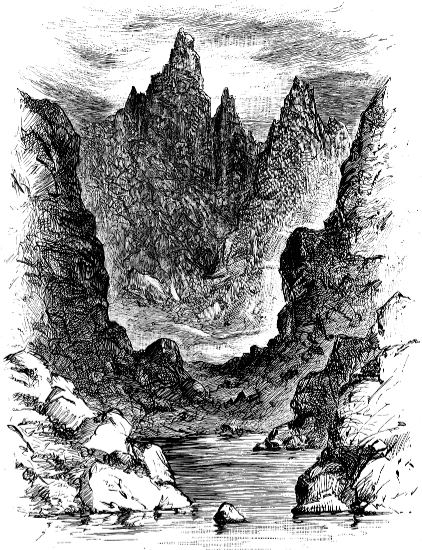

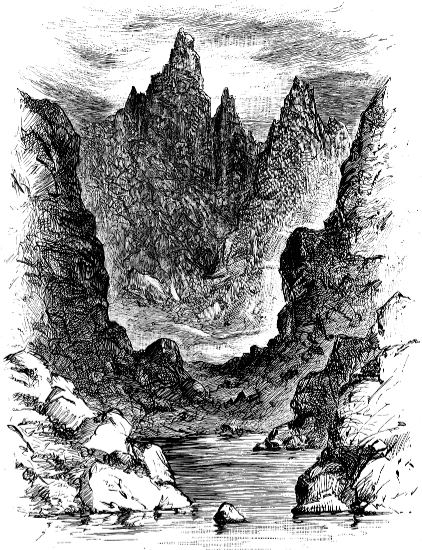

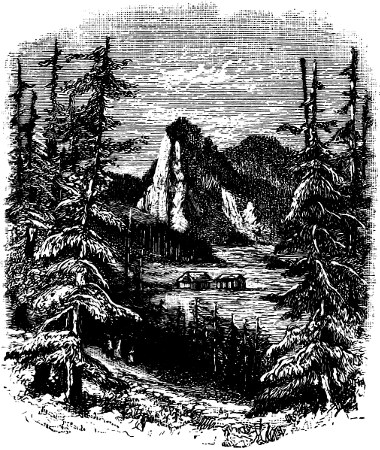

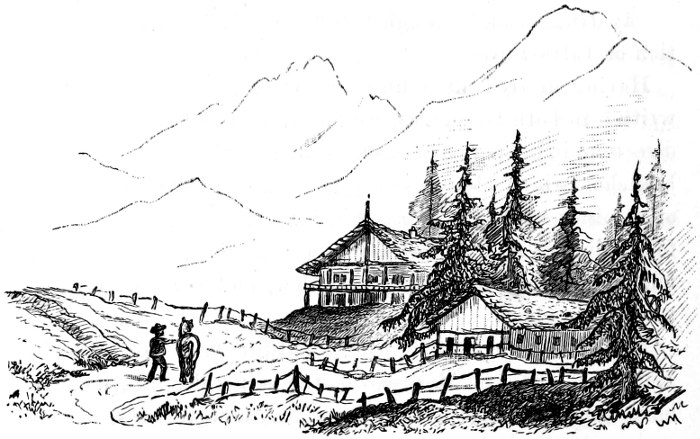

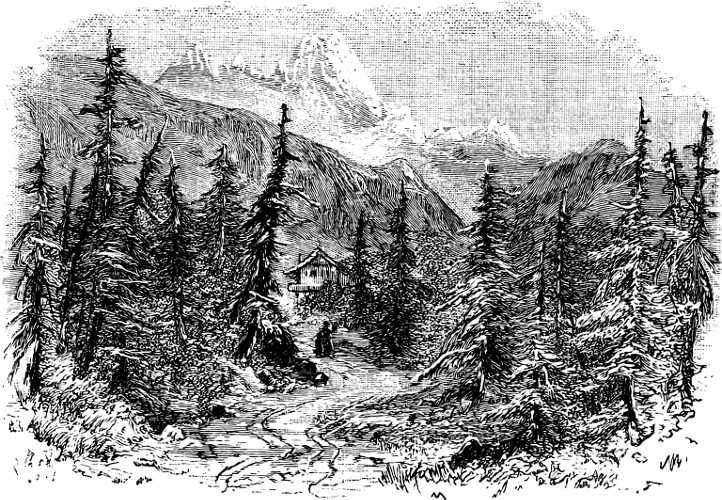

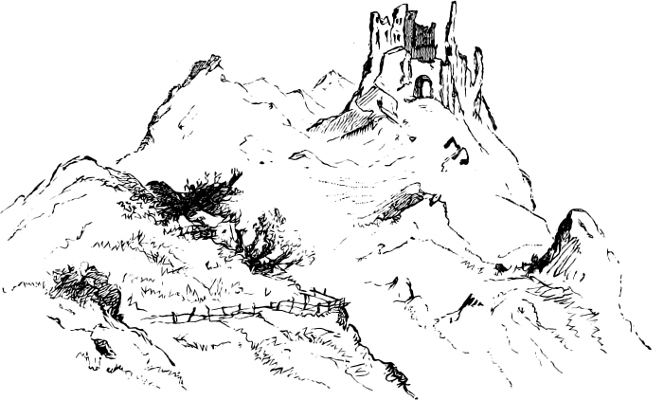

VALLEY OF THE FÜNF-SEEN.

Frontispiece, Vol. I.

Title: "Magyarland" Volume 1 (of 2)

being the narrative of our travels through the highlands and lowlands of Hungary

Author: Nina Elizabeth Mazuchelli

Release date: December 31, 2025 [eBook #77586]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1881

Credits: Peter Becker, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

VALLEY OF THE FÜNF-SEEN.

Frontispiece, Vol. I.

BEING THE NARRATIVE OF OUR TRAVELS THROUGH THE HIGHLANDS

AND LOWLANDS OF HUNGARY.

BY

A FELLOW OF THE CARPATHIAN SOCIETY,

AUTHOR OF ‘THE INDIAN ALPS.’

IN TWO VOLUMES.—Vol. I.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS.

LONDON:

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE, & RIVINGTON,

CROWN BUILDINGS, 188 FLEET STREET.

1881.

[All Rights reserved.]

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, Limited,

STAMFORD STREET AND CHARING CROSS.

Dedicated

TO

ALL WHO LOVE MOUNTAINS

BY

ONE WHO WORSHIPS THEM.

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| INTRODUCTORY | 3 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| THE PUSZTA | 17 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| A CAUTION TO SNAILS | 30 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| GIPSY MUSIC | 44 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| WE ARE MET BY OUR GUIDE | 55 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| DÉLI-BÁB | 66 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| THE AGÁS OR HUNGARIAN WELL | 78 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| DAWN IN THE ALFŐLD | 92 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| THE RACE | 104 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| PEST | 122 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| THE VOLKSGARTEN | 136 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

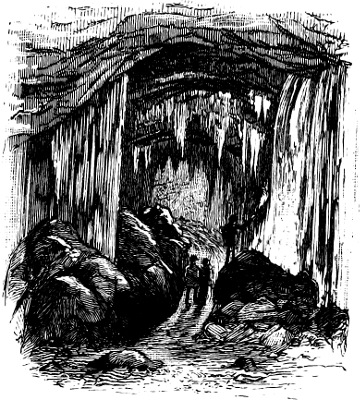

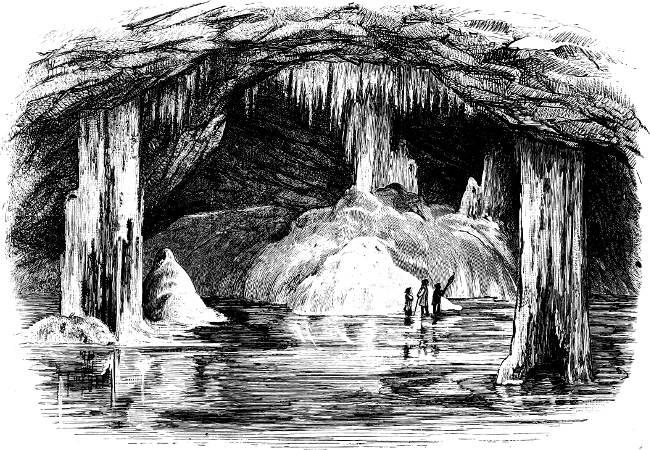

| THE ICE-CAVES | 154 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| A STORM IN THE MOUNTAINS | 169 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| SLOVAKS AND RUSNIAKS | 184 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| THE SNOWY TÁTRA | 196 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| GOBLINS OF THE MIST | 208 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| THE MOUNTAIN HOME | 222 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| THE GIPSY CAMP | 239 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| THE RED CONVENT | 252 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| ZAKOPANE | 265 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| THE CHAMOIS HUNTER | 277 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| ZIGZAGGING | 289 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| YETTA | 298 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| THE MOUNTAIN FUNERAL | 311 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| ANDRÁS IN DIFFICULTIES | 325 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| AFLOAT! | 340 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| A MOONLIGHT MEDLEY | 353 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| SHOOTING THE CATARACTS | 366 |

VOL. I.

| FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS. | |

|---|---|

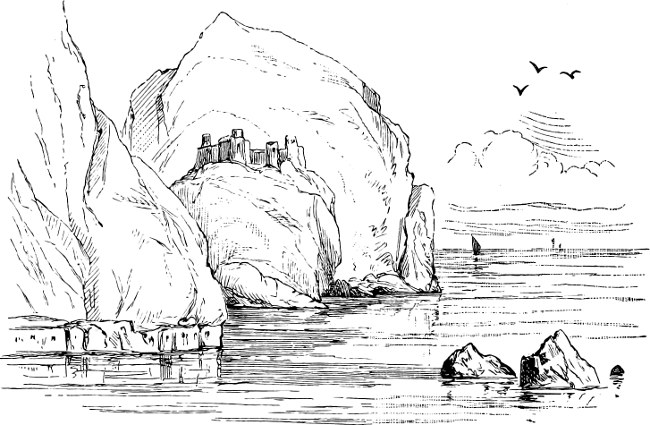

| Valley of the Fünf-Seen | Frontispiece |

| The Ice-caves of Dobsina | Facing page 155 |

| SMALL ILLUSTRATIONS. | |

| PAGE | |

| A young Hungarian Noble | viii |

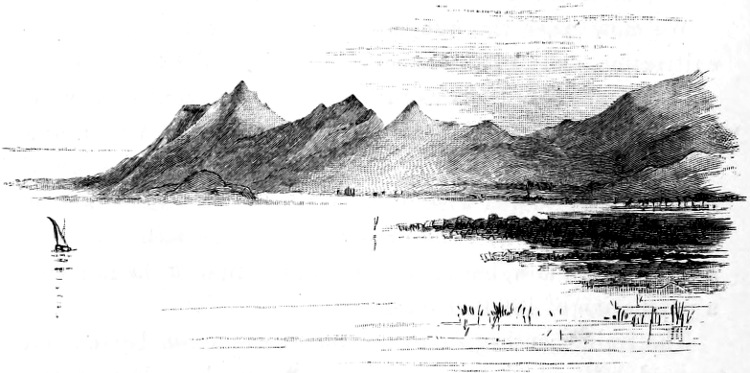

| View on the Gulf of Venice | 16 |

| Slovene Girl | 17 |

| Shepherd and Sheep on the Plains | 26 |

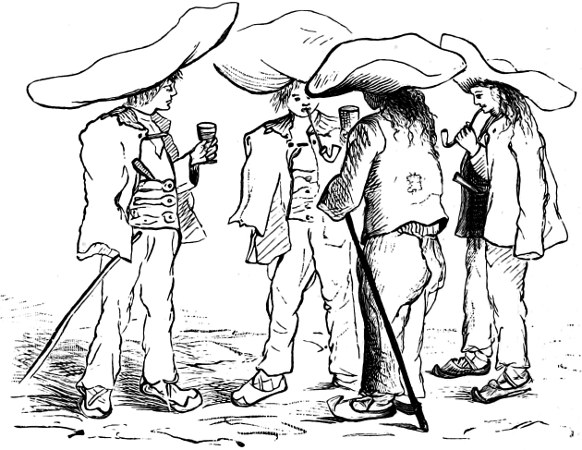

| Brigands | 29 |

| Old Hungarian Peasant | 30 |

| Peasants in Country Cart | 32 |

| Going to Church | 34 |

| “Little Nell” | 41 |

| “Carriages meet the Trains!” | 43 |

| Travellers bivouacking for the Night | 51 |

| Magyar Costumes | 54 |

| Our Guide | 56 |

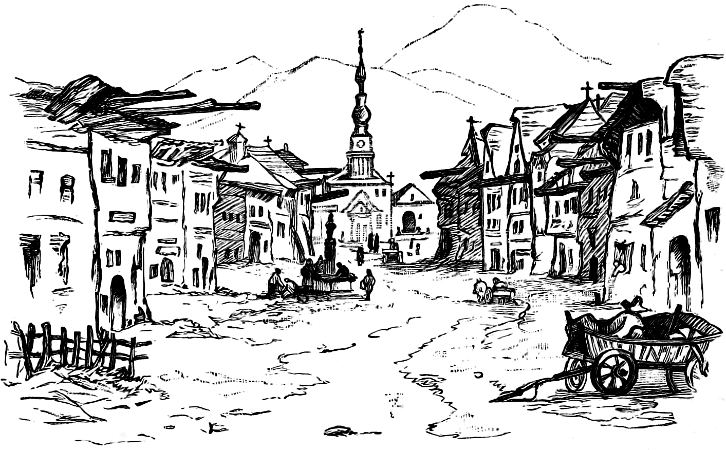

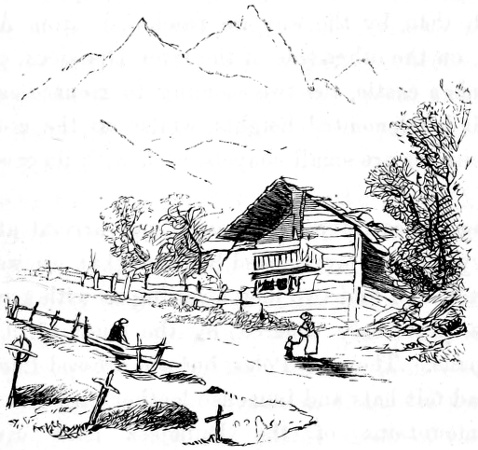

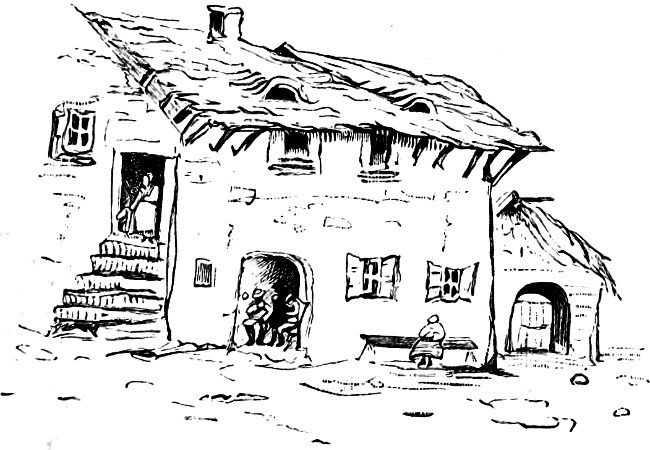

| A Hungarian Village | 58 |

| Gipsy-tent | 65 |

| The Threshold of Alfőld | 72 |

| Déli-báb (a Mirage) | 76 |

| Shepherd’s Hut and Well | 91 |

| Peasants at a Well | 95 |

| Cottage Doorway | 103 |

| A Rainy Day | 105 |

| Our Guide’s Wife | 111 |

| Jözsef | 121 |

| Church Steeple at Pest | 122 |

| A true Magyar | 133 |

| Our Chamber-maid | 135 |

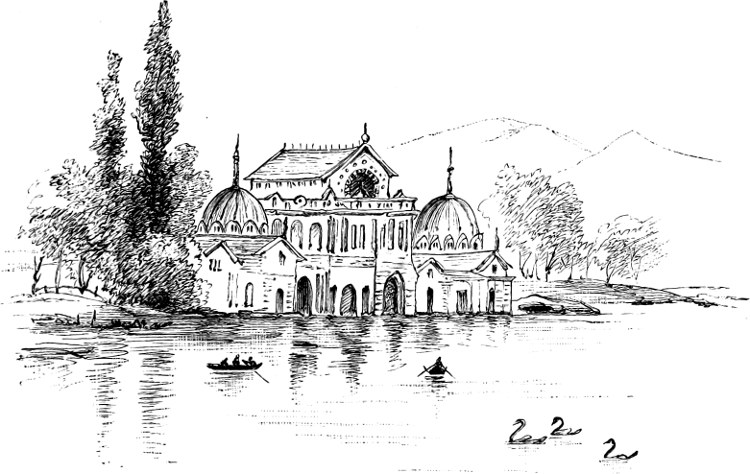

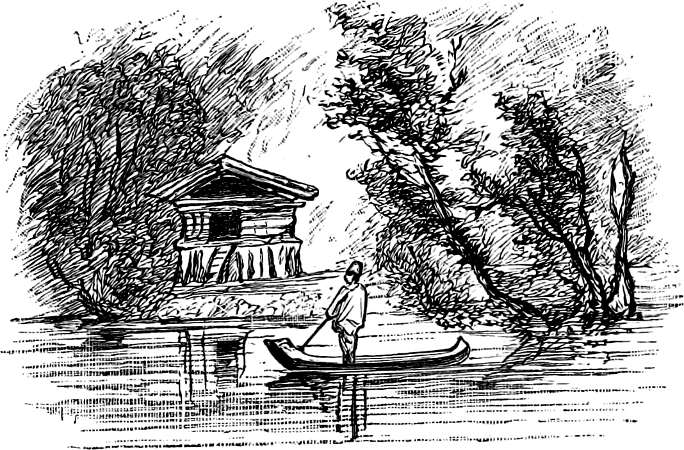

| Boat-house in the Volksgarten | 143 |

| A Magyar Lady | 147 |

| Under the Robinias | 153 |

| The “Corridor” in the Ice-caves | 154 |

| The Spitzenstein | 157 |

| Women washing in a Stream | 165 |

| Fetching the Milk | 168 |

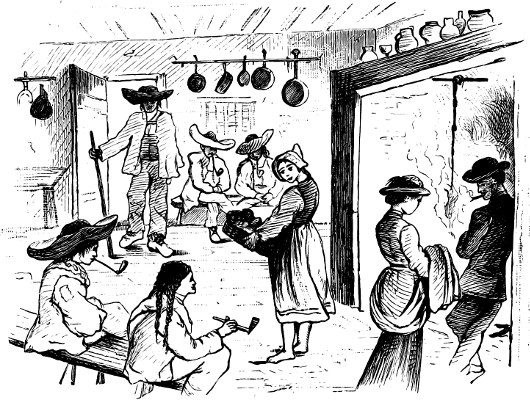

| An Inn Kitchen | 176 |

| Down the Mountain-side | 181 |

| A Corner in the Inn Parlour | 183 |

| Amongst the Slovaks and Rusniaks at Wernár | 188 |

| “The last sweet thing in Hats” | 190 |

| A youthful Slovak in Tears | 195 |

| Villa Sontagh | 202 |

| Tátra-Fűred | 204 |

| A Rusniak Brother! | 207 |

| Goblins of the Mist | 208 |

| Zigzagging | 211 |

| “Minsh’s” Flight | 221 |

| The Lomnitzer-Spitze | 236 |

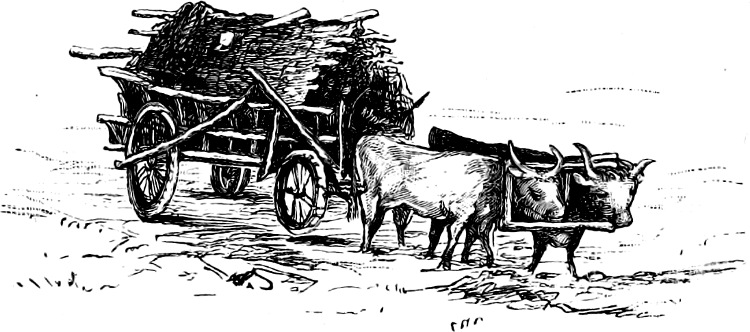

| A Carpathian Cart | 238 |

| Kesmark | 242 |

| Old Magyar Woman | 251 |

| The Red Convent | 254 |

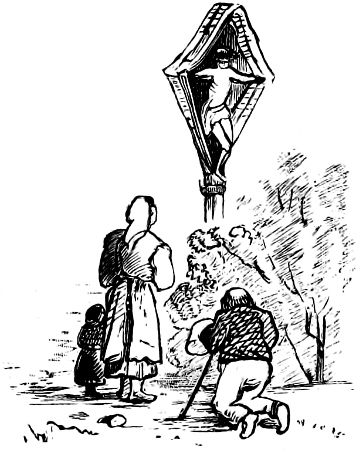

| By the Way-side | 256 |

| The “Royal Hungarian Mail” | 264 |

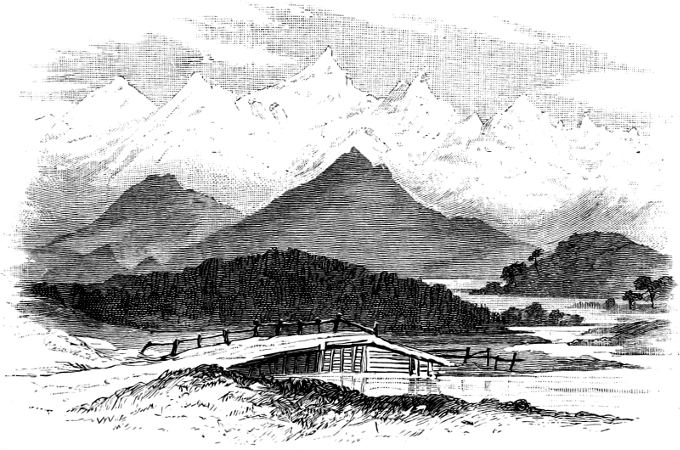

| Peaks of the Northern Tátra | 269 |

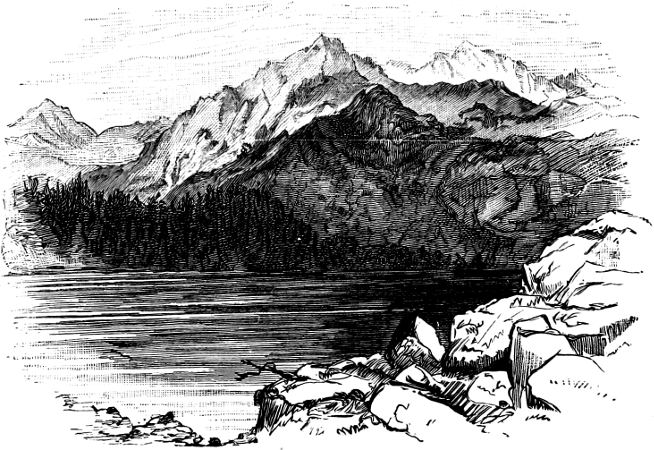

| Lake in the Mountains | 276 |

| The Herr Graf | 277 |

| Tátra Staff | 290 |

| A Mountain “Gottesacker” | 305 |

| Way-side Shrine | 310 |

| Slovak Sympathy | 319 |

| Covered Cart containing Zipser Peasants | 324 |

| More “Gentle Slovaks” | 332 |

| Greeting | 339 |

| Merchandise Boat on the Danube | 340 |

| A Swine-herd’s Hut | 346 |

| The Scullery-maid of S. S. Szechenyi | 352 |

| Our Danubian Jeannette | 361 |

| A Slavonian Boat | 365 |

| Castle of Golumbacz | 370 |

| The Bosnian Brethren | 374 |

| A Hungarian Country Inn | 379 |

[3]

“MAGYARLAND.”

The sun has sunk to rest in the warm bosom of the plains, and the porphyry hills of Buda stand out blue against the sky. In the long green avenue of robinias which line the quay, the flowers, drooping from the fervid heat of noontide, now unfold their perfumed petals and scent the evening air. Zephyrs, Oriental in their softness, come borne towards us over the Southern waves of the Danube, while from the gilded balconies of the houses along the shore are heard the melodious ring of voices and merry laughter, where the Magyar ladies sit to enjoy the cool breeze. Above the streets and squares of Pest, the black-and-gold cupolas glistening in the ruddy gleam of expiring day look like sentinels flashing emblazoned sabres.

What bright and pleasant recollections rise before us of the beautiful city as, in fancy, we visit it again and see its noble palaces that skirt the banks of the river casting the long reflections of their white façades in the deep waters beneath!

Immediately opposite Pest, separated by the monarch of[4] European rivers, lies Buda, linked to its sister-city by the most splendid suspension bridge the world yet boasts.

Passing once more in fancy the grim lions that guard its entrance and crossing over to the other side, what stirring memories come crowding into the mind! What changes have come over this ancient city of kings since Imperial Rome sat proudly enthroned within its confines, and in her days of pomp and power erected this amphitheatre, enduring type of her greatness and her brutality! How varied and mighty have been thy fortunes, proud Secambria, since thy proconsuls celebrated in this arena their cruel fêtes!

As the twilight falls, the busy hum and shouts of men, borne across the river, shape themselves in our present mood to the clamour of a barbarian camp. We catch the rumble of heavy chariots, and the tramp and neighing of their chargers, and we hear the triumphal strains of martial music that proclaim the overthrow of Rome and the erection of Attila’s iron throne.

But the shadows deepen—and who are these, the pitiless heathen, that come sweeping up with the mists on the river, till they too reach the shores of the Danube and Buda’s embattled walls? Hark! It is Arpád and his chieftains from the North, who celebrate in their turn, on the ruins of Attila’s palaces, with the music of lyres and the clash of cymbals, the Magyars’ conquest of Pannonia!

Slowly the moon rises, and lo! “a change comes o’er the spirit of our dream.” Turning our eyes to the citadel, crowned with its palaces as with a diadem, we catch the flicker of the Crescent above the gateways, see fluttering from the walls the pennon of the Moslem victors, and hear from the towers of the Christian churches, now minarets,[5] the watchman’s chant, “For Allah is great, and there is no God but He.”

Yet once more memory holds up its magic crystal, and, as the moon floats in placid triumph in the sky and the solemn stars stand ranged about her, there grows over the scene yet another change. The flicker of the Crescent pales and dies. The green pennon of Islam droops and disappears. For the conquering shadow of the Cross has fallen again upon the sleeping city, and, instead of the cadence of the watchman’s voice, there is borne upon the night air now, the pious music of Christian vesper-bells.

Truly, a wondrous history!

It was a lovely morning on which we stepped into the train that bore us in earnest and for the third time towards the land of the Magyar, a thoroughly old-fashioned May morning. The East wind had at length taken itself off to its own quarter, and the sun shone as benignly as if it actually meant to stay. It was just one of those rare days when a person of sanguine temperament might have been justified in entertaining a certain amount of confidence in the stability even of English weather. Nature had thrown off her dingy winter mantle, and clothed herself in a garb of fairest green. Everything seemed to say, “Summer is come! Summer is come!” The lark said it as he soared high in the azure depths: the blue-bell said it as she hung her head languidly in the high grasses in quest of shade: the bees said it as the perfume of the wild flowers called them to drink of their honey: the breeze said it as it fanned the slender stems of the ragged-robins in the hedgerows, and made billows of the emerald corn: the old[6] gentleman said it who sat opposite, and who, puffing like a steam-engine himself, arrived upon the platform just as the train was about to start.

What matter to us how the wind howl to-morrow, or the returning frost nip the newly-awakened spring-flowers? We are away, away! New costumes, new scenes, snow-capped mountains, foaming torrents, placid lakes, all chase each other through the brain in rapid succession like a perpetual dissolving view. At this distance no contretemps enter into our philosophy; no ferocious Hungarian officials who mistake us for Russian spies; no keen-sighted douaniers who look us through and through, as they demand whether we have anything to declare, awakening serious qualms of conscience concerning just that one little contraband something concealed in a mysterious corner of our belongings which we have determined not to declare; no days when we dine with Duke Humphrey and go supperless to bed. None of these things damp our ardour as we are borne through the smiling pastures of the West.

“The channel’s as calm as a fish-pond,” remarked the fat stewardess on our arrival on board the steamer. “And there’s scarce the leastest swell on.” But—exeunt passengers the following morning, woe-begone, dishevelled, wan, but hopeful.

On, past the quay, where the “merry fish-wives” cluster round the vessels, and bend under the weight of their large full creels. Through the quaint suburbs of the old Norman town, where more merry fish-wives sit surrounded by conical baskets full of red mullet, which at a short distance look like exaggerated pottles of ripe strawberries.

On, on, for we tarry nowhere, till we reach the fair capital of “La belle France.”

[7]

Here we linger for a day to call on a Hungarian merchant. He had promised to give us letters of introduction to some friends of his, who were landed proprietors in the north and south-east of Hungary, and which we believed would be very useful to us in that terra incognita. For such the greater portion of Magyarland still is to the ordinary tourist in spite of M. Tissot, for his interesting travels were strictly confined to Croatia, and the extreme west of the country.

The common and direct route to Hungary, and the one by which we entered it on our two previous visits, is viâ Munich and Vienna. But partly because we pined to breathe once more the balmy breezes of sunny Italy and bask in the smiles of her people if for ever so short a period, and partly because, unless compelled to do so, we rarely follow the conventional routes laid down in guide-books, we decided to go through Venice, and make that place our starting point to the “polyglot” country whither we were bound; a decision that greatly astonished a little Frenchman whom we saw in the merchant’s office in question.

“You should go to Munich,” said he, “and thence to Vienna, to reach Hungary.”

“Why?” we demanded.

“Oh! that is the regular route.”

“Yes! but we do not care to go by the regular route,” we replied; “we wish to see Hungary in its byways as well as in its highways.”

With a shrug of the shoulders, and an elevation of the eyebrows, as much as to say he hoped we should find the travelling to our liking, and muttering to himself “que les Anglais sont originals!” he turned away.

Here another voice broke in, proceeding from a tall[8] bony man, whose form, half hidden behind the sheets of Galignani, we had scarcely observed.

“There are no diligences, and no carriages in Hungary worth mentioning as such,” he exclaimed, and then subsided behind his newspaper again.

He pronounced the French word diligence as we pronounce our own familiar noun, and his speech betrayed his Transatlantic origin.

“Most Messieurs les voyageurs,” rejoined the Frenchman, returning to the charge, and evidently unwilling to surrender his point to another—“Most Messieurs les voyageurs rest satisfied with a visit to Pest.”

“Vous avez raisong, mussoo,” replied the American, without moving a muscle of his face, his eyes still fixed on the pages of his newspaper,—“Natur’ made Hungary a first-class country, but they’ve got a mode of locomotion there that whips all creation; as to railways they’ve none to speak of, and where you do find ’em the pace at which the lumbering old machines crawl along is a caution even to snails. If you want to do the Danube”—this time addressing himself to us—“take my advice and go down stream; you’ll do it in half the time: and if you’re thinking of doing the Carpathians, what I say is, don’t; you’ll soon get tired of cross-country work in Hungary, I can tell you, and as to the language——”

Happily at this juncture the conversation was brought to an abrupt conclusion by the entrance of the merchant himself, who had been absent on our arrival, but who now gave us the letters of introduction of which we stood in need, assuring us we should receive much hospitality and kindness from the gentlemen to whom they were addressed,[9] together with assistance on our travels, should any be required.

A brief examination, before leaving England, of Bradshaw’s Continental map had shown us that railway communication is now open the whole way from Venice to Pest, a distance in an almost direct line of five or six hundred miles. But the pages of that useful guide proved “too many” for us in their bewildering complications, and we were obliged to postpone the all-important question of “how to get there” till our arrival at Venice.

Arrived at that place, however, the question seemed as far from being solved as ever. The local railway guide conducted us as far as Udine, a comparatively short distance on our way, and then left us stranded high and dry on a shore of uncertainty. This being the case, we hail from the window of our hotel a passing gondola, and float off to the railway terminus to ascertain the matter for ourselves.

The hot weather had scarcely begun, and the wooden covers, with their black hearse-like fittings, had not been removed to give place to the bright-coloured awnings. As we glide through the sombre and silent ducts, walled in by ancient palaces which frown down upon us on either side, and skim over the glassy surface of the Grand Canal, the rocking motion of our dismal craft produces within us a vague and dreamy sensation; other black gondolas are following in our wake, the bell of a distant church is tolling, and being English, and taking “our pleasures sadly,” we feel we must be on our way to our own funeral, till we are jerked into consciousness and life again by the grating of the prow on the mainland close to the terminus itself.

The ticket office is of course closed, and there is not the[10] shadow of an official to be seen anywhere. But wandering along to the great platform in the dim hope of finding some one there who can help us, we are at length cheered by the sight of a person in the garb of a railway official of some sort coming towards us from the farther end. His footsteps echo dismally in the vaulted space, and for utter loneliness in his surroundings he might have been “the last man.”

Could he inform us what time the train left for Pest? we eagerly inquired as he approached us.

“Pest! Pest!” he exclaimed, looking bewildered—he could scarcely have been more so had we inquired the way to the moon.

“The capital of Hungary,” we suggested.

“Yes! yes!” he knew it was in Hungary somewhere; but here his stock of geographical knowledge came to an end, at any rate so far as that particular branch of the subject was concerned, and, with a bow and polite wave of the hat, he passed on his way, leaving us more benighted than before.

Whilst ruminating what next to do, we heard a quick step behind us, and he again appeared.

“Perdono, Signore! It strikes me that you must go hence to Vienna, and you will then have no difficulty in reaching Pest.”

Now to travel due north to Vienna, when Hungary lay in an easterly direction, was quite beyond the endurance of any enlightened travellers, particularly that of such experienced and enterprising ones as ourselves. It was not to be contemplated for a moment, but as we strolled back to our gondola, we began to wonder whether after all we had not for once been mistaken in deviating from the orthodox route and in creating one for ourselves.

[11]

On mentioning the source of our disappointment to our swarthy Charon, a bright idea seizes him.

“Ma ecco! Why will not his Eccellenza go to the Signor Inspettore himself? He lives up those steps yonder”—pointing to a house close by.

Why not indeed? Acting on our brave gondolier’s suggestion, we go at once in quest of him.

The Signor Inspettore was fortunately at home, and greeted us with the pleasant smile and ready courtesy which one invariably meets with in the people of this land. We were, however, once more doomed to failure. He knew everything apparently but that which we had come to learn; he certainly did not know the way to Pest, but bidding us wait, he retired to an inner chamber, whence he soon returned bearing under his arm an enormous map, his radiant countenance proclaiming that he had at last solved the difficulty.

“Perdono, Signore! I have ascertained. You must go hence to Nabrisina. There you will have to wait two hours, when another train will take you on through Cormöns to the Hungarian frontier.” And by the way he spoke of Cormöns one would have supposed it to be the extreme limits of civilisation.

“Not many strangers travel this way to Hungary,” added he.

“But do not your people sometimes travel?” we inquired.

“Ma no!” was the reply, given in that sharp, incisive tone in which every Italian pronounces that latter monosyllable. “We do not often travel, and to Hungary never. Basta! the climate of Hungary e una clima da Diavolo;”[12] adding with a shrug of the shoulders—the full significance of which we duly appreciated—“Perdono, Signore! Only the English go there.”

The moon had risen a full round orb as, the object of our quest accomplished, we once more stepped into our gondola and, gliding away, soon formed one of the many black specks crossing her silvery pathway on the great Lagoon.

The brilliantly-lighted shops in the colonnades of the Piazza di San Marco remind us that we have still something to do before we are fully equipped for our Hungarian travels. We had, as I have said, seen Hungary on two previous occasions; seen it, that is, in its highways. This time we meant to see it in its byways also; for which purpose it was necessary that we should equip ourselves for that cross-country travelling of which the American had hinted such dark things. Experience, too, that stern schoolmaster, likewise taught us the desirability of rendering ourselves independent, as far as possible, of the accommodation to be met with at small out-of-the-way inns. For these, however full of promise externally, are inwardly, except in rare instances, replete with disappointment; and black bread, kukoricza, bacon, and “paprika hendl”—a national dish, in which a fowl that, in blissful unconsciousness of the immediate future, has been picking up the crumbs that fell from the traveller’s table as he partook of his first course, may, at his last, appear in the form of a hasty stew, thickened with red pepper—are the only things to be found wherewith to fortify the inner man.

In addition, therefore, to a case of hermetically-sealed provisions brought with us from England, we here invested in a number of small items in the culinary line necessary[13] for our anticipated wayside bivouacs, including a singular contrivance for easy cooking, whereby the mysterious operation of roasting meat in a species of saucepan is accomplished; the vessel in question being called a cazarola. Besides these, there was yet one other item we had to provide ourselves with; namely, some dozen yards of stout rope, a very necessary adjunct to cross-country travel in Hungary.

For the necessities of the outer man we were already well provided by the possession of a large bunda—a relic of our former travels. This magnificent garment of Hungarian invention is a glorious institution, than which in the whole sartorial art there is none so grandly adapted to its purpose, or to the climate of the country, where the changes are exceedingly rapid. The chill which immediately follows the setting of the sun often causes the temperature to sink 20° Réaumur in the short space of two hours, and without this garment the traveller will very probably fall a victim to the Hungarian fever occasioned by the exhalation from the marshes. In fact, as the Venetian station-master delicately hinted, Hungary, like England, may be said to have “no climate, only weather.”

The majestic Alfőld, or plains of Hungary—the European Pampas as they have been called—though hardly as boundless as the ocean, are scarcely less fickle: now soft and tender under a calm and cloudless sky as they slumber in the dreamy haze of sunny noontide, now all glorious in the resplendent hues of the out-goings and in-comings of Day; anon fierce and tumultuous, as a violent wind sweeps over them, which, meeting with no obstacle whereon to spend its fury, whirls shrieking in frantic circles like an angry demon, tosses the[14] trembling and resistless hillocks of sand into billows, or, with a hissing noise, lashes them into fragments like ocean spray. Here also, in summer, as on the great African desert, the traveller crossing the sandy wastes is often misled by the delusive mirage. In the distance a lake, or village, or lonely csárda (tavern) lures him on, and causes him to lose his way.

No landscape, however, is so impressive as that afforded by these plains—plains so vast that they appear to embrace the Infinite; where the sun at setting seems to sink into the very bosom of the earth, and the stars burn red to the verge of the horizon. Who can describe the awful grandeur and stillness that reigns over this boundless region, as Night comes hastening on, bringing with it the stars, to hang like silver lamps in the sapphire deeps; or the beauty of the heavenly arch when the “milky way” is stretched across the zenith like a spangled veil, and the planets burn with such a steady light that they seem to cast a path of glory athwart the plains beneath?

Fitful as the climate is, there are however, happily for the traveller, two months in the year when he may almost depend upon fine weather, viz. May and June. The long winter’s frost and snow have at length by that time passed away; the intense heat of July and August has not yet begun, nor the autumnal rains which render the Hungarian roads (bad enough at the best of seasons) absolutely impassable.

After two more deliriously happy days at Venice, spent in loitering about its colonnades, sitting in the beautiful Piazza di San Marco listening to the strains of the military bands and sometimes floating over the glassy surface of the canals, we bid adieu to the “Bride of the Sea.”

[15]

In the railway carriage with us were two priests whom we had met at the hotel “Due Torri” at Verona, and who were, they informed us, to be our fellow-travellers as far as Udine. There was also a lady from Carniola on her way to Laibach, whose head was covered with a kind of Spanish mantilla and who spoke Slovenic, a dialect of the Wendish.

As soon as the train had fairly started, the priests, taking off their broad-brimmed beaver hats and exchanging them for more comfortable skull-caps, began reading their breviaries, following the contents with a motion of the lips, but without utterance of the faintest sound.

We now pass through an undulating country rich in cultivation, and olives and mulberry-trees take the place of vines. Our route leads us through the classic land of Illyria, a name rendered immortal by the poems of Virgil and Dante. After leaving Izonzo, we reach the ancient town of Monfalcone, situated within a few miles of the once famous city of Aquileia, where the Emperor Augustus often resided—a mere village now, but containing, in the time of the Romans, a population of 100,000 souls.

The train soon begins to ascend one of those barren and rugged hills which form the north-eastern boundary of the Adriatic Sea. Here all vegetation ceases except that of stunted herbage, and as far as eye can reach nothing is visible but rocky and conical hills.

As the engine labours up the steep gradient the blue waters of the Adriatic suddenly burst upon the view. To the left stretch the marshy plains which, extending over a vast area, constitute the “Littorale,” or northern shores. Away, in the distance, rise the purple mountains of Istria,[16] whilst below, embosomed in green hills, lies Trieste. The scene is calm, beautiful, and majestic in the evening light, recalling many a sad association connected with the life of the author of the “Divina Commedia,” as well as many an episode of early lore.

[17]

“Is there anything to be seen here?” we inquired of a pretty Slovene girl, who, in short red skirt, velvet bodice, and top-boots, was stumping about the platform as we alighted from the train the next morning, and at last stood on Hungarian soil.

Knowing just sufficient German to comprehend the nature of our question, she turned round, and pointing first in the direction of the desolate little station itself, then at a group of sheds opposite, and finally at a long straight road which apparently led nowhere, she showed two rows of pearly teeth, and looking up at us archly, burst out laughing at her own humour.

Pragerhof, the place at which we have just arrived—the junction of the Vienna and Trieste line—is in very truth a dreary spot to be set down at; but wishing to reach Sió-Fok[18] the next day, it was necessary to break our journey here. Nothing could present a more utterly forlorn aspect, and why the spot should have been favoured with a name at all is an enigma, seeing that it consists solely—as our naïve little Slovene had intimated—of the station itself, three or four sheds, and the small fogado (inn). Probably, however, the signification may have reference to a town or village hard by; “hard by,” that is to say, in a Hungarian sense, for in this part of the country, where villages are few and far between, people often call men “neighbours” who live twenty, thirty, and even forty miles distant, and not unfrequently convey their farm produce to fairs and markets full as many miles away.

We have now reached the threshold of the great plains, and, looking north, south, east, and west, not a sign of habitation is visible; nothing, in short, but the straight road already alluded to, and the long line of railway which vanishes only with the horizon.

The lonely fogado in which we have come to anchor till the morrow forms a tolerable example of all wayside inns in Hungary, except in the position of the stranger’s bedroom, which, instead of being on the ground-floor, is in this instance approached by a movable ladder. The salle à manger, as is invariably the case, not only adjoins, but commands an extensive view of the kitchen; and the traveller can—if he feel disposed—watch as he sits at table the interesting process of the cutting up and frying of his cutlets, and stewing of his paprika hendl; as well as the slaughter of the innocent itself. For our present hosts form no exception to the generality of Hungarian innkeepers in the very open manner in which they carry into effect their[19] culinary assassinations, and a scuffle, a sharp, piteous cry, followed by a “thud,” and the sight of a quivering victim hanging head downwards to a door-nail in full view, were our immediate welcome to the shelter of this solitary little inn.

We are here plunged all at once into the very vortex of the Magyar language, which no other south of the Volga aids the uninitiated stranger to interpret, but which was, nevertheless, already spoken in this country by a Turanian people of kindred race at the Roman conquest of Pannonia.

The landlord of the inn, who is a Magyar, can only just manage to render himself intelligible in German; whilst the young woman we addressed on our arrival at the station, and whom we find to be the waiting-maid, can only speak Hungarian and her mother-tongue, a Sláv dialect spoken west of the Hungarian frontier.

The vast prairies we have now entered, so deeply interesting in their historical associations, cover the prodigious area of 37,400 English square miles, and the insular mind almost loses itself in contemplating their extent.

Although Hungary contains within its embrace mountainous districts of vast extent, and beauty unsurpassed by any country in Europe, yet its principal characteristics may be said to be plains and rivers. In some portions of the former, which are as level as the ocean, the soil is in a high state of cultivation; others are mere sandy wastes; whilst in others again, Nature having spread a green and flowery carpet of her own weaving, thousands of wild horses and cattle are allowed to roam over it unfettered, and these, wandering about in immense herds, form one of the chief features of the Puszta landscape.

[20]

Here the sportsman may find ample food for his gun; for the marshes in the vicinity of the great rivers abound in wild fowl, particularly in the spring, when they are the haunt of storks, which may be seen pluming themselves all day long amongst the tall reeds and feathery grasses, or else leading their little family of storklings out for an airing on the confines of their watery domain. Flocks of noisy plovers too are everywhere seen, and not unfrequently a pelican; whilst throughout the length and breadth of the Alfőld, the harsh scream of the falcon is heard, wheeling overhead as it scours the air in quest of smaller birds, or swoops down upon a marmot.

Scattered about these vast steppes, at long distances apart, are towns and villages. In the neighbourhood of the post roads they occur every three or four hours; but in other districts farther in the interior the traveller may often journey a whole day by carriage or leiterwagen, in going from one village to the next.

No wonder is it then that this thinly populated region has ever been considered the El-Dorado of brigands, who until recently, that is to say until ten or twenty years ago, kept the otherwise peaceful dwellers of the plains in a perpetual state of terror and alarm. Many of the peasants and small landed gentry, however—paradoxical as it may appear—were known to harbour these “heroes;” thus encouraging brigandage whilst trembling for their own safety. In fact, so daring and numerous at one time were these robbers, that they often demanded board and lodging from the inhabitants as a right; whilst so lonely were the majority of the farmsteads, that the occupants, completely at their mercy, were compelled to yield without resistance to[21] their demands. It was even customary a few years ago—a custom which, I believe, still exists in some remote parts of Hungary—for the inhabitants to pay what is called felelat, or “black-mail,” to these freebooters, to secure themselves from the plunder of their cattle, just as formerly existed in Scotland. Brigandage in Hungary is, in fact, of “noble” origin, for, intrenched within their strong castles and encompassed by fortifications, many of the nobles in the fifteenth century exercised the function of robber-knights, enlisting numbers of the peasantry in their exploits.

Amongst these brigands of modern time were men of education and family; not only this, it has even been darkly hinted that magnates, who at one time held responsible positions under government, have been more than suspected of joining these marauders for the purpose of recruiting their enfeebled finances. The ruling powers have done their utmost to suppress these bandit hordes by offering large sums in the shape of “blood-money” for the capture of the leaders of the gangs, or the betrayal of their hiding-places to the police, but this has never been an easy task to accomplish in a country where so many of the inhabitants sympathise with the delinquents.

The Hungarians are a manly, brave, and chivalrous race, but lately emerged from barbarism, for the Turks held the greater part of their country in possession until a comparatively recent date; and there no doubt exists to some extent, even at the present time, an innate disposition in the minds of some—a disposition not confined to one class of society in particular, but existing in the highest as well as in the lowest—to wink at, if not actually condone, all offences of whatever kind, provided they have been[22] committed with valour and daring. These, of course, are very questionable ethics, but this state of things has always existed in Hungary; and far greater than the fears for their own safety has been the chivalrous feeling which has caused so many of the Hungarians to shelter these robbers, and treat them as heroes when pursued by the hands of justice. For this sentiment they are probably indebted as much to their past history as to the character of their surroundings. Men’s minds are much more influenced by external nature than we are often aware, and these limitless plains on which the Hungarians gaze from morn till eve have no doubt imbued them, unconsciously to themselves, with a notion of freedom of action, fettered by no boundaries and ruled by no human laws.

So daring at one period were these robber-bands that they were occasionally known to attack caravans of merchandise even in broad day; whilst the extent to which brigandage prevailed only a few years ago may be inferred from the fact of there having been no fewer than twelve hundred of these robber-criminals imprisoned at the same time within the walls of the fortress of Szegedin—the capital of the Alfőld—amongst whom was the most daring and celebrated bandit modern Hungary has ever known; a man who rejoiced in the euphemistic appellation of Alexander Rose (Rózsa Sándor), and whose particular form of the profession was cattle-lifting, but who only eleven years ago attacked with his robber-band a train on its way through the plains, and is said to have murdered during his “brilliant career” upwards of a hundred persons. This “dashing hero,” who was pelted with flowers by the peasant girls when he was at length captured by the police, died, scarcely more than a[23] year ago, a natural death in the citadel where he was confined, having escaped the punishment he so richly deserved by the clemency of the Emperor of Austria, who is said to possess an extreme dislike to signing death-warrants.

The term often applied to these Hungarian brigands is that of szégény légény, or “poor lads,”—a term no doubt due, in the first instance, to the fact that many were originally fugitives from the Imperial conscription; whilst the romantic sentiment entertained concerning them and their lives arises from the intense and very natural repugnance to the Austrian army existing amongst all classes. The Magyars are radicals in all political and national affairs, hence their tolerance of, if not actual desire to shield, those who seek to evade the Imperial conscription, no less irksome to the inhabitants of this country than it was to the Italians when under the same yoke.

Previous to 1848, a period that marks what the people of this country call the “War of Independence,” various forms of conscription were in force, some of which were especially obnoxious to the Hungarians. Many, therefore, fled from the hard fate it imposed, preferring freedom, with self-inflicted exile, to serving a foreign power. Some sought refuge in the wooded districts of the mountains, others in the vast fields of Indian corn found on the plains, in whose green labyrinths they could not easily be tracked. Concealed here until exhausted nature could hold out no longer, they at length crept from their hiding-places to begin a vagabond existence, begging of the peasantry as they wandered from place to place, with the shed of some lonely tavern, the favourite haunt of brigands, as their only shelter by night.

[24]

No wonder then that these “poor lads,” after pursuing for a time a life of vagrancy, should end in becoming robbers likewise, the more so as they knew full well they would be protected from the vigilance of the pandúrok by the peasantry, who, as I have said, were frequently known to conceal them in their houses when pursued by those officers of justice.

The “poor lads,” however, differ somewhat from the orthodox brigand. The former plunder in order to live, and rarely commit murder, their weapons seldom consisting of anything more formidable than a bludgeon. But the brigand “proper,” besides being armed to the teeth, wears a cuirass, and carries in addition to his lance, loaded hatchet and brace of pistols, a lasso, in the use of which he is as dexterous as the Spaniards of South America, and forms in appearance, with his slouching “sombrero,” bronzed chest and flowing black hair, as noble a type of his order as any to be found in the mountain fastnesses of Calabria. But no matter whether he be an orthodox brigand or “poor lad,” when one of special notoriety happens to be captured he is, as in the case of Rózsa Sándor, pelted with flowers by the “kisleány,” or dark little maidens of the Alfőld, who always sympathise with these daring freebooters, of whatever type.

During our present visit to Hungary some alarm was created by the announcement that three hundred banditti under the leadership of Milan, the notorious chief, had crossed the Danube from Servia, and were on their way to the Hungarian plains. A battalion of troops, however, sent to welcome them on the shores of the river, opposite Gradista, drove them back upon Belgrade by a more[25] hasty retreat than they apparently expected, accompanied by an intimation in explosive terms that Hungary had quite as many brigands as she wanted without drawing upon the resources of Servia.

The “Alfőld”—which literally interpreted signifies lowlands, in contradistinction to “Felfőld”—by which the Hungarians designate the mountainous districts of their land, is, strictly speaking, confined to that portion of the country which lies to the north of the river Marős and east of the Danube. It may however be appropriately applied to the whole of the plains, not excepting the “Pettaurfeld,” or “little Hungarian plains,” as the lowlands lying between Pragerhof and Lake Balaton are called, and upon which we have just entered. In the winter they are like a frozen sea—one great and boundless wilderness of white. The flocks that roam these rich prairies free and unfettered in summer-time are gone, and the tinkling of their bells is heard no longer; all are housed in huge clusters of sheds, where they low plaintively as they dream of the sunny herbage of the past. No sound is audible save the hoarse croak of the raven, which seems but to awaken the dreariness of the scene and make the silence live; whilst the very sun himself looks frozen as he peers forth from the pale blue sky.

It is at this season that the stranger, unused to such scenes, is impressed with the awful loneliness and stillness of his surroundings, together with the profound majesty and immensity of nature, as his eye, wandering over the vast expanse of white, traces no boundary, and his ear detects no sound of living thing.

In the spring, when the lingering winter snow has at length[26] melted, and the warm sun showers his blessed life-giving rays upon the dormant earth, the shepherd with grateful and rejoicing heart once more wanders forth with his flock to the green pastures; and in the cultivated districts the husbandman, shouldering his simple and primitive implements of agriculture, just scratches the surface of the rich alluvial soil, which—as some one says—only needs to be “tickled” and sown with seed, to laugh all over at harvest-time with smiling grain.

It is glorious summer now, and as we sit under an arbour of vines in the little sun-baked, sandy garden of our fogado, there come to us across the plains the plaintive sounds of a shepherd’s flute, and the pensive cadence of tinkling bells. Strolling off in the direction of the sound, we come to a large flock of sheep browsing on the short and tender herbage, whilst the shepherd, in his shaggy sheepskin cloak, wanders about amongst them, playing a small instrument here called a telinka, and looking, wrapped in his bunda with[27] its long wool outside, strangely in keeping with the flocks he is tending. About half a mile distant is another shaggy, fur-clothed man watching a herd of long-haired goats, whilst farther still three dark spots on the silent landscape indicate the existence of a gipsy encampment, the shepherd and the gipsy forming two of the most marked characteristics of the Alfőld, the one giving to it a pastoral, the other, with his little colony of tents, an almost Eastern aspect.

The shepherd’s life is a lonely and monotonous one. During the summer he remains night and day with his flock, and for whole months together holds communication with no one, except with some other of his class with whom he comes in contact, as he wanders from pasture to pasture with his woolly family. His life however, though lonely, is not so dreary as might be imagined; the Alfőld to him is a Garden of Eden, a smiling land of a bounteous heaven: his isolated and pastoral existence frequently leads him to be a poet, and to the idyllic music of the telinka, a little instrument he manufactures himself, and as primitive as that by which Pan of old awoke the stillness of the dawn, he composes rhymes full of simple poetry and pathos.

We had wandered fully two miles across the vast and trackless plains, yet lingered till the sun began to sink below the horizon and the chill of evening warned us to return. It is in regions like these that the wonderful phenomenon of the afterglow is best seen. As the sun leaves the earth which it has gladdened with its smiles, and the last crimson streak fades slowly in the west, twilight’s shadows gather over the warm bosom of the plains, and a cold white vapour begins to rise from the marshes; the shadow lingers for a while, till suddenly, as if by the agency of a magician’s[28] wand, there comes a wondrous flush of glory—whence none can tell—that once more bathes both earth and heaven in a flood of gold and amber. But soon, fainter grow the colours in the west, colder and more tangible the snake-like vapours ascending from the hollows, deeper the transparent arc above, till evening at length sinks into the embrace of night. As we turn our faces homewards all sound is hushed; the wild fowl have sought their nests in the thick sedges which border the marshes, the marmots their holes in the warm sand; and the shepherd, weary with his day’s watch, wrapped in his bunda, lies stretched on the darkling ground fast asleep, beside him his faithful dog, whose paws twitch spasmodically in an imaginary race after some erratic sheep that has doubtless disturbed his equanimity during the hours of day, and which he now chases in his dreams. From the distant camp the smoke curls idly upwards in graceful wreaths above the ruddy fire; in the foreground a group of oxen chew the cud, and everything is suggestive of repose.

Beautiful, however, as are our surroundings in their wondrous breadth of calm, we are after all but gregarious animals, and two hours later, whilst sitting in the crazy wooden balcony of the fogado, I find myself sighing for the rosy fruit of the Lotus, that I may eat and again mingle with the gay and festive throng in the Piazza di San Marco, and catch an echo of the music that so delighted me when there. F., on the contrary, like Odysseus, casts his mind forwards to the Ithaka of his love, the region of the snowy Carpathians, whither our steps are tending. But we both retire for the night with the conviction that Pragerhof in its absence of human life and maddening isolation is just[29] one of those places in which more than one day’s sojourn must end in suicide.

That melancholy catastrophe was at any rate averted for the present, for we found ourselves still alive on the following morning, when the little waiting-maid came stumbling and stumping up the ladder, bringing coffee as a preliminary to toilet and breakfast; which ceremonies completed, we welcome as a rescuing angel the train that at a quarter-past nine draws leisurely up to the station.

[30]

The day had dawned with a glorious awakening. How bright and fair all was under its glistening veil of sparkling dewdrops, as we sat by the open door of the fogado and partook of our simple breakfast! Beyond were the green plains and the distant sea-like horizon; near us broad vine-trellises, through which the sunshine flickered like a shower of gold. From afar came the distant lowing of cattle and the muffled bark of a sheep-dog; whilst all around us was so still, so very still, that we might have been in the vast prairies of the New World. The birds, playing at hide-and-seek amongst the reddening, dust-covered vine-leaves, or perched high up in the sooty eaves of the little[31] station, chirped and bubbled over with song, as if their smoky and sandy domain had been the umbrageous aisles of some lonely forest. How grateful they were for their meagre mercies as they carolled forth their hymn of praise this dewy golden morning whilst we waited for the train, how glad they seemed to live, and what joy was there in their little lives as the Slovene waiting-maid scattered towards them the crumbs from the table-cloth of the restaurant!

Our train was announced to leave at ten minutes to ten; but overdue, it did not arrive from Trieste until half-past eight o’clock, and how could any one be so unreasonable as to expect it to be got ready to start again in the short space of one hour and twenty minutes? At the time specified the engine-driver, seated on a heap of sand outside the platform, was dozing over his pipe, and the guard leisurely finishing his breakfast in the inn kitchen. And why not? No one thinks of hurrying himself in Hungary, where everybody has plenty of time for everything.

The trains, punctual enough in their departure from large stations, are wholly indifferent as to the time they either arrive at or start from the smaller ones, which are generally situated in districts where persons take life easily, and with whom the railway authorities appear to think an hour or so out of the twenty-four can make no possible difference.

Taking our places at last, and dragging slowly on, we pass here and there, at long intervals, true specimens of Hungarian villages, with their low-roofed one-storied houses, and cemeteries filled with small red, blue, and white crosses, which, just showing above the rank grass, look from a distance like wild flowers growing in a meadow. The traveller[32] seems here to have been suddenly carried back to some remote period of the world’s history, everything is so heavy and so slow. At the stations at which we stop, curious-shaped vehicles are waiting to take the arrivals to towns and villages—who shall say how many miles away? Long waggons made simply of planks of wood nailed together, and others with open ladder-like sides, drawn by three horses abreast, or small light carts, called szekérs, to which, by a most uncomfortable arrangement, one poor, lean, miserable horse is harnessed to a pole. All are driven by strange-looking men in sheepskin cloaks or hussar-jackets called mentes, embroidered in divers colours of needlework, and wearing such full white trousers that they look like petticoats. Stranger people still get into these vehicles—women wearing sheepskin cloaks like the men, strange head-gear and top-boots—and, leaving the enclosure which surrounds the station, jog away over quagmires that seem to lead to nowhere, or to some distant world far beyond our ken.

Turf is burnt in the engine, so that the speed, as may be imagined, is not very alarming—its “linked sweetness long drawn out” scarcely exceeding ten miles an hour; besides[33] which we linger at the various stations, time, as we have seen, being no object in this primitive country.

Railway travelling in Hungary has in fact frequently been known to produce in the passenger—especially if he happen to have come from Western Europe—a species of temporary insanity; the particular form which the malady assumes causing the unfortunate sufferer to lose for the nonce all sense of his own individuality, and to imagine himself the “Wandering Jew,” destined to go on to all time.

À-propos of the slowness of the Hungarian locomotives, it is related that a certain peasant, when asked one day by a friend why he did not take the train to the market town, replied, “I have no time to-day; I must walk, or I shall arrive there too late.”

As we wait, the villagers, leaning over the wooden palisades, gaze at us wonderingly, or gossip with the guard; the women clothed in the shortest of short petticoats, worn over a number of white under-garments frilled at the edges, and which, hanging a few inches below each other and starched almost to the stiffness of a board, are intended to serve as a hoop to keep the top skirt out.

It is a festival of some sort, and, as we approach the villages, the cracked bells from the church towers are chiming away joyously, and all the people are dressed in their red-letter day attire, the women with black, red, or green bodices, full white sleeves and white chemisettes embroidered at the throat. Quaint children stand beside them, who, dressed in every respect precisely like their elders, even to top-boots, look like small men and women seen through the wrong end of a telescope.

[34]

Entering the district of the river Drave, we are all at once surrounded by low, undulating hills which rise out of the plains, and wherever we turn our eyes, we see persons on their way to distant churches; the men walking together in front, and the women following at a respectful distance. The roads are muddy, and the women gather up their voluminous petticoats over their top-boots in a most exemplary manner; whilst the children, emulating the example of their mothers and holding up their little petticoats likewise, form one of the most amusing spectacles possible.

Presently we reach a large town, situated in the midst of what appears to be a ploughed field, the houses so wretched that they seem not to have been built, but to have grown there like cabbages or mangel-wurzel, or to[35] have been heaved up from beneath by ill-conditioned and untidy gnomes.

Whilst staying at this place, persons arrive from distant and unseen towns far away beyond the limits of the visible horizon, in vehicles more strange even than any we have yet seen, and such as might have existed in the camp of Attila. A score of tired but patient men and women are lying on their bundles, waiting the arrival of the down train from Buda-Pest to take them to their destination, whilst others are standing or walking about the platform; women, whose heads and faces enveloped in dark-blue kerchiefs, and sleeves padded at the shoulders, give them a strange incongruous look, half-Turkish, half-European; men—what splendid fellows! with manly faces bronzed by the fierce summer sun of the Alfőld, and with limbs as muscular as those of athletes.

The times of the arrival and departure of the trains are indicated in a somewhat primitive manner on a slate; and whilst we are wondering what on earth can be keeping us here so long, we see a carriage drawn by six horses and surrounded by a cloud of dust, coming along the road at a terrific pace, the horses galloping furiously under the lash of the driver’s long whip. Possibly it is for this we have been tarrying. A tall, graceful, and very pretty woman descends from the carriage—a kind of calèche. Two men, one of whom wears a feather in his hat, the other a bunch of wild-flowers—servants apparently, who had previously arrived with the luggage—stoop and kiss her hand as they see her into the train; and as soon as the engine-driver and guard have charged their pipes afresh, the heavy, lumbering machine slides out of the station, and we drag on[36] again as though it were a matter of the most sublime indifference as to what time we arrive at the end of our journey—if we ever do.

In process of time, however, we do reach Gross Kanizsa, where our line of railway joins that from Agram and Vienna. At this place, which contains twelve thousand inhabitants, the sandy enclosure of the station is so full of girls in holiday attire that it looks like a flower-garden, and we feel we are in Hungary indeed, the land of beautiful women. Was anything half so ravishing as those little scarlet leather top-boots embroidered at the side, and which, adorned with rosettes, look like scarlet clappers as they peep forth from the bell-like skirts? What little darlings are the wearers, with their demure but coquettish faces, some blonde, some brunette, the plaits of their hair—which hang loosely down the back—ornamented with many-coloured ribbons reaching almost to the heels! Near some of these Kanizsa belles stand their brothers or sweethearts, wearing embroidered cloaks or little jaunty hussar-jackets, thickly covered with bright silver buttons, and white plumes in their small caps.

Whilst waiting at this station, we are reminded of a very different scene that occurred the last time we were here. We had just arrived by train from Croatia, and on going into the buffet, which we found already crowded with passengers, many of whom were not only Croatians, but Servians, Slavonians and people from Lower Hungary, we could not help observing that our entrance seemed to be regarded as an intrusion. Seeing vacant seats at a table near the centre of the room, round which our fellow-travellers were already partaking of a table-d’hôte repast, we also took our places,[37] wondering greatly at the disturbance which our presence evidently created.

In a few moments several persons who had been sitting near us, with a surly glance and muttered exclamation, withdrew from the table, and walked to the farther end of the room. It was impossible to help perceiving that an insult was intended, although, as may be imagined, we were perfectly ignorant of the cause.

Shortly after this, as we were doing our best to swallow the affront together with our soup—a doubtful compound called ungarischer sauerkraut, consisting of cabbage cut into thin strips and immersed in a colourless liquid in which small slices of sausage were floating—and washing down the whole with draughts of consoling badacsony, made of grapes grown on a mountain near Lake Balaton, a gentleman came across from the opposite side of the table and took his seat beside us. Addressing us in Latin, the frequent medium of communication between educated Englishmen and Magyars of Central Hungary, he explained the cause of his countrymen’s behaviour, and apologised profoundly for the rudeness to which we had been subjected. They had, he informed us, taken us for Russians, the political feeling against whom was very strong during that particular crisis of the Russo-Turkish war, then just at its height, especially amongst Hungarians of the lower provinces; but having been in England himself, though not for a sufficiently long period to acquire the language, he had at once recognised to what nation we belonged.

“Pileus ejus,” said he, looking towards me, and alluding to my hat, which was of the species familiarly known as[38] “pork-pie,” turned up with a broad band of fur—“the Russian ladies wear precisely such hats as the one you have on, and take my word for it, wherever you go in Hungary, you will be mistaken for a Russian, unless you change it for another.”

Our train lingered here an hour, and whilst walking about the platform, we were more than ever struck with the variety of nationalities met with in this singular country. Standing round the door of the restaurant was a group of men, whose soft and effeminate tongue, delicate features, and supple figures, contrasting strongly with the manly energy and powerful physique of the Magyars, proclaimed them to be Yougo-Slávs from Croatia and Slavonia; there were others again, whose sandalled legs and feet, and lambswool caps the shape of mops, declared them to be Wallachs from Transylvania or the Lower Danube; besides Servians from their little colony in the capital, and men on their way to their homes in the Northern Carpathians, all of whom our previous acquaintance with Hungary enabled us at once to recognise.

Amongst the many peculiarities which exist in this interesting country, there is not one that perhaps strikes the stranger so forcibly as the variety of races. By far the largest portion of it is inhabited by the Magyars, or ruling people; next to them in importance come the Wallachs, occupying the most eastern portion of the territory; whilst sprinkled here and there over the vast area which constitutes the Alfőld are little colonies of Germans, exclusive of the so-called Saxons and Szeklérs in the south-east, each of whom forms a distinct nationality. All the above-named races, however, inhabit the central and south-eastern portion of the kingdom; but, in the entire realm of the Magyar, no[39] fewer than eight languages are spoken, not including the various Sláv dialects.

In the south, divided from Bosnia and Servia by the river Save, lie the Hungarian provinces of Croatia and Slavonia, peopled by Croat-Serbs, whilst that portion of territory which extends south-west of the Northern Carpathians is inhabited by Slovaks, who border immediately on the Poles of Gallicia and the Tcheks of Moravia; the province south-east of the Northern Carpathians being inhabited by Rusniaks, or Ruthenians, there being no fewer than seventeen thousand Slavs in the dual-Monarchy. Besides these nationalities, there are also colonies of Greeks, Arnauts, and Armenians, spread over various parts of the kingdom.

The chief cause of the existence of these various races is the frequent invasions, and final occupation of the greater portion of it by the Turks, who in the fifteenth century, penetrating into the very heart of Aryan Christendom, desolated the whole face of Hungary by fire and sword. Not only did these invaders and subsequent conquerors of the country lay waste the entire surface of the fertile plains, but by burning the towns and villages, rendered them wholly uninhabitable. To such an extent did the incursions of the Moslem hordes affect the region of the Alfőld, that it is only within the present century that the Magyars may be truly said to have begun to recover their lost ground.

It is a common saying amongst Hungarians that “where the Turk treads no grass grows,” and so effectually was the country rendered desolate by the ravages of this foe, that after their final expulsion in 1777, by a series of battles nobly fought by the Hungarians, immigrants were called in, and encouraged by grants of land to re-occupy the ruined[40] villages, and cultivate the soil rendered barren and unfruitful by the hated Moslem.

Thus Hungary became what we find her to-day,—a country peopled by many nations, all subject to the parent State; each retaining, besides, its language, its own costume, and distinct characteristics; and continuing—and this is perhaps the strangest fact of all—as isolated in point of individuality of existence and territorial position as if each race constituted a separate nation in itself. Hungary is, in fact, unlike any other country in the world, and there is a novelty and a charm about it that fills the traveller with delight.

“When I hear its name mentioned,” exclaimed a popular German author, “my waistcoat seems too tight for me; an ocean stirs within me; in my heart awaken the traditionary exploits of long ago, the poetry and song of the Middle Ages. Its history is that of yore; the same heroism lives within its borders, the names of its heroes alone have changed.” And he is right. There is an inborn chivalry and heroism in the character of the Magyars—traits evinced not only in their past, but recent history; the same noble and dauntless spirit that dwelt in their heroes of the Middle Ages lives in them now, and there is a bold and fearless independence, a straightforwardness, and high principle that cannot fail to win the love and admiration of all who really know them.

Returning to our places in the train, we observe standing near the steps of our compartment a lady engaged in earnest conversation with a poor woman clad in the costume of the Alfőld peasantry, and holding in her arms a little golden-haired child of about four years old. The woman was weeping[41] bitterly, and the fragile body of the child was convulsed with suppressed sobs.

Our interest in both mother and child was kindled in a moment, and we subsequently learnt from a German-speaking Magyar who travelled with us that the lady was taking the little creature—the child of one of her husband’s földmevelök (farm-labourers)—to the hospital at Pest, to undergo a surgical operation that might detain her there for several months.

The parting of mother and child was one of the most touching things I ever witnessed. We could not understand their lip-language, but the heaven-born utterance of human love needs no mortal speech to express its meaning, and we felt all that their feeble, broken words conveyed.

No sooner had the train left the platform than—the necessity of restraining her feelings past—burying her face in the cushions, “Little Nell” (for so we called her) gave way to a wild burst of grief.

“Anyám! Anyám!” (Mother! mother!) was her agonising cry.

Poor child! like many another, she had entered all too soon within the portals of the “sanctuary of sorrow.” Did anything, I wonder, whisper to her heart that which on inquiry at the hospital we subsequently ascertained, viz. that she was not to see her mother again till they were folded in each other’s arms in Paradise?

[42]

The Hungarian gentleman sitting opposite wiped his spectacles, whilst F., turning abruptly to the window, began taking a most unwonted interest in the features of the country, and I doubt whether there was a dry eye between us, so truly does

But we are approaching our destination; and having passed through an immense forest of oaks, once notorious as the hiding-place of robber bands, and forming even yet a refuge for those szegény legény, or “poor lads,” over whom the popular sentiment of the country has thrown such a mistaken charm, we emerge again into the open plains, and see beyond us an azure lake lying calmly in the bosom of undulating hills. To the right stretches a vast tract of uncultivated land, roamed by wild horses, which with manes flying madly gallop away as we draw near, until they are almost out of sight and form mere dark specks in the distance, and we soon enter the swampy ground which marks the vicinity of the lake.

The Platten-See, or Lake Balaton as it is often designated—both names being derived from the Sláv word “blats,” signifying swamp or marsh—is the second largest lake in Europe. Although bounded on the northern side by lofty hills, to the south it is almost shoreless, except here and there where fishermen, availing themselves of the gentle undulations of sandy soil, have erected rude huts of plaited reeds. In many places tall grasses eight or ten feet high cover the marshes in dense jungly masses, and the surrounding country is so inundated that the whole, save on the northern shore, presents an appearance of a series of lakes.

Opposite Böglar, in the midst of vine-clad hills, rises the[43] conspicuous mountain Badacson, from the grapes of which the celebrated wine is made; whilst jutting far into the lake a rocky promontory, crowned by an ancient abbey, stands boldly out against the fainter outline of the more distant hills.

And then we reach Sió-Fok, and our railway journey is at an end at last.

“Little Nell,” the golden-haired child, had long ago sobbed herself to sleep. That blessed nepenthe which mercifully follows childhood’s sorrow had folded her in the peace of heaven, and there was no sign of pain on her placid upturned face, as with an unspoken “God bless her!” we left the train for the steamer which was waiting to take us across the lake to Fűred.

[44]

“Magyars! Magyars!” I once heard a lady exclaim, who was not quite so well up in the science of ethnology as she might have been in these enlightened days, and who evidently confounded them in a nebulous kind of way with the natives of Madagascar or some other out-of-the-way island in the Indian or South Pacific Ocean—“a very interesting people, I dare say, but as to myself I never could feel interested in those poor savage Blacks!”

What then is the origin of these men of the house and lineage of Arpád—this non-Aryan people whom Voltaire describes as une nation fière et généreuse, le fléau de ses tyrans et l’appui de ses souverains, and who, constituting the only Turanian race that has ever been recognised as forming a portion of the great European family, are well worthy of careful study, yet of whom the majority of persons know so little, and some nothing at all?

They are the descendants of a Finnish people, who, emigrating southwards through the passes of the Carpathians from their home in the far North, approached Hungary in 886.

The word “Magyar” (pronounced Mad-yar), however, is of very ancient origin, and has baffled the wisest philological[45] heads to determine its precise meaning. It was supposed in the Middle Ages to have been derived from Magog, son of Japhet, the popular superstition of that period recognising in these “pitiless heathen,” as they were called, “the Gog and Magog who were to precede the approaching end of the world.” Modern historians, however, have attributed to it various other origins, the most recent affirming that the word signifies “confederate.” But whatever may be its derivation, Max Müller, by the unerring guide of language, has traced the original seat of this interesting people to the Ural mountains which stretch upwards to the Arctic ocean; and pointing out the close affinity the Magyar tongue bears to the idiom of the Finnish race spoken east of the Volga, declares that the Magyars form the fourth branch of the Finnish stock, viz. the Ugric; and in his ‘Science of Language’ he gives striking examples of the similarity and connection which exist in the grammatical structure of the Magyar and the Ugro-Finnish dialects, particularly in the conjugation of verbs, which have aptly been called the “bones and sinews” of a language; and there is little doubt that the Magyars are none other than the same race that, under a different name, were called in the fourth century “Ugrogs.”

Hungary—the “beata Ungaria” of Dante—has been peopled since the beginning of the Christian era, as we have already seen, by three distinct and separate colonies of barbarians, whose birthplace was in the regions of the frozen North. Here, led by Attila, the Huns established themselves between the third and fourth centuries, and hither a century or two later came the Avars, belonging to the same northern race, each destined to accomplish its rôle in the history of nations, to rise to its meridian and then decline, till finally[46] overwhelmed by other warlike barbarians similar to themselves. Lastly—though these have shared a better fate—came the Magyars, the great conquering army with Arpád at its head, in whom the Ugro-Finnish type once more reappeared in all its pristine energy, the same that is believed to have existed in the bands of Attila: a nomad people who, though also composed of savage hordes, became by their daring and warlike propensities the scourge of Aryan Christendom, and were destined not only to become a great empire and take their place amongst the civilised nations of Western Europe, but, by their arms raised against the enemies to its peace, to be in after-ages its surest bulwark of defence against Mahomedan aggression.

A little red steeple, and a sea of mud through which the stranger has to plough his way to the shore of the lake, under the full apprehension that each succeeding step must cause him to disappear in its apparently bottomless depths, introduce us to the village of Sió-Fok, situated on a small river into which the Platten-See falls, and which, by means of canals, is made to drain many of the marshes of the surrounding country; the Sió, which winds away in a southerly direction, being in fact one of those nine streams that are supposed to flow underground and communicate with the Danube.

As soon as we have embarked, the steamer—which, lying amongst tall reeds and willows, was almost hidden till we came alongside her—breaks from her moorings and goes bounding away into the beryl waters of the lake. Skimming over its glassy surface, we pass scores of wild fowl as white as snow, which, not the least disconcerted at our near approach, stand gravely pluming themselves on the low[47] sandy islands just appearing above the water, or watch with the keen eyes of anglers for the fish that the wash of the steamer may chance to lay at their feet.

The Platten-See is at its narrowest here, and the steamer takes us across to Fűred in rather less than an hour, where, after travelling over the nearly desolate plains, we seem to have arrived all at once at the very centre of civilisation.

Fűred itself lies at the foot of a range of volcanic hills, and is much resorted to by the Hungarians on account of its mineral springs. In the summer months the little place is crowded, and it is then difficult, if not altogether impossible, to find accommodation at either of the hotels or boarding-houses unless rooms have previously been secured. Should the traveller have failed to do this, he can have recourse to Arács, a neighbouring village, where “casuals,” “for a consideration,” can generally be “taken in and done for.” The season, however, had as yet not quite set in, so that we entertained no fears concerning our shelter for the night.

Arrived at the opposite shore, we are met by porters who quarrel over us; two lay hold of our portmanteau, one at each end, while a third seizes it affectionately round the centre. They scramble for each article as it is disgorged from the steamer. Walking-sticks, umbrellas, dressing-bag, binoculars, are all alike severally snatched from our grasp. The landlord of the hotel to which we are bound also meets us, and, foreseeing in our persons a long line of prospective tourists, almost embraces us on the spot. Scanning us from the crown of the head to the sole of the foot, to ascertain whether there is another mortal thing left to be carried, he at length espies a small sketching-block under my arm, on which a precious unfinished picture is reposing, and lays[48] violent hands upon it. A struggle ensues for its possession, during which, holding on to my treasure as for dear life, I come off panting, but victorious.

Calmness once restored, we proceed in hurried procession to the hotel, where waiters rush out upon us and repeat the ceremony. They help us up the steps, they insist officiously on brushing the dust off our travel-stained garments, they almost pat us on the back in their great joy at the arrival of—what we afterwards found ourselves to be—the first real live tourists of the season. Overwhelmed with this consideration, their feelings do not permit of their leaving us for an instant. They follow us up the stairs, where, as our footsteps echo through the empty passages, they are joined by other domestics, who appear suddenly and mysteriously from unseen and hidden apartments. The landlord, the waiters, the porters, the cook, the chambermaid, the slavey from the shades—who arrives upon the scene, beaming but out of breath, just at the last moment—one and all either precede or follow us into the very precincts of the guest-chamber.

On descending to the salle à manger, we find covers laid for four persons at a side table, whilst in the middle stand other tables, round which, closely placed together, are chairs, arranged in readiness for the visitors whose advent is now daily expected; and as we sit awaiting the arrival of our repast, Fancy, in the stillness of the great chamber, conjures up the spirits of its future occupants, and peoples it with cheerful guests, till the walls resound with merriment and laughter. Pretty, piquante Magyar women and girls; Hungarian officers in stiff backs and much-padded uniforms; Hungarian civilians—heavy fathers in ponderous braidings[49] and more ponderous manners; German and Hungarian Jews and Jewesses—all are once more before us just as we saw them gathered in this festive hall three long years ago.

At this juncture of our imaginings, a merry laugh and light steps herald the arrival of two ladies, who, advancing to our table, take seats beside us. The long aquiline nose and protruding upper lip proclaim them at once to belong to the family of Israel.

The external characteristics of this people are not so strongly marked here as in many other countries, but it is nevertheless impossible to mistake them. In Hungary alone they number upwards of 1,100,000, and, like the gipsies, are met with at every turn. The ladies above referred to—mother and daughter, I imagine, from the likeness they bore to each other—were both strikingly handsome. Indeed, whether belonging to Jew or Gentile, it is seldom one sees a plain woman in this happy country. They were from Presburg, they informed us, and had arrived soon after ourselves. Fortunately they could both speak German, or our limited knowledge of the Magyar language would have rendered conversation impossible.

The repast that was at length placed before us was both good and abundant, with the exception of the renowned Fogas (Perca lucioperca), a fish for which the lake is justly celebrated, and which—O ye epicures!—was garnished with shavings of raw onions.

Now, I hope we are not delicate to a fault in the matter of food, provided its ingredients be not unclean, and we have more than once partaken—unwittingly, it is true, but[50] not without relish—of a dainty viand afterwards discovered to have been minced snails fried in butter and bread-crumbs, which, if you “make believe” very hard indeed, tastes like scalloped oysters; but boiled fish and onions, cooked or uncooked, I hold to be an outrage on the gastronomic art quite unpardonable in any civilised nation.

The familiar French proverb, however, was never more strikingly exemplified than in this particular instance, for both our fair companions partook of the—to us—unsavoury combination, and were still enjoying their bonne bouche when, leaving them, we strolled out in the evening air.

It is a lovely evening, and the setting sun, a ball of fire, floods all nature in a sea of glory. Away in the marshes, the lakelets are kindled into a harmonious mingling of vermilion and bronze, save where they reflect the pale soft azure of the zenith. Then as the fiery god sinks at last—as he appears to do—into the very bosom of the earth, what transcendent effects of light break like magic over earth and sky! What exquisite gradations of colour! What infinite depths of saffron and rose and violet stretch upwards, till they fade in the liquid purple of the arc above!

Watch now the long lines of rich warm colour as they gradually stretch across the darkling landscape! Here and there some darker object still, a clump of trees or gipsy encampment, stands out black against the paler colouring of the “off-scape.” What is that dark mass yonder? The clear atmosphere, aided by our field-glass, at once declares it to be a party of travellers bivouacking for the night, reminding one of an Eastern caravan.

What a statuesque group they make against the amber[51] sky, and what a subject for an artist! Men standing in their long fur-lined mantles, others crouched on the ground making a fire or unpacking provisions for their evening meal; by their side lie numerous gourds and leathern bottles, just such as Hagar carried in the wilderness: while the rich colouring of their garments mellowed in the dying light, and the long shadows thrown across the golden sward, assist in forming a most picturesque combination.