Title: The brave little maid of Goldau

Author: Mary Elizabeth Jennings

Release date: December 1, 2025 [eBook #77374]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Anson D. F. Randolph & Company, 1892

Other information and formats: www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/77374

Credits: Carol Brown, Richard Illner and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BY

NEW YORK

ANSON D. F. RANDOLPH & COMPANY

(INCORPORATED)

182 FIFTH AVENUE

Copyright, 1892, by

Anson D. F. Randolph & Company.

(Incorporated).

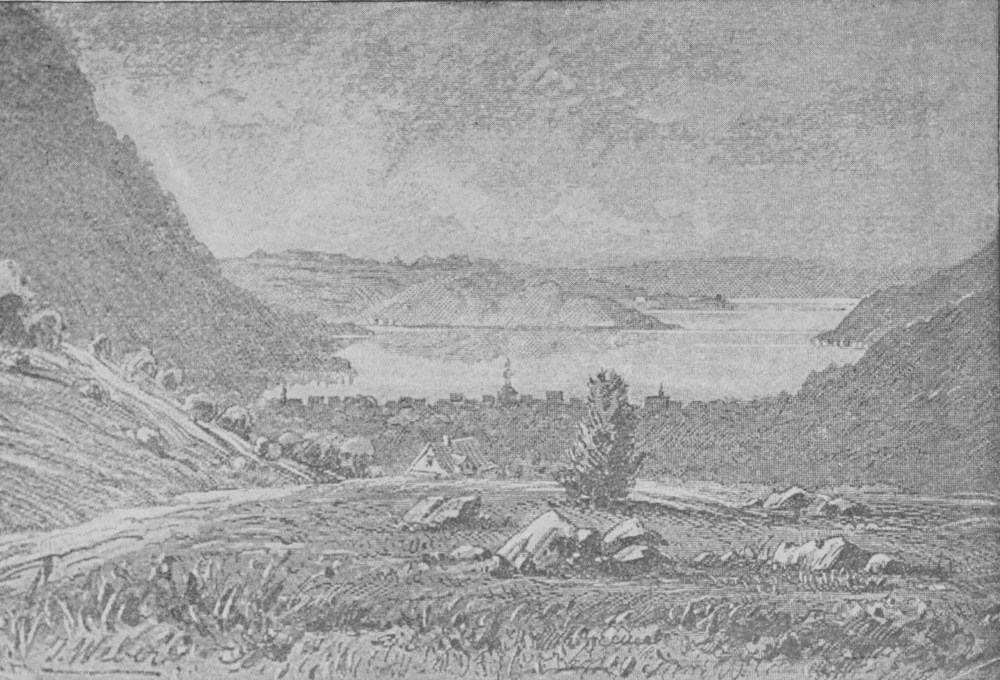

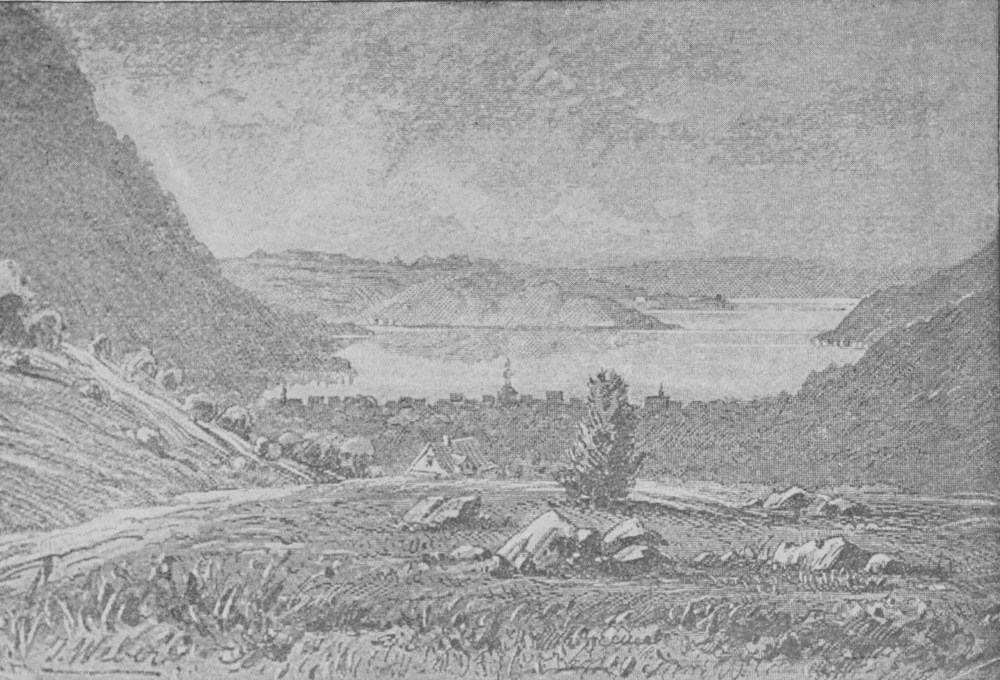

A Nestling Village.—Frontispiece.

The Land-Slide.—To face page 13.

The Peaceful Valley.—To face page 33.

Evening Bells.—To face page 38.

Throughout Switzerland, the summer of 1806 is always spoken of as “The wet Summer.” During May, June, and July, many and heavy showers fell, but in August it rained almost every day. In the Canton of Schwytz, the sky was so dark and forbidding that the clouds left the upper spaces, and chased each other quite down the mountain sides: and shut out the lovely little valley, which lay between Mount Rossberg and Mount Rigi, from the rest of the world. The people cared little for this, however, for was not the grass in the meadows on the mountain side as sweet as sweet could be? had the cows ever given richer milk? had ever such butter and cheese been made before, or so good a price received for it? And look at the gardens; such cauliflower! such cabbage! such potatoes! And above all, look around at the “over world,” the mosses, the vines, the shrubs, and trees, whose leaves, from the tenderest brown to the darkest green, seem as though tipped with diamonds, they sparkle so! And the flowers; were their colors ever more soft and lovely? No, everything was beautiful! beautiful! True, the tourists grumbled at the weather, but they always had a way of grumbling at something, and perhaps it might as well be the weather as anything else: and so the Fraus talked, and smiled, and nodded their heads, which made their words all the more reliable.

At the foot of the Rossberg nestled the pretty little village of Goldau. The mountain lifted its head five thousand feet above the village, but it smiled down upon it so kindly, and when the sharp winds blew shielded it so securely, that the people looked up with grateful eyes and spoke of it as their own beautiful mountain. And it was indeed beautiful. Near the top, and extending for a good way down its side, grew strong large trees, with little trees in between; quite a wood in fact; and when the wind passed over the mountain tops, the leaves rustled, shook hands, and laughed and talked in the pleasantest way imaginable. Below the wood, lay the great green meadows, where the grass grew soft and thick like velvet; and gardens too, for the people of Goldau not only kept many cows, but thought much of their cauliflower, cabbage, and potatoes. A little higher on the mountain side than most of the houses in the village, stood the home of young Kaspar Bernstein, Josepha his wife, three pretty children, and a little maid named Franziska Ulrich. Heinrich, the eldest, was a stout lad of eight years, who helped his father drive the cows to and from the pasture, and pulled the weeds in the garden. But the pet of the household was wee, blue-eyed Gretchen, a demure little maid of six years, who helped her mother, or thought she did, and made the hours pass happily for baby Fritz. Their home was a very pleasant one, clean and comfortable; the floors white with frequent scrubbings,—the pretty blue picture dishes at which Gretchen never tired of looking as the plates stood on edge in the racks on the wall; the tinware polished until it shone like silver; and the great square tile stove, with the bench around three sides of it, so that all could sit with their backs against the warm tile of an evening, while the top was large enough to make a bed upon in the coldest winter nights,—oh, it was as cozy and comfortable as a home could well be! And in the Summer time, how breezy the house was when the doors and windows were all wide open; why, one could stand in the front door, and look right out through the back door at the mountain. And the view of Goldau, with other little towns all lying so close together, and the shimmering water of the lake, made a picture always lovely to look upon; and when the sweet tones of the church bells floated up to them, morning and evening, their joy was complete.

The second morning of September opened dark and uncomfortable enough. The rain fell in torrents; at seven o’clock it was still too dark to see without a candle. Kaspar went out and attended to his cattle, and when he brought in the milk said to his wife,—

“Frantz Schwartz was on top of the mountain yesterday; he says that the little crack up there has so widened that he cannot now jump across it.”

“Is there any danger, think you?” anxiously asked the wife, setting the wooden pail on the floor and looking up at him.

“No, no,” answered Kaspar carelessly, shaking the water from his cap, “if there should be a split-off, it won’t get any further than the trees; they’ll hold it, never fear,” and turning from her he went off to his work, whistling merrily.

But Frau Bernstein did not feel so sure, and many times during the morning she opened the door and looked long and anxiously toward the top of the towering mountain.

“I know not what makes me feel so afraid,” she said to Franziska, who was holding and amusing baby Fritz, “yet I cannot help it; even the trees seem to be worried about something, the leaves all hang their heads so.”

“What nonsense,” laughed Kaspar, coming in just in time to catch her last words; “the leaves are soaked through and through with water, and are too heavy to hold their heads up.”

But there was work to do, and, in spite of anxiety, the morning hours passed quickly.

About dinner-time the rain stopped falling, but the black, angry clouds settled down more heavily over meadow and town, and after a few moments of quiet a gust of ice-cold wind swept down the mountain sides, followed by a furious, though short, storm of hail.

The afternoon wore away with no return of the storm, and the hearts of all grew lighter.

“Now God be thanked that it no more rains and the danger is over,” said the mother.

About five o’clock Kaspar looked in and said, “Josepha, come out and see what the hail has done; the trees no more bear leaves but ribbons on their branches; the vines are stripped, and nothing is left in the garden.”

Baby Fritz was asleep in his cradle, Gretchen busy with her play, and leaving Franziska to care for them, Frau Bernstein, followed by Heinrich, passed out through the kitchen leaving the door open,—

“It will be good for the house that the air enter; the rain has made it so damp,” said she.

Franziska watched them until Gretchen called,—“Freddie! Freddie! come see the funny little birds.”

Franziska hurried to the window, then opened the front door, and stood upon the steps, Gretchen close beside her.

How strangely the birds acted, to be sure. They flew round and round in the air, all the time uttering a plaintive little cry: the cattle, too, showed great uneasiness, and began to run about the meadows lowing as they ran. What could it all mean? Kaspar and his wife asked the same question, and, as if in answer, a huge boulder left the mountain top and crashed into the trees. It fell no further; the trees held it; but when three or four others rolled down together, that was more than the trees could stand; they bent and broke and the huge rocks came rolling down the mountain side into the village below. Kaspar looked at the mountain and saw the trees tottering and falling, and the ground all in motion, and seizing Heinrich with one hand and his wife with the other, he shouted, “A land slide! run! run!!”

Now, in times of great excitement, a father may forget his children for a moment, but a mother never; so tearing herself from her husband’s grasp with the words, “Gretchen! Fritz!” Frau Bernstein ran toward the house as fast as she could run, not minding in the least that she was in the track of the falling stones. As she reached the door, she caught Gretchen up in her arms, and rushed into the room where baby Fritz lay sleeping. Handing Gretchen to Franziska, who had followed her, it was the work of a moment only to lift the baby from his cradle, but as Franziska turned to leave the room she saw, with horror-stricken eyes, what seemed to be the whole mountain side coming through the back door. One step only when a crashing, splintering, grinding noise filled her ears; and then all became a blank. When she came to herself, she was in the dark; so dark it was she could not see at all, but worse than that, she was buried to her shoulders in wet earth and stones, and the blood was running down her face from a sharp cut in her forehead.

After struggling a few moments she succeeded in freeing one of her hands, and as she wiped the blood away, the horrible truth flashed upon her—she was buried alive! Then how she struggled, and cried, and prayed, and shouted for help; but the cruel earth held her close, and there was no one to hear or answer her. “Oh, if with the rest of them I too had died!” she sobbed, when the first paroxysm of terror had spent itself,—“but to starve here is horrible! horrible!” and again she sought to free herself from the earth around her, but in vain.

A low moan, followed by sobs of fright and pain, with a piteous cry of “Mutter! Mutter!” broke upon her ear; it was little Gretchen’s voice.

At the sound, all that was noble and heroic in the girl’s nature asserted itself; her own pain and danger were forgotten; she must save Gretchen somehow, but first she must soothe and comfort her. “Gretchen! Gretchen!” she called, “where are you, dear?”

“Don’t know,” answered the little one between her sobs.

“Come here, darling, you can come to Freddie, can’t you?”

“I can’t get up,” wailed the child after a moment’s silence; “something won’t let me go.”

“Don’t cry so, darling,” said Franziska; “can you see anything?”

“Can’t see anything but a little star in the dark,” replied the plaintive little voice. At this answer, a great hope filled the heart of Franziska; the little star must be a small opening through which the fading daylight found an entrance; they were not so deeply buried as she had feared.

“Want a drink of water,” wailed the little one,—“Freddie, come and give Gretchen a drink.”

Oh, how she longed to go.

“What shall I do! oh, what shall I do!” she moaned under her breath; then with a great effort at self-control she said aloud,—“Gretchen, darling, Freddie can’t come, so fast the dirt holds her; but perhaps ‘der Vater’ will come soon, and he will give Gretchen water; only be patient, darling, and do not be afraid, Freddie is close here; now don’t cry any more and she will tell you a story; you want to hear again the story, don’t you, Gretchen, about the prince who found the real princess?”

No answer, but the sobbing grew less violent. The tears were running down her own cheeks, but she began bravely,—

“Once, upon a time, there was a prince who wished to marry a princess, but he wanted her to be a real princess. He travelled all around the world to find one; not that there was any lack of princesses, but as to whether or no they were real ones, he could not always make out; there was sure to be something about them not just satisfactory. At last he went home quite unhappy, so disappointed was he at not finding a real princess.

“One evening there was a furious storm. It thundered and lightened, and the rain poured down till it was quite dreadful. Between the thunderclaps there came a knock at the town-gate. The old king, after thinking a moment, said the gate should not be opened; no good person would be out in such bad weather; and if he were, he had no business to be. But he was a kind-hearted old king, and when it thundered and lightened and rained harder than ever, he went himself and opened it.

“A princess stood outside the gate, but,—oh dear—what a state she was in from the rain and the bad weather! The water was dripping down from her hair and her clothes, and running in at the tips of her shoes and coming out at the heels. Yet she said she was a real princess. Well, that we’ll presently see, thought the old queen, the king’s wife, but she said nothing. She opened the door into a large room. ‘Oh, my!’ said the princess, as she looked around. Except where the windows were, the walls were all covered with closets and mirrors: first a closet, and then a mirror; then a closet, then another mirror, and so on all around the room. The old queen opened a closet door. There were the prettiest little slippers the princess had ever set her eyes upon. Slippers of white satin, slippers of black satin, slippers of red satin, slippers of gold satin,—indeed there were slippers of every color under the sun.

“The princess peeped into another closet. On shelves lay piles of the softest silk stockings,—a pair of stockings for every pair of slippers. ‘Oh, my!’ again said the princess. In the other closets hung gowns of satin, and gowns of silk, and indeed there was everything a princess could have need of.

“‘Now, help yourself,’ said the old queen, and off she went to the kitchen to hurry up the dinner; for when princesses have been out in the rain they are apt to be hungry.”

“Gretchen’s hungry too,—give Gretchen some bread,” came in faint tones.

“When ‘der Vater’ comes, darling. Just hear the rest of the story.

“The princess stood a long time in thought. She could not make up her mind just what to put on. Black would be the most appropriate, she at last decided; she was not in mourning, but she was in trouble, and that was the next thing to it. So she put on the black silk stockings, the black satin slippers, and a black satin gown; then she stood in the middle of the room and looked at herself in the mirrors.

“‘Oh, my,’ said the princess, ‘how fine it is to see one’s self all around at the same time, and not have to turn first this way and then that.’

“When the princess came out of the room how lovely she did look, to be sure. Her hair curled all around her face in little rings; her eyes were blue as a bit of the sky in sunshiny weather, her hands were white as milk, and when the prince touched one of them he thought he had never felt anything softer. So delighted was he, he wished to marry her on the spot, but the old queen was not quite satisfied. ‘She looks well, and she eats well, but wait and see how she sleeps,’ said she. So she went into the chamber and took off the bedding and laid a bean upon the mattress. Then she laid twenty mattresses upon the bean, and piled twenty eider-down beds on top of the mattresses.

“The princess lay upon them the whole night. In the morning, ‘How did you sleep?’ asked the old queen.

“‘Oh, very badly,’ said the princess; ‘I scarcely closed my eyes all night! I do not know what was in the bed! I laid upon some hard thing which has made me black and blue all over. It was quite dreadful!’

“It was now evident that she was a real princess, since she perceived the bean through twenty mattresses and twenty eider-down beds. None but a princess could have such delicate feeling. So the prince married her, for he knew he had found a real princess, and they lived happy ever after.

“Now, wasn’t it nice that the prince found a real princess after all?”

No answer.

“Gretchen, can’t you hear me?” she cried.

Still no answer.

“Gretchen! Gretchen!” she called, now thoroughly frightened, “speak to Freddie!” but there was no sound save her own voice. Then despair filled the heart of poor Franziska. “Oh! she is dying! she is dead! my little Gretchen! if I could only go to her I could get her out from under the dirt and stones, so strong am I”; and she dug desperately at the earth surrounding her with her one poor hand, but how vain were all her efforts—and soon realizing this, she stopped struggling.

The long hours in their slow march seemed almost to pause beside her. How cold she was, all except her head,—that seemed on fire. How the earth pinched her; if it held her so tight long, her heart must stop beating,—how still everything was;—she had heard of the quiet of the grave, now she knew what that meant;—only she had never thought it could press down upon and hurt her so;—and the night wore itself slowly out, with now no sound save the creaking of some heavy timber as it sank prone upon the ground under its load of earth and stones.

The faint, sweet tones of the morning bell penetrated her prison, arousing her from the stupor into which she had fallen.

“Oh, I cannot die! I cannot die, when it is morning and the earth is so near! my sweet bells! how you torture me. Heilige Maria, bitt für uns!—bitt für uns!”

Her piteous cry pierced little Gretchen’s returning consciousness, and feebly she answered her.

Above, Kaspar Bernstein was searching frantically for the location of his lost home. As the bells died away, with the full force of his strong lungs he shouted, “Josepha! Josepha! Jo-se-pha!”

Franziska heard, and, with the cry—“Oh, Gretchen! hear you? it is ‘der Vater’s’ voice,”—answered him with all her strength, but her voice failed to reach the outer air.

Still shouting he wandered to and fro, now near them, now more remote.

“Gretchen!” she called, “answer ‘der Vater’; perhaps he can hear you through the little star.”

Gretchen only moaned.

“Gretchen, you must answer! ‘der Vater’ will not find us; he will go away and leave us here to die,—Gretchen darling—shout as loud as you can—for the love of God, Gretchen!” And the little one lifted her feeble voice and called, “Vater! Vater!”

Overwhelmed by sorrow, as Kaspar stood a moment motionless, that faint cry reached him like a whisper from God. Oh, how desperately he dug, throwing the earth and stones in all directions in his eager haste to reach his darling, while he shouted words of hope and comfort to her.

It was not long before he came upon the front room of his ruined home. There, beside the crushed cradle, lay his dead wife, little Fritz clasped in her arms. He lifted them tenderly, and laid them carefully down out in the open air. He would go back to them later; there would be time for grieving, but not now. A little further on lay Gretchen, under a pile of dirt and stones. She was badly bruised, and her hip was broken. As he raised her in his arms, the blue eyes opened; a slight smile flitted over the pale face as she whispered “Vater.”

The tears which had not started when he beheld his dead wife and baby now ran down his cheeks, and he felt as though he could never let her go; but there was still work to do, so placing her in the arms of a kind-hearted Frau from a neighboring village, he carefully dug his way towards Franziska. As the light entered her prison she looked about her. Some of the beams and boards of the house were jammed together about six inches above her head, and held back the earth that must otherwise have crushed her. When Kaspar reached her, he found her so wedged in between great stones and beams, he could not dig her out alone; so bidding her keep her hope and courage a little longer, he went for help.

The earth, which had so recently been disturbed, now and then fell in small quantities into the opening; and occasionally a stone rolled over the edge.

Franziska’s strength began to desert her;—how long it was since “der Vater” had left her;—what if the earth should cave in upon her before he returned;—the beams above her head,—she surely saw them move; and when at last help reached her she was unconscious.

The kind-hearted Frau who had taken Gretchen opened her heart and home to Franziska also; but many weeks passed before she knew any one. In her delirium she was constantly talking to Gretchen, telling her stories, begging her not to be afraid,—not to cry so; until the good Frau would turn away her head, and with her apron wipe her eyes. But, one day, when the ground was white with snow, she awoke and knew them, and when little Gretchen, who had grown quite well and strong, climbed up on the bed and kissed her over and over again, Franziska thought she must have died and waked up in heaven, such a wave of happiness rolled over her.

It was many days before Frau Brinkerhoff told her how on that never-to-be-forgotten day tons and tons of earth and stones broke away from the Rossberg, and came sweeping into the valley, burying four villages and five hundred souls; how the earth filled up one end of the lake, and the water rose in a great wall and swept out onto the land wrecking all before it; how Frau Bernstein and baby Fritz lay in the quiet church-yard, and how the beautiful laughing valley was beautiful no longer, but oh, so desolate!

When Spring came again, and Kaspar got his little family together, what could they have done without Franziska. She cooked, and scrubbed, and sewed, and mended, and kept the patches on Heinrich’s knees; she knit the long woolen stockings, and taught Gretchen all she could, just as the good “Mutter” would have wished. And as the years passed away, Kaspar and the children thought there never was a lovelier, sweeter maid than Franziska Ulrich.

Karl Schultzer thought so too; he told her so one day and asked her to be his wife. She put her hand in his, and, looking into his honest eyes, said, “Karl, I love you too, but the last thing ‘die Mutter’ said on that—that dreadful day when she gave me Gretchen, was, ‘Take care of her’;—I cannot leave her.”

“But now Gretchen is old enough to take care of herself,” urged Karl.

With a faint smile Franziska answered,—“Karl, you cannot change me; I thought it all out as I lay upon my bed when my head was no longer queer, and the first time I went to the church to pray to the ‘Heilige Mutter’ I told her I would be faithful;—my word I cannot break”; and seeing how it was with her, Karl kissed the eyes now full of tears and went back home disappointed, but not despairing.

So the years sped until Gretchen’s nineteenth birthday.

One evening she hid her head in Franziska’s lap, and, with many a break, confessed that the brave hunter from over the mountains had said that he loved her, and asked her to be his wife.

“His wife you wish to be?” asked the tender voice.

“I love him,” was the whispered answer, “and to-morrow he comes to ask ‘der Vater.’”

If, for a moment, Franziska’s faithful heart ached, Gretchen never knew it; and when “der Vater’s” yes had been spoken, no one entered more heartily into the work and plans than she. What love and sympathy and counsel, as well as work, she gave, no one save Gretchen ever knew.

On a bright morning, to the sound of music, there came marching down the long street Gretchen in gay attire, followed by her mates; the bridegroom and his friends, who had come over the mountain-passes to see him married. And when, in the dim old church, the gray-haired, fatherly priest had counselled them, married them, and blessed them, Gretchen kissed “der Vater” and Heinrich good-bye; clung for a moment to Franziska, as though she could not let her go;—then turned her face toward the snow-clad mountains, beyond which lay her husband’s home.

As the day passed, how desolate was the house without bright, laughing Gretchen. It seemed to Franziska as though she could not bear it, and when her work was done she stepped out into the twilight that “der Vater” and Heinrich might not see her grieving and her tears.

Suddenly Karl stood before her. He held out his hands and said, “So long have the years been, Franziska, and the home so lonesome is; will you now come?”

Then was her sorrow turned into joy, and she answered, “If you want me, oh so gladly will I come to you, my Karl”; and Karl was content.

All this happened long ago, and both Gretchen and Franziska lived to tell the story of their marvellous escape to their many grandchildren; while “der Vater” never wearied of repeating, or Heinrich’s children of hearing, how brave Franziska encouraged and cheered little Gretchen through that long and terrible night.

Some time ago I stood above the buried village and looked up at the Rossberg. The mountain has never smiled since that awful day. No trees or shrubs or grassy meadows grow upon its sides; all is bare and desolate. But in the valley the grass and moss grow green; the vines twine themselves over and around the great rocks, from under whose shadows ferns and lovely little flowers lift their heads.

Suddenly the soft, clear tones of the evening bell floated through the air,—that sweet-voiced bell whose music reached Franziska and called her back to hopes of life and home so long ago. How sweetly it sounded on the quiet air,—coming,—going,—softer,—fainter; and when at last it died away the sun had dropped behind the mountains, leaving the rosy-tinted clouds peeping over their rocky edges; while in the valley the shadows lay thick upon grass and vine.

Stepping softly, reverently, over the dead homes, Goldau and the night were left alone together.