Title: The history of a pot of varnish

Author: Anonymous

Release date: November 18, 2025 [eBook #77263]

Language: English

Original publication: Newark: Murphy and Company, 1880

Credits: Charlene Taylor, chenzw and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

FROM SCRIBNER’S MONTHLY.

PUBLISHED BY

MURPHY AND COMPANY,

VARNISH MAKERS.

Copyrighted, 1880, by Murphy & Co., Newark, N. J., and Cleveland, O.

[1]

Together with their love of the practical in the industrial arts, Americans have a ready faculty of discovering an interest touching almost on the romantic in the origin and production of what pass ordinarily for useful and prosaic things. Herein lies a part of the secret of their great success in mechanical pursuits. This inborn mechanical curiosity has led many a young American to take apart his mother’s self-winding tape measure, or the family sewing machine, just “to see how the thing was made.” We seldom, any of us, lose the desire to visit machine-shops and factories, and see with our own eyes how the work of creation, in a limited way, is carried forward, by men who, from habit, look upon their work as dull routine, while to our fresh eyes, every deft movement is filled with grace, and each stage in the transformation of the material into the manufactured object is a new wonder.

Everybody knows something about the bright, amber-colored fluid called varnish, but few persons, probably, know how varied and interesting a story is wrapped up in this subtle substance, which lends beauty and durability to almost every product of the workshop and studio. Varnish factories are comparatively few, and their doors seldom stand wide open. But there is nothing secretive about varnish. It speaks to the nostrils of close companionship with turpentine,—the pungent aroma of which [2]some affect to like, and most persons find very disagreeable. The linseed oil in the varnish cannot be detected by a novice; and thousands who are not practical painters, and only use the fluid as household amateurs, have doubtless wondered what could be the nature of the illusive material that gives to the varnish its sticky quality and elastic body. This third ingredient is the resinous juice of a tree. It is analogous to the little lumps of pitch that boys sometimes find on a pine board that has been exposed to the sun, and once in their lives discover to be a very sticky substitute for chewing-gum, which, in itself, is a kind of resin. Varnish resins are few in number compared with the vast number of resins of one kind and another. They are not got from the tree that produced them, but are mined a little below the surface of the earth, where they have lain and ripened for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years. This is true especially of gum copal, the commercial name of the most valuable of the varnish resins. These three ingredients, gum copal, linseed oil, and turpentine are brought to the door of the varnish maker. It is his province to mix them by applying formulas which are the result of years of experiment and hard-earned experience.

Varnish making is one of the new and growing industries of the United States. This is as it ought to be, for Americans use more artificial varnish than any other people, and even before they have reached the point of fully supplying themselves, begin to think seriously of providing their neighbors and transatlantic friends with a better article than can be sold abroad for the same money. Fifty years ago we relied mostly upon England and France for the vast quantities of varnish employed in the industrial arts of this country. Varnish manufacture was somewhat understood, but for many years the Americans were content to make for themselves only the coarse varieties of the article, while they went abroad for the higher [3]grades needed to impart luster to their coaches and pianos and to fine furniture. Finally came the ability and the desire to excel in this industry as in every other. Varnish materials were at hand. The enterprising traders of New-York and the once flourishing New England sea-ports, during their East India and African voyages, were not slow to discover in gum copal a profitable article for the return cargo, and to-day more than half of the varnish gums of commerce are brought to this country. Three large houses have almost a monopoly of the trade. It is further estimated that about two-thirds of the artificial varnish product of the world is used in the United States. In the main this is a matter of national congratulation. It is another proof of the unexampled growth of American manufactures, of the rapid increase of population and wealth, and of a wide-spread and active state of refined society. In no other country can be found so many comfortably furnished houses, in which the piano and other musical instruments, as well as furniture of equal adornment and use, are the rule rather than the exception. In no other part of the world does so large a part of the population ride in its own carriage; and in the matter of railway cars, those of America surpass the whole world in number and finish. All of these mechanical contrivances and articles of use require coats of varnish to render them attractive to the eye and proof against early decay. But from another point of view, the aspect of the immense varnish trade of this country is not so pleasing. It tells of national extravagance and wastefulness, and of the fragile character of many manufactured articles. Americans are the greatest carriage and furniture breakers in the world. They have more furniture, and replace it oftener, than citizens of the same relative classes in other countries. In Europe, the breaking of a carriage on account of the horses taking fright is a very rare [4]occurrence. American horses have extra wildness of spirits, and runaways and splintered carriages are every-day occurrences.

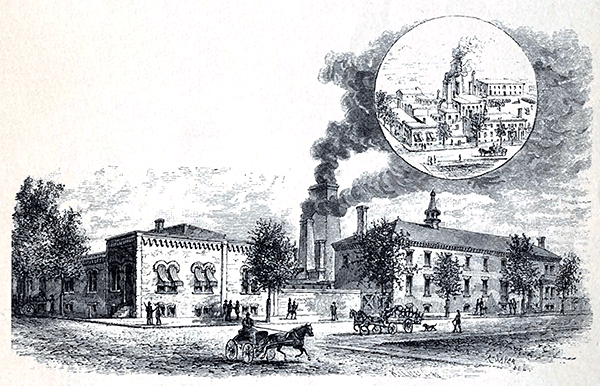

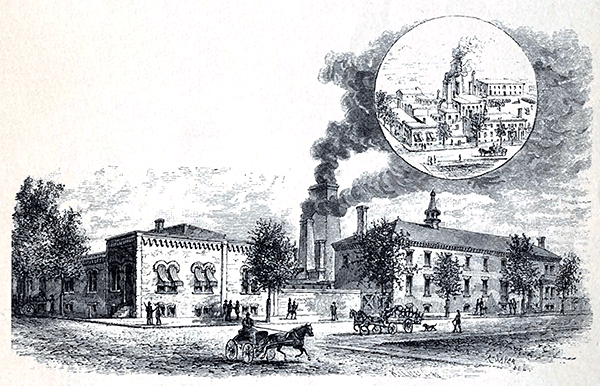

I was initiated into the mysteries of varnish manufacture at the factory of Murphy & Co., located in Newark, New Jersey, a great industrial city, which owes its growth and prominence to its nearness to the metropolis, its water and railroad facilities, and its ability to give cheap and comfortable houses to its working-men. A thirty-minute ride from New-York, by the Pennsylvania Railway, placed me at the Chestnut street dépôt in Newark, whence it was a three minute walk to McWhorter street, where goats and children were taking life pleasantly together in the September sunshine. Somber brick walls, surrounding plain brick buildings, succeeded one another along the street and gave tokens of activity within. I knew that Murphy & Co. were classed by the trade as one of the great varnish-making firms in the United States, and reaching No. 238, which appeared to be the beginning of the end of McWhorter street, the exterior of the long, rather low brick building made a very modest impression of the extensive out-buildings, warehouses, workshops and great chimneys which were concealed behind it. Fine shade trees added grace to the prim exterior, and the generally unkept street had suddenly assumed an air of care as well as of prosperity. The factory seemed to consume its own noise, for the street was very quiet, the stillness being broken only by a picturesque little colored boy in a peagreen jacket, and with his trousers rolled up to his knees, who was standing in the middle of the street, yelling “Pa!” at regular intervals, until a sturdy African put his head out of a warehouse door and soothed his offspring. Here was a coincidence: copal gum and the ebony descendant of the copal digger, in their distant wanderings from Africa, had found a home together at a varnish factory in Newark, New Jersey.

The office of the Factory, reached by a most unassuming street entrance, was commodious, elegant, and pervaded by a sense of order and business activity. The history of the firm is rather remarkable, and is an excellent illustration of American pluck, enterprise and method in business matters. From very small beginnings, the firm has attained its present growth and reputation in a short space of fourteen years. A solid foundation was laid at the beginning. They realized at the outset that the only road to success was by the closest personal supervision, and devotion to the principle that if they took care to attain a uniform perfection of quality in their products, the profits would take care of themselves. During the early years of the business, Mr. Murphy worked constantly over the kettles, and to-day every practical detail has his personal supervision. Having begun free from the set ways and prejudices of varnish-makers, he was the better prepared to discover and adopt improved methods. To-day they have, as a result of their efforts, a large capital invested in a thoroughly established business, which, during the past six years, has grown with steady and extraordinary rapidity.

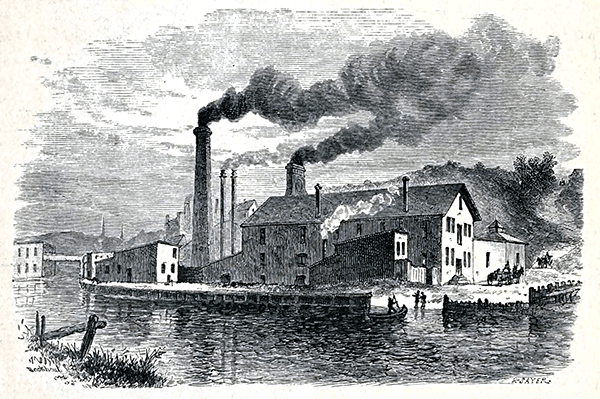

The extensive works of Murphy & Co., in Newark, are supplemented by equal manufacturing facilities in Cleveland, Ohio, but the Western department relies upon the Eastern factory for the highest grades of varnishes. Several years ago the firm was shrewd enough to see that the growth of domestic business was to be very largely in the West, and deemed it wise to establish branches, in 1871, in Chicago and Cleveland, and become directly identified with the business prosperity of those sections. Two years’ experience proved that it was better to consolidate their Western facilities at one point, and the erection of their extensive works in Cleveland, at Canal and [5]Harrison streets, was at once begun. During the past six years the business of the Western department has rapidly increased, and from Cleveland radiates their entire Western trade.

Before he introduces a visitor to the factory proper, Mr. Murphy always instructs the candidate for the honor in the first degree of the subject, in a knowledge of what copal is. For this purpose his museum of fossil resins affords an excellent means of object study. To pique the interest of his visitor he first hands him a little polished cylinder of a hard, yellowish-hued substance, resembling amber. Some opaque object darkens the otherwise clear and brilliant cylinder, which is brought between the eye and the light, disclosing a pale, lemon-colored butterfly in all the delicacy and beauty of its original creation. Encompassed in the pure, transparent mass, it is as perfectly posed as if it were in the sunshine of a June morning, resting its tissue wings and sipping the dew from a clover blossom. It looks as fresh as a bonnet in a milliner’s window, and as if it came out of the chrysalis only the day before; yet the butterfly, if we are to believe the sayings of science, first tried its delicate wings in some African forest of the tertiary period, how many thousands of years ago geologists do not venture to say. Happy insect, to have its beauty thus immortalized! How did the butterfly get within the cylinder? Probably it was playing listlessly from tropical flower to flower and tree to tree. It alighted on a limpid, enticing substance which adhered to the bark of a gigantic tree. This substance proved as fragrant as a flower and as treacherous as bird-lime. The unwary butterfly found itself glued to its grave. In a little while the oozing [6]sap covered its delicate head, the fluttering wings were stayed, and, in less than an hour, perhaps, the butterfly, in all its splendor, was embalmed for the ages. Before or during the decay of the tree, the hardened lump of sap fell on the sands and was buried beneath the mold. In the course of time the forest almost disappeared through the agency of wind and fire, or perhaps through slow decay. The lump of gum lay hardening, century in and century out, beneath the surface of a burning desert, until a naked negro, in his desultory search, brought it to light and sold it to the traders as fossil copal, which is solid varnish of the finest quality.

Western nations have derived the use of varnish from the Chinese and Japanese, who, originally, merely applied what nature placed ready-made [7]to their hand. What would an American painter think of walking into his grove of varnish-trees, when he wanted a pot of varnish, and returning in half an hour with a bucketful of the costly fluid, procured as easily as a Vermont farmer gathers a bucketful of maple sap in the spring of the year? This is a natural varnish and is called Lacquer, and everybody nowadays knows the beauty and excellence of the lacquer-ware of the ingenious Chinese and Japanese. The resin from the varnish-tree (which belongs to the same family as our poison ivy, dogwood and sumach, and to the botanical order of anacar diacea) is held in solution, in the right proportion for use, by oils which the tree simultaneously produces. But the resins of which the artificial varnish is made were deficient naturally in these solvents, and what of them they ever contained disappeared as the gum hardened. Varnish manufacture is the process of restoring these solvents in new and greater proportions. Many varieties of trees are producing varnish resins in different parts of the world to-day, but the resin is unfit for the finer grades of varnish until it has ripened, in the course of time, and become fossil gum. There are resin-producing trees the gum of which is [8]not suitable for the body of varnish, yet which produce one of the principal solvents,—turpentine. Such is the long-leaved pine of the Southern States. The Japanese and Chinese subject their natural varnish to a treatment of a simple character, to purify and increase its drying properties. The black varnish tree of Burmah and the gum-mastic tree of Morocco are allied to the Chinese and Japanese species. Efforts have been made to introduce the latter into this country without practical results. Young varnish-trees have frequently been brought to America, and specimens of the variety are now growing in the grounds of the Smithsonian Institute.

Amber, which is found chiefly in the alluvial deposits bordering the Black Sea, is the most valuable of the fossil resins. Its extra hardness is supposed to be the result of age, far ante-dating that of fossil copal. It used to be employed in varnish manufacture, but is now too rare and costly. Fossil copal is said to have been first found in the blue clay about Highgate, near London, but the most famous fields are the narrow strips of barren sea-coast on the eastern shores of Africa, opposite the island of Zanzibar.

In 1850, before the steamship and the submarine telegraph revolutionized the commercial methods of the world, the port of Zanzibar, the Sultan’s capital, located on the western side of the island, opposite the main coast, was then, as it is now, the chief outlet for the products of the east coast and the interior of Africa. Arabs and Hindoos formed the merchant and trading classes. Trading with the interior was carried on by means of caravans, which would be absent from Zanzibar sometimes five, eight, or even ten years. Traders and agents of the merchants traveled continually to and from the coast, where they traded with the native copal diggers and with such natives as occasionally brought a single ivory tusk to market. Copal barter was comparatively easy, but ivory barter was characteristically complex. Laying his ivory tusk on a box, the native owner would sit astride one end of the tusk and watch the covetous and expostulating trader pile up beads, cloth, and articles of barter on the other end, while the equally loquacious native would cling to his tusk, and firmly maintain that they had not yet found the equilibrium of trade.

The copal diggers are an improvident class, as natives of the tropics always are. [9]They dig for copal when dire necessity drives them to it, and seldom appear before the trader with more than a double-handful of gum to sell. On the eastern coast the diggers do not go much above the second parallel, or below the twelfth. In searching for a pocket of the gum they puncture the sandy surface to a depth of one or two feet with a short, small spear resembling the Zulu assegai. They sometimes dig a trench eight or ten feet deep if the find is sufficient to inspire them to make the necessary exertion. For the last twenty-five years, Europeans living at Zanzibar have talked of visiting the copal fields, and making an organized search for the gum. The undertaking would prove profitable but for the almost perfect certainty that the whites of the expedition would quickly succumb to the climate, and the Arabs and negroes cannot be prevailed upon to make a systematic effort. When India-rubber became a valuable article of commerce, the supply of copal from Zanzibar appreciably diminished, not because the fields are anywhere near exhausted, but because the indolent natives find it easier to gather India-rubber than to dig for gum copal. The superiority of Zanzibar copal to other varnish resins is apparent to a novice, for it is the hardest and clearest, and comes in thin, small flakes, a piece the size of a man’s hand being an uncommonly large lump. After being cleaned of its coating of dirt by immersion in strong lye, the surface of the copal is found to be uniformly covered with little round dots about the size of a pin’s head. This appearance is [10]called “goose skin,” and its cause is a matter of doubt and curiosity among scientific men. The most probable explanation is that the goose skin appearance is due to molecular action. It cannot be the imprint of the sand on the gum when it was soft, because in that case the surface would be pitted, instead of granulated. Copal trees are producing gum in Zanzibar to-day. The new product is comparatively soft, and of inferior value for varnish. The Sultan formerly claimed one-eighth of all the articles of commerce passing through the Zanzibar custom-house, the perquisites of which were farmed out to lesser officials.

As the demand for varnish gums increased, new fields were discovered. Accra, or “North Coast,” fossil resin is an excellent gum, and is found in Guinea and on the west shores of Africa, in about the same zone as Zanzibar. Some of the gum is very pale and clear in color. It is found in larger lumps than the East Coast gum, and is not so hard, nor has it the “goose skin” surface. For several years the greater part of the fossil resin of commerce has been obtained in the northern island of New Zealand. It is called Kauri gum, and is not found below the thirty-eighth parallel. This variety of resin is gathered by both whites and natives. It is of all degrees of age, hardness, and value, the better grades of kauri being found near the decayed stumps of trees, that have long since perished. The trees now bearing grow to a great height, and some of them are four and five feet in diameter at the base. The resinous juice exudes between the body of the tree and the bark, and runs down into the ground at the roots. The wood of the kauri-tree is much harder than Norway pine, and in color resembles mahogany, with which it cannot be compared in fiber or grain. It is a lumber-tree and the boxes in which the gum is shipped (usually about 200 lbs. to the box) are made of the lumber of the tree. Kauri gum varies in the size of the lumps, from a few ounces to seventy-five, and even one hundred pounds. A fossil resin of much value has been found in the Island of Madagascar. Benguela, Congo, and pebble gums (pebble gum is found in river-beds, worn to shapes resembling pebble stones) are found on the west coast of Africa. The Benguela gum formerly came into Europe through Lisbon. The Manilla, Macassar, and Dammar gums found in the Philippine Islands, are used for common grades of varnish. Resins suitable for varnish manufacture are also found in South America and Mexico. The product of the former country is commonly called animé, while the Zanzibar copal passes in the London market under the name of animi.

[11]

These two varieties most commonly contain insects, a fact which suggested their allied nomenclature. The Murphy museum holds many interesting specimens of insect copal. Ants feed upon the bark of the copal-tree, and, it is believed, frequently destroy its life. But the copal-tree has its revenge. For when the tree is wounded the resinous juice exudes and entraps the tiny enemy. Lumps of gum are frequently found as full of ants as a plum pudding is of fruit. Mr. Murphy has a fine specimen of accra gum which is the crystal tomb of a fly. One piece of Zanzibar shows a perfect grasshopper, which looks as if it had just hopped off a Western pasture. Another piece preserves a beautiful bumble-bee, in rich and velvety apparel. What a dreary existence he must have led in an age long, perhaps, before there were boys to sting! A third piece proves that the mosquito is a very venerable citizen of this earth. One of the workmen has a small piece of gum which is a witness to the predatory character of the spider. One afternoon an unlucky fly alighted on the bark of a copal-tree, and felt its feet involved in the sticky gum, past extrication. A spider traveled that way, and seeing the fly apparently too much engaged in sipping some sweet to heed his approach, pounced upon his prey, only to be caught as was the fly, and to be incarcerated in the gum with his booty in his fangs. Small lizards have been found in gum copal. Insects cannot be seen in the gum before it is cleaned. All varnish gums used to be shipped in the natural state, but to escape paying the American custom duties of ten cents, on a quarter of the weight, which is lost in cleaning, the gum is cleaned and purified superficially before shipment. The duty has been abrogated, but, nevertheless, it is found best to clean the gum before it is put in cargo. The boys that do the cleaning in Zanzibar appropriate the most curious specimens for themselves, and, for this reason, of late years, insect copal has become more rare.

Gum copal and the other varnish resins reach the factory of Murphy & Co. in the original packages. In a long, low room adjoining the storage warehouse, boys sit at a long table, placed against the wall, and give the gum a second cleaning, after which it is assorted and broken into small lumps for the melting-kettles, and stored in large bins in an adjoining room. In the cleaning, or chiseling process, the boys use a long narrow hatchet which has a blade at one end and a hammer-head at the other, and is grasped by the head and socket, and handled like a short chisel, for convenience in working around the irregular surface of the kauri-lumps. In breaking the lumps the hatchet is used like a hammer. The clippings, or chips, and the gum dust are saved, and form the body of a cheap varnish.

[12]

With the cleaning and the sorting begin the niceties of the business. Murphy & Co. owe much of their success—as every other manufacturing company that wins a permanent success must—to faithful attention to the smallest details. The gums are graded with considerable care before they are put up in commercial packages. This firm re-assorts the gum, making a number of additional grades, according to kind, clearness or purity, and hardness, and keeps the different lots separate throughout the process of manufacture, to which fact may be ascribed the homogeneity and unvarying quality of their products of each particular grade. The gum-room is in the remotest angle of the factory grounds, and there the gum is made ready for the melting-room and furnaces adjoining.

Two other ingredients have to be in store before the manufacturer can proceed with his work. Of these, turpentine needs no special treatment. It arrives at the factory in barrels, and is stored in four massive iron tanks, which together hold about ten thousand gallons.

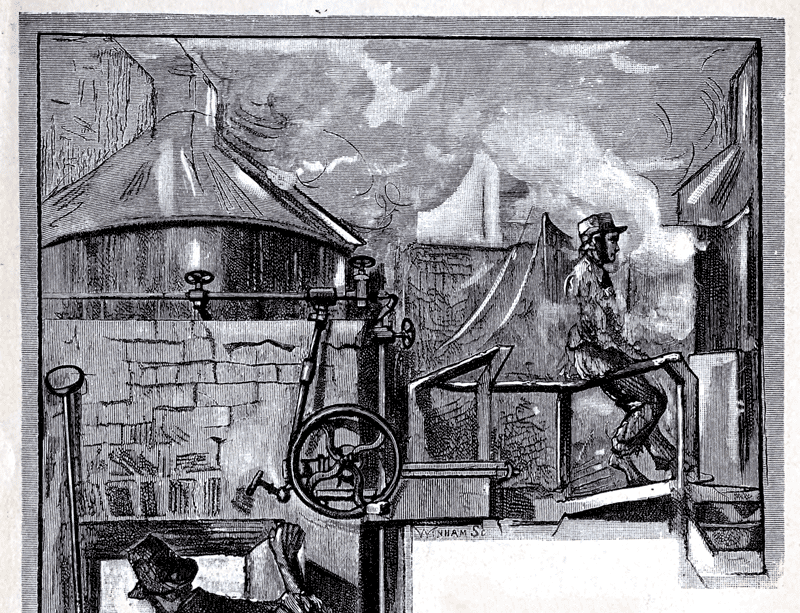

The oil-shop, where the oil is boiled and otherwise prepared, is a small, but massively built, structure, located in the center of the works, and contains two wrought iron kettles substantially set in masonry, each of which has a capacity for boiling five hundred gallons of oil. Experiments with the oil are made in the laboratory, and the ideas there developed are carried out in a practical way in the oil-shop. This department is in charge of Mr. Murphy’s younger brother, who brings to his work a natural liking for its duties, strengthened by a special technical education at the Columbia College School of Mines.

On the successful preparation of the oil, depend, in a great measure, the drying properties, elasticity, toughness, and clearness of the varnish; and the difficulties of a uniform treatment are very much increased by the want of uniformity in the raw oil. This does not arise from adulteration of the oil, but from the different characteristics of different lots of seed. The manufacture of linseed-oil consists simply in crushing the seed and expressing the oil by hydraulic pressure, but to secure the finest quality of oil, the linseed must be grown under favorable conditions, and harvested only after it is fully matured. If the season should be unfavorable, or if the crop is cut before it has fully ripened, or if a lot contains an undue percentage of foreign seed, the resulting oil is not suitable for the finest grades of varnishes. Each parcel of raw oil, therefore, is carefully tested by Murphy & Co., and only such accepted as meet the tests which their experience shows them are necessary to furnish satisfactory results in their work. As the oil is received in the factory it is pumped into large tanks in the second story of the main warehouse, which communicates by pipes with the large boiling-pots in the oil-shop. After treatment there, it is allowed to run out of the kettle into a large iron vat, and from that is pumped back into the main storehouse, into tanks of five hundred gallons each, and which, therefore, hold a single boiling. From one to six months is given it to settle and brighten. The foreign matter settles to the bottom of the pot, while the oil on top, which has become as clear as amber, is drawn off as it is required for mixing with melted gum. A dozen or more different kinds of prepared oils are kept in store, which vary in the quantity and the kind of the dryer boiled with them, according to the results sought for in the completed varnish. Thus the success or the failure of varnish-making must depend greatly on the care and fidelity of the foreman of the shop.

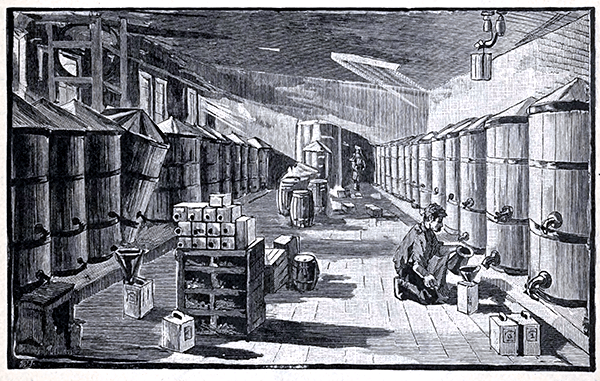

A double system of pipes, connecting with the boiled oil and turpentine storage [13]tanks, traverse the yard and enter all the out-buildings, where their ingredients are required for mixing with the melted gum. Nothing could exceed the neatness of the storage-room. The tanks are painted on the outside, and kept perfectly clean. There is a purpose in this. Good varnish cannot be produced if the workmen fall into careless and slovenly habits. To make cleanliness a habit, and, therefore, a matter of no special mental effort, the utmost neatness is maintained from the gum-room to the business office, and even in the factory yard.

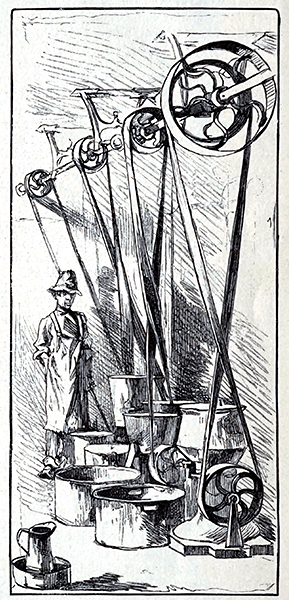

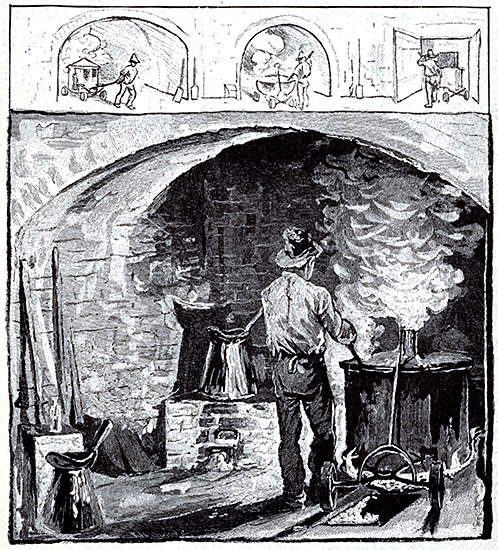

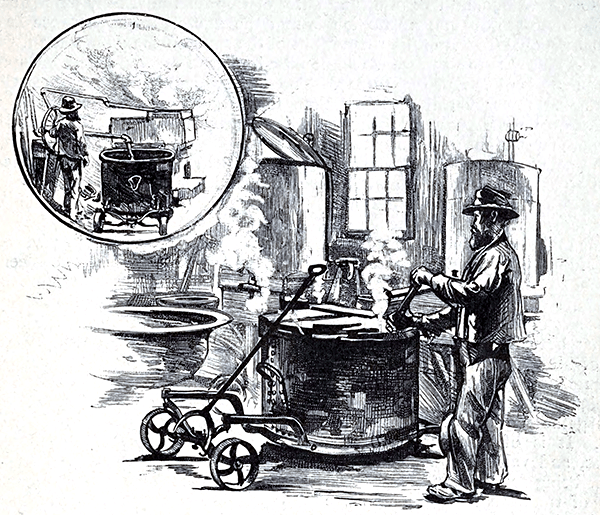

With the three ingredients at hand, the making of the varnish begins. It is desired to make a varnish of a certain quality. The foreman of the melting-room goes to the gum-room with his large copper kettle, holding 125 gallons, which is set on four small iron wheels. He takes from one of the many bins 100 or 150 pounds of the requisite kind of gum, returns with it to the melting-room, covers the kettle with a sheet-iron cover, which is provided with an exit for the thick and noxious fumes of boiling gum, and pushes the kettle into one of the great fire-places, which has almost the draft of a furnace. The fire directly underneath the kettles is very hot, and necessarily so, for the hardest kinds of gum will liquefy only after being subjected to a very high heat.

When the batch of gum is thoroughly melted the kettle is drawn from the fire, and a certain quantity of the prepared oil is poured in. The percentage of oil to gum varies greatly, according to the character of the varnish which is sought to be produced. After being thoroughly stirred, the mixture is pushed into the fire-place again and is boiled to a certain point, after which it is then drawn from the fire and the temperature of the mixture allowed to fall to about 300°. In the meantime the requisite amount of turpentine has been allowed to run into an upright receiver, with tube register attached. The kettle is drawn under the stop-cock, the turpentine mingles with the mixture of oil and gum, and the varnish is practically made. It is next strained through coarse muslin and filtered, after which it is brought into contact with another system of pipes, and is pumped into one of the three or four store-rooms, where large tanks, resting on stone platforms, preserve the varnish while it settles and ripens. The temperature of the varnish store-room is kept at 70° Fahrenheit during the winter.

In the finer grades of varnish, the ripening process requires from four to twelve months, and in many instances a much longer time is necessary to bring out its best qualities. This is not a matter of hap-hazard judgment on the part of the varnish maker. Every tank of varnish, during the time of ripening, is subjected to frequent tests by a practical carriage painter. It is tried on the same surfaces and under the same circumstances as it will be after it goes into the hands of the customer. The varnish must meet every test satisfactorily before it is allowed to go out of the factory. It is a very whimsical substance, and at times the best varnish is so unaccountably obstinate, that painters are agreed that it is in some manner allied to the evil spirit. What are called the “deviltries” of varnish come under fifty or more terms of opprobrium familiar to the paint-house, and may be divided into a dozen or more species; there is the “specky” family of deviltries, the “crawling” species, the “sweating” variety, the “blotching” class, the “peeling” genus, the “cracking” family, the “blistering” order, and other analogous misdemeanors that drag painters by a string of profanity into the hands of Satan. When varnish suddenly departs from its usual good conduct, and begins its pranks, just as the painter is in a hurry to finish [14]an important job, the painter is none too slow to lay the responsibility for his trouble on the varnish-maker, or somebody whose exact accountability he forgets in his rage, and is human enough not to see that he himself may be to blame. The “deviltries” of the business are as annoying to the varnish maker as the painter. If the varnish came from a first-class factory, the chances are as eight to ten that, if it is put to the purpose for which it was made and then behaves ill, the fault lay more with the painter, and with the conditions under which it was used, than with the material itself. Varnish loses its bad temper as a rule, in a dry, warm, well-ventilated paint-shop, which of course ought to be clean and free from dust. Varnish despises an ignorant painter as much as a horse does an ignorant driver. Varnish-makers have to bear the short-comings of ignorance with resignation and meekness. When a barrel of varnish is returned with the indorsement, that “it contains a devil,” the varnish-maker mutters: “Another stupid painter.” But like the father of the naughtiest boy in the neighborhood, he knows the character of the pesky thing too well, to assert that it was not as devilish as reported.

The precautions taken by Murphy & Co. to assure themselves that their varnishes will behave well, if properly treated, have assisted greatly in securing for their varnishes a reputation for “perfection of quality.” Not only is the varnish strained and filtered before it goes into the ripening tanks, but also again before it goes into the barrel for shipment. They have introduced an improvement into the filtering machine by which the ordinarily tedious process is urged forward with ten-fold rapidity. The neat cans with the handsome labels, and the barrels in which the varnish is shipped, are both made by the firm, a large building in the rear of the melting-room being set aside for that purpose. The ground floor is a cooper-shop, and the second floor a tin-shop, both departments being supplied with the most improved appliances, and the best material and skill. A large room has been reserved in the new warehouse, just completed, to be used for painting the barrels, which is an indication of the care paid by the firm to minor details. On the second floor of the same building, in the gable-end, has been constructed a room, which is supposed to be as fire-proof as iron and brick and stone and mortar can make an apartment. This is the new laboratory. The firm believe that it will be in the future, as it has been in the past, the most profitable room in the establishment. A unique branch of the establishment is the “Publication Office,” which occupies two large, cheery rooms in the basement. Two practical printers are in charge, and have at hand a full stock of job printing material and two modern presses. The neat typographical dress of the Company’s catalogues and price lists speak well of the practical success of this curious appendage to a varnish factory. A miniature newspaper, called “The Copal Bug,” is occasionally issued.

Murphy & Co. have made an important departure from the old methods of varnish manufacturing by establishing a factory for the manufacture of surfacers for coach and car work, as an auxiliary to their varnish business proper. This factory is several blocks removed from the main establishment, the two being connected by telephone. Since the “deviltries” of varnish, above described, are very frequently due to the improper preparation of the painted surface to which the varnish is to be applied, the firm believe that, by making surfacers already prepared for application and the best calculated for producing a suitable surface for varnishing, they would not only save themselves and the too frequently innocent varnish the anathemas of careless [15]painters, but confer a blessing on the painter as well. These prepared paints have been named “A. B. C. Surfacers,” and very appropriately, too, for the priming, leveling, and smoothing coats on which the varnish rests are the first steps toward the completed task of the painter, and if the first steps are badly taken, the best varnish in the world will not save the job.

Six or seven years ago American varnish-makers were vainly striving to compete in their own market with the highest grades of English coach and railway varnish. Murphy & Co. have led the way to a solution of this highly important problem for this country, and now produce a varnish which has the entire confidence of many of the first carriage builders and railway companies of the United States, and by some is regarded superior to English varnishes. In a very few shops the English article still maintains a show of supremacy, by virtue of the survival of the old-time prejudice against American goods. The best American varnishes are now making their way in the markets of Europe, and in this industry, as in so many other important branches of manufacture, America has cast off the yoke of dependence on the Old World.

Murphy & Company will be glad to send to any address, upon application, descriptive lists of their Varnishes, containing detailed information of each grade, with prices attached.