disappointment, and a sense that she had been made in some degree an accomplice. Partly this last consideration, and partly a vague hope that Mike might thus be shamed into right-doing, had spurred her to the desperate step of bringing Mrs M‘Gurk her fourpence. Now that the deed was done, however, she found, instead of relief, fears lest it should only confirm Mike in his felonious obduracy, or possibly draw the widow’s suspicions upon him. So she sat out a disconsolate twilight, which lingered and loitered, giving her time to finish Mike’s sock before she went indoors.

Mike himself had strolled on, and joined the little knot of men who were gathered at the front of Peter Ryan’s house. But he scarcely changed into pleasanter company, for, “Musha, good gracious,” he said to himself, “is there nothin’ in creation for people to be talkin’ about only that one’s ould shillin’?”

“Well now, that was comical enough,” Ody Rafferty was saying to Kit Ryan. “I didn’t see herself at all, and I bringin’ my shillin’; there was only the niece in it, but of course she would be tellin’ the widdy. And then you to come landin’ in a while after wid a different one, and[Pg 48] the same lie. You’d a right to ha’ tould me what you was intindin’, the way we might ha’ conthrived it better. But the foolishness of some folks would surprise the bastes of the field. Shankin’ up to her they are wid pinnies and sixpinnies, and tellin’ her they got them all on the one bit of ground. Sure an ould blind hin ’ud have more wit than to believe the likes of that. Howane’er, it’s right enough, so long as she’s contint to be lettin’ on herself, and not callin’ us all liars and thieves of the world.”

“She kep’ the shillin’ I brought her ready enough, bedad did she,” Kit said with a rueful complacency. “‘Is that me shillin’ you’re after findin’?’ says she the minyit she seen it, with the look of an ould magpie on her. ‘To be sure it is, ma’am,’ says I. ‘What else would it be at all, unless it was another one?’ says I. ‘Yourself’s the very cliver man entirely,’ says she to me, and wid that she grabs it up. ‘I’ll take and lose it agin,’ says she, ‘the next time I want to be makin’ me fortin’.’ I wouldn’t put it past her, mind you, to be meanin’ somethin’ quare. But as for findin’ her own shillin’ among them coarse-growin’ tussocks, a body might be breakin’ his back there till the Day of Judgment for any chance of it.”

“Take care somebody isn’t after gettin’ it, all the while, and keepin’ it quiet,” said Ody.

“Och, I wouldn’t suppose there was any person in Lisconnel would be doin’ such a dirty trick on the poor ould woman,” said Peter Ryan.

[Pg 49]

“She’s as rich as a Jew anyway, wid half the counthryside runnin’ off to her wid their savin’s,” said Mike. “It’s well to be her, bedad.” He soon sauntered on, but did not attach himself to any other party, being irked by the prevalent topic of conversation.

The next morning rose still and softly tinted, with a deep band of mist all round the far away horizon. Mrs M‘Gurk got up unusually early for Sunday, and set off alone to Duffclane in time for the ten o’clock Mass, so that she got back to Lisconnel a full hour before most of her neighbours. They found her seated on a convenient flat-topped boulder by the side of the road, just at the highest point of the slight rise over which it slips down to run between the few dwellings of Lisconnel. Here the returning congregations always halt for a final gossip, before they break up, dispersing themselves into the shadowy door-ways of cabins to the right and left. She descried from afar their approach along the ribbon of road, white in the afternoon sun, and singled out among the shawls and hoods and broad-brimmed black hats the heads of nearly all the neighbours whom she especially wished to interview. The Crehans, indeed, were absent, owing to Mike’s imminent departure; however, she hoped to fall in with him and Joanna by-and-by. When everybody had come up, and all were standing or sitting about, the widow rose, and began what was evidently a set speech in substance, if not in form. Her great-niece, Minnie Walsh, observed her[Pg 50] with some trepidation, a feeling which was more or less shared by others in her audience.

“Ody Rafferty,” she said, selecting this small old man for the object of her address, “I was thinkin’ just now of the way me poor grandfather would have me annoyed somewhiles, when I was a little girsheach, like Biddy Ryan there wid her mouth full of the red blackberries. For if ever I had e’er a pinny of an odd time, he would be biddin’ me run and plant it somewheres in the bit of garden, to see would it grow into a money-plant for me. Ragin’ I used to be, God forgive me, thinkin’ he was only makin’ a fool of me. But sure, he was right enough, poor man, and it’s meself was the fool; for here I am after droppin’ me shillin’ on the ground there scarce a week past, and here’s the half of yous coming up to me yesterday wid shillin’s, and pinnies, and all manner, that ye got growin’ in it. Bedad ’twas terrible quick goin’ to seed—for what other way could they be there? Unless it’s makin’ a fool of me ye were, and that I know right well ye wouldn’t have the impidence to be doin’. But ’deed now it’s not keepin’ the whole of the crop I’d be at all, and it not even raised on me own bit of land. So I brought your share of it along; Ody, and the other people’s too”—she drew out a little grey plaid rag of shawl, and undid a knotted corner—“This is your shillin’, Ody,” she said. “And here’s Kit Ryan’s and Mrs Fahy’s sixpinny.” She moved from one to the other of her would-be benefactors, restoring their contributions[Pg 51] with a firmness which obviously was not to be gainsaid. Perhaps no dramatic scene at the Ballytrave festival could well have afforded her a more enjoyable moment. Ody Rafferty alone ventured upon an audible remonstrance, “Begorrah now,” he said, “if it’s not a fool you are altogether, yourself’s the proudest-minded, stubborn, steadfast ould divil of a headstrong ould woman from this to Cork, and maybe that comes to much the same thing, supposin’ you had the wit to know it.” But even he did not utter this criticism until Mrs M‘Gurk was stalking away.

She wished to find Mike Crehan, whom she conjectured to be still at home, but before she reached the Crehans’ house, she met him coming along the road with his red cotton travelling-bag. A troop of his younger sisters were withdrawing against their will, having been dissuaded by forcible arguments from accompanying him further. “It’s follyin’ me to the end of the town they’d love to be,” he had said to himself. “Keenin’ like a pack of ould banshees, and makin’ a show of me before the lads.” He would have much preferred to avoid an interview with the widow, but that seemed impossible, and he halted reluctant.

“So you’re steppin’ along, Mike,” she said. “It’s well to be the likes of you, that has the soopleness yet in your limbs. Sure now, you might tramp the whole of Ireland before you’ll come on an ould man’s mile, that wants the end in the middle. And look-a, Mike, here’s the pinnies your sister Joanna was lavin’ up at my house last night by[Pg 52] some manner of misapperhinsion: belike you’d ha’ room for them in your pocket, and this shillin’ along wid them. They’re the handiest sort of luggage to be carryin’ after all, if they’re the hardest to get a hould on.”

A mixture of motives had incited Mrs M‘Gurk to bestow this gift. There was the need to be more than even with the Crehans on the score of Joanna’s attempted benefaction, and the desire to get rid of a coin the possession of which did but remind her of her disappointment, while to these was added an impulse of genuine benevolence towards the tall, ragged lad—in her own mind she called him “a slip of a young bosthoon”—whom she saw faring off alone into the wide, strange world, poorly enough provided for, she presumed, though she did not surmise the depths of his people’s penury. As she hurried away from him her feelings were mingled still, half-satisfied, half-regretful, and dominated by a sense that she had here definitely put off a flattering hope.

Mike’s feeling, on the contrary, was quite simple, and of such unfamiliar unpleasantness that he hailed with relief the sight of his sister Joanna waiting for him at the furze gap. He would otherwise have reprobated her for protracting the hateful farewell scenes, but, as it was, he hastily thrust two shillings into her hand, saying, “Och, Hanny, run after her the quickest you can—she’s just down the road—and be givin’ them back to her.”

Joanna looked at the shillings with eyes of[Pg 53] puzzled wonder. “Sure it wasn’t the both of them she lost,” said she. “Where at all did you get the other from?”

“Herself,” said Mike. “Run like the mischief now when I bid you.”

“I will that, Mike jewel,” she said, and started forthwith. Delight at his act of restitution, of which she had utterly despaired, although intending to make one last appeal, superseded for the moment every other consideration; but as she caught up Mrs M‘Gurk, climbing the steep footpath, she became suddenly aware that she had a confession to make, and that it might put Mike’s good name at the mercy of a third person.

“Mrs M‘Gurk, woman dear,” she said, rushing at her perilous explanation. “Here’s your shillin’ Mike bid me be bringin’ back to you, and thank you kindly all the same, for he couldn’t be robbin’ you of it, and he’s got plinty of money along wid him. And the other’s the one you dropped on the bog, ma’am; he and I found it a day or two back, and we just kep’ it a while be way of a joke. And I hope you won’t think bad of it, ma’am. Mike was biddin’ me this minyit to not forgit to bring it to you.”

“Saints above, it is me own one sure enough this time,” said Mrs M‘Gurk. “Well, now, that was the quare luck and the quare joke. And truth to tell you, Joanna Crehan, I’m thinkin’ yourself had neither act nor part in it, whativer you may say.” Joanna’s face corroborated this conjecture so disconcertedly that Mrs M‘Gurk[Pg 54] hastened to add: “But after all there’s no harm in a joke. Like enough I might take the notion in me head to have a bit of a one meself. Suppose I was to be lettin’ on to the rest of them I had the shillin’ lyin’ in the corner of me pocket all the while, and niver seen it, nobody could tell but that was the way it happint, and ’twouldn’t be too bad a joke at all.”

“’Twould be the greatest joke ever was, and yourself’s the rael dacint woman for that same,” Joanna declared with an enthusiasm which said little for her sense either of morals or of humour.

Then they went their several ways. As the widow opened her door, all her eager plans for the morrow were in brisk motion again, like clockwork freed from some hampering hitch. Joanna, running homeward, felt conscious of nothing except the happiness of knowing Mike to be safely quit of the crime with which she had feared that he would burden himself irretrievably. She found her mother and sisters looking out from a knoll whence the last glimpse was to be had of the dwindling road-ribbon along which Mike would presently pass from sight. Mrs Crehan was lamenting over the poor circumstances of her departing son. “The crathur,” she said, “trampin’ away wid himself into the width of the world, and ne’er a pinny to his name, any more than if he was a baste drivin’ to a fair. Not a shillin’ in his pocket has he.”

“He has not,” Joanna said, and added indiscreetly, “Glory be to God.”

[Pg 55]

All Abbey Dowling’s neighbours thought she was the very foolish woman to let her good-for-nothing father-in-law establish himself in her house again after his return from America, and many of them told her so frankly, but fruitlessly. This was not surprising, as everybody agreed that the Dowlings were always as headstrong as mules. Everybody agreed, too, that her poor husband’s people were none of them worth much, and that this old Patrick Mulrane, though not without some companionable qualities, was worth as little as any. Drinking and raising rows had hitherto been his constant occupation, and the whole parish of Clochranbeg knew what lives he had led his son and daughter-in-law, until, upon the death of the former, off he had gone to the States, whence nothing had been heard of him for the next dozen years and more, while the young widow was struggling to keep herself and her three sons, and her invalid sister, on their stony little bit of land. “So now, when the boys are[Pg 56] grown big, and able to be workin’, back he flourishes wid the notion he’ll have them supportin’ him in idleness, and he after lavin’ all of yous to starve, for any thanks it was to him. Raison you’ll have to repint it, if you take him in. Fightin’ wid the lads he’ll be, and frightenin’ poor Maggie there, and drinkin’ their earnin’s on you, besides learnin’ them all manner of villiny—that’s every hand’s turn he’ll be doin’ for you, ma’am, mark my words!” Her old and respected friend, Mrs O’Hagan, tramped down a long and rough way to exhort her thus. But the words might just as well have been spoken to the sea-gulls skirling about Mrs Mulrane’s door.