FACING OLD AGE

A STUDY OF OLD AGE DEPENDENCY IN THE UNITED STATES AND OLD AGE PENSIONS

Title: Facing old age

a study of old age dependency in the United States and old age pensions

Author: Abraham Epstein

Release date: December 29, 2025 [eBook #77562]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1922

Credits: Richard Tonsing, Charlene Taylor, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

“The days of our years are three score years and ten; and if by reason of strength they be four score years, yet is their strength labour and sorrow; for it is soon cut off and we fly away.”—90th Psalm.

| INTRODUCTION by John B. Andrews | xiii | ||

| PART I | |||

| ACTUAL CONDITION OF THE AGED | |||

| CHAPTER 1.—AFTER SIXTY—WHAT? | 1 | ||

| CHAPTER 2.—THE INDUSTRIAL SCRAP-HEAP, | 8 | ||

| CHAPTER 3.—PASSING BEYOND THE HALF CENTURY MARK, | 22 | ||

| CHAPTER 4.—THE COST OF FOLLOWING THE OSTRICH POLICY, | 46 | ||

| a—The Cost to the Tax-payer, | 46 | ||

| b—The Cost to the Institutional Inmates or Recipients of Charity, | 51 | ||

| c—The Cost to Industry, | 58 | ||

| d—The Cost to the Younger Generation and Society in General, | 59 | ||

| PART II | |||

| CAUSES OF OLD AGE DEPENDENCY | |||

| CHAPTER 5.—INDIVIDUAL CAUSES, | 67 | ||

| a—Superannuation, | 68 | ||

| b—Waning Earning Power, | 69 | ||

| c—Lack of Family Connections, | 71 | ||

| d—Industrial Accidents and Sickness, | 71 | ||

| CHAPTER 6.—THE CHASM BETWEEN THE COST OF LIVING AND WAGES, | 85 | ||

| CHAPTER 7.—SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND MORAL CAUSES, | 124 | ||

| a—Unemployment, | 124 | ||

| b—Strikes, | 130 | ||

| c—General Misfortune, | 133 | ||

| d—The Part Played by Moral Character, | 135 | ||

| viii | |||

| PART III | |||

| EXISTING METHODS OF RELIEF | |||

| CHAPTER 8.—INDIVIDUAL SAVINGS AND INDUSTRIAL PENSIONS, | 141 | ||

| a—Individual Savings, | 141 | ||

| b—Individual Pensions, | 147 | ||

| c—Railroad Pensions, | 158 | ||

| CHAPTER 9.—FEDERAL, STATE & MUNICIPAL EMPLOYÉS’ PENSIONS, | 162 | ||

| a—Introduction | |||

| b—Federal Employés’ Pensions, | 167 | ||

| c—Military Pensions, | 172 | ||

| d—Pensions for State Employés, | 176 | ||

| e—Municipal Employés’ Pensions, | 178 | ||

| f—Teachers’ Retirement Funds, | 183 | ||

| CHAPTER 10.—OLD AGE BENEFITS OF FRATERNAL AND TRADE UNION ORGANIZATIONS, | 190 | ||

| a—Fraternal Society Benefits, | 190 | ||

| b—Trade Union Superannuation Benefits, | 193 | ||

| PART IV | |||

| OLD AGE PENSIONS; WHAT THEY ARE AND THEIR OUTLOOK FOR THE U. S. | |||

| CHAPTER 11.—THE PURPOSE AND NATURE OF PENSIONS, | 213 | ||

| a—Introduction | |||

| b—Voluntary Insurance, | 216 | ||

| c—Compulsory-Contributory Insurance, | 218 | ||

| d—Straight or Non-Contributory Pensions, | 223 | ||

| e—Arguments Against Non-Contributory Pensions, | 228 | ||

| CHAPTER 12.—THE PENSION MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES, | 244 | ||

| ix | |||

| PART V | |||

| PENSION SYSTEMS OF FOREIGN COUNTRIES AND VARIOUS STATES | |||

| CHAPTER 13.—VOLUNTARY & SUBSIDIZED SYSTEMS OF OLD AGE INSURANCE, | 265 | ||

| a—Introduction | |||

| b—Belgium, | 266 | ||

| c—Canada, | 269 | ||

| d—Japan, | 271 | ||

| e—Switzerland, | 272 | ||

| f—Massachusetts, | 275 | ||

| g—Wisconsin, | 278 | ||

| CHAPTER 14.—COMPULSORY-CONTRIBUTORY OLD AGE INSURANCE, | 280 | ||

| a—Austria, | 280 | ||

| b—Czecho-Slovakia, | 282 | ||

| c—Chile, | 283 | ||

| d—France, | 284 | ||

| e—Germany, | 288 | ||

| f—Greece, | 295 | ||

| g—Iceland, | 295 | ||

| h—Italy, | 296 | ||

| i—Luxemburg, | 300 | ||

| j—Netherlands, | 302 | ||

| k—Norway, | 304 | ||

| l—Portugal, | 306 | ||

| m—Roumania, | 308 | ||

| n—Russia, | 308 | ||

| o—Spain, | 309 | ||

| p—Sweden, | 312 | ||

| q—Switzerland, | 315 | ||

| CHAPTER 15.—NON-CONTRIBUTORY OR STRAIGHT OLD AGE PENSIONS SYSTEMS, | 318 | ||

| a—Alaska, | 318 | ||

| b—Arizona, | 319 | ||

| c—Australia, | 320 | ||

| d—Denmark, | 322 | ||

| e—Great Britain, | 324 | ||

| f—New Zealand, | 332 | ||

| g—Uruguay, | 335 | ||

| x | |||

| PART VI | |||

| APPENDIX | |||

| A—Bill Introduced by Senator McNary, | 339 | ||

| B—Bill Presented by the Commission to the 1921 Pennsylvania State Legislature, | 342 | ||

| a—Administration, | 343 | ||

| b—Allowance, | 344 | ||

| c—Qualifications of Claimants, | 345 | ||

| d—Property Qualifications, | 345 | ||

| e—Calculations of Income, | 346 | ||

| f—How Administered, | 346 | ||

| g—Fines, Punishment and Criminal Procedure, | 349 | ||

| h—Funds and Expenses, | 351 | ||

| i—Annual Report Hearings Etc., | 351 | ||

This book is, frankly, an appeal for social action. It attempts to set forth the need for a constructive policy with regard to the aged. While the tide in social legislation seems to have turned during the past few years, so that in many states attempts are being made to repeal long sought for protective measures, there is on the other hand evidence of an awakening of many to the realization that the problem faced by the aged cannot be ignored or postponed much longer. There is a growing consciousness that social action is as inevitable for the United States as it was in most countries abroad. Suffice it to mention the many state commissions investigating the problem recently, the great number of industrial concerns grappling with it, and the numerous resolutions adopted by many church bodies, fraternal orders and trade union organizations endorsing government legislation with regard to the aged. The fact that twenty-six foreign countries have already adopted some form of social action for the relief of the aged is indicative further that the problem is a matter for social rather than for individual solution.

The writer did not approach the question of insurance with any preconceived notions. Three years of first hand study of the problems of the aged in one of our leading industrial states—Pennsylvania—convinces him, however, that no other way out is feasible. Our present methods, in dealing with the aged are antiquated, inefficient, ineffective, costly and demoralizing. Some constructive social policy must be inaugurated. In discussing the plans suggested for adoption, an earnest effort has been made to present the merits and demerits of each proposed scheme of legislation impartially. The xiiwriter may be accused, however, of a certain bias in connection with this presentation, to which he pleads guilty. Absolute impartiality in matters of social policy is only possible when convictions and interests are slight. After everything has been said and done it remains for the individual to determine what he understands by “right” and “truth,” and he can only be guided by his own conscience and convictions.

In describing the pension systems of foreign governments, an attempt has been made to bring the facts up to date. This was only partly successful. Since the beginning of the war, European documents which were readily obtainable under normal conditions, have been very meagre and limited, and some reports have not been brought up to date.

The subject matter in the book beginning with Chapter Eight has been drawn liberally from the report of the Pennsylvania Commission on Old Age Pensions which was written by the author in 1919. Everywhere, however, an attempt has been made to collect and present the latest available data.

The writer wishes to record his debt of gratitude to the Pennsylvania Commission on Old Age Pensions, which has so generously extended to him the time and the office facilities which were necessary in the preparation of this volume. The keen interest of members in the problem has been a constant encouragement and source of inspiration. He also wishes to acknowledge his indebtedness for helpful suggestions in preparing the manuscript to Professor Henry R. Seager of Columbia University, Mr. George M. P. Baird, formerly of the University of Pittsburgh, Miss Mary Bogue of the Mothers’ Assistance Fund of Pennsylvania, Miss Theresa Wolfson of the Consumers’ League of New York State, and Mrs. Helen Glenn Tyson, of the University of Pittsburgh.

During the past dozen years, America has made her greatest progress in manifesting public concern for her large numbers of bread-winners who are annually rendered incapable of self-support by accident, sickness, unemployment and old age. These four great contingencies in the life of the wage-earner—long recognized as social problems of pressing importance in countries of earlier industrial development—now claim our increasing attention.

The free access to tillable land, which long offered “another chance” to the dissatisfied industrial employee, has become to millions of American city dwellers nothing more than a dream. Meanwhile, as our country has become increasingly industrialized we have invited to our shores millions upon millions of immigrants whose course of thinking has not been influenced by American social and economic opportunities of the past. We have a diverse population that yearly becomes more and more like the populations of those older countries, and still less akin to our earlier sturdy sons of immigrants who half a century ago could and did sing “Uncle Sam is rich enough to give us all a farm!”

With the ever-increasing demand for essential workers in our industries has come a condition where matter-of-fact statisticians report 3,000,000 disabling accidents yearly causing 50,000,000 days lost time; and 250,000,000 days lost annually on account of sickness; while “four times in a single generation the numbers of the unemployed in the United States have been counted by millions and the idle capital of the country has been xivcounted by the billions of dollars.” All of this has its effect upon savings for old age.

The United States, a younger nation, and with traditions of individualism based on earlier opportunities, has been slower to face these industrial problems, but recently there have been signs of an awakening sense of responsibility. Voluntary efforts of trade unions and humanitarian experiments of the more thoughtful employers have blazed the way towards social action. Half-a-hundred official investigating commissions have collected, classified and disseminated information—resulting in most instances in recommendations for American legislation.

The industrial accident problem has been attacked in America by an intelligent method of social insurance, and although fully adequate benefits are not yet offered, within twelve years no less than forty-seven workmen’s compensation laws have been adopted. Naturally enough, the equally important problem of wage-earners’ sickness is now under constant investigation and the public is learning to look upon it as a subject which will in future claim far more sweeping legislative attention. Unemployment, the most complex of all industrial questions, periodically forces its way to the front pages of our newspapers, and in 1921 the Senate Judiciary Committee in one state legislature, by unanimous vote, recommended the adoption of compulsory unemployment compensation. The rapid spread of American social legislation, when once initiated, is strikingly illustrated by the adoption of Mothers’ Pension Laws in forty-one states and territories during the nine years 1911 to 1919.

Old age dependency has been less talked about, partly no doubt because this evil presents itself less dramatically—its saddest victims usually being hidden from the public eye—partly also, because fewer people realize its connection with our modern industrial methods. Men have always grown old, it is true, but now when they must seek work in a system whose xvdemands for intense application or speed are often merciless, they are rejected as unemployable and find themselves without means of support at an earlier age. In exceptionally fatiguing or dangerous trades the “human scrap-heap” age is distressingly low. A system which in the past has paid wages far too low to permit the average workmen to prepare for old age by saving, is annually refusing jobs to thousands who are “too old” to do its work.

The haphazard attempts to meet this problem through public or private charity, employers’ pension systems and trade union or fraternal society benefits, have proved to be not only inadequate and inhumane, but also both costly and wasteful. Recently great progress has been made toward scientific handling of the problem as it affects public employees, especially teachers.

The United States Government and many states and cities have organized successful pension systems for their public servants. A valuable record of a large scale American experiment is furnished in the report of the first year’s experience of the federal government with its pension plan covering nearly one-third of a million civilian employees in the classified service. But the problem of old age dependency for private employments, has not been adequately met in any part of the United States. Fortunately, signs of intelligent interest are becoming more and more evident. Half a dozen states have appointed commissions to study the subject, valuable material has been gathered, and bills drafted. Unofficial but equally interesting investigations have been carried on by labor organizations and fraternal orders. Americans are recognizing the urgency of this problem and are seeking authoritative information.

Not since the publication in 1912 of Mr. Squier’s “Old Age Dependency in the United States,” have we had a new and comprehensive book treating this problem. Appearing now when there is both need and demand for such information, Mr. Epstein’s xvivolume is especially timely and valuable. His experience as Director of the Pennsylvania Commission on Old Age Pensions has given him an exceptional opportunity for intensive study of the field, and the book contains a wealth of modern, well organized material presented from the modern American point of view. It is decidedly the most convenient compilation of up-to-date information on this very important subject.

The progress of a nation may be marked by the care which it provides for its aged. The nineteenth-century doctrine of laissez-faire, as applied to aged and superannuated wage-earners, has been practically discarded by most civilized nations, including every English-speaking country in the world except the United States. Instead, a definite policy of social legislation has superseded the chaotic and degrading practices of alms-giving and poor relief. The enemies of social legislation in this country, however, still contend that the millions of workers in our industries “are working for themselves; that they have unrestricted control over the expenditures of their incomes, and that they have their future fate in their own hands.”[1] As a nation, we are still frightened at the thought of becoming “our brother’s keeper.” In spite of superior wealth and accumulation of goods, our national conscience is not in the least disturbed when the former creators of our wealth are forced to drag out their final days, physically exhausted, friendless and destitute, in the wretched confines of a poorhouse, or to receive some other degrading and humiliating form of pauper relief.

To protect the wage-earners in their old age is merely to recognize the changes wrought in our industrial system. Old age was not universally dreaded before the industrial revolution or the advent of the modern factory system. On the contrary, it was even looked forward to with a certain feeling of satisfaction and accomplishment. In the patriarchal state, old age 2was revered and the aged person in tribal economy was considered the embodiment of wisdom and authority.[2] In an earlier system where the tribe or clan was a unit, the old remained supreme and their superiority continued beyond their productive years. Under the feudal system the lord was obliged to take care of his workers in case of sickness, accident, and old age. The artisan or labourer in mediaeval times ordinarily continued to work as long as he could produce something. In the early state of the factory system also the economic relations between men were more inter-dependent and of a more permanent character. The labour contract was usually lifelong, and the employer took a personal interest in the welfare of his workers. Again, in an agricultural society men and women are still useful in their old age, and their activities rarely cease before actual senility has set in. Under these conditions, men and women did not look with dread upon approaching economic old age, and there was little necessity for individual provision against it.

Our modern wage system presents an entirely different spectacle. Today, most men and women are dependent upon their daily toil for their daily bread. The pace of the present industrial system tends to wear workmen out rapidly. Fatigue produced by over speeding as well as the hazards characteristic of modern industry have shortened the period of effective 3production of industrial workers. Increased industrial efficiency, “scientific management,” the “bonus system” and specialized and standardized production are forces which are increasingly using up human energy at greater speed and in a briefer period of life. Often, at the age when the worker in agricultural pursuits is considered to be in his prime, the industrial worker is found to have become worn out and old. And, in industry, once the approach of old age becomes apparent, the worker is thrown upon his own resources.

Unlike the gradual physical decline in old age characteristic of agricultural and less developed industrial countries, economic superannuation, which takes place abruptly and earlier in life, stands like a spectre before industrial workers. Few industrial wage-earners may expect to continue at their accustomed work until the end of their days. Because of the developed efficiency standards, so essential to successful business, the wage-earner finds the problem of old age principally one either of increasing inability to find employment or at best of employment at low compensation. After a certain age has been attained, although the worker may still be able to do fair work, if he is no longer able to maintain his former speed, he is likely to be eliminated from industry. The old man finds it difficult to secure work even at low wages. Rowntree and Lasker, in a study of unemployment in Great Britain, found old age the primary causal factor in 23.3 per cent. of the cases studied. These investigators assert that: “It is unfortunately indisputable that when a skilled worker gets past 40, he finds it very difficult to meet with an employer who is willing to give him regular work.”[3] What is true in England in this respect is equally true in the United States.

Contrary to the conditions existing in the professions, in business, or in politics, where men often do their best work at about the age of 60, and where experience and long standing 4count a great deal, the industrial worker finds himself not infrequently eliminated from productive industry after passing his fiftieth birthday. With the continuous introduction of new machinery and newer processes of work, age and experience are of little value. The labor contract in the factory system is made only for a temporary period, and the employer ordinarily does not feel under obligation to support his workers during their declining years of inactivity. Thus it is not uncommon today to find aged and decrepit workers relegated to the industrial scrap-heap as useless and of no economic value. Says Prof. E. T. Devine:

“It is notorious that the insatiable factory wears out its workers with great rapidity. As it scraps machinery so it scraps human beings. The young, the vigorous, the adaptable, the supple of limb, the alert of mind, are in demand. In business and in the professions maturity of judgment and ripened experience offset, to some extent, the disadvantage of old age; but in the factory and on the railway, with spade and pick, at the spindle, at the steel converters there are no offsets. Middle age is old age, and the worn-out worker, if he has no children and if he has no savings, becomes an item in the aggregate of the unemployed. The veteran of industry who is crowded out by changes in processes and the use of new machinery is obviously an instance of maladjustment.”[4]

It will become evident in the discussions that follow, that the problem facing the aged today is largely the creation of the modern machine industry with its components of specialization, speed, and strain. It is a result of the elimination of large numbers of workers as soon as they are unable to keep up fully with the demands of modern methods of production. The introduction of new inventions and more specialized machinery, inevitable in the evolutionary process, while resulting in an ultimate good, always involves the replacing of men, which in the case of the aged, has an absolutely harmful effect, as it 5leaves them destitute. For, in addition to preventing their continuity in their regular work, it precludes also their adaptability to newer processes of work. The lot of the aged and superannuated worker is thus adversely affected by practically every step of industrial progress; and little or no benefit is derived by old wage-earners from industrial improvements.

Not infrequently when the difficulties facing the aged wage-earners are set forth, the smug and complacent citizen replies: “As one makes his bed, so he lies.” Poverty in old age, it is asserted, is chiefly the result of improvidence, intemperance, extravagance, thriftlessness, or similar vices. As a result of this convenient philosophy, we have made practically no attempt at the amelioration of the adverse conditions facing old age. More and more, however, it is coming to be recognized by all students of social and economic conditions that with the cost of living soaring continuously the great masses of wage-earners cannot lay aside from current wages sufficient to provide for possible emergencies. This has become especially patent as careful data on wages and incomes have been gathered by such students and responsible organizations as, Chapin, Ryan, Streightoff, Nearing, the United States Census, the Bureau of Labor Statistics in the United States Department of Labor, the National Industrial Conference Board, and many of the state bureaus. This entire problem will be discussed at length in Chapter VI. It is sufficient to state here, that under present economic conditions and those of the past decade, the average wage-earning family must indeed be possessed of great resourcefulness even to make both ends meet, to say nothing of being able to save. In this connection it must also be pointed out that saving for old age is especially difficult because the need is remote and current demands press. The dangers of poverty in old age hardly impress the minds of the young. Most people have a working belief that things will be different thirty or forty years hence, a time which, indeed, seems unreal and distant. As Professor Seager aptly points out:

6“The conditions of modern industry have failed to supply motives for saving sufficiently strong to take the place of those that are gone. It is true that saving is still necessary to provide for the rainy day, for loss of earning power due to illness or accident or old age, but against these needs is the insistent demand of the present for better food, for better living conditions, for educational opportunities for children. This demand is not fixed and stationary. It is always expanding.... One consequence of our living together in cities and daily observing the habits of those better off than we are is that we are under constant pressure to advance our standards. This pressure affects the wage-earner quite as much as it does the college professor. Both, when confronted with the problem of supporting a family in a modern city, find the cost of living as Mark Twain has said “a little more than you’ve got.””[5]

The problem to be faced in old age by wage-earners may thus be summarized as being two-fold in character. First, the wage-earner is confronted with the fact of being compelled to discontinue work much earlier in life than should be necessary, not because he is completely worn out, but because he is unable to maintain the pace necessary in modern production; and secondly, he faces the inability to provide individual savings to support himself in old age.

In addition, the above conditions of impotence in old age are augmented still further by the break-up of the family unit in modern society. With increasing rapidity home ties and family solidarity are being weakened and broken by the mobility so essential to modern industrial development. This is especially true in the United States and among wage-earners. The migratory and immigrant labourers move from lumber-camps to harvesting fields, railway construction, and public works as the change of employment offers. Thousands of aged workers find themselves in a strange country without friends or relatives. Many of these have never had children, or if they are parents, their children are unable to assist them. 7Ordinarily, the children are either unattached migrants or are married and have children of their own who must be supported and educated. No one contends that it is good social policy to have children undernourished and set to work early in life in order that they may help support the passing generation. And as a result one finds that the only source which secured sustenance and bare comfort to old age, in an earlier society, has disappeared for a great many. We, therefore, send these unfortunates, in our laissez-faire fashion, to the unfriendly poorhouses to secure the care and comforts available. Do they secure it? Says Professor Devine:

“Suicide, friendless old age, unemployment under ordinary industrial conditions, some forms of insanity and other disabling disease, immorality and crime, owe a part of their prevalence and their virulence to the absence of the capacity or opportunity for personal friendship, to the absence of those social props and safeguards which our friends naturally supply. The almshouse is the final apotheosis of friendlessness.”[6]

Indeed, once the difficulties faced in old age by the great majority of workers are realized, one cannot but wonder whether the fact that the aged population in the United States has increased from 3.5 per cent. for those 65 years of age and upward in 1880 to 4.3 per cent. in 1910, and that the expectation of life has improved, has been a desirable thing and is to be considered much of a blessing by the aged poor. Faced with conditions such as described above, and with the almshouse as the final destination of a life of destitution and drudgery, do they not look upon modern industrial development, as well as the advances made in medical progress and health as the creations of an evil spirit, which have, on the one hand, curtailed their period of production, and, on the other hand, prolonged their years of misery by the increased duration of life?

The prospects of living to old age are becoming increasingly better as methods of sanitation and public health are improved. According to the United States Life Tables, the American vital statistics in 1910 showed that out of every 100 persons at the age of 20, 64 will reach the age of 60; 54, the age of 65; and 42, the age of 70. Of 100 persons alive at the age of 30, 53 will reach the age of 65, and 48 will not die before 70. In other words, of all men alive at the age of 30, more than one-half will reach 65. A person who has reached the age of 65 may still expect to live 11 more years, and the person who has reached the age of 70 may still hope to have nine more years of life. In 1880, according to the U. S. Census, the number of persons 65 years of age and over in the entire population constituted 3.5 per cent. This aged population increased to 3.9 per cent. in 1890, to 4.2 per cent. in 1900, and to 4.3 per cent. in 1910. Of males 15 years of age and over, the number of those 65 and over increased from 54 per thousand in 1880 to 60 in 1890 and 63 in 1910. It is thus clear that the proportion of older persons in the United States has been constantly increasing.

In 1900 there were in the United States 3,083,995 persons 65 years of age and over, constituting 4.2 per cent. of the total population. In 1910 this number increased to 3,949,524 and constituted 4.3 per cent. of the population. Of the nearly four million persons 65 and over in 1910, 1,679,503, or 42.5 per cent., were between the ages of 65 and 69. The magnitude of the old age problem is more easily appreciated when one 9reflects that this aged group outnumbers the entire population of the United States during the time of the Revolution—the first Census of 1790 giving the total population of the United States as 3,929,214. No State in the Union, save the States of New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, and Ohio, has a greater population; and the aged population in 1910 was greater than the combined populations of the states of Arizona, Delaware, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Wyoming, the District of Columbia, and Alaska.

According to the United States Census of 1910 there were in the United States at that time 38,167,336 persons 10 years of age and over engaged in gainful occupations. These constituted 53.5 per cent. of the entire population of that age, an increase of 3.1 per cent. over those reported gainfully employed for the same ages in 1900, and an increase of 6 per cent. in the population of the same age as compared with the proportion gainfully employed in 1880. In the case of the male population 10 years of age and over, 81.3 per cent. were recorded as gainfully employed in the United States in 1910 as compared with 80.0 per cent. reported in 1900, and 78.7 in 1880. Of the female population 23.4 per cent. of those 10 years of age and over were reported gainfully employed in 1910 as compared with 18.8 per cent. employed in 1900, and 14.7 per cent. in 1880.

That few wage-earners are able to continue at work until the end of their lives is known to all. While the percentage of the entire population which must secure its livelihood through gainful work has steadily increased in the United States, it is significant to note that the same Census figures show that after middle age the percentages of those engaged in industry and trades have been continuously diminishing. Out of every 100 males in gainful occupations in the United States in 1890, thirteen and one-half were between the ages of 45 and 54; eight between the ages of 55 and 64, and five and three-tenths were 1065 years of age and over. In the same year, ninety-six and six-tenths out of every 100 males between the ages of 45 and 54 were found gainfully employed. Of those between the ages of 55 to 64, 92.9 per cent. were still found occupied, while of those 65 years of age and over, 73.8 were still recorded as engaged in gainful occupations. Ten years later, in 1900, the percentage of males employed between the ages of 45 and 54 was 95.5; of those between 55 and 64, 90 per cent., and the percentage of those over 65 who were still occupied dropped to 68.4, a decrease of 5.4 per cent. in 10 years. The 1900 Census figures also show that of all the males 55 years of age and over, 85 per cent. were found gainfully employed in 1890, but only 80.7 of the same were employed in 1900, a decline of 4.3 per cent. in 10 years.

The 1910 Census gives no age classification over 45. The information available shows, however, that while in 1900, 87.9 per cent. of all males over 45 were gainfully employed, the percentage declined to 85.9 in 1910. Assuming that the same rate of decrease of the gainfully employed males 55 years of age and over held true in the period between 1900 and 1910 as that which took place between the decade of 1890 and 1900, there would be only 76.8 per cent. of males 55 and over, in the United States employed in 1910, as compared with 80.7 in 1900, and 85 in 1890. Similarly, in regard to those 65 and over, 63 per cent. of the males in the United States would have been employed in 1910 as compared with 68.4 in 1900 and 73.8 in 1890. Thus it may be assumed that of the 4,660,379 males 55 years of age and over in 1910, 1,081,208 were already eliminated from the gainfully employed class.

| DECLINE OF GAINFULLY OCCUPIED MIDDLE-AGED MALES | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Gainfully Occupied | |||

| Ages | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 |

| 45–54 | 96.6 | 95.5 | |

| 55–64 | 92.9 | 90.0 | |

| 65 and over | 73.8 | 68.4 | 63 (estimate) |

| 55 and over | 85.0 | 80.7 | 76.8 (estimate) |

| 45 and over | 87.9 | 85.9 | |

11The steady reduction in the percentages of those gainfully employed in the later years of life, as shown by the United States Census reports, is largely due to the decrease in the population of those ages engaged in industrial and manufacturing pursuits rather than agricultural and professions. This is obvious from the following: Of the total 38,167,336 gainfully employed persons in the United States in 1910, 12,567,925, or 32.8 per cent., were engaged in agricultural pursuits; 10,807,521, or 28.4 per cent., were engaged in manufacturing and mechanical occupations; 7,605,730, or 20 per cent., in trade and transportation; 5,361,033, or 14 per cent., were found employed in domestic and personal services, and 1,825,127, or 4.8 per cent., were engaged in various professional vocations. The tremendous expansion in the manufacturing and mechanical pursuits is apparent from the fact that the population engaged in these occupations in 1900 was only 7,085,309. There was an increase of more than three and one-half millions in 10 years. On the other hand, of the 1,065,000 men 65 years of age and over reported gainfully employed in 1900, approximately 50 per cent. were engaged in agriculture, a considerable number were engaged in the professions and business, and only about one-third of the number were employed as wage-earners. In 1900 the persons 55 years of age and over constituted 12.3 per cent. in all occupations. When this group is classified in accordance with the nature of its work, it is found that 15.1 per cent. of this group were engaged in agricultural pursuits; 15 per cent. in professional vocations; 10.5 per cent. in domestic and personal services; 10.5 per cent. in manufacturing and mechanical pursuits, and 9.5 per cent. in trade and transportation. Thus while the aged group of 55 and over constituted 12.3 per cent. in all occupations it is much higher than this average in the case of agricultural and professional pursuits, but is much below the average in the case of manufacturing and transportation occupations. This is practically the reverse of the proportions 12found among those gainfully employed in the various industries in the earlier age groups.

Further light upon this phase may be gleaned from the Twelfth Census. According to the 1900 Census enumeration, the percentage of the total number of workers in all occupations between the ages of 45 and 54 formed 25.8 per cent. of workers of all ages employed in all occupations. The percentage of those employed between 55 and 64 was 12.3, and that of those 64 and over, 4.4 per cent. These figures were obtained after the elimination of certain occupations which have a large proportion of boys as well as those in which the majority of workers were women. A comparison of the percentages for all occupations with the percentages of those engaged in the industries given in the table below reveals the fact that, while in the outdoor industries the percentage of those employed between 45 and 54 holds approximately true, it is considerably below in the case of the heavier industries, and much below the general proportion after the 55th birthday has been reached.

| NUMBER AND PER CENT OF EMPLOYEES 45 AND OVER IN SELECTED INDUSTRIES IN THE UNITED STATES, 1900[7] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45 to 54 | 55 to 64 | 65 and over | ||||

| Occupation | No. | Percent | No. | Percent | No. | Percent |

| All Occupations | 6,187,927 | 25.8 | 2,925,122 | 12.2 | 1,065,275 | 4.4 |

| Marble & Stone Cutters | 14,339 | 26.3 | 5,264 | 9.6 | 1,498 | 2.7 |

| Painters, Glaziers, | ||||||

| Varnishers | 69,681 | 25.2 | 28,406 | 9.9 | 7,759 | 2.8 |

| Brewers and Maltsters | 5,204 | 25.1 | 1,686 | 8.1 | 419 | 2.0 |

| Steam Boilermakers | 5,938 | 17.0 | 2,103 | 6.3 | 527 | 1.5 |

| Iron and Steel Workers | 47,042 | 16.3 | 15,789 | 5.4 | 3,783 | 1.3 |

| Brass Workers | 3,822 | 14.7 | 7,394 | 5.3 | 360 | 1.3 |

| Potters | 1,950 | 14.7 | 691 | 5.2 | 208 | 1.5 |

| Glass Makers | 5,575 | 11.7 | 1,737 | 3.6 | 392 | 0.8 |

The Thirteenth Census does not give the age classifications which would make a similar comparison possible. However, the Massachusetts Commission on Old Age Pensions, Annuities, and Insurance, found in 1910, in a study of 870 aged persons, that the average age at which the wage-earning power was completely lost was 68 years. The average age at which the 13earning power was partially impaired, in a study of 872 partially incapacitated persons, was 64. In 1918, the Ohio Commission on Health Insurance and Old Age Pensions found in six foundries employing 500 moulders only three men over 50 years of age engaged in heavy floor moulding. Ten men over 60 were engaged in light bench moulding.

The table below shows succinctly that the strain of modern machine industry permits only a few wage-earners to remain at work after they have passed three score and five. It is further proof of the above figures pointing to the constant reduction of those 65 years of age and over engaged in mechanical and manufacturing pursuits. An examination of the table compiled in 1920, regarding the ages when actually pensioned as compared with the ages required by these large concerns for obtaining a pension, reveals the fact that in spite of the strict regulations provided, a number of these have actually been pensioned before the specified age. Thus more than one-half of those on the pension list of the United States Steel and Carnegie Pension Fund have retired before the age of 65, although the age for voluntary retirement is set at 65. In the case of the pensioners of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company, while the compulsory age of retirement is set at 70, 44 per cent. had been placed on the pension list before they had reached the compulsory retirement age. Similar proportions are found in the case of most of the other industrial pensioners.

| PENSIONABLE AGES PROVIDED AND AGES WHEN ACTUALLY PENSIONED BY LEADING INDUSTRIAL CONCERNS | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of Company | Pensionable Age Provided | Actual Ages When Pensioned | |||||||||

| Under 50 | 50 to 60 | 60 to 65 | 65 to 70 | 70 and over | |||||||

| No. | Percent | No. | Percent | No. | Percent | No. | Percent | No. | Percent | ||

| U. S. Steel & Carnegie Pension Fund. | Any age if permanently incapacitated; 65 at request. | 128 | 3.5 | 420 | 11.6 | 1,487 | 40.5 | 927 | 25.4 | 695 | 19.0 |

| Penna. R. R. | 70 compulsory, 65 to 69 at approval of Board. | 1,209 | 13.0 | 2,796 | 31.0 | 5,124 | 56.0 | ||||

| Philadelphia and Reading R. R. | 70 compulsory; 65 to 69 if incapacitated. | 20 | 2.0 | 15 | 1.5 | 24 | 2.5 | 201 | 20.5 | 716 | 73.5 |

| N. Y. Central Railroad | 70 compulsory; any age if unfit for duty. | 1,606 | 36.3 | 2,828 | 63.7 | ||||||

| Philadelphia Electric | No compulsory age; voluntary retirement, male 65, female 60. | 13 | 6.5 | 35 | 16.5 | 54 | 25.5 | 87 | 41.5 | 21 | 10.0 |

| Pittsburgh Coal Co. | No compulsory age; any age if incapacitated after 10 years of service. | 8 | 4.0 | 42 | 21.0 | 55 | 28.0 | 50 | 25.0 | 44 | 22.0 |

| Westinghouse Air Brake | 70 compulsory; by order of Board. | 3 | 3.0 | 8 | 7.5 | 8 | 7.5 | 16 | 15.5 | 69 | 66.5 |

| National Transit Co. | Compulsory, male 65, female 55; voluntary, male 55, female 50. | 4 | 6.1 | 23 | 35.5 | 21 | 32.2 | 17 | 26.2 | ||

| Pittsburgh and Lake Erie R. R. | 70 compulsory; any age if unfit for duty. | 2 | 3.7 | 1 | 2.0 | 4 | 7.3 | 6 | 11.0 | 41 | 76.0 |

The extent of disability of wage-earners as they are affected by both age and occupations has been brought out in a comprehensive manner by Dr. Boris Emmet from studies recently made of the Workmen’s Sick and Death Benefit Fund of the United States, for the United States Bureau of Labour Statistics.[8] These investigations show conclusively that age and occupation 15are the two most important factors in determining the duration and extent of disability. The average number of days of disability per member was found to be 6.6 per annum. An examination of the age groups shows that up to the age of 45 the disabilities’ duration is below the average, but from that age on, it increases steadily until it averages 15.2 in the case of those who are 70 years of age and over. By the different age groups the percentages above (+) or below (−) the average are as follows:

| Age Group | Average No. of Disability Days | Per Cent of Deviation from Average |

|---|---|---|

| Under 20 years | 5.2 | −21.2 |

| 22 to 24 years | 4.8. | −27.3 |

| 25 to 29 years | 5.0 | −24.2 |

| 30 to 34 years | 4.9 | −25.8 |

| 35 to 39 years | 5.6. | −15.1 |

| 40 to 44 years | 6.4 | −3.0 |

| 45 to 49 years | Same as average | |

| 50 to 54 years | 7.4 | +12.1 |

| 55 to 59 years | 9.0 | +36.4 |

| 60 to 64 years | 12.0 | +81.8 |

| 65 to 69 years | 13.8 | +109.1 |

| 70 years and over | 15.2 | +130.3 |

| All age groups | 6.6 | None |

The occupational hazards of certain of our large industries are presented so clearly in the table below that no comment at length is necessary. While in the professions the average number of days of disability per year is 2.6, it progresses continuously until in the case of miners it reaches 9.7, almost four times as great.

| ANNUAL DISABILITY DAYS FOR EACH OCCUPATION | |

|---|---|

| Occupation | Average Annual Disability Days per Year |

| Professional | 2.6 |

| Jewelers | 3.6 |

| Clothing Mfr. Employees | 4.4 |

| Textile Mfr. Employees | 4.5 |

| Trade and Clerical | 4.7 |

| Electrical Workers | 4.8 |

| Other Manufacturing Employees | 5.1 |

| Farmers, Gardeners, and Florists | 5.3 |

| Sheet Metal Workers | 5.6 |

| 16Plumbers | 5.6 |

| Plasterers | 5.6 |

| Unspecified Occupations | 5.7 |

| Molders | 5.8 |

| Leather Workers | 5.8 |

| Tanners | 5.8 |

| Auto, Carriage and Wagon Mfg. emp. | 5.9 |

| Barbers | 5.9 |

| Engineers and Firemen | 6.0 |

| Bartenders | 6.0 |

| Woodworkers | 6.1 |

| Printers and Engravers | 6.1 |

| Machinists | 6.1 |

| Food Employees | 6.2 |

| Cooks and Waiters | 6.2 |

| Dyers | 6.4 |

| Painters | 6.4 |

| Clay Products Mfg. emp. | 6.6 |

| Other Building Construction emp. | 6.0 |

| Carpenters | 6.7 |

| Tobacco and Cigars | 6.8 |

| Slaughtering and Meat Packing emp. | 6.9 |

| Blacksmiths | 6.9 |

| Labourers, not specified | 6.9 |

| Glass Workers | 7.1 |

| Bricklayers | 7.1 |

| Stone and Granite | 7.5 |

| Liquor Manufacturing emp. | 7.9 |

| Railway Employees | 8.4 |

| Drivers | 8.6 |

| Freight Handlers | 9.6 |

| Miners | 9.7 |

| Average of all Occupations | 6.4 |

A valuable investigation in regard to this phase of the problem was made by the Pennsylvania Commission on Old Age Pensions, during 1918–19. This Commission interviewed over 4,500 people, 50 years of age and over in a house-to-house canvass in the cities of Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Reading. It also made a study of the ages of partial and total impairment of workers in several industries. A case of partial impairment was assumed when the individual sustained a reduction in wages, either because of displacement or change in job as a result of sickness or old age. The Commission states that its studies revealed the following:[9]

17(a) The earning power of many workers in Pennsylvania is impaired before they reach the age of 40. The percentages of partial impairment at the age of 40 were found to vary from 2.6 per cent. among indoor and sedentary trades, to 16.4 in the steel industry, and 57 per cent. in the case of railroad workers. Only in the steel industry, however, were there many who were totally incapacitated before the age of 50. In the building trades, 12.6 per cent. were partially impaired before the age of 50; while 6.3 per cent. were totally incapacitated before reaching the same age. On reaching the above age it was found that 55.3 per cent. were partially and 14.1 per cent. were totally impaired in the case of steel workers. Of those engaged in casual occupations 26.7 per cent. have had their earning power partly, and 8.4 per cent. wholly reduced before attaining 50 years of age. Of indoor and sedentary trades the percentage of partially impaired workers before the 50th birthday was 15.2, while 8.3 were wholly disqualified for service at that age. Nearly 27 per cent. among glass blowers had had their earning power reduced before reaching 50 years of age, and 20 per cent. were permanently incapacitated at the same age. Of skilled workmen in the various trades, 29 per cent. were impaired partially and less than three per cent. entirely, before attaining their 50th birthday. Among railroad workers, those whose incomes were affected before the age of 50, the percentages were 64.3 to a partial extent, and 6.2 entirely.

(b) At the age of 60, the proportion of workers, whose earning power had not yet been affected, according to the various trades, were as follows: In the building trades, 55.1 per cent. suffered no loss of income before reaching the age of 60. In the steel industry only 13.2 per cent. were earning the same amounts as in their earlier days at the above age. Thirty-six per cent. of workers, at 60 years of age, were still found to be engaged in casual occupations. Among workers in indoor and sedentary trades, 46.4 per cent. were found without reduction in their earning power at the age of 60. Only 26.9 per cent. of glass blowers were in their full capacity at the age of 70. The percentage of skilled mechanics found in good health at 60 was 25.5, while 28.2 per cent. of railroad workers were found to be in unimpaired health at the age of 60.

The Commission concludes: “An examination of the total number 18of aged persons in all the three cities from whom the previous and present occupations were ascertained, shows that men past a certain age must quit even the skilled trades in which they have been engaged the greater part of their lives. Modern industry, apparently, has little use for the superannuated worker. A few men can continue working at the same occupation after they have reached a certain age. While 36 per cent. stated that they were skilled or semi-skilled mechanics in their earlier days, only 23.8 per cent. of men past 50 years of age were still engaged in the same occupation. The percentage of those doing unskilled or common labour or clerical labour, on the other hand, remained stable. It is also to be noticed that in their earlier days less than two per cent. were not working because of incapacity, but 26.6 per cent. were found not to be working among those 50 years of age and over. The fluctuations of the minor occupations are inconsiderable.”[10]

Similar studies of several hundred bituminous miners scattered through a dozen mining districts in Pennsylvania and of about two hundred steel workers were recently completed by the writer for the above Commission. The investigations disclose that of 368 miners, 50 years of age and over, 177 were still in fair or good health, while 191 or somewhat more than 50 per cent. of those investigated, were found to be either partially or totally incapacitated. Of the 112 reported as partially incapacitated, 79, or 70.5 per cent., became so before the age of 60; of the 79 reported as totally incapacitated 38, or 50 per cent., were thus disabled before the same age. While most of those reported as partially incapacitated were still engaged in some form of work or other, this was irregular and uncertain, as most of these persons were suffering either from chronic sickness or the consequences of serious accident.

In the case of 146 steel workers, 50 years of age and over, investigated in Homestead and Steelton, 90, or 62 per cent., were found to be either in part or completely impaired in respect 19to their health and earning power, the great majority of these becoming incapacitated before the age of 60. The causes of impairment assigned in more than three-fourths of the cases of both classes of labour were either sickness or accident. Old age, as such, was given only in a few instances as a direct cause of incapacity.

| AGES OF INCAPACITY OF MINERS AND STEEL WORKERS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miners | Steel Workers | |||

| Ages of Incapacity | Partial | Total | Partial | Total |

| Under 50 | 29 | 15 | 8 | 4 |

| 50 to 60 | 50 | 23 | 25 | 5 |

| 60 to 65 | 18 | 15 | 11 | 6 |

| 65 to 70 | 14 | 20 | 4 | 5 |

| 70 and over | 1 | 6 | 12 | 10 |

| Total Incapacitated | 112 | 79 | 60 | 30 |

The reports of the different State Industrial Accident Commissions and Compensation Bureaus corroborate further the evidence at hand that there are fewer persons past middle age engaged in industry than the proportion of the same group in the entire population. The Industrial Commission of Wisconsin reported in 1915 that of all persons injured at work in that state, 53 per cent. were under 30 years of age; 67 per cent. were under 40; 5 per cent. between 50 to 55, and only 5 per cent. more above that age. For the population 15 years of age and over as a whole, 7 per cent. were 50 to 55, and 16 per cent. were 55 and over.[11] The California Industrial Accident Commission reports that in 1918, of 2,100 permanent injury cases, 1,729, or 82.3 per cent., were under the age of 50; 257 were between 50 and 60, and 114 above that age.[12] Of 2,569 fatal accident cases which occurred in Pennsylvania in 1919, 1,932 or 75.2 per cent., were under 50 years of age; 262, or 10.2 per cent., were between the ages of 50 and 60, and only 136, or 5.2 per cent., were above that age. The ages of the rest were not ascertained.

20Even more significant in this respect are the disclosures of an investigation of several trade union locals recently made by the writer. Printers are known to work much longer in life than do workers in many other crafts. In spite of this fact, it was found that of a membership of approximately 1,500, the Philadelphia Typographical Union No. 2 had on its lists only 145 persons, approximately 10 per cent., who were 60 years of age and over; and 47 of these were already on the pension roll of the International Typographical Union. Local No. 98, Philadelphia, of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers had no one 60 years of age or over on its membership roll of approximately 1,250. Workers in the building trades, it is frequently asserted, work until very late in life. An examination of the ages of 450 members of Carpenters’ Local No. 287 in Harrisburg showed only 25 persons 60 years of age and over. Bricklayers’ Local No. 71, in the same city, had only 14 members between the ages of 50 to 60 and a similar number 60 and over among 152 members. Carpenters’ Local No. 1073, Philadelphia, has been in existence since 1902 and has a membership of over 1,400. There were in this local only 60 men who were 50 years of age and over, and only seven of these were above 60. A canvass of over 600 miners’ locals with a membership of over 120,000 persons, made a few years ago by a Committee of the United Mine Workers of America, showed that there were in these locals a total of 6,283 persons 60 years of age and over, of whom only 2,084 were 65 years and upwards.

From the foregoing evidence it seems obvious that modern industry finds little use for the worn-out workers. It replaces and discards these aged wage-earners as it is in the habit of replacing and discarding the worn-out and inefficient machinery. Once economic old age has set in, the road to dependence is short. Says Mr. L. W. Squier: “After the age of sixty has been reached, the transition from non-dependence to dependence is an easy stage—property gone, friends passed away 21or removed, relatives become few, ambition collapsed, only a few short years left to live, with death a final and welcome end to it all—such conclusions inevitably sweep the wage-earners from the class of hopeful independent citizens into that of the helpless poor.”[13]

The aged, for the purposes of our discussion, may be classified into three distinct groups. First, the small group of wealthy and independent persons whose economic and social security is assured. This group presents no problem such as those which are discussed in the pages that follow, and may be dismissed. Secondly, the great mass of the aged wage-earners who are presumably non-dependent because, in order to avoid the stigma of pauperism, they do not, as a rule, seek aid from charitable and philanthropic sources. These will prefer to make all sorts of sacrifices rather than seek asylum for their last days in either county poorhouse or benevolent home. Many of this group, therefore, while nominally non-dependent, may nevertheless be below the poverty line, and very often, although they find themselves in want through no fault of their own, will prefer to endure hardship rather than accept charity. From any point of view this group, which represents the great majority of wage-earners, has the greatest claim to protection and relief in old age. Their problems must not merely attract attention but must be studied thoroughly and met squarely with a constructive social policy. The third group, which is considerably smaller, is composed of the institutional and pauper classes and includes the inmates of the State, county and private charitable institutions, as well as the recipients of public or private relief from local poor boards, philanthropic organizations, churches and similar institutions. Knowledge of the actual conditions which compelled this unfortunate 23group to seek relief; an examination of the effects and consequences of our present methods of relief distribution; and a revaluation of these methods in terms of social justice, are essential in a study of this aged pauper group.

The proportion of the presumably “non-dependent” aged persons in the United States who are actually living in want and are in need of systematic relief is difficult to estimate accurately. The Census reports supply very meagre data for the determination of the extent of old-age dependency in the United States; especially is this true with regard to the non-institutional aged. However, a number of studies have been made recently which may be considered fairly indicative of the magnitude of the problem. The first study of dependency of the aged was made in 1908–9 by the Massachusetts Commission on Old Age Pensions, Annuities and Insurance. This Commission estimated the number of persons 65 years of age and over in Massachusetts to be 177,000 in 1910. Of this number 41,212, or 24 per cent., were found either to be residing in correctional institutions and public or private pauper and benevolent homes, or were the recipients of public or private outdoor relief, or United States pensions. One hundred and thirty-five thousand, seven hundred and eighty-eight, or 76 per cent., of these aged in Massachusetts were “non-dependent,” as far as could be ascertained. Basing his calculations upon the Massachusetts figures, L. W. Squier estimated that approximately 1,250,000 of those 65 years of age and over in the United States are dependent upon public and private charity.

This estimate was admittedly conservative, as Mr. Squier’s calculations were based upon cases of relief granted by the organized charitable agencies; and even the recipients of this form of relief could not have been, in the nature of such studies, completely gathered by the Massachusetts Commission. No account was taken of the unofficial and less known relief agencies, and it goes without saying that neither the Massachusetts 24Commission nor Mr. Squier could determine the amount of private charity extended. That Mr. Squier has under-estimated rather than over-estimated the total number of aged dependents, is shown by the 1915 decennial census of Massachusetts. In this state-wide enumeration there were found 189,047 persons 65 years of age and over, of whom 34,496, or 18.2 per cent. of the total population of that age, were receiving aid from one source or another. However, this number did not include those aged who were receiving pensions from the United States government. The number of this group was estimated at 29,150, or 14.8 per cent. The aggregate number of dependents thus constituted 33 per cent. While many of the latter did not need such assistance, their number doubtless increased the total dependents, and if used as a basis for the entire United States would have increased Mr. Squier’s estimate considerably.

Statistics dealing with those aged persons in the United States who are definitely dependent upon public or private relief are scanty and incomplete. The various groups of dependents are classified according to age in only a few instances by the United States Census. The 1910 Census reports that of a total of 84,198 paupers in almshouses in the United States, 35,943 or 42.7 per cent. were 65 years of age and over. In the same year there were 187,791 known insane and feeble-minded persons in the United States, 21,881 or 11.8 per cent. of whom were 65 and over. Of a total of 19,153 deaf and dumb persons in 1910, only 797, or 4.1 per cent., were 65 and over. The number of prisoners 65 and over is not given by the Census, but of the number committed to penal institutions during the year 1910, only 1.6 per cent. were 65 years of age and over. There were in 1910 also 98,846 adult inmates over 21 years of age in benevolent institutions, the large majority of whom were obviously of advanced age. Of the total 57,272 blind persons in the United States, 23,746 or 41.4 per cent. were past threescore and five years. There were in addition 25in that year 72,948 dependent adult inmates in hospitals and sanitoriums. No data are available to show the number of aged persons in receipt of either public or private relief. The recipients of this form of charity, however, generally constitute the large majority of dependents, and as shown by the different State Commissions, exceed the aggregate number of dependents of all other classes. Neither do the classes enumerated above include the great number who are in receipt of State and Federal pensions, as well as those receiving pensions from industrial establishments. It is, of course, impossible even to estimate the number of those receiving partial or entire support from individuals.

The Census figures seem to indicate also either a steady increase in aged dependency in the case of most pauper classes, or an increase in the longevity of most aged dependents. Thus, the blind 60 years of age and over increased from 36 per cent. of the total blind population in 1860, to 41.4 in 1910. The deaf and dumb of the same age group constituted 4.9 in 1860 and increased to 6.7 per cent. in 1910. In the case of almshouse paupers the percentage of the aged increased from 25.6 in 1880 to 42.7 in 1910.

Recently a number of special State Commissions on Old Age Pensions have added further light upon the extent of dependency in old age. The Wisconsin Industrial Commission in its report on old-age relief in 1915, states:

“The number of persons 60 years of age and upwards in Wisconsin may be estimated at 185,000. Of this number, probably two per cent. are recipients of public or private relief. Even including United States pensioners, the proportion scarcely exceeds 12 per cent. But that very much unrelieved distress exists no one can doubt who is familiar with the statistics of other countries. The inauguration of systematic old age relief invariably brings to light a vast mass of unsuspected poverty among the aged. Thousands of old people contrive to escape the clutches of the poor laws who nevertheless endure a pitiful struggle for existence. They 26work beyond their strength, they deny themselves proper food and clothing, they are aided by friends and neighbours, or they are supported by their children, too often at the expense of growing families.”[14]

The Ohio Commission on Health Insurance and Old Age Pensions states:

“The number of aged persons aided by private families or by relatives and friends is unknown and cannot be estimated. The Hamilton and Cincinnati surveys indicate that 15 to 25 per cent. of people over 50 were dependent upon relatives or friends. Nor can the number who are living an independent but precarious existence be accurately estimated.”[15]

The Pennsylvania Commission concludes that:

“Aside from the aged dependents found in almshouses, benevolent or fraternal homes, and those receiving public or private relief, there is a considerable proportion (43 per cent.) of the aged population, 50 years of age and over in the State, who, when reaching old age have no other means of support, except their own earnings.”[16]

As the studies made by the Pennsylvania Commission in regard to this phase of the problem of the aged, go into greater detail than those of the other State Commissions, its conclusions may perhaps be considered as fairly indicative of the extent of destitution in old age among the industrial population of this country. Based on the percentage found in Pennsylvania, it may be said that in 1910 there were approximately 1,700,000 persons in the United States who had passed beyond the half century mark and who had had no other means of support in their old age except what they could earn themselves. While it may be conceded that this proportion may 27be smaller in the less industrial States, the above estimate may nevertheless be fairly accurate for the entire United States, as the districts studied by the Pennsylvania Commission were largely inhabited by better paid American-born workers as contrasted with the more thickly populated foreign sections. Of course, it must not be presumed that all of these will apply for relief, either public or private, but it is obvious that the great majority of these will have to face a pitiful struggle for subsistence. Ultimately the majority of this number will become dependent, if not upon public charity, then upon children or relatives at the expense of self-respect, and in many cases also to the great detriment of the growing generation.

In the discussions that follow, the individual and social forces, as well as the moral factor that go to make for dependency and pauperism will be dwelt upon at length. At this juncture it is important first to examine and endeavour to understand sympathetically the immediate conditions confronting multitudes of superannuated workers which compel many to become paupers in their old age. Indeed, a comparison of the circumstances of the dependent aged, as disclosed by the different State Commissions’ reports, with those of the so-called non-dependent, discussed in the preceding pages, sheds much light upon the frequently repeated question: “Why is it that some workers succeed in remaining away from the pauper homes, while others, apparently of the same class, become dependent upon public charity?”

The age relativity among the different classes is significant. In the total population of 1910 the group between 65 and over constituted 4.3 per cent. of the population, and contained 4.2 per cent. of the males and 4.4 of the females of all ages. This percentage held true for the native whites of native parentage. Among the native whites of foreign or mixed parentage the aged constituted only 1.4 per cent., while of the foreign born 28whites, the same age group contained 8.9 per cent., and among Negroes 3.0 per cent. The proportion of the aged varies also considerably in the different sections. According to the 1910 Census, the percentage of those 65 and over to the total population was highest in the New England States, with 5.9 per cent., and lowest in the West South Central States with 2.8 per cent. The Middle Atlantic States gave 4.4 per cent.; East North Central, 5.1 per cent.; West Central, 4.6; South Atlantic, 3.6; East South Central, 3.5; Mountain, 3.0, and Pacific, 4.5 per cent.

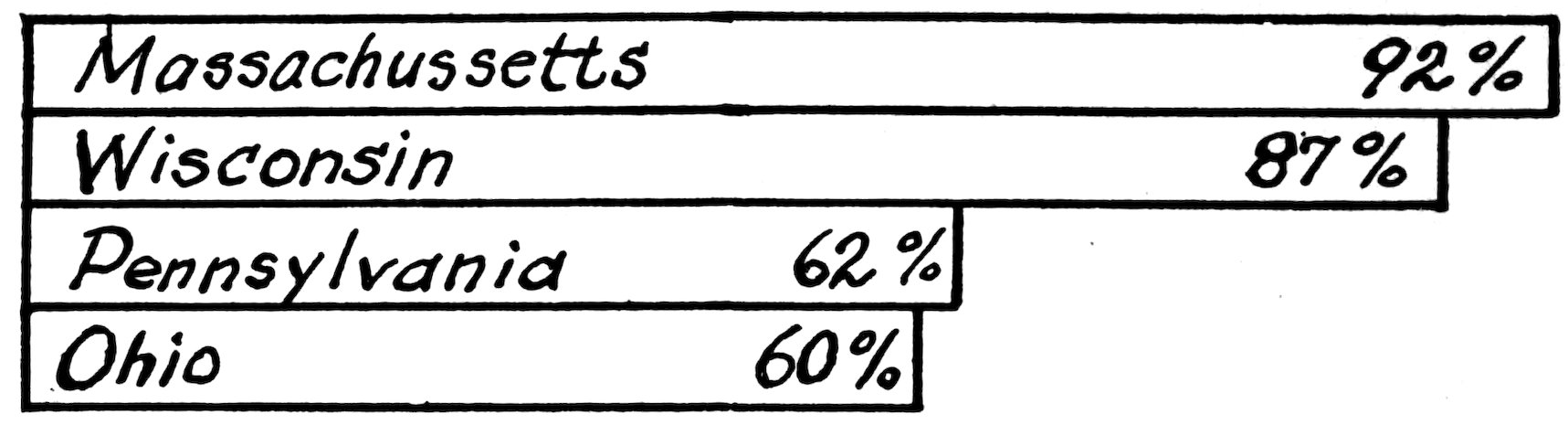

The dependent classes, as is to be expected, are largely made up of those of advanced ages. The relation of dependence to old age is so clearly indicated in the following reports that no additional comment is necessary. The Massachusetts Commission in 1910 found that:

“Less than one per cent. of those for whom the age at entrance was stated in the returns became inmates before the age of 40; only eight per cent. entered before the age of 60; thus 92 per cent. had passed the sixtieth year before they took up residence in the almshouse.”[17]

Commenting on this, the Commission adds:

“The strikingly high proportion of persons entering pauper institutions late in life points to the close connections between old age and institutional pauperism. It is clear that such pauperism is in most cases the result of the infirmity of advancing years, rather than of the misfortunes of earlier years.”[18]

The Wisconsin Commission reports regarding the almshouse population of that State, as follows:

“A very large proportion are of advanced age—only 17 per cent. are under 65, 40 per cent. are 75 and over and nearly 25 per cent. are 80 or above. In the population of the state at large, one-third of all persons over 59 fall in the age group 60 to 65 and 29only one-fourth are above 74. This fact, taken in connection with the great proportion of the entire almshouse population who are 60 and over, indicates a close co-relation between destitution and old age.”[19]

The Ohio Commission states:

“In regard to age distribution, the records of the Ohio Board of State Charities show that 4,772, or 60 per cent. of the regular infirmary inmates were over 60 years of age, 2,926 or 37.1 per cent. between 16 and 60 and 219, or 2.78 per cent. under 16 years of age.”[20]

The Pennsylvania Commission concludes that:

“It appears that only about 13 per cent. were admitted under 50 years of age; 24.87 per cent. were admitted between the ages of 50 and 60; 31.9 per cent. between 60 and 70, while over 24.78 per cent. were admitted after they had reached their seventieth year. A comparison between our figures and those obtained by the Massachusetts Commission on Old Age Pensions in 1908 is of interest. In the New England State only eight per cent. of those investigated entered the almshouses before the age of 60, and 92 per cent. had passed their sixtieth year before they took up residence in the almshouse. The higher rate of those entering almshouses below the sixtieth year in Pennsylvania may be explained by the highly developed industries peculiar to this Commonwealth, which, requiring greater physical strain, wear out and incapacitate men at an earlier age. For those admitted during the year 1910 to the almshouses of the entire country, the percentages were 17.7 between 50 to 59; 18 from 60 to 69 and 15.3 per cent. over 70 years.

“It is obvious, that the great majority of the aged inmates enter the institution late in life. This would indicate a close relationship between institutional pauperism and old age. The combination of advanced years and infirmity, when coupled with the fact, that in most cases these people have no one to depend or fall back upon is—as will be seen later—the chief cause compelling an 30aged person to go to the poorhouse. Most men will stay out of an almshouse as long as they can. When they are compelled to take up residence there, it is usually not due to personal or other misfortunes in earlier years, but in most cases, is the result of feebleness and lack of assistance from other sources.”[21]

PERCENTAGE OF PERSONS IN STATE PAUPER INSTITUTIONS WHO ARE 65 YEARS OF AGE AND OVER.

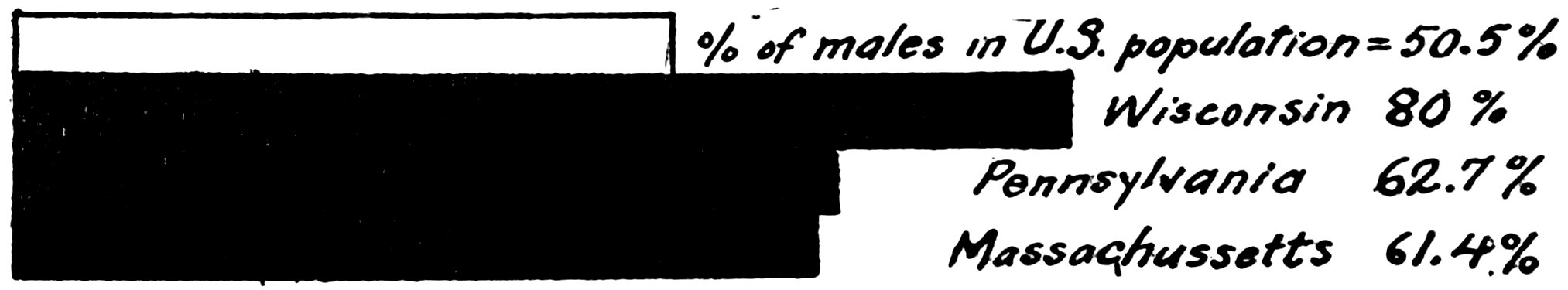

Of the 3,949,524 persons 65 years of age and over in 1910, 1,985,976, or 50.5 per cent., were males, and 1,963,548, or 49.5 per cent., were females. This group was, in addition, divided as follows in 1910: 1,693,010, or 42.8 per cent., urban, and 2,256,415, or 57.2 per cent. rural, while 1,183,349, or 29.9 per cent. were of foreign birth.

The 1910 Massachusetts Commission found the proportion of males and females in the almshouses of that State to be 61.4 per cent. and 38.6 per cent. respectively. In this respect, the Commission declares:

“The figures for the aged poor present a contrast to those for the general population of the State, which is divided between the sexes very evenly, with 48.7 per cent. males and 51.3 per cent. females. The lack of any uniformity in the division between the sexes in the case of the various classes is also striking. In the classes of almshouse inmates, recipients of State and military aid and non-dependent poor, the males preponderate; in the classes of inmates of benevolent homes and recipients of public and private outdoor relief, the males are greatly outnumbered. It appears that relief in charitable institutions and in the homes through 31public or private agencies is given more largely to women than to men.”[22]

In Wisconsin, the proportion of women in almshouses, the Commission finds,

“Is very small—only 20 per cent. as against 47 per cent. of the State’s population of 60 and over. This showing is the more remarkable because the Commission’s sample census indicates (what is true in other countries) that the number of aged widows and single women exceeds the number of aged widowers and single men. The explanation is that an elderly woman is better able than an old man to maintain a home of her own or to fill a useful niche in the household of a relative.”[23]

The Pennsylvania Commission found the almshouse population to be composed of 62.7 per cent. males and 37.3 females. It comments as follows:

“It is interesting to remark that the above percentages found by the Commission are in exact agreement with the percentages found by the Massachusetts Commission on Old Age Pensions in its study in 1908. The comparative difference between the sexes in the almshouses and that prevailing in the entire State population is significant. According to the Thirteenth United States Census, the percentage of males in the entire State population was 51.4 per cent. and that of females 48.6 per cent. The reasons for the disproportionate number of male paupers in institutions over female paupers may be explained in several ways. Children or relatives will make greater sacrifices in order to keep an old mother at home and prevent her going to a poorhouse, than they would for an aged father or other male relative. Aside from the sentimental reasons involved, the presence of an old woman around the home—unless she is absolutely invalided—entails little burden, as she can be made useful in numerous ways. This, however, is not the case with an aged man. Aged women are also more generously provided for by private charity than are aged men. The percentages of aged men and women who are inmates 32of benevolent and private Homes for the Aged, are 23.54 and 76.46 per cent. respectively. The relationship here is thus radically reversed from that of the almshouse population.”[24]

PERCENTAGE OF MALES IN ENTIRE U. S. POPULATION, AND IN PAUPER INSTITUTIONS.

The number of old persons applying for charity in no way indicates the degree of destitution in old age. Much of this suffering is kept concealed from the public eye by timid and sensitive children or relatives. This is borne out by the available data on the family connections of aged persons. Indeed, the investigations seem to disclose that pauperism among the aged is in inverse ratio to the number of family relations and is largely a result of the lack of family connections. The data below indicate that, in most instances, children or relatives will endeavour to support their aged dependents, regardless of the sacrifices thereby required of themselves or of their children.

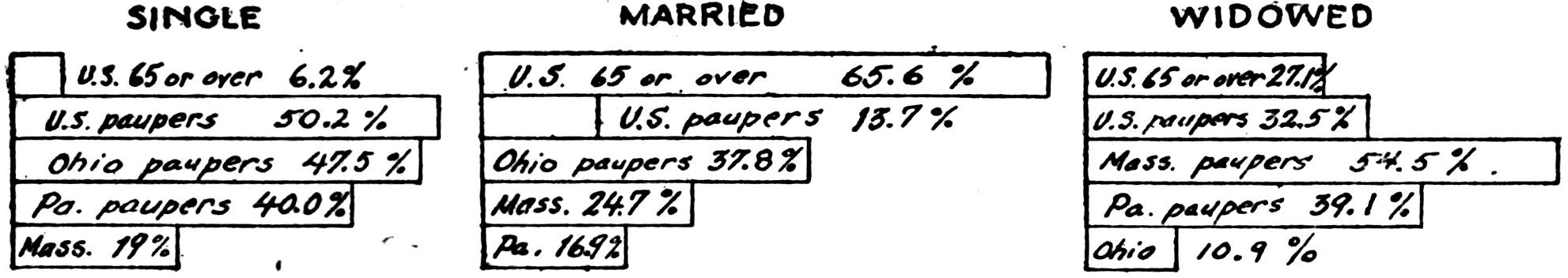

The Thirteenth United States Census gives the marital relationship of the aged as follows:—males, 6.2 per cent. single, 65.6 per cent. married, 27.1 per cent. widowed, and 0.7 per cent. divorced; females, 6.3 per cent. single, 35 per cent. married, 58.1 per cent. widowed, and 0.4 per cent. divorced. The Massachusetts Commission found that 6.2 per cent. of the aged persons investigated were single; 53.8 married; and 39.7 widowed. In Wisconsin, in 1915, in a sample census of 1,395 persons, 60 years of age and over, there were 35, or 2.5 per cent. single; 885, or 63.4 per cent. married; and 456, or 32.5 per cent. widowed. Of these, 76, or 5 per cent., lived alone; 885, 33or 63.4 per cent. lived with a spouse; 168, or 11 per cent. had unmarried children; and 206, or 14 per cent., had married children. The Wisconsin Commission concludes:

“It will be seen that substantially one-half of the women enumerated are widowed, divorced, separated or single, whereas nearly 80 per cent. of the men are married. The explanation is partly that women on the average live longer than men and partly that husbands very generally are older than their wives. The result is that a vast number of aged women are left without homes of their own.”[25]

MARITAL RELATIONS OF PERSONS 65 YEARS OF AGE AND OVER IN THE ENTIRE POPULATION IN THE CENSUS OF PAUPERS AND IN PAUPER INSTITUTIONS.

The preponderately greater number of elderly widows is also shown in a study of 100 aged persons in Greenwich Village, made by Miss Nassau in 1915.[26] Of 65 women investigated, Miss Nassau found 54 widowed, nine single, and two separated, while of the 35 men interviewed, 21 were still married, three were single, and two separated or divorced.

The Ohio Commission, in discussing this subject, states:

“In old age, marital condition, especially as regards women, is very important. The woman who becomes a widow after 50 is ill prepared to make her own living. She must, therefore, depend on her children or on the property left her by her husband. If her husband was a wage-earner, the most she can expect to inherit is a little home. One hundred and sixty-six or 50.8 per cent. of the 329 widows in the Hamilton survey owned their own homes. While the children remain unmarried, they contribute to the maintenance 34of their mother, but after marriage she can no longer depend upon them with any feeling of security. The single woman who has had to make her own living is also insecure in her old age. After 50 she finds it difficult to obtain steady employment and her wages, as a rule, have not been such as to permit much saving for old age. Only 37 of the 114 single women over 50 had any savings.”[27]

“When aged persons who have been unable to save lose their economic usefulness, they must depend on their children or relatives or on public charity. Three hundred and fifty-four, old, or invalided persons in Hamilton were dependent on children or relatives. One hundred and fifty of these were dependent on married children, all with families of their own; 144, on unmarried children, and the remaining 60, on relatives. Forty-eight of the 416 aged persons studied in Cincinnati were dependent on their children and 13 on other persons.”[28]

The Pennsylvania Commission found the marital conditions of 3,477 non-dependent persons 50 years of age and over, as follows: 5.4 per cent. single; 55.5 married; and 38.3 widowed. It also found 37.8 per cent. who have no one depending upon them; 31.5 having their wives to support, while the rest had one or more children in addition to support. It concludes that:

“It is evident that the possession of children in old age is a great protection against dependency. Thirty-one per cent. had one or two children living; forty-five per cent. had from three to six children living; while 12.7 per cent. had more than six children living. Of those children, only 3.3 per cent. were still under 16 years of age; 16 per cent. of the adult children were married, while 80.7 per cent. were still single.”[29]

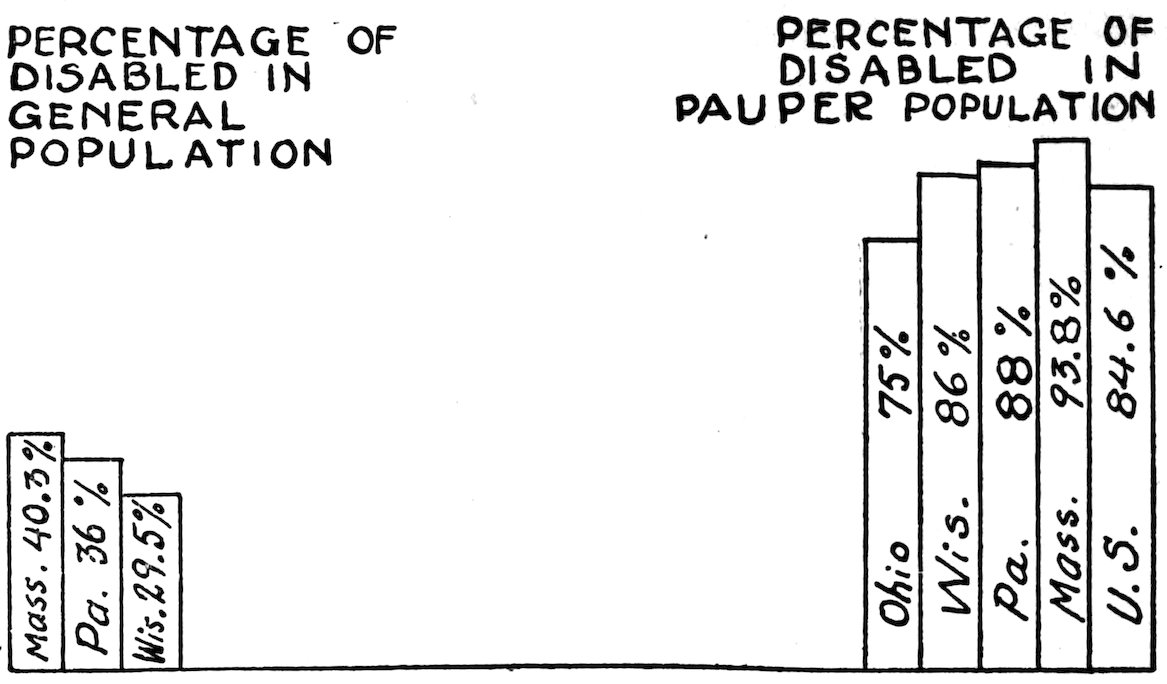

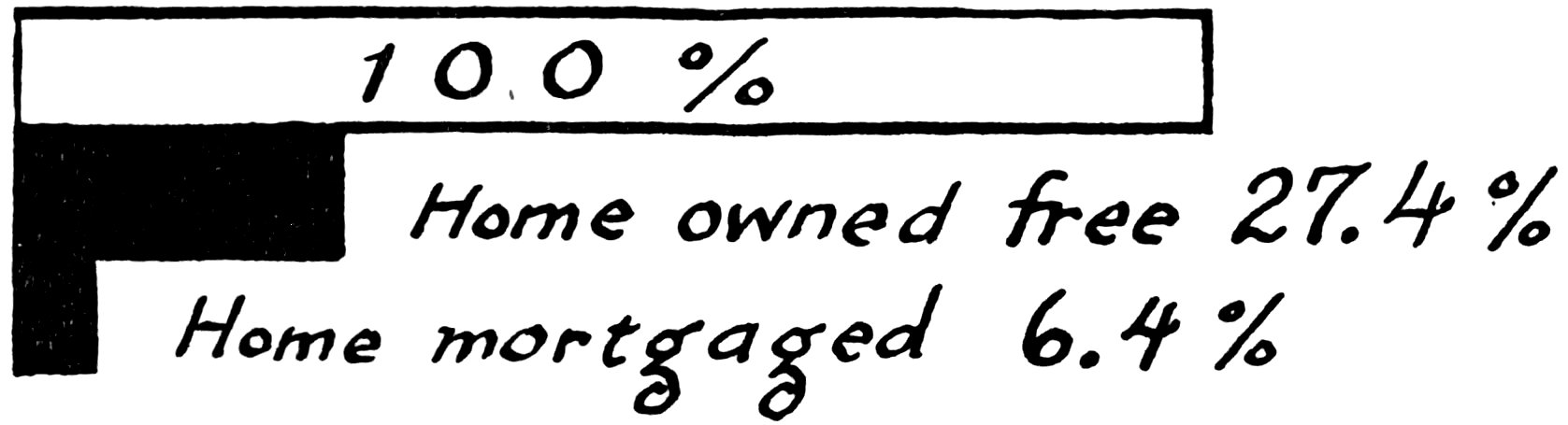

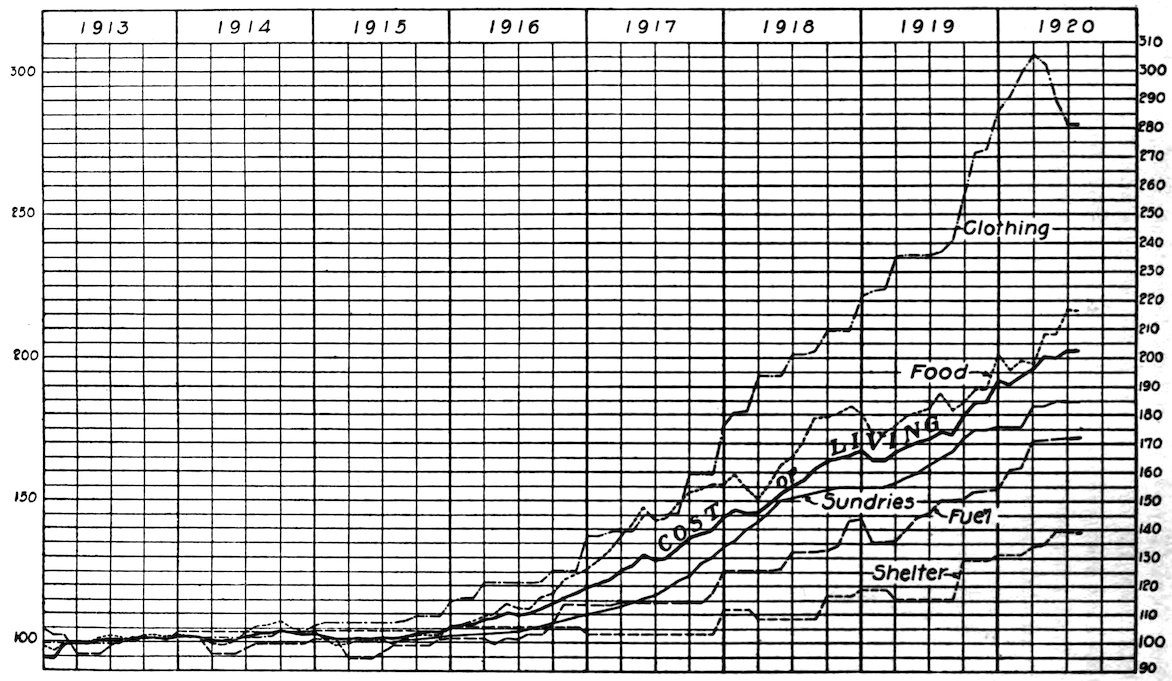

The marital condition of paupers is given by the 1910 Census as follows: 50.2 per cent. single; 32.5 per cent. widowed, and 13.7 per cent. married. The 1915 Massachusetts Decennial Census found the percentages of the marital dependents to be: 35single 19.0; married 24.7; widowed 54.4. In Ohio, 47.5 were single; 37.8 married, and 10.9 widowed. In Pennsylvania 40 per cent. were single; 16.9 married; and 39.14 widowed. The report of the last named Commission goes on to point out that the single and widowed in the almshouses of the State constitute nearly eighty per cent. of the total number of inmates. However, the marital conditions of people over forty-five years of age in the entire State, as given in the United States Census for 1910, was: for males, single, 9.1 per cent.; married, 77.7 per cent., and widowed, 12.6 per cent.; and for women the percentage for those over 45 years of age was, single, 10 per cent.; married, 60.3 per cent., and widowed, 29.2 per cent.

The Commission adds: