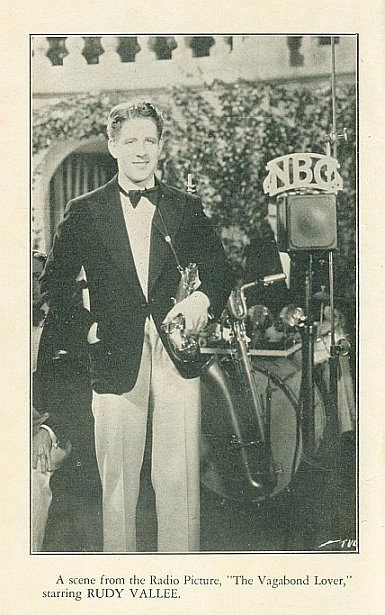

A scene from the Radio Picture, "The Vagabond Lover,"

starring RUDY VALLEE.

Title: The vagabond lover

Author: Charleson Gray

James Ashmore Creelman

Release date: December 2, 2025 [eBook #77384]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: A. L. Burt Company, 1929

Credits: Al Haines

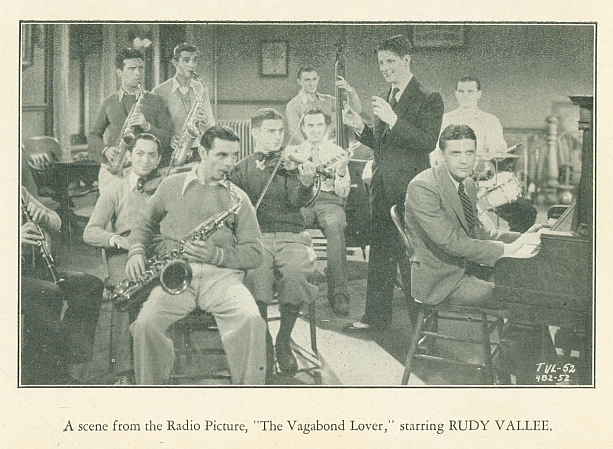

A scene from the Radio Picture, "The Vagabond Lover,"

starring RUDY VALLEE.

Novelized by

CHARLESON GRAY

from the Scenario

by

JAMES A. CREELMAN

Illustrated with scenes

from the

RADIO PICTURE

starring

RUDY VALLEE

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

Printed in the U. S. A.

Copyright, 1929

By A. L. BURT COMPANY

THE VAGABOND LOVER

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I The Unrewarded Quest

II Roadhouse

III Bravado

IV Revelry

V Conflict

VI Celebration

VII Homegoing

VIII The Old Home Town

IX Flight

X Engagement

XI A Decision

XII Portrait of a Celebrity

XIII False Colors

XIV A Personal Appearance

XV The Wings of Song

XVI Delay

XVII Escape

XVIII For The Benefit of All Concerned

XIX Dénouement

THE VAGABOND LOVER

A failure!

Rudy Bronson sat looking down at the puncture pattern on the tips of his shoes, his mouth twisted in a grim, unhappy line. He was a slim, apparently sensitive boy, with a crest of waving blond hair and eyes in which the spirit of the dreamer was fused with that of the romantic. With the late afternoon sun profiling his head and shoulders, casting a nimbus of warm light about his tousled hair and lighting up the clean lines of his features, a stranger might have found difficulty in understanding the phrase that came so harshly from his tense lips: "A failure!"

And what else was he? A whole year here at the State University, enjoying its every detail in his own quiet way, and then what? He kicked at a crumpled slip of paper on the worn carpet of the dormitory floor. He knew every brief line of its message, its succinct and banishing message: The Registrar wishes to inform you that, due to an insufficiency of passing grades, it will not be permissible for you to register in the University for the fall semester.

Flunked out! Like a dumb athlete. And for what? His eyes traveled mechanically across the room to where a tarnished and battered saxophone rested on a small table. Just because he had spent so much time practicing in an effort to make the school band that his studies naturally had suffered.

Nor was that all. The bandmaster had listened sourly to his try-out, and then dismissed him with the curt information that his playing was "just a little worse than rotten." He closed his eyes, as if seeking by the physical gesture to shut out a mental image which but stood clearer in the darkness.

It all returned with a rush. The full muster of the University's musically inclined had met on the bare stage of the auditorium. Brasses, woodwinds, string instruments, drums—each had been called in turn. Detained by a late class, Rudy had appeared at the end of the rehearsal, and been forced to make his attempt under the critical eyes of the other aspirants.

But despite them, relieved that their own trials were over and ready to laugh at the first false note, he had taken his place and started on his best piece... His hands clenched at the memory of the ensuing fiasco. Of course something had been wrong with his instrument. But no one was prepared for explanations or excuses. Their laughter had drowned him out before he had played two cracked bars, and the director had waved him down with the same condescending manner he might have used toward a half-wit.

It had all been terrible and humiliating past the understanding of one not so sensitive as Rudy Bronson. Yet it was but the next to the last failure of a collegiate career filled with failures. He kicked again at the paper on the floor. There was the last failure.

How different it all had turned out from his great expectations! Back home, with all the longing for distant places encouraged by life in a small town, he had looked forward to the State University as the end of the rainbow, a sort of dwelling place of dreams come true. He knew that his father had embarrassed himself financially in order to get him even this one year of higher schooling—and he had repaid the old gentleman by failing at everything he had attempted.

Too slender for football, not fast enough for baseball or basketball, he had been dropped from the freshman squads of those sports within a week of their inception. Distressed by his lack of athletic prowess, his natural shyness had deepened, and he had been overlooked in the rush for fraternity material. And with that failure to be pledged (he had felt) had departed his best chance of meeting Jean Whitehall.

As always, his heart quavered at the mere thought of her name. Jean Whitehall, the acknowledged queen of the campus, whose casual passing was enough to fill an unnoticed freshman's whole day with sunlight! How he had thought of her, dreamed of her, hoped to meet her! Now in his hour of defeat he honestly acknowledged to himself that his attempts to make the freshman teams had been prompted more by the desire to bring himself to Jean's notice than to win athletic glory.

The same wish had encouraged him to try and win recognition in the musical circles of the school. Seeing that he was not destined for a sporting career, he had turned a natural inclination toward music into a devout study of the instrument that might win him a welcome on Sorority Row—the saxophone.

Everyone knew that a good saxophonist was always in demand at the University dances. And if he couldn't be invited as a guest to Jean's exclusive organization—well, he might appear in the humble but willing role of musician. Being near her, having the chance to rest his eyes on her youthful loveliness was all he asked... And he had been denied even that.

"Just a little worse than rotten," the band-master had said—and put the mark of disapproval on his last, and therefore most desperately hoped for, attempt to bring himself above the level of the school's colorless and characterless nonentities. He had failed. Failed!

A brisk rap on the door punctuated his mental tirade. He looked up in surprise. He had few callers, and these ordinarily failed to knock. "Come in," he called.

The door opened immediately, and around it peered a fresh, roguish face decorated by an enormous pair of horn-rimmed glasses. For a moment Rudy had difficulty in recognizing Sport O'Malley. "Ah, there," greeted the newcomer. "Saw you sitting in the window and thought I would run up to ask how the saxophone lessons were progressing?"

Rudy smiled. He was fond of Sport O'Malley. The careless laughing youth was his one contact with the gayer side of the University; and though Rudy did not now see as much of him as he had when they had been together in high school back home, he nevertheless considered Sport to be his best friend in the institution.

"Not so good, Sport. The course calls for twenty lessons, and I've only got to the seventh. I was only on the fourth when I had my try-out for the school band. That's why I didn't do better. Why, I bet even Ted Grant couldn't have gotten by with only three lessons!"

"Probably not. But don't forget that musicians are born and not made. There's the chance that Ted Grant didn't take a lesson in his life. You've got to have something besides practice to become the greatest saxophonist in the world."

"I'll say you do," Rudy admitted. He said the words readily enough, but his tone was spiritless and disheartened. Sport was quick to change his manner.

"Don't take it that way! Gee, we can't all be Ted Grants—or else look how many orchestras would be cutting each other's throats! And look how many of us hopefuls would be blowing fish-horns instead of brasses."

"Oh, I don't mean to seem down, Sport. But it's tough. I put every possible hour into studying that sax, trying to get a break, trying to win a place on the band with the rest of you fellows—and all I got was the razzberry."

"That wasn't given you by the regulars," Sport was quick to say. "It was just those mutts who think that if they give the other guy the bird, they'll have a better chance themselves."

"It's all right," Rudy said wearily. "Whoever it was, I deserved it. I was rotten. I missed my chance. And now look." He pointed at the offending notice on the floor.

Sport whistled. It was apparent that from both experience and the color of the paper, he knew the significance of that communication. "Flunk?"

Rudy nodded. "Flat! No make-ups. No chance to register next year. No nothing!"

"Wam—that's tough! But I won't feel too sorry for you just yet a while. I haven't been over to my own diggings yet. I forgot that those little pals were coming out to-day. And there'll probably be one there to make me wish I'd not been reminded."

"Well, if there is," Rudy laughed, "we can hold each others heads on the train going home. What are you doing this summer, Sport?"

"Going to try and get up an orchestra and play at some of the hotels. You know, travel around like a special attraction. Those fellows with the puppet show from Yale have been cleaning up for several summers. People fall for that 'college' line in your billing. I think a hot band ought to go good."

"It should," Rudy agreed enthusiastically. "And if you should want a good saxophonist, you needn't look any farther than here."

Sport looked away, uncomfortable before the other's eagerness. "Gee, Rudy; you put me in sort of a tough spot. I know you're practicing hard on your instrument, and all—but you've only got to the seventh lesson, and I don't imagine that Ted Grant himself was much of a saxophonist at his seventh lesson."

"But you forget—great musicians are born, not made." Rudy laughed to cover the discomfort which they both felt; but he was stung by the abrupt dismissal of his offer to help. Was it going to be that way all his life—no chance to prove that he really had the stuff, just simply ticketed as incompetent and given no consideration at all? Why was it? Why was it?

He crossed the room, holding his head slightly averted so that Sport could not see his face. But Sport, with the keen perception granted to warm-hearted people, saw that he had hurt the shy, reserved boy whom he had known for years without really knowing him at all. He instantly sought some means of assuaging Rudy's injured pride.

"But why worry about all that? It isn't time to start fretting over summer jobs just yet a while—what concerns us just now are these failure slips. I think they deserve a party. And by the great god Whoopee, that's what they're going to have. A party in honor of the fact that the quietest boy in the whole University got shipped! That's a record that ought to stand for lo! these many years."

"What kind of a party?" Rudy asked. "Do you mean here, or up at your place?"

"Neither!" Sport cried. "We'll get the gang and go out to The Magic Lantern."

"The Magic Lantern!" How often Rudy had heard this rendezvous of the campus' more ardent spirits mentioned in jocular tones. Sport looked at him curiously. "Never been out there, Rudy?" He paused, smiling. "Say, I guess you haven't had a very good time here, all in all. Well, this is going to be one time that you'll have a good time!"

"That's mighty nice of you, Sport. No, I haven't had a particularly good time, socially. I've—been so busy with other things. Trying to make the teams, and practising on Ted Grant's correspondence course for the saxophone——"

"And you've gone to no dances? Parties? Had no heavy dates with the campus hot numbers?" As Rudy shook his head, Sport whistled shrilly. "My hat! You are a strange one, Rudy. But that's enough of that! I'll fix you up a party that they'll remember as long as one of the old school's stones stands upon another."

"How," said Rudy thoughtfully, "about girls? I'm not very well acquainted down on Sorority Row."

"Easily fixed," Sport assured him expansively. "The girls will all be crazy to come to this affair. Is there any baby that you'd like particularly? Just name her and she's yours!"

"I'd like Jean Whitehall," Rudy told him quietly.

Sport's jaw dropped. "I said you were strange," he gasped. "Boy, you're nuts! Why, she's the classiest number on the campus. She only goes out with varsity captains, when she isn't with the student body president or the manager of the welfare board!"

Rudy shrugged. "You asked me who I wanted," Rudy answered, "and I told you. And if you can't fix it, nobody else will do. I accept no substitutes."

"What a man!" Sport breathed. "Here I had you tagged as aching to step out with the janes—and you calmly tell me that if you can't have the best looker in the University for a partner, you won't have any. Why, Rudy," he added, "much as I hate to admit that being a sophomore keeps me from anything in this noble institution, I've got to break down and confess that the high and mighty Miss Jean Whitehall, girl-friend of our more ritzy seniors, doesn't even know I'm on earth."

"Then," said Rudy decisively, "our party will be a stag."

Sport touched him lightly on the arm. "You're too subtle for a roughneck like me, Rudy Bronson. But you're there. And I like you; damn it, I like you!"

There is a Magic Lantern near every American coeducational university. Sometimes its placard reads Paradise Pavilion, sometimes The Royal Palms, or The Moonlight Gardens. But usually the wording is The Magic Lantern. Dancing. Refreshments.

Even though there chances to be some slight variation in this legend, the place itself is unvaryingly the same. A plain, barn-like structure on the outskirts of town. A "hot" orchestra, a good dance floor, a number of tables, and a great many small booths. The menu is composed almost exclusively of startling combinations of the sandwich theme, and the rather dingy waiters seem to take for granted that you will want ginger ale—as a beverage, or a vehicle.

But herein the policy of this particular Magic Lantern differed from its fellows to so marked a degree that it might have been named something like The Coffee Pot. It was generally insisted that the ginger ale which its waiters dispensed was supposed to be for thirst-quenching purposes only. The menu bore a line: "Kindly do not embarrass the management by bringing intoxicating liquors to this establishment," and the floor-man had instructions to whisper politely but firmly in the ear of any young man who appeared to have enlargement of the hip. Thus was kept a tolerant attitude on the part of the University officials.

The "no drinking" edict was, of course, rather a startling position for a roadhouse to assume—especially a collegiate roadhouse. It seemed impossible that business could continue in the face of such strictness. But business did. The proprietor, asked for a reason, would point to the excellent sandwiches, the superlative floor, and the fact that his orchestra leader had come to his establishment by way of Paul Whiteman with stops for tutelage under Vincent Lopez and Roger Wolfe Kahn. Sport O'Malley, however, would have given a different answer.

Boys like Sport—whoopee-makers, the careless, riotous playboys of the university playgrounds—aside from knowing all the newest, smartest chatter and the freshest dance steps, customarily also know where liquor may be obtained. And Sport O'Malley knew that despite the advertised status of The Magic Lantern toward electrifying beverages, those beverages were to be had by anyone who had three dollars for a fifth of gin, or seven for a quart of whisky.

The proprietor of The Magic Lantern had seen them come—and go—these Sport O'Malleys. Each semester, sooner or later, every type of the whole collegiate world drifted into his place—looking for fun or for trouble, in curiosity or boredom, or merely in search of companionship. He liked them all from the grinds to the rowdies, and some he even respected. Others he did not. Others—like Rudy Bronson's friend.

Sport O'Malley knew of his rating with old Bland, and, oddly enough, it worried him. Oddly, because it is a self-evident fact that the Sport O'Malleys of American universities do not worry about anything—much less the esteem of roadhouse proprietors. Their one anxiety traditionally is maintained for those forbidding men, the deans; their only fear that they will fail to continue to escape official notice.

Of course they are well-known to everyone else on the campus, both for their personalities and their aims—which are modest, concentrated, and founded on logic. Their ambition solely is to have fun for a few of their best years, and they pursue that desire with the caution of a good cause. Wisely, theirs is never an active part among the noisy, conspicuous projects of the college; for, prefacing a distaste for labor, is the knowledge that the life of an "active" man is only one or two years. An attempt to tarry longer in the spotlight invariably leads to the discovery of clay feet—whereas there is no limit save that of inclination on the time a playboy may spend in school.

In fact, such is the usual Sport O'Malley's aptitude for glittering the social life of the institution, his stay is encouraged. No foes are bred among office-seekers to complain about the length of his record; no attention is focused by having rival coaches wail "That guy just can't be eligible again this year!" He avoids the dating evidence of program committees, centers his escapades far enough from the campus to escape unwanted official attention, and semester after semester glides gaily along.

Old Bland had seen them come and go, these Sport O'Malleys. Consequently, knowing both the attraction and the dangers of the type for impressionable young women, he was careful that his daughter should have as little to do with them as possible.

Molly Bland was that most delectable of creatures, a cute blonde. She had an impertinent small nose always quivering just a little because of the merriment which seemed always to be bubbling within her, and an impertinent small mouth always parted just a little as if in an instant she expected to receive a most delightful kiss. Sport O'Malley truthfully thought her one of the most engaging members of the opposing sex that he ever had encountered; and watching her in her role of hostess to the customers of The Magic Lantern, he now was plunged more deeply than ever in a conviction of injustice concerning the elder Bland's forbidding attitude.

Wasn't it fierce? Here was the old man always insinuating that he, Sport O'Malley, could balance a chair on his chin and walk under a worm, while all the while the proprietor was pouring his cheap, cut alcohol into the undergraduates of a university which had not banned his place only because it was supposed to be straight. Most of the fellows knew that all you had to do was drop a hint to one of the waiters, and after a bit a bottle would be slid into your lap! As a consequence of these ruminations, the opinion of customer for owner was even less than that of owner for customer. Old Bland thought Sport O'Malley worthless; but Sport thought of Molly's father as a two-faced crook.

"It gets me!" he burst out to Rudy. "In fact it gets me down!"

"What does?" Rudy inquired. He was looking about the long, table strewn room, drinking in his first contact with that stimulating atmosphere peculiarly associated with night resorts. "It all looks pretty swell to me."

"I'm talking about old Bland, who owns this place. I've got a crush on his daughter—see her over there? The little blonde? What a grand kid she is! I love her, Rudy, but her old man won't let me come near her. Treats me as if I were a leper or something."

"She's a very pretty girl," Rudy admitted. "What does he seem to object to about you—in particular, I mean?"

Sport grinned. "Oh, just the fact that I don't take life as seriously as—well, you do. He'd love you, Rudy. You're just the kind of young man that older people trust. Why wasn't I born with an appealing pan?"

"It hasn't seemed to bother you much so far," Rudy reminded him.

"Not in some places. But with fathers, for instance, it isn't so good. They trust eggs like you, who look honest and sincere and all that sort of thing." Suddenly his eyes lighted. "Say, I've a grand idea! I'll introduce you as my brother from home. He'll take a look at you—and then maybe he'll think that there's some good in the O'Malley family after all."

"But——"

"No buts! I need your help in this, and I'm going to get it or straighten the curl out of your hair with a table leg." He stood hurriedly. "Come on. The other fellows will be here any minute. With that gang around to crab our act, deception will be about as easy for us as skating is on one leg!"

Reluctantly, Rudy got to his feet and followed Sport across the dance floor. He was painfully embarrassed, not only because he felt that he lacked the necessary acting ability to carry out the masquerade, but because he hated deception of any kind. Too, he was rather worried about lending his so-called honest face to any project which Sport, with his eccentric notions of right and wrong, might introduce.

Rudy was no prude, but back of him was a line of New England forebears who had taken the truth as a serious business, who had asked honesty and straightforwardness before all things. Their shades restrained him now, and wending his way through the press of the dance, he was in a turmoil of indecision. He hated to let Sport down—but he hated more to lie.

Yet there seemed little he could do about the matter without causing the sort of scene from which his sensitive nature characteristically rebelled. And when Sport touched a short fat man upon the shoulder and said, "Mr. Bland, just to prove to you that we O'Malleys are not thoroughly a bad lot, I want you to meet my brother," there was little that Rudy could do but put out his hand and mutter, "Pleased to meet you."

"Rudy is just down from home. He's going to take me back in his flivver." Suddenly the good points of his improvisation struck him. He turned to Rudy. "You are going to take me back home in your flivver, aren't you, Rudy."

"Why, certainly," Rudy said. "If you want me to."

"Want you to!" snorted Mr. Bland. "Well, what else did you come down here for?"

"Oh," said Sport hastily, "coming down for me was only part of it. You see, Rudy is very anxious to be a good saxophone player. He's been taking a correspondence course from Ted Grant, the greatest saxophonist in the world. And he heard about your remarkable leader over there, and decided that the logical thing to do was come down and meet him. You know, one fine musician paying his respects to another."

It was evident that the canny Irishman had played on a sensitive chord in the proprietor's make-up. "Well, that's right nice of you, Mr. O'Malley," he said to Rudy. "I rather pride myself on having the best band in the state, insofar as regards places like this. And I've always thought that Bennie needn't take his hat off to any of them. Come on over and meet him."

"Sure," said Sport, "Bennie'll be happy to meet one of his admirers."

"Why, I—," Rudy began.

"Go along with him, Rudy. I'll follow in a minute. I've just seen a fellow over here that I've got to speak to."

With few doubts as to the sex of the "fellow" whom Sport had to talk to, Rudy allowed himself to be led over for an introduction to Mr. Bland's greasy little orchestra leader. That devil Sport! Making him lie in order that he might snatch a few minutes with his current flame! He was more than a little minded to tell Mr. Bland of the trick that had been played upon his credulity; but the old fellow was so obviously tickled that someone should have wished to compliment the music of his establishment that Rudy could not find it in his heart to disappoint him.

Bennie bowed condescendingly when the little proprietor made the introduction. "Oh, yes," he said, "I have a great many fans who I never have seen. It has become noised about that I played with Whiteman and Lopez, and—" as he talked on with the insufferable conceit of a small mind, Rudy began desperately to seek some way of escape.

But Sport was gone, and though the other members of their party by this time had arrived, he was unacquainted with them, and therefore to approach their table alone would have been an impossibility for one of his reserved temperament.

"You see," Bennie was going on patronizingly, while plump Mr. Bland beamed his pride, "after my experience with the leading orchestras of the country, I find it difficult to keep musicians in out-of-the-way places up to concert pitch. Most small town orchestras are recruited locally, and you boys, while undoubtedly willing——"

Rudy's face flamed. The gentlest and most inoffensive of young men, the oily leader's rambling barrage of self-praise at last had touched a point which he was unable to pass in silence.

"Perhaps you underestimate some of us, Mr. Harris," he said curtly. "It is true that I come from a small town. But it also happens that I am a pupil under the direct instruction of Ted Grant."

"Ted Grant!" Bennie's arrogance fell away like a dropped mantle. "You're studying under Ted Grant, the greatest saxophonist in the world?"

"None other," Rudy answered with a touch of pride. "Not only that, but the last time I heard from him he said that he was very pleased with my progress. He said that I showed the makings of a great musician."

Instantly Bennie stepped down from the slightly raised platform on which he stood. "Then," he said, "you must play for us! All my life I have been envious—and respectful—of Ted Grant. Many times I have tried to get into his band, to study his methods. And now you, one of his prize pupils, are right here where I can watch you play."

Rudy gulped. "But—but I haven't my instrument."

The leader immediately thrust his own saxophone into the boy's unwilling hands. "You will play mine. It is a genuine Ted Grant saxophone, his best model."

"But——"

Mr. Bland clapped him heavily on the shoulder. "Excellent, my boy! What an advertisement for my place to have a Ted Grant pupil play for us." He signaled to the drummer for a roll; and when he had the attention of the whole room, he climbed to the platform with outstretched arms.

"Ladies and gentlemen. We are greatly honored by having with us to-night the star pupil of Ted Grant, young Mr. O'Malley. Mr. O'Malley kindly has consented to play a number for us."

A great burst of applause rolled across to the trembling figure of Ted Grant's star pupil. But he did not hear it. Across the room he had caught sight of the open mouth and horror-stricken eyes of Sport O'Malley.

Sport was signaling frantically, shaking his head and waving his arms, giving every sign of protest aside from an actual shout that he wanted anything but for Rudy to play.

But his "brother" only grinned, rather painfully, and climbed up on the platform.

Rudy Bronson was that most astonishing of youths, a sensitive boy who, goaded into a hated situation, would go through with the task before him with a totally unsuspected power.

Balancing Bennie's saxophone in his hands, he was taken by a sense of capability regarding the instrument which heretofore had been totally alien to him. This was a real Ted Grant sax! How different it was from his own clumsy instrument; how delicate and yet how strong it felt beneath his touch.

"Just play anything that you like, Mr. O'Malley," he heard the plump proprietor of The Magic Lantern say. "Anything at all will be a treat."

Glancing toward Bennie, Rudy thought he noted a shade of malice in the orchestra leader's narrowly watching eyes. It suddenly was borne upon him that Bennie's offer to let him play a solo had been prompted by no other desire than that which he had stated—the chance to observe at close range some of the celebrated Ted Grant technique in operation.

Well, there was no backing out now. A wave of fright passed over Rudy at the thought. He looked over the floor of upturned faces beneath him. Faces waiting to be entertained; and if he failed them in that, ready to criticize, to give him the sort of razzing which he had received the day of the try-out for the school band.

Oh, why had he acted upon the crazy impulse which had caused Mm to fall in with Bland's wishes! Certainly it was absurd to think that he could offer a brand of playing equal to that of the old man's regular saxophonist. Bennie was good; of that there was no doubt. But here he was—and there now was nothing to do but play.

The first elements of the Ted Grant technique were a clean, rapid tongueing, accompanied by a similar nicety of fingering. With his old saxophone he often had sought for the precision in these attributes upon which his lessons had been so insistent. With this marvelous bit of metal within his hand, he felt that such skill would not only be possible, but inevitable.

Raising the mouthpiece to his lips, he blew gently and was gratified at the clear, melodious tone which ensued. Emboldened, he began one of the newer fox-trots, a lilting, catchy melody which he had been practicing for hours in his room without any great degree of success. But with the wonderful Ted Grant saxophone within his grasp, he did not feel that there could be a piece in the whole literature of syncopation beyond his capabilities. Not one.

As he played, he occasionally heard a note that did not seem to be quite all that it should be. But with closed eyes, deeply engrossed in the operation of the instrument he had come to love, he paid no heed to the world about him. He was in a world alone with his music—and the thought that beyond all things he wished that Jean Whitehall was there to hear him.

And with that wish was born the determination which one day was to bear surprising fruit. Sometime, some place, he vowed, he would play for Jean; would sing to her all the love songs which he had been keeping for the one girl in all the world for him.

With the last note of the number, he lowered the saxophone and bowed to an amount of applause quite unbecoming to a star pupil of Ted Grant. In fact, the only applause he received seemed to be that supplied by Sport O'Malley and his friends. Mr. Bland and Bennie clapped perfunctorily, and the head-waiter turned away without committing himself.

"Perhaps you had some difficulty with the strange instrument?" Bennie asked.

"To the contrary," Rudy answered, smiling his pleasure. "I found it the best sax I've ever played."

The leader frowned. "That's funny," he commented. "It sounded to me as if you were off key about two-thirds of the time."

Rudy bit his lip, flushing painfully. But before he could open his mouth to speak, the smooth voice of Sport O'Malley interposed: "You small-town yokels ought to get wise to yourselves," he said tartly. "Is that anyway to treat a guest star? Here my brother is, doing his stuff for you for nothing—and just because you don't know that the new Ted Grant technique calls for a tone just off key, you have the nerve to make a smart crack! It's an outrage, Mr. Bland!"

But the old proprietor had been listening to syncopation long enough not to be fooled by any such facile explanation. "Run along, Sport. I can thank your brother without any help from you." He turned to the unhappy Rudy, evidently taken by the boy's quiet and unassuming manner. "Good or bad, I thank you, Mr. O'Malley. And whether you're a good musician or a rotten one—if you always try as sincerely as you were doing up there just now, I don't see how anybody's got a right to complain."

"Thank you, Mr. Bland," Rudy answered. "That was mighty decent of you to say, if you thought I was rotten. Personally, I thought I never sounded better. But that's just an honest difference of opinion."

"Sure," interrupted Sport, "and now Rudy, my lad, we will go to yon table where await our convivial friends and pledge thee in a beaker of—" he glanced suddenly at Mr. Bland—"ginger ale!"

The convivial friends greeted Rudy boisterously. It was apparent that they were illuminated by spirits somewhat stronger than those naturally induced by the occasion. But loud as were their assurances that Rudy was the greatest saxophonist in the world, he was unable to derive much pleasure from their praise.

So he had been rotten, terrible! Even with a Ted Grant saxophone, he had been unable to play through one simple piece in a manner worthy of high recommendation other than that of a lot of half-boiled night owls. Rudy sat unhappily staring at the glass which had been placed before them. But he'd show them! He'd show them all—this crowd of kidders, that smirking little Bennie, Sport, yes, and Jean Whitehall, too, that he could bring as sweet a melody out of a saxophone as any man that ever lived!

"Drink up, Rudy!" Sport called. "This is your big night."

Smiling to cover his grim frame of mind, Rudy Bronson lifted his glass. His big night, indeed—though probably not in the manner which Sport had meant. But big nevertheless; because it was the night which had fired him with a definite ambition, given him a mark at which to shoot, had set for him a goal!

He got to his feet, his face alight with the flame of his newly fired purpose. "To my big night, men! Here's how!"

Caught by the ringing sincerity of his tone, there was a moment of silence as the little ring of young men answered his toast. Then Sport O'Malley shattered the seriousness of the tableau with a shouted "Skoal!" And the party was on.

College boys on a party are traditionally opposed to quiet, and Sport O'Malley's "coming out" party for Rudy Bronson scarcely was an exception to the rule. Within an hour, the booth in which the half dozen boys were crowded had become the focus of general attention. Within two, their hilarity was such that old Bland replaced his frowns and warnings with the even sterner edict that they quit the place.

This the whoopee-makers were loath to do. The evening was nearing its height. Bennie, the orchestra leader, had his men drawn to the last possible notch of syncopation. He was showing well what he had learned under Whiteman and Lopez and Ben Bernie. Showing it so well that the floor was packed with dancers.

Around the gliding figures, seeking booth openings, waiters scurried like black and white rabbits. Sound blazed like light. And over all was that tremulous, excited note which comes to a festivity only when its participants are very young and very alive.

"Aw, we don't want to go just yet, Mr. Bland!" Sport cried, waving his arms at The Magic Lantern's proprietor. "Gee, things are just beginning to get good. I'll make these guys be quiet."

"Yes, and who's going to make you keep quiet?" Bland demanded. "You're the noisiest one of the bunch."

"Why, Mr. Bland, I am surprised!"

"I'll make him quiet down, Mr. Bland," Rudy interposed. "I guess we have been pretty noisy. But we'll cool off a little bit."

"Sure, we will that," Sport seconded him. "Fact is, I'll go out and cool off now." He rose majestically, pointing at the others. "And if there is so much as one peep out of you bozos before I get back, I'll help Mr. Bland throw you forth upon your ears."

"You and who else?"

"Me and Mr. Bland, of course. He's all right."

"Who's all right?"

As one voice they answered: "Bland's all right."

Rudy got the uproarious Sport by the arm, and pulled him toward the door. "Lay off that stuff," he cautioned. "Gosh, I came down here and masqueraded as your brother, and gave a solo, just to get you in right—and then you try to toss away all that I've done for you by yelling like a hoodlum!"

"I know," Sport admitted. "But that guy burns me up, Rudy. Why can't he have some of the good traits of his daughter?"

"You're pretty fond of this girl, aren't you, Sport?" Rudy asked slowly.

"Oh, boy! You're conservative! I'm cuh-razy about that baby."

Rudy studied Sport for a moment. He liked the gay and light-hearted sophomore, and he knew that the boy was doing himself anything but good by the terrific pace he was hitting. The thought crossed his mind that perhaps this girl Molly, with her influence over Sport, might cause him to change some of the habits that eventually must be his undoing.

"You wait here a minute, Sport," he said, as they reached a bench under a tree outside the long, lighted building. "I want to go in and get some cigarettes. Stay here, now; I'll be right back."

"Oke," said Sport, relaxing comfortably against the tree trunk. "I'll be delighted to wait, old son."

In the doorway of The Magic Lantern, Rudy stood for an agitated moment, seeking in all that mad scene to win a glimpse of Molly Bland. A number of hails went up for him from the booth he so recently had quitted with Sport in tow, but he paid no more attention to them than to the university songs booming out under the baton of the orchestra leader. He frowned. That girl might be able to do Sport incalculable good.

The door to Bland's office gave directly upon the resort's main room, and to this door he now saw Molly Bland making her way across the dance floor. He plunged forward. "Miss Bland!"

The girl turned, acknowledged the hail with a cold glance, but failed to pause. Scowling, Rudy hurried to her side. "There's something I'd like to say to you!" he said, putting out a detaining hand.

Brushing away his hand, the girl stopped. Her eyes were cold in a pink face. "And there's something I want to say to you! What kind of a brother are you to let Sport drink the way he does? If you think it's smart—or amusing, or anything else—you have far different opinions than I do!"

Rudy grinned. "That's fine!" he cried. "That's exactly what I wanted to hear! You see," he explained hurriedly, "Sport's introduction of me as his brother was just a little joke. I'm not his brother—but I am his friend. And I hate to see him use liquor the way he does almost as much as you do. He's outside now—I wondered if perhaps I might ask you to go out and speak to him about it?"

The girl's eyes softened. "Say, you are nice," she said. "Where have you been? I wish that Sport had a few more friends like you."

"Never mind that," Rudy returned, his color heightening. "You just go out there and talk to Sport the way you talked to me."

"I will!" Molly assured him decisively, and with a brisk run of steps went through the door and out into the night. Rudy sank into an unoccupied booth. What fools young men were! How they wasted themselves and their opportunities in idle folly. Here was Sport O'Malley, one of the cleverest chaps he knew, burning his candle at both ends—and attacking the middle with an acetylene torch!

And to what purpose? Little that had anything to do with the career in modern music upon which he had pinned his rather casual ambitions. Well, it would be different in his own case. He would allow nothing to stand in his way. Nothing! And there would be no need for any girl to go out and berate him for destroying himself. He smiled ironically. Which was probably a good thing—so long as there was no girl who cared enough about him to mind whether or not he drank himself blind.

At that moment there was a small burst of newcomers, accompanied by an obligato of youthful laughter. Rudy's pulses quickened as he saw that among them was Jean Whitehall. She was escorted by the very attentive captain of the football team, while the president of the student body hung on the outskirts of the crowd, glowering with a resentment doubtless caused by that fact. In his official capacity, he frowned on The Magic Lantern, and he was there only because Jean had insisted upon seeing the place as a sort of prelude to the farewell dance her sorority was giving that night.

Rudy sank more deeply into the obscurity of the booth. For some odd reason he did not wish Jean to see him there—in his role of inconspicuous freshman. Rather, a silent voice counseled, let him wait until he could bring himself to her notice in a fitting manner. And then there would be no recollection in her mind of the poor fumbling boy who had failed in everything he had attempted at the University.

He found her gorgeously beautiful. For the moment he could not take his eyes from her glittering presence. When the party had been seated, with Jean as the colorful hub around which it revolved, Rudy slipped out of the booth and made for the outside door. When he was Rudy Bronson, the famous musician, there would be time to think of her. But until then——

In the sudden transition from the blazing light of the interior of The Magic Lantern to the cool dark of the night, Rudy had difficulty in adjusting his sight. He stumbled forward, and was almost upon the tree beneath which he had left Sport when he heard Molly's voice speaking, quietly and yet with a strange dignity:

"Oh, I know you're not too potted to walk—or to talk, Sport. But you're under the influence of liquor, nevertheless. And," suddenly her voice flared, "I hate it! You can't know how I hate it! You see," she went on with more calm, "before we came here, Dad used to have a saloon. I was only a very little girl, then; but night after night I've listened for him to come home. I always could tell by his step on the walk whether or not he'd been drinking with his customers. That was in the old days, Sport. You probably don't know anything about saloons, but, oh, I do! I've listened to Dad and Mother go over the question time and time again."

Almost against his will Rudy was forced to remain as an eavesdropper to the girl's troubled story. To walk away now might startle her, cause her to cease the even flow of words which he was certain Sport O'Malley needed as much as he needed anything on earth.

"It went along that way for what seemed ages," Molly continued, "until I got to hate anything in any way associated with alcohol, and I've never lost my horror of it... So you see it's hardly because you're a drinker that I care for you. I'm not the kind of person who thinks it is smart for you boys to make whoopee. Fun is fun, of course; but I'll bet that quiet friend of yours, the blond, has as much fun as any of you."

At this interjection of his name into the discussion, Rudy thought it time to make his appearance. Coughing slightly, he came around the trunk of the tree, holding a packet of cigarettes in his hand.

"Ah, there," he said in greeting.

Sport looked up listlessly. "Hello, Rudy. Do you know Molly Bland? Her father owns the place here. She's just been telling me that I drink too much."

"I guess most of the fellows do quite a bit of that nowadays," Rudy answered. "Prohibition is a swell idea—but when are we going to have it?"

"That's just it," Sport said with the air of one who has done much thinking on a subject. "If the stuff were either not forbidden, or impossible to get, everything would be all right. But you're tempted both ways as it is now."

For an instant Rudy feared that Sport was about to let slip the fact that the liquor which had stimulated him had been purchased in The Magic Lantern. A sudden thought came to Rudy. He had been supposing that it was old Bland who was doing the bootlegging in the resort. But it easily might be Nick, the floor man, or one of the waiters. Characteristically, he was seeking to think well of a stranger until definite and indisputable evidence had been presented to cause him to think otherwise.

Glancing at Sport and Molly, Rudy saw in their absorption in one another that they wished to be alone. With a brief "Guess I'll be trotting back inside," he turned in the direction of The Magic Lantern. But almost to the lighted doorway he paused. He suddenly knew that he wanted anything except to rejoin the party in Sport's booth, busy, as he knew, at their hilarious game of slopping drinks surreptitiously together. Let them carry on without him.

Slipping around a corner of the building, he located a second bench and meditatively got out his cigarettes. Stranger though he was to the sort of entertainment that was bubbling inside the building at his back, it even lacked the fascination of the unknown.

He looked reflectively at the lighted end of his cigarette. Imagine getting to be like this Bland—lying to your family, holding yourself up as a sort of plaster saint to the college authorities, and peddling booze while you did it. Almost against his will he was being forced to the conclusion that it was the proprietor himself who was doing the bootlegging in the resort.

And if it were Bland, what a chance he was taking! Running the risk that some empty-headed college boy would expose him. And then what? Imagine having to face a break like that!

Naturally, if trouble came, it would mean the end of Molly's chances for any sort of success at the University, where she intended entering, Sport had said, in the fall. Why she would have even a worse time than he, Rudy Bronson, had had!

Voices sifted out into the night. "Everything is all fine. He can complain. Imagine what sort of a reception Bland would get if he went running down to the desk with the yelp that somebody had gone south with a load of his hooch! Just imagine, if you can!"

Rudy glanced around. Behind and above him he saw a pale blotch of window. "You're sure everything's all set down there?" Against the coarse, guttural tones which Rudy recognized as belonging to Nick, the head-waiter, a second man's voice scratched weakly.

"Sure, everything's set," the first speaker agreed heartily. "We'll be waiting with the cars by the S.P. bridge. All you have to do is pull up there—and give us a hand unloading the stuff. I'll have the cars there to take it where I want it to go. Then you turn around and come back, and tell Bland that you got hijacked." He'll steam a little, maybe; but don't worry about him cracking to anybody. There's nobody that he can crack to. Who me? I'll get mine! And you'll get yours, too, when I get it.

"But that ain't all. It ain't just the dough. I'm sicka this collitch bunch, and I'm sicka Bland. It was just like him to try and beat my time, after finding out what kind of dough I been making selling the stuff to these kids. Well, I'll show him who's going to do the peddling here! I'll give him a jolt that will send him back to his soda pop and sandwiches for keeps. And if he smells a rat and gives me the air, all right. I'm sicka it around here anyway."

Rudy slid along the wall and around a corner of the building, laughter bumping his heart against his ribs. A cross-up! A frame, which, at the prices current for liquor, would cost Bland plenty. His face tilted toward the stars. And how the old fool deserved it! Trying to destroy Molly's apparently authentic affection for Sport because Sport drank—and all the while making himself rich by encouraging other boys like Sport to the same habit! Yes, he deserved to lose every cent that he would lose, and the irony of the jest was that he must take that loss without complaint. For the head-waiter was right, there was nobody to whom Bland dared complain.

Then Rudy's laughter halted in mid-career. Nobody? But wasn't there? Would the old man take his loss quietly? Rudy lighted a fresh cigarette. Old Bland was apt to do anything but that! He had a temper—Sport's experiences with him was testimony to that—and before he stopped to think it over, he might get hot-headed and spill the whole affair to the police. And then where would he be? How would he explain that he owned any liquor at all—much less a truck-load? And then where would little Molly be? Gee!

There was only one thing to do. The old man must be told. He raced up the steps. Inside the door of The Magic Lantern he paused. Jean and her party had left. Rudy was glad. With the evening nearing its close, the revelry was at its noisiest pitch. The room was a swirling, trooping mass of figures, and Rudy saw immediately that finding the proprietor in the few precious minutes that remained before his hired man started out with the truck of liquor was going to be impossible unless luck favored him. His teeth caught fretfully on his lower lip. The old man just had to know!

Then, so close that he could touch him with an outstretched hand, he found Bland talking with a tall dark man. Rudy promptly broke in upon their conversation. "Say, Mr. Bland, there's something very important that you should know about! I'm not fooling!"

The proprietor eyed him coldly. "I thought I had your promise to keep those boys quiet, Mr. O'Malley." He motioned to the now vacant booth. "But they got even noisier than before—and out they went! I only let them stay because you were with them, and apparently sober, but when you walked out like that I saw that you weren't to be trusted any more than the rest of them."

"Sure, I know I did," Rudy began; "but listen——"

"I'm not interested! If you boys can't come here and conduct yourselves as you should, I don't want you to come. Rules are rules, and laws are laws. And that's all there is to it." He started with his companion in the direction of his office. "And now, excuse me."

"But, Mr. Bland!"

"You heard what I said." Bland's heavy shoulder shunted him to one side. The office door slammed. A latch clicked.

Crimsoning, Rudy regarded its solid paneling. And this was the man he was trying to save from a frame-up! What a pleasure it would be to see them get away with every nickel the wretched old hypocrite owned! ... But for the sake of Molly, the girl whom he knew to be the one person capable of putting Sport O'Malley on his feet, he dared not let that frame-up go through.

Rudy whirled, making for the exit. In the dusk outside he paused, searching for Sport. In an instant his eyes located him, sitting dejected and alone, on the bench by the tree.

Grasping him by the wrist, Rudy jerked him to his feet. "Don't ask any questions!" he cried. "Just come with me!" And then with the dazed Sport in tow, he plunged off down the road in the direction of the disappearing tail-light of old Bland's delivery truck.

There were two cars parked in the shadow of the S.P. bridge. Two large cars parked in shadows deepened by the dark clothing of the men who watched over them.

As a truck lumbered down the highway, one of these dark figures climbed out of his car and moved forward, signaling with his flashlight. "All right, Fred. It's me, Nick! Right up here."

The truck swung to the side of the road, stopped.

"Say, who's that with——"

On him, and on the second man who had climbed out of his car and joined him, an avalanche abruptly descended from the driver's seat—an avalanche which immediately separated into two distinct and belligerent halves, Rudy Bronson and Sport O'Malley.

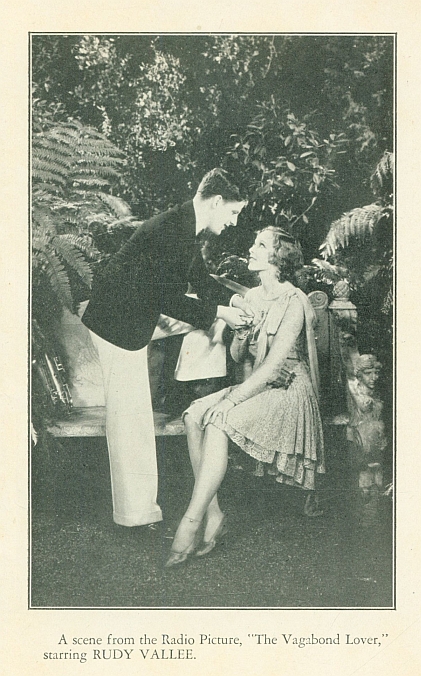

A scene from the Radio Picture, "The Vagabond Lover," starring RUDY VALLEE.

They had caught the truck three miles farther back, following Rudy's hasty explanation to Sport, and the driver who had started with it from The Magic Lantern now reposed in its bottom, neatly trussed. Sport had been in favor of administering a heavy cuffing; but Rudy had restrained him with: "Better save yourself. We might need that pep at the bridge."

He now saw the truth of his words realized. Jumping from the truck, he brought his first blow down with a force which, landing true, might have slain an ox. But it did not land true, and the head-waiter was a husky man. Nick reeled, but he came back a moment later, and came so fast that Rudy soon knew that Sport must attend to the other hijacker as best he could.

"Come on and fight," he snarled ragingly, and Nick obeyed.

It was a grand fight while it lasted, and it lasted a hard, long time. Nick was tough and willing, and not unskilled in the use of his fists. But Rudy, thoroughly aroused by his blows, fought with that grim ferocity of which only mild young men seem capable. He fought without much skill or science, but what he lacked of those attributes he more than compensated for in a determination that was not done even when Nick was stretched in a beaten heap on the highway.

When the head-waiter at last was down, Rudy turned, battered and torn, to see how Sport was faring. But it was apparent immediately that he need have no cause for worry in regard to Sport O'Malley. Sport's face hadn't been improved, and he was blowing like a porpoise as he rested—but it was upon Nick's companion that he rested. "Nice scrap, Rudy," Sport gasped, "I—didn't think—you had it——"

"A very nice scrap indeed!" echoed a voice.

Rudy lifted his throbbing head to face a little group coming forward from a touring car that had come to a stop behind the truck. A group headed by Bland himself. Good, now the old hypocrite could take his hooch and jump in the nearest lake. He was through. Rudy turned a little. And there was Molly. And Glen Patterson, the town's chief-of-police.

"A very nice scrap, indeed!"

Rudy stared at them for a hideous, suspended moment. So Bland had cracked! Had lost his head and cracked, just as he had feared! And here was Molly—Sport's girl—present to learn the truth as soon as Nick opened his mouth, which would be pretty quick now, for the head-waiter had attained his feet and was dizzily eyeing the crowd.

Rudy did not pause to think what he was doing. Across his mind flashed the knowledge that he had flunked out of school, that he was going home a failure. On the other hand, Molly and Sport had all the best of their college life still before them. Still shocked by the terrible beating he had taken, he gave no thought to the consequences of the gesture which he now made. Realizing only that Molly and Sport loved each other, and in his mind therefore must be protected at all cost, he stepped forward and spoke sharply:

"All right, Patterson," he said. "Let's cut the song and dance. There's booze in that truck—and it belongs to me! I guess Mr. Bland here heard that I was running it through to-night, and sent Nick and these other boys out to stop it. Well, they did. And here I am."

He stopped, reeling slightly. There was a silence. Bland's eyes did not move from Rudy's face. "What's in that truck, my boy?" he asked.

"I guess you know what's in there!" Rudy began angrily. Then he checked himself shortly. "Booze! What did you expect—soda-water?"

And then Bland laughed. Uproariously. "Yes, just that exactly. And if I don't find it I've spent a useless half-hour loading it!"

Patterson nudged his deputies toward Nick and the other hijacker. "You know who we came for. Do your stuff."

Rudy's head was whirling, but not so giddily that he could not hear Molly's voice excitedly explaining to Sport: "I saw you boys run after the truck and told Dad. He didn't know what to make of it until he remembered that Rudy had tried to speak to him. He suspected that Rudy had got wind of what Nick was going to do."

Sport caught feebly at the name. "Nick?"

"Yes, the head-waiter! Dad knew that he was selling liquor at The Magic Lantern. Of course he could have fired him outright—but you know how Dad is, always wanting to do a thing so thoroughly. He wanted to get Nick right. Naturally, he could have had him arrested for selling it at the place; but that would have caused a commotion he didn't want. So he fixed up the truck with this load of ginger-ale and had poor old Fred—what did you boys do with him?—hint to Nick that it was liquor."

"So that Nick——?"

"Would do just what he tried to do—hijack it."

"Oh," said Sport. Slowly he turned to look at Rudy. "And when it looked as though the cops had crashed in on our little plan to save Mr. Bland," he said slowly, "you stepped in and were going to shoulder the whole thing. Why did you do that, Rudy?"

Rudy turned away, his face blazing. Not for anything in the world would he have told these listening people that to his loveless life, love seemed the most precious thing in the world. He could not tell Sport that his quixotic gesture had been made to save a girl he scarcely knew—and, indirectly, Sport himself.

But Molly was a wise young woman. She looked from Sport's face to Rudy's. "I think I know why he did it, Sport. And if you think a moment, you'll realize why he did it, too. Can't you see that he thought by saving Dad he would be saving me—and us?"

Sport's hand shot out quickly, clasping Rudy's in a promise of everlasting regard. "Where have you been keeping yourself all this time, fella? Holy cow, you may be a bum saxophonist—but I'm thinking that you're just about the greatest guy in the world!"

There was not much conversation on the way back to The Magic Lantern. Rudy, riding with Mr. Bland in the front seat, could find little to say as the car bucketed over the uncertain roads. Sport, with her father's objections temporarily stayed, was quiet with Molly in the back seat.

At the resort, Mr. Bland pulled the car up with a roar of exhaust. The long building was darkened, its pale windows contrasting eerily with the somber darkness of the surrounding walls. The parked cars were gone, and the night seemed doubly silent because of its present variation from the scene which it had presented not long before.

"Well, here we are again," Sport observed in an attempt at lightness. "But too late to do anything but go home. What say, Rudy?"

"It's about time, I guess," Rudy agreed. He climbed from the car, and as Sport assisted Molly down, the girl came to him impulsively. "I just want to thank you again, Rudy," she said. "That was about the nicest, craziest thing I ever saw—and I want you to know that I appreciate it."

"It wasn't anything," Rudy protested.

"Boy, you're wrong!" Sport cried. "But let's be on our way. Mr. Bland wants to close up."

In truth, the squat proprietor seemed to wish to make some sort of speech of gratitude for what Rudy had attempted to do for him. But a natural inarticulateness hampered him, and he apparently was ready to let the praise of the others speak for him, too. He contented himself with, "Come and see us any time you feel like it, Mr. O'Malley," and tramped off in the direction of his office.

Sport bid Molly a brief good-night, and the two young men turned toward Sport's car. Thus the incident evidently was brought to a close. But both knew that it was the cornerstone of a friendship that was to gain an increasing value as time brought them more definitely together.

When the lights of the University lay ahead of them, Sport said: "I got my grades after I left you this afternoon, Rudy. No, I didn't roll out—but I came mighty close to it." He hesitated, as if loath to be seen in any but his usual, care-free frame of mind. "It's sort of brought me up short, seeing you flunk. It doesn't seem fair—you being expelled just because you wanted to do something that was beyond you—and me staying in when I've given hardly a thought to anything but whoopee-making."

Rudy slumped down on the base of his spine, his eyes looking straight down the road. "Maybe it's brought me up short, too, Sport. It's made me see that a chap who wants to succeed has got to work hard—harder than he ever thought of doing. Oh, I put in a lot of time on Ted Grant's course. But I haven't put in enough, that's obvious. I don't know of anything I want in this world quite so much as to be a top-notch musician—and I'm going to be one!"

"That's the boy!" Sport exclaimed enthusiastically. "You keep up that spirit, and I don't see how I can keep you off my band at home this summer."

"Do you mean that, Sport? That you'll give me a chance?"

"Give you a chance? I'll say I will!" They were trundling rapidly down the sacred precincts of Fraternity Row, past house after house of the great national organizations. Some showed splotches of light, betokening the studious; others were spectacular with the lights of late dances.

By University ruling, The Magic Lantern was forced to close at an earlier hour than that designated by the authorities as stopping time for the school affairs. On this last night of the college year, even this ban had been removed. Now, at close to one o'clock, several dances still were in progress.

"Want to crash one?" Sport asked carelessly.

Rudy shook his head. His characteristic shyness alarmed him at the idea which came to Sport with such little difficulty. "I guess I better be making for the hay," he said. "You go ahead, Sport, if you want to. I don't mind walking the rest of the way over to my dorm."

"Say, what do you take me for? Us separate on your last night in school? I should say not! I tell you, though," he went on; "so long as we're not dressed for any hop, let's go on over to my house and see if any of the dear brothers are still about looking for fun."

Rudy smiled. It was distressingly apparent that trying to curb Sport's eager spirit was like trying to put a check on a gushing, hilariously youthful waterfall. For an instant he was prompted to insist on going home to bed. But then he remembered that this was his last night as a member of the State University. With this single remaining bit of evening all that was left to him of the happy time toward which he had looked for so long, the idea of bed suddenly seemed obnoxious.

"A grand idea," he said. "I guess we've got it coming to us."

"That's talking!" Sport stepped on the accelerator, and soon they were drawing up in front of a large Colonial mansion set among a gracious grove of trees. "Here we are! Out you go!"

A wry smile twisted Rudy's lips as he followed Sport up the walk to the fraternity house. It struck him as rather cruelly funny that on his last night at the University he should be visiting one of its envied organizations for the first time.

In the living room they found two young men sitting on a long divan. As Sport and Rudy entered they glanced about. Then one of them once more lowered his face into his hands. The newcomers noted that it was reddened and pulpy with weeping. The second boy patted one of his rumpled shoulders. "'S all right, Mort. 'S all right. It's got to happen sometime—to everyone. Come on, kid, buck up!"

"What's the matter, Morton?" Sport asked. "You fellas know Rudy Bronson? Bill Morton, Fenwick Forbes," he introduced them. "My pal, Rudy Bronson."

Morton's handkerchief went to his nose. He bobbed his head at Rudy. "Sorry to be like this," he said with an effort at self-control. "But I flunked out today——

"Whoops," said Sport, "that puts you and Rudy here in the same boat."

The other youth on the divan fished a crumpled packet of cigarettes from his coat. "I was just telling him he ought to be yelping with joy," he commented. "No more books, nor teachers' dirty looks. Hot dog!"

"Aw," Morton again used his handkerchief, "that's just the trouble with you, Fen. Nothing means anything to you. You just live in a world of your own, and that satisfies you. But I'm different. If I like something I stay liking it. And I've got attached," a sob broke from him to mingle wretchedly with the ascending cigarette smoke, "I've got attached to the fellas and the University and everything. And I don't want to leave them. Any more than I'll bet Bronson there does!"

Sobs shuddered anew from the pillow in which he buried his face. Terrible sounds—a boy-man in pain.

"I know how he feels," Rudy said quietly.

Forbes and Sport did their best to console the unhappy Morton, but their efforts were of little avail. He rapidly was working himself into something close to hysteria. Suddenly Sport got to his feet and ran up the stairs to the floor above. In a few minutes he returned, a bottle in his hand.

"Up and at 'em, Mort, my son. Here is relief in a concentrated form." He held the cool glass against Morton's flushed face. "Imprisoned laughter of the maidens of Louisville. Now who's got a corkscrew?"

Morton grasped at the bottle. "How——?"

"Emery's trunk. Can you imagine it, he left his keys on his dresser—and after telephoning to his bootlegger in that bull-fiddle voice of his. He'll howl his head off——"

"Let him howl," Forbes said briefly. "I spent twenty bucks pledging that bimbo. Got a corkscrew, Mort?"

"No. Knock it out with the flat of your hand on the bottom of the bottle."

"Nothing stirring," said Sport. "The last time I did that the bottle broke and I nearly cut off my hand. Look at the scar."

"Tough—but come on. Bite the top off if you can't do anything else. If Emery comes in——"

"Let him come!"

Suddenly the cork yielded to the prying of Sport's penknife. Forbes ran out into the kitchen, to return with a quartet of glasses. "Why'nt you bring some clean ones?" Sport demanded. "What'll Rudy think of us?"

"Aw, you don't care about a little thing like that, do you, Rudy? Don't be an old woman, Sport."

"Say, talk nice to me or I won't play in your backyard!"

"No offence, Mr. O'Malley."

"'Pology accepted, Mr. Forbes."

"Come on, you guys," said Morton thirstily. It was apparent that the clever Sport successfully had diverted the boy's mind from himself and his troubles. Looking at Rudy, Sport wondered if he had been as successful there. But, Rudy, standing quietly with his glass in his hand and a slight smile on his handsome face, was as inscrutable and difficult for him to judge as ever. An odd one, this Rudy Bronson. But what a boy!

"Well, here's how!" Sport cried.

"Mud in your eye."

They took down their drinks, and exchanged water-dimmed glances, their mouths wryly puckered.

"Yow! Gimme a chaser of nitric acid!"

"You know," said Forbes bitterly. "I always was sorry I spent that twenty bucks on that egg Emery. Now I'm certain I am. Imagine buying such stuff."

Dubiously Sport inspected the label. "I wonder if he had another bottle of this. I haven't seen him around to-day, have you?"

"No, and I don't want to!"

"Oh, well——"

"All right, but let's get it down fast."

Rudy refused the second drink. "I haven't got this one finished yet," he protested.

"I don't blame you for hedging," Sport told him. "This stuff feels like a wildcat clawing down your throat. The only thing to do, though, is to get them down fast."

"To the sheepskin, Mr. Bronson," said Morton cheerfully. "To the sacred skin of the sheep for which we fought and bled and died countless deaths—only to get gypped and lose them."

"To the skins of our particular sheep, Mr. Morton," Rudy answered his toast.

"I stand corrected. Corrected as I can be. You know, fellas," he said. "This is just what I needed. My mind is beginning to expand. I quicken to life. I breathe. I expand."

They applauded him vigorously. He looked at them in surprise. "Do I sound silly? Am I getting tight?"

"Go right ahead," Rudy told him. "It's just what you needed."

"This is a swell kid, Sport," said Morton. "Where'd you get him? He's a philosopher. I like philosophers. The blinders are beginning to drop from my eyes. I see that before us lies—not the end—but the beginning. Do you see that, too, Rudy?"

"Yes," Rudy answered, "I see that, too. If you want a thing badly enough, there never is any end. You just keep going on, seeking, until you get it. And then you go on some more."

Suddenly Morton collapsed. "That's what I think, all right," he muttered. "Good egg, Rudy——"

Sport and Forbes lifted him, half carrying him, toward the stairs. "Poor kid's had a tough day, Rudy. We better take him up to bed."

"Fair enough," Rudy said. "I've got to get my things together if I'm leaving in the morning. You coming with me, Sport?"

"I'll say I am. I'll be ready when you come around. 'Night."

"'Night, Sport," Rudy said. "'Night, Forbes."

He went down the steps and out the walk. When he reached the sidewalk it behaved strangely. Objects passed in a blur. The little he had had to drink, coupled with his fatigue and excitement from the fight, had been enough to affect him.

Down the street he passed. He heard sounds of life going on about him, but was unable to attribute them to any definite source. It was all rather peculiar, and he paused to rid himself of the odd sensation.

Painfully his mental processes retraced their giddy path. The fraternity house, with its warm spirit of comradeship, the fight, The Magic Lantern, seeing Jean Whitehall——

Jean Whitehall. At thought of that magic name a sudden consciousness was borne to Rudy of the major reason why he had attempted to prevent any injury to the love of Molly and Sport. It was because he mentally had replaced Molly with Jean, and Sport with himself; and the idea of any danger coming to an event for which he wished so devoutly had been nothing short of insupportable.

A delicate tendril of music came to him, and looking about he saw that he was standing near the corner which held the local chapter house of one of the oldest and finest of national sororities. Jean's house!

Inside a dance was in progress. Across the lighted windows figures drifted as if under the influence of some deeply potent spell. He saw Jean pass by in the arms of the captain of the varsity. And as she did so, he caught a familiar melody from the orchestra.

Tempted by the curious aptness of the lyric, he waited until he thought Jean must be near the window again. Then, in a voice of gentle and persuasive loveliness, he began to sing:

"I love you, believe me, I love you,

This theme is the dream of my heart.

I need you, believe me, I need you,

I'll be blue when we two are apart—

You'll be my one inspiration,

You've changed my whole life from the start.

I love you, believe me, I love you,—

This theme is the dream of my heart!"

Then, not pausing to discover if he had been heard, Rudy broke into a run in the direction of his dormitory. His heart was high with a fierce and almost overwhelming delight. He had sung a love song to Jean—even though she had not heard!

But she had heard. Yet when she reached the window, there was no one in the street below.

"Just some punk freshman," the football captain told her.

Jean shook her head slowly. "Don't say that, Larry. I thought it was beautiful."

At ten o'clock the next morning Rudy had his belongings stacked in the middle of a denuded room. The walls were bare, the window seat had been shorn of its pillows, and the study table looked strange and forlorn minus its customary cargo of books and papers.

So this was the end of his college life! A far less spectacular departure than he had imagined. Those old dreams came back momentarily to haunt him—the Rudy Bronson he had pictured before entering the University, leaving in a blaze of glory on the shoulders of admiring classmates. Bells ringing, whistles shrilling, cheer-leaders leaping about with writhing arms as they cried: "Three big ones for the greatest hero the school has ever known. All right now—Bronson! Bronson! Bronson!"

He sighed. Quite different, this. With a last glance about the bare walls, he loaded himself with his meager possessions and went out the door and down the stairs.

The landlord appeared from his subterranean retreat as he was dumping his bags in the back of his flivver. "Sorry to see you go, Mr. Bronson. Heaven knows you've been a lot better tenant than most of the boys I get here. You've been quiet, and haven't broken a thing."

Rudy's mouth bent in a small smile. "Pretty model sort, eh? And yet the University says I better get out and stay out."

"You wouldn't have flunked if you had paid more attention to your studies and less to that saxophone," the old man told him. "Land sakes, the way you went at that thing a body would think you intended to take it up professionally."

"And that," Rudy answered coolly, "is just what I intend to do."

"But I thought you couldn't even make the school band!"

"That's true. But that was because I wasn't ready yet. I'm taking a course of lessons from Ted Grant, the greatest saxophonist in the world, and—" his hands clenched—"some time I'll show all these guys here that I'm a real musician! I haven't got very far along in my course yet—but when I've finished it, I bet there isn't an orchestra in the country but will be glad to have me in it!"

The landlord shook his head rather dolefully. "Well, ambition is a good thing, I guess. But never let it run away with you, says I. That's a rule I've always followed."

"Apparently," Rudy answered with a smile. He climbed beneath the wheel and tramped on the starter. "Good-by, Mr. Justin. Watch for my name in the papers."

The old man moved back into his house without a reply. But it was apparent what he was thinking.

Spinning in the direction of Sport O'Malley's fraternity house, Rudy's face was grim. Why was it that none of them were willing to credit him with any skill? Had he been so rotten that they thought he never could be any better? But he'd show them! He'd stick at his practise until one and all would be forced to admit they had been wrong about his natural ability. He would make good if he had to blow his heart out to do so!

Sport was, strangely enough, ready to leave when Rudy pulled up before the colonial front of his fraternity home. He came down the walk with two bulging suit cases. These he dropped unceremoniously in the tonneau with Rudy's things. "Waterville next stop," he said briefly.

Rudy pressed down the clutch and with a roar of ancient mechanism the little car put off in the direction of the small Connecticut town which the two boys called home.

"Like to stop at Bland's before we hit the highway?" Rudy asked.

Sport shook his head. "I said good-by on the telephone," he said. "Thanks to you, the old man's got a pretty good opinion of me now. If I went over there I might get sentimental, saying fond farewells to Molly, and get tossed out on my ear."

He spoke with his usual lightness, but there was a troubled and unhappy note in his voice which told Rudy that his casualness was mere pretense. "You'll be back next semester, Sport," he said comfortingly. "Don't take it so hard. You look as if you'd been drawn through a knot-hole."

Sport grinned. "Oh, I hate to leave all right. But that's only part of the reason I look tough. It's those examinations. I let everything go until the last minute, and then tried to crowd all my studying into a few nights. Gee! cramming like that is enough to sour you on the whole of college. And then you're not sure until the last minute whether or not you sopped up enough facts to get you through."

They rode for a few minutes in silence. Then Rudy suddenly asked. "Do you really think college is worth while, Sport?"

Sport shrugged. "Who can tell?"

"You can, of course!"

Sport did not answer for a time. "Really," he said at length, "I can't say. I like it, that's true enough. But if I should quit and go to work, whether I'd eventually be a better business man or barber or something else—well, that's something else. And as I see it that's not the important thing. College doesn't seem to me to fit you for the particular thing you want to do, but to, well, grease you so that you'll slip a little more readily through all of life."

"But what has it done for you thus far, Sport? Here you've been dashing about for two years, making whoopee, having a good time. And you'll probably do the same for two more, unless Molly takes you in hand. What if you'd stop now—or get stopped, like I did. Don't you think that you'd get a two years earlier start?"

"I guess that would be so if you're meaning the ordinary business routine, with the automatic method of advancing employees—one goes out and one goes up. But even if I did want to enter that kind of a business—which I don't!—what if some other industrious lad had hopped onto the adding machine sooner than I? Ye gods, you only work eight hours out of the twenty-four—what about the rest of the time?"

Rudy thought of his saxophone. "He might know that he was missing something, and study all the harder in his spare time."

But Sport's mind was fixed firmly on a different type of livelihood than that in Rudy's. "Maybe," he admitted, "but the chances are that while the boy who went to work was associating with his fellow clerks and salesmen, the one who didn't would be associating with people who happily didn't know an invoice from a bank messenger. On the other hand, they do know, perhaps, a great deal concerning the art of living."

"But are those people real? And is what they have to teach of any real value to you?"

Sport moved his shoulders negligently. "Outside of one or two or three, it will make little difference—either to them or to me—if our paths never cross again. But here's the point: we did learn from each other. Forbes and Morton and I, for instance, have traded contacts. If we never see each other again in all our lives, we will have gained that. We've taught each other to sharpen our social senses. And believe you me, that's no little thing!"

Rudy looked down the road. "That's pretty unsentimental talk from a fellow who has just walked out of his fraternity house."

"You're a nice kid, Rudy," Sport laughed, "but you take things too seriously. This fraternity brotherhood chatter is a lot of bunk. We're in fraternities because that's the nicest way to live while we're in college. But we don't join them because of any great and over-powering desire to become banded with a lot of men who, a week before we enter the University, we've never seen!"

"Maybe you'll think differently when September rolls around. But about this summer. Are you going to hit the ball? I should think you'd be a little tired of resting."

"Resting my eye! A fine lot of resting I've done in this past year! I don't know where all my time went—but I don't recall that much of it was spent in resting. Or studying or meditating or exercising, either, so far as that goes."

"Still, you're not sorry you went through it."

"Not in the least. There's plenty of time for me to do the things I should do. Maybe I'll do them next year." He stretched expansively. "College is a little bit of all right, Rudy. I'll be back next year, you can bet."