![[Cover]](images/cover_thumb.jpg)

Title: The sultan of the mountains

the life story of Raisuli

Author: Rosita Forbes

Release date: December 29, 2025 [eBook #77563]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1924

Credits: Galo Flordelis (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Large-size versions of illustrations are available by clicking on them.

THE SULTAN OF THE MOUNTAINS

By

ROSITA FORBES

Author of

“THE SECRET OF THE SAHARA: KUFARA”

“QUEST”, ETC.

![[Decoration]](images/logo.jpg)

NEW YORK

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

1924

Copyright, 1924

BY

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

Printed March, 1924

PRINTED IN

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

VAIL-BALLOU PRESS, INC.

BINGHAMTON AND NEW YORK

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Into the Days of Haroun er Rashid | 3 |

| II. | The Wild Land of Raisuli | 10 |

| III. | Raisuli Himself | 19 |

| IV. | Pride of Race | 25 |

| V. | Early Prowess in War | 33 |

| VI. | Prison, Torture and Escape | 41 |

| VII. | Raisuli’s Two Hostages | 57 |

| VIII. | More Power; Governor of Tangier | 66 |

| IX. | Plotting and Counter Plotting | 75 |

| X. | Dealings With Mulai Hafid | 90 |

| XI. | Building the Palace at Azeila | 98 |

| XII. | Legends of Cruelty | 105 |

| XIII. | Strained Relations with Spain | 120 |

| XIV. | Alarums and Excursions | 136 |

| XV. | War with Spain | 152 |

| XVI. | Arabian Astuteness | 168 |

| XVII. | Raisuli’s Strategy | 183 |

| XVIII. | Plotting for Peace | 199 |

| XIX. | The Treaty of Peace | 215 |

| XX. | Gossip of the Harem | 230 |

| XXI. | More Fighting | 244 |

| XXII. | Jordana’s Death | 261 |

| XXIII. | Leader of a Holy War | 276 |

| XXIV. | Siege and Retreat | 291 |

| XXV. | Popular Myths and Superstitions | 307 |

| XXVI. | Peace Again with Spain | 323 |

| XXVII. | Farewell | 337 |

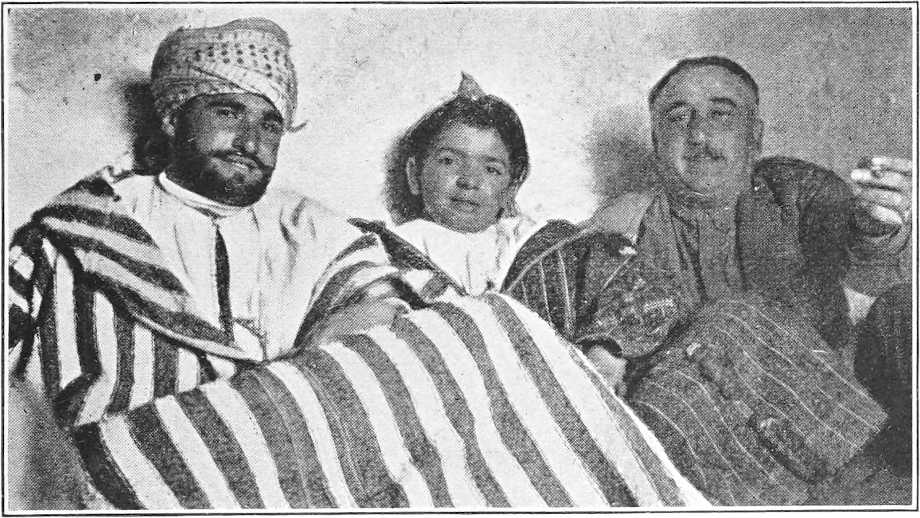

| Raisuli and Rosita Forbes at Tazrut | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| Map of Spanish Morocco | 4 |

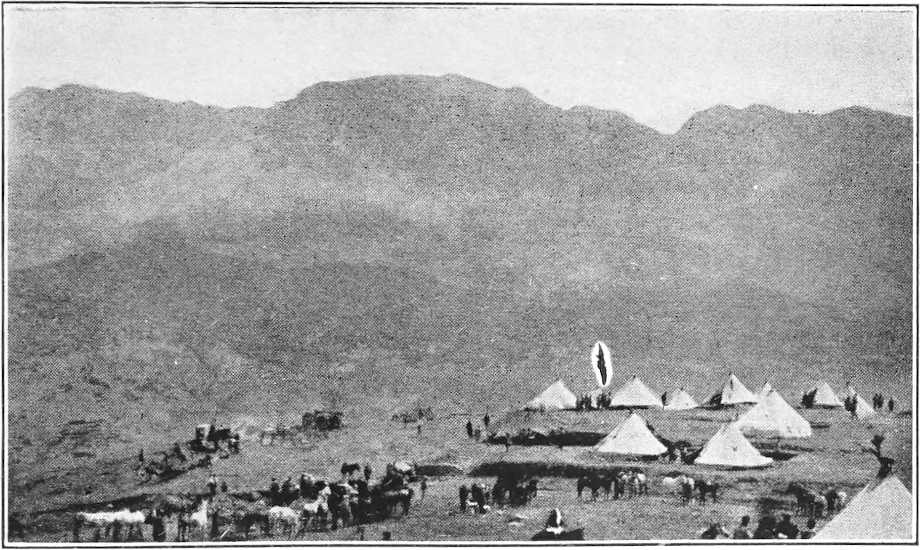

| Escort sent by Raisuli to meet Rosita Forbes | 10 |

| Powder play by Arabs | 10 |

| Snake eater at Suq el Khemis | 13 |

| Court of Raisuli’s palace | 16 |

| General view of Raisuli’s compound | 22 |

| Dinner at Tazrut | 22 |

| Rosita Forbes amidst Raisuli’s people | 32 |

| A halt on the way to Tazrut | 32 |

| Raisuli’s prison in Tazrut | 48 |

| Xauen with the ancient castle | 48 |

| Entry to Raisuli’s palace | 64 |

| Raisuli | 80 |

| Mulai Sadiq in his home at Tetuan | 96 |

| Nephew of El Raisuli | 96 |

| Sacred tree in Raisuli’s palace | 112 |

| Raisuli’s original house at Tazrut | 128 |

| Raisuli’s present house in Tazrut | 128 |

| Mulai Ahmed el Raisuli | 144 |

| Raisuli’s house at Tazrut | 160 |

| Raisuli’s qubba at Tazrut | 160 |

| Mohammed el Khalid | 176 |

| Raisuli’s house at the Fondak of Ain Yerida | 192 |

| Raisuli’s house—the Zawia—at Tazrut | 192 |

| Facsimile of a letter from Raisuli | 197 |

| [viii]Tazrut | 208 |

| Mosque at Tazrut | 208 |

| Spanish escort in Beni Aras | 234 |

| A Spanish port | 234 |

| A view of Tetuan, showing tower of mosque | 250 |

| Door of mosque at Tetuan | 266 |

| Azeila from the air | 282 |

| Gallery of Raisuli’s palace | 298 |

| The Sorceress mentioned by Raisuli | 314 |

| Gate of Raisuli’s Palace | 330 |

The 14th century of Islam has produced a number of remarkable personalities, but none is surrounded with such fabulous glamour as that of Mulai Ahmed er Raisuli Sherif, warrior and philosopher, saint, tyrant and psychologist. This Haroun er Raschid of Morocco is descended from the Prophet through an older branch of the imperial house which now reins in Fez.

By race, therefore, he is entitled to the respect of his people and he makes the most of the superstitious awe which has surrounded him since his childhood. Yet his personality is in no way the result of his great descent. Raisuli is a man whose mind, critical and peculiarly impersonal, must often have been at war with his spirit—a spirit steeped in the mysticism of the “baraka,” the traditional blessing which protects his house. Profoundly intelligent, with a knowledge of human nature, whether European or Arab, which is the result of unusual powers of observation, but which, to the Moor, appears supernatural, the Sherif’s audacity is as much mental as physical. He believes in the luck which invariably turns the most adverse circumstances to his final advantage, and is not above staking his remarkable immunity from danger against the credulity of his followers, but below this is the conviction of divine right. His charm, as powerful as it is elusive, is a revelation of the “baraka,” for it is purely spiritual and has no connection with the concentrated energy of his mind.

Raisuli represents to the Moors the champion of Islam against the Christian, of the old against the new; yet, from his youth, he foresaw the inevitable intervention of Europe[x] in Morocco and determined to manipulate such intervention to his own ends. The project, though ambitious, was not egoistic, for the Sherif conceives himself an instrument of fate—“This is my land and you are my people. While I live nothing shall be taken from me.” His ancient race is part of the soil of the mountains, and the 1,500 Alani Sherifs, of whom he is the head, are inseparable from the land they alternately oppress and protect.

Since there are no years in desert or hills, Mulai Ahmed has little idea of his age. A Spanish authority gives the date of his birth as 1868. Raisuli suggests 1871. As a child he was a student and a lover of books, with no other ambition than to write poetry and be a teacher of law and theology.

Adventure first called to him in the guise of a woman seeking redress against the bandits who had despoiled her house. The young Mulai Ahmed went to the hills with a band whose original quixotry was soon merged in lust of war and lust of gold—the two strongest passions in a primitive heart. The Sultan, Mulai Hassan, heard of the tribute levied on his caravans and ordered the arrest of the offenders. By treachery the capture was accomplished, and, for five years, Raisuli existed in the dungeons of Mogador. His imprisonment was probably the turning point of his life, for, with the Moslem heritage of patience and simplicity, he accepted his fate as “the will of Allah” and immersed himself in meditation. It is incredible to the European mind that any human being could support such tortures as the Sherif describes, but “What it is written, that shall a man endure.” Released before he was thirty, Raisuli had known the whole scale of suffering and emotion. His energy of mind and body had crystallized into a determination to wrest from circumstance a stable independence which should be the basis of his power. From this date[xi] (about 1900) he judged everything as a means to his ultimate end. The capture of Mr. Harris had neither financial nor political significance, but the American, Perdicaris, was used as a pawn in a great game. His seizure in 1904 forced 70,000 dollars from the American Government and the province of El Fahs from the Sultan.

Cruelty like morality, is a matter of latitude, for even tyranny is cherished if it is the result of tradition. Raisuli reduced his district to exemplary peacefulness, but the European Powers, objecting to their horizon being punctuated by decapitated heads, complained to the Sultan. The Sherif, as usual, retired to his mountains, successfully resisted the troops sent against him, and, in 1907, captured Sir Henry Maclean, which allowed him to make the last trick in a game played for profit rather than adventure. For the Englishman’s release, Raisuli acquired £20,000 and the protection of Great Britain. That such a transaction was but a step in his chosen career was proved when he waived his claim to both assets and identified himself with Mulai Hafid’s rebellion. In 1908 he visited the new Sultan at Fez, and, in secret, they swore the oath which affected the Sherif’s outlook as much as his subsequent life—“Never to cease from protecting the Moslem land and the Moslem people against the Christian.” It must have been a curious meeting between two such different characters, whose only bond was their mutual responsibility for the nation and the Faith in their charge. Both were far-seeing, but, whereas Mulai Hafid was afraid of a future in which he was destined to become the tool of France, Raisuli, arrogant because of his strength, a little baffled, perhaps, by the casuistry of a more subtle intelligence, saw only the need of unity among his co-religionists in face of a menace from which profit might yet be extracted. The compact between the roi fainéant who spent his last weeks of power haggling over[xii] the size of his pension, and the Sultan of the mountains to whom money was no more than the handmaid of power was sealed by the gift of the Western governorate, and it was never broken by Raisuli. The Sherif repaired to Azeila, where, as Pasha, he attempted to weld together different interests in the hopes of founding a united party among the educated which would be able to benefit by the advent of civilization.

Doubtless his projects were influenced by his friendship with Zugasti, the Spanish Consul at Larache, but from the beginning of his political life he chose Spain as the most suitable protector for his zone, believing her “strong enough to help the Arabs, but not strong enough to oppress them.” In accordance with the Sherif’s plan, Spanish troops landed at Larache in June, 1911, and the importance of his help can hardly be overestimated. It was a supreme step for a Moslem, the appointed champion of his Faith, to introduce a Christian army within the borders of the country he had sworn to hold inviolate, but Raisuli never wavered from his determination to benefit by the inevitable advent of Europe, rather than to oppose it. Had any other man but Silvestre, typical conquistador, been sent to command the Protectorate’s forces, the history of Morocco might have been different, but between two such imperious natures friction was inevitable. Raisuli protested against the General’s impatience, which made no allowance for circumstance and would brook neither advice nor the reasoning of a greater experience. Silvestre, dreaming of colonization rather than the gentle tutelage the situation demanded, was baffled by passive resistance and bewildered by the blunting of his most ardent weapons against walls of tradition and suspicion.

At one moment, owing to the Sherif’s eloquence, there was a rapprochement between the two men, during which[xiii] the Spaniard strongly recommended Mulai Ahmed for the vacant Kaliphate. Since this was the only logical solution of the problem, it is possible that Raisuli’s candidacy was tentatively approved by Madrid, but refused by France always afraid of his influence and suspicious of his attitude towards the Southern zone. The appointment of a puppet Kaliph, one Mulai el Mehdi, a cousin of the Sultan, was regarded by Raisuli as a deliberate betrayal, and the series of quarrels which ensued with Silvestre culminated in the Sherif’s departure for Tangier in January, 1913. From there he went to the hills and inaugurated a campaign which was defensive rather than offensive. At one time the Ulema of Xauen offered to proclaim him Sultan, on the ground that Mulai Adul Aziz was entirely in the hands of France and that Islam acknowledged no Kaliph under foreign protection. Raisuli refused, saying that he would resist the advance of his enemy Silvestre, but would not lead Moslem against Christian in a Jehad which must have disastrous results for his country. It is probable that at this time he still hoped to arrive at a satisfactory understanding with Spain, for he welcomed the High Commissioner’s conciliatory despatches from Tetuan while opposing Silvestre’s offensive from Larache. In May of 1915, owing to the unfortunate mistake of a subordinate, one of the Sherif’s envoys and intimate friends, Ali Alkali, was murdered while travelling with a Spanish “laisser passer.” General Marina (the High Commissioner), who had always been opposed to war, held himself responsible for the action, and sent in his resignation, insisting that Silvestre should follow his example.

The first action of the new High Commissioner, General Jordana, was to make peace with the Sherif, and, by the Pact of Khotot (September, 1915), Raisuli was virtually left in possession of the hill country, while Spain occupied the[xiv] littoral. For some months the mountaineers fought side by side with the Spanish army and the Tangier-Tetuan road was opened to Europeans, but this was the second year of the Great War and German intrigue was rife in Morocco.

The Sherif, determined that his country should benefit from whichever side won, kept in touch with both parties. While he paid little attention to the dazzling offers made by Mannisman, and categorically refused to attack the French zone, he considered the possibility of German protection for his son, made use of the Teuton arms and money which flowed into North Africa and took refuge in procrastination whenever Jordana wished to extend the active influence of the Protectorate.

The European Armistice and the death of Jordana occurred almost simultaneously (November, 1918). Consequently, at the very moment when Raisuli, relieved from the necessity of propitiating Germany, would have cooperated whole-heartedly with Spain, a new High Commissioner, Berenguer, arrived (in January, 1919) with the avowed intention of enforcing the authority of Spain by military occupation.

Raisuli gathered the tribes around him and succeeded in closing the Tangier-Tetuan road until October, 1919, when the key to inland communication, the famous Fondak of Ain Yerida was taken from him by a combined attack of three columns. During the summer he had been declared Sultan of the Jehad in a midnight ceremony before the tomb of his ancestor, Sidi Abd es Salaam, and it is probable that during the following year he had some 8,000 men behind him.

Xauen fell in October, 1920, and the Spanish armies, operating from there and from Larache attempted to effect a junction in the Ahmas Mountains south of the Sherif’s headquarters at Tazrut, thus completing the circle which[xv] enclosed Raisuli. The nature of the country made this impracticable, and, after a check at Akbar Kola, Berenguer advanced on Tazrut from the north through Beni Aros. After a three days’ bombardment the village was deserted and a few hundred mountaineers followed the Sherif to his last refuge among the forests and caves of Bu Hashim. The end of the war was in sight, when the “baraka,” or chance, intervened to save Raisuli from his enemies.

In July, 1921, news came of the disaster of Melilla and Berenguer hastened to the Eastern zone. Negotiations were begun with Raisuli, who took advantage of the respite, which he knew would only be temporary, to replenish his stores and ammunition. In September, the Spanish forces renewed the attack, and during the winter they captured the last outpost of the tribesmen, the Zawia of Teledi in the Ahmas. Still Raisuli held out. His people were starving, for the crops had been destroyed with the villages. Woman and children died from exposure and lack of food. All his most intimate friends had been killed. Every day deputations came to him imploring him to make peace. The illness, which is now expected to prove fatal, caused the man hours of agony when he could neither stand upright nor speak, but his answer was always the same: “It is Spain who will make peace.” “You talk of miracles, Sidi.” “A miracle will happen.” The miracle was the force of his personality which encouraged the doubting, strengthened the weak, imbued them with a reflection of his own faith. It is to the “baraka,” of course, that the Arabs attribute the fall of the Spanish Government early in 1922 and Berenguer’s recall, but it was on this that Raisuli, astute student of politics, had been counting.

Burguete was appointed High Commissioner in the summer of 1922, and, as soon as he arrived at Tetuan, he sent Zugasti and Cerdeira, lifelong friends of the Sherif, to arrange[xvi] a permanent peace. The conferences began in August, 1922, and an agreement was arrived at by which Spain was confirmed in her occupation of the whole Western zone. The Sherif disbanded his forces and returned to Tazrut. His nephews and other relatives were installed as Governors of the principal provinces, but Raisuli would accept no position nor stipend for himself, maintaining that his attitude had not changed since 1911. He would support the Spanish Protectorate, but he would not acknowledge the authority of the puppet Kaliph, Mulai el Mehdi.

True to this determination, Raisuli has never made his submission at Tetuan, though, at the urgent request of the High Commissioner, he sent some of his followers to represent him. He lives with the utmost simplicity in his mountain village, praying, fasting and studying. He is tired and his interests are mental rather than material, but the flame still burns. The flicker of it is seen when the tribesmen come in from the furthest limits of his country to consult him. He still manipulates the threads of Moroccan politics in those huge hands which, living, will never relax their hold.

Superficially Raisuli’s life appears one of wild adventure, of war, cruelty and political ambition, but his own story reveals him as a man of single purpose with considerable breadth of judgment. In so profound a nature there is room for many cross currents. One of the strongest and most secret of these is the mysticism which rises to the surface when he describes such ceremonies as the oath at Fez, his initiation at the hands of the Ulema of Xauen, his election as “Sultan el Jehad” on the moonlit peak of Jebel Alan. It is this faith, passionate, simple, indomitable, which marks him, in spite of his ruthless mentality, as a spiritual pilgrim, a searcher after Truth.

Rosita Forbes

[1]THE SULTAN OF THE MOUNTAINS

INTO THE DAYS OF HAROUN ER RASHID

“You go to see my cousin el Raisuli—to write about him,” said Mulai Sadiq at Tetuan. “For what reason? Between Africa and Europe there is a barrier higher than these mountains. You cannot cross it.”

I had gone to see the old Sherif with regard to my journey to Tazrut, for he acted as agent in Tetuan for his famous relative. His house was most attractive with its little court lined with mosaic and surrounded by white Moorish arches, from behind which peeped his slave-women, their brilliant crimson dresses showing through long coats of white muslin to match their turbans, corded with many-coloured silks. Mulai Sadiq is thin and wiry, aged about sixty, bald, with a grey beard. He has an ill-kept appearance, for he is an “alim” who considers that learning is very much preferable to cleanliness. He was willing to talk for hours of the adventures of ‘the Sherif,’[1] of whom he is the antithesis, since his face is intelligent and sympathetic and his hands talk even more expressively than his lips. When he got excited he took off his turban and thumped his fists on the ground, or flung them open above his head. I found him sitting on the floor, surrounded by immense tomes, with many others piled up behind him. He had to move a number before there was room for me to sit down, and then, with his spectacles pushed forward on his long nose, he began to talk about my journey.

“The Sherif will welcome you with great honour,” he said,[4] “but it is a long way and it is my duty to come with you, that you may travel in all respect.” Thus it was arranged, and he went off to telephone to the secretary of el Raisuli in primitive Tazrut!

The great Hispano-Suisa car flung itself on to the road as if it would devour the strip of dusty white which fled before it. The old walls of Tetuan disappeared. Away on the hillside a splash of green marked Samsa, where legend tells of a Portuguese Queen imprisoned in a subterranean maze. The dew was still on the sugar-cane, mist on the river. Peasants were driving their flocks to market; the men rode on donkeys, idle hands crossed on the pommel, the women, their haiks[2] bundled above their knees to show stout leather leggings, their hats, the size of umbrellas, hiding their faces, trudged behind their lords, bearing huge bundles of firewood or sacks of grain. A figure swathed in a burnous, rifle slung across his back, appeared on the skyline, and there was the watchword of Morocco—a veiled country, alert and suspicious.

Up and up soared the road, an incredible feat of engineering, and never for an instant did the driver slacken his pace. By precipices where the wheels spun on the edge of eternity, by nightmare twists and spirals where the path slipped eel-like from beneath us, the Spanish car took us into the land for which Spain and Raisuli had fought their amazing battle. Right and left rose the mountains, their first slopes thick with scrub and grass, their summits barren. Here and there a police post guarded the road, two or three men, shirts open to the sun, with their horses, and a tent as brown as the rocks. Where the river Hayera trickled through a wadi,[3] wild olives grew in profusion. Cactus lifted its spikes above thickets of pink oleanders,[5] the flower which the Arabs say brings death to any who sleep in its perfume. A Moorish village, the mud houses smothered under their weight of thatch, appeared among the boulders which strewed the landscape. On the hillside the Qubba of a saint drew white-robed figures to worship. A Sherif rode by on a mule with scarlet-trappings, and a servant running in front, crying, “Make way for the guest of God, the blessed one.”

The sun of Africa mellowed the scene, but, when a cloud crept over us, it showed a sinister land where the villages hid among rocks of their own colour and shape, so that one looked across a deserted prospect to the hills that tore the sky. A watchful land where a dozen of Raisuli’s snipers could hold up a Spanish column. Ben Karrish appeared as a serrated white wall. Here, the Spanish post is built round an old house of Raisuli’s to which the Sherif fled after the taking of Ain el Fondak. A few yards away is the mosque where he prayed for the miraculous intervention which his followers believe was afforded by the disaster of Melilla. A boy offered me flowers, a compressed bundle of morning-glory and yellow lilies. “There are but two good things in the world, flowers and women,” he said.

“Won’t you put the women first?”

“Ullah, they are the same thing! My master, the Sherif, has never refused the petition of a woman, but, Ullah, flowers are less trouble!”

Further on the road narrowed between wild vines and thickets of fig and dardara. “Raisuli’s tribesmen used to hide there and pick off our men like rabbits,” said the Spaniard who travelled with me. “Their chief is a strategist—we made war against shadows, and lost thirty men to their one.”

Across the hills in front toiled a line of great, grey beetles[6] which resolved themselves into lorries, packed with troops. The driver’s eye brightened. “It is possible that we may see some little thing, after all,” he vouchsafed, and spun past the nearest camion with two wheels down the bank. For an hour we overtook the various units of two columns en route for Dar Yacoba and the trouble that was reported vaguely “somewhere in the mountains to the East.”

A cloud of dust which looked like a battle surrounded a mountain battery and a long line of mules laden with Maxim-guns. Far up among the purple crags smoke appeared. “Is there really something doing?” murmured my companions, but I was unresponsive. It seemed to me very much too hot for any comfortable warfare.

One by one we left the marching columns and came into the purple wilderness of Jebel Maja, whose height so impresses the Moors that they say the daughter of Noah is buried on its topmost crag, the only one that showed above the Flood. Far up on every hilltop appeared a fort, its isolation emphasizing the inviolability of the land it watched. Goats strayed across the road, but the herdsmen were invisible. Then came the stir of guarded bridge-heads, and again the name of Raisuli—“Here a man was killed on either side of him, when he stopped at the height of the battle, a mark for the whole countryside, while his horse drank.” Rows of tents on the edge of a cliff, rows of mules tethered where those obstinate animals could have no desire to slip over it, showed us Dar Yacoba.

Then came the last steep kilometres to Xauen, the one-time city of mystery, of which men spoke in whispers, for it belongs to the Ahmas tribe, crudest and most savage of mountain folk. Twenty years ago they burned Christians in the market-place, and a certain street is still called the “Way of the burned.” The men of Xauen had a secret language, and, if a stranger could not give the password[7] at their gate, the most mercy he could expect was that his pickled head should adorn it, suspended by the ears. Xauen understands neither clocks nor calendars, and, when the Spanish troops entered in October, 1920, it was to find they had stepped back into the sixteenth century, from which the Jews, barefoot and bareheaded, hailed them with “Viva, viva, Elizabeth the Second!”[4]

Xauen’s claim to mystery lies in the fact that it is so deeply embedded in a cleft of the mountains as to be invisible till one is fifty yards from the walls. “We have arrived,” said the driver, and I looked blankly at the rocks and the deserted slopes. In another moment there was a town before us. By magic, white houses climbed one above another, madnas, tiled with the old faded green, soared from hedges of prickly-pear, and, below this huddled mass of roof and court, slipping like a cascade from the mountain-side, lay the great Berber castle, time-mellowed, sun-bleached, relic of an Empire whose very history is lost. We left the twentieth century outside the gate with the car, which could take us no further, and, preceded by a black slave carrying my luggage, passed into the days of Haroun er Rashid and the Thousand and one Nights. Veiled women stole into doors that looked as if it was the first time they had been opened since the beginning of time. Each arch, each window, was carved exquisitely and differently. A muazzin[5] cried the noon prayer from a mosque which overlooked the Qubba of a Rashid from Bagdad. The dim musk-perfumed shops framed the grey beards of Xauen’s “ulema,” a rosary between their fingers, their drapery flowing over the street.

One of these was a cousin of Raisuli’s, a man prematurely bent and worn. “He has been called upon to defend the[8] Sherif at moments when he would rather have been listening to his singing birds,” murmured a Kaid. A tiny scarlet door, with a lantern that once must have belonged to Aladdin, led us into the Qadi’s house. Slender Moorish arches surrounded a fountain, babbling to the swallows which perched in serried ranks upon the balconies.

Our host received us in a room whose ornamentation was particularly garish and crowded after the courts below. He had but two teeth, which hung from his mouth like tusks, but his manners were beautiful and unhurried. “The blessing of Allah, for you go to see the Sherif. He is a great man and the last of them.”

Seated on cushions and leaning against a wall lined with strips of satin, yellow, blue and red, we conversed gravely and with long silences, as befitted a first visit. “With el Raisuli will pass much of Morocco,” said our host. “You will not understand his ways—perhaps he will not speak at all—but, Ullah, his mind works all the time while he watches you. Nobody knows what he thinks, but he reads the minds of all men. That is his power.”

“It is true,” said the Spaniard. “He is an astute psychologist.”

The complicated apparatus necessary for a tea of ceremony was brought in by slaves, whose waistcoats paled the heaped-up colour in the room. Our host beckoned to another greybeard and slowly, meticulously, the tea was brewed with mint and spice and ambergris. “The Sherif likes mint—it is his only pleasure. There must always be fresh stores in his house. Otherwise he cares about nothing. He has no eye for beauty. He has never known love for anyone or anything.” Someone interrupted, “His son, Sidi Mohamed el Khalid. El Raisuli offered his whole fortune to anyone who would save his life when he was ill of fever.” The Qadi made a movement of protest. “It is[9] his race which lives in his son—the Sherifs of Jebel Alan. Besides, there is the curse. . . .” “What curse?” But somehow the question was not answered. Sweet cakes and biscuits were pressed upon us. Long-stemmed bottles of scent were offered that we might sprinkle our clothes, but the name of Raisuli was no more mentioned.

In the coolness after the early sunset, while the mountain walls turned slowly indigo, I explored the town. Its narrow streets ran downwards, steeply cobbled, by way of the Mosque and the Square where the Jews might not pass for fear of defiling its holiness. The suq, so narrow that two could hardly walk abreast, was roofed with mats, till it twisted abruptly to the cistern of ice-cold water that the Arabs believe will cure most ills. A leper bent over it, his face distorted to the semblance of a beast, and the Sheikh who was with me blessed him as we passed. “In the great war,” he said, “a German came here by night in disguise. He was the only European to see our town. Perhaps he came on business for the Sherif.” The German, of course, was Mannismann, the evil genius of North Africa.

THE WILD LAND OF RAISULI

Always there was the echo of the personality which had so impressed itself on Morocco that the soil of the mountains and the texture of men’s minds were equally impregnated with its forces. Here Raisuli saw a drunken Sherif, and, turning to the scornful onlookers, said, “The man is blessed of Allah. Your eyes see wrongly. He is in the throes of prophecy. Bring him to my camp.” The Sherif was never seen again, and legend says he was corporeally translated to Paradise!

Here Raisuli took shelter from the advancing Spaniards and, from the walls of Berber Castle, made the prophecy that is repeated from one end of the country to the other: “This is my country and you are my people. Nothing will be taken from me, but after my death it will all go.”

From Xauen it is possible to ride across the steep ridges of Jebel Hashim direct to Tazrut, but, because I wanted to see more of the country in which Raisuli had fought, we retraced our steps. Picking up the old Sherif, Mulai Sadiq, we continued by way of Wadi Ras and the Fondak of Ain Yerida, which was the Sherif’s headquarters for many months of war, to Azib el Abbas. There we left the main road and swung down through a desolate region, grey with boulders, to Beni Mesauer, the constant refuge of el Raisuli when hard-pressed. The house of el Ayashi Zellal, his sworn ally and father-in-law, is hidden somewhere among the crags, but we left the highlands for Wadi Harisha, where the olive trees are like round tents by a stream lost in vegetation,[11] and whole flocks shelter under their branches. For the first time I saw barley amidst the great stretches of millet. “These are the lands of the Sherif,” said the Mulai Sadiq, who had pulled forward the hood of his jellaba[6] till only a long nose and a pair of immense orange glasses were visible.

“Everything that you can see from now on belongs to him,” explained Mr. Cerdeira, the official interpreter between the Spanish Government and el Raisuli, who most kindly accompanied me to Tazrut, which he was the first European to visit, I believe. He added that, when Spain temporarily confiscated the properties of the Sherif during the recent war, they were valued at six million pesetas. Certainly these rolling downs, where villages were frequent, appeared to be excellent land for cultivation, though there were still as many acres of great, heavy-headed thistles as of grain. The post of Suq el Talata appeared on a hill-top in a haze of heat, and, after that, we clung panting to the sides of the car while we negotiated a track that, as the Sherif expressed it, after he had hit the hood several times, “jolted our backbones through our heads.” Sidi el Haddi, a valley where the stream made great pools between trees gnarled with lichen and thickets of the ubiquitous oleanders, gave us a little rest, and then up again by Sidi Buqir, a little white Morabit, where is buried one of the seven holy men of Beni Aros.

At last, when our throats were parched and our lips cracked, we had our first good view of Jebel Alan, on whose great peak was buried Sidi Abd es Salaam, the most famous of el Raisuli’s ancestors, and its twin mountain Jebel Hashim, the guardian of Tazrut. Below them, and most blessedly near, appeared the last big Spanish post, Suq el Khemis, and the little police camp of Sidi Ali. With a[12] series of mighty jerks the car leaped up and over the intervening track and deposited us, much exhausted, in the centre of a crowd which represented both the old Morocco and the new. On one side were the officers of the police post, cheerily apologetic because of a combination of pyjama jackets and puttees, speaking Arabic like natives, and saying that it was so long (two years) since they had seen a woman that they had forgotten what one looked like! On the other were the envoys of el Raisuli, with a guard of his mountaineers. Prominent among them, because of his bulk, appeared Sherif Badr Din el Bakali, and behind him, his jellaba turned back over a purple waistcoat and girt with a huge silver belt, the Kaid el Meshwar ed Menebbhe. These brought me greetings from the Sherif and expressed many ceremonious regrets that his eldest son, Mohamed el Khalid, had not been able to accompany them. I learned afterwards that the said youth, aged eighteen, having consistently neglected his studies during the festivities consequent upon his father’s recent wedding, had been put in irons by the Sherif, so that he might not be able to escape from his books!

It was then 108° Fahr. in the shade, and, personally, even in Arabia I have never felt anything hotter than the dry, burning wind, which appeared to issue from an oven among the hills. It was decided that while the Moslems prayed at the tomb of Sidi Mared, another of the sainted seven, fortunately conveniently near, the Christians should eat. We lunched with the hospitable officers, whose names I never knew, and a wonderful meal it was, not only on account of the inventive genius of the cook, but because no two people spoke the same language. Between us we mustered several different forms of Arabic and various European tongues, but the Tower of Babel would have been shaken by the efforts of the guests to communicate with[13] their hosts! We gave it up in the end and sat outside, in the largest patch of shade, looking over the plain where the great weekly market is held.

Hearing that strangers were in the camp, some gipsies came and stared at us over the edge of the sand-bags. One man held a snake in his hand to which he was crooning gently. Without much encouragement they began their unpleasant performance. A wild-looking youth with hair standing on end seized a glass and began crunching it up in his teeth. The man with the snake held it at arm’s-length and adjured it in the names of dead saints. Then, opening his mouth, from which foam dripped at the corners, he put out his tongue and let the reptile fix its fangs in it. Blood stained the foam and, with veins congested and eyes turned inwards, the gipsy began eating the living snake, first swallowing the head affixed to his tongue, and then chewing the body, which writhed up and struck him on the cheeks. All the time, the others kept up a curiously hypnotic chant which appeared to stimulate the hysteria or fervour of the performers, for, with a sudden shout, the eater of glass seized an iron mace which one of his companions was carrying. With this he struck his head so forcibly that the blood ran down under his matted hair. It was a disgusting spectacle, but evidently it delighted the remaining gipsies, who uttered bestial howls and flung themselves into a dance in which the maximum of contortion was achieved.

It was with great relief that I saw the approach of el Raisuli’s dignified envoys. “If we would arrive tonight, we must start,” said the Kaid, and, in another moment, there was the bustle of loading mules and mounting horses. The Kaid, evidently impressed by my boots, offered me his mount, a wild, grey stallion. “He is an Afrit[7]; so treat him with respect.” I did not need the warning. The look in[14] the Afrit’s eye was quite enough, but, fortunately, it is almost impossible to fall off an Arab saddle. Immensely wide and padded, with a high pommel back and front, it is girthed over half-a-dozen different-coloured saddle-cloths and has silver stirrups rather like coal-shovels.

The procession that moved away from Sidi Ali was imposing, for half-a-dozen officers, on their way to an outpost at Bugelia, rode with us, accompanied by their troopers; but, after we had clambered up and down a series of precipitous ridges, they left us, and we were in the hands of Raisuli.

The country became even wilder, the wadis a tangle of vine and blackberry, with high-growing shrubs nameless to me as to the Arabs, who called them “firewood.” First went the soldiers of the Sherif, stalwart mountaineers in short brown jellaba, with the rifles across their backs. They were followed by a couple of baggage-mules, behind whom rode a servant of the Kaid, a sporting Martini-Henry rifle ready for partridge or hare. His master was mounted on a gaily-caparisoned mule whose trappings went well with the gay colours of his turban and waistcoat. The Afrit and I danced uncomfortably behind him, generally sideways or in a series of bounds. Then came old Mulai Sadiq astride the plumpest of saddle-mules, his spectacles still balanced on the tip of his nose and a white umbrella over his head. Sidi Badr ed Din, his beard dyed with henna glittering in the sunshine, his horse almost hidden by his ample proportions, brought up the rear with the interpreter and some servants, who took off their outer garments one by one, to pile them on their heads against the fierceness of the sun.

For a couple of hours we rode across the mountains of Beni Aros, passing mud-built villages huddled under the shade of a cliff, their thatched roofs covered with wild vine, and wadis where the trees met above our heads, and grey[15] foxes slipped away into the bushes. After this there was only a goat track, which ran on the edge of a gully thick with blackberries, or across open pastures where the shepherds went armed, beside their flocks. The sun slipped low behind us as we clambered up the last rocks, blackened by recent fires, to the Qubba of Sidi Musa. There, at a well under wide-spreading trees, we stopped to rest. The Arabs said their afternoon prayers, bowing themselves till the earth grimed their foreheads, but I noticed that they drank out of the same cup as their Christian guest, without washing it. If the fanatics of Libia or Asir did such a thing by mistake, they would consider themselves defiled.

In the sunset we approached Tazrut, a cluster of white houses and green roofs, with the tower of the Mosque rising beside a thicket of oak. Seen across a stretch of scrub and rock, it looked an ideal hermitage for a saint and an admirable post of vantage for a warrior.

Tazrut is the strategical centre of Raisuli’s country. It lies midway between all his great positions and is within a day’s journey of most of them, yet it is in the heart of the mountains, commanding a wide expanse of country in front, where the hills of Beni Aros are piled, fold upon fold. Behind is the great barrier range, to whose summits the Spaniards are pushing their advance posts, but which a few years ago was only inhabited by wild pigs and monkeys. We pushed our tired horses across the last mullah[8] and found ourselves suddenly among ruins. On all sides were traces of the Spanish aeroplanes, which had bombed Tazrut for two days in 1922. Here were rough pits under the rocks, where the inhabitants had taken shelter, and great holes torn by bombs and shells. Not a house was undamaged. Roofless, with gaping walls and doors made of new sheets of galvanised iron or the wood of packing-cases,[16] they stood among cactus and thorn and curiously shaped boulders. I looked again, for there was something very odd about these rocks, and then I saw that, on the top of each, crouched an immobile figure in an earth-brown jellaba, with a rifle in his hands.

We passed various camps where mountain-men sat at the doors of their tents, profiting by the coolness, and then, among piled stones and broken walls, where the earth was gashed open below a mass of plaster, there appeared a splash of colour. “It is the sons of the Sherifs,” murmured someone, and I saw two vivid petunia jellabas, from the depth of whose hoods peered elfin faces with wild, tousled hair. In another moment we came to the paved road that runs between the mosque, miraculously untouched by war, the one complete building left in desolate Tazrut, and the dwelling of Raisuli. Slaves ran to hold out stirrups before the great arch which still kept some traces of its ancient carving. To the left was the domed tomb of Sidi Mohamed Ben Ali, a seventeenth-century ancestor of the Sherif; in front of us the passage leading into a space, half-yard, half-court. The compound was perhaps two hundred yards in length and, within its high walls, were various buildings. At one end was the Zawia, wherein were the rooms of el Raisuli, communicating with the old house which contained the family tomb and the women’s apartments. This was sacred ground, and no Christian might enter, but, during the Spanish occupation, photographs were taken of the interior court, one of which is reproduced in this book. Opposite was a large structure, temporarily roofed with corrugated iron. This contained, on the ground-floor, a series of storerooms and, above, a couple of reception chambers, where the Sherif ate with his friends and followers. At the other end of the yard was an old thatched building, once a residence of the Sherif, now his son’s school, with rooms for[17] visitors above. Near this was pitched a great black-and-white tent, with a fig-tree shading its porch, and various smaller tents behind.

“This is your home,” said Sherif Badr ed Din, beckoning me to enter, “and we are your servants.” The pavilion was lined with gay damask and carpeted with rugs piled one upon another. It was about twenty feet in diameter and round the walls were mattresses covered with white linen, and rows of very hard cushions. There was also a table with two huge brass candlesticks and several long-stemmed silver flasks containing orange-water and home-made scent of roses, but presumably this was an ornament, for we always had our meals on the floor. As a peculiar honour, the Sherif had lent the chair made specially in Spain to suit his colossal proportions, and, sitting in one corner of its great expanse, I drank my first cup of green tea at Tazrut.

The moon had risen and, outside the tent door, the breeze stole whispering across beds of mint and poppies. The figures of Mulai Sadiq and Badr ed Din looked like ghostly monks, sunk under the hoods of their voluminous drapery. From far away came the sound of chanting. “It is in the mosque,” said the Kaid. “Sidi Mohamed Ben Ali is buried there. It was he who won the battle of Jebel Alan (in 1542), where three kings were killed. The power of the Shorfa Raisuli began after that day, for Sidi Mahamed arrived with the tribes of the Jebala, when the Moslems were hard-pressed. ‘Have courage in the name of Allah,’ he cried, ‘for I tell you a Christian head will not be worth more than fifteen uqueia today.’” The three kings referred to by el Menebbhe were Don Sebastian of Portugal, the Sultan of Morocco, and the Moorish Pretender.

After the prayers in the mosque were over, Sidi Mohamed el Khalid, released from his irons in order that he might perform his religious duties, came to see us. Fair-skinned as[18] a girl, with an indefinite nose and hair clipped two inches back from his forehead and then dyed with henna and allowed to grow long, the boy greeted us shyly. His manners were clumsy for an Arab of great race, and he whispered instead of speaking out loud. When the Sherif Badr ed Din rebuked him, he said, “All we Moslems are savages, and I am the worst of them. My father wants to make me into an alim[9], for the ulema[10] of Beni Aros are famous throughout Islam, but I do not like books.” “What do you like?” “Only one thing, war. It is a pity that we have finished fighting!” “What do you do to amuse yourself now?” “I shoot. Will you come into the mountains and hunt monkeys? It is great fun! We go at night, when there is a moon, but it is very rough country; so we must leave our horses and walk. The monkeys come out one after another, screaming, and we shoot them.” “I have no rifle with me.” “That does not matter. You can have a choice of all kinds here, German, Spanish, French, or revolvers, if you like; but hunting is not so exciting as war.”

After this there was silence, and Mulai Sadiq left us, to pray in the Zawia. Soon his voice was heard leading the aysha prayers. In spite of his age, his words rang across the compound, and it seemed to me that I was listening to the voice of old Morocco protesting against the Christians who trod her borders and penetrated even to the threshold of her sanctuaries.

RAISULI HIMSELF

It is a long way from London to Tazrut and, during the whole journey, thoughts of el Raisuli had filled my mind. His name met me on the coast of Morocco and, wherever I went afterwards, I heard legends which magnified or distorted his personality. Small wonder that, sitting in his chair, a guest of his house, the moonlight sending fantastic shadows across the rough garden, my excitement to see this strange man grew until I forgot my hunger, forgot the tedium of the long ride. I only remembered that in a few moments I should see el Raisuli.

It was very still, except for the crickets. Even the breeze had stopped. The chanting in the mosque died suddenly, and Sidi Badr ed Din rose. “The Sherif comes,” he said. With racing pulses, I turned to meet a presence which blocked the way beneath the bushes. An enormous man stood before me. At first glimpse he seemed almost as broad as he was tall, but it was the breadth of solid flesh and muscle, not of fat. His round, massive face was surrounded by a thicket of beard, dyed red, and a lock of long terra-cotta hair escaped from under his turban. The quantity of woollen garments he wore, one over another, added to his bulk, and when, seating himself in a chair which seemed incapable of supporting his weight, he rolled up his sleeves, baring arms of incredible girth, I found myself looking at them fascinated and repelled, while he gave me the usual courteous greetings. “All the mountain is yours. You are free to go where you will. My people are your[20] servants, and they have nothing to do but to please you. I am honoured because of your visit, for I have great friendship with your country.” His voice was guttural and rich, but it appeared to roll over his thick lips from a distance which made it husky. His manners were gracious and his dignity worthy of his ancient race. After a few minutes’ talk I had forgotten the unwieldy strength of his body and was watching his eyes, the only expressive feature in Raisuli’s face. They were watchful eyes, dominant and fierce, in the midst of flesh, which it seemed to me they used as a veil. Sometimes, when he spoke of small things, they softened till they were almost wistful, but generally they watched and judged and revealed nothing.

I presented the gold-sheathed sword I had brought, with the Arab saying, “There is but one gift for the brave—a weapon.” The Sherif smiled. “You ought to have been a man,” he said, “for you have speech as well as courage.” Then I offered him some rolls of vivid-coloured brocades, purple, orange, rose-red and emerald-green, with heavy patterns in gold and silver.

“I heard, even in England, that you had been recently married, and I hoped, perhaps, that you would give these to the Sherifa with my greetings.”

Raisuli accepted the gifts with the simplicity of every Arab who considers that generosity is as common as sight or hearing, and it is rather the donor than the recipient who is blessed. Then a row of slaves appeared, with brass trays on which was every form of meat, with chickens, eggs, watermelons and grapes. These were placed on a leather mat on the floor of my tent, and the Sherif, with a soft “Bismillah,” bade me enter. “Tomorrow I will eat with you, but today I fasted all the day; so I ate an hour ago, after the aysha prayers,” he said, and sat down on the thickest mattress, to make conversation while we fed. Occasionally he picked[21] up a quart-jug of water and drank it in two or three draughts. Mulai Sadiq crouched beside him, looking like an old hawk, as he peered at one dish after another, picking out the tenderest portions with bony, but unerring, fingers.

It was hot inside the tent, and the Sherif moved restlessly in the middle of a discourse which revealed an intimate knowledge of European politics. I offered him one of those little mechanical fans which are worked by pressing a button, and I think he preferred it to any of my expensive gifts. “Allah, it is good! In this way one has the wind always with one.” But his thumb was so thick that it was very difficult for him to hold and work the slight machine.

We talked far into the night, till my head was whirling and my eyelids fell with automatic regularity. For us the day had begun before the dawn, and there came a moment when, my answers having become so vague as to be incomprehensible, the Sherif noticed my exhaustion. “In the pleasure of your conversation, I forgot that, after all, you are a woman,” he said. “Sleep with peace.” Without any loss of dignity, he heaved himself up, and his face was unexpectedly kind as he made his formal farewell. “Tomorrow we will talk of many things,” he promised, “and you shall begin your work, but Mulai Sadiq is my biographer. He knows my life better than I do, and as for these two men,” (he indicated Badr ed Din and the Kaid) “one has been my political adviser for fifteen years, and I have been in no battle without the other for twenty-five.”

. . . . . . . . . .

During the time that I stayed with el Raisuli, I was hardly ever alone, and counted myself lucky if I had four hours uninterrupted sleep at night. By 6 A.M. the place was astir, and I used to hear the Haj Embarik, a man from Marrakesh, who had travelled a good deal and understood my Eastern Arabic, murmuring outside the tent. I knew[22] that he was wandering about with a ewer of hot water, kicking the tent-ropes to attract my attention; so I had to throw off my tasselled blankets of red and white camel’s hair and prepare for a strenuous day.

Breakfast consisted of a bowl of thick vegetable soup with bits of fat floating in it—the “harira” that is given to children during the great fast of Ramadan. After that there was a painful gap so far as food was concerned till 3 or 4 P.M., when an immense meal of many meat courses made its appearance, borne shoulder-high by a line of slaves. Sometimes, when Mulai Sadiq announced that he was tired, we were provided at odd hours with green tea and very sticky pastry, sweet and heavy.

El Raisuli is always out by 6 A.M., and any one of his friends or his household may approach him in the garden, where he holds an informal council, seated on a broken wall or the steps inside one of the doors. Before noon he retires into the Zawia, where none may go to him unless he specially sends for them, except his eldest son and the ten little slaves, all under twelve years old, who attend on the harem. These small boys are rather like monkeys, but sometimes, when they are feeling important, they wear huge cartridge-belts over their inadequate shirts, and oil their top-knots till they look like coils of silk. Besides these minute servitors, there are fifteen slaves, coal-black men from the Sudan and Somaliland, under the orders of old Ba Salim. They are not allowed into the house, but two of them, Mabarak and Ghabah, are the personal attendants of the Sherif. When he rides on his roan stallion, they walk one at each stirrup. In battle they range their horses on either side of him and each carries a spare rifle, for el Raisuli never fights with less than three. During my stay at Tazrut, they were assigned to my service, which[23] was one of the highest honours the Sherif could pay to a guest.

About 4 or 5 in the afternoon, el Raisuli makes a second appearance, and, from then till midnight, or a much later hour, he transacts work and receives messengers, with the numerous reports and petitions that come to him from all over the country. The interviews I had with him were nearly always in my tent, or in the garden, or in one of the guest-rooms where a slave would hurriedly spread mattresses and rugs. The Sherif is a facile raconteur, and his memory is astounding. He never hesitates for a date or a name, but his eloquence consists more in the wealth of his similes than the richness of his language. His vocabulary is small, and he uses the same words continually. He recounts conversations word by word, with an annoying repetition of “qultu” (I said to him) and “qali” (he said to me). Obviously he is used to telling the story of his life, but this is natural, for very little Arab biography is written, in any case, till long after the death of the subject. Facts and anecdotes are handed down verbally, and it is part of the work of disciples to know by heart the life of their master, of schoolboys to learn the history of their ancestors.

The Sherif did not tell me a consecutive story, for often he would think of incidents that he had omitted, and indulge in much repetition in order to bring in a certain anecdote, but at different times he reviewed most of his life with a wealth of detail. Of course the episodes that most interested him and upon which he dwelt at length were often not those which would appeal to a European biographer. On the contrary, he showed no interest in events which to me were of historical value, and it needed a great deal of tact and patience to induce him to talk of them at all. At times his point of view was so biassed that it was palpably[24] incorrect, but his story, even though it often either exaggerates or lacks detail, is a record of an amazing life—a web of philosophy and atrocities, of war and psychology, of politics, ambition, and Pan-Islamism.

When he became interested in his narrative, the Sherif lost all sense of time. Once he talked from about 7 in the morning till nearly 3 P.M. and often he would arrive before dinner and, hardly troubling to eat, talk without a pause till 2 or 3 A.M. Mulai Sadiq and Sidi Badr ed Din acted as a sort of Greek chorus, reinforced on certain occasions by the two favourite slaves, who emphasised the story with murmured confirmation. When the Sherif was in the Zawia, his cousin permanently kept us company, while others dropped in for an hour or two’s “short talk.” My notes were always scribbled in the wildest confusion as I grasped the meaning of the Moorish dialect, or as the interpreter rendered it in French, but I got quite used to writing them up while a violent argument was going on between the Spaniard and three or four Arabs as to whether a soldier found wounded in the mountains had been fired upon by a tribesman, or had accidentally shot himself. The Moorish voices rose to a pitch that would indicate incipient murder in any other country, as they revelled in the game at which they excelled—prevarication!—and I admired the persistence of the interpreter in outscreaming them. The fate of that soldier haunted my stay at Tazrut, and it was with the greatest difficulty that I managed to exclude him from my book!

PRIDE OF RACE

When a Sherif of Yemen tells his lineage he generally begins with Noah, and, passing through the legendary Kahtan and Johtan, explains the union of Ishmael the son of Abraham with an ancestress of the Koreish, of whom was the family of the blessed Mohamed. Mulai Ahmed ibn Mohamed ibn Abdullah el Raisuli el Hasani, el Alani, began his with the Prophet.

“My house is of the Beni Aros, who are descendants of Abd es Salam Sherif, buried on the highest point of Jebel Alan. We are the greatest of the Western Sherifs, whose power has always rivalled that of the Caliphs. Go to Tetuan and you will see the veneration paid to the Qubba of our ancestor, Sidi Ali ibn Isa, and all through the country you will hear of the Sherifs Raisuli. When we go to visit (the tomb of) Sidi Abd es Salaam, we are fifteen thousand of the line of Jebel Alan, his descendants, though of the family of Raisuli there are but seventy. We have held great posts in the past and stood between our people and the oppression of the Sultans. It is our duty to protect the people, for they honour us as holy. For us who have the “baraka,”[11] the blessing of Allah, they would give their lives and their property. If I tell a man, ‘Start today for Cairo, or for Mecca,’ he would ask no questions, but pick up his jellaba and go.

“No one dies of starvation in Islam, but a Sherif may sit at the door of his house and the whole countryside will[26] come to him to kiss the edge of his robe and pour their tribute into his basket. I remember when I was a boy, small so”—he made a gesture towards the ground—“my father, on whom be peace, was angry with a slave. He ordered him to go out and tell the others to beat him—so many lashes. I met the man on the way and asked him where he was going. He told me, to get so many lashes. I asked him what crime he had committed, and he answered, ‘I do not know, but the Sherif knows, and without doubt it is a bad one.’

“Once it was necessary that someone should die for a crime that had been done, and it was not politic that the murderer should be given up at Tangier. The Sherif sent for a poor man and said to him, ‘Would you have your family live in plenty, and yourself gain a paradise? If so, remember that on such-and-such a date, you killed a certain person.’ The man answered, ‘If the Sherif wills it—it must be that I am guilty,’ and the Lord gave him wisdom to answer all questions that were put to him.

“Such has been the power of my house, and that is why men follow me in battle. Death beside me is a blessing, and, were I to kill a man, his family would know that I had sent him to paradise. Oh! Mubarak, bring me my keys.” The slave, who had been listening eagerly, brought a great leather box and, from it, el Raisuli extracted a key. “I will show you a paper that you may understand my words and see that my family are greater than the line of Mulai Idris who ruled in Fez.” Here is the translation of the document laid before us:

“Praise be to Allah. The genealogical relation of our Master the Sherif, the gifted, the great, the venerated, the excellent, the unique of his epoch, the chosen among those endowed with majesty and goodness in these times, the majestuous by his origin, of whom there is no peer or equal[27] at this moment, my master and lord Ahmed el Raisuli, el Hasani, el Alani—may Allah grant him holiness and power. My lord Ahmed; the son of Sidi Mohamed; son of Sidi Abdullah; son of Sidi el Mecki, who was the first Sherif Raisuli and who, by order of our master, Mulai Ismail—whom may Allah receive in his bosom, conceding him mercy—for the purpose of ennobling this city, came to Tetuan, which longed for a bond of union with Allah, the Almighty, through the baraka (blessing) which, by reason of descent from the Prophet, this family possesses—May prayer and peace be with him. Sidi el Mecki was son of Sidi Buker, son of Sidi Ahmed; son of Sidi Ali; son of Sidi Hassani; our master and lord Mohamed; son of our lord and master Ali, he who was first to bear the name of Raisuli, who died in the year of the hejira 930; son of Sidi Aissa and of Lal-la Raisuli;[12] son of Sidi Abderrahman, son of Sidi Ali; son of Sidi Mohamed; son of Sidi Abd-Alah; son of Sidi Yunis, brother of Sidi Mechich the celebrated, very holy and powerful Mulana Abd es Salaam, most learned Imam, also known as Sidi Abi-el Hassam Chedli. May Allah keep him in his mercy and pity. Our master Yunis was the son of Sidi abu Beker; son of Sidi Ali; son of Sidi Hormat; son of Sidi Aissa; son of Sidi Salaam; son of Sidi Mazuar; son of our master and the Prince of the Faithful the Sultan of Morocco, Mulai Ali, who was known by the name of El Hidarat, he who is always in places of danger in battle; son of the Prince of the Faithful, Sidi Mohamed; son of the Emir Al-mumenina our master Mulai Idris, founder of the holy capital of Fez, the white city which shines from a distance, the noble, the generous and beautiful; son of the Prince of the Faithful Sidi Idris the Great, a Conqueror for Islam of the Empire of the West, el Aksa. His tomb is in Mt. Serhen, venerated by all Moslems who believe in God. He[28] was the son of Inulana Abdallah el Kamel the Perfect, pretender to the throne of his ancestors in the Orient, which was usurped by the Abasides who, having defeated him, caused him to die loaded with chains; son of Sidi Hassan el Muzenna. In the person of Muzenna the trunk of the descendants of the Prophet divides into two branches; one of these we have already followed, and the other is that of Alanien, in whose hands today is the sceptre of empire and who are the descendants of Sidi Mohamed el Nefs Ezzakia, brother of our master Abdallah el Kamel. They came to Morocco more than fifty years after the ancestors of the Shorfa Raisuli, which proves that these Sherifs possess a greater right to the throne than the present Emperors. Hassan el Muzenna is son of the Emir Almumenina, our lord and owner, Hassan the 7th—may God receive him in his mercy;—son of the Prince of the Faithful, the fourth Caliph of the Mehidie (the Reformers), Sidi Ali; son of Abu Talib, uncle of the Messenger of God;[13] may peace and prayer be upon him and may his face be venerated and may he be united before God with our mistress Fatima, the daughter of our owner, the Prophet of Allah on earth. As the rain from heaven falls, rejoicing the earth, may there fall upon him prayer and peace.”

The slave kissed the document when it was given back to him, and el Raisuli continued, his voice rumbling at the back of his throat: “Once, when I was a boy, I was riding with an important Sherif, and, as we went by the outskirts of a village, a man was lying on the ground in the shade of an olive. It was hot and he did not trouble to salute the traveller, who stopped his mule quickly and asked the reason. ‘The sun was in my eyes, Sidi,—I did not see,’ answered the man. ‘You do not use your eyes, so you have[29] no need of them,’ said the Sherif, and, from that moment, the man was blind.

“It is also told of one of the brothers of the Sultan that when he was in prison in Rabat, having rebelled against his ruler, he found, by means of his friends, that the way was open for him to escape. A sentry stood at the door and tried to stop him, as was his duty. ‘If you do not let me pass, you will go blind for the rest of your life,’ threatened the Sherif. The sentry hesitated, but he knew that he would lose his head if he allowed the prisoner to escape, so reluctantly he still barred the way. ‘Very well, then, you are blind,’ said the brother of the Sultan, and the man fell back, putting up his hands to his face, for he could see nothing.” There was a moment’s silence. Then the slave, Mubarak, murmured, “These things are well known, and all me know that those who disobey my master lose their sight.”

“Yes,” whispered the Spaniard, “that is quite true; but by means of hot coins pressed on the eyelids, not by autosuggestion!”

“How old am I?” said el Raisuli. “I can tell you I was born in the year of the hejira . . . (1871 A.D.), but what matter the number of my years? No Arab keeps count of time. Ask Mubarak—oh, man, then, how old are you?” “As old as my lord wills.” Then, evidently anxious to satisfy, “Ten, eleven perhaps . . . or thirty. By Allah, I do not know.”

“I was born at Zinat,” said the Sherif. “You have seen the village, small houses with great roofs that you cannot pick out at a distance, and the hedges of cactus that even the dogs cannot get through. It was but a gun-shot to the top of the mountain, which commanded a wide view. I used to sit up there for hours and look at the country—[30] not like these hills but a rolling plain, golden with corn. I could see the women gleaning, and imagine how they cried ‘A-ee, A-ee!’ when the thistles tore their skin like needles. They used to make a shelter out of a haik spread on a pole for the heat of noon, and later, when it was cool, they would sit in a circle among the corn-sheaves and beat out the grain with wooden flails. I could hear their song like a thread, and away by the river I could see the boys bathing, but I never wished to be with them. I was happier alone. On the horizon were the hills of Beni Mesauer, from which came my mother, and I used to wonder why the others were content to work in the plain, when there was a great country beyond, full of valleys and rocks, where one could hunt in a different mountain each day. The ideas of a boy!

“When I was ten or eleven, I was already a ‘talib’[14] able to read and write and repeat the sayings of the Prophet. For this reason an ‘alim,’ a very learned man who came to the village, was interested in me and told me many things. I used to look after his mule for him in order that he would talk the more. He had the gift of speech, and he could make men weep or laugh. I decided that I would do the same; so I collected some of my friends (many were older and bigger than myself), and we went round the neighbouring villages with small white flags, to collect money for the alim who, as many wise men, was very poor. Sometimes people laughed at us, and would not give. Then I spoke to them, and, remembering the eloquence of my master, my words became swords to pierce their hearts, and they said to us, ‘Take this and that,’ even more than they could afford.

“When, after some days, we returned and poured the money into the alim’s robe, he blessed me and said that I should travel much and acquire much wealth. After that[31] my spirit was restless, and I would make up speeches on the mountain and declaim them to the birds and the goats. All that was told me I could remember, and, to this day, I can repeat every word that has been said in conversation between such and such people on such and such days. It is a blessing from Allah, but it astonished my master, as did my love of history. I wanted to know everything that had happened in the past, for, in those days, I believed that all wisdom lay in books. The right was not with me, for it is the study of one’s neighbours that brings wisdom. What book can tell you that which lies in the heart of your enemy?—it matters not about your friend, for you will see your own thoughts there—and how can you conquer him if you do not know his designs?

“When my feet grew too restless, I collected the same boys once more and, with white handkerchiefs tied round our heads, and staffs cut from olive-trees, our jellabas kilted up, we made a pilgrimage round the shrines of the neighbourhood. You have seen them, perhaps,—a pile of whitewashed stones under a bush from which flutters a strip of white stuff, or a Qubba high on a hill. We took nothing with us, neither water nor food, but the villagers gave to us plentifully—we had no need to beg—and some of them, who remembered me, said, “Here is the little messenger. Tell us stories, oh, master! Make us a speech, so that we see if our ears played us tricks.” I told them many stories, but always of war.

“It was at Tetuan that I finished my education, and there I lived till the death of my father, who is buried in the tombs of our family in the mosque of Sidi Isa. By this time I had studied law and jurisprudence. I knew the four codes of Islam and could interpret them according to the Koran. The mountains were shut out by the walls of Tetuan, and I thought of them no more. It was my intention[32] to be a lawgiver and a poet, for my world was closed between the covers of my books. When I went back to Zinat, people said, ‘He is a Faqih,’[15] and came a long distance to consult me. In the daytime I used to explain to them the law of the Prophet and the solution of their difficulties, and, at night, I used to walk on the mountain-side and watch the stars. Have you thought how great a part the stars play in our lives?—how the Prophet (may Allah bless him) spent nights in the desert, communing with them, how Jesus, the Breath of God, and David the father of Solomon, studied them while they kept their flocks? It was in those nights that I wrote verses, but none that were worthy of remembrance. Most of my wealth I gave away, for it seemed to me then that earning and silver did not live well together. The people heard of this, and, knowing that I had the ‘baraka,’ they came to me the more for advice, and carried out all that I said to them.”

EARLY PROWESS IN WAR

“My life was good when, suddenly one evening, about the time of the fourth prayers, a woman came to Zinat. Her clothes were torn and there was blood on her arms. She had walked many hours in the heat and her eyes were a little mad. She said that robbers had killed her husband and son, and taken all that she possessed. The wives of the village would have taken her in and comforted her, for hospitality was their duty, but the woman was from the mountains and she asked only a gun, that she might go back and take her revenge. ‘Is there no man who will go with me?’ she said, and the soles of my feet itched, and I saw my mother looking at me. . . .

“There were many youths in the village, and life was hard, for it was a season of poor crops. We put the woman on a horse, and all that night we went with her through the darkness. She took us to her empty house on the side of Jebel Danet, and from there we followed the robbers step by step. Many had seen them pass, but had been afraid to stop them because of the power of their chief. So they went slowly and we came up with them in a wadi, where they sat and bathed their feet in a stream. It was wild country, overgrown with oleanders that were higher than a man’s head, and great trees that would have hidden us, but the woman seized the gun from a youth’s hand and fired. There was a fight and the noise of the shots was drowned in our shouts, for it was like a hunt and the game could not escape for the rocks. We killed every one, and[34] took back the mules and the furniture which had been stolen from the woman. She cut off the head of the man who had killed her family, and took it away, that his soul might be destroyed and his body be incomplete in paradise.

“By Allah, perhaps the life of el Raisuli was decided by a woman, for, from that day, I was discontented with my books. I had no wish for a roof over my head, and I remembered that it is said of Beni Mesauer and the house of my mother, ‘They are born in the saddle, a gun in their hands.’ I spoke to the young men who knew me, and we formed a band and went out and lived in the hills, where no man could take us. We were famous in the countryside, and many came to us for help, but we were very poor. Our castles were the rocks and the trees our tents. Sometimes we had only goat’s milk as food; but I was very strong. I could live for days without food, and master a stallion with my hands.”

From this period date the fabulous tales of el Raisuli’s cunning and audacity, for he had everything to appeal to the imagination of a lawless and adventurous race. His physique was Herculean and he was so much a fatalist that he had no fear. To this must be added the prestige of his race, his indubitable learning, his eloquence, which throughout his life has been of great service to him, his skill as a rider and a shot, together with a curious gift of intuition which accounts for what he calls the infallibility of his psychology. There were many bands of brigands in Morocco at that time, for the authority of the Sultan’s Maghsen[16] was so attenuated as to be negligible. Brigandage was a paying game, if you had a better gun than your neighbour, but, whereas most of the famous robbers came to an unpleasant end, such as the Sultan’s lions or the knife of a[35] rival, Raisuli’s power increased with the stories of his supernatural power.

“In those days,” said the Sherif, “it began to be told of me that no ordinary bullet could touch me. I have heard that one of my enemies had a bullet of gold specially constructed, but, praise be to Allah, it flew wide, and the man only wasted his money.”

“It is said of my lord,” interposed the slave gently, “that the one on his right and the one on his left shall fall, but he shall be untouched. Those who wish to gain heaven swiftly claim these posts in battle, and it has happened many times. Once, at the great fight at Wadi Ras, it was a Spaniard who stood beside him, and my lord told him to go, but he would not, and whutt! he was shot!”

“Many tales are told of me,” said Raisuli, “and some are true, but always it is due to the ‘baraka’ which is in me, and perhaps a little to these.” He fumbled in his voluminous robes and produced two small grimy objects, which he held carefully and would not allow me to touch. One was the inside of a gazelle’s ear, complete with the long white hair, and the other a square inch of sticky black amber, tied up with some shreds of silk from the robe of a sainted ancestor. “A very potent charm,” said the slave. “Doubtless it saved my lord’s life in the day of the curse.” The Sherif frowned, and his rebuke was venomous enough to arouse my curiosity. This was the second time I had heard of the curse.

“It is long ago that we lived in the hills, without shelter, and imposed our will on the villages, but I still remember the cold of the nights when our jellabas were old and the sharpness of the rocks when our shoes grew thin. But a few months ago, a Faqih travelling from Fez stayed to see me on the way. He had walked so far that but half of his[36] shoes were left, so he asked me for another pair. Then I remembered my youth, and, because of the days when my shoes were tied up with a string and stuffed with leaves, instead of a pair of babouches[17] I gave him two horses, two mules and two slaves.”

“My lord is generous,” muttered the slave, but the Sherif continued, unheeding, “When my friends among the villages came to us for help, we were swift in vengeance. Once some robbers had carried off all the stored corn of a poor family, who were left defenceless against the winter. The man came to me, knowing our password, and showed us which way the robbers had gone, high up over the mountains, where it is very barren and few men travel. We followed them and caught them while they slept, and, for a punishment, we emptied some of the sacks into our jellabas and brought the corn down in this way. Then we tied up the robbers, and put one man into each sack, securely fastened and weighted with stones. After this, we left them on a ledge in the mountains and went away.”

“What happened to them?”

“Allah alone knows.”

There was a long silence. Perhaps the Sherif was thinking of the villagers whom he had alternately protected and oppressed. Generous in the extreme, but, of course, with other people’s money, incredibly daring and astute enough to leave nothing to chance, believing implicitly in his luck, which it was said that only treachery could destroy, he soon dominated the mountain country. His host was increased by volunteers from the tribes of Anjera, Beni Aros, Beni Mesauer and Wadi Ras, while a noted Sheikh gave him a daughter in marriage. In lieu of, or in addition to, a dowry, el Raisuli deposited at the Chief’s gate, all neatly strung on a cord and ready to be used for decorative purposes,[37] the heads of half-a-dozen bandits who had been annoying his prospective father-in-law by stealing his sheep!

“As the numbers of my followers swelled like the flocks in spring-time, we established a sort of customs in the hills. Each caravan had to pay according to its wealth, and, if it refused, well, then, the sight of a traveller sitting impaled on a spike probably made the next one open his purse. It was all business. I never refused a request and never betrayed my word, but the townsfolk were ungenerous and close-fisted. It took a long time to teach them their lessons, and by that time Mulai Hassan, the then Sultan, had heard of my affairs. I had an army in the mountains, and every man obeyed me because of my strength and my knowledge. It is well when there is one head in a country, but when there are many, there is trouble. There are caves in Beni Mesauer where a company may be hidden and hear the feet of their pursuers overhead. The country is rough and cushioned with scrub, and between the bushes run great cracks where a band may hasten, one after another, and no one know they are coming. In this land I lived and fought the forces of the Maghsen. When they said, ‘Where is el Raisuli?’ the tribesmen answered, ‘We do not know,’ for they were frightened to give me up. The soldiers of Mulai Hassan went here and there like dogs which have lost the scent, for one day it was said, ‘El Raisuli is here. Was he not seen this morning at the threshing of so-and-so?’ and a few hours later he was a hundred miles away.

“We had a password, and, one night, some men, riding below our camp, gave it, and added that the troops of the Maghsen were approaching up a gully on the right. Away we went to the left. He goes furthest and fastest who has few possessions! It was a trick, and before we had got into our stride we had fallen into an ambush, but Allah was[38] with us. We had come so much sooner than expected that the soldiers were not ready. They picked me out, saying, ‘We must kill that one! He is the Chief,’ and the bullets went through my jellaba, but did not touch me. Then they thought I was a magician and, being ignorant men, fled.